The Giant Factotum amusing himself

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Poetry of the Anti-jacobin, by

George Canning and John Hookham Frere and W. Pitt and Marquis Wellesley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Poetry of the Anti-jacobin

Comprising the Celebrated Political and Satirical Poems,

of the Rt. Hons. G. Canning, John Hookham Frere, W. Pitt,

the Marquis Wellesley, G. Ellis, W. Gifford, the Earl of

Carlisle, and Others.

Author: George Canning

John Hookham Frere

W. Pitt

Marquis Wellesley

Editor: Charles Edmonds

Release Date: November 15, 2020 [EBook #63778]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POETRY OF THE ANTI-JACOBIN ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Giant Factotum amusing himself

The fate which usually attends political and satirical writings that owe their origin to passing events, has in no way affected the Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, which, after a lapse of more than ninety years, still continues to interest and amuse. Public opinion never fails, sooner or later, to arrive at a just conclusion as to the merits both of individuals and actions; and though it may often neglect to preserve a meritorious work, never perpetuates a worthless one. Poetry which lashed with so remorseless a hand the patriotic proceedings, and held up to ridicule the persons and habits, of the most distinguished Whig leaders, must have possessed no common merit to have won the encomiums of such liberal politicians and such critics as Mackintosh and Jeffrey, Moore and Byron.

Moore, in his Life of Sheridan, observes: “The Rolliad and The Anti-Jacobin may, on their respective sides of the question, be considered as models of that style of political satire whose lightness and vivacity give it the appearance of proceeding rather from the wantonness of wit than of ill-nature, and whose very malice, from the fancy with which it is mixed up, like certain kinds of fire-works, explodes in sparkles”. This criticism might be applied to some of his own political squibs.

viAs the poems refer to occurrences long since past, a rapid glance at the state of events at that time (1797–8) may render them more intelligible to the generality of readers.

The affairs of England were then in a critical position. The ministry of Pitt was carrying on a fierce war with republican France, the necessity for which had split the public into two great parties. The liberal party alleged, that “the whole misfortunes of Europe and all the crimes of France had arisen from the iniquitous coalition of kings to overturn its infant freedom;—that, if its government had been left alone, it would neither have stained its hands with innocent blood at home nor pursued plans of aggrandizement abroad; and that the Republic, relieved from the pressure of external danger, and no longer roused by the call of patriotic duty, would have quietly turned its swords into pruning-hooks, and, renouncing the allurements of foreign conquests, thought only of promoting the internal felicity of its citizens”.

These sentiments, though supported by the extraordinary eloquence of Fox, Sheridan, Erskine, and others, had but little weight with the minister or the great body of the public. It was impossible to deny that the power of the French Republic was daily increasing, and threatened the subjugation of the greater part of Europe. Buonaparte had overrun Italy, and broken the power of Austria, which, by the treaty of Leoben, was compelled to cede the Netherlands to France, allow the free navigation of the Rhine, and recognise the independence of the newly-erected Italian republics. viiSpain, also, had declared war against Britain, which was thus left to contend singly against the power of France; for the Directory had refused the basis of peace proposed by Lord Malmesbury, that of a mutual restitution of conquests. To add to these embarrassments, during the year 1797 credit became affected, and the Bank of England suspended cash payments; mutinies broke out in the fleets at Spithead and the Nore; and Ireland was on the verge of rebellion. But the talents of Pitt were equal to the occasion, and his power rose higher than ever, when his prognostications were shortly after (in December, 1797) confirmed by the unprovoked attack upon Switzerland by the French. The impolicy of this proceeding was equal to its infamy; for nothing ever done by the revolutionary government contributed so powerfully to cool the ardour of its partisans in Europe, and to open the eyes of the intelligent and respectable classes in every other country to its ultimate designs. Its effect on the friends of freedom in England may be judged of from the indignant protest of Sir James Mackintosh, himself once a warm admirer of the French Revolution, who, in his defence of Jean Peltier, in 1803, for a libel on Buonaparte, declared, “the invasion and destruction of Switzerland an act, in comparison with which all the deeds of rapine and blood perpetrated in the world are innocence itself”. Even before this, the true character of the revolution had been detected by the democratic Coleridge, who gave public utterance to his feelings of horror and disgust in that noble Ode to France written in February, 1797. In a word, to say viiinothing of her other conquests, France, at the beginning of 1798, had three affiliated republics at her side, the Batavian, Cisalpine, and the Ligurian; before its close she had organized three more, the Helvetic, the Roman, and the Parthenopeian.

Pitt’s influence was further increased by the threatened invasion of Great Britain by the French, a proceeding which, as it affected every class in the country, raised the national enthusiasm to the highest pitch, inflamed as it already was by the recent glorious victories off Cape St. Vincent and Camperdown. That they were likely to be in earnest had been already shown by their expeditions to Bantry Bay and Pembrokeshire, and Buonaparte’s boast at Geneva, that “he would democratize England in three months,” proved how much he relied upon the support of the malcontents both in Great Britain and Ireland. The estimates and preparations for defence were, enormous; taxes, to an extent utterly unknown before, were laid on; the Volunteer Bill was passed (Sheridan assisting), by which, in addition to the regular army, a hundred and fifty thousand volunteers were, in a few weeks, in arms; The King was authorized by another bill, in the event of an invasion, to call out the levy, en masse, of the population; the Alien Bill was reenacted; and the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act continued for another year.

But the genius of one man, however great, can effect but little, unless suitably supported by others. The sagacious mind of Pitt had long seen that his party in Parliament were, with very few exceptions, no match for ixhis numerous opponents, powerful both in talent and social position; among whom were Fox, Sheridan, Erskine, Horne Tooke, Whitbread, Nicholls, Courtenay, Fitzpatrick, the Dukes of Norfolk and Bedford, Lord Stanhope, the Duchess of Devonshire, and others. He was always anxious, therefore, to secure whatever available talent presented itself, and immediately on their appearance enlisted under his banners Canning, Jenkinson, Huskisson, and Castlereagh, all men of the same standing, for the first three were born in 1770, and the last in 1769.

The important assistance of Canning was immediately felt, for he was, in the words of Byron, “a genius—almost a universal one; an orator, a wit, a poet, a statesman”. Though he entered Parliament at the early age of 23 (in 1793), and attained the post of Under-Secretary of State for the Foreign Department two years after, he was by no means inexperienced either as a writer or as an orator; for while a student at Eton he had won distinction by his contributions to The Microcosm, a weekly paper published by the more advanced Etonians, and also in the discussions of their Debating Society, which were conducted with strict regard to parliamentary usages. And afterwards, while studying for the law, he took an active part in the proceedings of the debating societies of the metropolis, in which he achieved so much reputation as to lead to his introduction to Pitt, whose party he unhesitatingly joined.

Canning early saw the necessity of the Government’s possessing some literary engine, which, like the Whig xRolliad, published some years before, should carry confusion into the ranks of its enemies. In a lucky hour he conceived the idea of The Anti-Jacobin, a weekly newspaper, interspersed with poetry, the avowed object of which was to expose the vicious doctrines of the French Revolution, and to turn into ridicule and contempt the advocates of that event, and the sticklers for peace and parliamentary reform. The editor was William Gifford, whose vigorous and unscrupulous pen had been already shown in his Baviad and Mæviad; and among the regular writers were: John Hookham Frere, Jenkinson (afterwards Earl of Liverpool), George Ellis (who had previously contributed to the Whig Rolliad), Lord Clare, Lord Mornington (afterwards Marquis Wellesley), Lord Morpeth (afterwards Earl of Carlisle), Baron Macdonald, and others. These gentlemen entered upon their task with no common spirit. Their purpose was to blacken their adversaries, and they spared no means, fair or foul, in the attempt. Their most distinguished countrymen, whose only fault was their being opposed to government, were treated with no more respect than their foreign adversaries, and were held up to public execration as traitors, blasphemers, and debauchees. So alarmed, however, became Wilberforce and others of the more moderate supporters of ministers at the boldness of the language employed, that Pitt was induced to interfere, and, after an existence of eight months, The Anti-Jacobin (in its original form) ceased to exist.

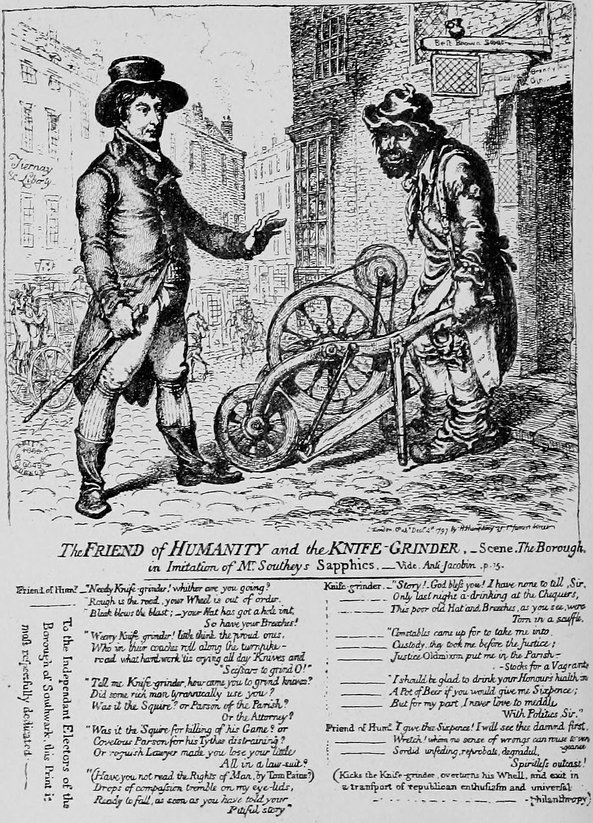

The Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin is not exclusively political. The Loves of the Triangles, a parody on Dr. Darwin’s Loves xiof the Plants, is, in the opinion of a celebrated critic (Lord Jeffrey) of the highest degree of merit; as is also The Progress of Man, a parody on Payne Knight’s Progress of Civil Society; and The Rovers, a burlesque on the German dramas then in vogue, the extraordinary plots of which, as well as their language, alternately ultrasentimental and domestically bathotic, well marked them out for ridicule, is distinguished by sharp wit and broad humour of the happiest kind. Canning and his coadjutors in this piece did a real service to literature, and assisted in a purification which Gifford, by his demolition of the Della Cruscan school of poetry, had so well begun. Of The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-grinder it is unnecessary to speak; perhaps no lines in the English language have been more effective, or oftener quoted.

But Canning’s greatest power is shown in New Morality, which, being the last of the series, seems to have been reserved as a concentrating medium for his pent-up scorn and contempt of the Whigs and their adherents. So that their blows fall thick (for he was powerfully seconded by Frere, Gifford, and Ellis), they care little who suffer from them, and the modern reader is surprised to find Charles Lamb and other non-intruders into politics, figuring as congenial conspirators with Tom Paine!

It is somewhat difficult to regard Pitt in the character of a Wit and a Poet, as from the narrative of most of his biographers, he might be considered as uniformly cold, stiff, and unbending; but his intimate friend Wilberforce, in his Memoirs, thus describes him: “Pitt, when free from shyness, and amongst his intimate companions, xiiwas the very soul of merriment and conversation. He was the wittiest man I ever knew, and what was quite peculiar to himself, had at all times his wit under entire controul. Others appeared struck by the unwonted association of brilliant images; but every possible combination of ideas seemed always present to his mind, and he could at once produce whatever he desired. I was one of those who met to spend an evening in memory of Shakespeare, at the Boar’s Head, Eastcheap. Many professed wits were present, but Pitt was the most amusing of the party, the readiest and most apt in the required allusions.” It is not, therefore, at all unlikely, that he now and then contributed witty verses to The Anti-Jacobin, in addition to those which the Editor has, on probable grounds, ascribed to him in the present volume.

“Critical commentary,” says a critic of the previous edition, “on the merits of The Anti-Jacobin, would be superfluous. Its satire is distinguished for the terse language of its poignant personality, which was often excessively stinging, but seldom offensively coarse. Its best contributors, Canning and Frere, were not mere pamphleteers in verse, like the writers for The Rolliad. They had poetical inspiration and a sprightly joyousness springing from a genial play of the mental faculties. They were ‘Conservatives’ not only in their politics but in their loyal adherence to the ordinances and traditions of classical English literature. False sentiment, tumid diction, mawkish cant, were chastised by them with exemplary efficacy. On the fourth edition of the complete xiiiwork (1799, 2 Vols. 8vo, containing both prose and poetry), they placed the epigraph, Sparsosque recolligit ignes; and in the very last paper (No. 36), the motto on discontinuance was exquisitely happy:—

“And these lines, taken from The Tempest (probably by Canning), have been prophetic of the popularity of their witty verse, still quoted and admired by all lovers of the genius that is airily elegant and strong.”

Water Orton, Birmingham.

Numerous new Biographical and other Notes.

Additions and Corrections to the List of presumed Authors of “The Poetry”.

Selections from the Prose portion of the work, written by the Rt. Hon. G. Canning and his coadjutors.

Account of the various Editions of The Anti-Jacobin, and its successors.

Enlarged articles on the opposition Newspapers abused by The Anti-Jacobin writers.

The curious Abusive and Satirical Index to The Anti-Jacobin; and specimens of a similar Index to The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine.

Selections from The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine—the successor to The Anti-Jacobin—showing that though written by a different body of Authors, both works were animated by the same spirit.

The Anti-Jacobin, or Weekly Examiner. Sparsosque recolligit ignes. From Nov. 20, 1797, to July 9, 1798. 4to.

Nos. 1 to 36; with a Prospectus (complete).

—— The Same. Second and third editions, in 4to.

—— The Same. Fourth edition, revised and corrected. 2 vols. 8vo.

Every Number contained Poetry, the presumed Names of the Authors of which will be found in the Table of Contents of the present volume.

The Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin. 4to.

This volume includes the whole of the Poetry contained in the original Anti-Jacobin, with a few verbal corrections. Previous to its publication, it was announced that it would be illustrated by 40 plates expressly designed by Gillray; but they never appeared. Numerous editions in 12mo subsequently appeared, but without any additions, till those mentioned below.

The Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin. A New Edition, with Explanatory Notes by Charles Edmonds. 12mo.

—— The Same. Second edition, by Charles Edmonds; with additional Notes, the original Prospectus (by the Rt. Hon. G. Canning), and a complete List of the Authors. Illustrated by six etchings after the designs of Jas. Gillray. 12mo.

The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine; or Monthly Political and Literary Censor. From the commencement in July, 1798, to its close in 1821. (The first few vols. contain engravings by Gillray and others, and much Poetry is scattered through the volumes.) 61 vols. 8vo.

For reasons stated on a previous page, Canning and other political friends of Pitt thought it prudent to withdraw themselves from the original Anti-Jacobin, but by a preconcerted arrangement it was determined that the spirit which had pervaded that work, and which had had so powerful an effect on the popular mind, and thereby, in connection with Gillray’s caricatures, so undoubtedly strengthened the hands of the Ministry, should not die, if it could be kept alive by other and congenial writers. In the words of Mr. Fox Bourne (in his valuable work on English Newspapers, 1887): “Though The Anti-Jacobin made its last appearance on July 9, 1798, there was started a few days before a monthly Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine of the same politics, but much less brilliant, and more ponderous. Strange to say, it also was edited by a Gifford, or one who so called himself. John Richards Green was a bold and versatile adventurer, who, having to fly from his creditors in 1782, returned from France in 1788, as John Gifford, and was connected with several newspapers [including the establishment of The British Critic], besides editing The Anti-Jacobin Review. [He also wrote a History of France, and other works.] Befriended in xviiimany ways by Pitt, he wrote a four-volume pamphlet [3 vols. 4to, and also 6 vols. 8vo, both dated 1809], styled the Life of William Pitt, after his patron’s death. James Mill, the friend and associate of Jeremy Bentham, was glad to earn money in his struggling days by writing non-political articles for The Anti-Jacobin Review. William Gifford, it is hardly necessary to state, besides editing Ben Jonson’s Works, and other useful occupations, was the first editor of The Quarterly Review in 1809.”

In the British Museum are two copies of The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine. In one of them the first six vols. contain the Names of the Authors of most of the articles, among whom are the Rev. John Whitaker, author of The History of Manchester, the Rev. Sam. Henshall, author of works on Domesday Book, the Rev. C. E. Stewart, a copious poetaster, etc., and many other clergymen.

The New Anti-Jacobin Review. Delenda est Carthago.

Nos. 1 to 3 seem to be all that were published, and appeared May 6, June 9, and June 23, 1827; price two shillings each.

No. 2 includes what is called a Patriot Portrait Exhibition, which is continued in No. 3. In the latter No. is also an article entitled Canningiana. Published by Saunders and Otley.

The New Anti-Jacobin; a Monthly Magazine of Politics, Commerce, Science, Literature, Art, Music, and the Drama.

Consists of only Nos. 1 and 2. Published by Smith, Elder, & Co., and Carpenter & Son; dated respectively April and May, 1833.

No. 2 contains Horace in Parliament; an Ode to William Cobbett; being a Parody on Horace—In Barinen, Ode 4, Lib. 2. It is accompanied by a full-length portrait of Cobbett.

The above two works, in accordance with their titles, advocate high Tory principles; but though written with great spirit they had but a very short existence. Copies of both will be found in the British Museum.

English Actors in the French Revolution, and Eye-witnesses of the same.

The most complete details hitherto furnished on these interesting subjects will be found in the Nos. for October, 1887, and July, 1888, of The Edinburgh Review, the work of Mr. John G. Alger, the Paris correspondent of The Times. They have since been published in a volume. (Englishmen in the French Revolution: Low & Co., 1889.)

The following notices of the writers of the Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin are derived from the copies mentioned below, and each name is authenticated by the initials of the authority upon which each piece is ascribed to particular persons:—

| C. | Canning’s own copy of the Poetry. |

| B. | Lord Burghersh’s copy. |

| W. | Wright the publisher’s copy. |

| U. | Information of W. Upcott, amanuensis. |

[Although many of the pieces in the following list are attributed to wrong authors, it has been thought more convenient to reprint them as they stood in the previous edition, in order to insert any corrections, as far as Frere is concerned. These are derived from the information of Frere himself given to his nephews, who afterwards edited his works in 1872. They are therefore placed beneath the Title of the piece—between brackets.

The pieces, printed in Italics—between brackets—appear for the first time in an edition of The Poetry.—Ed.]

| PAGE. | AUTHORS. | |

|---|---|---|

| Prospectus of the Anti-Jacobin | 1 | Canning. |

| Introduction | 12 | Canning. |

| Inscription for the Apartment in Chepstow Castle, where Henry Marten, the Regicide, was imprisoned thirty years | 16 | Southey. |

| Inscription for the Door of the Cell in Newgate, where Mrs. Brownrigg, the Prentice-cide, was confined previous to her execution | 16 | Canning, C. Frere, C. |

| The Friend of Humanity and the Knife Grinder | 23 | Frere, C. Canning, C. |

| The Invasion; or, the British War Song | 25 | Hely Addington, W. |

| La Sainte Guillotine: a New Song, attempted from the French | 29 | Canning, C. Frere, C. Hammond, B. |

| [By Canning and Frere only.] | ||

| [Meeting of the Friends of Freedom] | 32 | Claimed by Frere. |

| xxThe Soldier’s Friend | 38 | Canning, C. Frere, C. Ellis, B. |

| [By Canning and Frere only.] | ||

| Sonnet to Liberty. | 39 | Lord Carlisle, B. |

| Quintessence of all the Dactylics that ever were, or ever will be, written | 41 | Canning, B. Gifford, W. |

| Latin Verses, written immediately after the Revolution of the Fourth of September | 43 | Marq. Wellesley, U. |

| Translation of the above | 45 | Frere, B. |

| [Pearce, in his Memoirs of the Marquis Wellesley, gives the credit of this translation to the sixth Earl of Carlisle.] | ||

| The Choice; imitated from The Battle of Sabla, in Carlyle’s Specimens of Arabian Poetry | 48 | G. Ellis, B. |

| The Duke and the Taxing Man | 52 | Bar. Macdonald, C., B. |

| Epigram on the Paris Loan, called the Loan upon England | 54 | Frere, B. |

| [Not claimed by Frere.] | ||

| Ode to Anarchy | 55 | Lord Morpeth, B. |

| Song, recommended to be sung at all convivial meetings convened for the purpose of opposing the Assessed Tax Bill | 58 | Frere, B. |

| [By Canning, Ellis, and Frere.] | ||

| Lines written at the close of the year 1797 | 61 | |

| Translation of the New Song of The Army of England | 63 | |

| Epistle to the Editors of The Anti-Jacobin | 68 | |

| [This Epistle is now known to have been written by the Hon. Wm. Lamb, (afterwards second Viscount Melbourne, and Prime Minister). He was then only in his nineteenth year.] | ||

| To the Author of the Epistle to the Editors of the Anti-Jacobin | 71 | Canning, C. Hammond, B. |

| Ode to Lord Moira | 78 | G. Ellis, C., B. |

| A Bit of an Ode to Mr. Fox | 83 | G. Ellis, C. Frere, B. |

| Acme and Septimius; or, the Happy Union. | 88 | G. Ellis, C. |

| [Mr. Fox’s Birth-Day] | 90 | |

| To the Author of the Anti-Jacobin | 95 | Mr. Bragge, afterwards Bathurst. |

| xxiLines written under the Bust of Charles Fox at the Crown and Anchor | 99 | Frere, B. |

| Lines written by a Traveller at Czarco-zelo under the Bust of a certain Orator, once placed between those of Demosthenes and Cicero | 99 | G. Ellis, B. |

| [Jas. Boswell, jun., asserts, on the authority of the nephew of the great statesman, that the above lines were written by Pitt. This is not improbable: see Note on page 101.] | ||

| The Progress of Man. Didactic Poem | 102 | Canning, C. Gifford, W. Frere, B. |

| [Cantos 1 and 2 by Canning only; and Canto 23 by Canning and Frere only.] | ||

| The Progress of Man, continued | 107 | Canning, C. Hammond, B. |

| Imitation of Bion. Written at St. Anne’s Hill | 111 | G. Ellis, B. Gifford, W. |

| The New Coalition: Imitation of Horace, Lib. 3, Carm. 9 | 114 | |

| [The Honey-Moon of Fox and Tooke, another version of the same by the Rev. C. E. Stewart; published in the Anti-Jacobin Review, vol. i.] | 116 | |

| Imitation of Horace, Lib. 3, Carm. 25 | 119 | Canning, C. |

| Chevy Chase | 125 | Bar. Macdonald, C., B. |

| Ode to Jacobinism | 129 | |

| The Progress of Man, continued | 133 | Canning, C. Frere, C. G. Ellis, B. |

| The Jacobin | 141 | Nares, W. |

| The Loves of the Triangles. A Mathematical and Philosophical Poem | 150 | Frere, C. Canning, B. |

| [All but the last three lines Frere’s.] | ||

| The Loves of the Triangles, continued | 158 | G. Ellis, C., W. Canning, B. |

| [Down to “Twine round his struggling heart,” by Ellis. From “Thus, happy France,” to “And folds the parent-monarch,” by Canning, Ellis, and Frere. The next twelve lines, which were not in the first edition, 1798, were added by Canning.] | ||

| Brissot’s Ghost | 165 | Frere, B. |

| [Not claimed by Frere.] | ||

| The Loves of the Triangles, continued | 170 | Canning B., W., C. Gifford C. Frere C. |

| [By Canning, Ellis, and Frere.] | ||

| xxiiA Consolatory Address to his Gun-Boats. By Citizen Muskein | 182 | Lord Morpeth, B. |

| Elegy on the Death of Jean Bon St. André | 185 | Canning, B., C. Gifford, C. Frere, C. |

| [By Canning, Ellis, and Frere.] | ||

| Ode to my Country, MDCCXCVIII | 193 | Frere, C. B. B., C. Hammond, B. |

| [This is not claimed by Frere.] | ||

| Ode to the Director Merlin | 199 | Lord Morpeth, B. |

| The Rovers; or, the Double Arrangement | 205 | Frere, C. Gifford, C. G. Ellis, C. Canning B., C. |

| [Act 1, Sc. 1 and 2, by Frere—Song by Canning and Ellis; Act 2, Sc. 1 and 3, and Act 3, by Canning; Act 2, Sc. 2, and Act 4, by Frere. The preliminary prose by Frere and Canning.] | ||

| The Rovers; or, the Double Arrangement, continued | 224 | Frere B., C. Gifford C. Ellis, C. Canning, C. |

| An Affectionate Effusion of Citizen Muskein to Havre-de-Grace | 236 | Lord Morpeth, B. |

| Translation of a Letter from Bawba-dara-adul-phoola, to Neek-awl-aretchid-kooez | 242 | Gifford, C., B. Ellis, C., B. Canning, C., B. Frere, C., B. |

| [By Canning, Ellis, and Frere.] | ||

| [Buonaparte’s Letter to the Commandant at Zante] | 248 | |

| Ode to a Jacobin | 251 | |

| Ballynahinch; A New Song | 255 | Canning, C. |

| De Navali Laude Britanniæ | 257 | Canning, B. |

| [Translation of the above | 260 | The late A. F. Westmacott.] |

| [Valedictory Address] | 263 | |

| New Morality | 271 | Canning, B. C. Frere, C. Gifford, C. G. Ellis, C. |

| xxiii | ||

| LINE. | ||

| 1 | From Mental Mists | Frere, W. |

| 15 | Yet venial Vices, &c. | Canning, W. |

| 29 | Bethink thee, Gifford, &c. These lines were written by Canning some years before he had any personal acquaintance with Gifford. | |

| 71 | Awake! for shame! | Canning, W. |

| 158 | Fond Hope! | Frere, W. |

| 168 | Such is the liberal Justice | Canning, W. |

| 249 | O! Nurse of Crimes! | Frere, W. Canning, W. G. Ellis, W. |

| 261 | See Louvet | Canning, W. |

| 287 | But hold, severer Virtue | Frere, W. Canning, W. |

| 302 | To thee proud Barras bows | Frere, W. Canning, W. Ellis, W. |

| 318 | Ere long, perhaps | Gifford, W. Ellis, W. |

| 328 | Couriers and Stars | Frere, W. Canning, W. |

| 356 | Britain, beware | Canning, W. |

| 372 | So thine own Oak | attributed to W. Pitt. |

“Wright, the publisher of the Anti-Jacobin, lived at 169, Piccadilly, and his shop was the general morning resort of the friends of the ministry, as Debrett’s was of the oppositionists. About the time when the Anti-Jacobin was contemplated, Owen, who had been the publisher of Burke’s pamphlets, failed. The editors of the Anti-Jacobin took his house, paying the rent, taxes, &c., and gave it up to Wright, reserving to themselves the first floor, to which a communication was opened through Wright’s house. Being thus enabled to pass to their own rooms through Wright’s shop, where their frequent visits did not excite any remarks, they contrived to escape particular observation.”

“Their meetings were most regular on Sundays, but they not unfrequently met on other days of the week, and in their rooms were chiefly written the poetical portions of the work. What was written was generally left open upon the table, and as others of the party dropped in, hints or suggestions were made; sometimes whole passages were contributed by some of the parties present, and afterwards altered by others, so that it is almost impossible to ascertain the names of the authors. Where, in the above notes, a piece is ascribed to different authors, the conflicting statements may arise from incorrect information, but sometimes they arise from the whole authorship being assigned to one person, when, in fact, both may have contributed. If we look at the references, 167, 185, we shall see Canning naming several authors, whereas Lord Burghersh assigns all to one author. Canning’s authority is here more to be relied upon. New Morality Canning assigns generally to the four contributors. Wright has given some interesting particulars by appropriating to each his peculiar portion.”

“Gifford was the working editor, and wrote most of the refutations and corrections of the Lies, Mistakes, and Misrepresentations.”

“The papers on finance were chiefly by Pitt: the first column was frequently kept for what he might send; but his contributions were uncertain, and generally very late, so that the space reserved for him was sometimes filled up by other matter. He only once met the editors at Wright’s.”

“W. Upcott, who was at the time assistant in Wright’s shop, was employed as amanuensis, to copy out for the printer the various contributions, that the author’s handwriting might not be detected.”—E. Hawkins.

[The following is part of a review, under the above title, of the present editor’s previous edition of The Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, and appeared in The Edinburgh Review of July, 1858. It is reprinted in the Biographical and Critical Essays of A. Hayward, Esq., Q.C., 2 vols., 8vo., 1873. It is introduced here as throwing some additional light on the Writers of the various pieces.]

“... We can hardly say of Canning’s satire what was said of Sheridan’s, that—

But its severity was redeemed by its buoyancy and geniality, whilst the subjects against which it was principally aimed gave it a healthy tone and a sound foundation. Its happiest effusions will be found in The Anti-Jacobin, set on foot to refute or ridicule the democratic rulers of revolutionary France and their admirers or apologists in England, who, it must be owned, were occasionally hurried into a culpable degree of extravagance and laxity by their enthusiasm....”

“We learn from Mr. Edmonds that almost all his authorities practically resolve themselves into one, the late Mr. W. Upcott, and that he never saw either of the alleged copies on which his informant relied. As regards the principal one, Canning’s own, after the fullest inquiries amongst his surviving relatives and friends, we cannot discover a trace of its existence at any period. Lord Burghersh (the late Earl of Westmoreland) was under fourteen years of age during the publication of The Anti-Jacobin; and we very much doubt whether either the publisher or the amanuensis (be he who he may) was admitted to the complete confidence of the contributors, or whether either the prose or poetry was composed as stated. In a letter to the late Madame de Girardin, à propos of her play, L’École des Journalistes, Jules Janin happily exposes the assumption that good leading articles ever were, or ever could be, produced over punch and broiled bones, amidst intoxication and revelry. Equally untenable is the belief that poetical pieces, like the best of The Anti-Jacobin, were written in the common rooms of the confraternity, open to constant intrusion, and left upon the table to be corrected or completed by the first comer. The unity of design discernible in each, the glowing harmony of the thoughts and images, and the exquisite finish of the versification, tell of silent and solitary hours spent in brooding over, maturing, and polishing a cherished conception; and young authors, still unknown to fame, are least of all likely to sink their individuality in this fashion. We suspect that their main object in going to Wright’s was to correct their proofs and see one another’s articles in the more finished state. Their meetings, if for these purposes, would be most regular on Sundays, because the paper appeared every Monday morning. The extent to which they aided one another may be collected from a well-authenticated anecdote. When Frere had completed the first part of The Loves of the Triangles, he exultingly read over the following lines to Canning, and defied him to improve upon them:—

“Canning took the pen and added—

“These two lines are now blended with the original text, and constitute, we are informed on the best authority, the only flaw in Frere’s title to the sole authorship of the First Part. The Second and Third Parts were by Canning.

“By the kindness of [the late] Lord Hatherton, we have now before us a bound volume containing all the numbers of The Anti-Jacobin as they originally appeared, eight pages quarto, with double columns, price sixpence. On the fly-leaf is inscribed: ‘This copy belonged to the Marquess Wellesley, and was purchased at the sale of his library after his death, January, 1842. H.’ On the cover is pasted an engraved label of the arms and name of a former proprietor, Charles William Flint, with the pencilled addition of ‘Confidential Amanuensis’. In this copy Canning’s name is subscribed to (amongst others) the following pieces, which are also assigned to him (along with a large share in the most popular of the rest) by the most trustworthy rumours and traditions:—Inscription for the Door of the Cell in Newgate where Mrs. Brownrigg, the Prenticide, was confined previous to her execution; The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-Grinder; the lines addressed To the Author of the Epistle to the Editors of The Anti-Jacobin; The Progress of Man (all three parts); and New Morality.[1]

“With the single exception of The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-Grinder, no piece in the collection is more freshly remembered than the Inscription for the Cell of Mrs. Brownrigg, who

“The Answer to The Author of the Epistle to the Editors of The Anti-Jacobin is less known, and it derives a fresh interest from the fact, recently [c. 1854] made public, that The Epistle (which appeared in The Morning Chronicle of January 17, 1798) was the composition of William Lord Melbourne. The beginning shows that the veil of incognito had been already penetrated.

“After referring to ‘the poetic sage, who sung of Gallia in a headlong rage,’ The Epistle proceeds:—

“Happily the eminent and accomplished sons of these fathers will smile, rather than blush, at this allusion to their sires, and smile the more when they remember from which side the attack proceeded. It is clear from the Answer, that, whilst the band were not a little ruffled, they had not the remotest suspicion that their assailant was a youth in his nineteenth year. Amongst other prefatory remarks they say:—

“‘We assure the author of the epistle, that the answer which we have here the honour to address to him, contains our genuine and undisguised sentiments upon the merits of the poem.

“‘Our conjectures respecting the authors and abettors of this performance may possibly be as vague and unfounded as theirs are with regard to the Editors of The Anti-Jacobin. We are sorry that we cannot satisfy their curiosity upon this subject—but we have little anxiety for the gratification of our own.

“‘It is only necessary to add, what is most conscientiously the truth, that this production, such as it is, is by far the best of all the attacks that the combined wits of the cause have been able to muster against The Anti-Jacobin.’

“The Answer opens thus:—

“The ‘one good line’ was ‘By Leveson Gower’s crop-imitating wig,’ but the Epistle contains many equally good and some better. The speculations as to its authorship afforded no slight amusement to the writer and his friends....

“New Morality is commonly regarded as the master-piece of The Anti-Jacobin; and, with the exception of a few lines, the whole of it is by Canning. It appeared in the last number, and he is said to have concentrated all his energies for a parting blow. The reader who comes fresh from Dryden or Pope, or even Churchill, will be disappointed on finding far less variety of images, sparkling antithesis, or condensed brilliancy of expression. The author exhibits abundant humour and eloquence, but comparatively little wit; i.e., if there be any truth in Sydney Smith’s doctrine ‘that the feeling of wit is occasioned by those relations of ideas which excite surprise, and surprise alone’. We are commonly prepared for what is coming, and our admiration is excited rather by the justness of the observations, the elevation of the thoughts, and the vigour of the style, than by a startling succession of flashes of fancy. If, as we believe, the same might be said of Juvenal, and the best of his English imitators, Johnson, we leave ample scope for praise; and New Morality contains passages which have been preserved to our time and bid fair to reach posterity. How often are the lines on Candour quoted in entire ignorance or forgetfulness of their author....

“The drama of The Rovers, or Double Arrangement, was written to ridicule the German Drama, then hardly known in this country, except through the medium of bad translations of some of the least meritorious of Schiller’s, Goethe’s, and Kotzebue’s productions. The parody is now principally remembered by Rogero’s song, of which, Mr. Edmonds states, the first five stanzas were by Canning. “Having been accidentally seen, previously to its publication, by Pitt, he was so amused with it that he took a pen and composed the last stanza on the spot....”

xxvii“Canning’s reputed share in The Rovers excited the unreasoning indignation, and provoked the exaggerated censure, of a man who has obtained a world-wide reputation by his historical researches, most especially by his skill in separating the true from the fabulous, and in filling up chasms in national annals by a process near akin to that by which Cuvier inferred the entire form and structure of an extinct species from a bone. The following passage is taken from Niebuhr’s History of the Period of the Revolution (published from his Lectures, in two volumes, in 1845):—

“‘Canning was at that time (1807) at the head of foreign affairs in England. History will not form the same judgment of him as that formed by contemporaries. He had great talents, but was not a great Statesman; he was one of those persons who distinguish themselves as the squires of political heroes. He was highly accomplished in the two classical languages, but without being a learned scholar. He was especially conversant with Greek writers. He had likewise poetical talent, but only for Satire. At first he had joined the leaders of opposition against Pitt’s ministry: Lord Grey, who perceived his ambition, advised him, half in joke, to join the ministers, as he would make his fortune. He did so, and was employed to write articles for the newspapers and satirical verses, which were often directed against his former benefactors.

“‘Through the influence of the ministers he came into Parliament. So long as the great eloquence of former times lasted, and the great men were alive, his talent was admired; but older persons had no great pleasure in his petulant, epigrammatic eloquence and his jokes, which were often in bad taste. He joined the Society of the Anti-Jacobins, which defended everything connected with existing institutions. This society published a journal, in which the most honoured names of foreign countries were attacked in the most scandalous manner. German literature was at that time little known in England, and it was associated there with the ideas of Jacobinism and revolution. Canning then published in The Anti-Jacobin the most shameful pasquinade which was ever written against Germany, under the title of Matilda Pottingen. Göttingen is described in it as the sink of all infamy; professors and students as a gang of miscreants; licentiousness, incest, and atheism as the character of the German people. Such was Canning’s beginning: he was at all events useful, a sort of political Cossack’ (Geschichte des Zeitalters der Revolution, vol. ii., p. 242).

“‘Here am I,’ exclaimed Raleigh, after vainly trying to get at the rights of a squabble in the courtyard of the Tower, ‘employed in writing a true history of the world, when I cannot ascertain the truth of what happens under my own window.’ Here is the great restorer of Roman history—who, by the way, prided himself on his knowledge of England—hurried into the strangest misconception of contemporary events and personages, and giving vent to a series of depreciatory misstatements, without pausing to verify the assumed groundwork of his patriotic wrath. His description of ‘the most shameful pasquinade,’ and his ignorance of the very title, prove that he had never seen it. If he had, he would also have known that the scene is laid at Weimar, not at Göttingen, and that the satire is almost exclusively directed against a portion of the dramatic literature of his country, which all rational admirers must admit to be indefensible. The scene in The Rovers, in which the rival heroines, meeting for the first time at an inn, swear eternal friendship and embrace, is positively a feeble reflection of a scene in Goethe’s Stella; and no anachronism can exceed that in Schiller’s Cabal und Liebe, when Lady Milford, after declaring herself the daughter of the Duke of Norfolk who rebelled against Queen Elizabeth, is horrified on finding that the jewels sent her by the Grand Duke have been purchased by the sale of 7000 of his subjects to be employed in the American war.[3]

xxviii“Amongst the prose contributions to The Anti-Jacobin, there is one in which, independently of direct evidence, the peculiar humour of Canning is discernible,—the pretended report of the meeting of the Friends of Freedom at the Crown and Anchor Tavern.[4] The plan was evidently suggested by Tickell’s Anticipation, in which the debate on the Address at the opening of the Session was reported beforehand with such surprising foresight, that some of the speakers, who were thus forestalled, declined to deliver their meditated orations.

“At the meeting of the Friends of Freedom, Erskine, whose habitual egotism could hardly be caricatured, is made to perorate as follows, &c.... A long speech is given to Mackintosh, who, under the name of Macfungus, after a fervid sketch of the Temple of Freedom which he proposes to construct on the ruins of ancient establishments, proceeds with kindling animation, &c....[5]

“The wit and fun of these imitations are undeniable, and their injustice is equally so. Erskine, with all his egotism, was, and remains, the greatest of English advocates. He stemmed and turned the tide which threatened to sweep away the most valued of our free institutions in 1794; and (we say with Lord Brougham) ‘Before such a precious service as this, well may the lustre of statesmen and orators grow pale’. Mackintosh was pre-eminently distinguished by the comprehensiveness and moderation of his views; nor could any man be less disposed by temper, habits, or pursuits towards revolutionary courses. His lectures on The Law of Nature and Nations were especially directed against the new morality in general, and Godwin’s Political Justice in particular.

“At a long subsequent period (1807) Canning, when attacked in Parliament for his share in The Anti-Jacobin, declared that ‘he felt no shame for its character or principles, nor any other sorrow for the share he had had in it than that which the imperfection of his pieces was calculated to inspire’. Still, it is one of the inevitable inconveniences of a connection with the Press that the best known writers should be made answerable for the errors of their associates; and the license of The Anti-Jacobin gave serious and well-founded offence to many who shared its opinions and wished well to its professed object. In Wilberforce’s Diary for May 18, 1799, we find ‘Pitt, Canning, and Pepper Arden came in late to dinner. I attacked Canning on indecency of Anti-Jacobin.’ Coleridge, in his Biographia Literaria, complains bitterly of the calumnious accounts given by The Anti-Jacobin of his early life, and asks with reason, ‘Is it surprising that many good men remained longer than perhaps they otherwise would have done adverse to a party which encouraged and openly rewarded the authors of such atrocious calumnies?’

“Mr. Edmonds says that Pitt got frightened, and that the publication was discontinued at the suggestion of the Prime Minister. It is not unlikely that Canning, now a member of the House of Commons and Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, found his connection with it embarrassing, as his hopes rose and his political prospects expanded. Indeed, it may be questioned whether a Parliamentary career can ever be united with that of the daily or weekly journalist without compromising one or both. At all events, the original Anti-Jacobin closed with the number containing New Morality, and Canning had nothing to do with the monthly review started under the same name.”

[Considering The Anti-Jacobin from a national as well as a literary point of view, we cannot do better than use a portion of an Essay on English Political Satires by the late Jas. Hannay, in the Quarterly Review, April, 1857.]

“... In the case of The Anti-Jacobin, what are we to say? A hundred opinions may be adopted respecting the French Revolution. Some hate it with unmitigated hatred. Some regret it, but accept its consequences as beneficial to mankind on the whole. Some cherish its memory as a new political revelation of which they hope to see still further results. But a candid man of any of these persuasions must remember that the aim of The Anti-Jacobin was to keep Britain from revolution during 1797–8. It was therefore necessary to fight as our soldiers afterwards did in Spain—to wage such a literary war as suited the agitated spirit of Europe. While we blame Canning, therefore, for speaking as he did of Madame Roland, we must not forget the indecorum of her Memoirs, or that it was from persons of her party that vile aspersions were cast upon the character of Marie Antoinette. There were men quite ready to begin the same work over here that had been done in France, and that in a spirit of vulgar imitation, and under quite different circumstances. They had to be shot down like mad dogs; for a cur, though contemptible in ordinary cases, becomes tragic when he has hydrophobia.

“For The Anti-Jacobin must be claimed an honour which can be claimed for scarce one of the works we have passed under review. Let us waive the question how much we may have owed it for helping to inspire that unity and stout insular self-confidence which carried us through the great war,—whole within and impervious without. Let us consider it only in a literary point of view, and we shall find it enjoying the rare distinction that its best Satires live in real popular remembrance. The Knife-Grinder, with his

is almost as widely known as our nursery rhymes.

“But if The Anti-Jacobin excels all similar works in popularity, and in the eminence of its contributors, it also excels them in another important particular. It contains on the whole a greater number of really good things than any one of them. The Loves of the Triangles, in which,

is an irresistible parody, and likely to keep the original of Darwin [Loves of the Plants] in remembrance. Gray’s Odes have survived the burlesques of Colman; and the Country and City Mouse of Prior and Montague is neglected by nine-tenths of those who read with admiration the Hind and the Panther. But Darwin’s case is peculiar. Other poems live in spite of ridicule; and his Loves of the Plants in consequence of it. The Attic salt of his enemies has preserved his reputation.

“There is always a purpose in The Anti-Jacobin’s view something more important than the mere persiflage that teases individuals. Like the blade of Damascus, which has a verse of the Koran engraved on it, its fine wit glitters terribly in the cause of sacred tradition.”

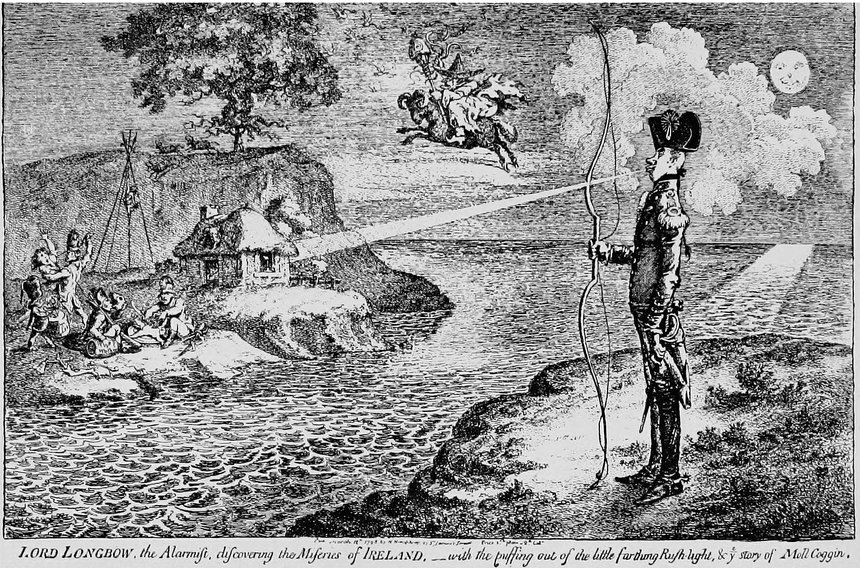

| THE GIANT FACTOTUM AMUSING HIMSELF. | (Frontispiece.) | |

| Pitt, with his right hand is playing at cup and ball; the latter being a globe to denote his influence over foreign countries as well as at home. His right foot is supported by Dundas and Wilberforce, and is extended to be submissively kissed by his ministerial followers, foremost of whom is Canning. With his left foot he has crushed the Opposition. On the same side is a document labelled “Resources for supporting the War,” with a collection of coin, evidently destined for foreign subsidies. On his right side are various official returns of volunteers, seamen, regulars, and militia. He is thus prepared to carry on the war abroad, and maintain tranquillity at home. | ||

| THE FRIEND OF HUMANITY AND THE KNIFE-GRINDER. | Page 23 | |

| Scene, the Borough of Southwark, with a portrait of George Tierney, its able and radical representative. Published Dec. 4, 1797, as a graphic illustration of the Parody of Southey’s poem, The Widow. | ||

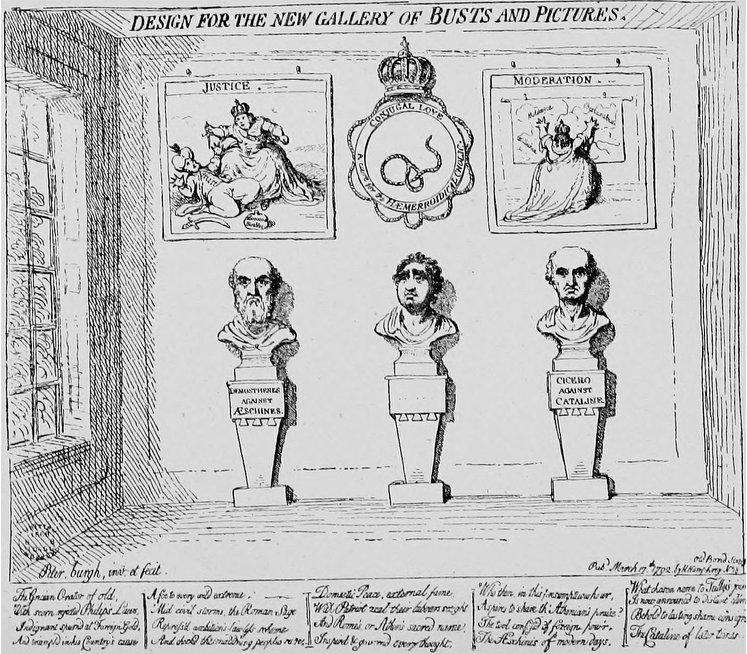

| LORD LONGBOW, THE ALARMIST, DISCOVERING THE MISERIES OF IRELAND. | Page 78 | |

| A characteristic portrait of the gallant and excellent Earl of Moira, afterwards Marquis of Hastings, and Governor-General of India. The engraving is in ridicule of his complaint, in the House of Lords, of the cruelties exercised by the Government troops on the Irish Rebels. In the distance is seen Moll Coggin, an Irish witch, mounted on a black Ram with a blue tail, and on the hill an Oak-boy, carrying an uprooted oak, on the branches of which are numerous swans—in allusion to the unfounded nature of his charges. | ||

| THE LOYAL TOAST. | Page 94 | |

| Representing the Duke of Norfolk giving at a dinner at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in honour of the birth-day of Fox his famous toast, “Our Sovereign’s Health—The Majesty of the People”. On the left is John Nicholls, Member for Tregony; next to him is the Duke of Bedford; on the other side of the table are Sheridan and Fox. | ||

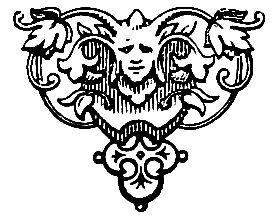

| DESIGN FOR THE NEW GALLERY OF BUSTS AND PICTURES. | Page 99 | |

| The statue of Fox was placed between those of Demosthenes and Cicero, by the Empress Catherine of Russia, as a compliment to him for having successfully opposed the sending of the armament prepared by Pitt, in conjunction with Prussia and Holland, to compel her to give up Ockzakow which she had seized. As this caricature, including the verses, was originally published in March, 1793, the latter in The Anti-Jacobin must have been suggested by them. | ||

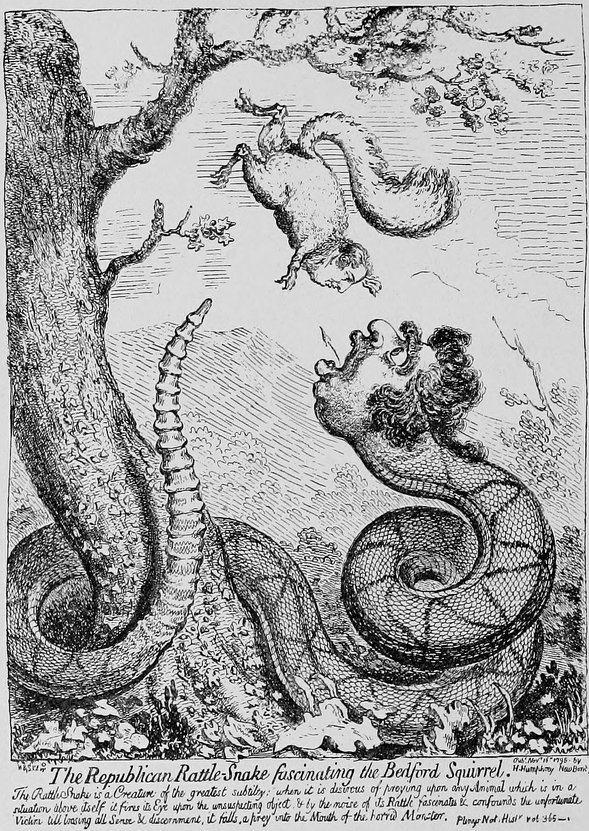

| THE REPUBLICAN RATTLESNAKE FASCINATING THE BEDFORD SQUIRREL. | Page 285 | |

| In allusion to the influence exercised by Fox over Francis, fifth Duke of Bedford, who had become one of the most zealous of the popular party. | ||

The First Number of which will be published on Monday, the 20th of November, 1797, to be continued every Monday during the sitting of Parliament. Price 6d.

At a moment, when whatever may be the habits of inquiry and the anxiety for information upon subjects of public concern diffused among all ranks of people, the vehicles of intelligence are already multiplied in a proportion nearly equal to this encreased demand, and to the encreased importance and variety of matter, some apology may perhaps be necessary for the obtrusion of a new Paper upon the World; and some account may reasonably be expected of the views and principles on which it founds its pretensions to notice, before it can hope to make its way through the crowd of competitors which have gotten the start of it in the race for public favour.

[As this Prospectus was written by Mr. Canning, and it has been prefixed only to the former edition of the Poetry by the present Editor, it is again considered an interesting addition to the present one.]

2The grounds upon which such pretensions have usually been rested by those who have engaged in undertakings of this kind, are accuracy, variety, and priority of Intelligence, connections at home, correspondence abroad, and, above all, a profession of impartial and unprejudiced attention to all opinions, and to all parties and descriptions of men.

On none of these Topicks is it Our intention to enlarge.

Of Our means of information, and of the use which We make of them, our readers will, after a very short trial, be enabled to form their own opinion. And to that trial We confidently commit ourselves: professing, however, at the same time, that if the only advantage which We were desirous of holding out to our Readers, were that of having it in our power to apprize them an hour or a day sooner than those Journals, which are already in their hands, of any event however important—We should bring to the undertaking much less anxiety for success, and should state our claims on public attention with much less boldness, than We are disposed to do in the consciousness of higher purposes, and more beneficial views.

Novelty indeed We have to announce. For what so new in the present state of the daily and weekly Press (We speak generally, though there are undoubtedly exceptions which we may have occasion to point out hereafter) as the Truth? To this object alone it is that Our labours are dedicated. It is the constant violation, the disguise, the perversion of the Truth, whether in narrative or in argument, that will form the principal subject of our Weekly Examination: and it is by a diligent and faithful discharge of this duty—by detecting 3falsehood, and rectifying error, by correcting misrepresentation, and exposing and chastising malignity—that We hope to deserve the reception which We solicit, and to obtain not only the approbation of the Country to our attempt, but its thanks for the motives which have given birth to it.

These are strong words. But We are conscious of intending in earnest what they profess. How far the execution of our purpose may correspond with the design, it is for others to determine. It is ours to state that design fairly, and in the spirit in which we conceive it.

Of the utility of such a purpose, if even tolerably executed, there can be little doubt, among those persons (a very large part of the community) who must have found themselves, during the course of the last few years, perplexed by the multiplicity of contradictory accounts of almost every material event that has occurred in that eventful and tremendous period; and who must anxiously have wished for some public channel of information on which they could confidently rely for forming their opinion.

But before We can expect sufficient credit from persons of this description, to enable us to supply such a defect, and to assume an office so important, it is natural that they should require some profession of our principles as well as of our purposes; in order that they may judge not only of our ability to communicate the information which We promise, but of our intention to inform them aright.

To that freedom from partiality and prejudice, of which We have spoken above, by the profession of which so many of our Contemporaries recommend themselves, We 4make little pretension—at least in the sense in which those terms appear now too often to be used.

We have not arrived (to our shame perhaps we avow it) at that wild and unshackled freedom of thought, which rejects all habit, all wisdom of former times, all restraints of ancient usage, and of local attachment; and which judges upon each subject, whether of politicks or morals, as it arises, by lights entirely its own, without reference to recognized principle, or established practice.

We confess, whatever disgrace may attend such a confession, that We have not so far gotten the better of the influence of long habits and early education, not so far imbibed that spirit of liberal indifference, of diffused and comprehensive philanthropy, which distinguishes the candid character of the present age, but that We have our feelings, our preferences, and our affections, attaching on particular places, manners, and institutions, and even on particular portions of the human race.

It may be thought a narrow and illiberal distinction—but We avow ourselves to be partial to the Country in which we live, notwithstanding the daily panegyricks which we read and hear on the superior virtues and endowments of its rival and hostile neighbours. We are prejudiced in favour of her Establishments, civil and religious; though without claiming for either that ideal perfection, which modern philosophy professes to discover in the other more luminous systems which are arising on all sides of us.

The safety and prosperity of these kingdoms, however unimportant they may seem in abstract contemplation when compared with the more extensive, more beautiful, and more productive parts of the world, do yet excite in 5our minds a peculiar interest and anxiety; and will probably continue to occupy a share of our attention by no means justified by the proportional consequence which speculative reasoners may think proper to assign to them in the scale of the universe.

We should be averse to hazarding the smallest part of the practical happiness of this Country; though the sacrifice should be recommended as necessary for accomplishing throughout the world an uniform and beautiful system of theoretical liberty: and We should at all times exert our best endeavours for upholding its constitution, even with all the human imperfections which may belong to it, though We were assured that on its ruins might be erected the only pillar that is yet wanting to complete the “most glorious fabrick which the Integrity and Wisdom of man have raised since the Creation”.

If, as Philosopher Monge[6] avers, in his eloquent and instructive address to the Directory, “The Government of England and the French Republick cannot exist together,” We do not hesitate in our choice; though well aware that in that choice we may be much liable, in the opinion of many critics of the present day, to the imputation of a want of candour or of discernment.

6Admirers of military heroism, and dazzled by military success in common with other men, We are yet even here conscious of some qualification and distinction in our feelings: We acknowledge ourselves apt to look with more complacency on bravery and skill, when displayed in the service of our Country, than when We see them directed against its interests or its safety; and, however equal the claims to admiration in either case may be, We feel our hearts grow warmer at the recital of what has been atchieved by Howe, by Jervis, or by Duncan, than at the “glorious victory of Jemappe,” or “the immortal battle of the bridge of Lodi”.

In Morals We are equally old-fashioned. We have not yet learned the modern refinement of referring in all considerations upon human conduct, not to any settled and preconceived principles of right and wrong, not to any general and fundamental rules which experience, and wisdom, and justice, and the common consent of mankind have established, but to the internal admonitions of every man’s judgment or conscience in his own particular instance.

We do not dissemble,—that We reverence Law,—We acknowledge Usage,—We look even upon Prescription without hatred or horror. And we do not think these, or any of them, less safe guides for the moral actions of men, than that new and liberal system of Ethics, whose operation is not to bind but to loosen the bands of social order; whose doctrine is formed not on a system of reciprocal duties, but on the supposition of individual, independent, and unconnected rights; which teaches that all men are pretty equally honest, but that some have different notions of honesty from others, and that the 7most received notions are for the greater part the most faulty.

We do not subscribe to the opinion, that a sincere conviction of the truth of no matter what principle, is a sufficient defence for no matter what action; and that the only business of moral enquiry with human conduct is to ascertain that in each case the principle and the action agree. We have not yet persuaded ourselves to think it a sound, or a safe doctrine, that every man who can divest himself of a moral sense in theory, has a right to be with impunity and without disguise a scoundrel in practice. It is not in our creed, that Atheism is as good a faith as Christianity, provided it be professed with equal sincerity; nor could We admit it as an excuse for Murder, that the murderer was in his own mind conscientiously persuaded that the murdered might for many good reasons be better out of the way.

Of all these and the like principles, in one word, of JACOBINISM in all its shapes, and in all its degrees, political and moral, public and private, whether as it openly threatens the subversion of States, or gradually saps the foundations of domestic happiness, We are the avowed, determined, and irreconcileable enemies. We have no desire to divest ourselves of these inveterate prejudices; but shall remain stubborn and incorrigible in resisting every attempt which may be made either by argument or (what is more in the charitable spirit of modern reformers) by force, to convert us to a different opinion.

It remains only to speak of the details of our Plan.

8It is our intention to publish Weekly, during the Session of Parliament, a Paper, containing,

First, An Abstract of the important events of the week, both at home and abroad.

Secondly, Such Reflections as may naturally arise out of them: and,

Thirdly, A contradiction and confutation of the falsehoods and misrepresentations concerning these events, their causes, and their consequences, which may be found in the Papers devoted to the cause of Sedition and Irreligion, to the pay or principles of France.

This last, as it is by far the most important, will in all probability be the most copious of the three heads; and is that to which, above all others, We wish to direct the attention of our Readers.

We propose diligently to collect, as far as the range of our own daily reading will enable us, and We promise willingly to receive, from whatever quarter they may come, the several articles of this kind which require to be thus contradicted or confuted; which will naturally divide themselves into different classes, according to their different degrees of stupidity or malignity.

There are, for instance (to begin with those of the highest order), the Lies of the Week; the downright, direct, unblushing falsehoods, which have no colour or foundation whatever, and which must at the very moment of their being written, have been known to the writer to be wholly destitute of truth.

Next in rank come Misrepresentations which, taking for their groundwork facts in substance true, do so colour and distort them in description, as to take away all semblance of their real nature and character.

9Lastly, The most venial, though by no means the least mischievous class, are Mistakes; under which description are included all those Hints, Conjectures, and Apprehensions, those Anticipations of Sorrow and Deprecations of Calamity, in which Writers who labour under too great an anxiety for the Public Welfare are apt to indulge; and which, when falsified by the event, they are generally too much occupied to find leisure to retract or disavow:—A trouble which We shall have great pleasure in taking off these Gentlemen’s hands.

To each of these several articles We shall carefully affix the name and date of the Publication from which We may take the liberty of borrowing it.

With regard to the Proceedings in Parliament, We shall not fail to mark to Our Readers the progress of the public business; though it does not enter into our Plan to give a regular detail of the Debates: nor would the limits of our Paper allow of it.

We have a further reason for not occupying this province, which will equally account for our determination, not to receive Advertisements—our earnest desire not to lessen the circulation of any existing Public Print.

It is obvious upon every ground of fairness and of policy, that We must entertain this desire very strongly with regard to the respectable Papers which are directed by principles and attachments like our own: an attachment (We have no wish to disguise it) to the cause of a Government, with whose support, whose popularity and consequent means of exertion, the circumstances of the present times have essentially connected the existence of this Country as an independent Nation.

10As little should we wish to circumscribe the sale of those Journals, upon whose errors or perverseness, upon whose false statements and pernicious doctrines We reckon for the main support, as they have been the principal cause of our undertaking. These We would entreat to proceed with fresh vigour and increased activity. It is our wish to be seen together, and to be compared with them. Every week of misrepresentation will be followed by its weekly comment; and with this corrective faithfully administered, the longest course of Morning Chronicles or Morning Posts, of Stars or Couriers, may become not only innocent but beneficial.

With these views then We commence our undertaking. Whatever may be the success or the merit of its execution in our hands, the want of something like it has so long been felt and deplored by all thinking and honest men, that We cannot doubt of the approbation and encouragement with which the attempt will be received.

We claim the support, and We invite the assistance, of ALL, who think with US that the circumstances and character of the age in which We live require every exertion of every man, who loves his COUNTRY in the old way, in which till of late years the LOVE of one’s COUNTRY was professed by most men, and by none disclaimed or reviled; of ALL who think that the Press has been long enough employed principally as an engine of destruction, and who wish to see the experiment fairly tried whether that engine, by which many of the States which surround us have been overthrown, and others shaken to their foundations, may not be turned into an instrument of defence for the one remaining Country which has Establishments to protect, and a Government with the spirit, 11and the power, and the wisdom to protect them; of ALL who look with respect to public honour, and with attachment to the decencies of private life; of ALL who have so little deference for the arrogant intolerance of Jacobinism as still to contemplate the OFFICE and the PERSON of a King with veneration, and to speak reverently of Religion, without apologizing for the singularity of their opinions; of ALL who think the blessings which we enjoy valuable, and who think them in danger; and who, while they detest and despise the principles and the professors of that NEW FAITH by which the foundations of all those blessings are threatened to be undermined, lament the lukewarmness with which its propagation has hitherto been resisted, and are anxious, while there is yet time, to make every effort in the cause of their COUNTRY.

Published by J. Wright, No. 169, opposite Old Bond Street, Piccadilly: by whom Orders for the Papers, and all Communications of Correspondents, addressed to the Editor of the Anti-Jacobin, or Weekly Examiner, will be received. Sold also by all the Booksellers and Newsmen in Town and Country.

In our anxiety to provide for the amusement as well as information of our readers, we have not omitted to make all the inquiries in our power for ascertaining the means of procuring poetical assistance. And it would give us no small satisfaction to be able to report that we had succeeded in this point precisely in the manner which would best have suited our own taste and feelings, as well as those which we wish to cultivate in our readers.

But whether it be that good Morals, and what we should call good Politics, are inconsistent with the spirit of true Poetry—whether “the Muses still with freedom found” have an aversion to regular governments, and require a frame and system of protection less complicated than king, lords, and commons:—

and there only—or for whatever other reason it may be, whether physical, or moral, or philosophical (which last 13is understood to mean something more than the other two, though exactly what, it is difficult to say), we have not been able to find one good and true Poet, of sound principles and sober practice, upon whom we could rely for furnishing us with a handsome quantity of sufficient and approved verse—such verse as our readers might be expected to get by heart, and to sing; as the worthy philosopher Monge describes the little children of Sparta and Athens singing the songs of Freedom, in expectation of the coming of the Great Nation.

In this difficulty we have had no choice but either to provide no poetry at all—a shabby expedient—or to go to the only market where it is to be had good and ready made, that of the Jacobins—an expedient full of danger, and not to be used but with the utmost caution and delicacy.

To this latter expedient, however, after mature deliberation, we have determined to have recourse; qualifying it at the same time with such precautions as may conduce at once to the safety of our readers’ principles, and to the improvement of our own poetry.

For this double purpose, we shall select from time to time from among those effusions of the Jacobin Muse which happen to fall in our way, such pieces as may serve to illustrate some one of the principles on which the poetical as well as the political doctrine of the New School is established—prefacing each of them, for our readers’ sake, with a short disquisition on the particular tenet intended to be enforced or insinuated in the production before them—and accompanying it with an humble effort of our own, in imitation of the poem itself, and in further illustration of its principle.

14By these means, though we cannot hope to catch “the wood-notes wild” of the Bards of Freedom, we may yet acquire, by dint of repeating after them, a more complete knowledge of the secret in which their greatness lies than we could by mere prosaic admiration; and if we cannot become poets ourselves, we at least shall have collected the elements of a Jacobin Art of Poetry for the use of those whose genius may be more capable of turning them to advantage.

It might not be unamusing to trace the springs and principles of this species of poetry, which are to be found, some in the exaggeration, and others in the direct inversion of the sentiments and passions which have in all ages animated the breast of the favourite of the Muses, and distinguished him from the “vulgar throng”.

The poet in all ages has despised riches and grandeur.

The Jacobin poet improves this sentiment into a hatred of the rich and the great.

The poet of other times has been an enthusiast in the love of his native soil.

The Jacobin poet rejects all restriction in his feelings. His love is enlarged and expanded so as to comprehend all human kind. The love of all human kind is without doubt a noble passion: it can hardly be necessary to mention that its operation extends to freemen, and them only, all over the world.

The old poet was a warrior, at least in imagination; and sung the actions of the heroes of his country in strains which “made Ambition Virtue,” and which overwhelmed the horrors of war in its glory.

The Jacobin poet would have no objection to sing battles too—but he would take a distinction. The 15prowess of Buonaparte, indeed, he might chant in his loftiest strain of exultation. There we should find nothing but trophies and triumphs and branches of laurel and olive, phalanxes of Republicans shouting victory, satellites of despotism biting the ground, and geniuses of Liberty planting standards on mountain-tops.

But let his own country triumph, or her allies obtain an advantage: straightway the “beauteous face of war” is changed; the “pride, pomp, and circumstance” of victory are kept carefully out of sight, and we are presented with nothing but contusions and amputations, plundered peasants, and deserted looms. Our poet points the thunder of his blank verse at the head of the recruiting serjeant, or roars in dithyrambics against the lieutenants of pressgangs.

But it would be endless to chase the coy Muse of Jacobinism through all her characters. Mille habet ornatus. The Mille decenter habet is perhaps more questionable. For in whatever disguise she appears, whether of mirth or of melancholy, of piety or of tenderness; under all disguises, like Sir John Brute in woman’s clothes, she is betrayed by her drunken swagger and ruffian tone.

In the poem which we have selected for the edification of our readers and our own imitation this day, the principles which are meant to be inculcated speak so plainly for themselves, that they need no previous introduction.

[Henry Marten was one of the most interesting and remarkable of the Regicides, not only from his abilities and consistent honesty, but from the elegance of his manners, his wit, and the fascinating gaiety of his conversation; and, moreover, from his humane disposition and generosity to fallen foes. His private life, however, was disgraced by the most reckless debauchery, which might seem more appropriate in such libertines as Rochester and Sedley than in a coadjutor of the strict Puritan party. But from a note in Grey’s edition of Hudibras, pt. ii., ch. i., p. 313, it would appear that the general opinion at that time was that profligacy of a pronounced character was indulged in privately by more than a few of that sanctimonious sect.

He was the son of Sir Henry Marten, LL.D., a loyal Judge of the Admiralty. After receiving a learned education at Oxford, he entered one of the Inns of Court, and travelled in France. Having a stake in Berkshire—for he inherited a property of £3000 a year, besides several thousand pounds in money—he was elected, 1640, one of the members for the county in the last two Parliaments of King Charles I. His chief seat was at Becket, in the parish of Shrivenham. He afterwards obtained a grant of £1000 a year to him and his heirs out of the forfeited estates of the Duke of Buckingham. His early marriage with a rich widow, selected by his father, but not affected by himself, also benefited his finances.

From the commencement of the Civil Wars he was a violent Republican; and as early as 1643 openly expressed his opinion of the desirability of the destruction of the King and his children, for which rather premature advice he was expelled from the House of Commons, and underwent a short imprisonment in the Tower. He was appointed by the House of Commons a Colonel of Horse and Governor of Reading, but made less mark as a soldier than as a rapacious spoiler of the adherents of the King, which earned him the opprobrious nickname of “Plunder-master General”.

Being empowered to dispose of the Regalia and royal trappings, he once invested George Wither—who had been made one of Cromwell’s Major-Generals—with them, and so accoutred induced the old Poet to strut up and down Westminster Abbey to the scandal of right-thinking people.

18To him also were referred the alterations in the public arms, the Great Seal, and the legends upon the money. Upon the latter was a shield bearing the cross of St. George, encircled by a palm and olive branch, and inscribed The Commonwealth of England, and on the reverse, God with us, 1648; which occasioned the remark “that God and the Commonwealth were not on the same side”.

Nothing apparently could damp the ill-timed jocosity too often prevalent in those troublous times, for at Marten’s trial, 16th October, 1660, Ewer, who had been his servant, swore that “at the signing of the warrant for the King’s execution he did see a pen in Mr. Cromwell’s hand, and he marked Mr. Marten in the face with it, and Mr. Marten did the like to him”. But many of his excesses were condoned in the eyes of both his friends and enemies by his generous and humane spirit.

D’Israeli, in his Commentaries on the life and Reign of Charles I., describes the ingenious way in which Marten saved the life of David Jenkins, a loyal and obstinate Welsh judge, who, when brought to the bar of the House of Commons to answer for imprisoning several persons for bearing arms against the King, peremptorily disowned their jurisdiction, and defied them in the following bold terms: “‘But, Mr. Speaker, since you and this House have renounced your allegiance to your Sovereign, and are become a den of thieves, should I bow myself in this House of Rimmon the Lord would not pardon me’. The whole House were electrified.... He was voted guilty of high treason without any trial. The day of execution was then debated. Harry Marten, who had not yet spoken, rose, not to dissent from the vote of the House, he observed, but he had something to say about the time of the execution. ‘Mr. Speaker,’ said he, ‘everyone must believe that this old gentleman here is fully possessed in his head resolved to die a martyr in his cause, for otherwise he would never have provoked the House by such biting expressions. If you execute him, you do precisely that which he hopes for, and his execution will have a great influence over the people, since he is condemned without a jury. I therefore move that we should suspend the day of execution, and in meantime force him to live in spite of his teeth.’ The drollery of the motion put the House into better humour, and he was reprieved. After being kept in various prisons for eleven years, he was released by Cromwell, and died in 1663, aged eighty-one.”