She pushed him back, but not quickly enough.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Garden of Evil, by Margaret St. Clair This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Garden of Evil Author: Margaret St. Clair Release Date: November 22, 2020 [EBook #63847] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GARDEN OF EVIL *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Even to a drug-soaked outcast ethnographer Fyhon

was a paradise planet. It was worth anybody's

life to find Dridihad, the secret city of dread!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1949.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Ericson returned to an awareness of his personal identity quite suddenly. He had an impression that it was a long time, months at least, since he had been in a state of normal consciousness. At the back of his mind a memory of pain had imprinted itself as a signet makes an impression in hot wax; he shied away from it. "Where am I?" he asked.

The green-skinned girl squatting beside him in the coppice looked at him sideways out of her dark jade eyes. "Hungry?" she asked.

"But where am—yes, I am hungry. Yes."

Mnathl—he knew, somehow, that that was her name. Didn't he remember her from the other side of the gulf in his memory, from the days when he had begged food in the streets of Penhairn? Mnathl handed him a nicely-roasted bosula rib. He ate it avidly. He had always thought the bosula was the best of the food animals of Fyhon.

When the bone was gnawed clean she passed him, in a folded fresh green leaf, a mixed grill consisting of bits of bosula liver, kidney, tripe, salivary glands, and eyes. He ate that, too. When his stomach was full Ericson lay back with his arms under his head and looked at the big puffy clouds drifting overhead. He had no desire to think about himself or the things that had been happening to him in the last three or four months, but the thoughts came anyhow.

The chief thing was pain—remorseless, long-continued, pain. Mnathl had come to him one day when he was sitting on the dock in Penhairn and told him they were going to Lake Tanais. He had got up and gone with her obediently; a byhror addict has little will of his own. The pain had begun after that.

There had been a barren island in the middle of the brackish, poisonous waters of the lake, and most of the time, until just latterly, he had been kept bound for fear he would drown himself in them. Mnathl ... Mnathl had swum over from the mainland to tend him; she had bathed him and kept his body free of sores and vermin, set food before him and tried to coax him to eat. And twice a day she had given him injections of mercapulan with a hypodermic syringe. His arm was pocked with the needle marks. Where had she got the syringe and the drug? She must have stolen them from the big Colony Hospital in Penhairn.

The injections had brought on the pain. Ericson, at the thought, felt sweat break out on his upper lip. What he had endured had been just at the edge of what a man could stand and still live. (His ordeal, had he known it, had been very much less than it would have been had he taken the drug cure in the hospital in Penhairn. Mnathl, though she had not disdained the help of terrestrial science, knew things about the Fyhonese flora and its properties that no terrestrial even suspected. Still, the ordeal had been bad enough.) Ericson shifted his position and sighed.

Mnathl had cured him of byhror addiction. In return, he had hated her. There had been weeks, he remembered, when his brain had held nothing but horrible pain and the wish to kill Mnathl. Once, when she had untied him for exercise, he had shammed sleep until she came close to him; then he had caught her by the throat. He had come close to killing her then. And no doubt in those long, maniacal days there had been other times.

Ericson raised himself on one elbow and looked at her. She was pouring water into a clay pot above the small, workman-like fire she had built, and was putting in bits of chopped bosula meat. Her greenish skin, the skin of a native of the South Polar continent, glittered slightly as she moved. "Mnathl ..." he said.

She turned toward him quickly, but did not speak. "Mnathl, I'm sorry I tried to ... hurt you on the island. I must have been pretty bad."

Mnathl almost smiled. "No matter," she said. "Pretty soon, soup."

The incident seemed to be closed. Ericson lay back in the shade again and watched the movements of the cloudscape across the deep turquoise of the sky. His eyes felt as fresh as Adam's. The trees were green with the greenness of living emeralds, and the sun had an ardor and a richness like no sun he had ever known before.

Winds blew with caressive, sweet-smelling tendrils over his face, and from the warm soil beneath him he could almost feel strength soaking up again into his body cells. He had visited several planets since he had first left earth; he had loved none of them as he did Fyhon. Fyhon....

Arnaldo, the chunky little head of the paleo-biology department of Penhairn University, had told him once that terrestrials loved Fyhon so because conditions on that planet were like those on Terra during the part of the Cenozoic when man was beginning to become man. Fyhon, he said, appealed to some deep-seated memory in humanity of what a planet ought to be.

Ericson had laughed at him. He was new to Fyhon then, with a temporary appointment as ethnographer to the South Polar Ethnographic Commission. Racial memory had seemed to him as out-moded a concept as spontaneous generation. But his temporary appointment had been extended once, and then once again, and by the end of the second period he had been wildly, hopelessly in love with Fyhon. He had hoped to get a permanent appointment, had hoped to stay on Fyhon for the rest of his life.

Ericson sighed again. After a while he raised one hand above his head and looked at it. He could see the bones and the joints of the bones and the movements of the sinews under the pale gold skin. The marks of Mnathl's hypodermic needle were faintly red. He ran his fingers down his body, surprised at the largeness and hardness of the rib cage, and the prominence of the sockets of his hips. His body felt attenuated and worn. But it was his body, no longer the property of byhror and the byhror emptiness. He held up his hand once more and looked at it against the light. He was beginning to realize that he was alive.

He drifted off into sleep. When he woke, Mnathl was holding out a steaming bowl to him. "Soup?" she said.

They stayed for some eight days in the coppice, while Ericson knotted his memories together. Byhror and the need for it were sinking back with the passage of each successive day into the status of things unalterably in the past. Mnathl set snares and hunted—she would not allow him to move a hand—and Ericson watched her almost incuriously. He felt a little more conscious every hour how good it was to be alive.

On the ninth day Mnathl poured water on the cooking fire. She nested the cooking pots together, slung them deftly over her shoulder, and contrived a belt of twisted vines for her hunting knife. "Go now," she announced.

Ericson got up obediently. "Are we going back to Penhairn?" he asked.

The corners of Mnathl's mouth twitched. "No," she said. "Way on up. On in. In Dridihad." She pointed with her thumb.

Ericson stared at her. "Dridihad?" he said. He'd heard the name before. It was ... now wait ... yes, it was the name the natives applied to the heart of the almost unknown South Polar Minor continent. "I can't go there. I've got to go back to Penhairn, now that I'm well. I've three years of byhror addiction to make up."

Mnathl's eyes narrowed. "Dridihad," she repeated stubbornly.

"But.... Listen, Mnathl, I'm terribly grateful to you for what you've done for me. I never can thank you enough. But I couldn't go to Dridihad now, wherever it is. I'd need equipment—cameras, notebooks, guns, a tent. Right now I've got to go back to Penhairn, see about getting a job."

"All sorts of things to see," Mnathl said. She edged up to him. "You like. You like good." There was a prick in his arm. Mnathl had made other things in her cooking pots the last few days beside soup.

Ericson felt a peculiar glassy lethargy creeping over him. The sensation was not entirely unpleasant. It was as if he looked at his limbs and his body through a sheet of perfectly transparent crystal. He could see his actions and his movements with absolute clarity, but he had nothing to do with them.

"You like see Dridihad," Mnathl said. "All sorts of things for eth—ethnog—for man like you to look at. Come on. You like good." She started along a shadowy, green-roofed trail.

While Ericson watched with resentful detachment, his body began obediently to follow her. Speech as well as volition had deserted him, and all he could do was to move silently in her steps.

As mile succeeded silent mile, memory and common sense came to his aid. There had been a time, nearly three years ago, when he had set out to explore the periphery of the minor polar continent by himself. His temporary appointment had expired, and he had been moving heaven and earth to get it made permanent. The one-man expedition had been a part of the general heaven-and-earth moving process; it had occurred to him that the Ethnographic Commission might be inclined to view his application more favorably if he could offer the Commission a piece of original ethnographic research, such as a report on the natives in the periphery would be.

His attempt had been a miserable failure; indeed, he owed his former byhror addiction to it. His supplies had been eaten by animals, he had poisoned himself with tainted chornis liver, fever had attacked him. In his fits of feverish delirium he had thrown away nearly everything, even his hunting knife. In order to get back to Penhairn at all he had had to resort to chewing the leaves of the byhror plant. The leaves contain a remarkable stimulant; Ericson had been able to get his fever-racked body back to civilization alive. But it had been at the cost of slavish addiction to the drug.

And now Mnathl—bless her greenish skin and queer flat eyes—was offering him a journey to the mysterious heart of the minor polar continent. Offering it to him on a silver platter. A piece of original ethnographic research. He had been ungrateful and a fool. "You like good," she had said. Well, she ought to know.

The effects of the drug she had pricked his arm with must be wearing off. Ericson found he could smile. "Why are we going to Dridihad, Mnathl?" he asked a little later.

Mnathl shook her sleek green head without even turning around to him. "No," she said.

The trip in to Dridihad was a seduction, an enchantment, a bliss. Ericson's strength came flooding back to him. His sick pallor was turning to rich gold. On the second day he whittled, under Mnathl's guidance, a spear and a throwing-stick for it, and on the third and fourth she taught him to set snares and kindle fires with a sliver of onchian. The country grew wilder and more beautiful, the trees taller, the sky a deeper blue, the waterfalls more loud. He tried to question the girl, but she never answered anything except "No", and after a little, in his happiness, he gave up asking questions.

What did it matter, after all? He was learning from day to day secrets that any geographer or ethnographer would have given the best years of his life to learn; the piece of original ethnographic research was becoming a reality; and who, except a fool, questions someone who has not only restored him to life but is giving him his heart's desire?

On the eighteenth day, when Ericson's body had filled out and been turned to a living gold by the sun, they came across the pyramid. It stood in a swale with purple flowers growing around it and a small river flowing around one side, and it was so tall that Ericson, looking dizzily up, swore he saw clouds floating around its top. He wanted to stay and look at it, to record it in his mind, but Mnathl was not impressed. She let him have two hours, and then she urged him on.

"But who built it, Mnathl?" he demanded when he had been pulled reluctantly away. "How did it get here?"

Mnathl seemed to be debating whether to answer him. He could never decide whether she was naturally taciturn, or whether she really grudged telling him things. "My people built it," she said at last. "Deidrithes. Long time ago. Long time ago." She motioned vaguely with her hand.

Something in the gesture made Ericson see with sudden clarity how deep the abysm of the past, even on this young world with the ardent sun, really was. Fyhon was young; but the Deidrithes had been living on Fyhon a long time.

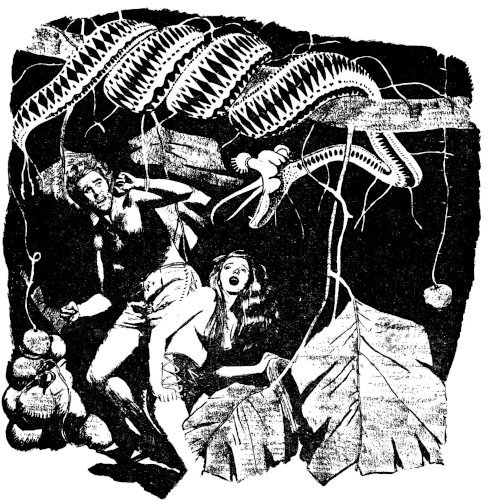

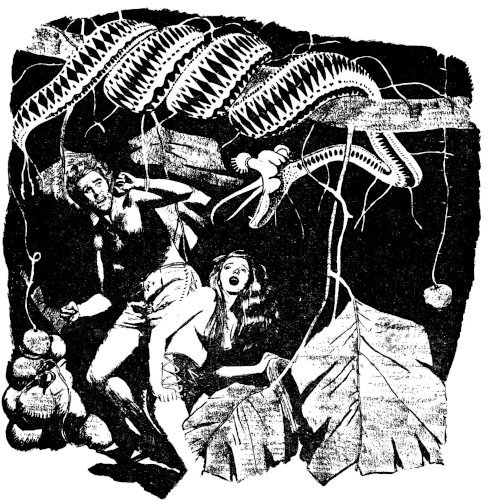

Two days later Ericson, contrary to their usual custom, was in the lead, breaking trail. Mnathl caught him suddenly around the waist and pulled him back, but she was not quick enough. The huge, thick-bodied snake with the red bandings lashed out at him and just fell short. But one glistening fang grazed his foot.

She pushed him back, but not quickly enough.

Mnathl, bleached by fear to the color of an inferior grade of jade, killed the snake with a stone. Then she made Ericson sit down on the grass, and slashed at his foot with her hunting knife.

"What is it, Mnathl?" Ericson asked. The wound was not especially painful, but his heart had already begun to beat slowly and wearily, as if beating were a burden almost beyond its strength, and at the same time it seemed to have grown until it threatened to burst his chest.

"Outis," Mnathl answered briefly. She hesitated for a moment. "Bad," she said, as if to herself. "Very bad. Could kill me too." Then she leaned over and set her lips to the bleeding gash her knife had made.

Ericson tried to draw away from her. He was so dizzy that he could hardly see. "No," he croaked, "don't. You mustn't suck it, Mnathl. I don't want you to risk your life."

The green-skinned girl shrugged. "No matter," she answered. "Will do. O.K."

Ericson tried to push her from him, but he was too weak. The world was receding from him in black waves. She sucked blood and poison from the wound, spat, sucked, spat, and sucked again.

He would have liked to protest, to thank her for her sacrifice, but he had no time. His pulse had begun to flutter feebly, and he fainted.

For the next several days he was in a stupor most of the time. Whenever he came back to consciousness, he saw Mnathl lying exhausted in the grass near him, and he knew without being told that the poison she had sucked from his wound was moving sluggishly and with slow malignity through her veins. Nevertheless, the wound on his foot was always cleanly dressed and plastered with fresh herbs, and from time to time she opened it with her knife and let the pus escape.

When they were finally on the road to Dridihad again, he tried to thank her for what she had done.

"Anything I can do for you, Mnathl," he wound up with some embarrassment (it is difficult to thank someone who refuses to look at you), "anything I can do for you, why, you let me know. I could have died there, without ever getting my permanent appointment or seeing Dridihad. We're friends, aren't we, Mnathl? Friends." He took her hand.

Mnathl nodded curtly. "O.K.," she said. She pulled her fingers from his. The Deidrithes, Ericson thought not for the first time, were an impassive, unemotional folk.

It took them nearly a month more to get to Dridihad. On the way they had to ford two swollen rivers and beat off the attack of a must-maddened bull rhodops. Neither of these incidents had any consequences. On the sixty-sixth day after their departure from Lake Tanais, they came to the foot of Dridihad.

For a week or so the ground had been rising steadily and the air growing crisp and thin. They had labored uphill, uphill. Dridihad itself, built on a high plateau, had been visible for three days before they reached it, a silhouette, faintly pinkish, against the clouds. When they had first caught sight of it, Ericson had felt an almost painful anticipation seize him, and even Mnathl, usually so impassive, had shown, in her glowing face and quickened breathing, how excited she was.

The ascent to the plateau itself, along a path so precipitous that Ericson was always having to clutch it with hands as well as feet, was so toilsome that fatigue had dimmed his curiosity a little when they arrived at the top. Earlier that day Mnathl had thrown the cooking pots and the knife contemptuously over the side of the cliff, and now, cupping her hands around her lips and standing almost arrogantly erect, she strode up to the rosy-red, eroded battlements.

"Klarete laoi!" she called. "Laoi, klarete!" So far as Ericson could see, no one at all was listening. But after a moment the massy doors of the gate began to open outward, ponderously, in the twilight. They went in.

Dridihad, Ericson saw at first glance, was much larger and more populous than he had supposed from below. The low, stepped buildings, all made of the rose-pink stone, seemed to stretch out for mile upon mile, as far as he could see. They made upon him an impression of antiquity so strong that it was almost disturbing. The small greenish people like Mnathl were everywhere. In dots, trickles and rivulets they were pouring out into the streets.

Mnathl's eyes fell on a man near her. She spoke to him. Instantly he bowed profoundly before her, and made a second, shallower obeisance to Ericson.

"Go with him," Mnathl said, turning to the ethnographer. "Sleep in his house." Obediently, Ericson followed his guide. When he looked around toward Mnathl, she had already disappeared.

The man (his name seemed to be Boator) took Ericson to an airy suite of rooms on the top floor of one of the biggest of the houses of red stone. Attendants waited on him with food and drink and water for bathing. They took away his dirt-encrusted, ragged clothing and brought him a heavy greenish robe. After Ericson had bathed and put it on, he inspected himself in the sheet of polished metal that served for a looking glass and decided that the color of the fabric made his curling beard and fair skin look as if they had been cast from yellow gold.

He was tired, but far too excited to rest.

The chief thing, the indubitable, the incredible thing, was that there was a very old, a very populous city, a city whose existence no one had even suspected, in the heart of the South Polar Minor continent. It was news to inflame an ethnographer to the point of hysteria. When Ericson got back to Penhairn with his report, it was going to revolutionize their whole concept of Fyhonese history; one would hardly exaggerate to say that it would be epoch-making news. No doubt there would be a period when they'd consider him the biggest liar since Marco Polo. But after the first skepticism wore off he'd have a permanent ethnographic appointment almost forced upon him. His report would shake established reputations, found new schools, would—oh, if he only had something to write on!

When the attendant came in again, Ericson made motions of writing in the palm of his hand, but the man's face remained blank. And when he asked for Mnathl the attendant merely shook his head and went out.

For want of anything better the young man hung out of the window watching the smoky flicker of lights in the city around him. It was not until the last one had gone out that he went, reluctantly, to bed.

Next morning, immediately after breakfast, Mnathl came to visit him. He hardly knew her at first. The scanty garments she had worn unconcernedly on their journey to Dridihad had been replaced by the stiff, hieratic folds of a dull purple robe embroidered in blue. On her head there was a silvery crown of antique workmanship, set with luminous purple stones, and she moved with the conscious dignity of a princess or a priest.

Her manner toward him, too, had changed. She smiled faintly when she first saw him, and everything about her seemed freer than Ericson had seen it before. She was animated, almost vivacious.

He asked her for something to write with. "No," she answered, still with that faint smile, "no use. Hunt now."

They left Boator's house by a side door (to avoid the crowd that would appear at once if they were glimpsed in the streets, Ericson surmised) and entered a small, walled court. There four improbably striped animals, about the size of small ponies, were waiting for them. Ericson mounted one of them, and Mnathl, tucking up her skirts, bestrode another. With two attendants they rode circuitously through Dridihad and out into the high plain.

The variety and abundance of game were amazing. There seemed to be more animals than there were trees, and they came in all sizes, shapes, colors, and coats. There was even a big blue-hued thing that reminded the young man a little of a kangaroo. He enjoyed himself, but he could not help wishing that he knew more about Fyhonese zoology than he did—to appreciate all those properly.

They got back to the city just before dark. Ericson ate, and then Mnathl took him to the temple. It was the tallest building in Dridihad, a stepped pyramid of unusually reddish stone, and Ericson was to grow fond, later, of the view from its flat top. The naos itself, however, was a small room skimpily scooped out of one side of the pyramid, and it was very badly lighted. Ericson, who had resolved, in default of paper to write on, to impress all he saw and heard irremovably upon his mind, had to strain his eyes to see anything.

Mnathl officiated. His first feeling that she was a priestess seemed to be correct. As to the ritual itself, it was highly impressive, especially when one considered that he did not know the language in which it was going on. It ended with the sacrifice of an animal like a bosula; while two attendants held it, Mnathl cut its throat, caught the blood in a cup, and poured it on the altar fire. Then she roasted pieces of the meat over the coals and dealt them out among the celebrants of the ceremony, partaking first herself. None of the collops was offered to Ericson; but, then, he could hardly be considered a communicant of the religion of the Deidrithes, whatever it was.

As the days passed, a possible explanation of Mnathl's treatment of him began to come to Ericson. He was not a conceited man, or it might have occurred to him earlier. And it bothered him to think that she was attracted to him, whereas he had never found her attractive in any way. Still, what other hypothesis would account for the facts?

They were together almost constantly and, except for the attendants who were always armed with heavy axes, always alone. She hunted with him, showed him the city, rode with him; she even taught him to play a rather childish game, something like the Sicilian Mora, which she always beat him at. Day after day she took him with her to witness religious rites which were obviously of the most hallowed character. Ericson had the impression that the rites were leading, in a series of slight graduations, up to some supreme event! and he tried to note and remember everything.

The climax came suddenly. One lovely evening, just as the full moon was rising, Mnathl took him with her up the steep sides to the top of the pyramid. The two attendants hovered discreetly in the background. For all practical purposes, he and the girl were alone.

Mnathl looked at him. There was a glint, warm, glowing, and facile, in her eyes that he had never seen there before. There was a short but rather embarrassing silence. At last Ericson, feeling like a boor and a churl, took her hand.

"Mnathl," he said, "I'm so grateful to you. You've done so much for me, helped me so much. You ... mean a lot to me, Mnathl." That, at least, was true.

Mnathl pulled her fingers away and regarded him. "What you mean?" she asked blankly. "What you mean?"

"That you ... that I ..." he stopped, too embarrassed to go on.

Mnathl threw back her head and laughed. It was the first time he had ever heard the sound from her, and there was something strange in it. She motioned to the axmen with her hand.

"Not like, not hate," she said blandly. "Let you see, let you hear, so you tell Them all that Deidrithes do. You our messenger. Then we eat."

Then we eat.... For a moment the words echoed meaninglessly in Ericson's mind. The axmen were forcing him to his knees near a depression in the center of the pyramid. "But why ..." he said.

"We hear about you the first time you try trip," Mnathl said. "Everybody know. No other men your color in Fyhon."

His color. Ericson began to understand. Mnathl's devotion, her self-sacrificing tenacity, her long kindness to him, everything—had all been nothing but the prelude to a ritual meal in which his rare blonde body was to be the chief support. No doubt a man of his color would be an especially choice offering to the gods. The gleam he had seen in Mnathl's eyes had been not love, but a kind of religious gluttony.

He began to laugh. Irony had always appealed to him; and besides he was remembering a sentence in the Ethnographic Commission's preliminary survey: "There is no doubt that ritual cannibalism is unknown among the natives of Fyhon."

"O.K., Mnathl," he said, recalling what he had been saved from, what he had seen and learned. "I'm ahead, no matter how you look at it. It's O.K."

He was still smiling when the axman on the right struck and Ericson's severed head went rolling along the surface of the pyramid.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Garden of Evil, by Margaret St. Clair

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GARDEN OF EVIL ***

***** This file should be named 63847-h.htm or 63847-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/3/8/4/63847/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.