Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

By FRANK T. BULLEN.

Deep-Sea Plunderings. 12mo. Cloth, $1.50.

The Apostles of the Southeast. 12mo. Cloth, $1.50.

The Log of a Sea-Waif. Being Recollections of the First Four Years of My Sea Life. Illustrated. 12mo. Cloth, $1.50.

Idylls of the Sea. 12mo. Cloth, $1.25.

The Cruise of the Cachalot. Round the World After Sperm Whales. Illustrated. 12mo. Cloth, $1.50.

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY, New York.

DEEP-SEA

PLUNDERINGS

BY

FRANK T. BULLEN, F. R. G. S.

AUTHOR OF “THE CRUISE OF THE CACHALOT,”

“THE APOSTLES OF THE SOUTHEAST,” ETC.

With Eight Illustrations

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1902

Copyright, 1901

By FRANK T. BULLEN

All rights reserved

Published March, 1902

TO

Dr. ROBERTSON NICOLL

A SMALL BUT SINCERE

TRIBUTE OF AFFECTION AND ESTEEM

F. T. B.

vii

Warned by previous experience, I do not propose to make any apology for the publication of these stories in book form, but I hope my generous critics will at least pardon me for expressing my gratitude for the way in which they have received all my previous efforts. Naturally, I sincerely hope they will be equally kind in the present instance.

F. T. Bullen.

New Bedford, Mass., September, 1901.

ix

| PAGE | |

| Through Fire and Water | 1 |

| The Old House on the Hill | 17 |

| You Sing | 53 |

| The Debt of the Whale | 93 |

| The Skipper’s Wife | 117 |

| A Scientific Cruise | 127 |

| A Genial Skipper | 141 |

| Mac’s Experiment | 157 |

| On the Vertex | 169 |

| A Monarch’s Fall | 179 |

| The Chums | 189 |

| Alphonso M’Ginty | 199 |

| The Last Stand of the Decapods | 211 |

| The Siamese Lock | 235 |

| The Cook of the Cornucopia | 259 |

| A Lesson in Christmas-Keeping | 269 |

| The Terror of Darkness | 279 |

| The Watchmen of the World | 289 |

| The Cook of the Wanderer | 297 |

| The Great Christmas of Gozo | 307 |

| Deep-Sea Fish | 319 |

| A Mediterranean Morning | 329 |

| Abner’s Tragedy | 335 |

| Lost and Found | 347 |

xi

| FACING PAGE |

|

| They met in full career, rolling each over each | Frontispiece |

| The toiling men were breaking out the junk’s cargo | 60 |

| Gently she covered their ruddy faces | 121 |

| The skipper produced from his hip-pocket a revolver | 163 |

| He gasped “In manus tuas, Domine,” and fell | 208 |

| He clutched his insulter by the beard and belt | 263 |

| She was to him brightest and best of all damsels | 309 |

| A huge sailing-ship crushed her into matchwood | 353 |

1

“What a clumsy, barrel-bellied old hooker she is, Field!”

Thus, closing his telescope with a bang, the elegant chief officer of the Mirzapore, steel four-masted clipper ship of 5000 tons burden, presently devouring the degrees of longitude that lay between her and Melbourne on the arc of a composite great circle, at the rate of some 360 miles per day. As he spoke he cast his eyes proudly aloft at the splendid spread of square sail that towered upward to a height of nearly 200 feet. Twenty-eight squares of straining canvas, from the courses, stretched along yards 100 feet or so in length, to the far-away skysails of 35 feet head, that might easily be handled by a pair of boys.

Truly she made a gallant show—the graceful ship, that in spite of her enormous size was so perfectly modelled on yacht-like lines that, overshadowed as she was by the mighty pyramid of sail, the eye refused to convey a due sense of her great capacity. And the way in which she answered the challenge of the west wind, leaping lightsomely over the league-long ridges of true-rolling sea, heightened the illusion2 by destroying all appearance of burden-bearing or cumbrousness. But the vessel which had given rise to Mr. Curzon’s contemptuous remark was in truth the antipodes of the Mirzapore. There was scarcely any difference noticeable, as far as the contour of the hull went, between her bow and stern. Only, at the bows a complicated structure of massive timbers leaned far forward of the hull, and was terminated by a huge “fiddle-head.” This ornament was carved out of a great balk of timber, and in its general outlines it bore some faint resemblance to a human form, its broad breast lined out with rude carving into some device long ago made illegible by the weather; and at its summit, instead of a head, a piece of scroll-work resembling the top of a fiddle-neck, and giving the whole thing its distinctive name.

The top-hamper of this stubby craft was quite in keeping with her hull. It had none of that rakish, carefully aligned set so characteristic of clipper ships. The three masts, looking as if they were so huddled together that no room was left to swing the yards, had as many kinks in them as a blackthorn stick; and this general trend, in defiance of modern nautical ideas, was forward instead of aft. The bow-sprit and jibboom looked as if purposely designed by their upward sheer to make her appear shorter than she really was, and also to place her as a connecting link between the long-vanished galleasses of Elizabethan days and the snaky ships of the end of the nineteenth century. In one respect, however, she had the advantage of her graceful neighbour. Her sails were of dazzling whiteness,3 and when, reflecting the rays of the sun, they glistened against the deep blue sky, the effect was so fairy-like as to make the beholder forget for a moment the ungainliness of the old hull beneath.

The wind now dropped, in one of its wayward moods, until the rapid rush past of the Mirzapore faltered almost to a standstill, and the two vessels, scarcely a mile apart, rolled easily on the following sea, as if in leisurely contemplation of each other. All the Mirzapore’s passengers, a hundred and twenty of them, clustered along the starboard poop-rail, unfeignedly glad of this break in what they considered the long monotony of a sailing passage from London to the colonies. And these seafarers of fifty-five days, eagerly catching their cues from the officers, discussed, in all the hauteur of amateur criticism, the various short-comings of the homely old tub abeam. Gradually the two vessels drew nearer by that mysterious impulse common to idly-floating things. As the different details of the old ship’s deck became more clearly definable, the chorus of criticism increased, until one sprightly young thing of about forty, who was going out husband-seeking, said—

“Oh, please, Captain James, do tell me what they use a funny ship like that for.”

“Well, Miss Williams,” he replied gravely, “yonder vessel is one of the fast-disappearing fleet of Yankee whalers—‘spouters,’ as they love to term themselves. As to her use, if I don’t mistake, you will soon have an object-lesson in that which will give you something to talk about all the rest of your life.”

4

And as he spoke an unusual bustle was noticeable on board of the stranger. Four boats dropped from her davits with such rapidity that they seemed to fall into the sea, and as each struck the water she shot away from the side as if she had been a living thing. An involuntary murmur of admiration ran through the crew of the clipper. It was a tribute they could scarcely withhold, knowing as they did the bungling, clumsy way in which a merchant seaman performs a like manœuvre. Even the contemptuous Curzon was hushed; and the passengers, interested beyond measure, yet unable to appreciate what they saw, looked blankly at one another and at the officers as if imploring enlightenment.

With an easy gliding motion, now resting in the long green hollow between two mighty waves, and again poised, bird-like, upon a foaming crest, with bow and stern a-dry, those lovely boats sped away to the southward under the impulse of five oars each. Now the excitement on board the Mirzapore rose to fever-heat. The crew, unheeded, by the officers, gathered on the forecastle-head, and gazed after the departing boats with an intensity of interest far beyond that of the passengers. For it was interest born of intelligent knowledge of the conditions under which those wonderful boatmen were working, and also tempered by a feeling of compunction for the ignorant depreciation they had often manifested of a “greasy spouter.” Presently the boats disappeared from ordinary vision, although some of the more adventurous passengers mounted the rigging, and, fixing themselves5 in secure positions, glued their eyes to their glasses trained upon the vanishing boats. But none of them saw the object of those eager oarsmen. Of course, the sailors knew that they were after whales; but not even a seaman’s eye, unless he be long-accustomed to watching for whales, possesses the necessary discernment for picking up a vapoury spout five or six miles away, as it lifts and exhales like a jet of steam against the broken blue surface. Neither could any comprehend the original signals made by the ship. Just a trifling manipulation of an upper sail, the dipping or hoisting of a dark flag at the mainmast head, or the disappearance of another at the gaff-end sufficed to guide the hunters in their chase, giving them the advantage of that lofty eye far behind them.

More than an hour passed thus tantalizingly on board the Mirzapore, and even the most eager watchers had tired of their fruitless gazing over the sea and at the sphinx-like old ship so near them. Then some one suddenly raised a shout, “Here they come!” It was time. They were coming—a-zoonin’, as Uncle Remus would say. It was a sight to fire the most sluggish blood. About five hundred yards apart two massive bodies occasionally broke the bright surface up into a welter of white, then disappeared for two or three minutes, to reappear at the same furious rush. Behind each of them, spreading out about twenty fathoms apart, came two of the boats, leaping like dolphins from crest to crest of the big waves, and occasionally hidden altogether by a curtain of spray. Thus they passed the Mirzapore, their gigantic steeds6 in full view of that awe-stricken ship’s company, privileged for once in their lives to see at close quarters one of the most heart-lifting sights under heaven—the Yankee whale-fisher at hand-grips with the mightiest, as well as one of the fiercest, of all created things. No one spoke as that great chase swept by, but every face told eloquently of the pent-up emotion within.

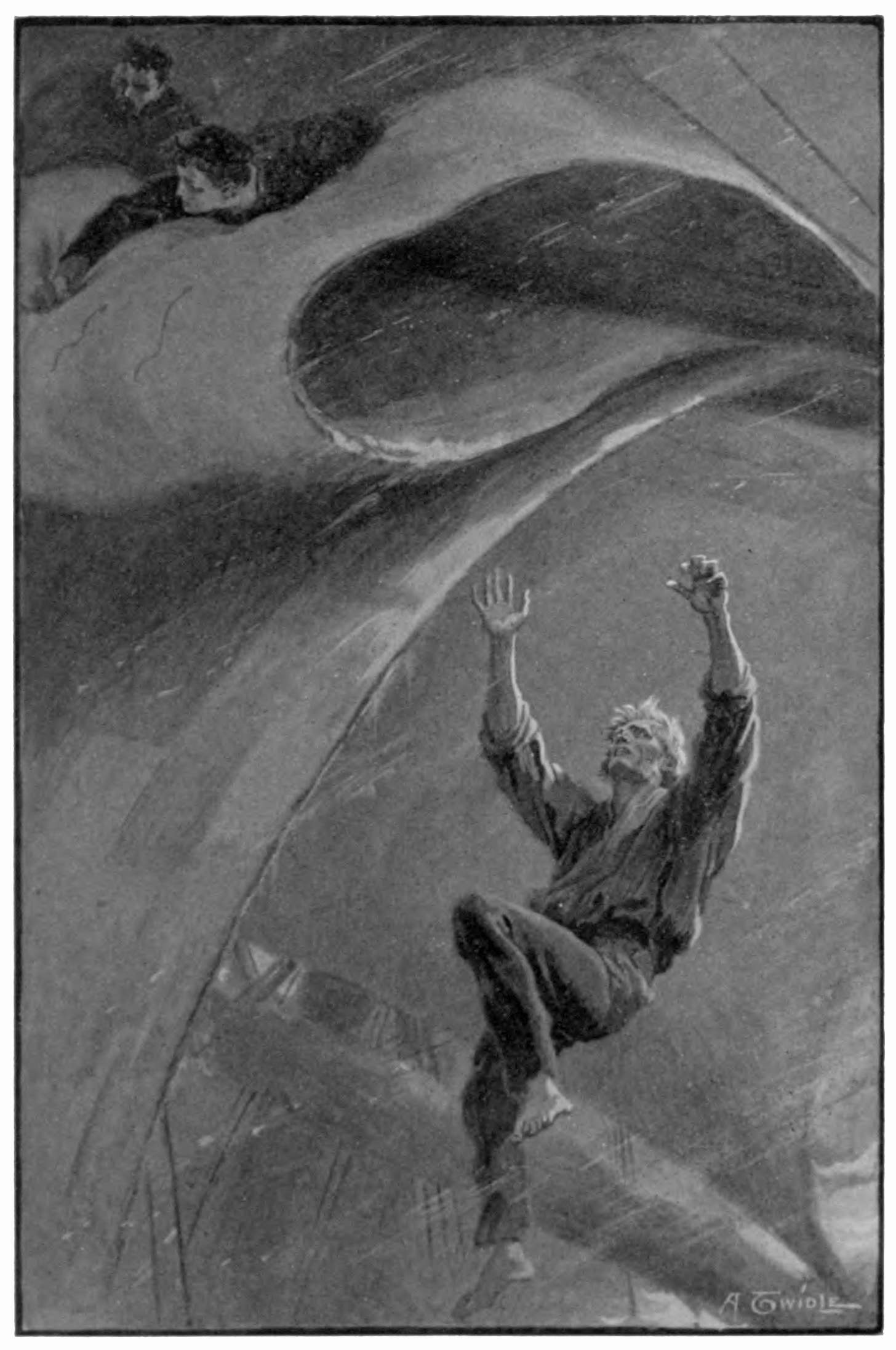

Then a strange thing happened. The two whales, as they passed the Mirzapore, swerved each from his direct course until they met in full career, and in a moment were rolling each over each in a horrible entanglement of whale-line amid a smother of bloody foam. The buoyant craft danced around, one stern figure erect in each bow poising a long slender lance; while in the stern of each boat stood another man, who manipulated a giant oar as if it had been a feather, to swing his craft around as occasion served. The lookers-on scarcely breathed. Was it possible that men—just homely, unkempt figures like these—could dare thrust themselves into such a vortex amongst those wallowing, maddened Titans. Indeed it was. The boats drew nearer, became involved; lances flew, oars bent, and blood—torrents of blood—befouled the glorious azure of the waves. Suddenly the watchers gasped in terror, and little cries of pain and sympathy escaped them: a boat had disappeared. Specks floated, just visible in the tumult—fragments of oars, tubs, and heads of men. But there was no sound, which made the scene all the more impressive.

Still the fight went on, while the spectators forgot all else—the time, the place; all senses merged in wonder7 at the deeds of these, their fellow-men, just following, in the ordinary way, their avocation. And the thought would come that but for an accident this drama being enacted before their eyes would have had no audience but the screaming sea-birds hovering expectantly in the unheeding blue.

The conflict ceased. The distained waters became placid, and upon them floated quietly two vast corpses, but recently so terrible in their potentialities of destruction. By their sides lay the surviving boats—two of them, that is; the third was busy picking up the wrecked hunters. And the old ship, with an easy adaptation of her needs to the light air that hardly made itself felt, was gradually approaching the scene. The passengers implored Captain James to lower a boat and allow them a nearer view of those recently rushing monsters, and he, very unwillingly, granted the request. So slow was the operation that by the time the port lifeboat was in the water the whaler was alongside of her prizes, and all her crew were toiling slavishly to free them from the entanglement of whale-line in which they had involved themselves. But when the passengers saw how the lifeboat tumbled about alongside in the fast-sinking swell, the number of those eager for a nearer view dwindled to half a dozen—and they were repentant of their rashness when they saw how unhandily the sailors manipulated their oars. However, they persisted for very shame’s sake, their respect for the “spouters’” prowess, and, through them, for their previously despised old ship, growing deeper every moment. They hovered about the old8 tub as they saw the labour that was necessary to get those two enormous carcases alongside, nor dared to go on board until the skipper of her, mounting the rail, said cheerily, “Wunt ye kem aboard, sir,’n’ hev a peek roun’?”

Thus cordially invited, they went, their wonder increasing until all their conceit was effectually taken out of them, especially when they saw the wonderful handiness and cleanliness of everything on board. The men, too, clothed in nondescript patches, with faces and arms almost blackened by exposure, and wearing an air of detachment from the world of civilized life that was full of pathos; these specially appealed to them, and they wished with all their hearts that they might do something to atone for the injustice done to these unblazoned warriors by their thoughtless, ignorant remark of so short a time before.

But time pressed, and they felt in the way besides; so, bidding a humble farewell to the grim-looking skipper, who answered the inquiry as to whether they could supply him with anything by a nonchalant “No, I guess not; we aint a-ben eout o’ port hardly six month yet,” they returned on board, having learned a corner of that valuable lesson continually being taught: that to judge by appearances is but superficial and dangerous, especially at sea.

Night fell, shutting out from the gaze of those wearied watchers the dumpy outlines of the old whale-ship. Her crew were still toiling, a blazing basket of whale-scrap swinging at a davit and making a lurid smear on the gloomy background of the night. One9 by one the excited passengers sauntered below, still eagerly discussing the stirring events they had witnessed, and making a thousand fantastic additions to the facts. Gradually the conversation dwindled to a close, and the great ship was left to the watch on deck. Fitful airs rose and fell, sharp little breaths of keen-edged wind that but just lifted the huge sails lazily, and let them slat against the masts again as if in disgust at the inadequacy of cat’s-paws. So the night wore on, till the middle watch had been in charge about half an hour. Then, with a vengeful hiss, the treacherous wind burst upon them from the north-east, catching that enormous sail-area on the fore side, and defying the efforts of the scanty crew to reduce it. All hands were called, and manfully did they respond; Briton and Finn, German and negro toiled side by side in the almost impossible effort to shorten down, while the huge hull, driven stern foremost, told in unmistakable sea-language of the peril she was in. Hideous was the uproar of snapping, running gear, rending canvas, breaking spars, and howling wind; while through it all, like a thread of human life, ran the wailing minor of the seamen’s cries as they strove to do what was required of them.

Slowly, oh, so slowly! the great ship paid off; while the heavier sails boomed out their complaint like an aerial cannonade, when up from the fore-hatch leapt a tongue of quivering flame. Every man who saw it felt a clutch at his heart. For fire at sea is always terrible beyond the power of mere words to describe; but fire under such conditions was calculated10 to paralyze the energies of the bravest. There seemed to be an actual hush, as if wind and waves were also aghast at this sudden appearance of a fiercer element than they. Then rang out clear and distinct the voice of Captain James—

“Drop everything else, men, and pass along the hose! Smartly, now! ’Way down from aloft!” He was obeyed, but human nature had something to say about the smartness. Men who have been taxing their energies, as these had done, find that even the spur actuated by fear of imminent death will fail to drive the exhausted body beyond a certain point. Moreover, all of them knew that stowed in the square of the main-hatch were fifty tons of gunpowder, which knowledge was of itself sufficient to render flaccid every muscle they possessed. Still, they did what they could, while the stewards went round to prepare the passengers for a hurried departure. All was done quietly. In truth, although the storm was now raging overhead, and the sails were being rent with infernal clamour from the yards, a sense of the far greater danger beneath their feet made the weather but a secondary consideration.

Then out of a cowering group of passengers came a feeble voice. It belonged to the lady querist of the afternoon, and it said, “Oh, if those brave sailors from that wonderful old ship were only near, we might be saved!”

Simple words, yet they sent a thrill of returning hope through those trembling hearts. Poor souls! None of them knew how far the ships might have11 drifted apart in that wild night, nor thought of the drag upon that old ship by those two tremendous bodies alongside of her. So every eye was strained into the surrounding blackness, as if they could pierce its impenetrable veil and bring back some answering ray of hope. The same idea, of succour from the old whale-ship, had occurred to the captain, and presently that waiting cluster of men and women saw with hungry eyes a bright trail of fire soaring upward as a rocket was discharged. Another and another followed, but without response. The darkness around was like that of the tomb. Another signal, however, now made itself manifest, and a much more effective one. Defying all the puny efforts made to subdue it, the fire in the fore-hatch burst upward with a roar, shedding a crimson glare over the whole surrounding sea, and being wafted away to leeward in a glowing trail of sparks.

“All hands lay aft!” roared the captain, and as they came, he shouted again, “Clear away the boats!”

Then might be seen the effect of that awful neglect of boats so common to merchant ships. Davits rusted in their sockets, falls so swollen as hardly to render over the sheaves, gear missing, water-breakers leaky—all the various disastrous consequences that have given sea-tragedies their grim completeness. But while the almost worn-out crew worked with the energy of despair, there arose from the darkness without the cheery hail of “Ship ahoy!”

Could any one give an idea in cold print of the revulsion of feeling wrought by those two simple12 words? For one intense moment there was silence. Then from every throat came the joyful response, a note like the breaking of a mighty string overstrained by an outburst of praise.

Naturally, the crew first recovered their balance from the stupefaction of sudden relief, and with coils of rope in their hands they thronged the side, peering out into the dark for a glimpse of their deliverers.

“Hurrah!” And the boatswain hurled the mainbrace far out-board at some dim object. A few seconds later there arrived on board a grim figure, quaint of speech as an Elizabethan Englishman, perfectly cool and laconic, as if the service he had come to render was in the nature of a polite morning call.

“Guess you’ve consid’ble of a muss put up hyar, gents all,” said he; and, after a brief pause, “Don’t know ez we’ve enny gre’t amount er spare time on han’, so ef you’ve nawthin’ else very pressin’ t’ tend ter, we mout so well see ’bout transhipment, don’t ye think?”

He had been addressing no one in particular, but the captain answered him.

“You are right, sir; and thank you with all our hearts! Men, see the ladies and children over-side!”

No one seemed to require telling that this angel of deliverance had arrived from the whale-ship; any other avenue of escape seemed beyond all imagination out of the question. Swiftly yet carefully the helpless ones were handed over-side; with a gentleness most sweet to see those piratical-looking exiles bestowed them in the boat. As soon as she was safely laden, another13 moved up out of the mirk behind and took her place. And it was done so cannily. No roaring, agitation, or confusion, as the glorious work proceeded. It was the very acme of good boatmanship. The light grew apace, and upon the tall tongues of flame, in all gorgeous hues that now cleft the night, huge masses of yellow smoke rolled far to leeward, making up a truly infernal picture.

Meanwhile, at the earliest opportunity, Captain James had called the first-comer (chief mate of the whaler) apart, and quietly informed him of the true state of affairs. The “down-easter” received this appalling news with the same taciturnity that he had already manifested, merely remarking as he shifted his chaw into a more comfortable position—

“Wall, cap’, ef she lets go ’fore we’ve all gut clear, some ov us ’ll take th’ short cut t’ glory, anyhaow.”

But, for all his apparent nonchalance, he had kept a wary eye upon the work a-doing, to see that no moment was wasted.

And so it came to pass that the last of the crew gained the boats, and there remained on board the Mirzapore but Captain James and his American deliverer. According to immemorial precedent, the Englishman expressed his intention of being last on board. And upon his inviting his friend to get into the waiting boat straining at her painter astern, the latter said—

“Sir, I ’low no dog-goned matter ov etiquette t’ spile my work, ’n’ I must say t’ I don’ quite like th’ idee ov leavin’ yew behine; so ef yew’ll excuse me——”

14

And with a movement sudden and lithe as a leopard’s he had seized the astonished captain and dropped him over the taff-rail into the boat as she rose upon a sea-crest. Before the indignant Englishman had quite realized what had befallen him, his assailant was standing by his side manipulating the steer-oar and shouting—

“Naow then, m’ sons, pull two, starn three; so, altogether. Up with her, lift her, m’ hearties, lift her, ’r by th’ gre’t bull whale it’ll be a job spiled after all.”

And those silent men did indeed “give way.” The long supple blades of their oars flashed crimson in the awful glare behind, as the heavily-laden but still buoyant craft climbed the watery hills or plunged into the hissing valleys. Suddenly there was one deep voice that rent the heavens. The whole expanse of the sky was lit up by crimson flame, in the midst of which hurtled fragments of that once magnificent ship. The sea rose in heaps, so that all the boatmen’s skill was needed to keep their craft from being overwhelmed. But the danger passed, and they reached the ship—the humble, clumsy old “spouter” that had proved to them a veritable ark of safety in time of their utmost need.

Captain James had barely recovered his outraged dignity when he was met by a quaint figure advancing out of the thickly-packed crowd on the whaler’s quarter-deck. “I’m Cap’n Fish, at yew’re service, sir. We haint over ’n’ above spacious in eour ’commodation, but yew’re all welcome t’ the best we hev’; ’n’15 I’ll try ’n’ beat up f’r th’ Cape ’n’ lan’ ye’s quick ’s it kin be did.”

The Englishman had hardly voice to reply; but, recollecting himself, he said, “I’m afraid, Captain Fish, that we shall be sadly in your way for dealing with those whales we saw you secure yesterday.”

“Not much yew wunt,” was the unexpected reply. “We hed t’ make eour ch’ice mighty sudden between them fish ’n’ yew, ’n’, of course, though we’re noways extravagant, they hed t’ go.”

The simple nobility of that homely man, in thus for self and crew passing over the loss of from eight to ten thousand dollars at the first call from his kind, was almost too much for Captain James, who answered unsteadily—

“If I have any voice in the matter, there will be no possibility of the men, who dared the terrors of fire and sea to save me and my charges, being heavily fined for their humanity.”

“Oh, thet’s all right,” said Captain Silas Fish.

17

There is something in the stress and struggle of tumultuous life in a vast city like London that to me is almost unbearable. Accustomed from a very early age to the illimitable peace of the ocean, to the untainted air of its changeless circle of waves and roofless dome of sky, I have never been able to endure satisfactorily the unceasing roar of traffic in crowded streets, the relentless rush of mankind in the race for life which is the normal condition of our great centres of civilization. Yet, for many years, being condemned by circumstances to abide in the midst of urban strife and noise without a break from one weary year to another, I lived to mourn departed peace, and feed my longing for it on memory alone, without a hope that its enjoyments would ever again be mine. Then came unexpected relief, an opportunity to visit a secluded corner of Wiltshire, that inland division of England which is richer, perhaps, in memorials of our wonderful history than any other part of these little islands, crowded as they are with reminiscences of bygone glorious days.

I took up my quarters in a hamlet on the banks of18 the Wylye, a delightful little river, taking its rise near the Somersetshire border, and wandering with innumerable windings through the heart of Wiltshire, associating itself with the Bourne and the Nadder, until at Salisbury it is lost in that most puzzling of all streams, the Avon. I said puzzling, for I believe there are but a handful of people out of the great host to whom the Avon is one of the best-known streams in the world from its associations, who know that there is one Avon feeding the Severn near Tewkesbury, which is Shakespeare’s Avon; there is another, upon which Bristol has founded her prosperity, and there is yet another, the Avon of my first mention, which, accumulated from numberless rivulets in the Vale of Pewsey, floweth through Salisbury, and loses itself finally in the waters of the English Channel at Christchurch in Hampshire. But I must ask forgiveness for allowing the wily Avon to lure me away thus far.

One of the chief charms of Wiltshire is its rolling downs rising upon either side of the valley, which in the course of ages the busy little Wylye has scooped out between them in gentle undulations, a short, sweet herbage for the most part covering their masses of solid chalk, coming to within a foot or two of those emerald surfaces. This is the place to come and ponder over the rubbish that is talked about the over-crowding of England. Here you shall wander for a whole day if you will, neither meeting or seeing a human being unless you follow the road that winds through the Deverills, five villages of the valley, all, alas, in swift process of decay. Even there the simple19 folk will stare long and earnestly at a stranger as he passes, before turning to resume their leisurely tasks, the uneventful, slumberous round of English village life. To me it was idyllic. A great peace came over me, and I felt that it was a sinful waste of nature to shut myself within four walls even at night. Long after the thirty souls peopling our hamlet had gone to bed I would sit out on the hillside behind the cottage, steeping my heart in the warm silence, only manifested—not broken—by the queer wailing cry of an uneasy plover as it fluttered overhead. And when, reluctantly, I did go to bed, I was careful to prop the windows wide open, even though I was occasionally awakened by the soft “flip-flip” of bats flying across my chamber, dazzled by the small light of my reading lamp.

The grey of the dawn, no matter how few had been my hours of sleep, never failed to awaken me, and, hurrying through my bath and dressing, I gat me out into the sweet breath of morning twilight while Nature was taking her beauty sleep and the dewdrops were waiting to welcome with their myriad smiles the first peep of the sun. And so it came to pass that one morning, just as the eastern horizon was being flooded with a marvellous series of colour-blends in mysterious and ever-changing sequence, that I mounted the swell of the down opposite to the village of Brixton Deverill, with every sense quickened to fullest appreciation of the lovely scene. Hosts of rabbits, quaint wee bunches of grey fur, each with a white blaze in the centre, scuttled from beneath my feet, and every little while, their curiosity overpowering natural fear, sat up with20 long ears erect and big black eyes devouring the uncouth intruder on their happy feeding grounds. Great flocks of partridges, almost as tame as domestic fowls (for it was July), ran merrily in and out among the furze clumps, or rose with a noisy whir of many wings when I came too close; aristocratic cock pheasants strolled by superciliously with a sidelong glance to see that the erect biped carried no gun, and an occasional lark gyrated to the swell of his own heart-lifting song as he rose in successive leaps to his proper sphere. I felt like singing myself, but Nature’s music was too sweet to be disturbed by my quavering voice, so I climbed on, all eyes and ears, and nerves a-tingle with receptivity of keenest enjoyment. Reaching the summit, I paused and surveyed the peaceful scene. Far to the left lay Longleat, its dense woods shimmering in a blue haze; to the right, Heytesbury Wood, in sombre shadow; and behind, the forest-like ridge of Chicklade. But near me, just peeping over the bare crest of an adjoining down, were the tops of a clump of firs, and, curious to know what that coppice might contain (I always have had a desire to explore the recesses of a lonely clump of trees), I turned my steps towards it, only stopping at short intervals to admire the gracefulness of the purple, blue, and yellow wild flowers with which the short, fine rabbit-grass was profusely besprent. Meanwhile the sun appeared in cloudless splendour, his powerful rays dissipating the spring-like freshness of the morning and promising a most sultry day. Yet as I drew nearer the dark fastness of the coppice I felt a chill, an actual physical sensation21 of cold. At the same time there arose within me a positive repugnance to draw any closer to that deep shade. This unaccountable change only made me angry with myself for being capable of feeling such a nonsensical, unexplainable hindrance to my purpose. So I took hold of it with both hands, and cast it from me, striding onward with quickened step until I really seemed to be breasting a strong tide. Panting with the intensity of my inward struggle, I reached the shadow cast by that solemn clump of pines, and saw the pale outlines of a wall in their midst. Now curiosity became paramount, and, actually shivering with cold, I pressed on until I stood in front of a fairly large house, surrounded by a flint wall on all sides, but at some yards distance from it. Through large holes in the encircling wall the wood-folk scampered or fluttered merrily but noiselessly; rabbits, hares, squirrels, and birds, and as I drew nearer there was a sudden whiff of strong animal scent, and a long red body launched itself through one of the openings, flitting past me like a flash of red-brown light. Although I had never seen an English fox before on his native heath, I recognized him from his pictures, and forgave him for startling me. Skirting the wall, I came to a huge gap with crumbling sides, where once had been a gate, I suppose. It commanded a view of the front of the house, which I now saw was a mere shell, its walls perforated in many places by the busy rabbits, which swarmed in and out like bees upon a hive. No windows remained, but the front door was fast closed and barred by a thick trunk of ivy, which had once22 overspread the whole building, but was now quite in keeping with it, for it was dead. The space between the wall and the house was thickly overgrown with nettles to nearly the height of a man, but there was no sign of any useful plant, and even the roof of the building, which was of red tiles and intact, had none of that kindly covering of house-leek, stone-crop, and moss, which always decks such spaces with beauty in the country. Upon a sudden impulse I turned, and behind me I saw with a shudder that only a few feet from where I stood there was a sheer descent of some thirty feet, a veritable pit some ten yards wide, but with its farther margin only a few feet high. Tall trees sprang from its bottom and sides, their roots surrounding a pool of black-looking water that seemed a receptacle for all manner of hideous mysteries. Involuntarily I shrank into myself, and looked up for a glint of blue sunlit sky, but it was like being in a vault, dark and dank and cold. Still, the idea never entered my head to get out until I had seen all that might be there to be seen, although I confess to comforting myself, as I have often done on a dull and gloomy day, with the reminder that just outside the sun was shining steadily.

Turning away from that grim-looking pit, I thrust myself through the savage nettle-bed, my hands held high so that I could guard my face with my arms, until I reached the first opening in the house wall that offered admission. With just one moment’s hesitation I stepped within, and stood on the decayed floor of what had once been the best room. And then23 I had need of all my disbelief in ghosts, for around me and beneath me and above were a congeries of all the queer noises one could conjure up. Soft pattering of feet, hollow murmurings as of voices, the indefinite sound of brushing past that always makes one turn sharply to see who is near. I found my mouth getting dry and my hands burning, in spite of the chill that still clung to me; but still I went on and explored every room in the eerie place, noting a colony of bats that huddled together among the bare roof-beams, prying into the numerous cavities in floors and walls made by the rabbits and the rats, but seeing nothing worthy of note until I reached a sort of cellar which looked as if it had been used as a bakehouse. Upon stepping down the decrepit ladder which led to it, I startled a great colony of rats, that fled in all directions with shrill notes of affright, hardly more scared than myself. The place was so dark that I thankfully remembered my box of wax matches, and, twisting two or three torches out of a newspaper I found in my jacket pocket, I soon had a good light.

It revealed a cavity in the floor just in front of a huge baker’s oven, into the dim recesses of which I peered, finding that it extended for some distance on either side of the opening. Lighting another torch, I jumped down and found—three oblong boxes of rude construction, and across them the mouldering frame of what had once been a man. At last I had seen enough, and with something tap-tapping inside my head, I scrambled hastily out of the hole, my body shaking as if with ague, and my lungs aching for air. I looked24 neither to the right nor the left as I went, nor paused, regardless of the nettle grove, until I emerged upon the bright hilltop, where I flung myself down and drank in great gulps of sweet air until my tremors passed away and the tumult of my mind became appeased.

Without casting another look back at that lonely place, or attempting to speculate upon what I had seen, I departed for home, and, after a hasty breakfast, sought out a friend in the next village, Longbridge Deverill, who had already given me many pleasant hours by retailing scraps of local history reaching back for hundreds of years. I found him in his pretty garden enjoying the bright day, with a look of deep content upon his worn old face—the afterglow of a well-spent life. Staying his rising to greet me, I flung myself down on the springy turf by his side, and almost without a word of preface, gave him a hurried account of my morning’s adventure. He listened in grave silence until I had finished, and then began as follows.

It is certainly a strange coincidence that you should stumble across that sombre place, because, after what you told me the other day about your family connection with this part of the country, I have no doubt whatever that the unhappy tenants of Pertwood Farm (as it is called even now) were nearly related to yourself. Their tragical story is well known to me,25 although its principal events happened more than sixty years ago, when I was a boy. The house had been built and enclosed, and the trees planted, by a morose old man who wished to shut himself off from the world, yet was by no means averse to a good deal of creature comfort. He lived in it for some years, attended only by one hard-featured man, who did apparently men and women’s work equally well—lived there until local rumour had grown tired of inventing fables about him, and left him to the oblivion he desired. Then one day the news began to circulate that Pertwood had changed hands, that old Cusack was gone, and that a middle-aged man with a beautiful young wife had taken up his abode there, without any one in the vicinity knowing aught of the change until it had been made. Then the village tongues wagged loosely for awhile, especially when it was found that the new-comers were almost as reserved as old Cusack had been. But as time went on Mr. Delambre, whose Huguenot name stamped him as most probably a native of these parts (you have noticed how very frequent such names are hereabout), leased several good-sized fields lower down the hill towards Chicklade, and began to do a little farming. This, of course, necessitated his employing labour, and consequently, by slow degrees, scraps of personalia about him filtered through the sluggish tongues of the men who worked for him. Thus we learned that his wife (your grandmother’s sister, my boy) was rarely beautiful, though pale and silent as a ghost. That her husband loved her tigerishly, could not bear that any26 other eyes should see her but his, and it was believed that his fierce watchful jealousy of her being even looked upon was fretting her to death. Quite a flutter of excitement pervaded the village here not long after the above details became public property, by one of the labourers from Pertwood coming galloping in on a plough-horse for old Mary Hoddinot, who had nursed at least two generations of neighbours in their earliest days. She was whisked off in the baker’s cart, but the news remained behind that twin boys had arrived at Pert’ood, as it was locally called, and that Delambre was almost frantic with anxiety about his idol. The veil thus hastily lifted dropped again, and only driblets of news came at long intervals. We heard that old Mary was in permanent residence, that the boys were thriving sturdily, and that the mother was fairer than ever and certainly happier. So things jogged along for a couple of years, until an occasional word came deviously from Pertwood to the effect that the miserable Delambre was now jealous of his infant boys. Self-tortured, he was making his wife a living martyr, and such was his wild-beast temper that none dare interfere. At last the climax was put upon our scanty scraps of intelligence by the appearance in our midst of old Mary, pale, thin, and trembling. It was some time before we could gather her dread story, she was so sadly shaken; but by degrees we learned that after a day in which Delambre seemed to be perfectly devil-possessed, alternately raging at and caressing his wife, venting savage threats against the innocent babes “who were stealing all her affection away from him,”27 he had gone down the hill to see after enfolding some sheep. He was barely out of sight before his wife, turning to old Mary, said, “Please put your arms round me, I feel so tired.” Mary complied, drawing the fair, weary head down upon her faithful old bosom, where it remained until a chill struck through her bodice. Alarmed, she looked down and saw that her mistress was resting indeed.

Although terrified almost beyond measure, the poor old creature retained sufficient presence of mind to release herself from the dead arms, rush to the door, and scream for her employer. He was returning, when her cries hastened his steps, and, breaking into a run, he burst into the room and saw! He stood stonily for a minute, then, turning to the trembling old woman, shouted “go away.” Not daring to disobey, she hurried off, and here she was. After much discussion, my father and the village doctor decided to go to Pertwood and see if anything could be done. But their errand was in vain. Delambre met them at the door, telling them that he did not need, nor would he receive, any help or sympathy. What he did require was to be left alone. And slamming the door in his visitors’ faces, he disappeared. Even this grim happening died out of men’s daily talk as the quiet days rolled by, and nothing more occurred to arouse interest. We heard that the boys were well, and were often seen tumbling about the grass-plot before the house door by the farm labourers. Rumour said many things concerning the widower’s disposal of his dead. But no one knew anything for certain, except28 that her body had never been seen again by any eye outside the little family. Delambre himself seemed changed for the better, less harsh and morose, although as secretive as ever. He was apparently devoted to his two boys, who throve amazingly. As they grew up he and they were inseparable. He educated them, played with them, made their welfare his one object in life. And they returned his care with the closest affection, in fact the trio seemed never contented apart. Yet they never came near the village, nor mixed with the neighbours in any way.

In this quiet neighbourhood the years slip swiftly by as does the current past an anchored ship, and as unnoticeably. The youthful Delambres grew and waxed strong enough to render unnecessary the employment of any other labour on the farm than their own, and in consequence it was only at rare intervals that any news of them reached us in roundabout fashion through Warminster, where old Delambre was wont to go once a week on business. So closely had they held aloof from all of us that when one bitter winter night a tall swarthy young man came furiously knocking at the doctor’s door, he was as completely unknown to the worthy old man as any new arrival from a foreign land. The visitor, however, lost no time in introducing himself as George Delambre, and urgently requested the doctor to accompany him at once to Pertwood on a matter of life and death. In a few minutes the pair set off through the heavy snow-drifts, and, after a struggle that tried the old doctor terribly,29 arrived at the house to find that the patient was mending fast.

A young woman of about eighteen, only able to mutter a few words of French, had been found huddled up under the wall of the house by George as he was returning from a visit to the sheepfold. She was fairly well dressed in foreign clothing, but at almost the last gasp from privation and cold. How she came there she never knew. The last thing that she remembered was coming to Hindon, by so many ways that her money was all spent, in order to find a relative, she having been left an orphan. Failing in her search, she had wandered out upon the downs, and the rest was a blank.

In spite of convention she remained at Pertwood, making the dull place brighter than it had ever been. But of course both brothers fell in love with the first woman they had ever really known. And she, being thus almost compelled to make her choice, with all a woman’s inexplicable perversity, promised to marry dark saturnine George, although her previous behaviour towards him had been timid and shrinking, as if she feared him. To the rejected brother, fair Charles, she had always been most affectionate, so much so, indeed, that he was perfectly justified in looking upon her as his future wife, to be had for the asking. This cruel blow to his almost certain hopes completely stunned him for a time, until his brother with grave and sympathetic words essayed to comfort him. This broke the spell that had bound him, and in a perfect fury of anger he warned his brother that he30 looked upon him as his deadliest enemy, that the world was hardly wide enough for them both; but, for his part, he would not, if he could help it, add another tragedy to their already gloomy home, and to that end he would flee. Straightway he rushed and sought his father, and, without any warning, demanded his portion. At first the grim old man stared at him blankly, for his manner was new as his words were rough; then, rising from his chair, the old man bade him be gone—not one penny would he give him; he might go and starve for ought he cared.

“Very well,” said Charles, “then I go into the village and get advice as to how I shall proceed against you for the wages I have earned since I began to work. And you’ll cut a fine figure at the Warminster Court.”

The threat was efficient. With a face like ashes and trembling hands the father opened his desk and gave him fifty guineas, telling him that it was half of his total savings, and with an evidently severe struggle to curb his furious temper, asked him to hurry his departure. Since he had robbed him, the sooner he was gone the better. The young man turned and went without another word.

That same night old Delambre died suddenly and alone. And Louise, instead of clinging to her promised husband, came down to the village, where the doctor gave her shelter. The unhappy George, thus cruelly deserted, neglected everything, oscillating between the village and his lonely home. The inquest showed that the old man had died of heart disease;31 and George then, to every one’s amazement, announced his intention of carrying out his father’s oft-repeated wish, and burying him beneath the house by the side of his wife.

And now we must needs leave Pertwood Farm and its doubly bereaved occupant for a while, in order to follow the fortunes of the self-exiled Charles. His was indeed a curious start in life. Absolutely ignorant of the world, his whole horizon at the age of twenty years bounded by that little patch of lonely Wiltshire down, and his knowledge of mankind confined to, at the most, half a dozen people. He had great native talent, which, added to an ability to keep his own counsel, was doubtless of good service to him in this breaking away into the unknown. His total stock of money amounted to less than £50, to him an enormous sum, the greater because he had never yet known the value of money. His native shrewdness, however, led him to husband it in miserly fashion, as being the one faithful friend upon which he could always rely.

And now the salt strain in his mother’s blood must have asserted itself unmistakably, if mysteriously, for straight as a homing bee he made his way down to the sea, finding himself a week after his flight at Poole. I shall never forget the look upon his face as he told me how he first felt when the sea revealed itself to him. All his unsatisfied longings, all the heart-wrench32 of his rejected love, were forgotten in present unutterable delight. He was both hungry and weary, yet he sat contentedly down upon the verge of the cliffs and gazed upon this glorious vision until his eyes glazed with fatigue, and his body was numbed with the immovable restraint of his attitude. At last he tore himself away, and entered the town, seeking a humble lodging-place, and finding one exactly suited to his needs in a little country public-house on the outskirts of the town, kept by an apple-cheeked dame, whose son was master of a brigantine then lying in the harbour. She gave the handsome youth a motherly welcome, none the less warm because he appeared to be well able to pay his way.

Against the impregnable fortress of his reserve she failed to make any progress whatever, although in the attempt to gratify her curiosity she exerted every simple art known to her. On the other hand he learned many things, for one of her chief wiles was an open confidence in him, an unreserved pouring out to him of all she knew. He was chiefly interested in her stories of her son. Naturally she was proud of that big swarthy seaman, who, when he arrived home that evening, loomed so large in the doorway that he appeared to dwarf the whole building. As Englishmen will, the two men eyed one another suspiciously at first, until the ice having been broken by the fond mother, Charles in his turn began to pump his new acquaintance. Captain Jacks, delighted beyond measure to find a virgin mind upon which to sow his somewhat threadbare stock of yarns, was gratified beyond33 measure, and thenceforward until long after the usual hour for bed, the young man was simply soaking up like a sponge in the rain such a store of wonders as he had never before even dreamed of. At last the old dame, somewhat huffed by the way in which Charles had turned from her garrulity to her son’s, ordered them both to bed. But Charles could not sleep. How was it possible? The quiet monotone of his life had been suddenly lifted into a veritable Wagner concert of strange harmonies, wherein joy and grief, pleasure and pain, love and hate, strove for predominance, and refused to be hushed to rest even by the needs of his healthful weariness.

Out of it all one resolve arose towering. He would, he must go to sea. That alone could be the career for him. But he would write to Louise. Knowing nothing of her flight from the old home or of his father’s death, he felt that he must endeavour to assert a claim to her, more just and defensible than his brother’s, even though she had rejected him. And then, soothed by his definite settlement of future action, he fell asleep, nor woke again until roused by his indignant landlady’s inquiry as to whether “’ee wor gwain t’ lie abed arl daay.” Springing out of bed, he made his simple toilet in haste, coming down so speedily that the good old dame was quite mollified. A hasty breakfast ensued, and a hurried departure for the harbour in search of Captain Jacks’ brigantine. Finding her after a short search, he was warmly welcomed by the gallant skipper, and, to his unbounded delight, succeeded in inducing that worthy man to34 take him as an extra hand without pay on his forthcoming voyage to Newfoundland. Then returning to his lodging, he made his small preparations, and after much anxious thought, produced the following letter, which he addressed to Louise, care of the old doctor at Longbridge.

“My Dearest Loo,

“Though you chose George instead of me I don’t mean to give you up. I mean to do something big, looking forward to you for a prize. I believe you love me better than you do George in spite of what you did. You will never marry him, never. You’ll marry me, because you love me, and I won’t let you go. I know you’ll get this letter, and send me an answer to Mrs. Jacks, Apple Row, Poole. And you’ll wait for my reply, which may be late a coming, but will be sure to come.

“Yours till death,

“Charles Delambre.”

A few minutes afterwards he was on his way down to the Mary Jane, Captain Jacks’ brigantine. He was received with the gravity befitting a skipper on shipping a new hand, and after bestowing his few purchases in a cubby-hole in the tiny cabin, returned on deck in his shirt-sleeves, to take part in whatever work was going on, with all the ardour of a new recruit. Next morning at daylight the Mary Jane departed. Under the brilliant sky of June the dainty little vessel glided out into the Channel, bounding forward before the fresh north-easterly breeze, as if rejoicing to be at35 home once more, and freed from the restraint of mooring chains and the stagnant environment of a sheltered harbour.

Charles took to his new life wonderfully, feeling no qualms of sea-sickness, and throwing himself into every detail of the work with such ardour that by the time they had been out a week he was quite a useful member of the ship’s company. And then there arrived that phenomenon, a June gale from the north-west. Shorn of all her white wings but one, the little brigantine lay snugly enough, fore-reaching against the mighty Atlantic rollers that hurled themselves upon her like mountain ranges endowed with swiftest motion. So she lay throughout one long day and far into the night succeeding, until just at that dread hour of midnight when watchfulness so often succumbs to weariness at sea, a huge comber came tumbling aboard as she fell off into the trough of the sea. For a while she seemed to be in doubt whether to shake herself clear of the foaming mass, and then splendidly lifting herself with her sudden burden of a deck filled with water, she resumed her gallant struggle. Just then it was discovered that her lights were gone. Before they could be replaced, out of the darkness came flying an awful shape, vast, swift, and merciless. One of the splendid Yankee fliers of those days, the Columbia, of over a thousand tons register, was speeding eastward under every stitch of sail, at a rate far surpassing that of any but the swiftest steamships. A good look out was being kept on board of her, for those vessels were noted for the excellence of their36 discipline and careful attention to duty. But the night was pitchy dark, the Mary Jane had no light visible, and before anything could be done her doomed crew saw the Columbia’s bow towering over their vessel’s waist like some unthinkable demon of destruction. Up, up, up, she soared above them, then descending, her gleaming bow shone clean through the centre of the Mary Jane’s hull, tearing with it the top-hamper of masts and rigging, and rushing straight through the wreckage without a perceptible check. One wild cry of despair and all was silent. Over the side of the Columbia peered a row of white faces gazing fearfully into the gloom, but there was nothing to be seen. The sea had claimed her toll.

As usual, after such a calamity, there was a hushed performance of tasks, until suddenly one of the crew shouted, “Why, here’s a stranger.” And there was. Charles had clutched instinctively at one of the martingale guys as the Columbia swept over her victim, and had succeeded in climbing from thence on board out of the vortex of death in which all his late shipmates had been involved. Plied with eager questions, his simple story was soon told, and he was enrolled among the crew. The Columbia was bound to Genoa, a detail that troubled him but little; so long as he was at sea he had no desire to select his destination. But he found here a very different state of things obtaining. The crew were a hard-bitten, motley lot, prime seamen mostly, but “packet rats” to a man, wastrels without a thought in life but how soon they might get from one drinking-bout to another, and at sea only37 kept from mutiny, and, indeed, crime of all kinds, by the iron discipline imposed upon them by the stern-faced, sinewy Americans who formed the afterguard. There were no soft, sleepy-voiced orders given here. Every command issued by an officer came like the bellowing of an angry bull, and if the man or men addressed did not leap like cats to execute it, a blow emphasized the fierce oath that followed.

Charles now learned what work was. No languid crawling through duties with one ear ever cocked for the sound of the releasing bell, but a rabid rush at all tasks, even the simplest, as if upon its immediate performance hung issues of life or death. “Well fed, well driven, well paid,” was the motto on board those ships, albeit there were not wanting scoundrelly skippers and officers, who, in ports where fresh hands were to be obtained cheaply, were not above using the men so abominably that they would desert and leave all their cruelly-earned wages behind. Strangely enough, however, Charles became a prime favourite. This son of the soil, who might have been expected to move in clod-hopper fashion, developed an amazing smartness which, allied to a keenness of appreciation quite American in its rapidity, endeared him specially to the officers. In the roaring fo’c’sle among his half-savage shipmates he commanded respect, for in some mysterious way he evolved masterly fighting qualities and dogged staying powers that gave him victory in several bloody battles. So that it came to pass, when Genoa was reached, that Charles was one day called aft and informed that, if he cared to, he might shift38 his quarters aft and go into training for an officer, holding a sort of brevet rank as supernumerary third mate. He accepted, and was transferred, much to the disgust of his shipmates forward, who looked upon his move aft as a sort of desertion to the enemy. But they knew Charles too well to proceed further with their enmity than cursing him among themselves, so that as much peace as usual was kept.

From this port Charles wrote lengthily to Louise at Longbridge as before, and to Poole to Mrs. Jacks, breaking her great misfortune to her, and begging her to write to him and send him at New York any letters that might have arrived for him. And then he turned contentedly to his work again, allowing it to engross every thought. He was no mere dreamer of dreams, this young man. In his mind there was a solid settled conviction that, sooner or later (and it did not greatly matter which), he would attain the object of his desires. This granitic foundation of faith in his future saved him all mental trouble, and enabled him to devote all his energies to the work in hand, to the great satisfaction of his skipper. Captain Lothrop, indeed, looked upon this young Englishman with no ordinary favour. A typical American himself, of the best school, he concealed under a languid demeanour energy as of an unloosed whirlwind. His face was long, oval, and olive-brown, with black silky beard and moustache trimmed like one of Velasquez’s cavaliers, and black eyes that, usually expressionless as balls of black marble, would, upon occasion given, dart rays of terrible fire. Contrasted with this saturnine stately personage, the fair,39 ruddy Charles looked like some innocent schoolboy, the open, confiding air he bore being most deceptive. He picked up seamanship, too, in marvellous fashion, the sailorizing that counts, by virtue of which a seaman handles a thousand-ton ship as if she were a toy and every one of her crew but an incarnation of his will. But this very ability of his before long aroused a spirit of envy in his two brother officers that would have been paralyzing to a weaker man. Here, again, the masterly discipline of the American merchantman came to his aid, a discipline that does not know of such hideous folly as allowing jealousy between officers being paraded before the crew, so that they with native shrewdness may take advantage of the house divided against itself. When in an American ship one sees a skipper openly deriding an officer, be sure that officer’s days as an officer are numbered; he is about to be reduced to the ranks. So, in spite of a growing hatred to the —— Britisher, the two senior mates allowed no sign of their feelings to be manifested before the crew. Perhaps the old man was a bit injudicious also. He would yarn with Charles by the hour about the old farm and the sober, uneventful routine of English rural life, the recital of these placid stories evidently giving him the purest pleasure by sheer contrast with his own stormy career.

In due time the stay of the Columbia at Genoa came to an end, and backward she sailed for New York. In masterly fashion she was manœuvred out through the Gut of Gibraltar, and sped with increased rapidity into the broad Atlantic. But it was now nearly winter,40 and soon the demon of the west wind made his power felt. The gale settled down steadily to blow for weeks apparently, and with dogged perseverance the Columbia’s crew fought against it. Hail, snow, and ice scourged them, canvas became like planks, ropes as bars of iron. Around the bows arose masses of ice like a rampart, and from the break of the forecastle hung icicles which grew like mushrooms in a few hours of night. The miserable crew were worn to the bone with fatigue and cold, and had they been fed as British crews of such ships are fed they would doubtless have all died. But, in spite of their sufferings, they worked on until one night, having to make all possible sail to a “slant” of wind, they were all on deck together at eight bells—midnight. With the usual celerity practised in these ships, the snowy breadths of canvas were rising one above the other, and the Columbia was being flung forward in lively fashion over the still heavy waves, when Charles, who was standing right forward on the forecastle, shouted in a voice that could be heard distinctly above the roar of the wind and sea and the cries of the seamen, “Hard down!” Mechanically the helmsman obeyed, hardly knowing whither the summons came, and the beautiful vessel swung up into the wind, catching all her sails aback, and grinding her way past some frightful obstruction to leeward that looked as if an abyss of darkness had suddenly yawned in the middle of the sea, along the rim of which the Columbia was cringing. The tremendous voice of Captain Lothrop boomed out through the darkness, “What d’ye see,41 Mister Delamber, forrard there?” “We’ve struck a derelict, sir,” roared Charles, and his words sounded in the ears of the ship’s company like the summons of doom. The ship faltered in her swing to windward, refused to obey her helm, and swung off the wind again slowly but surely, as if being dragged down into unknown depths by an invisible hand whose grip was like that of death.

In this hour of paralyzing uncertainty Charles rose to the full height of his manhood. Passing the word for a lantern, and slinging himself in a bowline, he ventured into the blackness alongside, and presently reappeared with the cheering news that no damage was done. A few strokes of an axe and they would be set free. And arming himself with a broad axe, he again disappeared into the outer dark, this time under the watchful eye of the skipper, and presently, with a movement which was like a throb of returning life to every soul on board, the Columbia regained her freedom. Charles was hauled on board through the surf alongside like a sodden bundle of clothing, unhurt, but entirely exhausted, having made good his claim to be regarded as one of the world’s silent heroes, a man who to the call of duty returns no dubious answer, but renders swift obedience.

This last adventure seemed to exhaust the Columbia’s budget of ill-luck for the voyage. Although the42 wind was never quite fair, it allowed them to work gradually over to the westward, and with its change a little more genial weather was vouchsafed to them. They arrived in New York without further incident worthy of notice, and Charles found himself not only the guest of the skipper, but honoured by the owner, who, as an old skipper himself, was fully alive to the glowing account given him by Captain Lothrop of Charles’s services to the Columbia. The other two officers left early, and Charles, now a full-blown second mate, saw his prize almost within his grasp. The more so that a letter (only one) awaited him; it was from Louise, and contained only these words—

“Dear Charles,

“It is that I am yours. Whenever it shall please you to come for me, I am ready. I leave the house to the day of your parting, for your father is dead immediately, and I go not there any more. I wait for you only.

“Louise.”

He accepted this news with perfect calmness, as of one who knew that it would come, and turned again to his work with a zest as unlike that of a love-sick youth as any one ever saw. Not a word did he say of his affairs even to his good friend the skipper, and when, their stay in New York at an end, they sailed for China, that worthy man was revolving all sorts of projects in his mind for an alliance between Charles and his wife’s sister, who, during Charles’ stay in New York, had manifested no small degree of interest in43 the stalwart, ruddy young Englishman. He, however, took no advantage of the obviously proffered opportunity, and in due course the Columbia sailed for Hong Kong, petroleum laden. Captain Lothrop carried his wife with him this voyage, and very homely indeed the ship appeared with the many trifles added to her cabin by feminine taste. A new mate and third mate were also shipped—the former a gigantic Kentuckian, with a fist like a shoulder of mutton, a voice like a wounded buffalo bull, and a heart as big and soft as ever dwelt in the breast of mortal man. Yet, strangely enough, he was a terror to the crew. Long training in the duty of running a ship “packet fashion” had made him so, made him regard the men under his charge as if they were wild beasts, who needed keeping tame by many stripes and constant, unremitting toil. The third mate was a Salem man, tall enough, but without an ounce of superfluous flesh on his gaunt frame. He seemed built of steel wire, so tireless and insensible to pain was he. With these two worthies Charles was at home at once. Good men themselves, they took to him on the spot as an Englishman of the best sort, who is always beloved by Yankees—that is, genuine Americans—and loves them in return in no half-hearted fashion.

It was well for them all that this solidarity obtained among them, for they shipped a crowd in New York of all nationalities, except Americans or English, a gang that looked as if they had stepped direct from the deck of a pirate to take service on board the Columbia. The skipper was as brave a man as ever44 trod a quarter-deck; but his wife was aboard, and his great love made him nervous. He suggested at once that each of his officers should never be without a loaded six-shooter in their hip-pockets by night or day, and that they should watch that crowd as the trainer watches his cage of performing tigers. Fortunately the men were all prime seamen, and full of spring, while the perfect discipline maintained on board from the outset did not permit of any loafing about, which breeds insolence as well as laziness, that root of mischief at sea. So, in spite of incessant labour and the absence of any privileges whatever, the peace was kept until the ship, after a splendid passage of one hundred days, was running up the China Sea under as much canvas as she could drag to the heavy south-west monsoon. All the watch were busy greasing down, it being Saturday, and, unlike most English ships, where, for fear of the men grumbling, this most filthy but necessary work is done by the boys or the quiet men of the crew, here everybody took a hand, and the job was done in about twenty minutes from the word “go.” A huge Greek was busy at the mizzen-topmast, his grease-pot slung to his belt, when suddenly the pot parted company with him and fell, plentifully bespattering sails and rigging as it bounded and rebounded on its way down, until at last it smashed upon the cabin skylight and deposited the balance of its contents all around.

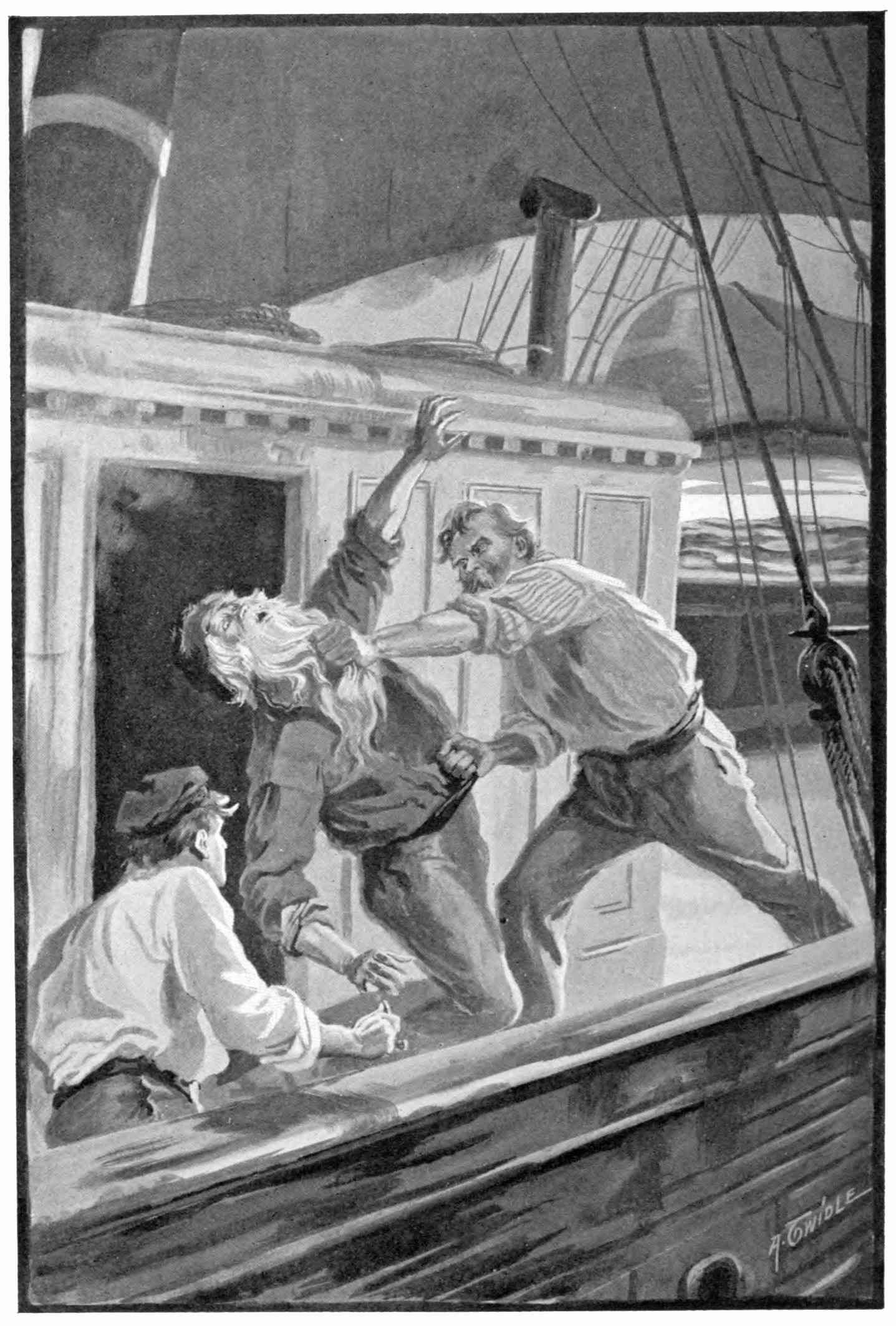

“Come down here, ye Dago beast!” bellowed the mate. Slowly, too slowly, ’Tonio obeyed. Hardly had he dropped from the rigging on to the top of the45 house when Mr. Shelby seized him by the throat, and, in spite of his bulk (he was almost as big as the mate himself), dragged him to the skylight, and, forcing his head down, actually rubbed his face in the foul mess. ’Tonio struggled in silence, but unavailingly, until the mate released him; then, with a spring like a lion’s, he leaped at his tormentor, a long knife, never seen till then, gleaming in his left hand. Mr. Shelby met him halfway with a kick which caught his left elbow, paralyzing his arm, the knife dropping point downwards and sticking in the deck. But the fracas was the signal for a general outbreak. The helmsman sprang from the wheel, the rest of the watch slid down backstays, and came rushing aft, bent on murder, all their long pent-up hatred of authority brought to a climax by the undoubted outrage perpetrated upon one of their number. But they met with a man. His back to the mizzen-mast, Mr. Shelby whipped out his revolver, and, as coolly as if engaged in a day’s partridge-shooting ashore, he fired barrel after barrel of his weapon at the rushing savages. Up came the skipper and the other two officers, not a moment too soon. A hairy Spaniard clutched at Charles as he appeared on deck, but that sturdy son of the soil grappled with his enemy so felly, that in a few heart-beats the body of the Latin went hurtling over the side. Then the fight became general. The ship, neglected, swung up into the wind and was caught aback, behaving herself in the fashion of a wounded animal, while the higher race, outnumbered by four to one, set its teeth and fought in primitive style. The groans of the wounded,46 the hissing oaths of the combatants, and the crack of revolver shots made up a lurid weft to the warp of sound provided by the moaning wind and murmuring sea. Then gradually those of the men who could do so crawled forrard, leaving the bright yellow of the painted deck aft all besmeared with red, and the victory was won for authority.

But a new danger threatened. Attracted, perhaps, like vultures, by the smell of blood, several evil-looking junks were closing in upon the Columbia, and but for the tremendous exertions of the officers, aided by the cook and steward and the captain’s wife, who, pale but resolute, took the wheel, there is no doubt that the Columbia would have been added to the list of missing ships. That peril was averted by the ship being got before the wind again, when her speed soon told, and she hopelessly out-distanced the sneaking, clumsy junks. And before sunset a long smear of smoke astern resolved itself into one of the smart little gun-boats which, under the splendid St. George’s Cross, patrol those dangerous seas. In answer to signals, she came alongside the Columbia, and soon a boat’s crew of lithe men-o’-war’s-men were on board the American ship, making all secure for her safe passage into Hong Kong. There she arrived two days later, and got rid of her desperate crew, with the exception of two who had paid for their rash attempt the only price they had—their lives.

From Hong Kong the Columbia sailed for London, arriving there after an uneventful passage of one hundred and twenty days. Charles, turning a deaf47 ear to the entreaties of the captain and his fellow-officers, determined to take his discharge. A load-stone of which they knew not anything was drawing him irresistibly into the heart of Wiltshire, and, with all his earnings carefully secreted about him, he left the great city behind, and set his face steadfastly for Longbridge Deverill. There he suddenly arrived, as if he had dropped from the sky, just as the short winter’s day was closing in. The few straggling villagers peered curiously at the broad, alert figure that strode along the white road with an easy grace and manly bearing quite foreign to the heavy slouch of their own men-folk. There was, too, an indefinable foreign odour about him which cut athwart even their dull perceptions and aroused all their curiosity. But none recognized him. How should they? They had hardly ever known him, except by rumour, which, during his absence of nearly two years, had died a natural death for want of something to feed upon. Straight to the old doctor’s house he went as a homing pigeon would. To his confident knock there appeared at the door Louise, the light of love in her eyes, her arms outstretched in gladdest welcome. Neither showed any surprise, for both seemed to have been in some unexplainable way in communion with the other. Yet, now the first speechless greeting over, the first caresses bestowed, instead of contentment most profound came unease, an indefinite fear lest this wonderful thing that had befallen them should by the sheer perversity of fate be swept away, leaving them in the outer dark.

48

The quavering voice of the old doctor removed them from each other’s close embrace, and shyly, yet with a proud air of ownership, Louise led the way into the cosy parlour, where the good old man sat enjoying the rest and comfort he so fully deserved. He looked up inquiringly as with dazzled eyes the big man entered the room, hesitatingly, and with a rush of strange memories flooding his brain.

“Who is it, Loo?” said the doctor. “I don’t recognize the gentleman.”

And, rising stiffly from his armchair, he took a step forward.

“It’s Charles, doctor, Charles Delambre,” faltered Louise.

“Yes, doctor; and I’ve come to take away your treasure. Also to thank you with my whole heart for your loving kindness in taking care of her. Without you what would she have done, me being so far away?”

Almost inarticulate with joy, the old man caught Charles’s hands in both his own, and pushed him into a chair. Then sinking back into his own, he gasped breathlessly—

“Ah, my boy, my boy, how I have longed for your return! It has given me more pain than you can think—the idea that I might die and leave this poor child friendless and alone in the world. But she has had no fear. She knew you would come, and she was right. But, Charley, my boy, before we say another word—your brother. You mustn’t forget him, and if, as I fear, your quarrel was fierce, you must forgive.49 His sufferings have been great. Never once has his face been seen in the village since you left, and, except that we hear an occasional word of him brought by a tramp, he might be dead. Go to him, Charles, and make it up, and perhaps the good Lord will lift the cloud of misery that has so long hung heavily over your house.”

Charles heard the kindly doctor’s little speech in respectful silence, then, speaking for the second time since entering the house, he said—

“You are right, doctor. I will be friends with George if he’ll let me. But I must first secure my wife. After all that has passed, I dare not waste an hour until we are married.”

Louise sat listening with the light of perfect approval on her fine face; and the doctor also in vigorous fashion signified his entire acquiescence. The rest of that happy evening was devoted to a recital of Charles’s wanderings, his escapes, and his good fortune, until, wearied out, those three happy people went to bed.

Next day Charles was busy. A special license had to be procured, and Louise must procure her simple wadding array. The facilities of to-day did not exist then, and the impatient young lover chafed considerably at the delay involved. But in due time the wedding came off, with the dear old doctor as guardian to give the bride away. The village was in a state of seething excitement; the labourers left their work, their wives left their household tasks, and all discussed with an eagerness that was amazingly different to their usual stolidity of demeanour the romantic happenings50 in their midst. Then, when the newly-married pair had returned to the doctor’s roomy house, and the villagers had drifted reluctantly homeward again, the ripples of unwonted disturbance gradually smoothed out and subsided. Charles and his wife sat side by side in the doctor’s parlour as the evening shadows fell, their benefactor’s glowing face confronting them, and the knowledge that half his home was theirs removing all anxiety for the immediate future from their minds.

They sat thus, holding each other’s hands in silence, until Louise, looking up in her husband’s face, said, “Charles, let us go and see George. I feel I must before I sleep.” And Charles answered, “Yes, dear; it was in my heart too to do so, but I’m glad you spoke first.” So, gently disregarding the remonstrances of the doctor, who protested that the morrow would be a more appropriate time, they departed, warmly wrapped up against the piercing cold, and carrying a lantern. As they passed from the village on to the shoulder of the swelling down a few soft snow-flakes began to fall....

All through that night the large round flakes fell heavily incessantly, until, when the pale cold dawn straggled through the leaden clouds, the whole country was deep buried in a smooth garment of spotless white. For three days the terrible, silent fall went on. The poor folk almost starved in their homes, and all traffic throughout the country was stopped. When at last communications could be opened, the old doctor, his heart aching with worry and suspense, made his way, accompanied by my father, to Pertwood Farm.51 There they found only a few hastily scribbled sheets of paper on the kitchen table. They contained words to the effect that George had been startled by a long wailing cry at a late hour on the night of the first snow. He had gone to the door, and there, on the very spot where she had lain years before, was his lost love. But this time she was dead. He had buried her by the side of his parents, and hoped to join the party soon.

A little search revealed the fact that after writing those lines he had gone down into the cellar and died, for his body lay across the rude box containing the remains of Louise. But of Charles nothing was ever again seen or heard. I have always felt that he might have been found at the bottom of that dank tarn among the pines, into which he may have fallen on that terrible night. But I don’t know, the mystery remains.

53