Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

GENERAL SIR EDMUND H. ALLENBY, G.C.B., G.C.M.G.

This book owes its publication to the warm interest taken in its initiation by a Committee comprised of the G.O.C., A.I.F., in Egypt; the G.O’s.C. Anzac and Australian Mounted Divisions and Brigades, and a number of other senior A.I.F. officers; and, later, to the generosity of the many contributors of paintings, sketches, photographs, verse and prose.

“Australia in Palestine” is in no sense intended as a complete picture of the Australians’ part in the Great Campaign. It is merely a Soldiers’ Book, produced almost entirely by soldiers in the field under active service conditions to send to their friends in Australia and abroad. An edition has also been published for sale to the general public, and any profits derived from it will go to one of the A.I.F. funds.

Thanks are due to our many contributors, and in particular to Mr. James McBey, the Official British Artist in Palestine, for his fine portrait of General Allenby (specially drawn for this book) and other sketches; to Captain Hodgkinson, British Press Officer, for permission to use many British official photographs; to Mr. Jeapes, British Official Cinema Photographer, for the loan of many snapshots; and to Sergeant E. A. Hodda, A.I.F., who took charge of the business arrangements, and to whose keen interest and ability our obligation is substantial.

We have also to thank Major N. D. Barton, 7th A.L.H. Regiment, and Messrs. H. M. Somer and Sydney Ure Smith for the valuable assistance they have given as Committee of Publication in Australia.

| Page | |

|---|---|

| Preface (Lieut.-Gen. Sir H. G. Chauvel) | xiii. |

| Fighting for Palestine (H. S. Gullett) | 1 |

| Anthem Bells (“Gerardy”) | 60 |

| Palestine Poppies (Charles Barrett) | 61 |

| Farming in Arcady (H. S. G.) | 64 |

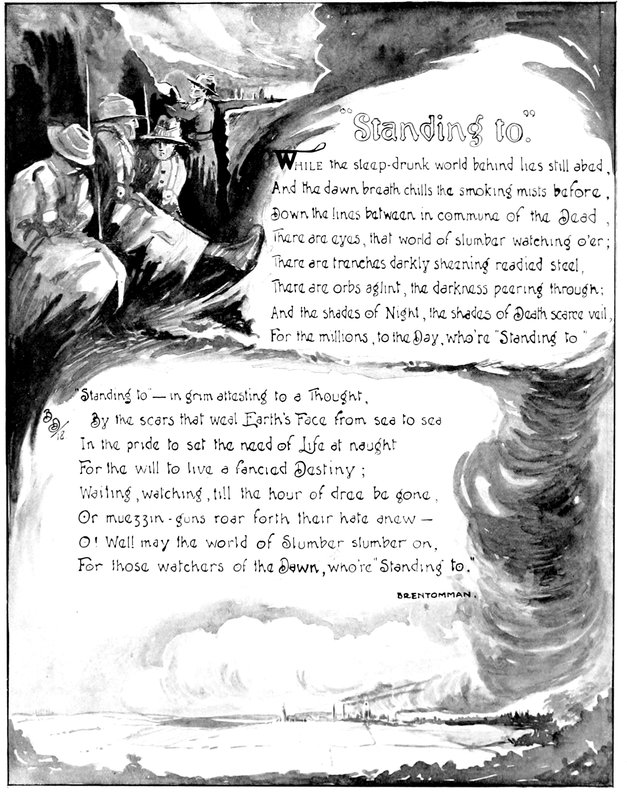

| Standing To (Brentomman) | 69 |

| A Waler’s Story (E. L. D. Husband) | 71 |

| The Horses Stay Behind (“Trooper Bluegum”) | 78 |

| One Too Many (“Anon”) | 79 |

| The Light That Failed (“Sarg”) | 83 |

| A Night March (“Aram”) | 87 |

| A Gloomy Outlook (“Aram”) | 90 |

| Reconciliation (“Gerardy”) | 91 |

| Mail Day (“Wil Cox”) | 92 |

| A Day Over The Lines (H. Bowden Fletcher) | 94 |

| Mounts and Remounts (“Acrabah”) | 99 |

| Concerning Medical Blokes (“Larrie”) | 102 |

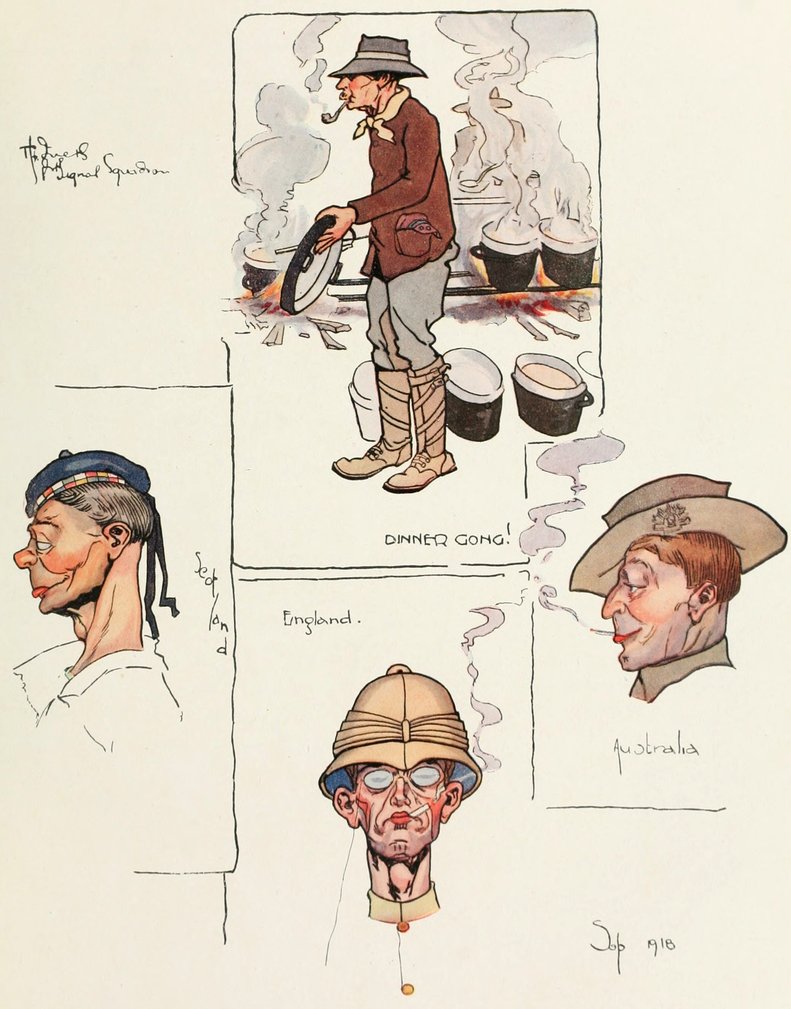

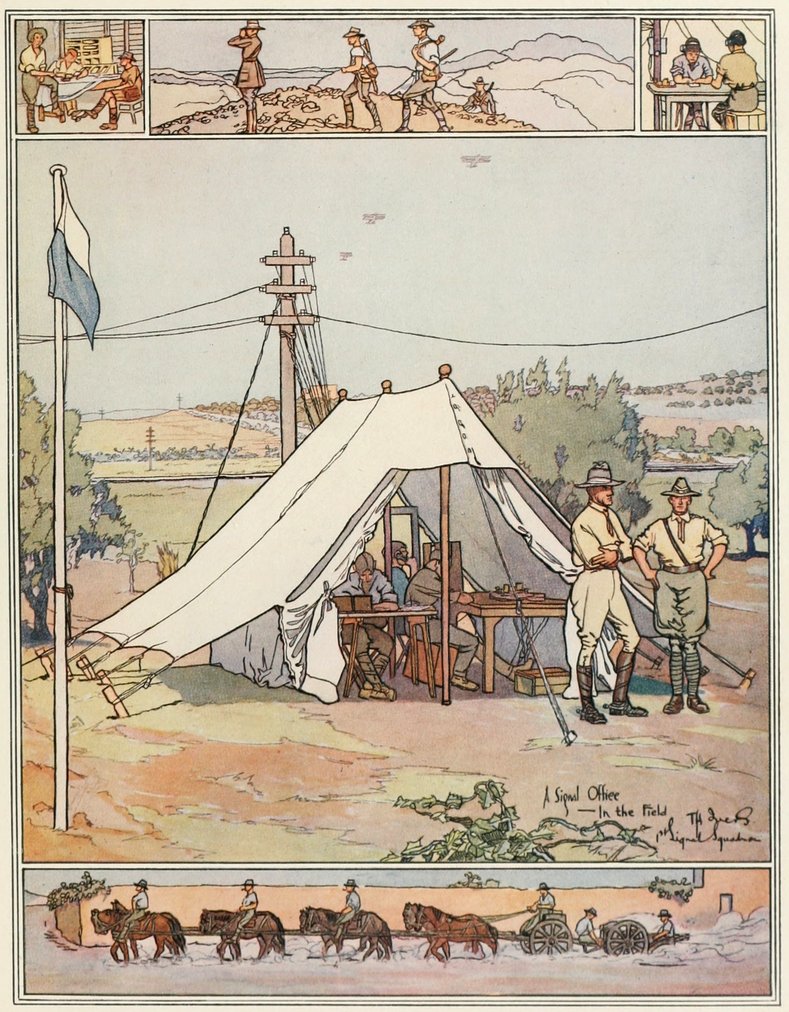

| The Signal Service (“Ack-Vic-Ack”) | 109 |

| Battle Song (“Gerardy”) | 114 |

| The Little Bint of Wady Hanein (“Camp Follower”) | 115 |

| Algy, Misfit (“Billzac”) | 121 |

| xPalestine (“Trooper Bluegum”) | 123 |

| The Camel Brigade (“Trooper Bluegum”) | 125 |

| Resting (“Tralas”) | 132 |

| The Mukhtar’s Goats (“2469”) | 137 |

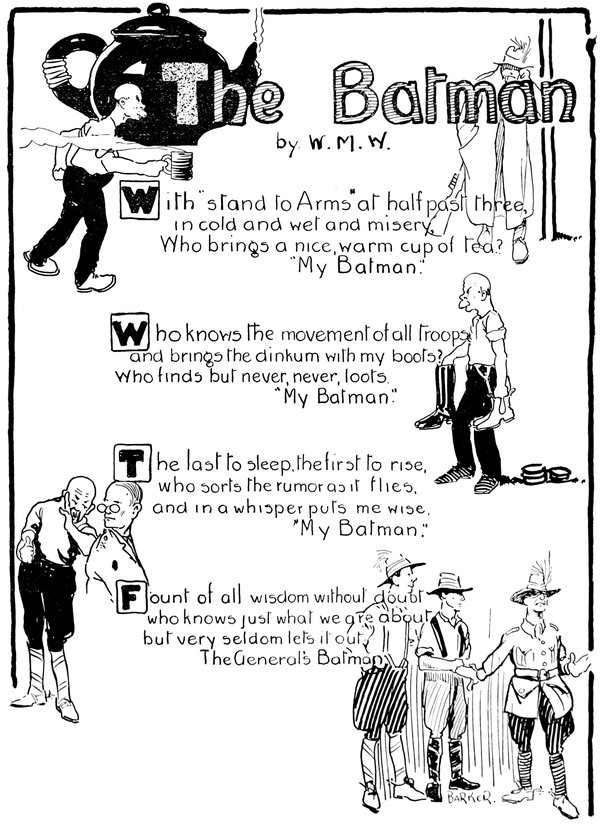

| The Batman (W. M. W.) | 139 |

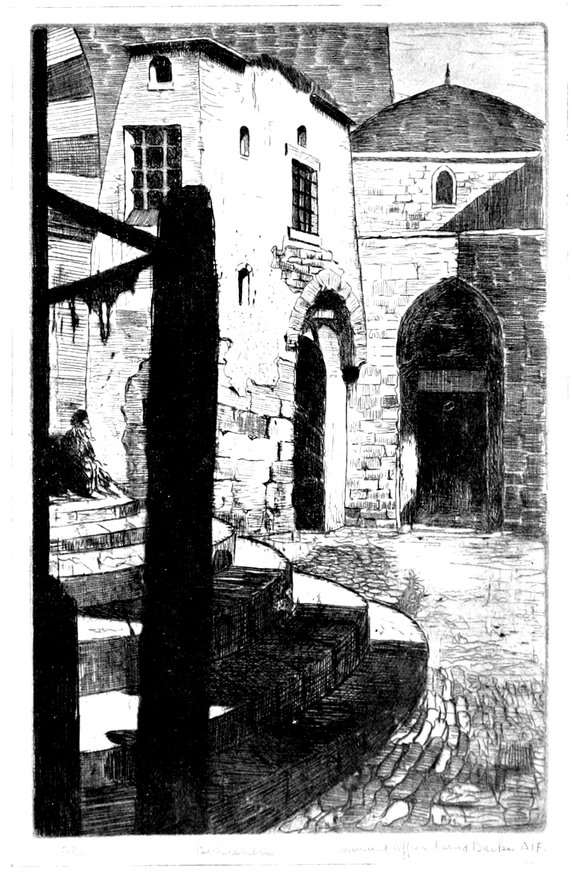

| Damascus (H. W. D.) | 140 |

| Malaria (“Koolawarra”) | 144 |

| Fall Out The 1914 Men (“Bataggi”) | 145 |

| Old Horse o’ Mine (T. V. B.) | 149 |

| Concerning Machine Guns (“Sarg”) | 150 |

| Delivered! (“Gerardy”) | 153 |

| COLOUR PLATES | |

|---|---|

| Page | |

| General Sir Edmund H. H. Allenby, G.C.B., G.C.M.G. | iii. |

| Jerusalem, from below the Mount of Olives | 4 |

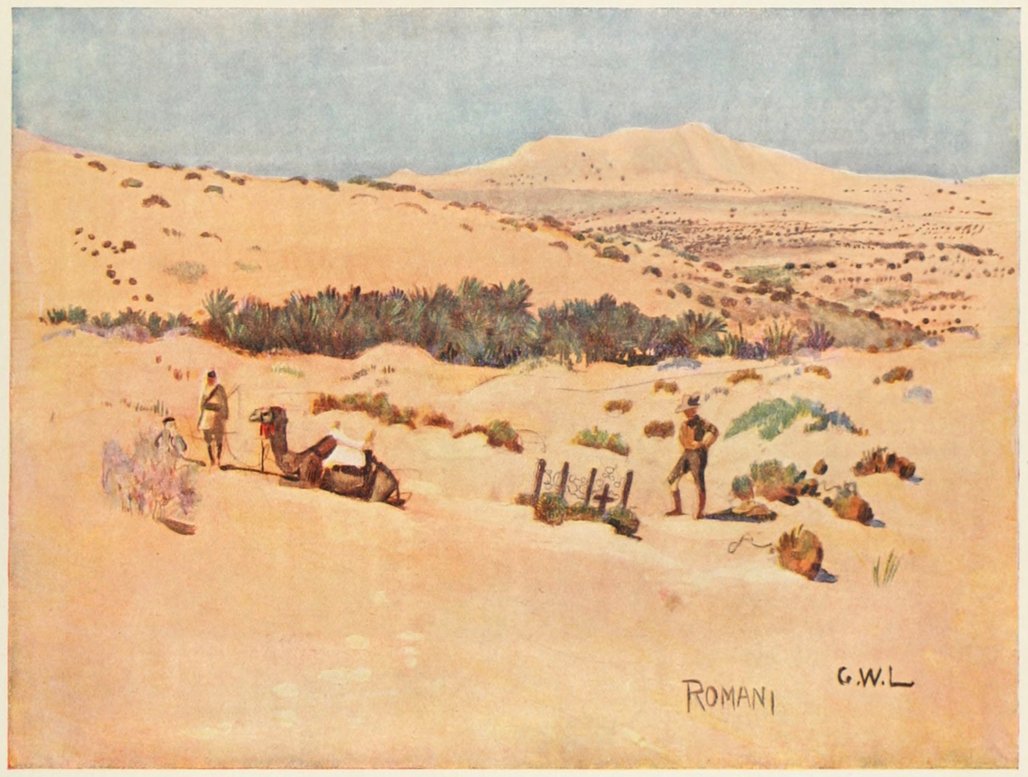

| Romani. Mount Royston in the distance | 14 |

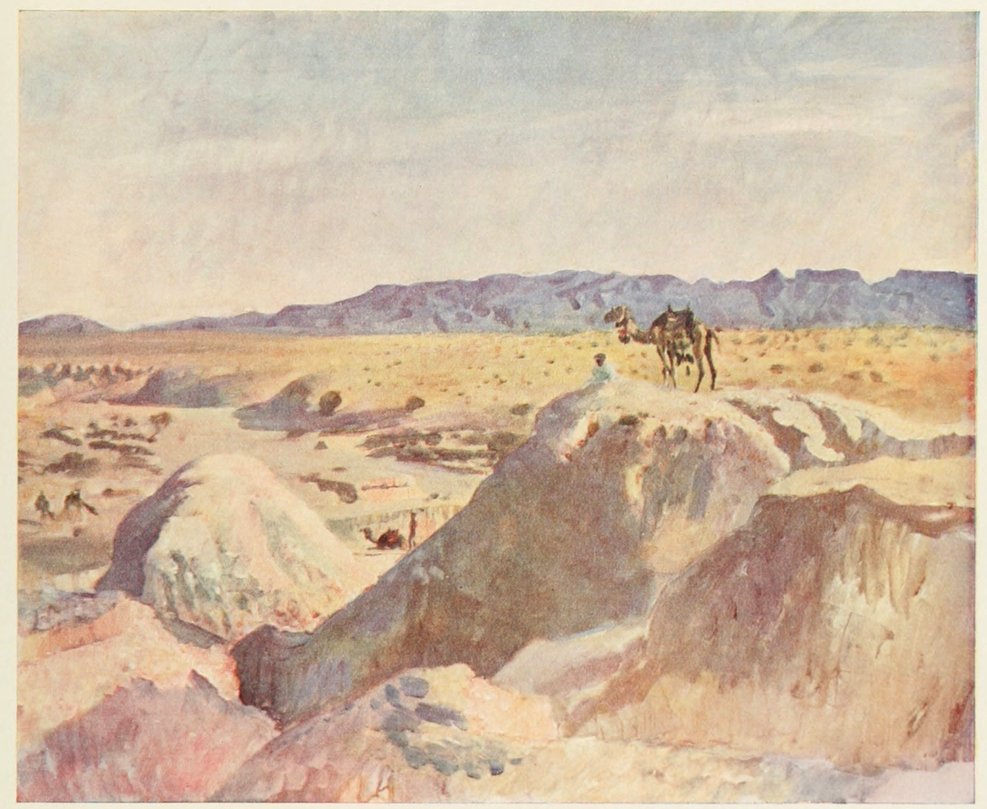

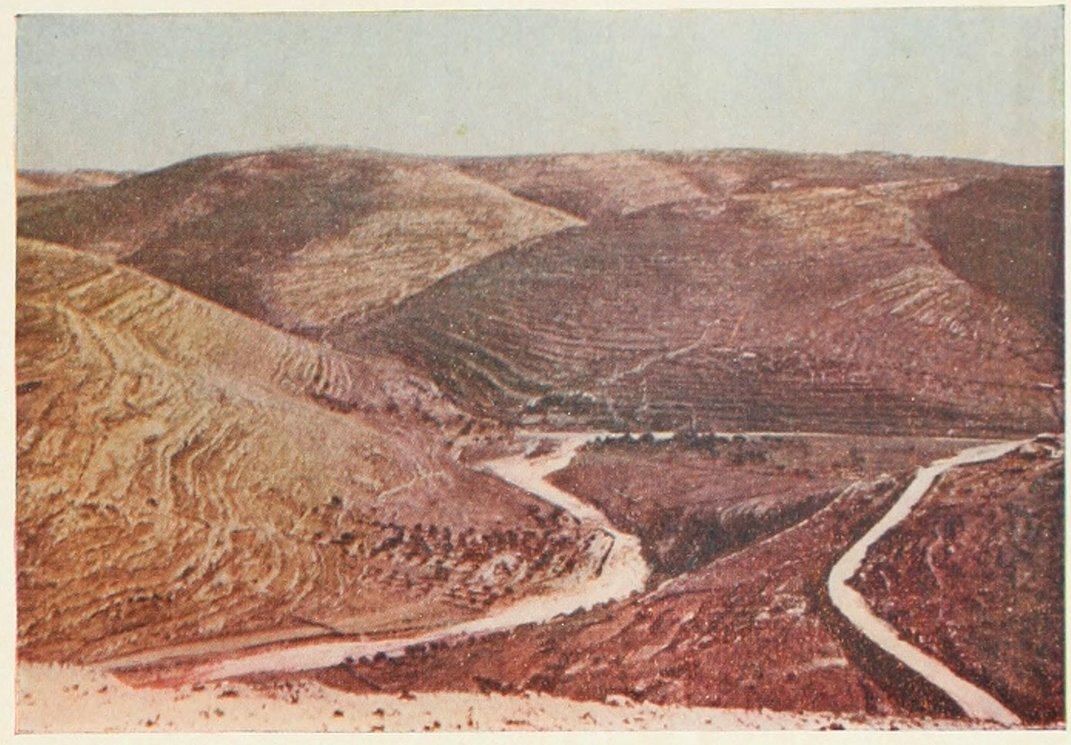

| Magdhaba, showing the Wady Bed about one mile from Turkish buildings | 26 |

| The Road to Jericho | 38 |

| The Dead Sea (Sunrise) | 42 |

| Australians on the Road to Jerusalem | 30 |

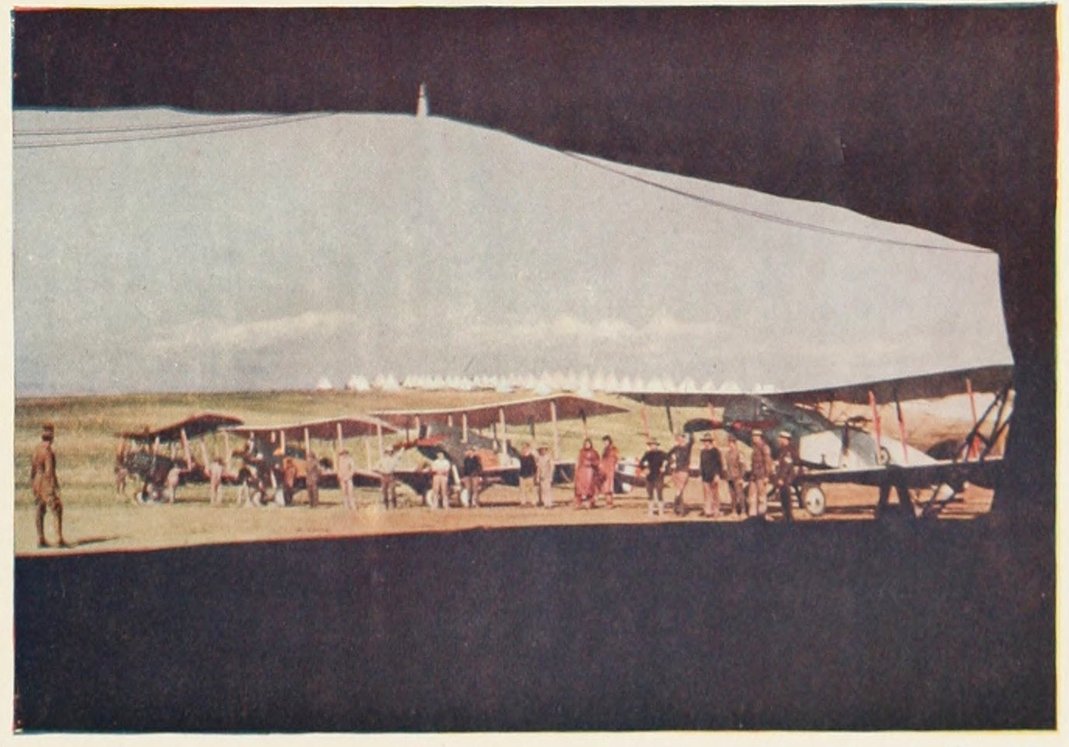

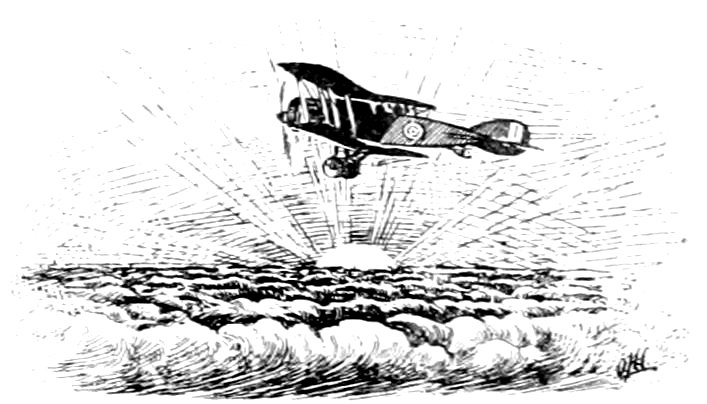

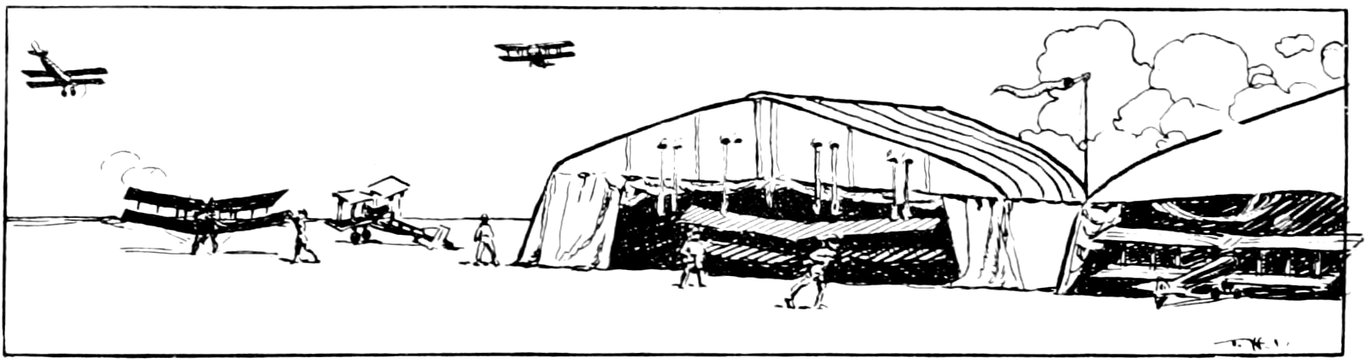

| An Australian Flying Squadron in Palestine | 50 |

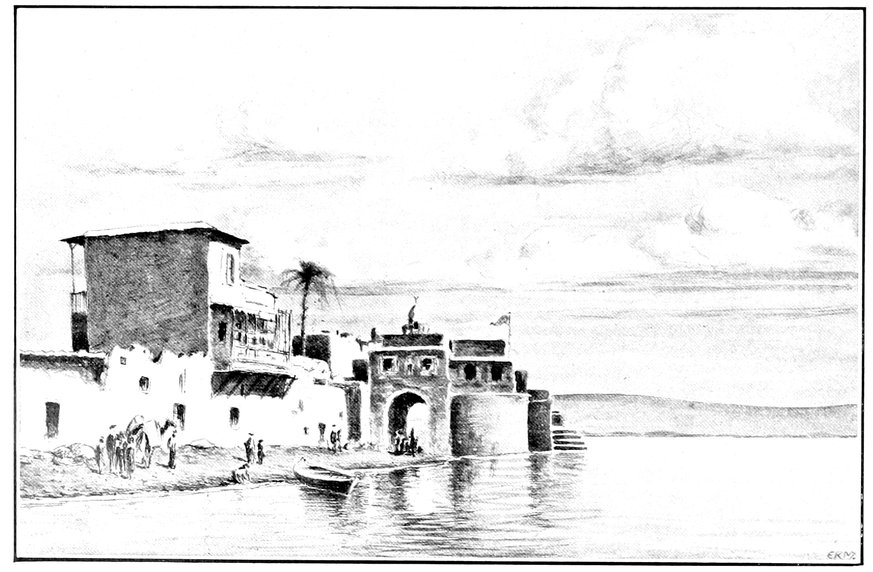

| Jaffa | 54 |

| Australians prior to the fight for Nalin | 54 |

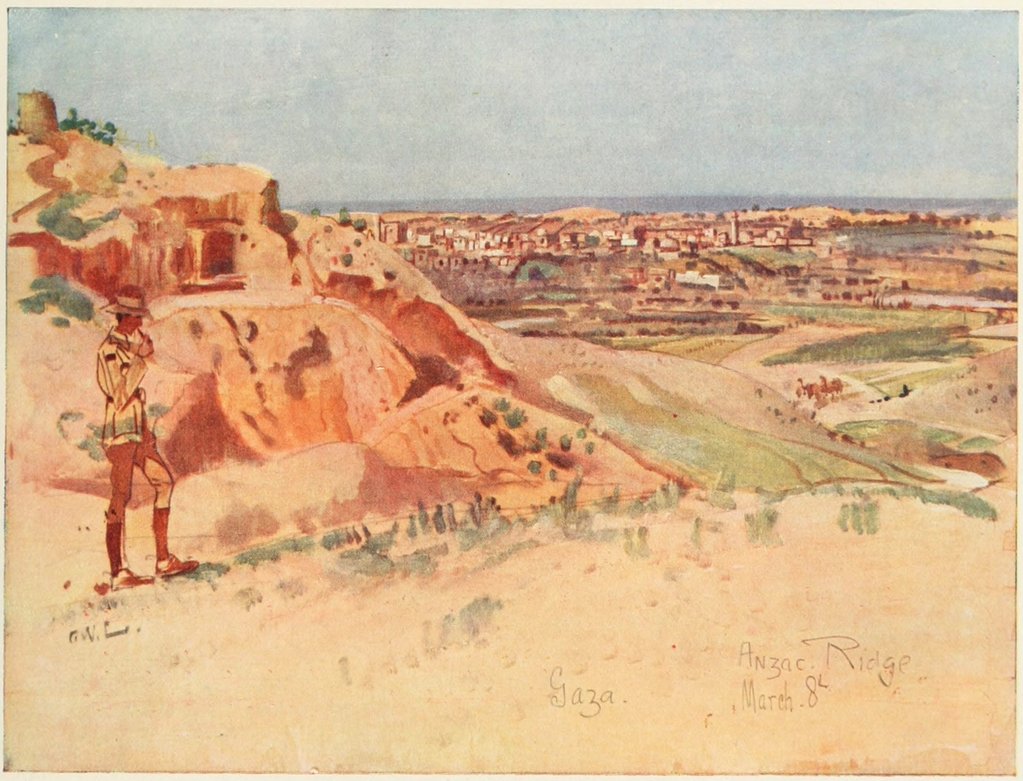

| Anzac Ridge, Gaza | 56 |

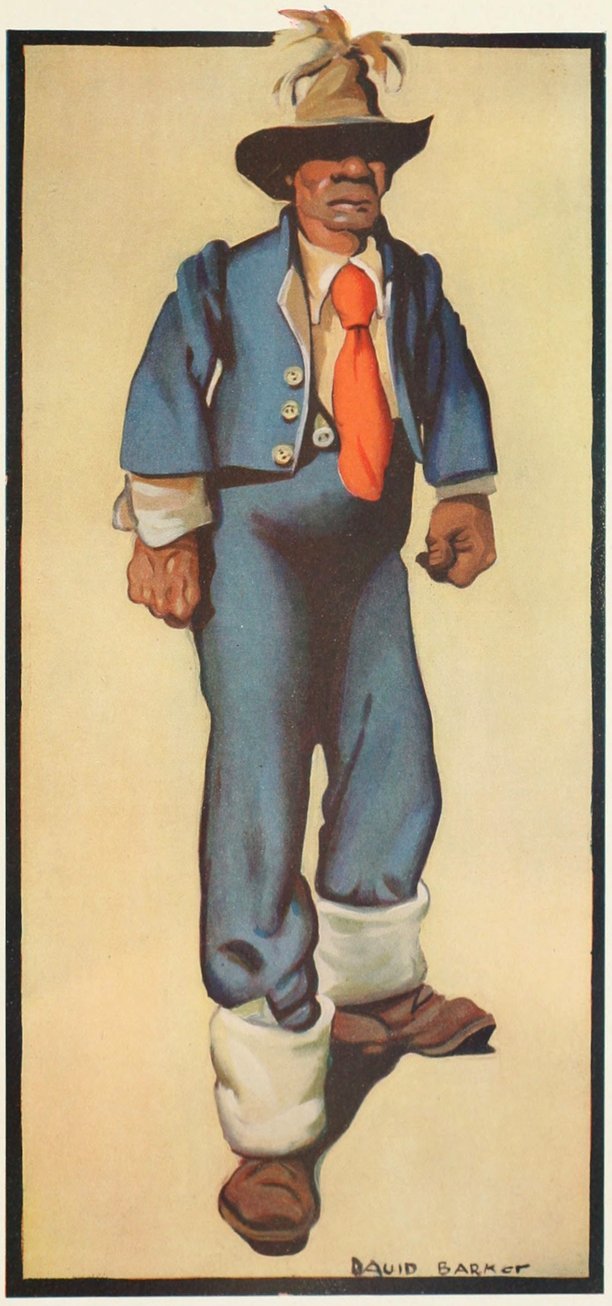

| National Types | 70 |

| Evening amongst the Judean Hills | 78 |

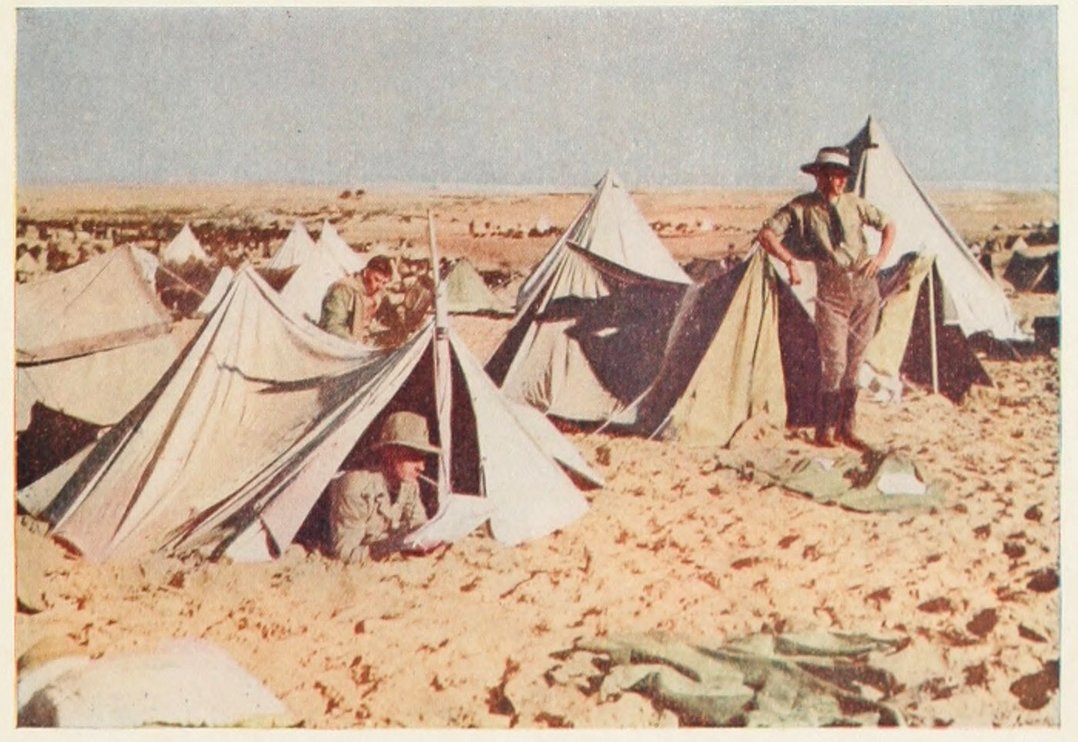

| A Camp in the Desert | 78 |

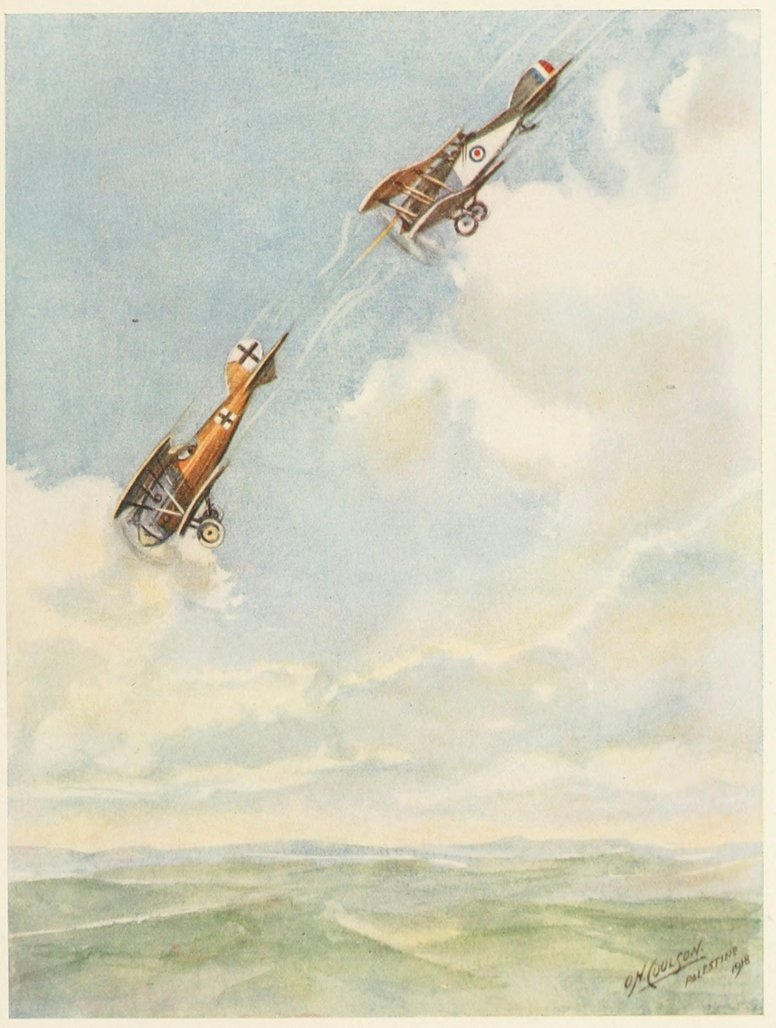

| Got Him Cold | 94 |

| The End of the Scrap | 96 |

| Convalescent | 106 |

| A Signal Office in the Field | 110 |

| Some Souvenir | 124 |

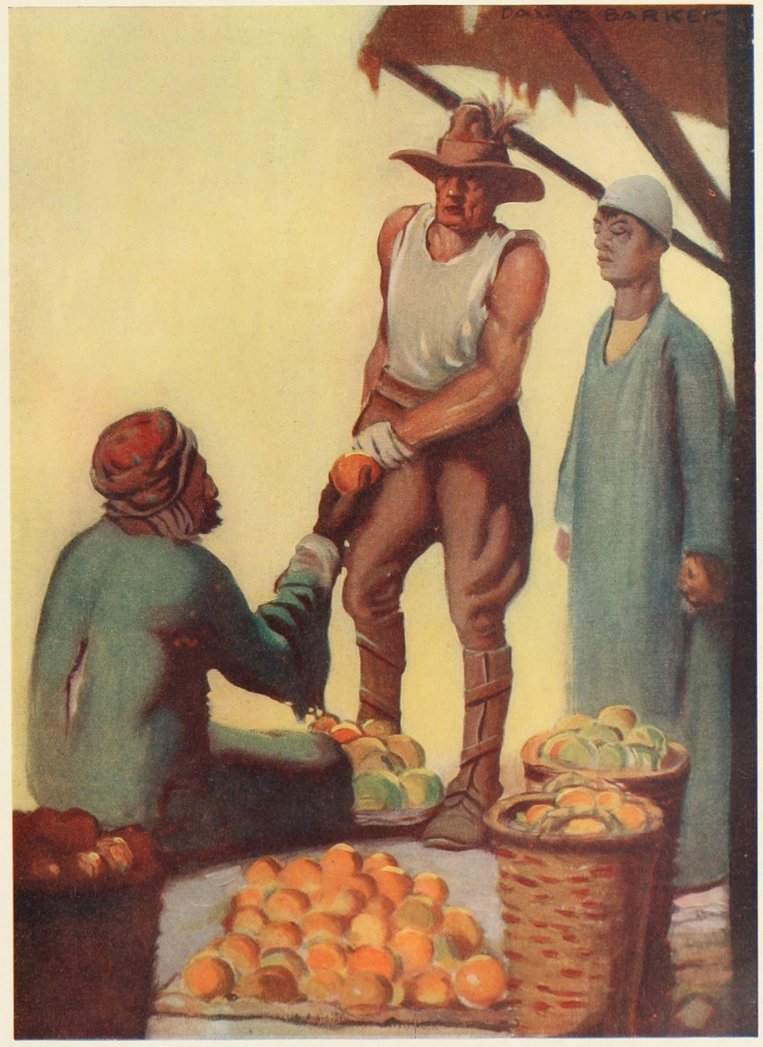

| Buying Oranges, Jaffa | 138 |

| PHOTOGRAPHS, Etc. | |

| Lieut.-General Sir H. G. Chauvel, K.C.B., K.C.M.G. | xv. |

| Jaffa | 4 |

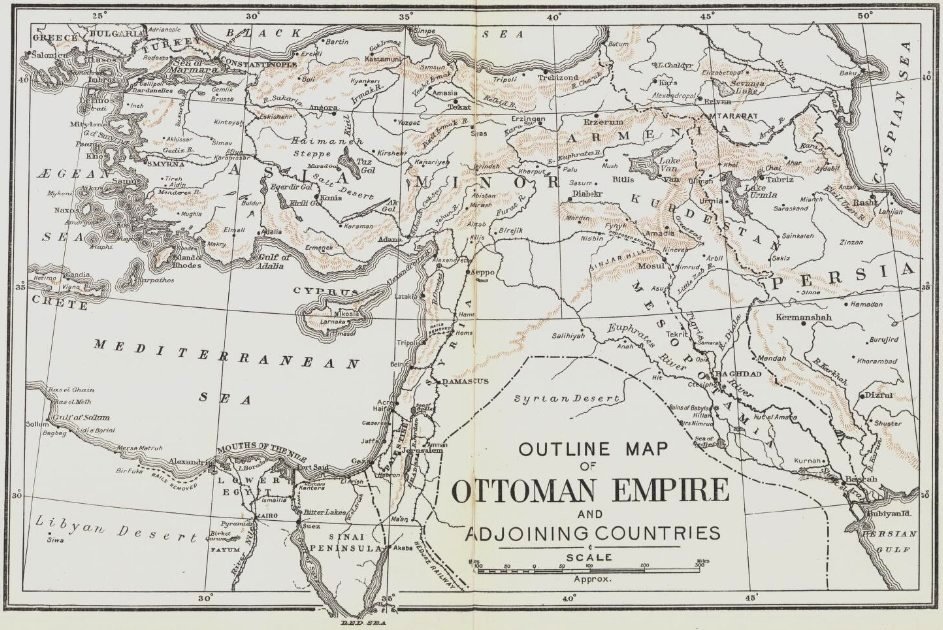

| Map of Ottoman Empire | 6–7 |

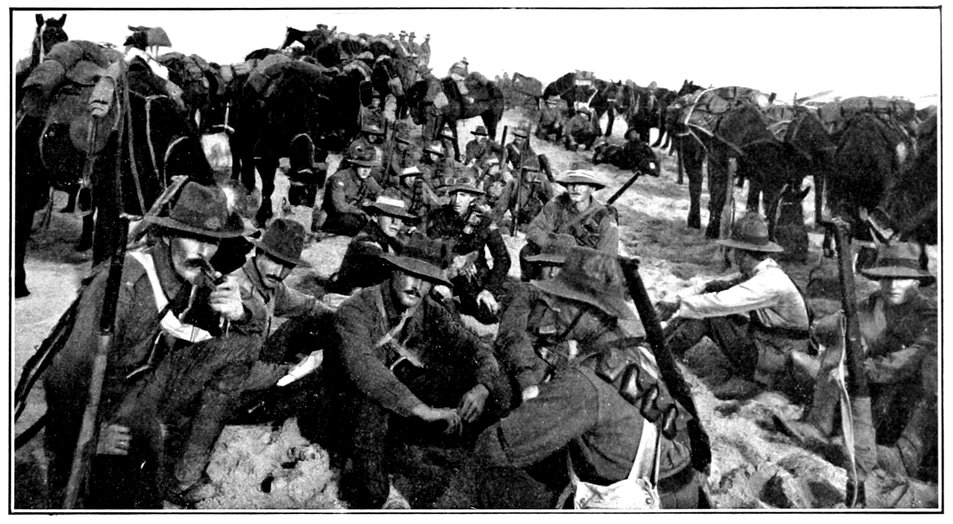

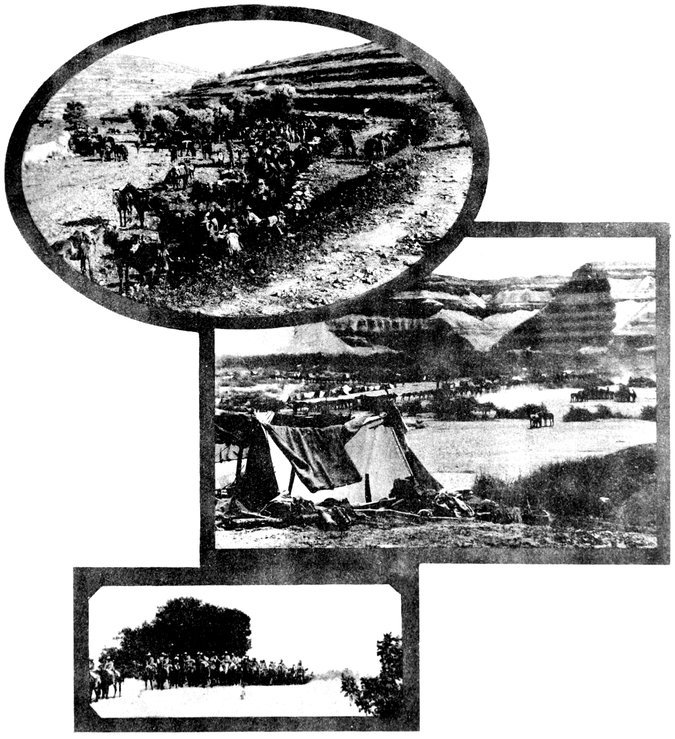

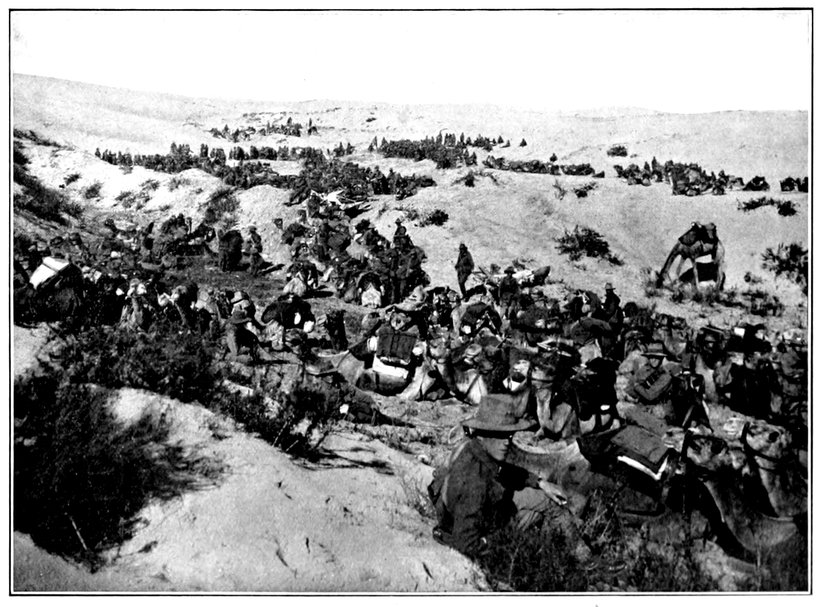

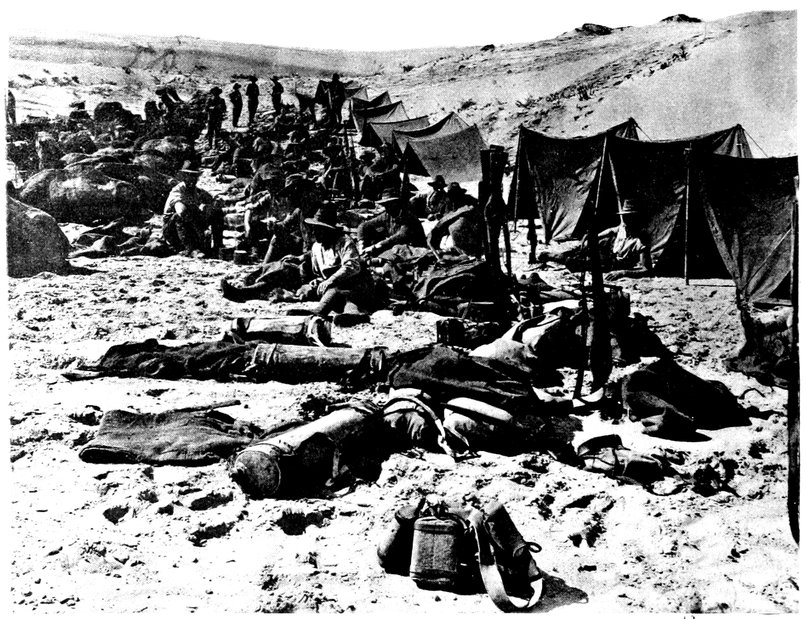

| A Brief Halt Richly Earned | 9 |

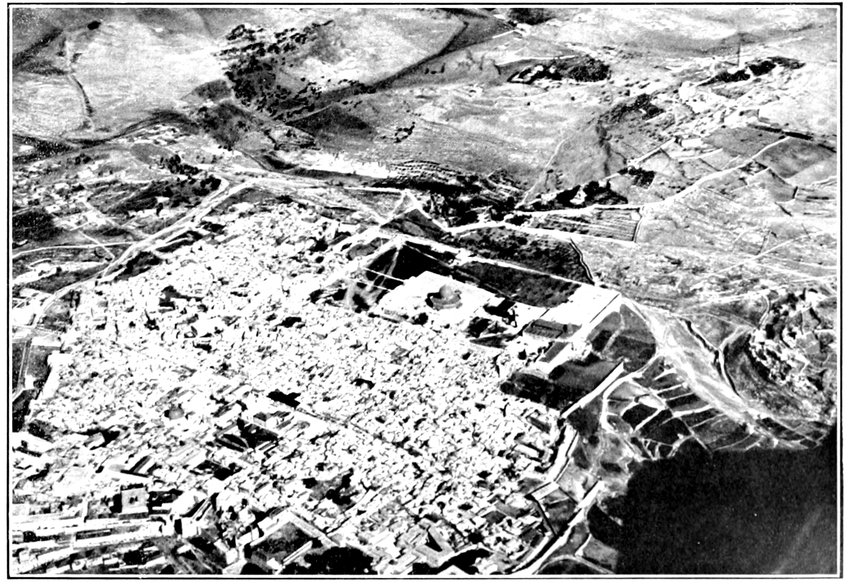

| Jerusalem from the Air | 9 |

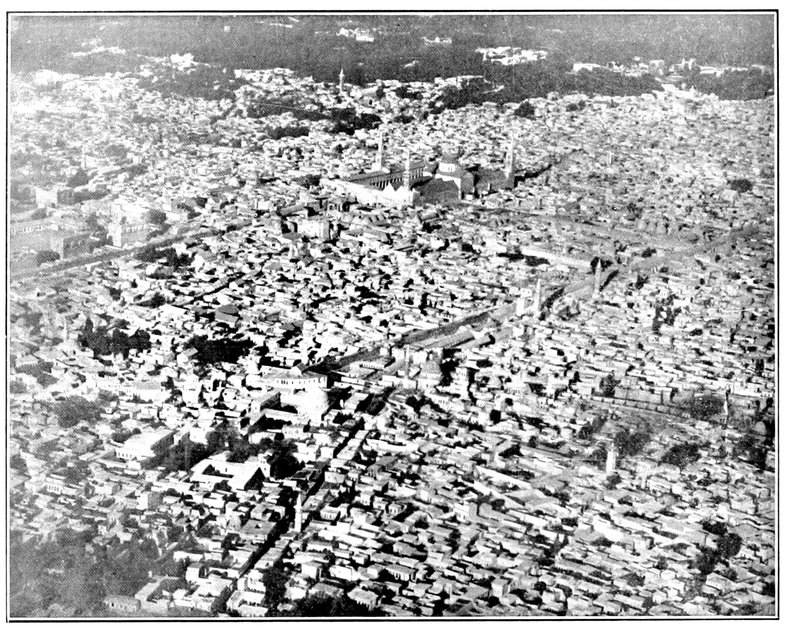

| Damascus from the Air | 10 |

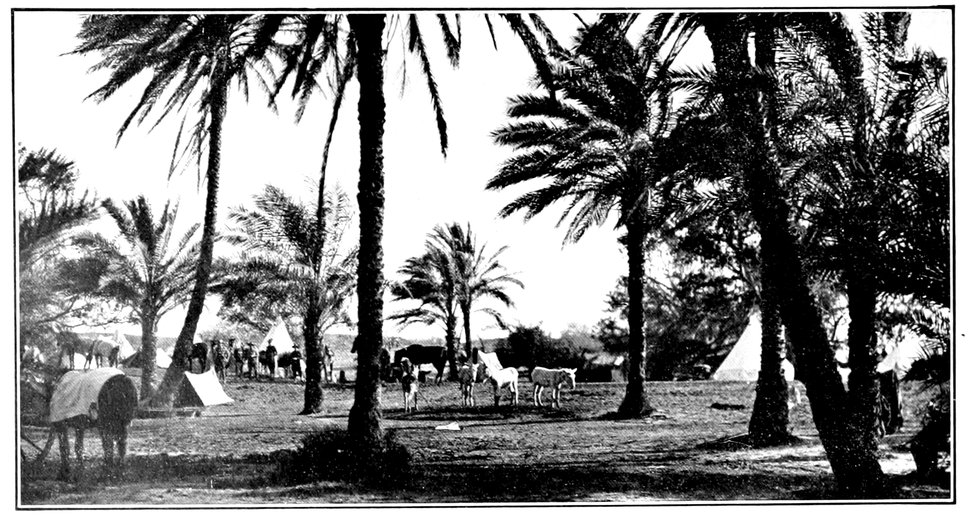

| 3rd L.H. Camp at Belah | 10 |

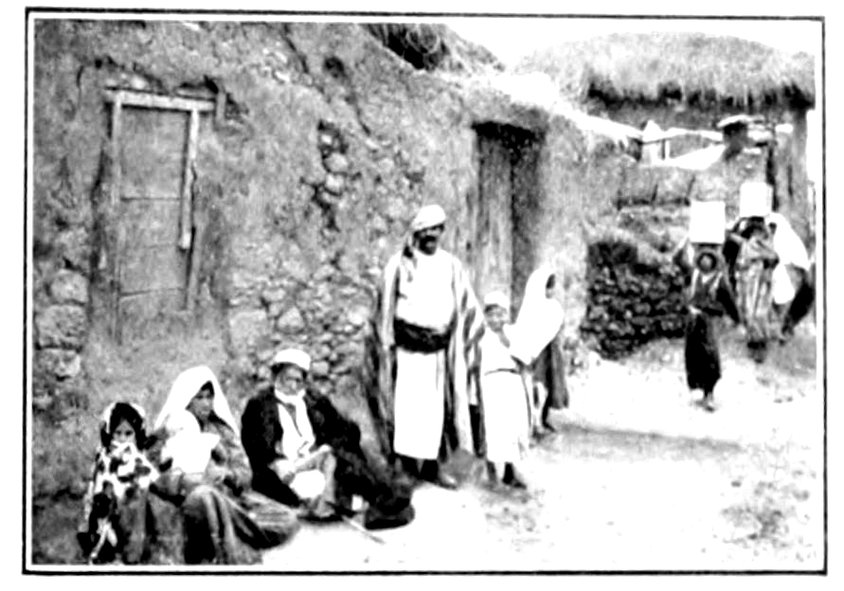

| In a Village Street | 14 |

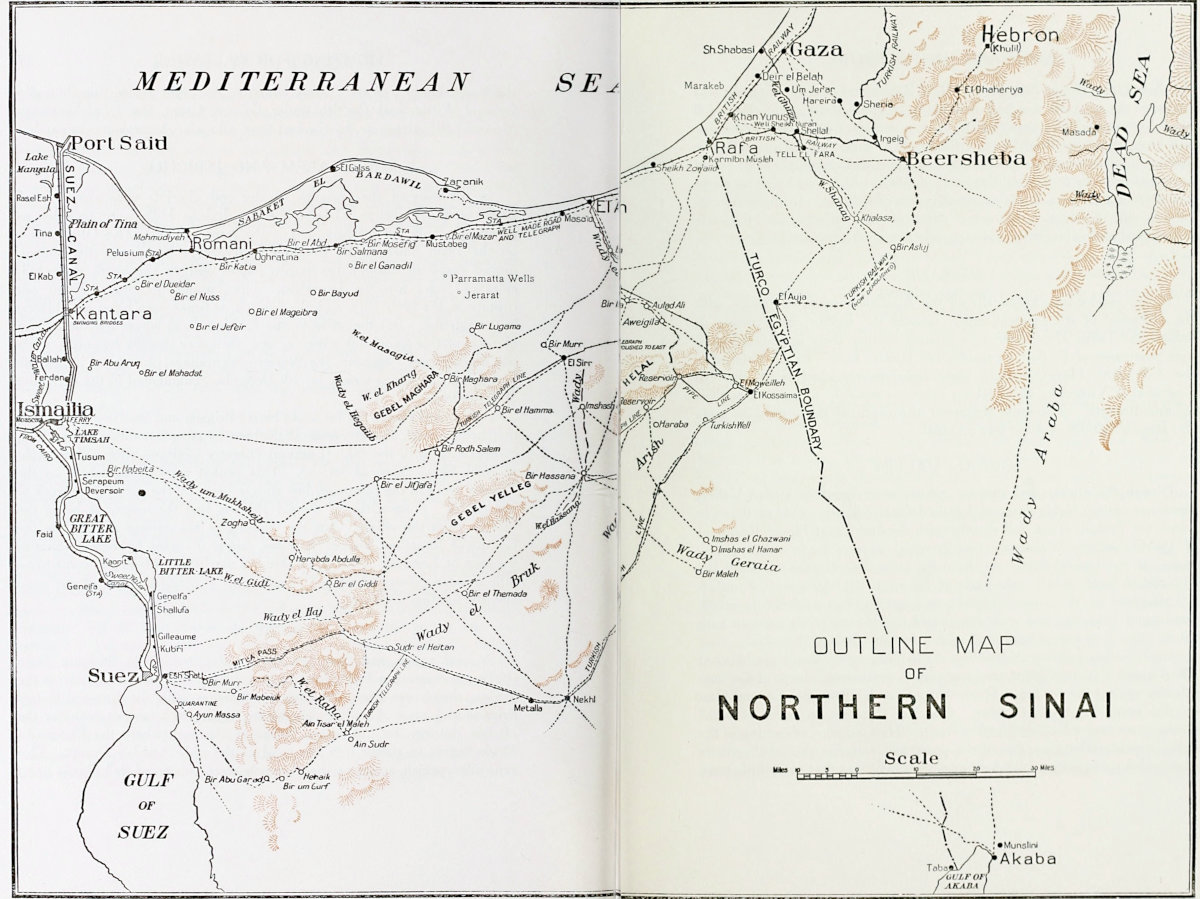

| Map of Northern Sinai | 18–19 |

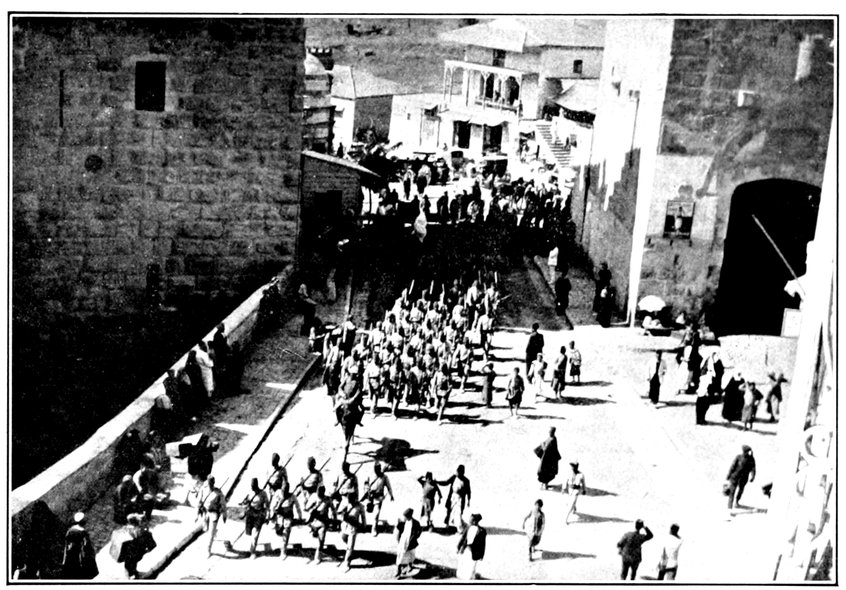

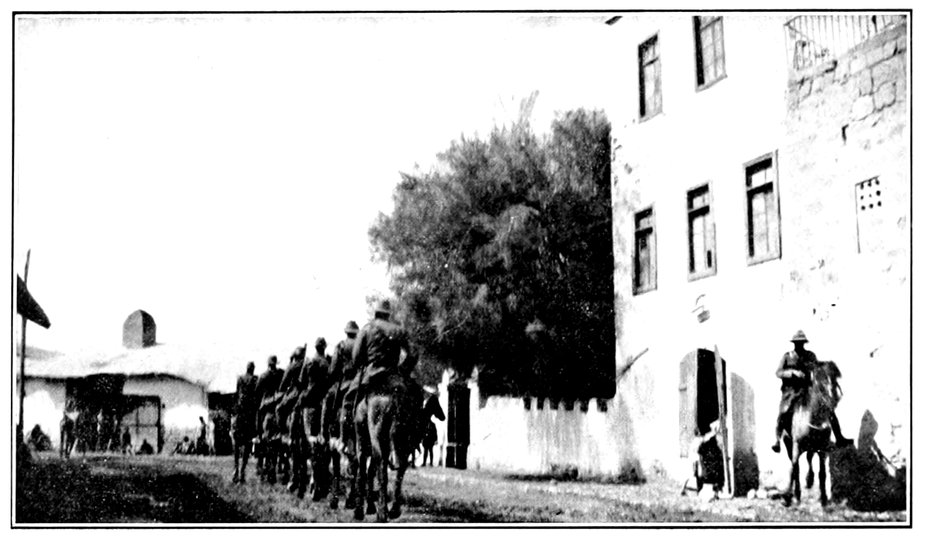

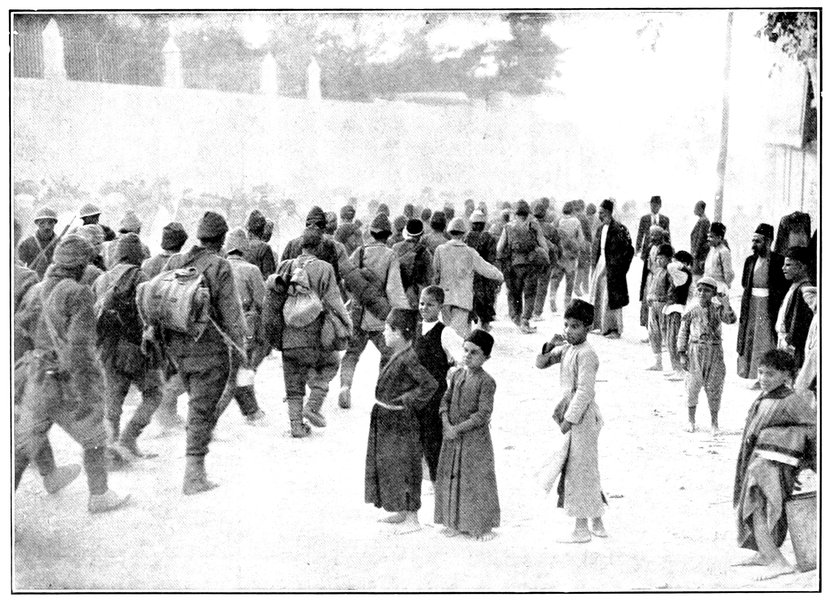

| Turks marching out of Jerusalem (1914) | 23 |

| Gaza | 23 |

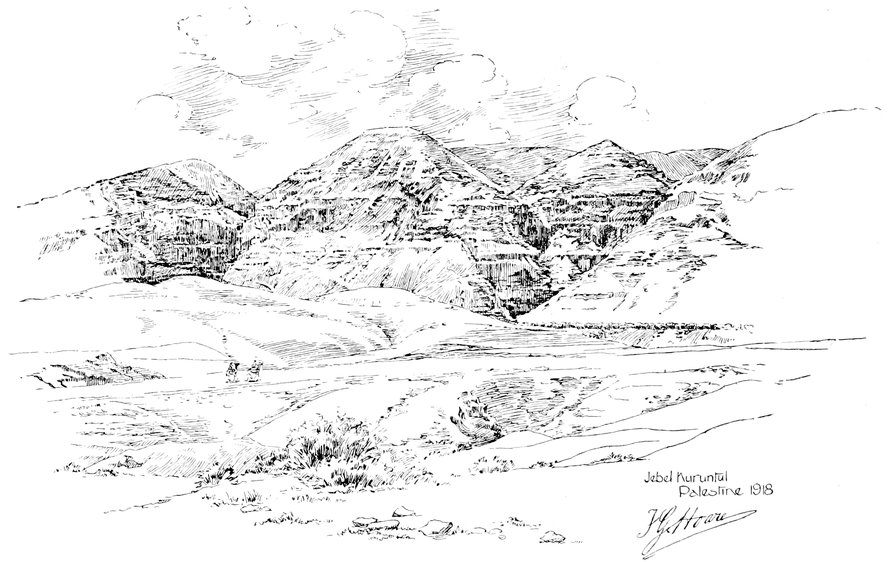

| The Mount of Temptation | 24 |

| All the World Over | 24 |

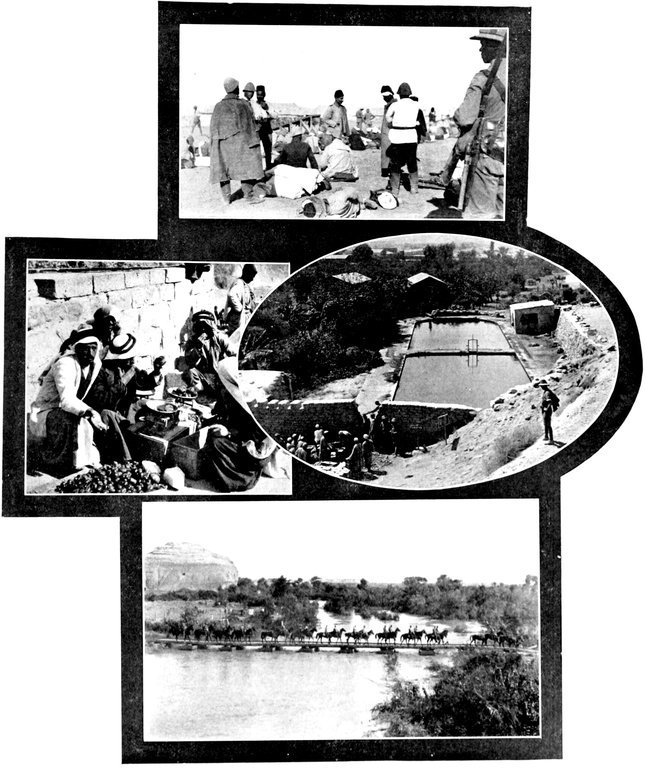

| Turkish Prisoners at Beersheba | 29 |

| Street Market, Jerusalem | 29 |

| Jericho, showing garden oasis | 29 |

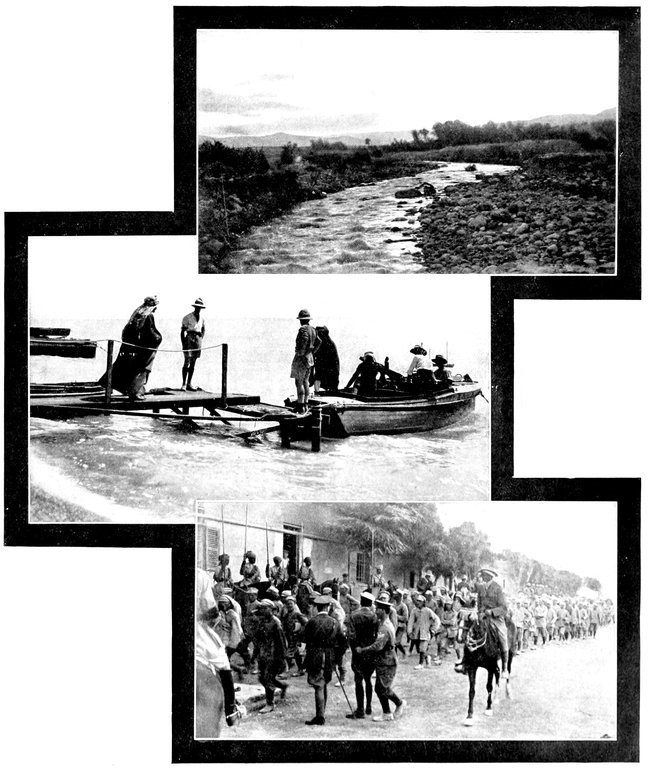

| Light Horse crossing Jordan | 29 |

| In the Jordan Valley | 30 |

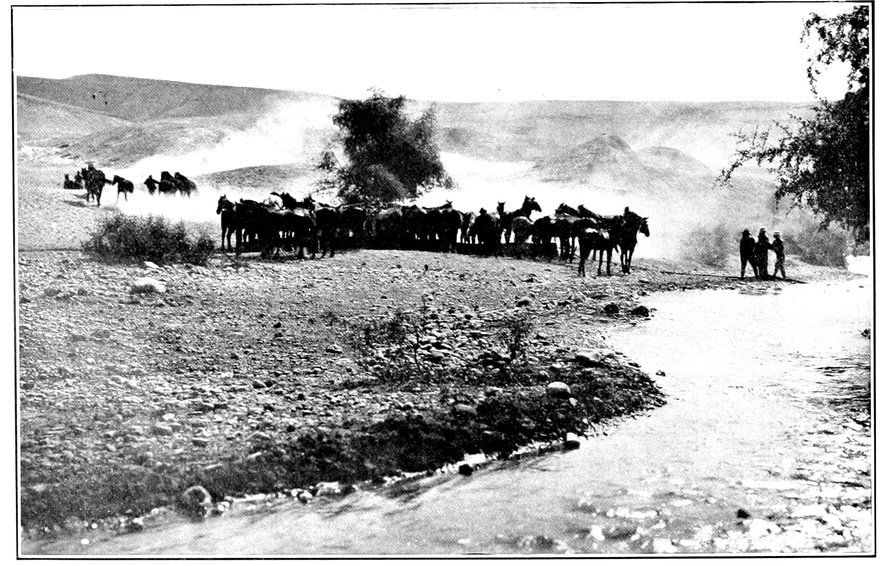

| Spring Water, Clear and Cold | 30 |

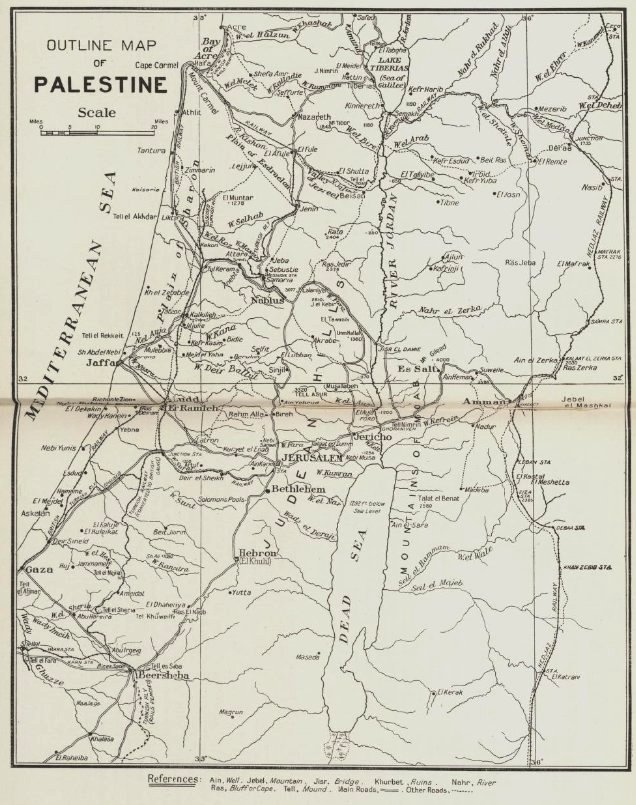

| Map of Palestine | 34–35 |

| Ismailia | 38 |

| In the Jordan Valley | 41 |

| Shopping in Jericho | 41 |

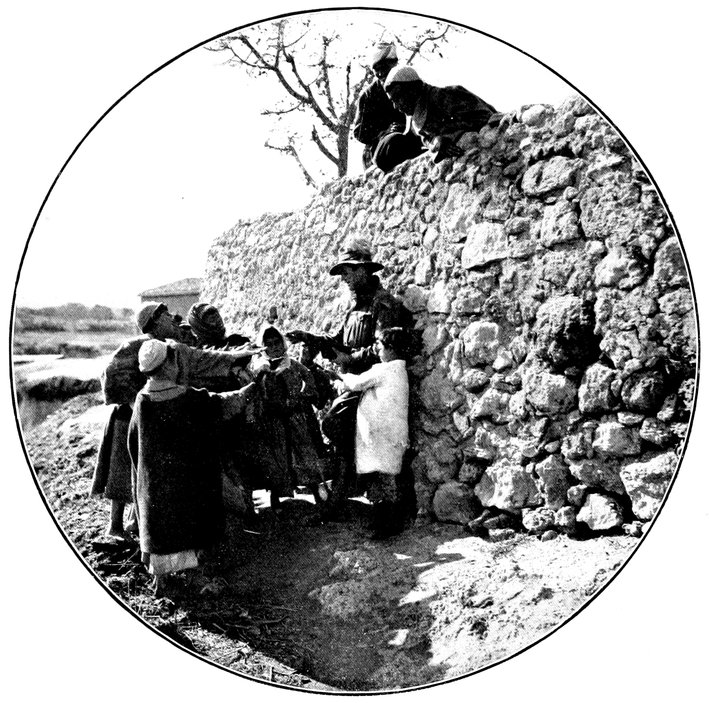

| “Baksheesh” | 42 |

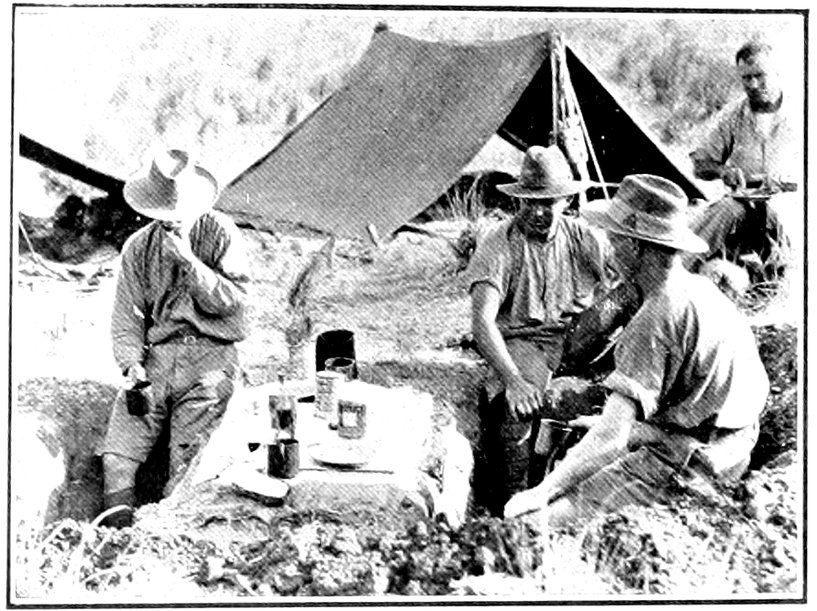

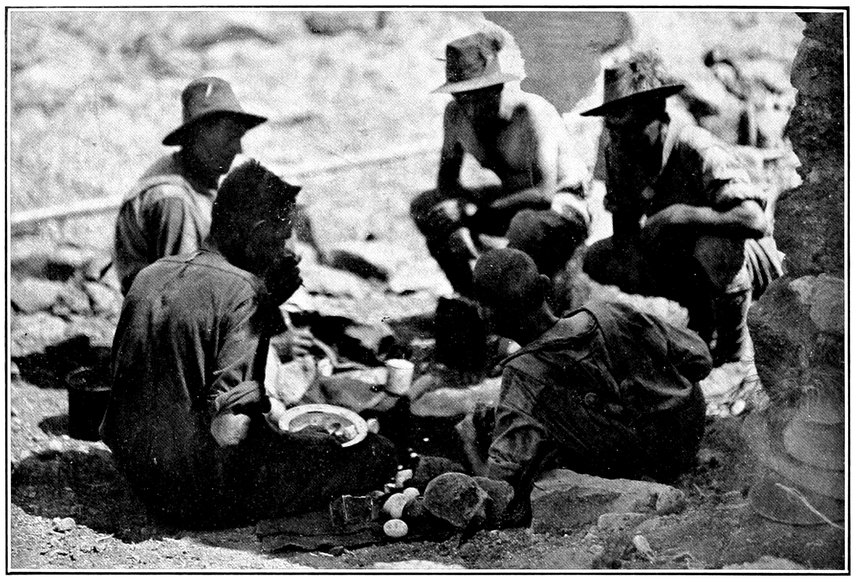

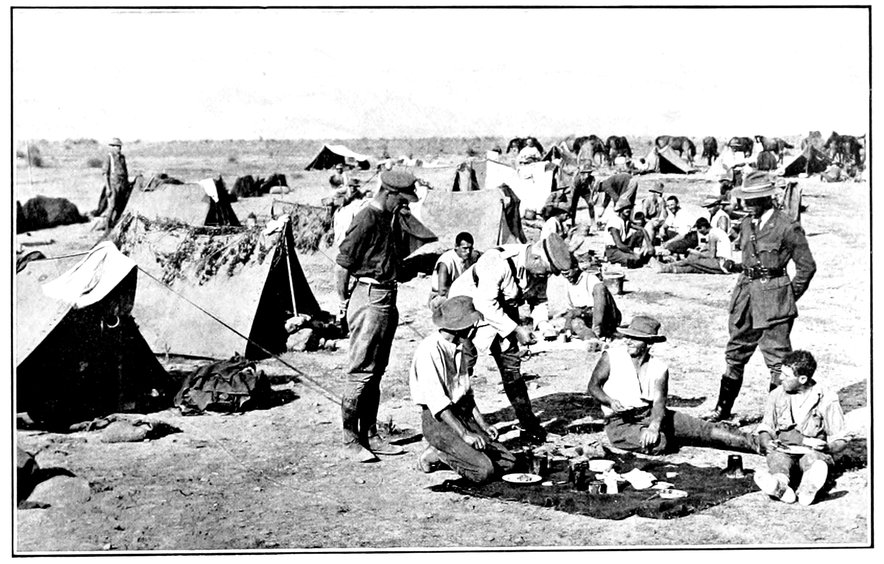

| A Meal outside the Bivvies | 42 |

| Scotties on a Route March | 42 |

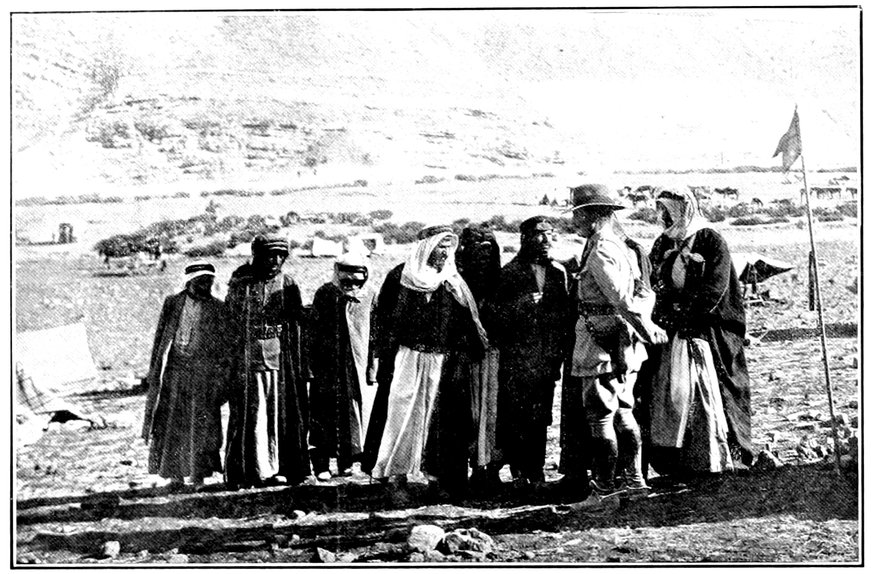

| Major-Gen. Chaytor receives Arab Chiefs | 46 |

| Jerusalem | 46 |

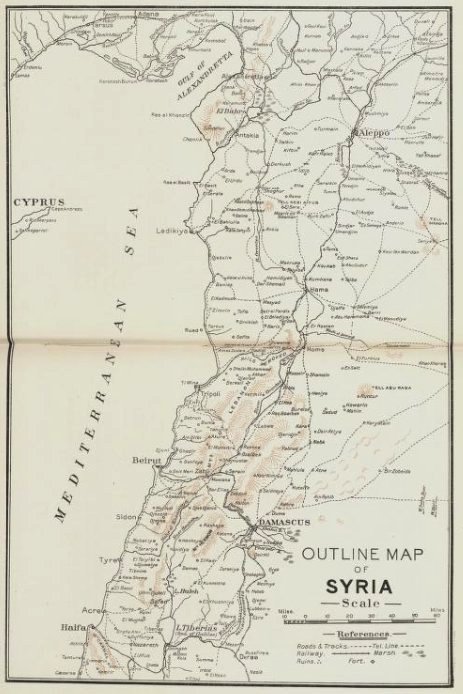

| Map of Syria | 48–49 |

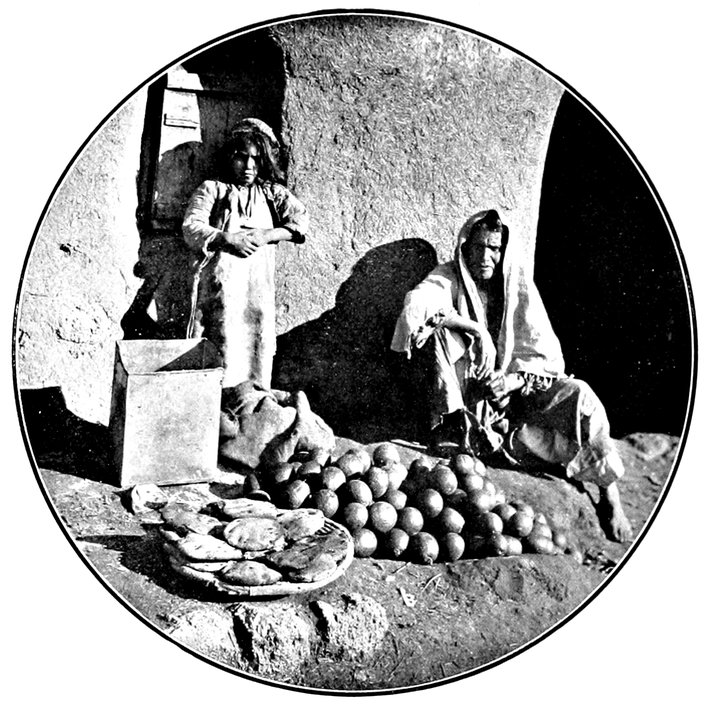

| Orange Seller, Jaffa | 53 |

| In the Shade | 53 |

| The Village Well | 54 |

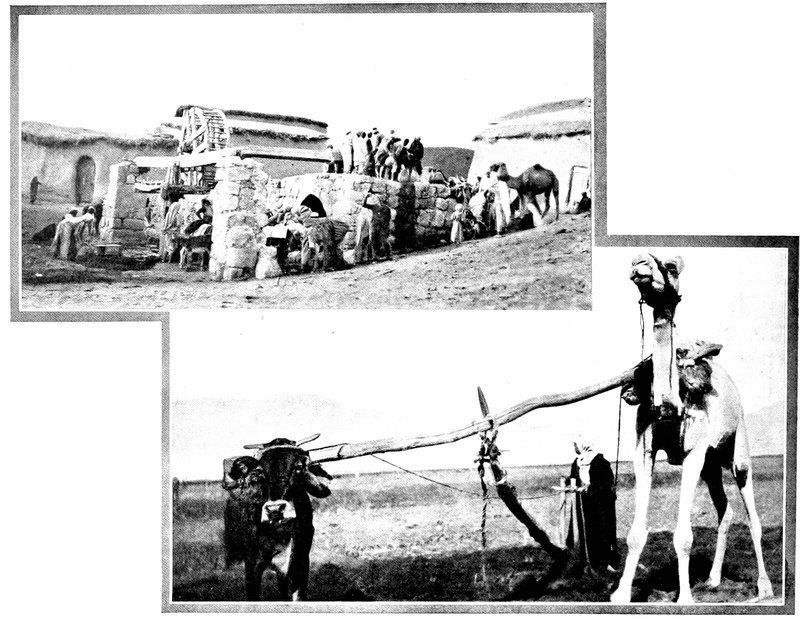

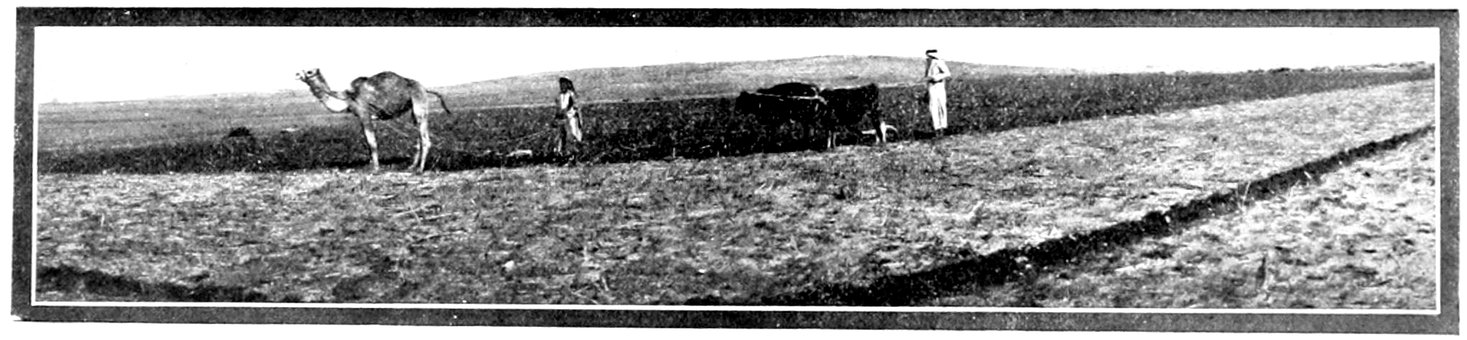

| Native Plough and Team | 54 |

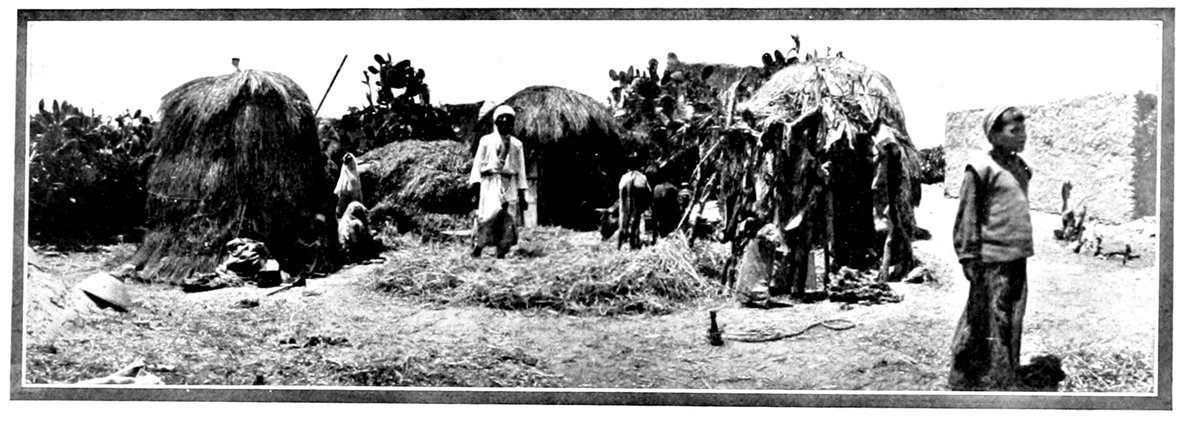

| Harvest Time | 65 |

| Ploughing as of Old | 65 |

| Native Stock | 65 |

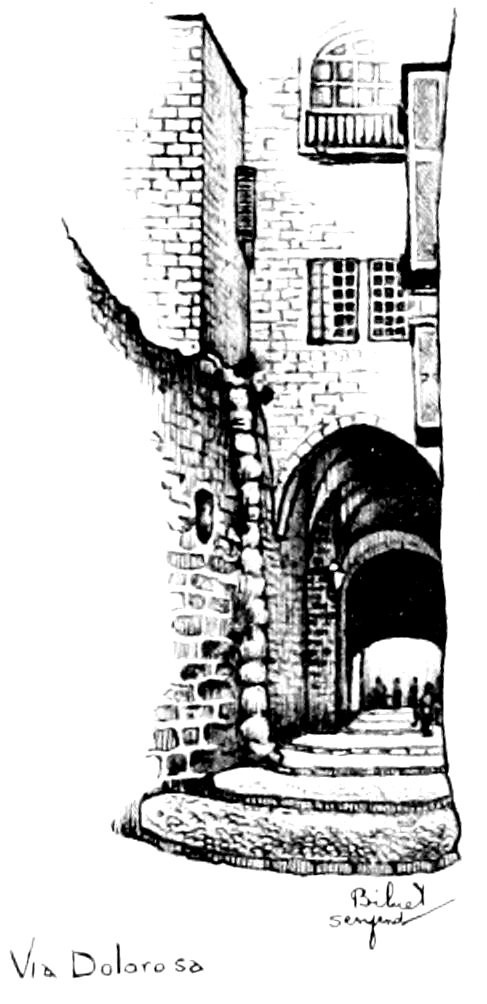

| xiiThe Franciscan Monastery | 66 |

| Lake of Tiberias | 66 |

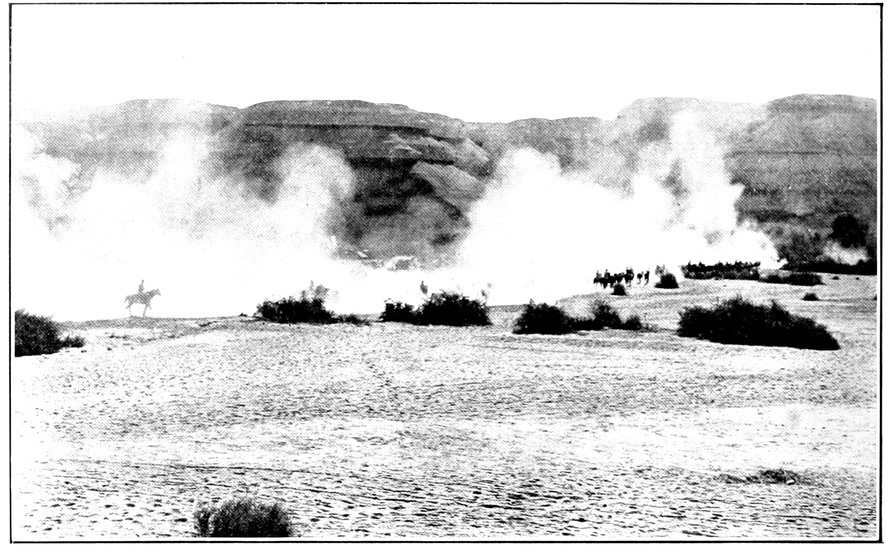

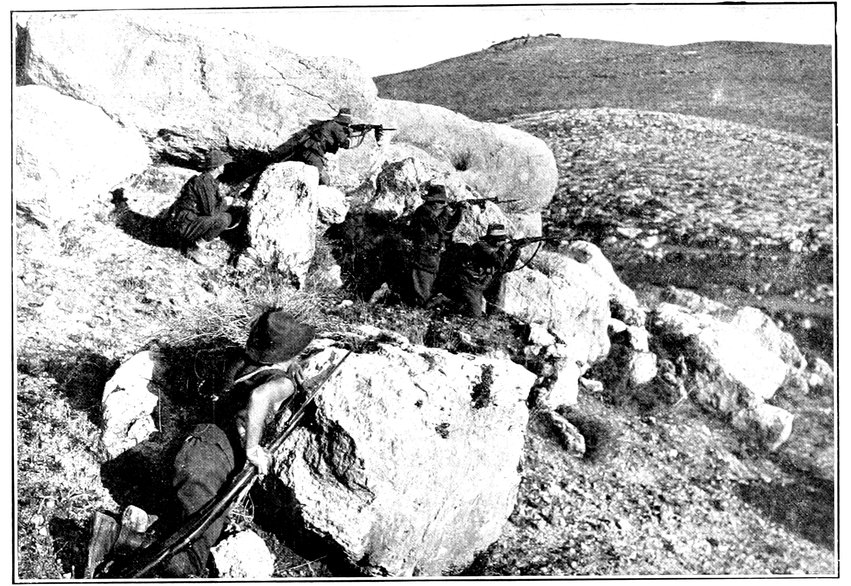

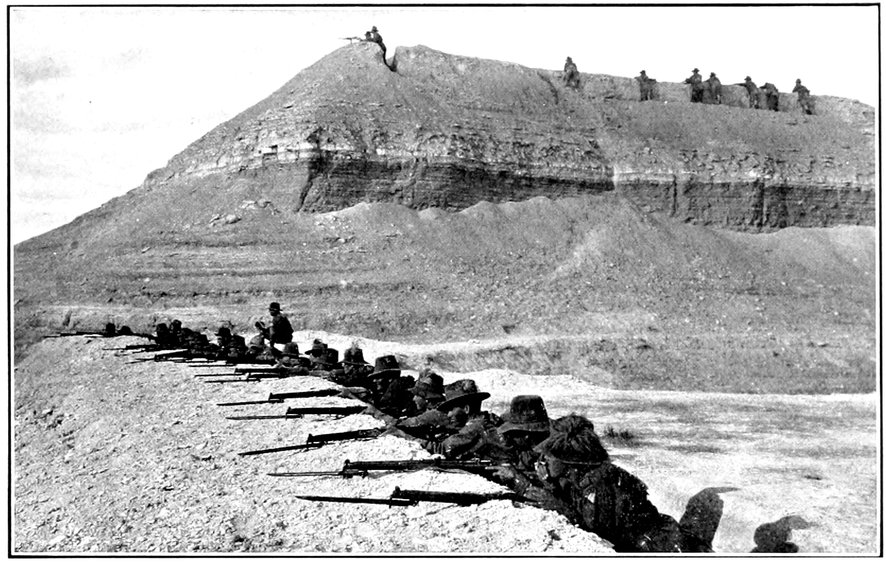

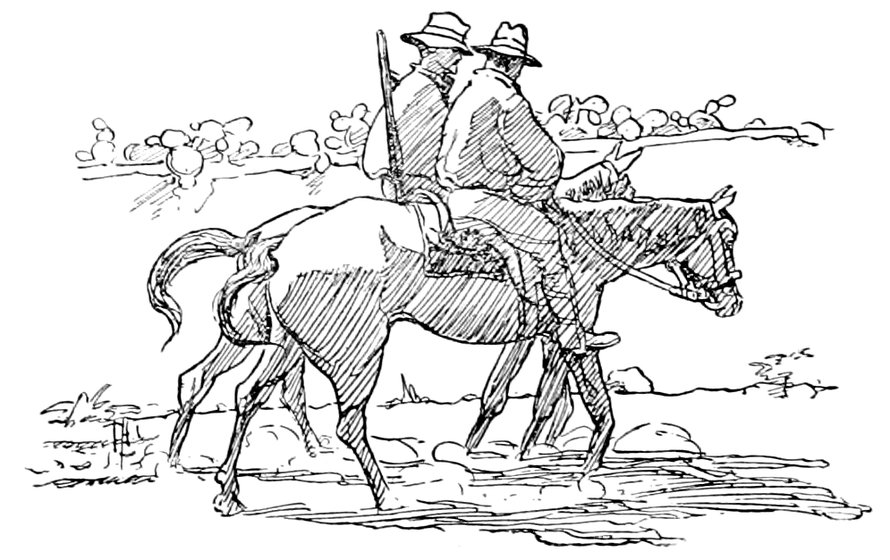

| Outposts | 70 |

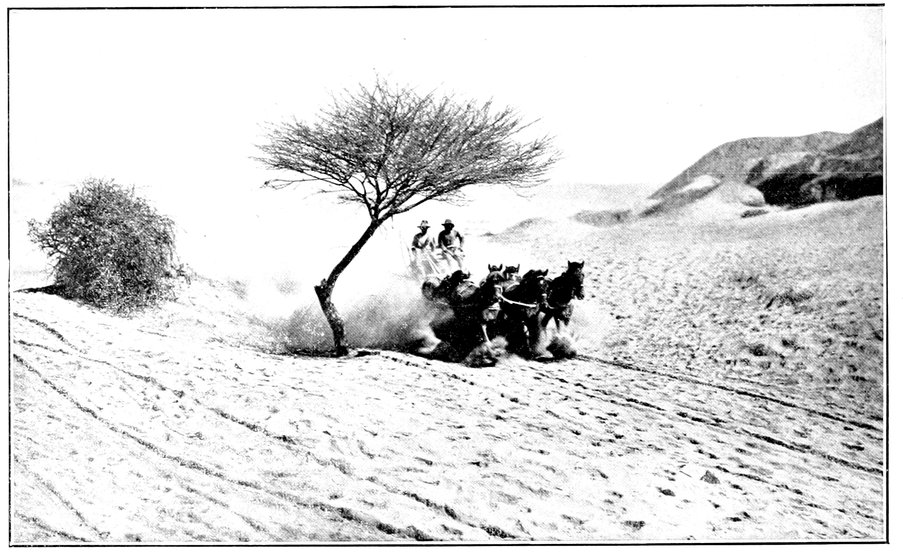

| Jordan Valley Dust | 70 |

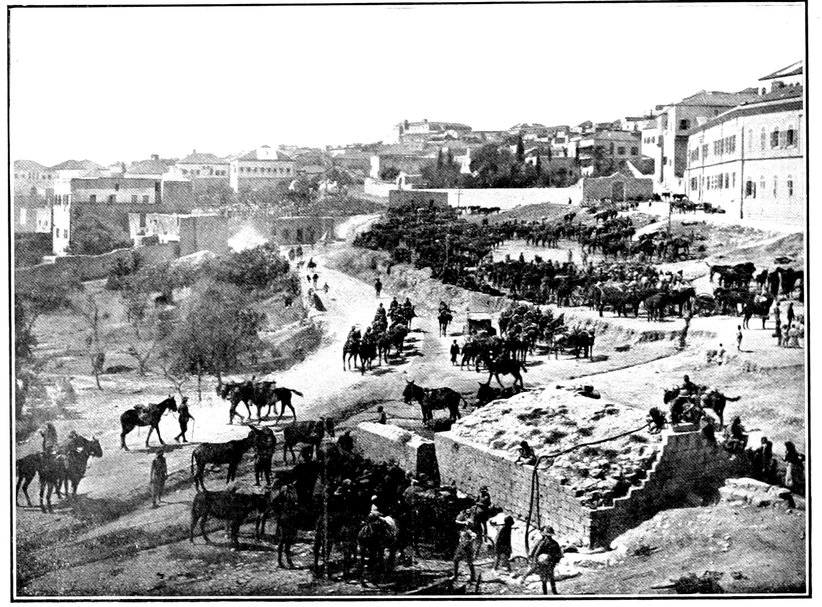

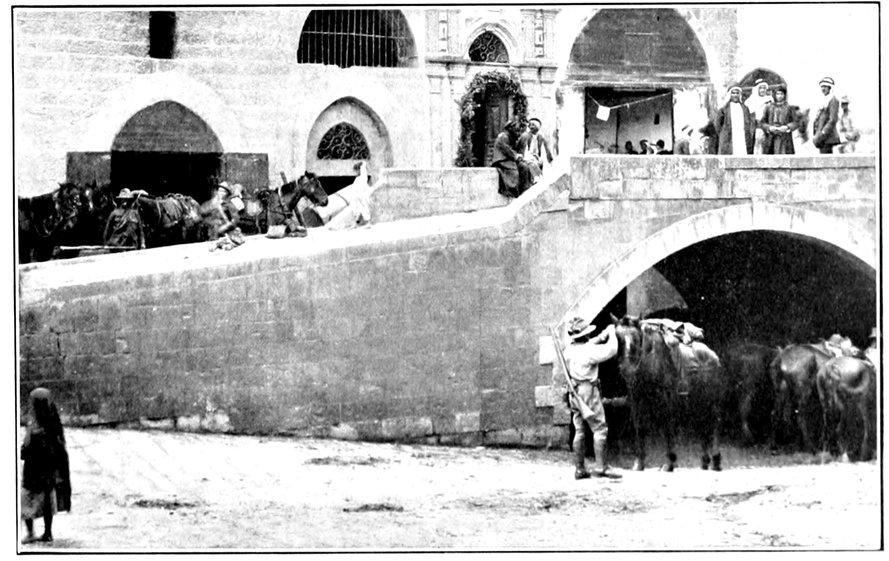

| 5th L.H. Brigade entering Nablus | 73 |

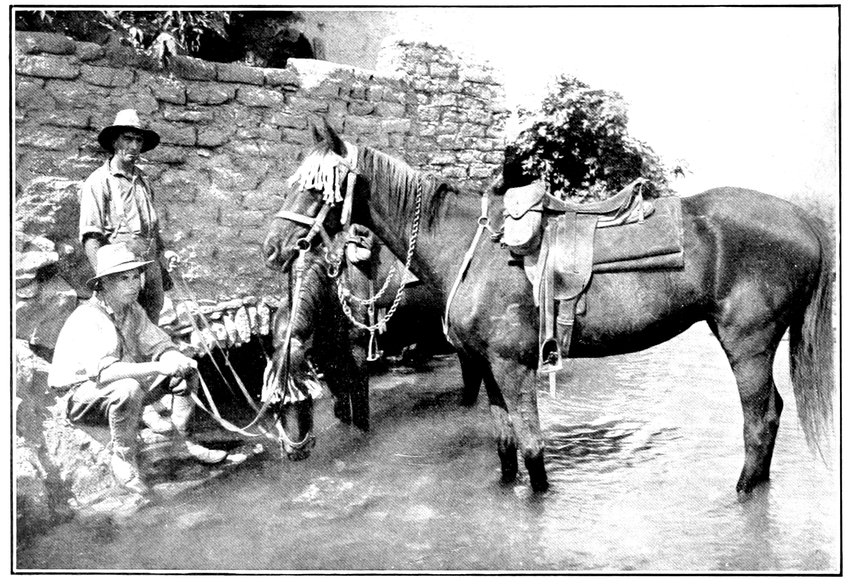

| Watering Horses, Es Salt | 73 |

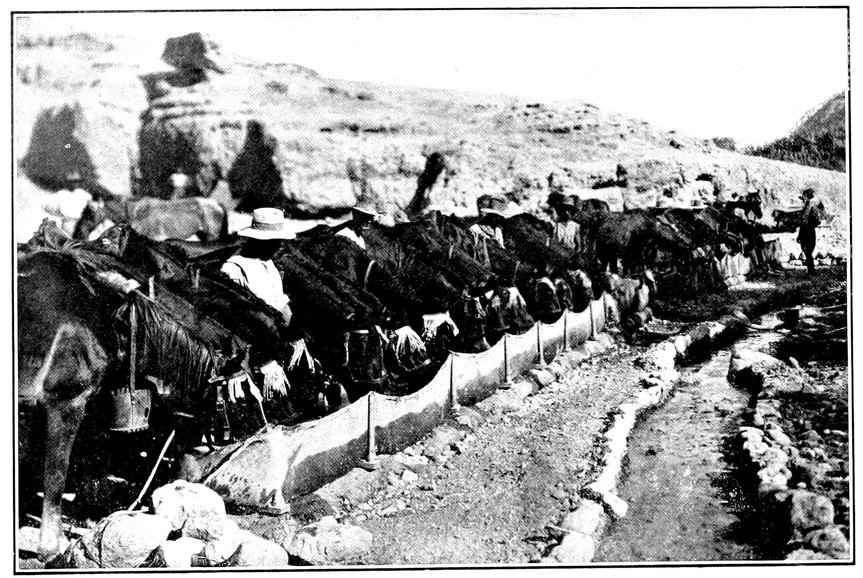

| Horses Thirsty | 74 |

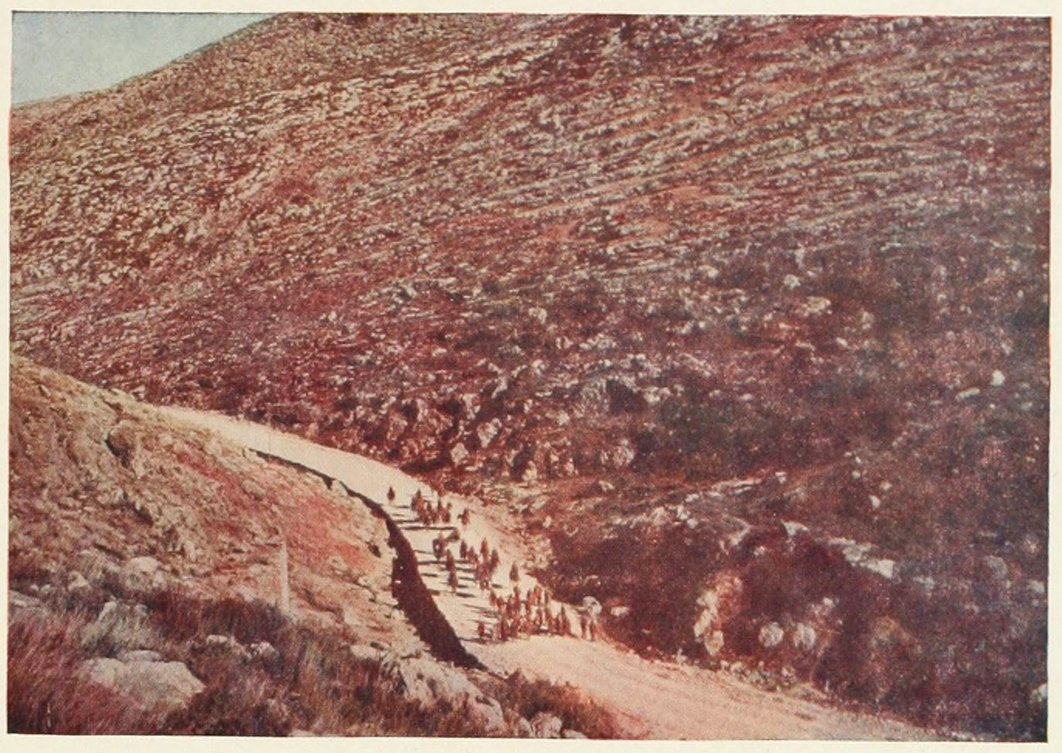

| Light Horsemen in Judean Hills | 74 |

| Wady Nimrin | 81 |

| Arab Agents | 81 |

| German Prisoners in Jericho | 81 |

| Meal Time | 82 |

| “She’s Boiling” | 82 |

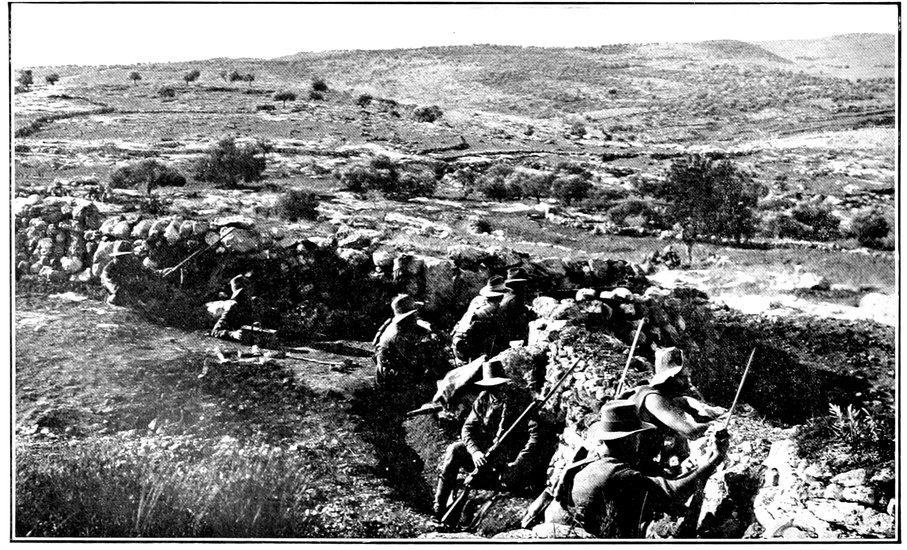

| Defences in the Ghoraniyeh Bridgehead | 85 |

| The Brickmaker | 85 |

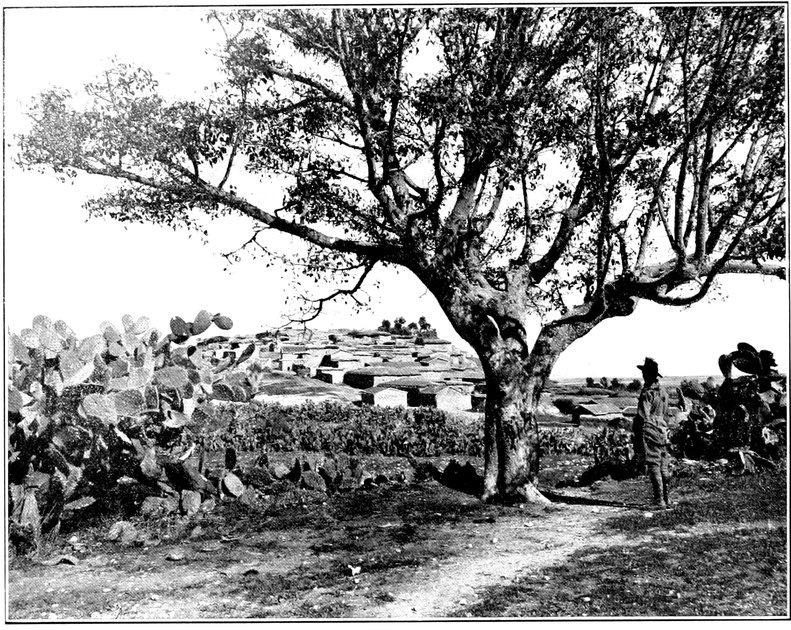

| A Typical Arab Village | 86 |

| 4th L.H. Brigade Watering Horses | 86 |

| Roman Fort, Jericho | 88 |

| Horses under cover | 89 |

| A.L. Horse in Camp | 89 |

| 2nd L.H. marching through Khan Yunis | 89 |

| Turkish Prisoners at Es Salt | 97 |

| Jericho | 97 |

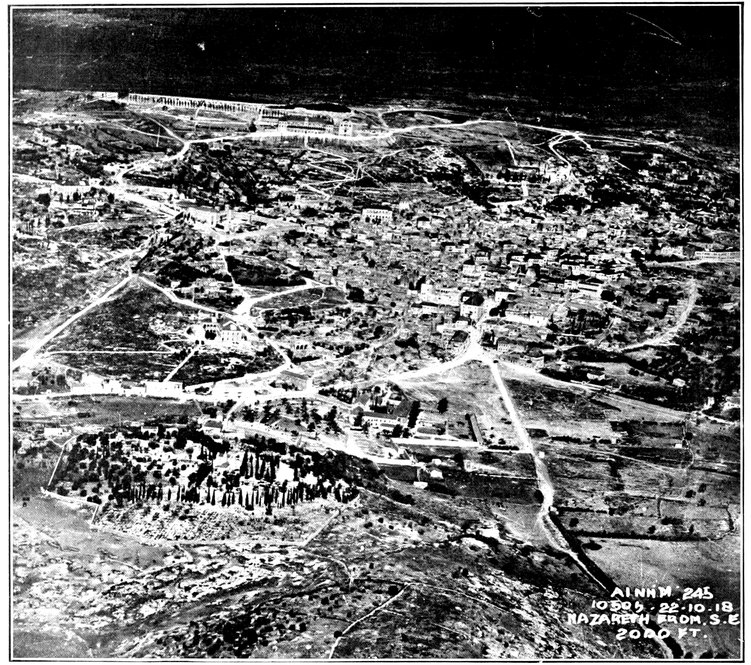

| Nazareth from the Air | 98 |

| “A Light Horse Type” | 101 |

| Mounting First Guard in Jericho | 107 |

| Halt and Rest | 107 |

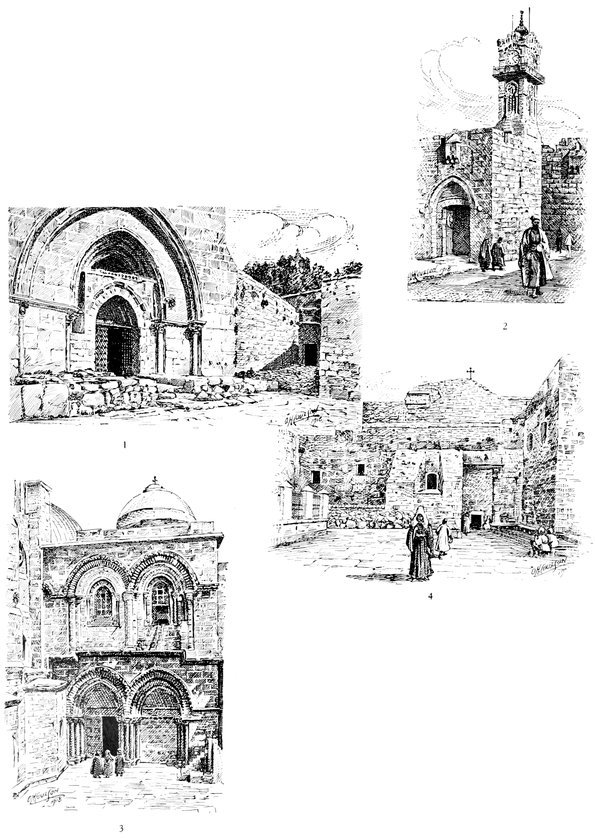

| Church and Tomb of the Virgin | 108 |

| Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem | 108 |

| Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem | 108 |

| Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem | 108 |

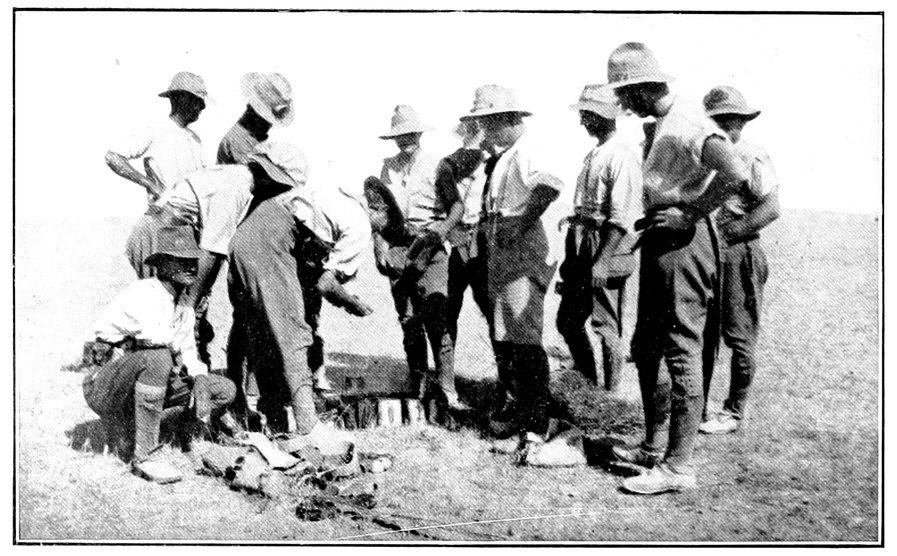

| Brig.-General Ryrie inspects the “Bully” | 119 |

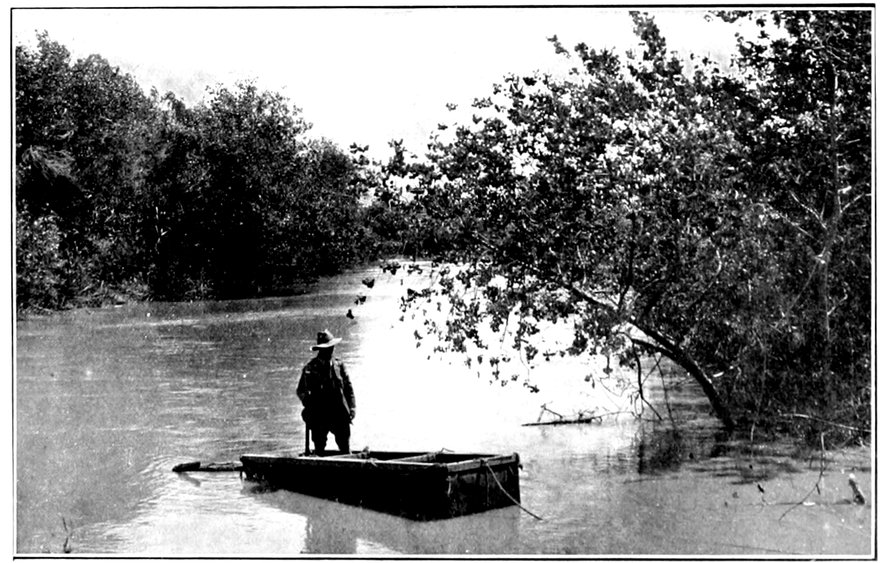

| Brig.-General Cox on River Jordan | 119 |

| A Wallad of Palestine | 120 |

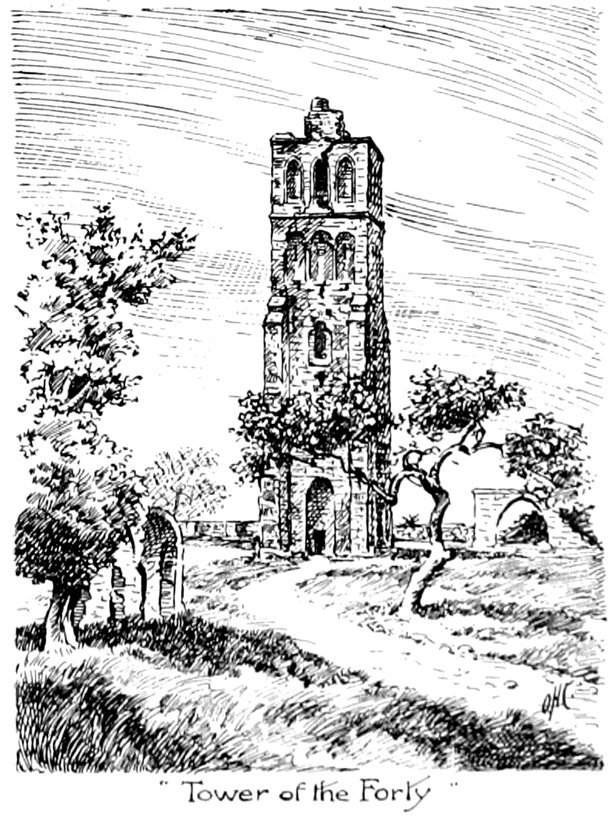

| “Tower of the Forty” | 123 |

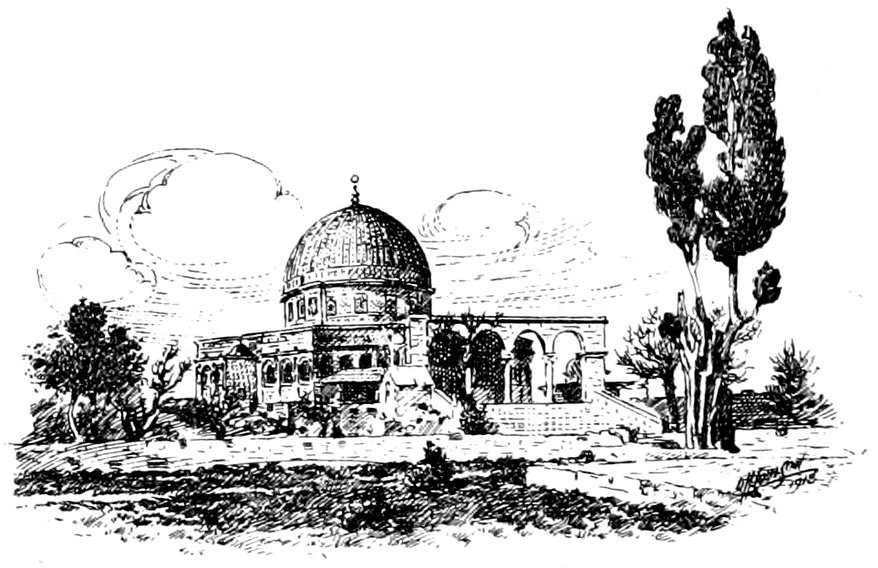

| Mosque of Omar | 124 |

| The Midday Halt | 126 |

| Brig.-General C. L. Smith, V.C., M.C. | 127 |

| Our Water Supply | 127 |

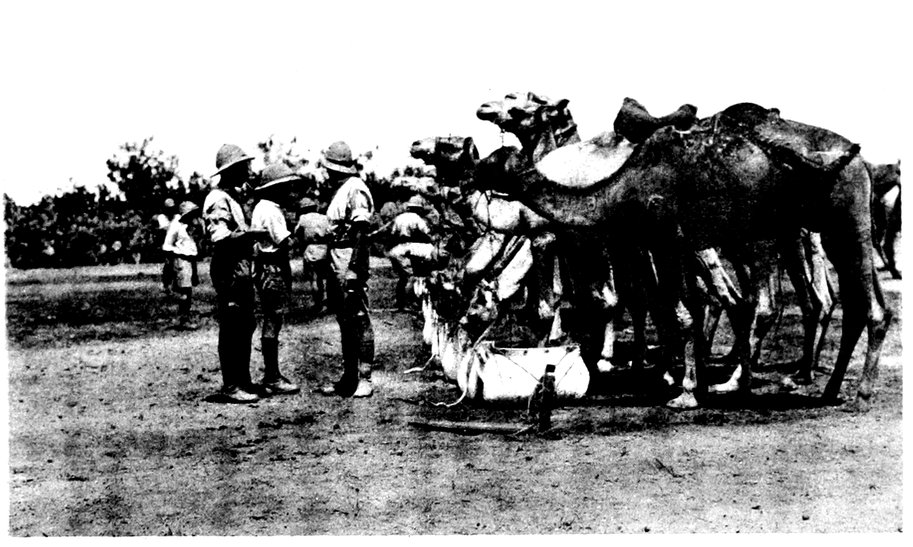

| Watering Time, Camel Brigade | 129 |

| “Prepare to Mount” | 129 |

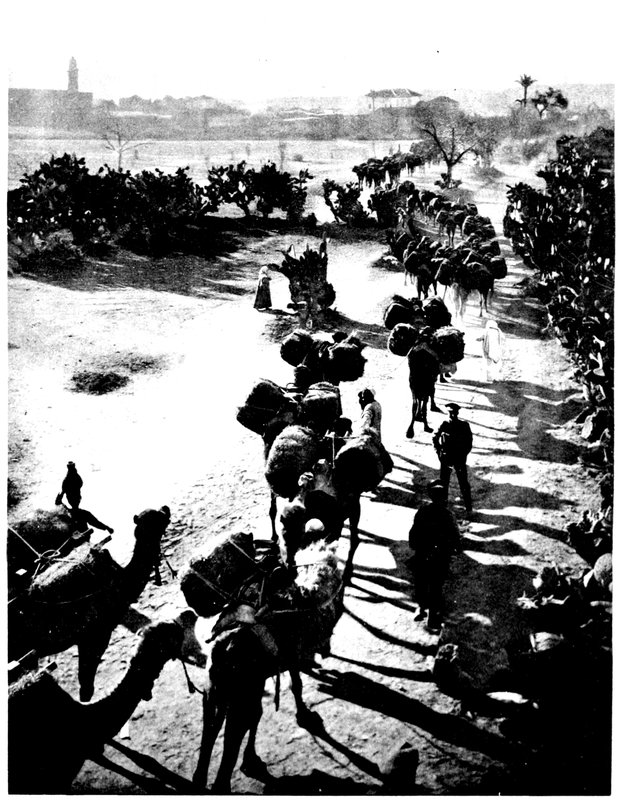

| Camels bearing Supplies on the Philistine Plain | 131 |

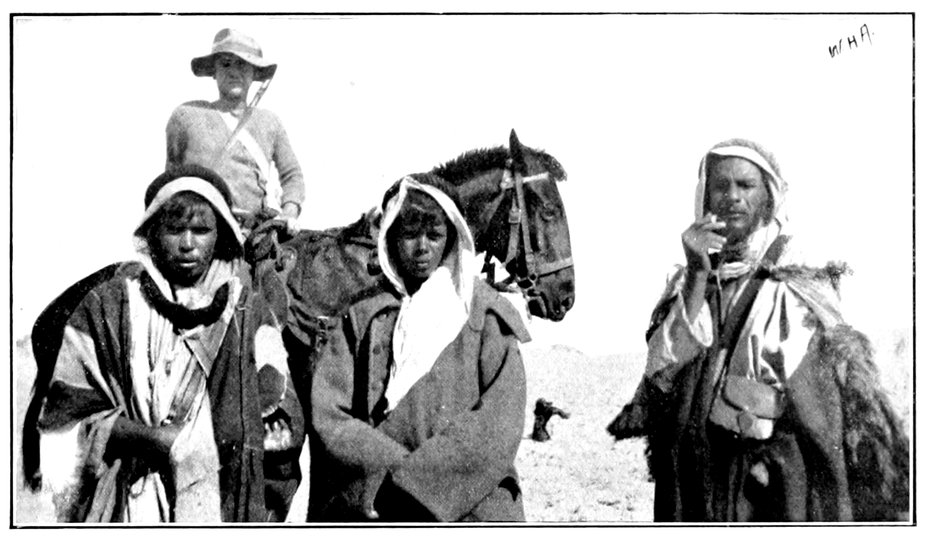

| Bedouins Captured at Hassaniya | 133 |

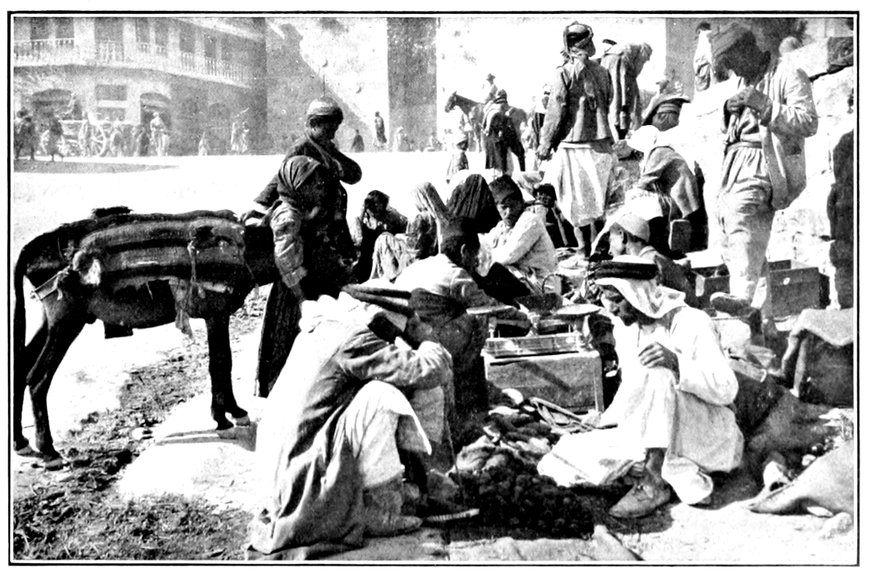

| Street Market, Jerusalem | 133 |

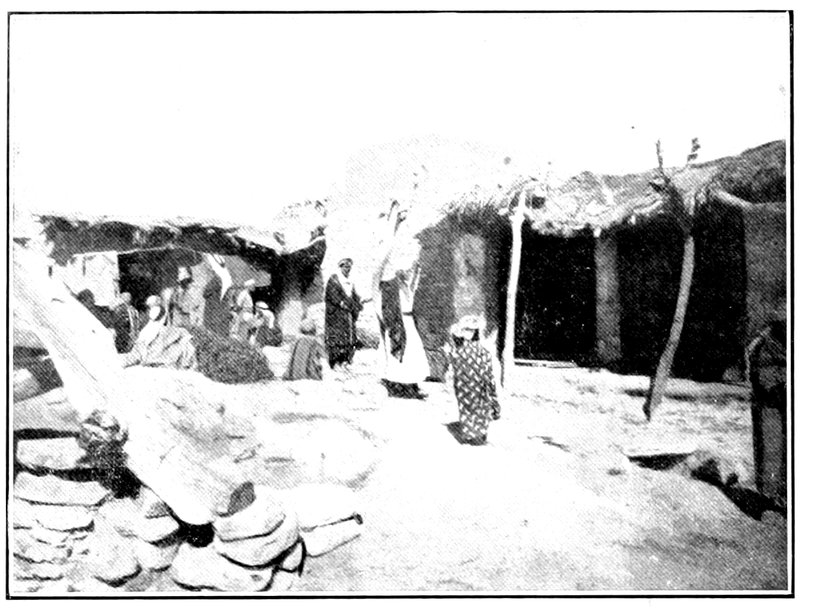

| Bedouin Village | 134 |

| Turkish Prisoners, Nablus | 134 |

| Mrs. Chisholm’s Canteen at Kantara | 146 |

| Bethlehem | 147 |

| Troopers entering Jericho | 148 |

| Damascus | 148 |

| Finish | 154 |

“Australia in Palestine” should prove of great interest to the people of Australia, and especially to those whose lives have been spent outside the great cities, for it includes a record of the achievements of their “very own”—the horsemen of Australia, and of the Flying Corps and the Anzac Section of the Imperial Camel Corps, which were recruited from them, and co-operated with them in the greatest war yet known to history.

The Australian Light Horseman—and under this name I include the Field and Signal Engineers and Medical Services connected with him, who come from the same stock—is of a type peculiarly his own and has no counterpart that I know of except in his New Zealand brother. His fearlessness, initiative and endurance, and his adaptability to almost any task, are due to the adventurous life he leads in his own country, where he has been accustomed to long hours in the saddle, day and night, and to facing danger of all sorts from his earliest youth. Perhaps these qualities are inherited from his pioneer parents. His invariable good humour under the most adverse conditions comes from the good-fellowship and camaraderie which exists in the free and open life of the Australian Bush. His chivalry comes from the same source, and it is one of his strongest points. In other words, the life he has been accustomed to lead has fitted him to become, with training and discipline, second to no cavalry soldier in the world.

As far as Australia is concerned, the Palestine Campaign may be said to have commenced with the crossing of the Suez Canal by the Anzac Mounted Division at Kantara on the 23rd April, 1916, to re-occupy Romani and the western end of the Katia Oasis Area. The mounted troops of Australia and New Zealand had already proved their extraordinary adaptability to circumstances as infantrymen in the hard school of Gallipoli, but it yet remained for them to show their value as cavalry. The occupation of Romani was followed by long and trying marches in the Desert of Sinai, during the hottest summer known in Egypt for many years, after an elusive xivenemy who did not appear in any force until July, 1916, when he advanced on Romani preparatory to his second attack on the Suez Canal. The disastrous defeat inflicted on the Turkish arms at Romani, and the pursuit which followed, not only demonstrated the inestimable value of the horsemen of Australasia as cavalrymen, but opened the way for the advance to the Eastern Frontier of Egypt which ended the enemy’s menace to Egypt. The systematic advance of the British Force from Romani to the Egyptian Border was covered by Australian and New Zealand horsemen, British Yeomanry and the Imperial Camel Corps, ably assisted by the reconnaissance of the R.F.C. and Australian Flying Corps. The victories of Magdhaba and Rafa completely cleared the enemy from Egyptian territory and opened the way for our advance into Palestine. The operations which began with the capture of Beersheba and concluded with the capture of Damascus and Aleppo, and eventually led to the complete surrender of the Turkish Forces, are dealt with in this volume, and I will say no more of them than that the brilliant part in those operations played by the Australian and New Zealand mounted troops has more than upheld the reputation they established on the battlefield of Romani.

The splendid record of the 1st Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps speaks for itself. It was formed in Egypt and has grown with the campaign to a state of efficiency which places it second to none of the same arm.

The casualties in action in this campaign have been light compared with the results achieved. In a very large measure this was due to the dash of the troops, which saved heavy losses on many occasions; but many brave fellows have given their lives through diseases contracted in areas which the exigencies of the service required to be occupied and fought in.

Before concluding, I would like to say a word for the Medical Services, which have endured the same hardships as the combatant arms, and always performed their duties cheerfully and efficiently under the most adverse conditions.

LIEUT.-GENERAL SIR H. G. CHAUVEL, K.C.B., K.C.M.G.

If the Turks had not aspired to the capture of the Suez Canal, and the reconquest of Egypt, they might still have been in quiet possession of the whole of Palestine. This campaign, so rich in brilliant exploits and so appealing to the imagination of the people of the world’s three greatest religions, was the direct result of Turkish aggression. Prompted by Germany, the Turk had, early in 1915, penetrated Central Sinai and, moving down the ancient route of the Wady Muksheib, attempted with a very inadequate force to cross and hold the Canal. He was easily driven off by a British force, which included a few Australian units. That was before our attack upon Gallipoli. It was not until the following year, when the heroic failure on the Peninsula had removed the menace to the heart of his Empire at Constantinople, that the enemy was able to attack Egypt with an army that gave him any promise of success.

Soon after the return of the Australians from Gallipoli, in 1916, at a time when the future of the Light Horse, which had fought as infantry at Anzac, was in considerable doubt, the Turk appeared in strength in northern Sinai. Thirty or forty miles across the desert from Port Said, there is a widely-scattered area marked here and there by hods, or little palm groves, which tell of the presence of water at shallow depth. The Romani area, as it is generally called, has always been of prime importance to the armies which, since the dawn of history, have marched east and west across the Sinai Desert between Egypt and Syria and Persia, and lands even further afield. Napoleon rested there before that precarious leap at El Arish which nearly cost him his army. Ancient invaders of Egypt always refreshed their thirsty and desert-worn troops around Romani before sweeping down upon the rich prize of the Nile Delta.

In 1916 the Turks began their forward operations by a raid in great 2strength, which beat down the resistance of Yeomanry posts at Katia and Oghratina. At that time, the organization and training of the Anzac Mounted Division was being completed at Salhia, west of the Canal. The 2nd Brigade, under Brigadier-General Ryrie, was immediately rushed out to Romani, where it was found that the enemy had temporarily withdrawn further east.

Steps were taken at once by the British Command to make the Romani area secure. The remainder of the Anzac Mounted Division, commanded by Major-General Chauvel, went out in support of the 2nd Brigade; British infantry followed. The railway was pushed vigorously forward. The 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades, with their camp at Romani, were engaged in ceaseless reconnaissance in force. Taking the task alternately in 24–hour shifts, they kept substantial touch with the enemy, who was all the while adding to his numbers, bringing up guns over the desert from El Arish, and pressing steadily onward. By the beginning of August a line of infantry strong posts extended at a right angle towards the north from the sea, covering Romani to the east. There we were invincible; so the Turk, moving swiftly and in strength, to the number of about 18,000, on the night of 3rd August attempted a great flanking movement past the south-western flank of the infantry line. His scheme was to drive in behind the infantry and Romani, cut our railway and other communications with the Canal, and envelop our entire forward force. Anticipating this move, however, General Chauvel had that night placed the 1st Light Horse Brigade, under the temporary command of Brigadier-General Meredith (General Cox being absent on sick leave in England), on a line of outposts joining up with the desert end of the infantry line, and thence swinging towards the Canal at a right angle. This disposition completely frustrated the enemy, and won us the battle of Romani.

The Turkish vanguard reached the Light Horse posts soon after midnight and attacked immediately. For hours an extraordinary hand-to-hand fight was waged in the dark among the sand dunes. The Light Horse line, ten times outnumbered, was pressed steadily back, but maintained an unbroken front to the enemy host. Soon after dawn the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, temporarily commanded by Brigadier-General Royston, a South 3African veteran (General Ryrie being absent on leave in England), was galloped forward in support and, dismounting, carried on the fight while the Regiments of the 1st Brigade passed through them to the rear for a brief breathing-space. All that day, the 4th August, the Turks gained ground on this flank, and at the same time kept our infantry in their posts by heavy shelling and a demonstration in strength from the east. A small number of infantry available was put in to support the Light Horse line, which, by nightfall, had been pushed back so close to the camp that some units were served with tea by the regimental cooks as they fought. But the end was now in sight. The New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade, and a Brigade of Yeomanry, both under Brigadier-General Chaytor, supported by a British infantry force, came swiftly down on the Turkish left flank, which was high in the air. By nightfall we knew that the battle of Romani was ours. At dawn next morning there was a slashing general attack with the bayonet. The enemy’s line broke, his retreat became a rout, and only the physical impossibility of getting speed out of our horses, many of which had been without water for nearly fifty hours, saved the whole Turkish army from destruction. The horses, burdened with an average load of 240 to 250 lbs., and often up to 280 lbs., laboured gallantly, but slowly, over the deep, hot sand.

Many thousands of prisoners, several guns, great quantities of munitions and other material were captured; but it was not until the retreating Turk had reached the large palm area around Katia, six miles away, and had been able to re-form his firing line in a reserve position there, that we were able to collect our scattered Brigades and give him fresh battle. The fight at Katia was drawn. On our side it was marked by a stirring charge of the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades and the New Zealand Mounted Brigade, in an unbroken line across the sands. In the preceding weeks the horses had frequently been watered in the hod at Katia, and this, doubtless, contributed to the spirit they displayed in the charge. The three Brigades, however, which had the support of a Brigade of Yeomanry, were compelled by heavy fire from the enemy batteries to dismount and fight on foot. The 3rd Light Horse Brigade, under Brigadier-General Antill, which had undertaken a wide flanking movement on the south, was held up by the enemy in Hamisah, where, in a brilliant little engagement, they smashed the Turk and took 440 prisoners, 4with a trifling loss on our side. The delay, unfortunately, kept the 3rd Brigade off the Turkish left flank at Katia, and enabled him stoutly to resist the frontal assault of the Australians and New Zealanders. Towards nightfall the engagement was reluctantly broken off.

Touch was maintained with the retreating Turks, and, a few days later, the same Brigades again engaged them at Bir el Abd, some fifteen miles further east. Once more a gallant dismounted frontal attack was made by our forces, but again the 3rd Brigade on the flank was obstructed, and its enveloping mission frustrated. In the main fight, which was much hotter than that at Katia, our men pressed in close with the rifle. The Turk was strongly supported by guns and machine guns in a very advantageous defensive position, and the Australians and New Zealanders were unable to reach him with the bayonet. The engagement was marked by many splendid acts of heroism and self-sacrifice, but it was doomed to be indecisive. The Turks evacuated the position the following day and were pursued to the edge of the oasis area, withdrawing with the remnant of their shattered Romani army to the neighbourhood of El Arish, fifty miles away.

After the fight at Bir el Abd there was ceaseless heavy reconnaissance and patrol work for the Light Horse, as the railroad, and with it the full strength of what was now an established British army of invasion, moved slowly, though inexorably, across the desert. On 21st December the Light Horse and Imperial Camel Corps entered El Arish and received a demonstrative greeting from the Arabs of that old village.

During these Romani operations, fraught with so much significance for Palestine and Egypt, the extreme right of the British line was entrusted to Colonel C. L. Smith, V.C., M.C., afterwards Commander of the Camel Brigade, who had under him a composite force made up of the 11th Light Horse Regiment, from Queensland, a London Regiment of Yeomanry and four companies of “Camels,” drawn from Australia, Scotland and Wales—a truly Imperial lot. A Turkish force, reported to be three thousand strong, was moving down from Magara in a south-westerly direction, with the intention of cutting in between Romani and the Canal. This estimate of enemy strength proved to be exaggerated, but our column had some sharp little fights against superior odds, and its work was warmly commended by the Commander-in-Chief. At Awedia the Camel companies went into action for the first time since their hurried formation; but as most of the Australians were old Light Horse and infantry veterans from Gallipoli, they were not strange to fire, and, like the remainder of the Australians fighting at Romani, they rejoiced in open warfare after the confined trench work of the Peninsula. A day or two later, the column fought sharply at Hilu and Baud, each time mauling the enemy severely and contributing substantially to the general disaster in store for the Turks.

JERUSALEM, FROM BELOW THE MOUNT OF OLIVES

By Lieut. G. W. Lambert

On the night of the 22nd December, the Anzac Mounted Division, made up of the 1st and 3rd Light Horse Brigades, commanded by Generals Cox and Royston, the New Zealand Brigade (General Chaytor), and the Imperial Camel Brigade (General Smith, V.C.) which included a majority of Australians, moved upon the Turkish post at Magdhaba, twenty-three miles away up the Wady El Arish. Again marching all night, they came at dawn within striking distance of the garrison settlement. Deploying swiftly, they soon had Magdhaba surrounded, and, galloping in as close as the Turkish fire, which came in strength from a number of well-concealed entrenched positions, permitted, dismounted and pressed forward in troop rushes with the bayonet.

The chief trouble for the Anzac Mounted Division at Magdhaba was the supply of water for the horses. If the Turks could not be smothered by nightfall, a withdrawal was imperative, for it was impossible to contemplate another day’s fighting with the horses still thirsty. In a country like this, where all the chargers are brought from far overseas, horseflesh must not be lightly thrown away. The struggle for Magdhaba was, therefore, as at Rafa a fortnight later, a struggle against time, a gamble against daylight. The Division, with the Imperial Camel Corps, fighting still under the able command of Major-General Chauvel, scored just on the call of time. As the day was closing vital Turkish strong posts fell almost simultaneously to our assaulting units on three sides of the settlement. In a wild rush the encircling troops overwhelmed the Turks, and met—with an extraordinary mingling of units coming in from every point—in the centre of the ring of battle. The survivors of the Turkish garrison, some 1250 officers and men, were made prisoners. Our total casualties were fewer than 150. Darkness fell swiftly, and, in the early hours of the night, there was an amazing scene as the prisoners were collected, and officers and men sought their units and searched for their led horses. Before midnight the Division was re-formed and, with the exception of a few squadrons left to clear the battle-ground and escort the wounded, our victorious little force was riding—for the second night in succession—back to water and rest at El Arish. As they tracked along in the darkness there were whole squadrons with not a man awake—a strange Christmas Eve!

Next came Rafa. On the evening of 8th January the Anzac Mounted Division, made up of the Brigades which had fought a few days before at Magdhaba, strengthened by the Camel Brigade and a Brigade of Yeomanry, cleared camp near El Arish and, riding all night, appeared before Rafa at dawn. The Turks held a strongly entrenched position consisting of three main systems of redoubts with many outlying rifle-pits on high ground, culminating in a knoll. On this knoll was a solitary tree, visible for many miles; and this, roughly speaking, was our objective. As at Magdhaba, the enemy was rapidly surrounded by Brigades moving at the trot and the gallop. Then the horses were raced back to places of safety, and the circle closed in on foot. The ground was more open than at Magdhaba, and our advance lay up long, bare slopes, swept by enemy fire. All day the cordon drew closer. Again, until the last moment, there was uncertainty as to whether the Turk could be smashed before nightfall. Again our horses were without water. And again victory came at sundown; this time after a series of long, sustained charges with fixed bayonets in the face of expert Turkish riflemen and German machine gunners, shooting at their best over specially prepared zones of fire. Rafa was a grim, deadly fight, waged up to the moment when our exhausted, but still excited, troopers jumped down on the Turks in their trenches.

That spirit of mercy which has distinguished so many Australian fights was shown here at its best. The Turks, who had shot at our men mercilessly and effectively until they charged home into the very trenches, then dropped their rifles and held out their hands—to have them warmly shaken by Australians! Such incidents, occurring frequently as they have in this campaign, may not be according to the rules of war, and the psychology disclosed may be difficult to follow; but the recollection of them, while it always moves our men who were concerned to shamefaced laughter, must clearly be a source of lasting gratification. At Rafa, practically every Turk who survived was made a prisoner, and we also secured many guns and much war material. Even in more marked degree than Magdhaba was Rafa placed to our credit at the eleventh hour, for not only was our force threatened by the lack of water and the approach of darkness, but heavy enemy reinforcements were rapidly approaching.

A BRIEF HALT RICHLY EARNED

JERUSALEM FROM THE AIR

DAMASCUS FROM THE AIR

3rd L.H. CAMP AT BELAH, A FAVOURITE RESTING GROUND BY THE SEA SOUTH OF GAZA

11This marked the passing of the desert. On the evening of the night march which brought us close to Rafa, our troops were still in the waste in which they had spent nearly a year without a glimpse of civilization or verdure. Travelling all night through the heavy sand, they came, just before dawn, on sounder going for their horses, and daylight showed them a wide, rolling landscape, gay with brilliant winter flowers—the fringe of Palestine.

No survey, however incomplete, of this fine campaign should fail to mention the countless little desert expeditions in Western and Central Sinai, in the early days of the fighting. These had various purposes. Sometimes they were political, but more than once they led to sharp fighting. The first time Australians were actually engaged east of the Canal was when the 9th Light Horse Regiment (chiefly South Australians, with a few Victorians), by a long night march and clever manœuvre, swooped down and bagged the Turkish outpost garrison at Jifjafa. Then there was a fine dash by the 11th Light Horse Regiment to Nekhl, the British pre-war administrative centre in Sinai. Later, two interesting expeditions were made up the Wady Muksheib, the ancient and central route across Sinai by which the Turks came in their feeble attack on the Canal, early in 1915. The drawback of that route was the shortage of water, and along the Wady bed some ancient power had excavated huge cisterns which filled during the rains. These cisterns are still intact. Once, the Light Horsemen pumped them out, and so closed the route for that season to the Turks; going out again, they sealed and covered them so as to make their rediscovery by the enemy very difficult.

Australian units from the Camel Brigade more than once rode across the desert to Akaba, at the head of the Persian Gulf. In October, 1916, a force marched thirty-five miles across the sandhills from Bayud to Maghara, and engaged in a vigorous reconnaissance in the foothills below the almost inaccessible, high-built Turkish garrison position. As an instance of the man-power and transport necessary to maintain a force in 12action on the desert for even a few days, the details of this little enterprise are remarkable. The column contained only 1100 rifles, and the operations covered but a few days; but no fewer than 7000 camels, 2300 horses and (including natives) 5000 men were employed to provide supplies of food and water for the force.

All these little side-shows necessitated long night marches across countless desert hillocks. To the untrained eye, one square mile of country in Sinai is indistinguishable from any other square mile, even by daylight. At night all movement was by compass and the stars, and the task of our guides was complicated a hundredfold by the constant change of route imposed by the steepness of many of the sand dunes. Very early the Light Horseman displayed that apparently inborn sense of direction which, almost alone, would have made him famous in this campaign. After a brief trial, the native guides provided by the Imperial authorities were found to be too slow and uncertain, while, if the enemy was close, fear usually reduced them to a state of imbecility. As soon as this was recognized, the whole of the guiding was done by our own officers, many of whom developed a certainty of location, whatever the circumstances, which amounted almost to inspiration.

Ten weeks after Rafa, on 26th March, came the first battle of Gaza. The scheme for the capture of this old gateway of Palestine proper was similar to that which succeeded so decisively at Rafa and Magdhaba. We were to move by night and envelop and isolate the town, with a view to its capture before the Turk could bring up reinforcements. But it was a far bigger enterprise than the two earlier raids. Modern Gaza is a fairly compact old town, which, before the war, contained 30,000 inhabitants. Most of the houses are of mud and straw, but there are also many substantial modern residences. The little city is graced by many mosques and minarets. Standing on a low hill on the inland edge of the wide belt of sand dunes, which, on this coast, everywhere fringe the Mediterranean, it is bounded on the north, east and south by an occasional fine orange grove, wide areas of olives and an intricate network of huge, sprawling cactus hedges surrounding hundreds of tiny fields. The Turks were soundly dug in, and well supported by many guns in commanding positions, while the irregular system of cactus hedges made an ideal barrier between them and the naked plain over which the attacking troops had to advance.

13Since Rafa a notable change had taken place in our force. The mounted troops had been reinforced by the arrival of large numbers of Yeomanry and, for the first time in the campaign, a substantial force of infantry was available for frontal attack. Marching in the darkness, part of our army surrounded Gaza, while a strong mounted force took up positions to the east and north to prevent the intervention of heavy Turkish reinforcements, which were within easy striking distance. British infantry attacked from the south and east. On their right flank was a Brigade of Yeomanry. Next came the New Zealanders, and on the extreme right, pushing in from the north, with their flank on the sea, was the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, with Brigadier-General Ryrie back in his old command. Unfortunately, a heavy morning fog prevented the infantry from getting into grips with the Turk in the earlier part of the day.

The mounted troops, moving faster, galloped first through the scattered groves of olives and then pressed forward, still on their horses, amidst the maze of cactus hedges. For our men it was a wonderful day of detached, individual fighting. Exact conformity was impossible. Regiments and squadrons, and even troops, fought wild little hole-and-corner combats of their own. There was much excited steeplechasing over the cactus. At times, our men and the Turks fought each other from either side of a hedge a few paces in width, the enemy on foot and our troops firing from their horses. Then the Light Horse, dismounting, hacked their way through the cactus with their bayonets, and did effective work with the steel. Our machine gunners, advancing in rushes in front and to a flank of the 2nd Brigade, maintained a clever and deadly covering barrage.

The fighting was marked by countless fine incidents. One Light Horse squadron gallantly rushed an important Turkish observation post. The New Zealanders, assisted by a Light Horse troop, took a number of enemy guns. Swinging one of these round, and sighting through the open barrel at point blank range, they demolished with a single shot a stone house containing a number of troublesome Turkish riflemen. By nightfall, both the infantry and mounted troops had won into the outskirts of the town, and captured large numbers of prisoners. But the garrison was still strong, and heavy Turkish reinforcements were closing in rapidly from three directions. We had missed by a hairsbreadth. The fight was broken off and our men, 14suffering a sense of disappointment scarcely less than that felt at the evacuation of Gallipoli, were withdrawn.

Three weeks later, on 19th April, the second battle of Gaza was fought on a long line extending from the sea eastward towards Beersheba. The Australians fought dismounted out on the right flank, and the day was the bloodiest our men have known in their Palestine fighting. For many hours they pressed forward in thin lines, up long, bare slopes, in the face of heavy and well-directed high explosive, shrapnel, machine gun and rifle fire. In places they made substantial headway and bent the Turks back. At one point, since known to fame as “Tank Redoubt,” two Australian companies of the Camel Brigade, co-operating with the British infantry on their flank, won temporary possession of a main key in the enemy line. Many splendid deeds distinguished this day’s hard fighting; they will rank with the best performances of Australian infantry in the war, and the exploit of the “Camels” at the Tank Redoubt with the greatest achievements of British arms in any age. But the Turk, though badly shaken, stood firm. The simple fact was that, in this Gaza-Beersheba line, which lent itself admirably to stout defence, we had encountered enemy forces so superior in number and equipment, that further advance was, for the time, physically impossible.

Between then and the end of the following October, when the Turkish position was shattered, significant additions were made to our strength. We were reinforced by some Divisions of infantry, and many guns of different calibre, while the Desert Mounted Corps was formed from the old Desert Column, consisting of the Anzac and Australian Mounted Divisions, and a Yeomanry Division. During this period, too, General Allenby arrived from France as Commander-in-Chief. In the great attack which demolished the enemy’s strong defensive system on this line, the Turk was out-witted and outfought. By a wide detour, covering several days and notable for its long, exhausting marches, and the remarkable performances of the Engineers in the development of water in desert areas, the Anzac Mounted Division appeared as a bolt from the blue to the south-east of Beersheba, on the morning of 31st October. Beersheba marked the end of the Turkish line of defence. Seen from the surrounding hills, the scattered modern town, with its wide, dusty streets planted with straggling eucalyptus and pepper trees, is not unlike some western townships in Australia. It lies in a basin below the southern end of the Judean Range, and had been strongly fortified by the enemy. The attack from the south-east, however, was a complete surprise to the Turk.

ROMANI. MOUNT ROYSTON IN THE DISTANCE

By Lieut. G. W. Lambert

IN A VILLAGE STREET

In the early morning the New Zealanders moved swiftly to the assault of Tel es Saba, a formidable mound, bristling with machine guns and rifles. At the same time, the 1st Light Horse Brigade went in to the south on the New Zealanders’ left, while the 2nd Light Horse Brigade dashed away on a long gallop under heavy shell-fire, and took up a position to the north, to cut off the retreat of the Beersheba garrison along the road leading over the Central Range, through Hebron and Bethlehem, to Jerusalem. After very heavy fighting on foot, over broken ground, the New Zealanders, supported by the 1st Light Horse Brigade, scaled and captured Tel es Saba. The day was well advanced. Beersheba had not fallen, and it was patent that, if we relied upon a dismounted attack, the town would certainly resist until nightfall; which would have given the enemy an opportunity to adjust his forces and perhaps upset our whole offensive. Four miles away to the south-east, the Australian Mounted Division was in reserve, and, shortly before sunset, Brigadier-General Grant received orders to attack the town with the 4th Light Horse Brigade. Between him and Beersheba lay a definite system of strongly-held Turkish trenches. As it was recognized that time did not permit of a dismounted advance, the decision was made to go in mounted, at a gallop. This hazardous enterprise of galloping infantry into an entrenched position was entrusted to the 4th Regiment, from Victoria, and the 12th Regiment, from New South Wales.

Moving off at a trot, and soon quickening the pace to a gallop, the regiments swept in a bee-line towards Beersheba. They were soon under heavy shell and machine gun fire, but this only served to speed the horsemen. Charging wildly down on the Turks, despite heavy rifle fire, leading troops of Light Horsemen jumped the advanced trenches at a gallop, going clean over the Turkish bayonets. Once within the enemy trench 16system, part of the force dismounted, and, jumping down with their bayonets among the startled enemy, soon cleared the position. Meanwhile the mad gallop of the other squadrons was continued through enemy resistance into the very heart of the town. The Turks were thrown into hopeless disorder, and, believing that the handful of Australians formed but the advance guard of a great cavalry force, put up an indifferent fight. Upwards of 1100 were captured, but the darkness, which fell immediately after our horse clattered into the town, enabled many more to escape. Nine field guns and a large quantity of material fell into our hands. The Light Horsemen had charged with fixed bayonets, not that they could make any use of them on horseback, but for the moral effect upon the enemy. This magnificent enterprise, establishing as it did that Turkish nerves were not proof against a resolute body of galloping horse, led to highly important results in the Great Drive which followed. The Yeomanry, who were equipped with cavalry swords, a privilege not then enjoyed by any of the Australian Light Horse, routed greatly superior numbers of Turks in a series of charges which rank with the greatest performances of British regular cavalry.

A few days after Beersheba the Turkish line was broken by the infantry at Sheria, and again between Gaza and the sea. The mounted men were turned loose on the heels of the retreating enemy, and the wild stern chase was continued for nearly fifty miles. The speed of the horsemen was regulated chiefly by difficulties of transport and water supply; but all the way the Turk fought clever rear-guard actions, making therein especially effective use of his strong equipment of machine guns. The Australians’ work was fast and bold throughout. There were scores of fights by night and day, which brought credit to the staff work and Brigade and Regimental fighting. Up till then it was the grandest cavalry drive in the war, and perhaps it has no equal in any campaign of the past. When the British forces came to a halt on a line running roughly from the coast a few miles north of Jaffa eastward to the mountains, the cessation of the pursuit was due not to enemy resistance, but to the impossibility, at that time, of extending our lines of communication any further. During this great cavalry drive, the Desert Mounted Corps, which embraced all the mounted troops, was under the command of Lieut.-General Sir H. G. Chauvel, who enjoys the distinction of being the first Australian to rise to 17the leadership of a Corps. And, with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade under General Wilson and the 4th under General Grant, the four Australian Mounted Brigades were, for the first time, all under Australian commands.

In the wars of the ancients, cavalry and chariots were always used down on the Philistine Plain, while the Judean Hills were regarded as practicable only for infantry. It is the same to-day. The Great Drive on the Plain finished, the British infantry, with Yeomanry dismounted, moved eastward through the narrow passes and up the harsh, rocky hillsides of Judea towards Jerusalem. The Turks stubbornly resisted our capture of the Holy City, and the fighting, at times, was bitter and bloody in the extreme. But the gallant little Londoners, to whom fell the honour of most of this significant advance, won their way steadily forward. Only one Light Horse Regiment, the Western Australians, played any immediate part in the operations which, on 9th December, culminated in the surrender of Jerusalem.

A few weeks later, the 1st Light Horse Brigade and the New Zealanders marched secretly, at night, from Bethlehem by steep mountain tracks, and, co-operating with the 60th (London) Infantry Division, after a sharp fight at Nebi Musa captured Jericho. This exploit was distinguished, as the Anzacs’ work in the campaign has always been, by the remarkable work of our guides. A squadron of the 1st Brigade had the honour of being the first to enter the village; but the winning of the Jordan Valley, like the capture of Jerusalem, was, in the main, due to the solid fighting qualities of the men of London. To-day, all through the Judean Hills, you come upon little wooden crosses which tell of the spirit and self-sacrifice of our good ally, the fighting Cockney.

A brief pause, and then, the Desert Mounted Corps Bridging Train (B Troop, Australian Engineers) having thrown the first bridge across the Jordan, the Anzac Mounted Division, together with the Imperial Camel Brigade and, once again, the Londoners, made their famous rush for the Hedjaz Railway, far out across Jordan to the east, where the Plateau of Moab begins to merge into the sand of the wide Arabian Desert. This expedition, which, so far as the Colonials were concerned, fell chiefly upon the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, the New Zealanders and the Camels, was perhaps the severest we had had since crossing the Canal. Rain fell almost unceasingly for many days. The mountain tracks were so narrow and broken that the Brigades, travelling only by night, moved in single file, leading their horses and camels. The weather was piercingly cold. Men were wet through for several days and nights in which they knew no sleep, and were almost ceaselessly engaged in heavy fighting. In these circumstances, the destruction of some miles of the railway, and the safe withdrawal of the force, was an especially good performance.

A few weeks later practically all the Australian mounted troops, with the exception of the Camels, again crossed the Jordan, and, cutting in behind the Turks after some rare mountaineering feats in the darkness, took possession of Es Salt, a considerable Turkish base. In this enterprise, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade particularly distinguished itself, the 8th Regiment of Victorians alone taking prisoners equal to at least twice their fighting strength. The same Regiment also captured thirty machine guns and large quantities of other war material.

During the spring and summer, which were spent in Jordan Valley, there were many highly successful little defensive fights. One of these, in which the Turkish attack fell mainly upon the 2nd Light Horse Regiment of Queenslanders, left nearly two hundred enemy dead within a few chains of our barbed wire. At about the same time, the foe assaulted the Musallabeh knoll, on the other side of the river, held by the 1st Battalion (Australians) of the Camel Brigade, and got to close quarters, in which bombs and bayonets, and even stones and hands were freely used on both sides. The Turks were beaten off with some hundreds of casualties.

On 12th July, a day on which the shade temperature stood for hours at 120 degrees, a stout attempt was made by a considerable force of German infantry against the 1st Light Horse Brigade under Brigadier-General Cox, on this same Musallabeh sector. Our line there was a series of small strong posts over a long and broken front. The Germans, advancing in the dark, penetrated between two of the posts, and actually reached the centre of our advanced position. A feature of this fight was that every little post, 21except one which was overwhelmed, successfully resisted the German attack, although all were surrounded and isolated for hours. In some, practically every officer and man became a casualty. The Germans were routed by a brilliant counter-attack of the 1st Light Horse Regiment (New South Wales), which was in reserve, and the affair cost the Germans 360 prisoners and about 1,200 casualties. Our losses were slight. Troops from four States, Tasmania, South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales, shared in the victory. On the same day, also in Jordan Valley, a troop of Queenslanders, men from the 5th Light Horse Regiment, twice left their lines with bombs, and, surprising enemy forces many times their number, brought in forty-five prisoners, and they had killed and wounded as many more in the fight. The casualties suffered by the troop were one officer and two men slightly wounded. Two cars of No. 1 Australian Light Car Patrol also took part with the Imperial Service (Indian) Cavalry in a brilliant counter-attack east of the Jordan.

The long, distressing summer in Jordan Valley died hard. In September, when the Anzac Mounted Division was there, the hottest days of the whole year were endured. The various mounted troops had held the Jordan sector in turn, those in reserve enjoying brief periods of rest on the bracing uplands about Solomon’s Pools, a little to the south of Jerusalem. There the sunny days were cool, and at night men who had known little sleep down on the Jordan rejoiced in the mountain mists and the unwonted comfort of their blankets.

In the course of the year there had been another interesting change in the composition of General Allenby’s army. Many of the Yeomanry and British infantry had gone to other battle fronts, and in their place came one hundred thousand Indian horse and foot. Many of our Light Horsemen had fought beside the Gurkhas and other Indians on the Peninsula; some of us had seen the Indian cavalry in France in the early days of the war; but to most of the Australians the Indians were strangers. To-day, after a few months and a stirring campaign together, the bond between the two races is a remarkably strong one.

The Australian soldier has, for a man of insular breeding, shown an extraordinary capacity for making friends. He has an easy way 22with peoples of all races and colours. In France he is completely at his ease among the French peasantry; and he saunters through the Arab villages in Palestine as familiarly and as confidently as he used to walk the streets of his townships and cities at home. His old enemy the Turkish ranker is his admired personal friend. But the strong bond which sprang up so quickly between the Light Horseman and the Indians was perhaps the strangest of all his new war friendships. They were divided by colour, the language barrier was absolute, and, most unpromising of all, there was the barrier of caste, which prevented the devout Indian from sharing his rations, and so made little acts of camp hospitality impossible. But the barriers, although they seemed impassable, were miraculously surmounted. The Indians made no secret of their admiration of the Light Horseman as a past-master at the game of combined mounted and dismounted fighting, while the Australian was genuinely appreciative of the splendid soldierly qualities of the highly-trained regular Indian cavalry. Moreover, nearly all the Indians rode Australian horses!

Every trooper in Palestine knew that a great campaign would be launched in the early autumn. General Allenby would, according to the camp-fire strategists, “hop in” during the brief season between the extreme heat and the beginning of the heavy rains in November. Further, the C. in C. would, in all probability, assail the enemy line at the full of the moon, so that we should have light for the great cavalry night marches that were anticipated. But it is doubtful whether any soldier in Palestine, who was not in the official secret, forecasted a scheme so bold as that General Allenby had resolved upon. Certainly, none dared to hope for a triumph so dazzlingly swift and complete.

The great campaign opened at dawn on the morning of 19th September, 1918. A fortnight after General Allenby flung his artillery bombardment at the enemy line, the great Turkish and German force in Western and Eastern Palestine had been destroyed, and our prisoners numbered 75,000. Of the 4th, 7th, and 8th Turkish Armies south of Damascus only a few thousand foot-sore, hunted men escaped. Practically every gun, the great bulk of the machine guns, nearly all the small-arms, and transport, every aerodrome and its mechanical equipment and nearly every aeroplane, an intricate and widespread telephone and telegraph system, large dumps of munitions and every kind of supplies—all had, in fourteen swift and dramatic days, been stripped from an enemy who for four years had resisted our efforts to smash him. It was a military overthrow so sudden and so absolute that it is perhaps without parallel in the history of war. And it is still more remarkable because it was achieved at a cost so trifling.

TURKS MARCHING OUT OF OLD CITY OF JERUSALEM AT BEGINNING OF WAR, 1914

(Captured German Photograph)

GAZA

THE MOUNT OF TEMPTATION

ALL THE WORLD OVER

25It was a stupendous result, gained by a simple scheme. The strategy was strikingly bold, but perhaps the most impressive thing about General Allenby’s triumph was the superb manner in which his plan was carried through. The campaign went with a bang from the moment the line was broken until Damascus, more than 150 miles distant, was taken. It galloped all the way. There was never a moment’s indecision, never a semblance of fumbling. Here was a British Army at its best, every man efficient, every man enthusiastic.

The scheme was obviously the conception of a confident leader of horse. General Allenby is a cavalryman, and he had under his command the most powerful cavalry force in the war. And he knew the quality of his mounted men. All of the Australians and New Zealanders and Yeomanry had been in the sixty-mile drive from Gaza, of the previous year, and most of them had been in the saddle in Egypt and Palestine for two and a half years. The dashing Indian cavalry had been with him for many months and had given many examples of their speed and love of battle. Again and again in the summer their advanced patrols had galloped down bodies of Turks, and their terrible use of the lance in those little actions had a highly useful effect on Turkish nerves. The cavalry was General Allenby’s special weapon for the campaign, but in addition, he had a substantial and fit force of veteran infantry. He had, too, a particularly brilliant lot of airmen, and in his supply services he possessed a vast organization of railway, motor, camel, horse, mule and donkey transport, which was efficient and resourceful in the highest degree, and had already performed miracles.

Altogether the British Army of Palestine was, when the final campaign opened, as near to perfection as any force ever was. All ranks were veterans and all were animated by that spirit which every army feels when confident of victory and happy in its leaders.

This was the scheme. We faced the Turks on a fifty-mile line running from a point on the Mediterranean coast about twelve miles north of Jaffa south-eastward across the Plain of Sharon, thence eastward over the 26Mountains of Samaria at a height of 1500 to 2000 feet, falling to 1000 feet below sea-level where it crossed the Jordan Valley, and terminating in the foothills of the Mountains of Gilead. The Sharon Plain sector was some fifteen miles in length, across Samaria fifteen miles, and the stretch in the Jordan Valley about eighteen. The Turkish position was a strong one. On Samaria, or the Central Palestine Range, south of Nablus, the enemy had ideal defensive country, rugged and broken, yet well served by rail—on the north-west to Haifa, and on the north-east across the Jordan at Beisan and by way of Damascus to Turkey; he had also good roads to Haifa and to Damascus by way of Nazareth.

To push the Turk on the mountains by a frontal attack would have meant at best the gradual withdrawal of his forces. In Jordan Valley the enemy’s safety lay in the fact that his guns on the foothills of either side covered the limited ground which was practicable for horse and transport. And, even if we had galloped up Jordan Valley, it would have been extremely difficult from there to swing in behind the Turkish position on the Central Range. General Allenby took the Plain of Sharon for his great enterprise. Forty miles behind the Turkish position the Jordan Valley and the Plain of Sharon are joined to the Esdraelon Plain—the old Plain of Armageddon. In other words, the Jordan and Sharon and Esdraelon formed a half-circle round the main central Turkish position on the mountains. All the enemy lines of communication led across Esdraelon. If we could seize the Plain swiftly, cut the railways and hold the roads, the Turkish army west of the Jordan was in our hands. It was a scheme calculated to test the mettle of any army. If we were to succeed, every branch of the service had to show at its best. First our airmen had to destroy or drive off the German aeroplanes and so keep the enemy ignorant of our plans; then the artillery barrage had to make the way possible for our infantry; in its turn, the infantry had, in one rush, to drive a gap for our cavalry, and the cavalry, galloping through the gap, had to cover fifty miles and reach Esdraelon Plain on the night of the first day. Lastly, the cavalry must hold the communications they had cut, and to do so, they had to be fed. The transport necessary for feeding tens of thousands of men and horse had to travel almost as fast as the cavalry. The scheme had to go through to time-table or it might not go through at all. If the artillery had failed to do its work in a swift half-hour’s bombardment, or if the infantry had faltered, the enemy would have had time to redistribute his forces, and General Allenby might have been robbed of his victory.

MAGDHABA, SHOWING THE WADY BED ABOUT ONE MILE FROM TURKISH BUILDINGS

By Lieut. G. W. Lambert

General Allenby took no chances. He followed the sound principle of fighting under the best possible conditions. By the aid of clever and greatly successful bluff, the Commander-in-Chief delivered his smashing blow at an unexpected point of the Turkish line. The enemy was led to believe that the British offensive would fall on the eastern sector. While a huge force of cavalry, artillery and infantry was being smuggled by night marches to the Plain of Sharon on the west, active and amusing camouflage preparations were being made in the Jordan Valley. For instance, many dummy camps were brought into existence, and large numbers of realistic canvas horses were tethered in them. Mules drawing sledges were driven about in the dust to suggest heavy traffic. Fast’s Hotel at Jerusalem, then being conducted for officers by the Canteen Board, was ostentatiously emptied of its inmates, two sentry-boxes were placed at the entrance, and a whisper was started in the bazaars that the hotel would be General Allenby’s advanced headquarters during the coming offensive. Simultaneously, the Arabs east of the Jordan made realistic sham preparations for an attack on Amman, out on the Hedjaz. They put down a big base, engaged in bold reconnaissance, and cut the line between Amman and Damascus. The deception of the enemy was complete. We know now that he expected and prepared for the blow on the east, and was stiffening his defences there until a few hours before our bombardment opened on the west, near the Mediterranean.

The airmen materially assisted in this hoodwinking. During the eight weeks preceding the offensive, the German air service was practically driven out of the sky. Fifteen machines were destroyed or forced down and enemy aerodromes were bombed. So complete was our ascendancy that not an enemy plane was seen over the threatened sector for eight days before the offensive began.

Blind as to our movement of troops, and mistaken by fifty miles as to where his line was to be assailed, the enemy’s plight was further accentuated by the destruction of his communications on the very evening of the bombardment. Pulling out at night from their sham camp near Amman, the Arabs rushed away up north, and cut the railway and telegraph communications between Deraa and the great Turkish base at Damascus. This left the enemy on his whole front without supplies for the fight. Other telegraph lines further west were severed at the same time, and a bomb from an Australian plane on the night before our advance 28destroyed his great forward telephone exchange at Nablus, which dislocated all his lateral communications. When our guns opened at dawn on 19th September, the Turks were already in a desperate plight.

On the night before the bombardment there was an atmosphere of perfect confidence in our camp close behind the line. Every man was moved by the prospect of a successful adventure, which would give vast immediate results and have an incalculable influence on the world war. The tropical intensity of Jordan Valley, where the Australian Brigades, with one exception, and some of the British and Indian cavalry had spent the whole summer, had left its mark. We had suffered much from malaria and other fevers, which, it was feared, might recur when we moved into the cooler north. The horses were, if not in poor condition, certainly on the light side; but these things were forgotten as the critical day approached. The Australian Mounted Division, commanded by Major-General Hodgson, and now made up entirely of Light Horse, except for one dashing, picturesque regiment of French Colonial regulars, had recently been armed with swords. The period of training in the new arm was very brief—for many Regiments only a few hours; but the men taking very keenly to it, soon reached a high standard of efficiency. Every trooper was excited at the thought of a true cavalry charge. The Anzac Mounted Division was still in the line in Jordan Valley.

During many nights before the push every road on the coastal sector was crowded with slow-moving, well-ordered traffic. By day all was normal, except for significant glimpses of camps in the wide olive groves around Ludd, and in the orchards and orange groves about Jaffa. But as darkness fell the whole countryside would become thronged with masses of horse and foot and guns, and every kind of transport, groping their way through blinding clouds of dust. The roads were impassable outside the organized columns; the night was loud with the shouts of drivers speaking divers languages. A few hours before the great push began this night traffic culminated in a general move northward, the cavalry moving up close behind the infantry, and the supplies following the cavalry. Every road was massed with motor-lorries and horse transport; every track with endless strings of camels. Each unit in the great army was pressing up as closely as possible to the starting gate.

[top]

TURKISH PRISONERS AT BEERSHEBA

[middle]

STREET MARKET, JERUSALEM

Inset—JERICHO

Showing the pretty little Garden Oasis

[bottom]

LIGHT HORSE CROSSING JORDAN

IN THE JORDAN VALLEY

SPRING WATER, CLEAR AND COLD

31The bombardment opened at dawn, a heavy barrage. For half an hour the startled Turks were battered in their trenches. Then, abruptly, the bombardment ceased. “Now the infantry,” said a Brigadier of horse “and then!...”

Our battalions leaped forward as the gunnery died away, and carried the Turkish trenches after a brief struggle. They simply overwhelmed the enemy riflemen, and even the German machine gunners and Austrian artillerymen, after a wild burst of bad shooting, were forced to flight or submission. Within half an hour the infantry had made a gap for the great force of Indian and Yeomanry cavalry waiting near the coast, and soon afterwards they opened another a few miles inland. The expectant horsemen jumped off like thoroughbreds from the barrier.

They rode away in the sunrise, the advanced squadrons trotting out after the ground scouts, the flank patrols galloping wide; Brigade after Brigade rode out over the rolling sandhills. The men were eager, the horses fought for their heads. The swords of the Yeomanry flashed and Indian lances glinted from each successive skyline. It was like a war scene of the picture galleries. Quickening the pace, the Regiments raced on past our guns, most of which were already limbered-up for the pursuit. The infantry, busy with their prisoners, cheered them as they passed, and soon they were speeding down on Turks who had fled from the onslaught of the infantry. But their sport with sword and lance was brief. In this Sharon sector, the enemy had no forward reserves, no second-line trenches. The Turkish front here had depended for its safety on a one trench system. From the crossing of the trenches until they reached the Esdraelon Plain, late in the night, the cavalry encountered no resistance. Once or twice they sighted small bodies of the enemy and made for them at the gallop. But the Turks would not give battle. Before the campaign was three hours old there began the long series of almost bloodless surrenders which were to be the most amazing feature of the sleepless fortnight.

The perfection of our organization was revealed very early. The cavalry was scarcely clear of the trench system before scores of field guns were rumbling in their wake. And, pressing on after the artillery by many tracks, good and bad, went mile after mile of camels and wheeled transport. 32Where the cavalry went the supplies must follow; and the cavalry rode from forty to fifty miles between sunrise and midnight. With nothing to check them, their pace was controlled only by the endurance of their horses. The men rode light; they carried only one blanket, and that as a saddle-cloth. Tent sheets and waterproofs were forbidden. It was a wild ride against time. But horses were loaded with three days’ rations, and few carried less than 250lbs.—many of them more than 280lbs.

At dawn next morning the Yeomanry were across the Esdraelon Plain and in Nazareth, where they caught most of the garrison of 3000 and the whole population still in their beds. They secured the town at the expense of eighteen casualties. By noon the Esdraelon Plain was in our hands, and the Turkish Army in Western Palestine left without a line of communication or retreat, except at Beisan on the north-east corner of the trap; and the capture of Beisan was already assured. How completely the enemy was deceived, and how light were his forces on the sector broken for the cavalry, is shown by the fact that on the first day, although our horse travelled fully forty miles on a wide front, only 900 prisoners were taken by them. Next day, as the net closed round the forward enemy forces on the Central Range, and they attempted to retreat across the Esdraelon Plain, our cavalry took upwards of 12,000.

At the beginning of the second day, we contained the Turkish western army on the south, west and north. The Anzac Mounted Division, which is two-thirds Australian and the balance New Zealanders, and a light infantry force, all under Major-General Sir E. W. C. Chaytor, were moved up the Jordan Valley on the east of the Turks and so the net was completed. But the task of the Anzacs was difficult. Before they could move, the enemy guns dominating the narrow ground on either side of the river had to be silenced or shifted. This meant that the Turks had to begin their retreat on the Samarian Range before the Division could race them for the crossings. Not until the second day did this come about, and then the Anzacs, riding fast, closed the fords and the Turkish Western Army was doomed. Forty hours after the fight commenced, as the second day was closing, the enemy began to stream down the tracks leading on to the Esdraelon Plain from his forward mountain position. He had already 33abandoned guns and transport, a tragedy which he owed mainly to the appalling havoc wrought with bombs and machine guns by our airmen.

At dusk on the second day a large force was reported to be heading towards Jenin, on the northern edge of the Esdraelon Plain. General Chauvel, who was directing the battle from Megiddo (now Lejjun), the actual site of ancient Armageddon, at once ordered the 3rd Light Horse Brigade to move to the attack. An hour later, the Brigade had captured a mass of prisoners, who subsequently counted out at more than 7000; and we had the first evidence of the demoralization of the enemy. As the Brigade approached Jenin, with the 10th Light Horse Regiment (Western Australians) leading and the 9th (chiefly South Australians) working round to the rear of the village, the Turks ran out and surrendered in thousands. We had one officer and one man wounded. The only shots fired at us came from nine German riflemen, who fought to a finish, although two of our machine guns were laid on them at a range of sixty yards. The plan had put our troops into certain positions and the Turks, as at sham fight, recognizing the checkmate, were surrendering without bloodshed. Any resistance which followed on the long ride to Damascus came almost entirely from the Germans.

An endeavour has been made in the preceding pages to show how the galloping cavalry cordon was thrown round the main enemy position on the Samarian Range. Before the close of the second day, our horsemen, stoutly armed with machine guns and automatic rifles, in addition to rifle and sword and lance, and further strengthened by many batteries of horse artillery, held all the roads and railways behind the Turks and Germans. The enemy was practically cut off from supplies and retreat. Worse than that, he was already irretrievably smashed by the attack of the British and Indian infantry on his front. Recoiling from this blow, and hastening to reach the Esdraelon Plain before the cavalry completed the net, he was caught by our airmen in narrow mountain passes, subjected to terrible bombing and harassing machine gun fire, and forced to abandon most of his guns and transport. At the same time, the 5th Australian Light Horse Brigade under Brigadier-General Macarthur Onslow, accompanied by one regiment of French cavalry, was thrown in during the first day on his right flank, about halfway between the old front line and the Esdraelon Plain. The Australians, moving very fast, scattered with their swords a force several thousand strong north of Tul Keram and took two thousand prisoners. Then, riding all night, they cut the enemy frontline railway close behind Nablus. A few hours later, the Brigade captured Nablus itself.

But before this the airmen had commenced their work in the passes. When our infantry broke the enemy’s line on the Plain of Sharon, many thousands of Turks, who were on the foothills eastward of the gap our cavalry had galloped through, had endeavoured to swing round and retreat to the highlands of Samaria. But the movement was at once detected by the Australian airmen. The Turks, with their transport, were seen to be heading for a narrow defile leading up from Tul Keram to Anebta. Using their wireless, the airmen called up aerodromes where dozens of British and Australian pilots were awaiting the signal. The doomed column, extending over upwards of two miles, was deep in the pass when the first flight arrived with its bombs. Beginning on the leading troops and vehicles, the airmen, flying low, had, in a few minutes, blocked the narrow track. Pilot after pilot, flying in perfect order, dropped his bombs, and then, assisted by the observers, raked the unfortunate Turks with machine guns. Their ammunition exhausted, the airmen sped back to their aerodrome for more, and returned again to the slaughter. Some pilots made four trips on that day. While the airmen attacked the column, the 5th Light Horse Brigade came up over the hills on either side of the track, and caught the Turks with their swords as they attempted to escape. Blocked in front, the battered, distracted procession closed up and telescoped, and fires broke out among the massed and broken vehicles.

Still more appalling, because of the greater magnitude of the disaster, was the fate of a column between Balata and Fermeh on its way down the range towards Beisan, on the Jordan. Flying over Samaria, you appreciate the opportunities which this retreating army offered to the airmen. The stony hills are not so rugged as in Judea, but they are still too steep to permit masses of troops to move off the narrow roads. These roads wind along beside the wadies and are flanked nearly all the way by abrupt hillsides. The Balata column contained the bulk of the enemy’s forward transport. It stretched, slow-moving and in full view from the air, over seven or eight miles of the confined track. An Australian reconnaissance pilot sighted it soon after dawn and, an hour later, dozens of British and 37Australian bombers and machine gunners, flying within a few hundred feet of the ground, were smashing it to splinters. Again they began at the head, and forced the helpless drivers to pile up from the rear. For hours the bombing was continued. Here the airmen worked unaided by any other arm of the service, and they had wrecked or disabled the whole of the transport before the infantry came up from the south and took the dazed survivors. The broken material afterwards collected in the pass included 90 guns, 840 four-wheeled and 76 two-wheeled horse and cattle vehicles, 50 motor-lorries and a large number of miscellaneous transport, such as water carts and travelling kitchens. The horror of the scene during the bombardment and afterwards need not be dwelt upon. As the bombs rained down with pitiless regularity, scores of lorries and wagons were overturned and dashed to pieces as they went hurtling down into the rocky beds of the wadies. Included in the column were large formations of infantry, and these and the drivers, rushing from the track to escape the bombs, were shot down by airmen. These air attacks were repeated many times on a similar scale in the first two days.

Rarely have the various services of an army worked in such perfect accord. The infantry drove the enemy from his front, the Australian and French cavalry, at the same moment, struck from the flank at his very heart at Nablus; as he attempted to retreat in good order, the airmen wrecked him from the skies, and, in a few hours, turned his army into a shell-shocked rabble, with few guns or munitions, and little food. The wretched Turks, in their tens of thousands, urged on by officers, came at last to the outlets into the Esdraelon Plain. When first the cavalry galloped down upon them, and they surrendered in hordes without the least attempt at resistance, we were astonished. It was not until we learned what had happened in the mountains that we understood the tragic state of their morale.

The air force achieved a notable victory. They had not only inflicted very heavy losses, but had incalculably lessened the task of both our infantry and cavalry. They had prevented the Turk from fighting effective rear-guard actions against the pursuing infantry, and had hammered him so soundly that he was incapable of any attempt to burst through our cordon of cavalry. Without this help from the airmen, General Allenby must still have won a great victory; but it would have been much short of the 38sensational one achieved. Progress must have been much slower, and our casualties heavier by many thousands.

Before the fight was two days old our aeroplanes were using aerodromes captured from the enemy. At one point on the march to Damascus, when we were a hundred miles from our starting-place, a number of airmen came up and established a flying ground abreast of our cavalry advance guard. Throughout the operations an air-post service was maintained between the leading troops and General Headquarters. An Australian Brigadier and a Colonel of the Light Horse, who were in hospital far down the line when the campaign opened, surprised their troops by alighting from aeroplanes in their midst, a hundred miles from our starting-point.

The few thousand Germans who were with the Turkish 7th and 8th Armies west of the Jordan met the same fate as their allies; nearly all were destroyed or captured. But one must give the Germans credit for a stout resistance. Throughout, they fought resolutely to avert the great disaster, and if all of them did not continue the struggle to the death, it must be remembered that they were in a desperate situation. They handled nearly all of the hundreds of machine guns, which were the most formidable weapons possessed by the enemy. All the way to Damascus they fought stout rear-guard actions.

Having the great body of Turks on Samaria safe, and most of them already accounted for, General Allenby decided to clear Haifa; the operation demonstrated the relative morale of the Turks and Germans. A flying reconnaissance of armoured cars and smaller cars of the Light Car Patrol was pushed into the outskirts of the town. About three miles from the town our force saw the heads of a party of Turks in a strong redoubt two hundred yards from the road. The armoured cars halted and swept the Turkish parapet with their machine guns. The white flag was at once hoisted, and about eighty Turks came out without firing a shot. Two miles further on, the British came upon an Austrian battery of light field guns, supported by German machine gunners. Our little probing expedition was at once brought to a standstill, and was not sorry to pull out. Next day the Indians and Yeomanry, supported by horse artillery, rode into the town, and again the only opposition came from the Austrians and Germans. “We tried to cover the Turks’ retreat,” said a captured German officer, “but we expected them to do something, if only keep their heads. At last we decided they were not worth fighting for.”

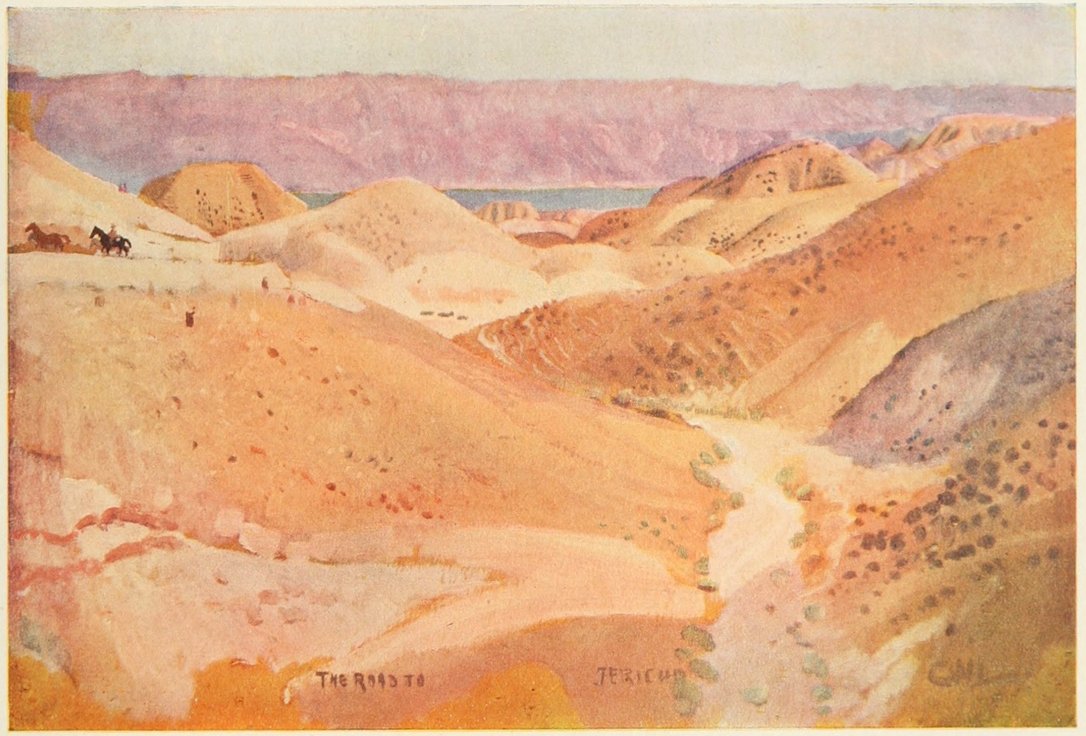

THE ROAD TO JERICHO

By Lieut. G. W. Lambert

ISMAILIA

Before Haifa fell our troops were moving swiftly east of Jordan. A Division of Indian and Yeomanry cavalry crossed the Jordan about Beisan and rode eastward. Simultaneously, the Anzac Mounted Division forded and swam the river further to the south, and moved on Es Salt and Amman. The Australians and New Zealanders were familiar with the country. This was their third expedition to the Plateau of Moab and the heights of Gilead. They knew every goat-walk on the steep mountain side. This time they had come to stay; the Fourth Turkish Army on the East was to share the fate of the 7th and 8th Armies on Samaria. The tactics employed on both sides of the river were broadly similar. General Allenby depended for success upon the speed and stamina of his horses. Before the operations commenced, the Turk held a defensive position which was roughly an extension of his line west of the Jordan. He was strong in the foothills of Gilead; on the mountain he had his base at Es Salt, and at Amman he had a substantial force guarding a vital series of tunnels and viaducts on his Hedjaz railway. Beyond the railway the Eastern Palestine Range flattens out on the wide desert, which extends right across to the Euphrates. On the fringe of the desert was the Army of the Sherif of Mecca, a picturesque, galloping, thrusting, well-armed force. The Arabs harassed the Turk by day and night, repeatedly dashing in and cutting his railway and telegraph communications with Damascus. When attacked, they would fade away into the wide desert and leave the slow-footed Turk in the air. While the Anzacs marched upon Es Salt and Amman, the Arabs made a detour in the desert, appeared on the flank of the enemy north of Deraa, and cut the railway where the Hedjaz line junctions with the line which supplied the Turks west of the Jordan.

Meanwhile the Indian and Yeomanry Division had crossed Eastern Palestine and reached Deraa, where it joined hands with the Arab army. Then the Arabs, the Indians and the Yeomanry sped on towards Damascus. There was still a chance of escape for some 20,000 Turks, who had moved northwards of Deraa before the arrival of our forces. These struggled gamely towards Damascus, hoping either to make a stand at that great base 40or to escape by rail to the north. But General Chauvel still had in hand the Australian Mounted Division and a strong force of Indians and Yeomanry, which had returned to the Jordan after the capture of Haifa. With the Australians leading, he marched from Esdraelon Plain north-east across Jordan for Damascus. Then ensued one of the grand races of the war. Our tired horses were called upon for the heaviest work of the lightning campaign. Marching by Beisan, the 4th Light Horse Brigade, after a stiff fight—the most expensive cavalry fight in the campaign—took Semakh, and then, co-operating with the 3rd Brigade, which had come down from Nazareth, occupied Tiberias. After a day’s partial rest, during which our men swam and fished in the blue waters of Galilee, the Australian Division marched swiftly for the Jordan crossing, a few miles south of Lake Huleh. But the enemy was now seized of our intention, and the German machine gunners put up a fine resistance. Their stand at Semakh aimed at preventing us reaching Damascus before the 20,000 Turks, who were retreating from the direction of Deraa, and to give time for the removal of as many military stores as possible from the city. South of Lake Huleh, also, the Germans fought well and delayed us for a few hours. We then ran through as far as Kunneitra, but, a few miles further on, were again held up by machine guns and a field battery.