The passengers of the captured ship had been brought to the saloon in whatever state of undress the ray had caught them.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Great Green Blight, by Emmett McDowell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Great Green Blight Author: Emmett McDowell Release Date: November 18, 2020 [EBook #63807] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GREAT GREEN BLIGHT *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Empire of Earth was crumbling. Space-liners fell

prey to savage phantom crews. A weird, green wave

of terror engulfed the Universe. Enslavement of the

Empire was near, and only a handful of men could halt

the final blow ... a handful of men who could not

act—for a single movement would mean their death.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Somewhere aboard the Super Space Liner, Jupiter, a resonant gong sounded three times. Norman Saint Clair started, glanced uneasily about the magnificent lounge. A gray fear gnawed at his vitals. With a sinking heart, he watched the crowd, who had come to see off the passengers, hurry out the port. This was his last chance to get off the ship.

"Excuse me," said a voice at his elbow.

Norman Saint Clair spun around, recognized a Universal Lines steward, grinned embarrassedly.

"First trip?" asked the yellow-clad steward.

The young man nodded.

"I wouldn't be too uneasy, sir. We'll pick up our escort this side of the moon. A full ship of the line, sir. We're carrying radium, you know. They wouldn't dare attack a ship of the line. May I see your book, sir?"

Norman Saint Clair fumbled in his wallet, handed the steward his book. Since Terra's ships had begun to disappear on the Earth to Jupiter run, the Terrestial Intelligence Service required them of everyone traveling through space. It contained his photograph, a three-dimensional likeness showing a gaunt likeable face crowned by short, crisp blond hair, a photostatic copy of his birth certificate, his description, nationality, business, fingerprints, history.

Satisfied, the steward said: "This way, sir," and led him to an acceleration chair at the after end of the lounge. "Strap yourself in, sir. We start in a few moments."

The young man eased his lank, six-foot-two frame into the seat, nervously fastened the belt. In spite of the steward's words, he was not reassured. Ship after ship had vanished into the blue. Nor had the vaunted Terrestial Navy or the T.I.S. been able to discover any trace of them thereafter. Somewhere beyond the orbit of Mars their radios crackled and blanked out. Space opened and swallowed them. It was unprecedented. Never before in the history of space travel had anything remotely like it occurred.

His eyes roved among the few passengers strapped in their chairs. They were subdued. The sailing, unlike the gay hectic affairs before the coming of the terror, was grim, quiet. No one, he realized, was making the trip unless it was unavoidable.

With a touch of panic, he considered demanding to be set back on Terra while there was yet time, but a stubborn streak made him hold to his course. It was the same stubborn streak which had led him to book passage aboard the Jupiter in spite of the terror. A hundred times he had regretted accepting the post of Lecturer on Ancient History at distant Ganymede. He loved the quiet sanctuary of his library with its collection of twentieth century authors. He had no ambition to exchange his secure academic life for the uncertainty of a crude, rowdy frontier. But the post had offered a good salary, much better than he could expect on Earth for years.

A party of Colonial Guards swaggering across the lounge drew his attention. They were a hard-faced lot, recruited from Earth's far-flung frontiers. They constituted, he knew, a special armed guard, traveling aboard the Jupiter at the company's request. Universal was taking no risk with the precious cargo of radium.

From the Colonial Guards his eyes strayed across to the occupant of the seat next to his. A girl. He stared, lost in admiration. He'd never seen a creature so beautiful. Her black curly hair framed a pale oval face. Her eyes were blue, her features delicate, chiseled. She was, he realized with a start, regarding him with a mixture of amusement and solicitude.

"First trip?" the girl asked, liking the frank scholarly face of the young man.

He nodded.

"Just relax in your chair," she advised him. "The acceleration's pretty fierce at first."

A second gong advised them the port was sealed. Several passengers hurried into the lounge, flung themselves into acceleration chairs. A voice, coming over the public address system, announced: "Strap yourselves in carefully. Acceleration begins in three minutes." Twice more the warning was repeated.

Norman Saint Clair's pulse beat rapidly. He felt frightened. Then a faint hum made itself felt rather than heard.

The girl said, "Listen, the engines."

He thought they sounded like the hum of bees on a warm summer day. He shivered, feeling that cold knife of fear slide into his vitals.

A giant hand slammed him in the chest, thrust him deep into the folds of the acceleration chair. His breath was driven from his lungs. He gasped, strained for air painfully. The die was cast, he realized bitterly. There could be no turning back now. They were off.

In a few minutes the pressure slackened. He could turn his head. The girl, he saw, had uncoupled her safety and was rising. He followed her example, stood up unsteadily. The artificial gravity, two-thirds that on Earth, was in effect. It gave him a light giddy sensation. He didn't think he was going to enjoy the voyage.

"Isn't it delightful?" said the girl. "It always makes me feel positively sylph-like."

Now that she was standing he could see how slim was her waist, how full her hips, how long her legs. She stirred some atavistic sense in him. A vein throbbed in his throat. I'm reacting like an animal, he thought. Disgusting.

The girl held out her hand, said, "I'm Jennifer Scott. I'm going home to Ganymede."

He took her hand, introduced himself. "I've been employed to lecture on Ancient History at the Ganymede Seminar."

Jennifer clapped her hands. "Grand. Papa is commandant of the military post. The fort is only a short distance from the Seminar. We'll be neighbors. You'll love Ganymede. It's so wild and primitive."

"No doubt," he replied dryly.

Jennifer glanced at her watch, said, "It's time for lunch. I'm ravenous. Shall we try the saloon or the grill." She seemed to have assumed proprietorship of him. He rather liked it. He said, "Let's try the dining saloon."

As he piloted her across the lounge, he observed again how few people had booked passage. The fear returned, squeezed at his stomach. He said:

"Do you think it was wise to make the crossing at a time like this?"

"What?" said Jennifer. "Oh. You mean the terror. No, I suppose it wasn't, and papa will be frantic. He sent me a spaceogram absolutely forbidding me to return. But I was fed up."

"Fed up?"

"Yes, fed up with Earth and their dull stuffy ways," said the girl passionately. "They're dead. They've forgotten how to play, or fight or make love."

Norman Saint Clair was shocked. People who went to the Colonies, he had always supposed, were driven to some such drastic step by the force of circumstance—economic, possibly, as was his case. This view came as a revelation, an unpleasant one.

"Anyway," continued the girl; "we're off. It's too late now."

They fell in behind a fat Earth woman, entered the passage which led to the dining saloon. He started to ask the girl what she had found so unpleasant about Earth, when the fat woman stopped, said: "Oh, my God!" Then she began to scream. The screams lifted the hair right off Norman Saint Clair's neck.

Jennifer cried, "What is it? What happened?"

Hesitantly, he peered over the screaming woman's shoulder, saw a man stretched on the deck. He lay on his stomach, his head on one side, disclosing a pale classical profile. He appeared young, little older than Norman himself.

"I don't know," the young man replied. "Someone's hurt, I think."

He forced himself to push past the fat woman, kneel at the unconscious man's side. What he saw made him sick. He looked away. A gout of blood had spurted from the man's neck, dyed the green fiberon carpet scarlet. His throat had been cut from ear to ear.

Several passengers, alarmed by the Earth woman's screams, dashed into the passage.

"What's wrong?"

"Something happened?"

"Dead!" the fat woman gasped. "My God, I almost stepped on him!" She burst into strangling sobs.

A yellow-clad steward appeared. He couldn't see the body because of the press. "What's the trouble, sir?"

Norman stared at him. "Murder," he said in a shocked voice. "This man has been murdered. His throat's cut."

"Murder!" repeated the steward. "I'll get the captain." He scuttled off down the corridor. The fat woman went into hysterics.

"Who could have done it?" breathed Jennifer. "Why?"

Norman Saint Clair shook his head. He rose from his knees, feeling weak, shaken. He had never seen a dead man before.

"Here," said a man brusquely. "I'm a doctor. Let me see that man." He shouldered to the front, knelt beside the body. Norman Saint Clair relinquished his place with relief.

"Powerful man did that," the doctor pointed out. "Almost cut his head off."

With a gulp Norman looked away.

"Here!" ejaculated the doctor. "Look at this!"

Curiosity dragged his eyes back. The doctor had rolled the body over, turned back the lapel of the dark gray business suit. Norman saw a small green disk pinned to the underside of the lapel. It was about the size of a dime and died out to represent one of Earth's hemispheres. Three letters in raised silver stood out on the green surface. "T.I.S." he made out.

"An agent of the Terrestial Intelligence Service," breathed Norman.

The doctor rose, drew a handkerchief, wiped his hands. He was a tall man, almost as tall as Norman, with gray hair. His brown eyes sought the young man's. "He must have been working on the terror."

Norman nodded, thought that it didn't require any brilliant deduction to guess that. Ninety percent of the T.I.S. force was trying to solve it. The entire resources of the Empire were being drawn upon to uncover the solution. Vital trade was at a standstill, and last week the Nebulae, a crack luxury liner, had disappeared between Earth and Mars with the Martian ambassador aboard. The incident had very nearly severed diplomatic relations between the two worlds.

The doctor bit his lip, frowned, "I wish the Captain would get here," he said. He glanced anxiously at the gaping crowd, discovered the blue-eyed, black-haired girl by Norman's side.

"Jennifer!" the doctor exclaimed.

"Hello, Doctor Pequod. I didn't want to interrupt your examination."

The doctor's frown deepened. "Jennifer, what's your father thinking to let you travel at a time like this? He should realize it's dangerous."

"He doesn't know," replied Jennifer simply. "Doctor, this is Mr. Saint Clair. He's going to lecture in the Ganymede Seminar."

Norman shook hands automatically. Although he refused to look at the body his mind persisted in picturing it. He said, "Doctor, do you realize there's a killer loose among us?"

"What do you take me for? A simpleton?" snorted the doctor.

"But Doctor," put in Jennifer; "if he was working on the terror, he must have discovered something. Else, why should they have killed him?"

"I'd thought of that," interrupted Norman. "Do you suppose we're headed for the same fate as those other ships? We're carrying radium."

"Nonsense," grunted the doctor. "That agent might have been on the trail of smugglers, anything. Oh, here comes the Captain."

The Captain, a brusque little man who appeared to be in his fifties, glanced briefly at the body, said: "Who found it?"

Several passengers pointed out Norman.

"I?" said Norman in haste. "I didn't find it. That—that...." He flung his eyes over the crowd in search of the fat woman, but she had been carried to her stateroom. He took a breath, began again. "Miss Scott and I were going to lunch. We were right behind an Earth woman. She saw the body first."

"You didn't see anyone enter or leave this passage?"

He emphatically shook his head.

"Steward!" called the Captain, turning away. "Get this body into the meat box."

"Yes, sir." The steward started to go for help.

"Here! Wait a moment. Clear these people out first."

Norman said to Jennifer, "Let's get out." More than anything else, he wanted to get away from that body. His voyage to Ganymede was turning out even worse than he had anticipated.

"Not you," said the Captain. "I want to see your book."

Norman could feel the eyes of everyone on him as he handed it over.

The Captain examined it, looked up into the pale scholarly face of the young man. "No," he said with a trace of contempt, "I suppose you wouldn't have seen anything at that. You may go."

Norman flushed, took his book back. A surge of anger welled up inside him at the Captain's tone. He was of a mind to register a complaint with the company.

"I said you may go," repeated the Captain.

"I am waiting for Miss Scott," replied Norman stiffly.

For a moment the two men's wills clashed. It was the Captain, oddly enough, who yielded. "Very well. May I see your book, Miss Scott?"

Norman felt a sense of triumph as Jennifer passed over her book.

The Captain accepted it, scanned it briefly. "I see your father is Commandant Scott. I know him very well. A capable man. We need more administrators like him in the Colonies. But Earth doesn't produce the men she used to. If it weren't for the Outlanders, the Empire would fall to pieces. Decadency; that's the sickness of Earth. Be sure to convey my respects to your father, Miss Scott."

Jennifer smiled, said, "Thank you, Captain."

"I believe you were with Mr. Saint Clair. Did you seen anyone ahead of you?"

Jennifer frowned in an effort to remember, shook her curly black hair. "I'm sorry, Captain."

Before he could reply an officer pushed his way into the group. Norman recognized him as the colonel in charge of the Armed Guard.

"Hello, Captain," said the Colonel. "One of my men just informed me of the murder." He glanced at the body. "I suggest you close off this corridor and take these people's names."

"I've done both," said the Captain tartly. "Since you've arrived, Colonel, I can leave the investigation in your hands. Meanwhile this must be reported to the T.I.S. You'll excuse me, Colonel?"

The Colonel nodded indifferently. He was a small wiry man with cold blue eyes. He requested all three of their books, examined them minutely while the doctor fidgeted and Norman sweated to get away from that still form on the deck. After questioning them again, he took their names in a notebook, dismissed them.

Once in the lounge, Norman lit a cigarette, inhaled it gratefully.

The doctor said, "I prescribe a stiff shot of brandy."

Norman didn't drink. He believed alcohol impaired thinking. Nevertheless, he seconded the doctor's suggestion. Spirits, he decided reluctantly, had their uses.

The murder had riven a crack in Norman Saint Clair's complacency. His safe world was crumbling about his ears. He recalled the Captain's charge that Earth was decadent. It was true that more and more Outlanders, men born in the colonies, were grasping power. Could it be possible that in his academic isolation he had missed the real pulse of life.

Jennifer said, "Whatever are you thinking, Norman? Your eyes look as if you were miles away."

With a start, he realized that the pair of them were waiting for him. "I? I was thinking that—that. Oh bother thinking. Let's get that drink."

II

Aboard the Jupiter day and night were artificially simulated. Norman Saint Clair awoke the next morning with a sense of disaster strong in his mind. He rose, stretched, went to the quartzite port. They had picked up their escort during the night.

The Terrestian warship paced the Jupiter silently, grimly. She wasn't half the size of the colossal liner, but her speed he knew to be fabulous, and he could count a hundred gun ports along her starboard side alone. A lean gray wolf of space, he thought. Nothing could stand up against that brutally efficient machine of destruction. Reassured, he began to dress himself carefully.

In the dining saloon he discovered the girl, Jennifer Scott. She was seated at a table having breakfast with a young man to whom Norman took an immediate dislike although it was possible to see only the back of his head. He felt surprised at himself. He wasn't in the habit of making snap judgements like that.

Jennifer saw him, waved gaily, beckoned him to come sit with them. The informality of the Outlanders never ceased to amaze him. They brushed aside conventions like cobwebs.

He said, "Good morning, Miss Scott. I trust yesterday's tragedy didn't disturb your rest too much." There was a touch of resentment in his tone. The girl appeared too buoyant, too vivacious. His own sleep had been wretched.

The girl's blue eyes were bright. She said, "Not too much;" and introduced her companion. "This is Mr. Vermeer. He's an agent of the Venusian Export Lines."

Norman observed Vermeer coolly, saw a black-eyed, black-haired man whose gray coat fit his chunky shoulders too tightly. There was a white scar on his upper lip, another above his right eyebrow. Mr. Vermeer extended his hand without enthusiasm, said, "Sit down, Saint Clair."

Norman eased his lank frame into the chair. "Have they caught the murderer, yet?"

Jennifer shook her head.

"Not likely," observed Vermeer with scorn. "There was a time when it would have been suicide to kill a T.I.S. agent. From Mercury to Pluto Earthmen were known as the scourge of the Universe. But now. Pah! They've grown fat and spoiled. The Empire isn't able to protect its own ships anymore."

Norman fidgeted angrily. "You're an Earthman, yourself," he accused.

"Not I," denied Vermeer. "I'm of Terrestial descent, but I was born on Venus. I'm an Outlander."

A waiter approached, took Norman's order.

Jennifer leaned forward. "Mr. Vermeer, do you believe this murder has any connection with the terror?"

"I wouldn't be surprised. I'd say the T.I.S. agent had stumbled across some information which made it necessary that he be silenced."

Although that was Norman's idea he said perversely, "I think you're making a mountain out of a molehill. The agent was probably on the track of smugglers."

Jennifer opened her blue eyes in surprise. Vermeer shrugged, turned to the girl, said: "They're giving a dance tonight. Would you be my partner?"

The girl hesitated, glanced roguishly at Norman who sat stiff-faced. "Thank you, Mr. Vermeer, but Mr. Saint Clair has already asked me."

Norman's mouth fell open. He had wanted to ask her but had hesitated because he didn't know her well enough. His heart leaped now with pleasure.

Vermeer glanced at Norman sourly, excused himself, left the table.

When he was out of earshot, the girl said, "There's something about that man that doesn't ring true. I hope you don't mind me using you as an excuse, Norman. You don't have to take me."

"Not take you?" he echoed. "Of course, I'm going to take you. You can't very well refuse now." He grinned triumphantly, feeling something of a devil. He rather liked the sensation.

The girl was suddenly serious. "Have you heard the news?"

"News? I haven't heard any news."

"It just came over the radio. The Comet disappeared three days out from Ganymede. She was escorted by a corvette of the Martian Navy, too."

The Comet, he knew, was a semi-passenger freighter of Martian register. "But the corvette?" he echoed blankly, feeling suddenly a bit frightened and confused.

"It vanished too." She snapped her fingers. "Just like that. But before they disappeared, they reported three flashes in space dead ahead. Then their signals stopped."

He opened his mouth.

"Wait," said the girl. "You haven't heard it all. The Observatory on Ganymede had them in sight all the time. A short while after the ship's radio messages stopped coming through, they noticed that the Comet was disappearing just as if she were disintegrating. The disintegration started at the stern and slowly worked forward until the ship was completely gone." She shuddered. "When I heard the news coming over the caster it reminded me of an old, old story of a grinning cheshire cat. The cat disappeared tail first until even the grin was gone."

"Alice in Wonderland," said Norman mechanically. "That was written by Lewis Carroll, a famous writer of antiquity."

"What do you think it is?"

He shook his head. "I'm no scientist, Jennifer. It sounds like atomic disintegration."

"But why?"

Again he shook his head. His food, he realized, was growing cold. He began to eat mechanically. He thought that if he ever reached Ganymede, he'd never venture into space again.

The girl said, "Vermeer was right about one thing. The Empire's crumbling. This never could have happened a hundred years ago." She hesitated, then added with a rush, "I wasn't going to tell you because I'm not sure, but Mr. Vermeer's stateroom is next to mine. When I first came aboard and was putting away my things, I noticed a man leave his stateroom. Norman, it wasn't Mr. Vermeer. I think it was that T.I.S. agent who was murdered."

"By Jupiter," ejaculated Norman, "do you think the T.I.S. man could have been making an investigation of this Vermeer?"

She nodded her head, wide-eyed.

"Have you told the Captain?"

"No," said the girl.

"But he should know."

She shook her head. "He'd think I was imagining things. The passengers have been reporting all sorts of nonsense since the murder. If I could only be sure." She bit her lip. "Norman, the dance tonight. He'll be there. We could search his room."

He looked at her aghast. "Search his room? Me? Suppose he walked in on us?"

"We could pretend we'd entered by mistake. My cabin is next door."

He shook his head. "I still think it should be reported to the Captain."

"He'd never believe me."

He glanced at her helplessly. "But...."

Jennifer rose. "I'll meet you at the dance tonight. We'll make sure he's there first."

He nodded unhappily. When the girl had left he pushed back his plate, called the waiter. "You can take this away," he said. "I've lost my appetite."

III

In spite of all the preparations by the Stewards Department, the dance was not a success. Everyone drank too much, tried too hard to be gay, but the shadow of the terror hung over the little floating world turning the celebrations tawdry.

Norman and Jennifer were seated at a table against the bulkhead. The orchestra was playing My Man's Done Left For Outer Space while a Martian girl gyrated in a barbaric dance which stirred Norman's pulse and shocked him beyond measure.

"There he is," said Jennifer in a low excited voice. "There's Vermeer now."

The Venusian Export Lines man had just entered the saloon. Norman saw him glance casually about the hall, saunter across to the bar.

"Come on," said Jennifer. "Let's get started."

Norman gulped down a last drink of the brandy, rose from the table. Jennifer took his arm. He could feel her grip tighten. They passed out a side entrance, down a companionway to the deck where Vermeer's cabin was located. Before the door of 312 they paused.

"This is it," said Jennifer in a whisper.

Norman gingerly tried the door. "It's locked," he said with relief. "Let's get back to the dance."

"Here," said Jennifer fumbling in her purse. "Try this. It's a pass key."

He stared at the little sliver of metal in consternation. "Where did you get it?"

"I bribed the steward."

Norman took the key. The door opened easily. Vermeer's stateroom contained a bunk, desk, two chairs, and a dresser. A spot reading light threw a round beam from the overhead to the desk. A door on the right opened into the bath. There was a second door on the left, but it was closed.

He drew Jennifer inside, closed and locked the door.

"Look through the desk," he commanded. He went to the closed door, opened it, revealing a closet.

"Look," he said. "What's this?"

Jennifer glanced up from the desk. Norman had pulled out a single piece garment with shoes, gloves and helmet attached like a diver's suit. It was made of a very sheer translucent material resembling oiled silk. A zipper-like fastener ran up the back. The suit was pale green, even the eye pieces being the same color.

Jennifer shook her head. "I never saw anything like it before. It isn't heavy enough for a space suit. What do you suppose it could be?"

Norman shrugged, put it back on the rack. He went through the pockets of the remaining clothes, found exactly nothing. From the closet, he turned to the built-in dresser. Again his search was fruitless.

"Have you found anything, Jennifer?"

The girl shook her head. "Not a thing. Except papers from the Venusian Export Lines. He seems to be an accredited agent of theirs after all."

"Let's get out of here," said Norman uneasily.

Jennifer clutched his arm. "Listen!"

He heard the grate of a key in the lock. He and the girl looked at each other in consternation.

"Quick," said Norman, struck by an inspiration. He embraced Jennifer clumsily. "Put your arms around me! Hurry! Now kiss me!"

Bewildered but obedient, she held up her lips. Norman kissed her. He held it until a discreet cough behind them caused them to spring apart guiltily.

Mr. Vermeer was regarding them from the open door, his black eyes sardonic. "Sorry to interrupt," he said, "but you've got the wrong cabin."

"I know it," said Jennifer in confusion. "My stateroom's next door. Silly mistake, isn't it?"

"Sorry, Vermeer," apologized Norman hastily. "Come on, Jennifer." He led the girl into the corridor. Vermeer closed and locked the door after them.

Jennifer unlocked her cabin, said, "Come in."

Norman limply followed her inside, collapsed on a chair.

"You were wonderful," she cried. "I never would have thought of that. It explained everything, even our confusion."

He began to feel rather proud of himself. He glanced about the girl's room. It was similar to Vermeer's except that it was not so tidy. Gauzy white undergarments of finest spun microweb lay on the chairs. He recognized a tiny vial of Venusian perfume on the dresser surrounded by a litter of brushes, mirrors, combs. There was a picture of a tall elderly man in a uniform.

"That's papa," exclaimed Jennifer.

"I wish I knew what that suit was used for," said Norman thoughtfully. "I've never seen anything like it before."

"You know," said the girl seating herself on the edge of the bed, "you're not like most Earth men. You're not stodgy and patronizing. You're cute."

He felt ridiculously pleased. He was convinced that he'd never met a more intelligent, a more charming, a more beautiful girl than Jennifer Scott. He said, "I've had to revise all my opinions of Outlanders since I met you."

Jennifer laughed, jumped to her feet. Stooping over, she kissed him lightly. "That's for a very pretty compliment. Now let's get back to the dance before I lose all my maidenly modesty."

IV

Beyond the orbit of Mars a tension gripped the passengers of the Jupiter. The killer of the T.I.S. agent remained at large, and the passengers were beginning to regard each other suspiciously. They were now in the zone where the terror operated. The battle ship had edged in closer. Constant radio contact was maintained between the two vessels.

Norman Saint Clair and Jennifer were on the observation deck in the forepeak. The quartzite dome arched flatly overhead. The chill immensity of space crowded all around them, black infinity pricked with a million blazing suns. It was Norman's first visit to the observation deck. Jennifer had brought him up.

"There's Jupiter," she exclaimed pointing to a large bright star dead ahead. Norman gazed at it, fascinated.

The lookout, a lean spaceman, stirred restlessly, then stiffened. Norman followed his gaze, saw three brief pin pricks of light stab out of the void.

"Look!" He clutched Jennifer's shoulder, but she had seen the flashes already.

The lookout grabbed the phone, said, "Observation deck reporting, sir. Three flashes two points on the port bow. Yes sir. Two points on the port bow." He hung up the phone.

Norman and Jennifer exchanged glances.

Jennifer said, "The Comet reported three flashes before she disappeared. It must be a signal?"

Overhead the general alarm rang furiously. A file of Armed Guards poured onto the observation deck, took up their posts. Norman pointed to the battle ship. Its guns were run out like bared fangs.

"Attention!" blared a voice over the public address system. "All passengers return immediately to their staterooms. Attention! All passengers return immediately to their staterooms."

"Come on," urged Norman. "We'd better go below."

"Do you mind if I stay with you?" asked Jennifer.

"Of course not. I wouldn't leave you alone, anyway."

They descended the companionway to their deck, entered Norman's stateroom. Through his port he could still observe the warship pacing them noiselessly.

He padded back and forth across the fiberon carpet. "I wish I had a dart gun, anything. I feel so helpless." He went to the door, opened it a crack, peered out. "Jupiter!" he breathed.

"What is it?" cried Jennifer, starting up from her chair.

"Not so loud," he cautioned. "Come here."

The girl sprang lithely across the deck. On tiptoe, her body pressed against his, she stared over his shoulder through the inch wide crack.

A strange figure stood back to them at the turn in the corridor, a man clad in loose green coveralls with helmet, gloves and boots attached so that no part of his figure was exposed.

"Vermeer!" breathed Jennifer. "He's put on the suit we saw in his closet."

Vermeer remained motionless, half crouched at the end of the hall as if waiting for some signal. A poisoned dart gun was buckled around his waist.

Norman eased the door shut, not allowing it to click, faced Jennifer.

"What is it?" she asked breathlessly.

"I don't know. But I think we should have reported that suit to the Captain."

Jennifer sank to the edge of the bed. He looked at her, thought again, how striking was the contrast between blue eyes and black hair. He felt dizzy, said, "Jennifer, do you notice anything?"

"I feel faint!" she gasped.

A numbing sensation spread through his limbs. The room tilted crazily, darkened. He cried, "Jennifer!" and fell forward limply on his face. He wondered vaguely, just before consciousness left him, if he were being disintegrated. Then the blackness of infinite space engulfed him.

When Norman Saint Clair returned to consciousness, he was still lying face down on the green fiberon carpet. He groped to his feet, swayed groggily. He glanced at the bed. Jennifer was gone.

Shaking his head to clear it of the cobwebs, he staggered to the door. It was locked. He was a prisoner in his own room.

Still something was missing, something intangible. Then he heard the silence. It screamed at him. The soft overtones of the motors were dead. The engines had been stopped.

He sprang to his port hole, glanced out. The bulk of the battle ship floated a little above the wounded Jupiter. His eyes opened wide in consternation. Half of the warship appeared to have been sheared off as if by a giant cleaver. Even as he watched she was slowly disintegrating.

Then he made out dozens of figures swarming over the hull like ants. They were men in space suits, he realized, and they were spraying the battle spacer with a film which no sooner solidified than it became invisible, hiding ship and all. A light absorbent matter, he guessed.

The warship was not disintegrating. She was being coated with a film which absorbed all the light rays and so rendered it invisible. That was the answer to the strange disappearance of the Comet and her escort. He looked closer, realized that the invisible stern of the warship was blocking out a patch of stars.

Above the battleship he saw a port open in space and from nowhere a two man tender was launched into the void. It was uncanny. Then he realized he was looking at the ship of the terror, invisible of course. That was how they had approached their prey without being detected. It was one chance in a million that anyone would notice the momentary blotting out of a star.

"Pirates," he thought. The word was archaic. It had almost disappeared from the vocabulary. He shuddered. They must have approached unseen, bathed the two ships in a ray which knocked everyone unconscious. The vaunted warship, the pride of the Empire, had been taken without firing a shot.

Vermeer, he thought. Of course, they would need a man aboard to shut down the engines, bring the Jupiter to a stop so they could board her. Vermeer's odd suit must have protected him from the effects of the paralysis ray.

He crossed to his bunk, sat down. He felt strangely indifferent to his own fate, but Jennifer! He clenched his hands until the nails bit into his palms. What were the beasts doing with Jennifer?

Abruptly the door opened. Norman sprang to his feet, saw a strange figure blocking the entrance.

It was a man dressed from head to foot in black. Black trousers were tucked into black boots. Blouse and helmet, all a somber black. His eyes though, were blue, his face clean shaven. He had a dart gun in his hand.

"Come along." He motioned with the dart gun. "You're wanted above." He stepped back, indicated that Norman should precede him.

They went silently along the corridor, the pirate collecting more men from the staterooms on either side. By the time they reached the companionway he was herding ahead of him quite a number of frightened prisoners.

"What are they going to do with us?" asked a fat man beside Norman.

They had reached the companionway.

"Up!" said their guard.

They mounted the stair, came out into the dining saloon.

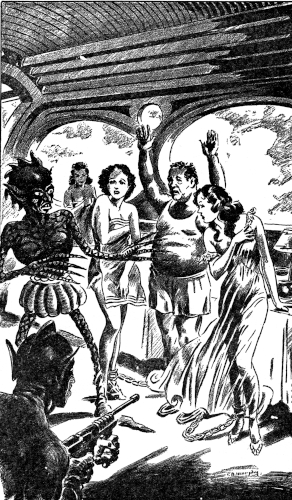

A scene of wildest disorder burst upon Norman's shocked gaze. A throng of black clad pirates moved among the passengers who had been routed from all parts of the ship. The missing women, he saw, were huddled in a frightened group at the opposite end of the hall. They had been brought to the saloon in whatever state of undress the ray had caught them; in evening dress, scant undergarments, in gowns and shorts, and one frightened girl, clutching a large bath towel about herself.

The passengers of the captured ship had been brought to the saloon in whatever state of undress the ray had caught them.

Norman was pushed into the group of men. His eyes, though, kept searching for Jennifer. With a sigh of relief, he discovered her at the same time she found him. She waved rather forlornly, and Norman almost dislocated his shoulder waving back.

The fat man said, "Pirates! The effrontery of those rogues. When the Terrestial Navy locates their lair, they'll blast them to atoms."

Norman recognized Dr. Pequod at his elbow. The doctor was clad nattily in the hair on his chest and a flaming pair of shorts.

"It's not so simple as that," the doctor answered the fat man. "You fail to realize the size of the Universe. Nine tenths of it remains unexplored, unmapped. And how will the Terrestial Navy trail an invisible enemy?"

The fat man blew himself up, said, "The resources of the Empire are unlimited."

"Sounds good," agreed the doctor; "but the Empire these days is living on its reputation."

A crowd of the frightened passengers were gathered about the two men.

"And I've a notion," the doctor went on, "that this is more than piracy. The Empire is crumbling. Some faction may be nibbling at its edges, growing strong from its life blood, the trading lines. Has it occurred to you that with every ship lost, the pirates are that much stronger and we that much weaker!"

"Nonsense," retorted the fat man, but his tone had lost conviction.

"Break it up," commanded one of their guards. "Silence!"

The main entrance to the saloon had swung open, admitting the strangest creature that Norman had yet seen. It appeared human, but obviously it was not from any known planet. Short and squat, with yellow wrinkled skin, it looked more like a rutabaga than a man. The pirates snapped to attention.

"Jupiter," breathed Norman. "Is it a man?"

Dr. Pequod scratched the shag on his chest. "Odd specimen. Wonder what corner of the Universe it hails from?"

The creature regarded the prisoners without any expression whatever on its parchment-like face. It was clothed in a harness which gave no clue to its sex. With a scrawny hand it beckoned the renegade Earthman who had been directing the operations, said something in a voice too low for anyone to overhear.

The Earthman nodded, turned to the captives. "Every able bodied man between the ages of nineteen and forty, step out," he shouted. As no one moved, he frowned, said, "In any case your books will be examined and your correct age determined. Get a move on!"

Norman accompanied by perhaps thirty percent of the male passengers advanced into the center of the room.

"That's far enough," advised the creature in a high reedy voice.

They halted uncertainly.

"Gentlemen," said the leader, for such the creature seemed to be; "I am here to offer you a choice of two courses. We are coming into possession of more vessels than we have recruits to man. Consequently, it is our custom to offer all able bodied humans between the ages of nineteen and forty the opportunity to join us. As a further inducement, the new recruits will share equally in the proceeds of this venture with the regular crew." He paused. Not a flicker of expression had marred the creature's face.

Norman Saint Clair's eyes narrowed thoughtfully. A forlorn hope presented itself, if only he had the courage to grasp it.

"Now, gentlemen," the turnip shaped leader continued; "it would only be fair to give you the opposite side of the coin. You are bound to us for life; not by anything so puerile as an oath. In fact you are at liberty to escape any time," he paused, "if you can.

"You will be given good quarters and food. Money for any pleasure or vices you wish to indulge will come as your share of the prizes taken. The alternative, gentlemen, which I mentioned at first, is slavery. We also need men and women to work our factories, maintain our living quarters. The fighting men do not work."

With a faint bow the creature turned on his heel, disappeared as suddenly as he had come.

A low buzz sprang up in the hall as everyone turned to his neighbors, questions tumbling from their lips. The pirates dropped their stiff pose, returned to their duties. The men grouped in the center of the floor shifted uneasily.

Norman bit his lip, frowned. He might be able to protect Jennifer as one of the pirates and eventually escape. He wished he could talk it over with her.

"All right," said the burly renegade. "How many of you are volunteering? Step forward."

Norman Saint Clair stepped out of the group. He did it like a man plunges off a high dive, quickly before his nerve departed. Nine of his fellow passengers straggled beside him.

"Is that all, gentlemen?" inquired the pirate. "This is your last chance. Either piracy or slavery. And let me warn you, slaves don't live an easy life."

Twenty-three more men straggled uncertainly around Norman.

"All right," said the pirate. "The rest of you can return to your fellows. Baldy! Hey, Baldy!"

A second Earth man strolled across the deck. He was short, older than most of the freebooters.

"Take these men aboard the Rocket," the first renegade directed. "You know what to do with them."

Baldy grinned, saluted. "Come along, you buccaneers," he commanded.

Norman caught Jennifer's eyes. She was staring at him in astonishment. He waved, trying to convey reassurance across the space that separated them. Slowly a flush burned up from the girl's throat. With a look of scorn, Jennifer deliberately turned her back.

Norman gaped after her in consternation. He had expected her to realize that he was joining the pirates in order to help her. He certainly had no ambition to go gallivanting through space capturing space ships.

"Hey you," said Baldy, "move along there."

Norman jumped, trailed after the new recruits. He would help the girl in spite of herself. He visualized himself standing off a dozen black clad figures while Jennifer boarded a small space craft. Then he tumbled in beside her, wrenched the controls wide open: "You're wounded," Jennifer cried. "Norman, I didn't understand. Can you forgive me?"

"Hey," growled the man in front. "For God's sake, quit tramping on my heels."

They had arrived at the air lock, he saw with a start. Baldy opened the port, revealing a small space tender. They wedged themselves inside. With the pirate at the controls the craft launched into space, speeding toward a shadow which blocked off half the heavens.

A port snapped open in space dead ahead. Norman blinked his eyes. Although he knew this was the pirate's ship coated with the light absorbent film the sight of an air lock appearing suddenly where nothing had been before was disconcerting. The tender eased into the lock, settled to the deck.

"Here we are, you volunteers," observed Baldy.

They passed from the lock through a corridor into a large square room. Half of the room was railed off. Behind the railing a man in a black uniform sat working at a desk. It reminded Norman of an employment bureau. The rest of the space was filled with benches set in evenly spaced rows.

"Sit down," said Baldy.

The recruits seated themselves nervously.

"You," said Baldy, indicating Norman. "Go up to the desk."

Norman rose, approached the middle aged pirate who sported a spade beard and dark brown eyes.

"Your book," he said.

Norman handed it over.

"Sit down," said the man. "Make yourself comfortable.

"You know, since the T.I.S. has inaugurated these books our jobs have been greatly simplified." He was making rapid notations on a form. "Lecturer on Ancient History," he read aloud. "Degrees in twentieth century literature." He looked up at Norman, smiled. "I'm an anthropologist myself. Was with an expedition to study the aborigines of Jupiter when the pirates captured our ship." He closed Norman's book, dropped it in a drawer.

"Now this is serious," he began in a different, somehow ominous tone. "What I am about to tell you is of the gravest importance. Every recruit is warned once and once only, so take heed.

"When you leave here you will be subjected to a machine which registers your personal wave length, particularly the subtle peculiarly individualistic vibrations emanating from your brain. Those vibrations will be impressed on an indestructible duraloid cylinder and sent to the control station in Behrl. The Dohlmites have devised a machine which can broadcast your death at any time, no matter where you may be. It operates through the wave length of your individual vibration."

"Dohlmites?" echoed Norman.

"Yes, Dohlmites. You saw one aboard your ship. The man who recruited you. They are a race so alien to mankind that we have nothing in common. The Dohlmites are the real masters here. All of us, fighting men and slaves, have had our vibrations recorded and are subject to instant death at the first sign of treachery.

"The Dohlmites can snuff your life out by simply turning a dial. Don't think I exaggerate. I have seen healthy men drop dead on the streets of Behrl. I have seen the lives of an entire rebellious crew extinguished like candles."

"But who are these Dohlmites. What are they?" Norman's brain was whirling.

"I think," replied the ex-anthropologist, "that they are plants."

"Plants!" ejaculated Norman Saint Clair.

"Yes, plants. Flora, not fauna. Their young are green in color. As they mature, ripen, I suppose is the correct word, they turn yellow. When they cut themselves, they bleed green. Sap, don't you know."

"This Behrl, where is it?" asked Norman.

"In Neptune. The planet is hollow. Just a shell. The city of Behrl is on the inside of Neptune." The ex-anthropologist sat back. "Whatever you do, don't try to escape. Even if you get away, when the Dohlmites missed you they would simply extinguish you wherever you were."

Norman's breath went out of him like air from a burst sack. The full implication of what the ex-anthropologist had revealed broke in his mind like an exploding shell. Gone were his hopes of escaping, and taking Jennifer with him. He was trapped. The net of the Dohlmites was perfect and he and the girl were caught in its meshes. Certainly, he thought bitterly, no human intelligence could have conceived such a devilish plan.

From the desk of the ex-anthropologist Norman was led into a small closet where the rays of the fatal machine bathed him from head to foot. Beyond the partition something click-clicked at irregular intervals like a beetle and an ominous scratching recorded his vibratory rate indelibly on the duraloid cylinder.

The machine stopped. The door of the closet opened.

Norman discovered a thick shouldered Martian grinning at him from the entrance.

"That's enough," said the Martian in the sibilant accent of the red planet. "You've been detailed to my squad."

As Norman slipped from the closet another recruit took his place. He noticed a low humming.

"The engines?" he asked.

"Yes," agreed the Martian. "We're off. Your ships have been coated with the light blanket."

"Where are they?"

"They're following us. We've put prize crews aboard. It was a rich haul. Radium." He rubbed his hands together, laughed as if in anticipation of the orgy he would be able to indulge in with his share.

Norman winced. The Martians as a rule were a cosmopolitan and cultured people.

"Don't judge too harshly," said the Martian as if reading the young man's thoughts. "You'll look forward to the brief time between voyages, too. But I'm forgetting. My name's Koal. I was a space pilot before I was captured."

Norman introduced himself.

The Martian grinned, shook hands. "Come along, Earth man, and get your issue. Then I'll show you your quarters."

At length they came to a chamber deep within the bowels of the ship. A counter ran along the back wall. A wizened yellow eyed Mercurian took Norman's measure, piled four changes of the somber uniform on the counter. With quick cat-like movements he added a helmet and boots, slug gun and Dixon Ray rifle. Wide-eyed, Norman watched the pile grow. It was a very complete outfit by the time the Mercurian paused.

Staggering under the load Norman and Koal ascended to the sleeping quarters, paused before a stateroom.

"This is your cabin," said Koal unlocking the door. "Slaves keep it cleaned." They went inside. "If you let me know the number of your stateroom aboard the Jupiter, I'll see that you get your personal belongings when we arrive in Behrl."

The cabin, Norman observed, was similar to the one he had left. He set about stowing away his gear.

"You have a great deal to learn," said Koal and sat down on the edge of the bunk. "The Dohlmites regard us as dangerous animals. But as long as we obey orders we are left alone."

"What happens to the prisoners?" Norman asked suddenly.

"They're sold from the block in the slave market."

"You mean anyone can buy a slave?"

"Certainly. An agent of the Dohlmites bids a flat hundred notes for each captive. If any of them strike your fancy you only need bid above the hundred notes. Of course when a pretty wench is auctioned off the bidding among the men gets rather wild."

"Jupiter!" breathed Norman pausing in the act of pulling on his blouse. "Was that right, what the Dohlmite said about the recruits sharing equally with the crew in the loot."

The Martian nodded. "Half goes to the Dohlmites. The remaining half is divided among the crew. That includes the cargo, whatever the captives bring on the open market and salvage value of the ships themselves."

Norman grinned. His first purchase with his share of the prize money would be Jennifer Scott.

The Martian pointed to a silver insignia, a small rocket ship of ancient design pinned to the right breast of Norman's blouse. "That," he informed the young man, "is the insignia of your clan. It is important. Never take it off. All the men aboard the Rocket belong to that clan."

"Why?" asked Norman, puzzled.

The Martian sighed. "There is no law in Behrl, so long as we don't interfere with the administration of the city. In the Human Colony anarchy reigns supreme. For our own protection, we've banded together."

The Martian rose from the bunk, went to the door. "I'll leave you to get settled now. We eat at fourteen-hundred." He opened the door, paused, turned back. "One thing more. Forget about escaping. Dismiss it from your mind. Most of us joined with the same intention that you have. But it's impossible. There was a Martian, a very good friend of mine, who tried it. He stole a space tender. He got all the way to Mars before he was missed. In sight of the quarters of the imperial guard he dropped dead." He paused, said, "I'll see you at fourteen-hundred," pulled the door shut after him.

Norman Saint Clair sank down on his bunk. Somewhere, there must be a weak link in the Dohlmites armor. He wished he had specialized in botany instead of ancient history. Botany, he thought wildly, horticulture, perhaps there lay the clue.

V

During the ensuing days Norman Saint Clair became acquainted with the other members of Koal's squad. There were nine. Two were Martians, one a Venusian, the rest Earthmen. All of them had been captured by the Dohlmites and had chosen piracy to slavery.

While yet a day from Neptune, everyone began feverishly to pack their gear in anticipation of the landing. Word was circulated when they were passing through the crust. Norman and Koal hurried to the corridor before the port, found it jammed with men. The huge ship settled with a slight jar. They had landed.

"Home," said Koal.

With a jolt Norman realized that this was home for him, too. The massive entrance slid aside. The men poured out. Caught in the stream, he and Koal were carried to the runway and down to the floor of the spaceport. He looked around curiously.

The road led between two empty troughs. At least he thought they were empty, until he realized he couldn't see beyond them. Invisible ships lay in the troughs. Overhead a large pinkish sun flamed unnaturally.

"Come along," urged Koal. "You've the rest of your life for sight seeing." He led Norman outside the yards to a massive building.

"What's this?" asked the young man as they passed through the doors.

"Emigration. Here's where you'll be assigned living quarters."

A Mercurian ensconced behind a grill like a bank teller took his name and ship, handed him a slip of paper. On it was printed F12-D234. He looked at it blankly.

The Martian laughed, explained: "F12 is the building. Everyone from the Rocket lodges in the same building. D is the floor, two-thirty-four your apartment number."

"Oh."

The Martian laughed again, said "Come along. You'll get the hang of things soon enough."

They returned to the street, entered a many storied garage. Here Norman saw hundreds of surface cars parked row upon row. A ramp led up to the next level.

"This is where our cars are stored while we're on a voyage. We aren't allowed flying vehicles. Only the Dohlmites can use them."

The Martian went to one of the cars, held open the door. "You'll want to buy one of these as soon as we're paid. The slaves manufacture them very cheaply."

Climbing in beside Norman, Koal pressed a button. The diminutive atomic motor burst into life. They rolled out onto the streets of Behrl.

"When will they auction off the prisoners?" asked Norman as the Martian guided the surface car through the traffic.

"Not for a day or so. You'll be notified. This is the manufacturing district."

One factory after another flowed past. Off to their left Norman observed a hill towering above the rest of the city. Its slopes were covered with balconied buildings rank with trees and flowers and shrubs like the fabled hanging gardens of Babylon.

"What's that?" He nudged the Martian.

"That's where the Dohlmites live. Whatever you do, don't go near that quarter of the city. A force wall surrounds it which is instant death if you come in contact with it. Their laboratories, the control station, the death machine, our wave length cylinders are all there."

In a few moments they had passed through the factory area and into a district of shops, restaurants, amusement centers.

"Who operates these?" he asked.

"Slaves. The profits go to the Dohlmites. Everything returns to their pockets."

The streets were crowded with people: barefooted women in short gay colored tunics, men in loose coveralls.

"Slaves," explained Koal.

The vastness of the plant men's enterprise became apparent as they sped through the streets.

"Koal," said Norman a little frightened. "When is it going to stop?"

The Martian looked at him grimly, "With the fall of the Empire," he replied bitterly. "With the enslavement of Mars and Venus and Earth. The Dohlmites are only a handful, but they plan to lop off the Empire colony by colony, enslaving the inhabitants just as they have us. Their ultimate goal is to have the individual wave recording of every human in the Universe. An Empire of slaves."

"Impossible!" he ejaculated.

"Why? The element of time is of no importance with them. Every ship they capture gives them more power, more slaves. It gathers force like a snowball rolling down hill. Before long, nothing can stop them."

Norman slumped back in his seat. What the Martian said was true. Unless the Dohlmites were stopped soon, they would be so strong that nothing in the Universe could halt their march to Empire.

"Is there a library in Behrl?" he asked the Martian suddenly.

"Yes," replied Koal in surprise. "A very fine one in fact, but no one uses it."

Norman's next question seemed irrelevant.

"Would the humans revolt if they thought there might be a slim chance of success?"

"Who would be a slave by choice?" grunted Koal angrily. "They'd rise as one man at the faintest sort of a chance and at no chance at all." For a moment, he glared straight down the street, then relaxed, glanced at Norman seriously.

"Look," he said in a quiet voice that was somehow more impressive. "Do you realize how hungry I am for the dry chill air of Mars. How hungry all these exiles are for their home planets? You don't think we've submitted meekly to the Dohlmites, do you? There have been mutinies and rebellions a dozen times since I've been here. And everytime the rebels have dropped dead on the streets, at their guns, in their beds. All of them. I tell you its impossible."

"Nevertheless," said Norman, "you've told me what I wanted to know."

The shops were behind them, many storied apartment dwellings having taken their place. With a grunt; the Martian swung the car down an incline leading to the basement under one of the buildings.

"This is F Twelve," he said, halted the car just inside the gate while a guard inspected their papers, waved them on.

"For our own protection." Koal nodded toward the guard as he parked the car. "No one but members of our clan and their households can enter this apartment building."

They crossed the basement parking area to a lift. Koal pressed a button. The car descended; the doors opened. He motioned Norman inside.

"Hello, Alicia," Koal greeted the operator, a girl in a short green tunic gathered in at her slim waist by a belt. He chucked her under the chin. "Glad to see me back?"

She was from Earth, Norman realized. She was barefooted and around her ankle was the metal band of the slave.

She said, "Did you bring me anything?"

He snapped his fingers. "How could I have forgotten?" but his grin belied his words.

The girl cried, "What did you bring me, Koal? Where is it?"

"Not so fast," he admonished. "You haven't met Saint Clair yet. He's a new recruit."

The girl turned brown eyes on Norman, saw his crisp blond hair and likeable features, his broad shoulders and flat hips. "Um, um," she said, "I know. You've brought me him."

Norman flushed hotly. The Martian laughed, reached in his pocket, pulled out a pair of earrings set with magnificent Venusian pearls. Norman recollected seeing them grace the ears of a Terranean dowager aboard the Jupiter.

Alicia squealed with delight, hastened to attach the earrings. She shot the lift upward jubilantly.

At D deck they left the car. Alicia looked at Norman.

"If you're lonesome tonight, I'm off duty at Seventeen-hundred." Before he could answer the doors slid shut.

"What did you do to her?" growled Koal. "I bring the earrings and she propositions you."

Norman grinned, preened himself. Alicia, he decided, was a remarkably pretty girl, intelligent, too.

"Here's your apartment," Koal interrupted his thoughts. They had stopped before a door which bore the numeral 234 in brass. "I'm two-forty-eight. If you want anything, step down the hall and knock." He started off, paused. "Meals are served three times a day in the dining room on A deck, or you can prepare your own food in your rooms. I think you'll find everything necessary in the kitchen. If not, call the steward."

Norman went inside, glanced around curiously. An entrance hall led him into a sumptuous living-room. A compact kitchen, which did everything mechanically but digest your food, opened from a dinette. Behind the front rooms lay three spacious bedrooms, which gave onto a balcony. He opened the glass doors, passed out into the sunshine.

Building number F12 was on the outskirts of Behrl, and a jungle of riotous vegetation met his eye. The horizon curved up like a bowl before disappearing in rosy mists.

Here on the inside of Neptune the sun always hung straight overhead. A land of high noon, he thought. The sun beat down on his head. He wondered what kind of phenomenon it was, possibly a ball of liquid fire slowly burning itself out. The resultant high percentage of carbon dioxide in the air might account for the evolution of plants into reasoning creatures rather than mammals.

He returned to the kitchen. The cabinets were stocked with food and he prepared a cold lunch, ate it hungrily. A feeling of contentment stole over him.

He returned to the bedrooms, chose the largest one, stripped and showered and flung himself into the bed. He was immediately asleep.

VI

Sometime later Norman was awakened by a rude hand shaking his shoulder.

Koal was grinning down at him.

"Wake up," said Koal. "You've been dead to the world for thirty-six hours, and the paymaster's here."

Norman sat up, reached for his trousers, which, to his surprise, were neatly hung over the back of a chair. Drawing on his clothes, he went into the kitchen. It had been cleaned, put to rights. Further exploration revealed that his things from the Jupiter had been delivered and stowed away in the closet and built-in bureau. Hordes of people must have trailed in and out of his apartment while he slept. He decided to prop a chair against the knob the next time he went to bed.

The Martian was watching him, an amused glint in his black eyes. "There is a bolt on your door, you know," he assured the young man.

A subdued buzzing announced a visitor.

"That's probably the paymaster now," said Koal. He opened the door, revealing a Mercurian with a black satchel in his hand.

The Mercurian said, "Norman Saint Clair?"

The young man nodded.

"First," said the Mercurian, opening the satchel, "here are your papers." He handed him a yellow envelope which contained a book similar to the one the T.I.S. had issued when he left Earth.

"The individual shares from the Jupiter's cargo," the Mercurian droned on, "plus the Terrestial warship amount to twenty thousand notes." He handed Norman a sheaf of yellow bills.

"Roughly," Koal interposed, "that is equal in value to twenty-five thousand Earth notes."

"Twenty-five thousand Earth notes!" gasped Norman. "It's a fortune."

"Sign here, please," said the Mercurian, handing him a ledger.

Norman affixed his name in a daze.

"That doesn't, of course," added the Mercurian, "include your share from the sale of the slaves. They are to be auctioned off at fourteen hundred." He snapped shut his satchel, bowed himself out.

"What time is it now?" asked Norman.

"We've time for something to eat before going twelve-hundred."

The slave market resembled an open-air theatre minus the seats. The same cosmopolitan crowd which Norman had observed on the streets eddied about the block. He caught sight of a figure clad in civilian clothes. It was Vermeer, the black-headed Outlander whom he had been sure was instrumental in the Jupiter's capture.

"Who's that?" he asked the Martian pointing to Vermeer.

"A Venusian Export Lines man. The Dohlmites needed an outlet for much of the material they captured. They established their own line of trading ships under a Venusian register because they are so much less strict on Venus. By the way, keep away from anyone connected with that company. Never talk sedition in front of them. Those men belong to the Dohlmites body and soul."

Just then the auctioneer, a lean, yellow-skinned Venusian, moved to the block. Two men led Dr. Pequod from the wings. The flaming shorts were gone. He was clad in exactly nothing. The doctor stalked to the block, glared at the buccaneers who had clustered around him.

"What am I offered?" began the auctioneer. "A little scrawny but sound and with a heart of gold."

The free booters cackled.

"A hundred notes," said the representative of the Dohlmites dryly. He was seated on the platform with the auctioneer.

"A hundred notes. I'm offered a hundred notes. Who'll say a hundred and ten—A hundred and five? Going for a hundred notes. Going. Going. Gone!" He cracked his gavel down. Dr. Pequod was led back into the wings.

The next three passengers were purchased by the agent of the Dohlmites for the standard one hundred notes. There was some lively bidding for the ex-chef of the Jupiter, who was finally knocked down to a big-bellied pirate. He hauled his prize off with triumph.

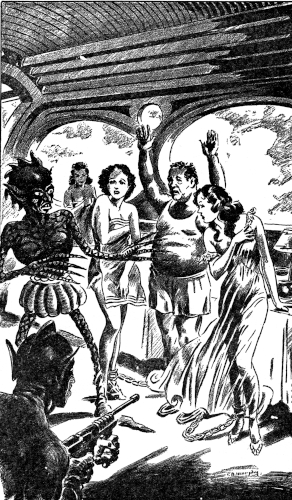

Then Norman's heart jumped. The sixth passenger to be led to the block was Jennifer. She was barefooted, the metal band gleaming about her naked ankle. A cape had been thrown about her erect shoulders.

The sixth slave to be led to the auction block was Jennifer.

The auctioneer lifted it off. There was nothing but girl underneath.

"Two hundred notes," a voice shouted from Norman's elbow.

Norman swung about, recognized Vermeer, the Venusian Export Lines agent.

"Hello," said Vermeer, "I see you've joined us."

Norman nodded shortly. "So it was you who killed the T.I.S. agent. I suspected it all along."

Vermeer merely smiled. The auctioneer cried, "Two hundred notes. Two hundred and ten," as another man bid. "Twenty. Twenty. Thirty." The bidding was growing lively.

"Three hundred," said Vermeer.

"Three hundred and five," Norman echoed.

"Five hundred," said Vermeer without blinking an eye.

Realizing that the two men were bidding against each other the rest dropped out. The audience seemed to settle back in expectancy. Men had been known to pay the complete prize money of a venture for a girl.

"Five hundred and five," Norman said in a determined voice.

"Really," said Vermeer; "you're wasting your time. I intend to have that girl. From one venture you can't possibly have enough money to outbid me. One thousand notes," he addressed the auctioneer.

"A thousand notes, I'm offered," chanted the auctioneer.

"A thousand notes. Do I hear more?"

Norman bit his lip. It was only too true that Vermeer could outbid him. With a sudden grim determination he balled his fist, walloped Vermeer in the temple. All his indignation was behind that blow, all the bone and gristle of six-foot-two of lecturer on Ancient History. Vermeer went down and out like a pole axed steer.

"One thousand and one," shouted Norman triumphantly.

For a moment a hush gripped the audience, then the men roared with laughter. No one liked the Venusian Export Lines men, the pet of the Dohlmites.

"Going," chanted the auctioneer, "going. Gone! To the impetuous gentleman with the good right fist!"

For the life of him, Norman couldn't help swaggering a little as he went up to claim the girl.

The auctioneer tossed Jennifer her cape. She snatched it closely about herself, leaped down from the platform.

Norman counted out the bills. Jennifer, without glancing at her purchaser, walked swiftly ahead of him through the throng.

A pirate reached out, clapped him on the shoulder. "She's worth it," he chortled. "She's worth it." But Norman was being beset by doubts. He hadn't liked the steely glint in the girl's blue eyes. It foreboded trouble. Koal joined them chuckling, as they left the market place.

Once outside Jennifer stopped, swung on Norman. "All right," she said in a suppressed voice. "You've bought me. But you'll regret it as long as you live, you, you—renegade!"

Her tone brought him up short. "Of all the ungrateful wenches," he flared; "you are the prize. I joined the Dohlmites with the express purpose of rescuing you. I plank down one thousand notes cash to save you from what in the old days was considered a fate worse than death."

The girl's features registered surprise, incredulity, contrition. She started to say, "I didn't know," but Norman was thoroughly wound up.

"Of course, I realize that view is no longer entertained by the best informed people, but if you are so anxious for Vermeer to buy you, I'll go throw a bucket of water in his face and present you to him with my compliments."

Indignation swept away all other emotions from the girl's features. "I think you're horrible," she said and turned her back on him.

Koal suddenly shouted, "Look out, Norman!"

The young man swung around, saw Vermeer boring down on him. The agent had a poisoned needle gun in his hand. His temple was swollen, his eyes furious. Scarcely three steps away he swung the needle gun up.

Norman heard the weapon plop softly. At the same instant something swished between him and the murderous dart gun. Jennifer, he realized, had pulled the cloak from her bare shoulders, flung it between them.

He snatched the cloak, flipped it over Vermeer's head and shoulders. His rush bowled the man over backwards. The dart gun dropped to the pavement. Norman snatched it up just as Vermeer flung the cloak off his head, sprang to his feet.

"Kill him!" shouted Koal. "Quick!"

Vermeer's face blanched. He turned, began to run back toward the slave market, bent over, zig-zagging wildly.

Norman brought the dart gun up, then let it fall helplessly at his side.

"I can't do it," he said.

He picked up the cloak, started to return it to Jennifer. His eye lit on a slender, three-cornered needle stuck halfway through the heavy material. He pulled the poisoned dart out. One scratch from that deadly missile would have killed him. The girl's instinctive action had saved his life. He felt weak.

"I'm sorry for what I said, Jennifer."

"For heaven's sake," she cried; "apologize later, if you must, but give me back my cloak now."

VII

Once back in his apartment, Norman flung himself down in a chair. They had stopped on the way home in an establishment which sold the short tunics proscribed by law for all female slaves and Norman purchased the girl a complete outfit. She had chosen one of the smaller bedrooms and was putting her things away now. Koal was lounging on the couch.

"Koal," began Norman, "I've an idea and I'd like your opinion."

"Go ahead," replied the Martian with a chuckle. "You really want me to agree with you. But if it has to do with escaping, I warn you, I shall be disagreeable."

Norman grinned, said, "Koal, twentieth century Eire was under the British crown, but for a long time an underground army had fought the English Black and Tans. Around Nineteen-twenty they threw off the English yoke. That party of liberation was known as the Sinn Feiners."

Jennifer wandered back in the room in time to hear the last of Norman's words. She sat down, listened.

"So?" said Koal.

"So," said Norman. "I think that if a little group of patriots like the Sinn Feiners could throw off the yoke of the British Empire, we should be able to turn the tables on the Dohlmites."

"I've seen rebellions before," began Koal stonily.

"I know. But Koal, I'm not proposing any premature mutiny. I do believe, though, we should band together secretly. If any opportunity for escape presents itself, we'll be ready for it; not just a disunited group of clans snapping at each other's throats."

The Martian appeared to waver.

"Koal," Norman went on urgently. "Only one thing stands between us and freedom. The death broadcasting machine."

"Yes, just that—and a force wall impossible to penetrate."

"What maintains the force wall?" asked Norman.

The Martian shook his head.

"Suppose we succeed in neutralizing it. We'd have a picked body of men to rush the Dohlmite station, destroy the cylinders."

Koal scratched his head speculatively. He said, "The men would have to be carefully chosen. It would be suicide should any word of the society leak to the Dohlmites." He rose, frowned. "Wait a moment," he said and hurried from the apartment.

"Norman," breathed Jennifer. "Do you think there's any chance?"

"I don't know," he replied, a worried expression on his gaunt features; "but if I can persuade the men to unite there's hope." He ran his fingers through his crisp blond hair. "It's more than that, too. We'll be the only force standing between the Dohlmites and the Empire. Somehow we've got to destroy them before they destroy us."

The door opened, readmitting Koal attended by a tall, lean, yellow Venusian. The blue star of the killer cast was tattooed on his forehead. A Fozoql! Norman was only vaguely familiar with the caste of mercenaries and assassins. They had the reputation of being loyal and ferocious and were in high demand by the constantly warring factions on Venus.

"Norman," said Koal, "this is Acpsahme. He and his brother with their wives were migrating to Ganymede when they were captured. His brother was killed by the broadcast machine while trying to escape. His wife was sold in the slave market to a renegade Earthman. I think I can vouch for his silence. Explain what you just told me."

Norman shook hands, launched into a passionate appeal for union among the men. Acpsahme's green eyes glowed.

"Good," he said from time to time, "good. But there must not be too many, and those must be carefully chosen. The success of the enterprise depends on secrecy."

Koal leaped to his feet, his broad pale brow furrowed. He strode back and forth across the thick carpet. "At nineteen-hundred," he said, "I am going to give a party in my quarters. A small, select party. Only the men I know best will be invited. Gentlemen, we'll bring the Sinn Fein Society back to life."

When they had gone, Jennifer looked across at Norman mistily. "You know," she said in a tender voice, "you really are rather wonderful."

It was an oddly assorted group who attended Koal's party at nineteen-hundred. Of the thirteen men present, there were renegade Earthmen, outcasts of the Empire, mad dogs feared from Pluto to Mercury. Another had been a T.I.S. agent before his capture. Pepperell was the name which Koal gave when he introduced him to Norman. Pepperell was a bland-faced, heavy-set Earthman with a gullible smile and a chunk of ice for a heart. The fifth had been a corporation lawyer. His noble brow and prematurely gray hair give him the benignity of a saint, but a thief, it had been whispered about on Earth during his remarkable career, had better ethics and a hungry tiger couldn't be half so rapacious. There were three Martians, urbane, pleasant-spoken, and a Venusian. The Venusian, an ex-dictator of a small state, had been fleeing from his irate people with the treasury, when he was captured. Norman, Koal, and Acpsahme made up the thirteen. Jennifer was the only woman present.

The men were gathered in animated groups, drinking, laughing.

"Gentlemen," began Koal, "may I have your attention. What you hear tonight must be held in the strictest confidence. If any word of this meeting reaches the Dohlmites, our lives are forfeit."

Pepperell, the T.I.S. agent, raised his eyebrows, said, "What do you propose to do? Release cut worms among the plant men?"

Jennifer grinned. No one else laughed.

"Thanks," said Pepperell to the girl. "I see we both have the same low sense of humor."

"This is serious," said Koal. "Norman, will you explain your plan to these gentlemen."

For the third time Norman delivered his impassioned appeal for union. "I know," he concluded, "that we haven't any definite means of attack, but how much greater is our chance of discovering one if we work together."

"But the danger of betrayal," protested Pepperell. "The more recruits to this underground army we gain, the more chances we run of admitting a traitor. No silly oath will hold some man from running to the Dohlmites in hopes of currying favor."

"True," agreed Acpsahme grimly. "But a committee of execution should be formed. A committee whose sole duty will be to track down and kill any informer. Gentlemen, this is no seminar fraternity. If I thought any of you were proposing to betray us, I'd shoot you down without a qualm." The blue star tattooed on his forehead lent authority to his quiet words.

"What powers the Dohlmite's force wall?" inquired Norman suddenly.

The men turned back to him, their eyes serious, intent.

"I've speculated about that," admitted Pepperell. "But no human is allowed within to learn."

"If it ever failed, and we were organized, we could rush the Dohlmites, capture the broadcast machine and destroy the cylinders."

"You forget the paralysis ray," observed one of the Martians quietly.

"There's a shield against the ray," Norman countered. "I saw one. Vermeer had one on when our ship was captured."

"A green suit," smiled the Martian. "But they are issued only to agents of the Venusian Export Lines."

"We can steal them."

A hungry look had come into the men's eyes as they recalled the past when they had been free in the Universe. Pepperell smashed his fist down hard on the buffet.

"I'm with you."

"And I." It was unanimous.

Jennifer squeezed Norman's hand ecstatically.

"A toast," proposed Koal, "to freedom."

The men lifted their glasses, drank. Then, with one accord, they shattered them on the floor in a very ancient custom, a custom which hadn't been observed in centuries. Norman's heart swelled at the significance of the gesture.

VIII

Immediately after the next sleeping period, Norman Saint Clair had Koal drive him into the shopping district where he purchased one of the surface cars. It had been agreed at the previous meeting of the new-born Sinn Fein Society that members should be introduced at small, apparently harmless parties. A list of possible recruits had been drawn up and Koal, after directing him to the library, left to set the machinery running.

The library was a large, well lit building with an imposing entrance hall. Norman searched the foyer, but could see no one. Apparently the library was deserted. He crossed the floor, peered over the counter.

There was a couch behind the counter and stretched at full length on the couch was a girl sound asleep. For a moment Norman continued to gaze at her in astonishment. Her blond hair spread out on the pillow like yellow gauze. She had on a rumpled green tunic, and her naked ankle bore the metal slave band. He coughed discreetly.

The girl sat up, stifled a yawn. "Hello," she said, regarding Norman with surprised interest. Her eyes were large and gray with black lashes.

"Excuse me, miss," he said doubtfully, "but are you the librarian?"

"My God," exclaimed the girl, "don't tell me you want a book!"

"Why, yes," he replied, uncertainty in his voice. "Isn't this the library?"

"It's the library, yes. But I've been in this vault for a month now, and you're the first person who's asked for a book. I'd rather be back at the factory."

"You used to work in a factory?"

The girl nodded. "Where they make the paralysis ray insulators."

"The green suits?" he ejaculated.

"Yes. They're green. Why?"

"No reason," he replied cautiously. "Do you have any volumes on botany, horticulture, plant growth, anything at all related to that subject?"

Her gray eyes opened wide. "How long have you been here?"

"Not very long."