This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States

and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not

located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this ebook.

** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below **

** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. **

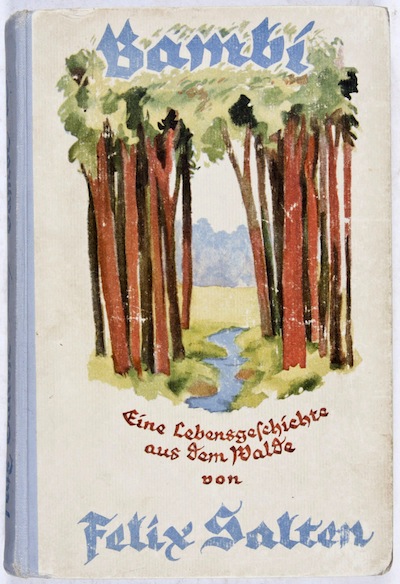

Title: Bambi

Author: Felix Salten

Release Date: November 22, 2020 [eBook #63849]

Most recently updated: November 28, 2020

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BAMBI***

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

It was in a space in a thicket that he came into the world, in one of those little, hidden places in the wood which seem to be open on every side but which in fact are completely surrounded by foliage. That is why there was so little room there, but just enough for him and his mother.

He stood up, he staggered on his thin legs as he wondered what was happening, looked out with eyes which were dull, wondered what was happening but saw nothing, dropped his head, shuddered severely, and was quite numb.

“What a beautiful child!” declared the magpie.

She had rushed to the place, drawn by the breathy groans she heard forced from Bambi’s mother by her pain. Now the magpie sat on a branch nearby. “What a beautiful child!” she exclaimed again. No-one answered her and she continued speaking excitedly. “And he can already stand up and walk. That’s amazing! That’s so interesting! I’ve never seen anything like it in me life. Well, I’m still young of course, it’s only a year since I left the nest, but I expect you know that. But I think it’s wonderful. A child like this ... he’s only been born a second and he can already stand. I think it’s very noble of him. And most of all, I find that everything done by you deer is very noble. Can he already run too?”

“Of course,” answered Bambi’s mother gently. “But you’ll have to excuse me, I’m not really in a good condition to chat with you. There’s a lot that I’ve got to do ... and besides, I’m feeling quite tired.”

“Oh, don’t let me disturb you,” said the magpie, “I’m in a bit of a rush today, too! But it’s not every day that you see something like this. I ask you, think of how awkward it is for us in these things, and how much hard work! The children just can’t do anything when they first hatch from the egg, they just lie there in the nest quite helpless, and need to be looked after, they always need to be looked after I tell you, I’m sure you’ve got no idea what it’s like. It’s so much hard work just to keep ‘em fed, and they need to be protected, it’s so worrying! I ask you, just think how strenuous all that is, getting food for the children and having to watch over them at the same time so that nothing happens to ‘em; if you’re not there they can do nothing for themselves. Am I not right? And you have to wait so long before they start to move, so long before they get their first feathers and start to look a bit decent!”

“Please forgive me,” Bambi’s mother said, “I wasn’t really listening.”

The magpie flew away. “Stupid person,” she thought to herself, “noble, but stupid!”

Bambi’s mother barely noticed, and continued vigorously washing her newborn. She washed it with her tongue and so performed several tasks at once, care for his body, a warming massage and a display of her affection.

The little one staggered a little under the weight of the stroking and pushing that gently touched him all over but he remained still. His red coat, which was still a little unkempt, had a sprinkling of white on it, his face, that of a child, still looked uncomprehending, almost as if he were in a deep sleep.

All around them grew hazel bushes, dogwoods, blackthorn bushes and young elder trees. Lofty maples, beech trees and oaks created a green roof over the thicket and from the firm, dark brown ground there sprouted ferns and wild peas and sage. Down close to the ground were the leaves, close together, of violets which were already in bloom and the leaves of strawberries which were just beginning to bloom. The light of the morning sun pierced its way through the thick foliage like a web of gold. The whole forest was alive with the sounds of countless voices which pierced through the trees with an air of gay excitement. The golden oriole performed a ceaseless song of joy, the doves never stopped cooing, the blackbirds whistled, the finches flapped their wings, the tits chirruped. The quarrelsome screech of the jay penetrated through all this, and the joking laughter of the blue magpie, the bursting, metallic cook-cook of the pheasants. From time to time the harsh short celebrations of a woodpecker would pierce through all the other voices. The shrill, bright call of a falcon would penetrate across the forest canopy and the choir of crows never stopped ringing out their raucous call.

The little one understood not a one of these many songs and calls, not a word of their conversations. He was still too young to listen to them. He also paid no attention to any of the many smells that the forest breathed. He heard only the gentle rustling that ran over his coat as it was washed, warmed and kissed, and he smelt only the body of his mother, close by. He nuzzled close to this body with the lovely smell, and hungrily he searched around it and found the source of life.

As he drank his mother continued to pet him. “Bambi,” she whispered.

Every few moments she would lift her head, listen, and draw the wind in.

Then she kissed her child again, reassured and happy. “Bambi,” she repeated, “my little Bambi.”

Now, in the early summer, the trees stood still under the blue sky, they held their arms out wide and received the power of the sun as it streamed down on them. The bushes in the thicket were coming into bloom with stars of white or red or yellow. On many of them the buds of fruit were beginning to be seen again, countless many of them were sitting on the fine tips of the branches, tender and firm and resolute they looked like little clenched fists. The colourful stars of many different flowers came up out of the ground so that the earth, in the subdued light of the forest, was a spray of silent but vigorous and gay colours. Everywhere there was the smell of the fresh foliage, of flowers, of the soil and of green wood. When morning broke, and when the sun went down, the whole wood was alive with a thousand voices, and all day from morning to evening the bees sang, the wasps buzzed, and the bumble-bees buzzed even louder through the fragrant stillness.

That is what the days were like when Bambi experienced his earliest childhood.

He followed his mother onto a narrow strip that led between the bushes. It was so pleasant to walk here! The dense foliage stroked his sides gently, and bent slightly to the side. Everywhere you looked the path seemed to be blocked and locked, but it was possible to go forward in the greatest comfort. There were routes like this in the woods, they formed a network going all through the forest. Bambi’s mother knew them all, and whenever he stood in front of what seemed to him like an impenetrable green wall she would immediately seek out the place where the path began.

Bambi asked her questions. He was very fond of asking his mother questions. For him, it was the nicest thing in the world to keep asking her questions and to listen to whatever answer she gave. Bambi was not at all surprised that he always thought of one question after another to ask her. It seemed entirely natural to him; it was such a delight for him. It was also a delight to wait, curious, until the answer came, and whatever the answer was he was always satisfied with it. There were times, of course, when he did not understand the answer he was given but that was nice too because he could always ask more questions whenever he wanted to. Sometimes he stopped asking questions and that was nice too because then he was busy trying to understand what he had been told and would work it out in his own way. He often felt certain that his mother had not given him a complete answer, that she deliberately avoided saying everything she knew. And that was very nice, as it left behind a certain kind of curiosity still in him, a feeling of something mysterious and pleasing that ran through him, an expectation that made him uneasy but cheerful.

Now he asked, “Who owns this path, mother?”

His mother answered, “We do.”

Bambi continued asking. “You and me?”

“Yes.”

“Both of us?”

“Yes.”

“Just you and me?”

“No,” said his mother, “we deer own it ...”

“What’s a deer?” asked Bambi with a laugh.

His mother looked at him and laughed too. “You’re a deer, and I’m a deer. That’s what deer are. Do you understand now?”

Bambi jumped into the air with laughter. “Yes, I understand. I’m a little deer and you’re a big deer. That’s right, isn’t it.”

His mother nodded. “There, you see now.”

Bambi became serious again. “Are we the only ones, or are there other deer?”

“Certainly,” said his mother. “There are lots of them.”

“Where are they?” Bambi exclaimed.

“They’re here, they’re all around us.”

“But ... I can’t see them.”

“You’ll see them soon enough.”

“When?” Bambi’s curiosity was so strong that he stopped walking.”

“Soon.” His mother walked calmly on.

Bambi followed her. He said nothing, for he was trying to work out what she could have meant by “soon.” He reached the conclusion that “soon” was certainly not the same as “very soon.” But he was not able to decide when it was that this “soon” would stop being “soon” and start to be “a long time yet.” Suddenly he asked, “Who was it who made this path?”

“We did,” his mother replied.

Bambi was astonished. “We did? You and me?”

His mother said, “Well, yes, ... we deer made it.”

“What deer?” Bambi asked.

“All of us,” was his mother’s curt reply.

They walked on. Bambi had had enough of it and wanted to jump off away from the path, but he was a good child and stayed with his mother. Ahead of them there was a rustling noise, coming from somewhere close to the ground. There was something moving vigorously, something concealed under the ferns and wild lettuce. A little voice, as thin as a thread, let out a pitiful whistle, and then it was quiet. Only the leaves and the blades of grass quivered to show where it was that something had happened. A polecat had caught a mouse. Then he dashed past them, crouched down to one side and set to on his meal.

“What was that?” asked Bambi excitedly.

“Nothing,” his mother reassured him.

“But...” Bambi stuttered, “but ... I saw it.”

“Well, yes,” his mother said, “but don’t be frightened. A polecat killed a mouse.”

But Bambi was terribly frightened. His heart was squeezed within a great, but unfamiliar, horror. It was a long time before he could speak again. Then he asked, “Why did he kill the mouse?”

“Because ...” His mother hesitated. Then she said, “Let’s go a bit faster, shall we?” as if she had suddenly thought of something else and forgotten about the question. She began to trot. Bambi hopped along after her.

A long pause went by and they had stopped walking so fast. Finally Bambi, feeling rather anxious, asked, “Will we ever kill a mouse?”

“No,” his mother answered.

“Never?” asked Bambi.

“No, never,” came her reply.

“Why not?” asked Bambi with some relief.

“Because we never kill anyone,” his mother told him simply.

Bambi became cheerful again.

There was a young ash tree next to their path from which a loud screeching could be heard. His mother paid no attention to it and carried on walking. But Bambi was curious and stopped. High in the tree’s branches there were two jays squabbling over a nest they had just plundered.

“You get out of it, you lout!”

“Don’t get excited, you fool,” the other answered. “I’m not afraid of you.”

“Go and get your own nests, you thief!” yelled the first. “I’ll punch your face in.” He was beside himself. “You’re just vile,” he snapped. “Just vile!”

The other bird had noticed Bambi. He flapped a few twigs down and snarled, “What are you looking at, brat? Get lost!”

Bambi felt intimidated and jumped away from them. Once he had reached his mother he continued walking behind her along the path, obedient and startled. He thought she had not noticed he had stayed behind.

After a while he asked her, “Mother, what does ‘vile’ mean?”

His mother said, “I don’t know.”

Bambi thought about it. And then he began again. “Mother, why were those two being so nasty to each other?”

His mother answered, “They were quarrelling about getting the food.”

Bambi asked, “Will we ever quarrel about food like that?”

“No,” his mother said.

“Why not,” Bambi asked.

His mother replied, “There’s plenty of food for all of us.”

There was something else that Bambi wanted to know. “Mother ...?”

“What is it?”

“Will we ever be nasty to each other too?”

“No, my child,” said his mother. “We don’t do that sort of thing.”

They carried on walking. Suddenly they saw light ahead of them, very bright light. The green confusion of bushes and shrubs came to an end, their path was at its end. Just a few steps further and they came out into the brightly lit free space that opened up ahead of them. Bambi wanted to jump forward, but his mother just stood where she was.

“What’s that?” he exclaimed, impatient and quite enchanted.

“The meadow,” his mother answered.

“What’s that, the meadow?” Bambi insisted.

His mother gave him a curt reply. “You’ll see that for yourself soon enough.” She had become serious and attentive. She stood there without moving, her head held up high, listening tensely, testing the wind with deep breaths, and she looked almost severe.

“Yes, everything’s alright,” she finally said, “we can go on out there.” Bambi was about to jump ahead but she blocked his way. “No, you wait until I call you.” Bambi did as he was told and immediately stood still. “Well done, Bambi,” his mother praised him. “Now, listen carefully to what I say.” Bambi listened carefully as his mother spoke and saw how agitated she was, he became very tense himself. “Going out onto the meadow is not as simple as it seems,” his mother continued, “it’s difficult and it’s dangerous. Don’t ask me why. You’ll learn that later on. For now, just do exactly what I tell you. Will you do that?”

“Yes,” Bambi promised.

“Good. So I’ll go out there first by myself. You stay here and wait. And don’t take your eyes off me. Keep me in sight and don’t look away, not for a second. If you see me start to run back here, then turn round and run away as fast as you can. I’ll soon catch up with you.” She became silent and seemed to be thinking, then, with much emphasis, she went on. “Whatever happens, run, run, run as fast as you can. Run ... even if something happens ... even if you see ... if you see me fall to the ground ... don’t pay any attention to me, understand? ... Whatever you see or hear ... just keep going, without delay and as fast as you can ...! Do you promise me that?”

“Yes,” said Bambi quietly.

“But if I call you,” his mother continued, “you can come. You come and play on the meadow. It’s nice out there, you’ll like it. Only ... this is something else you have to promise me ... if I call you, you must be at my side straight away. Whatever the circumstances! Do you hear?”

“Yes,” said Bambi, even quieter. His mother was being so serious.

She continued speaking. “Out there ... if I call you ... there’s to be no running about and no questions, you’re to run behind me like the wind! Don’t forget. No thinking about it, no hesitating ... if I start to run it means you get up immediately and get out of there, and you don’t stop till we’re back here in the woods. You won’t forget that, will you!”

“No,” said Bambi, feeling rather anxious.

“Alright, now I’ll go,” his mother told him, and seemed somewhat calmer.

She stepped out onto the meadow. Bambi, who did not take his eyes off her, saw how she went forward with slow and high steps. He stood there full of anticipation, full of fear and curiosity. He saw how his mother listened on every side, he saw her when something startled her and felt startled himself, ready to jump back into the thicket. Then his mother became calm once more and after a minute had passed she became cheerful. She lowered her neck, stretched it out far in front of her, looked contentedly back at Bambi and called, “Come on then!”

Bambi jumped forward. He was gripped with an enormous joy that was so magically strong that he forgot about the anxiety he had felt just before. All he had been able to see while he was in the thicket was the green treetops above him, and he saw the few scraps of blue above them only in short, rare glimpses. Now he could see the whole of the sky, high and wide and blue, and that made him glad, although he did not know why. Among the trees, all he had seen of the sun had been single, broad rays, or the gentle scattering of golden light that played between the branches. Now he suddenly found himself standing in a hot and dazzling power that forced itself on him, he stood within this copious blessing of warmth that closed his eyes and opened his heart. Bambi was exhilarated; he was completely beside himself, it was simply wonderful. He spontaneously jumped into the air, three times, four times, five times on the spot where stood. He could not help himself; he had to do it. Something yanked him up and made him jump. His young limbs had such powerful spring in them, the air went so deep and easily into his lungs that he drank it in, drank in all the fragrances of the meadow with so much overpowering cheer that he simply had to jump. Bambi was a child. If he had been a human child he would have shouted with joy. But he was a young deer, and deer cannot shout, or at least not in the same way as human children do. So he rejoiced in his own way. With his legs, with his whole body that threw him into the air. His mother stood nearby and was glad to watch him. She watched him going crazy. She saw him as he threw himself up high, dropped clumsily back down on the same spot, stared ahead in confusion and exhilaration, and then, in the next moment, threw himself back into the air over and over again. She understood that Bambi had only ever seen the narrow deer paths in the woods, in the few days of his existence had only ever become used to the narrowness of the thicket, and that he therefore did not move from the spot where he stood because he still did not understand that he was free to run around the whole of the meadow. She stretched out her forelegs and lowered herself onto them, gave a little laugh to Bambi, and she was suddenly away, rushing round in circles so that the tall grass swished loudly. Bambi was startled and remained motionless. Was that meant to mean he should go back into the woods? Don’t bother about me, his mother had said, whatever you see, whatever you hear, just get away, get away as fast as you can! He wanted to turn round and run away as he had been told. Then his mother suddenly came galloping towards him making a wonderful noise. She came to within two steps from him, lowered her body as she had done the first time, laughed to him and called, “Try and catch me!,” and rushed away from him. Bambi was astonished. What was all this supposed to mean? What had come over his mother all of a sudden? But then she was coming back again at such enormous speed it enough to make you dizzy. She poked him in the side with her nose and quickly said, “Try and catch me!,” and rushed away. Bambi stumbled after her. A few steps. But those steps soon became little jumps. They carried him, he thought he was flying; they carried him by themselves. There was space under his steps, space under his jumps, space, space. Bambi was beside himself. The grass made a glorious sound in his ears. It was deliciously soft, as tender as silk as he skimmed across it. His mother stood still for a while as she caught her breath. She only moved in the direction of Bambi as he rushed by. Bambi flew like the wind.

Suddenly it stopped. Bambi stopped running and went over to his mother in an elegant, high stepping trot, where he looked happily into her face. Then they walked along contentedly beside each other. Since he had come out here into the open Bambi had seen the sky, the sun and the wide stretch of green only with his body, only with a blinkered, drunken glance at the sky, with the cosy feeling of the warmth on his back and the invigorating feel of the sun that made him take ever deeper breaths. Now, for the first time, he began to enjoy the glory of the meadow with his eyes which surprised him with new wonders with every step he took. There were no scraps of bare earth that could be seen as there were among the trees. Here every spot was covered in dense grass, every blade cuddling close with others which swelled up in abundant glory, leant gently to one side under each step and immediately sprang back upright with no sense of insult. The broad green plain was starry with white daisies, with violets, with the thick red heads of the clover as it began to blossom, and with the shining majesty of the golden flowers held up high by the dandelions.

“Look, mother,” called Bambi, “there’s a flower flying away.”

“That’s not a flower,” his mother said. “That’s a butterfly.”

Bambi was delighted and watched the butterfly as it very gently freed itself from a stalk of grass and, in tumbling flight, floated away. Now Bambi saw that there were many such butterflies flying in the air over the meadow, they seemed to be in a hurry but they were slow, they tumbled up and down in a game that enchanted him. They really did look like flowers moving about, gay flowers that did not want to just keep still on their stalks and had got up to have a little dance. Or like flowers that had come down with the sun, still had not found a place for themselves and were carefully looking round for one, they would sink down and disappear as if they had already found a place but then they would fly straight up again, just a little way at first, and then higher in order to carry on with their search, always seeking because the best places were already occupied.

Bambi looked at all of them. He would have so liked to see one of them close up, would have so liked to examine just one of them, but he was not able to. They never stopped flitting about between each other. It made him quite dizzy.

When he once again looked down at the ground everything he saw brought him a thousand delights, nimble, living things that flew up when he stepped near them. All around him there was something jumping and sprinkling into the air, something that became visible in a tumultuous swarm and, the next second sank back into the green ground it had come from.

“What’s that, mother?” he asked.

“That’s the little ones,” she answered.

“Look,” called Bambi, “there’s a piece of grass that’s jumping up ... it’s jumping up so high!”

“That isn’t grass,” his mother explained, “that’s a nice grasshopper.”

“Why does it jump like that?” asked Bambi.

“Because we’re moving about,” his mother answered, “it’s frightened.”

“Oh!” Bambi went over to the grasshopper, which was sitting right in the white dish of a daisy.

“Oh,” said Bambi politely, “you don’t need to be frightened, we certainly won’t do anything to you.”

“I’m not frightened,” the grasshopper retorted in a rasping voice. “I was just a bit startled at first, as I was speaking to my wife.”

“Please excuse us for disturbing you,” said Bambi modestly.

“That doesn’t matter,” the grasshopper rasped. “As it’s you it doesn’t matter. But you never know who might be coming, and you have to watch out for yourself.”

“I haven’t been out here on the meadow before,” Bambi told him. “My mother ...”

The grasshopper stood there with his head lowered in a way that made him look very cross, his face looked serious and he grumbled, “I’m not interested in that. I haven’t got the time to be here chatting with you, I’ve got to go and find my wife. Hop!” And he was gone.

“Hop,” said Bambi, rather puzzled and astonished at the height of the leap the grasshopper had made as he disappeared.

Bambi ran to his mother. “Listen ... I’ve just been talking with him!”

“With who?” his mother asked.

“Well, with the grasshopper,” Bambi explained, “I was talking with him. He was so friendly to me. And I liked him so much. He’s so green, it’s wonderful, and on his back you can see right through him, there aren’t any leaves like that, not even the finest leaf.”

“That was his wings.”

“Was it?” Bambi continued speaking. “And he’s got such a serious face, as if he were thinking hard about something. But he was friendly to me anyway. And he can jump so high! That must be awfully hard. “Hop!! he said, and he jumped so high that I couldn’t see him any more.

They walked on. Bambi was very excited about his conversation with the grasshopper, and he was a little tired as it was the first time he had talked with a stranger. He was hungry, and pressed close to his mother so that he could refresh himself.

Then, when he was once more standing there for a while, just staring ahead of him in the sweet, little inebriation that always enveloped him when he had drunk all he had wanted from his mother, he saw a whitish flower down in the tangle of grass stems. It moved. Bambi looked closer. No, that was not a flower, it was a butterfly. Bambi crept closer.

The butterfly was hanging listlessly from a stem of grass, and gently moved his wings about.

“Please, stay where you are,” Bambi called to him.

“Why should I stay where I am? I am a butterfly, after all,” he asked in astonishment.

“Oh, please stay where you are, just for a little while,” Bambi begged him, “I’ve been wanting to see you close up for so long now. Please be so kind.”

“Alright then,” said the little white butterfly, “but not for too long.”

Bambi stood in front of him. “You’re so beautiful,” he said in enchantment, “so beautiful! Like a flower!”

“What?” The butterfly clapped his wings. “Like a flower? Well, everyone I know agrees that we’re much more beautiful than flowers.”

Bambi was confused at that. “Y..yes, certainly,” he stuttered, “much more beautiful ... please forgive me ... I just wanted to say ...”

“I don’t really care what you wanted to say,” the butterfly retorted. He started to show off by curving his narrow body and playing idly with his sensitive antennae.

Bambi was enthralled and continued to watch him. “You’re so elegant,” he said, “so fine and so elegant! And those white wings of yours, they’re so majestic!”

The butterfly lay his wings wide open, then he put them together above him where they looked like the taut sail of a yacht.

“Oh,” Bambi exclaimed, “now I understand how you’re more beautiful than the flowers. And you can fly as well, flowers can’t do that. They have to stay where they’re growing, that’s how.”

The butterfly raised himself up. “That’s enough now,” he said. “I can fly!” And he lifted himself into the air with such ease that it could not be seen and it could not be understood. His white wings moved gently and full of grace, and he was already drifting there in the air and the sunshine. “It was only for your sake that I remained sitting there for so long,” he said, and he jiggled up and down in front of Bambi, “but now, I will fly away.”

That was the meadow.

Deep in among the trees was a place that belonged to Bambi’s mother. It lay only a few steps from the narrow path used by the deer as they made their way through the wood but it was nearly impossible to find for anyone who did not know where the little gap through the dense bushes was.

It was only a narrow space, so narrow that it only just had room for Bambi and his mother to fit in, and it was so low that when Bambi’s mother stood up her head would be in among the twigs and branches. Hazel bushes, gorse and dogwood all grew here tangled in among each other and the little sunlight that came down through the forest canopy would be caught by them so that it never reached as far as the ground. This was the room where Bambi came into the world and this was where he and his mother made their home.

Now, his mother lay asleep, pressed down on the ground. Bambi had slept a little too, but now he had become quite lively. He stood up and looked around.

Here, deep in the woods, it was shadowy, it was almost dark. The wood could be heard gently rustling and soughing. Here and there the tits chirruped, here and there was the bright laughter of a woodpecker or the cheerless bark of a crow. All else, near and far, was quiet. Only the air became warm in the heat of midday, and even that could be heard if you listened carefully. Here in the woods it was humid and sweltering.

Bambi looked down at his mother. “Are you asleep?”

No, his mother was not sleeping. She had woken up straight away when Bambi had stood up.

“What are we going to do now?” Bambi asked.

“Nothing,” his mother answered. “We’re going to stay where we are. Just lie down, like a good child, and go to sleep.”

But Bambi did not feel like sleeping. “Come on,” he begged. “Let’s go onto the meadow.”

His mother raised her head. “To the meadow? Now ... to the meadow ...?” She sounded so astonished and so full of alarm that Bambi became quite frightened.

“Can’t we go to the meadow now, then?” he asked shyly.

“No,” came his mother’s answer, and it sounded quite conclusive. “No, that isn’t possible right now.”

“Why not? asked Bambi as he became aware that there was something very strange going on here. He became more afraid, but at the same time he felt the urge to learn about everything. “Why can’t we go onto the meadow now?”

“You’ll learn about all that later, when you’re a bit older ...,” his mother reassured him.

Bambi was insistent. “Why won’t you tell me now?”

“Later,” his mother repeated. “You’re still just a little child,” she continued gently, “and you don’t talk about things like this with little children.” She had become very serious. “Now ... on the meadow ... I just don’t want to think of it. In broad daylight ...!”

“But when we went on the meadow,” Bambi objected, “it was broad daylight then, too.”

“That was different,” his mother explained, “that was early in the morning.”

“Can you only go there early in the morning then?” Bambi had become too inquisitive.

His mother remained patient. “Only early in the morning or late in the evening ... or at night ...”

“And not in the daytime? Never ...?”

His mother hesitated. “Yes,” she said at last, “sometimes ... there are some of us who go out there in the daytime too, sometimes. But that’s under special conditions, ... I can’t really explain it to you, ... you’re still too little, ... some go out there, but then they put themselves in great danger ...”

“What is it that’s dangerous for them?” By now, Bambi was very excited.

But his mother did not want to explain it straight away. “They are in danger ... listen, my child, these are things that you won’t be able to grasp yet.

Bambi thought he would be able to understand anything, but he could not understand why his mother did not want to give him more details. But he said nothing.

“This is the way we have to live,” his mother went on, “all of us. Even if we love the daytime ... and children are especially fond of the daytime ... we have to live like this, we just have to accept it. We can only move about from the evening until the morning. Can you understand that?”

“Yes.”

“Now, my child, that’s why we have to stay here, where we are now. This is where we’re safe. That’s all there is to it! So now, lie down again and go to sleep.”

But Bambi did not want to lie down again. “What makes us safe where we are now?” he asked.

“Because all the bushes are watching over us, because the twigs on the bushes rustle, because the rough brushwood on the ground cracks and gives us warning, because the dead leaves from last year lie on the ground and rustle to give us a sign, ... because the jays are there, the magpies too, they keep watch over us, and that’s how we know there’s somebody coming a long time before they reach us ...”

“What’s that,” Bambi enquired, “the dead leaves from last year?”

“Come and sit beside me,” said his mother. “I’ll tell you all about it.” Bambi gladly went and sat beside her and snuggled in close while she explained to him that the trees do not stay green all the time, that the sunshine and the lovely warmth go away. Then it gets cold, the leaves turn yellow because of the frost, they go brown and red and, one by one, they fall off the trees so that they and the bushes reach their naked branches to the sky and look completely forlorn. But the dead leaves lie on the ground, and when they’re disturbed by somebody’s foot they rustle: There’s someone coming! Oh they’re very good, these dead leaves from last year. They do us a good service by being so eager and by keeping watch the way they do. And now, in the middle of summer, there are still lots of them hidden under the things growing on the ground and they warn about any danger long before it gets near.

Bambi pressed close against his mother. He forgot all about the meadow. It was so cosy to sit here and listen to what his mother told him.

Then, when his mother stopped speaking, he thought about what she had said. He thought it was very nice of the good, old leaves to watch over them so carefully even though they were dead and had been frozen and had gone through so many things already. He tried to think what that danger, that his mother kept talking about, could actually be. But all that thinking tired him out; it was all quiet around him, all you could hear was the heat of the air. And he went to sleep.

One evening, when he went back out onto the meadow with his mother, he thought he knew by now about everything that could be seen or heard there. But it turned out that he still did know as much as he had thought.

At first, everything was the same as his first time there. His mother allowed Bambi to play tag with him. He ran round in circles, and the wide open space, the lofty sky and the freedom of the air were all so exhilarating that he rushed about with joy. After a time he noticed that his mother was standing still. He stopped suddenly as he was turning, so suddenly that his four legs were spread wide apart. He jumped high into the air so that his sudden halt would be more dignified, and now he was standing properly. His mother, a little way away seemed to be talking with someone but he could not make out, in the long grass, who that could be. Curious, Bambi went closer. There, in the tangle of grass stems close in to his mother, there were two long ears twitching. They were greyish-brown, and the black stripes on them made them quite pretty. Bambi hesitated, but his mother said to him, “Come here Bambi, this is our friend, the hare. Come on then, let him see you.”

Bambi went up to her straight away. There sat the hare, and very honest he looked. His long ears rose in powerful grandeur high above his head, and then they fell back down and hung limply as if they had been suddenly transformed into something weak. When Bambi saw the hare’s whiskers, which extended stiff and straight all around his mouth, he began to think about them. But he noticed that the hare had a very gently face, all his features seemed to indicate a good nature, and his big round eyes looked modestly out at the world. He really did look like a friend, this hare. The thoughts that had flickered through Bambi’s head disappeared immediately. Remarkably enough, and just as quickly, he even lost all the respect that he had felt at first.

“Good evening, young sir,” said the hare with carefully chosen politeness.

Bambi merely nodded “Good evening” back to him. He did not know why, but all he did was nod. Very friendly, very nicely, though perhaps a little condescending. There was no other way he could do it. Perhaps it was something he was born with.

“What a handsome young prince!” said the hare to Bambi’s mother. He looked at Bambi carefully as he raised one of his ears high into the air, and then, soon after, the other ear, and then,soon after again, both of them, and sometimes he would let them drop suddenly and hang limply. Bambi did not like this. This gesture seemed to be saying, ‘No, not worth it’.

The hare continued gently to examine Bambi with his big, round eyes. His nose and his mouth, surrounded by its magnificent whiskers, were in continual movement, like the way someone’s nose and lips will twitch when he is trying hard not to sneeze. Bambi could not help laughing, and the hare immediately and with good will joined in with the laughter, only his eyes became more thoughtful. “I congratulate you,” he said to Bambi’s mother, “I sincerely congratulate you on having a son like this. Yes, yes, yes ... he will be a majestic prince one day ... yes, yes, yes, you can see that at first glance.”

He raised himself upright, and now sat erect on his back legs, which astonished Bambi immensely. After he had had a good look all around, his ears erect and his nose moving vigorously, he sat politely back down on all fours. “Please give my regards to the honourable gentlemen,” he said. “I have many different things to do this evening. Please give them my humble regards.” He turned around and hopped away, his ears pressed down on his shoulders.

“Goodbye,” called Bambi to him as he went.

His mother smiled: “He is a good hare, so simple and so modest. It is not easy for him in this world either.” There was sympathy in her words.

Bambi walked around a little, allowing his mother to eat her food. He hoped he would come across them who he had met earlier, and would also have liked to make some new acquaintances. It was not entirely clear to him what he was missing, but he always felt he was waiting for something. Suddenly he heard a gentle rustling from far across the meadow, and felt slight, rapid knocking in the ground. He looked up. Over where the woods began there was something that flitted through the grass. There was a ... no ... there were two of them! Bambi glanced at his mother, but she did not seem to be worried about anything and had her head deep in the grass. But at the other side of the meadow there was something rushing round in circles, just as he had been doing himself earlier on. Bambi was so astonished that he leapt backwards, as if he meant to run away. His mother noticed him and raised her head.

“What’s the matter?” she called.

But Bambi was speechless, he could find no words and merely stammered, “Th .. there...”

His mother looked in that direction. “Oh, I see,” she said. “That’s my cousin and you’re right, she has a little child too, ... no, she has two.” His mother had spoken cheerfully, but now she became serious: “No ... Ena with two children .. really, she has two ...”

Bambi stood and stared. Over there he could now see a figure, a figure that looked just like his mother. He had not noticed her before. Now he could see two things that continued moving in circles in the grass, but only their red backs could be seen, thin red stripes.

“Come on,” said his mother. “Let’s go over to them. You’ll have some company there.”

Bambi wanted to run there, but his mother only walked slowly, looking all around her with each step, so Bambi held himself back. He was very excited though, and very impatient.

His mother continued speaking. “I thought we’d come across Ena again some time. Now, where’s she hiding? I knew she had a child too. That was easy to guess, but two children ...”

They had long been spotted by the others, who now were coming towards them. Bambi had to say hello to his aunt, but he had eyes only for her children.

His aunt was very friendly. “Yes,” she said to him. “Now, that’s Gobo and that’s Faline. You can all play together any time you like.”

The children stood stiffly, without moving, and stared at each other. Gobo close beside Faline and Bambi in front of them. None of them moved. They stood and gaped.

“Go on then,” said Bambi’s mother, “you’ll soon all be friends!”

“What a nice-looking child,” Ena responded. “Really, very nice indeed. So strong, and with such good posture.”

“Yes, it’s alright,” his mother said modestly. We have to be satisfied with that. But Ena, you’ve got two children!”

“Yes, that’s what happens now and again,” Ena explained. “But you do know, my dear, I’ve had many children before.”

“Bambi is my first,” said his mother.

“Well, you see,” Ena reassured her, “it might be different for you too the next time.”

The children were still standing there and watching each other. None of them said a word. Faline suddenly jumped and dashed away. The whole thing had become too boring for her.

In an instant, Bambi ran after her, and Gobo did the same. The rushed around in semi-circles, they turned round as quick as a flash, they tumbled over each other, they chased each other up and down. It was wonderful fun. When they suddenly stopped, a little short of breath, they were all good friends with each other. They began to talk.

Bambi told them about how he had spoken with the good little grasshopper and the whiting.

“Have you been talking with the shiny beetle too?” asked Faline.”

No, Bambi had never spoken with the shiny beetle. He did not know him at all, he did not know who it might be.

“I often talk with him,” Faline explained, slightly boastfully.

“I was told off by the jay,” said Bambi.

“Really?” asked Gobo in amazement. “The jay was as cheeky with you as that?” Gobo was often in amazement at things, and he was exceptionally modest. “Then,” he added, “the hedgehog pricked me in the nose.” But he only mentioned that in passing, as it were.

“Who is the hedgehog?” Bambi asked cheerfully. It felt so wonderful to be standing there, to have friends and to be hearing so many exciting things.

“The hedgehog is a terrible creature,” exclaimed Faline. “Covered in big spikes all over his body ... and he’s very spiteful too!”

“Do you really think he’s spiteful?” asked Gobo. “He never does any harm to anyone.”

“What?” retorted Faline quickly. “Didn’t he prick you in the nose then?”

“Oh, that was only because I wanted to talk to him,” Gobo objected, “and it was only a little prick. It didn’t hurt very much.”

Bambi went closer to Gobo. “Why did he not want you to talk to him then?”

“He never wants to talk to anyone,” Faline put in. “As soon as anyone gets near him he rolls up into a ball with his spikes sticking out in every direction. Our mother tells us he’s one of those people who don’t want to have anything to do with the world.”

“Perhaps he’s just afraid,” thought Gobo.

But Faline understood it better. “Mother says you shouldn’t have anything to do with people like that.”

Bambi suddenly asked Gobo. “Do you know what it is ... this danger?”

Now the other two also became serious, and the three of them put their heads together. Gobo thought about it. He made a real effort to work it out as he could see that Bambi was very curious about the answer. “The danger ...” he whispered, “the danger ... that’s something very bad ...”

“Yes,” Bambi insisted, “yes, something very bad ... but what?”

All three of them shuddered at the horror of it.

Faline suddenly called out loudly and gaily, “The danger is ... when you have to run away from it.” She jumped away, she didn’t want to stay there and feel afraid. Bambi and Gobo jumped straight after her. They started to play again and tumbled about in the green and rustling silk of the meadow where they soon forgot about that serious question. After a while they stopped and stood close to each other as they had before and began to chat. They looked over to their mothers. They too were happily close to each other, eating a little and holding a gentle conversation.

Auntie Ena lifted her head and called over to her children. “Gobo! Faline! We’ve got to go soon ...”

And Bambi’s mother warned him too. “Come on Bambi, it’s time to go.”

“Oh not yet,” Faline begged crossly. “Just a little bit longer!”

Bambi begged too, “Oh please, let’s stay longer, it’s so nice here!”

And Gobo quietly repeated what they had said, “It’s so nice here ...Just a little bit longer!”

The three of them spoke at the same time.

Ena looked at Bambi’s mother. “There, what did I tell you? They’ve already become inseparable.”

Then something else happened, and it was something much bigger than all the other things that Bambi had experienced that day.

A thumping and a stamping coming out of the woods could be felt all through ground. Branches of trees cracked, twigs rustled, and before anyone could even prick up his ears it broke its way out of the thicket. One of them with a rustling and a banging, the other in a great rush behind him. They ran forward like a storm wind, completed a broad arch across the meadow, disappeared back into the woods where they could be heard galloping, they hurtled once more out of the thicket and then they suddenly stopped and stood quietly, twenty paces apart from each other.

Bambi looked at them and did not move. They looked a little like his mother and Auntie Ena. But on their heads there was a glittering crown of antlers made of brown pearls and bright white prongs. Bambi could not move; he looked at one, and then at the other. One of them was smaller than the other, and his crown was less developed too. But the other had a beauty that gave him an air of authority. He held his head high, and his crown was even higher. It sparkled from the darkness into the light, it was adorned with the majesty of many black and brown pearls, and the long, white tips glittered.

“Oh!” exclaimed Faline in amazement. Gobo repeated her quietly. Bambi, though, said nothing at all. He was captivated and silent.

The two of them now began to move, getting further apart from each other as they went, each of them to a different side of the meadow and there they went slowly back into the woods. The majestic figure came up quite close to the children, Bambi’s mother and Auntie Ena. His step showed a quiet glory, he held his noble head up high like a king and dignified no-one with as much as a glance. The children did not dare to breathe until he had disappeared back into the thicket. They looked around, trying to see him, but just at that moment the green doors of the wood closed behind him.

Faline was the first to break the silence. “Who was that?” she exclaimed. But her little, arrogant voice had a quake in it.

In a voice that could hardly be heard, Gobo repeated her: “Who was that?”

Bambi was silent.

Auntie Ena said joyfully, “Those were your fathers.”

Nothing else was said, and the group moved apart.

Auntie Ena went with her children into the nearest patch of undergrowth. That was the way they always went. Bambi and his mother had to go right across the meadow to the oak tree to get to the route they usually took. For a long time he remained silent until finally he asked, “Did they not see us?”

His mother understood what he meant, and replied, “Of course they saw us. They see everything.”

Bambi felt shy, and did not dare to ask any more questions, but the wish to do so overcame his shyness. “Why ...” he began, and then he was silent again.

His mother helped him. “What is it you want to say, my child?”

“Why didn’t they stay with us?”

“They don’t stay with us,” his mother answered, “only now and then ...”

“Why didn’t they speak to us?”

His mother said, “They don’t speak to us any more ... only, now and then ... We have to wait till they come, and then we have to wait till they talk to us ... if they want to.”

Bambi became cross and asked, “Will my father speak to me?”

“Of course he will, my child,” his mother promised him, “when you’re grown up he’ll speak to you and sometimes he’ll let you be with him.”

In silence, Bambi went closer to his mother, his mind filled with thoughts about the appearance of his father. “He’s so beautiful!” he thought, and then again, “so beautiful!”

His mother seemed able to read his mind, and she said, “If you’re still alive, my child, if you’re clever and avoid danger, you’ll be as strong and as beautiful as your father, and you’ll carry a crown on your head, just like his.

Bambi took a deep breath. His heart became big with happiness and anticipation.

Time went by and Bambi went through many new experiences. It sometimes even made him dizzy having so many things to learn.

Now he knows how to listen. Not just hear what is happening nearby, so close that it forces itself into your ears. No, there is certainly no art in that. Now he can listen properly and with understanding to anything that happens however gently it moves, he can listen to every fine rustling that the wind brings in. He knows, for instance, when there is a pheasant running through the undergrowth; he recognizes quite exactly that gentle scurrying that continually stops and then starts again. He can even recognize the mice in the woods from the sound they make as they run to and fro, from the little journeys they make. Then there are the moles who rush round in circles making a rustling noise under the elder bushes when they’re in a good mood. He knows the brash, clear call of the falcons and listens to it as it changes to an angry tone when a hawk or an eagle comes close; that makes them cross because they fear their territory might be taken from them. He knows the sound of the woodland pigeons as they flap their wings, the lovely, distant swish of the ducks as they flap their wings, and many other sounds.

He is slowly learning to understand things by his sense of smell. He will soon understand them as well as his mother. He can understand what he is smelling as soon as he draws in a breath. Oh, that’s clover and that’s rowan, he thinks when the wind is blowing in from the meadow, and he can smell when his friend, the hare, is outdoors; I can tell that very well. Also, in among all the smells of leaves, soil, herbs and wild onions, he can tell when the polecat is going past, by putting his nose to the ground and testing it thoroughly he can tell that the fox has been there, he might notice that somewhere nearby there are his relatives, Auntie Ena with the children.

He is now completely at ease with the night and he no longer feels such a great longing to go and run about in the light of the day. Now, he is happy to spend his days lying in the little, shady space in the undergrowth with his mother. He hears the heat of the air, and he sleeps. Now and then he wakes up and listens and smells, which is the proper thing to do. Everything is as it should be. There are only the little tits who would sometimes chatter with each other, the midges in the grass – who are almost never able to stay quiet-talk among themselves, and the wood pigeons never stop proclaiming their gentleness, and do so with enthusiasm. What does all that matter to Bambi? He goes back to sleep.

Now he is very fond of the night. Everything is gay, everything is moving. You also, of course, have to be careful in the night time, but you have less to worry about and you can go anywhere you want to. And everywhere you go you come across people you know, and they too will be more carefree than they are at other times. In the night the forest is solemn and silent. There are voices to heard but just a few of them and in all this stillness they seem loud, and they sound different from the daytime voices and they have more effect. Bambi enjoyed hearing the owl. She is so dignified as she flies, perfectly silent, perfectly effortless. A butterfly is quiet just because of her size, but the owl is so immense. And her face is so imposing, so determined, full of so much thought, her eyes are so majestic. Bambi admires her firm gaze with its quiet courage. He enjoys listening when she talked with his mother one time, or with anyone else. He stands slightly to one side, a little afraid of that imperious gaze he admires so much, he does not understand much of the clever things she says, but he does know that they are clever, and that enchants him, fills him with admiration for the owl. The the owl begins her song. Haa-ah - - hahaha - - haa-ah! she sings. It sounds different from the song of the thrush or the golden oriole, different from the friendly motif of the cuckoo, but Bambi loves the song of the owl because he feels a secretive earnestness in it, an indescribable cleverness and a mysterious melancholy. Then the tawny owl is there again, a charming little lad. Dignified, faithful and more inquisitive than most, he always wants to stir up a fuss. Uy-iik! Uy-iik! he calls, in a voice that is shrill, terrifying and very piercing. It sounds as if his life were in danger. But he is a cheerful character and it delights him when he startles someone. Uy-iik! he shouts, so loudly that it alarms anyone in the wood within half an hour’s distance. But then he has a gentle cooing laugh, just for himself, and you can only hear if you are right next to him. Bambi had realized that the tawny owl is pleased when he startles somebody or if somebody thinks something awful has happened to him, and ever since, whenever the tawny owl is nearby, he rushes to him and asks, “Has something happened to you?,” or he might sigh and say, “Oh, you really startled me!” Then the owl feels very satisfied. “Yes, yes,” he says with a laugh, “it’s quite a distressing sound, isn’t it.” He puffs up his feathers so that he looks like a soft, grey ball, and looks very charming.

A couple of times there was even thunder and lightning, both day and night. The first time it was by day and Bambi felt how he became afraid when, in his leafy bedroom in the woods, it became darker and darker. It seemed to him that the night had fallen down from the sky in the middle of the day. Then, as the storm roared its way through the woods so that the mute trees began to groan loudly, Bambi shook with fear. And as the lightning lit up the sky and the thunder roared, Bambi went mad with the horror of it and thought the world was about to be torn to pieces. He ran behind his mother, who was slightly unsettled, had jumped to her feet and was walking to and fro in the thicket. He was unable to think, unable to understand. Then the rain burst down in an angry gush. Everyone had hidden himself away, the woods seemed empty, and there was nowhere to flee. Even in the thickest undergrowth you were whipped by the water as it rushed through. But the lightning stopped flashing, its fiery beams no longer flamed their way through the tops of the trees; the thunder moved away and there was only a distant rumbling to be heard before it was entirely silent. Now the rain became gentler. Its broad patter could be heard everywhere but powerfully for another hour, the forest stood breathing deeply in the still air and allowed itself to be soaked, no-one, now, was afraid to stand in the open. That feeling was gone, washed away by the rain.

Bambi and his mother had never gone out onto the meadow as early as they did that evening. In fact it was hardly even evening. The sun was still high in the sky, there was a powerful freshness in the air, it had a richer fragrance than at other times and the woods sang with a thousand voices, for everyone had come out of his hiding place and was hurrying round to each other in their excitement to tell them about what they had just experienced.

Before stepping onto the meadow they had to pass by a big oak tree standing right at the edge of the woods, just beside their path. They had to pass by this big, beautiful tree every time they went out onto the meadow. This time there was the squirrel sitting on one of its branches, and he wished them good evening. Bambi and the squirrel were good friends with each other. The first time he met him Bambi thought the squirrel was a very small deer because of his red coat, and stared at him in amazement. But Bambi really was too young at that time and simply could not understand anything. Right from the start, he felt an exceptional liking for the squirrel. He was so well mannered in every way, the way he spoke was so pleasant, and Bambi adored the wonderful way he performed acrobatics, how he climbed, how he jumped and how he kept his balance. He would take part in the conversation while running up and down the smooth trunk of the tree as if that were nothing at all. He sat upright on a branch of the tree as it moved to and fro, he leant comfortably against his bushy tail which rose up high and handsome behind him, he showed his white breast, moved his front paws with great elegance, turned his head to left and right, laughed with merry eyes and in a very short time he would say so many entertaining or interesting things. Then he came down from the tree again, and did so fast and in such jumps that anyone would think he was about to fall down onto your head. He swung his long red tail vigorously and said, “Hello, Hello! So nice of you to drop by!” while he was still far above Bambi’s head.

Bambi and his mother stood where they were.

The squirrel ran down the smooth trunk. “Now then,” he began to chat. “Did you understand that alright? I can see, of course, that everything’s nice and tidy. And that’s always the main thing after all.” As quick as a flash he ran back up the trunk, saying, “No, it’s too damp for me down there. Just a moment and I’ll find a better place. I hope you don’t mind. Thank you. I thought you wouldn’t mind. And we can talk just as well from where we are now.”

He ran to and fro on a level branch. “What a business that was!” he continued. “So much noise, such a scandal that was! Just think how shocked I am. You squeeze yourself into a nook, keep perfectly quiet, hardly daring to move. That’s the worst thing of all, sitting there like that without moving. You hope, of course, that nothing’s going to happen, don’t you, and my tree certainly is especially suited for that sort of trick, no, it can’t be denied, my tree is especially suited ... it has to be said. I am content. However far I roam I don’t wish for any other. But when things happen like they did today it does get you so upset, it’s disgusting.”

The squirrel sat there, his beautiful erect tail close behind him, he showed the white of his breast and held his two front paws emotionally pressed against his heart. It was obvious that when he said he had been made cross he was telling the truth.

“We want to go out onto the meadow, now,” said Bambi’s mother, “so that we can dry ourselves off in the sunshine.”

“Oh, what a good idea,” the squirrel exclaimed. “You really are so clever, really, I always say that you are so clever!” With a single leap he was on a branch higher up. “There’s nothing better that you could do now than to go out onto the meadow,” he called down. Then he rushed around in nimble leaps hither and thither and up into the canopy of the trees. “I want to get up to where I can get some sunshine,” he chatted contentedly, “we’re all soaking wet! I want to get right up high!” He was not at all concerned about whether anyone was still listening to him.

On the meadow, it was already very lively. Bambi’s friend the hare was sitting there with his family all around him. Auntie Ena was standing there with her children and some other people she knew. Today, Bambi saw his father again. The came slowly out from the trees, some here, some there, then someone else appeared. They walked slowly up and down along the edge of the woods, each one in his own place. They paid no attention to anyone, they did not even talk to each other. Bambi frequently looked over at them, respectfully but full of curiosity.

Then he talked with Faline, Gobo and a few other children. He thought it would be alright to play for a little while. All of them said they agreed, and then the running round in circles began. Faline showed that she was the merriest of them all. She was so lively and nimble and she sparkled with sudden new ideas. Gobo, though, quickly became tired. He had been terribly afraid while the storm was raging, it had made his heart beat fast and it was still doing so. Maybe Gobo was a little bit of a weakling, but Bambi loved him because he was so good-natured and so helpful and never let anyone see it when he was a little bit sad.

Time passes, and Bambi learns how good grass tastes, how tender the buds of leaves are, and how sweet clover is. When he presses himself against his mother to get some refreshment she often pushes him away. “You’re not a little child any more,” she says. Sometimes she will be even more direct and say, “Go away, leave me in peace.” Sometimes his mother would even stand up in the middle of the day in their little place in the wood and just walk away without looking to see whether Bambi is following her or not. There are even times when she is walking along the familiar paths when she seems not to notice whether Bambi is trotting behind her like a good boy. One day his mother was not there, and Bambi does not know how that is possible, cannot understand it. But his mother is gone and Bambi, for the first time, is alone.

He is bewildered, he becomes uneasy, he becomes nervous and anxious, and he begins to long for her quite pitifully. Very sadly he stands there and calls to her. No-one answers, no-one comes.

He listens, he smells the air. Nothing. He calls again. Gently, inside himself, imploringly, he calls, “Mother ... Mother ...” All in vain.

Now he is gripped with doubt as to whether he can endure it, so he begins to walk.

He wanders along all the paths he knows, stops and calls out, walks on with hesitant steps, fearful and unable to understand. He is very sad.

He carries on walking and finds himself on paths where he has never been before, he finds himself in parts of the wood which are strange to him. He is lost.

Then he hears the voices of two children who are calling out like him:

“Mother ... mother ...!”

Surely that is Gobo and Faline. It must be them.

He runs quickly towards the voices and soon sees their red coats shining through between the leaves. Gobo and Faline. There they stand next to each other under a dogwood, looking forlorn and calling, “Mother ... mother ...!”

They’re glad that they can hear something rusting in the undergrowth, but they are disappointed when they see it is only Bambi. But they are a little bit glad to see him. And Bambi is glad that he is not quite so alone any more.

“My mother’s gone away somewhere,” says Bambi.

“Ours is gone too,” lamented Gobo.

They look at each other in their dismay.

“But where could they be?” asks Bambi, almost in tears.

“I don’t know,” sighs Gobo. His heart is beating fast and he is feeling quite miserable.

Suddenly, Faline says, “I think ... they’re with our fathers ...”

Gobo and Bambi look at each other in astonishment. They are immediately gripped by a sense of awe. “You mean ... with our fathers?” asked Bambi and shudders.

Faline shudders too, but she makes a face that seems to be saying a lot. She looks like someone who knows more than he is willing to say. She does not really know anything at all of course; she does not even know where she got the idea from. But as Gobo repeats, “Do you really mean that?,” she makes herself look clever and says each time, “Yes, I think so.”

That is, of course, a guess, but it is at least worth thinking about. It does not make Bambi any less uneasy though. He is not now capable of thinking, he is too anxious and too sad.

He moves away. He does not like to spend too much time on one spot. Faline and Gobo go with him a little way; all three of them call “Mother ... mother ...” But now Gobo and Faline have stopped; they do not dare to go any further. Faline says, “Where are we going? Our mother knows where we should be. So let’s stay there so that she can find us when she comes back.”

Bambi walks on by himself. He wanders through a thicket where there is a little bare patch. In the middle of the bare patch Bambi stops. It is as if he is held there by his roots and cannot leave the spot.

There, at the edge of the bare patch, in a tall hazel bush, he could make out a form. Bambi has never seen a form like this. At the same time a scent came to him in the air, a scent he has never smelt before. It is a strange aroma, heavy and sharp and exciting, enough to make you mad.

Bambi stares at the form. It is remarkably erect, exceptionally narrow, and it has a pale face which is quite naked on the nose and around the eyes. Horribly naked. This is a face that projects a dreadful horror. Cold and gruesome. This face has a monstrous power to it, a power that could leave you crippled. This face is painful to behold, hardly bearable to behold, but Bambi nonetheless stands there and stares at it, captivated.

The form remains there motionless for a long time. Then it reaches one leg out, a leg that is positioned high up, and puts it near its face. Bambi has not noticed that it was there at all. This terrible leg stretches right out into the air, and it is merely this gesture that sweeps Bambi away like a candle in the wind. In an instant he is back in the thicket he has just left. And he runs.

Suddenly his mother is back with him. She leaps through bush and undergrowth next to him. The two of them run as fast as they can. His mother leads the way, she knows the path, and Bambi follows. In this way they keep running until they are at the entrance to their chamber.

“Did you ... did you see that?” asks his mother gently. Bambi cannot answer, he has no breath left. He merely nods.

“That was ... that was Him!” she says.

The two of them shuddered in horror.

Bambi was often left alone now. But he did not have the same fear of it as he had the first time. His mother would disappear, and then, however much he called for her, she did not come. But then she would reappear unexpectedly.

One evening, feeling very lonely, he wandered once more along the paths. He had not found Gobo and Faline even once. The sky had already turned to a light grey and it was beginning to get dark, so that the tops of the trees could be seen over the bushes and undergrowth. Something rustled in the bushes, something hurtled its way between the leaves, and then his mother appeared Close behind her another deer made its way in. Bambi did not know who it was. Auntie Ena or his father or someone else. But Bambi’s mother saw immediately who it was, despite the speed at which she had rushed past him. He heard the shrillness of her voice. She screamed, and it seemed to Bambi that she did so only in fun, but then it occurred to him that there was a slight ring of fear in that scream.

Another time, it happened in full daylight. Bambi had been walking for hours through the dense woods and finally began to call. Not so much because he was afraid, but because did not want to remain so alone any more, and he felt he would soon be in a terrible state. So he began to call for his mother.

Suddenly there was one of their fathers standing in front of him, looking at him severely. Bambi had not heard him coming and he was startled. This elder stag looked more powerful than the others, he was taller and more proud. His coat was aflame with a deep dark red, but his face shone silver-grey; and a powerful, black pearled crown extended high above his playful ears.

“What are you calling for?” the old stag asked severely. Bambi trembled in awe of the elder stag and did not dare to make any answer. “Your mother hasn’t got the time to spend on you now!” the elder continued. Bambi was completely cowed by this imperious voice, but at the same time he felt admiration for it. “Can’t you be by yourself for a while? You should be ashamed of yourself!” Bambi would have liked to say that he could be by himself perfectly well, that he had often been by himself, but he said nothing. He did as he was told and became terribly ashamed. The elder turned round and left him. Bambi did not know how the stag left, where he had gone, did not even know whether he had left quickly or slowly. He was simply gone, just as suddenly as he had arrived. Bambi strained his ears, but he heard no steps moving away from him, no leaf being disturbed. That made him suppose the elder must still be quite near to him, and he smelt the air on every side. He learned nothing from that. Bambi sighed in relief as he was once more alone, but at the same time he yearned to see the old stag again and to make sure he was not displeased with him.

Then his mother arrived but Bambi said nothing about his meeting with the elder. Nor did he ever call for her, now, when she was out of sight. He thought about the old stag when he wandered about on his own; he felt a powerful wish to come across him. Then he would say to him, “See? I’m not calling for anyone.” And the elder would praise him.

He did speak to Gobo and Faline though, the next time they were together on the meadow. They listened with excitement and they had had no experience of their own that could compare with this. “Weren’t you scared?” asked Gobo excitedly. Yes! Bambi admitted, he had been scared. Just a little bit. “I’d have been terribly scared,” Gobo told him. Bambi answered that no, he had not been very scared, because the elder had been so majestic. Gobo told him, “That wouldn’t have been much help for me. I’d have been too scared even to look at him. When I get scared everything flickers in front of my eyes so that I can’t see anything and my heart beats so hard that I can’t breathe.” What Bambi had told them made Faline very thoughtful and she said nothing.

The next time they met, though, Gobo and Faline rushed to him in great leaps and bounds. They were alone once more, as was Bambi. “We’ve been looking for you for ages,” declared Gobo. “Yes,” said Faline with an air of importance, “as now we know exactly who it was that you saw.” Bambi was so keen to know he jumped in the air. “Who ...!?”

Faline took pleasure in saying, “It was the old prince.”

“How do you know that?” Bambi wanted to know.

“Our mother told us!” retorted Faline.

Bambi was astonished, and he showed it. “Did you tell her about it then?” The two of them nodded their heads. “But that was a secret!” objected Bambi.

Gobo quickly tried to excuse himself. “It wasn’t me. It was Faline who did it.” But Faline cheerfully called, “Oh, so what? Secret!? I wanted to know who it was, and now we do know, and that’s much more interesting!” Bambi was burning to hear all about this, and his wish was satisfied. Faline told him everything. “He’s the most noble stag in the whole wood. He’s the prince. There is no second most noble, no-one comes near to him. No-one knows how old he is. No-one knows where he lives. No-one knows who his relatives are. Very few have ever even seen him. Now and then there’s a rumour that he’s dead because he hasn’t been seen for a long time. Then somebody catches a glimpse of him and then everyone knows he’s still alive. No-one has ever dared to ask him where he’s been. He doesn’t speak to anyone and no-one dares to speak to him. He goes along the paths where no-one else ever goes; he knows every part of the wood, even the most distant corner. And nothing is a danger to him. Other princes might tussle with each other, sometimes as a test or in fun but sometimes they fight in earnest. It’s many years since he fought with anyone. And there’s no-one still alive who did fight with him a long time ago. He’s the great prince.”

Bambi forgave Gobo and Faline for having carelessly chatted about his secret with their mother. He was even quite satisfied about it as now, after all, it was him who had experienced all the all these important things. Nonetheless, he was glad that Gobo and Faline did not know everything quite precisely, that the great prince had said, “Can’t you be by yourself for a while?,” that they did not know he had said, “You should be ashamed of yourself!.” Bambi was glad, now, that he had kept silent about these admonitions. Faline would have told everything about that just like everything else, and then the whole forest would have been gossiping about it.

That night, as the moon was rising, Bambi’s mother came back again. She was suddenly there standing under the great oak at the edge of the meadow and looking round for Bambi. He saw her straight away and ran over to her. That night Bambi had another new experience. His mother was tired and hungry. She did not walk about as much as she usually did but satisfied herself there on the meadow where Bambi also usually took his meals. Together there, they munched on the bushes and as they did so, in that remarkably pleasant way, they wandered deeper and deeper into the woods. There was a loud noise that came through the greenery. Before Bambi had any idea of what was happening his mother began to scream loudly, just as she did when she was greatly startled or confused. “A-oh!” she screamed, jumped away, then stopped and screamed, “A-oh, ba-oh!.” Then, Bambi saw some immense figures appear, coming towards them through the noise. They came quite close. They looked like Bambi and his mother, like Auntie Ena and anyone else of their species, but they were enormous, they had grown so big and powerful that you felt compelled to look up at them. Like his mother, Bambi began to scream, “A-oh ... Ba-oh ...Ba-oh!.” He was hardly aware that he was screaming, he could not stop himself. The line of figures went slowly past, three or four enormous figures one after another. Last of all came one that was even bigger than the others, it had a wild mane around its neck and its head was crowned with a whole tree. Just to see it took your breath away. Bambi stood there and howled as loudly as he could, as he felt more frightened and bewildered than he ever had been before. His fear was of a particular kind. He felt as if he were pitifully small, and even his mother seemed to be the same. He felt ashamed, although he had no idea why, at the same time the horror of it shook him and he once more began to howl. “Ba-oh ... Ba-a-oh!.” It made him feel better when he shouted like that.

The line of figures had passed. There was nothing more to see and nothing more to hear from in. Even Bambi’s mother became silent. There was only Bambi who would whine briefly from time to time. He was still afraid.

“You can be quiet now,” his mother said, “look, they’ve gone away.”

“Oh, mother,” whispered Bambi, “who was that?”

“Oh, they’re not really that dangerous,” his mother said. “They were our big relatives ... yes ... they are big and they’re quality ... much higher quality than you or me ...”

“And aren’t they dangerous?” Bambi asked.

“Not normally,” his mother explained. “But they say there are many things that have happened. People say this and that about them but I don’t know if there’s any truth in these stories. They’ve never done anything to me or to anyone I know.”

“Why would they do anything to us when they’re relatives of ours?” thought Bambi. He wanted to be quiet, but he was still shaking.

“No, I don’t suppose they’ll do anything to us,” his mother answered, “but I’m not sure, and I get alarmed every time I see them. I can’t stop myself. It’s the same every time.”

Bambi was slowly soothed down by this conversation, but he remained thoughtful. Right above him, in among the branches of an alder tree, an impressive tawny owl shrieked. But Bambi was confused and forgot, for once, to show that he was startled. The owl, however still came down to him and asked, “Give you a shock, did I?.”

“Of course,” answered Bambi. “You always give me a shock.”

The owl gave a quiet laugh; he was satisfied. “I hope you don’t blame me for it,” he said. “It’s just the way I do things.” He fluffed up his plumage till he looked like a ball, sank his beak into his soft, downy feathers, and put on a terribly nice, serious expression. That was enough for him.

Bambi opened his heart to him. “Do you know,” he began in a way that seemed older than his age, “I’ve just had a shock that was far bigger than the one you gave me.”

“What?” asked the owl, no longer so satisfied with himself.

Bambi told him about his meeting with his enormous relatives.

“Don’t tell me about your relatives,” declared the owl. “I’ve got relatives too, you know. But all I have to do is look round me anywhere in the daytime and they’re all over me. Na, there’s not much point in having relatives. If they’re bigger than you they’re good for nothing, and if they’re smaller they’re even more good for nothing. If they’re bigger than you then you can’t stand them ‘cause they’re so haughty, and if they’re smaller they can’t stand you ‘cause they think you’re haughty. Na, I don’t want to know anything about anything of that.”

“But ... I don’t even know my relatives ...” said Bambi shyly and wishing he did. “I’d never heard anything about them and today was the first time I saw them.”

“Don’t you bother about those people,” the owl advised him. “Just take my word for it,” he said, rolling his eyes in a meaningful way, “take my word, that’s the best thing to do. Relatives are never as good as friends. Look at the two of us, we’re not related but we’re good friends, aren’t we, and very nice it is too.”