Curt watched them, screaming as they fled before the

shadow-things—the tortured humans of Earth. He

watched them die, crushed and seared by the spreading

blue flower, and he cursed himself. With all his

knowledge and strength he could not save his people.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1946.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Around them, space—implacable but generous, impalpable but tangible—shot through with a thousand far off suns.

Looming at starboard, blacking out a section of space, the dark starside of the Moon. Then hundreds of flickering fireflies moving out of the darkness, blinking on by ones ... twos ... threes ... as they passed the black moon's rim.

Curt Wing relaxing, his dark head nodding softly, his dark eyes widening as he stared into the teleplate. He stared into the plate, and his lips, for so many hours a thin gray line, pursed into an almost inaudible whistle.

Without turning his head, he said to the lean rangy blond lieutenant beside him.

"That did it, Packer. It flushed them from cover. Curiosity did it."

"Now?" Lt. George Packer asked, pulling on his helmet, reaching for the red button to sound the klaxon alarm. One long finger almost touched the scarlet dot which would send a hundred crews on a hundred Earth ships into the action which they had awaited for these long weeks.

Curt Wing, wing Space Commander, shook his black shock of hair with deliberate slowness, wiped the sticky sweat from the palms of his hands on his gold-striped blue breeches.

"Wait."

"But, Curt! We've waited two weeks. And for the last seven hours the crew has been going mad. They know the Mercurians must be out there now. We got the flash on the intercommunicator and it's tuned to all-ship length."

"I know," Wing said. "But what's another moment or two. This has to be right. We'll never get another chance like this again. Be patient, George."

Curt Wing still stared at the visaplate.

"They must have the whole fleet with them! I've never seen so many Mercurian ships in my life."

"They'll spot us," Lt. Packer said anxiously. "Let me signal, Curt."

"Easy, George. This is Earth's last chance. We've got to be sure it's good. They've got us—ten to one. Surprise is our only chance of whittling down the odds."

"But every minute, Curt, every minute counts. They'll spot us sure."

His eyes still soldered to the plate, Wing said, an overtone of exasperation in his deep-timbered voice; "We've been here two weeks. They didn't spot our black ships in the moon's shadow before. I hardly think they will now. Take it easy."

The two stood there, watching the black shadow of the plate, now flickering with swarms of silver Mercurian ships. Beads of sweat built up on Curt Wing's forehead, swelled, then rolled down his lean, harsh-planed face to make tiny plopping sounds on the duralloy deck beneath their feet.

"Man!" Lt. Packer burst out. "Curt, are you mad? We've got to strike now. Their black light visas'll pick us up any second."

Wing Space Commander Wing didn't answer. Seconds oozed away like viscous blobs of oil. Then:

"Now!"

Packer's itching finger stabbed the red button viciously. Muted through the thick bulkheads surrounding the plotting room came the ululating howl of the ready signal.

Curt Wing moved from the visaplate, clicked on the intercommunications speaker, came back to the plate. He studied it for a moment, unmindful of George Packer who was chewing his nails very deliberately.

Curt Wing lifted his head, turned toward the speaker and said casually,

"Fire at will."

Then his dark eyes turned back to the thousand fireflies flickering in the visaplate. Lt. Packer crowded his lean body alongside of him, stared at the screen.

The ship shuddered. The deck quivered beneath their feet like a restrained earthquake. Almost simultaneously, the fireflies in the visaplate were spotting with flowering bursts of bright-hued colors which hid other of the fireflies for a long moment.

A metallic voice echoed into the plotting room as the spotter's hit calculator started clacking from its eyrie in the nose of the ship.

"Seven direct ... no twelve ..." the metallic voice broke, then resumed and reflected the glee of the spotter. "Commander, this damn machine's gone mad. We're hitting them so fast it can't keep up!"

The flagship trembled again, and the visaplate was filled with the bright, blooming flowers as Mercurian ship after Mercurian ship tasted the atomic bolts, sucked them up and exploded.

Curt Wing's voice was no longer casual as he turned his lips toward the intercom.

"Sock it to 'em, you precious monkeys. You've got a million Earthmen to avenge!"

Then he kicked the tuning dial over, swept the visascreen from Earth ship to Earth ship. Only the flashing blue bolts identified most, but here and there an Earth ship blazed red, then white and molten metal dripped off into the darkness as the Mercurian ships lashed back at the dark shrouded hornets which were poisoning them with quick flashing death.

The huge Mercurian fleet, its thousands scattered through with broken hulks, was turning slowly, its own bolts searching out, lighting up the blackness which hid the tiny Earthian fleet.

The silver ships moved in, and concentrated hell poured on to one of the far-flung ships of Earth. The Earth ship exploded into myriad shells of molten metal, and the horrible atomic rays moved to the next blue flashing terrestrial ship.

Curt Wing's voice barked into the intercom:

"Plan L."

And the outnumbered Earth ships, pulling in their horns of atomic bolts, flashed away from the darkness, their rocket exhausts spurting fire. They blasted into the sky in unison, climbing above the slower Mercurian ships, and hurtled downward, their blue bolts thrusting before them, lashing at the silver ships.

The Mercurian ships swung upward, lumbering, but the Earth ships were darting in and out like slashing knives wielded by agile, practiced hands.

Curt Wing's tight-held breath relaxed, made a whistling sound in the plotting room. He said, "The longest chance I ever took, and it worked." His voice was very low, almost like a prayer.

"Look at them run!" Packer chortled. "You did it again." He was staring into the visaplate, watching the silver ships begin to scatter away from the black Earth ships above them. "This is the knockout punch. We'll drive them away now, forever. Five years they've been nagging us and all the time they waited until they were strong enough to strike."

"Yes," said Wing, "and they almost got us in the slaughtering pit by the asteroid belt. But now...." He halted, snapped into the intercom:

"Attack at will, you itchy-fingered monkeys. They're all yours. Take 'em."

The oval door to the plotting room burst open; a big-framed, heavy-paunched Blackbeard came plowing in.

"Gee, Cap," his heavy voice lumbered. "I bin missing somepin, huh?"

Commander Wing turned to the newcomer. The harsh planes of his face softened as he grinned.

"Yes, Dead-Eye, I guess you bin missing something all right. Making love to Elizabeth again?"

Dead-Eye Lindstrom grinned, his white square teeth glaring through the black of his bearded face.

"Yep, I sure have. Y'know, Cap, Elizabeth's coming along fine now. I jest got through placing five out of six slugs in the bull'e eye, and I warn't even looking. I jest grabbed leather and started fanning the hammer and whamo! Elizabeth put 'em right in thar."

Dead-Eye patted the bulky length of the archaic powder gun strapped to his right leg. Then he jerked his hand up quickly and the white steel of the ancient Frontier .44 revolver sparkled in the light.

"Pard," he said, "Pard, them were the days. You stood face to face with another owlhoot rider and reached. By gosh, you could see the whites of his eyes and whamo! You got him or he got you."

"Shut up, will you, Lindstrom?" Packer snapped. "You and your ancient history give me a pain. They buried the last beef striker—"

"Cowpuncher!" Dead-Eye corrected.

"Three hundred years ago," Packer went on. "And where you ever found that excuse for a pistol, only Neptune knows."

"Easy," said Curt Wing quietly.

Dead-Eye drew himself up to his full six feet six so that he towered a full head over Lt. Packer. "Brother," he growled, and his pale blue eyes were cold, "I'll match you Elizabeth against any of these modern guns and I'll kill you so quicker that you'll have to be cremated ahead of time. Why—"

An eerie whistle from the Earth panel halted him. The three turned at the summons, infraction of all space battle procedure except in cases of extreme urgency. Only once before in five years had that whistle sounded during either battle practice or battle. Then it was to announce war with Mercury.

Now....

The visaplate crawled up from black through purple to yellow and white. A voice came through but there was no face accompanying it.

"Signal six-two ... signal six-two...."

"No!" Wing cried out.

"Signal six-two ... signal six-two...."

Wing glanced at the battle visaplate. The Mercurians were in full rout.

We've got them licked, he thought; they're running.

Now this.

"Signal six-two...." the Earth voice repeated.

Lt. Packer said, "Commander Wing, what is signal six-two? I thought there were only sixty-one code numbers."

Curt Wing looked at Packer but his dark eyes were blank, the lips thinned and harsh.

"Signal six-two, lieutenant?" he asked, and there was no life in his voice. "It takes precedence over everything an Earthman has. Life, liberty, home, happiness—everything. We must return to Earth at once. To hell with the Mercurians. They're unimportant." Curt Wing spoke into the intercom:

"Commander to all ships. Abandon chase. Gain formation. We're returning to home base."

The formation board began to blink as ship captains acknowledged the order. But where each green light of acquiescence lighted up, below it came also the yellow light of query.

Wing pushed on the all-ship button on the officers' intercom system and said quietly:

"Signal six-two—you know what that means." The yellow query lights went off immediately, the green ones blinked off, on, then off again.

"Yes," Wing said to Lt. Packer, "The Mercurians are unimportant compared to this. Signal six-two is the emergency signal for earth catastrophe. What's wrong I don't know. But whatever it is, a mere interplanetary war is a kindergarten class." He ran his blunt-fingered hands through his hair.

"Gee, Cap," said Dead-Eye suddenly. "That's bad, huh?"

"Yes, Dead-Eye," Wing said softly. "It's bad. Very bad."

"You'll fix it, won't you, Cap?" Dead-Eye asked, and his light-blue eyes were trusting. "You can do anything, Cap. Why, didn't you find Elizabeth for me?"

Wing stared at Dead-Eye's hulking figure.

Finally he said, "I think this will be slightly more difficult than picking Elizabeth out of a museum case, Dead-Eye."

Earth below them now, its diadem of clouds winking in the reflected shafts of light from the moon.

What danger lay there? What danger so great that they must let a victory become a might-have-been. What catastrophe so important that a fight for interplanetary life was dismissed casually with the signal.

Curt Wing shrugged his shoulders, heard that incessant signal boring monotonously into his ears.

Then the breaking rockets were kicking, the high thin wail as the thickening atmosphere scratched along the black ship's bulk was deepening, and the deceleration was pushing lazy hands against him, urging him against the duralloy bulwark at his back.

"Gosh," Dead-Eye said, gaping open-mouthed into the visaplate. "Cap, looky here, the whole city is blue."

It was blue—this White City which in the long ago had been New York. A blue visible with an inner light of its own that absorbed the white moon beams and made even black shadows turn blue.

The city was like some huge blue flower, sunset blue for stamen and pistil, its hue lightening to aquamarine, cerulean, and pastel as its petals stretched farther out over the city. It was pulsing and each pulsation swelled its circumference.

Then the visaplate was flickering and the tiny red bulb centered in its plastic base began to blink, signaling power trouble. Then the screen went blank.

"What is it?" Packer exclaimed. His voice was loud and harsh in the plotting room now. The incessant signal six-two ... signal six-two ... had ceased. The instrument panel lights went dark, the rockets cut off abruptly, the only sound was the scrabbling fingers of the outside....

"Force field," Curt Wing said. "Something we've never been able to develop. But there it is. That's the catastrophe. It's swallowing White City, and if there's an intelligence behind it or not, mankind is done if we can't stop it."

"Force field?" Packer asked. "But didn't you...?"

"Yes," Wing said. "I created one once. A little thing less than an inch square. Balanced one magnetic field against another by firing four atomic guns at a coincident point. But a funny thing, the longer the field held the more power I had to shove into it.

"Then I didn't have any more power to give, and Dead-Eye says, 'Gee, what's happening to all those atoms?' So I grabbed him and ran like hell for the nearest sub-basement. When those compressed atoms let go it tore everything loose from the experimental station.

"When Dead-Eye and I crawled out, all it was was a desert. There wasn't a tree, a bush, a rock or a hill for ten miles around. It was the flattest place I ever saw, or hope to see again." He was staring blankly at the insentient visaplate.

"But, hell, I talk too much."

Jake Wilson, landing supervisor, pushed open the oval hatch, said: "Hang on, sir, we're volplaning in. It's lucky we got the vanes out before the power quit."

The shock spilled the chunky Wilson into the plotting room, clipped the legs out from under the three already there.

There was a moment of lift, then another shock a little less severe. The ship lifted again, struck, lifted once more and settled with an audible groan of metal stress.

They hurried from the plotting room, heading for the exit lock.

It was a peculiar sort of night outside, a benevolent blue softening the blackness. Curt Wing stared at the blue haloed city off to the west. He was licking his dry lips.

"Gosh, Cap," Dead-Eye asked suddenly. "What if that blows up?" A shudder quivered through his bulky frame.

Wing's dark eyes went blank. He put one hand on Dead-Eye's arm. He said nothing.

He was standing there, staring at the pulsating blue flower that was spreading out from the city, his fingers quiescent on Dead-Eye's arm when the red-uniformed riot officer jockeyed his speedy rocket car up to them....

The building was still untouched by the force field's encroaching maw. Curt Wing stood by the window staring out at the blue night scene. Finally he answered the men who sat at the long narrow table behind him.

"I don't know what we can do. My experiments with such a field taught me only that I could not control it once it was set in motion," he said quietly.

He turned then to face the men—the governors of the seven divisions of earth. "You have flattered me because of an experiment that ended in failure," he went on. "But even if we had a solution, a way to overcome this impossibility, we must not forget that is only one problem. We have this unknown to lick, yes; but meanwhile the Mercurians we left out by the moon can punch us to Stardust."

Jan Eliel, senior governor, shook his white head quickly. "No, we have only this force field with which to contend. We have nothing to worry about from the Mercurians. We gave them Earth's unconditional surrender only minutes after you were ordered back."

"Huh?" The exclamation, shot through with amazement, exploded from the shadows in the corner where Dead-Eye had buried himself. "Why, you!"

"Quiet, Dead-Eye!" Wing barked. Dead-Eye subsided, grumbling.

Wing's face had drained of color, the sharp planes of his face came into sharper relief, the muscles in his throat were working pulsating as if he could not catch a full breath.

His mind was shrieking. It's gone, Curt Wing! The loveliest world in the galaxy no longer belongs to Earthmen. It is owned by strangers, by Mercurians, by an alien people who will grind its beauty into a molten crucible so that it may support their hell-hot lives.

Gone! Everything worth fighting for, living for, dying for! Earth, who had flung her minions to the stars, first beings in the galaxy to solve space travel, first to probe across eternity in rickety ships, spanning the vast distances with blood and broken lives. Earth, who had struggled to bring her peoples together in peaceful harmony, finally succeeding in it, lifting them toward their destiny.

All this—Gone.

Curt Wing looked at the seven governors.

"If that's the case," he said finally. "I can't see any reason why we should worry about the force field. Let the damn Mercurians worry about it. Earth is theirs now."

"Wait, Wing!" Eliel cried out as Wing strode past the long narrow table, Dead-Eye's bulk dogging his heels. "You don't understand!"

Wing spun around. "I don't understand?" he repeated, and his deep voice was harsh.

"Look, you governors. There was only one way Earth could have licked this force field. Someone would have found the way out—the way to chop this blue flower off at its source if you hadn't taken it away.

"Scan back through Earth's history. Way back in the 15th century, a sea captain did the impossible. He crossed water as vast to him as space once was to us. He had a way. Earthmen flung their power at a dictator called Schickelgruber or some such name. It had been impossible to stop him. But a way was found."

"Then the moon rocket. That was impossible, too. There was no way to break gravity chains without killing any living thing on the ship. But a way was found. Oh, there are scores of instances where Earthmen did the impossible. But they had something worth fighting for. Columbus his adopted country; the united nations their people; Dawson and his moon rocket, the welfare of a world."

"We had Earth. Now what have we got? Not a mote of dust to call our own. I don't understand! Hell, I hope the Mercurians use you to fire those ghastly gas pots they use here to keep Earth's air from poisoning them."

Space Commander Curt Wing was balanced on the balls of his feet, leaning forward now, breathing hard, his fine-muscled body quivering as his dark eyes burned at the seven governors.

Jan Eliel said quietly, "We know how you feel, Curt Wing. But there wasn't anything else we could do. Wait!" He held up his hand as Wing threatened to interrupt him.

"We were like the fellow in the old story who stood at the gates of hell. He was damned if he opened the door and damned if he didn't."

"We had two alternatives—an unknown enemy and a known enemy, and we needed time, so we chose to capitulate to Mercury. We recognized the blue flower for what it was—and we needed you. Until you switched from building atomics to piloting them, you had made the greatest advance in the force field."

"We have time now—precious little since it will be only two weeks before the Mercurian fleet arrives with Mercury's Zhan Nekel. Earth still is ours. If you can solve the force field, we need not lose. We can turn it upon the Mercurians. They have fought with deceit and in this we must deceive them."

Jan Eliel sat up stiffly in his chair. "Will you desert us, Curt Wing?"

Wing's relaxed figure was their answer. The boyish grin which wiped the harsh planes of his face into softness was his promise. But Dead-Eye added emphasis, dragging his powder gun from his belt and waving it.

"Elizabeth and me'll help!" he declared.

The electric clock whirred softly—like a breathless metronone keeping time with Curt Wing's pencil. The metal desk was littered with crumpled and half-crumpled sheets of paper. Wing's black hair was rumpled and awry, his face dirtier by a ragged growth of beard, and when he lifted his aching eyes to the clock, they were blood-shot and watery with strain.

Behind him, the door sighed softly as it closed. Aware of a presence, but too weary to turn around Wing asked:

"Dead-Eye?"

"No," a quiet voice answered. Then a laugh, soft, so soft—like the whisper of leaves at nightfall, the murmuring of water sprites dancing on moonlit waters. Memory of a day—that day.

"Get out," Curt Wing said flatly. He did not look around.

"I won't go, Curt." That voice again—her voice. I didn't think it would ever hurt me again. I had it licked. I was living. Now—

Then that lovely, remembered presence was warming that ache, that cold, bitter ache in his heart, soothing it. But her words—those words which had turned him from science to adventure—stayed frozen in his heart.

"You're not a man, Curt Wing. You're a machine. You're too sufficient unto yourself. You don't need me. Your life is just a mixture of metal, paper and pencils. You just want me because you think a man should have a mate. So make one out of your metal, paper and pencils!"

Curt Wing stared wryly at the pencil held motionless between his thumb and forefinger. He forgot for a moment that into those fingers had been given the solution of an impossible problem—forgot that to him had been delegated a task so important that every second he relaxed meant the blue flower of destruction was spreading and Zhan Nekel's Mercurian fleet sped closer to Earth.

She was his own personal problem, breaking out from beneath the hard shell of pain he had built up within him. But his problem meant nothing at all if Earth no longer belonged to Earthmen. He had wanted her so much—still wanted her!—that there were times when he wanted to break down and bawl like a baby. Like now....

Then Curt Wing was chuckling. I'm feeling sorry for myself! At a time when there's no time for self-pity or anything else but work.

He turned around quickly. She still stood there just inside the door. She was more beautiful than he remembered! Her soft brown hair that felt like gossamer when it brushed against his lips; her blue eyes that could speak of love and hate, of pleasure and disgust so eloquently her lips need not move; the soft oval of her face—it was all that he remembered and more....

But he said,

"Business, Miss Packer?" There was no softness in the harsh planes of his face and his dark eyes were blank.

"No, Curt, not business."

"If you'll excuse me then?" Wing said, raising his eyebrows. "There's no time for anything else."

She smiled. "It won't take long, Curt. I just wanted to tell you something before it's too late.

"You never did and never will need me. I don't need you. But I hurt you, you hurt me, too, because I've loved you ever since you and dad first started your force field experiments."

"I still love you, you sweet fool!"

Then she was gone. Wing's cry, "Pat!" struck the closed door.

Wing hurled himself toward the door. Then stopped short as a sleepy "Whassa matter, Curt?" growled out of the corner where Dead-Eye had been napping.

"Nothing," Wing said abruptly. Then: "I thought you went home hours ago."

Rubbing bleary eyes and pulling on his beard, Dead-Eye, grinning through the black mass, said, "I pretended to, but I thought you might need me and Elizabeth for sumpin."

Wing glanced at the metal desk, heaped with the paper covered with a thousand figures he had set down as he tried again and again to find where in the long ago he had made his mistake in creating his field. If Prof. Packer were still alive, he could find that error. If I can only solve that maybe I can build up a neutralizing field.

"Come on, Dead-Eye, my brain's dulled with too much paper work. Let's go take a first hand look at that damn blue flower."

The blue flower was pulsing faster now, Wing decided, as he and Dead Eye approached a police captain who was directing people with clothing and valuables, toward the line of rocket buses.

Wing looked into the hazy depths of the force field.

Were those figures moving about in there? Or was his tired brain playing tricks on him?

"Gee, Cap," Dead-Eye exclaimed. "There's somebody inside!"

The police captain moved up to them. "We've reported what you see, Commander," he said. "They only became noticeable a half hour ago. But it didn't seem possible there could be any life in there."

"Life within that death?" Wing repeated. His blood-shot eyes peered at the police captain. "I don't see why not. Whoever created it must be able to handle it. They must have some protection, some armor against it. If we could capture one."

"That's it," the captain said. "They're inside and they won't come out. Before, those shadows looked like some sort of beings. They're dimmer now. They walk upright in a sort of shuffle, but they won't come out of the flower."

"If we could entice one of them out somehow," Wing said softly. "If we knew what they were, it might help us find a way of throttling that flower before it destroyed anything else."

The captain grinned ruefully. "We've tried everything to dent that field, and it didn't even change color. I guess maybe we'll just have to wait until they decide to come out, huh, Commander?"

Wing grinned back at the captain. "Maybe we ought to let sleeping dogs lie, Captain? Maybe you're right, but if one of them even looks like he intends to come out, buzz me on the visaplate at once."

Wing and Dead-Eye moved away from the captain, watched the red-clad police herd more homeless families into the rocket buses for transportation to other points. But unless that blue flower is killed, Wing thought, they can go to the far ends of the earth and they'll never escape it. And if they try to escape to other worlds the Mercurians will be their Nemesis.

Wing and Dead-Eye were threading their way through the crowd when the shout reached them:

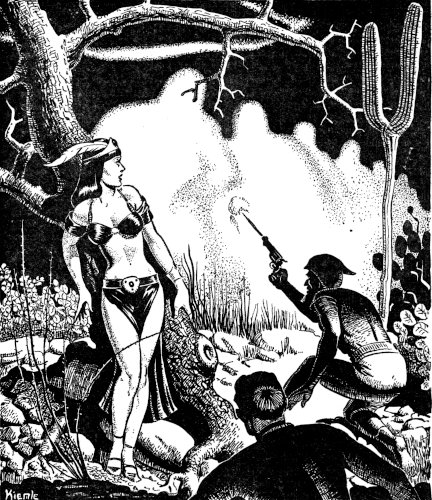

"Commander, one's coming out!"

Wing spun and sprinted back toward the captain, Dead-Eye's big heavy bulk lumbering behind him. Wing's atomic pistol was clutched in his hand as he jarred to a stop beside the captain. His eyes followed the pointing red arm.

One's coming out!

Tensely, Wing waited, aware of Dead-Eye's labored breathing beside him, of the pounding of his own heart, of the sudden quiet among the police and their homeless charges.

What was it? Did it hold the answer he and the Council of Seven were seeking? Would Earth be free of this voracious flower? Could the Mercurians be stopped before it was too late? Would it give up its secret which meant so much to Earth—and Pat's sweet face was smiling at him—and him?

One shadow was growing more distinct as it moved toward the rim of the blue force field. It shuffled along slowly, like an Earth diver moving across the ocean floor. Wing was aware of the police captain's gestures, drawing up a squad of red-clad police with their atomic rifles at the ready.

The shadow moved closer to the outside. As it approached, the blue flower immediately before it began to dim, to grow black as if some intangible hole were opening to let it through.

Then the shadow-thing was outside the blue flower.

The police captain's thumb pointed down. Atomic lightning from the police rifles lashed at the shadow-thing.

Wing saw the lethal bolts strike the shadow. Then a blast of sound and light deluged him, spinning him off his feet, hurling him against a blackness shot through with pain and searing heat.

The pain and the heat were still branded on his mind—raw wounds that made him want to scream out in protest—as he crept slowly back to awareness of the things around him.

His ears came to life first—and he heard the voice whispering over and over again. "Oh, Curt. Oh, Curt." Then his skin was responding to the warm, vibrant fingers caressing his cheek. Into his nostrils came the sweet scent of her loveliness. His eyes opened and he saw the soft brown head cradled on his breast.

Then his mind brushed aside the memory of pain and heat.

"We failed, didn't we?" He didn't recognize the broken, almost lifeless voice as his own.

Pat lifted her head. She didn't need to speak, not when her blue eyes were so eloquent.

"Dead-Eye?" Wing asked.

"Don't you fret, Captain. I'm all in one piece, even if Elizabeth did give me six nasty powder burns on my leg."

Curt Wing wearily turned his bandaged head, beheld a mound of bandages sprawled atop the bed beside him.

"You sure look like a hangover, Dead-Eye," Wing observed. Then: "Was it bad, Pat?"

She nodded. "Only a half dozen out of all those hundreds escaped. Most of them were killed in the explosion. The medics don't know how any one came out alive—especially you and Dead-Eye. You were right in the center of the blast."

"Well," Wing observed, and it was an effort to speak lightly, but something had to be done about the horror in her voice, "I don't feel the least bit alive. Maybe I'm a ghost."

Her laughter was a relief, but a little too full for such a flimsy joke. So he said:

"I suppose the shadow-thing wasn't harmed." It was more a statement than a question.

"No," she said flatly. And in the same flat voice, added, "I'd better go. You need rest and quiet."

"Wait," he called. But she was gone. "Pat," he called out, once, twice. That unemotional voice was a dead give away. Something worse had happened and she didn't dare tell him.

Curt Wing dragged his body out of the bed. It screamed in agonized protest. Somehow, his mind held together against the shock and hurt that poured into it as he pulled his body upright, focused his eyes, looking for something to wear instead of the brief hospital garment.

Dead-Eye, from the next bed, asked weakly, "Where you going, Cap?" Wing didn't answer. He was delving into a wall locker, dragging out a burnt tunic, finding torn and broken sandals.

A white-gowned nurse barred his way in the hall.

"You can't leave, Commander. In your condition, you'll kill yourself," she said gently.

"Why not?" Wing grated. "I should be dead anyway. What's a few more minutes more or less? Life won't be any fun anyway if Earth is lost." He had to use his hand to guide himself along the wall as he pushed his weary, beaten body toward outside.

Behind him, he heard Dead-Eye calling,

"Wait for me and Elizabeth, Cap. We're coming, too."

Outside, it was raining—unobtrusively but relentlessly. The early afternoon was drab, but in the little park across the hospital courtyard, there was color. The circular beds of pink roses, of multi-colored pansies, of bluebells seemed brighter for the rain which beat so gently at them.

Wing heard the muted twittering of birds as he stood on the hospital steps. He looked up into the lowering sky and let the raindrops beat at his bandaged face. The door behind him opened and Dead-Eye came stumbling out.

Wing breathed deeply of the wet air, felt it clearing the heat and pain from his mind.

He looked at Dead-Eye, then toward the east where the blue radiance suffused the sky.

"Let's go," he said simply.

They hadn't trudged far in the rain before they found out what Pat Packer's unemotional voice had meant.

Terror was riding through the city, whipping the men and women of Earth into madness and death.

As the two of them moved closer to the edge of the blue flower, wild-eyed humans fled past them, casting fearful glances behind.

These panic-stricken humans ran silently, except for the gasps which burst from tortured throats. Abandoned children sobbed as they ran, not knowing nor caring where they went—driven by the fear of what was behind them.

Behind them, flames from burning houses were growing brighter and dull explosions were growing louder. Soon there were no more humans running, but as Wing Commander Curt Wing and Dead-Eye plodded on, they saw charred and broken corpses and the smell of burnt flesh was mingling with the stench of wood and plastic and paint.

And then Wing and Dead-Eye saw Them.

They numbered in the hundreds—spreading in a long single line—moving sluggishly but steadily, bolts of blue flame flaring out ahead of them. The flashing blue bolts melted steel, sent plastic into exploding drops of fire, touched and charred humans who still moved in their path.

Wing dragged Dead-Eye out of the deserted street into a low shop building. They moved to a window and watched those blue bolts leap overhead to jab at building or human somewhere back from where they had just come.

"What are they?" Dead-Eye asked, peering at the thin line moving closer. "They're nothing but shadows, looks like."

"Another dimension," Wing suggested. "Probably on a higher plane than our own. Maybe that's why they're just shadows to us."

Dear God, he thought, what has humanity done to deserve this? We cannot fight them. We don't know what they are. Somehow, though, we must beat them. Earth must not die, not now, when we are on the very threshold of destiny.

We've come from the mud and slime of a new born Earth, clawed and fought our way out of nothing to start reaching for the stars. Is this our destiny—to come so far and then be snuffed out before we even realize our talents?

"We've got to beat them, Dead-Eye," Wing said harshly.

"Don't worry, Cap," Dead-Eye urged. "Shucks, they can't be so tough that they can lick us. Besides, Cap, us Earthmen always fight better when the going's rough. Why, just give me and Elizabeth a chancet at them. We'll knock 'em dead."

Wing's dark eyes were soft as they looked at Dead-Eye's earnest, bearded face.

"We sure will, Dead-Eye," he said. "We sure will knock 'em dead."

That is, Wing amended, staring at the relentless shadows as they moved slowly toward their haven, if They don't knock us dead first.

Wing and Dead-Eye hugged the buildings as they retreated. They picked their way along the rubble-strewn streets, their nostrils quivering at the intermingled odor of death, burnt flesh, charred and rain-wet wood.

Ahead and behind them as they retreated, the flashing bolts of the shadow-things smashed buildings, leveled the trees along the boulevard, sending them up in puffs of white smoke and flame, heaving up the walks as tree roots exploded.

The rain was turning heavier now, turning chill, soaking through their own burnt and tattered clothes. It was relentless, that rain, almost as if it were bent upon breaking the spirit of man as the shadow-things were rending and tearing the flesh.

The two limped on alone, ahead of the advancing shadow line. They walked alone through death and destruction as man's promise and hope darkened.

We're walking toward the end of our world, Wing thought. We'll soon be nothing but dust motes kicked up by the tread of a new, more powerful race.

The hell of it is, we're not even fighting back. Why, he thought in amazement, we're not even trying any more.

"Dead-Eye," he asked suddenly. "What are we running away for?"

Dead-Eye's slumped figure straightened suddenly. "Gee, Cap, I was wondering when you'd begin wondering about that. You ain't been acting natural at all. We never ran away from a fight before. Let's go knock 'em dead right now, huh, Cap?"

Wing looked at Elizabeth, strapped snugly to Dead-Eye's left hip, then at his own two empty bandaged hands.

"Well, Dead-Eye, here, as your owlhoot pard would say, 'here goes nuttin'."

Not for many days had Curt Wing felt such a sense of peace and relief as he did that moment when he turned back toward the unknown and implacable enemy. Deep inside he was chuckling. It was silly for the two of them to march against the shadows. Silly, sure, his proud spirit admitted, but wasn't that the way of man?

Wasn't it man's way to thumb his nose at impossibilities and forge ahead? It wasn't a matter of winning, really, but having the guts to go ahead and try.

Dead-Eye snapped open the cylinder of his powder gun, observed candidly: "I hope I don't get rattled again and try to shoot my toes off. Those six slugs jerked out of Elizabeth so fast before that there explosion I couldn't even control her at all."

They moved back deeper into hell.

All around them buildings, trees, streets and sidewalks were being flung about as the power of the shadows smashed. The rain was coming down in torrents now, and the two of them could barely see a few feet ahead.

But always they knew where the shadows were—the slashing bolts pointed them out unerringly. They were very close to that unseen line of shadows. The thunder of those bolts was rending the air and mixing in the fresh smell of ozone with the pall of smoke and putrid smells which even the driving rain could not beat to earth.

Suddenly, Wing and Dead-Eye stopped. It was as if they had walked into a solid wall. But this wall was different. It pushed them backward easily, although they strove to move ahead.

"A harmless force wall," Wing said in answer to Dead-Eye's query. "But we can't get through. There goes our grand gesture, Dead-Eye. We can hardly thumb our noses while we're being pushed backward."

"Huh!" grunted Dead-Eye. "I'll fix 'em." He levelled Elizabeth, aimed her into the unseen obstacle. His thumb flicked at the hammer, and Elizabeth's gruff voice broke through the cacophony of noise with amazing clarity. He strode forward, Wing beside him, and blasted at the invisible wall.

Of a sudden, the noise was gone. Wing halted in amazement. The tremendous symphony of sound which had been pounding at his ears now miraculously was stilled.

Elizabeth's last shot still echoed, but the crash of masonry and plastic, the scream of tortured steel, the growling crackling of the shadows bolts, the snapping as fire gulped at wood and inflammables—all these were gone.

But while they still marveled at this change from noise to silence, something happened. They were thrown off their feet, and they once more found themselves out in the noise and fire.

No more had they picked themselves up from the rubble than the invisible wall was nudging at them again, shoving them ahead of it.

The insentient wall kept nudging them backward—ever backward until there was no longer any sense of time or place to them. A confused roar of crashing buildings, explosions, groans of tortured metal; an indiscriminate blend of smells, of smoke, fire, charred flesh and wood; a heterogeneous awareness of pain, cold heat; a knowledge that this, for Earthmen, was the end.

What did it matter now that Zhan Nekel and his rocket fleet thundered ever closer to Earth? That Pat, who had come back with her promise of happiness, loved him? What did anything matter anymore, except dying like an Earthman should—in the ruins of his world, still trying to lick something so much stronger that his greatest effort was breath against a cylinder?

Curt Wing stumbled, fell. Then the force wall was rolling over him over and over, always back, back. The broken pavement, the shattered rubble pounded and tore at his already burned and battered body.

Then suddenly:

"Here they are, Pat!" The voice cut through into his dulled mind. A powerful light, hurting his eyes, struck at him, and in its reflection he caught sight of a figure in space blues, gargoyle eyes glinting. Lt. Packer! Packer shouted:

"Swing the rocket car around, Pat. Quick! Something's shoving Curt and Dead-Eye around and it might upset the car."

His light suddenly twisted crazily and Packer grunted, "Damn, it's like a moving wall." Then Packer swung back, lifted Wing to his feet, dragged him ahead of the crawling wall. Wing felt the heat of the rocket exhaust, muted by its muffler, fan his cheek. Then he was inside the car. Moments later, Dead-Eye's heavy bulk followed him, and Packer was leaping in with them, urging:

"Get going, Pat, but watch out for those rubble piles and holes." Then, in the bucking car, Packer was tearing open a package of antiseptic drug needles. Wing felt the sting in his neck, and the dullness and pain were fleeing from his mind.

"You're a couple of space zanies," Packer muttered, yanking the gargoyle-like smoke glasses from his eyes and pulling off his space crash-helmet. "Pat almost went crazy when she found you'd left the hospital. We've been searching for you ever since in this hell. It was only luck Pat spotted you with the infra-red, or you'd be rolling still."

Curt Wing leaned back against the car cushion. "Well, Lieutenant," he said, "I might as well be rolling still for all the good I can do against these shadow-things." He lifted his bandaged head, his dark eyes almost black now with weariness and hate of the beings who were casually flicking man into the limbo of forgotten things.

"You know what we're up against, don't you, George?" he asked. From the pilot seat, Pat said bitterly:

"We know, Curt. The whole world knows. The telecasts have been bombarding the world with it ever since the first shadow came out and hurled our own destruction back at us a hundred-fold."

George Packer added, "I was recruited to pull our biggest space guns out and hook them up on land rockets. The ships can't rise, somehow, and when we've called for ships from other points, they get so close and then their power gives out."

"But, gee," put in Dead-Eye, "this car's running. How come?"

"Don't know why, Dead-Eye," Packer added. "These, of course, don't have the new cyc motors; still run on the old combustion principle. The force field probably neutralizes the cycs, but doesn't faze the firing gas in the cars."

"The space guns didn't help, I suppose?" Wing asked.

"No," Packer said, twisted his face ruefully. "The shadows thrived on it and threw our bolts back ten times as hard. It wasn't nice to see."

"Sometimes," he said, wistfully, "I wish we were back in your beef-striker—sorry, Dead-Eye—cow-puncher days. It was man to man then, and you knew that it wasn't the weapon but the wielder." He ran his hands through his tousled blond hair.

"Yep," said Dead-Eye. "Elizabeth and me'd fix 'em if we could see 'em."

The bucketing car began to have smoother going; the darkness outside was lifting, and the beat of the rain seemed to decelerate.

In the comparative quiet and peace, Curt Wing's dulled mind, clarified by the stimulating drug, was beginning to work again; his spirit numbed and beaten down by pain and inability to solve the enigma of the shadows and their weapons was lifting itself, shaking itself from its lethargy, as something stirred within.

Just that buoyant spirit of man which refused to admit defeat? Wing was wondering. Or was despair so deep that I couldn't go any deeper so I have to come up toward hope again?

The rocket car suddenly sloughed to a stop.

"Sorry," Pat said softly, and laughed. There was a note of hysteria in that laugh. "But we're surrounded." The three men peered out through the plastic windshield. The shadow-things were ahead, moving toward them.

But no destruction was spitting from those ghostly figures. For the first time, Curt Wing had a chance to observe closely.

They seemed about the height of a man—but distorted like a man's shadow falling before him as he trudged up a hill with the sun behind. Yet not so distinct. They wavered, too, within themselves, although the outline remained constant.

The rain was only a light patter now and the sky was brightening as the three men and one woman crawled out of the rocket car. The shadows were very close now, but there still was no sign that their weapons would speak.

Silently the shadows moved, scores of them. That straight line they made began to bend and curve around the four who stood waiting.

No threatening gestures, no weapons visible, just that relentless, closing circle.

"Damn you," said Dead-Eye suddenly. "Elizabeth didn't get a chancet at you before. But she will now."

"No!" Curt Wing snapped. "I think they want to take us alive. Maybe we can learn something. No, Dead-Eye, no!"

But it was too late.

Dead-Eye had snapped his ancient powder gun from its holster, and his left hand was fanning Elizabeth's sharp-biting tongue. The hammer snapped down thrice—three shots blasted out.

In that breathless second before the awful blast of sound and light struck, Curt Wing saw three shadows suddenly disappear. Then the sound and light struck as Wing steeled his muscles and mind against it. But, amazingly, at the first touch, it was gone, and he was standing unharmed.

He twisted his head. Pat was standing close beside him, and George. But Dead-Eye was gone. Only Elizabeth, her metal twisted and white hot, lay smoking on the ground where Dead-Eye had stood.

Dead-Eye, Wing's mind was crying, you big, dumb, blundering bear, where are you? Oh, you damn fool, pitting an old, crazy powder gun against atomic power! You killed yourself, you crazy, gallant guy. Now you're gone—who am I going to have to look out for after this?

Pat's fingers were soft on his arm, drawing him back from the pain of the loss. "He always wanted it that way, Curt. Quick, while he was in action."

Rage began to boil in Wing's heart against these tenuous shadows who scorned giving an Earthman even a hopeless chance. The ache for Dead Eye, who was like a big good-natured puppy; that ever-conscious nagging of the doom of mankind at the hands of these callous shadows; the knowledge that even if this doom could be somehow stopped or turned aside there was Zhan Nekel's space fleet coming nearer, churned his mind. And from his whirling brain came only one driving thought. Avenge Dead-Eye—the thousands of Dead-Eyes who never would have the chance for their simple joys and pleasures if man knuckled down under this greatest threat!

With that rage came clear thinking. Little things—like Dead-Eye's firing into the invisible wall, combustion type engines firing when cyc-powered units went dead, shadows disappearing when Elizabeth spat at them; little things, simple things.

A thought coalescing, growing sharper, until it was burning in his mind, fueling his spirit with new hope.

"Thank you, Dead-Eye," he whispered. The harsh sharp planes of Curt Wing's face were softening.

"We've got a chance," he said. "Dead-Eye gave it to us, Pat. But we've got to get away—out of this circle somehow." He waved his hands at the tight circle of shadow-things that hemmed them in. "Any ideas, George? Pat?"

Lt. George Packer's shoulders had come up, he was touched by this new assurance in Curt Wing's voice, in the fire of those dark eyes. "Not," he said, and there was new life in his voice, too, "not unless an old wish comes true and the ground swallows us up."

"It can," Pat said, the words tumbling out. "We can fall in a hole, can't we? Look at them, Curt. They shuffle along, but they don't step into holes. They just float over them—like they do belong in another dimension and can't anchor themselves to Earth. See?" Her voice rang with excitement.

Wing laughed. "But what good would falling in a hole do us? All they'd have to do is fish us out again. And we'd have new bruises." The circle was tight now, and suddenly they felt the push of an invisible wall against them as the shadow-things moved closer. Then they were moving.

Pat didn't stop arguing. "If you were a fat man and you dropped something between your feet, wouldn't you have to get your stomach out of the way to see it?"

Wing looked at her sharply. "What are you driving at, Pat?"

"If they're from another dimension, and all the telecast say they are, and if their vision devices for this world are just for straight-ahead seeing, what would they have to do in order to look down?"

"Pat," Wing said softly. "It would be like riding in a rocket car. Once something gets underneath it, out of the range of the windshield, you can't see it. You have to back up or go forward. And if we pick a deep enough hole, the shadows can't back enough or go forward enough to see the bottom. Is that what you mean? Because the high sides cut off their vision?"

Her wide smile and sparkling eyes were his answer.

Curt Wing, nursing a new set of bruises after plunging into a fifteen-foot hole and scrambling out after the shadow-things had finally floated by above them, led Pat and lanky George Packer at a loping run back to the rocket car.

It was almost nightfall and the fire and noise and stench of White City were far behind them by the time the speedy little car made it to the mountain retreat of the Council of Seven.

During the ride, Curt Wing's sense of loss with Dead-Eye gone was softening, mingling with a gratitude deep and strong to the big, black-bearded giant.

With a child's intuition for solving a problem simply, Dead-Eye and his Elizabeth had given man a chance to fight.

"A chance, Curt?" Pat had overheard his whisper. Her hand on his arm was warm and vibrant. Curt clasped his fingers softly over hers.

"Yes," he said, "if there is only time."

Jan Eliel, senior governor of the Council of Seven, pulled his red-rimmed eyes from the telecast when Curt Wing and Pat and Lt. Packer entered the consultation room.

Old as his face had stamped him those few days ago when Wing had brought the fleet back, Jan Eliel now was a broken and bent caricature of the man who held the direction of a world in his hands.

"Yes?" he asked, and the life was out of his voice.

Then he saw the four miniature earths which still glinted proudly in a row across Wing's torn and burnt tunic's left breast.

"Wing!" He rose from his seat on the telecast bench, hurried forward. "You've solved it!"

Wing shook his bandaged head. "I don't know for sure, Governor, but I think we do have a way of stopping the shadows—if there's time."

Jan Eliel ran a shaking hand through his white hair.

"I don't know. Zhan Nekel's fleet is moving faster than we thought it would, and the fleet units you smashed at the Moon have been re-organized and now are swinging toward us. That, at the most, gives us two days—and I thought we'd have at least two weeks.

"But enough of that; what is the way to stop these terrible shadows?"

Instead of answer, Wing asked:

"How much of that obsolete Twentieth century artillery is available?"

Jan Eliel's old eyes widened.

"You're mad, Curt Wing," he said wearily. "We've tried everything we have, the finest weapons, the heaviest atom machines, and we get nothing in return except our own power turned against us. Powder would be worse than useless. You can't stop atomic power with an old-fashioned shell."

"My friend Dead-Eye was killed when he proved you can," Wing said quietly.

Jan Eliel's voice was cold. He spoke quite without emotion. "You've been under too heavy a strain, Space Commander Wing. You are not the clear-headed Wing we once knew. Go back to the hospital and rest. Perhaps you will be able to bring back some semblance of sanity and help your world when she needs you most."

"Damn you," Wing said. "Can't you see it? We've been throwing atomic power at an atomic shield, so it just bounces back at us. Suppose we threw something it couldn't bounce back right away, leaving us an opening to hurl our own atomic bolts into the heart of it?"

Jan Eliel had turned his back on them, once more was watching the telecast.

What's the use, Curt Wing? Why bother when the ruler of the world won't listen to what a big, blundering guy proved when he got mad and fired an old powder gun at a shadow? He's blinded as you were not so long ago by despair. Follow Dead-Eye's lead, show him the way and he may follow.

"Come on," Wing said abruptly. "We have a job to do."

The long low barracks at the Spacers' Training school outside Washington buzzed and growled with the hundreds of blue-uniformed spacers.

There at the far end of the hall on the little platform where the sergeants took the roll, Wing stood looking at the hard-bitten, space-burned men who had been land-bound since they turned from victory to answer that fatal six-two....

They had come because their commander had offered them a fight; a little different perhaps using old-fashioned projectile weapons, but nevertheless a fight; and they, who had used space guns against the shadow-things, who had been beaten back without a chance to fight, were spoiling for battle.

Some of them were reading the hastily-printed instructions that came with the bright, shining, but outmoded weapons. Some were a little jealous of other comrades who even now were hurling their atomic bolts through the skies over Earth as they harassed the vanguard of Zhan Nekel's Mercurian fleet.

But with the pangs of jealousy they had pride in themselves, too. While their shipmates battled a known enemy, they were going out to fight against an unknown enemy with untried weapons and only the promise of their Space Commander, Curt Wing, that these weapons, three centuries old, could win where atomics had so miserably failed.

Wing raised his hand for attention.

"Some of you knew Dead-Eye and his Elizabeth. He's gone now, but he destroyed three of the shadow-things with leaden pellets from his old sixshooter before he died. He showed me the way to lick those shadows. Simply, it's this. A concentration of powder can open a hole in the atomic shield of the shadows. But in our atomic weapons we have a flow of power and it's sucked away by the shield before it can concentrate.

"In Elizabeth, Dead-Eye had concentrated power—the leaden projectile. Its comparatively inert atoms struck the shield and broke through before it could be spread out evenly over the shield.

"For a moment, the shield was out of balance. That's your job and mine—keep that shield out of balance until we can find the invaders within and destroy them.

"I realize that you've had only five days to study what these old weapons are and how they operate—but we haven't any more time. We've got to lick an enemy from outside and an enemy from within at one and the same time.

"Do you think we can do it?"

A roar of assent greeted him.

They numbered in the thousands. Space rovers of the Twenty-fourth century, moving in a long, spread out line toward the edge of the blue flower that still pulsated and grew, reaching farther and farther out from White City.

Curt Wing's heart was filled with pride—pride in these thousands who, with strange, obsolete arms, were moving against a shadowy foe equipped with weapons the like of which they'd never dreamed; pride in that unbeatable spirit and courage of man, the magnificent fool, who had lifted himself by his own bootstraps from the caves of Earth to the vast reaches of the stars!

It was Curt Wing's powder gun which opened the attack when they struck against the invisible force barrier.

In the dawn light, all up and down that long thin line, the powder guns began snapping and crackling. Tommy guns, rifles and revolvers hurled their slugs at the wall.

The long line kept moving forward. Wing snapped on the portable radio phone strapped across his chest, and at his words, far behind him, a dozen space cruisers—those which could be spared from the battle against the Mercurians above Earth—rose and soon were scintillating in the rays of a sun still hidden by the rim of Earth.

As the line of marching men strode forward, the cruisers, their rocket motors vibrating the air, circled high above them.

The line reached the edge of the flower—and the intensity of the firing increased until it was the steady roll of a thousand drums.

Wing spoke into the phone again as the flower grew bluer along the edge. The blue deepened and deepened until it was almost black. Then Wing spoke into the phone once more.

The circling cruisers steadied. Their blue bolts spat at the blackness.

The shock of it could be seen for miles in the blue flower. The shield blackened in scattered spots. Where every black spot showed, the bolts from the Earth ships lashed.

The terrible power unleashed inside the shield began to show as the flower shrunk back into itself.

The ground smoked and trembled as it emerged from the retreating force field; great fissures opened and the ground trembled and shook as if in the grip of an earthquake.

Wing snapped a halt order to the captains on either side of him and the word moved rapidly down the line.

Bracing themselves against the shock of the quake, they waited.

It wasn't for long.

In the brightening day ahead of them, on the leveled plain behind them, the Earthmen saw the shadow-things approaching, their power bolts lashing out ahead of them. Every other man turned, so that half of them faced the shadows ahead and half the shadows behind.

The powder guns crashed, and the steel and lead and copper pellets whined a song of death in the ranks of the shadows.

The mist things exploded and disappeared as the multi-shaped spawn of Dead-Eye's Elizabeth struck their shields.

Like puncturing a kid's balloon with a needle, Curt Wing thought. He was laughing now—man had risen once again from the dust. No longer need he despair. He had been stopped only momentarily in his climb toward destiny. After this unbelievable enemy, the Mercurians would be, perhaps not simply, but finally, hurled back to their hell-pot planet.

It was a tired and weary Curt Wing who threaded his way through the smoking ash of what had been one of the mightiest of Earth cities. He moved toward the church, which stood so remarkably untouched by the tremendous forces which had been unleashed within the blue flower.

The two powder-burned and dirty spacemen who flanked the steel portals saluted him as he walked tiredly up the stone steps.

"Who phoned me?" Wing asked.

The redhead at the left of the portal saluted.

"I did, Commander. Jack and I saw this thing and we peeked inside and saw that funny light, so we thought we'd better call you."

Wing moved through the steel portals, stood in the quiet hush of the church. There, just before the altar rail was the curious blue light—like a hexagon of blue.

He walked slowly toward it and as he approached, the altar behind it seemed to fade away and he was looking into a silver hallway.

He halted within a foot of it. It was like looking through a doorway—why, it is a doorway, the doorway to the world these invaders came from!

He unsheathed the revolver, spun the cylinder to see that it was loaded, and with only a glimpse over his shoulder at the two spacemen silhouetted in the church doorway, he stepped through.

It was like stepping through fire—a fire that clawed and tore at the heart of him—but it lasted only a moment.

The hallway in which he found himself was of silver, tiny overlapping bits of silver plating that rippled and cast off flashes of light. He walked slowly ahead to the other doorway he saw before him.

Framed in the door, he looked above him, through a glass roof, up into a strange star-studded night sky.

Where is this world? Curt Wing wondered. Have I crossed a thousand, a million or a trillion light years to come here?

He looked down from the night sky and the vastness of the transparent roof reached as far his eyes could see.

It was only a whisper in his mind at first—then it grew stronger until it was as if his ears were hearing it.

"You're a man," the thought said. Curt Wing's dark eyes cast about for the source of it.

"You're a man," the emotionless thought repeated. "That is why we could not beat you. We are a dying race, trapped on a dying world. You are young and have your destiny still before you."

"Who are you?" Wing's mind called out. "Where are you?"

"We were never beaten until now. We knew that to survive this dying system we must fight across eternity to find another sun and another system. We started from mud and slime like you, and some day you too must come to this—the end of your destiny.

"You will fight as we have fought. We built a machine to warp space. For centuries our scientists labored to perfect it, just as other technicians created a space scanner to find a world suitable to us."

Curt Wing was trembling as he listened. Somehow, the measured cadence of those cold thoughts was fingering his heart, bringing a chill to it.

"We found your world—the world of man, Earth, but we didn't know it until now.

"We made a mistake—a mistake which is destroying us but will in your far distant future destroy you."

"A mistake?" Wing's mind asked.

"Yes, those scientists of ours who labored so hard and long, built a machine not to warp space, as we all thought, but to warp time.

"You see, Space Commander Curt Wing, we, too, are men. We were fighting our past, you your future on Earth, our common home. In attacking your world, we have destroyed ourselves."

"But why?" Wing's mind started to ask.

"You saw us merely as shadows, did you not? That's all you were to us, too. Shadows; but very, very stubborn. Never in our recorded history had we met such a stubborn and such an able foe. No wonder. We were fighting against ourselves.

"It's time to go, Curt Wing, before the time door closes and locks you forever here."

Man to climb so far into the stars and to die by his own hand, Wing was thinking bitterly.

"Do not despair," the thought intruded. "What is done is done, and nothing can be changed."

"Wait," Wing cried out. "We beat you because a big, dumb guy by the name of Dead-Eye had the quiet faith that we could. He showed us the way.

"Dead-Eye said," and the words came from his memory like a prayer, "don't worry, Cap. Shucks, they can't be tough enough to lick us. Earthmen always fight better when the going's rough. Why, we'll knock 'em dead.

"Take hope from Dead-Eye's words. We were in the depths of despair when he uttered them, and we came up that long, terrible road to hope. We licked our problem. You, because you, too, are men, can lick yours."

There was nothing in the emotionless thought that answered him, that told they were heartened.

Curt Wing turned his back on Man's future, walked down the silver hallway, through the hexagonal door to his own world. He stepped out in the quiet hush of the church.

He saw the two spacers still staring in as he walked out of the darkness of the church into the brightness of day.

One of the spacers called out:

"Commander, the light's fading!"

The shouted words echoed in his ears as he strode down the steps.

The light's fading.... Like hell it was! Somehow those future men would find a way. Wasn't it man's way to thumb his nose at impossibilities and forge ahead?

Space Commander Curt Wing's shoulders straightened. He lengthened his stride. He did not look back.