| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/inquestofeldorad00grah |

IN QUEST OF

EL DORADO

BY

STEPHEN GRAHAM

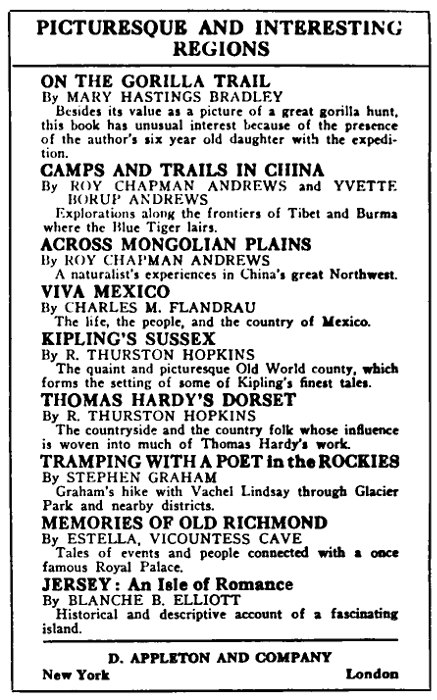

AUTHOR OF "EUROPE—WHITHER BOUND?" "TRAMPING

WITH A PORT IN THE ROCKIES," ETC.

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK :: :: MCMXXIII

COPYRIGHT. 1923. BY

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

The literary memory

of my friend

Wilfrid Ewart

Accidentally shot at Mexico City

Old Year's Night, 1922

Having voyaged twice to America from British ports and once from Copenhagen, I determined on my fourth visit to approach America from Spain and try to follow Columbus's keel over the waters. This study of the quest of El Dorado is mostly on the trail of the Spaniards. The motive of the first explorers and pioneers was generally the quest of gold. And even to-day most people who seek America do so to make money, many to make a fortune. There is, therefore, a continuity through the centuries of the quest of fortune.

My wife and I took Spanish ship from Cadiz in Spain to the Indies; landing at Porto Rico, whence we visited in turn Haiti and Cuba. I saw San Salvador, the first land Columbus found, and was also in the Bahamas. We proceeded to New Orleans and then to Santa Fé in New Mexico. I visited Panama, however, alone and climbed a peak in Darien, to realize once more what it meant to Balboa when for the first time his eyes lighted on the Southern Sea. After the Panama exposition I was joined by Wilfrid Ewart and with him we followed out some of the fantastic adventures of Coronado, and it took us to the famous Shaleco Dance at the "center of the earth." With him my wife and I rode to Jemez, and later we visited Mexico, where, unfortunately, Wilfrid Ewart was killed by a stray shot on Old Year's night. In Mexico we followed the trail of Cortes, visiting the places which are most memorable in his conquest of Mexico. This took us to the ancient pyramids of the Anahuac plateau and to the ruins and buried cities of the South.

Throughout the descriptions and interpretations, endeavor is made to measure the quest for power and the quest of gold in all these countries and territories. I have not visited the republics south of Panama, but have confined myself to what an American general has called "the necklace of the Caribbean"—the potential American dominion of the future. The drive of events is making democratic America into an empire. An imperial rôle is almost unavoidable. I have not, however, thought it necessary either to criticize or approve imperialism. I have made an Odyssey and I tell what I saw, not as Ulysses would have told it, but as one of those who at many points was ready to eat the lotus and not too mindful of Ithaca and home.

My thanks are due to the New York Evening Post, which published many letters from far-off places, and to the American Legion Weekly, which, under the title of "Panama and Pan-America," published my essay on the Canal.

Stephen Graham

| BOOK I | ||

| SPAIN | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In Madrid | 3 |

| II. | En Route for Cadiz | 21 |

| BOOK II | ||

| THE INDIES | ||

| III. | The Columbus Journey | 31 |

| IV. | Porto Rico | 40 |

| V. | Santo Domingo and Haiti | 52 |

| VI. | Cuba | 73 |

| BOOK III | ||

| NEW MEXICO | ||

| VII. | At Santa Fe | 87 |

| VIII. | Cowboys | 94 |

| IX. | Indians | 104 |

| X. | Mexicans of New Mexico | 121 |

| BOOK IV | ||

| PANAMA | ||

| XI. | From New Mexico to the Isthmus | 131 |

| XII. | Climbing a Peak in Darien | 135 |

| XIII. | Republics of Panama and Nicaragua | 157 |

| XIV. | The Canal | 163 |

| BOOK V | ||

| CIBOLA AND QUIVIRA | ||

| XV. | Panama to New York | 179 |

| XVI. | America of To-day Viewed from New York | 186 |

| XVII. | Across America North to South | 202 |

| XVIII. | The Dance of the Jemez Indians | 210 |

| XIX. | The Dance of the Zunyi Indians | 230 |

| XX. | Descent into the Grand Cañon | 250 |

| XXI. | Good-by to the Horses | 260 |

| BOOK VI | ||

| MEXICO | ||

| XXII. | The Gold | 265 |

| XXIII. | Approaching Mexico from the North | 269 |

| XXIV. | At Montezuma's Capital | 281 |

| XXV. | In the Footsteps of Cortes | 295 |

| 1. Cortes | 295 | |

| 2. Vera Cruz | 297 | |

| 3. The City of Jalap | 300 | |

| 4. At Tlaxcala | 303 | |

| 5. The Pyramid of Cholula | 306 | |

| 6. Texochtitlan | 310 | |

| 7. In the Marquisate of Oaxaca | 314 | |

| 8. Under the Great Tree of Tule | 323 | |

| 9. From the Ruins of Mitla | 326 | |

| 10. Ad Astra | 330 | |

SPAIN

IN QUEST OF EL DORADO

I carried on my shoulder through the streets of Madrid Maria del Carmen de Silva y Azlor de Aragon. She was too proud to admit that she was tired, but was ready to accept the unexampled adventure of being carried in that way. Beside us prattled her brother, Xavier de Silva y Azlor de Aragon, called Chippy for short. They are beautiful, evanescent-looking children, fairies rather than boy and girl, and nothing like the swarthy barefooted urchins who beg of you, who want to clean your boots, who want to sell you water, in every town of Spain. They look as if they had been studied from paintings before they were created. Velasquez painted them, and the children were created from his model—as the shadelike figures of the pictures of El Greco are reproduced in the ballet.

My mind went back to that morose figure of the history-book, Catherine of Aragon—Spain always makes the mind go back. Here I carried Carmen of Aragon on my shoulders, and it might be Henry the Eighth's first Queen, reincarnate as a little child.[Pg 4] It is part of the unfairness of the history-book that we only see a woman like Catherine soured and disillusioned and out of her national setting. She is only interesting as the wife who caused the English Reformation, and the mother of Queen Mary of the Smithfield fires. But she may have been some time a happy little child like Carmen, beautiful and innocent, a face to put with the Madonna, to look up at her with flowerlike adoration.

The uncle of the children is the present Duke of Alva, with the wonderful name of James Fitz-James Stuart and the amusing supernumerary title of Duke of Berwick, a tall and slender and haughty grandee who lives a life remote from public haunt, remote enough to-day from the page of history, the Low Countries and the scourge of heretics.

So Carmen of Aragon pinches my ears as we stoop to avoid awnings and sun-screens, and she laughs like a Raphaelesque infant-love, and the yellow parrots from upper windows scold us. Dark women, with nine-inch or foot-long combs standing up from their back hair, and black veils (mantillas) hanging over their heads instead of hats, stare at us and smile. They survey me from my brown boots to my brown mustache, to my red cheeks, to my blue eyes, and they recognize the brood of the pirates. Inglese, Inglese, they whisper.

I have not often been taken for an Englishman, but the Spaniards have no doubt. I may change my attire, I cannot change something. They have seen my like before. Instinctively they don't altogether like me. Instinctively I don't care too much for them, with their bull-like heads and all their somber[Pg 5] eyes. There's something in the air which bids me think of thumbscrews. It may be the inherited bad conscience of the Drakes and the Raleighs and the dogs who harried the Plate Fleet four hundred years ago, or it may be the horror in the bones which the association of Spain with human cruelty has bred in the mind.

We walk from the Puerto del Sol, the Harbor of the Sun,—has not every city in Spain and in the Indies a Puerto del Sol?—a confluence of streets and tramcars in the heart of the city, to a sort of baronial mansion in a narrow street. And there live a community of dukes and duchesses, marquises and marchionesses in suites of apartments. Though not castellated the house is massive as a castle, all of stone, and built sheer on the too narrow pavement of a narrow cobbled street. The entrance is from a recess in the frontage of this stronghold, and as you step inside you leave behind the street, its trams, its cries, and enter the stillness of history.

The stone stairways and stately halls are hung with historical paintings of the families and with the spoils of battles fought long ago. Here is a great lamp clutched by a Saracen's hand. It was taken after the battle of Lepanto. There, in cases, are great keys of the gates of the cities of Bruges and Ghent, taken in the wars of the sixteenth century. The gold, the jewels, come from the altars of Mexico and the idols of the Indians. The intervening centuries do not speak. Speaks only the great era of Spain.

The mind leaps from that romantic time back to ours, with those wars and quarrels from which the[Pg 6] Spain of to-day prefers to stand aloof. The gold which men got in quest of El Dorado, the gold which they piled on ships and guided past English and French pirates, gold which was the royal fifth, gold of the Plate Fleet, gold that was private fortune, the repairing of the splendor of the impoverished nobles of Castile, has been melted down and become national treasure, or currency, or personal adornment, or war-indemnity, or war-chest, or reparations. Some of it has been in the Treasure Tower of Spandau, some is in the vaults of Washington. All men have had their hands in it. Only a little remains in Spain, gilding altar-screens, making showy merchants' chains, weighing in the treasures of the Escurial. Rapacity for gold killed Spain, we are told, and yet Spain has survived in a quiet, old-fashioned, dignified mode of life, and cares less to-day for gold than the rest of the nations.

That, however, concerns very little my Carmen of Aragon, who will pass through life without ever knowing anything of reality, marrying some prodigiously polite grandee and not a bluff and cantankerous English Henry. She laughs, she imitates all I do or say, she walks away, and Chippy takes one of my hands in his and leads me to his mother, quiet and simple and pious and demure, all in dull black velvet. To-morrow I shall go to the Palace and see the King and Queen and the grandees and their ladies wait on twenty-four of the poor of Madrid.

You enter Spain through glass doors and see written up "Silence." You open your guidebook[Pg 7] and find you are looking at Exhibit A. I have been told that Spain is like Russia, but there is this difference. Belief in Russia will survive the decease of Russia by at least five hundred years. Something is coming out of Russia: yes, but out of Spain—?

No one goes to Spain to see the future. Many go there to see the past, sticking out as it were through the present. And so with me—to make a sentimental journey and trail an idea geographically across the world. I should like to see Columbus again, see him in the midst of the courtiers and mocked by them, and see upon him the smile or frown of Ferdinand and Isabella. My eyes would like to feast on the cloth of gold of the grandees of Spain—go back four centuries and yet be in to-day, and see as it were in a vision the gold of Old Spain and the gold of the Indies, the beautiful bright gold that may be sacrificed but must never be worshiped.

So I am pleased to go to the Royal Palace at Madrid on Maundy Thursday and see the King and Queen and the Court in the gorgeous ceremony of the washing and the feeding of the poor. Once every year it is done; the Queen tends twelve poor women, the King tends twelve poor men. They are usually all blind. It has been done for centuries. Ferdinand and Isabella did it also, and Columbus must have watched them in his day, saying of those who mocked him—"They are the blind; wash them and feed them also."

As we stand in an interior court of the palace behind a row of halberdiers in quilted coats the[Pg 8] chime of eleven o'clock seems to blend with Southern sunshine, and there breaks out from a hidden orchestra mysterious Eastern music heralding the approach of to-day's King and Queen. Searching, questing strains tell of mystery, of aching loneliness and hidden loveliness—the haunting introit of Milpager's "Jerusalem." Erect stand the stately halberdiers in their scarlet coats, holding at arm's length their bright halberds of Toledo steel. And along the corridors of the palace come carelessly and as it were at random, in twos and threes, talking together, the Duke of Alva, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the Duke of San Fernando, the Marquis of Santa Cruz, the Marquis of Torrecilla, and other nobles, all dressed in gold-embroidered coats and wearing orders and insignia and medals. They are the grandees of to-day, and their faces peer out strangely from the midst of their grandeur—peering out, as it were, from their family trees, from time itself.

Come the King and the Queen, and the King is wearing the uniform of an infantry captain, for this King is democratic, but over his shoulders hangs the magnificent collar of the Order of the Knights of the Golden Fleece. I wonder if the Emperor Charles Fifth, Cortes' Emperor, instituting this order of the Golden Fleece, thought first of his Spaniards as the Argonauts of the age, the youth of Spain aflame with a vision of gold. The golden collar hung in a long V on the King's back and seemed to have worked on it some noble history, reminding me there in the midst of the crush of the palace, of that perfect Spencerian verse,

Columbus was a Jason of a later time, and there were many other Jasons and would-be Jasons—Cortes, Pizarro, Balboa, Coronado.

The democratic King Alfonso wears his collar, however, with an easy grace, and there is upon his visage a whimsical expression which remains. The Queen looks more like a queen than he does a king. She is wearing the diadem, and she walks like a queen in a picture, her long cream veil of lace enveloping her, trailing downwards and backwards as she walks. Her ladies are in luminous silks, with high combs in their hair, and long lace mantillas like the Queen's, cream-colored, hanging from their combs to the hems of their robes, giving them the mystery of beauty which is part hidden and part revealed.

Following them go the diplomats of all nations, all differently dressed in the full Court dress of their respective nationalities. And they wear their stars and their ribbons, too. There goes the Chinese Ambassador with embroidered golden dragons on his velvet coat; there goes the American Ambassador in spotless lawn and glimmering white tie. The French and the Italian ambassadors look like diplomats, men with old secrets, profound players[Pg 10] of human chess; even the English Minister looks as if he knew more than he would ever say, but the American is quite different, a new piece of cloth on a very old garment, as it were upon Joseph's coveted coat of many colors. His fresh, clean-shaven and young face surmounted on its stiff linen collar may have been recruited to diplomacy, and quite likely was, from a guileless Christian brotherhood. Though why turn the light upon him, unless it is because the Power he represents is the power in the New World which to-day affects most the liberties of the children of Spain overseas. Their representatives are here also, of Mexico, of Nicaragua, of Cuba, of Colombia. And here in state comes the "Patriarch de las Indias" himself, and with him the Papal Legate to Spain, the leaders of the Cortes, the Prime Minister, the Government.

All pass, and the halberdiers close up and the public follows, the chosen public asked to witness the monarchs' charity. It is so arranged that all take up their places in the chamber where the poor are waiting, and then the King and Queen come in.

I stand away at the back and look through the veils and screens of the hundreds of ladies' mantillas which hang from the high combs in their hair. It is as if the scene were too gorgeous and had to be viewed through a glass darkly. But yonder are the poor blind waiting in stalls, twelve black-shawled old women waiting for the Queen, twelve empty-eyed men in silk hats waiting for the King. In front of them all stand golden ewers with water, and the ritual of washing commences. One spot of water is dropped on each foot. One rub of the[Pg 11] towel to each, and then, stooping, the Queen kisses each woman's big toe; the King kisses each man's big toe, too. Stately Queen Ena never changes her devout expression, but democratic King Alfonso, who rules by smiles, makes a comical face all the while.

Follows the feeding of them. All the grandees and their ladies take part. The Queen takes the center on one side of the room, the King on the other. Vast quantities of viands are brought from the kitchens and pantries of the palace. Begins the Comida de los Pobres, and every helping is enough to feed a family, and every helping is given personally by King and Queen to the chosen poor.

The King smiles all the time, and eats bits of what he gives, and tries to persuade the Archbishop to eat also and so break his fast, part of the King's prevalent facetiousness and jollity. Did he not make a wry face over kissing each old man's foot, as if it really were disgusting? Does he not on purpose break up the solemnity by dropping round rolling cheeses on the floor and letting oranges slip out of his hands? That makes all feel happy, all except the blind. They see nothing; they do not even eat; all that comes to them is taken away and packed into hampers to be sent to their homes. Their happiness is deferred. It is always so with the blind. They enjoy later what those who see enjoy in anticipation. As the King and Queen moved to and fro in that gilded crowd it seemed I saw Columbus there. He saw, and he gilded the grandees in time with a deeper crust of gold.

Spain's positive contribution to civilization is a sense of human dignity. This is shown in private life by elaborate manners and the instinctive respect of man for man. Other nations used to have it; it is a marked characteristic of Shakespearian drama, but revolutions have removed it. In Spain there is a delicacy of approach to strangers and even to friends which is unknown in the rest of the world. The bows, the marked attentions, the gravity and stately style of the Spaniard contrast remarkably with the self-enwrapped sufficiency of the Germans, the unrestraint of the Americans, the humorous slap-dash of the English and "devil take the hindmost" of the Scotch.

The Spanish houses too, with their noble portals, interior courts, patios, fountains, bespeak a sense of dignity. It is not a country of deal front doors and bottle-neck passages like England, nor of porches and porch-swings like America, nor of doors on the street like France. It is true that the interiors are devoid of fancy upholstery; there is a bareness as of a castle, an asceticism which expresses itself in straight-back chairs. But there will be flowers blooming and birds singing—there will be a graciousness which is often missed in the seemingly over-comfortable, over-hospitable interiors of English and American houses.

Gravity goes so far with the Spaniard that he hardly will be seen wearing tweeds. Loud attire is an offense. The Spaniard wears black and seems to wear it out of general respect. The women,[Pg 13] moreover, do not flaunt their fashions in the churches or the streets. In Madrid the reproach cannot be made that you cannot tell the monde from the demi-monde; the latter is always more indiscreetly dressed. The Queen of Spain has no legs.

You still drive with horses in Madrid; it is more decorous than the ill-mannered car bursting with speed even when going slowly. And the rudeness of the klaxon and the tooting horn are distasteful to the Spaniard. Behind fine horses, at ease, leisurely and graciously, there it is true the women will show what Paris wears.

Then in the ways of men to women the Spaniard surely has the first place for real politeness and regard. The French say place aux dames but do not give it. The Englishman is gallant with women when they are good looking or if they remind him of his mother. But the Spaniard's politeness is invariable.

Doubtless the French at their best come nearest to the Spanish in their respect for one another, just as the North-American Yankees are furthest from them. The French are the most humane people in the world, because the most tolerant; and ever so much less cruel in temperament than the Spanish. But their cochonnerie, the ribaldry of their burlesques, the wretched homes, the open and stinking conveniences of the capital of civilization, decency forbids in Madrid.

With all that, however, let a caveat be entered. The Spanish hold something which is increasingly[Pg 14] valuable in our modern human society because it is all the while getting rarer—the gold of good manners. That is true, and must remain after all adverse criticism of the race. But the Spanish have a negative characteristic which through the centuries has outraged the fellow-feelings of the rest of humanity, and that is cruelty, a lust for torture.

The Auto de Fe, the ordeals of the Inquisition dungeons, these in the past; the survival of the bull ring and the plaza de gallos, these to-day and, remarked at all times, the Spanish inhumanity to horses, seem to outweigh good manners. And the behavior of the crowd about the bull ring—hideously burlesque and unrestrained, may perhaps have marked the crowds who in Seville in the sixteenth century watched brother men burn to death for the good of the Holy Father at Rome and the greater glory of God.

Spain lovers have said to me, "Do not go to the bullfight!" But in facing Spain as in facing any other country with some desire to know it, not merely to be struck by it, one must face what is dark and sinister as well as what is beautiful and annunciatory.

Hence a visit to the Square of the Bulls at Madrid on Easter Sunday, and the King is there and the President of the Sport, and a vast populace in sun and shade. Christ rose this morning; this afternoon six bulls must die. He rose indeed. Fifty thousand church bells told the world, lilies triumphant rose from bare boards in every home; we and all the children ate eggs of peace. This[Pg 15] afternoon—Easter has gone—the populace will watch the bulls.

Next to me on the one hand sits a Japanese artist with a score of paper fans. In front are Madonna-faced women with high yellow combs in the crown of their hair and cream-colored lace hanging therefrom in an exquisite effect. The Japanese has crayons and decorates his blank fans rapidly. Group after group he sketches in on these fluttering fans, and then the grand parade of toreadors in all their finery, and then the picadors, and then the fighting. He is concentrated; he seems to feel nothing, but when his twenty fans are done he gathers them together, picks himself up, looks round him circumspectly, and departs.

I suppose bullfights are seldom described except in Spain and the Latin-American countries. In these, the descriptions may exclude all other news and cover whole issues of daily papers with colored supplements as well. But for peoples other than Spanish there is something that is intolerably cruel in the bullfight. It is even thought a little compromising in a public person to have visited one. A British Prime Minister on holiday in Andalusia indignantly denies that he went to a bullfight. It would lose him votes in England. Yet Spain is part of the civilized world and her conscience seems untroubled. Great crowds flock to see them, and in Madrid or Seville on a Sunday afternoon all the town is moving one way. Every city in Spain has its permanent amphitheater for bullfighting, and you may see as many as ten thousand spectators in the circles, tier upon tier, around the arena. On no[Pg 16] other occasion could one see as many Spaniards together. The bullfight is for them a great national turnout.

The bulls, which have led a happy country existence up till now, are waiting, each for his last gory twenty minutes. The picadors will prick him, the staff will plant the banderillas in him, the matador will endeavor to plunge a sword into his heart, the public will hiss or clap, the asses will drag the stiff carcass around the arena and away.

A great door opens. Into the arena plunges a big black bull—"into this universe and why not knowing." He is full of mad energy and bolts for any red flag at any distance that his short sight will show him. The elegant toreros save themselves by hiding behind screens or jumping low walls. And while the bull stands thwarted and puzzled, in comes a doleful procession from the wings. The picadors arrive—men with long lances mounted on starved, jaded, spectral-looking horses. The horses are blindfolded; they also have their vocal cords cut, and whatever happens to them, dumb animals will be dumb. The men mounted on them have strong wooden saddles with hooded stirrups and their legs are cased in iron. The toreros with their red and blue capes, and the attendants dressed in deep scarlet, try to lure the bull towards the horses. They stand in front of them and then nimbly step out of the way when the enraged bull charges at them. The picadors drive their lances deep between the shoulders of the bull; the bull murders the horse, lifts horse and rider in the air; the first picador saves himself. His work is done. The[Pg 17] second then comes forward, pricks the bull, and has his horse disemboweled. The third does the same. The fourth horse refuses to come into position to be butchered, and escapes with a laceration. The time allotted to the picadors has run out, anyway. One horse lies dead. The remaining horses are beaten till they rise, and the picadors mount them again, though the entrails are hanging out of them, and they ride them out of the arena.

The bull is bleeding. He is greatly enraged. He paws the ground like a dog seeking a bone; he bellows, he charges here and there, and always misses! But the toreros plunge colored darts into his back till he is hanging in a clatter of them, and he cannot shake them out. Then comes the matador, dressed like a gentleman, gold-embroidered, gallant, with his hair in a tiny queue behind, with his blood-red cape, with his straight flashing blade of Toledo. He faces the bull alone, and tempts him and fools him. It is part of his art to perform various showy tricks and deceits, jump the bull's back and the like. On these his repute as a bullfighter depends. Then he must beguile the bull into a convenient attitude for dispatching him in the right way. It is not too easy. The impatient crowd, which bawls and guffaws and cries out witticisms, now hisses and taunts the fighter and claps the bull when the bull makes an aggressive onslaught. The matador must take a risk and make an opportunity. Twice he essays; twice he loses his sword. New swords are brought him. And at the third attempt he puts two feet of steel into the life-blood of the bull.

The bull pauses, stares, still flourishes his horns, keeps his enemies at a distance and then, beginning to lose consciousness, kneels down on his front knees like a cow taking a rest in a meadow. The toreros are all around him. He stares at them with glazing eyes. Then the matador plucks out his sword and the bull rolls over dead. Trumpets blow; out comes the troikas of asses, and one set is harnessed to the dead horse and the other to the body of the bull. In the circles of the amphitheater ten thousand voices are busily discussing it, but ere they have got far in talk the arena has been cleared and all are hushed as the great door opens and bull number two comes rushing on to die.

It makes a devastating impression on the heart of the Northerner; makes you, for that afternoon at least, hate Spain. It is so depressing that for days you cannot get over it. The horror of it haunts one as if one somehow had learned that humanity had gone wrong and no life anywhere was worth while.

Curiously enough, however, you meet Englishmen and Americans who have been many times. I sat next to an Englishwoman who somehow had come to enjoy the fight—thought the matadors so elegant, so wonderful, thought they ran such a risk (and so they do), excused much on the ground that the meat was sold cheap to feed the people of the slums.

And now some time has elapsed, and I can well understand it. Despite all the horror and pain of it I also feel a persistent craving to go again. There is a fatal fascination in this brutal sport.[Pg 19] You want to see those fearsome bulls killed; want to look on at death. The last Englishman I met had been to twenty-two, yet at his first he was so ill he had almost to be carried out. Cruelty, like other lusts, grows on what it feeds on. Englishmen, though naturally they at first reject it, can take pleasure in cruelty also.

On the Texan Border where under United States law bullfighting is forbidden, the Spanish population still have mock bullfights at religious festivals. In these you may see Sancho Panza mounted on a turbulent ass as picador, and a lot of very broad farce. But there is often a religious element; the matador coming forth as Christ, and the bull, all in red, as Satan. A remarkable reversal of Christian symbolism this—He who returned to Malchus the ear which Peter had struck off will destroy evil with a sword! Still, it is only a game and well in keeping with the spirit of Church-plays in olden times. The parody of the bullfight is much happier than the fight itself.

A deficiency in Spanish character is humor. The Spaniard is very witty, unusually apt at repartee, but he does not easily smile. This is specially noticeable in the children. There is something of the morose in them which does not readily dissolve in laughter or tears. Perhaps this can be taken as a partial explanation of Spanish cruelty. They have somber minds.

Of course one ought not to make the mistake of placing upon the Spaniards the whole of our [Pg 20]iniquity. There is no race that can show a history devoid of cruelty. If the followers of Cortes burned the soles of the feet of the last of the Aztec kings to find out where his gold was hidden, did not the Barons of England do the same to the Jews to furnish them with money for the Crusades; though the Inquisition caused men and women to be burned to death for heresy in Seville are not people to be found in Georgia ready to do the same to-day to Negroes for a smaller offense? Is there a page in Spanish history which shows more inhumanity to man than has been displayed in the Russian Revolution?

The Spaniard is cruel, it is admitted, and he is cruel in ways which are particularly obnoxious to the Anglo-Saxon who, when he sees a man ill-treating a horse, is almost ready to rush in and kill the man. But other peoples can be cruel also. That does not extenuate the Spaniard's fault, but it is permitted to remark without offense, he is cruel, but he has remarkably good manners; he has a greater sense of the dignity of life.

Travelling by way of Rouen and Chartres to Burgos and Toledo, and by way of Bordeaux to Cordoba and Cadiz prompts certain comparisons—Spain is grander than France; France has more life.

The note of the Gothic is aspiration out of stone, but that of the Moorish is barbaric splendor within stone. The asceticism of stone reigns at Durham, at Rouen, and is somehow transfigured into the loveliness of doves' plumage at Chartres, but in the Spanish cathedrals speaks chiefly gold. It is the same at Burgos, gilded with some of the first gold of Mexico, as it is at the cathedral of Toledo; architecturally unremarkable but interiorly oppressed with riches. As you enter by the old doors it is not so much into the presence of God as into the power of the Church.

Spain is the most faithful son of the Church and France the most reprobate. France, like the prodigal, may nevertheless be nearer to salvation. France is germinative, and, if cynical, yet eternally curious, whereas Spain is incurious. Spain does not want to know. She is the last of the democracies of Europe to rebel. Probably the state of society in Spain could not be defined as a democracy.

The great ports of Spain are, however, different in temperament from the cities of the interior.[Pg 22] Boisterous Bilbao in the north and Barcelona in the south are insurgently democratic. In these is a revolutionary movement pointing against Church and Monarchy. In these there is an energy, a commercial hustle, a will to power, which reminds one of the cities of Northern Italy.

Geographers, map-makers of Europe, seem very much at fault in the way they print the names of Spanish towns. The faint print usually reserved for villages is used for Santander and Bilbao. But these are great and stirring cities with modern buildings which for beauty and strength of design can be compared only with the architecture of the greater cities of the United States. Again, how absurd it is to print Bayonne and Biarritz in large type and indicate San Sebastian, their neighbor across the Spanish frontier, in faint italics. San Sebastian is a magnificent city and a most beautiful resort. You can see Spain there, in the season, at its grandest.

But one would not have been surprised to find Toledo printed fine, for there truly, famous though it be in history, we have an obscure, unchanging seat of the past. Toledo is more truly Spain than is Bilbao or Barcelona. It is the Spain that was. Toledo is a close-packed, mountain-built city of winding, narrow, shady ways and high, overhanging, ancient houses. It reminds one of the Saracen villages high up on the cliffs above the sun-bathed Riviera. It was Moorish and Jewish before it was Spanish, famous throughout the Middle Ages for its steel. They try to sell you Toledo swords in a score of little shops to-day. And, in the past, has[Pg 23] not Toledo steel pushed its way through the vitals of innumerable duelists? And Spanish mail, Spanish armor, Spanish shields and Spanish swords have had an immense repute. It was the southern counterpart of Swedish steel. But Solingen has gone on and made domestic cutlery for the teeming populations of industrialism whilst Toledo still makes swords. Toledo has no street-cars. Toledo has no cinema. It has no Cable office. Its hotels, spacious and quaint, have no rooms with bath, no room telephones. There are barber shops, but the poles do not revolve. Nothing revolves.

There is a pack of some of the most persistent beggars I have seen. Blasco Ibañez says they live on the English and American tourists who visit the Cathedral, and he sneers at the tourists' stupidity and credulity. But if the tourists ceased to come the beggars would not cease to be. This beggary is a disgrace to a rich country like Spain. That small boys should rush in to beg the sugar you have left over from your morning cup of coffee is unseemly and out of keeping with the otherwise stately ways of the people. In Spain thousands beg who could quite well be earning a living, and the mendicancy of these defeats the case of the paralyzed, the blind, the aged, from whom few would otherwise turn away.

In Toledo, however, lurks the great Cathedral, like some strange, rare monster of the past. It is horribly cramped, and seems to be trying to hide its vast, aged form from modern gaze. There lies the dust of kings, emperors, archbishops; undisturbed, unprovoked. It seems the low notes of the[Pg 24] organ should never swell to anything clamorous and new. All is hushed as you walk around; gloom of unlighted centuries is upon you.

From this to the blue sea, what a change! From this to the fresh and breezy harbor of Cadiz. To Spain's window on to the New World, her most romantic starting point in all her history.

It is a long journey! I prefer to go third class. It makes a tremendous difference, for the carriages are always full, always emptying, changing, filling again with Spanish humanity. The second- and first-class coaches are more or less empty; empty also that curious apartment called a "Berlin." There is a train de luxe from Madrid to Cadiz. In that, of course, you can travel in comfort and sleep at night, sleep also by day, and pass the scenery and Spain as rapidly as a millionaire could wish.

This train is called a "mixto," like the smeshanny in Russia. When it comes to a halt the engine-driver gets out. A man on an ass starts off to tell the village that the train has come and that if any one wants to catch it he had better begin packing. It doesn't matter where you get to or when you get there. I took my first day's ticket to a name of a place at random—Vadollano. The booking clerk bade me repeat it, and then sold me the ticket. I occupied myself trying to imagine what sort of a hotel I'd find there. The train commenced its uneasy retardation onward, crawling upward over Spain. Dark but gentle-looking folk filled the carriage, always saluting with a buenos dias when they entered and an adios when they got out, and never starting to eat or drink anything[Pg 25] without offering all around to do the same. My wife and I kept a nicely filled basket and a bottle of sherry, and we joined very happily in the children's game of offering our food, knowing it would be declined. We found, however, that two invitations to a glass of sherry usually overcame the modesty of the peasants who, surprised and pleasantly shocked at finding the wine to be of Xeres, seemed, upon drinking it, to become our friends for life.

The men wore close-fitting black caps or those broad-brimmed, box-topped hats that one associates with pictures of West Indian planters. The women wore long earrings, commonly of tortoise-shell; the men and the children wore many rings; they traveled with birds, frequently bringing their canaries, of which they seemed very fond, into the train with them. In came beggars, in came singers. A blind boy sang folk-songs in a strange, wild tone, rather harsh at first hearing, but growing on the ear. His melodies went from the guttural into the minor, and touched one's heartstrings truly enough. Girls are wearing flowers in their hair, and here comes a sight that reminds me well of the Caucasus—a tight pig of wine. From out the little window we look upon many vineyards, brown, stubbly, scarce shooting green though the season is advanced. It is high land and bracing and yet also a wine country. Men come in with wooden boxes and in these boxes are bungs which they withdraw to drink from the hole.

How the people talk, as if there were springs in their mouths, and each sentence was rapidly and mechanically let loose from the lips. No one has any interest in the view from the window; the only[Pg 26] interest is human interest. However, we pass at points through bull farms, herds of Andalusian bulls waiting for their testing for the bull ring or, having been tested, waiting for that gory last half hour of torment and red flags. The bulls always take the eyes of the people. They have an enormous interest in them. One might almost say that the Spaniard had got a reflection of the bull in his countenance now. The bull is his national animal.

It was very dark by the time Vadollano was reached, for the train was late. I got out and was followed by a half-naked beggar boy who answered no questions, being so intent on begging. Outside the station there seemed to be nobody and no town. I sought a shelter and could find none. In dismay I returned to the station and found the ticket checker of the train, and he advised me to take another ticket to Baeza. The old train was waiting, had not budged, and would wait half an hour more.

And so to Baeza and a mosquito cage bed in a hotel which smelt as hotels smell when they are the worst. Next day we went on to beautiful Cordoba. Here was a new vision of Spain, one less ascetic and fierce than that of the North. The sun had driven out the somber. In Cordoba with its white houses and fresh-blooming flowers, its beautiful gates and doors and interior courts with palms and fountains, we had a vision of beautiful living. The whole of Cordoba is like a precious work of art. I suppose every one who learns to love it must be loath to leave it.

But we are making for that window on to the New World, longing for that new way to India—the [Pg 27]new Spain. The train goes on along the Guadalquiver valley through all the sherry vineyards growing green for miles, the town of Xeres itself, and onward to Gibraltar and the end of the world. And there at the end, far out on a loop of land on the loveliness of the sea, was Cadiz, the city of Armadas and the going and coming of the Plate Fleet, a city now of white houses, Spaniards, cats of all kinds, and innumerable parrots who out-talk humanity on its streets—of all that, but of few ships. I walk along the sea front on that street that bears the proud name Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, and I see three ships, and among them the one that is waiting for me.

THE INDIES

We left the beautiful harbor of Cadiz, with its white houses and palm trees and its daintily silhouetted towers and turrets, and the shores unclasped the blue bay and we rode upon the billows of the ocean.

The ship was a Spaniard and all the people on it were Spanish or West Indian, and the voyage we were making was the one Columbus made, seeking a new way to India and coming upon the Indies. And the first evening and every evening we pushed "our prows into the setting sun," not seeking, of course, but knowing, with the romance of the first journey mostly forgotten.

The passengers are mostly Cubans, and they kiss their hands to tell me what a fine place Cuba is, how perfect their capital. They put salt in their café au lait, plaster salt on their sliced oranges before eating them, and pour from the salad oil bottle on to every dish they eat. Their children, with bare legs, black hair, gold earrings, run about all day with little dogs on strings, and shout. There is no dancing on the ship, no orchestra, but instead Mass three times a week and the saloon made up as a chapel. The ladies are very big, if young, and lie in deck chairs doing nothing. The men play dominoes and smoke cigars.

We put in at Teneriffe and take on crates of onions for twenty-four hours. Boys in boats beset us with canaries in cages, pups in sacks, and fat, wise-looking parrots on perches. The reek of onions drives out the stowaways from the hold. Onions litter the bottoms of the empty barges, squashed onions disfigure our decks. Indeed, everybody and everything smells of onions for two days.

The food is Spanish and of a sort the sailors of Columbus must have known. All is cooked in olive oil, and I notice the Cubans and Porto Ricans are not pleased if the plates do not gleam. Heaped-up plates of rice and chicken, rice and little bits of rabbit, rice and bits of beef come nearly every day, and Spanish omelettes and olive stew and remarkable dishes of highly spiced fish covered with flaming pimento. There is an excellent table wine of which there is an inexhaustible supply and it is free as air, and there is a glass of sherry for every one on Sunday evening. The Spaniards do well on this. Even little Maria Luisa, aged ten, and Ysabel, aged eight, my two best friends, have their wine and sherry and disperse with vigor the oily heaps of food. One evening these precious little girls borrowed some matches—what to do?—to finish smoking a fat Habana cigar which one of the men passengers had left on deck!

The children talk to one another more by gestures than by words, and I shall never forget how one of them, Palmyra, described a bullfight she had seen at Barcelona and the horror of it, lowering her head between her shoulders and looking out with [Pg 33]gleaming eyes to imitate the bull, jumping to indicate terror and assault, putting her little hand before her eyes at the thought of the disemboweling of the horses, and showing with a horrified twinkling of her fingers the impression of the flowing of the blood. Bullfights are forbidden in Cuba, but these children had been to Spain on a holiday and so had seen the national and traditional festival for the first time.

In fifteen days on a little ship with two dozen passengers one naturally learns a great deal. An English person is a rarity on such a ship, and every one sought to engage me in conversation. They were as much interested in Cristobal Colon and Ponce de Leon and Nuñez de Balboa as I was, and had pictures of Columbus in their pocketbooks, and thought how greatly he'd have been struck to be traveling on such a boat as ours.

This one is a beautiful voyage, so serene, with blue skies every day and a just-waving sea and a breeze behind the boat that wafts our smoke ahead of it. It is delicious to sit up on the very nose of the vessel and be a Columbus now. We are splashing it new, splashing it white, in stars and white balls and darts of surprised foam. Green and yellow seaweed sags up from the depths of the ocean and, like untraversed liquid glass, the sea is ahead of us in curving lines, in natural wild parallels to the sun. It is afternoon, the sun is going over and will go under. He is drawing us on, and I could almost believe our steam counts for naught. He is illuminating the wide empty ocean, and we stare till we veritably see latitude and longitude upon[Pg 34] it. We ascend, we lift, we rive a way o'er the mirror in virginal v's of new frothing foam. We are making for the center of the far horizon, the sun ahead of us; we are making a new way to India; we are going to make West East.

Each still night we seem to pass through something, as it were through mists and veils which are hiding something new. Each morning we rush on to the decks whilst they are still wet and the Castilian sailors are swabbing them. We peer with glasses over the virginal, fresh, foaming blue. The sailors go. The sun dries the timbers. We partake of coffee and smoke a sweet-scented Habana cigarette. The sailors return and pull up white canvas awnings at the cracks and at the sides of which glimmers blue of sky and brightness of sea. The children come out from their cabins to play, tumbling over their pet dogs. All is happiness.

The men indulge in a new sport to while away the time—they try to catch the fast-passing seaweed which lies in sponges and coils in the limpid sea. While Columbus took heart of grace because of the banks of seaweed his ship encountered, believing it a sign of the proximity of land, we on our Spanish ship making in prosaic fashion a bought-and-paid-for passage to the Indies, find the same seaweed a means of fun. Four or five Cubans and Spaniards take a bottle and a rope and a tangle of wire, and fish for seaweed from the bows. The weather-side gets quite a little crowd upon it, for the crew also[Pg 35] take part in the joy of throwing out a bottle and wire to entangle floating green tresses of sea-maidens or big floating sponges of their toilets. Often the bottle flies through the air and often goes up the chorus of disappointment as it hits a wave instead of a bank of weeds. But the exultation is great when a tangle is caught and brought up on deck. It is very pretty and hairlike, and the little children press it between the pages of Ibañez' novels which form the only literature on board. That which heartened Columbus diverted us.

Then we entered the tropics and slept in the hot noontides, waking to clatter up on deck into the freshness of afternoon breezes. The evenings were very beautiful, sunset always giving a pageant. One night there came the most flaming and devastating sunset, descried beyond perilous and mountainous clouds, and from the north all the way to the west a grand processional mass of shadows was seen fleeing, like the pageant of the world's vanities going to judgment. To us it was poetry, but to Columbus and his companions it might well have suggested a growing nearness to the actual place of doom, to where the sun actually dipped down and went under the flat earth—a terrible thought, yet for a daring spirit a haunting and alluring one also.

I suppose there came a point in Columbus' voyage when he might as well keep on as turn back. Turning back became more terrible the longer they kept on. And curiosity must have fed on itself and increased. At any rate, it is still terrible to stand in the stern at night and look back. There in the[Pg 36] darkness lies the past like a book that is read, or written, and a door that is shut. It breathes silence. The clamorous Old World is far behind and cannot be heard.

We started with a young crescent moon, and she grew to the full with us over the still ocean. The stars seemed to wave, and our mainmast jagging to and fro seemed intent on sighting and taking aim at the loveliness in the sky. We are escaping; we are going away; we are doing what they did; we are shooting the moon.

All the Cubans and Porto Ricans and Haitians seem to take on more life, become more vivacious. There is no mistaking it, they are nearing their homes. They have been as homesick for the Indies as the mariners were homesick for Spain. It's all in reverse order. "You'd like Habana—it's bigger and better than Barcelona," I am told; "yes, better than Madrid."

The ship comes into more humid airs, and in the evening all the passengers begin to croon Spanish songs. They are all together and happy, men, women, and children, and they feel they are getting near their blessed islands. It infects the crew, infects every one, like an extra idleness, till we come at last one night to a balmy and dreaming coast, where the coconut palms like cobweb dusters rise up to the low clouds of the sky, and the full moon through the mists shines in silver—from the waves to the shore. We are there at last. We have got to the other side.

The ship goes still and hoots. We have our last supper together. There is plenty of wine. "Drink[Pg 37] deep," cry the Cuban passengers to those of us who disembark at Porto Rico. "It is ultimo vino, your last glass of wine."

"Porto Rico is not dry?"

"Oh, yes," say the Porto Ricans, mournfully. "You see, it belongs to the United States. Cuba is only under supervision of America, but Porto Rico belongs to her, and is dry."

"Seca! Seca!" they cry explanatorily in Spanish.

"Well, with the last glass, here's to Christopher Columbus, who discovered the island. He made the bridge from Old Spain and incidentally brought the first firewater too. All we who arrive, arrive after him."

We enter the harbor of San Juan de Porto Rico and leisurely pass the old stone castle on the rock and the Spanish fortifications. They look to be several centuries older than they are and are not unlike the weather-beaten ruins at the entrance to old ports on the east of Scotland. They mounted Spanish guns but were without power to repel the North American invader of 1898. The island was then wrested from Spain and added territorially to the United States. Natives of Porto Rico are now ipso facto American citizens. It was novel to me to realize that a whole population of American citizens was without English and that many did not know George Washington from Abraham Lincoln.

The boat was hailed by the quarantine authorities and stopped. The Spanish captain, the doctor, and the officers all seemed very nervous. This was[Pg 38] apparent to the American doctor and immigration officials, who strove to keep them calm. There was nothing to worry over—the inspection was only a formality. The crew and the passengers lined up and showed their arms to be free from skin disease. The "aliens" were vaccinated. The immigration officers were remarkably polite. They brought copies of the New York Times on board, and those who could read English glanced at the news. They sat us one by one in front of them and asked us all those funny questions—what is your nationality? what is your race? are you a polygamist? do you believe in subverting an existing government by force? have you ever been in jail? how much money have you got? where is your final destination? are you booked through? Imagine old Columbus being questioned by an immigration officer—there's something humorous about it. And Spaniards, whose forefathers manned the galleons of the Plate Fleet and lorded it on land and sea, now pay, in addition to ten dollars for passport visa, a head-tax of eight dollars ere they land. But all that is prose.

There is no poetry in it, as there is little poetry in the "White Books" of the United States—"lies, damned lies and statistics," as we say in England. The Americans are a light-hearted, humor-loving people, but they are dull and forbidding as officials. The Spanish, even in an old Spanish harbor, felt nervous.

At last the ship is free and moves upon the silken water towards the palm trees and the white houses and the brigantines and schooners and sailing boats[Pg 39] beside the shore. Negroes all in white, with fat cigars in their mouths, handle our luggage, and in ten minutes the passengers are dispersed to hotels and to their homes.

Porto Rico was discovered by Columbus in 1493, and he entered the port of San Juan, naming it San Juan de Porto Rico—St. John of the Fine Harbor—hence the name of the island itself—Porto Rico. The Indians there were in a low state of civilization and showed little sign of wealth. The island seems at first to have presented less interest than its neighbors: Santo Domingo became the beloved of Columbus, Cuba became the chief Spanish base for exploration and conquest. Porto Rico enjoyed therefore comparative peace for sixteen years after its fatal discovery. Then came Ponce de Leon, and after him plunderers and pacificators with sword and hemp; killing, ravishing, enslaving. The despoiling of the Indians of their gold and jewels was followed by dispossession of their lands and then the capture of their persons for the slave trade. Ships were fitted out in Cuba, with the sole mercantile objective of capturing the Indians of the islands and selling them into bondage.

Slaving may have proved profitable, but in the long run it was unpractical. The Indians entirely disappeared, and at the beginning of the seventeenth century were reported to Spain as extinct. There were no longer enough servile hands to do[Pg 41] the hard work. So in place of the lost Indians the Spanish colonists felt forced to import Africans.

The Negro slaves throve under conditions which killed Indians; they increased, and the Spaniards mixed their blood with them and bred from them. Hence the large Negroid population of the Indies at this day.

The same happened in Darien, Panama, Costa Rica—Negroes largely displaced Indians. In Mexico, however, Africans were not imported to any extent, as the Indians, though rebellious, were in large numbers and there were many tribes accustomed to slavery.

The Spaniards settled Porto Rico, and grew sugar and bananas which they brought over from the Canaries, and tobacco which was indigenous. They lived in a humdrum state, taxed, of course, interfered with a great deal by Spanish governors, but generally enjoying the wealth and ease of a luxuriant tropical island—thus for three centuries, when suddenly all the Spanish colonies followed the example of the North American demarche and endeavored to throw off the yoke of the mother country. Mexico, Guatemala, Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, Chile, all gained their freedom before 1825. Porto Rico fought for three years and failed (1821-1823). Spain remained in possession. Fifty years later slavery was abolished. The free republics of Central America had abolished it in 1824. However, in 1873 the Negroes of Porto Rico became free Spanish subjects. In 1897 Porto Rico even obtained[Pg 42] Home Rule under a Spanish Governor-general. But next year came the war between the United States and Spain, and Porto Rico was annexed.

Cuba had also failed in 1823, and for the rest of the century remained disaffected. The Cuban is of a much more violent disposition than the Porto Rican. Cuba has never been wholly in a state of peace and contentedness since it was discovered. A widespread guerrilla warfare lasted from 1868 to 1878, and in 1895 Maximo Gomez led another revolutionary war. By that time, despite constant unrest, foreigners had acquired considerable property in Cuba. There were American, British, and French planters besides Spanish ones. Naturally, in a state of civil war, as in Mexico during 1910-1920, there was much damage done to foreign property. At this, the United States took umbrage.

On February 15, 1898, the U. S. battleship Maine blew up in the harbor of Habana. The Spaniards say it blew up accidentally; the American impression given in the American press was that the Spaniards, to whom the presence of the vessel was thought to be distasteful, had blown it up on purpose. Others think the Cubans blew it up to instigate the war. On the other hand, some Cubans aver that the Americans themselves blew it up—but that is not credible. Probably it was an accident.

But this was the spectacular event which an emotional public needed, like the hauling down of the Flag at Fort Sumter in 1861, like the supposed onslaught of the Mexican Army upon the forces of General Taylor in 1846, the sinking of the Maine[Pg 43] was just what was needed to rouse the democracy of the North to war. An ultimatum was presented to Spain.

Spain must make immediate peace in Cuba. Spain was very polite and promised to do what she could. But the war feeling demanded more. On April 19, 1898, the United States Congress voted that Cuba was henceforth an independent state, and called upon Spain to give up Cuba. Next day the Spanish Ambassador left Washington and there was war.

In the arbitrament of force Spain stood no chance. There were a few months of one-sided warfare, and the honor of Spain was satisfied. Spain faced her challenger, shots were exchanged, Spain was wounded and retired from the field. Cuba was given liberty. Porto Rico was annexed.

Does one need to stress the annexation of Porto Rico? Is it worth while inquiring whether the Porto Ricans should also have been given their liberty? Perhaps not, generally speaking, as the government of States and Empires goes on to-day. Porto Rico has only a million and a quarter inhabitants, is only 3400 square miles in extent. But I stress the annexation in this study because it seems specially important in the development of the power of the United States of North America.

The Spaniards took Porto Rico for greed. No tears need be shed over them. The United States did not take it over from that motive. But it was a step forward in her quest of power. The [Pg 44]Castilian flag went down—the flag of the quest for gold. The American flag went up—the flag of the quest for power.

San Juan de Porto Rico is a gay and pretty little city, without crime, without dirt, and without much poverty. Revolvers are not fired promiscuously. Heaven's water-carts lay the dust each afternoon. There is a luxurious American hotel, and Spanish ones which are less luxurious. You eat to music, and can be fed in airy restaurants by eager Italians. Babbitt orders his stacks of hot cakes and soft-boiled eggs for breakfast; Francisco Morales sits down meekly to coffee and a small roll. The well-fed, broad-faced business men of the States walk with india rubber step—happy, tubby Texans, lordly lumps of Louisiana. The tropic, which dries the Spaniard, does not reduce the North American. The young men are clean-cut and handsome, but soon sag, owing to lack of exercise and the habit of bathing in hot water instead of cold. The Porto Rican is not so dependent on a car, eats less, and certainly bathes less, be it in hot or cold. You know the ex-Spaniard by his spare form and swarthy complexion. The Spanish sombrero is being chased off the island by standard American hats; likewise the Spanish shirt by the more expensive silk shirt of the American working man. The blue overalls or "slops" of the laborer are also common. It is difficult to buy an article of attire which is of local manufacture and style; even Panama hats it appears have to be sent to New York and reëxported. Inter-island trade is very scanty; once a month a small Dutch cargo[Pg 45] boat arrives from Jamaica, but it seems to bring very little.

Characteristic of modern San Juan is the barber shop with its striped pole revolving in glass case: there the Spaniards getting their hair cut have their necks shaved also and a bareness left above the ears; and having "gotten" a shave they get an American hot towel also pressed upon their brows and temples.

Truly, as you stand on the quay and watch the ferry boats, modeled on those of the Hudson River, go screaming across the harbor, you feel there is some justification for the saying that San Juan is a miniature New York.

One thing, however, it lacks, and that is an adequate number of "shoe-shine parlors." Like the Bedouins who have a monopoly of the visitors to the Sphinx, so a tribe exists in San Juan who hold the blacking brush to the world. When an imperial race arrives there is great competition among the natives as to who shall clean their boots. The tribe especially swarms around the town square which, banked with flora and shaded with luxuriant palms, might otherwise be a pleasant place of rest. Even at night, after supper, when the town band is playing to a flocking crowd under a dreaming moon, you are treated to a sort of jazz interposition of "Shine! Shine! Shine!"

The voices of the street urchins and news venders have the same quality of voice as those of Cadiz. Boy babies come forth from their mothers' wombs howling "Demokratia." The stones of the high houses repeat their cries. But there are no parrots[Pg 46] shouting on the streets of San Juan. There used to be, for Spanish sailors brought them. But in some streets of Cadiz one might have thought there was a riot, what with the news venders below and the parrots in the upper storys. Coming direct from Cadiz one noticed many divergencies in the detail of life. For instance, Cadiz had no cinemas; San Juan had five or six, showing all the Californian stars. In Cadiz there were several theaters with dancing and singing. In San Juan there was only one with a visiting Spanish artist. In Cadiz no one rocks or swings on a veranda. In San Juan, on the other hand, there are no bullfights. Most of what bound the island to Spain has been now cut. Only a few educated people know who is King of Spain.

Out in the country, however, life is more definitely Spanish and American influence is less felt. The Negro life is greater there and seems to relate neither to Spain nor to America. It hardly seems to relate to Africa either.

The Negroes live in saffron- and marine-colored boxes little bigger than bathrooms, and what they crowd into these cabins makes them like Noah's arks with all the toy furniture and animals inside. You'll see them stuck right in the midst of a swamp with thousands of land crabs crawling on the tips of their claws and feeling in the air with their portentous extra talons.

The mangoes hang their fruits like tassels. The palm trees rise up like vast, lissom, feminine forms swathed to the waist and then bright naked to their matted heads, where cluster their giant nuts. The[Pg 47] banana palms bask in solar radiance and hot mist; and last year's shabby sugar plantation stretches for a mile of bashed canes and sprawling withered leaves. And naked children improvise a throb of music with a tin can band while others dance to it a natural shimmy shake.

Living among the colored folk are poor white Spanish Porto Ricans on quite an equal basis, and their pale babies run about in the sun, too, only they are not musical and do not dance. The grown girls, white and black, are beautiful creatures, dazzling with their bright dresses, their vitality, and their unthwarted curves. The Negro men are finer than the Spanish ones, however, and naturally a long way simpler. I never saw Negro men so happy and untroubled as here—the Negro without a complex, without the blues.

Nearby goes the military high road, hard and straight, and along it hoot America's cars. The little island is traversed by a whole series of magnificent roads of great value from the point of view of war, but now a happy means of touring the country. The automobile parade from Packard to Ford goes past before your eyes, and beside private cars fly strings of little motor buses, all packed with people. Each bus has a name, and that adds greatly to the amusement of the road. Thus we have "Coney Island," "Cristobal Colon," "Excuse my Dust," "Maria Luisa," and a hundred more. These are worked by the Spanish-speaking people for Spanish-speaking people. You will seldom meet an American in one. I found afterwards in Colon and Mexico City, in Santo Domingo and[Pg 48] Port au Prince, and other places, these converted Ford trucks swarm, and are a great if risky means of locomotion. The Porto Rican wagonettes are if anything quieter in their demeanor than the Mexican ones. So they scour the ways from ports and tobacco-towns, over the low ranges of tree-covered sugar-loaf mountains, to other towns and ports and villas and resorts. When far away on the verdure-covered hills they show where the roads are by their turbulent dust.

You see almost the whole range of class life in Porto Rico from the bottom to the broad top, from yellow wooden cabin to the latest type of American home. For whites an American standard of life has been set. Rich as the island is, and simple and remote, the artificial prices of New York, nevertheless, range. Your room at the hotel, with bath and telephone, will cost you from three to five dollars a day. You will sit down to the characteristic breakfast of grapefruit, ham and eggs, corn cakes, and coffee. Ice and water continually tinkles in glasses. Yonder is the ice-cream soda bar. The suit pressers are all busy keeping proper creases in the breeches of the islanders. American men, wearing their white suits and linen collars, look smarter than the Porto Ricans, and the women, if quieter in looks, at least keep to the fashions.

Business of course is king. You feel that, at every turn, by the look of the advertisements and the trend of the talk. Porto Rico hums as it has never hummed before. It goes. It is a real live place. The dominant spirit of the Anglo-Saxon[Pg 49] has overcome the gentle, sluggish conservatism of old Spain. Rich Porto Ricans, and there are many of them, live in luxury, in beautiful villas with every possible means of material happiness—books, baths, electric light, fans, tiled floors, perfect mosquito nets, and the whitest sheets and the softest of pillows. And the water is pure and the drains are good—thanks in great part to a quarter of a century of ownership and exploitation by the U. S. A.

The material benefit which has come to Porto Rico through annexation is considerable. In 1901 she was included within the American tariff union and all her products could enter American harbors duty free. She entered the American postal unity. The American dollar became her unit of currency. American traders taught Porto Rican middlemen how to make money, and American planters from Louisiana showed the proper way to raise sugar. The annual output of sugar has been increased to ten times what it was in 1898.

On the other hand, there are material and political disadvantages. Though Porto Rico has free trade with America she has it not with the rest of the world. A high tariff excludes European goods. Spanish America has profited immensely by cheap German wares. But the Fordney tariff keeps them out of Porto Rico. Porto Rico pays excessively for scores of articles and commodities which she could otherwise import cheaply from France and Spain, to say nothing of England. Prohibition of wines and spirits is said to have been achieved by local option—but, if so, it was before the [Pg 50]population was able to vote. Trial by jury is not given in Porto Rico. Porto Ricans are citizens of the U. S. A., by virtue of the Jones Act of 1917. They were enabled to be conscripted for the Army. But they do not have the power to vote. They are represented in the United States Congress only by a Commissioner. They have no Senator. They have no part in electing the President.

Now there has sprung up what may be called a Porto Rican Sinn Fein movement, featured in a concerted attack on the Administration. Many Americans now advocate "Statehood" for Porto Rico. But the Porto Ricans clamor for independence. Porto Rico is in the anomalous condition of belonging to the U. S. A. but is not a State nor governed by the Constitution. She is a possession. And the general Spanish discontent which rules in Cuba, Haiti, and Santo Domingo outcrops in Porto Rico also. Just as the popular song "Es mi hombre" which tires the ears in Madrid has gone through these islands and is no doubt ravaging Mexico and all the mainland, so the one insurgent Spanish emotion has infected all the islanders. And, in Porto Rico, journalists in the newspapers and street orators in the squares are flirting with the idea of a revolt. The street politicians seemed very nervous when any one looking like an American came near.

It is difficult to know what test to apply to the institutions of Porto Rico where, for instance, trial by jury cannot be claimed. If the test of Empire, the trouble would be hardly worth considering; but if the test of Lincolnian democracy, the Porto [Pg 51]Ricans have grievances which could be removed. The removal would take little effort. The island is well governed, and is civilized and prosperous. Given her independence it is all too likely that her present happiness would fall away from her.

Over the sea in a tiny boat to the island of Haiti, and to the eastern half of it which is called Santo Domingo. The voyage is still westward and along the eighteenth parallel and not for long out of sight of land, be it the northern shore of Porto Rico or the southern shore of Santo Domingo. The sea reeks with warm exhalations, and in the turgid water lurk sharks. Don't fall off the ship as she lurches and rolls and you hold to the ropes—you may not be saved if you do.

Twenty-four hours brings you to the little tropic river where the massed palm trees with their bushy heads peep forth out of the jungle at the intruder. And we slush slowly along the banks through the heat to a jaded-looking dock and some clammy warehouses, and behold, it is the capital of the Dominican Republic; I suppose one of the meanest and dirtiest capitals in the world. Yonder is the Government Building, on which flies the white-crossed flag of the Republic and level with it the Stars and Stripes of the United States. For the republic has the brokers in. She borrowed heavily and unwisely, and then could not pay—and so the customs were seized, and, with the customs,[Pg 53] government itself. Santo Domingo is now virtually an American possession and part of the new empire which is springing into being and promising to condition the future of the American people. On a little hill outside the city is a training camp with its motto picked out in white stones in an attractive pattern: "In time of Peace, prepare for War." And one wakens in the morning to the strains of "The Star-Spangled Banner," played somewhere afar.

Down by that tropic little river stands the stump of Columbus's tree, the actual tree to which the discoverer moored his ship when he came in on that morning of the fifth of December, 1492, and was met by the amazed tribesmen. Nine months ago it was a still living tree, and it is part of the grievance of the Dominicans that the marines tried to preserve it for all time by cutting it open and filling its hollow center with cement. That killed it. But it is a mighty burly stump, some fifteen feet high and of great girth. It sprawls rather, it has a burly moving shoulder and a bearded aspect that suggests a sort of Rip Van Winkle Christopher Columbus, enchanted for four hundred and thirty years and now stepping ashore.

What a change for the old man to see! Those chiefs, those red men and women who gave jewels for beads, all killed to the last child two hundred years ago. Africans are in their place, smooth and black, everywhere, as if they had come and conquered it. But they came as slaves and then won their freedom from Spaniards and from [Pg 54]Frenchmen. Some speak Spanish, some speak bits of French. Further on, in Haiti all speak French. Where are the bold Spaniards with their flashing eyes and flashing blades, their wills, their lusts? Gone like the great trees of the river side. Gone like the Indians. Gone like the French who came after them. Mixed and married with the Negroes, or else gone soft and gentle as Orientals.

"These strapping fellows, these giants in sand-colored clothes?" Columbus might ask. "American soldiers," you would reply, and then conduct the poor old wight to the Carnegie Library and the shelves of the Encyclopedia Americana. It needs some explaining. Discovering America was child's play compared with explaining to Columbus the rise of the American Republic of the North.

Anyhow, here I am at the Hotel Inglaterra, and down below me is a bar where there is "beer on ice" and the "best old rum," for Santo Domingo has not been made dry, and there sit marines all in white and argue it over their pots. The question is: "Do not the Haitians eat their children at the age of five—not all of them, of course, but selected kids at festivals? Do not the outlaws and brigands of Santo Domingo need to be stamped out? Or again, Who has prior rights in the Panama Canal? Do not British warships come through without paying dues while American warships pay? Are not all vessels towed by electric mules through the canal?" They bet millions of dollars, they bet their adjectival shirts, because they know.

Outside is the city market place, where are sold live crabs and tortoises on strings and mangoes[Pg 55] and gourds and coconuts and sugar-candy babies on wire. And black girls with coral ornaments and vari-colored turbans or kerchiefs do the selling—while purchasers on asses, on backs of calves, or walking with huge bundles on their heads, go past. The black people laugh and shout. It doesn't seem to mean much to them that they have no President and that their republic is in abeyance. They do not bet on what is going to happen, and they do not know. When you buy an orange for a cent they say to you Grand merci and are ever so pleased. In the square is a fine statue of Cristobal Colon, who points west by southwest to Latin America, bidding all men still think of a new world. But I am forgetting. Did I not leave him in the Library with the encyclopedia? Is it not there, on the shelf, that he will find his true place, in a history that is past?

Though at first sight the population of the capital of the Dominican Republic may strike the traveler as being wholly black, there are nevertheless a number of persons of fairer complexion—the people of the first families, the aristokratia. One or two of these are German. These keep within their houses more than do the Negroes who trade and traffic and gossip in market place and main street.

The island has a bad history. Columbus loved it as the first large materialization of his dream of a beyond—a transatlantic land. But the Spaniards raised Cain there, and the Negroes and French after them. The Indians were killed off early, and[Pg 56] the Spaniards were soon killing one another. Bandits and pirates have lived there more securely than any one else.

It was in 1697 that the French came in. Spain ceded half the island to her. The French bred in rapidly with the colored people. The country became known as Haiti, and French was the spoken tongue. French Negro slaves in considerable numbers were imported. A hundred years later the rest of the island was ceded to France. That was in the Napoleonic era. England was at war with Spain, and in 1809 British warships stood off the little tropic harbor and gave encouragement to an uprising of Spanish colonists who proved successful in wresting the city from the French. By the Treaty of Paris in 1814 French rule was confined to the eastern part of the island—Haiti.

There came then speedily the great liberation movement of Latin America (1821-1825). Santo Domingo was able to succeed where Porto Rico failed. But hardly had the new republic proclaimed its independence when the Negroes of Haiti descended upon it and broke it up. Haiti by that time had also won independence. For nearly a quarter of a century the Haitians remained in control of the whole island. In 1844 a Dominican insurrection was successful, but there was no peace with Haiti, who seems to have been always the stronger power. Santo Domingo was forced to try to return to the bosom of Spain. In 1861 the president of the republic became governor, and the republic joined Spain. Two years later war against Spain was started and in 1865 the republic was [Pg 57]restored. In 1868 the republic tried to join the United States, but America was not then willing. Insurrectionary movements followed one another with rapidity till the Negro general Ulysses Heureux obtained control of the country. He, it is said, pursued the policy later adopted by Lenin in Russia of having all his enemies killed, but he himself did not escape and was assassinated at last. It is said he ran the republic very deeply into debt. One wonders why financiers should have been willing to lend money to such a State. Some five millions sterling were owing, later it became six and a half millions. There was talk of foreign intervention. Some European power might have felt entitled to seize the country.

American policy had, however, somewhat changed. In 1899 the United States entered into possession of Porto Rico and into control of Cuba. Santo Domingo was one half of the island that lay between. Rather than see a foreign power installed, America decided to control Santo Domingo also.

The republic was asked if she still required aid from Washington, and the United States agreed to control the customs, organize receipts, pay interest on debts and pension the government. This she has done very effectively and remains in economic and military control to-day; Santo Domingo with a constitution in suspended animation having become an American Protectorate.

Apparently now most Dominicans would like the Americans to go, but they have no power to make them. The Americans for their part can point[Pg 58] justifiably to the improved conditions on the island. If they went, the human dogfight would begin anew. However, let us to the country!