Transcriber Note: The cover image was created by the transcriber from the original cover and elements of the title page. It is placed in the public domain.

Transcriber’s Note: This is a full unabridged transcription that includes the Chinese text and illustrations contained in the original printed version.

Transcriber Note: The cover image was created by the transcriber from the original cover and elements of the title page. It is placed in the public domain.

VI. THE DEVAS CELEBRATING THE ATTAINMENT OF THE BUDDHASHIP.

BEING AN ACCOUNT BY

THE CHINESE MONK FÂ-HIEN

OF

HIS TRAVELS IN INDIA AND CEYLON

(A.D. 399–414)

IN SEARCH OF THE BUDDHIST BOOKS OF DISCIPLINE

TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED

WITH A COREAN RECENSION OF THE CHINESE TEXT

BY

JAMES LEGGE, M.A., LL.D.

Professor of the Chinese Language and Literature

Oxford

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

1886

[All rights reserved]

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | xi | |

| INTRODUCTION. | ||

| Life of Fâ-hien; genuineness and integrity of the text of his narrative; number of the adherents of Buddhism. | 1 | |

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| From Chʽang-gan to the Sandy Desert. | 9 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| On to Shen-shen and thence to Khoten. | 12 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Khoten. Processions of images. The king’s New monastery. | 16 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| Through the Tsʽung or ‘Onion’ mountains to Kʽeeh-chʽâ; probably Skardo, or some city more to the East in Ladak. | 21 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Great quinquennial assembly of monks. Relics of Buddha. Productions of the country. | 22 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| On towards North India. Darada. Image of Maitreya Bodhisattva. | 24 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| Crossing of the Indus. When Buddhism first crossed that river for the East. | 26 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| Woo-chang, or Udyâna. Monasteries and their ways. Traces of Buddha. | 28 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| Soo-ho-to. Legend of Buddha. | 30 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| Gandhâra. Legends of Buddha. | 31 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| Taksahśilâ. Legends. The four great topes. | 32 | |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| Purushapura, or Peshâwar. Prophecy about king Kanishka and his tope. Buddha’s alms-bowl. Death of Hwuy-ying. | 33 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| Nagâra. Festival of Buddha’s skull-bone. Other relics, and his shadow. | 36 | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| Death of Hwuy-king in the Little Snowy mountains. Lo-e. Poh-nâ. Crossing the Indus to the East. | 40 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| Bhida. Sympathy of monks with the pilgrims. | 41 | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| On to Mathurâ, or Muttra. Condition and customs of Central India; of the monks, vihâras, and monasteries. | 42 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| Saṅkâśya. Buddha’s ascent to and descent from the Trayastriṃśas heaven, and other legends. | 47 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| Kanyâkubja, or Canouge. Buddha’s preaching. | 53 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| Shâ-che. Legend of Buddha’s Danta-kâshṭha. | 54 | |

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| Kośala and Śrâvastî. The Jetavana vihâra and other memorials and legends of Buddha. Sympathy of the monks with the pilgrims. | 55 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| The three predecessors of Śâkyamuni in the buddhaship. | 63 | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| Kapilavastu. Its desolation. Legends of Buddha’s birth, and other incidents in connexion with it. | 64 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| Râma, and its tope. | 68 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| Where Buddha finally renounced the world, and where he died. | 70 | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| Vaiśâlî The tope called ‘Weapons laid down.’ The Council of Vaiśâlî. | 72 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| Remarkable death of Ânanda. | 75 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| Pâṭaliputtra, or Patna, in Magadha. King Aśoka’s spirit-built palace and halls. The Buddhist Brahmân, Rȧdhasȧmi. Dispensaries and hospitals. | 77 | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| Râjagṛiha, New and Old. Legends and incidents connected with it. | 80 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | ||

| Gṛidhra-kûṭa hill, and legends. Fâ-hien passes a night on it. His reflections. | 82 | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | ||

| The Śrataparṇa cave, or cave of the First Council. Legends. Suicide of a Bhikshu. | 84 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | ||

| Gayâ. Śâkyamuni’s attaining to the Buddhaship; and other legends. | 87 | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | ||

| Legend of king Aśoka in a former birth, and his naraka. | 90 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | ||

| Mount Gurupada, where Kâśyapa Buddha’s entire skeleton is. | 92 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | ||

| On the way back to Patna. Vârâṇasî, or Benâres. Śâkyamuni’s first doings after becoming Buddha. | 93 | |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | ||

| Dakshiṇa, and the pigeon monastery. | 96 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | ||

| In Patna. Fâ-hien’s labours in transcription of manuscripts, and Indian studies for three years. | 98 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | ||

| To Champâ and Tâmaliptî. Stay and labours there for three years. Takes ship to Singhala, or Ceylon. | 100 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | ||

| At Ceylon. Rise of the kingdom. Feats of Buddha. Topes and monasteries. Statue of Buddha in jade. Bo tree. Festival of Buddha’s tooth. | 101 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | ||

| Cremation of an Arhat. Sermon of a devotee. | 107 | |

| CHAPTER XL. | ||

| After two years takes ship for China. Disastrous passage to Java; and thence to China; arrives at Shan-tung; and goes to Nanking. Conclusion or l’envoi by another writer. | 111 | |

| INDEX | ||

| CHINESE TEXT: 法顯傳 | ||

| Sketch-map of Fâ-hien’s travels | To face Introduction, page 1 | |

| I. | ||

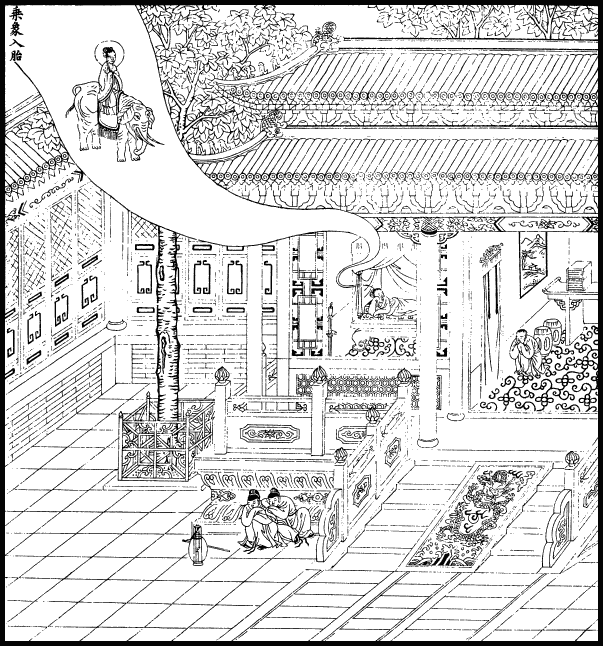

| Dream of Buddha’s mother of his incarnation | To face p. 65 | |

| II. | ||

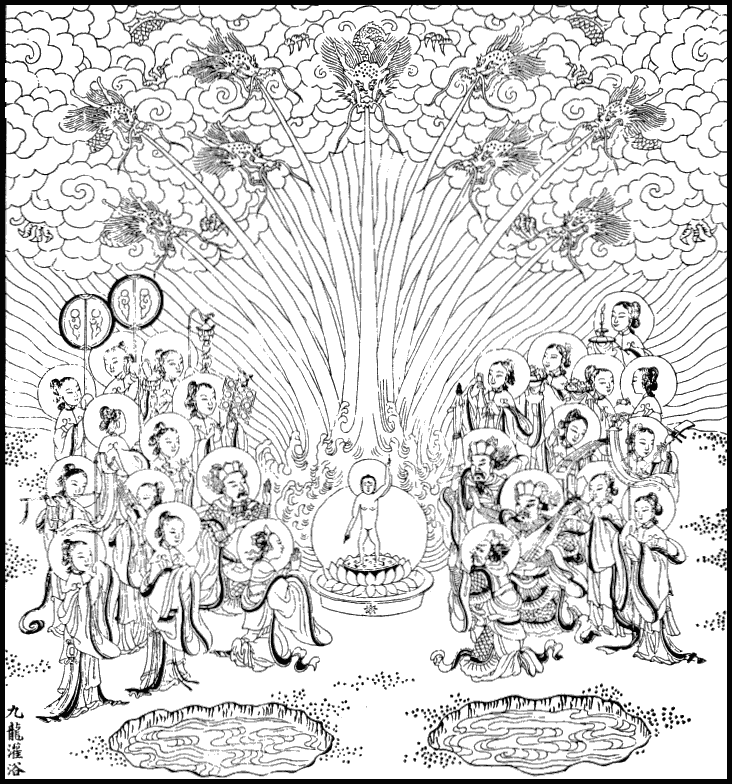

| Buddha just born, with the nâgas supplying water to wash him | To face p. 67 | |

| III. | ||

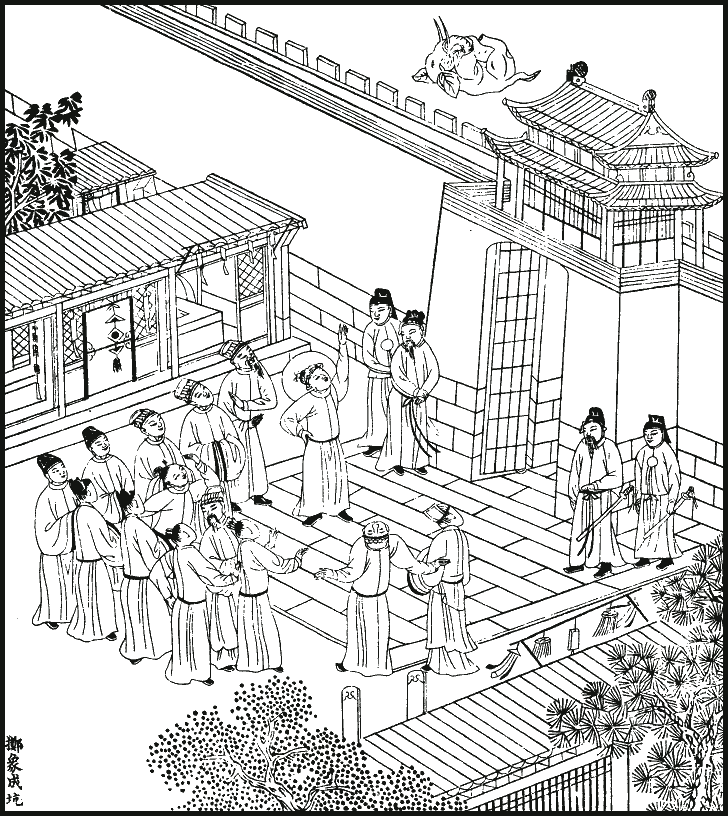

| Buddha tossing the white elephant over the wall | To face p. 66 | |

| IV. | ||

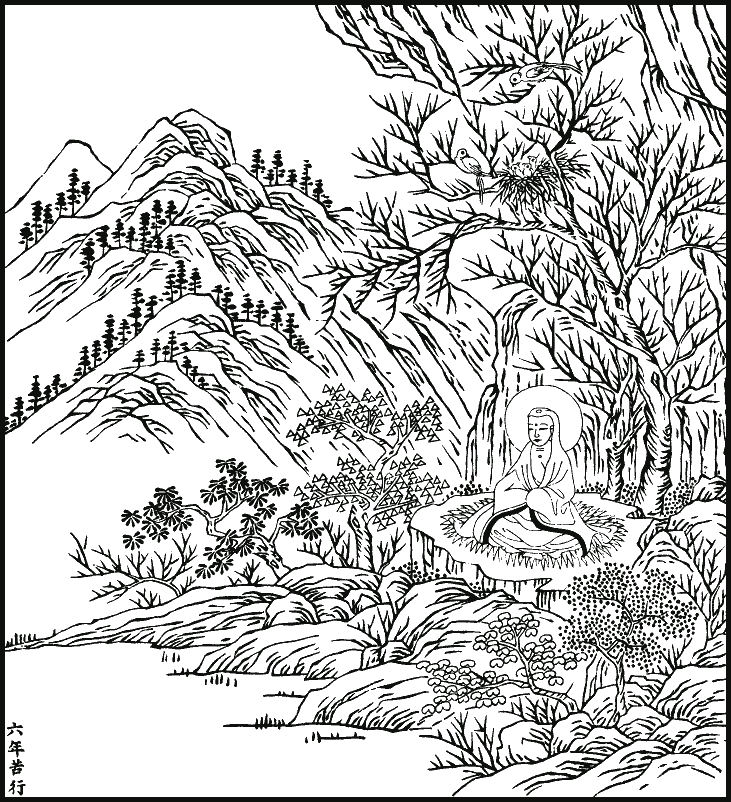

| Buddha in solitude and enduring austerities | To face p. 87 | |

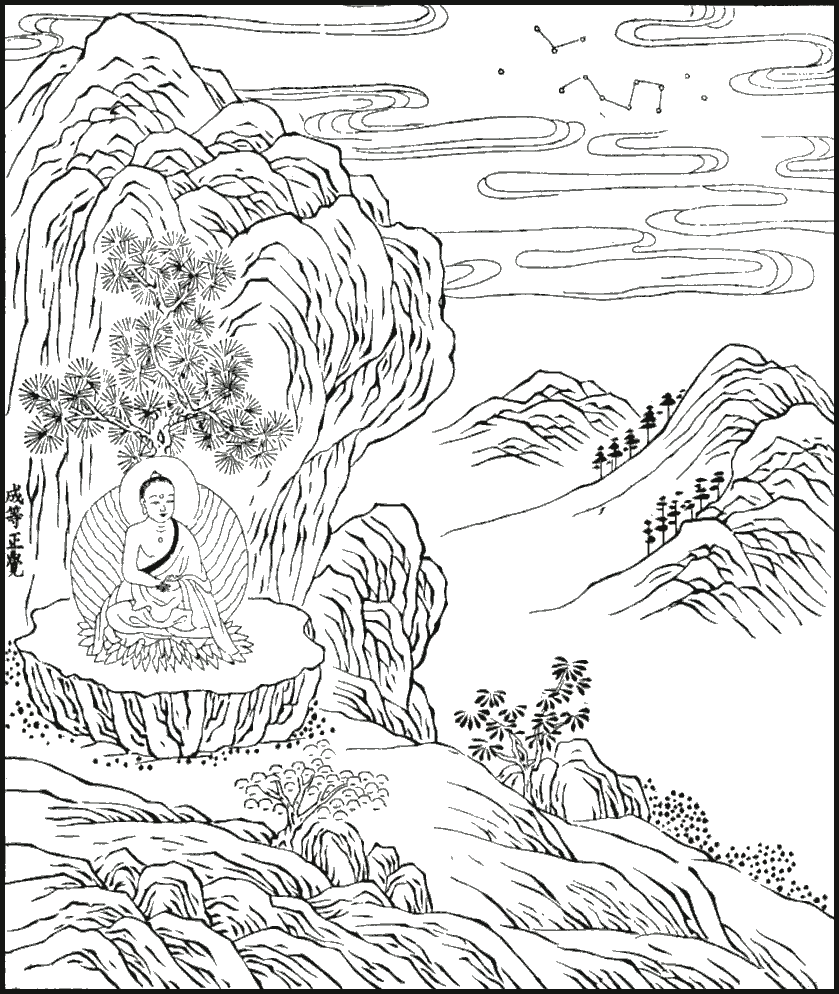

| V. | ||

| Buddhaship attained | To face p. 88 | |

| VI. | ||

| The devas celebrating the attainment of the Buddhaship | To face the Title | |

| VII. | ||

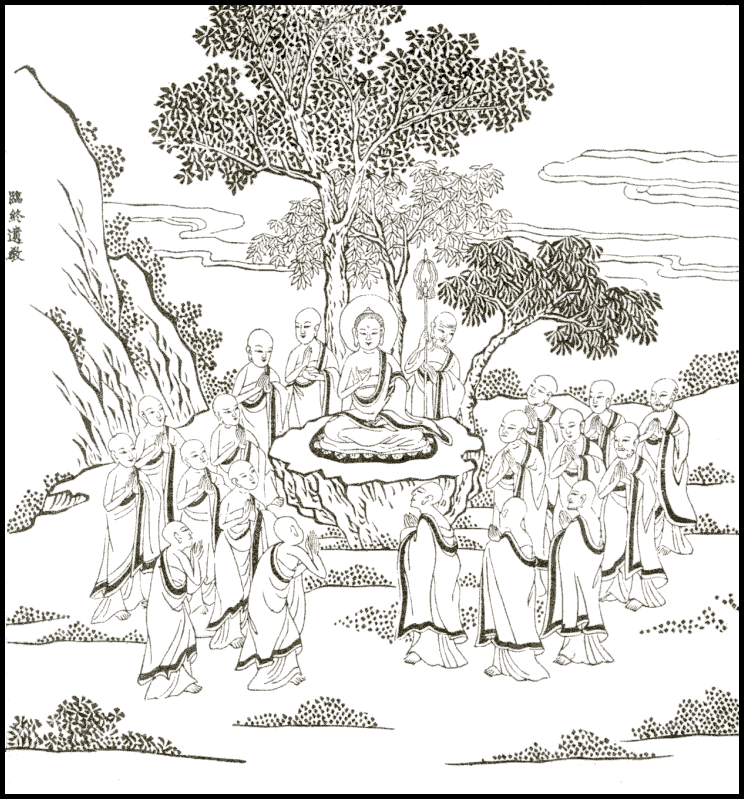

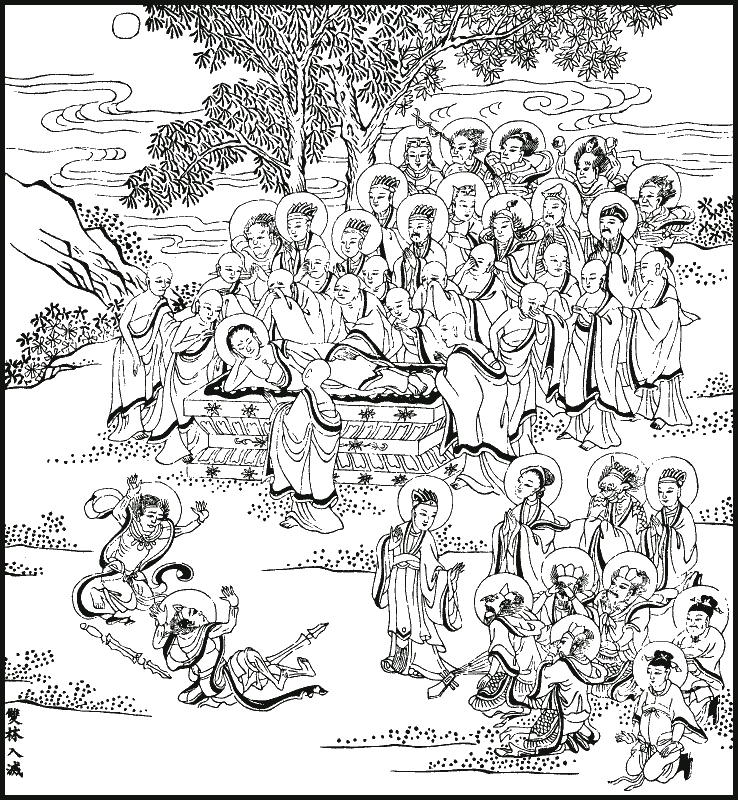

| Buddha’s dying instructions | To face p. 70 | |

| VIII. | ||

| Buddha’s death | To follow VII | |

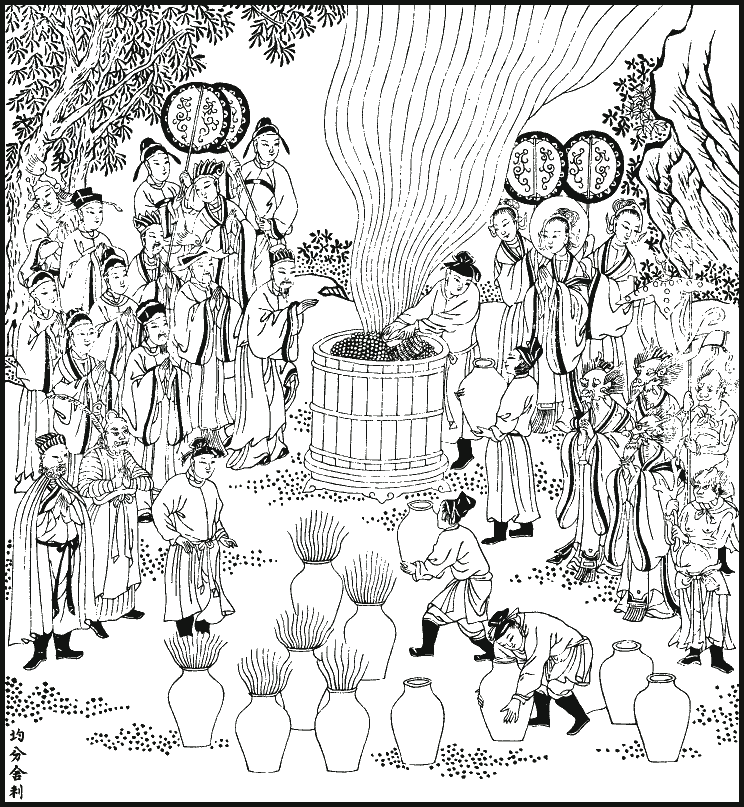

| IX. | ||

| Division of Buddha’s relics | To follow VIII |

Several times during my long residence in Hong Kong I endeavoured to read through the ‘Narrative of Fâ-Hien;’ but though interested with the graphic details of much of the work, its columns bristled so constantly—now with his phonetic representations of Sanskrit words, and now with his substitution for them of their meanings in Chinese characters, and I was, moreover, so much occupied with my own special labours on the Confucian Classics, that my success was far from satisfactory. When Dr. Eitel’s “Handbook for the Student of Chinese Buddhism” appeared in 1870, the difficulty occasioned by the Sanskrit words and names was removed, but the other difficulty remained; and I was not able to look into the book again for several years. Nor had I much inducement to do so in the two copies of it which I had been able to procure, on poor paper, and printed from blocks badly cut at first, and so worn with use as to yield books the reverse of attractive in their appearance to the student.

In the meantime I kept studying the subject of Buddhism from various sources; and in 1878 began to lecture, here in Oxford, on the Travels with my Davis Chinese scholar, who was at the same time Boden Sanskrit scholar. As we went on, I wrote out a translation in English for my own satisfaction of nearly half the narrative. In the beginning of last year I made Fâ-Hien again the subject of lecture, wrote out a second translation, independent of the former, and pushed on till I had completed the whole.

The want of a good and clear text had been supplied by my friend, Mr. Bunyiu Nanjio, who sent to me from Japan a copy, the text of which is appended to the translation and notes, and of the nature of which some account is given in the Introduction (page 4), and towards the end of this Preface.

The present work consists of three parts: the Translation of Fâ-Hien’s Narrative of his Travels; copious Notes; and the Chinese Text of my copy from Japan.

It is for the Translation that I hold myself more especially responsible. Portions of it were written out three times, and the whole of it twice. While preparing my own version I made frequent reference to previous translations:—those of M. Abel Rémusat, ‘Revu, complété, et augmenté d’éclaircissements nouveaux par MM. Klaproth et Landresse’ (Paris, 1836); of the Rev. Samuel Beal (London, 1869), and his revision of it, prefixed to his ‘Buddhist Records of the Western World’ (Trübner’s Oriental Series, 1884); and of Mr. Herbert A. Giles, of H.M.’s Consular Service in China (1877). To these I have to add a series of articles on ‘Fâ-Hsien and his English Translators,’ by Mr. T. Watters, British Consul at Î-Chang (China Review, 1879, 1880). Those articles are of the highest value, displaying accuracy of Chinese scholarship and an extensive knowledge of Buddhism. I have regretted that Mr. Watters, while reviewing others, did not himself write out and publish a version of the whole of Fâ-Hien’s narrative. If he had done so, I should probably have thought that, on the whole, nothing more remained to be done for the distinguished Chinese pilgrim in the way of translation. Mr. Watters had to judge of the comparative merits of the versions of Beal and Giles, and pronounce on the many points of contention between them. I have endeavoured to eschew those matters, and have seldom made remarks of a critical nature in defence of renderings of my own.

The Chinese narrative runs on without any break. It was Klaproth who divided Rémusat’s translation into forty chapters. The division is helpful to the reader, and I have followed it excepting in three or four instances. In the reprinted Chinese text the chapters are separated by a circle (〇) in the column.

In transliterating the names of Chinese characters I have generally followed the spelling of Morrison rather than the Pekinese, which is now in vogue. We cannot tell exactly what the pronunciation of them was, about fifteen hundred years ago, in the time of Fâ-Hien; but the southern mandarin must be a shade nearer to it than that of Peking at the present day. In transliterating the Indian names I have for the most part followed Dr. Eitel, with such modification as seemed good and in harmony with growing usage.

For the Notes I can do little more than claim the merit of selection and condensation. My first object in them was to explain what in the text required explanation to an English reader. All Chinese texts, and Buddhist texts especially, are new to foreign students. One has to do for them what many hundreds of the ablest scholars in Europe have done for the Greek and Latin Classics during several hundred years, and what the thousands of critics and commentators have been doing of our Sacred Scriptures for nearly eighteen centuries. There are few predecessors in the field of Chinese literature into whose labours translators of the present century can enter. This will be received, I hope, as a sufficient apology for the minuteness and length of some of the notes. A second object in them was to teach myself first, and then others, something of the history and doctrines of Buddhism. I have thought that they might be learned better in connexion with a lively narrative like that of Fâ-hien than by reading didactic descriptions and argumentative books. Such has been my own experience. The books which I have consulted for these notes have been many, besides Chinese works. My principal help has been the full and masterly handbook of Eitel, mentioned already, and often referred to as E.H. Spence Hardy’s ‘Eastern Monachism’ (E.M.) and ‘Manual of Buddhism’ (M.B.) have been constantly in hand, as well as Rhys Davids’ Buddhism, published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, his Hibbert Lectures, and his Buddhist Suttas in the Sacred Books of the East, and other writings. I need not mention other authorities, having endeavoured always to specify them where I make use of them. My proximity and access to the Bodleian Library and the Indian Institute have been of great advantage.

I may be allowed to say that, so far as my own study of it has gone, I think there are many things in the vast field of Buddhist literature which still require to be carefully handled. How far, for instance, are we entitled to regard the present Sûtras as genuine and sufficiently accurate copies of those which were accepted by the Councils before our Christian era? Can anything be done to trace the rise of the legends and marvels of Sakyamuni’s history, which were current so early (as it seems to us) as the time of Fâ-hien, and which startle us so frequently by similarities between them and narratives in our Gospels? Dr. Hermann Oldenberg, certainly a great authority on Buddhistic subjects, says that ‘a biography of Buddha has not come down to us from ancient times, from the age of the Pali texts; and, we can safely say, no such biography existed then’ (‘Buddha—His Life, His Doctrine, His Order,’ as translated by Hoey, p. 78). He has also (in the same work, pp. 99, 416, 417) come to the conclusion that the hitherto unchallenged tradition that the Buddha was ‘a king’s son’ must be given up. The name ‘king’s son’ (in Chinese 太子), always used of the Buddha, certainly requires to be understood in the highest sense. I am content myself to wait for further information on these and other points, as the result of prolonged and careful research.

Dr. Rhys Davids has kindly read the proofs of the Translation and Notes, and I most certainly thank him for doing so, for his many valuable corrections in the Notes, and for other suggestions which I have received from him. I may not always think on various points exactly as he does, but I am not more forward than he is to say with Horace,—

‘Nullius addictus jurare in verba magistri.’

I have referred above, and also in the Introduction, to the Corean text of Fâ-hien’s narrative, which I received from Mr. Nanjio. It is on the whole so much superior to the better-known texts, that I determined to attempt to reproduce it at the end of the little volume, so far as our resources here in Oxford would permit. To do so has not been an easy task. The two fonts of Chinese types in the Clarendon Press were prepared primarily for printing the translation of our Sacred Scriptures, and then extended so as to be available for printing also the Confucian Classics; but the Buddhist work necessarily requires many types not found in them, while many other characters in the Corean recension are peculiar in their forms, and some are what Chinese dictionaries denominate ‘vulgar.’ That we have succeeded so well as we have done is owing chiefly to the intelligence, ingenuity, and untiring attention of Mr. J. C. Pembrey, the Oriental Reader.

The pictures that have been introduced were taken from a superb edition of a History of Buddha, republished recently at Hang-chau in Cheh-kiang, and profusely illustrated in the best style of Chinese art. I am indebted for the use of it to the Rev. J. H. Sedgwick, University Chinese Scholar.

JAMES LEGGE.

Oxford:

June, 1886.

University Press, Oxford.

The accompanying Sketch-Map, taken in connexion with the notes on the different places in the Narrative, will give the reader a sufficiently accurate knowledge of Fâ-hien’s route.

There is no difficulty in laying it down after he crossed the Indus from east to west into the Punjâb, all the principal places, at which he touched or rested, having been determined by Cunningham and other Indian geographers and archæologists. Most of the places from Chʽang-an to Bannu have also been identified. Woo-e has been put down as near Kutcha, or Kuldja, in 43° 25′ N., 81° 15′ E. The country of Kʽieh-chʽa was probably Ladak, but I am inclined to think that the place where the traveller crossed the Indus and entered it must have been further east than Skardo. A doubt is intimated on page 24 as to the identification of Tʽo-leih with Darada, but Greenough’s ‘Physical and Geological Sketch-Map of British India’ shows ‘Dardu Proper,’ all lying on the east of the Indus, exactly in the position where the Narrative would lead us to place it. The point at which Fâ-hien recrossed the Indus into Udyâna on the west of it is unknown. Takshaśilâ, which he visited, was no doubt on the west of the river, and has been incorrectly accepted as the Taxila of Arrian in the Punjâb. It should be written Takshasira, of which the Chinese phonetisation will allow;—see a note of Beal in his ‘Buddhist Records of the Western World,’ i. 138.

We must suppose that Fâ-hien went on from Nanking to Chʽang-an, but the Narrative does not record the fact of his doing so.

1. Nothing of great importance is known about Fâ-hien in addition to what may be gathered from his own record of his travels. I have read the accounts of him in the ‘Memoirs of Eminent Monks,’ compiled in A.D. 519, and a later work, the ‘Memoirs of Marvellous Monks,’ by the third emperor of the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1403–1424), which, however, is nearly all borrowed from the other; and all in them that has an appearance of verisimilitude can be brought within brief compass.

His surname, they tell us, was Kung,1 and he was a native of Wu-yang in Pʽing-Yang,2 which is still the name of a large department in Shan-hsi. He had three brothers older than himself; but when they all died before shedding their first teeth, his father devoted him to the service of the Buddhist society, and had him entered as a Śrâmaṇera, still keeping him at home in the family. The little fellow fell dangerously ill, and the father sent him to the monastery, where he soon got well and refused to return to his parents.

When he was ten years old, his father died; and an uncle, considering the widowed solitariness and helplessness of the mother, urged him to renounce the monastic life, and return to her, but the boy replied, ‘I did not quit the family in compliance with my father’s wishes, but because I wished to be far from the dust and vulgar ways of life. This is why I chose monkhood.’ The uncle approved of his words and gave over urging him. When his mother also died, it appeared how great had been the affection for her of his fine nature; but after her burial he returned to the monastery.

On one occasion he was cutting rice with a score or two of his fellow-disciples, when some hungry thieves came upon them to take away their grain by force. The other Śrâmaṇeras all fled, but our young hero stood his ground, and said to the thieves, ‘If you must have the grain, take what you please. But, Sirs, it was your former neglect of charity which brought you to your present state of destitution; and now, again, you wish to rob others. I am afraid that in the coming ages you will have still greater poverty and distress;—I am sorry for you beforehand.’ With these words he followed his companions into the monastery, while the thieves left the grain and went away, all the monks, of whom there were several hundred, doing homage to his conduct and courage.

When he had finished his novitiate and taken on him the obligations of the full Buddhist orders, his earnest courage, clear intelligence, and strict regulation of his demeanour were conspicuous; and soon after, he undertook his journey to India in search of complete copies of the Vinaya-piṭaka. What follows this is merely an account of his travels in India and return to China by sea, condensed from his own narrative, with the addition of some marvellous incidents that happened to him, on his visit to the Vulture Peak near Râjagṛiha.

It is said in the end that after his return to China, he went to the capital (evidently Nanking), and there, along with the Indian Śramaṇa Buddha-bhadra, executed translations of some of the works which he had obtained in India; and that before he had done all that he wished to do in this way, he removed to King-chow3 (in the present Hoo-pih), and died in the monastery of Sin, at the age of eighty-eight, to the great sorrow of all who knew him. It is added that there is another larger work giving an account of his travels in various countries.

Such is all the information given about our author, beyond what he himself has told us. Fâ-hien was his clerical name, and means ‘Illustrious in the Law,’ or ‘Illustrious master of the Law.’ The Shih which often precedes it is an abbreviation of the name of Buddha as Śâkyamuni, ‘the Śâkya, mighty in Love, dwelling in Seclusion and Silence,’ and may be taken as equivalent to Buddhist. It is sometimes said to have belonged to ‘the eastern Tsin dynasty’ (A.D. 317–419), and sometimes to ‘the Sung,’ that is, the Sung dynasty of the House of Liu (A.D. 420–478). If he became a full monk at the age of twenty, and went to India when he was twenty-five, his long life may have been divided pretty equally between the two dynasties.

2. If there were ever another and larger account of Fâ-hien’s travels than the narrative of which a translation is now given, it has long ceased to be in existence.

In the Catalogue of the imperial library of the Suy dynasty (A.D. 589–618), the name Fâ-hien occurs four times. Towards the end of the last section of it (page 22), after a reference to his travels, his labours in translation at Kin-ling (another name for Nanking), in conjunction with Buddha-bhadra, are described. In the second section, page 15, we find ‘A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms;’—with a note, saying that it was the work of the ‘Śramaṇa, Fâ-hien;’ and again, on page 13, we have ‘Narrative of Fâ-hien in two Books,’ and ‘Narrative of Fâ-hien’s Travels in one Book.’ But all these three entries may possibly belong to different copies of the same work, the first and the other two being in separate subdivisions of the Catalogue.

In the two Chinese copies of the narrative in my possession the title is ‘Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms.’ In the Japanese or Corean recension subjoined to this translation, the title is twofold; first, ‘Narrative of the Distinguished Monk, Fâ-hien;’ and then, more at large, ‘Incidents of Travels in India, by the Śramaṇa of the Eastern Tsin, Fâ-hien, recorded by himself.’

There is still earlier attestation of the existence of our little work than the Suy Catalogue. The Catalogue Raisonné of the imperial library of the present dynasty (chap. 71) mentions two quotations from it by Le Tâo-yüen, a geographical writer of the dynasty of the Northern Wei (A.D. 386–584), one of them containing 89 characters, and the other 276; both of them given as from the ‘Narrative of Fâ-hien.’

In all catalogues subsequent to that of Suy our work appears. The evidence for its authenticity and genuineness is all that could be required. It is clear to myself that the ‘Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms’ and the ‘Narrative of his Travels by Fâ-hien’ were designations of one and the same work, and that it is doubtful whether any larger work on the same subject was ever current. With regard to the text subjoined to my translation, it was published in Japan in 1779. The editor had before him four recensions of the narrative; those of the Sung and Ming dynasties, with appendixes on the names of certain characters in them; that of Japan; and that of Corea. He wisely adopted the Corean text, published in accordance with a royal rescript in 1726, so far as I can make out; but the different readings of the other texts are all given in topnotes, instead of footnotes as with us, this being one of the points in which customs in the east and west go by contraries. Very occasionally, the editor indicates by a single character, equivalent to ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ which reading in his opinion is to be preferred. In the notes to the present republication of the Corean text, S stands for Sung, M for Ming, and J for Japanese; R for right, and W for wrong. I have taken the trouble to give all the various readings (amounting to more than 300), partly as a curiosity and to make my text complete, and partly to show how, in the transcription of writings in whatever language, such variations are sure to occur,

‘ maculae, quas aut incuria fudit,

Aut humana parum cavit nature,’

while on the whole they very slightly affect the meaning of the document.

The editors of the Catalogue Raisonné intimate their doubts of the good taste and reliability of all Fâ-hien’s statements. It offends them that he should call central India the ‘Middle Kingdom,’ and China, which to them was the true and only Middle Kingdom, but ‘a Border land;’—it offends them as the vaunting language of a Buddhist writer, whereas the reader will see in the expressions only an instance of what Fâ-hien calls his ‘simple straightforwardness.’

As an instance of his unreliability they refer to his account of the Buddhism of Khoten, whereas it is well known, they say, that the Khoteners from ancient times till now have been Mohammedans;—as if they could have been so 170 years before Mohammed was born, and 222 years before the year of the Hegira! And this is criticism in China. The Catalogue was ordered by the Kʽien-lung emperor in 1722. Between three and four hundred of the ‘Great Scholars’ of the empire were engaged on it in various departments, and thus egregiously ignorant did they show themselves of all beyond the limits of their own country, and even of the literature of that country itself.

Much of what Fâ-hien tells his readers of Buddhist miracles and legends is indeed unreliable and grotesque; but we have from him the truth as to what he saw and heard.

3. In concluding this introduction I wish to call attention to some estimates of the number of Buddhists in the world which have become current, believing, as I do, that the smallest of them is much above what is correct.

i. In a note on the first page of his work on the Bhilsa Topes (1854), General Cunningham says: ‘The Christians number about 270 millions; the Buddhists about 222 millions, who are distributed as follows:—China 170 millions, Japan 25, Anam 14, Siam 3, Ava 8, Nepál 1, and Ceylon 1; total, 222 millions.’

ii. In his article on M. J. Barthélemy Saint Hilaire’s ‘Le Bouddha et sa Religion,’ republished in his ‘Chips from a German Workshop,’ vol. i. (1868), Professor Max Müller (p. 215) says, ‘The young prince became the founder of a religion which, after more than two thousand years, is still professed by 455 millions of human beings,’ and he appends the following note: ‘Though truth is not settled by majorities, it would be interesting to know which religion counts at the present moment the largest numbers of believers. Berghaus, in his “Physical Atlas,” gives the following division of the human race according to religion:—“Buddhists 31.2 per cent, Christians 30.7, Mohammedans 15.7, Brahmânists 13.4, Heathens 8.7, and Jews 0.3.” As Berghaus does not distinguish the Buddhists in China from the followers of Confucius and Laotse, the first place on the scale really belongs to Christianity. It is difficult to say to what religion a man belongs, as the same person may profess two or three. The emperor himself, after sacrificing according to the ritual of Confucius, visits a Tao-ssé temple, and afterwards bows before an image of Fo in a Buddhist chapel. (“Mélanges Asiatiques de St. Pétersbourg,” vol. ii. p. 374.)’

iii. Both these estimates are exceeded by Dr. T. W. Rhys Davids (intimating also the uncertainty of the statements, and that numbers are no evidence of truth) in the introduction to his ‘Manual of Buddhism.’ The Buddhists there appear as amounting in all to 500 millions:—30 millions of Southern Buddhists, in Ceylon, Burma, Siam, Anam, and India (Jains); and 470 millions of North Buddhists, of whom nearly 33 millions are assigned to Japan, and 414,686,974 to the eighteen provinces of China proper. According to him, Christians amount to about 26 per cent of mankind, Hindus to about 13, Mohammedans to about 12½, Buddhists to about 40, and Jews to about ½.

In regard to all these estimates, it will be observed that the immense numbers assigned to Buddhism are made out by the multitude of Chinese with which it is credited. Subtract Cunningham’s 170 millions of Chinese from his total of 222, and there remains only 52 millions of Buddhists. Subtract Davids’ (say) 414½ millions of Chinese from his total of 500, and there remain only 85½ millions for Buddhism. Of the numbers assigned to other countries, as well as of their whole populations, I am in considerable doubt, excepting in the cases of Ceylon and India; but the greatness of the estimates turns upon the immense multitudes said to be in China. I do not know what total population Cunningham allowed for that country, nor on what principal he allotted 170 millions of it to Buddhism;—perhaps he halved his estimate of the whole, whereas Berghaus and Davids allotted to it the highest estimates that have been given of the people.

But we have no certain information of the population of China. At an interview with the former Chinese ambassador, Kwo Sung-tâo, in Paris, in 1878, I begged him to write out for me the amount, with the authority for it, and he assured me that it could not be done. I have read probably almost everything that has been published on the subject, and endeavoured by methods of my own to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion;—without reaching a result which I can venture to lay before the public. My impression has been that 400 millions is hardly an exaggeration.

But supposing that we had reliable returns of the whole population, how shall we proceed to apportion that among Confucianists, Tâoists, and Buddhists? Confucianism is the orthodoxy of China. The common name for it is Jû Chiâo, ‘the Doctrines held by the Learned Class,’ entrance into the circle of which is, with a few insignificant exceptions, open to all the people. The mass of them and the masses under their influence are preponderatingly Confucian; and in the observance of ancestral worship, the most remarkable feature of the religion proper of China from the earliest times, of which Confucius was not the author but the prophet, an overwhelming majority are regular and assiduous.

Among ‘the strange principles’ which the emperor of the Kʽang-hsi period, in one of his famous Sixteen Precepts, exhorted his people to ‘discountenance and put away, in order to exalt the correct doctrine,’ Buddhism and Tâoism were both included. If, as stated in the note quoted from Professor Müller, the emperor countenances both the Tâoist worship and the Buddhist, he does so for reasons of state;—to please especially his Buddhist subjects in Thibet and Mongolia, and not to offend the many whose superstitious fancies incline to Tâoism.

When I went out and in as a missionary among the Chinese people for about thirty years, it sometimes occurred to me that only the inmates of their monasteries and the recluses of both systems should be enumerated as Buddhists and Tâoists; but I was in the end constrained to widen that judgment, and to admit a considerable following of both among the people, who have neither received the tonsure nor assumed the yellow top. Dr. Eitel, in concluding his discussion of this point in his ‘Lecture on Buddhism, an Event in History,’ says: ‘It is not too much to say that most Chinese are theoretically Confucianists, but emotionally Buddhists or Tâoists. But fairness requires us to add that, though the mass of the people are more or less influenced by Buddhist doctrines, yet the people, as a whole, have no respect for the Buddhist church, and habitually sneer at Buddhist priests.’ For the ‘most’ in the former of these two sentences I would substitute ‘nearly all;’ and between my friend’s ‘but’ and ‘emotionally’ I would introduce ‘many are,’ and would not care to contest his conclusion farther. It does seem to me preposterous to credit Buddhism with the whole of the vast population of China, the great majority of whom are Confucianists. My own opinion is, that its adherents are not so many as those even of Mohammedanism, and that instead of being the most numerous of the religions (so called) of the world, it is only entitled to occupy the fifth place, ranking below Christianity, Confucianism, Brahmânism, and Mohammedanism, and followed, some distance off, by Tâoism. To make a table of percentages of mankind, and assign to each system its proportion, is to seem to be wise where we are deplorably ignorant; and, moreover, if our means of information were much better than they are, our figures would merely show the outward adherence. A fractional per-centage might tell more for one system than a very large integral one for another.

THE

TRAVELS OF FÂ-HIEN

OR

RECORD OF BUSSHISTIC KINGDOMS

Fâ-hien had been living in Chʽang-gan.1 Deploring the mutilated and imperfect state of the collection of the Books of Discipline, in the second year of the period Hwăng-che, being the Ke-hâe year of the cycle,2 he entered into an engagement with Hwuy-king, Tâo-ching, Hwuy-ying, and Hwuy-wei,3 that they should go to India and seek for the Disciplinary Rules.4

After starting from Chʽang-gan, they passed through Lung,5 and came to the kingdom of Kʽeen-kwei,6 where they stopped for the summer retreat.7 When that was over, they went forward to the kingdom of Now-tʽan,8 crossed the mountain of Yang-low, and reached the emporium of Chang-yih.9 There they found the country so much disturbed that travelling on the roads was impossible for them. Its king, however, was very attentive to them, kept them (in his capital), and acted the part of their dânapati.10

Here they met with Che-yen, Hwuy-keen, Săng-shâo, Pâo-yun, and Săng-king;11 and in pleasant association with them, as bound on the same journey with themselves, they passed the summer retreat (of that year)12 together, resuming after it their travelling, and going on to Tʽun-hwang,13 (the chief town) in the frontier territory of defence extending for about 80 le from east to west, and about 40 from north to south. Their company, increased as it had been, halted there for some days more than a month, after which Fâ-hien and his four friends started first in the suite of an envoy,14 having separated (for a time) from Pâo-yun and his associates.

Le Hâo,15 the prefect of Tʽun-hwang, had supplied them with the means of crossing the desert (before them), in which there are many evil demons and hot winds. (Travellers) who encounter them perish all to a man. There is not a bird to be seen in the air above, nor an animal on the ground below. Though you look all round most earnestly to find where you can cross, you know not where to make your choice, the only mark and indication being the dry bones of the dead (left upon the sand).16

After travelling for seventeen days, a distance we may calculate of about 1500 le, (the pilgrims) reached the kingdom of Shen-shen,1 a country rugged and hilly, with a thin and barren soil. The clothes of the common people are coarse, and like those worn in our land of Han,2 some wearing felt and others coarse serge or cloth of hair;—this was the only difference seen among them. The king professed (our) Law, and there might be in the country more than four thousand monks,3 who were all students of the hînayâna.4 The common people of this and other kingdoms (in that region), as well as the śramans,5 all practise the rules of India,6 only that the latter do so more exactly, and the former more loosely. So (the travellers) found it in all the kingdoms through which they went on their way from this to the west, only that each had its own peculiar barbarous speech.7 (The monks), however, who had (given up the worldly life) and quitted their families, were all students of Indian books and the Indian language. Here they stayed for about a month, and then proceeded on their journey, fifteen days walking to the north-west bringing them to the country of Woo-e.8 In this also there were more than four thousand monks, all students of the hînayâna. They were very strict in their rules, so that śramans from the territory of Tsʽin9 were all unprepared for their regulations. Fâ-hien, through the management of Foo Kung-sun, maître d’hôtellerie,10 was able to remain (with his company in the monastery where they were received) for more than two months, and here they were rejoined by Pâo-yun and his friends.11 (At the end of that time) the people of Woo-e neglected the duties of propriety and righteousness, and treated the strangers in so niggardly a manner that Che-yen, Hwuy-keen, and Hwuy-wei went back towards Kâo-chʽang,12 hoping to obtain there the means of continuing their journey. Fâ-hien and the rest, however, through the liberality of Foo Kung-sun, managed to go straight forward in a south-west direction. They found the country uninhabited as they went along. The difficulties which they encountered in crossing the streams and on their route, and the sufferings which they endured, were unparalleled in human experience, but in the course of a month and five days they succeeded in reaching Yu-teen.13

Yu-teen is a pleasant and prosperous kingdom, with a numerous and flourishing population. The inhabitants all profess our Law, and join together in its religious music for their enjoyment.1 The monks amount to several myriads, most of whom are students of the mahâyâna.2 They all receive their food from the common store.3 Throughout the country the houses of the people stand apart like (separate) stars, and each family has a small tope4 reared in front of its door. The smallest of these may be twenty cubits high, or rather more.5 They make (in the monasteries) rooms for monks from all quarters,5 the use of which is given to travelling monks who may arrive, and who are provided with whatever else they require.

The lord of the country lodged Fâ-hien and the others comfortably, and supplied their wants, in a monastery called Gomati,6 of the mahâyâna school. Attached to it there are three thousand monks, who are called to their meals by the sound of a bell. When they enter the refectory, their demeanour is marked by a reverent gravity, and they take their seats in regular order, all maintaining a perfect silence. No sound is heard from their alms-bowls and other utensils. When any of these pure men7 require food, they are not allowed to call out (to the attendants) for it, but only make signs with their hands.

Hwuy-king, Tâo-ching, and Hwuy-tah set out in advance towards the country of Kʽeeh-chʽâ;8 but Fâ-hien and the others, wishing to see the procession of images, remained behind for three months. There are in this country four9 great monasteries, not counting the smaller ones. Beginning on the first day of the fourth month, they sweep and water the streets inside the city, making a grand display in the lanes and byways. Over the city gate they pitch a large tent, grandly adorned in all possible ways, in which the king and queen, with their ladies brilliantly arrayed,10 take up their residence (for the time).

The monks of the Gomati monastery, being mahâyâna students, and held in great reverence by the king, took precedence of all others in the procession. At a distance of three or four le from the city, they made a four-wheeled image car, more than thirty cubits high, which looked like the great hall (of a monastery) moving along. The seven precious substances11 were grandly displayed about it, with silken streamers and canopies hanging all around. The (chief) image12 stood in the middle of the car, with two Bodhisattvas13 in attendance upon it, while devas14 were made to follow in waiting, all brilliantly carved in gold and silver, and hanging in the air. When (the car) was a hundred paces from the gate, the king put off his crown of state, changed his dress for a fresh suit, and with bare feet, carrying in his hands flowers and incense, and with two rows of attending followers, went out at the gate to meet the image; and, with his head and face (bowed to the ground), he did homage at its feet, and then scattered the flowers and burnt the incense. When the image was entering the gate, the queen and the brilliant ladies with her in the gallery above scattered far and wide all kinds of flowers, which floated about and fell promiscuously to the ground. In this way everything was done to promote the dignity of the occasion. The carriages of the monasteries were all different, and each one had its own day for the procession. (The ceremony) began on the first day of the fourth month, and ended on the fourteenth, after which the king and queen returned to the palace.

Seven or eight le to the west of the city there is what is called the King’s New Monastery, the building of which took eighty years, and extended over three reigns. It may be 250 cubits in height, rich in elegant carving and inlaid work, covered above with gold and silver, and finished throughout with a combination of all the precious substances. Behind the tope there has been built a Hall of Buddha,15 of the utmost magnificence and beauty, the beams, pillars, venetianed doors, and windows being all overlaid with gold-leaf. Besides this, the apartments for the monks are imposingly and elegantly decorated, beyond the power of words to express. Of whatever things of highest value and preciousness the kings in the six countries on the east of the (Tsʽung) range of mountains16 are possessed, they contribute the greater portion (to this monastery), using but a small portion of them themselves.17

When the processions of images in the fourth month were over, Săng-shâo, by himself alone, followed a Tartar who was an earnest follower of the Law,1 and proceeded towards Kophene.2 Fâ-hien and the others went forward to the kingdom of Tsze-hoh, which it took them twenty-five days to reach.3 Its king was a strenuous follower of our Law,4 and had (around him) more than a thousand monks, mostly students of the mahâyâna. Here (the travellers) abode fifteen days, and then went south for four days, when they found themselves among the Tsʽung-ling mountains, and reached the country of Yu-hwuy,5 where they halted and kept their retreat.6 When this was over, they went on among the hills7 for twenty-five days, and got to Kʽeeh-chʽâ,8 there rejoining Hwuy-king9 and his two companions.

It happened that the king of the country was then holding the pañcha parishad, that is, in Chinese, the great quinquennial assembly.1 When this is to be held, the king requests the presence of the Śramans from all quarters (of his kingdom). They come (as if) in clouds; and when they are all assembled, their place of session is grandly decorated. Silken streamers and canopies are hung out in, and water-lilies in gold and silver are made and fixed up behind the places where (the chief of them) are to sit. When clean mats have been spread, and they are all seated, the king and his ministers present their offerings according to rule and law. (The assembly takes place), in the first, second, or third month, for the most part in the spring.

After the king has held the assembly, he further exhorts the ministers to make other and special offerings. The doing of this extends over one, two, three, five, or even seven days; and when all is finished, he takes his own riding-horse, saddles, bridles, and waits on him himself,2 while he makes the noblest and most important minister of the kingdom mount him. Then, taking fine white woollen cloth, all sorts of precious things, and articles which the Śramans require, he distributes them among them, uttering vows at the same time along with all his ministers; and when this distribution has taken place, he again redeems (whatever he wishes) from the monks.3

The country, being among the hills and cold, does not produce the other cereals, and only the wheat gets ripe. After the monks have received their annual (portion of this), the mornings suddenly show the hoar-frost, and on this account the king always begs the monks to make the wheat ripen4 before they receive their portion. There is in the country a spittoon which belonged to Buddha, made of stone, and in colour like his alms-bowl. There is also a tooth of Buddha, for which the people have reared a tope, connected with which there are more than a thousand monks and their disciples,5 all students of the hînayâna. To the east of these hills the dress of the common people is of coarse materials, as in our country of Tsʽin, but here also6 there were among them the differences of fine woollen cloth and of serge or haircloth. The rules observed by the Śramans are remarkable, and too numerous to be mentioned in detail. The country is in the midst of the Onion range. As you go forward from these mountains, the plants, trees, and fruits are all different from those of the land of Han, excepting only the bamboo, pomegranate,7 and sugar-cane.

From this (the travellers) went westwards towards North India, and after being on the way for a month, they succeeded in getting across and through the range of the Onion mountains. The snow rests on them both winter and summer. There are also among them venomous dragons, which, when provoked, spit forth poisonous winds, and cause showers of snow and storms of sand and gravel. Not one in ten thousand of those who encounter these dangers escapes with his life. The people of the country call the range by the name of ‘The Snow mountains.’ When (the travellers) had got through them, they were in North India, and immediately on entering its borders, found themselves in a small kingdom called Tʽo-leih,1 where also there were many monks, all students of the hînayâna.

In this kingdom there was formerly an Arhan,2 who by his supernatural power3 took a clever artificer up to the Tushita4 heaven, to see the height, complexion, and appearance of Maitreya Bodhisattva,5 and then return and make an image of him in wood. First and last, this was done three times, and then the image was completed, eighty cubits in height, and eight cubits at the base from knee to knee of the crossed legs. On fast-days it emits an effulgent light. The kings of the (surrounding) countries vie with one another in presenting offerings to it. Here it is,—to be seen now as of old.6

The travellers went on to the south-west for fifteen days (at the foot of the mountains, and) following the course of their range. The way was difficult and rugged, (running along) a bank exceedingly precipitous, which rose up there, a hill-like wall of rock, 10,000 cubits from the base. When one approaches the edge of it, his eyes become unsteady; and if he wished to go forward in the same direction, there was no place on which he could place his foot; and beneath where the waters of the river called the Indus.1 In former times men had chiselled paths along the rocks, and distributed ladders on the face of them, to the number altogether of 700, at the bottom of which there was a suspension bridge of ropes, by which the river was crossed, its banks being there eighty paces apart.2 The (place and arrangements) are to be found in the Records of the Nine Interpreters,3 but neither Chang Kʽeen4 nor Kan Ying5 had reached the spot.

The monks6 asked Fâ-hien if it could be known when the Law of Buddha first went to the east. He replied, ‘When I asked the people of those countries about it, they all said that it had been handed down by their fathers from of old that, after the setting up of the image of Maitreya Bodhisattva, there were Śramans of India who crossed this river, carrying with them Sûtras and Books of Discipline. Now the image was set up rather more than 300 years after the nirvâṇa7 of Buddha, which may be referred to the reign of king Pʽing of the Chow dynasty.8 According to this account we may say that the diffusion of our great doctrines (in the east) began from (the setting up of) this image. If it had not been through that Maitreya,9 the great spiritual master10 (who is to be) the successor of the Śâkya, who could have caused the “Three Precious Ones”11 to be proclaimed so far, and the people of those border lands to know our Law? We know of a truth that the opening of (the way for such) a mysterious propagation is not the work of man; and so the dream of the emperor Ming of Han12 had its proper cause.’

After crossing the river, (the travellers) immediately came to the kingdom of Woo-chang,1 which is indeed (a part) of North India. The people all use the language of Central India, ‘Central India’ being what we should call the ‘Middle Kingdom.’ The food and clothes of the common people are the same as in that Central Kingdom. The Law of Buddha is very (flourishing in Woo-chang). They call the places where the monks stay (for a time) or reside permanently Saṅghârâmas;2 and of these there are in all 500, the monks being all students of the hînayâna. When stranger bhikshus3 arrive at one of them, their wants are supplied for three days, after which they are told to find a resting-place for themselves.

There is a tradition that when Buddha came to North India, he came at once to this country, and that here he left a print of his foot, which is long or short according to the ideas of the beholder (on the subject). It exists, and the same thing is true about it, at the present day. Here also are still to be seen the rock on which he dried his clothes, and the place where he converted the wicked dragon.4 The rock is fourteen cubits high, and more than twenty broad, with one side of it smooth.

Hwuy-king, Hwuy-tah, and Tâo-ching went on ahead towards (the place of) Buddha’s shadow in the country of Nagâra;5 but Fâ-hien and the others remained in Woo-chang, and kept the summer retreat.6 That over, they descended south, and arrived in the country of Soo-ho-to.7

In that country also Buddhism1 is flourishing. There is in it the place where Śakra,2 Ruler of Devas, in a former age,3 tried the Bodhisattva, by producing4 a hawk (in pursuit of a) dove, when (the Bodhisattva) cut off a piece of his own flesh, and (with it) ransomed the dove. After Buddha had attained to perfect wisdom,5 and in travelling about with his disciples (arrived at this spot), he informed them that this was the place where he ransomed the dove with a piece of his own flesh. In this way the people of the country became aware of the fact, and on the spot reared a tope, adorned with layers6 of gold and silver plates.

The travellers, going downwards from this towards the east, in five days came to the country of Gandhâra,1 the place where Dharma-vivardhana,2 the son of Aśoka,3 ruled. When Buddha was a Bodhisattva, he gave his eyes also for another man here;4 and at the spot they have also reared a large tope, adorned with layers of gold and silver plates. The people of the country were mostly students of the hînayâna.

Seven days’ journey from this to the east brought the travellers to the kingdom of Takshaśilâ,1 which means ‘the severed head’ in the language of China. Here, when Buddha was a Bodhisattva, he gave away his head to a man;2 and from this circumstance the kingdom got its name.

Going on further for two days to the east, they came to the place where the Bodhisattva threw down his body to feed a starving tigress.2 In these two places also large topes have been built, both adorned with layers of all the precious substances. The kings, ministers, and peoples of the kingdoms around vie with one another in making offerings at them. The trains of those who come to scatter flowers and light lamps at them never cease. The nations of those quarters all those (and the other two mentioned before) ‘the four great topes.’

Going southwards from Gandhâra, (the travellers) in four days arrived at the kingdom of Purushapura.1 Formerly, when Buddha was travelling in this country with his disciples, he said to Ânanda,2 ‘After my pari-nirvâṇa,3 there will be a king named Kanishka,4 who shall on this spot build a tope.’ This Kanishka was afterwards born into the world; and (once), when he had gone forth to look about him, Śakra, Ruler of Devas, wishing to excite the idea in his mind, assumed the appearance of a little herd-boy, and was making a tope right in the way (of the king), who asked what sort of thing he was making. The boy said, ‘I am making a tope for Buddha.’ The king said, ‘Very good;’ and immediately, right over the boy’s tope, he (proceeded to) rear another, which was more than four hundred cubits high, and adorned with layers of all the precious substances. Of all the topes and temples which (the travellers) saw in their journeyings, there was not one comparable to this in solemn beauty and majestic grandeur. There is a current saying that this is the finest tope in Jambudvîpa.5 When the king’s tope was completed, the little tope (of the boy) came out from its side on the south, rather more than three cubits in height.

Buddha’s alms-bowl is in this country. Formerly, a king of Yüeh-she6 raised a large force and invaded this country, wishing to carry the bowl away. Having subdued the kingdom, as he and his captains were sincere believers in the Law of Buddha, and wished to carry off the bowl, they proceeded to present their offerings on a great scale. When they had done so to the Three Precious Ones, he made a large elephant be grandly caparisoned, and placed the bowl upon it. But the elephant knelt down on the ground, and was unable to go forward. Again he caused a four-wheeled wagon to be prepared in which the bowl was put to be conveyed away. Eight elephants were then yoked to it, and dragged it with their united strength; but neither were they able to go forward. The king knew that the time for an association between himself and the bowl had not yet arrived,7 and was sad and deeply ashamed of himself. Forthwith he built a tope at the place and a monastery, and left a guard to watch (the bowl), making all sorts of contributions.

There may be there more than seven hundred monks. When it is near midday, they bring out the bowl, and, along with the common people,8 make their various offerings to it, after which they take their midday meal. In the evening, at the time of incense, they bring the bowl out again.9 It may contain rather more than two pecks, and is of various colours, black predominating, with the seams that show its fourfold composition distinctly marked.10 Its thickness is about the fifth of an inch, and it has a bright and glossy lustre. When poor people throw into it a few flowers, it becomes immediately full, while some very rich people, wishing to make offering of many flowers, might not stop till they had thrown in hundreds, thousands, and myriads of bushels, and yet would not be able to fill it.11

Pâo-yun and Săng-king here merely made their offerings to the alms-bowl, and (then resolved to) go back. Hwuy-king, Hwuy-tah, and Tâo-ching had gone on before the rest to Nagâra,12 to make their offerings at (the places of) Buddha’s shadow, tooth, and the flat-bone of his skull. (There) Hwuy-king fell ill, and Tâo-ching remained to look after him, while Hwuy-tah came alone to Purushapura, and saw the others, and (then) he with Pâo-yun and Săng-king took their way back to the land of Tsʽin. Hwuy-king13 came to his end14 in the monastery of Buddha’s alms-bowl, and on this Fâ-hien went forward alone towards the place of the flat-bone of Buddha’s skull.

Going west for sixteen yojanas,1 he came to the city He-lo2 in the borders of the country of Nagâra, where there is the flat-bone of Buddha’s skull, deposited in a vihâra3 adorned all over with gold-leaf and the seven sacred substances. The king of the country, revering and honouring the bone, and anxious lest it should be stolen away, has selected eight individuals, representing the great families in the kingdom, and committing to each a seal, with which he should seal (its shrine) and guard (the relic). At early dawn these eight men come, and after each has inspected his seal, they open the door. This done, they wash their hands with scented water and bring out the bone, which they place outside the vihâra, on a lofty platform, where it is supported on a round pedestal of the seven precious substances, and covered with a bell of lapis lazuli, both adorned with rows of pearls. Its colour is of a yellowish white, and it forms an imperfect circle twelve inches round,4 curving upwards to the centre. Every day, after it has been brought forth, the keepers of the vihâra ascend a high gallery, where they beat great drums, blow conchs, and clash their copper cymbals. When the king hears them, he goes to the vihâra, and makes his offerings of flowers and incense. When he has done this, he (and his attendants) in order, one after another, (raise the bone), place it (for a moment) on the top of their heads,5 and then depart, going out by the door on the west as they entered by that on the east. The king every morning makes his offerings and performs his worship, and afterwards gives audience on the business of his government. The chiefs of the Vaiśyas6 also make their offerings before they attend to their family affairs. Every day it is so, and there is no remissness in the observance of the custom. When all the offerings are over, they replace the bone in the vihâra, where there is a vimoksha tope,7 of the seven precious substances, and rather more than five cubits high, sometimes open, sometimes shut, to contain it. In front of the door of the vihâra, there are parties who every morning sell flowers and incense,8 and those who wish to make offerings buy some of all kinds. The kings of various countries are also constantly sending messengers with offerings. The vihâra stands in a square of thirty paces, and though heaven should shake and earth be rent, this place would not move.

Going on, north from this, for a yojana, (Fâ-hien) arrived at the capital of Nagâra, the place where the Bodhisattva once purchased with money five stalks of flowers, as an offering to the Dîpâṅkara Buddha.9 In the midst of the city there is also the tope of Buddha’s tooth, where offerings are made in the same way as to the flat-bone of his skull.

A yojana to the north-east of the city brought him to the mouth of a valley, where there is Buddha’s pewter staff;10 and a vihâra also has been built at which offerings are made. The staff is made of Gośîrsha Chandana, and is quite sixteen or seventeen cubits long. It is contained in a wooden tube, and though a hundred or a thousand men ere to (try to) lift it, they could not move it.

Entering the mouth of the valley, and going west, he found Buddha’s Saṅghâli,11 where also there is reared a vihâra, and offerings are made. It is a custom of the country when there is a great drought, for the people to collect in crowds, bring out the robe, pay worship to it, and make offerings, on which there is immediately a great rain from the sky.

South of the city, half a yojana, there is a rock cavern, in a great hill fronting the south-west; and here it was that Buddha left his shadow. Looking at it from a distance of more than ten paces, you seem to see Buddha’s real form, with his complexion of gold, and his characteristic marks12 in their nicety clearly and brightly displayed. The nearer you approach, however, the fainter it becomes, as if it were only in your fancy. When the kings from the regions all around have sent skilful artists to take a copy, none of them have been able to do so. Among the people of the country there is a saying current that ‘the thousand Buddhas13 must all leave their shadows here.’

Rather more than four hundred paces west from the shadow, when Buddha was at the spot, he shaved his hair and clipt his nails, and proceeded, along with his disciples, to build a tope seventy or eighty cubits high, to be a model for all future topes; and it is still existing. By the side of it there is a monastery, with more than seven hundred monks in it. At this place there are as many as a thousand topes14 of Arhans and Pratyeka Buddhas.15

Having stayed there till the third month of winter, Fâ-hien and the two others,1 proceeding southwards, crossed the Little Snowy mountains.2 On them the snow lies accumulated both winter and summer. On the north (side) of the mountains, in the shade, they suddenly encountered a cold wind which made them shiver and become unable to speak. Hwuy-king could not go any farther. A white froth came from his mouth, and he said to Fâ-hien, ‘I cannot live any longer. Do you immediately go away, that we do not all die here;’ and with these words he died.3 Fâ-hien stroked the corpse, and cried out piteously, ‘Our original plan has failed;—it is fate.4 What can we do?’ He then again exerted himself, and they succeeded in crossing to the south of the range, and arrived in the kingdom of Lo-e,5 where there were nearly three thousand monks, students of both the mahâyâna and hînayâna. Here they stayed for the summer retreat,6 and when that was over, they went on to the south, and ten days’ journey brought them to the kingdom of Poh-nâ,7 where there are also more than three thousand monks, all students of the hînayâna. Proceeding from this place for three days, they again crossed the Indus, where the country on each side was low and level.8

After they had crossed the river, there was a country named Pe-tʽoo,1 where Buddhism was very flourishing, and (the monks) studied both the mahâyâna and hînayâna. When they saw their fellow-disciples from Tsʽin passing along, they were moved with great pity and sympathy, and expressed themselves thus: ‘How is it that these men from a border-land should have learned to become monks,2 and come for the sake of our doctrines from such a distance in search of the Law of Buddha?’ They supplied them with what they needed, and treated them in accordance with the rules of the Law.

From this place they travelled south-east, passing by a succession of very many monasteries, with a multitude of monks, who might be counted by myriads. After passing all these places, they came to a country named Ma-tʽâou-lo.1 They still followed the course of the Pʽoo-na2 river, on the banks of which, left and right, there were twenty monasteries, which might contain three thousand monks; and (here) the Law of Buddha was still more flourishing. Everywhere, from the Sandy Desert, in all the countries of India, the kings had been firm believers in that Law. When they make their offerings to a community of monks, they take off their royal caps, and along with their relatives and ministers, supply them with food with their own hands. That done, (the king) has a carpet spread for himself on the ground, and sits down in front of the chairman;—they dare not presume to sit on couches in front of the community. The laws and ways, according to which the kings presented their offerings when Buddha was in the world, have been handed down to the present day.

All south from this is named the Middle Kingdom.3 In it the cold and heat are finely tempered, and there is neither hoar-frost nor snow. The people are numerous and happy; they have not to register their households, or attend to any magistrates and their rules; only those who cultivate the royal land have to pay (a portion of) the grain from it. If they want to go, they go; if they want to stay on, they stay. The king governs without decapitation or (other) corporal punishments. Criminals are simply fined, lightly or heavily, according to the circumstances (of each case). Even in cases of repeated attempts at wicked rebellion, they only have their right hands cut off. The king’s body-guards and attendants all have salaries. Throughout the whole country the people do not kill any living creature, nor drink intoxicating liquor, nor eat onions or garlic. The only exception is that of the Chaṇḍâlas.4 That is the name for those who are (held to be) wicked men, and live apart from others. When they enter the gate of a city or a market-place, they strike a piece of wood to make themselves known, so that men know and avoid them, and do not come into contact with them. In that country they do not keep pigs and fowls, and do not sell live cattle; in the markets there are no butchers’ shops and no dealers in intoxicating drink. In buying and selling commodities they use cowries.5 Only the Chaṇḍâlas are fishermen and hunters, and sell flesh meat.

After Buddha attained to pari-nirvâṇa,6 the kings of the various countries and the heads of the Vaiśyas7 built vihâras for the priests, and endowed them with fields, houses, gardens, and orchards, along with the resident populations and their cattle, the grants being engraved on plates of metal,8 so that afterwards they were handed down from king to king, without any daring to annul them, and they remain even to the present time.

The regular business of the monks is to perform acts of meritorious virtue, and to recite their Sûtras and sit wrapt in meditation. When stranger monks arrive (at any monastery), the old residents meet and receive them, carry for them their clothes and alms-bowl, give them water to wash their feet, oil with which to anoint them, and the liquid food permitted out of the regular hours.9 When (the stranger) has enjoyed a very brief rest, they further ask the number of years that he has been a monk, after which he receives a sleeping apartment with its appurtenances, according to his regular order, and everything is done for him which the rules prescribe.10

Where a community of monks resides, they erect topes to Śâriputtra,11 to Mahâ-maudgalyâyana,12 and to Ânanda13, and also topes (in honour) of the Abhidharma14, the Vinaya14, and the Sûtras.14 A month after the (annual season of) rest, the families which are looking out for blessing stimulate one another15 to make offerings to the monks, and send round to them the liquid food which may be taken out of the ordinary hours. All the monks come together in a great assembly, and preach the Law;16 after which offerings are presented at the tope of Śâriputtra, with all kinds of flowers and incense. All through the night lamps are kept burning, and skilful musicians are employed to perform.17

When Śâriputtra was a great Brahmân, he went to Buddha, and begged (to be permitted) to quit his family (and become a monk). The great Mugalan and the great Kaśyapa18 also did the same. The bhikshuṇîs19 for the most part make their offerings at the tope of Ânanda, because it was he who requested the World-honoured one to allow females to quit their families (and become nuns). The Śrâmaṇeras20 mostly make their offerings to Râhula.21 The professors of the Abhidharma22 make their offerings to it; those of the Vinaya22 to it. Every year there is one such offering, and each class has its own day for it. Students of the mahâyâna present offerings to the Prajñâ-pâramitâ,23 to Mañjuśrî,24 and to Kwan-she-yin.25 When the monks have done receiving their annual tribute (from the harvests),26 the Heads of the Vaiśyas and all the Brahmâns bring clothes and other such articles as the monks require for use, and distribute among them. The monks, having received them, also proceed to give portions to one another. From the nirvâṇa of Buddha,27 the forms of ceremony, laws, and rules, practised by the sacred communities, have been handed down from one generation to another without interruption.

From the place where (the travellers) crossed the Indus to Southern India, and on to the Southern Sea, a distance of forty or fifty thousand le, all is level plain. There are no large hills with streams (among them); there are simply the waters of the rivers.

From this they proceeded south-east for eighteen yojanas, and found themselves in a kingdom called Saṅkâśya,1 at the place where Buddha came down, after ascending to the Trayastriṃśas heaven,2 and there preaching for three months his Law for the benefit of his mother.3 Buddha had gone up to this heaven by his supernatural power,4 without letting his disciples know; but seven days before the completion (of the three months) he laid aside his invisibility,4 and Anuruddha,5 with his heavenly eyes,5 saw the World-honoured one, and immediately said to the honoured one, the great Mugalan, ‘Do you go and salute the World-honoured one.’ Mugalan forthwith went, and with head and face did homage at (Buddha’s) feet. They then saluted and questioned each other, and when this was over, Buddha said to Mugalan, ‘Seven days after this I will go down to Jambudvîpa;’ and thereupon Mugalan returned. At this time the great kings of eight countries with their ministers and people, not having seen Buddha for a long time, were all thirstily looking up for him, and had collected in clouds in this kingdom to wait for the World-honoured one.

Then the bhikshuṇî Utpala6 thought in her heart, ‘To-day the kings, with their ministers and people, will all be meeting (and welcoming) Buddha. I am (but) a woman; how shall I succeed in being the first to see him?’7 Buddha immediately, by his spirit-like power, changed her into the appearance of a holy Chakravartti8 king, and she was the foremost of all in doing reverence to him.

As Buddha descended from his position aloft in the Trayastriṃśas heaven, when he was coming down, there were made to appear three flights of precious steps. Buddha was on the middle flight, the steps of which were composed of the seven precious substances. The king of Brahmâ-loka9 also made a flight of silver steps appear on the right side, (where he was seen) attending with a white chowry in his hand. Śakra, Ruler of Devas,10 made (a flight of) steps of purple gold on the left side, (where he was seen) attending and holding an umbrella of the seven precious substances. An innumerable multitude of the devas11 followed Buddha in his descent. When he was come down, the three flights all disappeared in the ground, excepting seven steps, which continued to be visible. Afterwards king Aśoka, wishing to know where their ends rested, sent men to dig and see. They went down to the yellow springs12 without reaching the bottom of the steps, and from this the king received an increase to his reverence and faith, and built a vihâra over the steps, with a standing image, sixteen cubits in height, right over the middle flight. Behind the vihâra he erected a stone pillar, about fifty cubits high,13 with a lion on the top of it.14 Let into the pillar, on each of its four sides,15 there is an image of Buddha, inside and out16 shining and transparent, and pure as it were of lapis lazuli. Some teachers of another doctrine17 once disputed with the Śramaṇas about (the right to) this as a place of residence, and the latter were having the worst of the argument, when they took an oath on both sides on the condition that, if the place did indeed belong to the Śramaṇas, there should be some marvellous attestation of it. When these words had been spoken, the lion on the top gave a great roar, thus giving the proof; on which their opponents were frightened, bowed to the decision, and withdrew.

Through Buddha having for three months partaken of the food of heaven, his body emitted a heavenly fragrance, unlike that of an ordinary man. He went immediately and bathed; and afterwards, at the spot where he did so, a bathing-house was built, which is still existing. At the place where the bhikshuṇî Utpala was the first to do reverence to Buddha, a tope has now been built.

At the places where Buddha, when he was in the world, cut his hair and nails,18 topes are erected; and where the three Buddhas19 that preceded Śâkyamuni Buddha and he himself sat; where they walked,20 and where images of their persons were made. At all these places topes were made, and are still existing. At the place where Śakra, Ruler of the Devas, and the king of the Brahmâ-loka followed Buddha down (from the Trayastriṃśas heaven) they have also raised a tope.

At this place the monks and nuns may be a thousand, who all receive their food from the common store, and pursue their studies, some of the mahâyâna and some of the hînayâna. Where they live, there is a white-eared dragon, which acts the part of dânapati21 to the community of these monks, causing abundant harvests in the country, and the enriching rains to come in season, without the occurrence of any calamities, so that the monks enjoy their repose and ease. In gratitude for its kindness, they have made for it a dragon-house, with a carpet for it to sit on, and appointed for it a diet of blessing, which they present for its nourishment. Every day they set apart three of their number to go to its house, and eat there. Whenever the summer retreat is ended, the dragon straightway changes its form, and appears as a small snake,22 with white spots at the side of its ears. As soon as the monks recognise it, they fill a copper vessel with cream, into which they put the creature, and then carry it round from the one who has the highest seat (at their tables) to him who has the lowest, when it appears as if saluting them. When it has been taken round, immediately it disappeared; and every year it thus comes forth once. The country is very productive, and the people are prosperous, and happy beyond comparison. When people of other countries come to it, they are exceedingly attentive to them all, and supply them with what they need.

Fifty yojanas north-west from the monastery there is another, called ‘The Great Heap.’23 Great Heap was the name of a wicked demon, who was converted by Buddha, and men subsequently at this place reared a vihâra. When it was being made over to an Arhat by pouring water on his hands,24 some drops fell on the ground. They are still on the spot, and however they may be brushed away and removed, they continue to be visible, and cannot be made to disappear.

At this place there is also a tope to Buddha, where a good spirit constantly keeps (all about it) swept and watered, without any labour of man being required. A king of corrupt views once said, ‘Since you are able to do this, I will lead a multitude of troops and reside there till the dirt and filth has increased and accumulated, and (see) whether you can cleanse it away or not.’ The spirit thereupon raised a great wind, which blew (the filth away), and made the place pure.

At this place there are a hundred small topes, at which a man may keep counting a whole day without being able to know (their exact number). If he be firmly bent on knowing it, he will place a man by the side of each tope. When this is done, proceeding to count the number of men, whether they be many or few, he will not get to know (the number).25

There is a monastery, containing perhaps 600 or 700 monks, in which there is a place where a Pratyeka Buddha26 used to take his food. The nirvâṇa ground (where he was burned27 after death) is as large as a carriage wheel; and while grass grows all around, on this spot there is none. The ground also where he dried his clothes produces no grass, but the impression of them, where they lay on it, continues to the present day.

Fâ-hien stayed at the Dragon vihâra till after the summer retreat,1 and then, travelling to the south-east for seven yojanas, he arrived at the city of Kanyâkubja,2 lying along the Ganges.3 There are two monasteries in it, the inmates of which are students of the hînayâna. At a distance from the city of six or seven le, on the west, on the northern bank of the Ganges, is a place where Buddha preached the Law to his disciples. It has been handed down that his subjects of discourse were such as ‘The bitterness and vanity (of life) as impermanent and uncertain,’ and that ‘The body is as a bubble or foam on the water.’ At this spot a tope was erected, and still exists.

Having crossed the Ganges, and gone south for three yojanas, (the travellers) arrived at a village named Â-le,4 containing places where Buddha preached the Law, where he sat, and where he walked, at all of which topes have been built.

Going on from this to the south-east for three yojanas, they came to the great kingdom of Shâ-che.1 As you go out of the city of Shâ-che by the southern gate, on the east of the road (is the place) where Buddha, after he had chewed his willow branch,2 stuck it in the ground, when it forthwith grew up seven cubits, (at which height it remained) neither increasing nor diminishing. The Brahmâns with their contrary doctrines3 became angry and jealous. Sometimes they cut the tree down, sometimes they plucked it up, and cast it to a distance, but it grew again on the same spot as at first. Here also is the place where the four Buddhas walked and sat, and at which a tope was built that is still existing.

Going on from this to the south, for eight yojanas, (the travellers) came to the city of Śrâvastî1 in the kingdom of Kośala,2 in which the inhabitants were few and far between, amounting in all (only) to a few more than two hundred families; the city where king Prasenajit3 ruled, and the place of the old vihâra of Mahâ-prajâpatî;4 of the well and walls of (the house of) the (Vaiśya) head Sudatta;5 and where the Aṅgulimâlya6 became an Arhat, and his body was (afterwards) burned on his attaining to pari-nirvâṇa. At all these places topes were subsequently erected, which are still existing in the city. The Brahmâns, with their contrary doctrine, became full of hatred and envy in their hearts, and wished to destroy them, but there came from the heavens such a storm of crashing thunder and flashing lightning that they were not able in the end to effect their purpose.

As you go out from the city by the south gate, and 1,200 paces from it, the (Vaiśya) head Sudatta built a vihâra, facing the south; and when the door was open, on each side of it there was a stone pillar, with the figure of a wheel on the top of that on the left, and the figure of an ox on the top of that on the right. On the left and right of the building the ponds of water clear and pure, the thickets of trees always luxuriant, and the numerous flowers of various hues, constituted a lovely scene, the whole forming what is called the Jetavana vihâra.7

When Buddha went up to the Trayastriṃśas heaven, and preached the Law for the benefit of his mother,8 (after he had been absent for) ninety days, Prasenajit, longing to see him, caused an image of him to be carved in Gośîrsha Chandana wood,9 and put in the place where he usually sat. When Buddha on his return entered the vihâra, this image immediately left its place, and came forth to meet him. Buddha said to it, ‘Return to your seat. After I have attained to pari-nirvâṇa, you will serve as a pattern to the four classes of my disciples,’10 and on this the image returned to its seat. This was the very first of all the images (of Buddha), and that which men subsequently copied. Buddha then removed, and dwelt in a small vihâra on the south side (of the other), a different place from that containing the image, and twenty paces distant from it.