Famous Hymns of the World Series

ITS ORIGIN AND ITS ROMANCE

BY

ALLAN SUTHERLAND

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

BY

THE REV. HENRY C. McCOOK

D.D., LL.D., Sc.D.

Illustrated

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1905

By The Butterick Publishing Co., Ltd.

Copyright, 1906

By Frederick A. Stokes Company

BY THE

REV. HENRY C. McCOOK, D.D., LL.D., Sc.D.[1]

rom the earliest eras of

history, religion has been

wedded to song. In every

stage of civilisation and in

well-nigh every form of

worship this has been true. From the

rude ululations of savage medicine-men,

with the monotonous beat of tum-tums,

to the splendid Levitical choir of the

Hebrew temple that rendered the psalms

to the accompaniment of stringed and

iv

brazen instruments, the record does not

vary.

rom the earliest eras of

history, religion has been

wedded to song. In every

stage of civilisation and in

well-nigh every form of

worship this has been true. From the

rude ululations of savage medicine-men,

with the monotonous beat of tum-tums,

to the splendid Levitical choir of the

Hebrew temple that rendered the psalms

to the accompaniment of stringed and

iv

brazen instruments, the record does not

vary.

How rhythm and melody react upon the religious sentiment, and why religious experience naturally flows in rhythmic utterance, one need not here inquire. Such inquiries belong to the natural history of sacred psalmody. But there are our sacred books to attest the facts. A large part of them are poems. The poets of ancient Israel were true prophets. The core of the Hebrew religion and worship lay within its religious songs; and these are the portions of its ritual that have lived; and one may safely predict that they shall run the whole cycle of being with our race.

As far back as the days of Moses, we read of Miriam under a prophetic impulse breaking forth into song to commemorate the deliverance of Israel from the Egyptians on the peninsular shore of v the Red Sea. A refrain of that hymn has come down to us:

“Sing unto the Lord for He hath triumphed gloriously;

The horse and his rider He hath whelmed within the sea.”

That such religious songs were not rare and that their musical utterance was even then organized as a part of worship, appears from the fact that Miriam’s countrywomen accompanied her with their guitars, and joined in the chorus.

The Songs of Deborah illumined the period of the Judges. They have been given a place by competent critics among the noblest lyrics of antiquity. One of these, Heinrich Ewald, speaks of them as so artistic, with all their antique simplicity, that they show to what “refined art poetry early aspired, and what a delicate perception of beauty breathed already beneath its stiff and cumbrous soul.”

The Gospel era dawned in the midst of holy songs, hymned by angels, by holy men and women, and by the Mother of our Lord. From that day on the Church of Jesus has been vocal with psalmody. The primitive Church had her spiritual songs. The saintliness of the early Christian ages survives in the Greek and Latin hymns, and the pleasant task of translating and assembling the choicest of these has occupied many gifted minds.

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century was borne forward on waves of sacred song. The sweet voice of the student lad that appealed from the snowy street to the heart of Dame Ursula Cotta, and opened her doors to Martin Luther, was a type of the new time. The new songs of the Reformation and the old psalms renewed in the vernacular and in popular musical forms, vii prepared the way of multitudes for the revived truths of the Gospel.

Luther’s musical taste and talent impressed itself upon Germany, and thence upon Europe. His free spirit found utterance outside of the Biblical forms of praise in metrical renderings of his own and other religious experiences. Calvin saw the value and authority of popular praises, and encouraged and procured their use in the new organisation of reformed worship of which he was the chief agent. But his more conservative spirit in such matters held to the ancient psalms; and this influenced all Europe outside of Germany. The Church of England used the version of Sternhold and Hopkins, and these will be found appended to the early prayer-books. Rous’s version was substantially that best liked and approved by the Church of Scotland.

The historic “Huguenot Psalter” was the joint work of Clement Marot and Theodore Beza, the former having rendered into French metre the first fifty psalms, and the latter the remaining one hundred. These, set to popular music, caught the ear and heart of the people of all ranks. They ran rapidly throughout French-speaking nations, and became as well known as the “Gospel Hymns” in the palmy days of Moody and Sankey.

The Hebrew Psalter embodies the religious experiences of the chosen people, whose faith, more spiritual than that of any other nation of antiquity, was inbreathed and nurtured by the Holy Spirit. It is not to be supposed that the one hundred and fifty psalms included within the canonical psalter were the only ones that the poets of Israel hymned. But these, in the process of ix an inspired selection and a devotional development, were the ones that filled and satisfied the religious consciousness of that most spiritual people, and became the vehicle of not only a national but of an international praise.

For the Book of Psalms is a book for all nations. The very divinity of its origin insures its catholic humanity. It has proved its high ethnic qualities by ages of world-wide usage. A cloud of witnessing praises, rising from the Church of every age and name throughout centuries of testing, testifies to its fitness. If the taste of this era—much to the regret of some of us—has largely rejected metrical versions in the vernacular, yet their use, after the manner of the ancients, in chants, still holds and even widens in the Church’s service of praise.

It is significant that the hymns which x have fastened themselves upon the hearts of the devout in any one branch of the Church are those which are loved and used by all who honor and love the name of Christ. In all ages the truly devout are one in spiritual sympathy, and therefore the forms of praise which utter the devotions of one heart bear alike to God the aspirations of another. The Calvinistic Toplady, Watts, and Bonar; the Methodist Wesleys; the Anglican Heber, Ken, and Keble; the Romanist Faber and Newman, and all the goodly company of the sons and daughters of Asaph, when uttering the devotions of their souls, speak in one tongue.

There is something divine in the flame of sacred poesy that burns out therefrom the dross of sect. The hymns of the most rigid denominations are rarely sectarian. There is not a presbyter or xi priest in this whole land, who, with due tact and good faith, could not conduct a mission or service of song as chaplain of a congregation of soldiers or sailors made up of Protestants and Roman Catholics, of all phases of ecclesiastical opinions, without one discordant note and with perfect approval and enjoyment of all. This the writer, as a Government chaplain in two wars and for a quarter of a century in the National Guard, has repeatedly done and seen done.

Such great catholic missions as those of Moody and Sankey, Whittle and Bliss, Torrey and Alexander, which have appealed to all classes, conditions, and creeds, and have made their services so largely a service of song, have been and remain impressive witnesses of the substantial unity of the devout when they engage in the worship of praise.

Lead, kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on;

The night is dark, and I am far from home;

Lead Thou me on:

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene,—one step enough for me.

I was not ever thus, nor prayed that Thou

Shouldst lead me on;

I loved to choose and see my path; but now

Lead Thou me on.

I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears,

Pride ruled my will: remember not past years.

So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still

Will lead me on

O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till

The night is gone;

And with the morn those angel faces smile,

Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile.

ezekiah Butterworth,

an authority

on hymnology, pronounces

this to be “the

sweetest and most trustful

of modern hymns”; while Colonel

Nicholas Smith says, “Christians of all

denominations and of every grade of

culture feel its charm and find in it ‘a

language for some of the deepest yearnings

of the soul.’ The hymn-books do

not contain a more exquisite lyric. As

a prayer for a troubled soul for guidance,

it ranks with the most deservedly

famous church songs in the English

language.”

ezekiah Butterworth,

an authority

on hymnology, pronounces

this to be “the

sweetest and most trustful

of modern hymns”; while Colonel

Nicholas Smith says, “Christians of all

denominations and of every grade of

culture feel its charm and find in it ‘a

language for some of the deepest yearnings

of the soul.’ The hymn-books do

not contain a more exquisite lyric. As

a prayer for a troubled soul for guidance,

it ranks with the most deservedly

famous church songs in the English

language.”

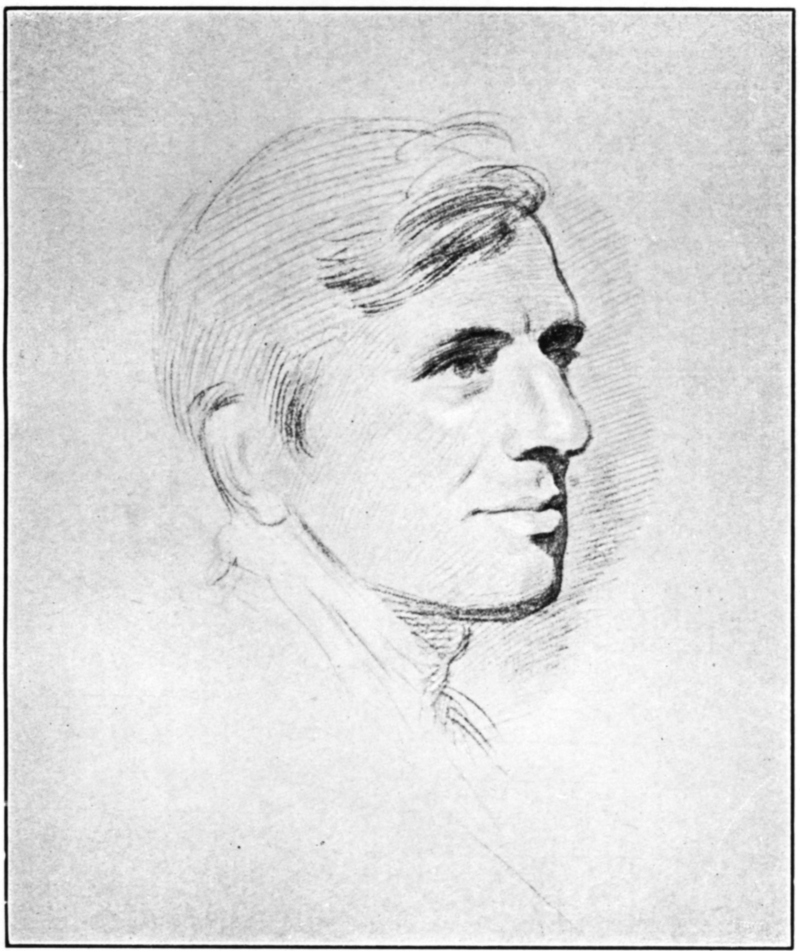

Its distinguished author, John Henry Newman, was born February 21, 1801, the son of a London banker, and seventy-eight years later became a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. At the early age of nineteen he was 2 graduated from Trinity College, Oxford, and became a tutor in Oriel College. He was ordained in 1824, and in 1828 was made vicar of St. Mary’s Protestant Episcopal Church, Oxford.

He was a popular, forceful preacher, with fluent speech, perfect diction, and a splendid fund of illustration which he always used with telling effect. He was deeply interested in the heart-life of men, and was ever ready to encourage them to speak to him freely of their experiences and temptations. He exercised a strong influence over the students who thronged his church.

In December, 1832, because of impaired health, he went with friends to southern Europe. The spiritual unrest, kindled by the “Oxford Movement,” which finally led him to unite with the Roman Catholic Church, in 1845, was already upon him; he sought eagerly and conscientiously for divine guidance in solving the great doctrinal problems 3 that vexed his soul. It was during this period of inner disquietude and of anxious thought for the future of the Established Church, of which he was still a member, that his noble hymn, “Lead, Kindly Light,” had birth—a hymn which has voiced the heartfelt prayers of thousands for spiritual guidance.

In the minds of many there is intimate association of thought between Newman’s supplication:

“Lead, kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on!”

and another intensely human heart-cry for direction and companionship in the hour of need—Henry Francis Lyte’s

“Abide with me, fast falls the eventide:

The darkness deepens: Lord, with me abide.”

It is interesting to know that both of these hymns were composed on the 4 sacred day of rest: Newman’s, on Sunday, June 16, 1833; and Lyte’s, on Sunday, September 5, 1847.

Newman has left us this very entertaining description of the circumstances under which his hymn was written:

“I went to the various coasts of the Mediterranean; parted with my friends at Rome; went down for the second time to Sicily, without companion, at the end of April. I struck into the middle of the Island, and fell ill of a fever at Leonforte. My servant thought I was dying, and begged for my last directions. I gave them, as he wished, but I said, ‘I shall not die.’ I repeated ‘I shall not die, for I have not sinned against the Light; I have not sinned against the Light.’ I have never been able quite to make out what I meant.

“I got to Castro-Giovanni, and was laid up there for nearly three weeks. Toward the end of May I left for Palermo, taking three days for the journey. Before starting from my inn, on the morning of May 26 or 27, I sat down on my bed and began to sob violently. My servant, who had acted as my nurse, asked what ailed me. I could only answer him, ‘I have a work to do in England.’

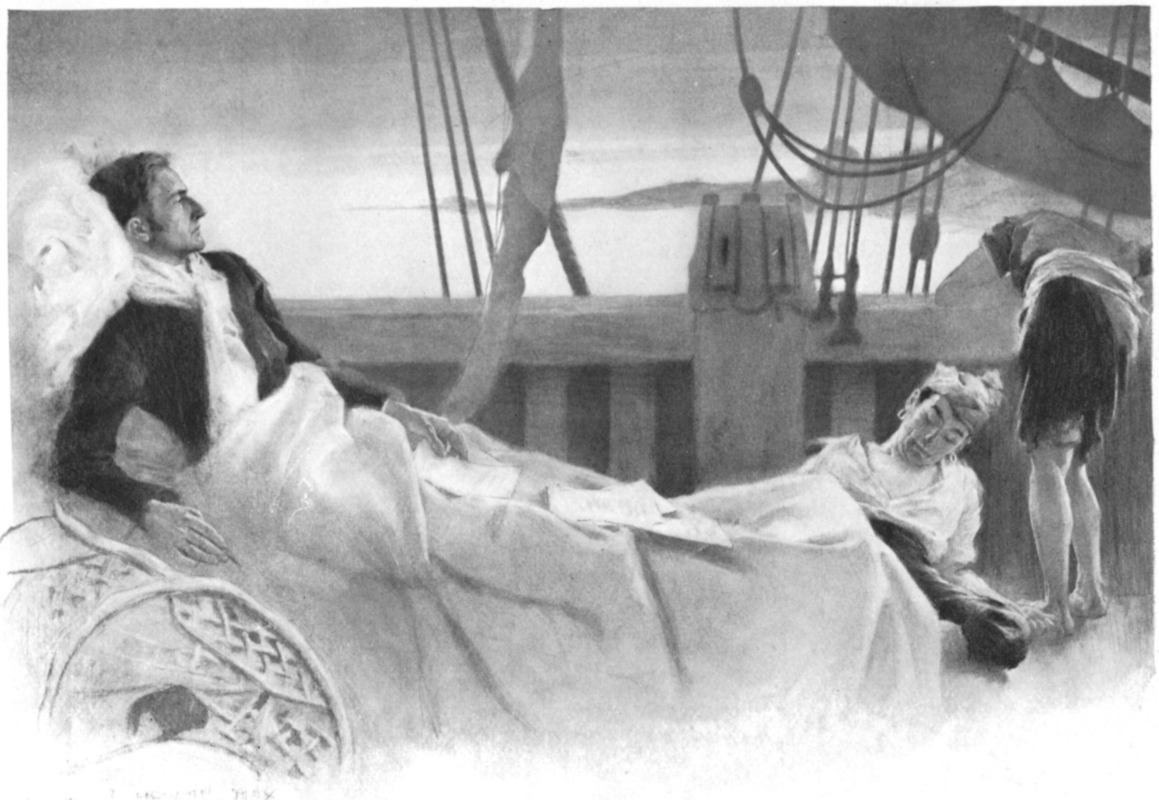

“I was aching to get home; yet, for want of a vessel, I was kept at Palermo for three weeks. I began to visit the churches, and they calmed my impatience, though I did not attend any of the services. At last I got off in an orange boat, bound for Marseilles. Then it was that I wrote the lines, ‘Lead, Kindly Light.’ We were becalmed a whole week in the Straits of Bonifacio. I was writing the whole of my passage.” Elsewhere he informs us that the exact date on which the hymn was written was June 16.

It is pleasant to think that this much-loved hymn, the fervent prayer of a 6 doubt-tossed soul, was written in one of the majestic calms that sometimes lull to sleep the sunny waters of the Mediterranean; and that it caught some of its delicious fragrance from the perfume that was wafted over the waters from the golden cargo with which the vessel was freighted. It would require but little imagination to picture the scene: the clumsy boat, the idly-hanging sails, the listless, swarthy crew, the brilliant young minister emaciated by mental and physical suffering, the solemn sea, and over all the matchless Italian sky and the tender twilight calm. Fit hour and surroundings for such a hymn to have its being.

In striking contrast, the music to which the words are inseparably wedded, was composed by Dr. John B. Dykes as he walked through the Strand, one of the busiest thoroughfares of London. It may be that the tumultuous street was typical of the wild unrest in Newman’s 7 heart when he began his hymn; if so, surely the quiet waters of the Mediterranean on that holy Sabbath evening might well represent his spiritual calm when it was ended—even though subsequent controversial storms were destined to beat fiercely upon his soul.

In this connection it may prove interesting to read the following from the Random Recollections of the Rev. George Huntington:

“I had been paying Cardinal Newman a visit. For some reason I happened to mention his well-known hymn, ‘Lead, Kindly Light,’ which he said he wrote when a very young man. I ventured to say, ‘It must be a great pleasure to you to know that you have written a hymn treasured wherever English-speaking Christians are to be found; and where are they not to be found?’ He was silent for some moments, and then said with emotion, ‘Yes, deeply 8 thankful, and more than thankful!’ Then, after another pause, ‘But, you see, it is not the hymn, but the tune, that has gained the popularity! The tune is by Dykes, and Dr. Dykes was a great master.’”

Perhaps nothing more fully illustrates the general acceptability of this beautiful hymn than the fact that “when the Parliament of Religion met in Chicago during the Columbian Exposition, the representatives of almost every creed known to man found two things on which they were agreed: They could all join in the Lord’s Prayer, and all could sing ‘Lead, Kindly Light.’”

When some one, a few years ago, asked William E. Gladstone to give the names of the hymns of which he was most fond, he replied that he was not quite sure that he had any favourites; and then, after a moment’s thought, he said: “Lead, Kindly Light,” and “Rock of Ages.”

“I know no song, ancient or modern,” writes the Rev. L. A. Banks, D.D., “that with such combined tenderness, pathos, and faith, tells the story of the Christian pilgrim who walks by faith and not by sight. No doubt it is this fidelity to heart experience, common to us all, that makes the hymn such a universal favourite. There are dark nights, and homesick hours, and becalmed seas for each of us, in which it is natural for man to cry out in Newman’s words:

“‘The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead Thou me on.’”

The Rev. James B. Ely, D.D., writes as follows: “It is my desire to relate one interesting incident in connection with ‘Lead, Kindly Light.’ This hymn was sung in the Lemon Hill Pavilion, Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, on a recent Sabbath morning, at a time when 10 the very atmosphere, the beautiful trees and the glowing sun seemed to emphasise and make very real the sentiments expressed. A young man in the audience, who was a Christian, but greatly burdened with many anxieties, felt while this hymn was being sung and the music repeated by the cornet, that God was preparing him for some special trial through which he must pass. During the day and all through the week the melody and the words haunted him; and there was also a growing feeling in his heart that he ought to go to his old home and visit his mother. Finally, on Friday noon, he determined that he would start that very evening, and made his plans to do so. Just before leaving his place of business, a telegram came informing him of his mother’s sudden death. While the news was a great shock to him, yet the singing of the hymn and its constant reiteration in his thoughts during the week had, 11 in a measure, prepared him for his sore bereavement. The hymn has since become one of his most sacred possessions. I have written regarding this unusual incident because the experience is so fresh in my mind and so real. I may add that this hymn has again and again been sung by large audiences, and always with telling spiritual effect.”

Many will recall that this hymn was a special favourite of the late President McKinley, and that it was sung far and wide in the churches on the first anniversary of his death and burial.

The last stanza of the hymn rings out with a grand declaration of triumphant, child-like faith and assurance:

“So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still

Will lead me on

O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till

The night is gone;

And with the morn those angel faces smile,

Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile.”

There has been some controversy as to the author’s meaning in the last two lines. Nearly a half century after they were written some one asked the Cardinal to give an explanation, and in a letter dated January 18, 1879, he thus wisely replied:

“You flatter me by your question; but I think it was Keble who, when asked it in his own case, answered that poets were not bound to be critics, or to give a sense to what they had written; and though I am not, like him, a poet, at least I may plead that I am not bound to remember my own meaning, whatever it was, at the end of almost fifty years. Anyhow, there must be a statute of limitation for writers of verse, or it would be quite tyranny if, in an art which is the expression, not of truth, but of imagination and sentiment, one were obliged to be ready for examination on the transient state of mind which came upon one when homesick, or seasick, or in any other way sensitive or excited.”

Cardinal Newman died August 11, 1890, fifty-seven years after his hymn had made his name immortal.

In addition to the quotations from Hezekiah Butterworth and Colonel Nicholas Smith, with which the study of this hymn begins, it will doubtless prove interesting to read what other men of prominence have said in this connection:

“This much-loved hymn.”—Dr. Louis F. Benson, author of “Studies of Familiar Hymns.”

“Its sincerity of feeling and purity of expression have made it universally acceptable.”—Samuel Willoughby Duffield, author of “English Hymns.”

“This is truer to the life of thoughtful men than almost any other hymn, but it is so subjective and personal that it is more for the closet than for the Church. It is the favourite hymn of our students.”—The President of a prominent University.

“It can scarcely be called either a great 14 poem or a great hymn, and certainly it is not a lyric. Yet it has certain striking passages, and appeals to those who for any reason are beset by darkness.”—Rev. David R. Breed, D.D., author of “The History and Use of Hymns and Hymn-Tunes.”

“The beautiful hymn, ‘Lead, Kindly Light,’ is of value to the Church for its poetry and its pathos. For times of depression and darkness come to nearly all of us, and this is just the cry which the heart bowed down would use at such times of anxious and sacred communion.”—Rev. G. L. Stevens, editor of “Hymns and Carols.”

“The most stirring thing I know is that struggling cry of the wanderer for light, ‘For I am far from home.’ The writer’s personality adds pathos to his tender song. Out of this song, appropriated by a struggling soul to himself, one is prepared for the sublime and recovering thought in the dream of the wanderer, ‘with sun gone down,’ and the way appearing ‘steps up to heaven.’”—Rev. William V. Milligan, D.D., Cambridge, Ohio.