3

|

Page.

|

|||

| Pl. | A view of Sia, showing a portion of village in ruins |

8

|

|

| Plaza, Sia |

10

|

||

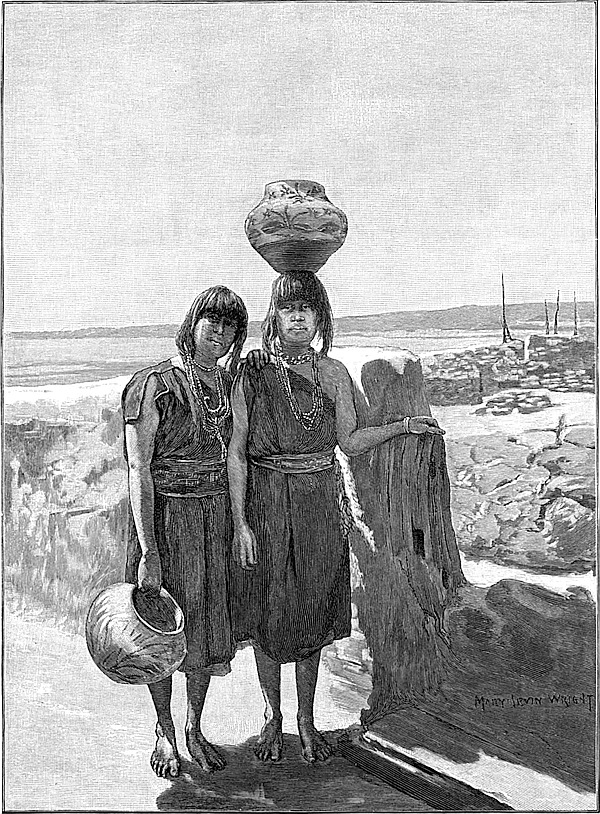

| Sisters; cleverest artists in ceramics in Sia |

12

|

||

| Group of Sia vases |

14

|

||

| The Oracle |

16

|

||

| Stone house showing plaster on exterior |

22

|

||

| Stampers at work |

24

|

||

| Pounders completing work |

26

|

||

| I-är-ri-ko, a Sia fetich |

40

|

||

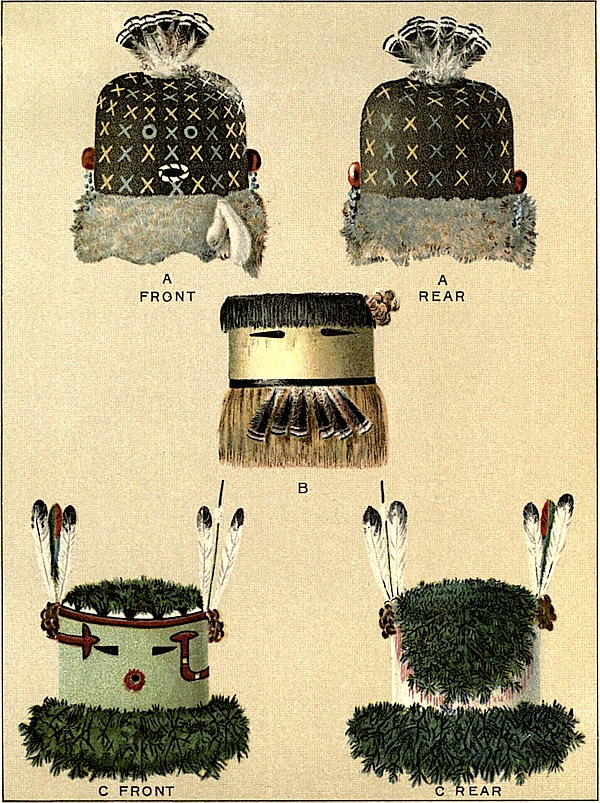

| Personal adornment when received into third degree of official membership in Cult society (A, Ko-shai-ri; B, Quer´-rän-na; C, Snake society |

70

|

||

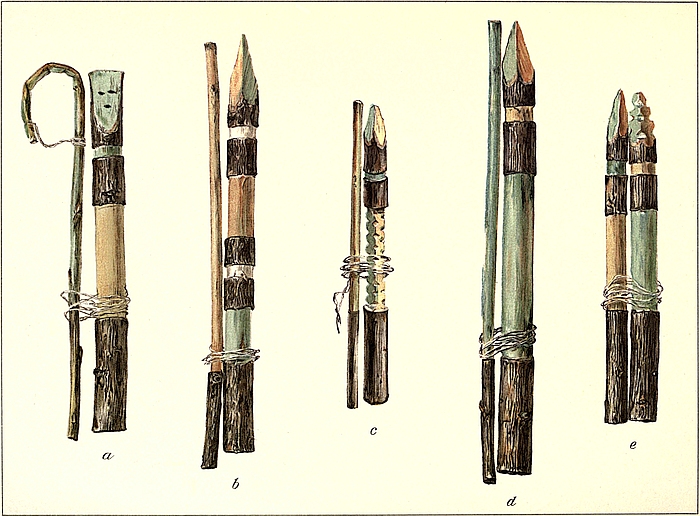

| Hä´-cha-mo-ni before plume offerings are attached (A, hä´-cha-mo-ni and official staff deposited for Sûs sĭs-tin-na-ko; B, hä´-cha-mo-ni and official staff deposited for the sun; C, hä´-cha-mo-ni and official staff deposited for the cloud priest of the north; D, hä´-cha-mo-ni and official staff deposited for the cloud priest of the west; E, hä´-cha-mo-ni and official staff deposited for the cloud priest of the zenith) |

74

|

||

| Hä´-cha-mo-ni with plume offerings attached (F, hä´-cha-mo-ni deposited for the Sia woman of the north and of the west; G, hä´-cha-mo-ni offered to the cloud woman of the cardinal points; H, gaming block offered to the cloud people; I, hä´-cha-mo-ni and official staff deposited for the snake ho´-na-ai-te of the north) |

76

|

||

| Hä´-cha-mo-ni with plumes attached (A, deposited for cloud priest of the north; B, deposited for Ho-chan-ni, arch ruler of the cloud priests of the world; C, deposited for cloud woman of the north; D, bunch of plumes offered apart from hä´-cha-mo-ni; E, bunch of plumes offered apart from hä´-cha-mo-ni) |

78

|

||

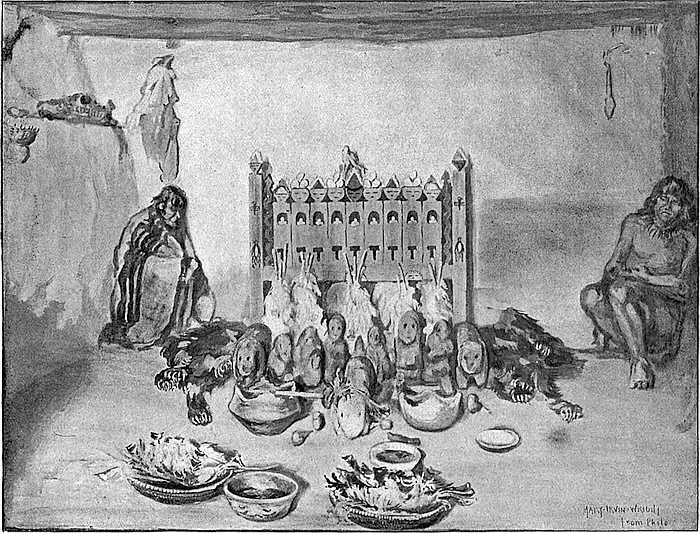

| Altar and sand painting of Snake society |

80

|

||

| Altar of Snake society |

82

|

||

| Ceremonial vase |

84

|

||

| Vice ho´-na-ai-te of Snake society |

86

|

||

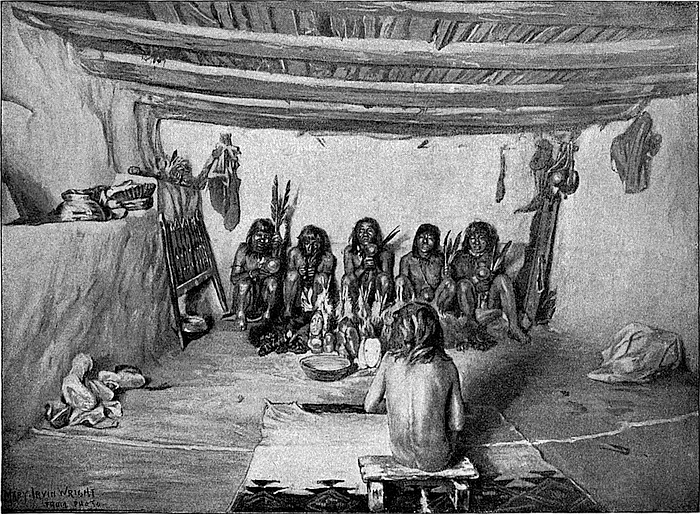

| Altar and sand painting of Giant society (A, altar; B, sand painting) |

90

|

||

| Altar of Giant society photographed during ceremonial |

92

|

||

| Ho´-na-ai-te of Giant society |

94

|

||

| Sick boy in ceremonial chamber of Giant society |

96

|

||

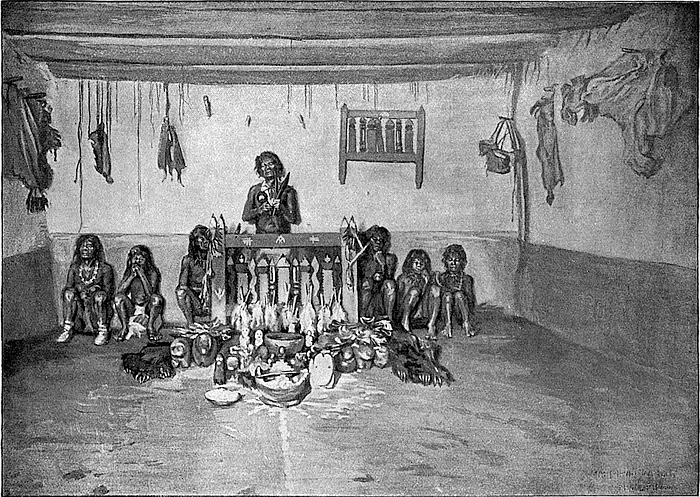

| Altar and sand painting of Knife society |

98

|

||

| Altar of Knife society photographed during ceremonial |

100

|

||

| Ho´-na-ai-te of Knife society |

102

|

||

| Altar of Knife society, with ho´-na-ai-te and vice ho´-na-ai-te on either side |

104

|

||

| Shrine of Knife society |

108

|

||

| Shrine of Knife society |

110

|

||

| Altar of Quer´-rän-na society |

112

|

||

| Altar of Quer´-rän-na society |

114

|

||

| Ho´-na-ai-te of Quer´-rän-na society |

116

|

||

| Sia masks (A, masks of the Ká-ᵗsû-na; B, mask of female Ká-ᵗsû-na; C, masks of the Ká-ᵗsû-na) |

118

|

||

| Sia masks (A, masks of the Ká-ᵗsû-na; B, masks of female Ká-ᵗsû-na) |

120

|

||

| Prayer to the rising sun |

122

|

||

| Personal adornment when received into the third degree of official membership of Cult society (A, spider; B, cougar; C, fire; D, Knife and Giant; E, costume when victor is received into society of Warriors; F, body of warrior prepared for burial, only the face, hands, and feet being painted) |

140

|

||

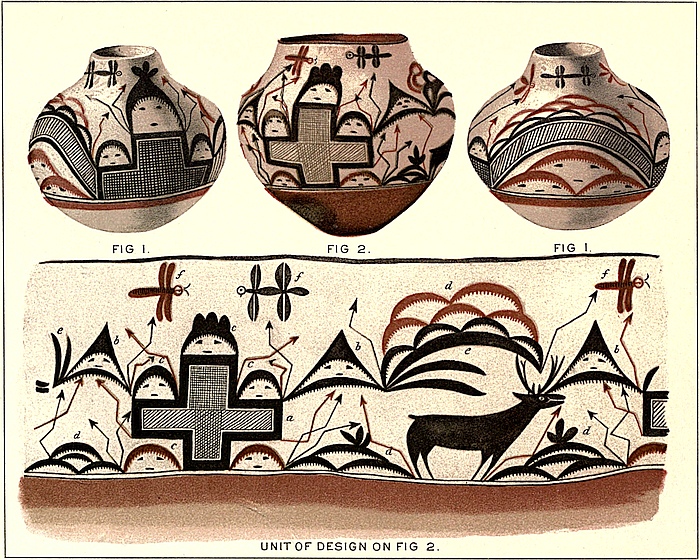

| Ceremonial water vases; Sia (A, a cross emblematic of the rain from the cardinal points; B, faces of the cloud men; C, faces of the cloud women; D, clouds and rain; E, vegetation; F, dragonfly, symbolic of water) |

146

|

| Fig. | Sia women on their way to trader’s to dispose of pottery |

12

|

|

| Sia women returning from trader’s with flour and corn |

13

|

||

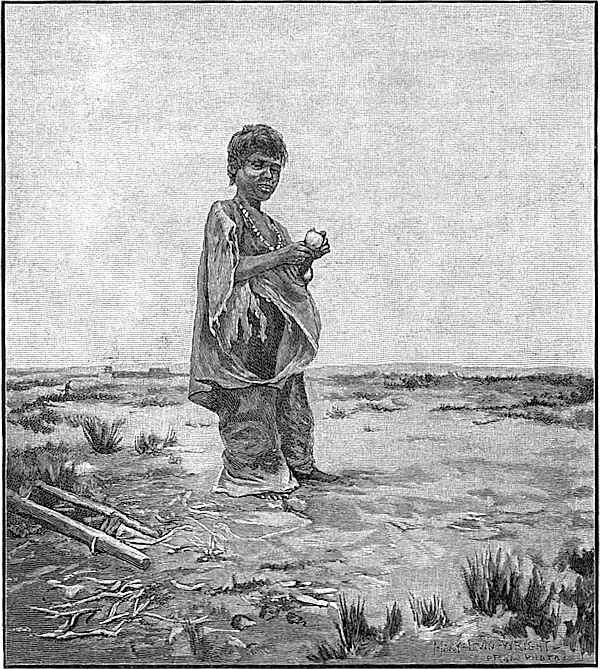

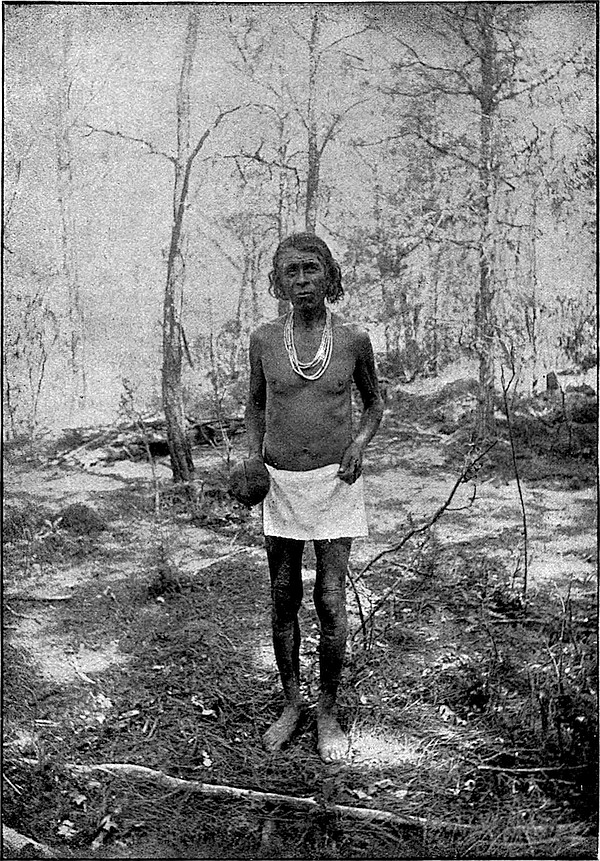

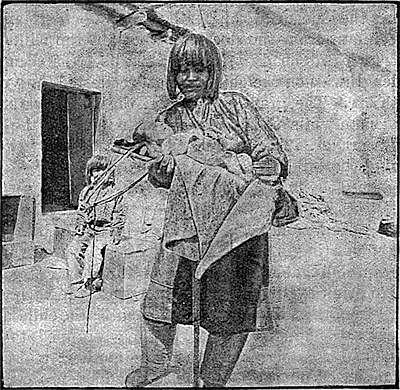

| Pauper |

18

|

||

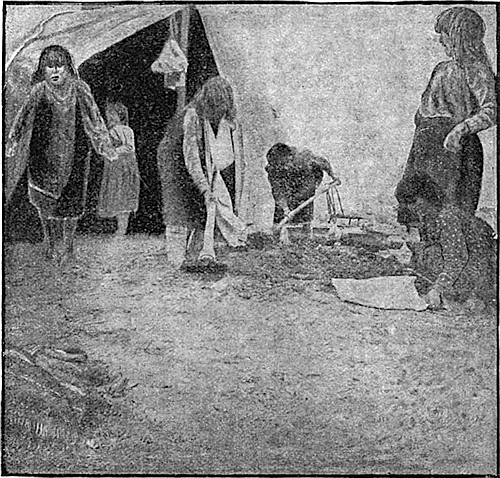

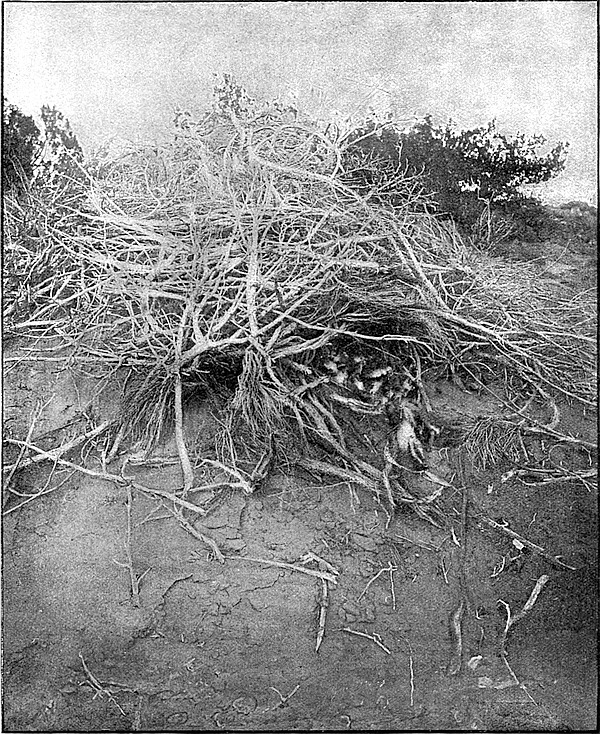

| Breaking the earth under tent |

21

|

||

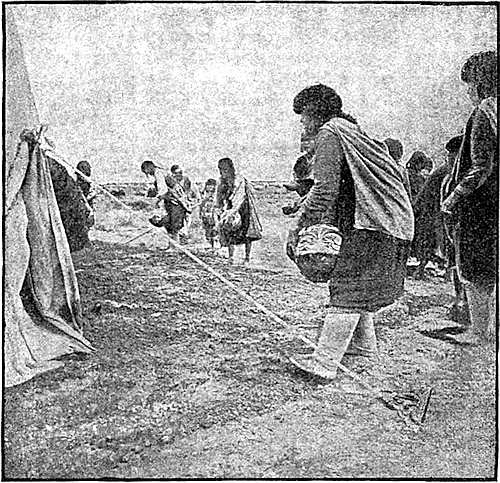

| Women and girls bringing clay |

22

|

||

| Women and girls bringing clay |

23

|

||

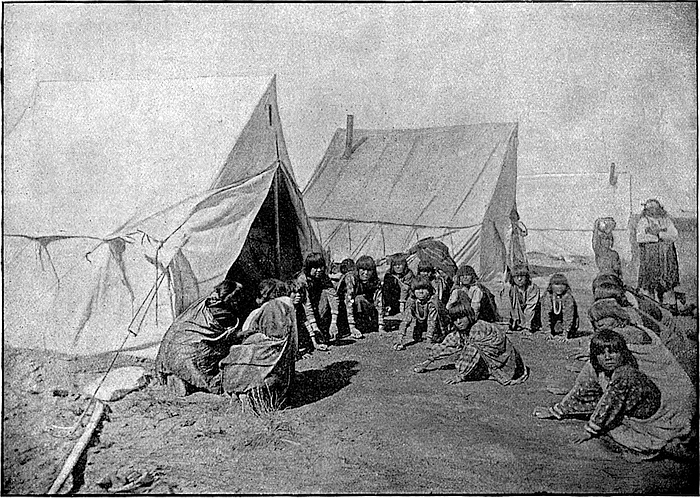

| Depositing the clay |

24

|

||

| Mixing the clay with the freshly broken earth |

25

|

||

| Women sprinkling the earth |

26

|

||

| The process of leveling |

27

|

||

| Stampers starting to work |

28

|

||

| Mixing clay for plaster |

29

|

||

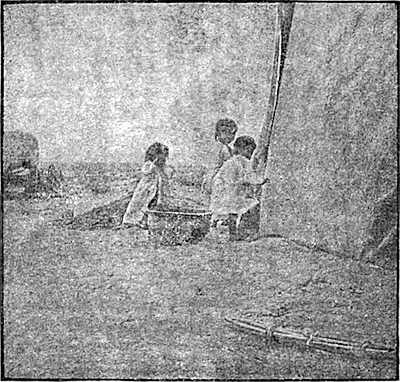

| Childish curiosity |

30

|

||

| Mask of the sun, drawn by a theurgist |

36

|

||

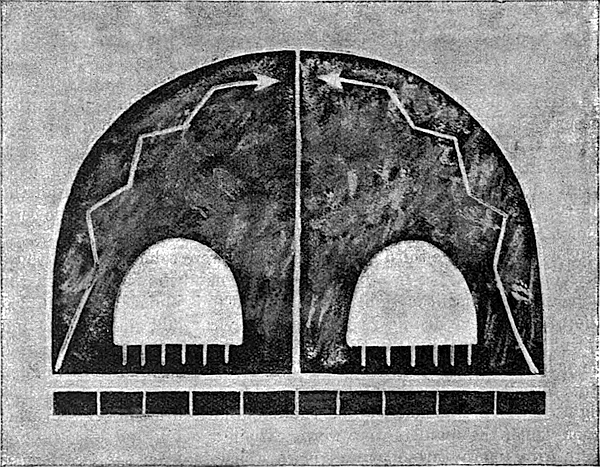

| Diagram of the White House of the North, drawn by a theurgist |

58

|

||

| The game of Wash´kasi |

60

|

||

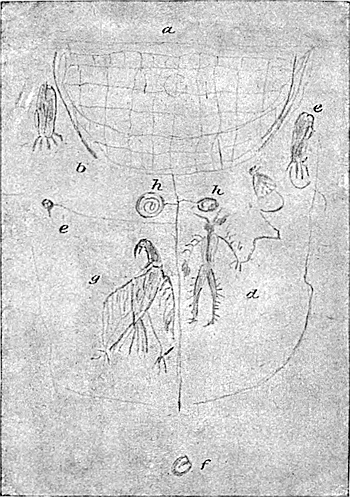

| Sand painting as indicated in Plate XXV |

102

|

||

| Sand painting used in ceremonial for sick by Ant society |

103

|

||

| Sia doctress |

133

|

||

| Mother with her infant four days old |

142

|

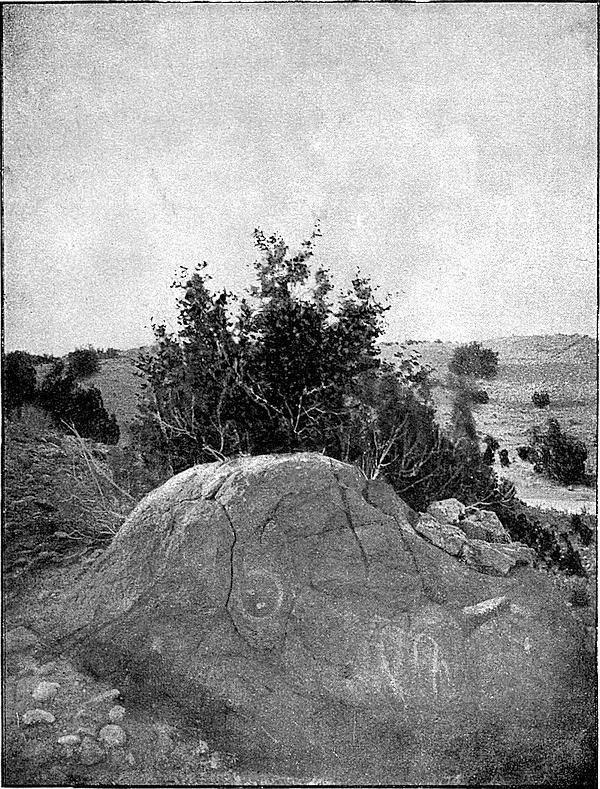

All that remains of the once populous pueblo of Sia is a small group of houses and a mere handful of people in the midst of one of the most extensive ruins of the Southwest (Pl. i) the living relic of an almost extinct people and a pathetic tale of the ravages of warfare and pestilence. This picture is even more touching than the infant’s cradle or the tiny sandal found buried in the cliff in the canyon walls. The Sia of to-day is in much the same condition as that of the ancient cave and cliff dweller as we restore their villages in imagination.

The cosmogony and myths of the Sia point to the present site as their home before resorting to the mesa, which was not, however, their first mesa home; their legends refer to numerous villages on mountain tops in their journeying from the north to the center of the earth.

The population of this village was originally very large, but from its situation it became a target during intertribal feuds. A time came, however, when intertribal strife ceased, and the pueblo tribes united their strength to oppose a common foe, an adversary who struck terror to the heart of the Indian, inasmuch as he not only took possession of their villages and homes, but was bent upon uprooting the ancestral religion to plant in its stead the Roman Catholic faith. To avoid this result the Sia fled to the mesa and built a village, but the foe was not to be thus easily baffled and the mesa village was brought under subjection. That these people again struggled for their freedom is evident from the report of Vargas of his visit there in 1692:

The pueblo had been destroyed a few years before by Cruzate, but it had not been rebuilt. The troops entered it the next morning. It was situated upon the mesa of Cerro Colorado, and the only approach to it was up the side of the plateau by a steep and rocky road. The only thing of value found there was the bell of the convent, which was ordered to be buried. The Indians had built a new village near the ruins of the old one. When they saw the Spaniards approach they came forth to meet and bid them welcome, carrying crosses in their hands, and the chiefs marching at their heads. In this manner they escorted Vargas and his troops to the plaza, where arches 10and crosses were erected, and good quarters provided them. He caused the inhabitants to be assembled, when he explained to them the object of his visit and the manner in which he intended to punish all the rebellious Indians. This concluded, the usual ceremonies of taking possession, baptism and absolution, took place.[2]

And the Sia were again under Spanish thraldom; but though they made this outward show of submitting to the new faith, neither then nor since have they wavered in their devotion to their aboriginal religion.

The ruins upon the mesa, showing well-defined walls of rectangular stone structures northwest of the present village, are of considerable magnitude, covering many acres. (Pl. ii.) The Indians, however, declare this to have been the great farming districts of Pó-shai-yän-ne (quasi messiah), each field being divided from the others by a stone wall, and that their village was on the mesa eastward of the present one.

The distance from the water and the field induced the Sia to return to their old home, but wars, pestilence, and oppression seem to have been their heritage. When not contending with the marauding nomad and Mexican, they were suffering the effects of disease, and between murder and epidemic these people have been reduced to small numbers. The Sia declare that this condition of affairs continued, to a greater or less degree, with but short periods of respite, until the murders were arrested by the intervention of our Government. For this they are profoundly grateful, and they are willing to attest their gratitude in every possible way.

The Sia to-day number, according to the census taken in 1890, 106, and though they no longer suffer at the murderous hand of an enemy, they have to contend against such diseases as smallpox and diphtheria, and it will require but a few more scourges to obliterate this remnant of a people. They are still harassed on all sides by depredators, much as they were of old; and long continued struggle has not only resulted in the depletion of their numbers, but also in mental deterioration.

The Sia resemble the other pueblo Indians; indeed, so strikingly alike are they in physical structure, complexion, and customs that they might be considered one and the same people, had it not been discovered through philological investigation that the languages of the pueblo Indians have been evolved from four distinct stocks.

Sia is situated upon an elevation at the base of which flows the Jemez river. The Rio Salado empties into the Jemez some 4 miles above Sia and so impregnates the waters of the Jemez with salt that while it is at all times most unpalatable, in the summer season when the river is drained above, the water becomes undrinkable, and yet it is this or nothing with the Sia.

For neighbors they have the people of the pueblo of Santa Ana, 6 miles to the southeast, who speak the same language, with but slight variation, and the pueblo of Jemez, 7 miles north, whose language, according to Powell’s classification, is of another stock, the Tañoan.

11

The Mexican town of San Ysidro is 5½ miles above Sia, and there are several Mexican settlements north of Jemez. The Mexican town of Bernalillo is on the east bank of the Rio Grande, 17½ miles eastward.

Though Protestant missionaries have been stationed at the pueblo of Jemez since 1878, no attempt has been made to bring the Sia within the pale of Protestantism. The Catholic mission priest who resides at Jemez makes periodical visits to the Sia, when services are held, marriages performed, infants baptized, and prayers offered for the dead.

The missions at Cia and Jemez were founded previous to 1617 and after 1605. They existed without interruption until about 1622, when the Navajos compelled the abandonment of the two churches at San Diego and San Joseph of Jemez. About four years later, through the exertions of Fray Martin de Arvide, these missions were reoccupied, and remained in uninterrupted operation until August 10, 1680. The mission at Cia, as far as I know, suffered no great calamity until that date. After the uprising of 1680 the Cia mission remained vacant until 1694. Thence on it has been always maintained, slight temporary vacancies excepted, up to this day. The mission of San Diego de Jemez was occupied in 1694 by Fray Francisco de Jesus, whom the Indians murdered on the 4th of June of 1696. In consequence of the uprising on that day, the Jemez abandoned their country, and returned, settling on the present site of their pueblo only in 1700. The first resident priest at Jemez became Fray Diego Chabarria, in 1701. Since that date I find no further interruption in the list of missionaries.[3]

The Sia are regarded with contempt by the Santa Ana and the Jemez Indians, who never omit an opportunity to give expression to their scorn, feeling assured that this handful of people must submit to insult without hope of redress. Limited intertribal relations exist, and these principally for the purpose of traffic.

Though the Sia have considerable irrigable lands, they have but a meager supply of water, this being due to the fact that after the Mexican towns above them and the pueblo of Jemez have drawn upon the waters of the Jemez river, little is left for the Sia, and in order to have any success with their crops they must curtail the area to be cultivated. Thus they never raise grain enough to supply their needs, even with the practice of the strictest economy according to Indian understanding, and therefore depend upon their more successful neighbors who labor under no such difficulties. The Jemez people have no lack of water supply, and the Santa Ana have their farming districts on the banks of the Rio Grande. Is it strange, then, that two pueblos are found progressing, however slowly, toward a European civilization, while the Sia, though slightly influenced by the Mexicans, have, through their environment, been led not only to cling to autochthonic culture but to lower their plane of social and mental condition?

The Sia women labor industriously at the ceramic art as soon as their grain supply becomes reduced, and the men carry the wares to their unfriendly neighbors for trade in exchange for wheat and corn. While the Santa Ana and Jemez make a little pottery, it is very coarse in texture and in form; in fact, they can not be classed as pottery-making Indians. (Pl. iii.)

12

As long as the Sia can induce the traders through the country to take their pottery they refrain from barter with their Indian neighbors. (Pl. iv.) The women usually dispose of the articles to the traders (Figs. 1 and 2), but they never venture on expeditions to the Santa Ana and the Jemez.

Each year a period comes, just before the harvest time, when no more pottery is required by their Indian neighbors, and the Sia must deal out their food in such limited portions that the elders go hungry in order to satisfy the children. When starvation threatens there is no thought for the children of the clan, but the head of each household looks to the wants of its own, and there is apparent indifference to the sufferings of neighbors. When questioned, they reply: “We feel sad for our brothers and our sisters, but we have not enough for our own.” Thus when driven to extremes, nature asserts itself in the nearest ties of consanguinity and the “clan” becomes secondary. At these times there are no expressions of dissatisfaction and no attempt on the part of the stronger to take advantage of the weaker. The expression of the men changes to a stoical resignation, and the women’s faces grow a shade paler with the thought that in order to nourish their babes they themselves must be nourished. And yet, such is their code of hospitality that food is always offered to guests as long as a morsel remains.

13

So like children are these same stoical and patient people that the tears of sorrow are quickly dispelled by the sunshine of success. When their crops are gathered they hold their saints’ day feast, when the Indians from near and far (even a few of the unfriendly Indians lending their unwelcome presence) surfeit at their board. These public dances and feasts of thanksgiving in honor of their patron saint, upon the gathering of their crops, which occur in all the Rio Grande pueblos, present a queer mixture of pagan and Christian religion. The priest owes his success in maintaining a certain influence with these people since the accession of New Mexico to the United States, by non-interference with the introduction of their forms and dances into the worship taught by the church. Hence the Rio Grande Indians are professedly Catholics; but the fact that these Indians and the Mission Indians of California have preserved their religions, admitting them to have been more or less influenced by Catholicism, and hold their ceremonials in secret, practicing their occult powers to the present time, under the very eye of the church, is evidence not only of the tenacity with which they cling to their ancient customs, but of their cunning in maintaining perfect seclusion.

When Maj. Powell visited Tusayan, in 1870, he was received with marked kindness by the Indians and permitted to attend the secret14 ceremonials of their cult. The writer is of the opinion that he was the first and only white man granted this privilege by any of the pueblo Indians previous to the expedition to Zuñi, in 1879, by Mr. Stevenson, of the Bureau of Ethnology.

The writer accompanied Mr. Stevenson on this occasion and during his succeeding investigations among the Zuñi, Tusayan, and the Rio Grande Pueblos. And whenever the stay was long enough to become acquainted with the people the confidence of the priestly rulers and theurgists was gained, and after this conciliation all efforts to be present at the most secret and sacred performances observed and practiced by these Indians were successful. Their sociology and religion are so intricately woven together that the study of the one can not be pursued without the other, the ritual beginning at birth and closing with death.

While the religion of the Rio Grande Indians bears evidence of contact with Catholicism, they are in fact as non-Catholic as before the Spanish conquest. Their environment by the European civilization of the southwest is, however, slowly but surely effecting a change in the observances of their cabalistic practices. For example, the pueblo of Laguna was so disturbed by the Atlantic and Pacific railroad passing by its village that first one and then another of its families lingered at the ranch houses, reluctant to return to their communal home, where they must come in contact with the hateful innovations of their land; and so additions were made to render the summer house more comfortable for the winter, and after a time a more substantial structure supplanted the temporary abode, and the communal dwelling was rarely visited except to comply with the religious observances. Some of these homes were quite remote from the village, and the men having gradually increased their stock of cattle found constant vigilance necessary to protect them from destruction by the railroad and the hands of the cowboy; and so first one and then another of the younger men ventured to be absent from a ceremonial in order to look up some stray head of cattle, until the aged men cried out in horror that their children were forgetting the religion of their forefathers.

The writer knew of but one like delinquent among the Zuñi when she was there in 1886. A son of one of the most bigoted priests in the village had become so eager to possess an American wagon, and his attention was so absorbed in looking after his cattle with a view to the accumulation of means whereby to purchase a wagon, that he dared to absent himself from a most important and sacred ceremonial, notwithstanding the current belief that for such impiety the offender must die within four days. The father denounced him in the strongest terms, declaring he was no longer his son. And the man told the writer, on his return to the village, “that he was afraid because he staid away, and he guessed he would die within four days, but some of his cattle had strayed off and he feared the cowboy.” The fourth day passed 15and the man still lived, and the scales dropped from his eyes. From that time his religious duties were neglected in his eagerness for the accumulation of wealth.

Thus the railroad, the merchant, and the cowboy, without this purpose in view, are effecting a change which is slowly closing, leaf by leaf, the record of the religious beliefs and practices of the pueblo Indian. With the Sia this record book is being more rapidly closed, but from a different cause. It is not due to the Christianizing of these Indians, for they have nothing of Protestantism among them, and though professedly Catholic, they await only the departure of the priest to return to their secret ceremonials. The Catholic priest baptizes the infant, but the child has previously received the baptismal rite of its ancestors. The Catholic priest marries the betrothed, but they have been previously united according to their ancestral rites. The Romish priest holds mass that the dead may enter heaven, but prayers have already been offered that the soul may be received by Sûś-sĭs-tin-na-ko (their creator) into the lower world whence it came. As an entirety these people are devotees to their religion and its observances, and yet with but few exceptions, they go through their rituals, having but vague understanding of their origin or meaning. Each shadow on the dial brings nearer to a close the lives of those upon whose minds are graven the traditions, mythology, and folklore as indelibly as are the pictographs and monochromes upon the rocky walls.

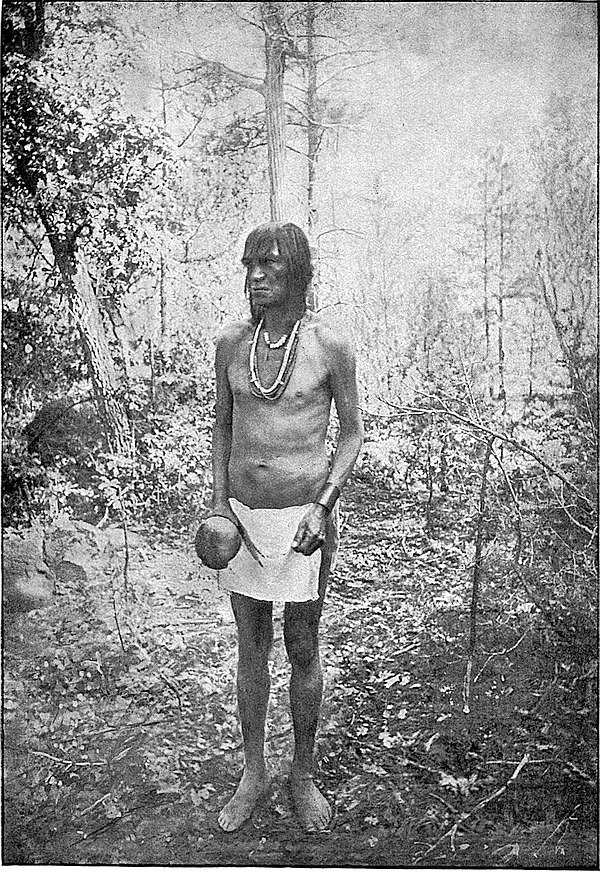

An aged theurgist whose lore was unquestioned, in fact he was regarded as their oracle (Pl. v), passed away during the summer of 1890. Great were the lamentations that the keeper of their traditions slept, and with him slept much that they would never hear again. There are, now, but five men from whom any connected account of their cosmogony and mythology may be gleaned, and they are no longer young. Two of these men are not natives of Sia, but were adopted into the tribe when young children. One is a Tusayan; the other a San Felipe Indian. The former is the present governor, amiable, brave, and determined, and while deploring that his people have no understanding of American civilization, he stands second only to the oracle in his knowledge of lore of the Sia. The San Felipe Indian is a like character, and if Sia possessed a few more such men there might yet be a future for that pueblo.

While the mythology and cult practices differ in each pueblo there is still a striking analogy between them, the Zuñi and Tusayan furnishing the richer field for the ethnographer, their religion and sociology being virtually free from Catholic influence.

The Indian official is possessed of a character so penetrating, so diplomatic, cunning, and reticent that it is only through the most friendly relations and by a protracted stay that anything can be learned of the myths, legends, and rites with which the lives of these people are so thoroughly imbued and which they so zealously guard.

16

The theurgists of the several cult societies, upon learning that the object of the writer’s second visit to Sia was similar to that of the previous one, graciously received her in their ceremonials, revealing the secrets more precious to them than life itself. When unable to give such information as she sought they would bring forth their oracle (the aged theurgist) whose old wrinkled face brightened with intelligent interest as he related without hesitancy that which was requested.

The form of government of all the pueblos is much the same, they being civil organizations divided into several departments, with an official head for each department.

With the Sia (and likewise with the other pueblos) the ti´ämoni, by virtue of his priestly office, is ex officio chief executive and legislator; the war priest (he and his vicar being the earthly representatives of the twin war heroes) having immediate control and direction of the military and of tribal hunts. Secret cult societies concerning the Indians’ relations to anthropomorphic and zoomorphic beings are controlled each by a particular theurgist. The war chief, the local governor, and the magistrate as well as the ti´ämoni and theurgists have each a vicar who assists in the official and religious duties.

While the Zuñi priesthood for rain consists of a plurality of priests and a priestess, the priest of the north being the arch ruler, the Sia have but one such priest. With the Zuñi the arch-ruler holds his office through maternal inheritance; with the Sia it is a life appointment. The ti´ämoni of Sia is chosen alternately from three clans—corn, coyote, and a species of cane. Though the first priest was selected by the mother Ût´sĕt, who directed that the office should always be filled by a member of the corn clan, he in time caused dissatisfaction by his action towards infants (see cosmogony), and upon his death the people concluded to choose a ti´ämoni from the coyote clan, but he proved not to have a good heart, for the cloud people refused to send rain and the earth became dry. The third one was appointed from the cane clan, but he, too, causing criticism, the Sia determined they would be obedient to the command of their mother Ût´sĕt, and returned to the corn clan in selecting their fourth ti´ämoni, but his reign brought disappointment. The next ruler was chosen from the coyote clan, and proved more satisfactory; but the people, deciding it was best not to confine the selection of their ti´ämoni to the one clan, appointed the sixth from the cane clan, and since that time this office has been filled alternately from the corn, coyote, and cane clans until the latter became extinct. The present ti´ämoni’s clan is the coyote, and that of his vicar, the corn. Their future appointments will necessarily come from these two clans, as practically they are reduced to these.

The ti´ämoni and vicar are appointed by the two war priests, the vicar succeeding to the office of ti´ämoni.

The present ti´ämoni entered his office without having filled the subordinate place, his predecessor, a very aged man, and the vicar, likewise 17old, having died about the same time. When the selection of a younger brother or vicar has been made, the vicar to the war priest calls upon the incoming ruler, who accompanies him to the house of the appointee to fill the office of vicar to the ti´ämoni. The younger war priest, followed by the ti´ämoni elect, who precedes the vicar, goes to the ancestral official chamber of the ti´ämoni, where the elder war priest, the theurgists of the several cult societies, with their vicars, have assembled to be present at the installation of the ti´ämoni. The war priest arises to meet the party, and, with the ti´ämoni immediately before him he says: “This man is now our priest; he is now our father and our mother for all time;” and then addressing the ti´ämoni he continues: “You are no more to work in the fields or to bring wood, the theurgists of the cult and all your other children will labor for you, our ti´ämoni, for all years to come; you are not to work, but to be to us as our father and our mother.” “Good! good!” is repeated by the theurgists. The war priest then presents the ti´ämoni with the ensign of his office—a slender staff, crooked at the end and supposed to be the same which was presented to the first ruler by the mother Ût´sĕt—the crook being symbolic of longevity. Upon receiving the crook the ti´ämoni draws the sacred breath from it and the war priest embraces him and sprinkles the cane with meal with a prayer that the thoughts and heart of Ût´sĕt may be conveyed from the staff to the newly-chosen ruler (Ût´sĕt upon presenting this cane to the first ti´ämoni of this world, gave with it all her thoughts and her heart), and now he, too, draws from the cane the sacred breath. The theurgists rise in a body, each one embracing the ti´ämoni and sprinkling meal upon the staff, at the same time drawing from it the sacred breath. The civil authorities next, and then the populace, including the women and children, repeat the embracing, the sprinkling of meal, and the drawing of the sacred breath.

The following day all the members of the pueblo, including the children, collect wood for the ti´ämoni, depositing it by the side of his dwelling.

The Sia are much chagrined that their present ti´ämoni (who is a young man) participates in the hunts, works in the fields, and is ever ready to join in a pleasure ride over the hills. This is not the tribal custom; the ti´ämoni may have a supervision over his herds and fields, but his mind is supposed to be absorbed with religion and the interests of his people, and he never leaves his village for a distance, excepting to make pilgrimages to the shrines or other of their Meccas. This young ruler is a vain fellow, having but little concern for the welfare of his people, but he is most punctilious in his claim to the honors due him.

The theurgists hold office for life, each vicar succeeding to the function of his theurgist, who in turn appoints, with the approbation of the ti´ämoni, the member whom he thinks best fitted to fill the position of vicar.

For the selection of the civil and subordinate military officers the18 ti´ämoni meets with his vicar, and the war priest and vicar in the official chamber of the ti´ämoni, in the month of December, to discuss the several appointments to be made; that of war chief and his assistant, the governor and lieutenant-governor, the magistrate and his deputy. After the names have been decided upon the theurgists of the secret cult societies are notified and they join the ti´ämoni and his associates, when they are informed of the decision and their concurrence requested. This is always given, the consultation with the theurgists being but a matter of courtesy. The populace then assemble, when announcement is made of the names of the new appointees. These appointments are annual; the same party, however, may serve any number of terms.

The war chief performs minor duties which would otherwise fall to the war priest. It is the duty of the war chief to patrol the town during the meetings of the cult societies and to surround the village19 with mounted guardsmen at the time of a dance of the Ka´-ᵗsu-na. A Mexican, especially, must not look upon one of these anthropomorphic beings. The war chief also directs the hunt under the instruction of the war priest and vicar. It is not obligatory that he participate in the hunt; his vicar, as his representative or other self, may lead the huntsmen. The governor sees that the civil laws are executed, he looking after the more important matters, leaving the minor cases in the hands of the magistrate. He designates the duties of his people for the coming day by crying his commands in the plaza at sunset.

Wizards and witches are tried and punished by the war priest; and it has been but a few years since a man and his wife suffered death for practicing this diabolical craft. Their child, a boy of some twelve years, (Fig. 3), is a pauper who at times begs from door to door, and at other times he is taken into some family and made use of until they grow tired of dispensing their charity. The observations of the writer led her to believe that the boy earned all that he received. Socially, held in contempt by his elders, he seems a favorite with the children, though this unfortunate is seldom allowed the joy of childish sport. He is, however, a member of one of the most important cult societies (the knife) belonging to its several divisions.

The clans (há-notc) now existing among these people are the

| Yá-ka |

Corn

|

| Shurts-ŭn-na |

Coyote

|

| Tá-ñe |

Squash

|

| Há-mi |

Tobacco

|

| Ko-hai |

Bear

|

| Ti-ä´-mi |

Eagle

|

There is but one member of the eagle, one of the bear, and one of the squash clan, and these men are advanced in years. There is a second member of the squash clan, but he is a Tusayan by birth. The only clans that are numerically well represented are the corn and coyote. There is but one family of the tobacco clan.

The following are extinct clans:

| Shi-kĕ |

Star

|

| T́a-wac |

Moon

|

| O´-sharts |

Sun

|

| Tä´ñe |

Deer

|

| Kurtz |

Antelope

|

| Mo´-kaitc |

Cougar

|

| Hĕn´-na-ti |

Cloud

|

| Shu´ta |

Crane

|

| Ha´-pan-ñi |

Oak

|

| Ha´-kan-ñi |

Fire

|

| Sha´-wi-ti |

Parrot

|

| Wa´pon |

White shell bead

|

| ᵗ´Zi-i |

Ant

|

| Ya´un-ñi |

Granite

|

| Wash´-pa |

Cactus

|

The writer could not learn that there had ever been more than twenty-one clans, and although the table shows six at the present time, it may be seen from the statement that there are virtually but two.

Marrying into the clan of either parent is in opposition to the old law; but at present there is nothing for the Sia to do but to break these laws, if they would preserve the remnant of their people, and while such marriages are looked upon with disfavor, it is “the inevitable.” The young men are watched with a jealous eye by their elders that they do not seek brides among other tribes, and though the beauty20 of the Sia maidens is recognized by the other pueblo people, they are rarely sought in marriage, for, according to the tribal custom, the husband makes his home with the wife; and there is little to attract the more progressive Indian of the other pueblos to Sia, where the eagerness to perpetuate a depleted race causes the Sia to rejoice over every birth, especially if it be a female child, regardless whether the child be legitimate or otherwise.

When a girl reaches puberty she informs her mother, who invites the female members of her clan to her house, where an informal feast is enjoyed. The guests congratulate the girl upon having arrived at the state of womanhood, and they say to her, “As yet you are like a child, but you will soon be united with a companion and you will help to increase your people.” The only male present is the girl’s father. The news, however, soon spreads through the village, and it is not long before offers are made to the mother for the privilege of sexual relations with the girl. The first offers are generally refused, the mother holding her virgin daughter for the highest bidder. These are not necessarily offers of marriage, but are more commonly otherwise, and are frequently made by married men.

Though the Sia are monogamists, it is common for the married, as well as the unmarried, to live promiscuously with one another; the husband being as fond of his wife’s children as if he were sure of the paternal parentage. That these people, however, have their share of latent jealousy is evident from the secrecy observed on the part of a married man or woman to prevent the anger of the spouse. Parents are quite as fond of their daughters’ illegitimate offspring, and as proud of them as if they had been born in wedlock; and the man who marries a woman having one or more illegitimate children apparently feels the same attachment for these children as for those his wife bears him.

Some of the women recount their relations of this character with as much pride as a civilized belle would her honest offers of marriage. One of the most attractive women in Sia, though now a grandmother, once said to the writer:

When I was young I was pretty and attractive, and when I reached womanhood many offers were made to my mother for me [she did not refer to marriage, however], but my mother knowing my attractions refused several, and the first man I lived with was the richest man in the pueblo. I only lived with three men before I married, one being the present governor of the village; my eldest child is his daughter, and he thinks a great deal of her. He often makes her presents, and she always addresses him as father when his wife is not by. His wife, whom he married sometime after I ceased my relations with him, does not know that her husband once lived with me.

This woman added as an evidence of her great devotion to her husband, that since her marriage she had not lived with any other man.

These loose marriage customs doubtless arise from the fact that the Sia are now numerically few and their increase is desired, and that, as21 many of the clans are now extinct, it is impossible to intermarry in obedience to ancient rule.

The Sia are no exception to all the North American aborigines with whom the writer is acquainted, the man being the active party in matrimonial aspirations. If a woman has not before been married, and is young, the man speaks to her parents before breathing a word of his admiration to the girl. If his desire meets with approbation, the following day he makes known to the girl his wish for her. The girl usually answers in the affirmative if it be the will of her parents. Some two months are consumed in the preparations for the wedding. Moccasins, blankets, a dress, a belt, and other parts of the wardrobe are prepared by the groom and the clans of his paternal and maternal parents. The clans of the father and mother of the girl make great preparations for the feast, which occurs after the marriage. The groom goes alone to the house of the girl, his parents having preceded him, and carries his gifts wrapped in a blanket. The girl’s mother sits to her right, and to the right of this parent the groom’s mother sits; there is space for the groom on the left of the girl, and beyond, the groom’s father sits, and next to him the girl’s father. When the groom enters the room the girl advances to meet him and receives the bundle; her mother then comes forward and taking it deposits it in some part of the same room, when the girl returns to her seat and the groom sits beside her. The girl’s father is the first to speak, and says to the couple, “You must now be as one, your hearts must be as one heart, you must speak no bad words, and one must live for the other; and remember, your two hearts must now be as one heart.” The groom’s father then repeats22 about the same, then the girl’s mother, and the mother of the groom speak in turn. After the marriage, which is strictly private, all the invited guests assemble and enjoy a feast, the elaborateness of the feast depending upon the wealth and prominence of the family.

Tribal custom requires the groom to make his home with his wife’s family, the couple sleeping in the general living room with the remainder of the family; but with the more progressive pueblos, and with the Sia to a limited extent, the husband, if he be able, after a time provides a house for his family.

The Sia wear the conventional dress of the Pueblos in general. The women have their hair banged across the eyebrows, and the side locks cut even midway the cheek. The back of the hair is left long and done up in a cue, though some of the younger women, at the present time, have adopted the Mexican way of dividing their hair down the back and crossing it in a loop at the neck and wrapping it with yarn. The men cut their hair the same way across the eyebrows, their side locks being brought to the center of the chin and cut, and the back hair done up similar to the manner of the women.

The children are industrious and patient little creatures, the boys assisting their elders in farming and pastoral pursuits, and the girls performing their share of domestic duties. A marked trait is their loving-kindness and care for younger brothers and sisters. Every little 23girl has her own water vase as soon as she is old enough to accompany her mother to the river in the capacity of assistant water-carrier, and thus they begin at a very early age to poise the vase, Egyptian fashion, on their heads.

There is no employment in pueblo life that the women and children seem so thoroughly to enjoy as the processes of house building. (Fig. 5.) It is the woman’s prerogative to do most of this work. (Fig. 6.) Men make the adobe bricks when these are to be used. In Sia the houses are adobe and small bowlders which are gathered from the ruins among which they live. It is only occasionally that a new house is constructed. The older ones are remodeled, and these are always smoothly plastered on the exterior and interior, so that there is no evidence of a stone wall. (Pl. vi.) The men do all carpenter work, and the Sia are remarkably clever in this branch of mechanism, considering their crude implements and entire absence of foreign instruction. They also lay the heavy beams, and they sometimes assist in other work of the building. When it became known that the writer wished to have the earth hardened under and in front of her tents the entire female population appeared at the camp ready for work, and for a couple of days the winds wafted over the plain the merry chatter and laughter of young and old.

The process of laying the tent floors was the same as the Sia observe in making floors in their houses. A hoe is employed to break the24 earth to about eight inches in depth and to loosen all rocks that may be found (Fig. 4). The rocks are then removed and the foreign earth, a kind of clay, is brought by the girls on their backs in blankets or the square pieces of calico which hang from their shoulders (Figs. 5 and 6) and deposited over the ground which has been worked (Fig. 7). The hoe is again employed to combine the clay with the freshly broken earth (Fig. 8); this done, the space is brushed over with brush brooms and sprinkled (Fig. 9) until the earth is thoroughly saturated for several inches deep. Great care is observed in leveling the floor (Fig. 10), and extra quantities of clay must be added here and there. Then begins the stamping process (Fig. 11). When the floor is as smooth as it can be made by stamping (Pl. vii), the pounders go to work, each one with a stone flat on one side and smooth as a polishing stone. (Pl. viii.) Many such specimens have been obtained from the ruins in the southwest. When this work is completed the floor is allowed to partially dry, when plaster made of the same clay (Fig. 12), which has been long and carefully worked, is spread over the floor with the hand, and when done the whole looks as smooth as a cement floor, but it is not so durable, such floors requiring frequent renovation. The floor may be improved, however, by a coating of beef’s or goat’s blood, and this process is usually adopted in the houses (Fig. 13), little ones watching their elders at work inside the tent.

25

Two men only are possessors of herds of sheep, but a few cattle are owned individually by many of the Sia.

The cattle are not herded collectively, but by each individual owner. Sometimes the boys of different families go together to herd their stock, but it receives no attention whatever from the officials of the village so long as it is unmolested by strangers.

The Sia own about 150 horses, but seldom or never use them as beasts of burden. They are kept in pasture during the week, and every Saturday the war chief designates the six houses which are to furnish herders for the round-up. Should the head of the house have a son sufficiently large the son may be sent in his place. Only such houses are selected as own horses. The herdsmen start out Saturday morning; their return depends upon their success in rounding up the animals, but they usually get back Sunday morning.

Upon discovering the approach of the herdsmen and horses many of the women and children, too impatient to await the gathering of them in the corral, hasten to the valley to join the cavalcade, and upon reaching the party they at once scramble for the wood rats (Neotoma) which hang from the necks of the horses and colts. The men of the village are also much excited, but they may not participate in the frolic. From the time the herders leave the village until their return they are on the lookout for the Neotoma, which must be very abundant judging from26 the number gathered on these trips. The rats are suspended by a yucca ribbon tied around the necks of the animals. The excitement increases as the horses ascend the hill; and after entering the corral it reaches the highest point, and the women and children run about among the horses, entirely devoid of any fear of the excited animals, in their efforts to snatch the rats from their necks. Many are the narrow escapes, but one is seldom hurt. The women throw the lariat, some of them being quite expert, and drawing the horses near them, pull the rats from their necks. Numbers fail, but there are always the favored few who leave the corral in triumph with as many rats as their two hands can carry. The rats are skinned and cooked in grease and eaten as a great delicacy.

The Sia have an elaborate cosmogony, highly colored with the heroic deeds of mythical beings. That which the writer here presents is simply the nucleus of their belief from which spring stories in infinite numbers, in which every phenomenon of nature known to these people is accounted for. Whole chapters could be devoted to the experiences of each mythical being mentioned in the cosmogony.

In the beginning there was but one being in the lower world, Sûs´sîstinnako, a spider. At that time there were no other animals, birds, 27reptiles, or any living creature but the spider. He drew a line of meal from north to south and crossed it midway from east to west; and he placed two little parcels north of the cross line, one on either side of the line running north and south. These parcels were very valuable and precious, but the people do not know to this day of what they consisted; no one ever knew but the creator, Sûs´sĭstinnako. After placing the parcels in position, Sûs´sĭstinnako sat down on the west side of the line running north and south, and south of the cross line, and began to sing, and in a little while the two parcels accompanied him in the song by shaking, like rattles. The music was low and sweet, and after awhile two women appeared, one evolved from each parcel; and in a short time people began walking about; then animals, birds, and all animate objects appeared, and Sûs´sĭstinnako continued to sing until his creation was complete, when he was very happy and contented. There were many people and they kept close together, and did not pass about much, for fear of stepping upon one another; there was no light and they could not see. The two women first created were the mothers of all; the one created on the east side of the line of meal, Sûs´sĭstinnako named Ût[´]sĕt, and she was the mother of all Indians; he called the other Now[´]ûtsĕt, she being the mother of other nations. Sûs´sĭstínnako divided the people into, clans, saying to certain of the people: “You are of the corn clan, and you are the first of all;” and28 to others he said: “You belong to the coyote, the bear, the eagle people,” and so on.

After Sûs´sĭstinnako had nearly perfected his creation for Ha´arts (the earth), he thought it would be well to have rain to water the earth, and so he created the cloud, lightning, thunder, and rainbow peoples to work for the people of Ha´arts. This second creation was separated into six divisions, one of which was sent to each of the cardinal points and to the zenith and nadir, each division making its home in a spring in the heart of a great mountain, upon whose summit was a giant tree. The Sha´-ka-ka (spruce) was on the mountain of the north; the Shwi´-ti-ra-wa-na (pine) on the mountain of the west; the Mai´-chi-na (oak)—Quercus undulata, variety Gambelii—on the mountain of the south; the Shwi´-si-ni-ha´-na-we (aspen) on the mountain of the east; the Marsh´-ti-tä-mo (cedar) on the mountain of the zenith, and the Mor´-ri-tä-mo (oak), variety pungens, on the mountain of the nadir. While each division had its home in a spring, Sûs´sĭstinnako gave to these people Ti´-ni-a, the middle plain of the world (the world was divided into three parts: Ha´arts, the earth; Ti´nia, the middle plain, and Hu´-wa-ka, the upper plain), not only for a working field for the benefit of the people of Ha´arts, but also for their pleasure ground.

Not wishing this second creation to be seen by the people of Ha´arts as they passed about over Ti´nia, he commanded the Sia to smoke, that29 clouds might ascend and serve as masks to protect the people of Ti´nia from view of the inhabitants of Ha´arts.

The people of Ha´arts made houses for themselves by digging holes in rocks and the earth. They could not build houses as they now do, because they could not see. In a short time the two mothers, Ût´sĕt and Now´ûtsĕt (the latter being the elder and larger, but the former having the best mind and heart), who resided in the north, went into the chita (estufa) and talked much to one another, and they decided that they would make light, and said: “Now we will make light, that our people may see; we can not now tell the people, but to-morrow will be a good day and day after to-morrow will also be a good day”—meaning that their thoughts were good, and they spoke with one tongue, and that their future would be bright, and they added: “Now all is covered with darkness, but after awhile we will have light.” These two women, being inspired by Sûs´sĭstinnako, created the sun from white shell, turkis, red stone, and abalone shell. After making the sun they carried him to the east and there made a camp, as there were no houses. The next morning they ascended a high mountain and dropped the sun down behind it, and after a time he began to ascend, and when the people saw the light their hearts rejoiced. When far off his face was blue; as he came nearer the face grew brighter. They, however, did not see the sun himself, but a mask so large that it covered his entire body.30 The people saw that the world was large and the country beautiful, and when the women returned to the village they said to the people: “We are the mothers of all.”

Though the sun lighted the world in the day, he gave no light at night, as he returned to his home in the west; and so the two mothers created the moon from a slightly black stone, many varieties of a yellow stone, turkis, and a red stone, that the world might be lighted at night, and that the moon might be a companion and a brother to the sun; but the moon traveled slowly, and did not always furnish light, and so they created the star people and made their eyes of beautiful sparkling white crystal, that they might twinkle and brighten the world at night. When the star people lived in the lower world they were gathered into groups, which were very beautiful; they were not scattered about as they are in the upper world. Again the two women entered the chita and decided to make four houses—one in the north, one in the west, one in the south, and one in the east—house in this instance meaning pueblo or village. When these houses were completed they said, now we have some beautiful houses; we will go first to that of the north and talk much for all things good. Now´ûtsĕt said to her sister: “Let us make other good things,” and the sister asked: “What things do you wish to make?” She answered: “We are the mothers of all peoples, and we must do good work.” “Well,” replied the younger sister, “to-morrow I will pass around and see my other houses, and you will remain here.”

After Ût´sĕt had traveled over the world, visiting the houses of the west, south, and east, she returned to her home in the north and was graciously received by Now´ûtsĕt, who seemed happy to see her younger31 sister, and after a warm greeting she invited her to be seated. Now´ûtsĕt had a picture which she did not wish the sister to see, and she covered it with a blanket, and said, “Guess what I have here?” (pointing to the covered picture) “and when you guess correctly I will show you.” “I do not know,” said Ût´sĕt and again the elder one asked, “What do you think I have here?” and the other replied, “I do not know.” A third time Ût´sĕt was asked, and replied that she did not know, adding, “I wish to speak straight, and I must therefore tell you I do not know what you have there.” Then Now´ûtsĕt said, “That is right.” After a while the younger sister said, “I think you have under that blanket a picture, to which you will talk when you are alone.” “You are right,” said the elder sister, “you have a good head to know things.” Now´ûtsĕt, however, was much displeased at the wisdom displayed by Ût´sĕt. She showed the picture to Ût´sĕt and in a little while Ût´sĕt left, saying, “I will now return to my house and no longer travel; to-morrow you will come to see me.”

After the return of Ût´sĕt to her home she beckoned to the Chas´ka (chaparral cock) to come to her, and said, “You may go early to-morrow morning to the house of the sun in the east, and then follow the road from there to his home in the west, and when you reach the house in the west remain there until my sister comes to my house to talk to me, when I will call you.” In the early morning the elder sister called at the house of the younger. “Sit down, my sister,” said the younger one, and after a little time she said, “Let us go out and walk about; I saw a beautiful bird pass by, but I do not know where he lives,” and she pointed to the footprints of the bird upon the ground, which was soft, and the tracks were very plain, and it could be seen that the footprints were in a straight line from the house of the sun in the east to his house in the west. “I can not tell,” said the younger sister, “perhaps the bird came from the house in the east and has gone to the house in the west; perhaps he came from the house in the west and has gone to the house in the east; as the feet of the bird point both ways, it is hard to tell. What do you think, sister?” “I can not say,” replied the other. Four times Ût´sĕt asked the question and received the same reply. The fourth time the elder sister added, “How can I tell? I do not know which is the front of the foot and which is the heel, but I think the bird has gone to the house in the east.” “Your thoughts are wrong,” replied the younger sister; “I know where the bird is, and he will soon be here;” and she gave a call and in a little while the Chas´ka came running to her from, the west.

The elder sister was mortified at her lack of knowledge, and said, “Come to my house to-morrow; to-day you are greater than I. I thought the bird had gone to the house in the east, but you knew where he was, and he came at your call; to-morrow you come to me.”

On the morrow the younger sister called at the house of the elder and was asked to be seated. Then Now´ûtsĕt said, “Sister, a word32 with you; what do you think that is?” pointing to a figure enveloped in a blanket, with only the feet showing, which were crossed. Four times the question was asked, and each time the younger sister said she could not tell, but finally she added, “I think the feet are crossed; the one on the right should be left and the left should be right.” “To whom do the feet belong?” inquired the elder sister. The younger sister was prompted by her grandmother, Sûs´sĭstinnako[4], the spider woman, to say, “I do not think it is either man or woman,” referring to beings created by Sûs´sĭstinnako, “but something you have made.” The elder sister replied,“You are right, my sister.” She threw the blanket off, exposing a human figure; the younger sister then left, asking the elder to call at her house on the morrow, and all night Ût´sĕt was busy preparing an altar under the direction, however, of Sûs´sĭstinnako. She covered the altar with a blanket, and in the morning when the elder sister called they sat together for a while and talked; then Ût´sĕt said, pointing to the covered altar, “What do you think I have there?” Now´ûtsĕt replied, “I can not tell; I may have my thoughts about it, but I do not know.” Four times Now´ûtsĕt was asked, and each time she gave the same reply. Then the younger sister threw off the blanket, and they both looked at the altar, but neither spoke a word.

When the elder sister left, she said to Ût´sĕt, “To-morrow you come to my house,” and all night she was busy arranging things for the morning, and in the morning Ût´sĕt hastened to her sister’s house. (She was accompanied by Sûs´sĭstinnako, who followed invisible close to her ear.) Now´ûtsĕt asked, “What have I there?” pointing to a covered object, and Ût´sĕt replied, “I can not tell, but I have thought that you have under that blanket all things that are necessary for all time to come; perhaps I speak wrong.” “No,” replied Now´ûtsĕt, “you speak correctly,” and she threw off the blanket, saying, “My sister, I may be the larger and the first, but your head and heart are wise; you know much; I think my head must be weak.” The younger sister then said: “To-morrow you come to my house;” and in the morning when the elder sister called at the house of the younger she was received in the front room and asked to be seated, and they talked awhile; then the younger one said: “What do you think I have in the room there?” pointing to the door of an inner room. Four times the question was asked and each time Now´ûtsĕt replied, “I can not tell.” “Come with me,” said Ût´sĕt, and she cried as she threw open the door, “All this is mine, when you have looked well we will go away.” The room was filled with the Ka´ᵗsuna beings with monster heads which Ût´sĕt had created, under the direction of Sûs´sĭstinnako.

Sûs´sĭstinnako’s creation may be classed in three divisions:

1. Pai´-ä-tä-mo: All men of Ha´arts (the earth), the sun, moon, stars, Ko´-shai-ri and Quer´-rän-na.

33

2. Ko´-pĭsh-tai-a: The cloud, lightning, thunder, rainbow peoples, and all animal life not included under the first and third heads.

3. Ka´ᵗsuna: Beings having human bodies and monster heads, who are personated in Sia by men and women wearing masks.

After a time the younger sister closed the door and they returned to the front room. Not a word had been spoken except by the younger. As the elder sister left she said, “To-morrow you come to my house.” Sûs´sĭstinnako whispered in the ear of the younger, “To-morrow you will see fine things in your sister’s house, but they will not be good; they will be bad.” Now´ûtsĕt then said: “Before the Sun has left his home we will go together to see him; we will each have a wand on our heads made of the long white fluffy feathers of the under tail of the eagle, and we will place them vertically on our heads that they may see the sun when he first comes out;” and the younger sister replied: “You are the elder and must go before, and your plumes will see the sun first; mine can not see him until he has traveled far, because I am so small; you are the greater and must go before.” Though she said this she knew better; she knew that though she was smaller in stature she was the greater and more important woman. That night Sûs´sĭstinnako talked much to Ût´sĕt. She said: “Now that you have created the Ka´ᵗsuna you must create a man as messenger between the sun and the Ka´ᵗsuna and another as messenger between the moon and the Ka´ᵗsuna.”

The first man created was called Ko´shairi; he not only acts as courier between the sun and the Ka´ᵗsuna, but he is the companion, the jester and musician (the flute being his instrument) of the sun; he is also mediator between the people of the earth and the sun; when acting as courier between the sun and the Ka´ᵗsuna and vice versa and as mediator between the people of the earth and the sun he is chief for the sun; when accompanying the sun in his daily travels he furnishes him with music and amusement; he is then the servant of the sun. The second man created was Quer´ränna, his duties being identical with those of the Ko´shairi, excepting that the moon is his particular chief instead of the sun, both, however, being subordinate to the sun.

After the creation of Ko´shairi and Quer´ränna, Ût´sĕt called Shu-ah-kai (a small black bird with white wings) to her and said:

“To-morrow my sister and I go to see the sun when he first leaves his house. We will have wands on our heads, we will be side by side; she is much taller than I; the sun will see her face before he sees mine, and that will not be good; you must go to-morrow morning very early near the house of the sun and take a plume from your left wing, but none from your right; spread your wings and rest in front of the sun as he comes from his house.” The two women started very early in the morning to greet the rising sun. They were accompanied by all34 the men and youths, carrying their bows and arrows. The elder woman, after they halted to await the coming of the sun, said: “We are here to watch for the sun.” (The people had divided, some being on the side of Now´ûtsĕt, the others with Ût´sĕt). “If the sun looks first upon me, all the people on my side will be my people and will slay the others, and if the sun looks first upon the face of my sister all the people on her side will be her people and they will destroy my people.”

As the sun left his house, the bird Shu´ahkai placed himself so as to obscure the light, excepting where it penetrated through the space left by the plucking of the feather from his wing, and the light shone, not only on the wand on the head of the younger sister, but it covered her face, while it barely touched the top of the plumes of the elder; and so the people of the younger sister destroyed those of the elder. The two women stood still while the men fought. The women remained on the mountain top, but the men descended into a grassy park to fight. After a time the younger sister ran to the park and cried, “This is enough; fight no more.” She then returned to the mountain and said to her sister, “Let us descend to the park and fight.” And they fought like women—not with arrows—but wrestled. The men formed a circle around them and the women fought hard and long. Some of the men said, “Let us go and part the women;” others said, “No; let them alone.” The younger woman grew very tired in her arms, and cried to her people, “I am very tired,” and they threw the elder sister upon the ground and tied her hands; the younger woman then commanded her people to leave her, and she struck her sister with her fists about the head and face as she lay upon the ground, and in a little while killed her. She then cut the breast with a stone knife and took out the heart, her people being still in a circle, but the circle was so large that they were some distance off. She held the heart in her hand and cried: “Listen, men and youths! This woman was my sister, but she compelled us to fight; it was she who taught you to fight. The few of her people who escaped are in the mountains and they are the people of the rats;” and she cut the heart into pieces and threw it upon the ground, saying, “Her heart will become rats, for it was very bad,” and immediately rats could be seen running in all directions. She found the center of the heart full of cactus, and she said, “The rats for evermore will live with the cacti;” and to this day the rats thus live (referring to the Neotoma). She then told her people to return to their homes.

It was about this time that Sûs´sĭstinnako organized the cult societies, instructing all of the societies in the songs for rain, but imparting only to certain ones the secrets whereby disease is extracted through the sucking and brushing processes.

For eight years after the fight (years referring to periods of time) the people were very happy and all things flourished, but the ninth year was very bad, the whole earth being filled with water. The water did35 not fall in rain, but came in as rivers between the mesas, and continued flowing from all sides until the people and all animals fled to the mesa. The waters continued to rise until nearly level with the mesa top, and Sûs´sĭstinnako cried, “Where shall my people go? Where is the road to the north, he looking to the north, the road to the west, he facing the west, the road to the south, he turning south, the road to the east, he facing east? Alas, I see the waters are everywhere.” And all of his theurgists sang four days and nights before their altars and made many offerings, but still the waters continued to rise as before. Sûs´sĭstinnako said to the sun: “My son, you will ascend and pass over the world above; your course will be from the north to the south, and you will return and tell me what you think of it.” On his return the sun said, “Mother, I did as you bade me, and I did not like the road.” Again he told him to ascend and pass over the world from the west to the east, and on his return Sûs´sĭstinnako inquired how he liked that road. “It may be good for some, mother, but I did not like it.” “You will again ascend and pass over the straight road from east to west,” and upon the sun’s return the father inquired what he thought of that road. His reply was, “I am much contented; I like the road much.” Then Sûs´sĭstinnako said, “My son, you will ascend each day and pass over the world from east to west.” Upon each day’s journey the sun stops midway from the east to the center of the world to eat his breakfast, in the center to eat his dinner, and midway the center to the west to eat his supper, he never failing to take his three meals daily, stopping at these particular points to obtain them.

The sun wears a shirt of dressed deerskin, and leggings of the same, reaching to his thighs; the shirt and leggings are fringed; his moccasins are also of deerskin and embroidered in yellow, red, and turkis beads; he wears a kilt of deerskin, the kilt having a snake painted upon it; he carries a bow and arrows, the quiver being of cougar skin, hanging over his shoulder, and he holds his bow in his left hand and an arrow in his right; he still wears the mask which protects him from view of the people of the earth. An eagle plume with a parrot plume on either side, ornaments the top of the mask, and an eagle plume is on either side of the mask and one is at the bottom; the hair around the head and face is red like fire, and when it moves and shakes the people can not look closely at the mask; it is not intended that they should observe closely and thereby know that instead of seeing the sun they see only his mask; the heavy line encircling the mask is yellow, and indicates rain. (Fig. 14.)

The moon came to the upper world with the sun and he also wears a mask.

Each night the sun passes by the house of Sûs´sĭstinnako, who asks him: “How are my children above, how many have died to-day, and how many have been born to-day?” He lingers with him only long enough to answer his questions. He then passes on to his house in the east.

36

Sûs´sĭstinnako placed a huge reed upon the mesa top and said: “My people will pass up through this to the world above.” Ût´sĕt led the way, carrying a sack containing many of the star people; she was followed by all the theurgists, who carried their precious articles in sacred blankets, on their backs; then followed the laity and all animals, snakes and birds; the turkey was far behind, and the foam of the waters rose and reached the tip ends of his feathers, and to this day they bear the mark of the waters. Upon reaching the top of the reed, the solid earth barred their exit, and Ût´sĕt called ᵗSi´ka (the locust), saying, “Man, come here.” The locust hastened to her, and she told him that the earth prevented their exodus. “You know best how to pass through the earth; go and make a door for us.” “Very well, mother,” he replied, “I will, and I think I can make a way.” He began working with his feet, and after a time he passed through the37 earth, entering another world. As soon as he saw the world, he returned to Ût´sĕt saying, “It is good above.” Ût´sĕt then called the Tuo´ pi (badger), and said to him, “Make a door for us; the ᵗSi´ka has made one, but it is very small.” “Very well, mother; I will,” replied the badger; and after much work he passed into the world above, and returning said, “Mother, I have opened the way.” Ût´sĕt is appealed to, to the present time, as father and mother, for she acts directly for Sûs´sĭstinnako, the creator. The badger said, “Mother, father, the world above is good.” Ût´sĕt then called the deer, saying to him, “You go first, and if you pass through all right, if you can get your head through, others may pass.” The deer after ascending returned saying, “Father, it is all right; I passed without trouble.” She then called the elk, and told him if he could get his head through the door, all could pass. He returned, saying, “Father, it is good; I passed without trouble.” She then had the buffalo try and he returned, saying, “Father, mother, the door is good; I passed without trouble.”

Ût´sĕt then called the I-shits (Scarabæus) and gave him the sack of stars, telling him to pass out first with the sack. The little animal did not know what the sack contained, but he grew very tired carrying it, and he wondered what could be in the sack. After entering the new world he was very tired, and laying the sack down he thought he would peep into it and see its contents. He cut only a tiny hole, but immediately the stars began flying out and filling the heavens everywhere. The little animal was too tired to return to Ût´sĕt, who, however, soon joined him, followed by all her people, who came in the order above mentioned. After the turkey passed out the door was firmly closed with a great rock so that the waters below could not follow them. When Ût´sĕt looked for her sack she was astonished to find it nearly empty and she could not tell where the contents had gone; the little animal sat by, very scared, and sad, and Ût´sĕt was angry with him and said, “You are very bad and disobedient and from this time forth you shall be blind,” (and this is the reason the scarabæus has no eyes, so the old ones say). The little fellow, however, had saved a few of the stars by grabbing the sack and holding it fast; these Ût´sĕt distributed in the heavens. In one group she placed seven stars (the great bear), in another three (part of Orion,) into another group she placed the Pleiades, and throwing the others far off into the heavens, exclaimed, “All is well!”

The cloud, lightning, thunder, and rainbow peoples followed the Sia into the upper world, making their homes in springs similar to those they had occupied in the lower world; these springs are also at the cardinal points, zenith and nadir, and are in the hearts of mountains with trees upon their summits. All of the people of Tínia, however, did not leave the lower world; only a portion were sent by Sûs´sĭstinnako to labor for the people of the upper world. The cloud people are so numerous that, though the demands of the people of the earth are great,38 there are always many passing about over Tínia for pleasure; these people ride on wheels, small wheels being used by the children and larger ones by the elders. In speaking of these wheels the Sia add: “The Americans have stolen the secret of the wheels (referring to bicycles) from the cloud people.”

The cloud people are careful to keep behind their masks, which assume different forms according to the number of people and the work being done; for instance, Hĕn´nati are white floating clouds behind which the people pass about for pleasure. He´äsh are clouds like the plains, and behind these, the cloud people are laboring to water the earth. The water is brought from the springs at the base of the mountains in gourd jugs and vases, by the men, women, and children, who ascend from these springs to the base of the tree and thence through the heart or trunk to the top of the tree which reaches to Ti´nia; they then pass on to the designated point to be sprinkled. Though the lightning, thunder and rainbow peoples of the six cardinal points[5] have each their priestly rulers and theurgists of their cult societies, these are subordinate to the priest of the cloud people, the cloud people of each cardinal point having their separate religious and civil organizations. Again these rulers are subordinate to Ho´chänni, arch ruler of the cloud people of the world, the cloud people hold ceremonials similar to the Sia; and the figures of the slat altars of the Sia are supposed to be arranged just as the cloud people sit in their ceremonies, the figures of the altars representing members of the cult societies of the cloud and lightning peoples. The Sia in performing their rites assume relatively similar positions back of the altars.

When a priest of the cloud people wishes assistance from the thunder and lightning peoples he commands their ti´ämonis to notify the theurgists to see that the labor is performed, he placing his cloud people under the direction of certain of his theurgists, keeping a general supervision himself over all. The people of Ti´nia are compensated by those of Ha´arts for their services. These offerings are placed at shrines, of which there are many, no longer left in view but buried from sight. Cigarettes are made of delicate reeds and filled with down from humming birds and others, minute quantities of precious beads and corn pollen, and are offered to the priestly rulers and theurgists of Ti´nia.

The lightning people shoot their arrows to make it rain the harder, the smaller flashes coming from the bows of the children. The thunder people have human forms, with wings of knives, and by flapping these wings they make a great noise, thus frightening the cloud and lightning peoples into working the harder. The rainbow people were created to work in Ti´nia to make it more beautiful for the people of Ha´arts to look upon; not only the elders making the beautiful bows, 39but the children assisting in this work. The Sia have no idea how or of what the bows are made. They do, however, know that the war heroes traveled upon these bows.

The Sia entered this world in the far north, and the opening through which they emerged is known as Shí-pa-po. They gathered into camps, for they had no houses, but they soon moved on a short distance and built a village. Their only food was seeds of certain grasses, and Ût´sĕt desiring that her children should have other food made fields north, west, south, and east of the village and planted bits of her heart, and corn was evolved (though Ût´sĕt had always known the name of corn, corn itself was not known until it originated in these fields), and Ût´sĕt declared: “This corn is my heart and it shall be to my people as milk from my breasts.”

After the Sia had remained at this village a year (referring to a time period) they desired to pass on to the center of the earth, but the earth was very moist and Ût´sĕt was puzzled to know how to harden it.

She commanded the presence of the cougar, and asked him if he had any medicine to harden the road that they might pass over it. The cougar replied, “I will try, mother;” but after going a short distance over the road, he sank to his shoulders in the wet earth, and he returned much afraid, and told Ût´sĕt that he could go no farther. She then sent for the bear and asked him what he could do; and he, like the cougar, made an attempt to harden the earth; he had passed but a short distance when he too sank to his shoulders, and being afraid to go farther returned, saying, “I can do nothing.” The badger then made the attempt, with the same result; then the shrew (Sorex) and afterward the wolf, but they also failed. Then Ût´sĕt returned to the lower world and asked Sûs´sĭstinnako what she could do to harden the earth so that her people might travel over it. Sûs´sĭstinnako inquired, “Have you no medicine to make the earth firm? Have you asked the cougar and the bear, the wolf, the badger and the shrew to use their medicines to harden the earth?” And she replied, “I have tried all these.” Then, said Sûs´sĭstinnako, “Others will understand;” and he told Ût´sĕt to have a woman of the Ka´pĭna (spider) society to use her medicine for this purpose. Upon the return of Ût´sĕt to the upper world, she commanded the presence of a female member of this society. Upon the arrival of this woman Ût´sĕt said, “My mother, Sûs´sĭstinnako, tells me the Ka´pĭna society understands the secret of how to make the earth strong.” The woman replied, “I do not know how to make the earth firm.” Three times Ût´sĕt questioned the woman regarding the hardening of the earth, and each time the woman replied, “I do not know.” The fourth time the question was put the woman said, “Well, I guess I know; I will try;” and she called together the members of the society of the Ka´pĭna and said to them, “Our mother, Sûs´sĭstinnako bids us work for her and harden the earth so that the people may pass over40 it.” The woman first made a road of fine cotton which she produced from her body (it will be remembered that the Ka´pĭna society was composed of the spider people), suspending it a few feet above the earth, and told the people they could now move on; but when they saw the road it looked so fragile that they were afraid to trust themselves upon it. Then Ût´sĕt said: “I wish a man and not a woman of the Ka´pĭna to work for me.” A male member of the society then appeared and threw out the serpent (a fetich of latticed wood so put together that it can be expanded and contracted); and when it was extended it reached to the middle of the earth. He first threw it to the south, then to the east, then to the west. The Na´pakatsa (a fetich composed of slender sticks radiating from a center held together by a fine web of cotton; eagle down is attached to the cotton; when opened it is in the form of an umbrella, and when closed it has also the same form minus the handle) was then thrown upon the ground and stamped upon (the original Na´pakatsa was composed of cotton from the spider’s body); it was placed first to the south, then east, west and north. The people being in the far north, the Na´pakatsa was deposited close to their backs.