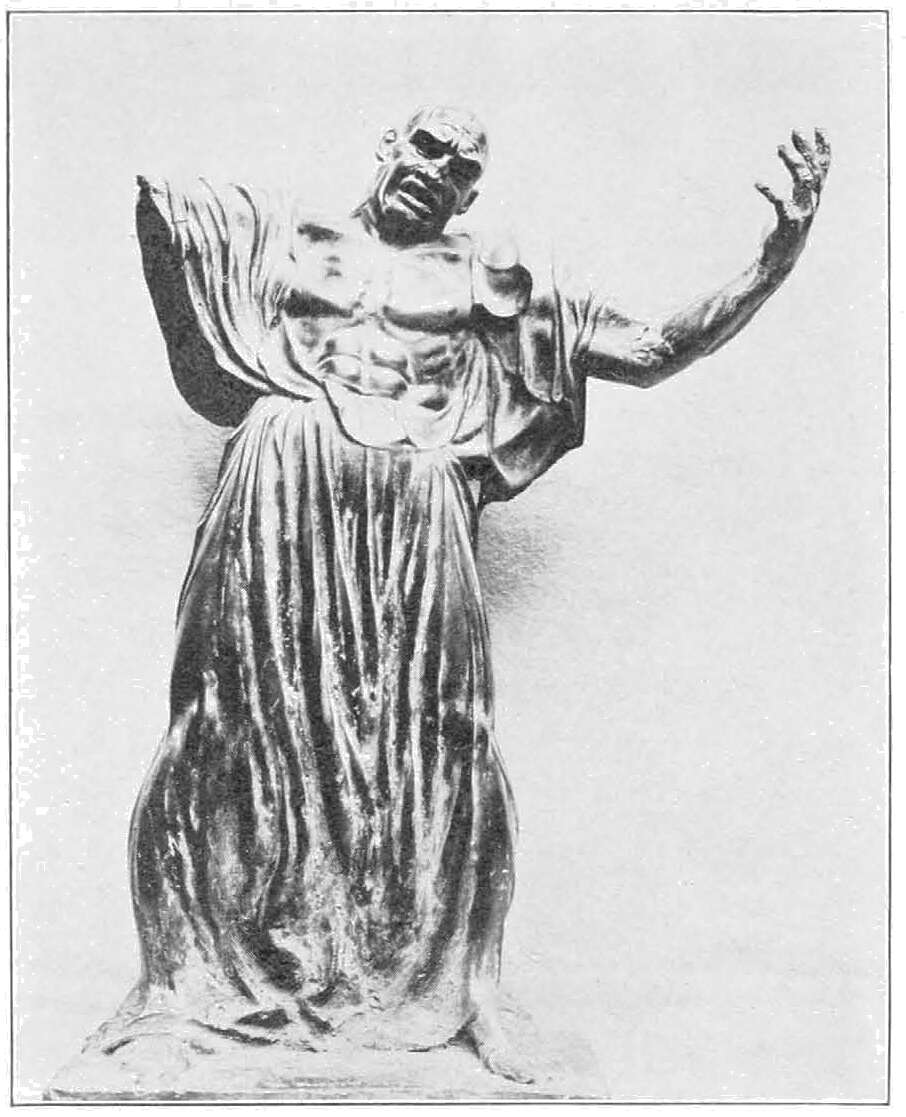

JEROME S. BLUM, The Trickster.

Literature Drama Music Art

MARGARET C. ANDERSON

EDITOR

NOVEMBER, 1914

| Lyrics of an Italian | Scharmel Iris |

| Zarathustra Vs. Rheims | George Soule |

| The Cost of War | Clarence Darrow |

| Wedded: A Social Comedy | Lawrence Langner |

| “The Immutable” | Margaret C. Anderson |

| Poems | Maxwell Bodenheim |

| The Spiritual Dangers of Writing Vers Libre | Eunice Tietjens |

| Tagore’s “Union” | Basanta Koomar Roy |

| War, the Only Hygiene of the World | Marinetti |

| Noise | George Burman Foster |

| The Birth of a Poem | Maximilian Voloshin |

| Editorials | |

| My Friend, the Incurable | Ibn Gabirol |

| London Letter | E. Buxton Shanks |

| New York Letter | George Soule |

| The Theatre | |

| Harold Bauer in Chicago | Herman Schuchert |

| A Ferrer School in Chicago | Rudolf von Liebich |

| The Old Spirit and the New Ways in Art | William Saphier |

| Book Discussion | |

| Sentence Reviews | |

| The Reader Critic |

Published Monthly

Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, Chicago.

Scharmel Iris

High in the forest of the sky

The stars and branches interlace;

As cloth-of-gold the fallen leaves lie

Where twilight-peacocks lord the place,

Spendthrifts of pride and grace.

The grapes on vines are rubies red,

They burn as flame, when day is done.

The Dusk, brown Princess, turns her head

While sunset-panthers past her run

To caverns of the Sun.

She throws cord-reins of sunbeams wrought,

About the sunset-panthers, fleet,

And rides them joyously, when caught,

Across the poppied fields of wheat—

Their hearts with terror beat.

They reach the caverns of the Sun,

The raven-clouds above them fly;

Dame Night her tapestry’s begun.

High, o’er the forest of the sky

The moon, a boat, sails by.

My son is dead and I am going blind,

And in the Ishmael-wind of grief

I tremble like a leaf;

I have no mind for any word you say:

My son is dead and I am going blind.

I loved her more than moon or sun—

There is no moon or sun for me;

Of lovely things to look upon,

The loveliest was she.

She does not hear me, though I sing—

And, oh, my heart is like to break!

The world awakens with the Spring,

But she—she does not wake!

(Struck at the double standard)

The woman who is scarlet now

Was soul of whiteness yesterday;

A void is she wherein a man

May leave his lust to-day.

’Twas with the kiss Ischariot

A traitor bore her heart away;

Her body now is leased by men

That kneel at church to pray.

I who am Giver of Life

Out of the cradle of dawn

Bring you this infant of song.—

He has a golden tongue

And wings upon his feet.

The apple of silver he holds

Once lay at the breast of the moon;

I give him an apple of gold

’Twas forged in the fires of the sun;

This apple of copper I give

That Sunset concealed in her hair.

When from the husk of dusk I shake the stars,

Down slumber’s vine I’ll send him dreams in dew,

And peace will overtake him like a song

Like thoughts of love invade a lover’s mind.

The spear-scars of the red world he will wear

As women in their hair may wear a rose.

On the rosary of his days

He will say a prayer for your sake,

The hounds-o’-wonder will lie at his side,

And lick the dust-o’-the-world from his feet.

The apple of silver will work him a charm

When under his pillow he lays it at night;

The apple of copper will warm his heart

When a heart he loves grows cold on his own;

The apple of gold will teach him a song

For children to sing when he blows on a reed;

The dew will hear and run to the sun,

The sun will whisper it in my ear,

And you, being dead, the song will hear.

George Soule

Hauptmann and Rolland have quarreled about the war, Hæckel has repudiated his English honorary degrees, and now Thomas Hardy has placed on Nietzsche the responsibility for the destruction of the cathedral of Rheims. The tragedy of nationalism, it seems, is not content with ruining lives and art; it must also vitiate philosophy and culture.

“Nietzsche and his followers, Treitschke, Von Bernhardi, and others,” writes Hardy. In the next sentence he speaks of “off-hand assumptions.” One is tempted to write, “Christ and his followers, Czar Nicholas, Kaiser Wilhelm, and others!”

Nietzsche has been claimed as a prophet by hereditary aristocrats, by anarchists, by socialists, by artists, and by militarists. There is even a book to prove that he who called himself “the Antichrist” was a supporter of the Catholic Church. One suspects, however, that the Jesuit who wrote it had a subtle sense of truth.

The most fundamental truth about Nietzsche is that the torrent of his inspiration is open to everyone who can drink of it. His value, his quality, consist not in the fact that he said this or that, but that life in him was strong and beautiful. This is true of all prophets; how much more so, then, of the one who threw to the winds all stiffness of orthodoxy and insisted on a transvaluation of all values! “O my soul, to thy domain gave I all wisdom to drink, all new wines, and also all immemorially old strong wines of wisdom,” said Zarathustra.

But even in his teachings we can find no justification of the present shame of Europe. It was Darwin who laid the foundation for the philosophy of the survival of the fittest and the struggle for existence. With the shallow inferences from these conceptions Nietzsche had no patience. If the fittest survives, the fittest is not necessarily the best. The brute force which makes for survival had no attraction for Nietzsche. He called upon man’s will to make itself the deciding factor in the struggle. When he argued for strength, he argued for the strength of the beautiful and noble, not strength for its own sake. Of what avail is a great individual to the world if he makes himself weak and sacrifices himself to an inferior enemy? The French gunners who defended the Cathedral of Rheims might justly claim the approval of Nietzsche. If the Allies had turned the other cheek and allowed their countries to be overrun by German militarism, they would then have proved themselves Christian and truly anti-Nietzschean.

Moreover, Nietzsche uncompromisingly opposed the supremacy of mere numbers, the supremacy of non-spiritual values. He argued after the war of 1870 that the victory of Prussian arms endangered rather than helped Prussian culture. Culture is a thing of the spirit; it was undermined by the tide of smug satisfaction in the triumph of militarism.

“You say that a good cause will even justify war; I tell you that it is the good war that justifies all causes,” wrote Nietzsche. It is the logic of the newspaper paragrapher which makes this statement a justification of militarism. The good war—what is that? It is the quality of heroism, the unreckoning love of beauty, the pride of the soul in its own strength and purity. It is the opponent of mere contentment and sluggishness. It is the militant virtue which has inspired great souls since the beginning of the world; it is the hope of future man. If a cause is not justified by the good war what can be said for it? It is a pathetic absurdity to think that Nietzsche would have found the good war in the present struggle for territory and commercial supremacy. No, gentlemen of letters, fight the Kaiser if you must, but do not aim your clods at the prophets in your hasty partisanship!

For it is in this very Nietzsche and his good war that mankind will now find its spirit of hope. We who see that wars of gunpowder are evil, we who intend to abolish them, cannot do so by denying our own strength and appealing helplessly to some external power in the sky. We must say with Zarathustra,

“How could I endure to be a man, if man were not also the composer, the riddle-reader, and the redeemer of chance!

“To redeem what is past, and to transform every ‘It was’ into ‘Thus would I have it!’ that only do I call redemption!

“Will—so is the emancipator and joy-bringer called: thus have I taught you, my friends!”

In Ecce Homo the word “German” has become something like his worst term of abuse. He believes only in French culture; all other culture is a misunderstanding. In his deepest instincts Nietzsche asserts to be so foreign to everything German, that the mere presence of a German “retards his digestion.” German intellect is to him indigestion. If he has been so enthusiastic in his devotion to Wagner, this was because in Wagner he honored the foreigner, because in him he saw the incarnate protest against all German virtues, the “counter-poison” (he believed in Wagner’s Jewish descent). He allows the Germans no honor as philosophers: Leibnitz and Kant were “the two greatest clogs upon the intellectual integrity of Europe.” No less passionately does he deny to the Germans all honor as musicians: “A German cannot know what music is. The men who pass as German musicians are foreigners, Slavs, Croats, Italians, Dutchmen, or Jews.” He abhors the “licentiousness” of the Germans in historical matters: “History is actually written on Imperial German and Antisemitic lines, and Mr. Treitschke is not ashamed of himself.” The Germans have on their conscience every crime against culture committed in the last four centuries (they deprived the Renaissance of its meaning; they wrecked it by the Reformation). When, upon the bridge of two centuries of decadence, a force majeure of genius and will revealed itself, strong enough to weld Europe into political and economic unity, the Germans finally with their “Wars of Liberation,” robbed Europe of the meaning of Napoleon’s existence, a prodigy of meaning. Thus they have upon their conscience all that followed, nationalism, the névrose nationale from which Europe is suffering, and the perpetuation of the system of little states, of petty politics.—George Brandes in “Friedrich Nietzsche.”

Clarence Darrow

Along with the many other regrets over the ravages of war is the sorrow for the destruction of property. As usual, those who have nothing to lose join in the general lamentation. There is enough to mourn about in the great European Holocaust without conjuring up imaginary woes. So far as the vast majority of people is concerned, the destruction of property is not an evil but a good.

The lands and houses, the goods and merchandise and money of the world are owned by a very few. All the rest in some way serve that few for so much as the law of life and trade permit them to exact. At the best, this is but a small share of the whole. All the property destroyed by war belongs to the owners of the earth; it is for them that wars are fought, and it is they who pay the bills. When the war is over, the property must be re-created. This, the working men will do. In this re-building, they will work for wages. Then, as now, the rate of wages will be fixed by the law of demand and supply—the demand and supply of those who toil. The war will create more work and less workmen. Therefore labor can and will get a greater share of its production than it could command if there was less work and more workmen. The wages must be paid from the land and money and other property left when the war is done. This will still be in the hands of the few, and these few will be compelled to give up a greater share. The destruction of property, together with its re-creation means only a re-distribution of wealth—a re-distribution in which the poor get a greater share. It is one way to bring about something like equality of property—a cruel, wasteful, and imperfect way, but still a way. That the equality will not last does not matter, for in the period of re-construction the workman will get a larger share and will live a larger life.

As the war goes on, the funds for paying bills will be met in the old way by selling bonds. These too will be paid by the owners of the earth. True, the property from which the payment comes must be produced by toil, but if the bonds that must be paid from the fruits of labor had never been issued this surplus would not have gone to labor, but would have been absorbed by capital. This is true for the simple reason that the return to labor is not fixed by the amount of production, the rate of taxation, the price of interest and rents, but by the supply and demand of labor, and nothing else.

If labor shall sometime be wise enough, or rather instinctive enough to claim all that it produces, it will at the same time have the instinct or wisdom to leave the rulers’ bonds unpaid.

But all of this is far, far away; in determining immediate effects we must consider what is, not what should be. And the jobless and propertyless can only look upon the destruction of property as giving them more work and a larger share of the product of their labor. Chicago was never so prosperous, or wages so high, as when her people were re-building it from the ashes of a general conflagration. San Francisco found the same distribution of property amongst its workmen after the earthquake and the fire had laid it waste, and her people were called upon to build it up anew.

Carlyle records that during the long days of destruction in the French Revolution the people were more prosperous and happy than they had ever been before. True, the Guilotin was doing its deadly work day after day, but its victims were very few. The people got used to the guilotin, and heeded it no more than does the crowd heed a hanging in our county jail, when they gayly pass in their machines.

After the first shock was over, during the four years of our Civil War, wages were higher, men were better employed, production greater, and distribution more equal than it had been at any time excepting in the extreme youth of the Republic. Then land was free.

Then again, this world has little to destroy. After centuries of so-called civilization, the human race has not accumulated enough to last a year should all stop work. The world lives, and always has lived, from hand to mouth. This is not because of any trouble in producing wealth, but because things are made not to use, but to sell. And the wages of the great mass of men does not permit them to buy or own more than they consume from day to day.

It is for this reason that half the people do not really work; that the market for labor is fitful and uncertain, and never great enough; and that all are poor. After a devastation like a great war, the need of re-creating will turn the idle and the shirkers into workmen, because the rewards will be greater. This will easily and rapidly produce more than ever before. From this activity, invention will contrive new machines to compete with men, going once more around the same old circle, until the world finds out that machines should be used to satisfy human wants and not to build up profits for the favored few.

One may often regret the impulses that bring destruction of property, but before any one mourns over the destruction of property, purely because of its destruction, he should ask whose property it is.

A Social Comedy

Lawrence Langner

Mrs. Ransome.

Janet Ransome: Her daughter.

Rev. Mr. Tanner: A Clergyman.

(The “best” parlor of the Ransomes’ house, in a cheap district of Brooklyn. There is a profusion of pictures, ornaments, and miscellaneous furniture. A gilded radiator stands in front of the fireplace. Table, center, on which are some boxes and silver-plated articles arranged for display. Over the door hangs a horseshoe. White flowers and festoons indicate that the room has been prepared for a wedding. To the left is a sofa, upon which lies the body of a dead man, his face covered with a handkerchief. There is a small packing-case at his side, upon which stand two lighted candles, a medicine bottle, and a tumbler. The blinds are drawn.)

(Janet, dressed in a white semi-bridal costume, is on her knees at the side of the couch, quietly weeping. After a few moments the door opens, admitting a pale flood of sunshine. The murmur of conversation in the passage without is heard. Mrs. Ransome enters. She is an intelligent, comfortable-looking middle-aged woman. She wears an elaborate dress of light gray, of a fashion of some years previous, evidently kept for special occasions. She is somewhat hysterical in manner and punctuates her conversation with sniffles.)

Mrs. Ransome. My dear child, now do stop cryin’. Won’t you stop cryin’? Your Aunt Maud’s just come, and wants to know if she can see you.

Janet. I don’t want to see her. I don’t want to see nobody.

Mrs. Ransome. But your aunt, my dear—

Janet. No, mother, not nobody.

(Mrs. Ransome goes to door and holds a whispered conversation with somebody outside. She then returns, closing the door behind her, and sits on chair close to Janet.)

Mrs. Ransome. She’s goin’ to wait for your father. He’s almost crazy with worry. All I can say is—thank God it was to have bin a private wedding. If we’d had a lot of people here, I don’t know what I should have done. Now, quit yer cryin’, Janet. I’m sure we’re doin’ all we can for you, dear. (Janet continues to weep softly.) Come, dear, try and bear up. Try and stop cryin’. Your eyes are all red, dear, and the minister’ll be here in a minute.

Janet. I don’t want to see him, mother. Can’t you see I don’t want to see nobody?

Mrs. Ransome. I know, my dear. We tried to stop him comin’, but he says to your father, he says, “If I can’t come to her weddin’, it’s my duty to try to comfort your daughter”; and that certainly is a fine thing for him to do, for a man in his position, too. And yer father—he feels it as much as you do, what with the trouble he’s been to in buying all that furniture for you and him, and one thing and another. He says that Bob must have had a weak heart, an’ it’s some consolation he was took before the weddin’ and not after, when you might have had a lot of children to look after. An’ he’s right, too.

Janet (Talks to body). Oh, Bob! Bob! Why did you go when I want you so?

Mrs. Ransome. Now, now! My poor girl. It makes my heart bleed to hear you.

Janet. Oh, Bob! I want you so. Won’t you wake up, Bob?

Mrs. Ransome (Puts her arms around Janet and bursts into sobs). There—you’re cryin’ yer eyes out. There—there—you’ve still got your old mother—there—there—just like when you was a baby—there—

Janet. Mother—I want to tell you something—

Mrs. Ransome. Well, tell me, dear, what is it?

Janet. You don’t know why me and Bob was goin’ to get married.

Mrs. Ransome. Why you and Bob was goin’ to get married?

Janet. Didn’t you never guess why we was goin’ to get married—sort of all of a sudden?

Mrs. Ransome. All of a sudden? Why, I never thought of it. (Alarmed.) There wasn’t nuthin’ wrong between you and him, was there? (Janet weeps afresh.) Answer me. There wasn’t nuthin’ wrong between you and him, was there?

Janet. Nuthin’ wrong.

Mrs. Ransome. What do you mean, then?

Janet. We was goin’ to get married—because we had to.

Mrs. Ransome. You mean yer goin’ to have a baby?

Janet. Yes.

Mrs. Ransome. Are you sure? D’ye know how to tell fer certain?

Janet. Yes.

Mrs. Ransome. Oh, Lor’! Goodness gracious! How could it have happened?

Janet. I’m glad it happened—now.

Mrs. Ransome. D’ye understand what it means? What are we goin’ to do about it?

Janet (Through her tears). I can’t help it. I’m glad it happened. An’ if I lived all over again, I’d want it to happen again.

Mrs. Ransome. You’d want it to happen? Don’t you see what this means? Don’t you see that if this gets out you’ll be disgraced ’till your dying day?

Janet. I’m glad.

Mrs. Ransome. Don’t keep on sayin’ you’re glad. Glad, indeed! Have you thought of the shame and disgrace this’ll bring on me an’ your father? An’ after we’ve saved and scraped these long years to bring you up respectable, an’ give you a good home. You’re glad, are you? You certainly got a lot to be glad about.

Janet. Can’t you understand, mother? We wasn’t thinking of you when it happened—and now it’s all I have.

Mrs. Ransome. Of course you wasn’t thinkin’ of us. Only of yourselves. That’s the way it is, nowadays. But me and your father is the ones that’s got to face it. We’re the ones that’s got to stand all the scandal and talk there’ll be about it. Just think what the family’ll say. Think what the neighbors’ll say. I don’t know what we done to have such a thing happen to us. (Mrs. Ransome breaks into a spell of exaggerated weeping, which ceases as the door-bell rings.) There! That’s the minister. God only knows what I’d better say to him. (Mrs. Ransome hurriedly attempts to tidy the room, knocking over a chair in her haste, pulls up the blinds half-way and returns to her chair. There is a knock at the door. Mrs. Ransome breaks into a prolonged howl.) Come in.

(Enter Rev. Mr. Tanner. He is a stout, pompous clergyman, with a rich, middle-class congregation and a few poorer members, amongst which latter he numbers the Ransomes. His general attitude is kind but patronizing; he displays none of the effusive desire to please which is his correct demeanor towards his richer congregants. The elder Ransomes regard him as their spiritual leader, and worship him along with God at a respectful distance.)

Tanner (He speaks in a hushed voice, glancing towards the kneeling figure of Janet). Bear up, Mrs. Ransome. Bear up, I beg of you! (Mrs. Ransome howls more vigorously; Tanner is embarrassed.) This is very distressing, Mrs. Ransome.

Mrs. Ransome (Between her sobs). It certainly is kind of you to come, Mr. Tanner, I’m sure. We didn’t expect to see you when my husband ’phoned you.

Tanner. Where is your husband now?

Mrs. Ransome. He’s gone to send some telegrams to Bob’s family, sir—his family. We’d planned to have a quiet wedding, sir, with only me and her father and aunt, and then we was goin’ to have the rest of the family in, this afternoon.

Tanner. It’s a very sad thing, Mrs. Ransome.

Mrs. Ransome. It’s fairly dazed us, Mr. Tanner. Comin’ on top of all the preparation we’ve bin makin’ for the past two weeks, too. An’ her father’s spent a pile o’ money on their new furniture an’ things.

Tanner (Speaking in an undertone). Was he insured?

Mrs. Ransome. No, sir, not a penny. That’s why it comes so hard on us just now, havin’ the expense of a funeral on top of what we’ve just spent for the weddin’.

Tanner. Well, Mrs. Ransome, I’ll try to help you in any way I can.

Mrs. Ransome. Thank you, Mr. Tanner. It certainly is fine of you to say so. Everybody’s bin good to us, sir. She had all them presents given her—most of them was from my side of the family.

Tanner. Did he have any relatives here?

Mrs. Ransome. Not a soul, poor fellow. He came from up-state. That’s why my husband’s gone to send a telegram askin’ his father to come to the funeral.

Tanner. How long will your husband be? (He glanced at his watch.)

Mrs. Ransome. I don’t think he’ll be more than half an hour. He’d like to see you, if you could wait that long, I know.

Tanner. Very well. I have an engagement later, but I can let that go if necessary.

(Tanner and Mrs. Ransome sit down in front of the table.)

Mrs. Ransome. It certainly is a great comfort havin’ you here, Mr. Tanner. I feel so upset I don’t know what to say.

Tanner. Bear up, Mrs. Ransome. You are not the greatest sufferer. Let me say a few words to your daughter. (He rises, goes to Janet, and places his hand on her shoulder, but she takes no notice of him.) Miss Ransome, you must try to bear up, too. I know how hard it is, but you must remember it’s something that must come to all of us.

Mrs. Ransome. She takes it so bad, Mr. Tanner, that the Lord should have took him on their weddin’ mornin’.

Tanner (Returning to his chair). We must not question, Mrs. Ransome, we must not question. The Almighty has thought fit to gather him back to the fold, and we must submit to His will. In such moments as these we feel helpless. We feel the need of a Higher Being to cling to—to find consolation. Time is the great healer.

Mrs. Ransome. But to expect a weddin’ (Sobs) and find it’s a funeral—it’s awful; (Sobs) and besides—Mr. Tanner, you’ve always been good to us. We’re in other trouble, too. Worse—worse even than this.

Mrs. Ransome. Yes, much worse. I just can’t bear to think about it.

Tanner. Your husband’s business?

Mrs. Ransome. No, sir. It’s—I don’t know how to say it. It’s her and him.

Tanner. Her and him?

Mrs. Ransome. Yes, sir—I’m almost ashamed to tell you. She’s goin’ to have a baby.

Tanner (Astounded). She’s going to be a mother?

Mrs. Ransome. Yes. (Sobs.) Oh, you don’t know how hard this is on us, Mr. Tanner. We’ve always bin respectable people, sir, as you well know. We’ve bin livin’ right here on this block these last ten years, an’ everybody knows us in the neighborhood. Her father don’t know about it yet. What he’ll say—God only knows.

Tanner. I’m terribly sorry to hear this, Mrs. Ransome.

Mrs. Ransome. I can forgive her, sir, but not him. They say we shouldn’t speak ill of the dead—but I always was opposed to her marryin’ him. I wanted her to marry a steady young fellow of her own religion, but I might as well have talked to the wall, for all the notice she took of me.

Tanner. It’s what we have to expect of the younger generation, Mrs. Ransome. Let me see—how long were they engaged?

Mrs. Ransome. Well, sir, I suppose on and off it’s bin about three years. He never could hold a job long, an’ me and her father said he couldn’t marry her—not with our consent—until he was earnin’ at least twenty dollars a week—an’ that was only right, considerin’ he’d have to support her.

Tanner. I quite agree with you. I’m sorry to see a thing of this sort happen—and right in my own congregation, too. I’ve expressed my views from the pulpit from time to time very strongly upon the subject, but nevertheless it doesn’t seem to make much difference in this neighborhood.

Mrs. Ransome. I know it’s a bad neighborhood in some ways, sir. But you got to remember they was going to get married, sir. If you’d bin here only an hour earlier, Mr. Tanner, there wouldn’t have bin no disgrace. (Points to official-looking book lying on table.) Why, sir—there’s the marriage register—Mr. Smith brought it down from church this morning—all waiting for you to fix it. If you’d only come earlier, sir, they’d have bin properly married, an’ there wouldn’t have bin a word said.

Tanner. That’s true. They might have avoided the immediate disgrace, perhaps. But you know as well as I do that that isn’t the way to get married. It isn’t so much a matter of disgrace. That means nothing. It’s the principle of the thing.

Mrs. Ransome (Eagerly). Oh, Mr. Tanner, do you mean it? Do you mean that the disgrace of it means nothin’?

Tanner. Well—not exactly nothing—but nothing to the principle of the thing.

Mrs. Ransome. An’ would you save her from the disgrace of it, if you could, Mr. Tanner, if it don’t mean nothin’?

Tanner. I’ll do anything I can to help you, within reason, Mrs. Ransome, but how can I save her?

Mrs. Ransome (Eagerly pleading). Mr. Tanner, if she has a child, as she expects, you know that respectable people won’t look at us any more. We’ll have to move away from here. We’ll be the laughing stock of the place. It’ll break her father’s heart, as sure as can be. But if you could fill in the marriage register as though they’d bin married, Mr. Tanner, why, nobody’s to know that it isn’t all respectable and proper. They had their license, and ring, and everything else, sir, as you know.

Tanner (Astounded). Me fill in the marriage register? Do you mean that you want me to make a fictitious entry in the marriage register?

Mrs. Ransome. It wouldn’t be so very fictitious, Mr. Tanner. They’d have bin married regular if you’d only come half an hour earlier. Couldn’t you fill it in that they was married before he died, sir?

Tanner. But that would be forgery.

Mrs. Ransome. It would be a good action, Mr. Tanner—indeed, it would. Her father an’ me haven’t done nothing to deserve it, but we’ll be blamed for it just the same. It wouldn’t take you a minute to write it in the register, Mr. Tanner. Look at all the years we’ve bin goin’ to your church, and never asked you a favor before.

Tanner. My good woman, I’m sorry; I’d like to help you, but I don’t see how I can. In the first place, don’t you see that you’re asking me to commit forgery? But what’s more important, you’re asking me to act against my own principles. I’ve been preaching sermons for years, and making a public stand too, against these hasty marriages that break up homes and lead to the divorce court—or worse. The church is trying to make marriage a thing sacred and apart, instead of the mockery it is in this country today. I sympathize with you. I know how hard it is. But for all I know, you may be asking me to help you thwart the will of God.

Mrs. Ransome. The will of God?

Tanner. Mind you, I don’t say that it is, Mrs. Ransome, but it may very well be the Hand of the Almighty. Your daughter and her young man, as she has confessed herself, have tried to use the marriage ceremony—a holy ceremony, mind you—to cover up what they’ve done.

Mrs. Ransome. Oh, don’t talk like that before her, Mr. Tanner.

Tanner. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to hurt her feelings. I’m sorry I can’t help you. It wouldn’t be right.

Mrs. Ransome. But they was goin’ to get married, sir. You got to take that into consideration. My girl ain’t naturally bad. It isn’t as though she’d pick up any feller that happened to come along. Hundreds and thousands do it, sir, indeed they do, and most of them much worse than she and him, poor fellow.

Tanner. Yes, there you are right. Thousands do do it, and I’ve been making a stand against it in this neighborhood for years. I may seem hard, Mrs. Ransome, but I’m trying my best to be fair. I sincerely believe that no minister of the Gospel should ever legalize or condone—er—misconduct—that is, before marriage.

Mrs. Ransome (Pleading hard). You can’t know what this means to us, sir—or you’d pity us, indeed you would. Her father’ll take on somethin’ dreadful when he hears about it. He’ll turn her out of the house, sir, as sure as can be. You know him, sir. You know he’s too good a Christian to let her stay here after she’s disgraced us all. And then, what’s to become of her? She’ll lose her job, and who’ll give her another—without a reference—an’ a baby to support? That’s how they get started on the streets, sir (Sobs), an’ you know it as well as I do.

Tanner. Yes, I know. I wish I could help you. It’s very distressing—but we all have to do our duty as we see it. But I do pity you, indeed I do. From the bottom of my heart. I’ll do anything I can for you—within reason.

Mrs. Ransome (Almost hysterical, dragging Janet from the side of the body). Janet, Janet! Ask him yourself. Ask him on your bended knees. Ask him to save us! (Janet attempts to return to side of the body.) Janet, do you want to ruin us? Can’t you speak to him? Can’t you ask him? (Mrs. Ransome breaks into sobs.)

Tanner. It is as I feared, Mrs. Ransome. Her heart is hardened.

Janet (Rises and turns fiercely on him). Whose heart’s hardened?

Tanner. Come, come. I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings. I can’t tell you how sorry I am for you, and your parents, too.

Janet. Well, I’ll tell you flat, I don’t want none of your pity.

Mrs. Ransome. Janet, don’t speak like that to him. You’re excited. (To Tanner). She don’t mean it, sir—she’s all worked up.

Janet (Her excitement increasing, and speaking in loud tones). All right, mother—I’ll tell him again—I don’t want none of his pity. I c’n get along without it. An’ if you and him think that writin’ a few words in his marriage register—or whatever he calls it—is going to make any difference, well—you’re welcome to.

Tanner. My dear girl. Don’t you understand, if it was merely a question of writing a few words, I’d do it in a minute. But it’s the principle of the thing.

Janet (Bitingly). Huh! Principle of the thing! I heard it all. You preached against it, didn’t yer? It’s a pity you never preached a sermon on how me and him could have gotten married two years ago, instead of waiting till now, when it’s too late.

Tanner. Others have to wait.

Janet. We did wait. Isn’t three years long enough? D’ye think we was made of stone? How much longer d’ye think we could wait? We waited until we couldn’t hold out no longer. I only wish to God we hadn’t waited at all, instead of wastin’ all them years.

Mrs. Ransome (Shocked). Janet, you don’t know what you’re sayin’.

Janet. I do, an’ I mean it. We waited, an’ waited, an’ waited. Didn’t he try all he could to get a better job? ’Twasn’t his fault he couldn’t. We was planning to go West, or somewhere—where he’d have more of a chance—we was savin’ up for it on the quiet. An’ while we was waiting, we wanted one another—all day an’ all night. An’ what use was it? We held out till we couldn’t hold out no longer—an’ when we knew what was goin’ to happen, well—we had to get married—an’ that all there’s to it!

Tanner (Making a remarkable discovery, supporting all his personal theories on the subject). Ah! Then your idea was to marry simply because you were going to have a baby!

Janet. Of course it was. D’ye think we wanted to marry an’ live here on the fifteen a week he was getting? We’d have bin starvin’ in a month. But when this happened—we had to get married—starve or not. What else could we do?

Tanner. Well, I don’t know what to say. It seems to me that you should have thought of all this before. You knew what it would mean to have a baby.

Janet. D’ye think I wanted a baby? I didn’t want one. I didn’t know how to stop it. If you don’t like it—it’s a pity you don’t preach sermons on how to stop havin’ babies when they’re not wanted. There’d be some sense in that. That’d be more sense than talkin’ about waitin’—an’ waitin’—an’ waitin’. There’s hundreds of women round here—starvin’ and sufferin’—an’ havin’ one baby after another, and don’t know the first thing about how to stop it. ’Tisn’t my fault I’m going to have one. I didn’t want it.

Tanner. Miss Ransome, your views simply astound me.

Janet. I can’t help it. People may think it wrong, an’ all that, but it ain’t his fault and it ain’t mine. Don’t you think we used to get sick of goin’ to movies, an’ vaudeville shows, an’ all them other places—time after time? I wanted him to love me, an’ I ain’t ashamed of it, neither.

Mrs. Ransome. Janet, how dare you talk like that in front of Mr. Tanner? (To Tanner.) She don’t mean it, Mr. Tanner. She don’t know what she’s saying. I’ve always brought her up to be innercent about things. She must have got all this from the other girls at the store where she works. She didn’t get it in her home, that’s sure.

Janet. No, that I didn’t. Nor nothing else, neither. You was always ashamed to tell me about anything, so I found out about things from other girls, like the rest of ’em do. I’ve known it for years and years, an’ all the while I suppose you’ve bin thinkin’ I didn’t know anything, I’ve known everything—all except what’d be useful to me. If I’m going to have a baby it’s your fault, mother, as much as anybody. You only had one yourself—but you never told me nothin’.

Mrs. Ransome. Janet!

Tanner. Miss Ransome, this is not a subject I ordinarily discuss, but since you know what you do know, let me tell you that there is nothing worse than trying to interfere with the workings of nature, or—if I may say so—of God.

Janet. Well, Bob said the rich people do it. He said they must know how to do it, because they never have more’n two or three children in a family; but you’ve only got to walk on the next block—where it’s all tenements—to see ten and twelve in every family, because the workin’ people don’t know any better. But I don’t want no pity from anybody. I can take a chance on it. I got a pair of hands, an’ I c’n take care of myself.

Tanner. Mrs. Ransome, it’s no good my talking to your daughter while she’s in this frame of mind. She appears to have most extraordinary views. Mind you, I don’t blame you for it. She seems to be an intelligent girl. There’d be some hope for her if she’d show a little penitence—a little regret for what’s been done and can’t be undone. You know I don’t like preaching out of church, but you’ve often heard me say in the pulpit that God is always willing to forgive the humble and the penitent.

Janet (With fine scorn). “God” indeed. Don’t make me laugh. (Points to body of Bob.) Look at him lyin’ there. God? What’s God got to do with it? (She kneels again at the side of the couch, rigid and silent. After an uncomfortable interval, Tanner rises.)

Tanner. Well, I’m afraid I must be going. I feel very pained by what your daughter has said, Mrs. Ransome. You know I have a deep regard for you and your husband. I’m frank to say that if your daughter had shown some signs of penitence—some remorse for what has happened—I might even have gone so far as to have made the entry in the register—seeing the punishment she’s already had. But as she is now, I don’t see what good it would do. Really I don’t, so I think I’d better go.

Mrs. Ransome (Appealingly). Oh, don’t go, Mr. Tanner. Wait just a minute while I talk to her, please. Janet, can’t you say you’re sorry for what you done? Can’t you see that Mr. Tanner only wants to be fair with you? Come, do it for our sakes—your father and me. You know how hard he’s worked, how he’s keep teetotal an’ everything. You don’t want to ruin us, do you? Can’t you see it isn’t only yourself that’s got to be considered? Think of what we’ve done for you. Tell him you’re sorry for it, do!

Tanner (Rising). It’s no use, Mrs. Ransome. I can see it’s of no use. I really must go.

Mrs. Ransome. Just one minute more. Please wait one minute more. Janet, what’s the matter with you? Can’t you see the disgrace it’ll be to all of us? Can’t you see it will ruin us to our dying days? They’ll all laugh at us—an’ jeer at us. It’ll follow us around wherever we go. You know how the folk round here make fun of your father—because he keeps himself respectable—an’ saves his money. Do you want them to laugh at him? Do you want them to be laughin’ at you an’ talkin’ about you? Do you want them to be making fun of your baby—an’ calling it a bastard—an’ asking who it’s father was?

Janet (Nervously). They wouldn’t.

Mrs. Ransome. Yes, they would. An’ all the time he’s growin’ up, the other children in school’ll be tormentin’ him, and callin’ him names. Didn’t the same thing happen with Susan Bradley’s boy? Didn’t they have to go an’ live out in Jersey, cos she couldn’t stand it no longer? You know it as well as I do.

Janet (Defiantly). They went away ’cos he was always gettin’ sick.

Mrs. Ransome. Of course he was always gettin’ sick—with all them devils makin’ fun of him—an’ makin’ his life a misery. Didn’t we used to see him goin’ down the block—with the tears runnin’ down his cheeks—an’ all of ’em yellin’ names after him. Just think of the baby you’re goin’ to have. D’ye want that to happen to your baby? D’ye want them to make its life a misery—same as the other one?

Janet (Lifelessly). They wouldn’t.

Mrs. Ransome. Of course they would. They’ll tease an’ torment it, just like the other—an’ when he’s old enough to understand—who’ll he blame for it? He’ll blame you for it. (Inspired) He’ll blame Bob for it—he’ll hate him for it. D’ye want your boy—Bob’s boy—to be hatin’ his own father? What’d Bob say? What’d he think of you—ruinin’ his baby’s life—an’ all just because you’re obstinate an’ won’t listen to reason. Can’t you see it? Just think—if you’d only say you was in the wrong—an’ do what Mr. Tanner asks you—he’d forgive you an’ make everything all right. Oh, Janet—can’t you see it? Ask him—beg him!

Janet. Oh, dear. Well—how c’n Mr. Tanner make it all right?

Mrs. Ransome. You know what I mean. Oh, Janet, it won’t take him a minute to write it. If he don’t, can’t you see it’ll ruin us all our lives?

Janet. Only a minute to write it—or it’ll ruin us all our lives.

Mrs. Ransome. Oh, Janet, this is your last chance. Tell him you’re sorry. (To Tanner, who has edged towards the door, and is about to leave.) Oh, Mr. Tanner, please don’t go. Just wait another minute.

Tanner. Really, I must go.

Mrs. Ransome. Oh, sir! I can see she’s sorry. You won’t go back on your word, sir?

Janet (Unwillingly feigning remorse). Let me think a bit. Oh, Mr. Tanner, I suppose I’m in the wrong—if you say so. It didn’t seem to me to be wrong—that’s all I got to say. I hope you’ll forgive me. I’m sorry for the way I spoke—and what I done.

Tanner (Returning). My child, it’s not for me to forgive you. I knew I could appeal to something higher in you, if you’d only listen to me. Are you truly repentant—from the bottom of your heart?

Janet. Yes, sir.

Tanner. As I said to your mother just now, I don’t like preaching sermons, but I hope this has taught you that there can be no justification for our moments of passion and wilfulness. We must all try to humble our pride and our spirit. I won’t go back on my word, but when you start out afresh you must try to wipe out the past by living for the future.

Janet. I’ll try to, sir.

Tanner. And now, Mrs. Ransome, I suppose I’ll have to make the entry as though it had happened an hour or so ago. I know I may seem soft-hearted about it. But I feel I am doing my duty. This may save your daughter from a life of degradation. I think the end justifies the means. But first, let me ask you, who knows that the ceremony wasn’t performed before he died?

Mrs. Ransome. Only me—an’ her father—an’ my sister outside.

Tanner. Can she be relied upon to hold her tongue?

Mrs. Ransome. She surely can, sir.

Tanner. Well, you understand this is a very serious thing for me to do. If it becomes public I shall be faced with a very unpleasant situation.

Mrs. Ransome. Oh, I promise you, Mr. Tanner, not a soul will know of it. We’ll take our dyin’ oaths, sir, all of us.

Tanner. All right. But first let me lend your daughter this prayer-book. (Takes prayer-book out of pocket; addressing Janet.) Here’s a prayer-book, Miss Ransome. I’ll go with your mother now into the back-parlor, and meanwhile I want you to read over this prayer. Try to seek its inner meeting. Come, Mrs. Ransome, you can carry the register, and we’ll come back later and discuss the funeral arrangements.

Mrs. Ransome (Takes the marriage register). Oh, Mr. Tanner, I don’t know how to thank you.

Tanner. Well, Mrs. Ransome—I shall expect your husband to send us something for our new mission to spread Christianity amongst the Chinese.

(Exit Tanner and Mrs. Ransome. Janet closes the door. She walks towards the couch, looks at the prayer-book, then at the couch. She flings the prayer-book to the other end of the room, smashing some of the ornaments on the mantle-shelf, and throws herself upon the side of the couch, sobbing wildly.)

Slow Curtain.

Margaret C. Anderson

In a world where flippancies arrange an effective concealment of beauty there are still major adventures in beauty to be had beneath the grinning surface. One of them is the discovery of those rare persons to whom flippancies are impossible—those splendid persons who take life simply and greatly. Several months ago I tried to write an impression of Emma Goldman, from an inadequate background of having merely heard two of her lectures. Since then I have met her. One realizes dimly that such spirits live somewhere in the world: history and legend and poetry have proclaimed them, and at times we hear of their passing; but to meet one on its valiant journey is like being whirled to some far planet and discovering strange new glories.

Emma Goldman is one of the world’s great people; therefore, it is not surprising to find her among the despised and rejected. Of course she is as different from the popular conception of her as anyone could be. The first thing you feel in meeting her is that indefinable something which all great and true people have in common—a quality which seems to proceed on some a priori principle that anything one feels deeply is sublime. Then a sense of her great humanity sweeps upon you, and the nobility of the idealist who wrenches her integrity from the grimest depths. A terrible sadness is in her face—as though the suffering of centuries had concentrated there in some deep personal struggle; and through it shines that capacity for joy which becomes colossal in its intensity and tragic in its disappointments. But the thing which takes your heart in a grip, and thrusts you quickly into the position of the small boy who longs to die for the object of his worship, is that imperative gift of motherhood which is hers and which spends itself with such utter prodigality upon all those who come to her for inspiration. Emma Goldman has ministered to every kind of human being from convicts to society women. She has no more idea of conservation than a lavish springtime; and where she draws courage and endurance and inspiration for it all will remain one of those mysteries which only the artist can explain. A mountain-top figure, calm, vast, dynamic, awful in its loneliness, exalted in its tragedy—this is Emma Goldman, “the daughter of the dream,” as William Marion Reedy called her in an appreciation written several years ago. “A dream, you say?” he asked, after sketching her gospel. “Yes; but life is death without the dream.” In that rich book of Alexander Berkman’s, Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, she is given a better name. “I have always called you the Immutable,” is the way the author closes one of his letters to her. And this is the quality which distinguishes Emma Goldman—a kind of eternal staunchness in which one may put his fundamental trust.

This is the woman America has hated and persecuted, thrown into jail, deprived of her citizenship, and held up as an example of all that is ignorant, coarse, and base. America will recognize its failure some day, after the brave spirit has done its work—after the spasm of the new war has ushered in quite simply some of the changes which Emma Goldman has been pleading for during her years of fighting. But it takes education to produce such awakenings, and there is no immediate hope of such a general enlightenment. The stupidity of the situation regarding Emma Goldman is that other prophets have raised their spears to the same heights and have been misunderstood or ignored but not outraged by the peculiar ignorance which Americans alone seem capable of. Had Ibsen appeared among us to lecture on the rightness of Nora’s rebellion or to denounce the pillars of society as he did in his writing, he, too, would have been thrown into prison for free speech or accused of a president’s assassination. The cruelty of the situation regarding Emma Goldman is that she has so much work to do which so many people need, and that she cannot break through the prejudice and the superstition surrounding her to get at those dulled ones who need it most. Ten years ago she was preaching, under the most absurd persecution, ideas which thinking people accept as a matter of course today. Now the ignorant public still shudders at her name; the “intellectuals”—especially those of the Greenwich Village radical type—dismiss her casually as a sort of good Christian—one not to be taken too seriously: there are so many more daring revolutionists among their own ranks that they can’t understand why Emma Goldman should make such a stir and get all the credit; the Socialists concede her a personality and condone her failure to attach herself to that line of evolutionary progress which is sure to establish itself. “Unscientific” is their damning judgment of her; her Anarchism is a metaphysical hodge-podge, the outburst of an artistic rather than a scientific temperament. And so they all miss the real issue, namely, that the chief business of the prophet is to usher in those new times which often appear in direct opposition to scientific prediction, and—this above all!—that life in her has a great grandeur.

How do such grotesque misconceptions arise? Why should it have happened that all this misapprehension and ignorance should have grown up about a personality whose mere presence is a benediction and whose friendship compels you toward high goals you had thought unattainable? There is no use asking how or why it happened; it is a perfectly consistent thing to have happened, for it happens to everyone, in greater or less degree, who strives for a new ideal. But if I could only get hold of all the people who are unwilling to understand Emma Goldman and force them to listen to her for an hour:—what a sweet triumph comes with their “Oh, but she’s wonderful!”

And now about her ideas. If you have read Wilde’s Soul of Man Under Socialism you know the essence of Emma Goldman’s Anarchism. What is there about it to cause an epidemic of terror? It is merely the highest ideal of human conduct that has ever been evolved. Well, it is possible to get even the prejudiced to admit this much. Nearly everyone can see that government in its essence is tyranny; that one human being’s authority over another is a degrading thing; that no man should have the power to force his neighbor into a dungeon on the flimsy pretext that punishment is a prevention and a protection; that no man should dare to take the life of another man, on any basis whatever; that crime is really misdirected energy and “criminal types” usually sick people who should be treated as such; that “abnormal” people are those who have not found their work; that people who work should have some share of their production; that the holding of property is a source of many evils; that possessiveness and “bargaining” are mean qualities; that co-operation and sharing are splendid ones; that there should be an equality between giving and taking; that nothing worth while was ever born outside of freedom; and that men might live together on this basis more effectively than on the present one. Even your “reasonable” man will grant you this premise; but then he plays his trump card: It may all be very beautiful—of course it is; but it can never happen! Oscar Wilde answered him in this way: “Is this Utopian? A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realization of Utopias.”

Emma Goldman believes this. She does not belong with the rank and file of Anarchists. Cults and “isms” are too restrictive for her. “But you are an extreme Individualist,” the Socialists tell her. “No, I am not,” she answers them. “I hate your rigid Anglo-Saxon individualism. It is just because I am so deeply social that I put my hope in the individual.” It is because she hates injustice of any sort so passionately that she adopted Anarchism as the soundest method of combating it. If you have laws you must accept the abuses of law. Why not be more completely simple—why keep on pretending that we need a machinery which fosters tyrannies instead of giving freedom an unhandicapped path to begin upon its great responsibilities? This was the idealism upon which the American founders built—a minimum of government, at least, when that evil seemed to become a necessity. In her remarkable book that has just been published, Voltarine de Cleyre discusses this phase of the matter brilliantly in a chapter called “Anarchism and American Traditions.” There is no possibility of going into it minutely here, except to ask those who insist upon regarding Anarchism as an unconstructive force to read it.

These are the things Emma Goldman is trying to preach. She does not expect to see a new order spring up in response to her vision; so the facetious ones who poke their stale jokes at the unspeakable humor of a communistic society might save their wit for more legitimate provocations. All she hopes is to quicken the consciousness of those through whom such changes will come—to improve the individual quality. It reminds you of Comte’s suggestion, at the time when he fell deliriously in love, that all the problems of society could be solved on that divine principle. It is like Tolstoy’s dream prophecy—his prediction of the time when there will be neither monogamy nor polygamy, but simply a poetogamy under which people may live freely and beautifully.

And so Emma Goldman continues her work, talking passionately to crowds of people, sickened by audiences who listen merely out of curiosity, disheartened by the vapid applause of those who make their own incapacities the burden of their rebellion, heartbroken by the masses who cannot respond to any ideal, cheered by the few who understand, dedicated to an eternal hope of new values. This is the real Emma Goldman—a visionist, if you will, but at the same time a woman with a deep faith in the superiority of reality to imagination. How she has lived life! How gallantly she makes the big out of the little and accepts without complaining the perverted role which has been thrust at her. To have seen her in her home with its hundreds of books and its charming old pictures of Ibsen and Tolstoy and Nietzsche and Kropotkin; to have seen her friends, her nephews and nieces offering her their high adoration; to have watched her gigantic tenderness, her gorgeous flinging away of self on every possible pretext; to have listened with her to great music in a kind of cosmic hush that music is made by and for such spirits; to have heard her, “the crucified,” talk of the ideal she cherishes and how her expression of it has been so far below her dream; to have compared her, an artist in life, as incapable of spiritual vulgarity as a Rodin or a Beethoven, with a sensitiveness which makes her almost fear beauty, with a sweetness that is overwhelming—to compare her with the vulgarians who denounce her is to fall into a mad rage and long to insult them desperately. I said before that Emma Goldman was the most challenging spirit in America. But she is so much more than that: she is many wonderful things which this article merely touches upon, because it is impossible to express them all.

Science is after all but a reassuring and conciliatory expression of our ignorance.—Maeterlinck.

Maxwell Bodenheim

Dawn?—no, the stunted transparency of dawn—

Color taken from the birth of a white throat

And shaken in a still cup till it gradually reaches strength

A sudden scattering of strained light—

The smile has lived and seemed to die.

Thought?—no, the invisible shudder of a perfume

Trying to leave the shadowy pain of a flesh-flower

A whisp of it whips itself away,

And leaves the rest—a cool, colorless struggle.

Sadness?—no, the growth of a pale inclination

Which knows not what it is;

Which tries to form the beginning of a swift question,

But has not yet developed trim lips.

And then what seems a smile

But is the sleeping body of a laugh.

It almost awakes, and throws out

Long breaths, in a green and yellow din.

His anger was a strained yellow wire.

You leapt into it thinking to snap it,

But it flung you off silently.

Her happiness was too apparent—

Pleasant flesh in which you sensed heavy blood-clots.

Veering, weary birds were her hatreds.

They rested on you for years,

Then circled away, still weary.

Her sorrows were clumsy, black bandages

Which seemed to hide wide wounds,

But only covered scratches.

You are a broad, growing sieve.

Men and women come to loosen your supple frame,

And weave another slim square into you—

Or perhaps a blue oblong, a saffron circle.

People fling their powdered souls at you:

You seem to loose them, but retain

The shifting shadow of a stain on your rigid lines.

Distorted ducks, smirking women and potshaped blossoms

Fastened to pale plates, you are dreary symbols of those who painted you.

O ducks, you were made by women

Who sway in and out of the waters of life,

Content to catch morsels of food from birds flying overhead.

And you smirking women, were painted by men

Who unrolled little souls on plates,

Gave them faces which could not quite hide their ugliness ...

You alone almost baffle me, potshaped blossoms—

Were you fashioned by childless women, who made you the infants

Denied them by life?

Her forehead is the wind-colored, sun-stilled wall of a country church.

Trailing cloud-shudders overhead narrow it to a thin band of vague light:

Two tarnished, exultant cerements of earth—cheeks—meet it,

And the three speak clearly, languidly.

Life was a frayed, pampered lily to him—

A lily which still clung to his gray coat,

Like an unbidden word whitening the death of a smile.

The half-smooth perfume of it touched the slanting, cambric curtain of his soul,

And stirred it to low song.

Eunice Tietjens

The spiritual dangers that beset a struggling poet are almost as numerous as his creditors, and quite as rampant. And woe unto him who falls a prey to any one of them! For poetry, being the immediate reflection of the spiritual life of its author, degenerates more quickly than almost any other form of human expression when this inner life goes astray.

There is first of all the danger of sentimentality, an ever-present, sticky danger that awaits patiently and imperturbably and has to be met afresh every day. True, if the poet yields to this danger and embraces it skillfully enough, the creditors aforementioned may sometimes be paid and much adulation acquired into the bargain—witness Ella Wheeler Wilcox—but it is at the price of artistic death.

There is the danger of giving the emotions too free rein, of producing, as Arthur Davison Ficke has said in a former number of The Little Review, merely “an inarticulate cry of emotion” which moves us like “the crying of a child.” Much of our sex poetry is of this type. On the other hand, there is the equally present danger of becoming over-intellectualized—of drying up and blowing away before the wind of human vitality. Edmund Clarence Stedman went that way. Then there is the danger of determined modernity, of resolutely setting out to be “vital” at all costs and crystallizing into mere frozen impetuosity, as Louis Untermeyer has done—and the other danger of dwelling professorially in the past with John Myers O’Hara. There is too the new danger of “cosmicality,” of which John Alford amusingly accuses our American poets of to-day. And there are many, many other pitfalls that the unsuspecting poet must meet and bridge before he can hope to win to the heights of immortality.

But there seems to be a whole new set of dangers, especially virulent, that attend the writing of vers libre, free verse, polyrhythmics, or whatever else one may choose to call the free form so prevalent to-day. These dangers are inherent in the form itself and are directly traceable to it. For contrary to the general notion on the subject, it takes a better balanced intellect to write good vers libre than to write in the old verse forms. It is essentially an art for the sophisticated, and the tyro will do well to avoid it.

The first of these dangers, and the one in which all the others take root, is a very insidious peril, and few there be who escape it. It is the danger of being obvious.

In writing rhymed or even rhymeless poetry of a conventional rhythmical pattern the mind is constantly obliged to sift and sort the various images which present themselves—to test them, and turn them this way and that, as one does pieces in a mosaic, till they at last fit more or less perfectly into the pattern. This process, although it sometimes, owing to the physical formation of the language, distorts the poet’s meaning a little, has the great artistic advantage of eliminating many casual first associations, which on careful thought are found not worth saying. It is precisely this winnowing, weighing process which the form of free verse lacks. Anything that comes to mind can be said at once, and with a little instinct for rhythm, is said. The result of this mental laziness is that the ideas expressed are often obvious.

But here a curious phenomenon of the human mind comes into play. Just as a physically lazy man will often perform great mental exertions to avoid moving, so the mind will frequently go to quite as great lengths to find unusual methods of expression to conceal, even from itself, this laziness of first thinking. The result is the attempt to cover with words the fundamental paucity of the ideas.

There are several principal effects which may result from this. One is brutality. A conception which, if spoken simply, is at once recognized as trite, may if said brutally enough pass muster as surprising and “strong.” A crude illustration of this is to be found in the recent war poetry of “mangled forms” and “gushing entrails.” Ezra Pound furnishes the most perfect example. Another effect is the tendency to the grotesque. This device is more successful in deceiving the poet himself than the other, though it has less general appeal. For it is possible, by making a thing grotesque enough, to cover almost completely the underlying conception. Skipwith Cannéll runs this danger, along with lesser men. A third peril is that which besets some of the Imagistes—the danger of reducing the idea to a minimum and relying entirely on the sound and color of the words to carry the poem.

Still another result of the complete loosening of the reins possible in vers libre is the immediate enlargement of the ego. It is not so easy to see why this should result, but it almost invariably does, and has since the days of Whitman. It usually goes to-day with the effect of brutality. The universe divides itself at once into two portions, of which the poet is by far the greater half. “I”—“I”—“I” they say, and again “I”—“I”—“I.” And having said it they appear to be vastly relieved.

The next step is to lay about them gallantly at every person or tendency that has ever annoyed them. “I have been abused” they say, “I have been neglected! You intolerable Philistines, I will get back at you!” It is odd that it never seems to occur to these young men that they can only hit those persons who read them, and that every person who reads them is at least a prospective friend. Those who neglect them they can never reach—and slapping one’s friends is an unprofitable amusement.

Examples of these unfortunate spiritual results of abandoning oneself too recklessly to the free verse form are numerous. James Oppenheim’s latest volume, Songs for the New Age—although it is in many ways an excellent work and deserves endorsement by all who really belong to the new age and are not merely accidentally alive to-day—nevertheless shows in places the tendency to obviousness and slack work.

More flagrant examples are to be found elsewhere. Take for instance Orrick Johns. Here are some stanzas from his long poem, Second Avenue, which took the prize in Mitchell Kennerley’s Lyric Year:

“How often does the wild-bloom smell

Over the mountained city reach

To hold the tawny boys in spell

Or wake the aching girls to speech?

The clouds that drift across the sea

And drift across the jagged line

Of mist-enshrouded masonry—

Hast thou forgotten these are thine?

That drift across the jagged line

Which you, my people, reared and built

To be a temple and a shrine

For gods of iron and of gilt—

The same Orrick Johns wrote this blatant bit of free verse in Poetry a few months later. Both the paucity of ideas and the enlarged ego are very well shown here:

No man shall ever read me,

For I bring about in a gesture what they cannot fathom in a life;

Yet I tell Bob and Harry and Bill—

It costs me nothing to be kind;

If I am a generous adversary, be not deceived, neither be devoted—

It is because I despise you.

Yet if any man claim to be my peer I shall meet him,

For that man has an insolence that I like;

I am beholden to him.

I know the lightning when I see it,

And the toad when I see it ...

I warn all pretenders.

But to see the tendencies of which we have spoken in their most exaggerated form it is necessary to go to Ezra Pound, the young self-expatriated American who wails because “that ass, my country, has not employed me.” His earlier work was clean-cut, sensitive poetry, some of it very beautiful. This for example:

Beautiful, tragical faces,

Ye that were whole, and are so sunken;

And, O ye vile, ye that might have been loved,

That are so sodden and drunken,

Who hath forgotten you?

O wistful, fragile faces, few out of many!

The gross, the coarse, the brazen,

God knows I cannot pity them, perhaps, as I should do,

But, oh, ye delicate, wistful faces,

Who hath forgotten you?

This, from Blast, the new English quarterly, is the latest from the same hand. The capitals are his own. The contrast needs no comment:

Let us deride the smugness of “The Times”:

GUFFAW!

So much the gagged reviewers,

It will pay them when the worms are wriggling in their vitals;

These were they who objected to newness,

HERE are their TOMB-STONES.

They supported the gag and the ring:

A little black BOX contains them.

SO shall you be also,

You slut-bellied obstructionist,

You sworn foe to free speech and good letters,

You fungus, you continuous gangrene.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I have seen many who go about with supplications,

Afraid to say how they hate you

HERE is the taste of my BOOT,

CARESS it, lick off the BLACKING.

To attempt to lay the entire onus of so flagrant a spiritual and cerebral degeneration to the writing of vers libre alone is of course impossible. But the tendency is clear. Fortunately, however, we are not all Ezra Pounds and there are still poets balanced enough to appreciate these dangers and to make of free verse the wonderful vehicle it can be in the hands of a genius.

Rabindranath Tagore

(Translated from the original Bengali by Basanta Koomar Roy, author of “Rabindranath Tagore: The Poet and His Personality.”)

Beloved, every part of my being craves for the corresponding part of yours. My heart is heavy with its own restlessness, and it yearns to fall senseless on yours.

My eyes linger on your eyes, and my lips long to attain salvation by losing their existence on your lips.

My thirsty heart is crying bitterly for the unveilment of your celestial form.

The heart is deep in the ocean of being, and I sit by the forbidding shore and moan for ever.

But to-night, beloved, I shall enter the mysteries of existence with a bosom heaving with love supreme, and my entire being shall find its eternal union in thine.

F. T. Marinetti

(Translated from the French by Anne Simon)

I want to explain to you the difference between Futurism and Anarchism.

Anarchism, denying the infinite principle of human evolution, suspends its impulse at the ideal threshold of universal peace, and before the stupid paradise of interlocked embraces in the open fields and midst the waving of palms.

We, the Futurists, on the contrary, affirm as one of our absolute principles the continuous growth and the unlimited physiological and intellectual progress of Man.

We aim beyond the hypothesis of the amicable fusion of the different races, and we admit the only possible hygiene of the World: War.

The distant goal of the anarchistic conception (a kind of sweet tenderness, sister to baseness) appears to us as an impure gangrene preluding the agony of the races.

The anarchists are satisfied in attacking the political, judicial, and economical branches of the social tree. We strive to do much more than that. We want to uproot and burn its very deepest roots; those that are planted in the brain of man, and are called:

Mania for order.

The desire for the least effort.

The fanatical adoration of the family.

The undue stress laid on sleep, and the repast at a fixed hour.

Cowardly acquiescence or quietism.

Love for the antique and the old.

The unwise preservation of everything that is wicked and sick.

The horror of the new.

Contempt for youth.

Contempt for rebellious minorities.

The veneration for time, for accumulated years, for the dead, and for the dying.

The instinctive need of laws, chains, and impediments.

Horror of violence.

Horror of the unknown and the new.

Fear of a total liberty.

Have you never seen an assemblage of young revolutionaries or anarchists?... Eh bien: there is no more discouraging spectacle.

You would observe that the urgent, immediate mania, in these red souls, is to deprive themselves quickly of their vehement independence, to give the government of their party to the oldest of their number; that is to say, to the greatest opportunist, to the most prudent, in a word, to the one who having already acquired a little force, and a little authority, will be fatally interested in conserving the present state of things, in calming violence, in opposing all desire for adventure, for risk, and heroism.

This new president, while guiding them in the general discussion with apparent equity, shall lead them like sheep to the fold of his personal interest.

Do you still believe seriously in the usefulness or desirability of conventions of revolutionary spirits?

Content yourself then, with choosing a director, or, better still, a leader of discussion. Choose for that post the youngest amongst you, the least known, the least important; only his role must never supersede the simple distribution of the word, with an absolute equality of time that he shall control, the watch in his hand.

But that which digs the deepest ditch between the futuristic and anarchistic conception, is the great problem of love, with its great tyranny of sentiment and lust, from which we want to extricate humanity.

Genius-worship is the infallible sign of an uncreative age.—Clive Bell.

The least that the state can do is to protect people who have something to say that may cause a riot. What will not cause a riot is probably not worth saying.—Clive Bell.

George Burman Foster

There is a discovery, by no means pleasing or edifying, that the student makes as he broadly surveys the history of humanity. All the great turning-points of that history seem to be inwardly associated with violent upheavals and fearful revolutions. And of all these revolutions, it may be doubted whether history records any one on so large a scale as that which confronts us under the name of Christianity, in the transition from ancient to mediæval ecclesiastical culture. It was not a single Crucified One that gave Christianity the sacred symbol of its religion; unnumbered thousands—mostly slaves—breathed out their poor lives on martyrs’ crosses. The old culture went down in rivers of blood—not too figuratively meant—and a new arose, or, better, was created. Now, what is true of this most important revolution of our antecedent cultural life is true also, in corresponding measure, of every new “becoming” in the history of peoples. No state, no church, no social form, has ever arisen but that the path of the new life has passed over ruins and graves.

Must this be so? Must it be eternally so? Is it a thing of historical inevitability, is it even a law of the very order of the world itself? The answer—first answer, at all events—is, Yes! To affirm itself, to persist as life,—this belongs as nothing else does to life’s very nature. What newly arises negates what has already arisen. All that is living pronounces a sentence of death upon all that has been alive and that now sets itself against the new life. Accordingly, we are wont to call life a struggle for existence. Old Greeks coined a phrase, Polemos pater panton: war is the father of all things. The right to life is the right of the strong.

In view of these things, may we fairly raise the question as to whether there are exceptions to so universal a rule? Were we to set up a different right, would it not be the right of the weak? Would it not be to make the sick and the infirm masters over the well and the strong? Would it not be to preach a decadent morality as do all the pusillanimous and the hirelings who beg for the protection of their weakness because they do not have the strength to drive and force their way through life?

The man who, for a generation, has been called the prophet of a new culture, this Friedrich Nietzsche, is he not, then, precisely the apostle of this man of might and mastery, of ill-famed Herrnmoral, master’s morality, especially? Napoleon, his Messiah—do you think? Did he not gloat and glory over the time when the wild roving blonde Bestie was still alive in the old Germans? Did he not worship the beast of prey, memorialize the murderer, stigmatize the morality of Christianity as a crime against life, because of its saying, Blessed are the poor and the sick, the peaceable and the meek? If, now, the word of this new prophet should make disciples, should even revolutionize the times, should we close our churches and stop our preaching, as the first thing to be done? For the churches preach goodness and love, not might and dominion; see in man child of God, not beast of prey.

If all this were a partisan matter—for or against Nietzsche—I would have nothing to do with it. To join in the damnatory fulminations against this man, or to advertise mitigating circumstances for his thought, and to re-interpret the whole from such a standpoint, until the whole should seem less brutal and less dangerous—to do either the one or the other is not for me, but for those polemicists and irenicists who are adding to the gayety of nations in these otherwise heartbreaking times, by the high debate as to whether Nietzsche be both the efficient and the final cause of our present world war. Not to defend Nietzsche, not to condemn him, but to wrestle for a firm, clear, moral view of life in our seething times, this alone is most worth while, and this too is my task.

But for all that, I do believe we must penetrate much, much deeper into this new prophet’s spirit than either friend or foe has yet done, if we are to win from Nietzsche a deepening of our own and our time’s moral view of life.

Would that we might forget, for a moment at least, all that partisan praise and blame have scraped together respecting this most modern of all philosophers; would that we might accompany him into the most hidden workshop of his own thoughts and hearken to the personal confessions of his wonderful soul! And what would we hear there? This preacher of crash and catastrophe and cataclysm, temporal and eternal, speaking of “thoughts which come with dove’s feet and steer and pilot the world”; of “the stillest hours which bring the storm.” Zarathustra-Nietzsche hears the Höllenlärm, the hellish alarum, that men make in life, that life itself makes; he observes how men lend their ears to this noise, how they are frightened by it, or exult over it, how they think that the truth is the truer where the noise is the louder, how the howling of the storm signifies to men that something good and great must be taking place, some great event of history must be under way. Then Nietzsche sets himself like a flint against this evaluation of things: “The greatest experiences, these are not our noisiest, but our stillest hours. It is not around the inventor of new noise, it is around the inventor of new values that the world revolves, inaudibly revolves.” I speak for myself alone, but these are words, Nietzsche words, for which I would gladly sacrifice whole volumes of moral and theological works. These words sharpen the eye and the ear for life-values which the majority of men today pass by—pass by more heedlessly perhaps than ever. These great words supply us with a criterion for the evaluation of questions of the moral life, a criterion that no one will cast aside who once comes to see what it means. It is a criterion without which we do not yet comprehend life in its depths, because we so constantly contemplate things from a false angle of vision. Something of the men who are carried away by “hellish alarum” lives in all of us. Let there be stillness without, and we think that there is nothing going on. Let nature peal and groan outside there, so that all gigantic forces seem to be released; then we have respect for her, we discern in such over-power even a divine creative force or a divine destructive will. Let people collide, the earth quake from thunder of cannon, and we signalize such a day in our history, pass it down from child to child, and we call such and such a battle a world-historical event.

But we forget the best. A blustering and brewing pervades nature when Spring comes over the land to conquer Winter. When we hear the conflict we cry: “Spring has come!” Not so. The true, genuine Spring-life, nascent underneath the fury, makes no noise at all, weaves away inaudibly, invisibly, in tiny seeds, and conceals in itself the noiseless new germs of life.

Thomas Carlyle, though a trifle noisy himself at times, could finely write: “Silence is the element in which great things fashion themselves together; that at length they may emerge, full-formed and majestic, into the daylight of Life, which they are thenceforth to rule.” Wordsworth, not unmindful of

“The silence that is in the starry sky”

yet, gazing on the earth about him, sang

“No sound is uttered,—but a deep

And solemn harmony pervades

The hollow vale from steep to steep

And penetrates the glades.”

And for Longfellow there is

“Hoeder, the blind old god

Whose feet are shod with silence.”