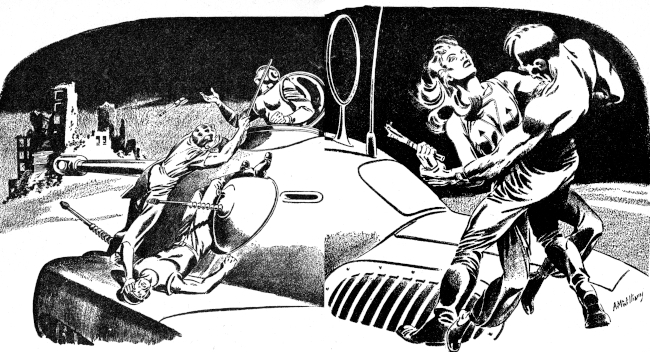

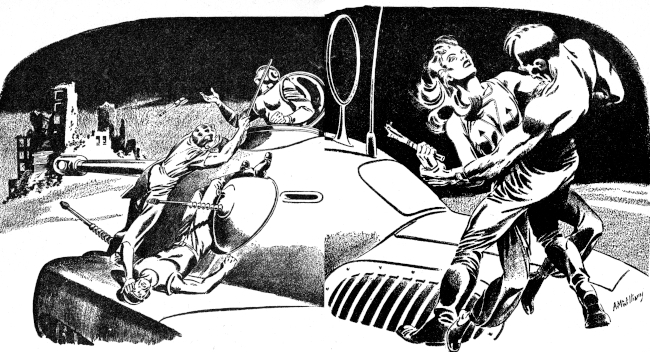

Torcred struck viciously, denting the man's helmet.

Only savage engines roamed that arid world,

charging one another with snarling guns beneath

those grinding treads. And two puny machine-less

humans like Torcred and Ladna should die quickly.

That they suddenly could become the most dangerous

things alive must surely be some dead god's joke.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1949.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The terrapin was traveling eighty miles an hour—far too fast for such uneven country. Over maddeningly repetitive dunes it scudded, rising with a swoop to each windward slope and hurtling clear of the ground beyond each wave-like crest, to plunge through the trough in a hurricane of flying sand.

The wiry little man who crouched tensely, hugged by a padded safety belt, in the pitching, vibrant interior of the midget combat car, was impatient, furiously so. Thanks to an unusually stubborn case of engine trouble, he was a full two hours behind the rest of his troop; by now they must have sighted the new camping place on the shore of the Salt Sea. And the blazing sun was already sinking toward the dusty horizon haze. Torcred the Terrapin came of a people unused to fear—but his shrewd intelligence, calculating the risks he must run before he rejoined the others, found the daylight dangers enough and to spare, and nothing attractive in the thought of an encounter with any of the things that prowled the desolate plain after the sun went down.

So the terrapin fled at reckless speed westward over the dipping dunes, and Torcred's deepset irongray eyes, squinting against the glare that even the polarized glass in the narrow vision slits could only cut down, were anxious. Under his breath he chided his own nervousness; probably after all nothing would happen....

Midway in the thought it did happen, and with almost catastrophic suddenness. The black silhouette of a flying thing materialized out of the sun's glare, diving straight at him. It flattened out and was gone overhead, while the roar of its passing echoed behind it. And the terrapin had rocked to the impact of bullets all the more fiercely driven by the aero's terrific velocity; its armor rang and steel splinters hummed like wasps inside it.

Torcred slammed down one foot pedal and the terrapin slewed crazily and slid sidewise for a score of yards, in a cloud of sand that momentarily hid it from the eyes above. Coming out of the skid he gave full power to the spinning wheels, operating the throttle with one hand while the other switched on his radar screen and leaped from it to the firing control of the turret gun. It was long seconds before the scanning beam located its flitting target; then, though the terrapin was traveling in the quick swerves and dashes of a desperately evasive course, the automatic control held the image reasonably well centered on the projected crosshairs of the turret gun's sight. The image swelled, grew wings, as the aero came in in a second howling dive.

Torcred's reflexes, hardly less automatic than his machine's, depressed the firing button, and the gun's stammering blast numbed his ears, mingling almost at the same moment with the clang and shriek of steel on steel as the terrapin took more hits. But the flying enemy leveled off far higher than before and zoomed away more steeply; its great advantage had been lost when the first attack failed to cripple or kill.

The Terrapin's eyes burned into the screen as his own wild zigzags flung him painfully against his safety belt. The aero might let things go at that.... No, the screen's image expanded again. His finger closed once more on the firing button.

The winged outline grew with ominous determination. Careless now of the single gun that rattled defiance, it was coming down for the kill. With the corner of his eye Torcred saw the vicious puffs of sand that strode to meet the racing terrapin; he swerved instantly, but in that same instant the car staggered and spun out of control. He did not hear the thunderous concussion that stung his face and hands. The forepart of the roof bowed inward, and there was a knife-like fragment of steel, inches long, in the cushion almost touching Torcred's ear.

Dimly he realized that his wheels were spinning futilely, the car canted far over; it had nosed into a dune and half-buried itself. The fight was over....

But ten, twenty seconds went by and no fresh storm of destruction burst on him. Incredulously his eyes found the radar screen. It was still working, and the image that filled it wavered strangely, neither receding nor coming nearer.

He threw his machine into reverse and opened the throttle; the front wheels took hold and the terrapin bucked itself free of the sand. Then Torcred leaned sidewise, recklessly flung open a steel shutter and looked out.

He blinked, dazzled, at the sweep of desert and bright blue sky before his eyes found the falling shape, twisting and fluttering as it fell despite its weight of tons. As he watched, the aero almost leveled out, teetered on one wing and sideslipped out of sight behind a distant dune. A cloud of dust sprang up and drifted away, but no smoky death-pall rose after it.

The Terrapin shook his dizzy head, and his narrow hawk face hardened. He pressed the pedals and sent the combat car rolling swiftly toward the spot that his practised eyes had marked accurately in the midst of the featureless desert.

The black-and-yellow aero's nose was sunk deep into the loose sand that had slid down to partly bury the wreck, its blunt tail pointed into the cloudless sky it had left forever. One wing had been torn off and hurled yards away, the other was crumpled beneath the slanted fuselage.

The terrapin slowed to a crawl along the crest of the nearest sandhill as its pilot surveyed the scene. But he was about to wheel away once more when he noticed the sprawled figure in bulky dark-blue flying clothes, that lay face down in the shadow of a brown drift.

Deftly Torcred sent the terrapin careening down the slope to halt close to the motionless enemy. He hesitated briefly, then, shrugging, unsnapped his belt, wrestled open the almost-jammed door and clambered out. Dead or stunned, he had to make sure, and there was no harm in indulging a trifling curiosity.

Under the remote blue curve of the sky, he shrank into himself a little. It was always so outside the steel shelter of the terrapin in which he had spent most of his days since childhood; he felt an oddly naked helplessness. But he looked down with interest on the body, his hand gripping the haft of the broad-bladed knife at his side. He had never before seen in flesh and blood a member of the lofty peoples of the air.

As if roused, the limp form twitched a foot, shivered, and rolled over with a sigh. A pale face, closed eyes were upturned to the glaring sun and the startled gaze of the Terrapin. Startled he was, for the face was a girl's.

She could not have passed twenty. In spite of the heavy coverall worn against the stratosphere's chill, and a wide strawberry mark where her left cheek had met the sandy soil, she contrived to be pretty. No more—but the terrapin women were brown and sturdy and coarse-featured, hardened by the drudgery of the camps. This girl's face was very white in the frame of dark hair that escaped the oversize plastic helmet. She breathed slowly and fitfully, and Torcred guessed at a state of shock; she might be badly injured.

He shook off an unaccustomed indecision and knelt beside her. His face was unpleasantly hard as the knife slid from its sheath with a faint whisper, as he laid its thin edge along the exposed curve of the girl's throat, where a flutter marked the great artery. One quick slash, she would never wake....

But it was as if a restraining hand fastened on his wrist. Slowly he drew back the glittering blade and returned it to its place. He stood up and scowled down at the still, slight figure, brushing sand savagely from the knees of his heavy breeches.

Angrily Torcred told himself that he had only to turn and go. The desert would finish the job, and no one would know that his courage had failed him. But still he stood and stared, not consciously admitting his strange desire to know the color of the eyes behind those closed lids.

They were blue, he saw as they flickered wide without warning. Not cold sapphires, but the living blue of a desert sky or of electric flame. They were alive as a small bird's eyes—but of course Torcred had never seen a bird. Rather, he called the girl a bird, as he called himself a terrapin.

Still he did not move, even as the bird-girl struggled to a sitting position and gathered her feet under her. Dismay came into the blue gaze fixed on him; she half raised a hand as if in defense.

And Torcred's determination slipped again. "You are my prisoner," he announced in a hollow voice that did not sound at all like a victor's.

Without answering, the bird-girl sprang nimbly to her feet; then her mouth twisted with pain and she swayed dizzily, but her eyes never left Torcred's expressionless face.

"You are the terrapin?" she gasped. Her voice had the exotic accent of the bird-people's speech, and in her inflection of the word "terrapin" rang a contempt that was like a whip across the face. She glanced swiftly about, at the boat-shaped gray machine that crouched, purring, like a waiting animal on its six wheels some yards away, then at the broken wreck that had been her aero. Her eyes went wide with a blue flame of horror and regret, and her right hand darted to her side.

Torcred exploded from rigidity into action; his feet dug into the sand as he lunged, and his hand closed on the girl's slender wrist, halting the sharp point of her dagger an inch above her left breast.

Her free hand struck viciously at his hastily averted face. The Terrapin ground his teeth and twisted her wrist mercilessly until the long knife fell among their scuffling feet. Then he thrust the girl away and set his foot solidly on the weapon, pressing it into the sand. He glared at her deadwhite face.

"I said you're my prisoner. That means you'll live while I want you to!"

The bird-girl was trembling uncontrollably. "My ship is destroyed," she said in a stifled voice. "I am already dead. It is the law."

Torcred's black brows knitted in anger—at her and at himself for the impossible situation into which he had blundered. "Get yourself another aero," he growled unreasonably, knowing the truth of what she said. On land or in the air, the code was the same. With destruction of the fighting machine, the poor, soft being of flesh did best to perish too. He snapped, "Be quiet and do as I say. Come along!" He half-turned toward the waiting terrapin.

The girl stiffened. "Well!" she said on a note of cold, controlled scorn. "You crawlers keep slaves?"

That was absolutely untrue, and was exactly what was bothering the Terrapin. His people kept no slaves and took no prisoners. He barked, beside himself: "You will obey me! Or stay here and die—slowly—of thirst."

Her lips parted as if to retort, but her gaze slipped past Torcred to sweep the remote horizon and the dun wilderness that stretched to it without path or landmark. In the two expanses of sand and sky there was no life visible. The thin shoulders under the heavy flying suit seemed to sag.

"All right, terrapin," she said with weary disdain. "You win, for the time being."

II

The little machine held two well enough; married terrapins on the march carried their wives beside them and children stowed somehow and anyhow in the rear compartment. Torcred snapped the catches of his safety belt and motioned the girl to do the same; when she was slow to obey, he leaned over and fastened the belt himself, drawing it painfully tight about her slim waist. Then the engine's hum rose as he opened the throttle; the wheels spun and gripped, and the terrapin bounded away, bearing westward over the dunes. As it picked up speed Torcred was touched by the familiar sense of power and mastery in the deep throb of the motor and the ready surge of the armored car. But he brooded darkly as mountain and desert rolled past in monotonous succession, as the minutes heaped themselves into hours....

The sun was a redhot disc descending into a bath of fire in the west. And minute by minute the angry light crept higher up the sky and assumed new forms, clouds and streamers, for it was a mighty redlit pall of dust that was ever higher and nearer to the rushing terrapin.

Torcred glanced sidelong at the girl beside him. Her face was even whiter under the harsh light of sunset, her eyes closed beneath long lashes. Watching that smooth, tragic face, Torcred realized again how young she was; he shook his head somberly. The air-people were a strange race, who sent their young females on missions fit only for grown men. The terrapins were far more sensible.

But no terrapin woman had the strange beauty of this alien creature from the sky....

Presently he said, "Look. Ahead."

The girl's eyes opened listlessly. They were dark-blue, opaque. But faint interest stirred them as she scanned the view ahead.

The flaming dust cloud had climbed to the very zenith; the smell of it was in the terrapin, its feel between the teeth. Miles ahead across the desert, a dim encarmined shimmer marked the waters of the Salt Sea.

Nearer, but still far ahead, a black stream was moving across the rippled plain at right angles to the terrapin's course. It was without beginning or end, pouring steadily from north to south. A distant vibration seemed to shake the earth beneath the sway and swoop of the moving vehicle.

"The trailer herd," said Torcred. "Thousands on thousands of them, moving south with the sun that feeds them. The fall migration is farther west this year, and they are coming in greater numbers than any of our troop can remember."

The girl said nothing. He added irritably, "You understand—there will be good hunting."

She shocked him by laughing. "Is that all you think of?" she inquired mockingly. "Good hunting—a full stomach and a full fuel tank. You crawlers lead poor, empty lives."

"We don't crawl," said Torcred shortly, eyes fixed on the speedometer that registered a hundred miles an hour.

The bird-girl laughed again. "You know so little, you earthbound creatures," she taunted. "You've never known the joy of flight—to climb up and into the clear bright stratosphere, and see the Earth with all its secrets unroll below you.... You creep from place to place and cower in your camps, but we range farther than you dream, and know the world and all its peoples that fly and swim and crawl and burrow. And we are the highest race of all."

"Higher than the buzzards?" asked Torcred.

She hesitated, then said defiantly, "Of course! Those evil things are huge and powerful, but we'll defeat them in the end, never doubt it. And then—we will have the rule of the sky, which is the rule of the Earth."

She sounded very certain, and Torcred could think of no adequate counter-argument. He said brutally, "We? Who do you mean? Your wings are clipped, bird!"

Then unexpected remorse stung him as he saw how the girl shrank into herself, how the brief glow of enthusiasm left her face. She made no answer, and Torcred too fell sullenly silent.

In silence he closed the throttle and the hurtling terrapin slowed. Close ahead, now, the trailer herd was an amorphous black river in the gathering dusk. Earth and air shook to its thunder, the rumbling of countless wheels and engines and couplings and the strident bleating of thousands of horns as the vast herd jostled and protested.

Closer and closer to the flank of the moving mass rolled the little terrapin, darting over the crests of the dunes and stealing along under their cover. The girl's eyes grew wide at the glimpses they had of that dark dangerous-looking stream; she seemed to flinch from its pounding clamor.

Torcred smiled grimly as he brought the terrapin to a poised halt half-sheltered by a low swell. A scant hundred yards away the migrating trailers rolled obliviously past, one close behind the other, huge box-like monsters on wheels behind a tiny cab. Torcred knew their ways of old; the trailer sections housed women and children, who tended the apparatus that made food, fuel, and ammunition from sunlight and water and air and the minerals extracted from the sterile soil. The trailer-men were drivers and gunners; but the great machines were clumsy and ill-armed, finding safety against the fierce mechanical predators chiefly in their numbers.

The Terrapin waited only for moments; then he opened his throttle wide and sent the little combat car swerving into the heart of the herd.

All around rolled rumbling iron giants; the clank of couplings, the roaring of unmuffled engines were deafening. A hooting of furious horns arose as the terrapin darted and zigzagged between the moving units of the herd. But there was no blaze of gunfire.

"So we hunt them," Torcred flung over his shoulder at the breathless girl. "They can't shoot when we're in among them; we disable one and shelter behind it until the herd passes on...."

The terrapin dashed through narrowing gaps, slowed and spurted again, as Torcred threaded his way skilfully on an oblique course across the roaring stream. At last he saw open ground ahead; he grinned exultantly and put on a final burst of speed that carried him into the clear. The little car swooped with a sickening rush into a shallow valley, and behind it thundering flashes leaped along the flank of the trailer herd and bullets exploded around or ricocheted screaming overhead.

As he slowed to a more moderate pace under cover of the farther dunes, Torcred turned, still grinning, to the bird-girl. "That," he commented, "was the dangerous part."

She shivered slightly. "I was afraid," she admitted candidly.

"That's hardly as simple as attacking a mere crawling terrapin from the air, eh?"

The girl turned her face away. "That was necessary, terrapin ... I passed my fledgling examination only two days ago; it was my second flight beyond the safety zone. The novice must defeat some machine of prey in single combat, before he is accepted."

"And if he fails?" Torcred's eyes were fixed ahead, where a pale light was reflected by the ground that was flat now and gleamed whitely, encrusted with salt.

"And if he—or she—fails," the girl's voice dropped low, "it is the last time." A sob came into her voice. "Even if I could go back to my people, I would be degraded to menial labor or breeding—could never fly again."

Torcred felt pity for her despite his prejudices; and at the same time her words recalled his own worries, and he frowned blackly. The girl mistook his expression for an indication that she had somehow said too much, and she sank back into brooding silence.

She glanced up only when the car's wheels ground to a stop on the salty crust, and Torcred, with a relaxing sigh, was already unsnapping his safety belt and switching off the panting motor. The girl saw flames and shadows amid which black figures moved, and she shrank back in fright, uncomprehending. As the Terrapin flung open his door, mingled sound of clanging metal and hissing fire rushed in to increase her confusion.

He paused momentarily; his expression was unreadable as he gazed on her white face.

"Stay where you are and make no noise," his low voice rasped sternly. "I'll come back."

Torcred closed the door firmly and heard its lock click. The girl, if she foolishly wanted to escape, probably could not find the catch inside, and there was nothing she could hurt herself with if she still felt suicidal. There at least she would be safe from prying eyes, until he could untangle the tumult of unaccustomed emotions that were struggling within him. A terrapin had only one place to himself, the interior of the fighting machine—those with families, of course, knew no such word as privacy.

He turned, straightening his back resolutely, and advanced into the midst of the terrapin camp.

III

Spaced shadows resolved themselves into a double rank of parked terrapins, forming concentric circles about the encampment. Such was the pattern of a terrapin camp from time immemorial; it was safety against attack by other raiders of the wasteland, and on each day one ring could go forth to hunt, the other remain in place to guard the women, the young, and the booty.

Even here the warm night air quivered ever so faintly with sound from the east, the endless motion of the great trailer herd. By morning it would have passed, and the hunters would follow it southward.

Within the great circle the women and older children were busy now, while the men lounged about, talking quietly, boasting perfunctorily of the day's deeds. The first day's hunt had been only a hit-and-run affair at twilight, but in the midst torches flared sputteringly over the remains of dismantled trailers; there were neat piles of steel beam-lengths and undamaged armor plate, and sprawling heaps of metal scrap that would be abandoned when the troop rolled south. To one side a red glow came from the maw of a small furnace, melting aluminum to be made into castings; the terrapins did not smelt steel, leaving that to the giant scavenger machines that followed the herds at a more respectful distance. Fuel, food, and usable ammunition had naturally been transferred first of all from the captured trailers to the tanks and storage compartments of the terrapins.

From the shadows of the inner circle a voice hailed Torcred by name, and its owner came out into the light to meet him—a short man, unusually plump for a terrapin, with heavy black eyebrows that seemed pasted high on his round bald forehead, giving him a look of perpetual astonishment.

He greeted the newcomer effusively. "My dear Torcred! We came very near giving you up! And from the look of your machine, you must have had a narrow squeak."

Torcred frowned imperceptibly. It seemed an evil omen that he should be met by the only one among his fellow-terrapins whom he actively disliked—Helsed, the talker, who was always close to the chief's ear in council, but far from his side in the battle.

"That's right," admitted Torcred curtly, and started to brush past the other and his brimming questions. But he found himself face to face with another terrapin who had risen from the shadow, a taller man whose hair shaded from the usual black into gray, and whose face was permanently lined in a stern expression of command. He was Vazcled, the chief. Torcred fell back a step and inclined his head in salute.

"What happened to you?" inquired Vazcled quietly.

"I was attacked," said the younger man with reluctance.

"By what?"

"An aero."

Even the chief's face showed surprise, and the listening Helsed's eyebrows went up steeply. Vazcled said, "You are lucky to have escaped so easily."

"I didn't escape. I shot it down."

Helsed exclaimed aloud and stared at his brother-terrapin enviously. The chief's withered lips smiled. "Such victories are rare," he said approvingly. "I know of only two or three in the past fifty years. You must tell us the story tonight, and Hiyik can make a song of it.... Did you bring any trophy from the wreck?"

Torcred licked his lips nervously. "No," he said. "It fell a long way off...."

"Well, no matter," the chief shrugged. "We will find the spot on the back trail." Already—Helsed, the eager newsbearer, had dashed off without waiting for details—they were surrounded by a growing audience, afire to know more about Torcred's almost unheard-of exploit.

Torcred, dazed, found himself sitting atop someone else's machine, relating his battle with the aero to an enthusiastic mob of his fellow-warriors. The terrapins lost their customary reserved poise and grew festive; while Torcred almost choked on the lies with which he ended his narrative, they pressed food and drink on him and made him go back over the most stirring parts. Then Hiyik the poet had his turn, and retold the story in improvised verses, his chanting voice mingling with the hiss and clangor of the workshop in the midst of the circle on whose rim the warriors were gathered.

But the hero of it all sat moody, well-nigh oblivious, his brow wrinkling painfully from time to time. The thoughts he was thinking hurt. For what he was planning was treason, what he had already done was treason—more than that, sacrilege, abomination, a trampling of the laws that kept the diverse races of Earth eternally apart.... Lesser breeds might hold such laws lightly—but not the proud terrapins. For them all other peoples were enemies, or prey, or vermin beneath contempt.

The bird-folk were enemies. And the crime of giving aid and comfort to an enemy deserved the ultimate in punishment.

Torcred's mouth tightened grimly at the thought, and the logically following reflection that he, Torcred the Terrapin, must have gone quite insane. But even here, in the midst of his noisy comrades, he could not forget the glimpse of a strange beauty that had fallen out of the sky to destroy him—if not by the swift vengeance of outraged tradition, then by returning and returning to haunt him all his days.

With a chill he realized that the chief was watching him thoughtfully, and he strove to give his features a dignified impassivity appropriate to the modesty of the feted hero.

The face of Helsed, hugging the spotlight as always, was at his elbow, wearing a vapid smile which Torcred's hypersensitized suspicions saw as a knowing smirk. And in reality, he knew, the fat terrapin's air of loud thickheadedness masked a sharp scheming brain—and Helsed hated him. Helsed had talked and toadied his way into the graces of the council of elders and the chief, and he had hopes—the latter's successor must be chosen soon from among the younger men. And in the taciturn Torcred he saw his most dangerous rival, for the young warrior's deeds spoke for him.

Sunk in thought, Torcred hardly realized the passage of time or that the gathering was breaking up. Hiyik had ceased his recitative. One by one the terrapins yawned, stretched, and moved off toward their own vehicles; it was late, and tomorrow, first full day of the great hunt, would be hard. The noisy labor in the camp's center went on unabated.

Torcred forced himself to yawn and stretch as elaborately as the others, to rise unhurriedly to his feet. His plans, such as they were, were complete; during the next day's farflung maneuvers and attacks on the trailer herd, he should be able to slip off unnoticed and, traveling fast, reach the vicinity of the aeros' nearest eyrie. There he would leave the bird-girl. Whatever her fate then, she would be alive among her own kind; and perhaps later she would be grateful to the terrapin who had befriended her. Beyond that his thoughts did not go....

As he started to walk away, the chief's voice rooted him to the spot.

"Wait a moment. I understand your machine was damaged; perhaps it needs immediate repairs."

Torcred turned swiftly toward him. "No!" he exclaimed hastily. "There's not much damage—a few bullet holes, a dent. No use bothering with it now."

"You never can tell." Vazcled rose; despite the hour's lateness the wiry old man seemed untouched by fatigue. The bright eyes that dwelt on Torcred's face held only friendly concern. "You are confident now; but a failure of mechanism can betray the bravest. Let me look your terrapin over and judge for myself."

The chief's wish was a command. Torcred's spirit quailed as, walking like an automaton, he led the way. He derived a little comfort from noting that Helsed had already disappeared; when worst came to worst, he would at least be spared, in the moment of disaster, the sight of his enemy's triumph.... And he could still hope that the chief would content himself with an outside examination.

Vazcled studied without speaking the stove-in nose of the terrapin. His experienced hands felt out the damage that was invisible in the uncertain light; he clicked his tongue.

"That's no dent," he said at last. "You ran head-on into a shell. I'd better look at it from inside; open the door."

With wooden fingers Torcred produced the key. Silently he handed it to the chief; he did not think, in that whirling moment, of the symbolism of the action, but Vazcled stared at him curiously before turning to the door. For a terrapin to surrender the key of his vehicle was a gesture of abject self-humiliation.

The simple lock clicked. Torcred fell back a step, his shoulders hunched tensely and his hand convulsively closing on the haft of his dagger.

The door swung open. The chief fumbled and switched on the inside light; he grunted softly, squinting up at the fore part of the roof. Past him Torcred could see the whole cramped interior of the armored car; it was empty.

Across the chaos of his mind fluttered one clear thought; the girl had escaped. And he was at once limp with relief and taut with a new and formless fear, mixed with an odd empty sense of loss.

Vazcled grunted again, emerging. Pressing the key into Torcred's damp palm, he said pointedly, "Keep that."

Matter-of-factly he added. "You need repairs. Drive into the center, then look up somebody with room for an extra sleeper. You won't be called for guard duty; you've earned a good night's rest." The chief's wrinkled hand rested affectionately on the young man's shoulder, but to Torcred's imagination it burned like fire.

His mumbled response was swallowed by a sudden burst of noise from the outer periphery. A voice and then voices cried out confusedly, and then a light blazed, silhouetting the parked terrapins. And Torcred was already running among them, but even as he ran his world was crashing and crumbling about his ears, and he knew he had been most cruelly mocked by fate.

On the edge of the encampment a space of sand was white in the glare of lights. White too was the face of the girl who swayed, fast in the grip of two men. Others pressed round with flashing knives, and more warriors, half-dressed and sleepy-eyed, appeared to reinforce them. They looked questioningly at one another; somehow the appearance of a lone alien being, with no machine in evidence, was more sinisterly alarming than would have been the onslaught of a horde of armed and armored juggernauts.

Torcred halted and stood rigid, his gaze stabbing into the knot of men. And before him they opened out, pushing the girl to the fore, as if in accusation. The next moment he realized that that was because the chief stood beside him. And he saw that one of the bird-girl's arms was pinioned by a sentry, and that Helsed, puffing himself with menace grasped the other.

"Silence!" roared Vazcled's voice of command. "Bring her nearer. Where did she come from? What is she?"

No one answered at once. Torcred's eyes were on the bird-girl. For a moment her gaze met his, then she looked past him. On her pale face was written the fierce pride he had seen before, and he knew she could never betray him.

"Shall we make her answer?" Helsed grinned ingratiatingly at the chief, and as if in demonstration of the methods he proposed, his grip tightened on the girl's arm, twisting. She winced and closed her eyes, making no sound.

And Torcred, his remnants of caution whirled away like chips on a flood tide of fury, was on the torturer in one catlike spring. He would have used his knife, but he had forgotten it; his fist, with all his weight behind it, crashed squarely into Helsed's hateful grin. Helsed was hurled backward and rolled over limply on the sand.

Torcred stood watching him, poised to renew the attack. The other man who had been holding the girl involuntarily released her and stepped back, leaving her standing alone beside Torcred—but she too shrank away from him; his berserk rage had made him terrible. The surrounding warriors hesitated, and behind them, from among the cars or from vantages atop them, the women and children stared open-mouthed.

In the stunned silence, Torcred could hear the whisper of night wind, and from far away the faint mutter of gunfire as nocturnal machines of prey still took their toll of the trailer herd. He had other random impressions: the feel of the soft sand underfoot, the hard brightness of the stars overhead, the odor of fuel and heated metal that hung about the camp.

Then he turned, straightening: his eyes sought out Vazcled beyond the ring of men who were warily beginning to close on him. And he laughed, having cast away his world.

"See, chief!" he shouted. "See, terrapins! I brought home a trophy, after all!"

IV

It was a red dawn, for the sun rose behind the dust that still hovered over the track of the southbound herd. In the west the sky was dark blue above the flatly shimmering water of the great dead sea.

The whole terrapin tribe, save for the indispensable lookouts, was assembled in the open space of the ringed camp. A hush lay on them as they gazed on the prisoner in their midst—honored last night among his peers, this morning guilty of hideous treason. There was no need for trial; it only remained to condemn him.

A cool, salt breeze blew from over the lake and stirred Torcred's tousled black hair. His gray eyes were bloodshot and staring.

Helsed was there, insinuating himself into the council of elders at the chief's elbow, and mumbling implacable hatred past swollen lips and missing teeth. His clearest and oftenest-repeated word was "Death!"

Vazcled's face was set in sorrowful lines; there was regret and a hopeless question in the old man's eyes as they met Torcred's.

A small voice beside Torcred asked, "What are they going to do, terrapin?"

He half-turned and really saw the girl for the first time that morning. She was composed, her blue eyes unafraid.

"I don't know," muttered Torcred. "This has never happened before—not in anyone's memory." In his mind were horrific legends heard in childhood, but he tried not to repeat those even to himself.

Vazcled's first words were to the girl. He asked, "Who are you, stranger? What is your race?"

She returned his gaze, decided to answer. "My name is Ladna, and I am of the race of birds." Torcred realized that he had not known her name before; it had not occurred to him that such remote beings used names....

"Who brought you to this place?"

The girl's lips tightened; deliberately she turned her back on the chief and stared away over the lake. She seemed oblivious of all the hostile eyes around—in particular the swarthy faces of the terrapin women reflected unpleasant ideas as they greedily ogled this creature of the air.

"No matter," Vazcled said heavily. "The criminal stands self-accused.... Have you any explanation of your conduct, Torcred the Terrapin?"

Torcred shook his head dumbly.

"Then—" the chief turned to the elders, "there is question only of the punishment."

Helsed thrust himself forward eagerly. "Death!" he mouthed. "Such a crime deserves no less!"

The chief looked at him coldly. "Did I ask your advice?" he inquired bitingly.

Helsed beat a retreat. "I am sorry.... But it is true that I have a special grievance in this matter...."

"Be quiet!" snapped Vazcled.

The oldest member of the council spoke, and the rest listened respectfully. "Everyone knows the story of Fuwu, who took to himself a dragon woman. He was cast out of the tribe according to the ritual, and left to die in the desert with his seductress—a sentence lighter and heavier than mere death, and one which did not stain the hands of the tribe with the blood of a terrapin."

The other judges nodded in token of their remembrance and approval of the precedent. The chief saw their decision, and faced the prisoners again. At this curt command the guards seized Torcred and thrust him forward unresisting. Vazcled, knife in hand, looked him in the eyes, his face a stern formal mask. He intoned:

"Torcred the Terrapin, your sin is past forgiveness. I pronounce you outcast and abhorred; none shall take notice of you any more, either to help or hurt. You are no longer one of us; we give you to the wilderness. Torcred, no longer Terrapin, I mark you as such!"

The knife point rose and made two quick motions. Torcred did not flinch; on his forehead was a tau cross in oozing drops of blood. The chief bent, took a pinch of sand, and rubbed it into the wound to make sure that it would scar—if the victim lived that long.

Vazcled turned away. "Cast them out!" he ordered over his shoulder, to the guarding warriors.

"The girl too?" Helsed asked hastily; his eyes lingered.

"Of course!" rasped the chief. "It is the tradition—and what else should we do?"

Helsed licked his battered lips nervously. "Of course," he agreed. "What else?"

V

Torcred sat, head sunk limply in his hands, on the white salt beach facing the lifeless sea. The throb of motors and swirl of dust behind the departing terrapins had died down in the south; instead of hunting today as planned from this camp, they had left the spot that had become accursed. And Torcred sat numb with despair, passively waiting for the end.

Near him Ladna, the bird-girl rose to her feet. She looked in the other direction, out over the lifeless waste of sand, and then at the man's slumped, motionless figure.

Her voice was hard and scorn-edged. "So—a terrapin shorn of his armor is less than a bird clipped of her wings?"

Torcred raised his head and looked at her glassy-eyed. "You heard," he growled. "I'm not a terrapin any more."

"You'll always be a terrapin to me," she said. "A miserable, beaten crawler."

He stared without understanding. Around them was the thirsty, deadly desert; the sun was hot already, his mouth was dry, and the poisonous sea lapped mockingly at its flat shore. The girl had been ready to die when her aero crashed—but now her slender body was vibrant with the will to live.

But her bitter words could not fail of effect. Torcred stumbled erect and snapped, "I'm not beaten until I'm dead! But—what chance do we have?"

She accepted the we with a faint smile, and said in a softer tone, "There is an aero eyrie—not my own, but one with which we have friendly relations—about seventy miles east of here, in those blue mountains you can see. Perhaps we can make it there on foot."

"That's all very well for you," said Torcred somberly. "But for me—what could I expect from your people?"

"We are not so narrow-minded as the terrapins. We see more and tolerate more. You can be taken in and given tasks to perform in return for your keep." She frowned at his doubt, and explained further, "Some day—soon—we birds will rule all the Earth. And we do not want to wipe out all the other races; we'll preserve them to do the jobs that must be done on the ground, and all of our people will be free to fly."

The picture of conquest she painted so naively repelled Torcred, reared in the terrapin tradition of a barbaric individualistic freedom. "You offer me slavery," he said harshly.

"No, no," protested Ladna. "According to our law, you will be free to leave if you wish." He snorted. "And—" she hesitated, "I will be in the same condition, now that I have lost my wings."

Torcred stared at the ground, shrugged. "It's better than dying here—perhaps. And we may not make it. How fast can one travel on foot?"

"Ten miles an hour?" the girl hazarded.

"Less than that, I think. It will be a long way—and I know of no water holes." Ladna shook her head at the question in his glance. "It may be impossible to walk that far without water; I never heard of anyone's doing it. But we can try."

The blue flat-topped mountains still shimmered unreally, far away as ever, across the heated plain. The sun was at its height and the sand was blistering. The two huddled in the scant shadow of a dune. Both were sunburned, maddeningly thirsty, and discouraged. They could not have covered more than a dozen miles before the heat had driven them to seek shelter.

They talked very little; as the burning midday dragged on, Ladna slept for a time. When she woke she looked round feverishly, and a moan escaped her lips.

"What's the matter?" asked Torcred.

"I was dreaming," the girl said in a choked voice, and, shockingly, two tears rolled down her cheeks.

"Don't cry," ordered Torcred harshly. "We've got to conserve all possible moisture."

She bit her lip, and no more tears came.

When the shadows lengthened somewhat they set out again to the east. During the morning they had seen some signs of life—had flattened themselves on the ground while a cavalcade of fire-breathing dragons passed one by one along the crest of a distant ridge, the long snouts of their flame projectors thrusting before them, and had skirted a colony of the queer crusty pillbox people who had sacrificed mobility for an almost invulnerable security. But during the long afternoon the desert seemed utterly empty. Only at dusk they saw, far over head, three vast black shapes flying in wedge formation, and the drone of motors beat down out of the hollow bowl of the sky.

"Buzzards!" whispered the girl, and shrank against the sand.

Torcred knew that the buzzards were the aero people's hereditary foes, but that did not seem adequate to explain the bright bitterness of hatred in the girl's eyes.... He was about to ask a question, when his eyes caught movement in the near distance and he froze, mouth open.

A hundred paces ahead on the way they had been going, atop a low mound, stood a figure—a man in queer garments, not identifiable with any of the races Torcred knew. When the Terrapin tried to make out his face, the man seemed to waver in the fading light; then he raised a hand in a gesture beckoning them toward him.

The bird-girl, back to the apparition, looked wide-eyed wonder. Torcred croaked wordlessly and pointed; and with the motion the stranger was gone from the ridge.

"What's the matter?" asked Ladna puzzledly.

"Nothing," Torcred managed to get out. "The shadows play tricks...."

As they crossed the rise, Torcred halted to tie a bootlace that didn't need tying. There were no tracks in the soft sand. Torcred remembered fearfully what he had heard of the visions that heralded death by thirst—but even sane people saw things that weren't there, such as the phantom lakes that had mocked them in the midday heat.

But he had been sure that vision was looking at him....

Two or three miles further on, it was almost dark. Torcred sank wearily down in the lee of a high ridge. "We'd better stop here. Perhaps a night's sleep will give us strength."

The girl sighed. "I think we will die on this desert, terrapin."

Torcred felt a stirring of the anger her use of that word always roused in him. But he said only, "We've covered perhaps a third of the way. Two more days, then."

He remembered that pebbles in the mouth ease thirst; they tried that, and it helped a little. Then they scooped hollows in the sand for sleep. Ladna wriggled out of the heavy flying suit that, stickily uncomfortable as it was, had protected her from the sun. The sleeveless shirt and shorts she wore beneath clung damply to her; even through a haze of exhaustion Torcred was stirred by the sight of her slender body, her mildly rounded breasts and long straight legs....

He slept like a log, and woke in the dim pearly light before dawn, still tired, his mouth like a furnace.

It was a moment before he realized that the bird-girl's piercing whisper had wakened him, and sat up abruptly. Spots danced before his eyes; he felt her hand tighten in warning on his arm.

Then he saw by that ghostly light, not a hundred yards away, a thing of nightmare.

It was a huge gray monster of metal, a moving fortress going steadily forward on endless treads that hardly dented the soft sand beneath it, though it must have weighed half a hundred tons. Shod with silicone-rubber, it rolled in an unreal silence, the purr of its engine scarcely audible in the early hush, past the two frightened watchers under the dune, and vanished over another crest.

The girl still clutched Torcred's arm, finding perhaps some flimsy reassurance in the resilient hardness of his tensed muscles. "What was it?" she gasped.

"That was a panzer," Torcred informed her in a low voice. "A big relative of the terrapins, that prowls the desert alone, by night. It carries a crew of three to six, can see in the dark and move without a sound. It's one of the most formidable land machines in the world."

Ladna drew a shuddering breath. "I hope it doesn't come back."

"Don't worry. I told you it was nocturnal—at this hour it's hunting a good safe spot to lie up for the day."

The girl was wearily pulling on her coveralls; her fire-blue eyes were clouded with hopelessness as they gazed into the gray dawn. "Perhaps it would have been better if it had seen us—better than what's ahead of us."

Torcred did not answer; he was frowning in thought. Suddenly he rose to his feet—wincing a little as he put his weight on them; with gentle firmness he turned the girl around and faced her toward the west, suggesting, "Let's go back a little way."

"Back! Are you crazy, terrapin?"

"Remember the wreck of an armadillo we saw about a quarter of a mile back? I want to get something there."

"That wreck was years old," sniffed Ladna. "There couldn't be any supplies left in it."

"I have an idea," said Torcred. Then, as he saw her unyielding disbelief, "I intend to capture the panzer."

And he trudged off purposefully to the west. The girl followed, still protesting in an undertone, as all their argument had been carried on. "You are sunstruck! That monster—and we've not got so much as a knife—You might as well try to tear down that mountain peak," she pointed toward a distant blue height, wreathed in cottony clouds, "with your bare hands."

"Maybe I will," said the Terrapin.

The smashed armadillo had long since been stripped of usable parts by the desert's scavengers. The remaining wreckage was widely strewn, half-buried in the sand and eaten by rust.

Torcred searched with a grim intensity, tugging at the projecting steel ribs. Some were deeply buried, others too badly bent, still others too short. At last he found what he was looking for; a narrow T-beam, six straight feet of alloy steel, light but tremendously strong. He hefted it with satisfaction.

"You don't intend to attack the panzer with that!" exclaimed Ladna.

"I do," said Torcred. He looked into her wide blue eyes for a moment, then pointed down at something that had been disturbed when he pried loose the beam. A chalk-white skull with empty eyes. He kicked at it, and it crumbled. "Of such are we made, bird-girl. A fragile framework compared with the machines'. But alive, we have intelligence, and with intelligence and this weapon I mean to take the panzer."

They tramped eastward again, following their own tracks, under a sun already growing hot. After a while the girl asked in a meek voice, "How can you hope to do it?"

Torcred smiled inwardly at the impression his—largely assumed—confidence had made. He answered, "This morning I noticed some of the thing's weaknesses."

"It didn't look weak to me."

"In the first place, its guns are set high on that huge frame—above the housing of the treads. They couldn't hit a man standing right beside it. And I think I can get that close to it, because it will be resting now, the crew asleep—or one of them may be watching, but he can't watch all ways at once. There will be automatic alarms, of course, but I don't think they'll respond to anything as small and harmless as a lone man."

Ladna drew breath sharply. "Perhaps you're right—But even so, what then? You can't dent its armor with that bar, and it can simply move away and shoot you down!"

"It has another weak point. It runs on caterpillar tracks—that is, really, on wheels turning inside an endless belt that gives a wider basis of support. But if any sizable, hard object finds its way between wheel and track—"

He paused significantly, and the bird-girl's eyes met his in a luminous dawn of understanding and hope.

They had no trouble finding the trail of the panzer. As he scanned those yard-wide tracks, paralleling each other ten feet apart, Torcred's grip tightened on his T-beam; it did not seem quite so thick and heavy now, against all those tons of rolling metal might.

But he had boasted recklessly, and he was going through with it if it killed him.

VI

Stealthily they crept along the trail in the direction the monster had taken, lying prone to peer with immense caution over the wave-crest of each dune it had breached in crossing.

Beyond the sixth or the seventh crest, it was there. Lying still in a hollow of the sand, its gray paint blending with the drab earth to make it almost invisible from the air—and its radar alarms, no doubt, keeping watch for any moving threat. Encased in armor almost to the ground, over the great treads, and its three rounded turrets astare with guns.

At first glimpse Torcred jerked his head back like the extinct land reptile whose namesake he was. His palms grew sweaty and his insides quivered. If he had been alone, he might have slid quietly down the slope and stolen away, leaving his T-beam behind him. But he heard Ladna's quickened breathing at his back, and knew she knew he had seen the panzer.

Before he could check her she had wriggled up beside him and peered over the edge. When she drew back her face was shades paler beneath its peeling sunburn. Her lips framed words: "Are you going to try?"

Torcred nodded, jaw set. "You stay here," he hissed, and, gripping his weapon, began to slither over the crest of the dune.

When he was on the far side and nothing had happened, he felt reasonably sure he had passed below the horizon of its radar. But he continued to crawl, eyes fixed on the giant enemy, watching for the first stir of motion about it that would be followed by a smoky blast of death.

Halfway there—Almost there—He reached the edge of the panzer's shadow. Then he distinctly heard a low burring sound from inside it. Alarm! A magnetic mine detector, probably, tripped by the metal beam; Torcred realized that even as he flung himself forward in a scrambling rush that carried him the rest of the way.

The driver must have been alert. Even as Torcred caught himself with a hand against the gray steel flank, the muffled motor throbbed into life and the great machine surged forward.

Torcred ran stooping beside it, eyes measuring the gap between armored housing and racing tread. Seconds to live if he missed—already his lungs were bursting and the great gray side was slipping past. With both hands he drove the T-beam straight into that gap.

It was wrenched from his hands, its end snapped off and hurled spinning with terrific force. Then a grinding shriek of tormented metal, and the panzer's vast mass shook and wheeled half round in a storm of sand as the jammed tread stopped and slid.

Almost before the machine had lurched to a full halt with a tremendous clank and rattle, Torcred had snatched up the broken end of his bar and was swarming up its side.

In a moment he was perched atop it within easy reach of the single exit port, leaning against the smooth warm steel, feet braced solidly against the tread housing. A quick glance assured him that there were no vision slits giving a view of the panzer's back to those inside. He set himself and waited, controlling his labored breathing.

The wait was not overlong. The panzer-men, seeing no attacker outside, but having heard their alarm and found their machine inexplicably crippled an instant later, had no choice but to come out and investigate.

The port-cover swung aside, and a man's crash-helmeted head and gray-clad shoulders emerged, back to Torcred. The Terrapin struck viciously and dented the helmet; almost before its top slid out of sight, he vaulted after it into the opening, disregarding the ladder.

Torcred struck viciously, denting the man's helmet.

He landed in a tangle of arms and legs—the man he had stunned sprawled atop another who struggled to free himself. Torcred sprang clear and, across the cramped central compartment of the panzer, faced a third gray-clad man with a drawn knife.

Incredulity and fright were written large on the panzer-man's face. Out of sheer desperation he lunged forward in a stabbing rush; but he was no knife-fighter, and the two-foot length of steel in Torcred's hands was a far superior weapon. The knife flew wide and its wielder stumbled back, nursing a bruised forearm.

Another figure appeared in the narrow door forward and stared at the scene with popping eyes—the driver, no doubt. Torcred greeting him with a ferocious grin and swung his club whistling back and forth. He looked and felt invincible.

Then Ladna's voice behind him screamed, "Torcred! Look out!"

He whirled, and the knife-blade gashed his shoulder instead of sinking into his back. Then Torcred struck a two-handed blow and felt bone give way beneath it. He took a couple of steps back from the crumpled body of the panzer-man who had unluckily disentangled himself from his unconscious comrade, and set his back against a solid bulkhead; on his face was still the savage grin that had frozen the driver in his tracks.

The bird-girl dropped lightly from the ladder and came to his side, scooping up the knife that was red with Torcred's blood. Her shining eyes reflected his fierce elation of victory.

Torcred realized that if he lost time his psychological advantage might go with it. He snapped at the two remaining panzer-men, his voice rasping strangely from his dry throat, "Quick! Do you want to live?"

They stared at him dumbly; it was almost beyond their power to grasp that this bloodstained, primitive being had got inside their defenses, that the far-ranging guns whose breeches thrust into the compartment were useless.

Torcred took a step toward them, swinging his bar ominously. The man who was clutching his right arm asked sullenly, "What are you? What do you want?"

"I am Torcred," and he added with brief thought, "the Terrible. And we want very little from you—food, water, weapons from your stores. You can keep your lumbering panzer; we've got no use for it." The two men exchanged fearful glances, sure now they had to do with a mad creature. He gave them no chance to think it out. "Right now, we want to look around in peace. Ladna! Find something and tie them up."

The girl, dagger in hand, opened the door of the rear compartment; a whimper of terror came from the darkened interior, where two women and an indeterminate number of offspring hugged one another in paralyzed panic. Ladna spoke to them with a soothing softness that amazed Torcred, rummaged inside and came out with a coil of strong wire. The solitary panzer, an economy in itself, carried a little of everything.

Under the menace of Torcred's club, the terrorized panzer-men submitted. Then the two invaders found the machine's provisions, and satisfied first their raging thirst and afterwards the hunger that had been forgotten in the face of the greater need for water. But Ladna broke off eating to bandage Torcred's slashed shoulder with strips torn from a gray garment.

It was then he remembered to scold her. "What did you mean," he demanded between bites, "by rushing in here, after I distinctly told you to keep in the clear?"

Her blue answering gaze held an impudence that was a new thing to him. "I saw you had stopped it, Torcred the Terrible, so I came. And—where would you have been if I hadn't?" Her strong slender fingers closed for a moment painfully on his wounded shoulder.

He was silent, remembering with a queer excitement what her warning cry had been. "Torcred!" not "Terrapin!" ...

The bandage finished, he stood up and said brusquely, "We'd better get ready to leave."

"You plan to go on foot again—now that we've captured a machine?"

"It's the only sensible way," asserted Torcred flatly. "Neither of us knows how to repair the caterpillar tread, or, if we managed that, how to maneuver and fight the panzer; if we were attacked, it would be a death trap for us. Afoot, we're in very little danger—what machine of prey would be likely to consider us worthy of notice?"

They looted the best of the provisions, and the girl's deft fingers fashioned for each a strap of sorts from a roil of cellotex fabric. Torcred went up to the driver's cabin, located the engine under the floor, and did things to it that would keep the panzer immobilized until long after the blowing sand should have covered their traces. The woman could untie their men as soon as they gained courage to come out of hiding....

Terrapin and bird-girl set their faces to the east and began to trek again. They trudged on with lightened hearts.

They had gone about a mile when a fold of the land revealed a wide swathe of desert dotted with camouflaged steel hemispheres, mostly buried in the sand—a big colony of the pillbox people.

They ducked back behind the shelter of the sand-hills and began what looked like the shortest detour. Suddenly Ladna, glancing back the way they had come, cried out sharply.

Torcred turned, and saw a plume of dust above the far-off dunes—then a gray scurrying beetle-thing that rose to a crest, vanished, and reappeared on a nearer swell.

It was a terrapin, travelling fast, and as it raced closer there was less and less doubt that it was following their own plainly marked trail. Torcred strained his eyes through the heat-shimmer to make out the identifying mark on its blunt nose; he stiffened, and his hand dropped to the knife he had taken from the panzer.

"Helsed! He's picked up our trail somehow—but what does he want?"

"The fat terrapin, the one that twisted my arm? I think I know," the bird-girl said in a low voice.

Torcred's dark face went hard as flint. His mind seethed: there was no hiding here, no use trying to flee from the hundred-mile-an-hour pursuer—or was there?

Uncertain, he stood stockstill. The girl pressed shivering against him. Helsed would not open fire, of course, for fear of hitting her; there might be a chance of parleying. If he could only lure the fellow into the open—

The Terrapin swung broadside—on a stone's throw from them. Its door opened, and Helsed half slid out of the seat. He eyed the pair, swarthy brows rising in seeming amusement.

"Ah, still together," he observed. "Torcred, my dear fellow—you shouldn't be traveling in such company, even in your present status. Suppose you run along and let me take care of her."

Torcred controlled his voice with an effort, "You're a terrapin in good standing, Helsed. Would you discard your honor—"

The other smirked. "Don't worry. I'm not a fool like you; I won't take her home with me."

Torcred ground his teeth. "You're crazy!"

"I had to leave the hunt and make good time to catch you—I don't feel like being disappointed." The viciousness in Helsed's smooth voice crept into the open. "And I have a score to settle with you anyway." He jerked the terrapin's door shut, and its nose gun started to swing around.

Torcred spun and ran, crouching, knowing the girl would follow. They plunged over the dune-top close together; the terrapin's gun wavered and did not fire, then its motor snarled into life and it bounded after them.

Torcred, with Ladna close behind, ran panting down the windward slope, straight toward a cluster of domed, sunken structures. Sheer amazement of the pillbox-dwellers must have kept them alive so far; every moment he expected a murderous barrage.

It came. The nearest pillbox erupted flame, and beyond it others. The explosions rolled flatly, echoless across the desert. Torcred caught the girl round the waist and flung her down beside him; hugging the ground, he raised his head slightly and looked back.

The terrapin swerved agilely among spouting columns of sand. Then all its wheels left the ground at once, it tilted in the air and rolled over and over down the long slope of the dune. Black smoke poured from its punctured armor.

VII

Torcred stared long at the blackened wreck, hardly noting that the guns were silent, the haze settling. He knew none of the exhilaration that had been his when he took the panzer; a sickish sensation nested in his stomach. He had killed—by subterfuge, true, but killed all the same—a brother-terrapin, and now in his own mind rose up against him a lifetime's training, all the blood-ties with his own kind....

His own kind. The terrapins. But were they? What was he?

The breeze, laden with sharp smoke of explosive, made his eyes twitch and smart. He blinked, and saw the man standing on the dune's edge above them. Much nearer this time, so that there could be no doubt that the eyes were looking at him, that the lips smiled. That smile, and the careless stance that went with it, seemed to radiate confident power.

Beside Torcred the girl gasped, and he knew with sudden relief that she too had seen the stranger.

And so did the others. The bright air was split again by thunder as some touchy pillbox fired a shell. It struck squarely at the stranger's feet, and they saw him blown to fragments. But the burst drifted down the wind, things crawled and flickered in the air, and he was there again, smiling more broadly than before. He glanced aside, at the smashed terrapin, then back at Torcred, and raised his right hand in a gesture—thumb and finger forming a circle—that some of the desert peoples used as a sign of approval and encouragement.

Then he rippled slightly, like a reflection in water, and was gone.

Torcred was hardly conscious of how they squirmed out of range of the pillbox people's venomous annoyance. Ladna, brushing tangled black hair out of her eyes, was first to break the silence.

"Was that what you saw yesterday?"

"Uh-huh," admitted Torcred glumly. "But you saw. He wasn't real at all."

"Did we see the same? He was blown to bits, and reassembled himself unhurt?" Torcred nodded. "Then there was something there."

"What?" he demanded, irked by her superior reasoning.

"I don't know.... But I remember something. A month ago, a man in strange clothing like that—a real man of flesh and blood—came to our eyrie. No one knew where he came from, or where he went when they laughed him to scorn."

"They laughed—why?"

"Because he talked about 'civilization' to every one who would listen—but he didn't seem to realize that the civilization of the air is necessarily the highest. And he said we should make peace with all other creatures—even the buzzards!—and refrain from hunting, and practise photosynthesis like the lesser races." She wrinkled her peeling nose. "If that weren't enough, he mixed his talk with old legends—stories of the ancients, and the floating cities."

"I've heard—" Torcred began, looking impressed. The girl smiled loftily.

"Those are tales that have lost their substances, fit for the young, the ignorant, and the uncivilized. Certainly the great ancients existed—they were an air-people like us, who ruled the world long ago, as we shall in time to come. But that they were immortal and are still alive, drifting somewhere in midocean out of sight of land—that's nonsense."

"Maybe so," Torcred grunted stolidly. In the cosmogony he knew, the ancients were mighty terrapin heroes of the world's youth, from whose stock all other races had degenerated; they still lived somewhere, and would return to make the terrapins supreme again.... He said matter-of-factly, "If you want to know what I think—we are being watched, by something that is alive and powerful here and now."

Ladna started and looked nervously round. She had begun to respect the Terrapin's shrewd native intelligence. As they plodded on across the desert, she said no more, infected by his dark preoccupation.

But in Torcred's brain the question of the stranger's identity loomed less large than that of his own. What was he? Ex-warrior and hunter, ex-hero, ex-terrapin—he could think of things he had been and was not.

I am a—

He had no word. Outcast, traitor, criminal? A newborn pride in him rebelled against the labels he would have accepted without question before his battle with the panzer. He had earned a name, but he had no name.

The west veiled its face in flame again, and darkness overtook them in the wilderness. Torcred dreamed that he stood naked in the middle of a vast circle of formidable machines that snarled and hooted, demanding his name and lineage; and he had no answer. In desperation he cried, "I am I!"—and a thousand motors roared, the armored mass rolled inward to crush him.

He woke staring into a dawn-lit sky where a black flight of buzzards droned northward thousands of feet overhead.

Ladna was awake too and looking up, the old tense fear-born hatred expressed in every line of her body.

"They're insolent," she murmured half to herself. "So close.... This is already my people's land," she explained to Torcred, and her gaze led his toward the mountains, where gray and red and yellow cliffs and slopes stood out now from the blue haze of the canyons. "I don't know how those buzzards dare to fly so near."

"Why do you hate them so?" asked Torcred.

"They're evil. They want to rule the world."

"Well—" Torcred scowled, still out of sorts after his nightmare. "Don't you bird-folk have the same grand plans?"

"That's different!" she cried vehemently. "Don't dare to compare us to the buzzards! We're hunters, like the terrapins, but the buzzards kill and destroy for sport. The milk of their mothers is bitter with cruelty! Oh, if those things should win—" she made a swift gesture to ward off evil—"you'll learn what terror can be!"

A skeptical part of Torcred's mind reflected that that was one side's story. But he wanted to believe the girl when her blue eyes blazed so and her voice trembled with passion. Once he had wanted to hurt her and humble her. That had been long ago....

But there was a strained silence between them as they made ready to resume the march.

They had hardly gone fifty paces when they heard again the noise of engines aloft, nearer this time, and looking up saw a second trio of buzzards passing over. But one of these had left the others and was dropping steeply earthward, heading, it seemed, straight toward them.

Torcred stared stupidly at the great machine—it could not possibly mean to attack them in their utter insignificance. Ladna was less confident; she shrilled, "Down!" and Torcred dropped to all fours and flattened himself to the sand beside her, just as the buzzard leveled off and shot overhead so low that they could see the landing wheels folded like talons under it, could see a door open in its black belly. Something appeared through the aperture and vanished in the speed of its fall. The buzzard had laid an egg, and it hatched mere yards away with a flash and roar that left them blinded, deafened, smothered, feeling that the earth had heaved up to meet the falling sky and pinned them between.

Torcred sat up, swaying, his head a ringing void. He glimpsed Ladna's face, tears of rage furrowing the grime of sand on her cheeks as she glared after the receding and climbing buzzard.

And not far away, among loose heaps of sand on the rim of the blast crater, he saw a strange thing. A massive cone of metal, with the spiral grooves and flanges of a screw, thrust slantingly from the ground; it was turning slowly, earth dropping from it, and as he stared it turned faster and moved forward and upward, drawing after it a glistening rounded back.

Dazedly Torcred walked toward the thing, and as he did so a port-cover lifted in the armored back and a man's head thrust out. He blinked at Torcred with a look of stunned confusion.

"What happened?" demanded the mole in a shaken voice. "I was coming up for a breath of air, then—bang!" He looked around wildly. "My garden! What have they done to my garden?"

The moles, Torcred knew, made gardens—sheets of cellotex impregnated, like the sun-screens of the trailers and like machines, with photosynthetic chemicals. Even the predators left them alone, for the most part, since the moles were a peaceful and harmless race. That, then, had been the bomb's target.

The mole peered at Torcred, seemed to come to himself. "What are you?" he gasped, and without waiting for an answer, ducked inside. The hatch-cover slammed, the great screw reversed and revolved furiously, and the burrowing machine slowly sank from sight under the sand.

"Now do you believe me—about them?" demanded Ladna's stifled voice.

Torcred nodded slowly, feeling sorry for the poor frightened mole, and rather surprised at himself for it, as he had been when he had spared the beaten crew of the panzer.... Torcred the Terrapin was never like that. Mechanically his fingers caressed the half-healed mark on his forehead.

The girl's tongue seemed loosened by their near escape, and as they journeyed on, she talked, with a calm bitterness now, of the enemy. Torcred knew vaguely that, somewhere far to the north, was Buzzard Base, an immense fortress with subterranean dwellings and hangars where the black monsters bred and swarmed. Ladna enlightened him further. "Some of our spies"—the word meant nothing to Torcred—"got inside the place not long ago. They reported things stirring, the buzzards building airframes and engines at a furious rate, obviously planning a new move. Naturally, we increased our construction tempo to keep pace with them, but we've been puzzled; you see, there were rumors that the chief buzzards were worried about something else, besides the old dragging stalemate. But whatever it was, they were keeping it secret even from their own rank and file."

Torcred shook his head bewilderedly; he was lost in her world with its vastness and complexity of organization and politics and schemes for domination. With the openmindedness of confusion he had to admit that the civilization of the air was such as the free terrapins did not dream of.... And he felt an inward hurt as, in the girl's talk of her people and their life, he sensed the widening of the distance between them, which had almost dwindled away while they wandered and struggled to survive and nearly died together in the desert.

But the mountains were close now, and they made good time that day. They did not need to evade any of the prowling land machines, for the desert here was utterly empty, unmarked by wheels, under the threat of the desolate plateaus above and ahead, from which deadly flying things ranged far and wide.

A couple of times they glimpsed winged squadrons in the sky, and the girl's eyes shone, and the shadow on Torcred's face grew deeper.

As evening came on, the mesas rose bare and sheer before them out of the sandy waste. They climbed laboriously over smooth rock and gravel slides; Ladna led the way upward, trying to sight landmarks that were meant to be seen from the air.

At last she gave a little cry of joy, and pointed up the dry streambed they were ascending. Torcred looked, and saw nothing but the rock-rimmed head of the canyon; but the girl had seen some sign that wholly escaped him. "We're practically there!"

Behind her back Torcred passed a hand across his eyes. "Well, then," he said with assumed casualness, "you'll be all right from here on."

She whirled and gave him a searching look. "What are you talking about?"

Torcred's jaw muscles twitched. "I'm wishing you a happy homecoming," he answered, "by way of saying goodbye."

"But you're coming with me!... Aren't you?... What else can you do?"

He shook his head somberly. "I'm too used to freedom, Ladna. I'll take my chances with the desert again."

"I told you my people will accept you, and your fate among them will be no worse than mine...." Her protest trailed off as she read the inflexible refusal in his impassive face.

"Earth and sky can't meet." He looked back down the canyon, toward where a wedge of the barren plain, pink with reflected sunset, showed between the rock walls. Then the girl was in front of him again. Her eyes were very large, and her red lips spoke no more useless words of pleading.

Instead—her hands were on his shoulders, her arms slipped round his neck as her slim body swayed against him, her face blurred with nearness, tilted up....

Gravely, according to the terrapin custom, Torcred touched noses with her.

He felt her go tense, and she drew back. Her eyes glistened with a shock and disappointment he was at a loss to understand. She said in a choked voice, "Good-bye!" and turned and fled up the ravine.

Mechanically Torcred picked up the satchel with the remainder of her share of the food and water, which she had remembered to leave behind. His muscles tightened with a violent urge to run after her and bring her back by force.

But how could he hold her with him? She still had her place, however small, in the world of machines that had cast him out.... Suddenly he hated them all without exception, all the iron monsters that ruled the world in whose sight flesh and blood were helpless, hopeless, as nothing.

He stumbled down the mountain, going into an exile lonelier than that stigmatized by the brand on his forehead. Yet withal, loneliness and hatred, he felt a curious inner peace. His brain was no longer a battlefield of hostile allegiances and longings. He still had no name for what he had become. But it didn't matter any more.

He reached the bottom of the last rock slide, and looked back; in the failing light he could just make out the mesa rim, above which must lie the aeros' eyrie. Nothing moved up there. She would be at home now, among her own kind.

VIII

When he turned away, he saw the stranger standing not far off, beneath a great stone promontory that thrust out into the sea of sand, his back to a deep black cleft in the rock. Torcred could see his face clearly this time, and this time it was unsmiling, the brows drawn together and lips compressed in an expression of anxiety. The stranger beckoned with a jerky urgency, half-turned, and pointed toward the crevice of the cliff.

Torcred took a step toward him, his anger boiling up dangerously, blood drumming in his ears. "What are you?" he shouted. "What do you want? You've dogged my steps, watched me, and applauded my downfall. Now what—"

The stranger's eyes shifted, and he moved his head as if listening to a voice that Torcred did not hear. His eyes widened with alarm, and he vanished like a blown-out flame.

Torcred blinked baffledly. The hand on the hilt of his knife relaxed, but the roaring in his ears grew louder. Almost it might be real....

He threw back his head and looked up. Far above, individually almost indistinguishable in the pale twilight sky but making it alive with their massed formations, V after V of black flying shapes were moving. The air throbbed with the vibrant roar of many engines.

The leading squadrons were already over the mountain when the first dart of flame leaped from it and climbed with a whistling rush to meet them. Others followed, the clatter of their guns mingling with the multiple crescendo shriek of the first sticks of falling bombs.

Torcred crouched involuntarily, bracing himself for the concussions that must shake earth and air.... But only dull thudding sounds rolled down from the mesa, as if the rain of projectiles fell without exploding.

Over the mountain two buzzards dropped out of formation and wobbled earthward, trailing smoke down the sky, and a third burst into bright flame and disintegrated in a meteoric shower. New formations still came droning out of the north—the buzzards were attacking in force. Their bombs kept landing with sullen thumps, almost inaudible under the roar of motors, the sputter of guns and the flat reports of aerial cannon.

But to Torcred, hugging the lee of a great boulder and trying with straining eyes to pierce the darkness that increasingly shrouded the mesa, those dull incessant impacts became an ominous sound. Ladna had gone up there—she had had plenty of time to reach safety in the buried heart of the eyrie, which even the mightiest explosives could scarcely touch—but without knowing why, Torcred edged out of his shelter and began once more, creeping from rock to rock, to clamber up the steep ravine that the two of them had ascended together.

He had not progressed far—in the dark the uncertain footing was dangerous—when the breeze, sighing down the canyon with cool mountain-top air for the hot plain, brought confirmation of his fear with it.

A whiff of strange odor that stung in his nostrils and tickled his windpipe harshly. Then his eyes began to smart as it grew rapidly stronger; the gas the buzzards had used to blanket the mesa was a dense one, designed to seek out the aero people in the depths of their underground fortress.

Torcred halted, blinking, struggling with the growing need to cough. He recognized the odor after a moment—the same poison that the machines called skunks used against their enemies. He knew that enough of it was deadly. And a cold hand of terror clutched at his heart.

He flung caution from him and started to scramble recklessly, planlessly upward. Denser clouds of gas met him, and, half-blinded, he stumbled against sharp rocks and almost fell when fits of coughing shook him. His chest became a rasping furnace, and each deep panting breath was a flame. Bitterly he knew that his will could not drive him much longer into that torment....

In the air something flew burning, and the light of its destruction fell bright as day into the canyon and threw shifting shadows. Torcred's tear-filled eyes blurred the glare, but he glimpsed a small dark-clad figure huddled on the rocks not ten feet from him, across a black crevice that might be five or fifty feet deep.

He crouched and sprang; weakened knees betrayed him, he landed clawing on the rounded lip of the chasm and barely managed to pull himself up to the girl's side. But new strength steeled him as he gathered his feet under him and dragged both her and himself erect.

Ladna was alive and conscious; she leaned against him, coughing weakly.