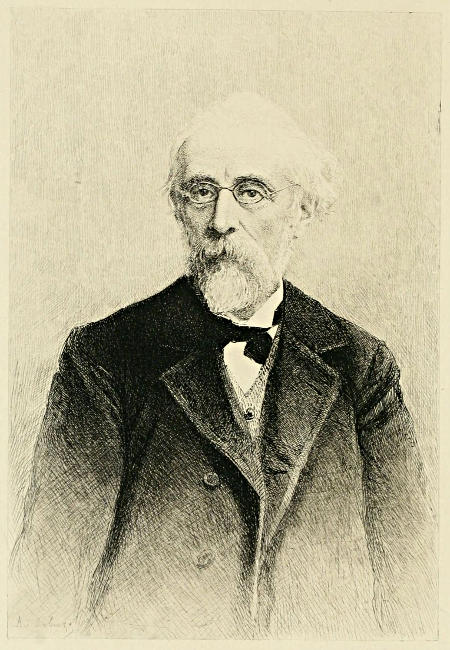

NÖLDEKE

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Historians' History of the World in

Twenty-Five Volumes, Volume 08, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Historians' History of the World in Twenty-Five Volumes, Volume 08

Parthians, Sassanids and Arabs; The Crusades and the Papacy

Author: Various

Editor: Henry Smith Williams

Release Date: October 17, 2020 [EBook #63489]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORIANS' HISTORY OF THE WORLD, VOL 8 ***

Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

NÖLDEKE

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME VIII—PARTHIANS, SASSANIDS, AND ARABS

THE CRUSADES AND THE PAPACY

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1904

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

New York, U. S. A.

| VOLUME VIII | |

| PART XII. PARTHIANS, SASSANIDS, AND ARABS | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory Essay. The Scope and Influence of Arabic History. By Dr. Theodor Nöldeke | 1 |

| History in Outline of Parthians, Sassanids, and Arabs (250 B.C.-1375 A.D.) | 25 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Parthian Empire (250 B.C.-228 A.D.) | 47 |

| Justin’s account of the Parthians, 47. Their customs, 48. Seleucus and Arsaces, 49. Wars with Rome, 51. Modern accounts of Parthia, 53. The Parthian empire, 53. Arsaces and the Arsacids, 54. Bactria and Parthia consolidate, 55. Conquests of Mithridates, 57. Media and Babylonia conquered, 58. Parthian “kingdoms,” 59. Scythian conquest of Bactria, 60. The Scythians ravage Parthia, 61. First conflict with Rome, 62. Orodes defeats the Romans, 63. Plutarch’s account of the battle of Carrhæ, 63. Phraates IV repels Mark Antony, 68. Anarchy in Parthia, 70. The Romans intervene, 72. The decay of Parthian greatness, 74. Persia conquers Parthia, 75. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Empire of the Sassanids (228-750 A.D.) | 76 |

| Sassanian power, 77. Sapor fights Rome, 78. The war with Palmyra, 79. A new war with Rome, 81. Ardashir II to Bahram IV, 82. The rule of Yezdegerd I, 83. The Arabs aid in war with Rome, 84. War with the Hephthalites, 85. Kavadh I, 86. New conflict with Rome, 86. Exploits of Mundhir, 87. Chosroes the Just, 88. Chosroes attacks Rome, 88. Hormuzd IV, 91. Civil war, 91. Vices of Chosroes II, 93. Conflict with Heraclius; fall of Chosroes II, 94. Successors of Chosroes II, 95. Anarchy and chaos, 96. Arab incursions, 97. Arab conquest, 98. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Early History of the Arabs (ca. 2500 B.C.-622 A.D.) | 100 |

| Arab history before Mohammed, 105.[x] | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Mohammed (570-632 A.D.) | 111 |

| Mohammed ben Abdallah ben Abdul-Muttalib, 111. Religious unrest, 111. Mohammed’s life, 113. His marriage with Khadija, 113. Mohammed as a prophet, 115. Mohammed an outlaw, 116. The Hegira, 117. Battle of Bedr, 120. Battle of Ohod, 121. Expedition against the Jews, 123. Siege of Medina, extermination of the Jews, 123. Mohammed’s pilgrimage to Mecca, 125. Subjection of Mecca, 126. The victory of Honain and Autas, 128. The last years of Mohammed’s life, 130. Gibbon’s estimate of Mohammed and Mohammedanism, 132. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Spread of Islam (632-661 A.D.) | 145 |

| Abu Bekr, first caliph after Mohammed, 145. The caliph Omar, 150. The conquest of Persia, 151. The Syrian conquest completed, 156. Egypt captured, 160. The alleged burning of the library, 163. Othman, the third caliph, 167. Ali, 170. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Omayyads (661-750 A.D.) | 175 |

| Foundation of the Omayyads, 175. Yazid made caliph, 176. Siege of Mecca, 177. Abdul-Malik, caliph, 179. Siege of Mecca, 180. The eastern caliphate, 184. Suleiman’s ambitions, 185. The last Omayyads, 186. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Arabs in Europe (711-961 A.D.) | 191 |

| The invasion of France, 198. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Abbasids (750-1258 A.D.) | 209 |

| Founding of Baghdad, 209. Harun Ar-Rashid, 210. Al-Mamun and his successors, 211. Baghdad under the caliphs, 213. Gradual decline of Arabian dominion in the East, 215. The various religious sects, 220. The Seljuk Turks, 225. Arabs and Turks unite against the Christians, 227. Saladin and his successors against the crusaders, 228. The Mongols under Jenghiz Khan invade western Asia, 230. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Decline of the Moslems in Spain (961-1609 A.D.) | 233 |

| Almansor, 233. Decay of power, 235. End of the Omayyads, 238. Independent kingdoms, 239. The Almoravids, 240. Dynasty of the Almohads, 246. Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, 247. The decline of Arab power, 248.[xi] | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Arab Civilisation | 260 |

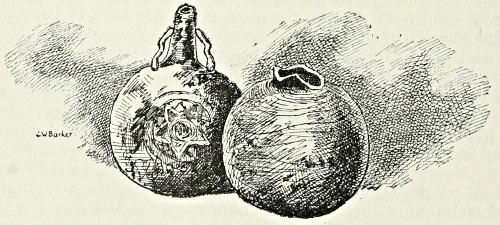

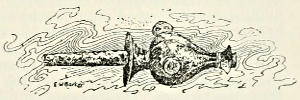

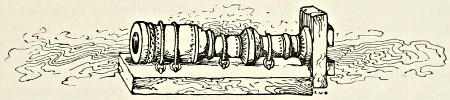

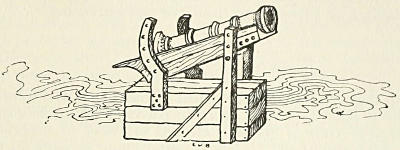

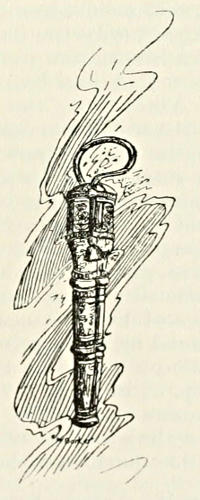

| The Koran, 260. Doctrine of Islamism, 265. The pilgrimage to Mecca, 267. The holy war, 270. Arab culture, 271. Commerce and industry, 273. Paper, compass, and gunpowder, 274. Influence of the Arabs on European civilisation, 276. Scholasticism, 277. Mathematical science, 278. Medicine, 279. Architecture, 281. Music, 282. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Tribal Life of the Epic Period | 284 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| The Principles of Law in Islam | 294 |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 305 |

| PART XIII. THE CRUSADES AND THE PAPACY | |

| BOOK I. THE CRUSADES | |

| Introductory Essay. The Value of the Crusades in the Light of Modern History. By the Reverend William Denton, M.A. | 311 |

| History in Outline of the Crusades (1096-1291 A.D.) | 314 |

| CHAPTER I | |

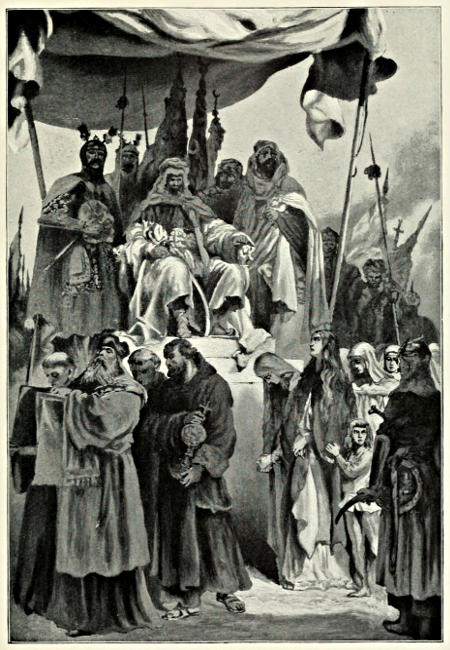

| Origin of the Crusades (306-1096 A.D.) | 320 |

| Early Christian pilgrimages, 322. Jerusalem under the Saracens, 324. Character of the pilgrims, 326. The Turks in power, 328. Peter the Hermit, 330. The appeal of the emperor Alexius, 331. Councils of Placentia and Clermont, 332. The frenzy of Europe, 334. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

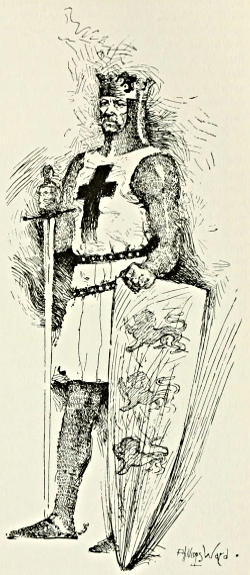

| The First Crusade (1096-1147 A.D.) | 338 |

| Peter the Hermit and his rabble, 339. The leaders of the First Crusade, 340. Alexius compels homage, 342. Numbers of the crusaders, 343. The siege of Nicæa, 344. Battle of Dorylæum, 345. Principality of Edessa founded, 346. Siege of Antioch, 347. A typical miracle, 349. Jerusalem besieged, 351. The Arab account, 352. Godfrey elected king, 353. Results of the First Crusade, 356.[xii] | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Second Crusade (1147-1189 A.D.) | 358 |

| St. Bernard, 358. Disasters of the Germans, 361. The French failure, 362. The rise of Saladin, 364. Moslem accounts of the battle of Tiberias, 374. The fall of Jerusalem, 376. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

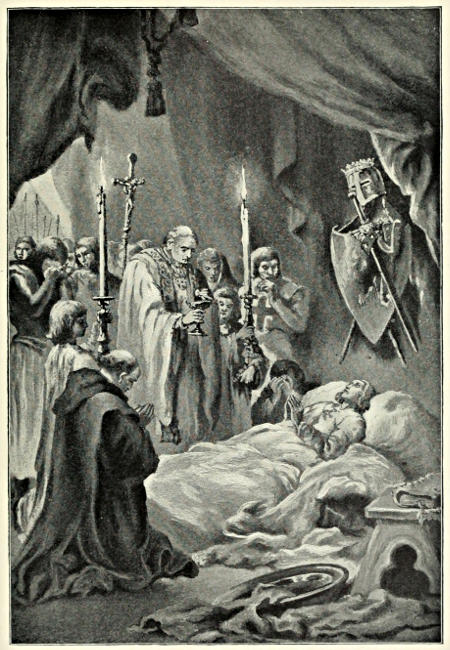

| The Third Crusade (1189-1193 A.D.) | 379 |

| The Saladin tithe, 381. Barbarossa’s crusade and death, 382. The siege of Acre or Ptolemais, 383. Geoffrey de Vinsauf’s account of Acre, 383. Richard’s voyage, 386. The French sail to Acre, 387. Dissension between the French and English kings, 388. Review of the siege, 390. The crusaders move on Jerusalem, 392. The enterprise abandoned, 396. Vinsauf’s account of Richard at Joppa, 397. Peace between the kings, 402. End and review of the Third Crusade, 404. Death of Saladin; Arab eulogies, 407. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Fourth to the Sixth Crusades (1195-1229 A.D.) | 410 |

| Pope Celestine III promotes a crusade, 410. The Fourth (or German) Crusade, 411. The Fifth Crusade, 413. Results of the Fifth Crusade, 417. The Children’s Crusade, 419. The Sixth Crusade, 422. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Last Crusades (1239-1314 A.D.) | 431 |

| Richard of Cornwall’s Crusade (the Seventh), 432. The Tatar Crevasse, 433. The crusade of St. Louis (the Eighth), 434. Battle of Mansura, 436. De Joinville’s account of the battle of Mansura, 437. Results of Mansura, 441. St. Louis a prisoner, 442. Moslem account of St. Louis’ capture, 443. The Christians quarrel among themselves, 448. History of Antioch, 449. Ravages of Bibars, 450. Second crusade and death of Louis IX, 450. Prince Edward leaves England, 451. Vain efforts of Gregory X, 452. Progress of the mamelukes, 453. Total loss of the Holy Land, 454. Fate of the military orders, 456. Knights of St. John, 456. The Templars in France, 457. In other countries, 458. Council at Vienne, 458. The order suppressed, 459. The Crusades in the West, 459. The Teutonic Crusade, 460. The attack on the Albigenses, 461. Western assaults on the Arabs, 463. Comparison of the two crusades, 466. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Consequences of the Crusades (1096-1291 A.D.) | 467 |

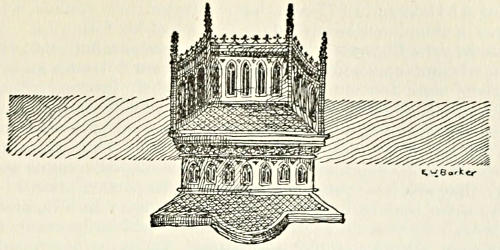

| Moral effects, 468. Political effects, 469. Influence upon commerce, 471. Enrichment of cities, 472. Colonisation, 472. Influence on industry, 474. The masons organise, 475. Gothic architecture, 476. Sculpture and painting, 476. Herder’s opinion of the Crusades, 477. Gibbon on the results of the Crusades, 479.[xiii] | |

| APPENDIX | |

| Feudalism (800-1450 A.D.) | 481 |

| Bryce and Hegel on feudalism, 482. Commencement of the feudal régime, 483. Reciprocal obligations of vassal and lord, 484. Feudal justice, 485. Ecclesiastical feudalism, 487. The Church and the feudal army, 488. Serfs and villeins, 489. Anarchy and violence; frightful condition of the peasants and some happy results therefrom, 491. Geographic outlines of the kingdom of Germany, 494. The transition from feudalism to monarchy, 494. Progress in Germany, 495. Influence of gunpowder, 497. Monarchism in Italy, 497. In France, 498. In England, 499. The papacy and feudalism, 500. Hegel on the rise of mankind through feudalism, 500. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 502 |

| BOOK II. THE PAPACY | |

| History in Outline of the Papacy (42-1878 A.D.) | 503 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Origin and Rise of the Papacy (42-842 A.D.) | 519 |

| The papacy in connection with the Frankish Empire, 524. Gregory the Great, 531. Christian mythology, 534. Worship of the Virgin, 535. Angels and devils, 536. Martyrs and relics, 536. Sanctity of the clergy, 537. State after death, 538. Gregory’s successors, 539. Draper on the origin of iconoclasm, 544. Milman on iconoclasm, 545. The war of iconoclasm, 546. Constantine Copronymus, 548. Third Council of Constantinople, 549. The war on monasteries, 550. Helena and Irene, 552. Second Council of Nicæa, 552. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| “The Night of the Papacy”—Charlemagne to Otto the Great (740-985 A.D.) | 555 |

| Independence of the Roman bishops, 556. The appeal to the Franks, 556. Charlemagne and the pope, 558. The donation from Constantine, 559. Charlemagne’s third and fourth entrances into Italy, 561. The realm of the popes, 562. The trial of the pope and the crowning of Charlemagne, 563. Papal ambition after Charlemagne, 565. The myth of the woman pope, 567. Rivalry of Nicholas and Photius, 569. Synod at Constantinople, 570. The false decretals, 571. Adrian II, 574. Pope Formosus, 577. Theodora in power, 579. The infamous Marozia, 581. Rebellion of Rome, 582. Pope John XII, 583. Trial of the pope, 583. Charles Kingsley on temporal power, 587.[xiv] | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The High Noon of the Papacy (985-1305 A.D.) | 589 |

| The dream of Otto III, 590. The German popes, 591. The college of cardinals, 592. Milman on the mission of the papacy, 593. Simony, 596. Celibacy of the clergy, 596. Gregory’s synod at Rome, 597. Bryce on the consequences of the Concordat, 602. Rival claimants, 602. Adrian IV versus Barbarossa, 603. Adrian’s firmness, 605. Two rival popes, 606. Innocent III, 607. The influence of the crusades on papal power, 608. The autocracy of Innocent III, 610. Universal sway of the pope, 611. Milman’s estimate of Innocent III, 612. Frederick II at war with the papacy, 614. Council at Lyons, 616. Accession of Boniface VIII, 618. Philip the Fair overpowers the papacy, 618. Hallam on the climax of papal power, 620. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| From Exile to Supremacy (1305-1513 A.D.) | 623 |

| Clement V, 624. The fate of the Templars, 625. John XXII to Urban V, 626. The Great Schism of the West, 630. Relation of the national churches to the state, 632. Moral condition of the clergy, 633. The great councils of Pisa and Constance; John Huss, 634. Milman on Nicholas V and the fall of Constantinople, 640. Popes to 1503, 642. Alexander VI, the Borgia, 644. Estimates of Alexander VI, 645. Julius II, 647. Prevalence of secularism in the Church, 648. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 651 |

PART XII

THE HISTORY OF PARTHIANS,

SASSANIDS, AND ARABS

BASED CHIEFLY UPON THE FOLLOWING AUTHORITIES

ABDUL-LATIF, ABUL-FARAJ, ABULFEDA, MAX DUNCKER, I. GOLDZIHER,

A. VON GUTSCHMID, WILLIAM MUIR, TH. NÖLDEKE, L. A.

SÉDILLOT, L. VIARDOT, JULIUS WELLHAUSEN,

GUSTAV WEIL

TOGETHER WITH

A CHARACTERISATION OF THE SCOPE AND INFLUENCE

OF ARABIC HISTORY

BY

THEODOR NÖLDEKE

AN ESSAY ON

THE TRIBAL LIFE OF THE EPIC PERIOD

BY

JULIUS WELLHAUSEN

AND A STUDY OF

THE PRINCIPLES OF LAW IN ISLAM

BY

I. GOLDZIHER

WITH ADDITIONAL CITATIONS FROM

ARTEMIDORUS, BAILLY, BEN-HAZIL, THE HOLY BIBLE, DION CASSIUS, L. A.

SILVESTRE DE SACY, DIODORUS, R. DOZY, S. A. DUNHAM, EL-MAKIN,

ERATOSTHENES, EUSEBIUS OF CÆSAREA, EUTYCHIUS, E. GIBBON,

STANISLAS GUYARD, HAURÉAU, HERODOTUS, HUMBOLDT, JUSTIN,

HAJI KHALFA, IBN KHALDUN, KIESEWETTER, MAKRISI, AMMIANUS

MARCELLINUS, J. A. ST. MARTIN, H. H. MILMAN,

J. E. MONTUCLA, F. A. NEALE, S. OCKLEY, W.

G. PALGRAVE, PLINY, GIRAULT DE PRANGEY,

JOSEPH VON HAMMER-PURGSTALL,

IBN SAAD, SAMPIRO, W. C.

TAYLOR, GEORG WEBER,

JOSEPH WHITE

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Written Specially for the Present Work

By Dr. TH. NÖLDEKE

Professor in the University of Strasburg, etc.

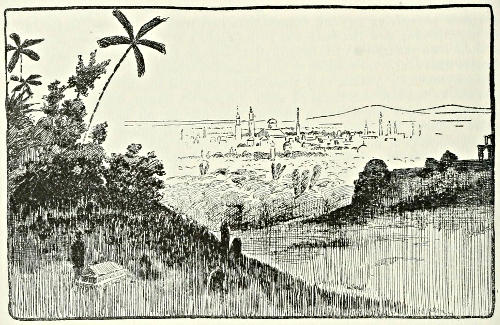

If there is a region in the world which constrains its inhabitants to adopt a particular mode of life, that country is Arabia and the regions that border it on the north, the Sinaitic peninsula and the Syrian and Mesopotamian deserts. The great majority of the dwellers in these parts are forced to lead a nomadic life by the fact that the spots in which agriculture is possible are comparatively rare, and the infrequent rains, which only extend over limited areas, provide pasture for their flocks now in one part and now in another, but never for any length of time. The whole character of the Bedouin is conditioned by this nomadic mode of life (full of hardships and privations, though not laborious) with its constant struggles with competitors for the prime necessaries of life. The inhabitants of the oases, who are permanently settled in favoured spots, differ from the Bedouins in many respects, but are nevertheless strongly influenced by Bedouin modes of life and thought. Throughout this vast area life runs its course in perpetual change, yet remains in essentials ever the same. If one tribe perishes, migrates elsewhere, or turns to agricultural pursuits somewhere in the vicinity of the desert, its place is taken by another, which lives exactly as it had lived. The course of history, however, has shown that intellectual forces were existent in this desert race which seem to be lacking in others living under precisely similar conditions, such as the Berbers of the Sahara.

We have no certain knowledge of the relation in which the Semitic tribes of the desert, whom we first meet with in the Old Testament (Ishmaelites, Midianites, etc.), and who there appear as closely akin to the Israelites, stand to the Arabs of later times. As far as we can tell, however,[2] they resemble them exactly. The son of the desert likes to reap where he has not sown; he not only plunders the camels and smaller cattle of alien tribes of Bedouins, but he devours the cornfields of the peasants who dwell on the borders of the desert whenever he has a chance, or carries off the garnered fruits of their toil. Thus in old days the desert tribes on one occasion actually came across the Jordan into central Palestine and utterly despoiled the inhabitants, until the latter under the leadership of Gideon drove them forth and inflicted a severe humiliation upon them (Judges 6-8). Somewhat later a horde of Amalekite inhabitants of the Sinaitic peninsula invaded southern Judea and Philistia, but were severely chastised by David, who was living there in exile (1 Samuel xxx). Such tribes have often in like manner proved extremely troublesome to the agricultural population on the margin of the desert. But if the states to which these peasants belong will only put forth a certain amount of exertion in defence of their territory the danger is not serious; for at heart the Bedouins are not eminently brave. In many cases peasants who will protect their own property can successfully ward off these predatory incursions. The non-nomadic settlers in the interior of Arabia, in particular, seem invariably to have been more valiant than the nomadic tribes. The latter would find it hard to do without the produce of agriculture and date-palm culture, while the dwellers in the oases, if they desire to have any intercourse with other regions, are obliged to keep on a friendly footing with the Bedouins through whose haunts their trade routes lead. Hence treaties are concluded in the interests of both parties, and the true Arab is an observer of treaties.

By a lamentable process of events it has come to pass that the nomads have extended their domain considerably at the expense of the husbandman. Even in Palestine the Bedouin tent-dweller now pastures his camels in many spots where formerly the Israelite farmer sat under his own vine and his own fig-tree and tilled his land with ox and ass.

The real meaning of the name “Arab” seems to be “desert.” It is first met with, or so it seems, in varying forms in Assyrian inscriptions of the ninth century.[1] In the Old Testament it cannot be identified with certainty before the time of Jeremiah.[2] In the inscriptions of King Darius Hystaspes, Arabaya appears to mean the Mesopotamian, Syrian, and Sinaitic desert. Amongst the Greeks we meet with the terms “Arab, Arabia” first in Æschylus (Persians 316; Prom. 422), but the poet’s ideas of the situation of the country are altogether mythical. Herodotus, on the contrary, is fully conversant with it; he is specially interested in that district, populated by Arabs, that constitutes the connection between Palestine and Egypt which was of such importance to the Persian kingdom, and not to it alone. His contemporary, Nehemiah, is quite familiar with the name of “Arab” (Ch. 2, 19; 4, 7; 6, 16) and so is Xenophon. The latter uses the name “Arabia” of the Mesopotamian desert in particular (Anab. 1, 5, 1); and this very region is called “Arab” pure and simple by the later Syrians. The name has survived from that day to this, especially amongst the people themselves.[3] It has long stood for both the nationality and the language. It is true that even in times tolerably remote Arab was understood to mean more particularly Bedouin; as is the case even in Sabæan inscriptions. The latter are, however, more exactly distinguished from the settled inhabitants of the country by the use of the plural, in its old form A’rab, later more frequently Orban.

Many scholars assume that all civilised Semitic nations actually took their rise from Arabia and are, as Sprenger[3] phrases it “Bedouin deposits” (“abgelagerte Beduinen”). The question of whether, in the last resort, Arabia was the original home of the Semites or whether they migrated thither from Africa in primitive times is not affected by this assumption.[4] In any case the language of the Hebrews and Aramæans still bears traces of the fact that their forefathers were at one time a nomadic race, which (with regard to the former at least) is to some extent confirmed by Old Testament tradition. It is true that wherever we have any historic record the contrast between these civilised peoples and the dwellers in the desert is evident. But we can imagine that the same thing happened with them as we may observe repeatedly in Arab tribes of later days. They press forward, gradually in part and in part rapidly, out of Arabia proper. The Syrian and Mesopotamian deserts, barren as they seem to us, offer the nomads certain advantages over the regions to the south. The rainfall is somewhat more copious. The nomads come into closer contact with settled peoples, and much as the Bedouin (proud of his freedom and happy in his leisure) may look down upon the industrious peasant and even upon the artisan, yet the greater security and the certainty of obtaining daily food prompts him to take to husbandry in the region of verdure when opportunity offers. The process was sometimes accompanied by violence towards the earlier settlers, but it often came about peaceably. Thus one wave of Arabs slowly overtook another. The names which predominate in the older portions of the Old Testament (Ishmaelites, Midianites, etc.) soon fall into the background. The appearance of the name “Arab” may be in itself an indication of the arrival of fresh tribes in these regions.

In the fourth century B.C. we find the Arab tribe of the Nabatæans to the south of Palestine, and the same tribe soon afterwards formed a settled state which extended eastwards from the ancient territory of Israel as far as to Damascus, rose to a considerable height of civilisation, and maintained a position of lax dependence upon Rome until Trajan destroyed it in the year 106; certainly not to the real advantage of the empire. In the first century of our era we meet with princes and nobles with Arabic names in Edessa, Palmyra, Emesa, and Hatrá. The abundant store of inscriptions at Palmyra shows that the greater part of the population of this Aramaic-speaking trading city, encompassed on all sides by the desert, was of Arab origin. It seems that during the gradual decay of the Seleucid kingdom, Arabs in several cases acquired dominion over these districts, just as at a later period members of various Bedouin tribes rose to eminence in Syria and Mesopotamia, during the decadence of the caliphate dynasty. Thus numerous settled Arab tribes lived in many parts of Syria as Roman subjects. In process of time all these[4] Arabs who dwelt in towns or villages grew to be Aramæans; even before that they had always used the Aramaic language in their inscriptions—where they did not write in Greek—because Arabic was not then regarded as a suitable language for use in writing.

At this time two new names for the Arabs came into existence, “Saracens” and “Taits.” Ptolemy (5, 16) mentions Σαρακηνή as a district in the Sinaitic peninsula.[5] The inhabitants of this district, who are unknown to Arab tradition, must have made themselves notorious in the Roman provinces in their vicinity; we can hardly suppose by other means than predatory incursions by hindering the march of caravans or levying heavy tolls upon them. Thus in that region all Bedouins came to be called Saraceni (Σαρακηνοί), in Aramaic Sarkaje, usually with no very favourable meaning. We meet with the latter form in a dialogue concerning Fate, written about 210 A.D. by a pupil of Bardesanes.[6] The designation then became general; thus it occurs very frequently in Ammianus Marcellinus. The name “Saracen” continued to be used in the West in later times probably rather through the influence of literature than by oral tradition, and was applied to all Arabs, and even to all Moslems, without distinction.

In precisely the same fashion and at exactly the same time the designation “Taits” came to be used for all Arabs by the Syrians of Edessa and the inhabitants of Babylonia. Only, while we know nothing of a distinct tribe of Saracens, which must very early have ceased to exist as such, we have plentiful and trustworthy information concerning the Tai in Arab literature. Their principal seat was in northern Nejd, but they spread abroad in many directions. Even now their name has not wholly passed out of remembrance.[7] By degrees the Aramæans came to style all Arabs “Tayaye,” and the Persians adopted the name from them.[8] Amongst the latter it is pronounced Tadjik, Tazik, in its more ancient form (with the Persian suffix), and Tazi in the later form.[9] The Arabs themselves reckon the Tai among the tribes which were once settled in the south of the Arabian peninsula. We are probably right in connecting their appearance in the north with a fresh wave which carried quite a number of the tribes of south Arabia into the northern districts; a tribal migration of which Arab tradition has much to tell, and some of it authentic.

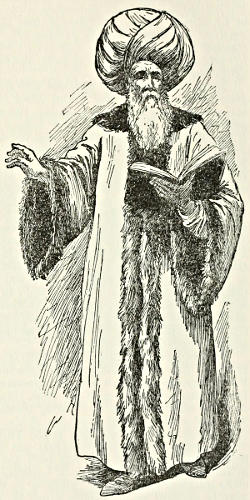

The Arabs were known at that period only as a wholly savage race. Ammianus says of them: “natio perniciosa” (14, 4, 7), “nec amici nobis unquam nec hostes optandi” (14, 4, 1). The whole description, which he gives from contemporary information (14, 4), is very instructive, though somewhat one-sided and exaggerated in certain particulars. When he says that the Saracens live upon flesh and milk, and that most of them are unacquainted with wheat or wine, the statement agrees with that in the not much later Syrian Vita of Simeon Stylites[10] that many “Taits” did not know what bread was, but lived entirely upon flesh. There can be no question that the northern Bedouins, the only ones the author had in mind, can seldom have had an[5] opportunity of procuring dates. Bread is an article of luxury in Arabia even at the present time. The Bedouins of the Sinaitic district, with whom S. Nilus (fifth century A.D.) had to do, were quite exceptionally barbarous.[11]

We have hitherto completely ignored the seats of higher civilisation which were to be found in ancient times in the peninsula of Arabia. As early as the second millennium B.C. southwest Arabia, the Yemen, the country of the Sabæans and Himyars, which was well adapted for agriculture on account of the regular rains of its tropical summer, had developed a civilisation which has left, in the ruins of huge buildings and numerous inscriptions, monuments which still excite our admiration. The Greeks and Romans were not without justification when they spoke of a εὐδαίμων Ἀραβία, Arabia Felix, though their ideas of the character and extent of this “rich”[12] country were for the most part tolerably vague.[13] But several passages in the Old Testament bear witness to the high repute of the glory and splendour of the Sabæans. This is particularly evident in the legend of the queen of Sheba’s visit to Solomon (1 Kings x, 1-10). Not the least part of the wealth of the Sabæans was due to their monopoly of the trade in certain fragrant substances, especially in the incense which in old times was used in immense quantities at sacrifices. These perfumes, especially incense, are mentioned in various passages of the Old Testament, together with gold and precious stones, as amongst the treasures of the Sabæans (1 Kings x, 2, 10; Jeremiah vi, 20; Ezekiel xxvii, 22; Isaiah lx, 6). These and other products were carried to the north by Sabæan caravans (cf. Isaiah lx, 6; Tobit vi, 16). In the inscriptions of northern Hijaz we now have documentary evidence to prove that the Sabæans established permanent trading-stations at a distance from their own country. At the height of their prosperity they must have exercised a civilising influence of no mean importance upon the rest of Arabia, especially upon those parts of the west which they traversed in their regular journeys. To them the Thamudæans, with whose buildings (known before only by the report of Arab writers) the labours of Doughty and Euting have made us acquainted, and the Nabatæans, who were closely connected with the Thamudæans, probably owed the first elements of their culture. Written characters, which came to the Sabæans from the north in very early days, were by them disseminated in every kind of transmutation over large portions of Arabia, as far as the neighbourhood of Damascus on the one hand and Abyssinia on the other. Nevertheless, take it all in all, the civilisation of the ancient Yemen bore little fruit for the world beyond. The countries about the Mediterranean received no intellectual stimulus worth speaking of from this remote region, nor did the old Semitic civilisation, nor Iran, receive more. And since the glory of the land of the Sabæans has departed its influence on other Arabs has become insignificant.

The decadence of the nation was probably due to various causes. It is certain that the Arab tradition which sees in it the effect of a single catastrophe—the[6] bursting of the dam at Marib, which was indispensable for regular irrigation—is far from being an adequate explanation. The bursting of the dam must itself have been the consequence of neglect on the part of a degenerate race. But there may well be some truth in the tradition, which connects the decline of this remarkable people, indirectly, at least, with the great migration of Yemenite tribes to the north. At that time—about the second century A.D.—a kind of retrograde movement seems to have set in throughout the civilisation of a large part of Arabia. At certain periods large numbers of Arabs had been able to write, at least in rude characters, as is sufficiently proved by numerous brief inscriptions; about the year 600 the art of writing in Arabia was the secret of the few. Even in Yemen tolerably trustworthy traditions of its palmy days survived only amongst individuals. The conquest of the country by the hated Abyssinians (525 A.D.) probably shattered the last remnants of national vigour, and the Persian conquest (about 570 A.D.) failed to quicken it afresh. It is true that the civilisation of Yemen was still superior to that of the rest of Arabia; for example, it carried on a fairly important manufacture of weapons and materials for garments. A dim consciousness still survived of great things that the country had wrought. But, since there were no historic records of such, the later Yemenites endeavoured to vindicate the fame of their forefathers by extravagant inventions and to show that they had done far greater deeds than were done by the Koreishites at the head of the Moslems.

Nevertheless the fact remains that the civilisation of the Sabæans need scarcely be taken into account in determining the place of Arabia in history. It counts for less than the inferior civilisation of other nations less remote from the main theatre of events. The principal scene of the old quarrel of East and West, which had presented itself so vividly to the eyes of the Greeks in the Persian wars, in the last century before Christ was transferred to Syria and the countries about the Euphrates and Tigris. The Arabs of the northern districts were drawn into the struggle of the Romans with the Parthians and Persians. They were always available for pillaging the enemy’s territory or harassing their compatriots on the other side. It was hardly possible for the great powers to rule the desert, and it would have been a somewhat thankless task; but they could influence the Bedouins strongly by various indirect methods. The Arab dynasties in the frontier districts were particularly useful for the purpose; they occupied a position of independence none too strict, and were invariably regarded with suspicion, but they could keep their savage kinsmen, with whom they were constantly in touch, far more effectually in check than regular imperial or royal officials could have done.

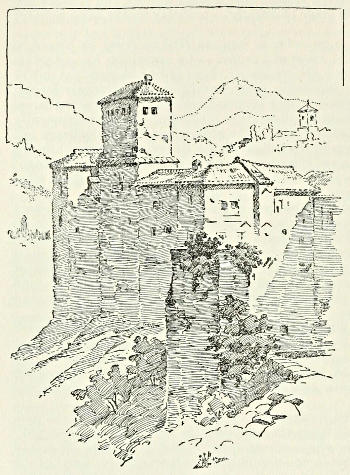

In this connection the Christian phylarchs of the tribe of Ghassan are worthy of special mention on the Roman side. Their capital was not far from Damascus and they played a somewhat important part in the events of the sixth century. On the Persian side there were for many years the vassal kings of the tribe of Lakhm, which dwelt in the important city of Hira, near the ancient Babylon. Both dynasties were respected and feared nearly as far as the confines of Arabia. Some scattered monarchies had likewise arisen in the interior of the country. In particular, we know of some sovereigns of a family of the Kinda tribe, whose home was at Hadramaut, far to the south; they ruled with vigour in various parts of Arabia, much like the princes of the Haïl dynasty at the present day.

But this sovereignty was of no long duration. Arabia is not suited to monarchy. The Bedouin has too strong a taste for independence; he is[7] averse even from peaceful enterprises for his own profit, if they call for discipline and subordination. A government must be equally wise and firm if it is to control the intractable nomad, with his loose ties to the soil. The Bedouin clings to his family, his tribe, his race. He yields willingly to the suggestions of the most distinguished and experienced chiefs of his tribe, but only so far as he pleases. There can be no question of a real government authority. This was the case even in the few cities of the interior. The decisions of the heads of families had considerable weight, but no coercive force. It might happen that individuals or families held aloof from a campaign undertaken on the initiative of the most distinguished men of the tribe, or turned back before its object was attained, nor could any one prevent them from so doing. They would perhaps have to endure scorn and mockery in prose and verse, and to that the true Arab is as sensitive as he is accessible to hyperbolical eulogy. In Arabia, then as now, peace never prevailed for any length of time. Sometimes there were feuds between large tribes or groups of tribes, sometimes quarrels within narrower limits. Camel-lifting and the use of pasture and wells belonging to another tribe constituted frequent grounds of quarrel. If blood were shed (which usually happened unintentionally) it cried aloud for blood. The Arab is not naturally blood-thirsty, but the passion of revenge for his slaughtered kin can lash him to furious blood-thirstiness. Fear of blood-revenge and the reflection that, in the peace which must ultimately be concluded, wergild must be paid to the tribe that has suffered most severely, in proportion to its losses, usually induce the combatants to be careful not to slay too many enemies, even in the stricken field. A murder or even a grievous injury may provoke long years of feud between families closely akin.

A powerful corrective to lawlessness is, however, supplied by the sway of custom and tradition. Authority (as has been intimated before) makes up to a great extent for the lack of political restraints. Authority of this character tells most strongly amongst a people of the aristocratic temper which the Arabs share with other nomadic races. An alien has no natural rights, but if any member of the tribe takes him under his protection he gains that of the whole tribe, and consequently security for his life and property.

By the year 600, and probably a considerable time before, the Koreish of Mecca had attained a curious and exceptional position. There, in an absolutely barren valley and near a spring of brackish water, a sanctuary stood. Some families of the Fihr clan, which belonged to the Bedouin tribe of Kinana, had settled round about it and established, under the name of Koreish, a lax commonwealth of the kind frequently found in Arabia. A considerable area in the immediate vicinity of their sanctuary may possibly have been respected as holy ground, in which no blood was to be shed, long before the Koreish took possession of it. Thus secured from harm, and held in high esteem as the guardians of the Kaaba (a small, square primitive house enclosed within a building open to the sky), the Koreish had turned their attention to commerce. They sent forth their caravans far and wide, as the Ishmaelites and Sabæans had done of old.[14] Koreishites travelled as merchants to Gaza, Jerusalem, and Damascus, to Hira on the[8] Euphrates, to Sana in Yemen, and even crossed the Red Sea to Abyssinia. By these means they not only acquired considerable wealth according to Arab standards, but what was of much greater value—a wider mental horizon than the Bedouins and the inhabitants of the oases, and a knowledge of men and affairs. Although they never quite attained a regular political organisation, yet Wellhausen is right when he says, “We note something of an aristocratic hereditary wisdom, as in the case of ancient Rome and Venice.”[15]

One consequence, it must be owned, of the practical temper and sober-mindedness of the Koreish was that they produced no poet of any note, while each and all of the poverty-stricken tribes of Bedouins about them had great achievements in this field to show. Better fed than the Bedouins (though by no means luxuriously) and not decimated by conflicts, they increased more rapidly in numbers, and in Arabia the numerical strength of a tribe has much to do with the esteem in which it is held. Their prosperity allowed them to exercise a liberal hospitality, and the hungry Bedouin appreciates highly the host who lets him for once eat his fill. We may well conjecture that it was the Koreish who established the connection between the annual pilgrimage to the mountain of Arafat, which lay just beyond their holy ground and the valley of Mina, with the temple of Mecca, which lay within it. Thus Mecca became the place where Arabs of the most diverse tribes met together from far and near every year. Even before the days of Islam the Koreish tribe was held in high esteem far and wide. But, however much we may study the causes which raised them above other Arabs, it still remains something of an enigma that this torrid and barren eyrie should at that time have brought forth so large a number of men, exclusive of the prophet, who, when their turn came to be placed in circumstances wholly unfamiliar, acquitted themselves magnificently as generals and statesmen. History sets us several problems of a similar nature in the sudden appearance of many notable men at the same spot.

At that time there were many survivals of barbarism among the inhabitants of central Arabia. For instance, the practice of burying newborn daughters alive was very general. The cost of feeding and bringing up girls in that inhospitable country was a burden unwillingly borne; probably the horrible manner in which they were got rid of had originally some connection with religious ideas. In remote antiquity the Semites, like many other nations, reckoned consanguinity only by the surest guarantee, that of a common mother. Among the Arabs and other peoples we find a relic of this view, otherwise abandoned long since, in the fact that a man might regard his stepmother as part of his inheritance and take her to wife. The father of the great Omar was the issue of such a marriage.

Nevertheless we cannot but observe a distinct intellectual advance among the Arabs of the period we are now considering. This is specially marked in the efflorescence of poetry. It is of a purely national character and differs wholly from the poetry of northern Semitic races both in structure and substance. We know it only in its fully developed form, the oldest poems which have come down to us in tolerable preservation are of precisely[9] the same character as the later ones, but even they only date back to the first half of the sixth century at farthest. All Arabic poetry is rhymed, and rhyme predominates even in certain solemn modes of speech not subject to strict metrical rule, such as the apothegms of soothsayers. Now, seeing that this form of poetry, up to that time everywhere unknown, springs into prominence in Latin and Greek poems of a popular and devotional character after the fourth century, we are led to conjecture that there may be a connection of some sort with occidental poetry in the employment of this artistic method, which may very well have come into use among the Arabs about the same time. The point of common origin might be Palestine or Syria. Rhymed prose was probably the original form. The whole matter is, however, beyond proof.

The acceptance of this conjecture would not impair the originality of Arabic poetry. Among its great merits is the extremely fine feeling for rhythm which the entirely illiterate Arab authors of these poems and of the rhapsodies which were handed down orally display, by the careful observance of metres which carry out the principle of quantity far more strictly than those of Greek and Latin poetry. In substance these poems generally turn upon the ordinary subjects and interests of Bedouin life, though frequently idealising them; and loftier thoughts are not seldom conspicuous. Some famous poets who took long journeys, sometimes living among Christian surroundings at the courts of Arab vassal kings, sometimes going as far as to Yemen, prepared the way for Islam by disseminating ideas tinged with Christian thought. The spirit that animates the noble tales of Arab heroes and worthies which originated at this time points to an advance in culture. One singular institution appears to have had very advantageous results; during certain months all heathen Arabs observed a truce of God, in which arms were laid aside and no blood was shed. During this period friends and foes met together at certain times and places, originally, no doubt, to celebrate religious rites. By degrees, however, the latter receded into the background; negotiations were carried on, treaties concluded, the poets found an audience, merriment and brisk traffic were the order of the day. Even in the festival at Mecca, which retained more of its religious character, the varied programme ran its round.[16]

Concerning the religion of the ancient Arabs we have no great amount of knowledge. Wellhausen rightly entitles his admirable work on the subject Reste arabischen Heidenthums. Nevertheless we can make certain of some points of special importance with regard to our present consideration. The heathen Arabs possessed many holy places and many ceremonial rites, but very little earnest religious conviction. Excessively conservative by nature, the people observed the customs of their fathers without troubling their minds about their original significance, offered sacrifices to the gods (rude stone fetiches for the most part), and marched in procession round their sanctuaries, without counting much upon their aid or standing in any great awe of them; they cried to the dead, “Be not far from us,” without associating with the cry the idea of a future life which alone gave it meaning. In the north the savage king Mundhir ben Ma-assama (505-554) still sacrificed multitudes of Christian captives in honour of the goddess of the[10] planet Venus, even as the Israelites had done long ago in honour of their God.[17] The Arabs of the Sinaitic peninsula likewise offered human sacrifices to the planet Venus,[18] and we have other accounts of similar human sacrifices among the Arabs of the north. Possibly their close contact with Christians and the adherents of other superior religions may have to some extent revived the old Semitic religious zeal and fanaticism among the Arabs there. Farther south we find only faint traces of human sacrifice and we may regard it as practically extinct by the time of Mohammed.

In the meantime, however, the Arabs who had entered into closer relations with the Roman Empire, and the majority of those who occupied a like position towards Persia, had adopted at least a superficial form of Christianity. There were also some Christians in the interior of Arabia, while in the south Christianity had long since gained a considerable following. It had been persecuted for a while by a Jewish ruler; it was ultimately delivered by the Abyssinian conquest, but had made small progress since then. Christianity as practised by the Syrians, or, worse still, the Abyssinians, was not well adapted to win proselytes among the Arabs. If only the disciplined strength of Rome had acted upon these regions the case would probably have been different. There were Jews here and there in Arabia, and like the Jews of Abyssinia most of them seem not to have been genuine children of Israel, but native converts to Judaism. The Arab Jews, though possessed of no great theological knowledge, adhered strictly to their religion. The majority of Arabs was composed of heathen who had outgrown their religion. There were probably men who were conscious of the defects of this state of things, and recognised that the Christians had in many points an advantage over the heathen. We are told of certain persons from Mecca and its vicinity who adopted, and even preached, a monotheistic faith more or less Christian, but the details are very obscure. Certainly at the beginning of the seventh century not even the profoundest and acutest observer could have foreseen that in the heart of Arabia a religion was soon to arise and to result in the establishment of an Arab empire destined to give new shape to vast regions of the world, including the countries which had been the homes of the oldest civilisations.

The man whose energy gave clear and practical expression to the obscure impulse towards a purer religion arose amidst the worldly-wise Koreish. Flouted at first by his sober-minded fellow tribesmen, he gradually won the victory for his faith, and died the temporal and spiritual ruler of Arabia. To the very combination of qualities to some extent contradictory in his character, he owed his success with such a race as this. He firmly believed in his mission and was unscrupulous in his choice of means; he was a cataleptic visionary, and a great statesman; steadfast in his fundamental convictions and often weak and vacillating in details, he had great practical sagacity and was incapable of keen logical abstraction; he had a bias towards asceticism and a temperament strongly sensuous.

We not only have the fullest accounts of Mohammed’s whole character, but we possess his authentic work, the Koran, which he preached in the name of his God; and yet the extraordinary, attractive, and repulsive man remains in[11] many respects an enigma. He had come across much of Judaism and Christianity, but by verbal report only. For though it remains an open question whether Mohammed was actually ignorant of reading and writing, it is certain that he had neither read the Bible nor any other books. The persons from whom he gathered his information concerning the older monotheistic religions must have been somewhat unlettered folk. This holds good of his Christian instructors more particularly. Certain Judæo-Christian ideas, however, had early laid powerful hold upon him; resurrection, judgment, heaven and hell, strict monotheism and the vanity and culpability of all forms of idolatry. Feeling in himself the divine call, he uttered the thought that possessed him as the word of God; that which the prophets of Israel had done in exceptional cases became with him the set form of his teaching. We may be but ill pleased with the grossness of imagination, the lack of logic, the undeniable poverty of thought, and much besides in the Koran, but this was not the effect it wrought upon his hearers, especially when once their attention had been riveted. It was all new to them, they were thrilled with terror and delight by those gross representations of hell and heaven, to these naïve people the weakness of the reasoning was not apparent, while the strenuousness of assertion took full effect. Moreover they heard only scattered fragments at a time. The revelation of the Koran was accomplished gradually, it extended over a period of more than twenty years, and thus the monotony that repels us was not realised.

But, as has already been said, Mohammed met with small success in his native town, although he was joined by some of the best and most earnest-minded men, like Saad ben Abi Wakkas and Omar. It was not until he took a step unprecedented among the Arabs, and, abandoning his own tribe, migrated with his handful of Meccan followers to dwell among the inhabitants of Yathreb, that he gained a firm footing. The latter, palm-dressers and husbandmen, were a vigorous race, but not intellectually equal to the Koreish. They had given proof of their valour chiefly by perpetual civil broils between the two clans of which they consisted. Through their Jewish neighbours they were at least superficially acquainted with many of the religious ideas with which Mohammed was occupied. The prophet soon gained a large following among them. He established peace within their borders, they recognised him (though not without some exceptions) as their leader, and together with the companions of his wanderings constituted at first the bulk and afterwards the flower of his army.

Mohammed conquered the Meccans mainly by paralysing their caravan trade. When, in the eighth year after his departure from his native town, he made his triumphal entry into it once more, it needed only one great encounter with certain Bedouin tribes to bring the whole of Arabia to his feet and to his faith. If the Bedouins had concluded binding alliances against him in defence of the religious usages of their forefathers and (what was still more important to them) their own independence, he would have laboured in vain; but the inability of the pure Arab to unite for common action and act under discipline, even for the attainment of great ends, made it possible for him to bring one tribe after another over to his side by force or friendly means. He even contrived to turn to practical account the old connection between his family and the tent-dwelling Choza’a in the neighbourhood of Mecca. He retained old customs wherever it was possible so to do, instinctively rather than by deliberate intention. Thus even the greater part of the heathen worship of Mecca was adapted in externals to monotheism and incorporated bona fide into Islam. The first important[12] successes, especially the battle of Bedr (a great battle according to Arab notions), in which the men of Mecca lost about seventy dead and seventy wounded, made a deep and immediate impression: success is the test of proselytisers. The costly presents which Mohammed gave out of his spoils to such distinguished men as had not at once become converts at heart also wrought effectively; in most cases a genuine conversion followed in time. One fact (among others), by which we can estimate the striking impression the prophet produced upon the Arabs, is that as each tribe submitted or adopted his religion it renounced the right of retaliation for the blood shed in the struggle. Under other circumstances this renunciation of blood-revenge, or of wergild at least, would have seemed to the Arab the lowest depth of humiliation. But hard as it might be for the Arabs in general to acknowledge the prophet as their lord, there was at that time no pagan who would have fought in earnest for his religion. At the utmost, an old woman here and there raised a clamour when Mohammed destroyed her idols. Compare this with the fashion in which other Semites fought for their faith, in which the Arabs themselves afterwards fought for Islam. Hence, it is evident that, as has been said, the Arabs of that period had outgrown their religion.

But Mohammed was scarcely dead (632) before the existence of his religion and his empire was again called in question. He had left no instructions as to how the government was to be carried on after his death. A ruler was indeed promptly set up to succeed him. Yathreb, now called Medinat an nabi (the city of the prophet), or merely Medina (the city), was the capital as before, but the simple-minded proposal of the Medinese that they should have one sovereign and the people of Mecca another was rejected with decision by the latter. Abu-Bekr, Mohammed’s most intimate friend, and the father of his favourite wife, became his successor or vicegerent (khalifa, caliph). This is another proof of the high esteem the Koreish enjoyed; for it was a matter of common knowledge that the Arabs would never submit to a non-Koreishite.

For a while, however, most of them displayed but little inclination to remain subjects of the new ecclesiastical state. The utmost concession they would make was to profess their willingness to continue to perform the salat[19] five times a day, but they would henceforth no longer submit to pay an annual quota of their cattle or dates in taxes. Nearly all the old friends of the prophet, even Omar, who now wielded the greatest authority next to the caliph, despaired of subduing the Arabs again. And here we recognise once more the faith that moves mountains in fullest and most effective action. Abu-Bekr was not a man of lofty intellect, but he was firmly convinced that what Mohammed had preached was pure truth, that his orders must be obeyed absolutely, and that God would then give his religion the victory. And the event proved him right. He even insisted on weakening the army of which he had such sore need by despatching a body of troops for an expedition to the north which was by no means urgently necessary, merely because Mohammed had given orders for it, not foreseeing his own death. But otherwise the difficult task of once more subjugating the Arabs was[13] prosecuted with the utmost vigour. Their inability to combine voluntarily for any great object was more patent than ever. Their scattered forces could not withstand a foe united under a single command and with a definite aim in view. The separate tribes were speedily subdued, in most cases without recourse to the strong arm. The inhabitants of the district of Yamama offered frantic resistance; they were tillers of the soil and followers of Maslama (called by the Mohammedans in scorn Musailima, or “little Maslama”), who had set himself up as an opposition prophet in Mohammed’s later years. They fought for their settled homes and their faith, and the battle against Maslama was far more sanguinary than any previous conflict.

The second conquest of Arabia could scarcely have been achieved had not the Koreish stood by Abu-Bekr to a man. The leaders, who for years had striven against the prophet in the stricken field and lost their nearest kin in the struggle, had begun to realise (some of them before the taking of Mecca and the majority directly after) that they would gain enormously in power and consequence by the supremacy of a Koreishite. Mohammed’s marvellous success had made most of them to a certain extent believers. Several of those who had been his most zealous opponents afterwards fell or were severely wounded as champions of his religion. The commander who bore the brunt of the battle for the subjugation of the rebel Arabs, displaying an equal measure of sagacity and energy, was a Koreishite, Khalid ben al-Walid, the same who had been mainly responsible for the victory of the Koreish over the hosts of Mohammed at Mount Ohod, close by Medina, eight years before.

Arabia was hardly reconquered before the great invasion of other countries began. The prophet himself had set on foot some enterprises against Syria, but without any particular result. The great thing now to be accomplished was to transform the Arab hordes from recalcitrant subjects into joyful warriors of God by the twofold prospect of earthly spoil and heavenly rewards. Here we recognise the hand of Omar, to whom the sovereignty passed directly on the death of Abu-Bekr soon after. The wars of conquest which he inaugurated were crowned with brilliant success. It is worth while to consider the subject briefly in detail.

Troublesome enemies as the Arab tribes had often proved to the subjects of the Roman and Persian empires, no one had ever dreamed that they could constitute a menace to either. It is true that when the Moslem inroads began, the districts first affected were in a sorry plight. The frequent wars between the Romans and Persians had sorely enfeebled both empires, and this was more particularly the case with the last great war, which had lasted from 607 to 628. Large areas of Roman territory, especially in Palestine, Syria, and Egypt, had been frightfully ravaged and occupied for years by the Persians. The valiant and wily emperor Heraclius, however, succeeded in turning the tide of fortune, and ultimately dictated terms of peace to the Persians on their own soil. After that the Persian empire had been torn asunder by quarrels over the succession. Both empires had lost the Arab outpost they once possessed. The Persians had annihilated the Roman vassal kingdom of the Ghassanids, and their own subject dynasty in Hira (which had latterly adopted the Christian faith) had been dethroned by King Chosroes II. The folly of this was soon apparent. The Bedouins[14] of the Shaiban tribe utterly routed the royal armies of Persia at Ibu Kar on the frontiers of Babylonia, probably at the very time when the king’s forces were pursuing their victorious progress through the distant west. It was not a great battle, and probably its only direct consequence was that the unwarlike peasants of neighbouring districts were pillaged by the Bedouins; but a victory over an army composed in part of regular troops gave the Arabs confidence. This very Shaiban tribe distinguished itself in the first Moslem advance into Persian territory.

Nevertheless there is much that remains enigmatical in the immense success that attended the Moslems. Their armies were not very large. The emperor Heraclius was an able man, with all the prestige of victory behind him. When the great struggle of Moslem and Persian began, the civil wars of the empire were over, and it had a powerful leader—not indeed in Yezdegerd, its youthful monarch, but in the mighty prince Rustem, who had procured the crown for him. The great financial straits to which both empires were unquestionably reduced must have had its effect upon the number and efficiency of their troops, but that they were still good for something is clear from the fact that both the decisive battle on the river Yarmuk (August, 636) in which the Romans were defeated, and that of Kadisiya (end of 636 or beginning of 637) in which a like fate waited on the Persian arms, lasted for several days. The resistance offered must have been very obstinate. The Roman and Persian armies may have included irregular troops of various kinds, but they certainly consisted largely of disciplined soldiers under experienced officers. The Persians brought elephants into the field, as well as their dreaded mounted cuirassiers. Among the Arabs there was no purely military order of battle; they fought in the order of their clans and tribes. This, though it probably insured a strong feeling of comradeship, was by no means an adequate equivalent for regular military units. Freiherr von Kremer[20] rightly sees in the salat a substitute, to some extent, for military drill. In that ceremony the Arabs, hitherto wholly unaccustomed to discipline, were obliged en masse to repeat the formulæ with strict exactitude after their leader and to copy every one of his movements, and any man who was unable to perform the salat with the congregation was none the less bound to strict compliance with the form of prayer in which he had been instructed. But the main factor was the powerful corporate feeling of the Moslem, the ever increasing enthusiasm for the faith even in those who had at first been indifferent, and the firm conviction that the warriors for the holy cause, though death in the field would prevent them from taking a share in the spoils of victory on earth, would yet partake of the most delightful of terrestrial joys in heaven. Thus the masterless Arabs, who, for all their turn for boasting, had but little stomach for heroic deeds, were transformed into the irresistible warriors of Allah. It was the highest triumph of Semitic religious zeal, a manifestation on a vast scale that among the Arabs the sense of religion had only slumbered, to awaken when occasion arose with true Semitic fury. The same thing has since come to pass again and again on a smaller scale.

For the rest, so far as we can tell, the Arab tribes were not all alike concerned in these wars of conquest. The great camel-breeding tribes of the highlands of the interior, in particular, seem to have taken a much smaller share in them than the tribes of the northern districts of Yemen. It was a point of the utmost importance that the supreme command was almost[15] throughout in the hands of men of the Koreish, who at that time proved themselves a race of born rulers. They led Islam from victory to victory, proving themselves good Moslems on the whole, but without renouncing their worldly wisdom. Above all we are constrained to admire the skill, caution, and boldness with which, from his headquarters at Medina, Omar directed the campaigns and the rudiments of reorganisation in conquered countries.

This unpolished and rigidly orthodox man, who lived with the utmost Arab simplicity while an incalculable revenue was flowing into the treasury of the empire, proved one of the greatest and wisest of sovereigns. His injunction that the Arabs should acquire no landed property in the conquered countries, but should everywhere constitute a military caste in the pay of the state, was grandly conceived, but proved impracticable in the long run. Some of the Christian Arabs at first fought against the Moslem, but without any very great zeal. The majority of them soon exchanged a Christianity that had never gone very deep for the national religion. The great tribe of the Taghlib in the Mesopotamian desert was almost the only one in which Christianity retained its ascendency for any length of time, but it nevertheless fully participated in the fortunes of the Moslem empire, and even there the older faith gradually passed away, as it seems to have done among all Arabs of pure blood.

The victories of the Moslems under Omar were continued under his successor Othman. Syria, Mesopotamia, Babylonia,[21] Assyria, the greater part of Iran proper, Egypt, and some more of the northern parts of Africa were already conquered. The inhabitants of the Roman provinces had almost everywhere submitted to the conquerors without a struggle; in some cases they had even made overtures to them. The deplorable Christological disputes contributed largely to this result: the bulk of the Syrians and Copts were Monophysites and were consequently persecuted in many ways by the adherents of the Council of Chalcedon, who had gained the ascendency at Constantinople. Moreover in other respects the Roman government of the period was not qualified to inspire its Semitic and Egyptian subjects with any great devotion. The rule of the Arabs, though severe, at first was just, and above all they scrupulously observed all treaties whatsoever concluded with them. And the inhabitants of those countries were accustomed to subjection. It is, however, unlikely that they did the victors much positive service beyond occasionally acting as spies, and we must not lay too much stress upon the subjugation of what was on the whole an unwarlike race. Even in Iran, where Islam was confronted by far stronger opposition on national and religious grounds, the bulk of the population, especially in rural districts, offered at most a desultory resistance, while the victors had still many a battle to fight with the forces of the king and the nobles.

This career of conquest was interrupted by the great civil wars. The Arabs knew of nothing between entire liberty and absolute monarchy. The latter was the form which the caliphate first took, but it was universally assumed that the ruler was bound to abide strictly by the laws of religion.[16] When Othman, grown old and feeble, was led by excessive nepotism and other causes into a breach of the latter, the result was a rebellion, in which he ultimately perished (656). The murder was followed by years of civil broils, and some decades later the whole thing was enacted afresh. The war was waged under religious pretexts, and to some extent from religious motives; but it was in the main a struggle for sovereignty between various members of the Koreish. Tribal animosities old and new were brought into play, and induced the tribes to throw in their lot with one or other of the leading parties. The outcome of the two great civil wars was that in each case the ablest man placed himself at the head of the empire; the first to do so, after the murder of Ali, Mohammed’s son-in-law, being the Omayyad Moawiya, son of Abu Sufyan, the leader of the heathen of Mecca against Mohammed. In his reign Damascus, where he had lived as governor for many years before, became the capital in place of Medina. The victor in the second instance was Abd al-Melik, of another branch of the Omayyad family. They were both men of great capacity but essentially worldly-minded. One of the prophet’s grandsons, a son of Ali, had made his peace, while another, Husain by name, fell in a foolish attempt at rebellion (680); though he was thenceforth regarded as a martyr, and much blood was shed to avenge his death on the rulers de facto. The pious stood aloof, sorrowful or indignant, but the sovereignty remained in the hands of the Omayyads. To Europe these civil wars were nothing short of salvation. Had they not checked the career of Arab conquest, Islam might even then have subjugated Asia Minor, the Balkan peninsula, and the whole of Spain, and spread beyond it to Gaul and remoter lands.

The Arabs of that period knew how to conquer and to hold fast what they had won; for organisation they had less aptitude. Wherever they could they left administration, and taxation more especially, as they found it. At first the register of taxes was kept in Greek in the former dominions of Rome, and in Persian in those of Persia; and not until after more than half a century did the Arabic language become predominant in official book-keeping. The Omayyads had gained the mastery by the loyalty of the Arabs of Syria; they were tied to Syria, and the great tracts of territory to the east were hard to rule from thence. Moreover the Moslems of Babylonia, in many respects a more important province, were on the whole hostile to them. And, what was worse, the old lack of discipline among the Arabs had manifested itself strongly in a new form. Instead of small clans being at feud with one another, as had usually been the case in former days, they had ranged themselves in large and mutually hostile groups. One of these was composed of the Arabs of Yemen (real or reputed), two others of the tribes which claimed descent from Ishmael, the Mudhar and Rabia. If a caliph or a caliph’s vicegerent sided with the Yemen he had the Mudhar against him; if he favoured the Rabia the Mudhar were likewise hostile, etc. In the remoter provinces the hostile Arabs sometimes waged regular wars with one another on their own account. To add to this, there were risings of fanatics of various kinds. None but the ablest of the Omayyads (and on the whole they were an able dynasty) could maintain even tolerable order in the vast empire which extended its borders farther and farther when once the civil wars were over. The brief reign of a weakling or a libertine was enough to spoil everything. The purely Arab empire lacked the elements of stability.

Meanwhile, however, great masses of the conquered peoples had gone over to Islam. Temporal advantages on the one hand, and on the other[17] the suitability of this coarse-grained religion to the Semites, and probably to the less educated Egyptians too, led steadily to the abandonment of a Christianity which in these parts was but little superior to Islam. But in Iran also the new religion soon made great advances on its own merits, though in some places (it must be admitted) very much at the expense of the purity of its pristine character. The national pride of the Arabs could not endure the practical application of the theoretical precept of Islam that all believers should be on an absolutely equal footing. The new converts remained Moslems of the second class, and, in certain districts at least, they felt the distinction bitterly. Even at the time of the second great civil war these so-called “clients” (mawali) had on one occasion played a prominent part, though only as the tools of an ambitious Arab.

The action of a “client” population of this sort was fraught with far greater consequences when another Koreishite family—the Abbasids, descendants of an uncle of Mohammed—rose up against the Omayyads. One of their great emissaries placed himself at the head of the Moslem natives of eastern Persia (Khorasan) and by the help of these Iranians the Abbasids secured the throne (750). The change must be regarded as in great measure a strong reaction of the Persian element against the Arab. The long succession of great oriental empires had been interrupted by an empire purely Arab, and the sequence was now renewed. The seat of government was once more transferred to Babylonia; Baghdad took the place of Babylon and Ctesiphon. The great offices of state were already largely filled by persons of other than Arab descent. The old Arab pride of birth was outraged by the fact that no weight was now attached to the consideration of whether the mother of the ruler had been a free woman or a slave, and that thus the Arab strain of the reigning dynasty became more and more interfused with foreign blood as time went on. A second Persian reaction is signalised by the victory won, after a protracted struggle, by the caliph Mamun, the son of a Persian woman, over his brother Amin, whose mother was of the stock of the Abbasids (813). Mamun’s troops were nearly all of them Persians. Their leader, the Persian Tahir, founded the first semi-independent sovereignty on Iranian soil. The forms of government remained Arab to a great extent, and Arabic likewise remained the official language, but genuine Arabdom receded more and more into the background. Above all, professional troops recruited from the peoples of the East, or even of the far West, had almost wholly superseded the Arab levies.

The process of Arabisation went on apace, in the north Semitic countries, Egypt, and even in great tracts of the “Occident” (Maghreb),[22] but this Arab-speaking population, with its profession of Islam and its preponderance of non-Arabic elements, differed widely in thought and feeling from the Arabs of pure blood, who from that time forward were represented (much as they were before the days of Islam) almost entirely by the Bedouins and dwellers in the oases of Arabia and a few places in Africa. The great historic rôle of the pure Arab was played out. But this neo-Arabic nationality gave more or less of the same character to all Islamite countries. This holds good in great measure of Iran and the countries that bordered on it to the northeast, south and southeast, in so far as they fell under the influence of the Arab religion.[23][18] Nevertheless the eastern provinces of the caliphate no more adopted the Arab tongue (which gained the mastery in the principal countries of the western half and even in a great part of the Maghreb) than the eastern half of the Roman Empire had adopted the Latin tongue at the time that the west was almost completely Romanised. The Arab tongue exercised a profound influence none the less upon the Persians and all such nations as drew their culture from Persia. It was not for nothing that even in the last-named country Arabic was long the language of government, religion, erudition, and poetry, and so remained to some extent even after the native language had reasserted itself. Persian (and Hindustani, Kurdish, etc., likewise) had borrowed largely from Arabic, especially in the department of abstract terms—a thing we should not have expected in view of the antiquity of Persian civilisation and the newness of that of Arabia. The influence of Arabic is apparent even in the remotest branches of modern Persian literature, just as all Teutonic languages bear traces of the profound influence of Latin, which formerly occupied a position in Europe analogous in many respects to that of Arabic in Islamite countries.

But if the Arab spirit modified the spirit of Persia in many ways, the converse action was no less strong, possibly stronger. Many political institutions, the forms of polite society, nay, of town life as a whole, luxury, art, and even the fashion of dress, came to the Arabs from Persia. In the Omayyad period Arabic poetry remains in essentials true to the methods of the old heathen Bedouin poets; though side by side with them—and more particularly in the works of the best poets—we mark the gradual growth of a more elegant style, suited to the more cultivated tastes of the towns, and even of a courtly school of poetry. Even in later times, however, the methods of the elder poets found many imitators. But after the Abbasid period the writers of Arabic poems, taken as a whole, were no longer men of pure Arab descent; many were freedmen or of humble origin and Persian or Aramaic nationality. Thus during the Moslem period even the native poets of Persia began by writing in Arabic, and hence the rising school of Persian poetry adhered closely to the traditions of the Arabic school, both in metre and all points of structure, and in subject-matter and verbal expression. Unhappily it showed itself equally ready to imitate the artificiality into which Arabic poetry had sunk at that period. It is true, indeed, that from the outset Persian poetry displayed certain distinctive features, and that its noblest achievement, the national epic, is, broadly speaking, original, though even there Arabic influence is potent in the details.

The lustre of Arab culture, especially as displayed in the large cities of Babylonia, the central province, arose from a liberal intermixture of Persian and Arab elements. In some of these cities Persian was actually spoken by the bulk of the population, at least in the early centuries of Islamism. The influence of Byzantine civilisation on that of Arabia, though far slighter, should not be overlooked. For centuries the upper classes of Babylonia, luxurious and often frivolous as they were, maintained a high level of intellectual activity. The gift of expressing oneself in elegant Arabic with Persian charm and Persian wit was held in the highest esteem. Similar centres of superior culture existed in other Arabic-speaking countries right across to Spain, and for a time even in Sicily. Through all the wide domains of[19] Islam men travelled much, partly to complete their education and acquire the polish of the man of the world, partly for pure love of travel and thirst of adventure. Public and private societies of beaux-esprits and scholars existed in every town of any importance. A brisk trade by land and sea did much to insure the rapid interchange of commodities between regions the most remote, even such as lay far beyond the pale of Islamism, and the result of trade was the accumulation of vast wealth in the great cities. Thither also flowed the taxes levied per fas et nefas, upon the inhabitants of the plains. Of course there was no lack of misery in the great cities of the Arab world, any more than in those of Europe and America at the present day.

The Moslems very early began to hand down biographical records of the prophet, at first by oral, but in the main authentic tradition. More important still to the whole Moslem world was the transmission and collection of precepts covering the whole of life, which pretended to be preserved in the exact form in which they had been uttered by the prophet or made current by his act.[24] It is of the utmost advantage to us to-day that the history of Mohammed’s successors, of their great conquests, and of the empire, follows so immediately upon his own. The several records used to be handed on with the names of those who vouched for them, from the first eye-witness down to the last teller of the tale, variations of statement being placed close side by side. In this way narratives told from the point of view of absolutely different parties have come down to us side by side, many of them dealing with the most important events of the first centuries of Islam, so that historical criticism is frequently in a position to ascertain the main features of what really took place with far greater certainty than if the Arabs themselves had proceeded to draw up a regular history and had manipulated their authorities in their own fashion. The tradition of the deeds and adventures of the ancient heroes of Arabia, too, was carefully cherished, and much of it has come down to us.

In this, as in all branches of exact learning of the Moslems, the Arabic language stands alone at first and even in later times occupies the foremost place, whether the student immediately concerned was of pure Arab descent (which was probably very seldom the case) or of mixed or foreign blood. This holds good of the sciences related to theology, above all, and of all branches of knowledge taught in the schools. Not one of the sciences properly so called was evolved by the Arabs (and the word may be taken in the most comprehensive sense) out of their own inner consciousness, not even grammar, the first branch of learning to assume the form of an exact science; some of the fundamental conceptions involved in it originated in the logic of Aristotle. This science, arising, as it did, out of the necessity of expounding the Koran and ancient poetry and the desire to preserve the classic[20] tongue of the Bedouins, which was liable to rapid alteration in the lands they had conquered, developed then, it is true, on very independent lines. Above all, Arab philosophy is wholly dependent upon Greek works, most of them translated from the original by Syrians or known through Syrian versions.[25] Even Islamite dogmatism found itself constrained to adopt the methods of the pagan philosophy of Greece.