Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,’ from October, 1913. The table of contents, based on the index from the May issue, has been added by the transcriber.

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation have been retained, but punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Passages in English dialect and in languages other than English have not been altered. The footnote has been moved to the end of the corresponding article.

Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. All rights reserved.

| PAGE | ||

| AMERICANS, NEW-MADE. Drawings by | W. T. Benda | |

| Facing page 894 | ||

| AUTO-COMRADE, THE. | Robert Haven Schauffler | 850 |

| CARTOONS. | ||

| Died: Rondeau Rymbel. | Oliver Herford | 955 |

| A Triumph for the Fresh Air Fund. | F. R. Gruger | 957 |

| Newport Note. | Reginald Birch | 960 |

| CASUS BELLI. | 955 | |

| DEVIL, THE, HIS DUE | Philip Curtiss | 895 |

| DINNER OF HERBS,” “BETTER IS A. Picture by | Edmund Dulac | |

| Facing page 801 | ||

| GARAGE IN THE SUNSHINE, A | Joseph Ernest | 921 |

| Picture by Harry Raleigh. | ||

| GHOSTS,” “DEY AIN’T NO | Ellis Parker Butler | 837 |

| Pictures by Charles Sarka. | ||

| HOME. I. AN ANONYMOUS NOVEL. | 801 | |

| Illustrations by Reginald Birch. | ||

| HOMER AND HUMBUG. | Stephen Leacock | 952 |

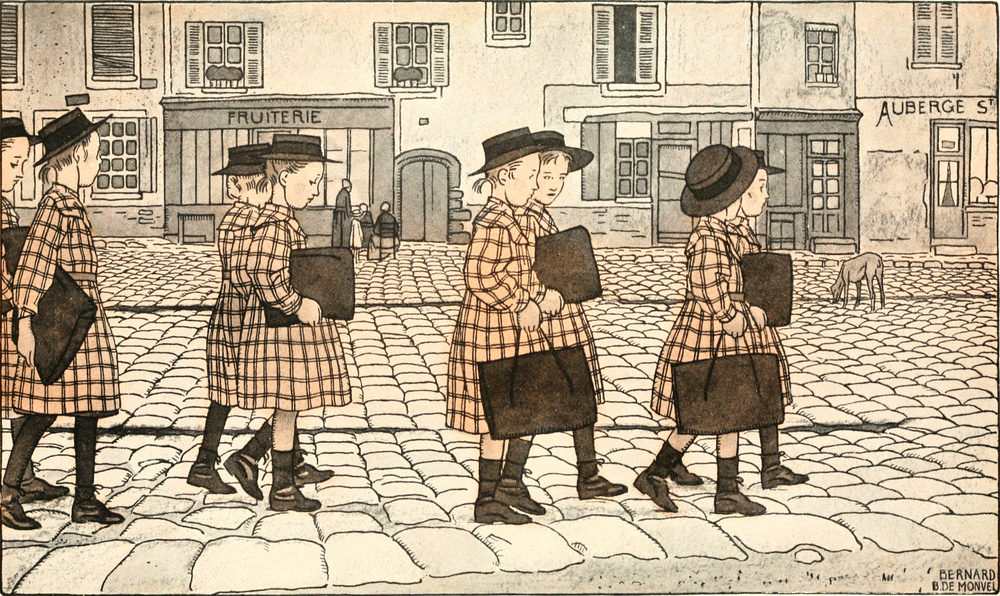

| NEMOURS: A TYPICAL FRENCH PROVINCIAL TOWN. | Roger Boutet de Monvel | 844 |

| Pictures by Bernard Boutet de Monvel. | ||

| PADEREWSKI AT HOME. | Abbie H. C. Finck | 900 |

| Picture from a portrait by Emil Fuchs. | ||

| PARIS. | Theodore Dreiser | 904 |

| Pictures by W. J. Glackens. | ||

| PROGRESSIVE PARTY, THE | Theodore Roosevelt | 826 |

| Portrait of the author. | ||

| SCULPTURE. | Charles Keck | 917 |

| SENIOR WRANGLER, THE | 958 | |

|

Snobbery—America vs. England. Our Tender Literary Celebrities. |

||

| SUMMER HILLS,” THE, IN “THE CIRCUIT OF | John Burroughs | 878 |

| Portrait of the author by Alvin L. Coburn. | ||

| SUNSET ON THE MARSHES. From the painting by | George Inness | |

| Facing page 824 | ||

| TRADE OF THE WORLD PAPERS, THE | James Davenport Whelpley | |

| XVIII. The Foreign Trade of the United States | 886 | |

| T. TEMBAROM. | Frances Hodgson Burnett | 929 |

| Drawings by Charles S. Chapman. | ||

| WHITE LINEN NURSE, THE | Eleanor Hallowell Abbott | 857 |

| Pictures, printed in tint, by Herman Pfeifer. | ||

| YEAR, THE MOST IMPORTANT | Editorial | 951 |

VERSE

| BEGGAR, THE | James W. Foley | 877 |

| EMERGENCY. | William Rose Benét | 916 |

| HUSBAND SHOP, THE | Oliver Herford | 956 |

| Picture by Oliver Herford. | ||

| MOTHER, THE | Timothy Cole | 920 |

| Picture by Alpheus Cole. | ||

| MYSELF,” “I SING OF | Louis Untermeyer | 960 |

| PARENTS, OUR | Charles Irvin Junkin | 959 |

| Pictures by Harry Raleigh. | ||

| SOCRATIC ARGUMENT. | John Carver Alden | 960 |

AN ANONYMOUS NOVEL

(TO BE COMPLETED IN FOUR LONG INSTALMENTS)

RED HILL drowses through the fleeting hours as though not only time, but mills, machinery, and railways were made for slaves. Hemmed in by the breathing silences of scattered woods, open fields, and the far reaches of misty space, it seems to forget that the traveler, studying New England at the opening of the nineteenth century through the windows of a hurrying train, might sigh for a vanished ideal, and concede the general triumph of a commercial age.

For such a one Red Hill held locked a message, and the key to the lock was the message itself: “Turn your back on the paralleled rivers and railroads, and plunge into the byways that lead into the eternal hills, and you will find the world that was and still is.”

Let such a traveler but follow a lane that leads up through willow and elderberry, sassafras, laurel, wild cherry, and twining clematis—a lane alined with slender wood-maples, hickory, and mountain-ash, and flanked, where it gains the open, with scattered juniper and oak, and he will come out at last on the scenes of a country’s childhood.

At right angles to the lane, a broad way cuts the length of the hill, and loses itself in a dip at each end toward the valleys and the new world. The broad way is shaded by one of two trees, the domed maple or the stately elm. At the summit of its rise stands an old church the green shutters of which blend with the caressing foliage of primeval trees. Its white walls and towering steeple dominate the scene. White, too, are the houses that gleam from behind the verdure of unbroken lawns and shrubbery—all but one, the time-stained brick of which glows blood-red against the black green of clinging ivy.

Not all these homes are alive. Here a charred beam tells the story of a fire, there a mound of trailing vines tenderly hides from view the shame of a ruin, and there again stands a tribute to the power of the new age—a house the shutters of which are closed and barred. White now only in patches, its scaling walls have taken on the dull gray of neglected pine.

For generations the houses of Red Hill have sent out men, for generations they have taken them back. Their cupboards guard trophies from the seven seas, paid for with the Yankee nutmeg, swords wrought from plowshares and christened with the blood of the oppressor, a long line of collegiate sheepskins, and last, but by no means least, recipes the faded ink and brittle paper of which sum the essence of ages of culinary wisdom.

Some of these clustered homes live the year round at full swing, but the life of some is cut down to a minimum in the winter, only to spring up afresh in summer, like the new stalk from a treasured bulb. Of such was the little kingdom of Red Hill. Upon its long, level crest it bore only three centers of life and a symbol: Maple House, the Firs, and Elm House, half hidden from the road by their distinctive trees, but as alive as the warm eyes of a veiled woman; and the church.

The supper call had sounded, and the children’s answering cries had ceased. Along the ribbon of the single road scurried an overladen donkey. Three lengths of legs bobbed at varying angles from her fat sides. Behind her hurried a nurse, aghast for the hundredth time at the donkey’s agility, never demonstrated except at the evening hour.

Half-way between Maple House and the Firs stood two bare-legged boys, working their toes into the impalpable dust of the roadway and rubbing the grit into their ankles in a final orgy of dirt before the evening wash. They called derisively to the donkey-load of children, bound to bed with the setting sun.

ON a day in early spring Alan Wayne was summoned to Red Hill. Snow still hung in the crevices of East Mountain. On the hill the ashes, after the total eclipse of winter, were meekly donning pale green. The elms of Elm House were faintly outlined in verdure, and stood like empty sherry-glasses waiting for warm wine. Farther down the road the maples stretched out bare, black limbs whose budding tufts of leaves served only to emphasize the nakedness of the trees. Only the firs, in a phalanx, scoffed at the general spring cleaning, and looked old and sullen in consequence.

The colts, driven by Alan Wayne, flashed over the brim of Red Hill to the level top. Coachman Joe’s jaw was hanging in awe, and so had hung since Mr. Alan had taken the reins. For the first time in their five years of equal life the colts had felt the cut of a whip, not in anger, but as a reproof for breaking. Coachman Joe had braced himself for the bolt, his hands itching to snatch the reins. But there had been no bolting, only a sudden settling down to business.

“Couldn’t of got here quicker if he’d let ’em bolt,” said he in subsequent description to the stable-hand and the cook. He snatched up a pail of water and poured it steadily on the ground. “Jest like that. He knew what was in the colts the minute he laid hands on ’em, and when he pulls ’em up at the barn door there wasn’t a drop left in their buckets, was there, Arthur?”

“Nary a drop,” said Arthur, stable-hand.

“And his face,” continued the coachman. “Most times Mr. Alan has no eyes to speak of, but to-day and that time Miss Nance stuck him with the hat-pin—’member, cook?—his eyes spread like a fire and eat up his face. This is a black day for the Hill. Somethin’ ’s going to happen. You mark me.”

In truth Mr. Alan Wayne had been summoned in no equivocal terms and, for all his haste, it was with nervous step he approached the house.

There was no den, no sanctuary beyond a bedroom, for any one at Maple House. No one brought work to Red Hill save such work as fitted into swinging hammocks and leafy bowers. Library opened into living-room and hall, hall into drawing-room, and drawing-room into the cool shadows and high lights of half-hidden mahogany and china closets. And here and there and everywhere doors opened out on to the Hill. It was a place where summer breezes entered freely and played, sure of a way out. Hence it was that Maple House as a whole became a tomb on that memorable spring morning when the colts first felt a master hand—a tomb where Wayne history was to be made and buried as it had been before.

Maple House sheltered a mixed brood. J. Y. Wayne, seconded by Mrs. J. Y., was the head of the family. Their daugh[Pg 803]ter, Nance Sterling, and her babies represented the direct line, but the orphans, Alan Wayne and Clematis McAlpin, were on an equal footing as children of the house. Alan was the only child of J. Y.’s dead brother. Clematis was also of Wayne blood, but so intricately removed that her exact relation to the rest of the tribe was never figured out twice to the same conclusion. Old Captain Wayne, retired from the regular army, was an uncle in a different degree to every generation of Waynes. He was the only man on Red Hill who dared call for a whisky and soda when he wanted it.

When Alan reached the house, Mrs. J. Y. was in her garden across the road, surveying winter’s ruin, and Nance with her children had borne the captain off to the farm to see that oft-repeated wonder and always welcome forerunner of plenty, the quite new calf.

Clematis McAlpin, shy and long-limbed, just at the awkward age when woman misses being either boy or girl, had disappeared. Where, nobody knew. She might be bird’s-nesting in the swamp or crying over the “Idylls of the King” in the barn loft. Certainly she was not in the house. J. Y. Wayne had seen to that. Stern and rugged of face, he sat in the library alone and waited for Alan. He heard a distant screen-door open and slam. Steps echoed through the lonely house. Alan came and stood before him.

Alan was a man. Without being tall, he looked tall. His shoulders did not seem broad till you noticed the slimness of his hips. His neck looked too thin till you saw the strong set of his small head. In a word, he had the perfect proportion that looks frail and is strong. As he stood before his uncle, his eyes grew dull. They were slightly blood-shot in the corners, and with their dullness the clear-cut lines of his face seemed to take on a perceptible blur.

J. Y. began to speak. He spoke for a long quarter of an hour, and then summed up all he had said in a few words:

“I’ve been no uncle to you, Alan; I’ve been a father. I’ve tried to win you, but you were not to be won. I’ve tried to hold you, but it takes more than a Wayne to hold a Wayne. You have taken the bit with a vengeance. You have left such a wreckage behind you that we can trace your life back to the cradle by your failures, all the greater for your many successes. You’re the first Wayne that ever missed his college degree. I never asked what they expelled you for, and I don’t want to know. It must have been bad, bad, for the old school is lenient, and proud of men that stand as high as you stood in your classes and on the field. Money—I won’t talk of money, for you thought it was your own.”

For the first time Alan spoke.

“What do you mean, sir?” With the words his slight form straightened, his eyes blazed, there was a slight quivering of the thin nostrils, and his features came out clear and strong.

J. Y. dropped his eyes.

“I may have been wrong, Alan,” he said slowly, “but I’ve been your banker without telling you. Your father didn’t leave much. It saw you through junior year.”

Alan placed his hands on the desk between them and leaned forward.

“How much have I spent since then—in the last three years?”

J. Y. kept his eyes down.

“You know more or less, Alan. We won’t talk about that. I was trying to hold you, but to-day I give it up. I’ve got one more thing to tell you, though, and there are mighty few people that know it. The Hill’s battles have never entered the field of gossip. Seven years before you were born, my father—your grandfather—turned me out. It was from this room. He said I had started the name of Wayne on the road to shame and that I could go with it. He gave me five hundred dollars. I took it and went. I sank low with the name, but in the end I brought it back, and to-day it stands high on both sides of the water. I’m not a happy man, as you know, for all that. You see, though I brought the name back in the end, I never saw your grandfather again, and he never knew.

“Here are five hundred dollars. It’s the last money you’ll ever have from me; but whatever you do, whatever happens, remember this: Red Hill does not belong to a Lansing or to a Wayne or to an Elton. It is the eternal mother of us all. Broken or mended, Lansings and Waynes have come back to the Hill through generations. City of refuge or harbor of peace, it’s all one to the Hill. Remember that.”

He laid the crisp notes on the desk. Alan half turned toward the door, but stepped back again. His eyes and face were dull once more. He picked up the bills and slowly counted them.

“I shall return the money, sir,” he said and walked out.

He went to the stables and ordered the pony and cart for the afternoon train. As he came out he saw Nance, the children, and the captain coming slowly up Long Lane from the farm. He dodged back into the barn through the orchard and across the lawn. Mrs. J. Y. stood in the garden directing the relaying of flower-beds. Alan made a circuit. As he stepped into the road, swift steps came toward him. He wheeled, and faced Clem coming at full run. He turned his back on her and started away. The swift steps stopped so suddenly that he looked around. Clem was standing stock-still, one awkward, lanky leg half crooked as though it were still running. Her skirts were absurdly short. Her little fists, brown and scratched, pressed her sides. Her dark hair hung in a tangled mat over a thin, pointed face. Her eyes were large and shadowy. Two tears had started from them, and were crawling down soiled cheeks. She was quivering all over like a woman struck.

Alan swung around, and strode up to her. He put one arm about her thin form and drew her to him.

“Don’t cry, Clem,” he said, “don’t cry. I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

For one moment she clung to him and buried her face against his coat. Then she looked up and smiled through wet eyes.

“Alan, I’m so glad you’ve come!”

Alan caught her hand, and together they walked down the road to the old church. The great door was locked. Alan loosened the fastening of a shutter, sprang in through the window, and drew Clem after him. They climbed to the belfry. From the belfry one saw the whole world, with Red Hill as its center. Alan was disappointed. The Hill was still half naked, almost bleak. Maple House and[Pg 806] Elm House shone brazenly white through budding trees. They looked as though they had crawled closer to the road during the winter. The Firs, with its black border of last year’s foliage, looked funereal. Alan turned from the scene, but Clem’s little hand drew him back.

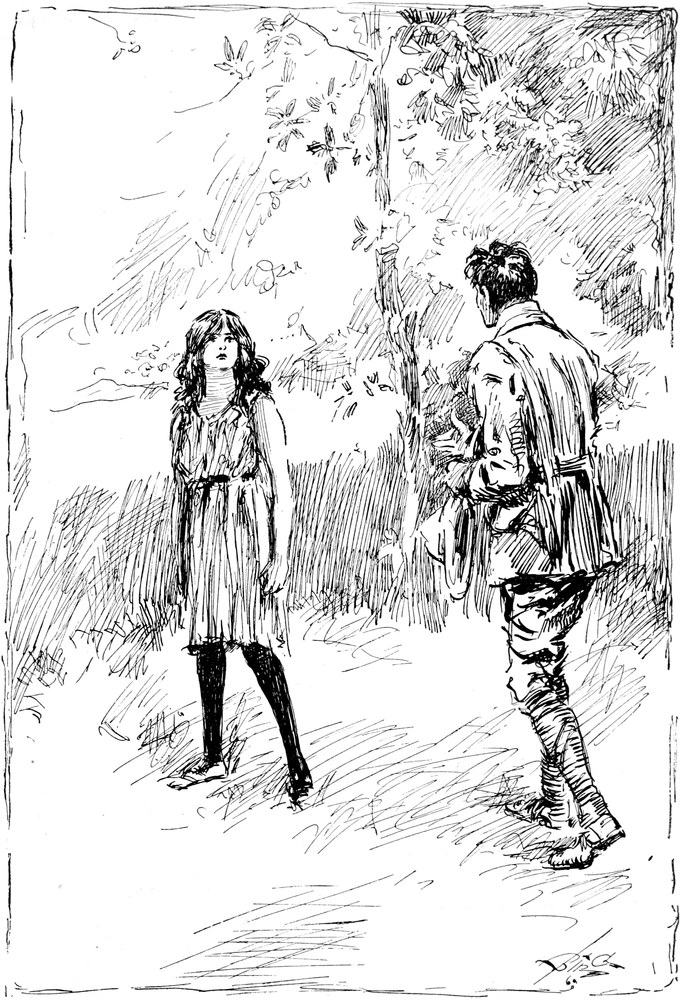

Drawn by Reginald Birch

“HER SKIRTS WERE ABSURDLY SHORT. HER LITTLE FISTS, BROWN AND SCRATCHED, PRESSED HER SIDES”

Clematis McAlpin had happened between generations. Alan, Nance, Gerry Lansing, and their friends had been too old for her, and Nance’s children were too young. There were Elton children of about her age, but for years they had been abroad. Consequently, Clem had grown to fifteen in a sort of loneliness not uncommon with single children who can just remember the good times the half-generation before them used to have by reason of their numbers. This loneliness had given her in certain ways a precocious development while it left her subdued and shy even when among her familiars. But she was shy without fear, and her shyness itself had a flower-like sweetness that made a bold appeal.

“Isn’t it wonderful, Alan?” she said. “Yesterday it was cold and it rained and the Hill was black—black, like the Firs. To-day all the trees are fuzzy with green, and it’s warm. Yesterday was so lonely, and to-day you are here.”

Alan looked down at the child with glowing eyes.

“And, do you know, this summer Gerry Lansing and Mrs. Gerry are coming. I’ve never seen her since that day they were married. Do you think it’s all right for me to call her Mrs. Gerry, like everybody does?”

Alan considered the point gravely.

“Yes, I think that’s the best thing you could call her.”

“Perhaps when I’m really grown up I can call her Alix. I think Alix is such a pretty name, don’t you?”

Clem flashed a look at Alan, and he nodded; then, with an impulsive movement she drew close to him in the half-wheedling way of woman about to ask a favor.

“Alan, they let me ride old Dubbs when he isn’t plowing. The old donkey she’s so fat now she can hardly carry the babies. Some day when you’re not in a great hurry will you let me ride with you?”

Alan started down the ladder.

“Some day, perhaps, Clem,” he muttered. “Not this summer. Come on.” When they had left the church, he drew out his watch and started. “Run along and play, Clem.” He left her and hurried to the barn.

Joe was waiting.

“Have we time for the long road, Joe?” asked Alan as he climbed into the cart.

“Oh, yes, sir, especially if you drive, Mr. Alan.”

“I don’t want to drive. Let him go and jump in.”

The coachman gave the pony his head, climbed in, and took the reins. The cart swung out, and down the lane.

“Alan! Alan!”

Alan recognized Clem’s voice and turned. She was racing across a corner of the pasture. Her short skirts flounced madly above her ungainly legs. She tried to take the low stone wall in her stride. Her foot caught in a vine, and she pitched headlong into the weeds and grass at the roadside.

Alan leaped from the cart and picked her up, quivering, sobbing, and breathless.

“Alan,” she gasped, “you’re not going away?”

Alan half shook her as he drew her thin body close to him.

“Clem,” he said, “you mustn’t. Do you hear? You mustn’t. Do you think I want to go away?”

Clem stifled her sobs and looked up at him with a sudden gravity in her elfish face. She threw her bare arms around his neck.

“Good-by, Alan.”

He stooped and kissed her.

IF Alix Deering had not barked her pretty shins against the center-board in Gerry Lansing’s sailing-boat on West Lake, it is possible that she would in the end have married Alan Wayne instead of Gerry Lansing.

When two years before Alan’s dismissal Nance had brought Alix, an old school friend, to Red Hill for a fortnight, everybody had thought what a splendid match Alix and Alan would make. But it happened that Alan was very much taken up at the time with memory and anticipation of a certain soubrette, and before he awoke[Pg 807] to Alix’s wealth of charms the incident of the shins robbed him of opportunity.

Gerry, dressed only in a bathing-suit, his boat running free before a brisk breeze, had swerved to graze the Point, where half of Red Hill was encamped, when he caught sight of a figure lying on the outermost flat rock. He took it to be Nance.

“Jump!” he yelled as the boat neared the rock.

The figure started, scrambled to its feet, and sprang. It was Alix, still half asleep, who landed on the slightly canted floor of the boat. Her shins brought up with a thwack against the center-board, and she fell in a heap at Gerry’s feet. Her face grew white and strained; for a second she bit her lip, and then, “I must cry,” she gasped, and cried.

Gerry was big, strong, and placid. Action came slowly to him, but when it came it was sure. He threw one knee over the tiller, and gathered Alix into his arms. She lay like a hurt child, sobbing against his shoulder.

“Poor little girl,” he said, “I know how it hurts. Cry now, because in a minute it will all be over. It will, dear. Shins are like that.” And then before she could master her sobs and take in the unconscious humor of his comfort, the boat struck with a crash on Hidden Rock.

The nearest Gerry had ever come to drowning was when he had fallen asleep lying on his back in the middle of West Lake. Even with a frightened girl clinging to him, it gave him no shock to find himself in the water a quarter of a mile from shore. But with Alix it was different. She gasped, and in consequence gulped down a large mouthful of the lake. Then she broke into hysterical laughter and swallowed more. Gerry held her up, and deliberately slapped her across the mouth. In a flash anger sobered her. Her eyes blazed.

“You coward,” she whispered.

Gerry’s face was white and stern.

“Put one hand on my shoulder and kick with your feet,” he said. “I’ll tow you to shore.”

“Put me on Hidden Rock,” said Alix; “I prefer to wait for a boat.”

“It will take an hour for a boat to get here,” answered Gerry. “I’m going to tow you in. If you say another word I shall slap you again.”

In a dead silence they plowed slowly to shore, and when Gerry found bottom, he stood up, took Alix in his arms, and strode well up the bank before he set her down.

During the long swim she had had time to think, but not to forgive. She stamped her sodden feet, shook out her skirts, and then looked Gerry up and down. With his crisp, light hair; blue eyes, wide apart and well open; and six feet of well-proportioned bulk, Gerry was good to look at, but Alix’s angry eyes did not admit it. They measured him scornfully; but it was not the look that hurt him so much as the way she turned from him with a little shrug of dismissal and started along the shore for camp.

Gerry reached out and caught hold of her arm. She swung around, her face quite white.

“I see,” she said in a low voice, “you want it now.”

Gerry held her with his eyes.

“Yes,” he answered, “I want it now.”

“Why did you yell at me to jump into your horrible boat?”

“I took you for Nance.”

“You took me for Nance,” repeated Alix with a mimicry and in a tone that left no doubt as to the fact that she was in a nasty temper. “And why,” she went on, her eyes blazing and her slight figure trembling, “did you strike me—slap me across the face?”

“Because I love you,” replied Gerry, steadily.

“Oh!” gasped Alix. Her slate-gray eyes went wide open in unfeigned amazement, and suddenly the tenseness that is the essence of attack went out of her body. Instead of a self-possessed and very angry young woman, she became her natural self—a girl fluttering before her first really thrilling situation.

There was something so childlike in her sudden transition that Gerry was moved out of himself. For once he was not slow. He caught hold of her and drew her toward him.

But Alix was not to be plucked like a ripe plum. She freed herself gently but firmly, and stood facing him. Then she smiled, and with the smile she gained the upper hand. Gerry suddenly became awkward and painfully aware of his bare arms and legs. He felt exceptionally naked.

“When did it begin?” murmured Alix.

“What?” said Gerry.

“It,” said Alix. “When—how long have you loved me?”

Gerry’s face turned a deep red, but he raised his eyes steadily to hers. “It began,” he said simply, “when I took you in my arms and you laid your face against my shoulder and cried like—like a little kid.”

“Oh!” said Alix again, and blushed in her turn. She had lost the upper hand and knew it. Gerry’s arms went around her, and this time she raised her face and let him kiss her.

“Now,” she said as they started for the camp, “I suppose I must call you Gerry.”

“Yes,” said Gerry, solemnly. “And I shall call you Little Miss Oh!”

So casual an engagement might easily have come to a casual end, but Gerry Lansing was quietly tenacious. Once moved, he stayed moved. No woman had ever stirred him before; he did not imagine that any other woman would stir him again.

To Alix, once the shock of finding herself engaged was passed, came full realization and a certain amount of level-headed calculation. She knew herself to be high-strung, nervous, and impulsive, a combination that led people to consider her lightly. On the day of the wreck Gerry had shown himself to be a man full grown. He had mastered her; she thought he could hold her.

Then came calculation. Alix was out of the West. All that money could do for her in the way of education and culture had been done, but no one knew better than she that her culture was a mere veneer in comparison with the ingrained flower of the Lansings’ family oak. Here was a man she could love, and with him he brought her the old homestead on Red Hill and an older brownstone front in New York the position of which was as unassailable socially as it was inconvenient as regards the present center of the city’s life. Alix reflected that if there was a fool to the bargain it was not she.

All Red Hill and a few Deerings gathered for the wedding, and many were the remarks passed on Gerry’s handsome bulk and Alix’s scintillating beauty; but the only saying that went down in history came from Alan Wayne when Nance, just a little troubled over the combination of Gerry and Alix, asked him what he thought of it.

Alan’s eyes narrowed, and his thin lips curved into a smile as he gave his verdict:

“Andromeda, consenting, chained to the rock.”

TO the surprise of his friends, Alan Wayne gave up debauch and found himself employment by the time the spring that saw his dismissal from Maple House had ripened into summer. He was full of preparation for his departure for Africa when a summons from old Captain Wayne reached him.

With equal horror of putting up at hotels or relatives’ houses, the captain, upon his arrival in town, had gone straight to his club, and forthwith become the sensation of the club’s windows. Old members felt young when they caught sight of him, as though they had come suddenly on a vanished landmark restored. Passing gamins gazed on his short-cropped gray hair, staring eyes, flaring collar, black string tie, and flowing broadcloth, and remarked:

“Gee! look at de old spoit in de winder!”

Alan heard the remark as he entered the club, and smiled.

“How do you do, sir?”

“Huh!” grunted the captain. “Sit down.” He ordered a drink for his guest and another for himself. He glared at the waiter. He glared at a callow youth who had come up and was looking with speculative eye at a neighboring chair. The waiter retired almost precipitously. The youth followed.

“In my time,” remarked the captain, “a club was for privacy. Now it’s a haven for bell-boys and a playground for whipper-snappers.”

“They’ve made me a member, sir.”

“Have, eh!” growled the captain, and glared at his nephew. Alan took inspection coolly, a faint smile on his thin face. The captain turned away his bulging eyes, crossed and uncrossed his legs, and finally spoke. “I was just going to say when you interrupted,” he began, “that engineering is a dirty job. Not, however,” he continued after a pause, “dirtier than most. It’s a profession, but not a career.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Alan. “They’ve got a few in the army, and they seem to be doing pretty well.”

“Huh, the army!” said the captain. He subsided, and made a new start. “What’s your appointment?”

“It doesn’t amount to an appointment. Just a job as assistant to Walton, the engineer the contractors are sending out. We’re going to put up a bridge somewhere in Africa.”

“That’s it. I knew it,” said the captain. “Going away. Want any money?”

The question came like solid shot out of a four-pounder. Alan started, colored, and smiled all at the same time.

“No, thanks, sir,” he replied; “I’ve got all I need.”

The captain hitched his chair forward, and glared out on the avenue.

“The Lansings,” he began, like a boy reciting a piece, “are devils for drink, the Waynes for women. Don’t you ever let ’em worry you about drink. Nowadays the doctors call us non-alcoholic. In my time it was just plain strong heads for wine. I say, don’t worry about drink. There’s a safety-valve in every Wayne’s gullet. But women, Alan!” The captain slued around his bulging eyes. “You look out for them. As your great-grandfather used to say, ‘To women, only perishable goods—sweets, flowers, and kisses.’ And you take it from me, kisses aren’t always the cheapest. They say God made everything down to little apples and Jersey lightning, but when He made women the devil helped.” The captain’s nervousness dropped from him as he deliberately drew out his watch and fob. “Good thing he did, too,” he added as a pleasing afterthought. He leaned back in his chair. A complacent look came over his face.

Alan got up to say good-by. The captain rose, too, and clasped the hand Alan held out.

“One more thing,” he said. “Don’t forget there’s always a Wayne to back a Wayne for good or bad.” There was a suspicion of moisture in his eye as he hurried his guest off.

Back in his rooms, Alan found letters awaiting him. He read them, and tore all up except one. It was from Clem. She wrote:

Dear Alan: Nance says you are going very far away. I am sorry. It has been raining here very much. In the hollows all the bridges are under water. I have invented a new game. It is called “steamboat.” I play it on old Dubbs. We go down into the valley, and I make him go through the water around the bridges. He puffs just like a steamboat, and when he gets out, he smokes all over. He is too fat. I hope you will come back very soon.

CLEM.

That evening Clem was thrown into a transport by receiving her first telegram. It read:

You must not play steamboat again; it is dangerous.

ALAN.

She tucked it in her bosom and rushed over to the Firs to show it to Gerry.

Gerry and Alix were spending the summer at the Firs, where Mrs. Lansing, Gerry’s widowed mother, was still nominally the hostess. They had been married two years, but people still spoke of Alix as Gerry’s bride, and, in so doing, stamped her with her own seal. To strangers they carried the air of a couple about to be married at the rational close of a long engagement. No children or thought of children had come to turn the channel of life for Alix. On Gerry, marriage sat as an added habit. It was beginning to look as though he and Alix drifted together not because they were carried by the same currents, but because they were tied.

Where duller minds would have dubbed Gerry the Ox, Alan had named him the Rock, and Alan was right. Gerry had a dignity beyond mere bulk. He had all the powers of resistance, none of articulation. Where a pin-prick would start an ox, it took an upheaval to move Gerry. An upheaval was on the way, but Gerry did not know it. It was yet afar off.

To the Lansings marriage had always been one of the regular functions of a regulated life, part of the general scheme of things. Gerry was slowly realizing that his marriage with Alix was far from a mere function, had little to do with a regular life, and was foreign to what he had always considered the general scheme of things. Alix had developed quite naturally into a social butterfly. Gerry did not picture her as chain-lightning playing on a rock, as Alan would have done; but he did in a vague way feel that bits of his impassive self were being chipped away.

Red Hill bored Alix, and she showed it. The first summer after the marriage they had spent abroad. Now Alix’s thoughts and talk turned constantly toward Europe. She even suggested a flying trip for the autumn, but Gerry refused to be dragged so far from golf and his club. He stuck doggedly to Red Hill till the leaves began to turn, and then consented to move back to town.

On their last night at the Firs, Mrs. Lansing, who was complimentary Aunt Jane to Waynes and Eltons, entertained Red Hill as a whole to dinner. With the arrival of dessert, to Alix’s surprise, Nance said, “Port all around, please, Aunt Jane.”

Lansings, Waynes, and Eltons were heavy drinkers in town, but it was a tradition, as Alix knew, that on Red Hill they dropped it—all but the old captain. It was as though, amid the scenes of their childhood, they became children, and just as a Frenchman of the old school will not light a cigarette in the presence of his father, so they would not take a drink for drink’s sake on Red Hill.

So Alix looked on interestedly as the old butler set glasses and started the port. When it had gone the round, Nance stood up, and with her hands on the table’s edge leaned toward them all. For a Wayne, she was very fair. As they looked at her, the color swept up over her bare neck. Its wave reached her temples, and seemed to stir the clustering tendrils of her hair. Her eyes were grave and bright with moisture. Her lips were tremulous.

“We drink to Alan,” she said; “to-day is Alan’s birthday.”

She sat down. They all raised their glasses. Little Clem had no wine. She put a thin hand on Gerry’s arm.

“Please, Gerry! Please!”

Gerry held down his glass. Clematis dipped in the tip of her little finger, and, as they all drank, gravely carried the drop of wine to her lips.

AS Judge Healey, gray-haired, but erect, walked up the avenue his keen glance fell on Gerry Lansing standing across the street before an art dealer’s window. Gerry’s eyes were fastened on a picture that he had long had in mind for a certain nook in the library of the town house.

It was the second anniversary of his wedding, and though it was already late in the afternoon, Gerry had not yet chosen his gift for Alix. He turned from the picture with a last long look and a shrug, and passed on to a palatial jeweler’s farther up the street.

For many years Judge Healey had been foster-father to Red Hill in general and to Gerry in particular. With almost womanly intuition he read what was in Gerry’s mind before the picture, and acting on impulse, the judge crossed the street and bought it.

While the judge was still in the picture shop, Gerry came out of the jeweler’s and started briskly for home. He had purchased a pendant of brilliants, extravagant for his purse, but yet saved to good taste by a simple originality in design.

He waited until the dinner-hour, and then slipped his gift into Alix’s hand as they walked down the stairs together. She stopped beneath the hall light.

“I can’t wait, dear; I simply can’t,” she said, and snapped open the case.

“Oh!” she gasped. “How dear! How perfectly dear! You old sweetheart!”

She threw her arms about his neck and kissed him twice; then she flew away to the drawing-room in search of Mrs. Lansing and the judge, the sole guests at the little anniversary dinner. Gerry straightened his tie and followed.

Alix’s tongue was rippling, her whole body was rippling, with excitement and pleasure. She dangled her treasure before their eyes. She laid it against her warm neck and ran to a mirror. The light in her eyes matched the light in the stones. The judge took the jewel and laid it in the palm of his strong hand. It looked in danger of being crushed.

“A beautiful thing, Gerry,” he said, “and well chosen. Some poet jeweler dreamed that twining design, and set the stones while the dew was still on the grass.”

After dinner the four gathered in the library, but they were hardly seated when Alix sprang up. Her glance had followed Gerry’s startled gaze. He was staring at the coveted picture he had been looking at in the gallery that afternoon. It hung in the niche in which his thoughts had placed it. Alix took her stand before it. She glanced inquiringly at the others. Mrs. Lansing nodded at the judge. Alix turned back to the picture, and gravity stole into her face. Then she faced the judge with a smile.

“We live,” she said, “in a Philistine age, don’t we? But I’ve never let my Philistinism drive pictures from their right place in the heart. Pictures in art galleries—” she shrugged her pretty shoulders—“I have not been trained up to them. To me they are mounted butterflies in a museum, cut flowers crowded at the florist’s. But this picture and that nook—they have waited for each other. You see the picture nestling down for a long rest, and it seems a small thing, and then it catches your eye and holds it, and you see that it is a little door that opens on a wide world. It has slipped into the room and become a part of life.”

A strange stillness followed Alix’s words. To the judge and to Gerry it was as though the picture had opened a window to her mind. Then she closed the window.

“Come, Gerry,” she said, turning, “make your bow to the judge and bark.”

Gerry was excited, though he did not show it.

“You have dressed my thoughts in words I can’t equal,” he said, and strolled out to the little veranda at the back of the house. He wanted to be alone for a moment and think over this flash of light that had followed a dark day. For the first time in a long while Alix had revealed herself. He did not begrudge the judge his triumph. He knew instinctively that coming from him instead of from the judge the picture would not have struck that intimate spark.

The next day Gerry gave his consent to Alix’s plan for a flying trip abroad, but with a reservation. The reservation was that she should leave him behind.

Judge Healey heard of this arrangement only when it was on the point of being put into effect. In fact, he was only just[Pg 812] in time at the steamer to wave good-by to Alix. Leaning over the rail, with her high color, moist red lips, and excited big eyes making play under a golden crown of hair and over a huge armful of roses, Alix presented a picture not easily forgotten.

The judge turned to Gerry.

“She ought not to be going without you, my boy.”

“Oh, it’s all right,” said Gerry, lightly. “She’s well chaperoned. It’s a big party, you know.”

But during the weeks that followed the judge saw it was not all right. Gerry had less and less time for golf and more and more for whisky and soda. The judge was troubled, and felt a sort of relief when from far away Alan Wayne cropped into his affairs and gave him something else to think about.

When Angus McDale of McDale & McDale called without appointment, the judge knew at once that he was going to hear something about Alan.

“Lucky to find you in,” puffed McDale. “It isn’t business exactly or I’d have ’phoned. I was just passing by.”

“Well, what is it?” asked the judge, offering his visitor a fresh cigar.

“It’s this. That boy, Alan Wayne—sort of protégé of yours, isn’t he?”

“Yes, in a way—yes,” said the judge, slowly, frowning. “What has Alan done now?”

“It’s like this,” said McDale. “Six months ago we sent Mr. Wayne out on contract as assistant to Walton. Walton no sooner got on the ground than he fell sick. He put Wayne in charge, and then he died. Now, this is the point. Mr. Wayne seems to have promoted himself to Walton’s pay. He had the cheek to draw his own as well. He won’t be here for weeks, but his accounts came in to-day. I want to know if you see any reason why we shouldn’t have that money back, to say the least.”

The judge’s face cleared.

“Didn’t he tell you why he drew Walton’s pay?”

“Not a word. Said he’d explain accounts when he got here, but that sort of thing takes a lot of explaining.”

“Well,” said the judge, “I can tell you. Walton’s pay went to his widow, through me. I’ve been doing some puzzling on this case already. Now will you tell me how Alan got the money without drawing on you?”

“Oh, there was plenty of money lying around. The job cost ten per cent. less than Walton’s estimate. If he’d come back, we’d have hauled him over the coals for that blunder. There was the usual reserve for work in inaccessible regions, and then the people we did the job for paid ten days’ bonus for finishing that much ahead of contract time.”

The judge mused.

“Was the job satisfactory to the people out there?” he asked.

“Yes, it was,” said McDale, bluntly; “most satisfactory. But there was a funny thing there, too. They wrote that while they did not approve of Mr. Wayne’s time-saving methods, the finished work had their absolute acceptance.”

The judge was silent for a moment.

“You want my advice?” he asked.

“Yes; not for our own sake, but for Wayne’s.”

“Well,” said the judge, “I’m going to give it to you for your sake. When you stumble across a boy that can cut ten per cent. off the working and time estimates of an old hand like Walton, you bind him to you with a long contract at any salary he wants. And just one thing more: when Alan Wayne steals a cent from you, or fifty thousand dollars, you come to me, and I’ll pay it.”

McDale’s eyes narrowed, and he puffed nervously at his cigar. He got up to take his leave.

“Judge,” he said, “your head is on right, and your heart’s in the right place, as well. I begin to see that widow business. Wayne sized us up for a hard-headed firm when it comes to paying out what we don’t have to, and we are. It wasn’t law, but he was right. Walton’s work was done just as if he’d been alive. Even a Scotchman can see that. You needn’t worry. A man that you’ll back for fifty thousand is good enough for McDale & McDale.”

IT was Alix who discovered Alan as the Elenic steamed slowly down the Solent. He was already comfortably established in his chair, with a small pile of fiction beside him.

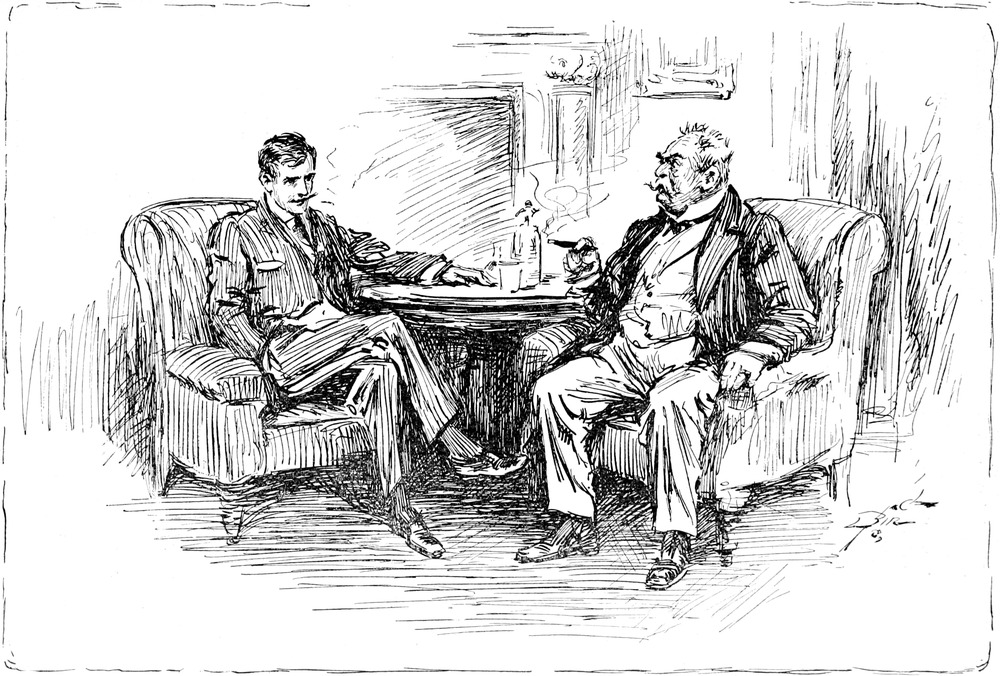

Drawn by Reginald Birch

“‘IN MY TIME,’ REMARKED THE CAPTAIN, ‘A CLUB WAS FOR PRIVACY. NOW IT’S A HAVEN FOR BELL-BOYS AND A PLAYGROUND FOR WHIPPER-SNAPPERS’”

She paused before she approached him. Alan had always interested her. Perhaps it was because he had kept himself at a distance; but, then, he had a way of keeping his distance from almost everybody. Alix had thought of him heretofore as a modern exquisite subject to atavic fits that, in times past, had led him into more than one barbarous escapade. It was the flare of daring in these shameful outbursts that had saved him from a suspicion of effeminacy. Now, in London she had by chance heard things of him that forced her to a readjustment of her estimate. In six months Alan had turned himself into a mystery.

“Well,” she said, coming up behind him, “how are you?”

Alan turned his head slowly, and then threw off his rugs and sprang to his feet.

“The sky is clear,” he said; “where did you drop from?” His eyes measured her. She was ravishing in a fur toque and coat which had yet to receive their baptism of import duty.

“Oh,” said Alix, “my presence is humdrum. Just the usual returning from six weeks abroad. But you! You come from the haunts of wild beasts, and from all accounts you have been one.”

“Been one! From all accounts!” exclaimed Alan, a puzzled frown on his face. “Just what do you mean?”

They started walking.

“I mean that even in Africa one can’t hide from Piccadilly. In Piccadilly you are already known not as Mr. Alan Wayne, a New York social satellite, but as a whirlwind in shirt-sleeves. Ten Per Cent. Wayne, in short.” She looked at him with teasing archness. She could see that he was worried.

“Satellite is rather rough,” remarked Alan. “I never was that.”

“All bachelors are satellites in the nature of things—satellites to other men’s wives.”

“Have you a vacancy?” said Alan.

The turn of the talk put Alix in her element. She had never been an ingénue. She had been born with an intuitive defense. Finesse was her motto, and artificiality was her foil. It had never been struck from her hands. On the other hand, Alan knew that every woman who accepts battle can be reached, even if not conquered. It is the approaches to her heart that a woman must defend. Once those are passed, the citadel turns traitor.

They both knew they were embarking upon a dangerous game, but Alix had played it often. No pretty woman takes her European degree without ample occasion for practice, and Alix had been through the European mill. She threw out her daintily shod feet as she walked. She was full of life. She felt like skipping. The light of battle danced merrily in her eyes. She made no other reply.

“I met lots of people we both know,” she said at last.

“Which one of them passed on the news that I had taken to the ways of a wild beast?”

“Oh, that was the Honorable Percy. I caught only a few words. He was telling about a man known as Ten Per Cent. Wayne and the only time he’d ever seen the shirt-sleeve policy work with natives. When I learned it was Africa, I linked up with you at once and screamed, and he turned to me and said, ‘You know Mr. Wayne?’ And I said I had thought I did, but I found I only knew him tiré à quatre épingles, and wouldn’t he draw his picture over again. But just then Lady Merle signaled the retreat, and when the men came out, somebody else snaffled Collingeford before I got a chance.”

“Oh, Collingeford,” said Alan. “I remember.” He frowned and was silent.

“Alan,” said Alix after a moment, “let me warn you. I see a new tendency in you, but before it goes any further than a tendency, let me tell you that a thoughtful man is a most awful bore. When I caught sight of you I thought, ‘What a delightful little party!’ But if you’re going to be pensive, there are others—”

Alan glanced at her.

“Alix,” he said, mimicking her tone, “I see in you the makings of an altogether charming woman. I’m not speaking of the painstaking veneer,—I suppose you need that in your walk of life,—but what’s under it. There may be others, as you say,—pretty women have taken to wearing men for bangles,—but don’t you make a mistake. I’m not a bangle. I’ve just come from the unclothed world of real things. To me a man is just a man, and, what’s more, a woman is just a woman.”

“How un-American!” said Alix.

“It’s more than that,” said Alan; “it’s pre-American.”

Alix was thoughtful in her turn. Alan caught her by the arm and turned her toward the west. A yawl was just crossing the disk of the disappearing sun. Alix felt a thrill at his touch.

“It’s a sweet little picture, isn’t it?” she said. “But you mustn’t touch me, Alan. It can’t be good for us.”

“So you feel it, too,” said Alan, and took his hand from her arm.

During the voyage they were much together, not in dark corners, but waging their battle in the open—two swimmers that fought each other, forgetting to fight the tide that was bearing them out to sea. Alan was not a philanderer to snatch an unrequited kiss. To him a kiss was the seal on surrender. But to Alix the game was its own goal. As she had always played it, nobody had ever really won anything. However, it did not take her long to appreciate that in Alan she had an opponent who was constantly getting under her guard and making her feel things—things that were alarming in themselves, like the jump of one’s heart into the throat or the intoxication that goes with hot, racing blood.

Alan’s power over women was in voice and words. If he had been hideous, it would have been the same. With his tongue he carried Alix away, and gave her that sense of isolation which lulls a woman into laxity. One night as they sat side by side, a single great rug across their knees, Alan laid his hand under cover on hers. A quiver went through Alix’s body. Her closed hand stirred nervously, but she did not really draw it away.

“Alan,” she said, “I’ve told you not to. Please don’t! It’s common—this sort of thing.”

Alan tightened his grip.

“You say it’s common,” he said, “because you’ve never thought it out. Lightning was common till somebody thought it out. I sit beside you without touching you, and we are in two worlds. I grip your hand like this, and the abyss between us is closed. While I hold you, nothing can come between.”

Alix’s hand opened and settled into his. Alan went on:

“Words talk to the mind, but through my hand my body talks to yours in a language that was old before words were born. If I am full of dreams of you and a desert island, I don’t have to tell you about it, because you are with me. The things I want, you want. There are no other things in life; for while I hold you, our world is one and it is all ours. Nothing else can reach us.”

For a while they sat silent, then Alix recovered herself.

“After all,” she said, “we’re not on a desert island, but on a ship, with eyes in every corner.”

Alan leaned toward her.

“But if we were, Alix! If we were on a desert island, you and I—”

For a moment Alix looked into his burning eyes. She felt that there was fire in her own eyes too—a fire she could not altogether control. She disengaged herself and sprang up. Alan rose slowly and stood beside her. He did not look at her parted lips and hot cheeks; he had suddenly become languid.

“That’s it,” he drawled—“eyes in every corner. I wonder how many morals would stand without other people’s eyes to prop them up?”

Alix left him. She felt baffled, as though she had tried desperately to get a grip on Alan, and her hand had slipped. She felt that it was essential to get a grip on him. She had never played the losing side before, and she was troubled.

Premonition does not come to a woman without cause. Toward the end of the voyage Alix faced, wide-eyed, the revelation that the stakes of the game she and Alan had played were body and soul.

“Alan,” she said one night, with drooping head, “I’ve had enough. I don’t want to play any more. I want to quit.” She lifted tear-filled eyes to him. The foil of artificiality had been knocked from her hand. She was all woman, and defenseless.

Alan felt a trembling in all his limbs.

“I want to quit, too, Alix,” he said in his low, vibrating voice,[Pg 816] “but I’m afraid we can’t. You see, I’m beaten, too. While I was just in love with your body, we were safe enough; but now I’m in love with you. It’s the kind of love a man can pray for in vain. No head in it; nothing but heart. Honor and dishonor become mere names. Nothing matters to me but you.”

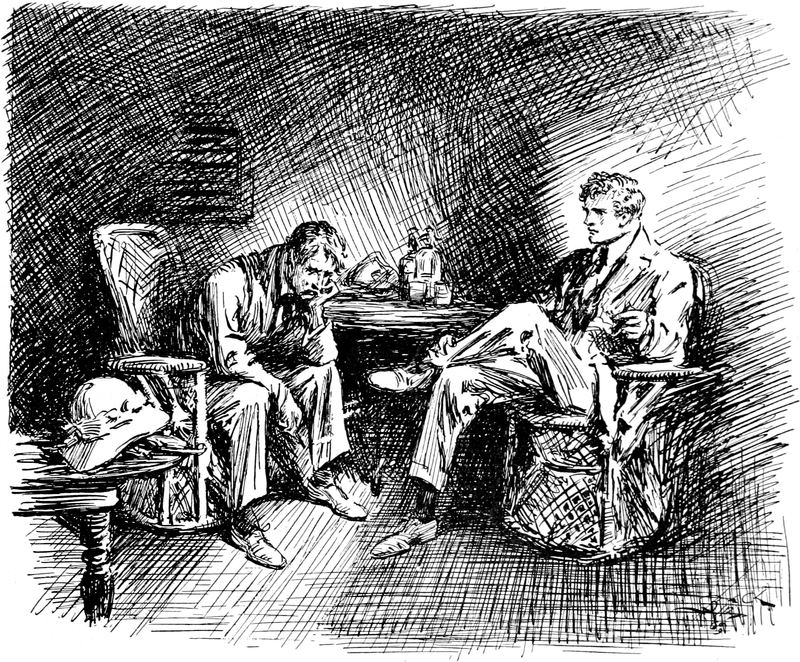

Drawn by Reginald Birch

“’HE’D SAIL FOR AFRICA TO-MORROW AND THINK FOR THE REST OF HIS LIFE OF HIS ESCAPE FROM YOU AS A CLOSE SHAVE’”

Tears crawled slowly down Alix’s cheeks. She stood with her elbows on the rail and faced the ocean, so no one might see. Her hands were locked. In her mind her own thoughts were running. Somehow she could understand Alan without listening. If only Gerry had done this thing to her, she was thinking, the pitiless, wracking misery would have been joy at white heat. She was unmasked at last; but Gerry had not unmasked her. Not once since the day of the wreck and their engagement had Gerry unmasked himself.

Alan was standing with his side to the rail, his eyes leaving her face only to keep track of the promenaders, so that no officious friend could take her by surprise. He went on talking.

“Our judgment is calling to us to quit, but it is calling from days ago,” he said. “We wouldn’t listen then, and it’s only the echo we hear now. We can try to quit if you like; but when I am alone, I shall call for you, and when you are alone, you will call for me. We shall always be alone except when we are near each other. We can’t break the tension, Alix. It will break us in the end.”

The slow tears were still crawling down Alix’s cheeks. In all her life she had never suffered so before. She felt that each tear paid the price of all her levity.

“Alan,” she said with a quick glance at him, “did you know when we began that it was going to be like this?”

“No,” he answered. “I have trifled with many women, and I was ready to trifle with you. No one had ever driven you, and I wanted to drive you. I thought I had divorced passion and love. I thought perhaps you had, too. But love is here. I am not driving you. We are being driven.”

ALIX and Alan were in the grip of a fever that is hard to break save through satiety and ruin. They were still held apart by generations of sound tradition, but against this bulwark the full flood of modern life,[Pg 817] as they lived it, was directed. In Alan there was a counter-strain, a tradition of passion that predisposed him to accept the easy tenets of the growing sensual cult. As he found it more and more difficult to turn his thoughts away from Alix, he strove to regain the clear-headedness that only a year before had held him back from definite moral surrender.

With her things had not gone so far. From the security of the untempted she had watched her chosen world play with fire, and only now, when temptation assailed her, did she realize the weakness that lies in every woman once her outposts have fallen and her bare heart becomes engaged in the battle.

One early morning Nance sent for Alan. He found her alone. She had been crying. He came to her where she stood by the fire, and she turned and put her arms around his neck. She tried to smile, but her lips twitched.

“Alan,” she said, “I want you to go away.”

Alan was touched. He caught her wrists and took her arms from about his neck.

“You mustn’t do that sort of thing to me, Nance. I’m not fit for it.” He made her sit down on a great sofa before the fire and sat down beside her. “You remind me to-day of the most beautiful thing I ever heard said of you—by a spiteful friend.”

“What was it?” said Nance, turning her troubled eyes to him.

“She said, ‘She is only beautiful in her own home.’ I never understood it before. It’s a great thing to be beautiful in one’s own home.”

“Oh, Alan,” said Nance, catching his hand and holding it against her breast, “it is a great thing. It’s the greatest thing in life. That’s why I sent for you—because you are wrecking forever your chance of being beautiful in your own home. And worse than that, you are wrecking Alix’s chance. Of course you are blind. Of course you are mad. I understand, Alan, but I want to hold you close to my heart until you see—until the fever is cooled. You and Alix cannot do this thing. It isn’t as though her people and ours were of the froth of the nation. You and she started life with nothing but Puritan to build on. You may have built just play-houses of sand, but deep down the old rock foundation must endure. You must take your stand on that.”

Her eyes had been fixed in the fire, but now she turned them to his face. Alan sat with head hanging forward, his gaze and thoughts far beyond the confines of the room. Then he shook himself and got up to go.

“I wish we could, Nance,” he said gravely, and then added half to himself, half to her, “I’ll try.”

For some days Alan had been prepared to go away and take Alix with him, should she consent. Upon his arrival he had had an interview with McDale & McDale, in the course of which that firm opened its eyes and its pocket wider than it ever had before.

“You are out for money, Mr. Wayne,” had been the feeble remonstrance of the senior member.

“Just money,” replied Alan. “If you owed as much as I do, you would be out for it, too. Of course you’re not. What do you want? You’ve got my guaranty—ten per cent. under office estimates for work and time.”

When Alan left McDale & McDale’s offices he had contracted more or less on his own terms, and McDale, Jr., said to the senior:

“He’s only twenty-six—a boy. How did he beat us?”

“By beating Walton’s record first,” replied McDale, Sr. “And how he did that, time will show.”

As he walked slowly back from Nance’s, Alan was thinking that, after all, there was no reason why he should not cut and run—no reason except Alix.

He reached his rooms. As he crossed the threshold a premonition seized him. He felt as though some one were there. He glanced hurriedly about. The rooms were still in the disorder in which he had left them, and they were empty. Then he saw that he had stepped on a note that had been dropped through the letter-slip. He picked it up. A thrill went through him as he recognized Alix’s handwriting. There was no stamp. It must have been delivered by hand. He tore it open and read: “You said that a moment’s notice was all you asked. I will take the Montreal express with you to-day.”

Alan’s blood turned to liquid fire. The[Pg 818] note conjured before him a vision of Alix. He crushed it, and held it to his lips and laughed, not jeeringly, but in pure, uncontrolled excitement.

IT was not a coincidence that Gerry had sought out Alix at the very hour that Nance was summoning Alan. Gerry and Nance were driven by the same forewarning of catastrophe. Gerry had felt it first, but he had been slow to believe, slower to act. He had no precedent for this sort of thing. His whole being was in revolt against the situation in which he found himself. It was after a sleepless night, a most unheard of thing with him, that he decided he could let things go no longer. He went to Alix’s room, knocked, and entered.

Alix was up, though the hour was early for her. Fresh from her bath, she sat in a sheen of blue dressing-gown before the mirror doing her own hair. Gerry glanced about him and into the bath-room, looking for the maid.

“Good morning,” said Alix. “She’s not here. Did you want to see her?”

Gerry winced at the levity. He wondered how Alix could play the game she was playing and be gay. Alix finished doing her hair.

“There,” she said with a final pat, and turned to face Gerry.

He was standing beside an open window. He could feel the cold air on his hands. He felt like putting his head out into it. His head was hot.

“Alix,” he said suddenly without looking at her, “I want you to drop Alan.”

“But I don’t want to drop Alan,” replied Alix, lightly.

Gerry whirled around at her tone. His nostrils were quivering. To his amazement, his hands fairly itched to clutch her beautiful throat. He could hardly control his voice.

“Stop playing, Alix,” he gulped. “There’s never been a divorcée among the Lansings nor a wife-beater, and one is as near this room as the other right now.”

Gerry regretted the words as soon as he had said them, but Alix was not angry. She looked at him through narrowed eyes. She speculated on the sensation of being once again roughly handled by this rock of a man. Only once before had she seen Gerry angry and the sight had fascinated her then, as it did now. There was something tremendous and impressive in his anger and struggle for control—a great torrent held back by a great strong dam. She almost wished it would break through. She could almost find it in her to throw herself on the flood and let it carry her whither it would. She said nothing.

Gerry bit his lips and turned from her.

“And Alan, of all men!” he went on. At the words the current of her thoughts was changed. She found herself suddenly on the defensive. “Do you think you are the first woman he has played with and betrayed?” Gerry’s lip was curved to a sneer. “A philanderer, a man who surrounds himself with tarnished reputations.”

A dull glow came into Alix’s cheeks.

“Philanderers are of many breeds,” she said. “There are those who have the wit to philander with woman, and those who can rise only to a whisky or a golf-club. Whatever else Alan may be, he is not a time-server.”

Once aroused, Alix had taken up the gantlet with no uncertain hand. Her first words carried the war into the enemy’s camp, and they were barbed.

“What do you mean?” said Gerry, dully. He had not anticipated a defense.

“I mean what you might have deduced with an effort. What are you but a philanderer in little things where Alan is in great? What have you ever done to hold me or any other woman? I respected you once for what you were going to be. That has died. Did you think I was going to make you into a man?”

Gerry stood, breathing hard, a great despondency in his heart. Alix went on pitilessly:

“What have you become? A monumental time-server on the world, and you are surprised that a worker reaches the prize that you can not attain! ‘All things come to him who waits.’ That’s a trite saying; but how about this? There are lots of things that come to him who only waits that he could do without. The trouble with you is that you have built your life altogether on traditions. It is a tradition that your women are faithful; so you need not exert yourself to holding yours. It is a tradition that you can do no wrong; so you need not exert yourself to doing anything at all. You are playing with ghosts, Gerry. Your party was over a generation ago.”

Alix had calmed down. There was still time for Gerry to choke her to good effect. The hour could yet be his. But he did not know it. Smarting under the lash of Alix’s tongue, he made a final and disastrous false step.

“You try to humiliate me by placing me back to back with Alan?” he said, with his new-born sneer. Alix appraised it with calm eyes, and found it rather attractive. “Well, let me tell you that Alan is so small a man that if I dropped out of the world to-day, he’d sail for Africa to-morrow and think for the rest of his life of his escape from you as a close shave.”

Alix sprang to her feet. She was trembling. Gerry felt a throb of exultation. It was his turn to wound.

“What do you mean?” said Alix, very quietly; but it was the quiet of suppressed passion at white heat.

“I mean that Alan is the kind of man who finds other men’s wives an economy. He would take everything you have that’s worth taking, but not you.”

Alix’s eyes blazed at him from her white face. “Please go away,” she said. He started to speak. “Please go away,” she repeated. Her lips were quivering, and her face twitched in a way that was terrifying to Gerry. He hurried out, repeating to himself over and over: “You have made Alix cry. You have made Alix cry.”

Alix toyed with the silver on her dressing-table until he had gone, and then she swept across the room to her little writing-desk and wrote the note that Alan had found half an hour later in his rooms.

GERRY stood in the hall outside Alix’s room for a moment, hoping to hear a sob, a cry, anything for an excuse to go back. Instead he heard the scratch of a pen; but he was too troubled to deduce anything from that. He went slowly down the stairs and out into the street. The biting winter air braced him. He started to walk rapidly. At the end of an hour he found himself standing on a deserted pier. He took off his hat and let the wind cool his head.

“I have been a brute,” he said to himself. “I have made a woman cry—Alix!” He turned and walked slowly back to the avenue and into his club, but he still felt uneasy. A waiter brought a whisky and soda and put it at his elbow. Gerry turned on him.

“Who told you to bring that?” Then he felt ashamed of his petulance. “It’s all right, George,” he said more genially than he had spoken for many a day; “but I don’t want it. Take it away.”

He sat for a long time, and at last came to a resolution. Alix loved roses. He would send her enough to bank her room, and he would follow them home. He went up the avenue to his florist’s, and stood outside trying to decide whether it should be one mass of blood red or a color scheme. Suddenly the plate glass caught a reflection and threw it in his face. Gerry turned. A four-wheeler was passing. He could not see the occupant, but on top was a large, familiar trunk marked with a yellow girdle. On the trunk was a familiar label. He stared at it, and the label stared back at him, and finally danced before his mazed eyes as the cab disappeared into the traffic.

Gerry stood for a long while, stunned. He saw a lady bow to him from a carriage, and afterward he remembered that he had not bowed back. Somebody ran into him. He looked back at the flowers massed in the window, remembered that he did not need them now, and drew slowly away. Two men hailed him from the other side of the street. Gerry braced himself, nodded to them, and hailed a passing hansom. From the direction Alix’s cab had taken he knew the station for which she was bound. As he arrived on the platform they were giving the last call for the Montreal express. He caught sight of Alix hurrying through the gates, and followed. As she reached the first Pullman, somebody rapped on the window of the drawing-room. Gerry saw Alan’s face pressed against the pane. He watched Alix stop, turn, and climb the steps of the car, and then he wheeled and hurried from the station.

Where could he go? Not to his club and Alan’s. His face would betray the scandal with which the club would be buzzing to-morrow. Not to his big, comfortable house. It would be too gloomy. Even in disaccord, Alix had imparted to its somber oak and deep shadows the glow of[Pg 820] buoyant life. When she was there, one felt as though there were flowers in the house. Gerry was seized with a great desire to hide from his world, his mother, himself. He pictured the scare-heads in the papers. That the name of Lansing should be found in that galley! It was too much. He could not face it.

He bought a morning paper, full of shipping news, and, getting into a taxi, gave the address of his bank. On the way he studied the sailings’ column. He found what he wanted—the Gunter, due to sail that afternoon for Brazil, Pernambuco the first stop.

At the bank Gerry drew out the balance of his current account. It amounted to something over two thousand dollars. He took most of it in Bank of England notes. Then he started home to pack, but before he reached the house a vision of the servants, flurried after helping their mistress off, commiserating him to one another, pitying him to his face perhaps, or, in the case of the old butler, suppressing a great emotion, was too much for him. He drove instead to a big department store, and in an hour had bought a complete outfit. He lunched at one of the quiet restaurants that divide down-town from up-town.

He had avoided buying a ticket. As the Gunter warped out, the purser came to him.

“I understand you have no ticket.”

“No,” said Gerry, drawing a roll of bills. “How much is the passage to Pernambuco?”

The purser fidgeted.

“This is irregular, sir,” he said.

“Is it?” said Gerry, indifferently.

“I have no ticket-forms,” said the purser, weakening.

“I don’t want a ticket,” said Gerry. “I want a good room and three square meals a day.”

Long, quiet days on a quiet sea are a master sedative to a troubled mind. Gerry had a great deal to think through. He sat by the hour with hands loosely clasped, his eyes far out on the ocean, tracing the course of his married life, and measuring the grounds for Alix’s arraignment. Gerry was just and generous to others’ faults, but not to his own. He had forgotten the sting of Alix’s words, and, to his growing amazement, saw in himself their justification. A time-server he certainly had been.

The landfall of Pernambuco awoke him from reveries and introspection. He did not look upon this palm-strewn coast as a land of new beginnings; he sought merely a Lethean shore.

The ship crawled in from an oily sea to the long strip of harbor behind the reef. Above, the sun blazed from a bowl of unbroken blue; on land, the multicolored houses spread like a rainbow under a dark cloud of brown-tiled roofs. Beyond the trees was a line of high, stuccoed houses, each painted a different color, all weather-stained, and some with rusted balconies that threatened to topple on to the passer-by. One bore the legend, “Hôtel d’Europe.” There Gerry installed himself.

BETWEEN the hour of writing her note to Alan and the moment when she stepped on the train Alix had had no time to think. She was still driven by the impulse of anger that Gerry’s words had aroused. She did not reflect that the wound was only to her pride.

Alan held open the door of the drawing-room. She passed in, and he closed it. She did not feel as though she were in a train. On the little table stood a vase. It held a single perfect rose. Under the vase was a curious doily, strayed from Alan’s collection of exotic things. A cushion lay tossed on the green sofa, not a new cushion, but one that had been broken in to comforting. Alix took in every detail of the arrangement of the tiny room with her first breath. What forethought, what a note of rest with which to meet a troubled and hurried heart! But how insidious to frame an ignoble flight in such a homelike setting! She felt a slight revolt at the travesty.

Alan was standing with blazing eyes and working face, like an eager hound in leash. Alix threw back her veil and looked at him. With a quick stride forward he caught her to him, and kissed her mouth until she gasped for breath. With a flash she remembered his own words, “If ever I kiss you, I shall bring your soul out between your lips.” To Alix’s amazement, she did not feel an answering fire. Her body was being lashed with a living flame, and her body was cold. In that instant this seemed a terrible thing. She[Pg 821] had sold her birthright for a price, and the price was turning to dead leaves. She made an effort to kiss Alan in return, but with the effort shame came over her. There was so much in Alan’s kiss! The kiss had brought her soul out between her lips. Her soul stood naked before her, and one’s naked soul is an ugly thing. The kiss disrobed her, too, and from that last bourn of shame Alix suddenly revolted.

Gasping, she pushed Alan from her. Their eyes met. His were burning, hers were frightened. She moved slowly backward to the door, and with her hand behind her opened the latch. Alan did not move. He knew that if he could not hold her with his eyes, he could not hold her at all. The train started. Alix passed through the door and rushed to the platform. The porter was about to drop the trap on the steps. Alix slipped by him. With all her force she pushed open the door and jumped. The train was moving very slowly, but Alix reeled, and would have fallen had it not been for a passing baggageman. He caught her, and still in his arms, Alix looked back. Alan’s white face was at the window. He looked steadily at her.

“Ye almost wint with him, miss,” said the baggageman, with a full brogue and a twinkling eye.

Alix was tired and hungry when she got back home, but excitement kept her up. She felt that she stood on the threshold of new effort and a new life. After all, she thought, it was she who had made her dear old Gerry into a time-server. She could have made him into anything else if she had tried. She longed to tell him so. Perhaps he would catch her and crush her in his arms as Alan had done. She laughed at herself for wanting him to. She rang for the butler.

“Where’s your master, John?”

“I don’t know, ma’am. Mr. Gerry hasn’t come back since he went out this morning.” To John, Mr. Lansing was a person who had been dead for some time. His present overlords were Mr. and Mrs. Gerry and Mrs. Lansing when she was in town.

“Telephone to the club, and if he is there, tell him I want to see him,” said Alix, and turned to her welcome tea. The sandwiches seemed unusually small to her ravenous appetite.

Gerry was not at the club. Alix dressed resplendently for dinner. Never had she dressed for any other man with the care that she dressed for Gerry that night. But Gerry did not come. At half-past nine Alix ordered the table cleared.

“I’ll not dine to-night,” she said to John. “When your master comes, show him in here.” She sat on in the library, listening for Gerry’s step in the hall.

From time to time John came into the room to replenish the fire. On one of these occasions Alix told him he might go to bed; but an hour later he returned and stood in the door. Alix looked very small, curled up in a great leathern chair by the fire.

“It’s after one o’clock, ma’am,” said John. “Mr. Gerry won’t be coming in to-night.” Alix made no answer. John held his ground. “It’s time for you to go to bed, ma’am. Shall I call the maid?”

It was a long time since John had taken any apparent interest in his mistress. Alix had avoided him. She had felt that the old servant disapproved of her. More than once she had thought of discharging him, but he had never given her grounds that would justify her before Gerry. Now he was ordering her to bed, and instead of being angry, she was soothed. She wondered how she could ever have thought of discharging him. He seemed strong and restful, more like part of the old house than a servant. Alix got up.

“No, don’t call the maid. I won’t need her,” she said. Then she added, “Good night, John,” as she passed out.

John held wide the door, and bowed with a deference that was a touch more sincere than usual. “Good night,” he answered, as though he meant it.

Alix was exhausted, but it was long before she fell asleep. She cried softly. She wanted to be comforted. She had dressed so beautifully, she had been so beautiful, and Gerry had not come home. As she cried, her disappointment grew into a great trouble.

She awoke early from a feverish sleep. Immediately a sense of weight assailed her. She rang, and learned that Gerry had not yet come home. Then his words of yesterday suddenly came to her, “If I dropped out of the world to-day—” Alix stared wide-eyed at the ceiling. Why had she remembered those words? She lay for a[Pg 822] long time, thinking. Her breakfast was brought to her, but she did not touch it. It was almost noon in the cloudy Sunday morning when she roused herself from apathy. She sprang from the bed. She summoned Judge Healey with a note and Mrs. Lansing with a telegram. The telegram was carefully worded:

Please come and stay for a while. Gerry is away.

The judge found Alix radiating the freshness of a beautiful woman careful of her person; but it was the freshness of a pale flower. Alix was grave, and her gravity had a sweetness that made the judge’s heart bound. He felt an awakening in her that he had long watched for. She told him all the story of the day before in a steady monotone that omitted nothing and gave the facts only their own weight.

When she had finished, the judge patted her hand. “You would make a splendid witness, my dear,” he said. “Now, what you want is for me to find Gerry and bring him back, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” said Alix, “if you can.”

“Nonsense! Of course I can. Men don’t drop out of the world so easily nowadays. But I still want to know a thing or two. Are you sure Gerry knew nothing of your—er—excursion to the station?”

Alix shook her head.

“From the time he left my room and the house he has not been back.”

“Has he been to the club?”

Alix colored faintly. “I see,” said the judge, quickly. “I’ll ask there. I’ll go now.” He went off, and all that day he sought in vain for a trace of Gerry. He went to all his haunts in the city; he had telephoned to those outside. At night he returned to Alix, but it was Mrs. Lansing who received him in the library.

The judge was tired, and his buoyancy had deserted him. He told her of his failure. Mrs. Lansing was thoughtful, but not greatly troubled.

“Gerry,” she said, “has a level head. He may have gone away, but that is all. He can take care of himself.” She went to tell Alix that there was no news. When she came back, the judge turned to her.

“Well,” he asked, “What did she say?”

“Nothing, except that she wanted to know if you had tried the bank.”

The judge struck his fist into his left hand. “Never thought of it,” he said. “That child has a head!” He went to the telephone. From the president of the bank he traced the manager, from the manager, the cashier. Yes, Gerry had been at the bank on Saturday. The cashier remembered it because Mr. Lansing had drawn a certain account in full. He would not say how much.

“There,” said the judge, with a sigh of relief, “that’s something. It takes a steady nerve to draw a bank-account in full. You must take the news up-stairs. I’m off. I’ll follow up the clue to-morrow.”

There was a new look of content mingled with the worry in Mrs. Lansing’s face that made the judge say, as he held out his hand in farewell, “Things better?”

Mrs. Lansing understood him.

“Yes,” she answered, and added, “we have been crying together.”

There had been strength in Mrs. Lansing’s calm. She had been waiting, and now the waiting was over. Alix had given herself, tearful and almost wordless, into arms that were more than ready, and had then poured out her heart in a broken tale that would have confounded any court of justice, but which between women was clearer than logic.

At the end Mrs. Lansing said nothing. Instead, she petted Alix, carried her off to bed, and kept her there for three days. In her waking hours Alix added spasmodic bits to her confession—sage reflections after the event, dreamy “I wonders” that speculated in the past and in the measure of her emotions.

On the fourth day Alix got up, but on the fifth she stayed in bed. Mrs. Lansing found her pale and frightened. She had been crying.

“Alix,” she whispered, kneeling beside the bed, “what is it?”

Alix told her amid sobs.

“Oh, my dear,” said Mrs. Lansing, throwing her arms about her, “don’t cry. Don’t worry. The strength will come with the need. In the end you’ll be glad. So will Gerry. So will all of us.”

“It isn’t that,” said Alix, faintly.[Pg 823] “Oh, it isn’t that! I’m just thinking and thinking how terrible it would have been if I had run away—really run away! I keep imagining how awful it would have been. It is a nightmare.”

“Call it a nightmare if you like, sweetheart, but just remember that you are awake.”

Drawn by Reginald Birch

“’I USED TO THINK I COULD GO HOME, THAT IT WAS JUST A QUESTION OF BUYING A TICKET. BUT—’”