Firelie Gluck fell against him suddenly and pinched him. Condemeign shuddered, for he felt the planners sculpturing death out of dreams into quiet, almost joyous forms.

Life could be for a whole forest of

years, but dying took just as long as one

wished. Condemeign reckoned he might as

well do the world a bad turn while he was

about it. One might as well have one's

little joke. The world had had one on him.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories January 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

With a stroke of his pen, Condemeign signed a death sentence on a toffish nephew and condemned an older and even more lethal bore of a brother to a swinish end. The new provisions of the will took most of what Condemeign had left in his bank balance. He sighed. There was just so much undiluted evil that one might create with just about twice the money he had signed away. He might also have written another Greater Testament, one that would have corrupted, instead of admonished. But the unconscious Villons and Des Esseintes of his world were hapless, constricted anachronisms. The universe had expanded, but, somehow, it had also fenced in common elbow room.

The other details took only another minute. The apartment would be repossessed by the housing authorities. The car would be melted down into cash to satisfy certain codicils of the wills. Odds and ends were plainly earmarked for the trash chutes, destined to wind up part of a great garbage boat hurtling into the sun, to be reduced to light and warmth.

Beyond that, he thought, ruminating on the promises of Nepenthe, Incorporated's slick paper brochure that had fallen into his hand, and barring, of course, what he was wearing at present, there was a comforting zero. Not even the mice would get that. There were no mice, no insects nor even a great variety of bacilli on the great three-mile-square cube spinning its slow orbit one hundred thousand miles beyond the limits of the atmosphere. The brochure had been more than insistent on that point. The little distractions were to vanish. Nothing was to mar the serenity or adventure of the final hours or days.

Condemeign did not bother to glance round the tidy, clean room. He took a swig of gin and picked up the telephone receiver, dialing with his free hand. When the receiver clicked and a rather corpsy female voice greeted him at the other end of the wire he spoke his name into the mouthpiece and hung up. Then he finished the gin and waited.

The man who came for him could not have been told from a thousand. His face had a slow, blurred look, as though someone had blotted it with a sponge while it was drying. His clothes were seasonal, decent and reasonably gay. Condemeign could not place him as a latter-day Charon, but then he remembered that there was an inevitable difference between the man who takes your ticket and the navigator who swings the steel coracle out into the Styx.

The ride to the spaceport was curiously dull. Condemeign, having embarked upon oblivion, realized instantly the futility of even one final journey. A dry disappointment crinkled his tongue. He leaned forward in the aircar's seat to call a sardonic halt, but it was not even necessary for his companion to put out a restraining hand. Condemeign relaxed. His pulse had not accelerated by the slightest degree. But that could only be because he wasn't staring into black jaws as yet. Barbiturates in a bathroom in sufficient doses were simply bourgeois. The way to end, as Nepenthe promised, was on a grander scale, with the cosmos a bated spectator and the sun exploding in one's face.

They walked to the small tender. Condemeign had been curious as to when the thin sheaf of banknotes in his pocket was expected to change hands. His guide halted at the flight of steel steps and squinted a little at the sun that drenched the spaceport. His eyes caught on the tall needle of an interplanetary freighter and then he looked at Condemeign.

"There is a little matter of the money," he said.

"Better count it," Condemeign said. "Twenty-five thousand in large bills. And if you think I went to all the bother of having the serials copied, it is because you fail to understand the thoughts of a man quite eager to die."

The blurred features came into sharp focus like a viewplate clearing. It was Charon, now, counting the bills rapidly.

"It is true that not all the final reports have been examined by our psychological department, Mr. Condemeign," he said. "But you wouldn't have gotten even this far if you had been found grossly wanting." He put the bills away and waved a hand gracefully at the great billiard table of the spaceport, the bulking, far-off mountains and the quiet sky. "It is a beautiful day, Mr. Condemeign. Perhaps you had better take a last look around."

"I did," Condemeign sighed. "Last night. And it wasn't any fun at all." He climbed aboard the tender. When he and his guide had gotten into their straps there was a faint hiss and the bright airport began to drop away quickly.

The sense of strangling boredom never left him. Not even when the great corona flared out of the paling blue and pulsed through the border between earth and sky. He had never seen it before, and his absolute ennui confirmed his decision. From the tangled roots of the flower to the last Einsteinian closed curve there was dull sameness in the universe. If there was a god it was only because he had never heard of Nepenthe, Inc.

Then the multi-miled palace of death swam sluggishly into view, a fat, tin-colored cookie can, with thousands of blind eyes.

The pilot who sat abstemiously on the edge of his seat threw a bunch of fingers at the cookie can. He was a short, pulpy man with eyes that looked as though they had seen stars topple and blinked for the dryness.

"Never seen anything like that hanging in the sky, did you?" he asked.

Condemeign frowned. He edged an eye toward the sun, gaudy in its necklace of gas and stars.

"What about the moon?" he said. "What about half of that thing with its guts coming out?"

The guide smiled gently.

"Quite impossible, Mr. Condemeign. Nepenthe is surrounded by a force screen that could deflect a planet."

Condemeign brooded.

"With that sort of invulnerability, someone might...."

"Someone tried. And after that, even the sun wouldn't have him. He's poking out around the Andromeda nebula, now, quite helpless, of course. He can't turn the power off. Not in his lifetime, anyway."

A wide mouth gaped in the now faintly visible force screen through which an ordinary blue light ray pulsed, serving as a beam, and the tender turned slowly, pointing its narrow nose at the welcoming maw.

Condemeign watched the pilot make small, hushed motions at the instrument. When he looked up again the airlock had closed behind them and a wiry steel claw reached out to wrap the tender in its cradle.

He had half expected to see a winding line of neophytes clad in robes of white writhing somewhere into a leafy nothingness with a mist-driven tempo, perhaps from Debussy to waft them on to their Dies Irae. An attendant helped him descend into the square steel room. His guide paused and looked about, floating.

"A trifle businesslike and grim," he noted. "Inside there's gravity laid on, good atmosphere. Nothing like this hot steel smell. And you can walk. Excellent footing. Just like home."

They passed, mainly by violent swimming motions into a large hall. Condemeign fell jerkily back on his feet, coming instantly again to grips with the pull of gravity. Everything was steel walls fussily disguised with a sort of furry, plastic lining laid on in thin sheets. The guide walked him up to a desk against one wall, near a door. Condemeign blinked at the soft blue illumination. The guide shook his hand.

"I must be going," he said. "Glad to have met you, Mr. Condemeign."

The guide's hunched back faded through the door. Condemeign turned listlessly to the figure at the desk. It was a woman, and before his eyes focussed in the filmy light he got an odd impression of a brown, papery bundle incongruous in its chiaroscuro lacings and bulgings.

"I am Miss Froon," she said. The smile that lit her face had last been seen on Madame La Farge. It had cut its teeth on sad suttees. It was thoroughly unoriginal.

Condemeign sighed. The perfect servant. The timeless, obsequious recorder. Was Miss Froon, perhaps, the key to the last portal. She was distressingly unattractive, rather flat in the chest and sported an overly aseptic set of teeth that flashed. He noted the brown laths of legs that poked from under the denim shorts. Miss Froon, he decided, looked really like an underdone chicken.

Miss Froon rustled the papers before her. She tapped, almost frigidly, on the glassy top of the desk.

"There are a few questions, Mr. Condemeign."

"Whose questions?"

Miss Froon clucked.

"Ours first, and then, if you wish, a few of yours."

Condemeign sighed and then he almost smiled. It would be a blind of course, a subtle blind to confuse and reassure him. But then, weren't the blind always getting kicked. Wasn't someone always dropping lead nickels into the cups?

"The brochure mentioned nothing about questions, Miss Froon," he said.

"We do not insist upon it, Mr. Condemeign. You may answer the questions or not. Nepenthe, Inc., as you already know, has investigated your case. These are linking questions, Mr. Condemeign. They may be of use to science."

So the almighty dollar had feet of clay. Even in space, between earth and moon, beyond the one hundred thousand mile limit where the state power ended and anarchy began, despite the insulation of distance and depth, quite coldly independent of even the mighty barriers of pelf, science was poking and treading about, listening and noting and breathing down his neck. Well, what of it, he thought, finally. Life was ceaseless obligation. He was beginning to realize that death might be the same.

"Have you ever wanted to die before, Mr. Condemeign?" Miss Froon seemed almost penetratingly aware of the verdict in his eyes.

"Often, Miss Froon." He lit a cigarette and watched her making the first notations with a pencil. "It is only in late years, however, that I have been able to afford it."

Miss Froon almost blushed. When she recovered she said: "Are you afraid of death, Mr. Condemeign?"

"I hope so, Miss Froon. Like a certain Cardinal of Ragusa—you have probably never heard of him—I am inclined to put a high price on existence before it ceases." He paused and settled on the edge of the desk, musing. "Yes, I rather hope so. There is little else to be afraid of." He watched her through the smoke of his cigarette, blinking, a wet stain of puny resentment and annoyance on the blotched beak. She hesitated for an instant, but the flying fingers never stopped.

"Would you care to disclose the reason you wish to die?" she asked.

Let science in for one final peek, a last eyebrow lifting look at the raised chemise. Why not? Even science might be persuaded that life was unrecognizable from death except in the shifting phantasm and utterly real land of sleep. He drew a deep breath.

"I think so, Miss Froon. It is, simply, that there is no meaning to life, no meaning at all. I think this particular view is disguised under a number of well-known philosophic terms and bodies of thought. One might call it a sort of nihilistic Existentialism, to be more concrete and specific. However," he paused and smiled charmingly and with just a touch of sadness in his eyes, "I would not call myself an Existentialist by any means. That sort of person playing Russian Roulette, for instance, cannot help but manifest an interest in his chances for life. He clings, so to speak, to even a tiny thread that ravels enticingly from the million-threaded rope of ordinary existence. Now, I"—Condemeign watched his left leg go back and forth in a short arc—"I do not see the thread, though I know it is there as I know the rope is there. Both a thread and a rope can hang a man. In fact, in this case, they have."

He watched her, hoping for one flicker of interest, one sign that he had said something original, for, beyond doubt, she was the supreme critic, an unfailing reflection of all the prejudices that Nepenthe had compassed, and even more. There was only the flayed blankness of a blind wall in her eyes. He rocked, suddenly, seeming to see great carven doors shutting him out, shoving him into the remotest corner of a vibrant oblivion. Then, as it always had, silent Homeric laughter saved him. He was an honest Cagliostro after all, an albuminous series of endless, mystical passes that could never pretend to be anything more than motion. Next question he thought. But none came, and then he said, suddenly, "Is it painful, Miss Froon?"

Miss Froon did not bother to smile with all the prejudices of a woman of the world. Her eyes glittered dully like a toad's and he perceived in their depths the first awakening to him as something more than a client, a case, a filing card to be abstracted. Miss Froon's voice, he discovered suddenly, had more in it than the pride of neon and the inexorable drive of continuity.

"It is never painful, Mr. Condemeign." She hesitated and then went on. "It is sometimes interesting and often dramatic, but," and she cracked the roast-brown crust of her face with a corpsy smile, "I think we can safely say it is never painful. If—ah—oblivion were painful, we should have no clients at all."

Done to a turn, he thought, and then a small man with a hint of Mephistophelian humor glinting in his eyes and spraying off from the sharpness of his chin, came in through the door by which his guide had departed. He was smoking an oval cigarette and Miss Froon jumped to her feet and filed Mr. Condemeign's papers in a wall recess before she said anything.

"This is Mr. Condemeign, Dr. Munro," she said, turning to press a few buttons, and Condemeign knew he had come to the end of the line.

"I am the Director of Nepenthe, Mr. Condemeign." Dr. Munro extended a small, brown hand and Condemeign took it absently. "You have found our establishment comfortable so far?" Condemeign nodded. Dr. Munro turned to Miss Froon and said, "You may go, Miss Froon. It will be over an hour before the next arrival."

"Very well, Doctor," she said and glanced up rather shyly before she left. "You will find Mr. Condemeign interesting, I think."

"I rather thought so," the doctor said. "Yes, I rather thought so." He nudged Condemeign with a slight pressure of his eyes down a short passageway and presently they came out into a small domed room through which the stars peered brightly. Dr. Munro indicated a comfortable chair and seated himself after Condemeign.

"I could not help hearing your last question, Mr. Condemeign," the Doctor said. "And I can assure you that Miss Froon answered correctly. We do not accept neurotics or certifiable psychotics on Nepenthe." Doctor Munro's eyes fixed Condemeign's with a stare of almost unbearable morality. "We are not Torquemadas, sir, nor Satanists, pandering to the perverted tastes of common debauchees. You will find no connoisseurs of pain and anxiety among our—ah—staff, though if one is ever required, I am sure that I myself could pass muster...." Doctor Munro's eyes sharpened suddenly and a long purl of smoke went raging past his lips. "Though, of course," he said hurriedly, "the occasion has arisen only twice before. Both times in the case of an extremely clever penetration of our screening system by agents of Bios. They regretted it, of course, rather screamingly, as I remember."

"Bios?" Condemeign's eyebrows raised themselves the merest part of an inch.

Dr. Munro laughed unpleasantly. He plucked at the latex lining of his chair with quick, wrenching motions.

"Bios, Mr. Condemeign, is an organization of fanatical, reactionary crackpots, cloudcuckoolanders and philosophical maunders who derive their ideas from the old Hindus, holding that the taking of life for whatever reason and in whatsoever fashion is a sin against the prime law of the universe—so they call it—which is that life is destined to animate all inanimate matter. They have an abhorrence of the latter which extends to such absurdities as claiming that the planets themselves are living creatures to absolve themselves of the horror of even walking on inactive materials."

"I should imagine that the Biosonians would have some difficulty reconciling themselves to clothes," remarked Condemeign dryly.

Dr. Munro chuckled, rubbing his hands.

"You are perspicacious, Mr. Condemeign. They are, of course, invariably arrested when they appear on the streets, for they go naked. That is the least of their depredations, however."

"There are others, more serious?"

Dr. Munro leaned back in his chair and lit the fourth or fifth oval cigarette he had begun since meeting Condemeign.

"They recognize Nepenthe, of course, as the prime obstacle to what they consider their main objective—the preservation and extension of life." Doctor Munro's voice rose abruptly in annoyance. He brought his fingers together, steepled, in what almost sounded like a violent snap. "Mind you, wars may drench Earth and the other planets in blood. Their contribution to the various peace funds are non-existent. Disease and the various corruptions of mind and soul annihilate millions. One would imagine that this absurd organization would devote its cloak and dagger activities to wiping out such horrors, in raising the standard of living, in forcing the various state powers to abolish poverty. But no! No, Mr. Condemeign! This insane group of malefactors...." Dr. Munro's palate clacked in the back of his mouth with indignation.... "This outrageous conspiracy against one of the most sacred rights of life itself, which is, of course, to end it, can find nothing better to do than interfere with a business which, though not legitimate in the legal sense of the word, serves a purpose nobler than most and certainly more artistic."

"They are really dangerous people, then?" Condemeign asked.

"Fanatics, sir, are seldom anything else. It is the sworn purpose of Bios, frequently communicated to us in raffish notes and wax-sealed manifestos delivered to us in numerous antediluvian manners, to destroy Nepenthe."

"Rather Jesuitical," rejoined Condemeign. "In fact, hardly worth the trouble."

Dr. Munro fussed. He peered out into the star-lit heavens nervously. "They cannot, of course, possibly penetrate our force screens. But men are more insidious than pointed projectiles. In fact...." He turned his face to Condemeign's. "In fact...."

"You are rather wondering if I might not myself have waggled in an atom bomb; that I am, myself, a Biosonian fanatic," said Condemeign. He accepted a cigarette from Munro who leaned forward, his flashing little eyes fastened on Condemeign's face.

"Not at all, Mr. Condemeign," Dr. Munro's lips parted in a smile. "We can never be too sure about anything, you know, and it is possible, ultimately inevitable, that Bios could successfully smuggle an agent or agents past our screening." His voice dropped to a confidential level, and Condemeign thought it might also be appealing. "I myself would not wish to be present when that interesting event takes place. I'm just wondering, Mr. Condemeign, whether or not you really are a fanatic." A fluttery, almost frightened look crept into Dr. Munro's eyes. "We are quite used to death on Nepenthe, and yet, somehow, it never seems to lose its novelties or its terrors."

"I'm afraid I'm not a fanatic, Dr. Munro, nor an adherent of Bios."

The Doctor's eyes grew sadder.

"Somehow, I wish you were a fanatic, Mr. Condemeign. A fanatic about something."

"Why?"

"Because a fanatic is far from being the most dangerous person in the world." Dr. Munro's pointed chin quivered.

"And just what kind of person is, Dr. Munro?"

The Doctor rose, stubbing out his cigarette. "I think—I think ..." he said slowly, "that every man is entitled to a few professional secrets. And that fact is one of mine." His voice became explosive. "Come, come, Mr. Condemeign, surely you have a better question than that. One usually does."

Condemeign smiled. He had, of course. The obvious one. The last surrender to the delicious, trivial preoccupation with the ordinaries. The already flagellant skin eager for roughening against the last bark edges of the grain. He saw himself, just once more, not abject at the foot of the cross, but smiling into the wide bore of a pregnant pistol. And a tiny chill shot through him, small, diffuse, but cold as the black spaces beyond the dome.

"I really would like to know if the manner of my departure has already been arranged."

Dr. Munro measured him with a professional eye. To Condemeign it seemed as though invisible tapes were recording his dimensions, that hammers and saws were already building a coffin. But there would be no coffin, he knew. There hadn't been for hundreds of years.

"I rather think so, Mr. Condemeign," the Doctor remarked. "As you know—as Miss Froon told you—all of the reports have not been fully checked, but they are, most likely on my desk now. Of course, I can't show them to you. We take special pains to...."

"I quite realize that," said Condemeign, satisfied. "Of course, I hope that your staff has devised a suitable end."

Dr. Munro slithered close to Condemeign. He expanded. Whole ideologies, entire universes of bulked emotion framed in his eyes.

"The best staff in the System, sir! You may be sure of it!" His voice sank as it indicated scorn. "Nepenthe is worlds ahead of any of its competitors. In fact, I might even say that Bios disdains to notice any service agency of our sort except Nepenthe. Here we have the greatest body of experts on their specialty ever gathered together under one roof. Nepenthe has spared no expense to insure that taste, variety and ingenuity surround every client on his way to the final goal. You will not be surprised, Mr. Condemeign, when I tell you that literally hundreds upon hundreds of man-hours are consumed in the devising of an individual death, with as much care lavished on those of more moderate income as upon those who could afford it several times over. A staff of forty-three experts! Imagine!"

Dr. Munro's fingers rang, snapping in the air. A sort of glow haloed his chattering face. "And every one of them an artist, a dreamer, a virtuoso in his special subdivision of the field! Every man and woman of the team selected from prepared lists. And then, Mr. Condemeign, to accommodate this great body of talent thousands upon thousands of acres of halls, corridors, playrooms, an infinitude of stages on which their immense dramas or comedies—it is important to remember that death can be a comedy—are contrived, controlled and brought to a denouement!"

Condemeign chuckled grimly.

"Just where is the body delivered, Dr. Munro?" It would not be an Irish wake, he thought, with keening over the body, and a hearty toast to the departed, rosy-cheeked and a-squat in the bier.

Dr. Munro, checked, gathered in the remnants of his dignity with a wave of his fingers.

"There is no 'body' left, Mr. Condemeign," he said. "What is left is discreetly disposed of in our private crematorium, and a death certificate is secretly deposited in its proper place in the local Hall of Records ... eh?" The Doctor started methodically and nervously as a uniformed attendant stepped from behind a hanging. "Eh, what is it?"

"Case 27, Doctor." The man looking significantly at Condemeign.

"Oh, go ahead," Munro said petulantly. "It's all right."

"Case 27 is closed, Dr. Munro."

Condemeign blinked his eyes.

"You know, Doctor Munro, I appreciate your interest in me. I rather imagine that you don't draw the curtains this far for everybody."

"Not for everybody, Mr. Condemeign," the Doctor said. "For you, why not? It is not that you are interesting, Mr. Condemeign. It is, frankly, that you are not a fanatic." He bowed gracefully.

"I'm afraid you will have to pardon me, Mr. Condemeign," the Doctor continued. "I must report to my office. In the meantime, Sismus, here, will show you to your room. You needn't bother too much about him. He will merely be around to make the beds, help you dress and perform any other little services you may desire. It is all in the brochure. Consider Nepenthe at your disposal."

Sismus plucked at Condemeign's arm as the Doctor disappeared. They walked through several interconnecting corridors, got into a gravity tube and emerged, according to Sismus, on the other side of Nepenthe, in an identical arrangement of passageways that reminded Condemeign of the corridors of an ordinary space liner, opening out into staterooms. His own room was little more than an over-sized cell, furnished with a plain bed, a deep over-stuffed chair and several highboys. Condemeign immediately inspected them. They were jammed full of bright-colored lounging pajamas, the customary costume of clients of the firm. Sismus helped him disrobe and put on a pair. Condemeign watched his clothes swept into a disposal chute and replaced the wristwatch on his arm.

The attendant indicated an aperture in the wall beside the disposal chute which seemed to perform most of the duties of a dumbwaiter. A muddy-colored pair of socks fell through the aperture at the touch of a button, as did a tall drink of gin-and-sugar.

"Your meals are served in the same way, sir," remarked Sismus, as a small red light blinked and a bit of paper wafted in. "This is the menu for the next meal." He handed the paper to Condemeign. "You need only check off the items you wish and simply throw the paper back in the slot."

Condemeign studied the really fine bill of fare. So they had abolished days and time and the whole anachronism of boxing and correlating. The sense of passage was to be dulled, and a fine, chaotic unconcern inoculated, like a diffuse spray of forgetfulness coursing through the body.

"The advantages of Nepenthe are overwhelming, Sismus," remarked Condemeign, sipping his drink. "I am surprised that it is not run purely as a hotel."

"Television is also laid on, sir," interrupted Sismus. "You may select any live or recorded program you wish." He took a metal-covered book from a shelf and handed it to Condemeign.

Condemeign flipped the pages. His eyes widened. He whistled, muttering.

"What's this ... 'The Perfumed Garden', 'Arabian Night', 'Fanny Hill'?" He paused, breathless. Sismus was unconcerned.

"Nothing but the best of classic pornography, sir. You needn't worry. We are outside of all the legal limits here. Will there be anything else, Mr. Condemeign?"

"You can go, Sismus. Yes, thank you." The attendant, leaving, handed him a guide to Nepenthe. "I'll manage, though the place is a bit complicated." He gazed pointedly at the door and Sismus went away.

Over a second drink he examined the guide. Nepenthe, he decided, was utterly fabulous. The rise and fall of several nations might take place in only half the space. He selected a rococo dining hall, shaved at the small sink and found where he wanted to go without any difficulty at all.

There was no roof, nor a rounded dome. He sat at a small table in the dining hall and dined with the silvery pinpoints passing overhead very slowly as the cube tumbled end over end in its swift orbit. The meal was sumptuous; a rasher of truffles dipped in goose butter and eked out with an excellent and deathly dry champagne. He drank a lot of the champagne and about an hour later it went to his head with the last of the magnum. Two and a half quarters is a lot of champagne to drink he mused, getting to his feet, and he wouldn't have missed a drop of it. The novelty of not having to pay a bill took his fancy and he filled up with a few fancy cigars at a dispensing machine and then dropped in at a solidographic playing of a new version of Hamlet.

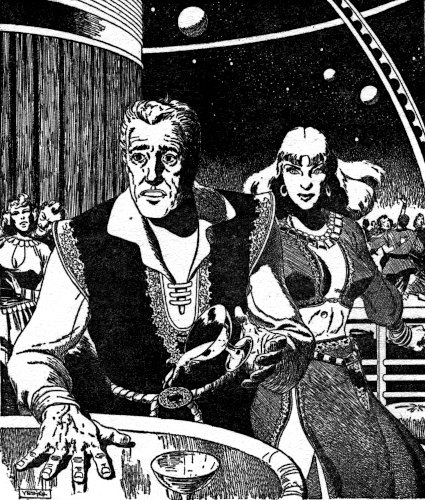

Leaving the theater with a jaded eye some hours later, he bumped into a tipsy young man dressed in bright yellow pajamas who seemed to be falling in the general direction of a large party being given in one of the great ballrooms. The atmosphere became distinctly Louis Quatorze as they passed under the curving archway and through a few drapes.

"Very interesting and doubtless enjoyable," Condemeign said, and glanced at his wristwatch. "But I am afraid...."

The young man who was fair-haired and had a long, dissipated face that verged on the degenerate, smirked.

"Nonsense, you have plenty of time. There's always plenty of time on Nepenthe. You can't let yourself think any other way."

Condemeign pulled away gently, but the other seized him by the arm.

"Look here," he said, and grinned foolishly. "You might as well stay here. How do you know all this isn't part of your particular exit?" He glanced swiftly around and pointed. "See, there and there. Belted and sworded. Maybe they're intended to pick a quarrel with you. Personally I'd hate to go that way. It's heroic, but I just can't stand the touch of cold steel." He reeled a little and Condemeign put out a steadying hand. "Thanks, old chap. I didn't realize I'd had a bit too much."

Some revelers tore by, scattering bits of streamers and winy breaths. A cold breeze blew suddenly through one of the ventilators and Condemeign, half-carrying the other, went rigid. Death seemed at his elbow, jerking and pulling and being mulishly obstinate about staying. Death? His spine abruptly became a rod of ice. Where did it lie for him? In that shiny door knob, quivering in immobility under the fluorescents with frying voltage?

Was it a frozen Borgia smirk on some papier mache mask? Or did it leer at him from the folds of a tunic that was visibly unable to perform its office of hiding a pair of magnificent breasts? The weight in his arms grew leaden. Could death, he thought, be approaching, lanced and ready-levelled in the fine black eyes of the old man who was approaching, tottering and rubbing his aged hands together. The ancient wreck passed and Condemeign suddenly felt he could breathe.

A girl came striding out of a giggling group. She paused as Condemeign got in her way, hefting his charge to a nearby chair.

"When did it happen?" she asked. Her gray eyes widened.

"Happen? When did what happen?"

She reached out a hand and drew it back, while the body of the young man shuddered convulsively and one of Condemeign's supporting hands ran suddenly red with blood. Then he saw the dagger in her hand and his teeth chattered. The body clumped to the floor.

"Don't be so upset," the girl said. "It's probably the way he was intended to go anyway."

"But they said it wouldn't be painful!" he protested.

She was very pretty, with a high-built head of red hair, a rather good nose and pale cheeks. She smiled.

"I think it usually isn't," she said. "But one thing they don't tell you is that anything really goes. There are no laws against murder on Nepenthe, or against anything else. If you happen to get in the way of someone who doesn't like you before the death department has a chance to arrange their histrionics, the front office calls it cricket."

"I suppose ... I suppose," began Condemeign, wiping his sweaty forehead with the sleeve of his pajamas, "that the death department never wastes a good set-up." He stepped back as a couple of attendants came out of a corner, finally, and took the body away. A few interested revelers went back to their carousing.

"I haven't been here long enough to find out," the girl said. "But those boys and girls are high-priced talent. And Doctor Munro is a cagey sort. He probably has the first penny he ever made in his counterfeiting machine as a boy." She paused, watching Condemeign's face flicker from white to pink and back again. "Wait here a minute," she said, and then came back with a beaker of something alcoholic and highly refreshing.

"I'm Firelie Gluck," she remarked, following the convulsions of his Adam's apple as he drained the glass.

He tossed the beaker onto a pile of dead streamers and stood up.

"I'd like to know how he was killed without my knowing it," he said.

"Somebody probably slipped that dirk into him when you weren't looking. You know, like this...." She fell against him suddenly and pinched his ribs. Then she recovered, laughing. Condemeign shuddered. In the thin, sharp shock of her fingers he felt the planners sculpturing death out of dreams into quiet, almost joyous forms. Suddenly he seized her hands and examined the fingers while she smiled up into his face. Then he sighed with relief. There was no poison ring, no barbed, dripping hypodermic crawling its point with icy death. Her nails were clean, unpainted. He tore at her wrists and she giggled, writhing in his grasp, and there was nothing there, up to the elbow, but smooth, pink skin.

Firelie Gluck fell against him suddenly and pinched him. Condemeign shuddered, for he felt the planners sculpturing death out of dreams into quiet, almost joyous forms.

"Firelie Gluck," he whispered, and laughed. "I heard a name once before like that, at a circus."

"Was she pretty?"

Condemeign stared at the hands of an old grandfather's clock across the great room.

"She was the bearded lady," he said. He walked away from her, thumbing his guide to Nepenthe. He hoped the drink she'd given him wasn't a watery passport to hell, for a while at least.

The guide advertised an excursion service on the outer skin of the great cube. He'd known about this, of course, but now he also knew how to reach it. The trip consumed a few gravity lifts, a turn or two in branching corridors and ended in an airlock attached to a luxurious bar. He had a Manhattan or two while an attendant fitted a spacesuit on him.

"You're sure you're not subject to giddiness, sir? If you are, I wouldn't advise shutting off the magnetic shoes. The bulk of the structure will keep you from flying away too far, but...."

"It will be quite all right," Condemeign said. He drained the last glass and let the attendant help him to the airlock opening.

"The oxygen cartridge lasts just an hour, sir, remember that," the attendant said.

Condemeign smiled. For him it might last two minutes. But the clock over the bar told him that even with that, and given a few more minutes of slow, numbing asphyxiation, he'd be able to do the job he'd come to Nepenthe to do. In fact, if they weren't too fussy about picking up bodies before the oxygen cylinder exhausted itself, he could do the job dead as well as alive.

The door closed behind him and then a great glass wheel in front of him opened and there was a little, abrupt snowfall as the air in the chamber condensed into crystal. He inched forward to the edge of the cube and pulled himself out on the surface.

Above and behind him, the sun blazed hot and silent in the crawling sky. He watched the slow revolution of the heavens above him, fascinated, for a moment, stared as the great ball of the earth jumped over the far boundary of the great metal field and began climbing up, dragging its moon. He staggered. The flat side of the three mile cube seemed to wobble and he realized that the attendant's warning had been far from overcautious. A man might go mad out in this absolute silence, bounded now by nothing but the great black wall of the universe and its billions of pinholes. He closed his eyes, listening to the tick of his wristwatch and then opened them suddenly, as he realized that the watch was gone.

He remembered how close she'd been, how neatly she'd fallen against him, pinching him with one hand, while, with the other she slipped the simple catch of the watchband and palmed it. And he'd never noticed.

Firelie Gluck. He laughed.

Ironically he saluted the climbing blue globe of the Earth. They would wait another time now, another try. But he would not sacrifice his own money. He had spent $25,000 for a job well done, and, of course, the only way to do it right was to do it himself.

The glass of the faceplate was too thick for even a steel-mailed fist to smash. Condemeign walked to a garbage disposal tube that projected a few feet out off the level surface of the cube side. The champagne and the other drink were wearing off. The steel plates bucked under his feet and he knew that in another minute he'd be retching, with the majestic background for a perfectly dramatic exit cut off by a spew of vomit. Kneeling, he brought the faceplate of the helmet down with a sharp crack on the steel projection. The glass shattered with a gay burst and just for a second he heard the awful silence of the imponderable ether.

In Dr. Munro's office, Firelie Gluck handed him Condemeign's wristwatch. Munro grunted.

"You have been very useful, Miss Gluck," he said. "You are a most intelligent and perspicacious woman." He tossed the wristwatch to the desk top and watched it with fascination while his lips moved. "You won't reconsider your decision?"

Firelie lit a cigarette with slow animation.

"I don't think so, Doctor. When I came to Nepenthe I had every intention of seeing it through. I was not only bored with life, but I had something of the same point of view that Mr. Condemeign professed."

"Yes, I know. That's why we used you. But there is more to it than that."

Firelie fastened her eyes on the watch.

"Thank goodness there is. Just one step further, in fact. And once you take that, even the meaningless becomes worth the effort."

"I—I don't suppose you would care to reveal exactly what you mean," the Doctor asked, hesitatingly.

"Not unless you want to refund more than my original down payment. Say a million dollars more."

Dr. Munro chuckled dryly.

"Your price will come down, Miss Gluck. We'll get in touch with you on the question when it does. Naturally, you'll have to guarantee not to reveal it to anyone else, otherwise we might be tempted to give you a free treatment here."

Firelie Gluck said nothing, but her eyes laughed grimly.

A buzzer sounded beneath the desk. Dr. Munro clicked a switch and transferred his oval cigarette to the other hand.

"Yes?"

"This is Miss Froon," Miss Froon's voice, though a trifle reedy, was pregnant with import. "I have something to report, Dr. Munro—on Mr. Condemeign's case. Number 32."

The Doctor relaxed in his chair. A flicker of interest tinged with bored annoyance crossed his face.

"Go ahead, Miss Froon."

There was a mechanical squawk from the instrument and then it cleared and Miss Froon began. She seemed happiest now. When she finished, Dr. Munro blew a long stream of smoke toward Firelie Gluck and tapped his cigarette case. Miss Gluck lit up, settling back with a smug air of being on the inside for the first time. It was not the least reason why she had been willing to cooperate.

"Oh?" Dr. Munro's voice was tainted with sincere remorse. "I am sorry to hear of it. Mr. Condemeign, of course. Was the end painful?"

Firelie turned her ears toward the blind receiver with some interest.

"I don't think so, Doctor," Miss Froon said. "Mr. Condemeign perished of ordinary asphyxiation. He had apparently smashed the faceplate of his helmet."

"Yes, yes, we can't have them dying like that." Dr. Munro looked at Firelie Gluck and he winked.

There was a pause and then the mechanical voice went on:

"Isn't—isn't that rather expected, Dr. Munro, in any case? On Nepenthe, I mean?"

The Doctor closed his eyes and then opened them wearily.

"We won't go into it, Miss Froon, but I would advise you to make a note of the entire reports on this case and study them, say in three years time when you graduate to the psychological department. But I will give you a hint now on which you may ruminate. Mr. Condemeign was not only unworthy of our services but he almost caused the total annihilation of Nepenthe."

He heard a restrained clucking and he knew that the chicken skin had gone white. Within a reasonable time, something else would be green.

"That's right, Miss Froon. You will immediately see the value of attention of minute detail. You have undoubtedly very often wondered whether or not you couldn't handle my job as well. In my opinion, Miss Froon, you will be ready when you notice all the details."

He clicked his teeth against a very long cigarette holder, waiting, while Miss Froon crowded herself down. There was a hesitant clearing of the metal throat and then:

"Have you any instructions for the disposal of the body, Dr. Munro?"

The Doctor made a small notation on a pad.

"I think it would be appropriate," he said finally, "if Mr. Condemeign were found drowned and heavily bruised about the body at some beach or other in his own city. Make the usual arrangements and.... Yes, Miss Froon—refund the $25,000 to Mr. Condemeign's personal account. No doubt we shall see it again when his heirs have gotten somewhat beyond their capacities."

The click of the switch on the other end of the wire was deafening.

Firelie Gluck closed one eye.

"I don't suppose you'd care to tell me just what it's all about?"

"I'd be glad to, Miss Gluck, if...." And Dr. Munro paused significantly, poring over her as he would a colored relief map.

Miss Gluck didn't hesitate. She crossed one leg over the other and smiled.

"Any time you say, Doctor. I'm about ready to graduate anyway."

Dr. Munro settled back in his chair. He pressed a button and a fuzzy-lined steel wheel rolled back on its gymbals and let them look out on the framed earth and moon.

"You can keep a loose tongue on anything I tell you, Firelie, because Nepenthe is only too anxious to let Bios know that we trumped their ace again. I'd suggest Munson of International News. He's pretty good at Sunday supplements and ghostly little television fillers. But don't quote me. If you do, you'll find yourself in the middle of an Egyptian passion play, or maybe Inca—I forget which culture the death department recommended for you. Anyway, you'll be the chief victim." He paused, leaned forward to pat her hand which lay vibrant on one of the arms of her chair and resumed, after she nodded softly in complete understanding.

He pointed to the watch.

"Condemeign never thought we'd examine his wristwatch of course. Very probably he knew very little about our precautions. After all, the only two other Bios agents we caught never got back. X-rays taken in the tender that brought him to Nepenthe showed an intricate mechanism concealed in the stem head. It warranted investigation, because that was all he had on him that could cut ice. Nothing concealed in his clothes or in various bodily orifices—you'll pardon my frankness, of course."

"No offense," she said. "What's dangerous about a watch stem?"

"Bios couldn't bring an atom bomb aboard in any case. They couldn't bring it inside, so they decided to work on an outside job."

"Second-story stuff?"

Dr. Munro watched the rim of the moon follow its mistress down the solid curve of the window well. His eyes were still frightened, still shaken by the forgotten memory of utter annihilation.

"In the little watch stem was a most ingenious device, a device for polarizing two pieces of atom-bomb explosive that had been fired from diametrically opposite directions at Nepenthe. Their velocity, of course was extreme, more than sufficient to enable them to reach the proximity point of critical mass once their courses were brought into alignment."

Dr. Munro let a heavy glass ash tray drop on Condemeign's watch. The stem wheel with its axle fell out and rolled, flattened and broken on the desk top. He swept the debris together and tossed it into a disposal chute.

"That was supposed to correlate the courses of the two oncoming, opposing containers, each of which was able to correct its direction when it received the proper signal from the watch stem." The Doctor sighed. "Thank heaven, neither of them did. Condemeign would have had to work it from outside Nepenthe—our power plants tended to blank out the radio signal—and he couldn't, of course."

"You mean those two components were supposed to reach critical mass just over Nepenthe?"

The Doctor whistled softly.

"I hardly think it would have blown us entirely to flinders, but undoubtedly we would have gone out of business."

Miss Gluck rose and went to the round window well.

"But I still don't understand about Condemeign. You said he wasn't a fraud at all."

Dr. Munro plucked at her hand. He hardly seemed to be concentrating on what he was saying. He had eyes for other things.

"No, he wasn't a fraud. He was a member of Bios and he really wanted to die, and that's why they sent him."

Miss Gluck uttered a low moan. It was not a moan of pain.

The Doctor continued.

"The watch stem was conclusive, of course. But we were curious. We collect data, you know. We aren't entirely a cube for coining money. That question about his reason for dying. He was a nihilist, a man to whom nothing means anything, or who thinks it doesn't. Of course something always does. And the thing that did was his loyalty to Bios."

Miss Gluck managed to speak. She was unquestionably a woman thirsty for knowledge above all else. Her voice was a voice in a dream.

"Yes, I was curious about that. His loyalty to Bios, despite the fact that he wanted to die."

Dr. Munro didn't answer for about fourteen seconds. Then he did.

"He just thought he was a nihilist. But the last thing he had to do was a job for Bios and that was going to be his last joke on everything, you, me, Nepenthe. Of course he didn't care for anything—and of course he cared for something. Everyone does so long as they're alive. Otherwise, why bother to even die?"

Firelie Gluck said nothing in reply to that. But after a minute the Doctor said:

"Of course he had to tell the truth because he thought nothing meant anything at all. That's why Miss Froon asked him those questions I wrote out. What's that, Firelie? Who cares about Miss Froon?"

And then for about twenty minutes neither of them strictly speaking, said anything.

Later, when Miss Gluck had gone off to the waiting tender, the Doctor watched it blast off toward Earth. He was in a characteristic mood, sitting rather despondently at his desk when a small aperture in the wall behind him uttered a cheerful bleat and disgorged a sheaf of papers on his desk. They were stamped with the tasteful insignia of the death department and everything was there, drawings, full instructions down to the last detail and even small paper mache figurines. He thoughtfully erased Condemeign's and Miss Gluck's names from the folder covers and put them aside.

In any case, science be served. And nothing would be wasted after all. The clients whose payments fell in the parsimonious brackets, whose incomes just barely entitled them to the right to a managed exit, would hardly notice the difference. They would be full of the blandishments of the brochure.

Abruptly, he brightened, as though the invisible sun had winked impudently through the window well, as though a gate had opened on some blue sky over a green-grown cemetery. He hummed a solemn tune, hoping that one day he too would be a bright case in the annals. Privately, in point of ingenuity, that would cause the death department many a fine headache, and especially in originality, he would be near the top, he knew.

In the meantime, to the accompaniment of its inevitable greeting, the little aperture had delivered more work. The day was wasting.

He shook himself back to a saturnine countenance. Like all other days it was a fine day for dying. A fine time.

What else was time for?