BY

AUTHOR OF

IN THE DAYS OF AUDUBON, IN THE BOYHOOD OF LINCOLN,

IN THE DAYS OF JEFFERSON, ETC.

Copyright, 1903

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Published September, 1903

The writer has heretofore produced in the vein of fiction, after the manner of the Mühlbach interpretations, several books which were anecdotal narratives of the crises in the lives of public men. While they were fiction, they largely confided to the reader what was truth and what the conveyance of fiction for the sake of narrative form. It was the purpose of such a book to picture by folk-lore and local stories the early life of the man.

The folk-lore of a period usually interprets the man of the period in a very atmospheric way. Jonathan Trumbull, Washington’s “Brother Jonathan,” who had a part in helping to save the American army in nearly every crisis of the Revolutionary War, and who gave the popular name to the nation, led a remarkable life, and came to be held by Washington as “among the first of the patriots.” The book is a folk-lore narrative, with a thread of fiction, and seeks to picture a period that was decisive in American history, and the home and neighborhood of one of the most delightful characters that America has ever known—the Roger de Coverley of colonial life and American knighthood; very human, but very noble, always[vi] true; the fine old American gentleman—“Brother Jonathan.”

It has been said that a story of the life of Jonathan Trumbull would furnish material for pen-pictures of the most heroic episodes of the Revolutionary War, and bring to light much secret history of the times when Lebanon, Conn., was in a sense the hidden capital of the political and military councils that influenced the greatest events of the American struggle for liberty. The view is in part true, and a son of Governor Trumbull so felt that force of the situation that he painted the scenes of which he first gained a knowledge in his father’s farmhouse, beginning the work in that plain old home on the sanded floor.

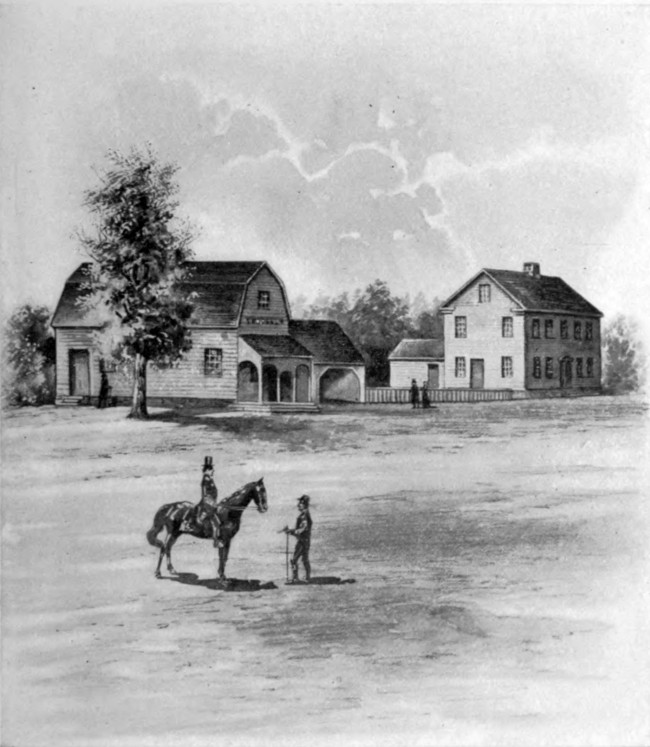

From Governor Trumbull’s war office, which is still standing at Lebanon, went the post-riders whose secret messages determined some of the great events of the war. Thence went forth recruits for the army in times of peril, as from the forests; thence supplies for the army in famine, thence droves of cattle, through wilderness ways.

Governor Trumbull was the heart of every need in those terrible days of sacrifice.

His wife, Faith Trumbull, a descendant of the Pilgrim Pastor Robinson of Leyden, was a heroic woman to whom the Daughters of the Revolution should erect a monument. The picture which we present of her in the cloak of Rochambeau is historically true.

The eminent people who visited the secret town of the war during the great Revolutionary events were many, and their influence had decisive results.

Look at some of the names of these visitors: Washington, Lafayette, Samuel Adams, Putnam, Jefferson, Franklin, Sullivan, John Jay, Count Rochambeau, Admiral Tiernay, Duke of Lauzun, Marquis de Castellax, and the officers of Count Rochambeau and many others.

The post-riders from Governor Trumbull’s plain farmhouse on Lebanon Hill (called Lebanon from its cedars) represented the secret service of the war.

When the influence of this capital among the Connecticut hills became known, Governor Trumbull’s person was in danger. A secret and perhaps self-appointed guard watched the wilderness roads to his war office.

One of these, were he living, might interpret events of the hidden history of the struggle for liberty in a very dramatic way.

Such an interpreter for the purpose of historic fiction we have made in Dennis O’Hay, a jolly Irishman of a liberty-loving heart.

In a brief fiction for young people we can only illustrate how interesting a larger study of this subject of the secret service of the Revolution at this place might be made. We shall be glad if we can so interest the young reader in the topic as to lead him to follow it in solid historic reading in his maturer years.

Hezekiah Butterworth.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I.— | Two queer men meet | 1 |

| II.— | The jolly farmer of Windham Hills and his flock of sheep | 20 |

| III.— | The first of patriots at home | 30 |

| IV.— | “Out you go” | 44 |

| V.— | The war office in the cedars—An Indian tale—Incidents | 58 |

| VI.— | The decisive day of Brother Jonathan’s life | 79 |

| VII.— | Washington speaks a name which names the republic | 104 |

| VIII.— | Peter Nimble and Dennis in the alarm-post | 123 |

| IX.— | A man with a cane—“Off with your hat” | 135 |

| X.— | Beacons | 156 |

| XI.— | The secret of Lafayette | 170 |

| XII.— | Lafayette tells his secret | 187 |

| XIII.— | The bugles blow | 199 |

| XIV.— | A daughter of the Pilgrims | 215 |

| XV.— | “Cornwallis is taken!” | 237 |

Dennis O’Hay, a young Irishman, and a shipwrecked mariner, had been landed at Norwich, Conn., by a schooner which had come into the Thames from Long Island Sound. A lusty, hearty, clear-souled sailor was Dennis; the sun seemed to shine through him, so open to all people was his free and transparent nature.

“The top of the morning to everybody,” he used to say, which feeling of universal brotherhood was quite in harmony with the new country he had unexpectedly found, but of which he had heard much at sea.

Dennis looked around him for some person to whom he might go for advice in the strange country to which he had been brought. He did not have to look far, for the town was not large, but presently a man whose very gait bespoke importance, came walking, or rather marching, down the street. Dennis went up to him.

“An’ it is somebody in particular you must be,” said Dennis. “You seem to me like some high officer that has lost his regiment, cornet, horse, drum-major, and all; no,[2] I beg your pardon. I mean—well, I mean that you seem to me like one who might be more than you are; I beg your pardon again; you look like a magistrate in these new parts.”

“And who are you with your blundering honesty, my friend? You are evidently new to these parts?”

“And it is an Irishman that I am.”

“The Lord forbid, but I am an Englishman.”

“Then we are half brothers.”

“The Lord forbid. What brings you here?”

“Storms, storms, and it is a shipwrecked mariner that I am. And I am as poor as a coot, and you have ruffles, and laces, and buckles, but you have a bit of heart. I can see that in your face. Your blood don’t flow through a muscle. Have you been long in these parts?”

“Longer than I wish to have been. This is the land of blue-laws, as you will find.”

“And it is nothing that I know of the color of the laws, whether they be blue, or red, or white. Can you tell me of some one to whom a shipwrecked sailor could go for a roof to shelter him, and some friendly advice? You may be the very man?”

“No, no, no. I am not your man. My name is Peters, Samuel Peters, and I am loyal to my king and my own country, and here the people’s hearts are turning away from both. I am one too many here. But there is one man in these parts to whom every one in trouble goes for advice. If a goose were to break her leg she would go to him to set it. The very hens go and cackle before his door. Children carry him arbutuses and white[3] lady’s-slippers in the spring, and wild grapes in the fall, and the very Indians double up so when they pass his house on the way to school. His house is in the perpendicular style of architecture, I think. Close by it is a store where they talk Latin and Greek on the grist barrels, and they tell such stories there as one never heard before. He settles all the church and colony troubles, which are many, doctors the sick, and keeps unfaculized people, as they call the poor here, from becoming an expense to the town. He looks solemn, and wears dignified clothes, but he has a heart for everybody; the very dogs run after him in the street, and the little Indian children do the same. He is a kind of Solomon. What other people don’t know, he does. But he has a suspicious eye for me.”

“That is my man, sure,” said Dennis. “Children and dogs know what is in the human heart. What may that man’s name be? Tell me that, and you will be doing me a favor, your Honor.”

“His name is Jonathan Trumbull. They call him ‘Brother Jonathan,’ because he helps everybody, hinders nobody, and tries to make broken-up people over new.”

“And where does he live, your Honor?”

“At a place called Lebanon, there are so many cedars there. I do not go to see him, because I did so once, but while he smiled on every one else, he scowled this way on me, as if he thought that I was not all that I ought to be. He is a magistrate, and everybody in the colony knows him. He marries people, and goes to the funerals of people who go to heaven.”

“That is my man. What are the blue-laws?”

“One of the blue-laws reads that married people must live together or go to jail. If a man and woman who were not married were to go to him to settle a dispute, he would say to them—‘Join your right hands.’ When he rises up to speak in church, the earth stands still, and the hour glass stops, and the sun on the dial. But he has no use for me.”

“That is my man, sure,” said Dennis. “Trumbull, Trumbull, but it was his ship on which I sailed from Derry, and that was lost.”

“He has lost two ships before. It is strange that a man whose meal-chest is open to all should be so unfortunate. It don’t seem to accord with the laws of Providence. I sometimes doubt that he is as good as all the people think him to be.”

“But the fruits of life are not money-making, your Honor. A man’s influence on others is the fruit of life, and what he is and does. A man is worth just what his soul is worth, and not less or more. He is the man that I am after, for sure. How does one get to his house?”

“The open road from Norwich leads straight by his house, all the way to Boston, through Windham County, where lately the frogs had a great battle, and millions of them were slain.”

Dennis opened his eyes.

“Faix?”

“Faix, stranger. Yes, yes; I have just written an account of the battle, to be published in England. After the frogs had a battle, the caterpillars had another, and[5] then the hills at a place called Moodus began to rumble and quake, and become colicky and cough. This is a strange country.

“But these things,” he added, “are of little account in comparison to the fact that the heart of the people is turning against the laws that the good king and his minister make for the welfare of the colony. They allow the people here to be one with the home government by bearing a part of the taxes. And the people’s hearts are becoming alien. I do not wonder that frogs fight, and caterpillars, and that the hills groan and shake and upset milk-pans, and make the maids run they know not where.”

“I must seek that man they call ‘Brother Jonathan.’ Something in me says I must. That way? Well, Dennis O’Hay will start now; it is a sorry story that I will have to tell him, but it is a true heart I will have to take to him.”

“I am going back to England,” said Mr. Peters.

“Well, good-by is it to you,” said Dennis, and the young Irishman set his face toward Lebanon of the cedars, on the road from Boston to Philadelphia by way of New York. He stopped by the way to talk with the people he met about the warlike times, and things happening at Boston town.

His mind was filled with wonder at what he heard. What a curious man the same Brother Jonathan might be! Who were the Indian children? What was the story of the battle of the frogs, and of the caterpillars; what was the cause of the coughing mountains at Moodus; why did Brother Jonathan, a man of such great heart,[6] scowl at the same Mr. Peters, and who was this same Mr. Peters?

Dennis took off his hat as he went on toward Lebanon, turning over in his mind these questions. He swung his hat as he went along, and the blue jays peeked at him and laughed, and the conquiddles (bobolinks) seemed to catch the wonder in his mind, and to fly off to the hazel coverts. Rabbits stood up in the highway, then shook their paws and ran into the berry bushes by the brooks.

Everything seemed strange, as he hurried on, picking berries when he stopped to rest.

At noon the sun glared; fishing hawks, or ospreys, wheeled in the air, screaming. A bear, with her cubs, stopped at the turn of the way. The bear stood up. Dennis stood still.

The bear looked at Dennis, and Dennis at the bear. Then the bear seemed to speak to the cubs, and she and her family bounded into the cedars.

This was not Londonderry. Everything was fresh, shining and new. At night the air was full of the wings of birds, as the morning had been of songs of birds.

The sun of the long day fell at last, and the twilight shone red behind the gray rocks, oaks and cedars.

Dennis sat down on the pine needles.

“It is a sorry tale that I will have to tell Brother Jonathan to-morrow,” said he. “It will hurt my heart to hurt his heart.”

Then the whippoorwills began to sing, and Dennis fell asleep under the moon and stars.

If the reader would know more about Mr. Peters,[7] Samuel Peters, let him consult any colonial library, and he will find there a collection of stories of early Connecticut, such as would tend to make one run home after dark. The same Mr. Peters was an Episcopal clergyman, who did not like the Connecticut main or the “blue-laws.”[1]

[1] See Appendix for some of Rev. Samuel Peters’ queer stories.

Dennis came to the farming town on the hills among the green cedars; he banged on the door of the Governor’s house with his hard knuckles, in real Irish vigor.

The Governor’s wife answered the startling knock.

“And faith it is a shipwrecked sailor. I am from the north of ould Ireland, it is now, and would you be after a man of all work, or any work? There is lots of days of work now in these two fists, lady, and that you may well believe.” He bowed three times.

“The Governor is away from home,” said my lady. “He has gone to New Haven by the sea. What is your name?”

“My name is Dennis O’Hay, an honest name as ever there was in Ireland of the north countrie, and I am an honest man.”

“You look it, my good friend. You have an honest face, but there is fire in it.”

“And there are times, lady, when the coals should burn on the hearth of the heart, and flame up into one’s cheeks and eyes. A storm is coming, lady, a land storm; there are hawks in the air. I would serve you well, lady. It is a true heart that you have. I can see it in your face, lady.”

“And what can you do, Dennis O’Hay? You were bred to the sea.”

“And it is little that I can not do, that any man can do with his two fists. You have brains up here among the hills, lady, but there may come a day that you will need fists as well as brains, and wits more than all, for I am a peaceable man; I can work, and I could suffer or die for such people as you all seem to be up here. The heart of Dennis O’Hay is full of this new cause for liberty. I could throw up my hat over the sun for that cause, lady. I would enlist in that cause, and drag the guns to the battle-field like a packhorse. Oh, I am full of America, honest now, and no blarney.”

“I do not meddle with my husband’s affairs, but I can not turn you away from these doors. How could I send away any man who is willing to enlist for a cause like ours? Dennis O’Hay, go to the tavern over there, and ask for a meal in the name of Faith Trumbull. Then come back here and I will give you the keys to the store in the war office, for I can trust you with the keys, and when my goodman comes back I will send him to you.”

“Lady, this is the time to say a word to you. Ask about me among the other sailors, if they come here, so that you may know that I have lived an honest life. Does not your goodman need a guard?”

“I had never thought of such a thing.”

“You are sending soldiers and food and cattle to the camps, I hear; who knows what General Gage might be led to do? They have secret guards in foreign parts, men of[9] the ‘secret service,’ as they call them. Lady, there are things that come to one, down from the skies, or up from the soul. It is all like the ‘pattern on the mount of vision’ that they preach about. A voice within me has been saying, ‘Go and work for the Governor among the hills, and watch out for him.’ But you must test me first, lady. I would keep you from harm; there is nothing that should ever stand between these two fists of Dennis O’Hay and such as you. But that day will come. I will go to the tavern now, and God and all the saints bless you, and your goodman forever, and make a great nation of this green land of America, and keep the same Dennis O’Hay, which I am that, in the way of his duty.”

The tavern, which became an historic inn, where some of the most notable people of America and of France were entertained during the days of the Revolution, stood at a little distance from the Governor’s house. Dennis O’Hay went there so elated that he tossed his sailor’s hat into the air.

“It is little that I would not do for a lady like that,” he said. “The sea tossed me here on purpose. Night, thou mayest have my service; watch me, ye stars! Liberty, thou mayest have my blood; call me, ye fife and drum. Let me but get at the heart of the Governor, and his life and home shall be secure from all harm under the clear eye of Dennis O’Hay. Hurrah, hurrah, hurrah! and it is here I am in America!”

The landlord stood in the door.

“And who are you, my friend?”

“Dennis, your Honor.”

“And what brings you here?”

“Not the ship; for the ship went down. What brings me here? My two legs—no——”

He paused, and looked reverent.

“The Hand Unseen. I came to enlist in the struggles for the freedom of America. Give me a bite in the name of the lady down the road.”

“My whole table is at your service, my friend. I like your spirit. We need you here.”

“And here I am—how I got here I do not know, but I am here, and my name is Dennis O’Hay.”

He waited long for the return of the Governor to the war office, or country store, looking out of the window over the tops of the green hills.

“An’ faix, I do believe,” he said at last, “I minds me that this is the day when the world stands still. But, O my eyes, what is it that you see now?”

A light form of a little one came out of the door of the Governor’s house and walked to the war office. It was a girl, beautiful in figure, with a sensitive face, full of sympathy and benevolence.

She opened the door.

“My name is Faith,” said she. “I am Mr. Trumbull’s daughter. I keep store sometimes when my father, the Governor, is away late. I thought I would open the store this afternoon. Customers are likely to come, near nightfall.”

“I would help you tend store,” said Dennis O’Hay, “if I only knew how. It is not handy at a bargain that I would be now, and barter people, if you call them that[11] here, would all get the best of me. But I may be able to do such things some day.”

He looked out of the window, and suddenly exclaimed—“Look!”

A man on a noble horse was coming, flying as it seemed, down the Lebanon road from the Windham County hills. His horse leaped into the air at times, as full of high spirit, and dashed up to the store.

Faith, the beautiful girl, went to the door.

The rider gasped—“Where is your father, Faith?”

“He is gone to New Haven, Mr. Putnam.”

“I want to see him at once; there is secret news from Boston. But I must see him. I must not leave here until he returns. I will go over to the tavern and wait.”

Dennis came out and stood in front of the store.

“Stranger,” said the rider, “and who are you? You do not look like a farmer.”

“Who am I? I am myself, sure, a foreigner among foreigners, Dennis O’Hay, a castaway, from the north of Ireland.”

“And what brings you here?”

“I came to enlist,” said Dennis.

“You will be wanted,” said Mr. Putnam. “You have shoulders as broad as Atlas, who carried the world on his back.”

“The world on his back? What did he walk upon?”

“That is a question too much,” said the rider. “I’ll leave my horse in your hands, Dennis O’Hay, and go to the tavern and see what I can find out about the Governor’s movements there.”

He strode across the green.

The sun was going down, sending up red and golden lances, as it were, over the dark shades of the cedars. On the hills lay great farms half in glittering sunlight, half in dark shadows.

“Have you any thought when the Governor will return?” asked the rider of the tavern-keeper.

“No, Israel, I have not—but I hear that there is important news from Boston—that it is suspected that the British are about to make a move to capture the stores of American powder at Concord. The Governor, I mind me, knows something about the secrets of powder hiding, but of that I can not be sure.”

“Great events are at hand,” said Putnam. “I can feel them in the air. I had the same feeling before the northern campaign. I must stay here until the Governor arrives.”

“You shall have the best the tavern affords,” said the innkeeper.

The sun went down blazing on the hills, seeming like a far gate of heaven, as its semicircular splendors filled the sky. Then came the hour of shadows with the advent of the early stars, and then the grand procession of the night march of the hosts of heaven that looks bright indeed over the dark cedars.

The air was silent, as though the world were dead. The taverners listened long in front of the tavern for the sound of horses’ feet on the Lebanon road.

“Will the Governor come alone?” asked Dennis O’Hay of Israel Putnam, the rider.

“Yes, my sailor friend; who is there to harm him?”

“But there will be danger. There ought to be a guard on the Lebanon road. Did not the Governor save the powder, ammunition, and stores, in the northern war? So they said at Norwich. Some day General Gage will put a long eyes on him.”

“Silence!”

The taverners went into the tavern and sat down in the common room.

“I will wait until midnight before I go to my room. My message to the Governor must be delivered as soon as he returns.”

The public room was lighted with candles, and a fire was kindled on the hearth. It was spring, but a hearth fire had a cheerful glow even then.

The taverners talked of the military events around Boston town, then told stories of adventure. Dennis came from the store, and sat down with the rest.

“Mr. Putnam,” said one of them, “the story of your hunting the she-wolf is told in all the houses of the new towns, but we have never heard it from yourself. The clock weights sink low, and we wish to keep awake. Tell us about that wily wolf, and how you felt when your eyes met hers in the cave.”

“I never boast of the happenings of my life,” said Israel Putnam. “It is my nature to dash and do, and I but give point to the plans of others. That is nothing to boast of. Put on cedar wood and I will tell the tale[14] of that cunning animal, a ‘witch-wolf,’ as some call her, as well as I can. The people at the taverns often ask me to kill time for them in that way.

“I came to Pomfret in 1749. For some years I was a busy man, toiling early and late, as you may know. I raised a house and barn; some of you were at the raising. I chopped down trees, made fences, planted apple-trees, sowed and reaped.

“My farm grew. I had a growing herd of cattle, but my pride was in my flock of sheep.

“One morning, as I went out to the hill meadows, I found that some of my finest sheep had disappeared. I called them, and I wandered the woods searching for them, but they were not to be found. Then a herdman came to me and said that he had found blood and wool in one place, and sheep bones in another, and that he felt sure that the missing sheep had been destroyed by powerful wolves.

“In a few days other sheep were missing. Day by day passed, and I lost in a few months a great number of sheep.

“One morning I went out to the sheepfolds, and found that some animal had killed a whole flock of sheep.

“‘It is a she-wolf that is the destroyer’ said a herdman, ‘a witch-wolf, it may be. Would you dare to attack her?’

“My brain was fired. There lay my sheep killed without a purpose, by some animal in which had grown a thirst for blood.

“‘Yes, yes—’ said I, ‘wolf or demon, whatever it be,[15] I will give my feet no rest until I hold its tongue in my own hands, and that I will do. I have force in my head, and iron in my hands. Call the neighbors together and let us have a wolf hunt.’

“The neighbors were called together, and the conch shell was blown. We tracked the wolf and got sight of her. She was no witch, but a long, gaunt, powerful she-wolf, a great frame of bones, with a sneaking head and evil eyes.

“We pursued her, but she was gone. She seemed to vanish. ‘She is a witch,’ said the herdman. ‘She is no witch,’ said I, ‘and if she were, it is my duty to put her out of existence, and I will!’

“We hunted her again and again, but she was too cunning for us. She disappeared. She would be absent during the summer, but in the fall she would return, and bring her summer whelps with her. She fed her brood not only on my flocks but on those of the farms of the country around. We gathered new bands to hunt her; the people rose in arms against her—against that one cunning animal.—Put cedar wood on the fire.

“I formed a new plan. We would hunt her continuously, two at a time.

“She lost a part of one foot in a steel trap at last. Then the people came to know that she was no witch. We could track her now by the mark of the three feet in the snow. She limped, and her three sound feet could not make the quick shifts that her four feet had made of old.

“One day we set out on a continuous hunt. We followed[16] her from our farms away to the Connecticut River. Then the three-footed animal came back again, and we followed her back to the farms.

“But the bloodhounds now knew her and had got scent of her, and they led us to a den in the woods. This den was only about three miles from my house. She may have hidden in it many times before.

“We gathered before the den, and lighted straw and pushed it into the den to drive her out. But she did not appear.

“Then we put sulphur on the straw and forced it into the den, so that it might fill the cavern with the fumes. But the three-footed wolf did not come out of the den. The cave might be a large one; it might have an opening out some other way.

“We called a huge dog, and bade him to enter the cave. He dove down through the opening. Presently we heard him cry; he soon backed out of the opening, bleeding. The wolf was in the cave.

“Another dog, and another were forced to enter the cave, both returning whining and bleeding. Neither smoke nor dogs were able to destroy that animal that had made herself a terror of the country round.

“I called my negro herder.

“‘Sam,’ said I, ‘you go into the cave and end that animal.’

“‘Not for a thousand pounds, nor for all the sheep on the hills of the Lord. What would become of Sam? Look at the dogs’ noses. Would you send me where no dog could go?’

“‘Then I shall go myself,’ said I, for nothing can stop me from anything when my resolution has gathered force; there are times when I must lighten.

“I took off my coat and prepared to go down into the cave. My neighbors held me back. I took a torch, and plunged down the entrance to the cave, head first, with the torch blazing.

“Had I made the effort with a gun, the wolf might have rushed at me, but she crouched and sidled back before the fire.

“The entrance was slippery, but my will forced me on.

“I could rise up at last. The cave was silent; the darkness might be felt. I doubt that any human being had ever entered the place before.

“I walked slowly, then turning aside my torch, peered into the thick darkness.

“Two fierce eyes, like balls of fire, confronted me. The she-wolf was there, waiting for some advantage, but cowed by the torch.

“Presently I heard a growl and a gnashing of teeth.

“I had drawn into the cave a rope tied around my body, so that I might be drawn out by my neighbors if I should need help. I gave the signal to pull me out. I understood the situation.

“I was drawn up in such a way that my upper clothing was pulled over my body, and my flesh was torn. I grasped my gun and crawled back again.—Put more cedar wood on the fire.

“I saw the eyes of the wolf again. I heard her snap and growl. I leveled my gun.

“Bang! The noise seemed to deafen me. The smoke filled the cave.

“I gave a signal to my neighbors to draw me out. I listened at the mouth of the cave. All was silent. The smoke must have found vent. I went into the cave again.

“It was silent.

“I found the body of the wolf. It was stiff and was growing cold. I took hold of her ears and gave a signal to those outside to draw me out.

“As I was drawn from the mouth of the cave I dragged the wolf after me.

“Then my friends set up a great shout. My eyes had met those of the she-wolf but once, then there was living fire in them, terrible but pitiful. Hark—what is that?”

There was a sound of horses’ feet.

“The Governor is coming,” said one of the taverners.

Israel Putnam ran out to meet him, and spoke to him a few words.

“Let us go to the war office at once, and shut the door and be by ourselves,” said the Governor.

They hurried to the war office, and the Governor shut the door, not to open it again until morning.

Dennis O’Hay went back to the tavern, and wondered and wondered.

“Faix, and this is a quare country, and no mistake,” said he. What would the Governor say to him?

Would he be the first to tell him that the ship had gone down?

He talked with taverners about the subject.

“I must break the news, gently like,” he said. “I would hate to hurt his heart.”

“He has lost ships before,” said one.

“His losses have made him a poor man,” said another. “But he marches right on in the way of duty, as though he owned the stars.”

Dennis fell asleep on the settle, wondering, and he must have dreamed wonderful dreams.

There was an old manor in sunny England to which Lord Cornwallis used to resort, and a certain Captain Blackwell purchased a territory in Windham, Conn., among the green hills and called it Mortlake Manor, after the English demesne. Here Israel Putnam purchased a farm of some 500 acres, at what is now Pomfret, Conn., and began to raise great herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, and to plant apple-trees.

He was made a major in the northern campaign, afterward a colonel, then in the Indian War he became a general. They called him “Major Putnam,” for the title befitted his character, and he wished to be sparing of titles among the farmers of Windham.

Israel Putnam was born a hero. He had in him the spirit of a Hannibal. He had character as well as daring; his soul rose above everything, and he never feared a face of day.

He had the soul of Cincinnatus, and not of a Cæsar. He could leave the plow, and return to it again.

His conduct in the northern campaign had shown[21] the unselfish character of his heroism. A jolly farmer was he, and as thrifty as he was jolly. He could strike hard blows for justice and liberty, and like a truly brave man he could forgive his enemies and help them to rise in a right spirit again.

Why had he come here at this time?

Let us go into the store, or, as it was beginning to be called, the “war office,” with these two men of destiny.

“Governor Trumbull,” he said, “I am about to go to Boston, and I want your approval. Boston is being ruined by British oppression. She is almost famine-stricken, and why? Because her people are true to their rights.

“Governor, I can not sleep. Think of the situation. Here I am on my farm, with hundreds of sheep around me, and the men of liberty of Boston town are sitting down to half-empty tables. Some of my sheep must be driven away.

“They must be started on their way to Worcester, and to Newtowne, and to Boston, and, Governor, the flock must grow by the way.

“I am going to ask the farmers to swell the number of the flock as I start with my own. Boston Common is a British military post now—but I am going to Boston Common with my sheep, and my flock will grow as I go, and I will appear there at the head of a company of sheep, and if the British Government does not lift its hand from Boston town, I will go there with a company of soldiers. Have I your contentment in the matter?”

“Yes, go, hero of Lake George and of Ticonderoga,[22] go with your sheep and your flock, increase it as it goes; but as for that other matter you suggest, let us talk of that, the matter of what is to be done if British oppression is to increase.”

They talked all night, and Putnam said that the liberties of the colonies were more than life to him, and that he stood ready for any duty. He rode away in the light of the morning.

As he passed the tavern, Dennis O’Hay went to the war office, where the Connecticut militia used to appear, to meet the Governor.

“The top of the morning to you, Governor,” said Dennis, holding his cap in his hand above his head.

“My good friend, I do not know you,” said the Governor, “but that you are here for some good purpose, I can not doubt. What is your business with me?”

“I was a sailor, sir, and our ship went down, sir, but I came up, sir, and am still on the top of the earth. I am an Irishman, sir, from Ireland of the North, that breeds the loikliest men on the other side of the world, sir, among which, please your Honor, I am one.

“I have heard about the stamp act, sir. England has taxed Ireland into the earth, sir. We live in hovels, sir, that the English may dwell in castles, sir. I wouldn’t be taxed, sir, were I an American without any voice in the government, sir. That would be nothing but slavery.

“I would like to enlist, sir. I have heard of the minutemen, sir, and it is a half-a-minute man that I would like to become.”

“I see, I see, my good fellow; I read the truth of[23] what you say in your looks. Let me go to my breakfast, and I will talk over your case with my wife, Faith, and my daughters, and my son John. In the meantime, go and get your breakfast in the tavern.”

“The top of this earth and all the planets to you, sir.”

After breakfast the Governor summoned Dennis to the store, which came to be called the “war office.” The back room in the store was the council room.

“Did you notice that man who rode away in the morning?” he asked.

“Sure, I did, sir. I heard him tell a story last night in the tavern. The flesh was gone from one of his hands.”

“It was torn from his hand while pouring water on a fire which was burning the barracks near a magazine which contained 300 barrels of powder. That was in the north.”

“Did he save the magazine?”

“Yes, my good friend. He is a brave man, and he is soon going with a drove of sheep to Boston.

“You ask for work,” continued the Governor. “I want you to go with that man, Major, Colonel, General Putnam, and his drove of sheep to Boston, and to keep your eye out on the way, so, if needed, you might go over it again. I wish to train a few men to learn a swift way to Boston town. You may be one of them. I will have a horse saddled for you at once; follow that man to Pomfret, to the manor farm at Windham. I will write you a note to him, a secret note, which you must not open by the way.”

“Never you fear, Governor; I couldn’t read it if I did, but I can read life if I can not read messages.”

In a few minutes he was in the saddle, with his face turned toward the Windham hills.

He found General Putnam, the “Major,” on his farm.

“It is the top of the morning that I said to the Governor this morning, and it is the top of the evening that I say to you now. I am Dennis O’Hay, from the north of Ireland, and it is this message—which may ask that I be relieved of my head for aught I know—that the Governor he asked me to put into your hand. He wants me to learn all the way to Boston town, so that I may be able to drive cattle there, it may be. I am ready to do anything to make this country the land of liberty. After all that ould Ireland has suffered, I want to see America free and glorious—and hurrah, free! That word comes out of my heart; I don’t know why I say it. It rises up from my very soul.”

“You shall learn all the way to Boston town,” said the Major, “and I hope I shall not find you faithless, or give you over to the British to be dealt with according to the law.”

Putnam was preparing to leave for his long journey on the new Boston road. His neighbors gathered around him, and young farmers brought to him fine sheep, to add to those he had gathered for the suffering patriots of Boston town.

The driver of this flock knew the way, the post-houses, the inns, the ordinaries, and the Major assigned Dennis to him as an assistant.

Putnam was a lusty man at this time, in middle life. He wore homespun made from his own flocks. His great farm among the hills had been developed until it was made sufficient to support a large family and many work-people. He raised his own beef, pork, corn, grain, apples and fruit, and poultry. His family made their own butter and cheese; his wife wove the clothing for all; spun her own yarn. The manor farm might have been isolated for a hundred years, and yet thrift would have gone on.

No one was ever more self-supporting than the old-time thrifty New England farmer. His farm was more independent than a baron’s castle in feudal days.

He “put off” his butter, cheese and eggs, or bartered them for “West India goods”; but even in these things he might have been independent, for his maple-trees might have yielded him sugar, and roasted crusts and nuts a nutritious substitute for coffee and tea.

Putnam drove away his sheep, stopping at post-houses by the way, and telling some merry and some thrilling stories there of the wild campaign of the north, and of his escapes from the Indians under Pontiac.

He arrived at Boston and was welcomed by the patriot Warren.

A British officer faced him.

“And you have come down here,” said the British officer, “to contend against England’s arm with a lot of sheep. If you rebels do not cease your opposition, do you want to know what will happen?”

“Yes.”

“Twenty ships of the line and twenty regiments will be landed at the port of Boston.”

“If that day comes, I shall return to Boston, and I shall bring with me men as well as sheep.”

“Ho, ho!” laughed the British officer. “That is your thought, is it, hey? It is treason, sir; treason to the British Crown.”

“Sir,” said Putnam, “an enemy to justice is my enemy; is every man’s enemy. It is a man’s duty to stand by human rights.”

Dennis studied every farmhouse and nook and corner by the way. He had a quick mind and a responsive heart, and he was learning America readily.

He could read lettered words, so he looked well at the sign-boards at four corners and on taverns and milestones. He “stumbled” in book reading, but could define signs.

“Could you find your way back again?” asked the Major of him, as they rested beneath the great trees on Boston Common.

“And sure it is, Major. I would find my way back there if I had been landed at the back door of the world.”

“Well,” said the Major, “then you may go back in advance of us alone.”

Dennis parted from the Major, and dismounted in a couple of days or more before the Governor’s war office with

“And it is the top of the morning, it is, Governor.”

“Did you bring a recommendation from the Major?” asked the Governor.

“No, no, he sent me on ahead, but I can give a good report of him.”

“That is the same as though he brought a good report of you. A man who speaks well of his master is generally to be trusted.

“Well, you know the way to Boston town. I think that I can now make you useful to me, and to the cause. We will see.”

Dennis found work at the tavern. He would sit on the tavern steps to watch for the Governor in the evenings when the latter appeared on the green. He soon joined the good people in calling the Governor “Brother Jonathan.”

Dennis was superstitious—most Irishmen are—but he was hardly more given to ghostly fears than the Connecticut farmers were. Nearly every farmstead at that period had its ghost story. Good Governor Trumbull would hardly have given an hour to the fairy tale, but he probably would have listened intently to a graveyard or “witch” story.

People did not see angels then as in old Hebrew days, but thought that there were sheeted ghosts that came out of graveyards, or made night journeys through lonely woods, and stood at the head of garret stairs, “avenging” spirits that haunted those who had done them wrong.

So we only picture real life when we bring Dennis into this weird atmosphere, that made legs nimble, and cats run home when the clouds scudded over the moon.

Dennis had heard ghost story after ghost story on his[28] journey and at the store. Almost everybody had at least one such story to tell; how that Moodus hills would shake and quake at times, and tip over milk-pans, and cause the maid to hide and the dog to howl; how the timbers brought together to build a church, one night set to capering and dancing; how a woman who had a disease that “unjinted her jints” (unjointed her joints) came all together again during a great “revival”; how witches took the form of birds, and were shot with silver bullets; and like fantastic things which might have filled volumes.

“I never fear the face of day,” said Dennis, “but apparitions! Oh, for my soul’s sake, deliver me from them! I am no ghost-hunter—I never want to face anything that I can’t shoot, and on this side of the water the woods are full of people that won’t sleep in their graves when you lay them there. I shut my eyes. Yes, when I see anything that I can’t account for, I shut my eyes.”

That was the cause of the spread of superstition. People like Dennis “shut their eyes.” Did they meet a white rabbit in the bush, they did not investigate—they ran.

Dennis would have faced a band of spies like a giant, but would have run from the shaking of a bush by a mouse or ground squirrel in a graveyard.

He once saw a sight that, to use the old term, “broke him up.” He was passing by a family graveyard when he thought that an awful apparition that reached from the earth to the heavens rose before him.

“Oh, and it was orful!” said he. “It riz right up out[29] of the graves into the air, with its paws in the moon. It was a white horse, and he whickered. My soul went out of me; I hardly had strength enough in my legs to get back to the green; and when I did, I fell flat down on my face, and all America would never tempt me to go that way again.”

The white horse whose “paws” were in the moon was only an animal turned out into the highway to pasture, that lifted himself up on the stout bough of a graveyard wild apple-tree to eat apples from the higher limbs. Horses were fond of apples, and would sometimes lift themselves up to gather them in this way.

The ghost story was the favorite theme at the store on long winter evenings.

“If one could be sure that they met an evil ghost, one would know that there must be good spirits that had gone farther on,” reasoned the men.

“They may as well all go farther on,” said Dennis. “Such things do not haunt good people.”

A noble private school first made Lebanon of the cedars famous. It had been founded by the prosperous hill farmers under the influence of the Governor. To this school the latter sent his five children, who prepared there for college or the higher schools.

The Governor possessed a strong mind, that was so clear and full of imagination as to be almost poetic and prophetic.

The Scriptures were his book of poems, and he read many books—Job in Hebrew, and John in Greek.

At home among his five children, all of whom were destined to be notable, and two of them famous, he was an ideal father. His one thought was to educate his children for usefulness.

One of his sons was named John, born in 1756. Nearly all of my readers have seen his work, for it was his gift to paint the dramatic scenes of the Revolutionary War, and these great historical paintings adorn not only the rotunda of the Capitol at Washington, but several of them most public halls, and tens of thousands of patriotic homes in the country, especially The Battle of Bunker Hill, The[31] Signers of the Declaration of Independence, The Death of Wolf, The Surrender of Cornwallis, and Washington’s Farewell to his Army.

The home of the Governor may have been matted, but was not carpeted. It was the custom at that time to strew white sand over floors and to “herring-bone” spare rooms. Of this sand we have a curious story.

Two of the daughters, Faith and Mary, were born to a love of art. They were sent to school in Boston after graduating at the Lebanon school, and there Faith began to admire portraits painted in oil.

She studied painting in oil, and she returned to her plain and simple home. She hung upon the walls two portraits painted by her own hand that were a local wonder.

The Governor looked upon his gifted daughter’s work with commendable pride.

“You have done well, Faith. I did not expect such gifts of you. To detain age, in keeping the face at the age in which it is painted, is indeed a noble art. It is worthy of you, Faith.”

At this time John Trumbull was a little boy. He had been housed and nursed tenderly by his mother, because he had a misformed head which had to be shaped out of a defect by pressure.

This boy turned his face to his sister Faith’s paintings with surprise, as they transformed the walls of the room.

“I want to paint, too,” said he.

“No, no,” said the Governor, “painting is not for boys.”

He asked his sister for oils.

“You are too young,” thought the artistic Faith, who was a loving, noble sister.

“But I must, I must.”

One day his mother entered the sanded room. The white sand had been disturbed. It was lying about in curious angles. She stopped; the sand had formed a picture. Whose picture—probably it was intended for herself.

The boy’s face met hers, possibly at an opposite door.

“My son, what have you been doing with the sand?”

“Painting, mother.”

“But what led you to paint in that way?”

“Faith’s pictures on the wall. I had to paint. I must. I will be a painter if I grow up. The things that father does will not live unless they are painted. Pictures make the past now—they hold the past; they make it live.”

“My little boy sees the value of the art like a philosopher. You and Faith have a gift that I little expected. I have nursed that little head of yours many an hour; there may be pictures in it—who knows?”

“But father thinks that painting is girlish. How can I get him to let me paint?”

“You may be able to paint so well, that he will be proud of your art.”

The next day the sand took new form; another picture filled the floor, and so day by day new pictures came to delight the good mother’s heart.

The Governor saw them.

“There is a gift in them,” said he. “It is all right for a little shaver like him. Boys will have to wield something stronger than the brush in the new age that is upon us. But we must not crush any gift of God.”

He turned away.

His family loved to be near him, and he told them wonderful tales from the Hebrew Scriptures.

Queer tales of early times in the colonies he related to them, too; stories that tended to correct false views of life and character. Suppose we spend an hour with the good Governor in his own home.

It was early evening; snow was falling on the green boughs of the cedars of Lebanon. A great fireplace blazed before the sitting-room table, on which were the Bible and books.

On one side of the fireplace hung quartered apples drying; on the other a rennet and red peppers, and on the mantelpiece were shells from the Indies, candlesticks, and pewter dishes.

The room became silent. The Governor’s thoughts were far away, planning, planning, almost always planning.

The stillness became lonesome. Then little John, the painter in the sand, ventured to ask his mother for a story, and she said:

“I am narrowing now in my knitting; ask your father, he is wool-gathering; call him home.”

Little John touched his father on the arm.

“It is a story that you would have,” said the Governor.[34] “I am thinking all by myself on a case that comes up before me to-morrow, of a young man who has broken the law, but did not know that there was any such law to break. He had just come in from sea.

“Now, what would you do in such a case as that, Johnny? I am thinking how to be merciful to the man and just to others.”

“I would do what mother would do—mother, what would you do in a case like that?”

“I do not know; there may be things to be considered. I would follow my heart; if it would not endanger others.”

“Father, what will you do? Animals break laws about which they do not know. I pity them.”

“Well said, John,” said the Governor.

He added, beating on the back of his chair:

“I may have to follow my heart; but I will tell you a story of an old Connecticut judge who followed his heart, and something unexpected happened.”

The Governor dropped his stately tone, and used the language of home. That was a charm, the home tone.

“It was at the time of the blue-laws,” he said. “Those laws in one part of the State were so strict as to forbid the making of mince pies at Christmas-time.

“One of these laws forbid a man to kiss his wife in public on Sunday.”

The Governor seldom used story-book language. He was going to do so now, and it would make the very fire seem friendly.

“Wandering Rufus was a merry lad. He married a young wife, a very handsome girl, and he loved her. Soon after his marriage he went to sea, and it was after he went to sea that the law was enacted against the Sunday kissing. The lawmakers little thought of the men at sea.

“His wife looked out for him to come back, as a good wife should. She pressed her nose against the pane. She dreamed and dreamed of how happy she should be when he should come leaping up from the wharf to greet her.

“Three years passed, for he was a whaler as well as a sailor.

“Three years!

“One day there was heard a boom at sea—boom off New Haven. The ship was coming in, and it was Sunday.

“The young wife dressed herself in her best gown, and she never looked so pretty before. Her cheeks glowed like roses in dew-time.

“She hurried down toward the wharf to meet him, just as the bells were ringing and the people were all going to meeting.

“He came up the highway to greet her, leaping—not a becoming thing, I will allow. And he rushed into her arms, and gave her smack after smack, and her bonnet fell off, and the people stopped and wondered. The magistrate wondered, too.

“There was a man in the seaport who was like Mr. Legality in the Pilgrim’s Progress. The next day he had[36] the young sailor arrested for unbecoming conduct on the street on Sunday, and I mind me that his conduct was not altogether becoming.

“The judge came into court, and read the law, and asked:

“‘Rufus, my sailor boy, what have you to plead?’

“‘I did not know that there was any such law, your Honor; else I would have obeyed it.’

“You may see that he had a true heart, like a robin on a cherry bough.

“‘I must condemn you to have thirty lashes at the whipping-post,’ said the judge—‘No, twenty lashes—no, considering all the points of the case, ten; or five will do. Five lashes at the whipping-post. This is the lightest sentence that I ever imposed. But he did not know the law; and he was a married man, and he had not seen his wife for nearly three years; I must be merciful in this particular case, and I will not say in this same case how hard the lashes shall be laid on.’

“So the young sailor was whipped, and Mr. Legality said that five lashes would not have scampered a cat.

“Rufus, the wanderer, prepared to go whaling again.

“Now, the captain of the ship had caused a chalk-mark to be drawn across the deck of the ship, and had made a ship law that if any one but an officer of the ship should cross the mark, the person violating the law should be whipped with a cat-o’-nine-tails.

“I am sorry to say that our young sailor should have had a revengeful spirit, but he seems to have shown a disposition not altogether benevolent. He invited Mr.[37] Legality to go on board the ship with him, just as the ship was about to sail. Mr. Legality to atone for his want of charity went, and he had hardly got on board before he stepped over the chalk-line.

“‘Halt, halt!’ said Rufus. ‘We have a law that if any one steps over the chalk-line he must be whipped.’

“‘But I did not know that there was any such a law,’ said Mr. Legality.

“‘But it is the law,’ said Wandering Rufus.

“‘But how could I have known?’ asked Mr. Legality.

“‘How could I have known that there was a law that a man must not kiss his wife on the street on Sunday?’ asked Rufus.

“‘I see, I see; but don’t let me be whipped with the cat-o’-nine-tails.’

“‘That I will not, for I am a hearty sailor. If any one is whipped it shall be me. I wanted to show you how the human heart feels.’

“Mr. Legality left the ship as fast as his legs would carry him, and somehow that story sometimes rises before me like a parable. I think I shall follow my heart with this new case that comes off to-morrow.”

“Do, do,” said the children, all five; and the mother, lovely Faith Trumbull, said, “Yes, Jonathan, do.”

“And now,” said the Governor, “let us read together the most beautiful chapter, as I mind, in all the Epistles.”

The snow fell gently without; the fire cracked, and they read together the chapter containing “Charity suffereth long, and is kind.”

“Beareth all things, endureth all things,” read little John. Then tears filled his eyes, and he said:

“Father, I love you.”

But there was another side to the love and loyalty of this sheltered town in the cedars. There were Tories here, and they did not like the patriarchal Governor. You must meet some of them, if it does change the atmosphere of the narrative.

It has been said that no dispute could ever stand before Brother Jonathan; it would melt away like snow on an April day when he lifted his benignant eyes and put the finger of one hand on the other, and said, “Let me make it clear to you.”

Queer old Samuel Peters, the Episcopal agent, or missionary in the colony, made so much fun of the good people in his History of Connecticut, and so led England and America to laugh by his marvelous anecdotes and description of the blue-laws, that the really thrifty and heroic character of these people has been misjudged.

A wonderful family had Brother Jonathan. His children who lived to become of age became famous, and they were all remarkable as children. Jonathan Trumbull, Jr., could read Virgil at five, and had read Homer at twelve, and could talk with his father in Latin and Greek, and discuss Horace and Juvenal when a boy. He, as we have said, became a great painter, and commenced by drawing pictures in the sand which was sprinkled on his father’s floor. They used “herring-bone” to tidy rooms in those days, spare rooms, by dusting clean sand on the floor, in a wavy way, leaving the floor in[39] the angles of a herring-bone. We do not know that it was in such herring-boning sand that young Trumbull began to draw pictures, but it may have been so.

We have visited the rooms in the old perpendicular house where he began to draw. His good father did not approve of his purpose to become a painter, but he thought that genius should be allowed to follow its own course. A man is never contented or satisfied outside of his natural gifts and haunting inclinations. So the battles into which his father’s spirit entered, John made immortal by painting, and his work may be seen not only in the rotunda of the Capitol at Washington, but in the “Trumbull Collection” at Yale College.

Young Trumbull was led to continue to paint by his sisters Faith and Mary, who went to Boston to school. This was the Copley age of art in Boston. You may see Copley’s pictures at the Art Museum, Boston, and among them the almost living portrait of Samuel Adams. When these girls returned from visits to Boston, Mary began to paint inspiring pictures and to adorn the rooms with them.

She and her brother studied the lives and works of the old masters. How? We do not know, but genius makes a way.

A thrifty farmer and merchant was Col. Jonathan Trumbull in his young days. You laugh at these old-fashioned men, but look at what this man, who could discuss Homer and Horace with his boys, and the arts of Greece with his girls, accomplished through the good judgment and private thrift in his early life. Says his principal biographer, G. W. Stuart, of the fine young farmer,[40] who had ships on the sea, and was beginning to turn from a farmer to a notable merchant:

“So the first years of Trumbull’s life as a merchant passed in successful commerce abroad, in profitable trade at home, and with high reputation in all his contacts, negotiations, and adventures. And ‘his corn and riches did increase.’ A house and home-estate worth over four thousand pounds; furniture, and a library, worth six hundred pounds; a valuable store adjacent to the dwelling; a store, wharf, and land at East Haddam; a lot and warehouse at Chelsea in Norwich; a valuable grist-mill near his family seat at Lebanon; ‘a large, convenient malt-house;’ several productive farms in his neighborhood, carefully tilled, and beautifully spotted with rich acres of woodland; extensive ownership, too, in the ‘Five-mile Propriety,’ as it was called, in Lebanon, in whose management as committeeman, and representative at courts, and moderator at meetings of owners, Trumbull had much to do; a stock of domestic animals worth a hundred and thirty pounds—these possessions, together with a well-secured indebtedness to himself, in bonds, and notes, and mortgages, resulting from his mercantile transactions, of about eight thousand pounds, rewarded, at the close of the year 1763, the toil of Trumbull in the field of trade and commerce. In all it was a property of not less than eighteen thousand pounds—truly a large one for the day—but one destined, by reverses in trade which the times subsequently rendered inevitable, and by the patriotic generosity of its owner during the great Revolutionary struggle, to slip, in large part, from his grasp.”

Here is a picture of thrifty life in a country village estate in old New England days.

He preached at first, then became a judge, and he “doctored.”

They were queer people who doctored then, with wig and gig. Brother Jonathan doctored the poor. He doctored out of his goodly instincts more than from a medical code, though he could administer prescriptions from Latin that it was deemed presumptuous for the patient to inquire about. Now people know what medicine they take, but it was deemed audacious then to ask any questions about Latin prescriptions, or to seek to penetrate such an awful mystery as was contained in the “Ferrocesquicianurit of the Cynide of Potassium,” or to find out that a ranunculus bulbosus was only a buttercup.

Among the good old tavern tales of such old-time doctors was one of a notional old woman, who used to send for the doctor as often as she saw any one passing who was going the doctor’s way. Once when there was coming on one of these awful March snow-storms that buried up houses, she saw a teamster hurrying against the pitiless snow toward the town where the doctor’s office was.

“Hay, hay!” said she to the half-blinded man. “Whoa, stop! Send the doctor to me—it is going to be a desperate case.”

The doctor came to visit his patient, and found her getting a bountiful meal.

“The dragon!” said he. “Hobgoblins and thunder, what did you make me come out here for in all this dreadful storm?”

“Oh, pardon, doctor,” said she, “it was such a good chance to send.”

In ill temper, the country doctor faced the storm again.

There was both an academy and an Indian school in the town, and all the children loved Brother Jonathan.

The children of Boston used to follow Sam Adams in the street in the latter’s benign old age, and the white children and red tumbled over their dogs to meet Brother Jonathan, when he appeared in his three-cornered hat, ruffles and knee-breeches, and all, in the snug village green around which the orioles sung in the great trees.

He had some kind word for them all. When his face lighted up, all was happiness.

Among his neighbors was William Williams, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a man of beautiful soul.

The old church gleamed in air over the green. On the country roads they held meetings in smaller churches and in schoolhouses.

A queer story is told of one of these churches at the time of foot-stoves; how a good woman took a foot-stove to church and hid it under her cloak. The stove smoked, and the warm smoke rose up under her cloak, which was spread around her like a tent, and caused her to go to sleep. As she bent over the smoke came out of her cloak at the back of her neck and ascended into the sunlight of a window. Now smoke is likely to form a circle as it ascends, and the good people, who did not know of the foot-stove, thought that they saw a crown of glory hanging[43] over her head, and that a miracle was being performed.

Brother Jonathan and his good wife and children were always in their pew on Sunday. Probably there was a sounding-board in the primitive church and an hour-glass. Possibly, a tithing man went about with a feather to tickle sleepy old women on the nose, who lost consciousness between the 7thlys and the 10thlys, and so made them jump and say, “O Lud, massy sakes alive!” or something equally surprising and improper.

Old Peter Wetmore, of Lebanon, was suspected of being a Tory, but he kept shut lips. “Don’t open the doors of your soul,” he used to say, “and people will never know who you are. They can’t imprison your soul without the body, nor the body unless the soul opens its gates,” by which he meant the lips. “What I say is nothing to nobody. I chop wood!”

Morose, silent, grunting, if he spoke at all, he lived in a mossy, gable-roofed house, with a huge woodpile before his door.

There was a great oak forest on rising ground above him. Below him was a cedar swamp, with a village of crows and crow-blackbirds, which all shouted in the morning, and told each other that the sun was rising.

He was in his heart true to the King. When the patriots of Lebanon came to him to talk politics after the Lexington alarm, he simply said, “I chop wood.”

Chop wood he did. His woodpile in front of his house was almost as high as his house itself. But he chopped on, and all through the winter his ax flew. And he split wood, hickory wood, with a warlike expression on his[45] face, as his ax came down. He had one relative—a nephew, Peter, whom he taught to “fly around” and to “pick up his heels” in such a nervous way that people ceased to call him Peter Wetmore, but named him Peter Nimble. The boy was so abused by his uncle that he wore a scared look.

Lebanon was becoming one of the most patriotic towns in America. At one time during the Revolutionary War there were five hundred men in the public services. The people were intolerant of a Tory, and old Peter Wetmore, who chopped wood, was a suspect.

A different heart had young Peter, the orphan boy, who was for a time compelled to live with him or to become roofless.

The Lexington alarm thrilled him, as he heard the news on Lebanon green.

He caught the spirit of the people, and as for Governor Trumbull, he thought he was the “Lord” or almost a divinity. The Governor probably used to give him rides when he met him in the way. The Governor did not “whip behind.”

When Peter had heard the news of the Lexington alarm, he said:

“I must fly home now and tell uncle that.”

It was a long way from the green to the cabin that Peter called “home.”

He hurried home and lifted the latch, and met his uncle, who was scowling.

“What has happened now?” said the latter, seeing Peter had been running.

“A shot has been fired on the green.”

“What, on Lebanon green?” gasped the old man in alarm.

“No, on Lexington green.”

“That doesn’t matter. Lexington green is so far off. Who fired the shot? The regulars,” he added.

“The young men at Lebanon are all enlisting. I wish I were old enough to go!”

“For what?”

“To fight the British.”

“What, the King?”

“Yes.”

“The King? Do I hear my ears, boy?”

“Uncle?”

“I am going to pull the latch-string, and out you go. Don’t talk back. Do you hear? Out you go, and you may never be able to tell all you lose.”

The boy half comprehended the hint, for he believed that his uncle had money stored in the cellar, or in some secret place near the house. As the latter would never let any one but himself go to the soap-barrel in the cellar, the boy suspected the treasure might be there, or in the ash-flue in the chimney.

Young Peter turned white.

Old Peter tugged his rheumatic body to the door, and turned.

“I am going to pull the string, Peter.”

To the boy the words sounded like a hangman’s summons.

“Where shall I go, uncle?”

“That is for you to say. I’ve got store enough, boy. Somebody will bury me if I die. But the King, my King, he who goes against the King goes against me. Who do you go for?”

“The people.”

“The people!” shrieked the old man. “Then out you go; out!”

“There is one house, uncle, whose doors are open to all people who have no roof.”

“Which one is that—the poorhouse?”

“No, the Governor’s.”

“That makes me mad—mad! I hate the Governor, and his’n and all! I can live alone!”

He pulled the latch-string and cried, in trumpet tone:

“Out!”

Peter went out into the open April air, into the wood. He went to the Governor’s, and told him all, but in a way to shield the old man.

“He is a little touched in mind,” said Peter, charitably.

“You shall have a home with me, or mine,” said the Governor. “My son-in-law over the way will employ you as a shepherd. If he doesn’t, others will. And you can use the hills for a lookout, while you herd sheep. Dennis will find work for you to do at times in his service. Boy, perilous times are coming, and you have a true heart. I know your heart; I can see it—I know your thoughts, and people who sow true thoughts, reap true harvests. Don’t be down-hearted; you own the stars. I will cover you.” He lifted his hand over him.

“You won’t harm uncle for what I have said?”

“No, no, I will not harm the old man for what you have said now. It is better to change the heart of a man and make him your friend than to seek to have revenge on him. He will turn to you some day, and perhaps he will leave you his gold, for they say that he has gold stored away somewhere. You have a heart of charity—I can see—as well as of truth. Charity goes with honor. As long as you do right, nothing can happen to you that you can not glorify.”

Peter was made acquainted with Dennis by the Governor, who was a father to all friendless children, and he was employed as a shepherd boy, on the hills.

The hills were lookouts now.

People went to the old man to reprove him for his treatment of his nephew, but he would only say:

“I am cutting wood!”

While he lived with his Tory uncle, Peter used to hear strange things at night.

The old man would get up, bar all the doors, light the bayberry candle, and bring something like a leather bag to his table.

Then he would talk to himself strangely.

“One,” he would say, putting down something that rang hard on the table.

“One, if he stays with me, and is true to the King.

“Two.”

There would follow a metallic sound.

“Two, if he stays with me, and is loyal to the King.

“Three, if he stays and is loyal.

“Four. All for him when I go out, if only he is true.”

Then the bag would jingle. Then would follow a rattling sound.

“Five, six, seven, eight,” and so on, adding up to a hundred. He seemed to be counting coin.

Then there would be a sound of sweeping hands. Was he gathering up coin—gold coin? Presently there would be sounds of chubby feet, and a chest would seem to open, and the lid to close, and to be bolted.

“All, all for him,” the old man would say, “if he only stays with me and is loyal to the King, whose arms are like those of the lion and the unicorn.”

Then he would lie down, saying, “All for him,” and the house would become still in the still world of the cedars.

The boy wondered if “him” were the King, or if it were he, or some unknown relative, or friend. He could hardly doubt that the old man had treasure, and counted it at night, either for the King, or for himself.

So now, often when the great moon shone on the cedars, he lay awake and wondered what the old man meant. Had he missed a fortune by his patriotic feeling?

The words, “if he stays with me and is loyal to the King,” made him think that the wood-chopper meant himself, or some unknown relative.

But “if he stays with me” suggested himself so strongly, that he often asked himself, if the hard old man really loved him and was carrying out some vision for his welfare in his silent heart.

Peter used to meet Brother Jonathan as the latter crossed the green, which he did almost daily. The Governor was usually so absorbed in thought that he did not seem to see the shining sun, or to hear the birds singing; he lived in the cause.

But when he met Peter he would stretch out his hand in the Quaker manner, and look pleasant. To see the old man’s face light up was a joy to the susceptible boy; it made him so happy as to make him alert the rest of the day.

One day as the two were crossing the green, in near ways, the Governor suddenly said:

“Let us consider the matter:

“My young man, for so you are before your time, I must have a clerk in my store, and he must be no common clerk; he must be one that I can trust, for he must do more than sell goods and barter; he must look out for me, when I am in the back room, the war office; and he must be the only one to enter the war-office room when the council is in session. The council has met more than three hundred times now. And, Peter, Peter of the hills, shepherd-boy, night-watch—my heart turns to you. You must be my clerk—that is, to the people; meet customers, barter, trade, sell; but to me, you must be the sentinel of the door of the war office. Peter, I can see your soul; you will be true to me. I am an old man; don’t say it, but I forget, when I have so many things to weigh me down. You shall stand between the store and the war office, at the counter, and I will give you the secret keys, and if any one must see me, you must see about the matter.[51] Peter, the Council of Safety is a power behind the destiny of this nation. It is revealed to me so. Will you come?”

“Yes, yes, Governor. I live in my thoughts for you. Yes, yes, and I will be as faithful as I can.”

“Of course you will. Come right now. You may sleep in the store at night. The drovers will tell you stories on the barrels. I can trust you for everything. So I dismiss myself now—you are myself. Here is the secret key. Don’t feel hurt if I do not speak to you much when you see me. I live for the future, and must think, think, think.”

The Governor went into the tavern, and Peter, with the secret key, went to the store. The Governor had considered the matter. He used the word consider often.

The Governor soon began to send almost all people who came to see him, except the members of the council, to Peter. “Go to my clerk,” he would say, “he will do the best he can for you.”

Peter rose in public favor. Two plus two in him made five, as it does in all growing people. He was more than a clerk. He was keen, hearty, true.

Peter received news from couriers for years. What news was reported there—The battle of Long Island, the operations near New York, Trenton, Princeton, Morristown, Burgoyne’s campaign, Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, the southern campaign, the exploits of Green, and hundreds, perhaps thousands, of incidents of the varying fortunes of the war!

The couriers, despatchmen, the wagoners, the drovers, came to the war office and went. They multiplied.

But the activity diminished as the army moved South.

People gathered in the front store in the evenings to hear the news, and often to wait for the news. They saw the members of the Council of Safety come and go; and while the things that lay like weights in the balance of the nation were there discussed, the men told tales on the barrels that had come from the West Indies, or on the meal chests and bins of vegetables. What queer tales they were!

Let us spend an evening at the store, and listen to one of the old Connecticut folk tales.

It is a winter night. The ice glares without in the moon, on the ponds and cedars. There is an open fire in the store; in the window are candy-jars; over the counter are candles on rods, and on the counter are snuff-jars and tobacco.

One of the old-time natural story-tellers sits on a rice-barrel; he is a drover and stops at wayside inns, and knows the tales of the inns, and especially the ghost-stories. Such stories did not frighten Peter as they did Dennis, who was new to the country. Peter had become hardened to them.

Let us give you one of these peculiar old store stories that was told on red settles, and that is like those which passed from settle to settle throughout the colony. The speaker is a “grandfather.”

“Oh, boys, let me smoke my pipe in peace. How the moon shines on the snow, far, far away, down the sea! That makes me think of Captain Kidd. Ah, he was a hard man, that same Captain Kidd, and he had a hard, hard heart, if he was the son of a Scotch preacher.”

Here the grandfather paused and shook his head.

The pause made an atmosphere. The natural story-teller lowered his voice, and the earth seemed to stand still as he said:

Here the old man paused, pressed down the tobacco in his pipe with a quick movement of his forefinger, and shook his head twice, leaving the impression that the said Captain Kidd was a very bad sea-rover.

The room was still. You could hear the sparks shoot out; the corn-sheller stopped in his work. The old maiden lady who had come in for snuff touched the pepper pods: the air grew peppery, but no one dared to sneeze.

The old man bobbed up his head, as making an atmosphere for highly wrought work of the imagination.

“There was once an old couple,” he said, “who lived down on Cape Ann, and beyond their cottage was a sandy dune, and on the dune there was a thatch-patch.

“They had grown old and were poor, and both thought that their lot had been hard, and the old woman said to the old man:

“‘It was you who made my life hard. I was once a girl, and what I might have been no one knows. Ah me, ah me!’

“One fall morning the old man got up, and frisked around in an unusual way.

“‘What makes you so spry?’ asked the old woman.

“‘I dreamed a dream last night in the morning.’

“‘And what did you dream?’

“‘I dreamed that Captain Kidd hid his treasure in an iron box under the thatch-patch, right in the middle of the patch, where the shingle goes round.’

“‘Then go out and dig. If you don’t, I will. Think what we might be, if we could find that treasure. We might have a chariot like the Pepperells, and fine horses like the Boston gentry, the Royalls, and the Vassals.’

“‘But I can have the treasure only on one condition.’

“‘What is that?’

“‘I must not speak a word while I am digging.’

“‘That would be hard for you. Your mouth is always open, answering your old wife back. I could dig without a word, now. Well, well, ah-a-me! If you should dream that dream a second time, it would be a sign.’

“The next morning the old man got up spryer than before. He clattered the shovel and the tongs.

“‘Wife, wife, I dreamed the same dream again this morning.’

“‘Well, if you were to dream it a third time, it would be a certainty—that is, if you could dig for the treasure without speaking a word, which a woman of my sense and wit could do. Go and dig.’

“‘But the voice that came to me in my dream told me to dig at midnight, at the rising of the moon.’

“That night as the great moon rose over the waters of Cape Ann, like the sun, the old man took his hoe and hung on to it his clam-basket, and put both of them over his shoulder. He went out of the door over which the dry morning-glory vines were rattling.

“‘Now, husband, you stop and listen to me,’ said the old wife. ‘Remember all the time that you are not to speak a word, else we will have no chariot to ride past the Pepperells, nor cantering horses, leaving the dust all in their eyes. Now, what are you to do?’

“‘Never to speak a word.’

“‘Under no surprise.’

“‘Not if the sea were to roar, nor the sky to fall, nor an earthquake to uproot the hills, nor anything!’

“‘Well, you may go now, and when you return we will be richer than the Governor himself. I have always[56] been dreaming that such a day might come to us as a sort of reward for all that we have suffered. But they say that Captain Kidd tricks those who dig for his treasures. His ghost appears to them. Never you fear if he lays hands on you.’

“The old man went down to the sea. The moon rose so fast that he could see it rising.

“The old couple had a black cat, a very sleek, fat little animal, which lived much on the broken clams that the clam-diggers threw out of their piles of bivalves at low tides.

“When she saw that the old man was going down to the sea, she started after him, with still feet—still, still.