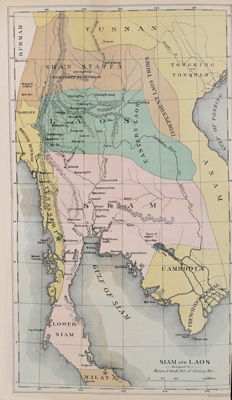

SIAM AND LAOS

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Siam and Laos, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Siam and Laos

as seen by our American Missionaries

Author: Various

Release Date: November 25, 2020 [EBook #63879]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIAM AND LAOS ***

Produced by Carol Brown, Brian Wilson, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Double click for larger image.]

AS SEEN BY

“Siam has not been disciplined by English and French guns, like China, but the country has been opened by missionaries.”—Remark of His Grace the late Ex-Regent of Siam.

FULLY ILLUSTRATED.

PHILADELPHIA:

PRESBYTERIAN BOARD OF PUBLICATION,

No. 1334 CHESTNUT STREET.

COPYRIGHT, 1884, BY

THE TRUSTEES OF THE

PRESBYTERIAN BOARD OF PUBLICATION.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Westcott & Thomson,

Stereotypers and Electrotypers, Philada.

This volume is a response to calls for information on Siam and Laos. A score of missionaries have contributed chapters. Some have written amidst conflicting claims of the crowded field-life; others, during brief visits to the home-land; several are children of missionaries and were born in Indo-China; others are noble pioneer workers, whose long years of service abroad are now ended. A few of the chapters originally appeared in a missionary periodical. Two of the writers have “entered into rest.” The editor is much indebted also to the standard works of Pallegoix, Bowring, Crawford, Mouhot and several more recent travelers, to geographical papers and official reports, and to valuable original data furnished by Dr. House, Dr. Cheek and others.

Adaptation and necessary condensation of the information thus gathered make special credit often impossible, but doubtful points have been verified by reference to competent authority, so far as practicable.

The contributions of our missionaries have special value. For years they have been brought into close contact with the people in their homes, schools, wats and markets, mingling as honored guests in social gatherings and at official ceremonials, enjoying full opportunity of studying the natives at work, at play and at worship. As teachers, physicians, translators and trusted counselors they are recognized as public benefactors by the king and many high officials. Siam owes the introduction of printing, European literature, vaccination, modern medical practice, surgery and many useful mechanical appliances to our American missionaries. They have stimulated philosophical inquiry, paved the way for foreign intercourse with civilized nations, given a great shock to the grosser forms of idolatry among the more enlightened, leavened the social and intellectual ideas of the “Young Siam” party, and, almost imperceptibly, but steadily, undermined the old hopeless Buddhist theories with the regenerating force of gospel truth.

The young king publicly testified on a late occasion: “The American missionaries have lived in Siam a long time; they have been noble men and women, and have put their hearts into teaching the people, old and young, that which is good, and also various arts beneficial to my kingdom and people. Long may they live, and never may they leave us!”

May this volume aid in arousing a more intelligent and generous interest in this field—the sacred trust of our American Presbyterian Church; may it promote a truer sense of the heroic sacrifices, the patient and multiplied labors, of the noble band who for the past half century have toiled and waited in hope for the spiritual regeneration of the Siamese and Laos!

Schenectady, May, 1884.

N. B. Uniformity in the spelling of Siamese and Laos proper names is not yet attainable. Different ears catch the foreign sounds and transliterate them differently, giving an endless variation. Thus the single city which we give as Cheung Mai, following Dr. Cheek, may be found in books and maps as Cheng Mai, Cheang Mai, Zimma, Chang Mai, etc. To ascertain the pronunciation in such cases, see what one pronunciation can be made to cover all of these spellings. It is hoped that the present volume is a step in the direction of a correct transliteration of Siamese names.

| PART I. | ||

| SIAM. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| The Indo-Chinese Peninsula. | An Introductory Sketch. | PAGE 15 |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Sight-Seeing in Bangkok. | 81 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Touring in Siam. | 96 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| In and About Petchaburee. | 112 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Animals of Siam. | 120 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| The Chinese in Siam. | 145 | |

| PART II. | ||

| VARIETIES OF SIAMESE LIFE. | ||

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| A Siamese Wedding. | 162 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| Housekeeping in Siam. | 175 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| Child-Life in Siam. | 184 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| First Hair-Cutting of a Young Siamese. | 193 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| The Schools of Siam. | 206 | |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| Holidays in Siam. | 224 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| A Gambling Establishment. | 233 | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| Siamese Theory and Practice of Medicine. | 236 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| Cholera-Times in Bangkok. | 241 | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| Siamese Customs for the Dying and Dead. | 247 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| The Wats of Siam. | 269 | |

| PART III. | ||

| HISTORICAL SKETCHES. | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| Historical Sketch of Siam. | 304 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| Missionary Ladies in the King’s Palace. | 320 | |

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| Coronation of His Majesty the Supreme King of Siam. | 338 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| History of the Missions in Siam and Laos. | 351 | |

| PART IV. | ||

| LAOS. | ||

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| Laos Land and Life. | 419 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| From Bangkok to Cheung Mai. | 460 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| Recollections of Cheung Mai. | 479 | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| A Day at Cheung Mai. | 491 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| A Laos Cabin. | 497 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| Superstitions of the Laos. | 504 | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| Treatment of the Sick. | 511 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | ||

| A Tour in the Laos Country. | 525 | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | ||

| China to British India, via Cheung Mai. | 543 | |

| PAGE | ||

| His Supreme Majesty, Chulalangkorn I., King of Siam. | ||

| Frontispiece. | ||

| Burmese Temple | 23 | |

| Ruins of a Pagoda at Ayuthia | 29 | |

| Siamese Gentleman in Modern Court-Dress | 32 | |

| Siamese Lady in Modern Court-Dress | 33 | |

| View of Paknam, on the Menam | 37 | |

| Port of Chantaboon | 41 | |

| Lion Rock, at the Entrance of the Port of Chantaboon | 44 | |

| Types of Women of Farther India | 57 | |

| Scene on an Oriental River | 65 | |

| The Bread-Fruit | 72 | |

| The Lotus | 74 | |

| Bird of Paradise | 77 | |

| Monkeys Playing with a Crocodile | 79 | |

| Bangkok, on the Menam | 83 | |

| House-Sparrow | 84 | |

| Floating Stores at Bangkok | 89 | |

| Missionary-Boat for Touring in Siam | 97 | |

| Prabat | 103 | |

| House at Petchaburee | 113 | |

| View of the Mountains of Petchaburee | 116 | |

| Monkeys | 121 | |

| Java Sparrows | 122 | |

| The Cobra | 123 | |

| Hunting the Crocodile | 127 | |

| Elephants at Home | 129 | |

| An Elephant Ploughing | 131 | |

| The White Elephant | 141 | |

| Home of Rich Chinaman | 146 | |

| Chinese Boat-People | 151 | |

| Chinese Cemetery | 152 | |

| Paper Prayers | 155 | |

| Parlor of Chinese House | 156 | |

| Mission-House | 171 | |

| Siamese Ladies Dining | 179 | |

| A Young Siamese Prince | 189 | |

| A Chinese Street-Show | 191 | |

| Removal of the Tuft of a Young Siamese | 195 | |

| A School in Siam | 215 | |

| A Few of the Children of the Late First King of Siam | 223 | |

| Carrying the King to the Temple | 231 | |

| Siamese Actress | 234 | |

| Cremation Temple: A Temporary Building | 251 | |

| Tomb of a Bonze | 263 | |

| Banyan Tree | 270 | |

| Siamese Temple | 271 | |

| Temple at Ayuthia | 275 | |

| Monastery of Wat Sisaket | 277 | |

| Brass Idol in a Temple at Bangkok | 279 | |

| The Great Tower of the Pagoda Wat Cheug | 283 | |

| Buddhist Priest | 285 | |

| Buddhist Priests gathering Food | 295 | |

| Ruins of a Temple and Statue at Ayuthia | 303 | |

| Attaché of Siamese Embassy: Court-Costume in 1883 | 313 | |

| The Late First King and Queen | 323 | |

| Somdetch Chowfa Chulalangkorn | 339 | |

| Hall of Audience, Palace of Bangkok | 341 | |

| Brahman at Worship | 345 | |

| Coronation of a Laos King | 421 | |

| A Laos Funeral | 429 | |

| Tapping the Borassus Palm | 449 | |

| A Laos Home | 499 | |

| Camping in a Laos Forest | 529 | |

PART I.

SIAM.

When about to visit a foreign country the prudent traveler is careful to seek in guidebooks and from maps some data in regard to its position, prominent features and relation to adjacent regions. Such information adds interest to each stage of his journey. Climbing a mountain, he overlooks two kingdoms. Such a valley opens into a rich mining district; the highlanders of that range are descendants of the original lords of the soil; the navigability of this river is of commercial importance as a possible trade-route.

In like manner, bold outlines of the whole peninsula furnish the best introduction to a careful study of Central Indo-China, showing the trade-connection of Northern Laos with Burmah and the richest mining province of China, and the relation of Siamese progress to certain Asiatic commercial problems. New views also are thus gained of the great work actually accomplished by our American missionaries for science and civilization in this corner of the globe during their self-imposed exile of half a century.

Indo-China is the south-east corner of Asia, a sharply-defined, two-pronged peninsula outjutting from China just below the Tropic of Cancer, its long Malayan arm almost touching the equator, bounded east, south and west by water. Southward, the Eastern Archipelago stretches toward Australia, “a kind of Giants’ Causeway by means of which a mythological Titan might have crossed from one continent to another.”

Along the north the extreme south-west angle of the Celestial Empire, by name Yunnan, lies in immediate contact with the Burmese, the Laos and the Tonquinese frontiers, whence the main rivers of the peninsula divide their streams.

Yunnan may be regarded as a lower terrace projecting from the giant Thibetan plateau—an extensive, uneven table-land, separated for the most part by mountains from contiguous regions. The northern portion is a confused tangle of lofty ranges, with peaks rising above the snowline, and few inhabited valleys—a region, in a word, compared to which Switzerland is an easy plain—of wild romantic scenery, ravines, torrents and landslips, but with little industry or commerce. Maize is used for food throughout the sparsely-populated district, since rice cannot be cultivated at such altitudes. The main ranges have a north-and-south trend, subsiding some thousand feet before reaching the Indo-Chinese frontier. Parallel to the lower south and south-east chains of mountains are a series of rich upland valleys, each basin supplied with its own watercourse or lake, and tenanted more or less densely by the busy villages situated near the water. Rice, pepper and the poppy are extensively cultivated.

The choicest portion of this province lies within the open angle formed by the divergence of four large rivers—viz. “the Yangtse, taking its course due north, till, bending to the east, it makes its final exit into the Chinese Sea at Shanghai; the Mekong, pursuing a tortuous course south to the China Sea near Saigon; the Si-Kiang, originating near the capital of the province, flows due east to Canton; while a fourth, the Songkoi, or ‘Red River,’ goes south-east to Hanoi and the Gulf of Tonquin. A central position amidst such mighty waterways and with so wide a circumference of outside communication indicates the great importance of the district either for administration or trade—a fact early appreciated by the sagacity of the Chinese, who as far back as the third century established fortified colonies among the then savage and recalcitrant tribes of Yunnan. For export Yunnan has three capital products to offer—opium, tea and metals. The opium-yielding poppy grows almost everywhere. The celebrated tea of the south-east is in great request, being considered by the Chinese themselves superior to all other qualities of tea throughout the empire. Its cultivation offers no difficulties, the high price it commands outside of the region being solely due to the costliness of transport. But it is the metal-trade which will in all probability be the prominent feature of commerce. The great tin-mines have supplied the whole of China from time immemorial; copper abounds throughout the province; lead, gold, silver, iron, and last, but not least, coal, make up the list. Curiously enough, the vast Chinese empire includes no other truly metalliferous province except the bordering region of Western Ssu-ch’nan, geologically, though not administratively, a part of Yunnan; nothing but the inaccessibility, and too-often disturbed and lawless condition, of the country has thus far hindered its mines from becoming sources of really incalculable wealth to the province, to the Chinese empire at large, and, by participation, to foreign commerce.”

The affluent circumstances of the peasantry in the southern districts are in marked contrast with those of the north. The women do not compress their feet. Many of the men bear the Muslim’s physique and features. Indeed, before the merciless massacre of the Panthays, Mohammedans formed the majority of the population. But the last quarrel, begun by miners in 1855, only ended in 1874 by wellnigh the extermination of the entire Muslim community. Mounted expresses were despatched to seventy-two districts with instructions to the principal mandarins from the governor of the province. Families were surprised and butchered by night, their homes sacked and mosques burned. A cry of horror ran from village to village. The Mohammedans rushed to arms, collecting in vast numbers, and upward of a million Chinese were killed in revenge. In the end the Panthays were crushed out, but more than one-fourth of the inhabitants of Yunnan had perished or emigrated. Plague and famine followed the great rebellion and fearfully devastated the whole region, which is only now slowly recovering its former prosperity.

The aboriginal inhabitants of Yunnan are apparently of the same stock as the Laos, just across the border. The variety of their clans and picturesque costumes recalls the wild Highlanders of Scotland.

The chief lack of Yunnan is good roads. Going east or west, the highways run up the ridge, over the saddle or watershed, and dip down into another valley, and this up-and-down process must be repeated from town to town; ravines must be crossed, torrents must be bridged, and often the narrow causeway lies along the side of a precipice or the ascent may be some hundred feet up the face of a mountain. Merchandise crossing the Laos frontier must be carried long distances at an enormous cost. Thus the celebrated so-called Puekr tea of North-eastern Laos, just a little south of the Yunnan border, while freely used by the peasantry of that province, is too expensive by the time it reaches the nearest Chinese port to export to Russia or Europe. Yet the amount of goods and produce that move to and fro viâ Szmao, the last Chinese administration town, to Laos, and viâ Cheung Mai to Burmah, is surprising,—thus affording the best possible guarantee for an increased amount to follow were only communication facilitated. Railroad communication for an overland route is warmly advocated. “From Yunnan,” as Baron Richthoren puts it, “the elongated ridges of the Indo-Chinese peninsula (the land of the Burmese, Malays, Siamese, Laos and Cochin-Chinese) stretch southward as fingers from the palms of a hand.”

The configuration of the peninsula is easily remembered as separated by longitudinal belts of hills, spurs from the northern ranges, into principal basins, or funnels, for the rich drainage of the surrounding highlands, viâ Burmah, or the basin of the Irawaddy; the valley of the Menam and that of the Cambodia or Mekong River; and Tonquin, connected by a narrow coast-strip with the French delta.

The fluvial system of each of these great valleys is dominated by one important river, whose downward course is more or less impeded by cataracts, until the upper plateaux gradually subside into undulating tracts, which increase in width and levelness as they approach the several deltas. Throughout Indo-China these waterways, with their intersecting streams and canals, are the main highways of population, commerce and travel. Native villages often consist of one long water-street running through a perfect jungle of palms and other tropical trees, the little bamboo huts and the wats nearly hidden in the foliage. Boats are used instead of carts, carriages or cars. In the upland districts buffaloes and elephants are used; but, with the exception of the pack-peddlers and caravans at certain seasons, the traveler off the waterways would rarely meet any trace of human life.

I. THE FIRST BASIN—BURMAH.

The westernmost basin embraces the kingdom of Ava, ruled by a most cruel native autocrat, and the three British provinces of Lower Burmah, governed by a chief commissioner residing at Rangoon and subject to the viceroy of India at Calcutta.

What is known of Burmah is chiefly embraced in the valley of the Irawaddy. This large stream, rising in Thibet, flows almost due south some twelve hundred miles, receiving tributaries east and west, and communicating by numerous branches with the Salween, running parallel on the east, but almost useless for travel, owing to its rapids.

The Burmese delta (a network of intercommunicating waters from the Indian border-ranges to the banks of the Salween near the Siamese frontier) has some fourteen outlets, but most of these are obstructed by sandbars and coral-reefs. Bassein and Rangoon are the seagoing ports. The latter is a large city of over one hundred thousand inhabitants, and now ranks third in commercial importance in the Indian empire. This plain from the coast to Prome is subject to periodical inundations and is exceedingly productive. It is a great rice-district. Below the northern frontier of British Burmah the Irawaddy is nearly three miles broad. In the neighborhood of Prome the face of the country changes. Ranges of lofty mountains approach nearer and nearer, and finally close in on the stream, the banks becoming precipitous and the valley narrowing to three-quarters of a mile. Above the latitude of Ava the whole region is intersected by mountains, and not far from Mandalay, the capital of Upper Burmah, is their lowest defile. The banks at this point are covered with dense vegetation and slope down to the water’s edge. Still ascending the river, before reaching Bhamo one enters an exceedingly picturesque defile, the stream winding in perfect stillness under high bare rocks rising sheer out of the water. The current of the upper defile above Bhamo is very rapid, and the return waters occasion violent eddies. When the water is at its lowest no bottom is found even at forty fathoms.

For centuries the Irawaddy has furnished the sole means of communication between the seaboard and interior. The Irawaddy Flotilla Company, started in 1868, employs over one thousand hands, and sends twice each week magnificent iron-clad steamers with large flats attached to Mandalay. The time-distance between the two capitals is greater than from New York to Liverpool. Smaller vessels go on to Bhamo. The native craft are estimated at eight thousand. The rapid increase of trade along this river attracts colonists and has greatly enriched British Burmah.

Bhamo, on the left bank, near the confluence of the Taping and close to valuable coal-mines, is within a few miles of the Chinese frontier. The old trade-route noted by Marco Polo is still in use, but the ranges to be crossed, the great cost of land-carriage, together with the dangerous neighborhood of the Kachyen banditti, render the road of limited avail for trade-purposes beyond the fertile Taping valley. The China Inland Mission and the American Baptists have stations at Bhamo.

The Rangoon-Prome railroad was opened in 1878. The Rangoon-Toungoo line will be in use this year, following the Sittang valley to the borders of Siam. British capitalists have now under contemplation a road crossing from Maulmain to Cheung Mai, a distance of about one hundred and sixty miles, with only one comparatively low hill-chain east of the Salween River. A terminus at Cheung Mai would create an increased traffic, leading to a further extension viâ Kiang Kung to Szmao on the Yunnanese frontier, a distance roughly estimated at two hundred and forty miles, with no intervening mountain-system. Although as yet untraveled by European exploration, this track is in use by the native caravans, and the projected railroad will open a most important exchange market with millions of well-to-do, industrious inhabitants, occupying some of the richest mining and agricultural districts of Southern Asia.

The official census report of Burmah states: “There is possibly no country in the world whose inhabitants are more varied in race, customs and language. There are said to be as many as forty-seven different tribes in the narrow boundaries of the two Burmahs, but these may be classed under four—Peguans, Burmese, Karens and Shans or Laos. The Peguans seem to have first occupied the country. The Burmese followed, and took possession of the plains and valleys of Upper and Lower Burmah. Their language is used in the English courts of justice, and is probably destined to be the prevailing language of the country. The Laos, occupying the north-eastern plateaux skirting the Chinese border, are from a great trunk of uncertain root which appears to have been derived originally from Yunnan, where the main stem still retains its primitive designation of La’o—a name commonly exchanged for ’shan’ in the language of the modern Burmese and English writers. The Karens, scattered along the Siamese frontiers, are various tribes having their own customs, dialects and religion. They have a tradition that when they left Central Asia they were accompanied by a younger brother, who traveled faster, went directly east and founded the Chinese empire. Before the British acquired Lower Burmah these simple mountaineers were subjected to brutal persecutions. So late as 1851 the Burmese viceroy told Mr. Kincaid that he ‘would instantly shoot the first Karens he found that could read.’”

The Karens live among the vast forests, now in one and anon in another valley, clearing a little patch for rice-fields and gardens, their upland rice and cotton furnishing food and clothing and the mountain-streams fish in abundance. They seldom remain more than two seasons in one spot, and all through the jungles are found abandoned Karen hamlets, where rank weeds and young bamboo-shoots supplant the cultivated fields.

II. THE SECOND BASIN—SIAM.

The river Menam (or Meinam) is formed by the union of streams from the north. About halfway in its course mountains close upon the river, which passes from the upper plateaux of Laos into the valley of Siam proper through some of the finest mountain-scenery in the world.

The rich alluvial plain of Siam is estimated at about four hundred and fifty miles in length by fifty miles average breadth. The main stream, above Rahany, is known as the Maping. Below the rocky defiles the river divides several times, and contains some larger and smaller islands; Ayuthia is built on one of the latter. The founding of this city, about 1350 A. D., was one of the most memorable events in Siamese history. In 1766 the Burmese depopulated the country and burned Ayuthia. A new dynasty, with Bangkok for the capital, was founded about a century ago.

Bangkok, sometimes called “the Venice of the Orient,” is the Siamese metropolis—the first city in size, wealth and political importance. Old Bangkok is changing rapidly. European fashions and architecture are introduced among the nobility and wealthy. The new palace is a mixture of European architectural styles, retaining the characteristic Siamese roof. The furniture is on a most costly scale, having been imported from England, it is stated, at an expense of some seventy-five thousand pounds. The large library is filled with books in several languages and furnished with all the leading European and American periodicals. The royal guards are in European uniform, but barefooted, only the officers being permitted to wear boots. In the surrounding area are courts and rows of two-storied white buildings, the barracks, mint, museum and pavilions. The entrance to the throne-room is up a fine marble staircase lined with ferns, palms and plants. The throne-room is a long hall hung with fine oil paintings and adorned with costly busts of famous personages. The spacious drawing-room adjoining is furnished in the most luxurious European style.

The palace of the second king (named George Washington by his father, who was a great admirer of our celebrated American statesman) is also European in many of its appointments, with mirrors, pictures and English and French furniture. This prince, still in the prime of middle life, devotes a great part of his time to scientific pursuits, and has collected in his palace much machinery, including a small steam-engine built by himself. He is fond of entertaining European guests in European style; his reception-room is brilliantly illuminated with innumerable little cocoanut-oil lamps.

The Krung Charoon, or main highway of Bangkok, is several miles in length, and used by the nobility and foreigners for driving, except during the high tide of the river, when it is often partly under water. The liveliest quarters in the capital are those mainly occupied by the Chinese, with their eating-houses, pawnbrokers’ and drug-shops and the ubiquitous gambling establishments, and with a Chinese waiang, or theatre, near by.

The finest view of the city and its surroundings is from the summit of Wat Sikhet.

The summer palace recently erected by His Majesty, a few miles below Ayuthia, is a large building in semi-European style, standing amid lovely parks and gardens, ornamented with fountains and statuary, with streams spanned by bridges, and a fine lake with an island on which is built a most delightful Siamese summer-house. The royal wat (temple) opposite this palace is a pure Gothic building fitted with regular pews and a handsome stained-glass window.

“There are a few houses in Bangkok, occupied by the ‘upper ten,’ built of stone and brick, but those of the middle classes are of wood, while the habitations of the poor are constructed of light bamboos and roofed with leaves of the atap palm. Fires are frequent, and from the combustible character of the erections hundreds of habitations are often destroyed. But in a few days the mischief is generally repaired, for on such occasions friends and neighbors lend a willing hand.”

Some of the entertainments of the nobility are in the European style. Miss Coffman describes one given to the foreign residents by the Kromatah, or minister of foreign affairs, to celebrate the birthday of the young king: “The city was illuminated. We left home about eight and returned at eleven P. M. In front of the house was latticework with an archway brilliantly illuminated. A strip of brussels carpet was laid from the archway to the steps. The house was elegantly furnished in foreign style. In the reception-room were three flower-stands, the centre one of silver and the other two glass, each having little fountains playing. The sofas and chairs were cushioned with blue silk. An excellent band discoursed harmonious music, and on the arrival of His Majesty a salute was fired.”

The dress and habits of the court-circles have undergone an entire revolution within the last few years. The men wear neat linen, collar and cravat; an English dress-coat, with the native p’anoong arranged much like knickerbockers; shoes and stockings. The court-dress of a Siamese lady consists of a neat, closely-fitting jacket, finished at throat and wrists with frills of white muslin and lace, and a p’anoong similar to that worn by the men. The artistic arrangement of the scarf is a matter of much importance. Before a new one is worn the plaits are carefully laid and the shawl placed in a damp cloth and pounded with a mallet till it is dry. This fixes the folds so that they last as long as the fabric, and also gives a pretty gloss to the goods. Since the introduction of the jacket, instead of the many chains they wear valuable belts of woven gold with jeweled buckles, and instead of a number of rings on every finger, fewer and more valuable gems.

It is difficult for a stranger to distinguish a woman of the lower classes from a man, as in dress, manner, appearance and occupation they seem so much alike. The streets, the marketplaces and the temples are crowded with women. Housekeeping and needlework form so small a part of female labor here that much opportunity is given for out-of-door work.

John Chinaman too is everywhere in Bangkok, and at the floating Chinese eating-shops or little boats a simple meal of rice, curry and fish can be had for a few cents.

The king’s garden is thrown open once a week to the public, and an excellent native band plays for several hours.

Progress marks the condition of things in Bangkok. The young king is one of the most advanced sovereigns of Eastern Asia. He has made a study of the laws and institutions of Western civilization, and has a manly ambition to make the most of his country. All foreigners who meet him speak well of him. He is bright, amiable and courteous in his personal intercourse, and devotes much time to state business, assisted by his brother and private secretary, usually called Prince Devan, who, though young, has the reputation of being a keen, thoughtful statesman. A younger brother is at present being educated at Oxford. The king is a little over thirty, slight in figure, erect, with fine eyes and fair complexion for a Siamese. He was born on the 22d of September, 1853, and came to the throne when only fifteen years of age.

Paknam is situated near the entrance of the eastern mouth, an extensive mud-flat obliging the largest vessels to find anchorage on the open roadstead at the head of the gulf. Five miles above Paknam is Paklatlang, the entrance of the canal which shortens one-half the distance by river from Bangkok. This canal, however, is only available for small boats. A carriage-road runs from Bangkok to Paknam, some twenty-five miles, and here is the custom-house and port of Bangkok. The last division of the Menam occurs below Bangkok, and the river finally disgorges itself by three mouths into the gulf.

Two rivers from the west fall into the middle and westernmost mouths—the Sachen, with its towns and villages, sugar-plantations and mills scattered all along its elegant flexions, connecting by canals with the Menam east and the Meklong west; and the Meklong, an independent stream from the Karen country, flowing through a narrow but extremely fertile valley in which hills and plains of some extent alternate. The capital of the province is situated at the junction of the canal—a town of twenty to thirty thousand inhabitants, noted as the birthplace of the Siamese Twins.

The “Sam-ra-yot,” or Three Hundred Peaks, separate Siam from Burmah. This chain consists of a series of bold conical hills, extremely ragged on their flanks and covered with immense teak-forests stretching hundreds of miles over mountains and valleys. The noted pass of the Three Pagodas across this range follows a branch known as the Meklong Nee to the last Karen town on the Siamese frontier, thence on foot or elephants across the summit to the head-waters of the Ataran, and by canoes, shooting the rapids, a somewhat abrupt descent, to Maulmein.

Petchaburee, on the western side of the gulf, near the foot of this range, is a sanitarium for natives and Europeans. Here is the Presbyterian mission compound, and on the summit of a neighboring hill is the king’s summer palace. The Tavoy road leads through this town. The Laotian captives who built the royal palace are settled in villages all over the Petchaburee valley; “their bamboo huts with tent-like roofs, thatched with long dried grass, rise from the expanse of level plain among fruit and palm trees like green islands in the sea.” Each hut has its well-tilled kitchen-garden, its tobacco- and cotton-plot. The latter, dyed with vegetable and mineral substances, the women weave on their own looms for family use. With the exception of a few Chinese articles, everything about these hamlets is of native make. The Laotian serfs are superior to the Siamese physically, and have more force of character.

The Malay peninsula projects from the Isthmus of Kraw (lat. 10° N.), six or seven hundred miles to Cape Romania, opposite Singapore. If the estuaries between the Pakshan and Chomphon Rivers are ever united by a ship-canal, the peninsula would be put where it ethnically and geographically belongs, as one of the islands of the Eastern Archipelago.

Much of the peninsula is still one of the unexplored portions of the globe. The rich stanniferous granite of the rocky spine running from Kraw Point to the alluvial plain at the south is probably the most extensive storehouse of tin in the world. Across the mountains there are scarcely anywhere beaten tracks, and the natural passes between the coasts are mostly overgrown with jungles. Numerous hot springs and frequent earthquakes attest the presence of active igneous forces. Coal has been recently discovered near Kraw Point. Gold and silver are associated with the tin, and iron abounds in the south.

Apart from the Chinese immigrants, who here, as elsewhere, monopolize trade, the inhabitants may be classed under three heads—the fullblooded Siamese of the North; the Samsams, or mixed Malay and Siamese population; and the southern Malays, subdivided into the rude aborigines, who inhabit the wooded uplands of Malacca, and the more cultivated Mohammedan Malays, who under the influence, first of the Hindoos and then of the Arabs, have developed a national life and culture and formed states in various parts of the Archipelago. They are migratory in their habits, and perhaps come next to the Chinese as sailors and traders and in the spirit of adventure. Like most followers of the False Prophet, they are devoutly attached to their faith, though in all other respects they readily accommodate themselves to the social usages of the Siamese and Chinese. They wear turbans and loose trousers and carry a bent poignard. Though not a quarrelsome race, when excited they become reckless and ferocious. For a long time this Malay race was classed as an independent division of mankind, but is now considered as affiliated with the Mongol stock, closely resembling the Siamese. The Malayan tongue, with its simple structure and easy acquirement, is a valuable instrument of communication throughout the whole of Farther India.

The Bang Pakong, thirty miles east of Paknam, has its sources in the Cambodian Mountains and drains a highly-productive country. Sugar and rice are extensively cultivated along its banks. Bang Pasoi, its port, has a considerable trade with the interior. A delightful view of the surrounding country may be enjoyed from a small mountain south of the town. To the west are extensive salt-works, the sea being let into large flats enclosed by embankments and left to evaporate with the heat of the sun. Cartroads lead off to the neighboring villages, to Anghin, and thence to Chantaboon, five or six days’ journey. Buffaloes are used here for carts, and there are also some riding horses and elephants.

Anghin is a little village frequented by foreigners for a few weeks in February or March for surf-bathing. A sanitarium was erected there some years ago, and the following advertisement appeared in the Bangkok newspaper, August 29, 1868:

“His Excellency Ahon Phya Bhibakrwongs Maha Kosa Dhipude, the Phra Klang, Minister of Foreign Affairs, has built a sanitarium at Anghin for the benefit of the public. It is for the benefit of the Siamese, Europeans or Americans to go and occupy when unwell to restore their health. All are cordially invited to go there for a suitable length of time and be happy, but are requested not to remain month after month and year after year, and regard it as a place without an owner. To regard it in this way cannot be allowed, for it is public property, and others should go and stop there also.”

The eastern coast of the gulf is lined with numerous hills, and a little way out in the gulf are islands, many of them extremely precipitous and wild and romantic in appearance. Chantaboon, the most eastern Siamese province on the gulf, is one of the most fertile and populous districts. The government regards it as of much importance, and has fortified it at great expense.

The plain is irrigated by a network of short streams. The coast west of the bay is mountainous, and a projecting arm guards the entrance. The river near its mouth is perfectly clear, while the Menam is muddy. Ten miles inland of the coast the Sah Bap hills extend some thirty miles. Bishop Pallegoix says that in an hour or two’s wandering through these mountains his party collected a handful of precious stones. Gems are more abundant on the frontiers of the Xong tribes, at the north-east corner of the gulf, where the mountains form an almost circular barrier and the wild highlanders are accused of poisoning the frontier wells to keep off strangers. Ship-timber abounds near Chantaboon, and building after European models is prosecuted with vigor at the government dockyards. The chief town is situated some miles inland, near Sah Bap, where the windings of the little streams, the high forest-clad mountains, give a varied and picturesque aspect, and the climate, owing to the mixture of sea- and mountain-air, is more propitious than at Bangkok.

The famous Lion Rock, a mass of rudely-shaped stone which stands like the extremity of a cape near this port, is held in great veneration by the natives. “From a distance,” says M. Mouhot, “it so resembles a lion that it is difficult to believe that nature unassisted formed this singular colossus. Siamese verse records an affecting complaint against the cruelty of the Western barbarian—an English captain, whose offer to purchase had been refused, having pitilessly fired all his guns at the poor animal.”

The small tributary kingdom of Korat, north-east of Bangkok, can only be reached through an extensive malarious jungle called, on account of its fatal character, “Dong Phya Phai,” the Forest of the King of Fire. All sorts of wild tales and legends are told of perils from robbers, wild beasts and malarious sickness—supposed to be the curse of evil spirits inflicted on those hardy enough to venture into this lion’s den. Dr. House was the first white man who ever visited Korat, in 1853, while engaged in an extensive missionary tour through the Cambodian valley, and M. Mouhot came several years later. But the whole province is little more than a nest of robbers, largely made up of vagrants, escaped prisoners and slaves. Nine miles east of Korat, the principal town, is a remarkable ruin of the same general style as the Cambodian ruins of Siamrap.

Cambodian Ruins of Siamrap.

In Eastern Siam, about fifteen miles north of the great lake of Cambodia, are some of the most extraordinary architectural relics of the world.

A trip of several hundred miles through a land where salas bare of furniture are the only inns makes it advisable to carry our own bedding, lay in supplies and provide a cook before leaving Bangkok. A Cambodian servant to act as guide and interpreter is also needed.

A canal-trip due east from Bangkok brings us to the Kabin branch of the Bang Pakong River. Mr. Thomson describes this as “a romantically beautiful little stream, where we seemed to have retired to a region unknown to men, inhabited only by the lower order of animals. Monkeys walked leisurely beside the banks or followed us with merry chattering along the overhanging boughs, while tall wading-birds with tufted heads and snow-white plumage and rose-tipped wings paused in the business of peering for fish to gaze with grave dignity upon the unfamiliar intruders. Some were so near that we could have struck them down with our oars, but to avoid this outrage they marched with a calm and stately stride into the thickets of the adjoining jungle.”

Kabin is the entrepôt of trade with the far interior. Chinese merchants here waylay the elephant-trains from Battabong and Laos, exchanging salt and Chinese or European wares for horns, hides, silk, oil and cardamoms. Mines near Kabin are said to furnish the most ductile gold in the world.

Leaving our boats, elephants and a buffalo-cart are engaged. We step from the veranda of the hut perched on poles to the elephant’s head and into the howdah. The driver sits astride his neck, guiding when needful with an iron-pointed staff. A military road from Kabin leads to the borders of Cochin-China. Sesupon, the first Cambodian town, on the frontier of provinces wrested by Siam from Cambodia a century ago, is first reached. Some of the people, including the Siamese governor and officials, speak both languages.

It is possibly harvest-time; in the fields the reapers are among their crops. Some of the plains are covered with tall grass ten feet high. There are perhaps burnt patches or a spark has just started a fire, and the flames, swept on by the wind, are roaring, crackling and sending up dense columns of smoke in their wake. As we pass under the overarching branches of trees in the forest our elephant keeps an eye the while ahead, and when some lower limb would strike the howdah he halts, raises his trunk and breaks it off. We toil up and over the watershed and down a steep bank to the river’s brink through the tall grass and bamboos, our beast sometimes sliding on his haunches, then bracing and feeling the way with his trunk, or plunging into the soft ooze of the river, wading through water so deep that nothing but the howdah and elephant’s head and trunk appear above the surface, and then climbing with slow but sure steps up a bank at least forty-five degrees steep.

Overtaken at night away from a town, we encamp under the trees. Our attendants make an enclosure with the cart and branches of trees, placing the cattle inside. We cook and eat our evening meal, making a great fire and boiling the coffee and rice over the bright coals. Our bivouac is underneath the stars on branches piled high above the malarious surface of the ground. The natives watch in turn, keeping up the fire to drive off wild beasts. Elephants prowl in droves outside the enclosure and cries of jackals disturb our dreams. Possibly in the morning tiger-tracks are pointed out to us.

On the higher waters of the Sesupon River, running south to the lake, are the first traces of the ancient Cambodian civilization in the shape of a ruined shrine buried beneath overgrown jungle; other ruins are found in more than forty different localities up to the confines of China.

Diverging to the north-east, evening finds us sheltered in a sala near the quaint old town of Panomsok. To the north are the first altitudes of the upland steppes of Laos. After such toilsome days and nights of exposure, crossing some sunny eminences and ancient stone bridges, we finally reach Siamrap, situated on a small stream about ten miles from the head of Thalay Sap.

It is a walled city, the teakwood gates thickly studded with large iron nails, the gateways surmounted by curious pointed towers. Houses similar to those of the middle class in Bangkok, the court-house and governor’s residence, are the only substantial buildings. Extensive, straggling suburbs extend southward for several miles on either bank of the river. The province has from eight to ten thousand inhabitants, all Cambodians. Dr. McFarland reports: “We found but two or three persons who understood the Siamese language. The governor was a rather intelligent young Cambodian who had been educated at Bangkok, and of course spoke Siamese. He was pleasant, affable and very fond of foreigners.”

The communication with Panompen, the Cambodian capital, is by boat down the river and crossing to the lower end of the lake, then by the river which connects the lake with the Mekong. From Siamrap to Panompen requires six days by boat.

Half a dozen miles north of Siamrap, in the midst of a lonely forest, we come upon the celebrated ruins of Nagkon Thom, or Angkor the Great, and Nagkon Wat, the City of Monasteries, is a few miles off. The city ruins to-day are little more than piles of stone among the jungles. The outer wall, built of immense volcanic rocks, is best preserved. The natives say an entire day is necessary to circumambulate the walls. A mutilated statue of the traditional leper king is seated on a stone platform near the gate of the inner wall, protected by a grass thatch. The pedestal has an ancient inscription on stone. The ruins are in the charge of a provincial officer, who lives in a lodge near the palace. There are some old towers still standing.

Some thirty miles distant are the Richi Mountains, said to contain the quarries from which the supply of stone was obtained. A broad causeway, still in serviceable repair, leads to the foot of these hills. Mr. Thomson tried to go there, but the thick jungle made it impossible to penetrate to the quarries even on elephants, although the officer who accompanied him made a series of offerings at several ruined shrines in order to propitiate the malignant spirits supposed to infest these wilds.

Concerning Angkor the Great ancient tradition speaks in most extravagant terms, as being of “great extent, with miles of royal treasure-houses, thousands of war-elephants, millions of foot-soldiers and innumerable tributary princes.” A road through the forest connects this once royal city with Nagkon Wat. Along this road a side-path leads to an observatory, overgrown with shrubs and vines, standing on a terraced hill and commanding a wide view of the surrounding region.

The main entrance approaches the wat on the west, crossing by an immense stone causeway over a deep, wide moat and under a lofty gateway guarded by colossal stone lions hewn, pedestal and all, from a single block. The structure rises in three quadrangular tiers, of thirty feet, one above the other, facing the four points of the compass, on a cruciform platform. Out of the highest central point springs a great tower one hundred and eighty feet high, and four inferior corner-towers rise around. It has been suggested that Mount Menu, the centre of the Buddhist universe, with its sacred rock-circles, is symbolized, the three platforms representing earth, water and wind. Flights of steep stairways, each step a single block and some having fifty or sixty steps, lead from terrace to terrace. Long galleries with stone floors, stone roofs, and walls having a surface smooth as polished marble, covered with elaborately chiseled bas-reliefs, are flanked by rows of monolithic pillars whose girth and height rival noble oaks. The centre compartments are walled in, and the remaining two-thirds of the space consists of open colonnades. The inner walls of these open galleries have blank windows; seven stone bars, uniform in size and beautifully carved with the sacred lotus, form a sort of balcony to each window.

The bas-reliefs have thousands of nearly life-size figures, representing scenes from the great Indian epic Ramayana—battle-scenes, processions of warriors, and the struggle of the angels with the giants for the possession of Phaya Naght, the snake god. The majority of these are executed with care and skill, and form one of the chief attractions of the wat. Specimens of the more beautiful, and also casts of the inscriptions, have been transported to the Cambodian Museum of Paris, but, unfortunately, M. Mohl, the celebrated Orientalist entrusted with the task of deciphering these unknown characters, died before reaching any satisfactory conclusion. Scholars seem inclined to regard the inscriptions as derived rather from the Pali or Sanskrit than the Malay or Chinese language.

Mr. Thomson, the English traveler, with his photographs, has best introduced these wonderful ruins to English readers. Mr. Frank Vincent’s very readable account of his visit to these ruins in company with Dr. McFarland, in 1871, also gives us much valuable information and reproduces some of the English photographs. Dr. McFarland states that “this wonderful structure covers an area of over ten acres—that the space enclosed within the temple-grounds is two hundred and eight acres, and the space within the walls of the city is over two thousand acres. The temple is built entirely of stone. These stones were brought a distance of about thirty miles, and must have required the labor of thousands of men for many years. There is no such thing as mortar or cement used in the building, and yet the stones are so closely fitted as in some places to appear without seam. These ruins, together with the beautiful little lakes that dot the plain and the remnants of splendid roads that once traversed the country, show that those formerly inhabiting this valley were a powerful race.”

And as we in turn ponder and gaze on these evidences of an unknown civilization a spell falls upon our imagination. We seem to see these forsaken altars thronged by devotees, and through the valley are busy cities adorned with stately palaces, astir with the human life of a powerful, opulent kingdom. But vainly do we conjecture how ruins of such solidity, so stupendous in scale, of elaborate design and excellent execution, could have lain forgotten through centuries in this lonely forest-district of an almost unknown portion of the globe; nor can the sloth and ignorance of the present semi-civilized inhabitants offer any trustworthy solution of the problem. They reply, “We cannot tell,” “They made themselves,” “The giants built them,” or refer to a vague local tradition of an Egyptian king, turned into a leper for an act of sacrilege, as the reputed founder of the wat.

The present good condition of the ruins of Nagkon Wat is largely due to the late king of Siam, who gave them in charge of the small religious brotherhood now living in little huts under the very shadow of the gray walls.

Travelers describe Nagkon Wat as “a rival of Solomon’s temple” and “grander than anything left us by Greece or Rome,” “occupying a larger space than the ruins of Karnac,” “imposing as Thebes or Memphis, and more mysterious.”

But the credit of what might be called the rediscovery of these wonderful remains amidst the forest solitudes of Siamrap is due to M. Mouhot, after these remnants of a lost past had for ages been forgotten by all the world outside of their immediate vicinity. The innumerable idols and thousands of bats hanging from the ceilings would seem to have held undisturbed possession for centuries.

Fergusson’s opinion, that this shrine was devoted to the worship of the snake god (see Tree and Serpent Worship), is not in accord with the views of Garnier, Thomson and others, who agree that it must have been erected in honor of Buddha. Dr. Bastian, president of the Berlin Geographical Society, thinks, with Bishop Pallegoix, that the probable date of the building—at least its commencement—was the grand event from which the civil era of Siam dates—viz. the introduction of the sacred Buddhist canon from Ceylon in the seventh century. The general appearance of the worn stairways, and the dilapidated condition of the city, slowly mouldering under the destructive encroachments of a tropical jungle, would seem to indicate great age. Yet the mediæval narrative of Cambodian travel by a Chinese officer, late in the thirteenth century, recently translated by M. Remusat, contains no allusion to this great temple, which has induced some to conclude that the building belongs to a later period. In 1570 A. D. a Portuguese refugee from Japan refers to these “ruins” and the inscriptions thereon as being in “an unknown tongue.”

III. THE THIRD BASIN—VALLEY OF THE MEKONG.

The hill-country which separates the valley of Siam from that of the Mekong (or Mekaung)—known in its lower course as the Cambodian River—is of moderate elevation and the boundary-lines not well defined.

The Mekong is one of the most remarkable streams of Asia. It rises in Thibet, passes through Western Yunnan parallel with the Yangtse and Salween, till, breaking through the mountains not far from each other, the Yangtse flows across China and the Salween to the Bay of Bengal, while the Mekong, crossing Laos and Cambodia, after a somewhat devious course of at least two thousand miles reaches the Cochin-China delta.

The broken character of the Laos country gives the Mekong in its rapid descent from plateau to plateau during its upper course the velocity of a mountain-torrent as it tears along, with a noise like the roaring of the sea, through deep gorges overshadowed by rocky defiles. In Upper Laos the river is from six to eight hundred feet wide, and has in the dry season an average depth of twenty feet, while the banks are some twenty-five feet above the water, the difference between the ordinary height and floodmark being very great. The rainy season begins in April with the melting snow; the water rises gradually from that time to July or August, when the country is flooded.

It was at Garnier’s suggestion that the great French commission of exploration was sent up this river through Laos and Yunnan to Thibet, 1866–68. Garnier being considered too young, the chief command was entrusted to Captain Doudart Lagrée. De Carné (the brilliant journalist of the Deux Mondes) formed a third, and an armed escort accompanied them. The pluck and resolute endurance of this gallant band of Frenchmen, who during two years of exposure and hardships toiled over some five thousand miles of a country almost unknown to Europeans, command our admiration. Garnier took nearly all the observations, and shortly after the death of Lagrée assumed command and conducted the expedition safely to its close. De Carné describes the Mekong as “an impassable river, broken at least thrice by furious cataracts, and having a current against which nothing can navigate.” M. Mouhot, the pioneer of European explorers in this valley, says that his boatmen sometimes sought fire at night where they had cooked their rice in the morning. He went as far as Looang Prabang, the north-eastern Laos province tributary to Siam, where he died. Here the channel is very wide and lake-like in its windings through a sort of circular upland valley some nine miles in diameter and shut in by mountains north and south, reminding one of the beautiful lake-scenery of Como and Geneva. “If it were not for the blaze of a tropical sun, or if the noonday heat were even tempered by a breeze, this Laos town would be a little paradise,” is one of the latest entries in Mouhot’s journal.

If there is almost an excess of grandeur in the upper courses of the Mekong, the general aspect of the scenery as it reaches the comparatively low level of Siam and Cambodia is sombre rather than gay, though there is something imposing in the rapidity of so large a volume of water. Few boats are to be seen, and the banks are almost barren on account of the undermining of the forests, trees constantly falling with a crash into the stream. For some two hundred miles from its mouth the river is nearly three miles wide, and is studded with islands, several of which are eight or nine miles long and more than a mile broad. The discovery of the impracticability of the Mekong for inland communication with Laos and China has robbed the French delta of much of its supposed value.

The bulk of the Laos tribes are spread over the north-eastern valley of the Mekong, from 21° to 13° north latitude. This extensive region is a sort of terra incognita, reported to be thickly settled except along the regions contiguous to the Tonquin Mountains, where the villages are exposed to sudden raids from the wild tribes known as “inhabitants of the heights,” who sometimes strike hands with the Chinese refugees in making a foray over the border, carrying off the peasants as slaves and driving away cattle, with whatever in the shape of plunder can be moved. The caravans of pack-traders from Ssumao on the Yunnan frontier bring back large loads of the celebrated so-called Puekr tea and cotton; whence it is inferred this plain must be fertile and extensively cultivated.

Talā Sap (Sweet-water Lake), the great lake of Cambodia, forms a sort of back-water to the river Mekong, with which its lower end connects by the Udong. It belongs partly to Siam and partly to Cambodia. It is one of those sheets of water called in Bengal jhéts—viz. a shallow depression in an alluvial plain, retaining part of the annual overflow throughout the entire year, hence subject to great variations of extent and depth. In the dry season the average depth is four feet, and the highest floods entirely submerge even the forests on its banks. It takes about five days to traverse the lake when full.

Extensive fishing-villages, erected on piles, stud the lake, reminding Mr. Thomson of “the pre-historic lake-dwellings of Switzerland.” The houses are above a bamboo platform common to the entire settlement and used for drying fish. This lake is an object of superstitious veneration to the natives, the fish furnishing them with the most important source of their livelihood. Enormous quantities are exported, dried or alive in cages, while immense supplies are furnished to Anamese villages to be boiled down into oil, thus giving lucrative employment to thousands.

The small remnant of the ancient kingdom of Cambodia forms a rough parallelogram, consisting in large part of an alluvial plain lying athwart the Mekong, uncomfortably wedged in between Siam, Anam and the French delta, with a very short west coast-line.

It would appear from Chinese annals that at an early period the Cambodians were an exceedingly warlike race, and that their authority extended over many of the Laos and even Siam. But for centuries Cambodian influence in Indo-China has been on the decline. It has little more than the name of an independent government at present, being under a joint protectorate of Siam and France, and tributary to both.

The Cambodians differ from the Siamese in language, but in habits and religion resemble them, with the usual Indo-Chinese type of government. There are Roman Catholic, but no Protestant, missionaries in Cambodia or Cochin-China, though several years ago strong reasons were urged for the establishment by the American Presbyterian Mission of an out-station at one of the principal Cambodian towns.

Panompen, the present capital, is connected by a small steamer, which makes regular trips, with Saigon. Below Panompen the river divides into two streams, which flow south about fifteen miles apart, and empty themselves into the China Sea. There is a labyrinth of intersecting branches, creeks and canals across the delta, and the low shores are mostly grown wild with jungle.

Saigon, on an offshoot narrow, tortuous, but navigable for vessels of the heaviest tonnage, is situated about twenty-five miles inland. The French governor resides here, and is assisted in the control of the province by a legislative and executive council. Extensive parks surround the palace; macadamized roads run through the city. There is a public promenade along the river, and botanical gardens, where foreign plants have been introduced with the intent of their propagation. The spacious harbor with its floating dock contains a fleet of iron-clad steamers, and flags of the different consulates are floating from the line of mercantile and government offices along the bank. Telegraph lines connect Saigon with all parts of the peninsula, and submarine cables with the outside world.

IV. THE FOURTH BASIN—TONQUIN.

Tonquin, the north-east corner of Indo-China, is a province of Anam. It is separated by mountains from Laos and Siam and also from the Chinese empire. The Songkoi, or Red River, dominates the whole fluvial system, several streams from the north and west uniting, and then dividing and diverging, so as to form a triangle or delta. Upon these streams are situated the important towns. This Tonquinese river connects Yunnan with the sea, forming an important trade-route. Its port is Hanoi, at some little distance up the river, just as Bangkok is in regard to the Menam. For the acquirement and control of this waterway French enterprise seems to have taken the satirical counsel of Horace, “Si possis recte; si non, quocunque modo.”

The French colonial government covers an empire in Indo-China similar to that of Great Britain in India, and would like to annex not only Anam, but Cambodia and Eastern Siam. Early in this century, at the instigation of Roman Catholic missionaries, who have played an important part in the political complications, the French assisted Gialong, an Anamese aspirant to the throne, making their services the basis of a treaty which virtually gave them the protectorate of the whole eastern coast. This claim, being disputed by the successors of the prince, was the pretext for further encroachments. The court of Hué, too weak to resist, again and again memorialized the Chinese government, and each time a strong protest was made by China, who naturally objected to a foreign power holding the trade-keys of some of her richest provinces. These remonstrances have been ignored, and the frank statement of Dr. Hammand, the French civil commissioner in Tonquin, is not calculated to commend Christian ethics to the Buddhists of Southern Asia. “When a European nation,” he affirms, “comes in contact with a barbarous people, and has begun to spread around its civilizing influences, there comes a time when it becomes ipso facto a necessity to extend its boundaries. There is no country more favorable to our development than the kingdom of Anam. The Anamese recognize that we are incontestably their superiors. It is necessary to force Anam to accept our rule.” This has been done.

An able writer in the London Quarterly (October, 1883) says: “The railroad route from Maulmein across the Chino-Shan frontier being assured, an upland cross-road of some seventy or eighty miles north-east would lead to Yuan-Kiang on the main stream of the Songkoi, whence a road would lie open to the capital, Yunnan-fu, or south to the mart of Manhao, which is the head wharf of the Songkoi River navigation within the province of Yunnan, and thence to the Gulf of Tonquin.… Siam, the Laos provinces tributary and independent, Yunnan and Tonquin can thus be brought into the closest and most profitable connection with Burmah, all on one line, at once the easiest and most expeditious across the peninsula, and thus a short direct line for goods-transit be provided from the Gulf of Tonquin to the Bay of Bengal.… This, then, is the answer to the riddle of the Sphinx of the Far East, this the true solution of the Indo-Chinese overland route problem; by this the long-sought goal will be obtained, and the highest benefits conferred, not on Burmah and Yunnan only, but on India and China; on Siam and the Laos country, and Tonquin; on British and European enterprise throughout the China Sea and Indian Ocean alike—the vision of Marco Polo and his gallant successors realized.”

This northern province is more closely connected with China in government, literature and sympathy than with the rest of Anam. The Tonquinese use the Chinese characters for the written language, and near the frontier the Anamese tongue is hardly spoken; their laws and customs are modeled on those of China; the internal trade is in Chinese hands; the merchant quarter of Hanoi, with its shops and well-paved streets, is purely Chinese; the external trade-centre is at Hong Kong. Chinamen marry the women of the country, and all around the fringe of the delta Chinese and half-breeds form the dominant race. It is even hard to say just where Tonquin ends and China begins, for there is a belt of debatable land along the frontier, narrow in the north, but widening to over one hundred miles in the hills, and in some of the border fortresses Chinese and Anamese exercise joint control.

This plateau country, along the upper banks of the Songkoi and Claire Rivers, is infested by wild native tribes and Chinese brigands under the names of “Yellow Flags” and “Black Flags,” who erect barriers along the streams, so that travel in these parts is dangerous. Hence the importance of the fortified towns of Sontay and Bacninh, situated close to these outlaw districts. From Sontay to Hanoi there is a well-made embankment, shaded by fine trees. It was along this road that Garnier and Revière met their deaths in 1873. Most of the travel is along the river. Throughout the province almost the only highways are footpaths across the jungles. From Hanoi roads lead north to China and south to Hué. The influence of Hanoi, through Anam, is widespread as a centre of fashion as well as of authority. A French writer calls it the “Paris of the Anamese empire.” What more could he say?

The thickly-populated delta, intersected by streams and tidal creeks, is subjected to periodical inundations, when the whole face of the country has the appearance of an enormous lake, with here and there clumps of trees, villages and pagodas. Away from the delta only the valleys and lower slopes are cultivated, and the rest of the province is a tangle of mountains covered with dense forests, of which little is known, apart from the Songkoi and minor waterways, unless from the reports of the natives or Roman Catholic missionaries. The population of the province is estimated not to exceed ten millions, probably less. The Anamese differ from those of the south, the race being formed by a union of the hill-aborigines with the seaboard people. The climate is not considered favorable for Europeans. There are no Protestant missions in Anam.

This survey of the principal basins of Indo-China will enable the reader to appreciate how largely the agricultural wealth and commercial importance of all these countries depend on its rivers. It is scarcely exaggeration to state that a few inches of water often determine whether the receding flood at the annual inundation will leave a bright, grain-laden plain or a sterile waste of ruined crops. It should also be remembered that while periodical floods are common to all the deltas, each valley has its own period, indicating that the table-lands in which the rivers have their sources are at unequal distances. Moreover, travel throughout the peninsula being so largely aquatic, not only north and south along the main trunks, but across the same valley by means of intersecting canals, tide plays an important part in these waterway trips, and many smaller streams being filled and emptied daily, a careful study of tidal influences will avoid delay, as at times the water, suddenly receding, leaves a boat stranded on the banks of some creek for hours, with no water even for cooking or drinking purposes.

V. CLIMATE, PLANTS AND ANIMALS.

Far India, as this south-eastern corner of Asia is sometimes called, has a tropical climate. At seasons the heat is intense, but in many portions the warm air is genial and not unhealthy, though Europeans need from time to time a change to a more bracing region. The seasons are two—the wet and the dry: the former embraces our spring and summer months, and ranges from May to October; the latter, the remainder of the year. March and April are the hottest months; November, December and January, the coolest. The winter is mild and summer-like—doors and windows all open and no fire. Houses are built without window-glass, and the shutters are seldom closed except at night or to keep out the sun. Here, too, is the verdure of perpetual summer—lands where the foliage is always green, where roses bloom from the first to the last day of the year, and the orchards are always laden with their luscious store—lands of Italian sunsets, picturesque mountains, loveliest valleys, and long stretches of comparatively still waters, said to resemble the Swiss mountain-lakes, clear as crystal, reflecting the sky and great mountain-shadows, and filled with fish; the grandest caves, the richest mines of precious metals and valuable gems. Rice, the principal article of food among the natives, grows almost spontaneously, and is used on the table at an expense of three cents a pound, while bananas are sold for two cents a dozen and oranges for half a cent each.

It does not cost much to build a little bamboo house after the native fashion. For example, Miss Cort paid for one of her schoolhouses at Petchaburee, fourteen by twenty-two feet, only $6.38 for the materials, including a lock and key; $5.44 for the wages of the men and women who built it—making the entire cost $11.82. But then we should think it a very queer schoolhouse, with its basket-like walls of woven bamboo, its roof of leaves sewed together, its three little windows without any glass, and two doors; nor would its strangeness be less striking if we saw the native teacher and children all sitting on the floor. But things move slowly in these warm Eastern countries. If you want to build a more substantial house, you must begin by buying earth to make the bricks, and oftentimes rough logs to be worked up into boards; and, though labor is cheap, a day’s work in Indo-China will not mean anything like as much accomplished as in the same space of time in America.

In the useful arts the inhabitants of this peninsula are far behind Chinese and Hindoos, though there are said to be ingenious workers in copper and iron, and in the manufacture of gold and silver vessels they display considerable skill.

Agriculture is the main employment of the natives. In many parts of this peninsula the land is prepared by turning in the buffaloes during the rainy season to trample down weeds and stir the soil, which is afterward harrowed by a coarse rake or thorny shrub, the stubble being burnt and the ash worked in as manure.

But the Chinese are everywhere introducing improved methods. The best quality of rice is transplanted, the plants lying partially covered in the still pools of water between the rectangular ridges marked off for the purpose of irrigation; and rice growing above the rising water looks very like a field of wheat or tall grass. At high-flood seasons it is a pretty sight to see the planters moving about in boats attending to their crops. The growth is almost spontaneous. Little care is needed until the whole family must turn out to drive off the immense flocks of little rice-birds. The rice is sown in June, transplanted in September and harvested late in December or in January. In the fields at this season may be seen the reapers, multitudes of sheaves and stacks of grain. The rice is generally threshed by buffaloes, a hard circle being formed around each stack. The carts have large wheels, four or five feet apart, with the sheaves placed in a small rack. The driver guides the oxen by means of ropes fastened in the septum of their noses, reminding one of the Scripture, “I will put my hook in his nose.”

Sugar is produced almost everywhere, in Siam especially, under the Chinese settlers, its quality yielding to that of no other sugar in the world, so that it is fast becoming one of the most important Siamese exports. Almost all the spices used throughout the world find their early home in the peninsula or the neighboring islands—the laurel-leaf clove; the nutmeg, like a pear tree in size, its nut wrapped in crimson mace and encased in a shell; the cardamom, a plant valuable for its seeds and the principal ingredient in curries and compound spices. A pepper-plantation is a curious sight, the berries growing, not in pods, but hanging down in bunches like currants from a climber trained much like a hop-vine, yielding two annual and very profitable crops. Tea is cultivated in the Laos provinces, and coffee and cotton are also raised. Tobacco is largely grown, and its use is almost universal; even babies in their mothers’ arms are often seen puffing a cigar. A fine aromatic powder, made from the deep golden root of the curcuma, is sold by the boatload in Bangkok; Siamese mothers may be seen in the morning yellowing their children with it for beauty. It is also used to give color to curries, and mixed with quicklime makes the bright pink paste wrapped in seri-leaf around the betel-nut for chewing purposes.

Vegetable-gardens and fruit-orchards surround most of the villages. The neat Chinese gardens near Bangkok are worth a visit. The land is made sufficiently dry by throwing it up in large beds ten to twelve feet high, extending the whole length of the grounds. The deep ditches between have a supply of water even in the dry season, and a simple instrument is used to sprinkle the plants with it several times a day. The gardener lives within the premises, his small dirty hut guarded by a multitude of dogs and a horrible stench of pigsty. The artificial ridges of the paddy-fields beyond, three feet high, make quite comfortable footpaths in the dry season.

The Indo-Chinese fruits are of great excellence of flavor, and almost every day of the year furnishes a new variety. The best oranges are plentiful; pineapples are a drug in the market; lemons, citrons, pomegranates are abundant and very cheap. As the season advances, mangoes, guavas, custard-apples and the like follow in quick succession; on some kinds of trees buds, flowers, green and ripened fruit may be found at the same time. The small mahogany-colored mangosteen is perhaps the most popular of tropical fruits. One species of the sac has a fruit weighing from ten to forty pounds, which cut in thick slices will supply a meal to twenty persons, and a single tree will produce a hundred such fruit; the bright yellow wood of this tree is used for dyeing the priests’ robes. The tamarind grows to an enormous height and lives for centuries; under its shade the Siamese assemble for most of their social games. The durian, a child of the forest, has something the appearance of an elm; the large fruit, cased in a thick hard rind as difficult to break as a cocoanut-shell and covered with strong spines, gives a dangerous blow in falling. The five shells within each contain several seeds rather larger than a pigeon’s egg filled with custard-like pulp of a strong odor and unique flavor. The plantain or banana has some forty varieties, with fruit varying greatly in size as well as in flavor. It is the first fruit given to babies, and, the Moslems say, was the gift of Allah to the Prophet in his old age when he lost his teeth. The trees bear fruit but once, and then are followed by others from the same root. The useful bamboo is a tree-like plant with a jointed stem, producing branches with willow-shaped leaves, which wave in the wind, giving an elegant feathery appearance. So rapid is its growth, sometimes two feet in a single day, that the plant attains its height of sixty to seventy feet in a few months. It is said to have seven admirable qualities—strength, lightness, roundness, straightness, smoothness, hollowness and divisibility. The short succulent shoots are served on the table like asparagus, pickled or candied. According to the Chinese proverb, the grains are “more abundant when rice fails.” The stems furnish bottles, buckets, baskets, fishing-rods, posts, bridges, walls, floors, roofs, and even the string that lashes together rafter and beam of the common native house in Indo-China.

Under the stimulating sunshine of the tropics a profusion of rare shrubs and some of the most beautiful flowers reward slight labor with a rapidity of growth and bloom unknown in colder regions. Roses of one sort or another are perennial. Bright geraniums, brilliant lilies and numberless plants indigenous to the country are in great demand and cultivated extensively for domestic or religious uses. There are seven varieties of the lotus, the favorite sacred flower of all Buddhist countries. The red pond-lotus is most common; the blue, green, light and dark-yellow flowers are rarer. The smallest variety has a white flower scarcely larger than a daisy, and is found in the rivers, principally at the season of inundation. The rose-colored lotus, whose golden stamens breathe a delicious fragrance, is the ornament of all festivities, and is sent as an offering to royalty, the priests and Buddha himself. The mali, a fragrant white flower about the size of a pink, is much cultivated in the neighborhood of Bangkok. It grows on a shrub about three feet high. The wreaths worn around the topknots of children are braided from this flower, which is also used for necklaces, bracelets and to perfume water. Rare and beautiful orchids are also here in large numbers, and many of the varicolor-leaved plants find this their native home.