HOKE-TI-CHEE. LITTLE GIRL WITH THE BRIGHT EYES

THE SEMINOLES

OF

FLORIDA

MINNIE MOORE-WILLSON

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

MOFFAT, YARD AND COMPANY

1920

Copyright 1896, 1910 and 1920

by

MINNIE MOORE-WILLSON

| First | Edition, | Jan., 1896 |

| Second | ” | Jan., 1910 |

| Third | ” | Dec., 1911 |

| Fourth | ” | Sept., 1912 |

| Fifth | ” | Aug., 1914 |

| Sixth | ” | Oct., 1916 |

| Seventh | ” | Feb., 1920 |

Printed in the United States of America

MEMORIAL TRIBUTE

MRS. ELIZABETH STAUFFER-MOORE

IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF HER PHILANTHROPIC

INTEREST IN A BRAVE AND HEROIC REMNANT OF THE

ABORIGINAL AMERICANS, THE SEMINOLES OF FLORIDA,

THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED.

HER TIMELY AID IN THE CRISIS OF THEIR EXISTENCE

HELPED TO RESCUE THEM FROM OBLIVION AND TO

PROVIDE FOR THEM THE RIGHTS OF A FREE PEOPLE.

Minnie Moore-Willson.

When most of the Seminoles were moved from Florida to Indian Territory, a few score of them were unwilling to go. Of these who remained, the descendants, ten years ago, numbered about six hundred. An effort was made at that time to buy for this band the land on which they lived and a few hundred dollars was given for that purpose.

In the study of this fragment in their singular surroundings as portrayed in the pages of this book, one gets, as it were, a glimpse of their camp-fire life, a view of their sun-bleached wigwams and an insight into the character of these proud but homeless people.

Not much apparently can be done for this home-keeping remnant of the Florida aborigines, but it is help and a protection to them that their continuing presence in Florida and the conditions of their life there should be known to the rest of the Americans and especially to those who go to Florida or are concerned with the development of that State.

To diffuse this helpful knowledge and give these Indians such protection as may come from it, is the aim of the present book.

Edward S. Martin.

New York, Nov. 9, 1909.

That there is yet a tribe, or tribes of Indians in Florida is a fact unknown to a large part of the people of this country; there are even students of history who have scarcely known it. These people, driven, about seventy or more years ago, into the dreary Everglades of that Southern Peninsular, have kept themselves secluded from the ever encroaching white population of the State. Only occasionally would a very small number visit a town or a city to engage in traffic. They have had no faith in the white man, or the white man’s government. They have aimed to be peaceful, but have, with inveterate purpose, abstained from intercourse with any of the agencies of our government. My friends, Mr. and Mrs. J. M. Willson, Jr., of Kissimmee, Florida, have found their way to a large degree of confidence in the hearts of this people. They have learned something of their history, and have studied their manner of life, their character and habits.

Mr. Willson has been allowed, and invited to go with some of their men on familiar hunting expeditions. He has seen them in the swamps, in their homes, and in their general life environments. He has been admitted to their confidence and friendship. He has consequently become deeply interested in them. Mrs. Willson also has become acquainted with some of their chief personages. Both have learned to sympathize with these Indians in their hardships and in their treatment at the hands of the white race.

Mrs. Willson began to write about them and her writing has grown into a book; and she has been encouraged to give this book to the world, in the hope that the attention of good people may be drawn toward them, and that at least a true interest may be awakened in their moral and material well-being. They are truly an interesting people, living, although secluded, almost at our doors.

Mrs. Willson has written earnestly, enthusiastically, and lovingly regarding them, and it is to be hoped that a new interest may soon be taken in them both by the churches and the government, and that they may soon enter upon new realizations, and be encouraged to place a confidence in the white race to which, until quite recently, they have been utter strangers.

Mr. Willson has prepared the vocabulary. The words and phrases here given have been gathered by him in the course of ten or fifteen years of friendly intercourse with members of the tribe. They have assisted him in getting the true Indian or Seminole word and in finding its signification. Old Chief Tallahassee has been especially and kindly helpful; so has Chief Tom Tiger. This vocabulary of this peculiar Indian tribe, though not complete, ought to prove helpful to those who are interested in the languages of the people who roamed the forests of this great land before it became the home and the domain of those who now live and rule in it.

This book, in its first part, gives some account of the earlier years of the Seminole history. In the second part the reader is introduced to the later and present state of things and facts regarding them.

In the third part is found the vocabulary—a number of Seminole words, phrases and names, with their interpretation into our own tongue.

This little book is given to the world in the hope that it will be found both interesting and valuable to many readers.

R. Braden Moore.

| PART FIRST | |

| PAGE | |

| Facts of the Earlier Days | 1 |

| Origin of Troubles | 6 |

| Efforts at Indian Removal | 11 |

| The Massacre of General Thompson and of Dade’s Forces | 15 |

| A Dishonored Treaty | 19 |

| As-se-ho-lar, The Rising Sun, or Osceola | 21 |

| Osceola’s Capture | 26 |

| The Hidden War Camp | 30 |

| Wild Cat and General Worth | 33 |

| Indian Warfare | 38 |

| “Dat Seminole Treaty Dinner” | 41 |

| PART SECOND | |

| The Present Condition and Attitude of the Seminoles | 53 |

| National Indian Association, Its Work, and Its Results, Episcopal Mission | 65 |

| The Friends of the Florida Seminoles | 68 |

| Our Duty to These Wards of the Nation | 76 |

| Chieftain Tallahassee | 79 |

| Increasing | 84 |

| Appearance and Dress | 87 |

| Independence and Honor | 90 |

| The Seminole’s Unwritten Verdict of the White Race | 93 |

| Endurance and Feasts | 95 |

| The Hunting Dance | 100 |

| Slavery | 106 |

| Hannah | 107 |

| Unwritten Laws | 108 |

| Gens and Marriage | 114 |

| Beauty and Music | 116 |

| Relationship to the Aztecs and Eastern Tribes | 118 |

| Seminoles at Home—The Everglades | 126 |

| Alligator Hunting | 139 |

| Bear Hunting with the Seminoles | 142 |

| Captain Tom Tiger (Mic-co-Tus-te-nug-ge) | 148 |

| Nancy Osceola | 154 |

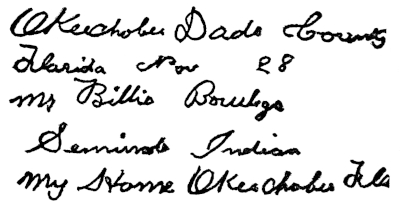

| Billy Bowlegs | 155 |

| Religion | 162 |

| Brought Back | 168 |

| Mounds | 169 |

| Picture Writing | 171 |

| Medicine | 172 |

| Abiding Words of Beauty | 174 |

| Conclusion | 179 |

| SUPPLEMENT | |

| The Least Known Wilderness of America | 185 |

| The Land of the Seminole | 187 |

| Crossing the Everglades by Aeroplane | 190 |

| Everglade Geyser | 192 |

| Seminole History Reviewed | 194 |

| The 1917 Land Bill | 199 |

| A Visit to a Seminole Camp | 204 |

| Visitors from the Everglades | 207 |

| Stem-o-la-kee | 214 |

| Home and Religion | 223 |

| Seminole Incidents | 224 |

| Messages from the Everglades | 227 |

| Seminoles First Suffragists | 229 |

| Osceola—the Garibaldi of the Seminoles | 231 |

| Shall Osceola’s Bones Be Removed? | 234 |

| A Bronze Statue in the Everglades | 236 |

| The Pocahontas of Florida | 242 |

| VOCABULARY | |

| Introduction to Vocabulary | 253 |

| Words Regarding Persons | 255 |

| Parts of the Body | 256 |

| Dress and Ornaments | 258 |

| Dwellings, Implements, etc. | 260 |

| Food | 264 |

| Colors | 265 |

| Numerals | 265 |

| Divisions of Time | 266 |

| Animals, Parts of Body, etc. | 268 |

| Birds | 269 |

| Fish and Reptiles | 270 |

| Insects | 271 |

| Plants | 272 |

| The Firmament, Physical Phenomena, etc. | 273 |

| Kinship | 274 |

| Verbs, Phrases, Sentences | 274 |

| Indian Names of Some Present Seminoles | 279 |

| Rhythmical Names of Some Florida Rivers and Towns | 280 |

| PAGE | |

| Hoke-ti-chee, “Little Girl with the Bright Eyes” | Frontispiece |

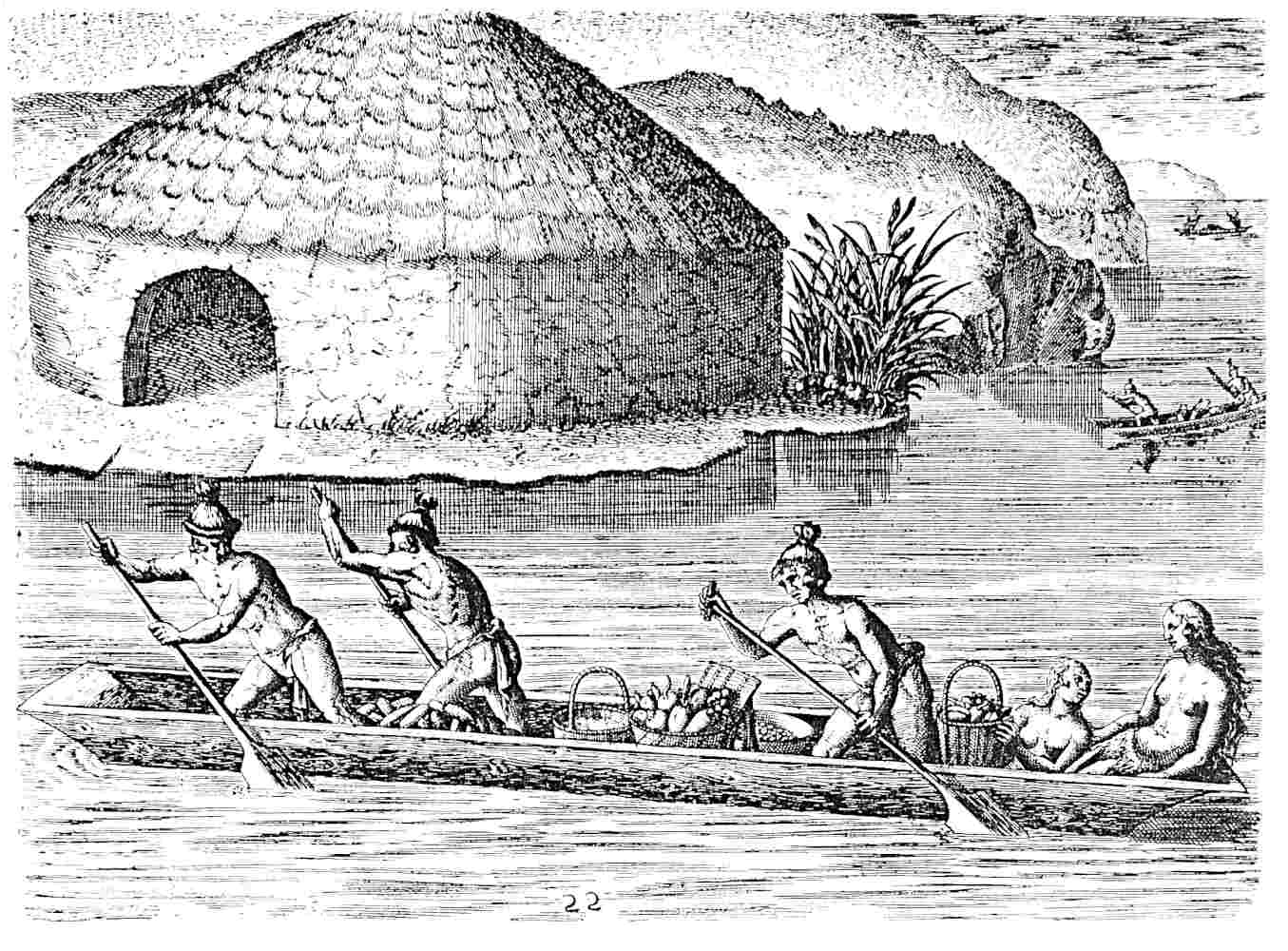

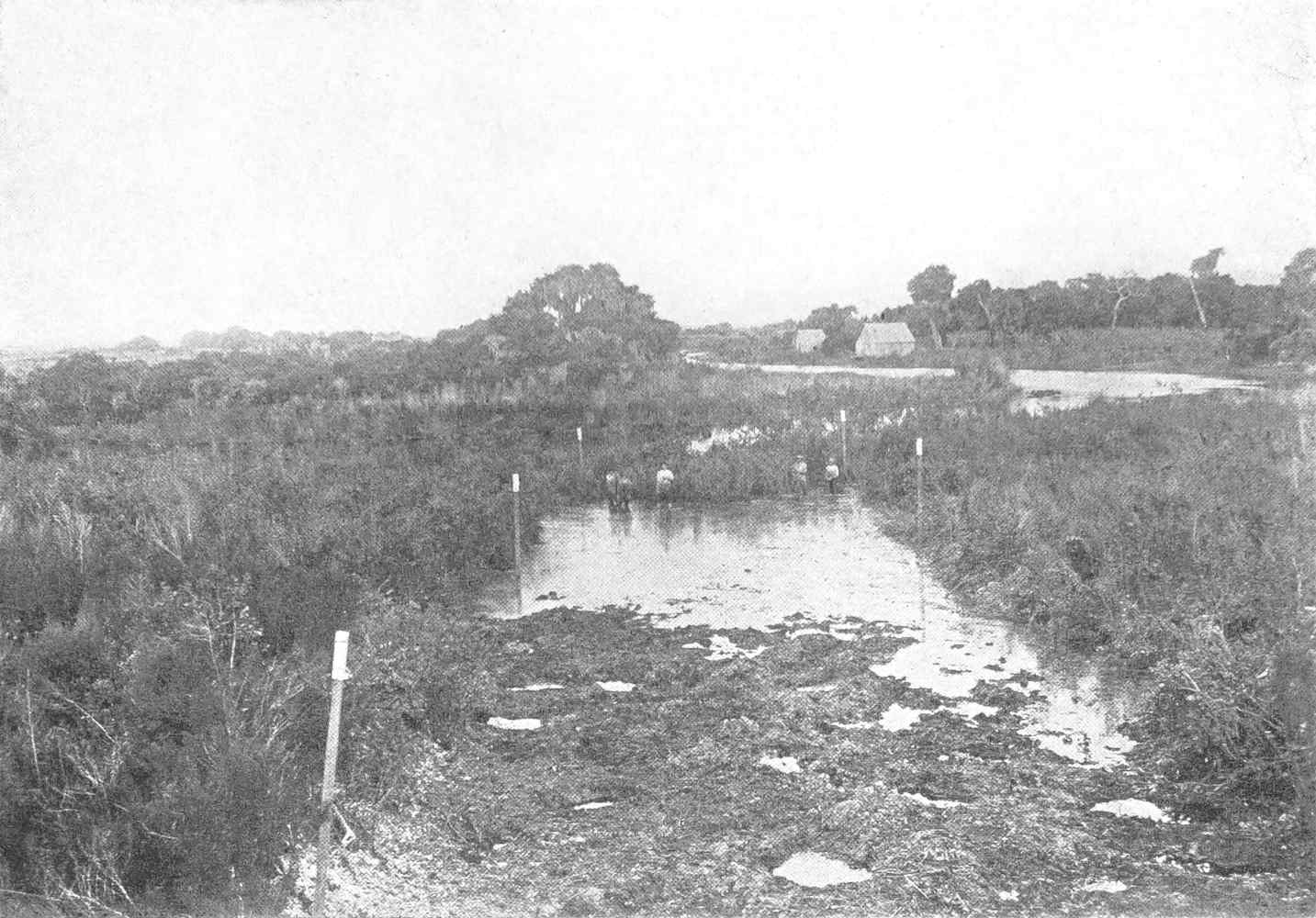

| Florida Indians Carrying Their Crops to the Storehouse | 6 |

| An Indian Retreat During the Seminole War | 16 |

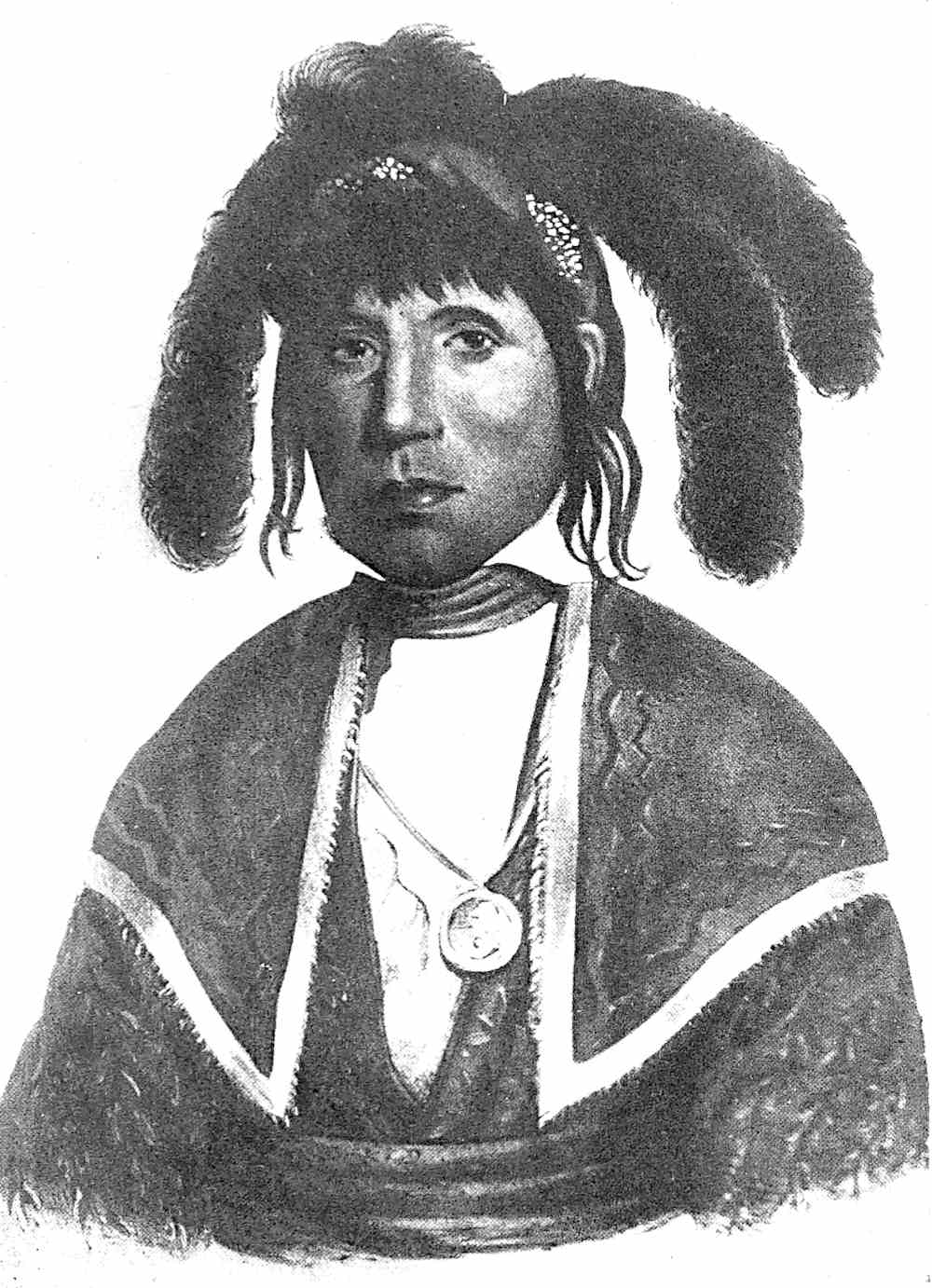

| Micanopy | 20 |

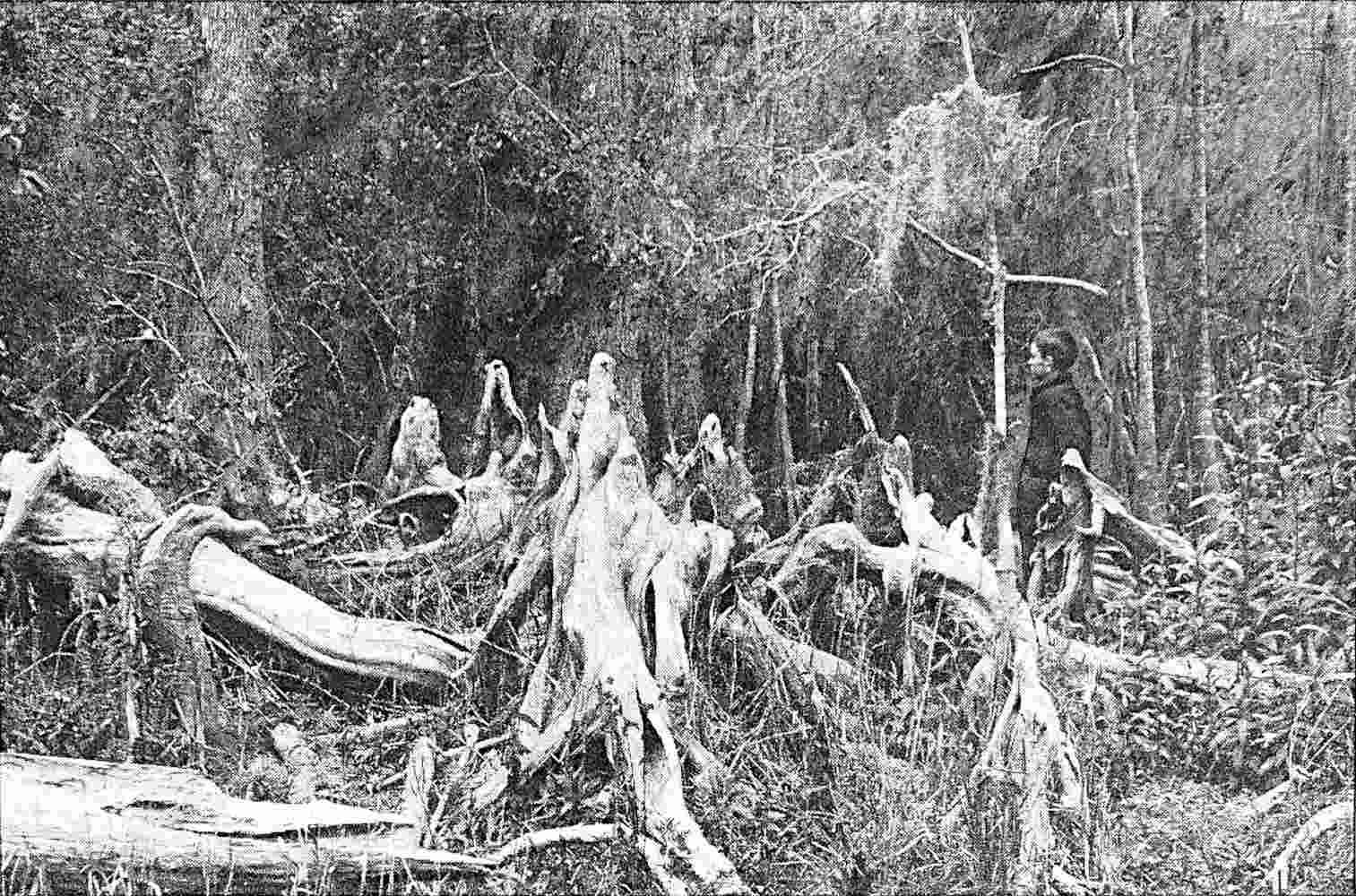

| One of the Last Seminole Battle Grounds | 24 |

| Osceola | 30 |

| Martha Jane, “Bandanna Mammy” | 42 |

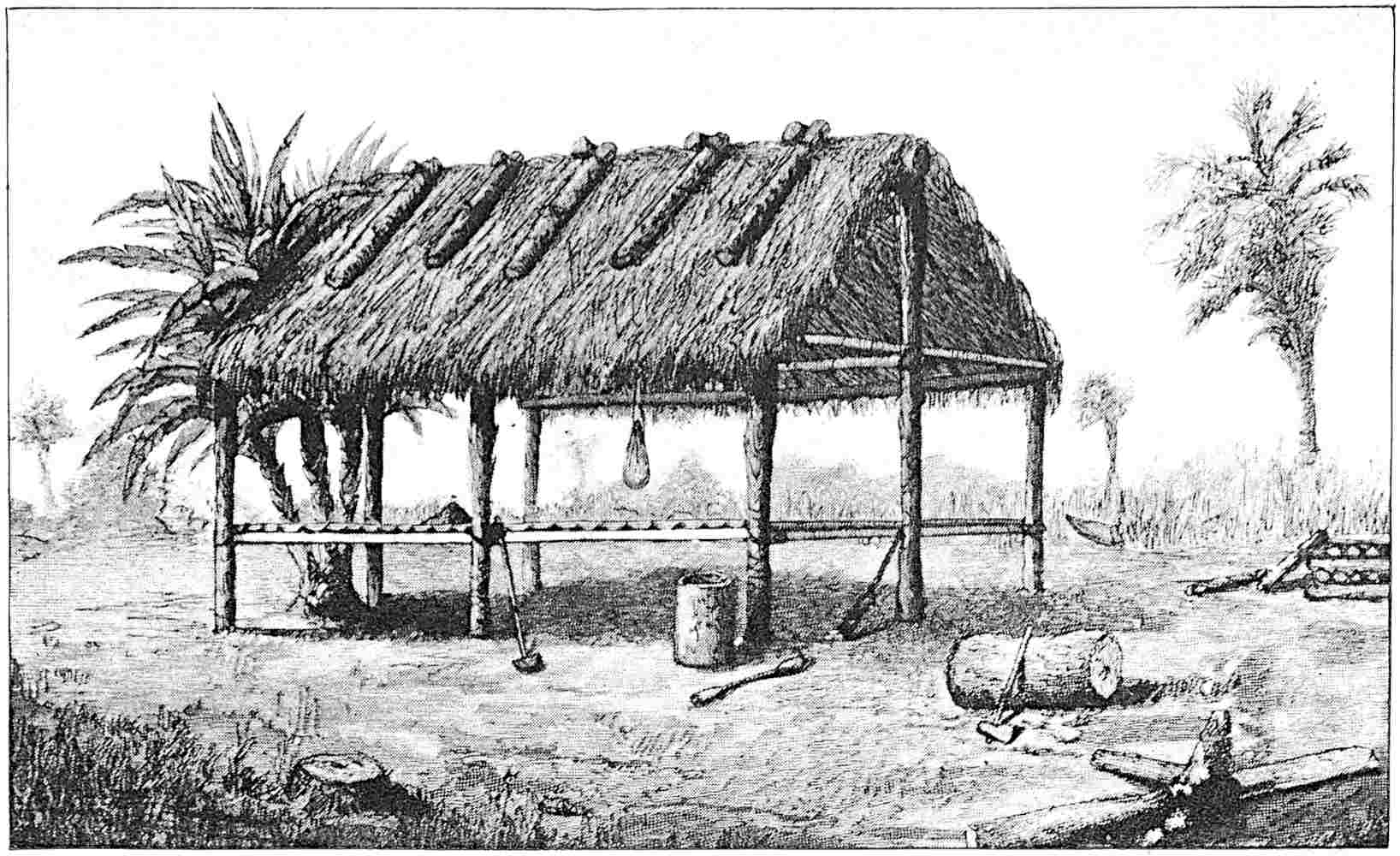

| A Seminole Dwelling | 60 |

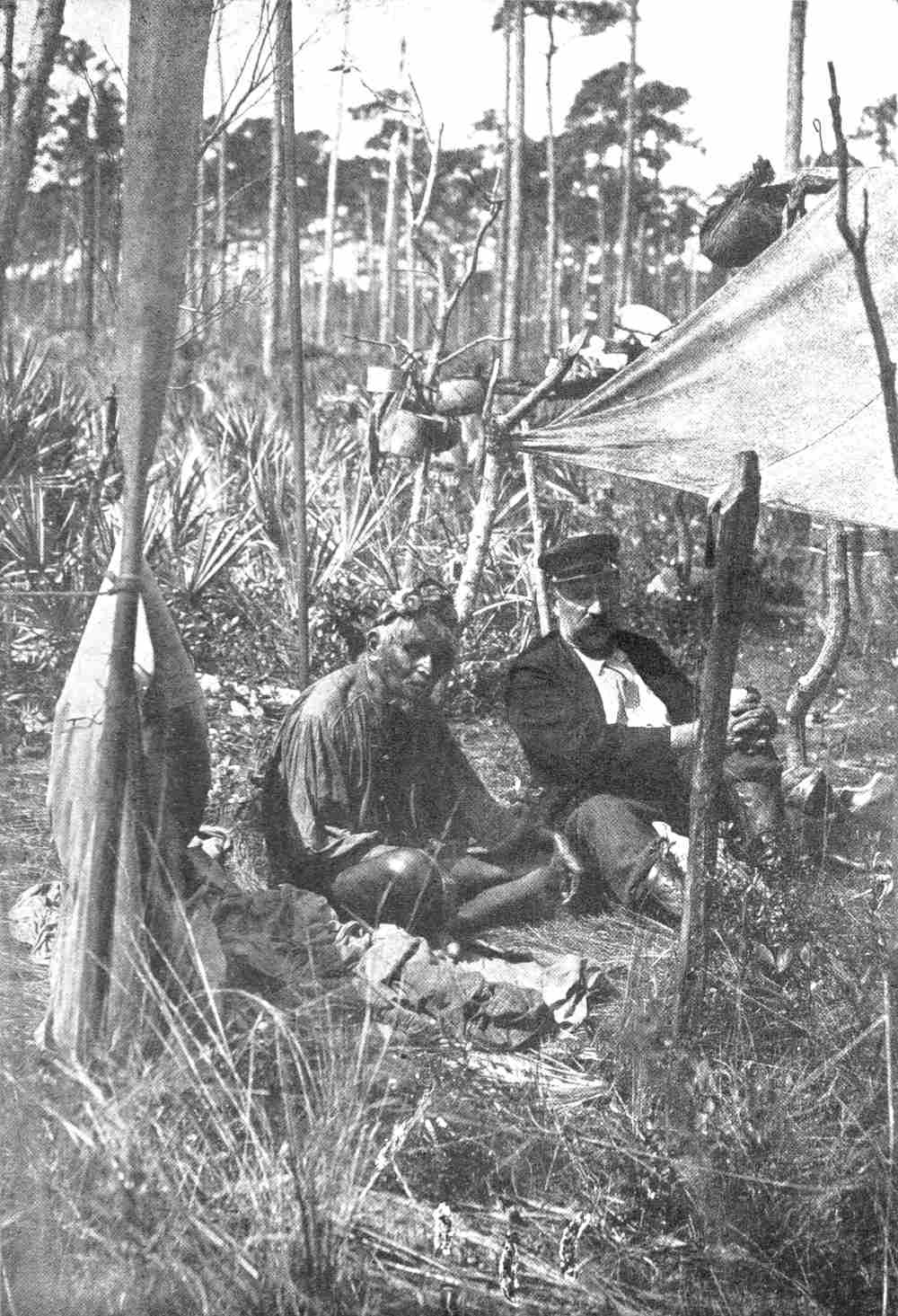

| A Seminole Camp-fire | 70 |

| Chieftain Tallahassee | 76 |

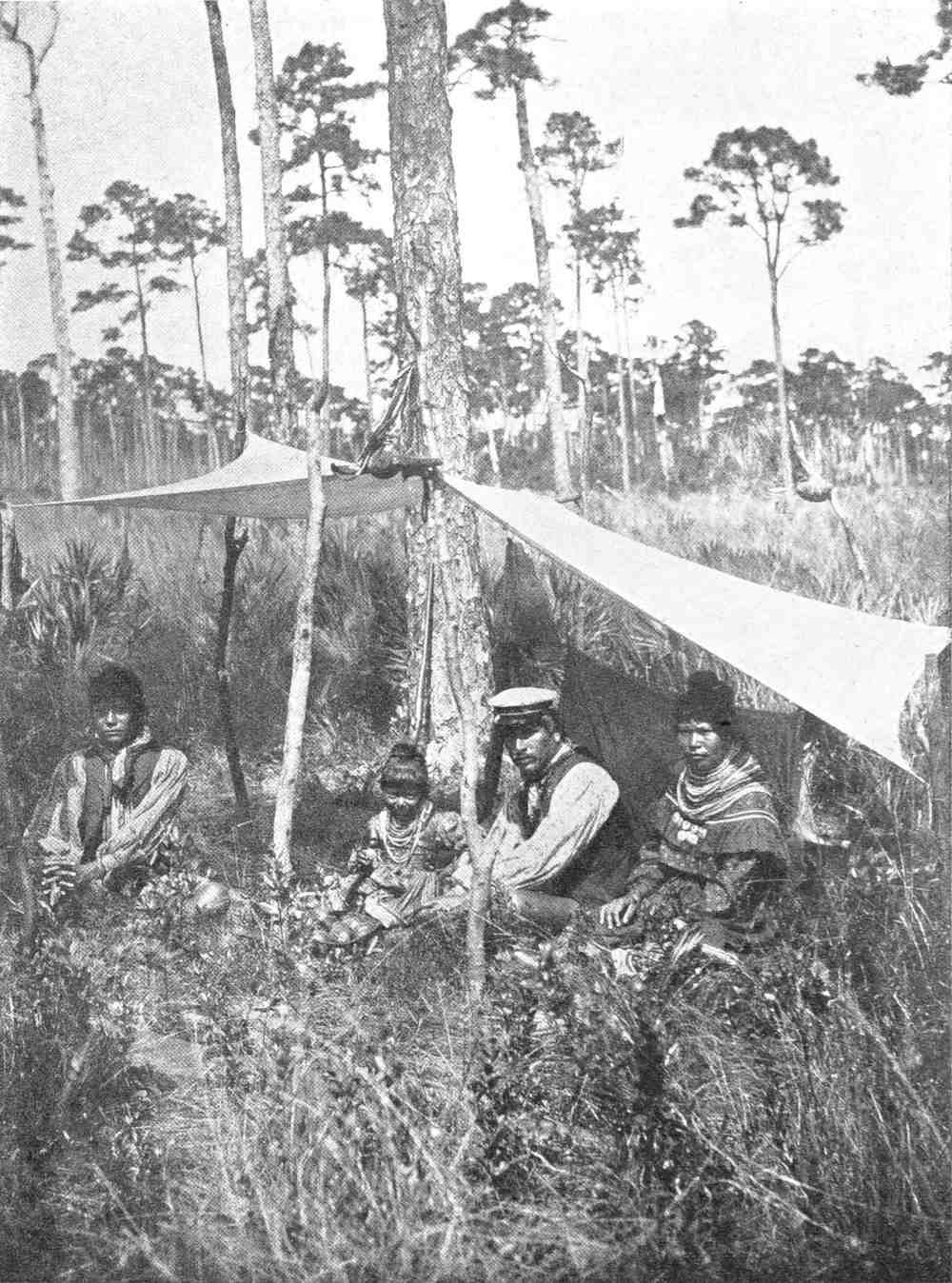

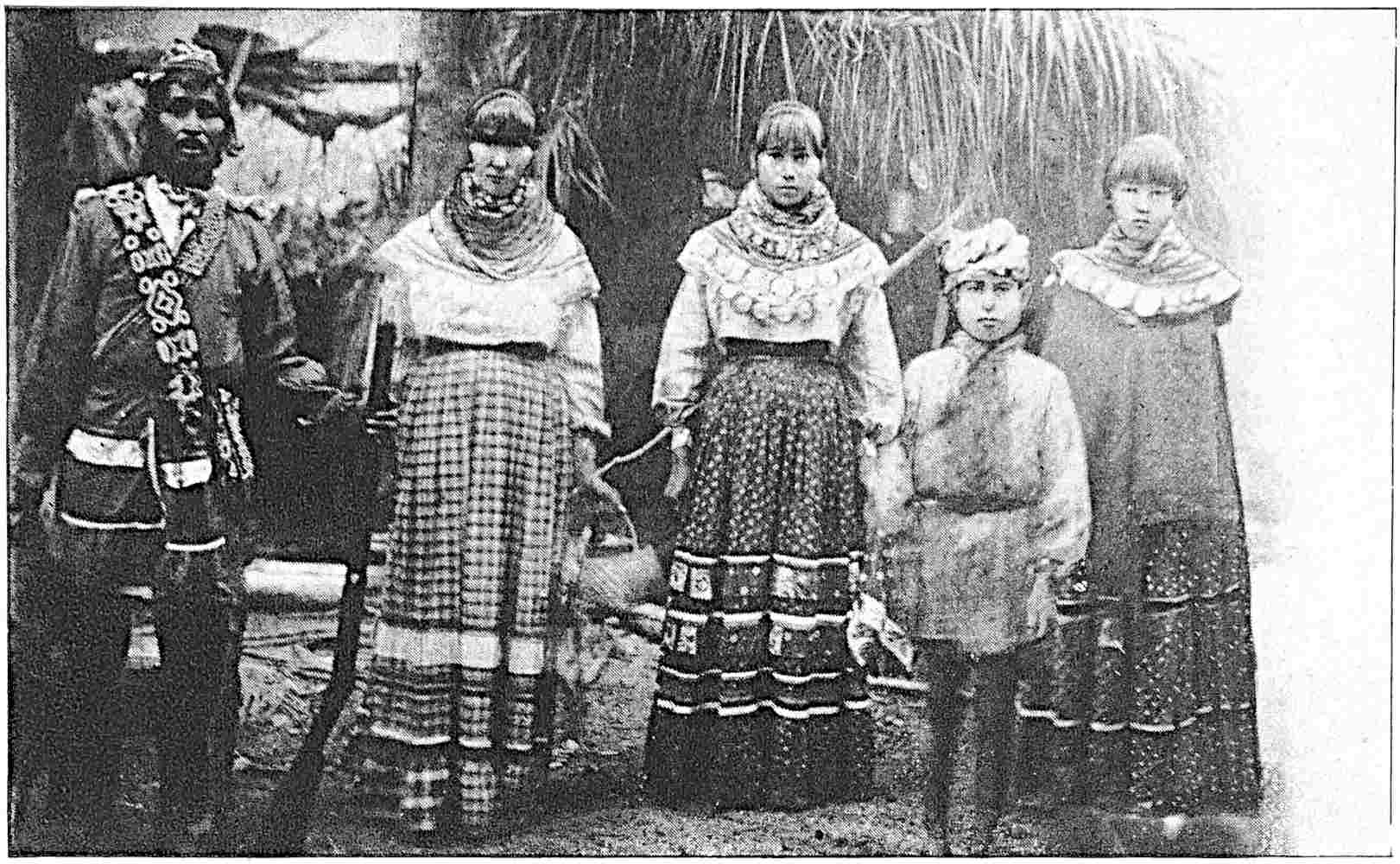

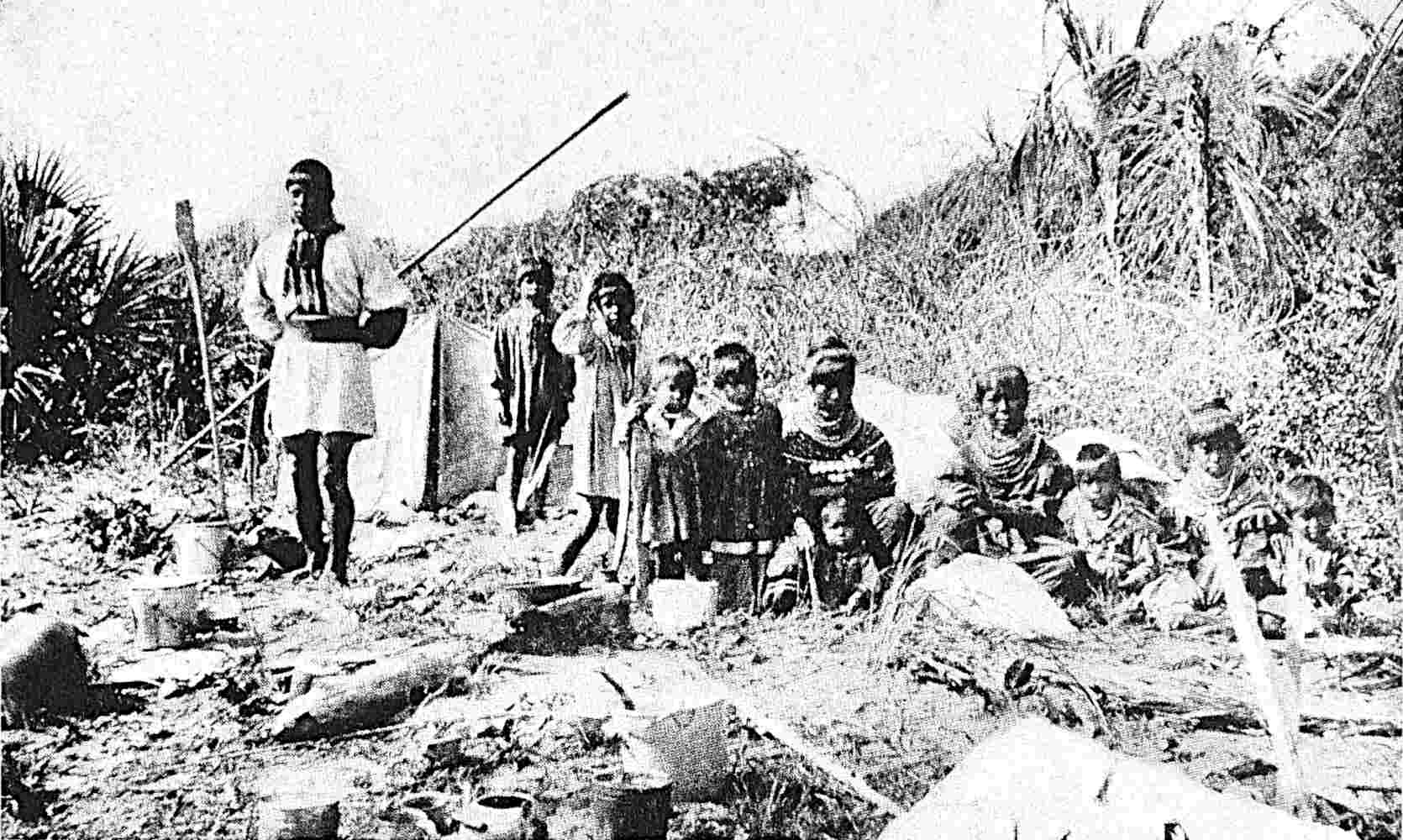

| A Seminole Group of the Tallahassee Band | 86 |

| Chief Tallahassee, Martha Tiger, She Yo Hee, Tommy Hill and Milakee | 90 |

| Billy Bowlegs and Tommy Doctor | 98 |

| Hannah, the Only Remaining Slave of the Seminoles | 108 |

| A Picturesque Group | 114 |

| An Enchanting Study of the Younger Generation | 122 |

| Seminoles on the Miami River | 130 |

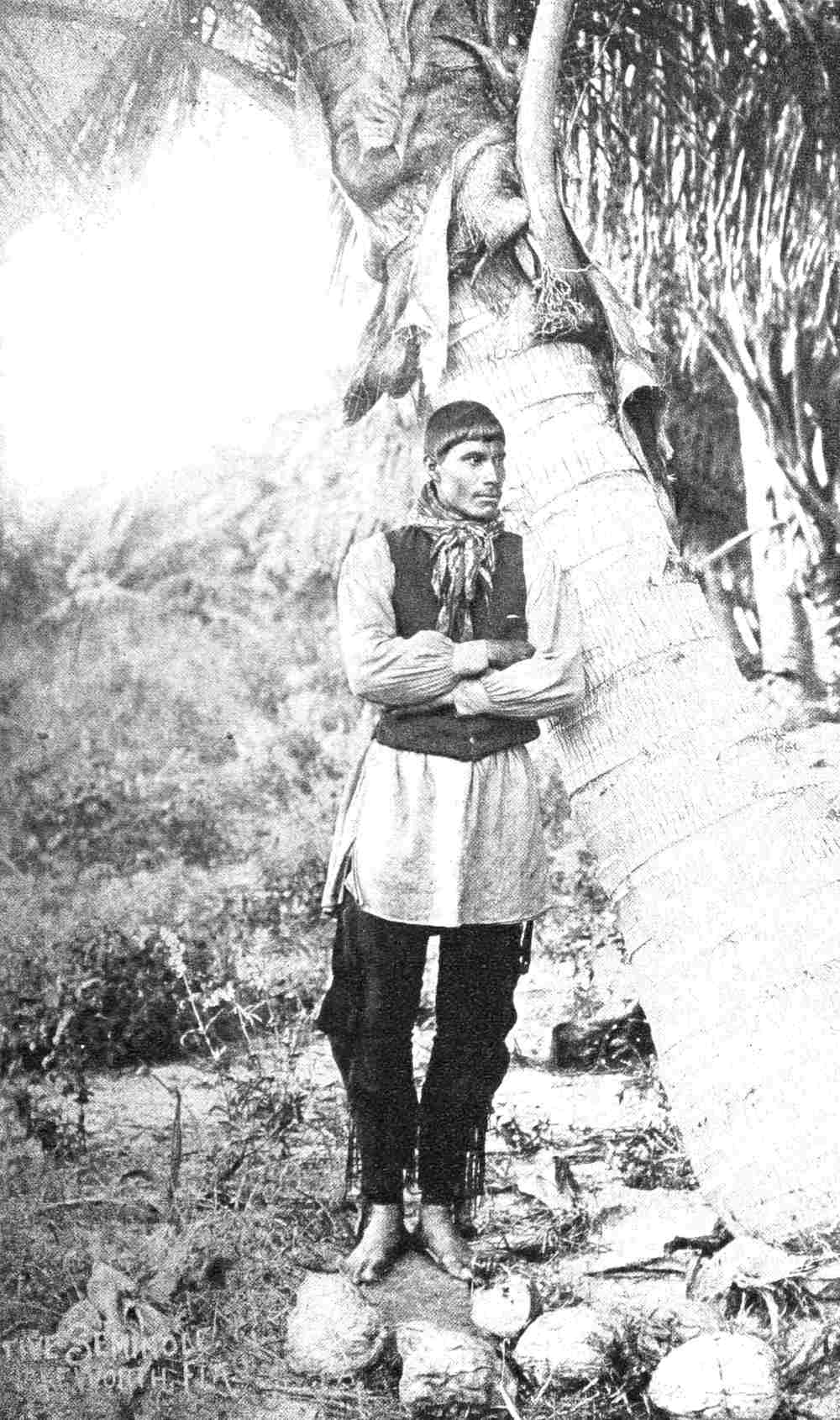

| Tiger Tail | 140 |

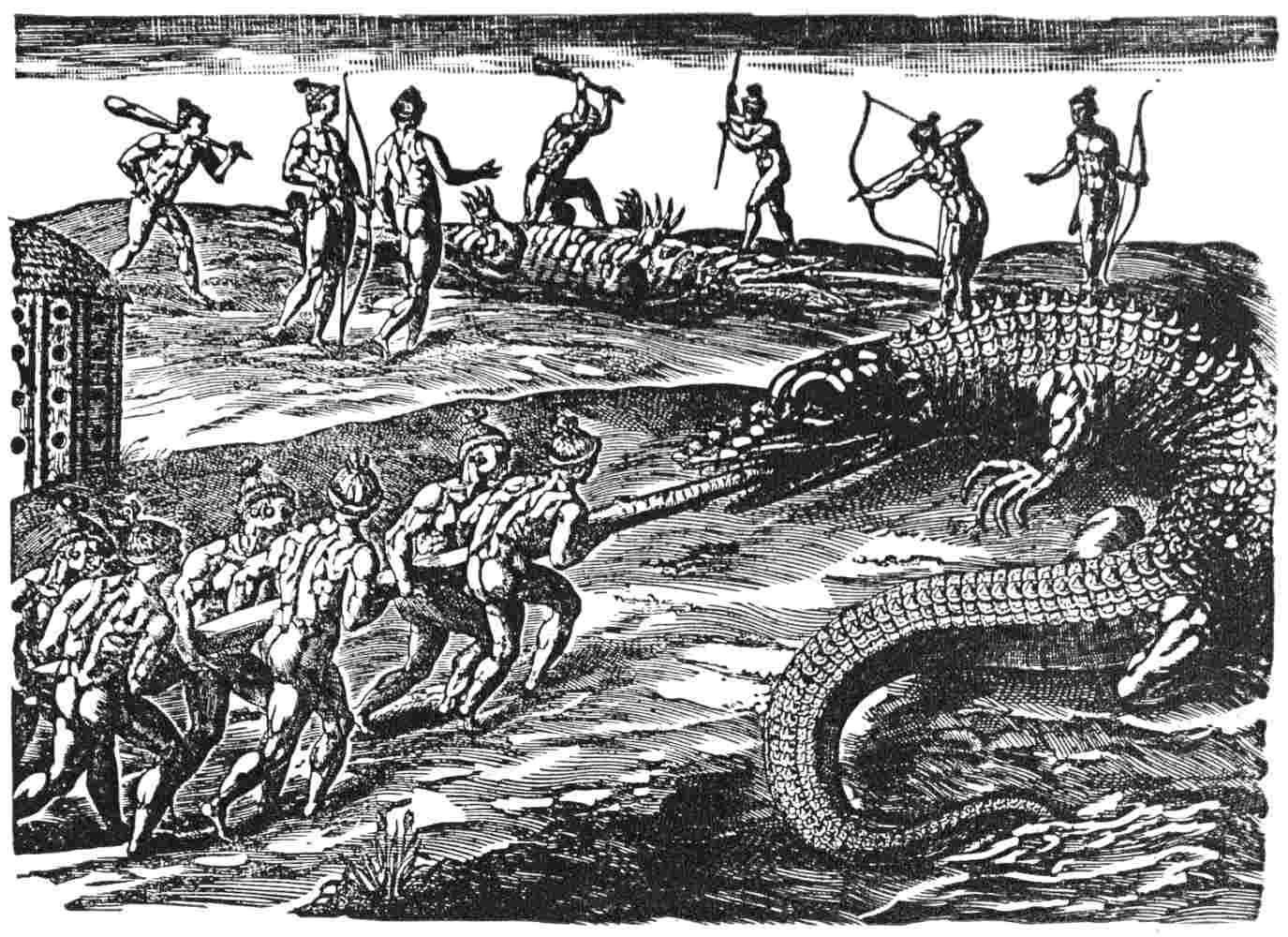

| Indian Mode of Hunting Alligators in Florida | 144 |

| Captain Tom Tiger | 148 |

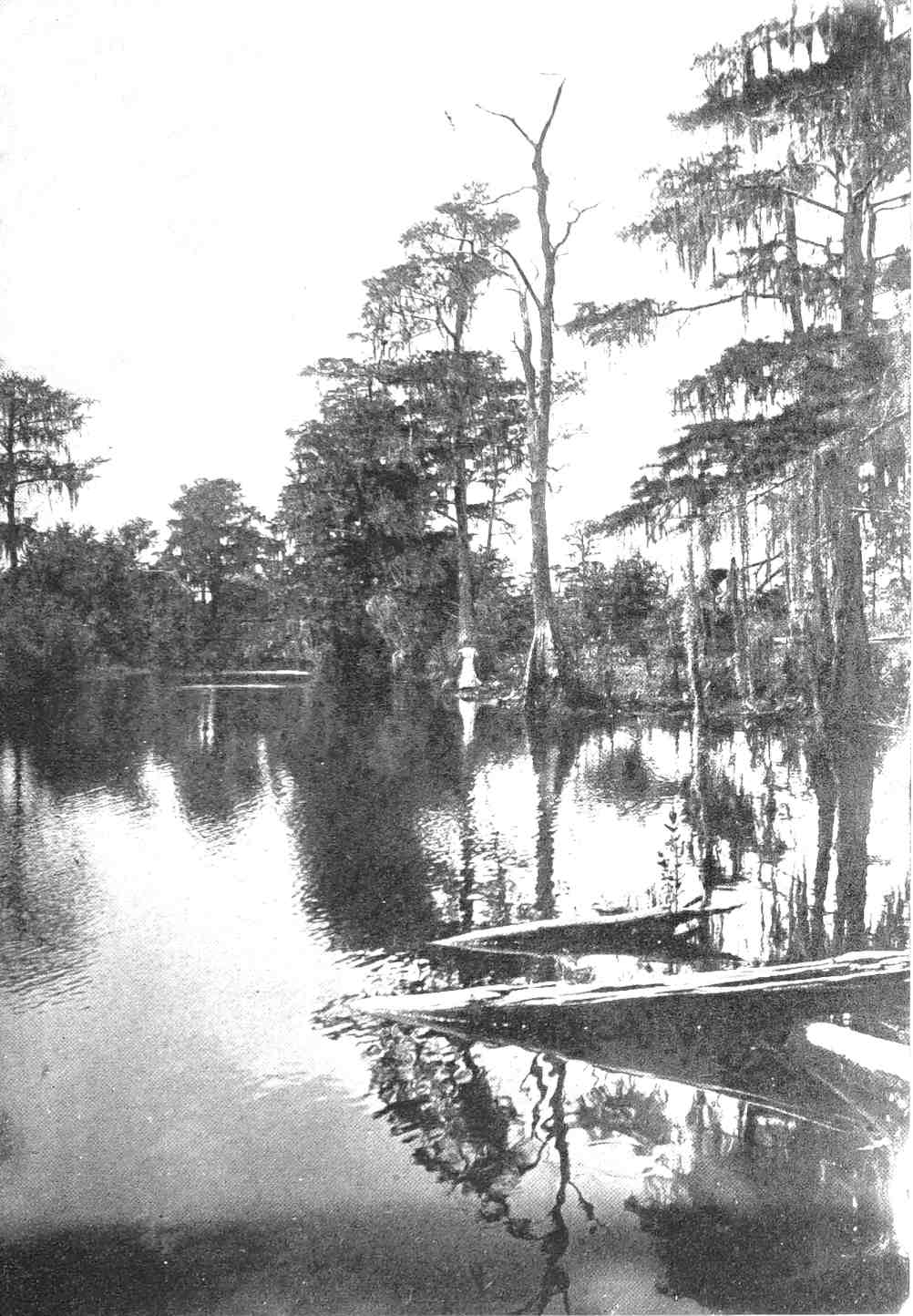

| The Indian’s Hunting Ground | 150 |

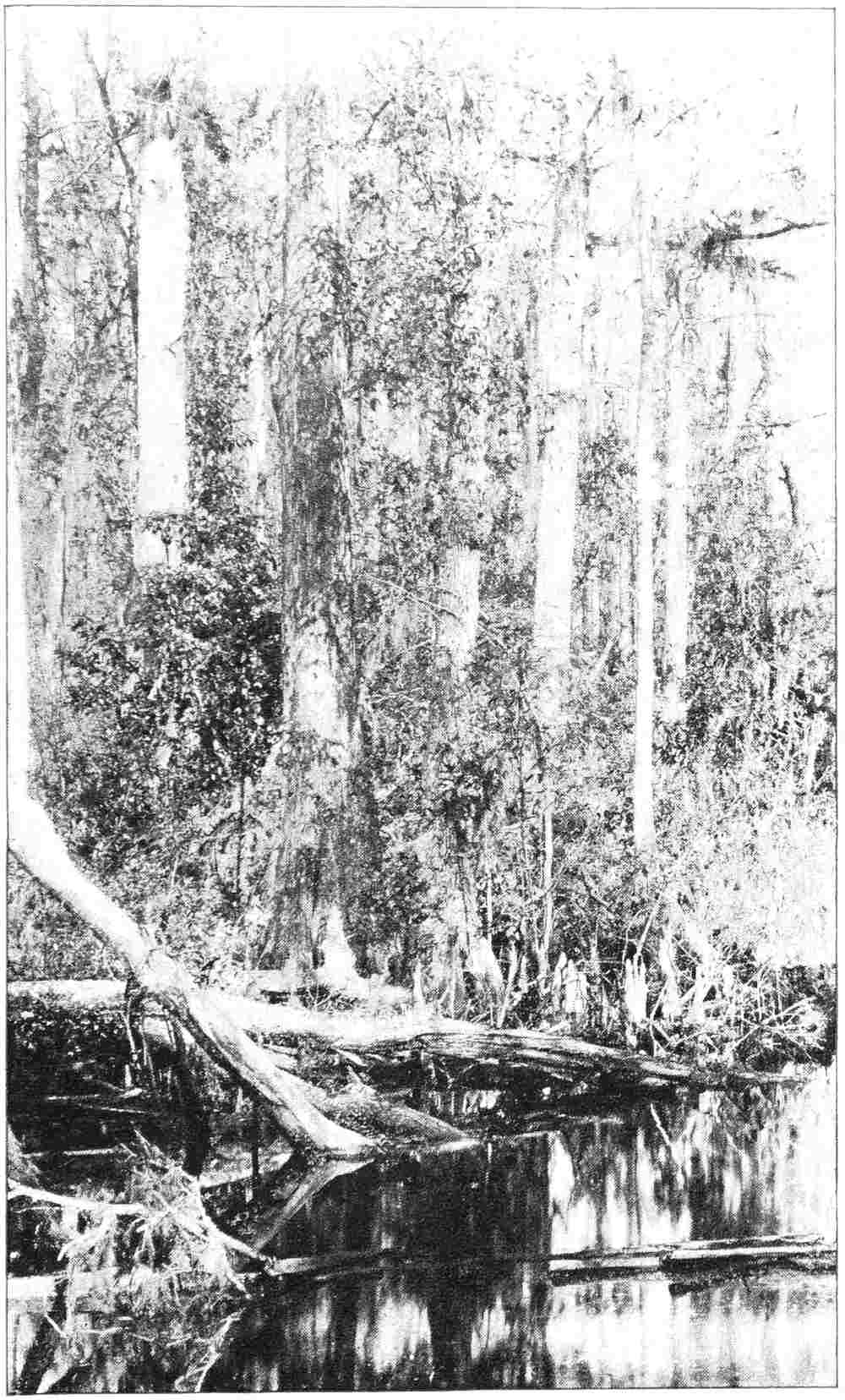

| A Section of a Saw Grass Swamp | 156 |

| Hi-e-tee, Captain Tom Tiger, Ho-ti-yee and “Little Tiger” | 164 |

| Dr. Jimmie Tustanogee with His Two Wives and the Children | 168 |

| Billy Buster, Tommy Hill, Tallahassee and Charlie Peacock | 172 |

| The Wild Heron in Domestication | 176 |

| The White Plumed Egret in a Florida Yard | 180 |

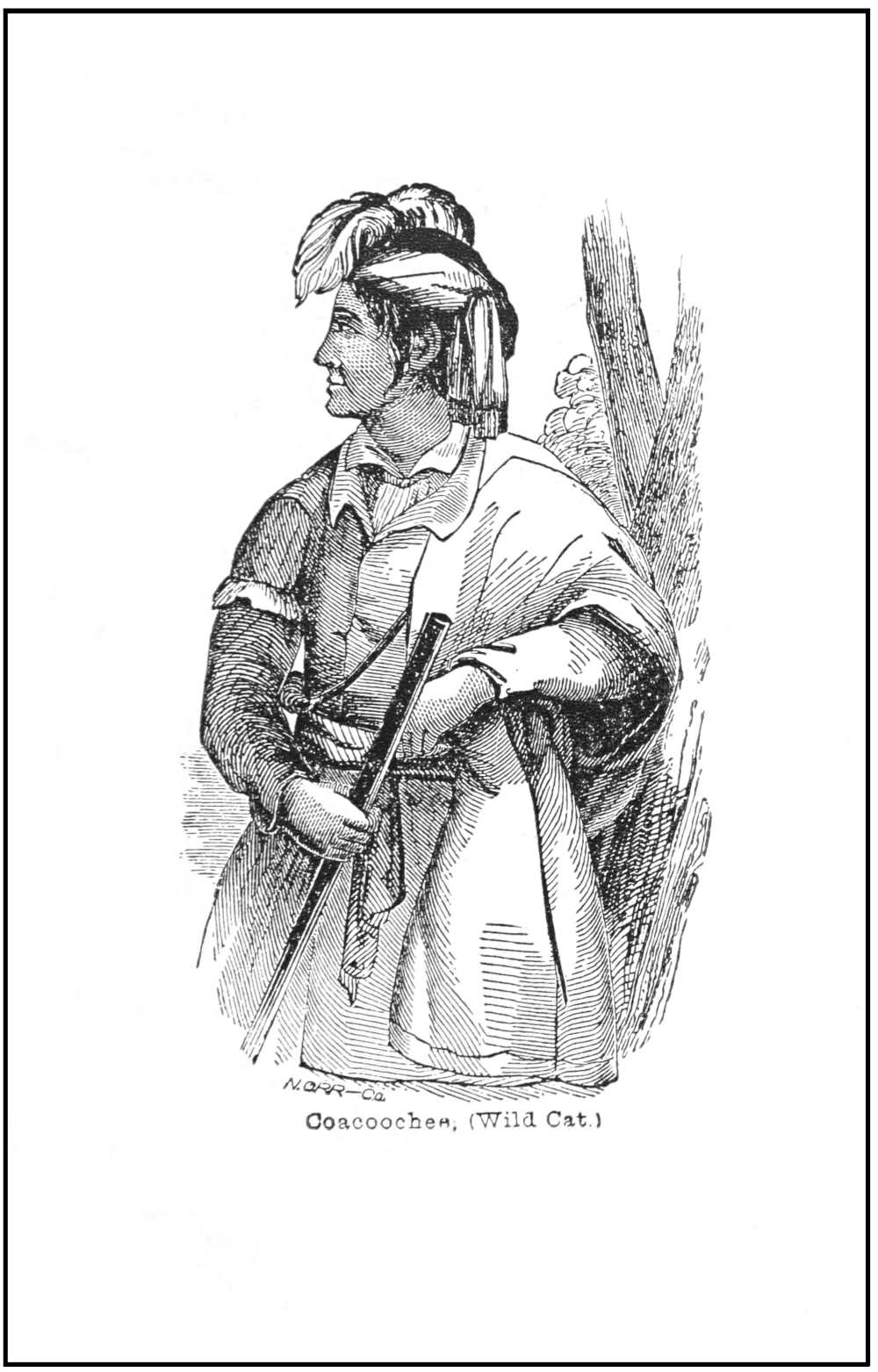

| Coacoochee | 188 |

| Latest Photograph of Billy Bowlegs | 192 |

| Billy Bowlegs and His Sister | 194 |

| Osceola, the Napoleon of the Seminoles | 200 |

| Billy Bowlegs Photographed While Visiting the Author | 202 |

THE SEMINOLES OF FLORIDA

The history of the American Indian is a very Iliad of tragedy. From the day Columbus made the first footprints of the European in the damp sands of Cat Island, the story of the original owners of fair America has been full of melancholy, and fills with its dark pages every day of a quartet of centuries.

Columbus describes the innocent happiness of these people. “They were no wild savages, but very gentle and courteous,” he says, “without knowing what evil is, without stealing, without killing.” They gave to him a new world for Castile and Leon, while in exchange he gave to them “some glass beads and little red caps.” The tragedy of the new world began when we find this same admiral writing to the Spanish majesties that he would be able to furnish them with gold, cotton, spices, and slaves—“slaves! as many as their Highnesses shall command to be shipped”; and thus, this land, a paradise of almost primeval loveliness, was transformed into a land of cruel bondage, desolation and death.

History scarcely records an instance when hospitality[2] was not extended by the red man to our first explorers. Swift canoes shot out from the shaded shores, filled with men clad in gorgeous mantles, and, in broken accents, their greeting was “Welcome!” “Come, see the people from Heaven,” they cried, but were soon destined to believe they were from a very different region.

From old Spanish accounts we conclude that the Indian population of De Soto’s time was very large, and that the natives were in a higher state of civilization than at any later period; that their speech, though brief, was chaste, unaffected, and evinced a generous sentiment. Cortez found the Aztecs and their dependencies challenging comparison with the proudest nations of the world, and in their barbarous magnificence rivaling the splendors of the Orient. Advanced in the arts, dwelling in cities, and living under a well-organized government, they were happy in their position and circumstances.

Who were the barbarians of the early history of America, our Mayflower ancestors, or the Red Men of the forest?

With a careful study of the early records, the question answers itself.

Four hundred years ago Indian warfare began. Shall it continue until we exterminate the race? When it is, alas, too late, the American people will awaken to the fact that the preservation of the Indian race will be a theme that will stir the very heart of the Nation.

Shall Justice blush as the future historian pens the[3] account of the vanished Indian and our treatment of his race? Will Patriotism hang her head in shame and confusion as the pen portrays the history of the red heroes, who gave up their lives for their home and liberty?

Since that sunny day in May, 1539, when De Soto, amid the salutes of artillery, the music of trumpets, the cheers of thousands of Castilians, sailed into Tampa Bay, Florida has been the scene of stirring events—with the Aborigines forming a tragical background.

Marching across the flower-bedecked country with his gallant men of Spain, with his cavalry, with fleet greyhounds and furious bloodhounds to turn loose upon the savages, also handcuffs, chains and collars to secure them, with priests, workmen and provisions, this proud adventurer reached the present site of Tallahassee. Here, in this vicinity, they came upon a fruitful land, thickly populated.

Ever pressing onward for the gold that was supposed to abound in this new land, one village after another was passed, when provisions and welcome were furnished by the Laziques.

On, on, the proud and haughty Spaniards marched, until they reached the province of Cofaqui. Here the splendor of the reception would amaze us, even to-day. The chieftain and the people gave up their village for the Spanish quarters, moving to another town for the occasion. The following day the chief returned, offering De Soto 8,000 armed Indians, with maize, dried fruits and meat for the[4] journey, 4,000 to act as defenders, 4,000 as burden bearers, to escort the Spaniards through a wilderness of several days’ journey. Such were the proud and generous people the Caucasians found in America.

The haughty Castilian continued his march till he reached the banks of the Mississippi, where he halted and sent his carrier to the chief on the opposite shore, with the usual message, that he was the “Offspring of the Sunne, and required submission and a visit from the chief.” But the chieftain sent back a reply, both magnanimous and proud, that if he were “the Childe of the Sunne, if he would drie up the River, he would believe him; that he was wont to visit none; therefore, if he desired to see him he would come thither, that if he came in peace he would receive him in special good will, and if in Warre in like manner he would attend him in the Towne where he was and for him or any other he would not shrinke one foot backe.”

Old history says this haughty repulse aggravated the illness of De Soto, “because he was not able to passe presently to the River and seeke him, to see if he could abate that Pride of his.”

Notwithstanding the hospitable treatment shown by the natives to the newcomers, the Castilians destroyed them by the thousands: One explorer after another wrote of these friendly people in the new land. “They are very liberal,” says the narrator, “for they give what they have.” Sir Ralph Lane describes the welcome by the natives, who came with[5] “Tobacco, Corne and furs and kindly gestures to be friends with the strange white men,” etc., etc., but adds, “the Indians stole a Silver Cup, wherefore we burnt their Towne and spoylt their Corne,” etc., etc.

The time will soon be over for the study of the Aborigines of America. We have in 250 years wasted them from uncounted numbers to a scattering population of only about 275,000, while in the same length of time a cargo of dusky slaves from the African shores have become a people of millions, slaves no longer, but protected citizens. In the redskin, whom we have dispossessed of his native rights, we recognize no equality; yet the descendant of the barbarous black, whose tribe on the Golden Coast still trembles before a fetish, may now sit at the desk of Clay or Calhoun. Truly the tangled threads of modern morals are hard to unravel.

The first explorers made captives of the Indians, and carried them in irons to Spain, where they were sold as slaves to the Spanish grandees. Two hundred years later the people of Carolina sought to enslave those among them. The red men rebelled at the subjection, and in order to escape bondage, began to make their way to the “Indian country,” the present site of Georgia. African bondsmen soon followed the example of the Indian captives, and in time continued their journey to Florida.

In the attempts to recapture runaway slaves, is based the primeval cause of the Seminole wars.

The history of the Seminoles of Florida begins with their separation from the Creeks of Georgia as early as 1750, the name Seminole, in Indian dialect meaning wild wanderers or runaways. Sea-coffee, their leader, conducted them to the territory of Florida, then under Spanish colonial policy. Here, they sought the protection of Spanish laws, refused in all after times to be represented in Creek councils, elected their own chiefs, and became, in all respects, a separate tribe.

To-day the Seminoles of Florida are only a frail remnant of that powerful tribe of Osceola’s day. Their history presents a character, a power, and a romance that impels respect and an acknowledgment of their superiority. Of the private life of the Seminole less is known, perhaps, than of any other band in the United States. His life has been one long struggle for a resting-place; he has fought for home, happy hunting grounds and the burial place of his fathers. At present we can only see a race whose destiny says extinction.

FLORIDA INDIANS CARRYING THEIR CROPS TO THE STOREHOUSES

The wilds of Florida became a home for these Indians as well as for the fugitive negro slaves of the Southern States. The Indian and the negro refugee, settling in the same sections, became friendly, and in time some of their people intermarried. The same American spirit that refused to submit to “Taxation without Representation,” was strong in the breast of the Seminole, and Florida, belonging to Spain, afforded [7]him a retreat for his independent pursuits. Subject only to the Spanish crown, the exiles found a home safe from the inexorable slave catchers. The Seminoles were now enjoying liberty, and a social solitude, and refused to make a treaty with the colonial government, or with the Creeks from whom they had separated. One demand after another was made upon the Spanish government at St. Augustine for the return of the fugitives, which was always rejected. African slaves continued to flee from their masters to find refuge with the exiles and the Indians. They were eagerly received, and kindly treated, and soon admitted to a footing of equality. The growing demand for slaves in the southern colonies now made the outlook serious, and from the attempts to compel the return of the negroes grew the first hostilities.

One of the first communications ever sent to Congress after it met was by the Georgia colony, stating that “a large number of continental troops would be required to prevent the slaves from deserting their masters.” But, in that momentous year of 1776, Congress had more important duties on hand, and it was not until 1790 that a treaty was entered into between the Creeks and the United States. In this treaty, the Creeks, now at enmity with the Seminoles, agreed to restore the slaves of the Georgia planters who had taken refuge among them. The Seminoles refused to recognize the treaty; they were no longer a part of the Creeks, they resided in Florida and considered themselves subject only to the crown[8] of Spain. One can readily believe that the Spanish authorities encouraged their independence. Legally the exiles had become a free people.

The Creeks now found themselves utterly unable to comply with their treaty. The planters of Georgia began to press the Government for the return of their fugitive slaves. Secretary Knox, foreseeing the difficulty of recovering runaway slaves, wrote to the President advising that the Georgia people be paid by the Government for the loss of their bondmen. The message was tabled, and until 1810 the Seminoles and negroes lived in comparative peace.

The people of Georgia, now seeing the only apparent way to obtain possession of their slaves would be by the annexation of Florida, began to petition for this, but the United States, feeling less interest in slave catching than did the State of Georgia, manipulated affairs so slowly that Georgia determined to redress her own grievances, entered Florida and began hostilities. The United States was too much occupied with the war with Great Britain to take cognizance of Indian troubles in a Spanish province, hence the Georgia intruders met with defeat. For a short time after these hostilities ceased the Seminoles and their allies enjoyed prosperity, cultivated their fields, told their traditions and sang their rude lays around their peaceful camp fires. Seventy-five years had passed since their ancestors had found a home in Florida, and it was hard for them to understand the claims of the southern planters.

The year 1816 found the Seminoles at peace with[9] the white race. In a district inhabited by many of the Indians on the Apalachicola river was Blount’s Fort.

The fort, although Spanish property, was reported as an “asylum for runaway negroes.” General Jackson, now in military command, ordered the “blowing up of the fort, and the return of the negroes to their rightful owners.” The exiles knowing little of scientific warfare believed themselves safe in this retreat; and when in 1816 an expedition under Colonel Duncan L. Clinch was planned, the hapless Indians and negroes unknowingly rushed into the very jaws of death. A shot from a gunboat exploded the magazines and destroyed the garrison. History records that of 334 souls in the fort, 270 were instantly killed! The groans of the wounded and dying, the savage war whoops of the Indians inspired the most fiendish revenge in the hearts of those who escaped, and marks the beginning of the First Seminole War.

Savage vengeance was now on fire, and “Blount’s Fort” became the magnetic war cry of the Seminole chiefs as they urged their warriors to retaliation. This barbarous sacrifice of innocent women and children conducted by a Christian nation against a helpless race, and for no other cause than that their ancestors, one hundred years before, had been born in slavery, marks a period of cruelty, one of the most wanton in the history of our nation.

The inhuman way in which the massacre was conducted was never published at large, nor does the[10] War Department have any record of the taking of Blount’s Fort, as is shown by the following:

An examination of the records of this Department has been made, but no information bearing upon the subject of the taking of Blount’s Fort, Florida, in the year 1816, has been found of record.

By authority of the Secretary of War,

F. C. Ainsworth,

Colonel, U. S. Army, Chief of Office.

Washington, July 25, 1895.

History does not dwell on the cruel treatment the Indians received from the United States authorities during the Seminole Wars, yet pages of our National Library are devoted to the barbarity of the Seminoles. There are two sides to every question, and it is only what the Indian does to the white man that is published, and not what the white man does to the Indian.

The facts show that instead of seeking to injure the people of the United States, the Seminoles were, and have been, only anxious to be free from all contact with our government. In no official correspondence is there any reference made to acts of hostility by the Indians, prior to the massacre at Blount’s Fort.

But Floridians, who had urged the war with the hope of seizing and enslaving the maroons of the interior, now saw their own plantations laid waste, villages abandoned to the enemy, and families suffering for bread. The war had been commenced for[11] an ignoble purpose, to re-enslave fellow-men, and taught that every violation of justice is followed by appropriate penalties.

Few of the people of the United States knew the true cause of the war, nor the real inwardness of the purposes of those in command, as history and official documents show that affairs were in the hands of the Executive rather than in those of Congress. The first war was in itself an act of hostility to the King of Spain; yet nothing was gained by our government except possession of part of the fugitives. Military forces could not pursue the Indians into the fastnesses of the Everglades, and after two years of bloodshed and expenditure of thousands of dollars, peace was in a manner restored, and the army was withdrawn without any treaty being signed.

The Indians had set the American government at defiance. The slaves of Southern States continued to run away, taking refuge with the exiles and Seminoles; the slave-holders of Georgia became more clamorous than ever. The Spanish crown could not protect herself from the invasion of the Americans when in pursuit of runaway negroes. She had seen her own subjects massacred, her forts destroyed or captured, and her rights as a nation insulted by an American army. In 1819, by a combination of force and negotiation, Florida was purchased from Spain for $5,000,000.

Thus the Seminoles were brought under the dominion they so much dreaded. Slave-holders once more petitioned to the United States for aid in the capture of their escaped property. The United States, foiled in their treaty with the Creeks, now recognized the Seminoles as a distinct tribe, and invited their chiefs to meet our commissioners and negotiate a treaty. The Seminoles agreed in this treaty to take certain reservations assigned to them, the United States covenanting to take the Florida Indians under her care and to afford them protection against all persons whatsoever, and to restrain and prevent all white persons from hunting, settling or otherwise intruding upon said lands.

By this treaty all their cultivated lands were given up to the whites, and the Seminoles retired to the interior. Once more this long persecuted people found refuge, but it was only for a short time. The value of slaves in States North caused slave catchers with chains and bloodhounds to enter Florida. They seized the slaves of the Indians, stole their horses and cattle and depredated their property. With such a violation of the treaty, renewed hostilities were inevitable.

The Indians petitioned for redress, but received none. Affairs grew worse until 1828, when the idea of emigration for the Indians was submitted to the chiefs. After much persuasion, a few of the tribal leaders were induced to visit the Western country. They found the climate cold, and a land where “snow covers the ground, and frosts chill the bodies[13] of men,” and on general principles, Arkansas a delusion and a snare. The chiefs had been told they might go and see for themselves, but they were not obliged to move unless they liked the land. In their speech to the Commissioner they said: “We are not willing to go. If our tongues say ‘yes,’ our hearts cry ‘no.’ You would send us among bad Indians, with whom we could never be at rest. Even our horses were stolen by the Pawnees, and we were obliged to carry our packs on our backs. We are not hungry for other lands; we are happy here. If we are torn from these forests our heartstrings will snap.” Notwithstanding the opposition to a treaty, by a system of coercion a part of the chiefs were induced to sign, and fifteen undoubted Seminole cross-marks were affixed to the paper. This was not enough, according to Indian laws, to compel emigration. The stipulations read, “Prepare to emigrate West, and join the Creeks.” There was no agreement that their negroes should accompany them, and they refused to move. To expect a tribe which had lived at enmity with the Creeks since their separation in 1750 to emigrate and live with them was but to put weapons into their hands, and did not coincide with the ideas of the Seminoles.

The United States prepared to execute; not a redskin was ready, and troops were sent. The Indians began immediately to gather their crops, remove the squaws and pickaninnies to places of safety, secure war equipments—in short, prepare for battle.

It was a question of wonderment many times[14] among the officers how the Indians procured their ammunition in such quantities, and how they kept from actual starvation. Hidden as they were in their strong fortresses—the fastnesses of the swamps—many believed that they would be starved out, and would either stand a fair field fight or sue for peace. An old Florida settler who carried his rifle through seven years of Indian warfare explains the mystery. He says: “The Indians had been gathering powder and lead for years, ever since the time Chief Neamathla made his treaty with General Jackson. Besides, Cuban fishing smacks were always bringing it in, and trading with the redskins for hides and furs. As for provisions, they had their ‘Koontie’ flour, the acorn of the live oak, which is fair eating when roasted, and the cabbage of the palmetto tree. For meat, the woods were full of it. Deer and bear were abundant, to say nothing of small game, such as wild turkey, turtle and squirrel.” The Seminoles at this time, 1834, owned, perhaps, two hundred slaves, their people had intermarried with the maroons, and in fighting for these allies they were fighting for blood and kin. To remove the Indians and not the negroes was a difficult thing to do. The Seminoles, now pressed by the United States troops, committed depredations upon the whites; bloody tragedies occurred, and the horrors of the second Seminole War were chronicled throughout the land.

It was now that the young and daring warrior, Osceola, came into prominence. He had recently married the daughter of an Indian chief, but whose mother was the descendant of a fugitive slave. By slave-holding laws, the child follows the condition of the mother, and Osceola’s wife was called an African slave. The young warrior, in company with his wife, visited the trading post of Fort King for the purpose of buying supplies. While there the young wife was seized and carried off in chains. Osceola became wild with grief and rage, and no knight of cavalier days ever showed more valor than did this Spartan Indian in the attempts to recapture his wife. For this he was arrested by order of General Thompson and put in irons. With the cunning of the Indian, Osceola affected penitence and was released; but revenge was uppermost in his soul. The war might succeed or fail for all he cared; to avenge the capture of his wife was his every thought. For weeks he secreted himself, watching an opportunity to murder General Thompson and his friends. No influence could dissuade him from his bloody purpose. Discovering General Thompson and Lieutenant Smith taking a walk one day, Osceola, yelling the war cry sprang like a mountain cat from his hiding-place and murdered both men.

His work of vengeance was now complete, and almost as wild as a Scandinavian Saga was the fight[16] he now gave our generals for nearly two years.

While Osceola lay in wait for General Thompson, plans were being completed which resulted in the Dade Massacre.

The enmity of the Indian is proverbial, and when we reflect that for fifty years the persecutions by the whites had been “talked” in their camps, that the massacre of Blount’s Fort was still unavenged, that within memory fathers and mothers had been torn, moaning and groaning from their midst, to be sold into bondage, with their savage natures all on fire for retaliation, no vengeance was too terrible.

Hostilities around Fort King, now the present site of Ocala, becoming severe, General Clinch ordered the troops under Major Dade, then stationed at Fort Brooke (Tampa), to march to his assistance. Neither officers nor soldiers were acquainted with the route, and a negro guide was detailed to lead them. This unique character was Louis Pacheo, a negro slave belonging to an old Spanish family, then living near Fort Brooke. The slave was well acquainted with the Indians, spoke the Seminole tongue fluently. He was reported by his master, as faithful, intelligent and trustworthy, and was perfectly familiar with the route to Fort King.

The affair of Dade’s Massacre is without a parallel in the history of Indian warfare. Of the 110 souls, who, with flying flags and sounding bugles merrily responded to General Clinch’s order, but two lived to describe in after years the tragic scenes. One was [17]Private Clark, of the 2nd Artillery, who, wounded and sick crawled on his hands and knees a distance of sixty miles to Fort Brooke. The other was Louis Pacheo, the only person of the command who escaped without a wound.

The assault was made shortly after the troops crossed the Withlacoochee river, in a broad expanse of open pine woods, with here and there clumps of palmettoes and tall wire-grass. The Indians are supposed to have out-numbered the command, two to one, and at a given signal, as the troops marched gayly along, a volley of shot was poured into their number. The “gallant Dade” was the first to fall, pierced by a ball from Micanopy’s musket, who was the King of the Seminole nation. A breastwork was attempted by the soldiers, but only served as a retreat for a short time; the hot missiles from the Indians soon laid the last man motionless, and the slaughter was at an end.

On February 20, 1836, almost two months after the massacre, the dead bodies of the officers and soldiers were found just as they had fallen on that fatal day. History is corroborated by old settlers, who say “that the dead were in no way pillaged; articles the most esteemed by savages were untouched, their watches were found in their pockets, and money, in silver and gold, was left to decay with its owner—a lesson to all the world—a testimony that the Indians were not fighting for plunder! The arms and ammunition were all that had been taken, except the[18] uniform coat of Major Dade.” Their motive was higher and purer; they were fighting for their rights, their homes, their very existence.

What became of the negro guide? History records that Louis, knowing the time and place at which the attack was to be made, separated himself from the troops. As soon as the fire commenced, he joined the Indians and negroes, and lent his efforts in carrying forth the work of death. An account printed over forty years ago describes the character of the negro Louis. It reads as follows:

“The life of the slave Louis is perhaps the most romantic of any man now living. Born and reared a slave, he found time to cultivate his intellect—was fond of reading; and while gentlemen in the House of Representatives were engaged in discussing the value of his bones and sinews, he could probably speak and write more languages with ease and facility than any member of that body. In revenge for the oppression to which he was subjected, he conceived the purpose of sacrificing a regiment of white men, who were engaged in the support of slavery. This object effected, he asserted his own natural right to freedom, joined his brethren, and made bloody war upon the enemies of liberty. For two years he was the steady companion of Coacoochee, or, as he was afterwards called, ‘Wild Cat,’ who subsequently became the most warlike chief in Florida. They traversed the forests of that territory together, wading through swamps and everglades, groping their way through hommocks, and gliding over prairies. For two years they stood shoulder to shoulder in every battle; shared their victories and defeats together; and, when General Jessup had pledged the faith of the nation that all Indians who would [19]surrender should be protected in the enjoyment of their slaves, Wild Cat appeared at headquarters, followed by Louis, whom he claimed as his property, under slaveholding law, as he said he had captured him at the time of Dade’s defeat.”

Following Louis Pacheo’s career, we find him sharing the fortunes of Wild Cat in the Indian Territory. Subsequently, Wild Cat, with a few followers, Louis among the number, emigrated to Mexico. Fifty-seven years passed from the date of the Dade massacre, when Louis Pacheo, venerable and decrepit, once more appeared on Florida soil. The old negro, longing for the scenes of his youth, returned to end his days in the hospitable home of his “old missus.” In his confession, he claims to be innocent of the charge of betraying the troops, and asserts that he was forced into remaining with the Indians. The vagaries of a childish mind may account for his diversion from well-established history. The old slave lived for three years after his return to Florida, and died in January, 1895, at age of 95 years.

The tragic news of the Dade Massacre convinced the United States that war had commenced in real earnest. From this time on, skirmish after skirmish ensued, bloody murders were committed by the redskins, thousands of dollars were being expended by our government, and the white population of Florida was in a suffering condition. The Indians were not[20] suffering for food. The chameleon-like character of the war prevented any certainty of success. General Jessup, considerably chagrined, wrote to Washington for permission to resign both the glory and baton of his command.

There could scarcely arise a more painful theme, or one presenting a stranger variety of aspects, as it whirled scathing and bloodily along, than did the Indian War. Yet it is a remarkable fact that no Seminole warrior had ever surrendered, even to superior numbers. Our military forces had learned what a hydra-headed monster the war really was, and attempts were again made to induce emigration. The horrors of the Dade Massacre and of Fort King had reached the world. General Jessup sought negotiations, but found the same difficulties to encounter as before, viz.: that the chiefs would not enter into an agreement that did not guarantee equal rights to their allies as to the Indians. Official documents show that General Jessup agreed that “the Seminoles and their allies who come in and emigrate West, shall be secure in their lives and property; that their negroes, their bona fide property, shall accompany them West, and that their cattle and ponies shall be paid for by the United States.” The Indians, under these terms, now prepared to emigrate. History records that even Osceola avowed his intention to accompany them. Every preparation was made to emigrate, and a tract of land near Tampa was selected on which to gather their people. Hundreds of Indians and negroes encamped there. Vessels[21] were anchored to transport them to their new homes. Peace was apparent everywhere, and the war declared at an end. At this point a new difficulty arose. Slave-holders became indignant at the stipulations of the treaty, and once more commenced to seize negroes. The Seminoles, thinking themselves betrayed, with clear conceptions of justice, fled to their former fastnesses in the interior, and once more determined to defend their liberty.

MICANOPY—HE WAS THE KING OF THE NATION

In the violation of the treaty, to use General Jessup’s words, all was lost!

All the vengeance of the Indian was again aroused, and the wild Seminole war-cry, “Yohoehee! yohoehee,” again broke through the woods.

The fame of Osceola now reached the farthermost corner of the land. His name, signifying Rising Sun,[1] seemed prophetic, and he became at once the warrior of the Ocklawaha, the hero of the Seminoles. The youngest of the chiefs, he possessed a magnetism that Cyrus might have envied, and in a manner truly majestic led his warriors where he chose.

In the personal reminiscences of an old Florida settler, in describing Osceola, he says, “I consider him one of the greatest men this country ever[22] produced. He was a great man, and a curious one, too; but few people know him well enough to appreciate his worth. I was raised within ten miles of his home, and it was he who gave me my first lessons in woodcraft. He was a brave and generous foe, and always protected women and children. An act of kindness was never forgotten by him.” Osceola had received a favor from one of the officers who led the battle of the Withlacoochee. Observing him in the front ranks, he instantly gave orders that this man should be spared, but every other officer should be cut down. Osceola’s father was an English trader named Powell, and his mother the daughter of a chief known as Sallie Marie, a woman very small in stature, and with high cheekbones. Osceola lacked this peculiarity, and was one of the finest-looking men I ever saw. His carriage was erect and lofty, his motion quick, and he had an air of hauteur in his countenance which arose from his elevated pride of soul. His winning smile and wonderful eyes drew from an army officer these glowing words of admiration, “But the eye, that herald of the Soul, was in itself constituted to command. Under excitement it flashed firm and stern resolve; when in smiling it warmed the very heart of the beholder with its beams of kindness. I tell you, he was a great man; education would have made him the equal of Napoleon. He hated slavery as only such a nature as his could hate. He was Indian to the heart, and proud of his ancestry. He had too much white blood in him to yield to the cowardly offers of the[23] government, and had he not been captured, the Seminole War would have been a more lasting one than it was. I could talk all day about Osceola,” remarked the old Captain, as he drew a sigh. “Did the Indians take scalps, Captain?” “Take scalps? Well, yes, if Osceola wasn’t around. He was too much of a white man to allow it himself.”

The admixture of Caucasian blood stimulated the ambition of Osceola’s Indian nature; his education, together with the teachings of nature, made him able to cope with the most learned. Living until he was almost twelve years of age in the Creek confederacy of Georgia, his youthful mind received deep and lasting impressions from Tecumseh’s teachings. To these teachings, as well as the blood he inherited from his Spartan ancestors was due, no doubt, his supremacy in the Seminole War. In the manner in which he led the Seminoles may be seen the influence of the great Shawnee.[2] Osceola’s power was in his strong personal magnetism; he swayed his warriors with a look; a shout of command produced an electric effect upon all. He was a hero among his people, he was feared and dreaded by our officers. In this day, as we study his life and character, we must recognize in the young Seminole fighter the greatest of chiefs, the boldest of warriors. In an old Greek fable, a man seeks to prove the superiority of his race by reading to a lion accounts of various[24] battles between men and beasts, to which the lion replied, “Ah, had we written that book other tales would have been told.” In the case of the Indian chieftain no such records exist, yet even from the testimony of his enemies we must know Osceola.

Interviewing old settlers who well remember events of those stirring times, one finds the heroic part of Osceola’s character to have been not overdrawn in history. The Seminole chief, Charles Omatla, was an ally of the whites, and was attacked and murdered by Osceola’s warriors. On his body was found gold, which Osceola forbade his men to touch, but with his own hands he threw the gold himself as far as he could hurl it, saying, “it is the price of the red man’s blood.”

Osceola’s pride was majestic; he was imperious, full of honor, but with the quickness of the Indian he noted the path to popular favor. His power was recognized by the officers. “Talk after talk,” with the Indians was the order of the times. It was at one of these meetings that Osceola in the presence of the commissioners attracted attention by saying, “This is the only treaty I will ever make with the whites,” at the same time drawing his knife and striking it into the table before him. The cause of this outburst was that the stipulations of the treaty guaranteed no protection to the allies. He was arrested for his insolence, but was released on a compromise. His vengeance became more terrible than ever, and in defiance “Yohoehee” echoed through the woods and “war to the knife” was resumed.

It was now that the daring chief made the bold and well-conducted assault against the fort at Micanopy. A short time after, this savage hero performed a piece of strategy before unheard of in the annals of war. Surrounded by two armies of equal strength with his own, he carried away his warriors without leaving a trace of his retreat. That host of Indian braves melted out of sight as if by magic, and our disappointed generals could not but agree that a disciplined army was not adapted to the work of surprising Indians. They were learning to recognize the character of the men our nation had to deal with.

The Indian method is to decoy by a broad plain trail, then at a certain distance the foremost of the band makes a high, long step, leaves the trail and, alighting on the tip of his toe, carefully smoothes out the brushed blades behind him. The rest of the band go on a few yards farther and make their exit the same way, and so on till the end is reached. Many times our troops made long night marches to find—what? Nothing but a few smouldering camp fires.

The war raged on in defiance of the power of a mighty nation, a nation that had said to old King George, “attend to your own affairs” and he obeyed.

What shall we say of the capture of the great Indian chief? Is not the seizure of Osceola America’s blackest chapter? Was Osceola treacherous? The United States failed to observe even one important article of the three treaties made with the[26] Seminoles. Was Osceola a savage? It is not denied that he protected women and children when he could. It is not denied that the soldiers of the United States shot down women and children, destroyed all dwellings, crops and fruit trees they could reach.

After months of warfare, a conference among the Indians with a view to a treaty of peace was held. An Indian chief was sent to the American quarters.

Picture, if you will, an American camp, in the wooded wilds of Florida, and peer beyond the confines of the magnolia and the palms and you see a single Seminole chieftain, heralding his white flag. He approaches our General, the representative of proud and free America, and presents him with a white plume plucked from the egret, with a message from Osceola, with these words, “the path shall be white and safe from the great white chieftain’s camp to the lodge of Osceola.”

General Hernandez immediately despatched Coacoochee with a pipe of peace, kindly messages and presents.

What was the result? Osceola, in company with Wild Cat and other chiefs, accepted the truce and, under the sacred emblem of the white flag, met General Hernandez on October 21, 1837 at St. Augustine.

With that grave dignity characteristic of the red man, dressed in costume becoming their station, with as courtly a bearing as ever graced Kings,[27] heralding their white flags they approached the place of meeting.

History verifies the Seminole account of this blot on our nation that, as the officers approached, they asked of Osceola: “Are you prepared to deliver up the negroes taken from the citizens? Why have you not surrendered them as promised by your chief Cohadjo?”

According to history, this promise had been made by a sub-chief and without the consent of the tribe. A signal, preconcerted, was at this moment given and armed soldiers rushed in and made prisoners of the chiefs.

An account of this violated honor, recently given by the venerable John S. Masters, of St. Augustine, Florida, is opportune at this point. The old soldier in speaking of the affair said, “I was one of the party sent out to meet Osceola when he was coming to St. Augustine under a flag of truce.” “Did you honor that truce?” was asked. “Did we? No sir; no sooner was he safe within our lines than the order to seize him, kill if necessary, was given, and one of the soldiers knocked him down with the butt of his musket. He was then bound and we brought him to Fort Marion and he was put in the dungeon. We were all outraged by the cowardly way he was betrayed into being captured.”

At this violation of the sanctity of the white flag our officers wrote: “The end justifies the means; they have made fools of us too often.”

The foul means used to capture the young Seminole[28] leader was not blessed by victory, as a continuance of the bloody war for five years proved that the God of justice was not wholly on the white man’s side. The stain on our national honor will last as long as we have a history. Osceola with the other chiefs was confined for a short time in St. Augustine, but the daring savage was too valuable a prize to trust on Florida territory, and he was taken to Fort Moultrie where he died January 30, 1838, at the age of thirty-four years.

It is related that Osceola on being questioned as to why he did not make his escape, as did some of the other chiefs from Fort Marion, replied, “I have done nothing to be ashamed of; it is for those to feel shame who entrapped me.” Chas. H. Coe, in his Red Patriots says, “If the painter of the world-famed picture, Christ before Pilate, should seek in American history a subject worthy of his brush, we should commend to him, Osceola, before General Jessup. Osceola, the despised Seminole, a captive and in chains; Jessup, in all the pomp and circumstances of an American Major-General; Osceola, who had “done nothing to be ashamed of,” calmly confronting his captor, who cowers under the steady gaze of a brave and honorable man!”

But such is the Irony of Fate. Osceola, the free son of the forest, fettered by the chains of Injustice, was destined to eat out his heart in a musty dungeon.

Thoroughly and thrillingly dramatic was the death scene of the noble Osceola as given by Dr. Weedon[29] his attending surgeon. Confinement no doubt hastened his death, and his proud spirit sank under the doom of prison life. He seemed to feel the approach of death, and about half an hour before the summons came he signified by signs—he could not speak—that he wished to see the chiefs and officers of the post. Making known that he wished his full dress, which he wore in time of war, it was brought him, and rising from his bed he dressed himself in the insignia of a chief. Exhausted by these efforts the swelling heart of the tempest-tossed frame subsided into stillest melancholy. With the death sweat already upon his brow, Osceola lay down a few minutes to recover his strength. Then, rising as before, with gloom dispelled, and a face agleam with smiles, the young warrior reached forth his hand and in dead silence bade each and all the officers and chiefs a last farewell. By his couch knelt his two wives and his little children. With the same oppressive silence he tenderly shook hands with these loved ones. Then signifying his wish to be lowered on his bed, with slow hand he drew from his war belt his scalping knife which he firmly grasped in his right hand, laying it across the other on his breast. In another moment he smiled away his last breath, without a struggle or a groan. In that death chamber there was not one tearless eye. Friends and foes alike wept over the dying chief. Osceola died as he lived—a hero among men.

OSCEOLA—PATRIOT AND WARRIOR,

DIED, JAN. 30,—1838.

Such is the inscription, that marks the grave of the hero of the Seminoles.

Even at this writing, it is a melancholy satisfaction to know that the great Indian leader was buried with the honor and respect due so worthy a foe.

A detachment of the United States troops followed by the medical men and many private citizens, together with all the chiefs, and warriors, women and children of the garrison in a body, escorted the remains to the grave, which was located near the entrance to Fort Moultrie, Charleston Harbor. A military salute was fired over the grave and as the sound reverberated over the dark waters of the bay, Justice and Patriotism, must have pointed with fingers of scorn to our great Nation, yet with tender pity, said “Osceola—the Rising Sun, may the Great Spirit avenge you, keep you, love you and cherish you,—the Defender of your country.”

Wild Cat and Cohadjo were allowed to remain in old Fort Marion the prison at St. Augustine, Florida. Wild Cat feigned sickness and was permitted, under guard, to go to the woods to obtain some roots; with these he reduced his size until he was able to crawl through an aperture that admitted light into the cell. Letting himself down by ropes made of the bedding, a distance of fifty feet, he made his escape, joined his tribe and once more rallied his forces against our army. Latter day[31] critics have questioned the correctness of this bit of written history. Last winter, during the height of the season, the Ponce de Leon guests enjoyed a unique entertainment. A wealthy tourist made a wager of one hundred dollars that “Wild Cat never could have made his escape through the little window in the old castle.” Sergeant Brown accepted the wager and himself performed the feat, to the great delight of the excited spectators.

OSCEOLA

A copy from Catlin’s painting.

Our soldiers fighting in an unexplored wilderness, along the dark borders of swamp and morass, crawling many times on hands and knees through the tangled matted underbrush, fighting these children of the forest who knew every inch of their ground could hope for little less than defeat. Even General Jessup in writing to the President said: “We are attempting to remove the Indians when they are not in the way of the white settlers, and when the greater portion of the country is an unexplored wilderness, of the interior of which we are as ignorant as of the interior of China.”

By way of illustrating the enormity of the task the government had in subduing the Seminoles, it is only necessary to describe one of the many Indian strongholds in the swamps of Florida. About ten miles from Kissimmee, west by south, is a cypress swamp made by the junction of the Davenport, Reedy and Bonnett creeks. It is an aquatic jungle, full of fallen trees, brush, vines and tangled undergrowth, all darkened by the dense shadows of the tall cypress trees. The surface is covered with water, which, from appearance[32] may be any depth, from six inches to six feet; this infested with alligators and moccasins would have been an unsurmountable barrier to the white troops.

A few years ago when the Seminoles yet frequented this section for trading purposes old settlers have seen them coming from the swamp carrying bags of oranges. Interrogations received no answers and white settlers year after year searched for the traditional orange grove, but without success.

So difficult to penetrate and so dangerous to explore is the swamp that it was not until fifty years after the Indians had left their island home that a venturesome hunter, during a very dry season, accidentally discovered the old Seminole camp. The Indian mound, the broken pottery and the long hunted for sweet orange grove were proofs of the old camp. The majestic orange trees laden with golden fruit were an incentive to further research. With a surveyor working his way, as guided by the point of the compass, this wonderland was explored, and proved to be a complete chain of small hommocks or islands running through from one side of the swamp to the other; the topography of the marsh being such that a skirmish could take place on one side of the jungle and an hour later, by means of the secret route through the swamp, the Indians could be ready for an attack on the other side, while for the troops to reach the same point, by following the only road known to them, it would have required nearly a day’s marching. The Indian trail is lost in the almost impenetrable[33] jungle; but the tomahawk blazes are perfectly discernible. The Seminoles held the key to these mysterious islands and in the heart of the great swamps they lived free from any danger of surprise. This retreat must have been a grand rendezvous for them, as its geographical position was almost central between the principal forts. Lying between Fort Brooke (Tampa) and Fort King (Ocala), within a distance of thirty miles from the scene of the Dade massacre, about forty miles from Fort Mellon, the present site of Sanford, the camp could have been reached in a few hours by Indian runners after spying the movements of the troops at any of the forts. The old government road, over which the soldiers passed in going from Fort Brooke to Fort Mellon, passes so close to the old Indian camping ground that all travel could have been watched by the keen-eyed warriors.

At this period of our national history we are unable to picture or appreciate the condition of those slave days, when all blacks of Southern States were regarded as the property of the whites. The fear, the torture, the grief suffered by the negroes and half breeds, who had been a people with the Seminoles almost one hundred years, is beyond our conception. When Indian husbands were separated from wives selected from the exiles, when children were torn from their homes and carried to slavery, the vengeance[34] of these persecuted people was constantly alive. Persons of disreputable character—gamblers, horse thieves—were employed as slave catchers and showed no mercy to the helpless victim.

After the violation of the treaty at Tampa, and the capture of Osceola and Wild Cat, under the sacred truce of the white flag, Wild Cat became a most daring enemy to the troops, and kept his warriors inspired to the most savage hostilities.

General Scott was now placed in command of the army, yet the same harassing marches continued, and it was not until seven generals had been defeated at the game of Indian warfare by the wily chieftains that any sign of success was apparent.

Our government, discouraged at being unable to conquer the Indians or protect the white settlers, again negotiated for peace, but using a more powerful weapon than in former years, that of moral suasion. Executive documents show that, all through the war, artifice and bad faith were practiced upon the Indians. The government was astonished that a few Indians and their negro allies could defy United States troops. All efforts had failed, even to the horrible policy of employing bloodhounds. To-day we shudder at the barbarity of such an act, but official documents show how much the subject was discussed by Congress and war authorities. A schooner was dispatched to Cuba and returned with thirty-five bloodhounds—costing the Government one hundred and fifty dollars apiece. They were speedily put upon the scent of Indian scouting parties,[35] but proved utterly inefficient. The public believed the hounds were to trail Indians, but reports show their use was to capture negro slaves. The Seminoles were a species of game to which Cuban hounds were unaccustomed and they refused to form acquaintance with the new and strange objects. The Indians had a secret peculiarly their own of throwing the dogs off the scent, and the experiment, to close the war thus, proved a failure and served no other purpose than to reflect dishonor on our nation.

Wild Cat, after his escape from prison, was a terrible and unrelenting foe. Occupying with light canoes the miry, shallow creeks, and matted brakes upon their border, he was unapproachable. A flag was sent him by General Worth, but, remembering well another flag which had meant betrayal, capture and chains, the daring hero fired upon it and refused to meet the general. In the summer of 1841, General Worth’s command captured the little daughter of Wild Cat and held her for ransom. The little girl,—his only child—was the idol of the old warrior’s heart. On learning of her capture, Wild Cat relented, and, once more guarded by the white flag, was conveyed to General Worth’s camp. History gives an interesting account of the old chief’s approach. His little daughter, on seeing him, ran to meet him, presenting him with musket balls and powder, which she had in some way obtained from the soldiers. So much overcome was the fearless savage on meeting his child that the dignified bearing[36] so carefully practiced by all Indians gave way to the most tender emotions.

The moral suasion, the humanity of General Worth made a friend of Wild Cat, and he yielded to the stipulations.

The speech of the old chieftain, because it breathes the same sentiment of the Seminoles of to-day, we give below. Addressing General Worth, he said:

“The whites dealt unjustly with me. I came to them when they deceived me. I loved the land I was upon. My body is made of its sands. The Great Spirit gave me legs to walk over it, eyes to see it, hands to aid myself, a head with which I think. The sun which shines warm and bright brings forth our crops, and the moon brings back spirits of our warriors, our fathers, our wives, and our children. The white man comes, he grows pale and sickly; why can we not live in peace? They steal our horses and cattle, cheat us and take our lands. They may shoot us, chain our hands and feet, but the red man’s heart will be free. I have come to you in peace, and have taken you by the hand. I will sleep in your camp, though your soldiers stand around me thick as pine trees. I am done. When we know each other better, I will say more.”

Through the gentleness and humanity of the “gallant Worth,” Wild Cat at this meeting agreed to emigrate with his people. He was permitted to leave the camp for this purpose. By some contradictory order, while on his way to his warriors, he was captured[37] by one of our commands, put in chains and transported to New Orleans.

When General Worth learned of this violation of his pledge he felt the honor of our country had again been betrayed, and acting on his own discretion sent a trusty officer to New Orleans for the return of Wild Cat. General Worth by this act not only showed the nobility of his own character, but proved that the savage heart can be touched with kindness and is always keenly alive to honor and faithful pledges. Moreover the justice of the act had much to do with the successful turning of the war.

When the ship which brought the chief reached Tampa General Worth was there to meet it and publicly apologized to the brave old warrior for the mistake that had been made. Our gallant commander had proven his humane heart, although at expense of both time and money. Through the policy of General Worth, the whole character of the war was changed. On the 31st of July, 1841, Wild Cat’s entire band was encamped at Tampa, ready to be transported to their new homes.

The original idea of re-enslaving the fugitives was abandoned. General Worth and Wild Cat now became the most ardent friends, the general consulting with the famous chieftain until every arrangement for the removal was perfected. Seeing a chief of such prominence yield to emigration, band after band gave up the fight and joined their friends at Tampa. From the time of Wild Cat’s removal in[38] the fall of 1841, until August, 1843, small bands of Indians continued to emigrate. General Worth now advised the withdrawal of the troops. A few small bands throughout the State refused to move, signed terms of peace, however, by which they were to confine themselves “to the southern portion of the Peninsula and abstain from all acts of aggression upon their white neighbors.” As vessel after vessel anchored in Tampa Bay to carry these wronged and persecuted people to their distant homes, the cruelty of the undertaking was apparent to the most callous heart. With lingering looks the Seminoles saw the loved scenes of their childhood fade away. The wails and anguish of those heart-broken people, as the ships left the shores, touched the hearts of the most hardened sailor. They were leaving the graves of their fathers, their happy hunting grounds, beautiful flowery Florida. But it is the destiny of the Indian. Among that band there was not one voluntary exile. Poets and artists picture the gloom, the breaking hearts of the French leaving Acadia; at a later day the same sad scenes were witnessed on the Florida coast, but it was not until years after that a philanthropist gave to the world an intimation of the melancholy picture of these poor struggling, long hunted Seminoles leaving the shores of their native lands.

There is something intensely sad in the history of the Indians who were left in Florida at the close[39] of the “seven years’ war.” Keeping faith with their promise to abstain from all aggression on their white neighbors, retiring to the uninhabited marshes of the Southern Peninsula, they lived happy and contented for thirteen years. Then came reports of outbreaks and the United States again opened military tactics with the resolve to drive this brave and liberty loving remnant from their last foothold on Florida soil.

According to the most authentic reports, the trouble was brought on by some white engineers encamped near the border of the Big Cypress. It was in the year 1855 and the United States was making a general survey of Florida. Old Billy Bowlegs, recognized as the head of his tribe, and living at peace with all the world, had a fine garden in this swamp and in it were some magnificent banana plants, which were the delight of the old Indian’s heart.

As the old warrior visited his garden early one morning, he discovered some ruthless hand had ruined his garden. They were deliberately cut and torn to pieces. Going to the engineers’ camp, he accused the men of the outrage, when they insolently admitted it, refusing to make amends, and saying that they wanted to “see old Billy cut up.” And they did!

The government paid for it to the extent of several thousand dollars, a number of lives and adding another dark page in the history of our Nation.

No white man would have submitted to the outrage,[40] neither did the famous Chief. Summoning his braves early the next morning, the war cry “Yo-ho-ee-hee,” was heard and Lieutenant Hartsuff and his men were fired upon, some of them being wounded.

Like a flash of electricity the news encircled Florida, and Billy Bowlegs became the target of many old muskets.

Then came the clamor of white settlers for the removal of the “savages” and white guerrillas dressed and painted as Indians went about the country robbing and murdering mail and express riders, driving off stock, burning houses and committing other lawless deeds. Old inhabitants tell of these depredations. But there was a reason for such cowardly acts. The Government at Washington was perplexed and, not grasping the fact that the raids were perpetrated by white men, disguised as Indians, believing that military forces could do nothing towards breaking up the warfare, designed the plan of offering the sum of $100 to $500 for living Indians delivered at Fort Brooke (Tampa) or at Fort Myers. After Governmental hunting for three years, the white guerrillas still busy with their malicious depredations, Old Billy Bowlegs, with his band of one hundred and fifty persons, was induced to emigrate, but they went with sore unwillingness, silent or weeping towards the land of the setting sun, driven before the power of the white man, a group of broken-hearted exiles.

The author begs the indulgence of the reader in giving the following dialect story of that historic Treaty Dinner, when our gallant American General Worth made peace terms with the Indians in 1842.

The treaty was signed at Fort King, now the present site of Ocala, Florida, and as one listens to the story of that eventful day, a story complete in its setting as told by our old Bandanna Mammy, the heart throbs and the pulse grows quicker—so vivid is the recital.

As the tale is related a most picturesque scene comes before the mind, the garrison with its stack of arms, dusky warriors mingling with American soldiery, glittering sunshine and singing birds, tables spread under the great live oaks, joy on every countenance—the end of the Seven Years’ War. Because this old ante-bellum slave is a bright link, forging as it were, those olden days of warfare with the present, a few words of her individuality must interest.

Martha Jane, for so she was christened full ninety-five years ago when, a little shining black pickaninny, her birth was announced to the mistress of the old Carter plantation, is the true type of the old time loyal, quaintly courteous Bandanna Mammy of ante-bellum days. Leaving Richmond about 1839, she[42] was brought to Florida with a shipload of slaves. Since that time her life has been a rugged and an eventful one—a servant for the wealthy, nursing the sick, sold again and again, hired out, and, since freedom, working for her daily bread.

This white haired relic of Old Virginia is worthy a place in the pages of history. She is old, decrepit and poor, the muscles of her once powerful arms are shrunken and her hands gnarled with the labor of years, but she has a memory as keen as when almost 80 years ago she watched the “stars fall” from the upper windows of the Old Swan Hotel in Richmond. She has kept pace with many points in history, particularly of the wars of the country.

As the old dame—a study in ebony—rocks back and forth in the creaking split-bottom chair, memory runs back to the imperial days of Virginia when the cavalier was supreme, and she the pampered nurse girl of the little mistress. She says, “Oh, dem was dream days. I hab nebber seed any days like ’em since. De mounfulest day I ebber seed was when dey took me from my mistress, for the sky was a drippin’ tears and de wind was a groanin’.”

“No, honey, dey ain’t stories ’bout dem Seminole war days, dey is de Lord’s blessed truf, what ole Marthy see wif dese same ole eyes.

“Oh, dem wuz high times! I reckelmember dat Krismas day jest like hit wuz yisterday; the sun wuz a shinin’ an’ de birds a singin’ (you see, de mokin’ birds didn’t sing while dat cruel war wuz a goin’ on) an’ ebbery body wuz a laughin’ an’ a talkin’ an’ de[43] white ladies wuz a coquettin’ wif de sojers an’ dem Indians wuz as thick as hops an a laughin’ an’ a jabberin’ too.

“When Colonel Worth see dem long tables settin’ under the big live oaks an’ see dem beeves an’ muttons an’ turkeys an’ deer we cooked, he jest natchelly laughed an’ say, ‘Clar ter goodness, what kin’ o’ Krismas doin’s is dis’; an’ how dem sojers an’ Indians did eat.

“How come I ter cook de treaty dinner?

“Well, I wuz livin’ out on ole Marse Watterson’ plantation, ’bout four miles from Fort King, dats to Ocala, now, you know, an’ Jim, dat wuz Colonel Worth’s servant, he ride out on dat big white horse o’ de Colonel’s an’ say ‘Colonel Worth want Marthy Jane ter cook de treaty dinner;’ so me an’ Diana Pyles an’ Lucinda Pyles cook dat dinner.

“Oh, Lordy, what scufflin’ roun’ an’ jumpin’ like chickens wif der heads off as we do dat day.

“All de sojers’ guns an’ de Indians’ guns, too, wuz stacked in dat garrison, an’ when de night come, dey make big camp fires an’ de white folks dance an’ de Indians wuz a dancin’ too, wif dem ole coutre (terrapin) shells a strapped ’roun’ der legs.

“Tell you ’bout Colonel Worth? He wuz de gem’men ob all dat crowd; he wuz de nobles’ lookin’ man an’ so kind an’ easy; de United States nebber would hab conquered dem Seminoles if dey had not induced Colonel Worth ter come down an’ argufy wif dem. Him an’ old Captain Holmes wuz de mos’ like our folks ob any ob dem big generals.

“Arter dey had all eat, an’ eat dem fine wituals we cook, den dey hab de speech makin’; oh, dat wuz high ’stronomy talk!

“I reckelmember jest like hit wuz to-day, me an’ Diana Pyles wuz a standin’ right inside de garrison an’ dat noble-lookin’ Colonel Worth wuz talkin’ kind an’ persuadin’ like ter dem savages an’ axin’ dem all ter come up an’ sign de treaty.

“You see dat treaty wuz foh dem ter quit fightin’ an’ go ter Arkansas.

“All dem chiefs walk up but two. Oh, Lordy mercy I kin jest see dat Sam Jones yit standin’ close ’side Colonel Worth. He wuz sut’n’ty a big Indian an’ could talk English good as we alls white folks.

“He jest look at de Colonel pizen like an’ I smell de trouble den, an’ he up an’ say, ‘My mother died heah, my father died heah, an’ be demned I die heah; yo-ho-ee, hee-ee!’

“How dat Indian could gib dat war whoop; an’ he walk right ober yonder ter dat big stack ob guns an’ take his rifle an’ ebbery Indian ob his band follow’ ’m an’ dey walk out ob dat garrison as easy as a cat arter a mouse.

“Colonel Worth did look so peaked, but twan’t no use, foh he couldn’t stop dese chiefs; he hab gib dem the promise dat if dey would all come in he would treat ’em all right.

“Dem wuz cruel days,” and old Martha Jane quivered with indignation as she brought her fat hand down upon her knee. “But hit wasn’t de Indians’ fault. No man what hab a gun is gwine ter let[45] somebody steal the cattle an’ horses, an’ dat jest what de white people do ter de Seminoles.

“Lord a mercy, I hab seed Paynes’ Prairie covered wif de cattle an’ horses dat ’longed ter de Indians, an’ de white rapscallions would carry ’em off a hundred at a time. Umph! I heah ’em brag how dey carry off de Indians’ horses. Ole Thorpe Roberts he wuz a ole fief. He would say, ‘We make many a good haul ob dem savages’ cattle, ten ob us come in at onct an’ drive off a thousan’ head.’

“Yes, Mistis, dat ole Seminole war make a heap o’ white folks rich in Florida.

“Oh, Lord hab mercy on all dem souls. Dey wuz hard times, times o’ misery, chile, but de Indians wuzn’t ter blame. God make ’em an’ dey hab ter hab a place ter stay, jest same as we alls white folks.

“De white people bring all dat ’struction on der own heads foh dey commence dat war. I see hit wif my own eyes; I see ’em kill de Indians’ slaves. You see de Seminoles hab slaves jest de same as white folks, an’ some ob der niggers wuz as fine-lookin’ black men as you ebber ’spect ter see in Ole Virginia.

“When de Indians would come ’roun’ ter esquire ’bout der cattle de white rapscallions (an’ a heap o’ dem wuz dem low down nigger traders too) dem white men would up an’ shoot de Indians.

“Lordy chile, when I gits ter ruminatin’ ’bout dem days I sees de longes’ line o’ haunts whats obtained in dis world o’ sin an’ sorrow.”

I laid down my tablet and looked up; the old woman’s[46] lip was quivering from suppressed emotion. Passing over the tragic she began again.

“No, chile, ’xcusin’ ob de truf, de United States nebber whipped de Seminoles; she whipped dem Britishers when George Washington wuz de captain, an’ de Mexicans, den she tuck a little ’xcursion ’cross ter Cuba an’ whipped dem Spaniards; but she nebber whipped the Seminoles. Umph; where wuz de Indians when de sojers wuz all shinin’ in dem new uniforms an’ der ammunition all packed up? Dem savages wuz all gone, hidin’ in dem hammocks an’ swamps what wuz so thick wif trees an’ bushes dat a black snake could skacely wiggle through.

“De sojers would go marchin’ ’long an’ way up in de tops ob some ob dem big trees some ob dem sly ole Indian scouts would be sittin’ wifout any clothes on, a watchin’ an’ a laughin’ at de sojers.”

“You want ter heah ’bout dat battle o’ Micanopy?

“De Seminoles didn’t hab no battles like dem Britishers in George Washington times; no chile, but dey hab scrummages an’ kill de white people jest like dey wuz black birds,” and the old negress, seemingly oblivious to the fact that cruel time has bowed her frame and dimmed the once bright eye, lives over again the story of those days so long ago, when she was the pampered slave of the old aristocracy.

“How come I ter see dat big fight, I b’longed ter Marster Mundane; de Mundane fambly wuz powerful rich and owned the big hotel where the officers wuz stayin’.

“Der warn’t no Indians ’roun’ der jest den, an’ ebbery thing wuz peaceful an’ quiet, an’ I heah de sojers a jokin’ an’ sayin’ day wuz jest a spendin’ de winter in de Sunny South an’ de Governmen’ wuz payin’ de grub bills.

“I reckelmember jest like I am tellin’ you ter day, I wuz standin’ on dat big piazza ’side o’ Missus; you know I wuz riz up ter be ’roun’ white folks, foh I wuz allus so peart dat my ole Missus in Virginia would call me in ter de parlor ter show me off ter de white ladies.

“Well, honey, dis mornin’ de sojers wuz a cleanin’ der guns an’ laughin’ an’ dey ax Mistis, ‘How many deer you want foh dinner?’ Den anudder likely young sojer would say, ‘How many turkeys you want, Mistress Mundane?’ an’ den dey went off a whistlin’ an’ a singin’; but oh, my God, what lamentations der wuz dat same night.

“Twan’t long will I heah, bang—bang—bang, an’ I says ter myself, Marthy Jane, too many deer, too many wild turkey, sound ter me like Indian shootin’; ’spect dem rapscallions sneak up on de sojers, an’ dis black chile gwine ter see foh herself. I jest slipped out o’ de house an’ kachunk! kachunk! I went down that big lane as fas’ as a horse can trot till I come ter de prairie an’ den I clumb in ter a big oak tree, den de nex’ thing I do I wrap dat gray moss ’roun’ me so dem debbils couldn’t see me.

“How dem Indians did shoot! If dat sight didn’t beat de lan’! Zipp—zipp—bang—bang, an’ ebbery time dey shoot dey yell like debbils, yo-ho-e-hee-eee[48] bang, den fall on de groun’ an’ load dat musket, stan’ up an’ shoot again; de sojers a droppin’ ebbery time a Indian shoot.

“De sojers wuz so skeered dey couldn’t load der guns when de Indians would gib dat Satan screech.

“An’ den de poor sojers jest dropped guns an’ run in ter de lake an’ de woods an’ dem savages would go an’ take de guns an’ de ammunition offen de dead bodies an’ den go runnin’ like a deer.

“Lord a mercy, hit seems ter me I heah de wind blowin’ ghosts an’ de sperits ob de brave gem’men what wuz killed on dat field ebbery time I talks ’bout dat day.

“Yes, Mistis, dat scrummage wuz called de battle ob Payne’s Prairie. When de Colonel found out de Indians killed so many ob de sojers, he tore roun’ like a wild bear an’ clar ’foh de Almighty dat he wuz gwine ter sen’ off an’ fetch de whole United States troops ter come down an’ kill ebbery Indian in Florida.