MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

THE

AMAZING EMPEROR

HELIOGABALUS

BY

J. STUART HAY

ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE, OXFORD

WITH INTRODUCTION BY

Professor J. B. BURY, Litt.D.

REGIUS PROFESSOR OF MODERN HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1911

The life of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, generally known to the world as Heliogabalus, is as yet shrouded in impenetrable mystery. The picture we have of the reign is that of an imperial orgy—sacrilegious, necromantic, and obscene. The boy Emperor, who reigned from his fourteenth to his eighteenth year, is depicted amongst that crowd of tyrants who held the throne of Imperial Rome, by the help of the praetorian army, as one of the most tyrannical, certainly as the most debased.

Few people have made any study of the documents which relate to this particular period, and fewer still have taken the trouble to inquire whether the accounts of the Scriptores are trustworthy or consonant with the known facts.

To this present time no account of the life of this Emperor has been published. Histories of the decline and fall of Imperial Rome there are in plenty; other reigns have been examined in detail; German critics have sifted the trustworthiness of the documents, few in number and all late in date, which[vi] refer to other reigns; so far nothing has been done on the life of Elagabalus.

The present writer started this study with the view that the Syrian boy-Emperor was, in all probability, what his biographers have painted him, and what all other writers have accepted as being a substantially correct account of the absence of mind, will, policy, and authority which he was supposed to have betrayed, along with other even more reprehensible characteristics.

The first reason to doubt this estimate came from the continually recurring mention of a perpetual struggle between the Emperor and his female relatives; a fight in which the boy was always worsting able and resolute women, carrying his point with consummate tact and ability, while allowing the women a certain show of dignity and position, where it in no way diminished the imperial authority or his own prerogative.

This circumstance alone was scarcely consonant with Lampridius’ account of a mere youthful debauchee, who had neither inclination nor will for anything, save a low desire to wallow in vice and unspeakable horrors as the be-all and end-all of his existence.

On further inquiry, another circumstance obtruded itself, namely, that the boy had a vast religious scheme or policy, which he was bent on imposing on his subjects in Rome, and indeed throughout the world. This policy was the[vii] unification of churches in one great monotheistic ideal.

Religion may be neurotic in itself, but the scheme of Elagabalus was not essentially so. Certainly the course of action by which he purposed to effect his ideal was not that of a mere sensualist. It showed understanding, persistency, and dogged determination; it was not popular, because in the general incredulity, the earlier deities had lost even the immortality of mummies.

Yet another reason which forced one to disagree with the usual summary of the character under discussion was that, despite (1) the awful accounts of the imperial orgies; (2) the accusations brought against the cruelty and incompetency of the government; (3) the announcement that all good men were exterminated in the general lust for destruction of such worthies; (4) the account of the class and calibre of the men employed in all state offices; (despite all this) the authors inform us that the state did not suffer from the effects of the reign. This was obviously an impossibility at the outset, and the terminological inexactitude became even more apparent when all the known good men were mentioned as peaceably holding office, not only during the reign in question, but in that of Elagabalus’ successor; either they had been resurrected or had never been exterminated.

Again, the account given of the military policy is not that which would be the work of a weakling.[viii] The fiscal policy may have been unchanged, but the edict which enforced the payment of Vectigalia in gold, showed a considerable amount of sense, in demanding the payment of taxes in the one coin whose standard had been maintained when all others had been debased by preceding Emperors, and no one had been worse than the great financier Septimius Severus in this debasing of the currency.

In legal matters alone we are told that the period was sterile, because only five decrees of the reign are recorded by the editors of the Prosopographia. This may be true, but it is quite possible, in fact more than probable, that in later redactions much of the work which Papinian, Paul, Ulpian, and other such produced during this reign has been embodied in later decrees or codifications, and one can scarcely imagine that these men were entirely sterile for four years in the zenith of their authority.

Again, it is most noticeable that in the mass of abuse and obvious animus which the “life” exhibits, there is not one definite act of cruelty reported; no wanton murder is cited; no hint given that the people were discontented with the appointments made, or that they suffered from any of the misrule which had been so prevalent for years past. On the other hand, we are told that the people considered Elagabalus a worthy Emperor, despite all that could be said to his discredit.

Chiefly it was this too obvious animus, shown on each page of the documents, which led the writer to[ix] examine the opinions of German and Italian critics on the measure of credibility which could safely be attached to the Scriptores Historiae Augustae. It was an agreeable surprise to find that their estimates of the Scriptores ranged from those of men who stigmatised the whole collection as an impudent and unenlightened forgery to men who, like Mommsen, contended that, though originally the lives might have had some real historical value, they had been so edited and enlarged as to lack the essential weight of historical evidence, and contained, as they stood, but a modicum of consecutive and unvarnished fact.

Authorities being so far in accord, the present writer set to work to sift the accounts which were obviously quite unnaturally biased, and to separate what was merely stupidly contradictory from what was mutually exclusive.

This method has been applied merely to the first seventeen sections of Lampridius’ work, the portion which professes to contain a more or less historical account of the events from Elagabalus’ entry into Rome to his disappearance into the main drain of the city.

In the latter portion of the life there is a wealth of biographical detail, which, in plain English, means an account in extenso of what has been already described too luridly in the foregoing sections. It is written in Latin, and has never been translated into English, to the writer’s knowledge, nor has he[x] any intention of undertaking the work at this present or any other time, as he has no desire to land himself, with the printers and publishers, in the dock at the Old Bailey, in an unenviable, if not an invidious and notorious position.

Those, however, who are capable of reading the Latin tongue, and therefore inured against further corruption, will find an excellent edition published in Paris by M. Panckoucke in 1847. The last three chapters in the present volume are an attempt to bring together all the material capable of publication in these seventeen sections, and take the form of three essays on the main figures of the Emperor’s psychological imagination. They are in no way an endeavour to expurgate the sections referred to, as any such attempt would leave one with the numerals as headings and the word “Finis” half-way down a sheet of notepaper. It is better for the sapient to read the chapters for themselves, and so all men will be satisfied.

It has also been impossible, on the same grounds, to criticise the statements here made; the greater part are, like those in the biographical portion, frankly impossible, when not mutually exclusive. It is needless to say that the author accepts the whole with all the Attic salt at his disposal.

Another anomaly that may strike the reader is the fact that various names are used to designate the Emperor. Tristran remarks that “they are as many as the hydra has heads.” The present idea is to[xi] use the titles which the boy bore at the different stages of his life, rather than apply to him on all occasions the nickname which was attached to him after his death.

In the earlier part of the work I have referred to the youth as Varius and Bassianus, the two names which appear most frequently, in reference to his reputed fathers, but have neglected Avitus, by which title he is occasionally known, in reference to his grandfather, as also that of Lupus, which is sometimes found in Dion, because, as Dr. Wotton remarks, there is no means of finding out whether he was so called (if ever he was given the name at all) on account of some ancestry, by reason of a false reading, or on account of some other matter now long laid to rest.

After the Proclamation, I have preferred to call the Emperor by his official name, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, or Antonine for short, as this is the only manner in which the coins, inscriptions, and documents describe him. After his death, it seems allowable to give him the nickname which his relations and later biographers have applied to him, namely, the latinised form of the name of his God. I have nowhere adopted the later Greek spelling or adaptation, Heliogabalus, either when referring to the God of the Emesans or to the Emperor himself. The only form in which the name occurs in inscriptions is in describing the Emperor as “Priest of Elagabal” or the Sun. Lampridius certainly[xii] Hellenised its form a century later, on what grounds is by no means clear, when one realises that neither the boy nor his God had any trace of Greek blood, tradition, or philosophy about them, and that the identification of a particular Syrian monotheism with Mithraism or general Sun worship is not universally admitted as a necessary consequence, either in the case of Elagabal, Jehovah, or indeed in that of any of the other “El” claimants to exclusiveness, though the balance of probability may lie on the side of the identification. It is further unnecessary to drag in the Hellenised form of the Emperor’s name in order to pander to a popular and erroneous conception of the reign, which conception this book is designed to combat and generally offend. Heliogabalus is nevertheless the sole title by which this Emperor is known to the world at large, in consequence of which I have allowed the name to stand on the title-page, chiefly in order that Mrs. Grundy’s prurient mind may know, before she buys or borrows this volume, that it is the record of a life at which she may expect to be shocked, though she will in all probability find herself yawning before the middle of the introductory chapter.

As I understand the reign, the main object on the part of the boy’s murderers in nicknaming him Elagabalus after his death, was to throw discredit on his memory by depriving him of the venerated title Antonine, and substituting therefor the name[xiii] of a Syrian monotheistic deity, who by his exclusiveness was an offence and a byword in the eyes of the virile, pantheistic philosophy which then held sway.

A word must also be said as to the attitude in leaving untouched much of the scandal attaching to this Emperor’s name. I have only been able to deal with the public side of his character, as there are no coins or inscriptions which refer to his private life, and have in consequence been forced to quote what the tradition, gained from his traducers’ writings, states was his unfortunate abnormality.

These traditions may be true wholly or in part, they certainly could only be disproved by the actual persons implicated, who have written neither for nor against the Emperor’s psychological condition. The traditions, however, as far as they treat of the public position and reputation of the Emperor, have been shown to be grossly unfair where they are not horribly untruthful, and may be—in all probability are—of an equal value, when they discuss private practices about which no one can have had any particular knowledge except his actual accomplices. Suffice it to say, that any stick is good enough to beat a dog with once he is incapable of defending himself, and in this case it has been laid about Antonine’s shoulders with almost diabolical ingenuity.

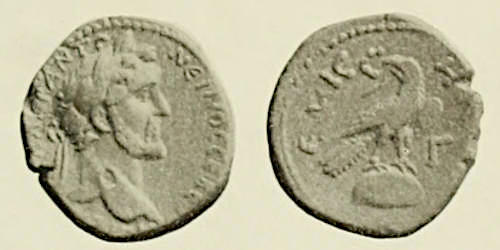

I much regret that I have been unable to find any portraits of the Emperor for whose authenticity[xiv] Bernouilli will vouch. Alone of the whole family there remain authentic busts of Julia Mamaea and Julia Paula, neither of whom are important enough to be included, since we are unable to give a portrait of Elagabalus himself. I have therefore confined myself to the use of coins, whose veracity is undoubted, hoping that the reader will supply from his imagination that charm and beauty which the biographers have been unwillingly forced to allow both to the Emperor and his mother.

In the preparation of this work I have had much valuable and kindly assistance, for which I desire to acknowledge my deep indebtedness here. First, to Professor Bury of Cambridge, for his unwearying and sage advice on my whole manuscript; also to Dr. Bussell, Vice-Principal of Brasenose College, Oxford, for his interest and kindly corrections; to the authorities in the Bodleian Library; to the assistants in the British Museum, especially to Mr. Philip Wilson and Mr. A. J. Ellis for their continued help in my work there, and to Mr. Allen for the time and care he has spent in helping me find the coins that explain the text.

I have also to acknowledge with sincere thanks the permission of Mr. E. E. Saltus of Harvard University to quote his vivid and beautiful studies on the Roman Empire and her Customs. I am deeply indebted to Mr. Walter Pater, Mr. J. A. Symonds, and Mr. Saltus for many a tournure de phrase and picturesque rendering of Tacitus,[xv] Suetonius, Lampridius, and the rest. I also desire to thank Dr. Counsell of New College, Oxford, and Dr. Bailey of the Warneford Asylum, not only for their help in correcting my proofs, but also for their assistance in the preparation of my chapter on Psychology.

To all these gentlemen I owe a great debt, which, I hope, the general public will repay by an appreciation of their work. We have endeavoured to right a wrong; if our efforts are in any way successful, the reader will acknowledge that this mauvais quart d’heure, which has been stigmatised as full of impossible situations and intolerable surprises, is in reality a very human life which, like our own, has its exquisite moments of which we would as soon deprive ourselves as Elagabalus.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | xxiii |

| PART I | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| General sketch of conditions, 1. The Augustan Histories and their writers, 2. Lampridius, author of the Life of Elagabalus, 4. First attempts at criticism, 4. Modern criticism, 4. Latin sources: Marius Maximus, 5. Greek sources: Dion Cassius, Xiphilinus, 7. Herodian, 8. General attack on the authenticity of the “Lives,” 9. Mommsen’s opinion, 10. Peter, Richter, Dessau, Seeck, Klebs, Kornemann, 11-15. Italian opinion, 15. General opinion of the biographies, 16. Reasons for the tainted sources, 18. Church historians, 19. Jurisprudence, 21. Numismatists, 21. Object of this work, 23. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Emesa, 24. High-Priest Kings, 25. Septimius Severus, 27. Julius Bassianus, 27. Julia Domna’s marriage, 28. Caracalla’s birth, 29. Septimius Severus, Emperor, 30. Julia’s court, 31. Maesa comes to Rome with her family, 31. Marriage of Soaemias, 34. Birth of Elagabalus, 35. Paternity of Elagabalus, 35. Birthplace of Elagabalus, 36. Julia Mamaea, her marriage, and her connection with Caracalla, 38. Macrinus Praetorian Praefect, 41. His plot against Caracalla, 42. Election of Macrinus, 43. Julia’s position, 43. Her work to recover the empire, 43. Banishment and death, 44. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Maesa’s return to Emesa, 46. Macrinus’ weakness and tyranny, 47. The legion at Emesa, 48. Bassianus High-Priest, 49. Worship of Elagabal, 50. Bassianus’ religious outlook, 51. Eutychianus and Gannys corrupt[xviii] the soldiers, 53. Date of the proclamation of Elagabalus, 55. Macrinus astonished, 56. The Empire in favour of Bassianus, Julian’s expedition, 59. Deserters to Bassianus, 61. Macrinus at Apamea, and Diadumenianus’ elevation, 63. Macrinus retires to Antioch, 66. Bassianus wins allegiance of soldiers at Apamea, 67. Dion on the dates of proclamation and battle, 67. Arval Brothers’ meeting, 68. Wirth, 69. Battle of Immae, 69. Antonine at Antioch, 71. Macrinus’ escape, 72. Capture and death, 74. Character of Macrinus, 75. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Antonine’s refusal to allow the sack of Antioch, 77. Chief minister, 78. Antonine’s temperament, 79. Acts of the new Government, 81. Amnesty, 83. Position of the Senate, 84. Delight of Rome, 86. Dismissal of troops, 87. Treasonable attempts and pretenders, 88. Elagabal to accompany the Emperor, 91. Journey to Nicomedia, 92. Winter in Asia Minor, 93. Illness of the Emperor, 94. Xiphilinus on Antonine’s religion, 95. Monotheistic or Mithraic not polytheistic, 96. Death of Gannys, 101. Antonine’s character, 102. His popularity and his taxation, 104. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Date of arrival in Rome discussed, 107. The entry into the city according to Herodian, 110. First marriage, 111. The temples, 112. The scheme for the unifying of religions, 114. The worship, 115. The Eastern cults, 115. Date of scheme discussed, 118. Reasons for its failure, 118. Women in the Senate, 119. Senaculum, 121. Lampridius on the Emperor’s popularity, 124. Charges against the Administration, 125. Divorce of Julia Paula, 126. Pastimes, 127. Summary, 128. Elagabal’s alliance with Vesta, Antonine’s with Aquilia Severa, 129. Pomponius Bassus’ plot, 131. Antonine divorces Elagabal from Minerva, himself from Aquilia Severa, 132. Sends for Tanit from Carthage, 133. Marries Annia Faustina, 134. Alliance of Maesa and Mamaea, 135. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Lampridius on Alexander, 137. Seius Carus’ plot, 139. Military expenditure, 140. Maesa’s plan for the adoption of Alexander, 141. The Emperor’s reasons for concurrence, 142. Name Alexander accounted for, 144. Date of adoption discussed, 145. Position after adoption, 146. Alexander’s titles, 147. Antonine’s endeavours, 148. Antonine’s resolve to divorce Annia Faustina and disown Alexander, 150. Accusations against the Government, 151. Antonine’s attempt to assassinate[xix] Alexander discussed, 152. Antonine goes to Praetorian camp, 154. Camp conference, 155. Hatred of Maesa and Mamaea testified against Antonine, 157. Mamaea’s precautions, 158. Antonine’s preparations for suicide, 160. Alexander designated Consul, 160. The Emperor’s refusal and reasons for his compliance, 161. Lampridius on Julius Sabinus, 163. Ulpian and Silvinus, 164. Reasons for the murder and the various accounts, 165. Criticism on the above, 170. The treatment of Elagabalus’ body, 171. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Emperor set free to further his cult, 173. The procession, 174. Mismanagement and appointments, 178. Freedmen, 180. Return of Aquilia Severa, 183. Desire for military glory, 184. The names of the Emperor, 185. Activity in building, 186. Military disaffection, its causes and result, 188. Date of Elagabalus’ murder and length of reign discussed, 191. Date for renewal of tribunician power discussed, 194. Elagabalus’ interest in public affairs, 198. The treatment of inscriptions, 198. Outlook of the Roman world, 200. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Roman views on matrimony, 203. Elagabalus’ marriage with Julia Paula, 205. Position of Julius Paulus, 206. Serviez, etc., on Julia Paula, 207. Dates of this marriage and divorce, 208. Elagabalus’ marriage with Aquilia Severa, 211. Vestals discussed, 211. Roman religion, 212. Elagabalus’ lack of prejudice, 214. His explanation to the Senate, 215. Family of Aquilia Severa, 215. Probable dates of marriage and divorce, 216-18. Maesa’s desire for an alliance with the nobility, 218. Annia Faustina chosen, her family discussed, 222. Her age and her divorce, 223. Further marriages discussed, 224. Elagabalus’ return to Aquilia, 225. | |

| PART II | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Lampridius’ Life of Elagabalus impossible, 227. Elagabalus a psycho-sexual hermaphrodite, not wicked, 229. The condition quite usual then as now, 229. Virtue a virile quality, not a neurotic negation, 229. The Phallus natural and omnipresent typifies joy and fruitfulness, 230. Elagabalus has strong homosexual nymphomania and every inducement[xx] to gratify his feminine instinct, 231. His nature incredibly open and affectionate, 232. Maesa an aggravating factor, 234. Modern authorities on similarly inverted cases to-day, 234. Biblical parallels, Greek instances, modern religious tendencies, 234. Normal intolerance largely hypocritical, 235. The usual instincts of such natures, 235. Elagabalus’ love of flowers, feasts, and teasing, 236. His marriages psychologically considered, 238. His castration and desire for an operation which might produce the female organs discussed, 238. Elagabalus’ marriage with Hierocles, 239. Hierocles and Zoticus discussed, 239. Comparison with Messalina, 240. Spintries, 240. Elagabalus’ love of colour, 241. His frankness, 241. Greek love opposed to effeminacy, 242. Gulick on the psychology, on Christianity, 242. Effeminacy, not homosexuality, disgusts Roman world and gives reason for Elagabalus’ downfall, 244. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Description of Nero’s golden house, 245. Elagabalus compared with Nero, 246. Pastimes, prodigalities, and dress, 246. Extravagances of ritual, 250. Congiaries and games, 251. Table appointments and food, 252. Maecenas’ feast, 254. Perfumes, 256. Fish, 258. The spectacles described, 260. Gladiators discussed, 262. Elagabalus’ skill as a sportsman, 263. The lotteries, 264. Elagabalus’ devices for suicide, 265. The psychology of extravagance, 266. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Elagabalus’ piety, 267. Constantine the opponent of other monotheisms, 268. Theories of religion, 269. Civilised religion becomes philosophical, 269. Rome both atheist and credulous, 270. Civic religion leaves the forces of sex and superstition out of count, 270. Gods always necessary to the superstitious, the more mystical the more attractive, 271. Semitic rituals attract the mob, 273. Elagabal exclusive and absorbs other cults, 273. Elagabalus’ scheme Erastian, compared with Tudor conception, 273. Elagabalus will not persecute, 276. Religion and castration, 276. Elagabalus no idolator, 277. His mistake in trying to amalgamate the hated Judaism with Roman deities, 277. Marriages of Elagabal, 278. Human sacrifices discussed, 280. The column for the meteorite, 281. Contest between religion and dogma, 282. The numbers of the mob prevail against the rationalists, 284. Rome bored with all Gods, hence Elagabalus’ failure, 285. | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 289 |

| INDEX | 299 |

| Facing page | |

| Coin of Antoninus Pius, struck at Emesa (British Museum) | 26 |

| Coin of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Caracalla) (British Museum) | 26 |

| Medal of Julia Domna Pia, Empress (British Museum) | 40 |

| Coin of Julia Maesa Augusta (British Museum) | 40 |

| Coin of Julia Soaemias Augusta (British Museum) | 40 |

| Coin of Julia Mamaea Augusta (British Museum) | 40 |

| Coin of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Caracalla) (British Museum) | 60 |

| Coin of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Elagabalus) (British Museum) | 60 |

| Coin of Macrinus recording Victoria Parthica, A.D. 218. (From a woodcut) | 60 |

| Coin of Diadumenianus as Emperor, A.D. 218 (British Museum) | 60 |

| Coin of A.D. 219 commemorating the arrival of Elagabalus in Rome (British Museum) | 110 |

| Liberalitas II. Coin struck in A.D. 219 for the Emperor’s marriage with Julia Cornelia Paula. (From the collection of Sir James S. Hay, K.C.M.G.) | 110 |

| Coin struck in A.D. 219 concerning the grain supply (British Museum) | 110 |

| Coin struck in A.D. 219 to commemorate the Emperor’s recovery (British Museum) | 110 |

| Thyatira Coin of Elagabalus (British Museum) | 142 |

| Coin struck to commemorate Alexianus’ adoption, A.D. 221 (British Museum) | 142 |

| Coin struck to commemorate Alexander as Pont. Max., A.D. 221 (British Museum) | 142 |

| Jovi Ultiori. The Eliogabalium as reconsecrated to Jupiter, A.D. 224. (From a woodcut) | 174[xxii] |

| Coin struck to commemorate the Procession of Elagabal, A.D. 221 (British Museum) | 174 |

| Coin of A.D. 221 representing the Eliogabalium. (From a photogravure) | 174 |

| Coin of A.D. 220, misread by Cohen as T.P. III Cos. IIII (British Museum) | 196 |

| Coin of A.D. 221, misread by Cohen as T.P. IIII Cos. IIII (British Museum) | 196 |

| Coin of A.D. 222 (British Museum) | 196 |

| Coin of Julia Cornelia Paula Augusta (British Museum) | 216 |

| Coin of Julia Cornelia Paula Augusta, A.D. 220-21 (British Museum) | 216 |

| Coin of Julia Aquilia Severa Augusta, A.D. 220-21 (British Museum) | 216 |

| Coin of Annia Faustina Augusta, A.D. 221-22 (British Museum) | 216 |

| Coin of Julia Aquilia Severa Augusta, A.D. 221-22 (British Museum) | 216 |

The Emperor who is studied in this volume has commonly been treated as if his reign had no significance, unless it were to show to what deep places the Roman Empire had sunk when such a monster of lubricity could wield the supreme power. If the chronicle of his naughty life has been exploited to illustrate the legend that the pagan society of the Empire was desperately wicked and infamously corrupt, he has not been taken seriously as a ruler. Yet Elagabalus appeared under too ominous a constellation to justify us in dismissing his brief attempt to govern the world as unworthy of more than a superficial description and a facile condemnation. His reign lasted less than four years; but those years fell in a period which was critical for the future of European civilisation, and he was brought up in a circle intensely alive to the religious problems which were then moving the souls of men. Mr. Hay has broken new ground, and he has done history a service, in making Elagabalus the subject of a serious and systematic study.

The third century, so obscurely lit by poor and meagre records, saw the Empire of Rome shaken to its foundations. There was a manifest decline in[xxiv] its strength and efficiency, marked by the insolent domination of the common soldier, and luridly illustrated by the statistical facts that from Septimius Severus to Diocletian the average reign of an Emperor was about three years and that there were only two or three sovereigns who were not the victims of a mutiny or a conspiracy. As one of the efficacious causes of this decline has often been suggested (most recently by M. Bouché-Leclercq) the detachment of men’s interest from the public weal by the attraction and influence of individualistic oriental religions, which did not aim at securing the stability of the state, like the old religions of Rome and Greece, but undertook to save the individual and ensure his happiness in a life beyond the tomb. It is undoubtedly true that in this period religious currents were stirring society to its depths, and several rival worships were engaged in a competition of which the issue was decided in the following century. And if the state was really weakened by a cleavage which had become sensible between the private spiritual interests of the individual citizen and the public interests of society, if its cohesion was endangered by the tendency to place the former interests above the latter, we can understand the statesmanship of Constantine the Great, who, by closely connecting the state with one of those individualistic religions, conciliated and identified the two interests. I do not suggest that Constantine formulated the problem in the general terms in which we may formulate it now; he was pushed to his far-reaching decision by a[xxv] variety of particular social facts, which involved the general problem, while they forced upon him a particular solution. But the problem which he solved had long been there, and a hundred years before Constantine established Christianity, another Emperor had attempted to solve it. That Emperor was Elagabalus.

The religious currents of the age of the Severi did not escape the notice, or fail to engage the interest, of the Court. Julia Domna, Julia Mamaea, Alexander Severus, were all under the influence of the spirit of the time. These were the days in which Julia Domna and Philostratus discovered for the world a new saviour in the person of Apollonius of Tyana. But the religious zeal of Elagabalus was more passionate than the intellectual interest of any of his house. He conceived a universal religion for the Empire, and his abortive attempt to establish it is examined by Mr. Hay with a full sense of its significance and an unprejudiced desire to understand it.

With all his unashamed enthusiasm, Elagabalus was not the man to establish a religion; he had not the qualities of a Constantine or yet of a Julian; and his enterprise would perhaps have met with little success even if his authority had not been annulled by his idiosyncrasies. The Invincible Sun, if he was to be worshipped as a sun of righteousness, was not happily recommended by the acts of his Invincible Priest. I have said “idiosyncrasies”; should I not have said “infamies”? But it is unprofitable as well as unscientific simply to[xxvi] brand Elagabalus as an abominable wretch. His life is a document in which there is something demanding to be comprehended. If all men and women are really bisexual, this Syrian boy was of that abnormal type in which the recessive is inordinately strong at the expense of the dominant sex; he was a remarkable example of psychopathia sexualis; but in his age there were no Krafft-Ebings to submit his case to scientific observation. From this point of view, which Mr. Hay has taken, Elagabalus becomes an intelligible morbid human being. And the young man, though so highly abnormal and spoiled by the possession of supreme power before he had reached maturity, was far from being repulsive. A salient feature of his character was good nature; he appears to have wished to make every one happy. His pleasures were not stained by the cruelties of Nero. It amused him to shock people, but he was always good-humoured. He is said to have genially inquired of some grave and decorous old gentlemen who were his guests at a vintage festival, whether they were inclined for the pleasures of Venus. The anecdote, if not true to fact, seems to be characteristic. It is told in the chronique scandaleuse of Lampridius, one of the writers of that Augustan History round which a forest of critical literature has grown up in recent times. The outcome of all the criticism is generally to the discredit of these authors, and Mr. Hay has the merit of having strictly applied this unfavourable result to the Life of Elagabalus.

But though the religious enterprise of this eccentric Emperor was doomed to fail, it was not by any means the wild project of a madman, which those who judge post eventum—after the triumph of Christianity—or who, like Domaszewski, see in it merely eine Vergöttlichung der Unzucht, are apt to take for granted that it was. In those days, it was not in the least certain, as yet, that Christianity would be chosen and its rivals left; this religion was not, as its apologists would have us believe, the only light in a dark world. To a disinterested mind it would appear that Mithra or Isis might have become the divinity of western civilisation. They were certainly well in the running. We may guess what circumstances aided the worship of Christ to rise above competing cults, but for inquirers, like Mr. Hay and myself, who hold no brief, and do not accept the easy axiom that what happens is best, it is unproven that Christianity was decidedly the best alternative. Perhaps it was. Yet we may suspect that, if the religion which was founded by Paul of Tarsus had, “by the dispensation of Providence,” disappeared, giving place to one of those homogeneous oriental faiths which are now dead, we should be to-day very much where we are. However this may be, it seems that in the third century the Christians were far from commending their doctrine to the rest of the world by any signal moral superiority in their own conduct. The bad opinion which pagans held of their morals in the time of Tertullian cannot be explained as a mere wilful prejudice, and Tertullian’s reply that the[xxviii] charge is only true of some but not of all nor even of the greater number (Ad nationes, 5) is a significant admission that, taking them all round, the Christians were not then conspicuous as a sect of extraordinary virtue. Moreover, there was nothing in the ethics of their system which had not been independently reached by the reason of Greek and Roman teachers, and they are entitled to boast that the success of their religion depended not on any superiority in its moral ideals to those of pagan enlightenment, but on its supernatural foundations.

Slander, with ecclesiastical authority behind it, dies so hard, that I may take leave to add a remark which to well-informed students of antiquity is now a platitude. The offensive performances of Elagabalus prove nothing as to the prevailing morality of his time, just as the debauches of Nero prove nothing for his. To judge the private morals of the pagan subjects of the Empire from the descriptions of Suetonius and Lampridius is even more absurd than it would be to portray the domestic life of Christian England from the reports of the Divorce Court. The notion that the poor Greeks and Romans were sunk in wickedness and vice is a calumnious legend which has been assiduously propagated in the interest of ecclesiastical history, and is at the present day a commonplace of pulpit learning. If pagans, in ignorance or malice, slandered the assemblies and love-feasts of the early Christians, it will be allowed that Christian divines of later ages have, by their fable of pagan corruption, wreaked a more than ample revenge.

Among readers of Gibbon, the very name of “Heliogabalus” will always “force a smile from the young and a blush from the fair.” But it may be expected that, after Mr. Hay’s investigation, it will be recognised that this Emperor made, according to his lights, a perfectly sincere attempt to benefit mankind, which must be judged independently of his own moral or physiological perversities.

J. B. BURY.

The age of the Antonines is an age little understood amongst the present generation. The documents relating thereto are few in number, and for the most part the work of very second-rate scandal-mongers. Like the Senate of the time, these writers had so far lost their sense of personal responsibility that they were quite willing to record anything that their “God and Master” ordered. The pleasures and vices of the age were lurid and extravagant. The menace of official Christianity, with its destruction of literature and philosophy, was almost at the gates of the city. All which facts serve to render this most magnificent period of Roman history unreal and fantastic to men of our more practical and rationalistic age.

The reign of Elagabalus is not a record of great deeds. It shows no advance in science or in military conquest. Save in the realm of jurisprudence, it is not an age of great men, because[2] these are born in the struggles of nations. It is not an age of poverty or distress. It is rather a record of enormous wealth and excessive prodigality, luxury and aestheticism, carried to their ultimate extreme, and sensuality in all the refinements of its Eastern habit. Such were the forces that swayed the minds of these eager, living men, made idle by force of circumstances.

It was a wonderful and a beautiful age, full of colour, full of the joy of living; and yet, as we look back upon its enervating excitements, who can wonder at the greatness of the decline which followed the triumph of so much magnificence? Rome was at the apex of her power; the Empire was consolidated; the temple of Janus was closed; the Pax Romana reigned supreme, and with it order and government in the remotest corner of that vast dominion. What mattered the extravagances of a foolish boy to the merchants of Lyons or to the traders of Alexandria, so long as they were undisturbed and taxation was at a minimum? What mattered the blatant outburst of a Semitic monotheism, when men’s minds—amongst the superstitious—were already attuned to the kindred mysteries of Mithra and the spiritual chicanery of Isis? The harm had been done both to reason and to ancient belief by the secret dissemination of other superstitions, whose effete neuroticism, whose enervating and softening influences had done almost more to ruin the glorious fighting strength of the Empire than all the luxury and effeminacy of the bygone world.

It was a pitiful exhibition, the powers of ignorance and mystery undermining the strength of knowledge and virility, till the barbarians, whom the very name of Rome had conquered and held entranced, overthrew a greatness which, in the age of reason, the world had found irresistible. It is pitiful, but it is true, and the record of merely a part will be found in the Augustan Histories.

The difficulties presented to the student of the Scriptores Historiae Augustae are manifold and ever increasing. Not the least of them lies in the variation of standard by which this collection has been judged, and in the diametrically opposing theories which eminent scholars have drawn from the same passages.

The criticism owes its origin to the confusions which are bound to exist in any series of lives covering a period of 167 years and purporting to be the work of several—though none of them contemporary—writers.

The Biographies which have survived are nominally the work of six authors, to wit, Aelius Spartianus, Julius Capitolinus, Vulcacius Gallicanus, Aelius Lampridius, Trebellius Pollio, and Flavius Vopiscus. The author of the Life of Elagabalus in this series is Aelius Lampridius, of whom personally nothing is known. Peter[1] postulates that he was not a plebeian, as he wrote at Constantine’s bidding, and presumably, from the virulence of his attacks, with some ulterior object in view. This was probably an attack on the Imperial author of that species of[4] Mithraic worship which Constantine desired to extirpate, as the most formidable opponent of his own new religion.

Lampridius dedicates his Life of Elagabalus to this Emperor, which at once shows us that at least 100 years had passed since the events recorded had taken place, and calls for an inquiry into the sources of Lampridius’ information. The text as it stands to-day is at times incomprehensible, largely through the efforts of scholars of the Bonus Accursius and Casaubon type,[2] while Dodwell in 1677 played his part in corrupting, according to his lights, what must always have been a document whose need of further mutilation was highly unnecessary. The first attempt at modern criticism of the texts began in 1838, when Becker[3] of Breslau endeavoured to reassign the various lives to their respective authors, without very much success. In 1842 Dirksen[4] of Leipzig attempted to ascertain the sources employed by the various Scriptores, and their use or misuse of the material to their hands. He founded his criticism mainly on the recorded speeches and messages of the Emperors, which, unfortunately for the theories then put forward, were discovered by Czwalina,[5] in 1870, to be largely spurious.

The next work of any importance was done by Richter[6] and Peter,[7] when the former tried to date[5] the Scriptores themselves from internal evidence; the latter threw light on the time when the actual lives were written, and, amongst others, assigns Lampridius’ Life of Elagabalus to a period in or about the year A.D. 324. In 1865 the same author[8] placed the study of the Scriptores on a firmer basis altogether, by introducing the system of textual criticism as applied to the sources, both Latin and Greek, from which the writers had drawn their facts.

Amongst Latin sources the chief name mentioned was Marius Maximus, of whose works nothing now remains. He was Consul under Alexander Severus and a devoted servant to that Emperor, at whose direction he attempted to complete Suetonius[9] by a popular and scandal-mongering edition of recent events. Mueller,[10] in 1870, after a careful investigation of all the references to this author, concluded that his work was the compilation of a volume styled De vitis imperatorum, which contained the lives of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus, Commodus, Pertinax, Julianus, Severus, Caracalla, and Elagabalus. That the last of these lives should have been written by the friend and servant of Elagabalus’ murderers is in itself unfortunate, as one immediately suspects that some attempt will be made to justify the crime, or at any rate that veiled malignancy rather than a true historical portrait will be the result. It is easily discovered from the shortest perusal of the wealth[6] of mere abuse which it contains that no veil was considered either necessary or expedient, and that if Lampridius drew his information of the Emperor Elagabalus from Maximus, as a sole source, his work was, historically speaking, as worthless a caricature as that with which Maximus had bolstered up Alexander’s government. Mueller, therefore, propounded the theory that though Maximus was the main Latin source, other authors were used by the Scriptores in a supplemental way. In this theory he was supported by Ruebel, Dreinhoefer, and Plew,[11] who cite, amongst other names, that of Aelius Junius Cordus, an author who is quoted with considerable frequency throughout the lives. This theory of one main Latin source—Maximus—held ground until quite recently, when the work of Heer, Schulz, and Kornemann, as we shall see, put a somewhat different, if less satisfactory, complexion on the matter. It may be remarked, in passing, that Niehues,[12] in 1885, attributes the earliest life of Macrinus and his son Diadumenianus—amongst other Emperors whose period does not concern us in this present inquiry—to Cordus rather than Maximus, which may account for a certain amount of impartiality about Macrinus’ life, there being no special end to serve either way.

The Greek sources used by the Scriptores are more easily fixed, for, though most of the authors have perished, the work of Herodian is preserved,[7] and the abbreviation of Cassius Dio, which was made by Xiphilinus of Trebizond for ecclesiastical purposes, is still readable. It is perhaps necessary to state Haupt’s[13] opinion that the Scriptores did not actually transcribe the Greek sources, and that these can only give one a certain idea as to how the writers used their materials. Unfortunately for the reign in question, neither of these two authors can be considered as unprejudiced authorities. Indeed, circumstances have conspired to obscure the history of Elagabalus at every point. Cassius Dio is by unanimous consent the best historian of the third century, infinitely superior to Maximus as a man of literary ability and historical insight; he is not highly exciting, and has an annoying habit of mistaking sententious platitudes for speculative philosophy. His impartiality is certainly very questionable, and his obviously superstitious credulity notable. But these defects are easily overlooked by the student, because his work does embody a vast store of information on the workings of the Imperial system. In all probability he was absent from Rome during the reign of Elagabalus, since he tells us (79-7) that Macrinus appointed him Curator of Smyrna and Pergamum in the year 218, from which posts he was not removed by Elagabalus.[14] When next he appears it is as the friend and servant of Maesa, at the beginning of Alexander’s reign. He was then—successively—twice Consul, Proconsul of Africa, Governor of Dalmatia and Pannonia Superior, and presumably[8] died under Alexander at 80 years of age, as we have no work from him after that date. As servant of the dominant faction, Dio’s history must have been compiled to support Maesa’s action in causing the murder of Elagabalus, and to justify the succession of Alexander, when once the women had cleared the headstrong boy and his mother from their path. Dio advances his information as that of an eye-witness, and as such it was presumably derived from the same source as that of Maximus—so much so, that Giambelli[15] in 1881 tried to prove that Dio’s main source for his history was Maximus throughout and none other.

The other Greek contemporary is Herodian, the facts of whose life are by no means certain. Kreutzer[16] thinks that he came to Rome about the beginning of the third century, and subsequently held some minor administrative posts in the government. He stands on a different plane from Dio, as he possessed very small qualifications as a historian. He narrates, it is true, salient features of court life and current foreign affairs, though he has small conception of their bearing and less regard for their chronology. In this matter it is only fair to remember that the ignorant emendations of Bonus Accursius and a tribe of mediaeval scholars may account for much that now looks so outrageous.

As regards the sources from which Dio and Herodian took their facts, much has been written, though the attempts[17] made since 1881 to show that[9] both used Maximus are at best poor and inconclusive. Mueller[18] in 1870 pointed out with some considerable weight that the similarities which exist between the parallel accounts found in Herodian and the Scriptores were probably due to the fact that both had used Maximus. This line of argument was developed by Giambelli and Plew[19] on the basis of a supposition that Herodian had been worked over before he was used by the Scriptores, thus endeavouring to account for the discrepancies between Herodian and Maximus, and supporting the Maximus-as-root-base theory of both authors. Boehme[20] in 1882 introduced the name of Dexippus as the probable intermediate writer, and pointed out that the references made by certain Scriptores to Herodian, under the name of Arrianus, are hard to understand if the scriptor had the correct name before him. Certain passages can however be shown to have been taken direct from Herodian, on account of which Peter[21] entirely rejected the Dexippus intermediary theory a few years later. In the main, however, the general authenticity of the sources, whether Greek or Latin, was accepted up to the year 1889, though one or two discoveries had been made which weakened their hold and prepared the way for the general attack.

The first was made by Czwalina[22] of Bonn in[10] 1870, who declared that the documents and letters in the Life of Avidius Cassius were spurious; and in 1880 Klebs[23] destroyed the authenticity of those at the end of Diadumenianus’ Life. Things were more or less quiet until the year 1889, when Dessau[24] opened his attack on the general authenticity of the Scriptores’ work, asserting from the strongest internal evidence, such as their mention of persons and things—in lives dedicated to Constantine as Emperor—which did not happen till after his death, that the lives were the work of a forger in the later part of the fourth century; a man who had been stupid enough to give an appearance of antiquity to his work by the use of names and dedications borrowed from older sources, but not smart enough to avoid the inclusion of glaring anachronisms.

Mommsen[25] at once undertook to defend the authenticity of the collection, asking saliently why a forger of Theodosius’ time should undertake to praise the extinct dynasty founded by Constantius. The very patchwork, he says, is enough to prove the collection no forgery. Again, the use of pre-Diocletian geographical names, such as those given to the legions, all date from a period prior to Diocletian. Mommsen then proceeds to his criticism, in the course of which he divides the lives into primary and secondary, which to his mind solved the problem, and on this basis he drew[11] entirely different conclusions from the facts which Dessau had adduced as proofs of forgery. The progress of Mommsen’s study forced him to admit what he had so entirely repudiated at first, that the lives do contain hints of a later period, all of which, he asserts, can be accounted for by the manner in which the collection took form. Mommsen’s opinion, as finally stated, was that about A.D. 330 an editor collected the available material and then filled in the gaps with his own work. Again, at a later time a reviser retouched this whole collection and added the evidence of the latest period, which has caused all the trouble. By him also the work resembling Eutropius and Victor was inserted. It is not the clearest of statements, and had to be so modified, as it proceeded, that it certainly has not the weight attaching to it that others of Mommsen’s works carry.

During the year 1890 two works appeared, the first by Seeck,[26] who attempted to assist Dessau, the other by Klebs,[27] who had accepted a modified Mommsen estimate of the authenticity of the Scriptores. Seeck began by pointing out that a work which was first heard of in the latter part of the fourth[28] century was not likely to arouse sufficient interest to induce any one to revise it during the earlier part of that century. He attacked the work attributed to Vopiscus, Pollio, and Spartianus in particular, pointing out, in the case of Vopiscus, that had he written under Constantine he would[12] not have put him second in the dedication,[29] or, if Pollio had written in the third century, when the title Mater Castrorum was commonly given to the Empresses, he would never have spoken of it as a speciality in Victoria’s case.[30] If Spartian wrote under Diocletian, it is obvious that he must have had a prevision of that Emperor’s sudden change of plan as to the succession. Klebs[31] in the same year further modified Mommsen’s position, and explained the similarities to Victor and Eutropius as due to the use of the same sources by these authors and by the Scriptores, and rejected the idea of a revision by a late hand on the ground that no one would be so foolish as to imitate the style of the original writers for the sake of inserting nonsense; certainly not the most convincing of the arguments which might have been used by a man who presumably had at least heard the history of the Gospel additions. A later article (1892)[32] was more conclusive, as here he attempted to prove that no one forger could have adopted the variety of attitude towards both the Senate and Christianity which we find expressed in the various sections of the “lives,” while the presence of geographical names and official titles, lost before the beginning of the fourth century, point to earlier authenticity, not later forgery.

Woelfflin[33] in 1891 supported Mommsen on[13] textual grounds. He traces the differences of style to the fact that certain authors had used Suetonius, others Maximus, while others again had trusted to their own retentive memories, not altogether a safe historical criterion. He states that the traces of similarity running through the works are due certainly to a reviser, but that the reviser was Vopiscus,[34] which either puts Vopiscus at a much later date than had ever been done before, or resigns the idea of a late reviser in the Mommsen sense.

Dessau[35] in 1892 replied with a scathing attack on this same Vopiscus, from the point of view of his age and the impossibility of his having seen and heard all he claims to have done. Seeck[36] in 1894 published a second article supporting Dessau with six points culled from titles and names not known till after the reputed dates of the Scriptores. He now considers that plurality of authors, or forgers, as the case may be, is certain, and that they wrote, or forged, as Diocletian and Constantine gave command, using for their work many sources, including the Imperial Chronicle. But it is an inconclusive article.

In 1899 an American, Dr. Drake[37] of Michigan, published some studies in detail on the life of Caracalla, which tended to establish the genuineness of certain portions which had been thought spurious. Heer[38] of Leipzig followed in 1901 with a[14] critical survey of the life of Commodus, dividing it into two parts, the first chronological, the second biographical, and came to the conclusion that, though the chronological part was trustworthy, the biography was derived from very poor sources, and was only in part contemporaneous. Schulz[39] in 1903 applied the same methods to the lives from Commodus to Caracalla, in 1904 to the life of Hadrian,[40] and in 1907 to the lives of the house of Antonine,[41] unfortunately leaving out Elagabalus.

Kornemann[42] in 1905 attempted to bring together the materials of the lives from Hadrian to Alexander Severus, much on the lines of Schulz’s work. He points out that the characteristic note was to be found in the author’s interest in the affairs of state, as opposed to those of war, and how Alexander Severus has been raised to his pinnacle of smug propriety on account of supposititious favours to the senatorial body, while extreme animus is betrayed towards the warlike Emperors or those who, like the paternal despots of the Antonine House, trusted in the army and only used the “slaves in togas” for ratifying any decree that they might think necessary, a mode of procedure in government to which that body had long been slavishly subservient. Kornemann goes on to suggest that this fondness for Alexander presupposes the writer’s work having been published[15] during that Caesar’s reign, especially as no trace is found of his work later. Kornemann then invents a new name for our old friend Marius Maximus, and calls him, with some further show of scholarship, one Lollius Urbicus,[43] a theory which still only interests Kornemann. Heer[44] in 1901 had given him a certain support, however, in refusing to believe that any one could have credited Maximus with any part in the chronological side of the lives, and Schulz in his Life of Hadrian adopted the same view, assigning the references to Maximus to a later hand. It was Peter[45] who, in 1905, asked pertinently why Maximus should be ousted from the authorship of the chronological source in favour of an unknown contemporary, though he admitted, with some freedom, that many of the citations from Maximus stood in passages of questionable value, or seem to have been thrust into the text.

In 1899 Tropea[46] of Padua published a treatise on the general literature of the S.H.A., in which he shows that the aim of the collection was political, and in the interest of the reigning house; in consequence of which he postulates that it is either falsified in fact, or wholly fabricated in the sense that Czwalina had already suggested. Tropea was followed by his pupil Pasciucco,[47] who examined the life of Elagabalus in detail in 1905. The result of this examination was to show that Lampridius had not only failed to examine his sources of information, but had exhibited a singular lack of order and[16] proportion in his imaginations. Pasciucco concluded with the illuminating remark that Lampridius’ sources are either fabulous or of little value, and answer only to the political complexion which that writer had adopted.

In 1904 Lécrivain[48] published an admirable conservative presentation of the available material, which, with Schulz’s work on the Imperial House of Antonine in 1907, leaves the textual criticism of the sources in a sufficiently nebulous condition to please the majority, at any rate for the time being.

In the light of the foregoing criticism and the almost universal conclusion, drawn by both parties, as to the obvious want of impartiality not only amongst the sources but also in the lives themselves, the scope of this work will limit itself to a psychological criticism of the life of Elagabalus, as contained in the Augustan Histories. These documents, as will be remembered from the foregoing summary, are a collection of heterogeneous and unenlightened compositions, to which Lampridius, by no means the ablest contributor, has added the life of the Syrian boy-emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Lampridius exhibits to a striking degree the want of method and order, the vain repetitions and frequent contradictions, the lack of historical insight and love of petty detail which characterise the whole collection. This he shows to such a degree that it would be as obviously unfair to regard his biographical compilation on Elagabalus as historical fact, as the more than questionable[17] “Tendenzschriften,” which were his sources of information; the perusal of which must have left the compiler with a distorted view of events, even had he started with a fair and unprejudiced mind. This certainly was not Lampridius’ outlook, as is evinced by the obvious animus against his subject portrayed on every page both in his unsupported accusations and in his puerile fault-finding.

In all probability this series of lives was never intended to be more than a succession of scandal-loving biographies, designed to take the place of the improper little novels which used to be imported from Greece, but whose supply was falling short with the decadence of Greek literature.

In the result, the biographies of the Augustae Historiae Scriptores are for the most part an inartistic farrago of unordered trivialities, which modern criticism has shown to be late in date, and with little or no individual significance. Their whole value depends on their source, or sources, and these have been proved, at least biographically speaking, to have been only too often untrustworthy. The Life of Elagabalus, as caricatured by the particular Scriptor, or forger, is not even an attempt to portray historical events in either their chronological or natural order; it makes no mention of the origin of the Emperor, his claims to the throne, his fight with Macrinus, nor yet of the facts of his subsequent government. It is merely one vast stream of personal abuse and ordures, directed against the memory of the great exponent of that monotheism which was the chief danger to Constantine’s[18] theories in a similar direction; while Lampridius’ sources are vitiated by the fact that they are Imperial attempts to blacken the memory of a murdered Emperor, whose popularity with the masses made his murderer’s position insecure on the throne of the world.

It may not be altogether fair to charge the young Alexander personally with the murder of Elagabalus, and even if one does, it is only right to remember that he claimed a certain justification for the deed.[49] Alexander affirmed that he had himself been in danger of death at his cousin’s hand on more than one occasion. Undoubtedly, the true instigators of the murder were Mamaea, Alexander’s mother, and Maesa, the common grandmother of the cousins. Both of these women saw power and authority passing from their hands, and could ill brook a second place in the direction of the government. By their machinations, bribery, and corruption, they had endeavoured already three times to suborn the Praetorian Guard. But the effort had failed. Sufficient men had always been wanting for the project, and only an unlucky chance threw the Emperor into the hands of those few on the day of his death. Alexander’s complicity in this crime might have been overlooked, on account of his youth, had not his strenuous efforts to justify the deed called attention to his attitude, not of regret, but of exultation in the crime. This attitude is most clearly seen in the scandalous literary productions which alone disgrace the name of Elagabalus, all issued from[19] the pens of Cassius Dio, Herodian, and Maximus,—or Lollius Urbicus,—all three servants and bedesmen of Alexander and his female relatives.

Surely if it had been possible to give proof of cruelty, tyranny, bloodthirstiness, deceit, or guile, the record of these deeds would have filled the pages of the paid traducers; but contemporaries, who loved Elagabalus too well for his generosity, charm, and beauty, would know better. The only course open to the writers, therefore, was to attack personal habits of which the outside world knew little and cared less, because they were habits that affected no one save the boy’s familiars, who were perfectly free to depart if they objected to his manners or conversation.

As regards the later compilers of Imperial histories, mention must be made of Zosimus and Zonaras, the twelfth-century editors of Cassius Dio, who, however, add little to our knowledge. They are of a certain value because they omit many of the scandals before produced, while the same may be said for Aurelius Victor and the Breviarium of Eutropius.

The Church historians make little mention of the period; they were undisturbed by persecutions, and had no emperor or praefect to abuse. They were, in fact, so busy inventing the difficulty of the diphthong and developing Pauline theories on the doctrine and position of Christ, that they had but little time for the real facts of life and progress around them. Origen is a slight exception, but then his pride had been flattered by a summons to Court,[20] where, Eusebius tells us, he discussed astronomical theology with the now visionary Julia Mamaea—who seems to have aped her aunt, Julia Pia, in these matters. Origen’s pride was further flattered by the dignity of a Praetorian escort on the journey to Antioch—he does not mention the return voyage—which was certainly a most astonishing honour, for which one would like to have other than sacerdotal confirmation.

Further literary authorities, such as Sextus Rufus, Orosius, John of Antioch, and Jordanis, though inferior in weight, have obviously got some of their information from sources other than those open to the Scriptores, and their statements may be accepted with reserve, unless they can be shown to be irrational and contrary to known facts.

When all is gathered in, the sum total of the recorded history, as Mr. Cotter Morison[50] says, is meagre to a degree. The investigation of the various isolated records in the light of what is known of the movements and tendencies of the age—combined with the psychology of the boy’s character—is and must be the key to much that at first sight seems contradictory and obscure in the scandals reported—none of which, as Niebuhr has said, are capable of historical treatment with anything like an assurance of accuracy. In this part of the biography Lampridius himself is of considerable use. In the course of his vituperation he is continually letting fall allusions and observations revealing a character, instincts, and religion which he is quite incapable[21] of comprehending, and can only malign with a vitriolic vehemence worthy of a better cause. His very vehemence is fortunate, since it has left the way open for psychology and science to proclaim the abuse, what we now know it to be, both malicious and untruthful.

The evidences from the jurisprudence of the reign are certainly unsatisfactory. Later codifications have left us with but few dated laws of a reign that stands in the golden age of Roman jurisprudence. Ulpian, Papinian, and Paul were not men to allow a break in the order of legal succession, and though Ulpian was presumably banished in connection with Alexander, it was not until within a few months of Elagabalus’ death. Sufficient remains to show us that the Empire suffered no break in the perfect autonomy of jurisprudence, justice, and government, throughout a period which Forquet de Dorne[51] has dignified under the pseudonym of the reign of military anarchy.

Cohen and Eckhel are of great importance in fixing, as nearly as possible, the chronology of the period, by their records of the medals and coins of the reign. The same may be said of the inscriptions which have escaped the vandalism of the Emperor’s enemies. Duruy, in his great history, is unwilling to give the medals much biographical weight, comparing them to the governmental journals of all times, which give only the account of events as seen through official spectacles, and on which as little reliance can be placed as on the[22] published bulletins of victories: witness the Parthian medal of Macrinus, the record of a great victory for the Roman troops over Artabanus; the real fact being a colossal defeat followed by a peace, the latter purchased in a manner disgraceful to both the people and the arms of Rome.

Inscriptions are unfortunately few and far between, owing to the fury with which Alexander and his relatives pursued Elagabalus’ memory. Undoubtedly it was no new thing to call upon the Senate to execrate the memory of a murdered rival. It was, in fact, one of that body’s most important functions during the period under discussion. Rarely has the work been done so thoroughly and effectively, which says something for the zeal of Alexander and the money he spent in extirpating all reference to the memory of Elagabalus.

The works of Valsecchius[52] and Turre,[53] amongst seventeenth-century scholars, are illuminating on the subject of the length of Elagabalus’ reign. Tristran’s[54] attitude shows the slavishness of tradition; certain of Saumaise’s[55] emendations show the same tendency despite his usual impartiality; in fact, all have accepted the tradition of wickedness without the least question as to its fons et origo. This work proposes to take the texts as they exist, and endeavour from their unwitting statements of the boy’s psychology to convict them of untruth. From their unsupported charges of secret crimes, to show that real crimes were largely non-existent, and[23] to throw the burden of all the ordures which have covered this Emperor’s name on to the shoulders of his relations and murderers, to whom alone it was a vital object to destroy his fair renown before a world which loved him. That his world did love him, despite all, there are manifold traces. The prodigal Emperors always were adored; so were their successors, the wicked popes. Man was too near to nature to be aware of shame, and infantile enough to like to be surprised. That was Elagabalus’ scheme; he amused his people and surprised them at the same time.

The whole spirit of tolerance of the unusual makes it difficult for us to picture Rome. Modern ink has acquired Nero’s blush; yet, however sensitive a writer may be, once Roman history is before him although he may violate it, may even give it a child, he never can make it immaculate. He may skip, indeed; and it is because he has skipped so often that you may fancy Augustus was immaculate. The rain of fire which fell on the cities that mirrored their towers in the Bitter Sea might just as well have fallen on him, on Virgil, on Caligula, Nero, Otho, Vitellius, Titus, or Domitian[56] why, then, condemn Elagabalus alone unheard, save for the fact that his relations hated him, and as far as we can see, hated him without a cause, or perhaps because he was growing too strong, and his unfortunate disease gave them their opportunity to gain that power after which the women were striving like grim death?

Great houses, says a historian, win and lose undying fame in less than a century; they shoot, bud, bloom, bear fruit; from obscurity they rise to dominate their age, indelibly to write their names in history, and after a hundred years give place to others, who in turn take the stage, while they descend into the crowd and live on insignificant, retired, unknown. This is true, in some periods, but not of the Imperial houses of Rome. Their flight across the stage was meteoric in its rapidity. A generation saw the rise and total extinction of many of those families who aspired to the Roman Purple, particularly the revived house of Antonine.

On the borders of the Orontes, in that part of Syria which is known as Phoenicia, lies a small, disagreeable, and melancholy-looking town, which to-day bears the name of Homs, or Hems. It is a construction of yellow and black stones mixed with mud and broken straw, and is the rendezvous of Curds, Bedouins, and Turkomans, a straggling village, where dirt, squalor, and misery proclaim the[25] absence of trade, roads, or contact with an outside world. A short distance away are the ruins of an ancient castle, built by the Crusaders to dominate the route to Antioch. Here alone is there a trace of fruitfulness, a sort of oasis of green gardens, extending along the river-bank towards what was once the graceful and beautiful capital of the Elagabal monarchy, the famous city of Emesa—celebrated under the independent High-Priest Kings of the family of Sohemais for the splendour of its palaces and the magnificence of its temple, and because it was the headquarters of the worship of the God of Gods, Elah-Gebal, or Baal, which is the name more familiar to Christian ears. For us the chief interest in this wretched village lies in the fact that it is the home of that race of Syrian Emperors who ruled Rome during the period of her greatest renown and prosperity—a period when the splendour of the Purple reached its apogee. Rome had been watching a crescendo that had mounted with the ages; it culminated in the revived Antonine house; but the tension had been too great, something snapped, and there was nothing left. So it had been with Emesa; her splendours endured sorrowfully until the twelfth century, and then were engulfed, as her house had long since been, in a great earthquake which devastated that part of Syria, along with lesser-known parts of the earth’s surface.

Little is known of the early history of the hereditary High-Priest Kings of Emesa. Strabo tells us that, like the neighbouring sovereigns of Jerusalem, their origin was sacerdotal, to which[26] functions they had attached the title and jurisdiction of secular rulers on the breaking-up of the Seleucid monarchy.

The most famous princes of the Emesan dynasty of High-Priest Kings were Samsigeramus and his son Iamblichus, the friend of Cicero. In the war between Octavius and Antony this prince found he had taken up arms on the wrong side, and was killed by Antony for fear of treachery. In the year 20 B.C. Augustus re-established the kingdom of Emesa in favour of the son of Iamblichus, which kingdom certainly continued until the time of Vespasian, according to Froelich, and probably until Antoninus Pius, during whose reign we have the first known Imperial coins of Emesa (Eckhel). The kingdom was small, and the wealth, except the revenue which came as religious offerings, insignificant—facts which undoubtedly decided the rulers of the time to yield gracefully before the advancing arms of the universal Emperor, who, in return, left the High-Priest Kings a certain amount of political as well as their inherent religious authority, much in the same way that he left the family of Herod their nominal monarchy, along with the support of a similar Babylonian religion. Certainly the fame of the temple at Emesa and the oracle of Belos at Apamea was widespread, and the hereditary High Priest in the year of grace 179 was an astute gentleman.

Coin of Antoninus Pius, struck at Emesa (British Museum).

Coin of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Caracalla) (British Museum).

In that first year of the reign of the Emperor Commodus there was appointed to the command of the fourth Scythian legion then quartered in Syria,[27] in all probability, as Peter thinks, at Emesa itself, an African, one Septimius Severus by name, a native of Leptis Magna in Tripoli, born in the year 146, and therefore about the age of thirty-three years.

Whether or not he was a widower at the time is uncertain. He had previously married a lady, by name Marcia, but as no children by her are known to have existed, it is probable that she was either dead or repudiated by that year, added to which his precocious inquiries as to the marriageable young women in the neighbourhood presuppose that the general was either free or at least travelling en garçon.

The High Priest of the period was—according to two references in the Epitome of Aurelius Victor—a certain Julius Bassianus, descended in hereditary line from the afore-mentioned Iamblichus. Certainly he was not a plebeian, as Dion says, somewhat sneeringly, when referring to his daughter’s origin, unless, of course, Dion meant in point of comparison with the rank to which she eventually attained.

It was certainly a happy chance that Bassianus possessed not only a wise prophet, but also a superstitious commander in the army of occupation, and was astute enough to work both for the miraculous profit of his house and lineage. Unfortunately he had no daughter old enough for an immediate marriage. She who is presumed the eldest, Domna by name, was at the time only nine years of age, having been born in the year 170, whilst her sister Maesa was presumably somewhat younger.

But to return to the Oracle. In the year of[28] grace 179, when Septimus found himself in a peaceful province, en garçon and very much admired, he took an interest in the marriageable daughters of important persons, like most young men of ambition in their more calculating moments, and—being a religious-minded man—he determined to consult the gods, especially the famous voice which spoke so near at hand. Here he learnt that to the elder daughter of Bassianus was reserved, according to her horoscope, the power of making the man whom she should wed a king. It was an ambitious height to which Septimius aspired, and an ambition which would have cost him his life had Commodus got bruit of the transaction. Nevertheless, being a prudent man, and at the same time ambitious, he resolved to let no chance slip. He did what Bassianus expected—demanded the lady’s hand and obtained the reversion thereof.

At what date the marriage took place is by no means certain; there are two references in Dion which are mutually exclusive. The first says that the Empress Faustine (who, by the way, the same Dion says, died in 175) herself prepared their marriage bed in the precincts of the temple, which sounds a highly unsatisfactory beginning to ordinary matrimony. But as he has just told us that the lady was of an age of five in the year above mentioned, it is highly improbable that her nuptial couch would be prepared by any one, or anywhere, for some time to come, especially as there is no indication that Septimius had heard of the lady before 179, when he consulted the Oracle.[29] Again, Dion assumes that Marcia did not die until Septimius was appointed Governor of Lyonese Gaul about the year 187, so that her husband could only have been playing with astrology, wise prophets, and other things against the time when the obex to solid matrimony should be removed. Possibly even Dion is referring—when he drags in the Empress Faustine—to Septimius’ first marriage, or, as has been suggested, the whole thing was a dream of either Septimius or Dion, probably both, as both were much addicted to such proceedings. Considering the so-called scandal against the lady’s character, her proclivities, and the knowledge that her eldest son Bassianus was born at Lyons on April 4, 188, it is most natural to conclude that the marriage took place some time in the spring of the year 187, though the pledges may have been given when the child was nine years old or thereabouts, and the actual marriage deferred till Julia’s seventeenth year, Septimius amusing himself in the interval, after the manner of soldiers. It must be admitted that, as the record of his scrapes is limited to two, he was more discreet than the majority of his profession.

His choice of a wife, if made on unusual grounds, was more than successful. Few Emperors have had more renowned ladies or more helpful spouses than Julia Domna Pia, the daughter of Bassianus, proved herself to Septimius. It was fortunate that she had more than a horoscope to assist her in her new position. Even the governorship of Lyonese Gaul was an important post, and there she had[30] large scope for the use of her wit, learning, beauty, and wisdom, in addition to her Syrophoenician adaptability for amorous intrigues. By means of which combination the family became people of renown throughout the length and breadth of Pertinax’s Empire, a circumstance which enabled them, on the murder of that Emperor, to assume the rôle of avengers, the deliverers of Rome, the saviours of the Empire, which had now three heads but no commander.

It was Julia, we are assured by Capitolinus, who decided her husband to assume the Purple; it was Julia who first amongst Empresses was Domna, or Mistress, Mater Castrorum, Mater Senatus, Mater Patriae, Mater Totius Populi Romani. Of course she had the sad notoriety of being mother to Caracalla, and late authors (vide Tertullian ad Nationes) have reproached her with many indiscretions—have even accused her of conspiring against her husband; but Dion, who is by no means partial to her, mentions neither accusation, and the absurdity of the latter throws doubt, at least on the public knowledge of the former story. In any case her elevated mind, her four children, and her rank, even when combined with her sun-warmed nature, ought to have protected her from anything except occasional amusements, of which she might have preferred her husband ignorant. Julia’s real fame rests on the basis of her character as a mathematician, an astrologer, and a wise counsellor. The fruit of her learning and philosophy has been handed down to all time by her friend and[31] associate Philostratus in the dedication to her of his Life of Apollonius, the miracle-worker of Tyana, the Thaumaturge whose life and miracles are supposed to form so large a part of the traditional life of Jesus as it exists to-day.