KURDISH SHEIKHS.

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

KURDISH SHEIKHS.

| G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS | |

| NEW YORK | LONDON |

| 27 WEST TWENTY-THIRD ST. | 24 BEDFORD ST., STRAND |

| The Knickerbocker Press | |

| 1895 | |

This is an important book. It deals with a burning question, and in a way which will command public attention and public confidence.

The author is thoroughly equipped for his task. Birth, residence, and travel in Turkey have made him personally acquainted with the situation which he discusses, and the independence of his position enables him to write without restraint and without prejudice. After nearly four years of service as a missionary of the American Board in Van, the centre of Armenia, during which no criticism of his course was ever made either by the Board or by the Turkish Government, he was recently ordered by his physician to return to America. Having resigned his connection with the American Board, he writes as the representative of no society, religious or political, and is connected with none. In issuing this book he is simply discharging what to him is a personal and unavoidable obligation; and as he frankly avows its authorship, it will be impossible for the Turkish Government to hold any one else responsible for it.

The author shows that the case of the subject races in the Ottoman Empire is desperate, that there is no hope of reform from within, and that relief vimust therefore come through the interference of the powers of Europe. Their action depends largely on the support of the public. “Public opinion,” therefore, “must be brought to bear upon this case,” as Mr. Gladstone said in the House of Commons six years ago. Since then there has been added a new chapter of horrors, and the demand for decisive action in the name of our common humanity has become more urgent. The facts furnished by this book ought to arouse such public opinion as will justify and compel prompt and efficient action on the part of the Powers.

The United States need not depart from its long-established foreign policy, but is bound to protect its own honor and the lives and property of its citizens.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I.— | A CHAPTER OF HORRORS | 1 |

| Certified Evidence of the Armenian Massacre, Preceded by an Endorsement of the Evidence, with Signatures in Fac-simile, and an Explanatory Note. | ||

| II.— | GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT EASTERN TURKEY | 43 |

| The Physical Aspects, Inhabitants, and Administration of the Country. | ||

| III.— | THE CHRONIC CONDITION OF ARMENIA AND KURDISTAN | 54 |

| Specific and Detailed Instances of Kurdish Plunder and Oppression.—The Turkish System of Taxation and its Abuses.—Why these Facts are so little Known.—What can be Done to Improve the Situation. | ||

| IV.— | OTTOMAN PROMISES AND THEIR FULFILMENT | 70 |

| The Treaty of Adrianople, 1829.—The Hatti Sherif, 1839.—Pledge of 1844.—Protestant Charter, 1850.—Hatti Humayoun, 1856.—Anglo-Turkish Convention, 1878.—Treaty of Berlin, 1878. | ||

| V.— | THE OUTCOME OF THE TREATY OF BERLIN | 76 |

| viii | British Naval Demonstration, 1879.—The Identical Note of the Powers, 1880, and the Turkish Reply.—The Collective Note of the Powers, and the Aggressive Response of the Sublime Porte.—The Circular of Great Britain, 1881, its Cool Reception by the Powers, and the Indefinite Postponement of Turkish Reforms.—The Effect of the Berlin Treaty in Arousing Armenian Aspirations and Increasing Turkish Oppression.—Armenian Revolution a Nightmare of the Turks.—The Real Armenian Position.—The Only Treatment for the “Sick Man” a Surgical One. | |

| VI.— | THE SULTAN AND THE SUBLIME PORTE | 87 |

| The Demands of his Office as Sultan-Calif.—Justice to Christian and Moslem both Impossible.—Status of non-Mohammedans.—The Palace and the Porte.—A House Divided against Itself. | ||

| VII.— | PREVIOUS ACTS OF THE TURKISH TRAGEDY | 95 |

| The Massacres of Greeks, 1822; Nestorians, 1850; Syrians, 1860; Cretans, 1867; Bulgarians, 1876; Yezidis, 1892; Armenians, 1894. | ||

| VIII.— | ISLAM AS A FACTOR OF THE PROBLEM | 110 |

| A Politico-Religious System.—Indissoluble and Incapable of Modification.—The Military, Civil, and Legal Rights of non-Mohammedans.—Freeman’s Conclusion. | ||

| IX.— | GLADSTONE ON THE ARMENIAN MASSACRE AND ON TURKISH MISRULE | 121 |

| X.— | WHO ARE THE ARMENIANS? | 131 |

| Their Origin, History, Church, Language, Literature, and General Characteristics. | ||

| XI.— | AMERICANS IN TURKEY, THEIR WORK AND INFLUENCE | 147 |

| Their Attitude and Recognized Position.—Statistics of the Direct Results of their Efforts.—Their Indirect Influence on All Classes.—The Present Threatening Attitude of the Turkish Government. | ||

| Appendix | A.—A BIT OF AMERICAN DIPLOMACY | 157 |

| B.—ESTABLISHMENT OF U. S. CONSULATES IN EASTERN TURKEY | 163 | |

| C.—DR. CYRUS HAMLIN’S EXPLANATION | 167 | |

| D.—THE CENSORSHIP OF THE PRESS | 169 | |

| E.—BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE SUBJECT | 171 | |

| General Index | 175 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

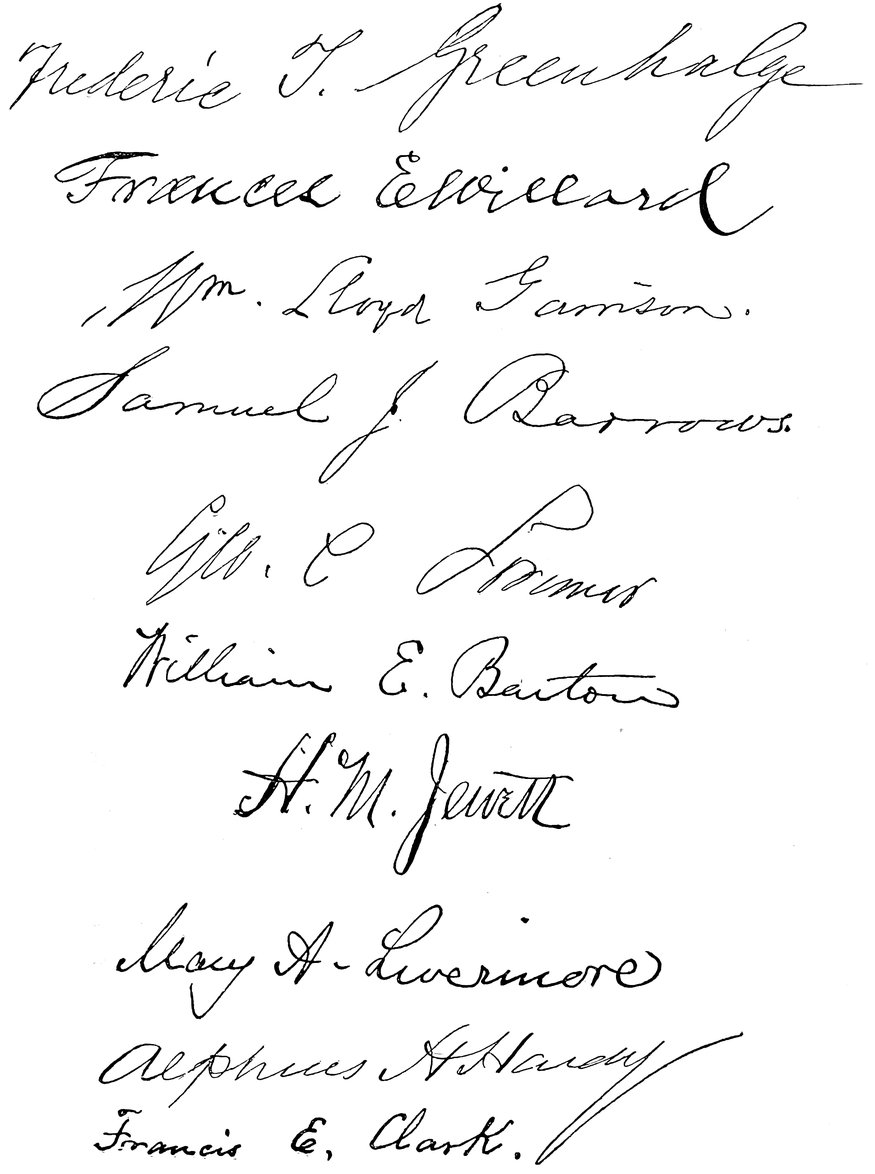

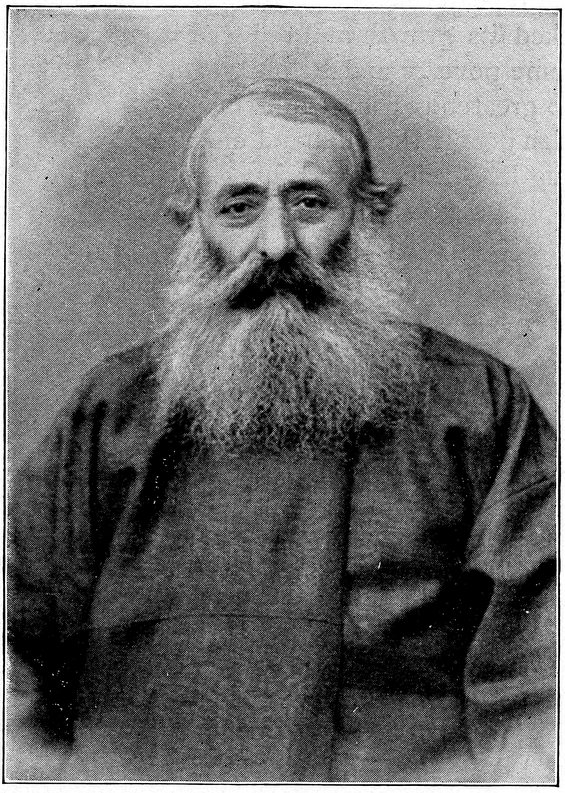

| KURDISH SHEIKHS | Frontispiece |

| FAC-SIMILE OF SIGNATURES | 2 and 4 |

| VICTIMS OF TURKISH TAXATION | 10 |

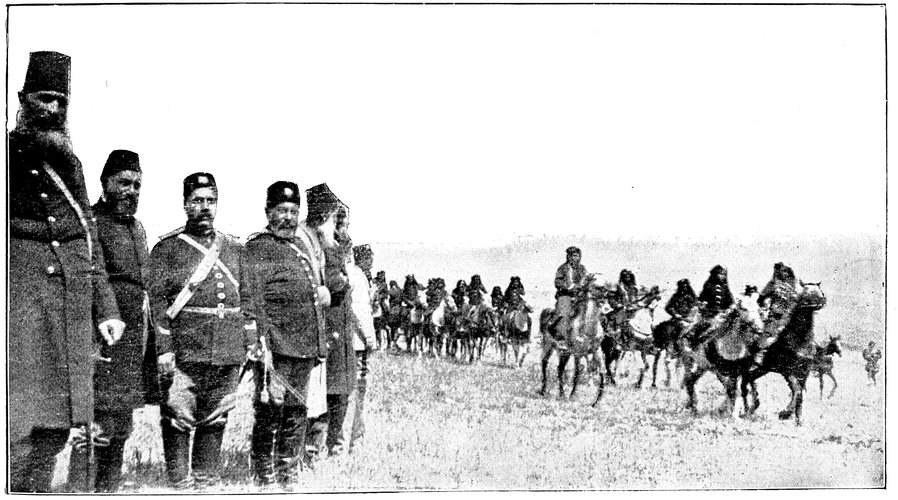

| REVIEW OF KURDISH CAVALRY | 19 |

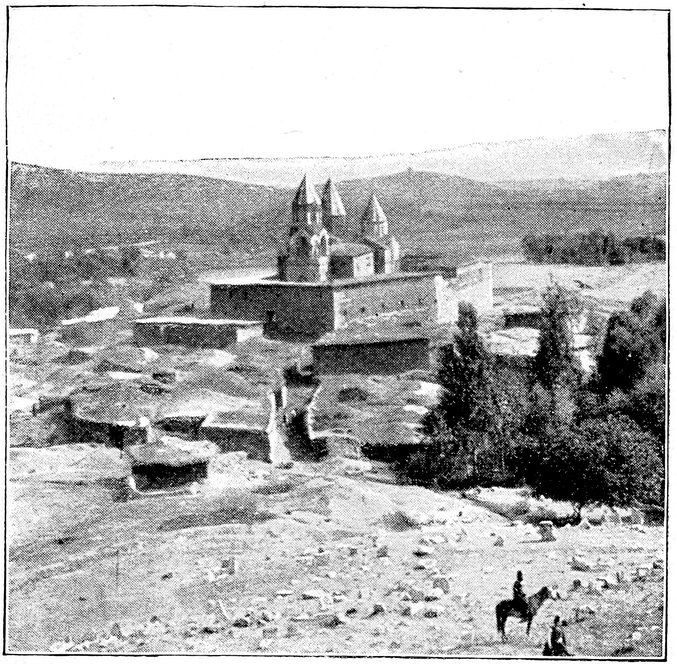

| NAREG: ANCIENT CHURCH AND MODERN HOVELS | 29 |

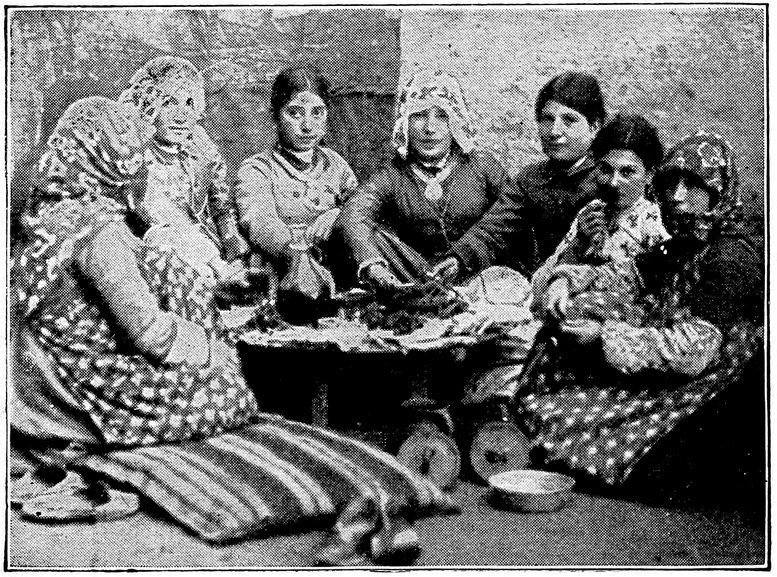

| ARMENIAN GIRLS OF VAN | 39 |

| A KURD OF THE OLD TYPE | 47 |

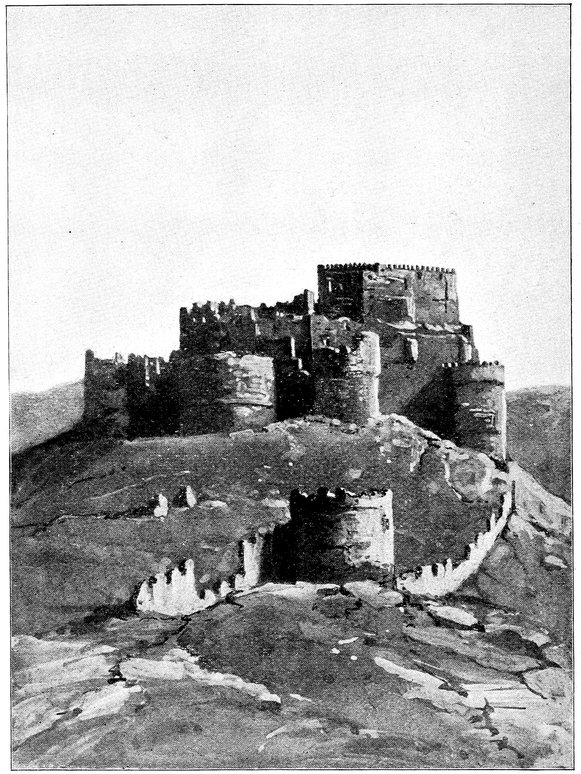

| RUINED KURDISH CASTLE AT KHOSHAB | 50 |

| MINAS TCHÉRAZ | 80 |

| ZEIBEK “IRREGULAR” | 83 |

| TURKISH SOLDIER, “REGULAR” | 85 |

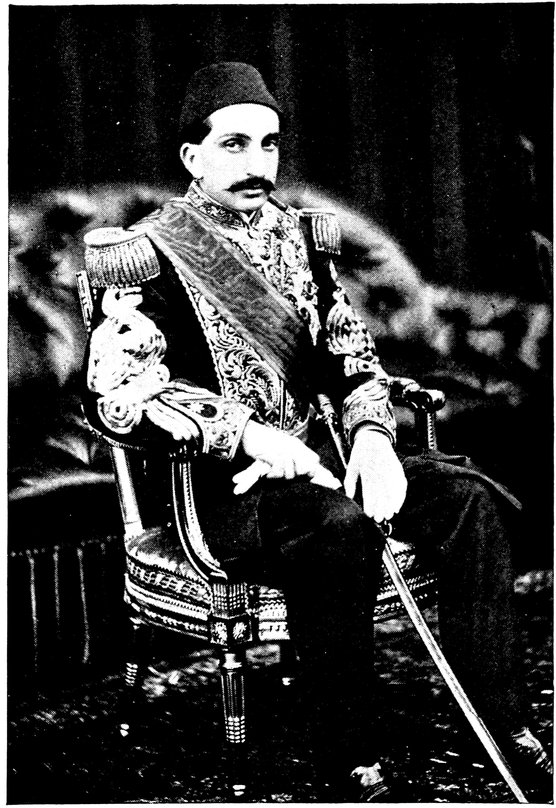

| H. I. M. SULTAN ABD-UL-HAMID KHAN | 91 |

| HIGHWAY IN ARMENIA | 105 |

| ARMENIAN REBELS WHO WOULD NOT PAY TAXES | 120 |

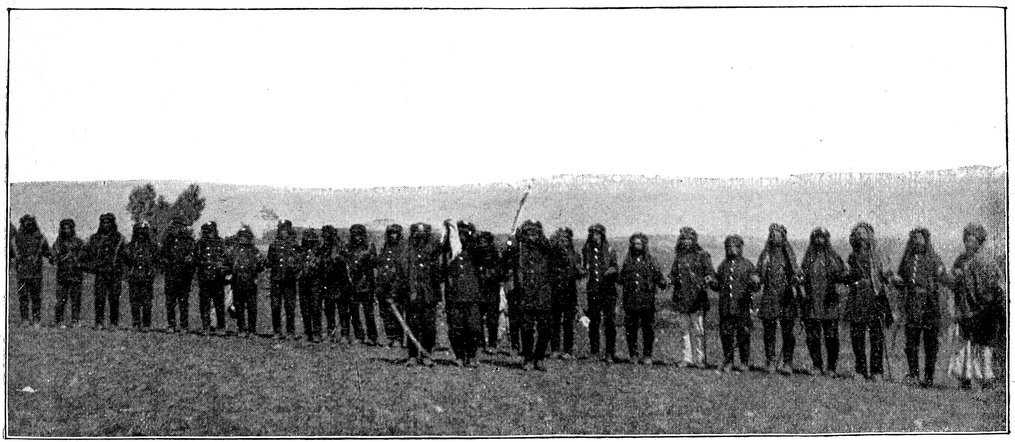

| KURDISH HAMIDIÉH SOLDIERS, EXECUTING THE “SWORD DANCE” | 127 |

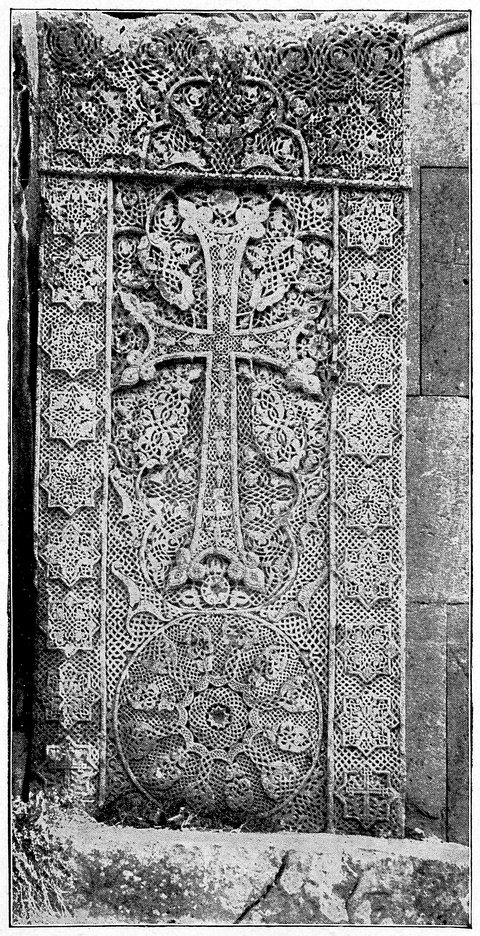

| ANCIENT ARMENIAN TOMBSTONE | 135 |

| THE CATHOLICOS OF ETCHMIADZIN | 139 |

| THE SUBORDINATE CATHOLICOS OF AGHTAMAR | 141 |

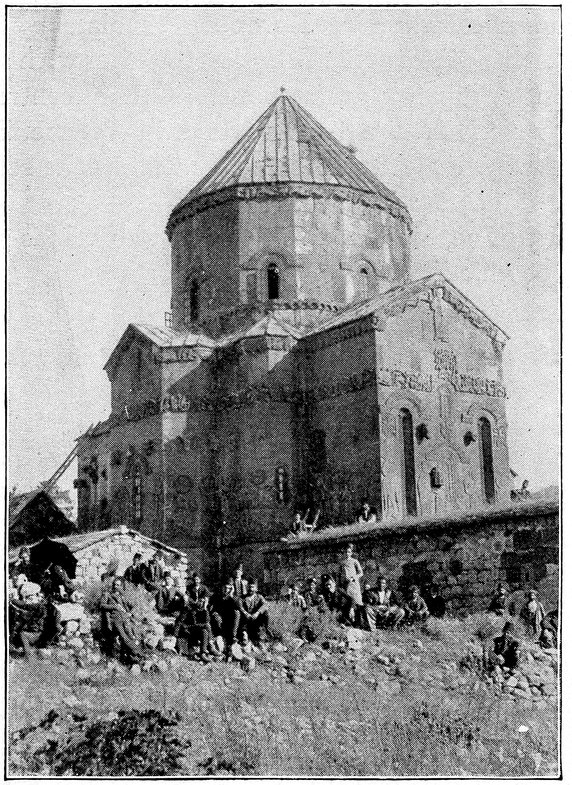

| THE ISLAND MONASTERY OF AGHTAMAR | 145 |

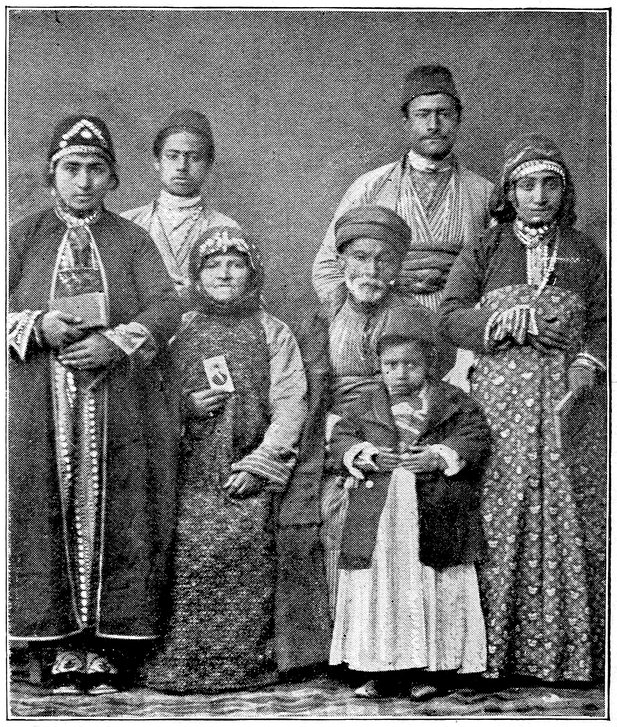

| ARMENIAN FAMILY OF BITLIS | 152 |

The writer has, from his birth, been a student of the Eastern Question, but makes no claim to having mastered it. What he has learned of the phases of that question here treated has been by absorption, observation, travel, residence, and investigation, in the land itself, and by study and reading in regard to it. The very short time allowed in the preparation of this humble contribution to the subject has necessitated a hasty and partial treatment at the expense of literary form. Some of the material of the second and third chapters and most of the illustrations in this book are reproduced from an article by the author in the American Review of Reviews for January, 1895, by the kind permission of the editor, Dr. Albert Shaw. No pains have been spared to insure accuracy. References to authorities have been given as far as possible, but in regard to much information from most reliable sources names must be withheld. It is a very significant feature of the situation in Turkey, that people who are thousands of miles away from her, and who may never set foot there again, do not dare to publicly state the facts, lest vengeance may be taken on their families and friends, still within reach of Turkish xiiviolence and intrigue. If His Imperial Majesty, the Sultan, but knew the real facts of the atrocious massacre of last year, and realized the disgrace attaching to the Turkish name on account of the unspeakably brutal deeds of his Turkish and Kurdish soldiers, officers included, we cannot but hope that some punishment would be visited upon them, experience to the contrary. He certainly should welcome the revelations of this book, and do all in his power to protect any who may aid him in bringing the facts to light and securing a better state of affairs. God help him, and save all his subjects, Turk, Arab, and Kurd, Christian, Jew, and Pagan, from the curse of a system of government not only “sick,” but dead and rotting!

I preach no crusade; none is needed. But it is high time for the conscience of Europe and America to assert itself—not simply the “non-Conformist conscience,” but the Established, the Orthodox, the Catholic, the Agnostic, and the Infidel conscience, in fact the human conscience—against this crime upon humanity. If this conscience is once aroused, I care not what parties are in power, or how the game stands on the diplomatic chessboard, the Eastern Question will be settled, instead of forever threatening the peace of Europe, and one more blot will be wiped out from the annals of the world.

I use the title The Crisis in Turkey because there is a crisis in the history of one of her most important races; there ought to be one throughout Turkey; and there may be one in Europe if selfishness, jealousy, and duplicity are forever to stifle all xiiiconsiderations of humanity, national honor, and—I blush to add it—of Christianity.

In order to protect “British interests,” for twoscore years, not to say longer, has “Christian” England stood guard at the Sublime Porte, warning all intruders away. With her hand on the door of the Turk’s disorderly house, she has complacently informed the world that she in particular—as well as the other Powers—has secured promises, and even guaranties, that all would go well. But all the while, Her Majesty’s Ministers, of whatever party, have heard the bitter and despairing cry of the poor wretches within. These Ministers have, since 1881, with rare exceptions, carefully suppressed in their archives the consular reports which have officially kept them informed of the real state of affairs.[1] And all the while, England’s share of the profits of this partnership with the unspeakable Turk has been steadily dropping into her overflowing coffers. Was Cyprus nothing? Is the interest on Turkish bonds nothing? Of course the creditor xivmust have his due, even though it is extracted in blood-drops by a pressure that England and the other Powers help to maintain.

A famous London divine recently preached a sermon in connection with the Armenian Massacre, using as a text Ezra ix., 3: “And when I heard this thing, I rent my garment and my mantle, and plucked off the hair of my head and of my beard, and sat down astonied.” May I suggest that it is high time to rouse oneself from mere astonishment, as did the Hebrew prophet? If the eloquent preacher is at a loss for an appropriate text for another sermon to an English audience, he can find it in the sixth verse of the same chapter: “O my God, I am ashamed and blush to lift up my face to thee, my God: for our iniquities are increased over our head, and our trespass is grown up unto the heavens.”

The very well informed correspondent of The Speaker wrote from Constantinople two months ago: “I fear there can be no doubt about the essential facts. We have already the official reports of the consuls at Van, Erzroom, Sivas, and Diarbekir, which have not yet been published, but which, we know, confirm the most horrible statements made in the newspapers. We have the reports of the Armenian refugees who were eye-witnesses. We have the reports sent to the Armenian Patriarchate here, and the reports of Catholic and Protestant missionaries in the vicinity of Sasun. Beyond this, and most horrible of all, we have the testimony of the Turkish soldiers who took part in the massacres. These soldiers ... have talked with the greatest freedom xvin public places, and to all who would listen, boasting of their deeds. We have full reports from all these places of the statements made by hundreds of these soldiers, and they agree in all essential points.”[2]

The author does not ignore the repeated and earnest efforts that have been made for years, by such individual Englishmen as the Hon. James Bryce, to call attention to the condition of Armenia. Their protests have kept alive Armenian hope that England at least would not entirely repudiate her obligations. But the futility of these same protests has also given assurance to the Sublime Porte in carrying out its policy of repression and extermination in Armenia.

Of course neither the party in power, nor its successors, will proceed energetically unless assured of the support of the people whom they represent. As soon as there is sufficient pressure from behind something more will be done than to dally with Turkish Commissions of Inquiry, sent under circumstances which make a true and full report simply a physical and moral impossibility.[3] The Turk is on trial and should be allowed to plead “Not Guilty.” But it is not customary, in courts where justice is the object, to allow the criminal at the bar the privilege of acting xvialso as the prosecuting attorney, and of summoning and examining the witnesses. As is well known, the most stringent measures have been taken by the Sublime Porte to prevent any representative of the press from watching the proceedings of the Commission of Inquiry at Moosh, or from making any independent investigation on the ground. Such precautions are hardly necessary, for all evidence of the massacre was concealed by torch and spade six months ago. If the executioners themselves overlooked any of their victims, the jackals, dogs, and vultures have surely found them by this time.

There are fifty native-born American citizens, not counting their children, who are now buried in Eastern Turkey. The fanatical outbreak which has slain thousands in their midst may yet involve them. The President of the United States long ago ordered a U. S. Consul to make a report as to the facts, simply for his own government, which has no official knowledge of what has or is taking place in that isolated region. The Sultan stamped his foot, and Consul Jewett was told to put his instructions in his pocket, where they still remain.[4]

As for France, who tattoos her fair figure with “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” wherever there is xviispace to write the words, she evidently confines her motto to herself. It is reported that at the close of the Berlin Treaty of 1878, Prince Bismarck expressed his sentiments by saying that he “would not give one Pomeranian grenadier for the Balkan Peninsula.” If so, probably he would sacrifice even less now for Armenia. Have the German people nothing to say?

Holy Russia feels so sure of the Armenian apple, which seems bound to fall into her lap, that she doesn’t even care to shake the branch, unmindful of the fact that the apple is tenacious of its hold, and is being pecked to pieces and rotting on the stem. Austria would not refuse the task of instituting reforms as far south as Salonica. Poor Italy is willing to be useful, and Greece does not care to be left out. They all want their share. Nobody expects or is trying to secure reforms from within, though promises to that effect may still be demanded, and will always be ready on demand.

As for official Turkey, she has long seen the sword of Damocles over her head, and will bow to the stroke of Fate whenever it falls. If it only comes hard enough, and is aimed true to the mark, she will even get out of the way. Not a drop of blood need be shed.

What is the real difficulty in Turkey? Is it a conflict of race or religion? Primarily it is neither, though both these elements complicate the case. In one word it is misgovernment. Do not be deceived by this rather mild word, and dismiss the subject with the reflection that “there is misgovernment everywhere.” Misgovernment as it exists in Turkey is an organization that breeds death and corruption. xviiiIt is a disease, of which the germs penetrate the whole system of the body politic. It is a disease, hereditary, chronic, and fastened upon the very vitals of its victim. No creed is exempt, every race is attacked by it. The more apparent result is outward impoverishment and material prostration. The more dangerous and deplorable symptom is the moral deterioration of all the races affected.

I am no eulogist of the mass of Armenians in their present condition. But I know their grand possibilities as a race, physically, intellectually, and morally. The depths to which an individual or a race can fall indicate the height which might have been attained. The only wonder is that a people of so great ability, energy, and spirit have so long submitted. But when one sees, as I have been compelled to, during years of residence both in Constantinople and the interior, how the fetters have been forged on every limb, and how the movement of a finger even brings down immediate and terrible vengeance, the wonder arises why these wretches are so foolhardy as to undertake revolution. The fact is they are not engaged in any such enterprise. Individual agitators there are, but even their object is only to force the civilized world to give attention to the despairing cry of their race, which even God does not seem, to them, to hear.

The case of the Armenians demands immediate and thorough attention. But the Armenian question should not be allowed to fill the whole horizon in the Levant. Just now the blaze comes from their house, but no one can tell when it may result in a general xixconflagration. All the other Christian races and the Mohammedan races, too, are equally concerned. Europe itself is endangered, as her statesmen well know, and safety depends only on their prompt and united action.

I have seen the crushing and—what is worse—demoralizing conditions from which the Armenian and all other races in Turkey suffer under Moslem misrule. I know how rapidly these fine races would advance along every line, were these conditions changed. It is my firm belief that such changes may now be secured, if the interest already aroused throughout the civilized world be expressed in intelligent and determined action. In the hope of such action I send forth this little book. If action is not taken, the effect of this book, as of all agitation in behalf of the victims of Turkey, will be to draw the fetters deeper. What result may follow to my many friends and former associates on the ground, with whom it is very difficult to communicate, I do not know. But I know them, and do not believe that there is one among their number who, to shield himself from danger, would stay my pen.

Reader, your voice and help are needed.

MAP OF

TURKEY IN ASIA

The shaded section is commonly called

ARMENIA

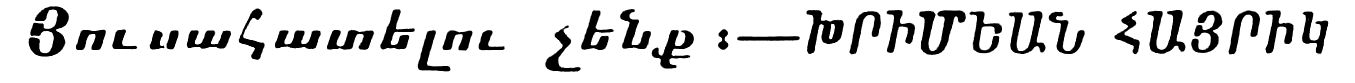

We, the undersigned, by examination and comparison, have satisfied ourselves that the following statements are verbatim reports, written under the dates which they bear, by American citizens who have spent from six to thirty years in Eastern Turkey. We have examined also the fact that they are written from six different cities from one hundred to two hundred miles apart, but forming a circle about the centre in which the massacres occurred. For the personal safety of the writers the names of the places cannot now be made public. They are independent reports from a country where refugees and returned soldiers of the Sultan speak of what they know. We have the utmost confidence in these statements and regard them worthy the belief of all men.

In the name of a suffering humanity we urge the careful perusal of these statements, and recommend that all readers take measures to make the indignation of an outraged Christian world effectually felt. We deprecate revolution among these helpless Turkish subjects, but bespeak cordial co-operation in bringing to bear upon Turkey the force of the righteous condemnation of our seventy millions of people.

These letters are written by men who can have no possible motive for misrepresenting the facts in the case, while, on the other hand, each writer subjected himself to personal danger by putting such statements upon paper and sending them through the mails. Several of the documents have gotten through Turkey by circuitous routes, in some instances having been sent by special messenger to Persia, and so on to this country. Others were never risked in the Turkish mails, but have come through the British post-office at Constantinople.

It must be borne in mind that no writer was an eye-witness of the actual massacre; nor could he have been, inasmuch as the whole region was surrounded by a military cordon during the massacre and for months after. The letters are largely based on the testimony of refugees from that region, or of Kurds and soldiers who participated in the butchery, and who had no hesitation in speaking about the affair in public or private until long after, when the prospect of a European investigation sealed their lips. Much of the evidence is, therefore, essentially first hand, having been obtained from eye-witnesses, 7by parties in the vicinity at the time, who are impartial, thoroughly experienced in sifting Oriental testimony, familiar with the Turkish and Armenian languages, and of the highest veracity. No one letter would have much force if taken alone, for it might be a large report of a small matter; but these sixteen letters are written independently of one another, at different times, and from seven different cities widely apart, five of them forming a circle around the scene of destruction. The evidence is cumulative and overwhelming.

There is absolute unanimity to this extent: that a gigantic and indescribably horrible massacre of Armenian men, women, and children did actually take place in the Sassoun and neighboring regions about Sept. 1, 1894, and that, too, at the hands of Kurdish troops armed by the Sultan of Turkey, as well as of regular soldiers sent under orders from the same source. What those orders were will probably never transpire. That they were executed under the personal direction of high Turkish military officers is clear. There can also be no doubt—for the official notice from the palace was printed in the Constantinople papers in November last—that Zekki Pasha, Commander of the Fourth Army Corps, who led the regular troops in the work of extermination, has since been specially honored by a decoration from the Sultan, who was also pleased to send silk banners to the four leading Kurdish chiefs, by a special messenger.

The latest, most accurate, and comprehensive document in this correspondence is No. 6, which is 8based on evidence obtained with special care at the nearest attainable point to the scene, and was prepared by parties in intimate relations with the European official who made the first investigation on the ground last October, but whose report has not yet been made public.

The letters are arranged in chronological order. In view of the fact that the names of the cities from which the various documents are dated must be withheld at present, these places are designated by letters of the alphabet. The separate extracts are also numbered to facilitate reference. In order that there may be no confusion, all explanatory comments of the author are enclosed in brackets.

[The reader should take notice that this first letter was written over four months before the massacre actually occurred.]

It does seem in this region as if the government were bent on reducing all those who survive the process to a grovelling poverty, when they can think of nothing more than getting their daily bread. There is good reason for thinking that unless so-called Christian nations extend a helping hand, they [the Armenians] will become wellnigh extinct. Of course I do not sympathize in any way with the extremists in other lands who are stirring things up here. Nor do I agree with those papers that decry this movement as very foolish because there is no hope for success. If I rightly interpret the movement in this region, the thought is not revolution at all, but a desperate effort to call the attention of Europe to the wrongs they are suffering and will ever continue to suffer under this government. They feel that they will never succeed in attracting that 10attention unless they show that they are desperate enough to sacrifice their lives. And there is no computing the lives that are going, not in open massacre as in Bulgaria—the government knows better than that,—but in secret, silent, secluded ways. The sooner it is known, the better. There never will be peaceful, prosperous conditions here until others take hold with a strong hand.

VICTIMS OF TURKISH TAXATION ABANDONING THEIR VILLAGE HOMES.

[This is the first report of the massacre.]

Troops have been massed in the region of the large plain near us. Sickness broke out among them, which took off two or three victims every few days. It was a good excuse for establishing the quarantine 11around, with its income from bribes, charges, and the inevitable rise in the price of the already dear grain. I suspect that one reason for placing quarantine was to hinder the information as to what all those troops were about in that region. There seems little doubt that there has been repeated in the region back of Moosh what took place in 1876 in Bulgaria. The sickening details are beginning to come in. As in that case, it has been the innocent who have been the greatest sufferers. Forty-eight villages are said to have been wholly blotted out.

[Efforts to conceal the truth as soon as Vice-Consul Hallward arrived on the scene, and to ward off investigation.]

As the time goes on the extent of the slaughter seems to be confirmed as greater than was first supposed. Six thousand is a low figure—it is probably nearer ten. Mr. Hallward, the new [English] Consul at Van, has gone directly there, and it is said that the other consuls from Erzroom have also been sent to investigate. The government tried to get the people here to sign an address to the Sovereign, expressing satisfaction with his rule, disclaiming sympathy with the Armenians who have “stirred matters up,” stating that the thousands slain in Talvoreeg met their just deserts, and that the four outsiders captured should be summarily punished, expressing 12regret that it has been thought best to send consuls to investigate, and stating that there was no need for their coming. From this document we at least get some facts that before were suppositions. It consisted of about two thousand words, and it was expected that it would be sent by telegraph with at least a thousand signatures. The Armenians here have not yet signed it, though in four districts similar papers have been secured properly sealed. The effect of such papers on foreigners will be much modified when they know the means used to procure them. Sword, famine, pestilence, all at once—pity this poor country!

[The following is from a different source.]

We have word from Bitlis that the destruction of life in Sassoun, south of Moosh, was even greater than was supposed. The brief note which has reached us says: “Twenty-seven villages annihilated in Sassoun. Six thousand men, women, and children massacred by troops and Kourds. This awful story is just beginning to be known here, though the massacre took place early in September. The Turks have used infinite pains to prevent news leaking out, even going to the length of sending back from Trebizond many hundreds from the Moosh region who had come this way on business.” This massacre was ordered from Constantinople in the sense that some Kourds having robbed Armenian 13villages of flocks, the Armenians pursued and tried to recover their property, and a fight ensued in which a dozen Kourds were killed. The slain were “semi-official robbers,” i.e., enrolled as troops and armed as such, but not under control. The authorities then telegraphed to Constantinople that Armenians had “killed some of the Sultan’s troops.” The Sultan at once ordered infantry and cavalry to put down the Armenian rebellion, and they did it; only, not finding any rebellion, they cleared the country so that none should occur in the future.

[This from a third place.]

Last year the Talvoreeg Armenians successfully resisted the attacks of the neighboring Kourds. The country became very unsettled. This year the government interfered and sent detachments of regular soldiers to put down the Armenians. These were assisted by the Kourdish Hamediéhs [organized troops]. The Armenians were attacked in their mountain fastnesses and were finally reduced by the failure of supplies, both of food and ammunition. About a score of villages were wiped out of existence—people slaughtered and houses burned.

A number of able-bodied young Armenians were captured, bound, covered with brushwood and burned alive. A number of Armenians, variously estimated, but less than a hundred, surrendered 14themselves and pled for mercy. Many of them were shot down on the spot and the remainder were dispatched with sword and bayonet.

A lot of women, variously estimated from 60 to 160 in number, were shut up in a church, and the soldiers were “let loose” among them. Many of them were outraged to death and the remainder dispatched with sword and bayonet. A lot of young women were collected as spoils of war. Two stories are told. 1. That they were carried off to the harems of their Moslem captors. 2. That they were offered Islam and the harems of their Moslem captors,—refusing, they were slaughtered. Children were placed in a row, one behind another, and a bullet fired down the line, apparently to see how many could be dispatched with one bullet. Infants and small children were piled one on the other and their heads struck off. Houses were surrounded by soldiers, set on fire, and the inmates forced back into the flames at the point of the bayonet as they tried to escape.

But this is enough of the carnage of death. Estimates vary from 3000 to 8000 for the number of persons massacred. These are sober estimates. Wild estimates place the number as high as 20,000 to 25,000.

This all took place during the latter part of August and [early part of] September. The arrival of the commander-in-chief of the Fourth Army Corps put a stop to the carnage. It is to be noted that the massacres were perpetrated by regular soldiers, for the most part under command of officers of high rank. This gives this affair a most serious aspect.

15A Christian does not enjoy the respect accorded to street dogs. If this massacre passes without notice it will simply become the declaration of the doom of the Christians. There will be no security for the life, property, or honor of a Christian. A week ago last Tuesday evening at sundown a Turk kidnapped the wife of a wealthy Armenian merchant of the town of Khanoos Pert. Next morning her cries were overheard by searchers and she was rescued from a Turkish house. No redress is possible.

Wild rumors have been abroad for a long time, but trustworthy information came to hand slowly. Everything has been done to hush it all up. Some of the minor details of the stories I have told above may not be exact, but I feel quite certain they are in the main. However, that a cruelly barbarous and extensive massacre of Christians by regular soldiers assisted by Kourdish Hamediéhs, under command of officers of rank and responsibility, has occurred cannot be denied.

What now will the Christian world do?

[This is the most complete account, compiled on the ground. The following document was carefully prepared in common by parties, the signature of any one of whom would be of sufficient guaranty to give great weight. One of the party, who is largely responsible for the data given, is a man of high position and wide influence. The material was collected with the greatest difficulty and under the 16constant espionage of Turkish officials. Armenian Christians who were known to appear at the place where the writer was staying, were arrested and some are yet in prison if they have not met a worse fate already. The documents were sent by secret, special carriers into Persia and came by Persian post to the United States. They left Turkey about the last of November, 1894. This document alone is sufficient to stir the indignation of a Christian world.]

There is uneasiness in Bitlis as to the safety of that city. Scrutiny of the mails by the Turkish authorities continues, and some letters addressed to residents and officials in the United States are failing to arrive.

The Hamediéh soldiers, who are Kourds, and who have been enrolled during the past three years, are uniformed to some extent, but left in their homes. They are committing all kinds of depredations. The government continues to exact taxes in the plundered districts, sends zaptiehs, or Turkish soldiers, to abide in the villages, and eat the people out of provisions until in some way they manage to secure the money. In the Bashkalla region many of the men find, on returning, that the government has taken possession of their property and refuses to restore it or allow them to remain in their old homes.

The authorities have taken and are taking every precaution to prevent accounts of the famous massacre of Moosh from reaching the outside world. The English consul, Mr. Hallward, went on a tour in 17the region affected. He was subjected to constant annoying espionage, and was absolutely unable to penetrate into the devastated region.

To what extent Armenian agitation has provoked the terrible massacre it is difficult to determine. For a year or more there seems to have been an Armenian from Constantinople staying in the region as an agitator. For a long time he skilfully evaded his pursuers, but was at last caught and taken to Bitlis. He demanded to be taken to Constantinople and to the Sultan, and, it is said, he is now living at the capital, receiving a large salary from the government. Evidently he has turned state’s evidence.

Late in May, 1893, an outside agitator named Damatian was captured near Moosh. The government had suspected that the Talvoreeg villages were harboring such agitators, and had sent orders to certain Kourdish chiefs to attack the district, assuming the responsibility for all they should kill, and promising the Kourds all the spoil.

Not long after Damatian had been brought to Bitlis, the first week in June, the Bakranlee Kourds began to gather below Talvoreeg. As the villagers saw the Kourds gathering day by day, to the number of several thousands, they suspected their designs, and began to make preparations. On the eighth day the battle was joined. The stronger position of the villagers enabled them to do considerable execution with little loss to themselves. 18The issue of the contest at sunset was some one hundred Kourds slain, and but six of the villagers, one of whom was a woman who was trying to rescue a mule from the Kourds. The villagers had succeeded in breaking down a bridge across the deep gorge of a river before a detachment of Kourds from another direction could join in the attack against them. The Kourds thus felt themselves worsted, and could not be induced to make another attack that summer.

At this juncture the Governor-general set out with troops and two field-pieces for Moosh, and infested the region near Talvoreeg, but either he considered his forces insufficient, or he had orders to keep quiet, for he made no attack, but merely had the troops keep siege. Before leaving, he succeeded, by giving hostages, in having an interview with some of the chief men in Talvoreeg, and asked them why they did not submit to the government, and pay taxes. They replied that they were not disloyal to the government, but that they could not pay taxes twice, to the Kourds and to the government. If the government would protect them, they would pay to it. Nothing came of the parley, and the siege was continued till snow fell. During the winter, while blackmail was rife in the vilayet, several rich men of Talvoreeg were invited to visit the Governor-General, but did not see best to accept.

In the early spring the Kourds of several tribes were ordered to attack the villages of Sassoun, while troops were sent on from Moosh and Bitlis, the latter taking along ammunition and stores, and ten muleloads of kerosene (eighty cans). The whole district was pretty well besieged by Kourds and troops. The villages thus besieged would occasionally make sorties to secure food.

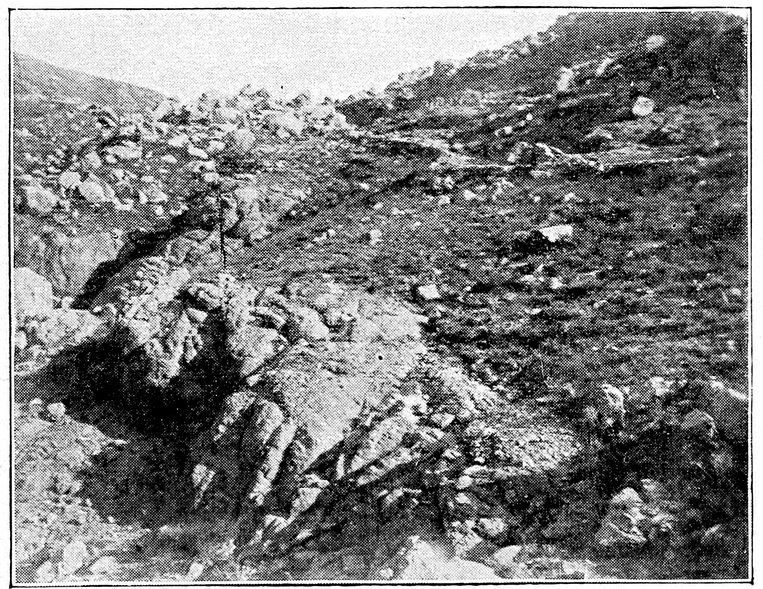

REVIEW OF KURDISH CAVALRY BY THE GOVERNOR OF VAN, BAHRI PASHA—AT THE LEFT.

20The Kourds on one occasion stole several oxen, and their owners tracked their property to the Kourdish tents, and found that one ox had been butchered. They asked for the others, and were refused, whereupon the villagers left, and later returned with some companions. A scrimmage ensued, in which two or three were killed on either side. The Kourds at once took their dead to the government at Moosh, and reported that the region was filled with Armenian and foreign soldiers. The government at once sent in all directions for soldiers, gathering in all from eight to ten taboors (regiments). Kourds congregated to the number of about twenty thousand, while some five hundred Hamediéh horsemen were brought to Moosh.

At first the Kourds were set on, and the troops kept out of sight. The villagers, put to the fight, and thinking they had only the Kourds to do with, repulsed them on several occasions. The Kourds were unwilling to do more unless the troops assisted. Some of the troops assumed Kourdish dress, and helped them in the fight with more success. Small companies of troops entered several villages, saying they had come to protect them as loyal subjects, and were quartered among the houses. 21In the night they arose and slew the sleeping villagers, man, woman, and child.

By this time those in other villages were beginning to feel that extermination was the object of the government, and desperately determined to sell their lives as dearly as possible. And then began a campaign of butchery that lasted some twenty-three days, or, roughly, from the middle of August to the middle of September. The Ferik Pasha [Marshal Zekki Pasha], who came post-haste from Erzingan, read the Sultan’s firman for extermination, and then, hanging the document on his breast, exhorted the soldiers not to be found wanting in their duty. On the last day of August, the anniversary of the Sultan’s accession, the soldiers were especially urged to distinguish themselves, and they made it the day of the greatest slaughter. Another marked day occurred a few days earlier, being marked by the occurrence of a wonderful meteor.

No distinctions were made between persons or villages, as to whether they were loyal and had paid their taxes or not. The orders were to make a clean sweep. A priest and some leading men from one village went out to meet an officer, taking in their hands their tax receipts, declaring their loyalty, and begging for mercy; but the village was surrounded, and all human beings put to the bayonet. A large and strong man, the chief of one village, was captured by the Kourds, who tied him, threw him on the ground, and, squatting around him, stabbed him to pieces.

At Galogozan many young men were tied hand 22and foot, laid in a row, covered with brushwood and burned alive. Others were seized and hacked to death piecemeal. At another village a priest and several leading men were captured, and promised release if they would tell where others had fled, but, after telling, all but the priest were killed. A chain was put around the priest’s neck, and pulled from opposite sides till he was several times choked and revived, after which several bayonets were planted upright, and he raised in the air and let fall upon them.

The men of one village, when fleeing, took the women and children, some five hundred in number, and placed them in a sort of grotto in a ravine. After several days the soldiers found them, and butchered those who had not died of hunger.

Sixty young women and girls were selected from one village and placed in a church, when the soldiers were ordered to do with them as they liked, after which they were butchered.

In another village fifty choice women were set aside and urged to change their faith and become hanums in Turkish harems, but they indignantly refused to deny Christ, preferring the fate of their fathers and husbands. People were crowded into houses which were then set on fire. In one instance a little boy ran out of the flames, but was caught on a bayonet and thrown back.

Children were frequently held up by the hair and cut in two, or had their jaws torn apart. Women with child were ripped open; older children were pulled apart by their legs. A handsome, newly wedded couple fled to a hilltop; soldiers followed, 23and told them they were pretty and would be spared if they would accept Islam, but the thought of the horrible death they knew would follow did not prevent them from confessing Christ.

The last stand took place on Mount Andoke [south of Moosh], where some thousand persons had sought refuge. The Kourds were sent in relays to attack them, but for ten or fifteen days were unable to get at them. The soldiers also directed the fire of their mountain guns on them, doing some execution. Finally, after the besieged had been without food for several days, and their ammunition was exhausted, the troops succeeded in reaching the summit without any loss, and let scarcely a man escape.

Now all turned their attention to those who had been driven into the Talvoreeg district. Three or four thousand of the besieged were left in this small plain. When they saw themselves thickly surrounded on all sides by Turks and Kourds, they raised their hands to heaven with an agonizing moan for deliverance. They were thinned out by rifle shots, and the remainder were slaughtered with bayonets and swords, till a veritable river of blood flowed from the heaps of the slain.

And so ended the massacre, for the timely arrival of the Mushire [Commander-in-chief of the Fourth Army Corps at Erzingan] saved a few prisoners alive, and prevented the extermination of four more villages that were on the list to be destroyed, among which was the Protestant village of Havodorick. This was the formidable army the government had massed so many troops and Kourds to vanquish.

24So far as is known, not more than ten or fifteen outsiders were among them, and all told it is not likely they had more than one hundred breechloading rifles.

Even if one were able to visit the district, it would be impossible to get more than an approximate estimate of the number of victims, for many were thrown into trenches, which the rain had washed out, and were covered with earth. Where no such trenches existed the bodies were piled up with alternate layers of wood, saturated with kerosene, and set on fire. But it seems certain that the villages of the whole district were wiped out. A Kourdish chief coming late with his men, and finding that there was nothing left for him to do, went off on his own hook and got all the plunder he could from the village of Maineeg, near Havodorick.

A soldier while in quarantine said he had killed five persons, and he had killed less than anybody else. Another confided to one that he had killed a hundred. A soldier got angry while trading with an Armenian the other day in the Bitlis market, and shouted out that they had slain a thousand thousand, and would turn to those in the city next.

It seems safe to say that forty villages were totally destroyed, and it is probable that sixteen thousand at least were killed. The lowest estimate is ten thousand, and many put it much higher. This is allowing for more fugitives than it seems possible can have escaped.

25To cap the climax, the Governor-General, through imprisonment and intimidation of various kinds, has forced the chief men in all the province (the city of Bitlis alone excepted), to seal an address of gratitude to the Sultan, that the Governor has restored order in the vilayet!!

[The following extract is from a personal letter written by one whose name would be immediately recognized by every reader were we at liberty to make public use of it. The writer is a person of broad influence; but for the present, owing to facts which we are not at liberty to relate, he cannot take a public stand. He will probably be heard from yet.]

The massacre which took place a few weeks ago—I do not know the exact date—occurred in the district of Talvoreeg which lies between Moosh and Diarbekir. It is an Armenian district, comprising thirty or forty villages, surrounded by Kourds.

Last year some of the Armenians there armed themselves and resisted the Kourds, who are constantly making raids on their villages and carrying off their property. The Governor sent some soldiers, who killed a few Armenians and received a medal from the government for having wiped out a great rebellion. This year there are said to have been ten or fifteen revolutionists among these Armenians. A 26Kourdish chief in order to get out of some difficulties that he had gotten into with the government set the ball rolling by carrying off some cattle belonging to certain of the Armenians. The Armenians endeavored to recover the cattle, and a fight followed, in which two Kourds were killed and three were wounded. The Kourds immediately carried their dead to Moosh, laid them down at the government house, reporting that Armenian soldiers were overrunning the land, killing and plundering them.

This furnished the government with the desired excuse for collecting soldiers from far and near. The general is said to have worn on his breast an order from Constantinople, which he read to the soldiers, commanding them to cut down the Armenians root and branch, and adjuring them if they loved their Sultan and their government they would do so. A terrible massacre followed. Between five and ten thousand Christians are said to have been butchered in a most terrible manner. Some soldiers say a hundred fell to each one of them to dispose of; others wept because the Kourds did more execution than they.

No respect was shown to age or sex. Men, women, and infants were treated alike, except that the women were subjected to greater outrage before they were slaughtered. The women were not even granted the privilege of a life of slavery. For example, in one place three or four hundred women, after being forced to serve the vile purposes of a merciless soldiery, were taken to a valley near by and hacked to pieces with sword and bayonet. In another place 27about two hundred women, weeping and wailing, knelt before the commander and begged for mercy, but the blood-thirsty wretch, after ordering their violation directed the soldiers to dispatch them in a similar manner. In another place a large company, headed by the priest, fell down before the officers saying they had nothing to do with the culprits, and pleading for compassion, but all to no purpose—all were killed. Some sixty young brides and more attractive girls were crowded into a little church in another village, where, after being violated, they were slaughtered, and a stream of human blood flowed from the church door. To some of the more attractive women in one place the proposition was made that they might be spared if they denied their faith. “Why should we deny Christ,” they said, and pointing to the dead bodies of their husbands and brothers before them, they nobly answered, “We are no better than they; kill us too,”—and they died.

After the above-mentioned events the Governor attempted to persuade and compel the Armenians to sign a paper thanking the Sultan and himself that justice had been done to the rebels!

[From another city to which soldiers returning brought details of what they had done.]

The Armenians, oppressed by Kourds and Turks, said, “We can’t pay taxes to both Kourds and the government.” Plundered and oppressed by the 28Kourds, they resisted them; there were some killed. Then false reports were sent to Constantinople that the Armenians were in arms, in rebellion. Orders were sent to the Mushire [Commander-in-chief] at Erzingan to exterminate them root and branch. The orders read before the army collected in haste from all the chief cities of Eastern Turkey was: “Whoever spares man, woman, or child is disloyal.”

The region was surrounded by soldiers of the army and twenty thousand Kourds also are said to have been massed there. Then they advanced upon the centre, driving in the people like a flock of sheep, and continued thus to advance for days. No quarter was given, no mercy shown. Men, women, and children shot down or butchered like sheep. Probably when they were set upon in this way some tried to save their lives and resisted in self-defense. Many who could fled in all directions, but the majority were slain. The most probable estimate is fifteen thousand killed, thirty-five villages plundered, razed, burnt.

Women were outraged and then butchered; a priest taken to the roof of his church and hacked to pieces; young men piled in with wood saturated with kerosene and set on fire; a large number of women and girls collected in church, kept for days, violated by the brutal soldiers, and then murdered. It is said the number was so large that the blood flowed out of the church door. Three soldiers contended over a beautiful girl. They wanted to preserve her, but she too was killed.

Every effort is being made and will be made to falsify (excuse the blots—emblematic of the horrible 29story) the facts and pull the wool over the eyes of European governments. But the bloody tale will finally be known, the most horrible, it seems to me, that the nineteenth century has known. As a confirmation of the report, the other day several hundred soldiers were returning from the seat of war, and at a village near us one was heard to say that he alone with his own hand had killed thirty pregnant women. Some who seem to have some shame for their atrocious deeds say: “What could we do, we were under orders?”

NAREG: ANCIENT CHURCH AND MODERN HOVELS.

[Later from the same place as the preceding extract. Evidence of a regular soldier who helped dispose of the dead.]

The soldiers who went from here talk quite freely about matters at Sassoun. A. heard one talk the other day. He said the work was mostly finished before the E... soldiers got there. There was great spoil—flocks, herds, household goods, etc.—but their chief work was to dispose of the heaps and heaps of the dead. The stench was awful. They were gathered into the still standing houses and burned with the houses. They say that the work of destruction was wrought by the Hamediéh, i.e., the newly organized Kourdish regiments. Those regiments are one of the chief elements of danger to the country now.

[From a city some distance from the scene.]

You may believe most all that the papers say about the mountains west of Moosh. I wrote you giving you a few more authenticated details. I hope that letter reached you. I give the outline here again. In August the Armenians were declared in rebellion. The regular soldiers and Hamediéhs were ordered to the spot. Orders were issued from Constantinople 31to put down the rebellion. Both regulars and Hamediéhs were used. The massacre began after the middle of August—about the 18th—and continued to about the 10th of September. The safe estimates put the number of victims at about four thousand, not less than three thousand five hundred, and, in all probability, more than four thousand.

Men, women, and children were most barbarously slaughtered—unnamable outrages were perpetrated on all. The less horrible outrages were some of the following: bayoneting the men, and in this wounded condition either burying or burning them; outraging women and then dispatching them with bayonets or swords; ripping up pregnant women; impaling infants and children on the bayonet, or dispatching them with the sword; houses fired, and the inmates driven back into the flames.

The unspeakable horror of those three weeks must have sent many a one crazy. The story is told that one soldier found a comely infant and took compassion on it and wished to save it. The mother was found in a crowd of poor, wretched women, but she was raving, calling for her children. She did not recognize the child, and nothing was left to the soldier but to dispatch it.

[Efforts to block the Commission and put the country in shape for inspection by emptying prisons of innocent people.]

The Bitlis Governor asks for a cordon on Moosh, as there is cholera reported there. So the Consular Commission is delayed. The Turkish Commission is at Moosh now. Only, the president of it was recalled. In the meantime Sassoun refugees are scattered over the country, begging. Their stories, together with the stories of the soldiers, confirm the most horrible of the reports of cruelty.

In all this, remember that the same thing has been going on on a lesser scale all over the country.

Two weeks ago thirty-six men were dismissed from B... prison after three years three months’ detention. A little over three years ago three Armenians were most barbarously murdered in the Narman district, north of this city and near the Russian boundary. Some Turks were called up for examination, and all were dismissed. Later, three Turks were murdered and mutilated, apparently in retaliation. The able-bodied men—sixty-two in number—of two villages were thrown into prison. Some of them were condemned to death, some to life imprisonment, and others to various terms of imprisonment. A number of them died—fifteen, I think—in prison. Thirty-six were released the other day, and eleven are still in prison. They have suffered horribly during these three years. In what condition will they find their homes when those who are released return? It is almost certain that none of them knew anything about the murder or had any hand in it. It is said that the murderer is well known, and is in Russia. This case is a Sassoun atrocity on a smaller scale.

33For God’s sake do not let the public conscience go to sleep again over this reign of terror. The land is almost paralyzed with horror and terror!

[The crisis and the need of keeping the issue clear. The real explanation of the massacre.]

The importance of the present crisis grows upon me. In the first place Turkey is preparing for a terrible catastrophe by squeezing Armenians, and arming Moslem civilians in Sivas, Aleppo, Castamouni, and other provinces; and in the second place it is putting on the screws tighter everywhere excepting in the three eastern provinces where the Commission is now commencing investigation. In Van and Bitlis the process of arresting and intimidating witnesses went on until the very hour of the departure of the Commission of Investigation. Then the order went out to stop, and those provinces are enjoying the first semblance of quiet that they have known for five years.

This policy of continued massacre and outrage is favored by the profound ignorance which prevails everywhere as to the actual state of things in Turkey. People think that the Sassoun massacre is something exceptional, and that until that is proved there is no evidence of a need of European interference in behalf of Christians in Turkey. What ought to be done is to fix on the mind of the public the fact that Turkey 34has taken up the policy of crushing the Christians all over the Empire, and has been at it for several years, so that even if the massacre had not taken place, the duty of Europe to prohibit Turkey from acting the part of Anti-Christ was still self-evident.

[Turks getting nervous, but not enough to forget taxes.]

The horrible stories are only being confirmed. It is said that unborn babes were cut from their quivering mothers and carried about on spear tops. The Turks themselves now see that they went a step too far, and they are feeling the awful tension of suspense as much as the Christians. However, the pitiless collection of taxes is causing fearful suffering.

[Prospects of the Commission of Inquiry, and its inadequacy in any case to do justice to the chronic state of the country.]

The people are in a state of horror because of the massacre. The Commission has been expected for some time, and without doubt the local authorities have used every means to cover up their tracks and terrorize still further those who may be probable 35witnesses. Those who are encouraged to testify will be again at the mercy of the Turks after the Commission rises. I have not the slightest doubt that some will be courageous enough to testify, but it will be at great odds. Almost everything is against the perfect success of the Commission’s work, or rather the favorable outcome of the work of the European delegates. It will not be right to stake the fate of Armenia on the outcome of the work of this Commission.

Rather it should be remembered that Sassoun is the outcome of a governmental system. There have been hundreds of Sassouns all over the country all through the last ten years, as you know. The laxity of Europe has afforded opportunity for the merciless working of this system in all its vigor. It is born of religious and race hatred, and has in mind the crushing of Christianity and Christians.

It is not the Kourdish robbers, or famine, or cholera that have to answer for the present state of the country. It is rather the robbery, and famine, and worse than cholera entailed on the country by the workings of this system. It is not alone the blood of five thousand men, women, children, and babies, that rises in a fearful wail to heaven, calling for just vengeance, but also the fearful suffering, the desolate homes, the wanton cruelty of tax collectors and petty officials, and the violated honor of scores and scores.

The Turk is on trial. Let not Sassoun alone go in evidence, but remember that the same wail rises from all over the country.

36[Evidence of an eye-witness, whose occupation saved him. Very few succeeded in escaping to tell the tale.]

I saw an eye-witness to some of the Sassoun destruction. He passed through three villages. They were all in ruins, and mutilated bodies told the horrible tale. For four or five days he was in one village. During the day parties of the scattered inhabitants would come in and throw themselves upon the mercy of the officer in command. About two hours after sundown each evening these prisoners of that day were marched out of camp to a neighboring valley, and the air was rent with their pitiful cries. He saw nothing more of them. He estimates that five hundred men disappeared in that way while he was there.

Between two hundred and three hundred women and children were brought into camp. They also disappeared, how he did not know. He was an Armenian muleteer pressed for the transport of the military. He was sent out of the district to Moosh. He and his companion are the only eye-witnesses we have seen.

Another refugee from a village on the border tells the story of how his mother, after terrible hardships, escaped to a monastery where this young man was a servant. She told of the merciless slaughter of all the rest of the household, and destruction of the village. She with her young child succeeded in reaching the monastery, where after a few days she died of her wounds.

37The country waits breathlessly the result of the investigation. May the Lord of nations stretch forth His almighty arm to save!

Eight to ten thousand breaths gone out is about enough, but the form beggars description. Some impaled, some buried alive, some burned in houses with the help of kerosene, pregnant women ripped up, children seized by the hair to have the head lopped off as if it were a worthless bud, hundreds of women turned over to the vile soldiery with sequence of terrible slaughter.

[The last letter was written in this country by one who has spent years in the very heart of the afflicted region.]

Up to May, 1894, when I left Van, the whole Christian population of that region was simply paralyzed by fear, and there was no manifestation of any revolutionary thought or intention by the Armenians. Certainly, if such a revolution were contemplated, you would expect to find it in the Van and Bitlis vilayets [provinces], where the provocation is the greatest.

38[Many other letters have been received which contain no new evidence, but which in every particular confirm what is here reported. It would add nothing to the evidence to give further extracts here.

Many who have given no reports, but knowing that some others have done so, say: “You can safely believe all, and more, for the sickening details that come in are becoming worse and worse.” “No report can be exaggerated as to the horrible event,” etc., etc.

All the sixteen preceding extracts, and the original letters from which they are taken, are endorsed by the twenty names which are reproduced in facsimile on pages 2 and 4. The following additional letters, which have arrived too late to be submitted with the above, have come through the same channels and are of equal weight.]

[This is an extract from a letter written from a town in the province of Erzroom, and has no connection with the Sassoun affair. It is the written testimony of a pure, sensitive Christian woman, who is only one of hundreds that have been and are being trodden in the mire of Moslem lust. It was intended for the eye of a beloved teacher of the poor victim who wrote it. If it is wrong for me to publish it to the world, let God and the reader judge. Remember that the silence of death reigns in Sassoun, and that 39throughout other regions terror paralyzes the tongue. It bears date, November 4, 1894, Old Style (i. e., November 16th). It is eloquent in its agonizing pathos, and shows the condition of the country in which such events are common occurrences, and against which there is no redress.]

ARMENIAN GIRLS OF VAN.

“I implore and earnestly entreat that you will remember one of your former pupils, and hear my cry for sympathy and protection. I have been outraged. Oh, woe is me, eternal pain and sorrow to my young heart! Evil disposed and lawless men have robbed me of the bloom and beauty of my wifely purity. It was H—— Bey, the son of Kaimakam (the local 40Turkish Governor residing in the village). It was in the evening between six and seven o’clock. I was engaged in my household work. I stepped outside the door, when I suddenly found myself in the grasp of four men. They smothered my cries and threatened my life, and by force carried me off to a strange house. Oh, what black hours were those till the sweet light of the sun once more arose! Though this is written with ink, believe me, it is written in blood and tears.”

[The following letter was written from an entirely different part of Turkey from the preceding letters. It is a region far remote from the massacres, and yet indicates a state of affairs that is deplorable. The writer is not an American nor is he a native of Turkey; he has spent several years in that country and is a man in whom all would have the highest confidence were we at liberty to give the name.]

Those cordons and quarantine, together with the extraordinary precautions, taken by the hitherto immovable Turk, with regard to cholera that was still far away and in an entirely different direction, were a mystery to all, although every person knew that the ostensible purpose was not the real one. Now that the tidings from Moosh have come in, the mystery 41of the series of cordons between here and Harpoot is explained. There is very strong evidence that a general massacre or a series of massacres of Christians has been understood by the local governments to be the order of the day. It is not likely that a definite order to that effect has been given out from the Capitol, but multitudes of recent events go to show that the everlasting persecutions and annoyances, and the methods used in past times to grind down the Christians, have come to be regarded as insufficient. Everywhere there is an activity, a watchfulness, and an energy displayed by the government in the recent efforts to encompass the Christians and to cut off their name and existence, that point to a newly formed plan to be put into execution with as little waste of time as possible. Woe to the poor remnant in this land if the European and American governments disregard recent events in Turkey! Christian nations in that case, even if they do not directly participate in what will certainly follow sooner or later, cannot be held guiltless of the blood of their fellow-men....

Another case in which I was concerned has gone the same way. Last spring a Protestant woman in Y. was assaulted and violated by three Turks. They were tried in F. and found guilty; but that infamous court in S., under the influence of the still more infamous Mutesarif (Governor), having recently reviewed the case, reversed the original judgment and released the guilty. There is no remedy. No appeal can be made. The only thing that can be done is to prosecute the court in S., but that, in the 42present state of things, would be utterly useless. The result will be that such crimes will become more frequent than ever—the perpetrators feeling confident that there is very little likelihood of punishment being meted out to them.

The government pretends to look with special suspicion on H. just now. The Vali (Governor-General) claims there are secret societies here. I told him there is nothing of the kind in H. now. The poor people are afraid to open their mouths or to go out of their houses. You can scarcely conceive the change that has come over the people within the past few months. Terror and amazement have taken hold of them to such an extent as to become manifest in their countenances even. All arms and weapons are being taken from the people here these days.

The Kaimakam (local Governor) and other officers walk the streets and the K. road every night. Attempts have been made by officers and soldiers to draw Christians into a quarrel, but they have hitherto failed. One night this week, the Commissaire (Chief of Police) without any provocation fired three times at a Christian, but the other offered no resistance. Moslem officers are taking possession of the property of Christians and doing just as they please without regard to law or justice....

The church and school in O. have been closed and for two months now the people have not been allowed to come together for worship. They are forbidden even to have prayers offered in their houses.

In order that the ordinary reader may grasp the situation in Armenia, information is given at this point in regard to the country itself, its administration, the elements that compose the population, and their relations to one another.

The massacre took place in the mountainous Sassoun district just south of Moosh, two days’ ride west of Bitlis, a large city where the Provincial-Governor and a permanent military force reside. It is near the western end of Lake Van, about eight hundred miles east of Constantinople, two hundred and fifty miles south of Trebizond on the Black Sea, and only one hundred and fifty miles from the Russian and Persian frontiers of Asiatic Turkey. These distances do not seem great until the difficulties of travel are considered. The roads are, in most cases, bridle paths, impassable for vehicles, without bridges, infested with highwaymen, and unprovided with lodging-places. It is, therefore, necessary to go to the expense of hiring government guards, and to burden oneself with all articles likely to be needed on the way—tents, food supplies, cooking utensils, 44beds, etc., which also imply cooks, baggage horses, and grooms. Thus equipped, it is possible, after obtaining the necessary government permits, often a matter of vexatious delay, to move about the country. The ordinary rate is from twenty to thirty miles a day. With a good horse and no baggage I have gone three hundred and fifty miles, from Harpoot to Van, in eight days, but that was quite exceptional. In spring, swollen streams and mud; in summer, oppressive heat; and in winter, storms, are serious impediments. In the neighborhood of Bitlis the telegraph poles are sometimes buried, and horses cannot be taken out of the stables on account of the snow. The mails are often weeks behind, both in arriving and departing, and even Turkish lightning seems to be yavash, and crawl sluggishly along the wires.

Turkish Armenia—by the way, “Armenia” is a name prohibited in Turkey—is a large plateau quadrangular in shape, and sixty thousand square miles in area, about the size of Iowa. It is bounded on the north by the Russian frontier, a line from the Black Sea to Mount Ararat, by Persia on the east, the Mesopotamian plain on the south, and Asia Minor on the west. It contains about six hundred thousand Armenians, which is only one fourth the number found in all Turkey. The surface is rough, consisting of valleys and plains from four to six thousand feet above sea-level, broken and shut in by bristling peaks and mountain ranges, from ten to seventeen thousand feet high, as in the case of Ararat. Ancient Armenia greatly varied in extent at different epochs, 45reaching to the Caspian at one time, and even bordering on the Mediterranean Sea during the Crusades. It included the Southern Caucasus, which now contains a large, growing, prosperous, and happy Armenian population under the Czar, whose government allows them the free exercise of their ancestral religion, and admits them to many high civil and military positions. The Armenians now number about four million, of whom two million five hundred thousand are in Turkey, one million two hundred and fifty thousand in Russia, one hundred and fifty thousand in Persia and other parts of Asia, one hundred thousand scattered through Europe, and five thousand in the United States.

The scenery, while harsh, owing to the lack of verdure, is on a grand scale. Around the shores of the great Van Lake are many views of entrancing beauty. The climate is temperate and the atmosphere brilliant and stimulating. It is a dry, treeless region, but fertile under irrigation, and abounding in mineral wealth, including coal. Owing to primitive methods of agriculture, and to danger while reaping and even planting crops, only a small part is under cultivation, and frequent famines are the result. The mineral resources are entirely untouched, because the Turks lack both capital and brains to develop them, and prevent foreigners from doing it lest this might open the door for further European inspection and interference with their methods of administering the country.

All local authority is practically in the hands of the Valis, provincial governors, who are sent from 46Constantinople to represent the sovereign, and are accountable to him alone. The blind policy which was inaugurated by the present Sultan of dismissing non-Moslems from every branch of public service—post, telegraph, custom-house, internal revenue, engineering, and the like—has already been carried out to a large extent all over the empire, and especially in Armenia. The frequent changes in Turkish officials keeps their business in a state of “confusion worse confounded,” and incites them to improve their chance to plunder while it lasts. Traces of the relatively large revenue, wrung from the people, and spent in improvements of service to them, are very hard to find.

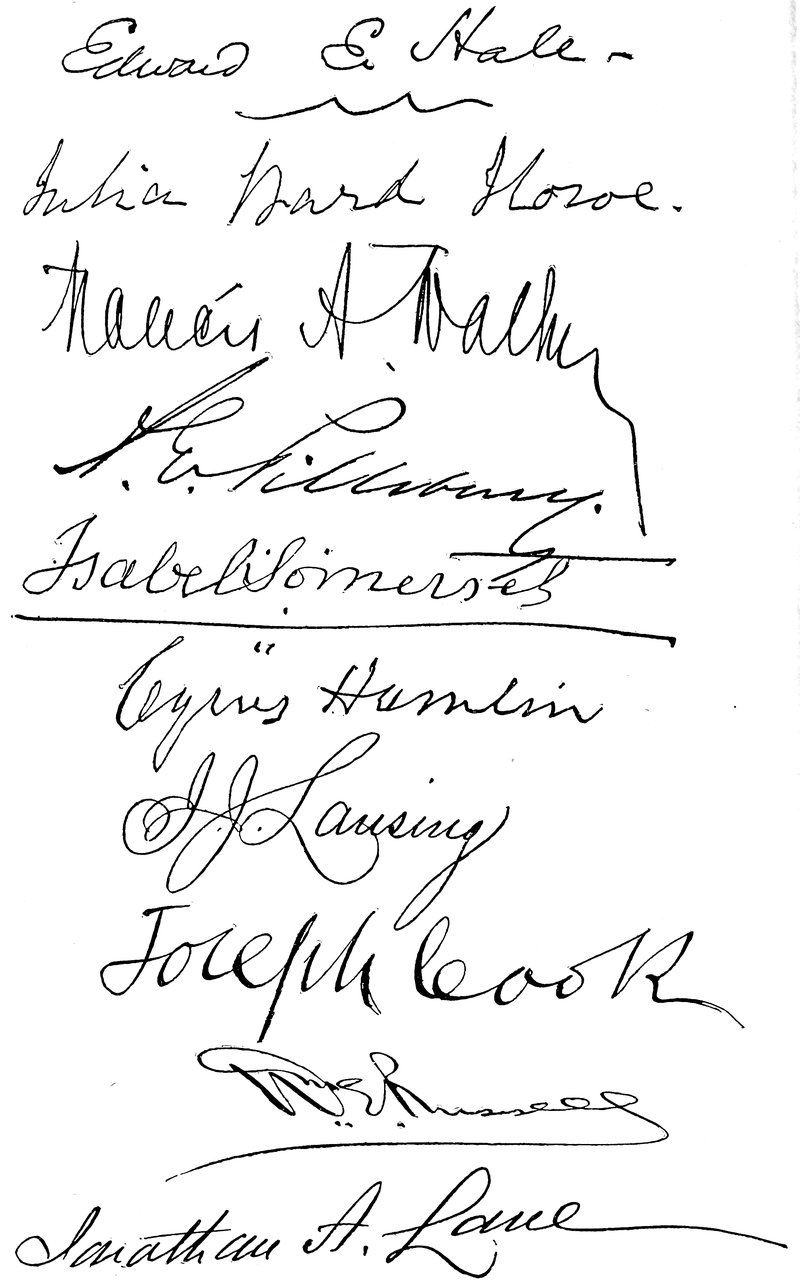

Probably about one half of the population of Turkish Armenia is Mohammedan, composed of Turks and Kurds. The former are mostly found in and near the large cities, such as Erzingan, Baibourt, Erzerum, and Van, and the plains along the northern part. The Kurds live in their mountain villages over the whole region. The term Kurdistan, which in this region the Turkish Government is trying to substitute for the historical one Armenia, has no political or geographical propriety except as indicating the much larger area over which the Kurds are scattered. In this vague sense it applies to a stretch of mountainous country about fifteen hundred miles in length, starting between Erzingan and Malatiah, and sweeping east and south over into Persia as far as Kermanshah.

A KURD OF THE OLD TYPE.

48The number of the Kurds is very uncertain. Neither Sultan nor Shah has ever attempted a census of them; and as they are very indifferent taxpayers, the revenue tables—wilfully distorted for political purposes—are quite unreliable. From the estimates of British consular officers there appear to be about one and a half million Turkish Kurds, of whom about 600,000 are in the vilayets of Erzroom, Van, and Bitlis, and the rest in the vilayets of Harpoot, Diarbekir, Mosul, and Bagdad. This is a very liberal estimate. There are also supposed to be about 750,000 in Persia.[6]

The Kurds, whose natural instincts lead them to a pastoral and predatory life, are sedentary or nomad according to local and climatic circumstances. Where exposed to a severe mountain winter they live exclusively in villages, and in the case of Bitlis have even formed a large part of the city population. But the tribes in the south, who have access to the Mesopotamian plains, prefer a migratory life, oscillating with the season between the lowlands and the mountains. The sedentary greatly outnumber the nomad Kurds, but the latter are more wealthy, independent, and highly esteemed. There is, probably, little ethnic distinction between the two classes.

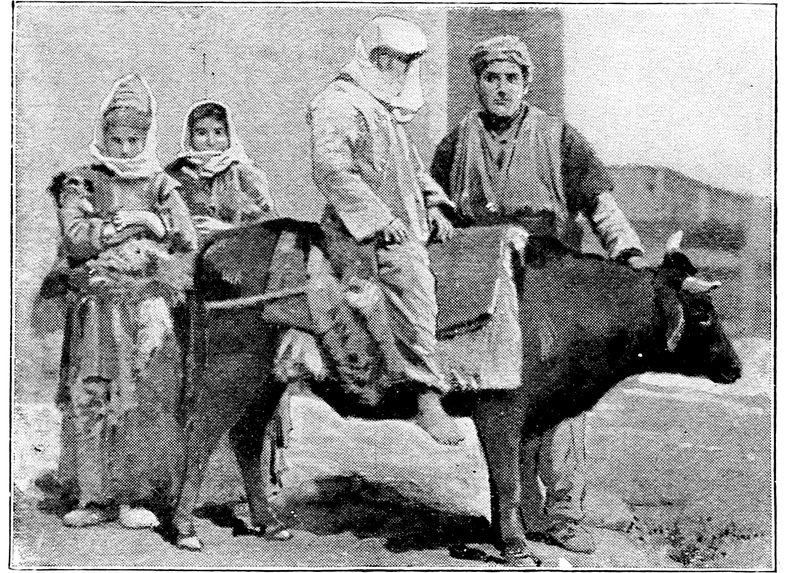

A fourteenth-century list of Kurdish tribes contains many names identical with those of powerful families who claim a remote ancestry. “There was, up to a recent period, no more picturesque or interesting scene to be witnessed in the East than the court of one of these great Kurdish chiefs, where, like another Saladin, [who was a Kurd himself,] the bey ruled in 49patriarchal state, surrounded by hereditary nobility, regarded by his clansmen with reverence and affection, and attended by a body-guard of young Kurdish warriors, clad in chain armor, with flaunting silken scarfs, and bearing javelin, lance, and sword as in the time of the crusaders.”[7] Within two days’ ride southeast of Van, I found the ruins of four massive Kurdish castles at Shaddakh, Norduz, Bashkalla, and Khoshab, which must have rivalled those of the feudal barons on the Rhine. The Armenian and Nestorian villagers were much better off as serfs of the powerful masters of these strongholds than as the victims of Kurdish plunder and of Ottoman taxation and oppression which they now are.

The Kurds are naturally brave and hospitable, and, in common with many other Asiatic races, possess certain rude but strict feelings of honor. But since their power has been broken by the Turks, their castles ruined, and their chiefs exiled, these finer qualities and more chivalrous sentiments have also largely disappeared under the principle of noblesse oblige reversed. In most regions they have degenerated into a wild, lawless set of brigands, proud, treacherous, and cruel. The traditions of their former position and power serve only to feed their hatred of the Turks who caused their fall, and their jealousy and contempt of the Christians who have been for generations their serfs, whose progress and increase they cannot tolerate.

RUINS OF A KURDISH CASTLE AT KHOSHAB.

One who has a taste for adventure and is willing to take his life in his hands, can find among them as fine specimens of the human animal as are to be found anywhere—sinewy, agile, and alert, with a steady penetrating eye as cool, cold, and cruel as that of a tiger. I vividly recollect having just this impression under circumstances analogous to that of a hunter who suddenly finds himself face to face with 51a lord of the jungle. There was no sense of fear, at the time, but rather a keen delight and fascination in watching the magnificent creature before me. His thin aquiline face, his neck and hands were stained by the weather to a brown as delicate as that of a meerschaum pipe, and on his broad exposed breast the thick growth of hair obliterated any impression of nudeness. For a few moments he seemed engaged in some sinister calculation, but at last quietly moved away. Perhaps he wanted only a cigarette. Perhaps he wondered if I, too, had claws. The Winchester rifle behind his back did not escape my notice, nor did the gun across my saddle escape his. It is hardly necessary to remind those who may desire such experiences as the above, that the usual retinue of cooks, servants, and zaptiehs should be dispensed with in order to secure the best opportunities for observation.

The Kurdish costumes, always picturesque, show much local variation in cut and color. The beys and khans of the colder north almost invariably prefer broadcloth, and find the finest fabrics and richest shades—specially imported for them—none too good. But the loose flowing garments of the Sheikhs and wealthy Kocher nomads of the south are often very inexpensive, and suggest Arab simplicity and dignity. There is, no doubt, considerable Arab blood in some of these families, who refer to the fact with pride.

The women of the Kurds, contrary to usual Mohammedan custom, go unveiled and have large liberty, but there is no reason to suspect their virtue. Their prowess, also, is above reproach, and rash would 52be the man, Turk or Christian, who would venture to invade the mountain home when left in charge of its female defenders. On the whole, the Kurds are a race of fine possibilities, far superior to the North American Indian, to whom they are often ignorantly compared. Under a just, intelligent, and firm government much might be expected of them in time.

They keep up a strict tribal relation, owing allegiance to their Sheikhs, some of whom are still strong and rich, and engage in bitter feuds with one another. They could not stand a moment against the Ottoman power if determined to crush and disarm them. But three years ago His Majesty summoned the chiefs to the capital, presented them with decorations, banners, uniforms, and military titles, and sent them back to organize their tribes into cavalry regiments, on whom he was pleased to bestow the name Hamediéh, after his own. Thus, shrewdly appealing to their pride of race, and winking at their subsequent acts, the Sultan obtained a power eager in time of peace to crush Armenian growth and spirit, and a bulwark that might check, in his opinion, the first waves of the next dreaded Russian invasion. In the last war the Kurdish contingent was worse than useless as was shown by Mr. Norman,[8] of the London Times.