The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

SVB SOLE VANITAS

These sketches of my dear aunt’s life were begun by her only a few years before she died. The discretion as to their publication was left to those on whose judgment she relied, and at their request I have undertaken to prepare the sketches for presentation to the public, and to add to them here and there a few explanatory notes of my own.

I have left her chapters almost exactly as she wrote them. They are well described in her Preface, and are very characteristic of herself. Like a light-winged butterfly she flits from flower to flower, resting long on none, nor caring to return to what she had apparently only quitted for a moment. As is natural to one writing after a lapse of years, she refers within the space of a page or two to events which happened at wide intervals of time.

She dwells with pardonable pride on her love for the drama and the dance. Those who knew well her proficiency in these will prefer to let their memory rest on the brilliant wit and imperturbable good nature which made her a welcome guest in many societies. As a girl she had many opportunities of sharing in the Court xlife of her own country and more than one continental state. Later she became intimate with literary men of the highest position. All through her life she had the entrée to many pleasant country houses, in which were gathered men of influence in affairs, and clever and amusing women full of knowledge of the events of the society in which they moved. She was everywhere popular, and this was not a little due to the fact that she hated scandal and eschewed gossip. She could not be ill-natured if she chose. Probably the severest thing she ever uttered was said of a young man who, seeking a greater prominence than he deserved, had somehow trodden on her toes. “Well, but, Mary, you must at any rate admit that he is a good mimic.” “Is he? then I wish he would always imitate some one else.” I have reason to believe she even repented this.

In my father’s house there was ever a room allotted to her and known by her name. It was occasionally my privilege to occupy it, and to read her collection of volumes of many sorts and many styles. It was there that I read much of Landor, Browning and Mrs Browning, and all, or nearly all, the novels of G. P. R. James, whom she called her literary godfather, and whose influence is traceable in her novels of “A State Prisoner” and “The Foresters.”

With my father’s children, when we were children, she was the object of the keenest admiration and the warmest love. She joyed in our joys, and soothed our sorrows with unfailing tact. In later years it was a source of no little regret to us that her roving life and xisomewhat restless disposition deprived us of some opportunities of returning the care she lavished on us when we were young.

I am probably not alone in wishing that she had written more than she did. The two novels to which I have referred have nothing to lose in comparison with those of later writers, who have had a far wider circulation than she. Graceful and graphic, they are marked by a purity of plot and a delicacy of taste which make no attempt to season pleasure with offence. She was not of those who consider it impossible to interest or amuse without the introduction if not of that which is unclean, at least of that which is bizarre. Later in life she produced a short sketch of character called “Tangled Weft,” which probably would have been more widely read had it been less refined.[1]

1. She also wrote a small volume of Poems, “My Portrait Gallery and other Poems.” Dedicated to Walter Savage Landor. Privately printed in London, 1849.

A kindly critic in the Athenæum of April 1890, immediately after her death, described her conversation as having a charm that was indescribable and perhaps unique. This was probably so. In her, judgment and good sense were as solid as her shafts of wit were keen. She never was the victim, happily for her, of the unreasoning adulation, which so cruelly affected the last years of the life of the most humorous as well as the wittiest Irishman whom it has ever been my good fortune to meet. I knew Father Healy when his life was spent among his friends. I knew him also when he was the xiiidol of a flattering throng, who knew not what they worshipped. Often have I seen him crushed into silence by the persistence of admirers who would never let him utter three words on any subject without beginning to laugh before he could get out with the fourth. Mary Boyle, perhaps because she frequented the society of only those who were friends, was not expected to drop pearls whenever she spoke.

In her letters it is possible that an equal charm might be found. But it would require some patience in seeking; for her handwriting had undoubted peculiarities. “We had a committee on your letter, dear Mary,” once wrote an intimate friend. “We placed it on a table and sat round it, and by dint of looking at it from every point of view we really made out a good deal.” Notwithstanding the difficulty, however, some of those who, like Charles Dickens, Lord Tennyson, and Browning, loved to correspond with her, kept up an exchange of letters which ended only with death.

If my aunt had lived to finish these chapters, the title she desired to apply to them might have been appropriate. As it is, they can scarcely be considered an autobiography. There are lacking, too, references to several houses[2] where she was a frequent guest, and to many circles of friends whose gatherings she helped to make merry. I miss, especially, allusions to Ireland, and above all to that happy shore, “washed by the farthest” lake, where to my knowledge she spent many days of unalloyed enjoyment. Her close friendship with Lady xiiiMarian Alford, the “your Marian” of Lord Tennyson’s verses, is not mentioned.[3] But of the society which Lady Marian loved to gather around her Mary Boyle was a welcome member. It was at Ashridge that some years before the present Bishop of Ely put on Lawn there flashed forth one of those keen answers with which she often delighted her hearers. They were discussing some important point of High Church—Low Church—Moderate Church. As luncheon was announced a prudent critic of the discussion said, “Well, after all, it is very true that via media securum iter.” “You don’t know what that means, Mary?” “Oh, yes, I do! that is what Lord Alwynne says, ‘caution is the way to secure a mitre.’”

2. See Supplementary Chapter.

3. See Supplementary Chapter.

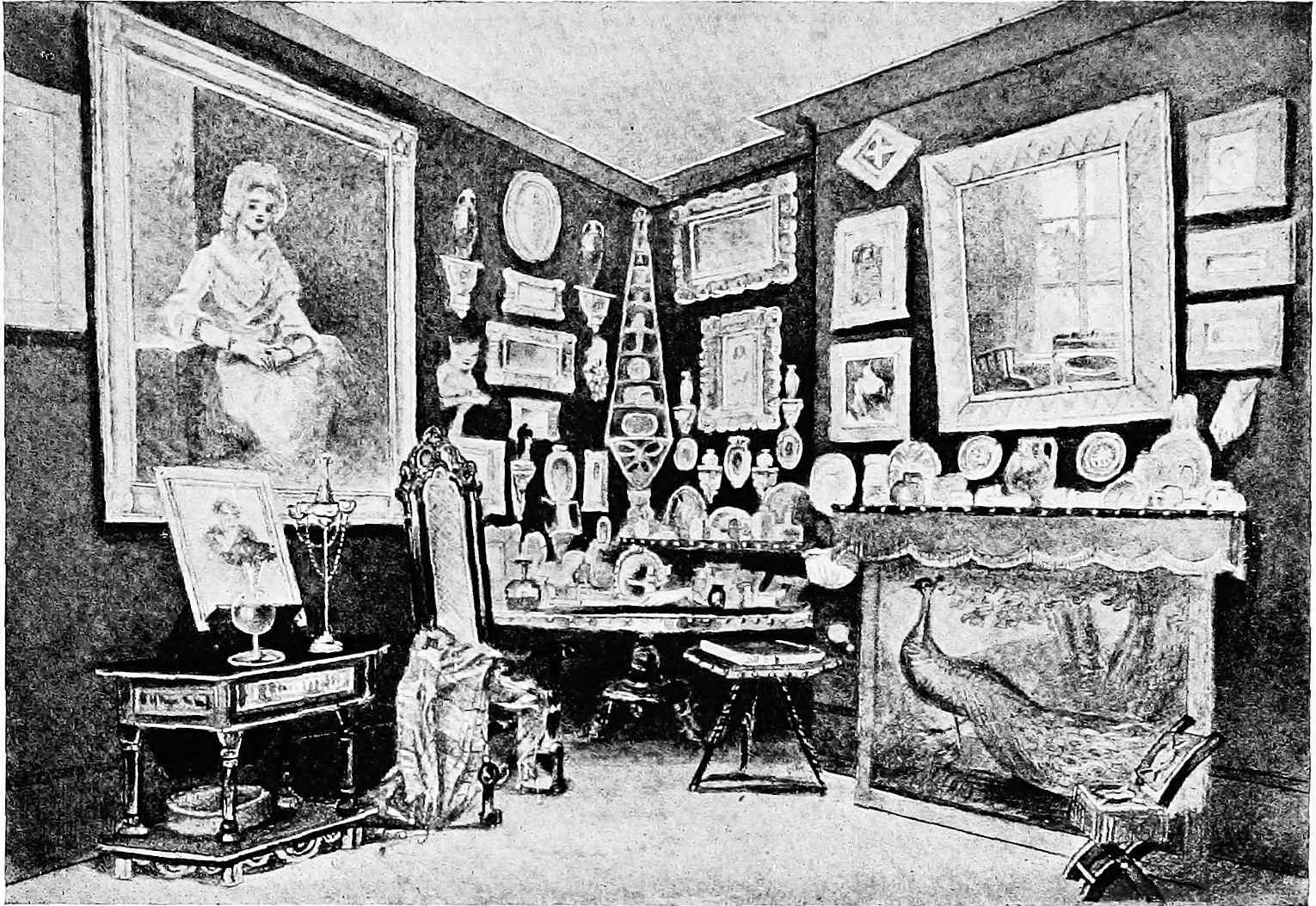

After my father’s death in 1868 Mary Boyle established herself in a small house in South Audley Street. James Russell Lowell, one of the many brilliant men who both got and gave pleasure by a visit to her tiny rooms, says of it: “No knock could surprise the modest door of what she called her bonbonnière, for it opened and still opens to let in as many distinguished persons, and what is better, as many devoted friends as any in London.” This was written in 1888, the last year of her occupancy, and two years before her death. “Miss Mary Boyle,” he goes on to say, “bears no discoverable relation to dates. As nobody ever knew how old the Countess of Desmond was, so nobody can tell how young Miss Mary Boyle is. However long she may live, hers can never be that most dismal of fates to outlive her friends while cheerfulness, xivkindliness, cleverness, and all the other good nesses have anything to do with the making of them.” She certainly had the faculty, a somewhat rare one, of making as well as keeping friends. I have met in the wee chamber, which she was wont to call a drawing-room, men of three generations all coming within the category to which Mr Lowell refers.

“THE BONBONNIÈRE”, 22 SOUTH AUDLEY STREET.

Nor were her guests all of one sex. Neither her cleverness nor her kindliness alone would have sufficed to keep the friendship of the many women who loved her till her death. Together they did. So her rooms were filled with those who were lovely and brilliant as well as those who were learned and clever. The friendship which Mary Boyle maintained with men of distinction in many spheres of life lasted for a long period of years. Mr Lowell in the passage I have quoted was preparing for publication some letters which were written to her by Walter Savage Landor.[4] Those who wish to read these letters in full may find them in the Century Magazine for February 1888. “They are most interesting,” says Lowell, “and have more clearly the stamp of the writer’s character than many of Goethe’s to the Frau von Stein. They give an amiable picture of him without his armour and in an undress, though never a careless or slovenly one.” They are too long to be set out at length here, but I may cite a few brief passages. The opening sentence of the first especially commends itself to me. Lowell thinks it was written in 1842:

“Your letter is a most delightful ramble. I believe I must come and be your writing-master. Certainly if I xvdid nothing else by drilling, I should make rank and file stand closer.”... “You ask me if I have ever seen Burleigh? Yes, nearly half a century ago. Nevertheless I have not forgotten its magnificence. No place ever struck me so forcibly. And then the grounds!”...

4. See Supplementary Chapter.

“And so, Carissima, you want to know whether I shall be glad to see you or sorry to see you on the twentieth. Well then—sorry—to have seen you, glad, exultingly glad, to see you. And now I am resolved not to tell you which I love best, Melcha or Mora.[5] Melcha colpisce fortemente—Mora piu ancora s’innamora: I have broken my word to myself all through you.”... “You see I have learnt to write from you—only I can sometimes get three or four words into a line—which you can never do for the life of you. But there are several in which I find two entire ones. I do not like to spoil the context, otherwise I would order them to be glazed and framed in gold.”...

5. Names of two characters in a poetical drama, which she wrote, called the Bridal of Melcha.

“It is only this evening that I received the Bridal of Melcha. I do not like to be an echo, but I am certain that I must be one in expressing my admiration of it. To-night is our Fancy Ball. You should be at it crowned with myrtle and bay. If I had opened the volume, but at the very hour of meeting my friends there, I could not have refrained from reading it through before I set out. It is indeed already late enough, and I suspect past the post-office hour, adieu, Musa Grazia! and call me in future anything but Dottissimo. Remember, you have a choice of Issimi.”...

xvi“It would grieve me to see religion and education taken out of the hands of gentlemen and turned altogether, as it is in part, into those of the uneducated and vulgar. I would rather see my own house pulled down than a Cathedral. But if Bishops are to sit in the House of Lords as Barons, voting against no corruption, against no cruelty, not even the slave-trade, the people ere long will knock them on the head. Conservative I am, but no less am I an aristocratic radical like yourself. I would eradicate all that vitiates our constitution in Church and State, making room for the gradual growth of what altering times require, but preserving the due ranks and orders of society, and even to a much greater degree than most of the violent Tories are doing.”

... She was associated with Tennyson, Wordsworth, and Landor in a small miscellany which Lord Northampton encouraged and edited in aid of the surviving family of Edward Smedley. Her contribution, “My Father’s at the Helm,” attracted a considerable amount of attention, and achieved some popularity. Better judges than myself encourage me to reproduce it:

Later in life she printed, for a limited circulation only, Historical and Biographical Catalogues of the Pictures at Longleat, Hinchingbrooke, Panshanger and Westonbirt, to xviiiwhich Lowell was probably right in attributing a serious value.

Of all her writings it may be said that their chief charm consists in their reproduction of herself. Standing alone they would have stood strongly. They were meant for her friends, and to her friends, who were many, they conveyed a pleasure which was largely due to connection easily traceable between what was written and her who wrote.

The marriage in 1884 of her niece Audrey, the only daughter of my uncle Charles, with Hallam Tennyson, increased the already keen friendship between her and our last great poet. How intimate it was and how much he valued it, may be gathered even by him who runs, from the stanzas which he sent to her with one of his latest poems. She received them in the spring of 1888 when still mourning the death of her friend Lady Marian Alford.

Close indeed were they both “to that dim gate.” She died in April 1890—and in 1892 the great writer, and the still more kindly man, answered the “one clear call,” and embarked to “meet his Pilot face to face.”

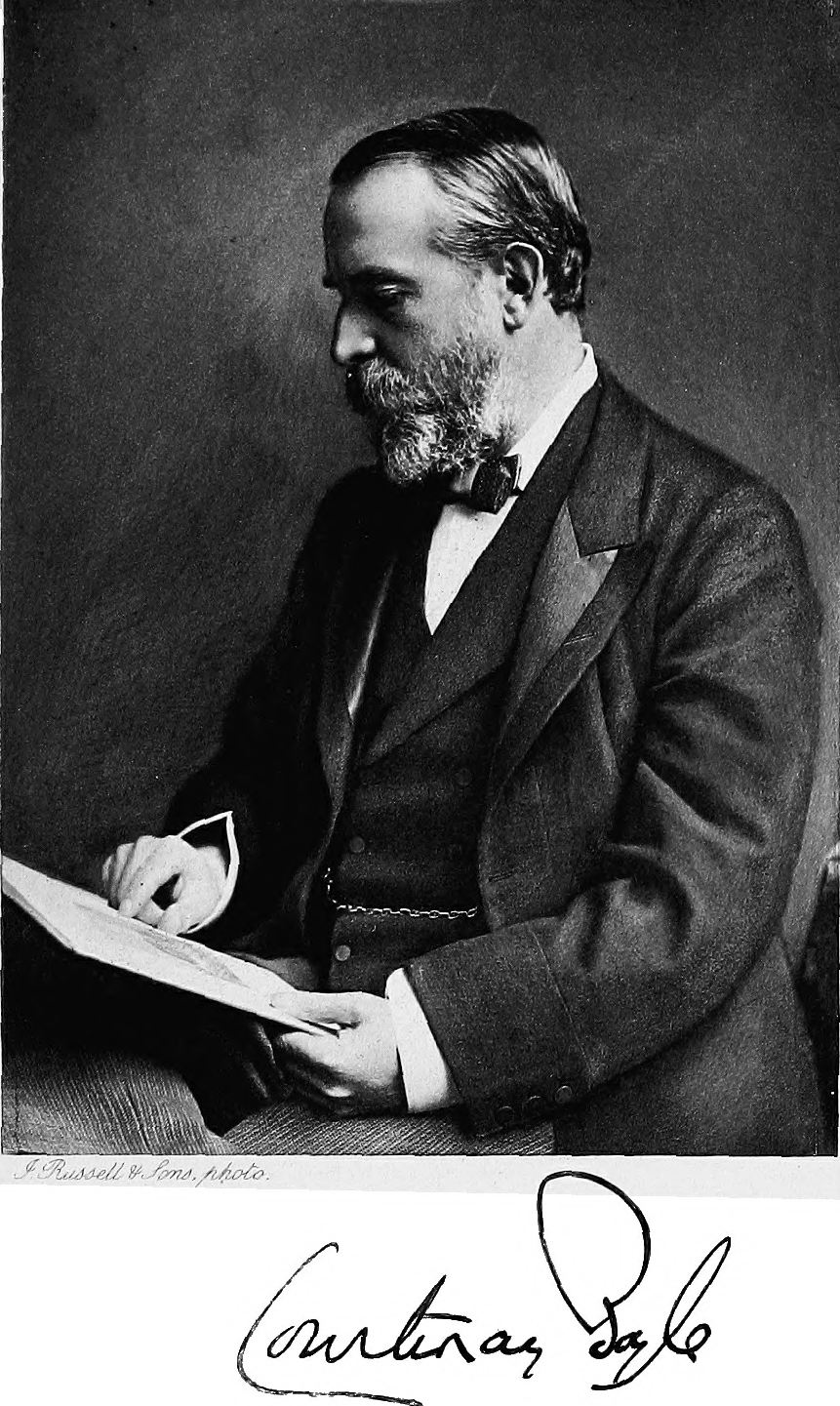

Thus far Sir Courtenay Boyle had written his Introduction to the Memoirs when to him also came the “one clear call,” and he too embarked to “meet his Pilot face to face.”[6]

6. Sir Courtenay Boyle died 19th May 1901.

xxThe papers which now form the Supplementary Chapter arrived too late. It was his intention to have incorporated them in the book, and they would doubtless have necessitated some slight modification in his Introduction. I have preferred to leave his work as he left it, and keep the supplementary papers separate.

September 1901.

J. Russell & Sons, photo.

Courtenay Boyle

I hope my readers, whether gentle or simple, will do me the favour to read this Preface, as I wish to explain a little, perhaps apologise a little, after the usual fashion of people who write their reminiscences. According to custom, I had better begin by stating that it was at the instigation of many personal friends, some of them men of literary tastes and distinction, that I overcame my cowardice to embark on what appeared to me a most hazardous enterprise; but one in which I have found so much pleasure and relaxation—during hours of failing health and growing blindness—that I have often been tempted to say, “Oh that these pages might amuse the reader half as much as they have done the writer.” The choice of a title, which, as Mr Motley in one of his delightful letters says, ought to be “selling and telling” occupied me for a very short time, as far as I myself was concerned. The name of “Vanessa” was endeared to me by old recollections, for I had gained that sobriquet on one occasion, when a goodly troop of friends and relations was assembled in the country house of a dear cousin.

These companions “who did converse and waste the xxiitime together,” enrolled themselves into a band and gave each other fanciful, and as they considered at the time, appropriate names, or nicknames, what the Italians might call Ottias. For instance, a much-loved member of my family, “who looked well to the ways of her household,” and “ate not the bread of idleness,” was christened “Melissa,” or the working-bee; another, whose short-sight was one of his only shortcomings, was dubbed “Belisarius,” while I was unanimously hailed as “Vanessa,” or the Butterfly.

This circumstance, coupled with the love I had for all that was bright, variegated, motley, for bright colours, bright flowers, bright scenes, bright sunshine, made me resolve on the “Autobiography of a Butterfly.” More than one friend argued against my choice, saying it conveyed a wrong impression of my character and ways of thinking, inasmuch as it sounded frivolous and superficial, but I do not think so; it appears to me that the joyous flittings of a butterfly through a summer garden give rather a suitable notion of a wandering, chequered life, replete with light and happiness, or to make use of another metaphor, broken up into bits like an ancient mosaic pavement containing many particles of gold, with an incomplete pattern, so I have stood by my original title and chosen for my emblem a butterfly on the gnomon of that dial, “which only counts the hours that are serene”; for although in recording the days of a long life, the shadow of sorrow and bereavement must necessarily fall on some of the pages, yet it has been my earnest desire to dwell on the brighter side of things—to interest and amuse, rather than to sadden or depress.

xxiiiIn this my chronicle I have striven as far as in me lies to avoid tedium, for is not tedium, either in writing or conversing, “the unpardonable sin”?—likewise the two faults which I have so often detected in the autobiography of others, viz. the pride that “apes humility,” and all the while calls out to the reader (if I may be allowed the vulgarism) “Am I not a fine fellow?” and the more palpable self-conceit and egotism that asserts the fact boldly. Another lesson I have learned in the writings of some of my predecessors, is to refrain from saying bitter things of those who can no longer take me to task for so doing, and from wounding the feelings of survivors who loved them.

One of the chief pleas which was urged on me, and which encouraged me to write the following pages, was the fact that I had been on terms of close and tender friendship with many great men, any mention of whom would be welcome to my readers. But it is one thing to appreciate and remember the delightful companionship of such eminent friends as I may enumerate in these pages, and another to convey to others the faintest idea of their individuality.

During the course of writing I have hit upon what appeared to me a novel expedient. After carrying on my narrative to a certain point, I have inserted detached chapters, treating of people and places which are calculated in my opinion to interest the general reader, and that without much reference to dates; indeed, as far as those terrible stumbling-blocks are concerned, I plead guilty in many cases to inaccuracy, offering as my excuse that xxivI have never kept a continuous journal, but rather have written a few spasmodic pages at intervals. One more excuse, and I have done. In my blindness, I have been helped by more than one kind and patient secretary, but I have sadly missed the power of myself looking over the manuscript and detecting fault in style or frequent tautology. For all these shortcomings I humbly beg pardon, and earnestly desire to be forgiven.

| PAGE | |

| EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION | ix |

| PREFACE | xxi |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | BIRTH, PARENTAGE AND FAMILY | 1 |

| II. | LIFE IN A DOCKYARD—FRIENDS, FAVOURITES AND RETAINERS | 15 |

| III. | MY FIRST PLAY—MARRIAGE OF THE DUKE OF CLARENCE—DEPARTURE FOR SHEERNESS | 25 |

| IV. | EARLY DRAMATIC RECOLLECTIONS—RESIDENCE AT HAMPTON COURT | 33 |

| V. | LIFE AT HAMPTON COURT | 41 |

| VI. | OUR EXTRA HOMES | 51 |

| VII. | MY GRANDMOTHER’S MAID | 64 |

| VIII. | OUR HOUSEHOLD | 73 |

| IX. | BRIGHTON—SCHOOLDAYS | 80 |

| X. | VISITS IN CUMBERLAND AND LEICESTERSHIRE—ACCESSION OF WILLIAM IV. | 92 |

| XI. | FIRST CONTINENTAL TRAVELS—TURIN AND GENOA | 103 |

| XII. | SUMMER AT THE BATHS OF LUCCA | 115 |

| XIII. | SHORT SOJOURN IN FLORENCE | 125 |

| XIV. | SUMMER AT NAPLES | 134 |

| xxviXV. | PISA AND FLORENCE | 145 |

| XVI. | RETURN TO ENGLAND—ACCESSION OF QUEEN VICTORIA—HER CORONATION | 158 |

| XVII. | MILLARD’S HILL—TENBY—CHARLES YOUNG AND A COURT BALL | 163 |

| XVIII. | 1844. TRIP TO THE CHANNEL ISLANDS | 170 |

| XIX. | WHITTLEBURY | 179 |

| XX. | MUNICH—SECOND VISIT TO ITALY | 187 |

| XXI. | ARRIVAL IN ROME, 1846—OCTOBER FESTIVALS AND “POSSESSO” | 194 |

| XXII. | SUMMER OF 1847—FLORENCE, VILLA CAREGGI | 201 |

| XXIII. | RESIDENCE IN FLORENCE—CHARLES LEVER—REVOLUTION, AND THE BROWNINGS | 210 |

| XXIV. | LAST DAYS AT FLORENCE—RETURN TO ENGLAND—MILLARD’S HILL, LONDON, 1848 | 221 |

| XXV. | ROCKINGHAM CASTLE—CHARLES DICKENS | 229 |

| XXVI. | PROTECTIONIST PARTY AT BURGHLEY | 244 |

| XXVII. | ALTHORP | 253 |

| WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR | 262 |

| VISCOUNT STRATFORD DE REDCLIFFE | 265 |

| CARLYLE | 267 |

| THE GROVE | 269 |

| HINCHINGBROOKE | 272 |

| OSSINGTON | 278 |

| ASHRIDGE | 279 |

| WREST PARK | 281 |

| SUB SOLE VANITAS, from a drawing by E. V. B. | Frontispiece |

| “THE BONBONNIÈRE,” 22 SOUTH AUDLEY STREET | xiv |

| SIR COURTENAY BOYLE, from a photograph by J. Russell & Sons | xx |

| MARY BOYLE, from a picture by Madame Perugini | 2 |

| VICE-ADMIRAL THE HON. SIR COURTENAY BOYLE AND THE HON. LADY BOYLE | 8 |

| HON. EDMUND BOYLE, AFTERWARDS EIGHTH EARL OF CORK, BORN 1787; HON. RICHARD BOYLE, ELDER BROTHER OF ABOVE, DIED YOUNG; HON. COURTENAY BOYLE, BORN 1770, AFTERWARDS VICE-ADMIRAL, K.C.B. | 52 |

| LONGLEAT | 54 |

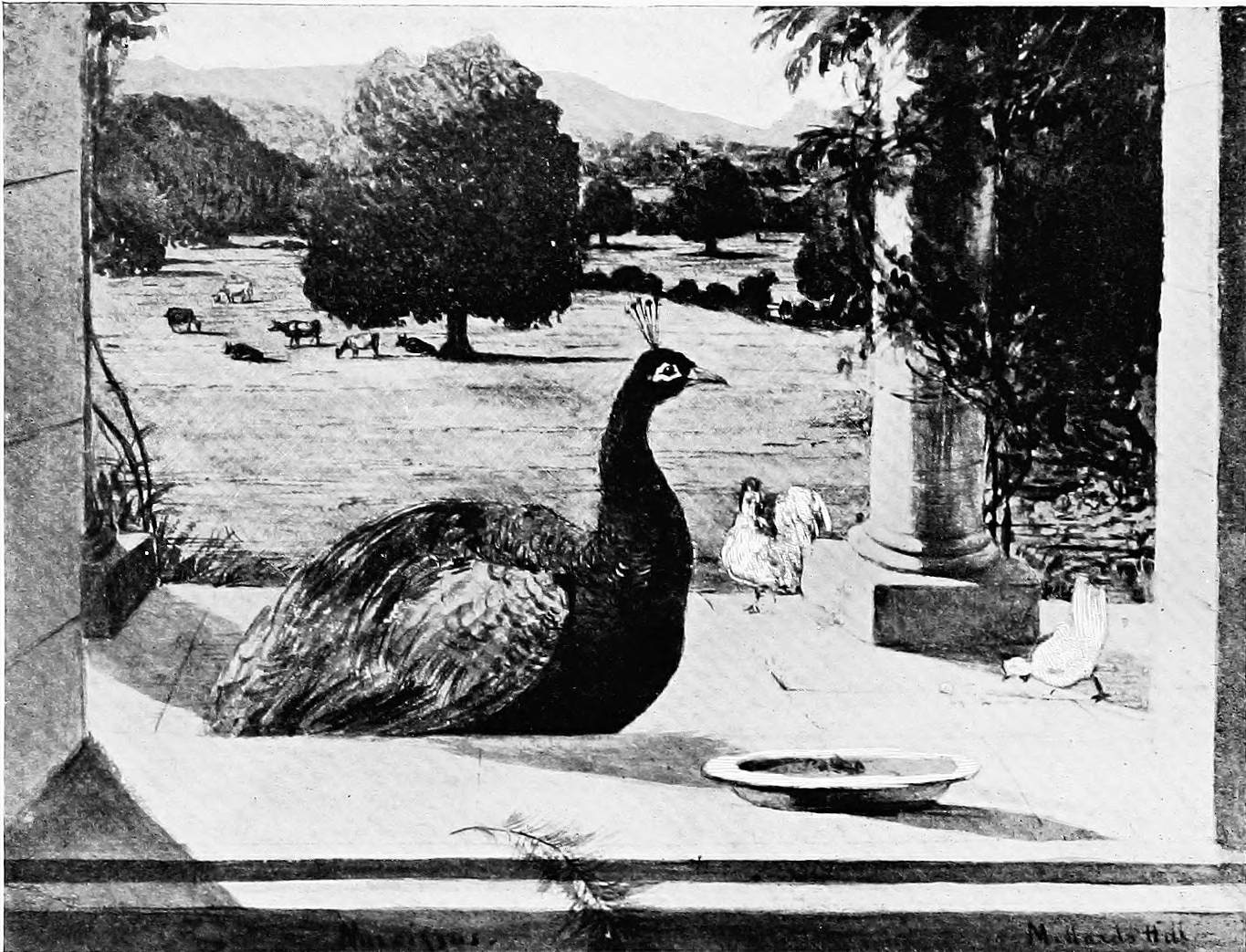

| MILLARD’S HILL, WITH “NARCISSUS” IN THE FOREGROUND, from a drawing by E. V. B. | 164 |

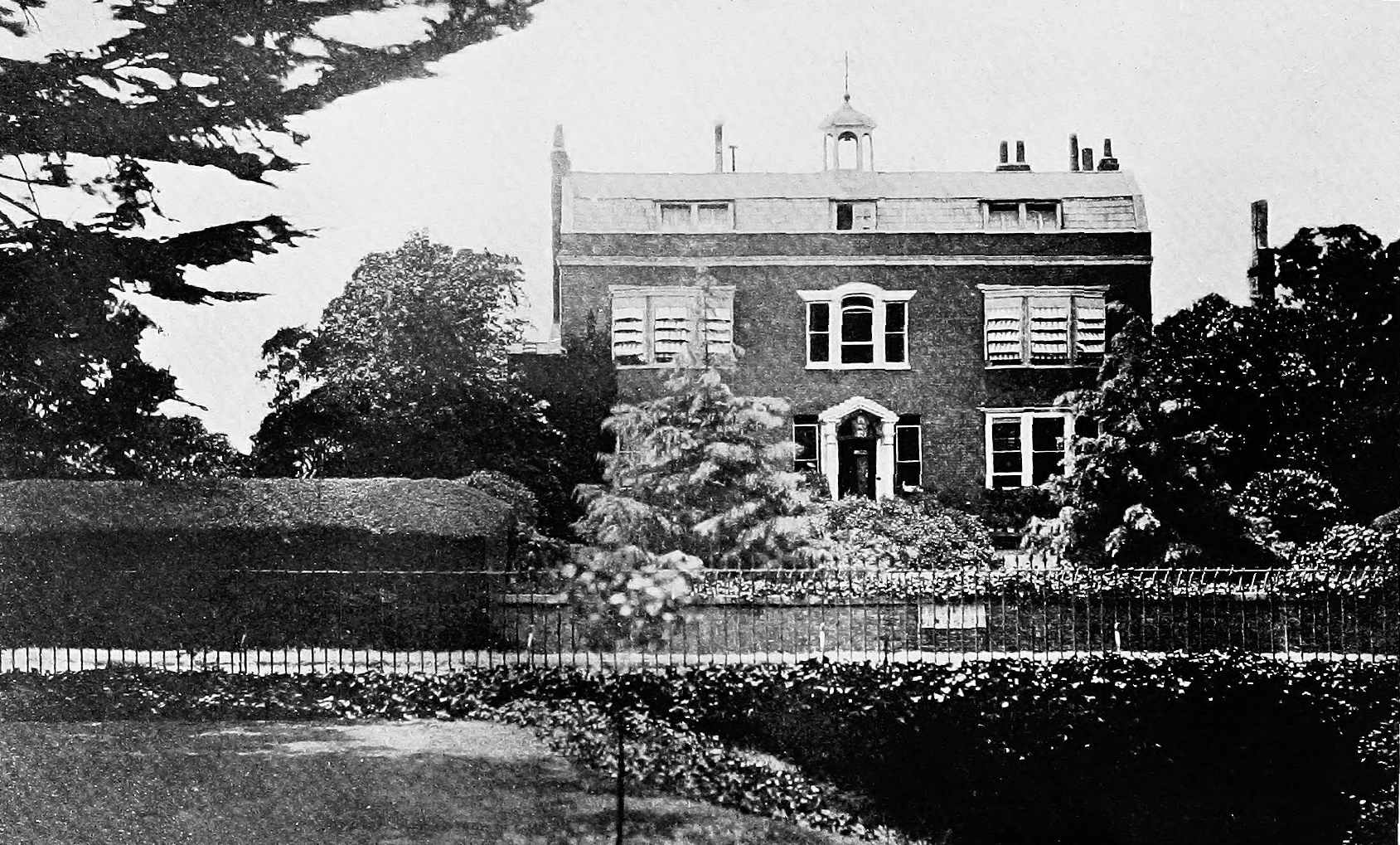

| GAD’S HILL | 238 |

| BURGHLEY | 244 |

| BOWOOD | 250 |

| ALTHORP | 254 |

| THE GROVE | 270 |

| HINCHINGBROOKE | 272 |

| ASHRIDGE | 280 |

The nineteenth century was still in its teens when I first saw the light. Let me pause, lest I make an inaccurate assertion, for I was born on the 12th November, the month of fogs, in Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, London, the home of fogs. It was under the sign Sagittarius, whose patronage, combined with the tastes inherited from two grandfathers, both masters of hounds, made me a “mighty huntress.” “Tuesday’s child,” says the old adage, “is full of grace,” hence my vocation for, and proficiency in, dancing. The motto of my natal month is “fidelity in friendship”; my patron plant, the ivy, which almost invariably clings to things nobler and loftier than itself. And truly in this respect I have been more than commonly blessed, for, through many adverse circumstances, the coffers of my heart have overflowed with the treasures of friendship, and good measure pressed down and running over has been cast into my bosom. 2It is usual, at the commencement of a story, to give the description of the heroine, but a few words will suffice in the present instance. In complexion and colouring I am very fair, and have often flippantly remarked—

Indeed, blondes have a great responsibility placed upon them, as in the old story-books the fair women are very good and the brunettes very bad, though I have not always found the distinction to be carried out in real life. The other chief characteristic of my exterior is that I am very diminutive, a subject on which I have been “chaffed” my life long. I have often been induced to complain that as “Greenwich is the standard for longitude, so Mary is the standard for shortitude.” In spite of which, it has been a cherished vanity of mine that I have very long legs in proportion to my height, and five feet and eight heads (Anglice) in drawing, was the strange description I gave of myself to a friend, whose natural rejoinder was, “What a very remarkable animal!”

One of my chief moral attributes was light-heartedness, and, as Autolycus says:

which is perhaps the reason of my having been an indefatigable walker. From my earliest childhood I have had a decided predilection—I might almost say passion—for all that is bright and brilliant, in garments, furniture, decorations. The “sick turned up with sad” which a few 3years ago held such universal sway in fashion, and which I devoutly hope is now in the wane, never had any charms for me. Firmly believing as I do that the colouring of our native island is not sufficiently cheering of itself to dispense with cheerful adjuncts, I have wooed external brightness, which does not seem unnatural to the tastes of a “Butterfly.” But let me proceed with my narrative.

M Boyle

Being a native of London, I am an undoubted Cockney, a circumstance which embittered many of my childish years, and although by no means of an envious disposition, I assuredly envied my sister the privilege of being born in a delightful old Queen Anne’s mansion, in a pretty room, overhanging a broad gravel terrace, the windows of which were embowered with roses, jasmine, and honeysuckle—Balls Park, the home of my uncle, Lord John Townshend—and I have often upbraided my mother for not having selected so delightful a spot for my entrance into the world.[7]

7. Mary Louisa Boyle, born November 1810, died April 1890.

At the time of my birth, we were in family three girls and two boys—Courtenay, Caroline (Caddy as she was always called), Charles, Charlotte, and myself. But one day, when I was between three and four, my mother asked me if I should not like a live doll to play with? Oh, rapture! Dolls were my passion, but a live doll!—the idea was ecstasy! How well I can recall my first sight of my youngest brother, seated on his nurse’s knee, crowned with one of those quilted contrivances of white satin and rosy pink, that seemed a link between a baby hat of the period and a pudding or bourlet of the olden time. Oh! 4how I then and there loved my live doll, my brother Cavendish—the little Benjamin of the family!—how I did love him with the love of more than half a century. How I love him still, though we no longer tread the earth together, and how fondly I cling to the hope of a reunion in that region—

But to return to the members of our family.[8] My parents were Captain (afterwards Admiral) Sir Courtenay Boyle, second surviving son of Edmund, seventh Earl of Cork and Orrery, and Carolina Amelia, daughter of William Poyntz, of Midgham House, Berkshire.

8. Vice-Admiral The Hon. Sir Courtenay Boyle, born 1770; married 1799 Carolina Amelia, daughter of William Poyntz, Esq., of Midgham, Co. Berks; died May 1844.

Issue of above:

Courtenay Edmund William, Capt. R.N., born 1800; married 1836 Mary, daughter of W. Wallace Ogle, Esq.; died 1859.

Charles John, born 1806, died 1885; married 1849 Zacyntha Moore, daughter of General Sir Lorenzo Moore.

Cavendish Spencer, born 1814; married 1844 Rose Susan, daughter of Captain C. Alexander, Royal Engineers; died 1868.

Carolina, born 1803, died 1883.

Mary Louisa, born 1810, died 1890.

As this is a book of confessions as well as of reminiscences, I may as well make a clean breast of it at once, and own that I take a pride in ancestry, and love Heraldry and History, and many of the “ries,” even as scientific people love the “ologies.” I am proud of my descent 5because my forefathers were many of them great and good men; and I once boasted that I could find five of them in Biographical Dictionaries, inclusive of Robert Boyle, “the Divine Philosopher of the World,” who has been described in one of the aforesaid books as “the Father of Chemistry and the brother of the Earl of Cork.”

I certainly admit, “that it is better to have a glory of your own, not borrowed of your fathers;” but surely it is better to have that than “none at all.”

“I do not care about ancestry,” said my dear friend, Mayne Dickens, to me one day.

“Well,” said I, “you are better off than any of us in that respect, for your great ancestor is still alive; but will not his children’s children glory in his name?”

On my mother’s side I claim collateral relationship with Rosamund Clifford. Now this involves a moral question. May I be pardoned for feeling any pride on that account? It is so romantic, so pathetic a tale, the scandal, if there were any, dates so many centuries back! The damsel was so fair. Besides, has not our beloved “Laureate” of late wiped the blot from fair Rosamund’s escutcheon?

My father had served with great distinction in the Navy, into which he had entered at the very early age of ten, and had been midshipman on board Lord Nelson’s ship, with whom he was a great favourite. I have in my possession two autograph letters of the Hero’s, one written with the right, the other with the left hand, which I will insert here. The first is addressed to Lord Cork; the second to my father.

My Lord,—I have received your letter of the 17th wherein you seem to think that my advice in regard to Courtenay may be of service to him. I wish it may, therefore will give it. In the first place, it is necessary he should be made complete in his navigation—and if this war continues, French is absolutely necessary. Drawing is an accomplishment that possibly a sea-officer may want. You will see almost the necessity of it when employed in foreign countries. Indeed the honour of the nation is so often entrusted to sea-officers, that there is no accomplishment that will not shine with peculiar lustre in them. He must nearly have served his time, therefore he cannot be so well employed as gaining knowledge. If I can at any time be of service to him, he may always call upon me. His charming disposition will ever make him Friends, and he may as well join the ship when his brother goes to the Continent.—I have the honour to be, my Lord,—Your most obedient humble servant,

Earl Cork.

My Dear Boyle,—I am very happy to have you in so fine a frigate under my command, for I am ever yours most faithfully,

Honble. C. Boyle,

H.M.S. Seahorse,

Malta.

During the war with France in the year 1800, my father 7suffered shipwreck on the coast of Egypt, and narrowly escaped with his life. He sent all his crew ashore before he himself left the sinking vessel, headed by an officer with a flag of truce, to make terms with a detachment of French soldiers (the country being then in the occupation of Napoleon’s army), and these soldiers stood on the beach, calmly watching the dangers and struggles of the shipwrecked mariners, as they endeavoured to gain the shore on hastily-constructed rafts, through surf which threatened to swamp them. The sea was running very high, and many of their provisions and possessions were floated off and lost to them for ever. The locality was near Rosetta, and the Frenchmen, in spite of promises of assistance and protection—which men of any chivalrous feeling would surely have afforded to an enemy in such straits—plundered the English sailors, ill-treated them, and threw them into prison, a fate which also befell their commanding officer on landing.

The history of that portion of my father’s life is a long, and to me, interesting one. Suffice it to say, that from all the officials with whom he had to deal, both he and his men met with the harshest and most unjust treatment. Many of his crew succumbed under the hardships to which they were exposed in their dreary and noisome prison-houses. The bright exception to these hard-hearted functionaries was Marshal Kléber, one of Napoleon’s most distinguished generals, a man of high courage, proverbial generosity, and great personal beauty. He was Governor of Cairo at the time, and showed my father especial favour, allowing him out of prison, “on parole,” and courting his society on 8every occasion. He also presented him with a sword, which I grieve to say did not become an heirloom in the family as my father made it an offering to the Prince Regent.

There were many among those who surrounded the Governor, to whom my father was an object of dislike and jealousy, and when General Kléber was assassinated by a fanatic, my father was accused of being an accomplice of the assassin, and condemned to death. His only companion and comforter in those terrible hours being his favourite pointer, “Malta,” who kept him warm by lying on his chest at night, and scaring away the rats and scorpions which infested the cell. While awaiting the completion of his sentence, the prisoner wrote a most pathetic and eloquent farewell to his wife in England, then expecting her confinement. I subjoin the letter, in order that my readers may judge if the epithets I have bestowed on it be ill-chosen. I have read it over and over again, at many periods of my life, and every time

VICE-ADMIRAL THE HON. SIR COURTENAY BOYLE.

THE HON. LADY BOYLE.

Should this ever come to the hands of my beloved wife, I shall be no more. Torn from this world by a cruel enemy, I have been bound to answer for the safety of another captive, a French prisoner in the hands of the Turks, our allies. Should I, however, innocent of the crime imputed to me, suffer this unmerited death, I trust in God that I shall possess sufficient fortitude to die as a man, and sufficient religion to die as becomes a Christian.

My last prayer will be for the happiness and comfort of 9my beloved wife, and of her child, should it have pleased God that she has survived her lying-in. So high an opinion have I of her devout mind and excellent heart, that I shall only recommend her to instil into this dear infant its mother’s principles and virtue.

Assure our friends, my loved Carolina, and particularly our dear mother, that my soul—which will pray to God to receive it during the last moments that it lingers here—will quit this world with emotions of gratitude for kindness to us both, and with a conviction of its continuance to you and to our child.... I cannot write more in the wretched prison where I am confined.

Summon, dear Carolina, your utmost fortitude, and endeavour by prayer to console yourself in this world of trial.

This is the tribute I ask to be paid to the memory of a husband, who wished only to live to promote your happiness. Let my just debts be paid; and give to John Stephens, an old and trusty servant of my father, fifty pounds. Prove this my last will—leaving and bequeathing everything I possess to my beloved wife, Carolina Amelia Boyle.

Wrote in prison, in the citadel of Cairo, after having had an audience with the French general-in-chief, Menou, who informed me that he had determined on my death, and that no application should make him move from his determination.

Adieu, for ever! My much-loved and esteemed wife, adieu!

The cruel sentence would assuredly have been carried into execution, but for the timely arrival in those waters of the gallant Admiral, Sir Sydney Smith, whose influence effected an interchange of prisoners; and so Captain Courtenay Boyle, with his faithful dog, “Malta,” returned in safety to his native land.

10My mother was one of the most beautiful women I have ever seen, in form, feature and complexion, and remained so till old age, and even after death. My eldest brother bore the name “Courtenay,” and, following the profession of his father, he also went to sea when quite a boy. I can well remember our sorrow at his departure, and how, shortly after, there was some vague dread and anxiety respecting him, which I did not quite understand at the time, till on his sudden re-appearance the mystery was solved. He had gone on his first cruise in the (not good) ship Meander, which proved unseaworthy, and narrowly escaped foundering. My brother was asleep in his berth at the moment of extreme peril, and one of the officers forbade that he should be disturbed. “Leave the poor little chap in peace,” he said, “and let him awake in Heaven.”... But our middy came back in safety and lived to be an admiral. He brought home with him specimens of the Meander’s timber, which would have made Mr Plimsoll’s hair stand on end, for they crumbled away in our hands like so much touchwood.

Courtenay’s first cruise I commemorated in rather a peculiar manner, by giving the name of “Meander” to my little bay mare, the first palfrey I ever mounted; and I am glad to say the name brought no ill-luck either to pony or rider. Courtenay was the very moral of a sailor—frank, light-hearted, open-handed, impulsive, of a most impressionable and susceptible heart, which he was in the constant habit of losing to every pretty girl he met. He was frequently engaged (perhaps I had better say entangled) before he had attained Post rank. His promotion came to him 11early. One day he arrived at Hampton Court (before the days that railroads made the old Palace little more than a suburb of London), when his appearance in a yellow “po chay” called forth astonishment and upbraidings at his extravagance. “How else,” was the proud reply, “should a Post-captain travel?” After passing through many vicissitudes in respect of affairs of the heart, Courtenay married one whose remarkable personal charms were her chief recommendation.

Next in succession came my sister Caroline (Caddy), who was often absent from home, going abroad with our Uncle and Aunt Poyntz, whose three daughters[9] were nearer her age and more fitted to be her companions than myself, her junior by several years. Wherever she went, Caddy was much admired. Her colouring was exceptionally bright, and even in her eightieth year, her eyes literally sparkled, and her complexion was of that red and white, so softly blent that it might have become an infant in the cradle. Yet the real, surpassing gift of beauty was reserved for my brother Charles. Ah! what a store of love and memory is connected with that dear name, and how well did the Greek epithet “Kalos” become him, which implies in its melodious sound both moral and physical beauty. The term beautiful does not appear, perhaps, often applicable to a man, but it certainly was to Charles. In feature, colouring and expression he was the counterpart of our mother, the same soft brown hair, the same sapphire blue eyes, the same faultless outline 12of profile. I have a very fine painting of him by Samuel Reynolds, the son of the celebrated engraver. I have also a sketch of his head, a crayon drawing of great beauty, which is doubly valuable to me, as the work and precious gift of our dear friend and world-famed painter, George Watts.

9. Frances, Lady Clinton; Elizabeth, Countess Spencer; Isabella, Marchioness of Exeter.

An earlier friend, John Hayter, brother of Sir George Hayter, some time President of the Royal Academy, also made an equestrian sketch in coloured crayons of Charles in a gorgeous Albanian costume, which he brought with him from Greece, on his return from a cruise with our sailor brother. I shall never forget the sensation caused at the fancy ball at Brighton, when our young Albanian appeared with his sister Caroline, also arrayed in a genuine Greek costume. They were indeed a most beautiful pair, and looked the very embodiment of the hero and heroine of one of Byron’s Eastern poems.

Fourth in succession came a little blue-eyed, fair-haired sister, Charlotte by name, who died when only six years old. In what high relief do such early records stand out on the tablet of a child’s memory. Never shall I forget the tone of deep melancholy in which my mother would 13exclaim: “No one knows what real sorrow is till they have lost a child.”

Charlotte’s burial-place is at Preston, in Kent, not far from Sheerness, where we were then living, and was chosen not alone on account of proximity. The church contains an elaborate monument erected by our ancestor, the first Earl of Cork, after he had made his fortune, to the memory of his parents, both natives of Kent. This monument has, I grieve to say, been suffered to fall into decay, although I have frequently raised my feeble voice in expostulation on the subject. My uncle, Lord John Townshend, wrote my little sister’s epitaph, which is inscribed on a marble tablet in Preston church. To me the lines have ever appeared pathetic, although penned in the old-fashioned style of those days. After recording the dates of her birth and death, they go on to say:—

Some years ago, when on a visit to my dear friend, Charles Dickens, I made a pilgrimage to the tombs of my ancestors, and that of my little sister. Knocking boldly at the door of the Rectory, I told my errand to the clergyman, asking him at the same time for the key of the church. He discreetly allowed me to remain alone 14for some time, and when he followed me, naturally enquired to whom he was speaking. Now, I flatter myself, that my mode of self-introduction was rather original. Pointing to a portion of the monument in question, recording the early demise of a certain Mary Boyle, who had died at least two hundred years before, “That is my name,” I said, “and I am very much obliged to you for your kindness.”

I came between Charlotte and Cavendish, and of the latter I shall make constant mention, as being closely bound up with my life and heartstrings.

Few people have had more homes than I, and few have resided in those homes for, comparatively speaking, so short a consecutive time. I have often said during a long life that I might lay claim in some measure to the character of a gipsy; but then, in the language of the profession to which I always boast that I belong by taste and inclination, I most assuredly never “looked the part.” The first home I recollect is that of Sheerness Dockyard, when my father was Commissioner, and where, with occasional flittings, we remained until I had attained my eighth year. Remote as that period appears in retrospect, Sheerness and its environs are indelibly impressed on my memory—the frightful town, the hideous chapel, the bustling dockyard with its numerous shipping, the comfortable house, where I can still walk in recollection through every room, the pleasant garden, and the pretty conservatory with a large aviary at the end, which contained our favourite birds.

Alas! how well I remember one day as I went in to pay a visit to my feathered friends, I found that the 16mousetrap which had been set for the robber of bird-seed, had caught and beheaded one of our prettiest bull-finches.

The life we led at Sheerness was very peculiar, and I question whether in those bygone days the Viceroy of India, or Ireland, or any other representative potentate, could have been held in higher consideration than the Commissioner of a Dockyard. I am speaking, of course, of our circumscribed official circle. As to the Commissioner’s children, they were looked upon as little else than princes and princesses on a small scale, and to our numerous retainers the slightest wish of the youngest member of the family was as law. This remark held good more particularly with the boat’s crew, who were the most devoted and loyal of our subjects. Two of these men were told off as running grooms to Cavendish and myself, and accompanied us in our daily rides to one of the few green spots in the neighbourhood, called the Major’s March. Here, slipping the reins by which they had led us for safety through the town, they would gaze with admiration on our juvenile feats of horsemanship—our wild careering over what then appeared to us a vast tract of country. Cavendish’s hack was a small Welsh pony, “Black Taffy,” the present of a clerk in my father’s office, who had imported the little charger from his native hills of Cambria. “Meander,” my pony, was a bright golden bay, and many were the races and wild gallops that pretty little pair of ponies afforded us.

Besides our nautical stablemen, the coxswain, a small but most efficient seaman, was a great favourite with us all; and once, during the absence of the men-servants, 17Lowe, as he was by name and stature, did not disdain to wait in the nursery. One day he caused us great merriment by stopping in the act of carrying in the children’s dinner, and placing the wooden tray on the ground with a bang, exclaiming in a stentorian voice: “God bless my soul, I’ve forgot the beer!”—the leg of mutton being left to cool on the carpet, while Lowe descended to the cellar to fetch what he doubtless considered the most important item in the repast.

Another remarkable member of the crew was “Long George,” a handsome giant, but decidedly a mauvais sujet, who was in constant scrapes and periodical danger of dismissal. When so placed, he would invariably steal up to the nursery, and with a timid knock, and in a coaxing tone, ask if “Miss Mary would be so very good as to beg Commissioner to let him off this once”; and downstairs would little Mary fly with a beating heart, to knock at the door of father’s office. After being kept in suspense for a few moments, which seemed to her as many hours, she would scamper back to her “ne’er-do-weel” with the joyful intelligence that he was forgiven, but it was positively for the very last time. Some last times are of frequent recurrence.

Another class of men who came frequently under our notice were the convicts employed in various ways in the dockyard. Our nursery windows commanded a view of a spot where important works were carried on—wharfage, transport, and the like. It rejoiced in the name of Powder-Monkey Bay, a title that did not convey a very clear meaning to our young minds, savouring as it did of a 18semi-zoological character. In those days criminals convicted of the worst offences wore round the waist an iron belt, from which were suspended heavy chains, fastened at each ankle, such as we see in Hogarth’s painting of “Macheath,” and other unworthies. From our windows, we often saw two boys thus accoutred at work, and never did so without a shudder; they were brothers, about fifteen or sixteen years of age, who had murdered their mother. A mother!—in our sight the most sacred, the most beloved of human beings. But there were different characters and various moral grades among these men, and perseverance in good conduct often shortened the period of their imprisonment. Those who had been artizans were allowed to carry on and dispose of their work while on board the hulks; and one of the convicts, who went by the name of “Tidy Dick,” was permitted to make shoes for the Commissioner’s children. We were very fond of him, and participated in his delight when he came to tell us he had obtained his release. We even added the mite of our small allowances to the subscription which our father and mother, the Admiral, and other dignitaries of the dockyard, had raised to fit out “Tidy Dick” with a new suit of clothes, in which he came to bid us good-bye. The word was not invented in those days, but there is no doubt about it, Dick was a regular “swell.”

Another member of the community caused much amusement to my father, who on one occasion went into his garden and found a convict at work after the hour that the warder and the other prisoners had left off for the day.

“What are you here for?” was the question asked in 19tones of surprise. The man jumped up hastily from his kneeling position, and pulling his forelock, answered in the most cheerful and unconcerned tones: “Oh! I am for bigamy, Commissioner.”

Another convict was a skilful tailor, and was permitted the privilege of making costumes for our dramatic company on the occasion of our first play—a subject of great importance, of which I shall treat hereafter.

But while writing of our friends and retainers, I should be ungrateful to omit the mention of a warder endowed with the unusual name of Orper. This man had in our childish eyes attained the very summit of high art, and if in those early times we had ever heard of Michel Angelo, we should have placed Orper on a level with that great man. It must be confessed his genius was not as versatile, neither did he even attempt the modelling of the human form divine; but then his birds! It must also be allowed that his young patrons displayed much discrimination in classing and naming the peculiar ornithological representations which he carved in wood for our delight. These works of art were more especially objects of our admiration and desire, when slightly coloured or tinted. In this respect Orper had an illustrious follower in the celebrated John Gibson, although we are fain to believe that that eminent sculptor had never heard of his predecessor.

I have now come to a portion of my narrative which entails delicate handling, but I have promised that these pages shall contain confessions, and I will therefore lose no time in owning frankly that I was ever a flirt, and will candidly enter on the subject of my juvenile flirtations.

20My first love was naturally much older than myself (being nearly fourteen), and very tall, a very handsome black-eyed fellow, the son of my father’s dear friend and colleague, the Port Admiral. He was by fits and starts very good and condescending to me, and accepted my devotion in rather a patronizing manner. In fact, he was the one qui tendait la joue. I blush to acknowledge that on the Sunday of my first appearance in church (I was then not much more than five years old) I spent nearly the whole of the sermon weighing in my own mind the probability of walking home with George. My wildest hope was fulfilled, little as I deserved it. Hand-in-hand we returned from church, where I had been an inattentive worshipper. My love often passed our nursery windows, of which there were four—two looking round the respective corners—and I invariably ran from one to the other, about the hour I expected his appearance, to watch that beloved, and to me gigantic, form, and follow it with my eyes out of sight. But my attachment though ardent, was not of very long duration; in my juvenile, if fickle, heart, George was ere long supplanted by no less a personage than the Commanding Officer of the Depôt. A man of his years, a soldier, a hero, who wore a Waterloo Medal and a brilliant uniform—a lover full of compliments—for

what chance had poor George the school-boy with such a rival? I used to walk with my sweetheart on the ramparts to hear the band play, and was often allowed to choose the air. To this very day I am not quite sure whether 21gratified vanity or real affection preponderated in my childish breast. I am inclined, at this distance of time, to decide in favour of the first-named feeling, for I was most decidedly puffed up and elated by my military conquest. He often assured me he could never part from me, and would ask my father to give me to him, and that he would place me under a glass case on the chimney-piece of his barrack-room in whatever quarters he found himself, with divers similar compliments of the kind, which, I doubt not, he had addressed before and since to other ears. I listened with intense delight to his declarations, for I had a very low opinion of my own personal appearance, as the other members of my family surpassed me greatly in comeliness. He also presented me with frequent gifts, two of which I yet possess, and I still remember him after the lapse of more than half a century, with feelings of real regard. I never saw him again, but I read of his death, which occurred at a very advanced age, with some emotion, and rejoiced at the encomiums which were passed on him as a man and a soldier. I had also an adorer of quite another stamp, age, and profession. He was a contemporary of my father’s, and a full admiral. I tolerated his attentions, and I am bound to say accepted many gifts, which was scarcely honourable in one whose heart was pledged to another. Sir Thomas Williams (for he was a baronet) gave me one day a pigeon of most beautiful plumage, who was so tame as to eat out of my hand, while I on my part, or rather my father for me, made him the more substantial offering of a cow. The pigeon was called “Tom,” the cow received the name of “Mary,” and the exchange was the cause of much 22bantering on both sides. He was a very benevolent man, and was the original founder or instigator of that excellent establishment “The Naval Female School,” to which, out of regard for my friend’s memory, I became a subscriber when shillings were even scarcer than they are now, and I still continue to take a deep interest in the charity.

I am afraid some of these revelations are not calculated to raise me in the estimation of my readers, yet I must make another, for I have pledged myself to tell the truth, and the truth I will tell, I cannot remember how it came about. I suppose I must have overheard my mother or my governess (who, by the way, was a most beautiful young woman) reading Shakespeare, but I took a most extraordinary (at least so it appeared to my elders) taste—I may say passion—for the plays of our immortal poet. I found out where these volumes were placed on the bookshelf, and, one after another, would take them down and devour them with my eyes—the Midsummer Night’s Dream, with its enchanting scenes of fairyland, being my especial favourite. So far, no harm was done; but alas! for the unfortunate day when I overheard (with the proverbially sharp ears of a little pitcher) my father enlarging to a friend of his on my wonderful taste in literature. The two men agreed that such a predilection and such a precocious power of appreciation showed undoubted promise of future talent. Alas! for the little eavesdropper, who had hitherto enjoyed her Shakespeare on her own account in a simple and single-minded manner. Now, for the first (do I boast, if I say for the last?) time in my life, I posed. When company came to dinner and I was allowed to 23appear in the drawing-room for the brief and dreary period which intervenes between the arrival of the guests and the announcement that “they are served,” I brought in my favourite volume, and was usually found by my father’s friends in an attitude of deep absorption, poring over the pages, and fondly hoping that the company would think me very clever indeed, for I knew father did. I little guessed at the time that I should look back upon myself as I do now, and have for many, many years past, as a revolting little prig. The poses are over, the audiences are not needed, and I love my Shakespeare for himself, and myself, without any ulterior consideration. On the occasion of these, usually official, banquets, I made profound reflections on the law of precedence, as I saw it carried out in one Commissioner’s house, and I came to the conclusion that I did not wish to be a lady of the first standing, as they never had a chance of going in to dinner with the Middies.

One more incident I must recall which was the cause of the greatest amusement and delight to us children, and was indeed planned entirely for our delectation. Two admirals, both well-known and honoured in later years, came to dinner rather early one evening. One was Sir James Gordon, afterwards Governor of Greenwich Hospital, a tall and handsome man, with only one leg, having replaced the other (which he lost, I believe, in action) by what was then called a “Greenwich pensioner”—an ordinary wooden substitute, such as was used by common seamen. The other was Sir Watkin Pell, and he also had but one leg, but, being more of 24a dandy in such matters, he had provided himself with a shapely cork leg and foot, with its smart silk stocking and jaunty pump. Sir James Gordon, on whose knee I was sitting at the moment, asked if the children would not like to see a race between the two one-leggers. The dining-room was divided from the drawing-room by a long and somewhat spacious hall. This he proposed as their race-course, and, amid the clapping of big and small hands, the cheering on and the backing of Sir James Gordon (who was our idol) by the younger ones, the two admirals started, and the Scotchman won in a canter, to our infinite delight.

I now come to a most important episode in my existence, namely my first appearance on what I still fondly call the right side of the footlights, a circumstance most deeply interesting to myself, in which I shall endeavour to enlist the sympathy of my readers.

A subject of such deep and vital interest, to a mind so dramatically constituted as mine, demands a separate chapter. My brother Charles came home for the holidays, from Charterhouse, just in time to celebrate the fourth anniversary of Cavendish’s birthday, and this we proposed to do on a scale of unprecedented magnificence. For we entertained the astounding idea of writing and performing a Tragedy, in which the company, though consisting only of three persons, were to enact seven characters, the principal rôle being undertaken by the authoress, as well as the stage management, decorations, costumes, properties and business.

The plot was of a most thrilling and sensational character, for the better understanding of which I subjoin a Bill of the Play—not as it was, but as it ought to have been.

| CAVENDISH, | King of Little Britain, a Crusader, a Hero and a Lover., | Cavendish Boyle. |

| OSMAN, | An Ex-Slave, a Rebel, and a Usurper, | Charles Boyle. |

| THEODORE, | The Brother-in-Arms and Confidant of the King, | Mary Boyle. |

| SELIM | Confidant of Osman, | Mary Boyle. |

| HIGH PRIEST, | Charles Boyle. | |

| IRENE, | A Converted Slave, betrothed to the King, | Mary Boyle. |

| ZAYDAH, | Her Countrywoman and Confidante | Charles Boyle. |

The name of Little Britain was given out of compliment to the tender years of its monarch, and had no special geographical significance. The curtain drew up on a scene in the palace, where Zaydah announces to her mistress that Osman, the would-be usurper of the throne, desires an audience in the absence of the King, he being deeply smitten with the charms of his lovely fellow-countrywoman. The idea is revolting to the mind of the beautiful Irene. She will not listen for one moment to one word from the lips of this monster of ingratitude, who, not content with endeavouring to supplant his master on the throne, would now attempt to do so in the affections of his beloved. But the rebel is not to be so easily dismissed, and with what a burst of virtuous indignation is he received by the Prima Donna, in whose lofty breast love for one man and hatred for another are now waging war! The words forbidding Osman to lift her hand to his lips—lest 27it should not be “worth her King’s acceptance” when soiled by his barbarous touch—were given in manner worthy of Mrs Siddons, and fairly brought down the house; while the swift transitions of dress and character would have done honour to Mr Irving’s Lyons Mail, had that eminent actor lived at the time. You had scarcely lost sight of the turban, trousers, and scimitar of the rebel, when your eyes were riveted by the charming confidante, Zaydah, like her lovely mistress, a convert to the Christian faith—for the play it may be seen had a decidedly religious as well as moral tendency.

A tender love-scene had no sooner passed between His Sacred Majesty and his betrothed wife, than he was to be seen in earnest conversation with his friend and brother-in-arms, the noble Theodore. In the character of this gallant soldier, Mary was universally allowed to show a masculine vigour and a warlike deportment scarcely to be expected from an actress, however talented. I can well remember how the pride of wearing a hat of unequivocally modern aspect, and flourishing a naked sword, much bigger than myself, made the moment of my appearance as Theodore one of the proudest of my life! In a drama of this nature, virtue was of course triumphant, vice and ingratitude defeated. A terrible scene ensued, in which Osman appeared on the stage flying before an unseen enemy, a victim to remorse, disappointed love and ambition, and commenced, before the audience, to commit that suicide which was supposed to be completed behind the scenes, whither he had repaired to change his dress. Here was our sister Caroline, who, not sharing to the 28full our dramatic enthusiasm, had refused to appear on the stage, but nevertheless “had kindly consented” (after the fashion of Mr Sims Reeves) to take the part of the “Insurrection,” in which character she was much admired in her spasmodic performance on the kettledrum.

The last scene was the Celebration of the Nuptials of King Cavendish and the lovely Irene, their hands being joined by a religious functionary of a most venerable aspect, a snow-white beard descending to his girdle, but of somewhat equivocal denomination. If any fault should be found with an inexperienced though talented author, in respect of calling the minister who performed the marriage ceremony a high priest, and dressing him in Judaical rather than Christian vestments, she would offer as an excuse the observation which a lady, famous for her lisp, once made when speaking of the late Lord Lytton: “We mutht make allowantheth for the ecthentrithiteh of geniuth.”

So fell the curtain on three first appearances, amidst the deafening and enthusiastic applause of an audience composed of very different ingredients; for the Admiral was there and his family, the clergyman and doctor with their wives, the Officer in Command of the garrison, and many other members of the highest importance and standing in the dockyard, as well as minor officials, warders, boat’s crew, and domestic servants, etc.

The whole community rang with the praises of the manner in which the great Dramatic Entertainment had been carried out. Indeed I never can forget the pride with which we listened to the verdict of the head-gardener, 29who was a man of culture (in every sense I emphasize the word), when he assured us that the latter part of the play was the finest thing he had ever seen in all his life. The tailor (a convict) who made the gentlemen’s costumes, also participated in the success, and I remember the delight with which my mother heard, on the day following the representation, how little Cavendish had thanked the costumier most graciously for making the royal robes so well. Let me pause to say they were indeed gorgeous, being constructed out of some old scarlet moreen curtains, bound with yellow cotton ferret, the kingly cap surmounted by a splendid brass ornament, which had fallen off one of the old chairs. “I wish I was really a king,” said the little four-year-old monarch to the convict, “and then I would set you free at once.”

Before taking leave of our life at Sheerness, I must mention that my father and mother were appointed to meet and welcome the Duke and Duchess of Clarence, when the Duchess first came to England as a bride. I am not sure where the meeting took place, but I have a vague idea that it must have been at Gravesend, and that my parents went there in the yacht, called the Chatham, which was always at the Commissioner’s disposal, and in which we often went to London, a voyage of exquisite delight to us children. At all events, I know that Queen Adelaide always said that my mother was her first English friend, while the Duke of Clarence had already shown great favour to my father, and had stood godfather to my poor little lost sister. The last incident that I can remember at Sheerness is being taken to the 30Ramparts, to see the flags of all the ships stationed in the harbour hoisted half-mast high, in consequence of the death of King George III. I have but a dim recollection of the circumstances of our departure, but I know it cost Cavendish and myself bitter tears to part from our humble friends, the boat’s crew, the warders, and the convicts, all of whom participated in our regret.

Thus it will be seen I have lived in the reigns of four sovereigns, and without myself having been attached to a Court, I have seen much at different times of a Court life, as both my father and mother, my eldest brother and sister, were all members of royal households. Moreover, our lines fell in royal residences. My mother in her capacity of bed-chamber woman to Queen Charlotte, had a small set of apartments apportioned to her in the intervals of waiting (and even after the Queen’s death) in St James’ Palace; and she subsequently became the occupant of an excellent suite of rooms in the Palace of Hampton Court. Again, my father who—on leaving the dockyard of Sheerness had an appointment at the Navy Board—came into possession of a very good house attached to that office, in Somerset House, which, likewise, comes under the category of royal residences, or at least did so at one time. In the days of which I am now speaking, there were no buildings on the opposite side of Wellington Street, or, at all events, not sufficient to obstruct the pretty view of the river as far as Westminster Abbey from our windows. Here, as at Sheerness, we children enjoyed great privileges. The terrace overhanging the Thames was a pleasant and favourite resort, and there 31was always a boat at the disposal of the governess and the schoolroom, and two boatmen of our own, successors in our regard to the Sheerness crew. One of them in particular, an intelligent little hunchback, won our esteem, although he, shortly after our arrival, obtained the name of “Danny Man,” from his unworthy prototype in the celebrated novel of the “Collegians,” a book which made so much noise at the time of its publication.

It was our great delight to go by water on Sunday afternoon to Westminster Abbey, and there is no doubt we occasionally cut a grand figure on the river; for when my father went out he had a splendid barge, rowed by boatmen clad entirely in scarlet, with black jockey caps, such as in those picturesque old days formed part of that beautiful river procession in honour of the Lord Mayor, on the 9th of November, over the disappearance of which pageant I have often mourned. We occasionally had picnics, and went down to Greenwich or elsewhere in our splendid barge; and I well remember one day when I had the honour (for so it appeared to me) of dancing a reel with one of our scarlet boatmen and a blue jacket, a regular salt, who was one of the family.

Whilst we are on river topics, I cannot refrain from recalling an incident which amused every one very much including the royal personage who figures in it. One day at Hampton Court when the City barge came down, we went to see her as she arrived in front of the water-gallery at the end of the terrace in the royal gardens. Here the Duchess of Clarence was to embark for luncheon, and, when the feast was ready, naturally walked first towards 32the companion, which was narrow and did not admit of two abreast. Suddenly, quick as a flash of lightning, came the Lady Mayoress, and, brushing past her royal guest, exclaimed: “Beg pardon, your Royal Highness, I take precedence here.”

And no doubt she had the pas, for the Lady Mayoress is queen of the river to within a certain distance of Temple Bar; but the good lady little knew of how much merriment she was the occasion.

Some of our more fashionable friends in London complained of Somerset House “being a long way off,” that ambiguous term which, I suppose in those days, meant a long way from exclusive Mayfair. So indeed it was, but it was not far from the theatres, which, in my estimation, represented Elysium. We had two cousins, both influential in regard to position and fortune, but whose grandeur came home to me as being part proprietors of Drury Lane and the Lyceum. My father was a great lover of the drama, and would often apply for one or other of our kinsmen’s boxes. I can still recall the thrill of joy with which I used to see, on our return from a walk or drive, the large silver ticket, looking more like some official badge, which the Duke of Devonshire had sent us, lying on the hall table, promising a night of rapture—for my father generally stipulated that little Mary should be of the party. I well believe that if I gave myself a little trouble I could bring back to my mind the names of almost every play, and every actor and actress I ever 34saw in those schoolroom days. One piece in particular captivated my girlish fancy: it was called The Cornish Miners, and it is worth my while to remember it, for in that play I first saw those matchless artistes, the Keeleys (hear it, ye gods!) before their marriage. Yes, Mrs Keeley, I venture to hope you will honour this poor tribute with a perusal. It was there I saw Miss Howard, as the boy hero who volunteered to go down the shaft and rescue his comrades, from what peril, and in what manner, I cannot say. My father predicted the future success of the charming young actress, and I can recall even now the delightful comedian who ere long became her husband, with his laughter-provoking face, and lackadaisical air, carrying a lighted candle in the band of his miner’s cap.

Of how many years of entertainment and genial amusement to me was that night the forerunner. I can also remember one of the first performances of the Freischütz, or, as it was then popularly called, the Der Freischütz, in London. Likewise some kind of musical burlesque, in which Madame Vestris sang all the favourite airs of that charming opera, showing how the nurse lulled her bantling to sleep, how the footman blacked the shoes, and how the housemaid trundled the mop, to the soft strains of the various choruses of Weber’s beautiful masterpiece. In those far-off days there was no elaborately-painted drop to give a cheerful termination to the end of the entertainment, but a gloomy, dark-green baize curtain, with which my spirits fell at the same moment, betokening a termination to that night’s joy; and who could tell when the delight-giving cousin would be again propitious. I amused my 35friend Mr Irving[10] by telling him one day that I had been brought up in the stage-box at his theatre, which was then the property of our cousin, Lord Exeter. Yes, it was there I first saw dear Charles Young in The Stranger, and cried so bitterly that my red and swollen eyes prevented my appearing at the ball to which I had been looking forward for weeks; it was then that I made acquaintance with Power, one of the best Irishmen that ever trod or tripped the stage. I say this, not excepting the inimitable Boucicault himself, or my true friend and fellow-actor, Charles Lever. But I must pull up, or my dramatic hobby will take the bit in his mouth, and convert every theatre into Astley’s. Adorable Astley’s!—what a treat you were to me, and how I loved Mazeppa and his horse, the friends of so many years, who continued to urge on his wild career far beyond the allotted span of an equine life; how often have I watched the dear old beast swimming across the mighty rushing river after the tempting bin of corn, visible to my eyes from a side-box.

10. Now Sir Henry Irving.

I am perhaps a little more fastidious now, but the dramatic passion exists in all its fervour, and will till the curtain drops and the lights are extinguished.

But to turn once more to real life. The neighbourhood of Somerset House had other advantages beside those of the theatres, for the Royal Academy still existed under its roof, and almost every Monday morning during the Exhibition, we young ones used to go with our governess to pay the pictures a visit immediately on the opening of the 36doors, when the rooms were empty, swept and garnished, before the crowd and its accompanying dust had arrived. Then there was a walk with father in the early morning to Covent Garden, when the alleys were all watered, the flowers all fresh and fragrant, and the market uncrowded.

Cavendish and I had several governesses before the Miss Richardson of whom I have spoken elsewhere, but the sad time arrived when my darling companion was to betake himself to the Charterhouse, which our brother Charles had lately left in the proud character of orator, a dignity which was afterwards reached in the next generation by another member[11] of our family. On the night ordained for Cavendish’s departure, an upper boy came to our house, who was to be his master at school. At that moment I half disliked good John Horner, because he carried off my beloved brother; but the transient dislike soon changed into a tender friendship, which lasted many years. To break the fall, as it were, my father allowed me to accompany him and the two boys to the old Carthusian edifice, and I proceeded thither with the heaviest of hearts, my position rendered all the more cruel, because I had been forbidden to shed one tear, and was desired to sit far back in the carriage and not show myself. For the school-boy that was to be, assured me that the fellows always chaffed a new arrival about his sister. This was a terrible wound, but in the course of time I became a frequent visitor at Charterhouse, was allowed to go on the green (cruel misnomer for the black 37patch where they played cricket), and, if the truth be told, made close friendships with some of the “fellows.” Alfred Montgomery, Frank Sheridan, and John Horner often came to our house with Cavendish from Saturday till Sunday night, to my inexpressible delight! There are none left now to talk over old Charterhouse days with me!

11. The Editor of these Memoirs, Sir Courtenay Edmund Boyle, K.C.B.

As I have said in my preface, I have not a good head for dates, and I may as well make a clean breast of it at once, and add, for figures of any kind. It may be from want of practice, as far as pounds, shillings, and pence are concerned, for I have never had much experience in counting up thousands on my own account. In respect of dates, then (which, I hope the reader will agree with me, are not of much importance in a narrative of this kind), I do not pretend to the strict order of succession, but I know it was in the year 1821 that George IV. was crowned, and I can well remember the excitement I experienced in seeing my father, mother and sister set off for the coronation. I looked from the window with longing eyes, deeply regretting I was not allowed to be of the party. My father was the most punctual of men—indeed he would have come under the category of those who overdid the virtue. The Duke of Wellington, it will be remembered, upon the Queen saying to him: “You see how punctual I am, Duke, I am even before my time,” replied with blunt veracity, “That, Your Majesty, is not punctuality.” My sister did not inherit this trait in her father’s character. She was late, and in answer to his vociferous summons from the carriage, ran downstairs, in her hurry, without 38her white satin shoes, which were thrown after her from the window. My father’s extreme anxiety to be early on the scene may, however, be accounted for by the fact that he was to form part of the procession, as train-bearer, or page of the coronation robes of his brother, Lord Cork. His dress was not picturesque, being a scarlet and gold frock-coat, or tunic, bound round the waist with a blue silk sash, and I am free to confess that I did not consider his age, stature, or costume in any way calculated to fulfil my ideal of a page; but then the page of my imagination was naturally of a dramatic sort. I do not know that I have yet recovered from the sorrow caused by my missing that magnificent sight. It is true that I have assisted since, at two other coronations, but in both of these there was no banquet, and worse than all, no Champion! The rest of the pageant was doubtless splendid in every sense of the word, but the idea of the Champion was so historical, so romantic, and was I not the most romantic of small human beings? Besides the description of the challenger, who flung down his gauntlet in Westminster Hall, and dared any one to hazard a doubt on the claim of the Sovereign to the throne, was there not a description, I say, of this remnant of chivalry in the pages of Walter Scott’s “Red Gauntlet?” Walter Scott! the god of my literary idolatry, with whose heroes I had fallen in love, in succession—whose heroines I had envied and admired one after another, encouraged thereto by our governess, who judged rightly that children could scarcely be too young to appreciate the beauties of that incomparable novelist. I must confess that 39several alleviations were offered to my regret at not witnessing that coronation. I had a beautiful toy given me of a kind which is now, I believe, obsolete—a small wooden case containing a roll of a coloured representation of the procession, several yards long, and commencing with the figures of Miss “Herb Strewer Fellowes”—for so the lady was designated on her visiting-card—and her maidens, and ending, as Royal processions do, with the most exalted Personage. This was my delight, and I was never tired of drawing it out and gazing at it; but better than all, I went to the theatre with my father, and saw as near a resemblance as could be produced on the stage, to the glories of that day. I can perfectly recall the bow with which Elliston the actor gave the very facsimile of that of His Majesty George IV., which was universally upheld for its surpassing grace. Then, oh joy! There was the Champion in complete armour, on a horse richly caparisoned, whose hoofs sounded on the wooden floor of the stage with a hollow, almost terrible, reverberation, as he backed—backed, and piaffed and caracoled and curvetted, according to all the strict regulations of the haute école.

Dear reader, it was no idle boast about royal residences, for when it came to pass that my father left his post at Somerset House, and, preferring to live in London, took up his abode in Upper Berkeley Street, where we often visited him, my mother and the rest of the family settled at Hampton Court. This proved to be the home of the longest standing I can remember, as with occasional, I may say frequent, flittings, we remained there till 1840. 40The grant of apartments in those days was in the gift of the Lord Chamberlain, and Lord John Thynne (afterwards Lord Carteret) had bestowed a set of rooms, some years before, on his friend and connection, Mrs Courtenay Boyle. Things altogether were at that time on a very different footing to what they are now, for the palace had gained the name of the Quality Alms House, and, as regarded the quality part of the title, it was well named, seeing that the inhabitants counted Seymours, Montagus, Pagets, Walpoles, Ponsonbys, and other names connected with the Upper House, many of them far from being bedesmen and bedeswomen, and for the most part better off than the present inmates of the palace. Then, too, such a minor detail as a husband did not disqualify a lady from being an occupant. Things are entirely on a different footing now. Now the grant of rooms is solely in the hands of the sovereign, and our beloved Queen,[12] who cares for the fatherless, and befriends the cause of the widow, takes more into consideration the needs of the candidates, and the services and merits of the husband or relative they survive, than any recommendation of family or of rank.

12. Her late Majesty Queen Victoria.