SWEDISH SOCIETY OF ANTHROPOLOGY

AND GEOGRAPHY

BY

CARL BOVALLIUS

STOCKHOLM, 1886

KONGL. BOKTRYCKERIET

P. A. NORSTEDT & SÖNER

TO

THE ROYAL ANTIQUARY OF SWEDEN

Dr. HANS HILDEBRAND

THIS WORK,

THE PUBLICATION OF WHICH HAS BEEN POSSIBLE

ONLY BY HIS KIND EXERTIONS,

IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED

BY THE AUTHOR.

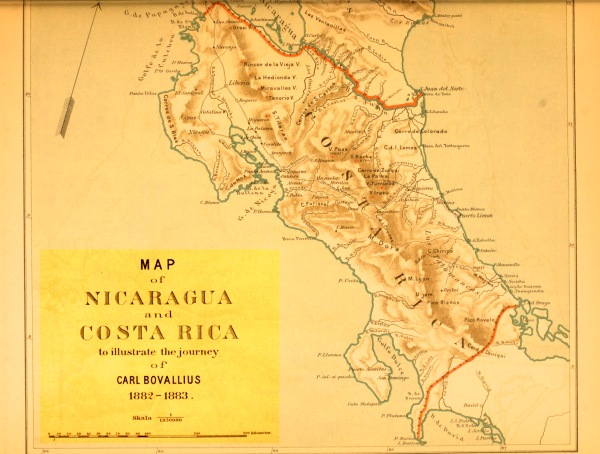

Nicaragua is a very rich field for research to the student of American Archæology, and so I found it during my two years stay in Central America. I had there the good fortune several times to meet with localities more or less rich in remains from the prehistoric or rather pre-spanish period. Not very much being known about Central American antiquities, and the literature on this subject being very poor, especially with regard to the Nicaraguan ones, I purpose here to describe briefly and to figure the more important statues, rock-carvings, ceramic objects etc., found by me in Nicaragua and partly delineated or photographed on the spot, partly brought home to Sweden. Unfortunately I wanted the means of carrying home any of the statues; but my Nicaraguan collections contain a number of more easily transportable relics, mostly examples of pottery. These are now deposited in the ethnographic collection of the R. Swedish State Museum. The accompanying plates are all executed after my original sketches or photographs taken on the spot. Most of the statues have never before been figured or described; some of them are mentioned and figured by E. G. Squier[1] in his splendid work on Nicaragua. As it turned out, however, on [Pg 2] comparisons being made by me on the spot, that some of Squier’s figures do not quite agree with the originals, I have thought fit to publish also my own drawings of these previously figured statues, 6 in number.

Although this sketch is certainly not the place for an account of the history of Central America or Nicaragua, yet I may be permitted to give a brief statement of those few and disconnected notices that we possess with regard to the nations inhabiting Nicaragua at that period, when the antiquities here spoken of were probably executed. The sources of our knowledge of these people and their culture are, besides the above quoted work of Squier, the old Spanish chroniclers, Oviedo, Torquemada, Herrera, and Guarros, the memoirs of Las Casas and Peter Martyr, the relation of Thomas Gage, and scattered notices in the works of Gomara, Ixtlilxochitl, Dampier a. o.

At the time of the Spanish invasion under the command of Don Gil Gonzales de Avila in the years 1521 and 1522, the region now occupied by the republic of Nicaragua and the north-eastern part of the republic of Costa Rica, was inhabited by Indian nations of four different stocks, which very probably may be considered as being of different origin and having immigrated into the country at widely separated periods.

The Atlantic coast with its luxuriant vegetation but damp climate and the adjacent mountainous country with its vast primeval forests were the home of more or less nomadic tribes, remaining at a low stage of civilization. It may be inferred, however, from certain indications in the account of the third voyage of Columbus, and from the scanty notices of several of the so-called buccaneers or filibusters, that those Indians were more advanced in culture and manner of life than the hordes, that may be regarded as their [Pg 3] descendants at the present day: the Moscos, the Ramas, the Simoos or Smoos a. o.[2]

Between this strip of country on the eastern shore and the two great lakes, Xolotlan (Managua) and Cocibolca (the lake of Nicaragua), the intermediate highland, which shelves gradually towards the lakes, was inhabited by los Chontales, as they are denominated by Oviedo. The name is still preserved in «Departemento de Chontales». They lived in large villages and towns and were agriculturists. Possibly they were of the same stock as, or closely related to, the large Maya-family which extended over the eastern parts of Honduras and Guatemala and furnished the population of Yucatan. This guess acquires a certain probability by the fact of several words in their language being similar to the corresponding ones in some Maya-dialects. The Poas, Toacas, Lacandones, and Guatusos may possibly be their descendants. These also are living at a decidedly lower stage of civilization than their supposed ancestors.

If the eastern part of Nicaragua, on account of its almost impenetrable forests and damp climate, is less fit to be the dwelling-place of a highly cultivated people, the western portion, on the contrary, is much [Pg 4] more happily endowed in this respect and seems to be marked out by nature itself to become one of the centres of mankind’s civilization. By its smiling valleys, fertile plains, and thinner, but shadowy forests, by its splendid lakes, gently flowing rivers, and verdant mountains the country appears well able to tempt even the most exacting people to settle in it. Indeed the country, on the arrival of the Spaniards, was found to be very densely populated, and divided amongst a great number of small sovereignities, which could however be referred to two separate stocks, differing in language and character. One of these, the third one of those stocks from which has sprung the population of Nicaragua, was los Choroteganos or Mangues. They occupied the territory between the two large lakes and all the fertile level country west and north of Lake Managua down to the Pacific and Bahia de Fonseca. Oviedo asserts that they were the aborigines and ancient masters of the country, without being able however to state any proofs in support of his opinion. Of los Choroteganos four groups are usually distinguished: 1:0) Los Cholutecas on the shores of Bahia de Fonseca; their principal town was the present Choluteca. 2:0) Los Nagrandanos between Lake Managua and the Pacific; their capital was Subtiaba, near the present Leon. 3:0) Los Dirianos between the lakes Managua and Nicaragua and down to the coast of the Pacific. Their largest town was Salteba near the present Granada and 4:0) Los Orotinas far separated from their relations, inhabiting the peninsula of Nicoya and the territory of Guanacaste, which comprises the north-eastern part of the republic of Costa Rica. Opinions vary, however, with regard to these groups, several authors being inclined to regard los Cholutecas as a detached branch of los Pipiles in El Salvador; they would then be of Toltecan origin. Certainly there is a number of local names within their district which seem to corroborate this opinion. Other writers [Pg 5] are disposed to ascribe a Mexican origin to the Orotinas and lastly Dr. Berendt[3] suggests that the whole Chorotegan stock may be considered as a Toltecan offspring, the name Choroteganos being only a corruption of Cholutecas.

The last or fourth of the tribes inhabiting Nicaragua was los Niquiranos. The territory occupied by this people was the smallest of all, viz.; the narrow isthmus between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific, together with the large islands, Ometepec and Zapatera, in Lake Nicaragua. But although comparatively small in extent this territory was perhaps the most richly blessed of all in this country, the darling one of nature. According to the concurrent testimonies of the old chroniclers the Niquirans were a Mexican people settled in the country at a comparatively late period. It is not clear whether they were Toltecs or Aztecs, and this question cannot probably be decided until the ancient remains, surely very numerous, that they have left behind them, shall have been accurately studied and compared with the better known Mexican antiquities. For my own part I incline to the opinion that they were Aztecs, and had immigrated into the country rather late, perhaps little more than a hundred years before the Spanish invasion. They lived in a state of permanent hostility with the Chorotegans and had probably, on their irruption, expelled the Orotinas, who were thus cut off from the main stock of the Chorotegans. The intelligent and well built Indians on the island of Ometepec are doubtless the descendants of the Niquirans; this is corroborated by their language, which the successful investigations of Squier have shown to be of Mexican origin and presenting a very close similarity to the pure Aztec tongue. They are now a laborious and [Pg 6] peaceful race, somewhat shy of strangers; in general they speak Spanish, but may be heard occasionally to talk Indian dialect with one another; with regard to this dialect they are, however, extremely unwilling to afford any explanations, generally answering «es muy antiguo» «no sé nada». The Indians of Belen and the surrounding region remind one of the Ometepec Indians, but are evidently intermixed with foreign elements.

According to Oviedo, Torquemada, and Cerezeda, the last one of whom accompanied Gil Gonzales de Avila in his expedition 1522, and thus is able to speak, like Oviedo, from his own personal observations, the Niquirans had reached a higher degree of civilization than their neighbours. However, the Chorotegans were also pretty far advanced in culture.

Indeed, reading the scanty descriptions of the last days of these nations, one feels tempted to assert that in harmonic development of the mental faculties they were superior to that nation, which, by its crowds of rapacious and sanguinary adventurers, honoured in history with the name of «los Conquistadores», has fixed upon itself the heavy responsibility for the annihilation of this civilization. For indeed so swift and radical was this annihilation, through the fanatical vandalism of «christian» priests and the bloody crimes of a greedy soldatesca, that history knows of no similar example. Thus the investigator of the comparatively modern culture of Central America is obliged to travel by more toilsome and doubtful roads than the student of the ancient forms of civilization of Egypt and India, although these were dead several thousands of years ago.

So much, however, has come to the knowledge of our time, as suffices to prove that the nations of Central America were very far advanced in [Pg 7] political and social development as well as in science and art. But no other way is left to us of gaining an insight in this culture, than to search the country perseveringly for the purpose of disclosing the monuments, hidden in the ground or enviously concealed by the primeval vegetation, that now reigns alone in many of those places, which were formerly occupied by populous and flourishing cities, and artistically ornamented temples.

By comparing these monuments with those of Mexican culture, somewhat better known in certain respects, we may hope finally to arrive at the solution of some of the intricate problems concerning the ancient nations of Central America and their history.

The antiquities figured by me were found for the greatest part in the island of Zapatera, the rock-carvings in the islet of Ceiba close to Zapatera, only some few ceramic objects are from the island of Ometepec. All these localities are contained within the territory occupied by the Niquirans, and on this account may probably be considered as specimens of Aztec art, or of an art very closely related to this. Those few statues that I have seen in the neighbourhood of Granada and in Las Isletas immediately off Granada, as well as the statues and high-reliefs in the little volcanic island of Momotombito in Lake Managua, the former belonging probably to los Dirianos, the latter to los Nagrandanos, appear to me to be much more rudely executed, without any attempt to copy the human body; whereas many of the statues of Zapatera testify to a pretty accurate study of the human body, often presenting faithfully elaborated muscle portions etc., so as to make it probable that the Niquiran artists used models. There certainly are found rather fantastic figures even among these statues, but in general their originators prove to be artists of a more realistic conception, and at the same time of more developed technics [Pg 8] than the Chorotegan artists. From the monuments etc. found farther northwards at Copan, Quiriguá, Uxmal, Palenque, and other places in Central America, the works here described differ most considerably, indeed so much that it is not easy to point out more than a few common artistic features.

With the exception of the meagre notices, communicated by Oviedo and Cerezeda and their compilers, the source of our knowledge of Nicaraguan antiquities is E. G. Squier’s interesting work «Nicaragua: its people, scenery, monuments and the proposed interoceanic canal». After Squier some other American investigators have followed in the road opened by him; Dr. Earl Flint of Rivas has during many years searched for and collected antiquities, partly in the Department of Rivas, partly in the island of Ometepec. I am obliged to Dr. Flint for much valuable information on the present subject, kindly communicated to me, when I had the pleasure of meeting with him at Rivas in January 1883. He has sent the collections gradually brought together by himself, to the Smithsonian Institution. In «Archæological researches in Nicaragua»[4] Dr. J. F. Bransford gives a highly interesting description of his researches in Ometepec, where he made a large collection of grave-urns, other vessels of pottery, and smaller relics of stone and metal. He occupied himself principally in investigating burying-places on the west side of the island and he has thrown a new light on this part of Niquiran archæology. His very large collection, of 788 numeros, is deposited in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. He has also figured several rock-carvings from Ometepec; these seem to be a little ruder and less complicated than those delineated by me from the island of Ceiba. [Pg 9] Dr. Bransford also describes several ancient relics from Talmac, San Juan del Sur in the department of Rivas, and some localities in Nicoya, in the republic of Costa Rica. From a linguistic point of view Dr. Berendt[5] has given very valuable contributions to our knowledge of the ancient civilisation of Nicaragua by his sharp-sighted and successful investigations into the Indian idioms of that country and into those of Mexico and of the northern parts of Central America.

In the night of the New-Year’s-eve 1882-1883 I arrived at Ometepec from Granada, and took up my head-quarters at the little borough of Muyogalpa, in the north-west corner of the island. From this point excursions were made in different directions, and, although my time was pretty severely taxed by zoological researches, I found however some opportunities of undertaking archæological diggings.

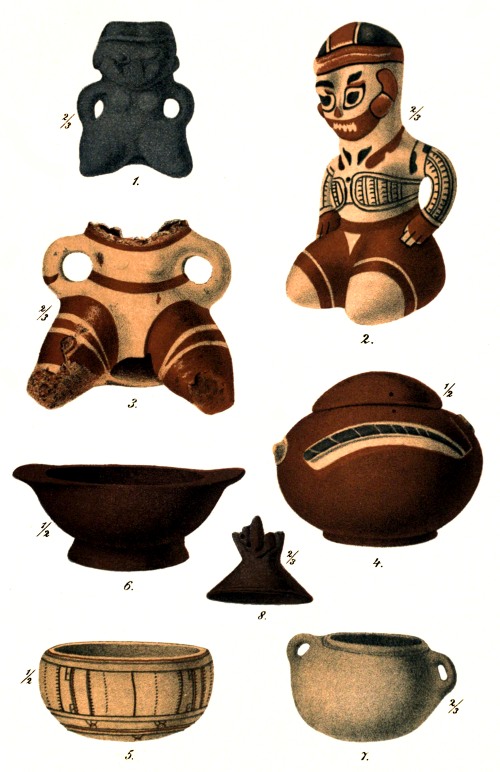

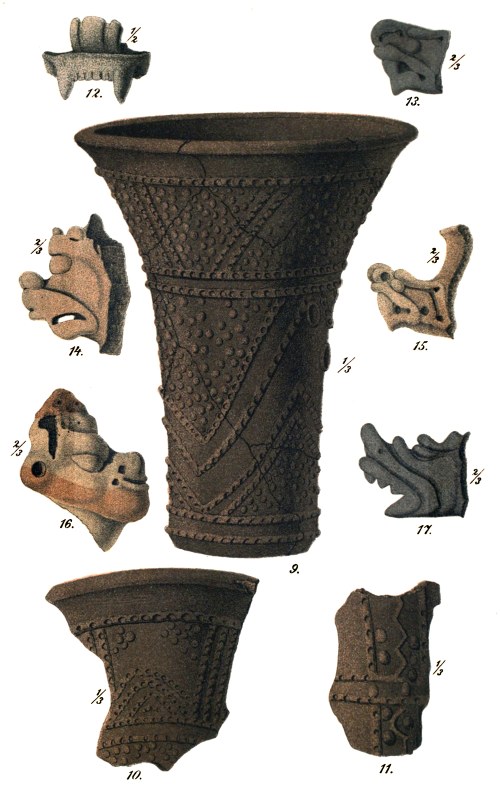

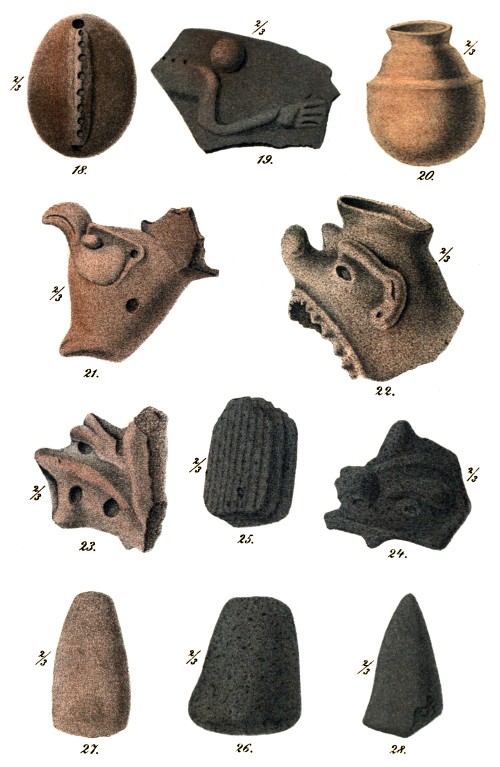

Hardly one kilometer to the west of the burying-place examined by Dr. Bransford, a symmetrical mound, rising one meter and a half above the ground, was dug through (Station 1). It contained a little bowl, pieces of a larger urn of an unusual thickness, feet and fragments of a tripod vase, and a little bronze figure of a saint, the last one evidently a foreign guest among the other objects. At Los Angeles (Stat. 2) two statues, both very badly frayed, were measured and sketched; some insignificant fragments of pottery were digged out. At a bay (Stat. 3) on the north side, between Muyogalpa and Alta Gracia, in a place said by the Indians to have formerly been a town, fragments of divers small pottery, two stone chisels, one «molidor», and perforated and polished shells of a species of Oliva and a species of Voluta, from the neighboring coast of [Pg 10] the Pacific, were dug out. In a valley, or rather ravine (Stat. 4), near Alta Gracia, where a heap of pretty large, partly cut stones seemed to indicate the site of a large building, several fragments of pottery were found together with a cup of earthen ware, and a well preserved little sitting image of painted terra cotta, pretty similar to that figured by Bransford, l. c., p. 59. At a height of nearly 350 m. above the level of the lake on the west side of the majestically beautiful volcanic cone (Stat. 5), while digging in a rather extensive stone-mound, a very pretty, vaulted earthen urn with lid, painted in three colours, was found, and, besides, a great many fragments of pottery. I made excavations also at six other places in Ometepec, for inst. in the isthmus between Ometepec and Madera, but without any results worthy of record.

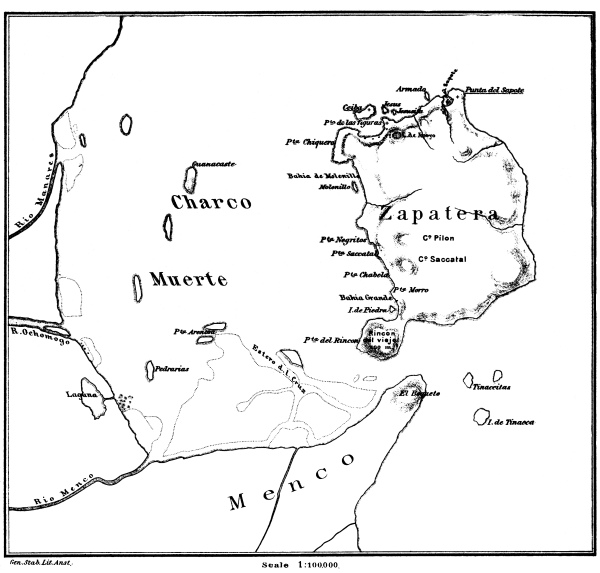

I stayed in this charming double-island for more than a month, roving through it on horse-back and on foot in all directions, ascending the volcano, rowing and sailing over the delightful lagoons and bays, that border its shores, and amongst which I shall late forget that very paradise for the hunter, Laguna de Santa Rosa and Charco Verde. Having left Ometepec about the beginning of February, my next visit was to «tierra firme», where I made some easily executed, but not very successful excavations, immediately to the north of San Jorge. From Departemento de Rivas’ I sailed to Las Isletas, also called Los Corales, an extremely beautiful little archipelago, just southwards of Granada. The whole group owes its existence to the volcano Mombacho, which towers high above it, the islands consisting exclusively of the remains of one or more eruptions of Mombacho. But the vegetation here is so powerful and luxuriant, that it has changed those piles of black [Pg 11] stones into smiling islands, which the traveller is never tired of admiring. Only on the outside of the archipelago, where the often angry lake of Nicaragua has checked the development of the verdant cover, the black, gloomy basalt is still open to the view, lashed by white-foaming waves. In several of the islets statues were measured and delineated, but unfortunately the photographic apparatus could not be used on this occasion. After a stay of some days among Las Isletas and a short visit to Granada for the purpose of completing my photographic outfit, I set sail for Zapatera. On my arrival I encamped for a long time on the playa of Bahia de Chiquero. Along the playa of the semi-circular bay there are now five houses, the homes of as many families, being the only inhabitants at the present time of this large and fertile island, which was, no doubt, formerly populated by many thousands of Niquirans, possessing rich towns and splendid temples. The islet of Ceiba is situated off Bahia de Chiquero (see map 2). According to my opinion, Zapatera is certainly a volcanic island, but in this manner, that its north-western part is the summit of a sunken volcanic cone, Bahia de Chiquero being the crater itself, the narrow, elevated mountain ridge which surrounds the bay, forming the edge of the crater and the islet of Ceiba the continuation of this edge, Laguna de Apoyo, situated scarcely one kilometer from the shore, may then be regarded as a side-crater.

Zapatera exhibits an abundant variety of beautiful scenery, delightful valleys, watered by streams and rivulets, fertile elevated plains, magnificent mountain-cones, clothed in verdure to the very summits, and bays and lagoons offering excellent harbours. Unfortunately I had not an opportunity of examining, in an archæologic point of view, more than a part of the north side of the island and the islet of Ceiba. My kind hosts of the settlement in the island, Don José Lobo, Donna Julia Solorzano, S:rita Virginia Mora, Don Jacinto Mora and others, zealously assisted me [Pg 12] in my zoological as well as archæological investigations. Through their warm-hearted benevolence my stay in Zapatera became the most pleasant remembrance of my long journey.

The results of my antiquarian researches in Zapatera may be referred to three stations: 1:0. The first station is Punta del Sapote; the extreme north-western point of the island, where statues, potteries, and stone relics were found. This station is beyond all comparison the most important one, because it has never, as far as I know, been examined, nor even mentioned. It possesses so much greater importance, as several statues were found in their original position, thus affording an insight into the manner how they were used. 2:0. The second station is Punta de las Figuras. It forms part of the edge of the crater, sloping softly towards the lake, between Laguna de Apoyo and Bahia de Chiquero. It has been previously visited by Squier, who has given figures of several of the statues. Besides those mentioned by him, many of which I did not find, I lighted upon some that had escaped his attention. In this locality only insignificant remains of pottery were met with. 3:0. The third station is the little island of Ceiba, which, instead of statues, that are wanting, offers some very well preserved rock-carvings of evidently very ancient date, and, besides, valuable relics of earthen-ware and stone. Although my visit to Zapatera was posterior in time to my stay in Ometepec, I shall begin the detailed description of the antiquities with those of the first station in Zapatera.

Punta del Sapote forms a broad, rounded peninsula, the greatest length of which is in N.E. and S.W. Its middle part is a large plateau, about 150 m. high, sloping rapidly both towards the lake and the neck of the peninsula, and thus forming an isolated height of somewhat more than one kilometer in length by scarcely one kilometer in breadth. The central portion of this plateau is perfectly level and, judging by the numerous statues met with here, and the regular form of the stone-mounds, round which they were placed, appears to have been a sacred place during the Niquiran period. On the very isthmus between the peninsula and the island of Zapatera rose a conical stone-structure, 30-40 m. high; it consisted of enormous, unhewn blocks, placed upon one another in pretty regular layers. Its diameter at the base might be estimated at about 40 m. The top of the cone was truncated, and appeared to form a plane of 6-8 m. in diameter. The steep sides were so densely covered by spinous bushes and lians, that I was soon obliged to desist from my attempts to mount the summit. The whole structure resembled a kind of beacon, and has possibly been a place of sacrifice, although its dimensions were so large, that it cannot well be regarded as such a «sacrificial pillar» as is mentioned by Peter Martyr under the name of «Tezarit». Maybe a little «casita» has stood on the platform above. Something of the same kind is known from Uxmal.

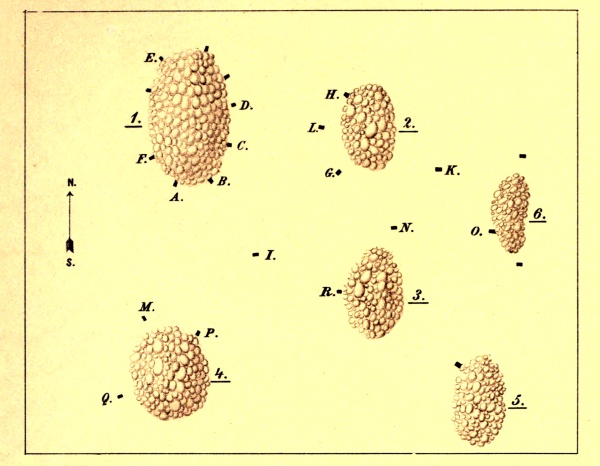

Due north of this cone, on the top of the above mentioned plateau, were six stone-mounds of oval form, but of very different size. The largest [Pg 14] (Pl. 41: 1) measured about fifty m. in length by thirty m. in breadth, the smallest (Pl. 41: 6) about fifteen m. in length by somewhat less than half in breadth. The greatest diameter of each mound was in N. and S. The stones of these mounds varied of course in size, but for the most part they were large, more or less cubical, from half a meter to one meter long and about half a meter broad. Their often regular shape and pretty plane sides, particularly in the mound 1, might lead one to infer that some of them have been hewn, and have formed the foundations and possibly also the walls of buildings, the ground plans of which are indicated by the form of the mounds and the situation of the statues, of which we are soon going to speak.

At the mound 1 (Pl. 41), the largest of all, and the one situated farthest to the north and west, several statues were found remaining in the same position, that they originally must have occupied, because the mound was still surrounded by six figures, standing in its circumference; and larger or smaller fragments of the pedestals of three others were found in the ground, although the statues themselves were thrown down beside them, and more or less broken. Judging by the regular distances between these statues, it is probable, that there have been twelve figures standing in the periphery of this building or temple. The fact that those remaining in the ground fronted outwards, and that their backs, which were turned towards the building, were not smooth, but only plane-cut, strengthens my hypothesis that the figures have formed part of a stone- or logwall enclosing the building. All those statues of the mound 1, of which the upper parts remained, with the exception of D, and another not delineated one, carried on their heads a more or less long and broad projection in the form of a tenon, and on this account I venture to propose the hypothesis, that they have served to support the wall-plate of a more or less circular building. All the statues were monoliths, cut from blocks of blackish basalt of a pretty considerable hardness. The roof itself has probably been covered with palm leaves, a supposition confirmed by certain indications in [Pg 15] Cerezeda and Oviedo. That the temples should have been open, as Squier seems to think, I venture to doubt, on account of the above described form of the statues; this appears to show that they must have been united with one another by a wall, probably of cut stones.

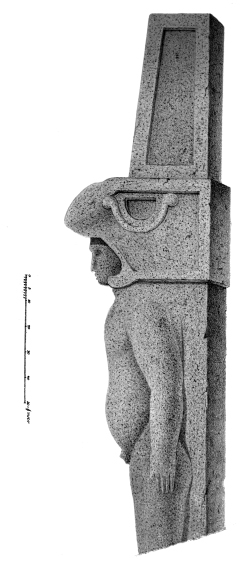

A

Pl. 1.

Male, standing figure, in an easy posture, with the arms hanging straight down. It stood quite upright, but was buried in the earth to the elbows; by digging round it, it was laid bare to just below the knees. It was the finest and most nobly sculptured of all the Nicaraguan statues that I have had an opportunity of seeing. The face, neck, and chest were carefully elaborated, the mouth closed with full lips, the Adam’s apple marked out at the throat, the muscles of the chest, as well as of the arms, correctly rendered; the hands on the contrary were somewhat stiff, with the thumbs in the same plane with the other fingers. The shoulders, elbows, and hips were well formed (the arms were, however, not detached from the body), but passed gradually backwards into the plane-cut back of the stone. The head was covered with a large, rounded hood or cap, projecting above, and drawn out in rounded flaps at the sides of the neck. Upwards and backwards this hood passed into a kind of capital, ornamented at the sides with a semi-circular depression, bordered by a rounded rim, with globularly enlarged ends. The tenon-shaped projection above the head was unusually large, tapering upwards, surrounded in front by a double frame, at the sides by a simple, broad, sharply cut one. The statue was perfectly equilateral. It did not seem to have been exposed to any injury whatever, and was on the whole the best preserved of all in this locality. The whole length of the statue from the upper edge of the tenon to the knee was 225 cm., the breadth across the shoulders 58 cm., the length of the tenon 65 cm.

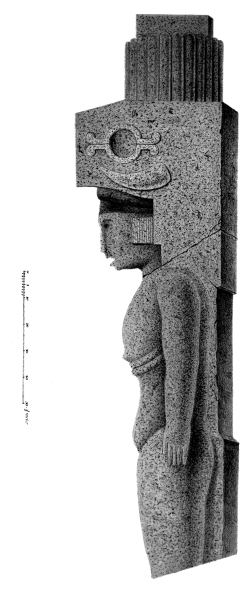

Female, standing figure, its head slightly bent forwards, and its arms hanging straight down. It was found erect, but imbedded in the earth to [Pg 16] the navel; the head was broken off, but was found close to the statue. The statue was very well sculptured, but not so carefully finished as the preceding one. The forehead was adorned with a low turban or round band, upon which was placed the heavy capital, with carvings in relief on the sides. The capital was surmounted by the square-shaped tenon, the lower part of which was surrounded by twenty staves with rounded tips. These ornaments seem to indicate, that in this statue, as well as in the former one, which was adorned with a double frame, the lower part of the tenon has been visible, and only its uppermost portion inserted into the plate of the building. The face and chest were well preserved, although not so accurately rendered as in A. The mouth was half-open, the eyes were well marked, deep cut, the ears hidden by large, square, flat, and grooved pieces. The breasts were held up by a double, round band. The breadth across the shoulders was extraordinarily great. The shoulders were high and thin, the arms very short and feeble in proportion to the body, not entirely detached, but much more so than in A. The length of the statue from the upper edge of the tenon to the knee was 226 cm., the breadth across the shoulders 66 cm.; the length of the tenon 34 cm.

C

Pl. 4.

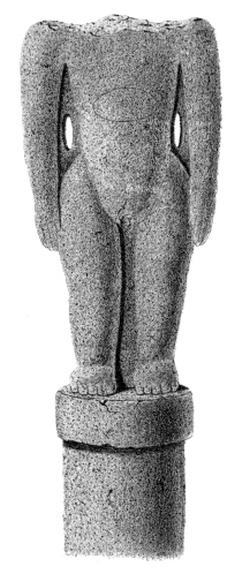

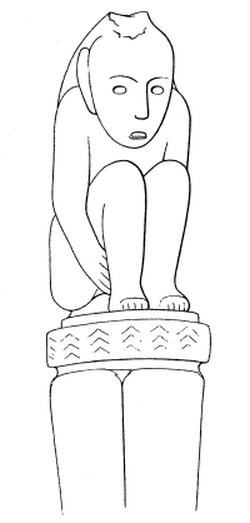

Male, half-sitting figure, with straight hanging arms; of considerably less size than A and B, and very badly damaged. The head and neck were broken off, and crushed into small fragments, impossible to reconstruct. The pedestal was round, column-shaped, without any ornaments. The figure had powerful arms, detached from the sides of the body. The legs were unusually thick and strong, the feet clumsy, with thick, short toes. In the middle of the chest there was a carved oval, with a little circle in its centre. The length of the statue from the shoulder to the sole of the foot was 110 cm., the breadth across the shoulders 56 cm.

C 1

Not figured.

Male, sitting figure, with its hands crossed on its knees. The pedestal was square, remaining erect in the ground. The statue itself was broken [Pg 17] in six pieces, its face entirely crushed. It carried on its head a round, column-shaped head-dress, similar to that delineated in figure F, ornamented with transverse furrows and ending upwards in a tenon. The ears were hidden by square, flat pieces 21 cm. in length, resembling those of figure B. The head itself was 39 cm. long from the base of the head-dress to the chin; 31 cm. broad across the forehead. The breadth across the shoulders was 60 cm.

D

Pl. 5.

Male, standing figure. Head, chest with arms, and upper part of legs broken off, and lying in four pieces on the ground. The pedestal was square, with the upper part ornamented with angular wreaths; it remained fixed in the ground in its original place, and carried still the feet and the legs (to the knees) of the figure. The face was of quite a different type from those of A and B, with very prominent cheek-bones, large lips, and strongly protruding under-jaw; it was adorned with a crown-shaped head-gear. The ears were also here hidden by flat pieces, thickening upwards, with the lower corners rounded. The back of this statue, as well as its position in the periphery of the stone-mound, points to its having formed part of the wall of the building; but it seems not, however, to have served the purpose of supporting the roof, because the upper part of the crown was finely chiselled, and exhibited no trace of a tenon. It differed in this point from all the other statues in the circumference of the mound 1, with the exception of E 1, that was situated almost opposite to D at the western longside. The height of the head from the upper rim of the crown to the lower edge of the chin was 45 cm. The length of the trunk from the shoulders to the thighs was 60 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 54 cm.

D 1

Not figured.

At a distance of 5 m. from D, in the periphery of the mound, there rose obliquely from the ground a male, half-sitting statue with its arms [Pg 18] crossed. The head and the uppermost part of the chest with the exception of the right shoulder were wanting, and could not be identified among the existing fragments. It wore a beard reaching to the crossed arms, being in this respect as well as in posture and workmanship very like F. It measured 102 cm. from the shoulder to the thighs. The breadth across the shoulders seemed to have been less than 50 cm.

D 2

Not figured.

Near the place that ought to have been occupied by the next statue, there were lying fragments of an unusually narrow, square pedestal or pillar. It was narrower than the following E, but in other respects it resembled this more than it did any of the others found here.

E

Pl. 5.

Contrary to the other images of this mound, indeed, of this whole locality, it did not represent a human figure, but formed a square pillar, provided with carvings on its front side. It carried a narrower superstructure (tenon), bordered in front by a sharp-cut frame, 6 cm. broad, 3 cm. deep. The carvings on the front side of the pillar itself consisted of wreaths somewhat more than 2 cm. deep with a breadth varying from 3 to 5 cm. They appeared to represent the head of an animal with an eye surrounded by two concentric circles. The sides of the pillar were narrower, smooth, without any traces of wreaths, but bordered by a square-cut frame, 6 cm. broad and 3 cm. deep. The back of the pillar, which was turned towards the building, was rough, without any frame. The front side was provided with a frame only above, and along the eastern side. The front side of the pillar was 50 cm. broad, the lateral sides 37 cm. broad. The tenon was 40 cm. in height by 38 cm. in breadth. The pillar was so deeply imbedded in the ground, that in spite of our digging strenuously, I did not succeed to lay bare more than about 125 cm. of its length, reckoned from the upper edge of the tenon. [Pg 19]

E 1

Not figured.

Male, standing, much damaged. The human figure supported on his head the head of a massive animal of the feline genus, by its form most reminding one of the African or Persian lion(!). The statue was thrown down and broken in several pieces; only the head of the animal was so far preserved as to enable one to discern something of the original sculpture. Upon this head was part of a square tenon. The length of the statue from the upper edge of the forehead to the thighs was 84 cm., the breadth across the shoulders 39 cm., the length of the face 24 cm. The head of the animal was 54 cm. high and 52 cm broad.

E 2

Not figured.

Fragments of a female, sitting statue were shattered in the vicinity of the place, that should have been occupied by the tenth statue. The head was adorned with a turban-shaped head-dress, without any trace of a tenon. It is, however, very uncertain whether this statue has formed part of the series.

Between the last-mentioned statue and F there was not the least vestige to be found of that statue which ought to have been the eleventh in number, when reckoned from A.

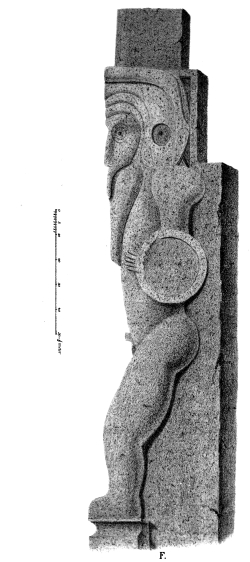

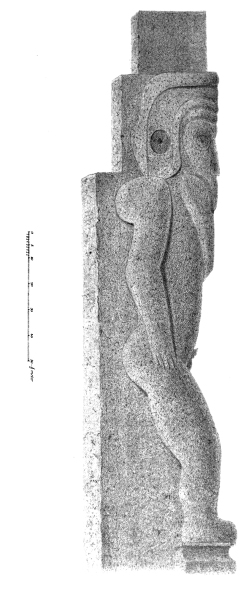

Male, half-sitting figure, with its right arm hanging straight down, and its left one bent, and resting on the chest. According to my impression, received on regarding the statue and sketching it, it represented a chieftain or warrior with a mask before his face and a helmet on his head. I have arrived at this conclusion from the reasons, viz. that the face was here incomparably much stiffer than in the other images, without the slightest attempt of indicating the muscles, the [Pg 20] cheeks, or the mouth; further that the eyes were marked by two concentric circles with a little (peeping-)hole in the centre, and that the whole face and the covering of the head were so much broader proportionally to the breadth of the body than in the other statues. (A somewhat similar head was found on the heavily injured statue at the mound 5.) The head-cover may be considered to exhibit the form of a helmet; this reached to the shoulders at both sides, hiding the ears completely; but nearly at the place of the ears there was on each side a shallow circular depression with a small excavation, probably representing a hole, in the centre. From the lower part of the helmet a thick elevation, grooved length-wise in front, came down over the chest. It may be regarded as representing a breast-armour, or possibly a beard. From the face itself, below the nose, a piece of the same shape as the just described elevation was seen to descend, but it was of much smaller dimensions. The left shoulder with the bent arm was somewhat more raised than the right. Both shoulders were uncommonly large and broad, so that the artist almost seems to have intended to indicate the blade-bone. The arms were pressed close to the body, disproportionately narrow when viewed from the front, but more than sufficiently broad when viewed from the side. On its left bent fore-arm the statue held a little round shield, at the anterior margin of which the hand projected, showing, unusually enough, the thumb of the same length with the index. The chest and abdomen were sculptured with some signs of muscles. The legs were short and thick, the feet clumsy, with no traces of toes. The image stood on a pedestal, the upper part of which showed a deep cavetto. The pedestal was deeply immersed into the ground. Immediately above the helmet was the square tenon. The length of the statue from the upper edge of the tenon to the upper edge of the pedestal was 207 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 57 cm., that of the head 36 cm. The statue was on the whole well preserved, and stood, no doubt, in its original situation.

As it seems to be beyond a doubt that the above described statues, which were found standing more or less erect, and at almost equal distances, nearly five meters from one another, remained in the situations where they had been originally placed, it cannot be considered too bold, to suppose that we have here before us an ancient [Pg 21] temple exhibiting an example of how such a building might be arranged with the Niquirans. It is evident that the ground-plan of the edifice has been a broad oval, and it is highly probable, on account of the back of the statues not being elaborated, but only roughly cut, that it has not been open, but enclosed by walls, the statues serving as pilasters. However, it must be admitted that this latter circumstance is far from being proved. The figures A and B, being larger than the others in the periphery, and more deeply fixed in the ground, may possibly have stood at each side of the entrance or perhaps of a flight of steps, leading up into the temple. The roof was probably supported by a plate of stone or wood, carrying light rafters, covered with palm leaves or such like materials.

This mound, also oval, was much smaller than mound 1; its longer diameter was eighteen meters, the shorter twelve. It was situated due E. of 1, separated from it by a depression in the ground, ten to twelve meters in breadth, and was made up of more or less irregular stones. It is impossible to decide whether this mound has also been surrounded by a series of statues, and in such a case, by which, because even those statues which were found in the neighborhood of it, did not remain in situ, but were overthrown, and more or less broken. The same was also the case with the four remaining stone-mounds. Thus I shall only briefly indicate their situations, and then return to the description of the statues in the order that they were measured and delineated.

It was situated due S. of mound 2, and held rather the same dimensions, but it was less symmetrical in form. Near it only R and R 1, two large stone-slabs, lids, or parts of a wall, ornamented with human figures in high-relief, were found. [Pg 22]

Due S. of mound 1. Respectively twelve and ten meters in diameter. Near it the statues M, P and Q were found, none of which can, however, be with certainty alleged to have been roof-supporter. P has surely stood quite free.

Situated furthest southwards, of the same dimensions as mound 2, but containing a much less quantity of stones. Only one statue, F 1, was found there.

The smallest of all, situated furthest to the east, of a more irregular form. In its vicinity three statues were found, of which only one, O, was delineated. The others were crushed into small fragments.

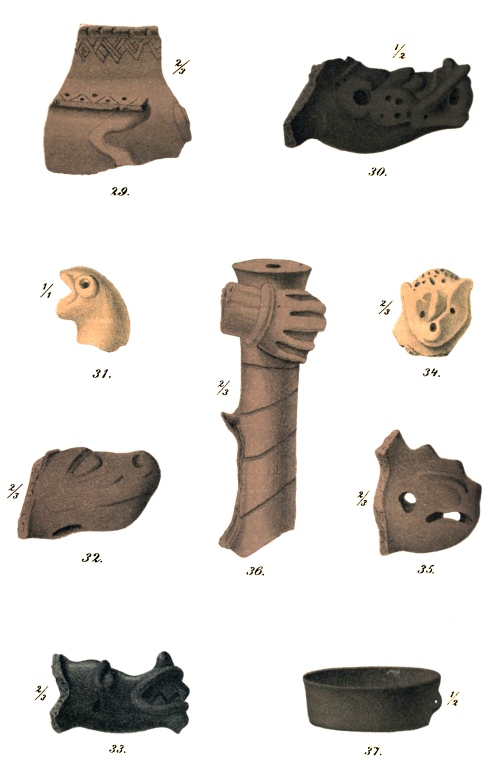

The smaller objects found by excavations made in, and beside these mounds, will be spoken of in connection with the other ceramic relics, discovered in Ometepec and Zapatera.

I now return to the description of the several statues.

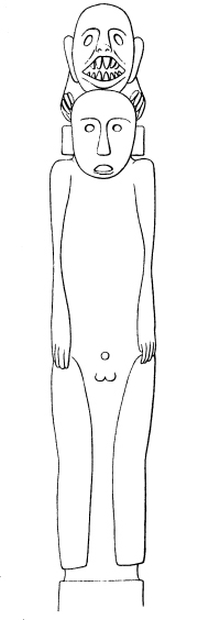

This statue, a double figure, was dug up out of the ground between the mounds 1 and 2. It has probably stood free, because considerable portions of its back were well elaborated. It is quite evident, that it [Pg 23] has not served to support a roof, as the upper part of the head of the upper figure wanted every trace of a tenon, and was carefully finished. It represented a male figure, somewhat stooping, with bent arms, the hands leaning on the hips. Upon this human figure that of an animal was seated, embracing with its fore-paws the head of the male figure. The animal was probably intended to represent a monkey. The male figure had an ugly face, with a long straight nose; the eyes were formed by quite circular cavities, the mouth was widely open, and the chin very short. The ears were covered by thick, square, flat pieces, as in the image B. The neck was long, the shoulders were much raised, large and powerful; the arms were bent, pressed close to the sides of the body, very narrow when seen from the front, broad and flat when seen side-ways. The chest and stomach were pretty roughly worked; the muscles however were sharply marked. The legs were short, without any trace of muscles or even of knees. The feet were completely wanting, the legs being abruptly cut off. The second figure, the monkey, rested its lower jaw upon the head of the principal figure, clasping the hind part of it with its long fingers. The head was large, with prominent muzzle and jaws, low, curved forehead, and broad nose, with round nostrils. The hanging ears were long and broad, rounded backwards. The mouth was open, showing strong, sharp teeth. The fore-legs or arms were very long, the fore-arm was bent at a right angle to the upper arm, the shoulder-blades were very broad and powerful. The back was strongly curved inwards, the tail long, longer than the animal itself, hanging straight down. The hind legs were short, strongly bent, drawn up towards the abdomen, and abruptly cut off above the feet, as in the principal figure. The length of the statue from the top of the animal’s head to the upper edge of the pedestal was 175 cm. The breadth of the human figure across the shoulders was 31 cm.; the breadth of the monkey across the shoulders was 21 cm.

G 1

Not figured.

It was of the same kind as G, i. e. representing a human figure, on whose shoulders and head an animal was seated. It was much damaged, and [Pg 24] almost impossible to delineate. The anterior portion of the animal’s head was crushed, as were also the legs and arms of the human image, whose face seemed designed to represent a skull with a long neck. The face of the principal figure was 21 cm. long. The length of the animal from the crown of the head to the root of the tail was 50 cm. The legs and claws of this animal were larger than those of the monkey in G.

G 2

Not figured.

Male torso, impossible to complete. It was lying near G, and seemed to have belonged to the mound 2. It measured 57 cm. from the shoulder to the thighs. The breadth across the shoulders was 48 cm.

H

Pl. 11.

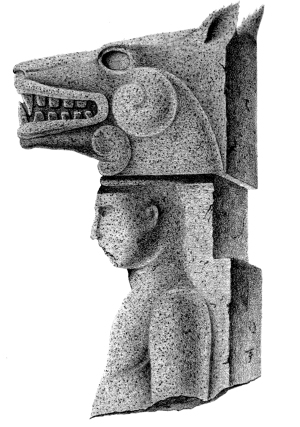

Male, sitting image. This is the first representative of a kind of idol, of which, as far as I know, not more than a single one from Central America previously has been figured.[6] Squier has also given an illustration of a statue from Pensacola (Las Isletas), in which a head of an animal is placed upon the head of a human figure, but there the animal’s head evidently serves only as a helmet; this seems also to be the case with the above-mentioned image E 1, from the western side of the stone-mound 1. With regard to the present image, on the contrary, I believe that the head of the animal is the more important figure, representing a deity, the human figure being nothing but the bearer of the god, viz. a kind of caryatid. I formed this opinion on account of the very strongly marked supporting postures exhibited by the three human figures, bearing heads of animals, which follow next in my description. Of the image H only the upper portion remained; this showed, that the human figure had been sitting, or half-sitting, but not in what manner the arms had been used as supports. The head of the animal was a splendid head of a jaguar, very finely elaborated, and pretty well preserved. The mouth was somewhat open, showing distinctly elaborated lips, blunt molars and [Pg 25] sharp, large cuspids. The muzzle was somewhat longer than necessary, the nostrils oval, somewhat widened; the eyes formed oval cavities, powerfully cut; the ears were rather small, with the margins, as it were, indented. Two volutes and a powerful intumescence at the sides were possibly designed to mark the strong muscles of the head. The human figure was carefully elaborated. The face was well preserved, with the exception of the mouth and the chin, that were cut off with a chisel, or some other keen instrument. The forehead was rather low and separated from the head of the jaguar, by a roll or fillet. The nose was large, almost straight; the eyes were rather small, the cheeks full, the cheek-bones not prominent. The ears were unusually small, of natural shape. The neck was particularly vigorous, the muscles of the breast well developed. The shoulders and upper arms were full, and well cut, the arms not quite detached from the sides. The back of the statue not being elaborated seems to indicate that it has been placed against or in a wall. That it has not served the purpose of supporting a roof, is proved by the finely hewn upper side of the jaguar’s head with its erect ears. The head of the jaguar was 63 cm. long; its height from the top to the lower hinder corner was 42 cm. The height of the ear was 10 cm. The length of the face of the human figure was 24 cm.

I

Pl. 12.

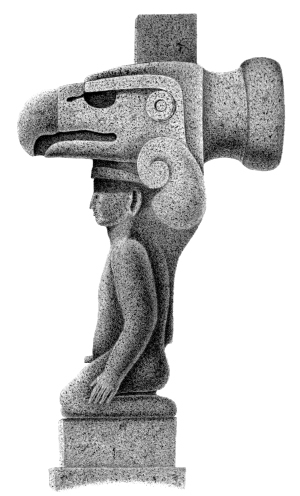

Male, kneeling figure, supporting the head of a great vulture or «Rey de Zopilotes». It belonged to the same category as H, but has probably stood isolated, as the back was as neatly cut as the front. The head of the vulture was colossal in proportion to the human figure supporting it, and very carefully sculptured. The beak was very true to nature, the eye formed a semi-circular cavity, the anterior corner of the eye was well indicated. Backwards projected a massive round process, a sort of crest on the back of the head. On the top of the head was a tenon-shaped projection, which, however, could hardly have served the purpose of a tenon, as it was unusually thin in comparison with the tenons found on the statues around the mound 1. It may possibly have been designed to represent the comb of the beak of the vulture, though [Pg 26] in such a case it was placed too far backwards. The anterior part of the head and the cheeks were carved with softness and elegance. Behind the head of the human figure the head of the vulture was united to its support by a snailshaped spiral (volute) with wide aperture. Although the kneeling male figure was not perhaps so well worked as the image H, yet it was well balanced, and of an easy posture. The forehead was straight, the nose slightly curved, the mouth closed, the lower lip thin, prominent; the cheeks were rather thin, the ears disproportionately large, and placed too far backwards. The neck was long, the Adam’s apple was indicated on the throat. The chest was rather little developed, the shoulders and upper arms vigorous, the hands pressed against the sides of the legs. The male organ was placed high up on the abdomen. The legs below the knees were of equal thickness throughout, without any trace of muscles, smoothly rounded backwards, without feet. The pedestal being broken, the statue was thrown down in the middle of the «plaza», the open place or square between the mounds 1, 2, 3 and 4. The length of the vulture’s head from the anterior edge of the beak to the posterior edge of the process at the back of the head was 100 cm., the height of the head from the top to the inferior edge of the lower jaw 37 cm. The whole length of the statue from the upper edge of the tenon-shaped projection to the upper edge of the pedestal was 154 cm. The upper part of the pedestal formed a square plinth, on which the human figure was kneeling.

K

Pl. 13.

Male, sitting figure, with its head strongly bent forward, supporting on its shoulders and the back of its head the large head of an animal, which was possibly meant to represent the head of a tortoise or a lizard. This head was rather little elaborated, evenly rounded above, having in front a round, beak-shaped mouth. A circular cavity before and over the posterior corner of the mouth represented the eye. At the back this head carried two high, rectangular, double plates, which may possibly be regarded as representing the beginning of the back armour of the tortoise, or perhaps the scales of a lizard or a serpent. The human figure was very well elaborated; next to the figure A it was [Pg 27] certainly, from an artistic point of view, the most carefully finished one of all the statues at Punta del Sapote. The head was bent strongly forwards, as if depressed by the gigantic load; the forehead was high, the nose straight, the eyes were well cut out, the cheeks rounded, the ears small. The neck was stretched forth, very thick and muscular. The shoulders were not so powerful as should have been expected from the thickness of the neck, but they were neatly molded. The trunk and the back were very nobly and elegantly sculptured, and formed the best portion of the statue. The upper arms were rigorous and well proportioned, the lower arms perhaps a little too short. The hands were closed, resting on the knees. The legs were thick, and not so well worked as the upper portion of the statue, the feet clumsy, without distinct toes. The figure was seated on a high socle, with a low foot-stool under its feet. As was demonstrated by the unusually careful workmanship expended on the back portions, the statue has quite certainly stood isolated. The height of the statue from the summit of the head of the animal to the upper edge of the pedestal was 137 cm. The length of the face of the human figure was 20 cm. The length of the head of the animal was 82 cm., its greatest height 36 cm. This statue was pretty deeply imbedded in the earth, and was found nearly in the middle of the open place between the stone-mounds 2, 3, and 4.

K 1

Not figured.

Male, standing figure. This statue did not belong to the same category with H, I and K, but had probably served as support in the wall of a building, because the turban-shaped head-dress was surmounted by a tenon, and the back was not elaborated. It had suffered so much from the violence of human hands, and from the effects of the climate, that its outlines could hardly be distinguished. From the upper edge of the tenon to the thighs it measured 123 cm. The length of the face was 24 cm. It was found immediately north of the mound 6.

L

Pl. 14.

Male, sitting figure, with its head bent forward, supporting the gigantic head of a crocodile. The back side being only plane-cut, it [Pg 28] has probably stood against a wall; but as it wanted a tenon, it did not seem to have supported the roof. In posture it much resembled K and M, but it was worked without the elegance that distinguished K. It is highly probable that the head of the animal represented that of a crocodile, although it was executed, in a rough manner, the style being altogether peculiar to this statue; the head was square-cut and the outlines not at all rounded. The characteristic knob or protuberance on the snout of the crocodile was boldly molded, but square. The eyes were marked by triangular cavities, the teeth pyramidal, sharp-pointed. The ears were the only portions of the head exhibiting curved outlines; their form was almost human. The human figure, as has been said before, was of far coarser workmanship than the statue K. The face was well preserved, the forehead high, the nose small, the mouth half-opened, the ears large and hanging, resembling those of a dog. The neck was very long and thick. The muscles of the breast were vigorous. The arms were fleshy and vigorous, straight, stretched down, leaning with the palms against the upper surface of the block, on which the figure was seated. The thick fingers were extended straight down. The legs were rather thick; the feet, which were short and clumsy, with slightly indicated toes, rested on a little foot-stool. The figure, sitting with the hands pressed against the stone block, exhibited a posture quite able to support a very heavy weight. The block that served as a seat, had the form of a truncated pyramid. The statue was overthrown; it was lying pretty close to the mound 2, between it and mound 1. The height of the statue from the highest point of the head of the crocodile to the upper edge of the pedestal was 147 cm. The length of the face of the human figure was 19 cm. The length of the head of the crocodile was 91 cm., its height 47 cm.

M

Pl. 15.

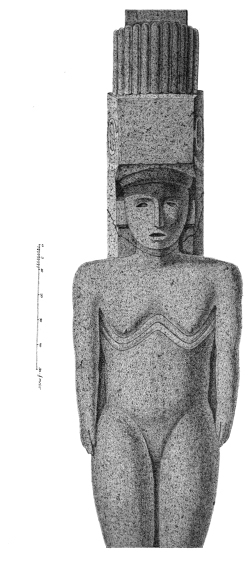

Female, sitting with straight arms, the hands pressed against the stone seat in a posture just able to sustain the pressure of a heavy load. The head was wanting, but the well marked posture, as compared with that of the just described figure, seems to justify the conclusion that [Pg 29] this figure has also supported upon its head the large head of some animal. The entire figure was heavy and clumsy, but the circumstance of the muscles of the body being indicated both in front and behind, makes it not improbable that this statue has stood insulated, like K. The arms were quite detached from the body, and uncommonly thick and heavy, as were also the legs. The hands were heavily pressed against the block, on which the figure was seated, the right hand with the palm, the left one with the knuckles. The most remarkable feature of this statue was perhaps the bench on which it was seated; this was cut out from the block so as to be quite free and detached. The statue, like all above described ones, was sculptured from a single block, a monolith. The height of the statue from the shoulders to the upper edge of the pedestal was 107 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 69 cm. It was found pretty close to the mound 4.

M 1

Not figured.

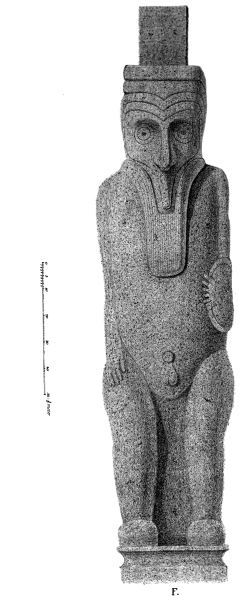

Male, standing figure, its head adorned by a high conical head-dress. Very like the figure F. Its face was hidden by a mask, with round holes for the eyes. It had a long, hanging beard or breast-armour. The arms were stretched straight down. It was broken in four fragments, and was found in the periphery of the mound 5.

N

Pl. 16.

Female, sitting figure, with a child in its lap. It has probably stood insulated, as the back portions were pretty well elaborated, and, besides, the pedestal was adorned with a free border, which was not the case in any of the statues remaining in the circumference of the mound 1. This statue was, more-over, remarkable by its large head, not being turned straight forward, but somewhat upwards and side-ways. The statue was rudely executed, far inferior in workmanship to most of those mentioned before. There was no attempt at imitating the muscles of the body; the arms and legs were thin and short, not detached from [Pg 30] the block. It was only in the molding of the face that some endeavours to follow nature were to be detected; the eyes were formed by deep, oval cavities; the nostrils and cheeks were indicated; the mouth was closed, with thick lips; the ears were very large and projecting. The short, vigorous neck was ornamented by a broad neck-lace, formed of three round bands. The head was covered by a turban-shaped head-dress. The right shoulder was somewhat higher than the left. On the front of the body only the two semi-spherical breasts were elaborated; with this exception, the chest and abdomen were on a line with the block itself. The figure held before it a child or a smaller figure with very large head, large, projecting ears, clumsy body, and short, thin legs. In execution this statue strongly reminded of the figure η from Punta de las Figuras, though it was superior with regard to the face. It was found near the mound 3, but not in its periphery. The height of the statue from the upper edge of the turban to the upper edge of the pedestal was 170 cm. The length of the face from the lower edge of the turban was 34 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 60 cm. The length of the smaller figure was 51 cm.

O

Pl. 17.

Female, standing figure. It reminded somewhat of the preceding one, but was much better executed. It certainly had a free position, as the back and shoulders were well sculptured. It carried on its head a very large, round, thick slab of stone, between which and the head there was a kind of turban, made of two round rolls. The face was unusually broad, and particularly remarkable in that respect that the eyes were placed obliquely. It was the only statue in which such was the case. The nose was large, straight; the mouth broad, closed; the ears very large, prominent, the left one longer than the right one. The shoulders and breast were pretty well elaborated. The lower portions were broken in many pieces. The diameter of the slab on the head was 72 cm.; its thickness 45 cm. The length of the face from the lower edge of the turban was 32 cm., its breadth 31 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 72 cm. The statue was found at the periphery of the mound 6. [Pg 31]

P

Pl. 18.

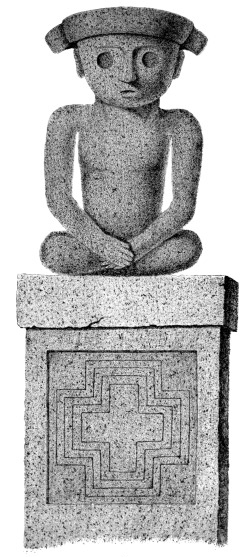

Male, sitting figure, with crossed legs, and the hands crossed in its lap. The figure was unusually small, and not very artistically executed. The head was large and very broad, adorned by a low turban with flaps projecting side-wise. The forehead was low, the nose large; the eyes were formed by unusually large, circular cavities; the mouth was small; the ears were large, but not so prominent as in the image O. The chest and back were equally elaborated, though the muscles were but slightly marked. The arms were long, and, unusually enough, cut out so as to be perfectly detached from the sides. The legs were very short and weak. The figure was seated immediately on the square pedestal, that was surrounded above by a prominent border on all the sides. The front of the pedestal was ornamented by an engraved cross, its sides and back by rhombic figures, forming inter-woven garlands. This statue has certainly been insulated. It measured 92 cm. from the upper edge of the turban to the upper edge of the pedestal. The length of the face from the lower edge of the turban was 25 cm., its breadth 35 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 54 cm.

Q

Pl. 19.

Male, sitting figure. The broad, short face showed it to appertain to the same type as the figures N, O and P, which it resembled also with regard to the careless workmanship. It wore on its head a conical hat, with a raised, circular ornament on each side; the hat widened below into a thick brim, adorned by an ornament in relief, formed like a chain. The face was but little elaborated, the forehead low, the nose long, broad, and straight; the eyes were middle-sized, circular cavities; the mouth was broad, open, almost square. The ears were long, extending, with perforated lobes. The neck was short. The chest and abdomen showed some signs of muscles. The shoulders were quite straight. The arms were narrow, without muscles; the left one hanging [Pg 32] straight down, with the fingers extended; the right one bent upward towards the shoulder, with the fingers doubled, so as to form a hole. It has probably clasped a lance or stick, or something of that kind. The legs were rather large, broken above the knees. The back of the statue was only plane-cut. The length from the lower edge of the hat to the thighs was 103 cm.; that of the face from the same point 33 cm.; the breadth of the face 32 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 52 cm. The statue was found near the western margin of the mound 4.

R

Pl. 20.

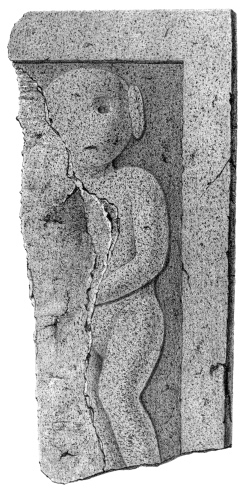

High-relief, representing a female figure. With regard to the type of the face, it came near to the immediately preceding ones. It was a big-headed figure of full size, sculptured in feeble high-relief on a large rectangular slab of stone, about 25 cm. in thickness. It had been very badly injured, so that only the left half of the figure could be anyhow discerned. The face was almost circular, the eye a circular cavity, the nose wanting, the mouth closed, the ear large, hanging, like the ear of a dog, the shoulder rounded, the arm bent inwards across the body, the leg slightly bent. The figure has been surrounded by a frame, nearly 20 cm. broad, and 4 cm. high. The length of the figure to the thighs was 106 cm. The length of the face 38 cm.; the breadth of the face 37 cm.

With regard to the type of the face, the figures found in this locality may be divided into two distinctly different classes viz., the images A to M, with oval faces, and, in general, of more artistic workmanship, and the images N, O, P, Q, R, with broad, almost circular faces, and more rudely executed. The latter are possibly of more ancient date than the former. None of the latter was found at the mound 1.

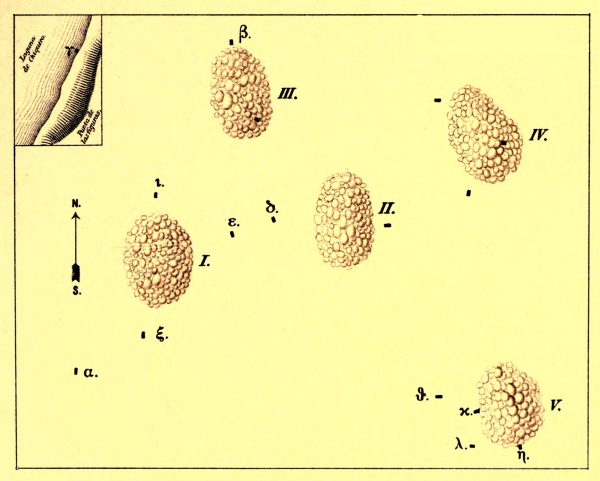

Squier visited this locality in December 1849; it is a little plateau, formed by an extension of the margin of the crater surrounding the Bahia de Chiquero. To the west it slopes pretty abruptly towards the Bahia; to the north it shelves gradually towards the low promontory, Punta de las Figuras, which is separated from the south-eastern point of the islet of Ceiba, Punta de Pantheon, by a sound, 50 m. broad; to the east the plateau descends rapidly towards the lake of Nicaragua, and to the south it falls steeply towards the little crater-lake Laguna de Apoyo. It is densely covered by gigantic trees, and between these by under-brush and lians, confusedly entangled. Here I found five large stone-mounds, that may possibly be the remains of temples or other large buildings. The relative situation of these mounds is approximately shown by the plan Pl. 41. Besides these larger mounds, which were more or less oval, with the longer diameter varying from 20 to 40 meters, several smaller, and more irregular ones, were met with. These, however, are not indicated in the plan. The mound I was that nearest to Bahia de Chiquero, the mound V the nearest to Laguna de Apoyo. In this locality no statues were found that could with any degree of certainty be regarded as remaining in their original places, nor were any lying or standing in such a position that it could be decided, whether they had been placed in the peripheries of the mounds, within the buildings, or in the open spaces between the mounds. In this respect the former locality was by [Pg 34] far more interesting. The statues were less well preserved, and had evidently been subjected to greater violence, probably also to attempts at removal. Indeed we know through Squier, that such has been the case. Some statues had been transported to Granada before his visit, and Squier himself sent some to Washington.

It has been before figured by Squier, l. c., vol. ii., in the plate facing p. 54, fig. 2, and described pp. 53, 54, and 58. In Squier’s list it has the no. 2. Bancroft has mentioned it in «The Native Races of the Pacific shores of North America», vol. iv., p. 41, with a copy of Squier’s figure p. 42, fig. 3.

It was a male figure, sitting on the ground, with the knees drawn high up, and the head bent forwards. On the back of the head and the neck, there rested a solid mass of stone, gradually passing into the outlines of the neck and the back. This mass tapered upwards, and seemed to have passed into a pyramidical tenon, which, however, was broken off. The face was broad, with rounded retiring forehead, the nose long and straight. The eyes were formed by circular cavities; the mouth was half-open; the ears were large and prominent. By the shape of the face, the figure recalled the image Q from Punta del Sapote. The neck was much too thick to be a human neck. The chest was only little elaborated, the shoulders much raised, the arms well cut, the left hand pressed against the left foot, the right one drawn back somewhat more. The legs were well molded, like the arms; the knees drawn up nearly to the chin. The back was round-cut. The pedestal was carefully hewn, forming a square pillar of considerable height, tapering downwards. Its uppermost portion, on which the figure was seated, formed a kind of round capital, ornamented on the side by a triple engraved angular wreath. The height of the statue from the crown of the head to the upper margin of the pedestal was 80 cm.; the length of the face was 34 cm., its breadth 25 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 44 cm. The statue has probably stood insulated. It was entire, lying south-west of the stone-mound I, nearest to the shore of the Bahia (except the figure γ) and had probably been the object of endeavours to remove it. [Pg 35]

β

Pl. 23.

It is figured by Squier, l. c., in the plate facing p. 65, and described pp. 64 and 65. Bancroft, l. c., p. 40, fig. 2.

Male figure, sitting on the ground. With regard to the posture it came most near to the image α, but could not be said to possess a human aspect. Indeed it deserved, if any, to be called a monster. Squier thought that it represented a tiger, but if we compare the head of the present statue with the head of the jaguar in the statue H, from Punta del Sapote, this opinion does not seem very likely. The face exhibited a low, arched forehead, small oval eyes, a broad, flat, long nose or muzzle with small, round nostrils. The mouth was not open. The upper lip was clearly to be distinguished, although it had been broken. The chin was broad; the ears were oval, placed far up. The neck was very thick and powerful, the body colossal, with large abdomen. The whole back of the body was also elaborated. The shoulders were highly raised, the upper arm was long, broad and thick, the lower arm short, at a right angle to the upper arm, the paws resting on the abdomen. The legs were very short, especially the small of the legs. The feet were pretty like human feet, with distinct toes. The upper part of the pedestal was enlarged in the shape of an Ω, ornamented at the sides with a garland, like that of the image α. The height of the statue from the highest point of the trunk to the upper edge of the pedestal was 150 cm. The height of the face was 40 cm., its breadth 30 cm. When found, it stood upright, immediately north of the mound III.

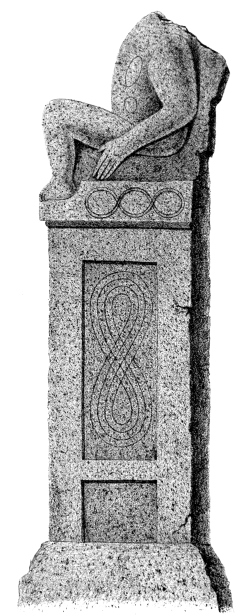

It is not mentioned by Squier.

Male, sitting figure. The head was broken off. The figure itself was much damaged; but the pedestal was well preserved, and exhibited fine ornaments. The chest of the figure was strongly arched, the upper arm short and broad, the lower arm and the fingers were long. On the sides [Pg 36] of the cornice of the pedestal, there was a symmetrical ornament of round coils; the sides of the pedestal itself were decorated with an oval coil twisted about quite symmetrically, in an excavated rectangular field; in front there was an angular ornament. The back of the figure and of the pedestal was not elaborated, but rather rough. It may thus be reasonably inferred that the statue has stood in or against a wall. The height of the statue from the upper edge of the shoulders to the lower edge of the feet was 52 cm. The height of the pedestal from the upper edge to the beginning of the lower, uncut part, which was intended to be imbedded in the ground, was 110 cm. This statue was not found on the plateau of Punta de las Figuras, but had been dragged off and was now lying, half in the water, on the shore of Bahia de Chiquero.

δ

Pl. 25.

Figured by Squier, l. c., on the plate facing p. 58, signed no. 4, treated pp. 54 and 58. Bancroft, l. c., p. 40, fig. 1.

It was no more a statue, but only a pedestal. The little, sitting figure described and designed by Squier was now entirely crushed and moldered. The pedestal was, however, the most elaborately finished of all found here. It was round, tapering gently downwards, adorned upwards with the same kind of angular ornament, as that mentioned on the front of the preceding pedestal; almost at the middle of its length it was surrounded by a broad band, embellished in the same fashion. The pedestal, lying on the ground, had quite the form of a canon. From the upper edge to the lower broken end it measured 215 cm.; the diameter at the upper end was 66 cm. It was found between the mounds I and II.

ε

Pl. 26.

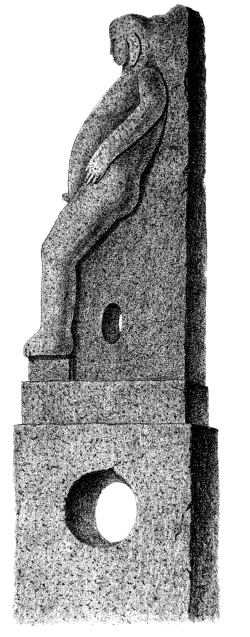

Figured by Squier, l. c., in the plate facing p. 58, signed no. 5, described p. 59.

Male, half-sitting figure, representing a very fat person with his hands resting on his hips. The face was badly injured, but showed that [Pg 37] the forehead and the nose were straighter than those figured by Squier. The ears were long, hanging, like the ears of a dog. The upper arm was very short; the abdomen swollen. Legs and feet were thick and clumsy. The back piece was very large in proportion to the figure, only plane-cut, and seemed to indicate that the statue had formed part of a wall or even served as a kind of coulisse or side-wall in a cella. The lower part of the back piece was pierced with a circular hole; another much larger hole perforates the pedestal, which was perfectly unadorned. The statue measured 98 cm. from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot. It was found lying near the preceding.

Figured by Squier, l. c., on the plate facing p. 52, described p. 52 and 58. Bancroft, l. c., p. 42, fig. 3.

Male, standing figure, with the hands resting on the abdomen. In this statue also the back piece was very large, proportionately even larger than in the preceding; on this account it may be conjectured to have had a similar use. The face was rather large and round, the forehead somewhat retiring, the eyes small, oval, the nose short, broad, and straight, the mouth closed, with thick lips, the chin broad; the ears were hidden by the projecting back piece which embraced, as it were, and overlapped the face. The chest was well cut. The arms, when viewed from the front, were very thin, pressed close to the sides of the body and to the back piece; when seen from the side, they are, on the contrary, broad and fleshy. The hands rested on the abdomen with the fingers somewhat extended. The legs were rather clumsy. The broad back piece projected above the head like a colossal mitre, ornamented in front with bosses and scrolls, and surrounded by a broad frame. The height of the entire statue from the top of the upper piece to the sole of the figure’s foot, was 210 cm.; its greatest breadth from the chest of the figure to the hinder margin of the back piece was 86 cm. The height of the figure from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot was 140 cm. The length of the face was 31 cm., its breadth across the shoulders was 36 cm. It had been raised up at a recent date, and now stood south of the mound Ι. [Pg 38]

η

Pl. 29.

Not mentioned by Squier.

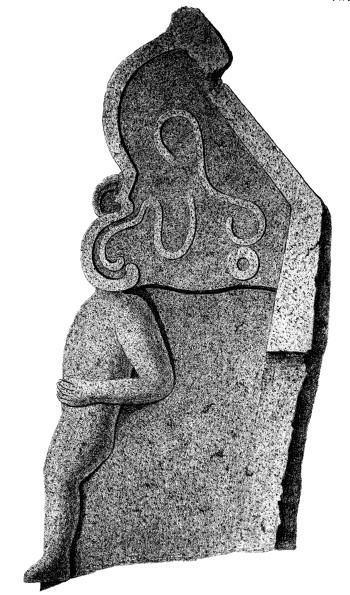

Male figure, sitting almost on the ground, bearing on the top of its head another head with a large neck. It is by half statue, by half high-relief. The body of the principal figure was cut out to the shoulders; then followed a portion of the stone that was quite rude on the sides and the back. On the front of this stone the neck and head of the statue and the long-necked head of a man or an animal that surmounts it, were sculptured in high-relief. The upper head had a low forehead, small, round, excavated eyes, long nose or muzzle of equal breadth, closed mouth, and long, prominent, hanging ears. The neck was very long and was placed immediately upon the head of the principal figure. The face of this figure presented a low forehead, large, oval, excavated eyes, a short nose broadening downwards, thick cheeks, small closed mouth, broad thick chin, and prominent, but not very long ears. The neck was short and vigorous. The chest exhibited no sign of muscles, being only a round-cut part of the original stone-pillar, and passing directly into the abdomen, and then into the front of the pedestal. The arms and legs were carved in a kind of relief. The hands rested on the abdomen. The pedestal was cylindrical; its uppermost portion, on which the figure was seated, was somewhat smaller than the rest of it. The height of the statue from the top of the upper head to the upper edge of the pedestal was 120 cm. The length of the upper face was 14 cm. The face of the principal figure was 27 cm. long, 22 cm. broad. The statue was found at the southern margin of the stone-mound V, nearest of all the figures to Laguna de Apoyo.

θ

Pl. 30.

Not mentioned by Squier.

Fragment of a high-relief or one-sided statue with only the head cut free. In comparison with the other high-reliefs found here, its size [Pg 39] was colossal. Contrary to all other Nicaraguan high-reliefs that I have had an opportunity of seeing, it was wholly in profile. The slab from which it was sculptured was very thin as compared to the size of the figure, no more than 30 cm. in thickness. It was broken in more than 20 pieces, only the head and part of the chest with the arm being in such a state as allowed of their being delineated. The head was slightly curved, carved on both sides, but having an eye, formed of two concentric excavations, only on the left or upper side. The head was truncated before, without any trace of a muzzle or mouth, and provided backwards with a very well sculptured buck’s (?) horn, though only on the upper side. The chest was indicated only by a slight curve. The arm, on the contrary, was pretty well molded, and the fingers were proportional. The lower part of the chest was quite unhewn, as was also the hind portion of the lower part of the head. It carried on the head a square crest or tenon, divided into three parts by transversal lines. The length of the head was 53 cm., its height from the upper edge of the tenon to the lower edge of the horn was 64 cm. The diameter of the eye was 12 cm. The length of the arm from the shoulder to the tip of the ringfinger was 102 cm. The statue was lying on the ground a little west of the mound V.

ι

Pl. 31.

Figured by Squier, l. c., p. 61, signed No. 9, described pp. 60, 61 and 62. Bancroft, l. c., p. 44, fig. 6.

High-relief, male figure, on a slab about 40 cm. in thickness. It represented a figure lying on its back, if the slab has been a covercle, or standing, if it has been a part of a wall, with straight arms, detached from the sides of the body. The face appeared to be covered by a mask (compare the figure F of Punta del Sapote); this seemed to be denoted by the large circular holes for the eyes, and the broad, hanging breast-plate or beard; the ears were protected by two flaps extending from the helmet or head-ornament. With the exception of the stiff mask before the face, the figure was well elaborated, with some hints of the muscles of the shoulders, abdomen, and legs. Above the slab there was a projection, broadening upwards, [Pg 40] which seemed to be a repetition of the helmet of the head. The outer edges of the slab formed a border five to six cm. broad and 3 cm. high. The slab was broken in two pieces, the lower portion was found lying far from the upper one. The entire slab measured 182 cm. from the upper edge of the upper projection to the lower edge of the border below the feet; its breadth across the body of the figure was 74 cm. The length of the figure from the top of the head to the lower edge of the feet was 135 cm. The length of the face was 28 cm., its breadth 27 cm. The length of the breast-plate from the chin was 30 cm. The breadth across the shoulders 45 cm. The statue was found on the ground immediately north of the mound I; the lower piece was found west of the mound III.

κ

Pl. 32.

Not mentioned by Squier.

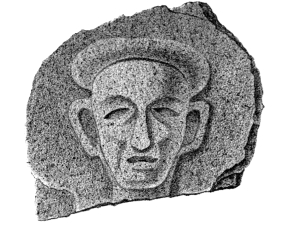

Male figure in relief. Broken in several fragments and impossible to reconstruct. Only the face could be delineated. The face was well preserved and originally uncommonly well executed. It was quite expressive; the forehead was broad, not low, covered with a round cap or low turban; the eyes were narrow, elliptical, boldly cut; the nose was straight, broadening downwards; the mouth half-open, with thin, but well-formed lips; the cheeks were lean, but carefully sculptured; the chin was broad and powerful. The ears were large, very prominent. The length of the face from the lower edge of the turban to the lower edge of the chin was 35 cm.; its breadth 26 cm. The thickness of the slab of stone was about 30 cm. Most fragments of this relief were lying at the western margin of the mound V.

λ

Pl. 32.

Not mentioned by Squier.

Relief representing a male figure with the face of a skull. It was of much rougher workmanship than the reliefs before described. The face was [Pg 41] formed only by an evenly curved, broadly oval elevation, with two circular cavities to mark the eyes, an irregularly triangular one for the nose, and a linear one for the mouth. The chest was evenly rounded, the arms only indicated by two round bands along the breast, ending abruptly with five narrow, round staves, placed at right angles to the arms, and designed to represent the fingers. The lower part of the slab with the legs was lost. Above the head were two sugar-loaf-shaped elevations, and above these a third one with parallel sides, downwards rounded. The slab had square incisions at the same height with the neck and the hands. The length of the figure from the crown of the head to the beginning of the hip was 82 cm. The length of the face was 32 cm.; its breadth 20 cm. The breadth across the shoulders was 24 cm.

Several fragments of broken statues were found on the plateau, but so shattered, disfigured, and intermixed with one another, that it would have taken much time and patience to reconstruct them. Several of the statues, mentioned by Squier as being in comparatively good condition, for inst. his nos. 3, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, and 18 were no more to be found in the place. Some of these have possibly been destroyed by human violence or by the effects of the climate during the thirty years between our visits, others may have been carried off to be deposited in museums or to form the hearth-stone of some Indian rancho.

In general, the statues of this locality chiefly remind of the last described group of statues at Punta del Sapote. Perhaps, from an artistic point of view, they must be considered as inferior even to these. None of the statues at Punta de las Figuras can be compared as a work of art, to the figures of the mound 1 at Punta del Sapote.

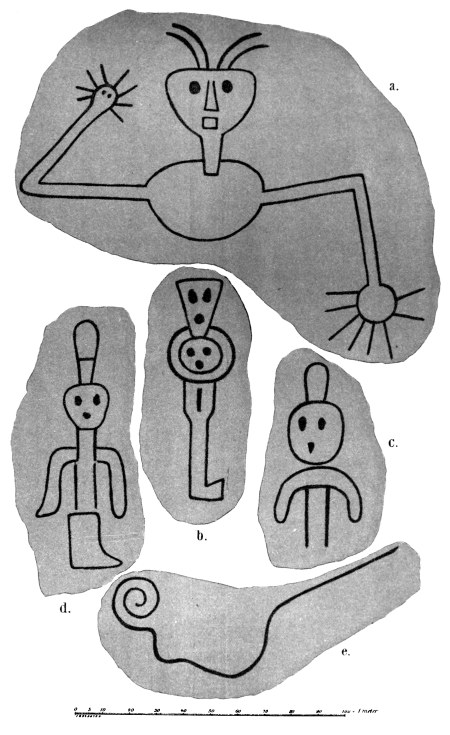

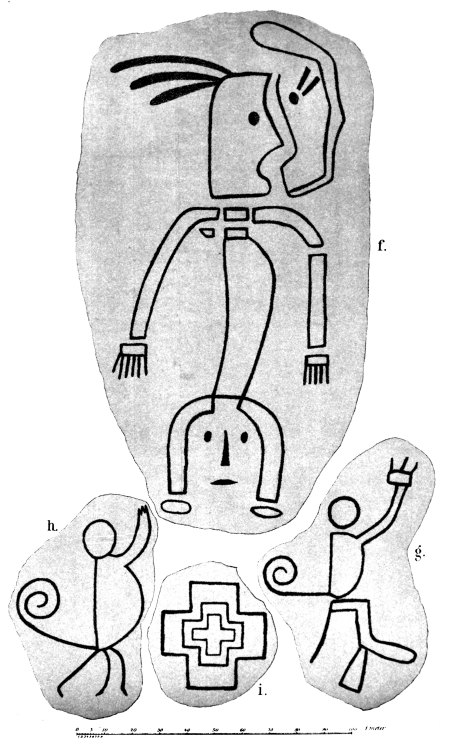

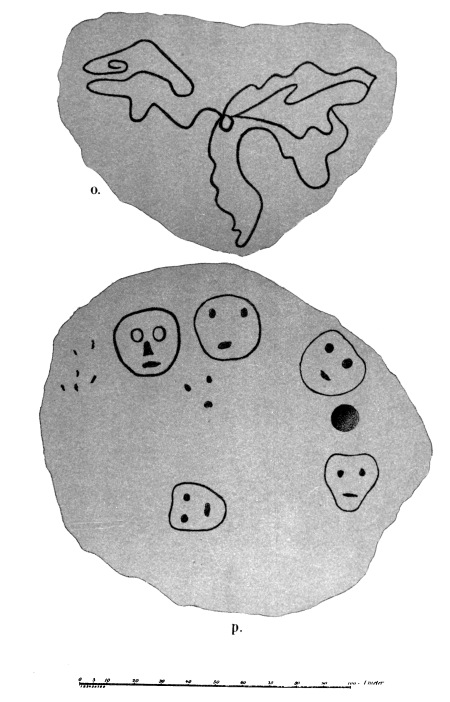

The fact that in most of the statues, found in Zapatera, the organs of generation were represented, and often more conspicuous than natural, gives corroboration to the suggestion of Squier that a phallic worship or a worship of the reciprocal principles existed among the Niquirans.