~MRS TUBBS.~

(100 years old.)

TOLD AND ILLUSTRATED BY

HUGH LOFTING

THE

STORY

OF MRS

TUBBS

Published by FREDK A. STOKES CO, 443 Fourth Av. NEW YORK

Copyright, 1923, by

Frederick A. Stokes Company

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

To

THE TWO

ELIZABETHS

The Story of Mrs. Tubbs

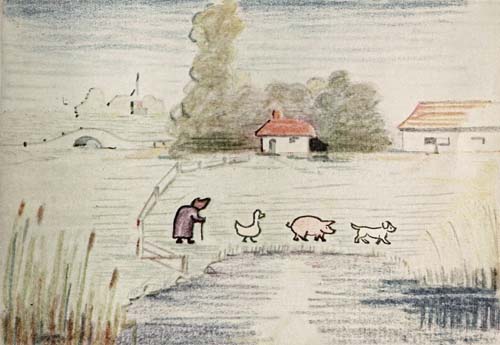

Once upon a time, many, many years ago, there lived a very old woman and her name was Mrs. Tubbs. She lived on a little farm, way off in the country. Her little house stood on the edge of the woods, not very far from a village with a little church, and a little river with a little bridge over it, flowed close by the house. There was a barn too for cows and horses, only the woman hadn’t any cows or horses; she lived all alone with a dog and a duck and a pig. The dog’s name was Peter Punk, the duck’s name was Polly Ponk, and the pig’s name was Patrick Pink. The old woman called them Punk, Ponk and Pink for short.

Mrs. Tubbs’s Farm

Punk and Ponk had known one another for many years and were very good friends. The pig they treated as a baby because they said he was very young and hadn’t much sense.

The old woman did not own the farm although she had lived on it so long. The farm belonged to a man up in London who never came there at all. This man, one fine day at the end of summer when the leaves were beginning to fall in the woods, sent his nephew, a very silly young man with a red face, down from London to live in the farm-house instead of Mrs. Tubbs.

Punk, Ponk and Pink and the old woman were all dreadfully sad at having to leave the home where they had been so happy together for so many years.

As the sun was going down behind the little church one evening at the end of Summer when the leaves were beginning to fall in the woods, they all left the farm together, Punk in front, then Pink, then Ponk and Mrs. Tubbs behind.

They walked a long, long way along the edge of the woods and at last when they saw a seat under a tree they all sat down to rest.

They all sat down to rest

“Oh dear, oh dear,” Mrs. Tubbs kept saying, “now I have no home, no place to sleep. And me an old woman. To be turned off the farm after all these years! What shall I do, where shall I go? Oh dear, oh dear!”

Then she stopped talking. Peter Punk and Polly Ponk both understood what she said because they had lived with her so long. Pink couldn’t understand because he was only a baby and he kept saying in animal language:—“Let’s go on. I don’t like this place. There’s nothing to eat here.”

“I do think it’s a shame,” Polly Ponk said to Punk, “that the old woman should be turned out. Did you see the way that stupid man slammed the door after we had gone? I’d like to see him turn me out of my house that way. I’d give him such a peck on his red nose he wouldn’t try it again! But of course she is old, very old. I often wonder how old she really is.”

“She is over a hundred, I know,” said Punk. “Yes, it is a shame she should have to go for that stupid booby. ‘Beefsteak-and-Onions’ I call him. But it isn’t altogether his fault. He’s only sent here from London by his uncle who owns the farm.”

“Well, what are we going to do with the old lady?” asked Ponk. “She can’t stay here.”

They set Pink to digging truffles

“We will wait till she falls asleep,” said Punk. “Then we’ll go into the woods and find a cave for her to spend the night in and cook something to eat.”

“Isn’t she asleep now?” asked Ponk. “Her eyes are shut.”

“No,” said the dog, “she’s crying. Can’t you feel the seat shaking? She always shuts her eyes and shakes when she cries.”

Presently the old lady and the pig began to snore together. So they waked poor Pink up and all three went into the woods. They set Pink digging truffles and Polly Ponk went off to the river and caught a fine trout while Punk got sticks together and made a fire.

“Now who’s going to do the cooking?” asked Punk.

“Oh, I’ll do that,” said Ponk.

“Can you cook?” asked the dog.

“Indeed I can,” said Polly Punk. “My Aunt Deborah used to cook at a hotel and she showed me how. You get the fire burning and I’ll soon have the fish fried.”

So very soon they had a nice meal ready of fried trout and truffles for the old lady.

“Now,” said Punk, “we must go into the cave and get a bed ready for Mrs. Tubbs.”

So they went into the cave and made a fine, soft bed of leaves.

“What shall we do for a pillow,” asked Punk. “Shall we use the pig, he would be nice and soft?”

“No,” said Ponk, “I’m going to use him as a hot-water bottle. It’s very important to keep the old lady’s feet warm. But I have some feathers back home which will make a fine pillow. They are some of my own which I kept last moulting season.”

“What did you do that for?” asked Punk.

“Well,” said the duck, standing first on one foot then on the other, “the fact is I’m not getting any younger myself and I thought that if, when I am very old, I should get bald, I could have them stuck on with glue or something. I’ll fly over to the farm and fetch them. I know just where I put them: they’re in the left-hand drawer of my bureau under my lavender bonnet.”

With a flap of her wings she flew over the tree-tops to the farm and in a minute was back again with the feathers in a bag.

When they had everything ready they went and fetched Mrs. Tubbs and showed her the supper they had prepared. But the old woman would not eat anything but kept saying,

“Oh dear, oh dear! What shall I do? I am turned out of house and home, and me an old woman!”

She cried herself to sleep

So they put her to bed in the cave, covered her over with leaves and placed Pink at her feet as a hot-water bottle. And presently she cried herself to sleep.

Punk and Ponk now began to worry over what they should do with the old woman next.

“She can’t stay here,” said Ponk. “That’s certain. You see, Punk, she isn’t eating anything. She is so upset and she is so old. What we’ve got to do is to find some way to turn that booby out of the farm so she can go back and live there.”

“Well, what shall we do?” said the dog.

“I don’t just know yet,” Polly Ponk answered.

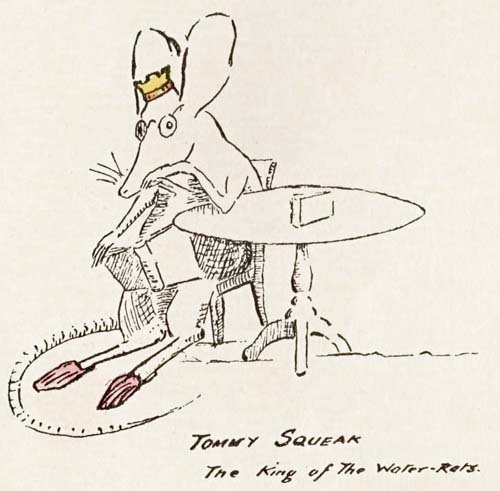

Tommy Squeak

The King of The Water-Rats.

“But in the morning before she wakes up, we must go back to the farm and see what can be done.”

So next morning, while the old woman was still asleep, off they all went as the sun was getting up behind the woods. Just before they got to the farm as they were crossing the bridge over the stream, they saw Tommy Squeak, the King of the Water-rats coming down for his morning bath in the river.

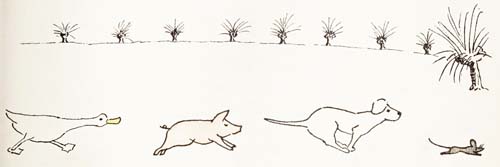

“Catch him!” said Ponk. “Perhaps he’ll be able to help.” And they all started running as hard as they could after the water-rat. Poor Tommy Squeak was dreadfully frightened at seeing a dog and a pig and a duck coming after him, and he made off for the river as fast as his legs would carry him. When he came to the river he jumped in with a splash and disappeared. Punk and Pink sat down on the grass and said,

“We’ve lost him!”

They all started running as hard as they could

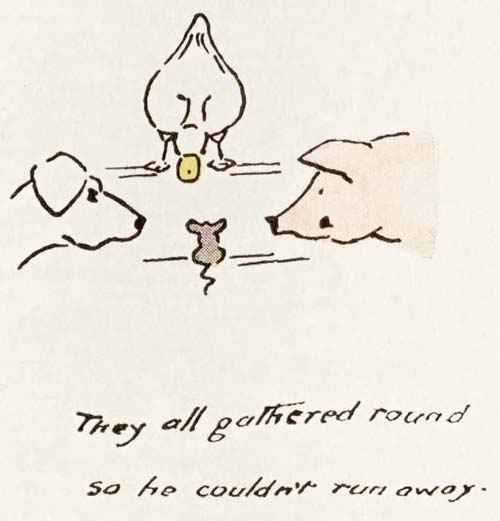

But Polly Ponk, running up behind, never stopped but dived into the river, swam under the water and just caught poor Mr. Squeak as he was popping into a hole way down at the bottom of the river. She pulled him up by his tail, carried him to the shore and put him on the grass. Then they all gathered round him so he couldn’t run away.

“Now,” said the duck, “don’t be frightened. Stay where you are and do as you are told and we won’t hurt you. Listen. Do you remember, last summer, when you were stealing cheese from the pantry up at the farm, and you fell into a bucket of water and Mrs. Tubbs came and caught you? Do you remember?”

They all gathered round so he couldn’t run away.

“Yes,” said Tommy Squeak, shaking the water off his whiskers, still very frightened.

“And she didn’t hurt you or give you to the cat. Do you remember?”

“Yes,” said Tommy Squeak.

“She let you go and told you never to come back again. Did she not?”

“Yes,” said Tommy Squeak.

“You know that she is the kindest woman to animals in all the world, don’t you?”

“Yes,” said Tommy Squeak.

“Allright,” said Polly. “Now listen. A red-faced booby from London Town has been sent down here to turn Mrs. Tubbs out of her house. She is terribly old, as you know; we have taken her up into the woods. But she won’t eat her food, she is so sad, and we can’t do a thing with her. The Winter is coming on and we must get her back into the farm somehow. Now you are the king of the water-rats and this is what you must do: Call all the rats of the river together—every one of them—thousands of them, and take them to the farm. Then worry the booby every way you can think of. Rattle the pans in the kitchen at night so he can’t sleep. Pull the stuffing out of the chairs. Eat holes in his best hat. Do everything you can to drive him out. Then, if he goes back to London Town, we can put Mrs. Tubbs back on the farm.”

“Allright,” said Tommy Squeak. “I’ll do my best for the old woman. She certainly ought to be put back on the farm.”

Then he stood up on his hind-legs by the river-bank and facing up the stream, he gave a long, loud, wonderful squeak. Then he turned and facing down the stream he gave another.

“Rats,” he said, “we have a job of work to do”

And presently there was a rustling sound in the grasses all around and a whispering sound in the bushes and a splashing sound from the water. And everywhere rats appeared, hopping and jumping towards him—big ones and little ones, black ones, grey ones, brown ones, piebald ones—families of them, hundreds of them—thousands—millions. And they gathered round Tommy Squeak the King-Rat in a great, great big circle. Their beady, black eyes looked very frightened when they saw a dog there but they didn’t run away because the king had called them.

Then Tommy Squeak stood up to speak to them and they all stopped cleaning their whiskers to listen.

“Rats,” he said, “we have a job of work to do. Follow me.” And waving his paw to Punk, Ponk and Pink, he led the way to the farm.

For a whole day and a night the rats worked very hard, trying to turn the man out. They rattled the pans in the kitchen at night. They pulled the stuffing out of his chair. They ate holes in his new, green hat. They stopped the clock. They pulled the curtains down upon the floor. But the man sent to London Town and got three wagon-loads of cats and the rats were all driven back to the river. Tommy Squeak came to Punk, Pink and Ponk on the second day and said,

“I am sorry. We did our best, but we couldn’t move him.”

Tilly Twitter

The Queen of the Swallows

So Ponk said to Punk, “Well, we must try something else.” And they left the old woman in the woods and started off again.

As they were crossing the river this time before they got to the farm, they saw Tilly Twitter, the Queen of the Swallows, sitting on the corner of the bridge.

“Good-morning!” said Tilly. “You all look very sad.”

“Oh, Tilly,” said Punk, with tears in his eyes, “Mrs. Tubbs has been turned out of house and home.”

“Good gracious!” cried Tilly. “You don’t say! Who turned her out?”

“A man from London,” said Punk. “I call him ‘Beefsteak-and-Onions.’ Do you think you can do anything to help us get her back to the farm?”

“Certainly I’ll do my best,” said Tilly, pushing her crown further back on her head. “I have built my nest over the old woman’s door for three Springs now. I would hate to have her leave the farm for good. I’ll see what I can do.”

Then she flew up into the air going round and round in circles. Higher and higher she flew and all the time she sang a beautiful song at the top of her voice.

And this is the song she sang:

Now every year when all the swallows heard Tilly Twitter sing this song they knew it was time for them to get together to fly to Africa because they don’t like the winter’s cold in England. So now when they heard it they got their children together and snatching up their bags and bundles, they all flew towards Mrs. Tubbs’s farm. So many of them came that the sky grew dark and people thought the night was come. And the farm-boys in the country around stopped their plough-horses and said, “There go the swallows, getting ready to fly to Africa. The frost will soon be here.”

For five hours they kept coming, more and more and more of them. They gathered around Tilly, sitting on house, on the barn and the railings, on the gates, on the bridge and on the stones. But never on the trees. Swallows never sit on trees. So many of them came that the whole land seemed covered with the blue of their wings and the white of their breasts.

And when they had all arrived Tilly got up and spoke.

“Swallows,” she said, “many years ago, when I first built my mud nest under the eaves of this farm, I had five children in my nest. They were my first family and I was very proud of them. That was before I became the Queen of the Swallows. And being a very inexperienced mother I built the nest too small. When my children grew up there was not proper room for them. Philip—a very strong child—was always twisting and turning in the nest and one day he fell out. He bumped his nose badly on the ground but it was not far to fall and he was not much hurt. I was just going to fly down and try to pick him up when I saw a large weasel coming across the farm-yard to get him. My feathers stood up on the top of my head with fright. I flew to the farm-house window and beat upon the glass with my wings. An old woman came out. When she saw Philip on the ground and the weasel coming to get him she threw her porridge-spoon at the weasel, picked Philip up and put him back in my nest. That old woman’s name was Mrs. Tubbs. She has now been turned out of her house and a very stupid red-faced man is living on the farm in her place. We have got to do our best to turn him out and put Mrs. Tubbs back in her house, the same as she put my child back in his nest. So I have called you all together a week earlier than usual this year for our long journey to Africa, and before we leave England we have got to see what we can do. The first thing we’ll do is to stop up his chimney so his fire won’t burn. Then put mud all over the windows so the light will not come in. Bring all the straw from the barn and fill his bed-room with it. Take his best neck-tie and drop it in the river. And do everything you can to drive him out.”

So the swallows set to work and Punk, Ponk and Pink went back to the old woman in the woods.

But after two days Tilly came to them and said,

“I am very sorry, but I have not succeeded. The cats have driven my swallows away. He has a thousand cats in the place. What can one do?”

So Punk said to Ponk, “We must go out and try something else.”

But Polly Ponk answered,

“No, you go alone this time. The old woman is getting a cold and I must stay and look after her.”

So Peter Punk went off with his tail dragging on the ground. He hung about the farm and was very sad and wondered what he could do to drive Beefsteak-and-Onions out of the house.

He looked into the hole

Presently, feeling hungry, he remembered he had hidden a ham-bone in the trunk of a tree behind the house some weeks ago and he went off to see if it was still there. When he got to the tree he stood up on his hind-legs and looked into the hole. A wasp flew out and stung him on the nose. He sat down on the grass and watched the tree for a minute and saw many wasps coming in and going out through the hole. Then he understood what had happened. Thousands of wasps had made a nest in the hollow tree.

They set upon him and stung him

So he thought of a plan. He went and got a big stick and threw it into the hole in the tree. Then all the wasps came flying out and tried to sting him. He went running towards the house with the wasps after him and ran in through the back door of the house. The wasps kept following him—though a few stopped to sting some of the cats that were hanging about the back door. Then he ran up the stairs by the front staircase, into the bedrooms and down by the back-stairs. In the hall he found Beefsteak-and-Onions, who had just come in from digging potatoes, with a spade in his hand. Punk ran between his legs and out through the front door.

When the wasps could not find Punk any more they thought the man had hidden him somewhere so they set upon him and stung him. And the rest of them stung all the cats they could find in the house and drove them away across the fields.

Poor Beefsteak-and-Onions ran out into the yard and shut himself up in the barn to get away from the wasps. Then he laid down his spade and put on his coat and said,

“I’ll leave this house today. My uncle can come and live here himself if he wants to. But I’m going back to London Town. I didn’t want to turn the old lady out anyway. I do not believe my uncle knew anyone was living here at all. I am going today.”

Punk was listening outside the door and heard him, so he ran off at once back to the woods. When he got to Ponk and Pink he started dancing on his hind-legs.

“What’s the matter?” asked Ponk. “Have you gone crazy?”

But all he answered was:

They all walked back to the farm by moonlight

Then he told them how he had at last succeeded and they both thought he was a very clever dog.

It was now getting late in the evening so they went and got Mrs. Tubbs and they all walked back to the farm by moonlight.

And the old woman was so happy to get back to her little house that she made them all a very fine supper. And Pink said,

“I am glad to get back. There is something to eat here.”

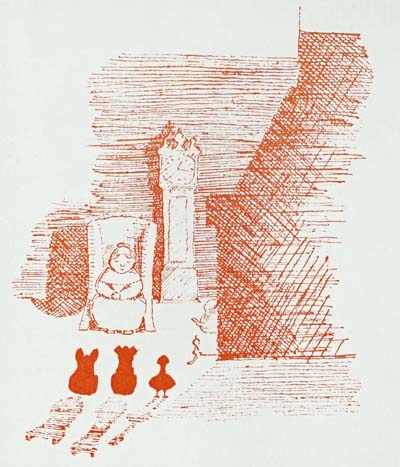

They used to sit round the warm fire

And so when the leaves were all fallen in the woods, and the trees stood bare waiting for the snow, they used to sit round the warm fire in the evenings toasting chestnuts and telling stories while the kettle steamed upon the hob and the wind howled in the chimney above. And they never had to leave the farm again and they all lived happily ever after.

THE END

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation have been standardized.

The cover image for this eBook was created by the transcriber using the original cover and is entered into the public domain.