O'Dea whirled—to face a lifted shock gun.

The Centaurians were making one last effort to

conquer Earth, and their tools were wise-cracking,

space-jaunting O'Dea and Hawthorne—two guys

to whom freedom was more than a word.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Fall 1944.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The frantic flares of the rockets lit up a murderous landscape as barrel-chested Paul Hawthorne wrestled with the controls. He fought to keep the ship from falling too swiftly, anxious eyes searching for a level spot to set down the partly-crippled vessel.

Behind him, Lance O'Dea clung to a chart table and growled.

"Put it down!" O'Dea ordered. "You're the Einstein who got us to this desert planet of Centauri; now get us landed safely!"

Hawthorne risked a second to turn his grimy face to the animated bean pole behind him. Like himself, O'Dea was unshaven and wrapped in the shapeless coveralls of spacemen. Hawthorne scowled and pushed his hairy arms back into the controls.

"If you think you can do any better," he grunted, "take over yourself!"

"No, thanks." O'Dea bent over to look through the port. The jagged terrain was closer, and a horrified shudder ran down his bony frame. "No, I'll let you answer to Saint Peter for the death of us both!"

His expression as he glared at Hawthorne was distasteful, but the makings of a grin played on the corners of his lips, and a thinly-hid concern was in his eyes.

"This is the end," he said. In one hand he clutched a photograph of a dark-haired girl. "The end, Mercedes! To think you'll be a widow before you're even a wife, all because that ape of a Hawthorne lost all our fuel in Centauri's asteroid belt—"

"Shut up!" the pilot demanded. One of his hands flipped a wad of something green back in O'Dea's direction. "Here's the ten platins I owe you. And get ready—this is it!"

A roughly level spot swept up at them—an uneven mesa that ended abruptly a few hundred feet ahead. Hawthorne dropped the vessel in a cushion of rocket blasts that were starting to cough for lack of fuel.

The ship bellied along the mesa, dipped into a pocket. O'Dea crashed into the stocky pilot as the ship turned end over end, then both struck the control board, smashing fifty thousand platins worth of instruments as they bounced around. The ship hesitated for a second at the edge of the mesa, balanced neatly, and decided to stay there.

Inside the ship, the lights were gone. For a few seconds there was a crashing of furniture, then silence.

"Lance!" Hawthorne's voice trembled slightly. "Are you killed? I h-hope—"

But the catch in his throat indicated he meant differently. From the darkness came O'Dea's answering drawl:

"No, you ape—I was just hoping the same about you. How about some light?"

Hawthorne fumbled around, found a battery-operated light that had survived the crash. He hobbled to where O'Dea was half buried in a heap of furniture and extricated him. The two of them rubbed their sore spots and looked glumly about.

"Centauri Six," Hawthorne mused. "You have the book l'arnin'. What's this planet like?"

O'Dea pressed fingers to his temples.

"Not inhabited by Centaurs," he said. "Which is one small break. At least we won't have those monsters—"

"I asked about the planet."

"If any Centaurs show up," said O'Dea shortly, "it'll make no difference about the planet. The Space Guide gives it the name Avignon. Hardly known by humans, of course—like the rest of this system. It has no water and no air. We'll die of thirst or suffocation here, but at least the Centaurs won't get us."

Hawthorne looked up from the aneroid set beside the airlock.

"As usual," he said, "you're wrong. We have an atmospheric pressure of ten pounds. And what's more, the instruments show it's a real atmosphere—like Earth's!"

"There's no such planet! Your instruments must be damaged!"

"No." Hawthorne shook his head. "These instruments don't lie. And they say we have an atmosphere. It may be thicker in the valleys!"

"Then," O'Dea insisted, "the Space Guide must be wrong, because my memory distinctly tells me—"

"Be damned to your memory! I brought this ship down, and I felt the atmosphere. What's more, all the planets inside the asteroid belt, except this one, are inhabited by Centaurs—and we're certainly inside the asteroid belt."

"You should know." O'Dea glared at him. "After letting that asteroid smash through our fuel tanks—"

"You make me tired," Hawthorne yawned. "We're getting on each other's nerves. Better get some sleep and cool off."

He cleared a place on the floor and relaxed. While O'Dea watched, fists knotted, the burly pilot started to snore.

O'Dea grinned suddenly and turned away. He stared thoughtfully out the port. It was dark. A feeble, distant sun was falling below a rugged horizon; and in the sky above he picked out ruddy Proxima.

But there should be a "real" sun due to rise soon. Nice thing about Centauri—there were enough suns to suit anybody.

His eyes fell on the wad of bills Hawthorne had thrown at him. He retrieved it happily, also finding the photograph. He gazed fondly at the deep dark eyes and rich lips of the girl, kissed the picture happily.

"Good night, Mercedes," he said. "We'll show him in the morning."

Brilliant sunlight flooded the cabin when they awoke. At this distance, the sun seemed somewhat smaller than Sol as seen from Earth, but it was brilliant and warm. They ate a fast concentrated breakfast and studied the airlock. Hawthorne voiced his verdict:

"We can repair it in a few hours. Get the tools out."

O'Dea was looking at the gravity indicator.

"Gravity is .92," he announced. "That's the correct figure for Avignon—no question about it. But I can't understand that atmosphere! It doesn't belong!"

He took the torch Hawthorne shoved at him and they went to work on the airlock. When they had unjammed the inner door, they found that the outer had somehow escaped injury.

They crawled into the lock, an almost vertical climb with the ship tilted as it was, and closed the inner door behind them. O'Dea shoved open the outer and pushed his nose over the edge of the ship. His eyes bulged.

"Gulp," he said, pointing.

Hawthorne's head appeared beside O'Dea's, and the two stared at the cañon floor a thousand feet below. Their space ship was partly hanging over the edge of the mesa.

"And I slept last night!" O'Dea marveled.

He swiveled his head in the other direction.

"Gulp!" he said again.

Three Centaurs, dominant beings of the Alpha Centauri system, faced them with drawn guns. The grinning creatures were vaguely manlike—they walked on two legs and breathed oxygen. At that point the resemblance ceased, for they also breathed methane or ammonia or practically nothing at all. They also had big eyes, a dozen arms, and more fingers than a moron could count without risking a headache.

O'Dea closed his eyes and moaned.

"This is it, Mercedes," he said softly.

"Shut up!" Hawthorne muttered. "Maybe they're an independent tribe—" He twisted his homely face into a grin and spoke in South Martian Vlandian, the lingua franca of space:

"Somu amiki ... neura barc s' arik—"

"Oh how lovely!" said the largest Centaur, in English. "Such a delightful ship and what wonderful specimens of homo sapiens we are find! This auspicious occurrence will aid our plans in the utmost manner!"

The creature assumed an expression that passed for a friendly smile among the Centaurs. This consisted of displaying all his teeth and snapping them together as he spoke.

"I am called Morguma," he announced. "In Bridgeport, Connecticut, I learn the English before comes the war—so sorry, the trouble!" He smirked apologetically. "It is with the most pleased pleasure I acquaint myself with you!"

O'Dea heard Hawthorne's voice, low in his ear. "Now we're in for it! He's no independent tribesman!"

The lanky spaceman shrank back from the Centaur, eyeing the gleaming molars suspiciously. He was remembering that the human race was at war with these beings, though there had been practically no fighting for ten years, since the time the Centaurs in the solar system were exchanged for human hostages held by the enemy.

While man was learning the rules of space flight, these creatures had been building their first spaceships. Strange contest! Though neither human nor Centaur suspected the existence of the other, each progressed about as rapidly, as if linked by cosmic telepathy. Each race colonized its own system and gradually built up speeds great enough for interstellar travel. Indeed, the first human ship had just left for Centauri when the first vessel of the Centaurs landed on Mars.

For a time, it seemed that a beneficial union of two races had been established. Then it was discovered that the aliens had moral standards so different from humans that life with them was impossible. Though small groups of them visiting Earth or the planets were well-behaved and gracious guests, they were likely when they outnumbered their hosts to turn their thoughts to vivisection. Or to casual massacre, if they decided that humans annoyed them.

So outraged humanity had declared war, driven the visitors from the system. But at that point the war virtually ended. It was impossible for either Earth or Centauri to send a serious invasion fleet into the other's home system because of the tremendous distance! In either case, the defenders would have an advantage that could not be overcome!

Lance O'Dea felt perspiration trickling down his face. He studied the happy aliens.

Morguma waved his weapon. "You will please to come out, our beloved brothers of Earth! It will create difficulty to remove your ship to a more auspicious location if you do not remove yourselves from it first!"

The two men descended from the lock. Above them a Centaur ship hovered, darted out pale green seizure beams. In the grip of the beams, the Earth ship slid back from the mesa edge to more secure ground.

Behind Morguma, more Centaurs were coming up, their features masked with broad happy grins. The Centaur leader stepped aside, motioned the men to precede him.

Flanked by the armed guards, they marched across the mesa, reached a broad trail that led into a valley below. O'Dea stopped short in surprise.

He stared into the broad valley.

"Is it not inspiring?" Morguma enthused, behind him. "Our beautiful rocket center that we created on this formerly barren world! Oh it makes my heart sing with joy!"

The two men, eyes wide, looked down at the teeming Centaur life that filled the immense valley. Great factories sprawled for miles, apparently engaged in manufacturing and servicing space ships. Thousands of craft were berthed in neat rows for as far as they could see. From small one passenger jobs to deadly battle cruisers they were taking off and landing by the hundreds.

"There aren't that many ships in the universe," O'Dea mumbled, dazed. "And millions of Centaurs! Of all the places we could have landed—"

He felt a polite prodding in his spine.

"Please to walk, our charming brothers of Earth!" came Morguma's voice. "It is with pleasure I will explain to you when we reach our destination."

Their destination was a sprawling building set in the noisy center of the rocket base. They were marched into a room where a gigantic Centaur sat shouting orders to lesser ones. Among the Centaurs, size was synonymous with rank. In this civilization so alien to human thought, the largest creature was king, though he should be only an idiot mentally!

O'Dea listened, bored, while Morguma explained in his native language to his chief. The leader stared in surprise at the two humans, then his mood suddenly became ecstatic. He spoke swiftly to Morguma, who turned to the men.

"Oh you fortunate people! It is your remarkable luck to be the first humans to inhabit this planet we create for our brothers of the solar system!"

"What's this all about?" Hawthorne growled.

Morguma waved several arms and translated the remarks of his chief:

"We were so devastated to have a misunderstanding with your wonderful people! We are so sorry not to associate with you that we are preparing this planet for human beings to inhabit!"

O'Dea and Hawthorne stared at each other.

"Like you people of Earth." Morguma went on, "we too have an asteroid belt in our system. And in our asteroids are included many delightful pieces of frozen oxygen, nitrogen, water and other ravishingly beautiful elements that gladden the heart of a human. We are bringing these life-giving substances to this planet, Avignon!"

"I told you!" said O'Dea. "My memory didn't fail me! Paul, maybe these two-legged crocodiles aren't so bad after all—creating a planet for us—"

"When this pleasant operation is concluded," said Morguma, "we will bring humans to this planet. They will have children, whom we shall take from their parents and educate in the proper manner—"

"What!" Hawthorne's fists knotted. He moved a step in Morguma's direction, stopped when he faced a line of drawn guns. Morguma continued:

"Oh it will be such rapturous delight to instruct these little innocents in such tasks as espionage work on Earth and killing of those misguided humans who continue to fight us—"

Morguma's eyes rolled piously—and, chuckled. He displayed his teeth in a friendly smile.

"And you two—oh you favorite sons of fortune! We shall allow you to help us in this gesture of interstellar good will! In your ship you may aid in securing the necessary elements from our asteroid belt!"

"In our ship—" O'Dea looked hopeful. "Oh, sure, we'll be glad to help. We'll go out right after it's patched up and loaded with fuel—"

"Of course," gurgled Morguma, "I should be overjoyed to enjoy your charming company; therefore I shall accompany you. Also, it is not necessary to give you more than enough fuel to reach the asteroid belt and come back here!"

"I knew there was a catch," O'Dea grumbled. "What do we do now, Paul?"

"You can do anything you please," Hawthorne snapped. "I've had enough!"

The heavy framed spaceman hurled himself at the grinning Centaur. A fraction of a second later O'Dea followed suit. Before they could cross the few feet that separated Morguma from them, the shock guns of the guards barked. The two men sprawled forward unconscious at the feet of the still grinning alien.

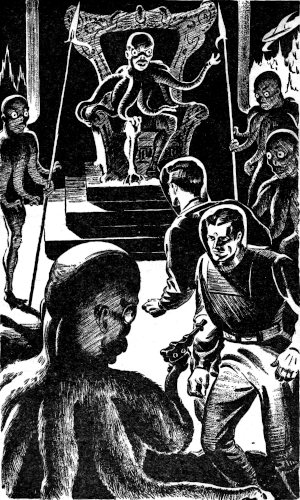

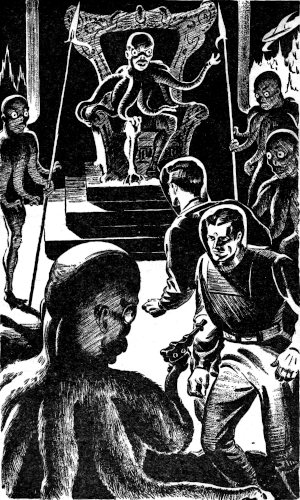

O'Dea whirled—to face a lifted shock gun.

"Oh how sad!" Morguma cried. "How unfortunate! We must revive these beautiful persons! I am sure they will see our point of view!"

II

O'Dea and Hawthorne watched their repaired vessel roll out of the Centaur repair shop. The smashed plates had been neatly straightened; the vessel gleamed from nose to tail.

An enthusiastic Centaur foreman accompanied the ship.

"Oh my intimate friends!" he sprayed in Hawthorne's face. "I too parlez-vous the English! For men I have the great love! It will give me tremendous enjoyment to help to populate this planet with human beings!"

"You go to Hell," Hawthorne growled. He shivered in Avignon's thin atmosphere and pulled the rough blanket Morguma had supplied tighter around him. He and O'Dea looked like a pair of Indian chiefs.

"Undertake to observe," said the foreman. "Seizure beams!"

He shouted something in his own language to his workers inside the ship. The pale green beams lanced out. The foreman's fangs protruded several inches.

"And the interior is so dainty!" the creature warbled. "Chenille curtains over the ports! Pastel wallflower paper! Furnishings of a luxuriance that would be of pleasure even to the dictator himself!"

Hawthorne spat disgustedly. "Pastel wallpaper! Chenille curtains! Who ever heard of curtains in a space ship, much less chenille!"

His homely face twisted in pain. "Chenille!" he groaned again.

"You have no soul," grinned O'Dea. "As long as these baboons are willing to supply us with the finer things of life, you might at least appreciate it."

"You know what I think of you," growled Hawthorne. "Chenille curtains—ugh!"

He spat disgustedly.

Morguma appeared and waved them to the open lock. He preceded them, and when they had mounted to the lock, he shoved them back gently with his huge paws until they faced a barrage of Centaur camera fiends. The three of them, Morguma in the middle with a giant smirking grin, stood framed in the lock while shutters clicked.

"I wish you wouldn't breathe in my face," O'Dea said. "You smell like something that forgot to die off in the Mesozoic era."

Morguma giggled. "All Centauri loves you! Your beautiful faces will be in all our newspapers now!"

They went into the control room. Hawthorne stared unbelievingly at the transformation. Flowers were spread profusely. Embroidered antimacassars graced the dainty chairs. And the curtains over the ports were indeed of chenille. The pilot groaned dismally.

But O'Dea's eyes lighted when he saw the huge portrait over the control board.

"Mercedes!" he shouted.

"Oh how happy I am to see you pleased!" exclaimed Morguma. "We found this divine female human being's picture and enlarged it as you see. She is an entrancing thing!"

"You talk the truth," O'Dea agreed. "But that won't change the fact that I don't like you. What happens now?"

Morguma looked mildly apologetic. "Now we must perform labor! The great task for which this ship has been fitted!"

The Centaur seated himself at the rear of the control room, produced an instrument that looked like a whip. It looked like a whip because it was one. He flicked it experimentally.

"Oh how devastated I would be," he told them, "if I should be forced to use this! You will take off and fly to our asteroid belt, following the intelligent directions I shall give you. We will find a substantial piece of some agreeable material and bring it back to Avignon."

The two men looked at each other and then at the whip. The alien snapped it lightly a few times as if nervous. They turned to the control board.

A few hours later they were in Alpha Centauri's asteroid belt, dodging debris. For a while they were nervous. It was here, in this field of small flying particles that was worse even than their Solar System's, that a baseball-sized rock had eluded their detectors and knifed through their vessel, passing through all three fuel chambers in its line of flight and taking a long stream of rocket fuel for its wake.

But the Centaurs evidently had perfected asteroid navigation; and when they saw several pieces of matter that were about to strike them deflected, they stopped worrying.

O'Dea manned a board lined with instruments the Centaurs had installed. They were simple to operate. He merely moved a telescope lens until a piece of cosmic scrap was in the cross hair, then he read a dial. The telescope was synchronized with a Centaur version of a spectroscope, and its reading was given in figures on the dial.

He felt the Centaur looking over his shoulder, checking up on him, so he had to do his work properly. Not that it made much difference. Whether he and Hawthorne played the game was of little importance as far as the Centaur's plans went, except that the creatures liked the symbolism created by having two humans work on the project.

"Morguma," he said. "Those spaceships on Avignon can't all be engaged in this work. There are types there that can be of no use."

"Oh you are so intelligent to reason that!" Morguma marveled. "This pretty planet of Avignon is the reservation we have set aside for all space work. All of our ships are built there and all are based there!"

O'Dea tracked down a likely looking asteroid.

"How come?" he asked.

"We Centaurs are a delicate sensitive people! We love the beautiful things of life, and dislike such noisy greasy articles as space ships. So a few years ago it was decided to remove all the dirty factories from our home planets. Now the only craft that disturb the peace of our people on the main planets of Centauri are the rockets that transport materials and workers to and from Avignon!"

"There's something wrong there." O'Dea centered his instrument on the asteroid. "You seem to be happy enough. And the other workers on Avignon—they didn't seem to be disgusted by the dirt and noise."

"Oh, I am ecstatic!" Morguma raved. "It is my aptitude! Rocket fuel is my life blood! There are those among us who have a love for this noisy distasteful life of space!"

"Sounds logical," O'Dea murmured. "Some humans enjoy doing the dirty work that nauseates the average person ... unpleasant, but necessary. As for that remark about rocket fuel's being your life blood, Morguma, I happen to know it's true!"

He chuckled at the look of discomfiture that spread over Morguma's features. The quintol that was a part of rocket fuel was the equivalent of alcohol to the metabolism of the Centaurs. Several times he had seen Morguma take a quick pull from a small bottle he kept in his leathery garment—the Centaur version of a hip flask.

Morguma changed the subject as O'Dea's throaty chuckle continued. He pointed to the grayish speck in the telescope.

"Oh a remarkable find! A lump of solid carbon dioxide, and of such a size! Oh how fortunate we are to have such fortunate fortune!"

Their vessel closed in on the chunk of almost pure carbon dioxide, a piece larger than the ship. Under the Centaur's directions, O'Dea fed out the seizure beams. He watched the rough mass become gradually rigid, fixed in space relative to them.

That seizure beam would interest Earth's scientists. But Earth was trillions of miles away.

Morguma clapped his paws together in foolish delight. "Oh how goody! We must hasten back to Avignon! On the way, we will analyze this precious find!"

As they blasted back toward Centauri's sixth planet, O'Dea learned from Morguma how the analysis was made by instrument. The figures they reported would be turned into a central office, along with the results of other ships engaged in the same task. In that way, the Centaurs checked the composition of the atmosphere they were creating for the planet, knew what elements were most necessary at any given moment.

They swooped low over the planet, on the side opposite the space base. Other Centaurs were bringing laden ships down, loosing their cargoes like sticks of bombs. A great plateau was speckled with white, and below, the ocean bed was filling with water.

Hawthorne joined the procession of Centaur ships. When they neared the surface, he barked at O'Dea to loosen their load. The seizure beams disappeared and the icy chunk splashed over several acres of ground.

"A successful mission!" Morguma giggled. "Now we return to our lovely base to rest!"

O'Dea and Hawthorne glowered.

The next day was similar to the first, and the one after it, and all the rest until they had turned in a dozen days of work as slaves in the asteroid belt. O'Dea became proficient in operating his instruments; and Hawthorne brushed up on precision bombing until he could have planted his loads on a dime, if anybody had provided the dime.

They found out that the Centaurs didn't believe in resting on the Sabbath. Working hours were roughly from sunup to sundown—about an eight hour stretch, since Avignon's day was shorter than Earth's.

At dawn, a skipping troop of young Centaurs invaded their chambers. The students were learning English, diplomatic French, South Martian Portuguese, and a score of other languages of which Hawthorne and O'Dea knew nothing.

Then Morguma came and led them to a huge boiler factory that was fitted as a dining room, where they toyed with Centaur food and ate vita-horm capsules salvaged from their ship.

After that, it was out to the asteroid belt for another load of frozen atmosphere.

"Oh, Hell," said O'Dea. They were going back to their quarters after another day's work. "If it wasn't for that picture of Mercedes, I'd throw in my buttons. I'm dying to see a human being again!"

Hawthorne's homely face turned suspiciously to him. "I'm here, ain't I?"

O'Dea raised an eyebrow and turned away. A fleet of powerful Centaur dreadnaughts was landing. They had just performed the fabulous task of transporting a huge frozen lake to Avignon—a miracle of coordination.

O'Dea filled his lungs with air. He removed the blanket from his shoulders, let his chest rise and fall evenly.

"Almost as good as Earth," he said. "This air is wonderful now, but it's wasted. Only two humans to breathe it—hey!"

He stared at the spindly mountain that rose to a dizzy peak at the far end of the valley. A thin stream of smoke rose from it.

"I never noticed that before. Morguma—is that a volcano?"

Morguma, who had paused to watch them enjoy the air, looked toward the steaming mountain top and uncovered his fangs in a friendly smile.

"Entirely without harm, my charming friends of Earth! Our great scientists have performed in full an investigation. There is absolutely no danger from that volcano!"

O'Dea peered suspiciously at the distant cone. "If that thing ever goes off, this valley will be buried!"

"Oh fear not that this luscious land will be demolished, my beautiful comrades! Not a hair of your lovely heads will be harmed!"

Hawthorne growled. O'Dea made a fist of his right hand, rubbed it thoughtfully. But he shrugged, looking at the Centaur's twelve arms. They continued into the noisy dining room.

As they entered, Hawthorne stopped short and glared. Suddenly shaking with anger, he waved his fist at Morguma.

"This is the limit! You can kill me, but I don't have to stand for—this!"

His gesture swept the huge room. On every chair was hung bouquets of riotously colored Centaurian flowers. The walls were padded with garlands, and huge vases were in the center of each table. From the ceiling, more streamers of blossoms dipped low.

O'Dea's lips twitched, trying to hold back a grin. He watched the solid, plain features of the husky pilot become dark with fury.

"Wait Paul," he said quickly, "until we find out what it's all about." He turned to Morguma. "What happens here, my reptilian amigo?"

"A holiday! Tomorrow is the birthday of his supreme magnificence, The Centaur! On the anniversary of his coming into the world as the son of a humble fish cleaner, we honor this great person by desisting from all labor!"

"Oh—the big shot's birthday." O'Dea held a hand on Hawthorne's arm as the pilot started to cool off. He stared at the huge portrait of a giant, moronic Centaur leering unintelligently down at them.

"A few little glands controlling a whole solar system," he mused. "I'm glad that rhino never leaves his palace."

He turned his eyes from the dictator's portrait, took Hawthorne's arm and guided him away. The two men walked to their customary places. When they found their chairs, Hawthorne stopped and growled again. He stared distastefully at the decorations on their chairs.

They were flowers—flowers from Earth.

And they were pansies.

Hawthorne pushed them disgustedly from the arms of his chair and settled down in glum resignation.

Morguma took his place at O'Dea's left. O'Dea glanced at Hawthorne on his right and chuckled. He turned to the Centaur,

"Terrestrial flowers? How come?"

"I ecstasize to see your pleasure," Morguma drooled. "One of our brave captains took a ship to your delightful world, succeeded in plucking fragrant specimens of fauna and flora to populate this world. There are now animals and vegetation from Earth thriving happily on this globe!"

"So ... any humans?"

A tear trickled down Morguma's leathery cheek. "Oh it was so sad! The humans resisted—poor misguided creatures! They all lost their valuable lives and we will have to return for more!"

O'Dea put down the Centaurian mushroom he had been preparing to taste. The grin disappeared from his face as he shoved back his chair and faced Morguma. There was a deadly something in his eyes that seemed out of place in the usually carefree features.

"Another of your nonchalant slaughters." His voice was a low monotone. "Morguma, you'll pay for that—you and your grinning murder pals—"

His hand closed around the steaming cup of Centaurian coffee and he flung the liquid into the Centaur's face.

III

An hour later he sat on his bed and rubbed his aching jaw. He peered through a puffed eye at Hawthorne beside him. The pilot's blunt face was all grin.

"So I'm the primitive savage!" Hawthorne doubled in laughter. "You're the one who acted intelligent like a guinea pig tonight!"

"Laugh, you ape!" O'Dea groaned and moved his jaw tenderly. "Not broken, I guess. But Morguma sure packs quintol in those cornerstones he uses for fists. All twelve of them!"

"Quintol—that's it." Hawthorne pulled a bottle from under his shirt. He looked patronizingly at O'Dea. "There's enough quintol here to get four Centaurs blind drunk!"

"Well, start slopping it up, slop!"

"This bottle," said Hawthorne patiently, "is our dictator's birthday present to our friend Morguma. The Centaurs will appreciate such a gesture of friendship!"

O'Dea stared through unbelieving black eyes at him. "Why, you—rat!—"

"Tomorrow," Hawthorne went on, "is a holiday. Nobody works except us. That's as a token of interstellar good will. We work and the Centaurs rest—except our good friend Morguma, who will be along to keep an eye on us. Morguma deserves a little fun, too."

O'Dea crawled out of his bunk and advanced with hard fists. He was promptly shoved back by the grinning Hawthorne.

"Don't you see?" Hawthorne demanded. "We get Morguma so pie-eyed he won't know what's going on. Then—"

He drew a stubby forefinger across his throat and made a croaking noise. O'Dea pried his puffed eyelids apart and beamed in pleased understanding. His lips parted slowly in a grin that would have done credit to a Centaur.

"Oh, I am ecstatic!" he said.

Morguma was ecstatic when he received his present. Tears of happiness gushed down his cheeks as O'Dea presented the vacuum bottle with a flowery oration. He seemed to have forgotten the incident of the previous night, and took no notice of O'Dea's bruised features.

The happy creature crushed O'Dea to his bosom with several bear-like arms.

"Oh my dear bosom friends! My heart would swell with song if I were able to sing! Oh you fortunate humans, to be able to sing!"

O'Dea broke loose from the embrace and rubbed his ribs. He looked cheerfully at Hawthorne.

"As soon as he's non compos mentis," he whispered, "we'll slug the lug, and—"

"Shut up," Hawthorne growled softly. "You'll queer everything."

The pilot took his place at the control board and they pushed out to the asteroid belt. Morguma settled himself in his usual chair at the rear of the control room and tantalized himself by smelling the quintol.

"Oh how wonderful!" he enthused. "Aged in the bottle, too! How I love humans!"

O'Dea glanced impatiently from the corner of his eye. The Centaur was in no hurry to consume the quintol. They were approaching the asteroid belt before he had put much inside him.

The two men stalled by chasing down worthless rocks until half the liquor was inside the Centaur. Morguma's six eyes gradually became glassier and glassier. He started to sway a little in his chair.

"Gonna get the mosh wonnerful piesh of d'lightful oshy—oshygen you ever shaw!" he announced. "There'sh shtupendous piesh. Oh I am rap—rapshurous!"

"It's only a piece of pumice!" O'Dea insisted.

"Itsh oshygen! Lovely beaut'ful delecbub—delect'ble oshygen!" Morguma staggered toward them. "Put sheizure beam on lovely oshygen!"

The seizures clamped on the stone as O'Dea shrugged and threw out the beams. Morguma took another long nip and let his eyes swim into focus on the dials. He looked hurt.

"Not oshygen? Not lovely oshygen? Oh I am eshcruchiated!"

The creature sobbed and took another drink. He staggered back and fell into his chair, where he fell into a weeping spree, his head buried in his hands.

O'Dea glanced swiftly. His elbow dug into Hawthorne's ribs.

Hawthorne nodded. They quietly picked up the wrenches they had kept nearby; started toward Morguma.

One on each side, they moved cautiously. Silently they moved forward until they came within striking distance.

Hawthorne waved O'Dea back, gesturing to his own powerful right arm. O'Dea nodded, poised his weapon for the follow up swing. Hawthorne raised the wrench.

And then Morguma's whip flicked out.

Hawthorne's eyes remained fastened to his empty hand as the wrench clattered into a corner. Again the snap of Centaur leather, and O'Dea's weapon joined the other. The two men stood foolishly, like a pair of boys caught stealing apples. Morguma spoke:

"Oh you bad bad people! Go back to control board; let poor Morguma alone. Oh I am deshicated to think you would do thish to poor old frien' Morguma!"

They slunk back to their posts. O'Dea raised his helpless eyes to the portrait above the controls.

"What can I do, Mercedes?" he whispered. "The guy is stiffer than King Tut and still you can't beat him!"

They avoided each other's eyes. Each knew what the other was thinking. Defeat meant that the Centaur had won. There would be no warning to Earth.

Avignon would become a planet of slave humans, blindly following the skillful teachings of the Centaurs. They would infiltrate Earth, tear down from within.... Generations would be required, but the Centaurs had time. They thought in long term strategy.

Hawthorne was staring unbelievingly through the telescope. His trembling fingers closed on O'Dea's arm.

"Let go, you ape—"

O'Dea stopped, impelled by the smoldering hope in the eyes that warned him to silence. He glanced swiftly to be sure that Morguma was still hunched stupidly in his chair, then followed Hawthorne's gaze. He gasped at what they saw.

In their line of vision was a mass that looked like twisted wire, coiled up in a planless tangle. O'Dea leaned forward, stared without belief.

"Our fuel," he breathed. "If we can get hold of that—"

Hawthorne waved him frantically, silently, to the seizure beams. O'Dea tiptoed to the levers, waited with one eye on Morguma while Hawthorne crept up on the precious fuel.

O'Dea eyed the dials, hands shaking on the control bars. There was no mistake! It was indeed their fuel, forced out of the hole in their tanks by internal pressure. Pressed out into space in a priceless ribbon, it had frozen into this amorphous mass!

O'Dea's heart was heavy in his ears. His suddenly feverish eyes darted to the apparently-sleeping Morguma, then to the smiling portrait of Mercedes.

Hawthorne nodded imperatively. The ship jolted slightly as the seizure beams went on. The fuel was clamped rigid before them. Morguma stirred and studied them with glazed eyes. His thick voice croaked:

"Whazzhat? Oshygen? Lovely precious oshygen?"

"That's right, Morguma. Oshygen—I mean oxygen." O'Dea brought the chunk closer, trying hard to look natural. "It looks so lovely I'd like to take a chunk on board and sniff it right now!"

"Oh whassa lovely ideas!" Morguma, still clutching his whip and his bottle, navigated by dead-drunk reckoning to the vision plate in the control room's belly. He peered stupidly at the coiled fuel. O'Dea feared that the sound of his breathing would sober the Centaur. He held the breath in his pounding lungs.

"'s funny oshygen!" Morguma mumbled. "Mosh funniesh oshygen I ever seen!" He brightened. "Mush be a rare ishotype! Oh mush be lov'liesh oshygen in whole galaxy!"

He closed all but one eye and tried to read the dials. Furtively, O'Dea turned the telescope into the asteroid belt, and the instruments swayed as badly as Morguma himself. The Centaur shuddered and turned away.

"Broken! All the metersh mush be drunk! Can't eshamine lovely oshygen!"

He started sobbing.

"Oh, come now, old man," said O'Dea, sympathetically. "We can bring a piece of it inside the ship and look at it first hand—"

"Wunnerful ideas! Wunnerful!"

Morguma slapped O'Dea's back affectionately. O'Dea picked himself off the floor and staggered in a great circle to the control board.

A thin seizure beam stabbed at a corner of the fuel, broke off a generous chunk. Under O'Dea's trained fingers, it moved toward the ship, through the belly lock.

Then it was in the cabin.

IV

Hawthorne had been doctoring the thermostats. In the heated room the highly volatile quintol-base fuel started swiftly to vaporize. O'Dea felt his head beginning to reel as the acrid fumes filled his lungs. His eyes burned.

But the effect on the Centaur was greater. He became rigid and turned even more glassy-eyed. He swayed and for a tense second seemed about to fall over. Then his eyes focussed with a desperate effort, almost sobered by fear.

"Quintol!" He raised the whip. "Not oshygen!"

He lost his footing as Hawthorne banked the ship. Ordinarily this would have been no strain on his Centaur sense of balance. But the quintol was too much for him. He crashed to the floor. When he picked himself up, he stood for a few seconds, stiff as rigor mortis, then he pitched down again on his face.

O'Dea unwrapped himself from a chenille curtain. He rubbed his head and stared at the prostrate Centaur.

"What a skinful! He looks almost as bad as you, Paul! Must be something he ate. Let's dump him through the lock and hurry back to Earth."

"Get into a space suit and stow the fuel away," growled Hawthorne. "I'll chain this critter up and we'll take him home with us. But first, we'll leave a souvenir to those Centaurs on Avignon!"

The fuel stowed in the tanks, O'Dea climbed back into the ship and pulled at his space suit fastenings. He looked happily at the well-manacled Centaur, still in a drunken stupor.

"The air is better now," he observed. "Let's get on our way back to Earth and—hey! What're you up to?"

Hawthorne was ripping the flowery seat covers and soft curtains from their fastenings, piling them near the airlock. When they were all gathered, he shoved them out and watched happily through the vision plate as they floated away from the ship.

O'Dea grinned. "You're cooking with quintol, at that. The boys would never let us forget it if we came home furnished like that!"

Hawthorne grunted and pulled at Morguma's manacles. He went back to the telescope, studied space ahead for a while. Then he nodded, satisfied.

"That one should do," he mused.

"Should do what?" O'Dea wondered.

"That big rock ahead should be a good farewell gift to the Centaurs. We'll fly over their camp, and—"

A knowing smile was on Hawthorne's lips as he nosed up on a tiny asteroid. When they came close enough, the asteroid proved to be bigger than the ship.

Gradually, they trapped it in the seizure beams. Hawthorne fought grimly against inertia. The asteroid began to pull ahead of its orbit, and finally it was under full control of their engines.

Space was clear all the way back to Avignon. No Centaur ships were off the ground—there was nothing to challenge them. Hawthorne blasted straight for the valley of Centaur ships.

The motors strained, overheated, with the huge asteroid they lugged. When they entered the atmosphere, the vessel dropped almost like a dead weight.

O'Dea looked worried.

"That big factory, Paul. That's the best objective, and you're way off from it. Bear right—"

"Small game!" Hawthorne leered, a superior smile on his lips. "Just do what I said—keep your fingers one inch above the release key and push down fast when I give the word!"

O'Dea stared into the valley below. They were falling fast and the huge chunk of rock almost cut off the vision. But they were moving forward as well as down, and the long lines of Centaur ships and factories were being left far behind. O'Dea shook his head, fingered with one hand some of his bruises.

Then his eyes widened. Dead ahead and coming up fast to meet them, was a mountain. From a pit in its narrow tip rose a trickle of smoke.

"Get ready!" Hawthorne shouted.

O'Dea could almost see into the crater. He held his sweating palm ready.

"Now!"

Before Hawthorne finished barking the command, O'Dea's hand shot down, releasing the seizure beams. The ship catapulted skyward as the weight was suddenly dropped. The pilot fought the pounding rockets. When it was under control, Hawthorne circled back over the valley.

They stared at the mass of earth that tumbled down the mountain side in a gathering avalanche. Their asteroid plunged bouncing into the valley below, shaking the entire volcano each time it hit. New avalanches started in its wake.

Then the volcano exploded.

A thousand feet of rocky cone disappeared in a fiery murderous cloud. Flaming lava and flying rock filled the air for miles. Hawthorne worked frantically for altitude as molten crimson streamers of hell streaked skyward.

In Avignon's stratosphere, they looked down through the glaring lava that hid the valley.

An anguished voice broke in:

"Oh I cannot believe it of you!"

And Morguma started to cry.

O'Dea pulled the pilot's chair to one side, reached into an opening in the floor beneath it. He drew forth two bundles of clothing. The two men stripped off their greasy coveralls, put on the clean clothes.

Morguma stared unbelievingly at the crisp olive green uniforms of Earth's space force. The grimy faces of Hawthorne and O'Dea grinned happily from under the jaunty caps. On the shoulders of each were the twin platinum bars of space captains.

"Spies! Oh you unnatural men, to bite the very hand that fed you—"

"—and cracked the whip," O'Dea finished sharply. "If you want to be technical, we were in uniform all the time—those coveralls are regulation work clothes. And all is fair in love and war, you know. We came to Centauri on a reconnaissance job, and ran into some luck."

He sighed happily, turned his eyes to the portrait above the control board.

Hawthorne chuckled. He was reading a thin tape that ran through his fingers.

"I have the ethertype machine running," he said. "News from Earth. And look at the very first item!"

He passed it over. O'Dea's grin disappeared as he read. He growled at the tape, flung it from him.

"So she married a rocket hand while my back was turned! Well—"

He frowned for a moment. Then his shoulders rose and fell in a carefree shrug.

"I go bigger for blondes, anyway. First thing I'm going to do after we report is head for Lidice, Venus, and go on the biggest tear in the history of the space guard. That'll be—"

There was a faintly disturbed look in Paul Hawthorne's eyes. But he soothed his conscience with the thought that O'Dea would be just as well off without Mercedes. So he saw no reason to tell Captain Lance O'Dea that he had typed out the story on the ethertype himself. Because all is fair in love as well as in war.

And Captain Paul Hawthorne was in love with Mercedes, too.