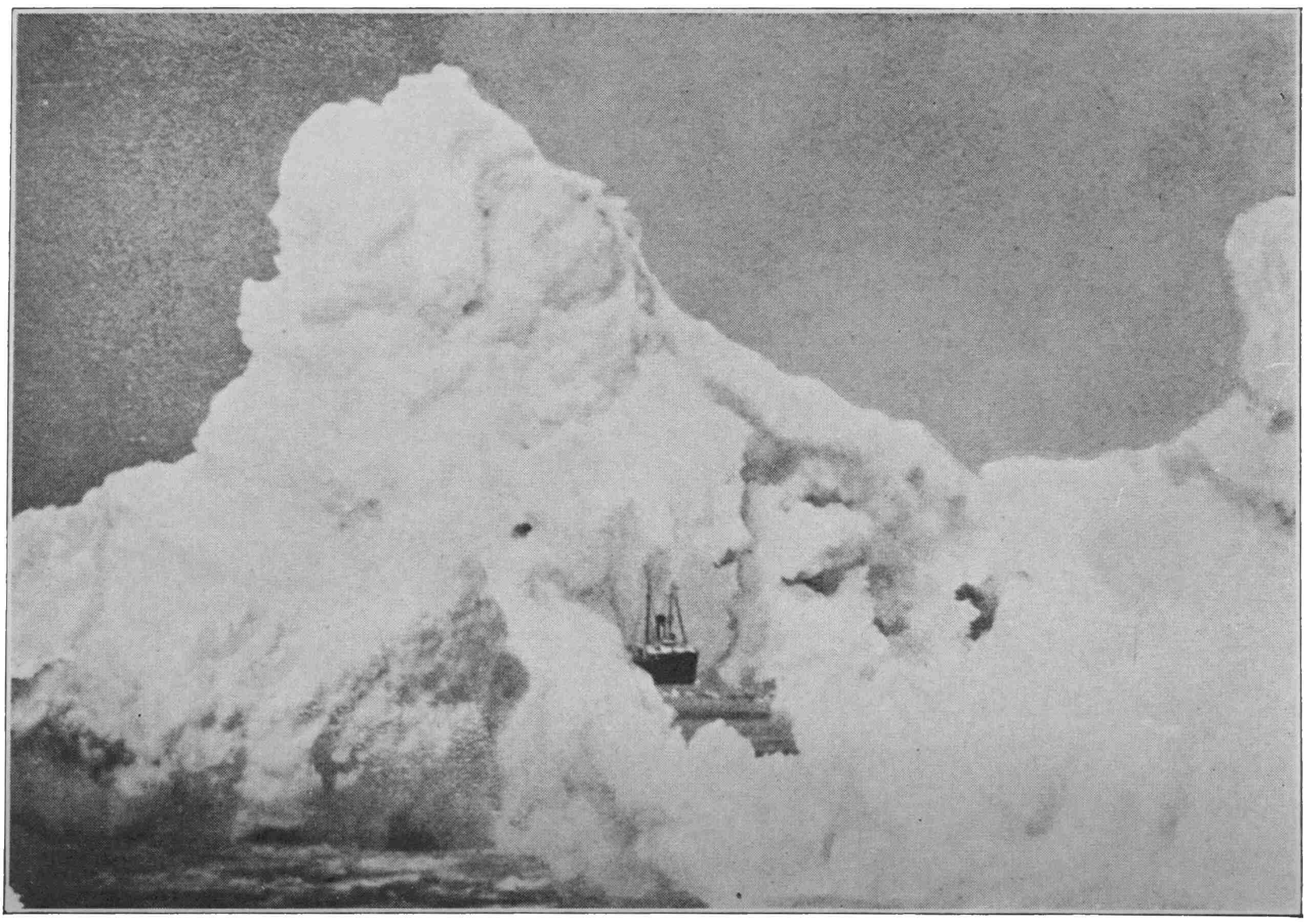

A U. S. Coast Guard Cutter Surrounded by Icebergs

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/wirelessoperator00thei |

IN CAMP AT FORT BRADY. A Camping Story. 304 pages.

HIS BIG BROTHER. A Story of the Struggles and Triumphs of a Little Son of Liberty. 320 pages.

LUMBERJACK BOB. A Tale of the Alleghanies. 320 pages.

THE WIRELESS PATROL AT CAMP BRADY. A Story of How the Boy Campers, Through Their Knowledge of Wireless, “Did Their Bit.” 320 pages.

THE SECRET WIRELESS. A Story of the Camp Brady Patrol. 320 pages.

THE HIDDEN AERIAL. The Spy Line on the Mountain. 332 pages.

THE YOUNG WIRELESS OPERATOR—AFLOAT. How Roy Mercer Won His Spurs in the Merchant Marine. 320 pages.

THE YOUNG WIRELESS OPERATOR—AS A FIRE PATROL. The Story of a Young Wireless Amateur Who Made Good as a Fire Patrol. 352 pages.

THE YOUNG WIRELESS OPERATOR—WITH THE OYSTER FLEET. How Alec Cunningham Won His Way to the Top in the Oyster Business. 328 pages.

A U. S. Coast Guard Cutter Surrounded by Icebergs

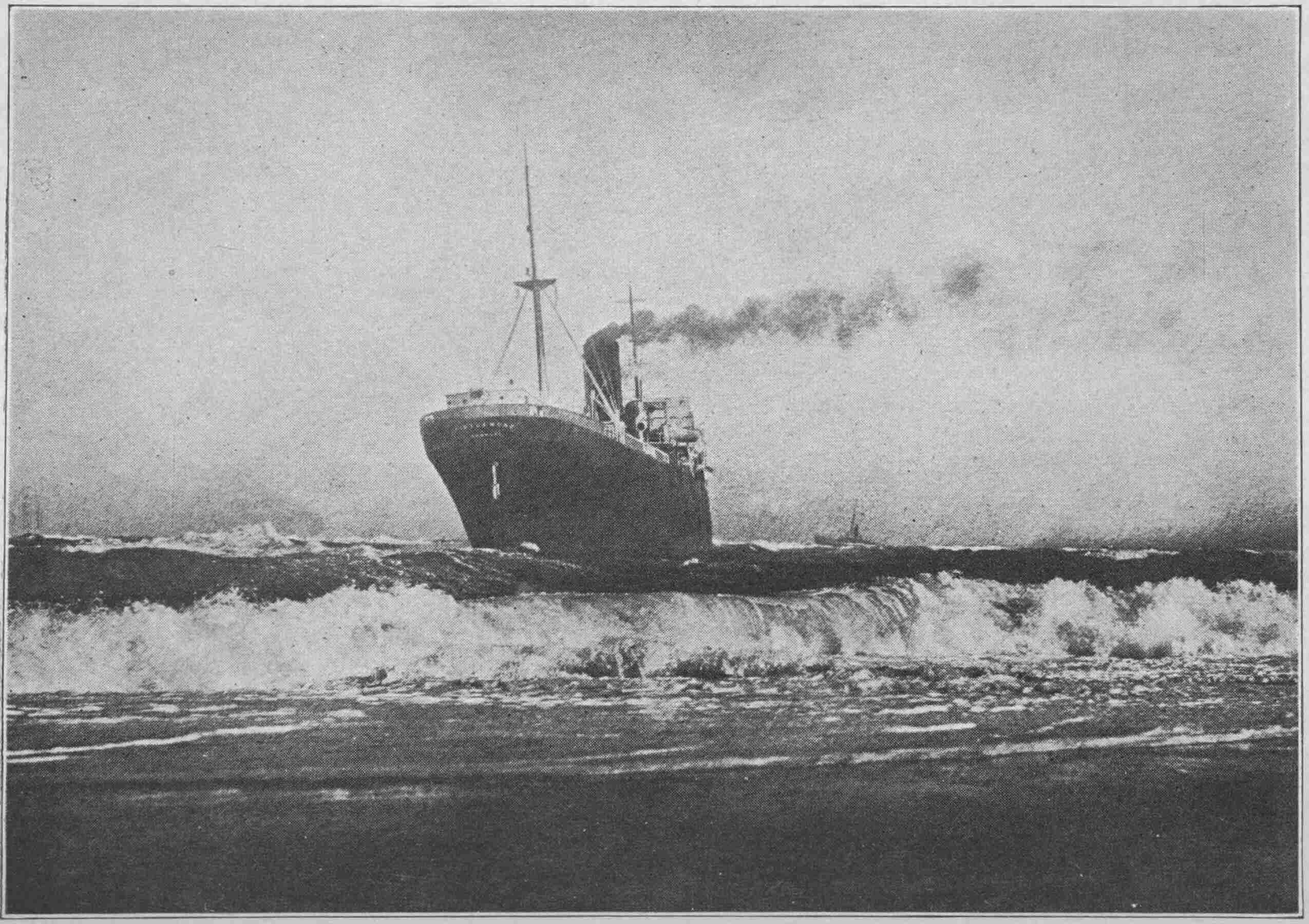

Among all the various arms of government in our nation, no arm is at once less known or more worthy of renown than the Coast Guard. Like the knights of the Table Round, this company of gallant surfmen and sailors is organized and exists almost solely for the protection of others. Though few in numbers, the Coast Guard accomplishes deeds that are mighty. Skill of the highest order, daring incredible, and discipline that is perfect, make a giant of this little service. Stout of heart, indeed, must be the men who belong to it; for when others are fleeing for their lives, the Coast Guard is always heading straight for the danger, to rescue those incompetent or unable to effect their own rescue. Let those who think the age of romance is past but read the story of the Coast Guard and they will change their minds.

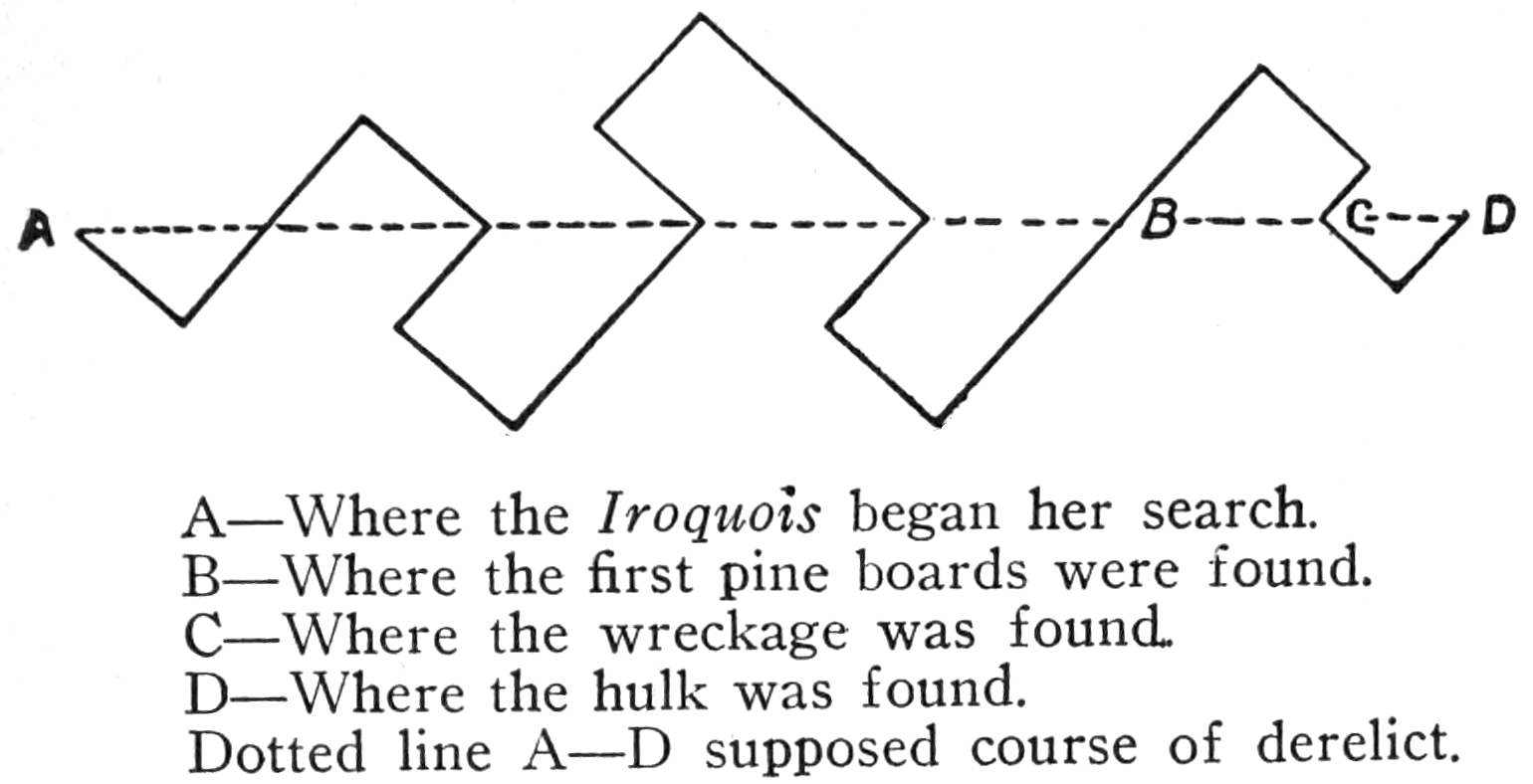

For those who demand that fiction be based upon actual occurrence, the author wishes to say that this book is hardly more than a transcript from life. Every major incident in it is based upon an actual happening. It was the Coast Guard cutter Yamacraw that lost six boatloads of seamen in the surf while attempting to rescue a helpless steamer. It was the Seneca that searched the wintry seas for the helpless oil tanker that had been abandoned by the tug towing it. And the final incident in the book, in which a stricken freighter sinks in a storm, and the wireless operator ministers calmly to his commander in the face of almost certain death, is but a poor attempt to recite the story of “Smiling Jimmy Nevins,” a mere lad, who went smiling to his death as a member of a volunteer crew from the Seneca, in an effort to save a torpedoed freighter for the Allies during the recent World War.

In preparation for the writing of this story, the author spent some time aboard both the Seneca and the Tampa. He wishes here to express his admiration for the Coast Guard as a whole, and his very great indebtedness to Captain B. H. Camden, of the Seneca, Captain Wm. J. Wheeler, of the Tampa, Lieutenant C. C. Von Paulson, of the Tampa, and Chief Electrician Belton Miller, of the Seneca, for their kindly assistance. Each of the four has played a heroic part in some of the deeds portrayed in this book.

Reading into the present the history of the early mariner along our shores, one is impressed with the march of civilization. Institutions having for their purpose the saving of human life are products of civilization—a part of the great scheme of humanization.

This volume, dedicated “To those unsung heroes, the men of the U. S. Coast Guard,” is an interesting, an engaging, and a compelling portrayal of the everyday work of the Coast Guard, with its vicissitudes, hardships, perils and accomplishments. The Coast Guard in fact is an establishment of service and opportunity—service to those whose fortunes are cast with the deep and along our shores, opportunity for the young men of the nation of character, stability and fixedness of purpose, to follow the Stars and Stripes in the ever-beautiful cause of humanity.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I. | Henry Seeks His Fortune |

| II. | A Fight for Life |

| III. | The Search for the Derelict |

| IV. | The Watch in the Dark |

| V. | The Destruction of the Derelict |

| VI. | A Call for Help |

| VII. | A Tramp of the Seas |

| VIII. | In the Cradle of the Deep |

| IX. | The City of Paul Revere |

| X. | A Ship in Distress |

| XI. | Lost in the Sea |

| XII. | The Rescue |

| XIII. | Henry Finds He Has an Enemy |

| XIV. | A Catastrophe |

| XV. | Under a Cloud |

| XVI. | The Mystery Grows Deeper |

| XVII. | A Ship in Distress |

| XVIII. | A Clue to the Culprit |

| XIX. | The Culprit Discovered |

| XX. | Henry’s Exoneration |

| XXI. | Among the Icebergs |

| XXII. | Victory |

Henry Harper was making his way down the longest street in the world as fast as the jam of traffic would allow. But this longest street in the world, Broadway in New York City, is also one of the world’s busiest thoroughfares, and, despite his haste, Henry Harper could proceed but slowly. It was the noon hour, and the sidewalks were jammed with thousands upon thousands of clerks, stenographers, business men, and other busy workers, going to or from their luncheons. The streets were overflowing with vehicular traffic, as the sidewalks were with foot-passengers. No matter to which side Henry darted, there was always some person or some vehicle in front of him, and so, though quivering with impatience, he was obliged to curb his speed and make his way the best he could among pedestrians and trucks. He was bound for the office of the United States Secret Service, and it seemed to him that he would never get there. He had just come to New York from his home in Central City, Pennsylvania, and he was on his way to see his old friend Willie Brown, who had some time previously won a position with the Secret Service.

When, finally, he did reach his destination, Henry found himself facing a situation that troubled him a great deal more than he cared to admit. Willie Brown was not in the office. What was more, Willie was not even in town. He had been sent away on some special duty. The office boy did not know when Willie would return. All he knew was that Willie had started on a trip that would probably last two or three weeks, and there was no one in the office who could give Henry any more definite information. All the clerks were out at luncheon, but they probably wouldn’t know where Willie was going, anyway. And the Chief, who had given Willie his orders in person, had left for the day.

If Henry had wanted to see Willie merely to renew old acquaintanceship, the situation would have been unpleasant enough. But it was a thousand times worse than that, for Henry had come to New York upon Willie’s express invitation, and the latter was going to try to help him get a job. Henry had not told him exactly when he would arrive, and so he could not blame him for not being on hand or for not leaving a message for him. Willie’s absence made it mighty unpleasant for Henry, though, for the latter had expected to be his guest, and his funds were slender. Indeed, he had little more than enough money to pay his return car fare. Two or three days at a New York hotel would exhaust these funds entirely. No wonder Henry looked worried as he slowly left the building and stepped once more into the seething jam on Broadway.

“I’ll slip over to the Confederated Steamship Office,” thought Henry to himself. “I know the Lycoming is at sea, and Roy won’t be back in New York for almost a week. But maybe I can find some one who can help me out of my difficulty.” So he headed hopefully toward the piers on the Hudson River front, occupied by the coastwise steamship line for which another of his old chums, Roy Mercer, now worked as a wireless operator on the steamer Lycoming.

Again he was doomed to disappointment. Not a ship lay in the docks. Not an official of any sort could be found about the place. Only a watchman was in charge, at the gate, and he proved to be gruff and surly. If only one of the Lycoming’s sister ships had been in port, Henry would have appealed to the wireless operator on her, and trusted to the freemasonry that exists among wireless men generally. But there was no such luck for him. Apparently there was no one he could reach to whom he could appeal. Here he was, stranded in the metropolis, without a friend or an acquaintance, with no job in sight, and with only a very few dollars in his pocket. It was a situation to take the heart out of almost any boy.

But Henry was no ordinary boy. To begin with, he was approaching manhood. In a year or two he would be old enough to vote. He was as large as most men, and as independent mentally as he was sturdy physically, so he did not become alarmed and panic-stricken, as a younger lad might have, but set himself to think out the best course he could pursue. He knew that all he had to do was to find some way to tide himself over until either Roy or Willie returned, and things would be all right.

Nevertheless he was worried about his money. For even though he could readily borrow from his friends upon their return, it wouldn’t be exactly an easy thing to repay the loan. The money in his pocket was about all the money he had in the world.

With Roy and Willie, he had belonged to the Camp Brady Wireless Patrol. Indeed, it was Henry himself who had organized that little group of boys, and who had made the first wireless set they possessed, by the use of some patterns given him by an uncle. And he had become probably the most expert wireless operator in the patrol. In fact, during an emergency he had served for a time as a government operator in the big wireless station at Frankfort, not so many miles from his home in Central City.

When he thought of those days Henry sighed, almost with bitterness. Then he was the leader in every respect. Not only was he the oldest boy in the Wireless Patrol, but he was farthest advanced. In the nature of things he should by this time have been far along the road to success, and in a position to help his friends; whereas it had actually turned out that he was behind them all, and that they were helping him instead. Yet it was no fault of Henry’s. His father’s death had thrown upon him the burden of supporting not only himself but his mother as well. Henry had given up his work at the high school for a time, but his mother had insisted upon his completing it. It had taken him twice as long to finish his course this way as it would have, could he have gone on without interruption. But now he was glad he had listened to his mother. Even though he was so late getting started, he knew he would go farther in the end.

But was he started? The question worried Henry so much that he could hardly think. He had come to New York with high hopes of getting a real start, and now he seemed about to waste the few remaining dollars he possessed. What should he do? The roar of the traffic disturbed him. He could not think connectedly. He wanted to compose himself, so he made his way down the water-front to Battery Park, where he might be undisturbed while he thought out his problem.

But the familiar scenes in Battery Park set a new train of thought in motion in his head, and utterly defeated, for the time, his plan to think out his course of action, for in front of him, as he sat on a park bench, was the old, familiar harbor, with its seething waters and its throbbing life. And straight across the rolling waves was Staten Island, where he had spent those memorable days in that never-to-be-forgotten hunt for the secret wireless of the Germans, during the war, when the Secret Service had accepted the proffered help of the Wireless Patrol in the search for the treacherous spies that were betraying the movements of American transports. How clearly all the incidents of that search for the secret wireless now stood out in Henry’s mind. He could recall, as though it had been but yesterday, the departure of the selected unit of the patrol—Roy Mercer and Lew Heinsling and Willie Brown and himself—from Central City, and their meeting with their leader, Captain Hardy, and the tedious watch for the German spies, lasting through weeks, which began in upper Manhattan and ended in Staten Island.

And when Henry thought of the snug little headquarters they had had in a private house in Staten Island, with a delightful elderly couple, he jumped to his feet and almost shouted with relief. Why hadn’t he thought of those old people before? They would take him in and tide him over until his friends returned. They would be glad to see him again, too. Henry felt sure of that, and, sighing with relief, he leaped to his feet, seized his little suit-case, and hustled over to the near-by municipal ferry-house, just in time to catch an outgoing boat for Staten Island.

Eased in mind, he now eagerly watched the harbor, thrilling with the stirring scenes before him. Six miles as the crow flies lay the course across the bay to Staten Island, and this six miles was alive with shipping. Everywhere vessels were moving. Sister ferry-boats were ploughing the waves straight toward Staten Island. In the Hudson and the East Rivers more ferry-boats were crossing back and forth. Big steamers were moving majestically along. Tugboats without number churned the choppy waves to foam, some riding in solitary state, and some towing long strings of barges at the ends of great hawsers. Others were snuggled in between big lighters, like porters with huge bandboxes under each arm. In the anchorages below the Statue of Liberty great tramp ships rode idly at anchor, awaiting cargoes. And on the opposite side of the bay, below Governor’s Island, stately sailing ships rolled gently in their moorings. Motor-boats, yachts, sailboats, even an occasional rowboat, moved this way and that. The surface of the water was crossed and recrossed with lines of yeasty foam, churned up by the passing craft, while the air was vibrant with the ceaseless tooting of ships’ whistles.

And there was Governor’s Island, with its antiquated round fort, and the ancient cannons atop of it. And farther along was the newly-made part of the island, filled in with thousands of loads of material brought by barges. On this made land now stood row upon row of government sheds and warehouses erected during the war. And Henry recalled the still more stirring scenes during those days of struggle, when every possible anchorage was occupied, and the boats of the Coast Guard went rushing about with their peremptory orders to incoming steamers, like traffic police of the harbor, as indeed they were. And as his boat drew near the ferry-house at St. George, Henry saw a Coast Guard cutter herself lying at anchor close to the Staten Island shore. How trim and beautiful she looked, in her shining white paint, with her flags flying, and her motor-boat lying lazily alongside.

But now the great ferry-boat was coming to rest in her dock. The clank of pawls, as the deck-hands made the huge craft fast, the lowering of the gangways, and the hurried rush of feet, made Henry take his gaze away from the fascinating harbor scene, for the crowd was moving and he had to move with it. In another moment he had stepped ashore and found himself outside the ferry-house.

An interesting place, indeed, was this St. George terminal. Henry had journeyed on the upper deck of the ferry-boat, and now he found himself in the upper part of the ferry-house. There were all the usual features of a great waiting-room—long rows of seats, and news-stands, and quick-lunch counters, and fruit-stands. None of these interested Henry. His attention was centred on the scene without. The edge of the island was a low-lying fringe of land, now given over wholly to shipping facilities—great wharves and piers and wide roadways skirting the water’s edge. Inland a few hundred yards the ground rose sharp and steep, and these sloping terraces were covered with buildings. Skirting the hilly heart of the island, roads wound downward, meeting directly in front of the ferry building, and reaching that structure by a long, sloping approach. These converging roads made Henry think of a huge funnel, with the sloping ferry-approach as its small end. And the idea of a funnel was carried out by the way this approach poured traffic into the ferry-terminal. Trolley cars, motor cars, and pedestrians swarmed down it in endless procession. Seemingly all the roads in Staten Island converged at the upper end of this ferry-approach, and shunted their burdens toward the crowded ferry-house.

Up this ferry-approach Henry made his way until he came to the end of it, where it split into divergent roads. A moment he stood here, waiting a favorable opportunity to cross the road. While waiting, he noticed a man on the opposite curb, who was likewise held up by the traffic, and who was evidently impatient of delay. Suddenly the man swung from the curb and tried to worm his way across the thoroughfare, among the moving vehicles. He had a bulging suit-case in one hand and a large package in the other. Henry judged that he was hurrying to catch a boat.

The stranger was halfway across the street, when a recklessly driven car, rushing up the ferry-approach, made the nearest drivers on the upper roads swing sharply to one side. That caused all the traffic to turn out. The man crossing the road was so laden with bundles that he could not move quickly enough, and he was caught directly in front of an oncoming motor truck. With a leap, Henry was at the pedestrian’s side. Seizing him by the arm, he dragged him to safety. But the car in passing knocked the parcel from the man’s arm and broke it open, scattering its contents on the road. The car behind promptly stopped, blocking the traffic. Henry snatched up the scattered contents of the parcel and jumped back to the sidewalk. Then he took the suit-case himself, while the stranger bundled the contents of the broken parcel under his arms, and together they made their way to the ferry-house.

Henry’s companion was a heavy-set man of ruddy complexion, whose strong face showed both firmness of character and kindness of spirit.

“That fellow would have got me sure,” he said indignantly, “if it hadn’t been for you, sir. They ought to put about half of these motor-car drivers in jail.”

“They’re pretty reckless,” Henry agreed.

“I don’t know how I am ever going to repay you,” said the man. “You probably saved my life.”

“I don’t want any pay,” said Henry. “If I really saved you from harm I am glad.”

They reached the ferry-house, but, instead of entering, the man turned to the right and went down a flight of steps. Then he walked across the lower road to the very edge of the wharf, and out on a little float. Henry saw at once that the man must belong on some one of the ships at anchor near by, and was probably waiting for a small boat to meet him.

“If I can be of no further help to you,” said Henry, “I must be on my way.”

“I guess I’m safe enough now,” laughed the man. “And I owe it to you that I got here with a whole skin.” He thrust his hand into his pocket and pulled out a little roll of bills. “Take these,” he said to Henry, “and my best wishes.”

Henry looked at the money longingly, but only for a second. “I thank you,” he said, “but I couldn’t do it, sir.”

“At least you will shake hands,” smiled the stranger, and he thrust out his hand. Henry took the proffered hand, shook it warmly, and, saying good-bye, turned on his heel. In a few moments he was back at the crossing, and a second later he had gained the farther curb and was absorbed in the study of the old town where he had spent such memorable days.

But what a difference! This was not the town of St. George as he knew it at all. How it had expanded and been built up. On every hand arose unfamiliar buildings. From a little town the settlement had altered into a city. Where once stood little cottages now arose great business blocks or towering apartments. No longer was this a sleepy little island. It was a pulsing part of a great city.

Rapidly Henry strode along, his pulse stirred, as always, by the throbbing life of the great metropolis. On he went, and on and on, until he came to the place where he should have seen the house of the German spy. It was no longer there. A great row of apartments had replaced it. And when Henry looked above, at the higher level where stood the house in which he and his comrades had spent so many thrilling days, again he saw a row of towering apartments. The house he was seeking no longer existed.

The realization shocked him. He stopped in his tracks and stared. His heart almost stood still. His last hope was gone. Then wildly he tore up the roadway to the higher level, still hoping that he might find some trace of the people he sought. His hope was vain. No name in any doorway even remotely suggested the name he was looking for, and all whom he questioned gave him the same reply,—they did not know any one of that name.

Almost stunned, Henry turned about and slowly retraced his footsteps. He was hardly conscious of where he was going, but he kept walking, and his footsteps naturally went downhill. Before he realized where he was, Henry found himself on the water-front. A great, wide, cobbled thoroughfare ran along the water’s edge, and here, projecting far out into the bay, stood pier after pier in a magnificent row, all built as a result of the war. But the pulsing life of the war days was gone. Many of the piers seemed empty or deserted. Few vessels lay in the docks. Yet the splendid water-front, once open and unobstructed, was now completely shut in by these hulking structures. To see the water here, one must either go back up the hill, where one could see over the pier-sheds, or else go to the seaward end of a pier. And no matter how keen his disappointment was, Henry did want to see the water-front here. After a little he would go back to Manhattan and try to find some quarters where he could exist until one of his friends returned, or until he could get a job. But before he went back he meant to have a good look at this lower end of the harbor, which he loved so well.

Carefully he made his way along the edge of a pier, outside of the pier-shed. It chanced to be unoccupied. Henry was glad it was so, for there would be no one to disturb him. He could enjoy the scene to his heart’s content. When he reached the outer end of the pier, he set his little suit-case down and gave himself up to full enjoyment of the scene. Not far below him were the buildings at the quarantine station, and a great steamer lay in the Narrows there, evidently detained by the quarantine officials. Here were no hurrying ferry-boats, but directly off the pier on which he stood were anchored a number of ocean-going craft. How huge they seemed. How alluring was the thought of a voyage aboard one of them, even if they were but clumsy freighters. There was nothing clumsy about the little Coast Guard cutter that lay near them, however, and again Henry admired the trim little craft. He saw her small boat returning from land with some passengers aboard, and he wondered at her speed and the way she darted through the waves. He could even see the man on watch, as he paced back and forth across the bridge.

Presently an ocean liner passed down the Narrows, headed for the open sea. How majestically she rode the waves! Her rails were lined with people. Henry wondered where they were going, and when they would be coming back again. He watched the great ship until she began to grow small in the distance. He was lost in thought, his mind with the voyagers on the great vessel. There was not a soul about to disturb his meditations. No one was on the pier, and no ships lay in the docks alongside. How he wished he might take a journey abroad, like the passengers on that great liner, and see distant lands and strange peoples.

Unconsciously Henry had approached the very edge of the pier. He hardly realized that only a foot or two of solid planking lay between him and the heaving waters. His thoughts were entirely centred upon the vanishing steamer. He wanted to watch her until he could see her no longer. Her course turned her slightly toward the shore, behind some pier-sheds and shipping farther down-stream. Henry craned his neck as far as he could, to watch the disappearing vessel. Then he took one step forward, and, as he did so, his toe caught under a spike which was sticking up an inch or so in the flooring of the pier. He lost his balance, and, before he could recover himself, pitched head foremost over the end of the pier. Then, with no one near to aid him, with not a soul to hear his startled cry for help, he sank far down into the cold and heaving waters.

So confused was Henry that he knew not in which direction to strike out. He could not tell which way was up and which was down. He was afraid to try to swim, lest he drive his body still deeper into the water, or swim against a piling and perhaps knock himself unconscious. Instinctively he had taken a deep breath just as he struck the water. It was fortunate, for he was a long time coming up, and before his natural buoyancy lifted him to the surface, he began to suffer for air. His lungs seemed to be bursting. He felt as though he were suffocating. But just when it seemed as though he could hold his breath no longer, his head shot up above the water.

With a gasp Henry sucked in a lungful of air, and with it he gulped down a mouthful of salt water. He began to cough and as he did so a choppy wave hit him smack in the face and he swallowed more water. Although he was an excellent swimmer, he was really in a bad way. All of his swimming had been done in smooth, fresh water. He was not accustomed to salt water and the roughness that usually accompanies it. With his face drenched with the spray, his eyes stinging with the salt water, and the choppy, uneven waves dashing over him, he knew not how to take care of himself, or hardly in which direction to try to swim.

Indeed, it would have bothered even a more experienced person to know just where to turn. The pier from which Henry had fallen contained not a soul, and no boats lay in the long, flanking docks. It was useless to look for help from that quarter. It was almost as useless to turn toward the ships that lay at anchor some hundreds of yards out in the water. Between them and the shore the tide was sweeping seaward with great power. Even if he could manage to keep afloat, it would be almost useless to swim toward these ships. He could never hope to stem that strong current, and the chance of being seen by any lookout on the ships seemed remote indeed to Henry. As for getting out of the water, there seemed no possible chance of that either. There were no ladders, no ropes, no steps visible anywhere along the piers, by which he could mount upward. Only the rounded pilings that upheld the pier floors offered space to cling to, and these were covered with rough barnacles and coated with slime. Besides, it would do little good to cling to them unless he could first attract the attention of some one.

With all his might Henry shouted, but he got no response. He was fast becoming chilled, for the water was very cold. His strength was ebbing, and the swirling eddies sucked him toward the pier. Once, indeed, he was drawn entirely under the pier, and the choppy water knocked him roughly against the pilings. His head banged hard against a great spile, and for a moment Henry almost lost consciousness. Then he recovered his full senses and set himself to fight for his life. His strength was going fast, and he knew it. Yet he did not allow himself to become panic-stricken. He took a grip on himself, turned away from the pier, and struck out with all his remaining strength. Whatever happened, he would get away from those deadly pilings. The thought of dying under the pier, among those slimy spiles, chilled him worse than did the cold water.

Incessantly the waves dashed in Henry’s face, blinding him. But he kept his mouth shut and quickly learned to breathe guardedly, so he swallowed little more water. Before him he could dimly distinguish the great black bulk of an anchored ship. Even at the risk of being swept seaward, he decided that he would try to swim to it.

Had it not been for his wet clothing and his shoes, which felt like lead, Henry might have been able to make it. But his garments held him back terribly. And so, though he continued to make headway, he was swept swiftly along with the tide, out toward the open sea. From time to time he shouted and waved a hand aloft, trying to attract attention. All at once he realized that he could never gain his goal, and the thought struck sudden terror to his heart. Still he struggled on, but his strokes grew feebler and feebler. His vision became so confused he could not see anything clearly. He was so utterly tired as to be almost exhausted. Indeed, his movements had become almost mechanical, and he had all but lost consciousness when he was startled by the sharp clang of a bell and the noisy churning of water close at hand. Then something took him by the coat-collar and he felt himself being bodily lifted out of the waves. Again the bell clanged sharply, once more a propeller churned the waters, and he felt himself moving swiftly over the tide.

It was a full minute before Henry could clear his brain and wipe his eyes clean, so that he could see. He found himself in a powerful little motor-boat, quite evidently built for use at sea, that was now scudding along under full power direct toward the little white Coast Guard cutter. Straight at the cutter charged the little craft. When it was only a few yards distant, the bell clanged once more, the propeller ceased to revolve, the little boat’s head came sharply about, and in another moment the craft was resting beside the ship’s ladder.

“Can you make it alone?” asked one of the sailors in the boat, as Henry rose to his feet and stepped on the landing-stage of the cutter.

“Sure,” said Henry, who was already recovering his strength.

“Then up with you, quick.”

“All right,” answered Henry, “but first I want to thank you men for saving me. I couldn’t have kept afloat much longer. You got to me just in the nick of time. I don’t know what to say, to make you understand how I feel.”

“Forget it,” smiled the sailor, “and hustle aboard. You’ll get pneumonia if you stay there in the wind.”

Henry turned and started to mount the ladder. He noticed that one of the sailors was close behind him, apparently ready to support him if he needed help. But Henry was not now in need of assistance. His strength was increasing every minute. He grasped the ladder-rail and mounted upward, and when he looked ahead of him, he saw that the cutter’s rail was lined with faces. Apparently the entire crew had been watching the rescue.

As he reached the deck, Henry looked about him. Dozens of sailors, in their strange blue uniforms, were gathered forward of the ladder. And just aft of it stood a group of officers, looking very brave and trim in their blue uniforms, with their gold-braided caps and their gold-embroidered sleeves and shoulders. The captain looked especially fine. He was a heavy-set man with a ruddy countenance. His uniform gave him an air of real distinction. Somehow, his face looked familiar to Henry, but it was not until the man spoke that Henry knew who he was.

“Bless my stars!” exclaimed the captain, when he had taken a good look at Henry. “If it isn’t the lad who saved me from that old motor truck a few hours ago!” Then, without a word to Henry, he said: “Hustle him down to the fireroom, rub him briskly, fill him up with hot coffee, get him some dry clothes, and, when you get him to sweating good, bring him to my cabin. Now, step lively.”

And step lively those sailors did, too. They rushed Henry forward and down a steep, iron ladder into the hottest room he had ever been in. And they stripped off his clothes and rubbed him with rough towels until they almost skinned him. Then they provided him with dry clothing. Meantime a mess-boy brought steaming hot coffee from the cook’s galley, and Henry drank cup after cup of it. Very grateful, indeed, was all this warmth after his chilly bath. Yet it was some little time before Henry was really warm. But presently he became more than warm. He grew hot. Then beads of perspiration broke out on his body, and presently he was sweating profusely. Meantime the ship’s surgeon had come into the fireroom and examined his pulse, listened to his heart beat, and given him some sort of a dose. Then the doctor led the way up to the deck and along to the after companionway and so down to the captain’s cabin.

“Well, how are you feeling?” asked the captain, as Henry and the surgeon entered the cabin, after knocking at the door.

“First rate,” laughed Henry, “but about as hot as a furnace itself.”

The captain chuckled. “That’s good news,” he said, “eh, Doctor?”

“The very best,” said the surgeon. “He’s all right, Captain. I think his ducking will not hurt him a bit. He shows no sign of chill or shock or any bad after-effect.”

“Very good, indeed. But keep your eye on him, Doctor. Now that we have got him, we don’t want to lose him.”

The surgeon withdrew, leaving the captain and Henry alone in the little cabin.

“Tell me, my boy,” said the captain, with great kindness, “how in the world you ever got overboard. And, by the way, what happened to your suit-case? Did you lose that overboard?”

“Gee!” said Henry. “I forgot all about that. It’s back on the pier that I fell from. Is there any way I could get it?” And he began to look much worried.

“Don’t be alarmed about it,” replied the captain. “We’ll have it on board in a jiffy.”

He stepped to the table in the centre of the cabin and pressed a call-button that hung over it. An attendant instantly responded.

“Rollin,” said the captain, “tell Lieutenant Hill that this lad had a suit-case, and that, unless some one has taken it, it is on the pier from which he fell. Ask the lieutenant to see that it is recovered at once.”

The attendant raced up the companionway, and a moment later Henry heard the clang of the bell in the little motor-boat and the churning of her propeller.

“I’m mighty sorry you fell overboard,” continued the captain, “but I’m also mighty glad to welcome you aboard the Iroquois. After what you did for me, it gives me the greatest pleasure to be of some slight service to you. Now tell me something about yourself. What is your name? And where do you come from? Seeing that you carry a suit-case, I judge that you do not live in New York.”

“No, I do not,” said Henry. “My home is in Central City, Pennsylvania, and my name is Henry Harper.”

“Well, we’ll shake hands, Henry. My name is Hardwick—Captain Hardwick.” And he thrust out a muscular palm.

Henry shook the proffered hand. “I owe you my life,” he said. “I never can thank you adequately, but please believe I am grateful to you.”

“Then we are quits. It is a case of tit for tat, isn’t it?” And the captain smiled genially. “Now tell me what brings you to New York and to Staten Island?”

“Well,” explained Henry, “I came over to New York to see an old friend of mine, Willie Brown. He won a place in the Secret Service recently and he promised to try to get me a job if I would visit him.”

The captain frowned ever so slightly. “So you have been bitten by the detective bug, too, have you?” he said.

“No, sir,” answered Henry. “I have no wish to be a detective, but I do want a job. You see, sir, I was graduated from high school only last June, and I want to get to work just as soon as I can. There do not seem to be many very good jobs open to a fellow in a little town like Central City.”

“I see. It always seems that way. Distance lends enchantment to view. But never mind about that. What luck have you had here?”

“About the worst possible,” said Henry, with a grim laugh. “Willie wasn’t in town, and won’t be for two or three weeks. And Roy Mercer, another of my friends, who is wireless man on the Lycoming, is at sea and won’t be in port for at least a week. And so I can’t find a soul I know.”

“But what took you to Staten Island?”

Henry hung his head. “You see, Captain Hardwick,” he said slowly, “I—I—didn’t exactly know what to do until Willie or Roy got back, and I thought maybe I could find some friends in Staten Island. I came here looking for them, but they have moved. It sort of upset me, and I went down to the water-front to think what I should do. Then I fell overboard.”

The captain looked at Henry searchingly. “You look big enough and experienced enough to take care of yourself for a week, even in New York. Why didn’t you go to a hotel and make yourself comfortable while you waited for your friends?”

“I’d have been only too glad to do so, Captain, but you see—you see—I came here expecting to be Willie’s guest—and I wasn’t prepared to—to——”

“Out with it,” said the captain. “You mean you haven’t the money, and you were worried about how to get along.”

“That’s exactly the case,” said Henry. “You see, Captain, my father is dead, and I had to work while I went to school, so it put me behind a little. Willie wanted to help me get a job, and he offered to take care of me while I was here. I had enough money to pay my car fare here and back, but that is about all. So you see I couldn’t very well go to a hotel.”

“Well, bless my stars!” ejaculated the captain. “And you wouldn’t take a cent from me this morning.”

“I couldn’t, Captain. Would you take pay from me for saving my life just now?”

“Certainly not, but that’s different. Saving life is part of my job. That’s what I’m paid for. Besides, I didn’t have a thing to do with it. The man on watch saw you fall overboard, and I merely ordered out the boat.”

“I can at least thank you for ordering out the boat. And I want to do something to show my gratitude to the men who fished me out of the water. I was almost gone when they got me, Captain Hardwick.”

Again the captain stepped to his call-bell. “Rollin,” he said, when the attendant appeared, “tell Lieutenant Hill to send the crew of the motor-boat to my cabin when they get back with this lad’s suit-case.”

“Yes, sir. I think they are here now, sir.” And the attendant hurried up the companionway.

A moment later three sailors appeared, one of them carrying Henry’s suit-case. They came into the cabin and stood at attention.

Henry jumped to his feet. “I don’t know your names,” he said, “but my name is Henry Harper. I want to thank you for what you did for me. If you hadn’t got me, my mother would have been left all alone, without any one to take care of her. I don’t know what to say to you, but please believe that I am deeply grateful.”

The sailors were pleased, though they made light of the event. “Forget it, kid,” one of them said. “It’s all in the day’s work.”

“Then I’ll say it’s a pretty fine sort of work you men do,” replied Henry. He shook hands heartily with his rescuers, and the three sailors went tramping up to the deck.

“You told the truth, Henry,” said the captain, after the sailors had gone, “when you said they were engaged in a fine sort of work. It is a life full of hardships, this life of a Coast Guard, and yet the men love it. If you are looking for a job, you can find an opening right in this service.”

“What could I do?” asked Henry. “I don’t know a thing about the sea. I don’t have any desire to be a mechanic, and so I wouldn’t make a good engineer. And I really would not care to be a sailor.”

“You might become a wireless man, like your friend on the Lycoming. You could doubtless learn to operate the wireless as well as he can.”

Henry smiled. “There wouldn’t be any trouble about the wireless,” he said. “I’ve already worked for Uncle Sam as an operator.”

“The dickens you have! Tell me about it.”

And Henry told Captain Hardwick all about the Wireless Patrol, about the capture by that patrol of the German dynamiters at Elk City, about the hunt for the secret wireless right in Staten Island, and about his serving as a substitute operator in the Frankfort wireless station.

The captain’s eyes opened wide as he listened to the story. “If there’s anything in having plenty of good operators aboard, we ought to be safe on this ship,” said the captain, “for you are going to stay here as my guest until your friends get back to New York. Meantime, you can find out a whole lot about the life on a Coast Guard cutter, and perhaps you might decide to enter the service yourself.”

“Do you mean it, Captain Hardwick?” asked Henry, his heart beating high at the prospect.

“Certainly I mean it.”

“And shall we go to sea?” cried Henry.

“Indeed we shall. I received orders just a little while ago to destroy a derelict that has been sighted off Nantucket Shoals. That’s what brought me aboard. You see I live in Staten Island—when I’m home. I’m waiting for my executive officer. The minute he comes aboard, we’ll hoist anchor.”

“Thank you, Captain,” cried Henry. “Won’t that be bully! I’ll be more than glad to go. But I ought to let my mother know what has happened to me. She’ll be worried when no letters come.”

“Entirely right,” said the captain. “Here’s my desk. You can write her a letter whenever you wish. If there was any way to reach her by wireless, we could send word to her at once from the ship.”

“Bully!” cried Henry. “Of course I can. The fellows at home will be listening in for me right after supper. We made that arrangement before I left home. I expected to call them up on the outfit Willie uses at the Secret Service headquarters.”

“Very good,” said the captain. “Then we’ll call it settled. And I hope you’ll enjoy every minute of our trip.”

So overjoyed was Henry at his sudden good fortune that he wanted to throw up his hat and cheer. But he knew that would never do. To hide the emotion that was struggling for expression, he stepped into the little stateroom that the commander now indicated was to be his, and so keen was his interest in this that he promptly forgot his desire to make a noise.

The captain’s cabin was in the after part of the ship, and the little staterooms, for there were two of them, occupied the very stern. These staterooms were twin compartments, one for the captain and one for his guests. A narrow passageway divided them. Each stateroom contained a snug-looking bunk, with a round air-port, or window, just above it, like a huge eye; and there was also a wardrobe, and a dresser with a mirror above it. Each stateroom, likewise, led into a private bathroom, as comfortably equipped as any similar room on land. The enormously high sides of the bathtub at once caught Henry’s attention, and he rightly guessed that these were to prevent water from slopping out of the tub when the ship was plunging in the waves. As soon as he had examined his quarters, he unpacked his little case, stowing his few articles of clothing in the dresser. Then he stepped back into the cabin to have a look at that.

Fortunately, the captain had gone on deck, and Henry was free to examine things to his heart’s content. The cabin would have filled the heart of any boy with delight. Occupying a cross section of the after part of the ship, it reached from side to side of the vessel, with rows of round air-ports on either side letting in air and light, and giving a view out over the water. Along either wall, directly under these air-ports, were leather-cushioned seats, where one could sit or lie at ease. In the centre of the room was a square oak table, now covered with a soft green felt cover. A sideboard was built into one side of the cabin, and Henry was interested to note how all the goblets and dishes were secured so that they could not fall from their places. Closets were also built into the sides of the room, and one corner was occupied by the captain’s desk, with his typewriter fixed on a movable shelf attached thereto. Doors led mysteriously into other parts of the ship, one of which, Henry later found, opened into the cabin of the captain’s steward or mess attendant. And of course there were comfortable chairs and electric lights everywhere, and books in a case, and some silver cups that Henry found had been won by the crew of the Iroquois at the annual manœuvres of the Coast Guard fleet at Cape May, and so many other snug and interesting things that he thought this was indeed the most delightful place he had ever been in. And now that the captain was not present, he wanted more than ever to give a loud whoop or two.

It is altogether likely that he would have done so, too, had he not just then heard the clang of the motor-boat’s bell alongside, and in another moment footsteps sounded in the companionway. Then the captain entered the cabin, followed by a tall, muscular-looking officer in full uniform.

“Mr. Harris,” said the captain, “this is my young friend, Henry Harper. He is going to be my guest for a few days. Henry, this is my executive officer, Mr. Harris.”

The two shook hands, and Henry knew at once that he was going to like the tall, frank-looking sailor before him. Honesty was written all over his face, and his wide-set blue eyes were as kindly as they were fearless. The moment he had finished greeting Henry, he turned to his chief expectantly.

“I just got a wireless order to destroy a derelict that was sighted off Nantucket Shoals, well offshore. Suppose you ask the chief engineer to get the ship under way at once, Mr. Harris.”

As the executive officer turned to go, the captain continued: “I don’t like the looks of the weather. Fog may shut down at any moment. We want to get out to sea before it catches us, if possible. So tell him to drive her hard.”

“Very well, sir.” And the captain’s right-hand man stepped out of the cabin.

“Henry,” said the captain, “I had better introduce you to the other officers at once. I’ll be busy in a little while, and might forget about it. Come into the wardroom with me.”

The captain was hard on the heels of the retiring executive officer. Henry followed his host through the companionway door, but instead of mounting the steps, the captain entered a second door directly opposite his own at the foot of the staircase, and Henry, following, found himself in the wardroom, or living-room, for the other commissioned officers. This was immediately forward of the captain’s cabin, and was not unlike it in size and furnishings. Several men in uniform sat about a table in the centre of the room, reading magazines, playing solitaire, or otherwise amusing themselves. All arose as the captain entered.

“Gentlemen,” said the commander, “this is Henry Harper, who is to be my guest for a few days.” Then the captain made Henry acquainted with each man separately, naming them as Chief Engineer Farley, Lieutenant Hill, Ensign Maxwell, and Dr. Drake, whom Henry had already met, although he did not until this time know his name.

“We’re short-handed, as you see,” said the captain, “but I guess we’ll manage to operate the ship anyhow.” And with a pleasantry or two, he withdrew. The executive officer delivered the captain’s order, and all the officers, hearing it, went to their stations.

“What did the captain mean when he said you were short-handed?” Henry asked the doctor.

“Oh! We don’t have our full complement of officers. We lack a junior engineer officer and a junior lieutenant. It makes it a little hard, because the officers we do have must perform extra duty.”

While they were talking Henry suddenly became conscious of a curious vibration in the ship, and a low, rumbling noise that filled the air. He suspected that the ship’s propeller must be turning. The ensign confirmed his suspicion when he said: “We’re moving. Would you like to go on deck and see how we get under way?”

Henry did not know it, but the ensign was quite as eager to see as Henry himself could possibly be. The ensign was fresh from the Coast Guard Academy, and this was his first trip as a commissioned officer. Henry was grateful for the courtesy, and gladly followed the young officer up the companionway.

“Come up on the bridge,” said the ensign. “As the captain’s guest, you will be free to go anywhere. We can see better there.”

Interesting as the sights about them were, the things to be seen on deck were even more interesting to Henry. And he made his way forward very leisurely, as he took the first good look at the Iroquois he had had opportunity to take. He noted that the after-deck, from the companionway to the taffrail, was entirely clear and open, and was roofed over with a tightly stretched awning. Amidships towered the smoke-stack. And here, too, was an array of skylights and ventilators, all open now, but so arranged, Henry saw, that in time of rough weather they could be securely battened down. And there were iron doors leading directly downward into the bowels of the ship. One of them was the door through which Henry had descended to the fireroom. Close by the after companionway rose a stately mast. High up on it was the barrel-like “crow’s-nest,” for a lookout aloft. And forward, just behind the wheelhouse, towered a second mast, also with a crow’s-nest, and with signal lamps on a cross-arm. Immediately Henry caught sight of the wireless antennæ stretched between these two masts, and his practiced eye noted every detail of the wiring, and traced the lead-in wire downward to a room beneath the wheelhouse. Amidships, along either rail, hung three or four lifeboats, swung outboard over the side of the ship, and lashed fast to big horizontal spars or strongbacks with stout rope shackles called gripes, so that they were held immovable, as in a vice. And here and there along the rails circular life buoys were fastened or “stopped” with short pieces of rope.

But before Henry could take in any more details, his companion had mounted a ladder that led directly to the bridge, where the captain had already taken his station.

The bridge was a steel structure, reaching from side to side of the ship, and raised high above the deck, so that an unobstructed view could be had of everything. It was railed in with strong, iron rails, reaching breast-high. Stout canvas covers were fastened all around it, extending from the floor almost to the level of the eyes, excepting immediately in front of the wheelhouse, where they were fastened lower. This was the weather cloth, to shut off the wind; and, as Henry was to learn, it was a welcome aid to the navigator. Compasses were balanced on strong pedestals at either side of the bridge, and there were various levers, to use in blowing the ship’s siren, and for other purposes as well, though, of course, Henry did not yet know what they were for, any more than he understood that the Franklin metal life-belts, or buoys, that hung at either end of the bridge could be dropped overboard by a single motion of the hand, and that when they struck the water the queer-looking tubes projecting from them would shoot out lights that would burn for a long period, showing persons struggling in the sea which way to swim for safety.

At present Henry was wholly engrossed in the action that was taking place before him. The ship was moving gently through the water. The anchor had been partly heaved up by the little hoisting engine on the forward deck, but in heaving it, the chain had become twisted around one of the movable flukes, so that the stem of the anchor could not be properly heaved in through the hawse hole. A warrant officer in uniform, and a small group of sailors, leaned over the bow rail, trying to release the fouled anchor. A slender rope ladder had been lowered over the side, and on this a sailor was creeping down to the anchor that hung partly in the water, with a small rope in his hand. The rope he cautiously slipped around a fluke, so that the anchor could be tilted up.

“That’s the boatswain, Mr. Johnson,” said the ensign, indicating the warrant officer in charge of the sailors.

Presently the anchor was freed. The boatswain signaled to the man at the hoisting engine, and slowly the huge anchor-chain was heaved taut, with the flukes of the anchor drawn up tight against the hawse hole. The moment the anchor was lifted free of the water, the boatswain notified the captain, who immediately signaled the engineer to crowd on steam. At once the vibration of the ship became more noticeable. Faster and faster she began to surge through the water, and presently she was steaming at top speed toward the open sea.

On some other occasion, perhaps, Henry would have centred his attention on the views without, but now he was wholly occupied with the mysteries of this wonderful ship, so he paid slight heed to the wonderful sights in the Narrows, and gladly followed the ensign when the latter suggested that they step inside.

They entered the wheelhouse, a tiny room just behind the bridge, where a sailor stood at the wheel, steering the ship in accordance with the captain’s low-spoken orders. Immediately they passed through a door into the chart-room. This was somewhat larger than the wheelhouse, though tiny at best. On a large shelf or table lay a number of charts, some dividers, pencils, erasers, sliding rules, and some binoculars. In a rack on the wall were various code-books and books of instructions to navigators. Lieutenant Hill was erasing some lines from a chart. A moment later the captain stepped in. The two consulted the chart, and made some measurements with the sliding rule.

“Our course is east, three-quarters south,” said the lieutenant.

“Very good,” replied the captain. “Mark it on the chart.”

The lieutenant laid his rule along the course indicated, and drew a line on the chart, while the captain stepped into the wheel room.

“Keep her east, three-quarters south,” he said to the man at the wheel.

“Aye, aye, sir. East, three-quarters south,” answered the helmsman.

“We’re laying a course direct for Ambrose Lightship,” said the lieutenant to Henry. “After we reach that we will head directly for the location of the derelict.”

Presently, as he heard a thin, shrill whistle piping on deck, Henry turned to the ensign.

“What was that?” he inquired.

“That’s the boatswain’s mate piping mess gear.”

“That’s all Greek to me,” laughed Henry.

“Well, that’s the nautical term for the call to table. The whistle blows ten minutes before meal time, and the men, except those who must remain on duty, must wash for supper. See them scurrying to get ready? Meals are served at seven-twenty, noon, and five at night. So it’s ten minutes of five now.”

Henry was watching the sailors hurrying below, when a hand was laid on his shoulder. “Well, youngster,” said the captain’s kindly voice, “it’s time that you and I got washed up, too, or Rollin will be in our wool.”

Thanking the ensign for his kindness, Henry followed the commander to the deck and then down the companionway to the cabin. What he saw made Henry open his eyes wide. A snowy table-cloth had replaced the green felt table-cover, and the square little table was beautifully set for two.

“You’ll find towels in your bathroom,” said the captain. “And if anything is missing, just ring for Rollin and he will bring it to you.”

In a few moments the captain and Henry sat face to face at the small table, and Henry was enjoying one of the pleasantest meals he had ever had.

Night was approaching when the meal was ended. “I must be getting my message off to my mother,” said Henry.

“Surely,” assented the commander. “We mustn’t forget that. Come with me and we’ll go get acquainted with Sparks.”

“Sparks?” queried Henry.

“Oh! That’s our pet name for Harry Sharp, the chief electrician. He has charge of all the electrical apparatus as well as the wireless itself.”

They found the chief electrician in the wireless house, for it was his trick at the key. “Mr. Sharp,” smiled the captain, “this is Henry Harper. He’s taking a little trip with us, and maybe he’ll be a Coast Guard man himself some day. Just now he wants to send a message to his friends at home, so that his mother won’t be alarmed about him. Will you help him out?”

Henry’s eyes shone bright as he looked about the small wireless room. There was a broad, desk-like shelf that stretched from side to side of the little room, and on this, and on the walls about him, were fastened a dazzling array of wireless instruments.

“Gee!” exclaimed Henry. “What a peach of an outfit!”

“It ought to be,” said the chief electrician with a smile. “It’s right up-to-date, and it cost Uncle Sam ten thousand dollars. Know anything about wireless?”

“A little,” said Henry. “I served as a substitute operator at the government station at Frankfort for a time.”

“Would you like to send your own message?”

“Would I? Gee! I should say so.”

“All right. Sit down here and let’s see what you can do. Call up your station.”

“Thank you,” said Henry. “Will you set her for two hundred and fifty meters, please?”

The electrician twirled his thumbscrews. Henry tested the key for a moment, then threw over the switch and sent his call speeding through the night: “CBWC—CBWC—CBWC—de—CBE.”

“You send well,” said the chief electrician.

For a few moments the two operators sat, their phones clamped to their ears, listening intently. There was no response.

“CBWC—CBWC—CBWC—de—CBE,” once more rapped out Henry.

This time there came a faint answer: “CBE—CBE—CBE—de—CBWK—K.”

“You’ve got ’em,” commented the electrician. “Go ahead.”

“Reached New York all right,” wired Henry. “Both Willie and Roy out of town. Made the acquaintance of Captain Hardwick, of the Coast Guard cutter Iroquois. Am going to sea for a short trip as his guest. We are now in Lower New York Bay, heading for Ambrose Lightship. We are to find a derelict and destroy it. Please tell mother to write me in care of Captain Hardwick. Will send her a letter as soon as we get back.”

There was a long pause. Then the receivers began to buzz again. “Your mother is here,” came the message. “Wants to know more about your trip.”

Henry turned to his companion. “They are talking from the workshop in our back yard,” he explained. “It’s headquarters for our wireless club. We call it The Camp Brady Wireless Patrol. They’ve called mother out to the shop.”

Then he pressed the key again. “Tell her I’ll write,” he flashed back, and turning again to the chief electrician, he said with a grin: “Gee! I’d never dare tell her that I fell overboard. She’d have a fit and order me right home.”

“Where can we get you?” came another query.

“Call the Iroquois.” Once more Henry faced his companion. “What is our call signal?” he asked.

“NTE,” was the reply.

And Henry hastily added to his message: “Our call is NTE. Can send no more. Goodbye.”

“Gee!” he exclaimed, as he laid down the receivers. “Won’t my chums be an astonished bunch! It was almost worth falling overboard to give ’em such a surprise! And won’t they envy me! I’m going to have the time of my life.”

The chief electrician was on watch for four hours, and Henry sat with him in the wireless shack, as the radio room on the Iroquois was called, until his watch was ended. Together they caught the nightly news-letters sent out by the various press associations. They heard myriads of commercial messages flashing through the air. At times the operator switched on the radio, and then, through the loud speaker, they heard some of the broadcasting programmes. Henry had told the truth when he said he was having the time of his life. Never had he seen such a wonderful wireless outfit as this one, for the Frankfort station equipment, which he had operated many months before, was naturally far from being the equal of these brand-new instruments.

Shortly before the chief electrician’s watch ended, the door of the wireless shack opened, and a sailor stepped within. At least, the lad was dressed like a sailor, though when Henry saw the red electric sparks embroidered on the young man’s blue sleeve, he judged that this must be the wireless relief. And so it proved, for the chief electrician at once said, “Mr. Harper, this is one of my assistants, Mr. Black.”

Henry thought the newcomer was well named. The fellow had a surly look, and his eyes were shifty. He was one of those individuals that never looks another squarely in the eye. But Henry jumped to his feet, thrust out his arm, and took the other’s limp hand in greeting.

“I am very glad to know you, Mr. Black,” he said. “We fellows back in the country have played at being wireless men, and it’s a great pleasure to meet real wireless operators.”

A sudden roll of the ship sent Henry reeling back against the wall of the wireless shack, and he realized what he had not noticed while he was still seated and engrossed in the wireless, namely, that the sea was evidently becoming rough. Henry would have been glad to stay on watch with this new operator, but the latter drew a soiled dime novel from his blouse and tilted back in his chair to read, utterly regardless of the fact that a visitor was present. The chief electrician frowned but said nothing. And Henry, seeing his presence was not desirable, turned to the chief operator.

“Would there be any objection to my looking about the deck?” he asked. “I’ve never been on a ship at sea before, and I’d like to know what it is like at night on deck.”

“Just come up on the bridge,” said the wireless man. “There’s nobody on deck, probably, but the man on watch in the bow. You’ll find Mr. Hill and the quartermaster on watch on the bridge. Maybe you’d like to stand watch yourself a while. Would you?”

“I’d be tickled to death,” exclaimed Henry.

“Then come to our quarters and I’ll fit you out. You’ll find it pretty chilly up on the bridge.”

Henry turned to say good-night to the assistant operator. The latter already had his nose buried in his novel. Henry could not help but notice how the fellow’s fingers were stained with tobacco, and what an evil look seemed to lurk on his countenance. He did not disturb him, but quietly followed Mr. Sharp out of the wireless shack. “I’d hate to trust the safety of the ship to a man like that,” he thought, but said nothing.

The instant the door was opened, his attention was drawn to other things. Across the deck an icy blast of wind was sweeping that made Henry shiver. From above came an eerie, humming, vibrating noise, as the rigging quivered in the breeze. Only soft lights were visible—such indirect illumination as shone through ports or windows or the deck lights,—discs of heavy glass set flush in the planking underfoot to let the sunlight into the interior of the ship. Aloft twinkled the ship’s sailing lights. Beyond the rails all was inky darkness, and it was a darkness that seemed almost to be alive. Out of it came sounds such as Henry had never heard before—the swish and sweep of swaying waters, the crashing of crested waves, the interminable roar of endless leagues of rolling billows.

Henry was amazed to find how the ship was moving up and down. He tried to imitate the wireless men, who skipped quickly around the after end of the wireless shack, but a lurch of the ship sent him flying across the deck. He brought up with a jolt at the leeward rail. With a chuckle he turned about and made for the door of the operator’s stateroom which the electrician was now holding open for him. A broad band of light illumined his way.

As Henry stepped through the doorway, he could see quite well what a snug little place this stateroom was. Three bunks, one above the other, occupied most of one side of the compartment. There were also a tall wardrobe, a washbowl with mirror above it, and a table with several chairs. On this table were a number of books and magazines. A young man sat at the table, his elbows on the edge of it, his chin propped on his hands, so deeply engrossed in a book he was reading that he was unconscious of the entrance of Henry and Mr. Sharp. By the device on the young man’s sleeve Henry saw that he, too, was an assistant wireless man.

“Jim,” said the chief electrician.

The reader looked up, startled. Then he laid down his book and arose.

“This is Mr. Harper,” said the electrician. “Mr. Harper, this is my other assistant, Jim Belford.”

Henry was sure he would like this young man. The lad had a fine face, and intelligence showed in his every feature. His smile was frank and winning. The two shook hands cordially.

“So you’re going to sea with us,” said the lad. “Are you a good sailor? It looks as though we’d have some rough water by morning.”

“I don’t know,” replied Henry. “I’ve never been to sea before. I suppose I shall know before long.” Then, his eye falling upon the book the young operator had laid down, Henry said, “Don’t let me keep you from your reading. You appeared to have something interesting.”

The lad passed the book to Henry. “It is very interesting,” he said. And when Henry examined the volume in his hand, he found that it was a treatise on electricity. He couldn’t help thinking of the contrast in the reading matter chosen by the two young operators.

“You must have lots of time for reading,” commented Henry, “and this is an excellent way to use it.” He handed back the book.

“We are on watch four hours and off duty for eight, so we have oceans of time, and I’m glad of it. I wasn’t able to finish my high-school course, and I’m trying to go on with my education. There’s a good chance to work up in this service if a fellow will only take it.”

“How do you get a job in the Coast Guard anyway?” asked Henry.

“The officers, of course, attend the Coast Guard Academy at Fort Trumbull, up in Connecticut. It’s just like West Point or Annapolis. It trains the officers for the Coast Guard ships. Everybody else gets his job by enlistment.”

“Are there good openings? Could I, for instance, get a position?”

“You could enlist as a seaman, or you could enlist for wireless duty if you know anything about wireless.”

“He does,” smiled the chief electrician.

“The Chief, here, would examine you. If he passed you, you’d become an assistant wireless man and rank as a third-class petty officer. This first examination is quite simple. You must be able to send and receive adequately and know how to handle your instruments, and that is about all you need to know to pass it. Three months after you become a third-class man, you could take another examination, and if you passed that, you’d become a second-class petty officer. This second examination would deal with wireless theory and codes and the semaphore and blinkers.” And noting Henry’s blank expression, the young wireless man continued, “You noticed the semaphores on the yardarm on the forward mast, didn’t you? And the lights there?”

“Sure,” said Henry.

“Well, we no longer use flags when we semaphore. We use the semaphores up on the yardarms. At night we use those lights or blinkers and make ’em wink by electricity. It’s really sending wireless messages with lights instead of sound waves.”

“And how does a fellow become a first-class radio man?”

“To become a first-class man, you’d have to have a good knowledge of all parts of the ship, and all radio laws and regulations and general radio procedure. You could take your examination nine months after you entered the service, but there are mighty few radio men who are ready to take it so soon.”

“What about Mr. Sharp here? He is chief electrician. How long does it take to become a chief electrician?”

“It would take at least three years to make that. You have to know an awful lot to become a chief electrician.” The lad paused, then added simply: “That’s what I am working for. Most fellows that qualify as wireless men have a high-school education. You see, I couldn’t finish my course. It’s an awful handicap to me now.”

“I’ve been through high school,” said Henry, and to himself he thought: “I’m certainly glad mother held me to it. I can see already what a difference it may make to me.” A moment later he said to the chief electrician: “I hadn’t any idea of ever belonging to the Coast Guard, but for a long time I have wanted to be a wireless man. Do you suppose there would be any chance for me on the Iroquois?”

“We have our full complement now,” said Mr. Sharp. “There wouldn’t be any opening on this boat unless we could get rid of—unless one of my assistants should leave.”

Henry looked sharply at the chief electrician. He believed he knew exactly what the wireless chief had started to say, and he believed it had to do with the man now on watch in the wireless shack. But of course Henry made no comment. “I’d like mighty well to be a Coast Guard radio man,” he said. After a moment’s pause he went on: “Won’t you please explain to me again about the officers? You said they were trained at the Coast Guard Academy. And you also said a fellow could enlist as a wireless man and yet rank as an officer. I don’t exactly understand.”

“I don’t wonder,” laughed the young wireless man. “You see there are three sorts of officers—petty officers, warrant officers, and commissioned officers. The captain of a ship appoints the petty officers from the enlisted crew. Petty officers are men like the boatswain’s mate, the chief yeoman, the gunner’s mate, and the like. From among these the captain chooses men he will recommend for appointment as warrant officers. They get their appointments from Washington. The boatswain, the gunner, the carpenter, and others are warrant officers. The commissioned officers are the trained navigators from the Coast Guard Academy, and bear the nation’s own commission as officers.”

“Thank you,” said Henry. “It’s very plain now.”

Meantime Mr. Sharp had been searching in the wardrobe. He now handed a thick sweater to Henry, and when the lad had pulled it on and buttoned his coat over it, the chief electrician produced a long, warm overcoat, which he made his visitor put on. Then, pulling on a long rain-proof overcoat himself, he led the way out of the cabin. Henry said good-bye to the young radio man, to whom he had taken a great liking, and followed the Chief.

Up to the bridge they mounted, and Henry was glad, indeed, that he was so warmly clothed. The wind swept past so fiercely that he could hardly get his breath when he faced it. A light was burning in the chart house. In the glass-fronted wheelhouse the compass was dimly illuminated. Otherwise it was dark. A figure stood within, silent, almost immovable, his arms grasping the handles of the steering wheel. As Henry peered into the wheelhouse, he saw that the steersman’s eye was on the compass. He was holding the ship true to her course—east three-quarters south.

On the bridge itself two human forms loomed in the darkness. Lieutenant Hill was standing on the port side. He said, “Good-evening,” as Henry stepped alongside him, then continued his vigil, looking steadily into the blackness of the night. When Henry crossed to the starboard side of the boat, he found Quartermaster Andrews also peering intently out over the weather-cloth. The chief electrician made them acquainted. Henry came up close to the rail and thrust his face out over the weather-cloth, but he drew it back in a hurry. The stinging blast struck him with sudden fury. He winked as though something tangible had hit him. Then he made a wild and fruitless grab at his hat, which the wind had torn from his head. The hat lodged against the wheelhouse and he rescued it.

“I had no idea it was blowing so hard,” he said to the quartermaster, “and I wouldn’t have believed that weather-cloth would be such a protection. Why, six inches behind it you can hardly feel any wind at all. It seems to shoot the breeze straight upward.”

The quartermaster smiled. “You’re right about the weather-cloth,” he said, “but this isn’t much of a wind yet. It looks as though we might have a gale before morning, though, and if we do you’ll have a good chance to see how the Iroquois behaves in a rough sea. We’ll be in shallow water for some hours yet, and it always gets rough out here when there is any wind.”

“I should think a fellow would freeze up here in real cold weather when it blows hard. It’s cold enough now. How do you ever stand it?”

“I’ve got on one of those wind-proof suits,” said the quartermaster. “It takes a pretty stiff gale to go through that.” And Henry, looking close, saw that his companion was dressed in a hooded blouse that had to be pulled on over the head, and that could be fastened tight about his head, so that only the face was exposed. The quartermaster also wore a knitted, blue watchcap that he could pull down over his ears.

When Henry stared into the dark void ahead of and around them he could at first see nothing. The sky was like a dome of black. No star, no feeblest ray of light of any sort, came from it. And the water beneath was its twin for darkness. Overhead the rigging sang ever more eerily, and, when the wind rose in sharp crescendo, the cordage fairly shrieked. The woodwork creaked and groaned. From every side came the tumultuous roar of the waves, a sound so overpowering, so insistent, so awesome, that Henry shuddered when he listened to it. A feeling almost of fear came to him. He could not help thinking how awful it would be if the ship should sink in such a wild waste of water. But when he glanced at the motionless figure in the wheelhouse, and when he thought of the radio, he was reassured. But he would have felt safer, he thought to himself, if young Belford or the chief electrician had been on watch in the wireless shack.

Already the latter had left the bridge and returned to his cabin. But Henry stayed on the bridge a long time. Occasionally he spoke briefly to the officers on watch, but mostly he watched in silence, peering into the darkness, drinking in the sounds of the night, filling himself with new sensations, not all of which were pleasant, for as the wind came ever stronger, and the ship rose and fell more noticeably, a strange feeling crept over Henry. He began to feel queer about his stomach.

“I must have indigestion,” he muttered to himself. “Maybe I ate something that didn’t agree with me.”

He kept getting sicker and sicker. Soon he suspected that he was seasick. Finally he could stand it on the bridge no longer. Trying hard to control himself, he said good-night to Lieutenant Hill, and made his way with trembling limbs down the ladder to the deck. Like a drunken man he went reeling aft, for the ship was beginning to roll. When he reached the after companionway, he felt worse than ever, for the motion was much more noticeable than it had been forward or amidship. He could stand it no longer. Making his way unsteadily to the leeward rail, he leaned over it and vomited. He had never felt so sick in his life. Every minute he seemed to feel worse. He was so weak he was afraid he would fall over the rail. He decided that he would try to get to his bunk.

He turned and started toward the companionway, when the ship rolled far over on her side. As though he were shot out of a cannon Henry went plunging across the deck. There was nothing he could grasp to stop himself. With terrific force he went crashing into the windward rail and was flung partly over it. With all the power at his command he clung to the rail as he balanced on top of it. For a moment his heart almost ceased to beat. He was afraid he was going overboard. His feet were clear of the deck. His body was half over the rail. All he could do was to cling fast, in the hope that he wouldn’t slide any further. But his position was so awkward he was fearful he could not keep himself from plunging on over into the sea. Suddenly the ship heeled in the other direction. Henry was flung back from the rail as violently as he had just shot into it. This time he struck the companionway. He grasped the door, opened it, took a grip on the handrail, and tottered down the steps. He found the captain’s cabin deserted. The commander had to go on watch later in the night, and was sleeping in preparation for it. Henry got to his stateroom, undressed, pulled on his nightclothes, and with a feeling of relief slid into his bunk. He had lost all interest in the sea and wireless and derelicts. His one hope now was that he would live until the Iroquois got back to port and he could get ashore.

Henry awoke early next morning. At first he did not know where he was. Then he remembered all. But life no longer looked sable. Indeed, there was a rosy tinge to it, just as there was about the eastern sky. The feeling of nausea had entirely left him. Gone were the terrible headache and the feeling of sickness that had affected his entire body. Though the ship was now rolling far more than it had rolled the preceding night, the motion no longer distressed him. He rose and dressed quickly.

Early as Henry was, the captain was up before him. The captain had taken his turn on the bridge, then snatched a little more sleep, and was now busy at some clerical work at his desk. He looked up as Henry stepped into the cabin.

“Good-morning, youngster,” he said. “How are you feeling? Didn’t make you sick, did it? There’s a pretty good sea going.”

“It made me sick as a dog,” admitted Henry, “but I’m fit as a fiddle now. A good sleep fixed me up.”

They ate breakfast and went to the chart-room. Though the ship was far out in the ocean, it was still many hours’ sail from the location given for the derelict. The captain began to study the ship’s logbook, as the sailing record is called.

“See here, Henry,” he remarked after a moment. “This logbook might interest you.” Henry looked at the book, and saw entered there a detailed record of what was done on shipboard, not only from hour to hour but even every few minutes. Glancing back, he saw that his own rescue was noted down, and the recovery of his suit-case, and the exact time the executive officer came aboard, as well as the time when the Iroquois got under way.

“Captain Hardwick,” he said presently, “what does this entry about the log mean? I see it is written down every hour.”