Project Gutenberg's Stories Pictures Tell Book 6, by Flora Carpenter This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Stories Pictures Tell Book 6 Author: Flora Carpenter Release Date: September 14, 2020 [EBook #63199] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STORIES PICTURES TELL BOOK 6 *** Produced by David Garcia, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| PAGE | ||

| “Sir Galahad” | Watts | 1 |

| “A Reading from Homer” | Alma-Tadema | 13 |

| “The Golden Stairs” | Burne-Jones | 27 |

| “Aurora” | Reni | 37 |

| “Avenue at Middelharnis” | Hobbema | 47 |

| “The Angelus” | Millet | 58 |

| “Sheep in Spring” (and “Sheep in Autumn”) | Mauve | 68 |

| Review of Pictures and Artists Studied | ||

| The Suggestions to Teachers | 78 |

Art supervisors in the public schools assign picture-study work in each grade, recommending the study of certain pictures by well-known masters. As Supervisor of Drawing I found that the children enjoyed this work but that the teachers felt incompetent to conduct the lessons as they lacked time to look up the subject and to gather adequate material. Recourse to a great many books was necessary and often while much information could usually be found about the artist, very little was available about his pictures.

Hence I began collecting information about the pictures and preparing the lessons for the teachers just as I would give them myself to pupils of their grade.

My plan does not include many pictures during the year, as this is to be only a part of the art work and is not intended to take the place of drawing.

The lessons in this grade may be used for the usual drawing period of from twenty to thirty minutes, and have been successfully given in that time. However, the most satisfactory way of using the books is as supplementary readers, thus permitting each child to study the pictures and read the stories himself.

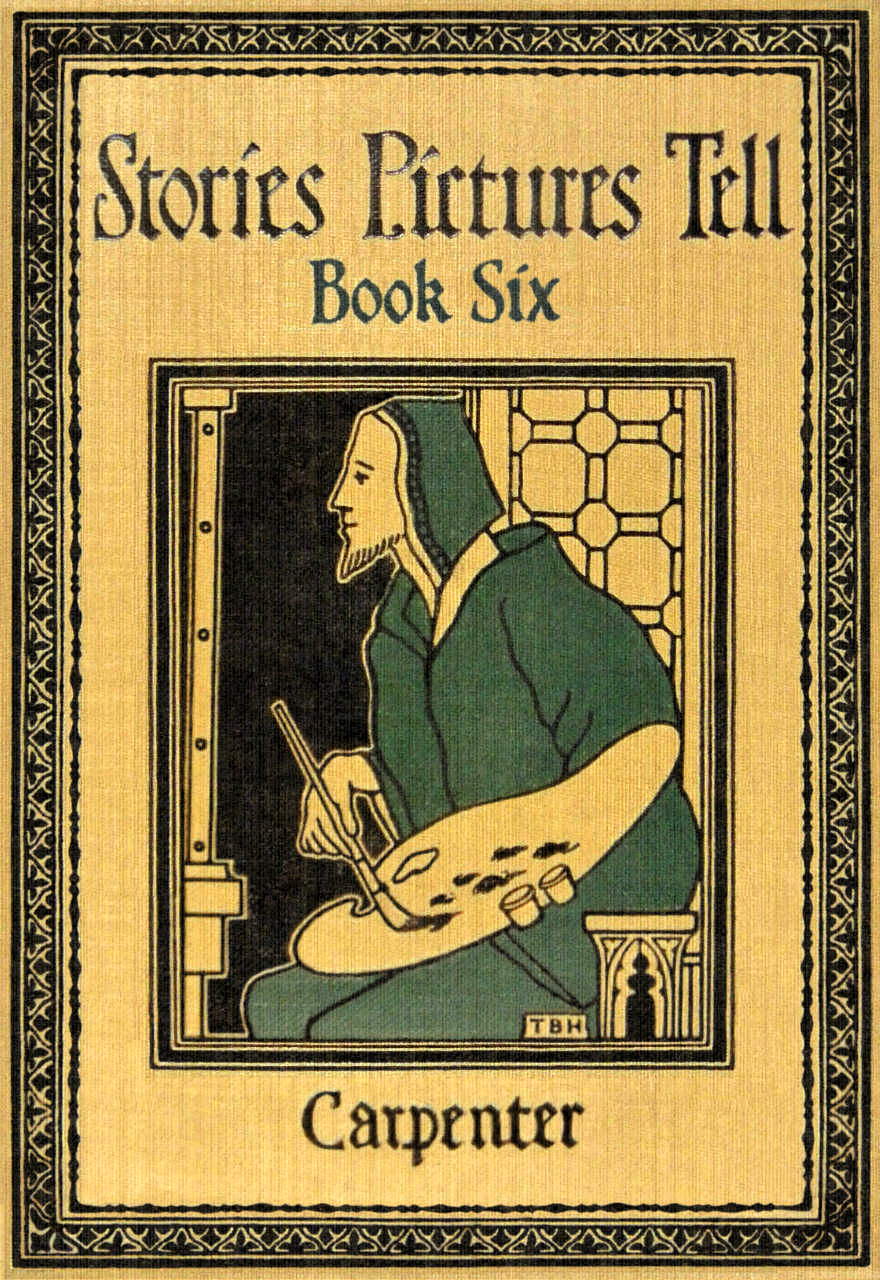

Questions to arouse interest. Who is this man? How is he dressed? What do his armor and title “Sir” tell us he is? How many have read Tennyson’s poems telling the story of the knights of the Round Table? What does Sir Galahad look as if he were about to do? Why do you think he is starting on a journey, rather than returning from one? Why do you think it must be an important journey? How will he go? What was expected of a knight in those days? Tell of some of their good deeds. What would you judge the character of this knight to be? Where is he represented in this picture? Is he walking, or standing still? looking at something in particular, or lost in thought? Does he appear angry, meek, determined, hesitating, thoughtful, or dreamy? What do his clasped hands indicate? What color is the horse? Upon what part of the man and horse does the light fall? What would you consider the main thought expressed in this picture?

The story of the picture. Many wonderful stories have been told of the famous knights of the Middle Ages, but none perhaps more interesting than the adventures of the knight Sir Galahad when he went in search of the Holy Grail.

In those times the greatest praise a boy could hope to receive was “You are brave enough to become a knight some day,” or “You are as courteous as a knight”; and his greatest ambition was to receive this title as he knelt before his sovereign or a superior knight. In those days boys were carefully trained for knighthood, just as for any other profession. They were sent away from home when very young, and spent at least ten years under severe discipline and training.

The boy Galahad had passed through these years of preparation. He had been taught to be quick in action,—managing a horse so that he could jump on or off while it was in full gallop,—to throw his spear with sure aim, to run swiftly, to obey all commands promptly; and, more difficult still, he had learned to wait patiently and uncomplainingly when he could not understand why he should wait.

Now he was twenty-one years old. Knighthood had been bestowed upon him, according to the custom, by a blow with the flat of the sword on his shoulder as he knelt, and the words, “Arise, Sir Galahad.” And now he was ready to start out on his quest for the Holy Grail.

The Holy Grail was the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper. It was bought from Pilate by Joseph of Arimathæa, and placed in a castle where it was guarded night and day. It was passed on to Joseph’s children, who received the charge in sacred trust, continuing to guard it faithfully. The cup itself was most mysterious and wonderful. It could be seen only by those who were perfectly pure in word, thought, and deed. If an evil person came near, it would seem to be borne away, completely disappearing from view. The sight of it was as food and new life to the one to whom it was revealed, and hence would enable him to live forever, make him very wise, and of course preserve him from death in battle. But there was one thing it did not do,—it did not take away temptation to sin. No matter how perfect the knight, he could still be tempted. He must continue to resist evil as long as he lived.

After a time, the Holy Grail was left in the care of a king named Amfortas, who, weakly yielding to an evil enchantment, was severely punished. Not only was the sight of the Grail denied him, but a spell was cast upon him and all his court, so that they lived in a sort of trance, neither sleeping nor waking. Thus they must remain and suffer until a knight should come, pure in body and soul, who should break the spell and set them free.

Many a young man began to plan the quest of the Grail. He must so live that by his good thoughts and deeds he might reach the enchanted castle, see the Holy Grail, and so set free the unhappy knights. He must be perfect, indeed, if he would achieve this, and full of courage, perseverance, and patience.

In our picture we see Sir Galahad all ready to mount his snow-white horse and start out on his search for the Holy Grail. He is in full armor. His coat of mail, which all knights wore, was proof against any opponent of the time, except one equally armed and armored. It is said that a party of knights could ride unharmed through a host of common soldiers. The horses, too, were protected. But if the knight were once unhorsed and thrown upon his back, he was so weighed down by the stiff and heavy armor that he could not rise again without help. The knight’s weapons consisted of the lance, the two-handed sword, and a short, sharp dagger.

Sir Galahad had secured his sword and shield in a most mysterious way. The sword had been discovered protruding from the side of a wonderful rock of red marble jutting out from the surface of a river. This wonderful sword no one had been able to draw out of the rock. But when Sir Galahad tried, the sword came out without the slightest difficulty, and when he placed it in his empty scabbard, it fitted there exactly. The shield had been found by Sir Galahad in an old church, where it had been left for him by an ancestor, and where it had remained undiscovered for those many years.

Then, too, when Sir Galahad came to the Round Table of King Arthur and his knights in Camelot, he found them in the midst of a solemn meeting. Launcelot had just declared that according to prophecy a knight should come that very day who should occupy the Siege Perilous. The Siege Perilous was a chair over which the magician Merlin had cast a spell: only a stainless knight could sit in it without danger of instant death. As Sir Galahad entered the room he was preceded by a strange old man, whom none had ever seen before. Then the doors and windows quietly and mysteriously closed of their own accord, and the room was filled with a strange light. These words, in letters of fire, appeared over the chair: “This is Galahad’s seat.” By all these mysterious happenings the knights knew that Sir Galahad would be successful in finding the Grail, and many accompanied him on his quest.

Sir Galahad met with many adventures on his quest for the Grail and, in all of them, came out victorious. At length he reached the Castle of the Grail, and here he met his first defeat.

Entering the castle he gazed silently about him, at the feeble old king and at the wretched company whom he had come to free from their living death. Before him passed the vision of the Grail, which he alone of all that company was permitted to see. But it was not enough to see all this; he was expected to ask the meaning of what he saw, and by his question remove the enchantment. But, overconfident in his own knowledge, he tried to solve the mystery without asking, and so was forced to depart without success.

Here, at the very moment he was about to succeed, he was found to be possessed of the one fault, overconfidence, lacking in that humbleness which seeks constantly for higher knowledge. Because of his failure to ask the necessary question, the enchanted company had to continue to suffer. His personal purity alone was not enough; wisdom was necessary, attainable not through himself alone, but from the experience and understanding of others. As he left the castle grounds the drawbridge closed with a crash, there was a great sound of groaning and of voices reproaching him for having failed in his quest, and the castle disappeared from his sight. Much discouraged, he sought it again through many years, until at last he found it once more, and this time, a much wiser man, he asked the vital question, broke the wicked spell, and eventually found the Holy Grail.

Tennyson has given us the story in verse in his “Holy Grail.”

This picture is one we often see in homes, as well as in schoolhouses, and in many public buildings. It stands for the search for higher ideals which we are all making, and so its appeal is universal.

The earnest, uplifted face of the knight is full of youth and beauty. The horse, with his great, intelligent eyes, seems to know the importance of his errand.

The light comes from before them, brightening the pathway as if it would lead them on and on through the tangle of vines and deep woods which opposes them.

If you have been fortunate enough to see a suit of armor in some museum, you know how the heavy steel coat is planned and how the helmet, which Sir Galahad has taken off, will protect his head and face.

It is a moment of deep meditation and prayerful thought, for Sir Galahad is about to start out upon an undertaking in which many have failed and in which he cannot be sure of success. There is much of humility in his expression, nothing of the proud, dashing air of the adventurer.

This earnest, thoughtful youth, starting out full of courage and determination, will always have time for the little courtesies of life, for they are a part of his creed. A true knight, he has been taught, should defend to the uttermost the oppressed, aid the weak, and be brave, courteous, chaste, temperate, generous, and pious.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Who was Sir Galahad? Upon what quest is he about to start? What preparation has he made for it? How old is he now? How did he receive the title “Sir”? What was the Holy Grail? What power had this cup? What could it not do for the person who saw it? Why was the sight of the Grail denied to

King Amfortas? What other punishment did he receive? Who could break this spell? how? What did Sir Galahad hope to do? How is he dressed? What protection was this armor? What might happen if he should be unhorsed? What weapons did he carry? How had Sir Galahad secured his sword and shield? Tell about the Round Table of King Arthur and the Siege Perilous. What happened when Sir Galahad entered? Of what did all these mysteries persuade the other knights? What happened when Sir Galahad came to the Castle of the Grail? Why did he fail? What was the result of this defeat? When did he succeed? What was the result? What is the main thought expressed in this picture?

The story of the artist. George Frederick Watts was born and raised in London, England. He learned to draw, we are told, much in the same way he learned to talk. His parents encouraged him always, and he seems to have had very few obstacles to overcome.

Though Watts entered the Royal Academy school of painting at an early age, he did not study there long. His art education was thus gained largely by his own efforts and observation. He studied ancient Greek sculpture closely and his work was always influenced by the classical standard.

Watts lived in an age when the spirit of reform was uppermost, and men were preaching, thinking, and living it. No wonder, then, his work is full of thoughtful purpose, urging us on to the best that is in us.

He said, “I want to teach people to live ... to teach something higher than money making or mere pleasure getting ... to suggest great thoughts.” He did not paint, as many others had, for the mere pleasure of it, or even from inspiration, but rather for some definite purpose. In the Tate Gallery at London is a great collection of the paintings which give the artist’s message to the world. In 1843 the Royal Commission appointed for the decoration of the new Houses of Parliament awarded one of the prizes to Watts for his fresco design. This enabled him to study in Italy for three years. There he gained much in the richness of his coloring and ease in brush-work.

Of his paintings for the government “The First Naval Victory of the English” and “St. George Overcomes the Dragon” are perhaps the best known. Other famous pictures by Watts are entitled “Ganymede,” “Orpheus and Eurydice,” and “Psyche.” In 1867 Watts became a member of the Royal Academy. He worked very hard, producing a great many paintings. With noble generosity he donated a large number of pictures to his country, particularly portraits of famous men, among them Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, Swinburne, Dante, Gabriel Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and William Morris.

The last few years of his life were devoted principally to portrait painting. When Tennyson was writing “Elaine,” he asked Watts to tell him his idea of a good portrait, and afterwards wrote this description from the answer:

Questions about the artist. Who was the artist, and where was he born? What help did he have in realizing his ambition to become an artist? What was his aim in painting pictures? Give in your own words Mr. Watts’s idea of what a good portrait should be. What helped him to go to Italy? What benefit did he get from his study in Italy? Name some great men whose portraits Watts painted.

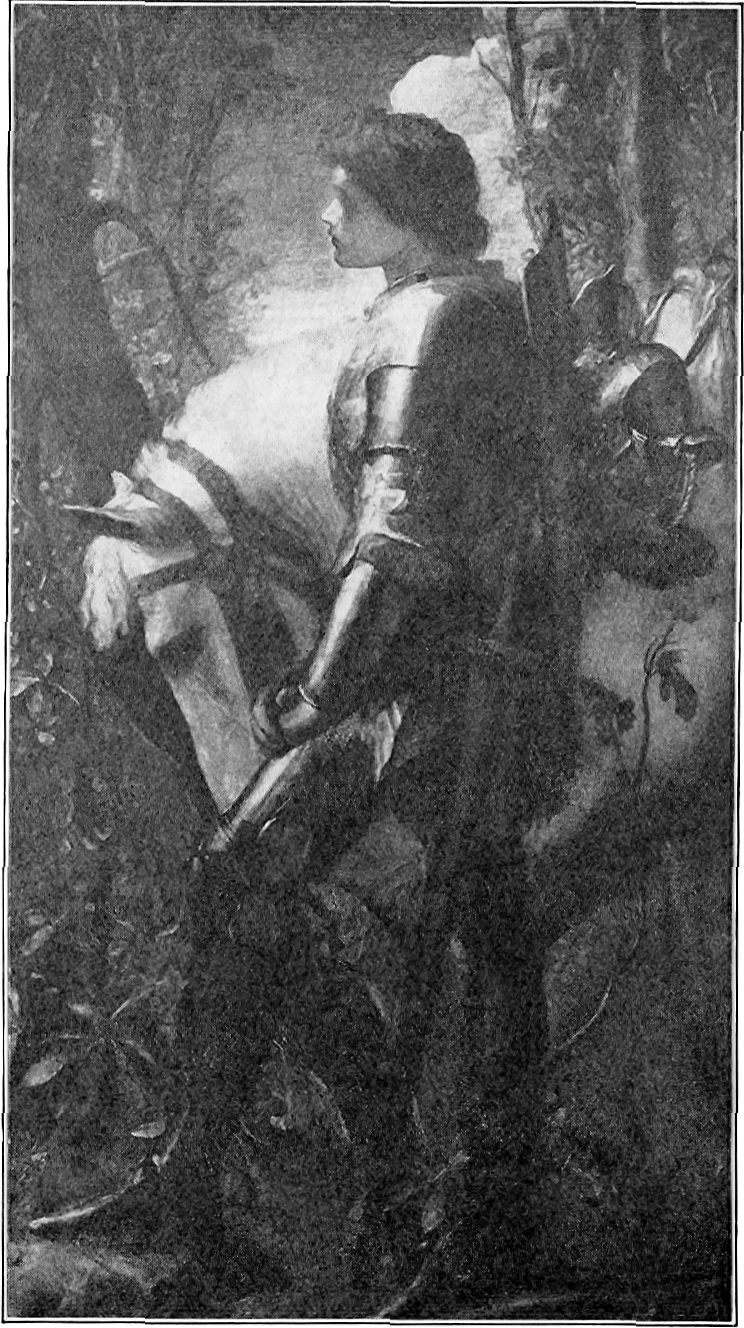

Questions to arouse interest. What nationality is represented in this picture? Why do you think so? To what are they listening? What do their expressions indicate their feelings to be? What musical instruments do you see in the picture? From the picture, would you say that the people are outdoors or indoors? why?

The story of the picture. Let us imagine ourselves in that great walled-in city of Athens at the time of its greatest prosperity (fourth century B.C.). At whatever gate we enter—and there are many of them—our attention will be drawn toward the high, steep hill called the Acropolis, around which the city is built. We may reach the top of this hill in a chariot driven over a road of marble, or climb the marble steps, entering the magnificent gateway where we find many beautiful statues, temples, and altars. From this height we obtain a fine view of the city, the sea, other small hills, temples, and flat-roofed houses. As we look about us, we are surprised at the absence of spires or towers. There are no high towers or tall buildings. Most of the houses we see are one-story. The reason for this, it is said, is the frequency of earthquakes. The exterior of the houses is very plain. They are built of common stone, brick, or wood, coated with plaster, and so close to the street that if the door opens outward, the owner is compelled to knock before opening it in order to avoid injuring the passer-by in the street. There are no windows on the lower floor at the front of the house.

Beside the door is a statue of Hermes (god of highways, doorways, and boundaries and the bringer of good luck), or an altar to Apollo (god of light and the sun, and the protector from all evil); and over the door we may notice an inscription such as “To the good genius,” followed by the name of the master of the house. We raise the handle of the great knocker, and scarcely has the sound echoed back to us when the door is opened by the porter. We must be careful to step in with our right foot first, as it is considered unlucky to cross the threshold with the left foot. A long corridor or hall leads us to the open court, where all is as beautiful as the exterior is plain. Usually a fountain and flowers brighten the marble court, while on each side of it are the banqueting, music, sitting, and sleeping rooms, picture galleries, and libraries.

But the Greeks spent so much time out of doors that a house was to them only a safe place for their families and their property—a shelter from storm. Most of the houses had porticoes or porches, and often the second story consisted of nothing but these porches around the open court. The flat tiled roofs were used as promenades.

Probably the Greeks in our picture are seated on one of these porches, or they may be in one of the summer pavilions which so many wealthy Greeks had erected in their yards or grassy plots back of the house. Here they spent their afternoons and were entertained with music or by the tales of wandering minstrels or readers.

The scene in the picture is represented as if it were in the open air; the column and stone wall behind the reader suggest a part of a house. In the distance we catch a glimpse of the blue sea. The slightly raised seat of the reader indicates that it is a place built expressly for this purpose.

Before the Greeks wrote their stories it was the custom of certain bards or readers to go about from place to place singing or reciting the stories of events which have made their national history. Even when the stories were written, these bards were in great favor, for the Greeks preferred to hear the music of verse recited, and to feel the thrill of enthusiasm which could be aroused by the human voice, and not by a lifeless tablet or book.

The swaying form of the reader, his rapt expression, his flashing eye, his musical voice rising and falling like the sea,—these were the result of inspiration and had power to arouse men to noble actions. In our picture we see such a reader giving an interpretation or reading, much as our best elocutionists do now. In his hand he holds a long scroll from which he reads.

The Greeks used the Egyptian papyrus, and later the more expensive, but finer, parchment, to write upon. The reed pen was used, and double inkstands for black and red ink, which could be fastened to the belts or girdles of the writers. In libraries, the scrolls were arranged on shelves with the ends outward, or in pigeon holes. The reader unrolled one end of the scroll with one hand, while with the other he rolled up the part he had read.

Of all the Greek stories none were more fascinating than those of the immortal Homer. According to tradition, Homer was a schoolmaster who, growing tired of teaching, began to travel. Wandering about from place to place, he finally became blind. After this great affliction came upon him, he returned to his native town, where he dictated his two great poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Afterwards he wandered about from town to town, singing them, and adding to them as inspiration came. It is not even known where he was born, but, according to an old Greek epigram,

He was a beggar, and yet he was a welcome guest at every home, for he could play upon his four-stringed harp and sing of the wonderful deeds of the Greek gods and heroes.

The subject of Homer’s Iliad is the story of the siege of Troy. In a contest between Aphrodite (Venus) and two other goddesses, Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, had promised Paris, son of the King of Troy, that if he would declare her the most beautiful of the goddesses he should have for his wife the handsomest woman of his time, Helen, wife of the King of Sparta. Paris granted her request and, going to Sparta, with Aphrodite’s aid he carried off Helen to Troy.

Of course her husband, the King of Sparta, objected. He appealed to all the Grecian princes to help him, and soon a hundred thousand men sailed away in eleven hundred and eighty-six ships across the Ægean Sea, and camped before the walls of Troy. The siege lasted ten years.

Troy was finally taken by stratagem. The Greeks pretended to abandon the siege, leaving behind them a great wooden horse as an offering to Athena (Minerva), goddess of wisdom, and the special defender of citadels.

The Trojans could not find out their reason for building the monster; but while they were talking about it and gazing at it some shepherds brought into the town a young Greek named Sinon, whom they had captured. He told a pitiful story. He said the Greek leader hated him, and had induced the Greek soothsayer to declare that he must be put to death as a sacrifice for their safe return to Greece. He had escaped, and hidden in a swamp until the Greeks had gone.

The Trojans were ready to be kind to any man whom the Greeks hated, and he was set free at once.

“But tell us,” said the king, “why that monster of a horse was built.”

Sinon declared it was a sacrifice to Athena because she was angry with them. He said, “It was made too large to pass through your gates, for they knew that if it was once within your walls it would protect you, and victory would come to you instead of to the Greeks.”

The Trojans believed every word of this, and ordered the huge horse brought within their city, even though they were obliged to take down part of the wall in order to make the opening large enough. That night the treacherous Sinon opened a door in the body of the horse and let out the armed Greeks who were hidden inside. They quietly slipped to the ground by means of a rope, killed the watchmen, and opened the gates to the Greek army which had returned and was waiting outside. A terrible battle followed, in which nearly all the Trojans were killed. Helen was taken back to Greece.

In Homer’s Odyssey he tells the adventures of Ulysses, King of Ithaca, during the return journey from Troy. Ulysses had been one of the bravest of the Greek leaders, and was one of the heroes concealed in the wooden horse. The poem is full of vivid description and noble sentiments, both pathetic and sublime, and it stirred the hearts of the Greeks with pride and joy.

It is easy to see the interest in the faces of the listeners in the picture. Partly robed in a rose-colored garment, the reader sits on a chair of marble, holding on his knees a roll of papyrus, from which he is reading to a group of four persons before him. A wreath of bay leaves crowns his head, and as he leans forward his face expresses enthusiasm while he tells the thrilling adventures of the hero of Homer’s story.

In the center of the background we see a woman. On her hair is a crown of daffodils, and in her left hand something resembling a tambourine. She half sits, half reclines, on a marble bench, a resting place which the Greeks always preferred to chairs. On the floor near her, in an attitude of careless ease, sits a young man who is very likely her lover, since he is holding her hand. His face expresses his interest in the story. In his right hand he holds a lyre, which suggests that the company has been listening to music, and that they will enjoy it again after this recital.

How intent their faces are as they follow in imagination all the adventures of their sturdy ancestors! Near the center of the picture and stretched out gracefully on the marble floor is a youth who appears anxious not to lose one word of the story. At the left we see a man standing. He wears a crown of flowers on his head, and wraps his long cloak closely about him. His face is wild and sad. His appearance seems to tell that he has duties elsewhere and ought to leave, but is being held by the story.

The people are all dressed in typical Greek costumes. The dress of Greek men and women was very much alike. When they appeared on the streets they wore a cloak which consisted of a large square piece of cloth so wrapped about them as to leave only the right arm free. It required much skill to drape it gracefully, and the manner in which this was done decided the taste and elegance of the wearer. The women and men of the higher classes wore what they called a chiton, or dress which consisted of two short pieces of cloth sewed or clasped together and fastened over the shoulder, leaving open spaces for the arms. It was fastened at the waist with a girdle. A man usually wore this chiton, although he was considered fully dressed in the cloak alone. It was the lower classes who wore the tanned skins, so the young man lying on the floor is probably a servant.

A touch of bright color is added to this picture by the flowers in the girl’s hair and those scattered on the bench beside her.

The flesh painting in this picture is claimed to be the most perfect that Alma-Tadema ever did, and the painting of the girl and her lover, one of his highest efforts. The reader is the center of interest in the picture. The light, the lines, and the position of the figures make this apparent.

The painting of these five large figures occupied the artist only eight weeks, but the preliminary studies before he began painting took eight months.

Alma-Tadema excelled in his painting of marble, and this picture gave him every opportunity to display his genius, since nearly the entire background is of marble. The delicate colors of the young girl’s costume, with the few bright touches of color in the flowers; the darker, richer colors of the men’s cloaks; and back of it all the clear opalescent colors of marble and the deep blue of the sea beyond give the picture a distinctive beauty which is most pleasing to the eye. A close student of Greek history, Alma-Tadema has been particular to see that every little detail is in harmony, and consistent with the age and country.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. What is the center of interest in this picture? What lines in the picture direct your eye to the reader? How does the light do this? the position of the figures? Tell something of Greek life; of Homer; of the siege of Troy. Why did it take the artist eight months to get ready to paint this picture?

To the Teacher: Each pupil may be asked to draw one Greek ornament from some history, encyclopedia, or dictionary.

The story of the artist. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, of Dutch parentage, was born in the little village of Dronrijp near Leewarden, the Netherlands, in the year 1836. When he was very young his father died, leaving his mother with a large family and small means, and it was decided from the first that Alma-Tadema must learn a good trade or profession. His progress at school caused his mother much anxiety, for the boy cared for nothing except Roman history, which he began to study by himself. Having secured some quaint old coins in the neighborhood, he spent much of his time copying the heads of the emperors on the coins.

He soon began to show remarkable talent for painting. A portrait which he painted of his sister was exhibited when he was only fifteen years old. But his mother wished him to become a lawyer, because she felt it would bring the best financial returns. He tried to please her, but a serious illness was the result. When the doctor advised the mother to let him become an artist she gave her consent, and it is said the boy recovered with astonishing rapidity.

He studied at Antwerp many years, winning such success that he sent for his mother and sister to come to live with him. Then he began to make a special study of Egypt, Greece, and Rome. After his marriage to an English lady he moved to London, where he lived the rest of his life.

His love for marble and the polished surfaces of bronze, gold, and other metals is clearly shown in most of his pictures. Even his portraits usually represent the sitter as glancing in a mirror or in some way reflected in it.

Perhaps no other artist has ever made so much use of flowers in his pictures. The flowers seem to add the one touch of bright color which beautifies the whole picture.

Alma-Tadema gives us a clear understanding of the home life of the Greeks and Romans, and so has become known as the “Painter of the Ancients.”

Alma-Tadema became a British subject in 1873. His home in St. Johns Wood, in the northwest part of London, is described as a most interesting place. The first glimpse of it, seen through the trees, shows the gilded weather vane in the form of a palette; later, the stone pillars of the Roman porch. In all its details the house is carefully and beautifully furnished: the brass knocker on the door, the entrance into a sort of sun parlor paved with tiles and bright with beautiful flowers, and the sound of a fountain near at hand. A flight of marble steps leads to a hall in which beautiful painted panels (the gifts of friends) are the chief decoration. Great tiger skins cover the floor.

Mrs. Tadema also is an artist, and has her studio on this floor. In her studio and the living rooms she has given full sway to her own fancy for the sixteenth-century old Dutch, most of their contents having been brought from the Netherlands. Alma-Tadema’s taste is purely classical, and his studio is consistent in all respects—marble pillars, carved wood-work, chairs, and cushions. Here he lived and worked with this motto before him:

Questions about the artist. Of what nationality was the artist? Why was his mother so anxious to have him learn a trade or profession? What did he like to study? What picture did he exhibit when he was fifteen years old? What prevented his becoming a lawyer? What countries did he prefer to represent? What materials did he excel in painting? For what has he become famous?

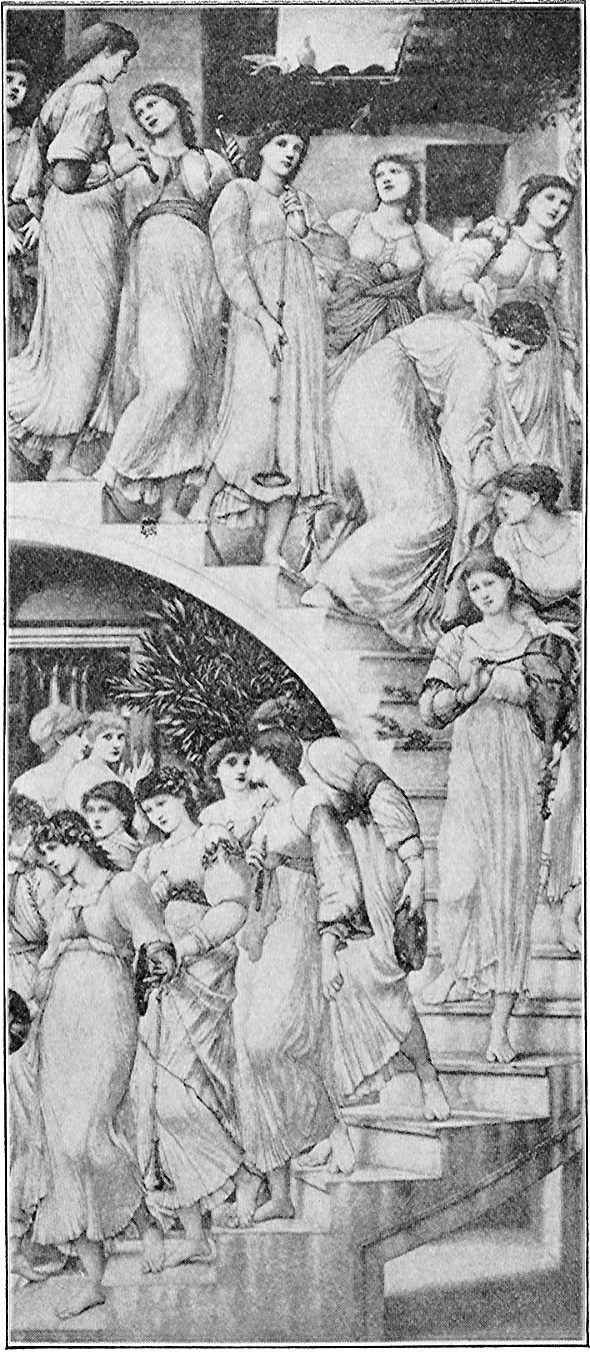

Questions to arouse interest. What does this picture represent? What is there unusual about this stairway? Why do you suppose Burne-Jones painted the stairs without a railing? What is there unusual about these figures? What are they carrying in their hands? Where are they going? Where did they come from? Do they seem to be standing still or moving? What makes you think so? Are they noisy or quiet in their movements? Why do you think so? Why has the leader raised her hand? What can you see in the window above the stairs? Is this a sad or a happy procession? Why do you think so? What do you like best about this picture?

The story of the picture. The artist, Burne-Jones, was a student and a dreamer. As a small, motherless boy he had been left much alone in a home in which storybooks were considered wicked, so there were none for him to read. His father was a strong churchman and intended his son for the ministry. He was endeavoring as best he knew how to fit him for his high calling by a training which, though perfectly sincere and honest in purpose, was rather gloomy and severe for the delicate, sensitive boy. However, little Edward was naturally of an imaginative mind, so he made up his own stories. A relative sent him a copy of Æsop’s Fables, and this book he was permitted to keep. It seems to have brought the turning point in the boy’s life. From that time on he dwelt in a fairyland of his own making.

When he was sent away to school to prepare for the ministry, he carried his fancies with him, adding to them the many legends of Greek mythology; of literature, especially those wonderful stories of King Arthur’s court; and of the Bible. His desire to become an artist was aroused by another student, William Morris, the two spending all their spare time drawing and painting. Nevertheless, he was twenty-three years old before he saw any of the great masterpieces in painting.

From the very first, Burne-Jones chose subjects which were mysterious, fairylike, and unreal, but his pictures were so filled with music, beauty, and happiness that it was a delight to look at them.

His idea of a good picture was very different from that of the practical, painstaking Millet, who represented everything and everybody as they actually appeared before him in the very field or place he had found them.

Burne-Jones tells us: “I mean by a picture a beautiful, romantic dream of something that never was, never will be, in a light better than any light that has ever shone, in a land no one can define or remember, only dream.” And so when asked to paint a decoration for a hallway in one of the fine old London homes he thought at once of a stairway, and the painting of “The Golden Stairs” is the result. It would seem indeed a dream, this angel host descending from we know not where and halting at that mysterious closed door which leads we know not whither. But hush! the leader has half raised her hand, turning this way as if to ask for silence. Each figure stops instantly, holding herself motionless, while the musical instruments are slightly lowered that all may listen more intently. And yet, this is a joyous procession,—the gayly colored wreaths of flowers which most of them are wearing, the musical instruments, the happy faces, all tell us this is an errand of pleasure. Might it not be that this host of angels is descending upon the sleeping world to soothe the restless, worried ones, and smooth the puckered, aching brows in quiet slumber? Lulled by their gentle music, or the rustle of their approaching footsteps, the weary one would soon find refreshing sleep.

The light in the picture seems to come from above, yet is all about and around the figures, as if they were the source of the illumination. They come from a darkened doorway, and enter one quite as dark except for the light they bring to it.

The greater part of the picture is painted in shades of gray, but it is relieved by the flesh tints, and the gayly colored flowers worn in wreaths or scattered on the steps. Here is delicate, exquisite coloring, and figures drawn with such careful attention to details that each seems complete in itself, yet all are held together in one great harmony.

It is interesting to draw an oblong of this same proportion and then represent the curved lines in this picture; it makes us feel the movement, swing, and rhythm which come to us like approaching music.

The picture is full of idyllic charm which takes us away from all the prosaic details of everyday life to a fairyland where this happy throng may come and go with music, flowers, and delight. The calm, thoughtful faces, so full of kindly purpose and high ideals, cannot fail to inspire us with good thoughts.

The dove in the upper casement window is typical of the peace that pervades this scene. The faint, far from earthly, shadows, the bare feet, even the stairway without a railing or protection of any kind, all suggest that our youthful maidens are celestial beings. Their destination we can only guess. Perhaps that is why the picture has had several names: “The King’s Wedding,” “Music on the Stairs,” and the one by which it is now known, “The Golden Stairs.”

Burne-Jones made many beautiful designs for stained-glass windows, and we can but regret that he did not produce this picture in that way also.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Tell about the boyhood and early training of the artist. What book influenced him most? How did it affect his choice of subjects to paint? How did he happen to become interested in art? How old was he before he first saw a great painting? Compare the subjects chosen by Burne-Jones and by Millet as to character and feeling. What was Burne-Jones’s idea of a good picture? How did he happen to paint “The Golden Stairs”? For what room was it intended? What colors did the artist use in this painting? In what ways does it suggest music? How would you explain the destination of these maidens? their errand? from whence they come? What would you consider the chief charm in the picture?

The story of the artist. We have heard how the small Burne-Jones was brought up by a rather strict but ambitious father, and perhaps have felt sorry for the boy who used to spend hours before the windows of a book store, gazing at the even rows of books with such wistful longing. But we need not feel so, for it was this very desire for books and stories that led him to use his own imaginative power.

When he was old enough to begin serious preparation for the ministry his father sent him to King Edward’s School. Here he earned a scholarship to Oxford. When he left home for Oxford it seemed as if his real life had begun, for it was here that he met friends who had the same tastes and longings as himself. One friend in particular, William Morris, shared with him his new-found delight in art. Both had intended to prepare for the ministry, but now they decided to give up all else and pursue the study of art. So at the age of twenty-three Burne-Jones left Oxford and went to London, where he began painting in earnest. From the very first he showed great originality both in his subjects and in his manner of representation.

Many of his subjects were taken from the Bible, from Greek mythology, or from stories of King Arthur’s court. Sometimes he painted with but the one idea of making something beautiful, as in this picture of “The Golden Stairs.”

Burne-Jones was fortunate in his first teacher, Rossetti, who was a man so filled with the beauty of a scene that he must paint it for sheer joy. In order to pay for this instruction Burne-Jones made designs for stained-glass windows, and became famous for the beauty of these windows. The one at Trinity Church, Boston, is called “David Instructing Solomon in the Building of the Temple.” At Oxford is the famous Saint Cecilia window he designed for Christ Church College.

It seems strange that Burne-Jones should wait until he grew to manhood before he discovered that he had the desire and the ability to draw. Other artists tell of the years spent in longing, and their constant struggle for the sake of their art. But when Burne-Jones made up his mind, he spent no time in experiment or even practice. He devoted all his time to the one idea which filled his thoughts. He made no effort whatever to find out whether his work would meet with popular favor or not, beginning at once with what he knew to be his right material.

The only difference to be noticed in his first and his last paintings was a difference in the speed and skill with which he handled the paints. New ideas occurred to him so rapidly that he formed the habit of making quick sketches and putting them aside until he had time to work them out carefully.

Burne-Jones had never rebelled against the profession his father chose for him. Indeed, he felt satisfied and made every effort to succeed in it. Perhaps if he had remained at home, or even if he had not met the enthusiastic William Morris just when he did, he might never have discovered his power as a painter.

The knowledge of the disappointment at home and the small means at his disposal did not hinder him from forsaking the profession his family had chosen for him, for was he not following the advice of the great painter, Rossetti? Not many young artists have found such a friend as Rossetti was to Burne-Jones. He not only gave the desired instruction but helped his pupil get such work as he was capable of doing. When the glass makers applied to Rossetti for a design for a stained-glass window, he declined to undertake the work but recommended his pupil instead.

A visit to Italy gave Burne-Jones new inspiration. Later when William Morris married and went to live in a house which had been built for him at Bexley Heath, he had difficulty in furnishing this house to suit his taste and desire for beautiful things. This led Morris to establish a firm to make such things. Of course Burne-Jones was heartily in sympathy with his friend and put his talents as a designer at the disposal of the firm. His wonderful imagination and fine powers of expression produced all kinds of decorative work, such as tapestries, embroideries, carved chests, book covers, book illustrations, and decorations for pianos, screens, and friezes.

Although he received so much praise in his later years, at first he, too, had to pass through the fire of criticism and even ridicule. At one time Burne-Jones was ridiculed in the pages of Punch, while in another magazine he was spoken of as the “greenery-yallery Grosvenor-gallery young man.” But these criticisms were soon forgotten, and all England was proud to honor this artist with medals. In 1894 Burne-Jones was given the title of baronet.

Questions about the artist. Tell about the boyhood of Burne-Jones; his education. What kind of subjects did he choose for his paintings? What was his idea of a good painting? Who was his first teacher? Why did he wait so long before he began to study painting? What can you say of his imagination? Tell about William Morris and his new home. What did Burne-Jones do for his friend?

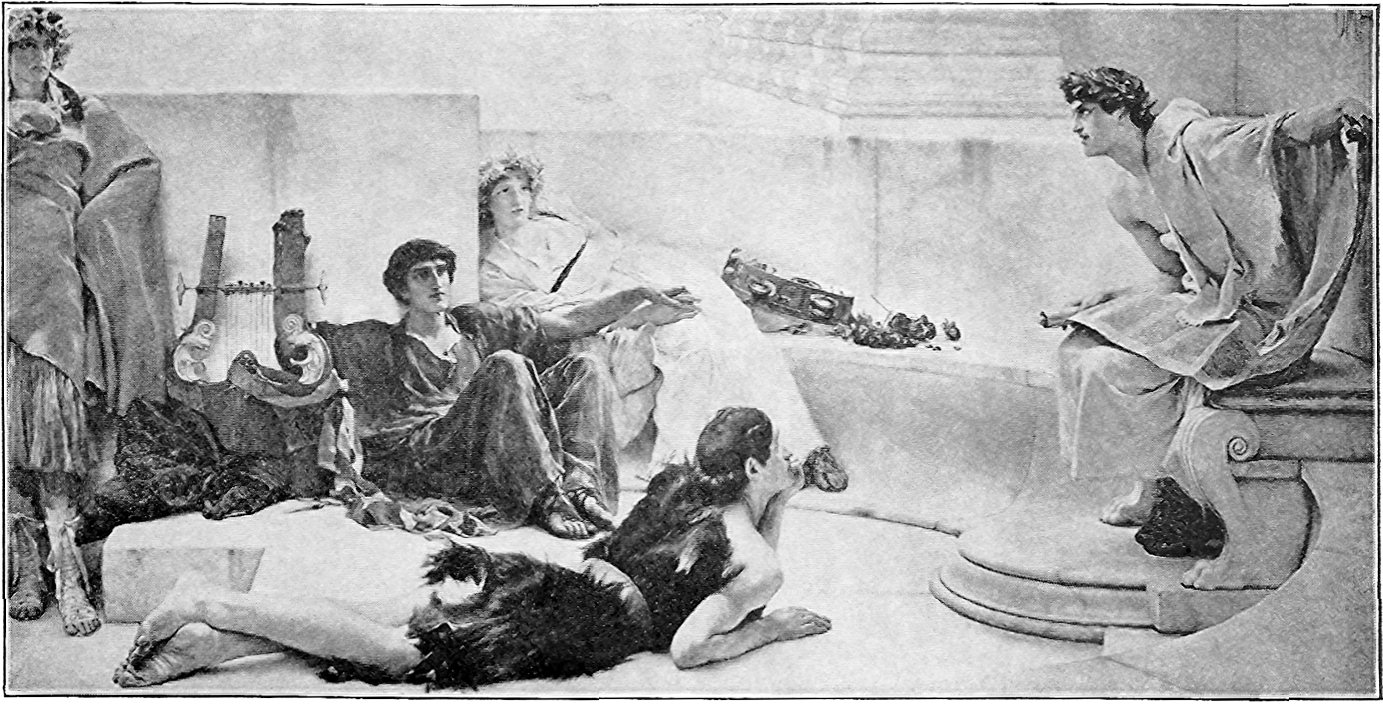

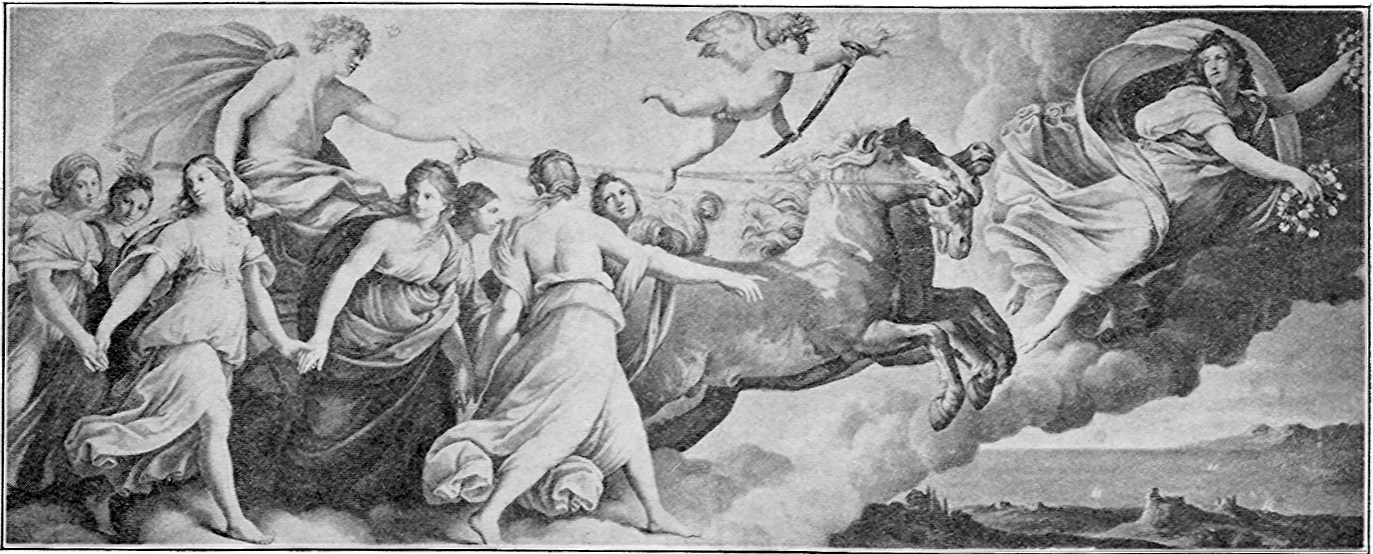

Questions to arouse interest. What goddess does this represent? Whom is she leading? Upon what do they rest? Over what are they passing? What has Aurora in her hands? Toward whom is she looking? In what is Apollo riding? How many horses has he? What has the cherub in his hand? Which way does the flame blow? why? What makes you think they are moving? In what direction do their garments blow? Who painted this picture? Why do you like it?

The story of the picture. Imagine yourself in that far-famed city of Rome, driving through its white streets to the great Quirinal Palace to see the original of our picture. The Quirinal, a very large and very ordinary looking building, has been the scene of many interesting events, and is always used as the meeting place for the cardinals who elect the pope. Our drive ends here, but it is only the beginning of our journey. After a delightful walk through a courtyard so completely surrounded by high stone walls that we should never have guessed its existence, we come to another palace. This palace is much more beautiful, although not so large. It is called the Rospigliosi Palace because it has always belonged to a family of that name. Then we pass on through a beautiful garden of magnolias until we reach the pavilion or casino of the palace, where we find our picture.

There are several rooms in this pavilion, but it is the middle room which holds our attention, for it is up on the ceiling of this room that we see Aurora, goddess of the morning, leading the way for the fiery steeds of Apollo, the sun god. As we enter, such a glow of color fills the room that we know instinctively this must be the place. First, we see Aurora herself, flying ahead, scattering the clouds of night and showering roses and dewdrops over the sleeping earth. She looks back toward Apollo, the sun god, to see if he is following her on his journey around the heavens in his chariot of the sun. The horses are restless and eager and it takes a steady hand to guide them.

Some idea of the difficulties attending such a journey may be gained from the Greek story of Phaëthon. According to this story, Apollo had a son named Phaëthon. One day the boy came to him, complaining that the other boys made fun of him when he told them who his father was. They said they did not believe that a boy who could do nothing at all could be the son of the mighty Apollo. This made the father very angry, and when Phaëthon asked him to let him do something that should prove to the world that he was Apollo’s son, Apollo told the boy he would give him permission to do whatever he asked.

The boy quickly asked permission to drive the sun chariot for one day. But this request alarmed Apollo, who said, “None but myself may drive the flaming car of day,—not even Jupiter, whose terrible right arm drives the thunderbolts.”

He urged his son to take back his request before it was too late, warning him it would prove his destruction. But the boy was only the more anxious to drive, and held his father to his promise.

Then Apollo told Phaëthon of the journey. “The first part of the way,” he said, “is so very steep that, although the horses start out in the best possible condition, they can hardly climb it; the next part is so high up in the heavens that I dare not look down upon the earth and sea below, lest I grow dizzy and fall; the last part of the journey is the most difficult of all, because the road descends rapidly and it is hard to guide the horses. And all this time,” Apollo went on, “the heavens are turning around and carrying the stars with them.”

But even as he spoke, Aurora threw open the cloud curtains which hid the earth, and there appeared the road upon which she cast her roses while beckoning to the eager boy. Hardly listening to his father’s anxious warnings, Phaëthon jumped into the golden chariot, grasped the reins of the four fiery steeds, and off they started.

At first he remembered what Apollo had said, and was careful, but he soon grew reckless, driving at full speed. The horses, knowing it was not their master’s hand, took the bits between their teeth and were soon out of his control. For a time they followed the road, but when that was lost they began to descend toward the earth so rapidly it seemed as if they would be dashed to pieces. Then up again they started in reckless, dizzy flight. At times they came so close to fields and woods as to scorch and blacken them. Other fields they did not pass, and these were frostbitten.

Then a great wail of complaint went up from the earth. This cry was heard by Jupiter, the most powerful of the gods, who, looking earth-ward and discovering the cause of all this trouble, was very angry. With his terrible right arm he drove a thunderbolt at the reckless youth, and in an instant Phaëthon fell from the chariot headlong into the sea. The horses, finding themselves free, returned to Apollo, and never since then has any hand but his been permitted to guide them.

The Greeks declared that the great desert of Sahara in Africa is the place where the sun’s chariot scorched the earth, and that it was then that the African negroes were burned black. Phaëthon’s boy friend, who was constantly diving down into the water trying to recover his body, was turned into a swan, and Phaëthon’s weeping sisters were changed into poplar trees.

In our picture we see Apollo holding the reins, accompanied by the Hours and preceded by Aurora and the cherub torch-bearer or morning star. They seem to be moving rapidly on their way, borne up by the clouds. The sky is a brilliant, golden yellow, and its fleecy clouds are tinged with purple. The graceful figures of the Hours are each represented in pale or brighter-colored draperies according to the time of day to which they belong. Aurora herself is clothed in rainbow hues, her draperies flying with her swift progress. Far below we see the land and sea, wrapped in slumber, awaiting the coming of the dawn.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Where is the original painting of the “Aurora”? What goddess does it represent? What is the Greek myth concerning her? What part has Apollo in this picture? How many horses does he drive? How are the Hours represented? What does the cherub carrying a torch represent? In what direction does the flame of the torch blow? Why is Apollo’s journey so difficult? Who was Phaëthon? What did he ask of Apollo? Why did he wish to do this? Why was Apollo alarmed? Tell about Phaëthon’s journey, and what happened to him. Upon what does the chariot seem to rest? Over what are they passing? What colors did the artist use in this painting?

The story of the artist. Guido Reni was born in the little village of Bologna, Italy. As a small child he gave every promise of becoming an accomplished musician. His father, himself a gifted performer, began to teach him to play the flute and harpsichord as soon as he was old enough to handle the instruments. Guido had a beautiful voice, and the father hoped to make a fine musician of him. But the boy also had a beautiful, sunshiny face which attracted the attention of an artist, who asked permission to paint him as an angel in several pictures. After watching this artist at work, Guido began to wish to paint pictures, too, and was permitted to take a few lessons.

His first picture was a surprise to the artist, causing him to urge Guido’s father to allow the boy to develop his talent. About this time, too, Guido began to make all kinds of interesting figures in clay, and his fingers were always busy.

At thirteen years of age he so excelled the other pupils of the artist that he was allowed to teach some of them.

Later Guido went to Rome, where he remained for twenty years in great favor. He then moved to Bologna and there opened a large school for art students. He made his home in Bologna during the rest of his life. Guido Reni might have lived all his life in splendor and ease, for he earned great sums of money; but as his fame grew he became more and more extravagant in his habits, and so was always in debt. He was obliged to paint hurriedly, and to the utmost of his genius, that he might have more pictures to sell.

However, his keen sense of beauty did not desert him, and his popularity continued to the end. He was especially skillful in representing beautiful upraised faces of women and children. One day a young nobleman met Guido Reni and asked him where he found such lovely models for his paintings. He said the other artists were wondering about it and thought him very selfish to keep them to himself. Guido replied in a mysterious voice, “Come to my studio, signor, and I will show you my beautiful model.” So, filled with delight and eager anticipation, the nobleman tiptoed after the artist up the stairs to the studio. You can imagine how he must have felt when Guido Reni called his color-grinder, who has been described as “a great greasy fellow, with a brutal look,” and posed him.

As the color-grinder sat quietly looking up through the skylight, Guido took a pencil and after sketching very rapidly for a few minutes, showed his guest a sketch of a beautiful Magdalen gazing upward. Then turning to his visitor, he said earnestly, “Dear Count, say to your ‘other artists’ that a beautiful idea must be in the imagination, and in that case any model will serve.”

Guido Reni had the greatest admiration for the paintings of Raphael and went to Rome just to study them.

As he loved to work with clay himself, he spent much of his time in Rome studying the beautiful pieces of statuary there. He tells us that his favorites were the Venus de Medici and Niobe.

Pleasant and courteous to all, he made friends everywhere and was greatly beloved. Once when he was very ill his friends hired musicians to play just outside his door. This pleased him greatly, as he was always passionately fond of music. He said to them, “And what, then, will be the melodies of Paradise?”

Guido Reni was a great favorite of Pope Paul V and many of his pictures were painted for the Pope. When he returned from Rome to Bologna, he found himself more popular than ever and quite overwhelmed with orders for pictures.

Of all his paintings, the “Aurora” is generally considered his best. The story is told of a little girl who had lived all her life in the country. Upon her first visit to her uncle in the city, she discovered a large and splendid copy of the “Aurora” in his living room. One morning her uncle came into the room and found his little niece gazing at the picture in rapt admiration.

“Well, Mary,” he said, “what do you think of it?”

“Oh, uncle,” she replied, “I like it ‘cause they are in such a hurry.”

So young and old have found one reason or another for liking this picture.

Guido Reni painted many portraits as well as many historical and mythological pictures. Some of the best known of Guido’s paintings are: “Reclining Venus with Cupid,” “St. Michael and the Dragon,” “Beatrice Cenci,” “Little Bacchus Drinking,” and “The Mater Dolorosa of Solimena.”

Questions about the artist. Where was the artist born? What two talents had he? How did he happen to study painting? How did he succeed with his first picture? What was his progress? Why was he never rich? What subjects did he choose? What did the young nobleman ask him? Tell of the nobleman’s visit to the artist’s studio. Whose paintings did Guido Reni admire greatly? What statues? How was he able to make so many friends? What was his masterpiece? What did the little country girl say about it? Name some of his paintings.

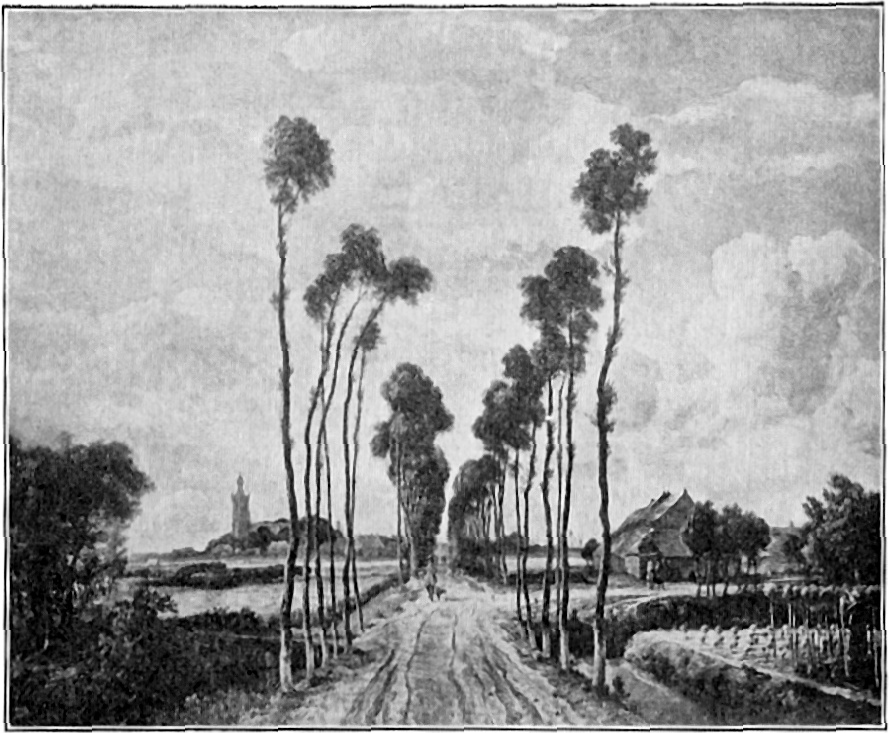

Questions to arouse interest. What occupies the most important part of this picture? Describe the trees bordering the road. Where does the road lead? What does it pass on its way to the village? Where must the artist have been standing? why do you think so? What can you say about the perspective of this road? How much of this picture is sky? What kind of lines predominate—curved, straight, vertical, or horizontal? In what country do you think it is? Why is it so level? What are the people in the picture doing? What do you like best about this picture?

The story of the picture. There is a little village in the Netherlands by the name of Middelharnis, and if we should go there to-day we should find just such an avenue of trees as this one in our picture. The artist, Hobbema, spent many years in this village, painting scenes in and around it. Probably he traveled over this very road countless times. It would seem as if we, too, were walking down the road guarded by those tall, slender trees which border each side of it. They are poplar trees, trimmed so high that we scarcely recognize them. They lead direct to the little village beyond, which we see between the tree trunks.

Since the village is almost surrounded by the North Sea, its high church tower is not only picturesque by day but useful at night as a lighthouse or beacon to guide the sailor to a safe port.

In our picture the sun is half hidden in a sky as full of fleecy clouds as the sky near the North Sea generally is.

We must expect no hills nor elevations of any kind in the Netherlands, a land lying lower than the ocean. The great protecting dikes and the many canals extending in every direction make it one of the most interesting of countries.

In the picture we see on each side of the road a deep ditch full of water. These ditches irrigate the land, flowing into deeper, wider canals on which sail boats of various sizes and kinds.

It is said that every true Hollander can skate. In the winter, when these canals are frozen, young and old go about upon their various errands on skates. It is a common sight then to see women skating to market, carrying upon their heads heavy baskets filled with rolls of butter, cheese, eggs, or other provisions. The children skate to school, and men go about their business in this same pleasant way. It is easy to reach all parts of the village or city by these canals, for there are so many of them; in some cities the people have no streets, but use canals instead.

At the right of our picture we catch a glimpse of a thrifty, well-kept nursery garden full of shrubs and fruit trees, which the man is busily trimming. He works contentedly, for all about him he sees the evidences of prosperity and peace.

Coming toward us along this straight and level road is a huntsman carrying his gun over his shoulder and preceded by his dog. A path leads away from the road to the picturesque little cottage or farmhouse at the right. Two peasants, a man and a woman, stand in the path talking. We do not doubt they will turn to greet our hunter, for it is a friendly countryside, where all are treated cordially.

We cannot see much on the extreme left of the picture except the trees which grow luxuriantly, and a flat meadow land which reaches almost to the village. It is a common, everyday sort of landscape, yet its charm seems to lie in this very fact.

We would know at once if the perspective were not correct, for we have solved just such problems ourselves with the tree tops, or perhaps telegraph poles, and it gives us an added sense of pleasure to be able to understand just the problem Hobbema had to solve as he placed his easel in the middle of the road and started to paint his great canvas.

The light is rather uncertain on this cloudy day. The artist used little color except grays and a peculiar green which he delighted in using in all his paintings. A touch of brighter color appears in the cheerful red of the roofs of his houses, which suggest something of the homely comfort and cleanliness that may be found in most Dutch homes.

The most striking characteristic of Hobbema’s painting is his severe combination of vertical and horizontal lines. The positive vertical lines of the tree trunks standing so tall and straight against the wide expanse of sky are reëchoed in the shorter but equally slender trunks of the fruit trees in the nursery garden, and of the trees at the side of the path leading to the farmhouse; also in the two straight figures standing in the path, and again in the church tower in the distance.

The horizontal lines are equally positive. They separate the garden from the road; they appear in the road itself, and in the horizon line beyond. If we make a sketch of the important lines in this picture, we find them either vertical or horizontal, and much more severe in outline than the usual diagonal or curving lines we have grown accustomed to looking for.

Critics seem to vary as to the feeling with which this picture inspires them, although all agree upon its value as a masterpiece. Some declare there is a sort of hopelessness in the landscape which suggests the unhappy life of the artist, who often went hungry, and whose paintings were not appreciated until after his death. To them the scene is full of hopeless beauty, suggesting all kinds of joys which are never realized, yet continue just out of reach throughout a long and cheerless life. So it is a sad beauty, and gives one a feeling of desolation even in a land where all is prosperity.

Other critics see only the thrifty, contented life of the Netherlands peasant, who by his intelligence and labor has overcome even the sea itself, and compelled it, by means of dikes and canals, to add to his safety and comfort.

We know how much Hobbema must have loved his work, for he received no return for it during his lifetime, unless it was the joy of work; and yet he persevered.

Can we not imagine him on a pleasant day, seated or standing at his easel in the middle of this road, quite forgetting poverty and even hunger, as he painted this beautiful landscape before him? Hobbema was certainly daring and full of courage when he attempted so severe and unusual a composition as this. He has placed his road almost exactly in the center of the picture, balancing the sides quite evenly, yet he has not made it monotonous or tiresome. The eye is constantly discovering new beauties in the landscape or the inclosing sky. Only a master could produce a work such as this.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. What country is represented in this picture? What kind of trees are those bordering the road? To what do they lead the eye?

Of what use could the church tower, in the distance, be? Why is the Netherlands such a level country? What can you see on each side of the road? Of what use are the canals? What is the man doing in the garden? Who else can you see in the picture? What colors did the artist use? How can you tell whether the perspective of the road is correct or not? What can you say of the sky? What can you say of the balance in the composition? the kinds of lines? What kind of a day is represented? What do some of the critics say about this picture? What is so unusual about this composition? Why do most artists avoid placing the center of interest in the middle of the picture? Why do you like this picture?

The story of the artist. We know very little about the artist, Meyndert Hobbema, except that he was a Hollander possessing so great a love for his native land that he continued to represent it on canvas in spite of the fact that his countrymen were quite indifferent to him and his work. His pictures were disposed of somehow, perhaps given away, for when a hundred years after his death the world suddenly began to value them, it was found that he had left enough canvases to have made him the wealthiest man in the country. Yet he died in the almshouse, and was buried beside his wife in a pauper’s grave. Now all the Netherlands would give him honor, but so neglected was he during his life that it is impossible to find out even where he was born. Three cities claim this honor, but it is generally conceded that he was born at Amsterdam. It is certain he was married and died there. We determine the date of his birth by the date and his age as given in the record of his marriage.

Hobbema’s paintings were so real that the people, who were used to more fanciful, idealized pictures, thought his commonplace and of no especial interest. Now they recognize the great sympathy with, and insight into, the very life of their country which Hobbema possessed in rare measure. He made it real to us, too, in his scenes of thrift and industry, prosperity, and smiling peace.

We are told that Hobbema was “a plain, practical, matter-of-fact” man and his pictures make us think he must have been. Like him, they are plain, unassuming, and natural; free from artificial grace or fancy. He did not hunt for scenes of unusual beauty with romantic or weird stories, but chose some pleasing view near at hand and painted it just as it was.

Sometimes he painted the same scene several times from exactly the same position. If all his works could be placed in one gallery for exhibition, we might find it rather monotonous to see so many just alike.

But although he did not have the inventive genius of Burne-Jones or of many other artists, his paintings were always true to nature. He has been called the painter of the afternoon sun because he seemed so fond of the sunlight showing through the trees and casting long shadows across the fields.

Many believe that Hobbema must have been a pupil of Ruysdael’s because their work was so much alike. We know that they lived in the same place at the same time and it is generally believed they were friends. Dealers often substituted the name of one for that of the other and later, when corrections were attempted, it was impossible to tell which was Hobbema’s work and which Ruysdael’s, because both had painted the same subjects.

At one time Hobbema was appointed gauger for the town. It was his duty to measure the quantity of all liquids imported into Holland. This position must have paid a fairly good salary, for Hobbema was married directly after his appointment. It must have taken all his time, too, for he painted very little for nearly twenty years. The fact that he had a means of livelihood did not spur him on to greater efforts. He painted only when he felt like it, not very often, and small, unimportant pictures. Whether he lost this office before or after his wife’s death is not known, but for some reason or other his last years were spent in extreme poverty.

Twenty-six years after his death his pictures began to sell, and soon picture dealers were scouring the country for his works.

His landscapes are not full of people, animals, or anything that might disturb the calm, quiet restfulness of the scenes. Like Ruysdael, he too was compelled to call upon other artists to draw the few figures he did use, as he found this part most difficult.

One thing we may be sure of when we look at his paintings, and that is, they were faithful representations of the place before him. So we may know just how this road leading to the village of Middelharnis really looked more than two centuries ago.

Other famous paintings by Hobbema are entitled: “Showery Weather,” “Village with Water Mills,” “Woody Landscape,” “Ruins of Brederode Castle,” “Forest Scene,” “Cottage in a Wood,” and “Entrance to a Wood.”

Questions about the artist. What kind of a man do you think Hobbema must have been? Why? In what ways do his pictures resemble him? What kind of pictures did he like to paint? What time of day? Why might an exhibition of all his paintings prove monotonous?

What would you consider one of the best things about his paintings? What other great artist lived at this time and in the same place? How did their paintings resemble each other? What office did Hobbema hold? What were some of his duties? How did this position affect his work? What became of his paintings? Why was he so poor? Why were his paintings not appreciated? How are they regarded now? Why do you think Hobbema must have loved his work?

By Permission of Braun & Co., Paris and New York

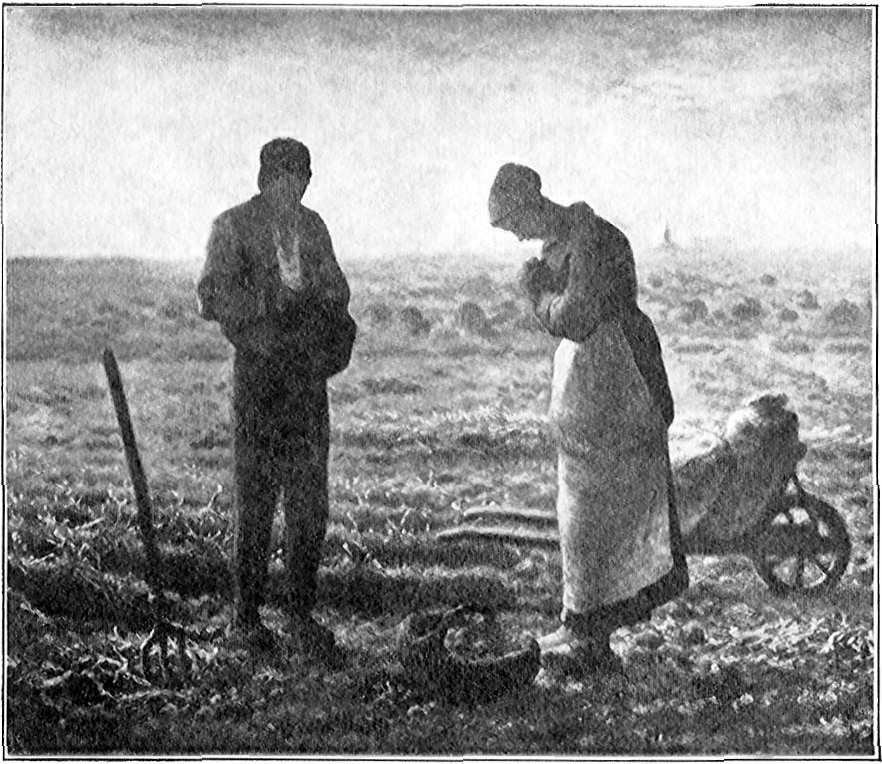

Questions to arouse interest. In what attitude are these peasants standing? What have they been doing? With what have they been working? What can you see in the background? From what direction does the light come? What time of day do you think it is? in what country? Why have they stopped their work? Who of you can tell what the Angelus is? What feeling does this picture give you—one of sadness, peace, quiet, noise prosperity, poverty, or happiness?

The story of the picture. Although our print is only black and white, we are made to feel the brightness of the sunset in this picture. The horizon, veiled in a haze, shows the church tower of the distant village faintly silhouetted against the sky, while the sinking sun casts its long shadows across the field. But our eyes do not dwell long on sky, church, or field, for the two figures draw our gaze. The bright rays from the setting sun fall directly upon the woman, who faces the west; the man, turning toward her, is partly in shadow.

No doubt these two peasants have been working in the fields, the man digging potatoes, as we may judge by those in the basket and the two well-filled bags on the wheelbarrow. As he digs them, the woman gathers them up in her basket and empties them into the sacks. Thus busily engaged, they suddenly hear the church bell; its great tone coming far across the field reminds them that it is the hour of prayer. So putting down the pitchfork and basket, they stand with bowed heads as they repeat the evening prayer.

The artist wished to paint a picture that would make us hear the bell sounding clearly across the deep stillness of the open field. He wished to make us feel, as do these peasants, the quiet solemnity of the hour.

Even as a little boy Millet was greatly impressed by the sound of the Angelus, or bell for prayers, which was rung each morning, noon, and night. One of his earliest remembrances was of a time when the villagers bought new bells for the church, and he went with his mother and a neighbor to see them before they were hung. It seems that two of the old bells had been used to make a cannon, the third was broken, and these new bells were in the church waiting to be baptized before they could be hung in the tower. They seemed immense to the small boy, and of course they must have been larger than he. Millet tells of the delight and awe he felt when the neighbor struck the bells with the great key to the church door, which she carried in her hand.

No wonder, then, that this picture was one of Millet’s favorites, for it reminded him of his boyhood home and brought back memories of the thoughts and experiences of his childhood. Grown to manhood, and himself a peasant, he, too, had heard the Angelus sounded forth from the village church tower, and had dropped his work to bow his head in prayer. The quiet and peace of such moments had left a deep impression which he wished to share with us.

The long stretch of field suggests the industry of the peasants; the distant church and their bowed heads against the bright sky tell us of their faith.

Can you not see them on their homeward journey, the man pushing the wheelbarrow with its heavy load, while the woman carries the basket? It looks as if it would be a long, tiresome tramp across the uneven field to the village so dimly visible in the distance.

This is the time of year when the peasants’ work is hardest, for during the winter there is little farm work to do. We are told that the women spend their winter days in spinning, weaving cloth, and making clothes, while the men weave baskets, make their garden tools, and do what little work there is to do.

The very simplicity of this landscape, with its lack of details, is part of its great charm. The quiet dignity of the man and woman, standing with bowed heads, the peace and quiet of the scene, and, above all, the sound of the sweet-toned Angelus, give us a feeling of restfulness and peace.

The horizon line is high in this picture, yet the sky space is large enough to contain the heads and shoulders of our two peasants. In this way we are made to feel that although they are bound to earth and are a part of it, their thoughts soar higher. There is another life besides the one of toil and privation.

At the time Millet painted this great picture he was wretchedly poor. He sent the picture to a friend in Paris, begging him to sell it and send the money as soon as possible. It sold for less than five hundred dollars. Yet not many years ago a French collector paid one hundred and fifty thousand dollars for this same picture.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. What time of day does this picture represent? What can you see in the distance? In what direction is the woman facing? How can you tell? What have these peasants been doing? Why have they stopped their work? Why is the picture called “The Angelus”? Tell about Millet and the new bells for the church. Tell something of the life of these peasants. How did the artist Millet know so much about their life? What can you say about the composition of this picture? What was the financial condition of the artist when he painted this picture? What did he do with this painting? About how much is it worth now?

The story of the artist. Let us try to imagine the artist, Jean François Millet, as a young man nineteen years old on his first visit to the great city of Paris. Brought up on a farm among the lowliest of the French peasants, he had met few except those with whom he labored in the fields or those who, poorer than they, were made welcome under the ever hospitable roof of the elder Millets. These neighbors and friends were mostly sailors or farmers, who looked upon the journey to Paris as a great event, as indeed it was. For weeks the kind old grandmother had kept her spinning wheel busy, spinning and weaving the cloth for his new suit of clothes. She was the tailor who cut, stitched, and pressed them. All her savings of years had been sewed into a belt and given to him for this journey. As he stood in the doorway, waiting for the old stagecoach which presently came rattling down the stone road of the village, he must have felt anew the great sacrifices they were all so willing to make to send him where he could study his beloved art.

In Paris, Millet presented an unusual appearance—six feet in height, slender, a downy beard on his face, his brown hair hanging to his shoulders. All his belongings were neatly packed in the sailor’s canvas bag which he carried over his shoulder. Is it any wonder that many did not see the straightforward, honest, manly look of the calm gray eyes? There was in that gaze and in the rude bearing a certain quiet confidence and strength which only the home folks recognized and valued. The boy could draw, and draw well they knew, and had not the drawing master of the village told them he would surely one day become a great artist?

Tired from the three days’ ride in the old stagecoach, jostled by the hurrying crowds, for it was evening and all were on their way home, he stood confused. A policeman, catching sight of the stupid-looking youth blocking the sidewalk with his great bag, asked him where he wanted to go. Is it any wonder that he answered, “Back to Gruchy”? We are told that he even inquired when the next coach left for Gruchy, but there was none until morning.

The policeman sent him to a boarding house of moderate prices, and the next morning he started out to find the great art gallery of the Louvre. He had attempted to inquire the way at the boarding house, but the boarders laughed at his Normandy accent and strange appearance and he did not wait for the answer. And so he wandered the streets for three days, not daring to ask the way for fear of being laughed at again, until at last he stood before the great gallery, recognizing it at once by the pictures he had seen of it.

In writing of it years later, Millet says: “My feelings were too great for words, and I closed my eyes lest I be dazzled by the sight, and then dared not open them lest I should find it all a dream. And if I ever reach Paradise I know my joy will be no greater than it was that first morning when I realized that I stood within the Louvre Palace.”

In the meantime he had found a room and place to board near by. The landlady having suggested that he had better not carry much money about with him, he immediately gave her all he had to keep for him; that was the last he saw of his money.

He spent a week just visiting the Louvre, and finally became acquainted with a student who was copying one of the paintings. This student took him to the artist Delaroche, who, after looking at his sketches, gladly admitted him as a pupil.

The other students were greatly amused at Millet’s awkward appearance and called him the “man of the woods.” It was almost impossible to persuade him to talk, and his answers to all questions were in monosyllables; but if pressed too hard he could use his fists effectively. They soon found out, too, that he could paint, and paint well. All idea of going home was given up, and Millet spent twelve years in Paris, enduring poverty and hunger but working faithfully and long. When he went back to his home for a visit he was so nearly starved that he fell fainting on the ground when he tried to work in the fields.

Millet painted landscapes, portraits, and signs, but fortune never seemed to smile on him long at a time. People said his pictures did not sell because he painted such common things and such poor people instead of choosing beautiful girls or fine gentlemen for his models.

But he painted the people he knew about and loved best—the French peasants—and as their lives were full of toil, he must represent them at their labor.

Returning to Paris, and finding his life there still one of continuous struggle with poverty, Millet with his wife and children went to live at Barbizon, a small village a day’s ride from Paris. Many descriptions have been written and pictures painted of the modest white stone cottage with its clinging vines and its thrifty gardens in which he spent the rest of his life.

It was not until the last few years of his life that he ceased to be wretchedly poor, for then at last his pictures were appreciated and he received the profit and honor that were his due.

He died at Barbizon, January 20, 1875.

Questions about the artist. Tell about Millet’s early training and the preparations made for his journey to Paris. How did he travel? Describe his first evening in Paris. How did he find the great gallery of the Louvre? Why did he not inquire the way? What became of his money? With whom did he study, and how did this happen? What did the other students call him? Why did they do this? How many years did he stay in Paris? What was his success there? Why did his pictures not sell? Where did he finally go to live? When were his paintings appreciated?

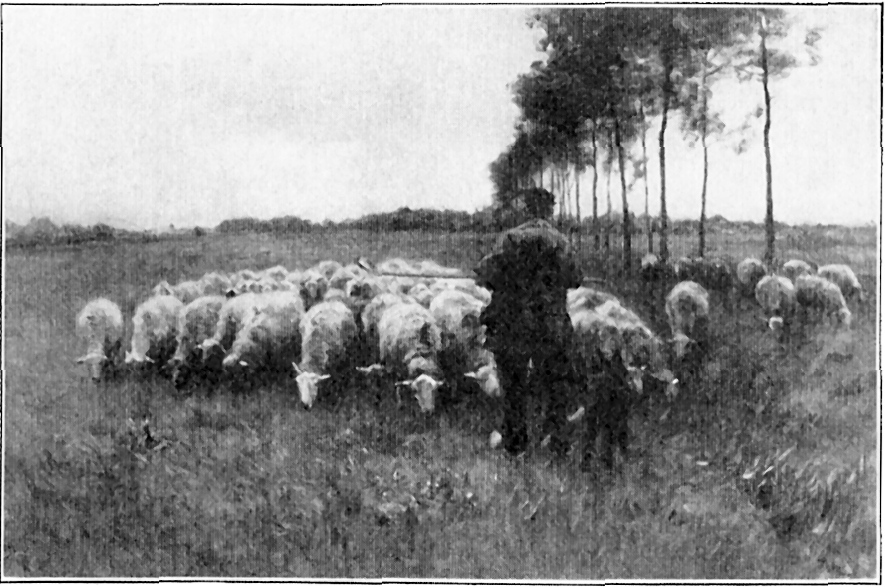

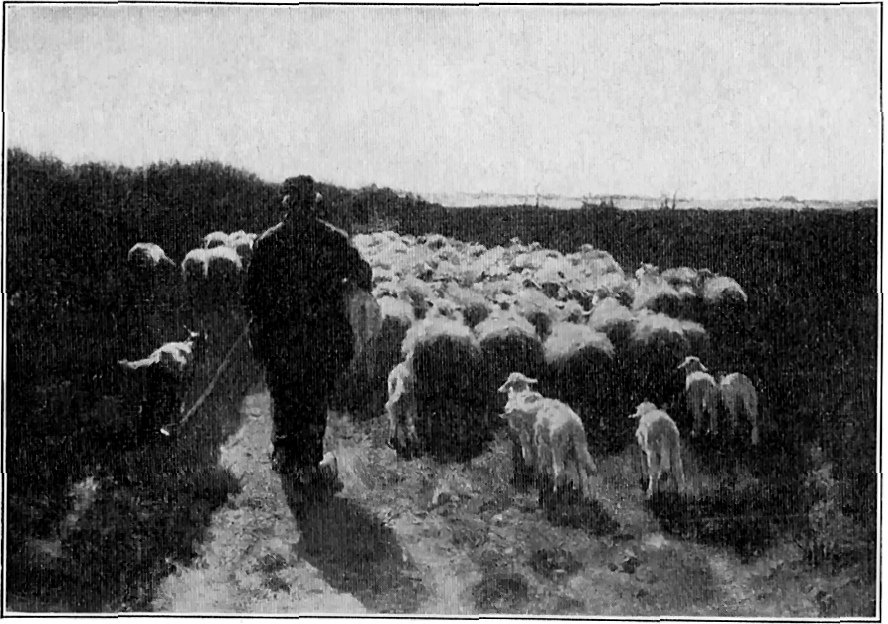

Questions to arouse interest. What is there in this picture that suggests the time of year? What are the sheep doing? How many have watched sheep eat grass? Why do the shepherd and his dog stand in front of them? Of what use is the shepherd’s crook or staff? What do you see in the distance? Do you think this is a scene in our own country or in some foreign country? How are the sheep farthest away represented? Where does the light fall upon the sheep and upon the man? What kinds of lines are there in this picture? Tell some of the duties of a shepherd; of a shepherd’s dog. Why do sheep need so much care? Of what use are they? Why do you like this picture?

The story of the picture. The artist has taken us to his own native country, showing us the beauties of the fields in spring, and giving us much of their feeling of calm and contentment. The shepherd has led his sheep safely past the freshly plowed field which we see at the left of the picture, and now he stands in front of them so they will go more slowly and eat the grass closer. If one of the sheep should go too fast he would probably reach out with his long crook, which he would place around the sheep’s neck, and draw it back. The dog, too, would do his part to keep it where it ought to be. Sheep prefer to run ahead, taking a bit of grass here and a bit there, but when they are held back by the man and dog as in this picture, they will mow the grass as closely and thoroughly as if a lawnmower had passed over it.

As we look at the picture we find that, though few details are shown, the sheep in the first row are distinct, while the rest are merely suggested. Anton Mauve has become famous for this very thing—the omission of minor details in his pictures and the simplicity with which he thus tells his story.

We feel the warmth and vigor of this beautiful day in spring, the fresh green grass with here and there a flower to relieve the green, the soft green leaves of the young and slender trees planted on each side of the road at the right of the picture. This road probably leads direct to the farmhouse we see in the distance. The long meadow, too, seems to reach as far as that same farmhouse, and no doubt will provide pasture all summer for the sheep. Their fleecy white wool will grow long. Then will come sheep-shearing time, and the wool will be sent away to be woven into cloth.