So they went back ... to discuss the matter reasonably....

Never before in history had such an

amazing, baffling and faintly horrifying

thing happened to anyone as happened to

Galahad McCarthy ... but—whaddyamean, history?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1947.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"Don't you think you might look up from that comic book long enough to get interested in a last minute briefing on the greatest adventure undertaken by man? After all, it's your noodle neck that's going to be risked." Professor Ruddle throbbed his annoyance clear up to his thin white hair.

McCarthy shifted his quid and pursed his lips. He stared dreamily at an enameled wash-basin fifteen feet from the huge, box-like coil of wire and transparencies on which the professor had been working. Suddenly, a long brown stream leaped from his mouth and struck a brass faucet with a loud ping.

The professor jumped. McCarthy smiled.

"Name ain't Noodleneck," he drawled. "Gooseneck. Gooseneck McCarthy, known and respected in every hobo jungle in the country, including here in North Carolina. And looky, bub, all I wanted was a cup of coffee and a pair of sinkers. Time machine's your notion."

"Doesn't it mean anything that you will shortly be one hundred and ten million years in the past, a past in which no recognizable ancestors of man existed? That your opportunities to—"

"Nawp!"

Blathersham University's greatest physicist grimaced disgustedly. He stared through thick lenses at the stringy, wind-hardened derelict whom he was shortly going to trust with his life's work. A granite-like head set on a remarkably long, thin neck; a body whose limbs were equally extended; clothes limited to a faded khaki turtleneck sweater, patched brown corduroy pants and a worn-out pair of heavy brogans. He sighed.

"And the fate of human knowledge and progress depends on you! When you wandered up the mountain to my shack two days ago, you were broke and hungry. You didn't have a dime—"

"Had a dime. Only it was lead."

"All right. All right. So you had a lead dime. I took you in, gave you a good hot meal and offered to pay you one hundred dollars to take my time machine on its maiden voyage. Don't you think—"

Ping! This time it was the hot water faucet.

"—that the very least you could do," the little physicist's voice was rising hysterically, "the very least would be to pay enough attention to the facts I make available to insure that the experiment will be a success? Do you realize what fantastic disruption you might cause in the time stream by one careless slip?"

McCarthy rose suddenly and the brightly-colored comic magazine slid to the floor in a litter of coils, gauges and paper covered with formulae. He advanced toward the professor whom he topped by at least a foot. His employer gripped a wrench nervously.

"Now, Mister Professor Ruddle," he said with gentle emphasis, "if'n you don't think I know enough, why don't you go yourself, huh?"

The little man smiled at him placatingly. "Now don't get stubborn again, Swan-neck—"

"Gooseneck. Gooseneck McCarthy."

"You can be the most irascible person I've ever met. More stubborn than Professor Dudderel for that matter. And he's that short-sighted mathematician back at Blathersham who insisted in spite of irrefutable evidence that a time machine would not work. Even when I showed him quartzine and demonstrated its peculiar time-dissolving properties, he wasn't convinced. The university refused to grant an appropriation for my research and I had to come out here in North Carolina. On my own time and money, too." He brooded angrily on unreasonable mathematicians and parsimonious trustees.

"Still ain't answered my question."

Ruddle looked up. He blushed a little under the fine wild tendrils of white hair. "Well, it's just that I'm rather valuable to society what with my paper on intrareversible positrons still uncompleted. Whereas everything points to the machine being a huge success, it's conceivable that Dudderel considered some point which I've—er, overlooked."

"Meaning there's a chance I might not come back?"

"Uh—well, something like that. No danger, you understand. I've gone over the formulae again and again and they are foolproof. It's just barely possible that some minor error, some cube root that wasn't brought out to the farthest decimal—"

The tramp put his hands in his pockets. "If'n that's so," he announced, "I want that check before I leave. Not taking any chances on something going wrong and you not paying me."

Professor Ruddle gulped. "Sure, Rubberneck," he said. "Sure."

"Gooseneck. How many times—Only make it out for my real first name. It's—" the tramp's voice dropped to a whisper—"It's Galahad."

The physicist added a final scribble to the green paper rectangle, ripped it out and handed it to McCarthy. Pay to the order of Galahad McCarthy one hundred dollars and 00 cents. On the Beet and Tobacco Exchange Bank of North Carolina.

Ruddle watched while the check was carefully placed in the outer breast pocket of the ancient sweater. He picked up an expensive miniature camera and hung its carrying strap around his employee's neck. "Now, this is fully loaded. You sure you can operate the shutter? All you do—"

"I know all right. Fooled around with these doohickeys before. Been playing with this 'un for two days. You want me to step out of the machine, take you a couple of snaps of the scenery—and move a rock."

"And nothing else! Remember, you're going back a hundred and ten million years and any action on your part might have an incalculable effect on the present. You might wipe out the whole human race by stepping on one furry little animal who was its ancestor. I think that moving a rock slightly will be a good first innocuous experiment, but be careful!"

They moved toward the great transparent housing at the end of the laboratory. Through its foot-thick walls, the red, black and silver equipment in one corner shone hazily. An enormous lever protruded from the maze of wiring like a metallic forefinger.

"You should arrive in the Cretaceous Period, the middle period of the age of reptiles. Most of North America was under water, but geological investigation shows an island on this spot."

"You been over this sixteen times. Just show me what dingus to pull and let me go."

Ruddle executed a little dance that a student of modern ballet might have called "Man with High Blood Pressure about to Blow his Top."

"Dingus!" he screeched. "You don't pull any dingus! You gently depress—gently, you hear!—the chronotransit, that large black lever, thus sliding the quartzine door shut and starting the machine. When you arrive you lift it—again gently—and the door will open. The machine is set to go back a given number of years, so that fortunately you have no thinking to do."

McCarthy stared down at him easily. "You make a lot of cracks for a little guy. I'll bet you're scared stiff of your wife."

"I'm not married," Ruddle told him shortly. "I don't believe in the institution." He remembered. "Who was talking about marriage? At a time like this.... When I think of allowing a stubborn, stupid character like yourself to run loose with a device having the immense potentialities of a time machine—Of course, I'm far too valuable to be risked in the first jerry-built model."

"Yeah," McCarthy nodded. "Ain't it the truth." He patted the check protruding from his sweater pocket and leaped up into the machine. "I'm not."

He depressed the chronotransit lever—gently.

The door slid shut on Professor Ruddle's frantic last word, "Goodbye, Turtleneck, and be careful, please!"

"Gooseneck," McCarthy automatically corrected. The machine seemed to jerk. He had a last, distorted glimpse of Ruddle's shaggy white head through the quartzine walls. The professor, alarm and doubt mixed on his face, seemed to be praying.

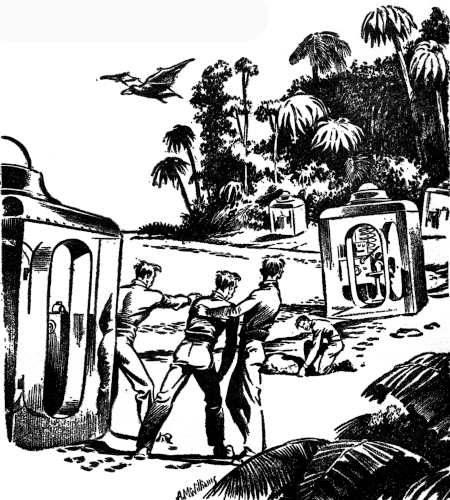

Incredibly bright sunlight blazed through thick bluish clouds. The time machine rested on the waterline of a beach to whose edge the lushest jungle ever had rushed—and stopped abruptly. The semi-transparent walls enabled him to see enormous green masses of horsetails and convoluted ivy, giant ferns and luxuriant palms, steaming slightly, rich and ominous with life.

"Lift the dingus gently," McCarthy murmured to himself.

He stepped through the open doors into an ankle-depth of water. The tide was evidently in and white-flecked water gurgled around the base of the squat edifice that had brought him. Well, Ruddle had said this was going to be an island.

"Reckon I'm lucky he didn't build his laboratory shack fifty or sixty feet further down the mountain!"

He sloshed ashore, avoiding a little school of dun-colored sponges. The professor might like a picture of them, he decided. He adjusted the speed of the lens and focused it on the sponges. Then a couple of pictures of the sea and the jungle.

Huge, leathery wings beat over a spot two miles in from the edge of the luxuriant vegetation. McCarthy recognized the awesome, bat-like creature from drawings the professor had shown him. A Pterodactyl, the reptilian version of bird life.

The tramp snapped a hasty photograph and backed nervously toward the time machine. He didn't like the looks of that long pointed beak, so ferociously armed with jagged teeth.

Some living thing moved in the jungle under the Pterodactyl. It plummeted down like a fallen angel, jaws agape and slavering.

McCarthy made certain that it was being kept busy, then moved rapidly up the beach. Near the edge of the jungle, he had observed a round reddish rock. It would do.

The rock was heavier to budge than he had thought. He strained against it, cursing and perspiring under the hot sun. His feet sank into the clinging loam.

Abruptly the rock tore loose. With a sucking sound it came out of the loam and rolled over on its side. It left a moist, round hole out of which a centipede fully as long as his arm scuttled away into the underbrush. A nauseous stink arose from the spot where the centipede had lain. McCarthy decided he didn't like this place.

Might as well head back.

Before he depressed the lever, the tramp took one last look at the red rock, the underside somewhat darker than the rest. A hundred bucks worth of tilt.

"So this is what work is like," he soliloquized. "Maybe I been missing out on something!"

After the rich sunlight of the Cretaceous, the laboratory seemed smaller than he remembered it. The professor came up to him breathlessly as he stepped from the time machine.

"How did it go?" he demanded eagerly.

McCarthy stared down at the top of the old man's head. "Everthin' O.K.," he replied slowly. "Hey, Professor Ruddle, what for did you go and shave your head? There wasn't much of it, but that white hair looked sorta distinguished."

"Hair? Shave? I've been completely bald for years. Lost my hair long before it turned white. And my name is Guggles, not Ruddle—Guggles: try and remember that for a while. Now let me see the camera."

As he slipped the carrying strap over his head and handed the instrument over, the tramp pursed his lips. "Coulda sworn that you had a little patch of white up there. Coulda sworn. Sorry about the name, prof; we never seem to be able to get together on those things."

The professor grunted and started for the darkroom with the camera. Halfway there, he stopped and almost cringed as a huge female form stepped through the far doorway.

"Aloysius!" came a voice that approximated a corkscrew to the ear. "Aloysius! I told you yesterday that if that tramp wasn't out of my house in twenty-four hours, experiment or not, you'd hear from me. Aloysius! You have exactly thirty-seven minutes!"

"Y-yes, dear," Professor Guggles whispered at her broad retreating back. "We-we're almost finished."

"Who's that?" McCarthy demanded the moment she had left.

"My wife, of course. You must remember her—she made your breakfast when you arrived."

"Didn't make my breakfast. Made my own breakfast. And you said you weren't married!"

"Now you're being silly, Mr. Gallagher. I've been married for twenty-five years and I know how futile it is to deny it. I couldn't have said any such thing."

"Name's not Gallagher—it's McCarthy, Gooseneck McCarthy," the tramp told him querulously. "What's happened here? You can't even remember my last name now, let alone my first, you change your own name, you shave your head, you get married in a hurry and—and you try 'n tell me that I let some female woman cook my breakfast when I can rassle up a better-tastin', better-eatin'—"

"Hold it!" The little man had approached and was plucking at his sleeve eagerly. "Hold it, Mr. Gallagher or Gooseneck or whatever your name is. Suppose you tell me exactly what you consider this place to have been like before you left."

Gooseneck told him. "And that thingumajig was layin' on that whatchamacallit instead of under it," he finished lamely.

The professor thought. "And all you did—when you went back into the past—was to move a rock?"

"That's all. One hell of a big centipede jumped out, but I didn't touch it. Just moved the rock and headed back like you said."

"Yes, of course. H'mmm. That may have been it. The centipede jumping out of the rock may have altered subsequent events sufficiently to make me a married man instead of a blissful single one, to have changed my name from Ruddle to Guggles. Or the rock itself. Such an intrinsically simple act as moving the rock must have had much larger consequences than I had imagined. Just think, if that rock had not been moved, I might not be married! Gallagher—"

"McCarthy," the tramp corrected resignedly.

"Whatever you call yourself—listen to me. You're going back in the time machine and shift that rock back to its original position. Once that's done—"

"If I go back again, I get another hundred."

"How can you talk of money at a time like this?"

"What's the difference between this and any other time?"

"Why, here I am married, my work interrupted and you chatter about—Oh, all right. Here's the money." The professor tore his checkbook out and hastily scribbled on a blank. "Here you are. Satisfied?"

McCarthy puzzled over the check. "This isn't like t'other. This is on a different bank—The Cotton Growers Exchange."

"That makes no important difference," the professor told him hastily, bundling him into the time machine. "It's a check, isn't it? Just as good, believe me, just as good."

As the little man fiddled with dials and adjusted switches, he called over his shoulder. "Remember, get that rock as close to its original position as you can. And touch nothing else, do nothing else."

"I know. I know. Hey, prof, how come I remember all these changes and you don't, with all your science and all?"

"Simple," the professor told him, toddling briskly out of the machine. "By being in the past and the time machine while these temporal adjustments to your act made themselves felt, you were in a sense insulated against them, just as a pilot suffers no direct, personal damage from the bomb his plane releases over a city. Now, I've set the machine to return to approximately the same moment as before. Unfortunately, my chronotransit calibrations can never be sufficiently exact—Do you remember how to operate the apparatus? If you don't—"

McCarthy sighed and depressed the lever, shutting the door on the professor's flowing explanations and perspiring bald head.

He was back by the pounding surf off the little island. He paused for a moment, before opening the door as he caught sight of a strange transparent object just a little further up the beach. Another time machine—and exactly like his!

"Oh, well. The professor will explain it!"

He started up the beach toward the rock. Then he stopped again—a dead-stop this time.

The rock lay ahead, as he remembered it before the shifting. But there was a man straining at it, a tall, thin man in a turtleneck sweater and brown, corduroy pants.

McCarthy got his flapping jaw back under control. "Hey! Hey, you at the rock! Don't move it. It's not supposed to be moved!" He hurried over.

The stranger turned. He had the ugliest face McCarthy remembered having seen on a human being; his neck was ridiculously long and thin. He examined McCarthy slowly. He reached into his pocket and came out with a soiled package. He bit off a chaw of tobacco.

McCarthy reached into his pocket and came up with an identically soiled mass of tobacco. He also took a bite. They chewed and stared at each other. Then they spat, simultaneously.

"What do you mean this rock ain't supposed to be moved? Professor Ruddle told me to move it."

"Well, Professor Ruddle told me not to move it. And Professor Guggles," McCarthy added as a triumphant clincher.

The other considered him for a moment, his jaw working like a peculiar cam. His eyes traveled up McCarthy's spare body. Then he spat contemptuously and turned to the rock. He grunted against it.

McCarthy sighed and put a hand on his shoulder. He spun him around. "What for you have to go and act so stubborn, fella? Now I'll have to lick you."

Without changing his vacant expression to one of the slightest hostility, the stranger aimed a prodigious kick at his groin. McCarthy dodged easily. That was an old hobo trick! He chopped out rapidly against the man's face. The stranger ducked, moved away and came back fighting.

This was a perfect spot for the famous McCarthy one-two. McCarthy feinted with his left, seemingly concentrating all his power at the other's middle. He noticed that his opponent was also making some awkward gesture with his left. Then he came up out of nowhere with a terrific right uppercut.

WHAM!

Right on the—

—on the button. McCarthy sat up and shook his head clear of bright little lights and happy hums. He had connected, but—

So had the other guy!

He sat several feet from McCarthy, looking dazed and sad. "You are the stubbornest cuss I ever saw! Where did you learn my punch?"

"Your punch!" They rose, glowering at each other. "Listen, bub, that there is my own Sunday punch, copyrighted, patented and incorporated! But this ain't gettin' us nowhere."

"No, it ain't. What do we do now? I don't care if I have to fight you for the next million years, but I was paid to move that rock and I'm goin' to move it."

McCarthy shifted the quid of tobacco. "Looky here. You've been paid to move that rock by Professor Ruddle or Guggles or whatever he is by now. If I go back and get a note from him saying you're not to move that rock and you can keep the check anyways, will you promise to squat still until I get back?"

The stranger chewed and spat, chewed and spat. McCarthy marveled at their perfect synchronization. They both spat the same distance, too. He wasn't such a bad guy, if only he wouldn't be so stubborn! Strange—he was wearing a camera like the one old Ruddle had taken from him.

"O.K. You go back and get the note. I'll wait here." The stranger dropped to the ground and stretched out.

McCarthy turned and hurried back to the time machine before he could change his mind.

He was pleased to notice as he stepped down into the laboratory again, that the professor had rewon his gentle patch of white hair.

"Saaay, this is gettin' real complicated. How'd you make out with the wife?"

"Wife? What wife?"

"The wife. The battle-axe. The ball and chain. The steady skirt," McCarthy clarified.

"I'm not married. I told you I considered it a barbarous custom entirely unworthy of a truly civilized man. Now stop babbling and give me that camera."

"But," McCarthy felt his way very carefully, "but, don't you remember takin' the camera from me, Professor Ruddle?"

"Not Ruddle—Roodles, Roodles. Oo as is Gooseface. And how could I have taken the camera from you when you've just returned? You're dithering, McCarney—I don't like ditherers. Stop it!"

McCarthy shook his head, forbearing to correct the mispronunciation of his name. He began to feel a vague, gnawing wish that he had never started this combination merry-go-round and slap-happy fun-house.

"Look, prof, sit down." He spread a great hand against the little man's chest, forcing him into a chair. "We're gonna have another talk. I gotta bring you up to date."

Fifteen minutes later, he was winding up. "So this character says he'll wait until I get back with the note. If you want a wife, don't give me the note and he'll move the rock. I don't care one way or t'other, myself. I just want to get out of here!"

Professor Ruddle (Guggles? Roodles?) closed his eyes. "My," he gasped. Then he shuddered. "Married. To that—battle-axe! That st-steady skirt! No! McCarney—or McCarthy—listen! You must go back. I'll give you a note—another check—here!" He tore a page from his notebook, filled it rapidly with desperate words. Then he made out another check.

McCarthy glanced at the slips. "'Nother bank," he remarked wonderingly. "This time The Southern Peanut Trust Company. I hope all these different checks are gonna be good."

"Certainly," the professor assured him loudly. "They will all be good. You go ahead and take care of this matter, and we'll settle it to everybody's satisfaction when you return. You tell this other McCarney that—"

"McCarthy. Hey! What do you mean—'this other McCarney?' I'm the only McCarthy—only Gooseneck McCarthy, anyway. If you send a dozen different guys out to do the same job...."

"I didn't send anyone but you. Don't you understand what happened? You went back into the Cretaceous to move a rock. You returned to the present—and, as you say, found me in somewhat unfortunate circumstances. You returned to the past to undo the damage, to approximately the same spot in space and time as before—it could not be exactly the same spot because of a multitude of unknown factors and because of the inescapable errors in the first time machine. Very well. You—we'll call you You I—meet You II at the very moment You II is preparing to move the rock. You stop him. If you hadn't, if he hadn't been interrupted in any way and had shifted that stone, he would have been You I. But because he—or rather you—didn't, he is slightly different from you, being a You who has merely made one trip into the past and not even moved the rock. Whereas you—You I—have made two trips, have both moved the rock yourself and prevented yourself from moving it. It's really very simple, isn't it?"

McCarthy stroked his chin and sucked in a great gasp of air. "Yeah," he mumbled wildly. "Simple ain't the word for it!"

The professor hopped into the machine and began preparing it for another trip. "Now as to what happened to me. Once you—You I again—prevented You II from moving that rock, you immediately precipitated—not so much a change as a—an unchange in my personal situation. The rock had not been shifted—therefore, I had not been married, was not married, and, let us hope, will never be married. I was also no longer bald. But, by the very fact of the presence of the two You's in the past, by virtue of some microscopic form of life you killed with your breath, let us say, or some sand you impressed with your feet,—sufficient alterations were made right through to the present so that my name was (and always had been!) Roodles and your name—"

"Is probably MacTavish by now," McCarthy yelled. "Look prof, are you through with the machine?"

"Yes, it's all ready." The professor grimaced thoughtfully. "The only thing I can't place is what happened to that camera you said I took from you. Now if You I in the personification of You II—"

McCarthy planted his right foot in the small of the little man's back and shoved. "I'm gonna get this thing settled and come back and never, never, never go near one of these dinguses again!"

He yanked at the chronotransit. The last he saw of the professor was a confused picture of broken glassware, tangled electrical equipment and indignantly waving white hair.

This time he materialized at the very edge of the beach. "Gettin' closer all the time," he mumbled as he stepped out of the housing. Now to hand over the note, then—

Then—

"Great sufferin' two-tailed explodin' catfish!"

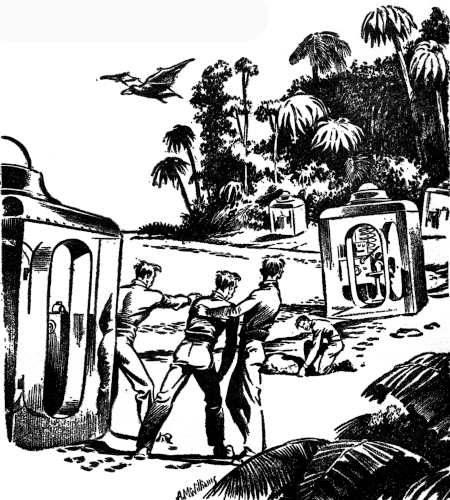

There were two men fighting near a red rock. They wore identical clothes; they had identical features and physical construction, including the same lanky forms and long, stringy necks. They fought in a weird pattern of mirror-imagery—each man swinging the same blows as his opponent, right arm crossing right, left crossing left.

The man with his back to the rock had an expensive miniature camera suspended from his neck; the other one hadn't.

Suddenly, they both feinted with their lefts in perfect preparation for what hundreds of railroad bulls had come to curse as "the Gooseneck McCarthy One-Two." Both men ignored the feint, both came up suddenly with their right hands and—

They knocked each other out.

They came down heavily on their butts, about a yard apart, shaking their heads.

"You are the stubbornest cuss I ever saw," one of them began. "Where—"

"—did you learn my punch?" McCarthy finished, stepping forward.

They both sprang to their feet, stared at him. "Hey," said the man with the camera. "You two guys are twins."

His former opponent differed with him. "You mean you two guys are twins!"

"Wait a minute." McCarthy stepped between them before their angry glances at each other could be translated into action. "We're all twins. I mean triplets. I mean—Sit down. I got somethin' to tell you."

They all squatted slowly, suspiciously.

Four chaws of tobacco later, there was a little circle of dark nicotine juice all around them. McCarthy was breathing hard, all three of him. "So it's like I'm McCarthy I because I've seen this thing through up to where I stop McCarthy II from going back to get the note that McCarthy III wants from Ruddle."

The man with the camera rose and the others followed. "The only thing I don't get," he said finally, "is that I'm McCarthy III. Seems to me it's more like I'm McCarthy I, he's McCarthy II—that part's right—and you're McCarthy III."

"Uh-uh," McCarthy II objected. "You got it all wrong. The way I look at it—now see if'n this doesn't sound right—is that I'm McCarthy I, you're—"

"Hold it! Hold it!" The two men who had been fighting turned to McCarthy I. "I know I'm McCarthy I!"

"How do you know?" they demanded.

"Because that's the way Professor Ruddle explained it to me. He didn't explain it to you, did he? I'm McCarthy I, all right. You two are the stubbornest bindlestiffs I've seen and I've seen them all. Now let's get back."

"Wait a minute. How do I know I still ain't supposed to move this rock? Just because you say so?"

"Because I say so and because Professor Ruddle says so in that note I showed you. And because there are two of us who don't want to move it and we can knock you silly if'n you try."

At McCarthy II's nod of approval, McCarthy III glanced around reluctantly for a weapon. Seeing none, he started back to the time machines. McCarthys I and II hurried abreast.

"Let's go in mine. It's closest." They all turned and entered the machine of McCarthy I.

"What about the checks? Why should you have three checks and McCarthy II have two while I only got one? Do I get my cut?"

"Wait'll we get back to the professor. He'll settle it. Can't you think of anythin' else but money?" McCarthy I asked wearily.

"No, we can't," McCarthy II told him. "I want my share of that third check. I got a right to it. More'n this dopey guy has, see."

"O.K. O.K. Wait'll we get back to the lab." McCarthy I pushed down on the chronotransit. The island and the bright sunlight disappeared. They waited.

Darkness! "Hey!" McCarthy II shouted. "Where's the lab? Where's Professor Ruddle?"

McCarthy I tugged at the chronotransit. It wouldn't move. The other two came over and pulled at it too.

The chronotransit remained solidly in place.

"You must've pushed down too hard," McCarthy III yelled. "You busted it!"

"Yeah," from McCarthy II. "Who ever told you that you could run a time machine? You busted it and now we're stranded!"

"Wait a minute. Wait a minute." McCarthy I pushed them back. "I got an idea. You know what happened? The three of us tried to come back to—to the present, like Professor Ruddle says. But only one of us belongs in the present—see what I mean? So with the three of us inside, the machine just can't go anywhere."

"Well, that's easy," said McCarthy III. "I'm the only real—"

"Don't be crazy. I know I'm the real McCarthy; I feel it—"

"Wait," McCarthy I told them. "This isn't gettin' us any place. The air's gettin' bad in here. Let's go back and argue it out." He pushed the lever down again.

So they went back a hundred and ten million years to discuss the matter reasonably. And, when they arrived, what do you think they found? Yep—exactly. That's exactly what they found.

So they went back ... to discuss the matter reasonably....