“Bow-legged runt, eh? And my Skewball pony’s a crow-bait, eh? And I’m too —— small for a growed-up man tuh tackle, am I?”

Each grunting, panting question was punctuated by a stinging slap. Shorty Carroway’s breath came in gasps from between a pair of bruised, bleeding lips.

His weight resting on the heaving chest of the big man under him, knees jammed into the bulging muscles of that beaten man’s forearms, Shorty’s full-swung slaps jolted the swollen, battered face. Then the little cowpuncher’s hand gripped the shock of hair and raised the big head from the sawdust-covered floor.

“Got a plenty?”

Shorty shifted his weight to one side and a sharp-roweled, long-shanked spur raked the ribs beneath the big man’s heavy mackinaw. He grinned mirthlessly into the bloodshot eyes of the heavyweight champion of the Little Rockies.

“Yuh made a crack a few minutes ago that you was the toughest gent in Montana,” grunted Shorty. “Yuh took in too much range, yuh sway-backed, muscle-bound, stove-up ox. Well I’m from Arizona, sabe? And down there, we got cripples that kin lay aside their crutches and whup you. Yuh picked on me because I’m kinda small and a stranger, and yuh grabbed yorese’f a handful uh hornets, didn’t yuh? Got a plenty, —— yuh?”

Another slap sent the miner’s head back into the sawdust.

Tad Ladd, partner of the fighting cowpuncher, paced up and down before a crowd of miners and cowpunchers who crowded backward behind the battered pool table and abandoned faro layout.

“That’s my li’l’ ol’ runt of a pardner, yonder,” he taunted the surly crowd. “My danged li’l ol’ bench-legged pard. Watch him, hombres! Watch him clost while yuh see yore Alder Gulch champeen git his needin’s. Got ary more sledge-swingin’, snuff-eatin’, loud-mouthed fightin’ men that wants tuh git worked down to Shorty’s size and whupped by a gent that does it scientific? Got ary more nasty remarks tuh make about the ponies that me and my pardner rides? Got ary——”

“What the —— goes on in here?”

The voice came from the doorway in no uncertain tones. A gray mustached, white-haired man of stocky build stepped through the swinging doors. To the lapel of his open vest was pinned a sheriff’s badge. A blue-barreled .45 covered Tad.

Behind the sheriff stood a mottle-faced, white-aproned man in shirt sleeves. The man’s clothes were torn and dust-covered. His pudgy hands and mottled face were covered with small cuts.

Tad shoved his gun back into the waistband of his faded overalls. He grinned pleasantly at the sheriff, nodded, then his grin widened as he looked at the portly man in the discolored apron.

“So yo’re back, eh?” he said pleasantly. “Jest like a danged jack-in-the-box. I pitch yuh out the window and yuh come back through the door.”

Tad turned to Shorty, who, heedless of the interruption, was lending an attentive ear to the pleadings of the whipped miner.

“Let up on the big rock-buster, Shorty,” he called. “John Law has done took chips in the game.”

Tad’s words had much the same effect as a bucket of ice water thrown on a couple of fighting dogs. Shorty got to his feet, felt of a discolored and partially closed eye, and reached for papers and tobacco. He grinned uneasily into the cold-blue eyes of the sheriff.

“Hand me my gun, Taddie,” he said, his breath coming in labored gasps. “We’d jest as well be moving along, I reckon.”

But the sheriff blocked the exit.

“I’m takin’ charge uh the shootin’ irons,” he said sternly. “Ante, big ’un. Butts first. Thanks.”

He shoved the tendered weapons into his waistband.

“Will you two come peaceable er do I put the ’cuffs on yuh?”

“Yuh mean we’re arrested?” gasped Shorty.

“Yuh don’t think fer a minute that you trouble hunters kin come into my town, bust out windows and raise —— in general, and not see the inside uh my jail, do yuh?”

Shorty turned a sorrowful gaze on his big partner.

“Kin yuh beat it, Tad? Kin yuh ever tie it? Looks like it’s ag’in the law tuh trim down oxes like that bohunk settin’ yonder, a-feelin’ his sore spots. Down home there’s a bounty on ’em.”

“But we’re a long ways from home, runt. And as the sayin’ goes, we has fell among strangers. Montana ain’t Arizona and our footin’ ain’t so —— solid as she might be.”

“But dang it all, Sheriff,” pleaded Shorty, “the low-down skunk was blackguardin’ my Skewball pony. The best hoss, barrin’ none, that ever packed a cow hand. Yuh seen him outside? Bald-faced black with stockin’ legs? The fastest cow pony north uh —— is Skewball, and I ain’t aimin’ tuh have no quartz-clawin’ pick-rassler hoo-rawin’ me regardin’ him! I’ll gouge his eyes outa him an’——”

Tad’s restraining hand kept Shorty from renewing the fight. The crowd surged forward angrily.

“Easy, runt,” cautioned Tad. “Yuh won yore fight. We’re plumb overmatched.”

“Why the —— don’t you take ’em to the hoosegow?” whined the white-aproned saloon man. “They’ll be gettin’ away if yuh ain’t careful.”

“I reckon not,” said the sheriff. “I got their guns.”

“Yo’re plumb welcome to the smoke-poles, Sheriff,” grinned Tad. “Neither uh the durned things is loaded. Like our pockets, our guns is empty, as the sayin’ goes. Likewise, our bellies. I hope yuh feeds yore pris’ners. We ain’t et since day afore yesterday.”

The sheriff gave the pair an odd look, then herded them outside. They almost collided with an extremely tall, black-clad man who stood on the sidewalk. The man had evidently been taking in the scene from outside. His height permitted him to see over the short, swinging doors into the saloon.

The long-tailed black coat, white shirt and black string tie gave the tall man the appearance of a minister. The man’s face, however, belied such a worthy calling. Lean, thin-lipped, unsmiling, it was a face without a single redeeming feature. His eyes were small, a pale gray in color, set close together on each side of a thin beak of a nose.

A wide-brimmed, weather-worn black Stetson covered the head that Tad felt sure must be bald. The man’s reddish eyebrows met in a scowl as he met the cowpuncher’s frankly curious gaze.

“I bet he’s a cross between a buzzard and a rawhide rope,” said Shorty as the sheriff shoved them along.

“One uh these here fire an’ brimstone sky pilots gone wrong, is my bet. Which of us wins, Sheriff?” added Tad.

“Neither.” The sheriff’s tone was sharp with annoyance. “You shore cooked yore goose with them bright remarks. Yuh’ll git the limit now when yore trial comes up. That was Luther Fox.”

“And who,” inquired the punchers in unison, “is Luther Fox?”

“Yuh mean tuh say yuh never heerd tell uh Fox?”

“We’re plumb strangers, mister. Let’s have it. Both barrels.”

“He couldn’t help hearin’ them remarks,” mumbled the sheriff, musing aloud. “Hmmm. ——’s tuh pay all around.”

“But you was goin’ to tell us about this Fox,” hinted Tad.

“Was I? I reckon not. I don’t talk to nobody about that gent.”

The sheriff’s tone was decisive.

Tad, glancing covertly at the old sheriff, caught a glimpse of tightly clamped jaws. Beneath shaggy white brows, the sheriff’s keen eyes smoldered with some inner fire. It was a dogged, sullen look, strangely out of keeping with the general make up of the grizzled law officer.

“Yuh don’t mean tuh say that ole scarecrow has yuh buffaloed?” put in Shorty, wincing as Tad’s spur raked his shin with meaning vigor.

The sheriff turned on Shorty, eyes ablaze with hot resentment.

“Who said I was scared? Whoever told yuh that, lied. Lied, hear me?”

The sheriff fairly trembled with fury. He seemed about to hit Shorty with the .45 in his hand.

Tad, poised easily on the balls of his feet, clenched his big fist and his practised eye picked the point where the well-placed blow would put the sheriff to sleep. There was a look of resignation in the big puncher’s eyes.

Then the sheriff, with an effort, regained control of himself and turned from Shorty. Tad gave a sigh of relief. Striking an officer, even in defense of his partner, was little to his liking.

The trio moved on in silence for some moments. Tad, meeting Shorty’s eyes, gave his little partner a ferocious look. Shorty squirmed uneasily.

“I’m askin’ yore pardon, Sheriff,” he said meekly. “I was jest tryin’ tuh be funny. It was a fool crack to make and I’m plumb sorry.”

His tone was sincere. The sheriff nodded his silent acceptance of the apology.

“I reckon it’s shore gally uh me tuh be askin’ ary favors, Sheriff,” Shorty put in as they halted before the padlocked door of the log jail, “but would yuh kinda look after our hosses while me and Tad is penned up?”

“Uh course,” agreed the sheriff. “Yore hosses will be took care of. Yuh won’t be needin’ ’em where yo’re goin’. Better sell ’em tuh git lawyer money.”

“Is it goin’ tuh be that bad?” asked Tad seriously.

“Wuss,” came the cryptic reply, and the two prisoners heard the click of the padlock as the sheriff locked them in.

In dejected silence, the two listened to the receding tinkle of the sheriff’s spurs.

“Well, my short-complected amigo, yuh shore done us proud this day,” Tad broke the silence. “You and that hair-trigger temper uh yourn kin shore git us into more trouble than ten judges and a herd uh law sharps kin git us outa. Yuh mighta put off the show till after we’d grazed some. I’m ga’ant as a dogie in the spring follerin’ a hard winter.”

“And if I hadn’t took it up when that box-ankled shovel swinger insulted us, we’d uh bin run outa town for a coupla uh sheepherders. You was doin’ a heap uh yellin’ and so on, fer a gent that hates fightin’. It was you that busted that purty, shiny window by th’owin’ that drink mixer through it. Yuh mighta slung him out the door, jest as easy, but no, yuh had tuh go bustin’ things. That glass’ll set us back the price of ten good drunks and a reasonable fine. Got ary terbaccer tuh go with this here brown paper, Ox?”

Tad handed over a thin sack with a pinch of tobacco in the bottom.

“Gimme butts on ’er, runt. It’s the tailin’s uh the last sack uh what was once a full caddy uh smokin. Fer which yo’re still owin’ me for yore half uh the price. Say, what ails that sheriff, I wonder? He like tuh busted a ham-string when yuh joshed him about that Fox feller. Shorty, there’s somethin’ danged queer about the whole deal. Raisin’ a li’l’ ol’ ruckus in yonder saloon ain’t no penitentiary offense. The way that ol’ sheriff took on, a man’d thought we’d killed a few folks. Is them bars yonder solid?”

“Solid as rocks, Tad. Even if they was loose, we bin on short grazin’ so long that we’re too weak to pry ’em loose. If the paint hoss hadn’t got drowned crossin’ the Missouri and our beds and grub got lost, we’d uh bin to the Wyomin’ line by now.”

“And if you and that overworked temper uh yourn hadn’t broke out and run hog wild yesterday, we’d uh got a square meal and a job with that outfit we struck at noon.”

“Work fer that spread after that black-muzzled wagon-boss asked me was I expectin’ boy’s wages and could I hold down a hoss wrangler’s job! I wisht yuh had let me finish workin’ that smart Aleck over, Ox. I was jest gettin’ my second wind when yuh drug me off him.”

“Say!”

“Huh?” Shorty, startled by the vehemence of his partner’s exclamation, turned from his inspection of the bars across the one window. “What bit yuh?”

“I was jest rememberin’ that black-whiskered gent’s talk. Yuh mind, Shorty? He says to us that Luther Fox don’t pay out good money to undersized gents that can’t do a man’s work.”

“Man’s work! I showed him what a man——”

“Dry up. Fergit it. Yuh don’t foller my meanin’. Luther Fox must own that cow outfit that Black Whiskers works for. Sabe?”

“Uh-huh. And supposin’ he does? What of it? Go on from there, big ’un, and let’s see if yore words makes sense.”

“Well, from where I was settin’, that round-up looked like a big spread. They was holdin’ a herd that a man couldn’t shoot across. Looked like three hundred head uh hosses in their remuda. If this Fox feller owns that outfit, he’s one danged big cowman, and son, we shore set into a hard game if we’ve hurt the ol’ rannyhan’s feelin’s. I don’t like the lay uh the land, Shorty; None whatsomever.

“If that ol’ wolf sets his mind to it, our hides’ll be hangin’ on the fence afore mornin’. Yeah. And if him and his black-muzzled wagon boss ever gits tuh makin’ medicine and the black gent ’lows we’re the same parties that rode into his camp and raised a ruckus, me and you is due tuh stretch some rope.”

“That big bohunk of a quartz wrangler’ll be rearin’ tuh work in the lead uh sech a necktie party, too,” was Shorty’s wry comment. “What’ll we do, Taddie? Shucks, I hates tuh stay bogged down here till they come tuh hang us. I don’t have no —— of a lot uh confidence in that ol’ sheriff feller, if it comes to a fight.”

“Yuh might uh done some heavy thinkin’ along them lines afore yuh got us into all this, yuh fire-swallerin’ li’l’ ol’ rooster. Now gimme butts on that smoke so’s I kin smudge some thoughts outa my brain.”

Shorty’s voice, loud and high pitched, filled the small cabin. For once, Tad found no fault with his partner’s singing. This, because the sound of the singer’s voice drowned out what noise Tad might be making as he whittled doggedly at the pine log wherein the iron bars of the window were embedded.

Shorty, eyes fixed on the heavy pine door, sang with the air of one who does his duty in the face of great obstacles. Without missing a note, he gathered in a handful of whittlings and shoved the shavings under his hat, which lay on the floor. Then his toe poked Tad’s shin with none too gentle contact and the whittling ceased. Shorty, resuming his seat on the edge of the bunk, sang on, head tilted upward, eyes half closed.

Thus the sheriff found them when he entered, bearing a heavily laden tray.

They looked innocent enough, these two. Shorty, reclining on the bunk, Tad gazing broodingly out between the rusty bars in an attitude of silent dejection.

“Ten o’clock breakfast, Taddie.” Shorty thus broke off his song. “Come and git it er I th’ow it away! Gosh a’mighty, Tad, it’s real grub! Steak and ’taters and pie! Sheriff, yo’re a plumb white man!”

The sheriff grinned and set the tray on the table. The grin gave the old officer an almost benign appearance.

“Have at it cowboys, afore she gits cold. It’s the best I could rustle at the Chink’s place. Yuh earned it, both uh yuh. My hat’s off tuh ary two gents that kin clean up Alder Gulch on empty bellies and with empty guns.”

“Yuh ain’t holdin’ no hard feelin’s?”

“Not me. Joe Kipp ain’t that kind. Personal, it done me good tuh see that big miner whupped. That —— bartender had it comin’ too.”

“Gosh!”

Tad swallowed a mouthful of food, washed it down with a swallow of coffee and eyed the sheriff in mild surprise.

“’Pears tuh me like you’d had a sudden change uh mind, Sheriff. Yuh acted plumb ringy when yuh nabbed us.”

“Folks was watchin’. The bartender had swore out a complaint and with Fox a-watchin’, I had tuh go through.”

“Yuh mean this Luther Fox gent is after yore taw? He’s rearin’ tuh jump yore frame?”

“Somethin’ like that. Him and me don’t waste no soft-spoke love words on one another.”

He paused, scowling at the floor as if worrying out some problem.

“There’s more than a few gents on this range that’ll tell yuh I’m scared uh Luther Fox and ‘Black Jack’,” he finished.

“Black Jack?”

“Fox’s wagon boss. Runs the LF spread.”

Tad and Shorty exchanged grins. “Black-whiskered gent? Eyes like a Injun?”

Kipp nodded.

“You boys know him?”

“We come by the LF round-up. Yeah, we know him tuh look at.”

“Ain’t yuh the boys from the south?” inquired Kipp. “I see yuh both ride double-rigged saddles and yore hosses pack strange brands.”

“We’re from Texas fust, Arizona after barb wire run us outa our home range. We come tuh Montana tuh close a deal that was hangin’ fire. Wound up our deal and was headin’ fer our home range when we loses our life’s gatherin’s in yore Missouri River. Pack hoss, bed, money, grub, the hull works goes. Shorty’s paint hoss which we’re packin’ makes a shore game fight, but ’twan’t no go. The undercurrent ketches him and he goes under and don’t come up no more.

“I’d uh gone the same way only fer Shorty. Yuh see, me’n my yaller hammer hoss bein’ brung up in a windmill country, we ain’t neither of us used tuh water in sech big doses. Mebbeso I got Yaller’s cinch too tight er he gits water in his ears er suthin’. Anyways, he goes belly-up in the middle uh the crick and fer a spell it looks like me’n him’s a-headin’ fast fer the Big Range.

“I’m a thinkin’ along them lines, as the feller says, when Shorty on his Skewball pony, bustin’ that water like a side gougin’ steamboat, jest nacherally ropes me, takes his winds and yanks me ashore. Yaller drifts to a sand bar and wades out while Shorty bails the mud and water outa me. Drunk er sober, my Shorty pard ain’t much tuh look at, but there’s times when he shows good p’ints.”

“Shucks, Sheriff, don’t pay no mind tuh Tad,” grinned the self-concious Shorty. “He shore likes the sound uh his own voice. If yuh was tuh th’ow him and mouth him, yuh’d find his front teeth plumb wore down. That comes from his havin’ his mouth open fer talkin’ so much. The wind, a-blowin’ to and fro across his teeth, consequential, has wore ’em down.”

The sheriff was beginning to like these two oddly mated partners thoroughly. He moved across the floor to a chair. As he did so, he accidentally moved Shorty’s hat, revealing the pile of whittlings. Shorty manfully stepped into the breach.

Before the sheriff noticed, the little puncher had grabbed the handful of shavings and shoved them into his mouth.

“Now swaller,” whispered Tad in an undertone, as he dropped his neckscarf on the sill to cover the freshly whittled notch at the base of the steel bar.

Shorty swallowed, choked, gasped and his tanned face grew purple.

Tad, moving swiftly, promptly up-ended Shorty, thumping him on the back with an unconcern that hinted of boredom. A wad of mashed potatoes, well wadded with shavings, spewed forth and Tad promptly kicked the sodden mass under the bunk.

“Will yuh hand me the water pitcher, Sheriff? Thanks. Now irrigate, runt.”

He held the pitcher to Shorty’s mouth and poured a generous potion down the little puncher’s throat. Then, with a paternal air, he sat Shorty on the edge of the bunk and loosened his collar.

“Ain’t I told yuh, time and again, not tuh swaller yore grub whole, little ’un? Dang me if I can see how yuh ever growed up without chokin’ tuh death.”

Tad turned to the sheriff with an apologetic grin.

“In spite uh all I tell him, that li’l’ varmint will wolf his grub. It ain’t the fust time he’s choked down on me thataway. Onct, at a ice-cream sociable down on the Gila, a brockle-faced school marm, a-ketch-in’ him off his guard with a face full uh cake, ast him was his hair nacherally curly afore it slipped and left him bald between the horns. I’m out in the kitchen when the play comes up and he like tuh perished complete afore I gits there. The fiddler, a-thinkin’ the li’l’ cuss had th’owed a fit, empties a pailful uh pink lemonade on him. I tips him upside down, knocks the hunk uh cake loose from where it’s lodged between his buck teeth and his briskit, and the show is over. We spends a good half-hour huntin’ the loose change which drops outa his pocket durin’ the proceedin’s. I bin thinkin’ serious uh knockin’ his teeth out so’s he’d have tuh graze on mush and sech light truck.”

“Aw, let a man be, Ox,” grinned Shorty, buttering his fourth biscuit. “If yuh gotta run off at the head, tell about the time that Hash-Knife hoss crow hopped with yuh and yore set uh store teeth swapped ends and like tuh bit yore tongue off. Only for the hoss a-pilin’ yuh into the sourdough pan, you’d uh gone through life without a tongue. Yuh mind, Taddie, how that kettle-paunched ol’ cook run yuh outa camp fer sp’ilin’ his batch uh bread dough? He’d uh whittled yuh down tuh his size and whupped yuh, too, only I tripped him up. There’s times when I wisht I’d let that ol’ grub sp’iler ketch yuh.”

A shadow passed the window. The grin on Kipp’s face vanished.

“Here comes Fox,” he whispered. “Play yore cards keerful, boys. Yuh whupped the best man he has in camp, Shorty. And he’s done heard how Tad stood off his gang uh tough men with a empty gun. Down in that black heart uh hisn, he respects nerve like yourn. He may put yuh some kind of a proposition. Better consider keerful afore yuh turn it down.

“He’s got yuh in a tight. He owns that saloon and the busted window. Fact is, he owns the camp. Reckon I’d better let him in now. He’s poundin’ out yonder fit tuh bust the door down.”

With a faint, uneasy smile, Kipp rose and unbolted the heavy door.

Luther Fox entered with one long stride. His gimlet eyes were fixed on the remains of the prisoner’s sumptuous dinner.

“Fancy victuals that you give your prisoners, Kipp,” he spoke in a rasping, flat voice. “County payin’ for such grub?” Kipp’s eyes took on a chilly look.

“I paid the chink outa my own pocket, Fox.”

Luther Fox’s thin lips twitched at the corners. It may have been meant for a smile. Devoid of mirth, it seemed to accentuate the cruelty that lurked behind the pale-gray eyes.

“I want that I should be left alone with these two men, Kipp. Clear out.”

It was the command of a man who was accustomed to being obeyed.

Tad, watching Kipp closely, saw the sheriff’s mouth tighten so as to leave the lips a bloodless, crooked line. For a long moment the officer and the cow man held each other’s gaze.

“Fox,” said Kipp, measuring his words with deliberate slowness, “I’m sheriff here. This jail is county property. I leave here when I get —— ready. If yo’re aimin’ tuh smell powder smoke, go fer yore gun.”

Fox’s upper lip lifted, revealing long, crooked, yellow teeth. They made the man hideous. His long fingers patted the butt of an ivory-handled .45 that swung in a tied holster, low down on his thigh.

“Whenever I pull my gun, Kipp, this county will be in line for a new sheriff. However, it’s bad luck to kill an officer of the law. Our quarrel will keep without spoilin’. I’ll word my wishes differently. I’d like a few minutes pow-wow with your prisoners, Sheriff Kipp. Will you be so kind as to grant so great a favor?”

His long frame bent at the waistline in a mocking bow. Rumor had it that Luther Fox, in his youth, had been a New England schoolmaster. Like rust corroding a steel blade, frontier contact had well nigh obliterated the polish that belonged to that former life. Occasionally it was visible, usually in the form of sarcasm.

Kipp, with a visible effort, fought down the hot rage that surged up inside him. He turned on his heel and walked to the door. Without a backward glance he closed the door behind him.

Inside the jail, Tad and Shorty looked up with curious gaze at Fox and waited for him to break the silence that followed Kipp’s departure. Fox’s lips were again twitching at the corners. Otherwise, his expression did not change.

“Well, what have you two got to say for yourselves?” he asked finally.

Long legs far apart, bony fingers twisting in a knot behind his back, he glanced coldly at the two punchers.

“It don’t look to me like it was our ante,” Tad grinned easily. “The sheriff tells us yo’re holdin’ the joker.”

“Exactly. The way the play stands, I can either make or break you two.”

He paused.

“Spread yore cards, mister.”

Tad forestalled the silence that Fox had anticipated, a silence during which he had expected to watch these two cow punchers squirm.

A frown of annoyance brought his reddish brows together. He had rather expected to find the prisoners afraid and eager to please him. Instead, both were grinning as if they enjoyed the situation.

“Very well,” he snapped. “I give you your choice. Either you go to the penitentiary or on the LF payroll.”

“Penitentiary?” said Tad slowly. “Since when has it got tuh be a penitentiary offense tuh mix in a two-bit saloon fight?”

“Assault with a deadly weapon means a stretch in the big house,” smiled Fox. “Crossing Luther Fox, you may find, is even a worse crime.”

“Yuh mean you’ll railroad us, eh?” said Tad evenly. He seemed to be musing aloud. “Yeah, I reckon yuh could. Me’n my li’l’ pard is strangers in a strange land and plumb broke. Yeah, reckon yuh could do it, mister. Now supposin’ we take yuh up on the other proposition? Jest what kind uh work do yuh aim that me and Shorty should do tuh earn our pay? I might as well tell yuh now, Fox, our guns ain’t fer hire, if that’s yore game.”

“The job I have in mind for you two is legitimate and within the law,” said Fox. “A rancher named Hank Basset owes me money. I hold his note for ten thousand dollars which falls due next week. It will be your job to ride to his ranch and collect that ten thousand dollars, in cash or steers. Since the man is broke, the payment will be made by turning over to me five hundred head of steers at twenty dollars per head.”

“Mighty cheap cattle,” grunted Shorty. Fox shrugged.

“Mebbeso. That’s beside the question. I am waiting for your answer and it ain’t healthy, as a rule, to keep Luther Fox waiting.”

Fox fished a long stogie from his pocket, repaired its broken wrapper with a cigaret paper and set fire to it. His little eyes surveyed them through the haze of blue smoke. Tad turned to Shorty.

“Supposin’ we leave it to the sheriff to decide fer us, pardner?”

“Suits me, Tad.”

Luther Fox’s eyes became pin-points of glittering gray through the smoke haze. His head thrust forward on a skinny neck, he peered at the two punchers. A sinister, hate-lined face, unchanging in expression. Behind his back, the long, bony fingers intertwined until the joints cracked.

“—— old buzzard,” was Shorty’s inward comment.

Without a word, Fox turned and strode to the door. He swung it open and shoved his head outside.

“Come in here, Kipp,” he snapped. “You’re wanted.”

Kipp, a stub of cigaret sticking from the corner of his mouth, rose from his squatting posture against the log wall of the jail.

“Fox wants me’n Shorty tuh collect a bad debt from a gent named Hank Basset,” said Tad, coming to the point. “We ’lowed we’d leave it up tuh you.”

Kipp nodded.

“Kinda figgered he might pick you boys fer the job. Take him up on it.”

“We’re obliged to yuh, Sheriff,” grinned Tad. “Mister Fox, yuh done hired two hands.”

Again the twitching at the corners of Luther Fox’s thin lips.

“Get your guns from Kipp and pull out. I heard your six-shooters were empty. You’ll find ammunition a-plenty in your saddle pockets. Likewise a Winchester apiece, in your saddle scabbards. Here’s an order on Basset for the steers.”

He held out a folded paper. Tad shoved it in his vest pocket. Fox turned to the sheriff.

“Kipp, these two men are now on my payroll. The charges against them are dropped. Give ’em their guns and let ’em go. They’re wasting LF time here and they have a long ride ahead. If you have any message for Hank Basset, carry it yourself, understand? My men are paid to carry out my orders, not to deliver your messages. I think, Kipp, that you savvy what I’m driving at, even if these men don’t.”

“I savvy, Fox,” returned the sheriff evenly, as he handed Tad and Shorty their guns. He ushered them outside.

“Boys,” he said, ignoring Fox, “I loaded both yore guns. Five shells in each six-gun, leavin’ a empty chamber under the hammers. When yuh ride away from Alder Gulch, jest remember this; them is good, honest ca’tridges, bought with clean, honest money. So-long and good luck.”

Kipp nodded a brief farewell and reentering the jail, swung the door closed behind him.

Tad and Shorty gave each other a puzzled look, then followed the scowling Fox toward the livery barn.

In the corral adjoining the barn were their private horses, saddled. Also six more horses and a pack mule, the latter bearing a bed covered by a new tarpaulin.

“That gives you three mounts apiece beside your privates,” Fox explained. “You’ll help Basset gather those steers. Use your own judgment about any difficulties that come up, the same as any regular ‘rep’ would do. One week from tomorrow, I’ll meet you at the lone cottonwood on Rock Creek and receive the cattle. I don’t want either of you to forget that you’re drawin’ LF pay, and top wages at that. You’ll govern yourselves accordingly.”

“Uh-huh,” grinned Tad. “Top wages, Fox, but not fightin’ wages. Me and my pardner is peaceful fellers lessen we gits tromped on. We don’t travel none on our shapes ner lead-slingin’ qualities. We ain’t wanted no place fer no crime and we don’t figger on leavin’ this country with a posse follerin’ us. We’ll gather them steers, but we won’t fight none tuh hold ’em. I bin punchin’ cows long enough tuh know that there’s a nigger in the woodpile somewheres on this deal er you’d either gather them steers yorese’f er send some uh yore regular hands tuh do the job. We taken the sheriff’s say-so about hirin’ out and we’ll see the play through to the last card, but we ain’t doin’ no dirty jobs fer no man, mister.”

Tad had swung aboard his horse and sat slouched in the saddle, watching Fox.

“Get the cattle and I’ll be satisfied,” replied Fox. “Yonder’s the trail. Basset’s home ranch lays at the foot of that hazy peak. You should make it by daylight tomorrow. Follow this trail till you come to the lone cottonwood, where the trail forks. Take the right hand trail.”

Shorty swung open the pole gate and Tad hazed the horses into the open.

Legs spread far apart, hands clenched behind his back, Luther Fox stood in the dusty trail and watched them out of sight. Once more the corners of his cruel mouth twitched oddly. As he watched the rapidly fading dust cloud that hid the partners, his eyes glittered with a look of cunning.

“I dunno jest why, Tad,” Shorty broke the silence, “but I shore feel sorry fer that Kipp gent. He’s right old tuh be pestered by a skunk like Fox. His nerves ain’t so steady as they once was. I seen his hand shake when he called Fox’s hand. A man can’t do good shootin’ when his hand shakes, Tad.”

“He’d a played his string out though, Shorty. Even when he knowed Fox ’ud beat him to the draw. Kipp’s game, and I reckon that’s why we kinda cottoned to him. Besides, he shore fed us good. I’m wonderin’ what he meant by sayin’ he’d put honest ca’tridges in our guns? Reckon we’re nosin’ into a range war? Danged if we don’t git into more jams than a burglar. Yonder’s the lone cottonwood.”

The sun had just set and the rolling hills were bathed in the subdued afterglow. The greasewood flat beyond took on the appearance of a dark-green carpet. Distant peaks reflected the last rays of the sun. A covey of sage hens whirred from the brush in front of the horses, then dropped out of sight. Tad and Shorty pulled up in front of the giant cottonwood, eyes fixed on a rudely lettered sign nailed to the wide trunk, a sign riddled with bullets.

Warning to LF men. This here tree is my north boundry. The line runs due west to Squaw Butte. Ary Fox man that crosses that line will be huntin’ trouble and he’ll shore find it. HANK BASSET.

Tad waved a hand toward the sign.

“Yonder’s the reason why me and you are picked fer the steer-gatherin’ job, runt. I knowed there was a ace hid up Fox’s sleeve. What do yuh say, pard? Do we turn back from here er go through with it?”

“We done hired out fer the job, Tad. Let’s play our string out. Shucks, I’d hate tuh be bluffed out by ary sign.”

Tad nodded thoughtfully.

“Kipp aimed that we should go through. There’s more to this play than a bad debt, and I’m right curious tuh turn the next page. Haze that hammer-headed, pack-slippin’ mule on to the trail and we’ll git goin’, pardner. I’m rearin’ tuh git a squint at this here Basset hombre, providin’ he ain’t linin’ his sights on my briskit. Likewise, li’l’ ’un, bear this in mind. Don’t go clawin’ fer no gun iffen we gits jumped. Set tight and lemme augur ’em some. We ain’t crossin’ this dead-line tuh burn powder. If it comes to the wust and there’s no other way outa the tight, we takes our own parts like gentlemen. We ain’t huntin’ no trouble and, on the other hand, we ain’t stoppin’ no soft-nosed bullets with our carcasses if we kin keep from it. And git a tail holt on yore ingrowed temper, sabe? The fust sign I reads uh you comin’ to a boil and buckin’ yore cover off, I knocks yuh between the horns. Hear me, runt?”

“Yeah. I hear yuh. Yo’re bellerin’ fit tuh be heard a mile. I ain’t growed deef on this trip. Fer a forty dollar a month cow hand, yuh shore kin git shet of a heap uh advice. I’ll remind yuh about it when yo’re yellin’ fer me tuh pull this Basset feller off yuh. Git along, mule.”

Hours passed and the moon rose. If the future held any fear for these two followers of the dim trails, they gave no sign. Shorty rode in the lead, picking the trail. Sometimes he sang and as the words of the lament drifted back to Tad, the lanky puncher grinned his appreciation and hummed an off-key accompaniment. Now and then they dozed, heads swaying gently with the movements of their horses. Innumerable cigarets were rolled, smoked and the butts pinched out. Thus the night wore on and the first streak of dawn found them halted before a pole gate.

Beyond the gate, lining the near-by creek, were innumerable tall cottonwoods. A thin spiral of smoke lifted from the chimney of a hidden cabin. Twenty feet beyond the gate was a buck-brush thicket. Not a sound broke the quiet of the morning.

Shorty leaned in his saddle to pluck forth the wooden pin that held the gate closed. A moment later he straightened.

“She’s locked with a stay chain and padlock, Tad,” he called softly.

“Reckon we better call out afore we goes further with the game. Haloooooo!”

He raised his voice in a wolf-like howl. Followed a moment of silence. Then, in an ordinary tone of voice that caused both punchers to jump with surprise, a man called from the brush patch:

“Hello yoreself. Jest set where yuh be till we looks yuh over a spell. Keep the little ’un covered with the shotgun, Ma.”

“I’ll make a sieve outa him if he makes ary move, Hank. ’Tend to the big feller. Know either of ’em?”

“Nope. Light’s too dim yet tuh read the brands on their hosses but ain’t that paint hoss the LF hoss we seen in town last week?”

“—— a’mighty, Tad,” groaned Shorty in an uneasy voice. “Start a talkin’ afore we’re killed complete.”

“We’re plum peaceful, mister,” called Tad. “That’s a LF hoss and so is the others, but hold yore fire. We come here tuh——”

“To finish robbin’ honest folks, eh?” snapped a feminine voice that carried the sharp edge of a newly whetted knife. “LF men, eh? Come to do the dirty work of that pole cat, Luther Fox! Gun toters, by the looks of yuh. You seen the sign on the cottonwood?”

“Yes’m, but we ain’t——”

“Shetup! Quit interruptin’ a lady. Hank, watch that big gent, he’s got a mean eye. Dim as the light is, I kin see it. You there, little feller, keep them hands where they belongs. There’s eighteen buckshot in both these barrels and I’m takin’ a rest across this boulder. Come to git them cattle that’s due Fox?”

“Yes’m. But we ain’t cravin’ no trouble ma’am, leastways, not with women-folks. Joe Kipp, the sheriff, ’lowed that we should come.”

“Huh!” snorted the hidden lady. “And what under the sun and seven stars has that old sage hen got to say about it? If Kipp had the gumption of a rabbit, he’d run the hull LF pack outa the country. He’s stood by like a lump on a log and seen a pore ol’ couple git robbed uh their eye teeth, and never once raised a finger to stop it. He don’t dast set foot on the place, he’s that ashamed uh hisself fer——”

“Hush, Ma,” cut in the voice of Hank Basset. “Joe done his best by us. His hands is tied, drat it, the same as ours is. Now, big feller, how come that Joe Kipp ’lowed that you should come here? Don’t try no lyin’ er we turns loose these shotguns. Yuh read the sign on the cottonwood and me’n ma is within’ our rights when we shoots. Git tuh talkin’, dang yuh.”

“Me’n my li’l’ pardner is strangers, Basset, and we ain’t takin’ up no man’s fight fer him. Kipp done told us tuh take Fox up on it, when Fox give us the offer uh the job. We was in jail at the time and the ol’ buzzard was aimin’ tuh cold-deck us into the pen, savvy? It was either take this job er go over the road fer a few years. We ain’t doin’ dirty work fer no man, mister. We’re cow hands, me and Shorty is, not gun-toters. We come here peaceful and we stays thataway, lessen we’re crowded bad.

“If I was a gun man, Basset, and was aimin’ tuh th’ow lead in yore direction, I’d be doin’ it now. That there bush yo’re a squattin’ behind ain’t so thick as she might be. I kin see yuh plain. Yuh’d orter pick a boulder fer shelter.”

A muffled curse and cracking of twigs came from the brush as Hank Basset shifted his position. Tad’s eyes followed the moving brush tops. His ruse had worked. He now knew where the cow man crouched. Shorty grinned his approval at Tad’s clever lying.

“Good guessin’, Taddie. Now shoo that there settin’ hen of a female from her nest and we’ll feel easier,” he whispered. “If it comes to the wust, we gotta run. We can’t noways shoot no female women. I might try a pot shot at Basset.”

“Hush up, runt.” Then, in a louder tone. “I said my say, Basset. She goes as she lays. We ain’t burnin’ no powder here ner elsewhere fer Luther Fox. Yo’re the doctor, sabe? If we’re messin’ into ary range war er such, we’ll go back the way we come, with our guns in the scabards, and leave the job tuh them that wants it. From what I seen of the LF hands, there’s plenty of ’em that’ll take it. There’s our proposition, Basset. Take it er leave it.”

There was a long silence, broken only by whispering between the cow man and his wife. Then the answer came from behind the boulder in the voice of Ma Basset.

“Shed yore guns and light. As long as we gotta be pestered with LF men, it’d as well be you two as them others. Keerful how you handle yore hands while yo’re coming through the fence. Keep to the middle of the wagon road that leads to the house. Hank and me’ll have yuh covered, every step.”

Tad and Shorty exchanged a quick look. Tad nodded briefly.

“Shed the cannon, pard, and we’ll take her up.”

They tossed their guns to the ground, swung from the saddle and approached with their hands in the air. The presence of a woman caused Shorty to blush confusedly, but Tad seemed to rather enjoy the situation. Once through the barbed-wire fence, they kept to the road. A bend in the road brought them in view of the buildings.

The sun was just rising and both cowpunchers gazed in surprise at the scene spread before them. Low walled, log buildings, the sod roofs covered with green grass and wild mustard. Well-built horse corrals, branding shute and branding pen beyond. A well-irrigated alfalfa patch, blooming and ripe for cutting. A small blacksmith shop surrounded by mowers, rakes, and two round-up wagons. Everything neat and orderly, rare indeed, for a cattle ranch.

The ranch house and adjacent bunk house were whitewashed, and climbing the walls were masses of morning glories. Wild rose bushes, pink blossoms wet with the early morning dew, lined the gravel walk that led to the doors. All around were the tall cottonwoods.

“Gosh!” whispered Shorty, and removed his hat.

Tad followed suit. They halted on the threshold of the open door, carefully wiping their feet on the burlap sack mat. Tad sniffed the warm air that came from the kitchen.

From the service-berry brush behind the cowpunchers, stepped the oddly mated couple with their shotguns.

Hank Basset, shorter by six inches and lighter by some eighty pounds than his wife, was clad in faded flannel shirt and freshly laundered, neatly patched overalls. Slightly bent over, tanned the color of an old saddle, a bald patch showing in the center of his silvery hair, he was anything but warlike in appearance. His mild blue eyes twinkled with humor, but there was a look about his straight mouth and square chin that told of hidden determination and a fearless spirit if he were roused.

Ma Basset, red of cheek, her well-combed, abundance of gray hair glistening in the morning sun, was as neat as her rose bushes, and as fresh looking, in her red-and-white checked gingham. Despite the scowl that furrowed her wide brow, there was everything in her make-up to denote a generous, mothering personality. A bit stout, to be sure, but her step was firm and alert and her bare arms were more muscular than fat. A woman of the pioneer stock, ranch born and raised. As much at home in the saddle as in her immaculate kitchen, a fair example of the cattle man’s wife whose courage and sacrifice has played so important a role in the building of the West. Even as her mother before her had fought Indians, so now, did Ma Basset wield her sawed-off shotgun in defense of her home.

Suddenly Tad sprang forward into the open door of the kitchen.

“Coffee’s b’ilin’ over!” he bellowed over his shoulder.

Shorty, left on the threshold, shoved his aching arms higher in the air and gazed with agonized eyes into the twin barrels of Ma Basset’s raised shotgun.

Tad now appeared in the doorway, holding aloft the steaming coffee pot as proof of his good intentions.

“—— a’mighty, yuh big lummox,” groaned Shorty. “Yuh like tuh got me killed.”

There was that in the appearance of the two partners to cause even the stoniest hearted to smile. Shorty, his swollen eye a sickly green, tanned face perspiring and red from suppressed emotion and embarrassment, gazing beseechingly at his partner. Tad, his homely, rough-hewn features wreathed in an infectious grin, holding aloft the huge granite-ware coffee pot.

“Shucks, Hank,” muttered Ma Basset in an undertone of relief, “them two boys ain’t no badmen. Why that pore little feller is nigh scared tuh death. Don’t suppose he ever hurt a livin’ thing in his hull life. My gracious but that big ’un did give me a start when he tore into the house thataway. I was sure certain he was aimin’ to make a fight of it. Lawzee!”

The elderly couple did not relax their vigilance, however, until breakfast was well on its way.

Tad, with his unaffected, loquacious manner, did much to quell suspicion. He insisted on putting on an apron and helping with the breakfast, all the while keeping up an aimless chatter with the lady of the house. More than often he had her chuckling gaily.

Shorty, in the front room with Hank, told a straightforward story of their sojourn in Alder Gulch.

“Yuh mean that you whupped that big miner by yoreself? Why, Fox claims that big hunkie is a ex-prize fighter!”

Shorty shrugged.

“I dunno about that, mister. If he’s a pug, he’s a pore ’un. You’d uh died laffin’ tuh see Tad a-holdin’ off that gang with a empty gun.”

“And you boys ain’t fightin’ fer Luther Fox?”

“Mister,” said Shorty solemnly, “when me and Tad draws our shootin’ irons, we does it because somebody’s crowdin’ us er our friends, bad. We’re aimin’ tuh go back tuh Arizony some day and we got friends down there that we want tuh look square in the eyes, sabe?”

“Breakfast is about ready,” called Ma Basset from the doorway.

Hank and Shorty got to their feet.

“Ma’am,” said Shorty, flushing hotly, “our hosses is outside the fence yonder. My grub ’ud plumb choke me if I was tuh set down to the table afore I’d took care uh my Skewball hoss. Tad, I reckon, feels the same about his Yaller Hammer hoss. He’d ’a’ said so hisse’f only he’s a-tormentin’ me by makin’ me axe yuh, kin we be excused while we ’tends to ’em. The big walloper pesters me continual when there’s women folks around.”

Shorty was the color of an Indian blanket by now. Tad, grinning widely, winked at Hank.

“Tush, son,” smiled Ma Basset. “Now don’t you pay no attention to him. He’d orter be ashamed uh hisself, tormentin’ a boy half his size. You boys hurry on now and tend to yore ponies. The key to the gate hangs on a nail on the gate post. Unsaddle and turn yore hosses into the pasture. There’s blue-joint grass and water a-plenty there. I’ll put the biscuits and eggs in the warmin’ oven. Hurry, now.”

Five minutes later there came the sound of splashing water. Ma Basset, looking out the kitchen window, nodded her approval.

“They’re washin’-up at the bunkhouse, Hank,” she whispered. “Those boys has had raisin’.”

“When a man sets down to his grub afore he’s took care uh his hoss, watch out fer him,” added Hank. “I was a-waitin’ tuh see if they was goin’ tuh let their animals wait. It don’t take no smart gent tuh see that they’re as different from the other LF riders as a gentleman is different from a sheep herder. I bin thinkin’, Ma, mebbe so them two boys kin help us. They’re kinda like home folks, sorter.”

“Help us?”

Ma Basset shoved a second pan of biscuits in the oven and closed the door thoughtfully. Then she straightened.

“Help us, Hank? I’m afeered not. The cattle’s gone, that’s all. They’re good boys, like as not, but they can’t make a herd uh cattle outa a handful uh sore-footed cows and wind-bellied calves. No, we’re beat and beat bad. But we ain’t hollerin’, neither of us. If only our Pete boy was back home, I’d feel as chipper as a meadow lark. But the thought uh him cooped up in a prison cell, kinda takes the warm feelin’ outa the sunshine, somehow.”

Tears glistened in her eyes. She seated herself on a chair and dabbed at the tears with the corner of her apron. Hank crossed over to her and put an arm about her shoulders.

Tad and Shorty had removed their spurs at the bunkhouse. They made but little noise as they came to the door and halted to wipe the dust from their boots. They could not help but see what went on inside the kitchen. Embarrassed, they looked at each other in silence.

“Our Pete sent over the road by that low-down LF spread, our cattle run off and a ten-thousand-dollar note due next week,” came the voice of Hank Basset whose back was toward the cowpunchers. “It’s hard lines fer folks as old as us, Ma. But we ain’t licked yet. I kin still hold down a job punchin’ cows.”

“And I kin beat ary round-up cook that ever burned a batch uh beans er turned a mess wagon over,” added Ma Basset bravely. “Yuh mind that fall when I cooked fer the outfit, Hank, and drove two broncs fer wheelers? I can do it again, too.”

Tad, a vise-like grip on his partner’s arm, backed quietly away from the door. On tiptoe they retreated to the bunkhouse. Then, with careless step and a whistle coming discordantly from Tad’s pursed lips, they again approached the kitchen.

Ma Basset’s eyes showed faint signs of redness and Hank seemed somewhat ill at ease. He led them back into the front room.

“Biscuits ain’t quite done,” he explained, waving the two punchers to chairs.

He moved stealthily to a cupboard and reached a hand in behind the curtain. It came forth holding a brown bottle.

“Ma keeps it fer snake bite,” he whispered. “Have a nip?”

But before he could hand the bottle to the expectant Shorty, an approaching step sounded from the kitchen. Hank deftly slid the bottle back behind the curtain, a second before his wife appeared in the doorway.

In Ma Basset’s hand was a piece of raw beefsteak and a strip of cloth.

“Fer your eye,” she told Shorty, and forthwith tied the piece of meat over the swollen and discolored member.

“Your pardner was a-tellin’ me how you fell off your hoss and bunged that eye up,” she smiled, standing aside to survey the bandage critically.

“Hoss th’owed me?” returned Shorty dazedly. “Shucks, I——”

“Nothin’ to be ashamed of,” she replied. “There ain’t a bronc rider livin’ that ain’t got it some time er another.”

“Never was a rider that never got th’owed,” chanted Tad, trying in vain to catch his partner’s eye. “Never was a bronc that never got rode,” he finished the rime.

But Shorty did not see. Hank was shifting uneasily in his rawhide-bottomed chair. He too, seemed to be trying to convey a silent message of some sort to Shorty.

“But, ma’am, I——”

“Ma, ain’t them biscuits a burnin’?” Hank was sniffing the air like a hound scenting a fox. Ma, her thoughts diverted to the bread, made her way hastily to the kitchen.

Hank’s hand darted to the cupboard and the bottle of whisky came forth once more. This time it went the rounds. Hank replaced the cork and the bottle vanished behind the curtain.

“Now, Ox,” growled Shorty. “How come yuh lied about this here eye?”

“Miz Basset ’lowed that them as mixed up in saloon fights was mighty low-down sorter humans, sabe? Tuh keep yuh from bein’ disgraced, I lied a mite about that black eye that miner hung on yuh.”

“Ma is plumb sot ag’in’ fightin’,” added Hank. “I aimed tuh wise yuh up, but it kinda slipped my mind. Onct, when I gits tangled up in a nice quiet scrap and shows up with a swole-up jaw, Ma kinda quarantined me off and I et, slept and subsisted, as the sayin’ goes, in the blacksmith shop. One uh the boys toted my grub to me. Doggone, she was on the prod. She don’t paw the earth ner beller loud ner bend no rollin’ pins across a man’s withers. No, sir. She jest swells up like a buck Injun, gits proud and haughty and kinda looks a feller over like he was lower than a sheep herder.”

Shorty was not cheered by this bit of news. Ma Basset summoned them to breakfast at this juncture and the little puncher inwardly writhed with the burden of a guilty conscience. Pangs of hunger conquered, however, and he ate as heartily as Tad.

“I ain’t noways aimin’ tuh be hollerin’,” explained old Hank, spraying a sage bush with tobacco juice. “I jest want that you boys should know what kind of a skunk yo’re workin’ fer and how he’s throwed the hooks to me.”

Tad and Shorty, riding on either side of the cattle-man, nodded.

“Two years ago, come July fourth, my son, Pete, gits into a jam over a hoss that Black Jack is abusin’ on the street in Alder Gulch. Black Jack pulls a gun. He’s tanked up on Injun whisky and onery as ——, sabe? He hates the Pete boy anyhow, and comes a rearin’ when Pete tells him tuh quit beatin’ the hoss over the head.

“His bullet ketches Pete in the thigh and Pete limbers up his six-gun as he’s a fallin’. Black Jack goes down with a .45 slug in his gun arm and the fight is over.

“But the Black Jack gent and Luther Fox is playin’ of a deep game and they sets out tuh bust us. They has Pete throwed in jail and tried fer attempt tuh murder. They’s a dozen LF pole cats that swears on the witness stand that Pete starts the fight and shoots fust. Pete, not havin’ ary witness, is railroaded.

“Trials is expensive, boys. Pete’s law sharp bleeds me fer all I kin scrape up. The price uh cattle is lower’n a rattler’s belly and I’m bad crowded tuh git the coin. I borrys ten thousand dollars from the bank and gives my note, never thinkin’ they’d sell the note tuh Luther Fox. I ain’t wise tuh them throat-cuttin’ tricks that’s called good business by some.

“That fall finds me busted and in debt. I’m doin’ business with Fox’s bank, buyin’ grub from Fox’s store and the pore specimens uh cowpunchers that’s workin’ fer me is drawin’ double wages from Fox and stealin’ me blind. Up till then, Pete has bin runnin’ the round-up and takin’ care uh that end. He’s made me and Ma take it easy like, sendin’ us to Californy and Florida fer the winters and a babyin’ us scan’lous thataway. Now we’re throwed up ag’in’ it onct more and we pitches in tuh do our dangdest.

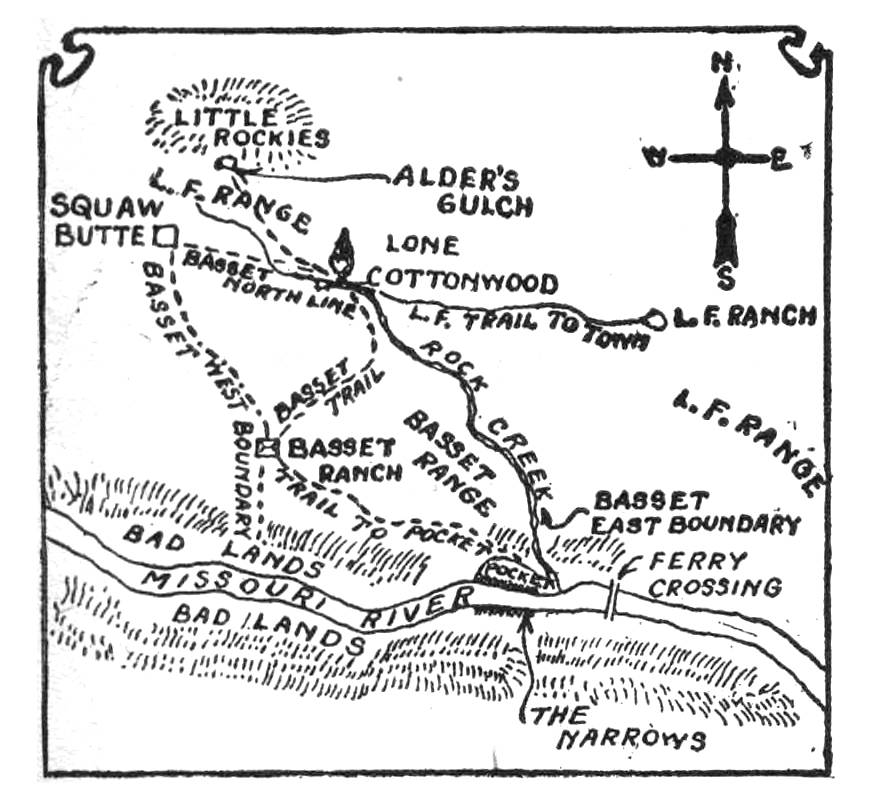

“The day Pete is sentenced to twenty-five years at Deer Lodge, Ma takes the train fer Helena tuh see the governor and I comes back and starts the fall round-up with as sorry a crew as ever rode a good hoss tuh death. My range covers the country between the lone cottonwood and the Missouri River. Some eighty thousand acres and she’s supposed tuh be fair stocked. Gents, it sounds scary when I tell it, and yuh kin believe it er not, but we works that range and we don’t gather five hundred head uh steers. Somebody’s beat us to it, understand, and I’m cleaned out complete!

“I ships the five hundred head which don’t bring no kind of a price, pays off these hoss killers, and gits Joe Kipp tuh help me home with the remuda uh sore-backed hosses. Then me and Joe starts in fer tuh hunt them stolen cattle.

“There’s old sign a plenty and when we cuts the main trail, we splits up and follers it into the bad lands. There’s mebbe so a stretch uh rough, timbered brakes fer fifteen-twenty miles betwixt the open prairie and the river. Timbered some and stood on end fer the most part. I follers a trail along a timbered ridge while Joe takes the main trail which seems tuh twist eastward towards the LF range.

“I’ve rode mebbe so eight-ten miles when my hat gits knocked off and I hears the pop of a 30-30. Some gent has drilled my hat. Over behind some boulders is a puff of white smoke. The range is upwards uh five hundred yards. I picks up my hat, unlimbers ole “meat-in-the-pot” and heads fer Mister Bushwhacker.

“Ping! Off goes my hat onct more and this time the shot comes from the other side, a good four hundred yards away.

Whoever is doin’ that shootin’ is —— good shots. Thinkin’ along them lines, and wonderin’ where the next bullet will hit, I jabs home the spurs and goes a shootin’ towards Mister Polecat behind the boulders.

“Wham! A Winchester barks and my hoss piles up, shot between the eyes. I takes my stand behind his carcass and throws some lead in the direction uh the brush patch where I sees the white smoke fadin’ away. When my gun is empty, I commences shovin’ fresh shells in the magazine. Then —— busts loose. Seems like a army is bombardin’ me. But every danged bullet is goin’ about a foot high. Sudden like, the shootin’ quits.

“Got a plenty?” calls a stranger voice. “We bin foolin’ up to now. The next shootin’ we does will be the real article. Git on yore laigs and hit fer home.”

“I feels the wind of a steel-jacket bullet as she misses my nose by about a inch. Mad? I was b’ilin’, gents. Only fer leavin Ma a widder, I’d uh stayed till they got me. But het up as I was, I sees how plumb useless it is tuh make a fight, so I drags it.

“At the edge uh the bad lands, where we’d split up, I finds Joe Kipp. He’s kinda white and shaky like, and he’s afoot, the same as me. The drawed look around his mouth and the way his eyes looks at me, makes me feel plumb sorry fer him. He’s takin’ it wuss than I am.

“‘They shot yor hoss and made a danged target outa yuh, Joe?’ I asks, not knowin’ how else tuh ease his feelin’s.

“‘Hank,’ says he, solemn like and earnest as ——, ‘I wish tuh —— they’d uh killed me, instead uh wingin’ me, like they did.’

“And he shows me his gun arm, busted between the shoulder and elbow by a soft-nosed bullet. I ties up the arm the best I kin and we commences that thirty-mile walk home. Ol’ Joe never whimpered onct durin’ that night’s walk, though I knowed he was sufferin’ bad. Ner did he do ary talkin’. Up till then he’d bin right hopeful about gittin’ them stolen cattle back. But bein’ set afoot and sech musta drug it outa him bad, fer he ain’t never bin the same man since.

“There’s them that claims he’s scared uh Fox, and sometimes it shore looks like they done read the sign right. Me, I don’t know. Seems like, if he was scared uh Fox, that he’d throw up his tail and quit. But he still holds the job down. Some day, I look fer him tuh kill Fox er git killed a-tryin’.”

“Didn’t yuh never make no more fight tuh find them cattle?” asked Tad after some silence.

“Kipp done went down into the hills two-three times. Each time he went there, he come back afoot, lookin’ like he’d seen a ghost. And somewhere in his hide ’ud be a bullet hole. Not bad, jest a kinda souvenir uh the occasion, as the feller says.

“Onct, I gathers me a posse uh cow-men from around the county and we slips into the brakes after night. Injuns couldn’t uh done it more quiet. We’d gone mebbe so five-six miles and was goin’ single file down a steep trail that led into a canyon. Sudden like, fifty feet ahead uh my hoss—I’m in the lead, sabe?—a match sputters. Before I kin unlimber my cannon, a heap uh brush blazes up. There we are, square in the light uh the blaze, the trail too narrer tuh turn around, with a dead drop uh two hundred feet on one side and a shale cliff on the other. On the trail behind us, afore we gits our senses good, another brush pile busts into flame.”

“‘Do you idjits turn back from here er does we start a shootin’?’ bellers a gent from the dark up above.

“It don’t take no more’n a half-witted sheep herder tuh decide which to do. We tells this gent that we’re turnin’ back.

“‘Fifty feet down the trail,’ says he, ‘the trail widens. When the front fire goes out, ride over it to that place and turn. Ary man that passes that wide point, gits a free ticket tuh ——. Us boys is holed up here fer a spell and we ain’t cravin’ no visitors. The next man that rides into these brakes, don’t see his happy home no more.’”

“That ended it, eh?” inquired Tad.

Hank nodded.

“I ain’t never bin back there. What’s the use? They got the bulge in that country. They kin set on a pinnacle and see every rider between the brakes and my place, if they got ary fieldglasses, which they likely has. The only way tuh git into the hills is along them trails and every danged trail is watched. Them cattle is like so many flies in a bottle and Fox’s hand over the mouth tuh keep ’em in. The same crew uh gun fighters that keeps folks from goin’ into the hills, keeps the cattle from driftin’ out.”

“Hmm,” mused Tad aloud. “Regular hole-in-the wall proposition, ain’t it? Yeah. How many trails leadin’ into that section, Hank?”

“Two,” came the prompt reply. ‘It’s a kinda pocket, widening out beyond where the brakes meets the bottom lands.”

“Trails along the river bottoms, ain’t there?”

“Nary trail ’ceptin’ late in the fall when the water’s low. It’s what they call the Narrows. Except fer where trails has bin cut out, a man can’t water his saddle hoss along the riverbank fer ten miles. Thirty and forty foot banks, sabe? And at each end uh the ten-mile stretch is a gorge cut out by spring rains and the cricks, which is so full uh quicksand that they’d bog a jacksnipe. A danged pocket, I tell yuh, a danged, gyp-water, soap-hole, shale-banked pocket. And they’s feed in them cañons tuh winter half the cattle in Montana.”

“Uh-huh. Yet, some way er another, Hank, it don’t sound noways reasonable that a man can’t git in there. Supposin’ that a man was tuh cross the river, say at one uh the ferries, ride back on the opposite bank till he come opposite them Narrers, then swim across to where one uh them trails is cut in the bank?”

Hank laughed mirthlessly. “Can’t be done, pardner. My boy Pete is the only human that ever done it and he crossed when the river was down. Now, at high water, the —— hisself couldn’t make it.”

“Yore Pete done it?” put in Shorty, silent up till now.

Hank smiled reminiscently.

“Pete knowed the river better’n ary human alive. As a kid, he used tuh kinda look after the hosses durin’ the summer. He’d go into the pocket with a pack outfit and stay there till time fer the fall round-up. Long afore I even knowed he could swim, that kid was bustin’ that river wide open, jest fer the fun of it. He like tuh drowned a dozen hosses, learnin’ ’em the channel. I never knowed nobody else that ever swum the Missouri at the Narrows.”

“Got ary uh them water hosses at the ranch, Hank?” Shorty’s eyes were dancing excitedly.

“Shore thing, but even if you was fool enough tuh tackle it, Shorty, the river’s up and boomin’ now and the current swifter’n a blue-racer snake. I wouldn’t let yuh tackle it, boy. ——’s bells, what ’ud yuh do if yuh did git across?”

“Now there’s where yuh got me guessin’,” grinned the little puncher, but that dancing light still flickered in his eyes as they rode on.

“If yo’re figgerin’ on playin’ fish, runt, fergit it,” grunted Tad as he licked the paper of a cigaret.

They rode on in silence for some time, heading back toward the Basset ranch.

“Hank,” Tad broke a lengthy silence, “Did Kipp ever try tuh git help from the Stock Association on this deal?”

“If he did, he never said so ner nothin’ ever come of it. Why?”

“I was jest a-askin’, that’s all,” came the evasive reply. “Jest tryin’ tuh git a squint at the lay from all sides. How long have yuh knowed Kipp?”

“Ever since he come to the country. Lemme see. About eighteen years, near as I kin figger.”

“Where’d he come from?”

“Don’t know as Joe ever said, and I never asked him. Look here, if yo’re figgerin’ that Joe Kipp is mixed up with Fox and ain’t square, yo’re plumb wrong. Joe’s honest, bank on that. I’d bet my last steer on it.”

“Mebbe so yuh done bet ’em already, and lost ’em,” laughed Tad.

Hank smiled bitterly.

“I reckon not, Ladd. Does ol’ Joe look like a crook er a cow thief tuh you?”

“No, Hank. If ever a man had honest eyes, it’s Kipp. A right nice ol’ feller from what me’n Shorty seen uh him. How long has this Fox pole cat bin clutterin’ up the range around here?”

“Three years. He leased and bought all the range he could git holt of and throwed in some dogie stuff from the south. Black Jack come with the cattle. He’s bin after my range ever since he come to these parts, but he never offered nowhere near a fair price. He told me, last time he made me a offer, that it was his top price and if I didn’t take it, he’d bust me. It looks like he’s shore doin’ it, too. Him and that black-whiskered Injun.”

“Is Black Jack a Injun?” asked Tad. “Half-breed, so they claim. Apache, I reckon, by his looks. It wouldn’t surprise me none if he’s a outlaw. If he wasn’t scared uh bein’ recognized, why does he wear them whiskers? I asked Joe but he ’lowed a man couldn’t arrest a man and shave him without havin’ danged good reason, and I reckon he’s right.”

They rode on, each of the three busy with his own thoughts. Ma Basset was waiting for them at the corral. Beside her stood Joe Kipp. Both seemed unusually excited. Ma Basset’s eyes showed signs of weeping.

“God help us and him, Hank!” she cried out as Hank dismounted, “Pete’s escaped the pen!”

“Have they caught him yet?” asked Hank, his lips white with fear.

“He got clean away, Hank,” said Kipp. “I rode over tuh tell yuh.”

If ever a man looked worried, it was Joe Kipp. Every feature of his tanned face was drawn and haggard. His eyes were bloodshot and seared with some tortuous pain. His hands shook so that he spilled the tobacco he was pouring into a brown paper.

“Pete was a sorter trusty at Deer Lodge,” he went on to explain. “He waited till the chance come, then made a clean getaway. He was gone two hours afore they found it out. I got orders tuh watch out fer him, Hank. Yuh see, they figger he’ll be showin’ up around these parts.”

“Look here, Joe Kipp,” said Ma Basset firmly, her eyes still wet, “I don’t intend to sit by with my hands in my lap while you or any other man is gunnin’ fer my Pete. Yo’re a law officer and there’s no way to keep yuh from hangin’ around here, but I’m givin’ yuh warnin’ here and now that no man kin take Pete while I kin hold a gun.”

She turned to her husband.

“Hank, I’m glad the boy’s loose and a breathin’ good clean air again. He ain’t goin’ back if I kin help it. Are you standin’ by yore wife and son er do you line up on the side uh the law that sends innocent boys tuh prison? Are yuh——”

“Hush, Ma, yo’re excited,” interrupted Hank. “Uh course, I’m stayin’ by Pete, right er wrong. But there’s no need tuh——”

Ma Basset sent him a withering glance and whirled on the uncomfortable sheriff.

“If you was as eager tuh git back them stolen cattle as yuh are tuh shoot our Pete boy, we’d not be facin’ poverty in our old age. It’s a wonder tuh me that you got the nerve tuh show yore face on this ranch, Joe Kipp.”

The sheriff winced as if struck. Shoulders sagging, eyes fixed on the ground, he made no reply. Tad and Shorty, unwilling spectators, were heartily wishing themselves elsewhere.

A mother cat will face a dog fifty times her size in defense of her young. Face him without fear. Men call it mother instinct and there is in this life no more courageous, more self-sacrificing, nor more beautiful trait. Not a man there but respected Ma Basset for the stand she took, Joe Kipp included.

“Ma’am,” he said, his eyes still fixed on the ground, “I don’t reckon I blame yuh none fer the way yuh feel. But yo’re plumb wrong about me gunnin’ fer Pete Basset. No matter how the play comes up. I ain’t drawin’ no gun on him if I should cut his trail. If I was as onery as you figger I am, I’d uh kept my mouth shet and laid low till Pete showed up. My idee in ridin’ over was tuh kinda let yuh know it in time tuh warn him. In doin’ that I’m violatin’ my oath uh office.”

Kipp turned abruptly and swung into his saddle. Before Hank Basset or his wife could say a word, he had ridden through the pole gate and was lost to sight in the trees.

“I’d orter have my tongue cut out,” said Ma Basset contritely. “Talkin’ to the pore ol’ feller thataway when he was doin’ us a good turn. Hank, git on yore hoss and ketch him. Tell him I was jest a fool woman talkin’ a lot uh fool nonsense.”

Hank shook his head.

“I reckon ol’ Joe savvys, Ma. He ain’t holdin’ no grudge. Supposin’ we tackles some grub? It’s past sundown and we kin talk this thing over better after we’ve took on a bait uh beef and beans.”

He jerked the saddle off his horse and followed his wife to the house.

“Holler when supper’s ready, Hank,” Tad told him. “Me’n Shorty wants tuh tack a shoe on one of our hosses.”

Hank nodded appreciatively. He knew that there was no horse to shoe and he thanked Tad with a look for the kindly lie that gave him and his wife a chance to discuss in private the escape of their son.

When Hank had gone in the house, Tad turned serious eyes on his partner.

“Shorty, I got a hunch that Joe Kipp’s a worryin’ over somethin’ besides this Pete gent. He’s sick inside as if he was gut shot and I aim tuh find out what’s eatin’ on him. Yuh seen how he flinched when Miz Basset lit on him?”

“Yuh don’t think the ol’ feller’s playin’ a double game do yuh, Tad?” Shorty’s voice dropped to a whisper.

“I hate tuh be thinkin’ he’s that ornary, but dang me if there ain’t some things about this deal that has me guessin’. I’m goin’ tuh foller Kipp and see what comes uh it. Tell Hank and Miz Basset some durned lie er another about why I rode off. Look fer me when yuh see me ride through yonder gate, sabe? This may be a hour’s job, er on the other hand, mebbe so it’ll take a week.”

“Why can’t we both go?”

“Because, my well-meanin’ but plumb onsenseless amigo, it’s a one man job, this trailin’ business. Stick around here, keep yore eyes peeled, and if the Pete boy shows up, tell him not tuh quit the flats till I show up and kin make a medicine talk with him. This deal has my curious bump a-itchin’ and we’ll see ’er through, no?”

“I’d tell a man. Taddie, ol’ war hoss, I’m rearin’ tuh tackle that river from yon side and——”

“Of all the plumb dehorned, knee-sprung, narrer-foreheaded idiots that ever dealt his pardner misery, yo’re the wust! We ain’t here tuh do no fightin’, dang it. And I don’t want tuh put in the rest uh the summer hangin’ around them sand bars waitin’ fer yore fool carcass tuh come floatin’ along. Haze that fool idee plumb outa yore system and start all over on some plan that listens sensible.

“A man ’ud think yuh had more lives than a tom cat. Fork yore geldin’ and come down the pasture with me while I ketches me my Yaller Hammer pony. And git this here idee circulatin’ through yore system, son: We’re peaceful cow hands, me and you. This ain’t our scrap that’s goin’ on and the best we’ll git is the sharp end uh the prod-pole if we cuts in heavy.

“Leave the thinkin’ parts tuh yore pardner. If I hollers fer he’p, come a runnin’ but not lessen I hollers. We want tuh be all in one piece and enjoyin’ health and prosperity, as the sayin’ goes, when we presses our ponies fer Arizony this fall. Keep yore tongue between yore jaws and yore gun in the scabbard and we stand a fair tuh middlin’ show uh makin’ our home range, come Christmas. Go rearin’ and fightin’ yore head and like as not we’ll winter in a two by four hoosegow somewheres in Montana.”

Ten minutes later, Shorty watched his partner ride his fresh horse out the pole gate and along the trail Kipp had taken. A wide grin spread across the little cow puncher’s weather-tanned face.

“Yuh long-legged preacher,” he muttered good humoredly. “Yo’re plumb —— on givin’ forth wise words, ain’t yuh? Yuh give more danged advice than a Jersey cow gives milk. Then yuh rides away tuh hog all the fun whilst I hangs around the kitchen door like a dad-gummed blowfly and whittles sticks till yuh chooses tuh come back. Now I gotta go in there and lie tuh cover yore trail, dang yuh. We’ll see about swimmin’ that river, big ’un.”

“Grub pile!” called Hank from the kitchen door, thus putting an end to Shorty’s muttered tirade against the tyranny of his big partner.

A wicked look gleamed in his eyes as he made his way to the cabin.

“Where’s yore partner?” asked Ma Basset.

“Gone,” said Shorty, shaking his head sadly.

“Gone? Gone where?”

“Tuh town, I reckon, ma’am. I done the best I could tuh stop him but ’twan’t no use. Yuh see, Miz Basset, he’s one uh these here habitual drunks. Goes fer months without tetchin’ a drop. Then, sudden like, he jest busts out. He’ll swim rivers, climb pinnacles, go afoot if he has tuh, till he locates licker. Then he bogs down till he’s soaked up enough tuh kill ary ten men, forks his hoss and comes back. And the queer part of it is, he looks cold sober all the time. I bet a new hat yuh won’t be able tuh tell he’s had a drink when he gits back.”

“Land sakes! The pore, diseased critter. Who’d uh thunk he was inflicted thataway, Hank? I hope he gits home safe.”

Hank gave Shorty a suspicious look and when Ma Basset’s broad back was turned, the little puncher winked broadly. Hank chuckled.

“Hank Basset!” Ma whirled at the sound. “Shame on yuh. Makin’ fun uh that pore, diseased boy. If that ain’t like a man. Cow punchers is the most cold-hearted humans livin’, I do believe.”

“Yes’m,” agreed Hank. “Shorty, if yuh’d crave the use of a brush and comb, I’ll herd yuh to it.”

He led the way into the living room and to the bed room beyond. As he passed the cupboard, his hand slipped behind the curtain and when the two gained the bed room, Hank uncorked the bottle of snake bite cure.

“Happy days, Hank.”

“Drink hearty, Shorty,” came the reply, soft whispered, barely audible above the ensuing gurgling noise.

With Shorty left behind to excuse his partner’s absence at supper, Tad, despite gnawing pangs of hunger, made no complaint.

In the graying dusk of twilight, he rode slowly along the dusty trail, a solitary, graceful figure as he sat his horse with a careless ease, a cigaret drooping from the corner of his straight lips. Not a trace of weariness was perceptible, in spite of the fact that he had been in the saddle since dawn. He had the appearance of some cowpuncher bent on a careless mission and time was a minor factor. Yet his keen eyes constantly swept the rolling hills with a restless gaze. Always, that gaze came back to focus on the moving speck far ahead on the trail.

“Looks like he was headin’ straight fer town, Yaller Hammer,” he said softly to the twitching, dun colored ears of his horse. “Mebbeso I’m havin’ this here ride fer nothin’, I dunno.”

From his chaps pocket he produced a weatherbeaten square of plug tobacco, gnawed to a ragged edge at one end. He surveyed it critically; wiped it carefully on the sleeve of his jumper and bit off a generous piece.

“Nothin’ like chawin’ tuh keep down the hungry feelin’s,” he mused aloud. “Ain’t smelt grub since daylight. Mebbeso won’t sniff none till mornin’, neither. It’s —— but it’s honest, pony, if yuh want tuh figger it thataway.”

Darkness slowly gathered and Tad and Yellow Hammer closed the gap that separated them from Joe Kipp. Tad grinned his thanks to the full moon that rose majestically from beyond the skyline.

He rode more alertly now, eyes and ears strained to catch any sign of the man he followed. Also, he watched the wagging ears of his horse. When those furry points stiffened, pointed forward, Tad would halt. Twice, when he thus stopped, he was rewarded by the sounds of a traveling horse, ahead on the trail. Once, Kipp’s horse had nickered and Tad’s big hands closed over Yellow Hammer’s black muzzle just in time to prevent an answering nicker. He allowed Kipp a bigger lead from that point on.

The hours dragged. Tad dared not risk lighting a cigaret now. The plug of tobacco was gradually being gnawed to smaller size. Then, silhouetted against the skyline, showed the lone cottonwood that marked Hank Basset’s border line. Tad could make out the form of a horseman, halted beneath the wide branches. The waiting man lighted a cigaret and Tad recognized the features of Joe Kipp.

Nodding sagely to himself, Tad dismounted and led Yellow Hammer into the tall greasewood.

“Hate tuh treat yuh so or’nary,” he whispered as he slipped a burlap sack across Yellow Hammer’s muzzle and fastened it to the cheek bands of his bridle, “but I jest can’t have yuh makin’ no hoss howdy’s, sabe? This ain’t the fust time I’ve cluttered yuh up with one uh these contraptions, so don’t act spooky. That’s the good hoss. I wisht Shorty had half yore sense, dang his or’nary li’l hide. I bet he’s in the saddle this minute, streakin’ it fer the river. Playin’ hookey like a school kid and worryin’ a man plumb ga’nt.”

With the caution of an Indian, Tad, devoid of spurs and chaps which were hung to his saddle horn, crept through the brush toward the cottonwood. Two horses stood beneath the lone tree now. The glowing ash of two cigarets showed where the dismounted horsemen squatted against the wide tree trunk.

A clear space separated the tree and the greasewood patch where Tad lay prone on the ground. A space wide enough to prevent him making out the words of the low-toned conversation. Only when the voices momentarily laid stress on some spoken thought, could he make anything of the murmur. The voice of Kipp was clearly recognizable. The other speaker’s voice was vaguely familiar.

“I tell yuh,” came Kipp’s voice, raised with emotion, “I’ve come to the breakin’ point! I’ve stood it till I can’t stand it no longer. Why, in ——’s name, can’t you and Fox let me quit and pull outa the country? I tell yuh now, I can’t be crowded no more. I’ll tell the whole —— miser’ble story!”

“Like —— you will,” came the sneering reply, low pitched, calm, distinct. “You’ll play yore string out. When we clean up the Basset deal, you kin go. Not till then. We need yore protection.”

Kipp’s reply came in a hoarse whisper, indistinguishable to the listener hidden in the brush.

A coarse, jeering laugh came from the other man in reply. A match flared to light a cigaret and Tad recognized the black-bearded face of the half-breed, Black Jack.

“You know —— well you won’t do no talkin’,” came the breed’s voice with cold conviction.

“Where’s Fox?” asked Kipp, breaking a brief silence.

“Somewhere on the LF trail, headin’ this way. And I don’t aim that he should ketch me here, neither. I’m draggin’ it for the Pocket.”

Black Jack got to his feet and took a step toward his horse. Then he halted.

“Goin’ to stay here all night? Better be gettin’ to town where yuh belong. Fox’ll be along directly and he’ll wonder what brung you here. Pete Basset breakin’ his stake rope has put the old gent in one —— of a humor, and he might treat yuh rough. Better hit the grit.”

“I’m aimin’ tuh wait fer Fox,” replied Kipp hoarsely.

“Don’t be a plumb —— fool. He’ll mebbe kill yuh.”

“Reckon not.”

“It’s yore funeral. I’m driftin’. Good luck. Mind what I say, now. Fox’ll beat yuh to it, if yuh make ary gun play. That ol’ ——’s a snake. So-long.”

Tad listened to the thudding of hoofs as the breed rode away into the night. A few moments and all was silent as a grave yard.

Kipp got to his feet, pinching out the glowing ash of his cigaret. He led his horse to a patch of brush beyond the tree. When he returned, the pale rays of the moon fell on the blued-steel barrel of the Winchester in the crook of his arm.

Tad, watching the sheriff’s every move, whistled noiselessly. He saw Kipp settle down behind a small patch of brush. This shelter hid Kipp from the trail but Tad could see him plainly, outlined against the pale sky. Came the clicking of the sheriff’s carbine lever as he threw a cartridge from the magazine into the barrel. Then the gun raised and Tad saw Kipp squint along the barrel.

“Testin’ his sights,” mused Tad. “If ever a man went through the motions uh bushwhackin’ a enemy, Kipp’s a-doin’ it now. He don’t noways aim tuh give Fox a chanct.”

Tad pondered this decision for some time, his eyes fixed on Kipp.

“——,” he muttered inwardly. “Puts me in one —— of a mess. Fox needs killin’ and needs it bad. Shore does. Even shootin’ him from the brush is mebbeso what’s comin’ to him, I dunno. But that won’t keep Kipp from bein’ a low-down, bushwhackin’ killer iffen he does the job. Looks tuh me like this Black Jack Injun and Fox is shore th’owin’ the hooks to the ol’ sheriff plumb scan’lous. They got him nigh loco, ’pears tuh me. But shore as he’s a foot high, Kipp’ll hate hisse’f fer pullin’ the trigger, afore his gun barrel cools off. Yessir. Bound tuh. Then what’ll he do? He’ll go to the bad, complete. Booze’ll put him in the bog fer keeps. Either that, er he’ll turn that gun on hisse’f and blow his own head off. Which won’t do nobody no good ’ceptin’ mebbe this Black Jack skunk. Hmm. I never cut into no man’s game up till now, but I’m shore declarin’ myse’f in on this.”