Reprinted from

THE GEORGIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Vol. XL No. 3 Sept. 1956

Publication No. 2

FORT FREDERICA ASSOCIATION

By Margaret Davis Cate[1]

The recent excavation of the building sites in the old Town of Frederica has stirred interest in this now “Dead Town” and in the fortification, Fort Frederica.

Fort Frederica, located at a bluff on the western shore of St. Simons Island, Georgia, and on the Inland Waterway, was founded in 1736 by the British under the leadership of James Edward Oglethorpe, as an outpost to protect the colony of Georgia and the other British possessions to the north against the Spaniards in Florida. It became one of the most expensive fortifications built by the British in America and the military headquarters for a string of fortifications erected along this southern frontier of Britain’s provinces in North America.

The Town of Frederica, adjacent to the fort, was settled by forty families brought here at that time. These settlers built Fort Frederica and manned the fortifications until the coming of the regiment of British soldiers two years later.

Occupying about thirty-five acres of land, the town was half a hexagon in shape, divided by Talbott Street, generally called Broad Street, into two wards—North Ward and South Ward—and was laid out into eighty-four lots, which were granted to the settlers and on which they built their homes. About half a mile from Frederica, and surrounding the town on three sides, were the garden lots while the fifty-acre tracts granted the settlers were located in various parts of St. Simons Island.

Later, a larger area of safety being necessary, the entire town was fortified and surrounded by a moat, the banks of which formed the ramparts of the town. A wall of posts ten feet high, forming the stockade and palisade, flanked both sides of the moat, with five-sided towers on the corner bastions. Entrance into the town was through the Town Gate.

This old Town of Frederica was a thriving community in its day. The streets were lined with houses, some built of brick, some of tabby, and others of wood. John and Charles Wesley, founders of Methodism, who came to Georgia in 1736 as missionaries of the Church of England, were in charge of religious affairs. The town government consisted of a magistrate, recorder, constables, and tythingmen. There were two taverns, an apothecary shop, and numerous other shops and stores. The trades and professions were represented by the hatter, tailor, dyer, weaver, tanner, shoemaker, cordwainer, saddler, sawyer, woodcutter, carpenter, coachmaker, bricklayer, pilot, surveyor, accountant, baker, brewer, tallow candler, cooper, blacksmith, locksmith, brazier, miller, millwright, wheelwright, husbandman, doctor, surgeon, midwife, Oglethorpe’s secretary, Keeper of the King’s Stores, and officers of Oglethorpe’s Regiment. Frederica was a barracks town, so that its business life was dependent on the money brought in by the soldiers of the Regiment.

After the British victory at Bloody Marsh and the defeat of the enemy in the Spanish Invasion of 1742 (War of Jenkins’ Ear), peace was made with Spain by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748; and the regiment of British soldiers was disbanded the following year.

Having gloriously achieved the purpose for which it was built, Frederica now became a “Dead Town.” Gone were the soldiers who had given it life, followed by the tradesmen and other settlers. The houses fell into decay, brick and tabby walls tumbled, and fire took its toll. Much of the old brick and tabby was hauled away and used in structures erected during the plantation era and, in time, no evidence remained on the surface to show that these houses had ever existed. Other families came, built their houses on these sites, and for generations lived within the confines of the old town.

Of the several buildings Oglethorpe had erected within Fort Frederica the ruin of only one remained and this was situated on the property of Mrs. Belle Stevens Taylor. In 1903, Mrs. Taylor, through her friendship for Mrs. Georgia Page Wilder, President of the Georgia Society of the Colonial Dames of America, gave to this Society the plot of ground on which stood this ruin, which the Colonial Dames repaired and saved for posterity.

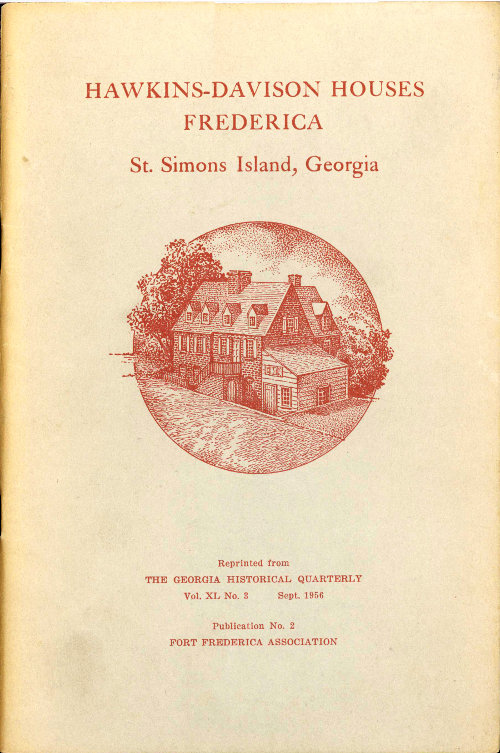

Map of Frederica made in 1796 by Joshua Miller, Deputy Surveyor, Glynn County, Georgia. Original in Georgia Department of Archives and History, Atlanta

Four decades later, under the leadership of the late Judge and Mrs. S. Price Gilbert of Atlanta and Alfred W. Jones of Sea Island, the Fort Frederica Association raised the funds necessary for acquiring the lands occupied by the old fort and town. In 1945 the property thus acquired was taken over by the National Park Service and is now known as the Fort Frederica National Monument.

Little was known about the lay-out of Frederica. Twenty-five years ago the only published map which gave information about the pattern of the town was that which forms the frontispiece for the chapter on “Frederica” in Dead Towns of Georgia by Charles C. Jones, Jr.[2] Though this map gave the plan of the old town, it was too small to be of any value.

The only maps available which gave any detailed information about the fort and the town were those made in 1796 by Joshua Miller, Deputy Surveyor of Glynn County, Georgia. These were made by order of the General Assembly of Georgia, which named Commissioners for the Town of Frederica, directing them to have a resurvey made to lay out the town “as nearly as possible to the original plan thereof....”[3] One was a detailed map of the Town of Frederica, showing the lay-out of the town, with the streets, wards and lots, together with the number of each lot. Then, for the first time was it possible to locate the exact lot on which any particular settler had lived.[4]

In 1952 original manuscript maps of Fort Frederica and the 206 Town of Frederica, dated 1736, were found in the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, R. I. The legend states that these maps were made “by a Swiss engineer,” whom the author has identified as Samuel Augspourger, a native of Switzerland, who was surveyor at Frederica in 1736.[5] The Augspourger map of Fort Frederica is most valuable, giving information about the fort, parapets, palisades, moat, and other details which had hitherto been unknown. However, Augspourger’s map of the Town of Frederica gave no information as to the lot numbers, names of streets, and other details which were desired.

Information about the Frederica settlers and their way of life has been buried in old letters and other records. Only by careful reading of available material in the scores of published and unpublished volumes of the colonial records of Georgia could small bits of such information be found and pieced together to give the picture of early days at Frederica. It is known that records were kept of the lot owners, for Oglethorpe wrote the Trustees in 1738, “I send you a Plan of ye Town of Frederica with the Granted Lotts & the names of the Possessors”[6] but this list has not yet been located among Georgia’s early records.

Even though these volumes of the colonial records contained the names of many of the settlers and told of the part they played in the life of Frederica, rarely did they contain information as to the number of the lot which such individuals occupied. Not until 1947 when the University of Georgia purchased a manuscript collection of Georgiana, known as the Egmont Papers of the Phillipps Collection, did this definite information become available. From material in this collection Dr. E. Merton Coulter and Dr. Albert B. Saye edited in 1949 A List of the Early Settlers of Georgia, which gives the lot numbers granted these settlers and makes it possible to locate each individual on the proper lot.

It is believed that this list was compiled in England by Viscount Percival, Earl of Egmont, President of the Board of Trustees for 207 the Founding of the Colony of Georgia, from information sent over from Georgia from time to time. As is so often the case with such records, there were errors. One such instance is the listing of lot number 2, South Ward, Frederica, for Samuel Davison and the same lot for Dr. Thomas Hawkins. Since the Hawkins and Davison families came to Frederica at the same time and were among the first settlers of Frederica, it is obvious that both of them could not have had lot number 2, South Ward.

Davison left Georgia in 1741,[7] moving to Charleston, S. C., and Dr. Hawkins returned to England in 1743.[8] In 1767 George Mackintosh petitioned for lot number 1, South Ward of Frederica “formerly belonging to Dr. Hawkins.”[9] His petition was not granted. In January of the following year Christian Perkins,[10] widow, petitioned the Colonial Council, stating that “there was a Lot in Frederica known by the Name of Dr. Hawkins’s which was left in the Care and Possession of the Petitioner’s late Husband by John Hawkins the said Doctor’s Brother who was supposed to be entitled thereto That her said Husband from the Time the said Lot was so left with him to the Time of his Death (being many Years) had the Possession thereof and constantly accounted for the Taxes and other Provincial Duties,” and asked that it be granted to her.[11] This was done, the lot being recorded as number 1, South Ward.[12] Thus, in this 1768 record we have proof that lot 208 number 1, South Ward belonged to Dr. Hawkins, leaving Samuel Davison in undisputed possession of lot number 2.

The families who occupied these two lots were different in every way. Dr. Thomas Hawkins and his wife, Beatre, who occupied lot number 1, were troublemakers; in fact, Mrs. Hawkins was known as “a mean woman.”[13] Samuel Davison, with his wife, Susanna, their little daughter, Susanna (born in England), and sons, John and Samuel (born at Frederica),[14] who lived on lot number 2, were good citizens and well liked by the other settlers.

Dr. Hawkins was one of the important personages in the community. Not only was he the surgeon in Oglethorpe’s Regiment and the medical doctor for Frederica and the other settlements nearby, but he kept the apothecary shop, and was First Bailiff. His house on Broad Street was his residence as well as headquarters for his work. Here he saw patients and dispensed drugs from his apothecary shop. He claimed his improvements were “superior to any other.”[15]

In addition to his pay as surgeon in the Regiment, Hawkins received a salary of thirty pounds a year as First Bailiff and was allowed twelve pounds, three shillings, four pence, for clothing and maintaining a servant, together with an allowance of four pounds for the expense of “public rejoicings, Anniversary Days, etc.” Also, he had an allowance of ten pounds for acting as correspondent with William Stephens of Savannah.[16]

The Trustees sent him quantities of drugs, sugar, and tallow, to use in his work. To enable him to go to Darien and other parts of the Colony to visit the sick, he was allowed twenty-five pounds a year for the upkeep of his boat, as well as the services of two of the Trustees’ servants. Hawkins made charges for equipment for this boat, such as blocks and rope, which the Trustees refused to pay. Likewise they refused to pay the charge of one shilling for sharpening two surgeon’s saws, and fifteen shillings for cleaning 209 and grinding his surgical instruments. In fact, he never seemed able to put through an expense account![17]

When he was not paid the sums he claimed, he wrote: “I continue the care of the sick, widows, servants and Indians and objects of charity as well as the bailiffship but cannot get regular payment....” He further claimed “my constitution [is] ruined by fatigue; character hurted by Malicious Aspersions, My Dues kept from me.”[18]

There were those, however, who did not think he had earned all he claimed. Thomas Jones wrote that “he had not administered one dose of physic to any poor person but refused, unless paid for which has been done by contributions from the inhabitants....”[19]

Oglethorpe defended Hawkins and wrote the Trustees: “I do well know that he has attended the Sick very carefully and that he constantly went up to Darien when I was here, and I suppose he did so when I was not, It is no little thing to go in open Boats in all Weathers near Twenty Miles & no small Expence to hire Men and Boats ... for tho he is very capable of Doing his Duty as a Surgeon he is very ignorant in Accounts.”[20]

Perkins, Moore, Calwell and Allen were among the Frederica settlers who had altercations with Hawkins and two of his neighbors wrote that “if it were not for debts and demands made on Hawkins there would be little use for Court at Frederica.” In 1742 he was removed from office as First Bailiff.[21]

Beatre Hawkins and her friend, Anne Welch, wife of John Welch, who with their three children lived a few doors down the street on lot number 7, South Ward[22] thoroughly disliked the Wesleys. The Hawkins and Welch families had crossed the Atlantic in the same boat with Oglethorpe and the Wesleys. During this voyage religious services had been held for the passengers 210 and Mrs. Hawkins had seemed greatly moved by John Wesley’s preaching and professed to be awakened to a new and better life. Charles Wesley, observing her actions, saw through her hypocrisy and warned his brother that her repentance was not genuine. She learned of this and, so, hated the Wesleys.[23]

After their arrival at Frederica these women attributed Oglethorpe’s puritanical sternness to the moral and religious influence of the Wesleys and conspired to bring about a break between Oglethorpe and the clergymen. They fabricated a fantastic story of their indiscretions and “confessed” these “misdeeds” to Charles Wesley, then told Oglethorpe that Charles Wesley was spreading this tale. It was not until John Wesley arrived from Savannah that the matter was cleared up, the truth known, and mutual respect restored between Oglethorpe and the Wesley brothers, a regard which was maintained throughout the remainder of their long lives.

After a few months in Georgia, Charles Wesley returned to England. However, Mrs. Hawkins persisted in her efforts to persecute John Wesley. On one of his later visits to Frederica she sent for him. When he entered the Hawkins house, she, brandishing a pistol in one hand and a pair of scissors in the other, threatened to shoot him. Wesley held her hands so that she could not use either weapon; whereupon, she seized his cassock with her teeth and tore both sleeves to pieces.[24]

Her altercations with her Frederica neighbors caused one of them to write, “If that W[oma]n is to be punished in this World, for her Wickedness, how dreadful will the example be? I grow sick with the thoughts of her,” and it was said, too, that Dr. Hawkins was “not atall beloved by the Inhabitants.”[25]

The Davison family, on the other hand, were good neighbors and were well liked by the other settlers. Charles Wesley called Davison “my good Samaritan” and wrote of him and his wife, 211 “to their care, under God, I owe my life....” Davison was said to be “one of the first of the industrious villagers.”[26]

In addition to keeping a tavern, Davison was Second Constable. In 1739 he was named Overseer of the Trustees’ Servants at a salary of twenty-five pounds a year, but Hawkins took this position away from him and named to this office one of the Trustees’ servants who had just arrived from Germany and spoke hardly a word of English. In 1740 Davison was named Searcher of Ships at a salary of forty pounds a year.[27]

For a time Davison seemed to enjoy life at Frederica. Writing to friends in London in 1738, he said that “we all of us here have been wonderfully protected by Almighty providence, very few of us have died, & none sickly; we have great encrease of Children, & women bear, that in Europe were thought past their time; The Cattle and Hogs yt. were given us on Credit, thrive very well, & Fowls in great abundance, & one may venture to say yt. ye place is blest on our Accounts....”

To another friend, he wrote “my crop wch. was but very small on Acct. of our being kept back in planting Season by ye alarms of the Spaniards, ye land I got cleared being very good, gave me great hopes; now this Year I have got at both plantations 6 acres & 38 perches of Land well fenced about 6 & 7 foot high; & planted, wch. I hope in God will afford me & my family Bread;... My wife was brought to bed of a John in July last, a fine thriving child, & little Susan grows apace.”[28]

However, in 1741, Davison with his family left Frederica and moved to Charleston, S. C., complaining of the treatment he had received from Dr. Hawkins and giving this as his reason for leaving.[29] It is not known when Samuel Davison died, but his wife, Susanna, died in St. Bartholomew Parish, Colleton County, S. C. in 1761. Her will (on file in the South Carolina Archives, Columbia) names Susanna (who married John Smith), John, and 212 Samuel, the children who had lived at Frederica; and William, who was born after they moved to South Carolina.

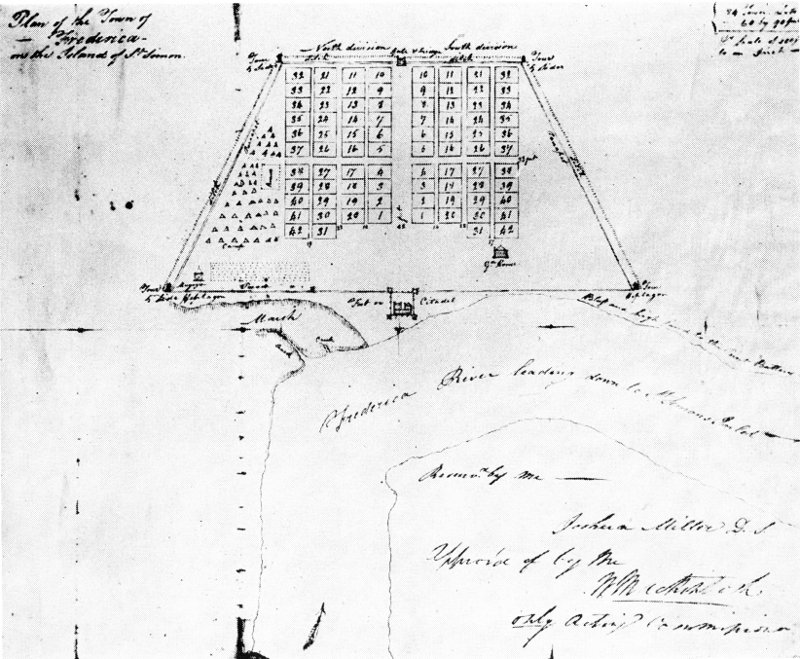

It was known that Hawkins and Davison had adjoining lots, that the houses had a “party wall,” that they were built of brick and three stories high. When funds were made available for excavating a small area in the Town of Frederica, it was decided to begin with these two lots. The location of the “party wall” would fix the lot line between these two lots, thus, making it possible to set up the exact boundaries of all the Frederica lots.

By Charles H. Fairbanks[30]

The object of archaeological excavations is usually to discover general information on the way of life of some people dead for long periods of time. In the case of these excavations we were faced with a more detailed problem, that of locating the remains of the Hawkins-Davison houses, whose existence and construction type was quite well known.

Fort Frederica National Monument is located on the western edge of St. Simons Island. It was established as a national monument to preserve the remains of the important 18th century fort and town founded by James Edward Oglethorpe as a defense against the Spanish in Florida. Only part of one building in the fort and part of the regimental barracks are still standing. The purposes of the excavation were to attempt to locate enough colonial features so that the original layout of the town could be tied to the existing topography, and to provide a field exhibit of colonial architecture. The documentary information on the town was compiled by National Park Service Collaborator Margaret Davis Cate. Mrs. Cate, in addition to her general research on the Town of Frederica, prepared a detailed evaluation of the documents pertaining to each lot. This was extremely helpful in appraising the historic material and formed the basis of the plan for excavating, as well as for this paper. In addition to the letters, the documents contained the Miller Map of 1796 which showed the arrangement of the lots, streets, fort, and barracks as well as showing the size of the lots and the width of the streets. The map contained certain inaccuracies and did not show any point that could be accurately located at the present time. In addition, it did not show the location of any house in the town. For these 214 reasons it was felt desirable to excavate a house site in the town that might be identified through descriptions in the colonial documents. The Hawkins-Davison houses filled these conditions, being built of brick and having a common “party wall.” Thus it was felt that these houses would probably yield identifiable remains and it might be possible to locate the land lot lines and the alignment of Broad Street, the main street of the town.

Dr. Thomas Hawkins, town physician and one of the magistrates, was a member of the “Great Embarkation” of 1735 which arrived in February, 1736. His household consisted of his wife, Beatre, and servants Thomas Ayot and Richard Carpenter.[31] Work was started on the houses for the first settlers in February of 1736 and seems to have consisted at first of simple huts of poles covered with palmetto thatch. Francis Moore, on his arrival at Frederica in March of 1736 says that “Each family had a bower of palmetto leaves, finished upon the back street in their own lands; the side towards the front street was set out for their houses. These palmetto bowers were very convenient shelters, being tight in the hardest rains; they were about twenty foot long, and fourteen foot wide, and in regular rows, looked very pretty, the palmetto leaves lying smooth and handsome, and of a good color. The whole appeared something like a camp; for the bowers looked like tents, only being larger, and covered with palmetto leaves instead of canvas.”[32] By November of 1736 the first two houses were nearly complete, three stories high, made of brick.[33] It is possible that these two were the Hawkins and Davison houses. Dr. Hawkins said, in a letter to the Trustees in November, 1737, that he had added half as much more to the length of his house.[34] In August of 1740 he had made another addition valued at £60.[35] This completes the direct mention of buildings and additions to the Hawkins house but a deposition taken in South Carolina in 1741 describes the two houses in some detail and is quoted at length:

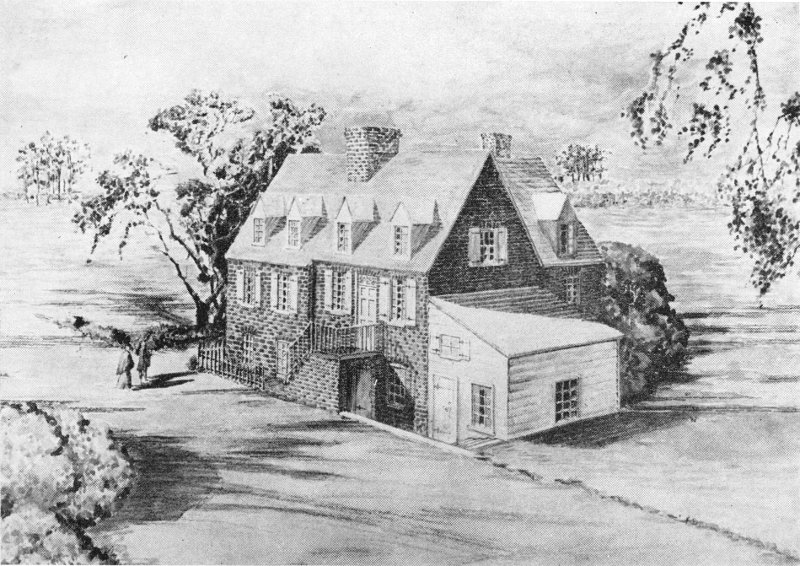

Architectural Drawing of Hawkins-Davison houses. Details based on historical documentation and archaeological evidence. Abreu & Robson, Architects.

Hawkins-Davison houses from the east. Davison house in foreground.

“John Robertson, late brick layer in Frederica, in Georgia, maketh oath and saith, that on or about the ninth of August last, being at work on Mr. Davison’s house, adjoining to Mr. Hawkin’s, at the said Frederica, on which the said Davison was putting a new roof, he did propose to the said Hawkins, to take up a few shingles, and a gutter belonging to the said Hawkins’s house, and put the said gutter on the party-wall, to which the said Hawkins agreed; saying that it would be a benefit to him, because he must be obliged to alter the roof of his own house soon: and the said Davison being to lay down a new gutter at his own expense, it would serve for both houses, and which must save one half the expense of the said gutter to the said Hawkins. But the said Hawkins being out of town, a day or two after General Oglethorpe sent to the said Davison, to forbid him to touch anything belonging to the said Hawkins’s house, though the said gutter encroached fourteen inches on the said Davison’s ground, and the said Oglethorpe’s own carpenter said it might be done in a few hours, and without harm to the Doctor.* [Hawkins—in footnote]. That the said Oglethorpe did soon after, on the same day, stand on the sill of the said Hawkins’s window, and put his head up betwixt the joists of the said Davison’s house, and ordered Mr. Cannon to build the said joists six inches lower; when the said Cannon told the said Oglethorpe they were but six inches deep; when the said Oglethorpe replied, he did not care, they might take it down, and build the house six inches lower; when the said Cannon said, that one roof would fall lower than the other, and that therefore it would be impossible to make the said Davison’s house tight, or keep it dry; then the said Oglethorpe said, you might have thought of that before. And further, that the said Oglethorpe did then say to the said Cannon, if you touch a shingle of what the Doctor (meaning Hawkins) has put down, I’LL SHOOT YOU, to which he added a great oath, for you have done more than you can answer in building so high as to stop up the Doctor’s window. That the said Davison being thus hindered from finishing his house, was forced to remove his goods from the said house (which was quite open,) and had only a stable for his family to be in, until this deponent left the said Frederica, which was on the 29th of September, 1741.”[36]

We also know that Dr. Hawkins had planted two hedges on his lot but there is no mention of fences.[37]

Samuel Davison was a chairman by trade but had been brought to Frederica to make musket stocks. He was married and had three children. His was probably one of the two brick houses nearing completion in November of 1736. By April of 1738 it was finished. In January 16, 1740 Davison complained to Egmont that Dr. Hawkins said “when my house was finished he would sell my children, one to the Carpenter, and the other to the Plasterer that did my house, which is very cutting to a tender parent.”[38] The deposition quoted at length on Dr. Hawkins’ house, of course, applies to Davison’s house as well. Davison also kept a tavern and other references indicate his lot was fenced.[39]

From these references it will be seen that the two houses were substantial enough to leave some remains, had a party wall which would follow the lot line, and the presumed location of the houses was in an area not heavily farmed in the last century.

It was hoped that the location of the party wall mentioned in the documents would lead to a determination of the present location of the original town lot lines. In this way we could locate streets, lots, houses and other features of the colonial town of Frederica. Rarely, I believe, has careful documentary research been so well vindicated as in this case. We uncovered the wall foundations of the Hawkins-Davison houses and clearly demonstrated the present location of the line separating South Ward Lots 1 and 2. The discovery of colonial wells yielded an additional dividend of many objects which illustrate the early 18th Century culture of the town of Frederica. In addition the exposed foundations serve as a vivid illustration of the existence of an English style of life established on the soil of Georgia.

The digging was started just to the west of the location for the two houses indicated by Mrs. Cate. As the excavation proceeded we uncovered the entire area of the two houses and tested the sides of the lots for evidences of fences. The area of Broad Street was trenched to prove the existence of the principal street. The wells encountered were cleaned as far as time permitted. In the 217 following account the features found will be described in the order in which they were constructed by the colonists rather than in the order of our discovery. This will give a much clearer picture of what existed there in the colonial period.

All of the colonial remains were found to be covered by a deposit of sandy humus from 0.7 to 1.0 foot deep. This had accumulated over the foundations after the buildings collapsed in the later part of the 18th Century. This was somewhat deeper than had been expected and indicated the rapidity with which remains are obliterated in the lush climate of the Golden Isles.

The house of Dr. Thomas Hawkins consisted of three rooms in ground plan and will be discussed in the order in which the rooms were constructed. At the west was a small room 10 feet east and west by 15.3 feet north and south. The room had undergone three periods of building but only the first period will concern us here. This consisted of a footing ditch 1.3 feet wide on the south and west sides. Six inch posts were placed in this ditch at intervals of about one foot. These posts formed the framework of a rather rude shed. The level of the floor is uncertain, as it had been destroyed by later construction. This pole building is believed to be the shed built at the time of the first arrival of settlers in 1736. It evidently served as a shelter during the construction of the main house which was built immediately to the east. The description by Francis Moore[40] of the palmetto bowers built in February of 1736 said that they were built on the backs of the lots. This hut was just the sort of construction one might expect from the description given by Moore. Yet it is on the front of the lot along Broad Street, and not on the back. The only explanation is that Dr. Hawkins did not build his palmetto bower on the back of his lot, or he may have built two, one at the back and one at the front. The front one was later incorporated into the main house.

Directly east and continuous with this original structure the 218 main house was erected. It measured twenty feet east-west and fifteen feet north-south, outside dimensions. The ditches for the wall foundations were dug to a point two and a half feet below colonial ground level. The walls were constructed of brick 3½″ x 2½″ x 8″ so the finished wall was one foot wide. The west wall was without a break throughout its entire length, as was the east wall which formed the party wall with Davison’s house. Both the north and south walls were broken by doorways three and a half feet wide in the centers. Evidences of wooden door casings were found in the doorways. The floor of the room had been excavated two and a half feet below colonial ground level. It had later been raised four times by sand fills averaging three inches in thickness. Mixed with the sands was an occasional brick as well as a few scattered English Delft sherds and bones of pig and beef.

It seems that the floors were made of dry-laid bricks set in sand without mortar. As the floor was raised each time, the bricks were taken up and replaced at the higher level. When the house was finally abandoned, the floor bricks were salvaged and thus were absent at the present time.

The east wall was the party wall with the Davison house. In the center there was a brick fireplace five feet wide and two feet deep formed by extending pilasters one foot wide out from the wall. The sides were plastered outside and inside with a lime plaster, as were most of the walls of the room. The fireplace had been re-built three times. The lowest level was the same as the lowest and earliest floor level. Subsequently the brick hearth had been removed, a sand fill five inches deep added and the brick replaced. Similar replacements took place whenever the floor was raised. The chimney evidently lay in the party wall and was used by both houses, probably with separate flues. In ashes resting on the hearth were found the broken remains of a stemmed glass goblet. It is tempting to speculate that this is evidence of the custom of hurling goblets, used in toasting royalty, into the fireplace; possibly a toast to the king after the Battle of Bloody Marsh.

Between the north wall and the fireplace was a bricked area 219 four and a half feet wide and two feet deep. The bricks showed no evidence of wear and this evidently represents the floor of a corner closet. The closet had evidently been removed before the floor was raised for the last time. On the floor lay a complete musket bayonet which had been placed there in its sheath as the copper sheath tip covers the point of the bayonet. There were also two parts of a door lock and a few scraps of English Delft and lead glass.

Three and a half feet north of the north wall of the room was a brick wall running east and west. It was connected to the main structure at the east by a short north-south wall and seems to have been an outside stairwell to the second floor. This wall was eleven and a half feet long, ending at the west just opposite the western edge of the doorway. In order to give access to the ground floor the steps must have run from the northeast corner up to the center of the second floor. Thus the entrance to the ground floor would be under the top of the steps. The area between this wall and the main wall of the house was floored with tabby which extended on the west to a point seven feet beyond the northwest corner of the building. This tabby floor was littered with broken crockery, glass, oyster shells, fish scales and animal bones. Evidently household refuse was allowed to accumulate here under the front steps, during the occupation of the house.

The next stage in the development of the house was a strengthening of the western, original hut. This was accomplished by putting wooden forms along the inside and outside edges of the posts of the west wall and pouring tabby around the posts to a height of one foot. This was applied only to the north ten posts on the west side. On the south side a series of bricks was found that evidently served as wedges against wall posts. The floor of the room was at this time slightly more than one and a half feet below ground level. A remnant of brick floor remained and it seems likely that the entire floor was bricked. The floor was littered with fragments of small glass bottles, small white Delft ointment jars, several glass bottle stoppers, and an ivory enema tube. This implies that the apothecary shop of Dr. Hawkins was 220 located in this western room. It is suggested that the strengthening of this hut into an addition to the house comprises the addition of half the length mentioned by Hawkins in 1737.[41] The 1740 addition was of brick and this west room is ten feet wide, half the length, twenty feet, of the main house. There is evidence of later repairs to the walls of this room but we do not know of what these alterations consisted.

During the time from 1736 to 1740 when the main room was in use two wells were in use successively just to the rear of the Hawkins house. First was a rectangular well three feet south of the rear wall and just east of the back door. This well had a rectangular pit four feet square with posts at the corners which supported a well house. The walls within the well were held up by wooden barrels placed one above another with the ends knocked out. The well was six and a half feet deep and there was less than one foot of water in this well. Several peach pits were found in the base of this well. The next well was circular directly south of the back door. It was dug six and a half feet deep and six feet in diameter. The well proper was bricked in, with a diameter of three feet. This well contained a variety of objects that had evidently been included in household trash which was used to fill up the well when it was abandoned. They consisted of:

1 small lead glass round bottle, 50cc. capacity

1 square bottle, 1 pint capacity, probably a snuff bottle

1 round bottle, 28 ounces capacity

1 English brown salt glaze stoneware bottle

1 English brown and gray salt glaze stoneware mug

1 English white salt glaze stoneware mug

1 Small white English Delft ointment jar

1 yellow and brown striped lead glaze pot with handle

1 Japanese Imara porcelain bowl, blue on white with red and gilt overglaze enamels

1 claw hammer, complete with handle

a quantity of watermelon seeds and peach pits.

The well was abandoned and filled when it was decided to make 221 another addition to the house. Tabby floor was laid over the filled well and soon sank slightly into the well.

The last addition to the Hawkins house was made at the back and measured sixteen and a half feet north-south and eighteen and a half feet east-west. The western side was aligned with the western wall of the main house, but the eastern wall did not use the party wall. Instead there was a gap of one and a half feet between the back rooms of the Hawkins and Davison houses. The brick of the walls measured 4″ x 2″ x 9″, definitely larger than those of the main house. At the southeast corner there was a large buttress outside the wall, evidently part of a chimney foundation. Inside the southeast corner was a corner fireplace set diagonally across the corner. As the tabby floor of this back room sank into the old well the depression was filled in with more tabby and later another floor level was added. There is some evidence that finally a wooden floor was installed, over the tabby.

There is no evidence as to the height of this back addition to the Hawkins house. However, the Roberson statement of 1741[42] says that Oglethorpe stood in the window and put his head between the joists of Davison’s house. It is further stated that Oglethorpe’s action involved the roof levels of the two houses. Thus it seems reasonable to assume that the joists mentioned are roof joists. As the only place in the Hawkins house where a window could face the Davison house is in the narrow gap between the south addition and the Davison house it seems this addition must have been three stories high. As this was the only addition to the house that was made of brick it seems to correspond to that mentioned as being completed by August of 1740 which cost £60.[43]

One other well belonging to the Hawkins lot was forty feet west of the house just inside the western line of the lot. It was circular and probably had a well house over it. Slightly over six feet deep the walls were supported by another series of bottomless barrels. It also had been filled with household trash including a very fine musket bayonet. All these wells had planks laid across 222 the bottom, apparently to prevent the well bucket from muddying the well. This last well had in addition a large square post of unknown use resting on the plank. Just west of the well was a poorly defined line of root disturbances which may mark the location of the hedge of pomegranates mentioned for Dr. Hawkins lot.[44]

The home of Samuel Davison lay to the east of the east wall of the Hawkins house. The front room was seventeen feet east-west and eighteen feet north-south. Directly back of this was an additional room twenty and a half feet east-west and eleven feet north-south. The east wall, however, was straight, the extra three and a half feet being taken up by a stairwell along the east side of the north room. The floor of the north room had originally been excavated to a level two feet four inches below colonial ground level. Only a disturbed sand strata remained of the lowest floor level, and it is not possible to determine of what the floor was originally composed. It was soon covered with a tabby floor whose upper surface was two feet below ground level. This floor was later covered by a brick floor, set with tabby mortar in a herringbone pattern. In the middle of the east wall there was a doorway four feet four inches wide opening into the stairwell on that side. The floor of this door appears to have joined a stair up to the stairwell, possibly to both sides. In the southeast corner of the north room was another doorway of the same width. A short flight of steps remained leading from the floor level up to the south. The steps are of brick with a four inch wooden nosing.

The north wall and the north half of the east wall were of brick. The south half of the east wall and the south wall were tabby. In the middle of the west (party) wall, directly opposite the fireplace of Dr. Hawkins house, was a fireplace five feet wide. It was formed by two short pilasters extending out from the wall. At first these were slightly less than two feet long, but they were lengthened at a later date to slightly less than three feet. The walls as well as the fireplace were plastered. This, however, was not 223 the finished wall. The brick and tabby floors did not come up quite to the wall. The space between the floor and wall, four inches wide, had contained wooden lath and a plaster coat “furred” out from the masonry or tabby wall. This gave the room a double wall and certainly made it drier and warmer than a plastered brick or tabby wall, as in the case of the Hawkins house. This suggests an explanation for the remark attributed to Dr. Hawkins, that he would sell the Davison children, “one to the Carpenter and the other to the Plasterer.”[45] It is perhaps understandable that the village doctor and magistrate would be irritated that his neighbor could afford a tighter, drier house. The south room was larger than the north but not so elaborately finished. Perhaps in this case the boys in the back room were the less favored customers at the Davison tavern. The walls appear to have been brick with the exception of the north wall which was tabby. All the walls had been salvaged down to the bottom course of brick so that it is not sure that they may have been of wood or tabby on a brick footing. However, the footings appear to be so similar to those for the other brick walls that I think we may conclude that they were, in fact, brick. The remains of a tabby floor covered part of the room area and it is possible the entire floor was so paved. There is a suggestion of steps down from outside to the northeast corner of the room, but very little remained in this section and the size of these steps cannot be determined. Just north of the Davison house a narrow ditch running parallel to the front wall was found. It is not certain what this represents except that it is clearly some sort of front fence.

Samuel Davison ran a tavern and it seems the lower floor of his house was the tap room. The large quantity of bottle fragments and stoneware mug fragments found around the house support this view. A total of 651 pieces of clay pipe bowls and stems were found in and around the house. They reflect the 18th Century custom of smoking in the taverns and give some idea of the frequency of smoking as well as the fragility of the pipes used.

The Davison lot was supposed to be completely fenced and efforts were made to locate the evidences of these fences along the east, west, and south sides. A row of postholes was found along the west side to the southwest corner and followed a short distance along the south side. The east side seemed to have another fence, but it was obscured by a series of wells as that along the west side of the Hawkins lot had been.

South of the Davison lot an open space fourteen feet three inches wide was found. South of that tabby remains were found, but time and funds did not permit their exploration. The Miller map of 1796 gives the width of the first street south of Broad Street as 14 feet. The open space south of the corner of lot 2 fits this width quite nicely. The 1736 Auspourger map says that the width of street “C” is sixteen feet. Only more thorough excavation will clear up this point. In any case the tabby to the south would be the remains of a building on South Ward Lot 19, belonging to Thomas Sumner, or to South Ward Lot 20, belonging to Daniel Prevost. The southwest corner of South Ward Lot 2, Samuel Davison, was located with some accuracy. Measuring north ninety feet, along the line of the party wall, the northwest corner was found to be three feet north of the northwest corner of the Davison house. The front stairwell of the Hawkins house extended out into the street alignment a matter of six inches. This line between lots 1 and 2 was taken as the base for laying out the grid of town lots as shown on the Miller and Auspourger maps. The town grid fits very well with the present contours that seem to represent colonial features. It can be assumed that the town grid of Frederica has again been determined. It should be possible to locate any specific town lot from the information now in hand.

Along the east side of the Davison lot a series of pits was excavated in an attempt to locate the fence along that side. There were postholes that very probably represent the fence but the area was taken up largely by three wells, two round and one square. Time permitted only the clearing of the square one. This well was exactly what might be expected on the Davison lot, the upper part had been filled with a solid mass of fragments of 225 bottles, a total of five thousand three hundred and ninety-five pieces. The quantities of glass and other household refuse in this and other wells suggest that the colonists saved such materials to fill old wells.

The present contours of the Frederica surface showed a depression, approximately ninety feet wide north and south and 190 feet long east and west, just in front of the Hawkins-Davison houses. East of this a similar depression extended on to the break in the town rampart which was believed to be the location of the town gate. This series of depressions had been considered as the trace of Broad Street. A trench was extended across the area to check the presumed location of the main street of the town. No definite evidence of Broad Street was found. There were no roadside ditches or any evidence of any sort of surfacing. Sixty-four feet north of the Hawkins front steps there was a slight depression in the old land surface. This ditch extended north another twenty feet. At that point a low ridge bounded the depression on the north.

The Miller map shows the width of Broad Street as 82 feet, while Francis Moore says it was twenty-five yards wide[46] and the Auspourger map says seventy-five feet. The contours of the ground fit the figure of eighty-two feet best. Until the recent discovery of the Auspourger Map of 1736, it had been assumed that the Francis Moore figure was an estimate and the Miller map gave the true width of Broad Street. Now that the 1736 map and Francis Moore both agree it may be assumed that Broad Street was laid out with a width of seventy-five feet. We know that the front steps of the Hawkins house infringed on the street a matter of six inches. The depression in the old land surface at the north side of the street marks the edge of the road in that area. Further work will possibly locate fences or hedge lines that will clarify this point.

At a point ninety-two feet north of the Hawkins house our excavation uncovered the remains of a tabby wall. It was badly decayed and was surrounded by the usual household debris which marks the sites of houses. It evidently marks the south or front wall of a house, built of tabby, on Lot 1 of the North Ward. This lot belonged to Mark Carr, founder of Brunswick. At the present time no records of a building on this lot are known. Time and funds did not permit further exploration of the structure.

Colonial archaeology is particularly fascinating because of the great quantities and intrinsic interest of the artifacts recovered. These objects are usually recognizable in spite of breakage and corrosion. They immediately call to mind a host of associations and functions that do much to enrich the picture of a living community. In many cases they are objects of considerable esthetic appeal and are prime museum exhibits. No detailed discussion of the various classes of colonial relics can be made here. It will be sufficient to call attention to those of special interest.

Items of military equipment were in a definite minority in the Hawkins-Davison houses. Those of us who have been working at Frederica have come to think its military aspects outweighed the civilian facets. In these two houses a few musket balls, two bayonets, and one sword scabbard tip indicate clearly that Frederica enjoyed a life with a minimum of emphasis on the martial, at least for the non-garrison people. Hinges, locks, nails, and other hardware give us a good idea of how the houses were constructed and furnished as to doors and windows. In this connection the great quantities of window glass may surprise many. What might be called the Daniel Boone Tradition has conditioned us to think of our colonial ancestors living in poorly lighted log cabins. Here at Frederica the wealthy, at least, lived in brick and tabby houses with completely glazed windows.

Salt glaze stoneware mugs found in excavation of Hawkins-Davison houses

The range of bottle sizes found in excavation of Hawkins-Davison houses

Many of the objects fall into the personal ornament and clothing class. Buckles were very common, of iron or brass and often tastefully ornamented. Buttons were generally of brass but several gilded or gold plated examples exist. Two single cuff-links or frogs were found. Both were made of copper or brass and set with small blue “stones” of glass. Coins were relatively rare, only three being found. All are George II English pennies bearing the dates of 1739, 1738, and 1757. Household objects included a brass candle-stick base, forks, knives, and spoons, one complete pewter spoon being found. A clock key bears the Latin motto “Tempora Mutant,” perhaps fitting for the stirring times in which Dr. Hawkins lived. Common pins were much like the modern ones and illustrate how little some everyday objects have changed in two centuries.

Ceramics are usually of great interest to the archaeologist because they reflect so clearly the changing styles and technology of the times. A wide variety of pottery and porcelain was found, surprisingly varied, as the excavations in the regimental barracks had led us to expect a rather limited variety. The great majority were simple earthenwares with various lead glazes. These were made in England and used for kitchen and domestic purposes. They range from large bowls to small oven casseroles. A few sherds of Spanish olive jars were found, evidently loot from Oglethorpe’s expeditions against Spanish Florida.

There was a large group of soft-paste ceramics with yellow and brown glazes that are the forerunners of the famous Staffordshire potteries. The design is a random trailing of brown lines on a yellow ground. They were apparently more kitchen than table wares. Especially common around the Davison house were pieces of English salt glazed stoneware mugs. White, grey, and brown examples were found. All are tall mugs with large handles on the side. They were apparently the common ale or porter mug of the Davison tavern. Red and tan wares of the Nottingham type were in a minority.

The chief table ware in both the Hawkins and Davison houses was the blue on white soft-paste ware called variously English Delft or English Faience. It is decorated with tin enamels on a soft body, generally in blue on white; although green, red, and 228 brown do occur. The designs mostly copy Chinese porcelains and quite a variety is known. From the Hawkins house and wells we have a number of small white English Delft jars that are evidently medicinal ointment containers. All the fragments found here seem to have been made in England, presumably in Lambeth or Bristol. It is clearly the common table ware of the better sort for the early 18th Century.

A relatively large number of porcelain sherds were found, especially in and near the Hawkins house. At first it was assumed that this was Chinese export porcelain. Expert identification indicates that the bulk of this porcelain is Japanese Imara ware. It was somewhat surprising as little trade with Japan might be expected in the first half of the 18th Century. Occasional pieces of Japanese porcelain had been noted from Spanish sites in Florida but such a large collection had not previously been located. The bulk of the porcelain is blue and white in floral designs. Sometimes green, pink, and gilt were added over-glaze to form very attractive decorations on handleless cups and shallow saucers. Several pieces of Chinese porcelain are included in the group. All this is another illustration of the rather luxurious life of some of the colonists. True porcelain then, as now, was expensive, especially so as it was not made to any extent in Europe at the time and the pieces had to be brought from China or Japan.

Glass formed an important part of the collections and consisted of several kinds. The most common was a squat round bottle of a light chartreuse color which appears black by reflected light. A few square bottles of the “Case Bottle” type are represented, but most were of the round type. Smaller bottles were usually in a clear or faintly bluish glass. The numbers found around Dr. Hawkins house suggest that they were medicine containers. Two types of glasses were present: tumblers and stemmed goblets. The tumblers were rare and the prevalent type of drinking glass was the stemmed goblet. Many of the stems had enclosed tear drops and some had engraved designs around the rims.

In the wells organic materials were preserved below waterline. Barrel staves and other wooden objects were quite common. Peach pits, squash, and gourd seeds indicate some of the agricultural 229 products. The second Hawkins well, sealed in 1740 by the back addition to the house, contained a number of peach pits. It seems doubtful that trees would have grown to bearing size in the four years since the founding of the town and one wonders if these pits may not be derived from Spanish trees found growing on the island.

It is difficult to summarize the results of these excavations in that the material found is really simply a demonstration of the facts learned from the documentary research already so ably conducted by Mrs. Margaret Davis Cate. However, we can point out that the Hawkins-Davison house proved to be exactly where the documents said it would be. All the additions and dimensions given in the colonial sources were demonstrated to correspond closely to those given. The location of the streets and their size agree closely with that given on early maps and the location of the town grid of Frederica now can be presumed to be firmly established. Of course, any excavation only whets the appetite for more and we hope to uncover more of the old Town of Frederica. In the artifacts we find a reflection of the life of the times. Each householder had in his home certain items of military equipment and was prepared to stand to the defense of his town and colony should the occasion arise. The houses, of some at least, were well built of brick and tabby, well glazed and sturdy if not commodious. Household appointments were as good as England, with her world trade, could provide at the time. The sturdy houses, lead glass goblets, and Japanese porcelain show that the colonists introduced into the new colony a gracious way of life such as was enjoyed in a highly prosperous England.