“Cheer up, Bunny,” chirped Bobby Robin

“Cheer up, Bunny,” chirped Bobby Robin

The air was blowing in at the mouth of his hole when Little Nibble Rabbit opened his eyes. That meant a cold south wind outside, a rainy wind. He could see the wet drops hanging from the top of his arched earth doorway. They would wet his back when he tried to go out and that wouldn’t be nice. He shivered and closed his eyes again. Then he huddled up tighter than ever into a little furry brown ball. Still he was cold, so he tried to cuddle into the very farthest corner where his mother always slept. It was empty!

That woke him up. “Mammy,” he called softly; “Mammy.” No answer. He put his nose to the earth and found it still warm. She could not have been gone very long. So he crawled to the mouth of the hole and thumped with his little hind feet, making all the noise he dared. Then he sat up and cocked his ears for her answering thump. He half expected a glimpse of her white tail bobbing down one of the tunnels through the Prickly Ash Thicket. But no mother was there.

“She can’t go off and leave me like this,” he said to himself, and he put down his nose to find her trail. It was all washed out by the rain. Thump, thump! he went again—and they were cross thumps because he was so terribly disappointed. Then he suddenly sat down on his little tufty tail and wailed “Mammy, mammy, mammy!” at the top of his voice.

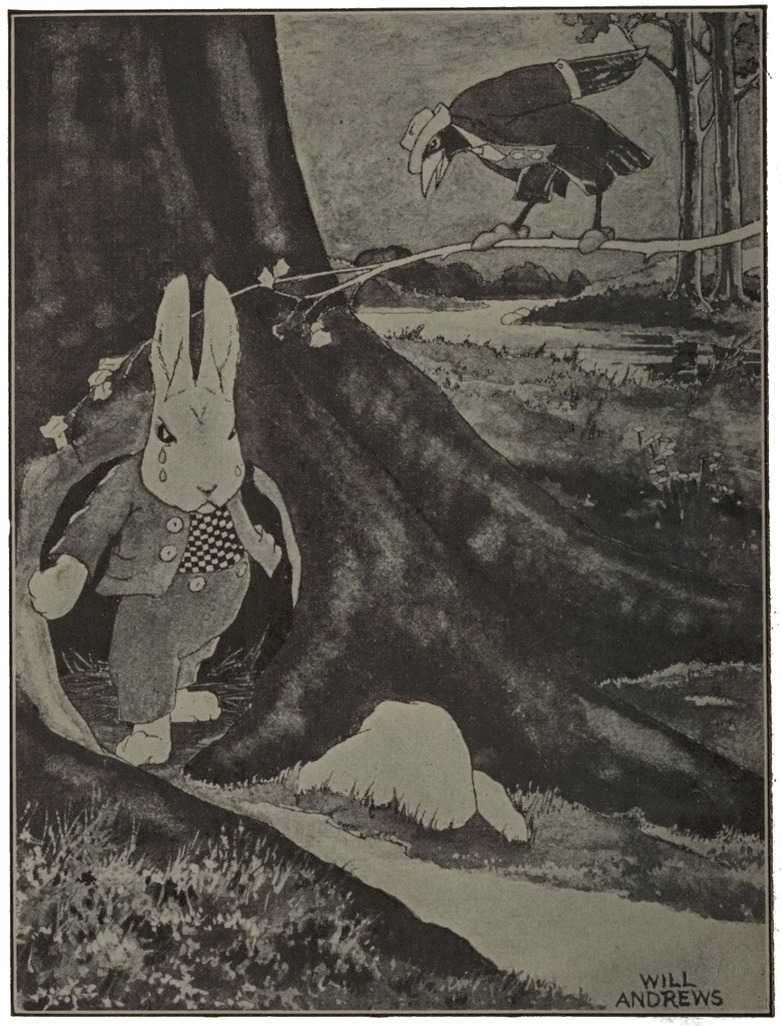

“Cheer up, Bunny. What’s wrong,” chirped some one from a branch just over his head. It was Bobby Robin, and he was peering down with the most puzzled and astonished look in his black eye.

“I’m Nibble,” sobbed the little rabbit, “and I’ve lost my mother.”

“Well, Nibble,” warned Bobby in his sensible way, “if she doesn’t come back pretty soon she’ll lose her son. Don’t you know better than to tell Killer Weasel and Silvertip the Fox, and Hooter the Owl, and any one else who wants to know where they’ll find a nice young rabbit for breakfast.”

But the tears ran faster than ever down Nibble’s whiskers. “It’s Hooter,” he sniffed. “He caught her when she went down to the brook for a drink. I know he did. She’d never leave me.”

“Nonsense,” said Bobby, and he said it peckishly, for no one likes to hear a little rabbit cry. “I know your mother, and she knows the law of the woods. You can fly—run, I mean—can’t you. And feed yourself?”

“Yes,” answered Nibble, for his brothers and sisters had gone to dig their own holes and find their own food weeks ago.

“Well, then,” finished Bobby, nodding wisely to himself, “if there’s any fresh rabbit fur under Hooter’s tree it’s not your mother’s.”

To his surprise Nibble stopped squeezing the tears from his eyes and opened them wide. “I’m going to look!” he announced. And he began to scrub his face and polish off his ears with his little soft forepaws.

“Going to look where?” asked Bobby Robin.

“Oh, lots of places—the Clover Patch, and the Brush Pile, and the Broad Field. But first I’m going to see if there’s any fur under Hooter’s tree.”

“What?” squawked Bobby. He came tumbling down to the ground where he could make Nibble look him straight in the eye and listen to an awful lecture.

“You’ll do nothing of the sort,” he said. “Now that you have to see and hear and smell and feel for yourself you will have to be twice as careful as you ever were before. You may remember all the things your mother taught you—now you’ll have to do them. And she took all that trouble with you so you could be a sensible, clever rabbit and keep out of danger, not so you’d run right off the minute she left you and offer Hooter a free meal.” Bobby was so worried about Nibble he forgot that the ground was no place for a sensible bird.

“But I must know if Hooter caught her,” pleaded Nibble, “and I will be careful.” He sat up and sniffed all around with his nice clean nose that had been all swollen from crying when Bobby Robin found him. And he pricked up his tidy ears, just to show how careful he meant to be. And he heard a soft little noise behind him. It wasn’t two grass stalks rubbing together, though it was as tiny as that. It was the scraping Glider the Blacksnake makes when he slips across a stone!

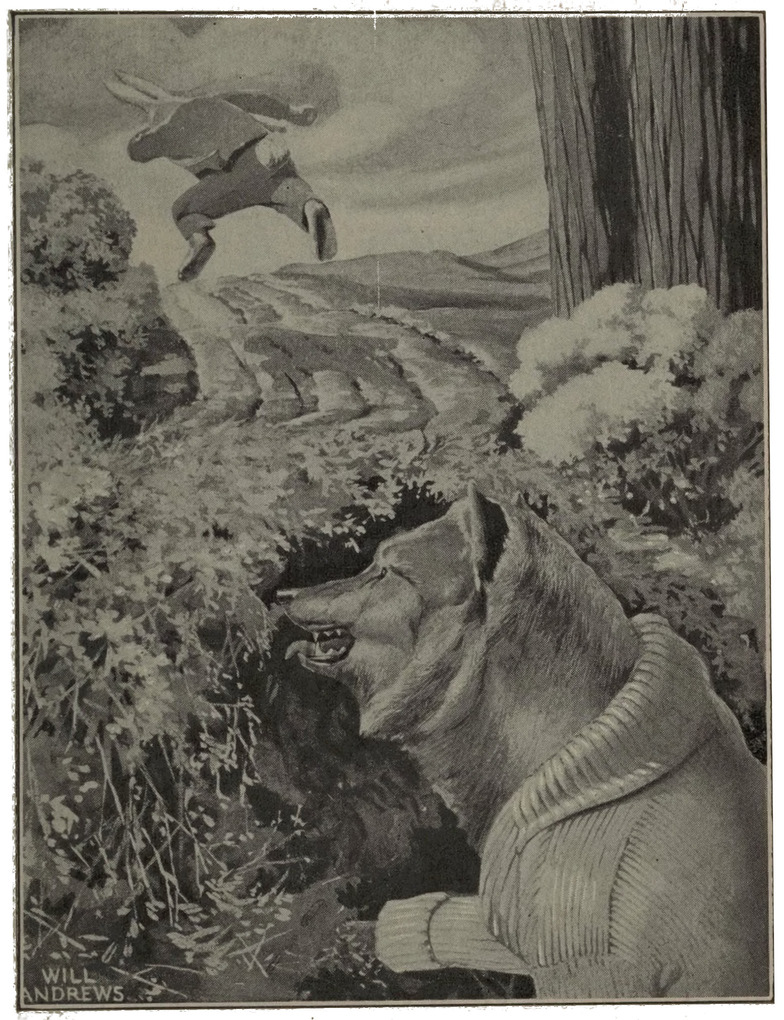

Nibble’s feet just bounced of themselves, and Bobby’s wings beat, and Glider’s ugly head landed right between them. For Glider hears everything that goes on along the ground. He had heard Nibble stamping to call his mother. If Mammy Rabbit had answered Glider would never have come. But she didn’t—so Glider did. And now lonely little Nibble Rabbit was racing off and Glider was after him, simply boiling over with rage, as fast as he could put tail to the ground. He didn’t think Nibble could run so very far. He was sure he would catch him.

For a minute Nibble thought so too. Scared! Nibble Rabbit was too scared to think. He just ran. Every jump he made was longer and higher than the one before until he was sailing over the tops of the tallest grasses. My, but he wanted his mammy—that was because he was so dreadfully scared. Then he wanted a place to hide. Presently he remembered the Brush Pile. He turned toward it and he didn’t even hide his trail the way he had been taught—that’s how scared he was.

But just as he reached it he remembered something his mother had told him, which was just what she hoped he would do. “If the thing that chases you wears feathers take to a hole. If it wears fur don’t put your nose into any hole that hasn’t another end. If it wears scales keep to the open and run as fast and as far as you can.” And scales are exactly what Glider wears.

Now he knew exactly what to do, and he wasn’t quite as scared. He just bounced up on the Brush Pile and kept on going until he bounced off again on the other side. He raced through the Clover Patch and down the Broad Field between the shocks of corn. The field was all muddy from the rain and his feet slipped and slid and his little heart went bump, bump, against his sides, as though some one were hitting him. He wasn’t even frightened any more—he was too tired. But he kept on.

Then he heard a voice calling him: “Nibble, Nibble, wait!” It was no hissy voice of a snake. It was Bobby Robin.

So he turned into one of the nice little tents made by the shocks of corn. And Bobby had to catch his breath before he could talk. “You’re safe,” he gasped. “You lost Glider way back there. I asked you if you could fly. You can. You fly faster than a thistledown in a north wind.” And Nibble twitched his nose into a pleased smile, while Bobby stopped to fan himself with his wings. “Glider couldn’t see you bounce oft on the other side of the Brush Pile,” he explained when he got his breath, “because his head is so near the ground.”

Nibble’s ears flew up in surprise. “Couldn’t he smell me?” he asked. If he couldn’t, then here indeed was a new thing he had learned.

Bobby cocked his head sidewise with a most mischievous air. “He could follow you to the edge of the Clover Patch. But he lost you the minute you went out into the Broad Field. Look at your feet, Nibble. You didn’t leave any scent after you got your little mud boots.”

Nibble held up one forepaw and looked at it. Then he put out a hind one and looked at that, too. Sure enough the sticky mud of the Broad Field had matted into his fur so that he was wearing a fine little set of boots that came half way to his knees. He looked down the row of slippy, slidy tracks he had made. “There’s where I got them,” he said. “I should think Glider would see where I’d gone.”

“Glider!” laughed Bobby scornfully. “Why, Glider’s too blind and stupid to see anything. He’s nosing around on the Brush Pile right this minute, looking for the hole you didn’t run into. And the little sticks tickle his stomach, and he’s getting hungrier and hungrier and crosser and crosser until—oh, I say, Nibble, I’ve just got to go back and see the fun. Come along!” Bobby giggled a throatful of chuckling notes and flitted off, winking his tail-feathers to beckon Nibble.

But it didn’t seem like fun to Nibble. He was still so weak and shaky after his run that he trembled every time Bobby spoke Glider’s name. What he wanted was to find his mother—or at least to know that she wasn’t a little matted ball of fur under Hooter the Owl’s tree. “I’d go and look right now,” he said to himself, “if I didn’t have to pass that Brush Pile.”

Suddenly he knew that now was his chance, while he still had his little mud boots on. Softly he crept through the Clover Patch for fear Glider might be lurking in the long grass, ready to pounce on him. But long before he reached the Brush Pile itself he knew exactly where the wicked snake was. He was right on top of it.

He was right on top of it, and what is more, Bobby Robin was circling about his ugly head to jeer at him. “Yah!” Bobby was shouting, “Heap big hunter, beaten by a bunny! Better go catch frogs in a marsh!”

Now Nibble knew that was a most insulting thing to say. For a frog is so stupid that almost anything can catch him—especially a snake. If a frog can possibly dive he hides under a lily pad. If he can’t he just squawks and waits to be eaten, like a helpless baby bird.

Bobby was squawking loudly enough, only he wasn’t waiting to be eaten. He was taking very good care not to be. But he was coming so close to it that Nibble almost forgot everything else in watching him. There was one thing he did remember, though, and that was that the wicked snake had nearly caught him by sneaking up from behind. So he took proper rabbit care that no one should do that again. He found a nice log where he could see what was going on, but he didn’t hop straight up on it. He took three short little leaps past it, and one great big bound back to his perch. Since he still had on his little mud boots which had hidden his trail from Glider out in the Broad Field, he felt pretty safe. And when he crouched down like a small brown knot on the log no one seemed to notice him.

Somebody might have noticed easily enough for Bobby and Glider were making such a terrible racket that every one was coming to listen to them. The grasses were full of mice and the bushes were full of sparrows who all hated the snake. Even Chatter Squirrel, who doesn’t get on with Bobby any too well himself, came leaping across his pathway among the branches.

Bobby and Glider were making such a racket that everyone was coming to listen to them

“Snail eater, snail eater!” yelled Bobby. Which was the awfullest thing he could have thought of. To accuse a blacksnake of eating those disgusting soft woodslugs—ugh! What he eats is nice warm food, like mice and bunnies and birds—if he can catch them. But he couldn’t catch Bobby Robin as he danced on his wings just out of reach. He missed a particularly ugly snap and slapped his nose very hard when it came down on a nubbly branch. That made him open his mouth and hiss like a small steam engine.

“That’s right,” said Bobby, pretending to be very sympathetic. “Spit the mud out of your mouth and maybe you’ll learn to sing.”

Chatter Squirrel laughed so hard at this that he had to hold on tight to a piece of bark to steady himself. And Nibble sat straight up with his muddy little paws dangling right against his clean shirt front and stared with all his eyes. He had his ear cocked so he wouldn’t miss a word of Glider’s answer. For now Glider was maddest of all. No snake can stand being reminded that he has to go around with his chin in the dust.

He stopped whipping his head about and tied himself into a tight coil, with his cold eyes glittering from the very middle of it. And he hissed in his cold voice: “I’ll teach you Woodsfolk whether you dare make fun of me!”

“Oh,” whispered a thrush perched right over Nibble’s head, “I’m afraid for Bobby. If Glider ever makes any one look him straight in the eye they never get away from him.” He said it in a scared voice and Nibble could see that was exactly what Glider was trying to do.

Suddenly he felt himself crouch back against the log again, ears tucked between his shoulders, whiskers twitching with the smell of fox in his nostrils. His muscles did these things of themselves before he really knew that Silvertip was standing at his very elbow. He had followed Nibble’s footsteps to the end of the trail right past the perch to where Nibble had jumped back.

Nibble didn’t move. Silvertip raised his head and cocked his ears at the noise over on the Brush Pile. Then he hung out his tongue in what wasn’t entirely a sly smile. It was partly thinking how good Glider the Blacksnake would taste. He made a little rush, with a bounce at the end, like Nibble’s bounce, right into the middle of the Brush Pile.

“Help!” shrieked Bobby Robin. But Glider never spoke a single word. Neither did Silvertip. His mouth was too full. Glider was in it.

Not one of the Woodsfolk could make a sound. It was all so sudden it took their breath away. Then the sparrows began to flutter and chirp in their noisy way, and Chatter Squirrel said to nobody in particular, “Great acorns! but that was exciting! One minute Glider is playing a trick on Bobby Robin, and the next Silvertip jumps up from nowhere at all and plays the biggest trick on Glider! Whew!”

“Well,” answered Nibble Rabbit, “I’ve just been thinking that it doesn’t matter to me which eats which. They’re both tried to eat me since morning.” He was still the little brown knot on his log that he had frozen into when Silvertip came past. “Chatter, is Silvertip looking?”

“No. He’s spread out in the sun sleeping off his meal,” answered Chatter, craning his neck to see where Nibble was hidden. And his eyes fairly popped when that little brown knot slipped down from the far side of the log and limped away.

He limped—for not only was Nibble a very tired rabbit from sitting so still, but his little mud boots that he got in the Broad Field when he was running away from Glider were all stiff and uncomfortable. How he did want a wash and a drink and a place to rest!

He could hear water whispering not far away, but he didn’t dare go through the tunnels in the Prickly Ash Thicket to get to it. So he didn’t find the brook he knew. He went farther down where it spread out into a broad pond. It was all edged with reeds and rushes that had some delicious watercress growing up between their roots. He could step on the last year’s stalks which had been bent down by the Winter Wind and keep his feet safe from the sticky mud below. Pretty soon he found a little raft hidden in the middle of a clump of cattails.

“This is the place for me,” he said to himself. “It’s warm in the sun and snug from the wind, and nobody’ll ever find me.” So he curled up and went fast asleep.

He awoke to feel a shadow falling across him. He looked up into the homeliest face he had ever seen. It was pointed, like his own, but fatter, and it had little cropped ears and sleepy, blinky eyes, and long yellow teeth that flashed when it said severely: “What are you doing here?”

Poor Nibble! He was only half awake. He had forgotten where he was, and it’s rabbit nature to jump first and think while you run. He jumped. His feet slipped, he splashed and the water closed over his long ears.

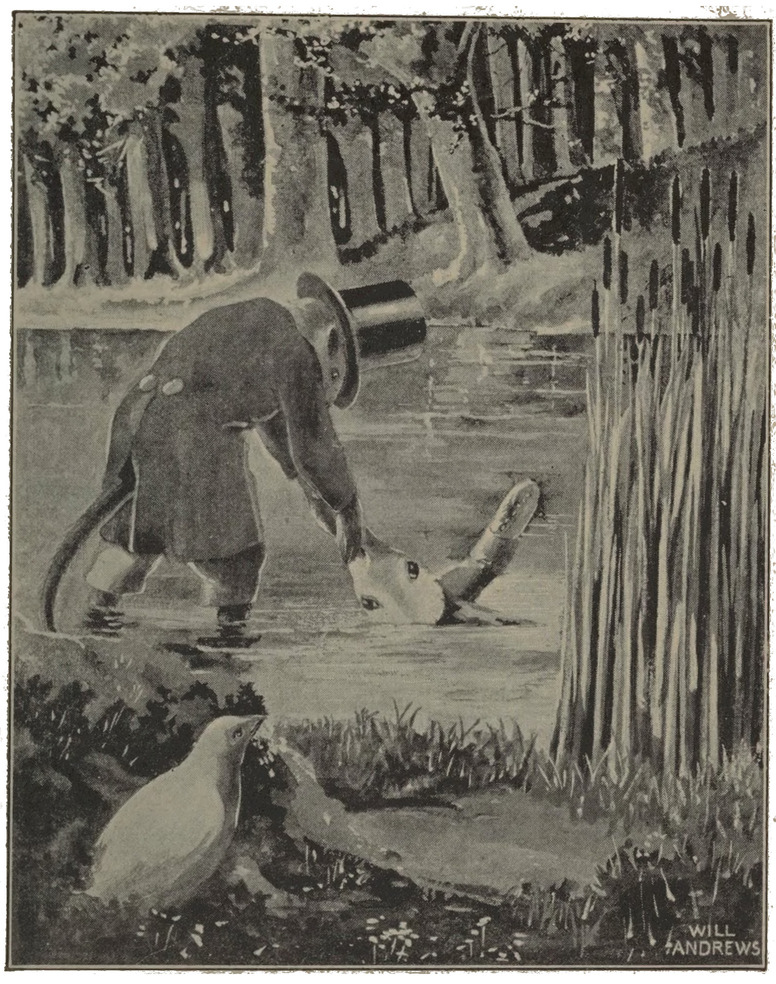

Then didn’t he kick and strangle! No sooner did he get his poor little nose out than it went under again. But the second time the green water parted and his scared eyes could see the rushes waving in the lovely air, and his lungs could get one more breath that tasted as sweet as clover in the spring, he felt a grip on the back of his neck. A gruff voice growled: “Take your time. You should learn to swim.”

The next thing he knew he was being shaken very hard. “Cough!” ordered the gruff voice. “Shake your head till you get the water out of your ears! Now eat this!” And Nibble swallowed a peppery bite of root that made his eyes pop, and set the tears streaming down his whiskers.

“Who are you?” he gasped.

“Doctor Muskrat, of course,” answered the voice. “You couldn’t be in better paws.” But poor Nibble Rabbit thought he couldn’t very well be in worse ones. Which was very ungrateful.

“I’d rather be eaten than choked to death,” he thought. “But this awful old animal is perfectly satisfied with himself for doing it! Ah! Oh! Uh-huh!” he coughed. And Doctor Muskrat sat back and looked more wise and pleased than ever.

“I knew that would open your eyes,” he explained. “It was a flagroot gnawed in the wax of the moon. You see I know what every plant in the marsh is good for and I dry them for my medicine chest.”

“What would have happened if you hadn’t given it to me?” asked Nibble weakly.

“I didn’t risk it,” said Doctor Muskrat, “so of course I don’t know. I gave you the proper remedy as soon as you could swallow, so of course you’re all right now.

he quoted. “That’s the rule for flagroot. Now I’ll put you to sleep with the other dose if you need a rest and I’ll stay right here and watch you.”

“Oh, no!” protested Nibble. He was just beginning to breathe and he didn’t want any more of kind Doctor Muskrat’s medicines. “I must look for my mother, under Hooter the Owl’s tree.”

“First,” said the doctor looking at him very severely, “you must clean yourself up and put your fur in order. If your feet hadn’t been all caked with mud you wouldn’t have slipped.”

“They were very uncomfortable, too,” Nibble agreed, glad that his swim had melted his boots, at last. “I kept them on so Glider the Blacksnake couldn’t track me.” And he told his experience with Glider and the Fox.

“Nevertheless,” said Doctor Muskrat, “you weren’t safe because you couldn’t keep your nose clean and smell all around you, nor your ears clean, so you could hear. Always be sure you know everything about it before you decide to try something new. For instance, rabbits don’t belong in a marsh, do they?”

“No,” murmured Nibble, “But it looked so hidden and so safe.”

“So hidden,” Doctor Muskrat snorted. “It’s a mercy it was I who found you and not Slyfoot the Mink. So safe that you nearly drowned when you tried to get away. Now you say you want to visit the owl’s tree. Is that any place for a rabbit? Answer me that!”

“No,” wailed Nibble. “But I want my mother and I don’t know where else to look. If that old owl did catch her he might as well take me too. Glider the Blacksnake ’most did, and Silvertip nearly ate me instead of him. He might as well. Nobody cares, anyhow, if my mother’s gone. Why didn’t you just let me drown?” Which was no way at all of thanking Doctor Muskrat for having rescued him. And tears of sorrow mingled with the tears that came from the awful medicine the old Doctor had given him.

But Doctor Muskrat’s feelings weren’t hurt in the least. He could see that poor little Nibble was badly scared and all clammy and cold from his ducking besides. “What you need,” he said in his gruff voice, trying to make it sound really kind, “is a nap and some light but refreshing nourishment. What’ll it be—a fat frog? No? I forgot that all of us don’t eat the same things. Let’s see—” He thought a minute and Nibble could see his nose twitch as though he imagined he were sniffing things as they came into his mind. Then he licked his lips. “I know,” he said, and at the word his scaly tail cut the water like a knife where it closed behind his vanishing heels.

A minute passed, two, four. What had happened to him? Nibble began to remember how ungrateful he had been. He also remembered that Slyfoot the Mink might be creeping up, or the Brown March Hawk peering about as he flew by. He craned his neck and saw something floating down from upstream as softly as a stick in the current. It was the fat old doctor with a big root in his mouth.

Dr. Muskrat pulls Nibble out of the broad pond

He slipped up beside Nibble without a sound. “I had to scour the bottom to find this,” he explained. “It’s water chinquapin and it has properties.”

He said this so mysteriously that Nibble dared not ask him what “Properties” were, so he tasted a little, very carefully, to see. Did you ever taste a water chinquapin yourself? It’s delicate and jelly-like, but so sweet and rich that you’d risk stepping on old Grandpop Snapping Turtle himself to get some more. Nibble scraped the very rind of it. And then he thanked Doctor Muskrat for taking so much trouble over him.

“Well,” growled the old doctor in a very pleased tone, “I’m glad you have found your manners, if not your courage. Now snuggle up and go to sleep.” And so Nibble cuddled against him in a nice warm lump to sleep off his fullness.

He didn’t wake until the pink reflections from the setting sun were dying out of the west and stars were already twinkling in the sky. Doctor Muskrat was studying their reflections where they sparkled in the pool. He was saying something to himself.

“Is that right?” and he pricked his ears. Nibble’s own ears flew up, but he couldn’t hear a word from those stars, dancing softly on the water in the night wind. That was because this was deep and secret magic.

“You awake?” asked Doctor Muskrat. “Well, that fortune was yours. I asked the stars most particularly. They wouldn’t tell me anything about your mother, but from the way they’re smiling I feel sure you’re going to find her in the end. They did say that Slyfoot had gone across the pond, so you had better hurry to the bank and find the quail.”

Which last was strictly true and not magic at all, because the stars had danced very hard in Slyfoot’s ripples.

“Go up on the bank and find the quail,” Doctor Muskrat had advised. So Nibble Rabbit set out as obediently as possible, because he meant to do exactly what the nice old gentleman told him to, though he didn’t know something that had happened while he was taking his nap on the snug little raft among the reeds.

You see, Doctor Muskrat had heard the quail come fluttering down to the pond for their evening drink, and he remembered that Bob White has the kindest heart in the world. So he squealed, very softly. And Bob flew right out to see what he wanted.

“Look at this bunny,” whispered the doctor, pointing his paddle paw at Nibble. “Whatever am I going to do with him? I can’t take him into the underwater door to my own house, because he can’t dive. And if I make a hole in my roof it will leak, and besides it will be far too convenient for that clever mink, Slyfoot. He’d come right in by my regular tunnel if he didn’t know I was asleep with my teeth bared at the end of it. Couldn’t you look after him until morning?”

“Surely I will,” answered Bob White. “Send him along as soon as he wakes. I’ll have our Watch Bird keep an eye out for him.” And off he flew.

So Nibble was hopping ashore repeating to himself his fortune that the stars had told the doctor for him.

And he wasn’t lonely any more because, you see, that was part of his fortune.

But this time he didn’t travel alone very far. For just as he passed a nice, home-like looking thicket, out stepped a bird. “Come along,” he called cheerfully. “The rest of the flock are settled down by this time. I’ll show you the way.” And he went scuttling ahead through the grasses with Nibble hopping at his heels.

They were right near a cluster of comfortable little thorn trees which grew on the edge of the Bluff where it leaned away out over the Sandy Beach below when they heard a startling noise. And the quail that was with Nibble spread his wings and hurried on as fast as he could fly. For the quail weren’t asleep at all. They were just ahead of him, all fluttering and scuttling and crying together.

“Danger!” thought Nibble. For it made his very heart beat fast just to hear them. “Which way shall I run?” Then he remembered the last line of his fortune; so he crept up closer instead. Presently he stopped to listen—a weak little voice from under his very feet called, “Whit, whit!” in the saddest tone.

He sat straight up and demanded: “What’s the trouble?”

“Oh,” mourned Bob White, frantically beating his wings, “my mother ran under the edge of the bank and the earth caved in. And we can’t dig her out again.”

And they couldn’t, either, for the clay was all full of the tough, tangled roots of the thorns.

“I can,” said Nibble Rabbit. “All troubles are mine but my own. Where do I begin?”

So they showed him the little bit of a hole where they had tried it themselves and he settled his strong hindfeet and moved the little clawed spades of his forepaws so fast they fairly twinkled. When he found a root he used his chisel teeth. As soon as he gnawed it through his paws would begin to fly again. And the quail crowded around and whispered to each other. Presently they began to croon a sort of song. “He’s coming, coming, coming soon.” And the little quail deep in the bank would answer.

The earth was loose, so she didn’t quite smother, but she did need a full breath of air. The time seemed very long to her. But it seemed longer still to Nibble Rabbit. Those roots were so tough his jaws ached. He had dug so hard his legs were getting numb. And the birds outside had lost sight of his tufty white tail. But they knew how he was working, for they could see the dirt fly when he kicked his strong hind feet to clear it out of the hole.

Nibble digs Bob White’s mother out of the bank

Soon his little claws almost refused to move. But he wouldn’t let them stop! Then the “Whit!” sounded almost in his ear. Now his feet fairly flew of themselves for a dozen strokes and—Victory! A weak little bunch of brown feathers burst through the clay wall. And he backed out and helped Mother Quail to the cool fresh air outside the hole.

Nibble saw the quail all crowd around her, smoothing her ruffled feathers, loosening the dirt that was caked into them, and making little soft noises of delight that she was safe again. Then gradually he didn’t see anything at all. He had come as near fainting as any wild thing ever does except Mister Possum, who mostly pretends, and scary little Keree the Rail. He had fallen into a sound sleep.

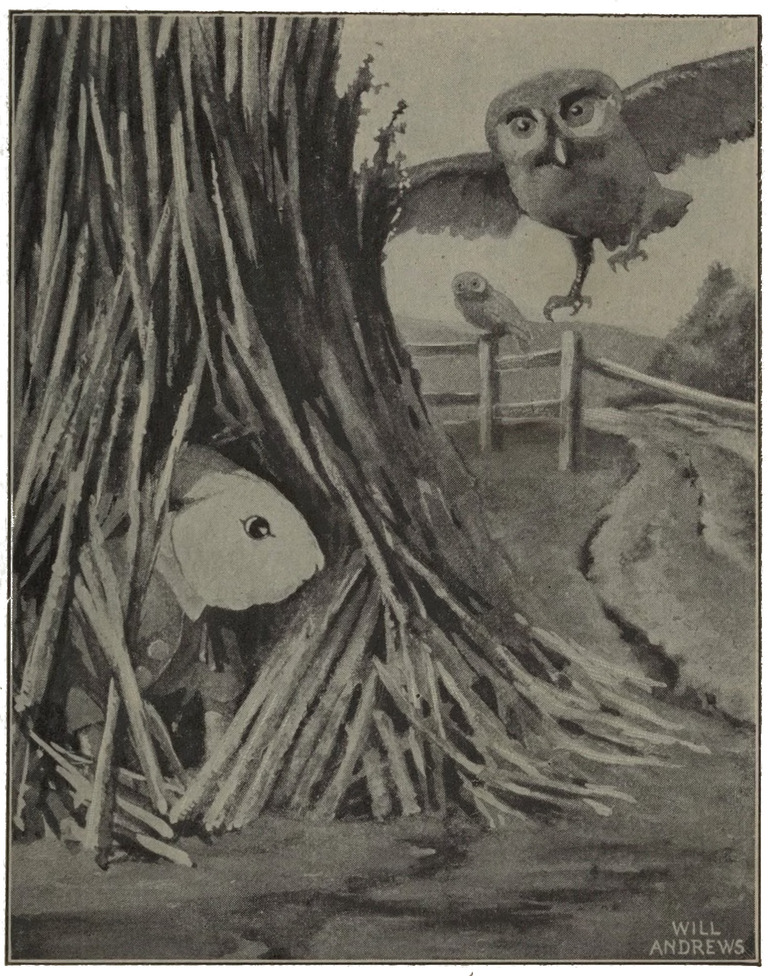

When he awoke he felt something tugging his ears. He opened his eyes and lay still, oh, so comfortable and warm. But the tugging kept up until he shook his head. Then Bob White whispered softly: “Come on, Nibble. Our Watch Bird has signalled that Slyfoot the Mink is swimming this way. We must hide.”

So Nibble sat up, very stiff and sore. And he found why he had been so snug. Little quail were cuddled all around him. One by one they took their heads from under their wings, shook themselves, and got ready to fly. And overhead in the darkness he could hear the Quails’ Watch Bird giving the hurry call. When he looked hard he could see the bird craning his neck against the dusky sky.

So he shook himself, too, and followed Bob White as he led the flock in and out of the bushes. Pretty soon Bob gave a low whispering whistle and the birds took wing. “Make a triangle, Nibble, over to the top of that log and then jump where you hear me call,” he said.

So Nibble limped off past the log, turned back on his trail and dragged himself up on it. My but he was tired. He almost fell asleep once more out in that cold wind. But Bob’s whistle waked him again. He jumped and found his legs all tangled in a wild grape vine.

That set Bob laughing softly. “It’s too bad,” he said, “but you see I forgot you couldn’t perch like a bird.”

But Nibble didn’t mind. He just kicked and wriggled until he tumbled to the ground and the blanket of little quail closed around him again.

Early in the morning a soft order woke him. “Hold your scent! Hold your scent!” He didn’t know exactly what it meant, but all the quail stopped ruffling their feathers to keep warm and closed them tight about their bodies. So he sleeked his fur and listened with all his ears. And he just caught the faintest sniffing—from the top of the log, not ten feet away. It wasn’t any bird. It was—Slyfoot! And, oh! how Nibble trembled. But the quail didn’t; they were only very still. And then Nibble heard another tiny sound—the sound of twigs scraping together. That was Bob White slipping through the branches. He was walking along an overhead pathway, so as not to make a whir with his wings.

Soon Nibble heard Bob beating and flapping over behind the log. “Oh,” he cried. “My wing—my poor wing! Oh, it’s broken! Help, Oh-h-h!” Nibble wanted to go, but the other quail held him still.

Plump! went Slyfoot, all feet at once, as he jumped for the crippled bird. “Har-r-r!” he snarled as he just missed a mouthful of feathers. He jumped again. “Oh-h! Help!” wailed Bob as he flapped off. And the sounds died in the distance.

But just as Nibble was beginning to scold the Quail because they wouldn’t let him go and lead Slyfoot away, Bob came sailing into the thicket with his wing as good as ever. He was laughing. “Topknots and Tail-feathers!” he exclaimed, “but I gave Slyfoot a merry chase! He’s over in the Briers by the Pasture fence with his feet as prickery as a set of thistle-burs.” He limped over the dry leaves to show how Slyfoot walked with prickers in his paws.

Nibble laughed with him. “Won’t he be angrier than ever?” he asked.

“He’s never anything else,” chuckled Bob cheerfully. “But he won’t bother us again until he thinks we’ve forgotten about him. So we’ll get our breakfast before we move.” And all the birds began scuttling about, making as much noise as they pleased. When Nibble dug himself a root they all crowded around for a taste of it, so there was very little left for himself. But they shook off some fresh thorn-apples for him and when he wanted to try the sumach they thought was so nice they perched on a branch until they weighed it down within his reach.

They ate and ate, for they were getting ready to travel. Of course they haven’t any trunks to pack, but they pack their little crops instead until they can hardly fly.

“We can’t sleep here again,” Bob explained, “until the dark of the next moon. Then you’ll know where to find us.”

“Why?” demanded Nibble curiously.

“Slyfoot will stay here until then, because he knows all the hiding places. You mayn’t believe it, but he’s afraid to travel by moonlight on account of Hooter the Owl. Just the same, he is as restless as we are. On the first dark night he looks for a new hunting place as far away as he can.”

“Where are you going?” Nibble wanted to know. He felt sorry to lose them.

Bob stood up and flapped his wings to feel the air. “East or west,” he answered. “This wind is north. And it’s very strong. We couldn’t go far against it and if we went south it would tip up our tails and send us tumbling. But if we fly across it will lift us and help us along.” He took a little trial trip. Then he settled beside Nibble again. “West,” he said, “to the deepest woods. There’s a smell of weather. Come on. Whit! Whit! Good-bye, Nibble.” And they whirred away before Nibble could ask what Bob meant.

Nibble darted into the first shock he came to

Nibble found out pretty soon what “a smell of weather” meant. When he went down to the Pond for a drink he saw a family of ducks. Some of them were paddling around and some had gone to sleep on shore in the sun. He spoke to one who had a beautiful green head and shiny blue feathers in his wings. “Good morning,” he said timidly.

“Eh? What?” quacked the duck in his hoarse voice, ruffling his feathers angrily. “Oh, a rabbit. Good morning.”

“Slyfoot the Mink lives here,” warned Nibble. “You might be caught before you know.”

“Thank you,” said the duck “we’re going South in half an hour.”

“Won’t the wind tip you?” Nibble meant to be kind.

“Ho, ho,” laughed the duck. “You’ve been talking to the quail. Of course not. We’re Mallards. We fly faster than the wind. Now I’ll tell you something. This wind is carrying more than ducks. Can’t you smell it?”

Nibble sat up and sniffed very carefully. “It’s queer and dry,” he said, “and it seems to make my fur want to stand on end.”

“Go make yourself a nest, Bunny,” said the duck good-naturedly. “What you smell is a Terrible Storm coming, and it’s coming mighty fast.” He turned back his shining green head to fix the little curly feathers that quirked up over his tail. Below his white collar he wore a vest of the rich red which all rabbits especially admire, and Nibble was quite awed by his elegance.

“Come along,” he called to the other ducks who were paddling about in the shallow water and feeding among the roots of the water lilies. “It’s time you put your wings in order for a long trip.” And he set the example by spreading his own feathers and laying them very cleverly with his wide beak.

Nibble noticed a lady duck who wore the same colours as himself. She stood on her head with just her tail and her yellow legs showing out of water, until he was really afraid she was drowning. When she did come up straight again she paddled ashore as fast as she could. “The fish know,” she told her mate. “There’s not a fin stirring, and that big pickerel I was afraid of has buried himself in the mud. When the fish know about a storm it’s high time we were gone.” And site began preening her feathers in a great hurry.

“Are you afraid of a fish?” Nibble was surprised.

“Sometimes,” said she. “If it’s big enough to catch us by the leg and pull us under the water. We take turns watching while we have our heads down. Everything is afraid of something. But I’m much more afraid of that big black cloud and the thing that’s driving it.” And she went back to preening harder than ever.

“You see, Bunny,” said her good-natured mate, “this is really no ordinary storm. We saw it grow. We were way up north where the wind sings in the pines and the ice cracks like the shot of a gun. And this storm woke up. It wasn’t very big at first, and it cried very softly. Pretty soon it stood up over the tree tops, taller and taller every minute. And then it began to howl. It howled so loudly that even the wolves stopped to listen. But we didn’t We came away very quickly, before it could catch us. And we’ll keep on going until it stops.”

“What will it do if it catches you?” demanded Nibble, opening his eyes very wide.

“It’ll throw snow all over us so we can’t see our way to fly,” answered the lady duck. “It’ll cover up all the water with ice so we can’t feed. When it’s very had we can’t even find a hole big enough to thaw our feet in. Ugh! I hate to fly so fast. We ought to have come three days ago. I knew what it was the first day when it snarled at the wind. It wasn’t afraid!”

“Afraid?” Nibble sat up and wiggled his ears at the idea. “Are storms ever afraid.”

“Of course,” said she, as though he ought to have known. “I told you everything is afraid of something.”

Nibble knew this was true. Here he was afraid of Slyfoot, and Slyfoot was afraid of Hooter. The ducks were afraid of the storm, and the storm was afraid of—

“Afraid of the wind!” finished Madame Mallard. “As long as a storm can keep its head nothing can stop it. But it doesn’t. Sooner or later it breaks into a rage and begins to thrash around. When a storm really loses its temper the next sensible wind can smash it into bits. It never pays to lose your temper. Something always happens if you do.”

Nibble was very much excited. But he wasn’t too excited to think of a good place to hide. There was that nice little tent made by a leaning shock of corn out in the Broad Field. As he passed the Brushpile, Chatter Squirrel was darting up a hickory tree with a mouthful of leaves. “There’s going to be a Terrible Storm,” called Nibble cheerfully, “the Mallards just told me about it.”

“Who doesn’t know that?” snapped Chatter, fussing with a clutter of leaves and twigs in the crotch of his hickory. “My home’s not half done. I thought I’d take my time and make a good one. Now here comes this Storm! If I can’t get it finished I’ll have to go over to that leaky old Oak that has bats in it. Yah!” And he swore in Squirrel language because one of the sticks he was using had snapped and he had to go for another one.

“The Ducks say you musn’t lose your temper, because something always happens,” quoted Nibble. And he didn’t mean to be impertinent. He was just pleased with himself for remembering it.

“It’ll happen to you, then,” Chatter retorted in a rage. “You and your ducks! You’ll stand there trying to mind my business for me until Silvertip catches you.” But there’s no way of knowing how much angrier Chatter might have been because right then something did happen. He gave one shriek—“Hooter!”—and made a flying leap for that hollow Oak Tree. And Mrs. Hooter clapped her beak at the hole.

“Stickly Prickles!” said Nibble to himself—that really isn’t swearing. “What are those owls doing out this time of the day?” For he could see Hooter flapping sleepily along behind his mate. It was too early in the day for him. It was a badly frightened rabbit who made the best of his chance while they were chasing Chatter to dart across the Cloverpatch and into the first shock he came to.

But he didn’t stay there. Just as he began to breathe again he heard the voice of Mrs. Hooter right above him. She was speaking crossly to her husband. “Pay attention,” she said. “It may be three days before we can hunt again. He went in there. I saw him.”

Nibble guessed that a small brown rabbit was the “he” they wanted, so he slipped out of the other side of that shock and ran across to the next.

“There he goes!” screeched Mrs. Hooter. “There he goes! Catch him, quick!” But Hooter was too slow. Nibble was safe again.

But was he? For in that second shock slept—Silvertip the Fox!

Silvertip was curled up in a ball with his tail about his feet. Of course he woke up the minute he heard the Hooters and pricked up his ears. Whatever were they shouting about?

In all that noise he never heard the soft sound of Nibble’s breathing right behind him. He never sniffed anything but Owl. For they were very close.

“Go in and drive him out!” ordered Mrs. Hooter.

“I—er—I’ve never done anything of the kind,” Hooter objected. “I don’t think I care to begin.”

“Coward!” hissed Mrs. Hooter. And she flew into a terrible temper. She shook him until his beak rattled. Then she bounced him down. “You see to it that you catch him when he comes out!” she raved. “I’ll go myself!”

And she did. Right into Silvertip! And let me tell you that for one minute feathers flew and fur frazzled. Then Mrs. Hooter flew squawking out one side and Silvertip limped yelping out of the other and Nibble said to himself, “I’m so glad it wasn’t my temper that was lost.” He had the little cornstalk tent all to himself. A clawful of feathers and a beakful of fur were all that was left of the fight. “And they can’t come back,” he said to himself, “because nobody could move in this awful wind.”

For right that minute the Terrible Storm swooped down out of its Black Cloud. “Look out,” it shrieked, “I’m bad! I’ll show you what I can do to you if I want to. Old Earth, I’m going to turn you upside down! I’ll make you into a rubbish pile, I will! Wow-w-w!” Which was very mean because it had no quarrel with the Old Earth and the poor wild things.

Nibble shook to the tips of his furry little toes when he heard it. Once he tried to poke his nose out, just a tiny bit, to see what was happening, but the Terrible Storm tweaked his whiskers and threw snow into his eyes. So he backed in again and listened to the trees shouting to each other. “Oh! Oh! I’m cracking! Hold me! Please, please—I’m going to fall!”

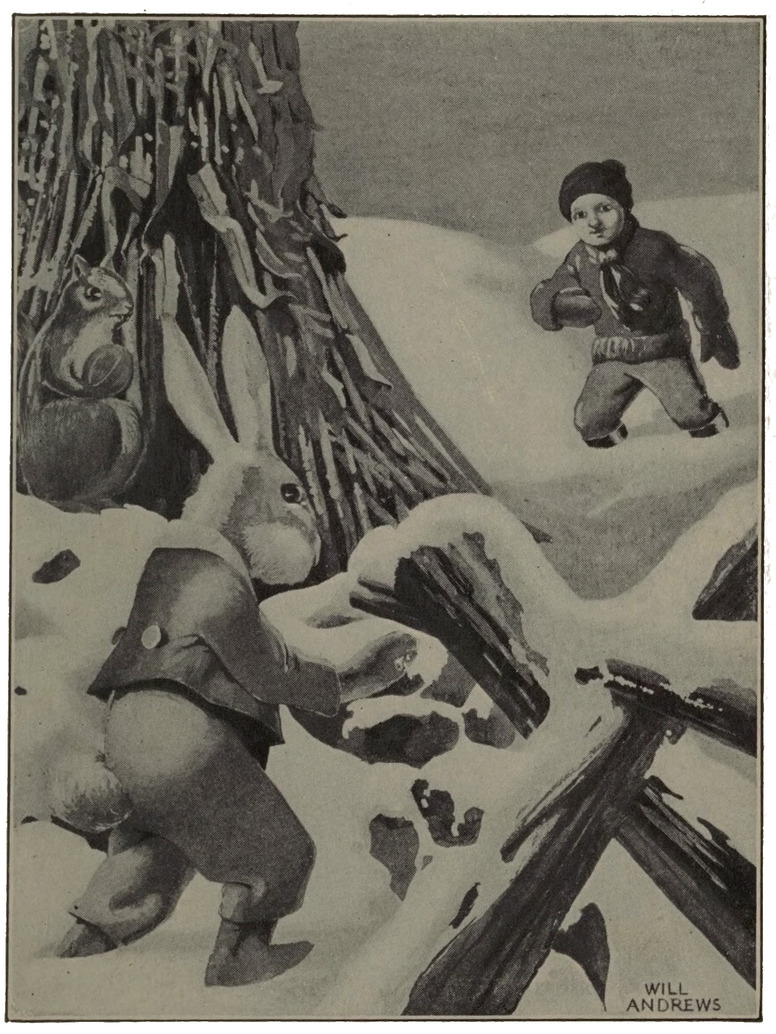

Pretty soon he heard a terrible groan with a crash at the end of it. And then he heard a little sound wailing above the wind and the trees. It was calling for help. It was Chatter Squirrel! Then he knew it was the Big Oak who stood alone by the Clover Patch that had blown down.

Suddenly Nibble found he wasn’t scared of that bully of a Storm. That is, not so very, very scared. Not too scared to crawl out of his tent, digging his little toes into the ground to keep from blowing away, his nose close down in the grasses, his eyes half closed to keep out the snow and look for poor Chatter. He called once or twice, but he was very close before Chatter could hear.

“Where am I?” he sobbed. “Oh, my nest is all smashed and I don’t know where I am. Is this the end of the world?”

“No,” said Nibble, and he nearly laughed because Chatter was so funny when he was afraid. “It’s only the end of the Big Oak. I have a place to sleep and plenty of food. Come along.”

“Me too,” called Gimlet the Little Downy Woodpecker who lived in a branch of the tree. “Us too,” chorused all the little field-mice who had burrowed in its roots. And “Us, too,” piped three partridges who had been snuggled in the bushes beside it. Even two little bats who had lived in the tall dark cave of its hollow trunk came scuttling and crawling, holding on tight to whatever fur they could touch.

Every one came but Cheewee the Chickadee who said he would do very nicely where he was, although his nest, an old woodpecker hole, was all queer and upside down.

They scuttled along together, traveling fast because now the wind was pushing them from behind. And the snow drove under their feathers and fur until it stung their very skins and nipped the ends of Nibble’s blowy ears, but he kept saying, “I’m going to have a party! I’m going to have a party!” so pleased and happy that every one was trying to smile by the time they reached his little cornstalk house.

The Terrible Storm had tried to knock that down, but only spread it out so there was more room in it than ever. And the snow had tried to smother it, but had only succeeded in stopping up the cracks so that it was snug and warm. And the bats hung themselves upside down from the middle of it and turned down their little webby tails over their toes like the flap of an envelope and went to sleep again.

For three days and three nights Nibble Rabbit’s storm party stayed in the little Cornstalk tent in the middle of the Broad Field. The Terrible Storm might behave as badly as it pleased but they were having too good a time to care. And it might yowl as loudly as it could but they were making too much noise to listen. For they knew that no one was going to interrupt them.

When nobody could eat any more they began to amuse themselves. First of all they had a dance. The three partridges could drum with their wings and Nibble with his feet, for they learned it from the Indians. Gimlet the Woodpecker tapped with much spirit on an empty corn cob, and Chatter Squirrel called out the directions, while the mice did the dancing.

The little lady mice held their tails like trains, sweeping the ground when they curtseyed, but their partners cocked their tails to the left side, and Chatter got so excited that he waved his about in time to his commands and curled the tip of it when they bowed. And the partridges thought he was so funny that they nearly had to stop drumming to laugh at him.

When the mice were so breathless from whirling and twirling that they had to stop they urged Nibble to take a turn. “We’ve seen you,” they said, “on moonlight nights when we dance inside the Fairy Rings.” You see the mushrooms make little dance halls for the Fairies to use on Midsummer Eve. They have smooth, velvety grass on the inside with a circle of little cushiony stools around them. And the mice use them after the Fairies are through. Only they use the seats to hide under when Hooter the Owl flits past. They nibble them, too, for refreshments. You can see their toothmarks on every Fairy Ring you find after midsummer.

“I can’t dance,” murmured Nibble. He felt a bit embarrassed. Rabbits do try sometimes out in the brush where they think no one can see them, but they are very clumsy about it. “I never learned,” he explained.

“Dear me,” said a lively little mouse. “Why don’t you step into a Charmed Circle some night when the moon smiles? Then you can’t help dancing.”

“Yes indeed,” chimed in Chatter, who calls out their dances for the elves and so knows more about them than anybody else. “You know the May Moon draws the Circle as soon as the trees bud their leaves, so she can tell where there is no danger of their casting a shadow on the Great Ball. Some of the wee Wild Folk count shadows very unlucky. From then until it is over, tooth may not crop without singing, nor foot step there without dancing.”

“Yes,” finished the lady mouse. “So we take our children there until they have danced three turns. After that they never forget it. But we don’t like to let them eat. Singing is unlucky for a mouse. But dancing is so delightful.”

“It looks so,” said Nibble soberly, “but no rabbit can dance until he grows a tail.”

“Gracious,” said the lady mouse. “I’d forgotten you hadn’t—a regular one.” When she saw Nibble’s feelings weren’t hurt, she asked, “Do you mind telling us why?”

“Certainly not,” Nibble assured her. “It happened back when the world was young and the new creatures were choosing where they would live. Some chose the mountains and some the plains, some the sea and some the air. But my great-great-great-great—I can’t know how many greats I ought to use—grandfather sat back on his elegant fluffy tail and wondered about it.

“Right near him sat a queer, snaky-looking animal. He had pricked up ears and a bushy tail but his voice was a hissy whisper. He was talking to a crowd of beasts and birds and they couldn’t take their eyes off him. No wonder, for the things he said made my great-grandfather’s ears stiff just to listen to.

“Mother Nature came by and she was very busy. ‘Speak up, you with the tall ears,’ she said. ‘Where do you choose?’

“‘Please,’ said my great-grandfather, ‘I don’t choose at all yet. I just want to live on the earth until I see what these things are eating.’

“‘Oh, ho!’ remarked Mother Nature, looking at him very hard. ‘You see with more than your ears. And what are you eating your own self?’

“‘A nibble here and a nibble there,’ answered my great-grandfather, ‘but I take nothing that will not be again as it was before.’

“‘Good!’ said Mother Nature. ‘Make your choice when you please and it shall be as you wish.’ Then she turned to those others near him. ‘Who are you?’ she asked the strange-looking one, ‘and where do you choose?’

“‘I’m the Weasel,’ he answered. ‘I came up from under the earth.’

“‘Ah,’ sighed Mother Nature, ‘I knew some of you would get here. But choose.’

“‘I shall live anywhere I can lay my foot,’ announced the Weasel boldly. ‘And I shall eat fish, flesh and fowl, whatever I can catch.’ And the other beasts all nodded at one another.

“‘For hunger?’ asked Mother Nature. And most of her beasts who had been listening to the Weasel answered, ‘For hunger,’ because they thought it was the thing to do.

“‘For the joy of killing!’ snarled the Weasel. ‘Like this—’ And he sprang at my great-grandfather.

“But my great-grandfather gave a mighty leap. He landed in a briar patch and began racing through it. And all the briars called, ‘He chooses us—a beast has chosen us. Catch him! Hold him!’ and they caught him by his tall ears and elegant fluffy tail so hard that they stopped him short.

“‘Let me go,’ he begged. ‘Please let me go. The Weasel will kill me.’

“Then the briars cried until the tears dripped from their twigs. ‘Nobody wants us,’ they sobbed. ‘Please choose us. If you lay back your ears and shorten your tail we’ll never stop you. We’ll shelter you from the summer sun and the winter wind. We’ll warn you of your enemies and bar your path behind you. We’ll serve you as long as you let us.’

“And just then my great-grandfather thought he could hear the Weasel very close, so he cried despairingly. ‘I’ll choose the Pickery Things.’ Down dropped his ears, up shrunk his tail, and away he ran. But we’ve never been sorry. The Pickery Things have kept their word.”

“Dear me, how interesting!” said the lady mouse when Nibble Rabbit had finished. “But could you have your long tail back if you wanted to?”

“It might be managed,” said Nibble. “Mother Nature said it wasn’t fair for the Weasel to begin living before the other things had all made up their minds. He really frightened my great-grandfather into making that choice. And it really wasn’t fair of the briars to hold him. But Mother Nature advised us to try it until we were sure we wanted our tails back again and then let her know. She didn’t actually promise to give them, as I remember,” he added honestly.

And then a commotion broke loose in the little cornstalk tent where Nibble’s party were hiding from the Terrible Storm. “Why don’t you grow one? What kind do you want? Try one like mine! Or mine!!” shouted all the voices until even Nibble’s long ears couldn’t hold all the noise.

“Your long leaps are almost like flying,” said the Partridge. “We couldn’t steer without our tails.”

“Yes, and then you could balance yourself in the trees,” advised Chatter Squirrel.

“Or hold on by it as we do,” said a wise old mouse.

“My cousin lost hers,” murmured Gimlet, shaking his red Woodpecker’s cap very seriously. “And she nearly starved before it grew out again. She couldn’t sit comfortably on a tree-trunk without it.”

“A tail,” squeaked the bats who hadn’t been heard from since they hung themselves up from the roof, “a tail is the handiest pocket in the world. You use it for flies in summer and to warm your paws in winter. Do have one.”

“I do use mine,” said Nibble laughing, “but not for any of the reasons you give. I flash mine so any rabbit behind me can tell whether it’s safe to follow me. Why, my mother never bothered to talk as long as she knew I could see her tail.” And he showed them how he could make the little white puff underneath it show and disappear.

“Well, I never thought it was any good at all,” marvelled Chatter.

“Another thing,” said Nibble. “Ours was no more use than Tad Coon’s. Just a great big brush to carry around. All you could possibly do with it was warm your feet. And we never slept half the year like Tad does, so where would be the use of that?”

“But Tad Coon’s was useful once,” argued Chatter. “His old great-aunt wanted to go on a pilgrimage early one spring. But the water was high in the marsh and she was so fat and crippled with age that she couldn’t swim. So Tad would go down every morning and stick in his tail to show her how deep it was. There would be a brown mark where the mud came and a white mark where the water washed it off above. Every morning the rings would be lower until there was only a little black mud stain on the very tip of it. Then she started off and all the black she got was a little on the very soles of her feet.”

“And he never bothered to wash it clean again,” said Nibble, “so you see how little use it is to him.”

“You’re just jealous,” giggled the lady mouse. “That puff you wear is no bigger than the fuzz off a pussywillow.” And then Chatter Squirrel and Gimlet the Woodpecker and the Partridge all tried their best to make Nibble say that even if he didn’t own a real tail he’d like to try one.

Which of course he wouldn’t. For no decent rabbit would go back on his great-grandfather’s bargain with the Pickery Things. “No,” he insisted, “I truly wouldn’t know what to do with one at all. If it dragged, my gawky legs would stumble on it. If it stood up, my floppy ears would get tangled in it. I guess I’d have to walk like this—” And he limped across the dancing floor pretending to get all mixed up in a tail that wouldn’t get out of the way. He tripped on it and he kicked it and at last he pretended to pick it up in his mouth and carry it.

Chatter Squirrel laughed until his feet danced under him. As for the lady mouse she simply squeaked with joy. But the bats, who live in the woods and sleep all day couldn’t understand. And they were very serious about it. A bat hasn’t any fun in him at all.

“He’s got a tail,” said one, peering at Nibble.

“Of course,” answered the other sleepily, not troubling to open his eyes to look. “Everything’s got a tail, Fish, Bird or Beast. They couldn’t get on without one. It stands to reason.”

“How about frogs?” demanded Gimlet sharply. “They haven’t any.”

Now the bat had never particularly noticed a frog. But you couldn’t fool him. “He’s got one,” he answered cheerfully. “Only sensible folks keep it folded up under them like we do. Quite proper, too. One that drags is so untidy.”

“Untidy!” snapped the lady mouse. “What do you call one with a skin pocket like yours, all cluttered up with fly-wings, Eh?”

“Oh, but he hasn’t,” said Gimlet, and Nibble echoed, “No, truly he hasn’t.”

“Then he’s not Fish, Bird, or Beast!” repeated the sleepy bat. “It stands to reason.” And the other creatures looked at each other curiously, for they didn’t know what to say.

“He isn’t Fish, Bird, or Beast, is he?” fluttered a partridge. And the bat nodded as though he knew it all the time.

“All right,” agreed Chatter cheerfully. “But how about Man?”

“Man?” shouted Nibble and the mice and the partridge all together. For this was news! When the Woodsfolk see a man they don’t stop to look at him; they run and hide. And Nibble had never even got a glimpse of one yet. Neither had the bats. But the sleepy bat just kept on insisting, “He’s neither Fish, Bird, nor Beast, if he hasn’t a tail.”

“Then what is he?” demanded Chatter. He thought he had asked something the bat couldn’t answer.

“What does he wear?” said the bat.

And now it was Chatter who didn’t know what to say. For a Man doesn’t wear scales or feathers or fur. “I think he wears a skin—like a frog,” he said at last.

“I told you so!” And the bat nodded away more conceitedly than ever. And nothing the others could say made any difference.

“But he’s not green,” objected Chatter. “And he doesn’t hop. He’s ever so much bigger, and he’s tan, like your vest, Nibble, or pink, like the inside of your mouth.” Chatter had seen the little boys at the swimming-hole and some of them must have been sunburned.

“Now isn’t that queer,” remarked a partridge. “The one we saw seemed all brown and wrinkly and shelly, like Grandpop Snappingturtle. And he made a noise like a Summer Storm.” She meant a man in a shooting-coat who fired a gun.

“Nothing queer about,” announced Gimlet cheerfully. Gimlet knows more than all the rest of them because he works for the man in the Orchard and is on very good terms with the whole Man tribe. “They come in as many shapes and sizes and colours as flowers.” You see Gimlet doesn’t know the difference between men and women and children. “They make as many different noises as all of us put together and do as many different things.”

“I’m going to take a good long look at the first man I see,” said Nibble. “I will, if I know him when I see him. That’s the only way I’ll ever understand what you’ve been talking about.”

Silvertip pricked up his ears

“Don’t do it,” shouted all the others. “Keep away from Man! Keep away from Man! He’s more dangerous than Silvertip!”

“Whiskers!” Nibble started to his feet at the very idea.

“What if the Terrible Storm should be over and Silvertip comes sneaking back!” And immediately they all looked very serious. They seemed to feel in their hearts that something had gone wrong while they were having their fun. A moment more and they knew it!

Nibble started to scratch away the snow that had drifted the door of the cornstalk tent closed behind them, three days ago. He clawed and he thumped and he pushed and he squirmed but at last he had to sit back and confess, “My nails won’t take a hold. It’s all solid ice outside. We’re frozen in!”

“Frozen in!” exclaimed the partridge. They knew what that meant. It meant that you couldn’t breathe through ice as you can through snow, so you smother in the long run. It seemed that Nibble’s lovely party was going to have a sad ending indeed.

The partridge tried but soon tired out. Then Gimlet tried, but he only froze his bill.

Suddenly, Bump! Bump! sounded from outside.

“It’s Silvertip,” said Chatter sadly. “He’s digging his way in.”

“He can’t catch us all,” answered Nibble, “unless we stay inside. We must burst out in a body, right in his face, and take our chances. Ready now—here we go!”

And at the word the snow crashed in on the tent floor and Nibble leaped through the hole, with the partridges roaring their wings behind him.

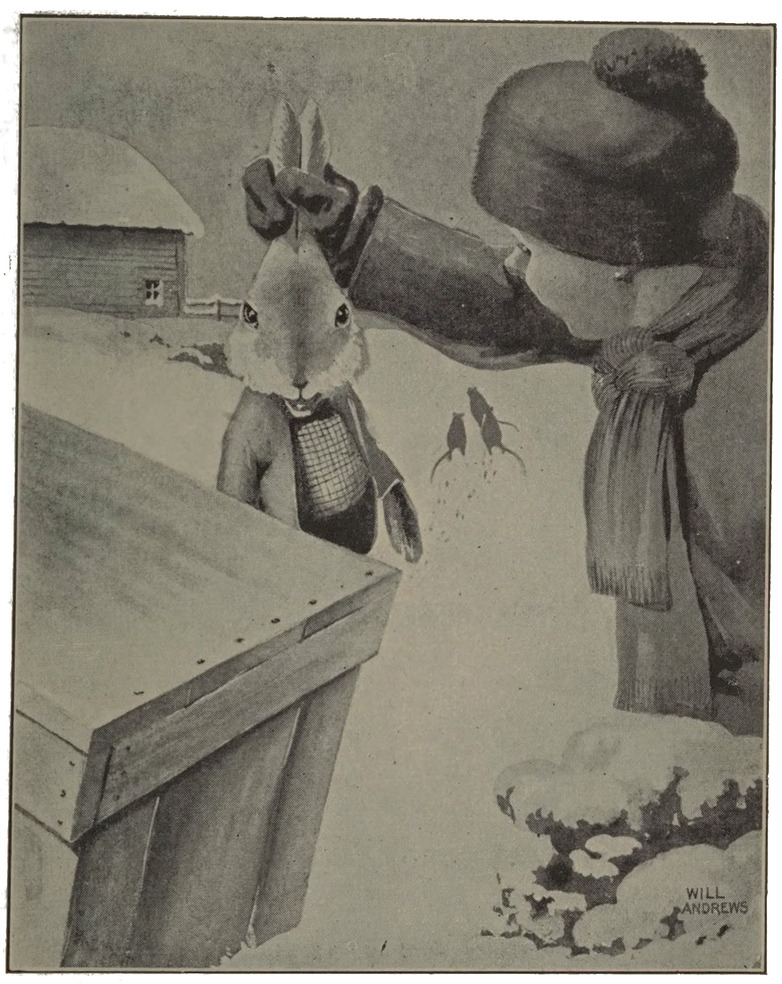

Nibble threw a frightened look over his shoulder as he ran to see if Silvertip were following. Then he stopped dead, and turned around, and sat up and took a good long look, exactly as he said he would. “That’s a Man,” he said to himself “That’s a Man, for sure and certain. What paws!”

It was Tommy Peel, in his new red mittens, who had kicked in the door with the heel of his tall rubber boots to see what was making that noise inside. And he was just about as grown-up for a Man as Nibble was for a Rabbit. And what he was doing out in the Broad Field was an awful secret.

Said Nibble to himself, “He’s not at all like a frog and he’s not like Grandpop Snappingturtle one little bit. He reminds me much more of Redwing the Blackbird.” That was because Tommy had on his dark navy-blue sweater and his new red mittens and his tall rubber boots. “That isn’t fur nor feathers nor scales he’s wearing, but it certainly isn’t skin. Nevertheless,” Nibble told himself, “he has no tail, so a man is all he can possibly be. But he hasn’t any hunger-light in his eyes. I wonder why he’s so much to be feared?”

“That’s the cunningest little bunny,” thought Tommy Peele. “I wish I could catch it and put it in a cage to play with. I believe I’ll set a trap for it.”

Now if Tommy had wanted to kill him, Nibble would have known by the way he looked. But Nibble never dreamed of a trap. That was another thing he didn’t know about. And Tommy didn’t think of killing Nibble because he was only nine years old and you have to be thirteen years old and in the eighth grade before you can have a gun.

Besides, wild things only hunt so that they can eat. But if Tommy Peele could only catch Nibble, he meant to be very good to him. He was going to give him the best of food and a fine cage. He didn’t think Nibble would be unhappy with a nice cosy place to live in. You see Tommy Peele lived in a house himself, which is a kind of a cage when you come to think about it. He didn’t think how different that was from living like a wild thing.

So the small boy and the smaller rabbit were looking at each other in a very friendly way. When all of a sudden the Wind told Nibble something. A light crunch of snow tickled his long ear and a soft whiff of scent tickled his nose. Silvertip the Fox had just jumped over the rail fence into the Clover Patch, right behind him.

“Danger! Come along!” he thumped with his little hind feet. “This way! It’s all clear ahead!” he flashed in rabbity signals from his puffy tail. And he dashed off down the Broad Field.

But Tommy Peele didn’t follow. You see he didn’t understand that sort of talk. He just turned and looked after Nibble, saying to himself, “I wish that little bunny wasn’t so skeery. Wonder if I couldn’t tame him?”

Nibble made a proper triangle and brought up under a thorn bush in the fence row before he dared to look behind him. And then his heart gave an awful bump. For there stood Tommy Peele in his red mittens, exactly where Nibble had left him. He had turned around so he could watch Nibble. And Silvertip was creeping up behind him! The wind was blowing straight from Silvertip to Tommy, warning him as plainly as it had warned Nibble two minutes before, but Tommy didn’t pay any attention. “Poor Man,” Nibble almost sobbed. “You won’t listen to the wind and you won’t listen to me— I wish your mother were here to take care of you.” He said that because he was still so lonely for his own mammy.

Silvertip sniffed about the first corn shock. Then he crept along, pretty carefully, to the one where the owls had found him, and Nibble had given his party. Suddenly he caught sight of Tommy Peele, red mittens, tall rubber boots, and all, standing with his back to him. And he leaped—but he leaped the other way as fast as ever he could. And Nibble wanted to kick up his heels with joy, because he knew something Silvertip was afraid of. But Tommy Peele never knew anything at all about it.

Nibble hid behind a fence post

Just about the time Silvertip’s tail dusted the middle rail of the fence, Tommy decided to follow the bunny and see where he had gone to. Nibble had been calling him to run away from Silvertip a minute or two before, but now he didn’t wait for Tommy Peele. “If that wicked fox is so frightened,” he said to himself, “I can’t be too careful. But I don’t see what he could do to me; he hasn’t any claws and he most certainly can’t run.”

Of course Tommy had to wade slowly through the snow while Nibble could go skimming and skipping over the top of it. So the little rabbit just went a short way farther and hid behind a fence post.

Tommy tramped and trudged until he had followed the bunny tracks to where Nibble had hidden in the bush. “Oh, ho!” said Nibble at last. “That Man doesn’t hunt like the Woodsfolk. Glider the Blacksnake could only smell, not see, where I had gone. This creature can see, and not smell. I’ve got to stop making tracks in this snow.”

He looked all around. Then he saw that he was in another field, farther from the Woods than he had ever dared to come. Cattle were walking about in it, dragging their feet the way they do, and ploughing away the snow with their broad black noses to get at the frosty grass. So Nibble danced down a sprawly cow track where his soft feet wouldn’t leave any trace. And then he jumped over to a small grey stone with a little peaked snow cap on it and snuggled up so close that he looked like a part of it. And Tommy Peele walked right by and never saw him.

Nibble thought this kind of hide and seek was pretty good fun. He was quite disappointed when Tommy went off without looking for him any longer. Still, the grass tasted very sweet where the cows had scraped off the snow for him. Pretty soon he said to himself: “I guess I’d better be thinking about getting back to the Woods again. I’ll be safer if I can reach the Clover Patch without meeting—”

And he stopped right on that word. For there, following his trail, was the very beast he was thinking of—Silvertip! And Silvertip doesn’t have to see any one to follow him!

“There’s only one thing for me to do,” thought the Bunny. “I’ll make a new triangle and end up on that big Brown Log over there.” So he did. And he crouched down on it as close as ever he could and held his breath while Silvertip came closer and closer. Now he was by the stone! Now he was at the grassy spot! Now—

Now that big Brown Log did a very queer thing. It began to move. It rocked and it heaved and then it raised itself right off the ground. Nibble was so stiff with fright that all he could do was dig in his toes and hold on. And then it switched its tail. It was a cow who had chosen a chilly spot to lie down!

That tail sent Nibble spinning. Luckily he landed right side up and went bouncing off faster than when Glider was chasing him. But Silvertip didn’t see him. Silvertip was too busy on his own account.

For that cow wasn’t the sleepy and serious kind. She was young and active. But Silvertip, coming along with his nose to the ground, didn’t see her.

She lowered her horns and rolled her eyes around, pawing footfuls of snow about her shoulders. “Wolf!” she suddenly bellowed and ran at him.

Nibble Rabbit thought his end had come. But his feet didn’t think at all; they just ran. They ran while he was turning a somersault through the air and they ran faster when they felt the fluffy snow. And if they hadn’t run right into the big haystack at the end of the pasture there’s no knowing how far they would have taken him. But there was a nice little hole under it, waiting for him to come right in and hide.

But you know Nibble. First he’s scared, and next he’s curious. Just as soon as he thought nothing was following him he stuck out his little whiskers to sniff about and put up his long ears to listen. And he heard a lot of little birds cheeping and gossiping up above him. One of them said, “There he is! I say, Bunny, what did you do that for?”

“Do what?” demanded Nibble, craning his neck so he could see who he was talking to. “What did I do, Mr. Chirp?”

“Tried to ride the red heifer,” answered Chirp Sparrow.

“But I didn’t! Indeed I didn’t!” cried the little rabbit. “Silvertip was chasing me, so I jumped back from my trail on to a log. I was going to slip down behind it and run away as soon as he had gone past, so he wouldn’t smell me on the ground. That’s what we always do. But something happened.”

“So it seems,” replied Chirp Sparrow in an amused voice. “Don’t you know what it was?”

“Not yet,” said Nibble, “My head’s still whirling.”

“I should think it might be,” laughed Chirp. And the other sparrows seemed to think it was so funny they all started to giggle and talk at once, which made Nibble’s head whirl harder than ever.

“Hush!” Chirp ordered. “I want to tell him myself. Well, that log you hopped up on was a cow. She was taking a nap and you woke her up. When she started to get up you dug your claws into her so she switched her tail—I wish you could have seen yourself. You went tumbling over and over like a curly thorn leaf in a west wind.” And he stopped to laugh again.

“But Silvertip?” asked Nibble anxiously.

“Yes, Silvertip was the funniest of all.” Chirp shook himself so he could sober up to tell the rest of it. “The cow looked all around to see who had been disturbing her and there was Silvertip. So she must have blamed it on him. You ought to have seen her chase him. Silly thing. He just tumbled through the fence, any old way, and made off, but she thinks she’s still after him.”

Sure enough, Nibble could see the red heifer with her swishy tail stuck straight up in the air, waving the tasselly tip of it, leaping and mooing and snorting at the other end of the field.

“I thought that was a queer log,” he said thoughtfully. “It made my toes all warm and there wasn’t any snow on top of it. But it had such a nice safe, warm-hole sort of a smell, with little clovery whiffs mixed in with it. Cows must be awfully dangerous!”

“Dangerous!” hooted Chirp. “A cow dangerous! Why, the only thing she’s dangerous to is a clover-top. That’s what she eats, and that’s why she smells of it.”

“But Silvertip was afraid of her.” Nibble was really puzzled.

“Silvertip? Oh, well. That’s another story,” said Chirp.

“Away back when the world was new—tell me about it.” Now Nibble was all pleased and excited.

“Exactly! Way back when the world was new,” began Chirp Sparrow. And then he stopped to squirm himself into a bunch of hay right beside Nibble Rabbit, so the wind wouldn’t muss his feathers, while he was talking. And Nibble crept to the very mouth of the hole in the bottom of the haystack where he was hiding, and sat on his toes and was very happy and comfortable.

“Away back when the world was new the cows and wolves began to have trouble.”

“Because the wolves chose to eat them, like the weasel chose to eat my great-great-grandfather?” interrupted Nibble excitedly.

“Not in the very first-off beginning,” said Chirp. “You see, the weasel was one of those who came up from under the Earth-that-was-common-to-all. He wasn’t one of Mother Nature’s own things. But the wolf was. He was just a little too clever, but she liked him and trusted him—more than most.

“Mother Nature had made a bargain with the plants. The beasts were to eat them. But she promised the plants that they wouldn’t die, but would spring up again stronger than ever. She would send the rain to keep them from getting thirsty, and they would put their roots into the Earth-that-was-common-to-all and get their food from it, and the winds were to keep their house swept clean and play with them, and the trees were to shade them from the hot sun and sing to them, so that they would be perfectly contented. And the beasts were to graze on them and the birds were to eat part of their seeds—but not all—so they were contented, too.

“Mother Nature got about half the earth in fine working order. Then she gave the rain and the wind orders and went down south, over the Far Horizon to look after the other half.

“Right away the wicked little raindrops went to playing in the brooks and leading them into no end of mischief. And the winds went up and played tag with each other on the mountain-tops. And the Sun got curious to know what Mother Nature was doing with the other half of the earth, because that was coming out all different, so he kept edging farther and farther south until by and by, he wasn’t paying any attention to the north half at all. And things went awfully wrong in the north half.

“Awfully wrong! The plants down in the brook bottoms cried: ‘We’re drowning! We’re drowning! If the wind and the sun don’t do their part we won’t be eaten.’ So they turned themselves into bulrushes and all kinds of tough, stringy things that can stand wet feet, but nothing in the world can eat them. And the plants on the higher lands cried: ‘We’re strangling! We haven’t had a drink in ever so long, and our backs are so stiff from standing still we’ll never be able to play again. If the rain and the wind don’t do their part we won’t be eaten!’ So they hid down in their roots under the Earth-that-is-common-to-all, most discouraged, and left only their skeletons standing. And the beasts starved. Especially the poor cows. But the wolves kept very fat. Only they weren’t telling any one how they managed it.

“And Mother Nature was almost through down south and getting ready to come north again. So the Sun hurried back to get busy. And the rain poured to make up for lost time, and the winds rushed down from the mountain tops, but their fingers were all cold, so they made things worse than ever. And the beasts were all cold, ’specially the cows.” Chirp stopped to stretch his wing.

“Please go on, Mr. Chirp,” pleaded Nibble. He was so excited and impatient! “Please get to the part about the wolves!”

“I will,” promised Chirp Sparrow. “Only these birds must settle down and be quiet. They get me all fluttered.” For every sparrow on the haystack was coming down close to the hole in the bottom where Nibble Rabbit was sitting. No one wanted to miss hearing about it.

“Well, Mother Nature came back,” Chirp went on. “And, my, but wasn’t she angry! Just wasn’t she? She said to the rain: ‘I don’t believe you’ve rained a drop since I’ve been gone or you wouldn’t be carrying on at this rate. Do you call this a shower? It’s a flood—and it’s perfectly disgraceful.’ Then she turned to the wind. ‘Do you think I don’t know where you’ve been?’ she scolded. ‘I can feel how cold your fingers are. Look how you’ve ruffled up the fur on my poor chilly beasts there!’ And she snapped at the Sun: ‘You needn’t look so good. Stop smiling and listen to me. Do you think I didn’t know where you were? Peeking right over my shoulder. You nearly burned a hole in the back of my neck when I was finishing up that last armadillo. You three have made a pretty mess of things. And I did so want one world where there wasn’t any winter!’ She nearly sat down and cried over it all, she was so disappointed.

“But, of course she hadn’t time. She had to put things back in order. First she coaxed the plants to begin growing again. Then she called the beasts so she could look them all over and see what she could do for them.

“And the cows came crawling up, as slow, as slow, with their poor bones all sticking out—but the wolves were fat as butter.

“And the cows said, ‘We’ve been so starvation hungry that we’ve worn our teeth right off.’ And so they had. And their teeth are still worn off, right to this day.

“And the wolves whimpered: ‘We’ve been so starvation hungry, too!’

“But Mother Nature looked at their fat sides and she said: ‘Show me your teeth.’

“And their teeth were perfectly sharp and new. And they still are.

“So Mother Nature frowned at them until they cringed. And they trembled so hard that their very claws clattered. For they knew that they had misbehaved and something serious would come of it. Then she asked: ‘What have you been eating?’

“‘Just dead beasts that we found lying about,’ they whined.

“Mother Nature looked at the poor cows, but the cows wouldn’t tell on the wicked wolves. Only they scratched the earth with their feet and sent it flying over their shoulders the way they do when they’re angry. Then she said: ‘Cows will always be angry with you like that because they smell the blood on you. Oh, wolves, it is bad to lie, but it is terrible to kill!’

“Of course the wolves knew that they had been found out, so they tried to look brave and answered: ‘We are too clever to starve like a stupid cow.’

“But Mother Nature shook her head sadly. ‘You’ll find that it’s better to be good and stupid than to be bad and clever. But bad and clever you will be to the end of all wolves, and the stupid cow will live to see the last of you. Cows, how shall I punish them?’

“Then the cows roared like a raging river: ‘Give us back our teeth and we’ll do it ourselves!’

“‘I can’t do that,’ she explained, ‘because nothing that has been lived can be done over again, but I can give you something newer and longer and sharper than the teeth of any wolf.’

“It was horns.”

“Is that all?” demanded Nibble Rabbit.

“All?” echoed Chirp Sparrow, cocking his head on one side. “Isn’t that enough?” But he was really very much flattered. For Nibble’s ears had stood straight up right through his story, and all the other sparrows on the haystack were saying, “Hush, hush!” so he would go on again.

“My beak!” Chirp exclaimed. “I’ve told you how winter came to be, because the sun and the wind and the rain didn’t behave while Mother Nature left this half of the earth to go down and start the other half. I’ve told you how the good stupid cows starved because the plants wouldn’t be eaten, and how the bad clever wolves took to eating the cows. And how Mother Nature gave them horns that were longer and sharper than the tooth of any wolf to make it up to them. What more do you want to know?”

“Lots of things,” insisted Nibble. “Why did that cow shout ‘Wolf’! at Silvertip?”

“Because she’s a cow. Too good and stupid to know the difference! Wolf, fox, or dog, it’s all the same family, only the fox is smaller, and cleverer—and wickeder—and the dog is the cleverest of all. But the cows didn’t make much use of their horns after they did get them, because they are so stupid.

“They say Mother Nature was sorrier over the wickedness of the wolves than over any of the rest because she trusted them more than most,” he went on. “You see, they were her own beasts, not like the weasel who came up from under the earth and was wicked from the very first.”

“Were lots of others bad, too?” demanded Nibble. “Bad things are always interesting, you know.

“Oh, yes. Even some of the birds.” Chirp said this as though it were the most wicked thing in the world for a bird to be bad. “But we weren’t. We’ve always been as good as good, no matter how much trouble we have with the hawks and the owls. We eat some seeds, but not all, and the bugs. Bugs come from under the earth, you know, and the plants hate them. But we didn’t have to ask for horns or claws to take care of ourselves—that’s because we’re so clever.” And he spread his lively little wings, with brown edges to every feather, and squinted conceitedly at them over his shoulder.

“And the mice?” added Nibble. He didn’t want birds to have all the credit.

“Mice, indeed!” chirped the sparrow, quite sharply. “Mice! Why, do you know what they did? They sneaked down under the earth and nibbled the very roots of the plants when they tried to hide under the Earth-that-was-common-to-all. And that was the meanest trick! It took Mother Nature half through the first spring to find out what they had been doing. Some were so ashamed of it that they stayed right there and got to be moles. But some of them pretended they just didn’t know any better.”

Nibble felt a bit flustered because he does it, too, and so does Doctor Muskrat. But then the quail and the sleek brown thrasher are just as bad, so he didn’t try to say anything. Fortunately Chirp went right on talking.

“The wickedest creature of all,” he said, “is Ouphe the Rat. He’s so horrid and dirty and disgusting that he eats even his own kind. He’s a cannibal! Everything hates him, whether it wears feathers or fur or scales—even the stupid cow. And he hates everything. He comes sneaking and creeping just when you least expect him, and—”

“Cheep!” went the watch bird of the flock. “Cheep!” echoed their voices and flutter went their lively little wings with brown edges to every feather. And Ouphe squeaked with rage because he’d missed them that time.

“You will talk about me!” he snarled. “You will, will you? Wait till you hatch and I’ll crunch your baby birds’ bones for you.” He clashed his yellow fangs horribly.

The little rabbit crouched down in the bole in the bottom of the haystack not three feet away from the wicked rat. But Ouphe hadn’t seen him. He was sure of it because Ouphe kept squalling at the sparrows all the nastiest things he could put his tongue to. And the sparrows, swinging from a branch of the elm tree that leaned above him, weren’t much more polite.

“Swapping lies with the field-mice, were you?” sneered Ouphe. “I’ll attend to them.”

“It wasn’t lies,” shrieked Chirp Sparrow indignantly. “Didn’t you come sneaking and creeping—just the way you always do? Thought you’d climb up the other side of the stack and surprise us when we weren’t expecting you, didn’t you? And isn’t that exactly what I said? Let me tell you, you’re one thing we always do expect. You’ll maybe catch us when you learn to fly—but not before.”

“I’ll catch you when I clean out these tattle-tales of field-mice,” snapped Ouphe, and he gnashed his teeth until the froth made his whiskers white.

“It wasn’t the field-mice, Smarty! They never said a word. It was your own scaly tail that told on you.” Chirp spread his wings, opened his beak and stuck out his tongue at the wicked old beast. And Ouphe lashed his own tattling tail in an awful rage.

“It wasn’t the field-mice, was it?” he snarled. “Then who were you talking to? I’ll slit your gossiping throat for you!”

Tommy held Nibble up by his long ears