TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

The Appendix had several passages marked with a vertical bar in the margin, indicating that the passages so marked were omitted from the published dispatches in 1900. In this etext these passages are enclosed in double parentheses {{ ... }} with a light gray background color.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

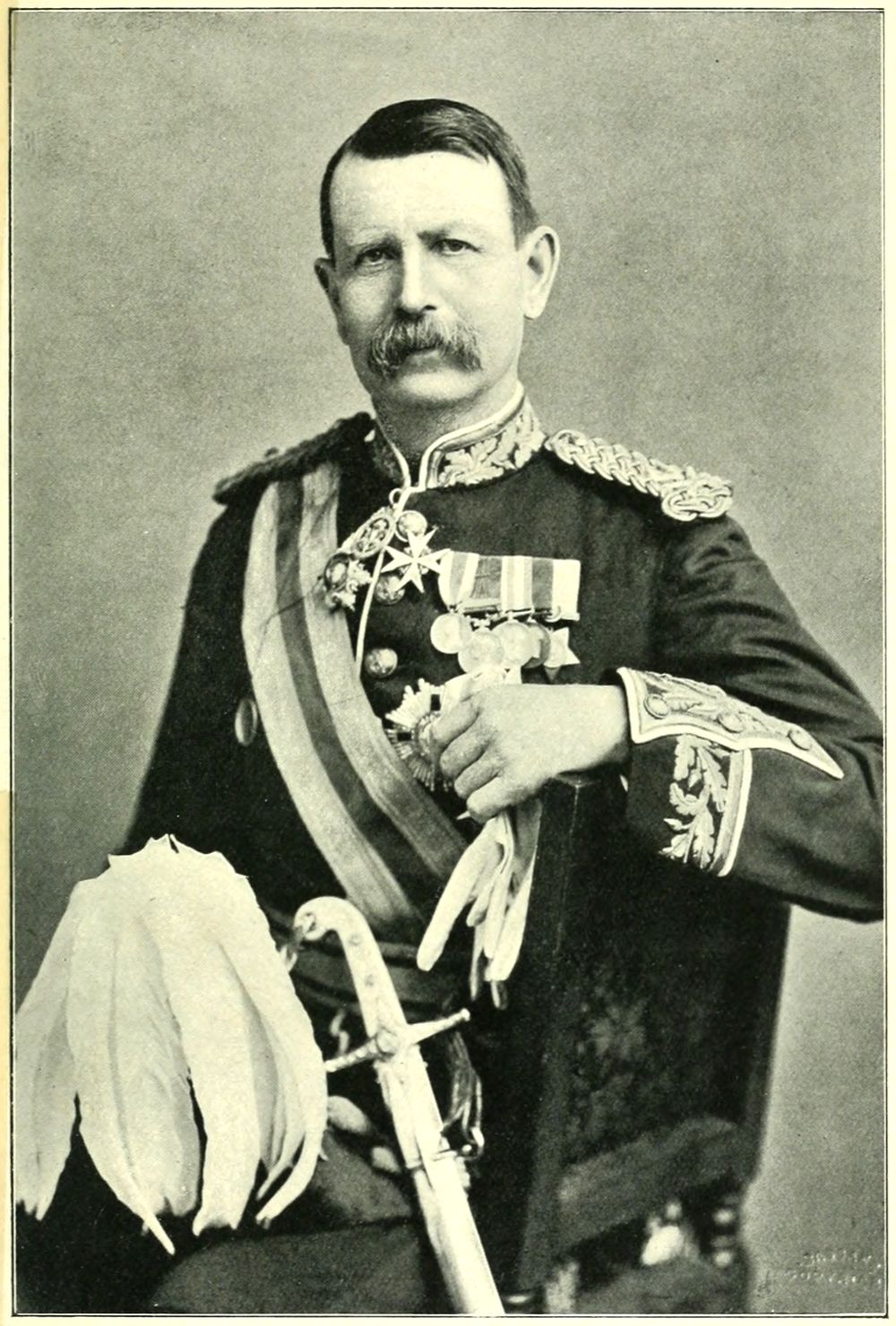

SIR CHARLES WARREN

AND

SPION KOP

A VINDICATION

BY

‘DEFENDER’

WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH, PORTRAIT

AND MAP

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1902

[All rights reserved]

It is now more than two years since the operation took place on the Tugela River in Natal, that ended in the capture and the unwarrantable abandonment the same day of the position of Spion Kop. The lapse of time since these events occurred naturally caused a loss of interest in this chapter of the history of the war in South Africa; but the recent publication of portions of the despatches omitted in the ‘Gazette’ of 1900, and also of other documents received at the time by the War Office but not disclosed, has again brought the subject into prominence, revived public interest in it, and offered an opportunity which we gladly seize to vindicate the conduct of an officer who has been condemned without being heard.

Whether Sir Charles Warren will be allowed any opportunity of defending himself against[vi] the strictures passed upon him by Sir Redvers Buller, either now or when the war is over, is doubtful; but at length, having before us all the documents received at the War Office, it is proposed to show in the following pages that, in spite of the difficult circumstances in which he found himself, Sir Charles Warren did his duty, and that, had Spion Kop not been recklessly abandoned by a subordinate, there is every reason to suppose that he would have gained a great success.

The publication of the despatches on Spion Kop in the parliamentary Easter recess of 1900 took the world by surprise—so much so, indeed, that a story was current that it was due to the mistake of a War Office clerk. It did not commend itself as either a useful or a desirable proceeding to publish to the whole world the strictures passed by the General in command in Natal upon his second-in-command, and those of the Commander-in-Chief in South Africa upon both, especially as those officers were still serving their country in the field.

The political mistake made by the Government was speedily demonstrated by the debates[vii] that took place on the reassembling of Parliament; but it now appears that a greater want of judgment was shown than was then supposed, and that having decided, however wrongly, to publish the despatches the Government would have done better to have published them in full. And this for several reasons—it would have made little difference to those censured, would have enabled the public to understand the Spion Kop operations, which could not be understood from the incomplete documents, and would have prevented a distinguished officer lying for two years under the shadow of unjust accusations.

Much capital was made by the Opposition in Parliament out of the suggestion of the Secretary of State for War that Sir Redvers Buller should rewrite his despatch, or rather should write a separate despatch for publication; but any one who has tried to get to the bottom of the business from the material available must have felt that Lord Lansdowne was perfectly right in suggesting that what was wanted was a simple statement from Sir Redvers Buller of what he intended to do, and how it was done or not done. Instead of this there were despatches giving formal cover[viii] to other despatches from Sir Charles Warren, and then criticising that officer’s actions unfavourably. No statement was to be found anywhere indicating what Sir Redvers Buller had intended to do, and as the instructions he issued were not published, the operation which Sir Charles Warren was directed to execute could only be gathered from the references he made to them in his reports. These reports were evidently written to his chief in the belief that the General commanding would write a full account of what he had proposed to do, and how far his orders had been successfully carried out, or otherwise.

To most men, conscientiously compelled to censure in an official despatch those employed under them, the suggestion from the War Office that such censure should be confined to a confidential communication, and that some account of the operation and the cause of failure should be written for publication, would have come as a welcome relief; and had Sir Redvers Buller seen his way to comply with it and at the same time to send copies to Sir Charles Warren of the confidential despatches, he would have placed himself[ix] in an unassailable position, he would have given Sir Charles Warren an opportunity of confidentially justifying himself, if he could do so, to the Secretary of State for War and the Commander-in-Chief, he would have enabled his countrymen to know more about the operations than was otherwise possible, and the world would have been spared a very painful exhibition.

To this course, however, Sir Redvers Buller would not consent. He prided himself on his integrity in resisting such a proposal, and has been much praised for refusing to write a despatch for publication, having already written one, which was mainly an indictment of his second-in-command, on whom he threw the responsibility for the failure of the operations.

It is the custom of the Service—and a very fair and proper custom it is—that an unfavourable confidential report made upon a junior officer by his superior shall be communicated to him before it is sent forward, so that he may have an opportunity either of excusing himself or of amending his conduct, and may have no reason to complain that advantage has been taken of a confidential communication to make un[x]favourable reports behind his back, of which he remains in ignorance.

Sir Redvers Buller does not appear to have been mindful of this custom, when, instead of writing a simple account of what he proposed to do, and how it failed of accomplishment, he used the opportunity to criticise most unfavourably the conduct of the distinguished officer, his second-in-command, still serving under him in face of the enemy, and left him in complete ignorance of the accusations made against him. This ignorance he knew must last in any case until the despatches were published, and, if they were not published, would never be removed. But Sir Redvers Buller went beyond this, for he attached to his despatch a separate memorandum, ‘not necessarily for publication,’ in which he reiterated his complaints of the conduct of Sir Charles Warren and accused him of such incapacity as unfitted him for independent command. But not a word of this reached Sir Charles Warren, whose exertions in the field during the succeeding month under Sir Redvers Buller contributed so greatly to the victory of Pieters and the relief of Ladysmith; and it was not until[xi] he saw the despatches in the newspapers, long after this campaign was over, that he knew of the secret stab his reputation had received at the hand of his commander. Two years later the recently published omissions have informed him how seriously the attack upon his reputation as a soldier was intended.

A correspondence between Mr. Henry Norman, M.P., and the Right Hon. A. J. Balfour, First Lord of the Treasury, published on 21st February last, contains some observations by the latter very much to the point on the want of any narrative of the Spion Kop operations in Sir Redvers Buller’s despatches. Mr. Balfour points out, as was done two years before in the parliamentary debates, that the General in command, ‘in accordance with the Queen’s Regulations, with the best precedents, and with public convenience,’ should have furnished a simple narrative, unencumbered by controversy, of the operations which took place. To this Sir Redvers Buller objected, in a letter published on the 26th March last, that he was not in command, that he was not present, and that therefore it was not his duty to write such a narrative. The[xii] reply of Mr. Balfour, from which an extract is appended, will be found to be fully borne out in the pages of this book.

Extract from a letter from Mr. A. J. Balfour to Sir Redvers Buller dated 10th March 1902.

‘You say that, not being in chief command, you were not the proper person to write an account of what took place. But can this be sustained? I find that on 15th January you ordered Sir Charles Warren to cross the Tugela to the west of Spion Kop; on the 21st and 22nd you gave him personal instructions as to the disposal of his artillery; on the latter day you agreed with him, after discussion, that Spion Kop would have to be taken; on the 23rd you definitely decided upon the attack; you selected the officer who was to lead it, detailing one of your Staff to accompany him; it was by your orders that on the 24th Lieut.-Colonel Thorneycroft assumed command on the summit of Spion Kop after General Woodgate was wounded, and all heliographic messages between the officers in the fighting line and Sir Charles Warren passed through your camp, and were seen by you before[xiii] they reached their destination. As you were thus in constant touch with the troops actually engaged on the top of the hill, so also you kept general control over the movements of the co-operative forces under General Lyttelton, with whom you were in communication during both the morning and the afternoon of the 24th. It is, of course, true that you were not present at the actual Spion Kop engagement. But if this was a reason for not writing an account of it, it was a reason equally applicable to Sir Charles Warren, whose headquarters, as I am informed, were very little nearer to the scene of action than were your own. It was on these grounds that I did not draw any distinction between your position during the days of Spion Kop and that of any other general conducting operations over an extended field, at every part of which he could not, from the nature of the case, be present. You were responsible for the general plan of action; you intervened frequently in its execution; you were not prevented either by distance or any other material obstacle from intervening more frequently still, had you deemed it expedient to do so. Was I wrong, then, in pointing[xiv] out that it would have been in accordance both with precedent and the Queen’s Regulations for you to have supplied the Commander-in-Chief with a narrative of these important military events based on your own observations and on the reports of those of your officers who were immediately engaged with the enemy?’

We have never been able to understand why the orders given to Sir Charles Warren were not published with the despatches two years ago. True they were called secret instructions, but of course the secrecy was a temporary matter, and they ceased to be secret when the operations were over. Without them there was no way for the public to learn officially, except in the most general way, what the General in command in Natal desired to do, and probably, owing to the wording of Lord Roberts’s despatch, a misconception arose, widely entertained in the army and highly prejudicial to Sir Charles Warren.

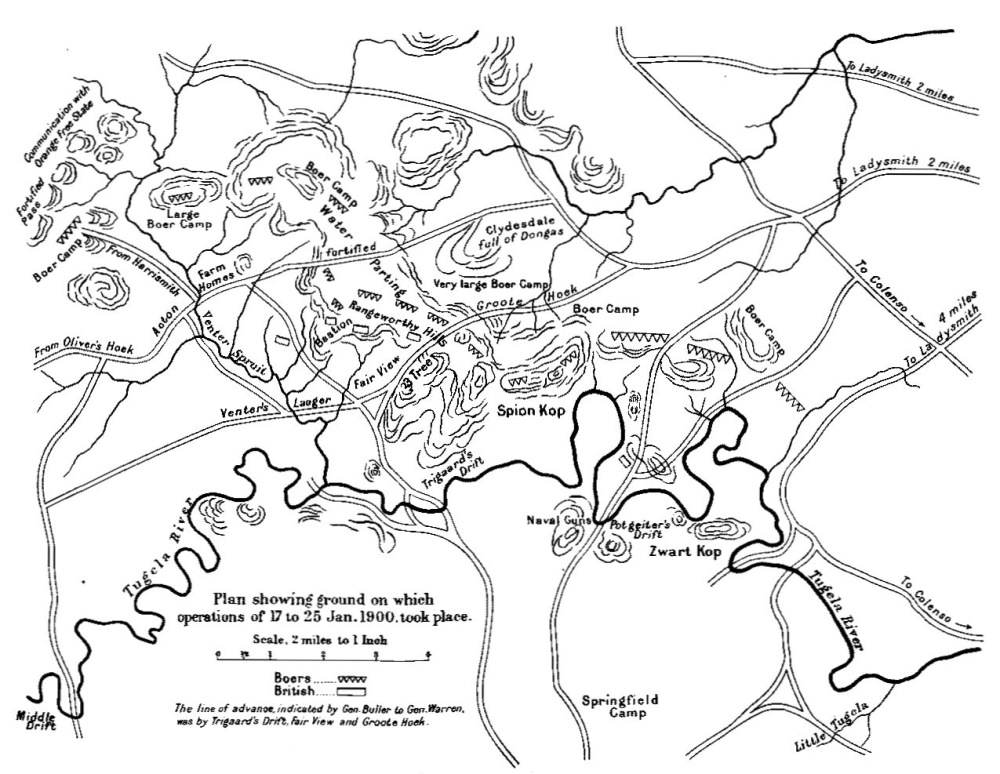

This misconception was that Sir Redvers Buller instructed Sir Charles Warren to make his turning movement by way of Acton Homes, instead of which Warren obstinately preferred the[xv] route by Groote Hoek. It was supposed that by the first of these two routes the force might have marched a long way round, but would have got into Ladysmith with little difficulty, whereas the (hypothetical) substitution by Warren of the Groote Hoek road had necessitated the capture of Spion Kop. The publication of the instructions upsets this theory. The Acton Homes road is never mentioned. The only references to the direction of the turning movement are vague—‘to the West of Spion Kop’—‘acting as circumstances require’—‘refusing your right and throwing your left forward’—and it now appears that Sir Redvers Buller intended Warren to go by the Groote Hoek route.

In vain has the Government endeavoured to shield the military reputation of Sir Redvers Buller at the expense of others. He has been consistent in his efforts to get the despatches published in full, even to the memorandum ‘not necessarily for publication’—a severe condemnation of Sir Charles Warren’s incapacity, but a more damning one of his own—and by his attitude has compelled the Government to give way. How truly applicable is an epigram of[xvi] Mr. Henry Sidgwick, quoted by Sir Henry Howarth in a recent letter to the ‘Morning Post’: ‘The darkest shadows in life are those which a man makes when he stands in his own light.’

In addition to the official documents on the subject of Spion Kop much information of a very varied character has accumulated during the last two years, and besides invaluable verbal observations and descriptions gathered from conversation with officers from the front who took part in the operations, there is a whole library of books by newspaper correspondents, officers, and others, which bear upon these operations and throw light upon much that is obscure in the official papers. Among many others may be mentioned ‘My Diocese during the War,’ by Bishop Baynes of Natal; ‘The Relief of Ladysmith,’ by Mr. J. B. Atkins; ‘The Natal Campaign,’ by Mr. Bennet Burleigh; ‘London to Ladysmith via Pretoria,’ by Mr. Winston Churchill, M.P.; ‘The History of the War in South Africa,’ by Dr. Conan Doyle; ‘The Relief of Ladysmith,’ by Captain Holmes Wilson; ‘Buller’s Campaign: With the Natal Field[xvii] Force of 1900,’ by Lieutenant E. Blake Knox, Royal Army Medical Corps.

Magazine articles have also appeared from time to time, some commenting on the operations themselves, others filling up gaps in the narrative, and others again incidentally referring to facts in connection with the operations. Among these last may be mentioned: (1) A series of articles contributed by Sir Charles Warren himself to the ‘National Review’ entitled ‘Some Lessons from the South African War’; (2) Mr. Oppenheim’s defence of Lieut.-Colonel Thorneycroft in the ‘Nineteenth Century’; (3) An instructive diary of Dr. Raymond Maxwell, who was serving with the Boers, in the ‘Contemporary Review’ for December 1901; and (4) ‘The Diary of a Boer Officer,’ by another of them, in the ‘United Service Magazine’ for February this year. Some reference should perhaps be made to one of a series of articles in ‘Blackwood’s Magazine’ by ‘Linesman,’ which was headed ‘Dies Iræ,’ and dealt with Spion Kop, because these articles have attracted a good deal of attention, are cleverly written, and have since been republished in book form. They do[xviii] not, however, impress the military reader as very accurate descriptions, but rather as war pictures, in which the colour is laid on with no sparing hand to obtain the highest effect, the aim being to please the sensation-loving reader. The value of the account of Spion Kop given in ‘Blackwood’ is discounted by ‘Linesman’ himself, who, having told us that ‘what the writer saw of the fight on the summit of Spion Kop was little enough’; that he had learnt ‘to describe—nay, believe nothing that one has not seen with one’s own eyes’; and that, ‘if the tongue is an unruly member, much more so is the ear’; nevertheless proceeds to describe in blood-curdling language what he did not see with his own eyes, and must have heard with ‘unruly’ ears.

The general result of all the information is to make it clear that Spion Kop was the key of the position dominating the country, and that the holders of it opened the way to Ladysmith; that no one was more astonished at its unauthorised abandonment than Sir Charles Warren, except the Boers themselves, who refused to credit the evidence of their senses, and at first believed its forsaken condition to be a trap! No longer,[xix] indeed, is it possible to regard the unwarrantable surrender of this position as a fortunate accident preventing an actual and impending disaster on the morrow, or, as Lieut.-Colonel Thorneycroft is reported to have said, ‘a mop up in the morning.’ Rather its abandonment was the blundering relinquishment of a hardly won and well assured success, only to be compared with the fatuous withdrawal in the morning of the storming parties which made the brilliant night attack and surprised the fortress of Bergen op Zoom on 8th March 1814.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v | |

| BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH | 1 | |

| I. | BEGINNING OF THE WAR—WARREN CROSSES THE TUGELA | 55 |

| II. | POSITION OF AFFAIRS | 75 |

| III. | ADVANCE TO VENTER’S LAAGER AND ATTACK OF THE RANGEWORTHY HILLS | 92 |

| IV. | BOER DEMORALISATION—TACTICAL IMPORTANCE OF SPION KOP | 119 |

| V. | CAPTURE OF SPION KOP AND ITS ABANDONMENT | 135 |

| VI. | AFTER WITHDRAWAL—BOER COMMENTS | 159 |

| VII. | SOME CRITICISMS | 169 |

| APPENDIX: EXTRACTS FROM DESPATCHES | 203 |

A short sketch of the career of Sir Charles Warren is an appropriate introduction to his appearance in South Africa as the leader of the 5th Division of the army in the Natal campaign, and as the Commander of the Field Force in the operations on the Tugela between 15th and 25th January 1900.

Lieut.-General Sir Charles Warren, G.C.M.G., K.C.B., F.R.S., is the son of the late Major-General Sir Charles Warren, K.C.B., Colonel of the 96th Foot, by his first wife, Mary Anne,[2] daughter of William Hughes, Esq., of Dublin and Carlow, and grandson of the Very Rev. John Warren, Dean of Bangor, North Wales.

His father served under the Duke of Wellington in the march to Paris after the battle of Waterloo, in India, and in South Africa, and the notes and sketches he there made upon expeditions into the interior were made use of by his son fifty years later, when reporting on the Bechuana and Griqua territories in 1876. He saw active service during a second tour in India, in China, and in the Crimean war, and was several times wounded. He retired after holding the command of the Infantry Brigade at Malta for five years, and was created a Knight Commander of the Bath. He had a natural turn for science, mathematics, and adventure, which, together with his love of soldiering, was inherited by his son Charles.

Lieut.-General Sir Charles Warren was born at Bangor, North Wales, on 7th February 1840. His early education took place at the Grammar Schools of Bridgnorth and Wem, and at[3] Cheltenham College. He then entered the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, and from that passed through the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich and received a commission as lieutenant in the Royal Engineers on 23rd December 1857. After the usual course of professional instruction at Chatham, Warren went to Gibraltar, where he spent seven years, and, in addition to the ordinary duties of an Engineer subaltern—looking after his men and constructing or improving fortifications and barrack buildings—he was employed on a trigonometrical survey of the Rock, which he completed on a large scale. He constructed two models of the famous fortress, one of which is now at the Rotunda at Woolwich, and the other at Gibraltar. He was also engaged for some months in rendering the eastern face of the Rock inaccessible by scarping or building up any places that might lend a foothold to an enemy. He was selected in 1865 to assist Professor Ramsay in a geological survey of Gibraltar, but it fell through. While at this station he invented a fitment to gun carriages to supersede the truck levers of the Service; an invention objected to at the time because it was[4] made of iron, but subsequently adopted into the Service.

In 1864 Lieut. Warren married Fanny Margaretta Haydon, a daughter of the late Samuel Haydon, Esq., of Guildford. On the completion of his term of service at Gibraltar he returned to England in 1865, was appointed Assistant Instructor in Surveying at the School of Military Engineering at Chatham, and a year later his services were lent by the War Office to the Palestine Exploration Fund.

The object of the Palestine Exploration Fund was the illustration of the Bible, and it originated mainly through the exertions of Sir George Grove, who formed an influential committee, of which for a long time Sir Walter Besant was secretary. Captain (afterwards Sir) Charles Wilson and Lieut. Anderson, R.E., had already been at work on the survey of Palestine, and, in 1867, it was decided to undertake excavations at Jerusalem to elucidate, if possible, many doubtful questions of Biblical archæology, such as the site of the Holy Sepulchre, the true direction of[5] the second wall and the course of the first, second, and third walls, involving the sites of the towers of Hippicus, Phasælus, Mariamne, and Psephinus, and many other points of great interest to the Biblical student.

The task was entrusted to Lieut. Warren, who was assisted by non-commissioned officers of Royal Engineers. The difficulties in the way of carrying it out were great—obstruction on the part of the Pashas, physical dangers, and want of money. As regards the first, only great tact and firmness prevented the complete suspension of the work. ‘Indeed,’ says Major-General Whitworth Porter in his ‘History of the Corps of Royal Engineers,’ ‘the Vizierial letter, under which the party was supposed to be acting, expressly forbade excavations at the Noble Sanctuary and the various Moslem and Christian shrines. How, in spite of this, Warren succeeded in his object is well told in his “Underground Jerusalem.”’

With regard to physical danger Dean Stanley wrote: ‘In the plain and unadorned narrative of Captain Warren,[1] the difficulties and dangers[6] of the undertaking might almost escape notice. Yet the perils will appear sufficiently great to any one who draws out from the good-humoured story the fact that these excavations were carried on at the constant risk of life and limb to the bold explorers. The whole series of their progress was a succession of “lucky escapes.” Huge stones were day after day ready to fall, and sometimes did fall, on their heads. One of the explorers was “injured so severely that he could barely crawl out into the open air”; another extricated himself with difficulty, torn and bleeding, while another was actually buried under the ruins. Sometimes they were almost suffocated by the stifling heat; at other times they were plunged for hours up to their necks in the freezing waters of some subterranean torrent; sometimes blocked up by a falling mass without light or escape.’

The third difficulty was want of money; for when Warren left London he carried off all the money of the Fund (300l.) for the expenses of the party, the Committee hoping that, as the excavations proceeded, public interest would be shown by a flow of subscriptions. The Com[7]mittee said: ‘Give us results and you can have money.’ Warren replied: ‘No money, no results.’ In fact, however, he had at one time advanced no less than 1,000l. out of his own resources.

The work went on for some three years with occasional interruptions. Warren returned home in 1870, and spent the following year in preparing the results of his work for the Committee of the Fund and for the Press.

Sir Walter Besant, in his ‘Twenty-one Years’ Work in the Holy Land,’ writes:

‘It is impossible here to do more than to recapitulate the principal results of the excavations, which are without parallel for the difficulties presented and the courage displayed in overcoming them.... It is certain that nothing will ever be done in the future to compare with what was done by Warren.... It was Warren who restored the ancient city to the world; he it was who stripped the rubbish from the rocks and showed the glorious temple standing within its walls 1,000 feet long, and 200 feet high, of mighty masonry: he it was who laid open the valleys now covered up and hidden; he who opened the secret passages, the[8] ancient aqueducts, the bridge connecting the temple and the town. Whatever else may be done in the future, his name will always be associated with the Holy City which he first recovered.’

So much was this the case that for a long time he was known as ‘Jerusalem Warren.’

In addition to ‘Underground Jerusalem’ he wrote ‘The Temple or the Tomb.’

What high value was placed upon Captain Warren’s services by the Administration of the Fund may be gathered from the following quotation from ‘Our Work in Palestine,’ published by Bentley & Son in 1875, a book which had then reached its eighth thousand:—

‘Let us finally bear witness to the untiring perseverance, courage, and ability of Captain Warren. Those of us who know best under what difficulties he had to work can tell with what courage and patience they were met and overcome. Physical suffering and long endurance of heat, cold, and danger were nothing. There were besides anxieties of digging in the dark, anxieties as to local prejudice, anxieties for the lives of brave men—Sergeant Birtles and[9] the rest of his Staff—anxieties which we may not speak of here. He has his reward, it is true. So long as an interest in the modern history of Jerusalem remains, so long as people are concerned to know how sacred sites have been found out, so long will the name of Captain Warren survive.’

In 1871 Warren returned to military duty, and was posted to Dover in command of the 10th Company of Royal Engineers, and for the next year was employed on the fortifications of the fortress, principally at Dover Castle and Castle Hill and Fort (Fort Burgoyne). He was then transferred, in 1872, to the School of Gunnery at Shoeburyness, where he remained for three years, and was very successful in his administration of the Engineer duties in regard both to the barracks and the experiments with big guns and iron plates carried out by the Ordnance Committee. He had also Engineer charge of the gunpowder magazine at Purfleet.

On his departure, in 1875, to take Engineer[10] charge of the Gunpowder and Small-arm Factories at Waltham Abbey and Enfield, he received the highest commendation from the Commandant of the School of Gunnery, who wrote to the War Office that Captain Warren’s professional reputation as a highly instructed and accomplished officer was so well established that it was unnecessary to refer to it, beyond stating that the station had benefited largely by his administration in carrying out the important duties entrusted to him, and that he placed on record not only the support and assistance received from him in all official matters, but that his social relations with the Commandant and all other officers of the establishment rendered his departure a subject of sincere regret to all.

He was a candidate in 1876 for the secretaryship of the Royal Engineers’ Institute, when Colonel (afterwards Sir) Peter Scratchley observed in his recommendation: ‘Captain Warren has been under my command for four and a half years, and is, in my opinion, a most able, conscientious, indefatigable officer, and one who would do credit to the Corps wherever employed. His literary tastes, general experience, and quali[11]fications particularly fit him for the appointment he is desirous of obtaining.’

Although unsuccessful his services were to be utilised in a wider sphere than his own Corps.

In October 1876 he was asked by the Colonial Office to undertake the duty of laying down the boundary line between Griqualand West and the Orange Free State, and his services were at once lent by the War Department. On leaving England he received a letter from Lord Carnarvon’s private secretary saying how much the Colony was to be congratulated on having obtained his services, and another from his late chief, Colonel Scratchley, regretting his departure and expressing his belief that he ‘would never meet an abler officer or a better fellow.’

The necessity for laying down a boundary line between Griqualand West and the Orange Free State had arisen from the rival claims of the Chief Waterboer of the Griquas and of[12] President Brand of the Orange Free State to the Diamond Fields. The British Government acquired the rights of the Waterboer, and, after some protracted negotiations, it was arranged that the Orange Free State should abandon its claim on receiving from Griqualand West the sum of 90,000l. Mr. de Villiers was the expert nominated by the Orange Free State to be associated with Captain Warren in laying out the boundary.

Warren, with two non-commissioned officers of Royal Engineers, arrived at Cape Town towards the end of November, and, after an interview with the Governor, Sir Henry Barkly, proceeded to Port Elizabeth by steamer, and thence by coach, via Graham’s Town and Cradock, to Kimberley, where Major Owen Lanyon, the Administrator, introduced him to his colleague, Mr. Joseph E. de Villiers, Government Surveyor. After an interview with President Brand at Bloemfontein he went into camp outside Kimberley towards the end of December, measured his base, took observations, and elaborated his general scheme of operations.

The heat was intense, the shade temperature[13] being over 100° Fahr. for hours together, the atmosphere was highly charged with electricity, and the thunderstorms were often terrific, the lightning playing all round the encampment or party, and the ground being struck in all directions. Mosquitoes and flies were also a great nuisance.

The work, however, proceeded satisfactorily and expeditiously, and on 18th April 1877 was completed and ready for inspection. A party composed of the two Commissioners and officials of the two States formally inspected the line from the Vaal to the Orange River, 120 miles, and an official notification of the completion of the work was made to the respective Governments. The plans were then drawn on a scale of three miles to the inch and completed before 15th May. Captain Warren was entertained by President Brand at Bloemfontein to meet the Volksraad at dinner. Votes of thanks from the Legislatures of Griqualand West and the Orange Free State were presented to each of the Commissioners, the former illuminated and very handsomely got up.

Sending his party home, Warren went to Kimberley, and thence to Pretoria and the Gold Fields and on to Delagoa Bay, intending to go to England by Zanzibar. An interesting account of this journey appeared in ‘Good Words’ two years ago. From Delagoa Bay, however, he was directed to return to Cape Town to see Sir Bartle Frere, and on arrival there was appointed Special Commissioner in Griqualand West for six months to investigate and arrange the various land cases in appeal before the High Court of Griqualand West. This delicate mission he accomplished with great ability, tact, and judgment, settling 220 out of 240 cases to general satisfaction, except that of the lawyers, and avoiding a great amount of litigation. He was made a Companion of St. Michael and St. George for his work on the boundary, and received a letter from H.R.H. the Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief, expressing his great satisfaction at the efficient manner in which he had performed the duties entrusted to him of marking off the boundary between the Orange Free State and[15] Griqualand West, and also of the settlement of the land claims in the latter province.

It was on his way to Kimberley from Cape Town viâ Port Elizabeth on this land claim business in Griqualand that he had the late Mr. Cecil Rhodes as his travelling companion. As they were driving over the brown veldt from Dordrecht to Jamestown, Warren noticed that Mr. Rhodes, who sat opposite to him, was evidently engaged in learning something by heart, and offered to hear him. It turned out to be the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England. In the diary of this journey, also published in ‘Good Words’ of 1900, Warren relates: ‘We got on very well until we arrived at the article on predestination, and there we stuck. He had his views and I had mine, and our fellow-passengers were greatly amused at the topic of our conversation—for several hours—being on one subject. Rhodes is going in for his degree at home, and works out here during the vacation.’

In January 1878 Warren proceeded to the Gaika war in command of the Diamond Fields Horse, raised at Kimberley, and was engaged for six months in Kaffraria. He bought his mounts and drilled his men on the way, and infused his own indomitable energy into every member of his command. He took part in numerous engagements, among which may be mentioned the action of Perie Bush in March, when he was injured by the falling of the bough of a tree, and the action at Debe Nek on 5th April, where with seventy-five of the Diamond Fields Horse he met 1,200 armed Kafirs of Seyolo’s tribe in the open, and gained a complete victory. The Governor-in-Chief telegraphed his congratulations on this brilliant success. A few weeks later Warren had another successful fight at Tabi Ndoda on 29th April, when he was slightly wounded. He was frequently mentioned in despatches, and his conspicuous personal bravery, no less than his skill as a commander, was brought to the notice of the Secretary of State for War. The Governor-in-Chief especially commended him in his[17] despatches for ‘energy, ability, and resource displayed under most trying circumstances.’ He had been promoted to be Major on 10th April 1878, and his services in the campaign were recognised by a brevet-lieutenant-colonelcy, dated 11th November 1878, and the South African medal.

Early in May the whole native population of Griqualand West, west of the Vaal river, broke out in rebellion and, joining their former enemies, the Kaal Kafirs (refugees from Cape Colony), commenced depredations to the west of Griquatown. In consequence of this critical state of affairs in Griqualand West the Executive Government telegraphed for the assistance of Warren and the Diamond Fields Horse from the Cape Colony. The regiment left King William’s Town on 14th May and arrived at Griquatown on 10th June.

While Colonels Lanyon and Warren were fighting the rebels in the far west the Bechuanas made incursions over the northern border,[18] murdering the white residents at Daniel’s Kuil and Cornforth Hill, wrecking the mission station at Moteto in Bechuanaland, and threatening the lives of the traders and missionaries in Kuruman itself. Lanyon and Warren fought several successful actions with the insurgent Griquas and Kaal Kafirs, particularly that at Paarde Kloof on 18th June. Lanyon then returned to Kimberley, leaving Warren in command of the Field Force with instructions to proceed to the northern border in case assistance were required there. Commandant Ford had been sent to the northern border for the express purpose of saving the Kuruman mission station, and on 2nd July met with a repulse at Koning (close to the border of Griqualand), but defeated the enemy at Manyering on 8th July, and the following day arrived at Kuruman. His force, however, was too small to do more than act on the defensive, and he asked for assistance. Warren arrived with the Field Force at Kuruman on 14th July, and Lanyon with a detachment of troops on the 16th. On the 18th Warren’s force attacked Gomaperi successfully, and on 23rd July carried Takoon by assault; and in August the[19] force returned to Kimberley, leaving a garrison to protect Kuruman.

In consequence of the rebels joining with the Bechuanas it was found necessary to continue the war, for Kuruman and Griqualand were both threatened. Warren was again entrusted with the command of the Field Forces on 21st September, and signally defeated the combined forces of the Griquas, Bechuanas, and Old Colony Kafirs on 11th, 12th, and 14th October at Mokolokue’s Mountain. He then issued a proclamation, which exhibited both firmness and tact, and offered an amnesty to all but the ringleaders and murderers. This had a good effect.

Hostilities recommenced on the northern border (Cape Colony) in January 1879, and subsequently in Bechuanaland and the Keate Award, and the Griqualand West forces were ordered to co-operate with those of the Cape Colony. On 11th February Warren was appointed Acting Administrator of Griqualand West and disarmed all the natives. During this and the following month the whole country was disturbed in consequence of the disaster at Isandhlwana, and Warren offered to take 500 white troops to the[20] assistance of Lord Chelmsford, but it was not considered desirable to take 500 white men away from Kimberley at so critical a time. As Special Commissioner Warren inquired into the land question of the Bloemhof districts, and in April commanded the Griqualand West Field Forces in the northern border of Cape Colony, and made arrangements to prevent the rebels breaking through again into Griqualand West. They were thus forced into Bechuanaland, and in conjunction with the Bechuanas again threatened Kuruman. The Bechuana and Griqua ringleaders and the Cape Colony rebels were defeated and captured by the Griqualand West forces in August, and Warren was able to reduce the strength of his columns in the field. He was invalided home in the autumn on account of the hurt he sustained from the falling tree. He left the Cape much to the regret of the South African people, among whom his name had become a household word, and his departure was regarded by them in the light of a personal loss. For his services during the past year he received a clasp to his South African medal and nothing more.

The Colonial Office made a strenuous but[21] unsuccessful endeavour to procure for him a brevet-colonelcy, and made the following representation to the War Office in December 1879:

‘Until August 1878 Colonel Lanyon appears to have remained in the field, but Lieut.-Colonel Warren, though not occupying a higher position than that of Chief of Colonel Lanyon’s Staff, appears to have acted to a great extent independently and not under his immediate supervision; and when, at the close of the engagement of 18th June at the Paarde Kloof, Colonel Lanyon arrived with the Southern Column, he left Lieut.-Colonel Warren in command to complete the victory, considering that the entire credit of the brilliant success then attained was due to Lieut.-Colonel Warren.

‘In the operations at Kuruman and the capture of Litako and Takoon Lieut.-Colonel Warren not only behaved with dashing personal bravery as on previous occasions, but contributed materially to the success of an operation which in many particulars clearly resembled those just concluded against Morosi’s Mountain and Sekukuni’s Town.

‘In September 1878 Colonel Lanyon, being fully occupied with the civil duties of his office, despatched Lieut.-Colonel Warren in independent command of a Colonial force organised by him, to operate against a combination of Griquas, Korannas, and Bechuanas who were assembled at the Mokolokue’s Mountain on the confines of the Kalahari desert, and were threatening the province with invasion. It will be seen from the Reports that Lieut.-Colonel Warren had here again to deal with the problem of capturing a fortified mountain, which had proved so difficult in recent South African warfare; and he effected his object by a brilliant strategical movement, taking the enemy in reverse, and driving them at once from their most formidable lines of defence, the work of clearing them from krantzes, in which they subsequently took up position, being successfully accomplished on the same day.

‘In January 1879 Warren succeeded Colonel Lanyon in the civil administration of Griqualand West, but still retained the military command in the province, and either personally conducted or directed further operations in the[23] south of the province, and to the north and north-west, beyond the provincial border....

‘Not only were Lieut.-Colonel Warren’s military operations successful throughout, but they were accompanied by a large measure of political success; his tact, humanity, and moderation in victory having done much to convert our enemies into friends, and to promote the permanent pacification of the districts to the north of the Orange River, over which our influence extends.

‘Lieut.-Colonel Warren has already been rewarded for his services in the Gaika war by the brevet of lieut.-colonel, but his subsequent services in Griqualand West form a distinct and very creditable episode in the history of the recent South African warfare, for which Sir Michael Hicks-Beach hopes that he may be considered entitled to fresh recognition in the form of the brevet of colonel, or such other mark of approbation as Colonel Stanley and H.R.H. the Field-Marshal Commanding-in-Chief may think proper to recommend.

‘The operations of 1878–9 throughout South Africa should be regarded as a whole, and Sir[24] Michael Hicks-Beach trusts that officers of the Regular Army who have organised and led to victory the Colonial Levies in separate commands may be thought not less deserving of the usual military rewards than officers who have served under the immediate direction of the General Commanding-in-Chief in leading her Majesty’s Regular Troops; indeed, those of the former class have some special claims to consideration on account of the difficulties which they had to overcome; and in organising not only a combatant force, but also the Transport, Commissariat, Pay and Hospital Departments of that force, Lieut.-Colonel Warren displayed a general knowledge of his profession which marks him as an especially intelligent and valuable servant of the Queen.’

The voyage home from South Africa was very beneficial to Warren’s health, and early in 1880 he was able to take up the duties of the post of Instructor of Surveying at the School of Military Engineering at Chatham, to which he had been appointed. It would be too little to[25] say he entered with his usual zest into his new duties, because he delighted in surveying, and nothing pleased him better than to have a number of young officers to train in all its branches, and to instruct in practical astronomy after Mess in the R.E. Observatory, to say nothing of the large classes of officers of the Line which passed through his hands and the training of the Sappers of his own Corps. In 1881 Warren contributed to the Professional Papers of the Royal Engineers a paper on the Boundary Line between the Orange Free State and Griqualand West.

But the even tenor of his way was broken in upon suddenly in the summer of 1882. It may, perhaps, be remembered that when events in Egypt in 1882 made it likely that we should have to undertake military operations in that country, Professor Palmer, Professor of Arabic at Cambridge, who was well acquainted with Syria and Arabia, and Captain Gill, R.E., a distinguished traveller, were sent in June to win over the chiefs of the Bedouin tribes in the South[26] of Syria and on the borders of the Suez Canal. They successfully accomplished their journey and arrived at Suez on 1st August. Professor Palmer reported that the Bedouins were favourably disposed, and that plenty of camels could be procured for the army. On 8th August he left Suez to go to Nakhl in the desert, half way between Suez and Akaba, to procure camels for the Indian contingent. He was accompanied by Captain Gill, who was attached to the Intelligence Department, and whose mission was to cut the telegraph line in the desert, and by Lieut. Charrington, R.N., flag-lieutenant to Admiral Sir William Hewett. The party carried 3,000l. in gold, and, although provided with a guide, no escort was taken, as no danger was apprehended. Soon after the party left Moses Wells opposite Suez, rumours reached Suez that their baggage had been plundered. Inquiries were set on foot in all directions with no definite result, and the country and the Government were alarmed and feared that some disaster had occurred.

Lieut.-Colonel Charles Warren, whose experience and qualification for dealing with an[27] inquiry among Arabs were highly thought of, was selected by the Government to go on special service under the Admiralty and take charge of a search expedition, and, should the rumours of the murder of the party prove true, to bring the murderers to justice. The task was a difficult and an exceptionally dangerous one—to go into the desert and search among the wild Bedouin tribes for the ill-fated expedition, with no loyal Arabs who could be called upon to assist.

Warren went off in August at twelve hours’ notice to Egypt, and, after reporting to the Admiral, proceeded to Tor, and at a later date to Akaba by steamer. He found the Arabs at both places singularly indisposed to enter into any communications; but up to the end of September, and even later, he did not despair of the travellers being still alive, and it was not until 24th October that he could report with certainty the story of their tragic deaths on the previous 10th August, and that he had found their remains.

Having no friendly Arabs to depend upon, Warren had to resort to the expedient of suddenly swooping down on some Bedouins about Zagazig, who had been fighting against us a week[28] before, and capturing several hundreds of them. These he sorted out, imprisoning some as hostages, and taking 220, selected from various tribes, with him as an escort into the desert. He was accompanied by Lieutenants Burton and Haynes and Quartermaster-Sergeant Kennedy, all of the Royal Engineers. After ascertaining that Professor Palmer had been murdered, the expedition entered the desert in search of the murderers; Warren made his arrangements for their capture, and succeeded in taking eight out of fifteen. These were brought to trial, convicted, and hanged.

During his hazardous operations Warren visited Akaba, where Arabi’s flag was flying, and reduced it to submission. He also captured Nakhl in the desert, which he reduced by surrounding it and cutting off supplies; this caused a mutiny in the garrison and they capitulated.

In the House of Commons on 16th November Mr. Gladstone said that ‘Colonel Warren had performed the task of investigating the circumstances of the murders with great energy and judgment, as well as knowledge.’

On 27th November Admiral Sir Beauchamp[29] Seymour conveyed to Warren by letter his entire approbation of the means he had adopted ‘at much personal danger to ascertain the fate of Professor Palmer and his comrades. The perseverance and zeal,’ he says, ‘manifested by you and by the subaltern officers of the Royal Engineers under your orders, more especially during the trying march between Nakhl and the Suez Canal, reflect the greatest credit on the noble Corps to which you belong.’

An Admiralty letter of 4th December 1882 to Lord Alcester desires him to inform Colonel Warren that the Lords of the Admiralty ‘are very grateful to him for the energy, courage, and good judgment with which he has prosecuted the inquiry, under circumstances of considerable difficulty and danger.’ And again on 1st January 1883 Captain Stephenson, the senior naval officer, conveyed their Lordships’ ‘high appreciation of the manner in which Colonel Warren had performed the difficult task of ascertaining the fate of Professor Palmer’s party.’ Captain Stephenson, who was at Suez when the search was going on, added: ‘I wish to add my testimony to the patient, but energetic [30]and persevering, manner in which you have traced the sad fate of the missing party, against many adverse circumstances in a part of the country so desolate that assistance from me would have been of no avail had any untoward circumstances occurred to your party.’

On 22nd January the Admiralty renewed their expression of their very high appreciation of Warren’s services, and the Commander-in-Chief of the army, H.R.H. the Duke of Cambridge, informed him of his high satisfaction at receiving a very favourable report from the Admiralty on the able manner in which he had carried out the duty entrusted to him, and his own appreciation of the ‘hazardous services’ he had performed. Warren, who was already a brevet-colonel,[2] was promoted to be a Knight Commander of St. Michael and St. George on the Queen’s birthday, 24th May, and the Admiralty congratulated him in a letter of 25th May 1883, expressing the gratification felt by the Board at this mark of the Queen’s approval of the most valuable services which he had rendered to her Majesty’s Government throughout[31] the whole time he was engaged in investigating the circumstances of the murder of Professor Palmer and his party, and in bringing the guilty persons to justice. Lieut.-General Sir Andrew Clarke, Inspector-General of Fortifications, wrote to him in January 1883: ‘You are doing your mission right well; we are all proud of you.’ Lord Northbrook wrote in the same sense, and afterwards told Sir Charles Warren that his exertions had saved the country an expenditure of at least two millions on an expedition into the desert, which must have been undertaken had he been unsuccessful. Warren received the Egyptian medal and bronze star, and was also decorated by the Khedive with the third class of the Order of the Mejidie.

On his return home he resumed his duties at Chatham as the head of the Surveying School. In 1884, when General Gordon was shut up in Khartoum and completely cut off by the Mahdi, Warren volunteered to go through Abyssinia and open communication with his old[32] friend. He was for some time in correspondence with Mr. W. E. Forster on the subject, and Lieut.-General Sir Andrew Clarke highly approved of the proposal, and wrote a minute in favour of it. In the end, however, the idea was abandoned when it was decided to send a relief expedition under Lord Wolseley. Warren found time during 1883 to write a pamphlet giving a concise account of the military occupation of South Bechuanaland in 1878–9, and he also contributed to the Professional Papers of the Corps of Royal Engineers ‘Notes on Arabia Petræa and the Country lying between Egypt and Palestine.’

In that part of Bechuanaland lying to the north of Griqualand West, the white man had been rapidly encroaching upon native territory since the days when Warren commanded the Field Force of Griqualand West and prevented the Bechuanas invading the province. Two republics had been established in Bechuanaland; one, called Stellaland, in which English and Dutch adventurers had already taken possession[33] of the land, ‘eaten up’ the native tribes, and become to some extent a settled people; the other, named Goshenland, in which Transvaal filibustering Boers plundered and oppressed the native race, and treated it with cruelty. These raiding Boers were supported by the Transvaal Government, which, since the so-called ‘magnanimous’ settlement, after the Majuba defeat of the British, and the exposure of the weak and vacillating policy of the British Government in the South African Colonies, had steadily set before it the substitution of a Dutch South Africa for a British, and had exhibited a contempt for the Queen’s authority which was rapidly developing.

All attempts to arrange with Mr. Kruger, President of the Transvaal Republic, for an equitable settlement of the Bechuanaland questions having failed, and further negotiations being useless, the Government had nothing left to them but to employ force. It was, however, desirable, in sending troops into the country to enforce the views of the Government, that the commander should be a man who had not only a thorough knowledge of the country and of the[34] questions in dispute, but was also regarded as an authority in the settlement of land questions by both the British colonists and the Boers. In this way it was hoped that perhaps the moral support of an adequate force might enable him to settle matters satisfactorily, without having recourse to fighting.

Colonel Sir Charles Warren was the man who best fulfilled the required conditions, and was selected for the command of the expedition, given the local rank of Major-General, and appointed Special Commissioner.

A force of 5,000 men was raised and equipped, and supplemented by special troops and corps from home, one of which was Methuen’s Horse. Warren’s instructions were to remove the filibusters from Bechuanaland, to restore order in the territory, to reinstate the natives in their lands, to take measures to prevent further depreciation, and finally to hold the country until its further destination was known. As Special Commissioner he was to be under the directions of Sir Hercules Robinson, Governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner in South Africa, but was to be left a large discretion as regards[35] local matters. In regard to operations in the field, he was to be responsible to the Secretary of State for War and the General Commanding in South Africa, and was not to be accountable to the Colonial Government or the High Commissioner.

Sir Charles Warren landed at Cape Town on 4th December 1884, and soon pushed his force up country into the disputed territory. The promptness with which he moved, and the efficiency of his force gave him the moral support which he required in carrying on negotiations with Mr. Kruger, and in these diplomatic dealings he exhibited the ability and tact which had distinguished him on previous occasions when called upon to settle disputes of a similar kind.

An officer of the expedition wrote home in August 1885:

‘Immediately after I despatched my last, it became evident that this Bechuanaland business was practically played out as a campaign. I should think there never before was such a case of a brilliantly executed advance into a distant country, followed by such complete inanition, as has fallen upon everybody (except, of course, the[36] General Officer Commanding, who has had plenty to do politically) as took place here. By 2nd April the General and Headquarters Staff were fully established up at Mafeking (Rooi Grond), with telegraphic communication—220 miles, working without a hitch, I am glad to say—from end to end of the occupied country, and stores enough along the whole length of line to feed the entire army for three months. It really was a master stroke, considering the slowness of transport, the sandy state of much of the road, and the scarcity of water. But when one has said that one has said everything—since that time we, as an expedition, have simply been standing still.’

But ‘they also serve who only stand and wait,’ and while the expedition was chafing at being kept idle, with no fighting to do, and the prospect of rewards and distinctions for the campaign fading away, the moral effect of its presence made itself felt. The Transvaal Government, finding itself unprepared to fight, changed its attitude and Sir Charles Warren was able to make a peaceful settlement with Mr. Kruger, though not without many difficulties. He returned to England after a bloodless cam[37]paign, receiving the thanks of Parliament and of the Colonial Legislature, and promotion to the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. But he was not made a supernumerary major-general after holding that rank in the field, and, on his return, reverted to the rank of colonel.

At the General Election of the autumn of 1885 Sir Charles Warren was invited to stand as a candidate for Parliament to represent the Hallam division of Sheffield in the Liberal interest, and in his address he took an independent position, making no mention of any party leader.

The principal points he laid stress on were:

(1) The Empire could not stand still. ‘Forward’ must be the motto.

(2) The prosperity of the nation depended on the moral tone of the people continuing at a high standard, which could only be maintained by unremitting attention to the religious education of the children. Instruction, therefore, in the truths of Christianity must be real and efficient.

(3) Education must be sound both as to mind[38] and body, and in elementary schools must be free, and the greatest attention paid to physical training.

(4) The connection between the Mother Country and the Colonies must be strengthened, a fixed colonial policy should be established clear of party politics, and a federal parliament of the Empire should be looked forward to.

(5) Ireland must remain part of the United Kingdom, but the greatest amount of self-government practicable should be accorded to it.

(6) County Councils should be established.

(7) Disestablishment of Church with State only desirable if wanted by both sides.

(8) Local option.

(9) Reforms regarding land tenure.

(10) Reform of House of Lords.

(11) Reforms in House of Commons to prevent obstruction.

Sir Charles was unsuccessful at the poll, but he had so won the hearts of the Liberal constituents that they paid the whole of his election expenses, and, on his leaving the constituency, presented him with an address and a handsome case of Sheffield plate and cutlery.

In January 1886 Sir Charles Warren was appointed to command the troops at Suakin, with the rank of Major-General on the Staff, and to be Governor of the Red Sea Littoral. On arrival at his headquarters, Suakin, he was greeted by a telegram from Simla containing congratulations on his appointment from Lord Dufferin, under whom he had served diplomatically when he was engaged in the Palmer Search Expedition.

Warren found that the Suakin garrison was composed of three nationalities—British, Indian, and Egyptian—all acting under different regulations, and he at once set to work to introduce a better organisation into the garrison, and to have a mobile force to drive inland the Hadendowa Arabs, who were in the habit of firing into Suakin every night. He took the friendly natives into service and put them in the field against the Hadendowas, and in a few days had a clear zone of several miles round the town. He also commenced arrangements to open up the country as far as Berber and to start commercial operations at various ports on the Red[40] Sea, to open up salt works, &c.; but he found no response from the Egyptian authorities at Cairo, and soon discovered that they did not wish to encourage trade by Suakin, as it would reduce that going through Cairo.

After three months in this appointment, when he was beginning to find that there was nothing to do but to sit down and hold the place, he received a telegram from Mr. Childers, the Home Secretary, offering him the Chief Commissionership of the Metropolitan Police, at a time when there had been a considerable panic in London, and Sir Edmund Henderson had resigned the office. He accepted the offer, and left Suakin at the end of March. Before leaving he received a very sympathetic address from the merchants in Suakin, recognising the effort he had made on behalf of trade with the interior and along the coast.

In his new position Warren had several difficult and complicated problems to deal with. During the very first year of office the Trafalgar[41] Square demonstrations, permitted by a weak Government, tested the powers of the police under their new chief to preserve public order. The Liberal party abused their own nominee, but he was firm. Then there were all the arrangements for the preservation of order at the Queen’s Jubilee in 1887, which were so ably carried out. He received many complimentary letters: one from the Home Secretary expressing her Majesty’s entire approbation of the excellent manner in which the arrangements for preserving good order were made by him; another from the Commander-in-Chief, H.R.H. the Duke of Cambridge, congratulating him on the admirable manner in which they were carried out, which in his opinion left nothing to be desired, and reflected the greatest credit on the Metropolitan Police Force; in a third the Prince of Wales, as Chairman of the Children’s Jubilee Festival, caused his thanks to be conveyed to him for the invaluable assistance he lent on the occasion; and finally Lord Salisbury informed him that he was very glad to be the medium of acquainting him that the Queen had been pleased to confer upon him, in special recognition of his[42] exertions in maintaining order in the metropolis during the past difficult year, and of his services at the Jubilee celebrations, a Knight Commandership of the Order of the Bath.

In July appeared a cartoon in ‘Punch’ with the following legend:

Other difficulties he had to try him during his term of office were an outbreak of burglaries, the muzzling of dogs, and the Whitechapel murders, all of which irritated the public and caused the police to be abused. He was not the man to stand by and hear his force unjustly criticised without defending it, and he contributed an article to ‘Murray’s Magazine’ on the subject.

In the spring of 1888 he did not think the Home Secretary, Mr. Matthews, gave him sufficient support, but rather endeavoured to minimise his authority as head of the force, and he tendered[43] his resignation. This was not accepted, and he continued in his post until the autumn, when he decided that he could no longer hold the appointment with due regard to the good of the force and his own credit.

The resignation was fully debated in the House of Commons on 14th November 1888, when the Home Secretary said:

‘He was glad to have the opportunity furnished by what fell from the Hon. Member for the Horsham Division, to do the fullest justice to Sir Charles Warren. Sir Charles Warren was a man not only of the highest character, but of great ability. During his tenure of the office he had displayed the most indefatigable activity in every detail of the organisation and administration of the force. By his vigour and firmness he had restored that confidence in the police which had been shaken—he believed with the right hon. gentleman, unjustly shaken—after the regrettable incident of 1886.... Sir Charles Warren had shown conspicuous skill and firmness in putting an end to disorder in the metropolis, and for that he deserved the highest praise.’

Again there appeared a cartoon in ‘Punch’ entitled ‘Extremes Meet,’ in which Sir Charles Warren and his predecessor were depicted exchanging views:

It was during his police work that he attended the meeting of the British Association at Manchester in 1887 as President of the Geographical Section and gave a very practical and useful opening address.

After some months of leisure Warren was appointed to command the troops in the Straits Settlements in April 1889, as a Colonel on the Staff with the rank of Major-General. Hitherto this command had been one with that of Hong-Kong, where the Headquarters were; but, owing to friction arising in 1888 between the civil and military authorities in the Straits Settlements, it was decided to send out an officer to Singapore in independent command[45] to endeavour to make things work smoothly. The difficulties arose from the peculiar nature of the agreement which had been made with the Straits Settlements when they were detached from India and established as a Crown Colony.

Sir Charles Warren soon found that the existing system was impracticable for efficiency, and it was altered, but in carrying out the alteration there arose a good deal of difference of opinion between the civil and military authorities. Moreover, as a member of council, Sir Charles Warren came to the conclusion that the annual military contribution should be a sum calculated pro rata to the revenue up to the amount required. This gave great offence to the colonists, who wished for a fixed sum, which was finally agreed to. But in two years the revenue of the Colony rapidly diminished owing to changes in the opium farming, &c., and the people found themselves paying a much higher sum than they would have done according to Sir Charles Warren’s proposal. Then they recognised his foresight, and popular feeling changed in his favour.

During the five years Sir Charles was in the Straits Settlements he did much travelling and occupied in the aggregate ten months (his two months’ leave per annum) in seeing India, Ceylon, Burma, Siam, Java, Japan, and some of the seaports of China. The Straits Settlements being within his command, he visited the several States as a duty, and, by request, inspected the armed constabulary (Sikhs) of Perak and Selangor and the troops of the Sultan of Johore. He penetrated into the uncivilised parts of the Straits Settlements and traversed the peninsula from east to west, over the mountains from Selangor to Pahang, through the Sakai country. At the time of the Pahang outbreak he was ready with his troops for all emergencies, and prepared and printed a field book for use in the jungle, should circumstances require it.

He encouraged sports among officers and men, and did much to keep up a good feeling between the troops and the inhabitants, and established (under the Garrison Sports Committee) four yearly events, for which he gave suitable challenge shields. The contests for these prizes had a stimulating effect on sport in the Malay peninsula.

In addition to his military duties he was for several months chairman of a committee to inspect and report on the police of the Straits Settlements. As District Grand Master of the Eastern Archipelago, he visited the several Masonic Lodges, presided at various functions, and, on his leaving the Settlements, was presented by the fraternity with a full-sized portrait of himself and a very handsomely illuminated address.

The readiness of the garrison of Singapore for defence was brought to a high pitch of perfection during his tenure of command. When he first arrived it took several weeks to mobilise, and, after much practice, he reduced the time to three days; when he arrived at this, he saw it was not perfect unless it could be done in three hours, and this was accomplished eventually. A practical test of this was given. One evening, when he was dining at Government House to meet the Admiral Commanding-in-Chief, the latter began to chaff at the unreadiness of the army in comparison with the navy, and asserted his opinion that Singapore could not mobilise under three weeks. Sir Charles[48] said that the Admiral would have to admit that it could be done in three hours, and guaranteed that, if the Admiral would be out at 6 A.M. at the jetty, he would find all the troops in their places, although some of them would have to march six miles or more in the dark, and cross the water in launches. The only point that would not be the same as in time of war was the getting the launches into their places, as they were in peace positions at the time. At 11 P.M. Sir Charles Warren ordered the launches to be in position at 3 A.M. and sent word to the troops to get ready at 1 A.M. They marched down from Tanglin and Fort Canning Barracks to the wharf, were taken across in launches and submarine miners, and were all in their places at 6 A.M., when the Governor and Admiral visited them in company with Sir Charles Warren. The Admiral gave the highest praise a sailor could give—that it had been done as well as if it had been done by the navy.

His services at Singapore are summed up in an article in the ‘Straits Times’ of 2nd April 1894, from which the following is an extract:

‘It is no new thing to speak praise of Sir Charles Warren; and in trying to estimate the services that he has rendered to the Colony it is difficult to do more than repeat ourselves. We have already said he found in Singapore a number of soldiers and some forts, while he leaves at Singapore a garrison in a fortress. He leaves a fortress that is one of the strongest in Asia, and he leaves a garrison whose readiness and perfection of mobilisation cannot be surpassed. But on that it does not seem necessary to enlarge, since it is a service that any soldier of first-rate capacity would have done, and all competent persons knew that Sir Charles Warren would do it. It is, perhaps, more interesting to record that in his time Sir Charles Warren has been the best abused man in the Colony, while at his departure he is as universally esteemed as any man could be. It is but a couple of years ago that he was the subject of persistent slander at the hands of persons who now sing his praises and lament his departure. That conquest of enmity Sir Charles has achieved by means at once simple and wise. When he was the subject of detraction he paid no attention, but proceeded quietly about the affairs he had in hand.[50] When the persons who had attacked him repented of their methods, he ignored that he had been attacked, and dealt with the advances of his new friends as if he had not known that they had been unfriendly. To put it briefly, he proceeded on the path of duty regardless either of praise or blame, until better knowledge rendered it impossible for any one to persist in detraction. Sir Charles leaves the Colony amidst a universal chorus of friendly greetings. To have achieved such a conquest of public opinion amidst so small a community is a great result. For the community is so small that no man can live in it for a number of years without giving ample opportunity to see his character in all its moods and tenses. From that scrutiny Sir Charles Warren has emerged with success. The community of the Straits feels that in losing him it loses not only a soldier and a scholar, but also a most excellent example of a kindly and simple-hearted gentleman.’

At one of the many farewell dinners in his honour Sir Charles Mitchell, the Governor, said: ‘Each man in his turn played many parts, but of all men he had known through his experience of[51] this somewhat difficult world, he knew none who in these times had played so many parts, and played all those parts so well, as their distinguished guest, Sir Charles Warren. As a man of letters, and as a man of action, Sir Charles Warren had distinguished himself.’

Although, when Sir Cecil Smith was Governor, official difficulties occurred between him and Sir Charles Warren on matters which could not readily be settled, yet the differences were solely official, and Sir Cecil Smith was one of the first to send Sir Charles Warren, when he was leaving England in November 1899 for Natal, hearty good wishes for his success and safe return with added glory to the high reputation he had already gained. Sir Charles Warren left the Straits Settlements on his return to England in April 1894, and he travelled by way of Vancouver and the American Continent, spending some weeks in exploring the Western States of the Union.

In 1895 Sir Charles Warren was appointed Major-General commanding the Thames District,[52] and was told that he was to organise the mobilisation of the Thames District for defence on the same model he had so successfully established at Singapore. He took it in hand at once, and in two years had so perfected the system that all troops coming into the district were enabled on sudden mobilisation to find their places and take up their duties immediately.

He was busily engaged, during his term of command, in the problem of defence of the Thames and Medway, in which a great advance was made, and in examining into the efficiency of the Royal Engineers for active service in all their branches, and frequently inspected them with this object in view.

He instituted field days between the various garrisons; marched all the infantry to Sheerness during the spring months, and practised defence of the coast there.

He took great interest in the various new regulations for the canteen system, and pointed out the difficulty of having one contractor of groceries. He favoured the tenant system for the dry canteen, while keeping the wet canteen in the hands of the military.

During the autumn of 1896 he commanded a division at the New Forest autumn manœuvres.

He established a District Rifle Association at Gravesend, and himself gave two shields for annual competition: one for rifle shooting and one for carbine shooting. He evinced great interest in the town of Chatham and worked, in conjunction with the Mayor and Corporation, to ameliorate its condition for the benefit both of the soldiers and of the inhabitants.

On leaving the command in 1898 he was entertained at a public dinner given by the Mayor, and presented with a silver salver bearing an inscription, and with an address from which the following is an extract:—

‘We sincerely thank you for the valuable services you have rendered to our town; and whilst we much regret that we are losing from our midst the presence of one so distinguished as a scholar, scientist, and soldier, we rejoice that whilst here you greatly promoted cordial relations between the military and civic authorities, and took great interest in the moral and intellectual welfare of the inhabitants of Chatham.’

Warren was now on the shelf, and took a house at Ramsgate, where he resided until his services were again required by his country, and he was appointed to the command of the 5th Division and embarked with it for South Africa on 25th November 1899.

The last year of the nineteenth century opened at a period of intense gloom for the British nation. The war in South Africa had found us, as most wars do, quite unprepared. The little force in Natal, under Sir George White, had been speedily surrounded by the mobile Boers, its line of communication had been cut, and it was itself shut up in an unfavourable position for defence at Ladysmith, and blockaded by a Boer force.

Large reinforcements were pouring into South Africa from England, and Sir Redvers Buller, who had arrived at Cape Town on 31st October to take supreme command, had gone to Natal. Here he made his first strategical mistake; and just as Sir George White, induced by political pressure, occupied positions in the extreme North of Natal, which he was not strong enough to hold, and had the consequences of[56] this departure from sound strategy burnt into him by the siege of Ladysmith, so Sir Redvers Buller, moved by clamours for the relief of Ladysmith and Kimberley, divided his force, sending part under Lord Methuen to relieve Kimberley, and himself taking the remainder to relieve Ladysmith, and learned a similar lesson.

Such inattention to the very elements of strategy might have speedily led to overwhelming disaster and to the triumph of the Boer States, and would undoubtedly have done so, had the Boers possessed a general worthy of the name. With what surprise and satisfaction would such a commander have observed the disposition of the British force in the North of Natal, with what rapidity would he have masked Sir George White’s division, and, crossing the Tugela, seized the railway at its mouth, and, by the capture of Durban, have held Natal in the hollow of his hand! But, although the generalship of the Boers was hopelessly timid, and they lost the opportunity of carrying all before them at the outset, and driving the British into the sea, the neglect of sound strategy on our side made itself seriously felt, and it was not until[57] Lord Roberts, at a later date, having collected and organised a large force, moved steadily on his objective—the capital of the Orange Free State—that either Kimberley or Ladysmith was relieved.

At the end of 1899 disaster after disaster had caused the public spirit at home to be much depressed, and men began to ask one another what was the reason. Was it the fault of our generals? or were the pluck and splendid bravery of our troops—so much in evidence—impotent, in these days of smokeless powder and quick-firing and long-range guns, against white men, equally well if not better armed, accustomed from their childhood to ride and shoot, stalk game, and avail themselves of cover, knowing the country and using every device to fight without endangering their own lives?

But to whatever depths the spirit of the nation sank at that terrible Christmas of 1899, however freely it was confessed that we had been too cocksure of success, had too much forgotten the God of battles, had despised our enemy, and arrogantly assumed that the war would be a walk-over; however much mothers[58] and sisters, widows and orphans, plunged into saddest mourning by the losses under Lord Methuen at Belmont, Eslin, the Modder River, and Majesfontein, under Major-General Gatacre at Stormberg, and under Sir Redvers Buller at Colenso, might bewail their loved ones who had died for their country on the battlefield, there was a most notable, a most wonderful, self-control among the people generally. Subdued by a distinct sense of disappointment and humiliation as one disaster after another occurred, there was no hesitation, no acceptance of defeat, but a dogged determination that the war, being a righteous war, must at any sacrifice be carried to a victorious conclusion. The national honour had been wounded by the impudent invasion of British dominions beyond the seas, and that wound could only be healed by the complete subjugation of the invader. The galling remembrance of the disasters of the previous Boer war—never retrieved—of the overbearing insolence and ingratitude which had rewarded the pusillanimous policy of so-called magnanimity, had formed amongst all classes a determination that there must be no more[59] Majuba treaties. Never again must a British defeat by Boers be allowed to conclude the matter, to rankle and fester in a way so difficult for a high-spirited people to bear, even when disguised under the name of magnanimity. Defeat must only mean renewed effort and determination to succeed. We were in the hands of God, but, so long as we could send out a man to fight, we were determined to go on, and, God willing, at whatever cost to end the matter, once for all, in such a way that our wounded honour should be healed, the susceptibilities of our invaded Colonies soothed, and the Boer taught to know his proper place, but as a member of a free and world-wide Empire and a subject of the Queen.

Such were the feelings of disappointment and sorrow, and yet of determination, by which the majority of people at home were animated when the last year of the nineteenth century commenced, and the successes of Major-General French at Colesberg, and of Colonel Pilcher at Douglas on New Year’s Day, cheered despondent hearts, and inspired a hope that the luck was about to turn.