ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND. By Lewis Carroll. With a Proem by Austin Dobson, and Thirteen Plates in Colour and numerous Text Illustrations by Arthur Rackham, A.R.W.S. Square crown 8vo, price 6s. net. [November 15.

RIP VAN WINKLE. By Washington Irving. With fifty-one Coloured Plates by Arthur Rackham. A.R.W.S. In One Volume, crown 4to, price 15s. net.

Times.—“It will be hard to rival this delightful volume.”

London: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

21 Bedford Street, W.C.

MARIANNE and AMELIA.

THE CHILDREN AND THE PICTURES: BY PAMELA TENNANT: PUBLISHED IN LONDON BY MR. WILLIAM HEINEMANN AND IN NEW YORK BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY: MCMVII

THE SKETCH ON THE TITLE-PAGE

IS BY ARTHUR RACKHAM, A.R.W.S.

ILLUSTRATIONS REPRODUCED BY

HENTSCHEL-COLOURTYPE

Copyright 1907 by William Heinemann

| PAGE | |

| I. | 1 |

| II. | 15 |

| III. | 21 |

| IV. | 30 |

| V. | 38 |

| VI. | 45 |

| VII. | 52 |

| VIII. | 60 |

| IX. | 67 |

| X. | 75 |

| XI. | 79 |

| XII. | 92 |

| XIII. | 107 |

| XIV. | 115 |

| XV. | 122 |

| XVI. | 129 |

| XVII. | 139 |

| XVIII. | 143 |

| XIX. | 152 |

| XX. | 161 |

| XXI. | 171 |

| XXII. | 178 |

| XXIII. | 187 |

| XXIV. | 191 |

| XXV. | 196 |

| XXVI. | 212 |

| XXVII. | 222 |

| To face | ||

| page | ||

| Marianne and Amelia | Hoppner | Frontispiece |

| Mrs. Inchbald | Romney | 4 |

| Robert Mayne, M.P. for Upper Gatton | Reynolds | 10 |

| Beppo | Reynolds | 12 |

| Peg Woffington | Hogarth | 16 |

| Children Playing at Soldiers | G. Morland | 18 |

| The Apple-Stealers | G. Morland | 20 |

| The Fortune-teller | Reynolds | 22 |

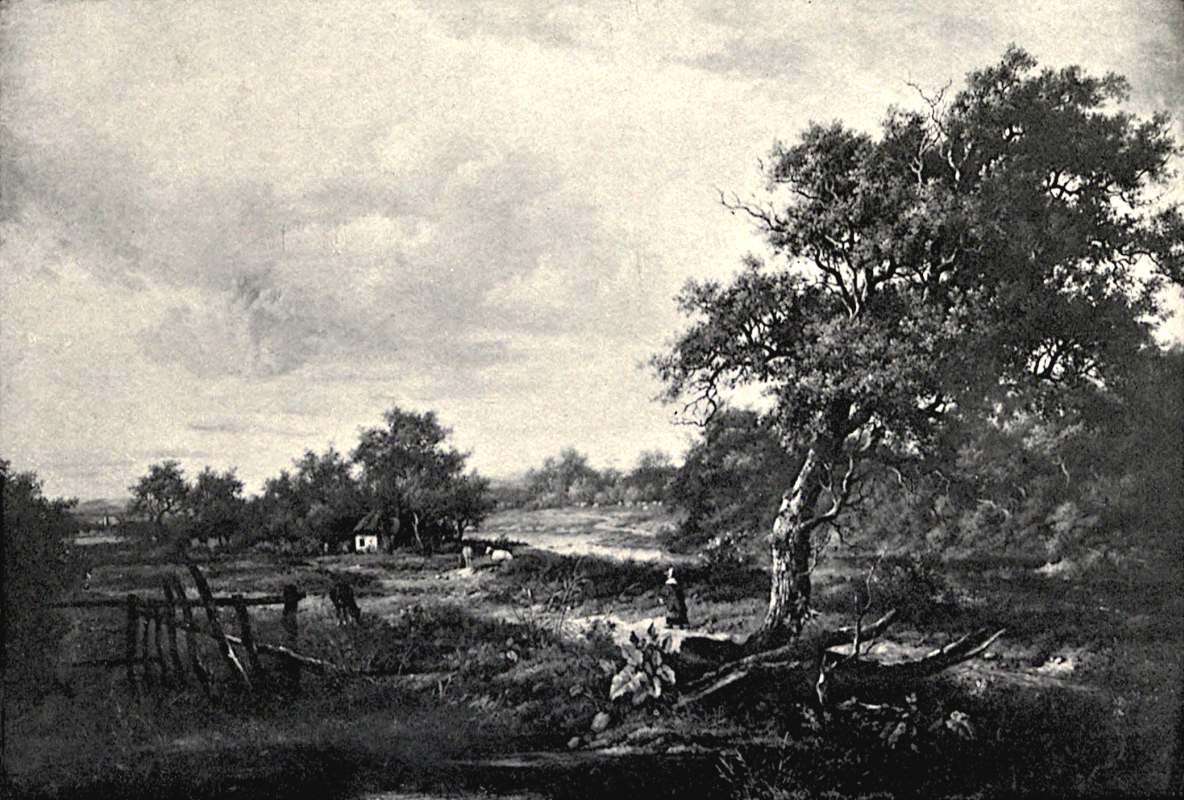

| Mousehold Heath | Cotman | 56 |

| Lewis the Actor | Gainsborough | 76 |

| Approach to Venice | Turner | 80 |

| Miss Ridge | Reynolds | 82 |

| Sir Joshua Reynolds | Reynolds | 84 |

| The Green Room at Drury Lane | Hogarth | 88 |

| The Leslie Boy | Raeburn | 92 |

| The Cottage by the Wood | Nasmyth | 96 |

| On the Seashore | Bonington | 154 |

| The Fish Market, Boulogne | Bonington | 180 |

| Miss Ross | Raeburn | 198 |

| Lady Crosbie | Reynolds | 214 |

| Dolorès | Reynolds | 222 |

thomas l. beddoes

NATALIE had been left downstairs, there was no doubt about it. She was not in her cradle, she was not in the toy cupboard, she was not on the shelf, she was not on the dresser; she must be downstairs on one of the drawing-room tables, and what is more, face downwards.

This is what passed in the mind of Natalie’s mistress as she lay warmly in her bed. She lay[Pg 2] looking at the nightlight shadows, but with this last thought she sat upright, and looked round her. Yes, she must have been asleep, for the nightlight was burning brightly and fully, as it does when it has been alight some time; not showing that melancholy little humpbacked flame with which its vigil commences. “I wonder what time it is,” thought Clare, “I wish I had remembered to bring Natalie up to bed with me.”

She lay down again, and tried to go to sleep, but one feels very wide awake indeed if one keeps thinking of one thing in particular. You feel even if you buttoned your lids down, they would still flutter wide.

There is a writer called George Herbert of whom you have heard, and in one of his poems he says,

and rest was impossible. So it was with Clare. She kept seeing Natalie nose downwards.

“I’ll go and fetch her,” she said, and she was out of bed in a twink.

[3]

Quietly she passed through her little room to the door, passing all the familiar shadows. There was the big one cast by the cupboard, that looked like a cloaked figure by the door. And there was the black corner with the sharp shadow jutting out of it, that was really only the chair-back, for she had moved the chair one night to make sure. And there lay her little pile of clothes on the chair itself, but even the sight of these did not make her remember to put on her slippers, and passing all these things and so through the room, she opened the door, and went out into the passage.

How light she felt! as if she’d left her body in bed and was going downstairs in her soul. The stair-rods touched the back of her heel strangely cold; how soft and deep the carpet was.

The floor round about the big landing window was flooded by moonlight, and by this Clare moved, but it did not reach very far, and soon she had to feel along the wall towards the drawing-room. Then she saw beneath the door a thin streak of light shed on the carpet, showing the lights had not yet been put out within.

“I wonder if they’ve been forgotten, or if Mummie’s still in there,” thought Clare, and she turned the handle.

[4]

The room was partially lit by one of the lamps, and Clare ran in to seize Natalie. There she lay, her furry eyelashes sweeping the faultless contour of a china cheek.

But in the far end of the room by the shaded light, some one was seated, writing. It was the figure of a woman. Clare ran forward eagerly, but a strange face was turned to her, strange, yet not wholly so, in some way it was familiar. The lady was dressed in white material, rather like stiff muslin, her face was eager, and shrewd. She had sharp brown eyes, and as she leaned back in her chair, turning sideways, Clare recognised her. She was Mrs. Inchbald. And as Clare realised this a little wave of fear swept from the nape of her neck to her heels, as she stood looking.

“Why aren’t you in bed, child?” Mrs. Inchbald said, in measured tones. She spoke slowly, with a controlled stammer. Clare felt as if she were not going to like her, very much.

“Why aren’t you in bed, child?” Mrs. Inchbald repeated. “Good Heavens, the way the children over-run this house is something unparalleled! Collina, Beppo, Dolorès and Leslie, not to mention Robin and Fieldmouse; but I see now, you are one of the others. Well, they make noise enough[5] in all conscience. Why, I repeat, are you not in bed?”

MRS. INCHBALD.

All this time Clare had been looking at the lady, and was now quite sure she didn’t like her. The wave of fear she had first experienced had receded, and she had only an overmastering inclination to be “rude back.” She knew now she was talking to one of the pictures, and “Why aren’t you in your frame?” was on the tip of her tongue to utter. But she knew she mustn’t say it, so she just stood and let her eyes grow as hard as Scotch pebbles, and she Scotch-pebbled Mrs. Inchbald with all her might.

Evidently that lady was one of those who do not need any answer, on the contrary who prefer conducting the talk, for she continued with a stammering fluency,

“I suppose there are nurses in the house; to be sure, I’ve seen them. But it’s all this modern movement among Mothers to have their children with them, I suppose. The Parent’s Review. I’ve seen it lying about on the tables. By the way, child, your Mother reads remarkably uninteresting books. I found mine on the table once, but only one was cut, and that partially. Why doesn’t she read Mrs. Radclyffe?”

“I suppose people who live framed by themselves,”[6] thought Clare, “may grow rather prosy”; but she had discovered the value of making comments inwardly. Even had she been about to speak, Mrs. Inchbald would have given her small hearing.

“Goodness me! I’ve heard the poor lady herself allude to her own room as Piccadilly when two nurses, three children, somebody with a note, the cook and the clock-winder, all focus their energies upon it at the same time.

“Then at dressing time it is like this:

“‘Will you hear me say my prayers to-night?’

“‘And mine?’

“‘And mine?’

“‘And mine?’

“‘Can I have a joo-joob?’

“‘Don’t you think Juno was awfully interfering?’

“‘When do we go to Peter Pan?’

“‘Well, good-night, good-night, I won’t speak again really,—but you’ll come and kiss me, won’t you Moth’?’

“‘Is to-morrow football?’

“‘O, my lips are so sore!’

“‘And mine!’

“‘And mine!’

“‘What have you got on, Mummie?’

[7]

“‘What?’

“‘O, your yellow. Well, good-night, boys!’

“‘When do we go on our expedition?’

“‘Oh! it’s soup.’

“‘I’ve got a flea-bite.’

“‘Have you? Where?’

“‘Will somebody brush the crumbs out?’

“And so on, indefinitely. How she stands it I can’t imagine, but there is peace at last. And then it’s the turn of the other children; but I’ll say this for them, they make very little noise.”

“What other children?” asked Clare, with a sense of growing excitement, “do you mean——”

“I mean the picture children of course, child. Leslie, Beppo, Collina, and the little Spencers. You interrupt me as callously as you do your poor Mother. My next novel shall be concerned with the amazing difference in the up-bringing of children, then and now. But how different it all is to Grosvenor Square!”

This caught Clare’s fancy. She loved people to criticise and draw comparisons. “O, what?” she said. “Is it different? Of course I know it is, but do tell me, don’t you like it? And did you like Grosvenor Square?”

[8]

“They knew how to live there,” said Mrs. Inchbald severely: “everything was in order, my dear. There was a butler, with all the punctuality of a heavenly body surrounded by his satellites, the footmen, who could be thoroughly depended on to keep up the fires....”

“Yes, even in the very warmest weather, Mother says. She doesn’t like footmen, you know, except in palaces; she’d rather men were soldiers, or ploughed fields. She doesn’t like to see them hand plates about, which women do far more prettily; besides, men stamp so, and blow down your back.”

“Perhaps the furniture,” continued Mrs. Inchbald, regardless of interruption, “perhaps the furniture was unsuited to child-life, holding the priceless china as it did ... the move was certainly courageous. But O, how we were loved!”

Something in Mrs. Inchbald’s voice made Clare listen. She liked her better now that her hard face softened so.

“Ah, that was something like belonging! it warmed us, my dear, it warmed us; that’s what made us alive. Do you think if your Grandpapa had never loved us in the way he did that we should be here walking and breathing—we, but semblances[9] of human form dwelling in pigment and paste? It’s only love that can make alive, and he did it. Sometimes, after all the lights were out and the folks in bed, the door would open and he’d enter. I can see him in his dressing-gown and slippers, the light shining on the mahogany door; his clean white hair, and shrewd face. His hands so swift in movement, so beautifully kept, his beard trimmed so neatly. Did you ever see him untidy, I wonder, or harassed, or wasting time? Never—it all went so easily, he had the long-houred day of a busy man. Time to read aloud to others, time to look over his old French books, time to saunter out and play golf earnestly, and time, above all, to spend, upon us. How he loved us. We shall never have that again.”

“O yes you shall,” said Clare, for she was warm-hearted really, for all the Scotch pebble in her eyes on occasion—“O yes, you shall. Why—we all, all like you we are all going to learn about you, Mother says so; it is only Lady Crosbie who sometimes ... bores her, you know.”

This came out rushingly, and Clare would have withdrawn it, but the spoken word is like a sped arrow, there is no calling either back. Mrs. Inchbald changed completely. Her brown eyes twinkled[10] comfortably, and she leaned in her eagerness, right out of her chair.

“You don’t say so? Well, I agree with her. I believe I shall get on with your Mother, after all, though she does let you all victimise her, and reads such dull books. But I shouldn’t have chosen the word bore exactly. I shouldn’t say Lady Crosbie ever bored people ... dear me, O no, she’s vastly entertaining, my dear, to those she thinks worth it....”

“Well, Mother says however charming she must have been in life, it is rather tiresome, in a picture, to be looking permanently mischievous. She says, although Lady Crosbie is flitting off into such a lovely landscape, she’s not really going to know how to enjoy the country at all.”

“My dear, your Mother’s talking about something she doesn’t rightly know about, begging your pardon, if she calls that country. That’s studio, my dear, sheer studio, and a very good studio landscape it is. But all the same, your Mother’s opinion interests me; I notice she keeps the light on some, and not so often on others. I wonder what she thinks about it all.”

ROBERT MAYNE, M.P. FOR UPPER GATTON.

“O well,” said Clare, “once she’s made up her mind she’s not to have bare walls (which is what[11] she likes best to live among), she says she likes you all, and Miss Ridge she loves. She says she knows she was a darling, and of course she loves Miss Ross, and so do we all, only we long to make her happy. And we like Lewis the actor, because he’s showing off so finely, and Bimbo longs for his sword. Robert Mayne’s got the loveliest clothes, and such a kind face, Mother says she feels he knows everything, before she’s spoken. She feels sure he’s a dear, and she says his face makes her feel bound to tell him what she’s been doing; and he’s never bored by trifles. And often when we come into the room, just for fun, Mummie says, ‘Well, we’ve come in again; it’s very windy and cold, but the crocuses are showing. I had a few things to do at Woollands, but it’s so vexing, I couldn’t find a match anywhere for the blue....’ And then she goes on, looking at him in his picture, and makes up all sorts of enjoyable nonsense, and says get away with us, she’s talking to Robert Mayne; and we love it when she’s in that mood; and say ‘Go on, go on,’ and sometimes she tells us what he says to her—but, the best of all was when....”

“Was when ... was when....” echoed a very pleasant voice beside her, and a hand was set on Clare’s shoulder. And, looking up, she saw Robert[12] Mayne standing there, M.P. for Upper Gatton. Never did she think his face looked nicer than at that moment, or his coat so warm and red.

“It’s only love that makes alive,” he repeated, looking at Mrs. Inchbald. “Was I right or was I wrong, Madam? Should you and I be talking to this little thing here to-night if they didn’t care?” His voice was so extremely comfortable that Clare felt wonderfully happy, just as one always feels if people are near one that understand. You feel stroked down and peaceful, and as if you needn’t talk much, because they know. And you think you never need feel as if your inside were made of red serge soaked in lemon juice, which is the feeling that another kind of person brings about. So Clare stood and watched him talking to Mrs. Inchbald, and enjoyed it very much.

“I think I had the pleasure, Madam, of travelling in the van with you, when we made the much-dreaded move?”

“You did, Sir, and you were mightily helpful staying as you did the needless chatter and tittle-tattle of the occasion.”

BEPPO.

“It was the morose forebodings that I felt grieved by,” said Robert Mayne, “the faithless despair, the manufactured misery of morbid minds. Why,[13] what need was there to fill the children with apprehension, to chill our own hearts with fear? You yourself, madam,” he continued with a charming bow, “had need that day of all your energy of character for which I have so much respect. You would not let the weaker moods possess your heart. How I wish we might then have shown those who were fearful, these sheltering walls, these fair white rooms, this Home!”

“You might show some folk the loaves upon the table, and they’d swear they were going to starve,” said Mrs. Inchbald crisply. “The children are well housed too, for that matter; really better than before. I don’t think yellow satin and brocade suits children—white-wash and brown holland, say I. And this house is as near to white-wash as the Mother can compass. Even the drawing-room curtains, I’m told, are to have a decidedly brown-holland appearance.”

“But the children,” said Clare, “are they really in the house? O, do let me see them, will you, Ma’am?”

“It’s time I were framed, and you were in bed, my dear, so we may as well go together”; and the brisk old lady rose in her stiff muslin and walked towards the door. Clare just had sight of Robert[14] Mayne settling himself comfortably to read in an arm-chair. Then Mrs. Inchbald led her out into the passage, and up the stairs to her own room. But one strong impression remained in Clare’s mind, that the passage seemed in some way different.

“That’s not my door,” she said, as she looked before her, “and Mother’s room is further on. I never noticed a door there before. O, Mrs. Inchbald, is it the children’s room?”

She stood in a long low apartment, the light shed from a nightlight falling softly on six beds. On each pillow lay a little head.

Clare stepped quietly beside them; how pretty they looked in their sleep, Collina and Beppo and Leslie, Dolorès and Fieldmouse and Rob.

There they lay, the pillows scarce dinted. How clearly she recognised them. And as she bent over the white bed of Dolorès, Clare saw the tear glisten wet on the rounded cheek.

[15]

j. b. tabb

WHEN Clare woke next morning it was almost time to rise. She could guess the hour by the wan light of a wintry sunbeam touching the inner edge of her window curtains, and the sound of housemaids stirring in the house. There lay the grapes by her bedside that her Mother had brought for her to find on waking. She put out her hand for these, and gradually as she lay there, there came back upon her remembrance, the strange experience of last night.

Had she dreamed it? If so, it was a vivid dream. How sincerely she hoped not. “Because if I’ve[16] dreamt it I shan’t be able to go on with it and, if it really happened, there is no reason why I shouldn’t see all the others, and what fun that might be. I should ask what it was Fieldmouse had just told Rob that made his eyes so round and shining, and what it is makes dear Miss Ross so sad, and I should ask how long Kitty Fischer has had her doves, and if they lay eggs all through the winter like Mummie’s; and....”

“Clare! d’epêche toi, ma mignonne, voyons, voyons, voyons;” and Mademoiselle entered the room concerned to find Clare still in her nightgown, and dawdling, with bare feet. But all day long, through the hurry and skirmish of an ordinary day, through the tedium of lessons and the ballyragging of the boys, Clare hugged her precious secret to her heart. She couldn’t bear to speak of it, for if it were only a dream, her longing for it to continue would be intensified. She had seen Mrs. Inchbald and Robert Mayne, and spoken to them, and the children in the pictures were real. If this were only a dream, then she’d rather not talk about it; but if it were true, if it were really true, then she’d tell Bim and Christopher about her wonderful discovery, and to-night, this very night it would be proved.

PEG WOFFINGTON.

[17]

Have you ever lived through a day that has some treasure of knowledge or expectation, that lies hidden beneath everything tiresome, beautifying the prosaic features of the day? To Clare it made it wonderfully easy to put up with all sorts of difficulties, this enchanting secret of hers.

Bedtime came, and after the usual bath-skirmish all three children were in bed. Prayers said, lights out, and the shadows in possession. Then, because she had had a long day and was tired, Clare slept. And when she awoke she heard her name repeated. She sat up wide awake, and saw Dolorès by her bedside—her little bodice crossed as prettily as in the picture, with tiny skirt, and lifted eyebrow, there she stood.

“Are you coming to play with us to-night, Clare? We’ve got the drawing-room to ourselves for an hour before the party, and it’s lovely, for the furniture is moved away. But we shall have to go to bed when Mrs. Inchbald says so, but there’s still time before that. Shall we go and fetch the others?”

Clare’s heart beat quickly, but she was out of bed in a moment, following Dolorès from the room.

“I must wake up Bim and Christopher,” she said. “Will you wait for me? Their room is not far away.”

[18]

She ran off, but came headlong in collision with somebody round the corner of the stairs.

“Mercy,” exclaimed a sharp voice, “the children again, I’ll be bound.” This was said with great asperity, and Clare, recovering as best she might from a stinging box on the ear, had just time to see Peg Woffington pass round the corner in the shortest skirt, and jauntiest little bodice imaginable.

“Bim said she looked cross, and isn’t she!” thought Clare, as she ran on into the boys’ room.

But what was her surprise to find the beds empty, Bim and Christopher were gone. “Never mind, come downstairs,” said Dolorès; “I dare say Leslie may have taken them down.”

No steps of Clare’s could take her sufficiently swiftly. To be left behind was to her something intolerable; the boys were already down and perhaps having all sorts of fun, and she’d gone in to wake them up, and it wasn’t fair. If you sound the letters pr very quickly for a second, it will give you some idea how quickly she ran downstairs.

CHILDREN PLAYING AT SOLDIERS.

Bim and Christopher were standing together talking to a group of children, and Clare heard Bim explaining:

“I’m so sorry; it’s my fault, but you must come, boys, another day. You see two of my[19] friends mayn’t play with children they don’t know, and so I hope you’ll come again and have a game with Christopher and my sister. My Mother wants you to wipe your boots on the mat as you go out, and I’ll send word when next we want you. Good-bye, good-bye, here’s a bun for each—and, wait a moment, take all this cake, won’t you?”

Clare’s first thought was, “Bim’s got his Wilsford village boys here, but how has he managed it?”

“O Bim,” she cried out, “who are they, what are you doing, why are they going away?”

“Wait a minute, I’ll tell you. You see, Leslie woke me and Christopher, and said we were going to have a jolly game. I had asked in the village boys as usual, and found out too late that Charlotte and Henry Spencer aren’t allowed to play with them, you know. I felt dreadfully awkward, but it’s all right now. I don’t know how people can have such swabs for Mothers. Anyhow, there it is, and as Charlotte and Henry came down first, I can’t very well go against it. Come on, children,” he called out suddenly, and Leslie and Beppo rushed up, their eyes glancing. But not before Clare had a glimpse of an astonishing sight. It was this. All the dear children to whom Bim had given cakes filed out into the passage. With her own astonished[20] eyes, she saw them walk up to the Morland pictures, and disappear into them among the trees. They were “the apple stealers,” and the “children playing at soldiers,” and as she ran up to the pictures with all her heart in her eyes to look closer she was just in time to hear that sound of ineffable beauty when the wind blows softly among a myriad leaves.

There was a cool smell of moss.

A bough swayed under the weight of a climbing boy, and she heard a dog bark in the distance.

Then the branches closed over, there was a rustle in the greenwood, and everything was still.

THE APPLE-STEALERS.

[21]

the prelude

AFTER the village children had disappeared into the wood, Clare turned to join her brothers. She found them clustered round Fieldmouse and Robin.

“Whose fortune shall I tell now, good people?” Mousie was saying, her upper lip drawn into a point, so that her mouth was shaped like the tiniest V.

[22]

“Mine, please,” said Clare, “how do you do it?”

“O,” said Rob; “she learnt it in our great adventure; she learnt it from the gipsies. Didn’t you know we’d had a great adventure?”

“No, when?”

“We were stolen by gipsies, and kept away from Mother and Father a whole six weeks,” said Robin.

“And then we only got back by being tied up in bags, so that they thought we were barley.”

“Oh, tell us all about it,” cried the others.

And as they cared to hear it, perhaps you will care to hear it, and so here is their story from beginning to end.

The Story of the Children and the Gipsies.

Charlotte and Henry Spencer lived with their father and mother at Blenheim Palace, in the County of Oxfordshire. Blenheim Palace was the name of their home, and it may be seen to this day, standing in all its magnificence in the midst of a great park. For Charlotte and Henry were the children of the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough, and Blenheim Palace was the gift of a grateful nation to their great-grandfather,[23] John Churchill, the first duke. He it is you read of in your History books, who won the battles of Ramilies and Malplaquet, Oudenarde and Blenheim, fighting against the French; and his Duchess Sarah was famous for her beauty, and was the friend of Queen Anne.

THE FORTUNE-TELLER.

These children then lived, as I have said, at this great Palace, and were dressed in red velvet and feathers, and taught to dance the minuet and gavotte. There were no trains in their day, and no telegrams or motor-cars. They travelled by the stage-coach if they came up to London, and life was in many ways rougher and cruder then than it is now.

If a message were needed, a man had to saddle a horse and gallop miles with it, or perhaps foot-runners were engaged. And this means that a man, footsore and mud-stained, might arrive suddenly at your father’s door, having run or ridden over half the country, with a note to deliver in his hand. Charlotte and Henry knew a very different England to what we know now in many ways; yet essentially it was the same. The flower seeds in their garden plots grew in just the same manner as do yours, and when they went bird-nesting they found just the same kind of nests in the same kind of[24] hiding-places as you do now. The wren’s nest, made of last year’s leaves, because it is built in a beech-wood, and the one made of green moss, because it is built in a yew-tree; these they knew just as you know them, because these belong to the kind of things that don’t change. So you may imagine them, when at last they had finished their lessons, which occupied many more hours of the day than yours, you may imagine them running out to the hay-field, which looked to them just as you see it, or running to the dairy, which held the same cool pans of creamy milk. But in one way perhaps their condition was different; they were so rarely left alone. They had always a nurse or governess or a tutor with them; and if they were with their parents, they had to sit so quiet in the large rooms that it was little or no pleasure to be there. They lived in the days that Miss Taylor writes of when she says:

[25]

Those were the days of strict upbringing and formal manners. If a little child wouldn’t dress quickly, she was left in her night-gown all day; or if two little girls quarrelled over two new dolls that they loved intensely, their mothers would send these two new dolls back at once to the shop from which they were bought; and no matter how many tears, no forgiveness.

Well, as one result of all this strict surveillance Charlotte and Henry developed a passion for being alone. The words “to escape” were to them words of magical import, and they would sometimes lean out of their little beds towards each other whispering long plans. It began something like this:

“Mousie?”

“Yes——?”

“Are you asleep?”

“No—are you?”

“No. I say.”

“Yes?”

“Shall we escape?”

“O-O-Oh....”

This was Mousie putting her lips in that particular way she has, and running her little eyebrows up. And this was not a conversation of one evening, it was a conversation of a hundred rush-light vigils, the burden of a hundred corner-talks. And to run from one end[26] of a hay-field to another was a joy, and to look at the wide world from the window of the family coach, was an enchantment.

One day, as they were walking with their governess in the gardens, something unusual occurred. Mousie cut her hand badly with a sharp strand of Pampas grass, and the blood flowed so swiftly from the fingers that the governess became alarmed. Hurrying the child into the gardener’s cottage she asked for cold water and a bandage for the wound. Robin followed, distressed and silent, while the gardener’s wife eagerly fetched everything she could supply.

“We must bathe it in vinegar before bandaging,” said the governess, “and if this is beyond your power to provide, my good woman, I will myself go and fetch some from the house. Lady Charlotte must take no undue exertion till the wound is properly tied.” And Mrs. Goodenough left the cottage immensely perturbed, walking past the good gardener’s wife in the doorway, as if no such person held open the door.

Mousie had other manners, however, and now her whole mind was centred on the actions of the kindly woman who had done all so willingly.

“I’m afraid your basin is stained, I am so sorry, I didn’t know that grass cut.”

[27]

“And how should you, my lady? ’tis a nasty cut surely, and as for the basin there’s no manner of harm done at all. I’m that sorry I’ve no vinegar for your ladyship, but Peter was to buy me some coming back from the fair.”

“From the fair! O, what fair?” said both the children.

“Why, Woodstock Fair,” said the woman; “the road has just been packed with gipsy vans and menageries, and tinkers, and droves of ponies—just packed, for the last few days! But you wouldn’t be seeing that, being never on the common roads, as a body might put it. But George and Peter are away to see the fun, and to bring us all fairings.” Smiling she went to the lintel to see if Mrs. Goodenough were returning from her quest. Mousie and Rob looked at each other, and their eyes exchanged the same thought.

What longing possessed them to visit the fair; they knew well enough what it meant, for they had had a nursery maid who used to tell them; and now to think the fat lady, and the mermaid in a bottle, and the double-headed calf and the clowns, and the cocoanuts were, so to speak, at their very door. How should they get there? It was no use asking to go, for fairs were common things; only common[28] people went to them, that is how Mrs. Goodenough would have answered the request. Yet go they must, thought Rob; and “Mousie,” he whispered, “shall we escape?”

Mrs. Brown was standing at the doorway and heard no sound of Robin’s whisper, nor caught a glimpse of Mousie’s bright-eyed response. She only turned away as being satisfied Mrs. Goodenough was not yet in sight, and she might set about some household task.

But Robin held his little black hat with the white plume across it in his hand, and in his finest manner stepped to meet her.

“We thank you very much, Mrs. Brown,” he said, “for your kindness. Charlotte’s hand is no longer bleeding, and we will follow Mrs. Goodenough from your door.”

“Do’ee stay, my dear,” said the cottage woman. “I shouldn’t like to see ’ee leave the cottage till Madam return: do’ee sit down by the settle and I’ll fetch the kittens for ’ee, they are but in the wood-shed at the back.”

But Robin’s mind had but one thought, and Mousie’s hand was clasped in his.

“Come away, come away,” he said, “Mousie, we’ll escape, we’ll escape to the fair.”

[29]

Do you think Mousie needed any further instigation? wasn’t the lovely freedom implied in the word “escape” enough? They had no one round them to whom their naughtiness would give pain; displeasure had till now but followed the commission of a fault. It is only when children really love those around them, that they hold some rein upon their fitful desires. Only when they stop to say: “Will it grieve Mummie if I do it?” is there a chance of their denying themselves.

Robin and Mousie knew only severity, so their inclination was a thing to be pursued, especially if it outweighed in pleasure the chastisement it might bring. They were soon running down the drive, and dodging among the bushes, clambering over fences, dropping into ditches, in the best manner of a runaway thief. How their hearts pounded against their ribs, how their cheeks glowed from running. And how wonderful it was to be alone; and to be so excited and happy.

Sometimes a rabbit would dart away among the bracken, its white scut bobbing up the hillside. And once when they sat down to rest, shielded by the high undergrowth, a large heron rose majestically from near.

“How lovely it all is,” sighed Robin; “at last we’ve escaped.”

[30]

t. l. peacock.

IT was not long before Robin’s pretty red coat had a good many holes in it. The lace was torn away from his throat and his flying cape, and that delightful little hat of his had disappeared altogether. Mousie was the best off in the matter, for her skirts had been kilted before starting. That is to say, the puce-coloured overskirt that she generally wore rather long, had been turned up round her waist, showing the cream-coloured petticoat.

It was an early fair and took place in the month of September, so they had good weather for their exploit.[31] While they were resting, rather weary, yet trying still to think it was pleasant, they heard strange voices among the trees. It sounded as if a man and a woman were quarrelling, and something about the sound made the children afraid. The man’s voice rose very roughly above that of the woman’s, and she seemed to be in pain. “Not if you strike me dead; I won’t do it, Bill, not if you strike me dead.”

“Then take that, and cease your misery, and leave your betters to do the work they’ve planned.”

And there followed the sound of blows and a clamour, half a strangled sob or cry, then a thud as if some one fell heavily. And silence for a time. And then there was the sound of footsteps slowly withdrawing through the dead leaves of the wood.

There was something dreadful to the children in this, something very frightening. Was somebody really lying there, quite close to them and quite still; somebody who had been talking and moving about just now, and who now made no movement whatever? What had happened? Had that dreadful man gone away? O, should Robin go and see? “No, no,” cried Mousie, hiding her face close to him, “no, no; let us go home, let us go home.”

But Robin was made of sterner stuff, and Mousie’s[32] fear only served to strengthen him. He found many brave things to say to her. Very soon he was upright and stealing through the trees, peeping and peering as he crept forward. Then he saw the figure of a woman lying quite still upon the ground. She had long black hair, and brown clothes on, and her face looked as if she were asleep. It was so white and pretty that Robin didn’t feel afraid of her, so he went quite near to look. And he touched the hand and thought how cold it was, and Mousie soon came creeping up.

Then the best thought that could have come to Robin, made him say: “I think she’s only asleep, because I saw her eyelids move. Run to the brook Mousie, and dip your hands in and bring as much water as you can.” And together they brought water, and patted the white face with it, and Robin laid his wet hands on the pale lips. And after a time the woman opened her eyes, very languidly and raised her head, and looked about her. And when she saw the children her eyes asked the questions her lips could hardly frame.

“You’re better now,” said Robin. And, Mousie, said, “I didn’t think dead people could come alive.” But the woman said: “Where’s Jasper?”

“If you mean the man who was, who was ...[33] talking to you,” said Robin politely, “he went away into the wood ... afterwards.”

“That was Bill, that was,” murmured the girl, “I remember now.” A sudden light came into her dark eyes, making her look scared and hunted.

“O, ’twasn’t to serve men like Bill that I come into the world, with his foul tongue, and his black heart, and his lies and cruelty and wickedness. ’Twasn’t to serve men like Bill, I tell yer! O my Gawd, why didn’t I die?”

“Because Robin told me to fetch water from the brook,” answered Mousie, “and directly I put the water on your face you came alive again.”

The girl rose slowly from the ground, and stood for a moment uncertainly, then she put out her hand to the children.

“Where do you come from, you innercents?” she asked, “dropped out o’ the clouds, eh? or may be fairies?”

“We’re not fairies, thank you,” said Robin. “I’m Henry Spencer you know, and this is Charlotte my sister, I’m eight and she’s nine, and we are on our way to the fair.”

“Then you kin take this here bit o’ paper for me. Keep straight along the road, and you’ll get a lift from a cart or a waggon, and do you take this bit o’[34] paper to the door of the mill by the stone bridge in the valley; and say it’s from Freedom Cowper.”

She swayed as she spoke, and Robin thought she was going to die again, for her eyes half closed, and she leaned against a tree. But soon she was speaking urgently, “O Gawd in Heaven, take the paper, give it to the man ... at the mill ... run, for I hear my folk comen, and they’ll never let you go, they’ll never let you go.”

There was a distant sound of footsteps, a far stir in the leaves. Robin and Mousie fled from the girl away among the trees, to the little wattle that surrounded the woodland, and scrambling over as best they might, they lay down on the further side.

They heard voices talking, and the girl’s voice hardly audible, and then footsteps going further and further away. At last there was silence and, their courage returning, they arose and pursued their way along the road.

But not now, alas, with a joyful anticipation. How willingly now would Mousie have seen home’s familiar aspects, and Robin was far hungrier than he had ever been. For it was now about six o’clock in the afternoon, and they had made their escape[35] about eleven, and they had walked and scrambled for seven hours, and had a severe fright as well.

But Robin held the bit of paper, and perhaps the idea of a lift in a waggon, made him urge Mousie along the road.

It was not long before they heard the sound of wheels behind them, and a hooded farm-cart appeared.

“Please give us a lift,” cried out Robin, and they were soon up beside the driver.

“We want to be put down at the mill, please, by the stone bridge in the valley.”

“Whoi that be farmer Dreege’s mill,” said the man; “but Farmer Dreege he be at the fair surely; there’ll not be a soul about I’m thinking, without Jasper Ford be left to mind the place.”

“Yes; that’s the man we want to see, Jasper Ford; we’ve got a message for him.”

But the driver of the cart was a man who minded his own business, for he said nothing more. He seemed content to drop the children with a nod, at their destination, when they reached the mill by the bridge.

Robin knocked at the door stoutly. A young man opened it, and stood looking quietly out upon them. He had the swart face of a gipsy, and the dark hair and flashing teeth; but his eyes were set[36] well under a broad brow, and looked out kindly upon you. So that Robin had no trace of fear and said: “This piece of paper’s for you, if you are Jasper Ford?”

Jasper read and re-read his bit of paper, the first time half-aloud; he was so earnest in his eager interest, so careful to decipher each word:

“Warn Doctor Thorpe’s household, rick-burning to-night, and robbery. Freedom.”

“Rick-burning to-night, and robbery! That means when the folk are all out to quench the fire, Bill and his lot will have the house to themselves. O, Freedom, if you would but have listened to me, and had nothing to do with the gang. But the Doctor, who Freedom owes her life to——” and Jasper thrust the paper in his pocket. “I must go, d’ye hear, youngsters? I must go now. Do ye sit and rest, and eat your bread and sop here, and I’ll come back and get your names from you when I return.”

“But tell us,” cried out Robin as Jasper turned to leave them, “tell us, how long does the fair go on; is it all over?”

“The fair? Why, the fair’ll go on till ten o’clock at night, youngsters: but you’d better be in bed by then.”

[37]

Mousie and Robin, well refreshed by food and drink, felt all their former zest for adventure returning.

“O, we’ll go to the fair, Mousie; it’s only half a mile further, and we’ll see all the shows after all.” And putting down the mugs and plates they had eaten from, Mousie and her brother left the mill.

[38]

benjamin franklin.

THE children set out with renewed pleasure, enheartened by the rest, and food.

Soon they heard a strange medley of sounds that their beating hearts told them came from the fair. Men’s voices shouting, the sound of wheels and stirring, a clamour of many musical instruments, each one not having anything to do with any other, and then they saw lights; and very shortly they were surrounded by a crowd of humanity, and an overwhelming sense of excitement and unrest.

The next time your father takes you to the Tate Gallery look at Mr. Frith’s picture of the “Derby Day.” It will give you some idea of the crowd of busy people and pleasure-seekers that Mousie and Robin suddenly found themselves among. The[39] lights were being lit along the little booths, blending strangely with the summer twilight, and Robin saw acrobats in spangles and scarlet climbing and leaping before their master’s show. He heard a roar of laughter and applause at a fellow grinning through a horse-collar, for there was a competition as to who could make the most excruciating grimaces, his visage embellished by this frame. The crowd was to determine who was the winner, and there had been already four competitors upon the little stage. This one was acquiring by his efforts immense applause, as he seemed to be able to twist his face anyhow; he stretched it longer than you would think possible; he would open his mouth and raise his eyebrows, so that his chin dropped still further and his forehead shot up into a point. Then, while the crowd was shouting encouragement, he would collapse his face suddenly, and all the length of it would fold into wrinkles, like the gurgoyle on the church tower at home. His very head seemed to flatten, and his ears grow out. Certainly he was a master of the art, and the children watched in amazement till their interest was taken by some other marvel of the fair. But Captain Marryat has described all this so well in “Peter Simple.” Why should we not have his words here?

[40]

“The coloured flags flapping in all directions, the grass so green, the white tents and booths, the shining gilt gingerbread. The variety of toys and the variety of noise, the quantity of people and the quantity of sweetmeats; little boys so happy and shop people so polite. The music at the booths and the bustle and eagerness of the people outside was enough to make one’s heart jump. There was Flynt and Gyngell, with fellows tumbling head over heels, playing such tricks, eating fire and drawing yards of tape out of their mouths. There was the Royal Circus, all the horses standing in a line with men and women standing on their backs waving flags, while trumpeters blew trumpets. And the largest giant in the world, and Mr. Paap the smallest dwarf in the world, and a female dwarf who was smaller still. The learned pig, the Herefordshire ox, and finally Miss Biffin, who did everything without arms or legs.”

So writes Captain Marryat. What a gay scene he paints. All honour to him for one of the best story-tellers. May all children read his books.

Just as Robin and Mousie were leaving Miss Biffin’s bower they heard shouts of “Fire! fire!” and suddenly the crowd of strollers and sight-seers all moved with one accord. Mousie and Rob were shoved and jostled till they were borne along in[41] the rush of people, as helpless as a couple of corks on a Scotch burn.

When they passed out from the narrowed alleys of the fair, made by the lines of booths and side-shows, the press became less great, and they were able to keep clear of the rush.

How frightened they were at this sudden stampede; and now, to add to their dismay and the general excitement, they saw a fierce conflagration among some ricks. These ricks were standing about four fields’ distant, and what at first had been one fitful tongue of flame climbing stealthily the side of the dark mass, swiftly grew to be sevenfold and leaping. And from sevenfold it spread like molten gold over the stack, as if fire had been poured over it. And now a strange rushing sound grew out upon the air, and the stack was brilliantly illumined. The figures of the onlookers were cut out black against the glare. Then a heavy scroll of smoke mounted up into the divine beauty of the night sky, defiling it with thick vapour. Now and then there would come a lull in the fierce demolition, as if even the insatiable maw of the fire were momentarily replete. Then again it would break out all the more fiercely, and a bevy of sparks would swing out, and sail away against the darkness, like[42] a great swarm of golden bees. The flames would mount ever higher and higher, and the rushing sound grow, and grow. How the antlered flames leaped and roared into the night sky, what a fierce light they shed on the surrounding world. How black and jagged the shadows were, how vast the columns of drifting smoke. The great elms in the hedgerow stood changed in the strange light, their lofty stillness intensified by the clamour, and all the depths of their cool leafage showing grey in the strong light.

The birds flew into the very faces of the onlookers, witless of their direction, and the rats ran from the burning hayricks among the crowd, blinded by the glare.

To Rob and Mousie, who had lived such sheltered lives, it was as if they had been transported to some other planet, to a world of tumult and alarm. They had no words to express their pitiful state; they stood dumbly clinging together.

And then two figures came towards them as they stood somewhat in the shadow—the figures of two men.

“The mischief’s done right enough, but it’s all for nothing, and we’ll get nothing for our trouble. We’re lucky if we gets quit of this; they’ve got[43] news of it after all. I’ve been to the side-door and the front-door, but the whole place is barred; why, the very windows have their shutters up, and the great bulldog in the yard that Freedom said she’d poisoned, standing right up against the opening, showing his teeth. There’s been foul play somewhere; we’ve been split upon; and if I can lay my finger on who’s done it, I’ll——” his speech lost itself in a string of oaths and maledictions while he trod heavily forward to where the children stood. And as he turned his great ugly visage upon them, Mousie screamed, “It’s the man in the wood, Robin! it’s the man who killed the woman in the wood!” And before Robin could say a word in answer, he felt a great blow, as if the earth had jumped up and slapped him, and he knew nothing more. Then one of the men caught the frightened Mousie and tied a cruel bandage so quickly round her that she could neither scream nor speak, and another picked up Robin where he lay quite still upon the ground, and between them they carried the children away swiftly.

The men walked till they came to a belt of trees, far out upon the Down. Here they set their burdens by the embers of a fire of charred wood. Two or three rail-backed ponies were picketed out[44] upon the green, and a great van loomed dark in the half-light. Several rough, unkempt faces peered at them, and dark forms crouched about the fire, stirring its embers to a fitful flame.

Mousie and Robin were in a gipsies’ encampment, and the very thick of their adventure about to begin.

[45]

w. blake.

IT was late the next day when Mousie opened her eyes. She had lain sensible of discomfort for some time before she wholly woke, and now a sense of movement and the gritting of wheels on a road shook sleep finally from her. She raised herself and looked round. She was lying in a little box-bed, only just large enough to hold her. A rough sheet was thrown across her of the dingiest nature, and the muscles of her neck and shoulders ached when she turned about. And there in the corner of the van, lying on the floor with his head on a bundle of clothes, lay Robin. A very old woman sat in a chair beside him, and every now and then[46] she would bend down and look earnestly into his sleeping face.

“Robin, wake up,” cried Mousie; “Robin, where are we?”

“Whist there, with your wake up,” said the woman in a low voice. “Be silent, will ’ee? rousing him from the first bit o’ quiet sleep he’s had the whole night long.”

She looked at Mousie long after her half-whispered words were uttered, scowling from under her shaggy brows; and the child kept her eyes fixed on the old woman’s evil face. She had never seen so sinister and wrinkled a countenance—it held her spell-bound; she dared not so much as move in her box-bed. Slowly the van ground along the flinty roads, sometimes lurching this way and that, sometimes almost overturning in the stony inequalities. The old hag moved about, but was never far from Robin, bathing his temples with a moistened rag, or forcing the pale lips asunder, and giving him a spoonful of brown liquid. Then Mousie saw that Robin moved languidly, and every now and then opened his eyes. That he should be awake and not seek her seemed strange, but so long as the old hag watched over them, she dared say nothing.

[47]

Then the van stopped, and the door was thrown roughly open. The old woman climbed down the steps into the fresh air.

“Now then, get up, and let’s see what you’re good for,” she said crossly, as she looked back threateningly at Mousie, and disappeared. The child rose from her box-bed and followed.

The delight was great to feel the warm clear sunlight round her, as she stepped out on to the soft grass. They were in a wide track with ragged thorn hedges, and two or three gipsies were unharnessing the horses. Freedom, the girl who had swooned in the wood, was building a fire with sticks and great branches. Mousie ran eagerly towards her, but to her surprise Freedom seemed hardly to recognise her, and Mousie shrank back before the strange void of her face. It was as if she moved in her sleep, barely conscious of her surroundings.

The gang consisted of seven gipsies, three men and three women, and a boy. There was Bill and Mr. Petulengro, a shrivelled old man, whose grey hair toned ill with the deep brown of his complexion. There was a younger man than Bill, whom they called Farrer, and the boy Abel. The other woman, Maria, had a baby in the shawl at her back.

[48]

Soon the men had picketed out the ponies, and gone their various ways, leaving Freedom, the old grandmother, and Maria, in charge of the encampment on the Down.

Mousie was made to do the old Grannie’s behests. She had to clean the utensils, see to the fire, haul out the murky rags that made their tents, and generally fetch and carry. She got more scoldings in half-an-hour than she had in a month at her own home, and there was no time to look peaky over it.

“Just ’ee set that sack down where ’ee took un from, and come ’ee here, and peel these potatoes, and if ’ee cut deeper than the rind, I tell ’ee I’ll cut into ’ee! Oho, my sweet pigeon, and it’s fine ladies we are, and the likes as I never see; and when you’ve done the potatoes do ’ee cut up that hill in double-quick time and bring me back some tent-pins, and if ’ee gather crooked ones, I’ll prick yer skin with them, I promise ye—I’ll prick yer pretty skin for ’ee! I’ll prick yer skin!”

She leered, and scowled, and coughed, and spat, while she shambled about talking, sometimes pinching Mousie’s cheek with her clawlike hand, or raising her skinny arm as if to strike her. It was a new experience for Mousie, and had she been given less to do, would have frightened her severely.[49] As it was she just obeyed, and dared not question, far less object or make delay. Meanwhile Maria sat on the steps of the van, crooning over her baby. And the words of her song were these:—

Mousie heard these words as she peeled the potatoes, and liked the list of the birds’ names. She didn’t know, however, that she was listening to a song hundreds of years old, a song that has been sung by voices long since dead and silent. Yet[50] there was the holly-tree in the hedge, as lusty as ever, his strong spiny leaves giving back the sunshine, each one a polished green. And below at his feet, creeping through a wattle and wrapping an old ash pollard, was the insidious ivy.

There are some characters like Ivy, gentle and clinging, yet as terribly strong. They cannot stand alone, others must support them—yes, till the weight kills. And Ivy, the dependent, takes this service. At first tentatively, even timidly—one tender little trail innocently feeling its way up the great stem; no one would think there is any mischief here. But Ivy must know while she weaves her mats and meshes, that she kills to live. For all the fruit she bears is bitter.

Throughout that day Robin lay sick and ailing in the gipsy’s van, and when Freedom came back from a long errand, she climbed into the van and stayed there, speaking to no one.

Towards evening the men returned, and old Granny prepared the dinner. Mousie liked the tripod with the heavy kettle hanging from it, and the smell of the burning wood. Then Freedom stepped out again carrying Robin in her strong[51] arms, and brought him to the camp fire. But when Mousie looked at him she cried out, for he was as brown as a nut all over. His little face and neck, and his hands and arms, and his feet and legs, all stained with walnut juice, and his curls cropped like a convict. This was Freedom’s doing, and Mousie’s heart sank when she realised it, for she had silently counted on Freedom as their friend. How should they ever get home again if Freedom wanted to hide and disguise them?

However, as the days went on, the children learnt to look on her once more as in some sort an ally, partly because she got almost as many harsh words as they, partly, because when no one was looking, she would do them a kindness if she could.

And so the hard days passed over, full of work and blows, and chidings; ugly with the sound of oaths, and rough voices, and coarse food.

[52]

w. blake.

ONE day the children went on a long expedition with Freedom. It was to a neighbouring race meeting. They started in the early morning, and it was a treat to them to escape for once the morning maledictions of Granny Petulengro, and the rough service of the camp. Freedom liked to have them with her, and it was the one day in all their long adventure that the children looked back on with delight.

It was nice to be with some one who was not always rating, and Freedom was a good companion for a walk. She stepped free and lightly, a slim brown hand always ready to help any one over[53] hedges or ditches, and, once away from the camp, the lines about her mouth fell into peace and happiness; and she would sing now and again—

She showed them how to gather the gipsies’ tent-pins, which are the thorns that grow on the sloe bushes. And she picked the thyme, that grew in scented cushions on the turf, to make tea from it later in the day. She saw squirrels before they did, and beetles whose noses bleed a bright ruby drop when you touch them—not because you’ve touched them too hard, but because that is their weapon of defence when in danger, and they do it to frighten you away.

And she showed them the larder of a butcher-bird, the bird who impales the things he is going to eat on the sharp points of thorns. Beetles and nestlings, and shrew-mice, and it’s interesting to[54] find a strike’s larder, because it’s not a thing you very often see.

And so on through the lovely day in September they walked on, or sang, or rested, or lay quite flat, and looked up through clinched eyelids to see who could best bear the light of the wide blue sky.

When they arrived at the race meeting, Freedom caught back her hair under a yellow kerchief, which she tied round her head, and the real fun of the day was over, for the children found themselves once more in a crowd. Freedom kept them closely with her, so that they might not get lost, and they were interested in listening to her telling people’s fortunes. Have you ever heard a gipsy tell a fortune? It is something like this. You must imagine a very rapid utterance, and a face thrust forward. An almost closed lid, veiling a very sharp eye, the face set sideways looking upwards, and a wheedling tone of voice.

“Shall I tell the pretty lady’s fortune? Bless her pretty heart, just cross the gipsy’s palm with a silver coin, my dear, and let the gipsy tell the fortune of the pretty lady, so her fate shan’t cross her wishes, but everything come true just as the lady (bless her pretty heart!) will be joyful and thankful for the good fortune to be. And[55] remember the poor gipsy girl when she gives her hand into the hand of her true lover, the sweetheart who has vowed to be true. It’s just a coin that does it, thank you, my lovely lady, cross the gipsy’s palm with a silver coin, and the good luck will follow it.... Thank you, my dear, thank you, place your hand on mine and let the lines tell the gipsy girl what never a print book can’t reveal, but only the stars as does it; yes, my dear; there’s a ship coming, a long journey, I see a distant land, but there’s happiness in store for those as believe it, though for those as sets their hearts agen’ it, it may be far from otherwise.

“I see a beautiful young man, a bee-utiful young man, O, but the strength of him, hasn’t he got an eye like a hawk, and a chin to him? There’ll be never no turning him from the pretty lady as he loves, not though others may say whatsoever they likes, but he’ll come straight as a beam of the morning, though I see a dark lady and two enemies what will do what they can, but don’t you believe ’em, my dear, never you believe the written words of crooked tongues, but you trust the gipsy girl, my dear, and she sees troth plighted, and love united, and a golden blessing, brighter than the stars; and a clergyman standin’ by and all.

[56]

“Now, there’s a letter to you coming, my dear, but don’t take nothing written on a Thursday, for the dark lady’s in it, and you must turn from your enemies if you trust the poor gipsy girl, for you’re one of those as may be led but can’t be druv, not though they stand never so. But three moons must shine before you hear what the gipsy girl sees in your pretty hand, but just cross the palm with another bit o’ silver, my dear, because then she can do it better with the cards, my dear, and bring the good fortune that tarries. Bless your heart, and thank you, my dear, and may you never go sorrowful, but find the lucky shoe-leather that’ll take you where you will.”

And so it goes on. The wheedling voice, the cringing manner, the crazy medley of sound and sense, with here and there a pretty phrase that is the garbled garrulity of the gipsy.

Perhaps it was this that made the children glad when the hours spent among the crowd were over. It was not pleasant to see Freedom change herself into this semblance of one of the most artful of her thieving tribe. But we know that she was bound over by the masterful nature of Bill, under whose tyranny she suffered, belieing indeed her beautiful name. While she belonged[57] to the camp she had to work for it, and to-day had she returned from the race meeting without any money, Bill would have been furiously enraged. She looked back to the days when Jasper had been one of the camp—Jasper who had broken away and had begged her to go with him. But a foolish waywardness had turned her to the stronger mastery of Bill. She had not seen or exchanged words with Jasper since then, with the exception of the written message sent by the children on the evening of the fire and the fair. But all this time she had been growing fonder of the children, and there was a plan for their release maturing in her mind.

MOUSEHOLD HEATH.

She knew that Bill was making for a wide common in the county of Norfolk, called Mousehold Heath. You may see the place in the picture, by Cotman, over the drawing-room mantelpiece. And if you look into it you will see it is an open common with several windmills, eight sheep, some poplars, and a white donkey, and a road of a warm red, that goes up the hill with a sudden jag in it, towards a row of cottages set on the crest of the hill.

It took the gipsies some time to reach this place. They had loitered, and lingered, and trespassed, and[58] poached their way through four counties, only the poorer by the boy’s coat, which had been left in a farmer’s hands one night while its owner was stealing hens.

Both children were stained brown, and clad roughly, in old unsavoury garments, and nearly all their high spirits and gaiety cuffed out of them by the old crone. We will not dwell on this part of the story, for at last there came a break in their dark sky.

Mousie woke one night to find Freedom bending over her, whispering.

“Listen, dear; it’s Freedom talking. Don’t answer now, but just move your hand if you understand. We mustn’t wake Granny, and old Petulengro is close outside. When you go with Robin to-morrow to fetch the water, leave the pitcher and make straight for the mill. You’ll see it standing high above ye, and never stop running till you reach the lintel, and there knock, and say ye come from me. I’ve told Robin; do ye understand me? Once in the mill, we’ll get ye home.”

The words seemed to dance and sing in Mousie’s ears. “Once in the mill, we’ll get ye home.” She saw them gold and shining[59] before her, and “O Freedom, dear,” she said, “O Freedom!”

But Freedom had stepped out again beneath the stars. Only old Granny snored and grunted, in her corner of the van.

[60]

Anything is worth what it costs; if it be only as a schooling in resolution, energy, and devotedness; regrets are the sole admission of a fruitless business; they show the bad tree.—g. meredith.

THAT day could not dawn too early for Mousie. She lay, after Freedom’s whisper had ceased, staring upon the darkness with wide lids. Her stay among the gipsies had deepened her nature in some measure. Before this the course of her being had been like that of a little burn, full of kinks and babblings, frothing round some obstructing but tiny stone, now conveying a straw as importantly as it had been a three-decker, now leaping in the sunshine doing nothing at all. But she had moments now of much thinking, and had gained some of that self-control, that comes to those who have faced the realities of life.

Soon the camp was stirring, and she rose from[61] her box-bed. She saw a look in Robin’s face that had not been there yesterday, and her heart gave a great throb.

“Where are the childer?” screamed the old Granny, who was always at her crossest in the morning, spoiling the shining hours with her rasping old tongue.

“Where be the childer? Off with yer! off with yer, I tell ’ee; and if ’ee don’t fetch the water in double-quick time, it’s Granny Petulengro that ’ull know it, and make you know it, ye lazy, loitering varmints, yer good-for-nothing brats! Now then get off wid ’ee, I tell ’ee; get off wid ’ee, ye brazen everlastin’ nuisance. I’ll come after ye, I will!” She stood and shook her fist, muttering angrily.

Robin and Mousie took up the pitcher and ran swiftly. They climbed over the little fence and bent their steps towards the brook, then hardly exchanging a word between them, they set the pitcher down, and crossing to the other bank, they sped up the rough hillside. How far off the hill looked—it seemed to recede before them. They ran and ran, till at last they had to slacken their pace, but now the mill seemed nearer. O, how thankful they were when they came up to[62] it, and heard the clank and lumber of the great sails going round in the fresh wind.

They flung themselves against the door that was to shelter them; they battered in their eagerness. And then the door opened, and Jasper Ford appeared. He drew them in with kind broad hands, that seemed full of pity and protection, and Mousie fell sobbing against his shoulder. The mill seemed full of people, about six pairs of eyes were looking on, expressing various degrees of sympathy.

Mousie and Robin were given something to eat, but every footstep outside was a terror. Then Jasper told them what was about to happen, that Freedom and he together had planned their escape. There was to be no time lost in getting the stain off, the hour of their departure was close at hand. Only Jasper required one thing of them—implicit obedience; and they were to trust him through all. Even if it seemed sometimes long, and as if he’d forgotten them, they must still trust him, and wherever and however they found themselves, they were to wait patiently and still.

Of course both children said “Yes,” and Mousie hugged Jasper, and thought how good his mealy[63] coat smelt, and said “yes” a hundred times more.

And then Jasper took out two sacks and tied the children up in them, and in half-an-hour’s time they were placed with about twenty other sacks in a long waggon, that came to the mill.

So once more they were upon the road driving. And Mousie and Robin spent the next hours learning to weave that garment of the soul called Patience, that hardly any children, and very few people, know anything about.

In the afternoon of that same day they reached Downham Market, and here Jasper was to deposit his empty sacks and return next day with them replenished, to Mousehold Mill. But in the meantime he must find a sure retreat for the lost pair, for it was thought Bill would come seeking them; but if once beyond a certain point, they might consider themselves safe.

Jasper’s first duty was to go to the Inn, where they kept post-chaises, and hire a messenger mounted on horseback, to take a note. He had money for this—the good people at Mousehold Mill had provided it when he told them the case. This mounted messenger was to ride straight to the town of Woodstock, taking with[64] him a small packet, neatly sewn in canvas to be safe. This parcel contained Mousie’s head kerchief, and one of Robin’s little shoes—two things that had been stored away by Freedom all this time. On a slip of paper were written the words:—

When the messenger had mounted his grey, and was well upon the road, Jasper had a difficult matter to settle. He had to decide the means to get them farther on their way towards Ely, for he himself had to return in the early morning to Mousehold Heath. And to do this he decided to hire a cart and drive them far on into the night, till he reached a turnpike cottage. Here an old hunchback lived to whom he had shown kindness. This turnpike cottage was on the public road, and the carriers’ carts passed it. He intended hiding the children with the hunchback, and commissioning him to put them into the carrier’s van on the morrow, with the message that they were to be left at Master Larkynge, till called for, at the “Wheatsheaf Inn.”

[65]

It was a lovely September night when Jasper drove the children from Downham Market in the hired gig. The moon rose large and full above them, but Mousie didn’t see it, for she was sound asleep at Jasper’s feet on a warm sheepskin.

Robin sat beside Jasper and counted the glow-worms till his eyelids began to droop.

And as they drove along the silver’d highway, the gorse bushes black against the grey Down, and the woods lying like great dark mantles thrown across the wold, Jasper sang. Surely a stanza of Freedom’s song, Robin thought. And the words of his song were these:—

At last they arrived at the turnpike cottage. The steam from the heated horse rose in clouds upon the night air, and the cart moved to his flanks heaving.

[66]

Jasper roused Mousie, and the door opened to his knock. A little bent old man with a great hunch on his back appeared with a lantern, a lantern that served more to blind every one than to help them to see, as he held it up inquiringly into their faces, narrowing his own eyes, to make out what manner of folk these were. Then Jasper carried the children in, dazed and sleepy, to the tiny room. And soon they were sound asleep in a bed in a corner of the cottage, for there was no upstairs whatever.

Mousie woke just enough to feel happy all over, with the comfortable knowledge that Jasper had really come and taken them away. So thankful did she feel that she tried with drowsy nodding head, not to forget her prayers.

And they blest it, for she slept profoundly. She dreamed she was playing with a white kid, on the lawn at Blenheim.

And it was daylight when she woke.

[67]

There is no private house in which people can enjoy themselves so well, as at a capital tavern. Let there be ever so great plenty of good things, ever so much grandeur, ever so much elegance, ever so much desire that everybody should be easy; in the nature of things it cannot be: there must always be some degree of care and anxiety.... Now at a tavern there is a general freedom from anxiety. You are sure you are welcome: and the more noise you make, the more trouble you give, the more good things you call for, the welcomer you are.... No, Sir, there is nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn.—samuel johnson.

THE children were so glad to be free from the arduous service of Granny Petulengro, that all through the early hours of the morning they were hardly aware of the anxiety that filled the hunchback’s heart. He feared lest the gipsies should appear before the carrier. Mousie could not restrain her eagerness to run hither and thither, but he would[68] not let the children out upon the road. Once inside the carrier’s hooded van he thought they would be safe, and though they were, properly speaking, no concern of his, his friendship was such for Jasper that he wished with all his heart to serve him. And a very good heart it was that beat within his shrunken body; a heart that would serve well to remind one, of the jewel hidden in the uncouthness of the toad.

At last there sounded a distant rumbling of wheels, and soon the hunchback was out upon the threshold. The children were bundled into the waggon in the sacks Jasper had brought with him, but they were not tied up as before. The sacks were to be secured round them only if any of the gipsy gang appeared. And so they started off once again upon their travels. But home was getting nearer and nearer.

After a wonderfully slow drive with old Thorn the carrier, who glowered out upon all wayfarers from the shadow of the hood, they reached the town of Ely; and here they were taken to Master Larkynge, at the sign of the Wheatsheaf. Thorn had been well paid by Jasper for his share in it, and asked no questions as to who the children were, yet both children were glad to see the last[69] of him; he had none of the hunchback’s gentleness, or the kindness of Jasper Ford.

There are some folk made of very common clay, very rough pottery turned on the potter’s wheel. People who go through life, morally shouldering their brothers out of the path, as it suits them. Old Thorn was one of these. Every movement of his body was one of determined aggression. When he stepped ponderously forward, his shoulders seemed to say,

“I’m coming along this way, and nobody’s not agoing to do nothin’ to stop me.” And when he looked round upon his audience after he had said anything, the lines about his mouth said, “And now anybody wots got anythin’ to say to the contrary had better keep it to hisself, that’s all.”

The horses of his carrier’s van seemed to know him. They would start, lifting their heads suddenly, to get beyond his reach. And as he dealt largely in extraordinarily bronchial expletives, he had not proved a very pleasant guide.

The Wheatsheaf was a different matter. Here all was cheerfulness and order. A great fire leaped and roared upon the hearth, piled bright with burning wood. A high-backed settle was turned towards the warmth, and the rosy light played[70] upon the red-brick floor, and the whitewash. Do you know certain rooms that express as you enter, “Come in, come in, and sit down and be comfortable.” And every chair says “Welcome” to you as you arrive? Well, the kitchen of the Wheatsheaf was just such a room. And every one, from the raven who stole the bones, to the cat who frightened him away to eat them herself, knew it. Prue, the daughter of Master Larkynge, wore a white cap with a full frill to it, and an apron with astonishingly small pockets. And there was pewter to drink from, and there was a humorous Ostler, and a painted sign that creaked as it swung, showing the most prosperous sheaf of corn ever garnered. Certainly everything about it spelt hospitality.

In these snug and enviable surroundings, were Robin and Mousie put to bed, in a wide four-poster with dimity curtains, and rough white sheets, that smelt of hay and lavender.

And because they were excited, and not very tired, Prudence sang them to sleep. She was very pretty, and rather sentimental, so she chose a very sad song. But if you want children to go to sleep, you had best not choose a song with a story in it, because they keep awake to know what[71] happens. But Prue didn’t know this, and being very fond of the tune, sang it to the very end. And the words of her song were these:—

[72]

This is certainly a sad song, but you should know the tune, to really feel its melancholy. It had far from a soporific effect on Mousie and Rob.

“Did he like being there?”

“Why did he stay?”

“What was his head like?”

“Who flung the leaf?”

But then Mistress Larkynge looked into the room with a flat candle in her hand, and a frilled cap like Migg’s. And she said, “Mercy on us, tell me one thing, is it thieves?”

And she roundly rated Prudence for keeping the children awake, and disappeared again in a very[73] bad temper—her white bed-jacket was like the one Mrs. Squeers wears—and her mouth full of anything but thimbles.

Then at last the children, frightened lest Mrs. Larkynge should return, lay down and really went to sleep. And when they awoke, it was on the day on which their parents came to the Wheatsheaf, to fetch them.

That was a joyful day. They had had enough of escaping. And when at last they found themselves once more at Blenheim, it is wonderful how pleasant it was. Even Mrs. Goodenough’s nose seemed the right shape, and their parent’s love and protection things to be grateful for. They were both of them in many ways the better for their adventure; it had brought out sound qualities in each.

Years after, when Robin was a grown man and Mousie a pretty lady, they went to Mousehold Mill to revisit it. And the white donkey was still alive, only being so much older, he carried his head even more despondently than before. The door was opened by Jasper, the same kind Jasper, only a little greyer, but all the nicer for that. And beyond by the fire stood Freedom, her hair as black as ever it was in the earlier days.

[74]

With the money the children’s father had given Jasper for his kindness, he had been able to set up for himself, and eventually he had married Freedom. Years afterwards, when the old proprietor of the mill had died, Jasper had bought it, and gone to dwell there; for although he came of gipsy stock, he had lost the love of wandering. And Freedom was a happy wife, as she deserved to be, and had many wonderfully brown babies.

Jasper would often stand at the open door in summer time, with his hands in his pockets and an eye on the cloud drift, and now and again as he worked, he would sing the song Rob heard him sing that night in the moonshine.

[75]

THE story finished, all the children bounded along the passage, laughing and leaping as they ran. They found the drawing-room lit, and a company assembled. It took Clare’s breath away, and at first she felt excited. Then she espied Mrs. Inchbald at the end of the long room, and ran towards her.

Mrs. Inchbald saw her approaching, and “La, child, what are you doing?” she said, “remember your minuet. That is not the way to move in a drawing-room, my dear.”

But Clare didn’t know a minuet. She lives, it is to be deplored, in the day of barn-dances, kitchen lancers, and general slouchback deportment. When little boys walk with their hands in their pockets (a most ungentlemanly attitude), and little girls stand with their heads set on their shoulders as if they were Odol bottles, poor things, and made that way.

[76]

“How well Mrs. Jordan stands,” said Mrs. Inchbald; “look at her, my dear, and learn to throw the small of your back in and to poise your head.”

Clare was getting good at keeping silence when censured, so she stood still while Mrs. Inchbald spoke. She was, moreover, immensely interested in watching the animated groups around her; she saw Bim as pre-occupied as possible, admiring Lewis, the actor’s, coat. Christopher was looking at a large russet-coloured leather book spread open before him, which Clare recognised as the portfolio belonging to the Misses Frankland; and as she looked round the room, in they came, those two pretty creatures, Amelia and Marianne. They sat down, with Christopher between them, and showed him their book. “Then they also live here? That accounts,” thought Clare, “for that dog I heard barking and whining just before I woke up this morning.”

But now the room was filling so quickly her eyes kept falling on new old friends. One group in particular attracted her attention; it was so very lively and vivid in effect. Yes, it was Barry, and Quin, and Miss Fenton—Miss Lavinia Fenton of the expressive hands. And towards this group[77] Lewis, the actor, was striding, and Mrs. Jordan was among them too.

LEWIS, THE ACTOR.

Clare was glad to see Kitty Fischer. You would hardly guess how pretty that grey dress of hers looked among all the brighter colours there.

Lady Crosbie was talking to Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Robert Mayne gave his arm to Miss Ridge. She looked prettier than ever, chief of the roguish school, and Robert Mayne looked amused and comfortable. Her face twinkled when she spoke.