Photograph by J. Alden Loring.

WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH ON A BIRD-HOUSE.

Young Folks' Nature Field Book

By

Formerly Field Naturalist to the United States Biological Survey and the United States National Museum at Washington, D. C., Curator of Mammals at the New York Zoological Park and Field Agent for the New York Zoological Society; Member of the American Ornithologists' Union, etc.

BOSTON

Dana Estes & Company

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1906

By Dana Estes & Company

All rights reserved

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U.S.A.

The plan of this work contemplates a short, timely nature story, or seasonable hint for every calendar day in the year, telling the reader just what time in the successive seasons to look for the different birds, beasts, flowers, etc., how to recognize and study them when taking observation walks for pleasure or instruction. Recognition of different creatures, etc., is assisted by numerous excellent illustrations, and alternate pages are left blank for reader's notes or record of things seen. A yearly report so kept, either by a single young person or a small group or club, cannot fail to be a source of continuous interest, not only while being made but after its completion. A club competing for the best and complete record so made should produce pleasure and instruction throughout the year.

This book is dedicated to my first wild pet, who was the most interesting and intelligent creature I have tamed. He chased the children into their houses by pinching their legs; he awoke the dog by pulling its tail, and he pecked the horse's feet, then jumped back and crouched low to escape being kicked. Because of his thieving instinct he kept me at war with the neighbors. His last mischievous act was to pull the corks from the red and the black ink bottles, tip them over, fly to the bed, and cover the counterpane with tracks. I found him dead in the work-room the following morning, his black beak red and red mouth black.

This little book was written for the lover of outdoor life who has neither the time nor the patience to study natural history. There are many persons who are anxious to learn the common animals and flowers, their haunts and their habits, that they may enjoy Nature when they visit her. If they will take a minute each day to read the entry for that date, or if they will carry the book with them on their strolls into the country and while resting turn its pages, it may prove the means of discovering in fur or feather or flowering bud something before unknown to them.

The subjects chosen are of common interest, and nearly all can be found by any person who hunts for them assiduously. As the seasons vary in different localities, it has been impossible to set a date for the appearance or disappearance of an animal or a flower, that will apply alike to all parts of the country for which this volume is intended. Eastern United States.

J. Alden Loring.

Oswego, N. Y.

| PAGE | |

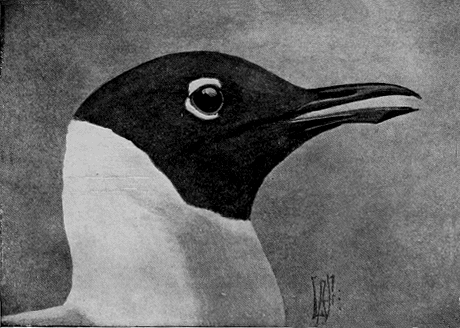

| White-breasted Nuthatch on a Bird-house | Frontispiece |

| White-breasted Nuthatch | 15 |

| English Sparrow | 25 |

| Purple Martins | 35 |

| Northern Shrike | 39 |

| Prairie Horned Lark | 47 |

| Loon | 53 |

| Hibernating Woodchuck | 57 |

| European Hedgehog | 75 |

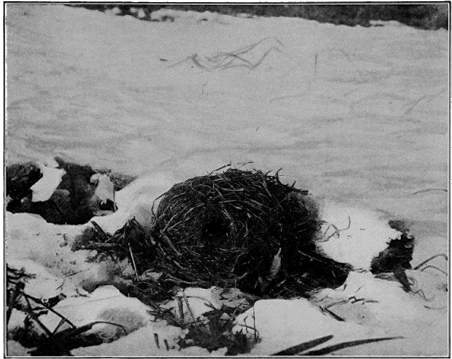

| Nest of a Meadow Mouse Exposed by Melting Snow | 85 |

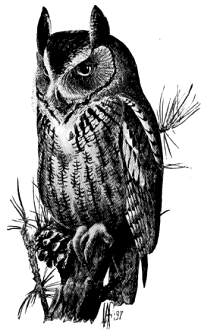

| Screech Owl | 89 |

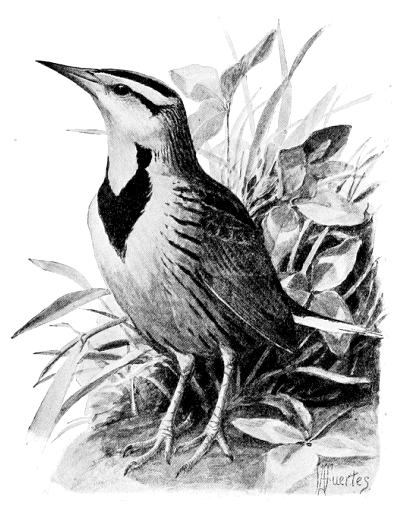

| Meadow Lark | 99 |

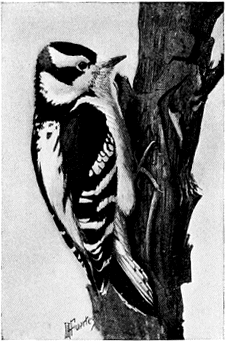

| Downy Woodpecker | 105 |

| Fox at Den | 119 |

| Chimney Swift | 125 |

| "One of your bird-houses should be tenanted by a wren" | 129 |

| Male Bobolink | 141 |

| Barn Swallow | 153 |

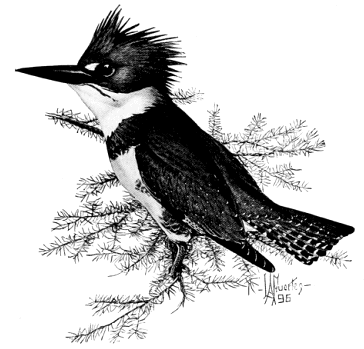

| Belted Kingfisher | 165 |

| « 14 »Catbird | 171 |

| Woodchuck | 183 |

| Song Sparrow | 191 |

| Yellow-billed Cuckoo | 199 |

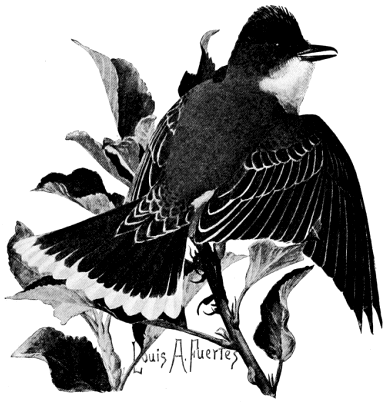

| Kingbird | 207 |

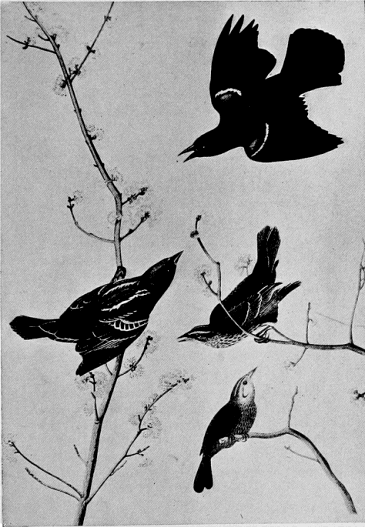

| Red-winged Blackbirds | 215 |

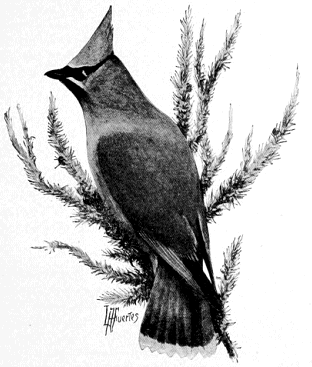

| Cedar Waxwing | 221 |

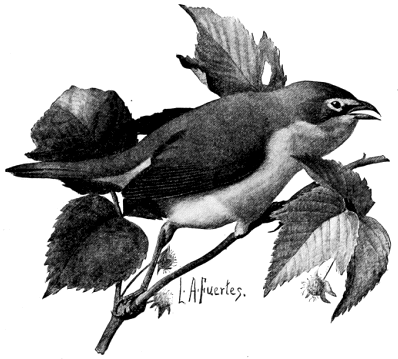

| Yellow-breasted Chat | 245 |

| Skunk Hunting Grasshoppers | 255 |

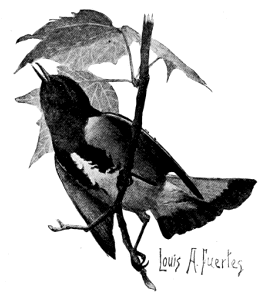

| American Redstart | 259 |

| Grebe | 277 |

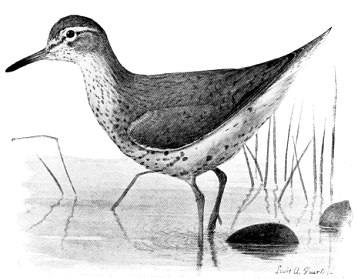

| Spotted Sandpiper | 281 |

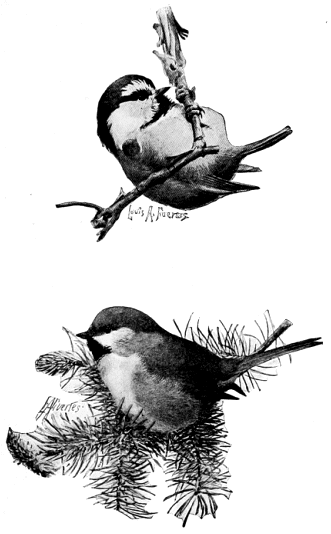

| Chickadees (Upper, Mountain; Lower, Hudsonian) | 287 |

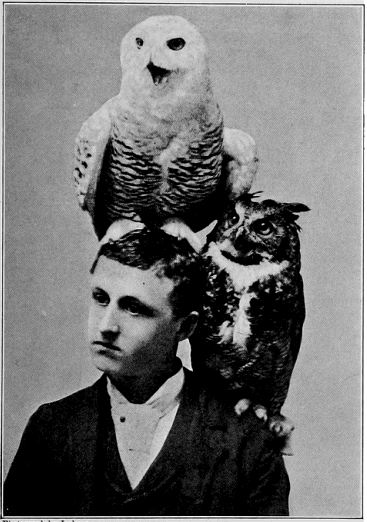

| "The great horned owl and the snowy owl can be tamed" | 301 |

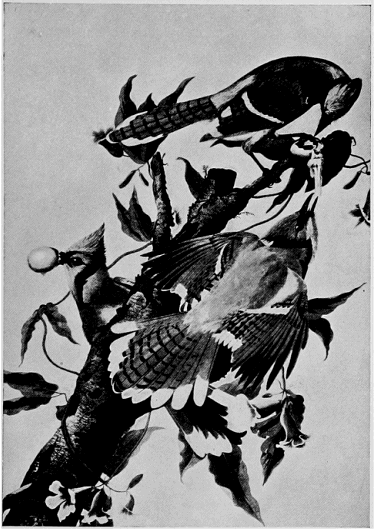

| Blue Jays | 305 |

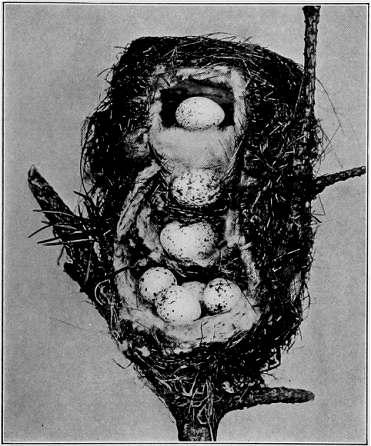

| A Four-storied Warbler's Nest. Each Story Represents an Attempt by the Warbler to Avoid Becoming Foster-parent of a Young Cowbird | 311 |

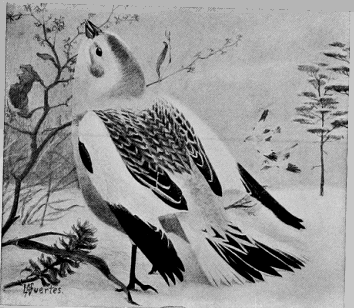

| Snow Bunting | 315 |

| Cotton-tail Rabbit Taking a Sun Bath | 331 |

| Bonaparte Gull | 337 |

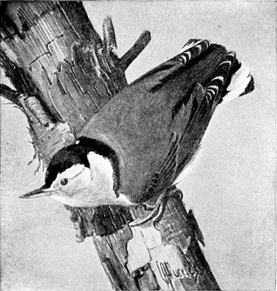

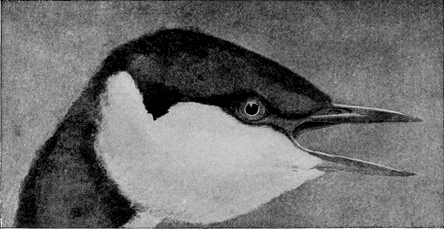

WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH.

The best New Year's resolution a lover of nature can make, is a promise to provide the feathered waifs of winter with free lunches. This may be done by fastening pieces of suet to limbs and trunks of trees, and by placing sunflower seeds, bird seeds, or cracked nuts on the veranda roof or on the window-sill of your room, where sharp eyes will soon spy them.

Your boarders will be the birds that either remain with you throughout the year, or have come from the frozen North to spend the winter. These are the birds that feed upon seeds of various kinds, or the feathered carpenters that pry into the crevices of the bark, and dig into the rotten wood in search of the insects and the insect larvæ hidden there.

The chickadee, white-breasted nuthatch, and the downy woodpecker, keep company during the long winter months. They will appreciate your lunches most, and will call on you frequently throughout the day.

Do not attempt to tame your visitors until they have made several calls for lunches. Then put a crude "dummy," with a false face, near the window, and raise the sash to let the birds enter. Within a few days the chickadees will perch upon Dummy's shoulders and take nut meats from his buttonholes.

Having thus gained the chickadees' confidence, hurry to the window when you hear them call, and quietly take the place of the dummy. Of course they will be suspicious at first, and probably you will meet with many disappointments, but when you have succeeded in taming them to alight upon your hand or shoulder, you will find enjoyment in calling them to you by the gentle whistle to which you should accustom them.

Tempting food, and slow movements when in the presence of birds, are the main secrets to successful bird taming. The chickadee, as you will find, is the easiest of these birds to tame. He has several songs and call notes, so do not expect always to hear him repeat his name, "chick-a-de-de-de-de."

Persons not familiar with birds often mistake the white-breasted nuthatch for a woodpecker, for their actions are much alike. The nuthatch creeps about the trees in all kinds of attitudes, while the woodpecker assumes an upright position most of the time and moves in spasmodic hops. The young and the female downy woodpecker do not have the red crescent on the back of the head. The hairy woodpecker is another "resident" that looks like his cousin, the downy, but he is once again as large.

Winter in the North is a season of hardship and hunger to wild creatures. The otherwise wary and cunning crow often puts discretion aside when in search of food, and fearlessly visits the village refuse heaps, or the farmer's barn-yard. In the orchards you will find where he has uncovered the decayed apples and pecked holes into them.

Even the mink, after days of fasting, is driven by starvation to leave his retreat in a burrow along a creek or river bank, and to forage upon the farmer's poultry. Poor fellow, he does not hibernate, so he must have food; fish is his choice, but when hard pressed, he will take anything, "fish, flesh, or fowl."

In the fields and lowlands, the scattered coveys of Bob-whites that have escaped the hunter, huddle for shelter from a storm under a stump or in a hollow log. Sometimes several days pass before they are able to dig through the drifts that imprison them. Should a heavy sleet-storm cover the snowy mantle with a crust too thick and hard for them to break through, starvation is their fate. Sportsmen living within convenient reach of quail coverts should watch over them in such weather and provide food and shelter for the birds.

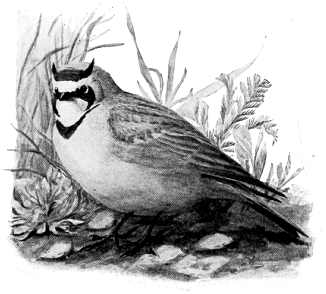

Even the flocks of horned (or shore) larks that feed on the wind-swept hilltops, pause occasionally and squat close to the ground to keep from being blown away. They have come from the North, and after passing the winter with us, most of them will return to Canada to nest.

A long period of cold freezes the marshes to the bottom, and compels the muskrats to seek the bushy banks, or to take shelter under the corn-shacks or hay-stacks in the fields. Poor things, they of all animals endure hardship; for one can often track them to where they have scratched away the snow while searching for grass-blades, roots, acorns or apples that have fallen and decayed.

When the wind sweeps over the fields and the cold nips your ears, you are apt to come suddenly upon a flock of snowflakes, or snow buntings. Hastening back and forth among the weeds along the bank, they reach up and pick the seeds and crack them in their strong bills. They, too, like the horned larks, have come from the North, and in March will return again.

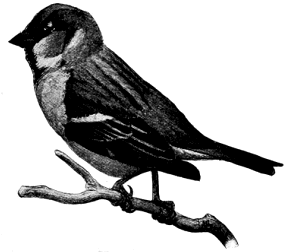

You cannot show your friendship for our native birds in any better way than by being an enemy of the English sparrow. He is a quarrelsome little pest and seems to be getting more pugnacious every year. He not only fights the other birds, but he has been seen to throw their eggs to the ground and to tear their nests to pieces. Be careful that he does not steal the lunches that you have provided for other birds.

How do the insects pass the winter? Much in the same way that our plants and flowers do. As the cold weather kills or withers the plants, leaving their seeds and roots to send forth shoots next summer, so most of the insects die, leaving their eggs, their larvæ, and their pupa to be nourished into life by the warm days of spring.

ENGLISH SPARROW.

Insects are more dependent on climatic conditions than are birds or mammals. Nevertheless, even on the coldest days of winter, one may tear away the bark of a forest tree and find spiders which show signs of life, and if kept in a warm room for a few hours, they become quite active.

The life of an insect which undergoes what is termed a "complete transformation," is divided into four stages: First, the egg; second, the larva; third, the pupa or chrysalis, and fourth, the adult insect or imago. Each of these changes is so complete and different from any of the others, that the insect never appears twice in an easily recognized form.

Let us take the common house-fly for an example, and follow it through the changes that it must undergo before becoming adult. The mother fly deposits more than a hundred eggs at a time, in a dump at the back of the stable. The eggs hatch in half a day.

Now we have the larvæ (maggots), as the second stage is called. These little creatures are white and grow very fast, shedding their skin several times before they take on a different form, which they do at the end of three or four days.

The third, or pupa, stage is reached when a tiny brown capsule-like formation has taken the place of the maggot. In this stage no movement is apparent, nor is any food taken; there is only a quiet waiting for the final change, which comes in about five days, when, out from one end of a chrysalis, a fully developed fly appears.

The wonderful changes just described take place throughout most of the insect world. The larvæ of butterflies and moths are caterpillars; the larvæ of June bugs or May beetles are grubs. Some moth and butterfly caterpillars weave silken cocoons about themselves; some make cocoons from leaves or tiny chips of wood; some utilize the hair from their own bodies, while others attach themselves to the under side of boards, stones, and stumps, where, after shedding their skin, they hang like mummies until spring calls them back to life.

Bird lovers often make the mistake of putting out nesting-boxes too late in the season. They forget that most of the birds begin to look for nesting-sites as soon as they arrive in the spring, therefore the boxes should be in place before the prospective tenants appear. March first is none too early for many localities.

A natural cavity in a root, cut from a rustic stump, or a short length of hollow limb, with a two-inch augur hole bored near the top, and a piece of board nailed over each end, makes an artistic nesting-place for birds. Some persons prefer a miniature cottage with compartments and doors; though birds will often nest in them, the simpler and more natural the home, the more suited it is to their wants.

A few minutes' work with hammer, saw, and knife, will convert any small wooden box that is nailed (not glued) together, into a respectable nesting-box. After it has been covered with two coats of dark green paint it is ready to be put in place. A shelf placed in a cornice, under a porch, or the eaves of a building, makes an excellent resting-place for the nest of a robin or a phœbe.

Nesting-boxes may be placed almost anywhere that there is shade and shelter. They ought to be put beyond the reach of prowling cats and meddlesome children, at least fifteen feet from the ground, and to reap the benefit of your labor, they should be near your sitting-room window.

It is better not to put an old nest or any nesting material in the houses. Birds prefer to do their own nest building, and they have their notions about house furnishing, which do not agree with our ideas. Birds have often refused nesting-boxes simply because over-zealous persons had stuffed them with hay or excelsior.

The birds that nest in bird-houses are the ones which, if unprovided with them, would naturally choose cavities in stumps, tree trunks, hollow limbs and the like. Almost without exception this class of nest-builders will return to the same nest year after year, so once a pair has taken up its abode with you, you may expect to see the birds for several summers.

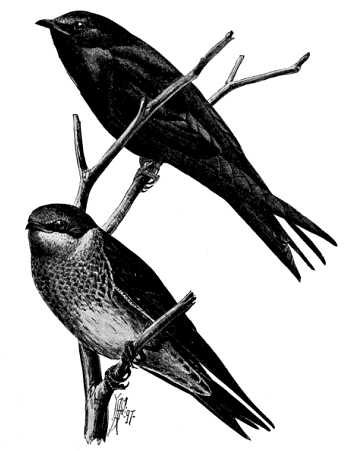

PURPLE MARTINS.

The following are common tenants of bird-houses: Purple martin, bluebird, house wren, chickadee, tufted titmouse, white-breasted nuthatch, and tree or white-breasted swallow. These birds are great insect destroyers, and most of them are sweet songsters, so they should be encouraged to take up their abode about our grounds.

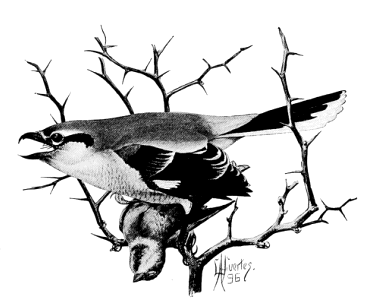

After a deep fall of snow, the Northern shrike, or butcher-bird, is forced into the villages and towns for his food. Dashing into a flock of English sparrows, he snatches one and carries it back to the country to be eaten at his leisure. He is the bird that impales small birds, mice, and large insects on barbed-wire fences, or thorn bushes, after his stomach has been filled, and hence his name.

Next to the beaver, the porcupine is the largest rodent in the United States; the largest porcupines live in Alaska. When on the ground, his short, thick tail drags in the snow, leaving a zigzag trail. When the snow is deep and the weather stormy, he spends much of his time in pine, spruce, and hemlock trees, feeding on the bark and twigs.

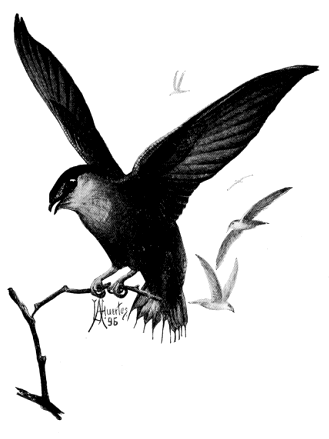

NORTHERN SHRIKE.

Hawks, before eating, tear away the skin and feathers from their prey; but owls eat everything, unless the prey be large, even bolting small birds and mammals entire. In the course of a few hours they disgorge pellets of indigestible portions, the bones being encased in the feathers or hair. The pellets may be found on the snow beneath the owl's roost, and they often contain skulls of mice as white and perfect as though they had been cleaned in a museum.

Mourning-cloak butterflies do not all die when winter comes. Those that hibernate are usually found singly or in clusters, hanging from the rafters in old buildings, or from the under side of stones, rails, limbs of trees, or boards. Those that appear in the spring with tattered wings, have probably been confined in buildings, and in their efforts to escape have battered themselves against the windows.

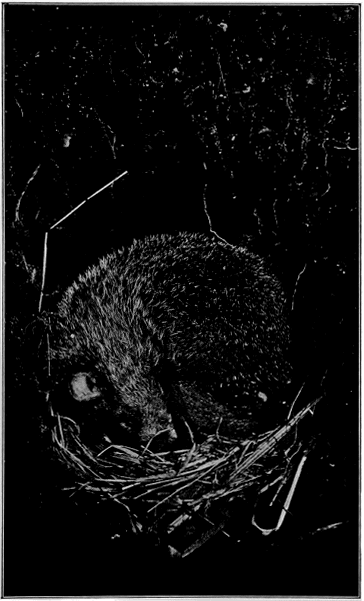

Does any one know how old the story is that tells us this is the day on which the bear and the woodchuck rub their sleepy eyes and leave their winter quarters for the first time? If they see their shadow they return and sleep six weeks longer, but should the day be cloudy, they are supposed to remain active the rest of the season. This of course is only a myth.

Frogs usually pass the winter in the mud at the bottom of a stream, lake, or pond, or below frost-line in a woodchuck, rabbit, or chipmunk burrow. However, it is not uncommon to find them active all winter in a spring, or a roadside drinking-trough supplied from a spring. I wonder if they know that spring-water seldom freezes, and that by choosing such a place, they will not have to hibernate.

The bloodthirsty weasel, which is reddish brown in summer (save the tip of his tail, which is always black), is now colored to match his surroundings, white. His tracks may be found in the woods and along the stump fences in the fields, where he has been searching for mice. He is one of the very few mammals that will shed blood simply for the pleasure of killing.

Students of nature will find it much easier to identify birds if they take this opportunity before the migrating birds arrive, to study carefully the haunts of the common species. Many birds, you know, are not found beyond the bounds of a certain character of country chosen for them by nature. So should you see in the deep woods a bird that you at first take to be a Baltimore oriole or a bobolink, a second thought will cause you to remember that these birds are not found in the woods, consequently you must be wrong.

The meadow lark, horned lark, bobolink, grasshopper sparrow, vesper sparrow, and savannah sparrow, are all common birds of the fields and meadows, and they are seldom seen in the dense woods or in the villages.

PRAIRIE HORNED LARK.

Among the birds that one may expect to see in the woods and groves are the great-horned owl, hermit thrush, wood thrush, blue-headed vireo, golden-crowned thrush, scarlet tanager, black-throated green warbler, and the black-throated blue warbler.

The swamp birds, and birds found along the banks of lakes, rivers, and streams, and seldom seen far from them, are the belted kingfisher, red-shouldered blackbird, spotted and solitary sandpipers, great blue, night, and little green herons, and the osprey, or fish-hawk.

Cleared woodlands overgrown with thick bushes, shrubs, and vines, as well as the bushy thickets by the waysides, are the favorite nesting-places for another class of birds. In this category the common varieties are the yellow-breasted chat, yellow warbler, chestnut-sided warbler, Maryland yellow-throat, catbird, brown thrasher, mocking-bird, indigo bunting, and the black-billed and yellow-billed cuckoos.

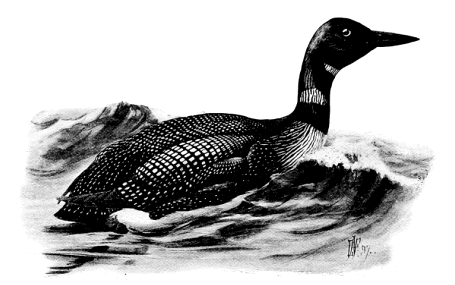

The swimming birds spend the greater part of their time in the water. Most of them nest in the lake regions of Canada. They are the ducks, geese, and swans, of which there are nearly fifty species; the grebes and loons, eleven species; the gulls and terns, thirty-seven species; and the cormorants and pelicans, beside many other water birds that we seldom or never see in Eastern United States.

Then, of course, there is a miscellaneous lot that nest in the woods, orchards, village shade trees, or any place where large trees are found. The flicker, downy and hairy woodpeckers, screech owl, white-breasted nuthatch, chickadee, robin, red-eyed vireo, warbling vireo, and the yellow-throated vireo, comprise some of the birds in this group.

About spring-holes the snow melts quickly and the grass remains green all winter. It is here that you will find the runways of meadow mice, or voles (not moles). They live on the roots and tender blades of grass, but at this time of the year hunger often compels them to eat the bark from fruit trees, vines, and berry bushes, and during severe winters they do great damage to apple trees.

LOON.

The whistle-wing duck, or American golden eye, attracts your attention by the peculiar whistling sound that it makes with its wings while flying. As it gets its food (small fish, and mussels), by diving, it is able to remain in the Northern States all winter and feed in the swift-running streams, in air-holes, or other open water.

The skunk is one of the mammals who can hibernate or not, just as he chooses. During prolonged periods of cold, he takes shelter in a woodchuck's burrow, and "cuddling down," goes to sleep but a few inches from the rightful owner, who, in turn, is also sleeping in a chamber back of the thin partition of earth which he threw out in front of himself when he retired in the fall.

The first bird to actually voice the approach of spring, is the jolly little chickadee. His spring song, "spring's-com-ing," sounds more like "phœbe" than does the note of the phœbe itself, for which it is often mistaken. It is a clear, plaintive whistle, easily imitated, and when answered, the songster can often be called within a few feet of one, where he will perch and repeat his song as long as he receives a reply.

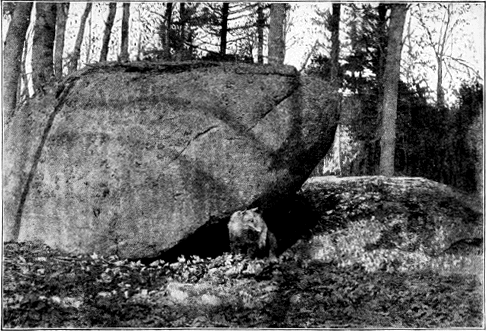

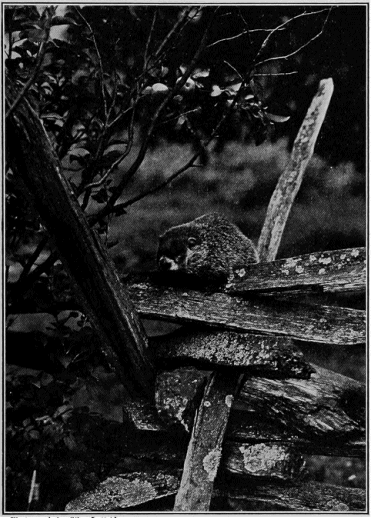

Photograph by Silas Lottridge.

HIBERNATING WOODCHUCK.

Even the coldest weather does not close the swift-running streams, which gives the muskrats a chance to exercise their legs. It makes you shudder to see one swim along the edge of the ice, then dive, and come to the surface with a mouthful of food. Climbing upon the ice, he eats it, then silently slips into the water again. His hair is so well oiled, that an ordinary wetting does not penetrate to the skin.

A crow's track can always be told from the tracks of other birds of similar size, because there is a dash in the snow made by the claw of his middle toe. Again, his toes are long and set rather closely together, and he seldom walks in a straight line, but wanders about as though looking for something, which is usually the case.

Many persons believe that a porcupine has the power to throw his quills, but it is not so. When alarmed, he hurries, in a lumbering sort of way, for shelter. If you close in on him, he stops at once, ducks his head, humps his back, raises his quill armor, and awaits your attack. Approach closely, and he turns his back and tail toward you, and the instant you touch him he strikes with his club-like tail, also armed with quills, leaving souvenirs sticking into whatever they come in contact with.

As the migrating birds are beginning to arrive in the Southern States, and will soon be North, let us consider the subject of migration. The reason why birds migrate North in the spring is not definitely-known. Of course they leave the North because cold and snow cut off their food supply; but why in the spring do they abandon a country where food is plentiful and make such long flights, apparently for no other object than to bring forth their young in the North?

Is it not wonderful how birds find their way, over thousands of miles of land and water, to the same locality and often to the same nest, season after season? How do we know that this is true? The reappearance of a bird with a crippled foot or wing, or one that has been tamed to feed from one's hand, is unmistakable proof.

Ducks and geese make longest flights of any of the migrating birds. They have been known to cover three hundred miles without resting. The smaller birds advance as the season advances, the early arrivals being the ones that do not winter very far south. Storm-waves often check their progress and compel them to turn back a few hundred miles and wait for the weather to moderate.

Most birds migrate at night; and a continued warm rain followed by a clear warm night is sure to bring a host of new arrivals. If you listen on moonlight nights, you can often hear their chirps and calls as they pass over. During foggy weather many meet with accidents by getting lost and being blown out to sea, or by flying against monuments, buildings, or lighthouses.

Mr. Chapman tells us that, when migrating, birds fly at a height of from one to three miles, and that our Eastern birds leave the United States by the way of the Florida peninsula. They are guided in their flight by the coast-line and the river valleys.

Some migrants fly in compact flocks of hundreds, like the ducks, for example, while others, like the swallows, spread out. Then, again, there are birds that arrive in pairs or singly. With still others, the male precedes his mate by a week or ten days. Not infrequently a flock of birds containing several different species will be seen. This is particularly true of the blackbirds and grackles.

You will notice that the birds are usually in full song when they arrive from the South. Save for a few calls and scolding notes, most of them are silent during the winter, but as spring approaches they begin to find their voices and probably are as glad to sing as we are to hear them.

The snow-shoe rabbit, or Northern varying hare, changes its color twice a year. In winter it is snow white, but at this season it is turning reddish-brown. In the far Northwest these hares are so abundant that they make deep trails through the snow, and the Indians and white trappers and traders shoot and snare large numbers of them for food.

It makes no difference to the "chickaree," or red squirrel, how much snow falls or how cold it gets. He has laid by a stock of provisions and he is not dependent on the food the season furnishes. He is as spry and happy during the coldest blizzard as he is on a midsummer day, for he knows well where the hollow limb or tree-trunk is that contains his store of nuts or grain.

The Carolina wren is the largest member of the wren family in the Eastern United States. It breeds sparingly in Southern New York and New England, but is common about Washington, D. C., where it is a resident. It is found in the forests, thickets, and undergrowth along streams and lakes. Mr. Hoffman says that its song "is so loud and clear that it can be heard easily a quarter of a mile."

A lady once asked me how to destroy the "insect eggs" on the under side of fern leaves. The ferns are flowerless plants, and they produce spores instead of seeds. Usually the spores are arranged in dotted lines, on the underside of the leaves (or fronds as they are called), and these are the "insect eggs" the lady referred to.

Even at this early date the female great-horned owl or hoot owl, in some sections of the country, is searching for a place to build her nest. She usually selects an abandoned hawk's or a crow's nest, and after laying her four chalky-white eggs, she is often compelled to sit on them most of the night to prevent them from freezing.

A question that is often asked is, what do the early migrating birds eat, when the ground is frozen and insect life is still slumbering. If you knew where to look, you would find many of the fruit-trees and vines filled with dried, or frozen fruit. Frozen apples and mountain-ash berries constitute a large part of the robin's and the cedar-bird's food early in the spring, and the bluebirds and cedar-birds eat the shriveled barberry fruit.

In Florida, the black bear can get food throughout the entire year, but in the North he is compelled to hibernate during the winter. He is now beginning to think of leaving his den (in a cave, crevice of the rocks, or under the roots of a partially upturned tree) to begin his summer vacation. We are apt to think that bears are poor when they leave the den, but this is not always true, although their pelage does get very much worn from coming in contact with protuberances in their winter quarters.

The first plant to thrust its head above ground and proclaim the coming of spring is the skunk cabbage, or swamp cabbage. Even before the snow has entirely left, the plant will melt a hole and by its own warmth keep itself from freezing. In many localities at this date the leathery hoods are several inches above the ground.

In America the cowbird, like the European cuckoo, lays its eggs in the nests of other birds. All of our American cuckoos build their nests and raise their young in a manner creditable to parents.

Clinging to the cliffs and rocks in the forests, the dark green leathery leaves of the polypody fern are nearly as fresh and green as when first snowed under. Hunt among the clusters until you find a fertile frond, then examine the back of it and see how closely together the spores are placed.

We will awaken some morning to find that during the night the song sparrows have arrived from the South; not all of them, to be sure, but just a few that are anxious to push North and begin nesting. All winter their merry song has been hushed, but now it gushes forth, not to stop again until the molting season in August.

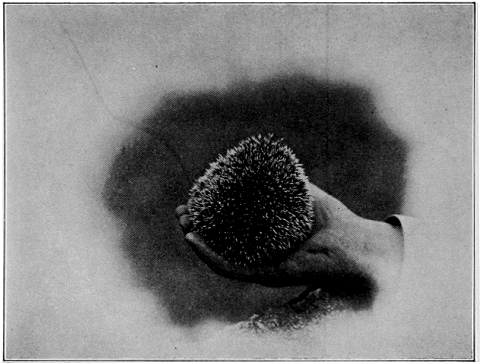

A porcupine should never be called a hedgehog. The hedgehog, an insectivorous animal, inhabiting Europe, is not found in the Western Hemisphere. It rolls itself into a ball when attacked, and the spines, which do not come out, are shorter, duller, and less formidable than those of the porcupine.

Photograph by E. R. Sanborn.

EUROPEAN HEDGEHOG.

People, knowing that the robin is an early spring arrival, are always alert to see or hear the first one. Consequently the first song that catches their ear is supposed to be that of a robin, whereas often it is the spring song of the white-breasted nuthatch, which really has no resemblance to the robin's song.

When you see a bird with a crest (not one that simply raises its head feathers) it must be one of the following species: A blue jay, tufted titmouse, pileated woodpecker, cardinal grosbeak, (also called redbird and cardinal), Bohemian waxwing, or a cedar-bird. These are the only birds inhabiting the Eastern States that wear true crests. The belted kingfisher and many of the ducks and herons have ruffs and plumes but these can scarcely be considered crests.

Some scientists contend that, owing to their intelligence, ants should rank next to man and before the anthropoid apes. They have soldiers that raid other ant colonies and capture eggs, and when the eggs hatch, the young are kept as slaves; they have nurses that watch and care for the eggs and helpless larvæ, and cows (Aphids) that are tended with almost human intelligence.

The Audubon Society has stopped the slaughter of grebes. Before the enactment of the laws framed by the society, these duck-like birds were killed for their snow-white breasts, which were used for decorating (?) women's hats. Grebes are now migrating to the lakes of the North, where they build floating nests of reeds.

The only sure way to tell a venomous snake is to kill the reptile, open its mouth with a stick, and look for the hollow, curved fangs. When not in use they are compressed against the roof of the mouth, beneath the reptile's eyes. They are hinged, as you can see if you pull them forward with a pencil. The venom is contained in a sack hidden beneath the skin at the base of each fang.

As a mimic and a persistent songster, the mocking-bird has no rival, but when quality is considered, I think we have several songsters that are its equal. The bobolink and the winter wren both have rollicking songs that are inspiring and wonderful, but to my ear there are no songs that equal those of the hermit thrush and the wood thrush. Still, the selection of a bird vocalist is a matter of choice which is often influenced by one's association with the singer.

If you will look into one of the large cone-shaped paper nests of the bald-faced hornet, which hang to the limbs of the trees or under the eaves of the house, you will be almost certain to find a few house flies that have passed the winter between the folds of paper. They now show signs of life, and are ready to make their appearance during the first warm spell.

Before the snow has left, you are likely to see dirt-stained spots on the hillsides where the woodchuck or ground-hog has thrown out the partition of dirt which kept the winter air from his bed-chamber. Of course he has not come out for good, but on warm, sunny days he will make short excursions from his burrow to see how the season is progressing. In the early spring, before vegetation sprouts, he finds it difficult to find good food in plenty.

The herring gulls that have been about our harbors and bays all winter, will not remain much longer. They are about to leave for their nesting grounds, in the marshes and on the islands of New England and Canada. In the fall they will return with their young, which wear a grayish plumage.

In winter meadow mice build neat little nests of dried grass on the ground beneath the snow. They are hollow balls, about the size of a hat crown, with a small opening in one or two sides. The outside is made of coarse, rank grass, while the lining is of the finest material obtainable. The heat from the little animals' bodies soon melts an air chamber around the nest, into which lead many tunnels through the snow. As soon as the snow has melted, you will find these nests scattered about the fields and meadows, but they are empty now.

The fish crow is a small edition of the common crow. He is a resident of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from South Carolina to Louisiana. His note resembles the "caw" of the Northern crow, minus the w, being more of a croak: "cak, cak, cak, cak." You will find him on the coast and along the rivers.

The white-tailed deer of the deep forests have dropped their antlers by this time, and a new set has started to grow. (Elk, moose, caribou, and deer have antlers; sheep, goats and cattle have horns, and retain them throughout life.) Antlers are cast off annually, and a new set will grow in about seven months.

Photograph by Alden Lottridge.

NEST OF A MEADOW MOUSE EXPOSED BY MELTING SNOW.

The purple grackle, or crow blackbird, should make his appearance in Southern New York about this time. He is the large, handsome fellow who lives in colonies and builds his nest in pine, hemlock, and spruce groves near human habitations. As soon as his young are hatched, he frequents the banks of rivers and lakes and walks along in quest of insects. He is one of the few birds that walks.

Screech owls are now nesting in natural cavities in apple-trees, but they should not be disturbed, for they feed on mice, beetles and other harmful animals. Owls are very interesting birds, but their wisdom is only in their looks. Their eyes are stationary, so in order to look sidewise, they must turn their head. Watch one and notice him dilate and contract the pupil of his eyes, according to the light, and the distance of the object at which he is gazing.

The American goldfinch, thistlebird, or wild canary, often spends the winter with us, but in his grayish-brown suit he is not recognized by his friends who only know him in his summer garb of black and yellow. The male and the female look alike now, but soon the male will don gorgeous colors and wear them until after the nesting season.

SCREECH OWL.

The scarlet heads of the velvet, or stag-horn sumach are very conspicuous on the rocky hillsides and gravelly bottoms. The fruit of the poison sumach hangs more like a bunch of grapes, while the stag-horn fruit is in a massive cluster. Persons susceptible to poisonous plants should never approach any poisonous shrub, particularly when the body is overheated.

From the swamps and river-banks comes the clatter of loud blackbird voices. Flocks containing hundreds of these noisy fellows perch in the tops of the trees, resting after their long migration flight. From the babble, you recognize the "konk-a-ree" of the red-shouldered blackbird, the harsh squeaky notes of the rusty grackle, and the purple grackle. As you approach, the flock takes flight, and you discover that all of the red-wing blackbirds are males; the females have not yet arrived.

In the dead of winter you may sometimes see a belted kingfisher along some swift-running stream, but as a rule, north of Virginia, few stay with us throughout the year. Most of them appear about this time, and you see them perched on some low limb overhanging a pond or a stream.

From bogs, shaded woods, and sheltered highways. Nature's question-marks, the "fiddle-heads," appear above the loam. They are baby ferns, preparing to expand and wave their graceful leaves in the face of all beholders. These queer, woolly sprouts the Indians use for food, and birds also eat them.

The clear, sweet, and plaintive whistle "pee-a-peabody, peabody, peabody," (which to the French Canadian is interpreted "la-belle-Canada, Canada, Canada") of the white-throated sparrow, or Canada bird, is a common, early spring song, now heard in the swamps and thickets. This sparrow may be found about New York City all winter, but it passes North to nest.

Beneath hickory-nut. Walnut, and butternut trees, you are sure to find large numbers of nut-shells that have been rifled of their contents by red squirrels, chipmunks, meadow mice, and white-footed mice. In nearly every instance, the intelligent little rodents have gnawed through the flat sides of the shell, directly into the meat, and taken it out as "clean as a whistle." But who "taught them" to select the flat side?

The noisy kildeer is rare in Pennsylvania and New York, but it is a common plover in Ohio. Its note, "kildeer, kildeer, kildeer," is emitted while the bird is on the ground or in the air. This plover is very abundant in the far West, and when a hunter is stalking antelope, it often flies about his head, calling loudly and warning the game of danger. For this trait it is sometimes called "tell-tale plover."

A question which puzzles scientists, is how the turtles and frogs (which have lungs) are able, at the close of summer, to bury themselves in the mud at the bottom of a river or pond and remain there until the following spring. The frogs appear a few days before the turtles are seen.

The meadowlark's song, "spring-o-the-year," is heard at its best in this month and in May; but the note is one of the few that may be frequently heard in southern New England, during the entire winter. As its name implies, the meadowlark is a bird of the fields and meadows only, but it will often alight in the top of a tall tree and send forth its joyful song. Watch and listen for it now.

As soon as spring arrives and the ice has left the streams, hordes of May or shad fly nymphs can be found working their way against the current a few inches from the shore. Catch a few of them and put them in a tumbler of water and watch their external or "trachea" gills working. The adult insects are abundant in summer, but at this time of the year (even earlier), the stone flies which flit over the melting snow are often mistaken for May, or shad flies.

MEADOW LARK

The name "purple finch" is very misleading, for the head, neck, breast, and throat of the bird are more crimson than purple. The female is often mistaken for a sparrow, as her color is dull, and her breast streaked. This finch often takes up its abode in the coniferous trees in the villages. "Its song bursts forth as if from some uncontrollable stress of gladness, and is repeated uninterruptedly over and over again." (Bicknell.)

If the season is not belated, you may expect to find the blood-root peeping through the rocky soil, on exposed brushy hillsides, or along the margins of the woods. You must look for it early, for its petals drop soon after the flower blossoms. The Indians used the blood-red juice which flows when the root is broken, to decorate their bodies.

The brush lots, roadways, and open forests in the Northern States, are now filled with juncoes on the way to their nesting grounds in Canada and the mountainous portions of this country. They are with us but a few weeks and will not be seen again until next fall. The pinkish bill and the two white outer tail-feathers are of great assistance in identifying this bird, for they are very conspicuous when it flies.

While walking along the bank of a stream you are quite apt to surprise a pair of pickerel lying side by side in shallow water. Save for the vibration of their fins, and the movement of their gills, they do not stir. As you approach they dart off, and you see a roily spot, where they have taken shelter among the aquatic plants.

The birds having white tail-feathers, or tail-feathers that are tipped with white, which show conspicuously when the owners are on the wing, are the meadowlark, vesper sparrow, chewink, snowflake, junco, blue jay, white-breasted nuthatch, Northern shrike, kingbird, hairy woodpecker, downy woodpecker, nighthawk, and whip-poor-will.

The clustering liverwort, hepatica, or squirrel cup, with its fuzzy stems and pretty flowers of various shades of blue, grow side by side with the white wood anemone, or wind-flower. As soon as the wood anemone blossoms, a slight breeze causes the petals to fall; that is why it is called "wind-flower."

DOWNY WOODPECKER.

One of the birds that sportsmen have protected by prohibiting spring shooting, is Wilson's snipe, or jacksnipe. Like many of the early migrants it does not nest in the United States; consequently it is only seen in the spring and fall. It is a bird of the marsh and bog, seldom seen except by those who know where and how to find it.

The gall-flies, or gall-gnats, cut tiny incisions in the oak leaves and golden-rod stems, and lay their eggs between the tissues. These wounds produce large swellings which furnish the larval insects with food. If broken into at this season, one discovers that the galls on the golden-rod stems are pithy. Embedded in the pith is a white "worm," or a small black capsule, but if the "gall" is empty, a hole will be found where the fly emerged.

The red-shouldered hawk is one of our common birds of prey. Its loud, somewhat cat-like cry, coming from the dense hardwood forests which border swamps, lakes, and rivers, at once attracts attention. A pair has been known to return to the same nesting locality for fifteen consecutive years. This hawk has proved itself to be of inestimable value to the farmer, and deserves his protection.

For the past six weeks, chipmunks have occasionally come out from their nests of dried grass and leaves, made in one of their several tunnels beneath the line of frost under a stone pile, or a stump. Now they are seen every day. It is only of recent years that we have discovered that chipmunks destroy grubs and insects, thus rendering service for the nuts and grain that they carry away in the fall.

Have you noticed how the robins congregate in the evening and battle with each other on the house-tops until dark? It is during the mating season that these fights take place. Long after the other birds have gone to bed. Cock Robin is awake, and shouting loud and defiant challenges to whoever will accept them.

Fungi are the lowest forms of plant life. They subsist on living and dead organic matter, and not from the soil, as do most other plants. The bread molds, downy mildew on decaying fruit and vegetables, and the fungus that kills fish and insects, are all forms of fungi. Patches of luxuriant grass are seen where decaying fungi have fertilized the soil.

The continuous "chip-chip-chip-chip-chip-chip——" of the chipping sparrow, like a toy insect that must run down before it can stop, is always a welcome sound at this time of the year. He can easily be tamed to take food from one's hand. Although a neat nest-builder, "chippy" selects poor nesting sites, and often the wind upsets his hair-lined cup and destroys the eggs or young.

At first the song of the spring peeper, which is really a frog, is heard only in the evening, but as the days get warmer, a perfect chorus of piping voices comes from swamps and stagnant pools. He strongly objects to singing before an audience, but it is well worth one's while to wait patiently and catch him in the act of inflating the skin beneath his chin.

On account of its tufted head, and clear, ringing song, "peto, peto, peto, peto" or "de, de, de, de," much like a chickadee (Chapman) the tufted titmouse is a well-known bird throughout its range: eastern United States, from northern New Jersey, and southern Iowa to the plains.

Where is the country boy or girl who does not know the "woolly bear," or "porcupine caterpillar," the chunky, hairy, rufous and black-banded caterpillar, that curls up when touched and does not uncoil until danger is over? They are the larvæ of the Isabella moth, and the reason for their appearance on the railroad tracks and wagon roads, is that they have just finished hibernating and are now looking for a suitable place to retire and change to chrysalides and then into moths.

In the Northern States, where the red-headed woodpecker is not very common, it is apt to be confused with other species of woodpeckers. The red-headed woodpecker is scarlet down to its shoulders. The eastern woodpeckers that have the red crescent on the back of the head are flicker, downy, and hairy woodpeckers.

The gardener, while spading about the roots of a tree, will often throw out a number of white, chunky grubs, about the size of the first joint of one's little finger. These are the larvæ of the June, or May beetle. In the fall, they dig below frost line, where they remain until the following spring. After three years of this life, they emerge from the ground in May and June, perfect beetles.

The myrtle, or yellow-rumped warbler, which spends the winter from Massachusetts, south, into the West Indies and Central America, and nests usually north of the United States, is very common now. It is found in scattered flocks. If in doubt of its identity, look for the yellow patch on the crown, and on the rump.

The dainty little spring beauty, or claytonia, is another of the early blooming flowers. "We look for the spring beauty in April or May, and often find it in the same moist places—on a brook's edge or skirting of wet woods—as the yellow adder's tongue." (Dana.)

Toads are now beginning to leave their winter beds, in the leaves, under stones and the like. Did you ever tie a piece of red cloth on a string, dangle it over a toad's head, to see him follow and snap at it? Toads exude a strong acid secretion from the pores of the skin, which is distasteful to most predatory animals, excepting the snakes.

The yellow-bellied sapsucker is the only member of the woodpecker family whose presence is objectionable. His habit of puncturing the bark of trees and then visiting the cups to catch the sap, is well known. At any time of the year, row after row of these holes may be seen on fruit-trees (usually apple and pear)—written evidence of his guilt. See if you can catch him in the act.

Turkey buzzards, or vultures, are repulsive and ungainly when on the ground, but they are by far the most graceful of all our large birds when in flight. They are rarely seen in New England, or in the Northern States of the Middle Atlantic group, but in the South they are common throughout the year. Mounting high in the air, they circle 'round and 'round with scarcely a flutter of the wings, but nervously tilting to right or left, like a tight-rope walker with his balancing pole.

This is about the time that young red foxes get their first sight of the wide, wide world. In the Southern States they have been prowling about with their parents for weeks; but north of New York City the farmer's boy, as he now goes for the cows in the morning, will frequently see a fox family playing about the entrance to their burrow.

FOX AT DEN.

So ruthlessly has the trailing arbutus, or "May-flower" as it is called in New England, been destroyed, that in places where it was once common, it is now almost extinct. Of its odor, Neltje Blanchan says: "Can words describe the fragrancy of the very breath of spring—that delicious commingling of the perfumes of arbutus, the odors of pines, and the snow-soaked soil just warming into life?"

Why are the robins so abundant? Because they are all pushing forward to their Northern nesting grounds. Even in Alaska you would find a few pairs that have made the long, perilous journey in safety, raising their young in the balsam-poplars along some glacial stream, while in Georgia and Florida, where large flocks of them winter, not one would now be seen.

If you will sow a few sunflower seeds in a corner of the garden and let the plants go to seed, in the fall you are sure to have feathered visitors in the shape of goldfinches, chickadees, and nuthatches. The nuthatches (no doubt thinking of the hard times to come) will carry the seeds away, and store them in the crevices of the bark of trees.

Of uniform grayish color, swift in flight, and shaped like cigars with wings, the chimney swifts might well be called the torpedo boats of the air. They never alight outside of chimneys or old buildings, and are usually seen flying high above the house-tops. For hours they chase each other through the air, keeping up a continuous "chip, chip, chip, chip, chip, chip," whenever the participants of the game come near each other.

No sooner does the frost leave the ground, than the moles begin to work close to the surface, making ridges where the earth is soft, and throwing out small mounds, when it is packed firm. The star-nose mole inhabits damp soil, while the common mole likes the dry highlands. Although moles' eyes are small, he who thinks that they cannot see, should hold his finger before one's nose and see how quickly it will be bitten.

The marsh marigold, which grows in thick clusters in the swamps and along the streams, is now in full bloom. These flowers are often sold on the streets for "cowslips," a name wholly incorrect. The leaves make fine greens.

CHIMNEY SWIFT.

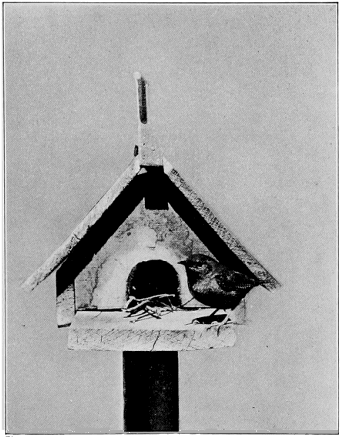

By this time one of your bird houses should be tenanted by a pair of house wrens. They migrate at night and the male arrives about a week in advance of his mate. Both birds assist in building the nest and in raising the young. As soon as the first brood has been reared, the lining of the nest is removed, and a new one built before the second set of six eggs is laid. Wrens may easily be tamed to take spiders and caterpillars (not the hairy ones) from the end of a stick and even from one's hand.

How much easier would be the work of nest building if we provided the birds with nesting material. Scatter strips of cloth, and pieces of coarse twine on the ground for the robins; hair from the tail and mane of horses for the chipping sparrows and wrens; twine and horse-hair for the orioles; bits of "waste" for the yellow warblers, and grapevine bark for the catbirds. None of these strands should be more than four inches long.

In some localities the shad-tree is now in full blossom. As you pause to cut off a few twigs, your ears are greeted by a never ceasing chorus of toad music. This is the toad's "love song"—a high-pitched, somewhat tremulous, and rather monotonous note.

Photograph by J. Alden Loring.

ONE OF TOUR BIRD-HOUSES SHOULD BE TENANTED BY A WREN.

Perched upon a stump, fence post, or low limb of a tree, the Bob-white sends forth his clear, far-reaching whistle "Bob-white." In the North this bird is known to every boy as Bob-white, or quail, while in the South he is called "partridge." The last two names are misnomers, for we have no native quails or partridges in this country.

The fronds of the sensitive fern resemble somewhat the leaves of the oak-tree, and in some localities it is called the oak-leaf fern. It is found in damp, shady spots, and is one of the common ferns of New England. The delicate, light green leaves wither soon after being picked, and it is the first of the ferns to fall under the touch of Jack Frost.

A low, squeaking sound made with the lips is understood by some birds as a signal of distress. Orioles, wrens, catbirds, cuckoos, warblers, vireos, robins, and many other birds may be called close to one, particularly if the intruder is near their nest. You should learn this trick, for often it is possible to coax a shy bird from a thicket in order that it may be identified.

In summer the most common of our Northern wood warblers, yet one of the most difficult to see, on account of its liking for the tops of the tall trees, is the black-throated green warbler. Its song is a cheerful, interrogative, "Will you co-ome, will you co-ome, will you?" (Wright), or "a droning zee, zee, ze-ee, zee." (Chapman and Reed.)

Why is it that the usually frisky and noisy red squirrels have become so quiet? If you could look into the nest of dried grass and bark, in a hollow tree-trunk, or a deserted woodpecker's nest, you would understand their reason for not wishing to make their presence known. Keep close watch of the opening, and some day you will see several little heads appear, and in a few days a family of squirrels will be scrambling about the trees. Pretty and graceful as these squirrels are, they do great damage by destroying the eggs and young of birds.

Wintering south of Central America, the veery, or Wilson's thrush, should now appear in the vicinity of Albany. "A weird rhythm" is the expression sometimes used to describe the song of this bird. Weird it certainly is, and beautiful, as well, coming from the depths of some sombre wood, growing more sombre still as the night falls.

The wood thrush is much larger than the veery, and easily distinguished from the six other species of true thrushes of North America, by the large black spots on the breast, and the bright cinnamon head. As you listened for the veery, you probably heard the wood thrush's pure liquid song—so far away that you could not catch the low after-notes. To me, the flute-like quality of the wood thrush's song makes it the most enchanting of all bird music.

At intervals during the day, a distinct booming sound is heard coming from the forests. At first the beats are slow and measured, but as they are repeated the time quickens, until they finally blend, and then gradually die away. This is the "drumming" of the ruffed grouse, produced by the cock bird beating with his wings against the sides of his body. At this time of the year it is his love song, but you can hear it at other seasons as well.

Visit again the locality where a week ago you heard so many toads, and what do you find? Long strings of gelatine-covered specks strewn on the bottom of the pond. These black spots are the eggs of the toad, and the gelatine is put around them to protect them and to furnish the first meal for the young polywogs.

To find a hummingbird's nest, snugly saddled on a branch of a maple or apple tree, ten feet or more above the ground, requires patience and keen eyesight. Unless you have seen one, you almost surely would mistake it for a bunch of lichens. It is a neat little structure of downy material covered with bits of lichens, fastened with spider and caterpillar webs.

It would interest you to visit a zoological park to study the growing antlers of a deer or an elk. A pair of black antlers, "in the velvet," as the hunters call it, have taken the place of the bony-colored ones shed in March. Just now they are somewhat flexible, and feverishly hot from the steady flow of blood that feeds them. If they are injured at this time, the owner might bleed to death.

"Caw, caw, caw, ka, ka, ka, ka-k-k-k-r-r-r-r." It sounds as though a crow were being strangled. Looking in that direction you see a large black bird fly from the woods to a meadow. After filling her beak with food she returns. No sooner is she within sight of the young crows, than they flap their wings, open their mouths and caw until the stifled, guttural sounds tell you that the morsel is being swallowed.

When perched or flying the bobolink sends forth his jolly song in such a flood of ecstasy that you would scarcely be surprised to see him suddenly explode and vanish in a cloud of feathers. Would that we could overlook the damage he does to Southern rice crops.

Before now you have noticed the dainty little Jack-in-the-pulpit in the damp, shady woods and marshes. Would you suppose that this innocent looking plant is really an insect trap? The thick fleshy "corm" when boiled is quite palatable, but who would think so after digging it from the ground, cutting into it, and feeling the sharp prickly sensation it gives when touched with the tongue?

The song of the brown thrasher can easily be mistaken for that of a catbird, particularly as both birds inhabit roadways, thickets, and open brush lots. The male, while singing to his mate, nearly always perches in the top of a tall bush or tree. His song is a disconnected combination of pleasant musical tones, which might be arranged so as to sound thrush-like in effect, but they are usually uttered in pairs or trios, rather than in the modulated phrase of the hermit or the wood thrush.

Photograph by J. Alden Loring.

MALE BOBOLINK IN SUMMER PLUMAGE.

Look intently at the bottom of shallow streams or ponds and you will see what appear to be small twigs and sandy lumps moving about like snails. These are the larvæ of the caddis fly. Pick up one and poke the creature with a straw. You now discover that it lives in a case made of gravel, or sand, or tiny shells, or pieces of bark, all glued together in a perfect mask.

Keep watch of any brown bird about the size and shape of a female English sparrow, that you see hopping about the trees and bushes, peeping under bridges, and looking into hollow limbs of trees. She is a cowbird, or cow bunting, looking for the nest of another bird who is away for the moment. When she finds one, she will slip into it and drop one of her eggs, which will be hatched and the birdling reared by the foster mother, unless she can manage to get rid of it.

The Greeks were persistent in their belief that the harmless red, or fire salamander, found only in damp and shady places, was insensible to heat. In reality the reverse is true. Its delicate skin cannot even withstand the sun's rays. During sunny days it hides under leaves and logs, coming forth only after storms, or at night.

If there are currant or gooseberry bushes about your grounds, you must know the yellow warbler, or summer yellowbird. He is the little chap, almost pure yellow, who hunts carefully under each leaf for the caterpillars that attack the bushes. The female lacks the reddish streaks on the under parts, and her crown is not as bright as that of the male. Do not confuse this bird with the male American goldfinch, which just now has a yellow body, but black crown, wings, and tail.

Quite unlike the strings of beady eggs of the toad, the eggs of the frogs are attached in a bulky mass to sticks or to the limbs of aquatic plants in sluggish or stagnant water. But there is the same gelatine-like casing around each black egg.

In the Northern States, where he nests, the redstart is often seen in the shade-trees along our streets, as well as in the groves and forests. "'Ching, ching, chee; ser-wee, swee, swee-e-s' he sings, and with wings and tail outspread whirls about, dancing from limb to limb, darts upward, floats downward, blows hither and thither like a leaf in the breeze." (Chapman.)

In the evening you often see a chimney swift (it is not a swallow) flying back and forth over dead tree-tops. Each time it pauses as though about to alight, but after what seems to be a momentary hesitation, it passes on. With a field-glass you might detect it snapping off the twigs and carrying them into an unused chimney, where it fastens them to the bricks with a glutinous saliva. One after another the twigs are glued together until a bracket-like basket is made, and in this the four white eggs are laid.

It is now time to look in the meadows for the dainty blue-eyed grass, or blue star; in the marshes for the purple or water avens, and the white hellebore, or Indian poke; and in the damp shady woods for the blossoming mandrake, or Mayapple.

Judging from the name, one might expect to find the pewee, or wood pewee, in the woods only, but his high plaintive "P-e-w-e-e, p-e-w-e-e," first rising, then falling, coming from the tops of the village shade-trees, is one of the last notes heard at the close of the day. Short as the song is, he frequently sings but half of it.

Birds are often great sufferers from heat. The open bill, drooping wings, and panting body, all testify to this fact. A bird sitting on an unshaded nest during a hot day is an object for our pity. Fill flower-pot saucers with fresh water, and place them in depressions about the grounds. The birds will get great relief from these drinking and bathing dishes, and your opportunity for observation will be increased.

One night last summer, a moth laid a circular cluster of eggs at the end of a limb. Not many days ago the eggs hatched and the caterpillars have begun to spin a silk tent in the crotch of several branches. Every time these tent caterpillars (for that is their name) go out to feed upon the leaves, they spin a thread by which they find their way home. After they have eaten their fill, they will drop to the ground to seek a hiding-place and there turn into moths.

The fertile fronds of the cinnamon fern break ground before the sterile ones come up. They appear to shoot from the centre of the crown-shaped cluster, and are light cinnamon color when mature. By the last of June the fertile fronds have withered, leaving only the sterile ones which the amateur is quite sure to confuse with the interrupted fern.

While driving in the country your attention is often drawn to the swallows that are flying about the barns. Two species are common, one has two long tail feathers that fork. This is the barn swallow, and his mate builds her nest inside the barn, on a rafter or against the planking. It is always open on top and lined with soft material.

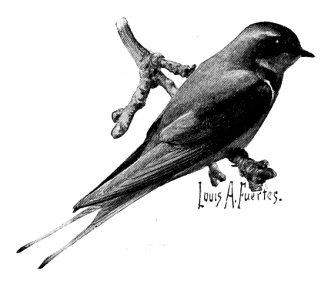

BARN SWALLOW.

The eave swallow lacks the forked tail, and the rump is cinnamon-buff. Usually the female builds her globular shaped mud nest under the eaves of an unpainted barn. Hundreds of mud pellets are neatly welded together and an opening is left in the front. As these swallows also build against cliffs, they are known as cliff swallows in some localities.

The nesting season is now at its height, and you will soon see young birds about the grounds. The old birds may be away looking for food. Let us remember that it is better to let Nature work out her own problems. Instead of catching the birdlings and forcing them to eat unnatural food (only to find them dead a few hours later), put them back into the nest when it is possible, or if they are strong enough, toss them into the air and let them flutter to the branches of a tree beyond the reach of cats.

This is about the time that turtles hunt for a sandy bank in which to make a depression where they may deposit their eggs—that look so much like ping-pong balls. The eggs are covered with sand and left for the sun to hatch. The young dig through the shallow covering and take to the water.

If you wish to see one of the most gorgeous of wood birds, the scarlet tanager, you must find him now, for, after the nesting season, he loses his black wings and tail and bright red dress, and dons the sober green hue of his mate. You will find him living in the maple groves, and the heavy forests of maple, oak, beech, and chestnut. His song, though not so loud as either, resembles both that of the robin and the rose-breasted grosbeak.

In the low-lying meadows, and in the marshes, the towering stems of the blue flag, or blue iris, have already blossomed. Nature has so constructed this handsome flower, that were it not for the visits of bees, and other insects, its seeds would remain unfertilized.

The orchard oriole is far from common north of the States parallel with southern New York. It migrates to Central America in winter, as does its cousin, the Baltimore oriole, who is named for Lord Baltimore. It lives in orchards, and you should look in apple and pear trees for its graceful pendent nest, built of the stems and blades of grass neatly woven together, like the nest of a weaver bird.

When by pure strategy you have outwitted a pair of bobolinks, and have succeeded in finding their nest, you have indeed achieved a triumph. To be successful, take your field-glasses, and secrete yourself near a meadow where you can watch a pair of bobolinks without being seen. Wait until one or both birds have made repeated trips to a certain spot, then with eyes riveted on the place, hurry forward, and as the bird rises, drop your hat on the spot and search carefully about it until the nest is found.

The robin, song sparrow, vesper sparrow, chipping sparrow, phœbe, and house wren by this time have their first fledglings out of the nest. They usually raise two, and sometimes three broods in a season. While the father bird is busy caring for the youngsters, the mother is building another nest or laying a second set of eggs.

In damp low-lying fields at this season, beds of bog cotton decorate the landscape. Its silken tassels sway gracefully in the breeze, and at a distance one could easily mistake them for true flowers.

Although the meadow lark and the flicker are about the same size, and each has a black patch on its breast, they need never be confused. The flight, as well as the difference in color, should help in their identification. The flicker's flight is undulating; while the meadow lark flies steadily, and the wings move rapidly between short periods of sailing. Again, the meadow lark's outer tail feathers are white, while the flicker's rump is white, both of which can be seen when the birds fly.

Visit the pool or waterway where you discovered the toad's eggs and you will find that they have hatched. The little black polliwogs, or tadpoles, have eaten their way out of the gelatine prison and are now schooled at the edge of the water. They subsist upon the decaying vegetation and minute animal life.

Our lawns are now the feeding ground of the first brood of young robins, great overgrown, gawky, mottle-breasted children, nearly as large as their parents. What a ludicrous sight it is to see them following their mother about, flapping their wings, opening their mouths, and begging for food every time she approaches them.

Leopard frogs and tiger frogs are often found in the tall grass a mile or so from water. Food is abundant and more easily caught in such places than along the streams. By the waterways the frog waits patiently for insects to pass, then springs at one with open mouth and, whether successful or not, he falls back into the water, swims ashore, and awaits another morsel.

A family of six young belted kingfishers perching on the edge of a bank, preparatory to taking their first flight, is a laughable sight indeed. Their immense helmet-like crests, their short legs, and their steel blue backs, give them a "cocky" appearance, and remind one of a squad of policemen on dress parade.

If the bird observer upon his first birding trip could be introduced to the song of a winter wren, there is scarcely a doubt that he would be a bird enthusiast from that minute. Mrs. Florence Merriam Bailey has come nearest to describing its song; "Full of trills, runs, and grace notes, it was a tinkling, rippling roundelay."

BELTED KINGFISHER.

Throughout the mountainous region of the eastern States, the mountain laurel (spoonwood, broad-leafed kalmia, or calico bush) is in full blossom. It is a beautiful, sweet-scented, flowering shrub, and the bushes are ruthlessly destroyed by those who have no regard for Nature's future beauty.

The habits of wasps and bees differ widely. Both orders are very intelligent. Wild bees live in hollow trees and make their cells of wax. At first they feed their young on "bee bread," which is made from the pollen of flowers, and afterward on honey. Wasps subsist on the juices of fruits, and insects; but they will eat meat. They make their homes in burrows in the ground, or in wood, or they construct nests of paper or mud.

The Maryland yellow-throat is more like a wren than a warbler, but it belongs to the warbler family. As you pass a thicket or a swamp, he shouts "This way sir, this way sir, this way sir;" or "Witchety, witchety, witchety;" and you might watch for hours without seeing him. But by placing the back of your hand against your lips, and making a low squeaking noise, you are likely to bring him to the top of a reed or bush.

It is quite easy to tell the difference between butterflies and moths. Remember, first of all, that butterflies are sunlight loving insects, while moths stir about only on cloudy days, or after dark. Butterflies, when at rest, hold their wings together over their backs; moths carry them open and parallel with the body. Again, the antennæ, or "feelers," of butterflies are quite club-like in shape, while the "feelers" of moths inhabiting the United States and Canada resemble tiny feathers.

If you are so fortunate as to have a pair of catbirds nesting in a small tree or a bush near your house, you have learned that the male is an accomplished songster. Have you ever noticed the father bird, when perched where he can overlook the nest, gently quivering his wings as though delighted at the thought of a nest full of little ones? After the eggs have hatched, these periods of delight are more frequent.

The bracket fungi that are attached to the trunks of forest and shade trees live to an old age. Some have been found over seventy-five years old. They are the fruit of the fungous growth that is living on and destroying the tissues of the tree. The puff-balls are edible fungi before they have dried.

CATBIRD

Some one has rightly called young Baltimore orioles the "cry-babies of the bird world." The approach of their mother with food is the sign for a general outcry, and even during her absence, they whimper softly, like disconsolate children. For the next ten days you may hear them in the shade-trees about our streets, particularly after a rain.

The long-billed marsh wren is found in tall, rank vegetation bordering rivers and lakes, and in the marshes at tide water. It nests in colonies in the rushes, and the male will build several other nests near the one his mate occupies. "While singing it is usually seen clinging to the side of some tall swaying reed, with its tail bent forward so far as almost to touch its head." (Chapman.)

The kingbird, because of its pugnacity, is considered a ruler of other birds, although it might rightly be called a watchman and protector of the feathered world. It is a sober colored bird, save for the concealed patch of orange on the crown of the head. It is always the first bird to detect the presence of a feathered enemy. With loud, defiant cries it sallies forth to attack, and is not content until it has driven the intruder beyond range.

The spittle insect, or spittle bug, not a snake, frog, or grasshopper, is responsible for that bit of froth found on the stems of weeds and grasses. Push away the foam, and you will find a small, helpless insect apparently half-drowned. The liquid is a secretion from the body, whipped into froth by the creature's struggles. These are the larvæ of the insects which, when full grown, fly up before you in myriads as you walk through the fields.

The swallows are noted for their strong and graceful flight. Watch one, as he sails gracefully through the air, now swerving to the right, now to the left, and then dipping down to take a drink or to pick an insect from the water, scarcely making a ripple. The barn and eave swallows feed their young in mid air. It would appear that they are fighting, when the food is being passed from the old bird to the youngster.

A common bird along the country roads is the indigo bunting, or indigo bird. He perches on a wire, or on the topmost limb of a tall bush or tree, and sings a song quite sparrow-like in quality. As you approach, he drops gracefully into the foliage. His nest probably contains young birds.

After a shower in early July, myriads of tiny toads swarm on the lawns and walks. They have just abandoned their aquatic life as tadpoles, and have taken up a terrestrial mode of living. Their skin is so delicate that sunlight kills them, so they remain hidden until clouds have obscured the sun.

"Whip-poor-will, whip-poor-will, whip-poor-will." From dusk until daylight you hear its mournful song. The whip-poor-will spends the day in the forest. At twilight it comes forth to catch its insect prey, which it captures while flying. It makes hardly any pretence at building a nest, but lays its eggs upon the ground among the leaves, and so closely do both bird and eggs resemble their surroundings, that one might easily step on them unknowingly.

Attached to stones, stumps, and tree trunks along the fresh water ponds and streams, are the cast-off jackets of the larval dragon-fly. These larvæ remain in the water for more than a year, feeding upon the larvæ of other insects. Finally they leave the water, and a long rent is seen on the creature's back, and soon the dragon-fly appear.

Similar to the whip-poor-will in shape, the nighthawk, or bullbat, differs from it in song and habits,—though, oddly enough, it perches lengthwise on a limb as the whip-poor-will does. It is neither a hawk nor a bat, for it is classed close to the chimney swift, and like the swift, it is of inestimable value as an insect destroyer. It is often seen in the daytime and the large white spot on the under side of each wing helps to identify it.

The horned-tails are the large wasp-like insects that we see about the elm, oak, and maple trees. They bore holes a quarter of an inch in diameter in the tree trunk, and in these holes the eggs are laid. Sometimes they get their augers wedged and are unable to free themselves. The horned-tails are destructive, and should be killed whenever found. They sometimes remain in the pupa state so long, that the tree may be cut down and the wood made into furniture before they finally emerge.

Before now you have probably seen the ruby-throated hummingbird poising over the flowers in your garden. Sometimes he goes through strange antics. Mounting ten or fifteen feet into the air, he swoops down in a graceful curve, then turns and repeats the performance time and time again.

In travelling from burrow to burrow, woodchucks often make roads a quarter of a mile long through the grass. Occasionally you will get a long distance view of the "'chuck" as he scuds to the mouth of his hole, and rising on his hind legs, stands erect and watches you, then bobs out of sight. He is the most alert and keen-eyed of all American rodents, and his presence in such numbers, despite the war waged upon him, proves his ability to take care of himself.

"The interrupted fern is less a lover of moisture than its kindred. The fertile fronds are usually taller than the sterile leaves, and they remain green all summer. The spore-bearing organs are produced near the middle of the frond" (Clute), thus "interrupting" the pinnæ growth of the leaf. It is also called Clayton's fern.

The hind feet of a honey bee are provided with stiff fringes. With these the bee scrapes from the rings of its body the oily substance that is exuded, and passes it to the mouth. After chewing and working it between the mandibles (for the bee has mouth-parts for biting, and a proboscis for sucking the juices and honey from plants), it becomes soft and is then built into comb.

Photograph by Silas Lottridge.

WOODCHUCK.

From the depths of the forest and thick underbrush, you will hear the "teacher, teacher, TEACHER, TEACHER" (in a swift crescendo) of the golden-crowned thrush, ovenbird, or teacher-bird. It is a note of such volume that, instead of a bird the size of a robin, you are surprised to find that the songster is no larger than a song sparrow. He is called ovenbird because his nest is covered over and resembles somewhat an old-fashion bake oven.

Some "glow-worms" are female fire-flies or lightning-bugs. There are at least a score of common insects that are luminous, besides some rare ones. With some species of fire-flies (our common fire-fly included) both sexes are winged, while with others the females lack wings and are known as "glow-worms."

With most birds, the female only builds the nest and incubates the eggs, after which both birds usually assist in bringing up the young. Some of the exceptions to this rule are the male Bob-white, house wren, catbird, blue-headed, yellow-throated, and warbling vireos, and the barn and eave swallows, each of which does his share of the domestic duties and takes care of the young birds.

Through ignorance we often persecute our best friends. The ichneumon fly is a parasitic insect that all should know. It lays its eggs in the larvæ of many injurious insects, and its larvæ feeds upon them. A great enemy to the horned-tails, it is invariably misjudged and killed, when discovered with its ovipositor inserted in one of the borings of the horned-tail fly.

How beautiful is the awakening of the evening primrose. No sooner is the sun beneath the horizon, than the calyx begins to swell and out springs a yellow petal. Then another and another appear before your very eyes, until the petals look like the blades of a screw propeller. The blossom is often less then five minutes in opening, and is immediately surrounded by tiny black insects.

Young spotted sandpipers, or "tip-ups," are able to leave their nest (in a slight depression in the ground) soon after the eggs hatch. It is indeed interesting to watch a family of these animated woolly balls on stilts, running along the shore with their parents. When pursued they sometimes will take to the water and cling to the vegetation on the bottom.

The perfectly round white heads of the button bush are now conspicuous along the streams, bogs, and lakes. The long slender styles project from all sides like the quills on the back of a frightened hedgehog. Although this shrub is a lover of water and damp soil, "it is sometimes found on elevated ground, where it serves, it is claimed, as a good sign of the presence of a hidden spring. The inner bark is sometimes used as a cough medicine." (Newhall.)

During the haying season the birds hold high carnival. Robins, song and chipping sparrows, orioles, bobolinks, goldfinches, meadow larks, and flickers, all feed upon the insects that are now so easy to catch. A seat in the shade overlooking a new mown field is at present a good point from which to study birds.