| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/mythologyinmarbl0000unse |

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

BY

LOUIE M. BELL

Educational Publishing Company

BOSTON

NEW YORK CHICAGO SAN FRANCISCO

Copyrighted

By EDUCATIONAL PUBLISHING COMPANY

1901

3

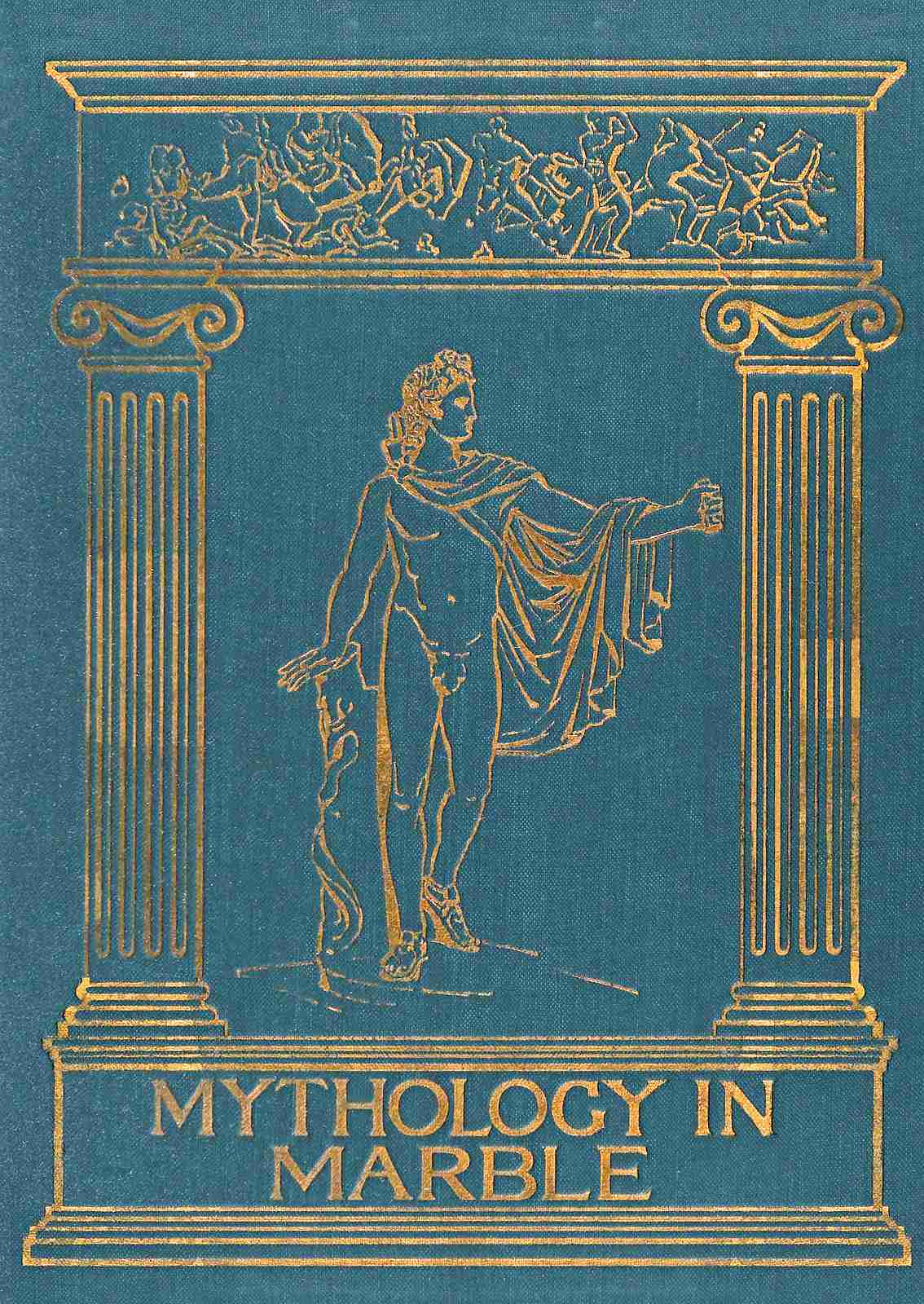

| Venus of the Shell | Frontispiece |

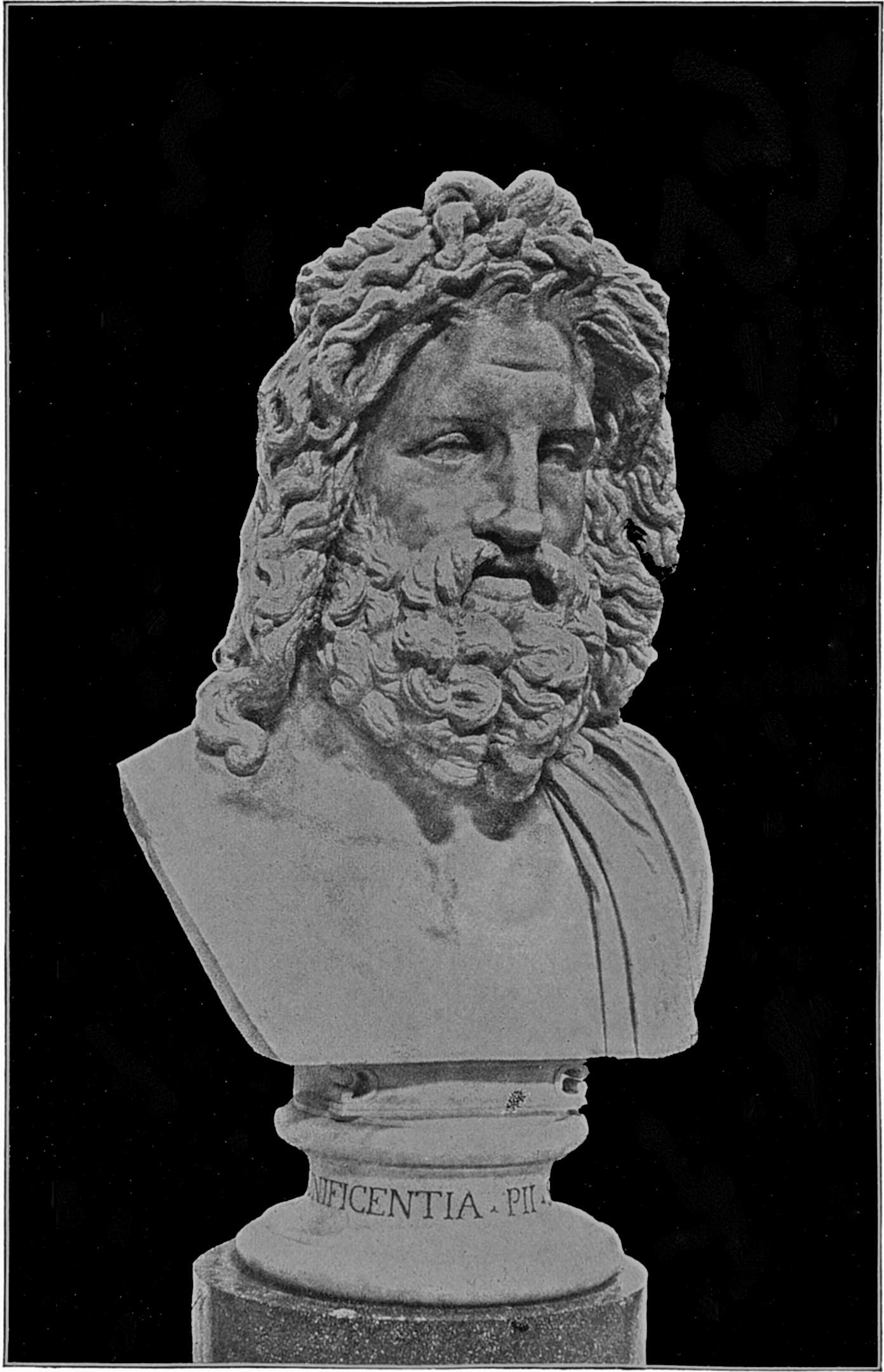

| Jupiter (Vatican) | 12 |

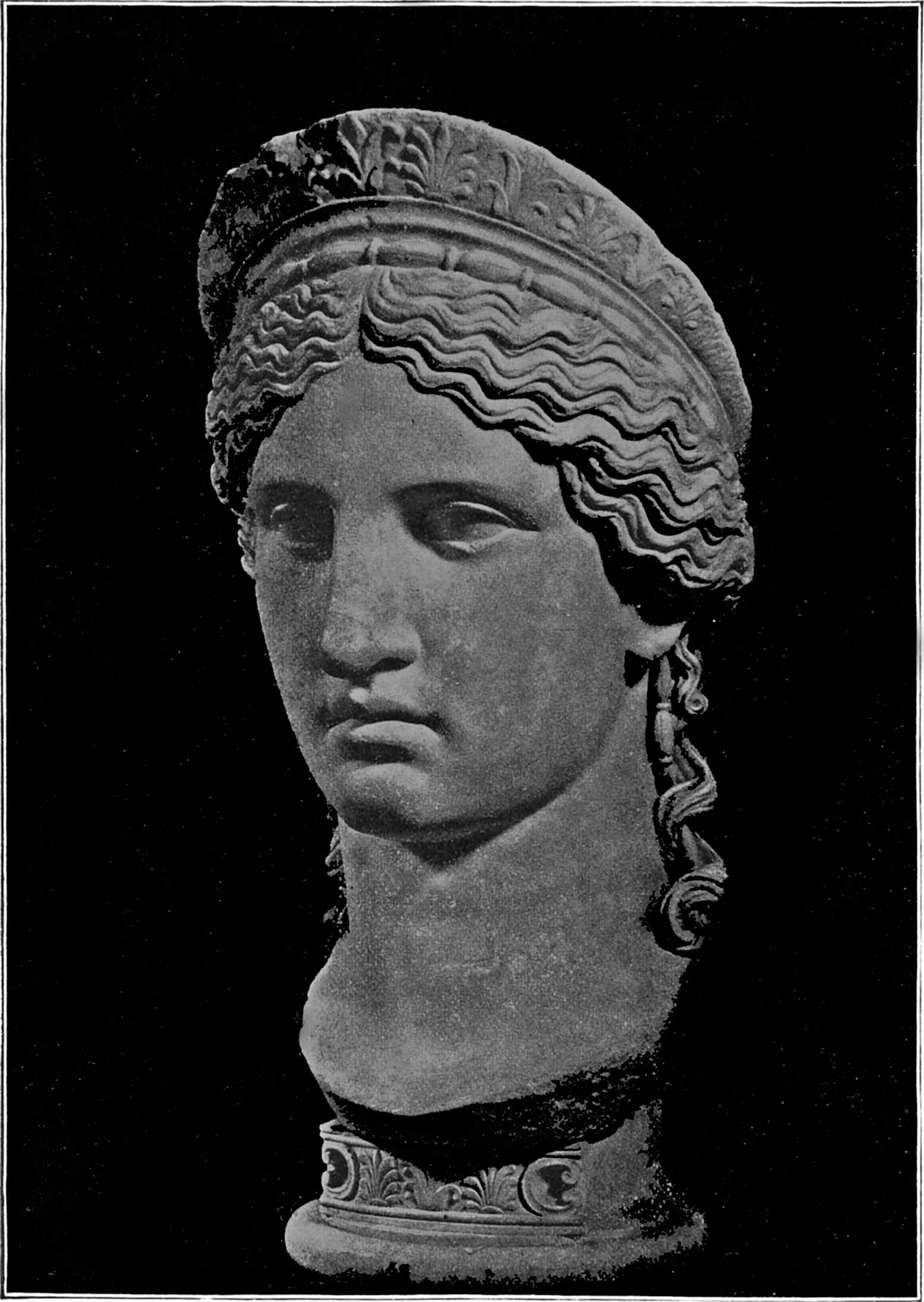

| Juno (Villa Ludovisi, Rome) | 16 |

| Apollo Belvedere (Vatican) | 20 |

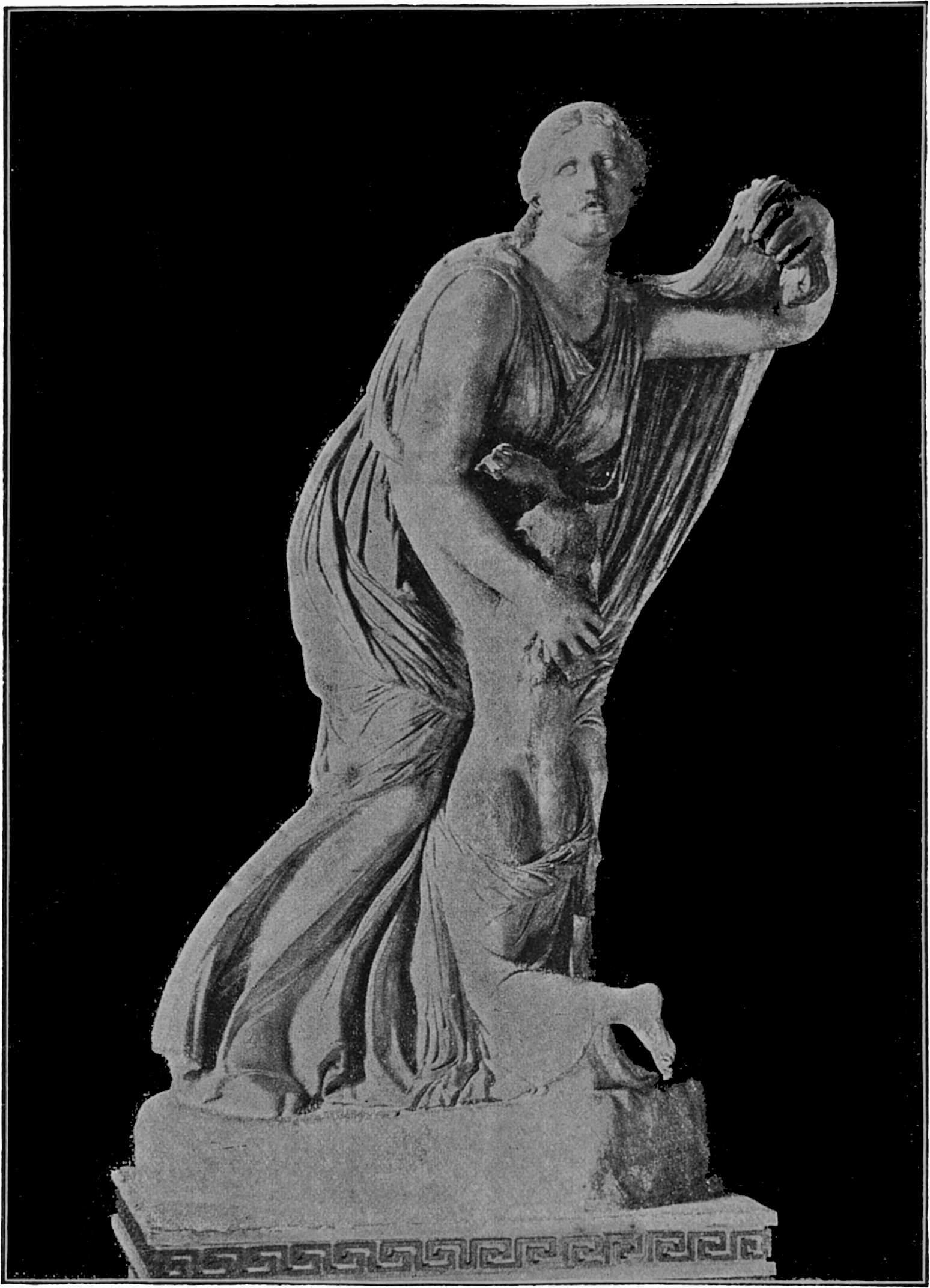

| Niobe (Uffizi, Florence) | 24 |

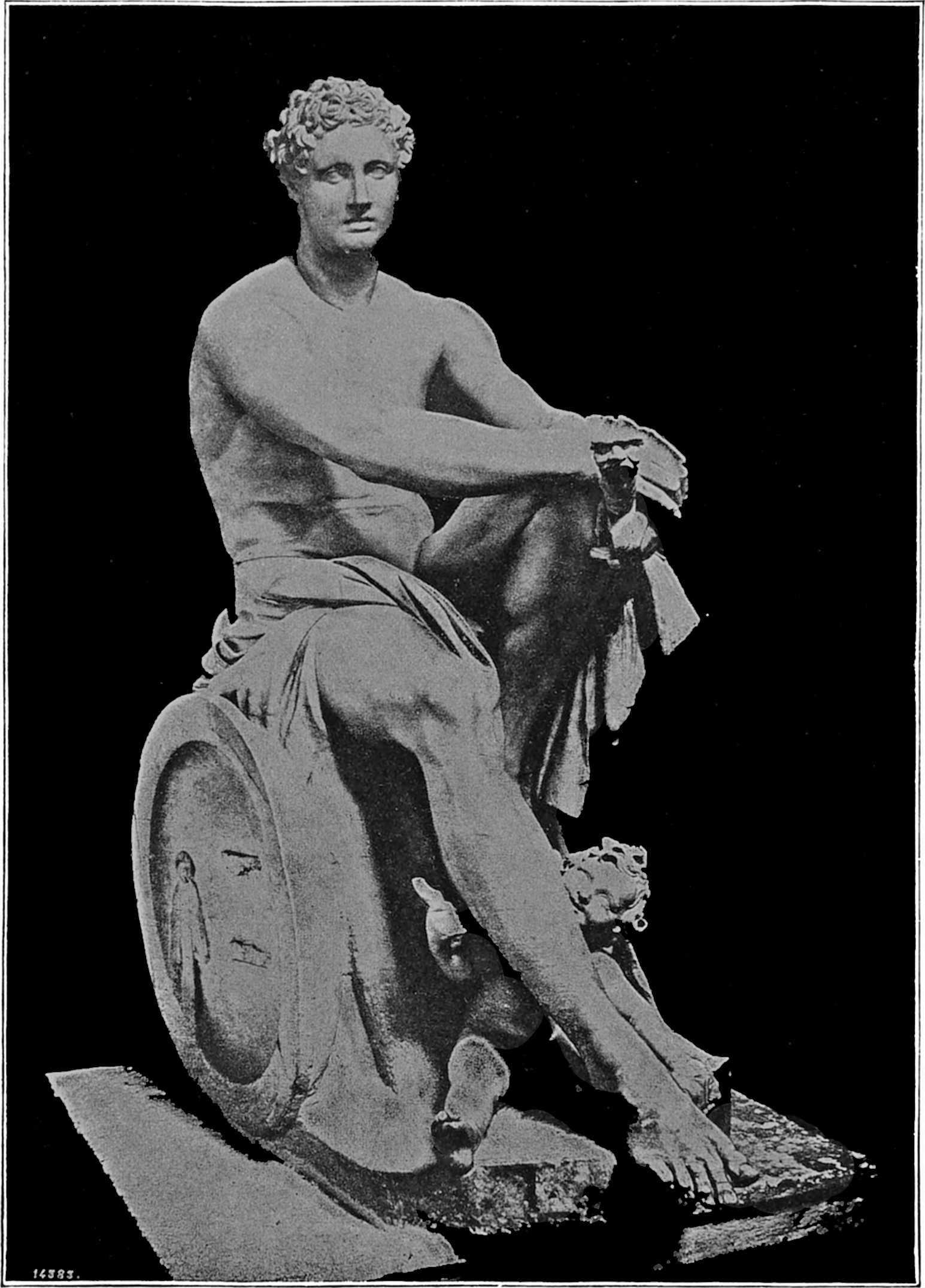

| Mars (Villa Ludovisi, Rome) | 28 |

| Laocoon (Vatican) | 32 |

| Venus de Milo (Louvre, Paris) | 36 |

| Farnese Hercules (Naples Museum) | 40 |

| Venus de Medici (Uffizi, Florence) | 44 |

| Hercules and Lichas (Torloni Palace, Rome) | 48 |

| Winged Victory (Louvre, Paris) | 52 |

| Three Fates (British Museum, London) | 56 |

| Meleager (Vatican) | 60 |

| Apollo Musagetes (Vatican) | 64 |

| Calliope (Vatican) | 68 |

| Diana (Vatican) | 72 |

| Sleeping Ariadne (Louvre, Paris) | 76 |

| Ariadne (Frankfort, Germany) | 80 |

| Minerva (Capitol, Rome) | 84 |

| Euterpe (Louvre, Paris) | 88 |

| Orpheus and Eurydice (Villa Albani, Naples) | 92 |

| Bacchus (Naples Museum) | 96 |

| Apollo and Daphne (Villa Borghese, Rome) | 100 |

| Proserpine (Villa Ludovisi, Rome) | 104 |

| Cupid (So. Kensington Museum, London) | 108 |

| Vulcan (Copenhagen, Denmark) | 112 |

| Perseus (Vatican) | 116 |

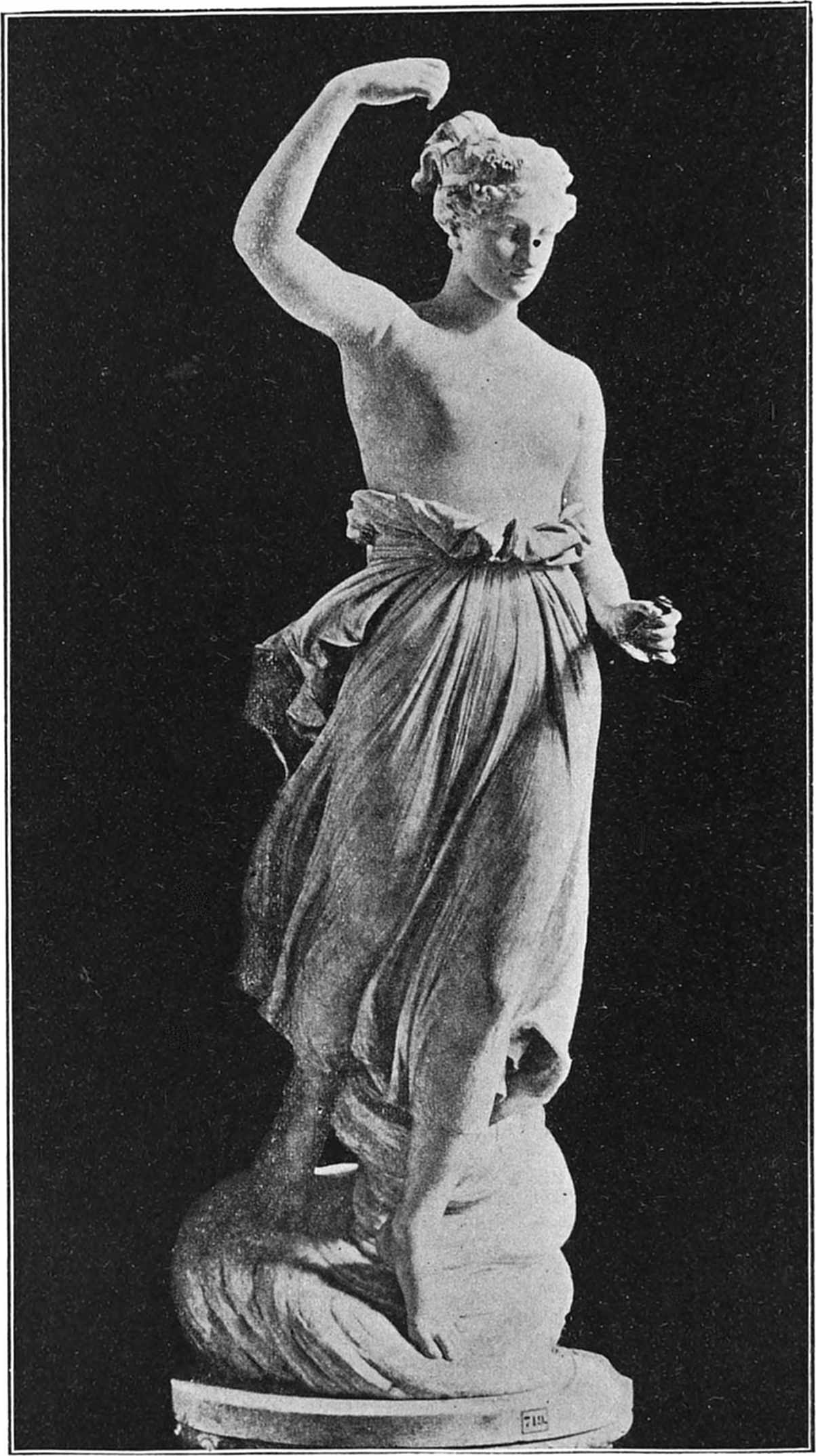

| Hebe (National Gallery, London) | 120 |

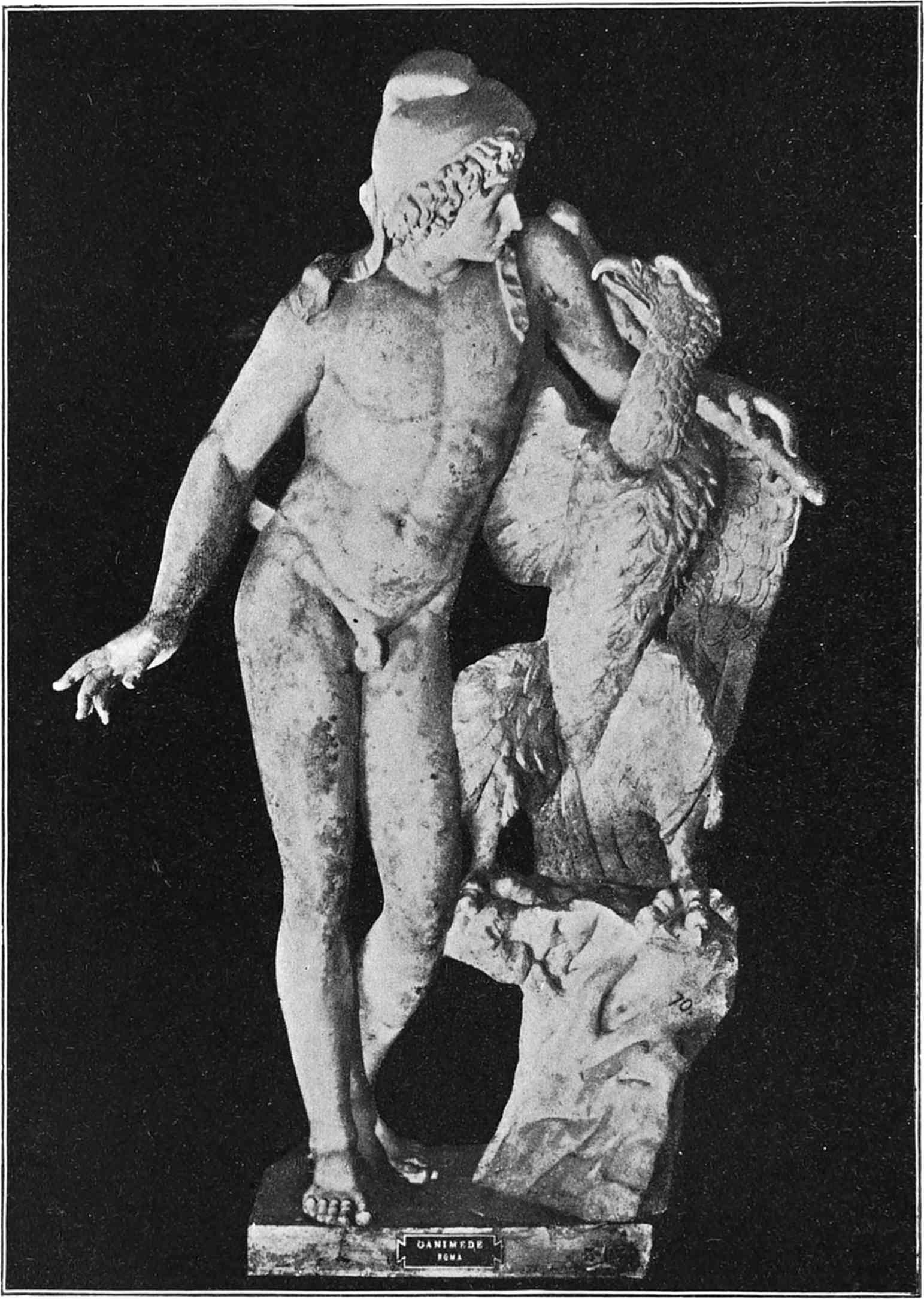

| Ganymede and the Eagle (Naples Museum) | 124 |

| Cupid Stung (Naples) | 128 |

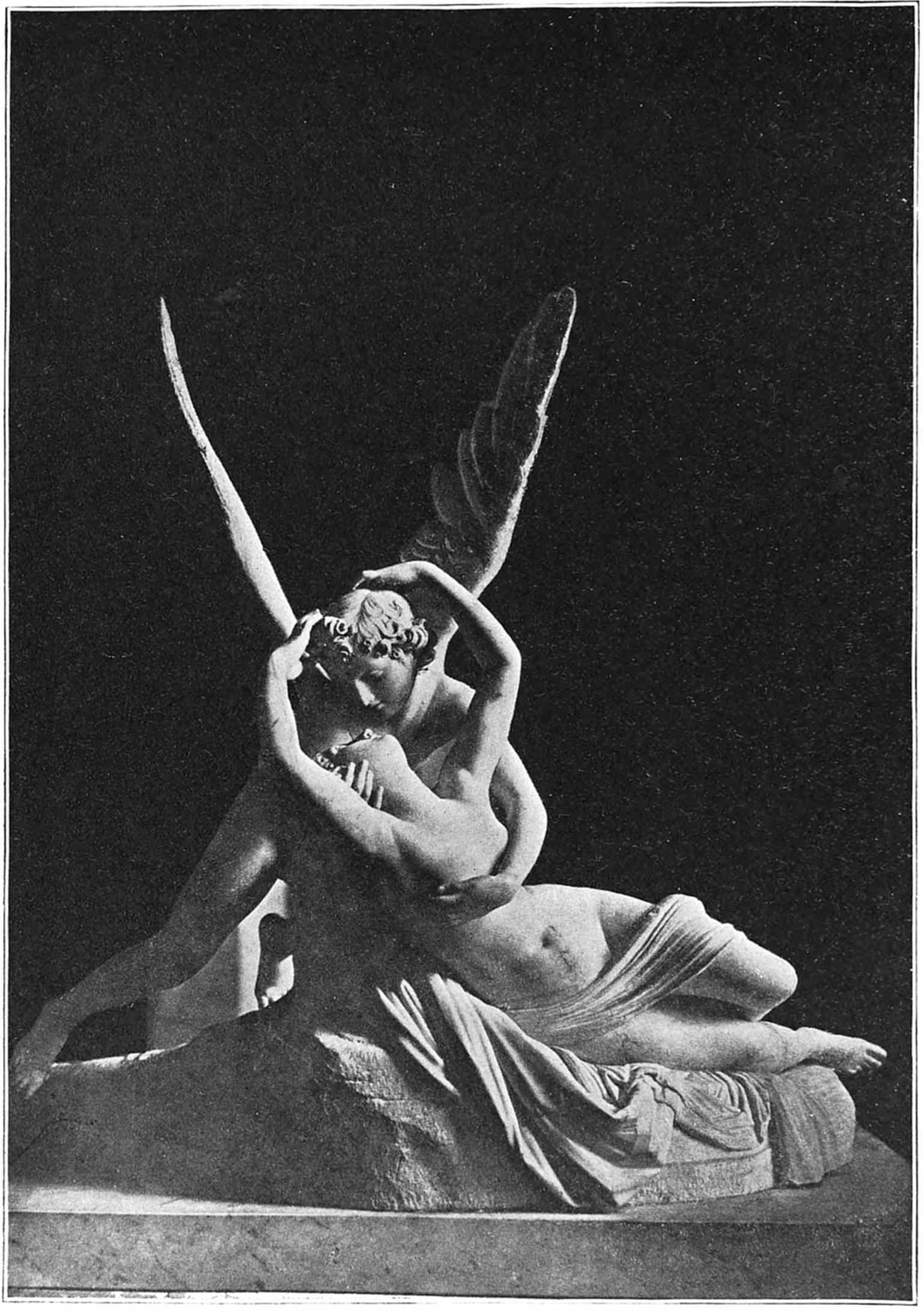

| Cupid and Psyche (Louvre, Paris) | 132 |

| Mercury (Luxembourg, Paris) | 138 |

| Mercury (Luxembourg, Paris) | 142 |

| Genius of Death (St. Peter’s, Rome) | 146 |

| The Graces (Borghese Gallery, Rome) | 150 |

| Pan (Luxembourg, Paris) | 154 |

| Hope (Luxembourg, Paris) | 158 |

4

In this practical age it is not to be supposed that busy people in general have time to make a thorough study of mythologic science: but to share understandingly the love of sculpture now awakened in the public mind, and for a better appreciation of our galleries of casts, it is desirable to have at least a suggestive knowledge of the myths and legends which have inspired so many artists in the moulding of their statues, for—

In this book the aim has been to introduce some of the best specimens of mythologic sculpture to those who wish to become acquainted with things which add to the resources of a happy imagination, but who find it impracticable to study set treatises on “fossil theology,” or to consider the historical development of art.

An unpretentious exposition of the myths has been given 5 together with their popular interpretations. The poets, ever the best commentators on mythology and sculpture, are freely quoted. These metrical lines, relating either to the statues or the stories, may serve to stamp indelibly on the mind facts otherwise effaceable.

A table of Greek and Roman synonymous deities and a list of suggestive readings in modern literature are appended.

—L. M. B.

10

12

13

Cronus, the father of Jupiter, was in the habit of swallowing his children at birth, but when Jupiter was born his mother, Rhea, hid him in a cave and gave to the unnatural father a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes which he accepted, unaware of the deception.

Jupiter grew up under the care of the nymphs, and, after a mighty conflict, overthrew the dynasty of the old gods and took possession of the throne and dominion of Cronus. He was then supreme14 ruler of gods and men, but had viceroys of the sea and the regions of the dead in Neptune and Pluto. His lawful wife, Juno, reigned with him in equal sovereignty. Their children were Mars, Vulcan and Hebe. Although wedded to Juno, Jupiter as the deity of the visible heavens, had brides and children in many lands. The abode of this wisest and most glorious of the divinities was on Mt. Olympus in the unclouded ether.

The strange story of Cronus, who swallowed his own children, has reference to the consumption and reproduction continually going on in nature.

The words Jupiter, Zeus, Jove, mean heaven, father, almighty.

This Carrara marble head was found at Otricoli, a small town near Rome, in 1775, and is called the most beautiful of all the representations of Jupiter. The high forehead is made to appear still higher by the lines of the hair which meet in the center in a pointed arch. A deep furrow divides the hair from the face. The curled beard seems admirably in keeping with Olympian dignity.

The work was probably executed in Rome in about the first century.

16

17

Juno’s marriage to Jupiter was one of the most auspicious events that ever took place on Mt. Olympus. To their union were traced all the blessings of nature and when they met as on Mt. Ida in a golden cloud, sweet and fragrant flowers sprang up around them.

It is recorded, however, that they had many quarrels and wranglings, the blame of which was18 usually traced to Juno. She was frequently angry, jealous and quarrelsome, and her character was proud and not free from bitterness. The Romans believed that every woman had her Juno who protected her through life. The peacock was sacred to Juno.

Juno is the personification of what may be called the “female powers of the heavens, that is, the atmosphere with its fickle, yet fertilizing qualities.” That phase of her life as bride is obviously associated with the phenomena of the heavens in the spring time when the return of dazzling light and warmth spreads everywhere affectionate gaiety and blooming of new life.

This marble head is in the Villa Ludovisi, Rome, and is considered the most beautiful of all the representations of Juno. It expresses great energy of character united with the utmost feminine grace and purity. The name of the artist is unknown, but he is presumed to have been an Athenian.

20

21

The slime with which the earth was covered by the waters of the flood, caused so excessive a fertility as to produce every variety of life, both good and bad. An enormous serpent, called Python, crept forth and lurking in the caves of Mt. Parnassus, became the terror of the people.

Apollo encountered this reptile, and, after a fearful battle, slew him with his arrows. In commemoration of this conquest he instituted the Pythian games, in which the victor in feats of strength, swiftness of foot or in the chariot race, was crowned with a wreath of beech leaves.

Apollo’s conflict with the serpent, Python, is a symbol of the victory of light and warmth over darkness and cold. He used his bright beams (arrows)22 against the demon of darkness (Python). His shafts slay men as does sun-stroke. Andrew Lang relates a strange coincidence of a German scholar, Otfried Muller, who had always opposed Apollo’s claim to being a sun-god. He was killed by a sun-stroke at Delphi. The god thus avenged himself in his ancient home.

This statue is given the highest place of honor in Europe’s most celebrated sculpture gallery, the Belvedere of the Vatican. It was discovered in 1503, amid the ruins of Antium and was purchased by Pope Julius II., who removed it to Rome.

It is for the modern world one of the most popular statues of the ancient world. Though it has been much studied and admired there has been a question as to its exact meaning. Collignon says that the object in the hand is a fragment of the Ægis with the Medusa head with which Apollo routed his enemies. Others think from the position and the quiver strap across the breast that the god is represented immediately after his victory over the Python.

24

25

Niobe, Queen of Thebes, was the daughter of Tantalus and wife of Amphion, who was the most famous of mythological musicians. She was the mother of seven sons and seven daughters. She became jealous of the Goddess Leto and commanded the Theban women to cease their worship of her, explaining that she considered herself far superior to Leto, who had but two children, while she had seven times as many. This so angered Leto that she commanded Apollo and Diana to kill all of Niobe’s children. The father, Amphion, overwhelmed by this calamity, destroyed himself. The proud mother, thus bereft of husband and children, wept continually night and day, until Jupiter turned her into stone; yet tears continued to flow; and borne on a whirlwind to her native mountain, she still remains a26 mass of rock from which a trickling stream flows, the tribute to her never-ending grief.

Niobe is the personification of winter, and the myth signifies the melting of snow and the destruction of its icy offspring under the rays of the spring sun.

This statue is attributed to Scopas. It was disinterred in Rome in 1583 and is now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

It is part of a group composed of seventeen figures—Niobe and fourteen children, a pedagogue and a nurse. The figure of the mother clasped by the arm of her terrified child is one of the most admired of the ancient statues. It is the highest instance in sculpture in which the body, itself exempt from pain, so wonderfully reflects the tortured soul. It ranks with the Laocoon and Apollo Belvedere as a work of art.

28

29

Mars, the son of Jupiter and Juno, was born in Thrace, a country noted for its fierce storms and war-loving people. He had quarrelsome tastes and delighted in the din and noise of warfare, never questioning which side was right. Strife and slaughter were the conditions of his existence. His attendants, Fear, Discord, Alarm, Dread and Terror, sympathized with him heartily and readily followed his lead.

Bellona, goddess of war, watched over him closely. She drove his chariot, warded off dangerous blows, and in other ways protected him. The altars of Mars and Bellona were the only ones given up to human sacrifice.

The shield and sword, the spear and burning torch are the emblems of Mars. His chosen animals30 are haunters of the battle field—the vulture and the dog.

The character of this fierce god of battles had a softer side. Although inconsistent and capricious, he loved and was beloved by Venus, the fair goddess of beauty.

The principal worshipers of Mars were Roman soldiers who believed that he marched in person at the head of their armies. Their exercising ground was called the Campus Martius or field of Mars. All the laurel crowns bestowed upon victorious generals were placed on his statues and a bull was their customary sacrifice to him.

The fury of the storm winds which threw heaven and earth into confusion furnished the conception of the god of war. The phenomena of the atmosphere with its tumults and uncertainty were well shown by his character.

This Mars, one of the most excellent works of ancient art, in the Villa Ludovisi, Rome, is sometimes ascribed to Scopas.

The god, with unused sword and shield, is 31 sitting in a careless, easy attitude absorbed in reverie. It would seem to us from the little Cupid at his feet that it is love for Venus which has overcome the god of battles.

32

33

Laocoon was a priest of Apollo at Troy and endeavored unsuccessfully to dissuade the Trojans from admitting into their gates the wooden horse which the Greeks gave out was intended as a propitiatory offering to Minerva, but in fact was filled with Achæan chiefs who, by means of this strategem, obtained entrance into the doomed city. Sinon, who had been left behind when the Greeks pretended to sail away, persuaded the Trojans that the horse would prove a blessing and they drew it inside the gates.

34

Laocoon also struck his spear into the side of the monster. His words and acts so offended Minerva that she sent two serpents out of the sea to destroy him and his sons. They were speedily enveloped in the creatures’ slimy folds and died in great agony.

Max Muller says that the meaning or root of the name Laocoon is symbolic of Sin the Throttler. The strange fate of Laocoon was readily believed to be a punishment for the violence he had done the sacred horse.

This group is wonderful as a work of sculpture and one of the most celebrated pieces in existence. It was found in the excavations of the Baths of Titus, Rome, in 1506, and was at once placed in the35 Belvedere of the Vatican, where it has ever since remained. The period of the statue is not definitely known.

The right arm of the father has been incorrectly restored. It is thought that it was originally bent in such a way that the hand was near the back of the head as then the general outline of the group would be pyramidal, and the summit of the pyramid would be the father’s head.

The three figures represent three acts of the tragedy. The eldest son is still unhurt, and if we did not know the story we might think his escape possible.

In the father is seen the highest tension of forces to free himself from the coils of the serpents. The straining muscles, the expanded chest and head thrown upward and backward, show his terrible effort.

The struggles of the younger son are weak and pitiable, showing that resistance is at an end.

The expression of physical and emotional pain in this statue is so materialistic as to be repulsive to sensitive natures. The scene is literally too sensational for sculpture. “Its pathology overpowers its pathos.”

36

37

Cradled on a great blue wave lay Venus when discovered by the lovely sea-nymphs. They immediately assumed her care, tenderly nursed her and watched over her until she became a calm, splendid woman. Her grace and beauty conquered every heart. Oceanides, Tritons and Nereids, all gave her rapturous admiration. At length the foster mothers entrusted her to Zephyrus, who gently wafted her to the island of Cyprus where she was met by the Muses, Hours and Graces and led to the assembly of the gods, who bent in homage to her surpassing beauty.

Her power soon extended over men as well as gods, and temples were reared in her honor upon every shore. She had favors for some and strong38 antipathies for others of the worshipers at her shrines, and many are the stories and romances which cluster round her name.

Venus is the image of the dawn, the most lovely of the sights of nature. In ancient times the power of admiring was one of the greatest blessings bestowed on mankind, and the beautiful morning, as embodied in Venus, was, therefore, intensely admired and worshiped.

This beautiful Greek original, the Venus of Milo, has been called “the marble realization of the dream of fair women.” While it is universally recognized as a great work of art, nothing is definitely known as to the period or school to which it belongs.

It was discovered in 1820, by a peasant on the 39 Island of Melos, in the niche of a wall which had long been buried. The French ambassador at Constantinople purchased and presented it to Louis XVIII., king of France, and it is now in the Louvre.

The statue is made of two blocks of marble joined above the drapery which envelops the lower limbs. The tip of the nose and the foot which projects beyond the drapery have been restored by modern artists. The restoration of the arms has often been unsuccessfully attempted.

In spite of the mutilated limbs of this marble Venus, she holds undisputed sway over the hearts of all beholders.

40

41

Hercules is one of the most significant figures in Grecian mythology. He was the son of Jupiter by a mortal maiden named Alcmene. Juno, who hated the children of her husband by mortal mothers, declared war against him from his birth. Through her decrees there were imposed upon him a succession of desperate undertakings which are called the Twelve Labors of Hercules. The variety and motives of these labors make up a story which might easily be turned into Christian allegory. Through them we learn not only of the strength of Hercules and his victories over monstrous evils, but also of his frailties which he vanquished by superhuman will.

42

Hercules is a sun hero, born of the sky (Jupiter) and the dawn (Alcmene). His twelve great tasks are interpreted to represent either the twelve signs of the zodiac, the twelve months of the solar year, or the twelve hours of daylight.

This colossal statue, called the Farnese Hercules, was found in 1540 in the ruins of the baths of Caracalla, Rome, and is now one of the chief attractions of the Naples Museum, where it was placed by the Farnese family in 1790. There has been much dispute as to its origin, but the conclusion to which criticism is now pointing is that it was executed by Glycon in the first century.

The anatomy of the figure, though exaggerated to be in keeping with the character of the hero, is well worth study.

44

45

A large proportion of the statues of Praxiteles represented the idealized beauty of women, and with common consent it is admitted that he created the type of Venus in his celebrated statue called the Venus of Cnidus. There is a story that he made two statues of her, one clothed and the other unclothed. The choice between the two was offered to the people of Cos, who, more modest than artistic, selected the draped statue. The Cnidians most joyfully bought the nude Venus and it was said to have made the seaport town so attractive that people flocked thither from all parts to view the beautiful marble goddess. But this statue has perished. It was seen in its beauty probably about 150, A. D. All that remain are but feeble echoes of its grace. Pausanius tells us that it was a portrait of Phryne, who was much beloved by Praxiteles and often served him as a model.

The moral conception of Venus as goddess of the higher and purer love, especially wedded love and fruitfulness as opposed to mere sensual lust, was but slowly developed in the course of ages.

The Venus de Medici claims direct descent from the Venus of Cnidus, and preserves some of the sweet unconsciousness which must have been the special charm of the original. It belongs to the Græco-Roman period of sculpture and was executed by Cleomenes. It was found in the ruins of Portico Octavio, passed at once into the possession of the Medici family, and is now in the Tribuna of the Uffizi, Florence. Its “divinity has vanished; the beautiful humanity alone remains.”

48

49

When Hercules’ twelve labors were ended he married Dejanira and lived in peace with her for three years. One day when they were traveling, in crossing a river, the ferryman, a Centaur by the name of Nessus, endeavored to carry away Dejanira, but Hercules heard her cries and pierced the Centaur through the heart with one of his poisoned arrows. With dying accents Nessus professed50 repentance and begged Dejanira to take his robe and keep it for its magic power.

Soon afterwards the news was brought to Dejanira that Hercules was in love with Iola and she sent to him by his page, Lichas, the robe given her by the Centaur. When Hercules donned the robe poison seized upon his frame.

Lichas vainly denied all knowledge of the treacherous deed, but Hercules, maddened by his agony, seized him by the foot and hair and hurled him into space. “Lichas congealed like hail in mid air and turned to stone, then falling into the Euboic sea became a rock which still bears his name and retains the human form.” Hercules wrenched off the garment, but it stuck to his flesh and with it he tore away whole pieces of his body. In this51 condition he ascended Mt. Œta, where he built a funeral pyre, and laying himself upon it, commanded his son to apply the torch. The flames soon put an end to his suffering and his spirit passed in a thunder cloud to Olympus. Dejanira, seeing the calamity she had unwittingly caused, took her own life.

The slaughter of the Centaur by Hercules signifies the dissipation of vapors by the sun. Dejanira, “the destroying spouse,” is daylight, Iola the beautiful twilight, and the bloody robe a sun cloud, now concealing, now revealing, the mangled body of the sun. Hercules ends his career in one grand flame, the emblem of the sun setting in a framework of blazing crimson clouds.

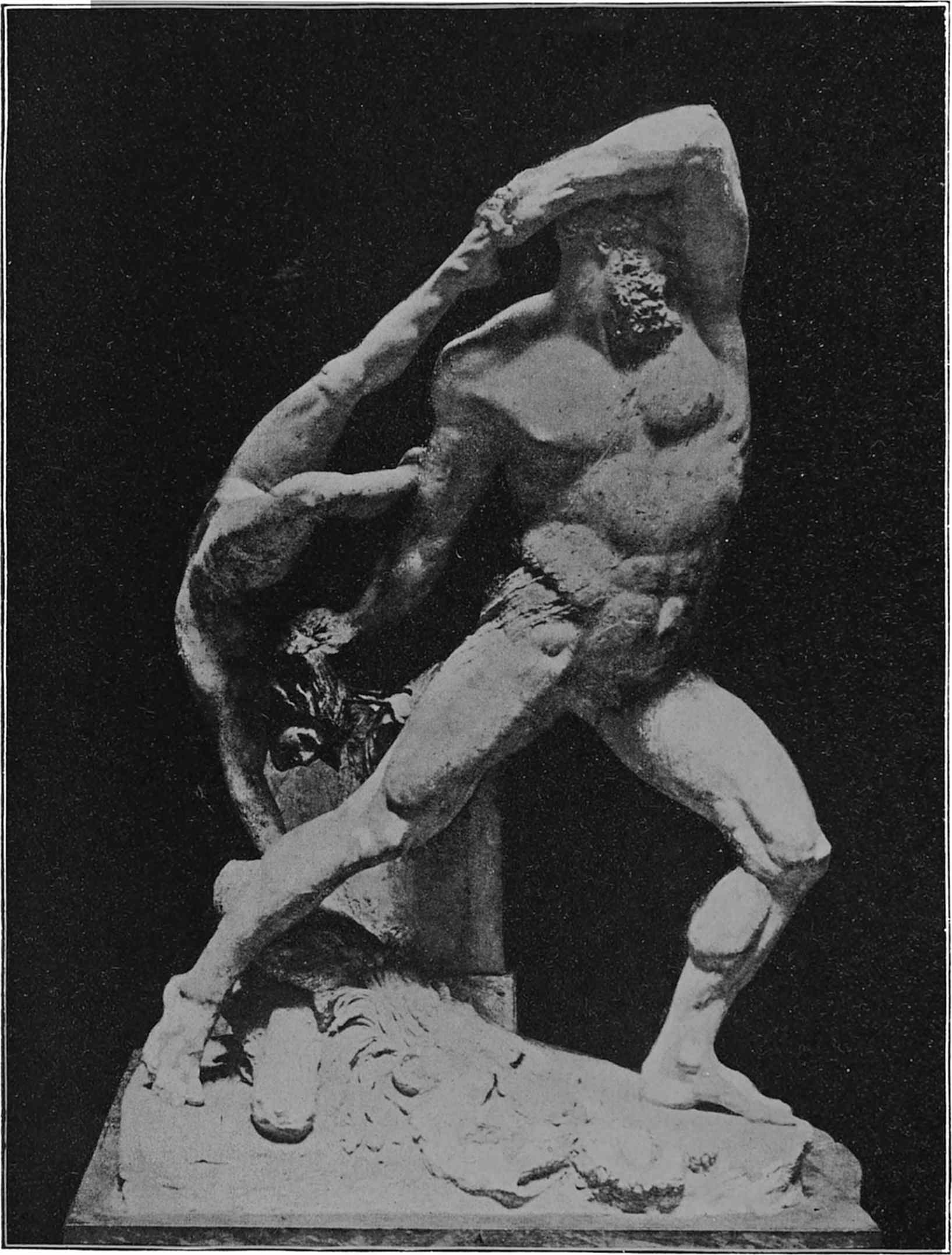

This spirited group by Canova, in the Torloni Palace, Rome, represents Hercules throwing Lichas into the sky. The poisoned garment clings most painfully to his body. The lion skin and club have slipped to the base of the altar upon which he was about to offer sacrifice.

52

53

The Goddess of Victory was the daughter of the giant Pallas and the Oceanid nymph Styx. Her attributes were a wreath, a palm branch and a trophy of armor. Sometimes she carried a staff as a sign of her power. She floated in the air with outstretched wings or appeared coming down to earth—now pointing the way to a victor, now placing a wreath upon his brow.

Victory was embodied in a winged goddess. In beholding this bold and graceful conception we realize54 how picturesquely the Greek fancy personified even passing events.

This marble, one of the most noticeable and interesting in the Louvre, is a colossal fragment of a winged Victory discovered in 1863 on the Island of Samothrace. The head, arms and feet are lacking. The statue must originally have been at least twelve feet high.

The figure seems sweeping down through the air and in the very act of alighting. Every fold in the floating garment has a direct purpose, at first indistinctly manifest, then widening and finally lost in the general mass.

The pediment on which the statue stood represents the prow of a ship, and makes it clear that it was executed to commemorate a naval victory of the Athenians off Cyprus, 306 B. C. As restored by Zumbusch, Nike holds in one hand a trumpet and in the other a rod intended to support the trophies.

56

57

The Fates were three sisters, daughters of Night, and were named Clotho (Spinner), Lachesis (Alotter), and Atropos (Unchangeable).

They exercised a great influence over human life from the cradle to the grave. They spent their time spinning a thread of gold, silver or wool—now tightening, now slackening, and at last cutting it off. This occupation was so arranged that Clotho put the thread around the spindle, Lachesis spun it, and Atropos, the eldest, cut it off—

58

Catullus thus gives a description of their spinning—

The three Fates are the embodiment of a doctrine of Necessity which has all things within its inexorable grasp. They represent the birth, life and death of every man—Clotho the birth, as she holds unwound the thread on the distaff, Lachesis the life, with the thread just passing through her fingers, Atropos the death, as she waits, holding the shears to cut the thread.

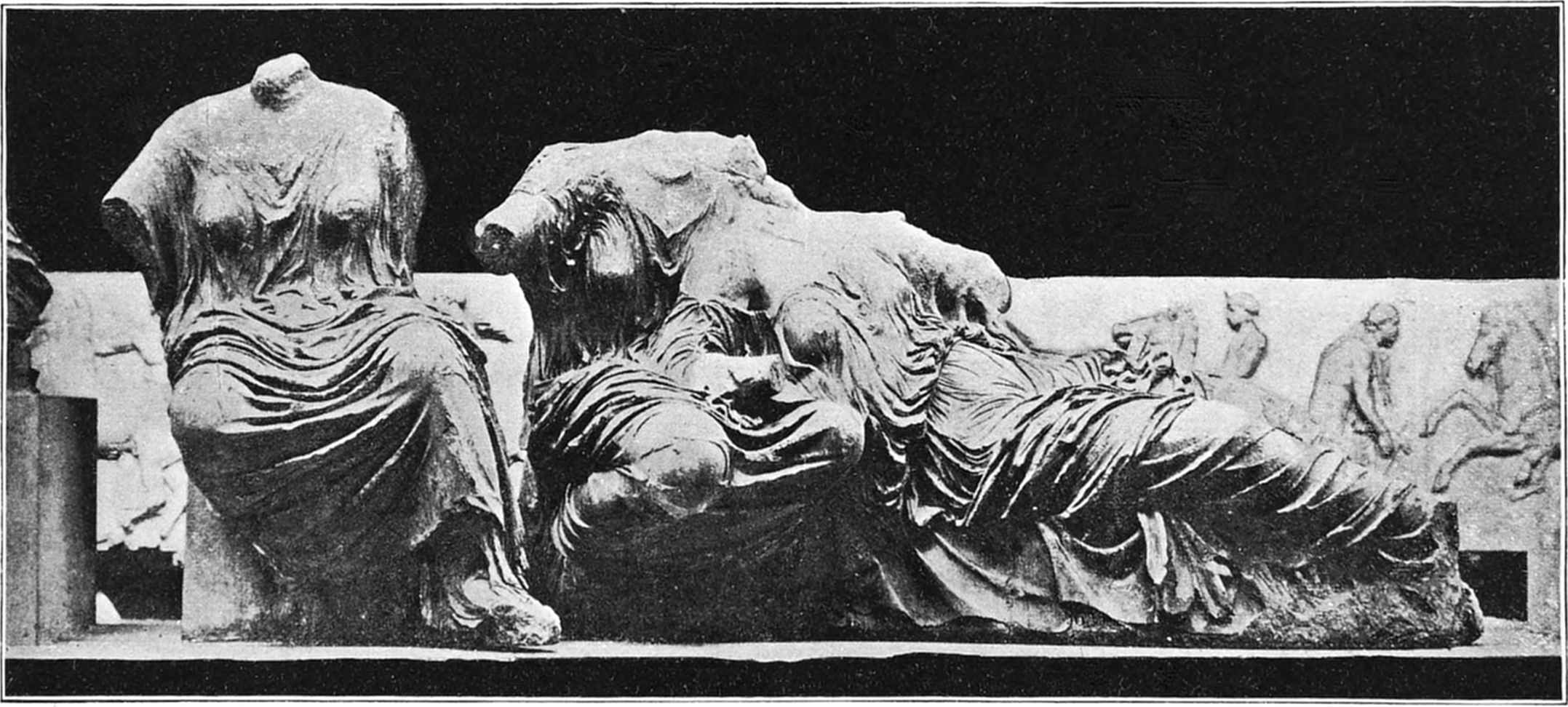

These figures in pentelic marble were taken by the agents of Lord Elgin from the east pediment of the Parthenon in 1801. They were bought by59 the English Government and are now in the British Museum, London. There are no restorations.

The “blind decrees of Fate” recline negligently on rocky ground. Two of them seem almost as if about to rise, the third is leaning on the bosom of her companion. Their forms are large and robust, but at the same time supple and graceful and expressing perfect maturity of womanhood. The flowing folds of their garments reveal as well as conceal the charming outlines of their limbs. “The dress is the echo of the form.”

60

61

Meleager was the son of Œneus and Althea, the king and queen of Calydon. When he was born the three Fates foretold that the child would live no longer than a brand then burning upon the hearth. The mother carefully quenched the brand and hid it away and Meleager grew to manhood.

Diana, thinking that she was not duly honored by the people of Calydonia, sent a wild boar of enormous size to lay waste the fields. The growing62 corn, the vines and olive trees were trampled and destroyed; the flocks and herds were driven hither and thither in confusion and slaughtered. Meleager called all the heroes of Greece to aid him in putting this monster to death. When they assembled for the hunt, Atalanta, a famous huntress, appeared, to the surprise of all.

After an exciting chase, with many narrow escapes, Atalanta first pierced the boar which was afterwards slain by Meleager. The hero, enamoured with the lovely huntress, bestowed upon her the head of the animal as a trophy of his success. The two uncles of Meleager, brothers of Althea, were envious of this act and snatched from the maiden the trophy she had received. Meleager, in a rage at the insult, slew them both.

When Althea saw the bodies of her murdered brothers, there came upon her a desire for vengeance on her son, and she brought forth the brand so carefully preserved all the years, and threw the precious bit of wood upon the hearth. The brand was consumed to ashes and as the last spark flickered out, Meleager’s life was “breathed forth to the wandering winds.” In remorse for her deed Althea took her own life.

63

Meleager is a solar hero. He slays the boar (drought), loves Atalanta (dawn) and is finally slain by his own mother (twilight). The twilight cannot long survive the setting of the sun.

Since the taste for classic art has existed this statue has attracted attention. It is said that Raphael and Michael Angelo were filled with admiration when beholding it. There has never been any attempt at restoration of the hand which undoubtedly held a spear. Few heads of the hero type can be compared with this for power of expression. Meleager’s unparalleled virtues and his morbid passion are both represented. The statue is probably a Roman copy in marble of some celebrated Greek original in bronze. It is in the Belvedere of the Vatican.

64

65

Apollo was skilled in the art of music and sang hymns of his composing to an accompaniment of his own upon a wonderful lyre which Hermes had made for him. He was the dearly loved leader of the nine Muses, and was surnamed Musagetes.

That he should be the god both of music and poetry does not appear strange, but that medicine should also be assigned to his province may. Armstrong, a physician as well as a poet, thus explains—

66

As the kindly beams of the “orb of day” (Apollo) spread light and warmth over nature there are heard everywhere happy, joyful sounds, the music of his lyre.

The sun was regarded as the natural restorer of all life and as such his power extended over human ailments and diseases.

This statue was found in the ruins of the so-called Villa of Cassius in 1774, and was added to the Vatican collection.

The rich and flowing draperies in which Apollo is clothed give the statue an almost feminine fulness of form. Although only indifferently executed, it has a graceful movement which renders it impressive. It is evidently a copy of a famous original, some critics say of Scopas.

The god is represented as gliding forward in the dance in which he leads the Muses.

68

69

Calliope, the fairest of the Muses and their chief representative, often appeared before the gods and many of them fell victims to the charms of her sweet voice and graceful manner. But of them all she loved the bright sun god best, and many were the verses she composed and sang in his honor. He returned her love with ardor. She readily consented to their union and became the proud mother of Orpheus, who inherited from his parents great musical and poetic gifts.

70

Calliope, the personification of the light of day and hence associated with Apollo, the sun god, became naturally, as her voice was song, the goddess of harmony and finally the Muse of epic poetry.

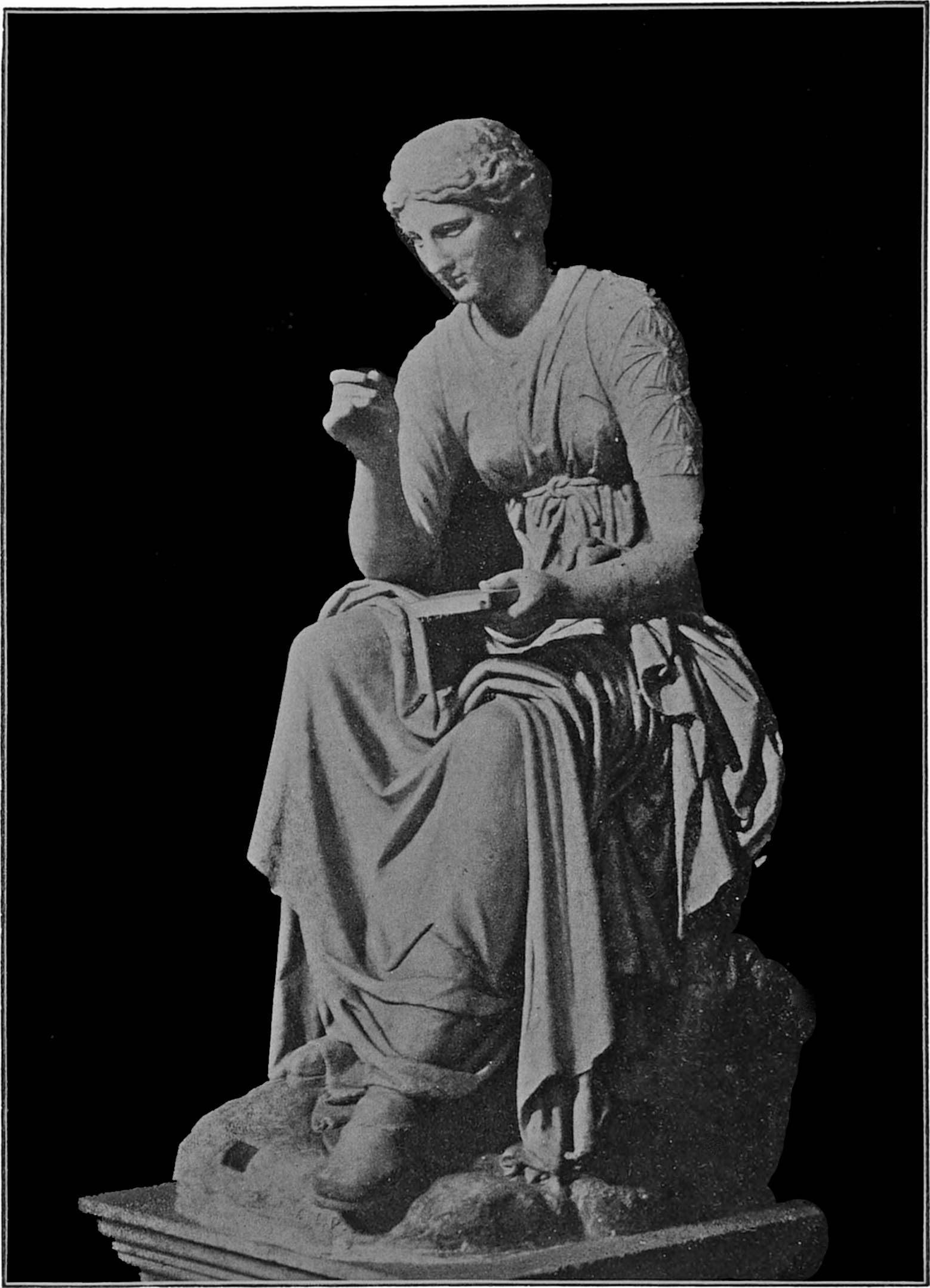

This statue of the Muse, found in 1774 in the ruins of the Villa of Cassius, and now in the Vatican, is graceful and artistically excellent.

Calliope is seated, her figure slightly bent in meditation. She holds a tablet in her left hand; while her right is poised in a manner to enhance the expression of thought. She seems to be debating just how best to word her song.

There are few works of art in which the artist’s conception is more clearly and admirably shown.

72

73

Diana was the twin sister of Apollo. She had many lovers, but her heart remained cold to all of them until one calm, clear night, in bending down from her moon-car over the shadowy, dream-like earth, she beheld Endymion sleeping. At once her heart was warmed by his surpassing beauty, and gliding gently from her chariot, she kissed him and watched lovingly over him while he slept.

74

Partly awakened, Endymion rested his eyes for an instant upon the bright maiden ere she vanished, but that one glance kindled a great passion in his heart. Diana descended night after night to caress him while he slept, and even while wrapped in slumber he watched for her coming and enjoyed the bliss of her presence. At last she threw over him the spell of eternal sleep and, that none might know of her passion, concealed him in a cave, where she continued always to come and gaze enraptured upon his face and press soft kisses upon his lips.

“This story suggests aspiring and poetic love, a life spent more in dreams than in reality, and an early and welcome death.” Mueller, the great authority on philology, says that in ancient language the people said, “Diana kisses Endymion to sleep,” instead of, “It is night.” Some mythologists consider Endymion the personification of sleep.

75

This beautiful representation of the gentle goddess of night in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican, was found in the ruins of Hadrian’s Villa, on the Tiber. Diana, in a very graceful attitude, with head bowed and hands outstretched, rapturously gazes at her sleeping lover. The forearms are modern, but the restoration is in admirable keeping with the motive and is undoubtedly correct.

76

77

Minos, the king of Crete, in revenge for the death of his son, slain by the Athenians, exacted a yearly tribute from them of youths and maidens. Theseus, a valiant youth of Athens, offered himself as one of the victims of this tribute, with the intention of slaying the Minotaur, a hideous monster to whom Minos was in the habit of feeding his captives. The cave in which the Minotaur was confined was a labyrinth so constructed that no man who entered could find means to escape before he was met and devoured.

The king’s fair daughter saw and fell in love with Theseus. She gave him a sword and a clue78 of thread so that he was enabled to slay the Minotaur and find his way out of the labyrinth.

Fearing the wrath of her father, Ariadne fled with Theseus to the Island of Naxos. But Theseus, ungrateful and selfish, deserted her while she was sleeping, and setting sail to his ship, was soon borne away.

Theseus is the sun: he slays the Minotaur (the terrible monster of darkness), and carries off Ariadne (dawn). Ariadne is forced to share the woes of all who love the sun god, and must be abandoned.

The eventful sleep of Ariadne on the Island of Naxos, during which Theseus deserted her, is here represented. It is an unquiet sleep as denoted by the attitude and the disorder of the beautiful but complicated drapery. The uneven surface, upon which the body reclines, causes it to be slightly drawn together, and adds to the idea of unrest. The gentle droop of the head, the relaxed, curving79 arms, and the languid air of sleep make the figure extremely graceful and feminine, though almost colossal in size.

The statue has been in the Louvre since the time of Pope Julius II.

80

81

The island where Ariadne was left when deserted by Theseus was a favorite haunt of Bacchus, the young god of wine. In wandering over the rocks one day, he came across Ariadne as she sat lamenting her fate. Her distress appealed to him, and in consoling her he became charmed with her beauty. His devotion and admiration caused her to forget her faithless lover, and, after a short courtship, Bacchus won her for his wife.

The bridegroom presented the bride with a 82 golden crown adorned with seven glittering gems. Shortly after the marriage, however, Ariadne sickened and died. The broken-hearted Bacchus took the crown and flung it into space, where, growing in brightness, it became a beautiful constellation known as Ariadne’s crown or corona.

As the female semblance of Bacchus, Ariadne appears to have been a promoter of vegetation. She alternated between the joy of spring and the melancholy of winter. By some mythologists she is thought to have been connected with star-worship.

This statue is the most celebrated work of the distinguished German sculptor, Dannecker (1758–1841). It is known to many people the world over through the generosity of Herr Bethmann of Frankfort, who admits visitors to his gallery, and from the many casts and pictures made of it.

The author did not choose the more touching and poetic character in which to represent Ariadne.83 She is here no longer the deserted and desolate one, but the triumphant bride of the god of the vintage.

The figure, which is larger than life, reclines on the back of a clumsy panther. The body and limbs are finely modeled, and the attitude is graceful and pleasing. Some critic has remarked that this statue makes the conduct of Theseus inexcusable.

84

85

Minerva was the daughter of Jupiter and was said to have leaped forth from his brain mature and in complete armor. She was warlike in her tendencies, but it was defensive war only with which she was in sympathy.

As a goddess of storms and battles the Greeks called her Athene, and as she also possessed gentle characteristics, she was styled Pallas.

She was the goddess of wisdom, of weaving and 86 of agriculture, and was forever a virgin, scorning the affections which were frequently offered her. As the especial divinity of the people of Athens she put to flight a deity named Dullness, who had ruled there.

Many temples and altars were dedicated to Minerva, the most celebrated of all being the Parthenon at Athens.

Minerva is a dawn goddess. Her Greek name, Athene, from the Sanskrit ahana, means the “light of daybreak.” She springs from the “dark forehead of the broad heavens,” searches out the dark corners, and fills all with her light. This conception of penetrating scrutiny passes readily into the idea of wisdom. The Latin Minerva, is connected with mens, the English mind.

It is easy to recognize statues of Minerva, as she wears an ægis or mantle of goatskin (the emblem of the storm-cloud), the clasp of which is the head of Medusa, won for her by Perseus. It87 has been suggested that this head so worn has an inner meaning, and that it is intended for a symbol of evil which, though always present, may be made powerless by virtue.

This well executed statue of Minerva in the Capitol, Rome, is a direct offspring of the colossal creation in ivory and gold by Phidias which stood in the Parthenon. The energetic, warlike figure is short and thick-set. The folds of the drapery, especially that of the upper garment, are sharp and angular.

88

89

The Muses were the daughters of Jupiter and Mnemosyne (memory), and were born at Pieria on Mt. Olmypus. To each was assigned some particular department of literature, art or science, over which she reigned as goddess.

Euterpe presided over the art of music and was called the “mistress of song.” Thalia was Muse of90 comedy and burlesque, Melpomene of tragedy, Urania of astronomy, Terpsichore of dance, Erato of love poetry, Polyhymnia of sacred poetry, Calliope of heroic poetry, and Clio of history.

Euterpe is the personification of those lofty aspirations of mortals which find expression in music. The name Euterpe means giver of pleasure.

This finely executed statue of Euterpe is in the Louvre and is believed to be a copy from Scopas. The pose and attitude are remarkable for regal grace. The arrangement of the draperies is unique.

92

93

Orpheus and his beloved wife, Eurydice, were constant companions, but one day Eurydice trod upon a poisonous snake, was bitten on the foot, and soon died. Her spirit was borne into Hades by Mercury. The husband, left desolate, boldly made his way into the land of shadows, presented himself before the throne of Pluto and Proserpine, and, with the aid of his lyre, persuaded them to again unite the thread of Eurydice’s life.

94

Eurydice was permitted to return to earth on condition that, as she followed her husband from the regions of the dead, he should not look behind him. Conducted by Mercury, they had all but passed the fatal limits of that gloomy world when Orpheus, no longer able to restrain his impatience, looked back, and so lost once more and forever his beloved Eurydice.

Eurydice, whose name comes from a Sanskrit word denoting the broad-spreading blush of dawn across the sky, is a personification of that light slain by the serpent of darkness at twilight.

Orpheus is sometimes considered as the sun, and the dawn (Eurydice) reappears opposite the place where he disappeared; as the dawn is no longer seen after the sun has fairly risen, the ancients said, “Orpheus has turned round too soon to look at Eurydice, and so is parted from the wife he loves.”

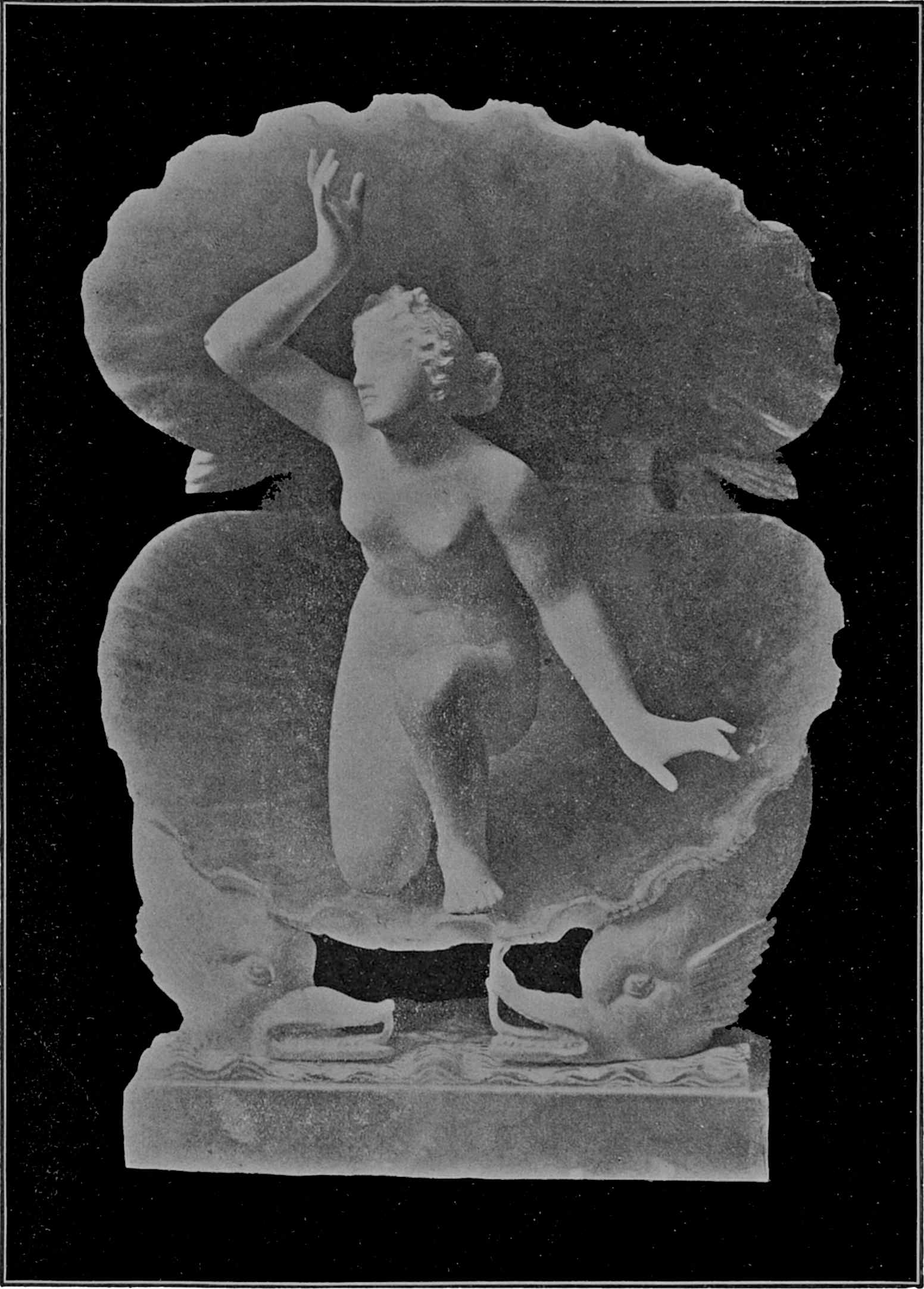

This marble relief, in the Villa Albani, Naples, is a fine illustration of one of the leading principles95 of Greek art—extreme moderation in the expression of passion. The greatest grief is most delicately yet most intensely expressed by a few voiceless gestures.

Orpheus, guided by Mercury, is leading Eurydice back from Hades. Contrary to his contract, he turns with irresistible longing to look at her before they are entirely past the portals. Eurydice lovingly puts her hand on his shoulder. But now their parting must come. Orpheus’ bitterness at his fate is expressed by his hand, which moves toward the hand of his beloved. Mercury, sad and pitying, takes her by the other hand to lead her again “down the darkling ways.”

96

97

Bacchus, the youngest of the gods, was the son of Jupiter and Semele. His mother, instigated by the jealous Juno, who appeared to her in disguise, demanded of Jupiter that he should reveal himself to her in all his power and majesty. Jupiter unwillingly complied and, making his thunder bolts milder than usual, appeared before her. The lightning which played about his head set fire to the palace and Semele was consumed. The child, Bacchus, was snatched from the flames by his brother Mercury98 and borne away to the nymphs, who guarded him most faithfully.

While still a youth Bacchus was appointed god of wine. Spring was a season of gladness for him, winter a time of sorrow. He delighted in roaming over the world borne by his followers or riding in his chariot drawn by wild beasts. His train was composed of men and women, nymphs, fauns and satyrs who drank wine made from water and sunshine, ate grapes, and sang the praises of their leader.

Semele is the personification of a fertile soil in spring which brings forth the productive vine. Bacchus is regarded as the spiritual form of the new vernal life, the sap of vegetation as manifest in the juice of the grape.

The orgies were but a poetic incarnation of blithe, spiritual youth. The idea of Bacchus is not a simple one. His many titles have given rise to an almost endless number of variations of his story which are in many cases inconsistent and complicated.

99

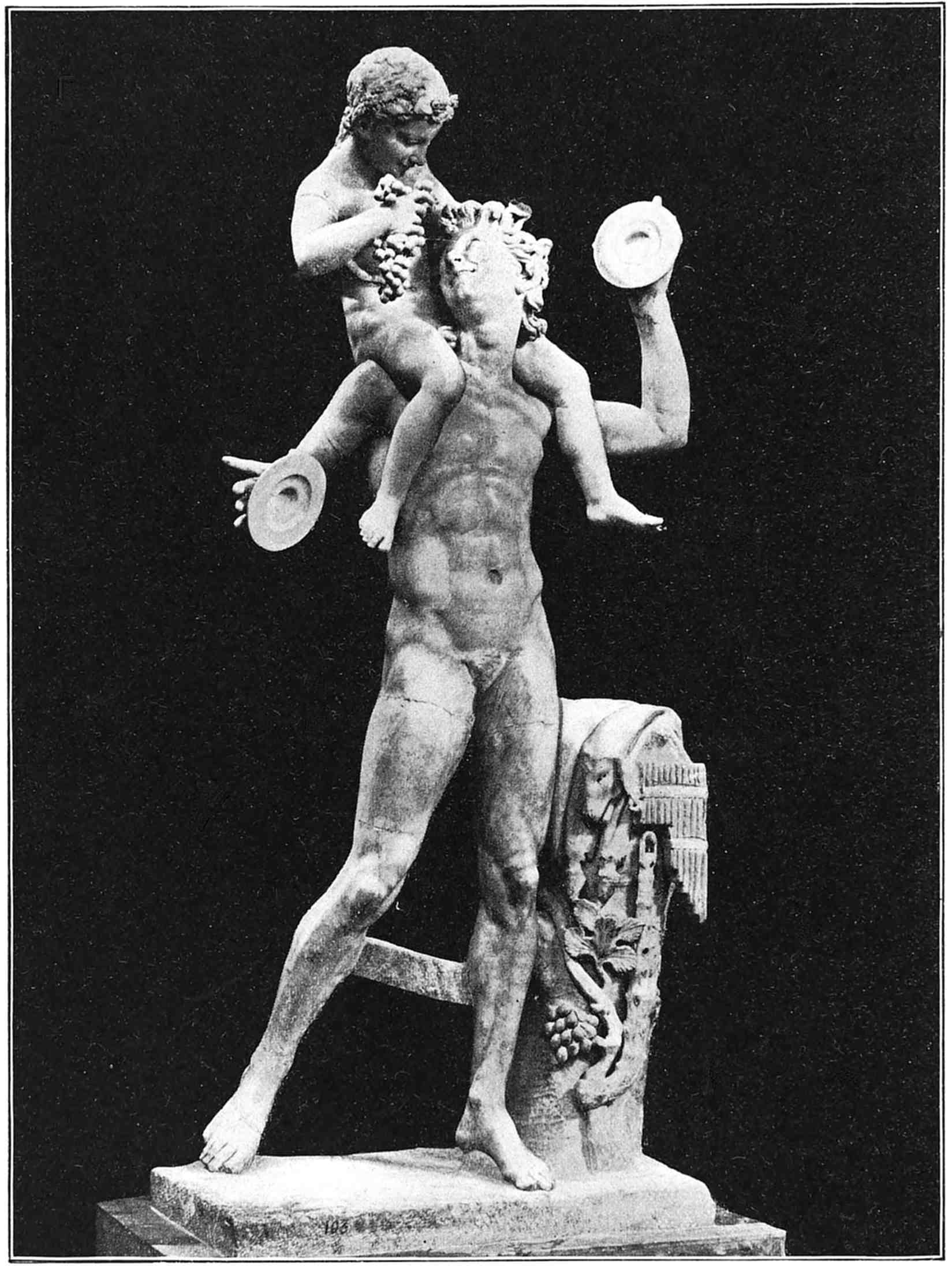

Of the many representations of Bacchus this statue in the Naples Museum is considered one of the most lovely. It is full of gladness and is simple, delicate and beautiful. The child Bacchus is carried on the shoulders of a faun. He holds a bunch of grapes in one hand and clasps the head of the faun with the other. The faun is playing on cymbals and looks back and up at Bacchus with a happy smile.

100

101

One bright morning Daphne, a charming nymph with flowing hair and sparkling eyes, was sporting in the forest. Apollo, passing by, saw the maiden and forthwith fell in love with her. He longed to obtain her, but before he could reach her side she fled. He called to her to dismiss her fears and listen to his love. He assured her of his sincerity, of his standing.

102

But Daphne continued her flight, pausing not a moment to listen to his plea. Apollo pursued and gained upon her in the race. She called upon her father, the river god, for protection. “Help!” she cried, “open the earth to enclose me or change my form which has brought me into this danger.” A moment more and her feet seemed rooted to the ground. A rough bark enclosed her quivering limbs. The woodiness crept upward and by degrees invested her whole body. Her trembling hands were filled with leaves. She was changed into a laurel tree. Apollo, reaching out to embrace her, clasped the still warm tree and showered kisses on its leaves.

Daphne is a personification of the morning dew which vanishes beneath the sun’s hot rays and leaves no trace of its passage except in luxuriant verdure.

103

This remarkable group was executed by Bernini—sometimes called Michael Angelo the second—when he was but eighteen years old, and is now in the Villa Borghese, Rome. Near the close of his long life Bernini declared that he had made little progress after its production.

The flying nymph is seized by the young god and is already being changed into a laurel tree. The upraised hands are terminated by twigs and leaves instead of fingers. The wonderful manner in which the lower limbs are barked about is difficult to describe.

The technical details and mechanical skill of this group excel anything of the kind ever attempted, and the work is such as would beforehand have been pronounced an impossibility.

104

105

Pluto, the king of Hades, stole Proserpine from her mother, Ceres, while she was playing in the flowery fields and bore her away to reign with him as his queen in the gloomy regions of the dead. For days the sorrowing mother wandered far and wide searching for her dearly loved child. The earth which had so long obtained her favors was neglected. The cattle died, the seed failed to germinate,106 there was drought, thistles and brambles were the only growth and famine threatened the people.

One day a water nymph, who heard the lament of Ceres, told her that as she had passed through the lower parts of the earth in her endeavor to escape from a too ardent lover, she had seen Proserpine reigning as the bride of the monarch there.

Ceres hastened to Jupiter and implored him to restore her daughter, promising that when she beheld her again the earth should be restored to fruitfulness, and

But the release of Proserpine was not complete. Jupiter’s law must be obeyed, but Pluto, before he let her go, persuaded her to eat a morsel of pomegranate by which he cast upon her a spell that would oblige her to return to him, for half of the year, while the other half she could spend with her mother. As soon as Proserpine returned to earth Ceres cheerfully and diligently attended to her duties and all was blessed with plenty. But when six months were gone all nature mourned and wept, for Proserpine left the bright world and returned to the darkness of Hades.

107

Pluto, “the unseen,” “the wealth giver,” greedily drew all things down to his dismal abode. Hades was a prison or storehouse containing the germs of all future harvests, and in spite of its darkness was regarded as a land of great riches. Ceres, the earth mother, expresses the gloom which falls on the earth during the cheerless months of winter. Proserpine, spring, typifies the yearly blooming of the flowers and the growth of the corn from the seed, and hence was obliged to dwell in the dismal underworld during the dark days of winter, but could return with each spring to give gladness and fertility to the mourning earth.

This group, called the “Rape of Proserpine,” the work of Bernini, is in the Villa Ludovisi, Rome. It has received much adverse criticism, but has also been greatly admired. It represents Pluto holding Proserpine in his brawny arms and, in spite of her struggles, carrying her off to Hades. In artistic excellence it does not compare with “Apollo and Daphne,” which Bernini executed much earlier in life.

108

109

Cupid was the beautiful but mischievous son of Venus. He was never without his bow and quiver of arrows, and whoever was hit by one of his magic darts straightway fell in love. The wound was at once a pain and a delight. Some traditions say that he shot blindfold, his aim seemed so often at random.

110

Although nursed with tender solicitude, he did not grow as other children, but remained a small, rosy, chubby child with gauzy wings and dimpled face. Alarmed for his health, Venus consulted Themis (Law), who oracularly replied, “He is solitary; if he had a brother he would grow apace.” In vain the goddess strove to catch the subtile significance of the answer. When Anteros, god of passion, was born, the secret was revealed. When with his brother, Cupid grew until he became a graceful, slender youth, but when away from him he always resumed his childlike form and bewildering pranks.

Cupid was the lord of the dawn. To a youthful race of men love was like a “morn radiating with heavenly splendor over their souls, pervading their hearts with a glowing warmth, purifying their whole being like a fresh breeze, and illuminating the whole world around them with a new light.” To express111 this feeling, the dawn of love, there was but one similitude,—the blush of day, the rising of the sun. They said “The sun has risen” where we say “I love.”

Cupid makes one of the most attractive subjects in sculpture. We know him at a glance, whether beside his mother, with Psyche, or alone.

The Cupid of the illustration is the work of Michael Angelo. It was discovered forty years ago hidden away in the cellars of the Ruccelli Palace, Florence, and passed by purchase into the possession of the English nation and is now in the South Kensington Museum.

Cupid is seen in the statue as a well-grown youth, a noble conception of the young god. He seems to stand for a love that is determined, for a love that conquers every obstacle. He has dropped on one knee to take an arrow from the ground. In his raised left hand he holds the bow.

112

113

Vulcan, the son of Jupiter, was born lame. He was flung from Olympus by his mother, Juno, who hated him for his deformity, and he fell into the sea, where the mother of Achilles found him. He made for her son a shield, which was a wonderfully clever piece of handiwork. Many celebrated pieces of metal work were ascribed to Vulcan. In revenge for his mother’s cruel treatment of him, he fashioned a cunningly devised throne which held her by invisible bonds against her will. The thunder bolts of Jupiter, the trident of Neptune and the girdle of Venus all came from his workshop.

114

The word Vulcan means the brightness of the flame. Vulcan is represented as lame and puny at birth because the flame comes from a tiny spark. He dwells in the heart of volcanoes where the intense heat keeps the metals malleable so that he can mould them at will.

Thorwaldsen’s favorite branch of sculpture was bas relief, in which he excelled. One of his numerous works in this department shows Vulcan forging arrows for Cupid. He is represented as an aged man hammering at his forge and indicating by his attitude the lameness with which, according to the myth, he was afflicted, but with such delicacy as in no wise to detract from the god-like dignity of his figure.

116

117

Perseus was sent by the tyrant, Polydictes, to attempt the conquest of the Gorgon, Medusa, a terrible monster, whose hair was hissing, writhing snakes, and who possessed petrifying power sufficient to turn all beholders into stone.

Perseus, favored by the gods and well equipped by them, sought the home of the Gorgons. He was rendered invisible by Pluto’s helmet, and drew near without detection. Minerva had loaned him her mirror-like shield and, watching in it the reflected form of Medusa, he severed her head and seizing it, bore it swiftly away to Polydictes, who, upon beholding it, turned to stone.

118

Perseus, the sun, “destroyer of evil and noxious things,” is forced by Polydictes, darkness, to journey to the home of the Gorgons, gloaming, and conquer Medusa, the star-lit heaven marred by ghastly vapors which stream like dark serpents across it.

This Perseus, by Canova, is in the Belvedere of the Vatican. It is a beautifully finished statue in which the artist evidently imitated the Apollo Belvedere. The head of Medusa is that of a young and lovely woman, with the serpents arranged about her face like curling hair—yet Canova has succeeded in giving her that expression of “freezing disdain which pierces the very soul.”

119

120

Hebe was the daughter of Jupiter and Juno. She waited upon the gods and filled their cups with nectar with which it was their wont to pledge each other. But one day she awkwardly tripped and fell, and was forced to resign her office to Ganymede.

She married Hercules after he was received among the gods. Later traditions represent her as a divinity who had it in her power to make aged persons young again.

Hebe, the goddess of youth, embodies the fleeting nature of human existence, particularly the delightful and elusive stage of youth.

121

This poetic creation in the National Gallery, London, was executed by Canova. The buoyant Hebe is purely beautiful as she springs away like the joy of youth. The light drapery does not interfere with the floating movement. In one hand she lifts high the vase of ambrosia, and in the other holds a goblet.

124

125

Jupiter was obliged to go in quest of another cup bearer to replace Hebe after she resigned her position. To facilitate this search, he assumed the form of an eagle and winged his flight over the earth. He had not flown far when he beheld Ganymede, a youth of marvelous beauty, alone on Mt. Ida. To swoop down, clutch him in his mighty talons and bear him safely off to Olympus, was the work of but a few moments. There the kidnapped youth, the son of the king of Troy, was carefully taught the duties he was called upon to perform.

126

Like Hebe, Ganymede personifies youth. Astronomers place him among the stars under the name of Aquarius. There is but little growth of mythical tradition about his personality.

This pleasing composition, referred by critics to the Alexandrian period, now in the Naples Museum, shows Ganymede standing by the side of the eagle and passing his arm about the bird’s neck. The eagle is placed on a stump so as to bring his head nearer to a level with the boy’s arm.

128

129

132

133

Psyche was the youngest of three daughters of a king and by her beauty incurred the jealousy and envy of Venus, who commanded her son, Cupid, to slay her. Cupid prepared to obey the command, but became so stricken with Psyche’s beauty that he fell in love with her and sent a Zephyr to convey her to a splendid palace where he became her husband. He visited her, however, only when the shades of night fell and entreated her to make no attempt to discover his name or see his face, warning her that if she did he would be forced to leave her, never to return.

134

Psyche promised to respect his wishes and when the first faint streak of dawn appeared he bade her farewell to return at night.

While the novelty of the situation lasted Psyche was happy, but soon her sisters came and filled her bosom with dark suspicions.

Psyche’s curiosity and suspicions overcame her discretion and accordingly when Cupid was asleep she took a lamp and, bending over him, beheld not135 a hideous monster, but the most beautiful of the gods. In the excitement of joy and fear, a drop of hot oil fell from the lamp upon his shoulder. He opened his eyes and fixed them full upon her, then spreading his white wings, flew away only stopping long enough to say:

Psyche, disconsolate, wandered over the earth seeking her lover, and at length came to the palace of Venus. Venus retained her as a slave and imposed upon her the hardest and most humiliating labors. She would have perished but that Cupid, who still loved her in secret, invisibly comforted her. One day he found her asleep by the roadside with the marks of grief upon her lovely face. He softly kissed her and said:

He bore her away to Mt. Olympus where their union was blessed by the gods.

136

Cupid is an emblem of the heart. The Greek word for butterfly is Psyche and the same word means soul.

The purpose of the story is to illustrate the three stages in the existence of a soul—its pre-existence in a blessed state, its existence on earth, its trials and anguish, and its future state of happy immortality.

One of the most beautiful of the many representations of this fascinating story is Canova’s statue in the Louvre of Cupid awakening Psyche. We cannot fail to have an exalted conception of true beauty after gazing upon it. It has been said that no kiss in modern art is so ideal as the one here enjoyed. The youthful figures show grace of form combined with an exalted spirituality. Only a refined nature could have conceived the subject so purely.

138

139

Mercury was remarkable for his dexterity and cunning. On the day of his birth he stole the “immortal oxen” of Apollo and drove them off to a secluded spot where he concealed them. When Apollo missed his cattle he began to search for some clue to their hiding place or to the thief, but found nothing except a few broken limbs and scattered twigs.

Suddenly he remembered that the babe whose birth had been announced that morning in high Olympus, had been appointed god of thieves. He soon discovered the young rogue hidden away in his cradle. Mercury put on a pretty air of innocence and denied all knowledge of the cattle; but Apollo140 was not easily deceived. He took the thief to Jupiter, who ordered him to make restitution. Mercury gave his lyre to Apollo who presented him in return with the divining rod, which afterwards became the caduceus, and they were then the best of friends.

Although Mercury in his lowest aspects was an accomplished liar and cunning thief, he was at the same time a swift and trusted messenger of the gods, the fair youth of whom Homer speaks:

“Straightway beneath his feet he bound his fair golden sandals divine that bore him over the wet sea and o’er the boundless land with the breathings of the wind.”

Mercury, when commissioned by the “high thundering Zeus” to perform an errand much to his distaste, thus soliloquizes:

Apollo (sun) possessed great herds of cattle (clouds). Mercury (wind), born in the night, after a few hours’ existence waxes sufficiently strong to141 drive away the clouds and conceal them, leaving no trace of his passage except broken branches and scattered leaves. His swiftness, his strength and his persuasive powers make him an ideal messenger.

This charming composition by J. A. Delorme, in the Luxembourg, represents Mercury preparing to depart upon some errand for the gods. He is seated upon a rock in an easy, graceful attitude and is binding on his sandals while he seems to be deliberating upon the nature of the task he is about to perform. His limbs give an impression of strength combined with agility.

142

143

Mercury was not only the swift messenger of the gods, but presided over commerce, wrestling and other gymnastic exercises, and was the giver of sweet sleep. To him was ascribed the invention of the lyre. He found one day a tortoise of which he took the shell, made holes in the opposite edges, drew cords of linen through, and lo, the instrument was complete. The cords were nine in number in honor of the nine Muses.

Mercury was the wind, and the music he invented was the “melody of the winds which can awaken feelings of joy and sorrow, of regret and yearning, of fear and hope, of vehement gladness and of utter despair.”

Chapu has here shown Mercury as a beautiful, vigorous youth with two light wings quivering on his head and winged sandals on his feet, emblematic of his swiftness. He is touching the ground with his magic wand round which two serpents entwine themselves.

The statue is in the Luxembourg.

146

147

Thanatos, or Mors, the god of Death and twin brother of Sleep dwelt in a dark cavern near the entrance to Tartarus. His office was to introduce all men to the subterranean abode and reveal to them its secrets. Occasionally he was followed with meekness and submission, but more often his approach was regarded with fear. He performed his task with such relentless severity that at the sight of his gloomy figure men’s hearts trembled and their minds were filled with awful thoughts.

The god of death has often been represented in art as a hideous, cadaverous looking deity, clad in a winding sheet and holding an hour glass and a148 scythe. We have a more attractive personification in Canova’s “Genius of Death,” a detail of the tomb of Clement XIII., in St. Peter’s, Rome.

The beautiful, pensive youth is sitting in a quiet, restful attitude holding an extinguished torch. The sleeping lion at his feet adds to the general air of repose.

150

151

Three sisters, Euphrosyne, Aglaia, and Thalia, in fair Venus’ train with the “rosy bosomed Hours,” were goddesses who enhanced the enjoyments of life by refinement and gentleness. They were young and modest maidens always dancing, singing or running, or decking themselves with flowers. Their home was on Mt. Olympus where they often danced before the deities. The Greeks believed that labor without gracefulness was in vain, and so Minerva, who presided over the serious business of life, often called in the aid of the Graces. They also assisted Mercury in his capacity of god of oratory.

152

The manifold beauty which the works of nature, especially in spring time, display would seem to have given rise in early times to a belief in the existence of certain goddesses at first simply as guardians of the vernal sweetness and beauty of nature, and afterward as the friends and protectors of everything graceful and beautiful. Purity and happiness in life and gratitude among men were associated with them. The name “Gratiæ,” or “Charites,” signifies the exercise of kind affection, or the charities of life.

These figures of the Graces by Canova, in the Borghese Gallery, Rome, are classic in outline and refined in treatment. They show not a trace of sensuality. Many artists have delighted in reproducing this type of the Graces.

154

155

Pan was god of the woods and fields, flocks and shepherds, and his favorite residence was Arcadia. He was fond of music and led the dances of the Hours and Graces.

The story goes that a coy nymph whom he loved and endeavored to gain was changed into a reed which he cut and fashioned into the Syrinx or Pan’s pipe. With this he charmed trees and flowers as well as men and animals.

Although Pan had a pleasant, cheerful face, he was curiously formed, having a man’s body and a goat’s legs and feet. He was supposed to delight in inspiring people with sudden and unfounded fears—hence the word panic.

The character of Pan was symbolic of Nature; the music of his pipes was the gentle, intermittent breeze.

The lower part of his body was that of a goat on account of the rough and rocky nature of his favorite haunts. His leaf-shaped ears—terminating in little peaks like those of some animals—indicate his wild, forest nature.

157

The face and figure of Pan as displayed in this statue by Fremiet, in the Luxembourg, give an idea of an easy, amiable creature. It is impossible to gaze long at it without conceiving a kindly sentiment towards it. The nose is almost straight, but curves inward slightly, giving the face a good-humored charm. The mouth seems so nearly to smile outright that one involuntarily smiles in return.

158

159

To Prometheus, a giant who first inhabited the earth, was attributed the creation of man.

It is also said that he stole fire from heaven and so cleverly used it for the benefit of humanity that it finally gave man dominion over all the earth.

160

Jupiter so grudged fire to mortals that he became furious with anger and in revenge ordered Vulcan to fashion a woman out of clay and send her to man to bring misery upon him.

The woman was named Pandora and on her were bestowed all the charms and weaknesses of human nature. Mercury led her to Epimetheus who, though warned by his brother Prometheus not to accept any gifts from the gods, succumbed at once to her beauty and made her his wife. He conveyed her to his home, where all went merrily until Pandora discovered a box hidden away in her husband’s house. She was seized with a curiosity to know its contents, but Epimetheus forbade her to meddle with it.

161

The allurement proved too great, however. Stealthily she raised the lid to take a peep within and lo, out flew a multitude of plagues and scattered themselves over the earth to forever torment hapless man with diseases, vices and crimes. All that remained was Hope. After many entreaties she came forth to heal the wounds inflicted by her former fellow prisoners. “Thus entered evil into the world bringing untold misery: thus followed Hope to point to a happier future.”

The progress of civilization is symbolized by fire and its adaptation to the uses of mankind.

Prometheus means forethought or Providence; Epimetheus afterthought. To be wise after an event is often to be wise too late. The temptation of Epimetheus came in the form of Pandora (all gifts), and was too fascinating to be resisted.

Diseases and evils can do no harm until they are let loose.

Thorwaldsen possessed in a remarkable degree the genuine antique spirit and in this figure of Hope he has embodied the calm simplicity and cheerful162 repose which make the key note of the best Greek sculpture. There is about it a noble charm which seems to be a reflex of an inward purity. The smile Hope wears is delicately expressive of her name.

163

Jupiter

Olympian Gods. W. E. Gladstone, N. A. Review, April, 1892.

Epic of Hades. Wm. Morris.

Jupiter and Danaë. J. G. Saxe.

Jove to Hercules. Schiller.

Juno

Hymn of Terpander to Juno. Landor.

Marble Faun, Chap. I. Hawthorne.

Apollo Belvedere

Apollo and the Fates. R. Browning.

Fable for Critics. Lowell.

Apollo. E. C. Stedman.

Apollo Pythias. R. W. Dixon.

The Sun’s Darling. Dekker.

Niobe

Songs Unsung. Morris.

Childe Harold. Byron.

Daphne and Other Poems. Tennyson.

Mars

Secular Masque. Dryden.

Faery Queen. Spenser.

Laocoon

Laocoon. Lessing.

Laocoon. James Sadolet.

Venus 164

Birth of Venus, New Symbols. Hake.

Venus Victrix. D. G. Rossetti.

Venus and Vulcan. J. D. Saxe.

Hercules

Hercules Spinning. J. D. Saxe.

Jove to Hercules. Schiller.

Neptune

Song of the Sirens. Lowell.

Hymn in Praise of Neptune. Campion.

Three Fates

Parcæ. T. B. Aldrich.

Meleager

Death of Meleager. Swinburne.

Muses

Prayer to the Muses. E. Arnold.

Spring. Pope.

Diana

Hymn of the Priestess, Diana.

To Artemis. A. Lang.

Endymion. Longfellow.

Ariadne

How Bacchus finds Ariadne. E. B. Browning.

Hanging of the Crane. Longfellow.

Minerva

Queen of the Air. Ruskin.

On an Intaglio Head of Minerva. T. B. Aldrich.

Orpheus 165

Orpheus: A Masque. Mrs. Jas. T. Fields.

Orpheus. Shelley.

Waking of Eurydice. Gosse.

Daphne

Daphne. Swift.

Daphne. Tennyson.

Proserpine

The Search for Proserpine. R. H. Stoddard.

The Appeasement of Demeter. Geo. Meredith.

Cupid and Psyche

Marius the Epicurean. Walter Pater.

Eros and Psyche. Dr. Paul Carus.

Marriage of Cupid and Psyche. E. B. Browning.

Cupid

Cupid’s Birth. Cosmopolitan, XX., 189.

Death and Cupid. J. G. Saxe.

Cupid Stung. E. Arnold.

Perseus

Wonder Book—Gorgon Head. Hawthorne.

Bacchus

Bacchus.

Bacchus—Poems. Emerson.

Praise of Dionysus. Gosse.

Dionysus—Greek Studies. Walter Pater.

Hebe

Hebe. Lowell.

Fall of Hebe. Moore.

Ganymede 166

Palace of Art. Tennyson.

Mercury

Mercury. Boyesen.

Phœbus and Hermes. Goethe.

Pan

The Dead Pan. E. B. Browning.

Pan in Love. W. W. Story.

Pan and Pitys. Landor.

Books recommended should further study be desired:

167

| Greek. | Roman. |

| Zeus (zūs) | Jupiter (jö´pi-ter) |

| Hera (hē´rä) | Juno (jö´nō) |

| Ares (ā´rēz) | Mars (märz) |

| Aphrodite (af-rō-dī´tē) | Venus (vē´nus) |

| Artemis (är´tē-mis) | Diana (dī-an´ä) |

| Athene (a-thē´nē) | Minerva (mi-ner´vä) |

| Demeter (de-mē´ter) | Ceres (sē´rēz) |

| Dionysus (dī-ō-nī´sus) | Bacchus (bak´us) |

| Eros (ē´ros) | Cupid (kū´pid) |

| Hades (hā´dēz) | Pluto (plö´tō) |

| Hephæstus (he-fes´tus) | Vulcan (vul´kan) |

| Hermes (her´mēz) | Mercury (mer-kū-ri) |

| Leto (lē´to) | Latona (lā-tō´nä) |

| Nike (nī´-kē) | Victoria (vik-tō´ri-ä) |

| Persephone (per-sef´ō-nē) | Proserpine (pros´er-pin) |

| Poseidon (pō-sī´don) | Neptune (nep´tūn) |

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in the original book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; unpaired quotation marks were remedied when the change was obvious, and otherwise left unpaired.

Page 63: “unparalleled” was printed as “unparalled”; corrected here.

Page 73: The poem attributed to Ben Johnson was written by John Keates, and differs from standard versions of the poem.

Page 167: “Hephæstus” was printed without the “t”, but the pronunciation was printed with it.