They rose and charged toward the space ship.

Was Earth on the wrong time-track? Ray Manning

stared as nation smashed nation and humans

ran in yelping, slavering packs under a sky

pulsing with evil energy—and knew the answer

lay a hundred years back. Could he return?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Spring 1949.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It was the end of March, and the wreck of the Dritten Reich lay in colossal ruin across Europe, where people were only beginning to crawl out of their burrows to face the job of rebuilding a world for better or worse. In Germany itself, the Allied Armies, driving forward behind the iron spearheads of their aircraft and their armor, were closing in to smash the still-defiant nucleus of the old world that had been for worse.

One column consisted of two jeeps and a canvas-backed truck, bounding and swerving at reckless speed over a rutted road that wound upward and deeper into the fir-shadowed Schwarzwald.

"Reconnaissance," grunted Ray Manning, between lurches of the transport truck. "They might have called it treasure hunting."

"Huh?" said Eddie Dugan, planted solidly and insensitively beside Manning on the jolting wooden seat. He took his eyes off the knees of the soldier opposite and searched his buddy's face. "What's the treasure?"

"Brains," explained Manning succinctly. "While the rest of the Seventh goes on handing body blows to the enemy, we're going after his gray matter. Brains are about the only article of value left in this bombed-out country. And Dr. Pankraz Kahl has one of the best."

"What's he keeping it in these woods for?" Dugan glanced out at the receding park-like scenery, green now with spring.

"Unless the jerk they picked up back in Freiburg sold Intelligence a fairy story, the Herr Doktor had some kind of a hideout here, where he was doing experiments—something that impressed the Nazis enough they were willing to finance him and leave him alone."

Dugan looked properly impressed. Of course, he had learned to expect such knowledge from Manning, who had been at M.I.T. and had managed to stay a combat soldier only by the grace of God and a lot of blarney.... Dugan was still looking impressed when the truck scuffed tires to a halt. Then he was first man out, and the rest of the troops followed in seconds—they needed no telling to get out of a stationary vehicle.

"Road ends," somebody remarked. It did, in a loop that took it back the way they had come. The lieutenant in charge of the detachment swung out of the lead jeep and called them together under the trees.

"We'll have to spread out," declared the lieutenant. "Groups of three. That hideout ought to be within a mile of here. If you find it and there's resistance, keep shooting at intervals and wait for the rest. Remember, we've got to make captures this time, not kills."

The sergeant rattled off names and the groups formed swiftly and took off. Manning and Dugan, naturally, were two corners of one trio; its third was a corporal named White.

With Dugan as point, they advanced up a brush-grown ravine, using caution and cover, skirting the path that curved up the hill. They topped a saddle, and saw the house—a sprawling mountain lodge, built of logs by somebody with a passion for privacy, its roof well camouflaged now with synthetic greenery—not a hundred yards away up a slight slope rankly overgrown with grass. It looked deserted. Dugan had taken a few steps into the open before something—perhaps a far-away tinkle of breaking glass—warned him, and he went down smoothly in to the grass and rolled sidewise toward a clump of young evergreens.

From the house came a splitting crack and a bullet hit the ground where he had been. Behind him, Manning jumped behind a comfortably thick tree-trunk, unslinging the automatic rifle he carried. But White was a moment too slow. The second bullet caught him as he turned, and he stumbled to his knees; two more shots rolled echoes down the ravine, and White collapsed on his face.

Manning sighted his automatic and gave the window from which the fire had come a short but intensive burst. The house was silent. He fired again at a venture; in answer, a bullet snapped past, coming from a different spot. There was more than one marksman up there, or one was moving fast.

From ahead came Dugan's voice, low-pitched but carrying. "Cover me, Ray. I'm gonna crawl around to the back."

"You damn fool, you don't know how many there are. Our guys'll be along in a few minutes."

"Hell with them," said Dugan. "Just cover me." He didn't mention White. But there was a compressed fury in his voice.

Manning sighed. "All right."

Dugan crawled like a weasel. Manning lost sight of him. He waited with humming nerves, firing spaced shots into the enemy's log fortress.

Then he noticed he had stopped drawing any return fire. That might mean things had started happening inside the house, if it wasn't a trick—He discarded most of his caution and darted into the open, zigzagging from scanty cover to cover—something must have happened inside—and flattened against the rustic wall beside one shattered window, just in time to hear a voice beyond it exclaim hoarsely, "Gut!"

That was all he wanted to know. If anything was going gut in there, it was time Ray Manning got into the picture. He cleared the window-ledge with automatic level.

There was a big, raftered room, and in the middle of the floor Eddie Dugan was struggling groggily to get up, while behind him stood a white-goateed civilian with a wrench, and in front of him a tough-looking younger man was lifting a rifle.

The two Germans saw the gun in Manning's hands and made a tableau as they were. It was broken as the burly one's grip relaxed and his Mauser clattered on the floor.

Manning motioned toward the goatee. "Dr. Kahl? Better drop that," he advised in German.

The little physicist looked down at his wrench and let it fall with an expression of disgust. Then he glared at Manning and called him a couple of names culled from biology rather than physics. "If your man hadn't caught Wolfgang reloading—As it is, you have interrupted my work at the most crucial point imaginable—a work that might yet save the Reich—" He woke up to the nature of his audience, and finished lamely, "And which is in any case the greatest scientific advance of all time."

Dugan got shakily back to his feet, scooped up his dropped Browning, and trained it on Wolfgang. "Is that Kahl?" he inquired sourly. "If I'd known this guy wasn't the one we had to capture, I'd have let him have it when I first got the drop on him."

Manning didn't answer. His eyes roved rapidly about the interior, alert against another surprise entrance; but anybody else on the premises was lying pretty low. One, in fact, was doing it just under the window Manning had first fired at. He was no longer a factor.

One end of the room was storage space for the overflow of Kahl's electrical equipment. Manning recognized some of the articles there and read the labels on a couple of crates, but they gave him no clue to the Herr Doktor's world-shaking research. The door behind Kahl was ajar on a room that, from what showed, might be his laboratory....

They'd taken the required prisoner, and all duty called for now was a short wait until Intelligence took him off their hands. But Manning's curiosity was needled. Kahl wasn't modest about whatever he'd done—but his wrath at the "interruption" was genuine, and there might really be something here. The soldier in Manning fought a brief battle with the student, and lost.

"What is this work of yours?" He made his voice authoritatively crisp, over the automatic's steady muzzle.

Kahl glanced momentarily toward the open door, then glowered at the American for a long ten seconds. "It is not for barbarian eyes."

"So there's something worth seeing—or a booby trap, maybe?" said Manning to himself. Aloud he snapped, "Suppose you show us what's in that room. Ahead of me—no, let Wolfgang go first. Keep him covered, Eddie!"

Dugan hadn't been able to follow the conversation—his German was limited to "Komm heraus mit die Hand in die Luft!" and a few other useful expressions from the American Tourists' Phrase Book, 1945 edition—but he didn't question Manning's wisdom. He did a silent and highly efficient job of shepherding Wolfgang through the doorway, and stood well aside as Manning followed, preceded by a cowed-looking physicist.

Manning was all eyes for Kahl's invention; his first impression was that the room was disappointingly small and bare. There was nothing that looked like a rocket motor, a guided missile, or even an improved submarine periscope. But then the American's eyes narrowed as they took in what was there.

There were no windows, and walls, floor and ceiling were metal or sheathed with metal. Around them ran what looked like medium-thick pipes, without openings or discernible use. The only furniture was a table, supporting a rather fantastic electrical setup—stuff in the thousands of megacycles, judging by the heavy dielectric tubes and coils that were just a copper twist or two; that was what Manning had glimpsed from outside.

Then a movement jerked Manning's gaze back to the prisoners—and he almost shot the Herr Doktor. For Kahl had contrived to halt near the apparatus-laden table, had taken one quick step and thrown a switch.

The damage—if damage there was—was already done; that thought stayed Manning's trigger finger. But nothing seemed to have happened; only when the contacts had touched the light had flickered briefly, and something had made a deep humming sound that rose in pitch like an electric motor starting under load—rose and snapped off in an instant.

But something stayed wrong. The unconscious faculty of observation that had been sharpened for Manning in shell-smashed towns where the ability to notice small wrongnesses might keep a man from touching off a hidden mine told him that.... He tried to read the expressions of the two Germans. Every wrinkle on Kahl's face beamed crafty triumph. But his helper's look made Manning blink. Wolfgang's Aryan-blue eyes bulged with panic. And they were staring past Manning, at the door.

Eddie Dugan broke the tense silence. "Ray—where's the light coming from?"

That was it! "Watch them!" rasped Manning, and whirled to face the door.

It was ablaze with green-gold sunlight.

II

And beyond it was not the gloomily raftered feast-hall of a Nazi baron, with gray March outside its windows—but a woodland rich with high summer. A breeze stole in from that preposterous outdoors and brought warmth and scent of firs, and of something else.... Suddenly there was a crashing in the thicket, a thud of racing hooves. "A deer," said Manning stupidly. "Something must have scared it." Dugan, sweating with his back to the door, relaxed slightly.

Like an echo from behind Manning came a dry cackle of laughter. He faced about again; his glare stilled even the Herr Doktor's hysterical glee.

"All right, how'd you do it?" he snapped in English, then, with returning control: "Erklaren Sie das sogleich!"

"Gern," grinned the scientist. "This room, all of it, is my invention. It was built into the house, but when I closed the switch, it moved, and left the house behind."

"Where are we, then? No riddles!"

"It is simple enough. What you see outside is the world of the future—no longer future to us, but present, though about a hundred years removed from the 'present' which we have just left. This room is my time traveler—der Kahl'sche Zeitfahrer!"

Meantime Dugan had taken a look out the door. He said nothing, but his eyes grew larger and larger in a paling face. Manning told him, tersely and without comment, what Kahl claimed to have done; in his own mind he had already accepted it as truth, the only possible explanation for the seeming impossible. He said stonily to the German: "The demonstration of your invention is very interesting. But now we must deliver it to American Intelligence, who will appreciate your genius. Set the machine to take us back where we came from."

"I could not if I would," retorted Kahl. "Because of your interference, I had no opportunity to make adjustments. I merely threw the activating switch, and the Zeitfahrer exhausted its power before coming to a stop. You see, the switch is still closed. Only the field has collapsed as the batteries went dead."

There was a sound like a sob. It came from the hard-faced Wolfgang. The man's patent terror was more convincing than Kahl's assertions.

Manning eyed him coldly, inwardly surprised at his own reaction to the news that they were stranded. Perhaps he was still dazed by the incredible—but his chief emotion was a waxing excitement and wonder at the thought of seeing with his own eyes that world of the future about which people dreamed and speculated, cursing the shortness of their lives....

Dugan had guessed more than he had understood the meaning of Kahl's words. But to him the situation suggested more routine concerns.

"Say, Ray," he inquired, "do you suppose we're AWOL?"

"I don't think so," Manning choked down an impulse to wild laughter. "No more than a guy that's blown off his post by an 88. Anyway, I don't remember any General Order that says you've got to be in the right year. But our program now will have to be: get oriented in this place, this time, I mean, and dig up some fresh batteries to send this thing back to 1945. In the twenty-first century batteries shouldn't be scarce; we'll just have to be careful about contacting the natives, so we don't get tossed in jail or the booby hatch.... To begin with, let's get out of here. This damn traveling vault is getting on my nerves." He motioned at Kahl and Wolfgang. "Outside."

Kahl didn't stir; his eyes narrowed slyly. "There is no sense in your treating us as prisoners, now. The war is ancient history."

"Until further notice," said Manning, "we'll continue as of 1945. Move!"

Grudgingly they moved. Kahl growled over his shoulder, "One thing does not seem to have occurred to you. This is Germany of the future, where Wolfgang and I are much more likely to find friends than you are."

Manning did not answer. He had halted, stiffening, on the time machine's threshold, and sniffed the air critically. To him came sudden recognition of the scent which mingled, strengthening, with that of spruce and fir: a heavy, tarry odor of burning. He looked upwind. Through the rifts of the treetops were clearly visible clouds of black smoke, boiling upward against the blue sky. Flames flickered angrily beneath, and to Manning's ears came the faint but subtly all-pervasive crackling of the fire. It was drowned out briefly by the alarmed croakings of a flight of ravens that circled overhead and then flapped away, and in the relative stillness that followed another sound was audible—that of human voices, raised in shouts and commands.

"Looks like the local fire department's on the job," remarked Dugan.

"The fire!" exclaimed Kahl hoarsely. "It is blowing toward us—If it reaches the Zeitfahrer—"

"Guess the man's right," said Manning. "If that is the fire department, we'd better get in touch with them." All four started to run, quartering across the visible face of the blaze toward the voices' source.

They had covered a hundred yards when from ahead, sharp above the snapping flames, a shot spanged. The two Americans instinctively hugged the ground; Kahl and Wolfgang, in advance, froze and stared at the screen of firs. From just beyond exploded a violent fusillade, with the hasty clatter of automatic fire setting the tempo; and in the midst of all the shooting was the noise of a racing motor and a rackety whir that could come only from spinning propeller blades.

The sound rose and seemed to hang overhead. Manning looked up and thought for an instant that he glimpsed the dark moving shape of a flying thing; but when he looked straight at the spot there was nothing. A moment later he was conscious that the roar of the engine had ceased and with it the noise of firing. The crackle of the forest fire came as from far away to deafened ears.

Dugan and Manning looked blankly at one another. They got to their feet and stood in indecision.

"Damned if I know," said Manning bewilderedly. "For a minute I thought we'd landed in the middle of another war. Now I don't know whether it was real or—"

"Halt!" barked a keyed-up voice on their right. "Still-gestanden, oder ich schiesse!"

The man who had appeared from the bushes, despite the unfamiliar uniform he wore, was at least real. So was the tommy gun he trained on the group, and the look of vicious eagerness that twisted his face.

"Das Gewehr fallen lassen!" he shouted.

"Better drop it," said Manning quietly to his companion. "We don't know what the score is yet. And that guy wants to shoot."

Other uniformed figures appeared behind the first man. All of them were armed and looked excited and dangerous. But surprising was the caution, amounting to anxiety, with which they fanned out and kept their weapons leveled; they seemed to expect some formidable and disconcerting counterattack from the disbanded and outnumbered captives.

The first arrival jerked a thumb toward the way he had come; his manner didn't encourage protest. And Manning, who had read science fiction stories, reflected that a time traveler's best bet was to keep his mouth shut.

Beyond the fir grove a meadow-like clearing opened out. Smoke was drifting across it and the fire licking at its edges, but that didn't seem to be what was bothering the men who swarmed about it. Some of them were squinting into the bright summer sky, nervously fingering guns, others arguing in loud groups. A crowd clustered about a helicopter which perched on the grass with slowly revolving vanes. Toward it the four prisoners were marched.

Under the intermittent shadow of the helicopter's blades a big man in curiously patterned civilian garments stood with arms akimbo, facing a soldier who was ramrod-stiff and obviously embarrassed before him.

"There was no chance, Herr Schwinzog," the latter was insisting. "They wore Tarnkappen, and they were inside the machine and had the engine going before we knew that anything was wrong. We fired on them as they rose, and they made the helicopter invisible. Of course, then it was too late to stop them—without shutting off the power over the whole district, and that would mean chaos—"

"Of course it was too late," said Herr Schwinzog bitingly, "since it was already too late when you started thinking. You may as well put your report in writing, Captain, and hope that your superiors don't see fit to demote you. For my part, I shall use my influence to see that they do."

He pivoted, grinding his heel into the turf, and snapped at the man at his elbow: "What is it?"

The soldier saluted jerkily. "Unauthorized persons, Herr Schwinzog. We apprehended four of them about two hundred meters to the northwest. Two were armed."

"Hum!" grunted the big man explosively. His eyes narrowed, coming to rest on the group of captives. His scrutiny was chillily penetrating. He held it on them while the shadows of the helicopter vanes swept across his face a dozen times. Then he said flatly, in slightly accented English: "You, no doubt, are Americans?"

Manning was silent, feeling the dream-sense of unreality overcome him again. That question tangled time and space—it and another thing: around the left arm of Schwinzog's oddly cut coat was a broad band, and in a circle on it sprawled a stark black swastika. A hundred years ago—if a hundred years had passed—American armies had been trampling that emblem in mud and blood.

But Dr. Pankraz Kahl burst out, "Wir sind keine Amerikaner! Wir—" including himself and Wolfgang with a sweep of the arm, "sind Deutsche!"

Schwinzog regarded him expressionlessly. "And you?" he turned abruptly on Manning and Dugan.

"We're Americans," said Manning steadily, in English. Schwinzog's face did not change. But something in the look with which he had received Kahl's statement had jangled an alarm in Manning's brain. And he was still determined to keep his mouth shut and his ears open as much as possible.

Immediately he knew he had been right; for Schwinzog turned again to Kahl. "You say you are German. Your citizen's card, then."

The Herr Doktor started automatically to fumble at a pocket, then paused and made a wry face. "I—we have no such papers as you want. Naturally, since we—"

"Since you are spies?" Schwinzog folded his arms and the fingers of his right hand caressed his swastika brassard.

"That is ridiculous!" shouted Kahl. "I am trying to explain to you that we are visitors from your past! We come from a hundred years ago!"

For the first time Schwinzog looked interested. "And how do you explain your presence in the year 2051 nach der Zeitwende?"

The scientist was soothed. "I am Dr. Pankraz Kahl, member of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, inventor of the world's first Zeitfahrer."

"A time traveler? A machine of some sort?"

"Of course."

"Then where is this machine?"

"Back there in the forest—the forest! The fire! It may have reached it—" Kahl plucked at Schwinzog's coatsleeve. "You must save my invention—"

The other shook him off. "When I see it I will save it."

"Come, then! Quick!"

The fire had rolled farther into the forest; everywhere the evergreens were burning like torches. Sparks rained down from overhead as they approached the time traveler's resting place, and directly ahead the thicket was a sheet of flame. From Kahl came a wounded cry; he broke from the guards and dashed forward. Then he stopped as if he had run into a stone wall.

The soldiers closed up, weapons thrusting.

"But this is the place!" Kahl was muttering feverishly. "It was right there—" He pointed at the bare, smoldering grass.

The ten-foot metal cube of the time traveler had burned to feathery ash and drifted away on the breeze—or it had in some no less unbelievable fashion vanished utterly.

Schwinzog's smile was not good to see. "Of course there is nothing there," he nodded satisfiedly. "Lieutenant Kramer, arrest these men. They are American saboteurs, and will be tried as such tomorrow by the Volksgericht."

"We," Eddie Dugan summed up the situation, "are up the creek without a paddle."

"And we don't know where the creek is," added Manning. "Only that this is 2051, and the Nazis evidently either won the war or staged a comeback somehow after losing. Neither idea seems possible, but here we are. Item, America is still fighting Nazism—at least, there are 'American saboteurs.' Item two, we landed smack in the middle of a wasp nest stirred up by those same saboteurs. They must have scored a success; did you see that building in the woods beyond that field?"

"What building?"

"I noticed it just as they were loading us into their armored paddy wagon. It had been a big place—already fallen in; the fire must have started there. And the boys that started it must have been the ones that German captain was talking about—the ones that wore Caps of Darkness and flew off in an invisible helicopter."

"I'm getting a headache," groaned Dugan.

"I'd like to meet them," said Manning thoughtfully.

They could not see each other, but they could talk between the adjoining cells. Kahl was in the cell on the other side of Manning's; he had raved most of the night at the guards and the equally responsive steel walls. The two Americans had slept long and refreshingly; they had long since learned to sleep under any and all conditions. There were no windows to show daylight, but they must have been there most of twenty-four hours.

They hadn't seen much of the world of the future, thought Manning ruefully; only the glimpse of a street filled with shiny silent automobiles and oddly garbed pedestrians, as they had been hustled from a rolling dungeon to a stationary one. But if the town was Freiburg, it had changed a lot since they had last seen it—a skeletonous waste of ruin, with nothing left standing that the American bombers had wanted to flatten.

"We shouldn't of let that Kahl talk so much," resumed Dugan gloomily.

"How could we stop him? Anyway, I have a feeling he talked himself in even deeper than he did us."

Their discussion was ended by a clatter of boots, the arrival of a bristling escort. They were being honored with treatment as dangerous and important prisoners—a distinction less flattering than ominous.

The "People's Court" before which they were being taken was obviously not the extralegal supreme court which Hitler had made into a bogey-man for scaring grown-up consciences to sleep; this was a local affair, in the same building that housed the jail. All four prisoners were herded into a rather small chamber, innocent of audience or jury. Opposite the entrance, beneath a huge hooked-cross banner, three men in black robes sat behind a desk. Two of them were old men who regarded the defendants with dull, incurious eyes; between them, his bulk dominating and shriveling them, sat Herr Schwinzog.

Into the deathly silence a hoarse voice cried, "Heil Hitler!"

It was Wolfgang, his conditioned reflexes spurred by sight of the swastika flag. The Americans stared at him; it was the first words they had heard him speak—perhaps they were the only ones he knew. Herr Schwinzog raised his eyebrows.

"What did you say?"

"Heil Hitler!" repeated Wolfgang mechanically.

"What does 'Hitler' mean?" asked one of the old men curiously.

"I don't know," said the other old man. "Perhaps he is feigning insanity."

Kahl found his voice. "But this is monstrous nonsense!" he shrilled. "Is this not the tausendjahrige Reich that Hitler promised us—"

"Silence!" snapped Schwinzog, and the scientist quailed. "You are not here to plead or talk gibberish, but to hear sentence. Your case has been decided after thorough investigation." He fixed all the prisoners with a frigid gaze. "You Americans are capable of more cunning than most Germans give you credit for; I know that well, for I was a colonial administrator in your country for ten years. Your attempt to masquerade as 'time travelers' shows originality in the conception and thoroughness in the execution. Needless to say, nothing directly incriminating was found among your effects. The experts report that even the metal identification tags found on the two who call themselves Ray Manning and Edward Dugan are authentic reproductions of those used by the American army at the time of the Conquest.

"However, you made the mistake of using too much imagination in the effort to confuse. Your story is too preposterous to be taken seriously, especially since our best scientists have declared time travel impracticable. Accordingly, we could sentence you to death for unauthorized presence inside the Reich and for evident complicity in the attempted sabotage of a German experimental station.

"In view of the absence of direct evidence of subversive actions, we have decided on leniency. The two prisoners, real names unknown, alias Pankraz Kahl and Wolfgang Muller—your claim to German citizenship has been checked with the central archive in Berlin and found to be false. Therefore I sentence you for the crime of imposture to five years in a concentration camp."

Kahl burst into a desperate, unheard babble of protest. At a wave of Schwinzog's hand the guards closed in. The Herr Doktor was dragged away bodily, shouting disjointedly about the blindness of the Philistines and Hitler's thousand years.

"As for you two," Schwinzog eyed Manning and Dugan with an oddly speculative air, "since you have admitted American nationality, your punishment is limited to immediate deportation—back to America."

They were more staggered than they would have been if he had said they would be executed for failure to wear monocles.

As the guards surrounded them, Schwinzog raised his hand, his face adorned by a mocking grin. "One more thing. You will be interested to know that the raid on the Black Forest experimental station missed its objective; the building destroyed was an unimportant storehouse. The actual refining plant is nowhere in the vicinity. The project of which your organization seems to be so well informed goes on as before and will be completed inside a week. You may carry the message to America: One week to live."

III

They had little opportunity, during the airplane flight to Hamburg, to exchange impressions or theories; they were constantly under the eyes of two nondescript, expressionless men who sat unblinking, with hands in the pockets of their civilian jackets.

Nor was it better after that; at Hamburg their watchdogs delivered them to another pair apparently shelled from the same pod. One of the first set passed the word laconically: "Two American spies. To be released in Neuebersdorf, by order of Gestapoleiter Schwinzog." And the new guards saw Manning and Dugan aboard a great transatlantic rocket.

It was from the rocket over Hamburg that they got their first real look at a twenty-first century metropolis. Only from twenty miles high could it be appreciated—the immense sweep of city in which straight-line highways connected innumerable village-like centers interspersed among the soft green of parks and woodlands, covering the broad plain of the Elbe mouth and sprawling away to the eastward to join with Lubeck across the base of the Danish peninsula. While they watched it, spellbound, in the mirror-ports, the fairy city sank away and vanished in the mist and shadow of evening; and the rocket ascended steadily and almost soundlessly into thinning layers of stratosphere, and the sun rose up in the west before it.

Manning fell covertly to studying the Germans who filled the seats of the pressure-cabin. Most of them were civilians; they had the subdued worried faces of suburban commuters on a train, and they looked quite oblivious to the wonder of their age, even to the miracle of the machine that was hurling them so swiftly and surely across the ocean. They didn't look like a Herrenvolk. Here and there were the color and brass gleam of uniforms, and with them went a tawdry arrogance, an overconscious effort to dominate and impress directed at the gray civilians and most of all, Manning observed, at the half-dozen nondescript women in the compartment.

Had these people conquered the world and planted themselves atop it?

And if so, what had they done with the rest of it? With America, for example—a German colony, Schwinzog had indicated.... Defeated, enslaved....

Then Manning remembered that he had seen with his own eyes evidence that America had not been wholly defeated, even after a hundred years; that someone, somehow, was still fighting on. His heart leaped up.

He addressed one of the guards for the first time: "Where are we bound?"

"Neuebersdorf," said the man curtly. He glanced at his watch, and in lieu of further explanation, leaned forward and twirled a knob beneath the port beside them; the scene mirrored in it shifted and swung to straight ahead, and they could see the coast line that had appeared in the west and was sweeping rapidly nearer. There was a great island and a sound, and at the latter's narrowest point was concentrated a smudge of city, almost as vast as the Hamburg of this time, but dark and jumbled beneath the afternoon sun, lacking the German seaport's ordered spaciousness.

"Hey!" exclaimed Dugan. "That's New York!"

The Gestapoman looked at him in silent contempt.

"It is—or was," amended Manning sorrowfully. As the rocket plunged closer, they see that much of the city was in ruin. The downtown district, in particular, showed an unrelieved prospect of devastation, empty windows in walls standing or fallen, and fields of shattered blocks and debris, testifying to a tremendous destruction and an even greater neglect. Something had toppled the towers that had stood there, and no one had come to clear away their wreck.

Manning turned from the window. Later on he would be curious to learn more of what German rule had meant to America—for the moment a sick feeling in his stomach told him he had seen enough.

On Long Island, however, where the ship landed, the desolation of New York was not in evidence; where Brooklyn had been was a German settlement, and there were fair dwellings, broad green lawns and trees, and smooth-paved streets along which shining traffic moved with the whisper of electric motors.

They saw this last outpost of the master race briefly as they were whisked through in a chauffeured car that had met the rocket; their destination lay across the river, where eroded heaps caricatured the skyline of Manhattan. Guards with machine guns passed them onto a narrow span that had replaced the vanished Triborough Bridge; and inside five minutes the car halted on the American shore. It stood with motor running, and one of the Gestapomen ordered, "Get out."

Manning and Dugan got out, feeling numb in mind and body, and looked at the waterfront. From the air nothing had been visible except the colossal ruin of the world's once greatest city; but from close by could be seen that which was far worse—the dwellings of its present inhabitants, sprung up among its rubble like the grass through the cracks of its pavements. The houses were less than peasant huts, built of stone and concrete fragments and rotting lumber, sometimes against the still-standing wall of a shattered building.

Some distance away a small crowd had collected and stood dumbly watching the activity about the gleaming vehicle that had come over the guarded bridge. Others peered from the doorways of the nearer huts. All were ragged and soiled and in their faces was the dull resignation of a beaten inferiority.

Those were the American natives of Neuebersdorf, which had been New York, U.S.A.—magni nominis umbra.... Manning wondered, with a surge of horror and pity, what made them grub here to construct their dens on the edge of the desolate city, whence they could look across the water and see the abodes of German pride and power and luxury—was it merely envy, or the need to nourish an undying hatred? The blankness of the watching faces gave no answer.

The car door slammed. The machine swung about and purred swiftly away up the bridge approach.

Dugan stared after it and said softly, "What the hell!" And when Manning failed to answer: "Well, Ray, what now?"

The other passed a hand across his forehead. "I don't know. But maybe we'd better start looking for invisible men."

"Fine," said Dugan. "When I see one, I'll yell."

Manning glanced toward the ragged crowd that had watched their arrival; it was already beginning silently to disperse, losing interest. Most of the two soldiers' clothing had been given back to them, but minus such items as leggings and steel helmets their 1945 combat dress looked sufficiently unmilitary and nondescript.

"No use just standing here," said Manning. They started to walk, turning at random into a narrow street that crooked among the ruins. Then Manning began to talk in a lowered voice. "If I'm not badly off, we're going to be followed and watched. Obviously the Germans have taken us for somebody else, and they didn't ship us across like ambassadors out of the kindness of their hearts. They think we belong to an American underground, and what we do now—they figure—is lead them to it. I wouldn't be surprised if—Uh huh." He pulled a hand out of the pocket of his field jacket with a small bundle of paper—money. It was marked, stamped Ausland. "They even slipped us a stake to make sure we didn't have any trouble in getting to underground headquarters—with the goon squad on our heels."

"Well, at least we can eat. And I guess we can wander around, looking as ignorant as we are, and lead them a wild goose chase.... That sounds like a hell of a life," Dugan appendixed glumly to his own description.

"You and me both. Sooner or later we've got to get in touch with whoever's still carrying on the war. Because the war's still going on, in spite of—this." He didn't gesture, and Dugan knew he meant more than the broken buildings around them—the broken look they had both seen in the eyes of the people.

"Sure we've got to," said Dugan fiercely. "But how?"

Manning shrugged. Their footsteps echoed, died away, echoed again in the deserted street, which here, in what must be the heart of the destruction, was hardly more than a tunnel between leaning walls where tons of masonry still hung in the twisted steel frames. From behind them the trick echoes brought briefly the sound of other footsteps. They were being followed, all right.

"If the Gestapo just knew it," muttered Dugan, "they'd come nearer what they're looking for if that guy was leading us."

Manning nodded somberly; then he drew sharp breath and looked at his companion with kindling eyes. "Maybe that's the answer to our problem, Eddie."

"What answer?"

"Just an idea—maybe there's nothing in it. But if I'm right, we'll meet the underground—and soon!"

"Okay," said Dugan. "Anything you say. But what do we do?"

"I think we can concentrate on digging up something to eat," said Manning judiciously. "The sun's still up here, but it's been all of eight hours since we had dinner."

They emerged at last, tired and hungry, from the labyrinth of total devastation into a more populous district—a squalid village sprung up amid the ruin of New York. Along the edges of its dusty main street, where no lights were lit against the descending dusk, stood or squatted the people, talking listlessly in low voices or merely staring at the passers-by. Before one of the larger groups Manning halted.

"There's a joint down the street says 'Eat'," Dugan nudged him.

"Wait." Manning faced the bunch of idlers and raised his voice. "Were any of you folks ever in Germany? It's a wonderful place. We just got back from there. They have beautiful cities with paved streets, millions of automobiles and helicopters and airplanes, with broadcast power to run them—"

"What are you giving us?" demanded a deep voice, its owner a blur in the twilight. "We know all that. And who the hell are you, anyway?"

"I know," insisted Manning. "I was in Germany only this morning."

A little, wrinkled man scurried out of a doorway and laid a protesting hand on Manning's arm. "You'd better shut up," he said sharply. "That's inflammatory talk, and it can get you in bad trouble."

"He's crazy," suggested another voice.

"I'm crazy," agreed Manning affably, and turned to go. Out of the tail of his eye he saw the little man go back inside, and he felt unreasonably optimistic.

"Now we can see about that chow," he told Dugan.

IV

The inside of the "eat" was not attractive, nor was the food the slovenly waiter brought them. Dugan ate fervently. It didn't matter to him that America was no longer America, or that American coffee was no longer coffee.

But Manning dawdled. He had sat down with his back to the wall, so that his eyes could rove freely over the whole cramped interior; and he was all taut expectation. He was waiting for a sign.

Within ten minutes after their entry, three men had come in and sat down, two of them together. They might have been ordinary customers, but to Manning's covertly searching gaze they did not look sufficiently undernourished to be twenty-first century Americans. They looked like Germans.

The next arrivals were a youthful couple, and then for a while no one came in. Manning ordered another cup of "coffee." Then he got a shock.

For when he looked down, reaching for his cup, it was gone. He blinked, and it was there, solid, chipped and stained. He glanced briefly up at the unnoticing Dugan, then back to the cup—and there was no cup. And then there was, and he sat and squinted at it, struggling with a glimmer of understanding that this was what he had been waiting for.

Their table was for four. Out of the corner of his eye Manning thought he saw somebody sitting in the chair at his right. He turned his head quickly, and there was no one. The chair was empty. Too empty. His brain tried to crystalize that intuitive conviction, but failed.

He glanced sidelong at the suspiciously well-fed men. They sat morosely over glasses of what looked like beer, and paid no attention. But Manning knew that there was an invisible man in the room.

He sat hesitating over his next move, when a voice screamed in his ear. It was a tiny thread of voice, not a whisper; it sounded like someone shouting frenetically over a bad telephone connection.

"Don't move," it commanded urgently. "I see you know I'm here beside you, and that you're being followed. Are you willing to follow instructions? If so, lay your right hand on the table."

Manning did so. The gnat-like voice shrilled, "All right. You leave here, turning left. Follow your nose and don't look back. About five minutes' walk will bring you to a bridge. Further instructions then. Act natural!"

Despite the final injunction, Manning hardly knew how they got out onto the street. Out of possible earshot of their shadows, he explained hurriedly to Dugan. "I thought they'd try to contact us. We have the Gestapo itself to thank for that, I'll bet. Even if it can't put the finger on the underground, it must know enough about them so that we were dumped off here for bait, it could let the word go out so that the underground would hear about us and grab at the bait right away. They didn't lose any agents on that raid in Germany, so they must have been pretty curious to learn that a couple of their men had been picked up on the scene and sent to New York! Now things are going to break."

The bridge loomed out of the darkness ahead. It was a wooden structure, crossing a narrow creek. Midway of the echoing span, they paused, and Manning pricked up his ears. He was not disappointed. The invisible presence said, "Good. I trust you can both swim? All right—drop over the railing, and swim straight back to the shore you just left, only come out under the bridge. I'll meet you there. Good luck!"

They looked at each other. "I heard him," Dugan said, and without more words placed a hand on the rickety railing and vaulted out over the black water. Manning gave him a few seconds to get clear, and followed. He came up clinging to his orientation, and struck out; when he splashed ashore, Dugan was already shaking himself on the narrow strip of sand below the bank.

And a third man emerged abruptly from the shadow of the bridge piles. He was an ordinary-looking man in a worn leather jacket and patched trousers, but his face was masked by a dark hood, blank save for eye-slits, and on his back he carried something like a small pack with two small levers protruding. In his right hand was a pistol, and in his left a bundle; he dropped the latter on the ground and stepped back.

"Put those on," he hissed. "Quick, before they get here!"

The bundle was two outfits such as the stranger wore. They donned them as instructed; the hoods were stiff with wire, and connected by a flexible cord to the packs. Manning eyed the gun speculatively; the masked man explained softly, "It's not that I don't trust you, but those gadgets are too valuable to take any chances with. They're invisibility units. Start them by pressing here." He pulled down one of the levers on his pack; he seemed to blur slightly, but they could still see him. "The headgear insulates you pretty well from the effect. Go on, start those units!" Heavy feet were thundering overhead on the bridge planks.

They obeyed; the packs made a faint hum. The stranger relaxed visibly. "Now we're okay," he said in a normal voice. "By the time they catch on, we'll be a long way from here."

Directly above, an angry snarl: "Sie sind grade ins Wasser gesprungen! Wer hatte erwartet—"

Somebody else answered, "Vielleicht wird ein Boot dort unten gelegen haben."

"Good guessing," approved the masked man cheerfully. He motioned Manning and Dugan toward where a small skiff lay beached between the piles. "Help me launch this. First, though, turn your units up to full power—like this—so they'll cover the boat."

Manning was startled at the man's bravado; as all three laid hold of the boat, he whispered anxiously, "Won't they hear—"

"Not if we shouted our heads off," the other answered. "With these units going, we're not only invisible, but inaudible and practically intangible. I've walked through a cordon that was closing in on me with linked arms." He sprang nimbly into the bow of the boat. "Grab an oar, you two, and make yourselves useful. I've been through a lot of trouble on your account." He seemed to decide that introductions were finally in order. "My name's Jerry Kane. At any rate, it's my favorite alias."

Manning and Dugan named themselves and fell to rowing. "Downstream," said Kane, and he gazed back at the bridge with interest as they pulled away. Manning glanced back over his shoulder; there were dark figures swarming on the bridge, and lights, and a car had stopped there; even as he looked a searchlight beam swayed out across the water, moving systematically back and forth. For a moment it fell full upon the rowboat, and Manning ducked involuntarily; but the light passed on and there was no outcry, no shots came.

Manning said hoarsely, "That light was on us! It didn't go through us, or anything of the sort. A body that reflects light is visible. So how the devil—"

"We're not optically invisible," answered Kane amusedly. "So far as I know, that's a physical impossibility. Actually, those Germans saw us, but they didn't notice us. Ever catch yourself looking right at something and not seeing it, because it was too familiar or because you were thinking about something else? That's the effect the field has. Anything in the middle of it hides behind a psychic block in the mind of whoever looks at it. That's why it works on hearing, too, and even on touch. It's not perfect; if you set off a magnesium flare in front of somebody, or punched him in the nose, he'd notice something was up—but hardly before. When you get acquainted with the effect it makes you feel like a ghost. Back in that cafe, I had to shout in your ear till I deafened myself before I could make you hear."

They glided down the current, and the lights and voices around the bridge receded rapidly. As Manning bent to his oar, his imagination was busy with the first item of twenty-first century technology which went completely beyond his twentieth-century knowledge. In Germany he had seen the evidences of a mighty and advanced civilization, but everything had been the logical perfection of inventions already known....

Kane seemed to read his thoughts. "Working like we do, we can't compete with the Germans in things that call for a lot of resources and equipment. They have all the big weapons—the rockets and tanks and atomic bombs. For anything to be useful to us, it has to be something that can be invented and built in a cellar. So we've had to open up brand-new lines of development—and in fields like psychoelectronics we're miles ahead of the Germans, because they didn't have to.... Better pull over. We don't want to get rammed," he interrupted himself.

A blinding eye was bearing down on them across the water. In its stark glare Manning felt nakedly visible again. But they veered sharply toward the bank, and the launch went past in a swish of foam, still scanning river and shore ahead.

"Where we going?" Dugan asked practically.

"We're about there," answered Kane. "Easy now." He pointed to where a jumble of ruins projected like a pier into the stream, the ripples lapping and gurgling in the spaces between the great piled fragments. "In there—the only space big enough for the boat. Better duck." Their craft slid with scant clearance into an opening like the mouth of a cave. Kane produced a flashlight, and they saw that a timbered tunnel ran back into the bank at right angles to the entrance.

"Up to the end," ordered Kane. They poled with oar-thrusts against the tunnel sides for a score of yards, until the boat bumped against a wooden platform at the end of the shaft. Kane sprang ashore and made fast, and the others followed. The flashlight beam searched out a trapdoor; below it were stairs that led downward. At the bottom they trod on cement, and there was another door, on which Kane knocked in a deliberate pattern.

Presently a bolt was shot back, and the door swung open. The man who opened it was hooded and it was a little hard to keep him in sight, even for those likewise protected. When he saw Kane, however, he switched off his invisibility unit. The new arrivals did likewise, and all of them slipped off their stifling hoods with relief.

Jerry Kane had a surprisingly youthful and unlined face, topped with curly blond hair which women must have loved to run their fingers through. He didn't look much like an underground plotter. The man who had opened the door fitted the role better; he was gaunt, blue-jawed and dour.

The room they had entered had begun life as a basement; it was big, concrete-walled, ill-lit by an electric bulb dangling from the low ceiling, its furnishings a long table and a number of chairs which indicated its use as a gathering-place for a good many people. The only other person in it now was a massive man who sat at the table, an open book spread out before him, and stared unblinkingly at those who had come in.

"Most of our regular agents are out—looking for you," Kane remarked. He waved them to seats, and sat down himself on the table's end. "However, we have here Harry Clark"—the blue-jawed man—"and Igor Vzryvov, one of the Russian members."

Clark nodded noncommittally. The big Russian rumbled in faintly accented English: "Pleased to meet you. I have never met any time travelers before."

They stared at him. Manning turned on Kane: "You know about us?"

Kane grinned. "You told the Germans you came out of the past. At least, that's what was reported in the camera session of the court which passed on your case this morning. One of our friends happened to be there—and at your trial, later on."

"Was there an invisible man there?"

"No, he was visible and you saw him. Remember two elderly jurists who served as a sounding board for Gestapoleiter Schwinzog? One of them is a friend of ours. We have a good many, even inside Germany."

"He calls them friends," growled Igor Vzryvov. "I say no German can be a friend."

"So—" Manning was numbed by surprise. "So you've had your eye on us from the start."

"Just about."

"And you believe our story?"

"Since the Germans didn't, I'm inclined to," admitted Kane. "We know that more things are possible than German imagination can swallow; we've got several such things here. Of course, it's always just possible that you're German spies, using a crazy wheels-within-wheels stunt to get on the inside. I don't think so, though, and fortunately I don't have to guess." He turned to Vzryvov. "Got the apparatus set up?"

"Since an hour ago," said the Russian.

Kane slid off the table top. He became brusque. "If you'll just step into the next room, we'll read your minds and settle all doubts."

Fifteen minutes later, Igor Vzryvov switched off the psychoanalyzer. Manning glanced up under the spidery hemisphere of wire that gathered the faint broadcasts of the brain, and met Kane's warm smile. The underground leader tossed aside the graphs he had been studying, and extended a welcoming hand.

"You're genuine, all right. No need to examine your friend—your mind says he came with you out of the past, and that's enough and to spare."

"Swell!" said Dugan. "I didn't much like the idea of having that thing poking around inside my head."

Kane caressed the machine affectionately. "This is one of the best achievements of cellar science. Thanks to it, we've got the only leak-proof organization this sinful world has ever seen. The Nazi party is one of the tightest setups ever created without benefit of the psychoanalyzer, and we've got men inside it—but we know that all our members are loyal and stable." His expression darkened. "Of course, if this and our other psychoelectronic developments got into German hands, we'd be sunk. With their resources, they could exploit the field a lot more thoroughly than we can. For example, Igor here has invented a death ray that kills by just convincing a man he's dead—but to make it an effective weapon would take a lot more power. We get a good deal of leakage here from the Long Island station, but we have to be careful about antennas."

The four of them sat around the table in the outer room. Harry Clark had disappeared—literally, and then gone out to pass the word to the agents scattered around New York that the men they sought had been found.

"Now," said Kane, "since you're really time travelers, I'm on fire to hear how you did it. A time machine might be a useful addition to our arsenal, though it sounds like a tricky thing to use...."

"I'm afraid we can't help on that score," said Manning, and related the whole story of their experience with Herr Doktor Kahl's Zeitfahrer.

Kane rubbed his chin thoughtfully. "So you're stranded in our time. I feel for you! At least the Germans didn't get the machine, either—though they have got the inventor. We may have to do something about that. And what about you? Have any plans?"

Manning met his eyes squarely. "A hundred years ago, we were fighting a war. It seems we lost it—how or why, I don't know. I don't think we lost it in the fighting, but probably before it ever began, when we were complacent and let the Germans get a head start in preparation and invention. Anyway, for us that's still unfinished business."

"And we'd like the chance to finish it!" stated Dugan bluntly.

Kane smiled with a touch of sadness. Vzryvov said explosively, "The end may be soon!" and his eyes burned.

In Manning's memory flashed the vision of a mocking face. He asked abruptly: "What did Schwinzog mean: 'A message for America—one week to live'?"

The shadow on Kane's face deepened, but he did not show surprise. "I guess he meant just that. That the Germans are about ready to do to America what they did to Russia fifty years ago.... But of course you don't know anything about the history of the last century. If you want to catch up on the missing chapters, I've got a fair-sized collection of books on the subject. All the ones dealing with events since the War of the Conquest are German, of course—English has just about stopped being a written language—and you'll probably find they don't even agree on what you know. You said, didn't you, that you were with an American army advancing into Germany?"

"That's right—and it was only one of several."

Kane grinned wryly. "The books don't even whisper that Germany was ever invaded in that war. They must have been a lot closer to defeat than they've ever admitted since. But—" he shrugged, "they won in the end, so what's the difference?"

"How could they win?" scowled Dugan. "Hell, we had them on the run!"

Kane gave him a pitying look. "You must have left some time before the Germans suddenly rose from the ashes and struck back at us. They attacked us with a new weapon—a radioactive dust, by-product of several big piles—atomic power plants—they had secretly got going by 1949. The occupation forces were wiped out—along with a million or so of their own people. In no time Western Europe was overrun again. The whole of Soviet Russia seems to have collapsed about the same time." He looked down at his hands, clasped on the table in front of him; his voice went on with the dispassionate recital of the dead past. "There was an attempt to defend England that folded up when London was dusted off the map. I haven't been able to find much information on the war in Asia, but I think they had a long tough fight putting down guerrilla resistance in Siberia and later on in China.

"Then came the attack on America, and for that they used the dust in combination with another ace in the hole—their own atomic bombs. The first one was dropped right here, on New York. It flattened five or six square miles and killed about half a million people. The defenses that we'd devised against the dust—inadequate as they must have been, because there isn't any real defense—were neutralized by the bomb. America fought for just one month, and after that there wasn't any United States—just a disorganized mob of survivors, dazed by the cities' destruction and the sterilization of big stretches of countryside.

"Germany proclaimed the New Order over the face of the whole Earth—humanity to submit to the leadership of the German Volk, its highest evolutionary type. Everywhere the nations surrendered without a fight.

"Since the Conquest there's been only one serious, organized rebellion in this country; that was in the year two thousand, fifty-one years ago. The Germans put it down with bombs and poison; a lot of innocent people were killed, and for a long time after that it was impossible to organize any resistance. Since our movement got started twenty years ago, we've been damn careful not to goad the Germans into making a wholesale slaughter. Now—" His face twisted in pain.

"They've decided to anyway?" asked Manning with studied calm.

"As a matter of policy, not revenge. You see, for a while after the Conquest they had a lot of use for slave labor, so the subject peoples were valuable to them; but now that they have plenty of atomic power, running nearly automatic factories and mechanized farms to supply all their needs and luxuries, the rest of the Earth's population looks to them like so much excess baggage. All they have use for is land, Lebensraum for their own growing people. They've calculated that the whole Earth could be covered by Germans by 2500 A.D. As far as they're concerned the rest of us can rot or starve—and we do; but we don't die out! So—they murdered Russia fifty years ago—that was what touched off the rising here—and we're next!"

Manning said unbelievingly, "What do you mean—'murdered'?"

"The technical term is 'genocide.' They did it with guns and gas and, when necessary, the atomic dust. It's quite a job to wipe out a whole nation, and the Germans bungled Russia pretty badly and met a lot of stiffer resistance than they expected, and a lot of people—such as Igor's parents—got away to other countries. But since then they've made improvements in the method.

"Sometime soon, in a few days, maybe—a rocket will take off for somewhere in Germany and proceed to a point in space about fifty thousand miles from the Earth. There it will discharge fifteen hundred metric tons of radioactive dust—a new mixture of ingredients having a few days' half life, for initial devastating effect, and of others with a period of about a year—to take care of anybody that tries to sit it out underground. The dust will drift toward Earth in an expanding cloud, whose size and shape they've calculated down to the last decimal, and which, when it falls on Earth's surface, will cover an area a little larger than the United States. It will be spread thin by then—about one gram to the acre—but that will be enough."

Manning sat silent. The idea of these new ways of all-compassing destruction was too much for a mind that had learned to regard high explosives, machine guns and flame throwers as adequately murderous. And the plan for exterminating a nation was too monstrous to think about, unless in the same light as it must be seen by the minds that conceived it—as something like dusting a field of grain to kill off insects whose only crime is that they eat what men want to eat.

"And you've known about this, and haven't stopped it?" he asked at last.

"They've been busy making and refining the dust for a year now, and we've known about it almost that long. And we've tried to stop them.

"We've tried to assassinate the men responsible for the plan. But the ruling clique, like your acquaintance, Schwinzog, aren't under any illusions and they aren't going to yield any power. We've tried to get them and mostly failed.

"Finally, one of our men got inside the Reichministerium fur Raumschiffahrt and learned that the space ship Siegfried had been assigned for conversion to the uses of the project. The raid you stumbled into was trying to locate and destroy it, but they didn't find it and blew up a building instead. That's our last chance even to gain time—if we can't wreck the dust ship, I don't know what we can do."

Igor Vzryvov broke his brooding silence. "You will do as we did," he proclaimed with flat conviction. "Save what you can of your organization by flight to other lands, whence you will carry on the fight—to the death, without the crippling reservations imposed by millions of hostages."

Kane looked at him with smoldering eyes. "What would be left to fight for?"

"Wait and see," insisted the Russian implacably. "You will really begin to fight when there is no more America to be saved, only Germany to be destroyed."

Manning put in hastily, "Your men didn't locate the—space ship. How do you know it's even in the Black Forest?"

Kane frowned, then shrugged. "We don't. But there's nowhere else it can be. We've checked every spaceport in the Reich."

"Maybe it's outside Germany."

"There aren't any ports in the subject countries. And if one had been built, and the Siegfried landed there—well, it simply couldn't have been done inconspicuously. We have psychoelectronic communicators scattered over the whole world, and what's more important, the best grapevine connections. We'd have heard."

"What about the polar regions? Antarctica?"

"I guess it would be technically possible—though enormously difficult and expensive—to build a spaceport there. But it just isn't reasonable. They aren't that scared of our interference."

Manning bit his lip. "One little thing," he murmured, half to himself, "makes me think that ship isn't in the Schwarzwald at all. Herr Schwinzog gloated that your raid missed the refining plant; he must have forgotten for a moment that you're supposed to believe the space ship is there too...." Abruptly he raised his head. "Listen—maybe there's one part of Germany you didn't investigate."

"What do you mean?"

"Where Eddie and I were, just this afternoon. Long Island."

Kane and Vzryvov looked at him with wild surmise. "You might be right," Kane said jerkily. "There's a field there that would do. But a space ship landing would have been seen for hundreds of miles—" His eyes widened with a sudden idea. "They needn't have landed it there, though. They could have brought it down in the ocean, and towed it in!"

"Sure," said Manning, though he hadn't thought of that. "An amphibious operation. The island's well-guarded?"

"Suspiciously so, now that you mention it. We don't have a single agent there—we've been concentrating on the expeditionary force in Europe, of course, and we've supposed the additional Long Island defenses were merely installed in fear of an attack on the German colony, when the people hear—But that could be it! They could have hidden the ship under our noses!"

He sprang to his feet; he wore a look almost of gaiety, but his eyes held feverish lights. "If we could only start after it tonight! But this things calls for preparation. They'll be ready for anything, invisibility units included.... But we've got to try tomorrow night. If the ship is there—it may not be much longer."

Manning and Dugan exchanged glances. Manning said pointblank: "Are we in on this deal? We were soldiers in our own time, and—Americans...."

Reading Kane's face, he realized he hadn't needed to ask.

V

The boat slipped silently, impelled by muffled oars, toward the shore that lay dark and seemingly lifeless a furlong away. The underground in New York had a couple of motor launches—but there might be sound detectors on that shore, which would not be fooled by the powerful invisibility unit that purred quietly, clamped to athwart amidships. So they rowed.

The boat was laden with men, weapons, and explosives. The men were monstrous-headed shapes, for they wore gas masks under the featureless hoods; but the poised alertness of Kane's figure, upright in the bow as he scanned the black shore and called soft directions to Vzryvov at the steering oar, expressed all their eager anxiety on the threshold of decision. Manning and Dugan sat side by side; in front of the former was lanky Clark, and beside him a chemist named Larrabie, who clasped between his knees a box full of bombs of his own making—canisters of a versatile compound which with a detonator had the violence of TNT, without one was an excellent substitute for thermite.

Manning had to remember that he had once taken part in another landing on a conquered shore—Normandy in 1944, when the air had been full of planes and the sea of ships, and the invasion had rolled ashore like a resistless juggernaut.... If those millions had failed, what could six men in a rowboat do?

The night before, in the room Kane had given them, Manning had lain long sleepless, and passed the time turning through Kane's books of history—titles like Aufstieg Deutschlands zur Weltherrschaft, Eroberung der Erde, Das deutsche Jahrhundert.... One thing about the oddly twisted story they told had piqued his curiosity, and he had sought earnestly before he found mention—in a footnote—of the fact that one Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) had occupied the civic office of Reichskanzler (later abolished) at the time of the Conquest. But the leaders of that period, according to the histories, had been the generals and military men such as Rundstedt, Rommel, Keitel and Doenitz.

The future had obviously not gone according to anybody's plans made prior to 1949. A new factor had come in—the monstrous reality of atomic weapons, which had suddenly made it possible for a few men in one nation to hold the threat of death over all life on Earth. America had had them first and had used them to subdue Japan. But the German onslaught had been too swift; the combination of atomic dust and atomic bombs had paralyzed the U.S.A. before she could strike back.

"Up oars," whispered Kane. The boat glided forward the last few yards as the dripping oars rose over the water, then sand crunched under the keel.

Cautiously they sloshed ashore. Vzryvov knelt in the boat for half a minute, working with wires and one of Larrabie's compact bundles of death—booby-trapping the priceless invisibility unit against possible discovery.

Each man carried a slung automatic rifle, three bombs, and a long knife. An invisible man could kill with a knife in the midst of a crowd and walk away before anyone noticed.

They started moving without time wasted in consultation or casting about. All had studied the available maps of the area until their eyes smarted; and the moon was up, which for them was a special advantage.

This stretch of shore was occupied by the sea-side villas of the German masters; it was a good hour's walk from the main colony and the rocket port. The Germans could hardly have protected the whole coastline with automatic alarms.

As they topped the seaward slope, though, from not far distant, where a house bulked in the shadow, exploded the barking of a watchdog. The raiders froze; Kane swore perfunctorily and said shortly, "Push on. Dogs can see us, or at least scent us. That one doesn't seem to have raised anybody yet—"

They pushed on, tramping across meadows and through woods, steering clear of the roads that might be watched by electric eyes—as the rocket port must be without doubt, if the dust ship was there.

Half a mile from the German colony, in sight of its lights and their glimmering reflection in the water of the East River, a high fence barred their way. It was plain wire, stretching to right and left out of sight—probably across the whole island.

"That wasn't on the map," said Dugan.

"Of course not," responded Kane. "That's the first line of defense. Touch it, and you'd alert the whole place." He didn't look unhappy about it, judging by the flash of his grin in the moonlight. "Brother, I think we've come to the right address!"

Vzryvov remarked imperturbably, "The road must pass through it yonder." He gestured to where an occasional moving light picked out the highway.

"Right," said Kane. They set out along the fence, keeping at a respectful distance from the wire.

The highway entrance was floodlighted and visibly protected by movable arms like those used at grade crossings. These, together with the sleepy squad of German soldiers that stood guard beyond the fence, would not have given pause to the invisible men. But there had to be invisible defenses too.

They waited on the shoulder of the in-going traffic lane. Manning and Dugan could scarcely quell the jittery feeling of being exposed in plain view of the enemy, but the others were unconcerned.

"We've got to hitch a ride," explained Kane softly. "Just passing through behind a vehicle wouldn't be good enough, you can bet...."

A car came rushing out of the darkness and swooped to a stop with screaming tires. It was a gleaming pleasure machine, transparent plastic top flung back to let the night air cool the heated faces of three young couples that occupied it, evidently on their way to continue in town a party that had outgrown the facilities of the countryside.

"Get a good look at their admission procedure," said Kane.

The guards bestirred themselves; one operated the gate mechanism, the rest surrounded the car, grasping shining steel blades on long shafts, barbed like medieval halberds. They swung their archaic weapons around and over the car, hacking the air viciously. The girls in the car squealed and snuggled as the driver eased forward under an interlocked arch of steel.

Manning said, "They're watching for us, all right!"

Kane nodded, then tensed as another automobile rolled up and stopped. "This one's O.K.," he said aloud. "Quick, now—get inside it!"

They went forward in a pellmell rush. Kane eased open a back door of the car—a sedan with a lone man at the wheel—and all six of them squeezed themselves into the back seat, pulling the door quietly to after them. They held their breath, but there was no cry of surprise or alarm. The soldiers went routinely but thoroughly through the ritual of halberds. Any invisible man clinging to the outside of the vehicle would have had to drop off or be dragged into the wicked blades.

The car rolled through the gate and picked up speed with the violent surge of an electric motor. The man hunched in the front seat drove with businesslike concentration, oblivious of his six unwanted passengers. The raiders grinned at each other, shifted their cramped positions a little and waited.

Presently the town's lights began to swim past. Kane, in a position to see out the left-hand window, muttered: "We're passing the rocket field—they've thrown a brand-new wall around it. If this guy would just slow down—well, we've got to stop the car." He wriggled up until he could lean over the front seat—and stiffened. All of them heard the moan of a siren closing up behind.

"Donnerwetter!" growled their chauffeur, and clamped on the brakes. A few feet behind loomed up a pair of headlights and a searchlight helped bathe the car ahead in a merciless illumination.

"Out!" said Kane sharply, flinging open the left-hand door.

They sprawled out and ran, stooping instinctively, through the patch of brilliance. Uniformed Germans were climbing out of the other vehicle and starting to form a cordon.

Dugan, the last man out, halted a moment to close the car door, then sprinted after the rest. They huddled against the forbidding wall that had been built around the rocket port. Larrabie, eyes on the brightlit scene, nervously hefted a bomb. Kane shook his head.

"Time enough to make big noises when we get inside," he advised. And to the whole party, "I spotted an entrance a couple of hundred yards back. Come on!"

They ran in single file under the frowning face of concrete. It might have been possible to form a human chain and get over the wall; but there was unquestionably alarms atop it, and ready guns.

Beyond the wall, a whistle began hooting. The field was being alerted.

Kane panted, "Don't know what tipped them off—but probably we were photographed at that gate."

The entrance to the field was solidly blocked by a massive iron grille. Beyond it, they could see men running and springing into position behind a concrete redoubt, through which a machine gun thrust menacingly, covering the opening in the wall.

"Damn!" said Kane. "No more time to be subtle. We'll have to knock that out."

Eddie Dugan was already unhitching one of the home-made grenades from his belt. "Stand out of line with the gate," he said grimly, "and I'll get it for you." He gauged the distance and the weight of the bomb and threw with trained precision. The missile rose in a high arc like a mortar shell's, and hit the ground almost as Dugan did in his dive for cover. Fragments of shattered concrete and metal clanged against the grillework and whistled out into the street. A crash of glass and frightened screams came from the houses across the way; and down the street the patrol-car siren wailed suddenly into life again.

Kane sprang to his feet, verifying with a glance the emplacement's destruction, and hurled another bomb at the gateway. Its explosion was blinding, but a moment later they saw the way clear, the grille blown off its hinges and twisted like spaghetti. Simultaneously a rattle of shots, insignificant-sounding after the deafening blasts of high explosive, told that the patrol-car, racing its motor up the street, had opened fire on the entrance.

Clark was down on one knee, finger closing on the trigger of his automatic. The oncoming car skidded and spun half around. Two men spilled out and fled for cover; Clark dropped one and missed the other.

The big noises had begun, and speed was the big thing now. The raiders dashed headlong through the wrecked gateway.

"Get clear!" shouted Kane, and on the heels of his cry came the sputter of machine gun fire, first from one side of the entrance and then from the other. Puffs of dust sprang out of the wall and ricochets whined plaintively. Other guard posts were covering the breach, but the German gunners must have hesitated before firing without a target, and they were seconds too late.

The Americans crouched, half-sheltered by the ruined emplacement. To the right from a cluster of buildings, the warning whistle shrieked hoarsely on, and they heard through the incessant gunfire the noises of excited voices. Ahead of them stretched the wide, seared waste of the rocket field, its boundaries invisible in the darkness.

"We're in," breathed Kane, "and there's the ship!"

Out on the field, far from all structures, it towered upright, its blunt nose five hundred feet above the blackened earth. Even though no light shone on or from it, they could recognize its lines as those of the vessel whose stolen plans they had gone over point by point—Siegfried, the dust ship.

"They must have raised it to launching position only tonight," said Kane harshly. "Otherwise we could have seen it from across the river. So—it must be loaded and ready to go!"

A thousand feet of open and empty field separated them from the space ship. With straining eyes they could see tiny human figures scurrying about its base in the moonlight, forming a protective circle. Then floodlights went on all over the field and left not a shadow anywhere. The Germans knew, or feared, that the invisible attackers had slipped inside their citadel.

The rain of steel on the gateway had stopped; instead came dull thudding concussions, and a creeping haze obscured the entrance. Gas.

They had prepared for that. But now a more formidable threat made itself known; from near the buildings came a frenzied barking of dogs.

"We've got to get across the open," snapped Kane. "Better stick together and run for it. If we can get among that gang around the ship—neither dogs nor instruments can tell the difference between visible and invisible men!"

They rose from their cover and pelted grimly across the endless-seeming field. To the right, parties of men with dogs were fanning out, too slowly to intercept the raiders. But they were only halfway to the ship when the lights suddenly snapped off—for a moment they stumbled, blinded, in darkness, and the lights flashed dazzlingly on again. A couple of seconds later the puzzling action was repeated—

And from the cordon about the ship, so near now, a voice screamed hysterically, "Da lauft einer!" On its heels came a thunder of shooting, and bullets snapped past the hurrying Americans.

They flung themselves flat on the scorched ground. The lights flashed again and again as if an insane hand were at the master switch. "What's happened?" gasped Manning. "Did they see us?"

"They've learned or guessed one of our weaknesses," said Kane in his ear. "When the whole field of vision is suddenly illuminated, the brain may register an invisible object, especially if it's moving, for a moment before it melts into the background." Something whimpered in the air and burst with an ear-splitting bang only a few yards away, showering the raiders with earth. "They've got our position. Get going—now!" as the lights flashed on.

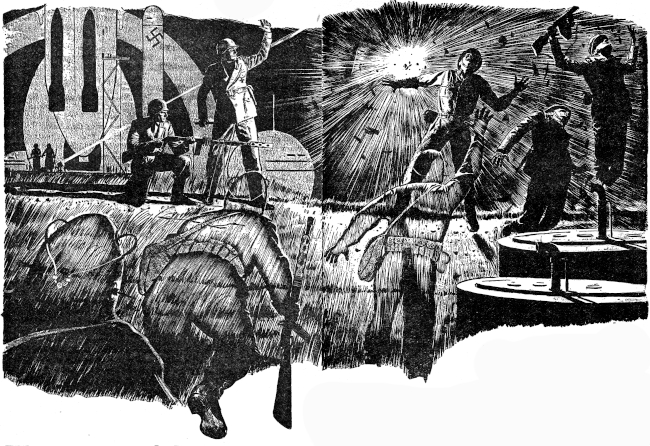

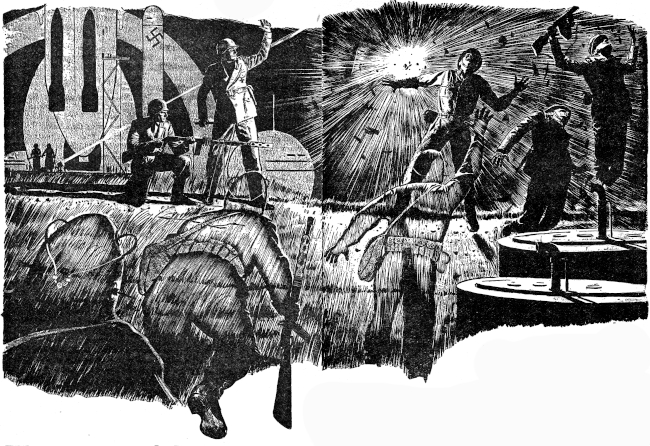

They rose and charged toward the space ship.

Kane's fingers had been busy fusing a bomb, and as he rose erect he threw it straight into the cordon. The crash of the explosion was followed by shrieks and then, as the lights flashed on again, by a prolonged volley of shots.

Larrabie sprung around in midstride and rolled on the ground. The long-legged Clark flung out his arm and pitched forward. "Get the—" His voice choked off.

The survivors charged at the gap where the bomb had wrought bloody havoc. The Germans were closing it from the sides. Manning caught a glimpse of sweating faces, staring eyes glazed with fear of an enemy they could not see; and he saw also the vast loom of the space ship above him. He fumbled woodenly with a detonator cartridge.