Every time he tore loose they brought him down again.

He was unnecessary. The first two had already

convinced Shoemaker there was only one cure for

his condition—and that was to get the hell away

from space-ships and onto a nice red wagon.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Shoemaker sat in the open sallyport of the ship and looked gloomily at a pale blue-green seascape, parted down the middle by a ghostly shoreline. The sea was a little greener, and the land was a little bluer; otherwise there was no difference to the eye. Once in a while a tiny breeze came in from the sea, and then the stink changed from sulphur to fish.

Venus, he decided, was a pest-hole. If he'd known it would be like this, he would have socked old Davies in the eye when he came to him with his damned plans. And then he'd have got roaring drunk to celebrate his escape.

Drunk.... Boy, he'd been squiffed last night! And every night, except one horrible period when they'd found his cache and it had been three days before he could shut off the engines and make more. Thinking of that, he shuddered. Better get started early tonight; no telling when the others would be back.

He rose and went back into the stifling heat of the ship. No cooling system in the thing; that's one item he hadn't thought of. But then, to hear Davies and Burford talk, Venus was going to be a kind of Turkish paradise, full of pomegranates and loose women. Nothing had been said about the temperature or the smells.

He walked down the narrow passageway to the hold, entered one of the compartments, and stopped before a patched section of the bulkhead. The ship was practically nothing but patches, and this looked no different from the rest. But it was.

Shoemaker stuck a fingernail under the lower end of the metal strip, and pulled. The strip came loose. He got his finger all the way under and lifted. The soldered edges tore away like so much glue.

He caught the section as the top came away, and laid it aside. Behind it, in a space where plastic filler had been removed, were stacked bottles of a colorless liquid. He took one of them out and shoved it into his back pocket. Then he picked up the patch sheet and, holding it in place with one hand, took a metal-foil tube out of his pocket with the other. The gunk in the tube was his own discovery; a phony solder fluid that was pretty nearly as strong as the real thing, except that the slightest leverage would pull it loose. He smeared a thin film of the stuff all around the patch, held the sheet for a few seconds more while it dried, then stood off to examine his work. Perfect.

The bottle in his pocket was uncomfortably warm against his thin rump. Well, he could fix that, too. He went down the passage to the next compartment, jockeyed an oxygen tank around until he could get at the petcock, and held the bottle in a thin stream of the compressed gas. In a minute the liquor was chilled.

He was sweating prodigiously. Gasping a little, he went back to the sallyport and sat down. He settled his broad back against the doorway, put the neck of the bottle against his pursed lips, and drank.

He was lowering his head after the fifth long swallow, when he saw something move against the misty boundary of sea and land. He followed it with his eyes. His long "Ahhh" of satisfaction ended in the sound of a man treacherously struck in the belly.

A little green man was standing there, a little poisonous-green man with blue-green whiskers and eyes like emeralds. He was about fourteen inches high, counting his big rabbit ears. He had an ominous look on his face.

Shoemaker gaped. Suddenly, the things Burford had been telling him, this morning before he and the other two had left to go exploring, began to run through his mind. Flesh and blood can stand just so much, Jim. One of these days a pink elephant or a polka-dot giraffe is going to step out of a bottle and say to you—

"Shoemaker, your time has come."

He jumped a foot. He was quivering all over.

Just as Shoemaker was telling himself that it couldn't possibly have happened, the little man moved a step forward and said it again.

Shoemaker dived for the door and slammed it after him. Ten minutes later, when he stopped shaking long enough to open it again, the little green man was gone.

This was not so good, Shoemaker told himself. Whether it was the d. t.'s or just a hallucination brought on by chilled liquor in a hot climate, that green man was nothing he wanted to have around.

He started thinking about what Burford and Davies and Hale would do if they found out he'd started seeing things. They'd taken a lot from him, because he was the only man who could hold the Space Queen together; but this might be too much.

For instance, there was his habit of stopping the engines whenever he ran out of liquor. Well, he had an alibi for that, anyway. Two days out of New York, they'd found his supply of Scotch and dumped it into space. Fighting mad, he'd waited until the others were asleep, then disconnected the transmutator that fed the rocket motors and adjusted it to turn out pure grain alcohol. With the addition of a little grapefruit juice from the stores, it made a fair-to-middling tipple. He'd kept going on it ever since.

But, if there were green men in it....

Shuddering, he went outside to wait for Davies and the other two. It was a little cooler now, with the sun clear around on the other side of the planet, but it was also a lot darker. Shoemaker turned on the light in the sallyport and stood under it, nervously peering into the blackness.

Presently he heard a hail, and then saw the three lights coming toward him. Three of them; that meant nobody had been devoured by saber-toothed pipicacas, or whatever cockeyed carnivores there were on this Turkish bath of a world. That was good. If anybody killed any of them—big, slow-thinking Davies, the chubby, drawling Hale—or Burford in particular—Shoemaker wanted it to be him.

That was Burford now. "Seen any elephants?"

Damn him. There went Shoemaker's idea of asking casually if they'd seen any little green creatures around. Burford was feeling sharp tonight, and he'd pounce on that like a cat.

The three slogged into the circle of light. They looked a little tired, even the whipcord-lean Burford. Their boots were crusted with blue-gray mud almost to the knees.

"Have any trouble finding your way back?" Shoemaker asked. Davies shook his big head slowly. He looked a little surprised. "No.... No, there's a river up yonder about a mile, you know. We saw it when we landed...."

"Jim was out cold at the time," Burford put in. He grinned nastily at Shoemaker.

"So we just followed it up a ways and then back," Davies finished, putting his knapsack down on the galley table. He sat down heavily. "We didn't see a thing ... not a thing. Looks like we'll have to pick up the ship and use it to cruise around ... but we can't spare much fuel, you know." He looked reproachfully at Shoemaker. "We used up so much correcting course every time you shut off the engines...."

Shoemaker felt himself getting hot. "Well, if you three commissars hadn't heaved out my Scotch—"

"Okay, okay, break it up," said Hale boredly. He let his soft bulk down into a chair. Burford stood up, leaning against the bulkhead.

"You hear anything on the radio, Shoemaker?" Hale asked.

Shoemaker shook his head. "Had it on all day," he said. "Not a peep."

"I don't get it," Burford said. "Radio signals started practically as soon as we hit atmosphere. They wavered, but we traced them down right about here. Then, as soon as we landed, they quit. There's something funny about that."

"Well, now," said Davies, wagging his head, "I wouldn't exactly say it was funny, Charley.... Now you take us, there might be any number of reasons why we'd quit signaling, if it was the Venusians landing on Earth instead of us the other way around...." He sighed. "But it comes to this, boys. If there are any animals on Venus, intelligent or otherwise, it makes no never-mind, we've got to find 'em. We got to have some kind o' specimens to take back, or we're sunk. You remember how much trouble we had, just getting the Supreme Council to subsidize us at all...."

Shoemaker remembered. Davies' math was all right; it was the only language he really knew his way around in. And he had the fuel, and the motor. All he needed was money to build a ship. But he'd picked the wrong time for it.

It had been just five years after the end of World War III when Davies had started making plans for his ship. The World Federation was only four and a half years old, and still bogged down in a quagmire of difficulties. What with two Balkan and three Indian principalities still "unreconstructed," ousted officials of other retarded nations raising hell with underground movements, the world rearming for still another war—plus a smashed, half-starving empire, smouldering with atomic fire, to deal with—the Supreme Council had little time or money to give to space flight.

Davies, though, had had his first and only non-mathematical idea, and it was a good one. This is the way it added up. The World Federation argued, reasonably, that the only way to police the world effectively against the possibility of another war was for everybody to come into the W. F. But the hold-out nations in Europe and America, who had been neutral during the last conflict—and were powerful out of all proportion simply because they had—plus the millions of emigres who had set up shop in South America and Africa, replied that the W. F. wasn't going to police them, and that they'd sooner have another war and, furthermore, that if the W. F. thought it could win it, let them go ahead and drop the first bomb.

The result was an impasse that was throwing the World's Cultural Rehabilitation Program all out of kilter. Well, said Davies, suppose it were possible to prove to the reactionary nations that Venus was habitable—wouldn't they jump at the chance to avoid World War IV by moving out entirely? Then the W. F. would be able to go about its business, organizing the Earth into One World—until it was so strong that the Venus colony would be a pushover, and serve them right.

Meanwhile, what if there were intelligent life on Venus—intelligent enough to be a new source of cheap labor, now that every world citizen was demanding that his working day be cut immediately to five hours?

The bored Bureau Chief to whom Davies had talked had nodded thoughtfully and said there might be something in it, and a few months later Davies had been set up as head of a new Department, with a wholly inadequate appropriation.

Burford and Hale had been assigned to the project by the North American Labor Bureau, and Shoemaker, appealed to by Davies, had joined up principally because it was a tough job. Then they'd gone to work, spending the money in driblets as they got it. They'd had to revise the specifications downward half a dozen times, and when they were through, the Space Queen was a rule-of-thumb monstrosity that only a mechanical genius could hold together. Shoemaker was the genius.

He thought about the time the meteor had hulled them, piercing both shop walls and banging hell out of the compartment across the corridor. Shoemaker had been in the shop, so drunk he could hardly stand up; but he'd held his breath long enough to slap a patch over the hole through which all the air in that section had gone whistling out, and seal it tight. Then he'd staggered to an oxygen flask, turned it on full and got enough air in his lungs to keep from passing out. By the time the others rolled out of bed and came down to see whether he was alive or dead, pressure was back to normal.

He remembered Hale's white face poked through the open seal-door in the corridor. "What happened, for Pete's sake?"

"Termites," Shoemaker had said.

What a trip, ye gods, what a trip. He'd done some cockeyed things in his life, but this junket a million miles from anywhere took the oscar. And now, if he was going to have the screaming meemies, he wanted to have them in a nice comfortable hospital—not in this watered-down version of a surrealist's nightmare.

Burford was saying something to him. Shoemaker roused himself. "What?"

"I said, what's with you, Edison? You've been sitting there with a dopey look on your face for half an hour. You haven't heard a word we've been saying, have you?"

Shoemaker made a quick recovery. "I was thinking, bird-brain. That's a little pastime us intellectuals indulge in. I'd teach it to you, but I don't think you'd like it."

Burford looked at him sharply. Shoemaker began to sweat. Was it showing on him already?

Burford said casually, "No offense. Well, think I'll turn in. Big day tomorrow." He strolled out, closing the door behind him.

Shoemaker got up to go a few minutes later, but Davies said, "Say, Jim, there was something I wanted to ask you. I know. Now just what was it? Wait a minute, it'll come back to me. Oh, yes. Jim, do you think—now, you understand, I just want a rough guess on this—do you reckon if we were to use up all the mercury we got, we could scout around and get us some of this sand, or maybe some ore from lower down—"

When he finally got it out, it appeared that he wanted to know if Shoemaker thought they'd be able to refine some local mineral enough to put it through the transmutator without blowing themselves up.

Exasperated, Shoemaker said, "Sure, easy. It would only take us five or six years to dig up the stuff, build a refinery, get hold of a couple of tons of reagents from Lord knows where, and adjust the trans-M to take the final product. Just a nice little rest-cure, and then we can all go home to glory and show off our long gray beards."

That started the old argument all over again. Davies said, "Now, Jim, don't excite yourself. Don't you see the thing is, if we go home with nothing but some mud and moss that we could have picked up anywhere, or some pictures that we could have faked, why, the Supreme Council will want to know what they spent all that money for. You know we'll get disciplined, sure as—"

Shoemaker's nerves got jumpier by the minute. Finally he said, "Oh, blow it out a porthole!" and slammed the galley door behind him.

He met Burford down the corridor, just turning in to his cubby.

"Where have you been?" he demanded.

"Where do you think?" Burford said rudely.

Shoemaker was half undressed when a horrible thought struck him. In his stocking feet, he hurried up to the compartment where his liquor was hidden. The patch was lying propped against the bulkhead; the concealed space was empty. A crowbar lay on the deck, fragments of real solder from other patches clinging to its edge.

Burning, he went back to the engine-room.

Burford had been thorough. The microspectrograph had been carefully pried off and disconnected from the rest of the transmutation rig. Without it, the setup was useless for either the designer's purpose—making fissionable plutonium—or Shoemaker's—the manufacture of 200-proof happy water.

Shoemaker didn't have to look to know that the spares were gone, too.

Luckily, he had about five quarts of the stuff hidden for emergencies in a canister marked "Hydrochloric Acid" down in the shop. With rationing, it would do. It would have to. Green men or no, he couldn't go dry. He'd been a quart-a-day man for as long as he could remember, and it would take more than a spook or two to scare him off it.

He had to admit to a certain apprehension, though, as he sat on watch in the sallyport the next evening. Land, sea and sky were the same slimy monotone; the occasional breath of wind that came in from the ocean bore the same broad hint of decaying marine life. It had been just about this time last night when that—

Restless, he got up and tramped around the ship. On the seaward side, beyond the huge muzzles of the rocket tubes, the greenish sand sloped downward abruptly in a six-foot embankment to the stagnant edge of the water. There was nothing out there, not even a ripple.

To landward, there was nothing but mud.

He sat down again, looked dubiously at his half-finished quart, decided to let it rest awhile. The glass had a green tinge from the sand around it. Resolutely, he turned his mind to the exploring party, tramping around in that godforsaken wilderness again. Well, what do you think, Shoemaker? he asked himself. How long will it take those supermen to give up their little paper-chase? Two more days? Three? A week? Shoemaker, he answered, I don't know and at this point I don't give a damn. I got more important things to worry about.

That seemed to settle that. He stared gloomily at the bottle, then picked it up and drank.

When he lowered the bottle again, pushing the cap shut with his thumb, the little green man was there.

No, it was a different one this time. Rigid with shock, he could still see that this one was fatter around the middle and had shorter whiskers.

But the expression was the same. Like a fiend on his way to a dismemberment party.

He found his voice. "Where did you come from?"

The little man smiled unpleasantly. "Mud and moss," he said.

Shoemaker wanted to yell. Holding a conversation with a hunk of mist, a non-existent goblin! He hardly recognized his own voice when he said, "What do you want?"

The green man walked toward him. "Heaved out my Scotch," he said, and leered.

Shoemaker did yell. Leaping to his feet, flinging his arms wide, he bellowed like a wounded carabao. The bottle slipped out of his fingers and looped gracefully into the sea. The goblin turned his head to follow it.

Then, astonishingly, he looked at Shoemaker, said, "It'll come back," and dived in after the bottle.

Neither of them came up, though Shoemaker hung onto the frame of the sallyport and watched for half an hour.

Shoemaker heard their voices through the hull when they came back that night.

"Where's the old soak?" That was Burford.

"Now, Charley, that isn't nice. He didn't say anything, but you could tell he wasn't feeling so good when he found out you'd located his cache. I dunno's we should of done that. He's sure to get real uncooperative on us, and we need him."

"All right!" said Burford. "But have you noticed how shaky he's been the last couple of days? What if he cracks up, then where'll we be? I say it isn't enough to just throw out his liquor—he'll make more as soon as we get into space again. We ought to make him take the cure. Force it down his throat if we have to."

"Sure," said Hale. "Just tell him we're through kidding around. He's got to take it and like it."

"Now, boys, take it easy," Davies said. "We've been all over this before...."

Shoemaker grinned sourly. So that was what they were cooking up. Well, forewarned was forearmed; as a matter of fact, he'd given this possibility some thought a long time ago, and acted accordingly. So he had one hole card, anyway. But getting them to agree to an immediate takeoff was another horse.

Wait a minute.... There was an idea. If he played it right—it was tricky, but it might work.

They were coming in the sallyport now. Shoemaker ducked down to the chem storeroom, found the bottle he was looking for and filled a small capsule from it. His hands were shaking, he noticed. That was what the fear of hellfire did to you.

Shoemaker had reached a decision. Delirium tremens wasn't a good enough answer; it didn't fit. If he thought it was that, he'd gladly take the cure, even though the idea made his belly crawl. Of course, it was too late for that, anyway—he'd thrown out the drug in Burford's sick-box and substituted plain baking soda long ago.

But Shoemaker thought he knew what was happening to him, and it wasn't d. t.'s. It wasn't the usual dipso's collection of crazy daymares at all; there was a horrid kind of logic to it. Instead of delirium, it was—judgment.

That was as far as he'd gone. He knew he had it coming to him, and now he thought he was going to get it. But he hadn't given up yet. There was one thing he could still do, and that was to run—get clear away from this damned planet. After that, he'd just have to take his chances. Maybe the things could follow him into space, maybe not. Shoemaker wasn't sure of anything any more.

He slipped the capsule into his pocket where he could get at it when he needed it, and went on up the passageway.

"Oh, there you are," said Burford. "We were wondering where you'd got to."

Shoemaker glared at him. "Okay, go ahead, ask me if I was digging for a microspectrograph mine."

Burford looked shocked. "Why, Jim, you know I wouldn't say a nasty thing like that." He took Shoemaker's arm. "Come on up to the galley. We're having a pow-wow."

Oh-oh, thought Shoemaker. This looks like it. He put his hand in his pocket and folded his handkerchief over the capsule.

Davies and Hale stared at him solemnly as he came through the door with Burford behind him. He looked back at them, poker-faced, and sat down.

Davies cleared his throat. "Er-um. Jim, we've been worried about you lately. You don't act like you're feeling too chipper."

"That's right," said Shoemaker, looking doleful. "I've been thinking about my poor old mother."

Burford snorted. "Your poor old mother died fifty years ago."

"She did," said Shoemaker, taking out his handkerchief, "and she died with one great wish unfulfilled."

"Yeah? What was that?" Burford asked skeptically.

"She always wanted to have a son like you," Shoemaker said, "so that she could whale the living daylights out of him." He blew his nose raucously, slipped the capsule into his mouth, put his handkerchief away and smiled beatifically.

Davies was frowning. "Jim," he said, "I wish you wouldn't make jokes about it. We all know what's the matter with you. You been fightin' the liquor too hard."

"Who says so?" Shoemaker demanded.

"Now, Jim, don't make things difficult. I don't like this any more'n you do, but—"

"Like what?"

Burford made an impatient gesture. "Go ahead, tell him, Lou. No use dragging it out."

"That's right," Hale put in, glowering.

"Shut up, you," said Shoemaker. He turned to Davies. "Tell me what? You're not going to bring up that 'cure' chestnut again, by any chance?"

Davies looked uncomfortable. "I'm sorry, Jim. I know you don't want to take it. I argued against it, but the boys finally convinced me. You know, Jim, if it was only you that we had to think about, I wouldn't try to make you do anything you didn't want to. But, don't you see, this is it—either we all stick together or we're sunk. If we don't all keep in good shape and able to do our jobs, why ... well, you see, don't you, Jim—"

"What he means," said Burford, "is that this time you're going to take the cure, whether you want to or not."

Shoemaker got up and put his chair very carefully out of the way.

"Let's see you make me," he said.

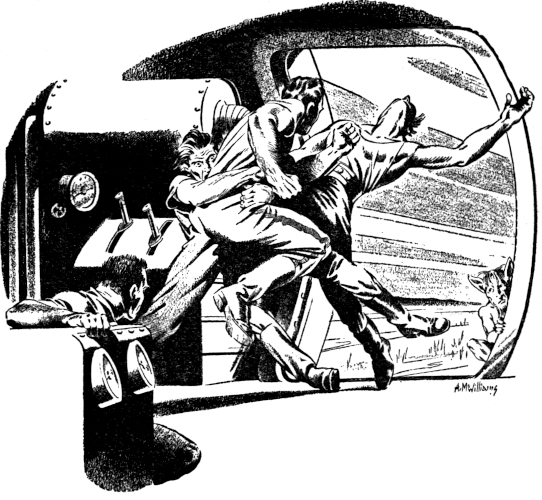

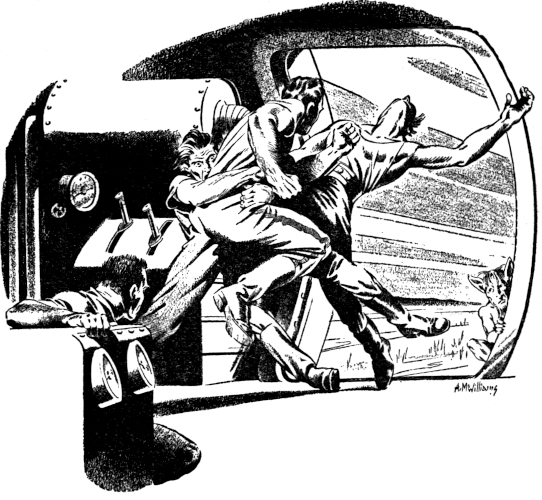

It had to look good, so when Burford grabbed for him he stepped back and swung a hearty right into the middle of Burford's face.

Burford staggered, but kept on coming. He clipped Shoemaker's jaw glancingly, swung again and missed, then gave him a beauty in the eye.

Shoemaker aimed for the midriff and got it. "Uff!" said Burford. Then Hale tackled him from behind and the three of them were all over him.

Every time he tore loose they brought him down again.

Shoemaker writhed, kicking, biting and using his elbows, but every time he tore loose they brought him down again. After a while he was beginning to wonder if he could get away even if he really meant it. Then, somehow, Davies got a half Nelson on him and bore down. Shoemaker decided it was time to quit.

He looked at his opponents. Burford had a black eye and several assorted contusions, Hale a puffed and bleeding cheek. He couldn't see Davies' face, but the pants-leg stretched out beside his own was ripped and hanging down over the boot, revealing a hairy thigh. Shoemaker felt pretty good.

"Whuff," said Burford, gazing at him with a new respect. He got up carefully, walked over to the sick-box and came back with a box of powders and a glass of water.

He knelt. Shoemaker glared at him. Burford said, "Okay, baby, open your mouth or we'll pry it open. Hold his head, Lou." Davies' big hand clasped Shoemaker's skull, and Burford pried at his lower jaw. The instant his lips parted, Burford tilted the powder into his mouth, then pushed it shut again. Shoemaker's eyes bulged. "Swallow," said Burford remorselessly, and grabbed Shoemaker's nose between a horny finger and thumb.

Shoemaker swallowed. "Now you get the water," Burford said, and held the glass to his lips. Shoemaker drank, meekly.

Burford stood up. "Well," he said uncertainly, "that's that." Davies let go of Shoemaker and eased out from under him. Then he stood beside Burford and Hale, and all three looked down at Shoemaker.

There were real tears in Shoemaker's eyes—from having his nose pinched in Burford's vise-like grip—and his face looked drawn. Slowly, like an old man, he got to his feet, walked to the table and sat down.

"Now, Jim," Davies began hesitantly, "don't take on. It isn't so bad. You'll be a better man for it, you know. You'll prob'ly gain weight and everything. Now, Jim—"

Shoemaker wasn't listening. His eyes were rigid and glassy, his jaw lax. Slowly he began to tremble. He slumped over and hit the deck with a thud, still jerking.

"Good Lord!" exploded Burford.

"What is it?" Hale demanded.

"Mitchel's reaction," said Burford. "Hasn't happened twice in thirty years. I never thought—"

"Is it dangerous, Charley?"

"Lord, yes. Wait till I get the handbook." Shoemaker heard his quick steps, then pages being riffled.

When he thought it was safe, Shoemaker sneaked a look out of one eye. The other two men were pressed close to Burford, staring over his shoulders. Their backs were to him, but he kept jerking his body occasionally anyway, just to be on the safe side.

"Treatment," said Burford hoarsely, "extended rest on soft diet, diathermy, u. v. irradiation, hourly injection of—Hell, we can't do that. We haven't got half the stuff."

"What happens if he don't get it, Charley?" said Davies nervously. "I mean to say, how long—"

Burford flipped pages. "General debility, progressing rapidly, followed by heart stoppage and death after four to ten weeks."

"Oh, my," said Davies. "What'll we do, Charley? I mean—"

"Wait a minute, here. Are you sure he's got what you think?" asked Hale skeptically. "How do you know he's not faking?"

"Faking!" said Burford. "Well—he's got all the symptoms." He riffled pages. "Immediate unconsciousness, violent tremors—oh-oh. Look at this."

The two heads craned forward eagerly. There was a moment of silence, and then Hale giggled. "Well, if he does that, I'll believe you!"

"Yes," said Davies seriously, "but, if he's unconscious, how can he—"

Burford glanced at the handbook again. "He should be coming to any time now," he said loudly. "When he does, we'll know for sure."

Shoemaker grinned to himself. He knew that section of the Medical Handbook by heart. Patient remains unconscious and cannot be roused for twenty minutes to one-half hour.... He kept his eyes closed and waited, jerking occasionally, for what he judged was a good twenty minutes, then another five for good measure. When he opened them again, he saw Davies' anxious face a few inches away, flanked by Burford's and Hale's.

"He's coming out of it!" said Burford. "How do you feel, old man?"

"Wha—?" said Shoemaker.

"You've had a little stroke," said Burford mendaciously. "Help me get him up.... You'll be all right, Jim, but you've got to do just as we tell you."

"Poisoned me," Shoemaker gasped, suffering himself to be hoisted limply erect.

"No, no," Davies protested. "We're trying to help you, Jimmy boy. Just go with Charley, that's right. Here, take this bottle, Charley."

Even Shoemaker was a little startled by what followed.

When they returned, Burford nodded solemnly. "It was blue, all right," he said.

"Poisoned me!" said Shoemaker, allowing himself to speak a little more emphatically.

"Oh, hell!" said Burford, lifting Shoemaker's quaking body into a chair. "So we poisoned you. We didn't mean to do it. Question is now, what's to be done?"

"Why, we've got to get him to a hospital," said Davies. "Got to start back to Earth immediately. Uh—but, Charley, will he be well enough to work on the trip?"

"It might not kill him," said Burford grimly. "But what about us? Are we going to go back empty-handed?"

"Oh, my," said Davies. "I forgot for a minute. No, we can't do that. But look here, Charley—if he dies while we're still here, how're we going to get back without him?"

"We'll have to, that's all," said Burford.

"Check," said Hale.

"Well, I got to admit you boys are right," said Davies promptly, with a long face. "Never had to make a more difficult decision in my life. Poor old Jim! When I think—"

He stopped with a gasp as Shoemaker rose to his feet, swelling visibly with rage. "When I think," said Shoemaker loudly, "of the chances I've had—" he found himself encumbered by the broken halves of the capsule under his tongue, and spat them out violently—"to strangle the whole murdering crew of you quietly in your sleep—" His fingers curled. He started toward Davies slowly, on stiff legs.

Burford was staring at the capsule-halves on the deck. Suddenly he bent and picked them up, saw the faint blue stain that still clung to their edges. Light broke over his face. "Methylene blue!" he said. "You knew—you hid this in your mouth and swallowed it. Why, you old—"

"I did," said Shoemaker, "and now I'm going to make you swallow it." He stepped forward and swung a vigorous right that knocked Burford through the open door.

Hale had picked up a chair. Shoemaker ducked aside as it whooshed down, meanwhile kicking Hale in the stomach. Then he looked around for Davies, but the latter, it seemed, was behind him. Something tapped Shoemaker on the back of the skull, and then everything faded away in gray mist....

The mist lifted once, while, with a throbbing head, he listened to Burford explaining that everything on the ship that could possibly be a weapon was locked up; that if he attempted any more reactionary violence they would as soon leave him dead on Venus as not; and that if he knew what was good for him, he would behave himself both before the takeoff—which would occur when they pleased—and after it.

He tried to tell Burford what he could do with himself, but he fell asleep again before he was half through.

When he woke, finally, it was evening, and low voices from the galley forward told him that the other three had returned from another day of hunting. He got up, feeling stiff and heavy, and prowled disconsolately down the passageway as far as his shop door, which was, indeed, locked. He was hungry, but he had a feeling that the sight of any one of the other three human faces on Venus would take away his appetite. For lack of anything better to do, he stepped into the airlock, closed the inner door quietly behind him, and sat down morosely in the sallyport.

Sky and sea were dull blue-green, without star or horizon. There was a stink of sulphur, and then a stink of fish, and then another stink of sulphur.... He sat and sweated, thinking his gloomy thoughts.

Shoemaker was not a moral man, but the sense of personal doom was strong upon him. Suppose there really were a Hell, he thought, only the preachers were wrong about everything but the heat.... A splitting skull.... No liquor.... No women.... A stinking, slime-blue seascape that was the same right-side up, upside-down, or crossways.... And the little green men. He had almost forgotten them.

When he looked up, he remembered.

The third little man was slimmer, and had no whiskers at all. He carried a shiny golden dagger, almost as big as himself. He was walking forward purposefully.

Shoemaker waited, paralyzed.

The little man fixed him with his gleaming eye. "We're through kidding around," he said grimly. "Question is now!"

And he laid the golden dagger in Shoemaker's quaking palm.

Shoemaker's first impulse was to cut his own throat. His second was to throw the dagger as far away as possible. Those two came in flashing tenths of a second. The third was stronger. He rose effortlessly into the air, landed facing the sallyport, and, mouth wide open but emitting no sound, ran straight through it. He passed the closed inner door more by a process of ignoring it than by bursting it open.

Directly opposite was the door of Burford's chubby, just now open far enough to show Burford's startled face. When he saw Shoemaker, he tried hastily to shut the door, but Shoemaker by now had so much momentum as to have reached, for practical purposes, the status of an irresistible force. In the next second, he came to a full stop; but this was only because he was jammed against Burford, who was jammed against the far wall of the room, which was braced by five hundred tons of metal.

"Ugg," said Burford. "Whuff—where did you get that knife?"

"Shut up and start talking," said Shoemaker wildly. "Where's the microspectrograph?"

Burford opened his mouth to yell. Shoemaker shut it with a fist, meanwhile thrusting the knife firmly against Burford's midriff to illustrate the point.

Burford spat out a tooth. As Shoemaker put a little more pressure on the blade, he said hastily, "It's in the—uhh!—fuel reservoir."

Shoemaker whirled him around and propelled him into the corridor, after a quick look to make sure that the way was clear. They proceeded to the engine room, in this order: Burford, knife, Shoemaker.

Without waiting to be persuaded, Burford produced a ring of keys, unlocked the reservoir, and withdrew the microspectrograph. "Hook it up," said Shoemaker. Burford did so.

"Uhh," said Burford. "Now what—whiskey?"

"Nope," said Shoemaker incautiously. "We're taking off."

Burford's eyes bulged. He made a whoofling noise and then, without warning, lunged forward, grabbing Shoemaker's knife arm with one hand and punching him with the other. They rolled on the deck.

Shoemaker noticed that Burford's mouth was open again, and he put his hand into it, being too busy keeping away from Burford's knee to take more effective measures. Burford bit a chunk out of the hand and shouted, "Hale! Davies! Help!"

There were bangings in the corridor. Shoemaker decided the knife was more of a hindrance than a help, and dropped it. When Burford let go to reach for it, he managed to roll them both away, at the same time getting a good two-handed grip on Burford's skinny throat. This maneuver had the disadvantage of putting Burford on top, but Shoemaker solved the problem by lifting him bodily and banging his skull against the nearby bulkhead.

Burford sagged. Shoemaker pushed him out of the way and got up, just in time to be knocked down hard by Hale's chunky body.

"Old idiot," panted Hale, "oof! Help me, Davies!"

Shoemaker got an ear between his teeth, and was rewarded by a bloodcurdling scream from Hale. Davies was hopping ponderously around in the background, saying, "Boys, stop it! Oh, my—the guns are all locked up. Charley, give me the keys!"

Shoemaker pulled himself loose from Hale, sprang up, and was immediately pulled down again. Burford, who was getting dizzily to his feet, tripped over Shoemaker's head and added himself to the tangle. Shoemaker got a scissors on him and then devoted himself to the twin problems of avoiding Burford's wildly threshing heels and keeping Hale away from his throat. Suddenly inspired, he solved both by bending Burford's body upward so that the latter's booted feet, on their next swing, struck Hale squarely in the middle of his fat face.

At this point he noticed that Davies was standing nearby with one foot raised. He grasped the foot and pushed. Davies hit the deck with a satisfying clang.

Shoemaker got up for the third time and looked around for the dagger, but it had been kicked out of sight. He paused, wondering whom to hit next, and in the interval all three of his opponents scrambled up and came at him.

Shoemaker thought, this is it. He spat on his fist for luck and hit Burford a beauty on the chin. Burford fell down, and, astonishingly, got up again. A little disheartened, Shoemaker took two blows in the face from Hale before he knocked the little man into a far corner. Hale got up again. Shoemaker, who had been aware for some time that someone was pummeling his back, turned around unhappily and knocked Davies down. Davies, at any rate, stayed down.

Burford, whose face was puffy, and Hale, who was bleeding from assorted cuts, came toward him. Hale, he saw, had the dagger in his hand. Shoemaker stepped back, picked up the unconscious Davies by collar and belt, and slung him across the deck. This time both men went down (Hale with a soggy bloomp), and stayed there. The dagger skidded out of Hale's hand and came to rest at Shoemaker's feet.

He picked it up, knelt at a convenient distance to cut off Hale's and Burford's noses, and threatened to do just that. Burford intimated that he would do as he was told. Hale said nothing, but the expression on his face was enough.

Satisfied, Shoemaker opened a locker with Burford's keys, got a coil of insulated wire and tied up Davies and Hale, after which, with Burford's help, he strapped them into their acceleration hammocks.

Burford was acting a little vague. Shoemaker slapped him around until he looked alive, then set him to punching calculator keys. After a few minutes of this, Burford looked as if he wanted to say something.

"Well, spit it out," said Shoemaker, waving the golden knife.

"You'll get yours," said Burford, looking scared but stubborn. "When we get back to New York—"

"South Africa," corrected Shoemaker, "where the Supreme Council can't ask us any questions."

Burford looked surprised, then said it was a good idea.

It was, too.

The lone star winked out in the blue-green heavens, and the winds of its passing died away. The throng of little rabbit-eared green men, floating on their placid ocean, gazed after it long after it had disappeared.

"What do you think?" said the slim one without whiskers. "Did they like us?"

The one addressed was yards away, but his long ears heard the question plainly. "Can't say," he answered. "They acted so funny. When we spoke to that one in their own language, so as to make him feel at home—"

"Yes," said a third, almost invisible in the mist. "Was that the right thing to do, d'you suppose? Are you sure you got the words right, that last time?"

"Sure," said the first, confidently. "I was right next to the ship all evening, and I memorized everything they said...."

They considered that for a while, sipping from their flasks. Other voices piped up: "Maybe we should have talked to them when they were all together?"

"Nooo. They were so big. That one was much the nicest, anyway."

"He took our present."

"Yes," said the slim one, summing it up. "They must have liked us all right. After all, they gave us this"—swinging his flask to make a pleasant gurgle of 150-proof grain alcohol. "That proves it!"

Burp!