The Dark Landers rioted under inhuman fear; in the blind panic which the pipes sang to them.

Proud Kery of Broina felt like a ghost himself;

shade of a madman flitting hopelessly to the

citadel of Earth's disinherited ... to recapture the

resonant pipes of Killorn—weapon of the gods—before

they blared forth the dirge of the world.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories November 1951.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The third book of the Story of the Men of Killorn. How Red Bram fought the Ganasthi from the lands of darkness, and Kery son of Rhiach was angered, and the pipe of the gods spoke once more.

Now it must be told of those who fared forth south under Bram the Red. This was the smallest of the parties that left Killorn, being from three clans only—Broina, Dagh, and Heorran. That made some thousand warriors, mostly men with some women archers and slingers. But the pipe of the gods had always been with Clan Broina, and so it followed the Broina on this trek. He was Rhiach son of Glyndwyrr, and his son was Kery.

Bram was a Heorran, a man huge of height and thew, with eyes like blue ice and hair and beard like a torch. He was curt of speech and had no close friends, but men agreed that his brain and his spirit made him the best leader for a journey like this, though some thought that he paid too little respect to the gods and their priests.

For some five years these men of Killorn marched south. They went over strange hills and windy moors, through ice-blinking clefts in gaunt-cragged mountains and over brawling rivers chill with the cold of the Dark Lands.

They hunted and robbed to live, or reaped the grain of foreigners, and cheerfully cut down any who sought to gainsay them. Now and again Bram dickered with the chiefs of some or other city and hired himself and his wild men out to fight against another town. Then there would be hard battle and rich booty and flames red against the twilight sky.

Men died and some grew weary of roving and fighting. There was a sick hunger within them for rest and a hearthfire and the eternal sunset over the Lake of Killorn. These took a house and a woman and stayed by the road. In such ways did Bram's army shrink. On the other hand most of his warriors finally took some or other woman along on the march and she would demand more for herself and the babies than a roof of clouds and wind. So there came to be tents and wagons, with children playing between the turning wheels. Bram grumbled about this, it made his army slower and clumsier, but there was little he could do to prevent it.

Those who were boys when the trek began became men with the years and the battles and the many miles. Among these was the Kery of whom we speak. He grew tall and lithe and slender, with the fair skin and slant blue eyes and long ash-blond hair of the Broina, broad of forehead and cheekbones, straight-nosed, beardless like most of his clan.

He was swift and deadly with sword, spear, or bow, merry with his comrades over ale and campfire, clever to play harp or pipe and make verses—not much different from the others, save that he came of the Broina and would one day carry the pipe of the gods. And while the legends of Killorn said that all men are the offspring of a goddess whom a warrior devil once bore off to his lair, it was held that the Broina had a little more demon blood in them than most.

Always Kery bore within his heart a dream. He was still a stripling when they wandered from home. He had reached young manhood among hoofs and wheels and dusty roads, battle and roaming and the glimmer of campfires, but he never forgot Killorn of the purple hills and the far thundering sea and the lake where it was forever sunset. For there had been a girl of the Dagh sept, and she had stayed behind.

But then the warriors came to Ryvan and their doom.

It was a broad fair country into which they had come. Trending south and east, away from the sun, they were on the darker edge of the Twilight Lands and the day was no longer visible at all. Only the deep silver-blue dusk lay around them and above, with black night and glittering stars to the east and a few high clouds lit by unseen sunbeams to the west. But it was still light enough for Twilight Landers' eyes to reach the horizon—to see fields and woods and rolling hills and the far metal gleam of a river. They were well into the territory of Ryvan city.

Rumor ran before them on frightened feet, and peasants often fled as they advanced. But never had they met such emptiness as now. They had passed deserted houses, gutted farmsteads, and the bones of the newly slain, and had shifted their course eastward to get into wilder country where there should at least be game. But such talk as they had heard of the invaders of Ryvan made them march warily. And when one of their scouts galloped back to tell of an army advancing out of the darkness against them, the great horns screamed and the wagons were drawn together.

For a while there was chaos, running and yelling men, crying children, bawling cattle, and tramping hests. Then the carts were drawn into a defensive ring atop a high steep ridge and the warriors waited outside. They made a brave sight, the men of Killorn, tall barbarians in the colorful kilts of their septs with plundered ornaments shining around corded throat or sinewy arm.

Most of them still bore the equipment of their homeland—horned helmets, gleaming ring-byrnies, round shields, ax and bow and spear and broadsword, worn and dusty with use but ready for more. The greater number went afoot, though some rode the small shaggy hests of the north. Their women and children crouched behind the wagons, with bows and slings ready and the old battle banners of Killorn floating overhead.

Kery came running to the place where the chiefs stood. He wore only a helmet and a light leather corselet, and carried sword and spear and a bow slung over his shoulders. "Father," he called. "Father, who are they?"

Rhiach of Broina stood near Bram with the great bagpipes of the gods under one arm—old beyond memory, those pipes, worn and battered, but terror and death and the avenging furies crouched in them, power so great that only one man could ever know the secret of their use. A light breeze stirred the warlock's long gray hair about his gaunt face, and his eyes brooded on the eastern darkness.

The scout who had brought word turned to greet Kery. He was panting with the weariness of his hard ride. An arrow had wounded him, and he shivered as the cold wind from the Dark Lands brushed his sweat-streaked body. "A horde," he said. "An army marching out of the east toward us, not Ryvan but such a folk as I never knew of. Their outriders saw me and barely did I get away. Most likely they will move against us, and swiftly."

"A host at least as great as ours," added Bram. "It must be a part of the invading Dark Landers who are laying Ryvan waste. It will be a hard fight, though I doubt not that with our good sword-arms and the pipe of the gods we will throw them back."

"I know not." Rhiach spoke slowly. His deep eyes were somber on Kery. "I have had ill dreams of late. If I fell in this battle, before we won ... I did wrong, son. I should have told you how to use the pipe."

"The law says you can only do that when you are so old that you are ready to give up your chiefship to your first born," said Bram. "It is a good law. A whole clan knowing how to wield such power would soon be at odds with all Killorn."

"But we are not in Killorn now," said Rhiach. "We have come far from home, among alien and enemy peoples, and the lake where it is forever sunset is a ghost to us." His hard face softened. "If I fall, Kery, my own spirit, I think, will wander back thither. I will wait for you at the border of the lake, I will be on the windy heaths and by the high tarns, they will hear me piping in the night and know I have come home ... but seek your place, son, and all the gods be with you."

Kery gulped and wrung his father's hand. The warlock had ever been a stranger to him. His mother was dead these many years and Rhiach had grown grim and silent. And yet the old warlock was dearer to him than any save Morna who waited for his return.

He turned and sped to his own post, with the tyrs.

The cows of the great horned tyrs from Killorn were for meat and milk and leather, and trudged meekly enough behind the wagons. But the huge black bulls were wicked and had gored more than one man to death. Still Kery had gotten the idea of using them in battle. He had made iron plates for their chests and shoulders. He had polished their cruel horns and taught them to charge when he gave the word. No other man in the army dared go near them, but Kery could guide them with a whistle. For the men of Broina were warlocks.

They snorted in the twilight as he neared them, stamping restlessly and shaking their mighty heads. He laughed in a sudden reckless drunkenness of power and moved up to his big lovely Gorwain and scratched the bull behind the ears.

"Softly, softly," he whispered, standing in the dusk among the crowding black bulks. "Patient, my beauty, wait but a little and I'll slip you, O wait, my Gorwain."

Spears blinked in the shadowy light and voices rumbled quietly. The bulls and the hests snorted, stamping and shivering in the thin chill wind flowing from the lands of night. They waited.

Presently they heard, faint and far, the skirling of war pipes. But it was not the wild joyous music of Killorn, it was a thin shrill note which ran along the nerves, jagged as a saw, and the thump of drums and the clangor of gongs came with it. Kery sprang up on the broad shoulders of Gorwain the tyr and strained into the gloom to see.

Over the rolling land came marching the invaders. It was an army of a thousand or so, he guessed with a shiver of tension, moving in closer ranks and with tighter discipline than the barbarians. He had seen many armies, from the naked yelling savages of the upper Norlan hills to the armored files of civilized towns, yet never one like this.

Dark Landers, he thought bleakly. Out of the cold and the night that never ends, out of the mystery and the frightened legends of a thousand years, here at last are the men of the Dark Lands, spilling into the Twilight like their own icy winds, and have we anything that can stand against them?

They were tall, as tall as the northerners, but gaunt, with a stringy toughness born of hardship and suffering and bitter chill. Their skins were white, not with the ruddy whiteness of the northern Twilight Landers but dead-white, blank and bare, and the long hair and beards were the color of silver.

Their eyes were the least human thing about them, huge and round and golden, the eyes of a bird of prey, deep sunken in the narrow skulls. Their faces seemed strangely immobile, as if the muscles for laughter and weeping were alike frozen. As they moved up, the only sound was the tramp of their feet and the demon whine of their pipes and the clash of drum and gong.

They were well equipped, Kery judged, they wore close-fitting garments of fur-trimmed leather, trousers and boots and hooded tunics. Underneath he glimpsed mail, helmets, shields, and they carried all the weapons he knew—no cavalry, but they marched with a sure tread. Overhead floated a strange banner, a black standard with a jagged golden streak across it.

Kery's muscles and nerves tightened to thrumming alertness. He crouched by his lead bull, one hand gripping the hump and the other white-knuckled around his spearshaft. And there was a great hush on the ranks of Killorn as they waited.

Closer came the strangers, until they were in bowshot. Kery heard the snap of tautening strings. Will Bram never give the signal? Gods, is he waiting for them to walk up and kiss us?

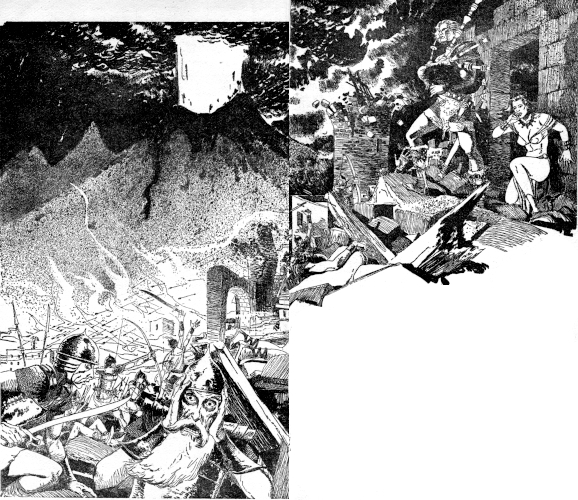

A trumpet brayed from the enemy ranks, and Kery saw the cloud of arrows rise whistling against the sky. At the same time Bram winded his horn and the air grew loud with war shouts and the roar of arrow flocks.

Then the strangers locked shields and charged.

II

The men of Killorn stood their ground, shoulder to shoulder, pikes braced and swords aloft. They had the advantage of high ground and meant to use it. From behind their ranks came a steady hail of arrows and stones, whistling through the air to crack among the enemy ranks and tumble men to earth—yet still the Dark Landers came, leaping and bounding and running with strange precision. They did not yell, and their faces were blank as white stone, but behind them the rapid thud of their drums rose to a pulse-shaking roar.

"Hai-ah!" bellowed Red Bram. "Sunder them!"

The great long-shafted ax shrieked in his hands, belled on an enemy helmet and crashed through into skull and brain and shattering jawbone. Again he smote, sideways, and a head leaped from its shoulders.

A Dark Land warrior thrust for his belly. He kicked one booted foot out and sent the man lurching back into his own ranks. Whirling, he hewed down one who engaged the Killorner beside him. A foeman sprang against him as he turned, chopping at his leg. With a roar that lifted over the clashing racket of battle, Bram turned, the ax already flying in his hands, and cut the stranger down.

His red beard blazed like a torch over the struggle as it swayed back and forth. His streaming ax was a lightning bolt that rose and fell and rose again, and the thunder of metal on breaking metal rolled between the hills.

Kery stood by his tyrs, bow in hand, shooting and shooting into the masses that roiled about him. None came too close, and he could not leave his post lest the unchained bulls stampede. He shuddered with the black fury of battle. When would Bram call the charge. How long? Zip, zip, gray-feathered death winging into the tide that rolled up to the wagons and fell back and resurged over its corpses.

The men of Killorn were yelling and cursing as they fought, but the Dark Landers made never a sound save for the hoarse gasping of breath and the muted groans of the wounded. It was like fighting demons, yellow-eyed and silver-bearded and with no soul in their bony faces. The northerners shivered and trembled and hewed with a desperate fury of loathing.

Back and forth the battle swayed, roar of axes and whine of arrows and harsh iron laughter of swords. Kery stood firing and firing, the need to fight was a bitter catch in his throat. How long to wait, how long, how long?

Why didn't Rhiach blow the skirl of death on the pipes? Why not fling them back with the horror of disintegration in their bones, and then rush out to finish them?

Kery knew well that the war-song of the gods was only to be played in time of direst need, for it hurt friend almost as much as foe—but even so, even so! A few shaking bars, to drive the enemy back in death and panic, and then the sortie to end them!

Of a sudden he saw a dozen Dark Landers break from the main battle by the wagons and approach the spot where he stood. He shot two swift arrows, threw his spear, and pulled out his sword with a savage laughter in his heart, the demoniac battle joy of the Broina. Ha, let them come!

The first sprang with downward-whistling blade. Kery twisted aside, letting speed and skill be his shield, his long glaive flickered out and the enemy screamed as it took off his arm. Whirling, Kery spitted the second through the throat. The third was on him before he could withdraw his blade, and a fourth from the other side, raking for his vitals. He sprang back.

"Gorwain!" he shouted. "Gorwain!"

The huge black bull heard. His fellows snorted and shivered, but stayed at their place—Kery didn't know how long they would wait, he prayed they would stay a moment more. The lead tyr ran up beside his master, and the ground trembled under his cloven hoofs.

The white foemen shrank back, still dead of face but with fear plain in their bodies. Gorwain snorted, an explosion of thunder, and charged them.

There was an instant of flying bodies, tattered flesh ripped by the horns, and ribs snapping underfoot. The Dark Landers thrust with their spears, the points glanced off the armor plating and Gorwain turned and slew them.

"Here!" cried Kery sharply. "Back, Gorwain! Here!"

The tyr snorted and circled, rolling his eyes. The killing madness was coming over him, if he were not stopped now he might charge friend or foe.

"Gorwain!" screamed Kery.

Slowly, trembling under his shining black hide, the bull returned.

And now Rhiach the warlock stood up behind the ranks of Killorn. Tall and steely gray, he went out between them, the pipes in his arms and the mouthpieces at his lips. For an instant the Dark Landers wavered, hesitating to shoot at him, and then he blew.

It was like the snarling music of any bagpipe, and yet there was more in it. There was a boiling tide of horror riding the notes, men's hearts faltered and weakness turned their muscles watery. Higher rose the music, and stronger and louder, screaming in the dales, and before men's eyes the world grew unreal, shivering beneath them, the rocks faded to mist and the trees groaned and the sky shook. They fell toward the ground, holding their ears, half blind with unreasoning fear and with the pain of the giant hand that gripped their bones and shook them, shook them.

The Dark Landers reeled back, falling, staggering, and many of those who toppled were dead before they hit the earth. Others milled in panic, the army was becoming a mob. The world groaned and trembled and tried to dance to the demon-music.

Rhiach stopped. Bram shook his bull head to clear the ringing and the fog in it. "At them!" he roared. "Charge!"

Sanity came back. The land was real and solid again, and men who were used to the terrible drone of the pipes could force strength back into shuddering bodies. With a great shout, the warriors of Killorn formed ranks and moved forward.

Kery leaped up on the back of Gorwain, straddling the armored chine and gripping his knees into the mighty flanks. His sword blazed in the air. "Now kill them, my beauties!" he howled.

In a great wedge, with Gorwain at their lead, the tyrs rushed out on the foe. Earth shook under the rolling thunder of their feet. Their bellowing filled the land and clamored at the gates of the sky. They poured like a black tide down on the Dark Land host and hit it.

"Hoo-ah!" cried Kery.

He felt the shock of running into that mass of men and he clung tighter, holding on with one hand while his sword whistled in the other. Bodies fountained before the rush of the bulls, horns tossed men into the heavens and hoofs pounded them into the earth. Kery swung at dimly glimpsed heads, the hits shivered along his arm but he could not see if he killed anyone, there wasn't time.

Through and through the Dark Land army the bulls plowed, goring a lane down its middle while the Killorners fell on it from the front. Blood and thunder and erupting violence, death reaping the foe, and Kery rode onward.

"Oh, my beauties, my black sweethearts, horn them, stamp them into the ground. Oh, lovely, lovely, push them on, my Gorwain, knock them down to hell, best of bulls!"

The tyrs came out on the other side of the broken host and thundered on down the ridge. Kery fought to stop them. He yelled and whistled, but he knew such a charge could not expend itself in a moment.

As they rushed on, he heard the high brazen call of a trumpet, and then another and another, and a new war-cry rising behind him. What was that? What had happened?

They were down in a rocky swale before he had halted the charge. The bulls stood shivering then, foam and blood streaked their heaving sides. Slowly, with many curses and blows, he got them turned, but they would only walk back up the long hill.

As he neared the battle again he saw that another force had attacked the Dark Landers from behind. It must have come through the long ravine to the west, which would have concealed its approach from those fighting Southern Twilight Landers, Kery saw, well trained and equipped though they seemed to fight wearily. But between men of north and south, the easterners were being cut down in swathes. Before he could get back, the remnants of their host was in full flight. Bram was too busy with the newcomers to pursue and they soon were lost in the eastern darkness.

Kery dismounted and led his bulls to the wagons to tie them up. They went through a field of corpses, heaped and piled on the blood-soaked earth, but most of the dead were enemies. Here and there the wounded cried out in the twilight, and the women of Killorn were going about succoring their own hurt. Carrion birds hovered above on darkling wings.

"Who are those others?" asked Kery of Bram's wife Eiyla. She was a big raw-boned woman, somewhat of a scold but stout-hearted and the mother of tall sons. She stood leaning on an unstrung bow and looking over the suddenly hushed landscape.

"Ryvanians, I think," she replied absently. Then, "Kery—Kery, I have ill news for you."

His heart stumbled and there was a sudden coldness within him. Mutely, he waited.

"Rhiach is dead, Kery," she said gently. "An arrow took him in the throat even as the Dark Landers fled."

His voice seemed thick and clumsy. "Where is he?"

She led him inside the laager of wagons. A fire had been lit to boil water, and its red glow danced over the white faces of women and children and wounded men where they lay. To one side the dead had been stretched, and white-headed Lochly of Dagh stood above them with his bagpipes couched in his arms.

Kery knelt over Rhiach. The warlock's bleak features had softened a little in death, he seemed gentle now. But quiet, so pale and quiet. And soon the earth will open to receive you, you will be laid to rest here in an alien land where the life slipped from your hands, and the high windy tarns of Killorn will not know you ever again, O Rhiach the Piper.

Farewell, farewell, my father. Sleep well, goodnight, goodnight!

Slowly, Kery brushed the gray hair back from Rhiach's forehead, and knelt and kissed him on the brow. They had laid the god-pipe beside him, and he took this up and stood numbly, wondering what he would do with this thing in his hands.

Old Lochly gave him a somber stare. His voice came so soft you could scarce hear it over the thin whispering wind.

"Now you are the Broina, Kery, and thus the Piper of Killorn."

"I know," he said dully.

"But you know not how to blow the pipes, do you? No, no man does that. Since Broina himself had them from Llugan Longsword in heaven, there has been one who knew their use, and he was the shield of all Killorn. But now that is ended, and we are alone among strangers and enemies."

"It is not good. But we must do what we can."

"Oh, aye. 'Tis scarcely your fault, Kery. But I fear none of us will ever drink the still waters of the lake where it is forever sunset again."

Lochly put his own pipes to his lips and the wild despair of the old coronach wailed forth over the hushed camp.

Kery slung the god-pipes over his back and wandered out of the laager toward Bram and the Ryvanians.

III

The southern folk were more civilized, with cities and books and strange arts, though the northerners thought it spiritless of them to knuckle under to their kings as abjectly as they did. Hereabouts the people were dark of hair and eyes, though still light of skin like all Twilight Landers, and shorter and stockier than in the north. These soldiers made a brave showing with polished cuirass and plumed helmet and oblong shields, and they had a strong cavalry mounted on tall hests, and trumpeters and standard bearers and engineers. They outnumbered the Killorners by a good three to one, and stood in close, suspicious ranks.

Approaching them, Kery thought that his people were, after all, invaders of Ryvan themselves. If this new army decided to fall on the tired and disorganized barbarians, whose strongest weapon had just been taken from them, it could be slaughter. He stiffened himself, thrusting thought of Rhiach far back into his mind, and strode boldly forward.

As he neared he saw that however well armed and trained the Ryvanians were they were also weary and dusty, and they had many hurt among them. Beneath their taut bearing was a hollowness. They had the look of beaten men.

Bram and the Dagh, tall gray Nessa, were parleying with the Ryvanian general, who had ridden forward and sat looking coldly down on them. The Heorran carried his huge ax over one mailed shoulder, but had the other hand lifted in sign of peace. At Kery's approach, he turned briefly and nodded.

"Well you came," he said. "This is a matter for the heads of all three clans, and you are the Broina now. I grieve for Rhiach, and still more do I grieve for poor Killorn, but we must put a bold face on it lest they fall on us."

Kery nodded, gravely as fitted an elder. The incongruity of it was like a blow. Why, he was a boy—there were men of Broina in the train twice and thrice his age—and he held leadership over them!

But Rhiach was dead, and Kery was the last living of his sons. Hunger and war and the coughing sickness had taken all the others, and so now he spoke for his clan.

He turned a blue gaze up toward the Ryvanian general. This was a tall man, big as a northerner but quiet and graceful in his movements, and the inbred haughtiness of generations was stiff within him. A torn purple cloak and a gilt helmet were his only special signs of rank, otherwise he wore the plain armor of a mounted man, but he wore it like a king. His face was dark for a Twilight Lander, lean and strong and deeply lined, with a proud high-bridged nose and a long hard jaw and close-cropped black hair finely streaked with gray. He alone in that army seemed utterly undaunted by whatever it was that had broken their spirits.

"This is Kery son of Rhiach, chief of the third of our clans," Bram introduced him. He used the widespread Aluardian language of the southlands, which was also the tongue of Ryvan and which most of the Killorners had picked up in the course of their wanderings. "And Kery, he says he is Jonan, commander under Queen Sathi of the army of Ryvan, and that this is a force sent out from the city which became aware of the battle we were having and took the opportunity of killing a few more Dark Landers."

Nessa of Dagh looked keenly at the southerners. "Methinks there's more to it than that," he said, half to his fellows and half to Jonan. "You've been in a stiff battle and come off second best, if looks tell aught. Were I to make a further venture, it would be that while you fought clear of the army that beat you and are well ahead of pursuit, it's still on your tail and you have to reach the city fast."

"That will do," snapped Jonan. "We have heard of you plundering bandits from the north, and have no intention of permitting you on Ryvanian soil. If you turn back at once, you may go in peace, but otherwise...."

Casting a glance behind him, Bram saw that his men were swiftly reforming their own lines. They sensed the uneasiness in the air. If the worst came to the worst, they'd give a fearsome account of themselves. And it was plain that Jonan knew it.

"We are wanderers, yes," said the chief steadily, "but we are not highwaymen save when necessity drives us to it. It would better fit you to let us, who have just broken a fair-sized host of your deadly enemies, proceed in peace. We do not wish to fight you, but if we must it will be all the worse for you."

"Ill-armed barbarians, a third of our number, threatening us?" asked Jonan scornfully.

"Well, now, suppose you can overcome us," said Nessa with a glacial cheerfulness. "I doubt it, but just suppose so. We will not account for less than one man apiece of yours, you know, and you can hardly spare so many with Dark Landers ravaging all your country. Furthermore, a battle with us could well last so long that those who follow you will catch up, and there is an end of all of us."

Kery took a breath and added flatly, "You must have felt the piping we can muster at need. Well for you that we only played it a short while. If we chose to play you a good long dirge...."

Bram cast him an approving glance, nodded, and said stiffly, "So you see, General Jonan, we mean to go on our way, and it would best suit you to bid us a friendly good-bye."

The Ryvanian scowled blackly and sat for a moment in thought. The wind stirred his hest's mane and tail and the scarlet plume on his helmet. Finally he asked them in a bitter voice, "What do you want here, anyway? Why did you come south?"

"It is a long story, and this is no place to talk," said Bram. "Suffice it that we seek land. Not much land, nor for too many years, but a place to live in peace till we can return to Killorn."

"Hm." Jonan frowned again. "It is a hard position for me. I cannot simply let a band famous for robbery go loose. Yet it is true enough that I would not welcome a long and difficult fight just now. What shall I do with you?"

"You will just have to let us go," grinned Nessa.

"No! I think you have lied to me on several counts, barbarians. Half of what you say is bluff, and I could wipe you out if I had to."

"Methinks somewhat more than half of your words are bluff," murmured Kery.

Jonan gave him an angry look, then suddenly whirled on Bram. "Look here. Neither of us can well afford a battle, yet neither trusts the other out of its sight. There is only one answer. We must proceed together to Ryvan city."

"Eh? Are you crazy, man? Why, as soon as we were in sight of your town, you could summon all its garrison out against us."

"You must simply trust me not to do that. If you have heard anything about Queen Sathi, you will know that she would never permit it. Nor can we spare too many forces. Frankly, the city is going to be under siege very soon."

"Is it that bad?" asked Bram.

"Worse," said Jonan gloomily.

Nessa nodded his shrewd gray head. "I've heard some tales of Sathi," he agreed. "They do say she's honorable."

"And I have heard that you people have served as mercenaries before now," said Jonan quickly, "and we need warriors so cruelly that I am sure some arrangement can be made here. It could even include the land you want, if we are victorious, for the Ganasthi have wasted whole territories. So this is my proposal—march with us to Ryvan, in peace, and there discuss terms with her majesty for taking service under her flag." His harsh dark features grew suddenly cold. "Or, if you refuse, bearing in mind that Ryvan has very little to lose after all, I will fall on you this instant."

Bram scratched his red beard, and looked over the southern ranks and especially the engines. Flame-throwing ballistae could make ruin of the laager. Jonan galled him, and yet—well—however they might bluff about it, the fact remained that they had very little choice.

And anyway, the suggestion about payment in land sounded good. And if these—Ganasthi—had really overrun the Ryvanian empire, then there was little chance in any case of the Killorners getting much further south.

"Well," said Bram mildly, "we can at least talk about it—at the city."

Now the wagons, which the barbarians would not abandon in spite of Jonan's threats, were swiftly hitched again and the long train started its creaking way over the hills. Erelong they came on one of the paved imperial roads, a broad empty way that ran straight as a spearshaft southwestward to Ryvan city. Then they made rapid progress.

In truth, thought Kery, they went through a wasted land. Broad fields were blackened with fire, corpses sprawled in the embers of farmsteads, villages were deserted and gutted—everywhere folk had fled before the hordes of Ryvan. Twice they saw red glows on the southern horizon and white-lipped soldiers told Kery that those were burning cities.

As they marched west the sky lightened before them until at last a clear white glow betokened that the sun was just below the curve of the world. It was a fair land of rolling plains and low hills, fields and groves and villages, but empty—empty. Now and again a few homeless peasants stared with frightened eyes at their passage, or trailed along in their wake, but otherwise there was only the wind and the rain and the hollow thudding of their feet.

Slowly Kery got the tale of Ryvan. The city had spread itself far in earlier days, conquering many others, but its rule was just. The conquered became citizens themselves and the strong armies protected all. The young queen Sathi was nearly worshipped by her folk. But then the Ganasthi came.

"About a year ago it was," said one man. "They came out of the darkness in the east, a horde of them, twice as many as we could muster. We've always had some trouble with Dark Landers on our eastern border, you know, miserable barbarians making forays which we beat off without too much trouble. And most of them told of pressure from some powerful nation, Ganasth, driving them from their own homes and forcing them to fall on us. But we never thought too much of it. Not before it was too late.

"We don't know much about Ganasth. It seems to be a fairly civilized state, somewhere out there in the cold and the dark. How they ever became civilized with nothing but howling savages around them I'll never imagine. But they've built up a power like Ryvan's, only bigger. It seems to include conscripts from many Dark Land tribes who're only too glad to leave their miserable frozen wastes and move into our territory. Their armies are as well trained and equipped as our own, and they fight like demons. Those war-gongs, and those dead faces...."

He shuddered.

"The prisoners we've taken say they aim to take over all the Twilight Lands. They're starting with Ryvan—it's the strongest state, and once they've knocked us over the rest will be easy. We've appealed for help to other nations but they're all too afraid, too busy raising their own silly defenses, to do anything. So for the past year the war's been raging up and down our empire." He waved a hand, wearily, at the blasted landscape. "You see what that's meant. Famine and plague are starting to hit us now—"

"And you could never stand before them?" asked Kery.

"Oh, yes, we had our victories and they had theirs. But when we won a battle they'd just retreat and sack some other area. They've been living off the country—our country—the devils!" The soldier's face twisted. "My own little sister was in Aquilaea when they took that. When I think of those white-haired fiends—

"Well about a month ago, the great battle was fought. Jonan led the massed forces of Ryvan out and caught the main body of Ganasthi at Seven Rivers, in the Donam Hills. I was there. The fight lasted, oh, four sleeps maybe, and nobody gave quarter or asked it. We outnumbered them a little, but they finally won. They slaughtered us like driven cattle. Jonan was lucky to pull half his forces out of there. The rest left their bones at Seven Rivers. Since then we've been a broken nation.

"We're pulling all we have left back toward Ryvan in the hope of holding it till a miracle happens. Do you have any miracles for sale, Northman?" The soldier laughed bitterly.

"What about this army here?" asked Kery.

"We still make sorties, you know. This one went out from Ryvan city a few sleeps past to the relief of Tusca, which our scouts said the Ganasthi were besieging with only a small force. But an enemy army intercepted us on the way. We cut our way out and shook them, but they're on our tail in all likelihood. When we chanced to hear the noise of your fight with the invaders we took the opportunity ... Almighty Dyuus, it was good to hack them down and see them run!"

The soldier shrugged. "But what good did it do, really? What chance have we got? That was a good magic you had at the fight. I thought my heart was going to stop when that demon-music started. But can you pipe your way out of hell, barbarian? Can you?"

IV

Ryvan was a fair city, with terraced gardens and high shining towers to be seen over the white walls, and it lay among wide fields not yet ravaged by the enemy. But around it, under its walls, spilling out over the land, huddled the miserable shacks and tents of those who had fled hither and could find no room within the town till the foe came over the horizon—the broken folk, the ragged horror-ridden peasants who stared mutely at the defeated army as it streamed through the gates.

The men of Killorn made camp under one wall and soon their fires smudged the deep silver-blue sky and their warriors stood guard against the Ryvanians. They did not trust even these comrades in woe, for they came of the fat southlands and the wide highways and the iron legions, and not of Killorn and its harsh windy loneliness.

Before long word came that the barbarian leaders were expected at the palace. So Bram, Nessa, and Kery put on their polished byrnies, and over them tunics and cloaks of their best plunder. They slung their swords over their shoulders and mounted their hests and rode between two squads of Ryvanian guardsmen through the gates and into the city.

It was packed and roiling with those who had fled. Crowds surged aimlessly around the broad avenues and spilled into the colonnaded temples and the looming apartments and even the gardens and villas of the nobility.

There was the dusty, bearded peasant, clinging to his wife and his children and looking on the world with frightened eyes. Gaily decked noble, riding through the mob with patrician hauteur and fear underneath it. Fat merchant and shaven priest, glowering at the refugees who came in penniless to throng the city and must, by the queen's orders, be fed and housed. Patrolling soldiers, striving to keep order in the mindless whirlpool of man, their young faces drawn and their shoulders stooped beneath their mail. Jugglers, mountebanks, thieves, harlots, tavern-keepers, plying their trades in the feverish gaiety of doom; a human storm foaming off into strange half-glimpsed faces in darkened alleys and eddying crowds, the unaccountable aliens who flit through all great cities—the world seemed gathered at Ryvan, and huddling before the wrath that came.

Fear rode the city, Kery could feel it, he breathed and the air was dank with terror, he bristled animal-like and laid a hand to his sword. For an instant he remembered Killorn, the wide lake rose before him and he stood at its edge, watching the breeze ruffle it and hearing the whisper of reeds and the chuckle of water on a pebbled shore. Miles about lay the hills and the moors, the clean strong smell of ling was a drunkenness in his nostrils. It was silent save for the small cool wind that ruffled Morna's hair. And in the west it was sunset, the mighty sun-disc lay just below the horizon and a shifting, drifting riot of colors, flame of red and green and molten gold, burned in the twilit heavens.

He shook his head, feeling his longing as a sharp clear pain, and urged his hest through the crowds. Presently they reached the palace.

It was long and low and gracious, crowded now since all the nobles and their households had moved into it and, under protest, turned their own villas over to the homeless. Dismounting, the northerners walked between files of guardsmen, through fragrant gardens and up the broad marble steps of the building—through long corridors and richly furnished rooms, and finally into the audience chamber of Queen Sathi.

It was like a chalice of white stone, wrought in loveliness and brimming with twilight and stillness. That deep blue dusk lay cool and mysterious between the high slim pillars, and somewhere came the rippling of a harp and the singing of birds and fountains. Kery felt suddenly aware of his uncouth garments and manners and accent. His tongue thickened and he did not know what to do with his hands. Awkwardly he took off his helmet.

"Lord Bram of Killorn, your majesty," said the chamberlain.

"Greeting, and welcome," said Sathi.

Word had spread far about Ryvan's young queen but Kery thought dazedly that the gossips had spoken less of her than was truth. She was tall and lithe and sweetly formed, with strength slumbering deep under the wide soft mouth and the lovely curves of cheeks and forehead. Blood of the Sun Lands darkened her hair to a glowing blue-black and tinted her skin with gold, there was fire from the sun within her. Like other southern women, she dressed more boldly than the girls of Killorn, a sheer gown falling from waist to ankles, a thin veil over the shoulders, little jewelry. She needed no ornament.

She could not be very much older than he, if at all, thought Kery. He caught her great dark eyes on him and felt a slow hot flush go up his face. With an effort he checked himself and stood very straight, with his strange blue eyes like cold flames.

Beside Sathi sat the general, Jonan, and there were a couple of older men who seemed to be official advisors. But it soon was clear that only the queen and the soldier had much to say in this court.

Bram's voice boomed out, shattering the peace of the blue dusk. For all his great size and ruddy beard he seemed lost in the ancient grace of the chamber. He spoke too loudly. He stood too stiff. "Thank you, my lady. But I am no lord, I simply head this group of the men of Killorn." He waved clumsily at his fellows. "These are Nessa of Dagh and Kery of Broina."

"Be seated, then, and welcome again." Sathi's voice was low and musical. She signaled her servants to bring wine.

"We have heard of great wanderings in the north," she went on, when they had drunk. "But those lands are little known to us. What brought you so far from home?"

Nessa, who had the readiest tongue, answered. "There was famine in the land, your majesty. For three years drought and cold lay like iron over Killorn. We hungered and the coughing sickness came over many of us. Not all our magics and sacrifices availed to end our misery, they seemed only to raise great storms that destroyed what little we had kept.

"Then the weather smiled again, but as often happens the gray blight came in the wake of the hard years. It reaped our grain before we could, the stalks withered and crumbled before our eyes, and wild beasts came in hunger-driven swarms to raid our dwindling flocks. There was scarce food enough for a quarter of our starving folk. We knew, from what had happened in other lands, that the gray blight will waste a country for years, five or ten, leaving only perhaps a third part of the crop alive at each harvest. Then it passes away and does not come again. But meanwhile the land will not bear many folk.

"So in the end the clans decided that most must move away leaving only the few who could keep alive through the niggard years to hold the country for us. Hearts broke in twain, your majesty, for the hills and the moors and the lake where it is forever sunset were part of us. We are of that land and if we die away from it our ghosts will wander home. But go we must, lest all die."

"Yes, go on," said Jonan impatiently when he paused.

Bram gave him an angry look and took up the story. "Four hosts were to wander out of the land and see what would befall. If they found a place to stay they would abide there till the evil time was over. Otherwise they would live however they could. It lay with the gods, my lady, and we have traveled far from the realms of our gods.

"One host went eastward, into the great forests of Norla. One got ships and sailed west, out into the Day Lands where some of our adventurers had already explored a little way. One followed the coast southwestward, through country beyond our ken. And ours marched due south. And so we have wandered for five years."

"Homeless," whispered Sathi, and Kery thought her eyes grew bright with tears.

"Barbarian robbers!" snapped Jonan. "I know of the havoc they have wrought on their way."

"And what would you have done," growled Bram. Jonan gave him a stiff glare, but he rushed on. "Your majesty, we have taken only what we needed...."

And whatever else struck our fancy, thought Kery in a moment's wryness.

"—and much of our fighting has been done for honest pay. We want only a place to live a few years, land to farm as free yeomen, and we will defend the country which shelters us as long as we are in it. We are too few to take that land and hold it against a whole nation—that is why we have not settled down ere this—but on the march we will scatter any army in the world or leave our corpses for carrion birds. The men of Killorn keep faith with friends and foes alike, help to the one and harm to the other.

"Now we saw many fair fields in Ryvan where we could be at home. The Ganasthi have cleared off the owners for us. So we offer you this—give us the land we need and we will fight for you against these Ganasthi or any other foes while blood runs through our hearts. Refuse us and we may be able to make friends with the Dark Landers instead. For friends we must have."

"You see?" snarled Jonan. "He threatens banditry."

"No, no, you are too hasty," replied Sathi. "He is simply telling the honest truth. And the gods know we need warriors."

"This general was anxious enough for our help out there in the eastern marches," said Kery suddenly.

"Enough, barbarian," said Jonan with ice in his tones.

Color flared in Sathi's cheeks. "Enough of you, Jonan. These are brave and honest men, and our guests, and our sorely needed allies. We will draw up the treaty at once."

The general shrugged, insolently. Kery was puzzled. There was anger here, crackling under a hard-held surface, but it seemed new and strange. Why?

They haggled for a while over terms, Nessa doing most of the talking for Killorn. He and Bram would not agree that clansmen should owe fealty or even respect to any noble of Ryvan save the queen herself. Also they should have the right to go home whenever they heard the famine was over. Sathi was willing enough to concede it but Jonan had to be almost beaten down. Finally he gave grudging assent and the queen had her scribes draw the treaty up on parchment.

"That is not how we do it in Killorn," said Bram. "A tyr must be sacrificed and vows made on the ring of Llugan and the pipes of the gods."

Sathi smiled. "Very well, Red One," she nodded. "We will make the pledge thusly too, if you wish." With a sudden flame of bitterness, "What difference does it make? What difference does anything make now?"

V

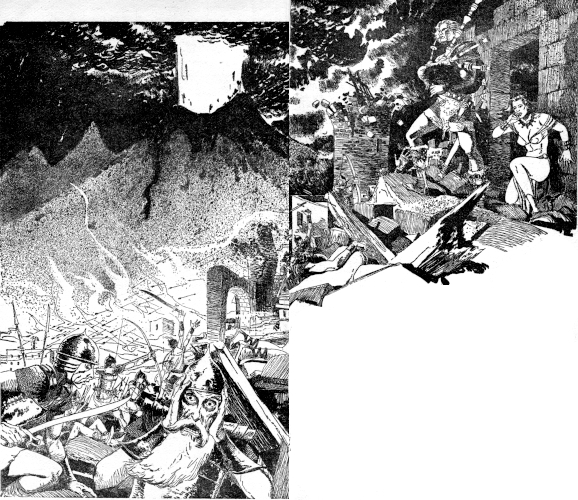

Now the armies of Ganasth moved against Ryvan city itself. From all the plundered empire they streamed in, to ring the town in a living wall and hem the defenders within a fence of spears. And when the whole host was gathered, which took about ten sleeps from the time the Killorners arrived, they stormed the city.

Up the long slope of the hills on which Ryvan stood they came, running, bounding, holding up shields against the steady hail of missiles from the walls. Forward, silent and blank-faced, no noise in them save the crashing of thousands of feet and the high demon-music of their warmaking—dying, strewing the ground with their corpses, but leaping over the fallen and raging against the walls.

Up ladders! Rams thundering at the gates! Men springing to the top of walls and toppling before the defenders and more of them snarling behind!

Back and forth the battle raged, now the Ryvanians driven back to the streets and rooftops, now the Dark Landers pressed to the edge of the walls and pitchforked over. Houses began to burn, here and there, and it was Sathi who made fire brigades out of those who could not fight. Kery had a glimpse of her from afar, as he battled on the outer parapets, a swift and golden loveliness against the leaping red.

After long and vicious fighting the northern gate went down. But Bram had foreseen this. He had pulled most of his barbarians thither, with Kery's bulls in their lead. He planted them well back and had a small stout troop on either side of the great buckling doors. When the barrier sagged on its hinges, the Ganasthi roared in unopposed, streaming through the entrance and down the broad bloody avenue.

Then the Killorners thrust from the side, pinching off the several hundred who had entered. They threw great jars of oil on the broken gates and set them ablaze, a barrier of flame which none could cross. And then Kery rode his bulls against the enemy, and behind him came the might of Killorn.

It was raw slaughter. Erelong they were hunting the foe up and down the streets and spearing them like wild animals. Meanwhile Bram got some engineers from Jonan's force who put up a temporary barricade in the now open gateway and stood guard over it.

The storm faded, grumbled away in surges of blood and whistling arrows. Shaken by their heavy losses, the Dark Landers pulled back out of missile range, ringed the city with their watchfires, and prepared to lay siege.

There was jubilation in Ryvan. Men shouted and beat their dented shields with nicked and blunted swords. They tossed their javelins in the air, emptied wineskins, and kissed the first and best girl who came to hand. Weary, bleeding, reft of many good comrades, and given at best a reprieve, the folk still snatched at what laughter remained.

Bram came striding to meet the queen. He was a huge and terrible figure stiff with dried blood, the ax blinking on his shoulder and the other hairy paw clamped on the neck of a tall Dark Lander whom he helped along with an occasional kick. Yet Sathi's dark eyes trailed to the slim form of Kery, following in the chief's wake and too exhausted to say much.

"I caught this fellow in the streets, my lady," said Bram merrily, "and since he seemed to be a leader I thought I'd better hang on to him for a while."

The invader stood motionless, regarding them with a chill yellow stare in which there lay an iron pride. He was tall and well-built, his black mail silver-trimmed, a silver star on the battered black helmet. The snowy hair and beard stirred faintly in the breeze.

"An aristocrat, I would say," nodded Sathi. She herself seemed almost too tired to stand. She was smudged with smoke and her dress was torn and her small hands bleeding from their recent burdens. But she pulled herself erect and fought to speak steadily. "Yes, he may well be of value to us. That was good work. Aye, you men of Killorn fought nobly, without you we might well have lost the city. It was a good month when you came."

"It was no way to fight," snapped Jonan. He was tired and wounded himself, but there was no comradeship in the look he gave the northerners. "The risk of it—why, if you hadn't been able to seal the gate behind them, Ryvan would have fallen then and there."

"I did not see you doing much of anything when the gate was splintering before them," answered Bram curtly. "As it is, my lady, we've inflicted such heavy losses on them that I doubt they'll consider another attempt at storming. Which gives us, at least, time to try something else." He yawned mightily. "Time to sleep!"

Jonan stepped up close to the prisoner and they exchanged a long look. There was no way to read the Dark Lander's thoughts but Kery thought he saw a tension under the general's hard-held features.

"I don't know what value a food-eating prisoner is to us when he can't even speak our language," said the Ryvanian. "However, I can take him in charge if you wish."

"Do," she nodded dully.

"Odd if he couldn't talk any Aluardian at all," said Kery. "Wanderers through alien lands almost have to learn. The leaders of invading armies ought to know the tongue of their enemy, or at least have interpreters." He grinned with the cold savagery of the Broina. "Let the women of Killorn, the ones who've lost husbands today, have him for a while. I daresay he'll soon discover he knows your speech—whatever is left of him."

"No," said Jonan flatly. He signalled to a squad of his men. "Take this fellow down to the palace dungeons and give him something to eat. I'll be along later."

Kery started to protest but Sathi laid a hand on his arm. He felt how it was still bleeding a little and grew silent.

"Let Jonan take care of it," she said, her voice flat with weariness. "We all need rest now—O gods, to sleep!"

The Killorners had moved their wagons into the great forum and camped there, much to the disgust of the aristocrats and to the pleasure of whatever tavern-keepers and unattached young women lived nearby. But Sathi had insisted that their three chiefs should be honored guests at the palace and it pleased them well enough to have private chambers and plenty of servants and the best of wine.

Kery woke in his bed and lay for a long while, drowsing and thinking the wanderous thoughts of half-asleep. When he got up he groaned for he was stiff with his wounds and the long fury of battle. A slave came in and rubbed him with oil and brought him a barbarian-sized meal, after which he felt better.

But now he was restless. He felt the let-down which is the aftermath of high striving. It was hard to fight back the misery and loneliness that rose in him. He prowled the room unhappily, pacing under the glowing cressets, flinging himself on a couch and then springing to his feet again. The walls were a cage.

The city was a cage, a trap, he was caught like a snared beast and never again would he walk the moors of Killorn. Sharply as a knife thrust, he remembered hunting once out in the heath. He had gone alone, with spear and bow and a shaggy half-wild cynor loping at his heels, out after antlered prey somewhere beyond the little village. Long had they roamed, he and his beast, until they were far from sight of man and only the great gray and purple and gold of the moors were around them.

The carpet under his bare feet seemed again to be the springy, pungent ling of Killorn. It was as if he smelled the sharp wild fragrance of it and felt the leaves brushing his ankles. It had been gray and windy, clouds rushed out of the west on a mounting gale. There was rain in the air and high overhead a single bird of prey had wheeled and looped on lonely wings. O almighty gods, how the wind had sung and cried to him, chilled his body with raw wet gusts and skirled in the dales and roared beneath the darkening heavens! And he had come down a long rocky slope into a wooded glen, a waterfall rushed and foamed along his path, white and green and angry black. He had sheltered in a mossy cave, lain and listened to the wind and the rain and the crystal, ringing waterfall, and when the weather cleared he had gotten up and gone home. There had been no quarry, but by Morna of Dagh, that failure meant more to him than all his victories since!

He picked up the pipe of the gods, where it lay with his armor, and turned it over and over in his hands. Old it was, dark with age, the pipes were of some nameless iron-like wood and the bag of a leather such as was never seen now. It was worn with the uncounted generations of Broinas who had had it, men made hard and stern by their frightful trust.

It had scattered the legions of the southerners who came conquering a hundred years ago and it had quelled the raiding savages from Norla and it had gone with one-eyed Alrigh and shouted down the walls of a city. And more than once, on this last dreadful march, it had saved the men of Killorn.

Now it was dead. The Piper of Killorn had fallen and the secret had perished with him and the folk it had warded were trapped like animals to die of hunger and pestilence in a strange land—O Rhiach, Rhiach my father, come back from the dead, come back and put the pipe to your cold lips and play the war-song of Killorn!

Kery blew in it for the hundredth time and only a hollow whistling sounded in the belly of the instrument. Not even a decent tune, he thought bitterly.

He couldn't stay indoors, he had to get out under the sky again or go mad. Slinging the pipe over his shoulder he went out the door and up a long stairway to the palace roof gardens.

They slept all around him, sleep and silence were heavy in the long corridors, it was as if he were the last man alive and walked alone through the ruins of the world. He came out on the roof and went over to the parapet and stood looking out.

The moon was near the zenith which meant, at this longitude, that it was somewhat less than half full and would dwindle as it sank westward. It rode serene in the dusky sky adding its pale glow to the diffused light which filled all the Twilight Lands and to the white pyre of the hidden sun. The city lay dark and silent under the sky, sleeping heavily, only the muted tramp of sentries and their ringing calls drifted up to Kery. Beyond the town burned the ominous red circle of the Ganasthi fires and he could see their tents and the black forms of their warriors.

They were settling down to a patient death watch. All the land had become silent waiting for Ryvan to die. It did not seem right that he should stand here among fragrant gardens and feel the warm western breeze on his face, not when steadfast Lluwynn and Boroda the Strong and gay young Kormak his comrade were ashen corpses with the women of Killorn keening over them. O Killorn, Killorn, and the lake of sunset, have their ghosts gone home to you? Greet Morna for me, Kormak, whisper in the wind that I love her, tell her not to grieve.

He grew aware that someone else was approaching, and turned with annoyance. But his mood lightened when he saw that it was Sathi. She was very fair as she walked toward him, young and lithe and beautiful, with the dark unbound hair floating about her.

"Are you up, Kery?" she asked, sitting down on the parapet beside him.

"Of course, my lady, or else you are dreaming," he smiled with a tired humor.

"Stupid question wasn't it?" She smiled back with a curving of closed lips that was lovely to behold. "But I am not feeling very bright just now."

"None of us are, my lady."

"Oh, forget that sort of address, Kery. I am too lonely as it is, sitting on a throne above all the world. Call me by my name, at least."

"You are very kind—Sathi."

"That is better." She smiled again, wistfully. "How you fought today! How you reaped them! What sort of a warrior are you, Kery, to ride wild bulls as if they were hests?"

"We of clan Broina have tricks. We feel things that other men do not seem to." Kery sat down beside her feeling the frozenness within him ease a little. "Aye, it can be lonely to wield power and you wonder if you are fit for it, not so? My father died in our first battle with the Ganasthi, and now I am the Broina, but who am I to lead my clan? I cannot even perform the first duty of my post."

"And what is that?" she asked.

He told her about the god-pipe. He showed it to her and gave her the tales of its singing. "You feel your flesh shiver and your bones begin to crumble, rocks dance and mountains groan and the gates of hell open before you but now the pipes are forever silent, Sathi. No man knows how to play them."

"I heard of your music at that battle," she nodded gravely, "and wondered why it was not sounded again this time." Awe and fear were in her eyes, the hand that touched the scarred sack trembled a little. "And this is the pipe of Killorn! You cannot play it again? You cannot find out how? It would be the saving of Ryvan and of your own folk and perhaps of all the Twilight Lands, Kery."

"I know. But what can I do? Who can understand the powers of heaven or unlock the doors of hell save Llugan Longsword himself?"

"I do not know. But Kery—I wonder. This pipe.... Do you really think that gods and not men wrought it?"

"Who but a god could make such a thing, Sathi?"

"I do not know, I say. And yet—Tell me, have you any idea of what the world is like in Killorn? Do you think it a flat plain with the sun hanging above, forever fixed in one spot?"

"Why I suppose so. Though we have met men in the southlands who claimed the world was a round ball and went about the sun in such a manner as always to turn the same face to it."

"Yes, the wise men of Ryvan tell us that that must be the case. They have learned it by studying the fixed stars and those which wander. Those others are worlds like our own, they say, and the fixed stars are suns a very long ways off. And we have a very dim legend of a time once, long and long and long ago, when this world did not eternally face the sun either. It spun like a top so that each side of it had light and dark alternately."

Kery knitted his brows trying to see that for himself. At last he nodded. "Well, it may have been. What of it?"

"The barbarians all think the world was born in flame and thunder many ages ago. But some of our thinkers believe that this creation was a catastrophe which destroyed that older world I speak of. There are dim legends and here and there we find very ancient ruins, cities greater than any we know today but buried and broken so long ago that even their building stones are almost weathered away. These thinkers believe that man grew mighty on this forgotten world which spun about itself, that his powers were like those we today call divine.

"Then something happened. We cannot imagine what, though a wise man once told me he believed all things attract each other—that is the reason why they fall to the ground he said—and that another world swept so close to ours that its pull stopped the spinning and yanked the moon closer than it had been."

Kery clenched his fists. "It could be," he murmured. "It could well be. For what happens to an unskillful rider when his hest stops all at once? He goes flying over its head, right? Even so, this braking of the world would have brought earthquakes greater than we can imagine, quakes that levelled everything!"

"You have a quick wit. That is what this man told me. At any rate, only a very few people and animals lived and nothing remained of their great works save legends. In the course of many ages, man and beasts alike changed, the beasts more than man who can make his own surroundings to suit. Life spread from the Day Lands through the Twilight Zone. Plants got so they could use what little light we have here. Finally even the Dark Lands were invaded by the pallid growths which can live there. Animals followed and man came after the animals until today things are as you see."

She turned wide and serious eyes on him. "Could not this pipe have been made in the early days by a man who knew some few of the ancient secrets? No god but a man even as you, Kery. And what one man can make another can understand!"

Hope rose in him and sagged again. "How?" he asked dully. And then, seeing the tears glimmer in her eyes: "Oh, it may all be true. I will try my best. But I do not even know where to begin."

"Try," she whispered. "Try!"

"But do not tell anyone that the pipe is silent, Sathi. Perhaps I should not even have told you."

"Why not? I am your friend and the friend of your folk. I would we had all the tribes of Killorn here."

"Jonan is not," he said grimly.

"Jonan—he is a harsh man, yes. But...."

"He does not like us. I do not know why but he doesn't."

"He is a strange one," she admitted. "He is not even of Ryvanian birth, he is from Guria, a city which we conquered long ago, though of course its people have long been full citizens of the empire. He wants to marry me, did you know?" She smiled. "I could not help laughing for he is so stiff. One would as soon wed an iron cuirass."

"Aye—wed—" Kery fell silent, and there was a dream in his gaze as he looked over the hills.

"What are you thinking of?" she asked after a while.

"Oh—home," he said. "I was wondering if I would ever see Killorn again."

She leaned over closer to him. One long black lock brushed his hand and he caught the faint fragrance of her. "Is it so fair a land?" she asked softly.

"No," he said. "It is harsh and gray and lonely. Storm winds sweep in and the sea roars on rocky beaches and men grow gnarled with wresting life from the stubborn soil. But there is space and sky and freedom, there are the little huts and the great halls, the chase and the games and the old songs around leaping fires, and—well—" His voice trailed off.

"You left a woman behind, didn't you?" she murmured gently.

He nodded. "Morna of Dagh, she of the sun-bright tresses and the fair young form and the laughter that was like rain showering on thirsty ground. We were very much in love."

"But she did not come too?"

"No. So many wanted to come that the unwed had to draw lots and she lost. Nor could I stay behind for I was heir to the Broina and the god-pipes would be mine someday." He laughed, a harsh sound like breaking iron. "You see how much good that has done me!"

"But even so—you could have married her before leaving?"

"No. Such hasty marriage is against clan law and Morna would not break it." Kery shrugged. "So we wandered out of the land, and I have not seen her since. But she will wait for me and I for her. We'll wait till—till—" He had half raised his hand but as he saw again the camp of the besiegers it fell helplessly to his lap.

"And you would not stay?" Sathi's tones were so low he had to bend his head close to hear. "Even if somehow Ryvan threw back its foes and valiant men were badly needed and could rise to the highest honors of the empire, you would not stay here?"

For a moment Kery sat motionless, wrapping himself about his innermost being. He had some knowledge of women. There had been enough of them along the dusty way, brief encounters and a fading memory.

His soul had room only for the bright image of one unforgotten girl. It was plain enough what this woman, who was young and beautiful and a queen, was saying and he would not ordinarily have hung back.

Especially when the folk of Killorn were still strangers in a camp of allies who did not trust them very far, when Killorn needed every friend it could find. And the Broina were an elvish clan who had never let overly many scruples hold them.

Only—only he liked Sathi as a human being. She was brave and generous and wise and she was, really, so pitiably young. She had had so little chance to learn the hard truths of living in the loneliness of the imperium and only a scoundrel would hurt her.

She sighed, ever so faintly, and moved back a little. Kery thought he saw her stiffening. One does not reject the offer of a queen.

"Sathi," he said, "for you, perhaps, even a man of Killorn might forget his home."

She half turned to him, hesitating, unsure of herself and him. He took her in his arms and kissed her.

"Kery, Kery, Kery—" she whispered, and her lips stole back toward his.

He felt rather than heard a footfall and turned with the animal alertness of the barbarian. Jonan stood watching them.

"Pardon me," said the general harshly. His countenance was strained. Then suddenly, "Your majesty! This savage mauling you...."

Sathi lifted a proud dark head. "This is the prince consort of Imperial Ryvan," she said haughtily. "Conduct yourself accordingly. You may go."

Jonan snarled and lifted an arm. Kery saw the armed men step from behind the tall flowering hedges and his sword came out with a rasp of steel.

"Guards!" screamed Sathi.

The men closed in. Kery's blade whistled against one shield. Another came from each side. Pikeshafts thudded against his bare head—

He fell, toppling into a roaring darkness while they clubbed him again. Down and down and down, whirling into a chasm of night. Dimly, just before blankness came, he saw the white beard and the mask-like face of the prince from Ganasth.

VI

It was a long and hard ride before they stopped and Kery almost fell from the hest to which they had bound him.

"I should have thought that you would soon awake," said the man from Ganasth. He had a soft voice and spoke Aluardian well enough. "I am sorry. It is no way to treat a man, carrying him like a sack of meal. Here...." He poured a glass of wine and handed it to the barbarian. "From now on you shall ride erect."

Kery gulped thirstily and felt a measure of strength flowing back. He looked around him.

They had gone steadily eastward and were now camped near a ruined farmhouse. A fire was crackling and one of the score or so of enemy warriors was roasting a haunch of meat over it. The rest stood leaning on their weapons and their cold amber eyes never left the two prisoners.

Sathi stood near bleak-faced Jonan and her great dark eyes never left Kery. He smiled at her shakily and with a little sob she took a step toward him. Jonan pulled her back roughly.

"Kery," she whispered. "Kery, are you well?"

"As well as could be expected," he said wryly. Then to the Ganasthian prince, "What is this, anyway? I woke up to find myself joggling eastward and that is all I know. What is your purpose?"

"We have several," answered the alien. He sat down near the fire pulling his cloak around him against the chill that blew out of the glooming east. His impassive face watched the dance of flames as if they told him something.

Kery sat down as well, stretching his long legs easily. He might as well relax he thought. They had taken his sword and his pipes and they were watching him like hungry beasts. There was never a chance to fight.

"Come, Sathi," he waved to the girl. "Come over here by me."

"No!" snapped Jonan.

"Yes, if she wants to," said the Ganasthian mildly.

"By that filthy barbarian...."

"None of us have washed recently." The gentle tones were suddenly like steel. "Do not forget, General, that I am Mongku of Ganasth and heir apparent to the throne."

"And I rescued you from the city," snapped the man. "If it weren't for me you might well be dead at the hands of that red savage."

"That will do," said Mongku. "Come over here and sit by us, Sathi."

His guardsmen stirred, unacquainted with the Ryvanian tongue but sensing the clash of wills. Jonan shrugged sullenly and stalked over to sit opposite them. Sathi fled to Kery and huddled against him. He comforted her awkwardly. Over her shoulder he directed a questioning look at Mongku.

"I suppose you deserve some explanation," said the Dark Lander. "Certainly Sathi must know the facts." He leaned back on one elbow and began to speak in an almost dreamy tone.

"When Ryvan conquered Guria, many generations ago, some of its leaders were proscribed. They fled eastward and so eventually wandered into the Dark Lands and came to Ganasth. It was then merely a barbarian town but the Gurians became advisors to the king and began teaching the people all the arts of civilization. It was their hope one day to lead the hosts of Ganasth against Ryvan, partly for revenge and partly for the wealth and easier living to be found in the Twilight Lands. Life is hard and bitter in the eternal night, Sathi. It is ever a struggle merely to keep alive. Can you wonder so very much that we are spilling into your gentler climate and your richer soil?

"Descendants of the Gurians have remained aristocrats in Ganasth. But Jonan's father conceived the idea of moving back with a few of his friends to work from within against the day of conquest. At that time we were bringing our neighbors under our heel and looked already to the time when we should move against the Twilight Lands. At any rate he did this and nobody suspected that he was aught but a newcomer from another part of Ryvan's empire. His son, Jonan, entered the army and, being shrewd and strong and able, finally reached the high post which you yourself bestowed on him, Sathi."

"Oh, no—Jonan—" She shuddered against Kery.

"Naturally when we invaded at last he had to fight against us, and for fear of prisoners revealing his purpose very few Ganasthians know who he really is. A risk was involved, yes. But it is convenient to have a general of the enemy on your side! Jonan is one of the major reasons for our success.

"Now we come to myself, a story which is very simply told. I was captured and it was Jonan's duty as a citizen of Ganasth to rescue his prince—quite apart from the fact that I do know his identity and torture might have loosened my tongue. He might have effected my escape easily enough without attracting notice, but other factors intervened. For one thing, there was this barbarian alliance, and especially that very dangerous new weapon they had which he had observed in use. We clearly could not risk its being turned on us. Indeed we almost had to capture it. Then, too, Jonan is desirous of marrying you, Sathi, and I must say that it seems a good idea. With you as a hostage Ryvan will be more amenable. Later you can return as nominal ruler of your city, a vassal of Ganasth, and that will make our conquest easier to administer. Though not too easy, I fear. The Twilight Landers will not much like being transported into the Dark Lands to make room for us."

Sathi began to cry, softly and hopelessly. Kery stroked her hair and said nothing.

Mongku sat up and reached for the chunk of meat his soldier handed him. "So Jonan and his few trusty men let me out of prison and we went up to the palace roof after you, who had been seen going that way shortly before. Listening a little while to your conversation we saw that we had had the good luck to get that hell-pipe of the north, too. So we took you. Jonan was for killing you, Kery my friend, but I pointed out that you could be useful in many ways such as a means for making Sathi listen to reason. Threats against you will move her more than against herself, I think."

"You crawling louse," said Kery tonelessly.

Mongku shrugged. "I'm not such a bad sort but war is war and I have seen the folk of Ganasth hungering too long to have much sympathy for a bunch of fat Twilight Landers.

"At any rate, we slipped out of the city unobserved. Jonan could not remain for when the queen and I were both missing, and he responsible for both, it would be plain to many whom to accuse. Moreover, Sathi's future husband is too valuable to lose in a fight. And I myself would like to report to my father the king as to how well the war has gone.

"So we are bound for Ganasth."

There was a long silence while the fire leaped and crackled and the stars blinked far overhead. Finally Sathi shook herself and sat erect and said in a small hard voice, "Jonan, I swear you will die if you wed me. I promise you that."

The officer did not reply. He sat brooding into the dusk with a look of frozen contempt and weariness on his face.

Sathi huddled back against Kery's side and soon she slept.

On and on.

They were out of the Twilight Lands altogether now. Night had fallen on them and still they rode eastward. They were tough, these Ganasthi, they stopped only for sleep and quickly gulped food and a change of mounts and the miles reeled away behind them.

Little was said on the trail. They were too tired at the halts and seemingly in too much of a hurry while riding. With Sathi there could only be a brief exchange of looks, a squeeze of hands, and a few whispered words with the glowing-eyed men of Ganasth looking on. She was a gallant girl, thought Kery. The cruel trek told heavily on her but she rode without complaint—she was still queen of Ryvan!

Ryvan, Ryvan, how long could it hold out now in the despair of its loss? Kery thought that Red Bram might be able to seize the mastery and whip the city into fighting pitch but warfare by starvation was not to the barbarians' stomachs. They could not endure a long siege.

But what lay ahead for him and her and the captured weapon of the gods?

Never had he been in so grim a country. It was dark, eternally dark, night and cold and the brilliant frosty stars lay over the land, shadows and snow and a whining wind that ate and ate and gnawed its way through furs and flesh down to the bone. The moon got fuller here than it ever did over the Twilight Belt, its chill white radiance spilled on reaching snowfields and glittered like a million pinpoint stars fallen frozen to earth.

He saw icy plains and tumbled black chasms and fanged crags sheathed in glaciers. The ground rang with cold. Cramped and shuddering in his sleeping bag, he heard the thunder of frost-split rocks, the sullen boom and rumble of avalanches, now and again the faint far despairing howl of prowling wild beasts of prey.

"How can anyone live here?" he asked Mongku once. "The land is dead. It froze to death ten thousand years ago."

"It is a little warmer in the region of Ganasth," said the prince. "Volcanos and hot springs. And there is a great sea which has never frozen over. It has fish, and animals that live off them, and men that live off the animals. But in truth only the broken and hunted of man can ever have come here. We are the disinherited and we are claiming no more than our rightful share of life in returning to the Twilight Lands."

He added thoughtfully: "I have been looking at that weapon of yours, Kery. I think I know the principle of its working. Sound does many strange things and there are even sounds too low or too high for the human ear to catch. A singer who holds the right note long enough can make a wine glass vibrate in sympathy until it shatters. We built a bridge once, over Thunder Gorge near Ganasth, but the wind blowing between the rock walls seemed to make it shake in a certain rhythm that finally broke it. Oh, yes, if the proper sympathetic notes can be found much may be done.

"I don't know what hell's music that pipe is supposed to sound. But I found that the reeds can be tautened or loosened and that the shape of the bag can be subtly altered by holding it in the right way. Find the proper combination and I can well believe that even the small noise made with one man's breath can kill and break and crumble."

He nodded his gaunt half-human face in the ruddy blaze of fire. "Aye, I'll find the notes, Kery, and then the pipe will play for Ganasth."

The barbarian shuddered with more than the cold, searching wind. Gods, gods, if he did—if the pipes should sound the final dirge of Killorn!

For a moment he had a wild desire to fling himself on Mongku, rip out the prince's throat and kill the score of enemy soldiers with his hands. But no—no—it wouldn't do. He would die before he had well started and Sathi would be alone in the Dark Lands.