In a cruel Cosmos one lived only to be killer or

killed. The One proved that. It killed

a hundred times a day. Thisbe II was its blood-red

preserve ... and now, throwing the challenge in Its

myriad faces was Pritchard, the brightest name in big-game

hunting throughout the length and breadth of Galaxy A.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories November 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Dawn on Thisbe II was much like dawn on Terra, except for the color. The giant star Piramus lifted its magenta disk above the little planet's fore-shortened horizon and, in that brief moment, sent orange corona flares shimmering out from its limb. An odd ionization effect caused faint ripples of light to flicker in the purple sky above.

As the sun ascended, the magenta brightened into a crimson dazzle with a lavender halo. The flanks of distant mountains flamed curiously, as if their sides were smooth and polished mirrors.

Yet nothing gleamed with such intensity as the good ship Apollo, towering a hundred and ten feet on her fins. Her surface—chrome-plated nickel-steel coated with a thick porcelain glaze—was expressly designed to bounce back every slightest beam of light.

So she stood now like a flaming sword, in the center of a wide black circle, the area of yesterday's landing burn, and lay across it a wide fan of reflected sunlight. Presently, a thing like an enormous grasshopper-leg unfolded from her side. In its grasp was something that looked like a tray full of erect ants. The tray touched ground softly, the ants walked off and became men, and the long derrick folded back into the Apollo, taking the tray with it.

The men left on the ground stood looking about them eagerly. After some of the barren, hostile worlds they had visited this one seemed little short of Paradise. From the eminence on which the ship stood they could look in every direction at rolling hills, among which clumps of feathery foliage rose profusely, and occasional startling upthrusts of rock, like clubs brandished from underground, leaning in every possible angle and having frequently such straight planes of cleavage that they almost seemed artificial. Olive-hued hills and dramatic fists of rock alike marched off to a disturbingly close-appearing horizon, where began a sky that was not blue but lavender.

They stamped the ground. It was one thing to have watched this wonder swell on the visiscreens as the ship tore around on its landing orbit, and to have craned and peered through the heavy leaded glass of the viewports after the landing in yesterday's sunset. Neither of these quite matched the delight of seeing it all with unaided and unimpeded vision. They smelled the air, so rich and invigorating after the ship's mustiness.

They were all young but one. And this one faced them now, a tall, saturnine man, but with an amusement lurking in his dark, deep-set eyes. "Attention, cadet hunters," he said briskly, "let's have another equipment check."

They rolled their eyes at him and quirked their mouths in simulated resignation. Yet the readiness with which they formed a semi-circle about him showed their pride in obeying his orders. They knew they were lucky to be under Pritchard, the brightest name in planetary big-game hunting throughout the length and breadth of Galaxy A.

For each of them had fought hard for his place in this latest expedition to be led by Pritchard. The ex-pilot-turned-sportsman regularly accepted certain hardy young neophytes of the chase as assistants on his expeditions; some aspired to follow in his footsteps and others merely sought the thrills and danger that lurked along the unknown trails of far-flung worlds.

Each one now showed his regular and special equipment to Pritchard. Butt-first, they held out their snappers—the light Thorp-Snell hand rocket-tube that launched a high explosive needle, deadly up to a thousand yards. Pritchard inspected load and action, and then thumbed the gleaming edge of each man's chopper, or matchet which had been derived from the old Terran hatchet and machete combined. It was really a long, broad blade with a flattened-out, hatchet-shaped head.

The special equipment consisted of a squawkie, the portable radio, carried by the phlegmatic Sturgis; the cam-rec, a light camera and tape recorder combined, slung over Kemp's plump shoulders; the flamer, or flame-thrower, its full plastic tank strapped to Majinski's back; the two packets of synthetabs or food concentrates enough for a week for them all should they get lost—hung to the belt of red-headed McManus; and the first-aid kit strapped to Pritchard's own lean shoulders. To the remaining five men would fall the pleasure of carrying all this stuff back when the little scouting party returned.

At last Pritchard beckoned to the squawkie-man and spoke into its 'phragm. "All set, Cap. See anything?" The voice of Captain Savage, high above the rocket batteries in the towering nose, came back as a thin rasping. His report was negative. "Must be a lull between the night carnivores and the daytime ruminants. Looks like a few flocks of birds far away."

"Fine. We'll head east and dig around in that jungle down there a bit. We'll turn back after noon chow."

The captain's "Good hunting" ended with a click. Pritchard turned calmly and started walking off the hard gloss the Apollo's hell-breathing stern tubes had made of this once-grassy spot, into the blackened wisps and dust. The men followed him in a loose, straggling group, ten men in all, swaggering for the benefit of the envious eyes of those remaining in the ship.

McManus strode rapidly until he had caught up with the tall hunter. The red-haired boy's idolatry was plain in his wide blue eyes.

"Why the jungle?" he said. "Why are you tackling the jungle, Mr. Pritchard?"

"Just for a sample. Also as a check. The whole planet's like this. Can't land anywhere without being near the jungles that seem to fill up every valley. I don't like cover like that so close to the ship. I want to see what's in it."

"Think we'll knock over anything?"

"Not trying for it," said Pritchard shortly. He punched the younger man on the biceps. "And unkink that trigger-finger of yours, hero boy."

McManus grinned shamefacedly. "Ah, change your tapes, will you? I only need one mistake to learn."

Pritchard snorted. "On that Deneb asteroid, you promised. You seemed to understand. Then you thought you'd like one of those big clamshells for a souvenir. Remember what came out of those shells after you fired?"

The boy moved his shoulders. "Remember! I dream about them regularly every tenth night."

"I'm also thinking about a man named Munson." Pritchard's tone had become soft and musing. "That name mean anything to you?"

McManus shrugged. "There must be a million Munsons. None of 'em ever meant anything to me."

"Every hunter remembers Munson," said Pritchard flatly. "And everybody on Terra remem—"

Something squeaked under his foot. Pritchard flung himself sideways into the blackened stubble, rolled, and came up in a crouch, snapper at ready, while McManus stood blinking at him. Pritchard came back slowly, narrowed gaze riveted on the spot where he had stepped. McManus backed away, raising his own snapper. The rest of the men came running up.

Pritchard knelt and picked up something. It was stiff and charred and smelt acridly, but the men clustering around could see it had six legs. There was a click and a whirr as Kemp started the cam-rec.

Then McManus said, "I'll be damned" and picked up something else. It squealed and squirmed in his hand, and it also had six legs.

"What is it?" queried Majinski over his shoulder. "Rabbit?"

"Or squirrel," put in Greene, a rangy blond boy.

"Some kind of rodent, anyway," said Pritchard. He ran a finger the wrong way through baby fur and the little sharp muzzle flicked around to snap at him. He stood up. "The mother shielded it from our stern jetwash. She died that Junior might live." He wiped his hands on his cordron breeches. "Bring it along, Tom. We'll drop it in the tall grass."

By the time they reached the tall grass beyond the perimeter of the burn, Tom McManus had become attached to the little fur-ball, with its whiskery nose and knob-like feet, and found that it snuggled nicely in his breast pocket. Pritchard smiled indulgently and they all waded into the waist-high grass.

They went slowly, partly out of caution and partly because the long, thick-growing blades clogged and bunched around their legs. Little things went hopping and chittering out of their way, and the sun began to lay its heat on them. Birds, as yet unseen, called and cried and whistled in the dense growth ahead.

They went down a long slope, and then bushes began to shoulder up above the grass-tips and trees sprang up, some arching their feathery fern-like trunks until they began to lace together overhead and others dangling enormous round leaves from long drooping stems.

The transition to jungle was gradual, with more and more sunlight filtered out of the growing shade, and vines and creepers becoming abundant about the ankles. The choppers appeared and began swinging and slashing, and all were grateful for the shade and its attendant coolness. Something crashed heavily away, hidden by the dark brown-green wall before them.

It began to be real jungle. Pritchard stopped before a sturdy hedge. He had chopped into it and found a long tough root from which the heavy chopper only seemed to bounce back.

"Hell," he grunted as McManus came up. "Joe," he called, "let's have the flamer here."

"Ah, what's the matter with you!" grinned McManus. He took his own chopper between both hands and raised it high over his head. "You must be ... getting ... old!" And he brought the heavy blade down with all his force.

Pritchard had stepped back, amusement twisting his lips. Majinski was shouldering forward with the flamer's nozzle ready. The chopper's edge chunked into the root—

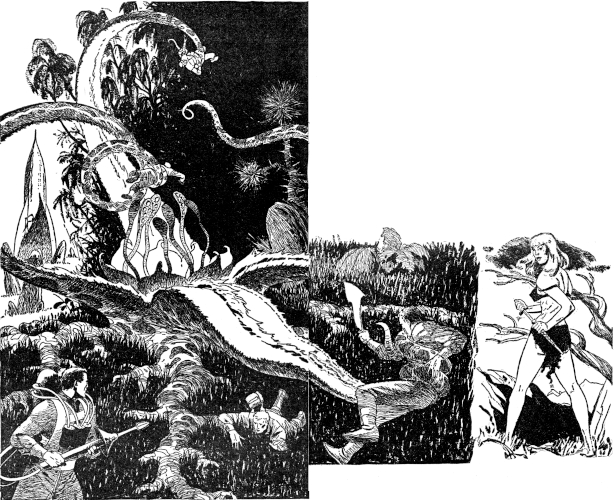

And it came alive. The whole length of it flailed up into the air, flinging the whirling chopper off into the gloom. The next instant the air was full of writhing ropey lengths that whipped down on the men, lashing thick branches off as they came.

"Look out!" yelled Pritchard needlessly, as the men cowered and ducked, arms flung over their heads.

Then something whipped about him hard, stinging and driving the breath from him. He felt himself swung up, his arms pinioned.

He caught a glimpse of other bodies rising with him, heard hoarse screaming and yelling.

Branches lashed by him and suddenly he was looking down on the jungle from high in the air, looking down on a sea of foliage, big, dish-shaped leaves lying atop the spreading ferns. Then he was curving down again, dizzyingly.

He saw it. A great maw, like the throat of an orchid, with a fringe of giant tentacles. It seemed to be rushing up at him.

Fighting to free his arms, he realized they were not held below the elbows. By crossing over with his left hand, he could draw his snapper and shift its butt into his right.

But he was descending into that obscenely working orifice, choking on its acrid stench, before he could manage it. The little needles went tseeu, tseeu, tseeu, down into the quivering pulp. They could be death for him at this range. Pritchard, dangling there in that moment of eternity, could only avert his face from the crisp blasts gusting back at him.

Abruptly he was flying through the air, his arms free. The snapper arced off in one direction and Pritchard went into his own gyrating, twisting, writhing parabola. A frond slapped him. A branch snapped under his hip. He was falling into foliage. A thick stem slithered along his hand and he grabbed at it, to hang on through an insane pendulum swing that carried him whisperingly close to the ground.

They found him crumpled at the foot of the tree against which he had been dashed.

Yet, within five minutes, he was reporting back to the ship that the party was intact. The giant hydra-type plant, in its death throe, had flung only him. The others had been held adangle in mid-air while it chose to feed on Pritchard first and, although he had been sent sailing, the tentacles gripping the others had simply loosened. One man, dropped upside down from ten feet, had a fractured collarbone, but they were even now cementing a flexicast in place and he would continue with the rest. Majinski had had the flamer torn from his hand and they weren't able to find it.

In fifteen minutes they were hacking steadily ahead again, more slowly now that they had no flamer, and having to stop to trace every creeper to its root before they chopped through it.

Pritchard straightened up from a tangle he'd been attacking and eased his bruised and aching back. He peered ahead into light-flecked gloom, the matted mass of vine, creeper and branch that grew so chokingly high they were virtually tunneling through. They would find no game this way, he reflected, their chopping and hacking and swearing spreading the alarm well ahead. The birds, for instance, had stopped singing. He glanced briefly to his left at young McManus grunting and swinging.

"Tom." Pritchard's tone was casual, but his eyes were alert and hard. The red-headed man held his stroke and peered ludicrously under his armpit.

"Freeze," said Pritchard.

The boy went rigid. "What is it?"

"On the branch above you." Pritchard's voice cracked out above the ringing blades. "Hold it, everybody! Hold it!" Then, in a lower tone, he gave orders, and the three or four cadet hunters near McManus slowly began to ease out their snappers. The cam-rec clicked into action.

"For the cripes sake, what is it?" whispered McManus, the red of exertion washing out of his face until it was a dripping ivory mask.

"I don't know." Pritchard began waving his arms slowly to attract the attention of the thing eighteen inches above that red hair. "I'd call it a scorpion if it didn't look like a spider. I'd call it a spider if it didn't look like a scorpion. It's not quite as big as a sheepdog." He uttered a chirping whistle and continued to wave his arms.

"For the love of God, blast it, then."

"I didn't finish telling you about Munson," remarked Pritchard conversationally. "Way back in 2018, he started the Venusian War—"

"Must we have a history lesson now?" said McManus through clenched teeth.

II

The thing above him made a convulsive movement, a quick clutching with its claws as if preparing to spring. McManus's face went from ivory to a dirty snow color. But the thing remained motionless, except that under its gleaming yellow carapace Pritchard could see its thorax pulsing evilly.

"Munson," Pritchard went on dryly, his arms still flagging away, although the spider-scorpion paid no apparent attention, "Munson was a great scientist. He trapped a big beetle and experimented on it for a week or so. Then he killed it for dissection. He had no idea it was a Citizen of Venus."

"Oh, I see," said the other sarcastically. "You're afraid to shoot this thing. It might be what passes for human on this mud-ball. If it drops on me, of course—"

"Shut up!" Pritchard dropped his hand to his snapper. The thing had stood up slowly, its segmented tail curving stiffly up behind it. "I think it's going to strike. You talk too much."

He brought the snapper up. "I'll do it, boys. I've got the clearest shot—"

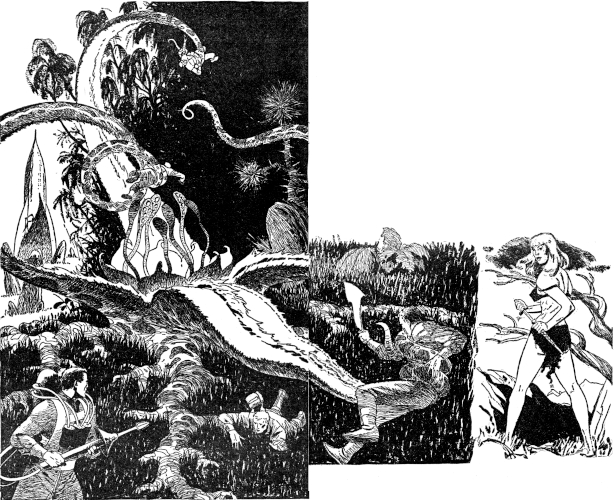

A sharp hiss broke from the jungle. The spidion (as he thought of calling it) jerked its ugly head about. Pritchard turned and caught his breath with a sharp intake. McManus slowly lifted his head to follow Pritchard's gaze. His chopper fell from his hand. All about them, men stood on tiptoe or stooped or craned sideways to look. Somebody said, "A woman!" Kemp panned the cam-rec about wildly until he caught her in its viewer.

She stood, straight and slim, on a gnarled stub protruding from a thick tree-trunk, some ten feet from the ground and about twenty feet from Pritchard, who was nearest her. Her honey-colored hair fell in crudely cut locks to her shoulders, framing a youthful, cleanly-chiseled face from which gray-green eyes gazed steadily. A strip of hide between her legs joined another strip of hide at her waist, from which hung a plaited grass sheath holding a long, narrow-bladed knife. A third strip of hide had the obvious main function of binding down her billowing breasts, rather than concealing them. Her skin had been tanned an even nut-brown all over.

From her lips came that sharp hiss again and she slapped her thigh smartly. The spidion was gone in a scuttling rush. McManus sagged weakly to the ground and drew a thick forearm across his forehead. "Geez, thanks, sister," he muttered.

"What are you doing here?" The girl's voice rang out through the jungle's stillness.

"Hunting," replied Pritchard.

"Hunting what?"

"Anything." He smiled up at her. "Anything big and tough. What are you doing here?"

He could just make out the corner of her mouth lifting in disdain. "What do you mean by 'anything big and tough?'"

Pritchard liked to have his own questions answered, too. "Who are you, anyway?" he rapped out sternly. "How come you speak Terran English? Where's the rest of your party?"

The girl only frowned down at him. "By what right do you come tramping in here killing all my people?"

"All your what?" Pritchard blinked.

"People, people, people. There are beings on this world who live and breathe and think just like you. But you seem to think it's all right to come in and kill them. For sport."

Gazing up into those blazing emerald eyes and that delicious figure, Pritchard felt an unaccustomed tingling through his nerves. Any woman, however crippled, deformed or aged, could provoke some excitement after the prison of deep space. But this beauty—

He glanced sideways at McManus who had moved up alongside him. The redhead had a feral grin on his freckled mug.

"Relax," muttered Pritchard from the corner of his mouth. "This one's for me."

He said to the girl, "We haven't killed anything, certainly not any people." The vision of that carbonized carcass back on the burn flickered across his mind. "What do you think we are, murderers? You're the first person we've seen."

She cut him off with an impatient gesture. "You're a pack of killers, all of you. I wouldn't expect you to understand."

"Hey, Mr. Pritchard," called out Sturgis, "I'll bet she's from that Havilland group. Ask her."

Pritchard cocked his head. "That's right! You are, aren't you? The Havilland Survey sent out by the Astrodetic Board. Unreported for four years. What happened? Where's your base?"

The girl nodded briefly. "And you're Pritchard, the notorious big-game hunter. I've heard about you. Nothing good, of course, but I've heard."

Pritchard smiled his sweetest smile. "That's right. I'm well known for my slaughter of helpless animals. But, come on, now," he coaxed, "how about a report on your party? The Board will appreciate any little message you care to send it."

The girl gripped a vine as if to steady herself. "Wiped out," she said tersely.

"Oh." He nodded, lips pursed. Then, as if it were an afterthought, he said, "How?"

"What does it matter?" The face above was momentarily tense, withdrawn. "With plenty of synthetabs—and the hydroponics laid out and producing—somebody still had to go out and kill. For fresh meat." Her voice trailed off.

"And—?" Pritchard prompted.

"Oh," she sighed wearily, "they came. They were the ones who got the fresh meat." She shuddered.

"Who's 'they?'"

"Please," she said, "I'd rather not discuss it any more. But I think you'd better leave. Certainly, you'd better not kill anything if you know what's good for you. Besides, you've done enough damage already."

Pritchard cleared his throat. The men behind him were whispering and snickering. "Speaking of leaving," he said, "how about you? If the Survey was wrecked—"

"I'm not interested in leaving," she said curtly. "I've got work to do here."

"What work?"

"I'm working with the people here."

"Oh, there are natives?"

"Certainly. This world is full of people."

He scowled his impatience. "What's their cultural stage?"

She favored him with a one-sided grin. "Some are foraging. A few are gregarious. You met one just now. Fortunately, I got here in time to save her life."

McManus's jaw dropped. "Save her life! You don't mean that crawly brute that tried to kill me just now?"

"If she threatened you," said the girl with careful enunciation such as she might use to a child, "it was because you had disturbed her peace."

"And it—she—was what you'd call a person?" demanded Pritchard, "Do you mean that you consider absolutely all the living, moving things here, people?"

The girl nodded firmly. Pritchard gazed at her, pawing his chin.

"Tell me," he murmured, "do they kill one another for fresh meat?"

She sighed. "They still do, but I'm trying to cure them of that. That's the work I'm doing. They only kill, after all, for food. I'm trying to cure them of the killing habit by getting them to switch to synthetabs. I've—"

The rest of her words were drowned in a tidal wave of laughter. The men exploded, beat each other, howled, and fell on the ground. She stared down at them, and her eyes began to smolder anew.

Pritchard fought his own face straight and wheeled on them. "Cut that out!" he yelled. "As you were!" They gurgled back at him, pleading their helplessness, hugging their sides. McManus gripped his cheeks and tried to squeeze his mouth straight, but strangled gusts still shook him.

The spectacle weakened Pritchard's own control and he turned quickly back to the girl. The sight of her beauty, now in a passionate rage, cut sharply across his mirth. He noticed with interest that the thin strip of hide across those heaving breasts was undergoing maximum strain.

"Please allow me to apologize for my men," he said gravely. "I'm sure they don't mean to be insulting. What is your name, by the way, so I can at least report it to the Board?"

Her chin was up. "Cornelia Boyce," she said haughtily.

"And how did you manage to survive the attack on the Survey camp?"

"I was away." She was calming a little. "They came at sunrise but I wasn't there. I was out, learning to ride one of the—the people."

Pritchard looked down quickly and coughed. Fresh gurgles sounded behind him. The cam-rec whirred on. "But you are all right here? You can take care of yourself?"

"I am in no danger," she said icily. "In four years I have won most of the people over to my side. They protect me. In turn, and in my own way, I protect them. I've learned how to make synthetabs and I also feed them from the 'ponics gardens. And now I'll do my best to protect them from you. I'm sure I can't appeal to your decency but I can appeal to your reason, and perhaps convince you that this is a poor world to hunt in."

"Now, listen, Miss Boyce," Pritchard cut in patiently, "we're not here on a mission of slaughter. I gather, and please correct me if I'm wrong, that you're one of that group back on Terra that opposes big-game hunting."

"You are completely correct about that," she interposed.

"—and are pushing through legislation to make it illegal under the Space Code. But we already adhere to the Space Code. We are most zealous, I assure you, to avoid bagging anything parahuman, anything that exhibits anything like human intelligence. We—"

"That's precisely why you should abandon your hunting here. My good man, just what do you consider intelligence?" She held up her hand to prevent his answering. "For instance, a good many of the what you would call animals on this little planet have developed a spoken language. And I don't mean a mother's warning to her cubs, or one male challenging another. I mean, for instance, the news I received this morning." She smiled. "Would you like to know what a little bird told me?"

He nodded. "I'm all ears."

"Well," she said thoughtfully, "it wasn't such a little bird, and it wasn't exactly news to me. After all, I'd seen your braking jets in the ionosphere and heard the cavitation rumble when you were settling into denser atmosphere in your orbit. But, anyway, here's what my birdie told me: 'A thing with sun-fire at both ends has come down out of the sky two flights from here. Now a flock of two-legged beasts from it are attacking the plants. We don't understand!'" Her face relaxed into a disconcerting smile. "They couldn't understand why you were so angry with the grass and the trees!"

"Extremely funny," he said gravely. "It just happens to be meaningless, also."

"Don't you see? They can communicate ideas!"

"Fine," he nodded. "What of it?"

"But—but that means they're intelligent. Too intelligent to be called 'animals'!"

He shook his head. "On Terra only one animal developed communications to a high degree. But we long ago decided that some other animals were fairly intelligent, for all that they didn't appear to speak among themselves. On many other worlds—and I can name you a score I've visited—lots of so-called 'animals', apart from the intelligences we dealt with, had developed fairly complex methods of communications that would put the old Terran elephants and ants to shame. That still didn't make them what we called 'people'."

Her eyes were hot with scorn. "I know that! If you'd lived with the Thisbeans as long as I have you'd understand. Why—"

"Now, look," said Pritchard with rising asperity, "we have satisfactory means of determining intelligence. If your 'people' are as you claim they're in no danger. But are you going to claim there are no killers here? They're what we're after, intelligent or not. And there are killers on every world, Miss Boyce."

She shook her head in despair at his stupidity. "There are no killers here, Mr. Pritchard. There are no killers anywhere on any world. Only variant life forms trying to live and eat, eating only to live. If we help them to find food, and guide their impulses...."

Pritchard gave up. The argument was futile. It struck him that the girl was mad. The horror of the attack on the Survey camp, followed by years of isolation from her kind, had left her in a hopelessly deranged state.

And a little plan took shape in his mind.

"That's all very fine," he said, cutting across her words, "but let me show you something that will prove to you we are not here to kill indiscriminately."

He turned to McManus. "Let's have your little pet, Tom." McManus raised his eyebrows, but fumbled the button of his breast pocket flap loose and pulled out the wriggling, six-legged infant rodent. Pritchard took it and held it out toward the girl.

"Here, Miss Boyce. My friend found this. He didn't bite its head off first thing. Now we'll turn it over to you for safekeeping."

"Aw," growled McManus.

"Quiet," Pritchard growled back at him. He lifted the wriggling little beast and it squeaked. "I guess I'd better not toss it."

The eyes of Cornelia Boyce were large and glowing with maternal pity. She dropped lightly to the ground and advanced, holding out her hand. Pritchard pulled back the hand with the little wriggler in it and his other shot forward to grip the girl's wrist.

She gasped and bent backward, striving to wrench loose. Her strength was such that Pritchard, turning to hand the cub back to McManus, almost lost his balance.

"Stop it," she cried. "You don't know what—"

Her lips moved for another second, but the words were lost in the sudden tumult that erupted about them. The jungle exploded, almost seemed to come alive at their very feet. Dimly-seen shapes came lurching and crashing toward them from every side, clambering and trampling and swinging from branch to branch. Here and there a tree cracked, splintered and fell.

The men whipped out their snappers and backed against each other, eyes rolling nervously in grim set faces. The girl frantically twisted out of Pritchard's fingers and stuck two fingers in her mouth.

A piercing, two-noted whistle stabbed through the mounting din. It stabbed again, and the uproar subsided into a confused rustling and shuffling. Silence fell across the dust-charged air.

All about, in the jungle surrounding the head of the path the scouting party had hacked, the vegetation barely concealed a shoulder-to-shoulder wall of hulking beasts, while smaller animals and what looked like maned gorillas crouched or stood along the bending branches. Tusks protruded from drooling jaws and hundreds of eyes blazed forth steadily.

"No shooting, no shooting!" Pritchard was bellowing. "She has them under control, boys. Hold your fire." Then he took a deep breath and turned toward Cornelia Boyce. She had backed off to a safe distance from him, her eyes twin pools of green contempt.

"My people." She bowed ironically. "At your service."

Pritchard grinned tautly. "You win. Of course, my intentions were only of the best. I thought you ought to come back to Terra for a little observation and examination, but—" he waved lightly "—let's skip it."

"You were lucky that I was able to stop them," she said. "Next time I might not be able to in time. Now if you're wise you'll just take your little ship and go home."

"Why, certainly, certainly." He bowed. "In the meantime it was a pleasure to have met you, Miss Boyce."

"I'm sure," she replied coldly. She lifted her head, and from her lips suddenly poured an astonishing babble, a mixture of coughing, grunting and chirping. There began to be movement in the brush, and some of the things there began lurching and crashing off.

"Where are they going?" Pritchard strove for a casual tone.

"I'm deploying them along your trail," she said with equal calm. "They will escort you out of this jungle and report to me when you re-enter the ship."

"And you were really talking to them?"

She shrugged, as if at a childish question. "Of course."

He studied her, and his long features slid into a crooked, embarrassed smile. "Miss Boyce, I owe you an apology. Maybe you've got something here after all."

She raised weary eyebrows. "If you're quite through looking at my body, you can go now."

He laughed shortly. "I wasn't, especially. Although it's very—"

"Good-bye!"

He bowed again and turned. "All right, boys. You heard what the lady said. Let's pull out of here. And let's keep our little hands away from our snappers, eh? The lady's friends appear to be quite numerous and a little touchy."

III

With a few dry, nervous chuckles, the cadet hunters hefted their equipment and started back up the trail. Just as the girl had predicted, shapes rustled in the foliage close by their sides, accompanied by an occasional growl or whine or snort that was somewhat unnerving. Pritchard could occasionally discern the shaggy shoulders of the gorilla-type, and some other lithe and slinking or lumbering shapes—with here and there a hump of slate-gray hide or a ridged, scaly back.

The return along the hacked-out trail was easier and quicker than their coming, and soon they saw the tip of the Apollo's bow in the sky beyond the shoulder of the hill. As they toiled back up the slope through the clogging grass, they became aware that the animals were not following them further, but backward glances could still make out some vague shapes in the foliage.

Pritchard became aware, also, of McManus's silence. The redhead, usually garrulous, had been silent from the start of their retreat, his square jaw clamped hard shut. The Chief Hunter slapped the young man's broad back.

"Relax, Tom. Men have backed down from women before. It's not considered bad form at all. Now and then they outmaneuver us, and that's all there is to it."

A couple of the others chuckled, but McManus continued his stolid slogging up the hill without a sign. Pritchard shrugged. They all trudged across the burn, and the great grasshopper-leg let down the platform for them.

Waiting for it to settle, Pritchard braced with one hand at the base of a towering fin and began slapping dust from his breeches. He heard Sturgis say, "Hey, watch that!" and the tseeu of a snapper.

He jerked erect in time to see McManus lower his weapon, and hear a distant explosion. Down over the hill, in the tall grass, what appeared to be a huge boar or pygmy rhino was writhing and kicking. Somberly, Pritchard watched its six twitching legs quiet down and stiffen.

"That was a good shot, Tom," he said.

McManus came toward him, grinning with relief. "I'd had about all I could take—" he started to say, and then Pritchard's fist slammed into his jaw. His feet left the ground and he fell heavily onto the hard ground under the tubes.

Pritchard was picking him up again when he heard Sturgis's voice again. "You'd better make it snappy, chief. I think they're working up to something."

Shapes were moving up through the distant grass. Wings were flapping or tilted in soaring across the jungle not far beyond. There came to the ship a dim, vast babble of cries, grunts, squeals, howls and barks.

They carried the inert McManus over to the platform in a hurry. But Pritchard let his finger rest on the buzzer-button while he looked over the array of animals now gathering in plain sight, fanning out around the perimeter of the scorched ground.

There were the slate-gray ones, like that which McManus had downed—six-legged, suber-snouted, long-tusked. There were hulking, scaly-hided ones, resembling ant-eating bears—also six-legged. In fact, the six-legged skeleton seemed to prevail among the fauna of Thisbe II. The canine-like ones running this way and that were six-legged, and so were certain slinking, feline types. On the other hand, the maned gorillas had but four appendages, and so had the ungainly-looking, leaping ones, that looked like hairless kangaroos except for their wicked, underslung jaws.

Quite suddenly, this horde was charging across the burn, converging on the shining cylinder towering above them, aiming for the platform still resting on the ground.

"What's he waiting for?" Pritchard heard the whisper above the rising thunder about them, knew he was meant to hear it. He jabbed home the button and the rising floor pressed their feet. He stepped over to the squawkie and spoke into its 'phragm. "Chief on, Savage. Hold your fire. We're clear." Turning to the men on the now rapidly rising platform, he said, "No shooting."

Soberly, they all gazed down at the horde sweeping up below, swirling about, bumping into the fins and one another. Their silence, other than the noise of their thousands of feet and hooves, was oppressive and menacing. A few of the leaping ones soared up at the platform, wriggling in mid-air and pawing, but it had gone too high and they fell back.

Then Pritchard glanced up. His hand started for his snapper. Toward them through the air came a cloud of flying things—great leathery-winged birds, smaller, faster, feathered ones—rising on a line of flight that would carry them above the platform to a point of interception, claws distended, beaks open and eager.

Thin and remote, a two-toned whistle sounded. Sounded again. The converging flocks wheeled, fluttered and fell away, gliding off toward the jungle. Far below, the milling horde flung up a varied array of heads, and then began to move, a drift that became a surge, trotting and hopping away across the burn.

"Phew!" said someone behind Pritchard. "That girl really has an army."

McManus sat up, shaking his head and staring at the smooth shining hull of the Apollo swinging down to them. He felt his jaw and squinted up at Pritchard.

"Quarters for you," the tall saturnine man said softly.

Late that evening Pritchard was in the chart room talking with Captain Savage. The Apollo's ventilation system had been in operation for over thirty hours now and the blowers had sucked out the last vestige of mechanically purified air, with its taint of ozone, metal and oil. It was pleasant to rock gently in the gimbal chairs and sniff the lush night air of Thisbe II. Aloft, in the nose, the watch was idly working out a game of kru, that old Martian solitaire involving domino-like counters. The autoscanner hooked to the magnar was ready to clang at the first blip on the screens. Below, in the wardrooms, the cadet hunters were amusing themselves with a runoff of the day's cam-rec spool ("Get this line about the synthetabs!" ... guffaws of laughter). Midway down the curving tail section Tom McManus sulked in his quarters, fingering the bruise on his jaw.

"So we'll pick up in the morning, hey?" mused the captain. His was a squat, ape-like body, surmounted by a long, goat's face and a grizzled skull.

"Yes." Pritchard drained his tall glass. "I'm not going to bother with her. If she can send a whole army of her animals against us it's going to make hunting a little difficult. We could set down on the other side and maybe get in a bit of shooting, but she'd catch up with us. Even if we try hunting from the air with the jet cruisers...." He shook his head. "It's too dangerous. I've got to look out for these boys, after all. No, I don't want to get messed up with her in any way." He stared calmly at the wall, seeing once again that lithe body straining out of his grasp, and knew himself for a liar.

"Well...." The captain rubbed his nose, furtively eyeing the other man's profile. He knew when a man was lying. It was one of the things one developed long before one got to be a hundred and thirteen years of age. He lowered his wrinkled old eyelids and went on, "... she's hung on here for four years. Maybe she isn't too crazy at that. Of course, it's kind of too bad to leave a filly like her running around loose."

"We'll just hope we won't be too much criticized for not bringing her home," Pritchard cut in quickly. "Thank God, we shot all that cam-rec footage. It'll—"

He lifted his head, his long nostrils flaring. "Murder! What's that stink coming from?"

The old man grimaced up at the air-grill.

"Eeugh! Low tide on Venus!"

Pritchard got up and went toward the intercom. "Something's died, I'd say, inside the ship or close by."

At that instant the intercom's tiny diaphragm screamed. Screamed, and broke off into a hoarse babble. The two men froze, scowling at each other. The babble rose again into a sharp screaming "NO!"—and then stopped.

Pritchard stepped to the 'phragm. "Chief on. All stations and quarters report, please."

Voices came back at him out of the wall. "Nose watch. All X here, Mr. Pritchard. What happened?"

"Stern watch. All X, chief. What—?"

"Wardroom, Greene on. All X. Something stinks, chief."

"Engine room. All X."

"Majinski on, retired to quarters. Pee-yew!"

Then, silence, pregnant with listening.

"McManus," snapped Pritchard.

"Louder," said the captain. "He may be asleep."

"McManus!" The tall hunter shouted. "TOM!"

Then he was out the door. The captain strode to the intercom. "All free hands to McManus. Fast!" he barked, and then ran after Pritchard who was already stepping into the axial lift.

McManus's quarters were well down in the tail. Pritchard found half a dozen men clustered at his cabin door which they had torched open. Their eyes were watering and they were gagging at the incredibly foul stench roiling the air.

"Where's McManus?" he demanded, starting to shoulder through them. The stench caught at his throat so that he choked on the words.

A cadet hunter clutched at his sleeve. "Don't go in there, chief," he gasped. "You can't do Tom any good now."

Savage was at the wall intercom. "Meyer, for God's sake, blow this ship out," he yelled hoarsely.

Pritchard shook off the detaining hand and stepped to the open door. He looked once at the dripping mess in the gimbal chair and jerked his head away.

The pie-shaped cubicle was otherwise normal at first glance. The hammock hung suspended between its swivels. The viewport was properly sealed. The bath and disposal unit in one far corner stood in spotless order, as did the sectional drawer case opposite.

What had come in here? And how had it gotten in? The door had been electro-locked in its sliding frame and the men, who had quite properly not waited for the magnekey Captain Savage alone carried, had had to burn through the lock wiring. There was no other way into the room.

Pritchard stepped over to the air-grill. His eyes swimming in the terrible stench in the cabin, he nevertheless could discern how the heavy chrome mesh had been torn loose from its bolts to lie at the foot of the wall. He shot one tortured, speculative glance at the six-inch hole in the wall and then hastily backed out, hand to mouth against his rising gorge.

The steel walls thrummed with the surge of the revved-up blowers. But there was no answering draft screaming up into a gale from the air grills. The lights flickered briefly, and then the blowers' thrum died.

"Shorted," a man muttered thickly.

More men were coming, sliding down the long poles until they reached the stench which was now spreading up through the ship. As soon as it hit their nostrils they gripped the poles to slow their descent, cursing. Down the passageway, two of those who had arrived first were now being sick.

Pritchard leaned against the wall trying to keep his breathing shallow, his eyes hard and steady on the open doorway and the lighted chamber beyond. Gradually, all eyes were turning to him, waiting, their owners breathing in short, labored gasps.

He stepped to the intercom. "All hands to the muster deck," he managed to choke out. "That means everybody. And use extreme caution. Something has boarded the ship and killed McManus. Listen to me. It is still on board! Arm yourselves and report to the muster deck immediately. Sturgis, step into the storeroom and break out the masks. Greene and Majinski, help him. Use the lift to bring them to the muster deck. Got it?"

Several strangling voices replied in order. Pritchard and Savage crowded into the lift with the rest of the men and went aloft.

"What do you think it is, son?" said Savage. Pritchard shrugged. "I don't know. What kind of thing or things could get through the ventilating system?"

The old man pursed his lips. "That's right. That's how we smelled it first. And then the blowers kicked off when all that compression backed up to them. You're right, Mr. Pritchard, whatever it is, it's still in the ducts."

The lift halted at the muster deck and the door slid open. "So here's what we'll do," said Pritchard as they stepped off. The old man heard him out and then nodded slowly, his rheumy eyes narrowing.

They waited while the men arrived, the whole ship's company of twenty cadet hunters (less McManus, now) and five crewmen. They all stood around eyeing Pritchard and the captain. The air was heavy with that lurking stench, but it was not too thick here to be unbreathable.

As soon as the gas mask detail had shoved the last of the cartons off the lift Pritchard started for the controls.

The muster deck was a heavily insulated circular chamber a bit forward from amidships.

The entire ship could be controlled from there. In emergencies it could be detached from the ship and used as a temporary space raft, having all necessary supplies in its padded wall lockers.

"First," announced Pritchard, "we're going to button this ship up tight." He reached for the ventilator switch and flicked it on.

Little motors all over the inner and outer hulls began wheeling shut the valves that closed the six-inch holes that were the ventilating system's intake and exhaust ports. In a matter of seconds the Apollo would stop breathing the wine-like night air of Thisbe II.

On the wall above the switch little green lights began to blink off one by one. As if gradually understanding his strategy, the men began to move up behind Pritchard, their eyes on the bank of fiery green points winking out.

The last little gem flickered, died, and then, strangely, flamed up again.

And, just as it went out for good, the entire muster deck gave a lurch. Feet scuffled, slipped, staggered. Here and there a body thudded to the steel plates of the floor.

Pritchard's voice rose thundering above the abrupt commotion. "Grab hold! Something's got the ship—something—"

The muster deck swung in a wild circle, men sliding helplessly, caroming off the walls. Pritchard's flailing hand caught something and his long bony fingers laced about it in a grip of steel.

In benumbed fascination, he saw his body lengthen out, straining against that grip, appearing to levitate from the deck. The whole chamber tilted slowly until it seemed to hang below him. Men were slipping and falling down into the curved well of its farther wall, but some had grabbed out at holds here and there—a door-pull, or a stanchion, and dangled like Pritchard.

At the last instant he understood that the Apollo was falling. He had just time to pull himself up, to give his arm some play against the shock to come—

The great pointed cylinder struck with an awesome, deafening clangor—fell with a single bounce across its landing burn and settled to roll over approximately one-third its circumference.

Pritchard's grip, he discovered later, was to the handle of a locked chart drawer. The massive wrench of that impact straightened his arm with a jerk, but at the same time the drawer's lock broke. He fell away in a shower of sheet film just as the Apollo rolled, and a curve of smooth steel wall swung out to catch him and break his fall into a plunging glide against a cushion of stunned men's bodies.

It was a miracle that nobody was seriously injured. The slowness of the ship's fall at the outset, the curvature of walls, the general fitness of trained minds and bodies—all combined to prevent anything more serious than cuts and contusions.

Captain Savage was the first Pritchard pulled out of the tangle. The wiry old man was unhurt, though dazed. In spite of his age he gamely pulled himself together with a terrier-like shake.

"What hit us?" he croaked.

"I think whatever was in the ship did it," said Pritchard. "But then, that must mean it's outside now. Think we sustained much damage?"

The old man scoffed. "Man, this ship was built for crash landings. The surface glaze must be cracked. And all the supplies we broke out after landing must be all over hell."

He gazed aloft at the muster deck's controls, now high overhead. "Have to right her," he muttered, "but I can't get at them. I'll have to get to the master set, I guess." His gaze switched dubiously to the hatch leading to the nose, halfway up the curving wall. "I can set her back up on her tail, firing the beam tubes."

"Majinski," called out Pritchard, "build a ladder or pyramid of men up that hatch so the captain can get to the controls. Sturgis, you and you and you—" he picked out half a dozen cadet hunters "—let's scout through the ship. I want to be sure our friend has left."

It was awkward work, clambering over girders and through crazily slanting doors and along upside down passages where, in deep space, they floated past with ease. They held their snappers ready while Pritchard opened door after door with the captain's magnekey.

They found something in the compression chamber of Number Two Blower. What they found, after taking down the side panel, was a long, flopping red thing—something like a ten-foot carrot, writhing and curling in on itself wetly. It was a foot thick at its big end.

It fell out on the curving wall beneath the blower. They watched it soberly as it twisted this way and that convulsively, contracting and lengthening out. It gave off that same sickening odor.

"Is this what gave us all the trouble?" somebody demanded.

"No." Pritchard's nostrils flared slightly. "Just a part of it, that's all. Most of it got away."

"Most of it!"

He nodded slowly. "It was leaving when I started closing those ports. It was leaving by this intake port—maybe the way it came in—and the valve started to slice into it. In other words, we had it by the tail. It tried to yank free and that's what tipped us over."

"Y-y-you mean—?" They stared at him, refusing to credit the comprehension dawning in their minds.

"What else?" Pritchard's cheeks twitched in amusement.

"Hey, that's big!" said Sturgis softly.

"Quite big," murmured the tall hunter. "And quite intelligent if it came for McManus."

Their jaws dropped and their eyes protruded glassily.

"On the other hand," went on Pritchard musingly, "it might not be as smart as the person who sent it."

IV

There was flame in the night, blinding flame, and raucous, screeching thunder. And a great round of gleaming metal rising shudderingly on a cone of dazzling, roaring light. Rising to teeter at last on the tips of long, sweeping fins, teeter and rock and walk a bit on those blades of tempered nickel-steel, until the swaying tower ceased to gyrate sickeningly across the stars, its motion settling into a quickening, shortening arc that died away into a tremble, a vibration, a stillness.

Captain Savage took his gnarled and stubby fingers away from the firing manuals and sat down, drawing a sleeve across his sopping brows.

"Nice work," said Pritchard. "One push and no correction blasts. Thy hand hath not lost its skill."

The old man took a deep breath and grinned. "It's work for a younger man. Next time I'm going to let you do it. Or Sturgis."

"There won't be a next time," said Pritchard flatly.

The captain cocked a bright eye up at him. Pritchard gazed out a viewport. The horizon of Thisbe II lay like a worn hacksaw blade against the purple glow of Piramus, rising.

"Set watches," he said briefly. "The rest of the company can turn to for six hours. Then Sturgis, Greene, Kemp and I are going off in the jets."

"Fishing, I suppose?" said Savage with gentle irony.

Pritchard smiled coldly and shook his head. "No. Witch-hunting."

Two plump silvery beetles screamed through the thin stratosphere high above the little planet. Behind them, dropping below the horizon, a needle stood gleaming in a black thumbprint. It was no longer possible to make out the smudge marring the Apollo's alabaster flank, much less the team now hanging in buckets from eyebolts high in the nose, chipping away the cracked and carbonized glaze—cracked by last night's fall and carbonized by the hell-fires of the righting operation.

In one beetle rode the wiry Sturgis and stocky Kemp. In the other, the rangy blond, Greene, handled the controls while Pritchard studied the face of Thisbe II rolling slowly under them.

"Got any ideas yet as to what hit us last night?" said Greene.

"Nope." After righting the ship, they'd turned on the floodlights, but neither then nor in the broad light of day was there any sign or trace of their visitor. A burial detail had laid McManus the traditional six feet into the crust of Thisbe II. The long red thing had flopped and tossed startlingly as they sank hooks into it and dragged it off into the grass.

"Must have been the tail of something big, huh? How come it got past the radar?"

Pritchard shrugged and continued to peer attentively ahead.

"Sure is a mighty pretty hunk of country," sighed the blond boy. "In places it reminds me of the stuff around the Cumberland Gap. If it weren't for that lavender sunlight, that is."

Pritchard didn't answer, his eyes steadily sweeping the terrain unfolding ahead.

"That was a hell of a thing happened to poor Tom last night," Greene went on. "Do you figure he had much pain before it finished him?"

Pritchard made no response.

"Tom was a right good boy, and a hard man to beat once he had the chance to get his feet under him. Remember the time big Hayes hit him?"

There was no answer. Greene sat relaxed, one foot on the rudder bar and an index finger curled indolently around the jet firing toggle.

"Boy, old Hayes let him have it before Tom was set. Just like you clipped him yesterday."

"I thought you'd say that." Pritchard's voice was even. "You an' the rest of the boys want to be sure I don't forget that, don't you?"

"I wasn't meaning a thing, chief," complained the other. "Hell, we understand. Tom made a mistake and—and—well...."

"You can pass the word," said Pritchard softly, his eyes remaining hard on the vista ahead. "You can pass the word that I haven't forgotten the last thing Tom McManus had from me. Nor am I likely to—"

He grabbed the mike. "Cut, Sturgis, cut! Cut and glide—after me."

Greene, following instructions meant for him, too, snapped the jet toggle closed. The high-pitched thunder that had been chasing them across the sky was chopped off into utter silence.

"What you got?" he managed to say and then Pritchard's hip swung against him, neatly bowling him off the seat as the tall hunter thrust his feet toward the rudder bar.

"Stand by to fire," snapped Pritchard over his shoulder. The younger man lurched toward the rocket controls in the nose in front of Pritchard as the jet cruiser heeled silently over into a dive.

The bowl of Thisbe II tilted up toward them and its features steadied in the face of that arrowing plunge. Dead ahead lay a meandering thread of river stitching up a wide, jungle-filled valley. At one point the river either split in two or broadened momentarily into a lake. At any rate, there was an island, right above the little flight-sight bead on the jet cruiser's prow.

The island swelled into detail. It was fairly large, for up from its center thrust one of those strange rock mountains, the three straight planes of its cleavage converging in a jagged, towering peak, making it seem an elongated triangular pyramid that had been driven forth at a slant and had then had its extreme tip snapped off. The primrose light of Piramus high above reflected now in a dazzling shimmer from one flank.

At its base, or at the base of one impossibly machine-smooth wall, there was a semi-circular mark, as if someone had carelessly strewn dirt across the olive-hued turf. The grains and clods of this dirt resolved themselves, as the jets whined on down, into a twinkling, tumbling cluster of ants—with gnats hovering and darting. Then they became something larger.

Greene turned to shout excitedly at Pritchard, but at that instant Sturgis's voice cracked from the two-way mike Pritchard had hung above him.

"Hey, chief, aren't those some of that girl's animals?"

"Right," barked Pritchard. "That's a big rumpus down there. Follow me on down for a look. Then I think we'll try a couple of passes."

"Passes? At what?"

"Those are Miss Boyce's 'people', all right. They're fighting."

There was no further chance to talk. Pritchard and Sturgis gripped their separate toggles almost simultaneously and their jets roared into life, feeding power to their dives for a pull-out. The ground-contact alarm chattered its warning that they were coming too close.

As soon as the jets took hold, the pilots leaned back, pushing hard against the rudder bars. The tail elevators lifted into the slipstream, and the two silver beetles howled through a long pendulum swing that flung them far off into the sky.

But the trained eyes aboard them had ticked off the essential details of the amazing battle being waged through the tall grass toward the mountain.

"Holy rockets!" came from the blond head in front of Pritchard. "That's a regular battle line they're holding. Did you see those babies fighting!"

"Hey, chief," cracked Sturgis, "What goes on down there, anyway? Who's fighting whom? Or what's fighting which?"

Pritchard trimmed off into level flight before answering. "As far as I can make out, Cornelia Boyce's people are under attack, but I can't figure out who's doing the attacking. They're trying to hold that defense arc, but they're being snowed under. They're catching it from the air as well as on the ground. I recognize the animals inside that line. They're her people, all right. But I can't make out the attackers."

He banked the cruiser around toward that now miles-distant little spine of mountain.

Sturgis's ship followed him around as if fastened by a wire.

"They looked like reptiles and big insects."

"That's what they looked like to me. I don't remember seeing any of them yesterday—except for that bad dream I tried to shoot away from McManus."

"Anyway, there's sure a mob of them," cut in Sturgis. "The water all around that island is alive with them."

"That kid was right about one thing," said Pritchard. "There's a much higher level of intelligence here than you'd find in Terran animals, for instance. But never mind that now. Listen, boys, this is a planned and directed attack. And we're going to buy ourselves a stack of chips and sit in on the game. But, first, did anybody see the girl?"

"No," cracked the mike, and Greene shook his head.

"Well, I've got a hunch she's down there. She's mixed up in this somehow. I've a feeling a big battle like this is pretty unusual. This has all the earmarks of a war of extermination. And if those are her 'people' protecting her—something, or somebody, has her cornered."

"Could be," came Sturgis's voice. "But, then, who's this somebody or something?"

"I don't know. I don't care. This scrap's nothing to us. But we want the wench, boys. We want her on account of last night. And maybe for a couple of other reasons. She'd better come home for a little psychotherapy, for one thing. Now, here's our plan of attack...."

Like the pointer of a sundial, the jagged spear of mountain lay its deep blue shadow across the curve of battle, as if to mark off the dwindling hours and minutes of life for those who struggled, writhed and lay with glazing eyes in that long ribbony grass, now mashed and matted flat for acres in every direction, its pliant green-brown blades stained and mottled dark.

Red-eyed and snorting, the slate-gray boars stood shoulder to shoulder from one end of the arc to the other. As each one fell, the others closed ranks, shuffling backwards until their hides rubbed together again. Close behind them stood a thinning line of great scaled bears, clawing and biting what got past the boars. In and out among all their stiffly planted legs ran the lesser carnivores and the canines, snapping and worrying at the things creeping through the grass. Behind, in the shrinking zone of defense, roved the six-legged bovines and equines, and the leaping ones, and the shaggy-maned gorillas, prancing, goring, trampling, crushing. Overhead circled and hovered a swarm of hawks and condors, plunging and tearing.

Against them came a nightmare horde. Those that could not fly or swim made clumsy rafts from odds and ends of vegetation and branches plundered from the jungle; some scurried across on swaying creepers, all along the banks.

Crawling, creeping things, reptilian and crustacean and multi-legged, undulating and gliding, disappearing into the grass to emerge at the last deadly moment. Scurrying, spiny things were there in force—scuttling over the mashed-flat grass in beady-eyed haste to be in at the kill. Above them flew skull-headed, mandible-snapping horrors, with membranous wings.

There were no tactics other than individual duel and the wearing down by sheer weight of numbers. Aloft, the winged ones met, clashed and fell, buzzing and flapping. Below, tusk and fang and claw and beak and hoof mandible rent and tore and worried and stung. The long, vicious lizards and the sudden-striking snakes kept coming through only to go down under churning, stamping hooves or be shredded by horns and claws and fangs.

Yet the battle was unequal. Slowly and wearily, the defenders gave before the superior numbers, the more skillful killing. The bodies they left dotting the meadow began to outnumber the crushed remains of the things they fought.

Deep in a cleft in the base of the mountain crouched a young Terran female. Every inch of her brown body shaking in helpless terror.

Cornelia Boyce's left hand gripped the handle of her long knife, still in its sheath. She would need it any time now.

For The One was coming for her at last. Why it had ordered Its people against hers, calling them with Its vicious mind from the far corners of this world, instead of coming for her directly, she didn't know. Perhaps It regarded her as the lesser objective and relegated the task of smashing her and her converts to this horde, while It moved against the ship. Perhaps It regarded the ship of the hunters with the same contempt It had had for the Survey ship and was moving against her first—and was using this battle to toy with her, show her death, as it were. Perhaps there was some other reason. It didn't matter. Nothing mattered any more, for this was the end.

It had tolerated her. For four of Thisbe II's years—not quite three Terran years—The One had left her alone, almost, it would seem, keeping out of her way. It was as if It realized that she, the only one of her kind to survive the debacle at the Survey camp, was essentially harmless. It had not minded her attempts to win over and tame and domesticate some of the people. After all, she had converted only the weaker and gentler of them with her synthetabs; she had gained control over only a small percentage of the killers, the lesser carnivores. No, she had never really threatened The One's dominance.

Pritchard was right. Now that her carefully woven veil of illusion was torn away, she knew that there were killers. Everywhere. Always had been. Killers, killers, killers....

The One proved that. It killed a hundred times a day. This world was Its preserve and It roamed and fed and slew as It chose, only occasionally for food. Perhaps this was the only reason for existence, in the last analysis—in a cruel Cosmos one lived only to be killer or killed.

It mattered not. This was the end. Angered by the advent of more of her kind, It had no doubt decided to wipe out both her and them, recognizing in them all a degree of intelligence which, in force, could threaten Its control. It would move against the ship, if indeed It had not already done so.

But It would certainly destroy her. This attack would have no other meaning.

But she would cheat It. The One could not move faster than her knife!

There was not much time now, and certainly no hope. The battle raging before her was mounting to its inevitable bloody climax.

Her people could not hold out much longer. Their courage and faith and loyalty might not survive so terrible an ordeal. Were not some of the birds already winging away to distant refuge?

It was too bad. She would have liked to see the tall hunter once more before she.... His eyes had been so piercing! She had forgotten what a man could be like. If only she had not been so balky yesterday!

But it was not to be. He had come, in one of those two jet cruisers, thundering across the killer-infested meadow, and he had gone. He had seen and not understood. Battles between alien beasts were of no concern to him. He might even return, to make cam-rec footage from aloft of this amazing battle.

Hope flashed. She could signal him! What could she use?

How could she catch a roving eye in a ten-mile-a-minute jet?

She tossed up her head, eyes suddenly narrowed.

Something came screaming around the mountain above her, followed by a second screaming something.

Then hell erupted beyond the battle line. Blast followed concussive blast, causing the big gorillas to cower and the other ones to charge about in helpless panic. Between the jarring blasts sounded the rippling crackle of dual-mounted automatic snappers.

The screams faded off into the sky. A stunned silence reigned along the battle perimeter. An acrid smoke drifted over the ground.

Then, just as groups were sporadically renewing their death-grips here and there, the twin screams sounded beyond the mountain again.

V

"Two laps around the track and then to the showers!" yelled Greene, his fingers dancing over the rocket release and snapper buttons.

Leaning back against the rudder bar, Pritchard grinned. "You forget the passes along the river banks. They make it four laps."

Then he threw a quick glance over his shoulder, but he couldn't make much through the welter of rising dirt columns.

They came around the mountain in a tight curve. As they flattened for a run on the meadow they could see things scurrying for the water. The meadow itself was a churned and pitted mess. Bodies were thickly strewn everywhere.

"There she is!" yelled Sturgis. "You were right, chief. See her—over by the mountain?"

A tiny figure, mounted on a six-legged equine, was riding furiously back and forth. The defense arc was swelling outward, as her "people" rose to the offensive and began charging the demoralized attackers.

Then the two cruisers were racing through their run on the as yet unstrafed portion of the meadow furthest from the mountain. Sturgis's craft bucked as it rode the shock-waves from Greene's rocket blasts. As they shot in a wide curve around the other side of the mountain Pritchard said, "We'd better skip our last pass. Let's just sit down and work in close. I don't want her to get away."

They cut jets and floated in over the jungle, side-slipping to lose speed. With feather-light fingers at their controls, the cruisers skimmed the trampled meadow grass and touched down their wheels. As they rolled, Pritchard and Sturgis flung open cockpit windows and let bright fire from their flamers spew over the ground, while Greene and Kemp sprayed right and left with their snappers.

Things struggled in the crisping, burning grass, crackling and roasting. Even as he turned the nozzle this way and that, Pritchard's face was a mask of disgust. All around the slowing ships, Cornelia's "people" galloped and raced with a vengeful, slaying lust.

"All out," said Pritchard. "Everybody take a flamer. We'll have to burn a path to the girl."

They climbed out and began walking toward the mountain four abreast, flame billowing ahead of them. There seemed to be only dead things in their path.

Then, suddenly, the girl was there, astride a magnificent six-legged equine type of animal, shaggy of coat and rather broad in the head. She had ridden around the wall of fire and her mount was trembling and shaking its head.

They turned off the flamers and stared up at her. Rumbling, whinnying sounds came from the equine's throat. She grunted and cooed back, as if soothing it. Then she turned her eyes on the men below.

"We wish to thank you." Her pale face was drawn and there was a suspicion of tears in her voice. "You came just in time."

She seemed small and absurdly girlish perched on that long back. Those inadequate strips of hide were still her only covering.

Pritchard nodded shortly. "If you'll be so good as to keep your be—people—out of our way, we'll sterilize this island. Just burn off all the cover and see to it there's none of them left. Why don't you herd your—uh—friends over onto what we've already—"

"That won't be necessary," she cut in. "They'll all be gone in another minute."

"What makes you so sure of that?"

"The One is probably calling them off."

"The—what?"

She put her face in her hands. Pritchard frowned his puzzlement. How had so helpless a child managed to survive in a world like this?

"I'd like very much to know what this is all about, Miss Boyce," he said gently. "In fact, the reason we happened along is that we are looking for you. We thought you might be able to explain what happened last night."

As he told her, she lifted her face from her hands and her brimming eyes grew round. Before he had finished describing what they had found in the blower, she was shaking her head in despair.

"This is all your doing. This world was at peace until you came. Now The One is aroused. You see, it was The One that went into your ship—"

"The One?" A crispness came into his voice. "Miss Boyce, I think you'd better start at the beginning and give us a complete explanation. Just exactly what is this 'One' you keep talking about?"

She closed her eyes again. A slight shudder ran through her body and she shook her head dazedly.

"The One," she murmured, "is after us all now. It began by entering your ship. Then It sent Its people against mine—against me. It won't stop until It has destroyed us all, and It—It's something I'd just as lief not describe.

"My people call it something which I have translated as 'The One'. To them, it means 'first', or 'leader', or something like that. It was in control of all the people here on Thisbe when the Survey arrived, and I'm afraid It still is. It wants to remain in control. You see, It's quite intelligent."

"I can believe that," Pritchard said. "It not only figured out how to get into the ship, but it also figured out how to find McManus."

"Oh, no, I don't believe it just went after him. Wasn't his cabin the nearest to the place it entered?"

"Well, yes, as a matter of fact, it was."

"Oh, you don't understand The One as I do," she cried. "It would never be satisfied with just one. It came into your ship to feed on all of you. McManus was just the first person It found. From what you tell me, It wasn't even finished with him. There wouldn't be—anything—left...."

"Then why did It go away?"

"I couldn't tell you. Perhaps when your blower short-circuited, it arced a little. The One is very sensitive to fire. But It's not through. It will come back, one way or another."

"I think we can deal with it if it does," Pritchard smiled. "And it sent these unpleasant things at you? How can it do that?" He shot an appraising glance around the torn and bloody meadow with its mounds of dead and dying things.

When he turned back the girl was weeping. Sobs she could not suppress were shaking those nut-brown, rounded shoulders. "It has some kind of mental control," came her muffled voice. "Besides, they fear It dreadfully. Oh, my people, my poor people."

"Well, now, look," soothed Pritchard, "it's all over now. You'd better come back with us. I guess you've learned you can't make people out of all these animals. Besides, you've got an interesting story to tell the Board—"

"D-damn the B-B-Board," she said a little unsteadily. "Then you'll take me with you?"

Pritchard smiled his broadest smile. "But of course!"

"Then let's hurry," she pleaded. "We have so little time."

"Why? What's the hurry?"

"The One! The One!" she burst out in sudden anxiety. "It'll come for us any minute, don't you understand?"

"Okay, okay," soothed Pritchard. He and the others were smiling at her excitement, when her equine suddenly reared so suddenly that she tumbled off. They started to her assistance, but she landed light as a cat on her feet. She stared wildly about her.

The equine uttered a growl and galloped off. The girl remained crouched, her eyes darting in every direction.

"Now what?" said Pritchard.

"The One," she breathed. "It's somewhere near. My sextuped would never have bolted like that otherwise."

"Oh, for Pete's sake," said Pritchard, taking her arm. "Come on—"

"Say, Mr. Pritchard, what's that thing over there?" Kemp pointed off to his left.

"Oh, God, no...." Cornelia's voice was a quavering moan.

Pritchard glanced where the stocky lad was pointing. What appeared to be an exceptionally tall and unusually red grass blade was wavering gently, as if bending to a mild breeze, about fifty yards off.

"Hell," muttered Sturgis, "that face is familiar."

Pritchard started walking toward it, the others following him. "Let's fan out a bit," he said, "until we see what this is."

"Come back, come back," came the girl's agonized whisper behind them. "Don't go near...."

They ignored her. At a distance of ten yards Pritchard halted. They all watched with consuming curiosity.

The slender red thing was growing. Or, rather, it was pouring out of the ground, crumbs of dirt sticking to its glistening scarlet wetness, its delicately tapering tip now some ten or twelve feet in the air.

Pritchard shifted the flamer tank on his shoulders and started to say, "I think—", when a maned gorilla loping across the meadow some hundred yards away gave a sudden scream and broke into a wild, shambling run in the other direction. Another animal gave bellowing voice, and another—and abruptly there was commotion, spreading over the island toward the mountain.

Pritchard cleared his throat. "Get around it, boys. Let it keep coming, but when I say the word give it a lick of fire."

The waving red spire stood some fifteen feet high now. As he circled into his position with the others, he noticed two things simultaneously. Another little scarlet tip was questing up through the trampled grass close to the first one. And, out of the corner of his eye he could see the animals that were Cornelia's people streaming either way along the base of the mountain, in a frenzied rout to get to the river on the other side.

Then Cornelia's hands were clenching his arm, her voice panting hysterically in his ear. "Run, Pritchard! You don't know what you're up against. Oh, believe me," she sobbed, "please, please, please believe me. This is The One."

His eyes focusing on the growing scarlet tips—the second one had grown almost as high as the first—Pritchard smiled indulgently. "We're going to stay for the fun," he said. "What happened to all your friends? Stampeded, didn't they?"

She opened her mouth to reply but her answer was cut off by Greene's sudden scream.

Greene screamed as McManus had screamed last night. Screamed and sank writhing to his knees. Some kind of frothing slime was running down over his shoulders and chest, dissolving the acid-repellent cordron jacket, running down over Greene from what had been his head.

From between the bases of the now thick, tall red tongues, another jet of liquid squirted toward Sturgis. He leaped sideways and it missed him clean. "Holy Damn!" he shouted.

Pritchard gripped the flamer's trigger. "Give it hell!" he roared.

Three streams of fire converged in a ball of flame on the twin red spires. They disappeared in the rippling, booming fire.

"Hold it!" Pritchard shut off his flamer and the others followed suit. Holding the nozzle before him, he walked to the place where the things had been.

There was nothing there, except a hole where the tangled grass had been disturbed, and a kind of pit in the ground, into which loose dirt was still dribbling. He backed a step and turned the flamer on, playing fire into the pit and around it. Then he shut it off.

"You fool," came the girl's voice at his elbow. "You damned fool. You just won't believe me, will you?"

Pritchard lifted his gaze toward what had once been Cadet Greene. Richard Harrison Greene, a rollicking lad from the Cumberland Gap. Thomas Guilfoyle McManus, a man with a red-haired soul. McManus, first, and, now, Greene. The hunter's face was turned to stone.

"Keep your eyes peeled," he said harshly to the others and stalked off to the place where the squirt of liquid had landed after missing Sturgis. Some thirty feet from where it had been ejected, there was no grass but a four-foot smear where the ground bubbled and frothed. The stench hovering over this spot was incredible, even to the man who had encountered it before.

He turned to confront Cornelia who had followed him. "I don't know whether I can get it through your thick head or not," she bit out, "you've simply got to get out of here. You can't—"

"Get this through your thick head, Miss Boyce," said Pritchard between clenched teeth. "This thing, whatever it is, has killed two of my men. I'm quite ready to believe it is intelligent, possibly the most intelligent organism on this planet. But it's a killer just the same and we're going to kill it. None of your idealistic theories are going to stop us, either."

She stared at him, beginning to shake her head a little wildly. "You can't kill it! That's what I'm trying to tell you. It can't be k—"

There was a sudden crash. Cornelia whirled and screamed. The three men and the girl stood transfixed.

Over by the river one of the jet cruisers was on its side, resting on a crumpled wing. The other was forty feet in the air, and rising, held in the coil of an impossible red monstrosity rearing its long wet self into the sky.

It was a worm, a very long, thin worm at least a hundred feet long, not counting what remained underground. It towered some fifty feet into the air, about thirty-five feet more of it wrapped around the cruiser. At its tip two fifteen-feet-long feelers writhed and wriggled, as if still smarting from the scorching they had received.

The coil slipped a little. The cruiser, looking more than ever like a beetle at this moment, slid slowly out and fell. And again it crashed into the cruiser on the ground and rolled ponderously off it.

"Good ... God!" came Sturgis's voice shakily at Pritchard's elbow. The Chief Hunter was still too appalled to speak. He stared as the worm's rope-like body came curving down out of the sky, down to the cruisers again. Seeing how that red length alternately thinned to a one-foot thickness and swelled again to three feet and more as it oozed around the cruiser that had remained on the ground, he had a vision of how it had entered the Apollo, shrinking itself to a mere six-inch thread that poured through the intake port, seeping along the duct, swelling, bulging at McManus's air-grill ... and coming out of the ground, probably close to the ship, it had evaded the radar field.

Cornelia's agonized face swam before his eyes. He felt his body shaking in the grip of her slender hands. Words—

"—fool, run! Listen to me! It's busy smashing your ships. We have a chance. Run—to the mountain! Oh, dear God...."

At first he was like a sleep-walker. They turned him around and pushed him into a stumbling run, but his head turned back, his eyes large and almost vacant on that scene by the river.