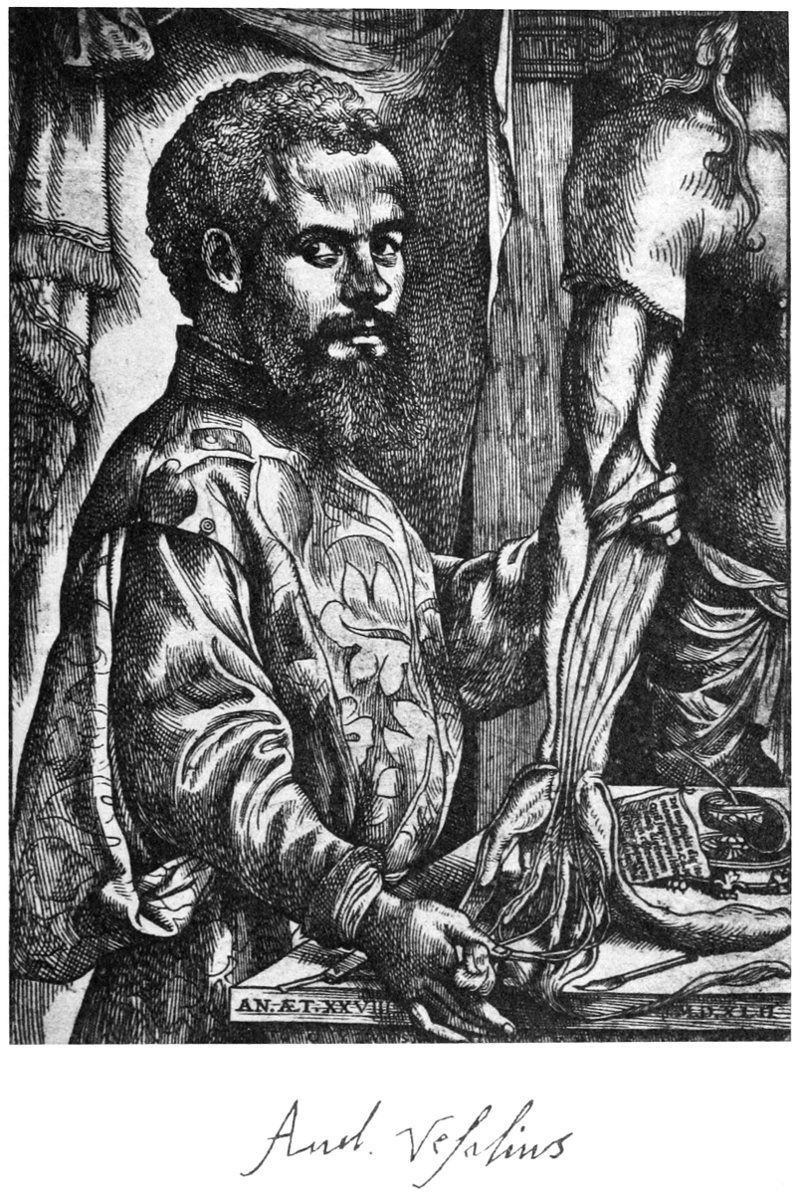

And. Vesalius

BY

JAMES MOORES BALL, M. D.

SAINT LOUIS

MEDICAL SCIENCE PRESS

MDCCCCX

Copyrighted, 1910

By James Moores Ball

All rights reserved

TO THE MEMORY

OF THOSE ILLUSTRIOUS MEN

WHO

OFTEN UNDER ADVERSE CIRCUMSTANCES

AND

SOMETIMES IN DANGER OF DEATH

SUCCEEDED IN UNRAVELLING THE MYSTERIES

OF THE STRUCTURE OF THE HUMAN BODY,

TO THE FATHERS OF ANATOMY

AND

TO THE ARTIST-ANATOMISTS

THIS BOOK

IS DEDICATED

In the annals of the medical profession the name of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels holds a place second to none. Every physician has heard of him, yet few know the details of his life, the circumstances under which his labors were carried out, the extent of those labors, or their far-reaching influence upon the progress of anatomy, physiology and surgery. Comparatively few physicians have seen his works; and fewer still have read them. The reformation which he inaugurated in anatomy, and incidentally in other branches of medical science, has left only a dim impress upon the minds of the busy, science-loving physicians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. That so little should be known about him is not surprising, since his writings were in Latin and were published prior to the middle of the sixteenth century. His books, IX which at one time were in the hands of all the scientific physicians of Europe, are now rarely encountered beyond the walls of the great medical libraries of the world. They are among the incunabula of the medical literature. That English-speaking physicians know little of Vesalian literature is due to the fact that no extensive biography of the great anatomist has appeared in our language. Most of the Vesalian literature which has been written by English and American authors has been in the form of brief articles for the medical press; these oftentimes have been incorrect and unillustrated. Perhaps the best example of this class is the article by Mr. Henry Morley which appeared originally in Fraser’s Magazine, in 1853, and later was published in his Clement Marot and Other Studies, in 1871. The chief data for Vesalius’s biography are to be found in his own writings, in the archives of the Universities in which he taught, and in the controversial literature of the period. Extensive as are these sources they leave much to be desired. A vast mass of Vesalian literature was printed, chiefly in the Latin language, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Much of it is based on insufficient evidence or on national prejudice. The Germans, the French, the Dutch and the Italians have all taken a turn at it. In modern times the monumental work of Roth, Andreas Vesalius Bruxellensis, Berlin, 1892, has served to epitomize this literature and to make clear many points which formerly were not understood. I have taken Roth’s book as a basis for this monograph, without using the voluminous references which are found in the work of this thorough historian.

The man who overthrew the authority of Galen; revolutionized the teaching of the structure of the human body; started anatomical, physiological, and surgical investigation in the right channels; first correctly illustrated his dissections; destroyed ancient dogmas, and made many new discoveries—this man, Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, deserves the name which Morley has given him, “the Luther of Anatomy.”

At long intervals a bright particular star appears in the intellectual horizon, endowed with genius of such a superlative order as seemingly to comprise within itself the whole domain of an entire science. These men do not belong to any particular epoch in the development of the human mind. They are the eternal symbols of progress, and their history is the history of the science which they profess. Such men were Bacon, Galileo, Descartes, Newton, Lavoisier, and Bichat; and such also was Andreas Vesalius the anatomist. Young, enthusiastic, courageous and diligent, Vesalius dared to contradict the authority of Galen, corrected the anatomical mistakes of thirteen centuries and before his thirtieth year published the most accurate, complete, and best illustrated treatise on anatomy that the world had ever seen. His industry, the success which crowned his efforts, the jealousies which his discoveries aroused in the breasts of his contemporaries, the honors which were conferred upon him by Charles the Fifth and Philip the Second, his pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and his tragic death—these are events which deserve to be chronicled by an abler pen than mine.

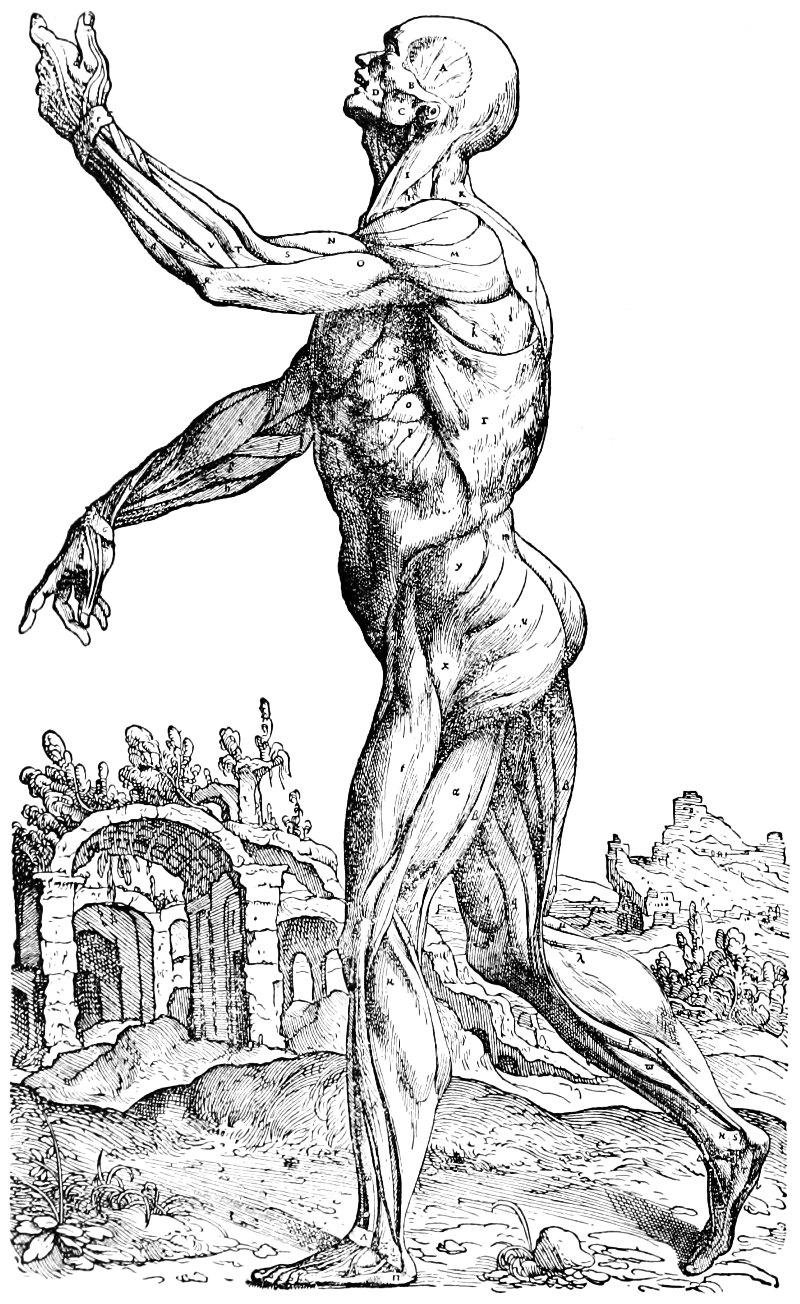

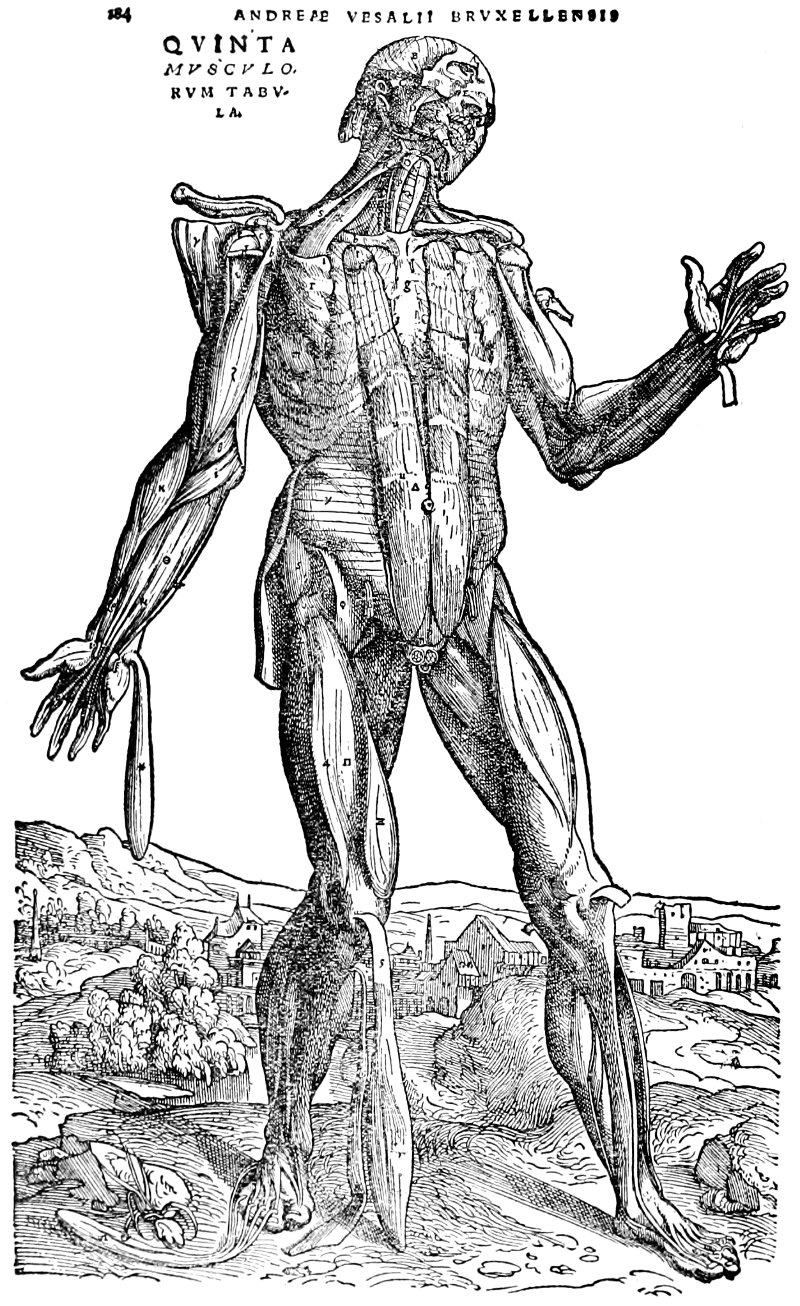

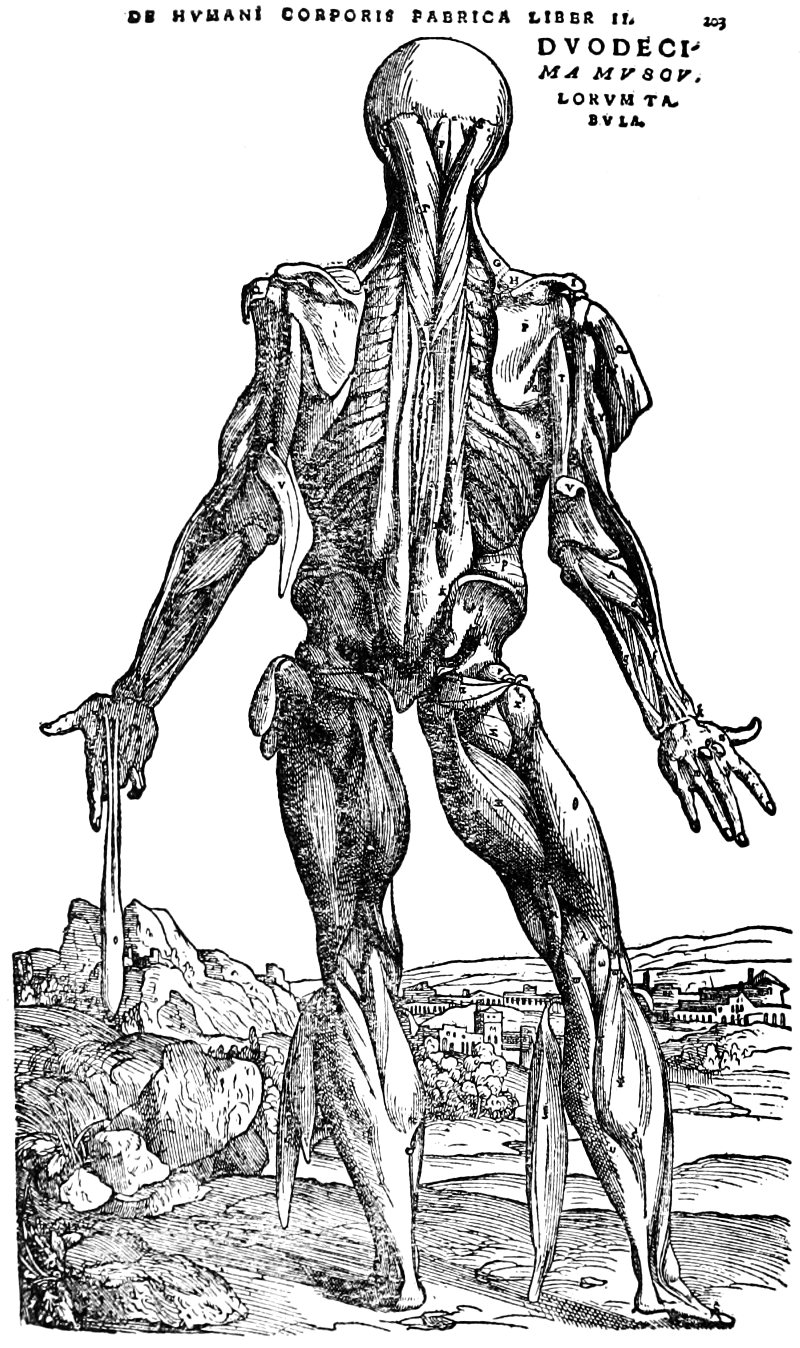

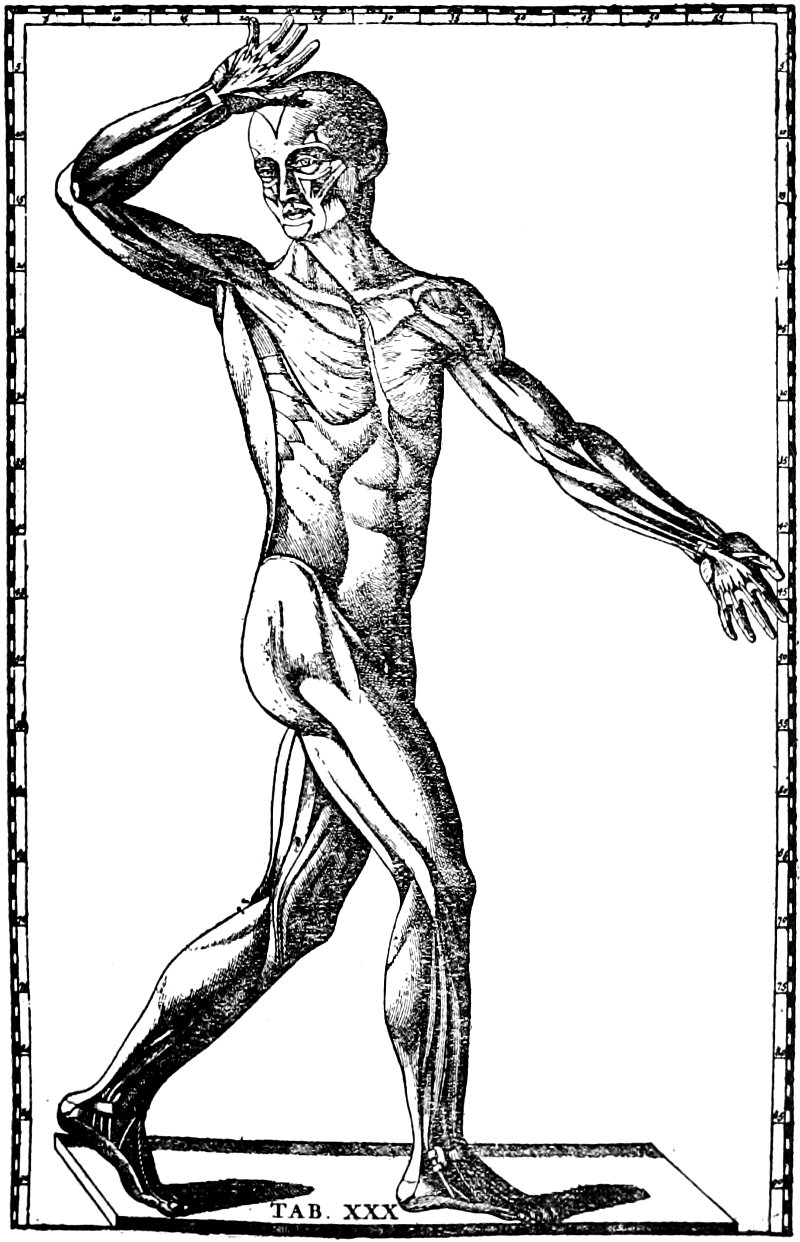

The year 1543 marks the date of a revolution which XI was won, not by force of arms but by the scalpel of an anatomist and the hand of an artist. The whole of human anatomy, as a study involving correct descriptions of the component parts of the body and accurate delineations thereof, may be said to have been founded by Andreas Vesalius and Jan Stephan van Calcar. As light pouring into a prism attracts little notice until it emerges in iridescent hues, so it was with anatomy: after passing through the brain of Vesalius it bore rich fruit which has been gathered by many hands. To turn from the writings of Galen, Mondino, Hundt, Peyligk, Phryesen, and Berengario da Carpi to the beauties of Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica is like passing from darkness into sunlight. To both anatomists and artists this book was a revelation. For more than a century after its appearance the anatomists of Europe did little more than make additions to, and compose commentaries upon the conjoint triumph of Vesalius and van Calcar. For more than two centuries the osteologic and myologic figures of the Fabrica formed the basis of all treatises on Art-Anatomy.

JAMES MOORES BALL.

Saint Louis,

MDCCCCX.

I. van Kalker p. I. Troÿen s.

ANDREAS VESALIUS

(From an old copperplate engraving)

The intelligent student of medical history has at his command an unfailing source of pleasure. To learn the successive steps by which Medicine has advanced from a priest-ridden and secret art practiced with mysterious rites in the Greek temples, passing through the schools of Greek philosophy into the light of publicity, is his privilege. To hunt through musty and worm-eaten volumes for facts regarding the great physicians of antiquity is his delight; and to communicate the knowledge thus obtained to others, who have not the time or the facilities for such research, is his duty. In every period are events and incidents of interest, but to the Middle Ages a peculiar fascination attaches; for it was during this period that Europe, emerging from an intellectual darkness of ten centuries’ duration, awoke to the Renaissance, and Medicine, as ever has been the case, kept pace with the general advance of knowledge.

The present book deals with the life of a master whose work was an essential factor in the evolution of the Anatomical Renaissance. In order to understand the New Birth of Anatomy it is necessary to know something of the scope and influence of the General Renaissance.

This, the Revival of Learning, includes an indefinite time in European history. The seeds of the new movement were planted in the Middle Ages, but they bore no fruit until the time had arrived for an apparently “spontaneous outburst of intelligence”. Definitions of the Renaissance will vary with the point of view. Artists and sculptors will say it was a revolution which was created by the recovery of ancient statues; littérateurs and philosophers look upon it as a radical change due to the discovery of the writings of the classical authors; astronomers and physicists will cite the names of Copernicus, Galileo, and Torricelli; geographers will point to the discovery of a New Continent; historians will name the extinction of feudalism and the capture of Constantinople by the Turks; inventors will recall the changed conditions of warfare brought about by gunpowder, the multiplication of books by the invention of printing, and the advent of new methods of engraving; and anatomists will sound the praises of Leonardo da Vinci and of Andreas Vesalius. All will agree that the Renaissance meant Revolution—revolution in thought, in conduct, in creed, and in conditions of existence. To no one fact can the Renaissance be attributed; nor can its scope be limited to any one field of human endeavor. The Renaissance was, and is, and will continue to be, as long as the race progresses.

The new movement began in Italy and grew rapidly. When, toward the end of the sixteenth century, the lamp of learning began to get dim in Italy, it was relighted by 3 the nations of northern Europe—the Germans, the Hollanders, and the English—and by them was transferred to us. The Revival consisted largely in the recovery of the buried writings of the ancient Greek and Roman authors, together with comments on what they had written, and the production of books which were modeled after their works. But it was broader than this. It included all branches of learning, although more progress was made in some lines than in others.

Italy, a country divided into numerous small States, and so-called Republics, offered great opportunities for individual development and became famous in those paths in which individualism has gained its greatest triumphs. Thus in literature, in law, in medicine, in painting and in sculpture, the Italians were preëminent. In architecture and in the drama they reached no such heights as were attained by the French, the Germans and the English. It was in the northwest part of Italy, in the province of Tuscany, that the Renaissance gained its greatest victories. Among the earliest of the leaders of the New Learning was the Florentine poet, Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). “To Dante”, says Symonds, “in a truer sense than to any other poet, belongs the double glory of immortalising in verse the centuries behind him, while he inaugurated the new age”. His Vita Nuova (New Life) and Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy) are essentially modern in thought, but ancient in the manner in which the thought is expressed.

Petrarch may be said to fairly open the new era. Like Dante, he was a Florentine. He was the apostle of 4 Humanism, that system of philosophy which regarded man “as a rational being apart from theological determinations” and perceived that “classic literature alone displayed human nature in the plenitude of intellectual and moral freedom”. To a revolt against the despotism of the Church, it added the attempt to unify all that had been taught and done by man. Petrarch was a poet, a lawyer, an orator, a priest, and a philosopher. He lived between the years 1304-1374. He was a great traveler, and visited the leading continental cities in order to converse with learned men. Petrarch delighted in the study of Cicero, in collecting manuscripts, and in accumulating coins and inscriptions for historic purposes. He advocated public libraries and preached the duty of preserving ancient monuments. He opposed the physicians and astrologers of his day, and ridiculed the followers of Averröes.

Boccaccio, who has been called the Father of Italian Prose, and is most widely known as the author of the Decameron, did not spend all of his time in describing the escapades of the knights and ladies of old. Influenced potently by Petrarch, Boccaccio regretted the years he had wasted in law and trade, when he should have been reading the classics. Late in life he began the study of Greek that he might read the Iliad and the Odyssey. What he lacked in genuine scholarship he made up in industry. He continued the work begun by Petrarch of hunting for lost manuscripts of the ancient Greek and Roman authors. Many of these precious documents were stored in the conventual libraries, where, too often, 5 they were either wantonly destroyed or were mutilated, the words of the author being erased from the parchment to make way for new prayers. Boccaccio tells of a visit which he made to the Benedictine Monastery of Monte Cassino near the city of Salernum. He wished to see the books and found them in a room without door or key. Many of them were mutilated. On making inquiry as to the cause, the monks answered that they had sold some of the sheets, having first erased the original words, replacing them with psalters. The margins of the old pages were made into charms and were sold to women.

It was owing to the unselfish labors of such men as Petrarch and Boccaccio that the works of Livy, Cicero, Quintilian, Terence, and others of the ancient authors, were preserved. In this enterprise they were encouraged by the rulers. Thus Cosimo de’ Medici in Florence, Alfonso the Magnanimous in Naples, and Nicholas V. in Rome, to say nothing of the despots of the smaller cities, rivaled one another in their zeal in unearthing and multiplying the manuscripts of the ancient writers. They spared neither time nor money to increase their store of manuscript books. They surrounded themselves with learned men who lived in high esteem, and who were supported by salaries paid by the State or by private pensions.

The fifteenth century, which was one of the most remarkable epochs in history, was rich in accomplishment. Almost all of the great events which have influenced European commercial and intellectual development can be traced to that period. The invention of printing, 6 the discovery of America, the fall of the Roman Empire in the East, the birth of the Reformation, and the rise of art in Italy, all belong to this wonderful century. In this period, when almost every city in Italy was a new Athens, the Italian poets, historians, and artists vied with the eminent men of the ancient world in carrying the lamp of learning. The Italian cities—Florence, Bologna, Milan, Venice, Rome and Ferrara—fought with one another, not for the spoils of the battlefield but for the victories of science and of art; not so much for the profits of commerce as for the wealth of genius and of learning. The intellectual development which occurred in northern Italy under the rule of the house of Medici, and particularly under the auspices of Lorenzo the Magnificent, forms one of the most interesting periods in European history.

It is impossible in the present work to trace the steps by which the exquisite taste of the ancients in works of art was revived in modern times. Nevertheless, a few words may be devoted to this subject. While much must be credited to those Greek artists who had left their country and had settled in the Italian peninsula, it must be conceded that many of the works of art of the native Italians were not the less meritorious. The same circumstances which favored the revival of letters, operated to further the cause of art; and the same individuals, who were interested in the preservation of the manuscripts of the older authors, also busied themselves with the collection of ancient statues, paintings, gems and tapestry. The freedom of the Italian Republics permitted the minds of men to expand to full 7 fruition; and the encouragement which was given by its rulers to artists, sculptors and artisans, made the city of Florence, in the fifteenth century, a not less renowned centre of culture than Athens had been in ancient times.

The revival of art dates from the time of Cimabue (1240-1300) and Giotto (1276-1336). The former is known as the Father of Modern Painters; the latter constructed the Campanile at Florence. To Giovanni Cimabue, scion of a noble Florentine family, is usually given the credit of being the restorer of art in Italy. He is thought to have been the first painter to throw expression into the human countenance. His work, if judged by present standards, would be called crude, rude and incomplete. Much of the fame of this painter is to be attributed to his being the first person whom Vasari chronicled in his Lives of the Painters. For more than a century after the time of Cimabue and Giotto, painters displayed only a smattering of anatomical knowledge.

Early in the fifteenth century two Flemish artists, Hubert van Eyck (1365-1426) and his brother John (1385-1441), in their polyptych of the Adoration of the Lamb, boldly struck out along new lines and committed the unheard-of deed of painting nude figures. Italy, however, was the real birthplace of Art-Anatomy. While the Flemings and others of the North painted everything that they saw, including the nude, the Italians were the first men of the Renaissance who thought of painting the nude figure before draping it. Leo Battista Alberti (1404-1472), in his works on painting, insists that the bony skeleton must first be drawn and then clothed with its 8 muscles and flesh. This was an important step in advance, since it shows that the Florentine artists were progressing towards realism and were breaking away from the symbolism of the early Christian painters and mosaic-workers. The new movement in art found a worthy champion in Antonio Pollaiuolo (1432-1498). In his knowledge of the anatomy of the human figure he surpassed all of the artists of his day; and as a result of his labors he may justly be named the founder of the scientific study of the nude. His knowledge of anatomy was so accurate, and so extensive, that it could have been gained only in the dissecting room.

Under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici and the guiding mind of Pollaiuolo, there occurred a revival of pseudo-paganism in Art. The old Church subjects were largely neglected; mythological subjects again became the fashion; draperies were either modified or were laid aside; and the scientific study of anatomy, both as regards the nude figure and the dissection of the individual parts, became the necessary training of the student. Of all the masters of this period, the palm for excellence in drawing the naked figure must be awarded to Luca Signorelli (1442-1524), from whose work Michael Angelo is known to have profited.

The alliance between skilled anatomists and master artists was of reciprocal benefit. The anatomical studies which were made conjointly by Leonardo da Vinci and the celebrated teacher of anatomy, Marc Antonio della Torre, were lost to the world by the untimely death of the latter, before he had finished a magnificent treatise 9 on human anatomy. Leonardo’s anatomical sketches, if they had been published during his lifetime, would have revolutionized anatomy both as regards discoveries in the body and the teaching of the structure of man. These masterpieces of anatomical illustration long remained hidden from the world; they were published only in the year 1902. Even now their cost is so great that only a few wealthy libraries can possess them. Leonardo’s long unpublished drawings show him to have been a most accurate anatomist. At the same time, he constantly kept in view the aim of fine art, which, in so far as practical anatomy is concerned, needs a knowledge of only the bones and the muscles.

Nor was Leonardo the only artist who made dissections. Raffaello Santi, Michael Angelo, Bartholomaus Torre, Luigi Cardi or Civoli, Jan Stephan van Calcar, Giuseppe Ribera, Arnold Myntens, and Pietro da Cortona studied practical anatomy. Rubens’s long-lost sketch-book[1], which was published one hundred and thirty-three years after his death, shows with what care he had studied human anatomy. Albrecht Dürer’s Treatise on the Proportions of the Human Body is also worthy of mention.

In the number and fame of her Universities, Italy showed supremacy. At the end of the fifteenth century she could boast of sixteen seats of learning, a number equal to that of the combined institutions of Britain, France, Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Bavaria.

This digression has led us away from the Humanists. Their list is a long one. Among them were Poggio 10 Bracciolini, who discovered the manuscript of the Institutions of Quintilian and the writings of Vitruvius; Poliziano, the first poet of the fifteenth century, and the translator of the works of Hippocrates and Galen; Pontanus, whose De Stellis and Urania were much admired by Italian scholars; Sannazzaro, whose epic on the birth of Christ cost him twenty years of labor; Vida, whose Christiad and other poems were much admired; and Fracastoro, whose Syphilis was hailed as a divine poem.

From the viewpoint of the medical historian an important event occurred in the year 1443, when Thomas of Sarzana, later known as Pope Nicholas V., discovered a manuscript copy of the De Medicina of Aulus Cornelius Celsus. This classic, which had been lost for many centuries, was one of the first medical books to pass through the press. It gave physicians an insight into Hippocratic medicine without the disadvantage of an imperfect translation. Physicians took an active part in the Renaissance. Thus Nicholas Leonicenus, of Ferrara, translated the Aphorisms of Hippocrates and the Natural History of Pliny; and Winter of Andernach did similar labor for the writings of Galen, Alexander, and Paulus Aegineta. Their efforts seem insignificant in comparison with those of Anutius Foesius, a humble practitioner of Metz, who spent forty years of his life in preparing a complete Greek edition of the works of Hippocrates. The New Learning was brought to England by two physicians, Thomas Linacre and John Kaye (Caius).

Some of the Humanists were printers. The history of printing in Italy naturally forms a part of the history of 11 the Renaissance. In 1462, Maintz was pillaged by Adolph of Nassau and its printers were scattered over Europe. Two of them wandered into Italy, living in a village in the Sabine mountains, where, in October, 1465, the first book was printed from an Italian press. It was a Latin edition of Lactantius. Six years later a press was established in Florence. In 1478, Mondino’s Anathomia was printed in Pavia. It has been estimated that before the first year of the sixteenth century, five thousand books had been printed in Italy. In those days the editions were small, 265 copies being considered one edition. An immense amount of labor was required to get out a new edition. First, the manuscripts of the ancient author had to be collected, compared and corrected, this work being done by learned men who resided in the home of the publisher. The corrections were made without the aid of dictionaries, grammars, or book-helps of any kind. The proof was read aloud to the assembled scholars and the final corrections were added. In time, Venice came to be the most noted of the Italian cities in the publishing business, owing chiefly to the family of Aldo. This family of printers became famous for finely printed Greek and Latin books, which are still called Aldine editions. Nine years after the printing of the first book in Italy, the art was practiced in England by Caxton.

Humanism in Italy began to decline toward the close of the fifteenth century. Long before this time it had degenerated into Paganism. The scholars influenced all life, customs and thought. Although the nation remained Catholic, it was such only in name. Everyone 12 bowed before the shrine of classical literature. Even in the christening of children the Christian name was sacrificed to paganism. The saints were forgotten, and the names most frequently chosen were those from heathen mythology. The polite authors described scenes, events and actions in their writings in terms which long since have been banished from good society. A spade was called by its true name. Bembo, the secretary of Leo X., could write a hymn to Saint Stephen or a monologue for Priapus with equal ease and elegance. The amours of the high and the low were flaunted in print. The nation degenerated into an intellectual and sensual state which involved even the Popes. Scholars and rich men alike vied with one another in returning to those pursuits, habits, and methods of thought which had ruled ancient Rome in her most corrupt days.

Such a condition could not exist forever. The turning-point came in 1527, when Charles the Fifth, engaging in war with Pope Clement VII., captured and sacked the city of Rome. After that event everything was changed. Not only had the scholars lost their influence, but many of them had lost their lives. Valeriano, who returned to Rome after the siege, pathetically exclaims: “Good God! when first I began to enquire for the philosophers, orators, poets and professors of Greek and Latin literature, whose names were written on my tablets, how great, how horrible a tragedy was offered to me! Of all those lettered men whom I had hoped to see, how many had perished miserably, carried off by the most cruel of all fates, overwhelmed by undeserved calamities; some dead of plague, 13 some brought to a slow end by penury in exile, others slaughtered by a foeman’s sword, others worn out by daily tortures; some, again, and these of all the most unhappy, driven by anguish to self-murder”. Such was the end of the men who made the Italian Renaissance. The Spaniards, the Inquisition, and the changed policy of the Church prevented a second revival of Humanism.

While the sack of Rome marks the end of the Humanists, the Revival in Medicine continued to grow in vigor and extent. Many of the greatest discoveries in anatomy were made, and most of the important books on this subject were written, in the middle and latter part of the sixteenth century. Italian history is rich in contradictions. While peace, ease and comfort are generally considered to be necessary to the development of science and culture, Italy offers the strange spectacle of the steady increase in medical knowledge in spite of wars and alarms. The Inquisition, which had been introduced from Spain in 1224, was given a new and horrible impetus when, in 1540, Paul III. appointed six cardinals to add to its tortures. One of them, Caraffa, became Pope Paul IV. in 1555, and four years later originated the Index Expurgatorius. Torn by civil and foreign wars, and terrorized by the Inquisition, which was not abolished until late in the eighteenth century, Italy gradually lost her commercial and intellectual supremacy. That she should have accomplished so much under such unfavorable circumstances, is now a matter of wonderment.

The origin of the Renaissance in Italy was due to many causes. The early Roman civilization was not entirely 14 blotted out by the invasion of the barbarians of the North. And in the matter of language the Italians possessed an advantage, since the transition from Latin to Italian was easier than from Latin to Spanish, French, English or German. The fertility of the country; the mildness of the climate; the division into semi-independent states; the infusion of new northern blood into the veins of the Italians; the removal of the papal court to Avignon in 1309; and the gradual rise of a powerful middle class, whose members included the devotees of the professions of law and medicine, were factors which determined that Italy, rather than France or Spain, should be the field for the Revival of Letters.

To Italy, then, belongs the glory of having been the first to free herself from the trammels of ancient scholasticism and the fetters of mediaeval theology. She abandoned the wordy dialectics and metaphysical gymnastics of the philosophers of old. In place of mortification, penance and solitary confinement in cloistered monasteries and convents, she began to have a proper conception of the dignity of man and his relation to nature.

Italy, in the time of her freedom, received the torch of learning from Greece; Italy revived its brilliancy, and, when her time of adversity and ruin arrived, she passed it on to the nations of Northern Europe. They in turn have transferred it to America, to Australia, to India, and to the uttermost parts of the earth.

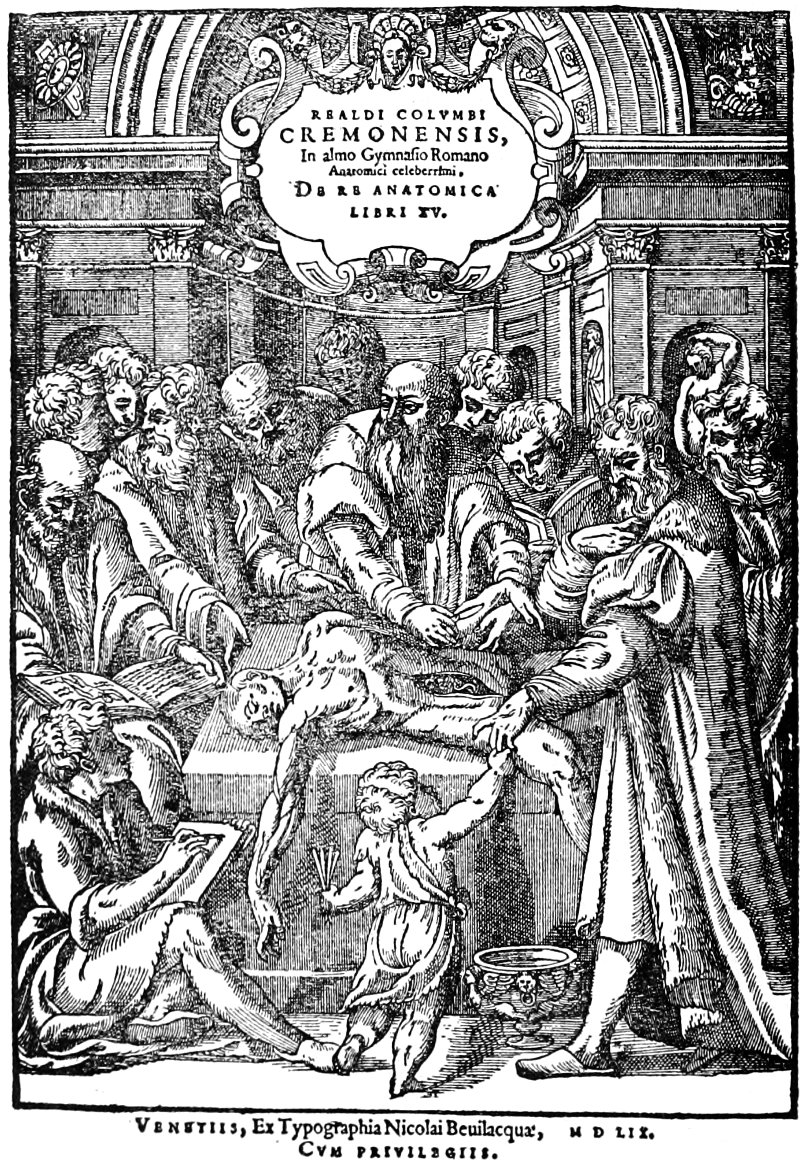

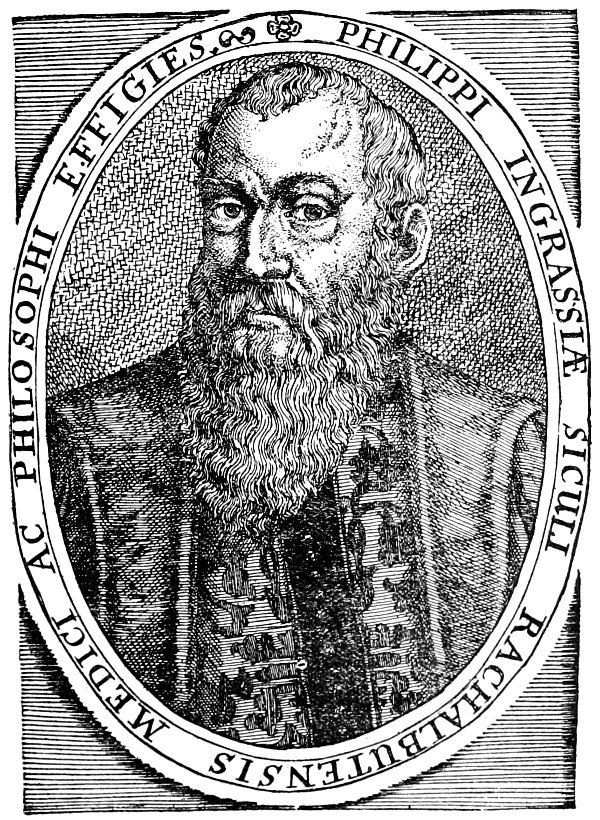

Italy in the sixteenth century was the fount from which issued a ceaseless stream of anatomical discoveries. The 15 ancient and illustrious Universities of Bologna, Pavia, Padua, Pisa and Rome, eclipsed the schools of Paris and Montpellier, of Toulouse and Salamanca; and the Italian peninsula, which, in early mediaeval times, had gloried in the skill of the physicians of Salernum, a second time became the medical centre of Europe. Vesalius and his pupil, Fallopius, taught at Padua; the ancient fame of Bologna was supported by Arantius and Varolius; Vidius, returned from establishing the anatomical school at Paris, taught at Pisa; Eustachius was at Rome, Ingrassias lectured at Naples, and the fame of the New Anatomy spread throughout the world. The Italian cities were filled with students from foreign lands. Padua had more than one thousand new students every year, salaries were paid to her one hundred professors, and medicine was looked upon as a noble profession.

While the Italians were the leaders in progress, the Germans were still lecturing on Galen and Avicenna, the English had done almost nothing, and the Collége de France was not established until 1530.

Legalized by imperial authority and sanctioned by the Church, dissection was no longer regarded as a crime. A bull by Pope Boniface VIII., issued in the year 1300, forbidding the evisceration of the dead and the boiling of their bodies to secure the bones for consecrated ground, as was done by the Crusaders, was wrongly interpreted as forbidding anatomical dissection. Two centuries later the Popes, standing in the vanguard of science, permitted dissections to be made in all the Italian medical schools, and paved the way for the Anatomical Renaissance.

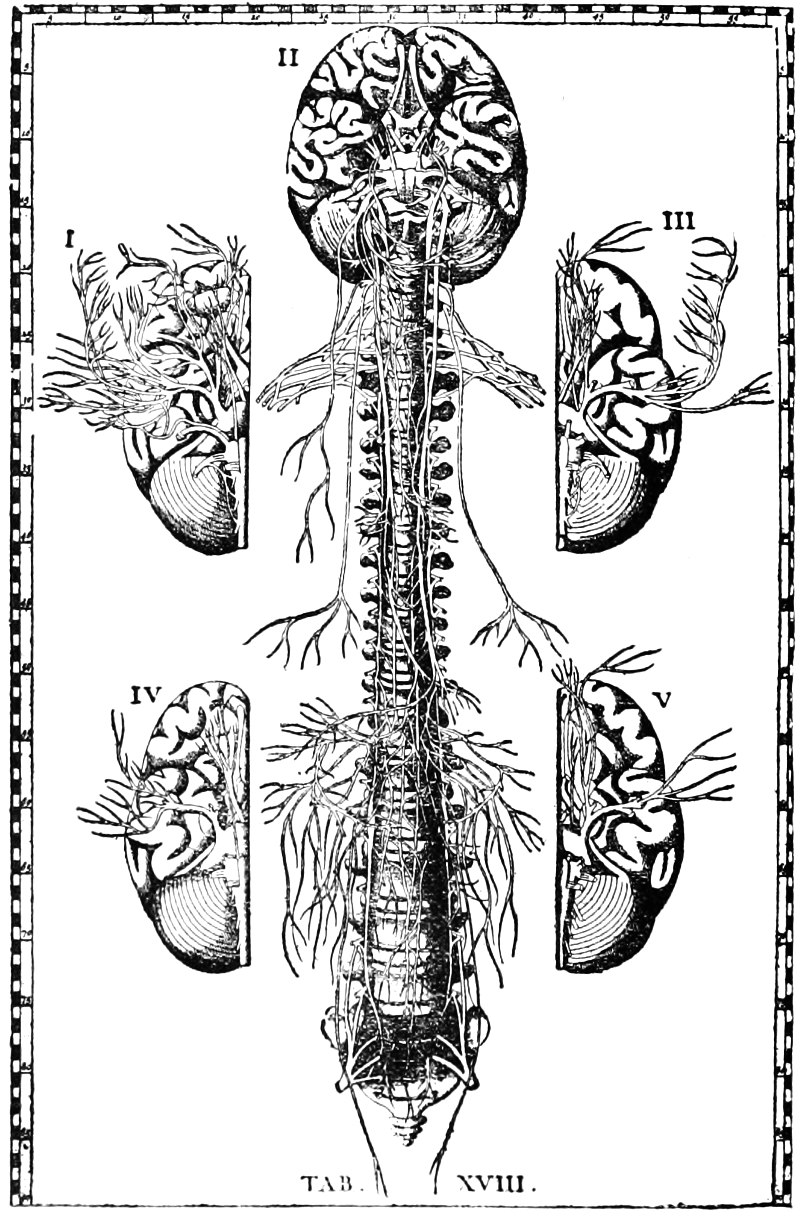

Great things were done in the sixteenth century. Under the scalpel and pen of Vesalius, anatomy was revolutionized. Surgery was guided into new paths by Ambroise Paré; and obstetrics, thanks to the labors of Eucharius Rhodion and Jacques Guillemeau, began to assume its legitimate place among the medical sciences. Servetus, visionary and argumentative, correctly described the pulmonary circulation in a theological work which was burned with its author. Eustachius, Columbus and Fallopius widened the path which had been blazed by Vesalius. Arantius, Caesalpinus and Fabricius added materially to anatomical science. The labors of all these great masters prepared the way for the greatest event occurring in the seventeenth century, namely, William Harvey’s discovery of the circulatory movement of the blood.

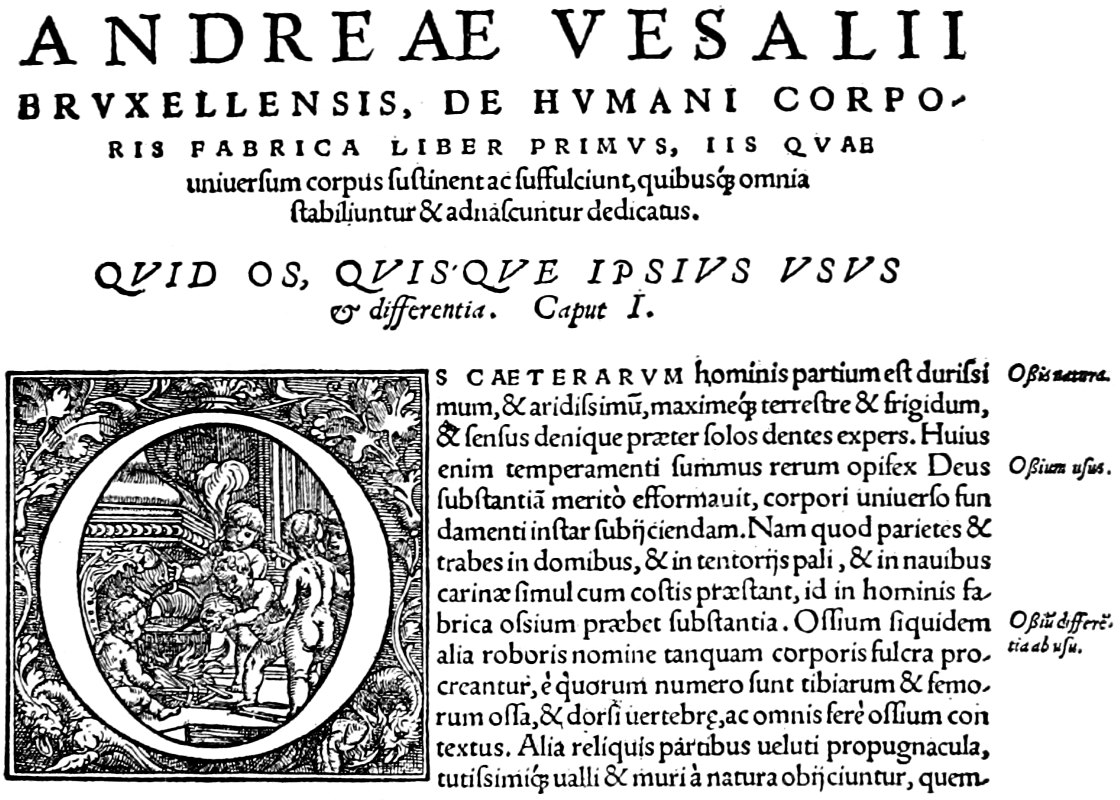

INITIAL LETTER BY VESALIUS

(From the “Fabrica”, 1543)

Egypt and Greece were the sources of the medical learning of the ancient world. Although the Egyptians and early Greeks possessed a certain amount of anatomical knowledge, which was gained in the one instance by the practice of embalming and in the other by an examination of the bones, no real progress could be made because of the laws, customs and prejudices of those ancient peoples. Thus we find the Egyptians stoning the operator who opened the abdomen in order that the body might be embalmed; and the Greeks inflicted the death penalty on those of their generals who, after a battle, neglected to bury or burn the remains of the slain.

HIPPOCRATES

In the time of Hippocrates, whose life extended approximately over the period between 460-377 B.C., Greek medicine emerged from the domination of the Asclepiadae, or priests of Aesculapius, who had followed it as an hereditary and secret art. Prior to this time in the numerous Asclepia, 18 or Temples of Aesculapius, votive offerings had been accepted, some of which were of anatomical interest. Thus the Temple at Athens received a silver heart and gold eyes. Pausanias states that Hippocrates gave to the Temple of Apollo, at Delphos, a skeleton which was made of brass. Possibly, as Moehsen[2] believes, this was a metallic figure representing a man who was much emaciated by the ravages of disease. In the Hippocratic writings, some of which are undoubtedly spurious, are few references to the opening of a dead body; and these examinations concern the investigation of the thorax and abdomen in order to determine the cause of death. While the Greek physicians knew little of the human muscles, of the nervous system and of the organs of sense, they were well acquainted with the anatomy of the bones. Their dissections were held upon the lower animals.

It is impossible to determine whether or not the Greek physicians of the Hippocratic period dissected the human body. “It has long been a matter of debate”, says John Bell[3], “whether the ancients were, or were not, acquainted with anatomy, and the subject, with its various bearings, has been much and keenly agitated by the learned. If anatomy had been much known to the ancients, their knowledge would not have remained a subject of speculation. We should have had evidence of it in their works; but, on the contrary, we find Hippocrates spending his time in idle prognostics, and dissecting apes, to discover the seat of the bile.”

Galen[4] states that the ancient physicians did not write works on anatomy; that such treatises were at that time unnecessary, because the Asclepiadae—to which family Hippocrates belonged—secretly instructed their young men in this subject; and that opportunities were given for such study in the temples of Aesculapius.

ARISTOTLE

The first systematic dissections seem to have been made by the Pythagorean philosopher Alcmaeon, who lived in the sixth century B. C., but it is uncertain whether he dissected brutes or men. The cochlea of the ear and the amnios of the foetus were named by Empedocles of Agrigentum, in the fifth century B. C. The nerves were first distinguished from the tendons by Aristotle, (384-322 B. C.), the most celebrated zoötomist of antiquity, who has been called the Father of Comparative Anatomy. For twenty centuries his views of natural phenomena were held in high esteem.

For a long period the early inhabitants of Rome were practically without physicians. During severe epidemics they had recourse to oracles, to the health deities of the Greeks, and to their native gods. As early as the fifth century B. C., during a pestilence, a temple was erected to Apollo as Healer. The worship of Aesculapius was 20 introduced into Rome in the year 291 B. C. Livy relates that the god of medicine in the guise of a serpent was transported from Epidaurus, in Greece, to the Isle of the Tiber where a temple was built in his honor.

The Romans, like the Greeks, were accustomed to leave votive offerings, or donaria, in their temples. Such gifts included surgical instruments, pharmaceutical appliances, painted tablets representing miraculous cures, and great numbers of images of various parts of the human frame shaped in metal, stone or terra-cotta. Among the remains of Roman anatomical art is the marble figure which was unearthed in the villa of Antonius Musa, the favorite physician of the Emperor Augustus. It is a human torso; the front of the chest and abdomen has been removed so as to expose the viscera. The heart is placed vertically in the middle of the thorax, thus corresponding to the position of this organ as described by Galen who made his dissections on apes. It is a human thorax with simian contents. The figure is supposed to have been constructed for the purposes of a teacher of anatomy.

ALEXANDER THE GREAT

It was in the famous Alexandrian University that human anatomy was first studied systematically and legally.

Alexander the Great, after the fall of Tyre (332 B. C.) and the siege of Gaza, ordered his fleet to sail up the Nile 21 as far as Memphis while he proceeded overland with the army. It was probably on this march, while viewing the pyramids and other marvelous works of the ancient Egyptians, that he conceived the grand idea of founding a city upon the banks of the Nile, which should be a model of architectural beauty, a centre of intellectual life and a lasting monument of his own greatness and magnificence. The foundation of Alexandria was laid by the warrior whose name it bears; but the credit of instituting the Library belongs to one of his lieutenants, Ptolemy Soter.

PTOLEMY SOTER

The new city which for centuries was the intellectual and commercial storehouse of Europe, Africa and India, was of oblong form. Lake Mareotis washed its walls on the south, while the Mediterranean bathed its ramparts on the north. Provided with broad streets, it was adorned with magnificent houses, temples and public buildings. At the centre of the city was the Mausoleum in which was deposited the body of Alexander, embalmed after the manner of the Egyptians. Alexandria was divided into three parts: the Regio Judaeorum or Jews’ quarter, in the northwest; the Rhacotis, or Egyptian section, on the west, containing the Serapeum with a large part of the Library; and on the north, the Bruchaeum, or Greek portion, 22 containing the greater part of the Library, the Museum, the Temple of the Caesars and the Court of Justice. The population was cosmopolitan in character; the statues of the Greek gods stood by the side of those of Osiris and of Isis; the Jews forgot their language and spoke Greek; and under the Ptolemies, who were of Greek descent, Alexandria became a centre of intellectual life and culture.

To the medical historian the most interesting feature of Alexandria was the Museum or University. Here were assembled the intellectual giants of the earth: Archimedes and Hero, the philosophers; Apelles, the painter; Hipparchus and Ptolemy, the astronomers; Euclid, the geometer; Eratosthenes and Strabo, the geographers; Manetho, the historian; Aristophanes, the rhetorician; Theocritus and Callimichus, the poets; and Erasistratus and Herophilus, the anatomists, all of whom labored in quiet upon the peaceful banks of the Nile. The early Christian church drew from “the divine school at Alexandria” such eminent teachers as Origen and Athanasius. Here were a chemical laboratory, a botanical and zoölogical garden, an astronomical observatory, a great library, and a room for the dissection of the dead.

In the Alexandrian school of medicine Erasistratus and Herophilus taught the science of organization from actual dissections. The generosity of the Ptolemies not only furnished them with an abundance of dead material, but condemned malefactors were used for human vivisection. Celsus[5] states that the Alexandrian anatomists obtained 23 criminals, “for dissection alive, and contemplated, even while they breathed, those parts which nature had before concealed.”

Herophilus made many anatomical discoveries. He traced the delicate arachnoid membrane into the ventricles of the brain, which he held to be the seat of the soul; and first described that junction of the six cerebral sinuses opposite the occipital protuberance, which to this day is called the torcular Herophili. He saw the lacteals, but knew not their use, and regarded the nerves as organs of sensation arising from the brain; he described the different tunics of the eye, giving them names which are still retained; and first named the duodenum and discovered the epididymis. He attributed the pulsation of arteries to the action of the heart; the paralysis of muscles to an affection of the nerves; and first named the furrow in the fourth cerebral ventricle, calling it calamus scriptorius.

Erasistratus gave names to the auricles of the heart; declared that the veins were blood-vessels; and the arteries, from being found empty after death, were air-vessels. He believed that the purpose of respiration was to fill the arteries with air; the air distended the arteries, made them beat, and in this manner the pulse was produced. When once the air gained entrance to the left ventricle, it became the vital spirits. The function of the veins was to carry blood to the extremities. He is said to have had a vague idea of the division of nerves into nerves of sensation and of motion; to the former he assigned an origin in the membranes of the brain, while the latter proceeded from the cerebral substance itself. He recognized the 24 use of the trachea as the tube which conveys air to the lungs. A catheter, the first invented, which was figured in ancient surgical works, bore the name of the catheter of Erasistratus. He gravely tells us, as the result of his anatomical studies, that the soul is located in the membranes of the brain.

The practice of human dissection did not long exist in the city of its origin, and after the second century was unknown. Then science underwent a retrogression; observations and experiments were replaced by useless discussions and subtle theories. The decline of the Alexandrian University was due to a series of disasters which began with the Roman domination and reached their climax with the capture of the city by the Arabs.

GALEN

Claudius Galenus, the celebrated Roman physician whose writings were for centuries accepted as authority and whose reputation was second only to that of Hippocrates, was obliged to base his anatomical treatises largely upon the dissection of the lower animals. He advised his pupils to visit Alexandria, where he had studied, in order that they might examine the human skeleton. He complained that the physicians of his time—in the reign of Marcus Aurelius—had entirely neglected anatomical knowledge and had degenerated into mere sophists. He appreciated the importance of anatomy, particularly to a 25 surgeon who is called upon to treat wounds and injuries. Hence he has endeavored in the four books, De Anatomicis Administrationibus, to cover this part of anatomy as exhaustively as possible.

Galen’s voluminous writings form a precious monument of ancient medicine. The works of the Alexandrian anatomists having been destroyed, we know of their labors chiefly from what Galen has said of them. His treatises show a remarkable familiarity with practical anatomy, although his dissections were made upon the lower animals. Galen’s knowledge of osteology was extensive. He described the bones of the skull, the cranial sutures, and the essential features of the malar, maxillary, ethmoid and sphenoid bones. He divided the vertebrae into cervical, dorsal and lumbar classes. He knew that both arteries and veins were blood-carrying vessels; he described the valves of the heart, and recognized this organ as the source of pulsation. He erroneously taught that the interventricular septum presents foramina through which the two kinds of blood become mixed.

In myology Galen made numerous advances. “Previous to his investigations”, says Fisher[6] “much confusion existed as to what constituted a single muscle; he adopted the general rule of considering each bundle of fibers that terminates in an independent tendon to be one muscle. He was the first to describe and give names to the platysma myoides, the sterno- and thyro-hyoides, and the popliteal. He described the six muscles of the eye, two muscles of the eyelids, and four pairs of muscles of the 26 lower jaw—the temporal to raise, the masseter to draw to one side, and two depressors, corresponding to the digastric and internal pterygoid muscles. He described also the brachialis anticus, the biceps flexor cubiti, the sphincter and levator ani, and the straight and oblique muscles of the abdomen. In short, he described the greater portion of the muscles of the body, his treatise differing chiefly from a modern one in the minute account of these organs and in the omission of some of the smaller muscles.” Galen studied the brain and named the corpus callosum, the septum lucidum, the corpora quadrigemina and the fornix; but erroneously stated that the nerves of sensation arise from the brain, and those of motion from the spinal cord. He denied the decussation of the optic nerves. He described the pneumogastric and sympathetic nerves; seven pairs of cerebral and thirty pairs of spinal nerves; and claimed the discovery of the ganglia of the nervous system. He located the seat of the soul in the brain, which also is the source of the rational mind; the heart to him was the source of courage and of anger, and the liver was the seat of desire. Many of Galen’s anatomical statements show that he derived his knowledge from comparative dissections.

The Galenic era was followed by that long period of ignorance, of slumber and of inaction which is justly known as the Dark Ages. While a few Greek and Arab writers, who came after Galen, contributed to the literature of medicine and surgery, they did nothing for anatomy. After the end of the fifth century even the works of Galen were forgotten. At this period, when medicine was chiefly in 27 the hands of the Jews, the Arabs and the bigoted clergy, nothing was done for science or for art. The whole influence of Christianity was exerted against the schools of philosophy. Illustrious apostles of the Church pronounced anathemas against the reading of the ancient classics;[7] and eminent ecclesiastics regarded disease as a divine penalty or as an invaluable aid to saintly advancement. Art and anatomy were practically forgotten. Their Renaissance occurred almost simultaneously.

During the period from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries the school of Salernum was for medicine what Bologna became for law and Paris for philosophy. Here, for eight hundred years, medicine was taught to thousands of students and the impress of the profession was so potent that the city called itself Civitas Hippocratica, and thus its seals were stamped. Here medical diplomas were first issued to waiting students who took a sacred oath to serve the poor without pay. Here with a book in his hand, a ring on his finger and a laurel wreath on his head, the candidate was kissed by each professor and was told to start upon his way. Here women were professors and vied with men in spreading the doctrines of our art.

For a period of several hundred years anatomy was taught at Salernum from dissections made upon pigs. Copho, one of the Salernian professors of the early part of the twelfth century, wrote a treatise, Anatomia Porci, 28 which gives minute directions regarding the manner in which the animal is to be dissected. Another anatomical work of later date, written by a member of the Salernian faculty, is entitled Demonstratio Anatomica; it also deals only with comparative anatomy. In the thirteenth century (A. D. 1231) Frederick II., Emperor of Germany and King of the Two Sicilies, and the author of a treatise which contained a complete anatomy of the falcon, decreed that a human body should be anatomized at Salernum at least once in five years. Physicians and surgeons of the kingdom were required to be present at the dissection. So far as is known, no record has been kept of these demonstrations. Creditable as was this anatomic decree, the great Hohenstaufen in other respects was not free from the errors of his age. A firm believer in Medicina Astrologica, he did not decide upon any undertaking until the stars had been consulted.

It was not alone at Salernum that dissection was legalized in the thirteenth century. A document of the year 1308, of the Maggiore Consiglio of Venice, shows that a medical college located in that city was authorized to dissect a body once a year. This, and other isolated examples, indicate that the time was approaching when anatomy should be taught from human dissections. The credit of reinaugurating the teaching of this useful department of science belongs to Mondino dei Luzzi of Bologna.

In the year 1315, in the old Italian city of Bologna, an event occurred which marks an important epoch in the history of medicine. A wondering crowd of medical students witnessed the dissection of a human cadaver—one of the few procedures of the kind that had occurred since the fall of the Alexandrian University. Acting under royal authority Mondino, a man far in advance of the age, placed the body of a female upon a table where for many centuries before only the cadavera of apes, of swine and of dogs had been studied.

Mondino, known also as Mundinus, Mundini, Raimondino, or Mondino dei Luzzi, was descended from a prominent Italian family. Little is known of his life. The year of his birth is disputed; probably 1276 was near the time. He was graduated in medicine in 1290 and in 1306 he became a professor in the University of Bologna, holding his chair with credit until his death in 1326. Like that of the illustrious Homer, Mondino’s nativity has been claimed by several rival cities. Guy de Chauliac, writing in 1363, states that Mondino was a Bolognese: Mundinus Bononiensis is Chauliac’s expression.

Mondino’s method of teaching anatomy is known from Chauliac’s testimony:—“Mundinus of Bologna, wrote on anatomy, and my master, Bertruccius, demonstrated it 30 many times in this manner:—The body having been placed on a table, he would make from it four readings; in the first the digestive organs were treated, because more prone to rapid decomposition; in the second, the organs of respiration; in the third, the organs of circulation; in the fourth the extremities were treated.” The innovation so auspiciously begun was not continued, and after the death of Mondino human dissections were made only at long intervals. The few instances in which, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the ecclesiastical and civil authorities granted the right to make dissections only prove the contention, that the practical study of human anatomy did not gain recognition until the sixteenth century.

When Mondino began his dissections the epoch of Saracen learning had ended, but the influence of Arab medicine exerted by the writings of Albucasis, Avicenna and Rhazes had not declined. The Arabian physicians had accomplished little for anatomy. In this line the influence of Galen was still potent, and was rarely questioned until the publication of the Fabrica of Vesalius in 1543. During a long period the little treatise of Mondino held full sway in the mediaeval schools. Medicine was taught in the University of Bologna, which as early as the twelfth century was celebrated for its departments of literature and of law. These studies were free of the difficulties which beset medicine. The prejudice against dissection was so great that for nearly a century after his death few men dared to repeat the acts of Mondino.

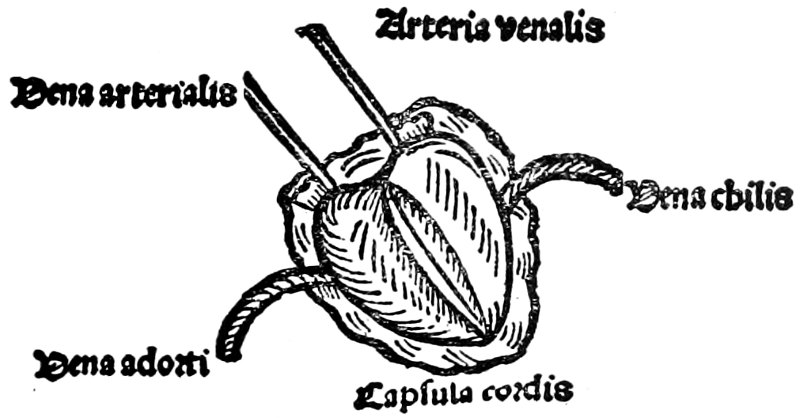

In 1316 Mondino issued his book which remained in manuscript form for more than one hundred and fifty 31 years, the first printed edition bearing the date 1478. Small and imperfect as it was, it marks an era in the history of science. By command of the authorities this book was read in all the Italian Universities. The work of Mondino contained no new facts; it was compiled largely from the writings of Galen and of Avicenna. The descriptions, to use the words of Turner, “are corrupted by the barbarous leaven of the Arabian schools, and his Latin is defaced by the exotic nomenclature of Ibn-Sina and Al-Rasi”. Mondino divided the body into three cavities, of which the upper contains the animal members, the lower the natural members, and the middle the spiritual members. Many of his names are borrowed from the Arab writers. Thus, he calls the peritoneum siphac, the omentum zyrbi, and the mesentery eucharus. His description of the heart is much nearer accuracy than would be expected. He resorted to vivisection, and tells us that when the recurrent nerves of the larynx are cut the animal’s voice is lost. In his book we find the rudiments of phrenology. He states that the brain is divided into compartments, each of which holds one of the faculties of the intellect.

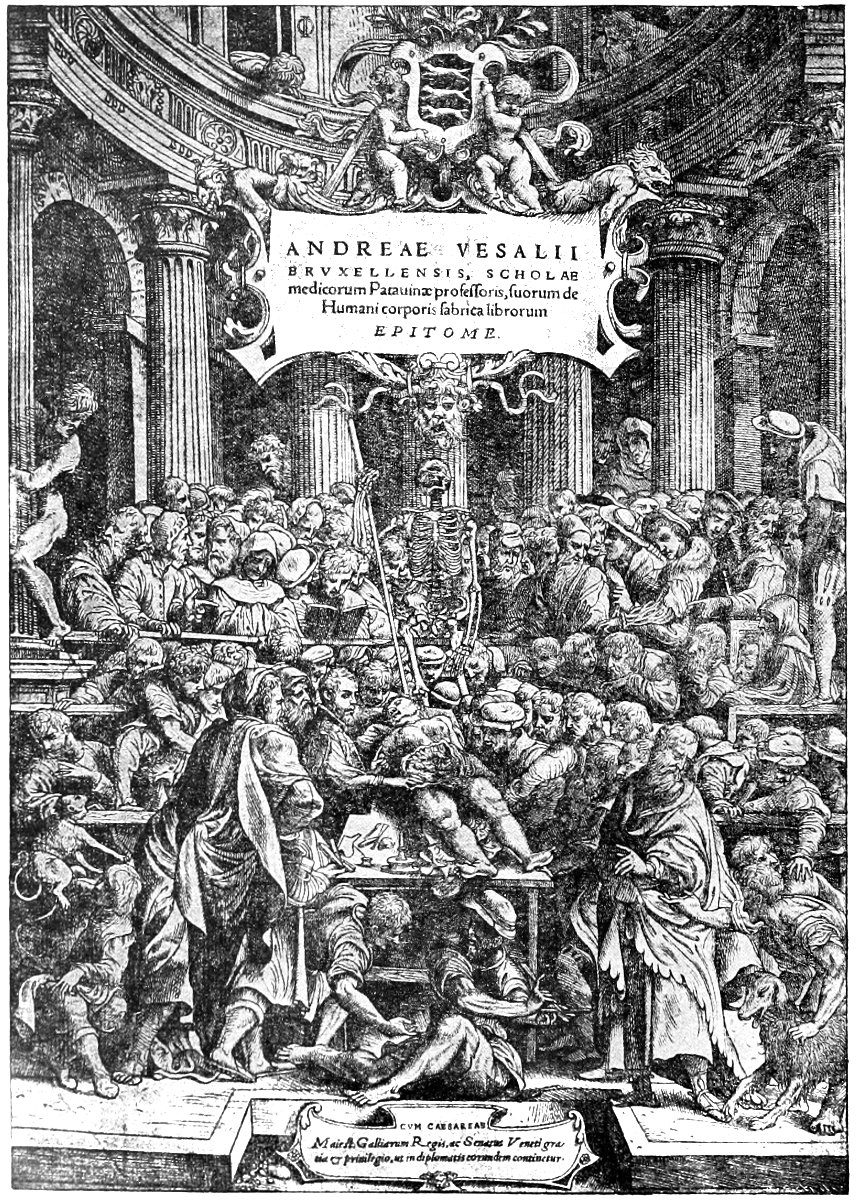

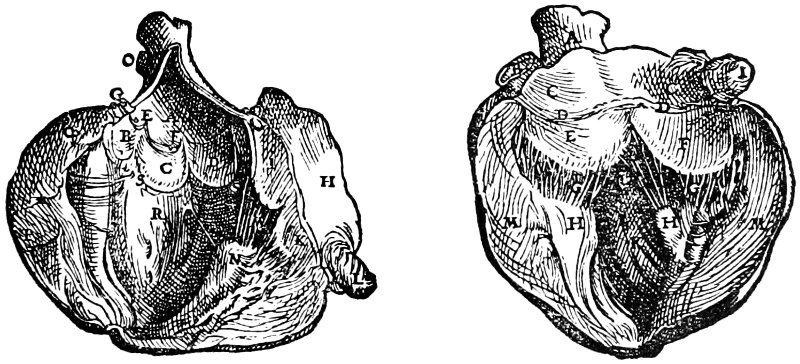

MONDINO’S DIAGRAM OF THE HEART, 1513

Mondino did not himself make the dissections which are credited to him. According to an ancient custom which lasted until the time of Vesalius, the actual cutting was done by a barber who wielded a knife as large as a cleaver. The professor of anatomy sat upon an elevated seat and discoursed concerning the parts, while a demonstrator, who also did not soil his fingers, pointed to the different structures with a staff. Originally Mondino’s book contained no figures; when the art of wood engraving was introduced in the latter part of the fifteenth century, a few rude woodcuts appeared which represent Mondino and his method of teaching. In the Fasciculus Medicinae of Joannes de Ketham, published at Venice in 1493, Mondino’s book is printed with an illustration showing a demonstration in anatomy.

According to Mondino the heart is placed in the centre of the body. The valves he considers “wonderful works of nature”. He describes a right, left and middle ventricle. The right ventricle has thinner walls than the left, because it contains blood; the left one contains the vital spirit, which passes through the arteries to the body; and the middle ventricle consists of many small cavities “broader on the right side than on the left, to the end that the blood, which comes to the left ventricle from the right, be refined, because its refinement is the preparation for the generation of vital spirit, which should be continually formed”. Mondino describes five bones of the head, separated by three sutures—coronal, sagittal and occipital. The brain has two membranes: dura and pia. There are three cerebral ventricles—anterior, posterior and middle—and in these he locates the various intellectual qualities. He describes the cerebral nerves: olfactory, optic, motor oculi, facial, vagus, trigeminal, auditory and hypoglossal. He calls the innominate bone os femoris: the femur, canna coxae; the humerus, os adjutori; while the bones of both leg and forearm are named focilia major and minus.

ANATOMICAL DEMONSTRATION IN 1493

(Joannes de Ketham)

TITLE-PAGE OF MONDINO’S ANATOMY

BY MELERSTAT

(Printed before 1500)

Like many anatomists who succeeded him, Mondino mingled surgical ideas with his anatomical statements. A break in the siphac causes hernia and a swelling in the mirach. He treated ascites by puncture and evacuation, making a valve-like opening. Wounds of the large intestines must be sutured; if the wound be in the small intestines he advises that “you should have large ants, and, making them bite the conjoined lips of the wound, decapitate them instantly, 35 and continue until the lips remain in apposition and then reduce the gut as before”. He gives an explanation of the length and convolution of the intestines; “for if it were not convoluted the animals would have to be continuously ingesting food and continuously defecating, which would impede engagement in the higher occupations”. Digestion is aided by black bile from the spleen and by red bile from the liver. The kidneys he regards as glands in which urine is extracted from the blood. The renal veins expand and form a fine membrane like a sieve through which the urine is filtered but blood cannot pass. He mentions renal calculi: if small they pass through the ureter; if large they are incurable except by incision, and this is to be avoided. The uterus and breasts are connected by veins, hence the sympathy between these organs. Inguinal hernia is to be operated upon; the spermatic cord and testicle may or may not be dissected out, or the hernia may be treated by the application of a caustic. An incision in the neck of the bladder will heal, because this part is muscular; but a cut in the body of the organ will not heal. He describes the operation for stone:—The patient being in proper position, the stone is conducted to the neck of the bladder by the finger in the rectum; an incision is made and the stone is pulled out with an instrument called trajectorium.

Mondino’s book passed through not less than twenty-three editions between the years 1478-1580. The only manuscript extant is in the National Library at Paris.

The first printed edition of the Anathomia Mundini, Pavia, 1478, is a folio of twenty-two leaves. The Strassburg 36 edition, 1513, is a small octavo volume of forty leaves. It contains a diagram of the heart and an astrological figure, a cadaver with the thorax and abdomen opened, surrounded by the signs of the zodiac. Such was the volume which for more than two hundred years was supposed to contain all that was to be said of human anatomy!

COLOPHON OF THE ANATOMY OF MONDINO, 1513

So numerous are the abbreviations in Mondino’s book, so barbarous is his style, that the making of a translation is a difficult task. His reasons for writing are these:—“A work upon any science or art—as saith Galen—is issued for three reasons; First, that one may help his friends. Second, that he may exercise his best mental powers. Third, that he may be saved from the oblivion incident to old age”.

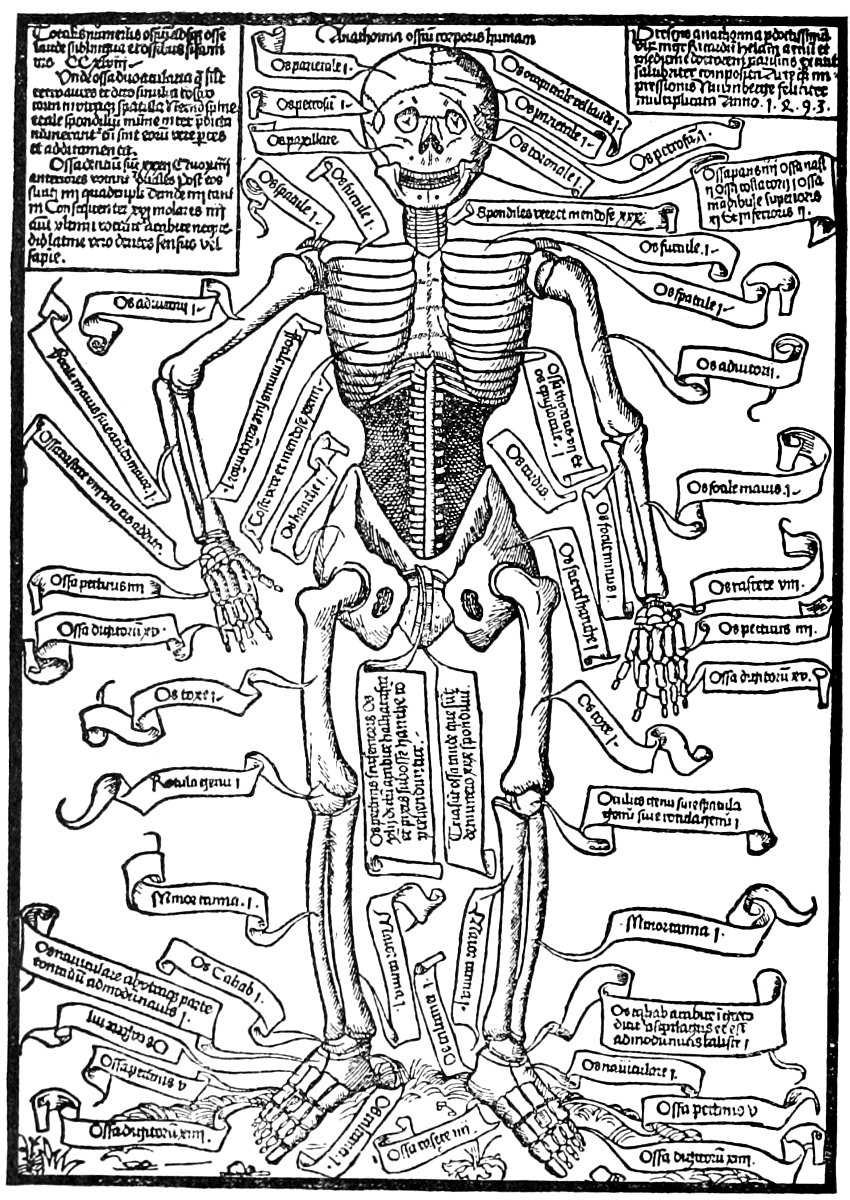

For two hundred years anatomists used Mondino’s book as a text for their lectures and for the same period anatomical writers did little more than comment upon this treatise. The new art of wood engraving was turned to anatomical use and crude illustrations of the various parts of the body were put into circulation. Some of these pictures were in the form of Fliegende Blätter, or flying leaves. A set of anatomical plates of this type was issued by a certain Ricardus Hela, a physician of Paris, as early as the year 1493. They were printed at Nuremberg. Their character may be judged by the accompanying illustration of the osseous system.

One of Mondino’s commentators was Gabriel de Zerbi (1468-1505), of Verona, who taught medicine, logic and philosophy in the Universities of Padua, Bologna and Rome. His book, Anatomia Corporis Humani, appeared at Venice in 1502. Zerbi imitated Mondino in style, abbreviations and language. The work, however, contains some original observations regarding the Fallopian tubes, the puncta lachrymalia and the lachrymal gland. From the fact that Zerbi describes two lachrymal glands in each orbit, it is known that many of his dissections were made upon brutes.

ANATOMICAL PLATE BY RICARDUS HELA, 1493

Zerbi’s reputation, which extended to all parts of Europe, was the cause of his death. The Venetians received from Constantinople the request for a skillful physician who should treat one of the principal Seigniors of Turkey. The Republic turned its eyes to Zerbi who went to Constantinople, apparently cured the Seignior, and, loaded with presents, started on the return voyage for Venice, Unfortunately the patient suddenly died after a debauch. The infuriated Turks overtook the ship on which Zerbi and his son were passengers and carried them back to Constantinople, where both the anatomist and his son were quartered alive.

PEYLIGK’S DIAGRAM OF THE HEART, 1499

Among the German anatomists of this period was John Peyligk, a Leipsic jurist, whose Philosophiae Naturalis Compendium, printed at Leipsic in 1499, contains crude anatomical illustrations.

Far more important was the Antropologium of Magnus Hundt (1449-1519), of Magdeburg, which appeared at 40 Leipsic in 1501. It contains four large and several small woodcuts which are among the earliest of anatomical illustrations. One of these shows the trachea on the right side of the neck, passing downward to the lungs; on the left side the oesophagus is represented. In the thorax are seen the lungs and the heart, the latter resembling the figure of this organ as presented on old playing cards. The pericardium has been opened, and the stomach and intestines are crudely figured. The diaphragm is absent.

ANATOMICAL FIGURE FROM MAGNUS HUNDT, 1501

Early in the sixteenth century a Holland physician, Laurentius Phryesen (Phries, Friesen), residing in the German city of Colmar and later at Metz, wrote a popular 41 book on medicine, Spiegel der Artzny, which was published at Strassburg in 1518. It contains two anatomical illustrations cut in wood, dated 1517, and supposedly made after the drawings of Waechtlin, a pupil of the Elder Holbein. These pictures tell their own story; they show a marked improvement over the figures which Hundt published in 1501. The other anatomical plate in Phryesen’s book is devoted to the skeleton.

ANATOMICAL FIGURE FROM LAURENTIUS PHRYESEN, 1518

The Italian physician Alexander Achillinus (1463-1525), professor of philosophy and medicine in Bologna, is deserving of mention for his anatomical knowledge. Zealously devoted to the Arab medical authors, Achillinus made numerous discoveries which are set forth in his general anatomy, De Humani Corporis Anatomica, Venice, 1516; and in a commentary upon Mondino’s book, In Mundini Anatomiam Annotationes, Venice, 1522. He discovered the duct of the sublingual gland, usually credited to Wharton; two of the auditory ossicles, the malleus and incus; the labyrinth; the vermiform appendix; the caecum and ileo-caecal valve; and the patheticus nerve. Portal credits him with a better knowledge of the bones and of the brain than was possessed by his predecessors.

ALEXANDER ACHILLINUS

DISSECTION BY BERENGARIO, 1535

Giacomo Berengario, Jacobus Berengarius Carpensis, also known as Carpus, was born in the small town of Carpi, in the Duchy of Modena, in the year 1470. His father, who was a surgeon, directed his studies, and for a time he was placed under the instruction of the learned Aldus Manutius. Graduating in medicine from the University of Bologna, Berengario became noted for his skill in surgery and anatomy. He taught these branches in Pavia, and was a member of the Bologna faculty from 1502 to 1527. Then he practiced for a time in Rome, where he amassed a fortune by the treatment of the victims of syphilis. The last twenty years of his life were spent in Ferrara, where he died in 1550. Berengario was one of the restorers of anatomy. His first dissection is said to have been made in the house of Albert Pion, Seigneur de Carpi. This demonstration was given publicly 44 upon the body of a pig. Soon the anatomist turned his attention to human subjects, of which it is said that more than a hundred passed beneath his scalpel.

Berengario’s later years are said by Brambilla to have been made miserable by the machinations of the agents of the Inquisition, who objected to some of his opinions regarding the organs of generation. He was unjustly accused of dissecting living men—an accusation which arose from his statement that the surgeon should observe the anatomy of the living body whenever it was opened by wounds or accidents.

SKELETON BY BERENGARIO, 1523

Berengario determined to improve Mondino’s book by making corrections in the text, and by adding suitable illustrations. No illustrations were to be found in the early editions of Mondino, and those which were added by later editors of the work were untrue to nature. To Berengario must be given the credit of furnishing some of the first anatomical illustrations that were published, and that were made from actual human dissections. These appeared in his “Commentaries of Carpus upon the Anatomy of Mundinus”, (Carpi Commentaria super 45 Anatomia Mundini), which was published at Bologna in 1521. The volume contains twenty-one plates which were cut in wood. They have been credited to the celebrated artist, Hugo da Carpi. While the drawing is somewhat coarse, the illustrations are true to nature and show a distinct advance over preceding pictures of this class. Berengario states that his plates will be of value not only to physicians and surgeons but also to artists (et istae figurae etiam juvant pictores in lineandis membris). Some of his figures are schematic; for example, those showing the abdominal muscles. So much better are his illustrations than those of his predecessors that it may fairly be claimed that Berengario was the first author to produce an illustrated anatomy.

MUSCLES BY BERENGARIO, 1521

Berengario also wrote a “Short Introduction to the Anatomy of the Human Body”, Isagogae Breves in Anatomiam Humani Corporis; and a work on Fracture of the Skull.

He was the first anatomist who described the basilar part of the occipital bone, the sphenoidal sinus and the tympanic membrane. Meryon[8] credits him with the 46 “first correct description of the great omentum (gastrocolic) and transverse mesocolon; of the caecal appendix vermiformis, of the valvulae conniventes of the intestines; of the relative proportions of the thorax and pelvis in man and woman; of the flexor-brevis-pollicis; of the vesiculae seminales; of the separate cartilages of the larynx; of the membranous pellicle in front of the retina (attributed to Albinus); of the tricuspid valve, between the right auricle and ventricle of the heart; of the semilunar valves at the commencement of the pulmonary artery; of the inosculation between the epigastric and mammary arteries, and an imperfect account of the cochlea of the ear”. He was the first of the mediaeval anatomists to deviate from the Galenic teaching in regard to the structure of the heart. He diplomatically states that in the human subject the foramina in the cardiac septum are seen only with great difficulty (sed in homine cum maxima difficultate videnter).

MUSCLES BY BERENGARIO, 1521

John Dryander, a German physician, whose true name 47 was Eichmann, called himself Dryander in accordance with the custom of adopting names derived from the Latin or Greek languages. He was born about the year 1500 in the Wetterau in Hesse. After obtaining proficiency in mathematics and astronomy, he went to Paris where he studied medicine for several years. Returning to Germany, he engaged in the study of practical anatomy and became a professor in Marburg, in which city he died in the year 1560. He is said to have conducted the first dissections that were made in Marburg, where he taught anatomy for twenty-four years, or from 1536 to 1560.

DRYANDER

Dryander, although he was a partisan of Mondino and da Carpi, and was a fierce and sometimes an unfair opponent of Vesalius, deserves to be regarded as one of the restorers of anatomy. He made several observations upon the distinction between the cortical and the medullary portions of the brain; and was one of the earliest practical anatomists of the sixteenth century to furnish anatomical illustrations. He made important astronomical observations and was the inventor of several useful instruments. He was the author of three medical works of 48 which two were upon anatomy. His Anatomia Mundini, which was published at Marburg in 1541, contains forty-six plates, many of which have been copied from Berengario’s work.

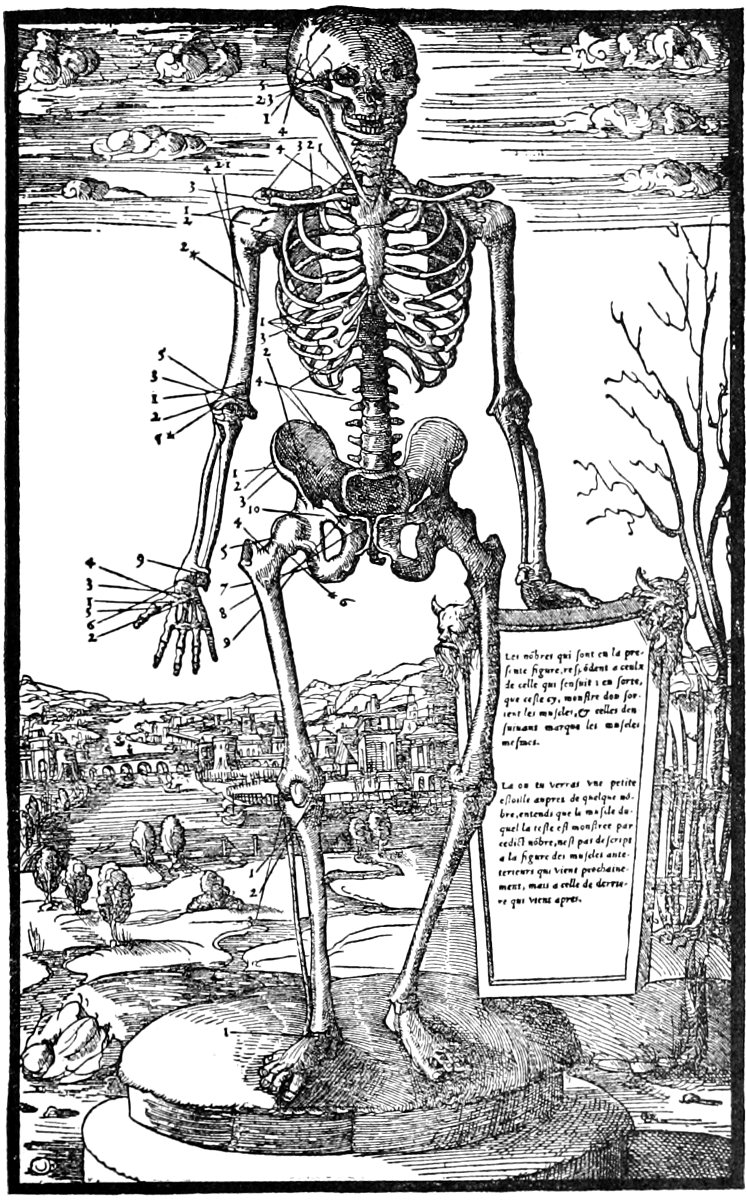

ANATOMICAL FIGURE BY ESTIENNE, 1545

SKELETON BY ESTIENNE, 1545

(Reduced one-half)

Charles Estienne, better known by the name of Carolus Stephanus, was a French anatomist whose work is worthy of remembrance. Born in the early part of the sixteenth century, he was given an excellent education. He belonged to a noted Huguenot family of scholars and printers who have made the Estienne name famous. Robert Estienne, the brother of Charles, became the victim of religious persecution; he was obliged to flee to save his life, and for a time the publishing business was conducted by Charles Estienne. The latter also suffered for his faith; he was thrown into a dungeon, where he died in the year 1564. Charles Estienne wrote numerous books on literature, history, forestry and botany. His anatomical treatise, De Dissectione Partium Corporis Humani, appeared at Paris in 1545 with sixty-two full page plates which combine anatomical clearness, beauty of form, and artistic representation. A French translation of Estienne’s Anatomy was published in 1546. This work was printed as far as the middle of the third book as early as the year 1539: some of the plates are dated as early as 1530. The illustrations have been excellently cut in wood; many of them show the entire body, with much ornamentation, so that the proper anatomical part seems small and irrelevant. Some of the plates show the subject in picturesque and even loathsome attitudes. The text of this work is especially valuable for the history of anatomical discovery. Although he was an ardent Galenist, Estienne made numerous original observations in anatomy. He described the synovial glands, a discovery which has been credited to Clopton Havers. Estienne was the first anatomist to discover the canal in the spinal cord; he described the capsule of the liver, a tissue which bears 51 Glisson’s name; and differentiated the eight pair from the sympathetic nerves. He was the first anatomist to see and describe the valves in the veins, which he called apophyses venarum— discovery which has been claimed for Jacobus Sylvius, Cannanus, Amatus and Fabricius.

The question of priority in the discovery of the valves of the veins gave rise to much controversy. It is reasonable to assume that these structures were noticed independently by all of the anatomists whose names are mentioned above.

SKULL BY DRYANDER, 1541

Andreas Vesalius, or Wesalius as the family name was inscribed prior to the year 1537, was born in Brussels on the last day of the year 1514. From astrological observations made by Jerome Cardan we learn that this event occurred about six o’clock in the morning, and under favorable stellar auspices. The placenta and caul, to which popular belief ascribed remarkable powers, were carefully preserved by the mother.

The Vesalius family originally was named Witing, (Witting, Wytinck, Wytings, according to various authorities) and adopted the name Wesalius from the town of Wesel, (Wesele, Vesel), in the Duchy of Cleves, which the family claimed as their native place. The three weasels (Flemish—“Wesel”), found in the Vesalian coat of arms, testify to this origin.

It may be said with truth that medical learning ran in the blood of the Vesalius family. Andreas’s great-great-grandfather, Peter Wesalius, wrote a treatise on some of the works of Avicenna and at great cost restored the manuscripts of several medical authors. Peter’s son, John Wesalius, held the responsible position of physician to Mary of Burgundy, the first wife of Maximilian the First; in his old age John taught medicine in the University of Louvain. From that time the Vesalius family was closely 53 associated with the Austro-Burgundian dynasty. Eberhard, son of John Wesalius, served as physician to Mary of Burgundy; he died before attaining his thirty-sixth year, and was long survived by his father. Eberhard, who was the grandfather of Andreas, wrote commentaries upon the books of Rhazes and on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates. He was also noted as a mathematician. Eberhard’s son Andreas, the father of the anatomist, was apothecary to Charles the Fifth and to Margaret of Austria. He accompanied the great Emperor upon his numerous journeys and military expeditions. In 1538 he presented Andreas’s first anatomical plates to the Emperor, and thus opened the way to the court to his son. The father remained in the imperial service until the day of his death, which occurred in 1546. Andreas’s mother, Isabella Crabbe, exercised a great influence upon the youth whom she believed to be destined to accomplish great things. She it was who preserved the manuscripts and books of the Vesalian ancestors. Isabella happily lived long enough to see the Fabrica, to witness the intellectual triumph of her son, and to know of his activity at the Spanish court.

THE OLD UNIVERSITY OF LOUVAIN

(Erected early in the Fourteenth Century. The New Building dates from 1680)

Little is known of the youth of Vesalius. The traditions of his ancestors, their accomplishments in the field of letters and in medicine, and their loyalty to their sovereigns, were themes which his mother must have recounted with pleasure. At an early age Andreas was sent to the neighboring city of Louvain, whose University, founded in the year 1424, in the early part of the sixteenth century eclipsed many institutions of greater age, and in the number of its students ranked second only to the University of Paris. The theologians of Louvain were noted for their orthodox Catholicism; from the very first days of religious controversy they had battled strongly against the rising tide of the Reformation. Her professors of jurisprudence and of philosophy were men of eminent talents. Within the University were four literary schools which were named Paedagogium Castri, Porci, Lilii, and Falconis, from their insignia:—a fort, a pig, a lily, and a falcon. Here also was the Collegium trilingue Buslidianum, which was founded by Hieronymus Busleiden (+1517) for teaching the Greek, Hebrew and Latin languages. Vesalius selected the Paedagogium Castri which he fondly mentions in laudatory terms in his Fabrica. Here, and in the Busleidinian College, he obtained that thorough knowledge of ancient languages which, in later years, astonished his hearers and served him well in numerous 55 literary controversies. The names of Vesalius’s teachers are unknown, although Adam[9] states that John Winter of Andernach was his professor of Greek. Vesalius speaks scornfully of one of his teachers, a theologian, who, in trying to explain Aristotle’s De Anima, used a picture of the Margarita Philosophica to show the structure of the brain. Among Vesalius’s school companions were Gisbertus Carbo, to whom the anatomist presented the first skeleton which he articulated (Fabrica, 1543, page 162); and the younger Granvella, who later was Chancellor to Charles the Fifth.

At an early age Vesalius possessed a desire to study the structure of the human body. His powers of observation were precociously developed. When a boy, learning to swim by the aid of bladders filled with air, he noted the elasticity of these organs, and he referred to the incident in his Fabrica (1543, page 518). When little more than a child, he tired of dialectics and tried to learn anatomy from the scholastic writings of Albertus Magnus and of Michael Scotus. He soon discovered that the true road to anatomical science led, not through books but through the actual handling of the dead tissues. He began the practical study of anatomy by dissecting the bodies of mice, moles, rats, dogs and cats.[10]

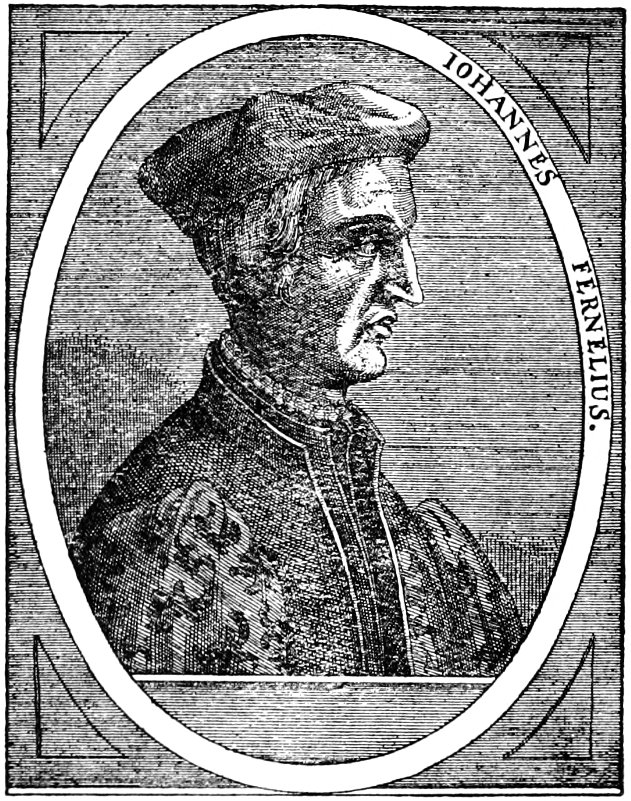

One thought was uppermost in the mind of Vesalius, and that was to follow the profession of his ancestors, just as in ancient Greece the sons of the Asclepiadae naturally adopted the vocation of their fathers. Andreas possessed an excellent preliminary education and was especially proficient in the Greek and Latin languages; he also knew something of Hebrew and much of Arabic. It was in the year 1533 that the young Belgian travelled to Paris for the purpose of obtaining a medical education. At that time the French capital was the Mecca of the medical world—Paris, that city where classical medicine first secured support (ubi primum medicinam prospere renasci vidimus)[11]. In Paris, under the leadership of Budaeus, Humanism had enjoyed a rapid growth; and here Petrus Brissotus, after gaining the doctor’s cap in the year 1514, produced a revolution by delivering his lectures from the books of Galen in place of the treatises of Averröes and of Avicenna. At his own expense Brissotus published Leonicenus’s translation of Galen’s Ars Curativa, in order that his pupils might not be misled by the incorrect text of the Arab authors. It will be recalled that, long before this time, classical Greek and Latin medical literature had 57 passed through the distorting crucible of Saracenic translations. At this period medical science, purified from Arabic dross, was taught in a splendid manner in Paris by such eminent professors as Jacobus Sylvius, Jean Fernel, and Winter of Andernach. At their feet sat young men from the remotest parts of Europe.

The most popular of the Paris teachers was Jacobus Sylvius, or Jacques Dubois, whose Latinized name is perpetuated in anatomical nomenclature. He was born at Louville, near Amiens, in 1478. In his early years he was noted for his scholarly attainments in the Greek, Latin and Hebrew languages and was the author of a French grammar. His anatomical knowledge was gained under Jean Tagault, a famous Parisian practitioner and surgical author.

SYLVIUS

Sylvius was noted for his industry, for his eloquence, and above all for his avarice. It was the inordinate desire for money which led him to abandon philology for medicine. While studying under Tagault he began a course of medical lectures, explanatory of the works of Hippocrates and Galen, with such success that the Faculty of the University of Paris protested on the score that Sylvius was not a graduate. He then went to Montpellier, whose medical professors had long held a high position, where, according to Astruc, he received the doctor’s cap at the end of 58 November, 1529. He was then above fifty years of age. Armed with this degree, he returned to Paris and immediately entered the lists as an independent medical teacher, but was again halted by the Faculty who ruled that he must first receive the Bachelor’s degree. This he gained on June 28, 1531. Sylvius then resumed his lectures with such success that his classes in the Collége de Tréguier numbered from four to five hundred, while Fernel, who was a professor in the Collége de Cornouailles, lectured to almost empty benches. In 1550, Henry the Second named Sylvius Professor of Medicine, as the successor of Vidus Vidius, in the recently established Collége de France. Sylvius died January 13, 1555, and was interred in the paupers’ cemetery as he had wished.

Sylvius was not only an eloquent lecturer but he was also a demonstrative teacher. He was the first professor in France who taught anatomy from the human cadaver. In his lectures on botany he used a collection of plants to elucidate the subject. His chief fault was a blind reverence for ancient authors. He regarded Galen’s writings as gospel; if the cadaver presented structures unlike Galen’s description, the fault was not in the book but in the dead body, or, perchance, human structure had changed since Galen’s time! In one of his early books[12], Sylvius declared that Galen’s anatomy was infallible; that Galen’s treatise, De Usu Partium, was divine; and that further progress was impossible!

The character of Sylvius was contemptible. He was a man of vast learning and at the same time was rough, 59 coarse and brutal. His avarice led him to endure the cold winters of Paris without the benefit of a fire; in severe weather he would play at football, or engage in other violent exercise in his room, to save the cost of fuel. Once, and once only, did his friends find him hilarious; they wondered and asked the cause. Sylvius said he was happy because he had dismissed his “three beasts, his mule, his cat and his maid”. He was notoriously rigid in exacting his fees from students, and on one occasion he threatened to stop his lectures until two delinquents should pay their dues. Although he was supposed to have amassed great wealth, little of it was found after his death, and these sums were secreted in secluded places. In 1616, when his former residence in the rue Saint-Jacques was demolished, numerous gold pieces were found. His reputation for miserliness followed him beyond the grave, as witness his epitaph:

Sylbius hic situs est, gratis qui nil dedit unquàm,

Mortuus et gratis quod legis ista dolet.

“Sylvius lies here, who never gave anything for nothing:

Being dead, he even grieves that you read these lines for nothing.”