Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

CONTAINING A

FAITHFUL AND AUTHENTIC ACCOUNT

OF THE

Horrid Acts of the Noted Resurrectionists,

BISHOP, WILLIAMS, MAY,

&c., &c.

AND THEIR

TRIAL AND CONDEMNATION

At the Old Bailey,

FOR THE WILFUL MURDER OF CARLO FERRARI;

WITH

THE CRIMINALS' CONFESSIONS AFTER TRIAL.

INCLUDING ALSO THE LIFE, CHARACTER,

AND BEHAVIOUR OF THE

ATROCIOUS ELIZA ROSS,

THE MURDERER OF Mrs. WALSH,

&c., &c.

Embellished with appropriate Engravings.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE PROPRIETORS.

SOLD BY T. KELLY, 17, PATERNOSTER ROW,

And all Booksellers in the British Empire.

——

1832.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY W. CLOWES,

Stamford Street.

| PAGE | |

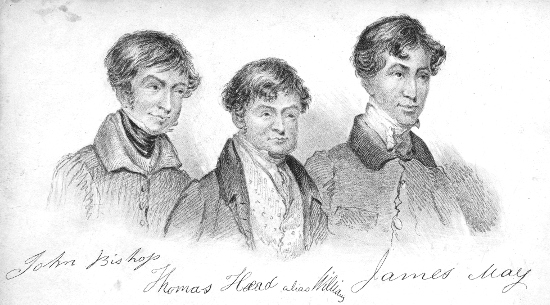

| Portraits of Bishop, Williams, and May, to face | Title |

| Bishop, &c. at Entrance of King's College | 41 |

| Carlo Ferrari | 135 |

| Bishop's Cottage | 157 |

| Eliza Ross | 279 |

| Elevation of Ross's House | 291 |

PUBLISHED BY

THOMAS KELLY, PATERNOSTER-ROW,

And sold by all Booksellers in the United Kingdom.

THE BRIGHTON MURDER.

An Authentic and Faithful History of the ATROCIOUS MURDER of CELIA HOLLOWAY, with an accurate account of all the Mysterious and Extraordinary Circumstances which led to the discovery of her Mangled Body in the Copse, in the Lover's Walk, at Preston, near Brighton; comprising other highly important particulars relating to that Horrible Act, which have never yet been made public; including also the TRIAL for the MURDER, and the Extraordinary Confession of JOHN WILLIAM HOLLOWAY; together with his LIFE, written by HIMSELF, and published by his own desire, for the benefit of Young People. Also, the History and Trial of ANN KENNETT, &c. The whole arranged from Authentic Documents, and information supplied by the Family of Holloway, and other individuals concerned in the Discovery of the Murder. Accompanied by Portraits from Life, and Views, taken on the Spot, of the local scenery connected with the Murder, drawn by Mr. Parez, and engraved expressly to illustrate this Work.

Published in Four Parts, at 2s., or Sixteen Numbers, at 6d. each.

THE POLSTEAD MURDER.

An Authentic and Faithful History of the MYSTERIOUS MURDER of MARIA MARTEN, with a Full Development of all the Extraordinary Circumstances which led to the Discovery of her Body in the RED BARN; including many very Interesting Particulars of the village of Polstead and its neighbourhood, never before printed. Together with the TRIAL AT LARGE of WILLIAM CORDER for the MURDER; specially taken in short-hand by the Author of this History, exclusively for the present Work; the whole being the result of laborious personal inquiry and investigation, aided by the Communications of the Family of Maria Marten, and many of the respectable inhabitants of Polstead and its vicinity. Illustrated by Portraits drawn from Life, and other highly interesting copperplate engravings of Plans, Views, &c. Published in Twenty-four Numbers, price Sixpence each, and in Six Parts at Two Shillings.

THURTELL, HUNT, AND PROBERT.

An Authentic and Faithful History of the MURDER of W. WEARE, with a Full Disclosure of all the Extraordinary Circumstances connected therewith; the TRIAL at LARGE of the prisoners, taken in short-hand by a Gentleman specially retained for this Edition. To which is added, the GAMBLER'S SCOURGE; or, a Complete Exposé of the whole system of Gambling in the Metropolis. Illustrated by Portraits drawn from life, and other highly interesting copperplate engravings of Plans, Views, &c.

Published in Twenty-two Numbers, price Sixpence each.

The NEWGATE CALENDAR IMPROVED; being Interesting Memoirs of the most Notorious Characters, who have been convicted of offences against the laws of England during the Eighteenth Century; and continued to the present time, chronologically arranged; comprising Traitors, Murderers, Incendiaries, Ravishers, Pirates, Mutineers, Coiners, Highwaymen, Footpads, House-breakers, Rioters, Extortioners, Sharpers, Forgers, Pickpockets, Fraudulent Bankrupts, Money-droppers, Impostors, and Thieves of every description; and containing a number of interesting cases never before published. With Occasional Remarks on Crimes and Punishments; Original Anecdotes; Moral Reflections and Observations on particular cases; Explanations of the Criminal Laws; the Speeches, Confessions, and last Exclamations of Sufferers. To which is added, a Correct Account of the various Modes of Punishment of Criminals in different parts of the World. By GEORGE THEODORE WILKINSON, Esq.

To be completed in about One Hundred and Fifty Numbers, price Sixpence each, and embellished with numerous curious and appropriate Engravings.

GALLOWAY AND HEBERT'S History and Progress of the STEAM-ENGINE; with a practical investigation of its Structure and Application; containing also Minute Descriptions of all the various Improved Boilers; the constituent parts of Steam-Engines; the Machinery used in Steam Navigation; the New Plans for Steam Carriages; and a variety of Engines for the application of other Motive Powers; with an Experimental Dissertation on the Nature and Properties of Steam, and other Elastic Vapours; the strength and weight of materials, &c., &c. Illustrated by upwards of Three Hundred Engravings. Published in Nine Parts, at Two Shillings, or Thirty-six Numbers, at Sixpence each.

OF THE

NOTED RESURRECTIONISTS,

BISHOP, WILLIAMS, MAY,

&c. &c.

Whatever may be said of the great advantages arising to the community at large from the march of intellect, which has almost become a bye-word for derision, it cannot be disputed that daily experience teaches us, that in regard to the atrocity of crime, in its most appalling nature, instances have of late occurred of the most unexampled extent and magnitude, and which cover us with confusion and dismay. It would appear, in fact, that with the growth of the illumination of the mind, the degeneracy of the heart has increased, and that fresh sources of guilt have opened themselves, in proportion as the endeavours of the schoolmaster have been directed to their extinction. It is true, indeed, that murder is a crime which has been committed in all ages, and in all countries. It was, in fact, the first crime by which the human race exhibited their natural depravity. But the idea of reducing murder to a system was reserved as the distinguishing feature of the present century; indeed, blots more deep and foul appear to be attached to this era, than to any that have preceded it; and although we may boast, with some degree of justice, that in some[Pg 2] instances it has its brighter spots, yet it is nevertheless a truth too melancholy to be questioned, that it has also its darker shades and its more appalling obscurations.

It is a trite axiom in politics, that private benefit must yield to public good; but it is not therefore a natural corollary, that private feelings are to be outraged, and the entire happiness of the social circle to be destroyed by the desperate acts of a gang of miscreants, who make a trade of human life, and murder the defenceless and unprotected, on the mere ground that it is contributary and indispensable to the interests and advancement of a particular science. Weak and imbecile must that government be, which, with the knowledge of the laws and customs of other countries in regard to the procuring of an adequate supply of human corpses for the purpose of instruction to the anatomical student, conjoined with the advice and experience of native talent, cannot devise some effectual measures for the remedy of an evil, which has of late years grown to such an alarming magnitude, as actually to alter the relations of society, and to establish a system of terror, at once inconsistent with individual happiness. The meritorious endeavours of Mr. Warburton during the last session of parliament were directed to this subject; but, with a most contradictory spirit of opposition, it was urged that the feelings of the inmates of a work-house, having no relations nor friends belonging to them, and who, at their death, would be huddled into a grave like so many dogs, were not to be harassed nor wounded; whilst, at the same time, the sanctity of the grave was to be violated,—the unprotected stranger in our land, perambulating our streets to earn his sorry pittance,—the wretched prostitute, discarded from her parents' house,—and, finally, the helpless decrepitude[Pg 3] of age, were to be sacrificed by the inhuman butchery of the systematic murderers; and the legislature of the most enlightened nation of the earth (that is, which is boasted to be such) was to look dispassionately on, and wink at the enormity of the crime, on the plea that the interests of science demanded it. The detection of the atrocities of Burke, confessing, as he did, to nineteen murders, ought to have been sufficient to arouse the vigilance of an enlightened legislature to the enactment of those laws which would have put an effectual stop to a repetition of such a horrid system of murder, and have rescued the country from the onus of that disgrace which now lies so heavily upon it. On this point, however, the supineness of the government has been culpable in the highest degree; for to question its knowledge of the existence of the evil, were to suppose that it possesses no information of the dangerous acts of certain individuals, or that it was utterly bereft of the means of detecting them, and of bringing them to justice for the enormity of their crimes. We do not hesitate to declare that an organised system of murder has been and is still carrying on in the metropolis, which makes humanity shudder, which cannot be paralleled in any other civilized country of the globe, and which, unless the legislature will rouse itself, and inflict the same punishment upon the receiver of the stolen property as upon the thief, will, in a short time, go to undermine all the happiness of social life. It has always appeared to us a strange anomaly in the distribution of the laws of this country, why the purchaser or receiver of a dead body, which, from its very nature and character, must be stolen property, should not be subject to the same punishment as the individual who purchases a stolen handkerchief or a watch. It is possible, and very probable, that the purchaser of the latter articles[Pg 4] does not know that it is stolen property; but if a resurrectionist presents himself at the door of the King's College, or any of the private dissecting rooms, bearing on his head a hamper containing the corpse of a human being, the purchaser then knows that the subject must be either murdered or stolen. If, then, according to the spirit of the laws of England, the receiver is equally guilty with the thief, where is the law that exempts the receiver of a stolen body from the full penalty of its infliction? We acknowledge that a difficulty may be here started, that it would not, perhaps, be practicable to establish a right of property in a corpse, and that, of course, it would not be possible for any individual to prosecute for the felony. But if such difficulty does actually exist, and we speak advisedly upon the subject, the legislature has it in its power to obviate it altogether by making the mortal contents of our cemeteries the property of the crown. Any person, therefore, abstracting any part of that property might be indictable for felony, and the receiver or purchaser of such property prosecuted as an accessory. The anatomical student will then undoubtedly exclaim against the government, and accuse it of having closed up the sources by which he is to perfect himself in the knowledge of the science. It will then become the aim of the legislature to discover other sources, which may yield to the student the necessary materials for his tuition, without inflicting so severe and incurable a wound upon the tenderest feelings of our nature, and giving support and encouragement to the horrid crime of murder.

It is to the foreign travellers in this country that we are principally indebted for a true and impartial history of our public and domestic polity. The proverbial partiality of an Englishman to his own country naturally renders him blind to its defects; but[Pg 5] what must be the opinion of a foreigner of the civilization of this country, when he is informed that there are regularly established houses in this metropolis[1], sanctioned by a licence from the magistrates as public-houses, which are known as houses of call for the different gangs of resurrectionists, and where, if a human corpse be wanted by any of the colleges, hospitals, or private dissecting rooms, an application is sure to meet with success. The offer of a good price is held out—the chance is not to be lost—success is dubious, and perhaps hopeless, by the regular process of exhumation; and then the first wandering outcast, who appears to have nothing in the world nor on the world belonging to him, is decoyed away to some obscure habitation, where, as in the cases of Bishop and Williams, the darkness of night is expected to cover the horrid crime of murder.

Melancholy, however, and deplorable is the truth, that there is a set of earthly fiends, bearing the human shape of women, who are the secret panders of the resurrectionists, and who, for a trifling share of the booty, will co-operate with them in their murderous practices. We allude to the female keepers of the low brothels in the different parts of the town,[Pg 6] and especially in the immediate neighbourhood of Wentworth Street, Spitalfields, the resort of the lowest class of prostitutes, where, if one of them be suddenly missed from her accustomed haunts, it is but the gossip of the moment; and, in certain cases, it is apparently so satisfactorily accounted for, that no further inquiry is deemed necessary; the practice adopted by the female wretch is generally upon the following plan:—Having selected her victim from the wretched horde, who appears to be the most destitute, or who will not tell that she has, or who, in reality, perhaps, has not any relations in the world, the information is given to the resurrectionist, who, under pretence of purchasing her favours, entices her away to some obscure place, where the work of murder is accomplished. She is missed by her companions, and the keeper of the brothel is questioned as to her knowledge of what has become of her. Ah! replies the wretch, it is a very bad business—she robbed a sailor of two sovereigns, and hearing that the police-officers were after her, she has thought it best for her to go out of the neighbourhood. It appears to all the inquirers that it is a very likely case, that the theft was committed; and it is equally natural that she should run away after it. The unfortunate creature is never seen again, and, in a very short time, it is forgotten that such a being existed upon the earth.

In the progress of this work we shall be able to expose many circumstances connected with this horrid traffic in human flesh, at which the human heart revolts, and which are of so hideous a character, that, were not our authority incontestable, we should treat them as fictions almost impossible to be realized in actual life; but when we state, that we know of the existence of human shambles, where the leg, or the arm, or the head of a human being, can[Pg 7] be purchased with the same facility as a leg of mutton or a sirloin of beef, we may then with shame ask ourselves the question—Can this be England—the most enlightened, the most civilized country of the globe? We wish to speak with respect of the established authorities of the land, and we will continue to do so, as long as those authorities act with a due regard to the interests of the people, and to the preservation of general and individual happiness; but when we see such alarming evils carried on under the immediate observation, and, we will go further and say, with the knowledge and tacit concurrence of an efficient and powerful magistracy, we consider that we are only performing a part of that duty which we owe to our country, to excite the legislature, by all the means in our power, and all the information we possess, to a serious and solemn investigation of the whole case, and, by the enactment of some strong and penal laws, bring down the merited degree of punishment on the heads of the offenders, and thereby rescue the country from the odium and the disgrace which are at present attached to it.

With this preliminary matter, we shall enter upon the immediate subject of our history, reserving to ourselves the privilege of interposing our own comments on those particular parts of it, which appear to us as possessing the greatest interest and importance.

It was on Saturday night, the 5th of November, that four men were brought in custody to Bow Street Office, guarded by a strong body of police, charged upon suspicion with the murder of a boy, whose name was unknown. From the appearance of the body of the deceased, and from the fact that two of the prisoners were well known resurrectionists, the rumour almost instantly spread, that the unfortunate boy was[Pg 8] burked by the prisoners; and the crowds which surrounded the office, and pressed forward to hear the examination, were far greater than were ever remembered on any former occasion. Several gentlemen belonging to the King's College were present.

As soon as the sitting magistrate, Mr. Minshull, had taken his place, the prisoners were placed at the bar, and answered to their names as follows:—James May, Michael Shields, Thomas Williams, and John Bishop.

Mr. Thomas, the Superintendent of the Police, then came forward, and having been sworn, said, that he charged the prisoners at the bar with the suspicion of having been concerned in the murder of a boy, aged about fourteen years, whose name he was unable to state. It was not in his power, at that time, to offer any direct evidence against the prisoners, but a gentleman, connected with the surgical department of the King's College, to whom the body had been offered for sale, was then present, and would state the circumstances which caused his suspicions, and induced him to cause the apprehension of the prisoners.

Mr. Richard Partridge, of Lancaster Place, was then sworn, and stated, that he was demonstrator of anatomy at the King's College, and had seen the body in question, which the prisoners had brought that day to the College. The body was that of a boy, apparently about fourteen years of age; and from the suspicious appearances which it presented, he was induced to believe that death had been produced by violence.

Mr. Minshull.—Be good enough to state upon what grounds you came to that resolution.

Mr. Partridge.—The body appeared to me to be unusually fresh, much more so than bodies generally[Pg 9] are, that are used for dissection; the face was much discoloured, and blood appeared to have been forced through the lips and eyes; the upper part of the breast-bone had the appearance as if it had been driven in, and there was a wound on the left temple, about an inch in length. The teeth were all extracted, and blood was flowing from the mouth.

Mr. Minshull.—Had the body, in your opinion, ever been buried?

Mr. Partridge.—I should say not; and I judge so from the rigidity of the limbs and muscles.

Mr. Minshull.—From all that you have observed, can you undertake to say, that the several marks of violence on the body, or any one injury in particular, occasioned death?

Mr. Partridge.—I have not as yet sufficiently examined the body, and am, therefore, not prepared to answer that question. The pressure on the breast-bone might have occasioned death, but I cannot, at present, say that it did, as I do not know the extent of the injury.

Mr. Minshull.—Do I understand you to mean, that, to the best of your belief, the body of the deceased had never been buried, and that, as far as you have as yet been able to form a judgment, the boy did not die a natural death?

Mr. Partridge replied, that such was his present opinion.

Mr. Thomas here observed, that a medical gentleman, of the name of Edwards, who had seen the body, stated his belief that death had taken place within the last twelve hours. That gentleman was not present, but he (Mr. Thomas) could send for him.

Mr. Minshull said, that he would probably require his attendance, but it was not necessary at present. The magistrate then asked what evidence[Pg 10] there was to connect the prisoners with the possession of the body.

Mr. Thomas replied, that the person was present who received the body when it was brought to the College.

A person named Hill then came forward, and having been sworn, said, that he held the situation of porter to the dissecting room at the King's College. Between two and three o'clock that day (Nov. 5) the body was brought to the dissecting room, by the four men at the bar; the prisoner Shields carried the body in a hamper on his head, and he, witness, observed to him, that he had not seen him lately. Shields then placed the hamper on the floor, and the prisoners, Bishop and May, assisted in unpacking it, and the body, which appeared to be that of a boy between fourteen and sixteen years of age, was then taken out.

We request particular attention to the evidence here given, as it is our intention to offer some serious comments on it, when comparing it with the evidence given during the trial. We were in court during the whole of it, and although the murderer is generally convicted on circumstantial evidence, yet, if the confessions of the criminals are to be relied on, which they voluntarily gave after their condemnation; perhaps, in no case of murder which ever came before a tribunal of this country, was a more erroneous evidence given as to the causes which were supposed to lead to the death of the murdered boy. It would be premature in this early stage of the business, to make any comment on the high eulogium which the Duke of Sussex was pleased to pass, on the manner in which the prosecution was conducted, and the consequent pride which inflated his breast, at the thought that he was a prince of the country in which such consummate ability was displayed—if his Royal[Pg 11] Highness had been most graciously pleased to add, that he was ashamed of being the prince of a country, in which such horrid crimes could be committed, so as to render such a prosecution necessary, we should have considered it as far more becoming his character, and smacking less of that fulsome panegyrical flummery, which the great are apt to use towards the great, in order to make themselves appear still greater in their own eyes than they really are.

We return to the examination.

Mr. Minshull.—Did anything particular strike you on seeing the body?

Hill.—Yes; I thought it looked unusually fresh, and I asked May what it had died of? He replied, that he neither knew nor cared, that it was no business of his, or words to that effect. I then made an observation respecting the cut which I saw upon the forehead, and Bishop accounted for it by saying that it was done in getting the body out of the hamper.

Mr. Minshull.—Was there anything on the floor when the body was taken from the hamper, which could have caused such a wound?

Hill.—Certainly not.

Mr. Thomas here observed, that the cut on the forehead had all the appearance of having been recently inflicted. The blood flowed from it in streams.

The prisoner May here said, Did not that blood proceed from the mouth, and was it not caused by the teeth having been drawn out?

The witness, Hill, replied, that it certainly might be so.

May.—Oh it might, might it!

Mr. Minshull asked the witness if he perceived any blood flow from the wound on the forehead.

Hill replied in the affirmative, but said, that the[Pg 12] greater flow of blood was from the mouth. It streamed from thence on the breast. He then resumed his statement, and said, that on perceiving the state in which the body appeared, he observed to the prisoners, that he did not like the appearance of the subject. It was too fresh. The prisoners did not appear to pay any attention to this, and May, pointing to the body, said, Is it not a fresh one? He, (witness,) replied, yes; and then the prisoners asked him for the money.

Mr. Minshull.—Do you mean the price which they were to receive for the body?

Hill.—Yes; but I wished to see Mr. Partridge before I should pay them, and I told the prisoners to come outside, as I could not pay them there. The witness then went on to say, that he went to Mr. Partridge, who on seeing the body, said he did not like to have anything to do with it; that it was too fresh, and had a very suspicious appearance; and he told witness to tell the prisoners to wait until change of a note was procured, which was done for the purpose of keeping them where they were until the police should arrive.

Mr. Minshull asked what sum had been agreed upon for the purchase of the body?

The witness said, that the men came to the dissecting-room in the morning, between eleven and twelve o'clock, saying, that they had a subject to sell, and to know if one was wanted. Witness communicated the offer to Mr. Partridge, who came into the room where the prisoners were. They then told him they had a subject to sell, and described it, saying that the price was twelve guineas. Mr. Partridge replied, that he did not particularly want a subject then, and soon after he left the room; but instructed him (the witness) to offer the prisoners nine guineas for the body. The prisoners consented[Pg 13] to take that sum, and said, they would go and fetch the body.

Mr. Minshull.—Was no inquiry made as to how the prisoners became possessed of the body, particularly after they had described it as being so fresh?

Hill.—I did not ask that question—we are not in the habit of doing so.

Mr. Minshull.—Was it by direction of the persons in the College under whom you act, that the prisoners were taken into custody?

Hill.—Certainly; Mr. Partridge, and the gentlemen who belong to his class, agreed, that the appearance of the body was so suspicious, that information should be given to the police.

Mr. Minshull.—In so doing they acted very properly.

The magistrate then asked whether the prisoners had in any way accounted for the possession of the body.

Mr. Thomas replied, that the prisoner Bishop told him he got the body at Guy's Hospital, and employed the prisoner Shields to carry it from thence to the King's College. As this declaration on the part of Bishop appeared to be very important, he (Mr. Thomas) sent a message to Guy's Hospital, to request to know whether a boy answering the description of the deceased, had died there lately. He received for answer, a slip of paper stating that, since the 28th ultimo, three persons had died there; that one was a woman, and the other two were males, aged thirty-three and thirty-seven, so that the statement of Bishop as to where he obtained the body could not be true.

Mr. Minshull asked if any person had been to claim the body?

Mr. Thomas replied, that a gentleman was present, whose son, a boy, aged fourteen, was missing[Pg 14] since Tuesday; he had been to see the body, but found it was not his son.

Mr. Hart, a respectable tradesman, residing at No. 356, Oxford-street, then came forward, evidently in great distress of mind, and in answer to questions by the magistrate, said, that his boy left home in the afternoon of Tuesday last, and was never seen since, although he had been advertised in the newspapers, and every possible means had been used for his recovery. The poor man wept bitterly, while he deplored his loss, and seemed to think that his son had been made away with by some abominable means, and disposed of to the surgeons; a circumstance which he considered not at all unlikely, from the facility with which bodies appeared to be disposed of at dissecting-rooms, as proved by the evidence of the witness Hill.

Mr. Minshull, addressing the prisoners, told them that he was ready to hear anything which they wished to state, but at the same time he felt it his duty to caution them as to what they should say, because it would be taken down in writing by the clerk, and, whether favourable or otherwise, it would be produced as evidence at their trial, if he should decide to commit them.

The prisoner Bishop said, that he had nothing to add to what he had already stated. He got the body at Guy's Hospital, and employed Shields to convey it to the King's College.

Williams and Shields declared their innocence, and the latter said, that he merely acted in the matter, as porter to Bishop.

The prisoner May, who was dressed in a countryman's frock, and who appeared perfectly careless during the examination, in answer to the question, if he wished to say anything, replied, that he knew nothing at all about the matter, and said that he[Pg 15] merely came to the College to get some money that was due to him. It was not my subject, he added, and I know nothing about it.

Here two or three constables, who were in the body of the office, exclaimed, that they knew May to be a noted resurrectionist; and one of them said, he had him in custody at Worship-street Office for stealing a dead body.

The prisoner turned furiously round to the quarter from which the voice proceeded, and dared the constable to produce his proof.

Mr. Thomas said that May's left hand was tied up, and it might be of importance to know whether it was owing to a cut.

Mr. Minshull requested Mr. Partridge to examine the wound; and having done so, he said that the top of the fore-finger of the left hand was slightly injured, either from a cut or a bite. It had been poulticed, and the wound might have been inflicted two or three days ago.

Mr. Minshull said that he should remand the prisoners until the following Tuesday, and in the mean time, he requested Mr. Partridge and some other professional gentlemen would closely examine the body of the deceased, so as to be enabled to come to a positive conclusion as to the cause of his death. He then directed that the prisoners should be confined in separate cells, and that no communication should be allowed to take place between them.

Mr. Thomas said that it would be necessary to watch them very closely, as they were all desperate characters, and made a violent resistance before they were secured.

The prisoners were then removed to the cells at the back of the office; and as they passed from the[Pg 16] bar, they were groaned and hissed at by some persons in the office.

Mr. Berconi, an Italian image-maker, residing in Great Russell Street, came to the office just as the prisoners were removed, and said he had seen the body of the boy, and from what he could judge of its appearance, he was induced to believe that the deceased was a Genoese by birth, and had obtained his livelihood by selling images in the streets.

The sequel will show, that in this opinion Mr. Berconi was decidedly in an error; but it is very probable that this opinion, expressed by Mr. Berconi, led to the idea, that the deceased was one of those itinerant Italians who perambulate our streets with their monkeys; and as one of them had been lately missing, it was immediately concluded that the deceased was the missing boy. It is not the least remarkable part of this extraordinary business, that the body of the deceased was never fully identified; on the contrary, Berin, the person who brought the boy from his native country, when called upon to identify the body as being that of Carlo Ferrari, unequivocally declared, that he could not positively speak to the identity of it, on account of the change which the countenance exhibited, arising from the violence that had been used. Mrs. Paragalli, it is true, swore to the body, as being that of the Italian boy, whose name she did not know, but whom she remembered perambulating the streets with a tortoise and some white mice. It will be proved in the sequel, from the confession of the murderers themselves, that the deceased was not an Italian at all, but a boy who had come from Lincolnshire with a drove of cattle; and thus we have an instance, hitherto unexampled in the annals of our criminal tribunals, of three persons being indicted for the[Pg 17] murder of a boy of the name of Carlo Ferrari, found guilty, and hanged for the crime, when the fact subsequently transpires, that the murdered boy was not Carlo Ferrari at all. We shall reserve any further comments on this most extraordinary affair, till we come to the confession of the murderers, when, unless their veracity be impugned, and the facts as stated by them altogether invalidated, we shall not hesitate to express our opinion, that, although the criminals have richly deserved the punishment which has been meted out to them, yet that they were convicted upon circumstantial evidence only, and that such evidence was in itself decidedly false.

It was not, however, Mr. Berconi himself who identified the body; but in the course of the following day (Sunday), several applications were made at the station-house to see the unfortunate boy, and then it was that two or three persons recognised him as the poor little fellow who used to go about the streets, hugging a live tortoise, and soliciting, with a smiling countenance, in broken English and Italian, a few coppers for the use of himself and his dumb friend.

Here then lies the origin of the mistake of the identity of the body; but it excites our surprise in no small degree, that any individuals should take upon themselves to identify a body, the features of which were wholly disfigured by a violent death, which features were only known to them, by a passing glance at the individual when alive, as an itinerant beggar upon the streets, and the impression of which might be wholly effaced from their memory a few minutes afterwards. There have been instances in which the countenance has been so altered, even by a natural death, as not to be identified by those who have been the daily associates of the individual whilst in life—how much more liable then to doubt[Pg 18] and suspicion must the identity of a body be, which has come to its death by violent means, and the acquaintance with which during life was nothing more than the casual passing glance in the public streets! The manifest error into which those persons fell, cannot fail to operate as a salutary warning to others, not to express their opinion so dogmatically and decisively, unless the fullest conviction is impressed on their minds of the truth of their depositions.

The deceased appeared to be about four feet six inches high, and had light hair and grey eyes. The former itself is a very unusual feature of an Italian boy. He had a scar on his left hand, and it was then supposed that the teeth had been removed for the double purpose of selling them to a dentist and preventing the identity of the body. The appearance of the corpse was that of perfect health. The face was covered with clotted blood, and the arms, back, and chest had evidently been rubbed with clay to give the body the appearance of its having been disinterred. The cut on the forehead, although small in size, appeared to have been inflicted with some deadly instrument, which had beaten in about half an inch of the temple, without, however, fracturing any part of the bone. There were some black spots on the left wrist, which appeared to have been occasioned by the death grasp of a powerful hand. The breast-bone, as described by the witnesses, appeared as if it had been forced in by violent pressure. The countenance of the boy did not exhibit the least distortion, but, on the contrary, it wore the repose of sleep, and the same open and good humoured expression, which must have marked the features in life, was still discernible. The eyes, however, were bloodshot, and there was a suffusion on the countenance, which in some degree indicated [Pg 19]strangulation. It was intended to have proceeded immediately to an examination by the surgeons, but this proceeding was obliged to be suspended until the arrival of the coroner's warrant, which was expected on Sunday night, the 26th.

The sensation which the murder of the boy excited in the metropolis may be said to be almost unprecedented; it was not regarded as one of those murders which stain our criminal annals; but when the fact transpired, that it had been committed by a gang of resurrectionists, the alarm spread into the bosom of every family. The dreadful deeds of Burke and his associates arose to the memory in all their appalling horrors, and if a child or a husband was absent a longer time from home than usual, the maternal fear immediately arose that the burkers had been at work. Thus, as we have stated in a former page, Mr. Hart, of Oxford-street, suspected that his son had been burked, but he was found drowned in the Regent's Canal. The following circumstance will, however, sufficiently show how much disposed the people were at this time to construe every act, having the least grounds of suspicion attached to it, as having an immediate reference to the acts of the burkers.

In the Times newspaper appeared a paragraph from Lambeth street office, telling a mysterious story of a drunken man having been taken from the middle of the street, and placed against the door of a house, which was shortly after opened, and the drunken man dragged in, while, in a short time afterwards, a cart was seen to drive up to the door, into which a coffin was put, after which the cart drove off at a furious rate. It was added, that the inhabitants of the house, although respectable, were not known in the neighbourhood, and the tenor of the article went to prove that it was a nest of body-snatchers. On[Pg 20] the Wednesday following, the case was fully explained at Lambeth street, when Mr. Wyatt, the occupant of the house referred to, stated that he had remained at home the last two or three days, being unwell, and while sitting in his parlour had observed persons stop and walk before the house; some made remarks on a hole in the wall, made to allow some fowls which he kept to pass in and out of the cellar, and others looked over the blinds into the room. All this he considered very singular, but could not account for it, until a neighbour called, and directed his attention to the statement which had appeared in the papers. He then went out to inquire into the origin of the rumour; and during his absence, on Tuesday evening, a mob collected round the house, making the most discordant yells and noises, and calling out 'Burkers!' and 'Body-snatchers!' to the great terror of his aged mother and sister, the only persons at home. He knew nothing of the drunken man having been placed against his door; but with respect to the other transaction, he explained, that the mother of Mr. Nutt had resided with his mother, and died in the house last week. The cart was sent by Mr. Nutt's undertaker to remove the body, she having expressed an earnest wish to be buried in Bermondsey, where she lived formerly. Mr. Nutt, in support of this explanation, produced a certificate of the burial of his mother on the 16th of November, signed by the Rev. J. E. Gibson, the Rector of St. John's, Bermondsey.

Mr. Hardwicke observed that the whole story was most absurd, and expressed himself in warm terms at the folly of giving it publicity. A case of mere suspicion ought, on no account, to be made public; and if it were not safe to hear such cases in the office, it would be necessary in future to hear them in a private room.

We do not mention these circumstances to repress proper precautions or due vigilance, but to show the weakness of giving way too freely to feelings of alarm groundlessly excited.

It was at three o'clock on Tuesday, the 8th of November, that the inquest was holden at the Unicorn public-house, corner of Henrietta-street, Covent-garden, before Mr. Gell, the coroner, with the view to ascertain the circumstances which led to the death of the Italian boy, whose name is unknown, and with the murder of whom four men, namely, Bishop, May, Williams, and Shields then stood charged. The room in which the inquest took place was crowded almost to suffocation. The prisoners were conveyed to Bow-street in the afternoon, under a strong escort of police, but the inquest having been adjourned, their presence was not required before the coroner.

We solicit particular attention to the evidence here given before the coroner, as facts are there sworn to, on which the conviction of the accused parties took place, but which have now been determined to be totally false.

William Hill was the first witness sworn. He resides at No. 7, Craven-buildings, Drury-lane. His evidence was to the following effect:—I am dissecting porter at King's College, Strand. The deceased was brought to the college on Saturday last, the 5th, between two and three o'clock in the afternoon; my bell was rung by one of the four men in custody, and, in consequence, I went to the door of the dissecting room; I there saw the four men, May, Bishop, Shields, and Williams. I had seen May and Bishop between eleven and twelve that morning, who asked me if I wanted any thing? I replied, not particularly; but I asked them what they had got? May replied, that he had got a male subject. I asked him what[Pg 22] age? he replied, fourteen. I then asked him the price of it? he answered, twelve guineas. I told him we would not give that price: but that I would speak to Mr. Partridge, the Demonstrator of Anatomy to the College. I then went to Mr. Partridge, and we both joined May and Bishop. The former was much in liquor; after some conversation with the men, Mr. Partridge went away; the men remained, and I followed Mr. Partridge, who desired me to offer them nine guineas. May said he would not take less than ten; but nine guineas were ultimately agreed to. The men then went away, and returned again between two and three o'clock, accompanied by Shields and Williams, who brought the body of the deceased in a hamper. I admitted May and Bishop only, and they deposited the body in a room of the College, and then they proceeded to unpack the hamper, and took out a sack containing the body of the deceased, and laid it on the floor. I observed to them, that the body was particularly fresh, and said, at the same time, I wonder what it could have died of. I made an observation respecting a cut in the forehead, when Bishop said, that cut had been done by May in taking the body out of the sack; adding, that he (May) was drunk. The body was stiffer than usual; the eyes appeared very fresh, although blood-shot, and the lips full of blood. I saw a quantity of blood on the chest, part of which seemed as if recently wiped off. They then asked for the nine guineas; and I went to Mr. Partridge, and stated to him, that I thought all was not right. Mr. Partridge then came and viewed the body. May and Bishop were not then present. Mr. Partridge, after viewing the body, went away; and, in the mean time, some of our pupils having seen the body, conceived it was that of a boy who had been advertised: they also said, that there appeared to be[Pg 23] marks of violence on the body; and a communication having taken place between Mr. Partridge and some of the gentlemen of his class, the police were sent for, and the four men were given into custody.

By the Coroner, at the suggestion of Mr. Thomas.—I did not ask them how they got the body, because I never ask such a question. It is not likely they would have answered me truly, if I had.

Mr. George Beaman, of 28, James-street, Covent-garden, examined. I am a surgeon, and was called upon by Mr. Thomas, Superintendent of Police, on Saturday last, to inspect the body of the deceased. I did so about twelve o'clock on the same night; the body appeared to me to have very recently died, and I should think not more than from twenty-four to thirty-six hours. The body was stiff, the face appeared swollen, the eyes full, prominent, and very fresh; the external coat of the eyes was much bloodshot, and there was a wound in the forehead, over the left brow, nearly an inch in length, and of the depth of about one-eighth of an inch; blood was flowing from this wound, and, upon my using pressure, to detect invisible fracture, a small additional quantity of blood then oozed out. All the front teeth had been drawn, the tongue was swollen, but I did not then perceive any more marks of violence on the body. I examined the neck, throat, and chest, very particularly: there were no marks of pressure on these parts, and I was induced to examine them more particularly, the face and tongue, and the eyes being so full and bloodshot. On the following evening (Sunday), with the assistance of Mr. Mayo, Mr. Partridge, and others, I commenced the dissection of the body. I then very particularly observed the external appearance of the neck, throat, and chest, and I used a sponge and warm water to cleanse them thoroughly. There were not the slightest marks of violence. I[Pg 24] then examined the head, and, upon turning back the skin, which covers the upper part of the skull, I detected a patch of extravasated blood directly beneath the skin. This patch must be the effect of accident or violence. The bone underneath was not injured. The skull-cap was then removed. The membrane investing the brain appeared rather more florid than usual. The substance of the brain was perfectly healthy throughout. The spine was next examined, and on the skin being removed from the lower part of the head, extending to the shoulders below, a good deal of blood was extravasated. This I have no doubt was the effect of great violence. There was no fracture of the spine; but on removing the arch, with the view of observing the spinal marrow, a quantity of coagulated blood was found within the spinal canal, pressing upon the marrow, and I have no doubt, in the present instance, that what I have just described was the cause of death, namely, the extravasation of blood into the upper part of the spinal canal.

Coroner.—Do you suppose that the death of the deceased would have been occasioned by the appearance you have described, without producing any external wound?

Witness.—I do. The wound on the forehead could not of itself produce death.

The witness then proceeded to state that, in his opinion, some blows must have been given to the deceased with a blunt stick, bludgeon, or other blunt instrument, or even by the fist of a strong man. It was impossible that the indigestion could have produced such effects. The body, in every other respect, was perfectly healthy. A fall, to occasion death, would have left some more serious external appearances. The heart and lungs were perfectly healthy, and upon removing the contents of the stomach, and[Pg 25] pouring them into a basin, for the purpose of being analyzed, he observed that it was of a perfectly healthy structure; digestion was going on at the time of death. He did not believe that the body had ever been interred. The stomach contained a tolerably full meal, and smelt slightly of rum (this circumstance is accounted for in the confession of Bishop). Unquestionably the deceased did not die from suffocation or strangulation.

Mr. Thomas here intimated to the coroner, that the Rev. Mr. Bernasconi had just seen the body, and recognized the boy as one of his flock, but could not tell his name.

Mr. Richard Partridge, of No. 8, Lancaster-place, Surgeon, sworn. I am Demonstrator of Anatomy at the King's College. I know nothing of the men now in custody; but on Saturday last, I saw two men, Bishop and May, as I have since understood their names to be, at the College, and I agreed to purchase of them the dead body of a youth aged about fourteen years. The body of the deceased was brought to the College that same afternoon, and in consequence of a message brought to me by the witness Hill, I went and examined the body, and on a second examination, the suspicious appearances which it presented struck me forcibly. I then went to the secretary's office, and having strong suspicions that all was not right, I procured some police-officers, who in my presence apprehended May and Bishop, and the other two men who were waiting outside. I delayed May and Bishop until the officers arrived, by showing them a fifty-pound note, which I told them I wanted the change of in order to pay them for the body.

The evidence of Mr. Beaman was here read over by the coroner, who asked Mr. Partridge if he [Pg 26]coincided with the testimony given by that gentleman, with regard to the appearances of the body.

Mr. Partridge observed, that he perfectly agreed with all that Mr. Beaman had said, with regard to the appearances described by him, and considered that the cause of death had probably arisen from the injuries described to have taken place at the back of the neck. Those injuries might have occasioned death, certainly, but all the other appearances, as described by Mr. Beaman, might have resulted from a natural death.

Thomas Davis examined.—I am porter at the dissecting-rooms, Guy's Hospital. On Friday evening last, May and Bishop brought to the hospital a sack, containing, as they said, a dead body, which they offered to sell. I told them that it was not wanted, as the gentlemen were already supplied. They then asked permission to leave it that night in the hospital, which I allowed. The next morning (Saturday), between, I think, eleven and twelve o'clock, I saw May and Bishop about the hospital. I went out, and on my return found that the body had been taken away, and that it had been removed at half-past twelve or one o'clock. My assistant, James Wix, delivered the sack containing the body to some persons, but to whom I cannot say.

By the Coroner.—I am persuaded that the body was never taken out of the sack whilst in the hospital.

Mr. Charles Starbuck, Stockbroker, of No. 10, Broad-street Buildings, City, one of the Society of Friends, on his solemn affirmation, deposed as follows:—In consequence of the report which I read in the Times newspaper of Monday last, I went to see the body of the deceased, and have no doubt that it is the body of an Italian boy, whom I have[Pg 27] frequently seen at the Bank. On last Thursday evening, the 3d instant, between half-past six and eight, I saw an Italian lad, whom I suppose to be the deceased, sitting near the Bank, with his face almost in his lap. He attracted attention from his position, having a mouse-trap under his arm. A youth told him to get up, as the police were coming, or words to that effect. I remarked to my brother, I think he is unwell; and my brother replied, I think he is a humbug, for I have frequently seen him in that position. There were several men and women around him. I have seen the body yesterday and to-day, and have little doubt but it is that of the Italian boy so described. I have not seen the boy since alive.

Margaret Perrigalli, of No. 11, Parker-street, Drury-lane, sworn.—On Sunday morning last I saw the body of the deceased. I do not know the name of the boy; he was an Italian. I have known him for the whole of last summer, and I am quite certain the dead body is that of the boy I have known so long. On Tuesday the 1st instant, I saw him alive in Oxford-street, carrying a mouse-trap.

Mr. George Duchoz, surgeon, of 34, Golden-square, was then sworn and examined. I attended the post mortem examination of the boy on Sunday evening last, and my opinion is, that he died suddenly, from external violence, and that the injuries at the back of the neck were quite sufficient to have caused death. I have seen similar appearances, however, in the body of a man, who died from having fallen down stairs. There is no doubt but that death, in this instance, must have been instantaneous, and might certainly have been produced by a blow from a bludgeon on the back of the neck. I observed a mark on the right wrist, apparently produced by pressure. Mr. Duchoz stated his firm opinion that[Pg 28] the boy had first been stunned by a blow on the head, and afterwards that his neck had been dislocated, in the same manner as it was usual to wring the neck of a duck.

We have given the latter part of this opinion in Italics, as, when we come to contrast it with the confession of Bishop, it will be found that just as much value ought to be attached to it, and that it was just as consistent with the real truth, as if Mr. Duchoz had declared that the boy had died by natural means. We speak it not personally, but it is sometimes deplorable to hear the opinion of professional men touching certain points connected with life and death, and which are afterwards to be made the groundwork of a criminal prosecution. We see no reason to dispute the veracity of Bishop or Williams' confessions; for in the awful situation in which they stood, falsehood could not avail them anything, nor can any ostensible motive be discovered for their leaving behind them an erroneous statement, which went to exonerate no one from any imputed charge, nor which subtracted in the least degree from their own criminality. They confess not only to one but to other murders; but they declare that the boy, whose corpse they attempted to sell at King's College, and on which they were apprehended, was not Carlo Ferrari, but a Lincolnshire youth, who had brought a drove of cattle from that county. What then becomes of the identity of Bernasconi, Starbuck, and Perrigalli? What becomes of the evidence of the professional men as to the cause of the death of the presumed Carlo Ferrari, when it is found, by the confession of the murderers themselves, to have been effected by wholly different means? And, lastly, we may ask, (and we shall have occasion, at a future period, to dilate more fully on the subject,) what sort of a character does the prosecution itself exhibit to the country, when three individuals can be[Pg 29] arraigned at the bar for the murder of a certain boy by a blow or blows on the back of the neck with an instrument, according to the jargon of the law, of no value whatever; that these same individuals shall be convicted of the crime, according to the declaration of the Recorder, on the most conclusive and incontrovertible evidence; and then, in less than twenty-four hours afterwards, it shall transpire, that the boy so murdered was not the boy for whose murder the parties were arraigned—that his death was not occasioned by any blow, but actually by suffocation, and consequently that the conviction took place on evidence which, throughout, was decidedly false.

We are willing to bestow on Mr. Thomas all the credit which he deserves for his meritorious exertions in bringing the miscreants to the bar of their country to answer for their crimes; but we cannot refrain from observing, that in collecting the evidence for the prosecution, recourse has been had to some measures which appear highly overstrained, and which, in fact, could never be received as evidence in any English court of justice. We will select the following as an instance.

Mr. Duchoz having informed the jury that the neck of the boy appeared to be dislocated in the same manner as it is usual to wring the neck of a duck, Mr. Thomas proceeded to state, that in consequence of a communication which he received on Saturday afternoon from the King's College, he sent officers to that place to take the four men into custody, which was done, after a desperate resistance had been made by the prisoners. Witness sent for the body, and asked Bishop what he was. He replied, "A b——y body-snatcher." He had seen the four prisoners within the last fifteen minutes, and asked them if they had any wish to see the jury.[Pg 30] May replied, "Not I—I have nothing to say about it." Bishop said, "The body is mine; and if you want to know how I got it, you may find it out if you can." Shields' answer was, that he was employed by Bishop to carry the body from Guy's Hospital to the King's College. The prisoner Williams said, that he knew nothing at all about the matter, and that he merely went with the prisoners to see the King's College. Mr. Thomas added, that he received a letter that afternoon, stating that a tortoise, similar to the one which it is supposed the deceased was in the habit of carrying about, was exhibited for sale in a shop in Middle Row, Holborn. He immediately went to the shop, and took possession of the tortoise now produced, (for which act Mr. Thomas rendered himself liable to an action for felony). He asked the woman of the shop how she became possessed of it; and she answered, that her husband had purchased it in Leadenhall Market, of a person whom she did not know; adding, that such things were usually bought and sold there.

Joseph Perrigalli, husband of the woman already examined, was then sworn, and stated, that he had known the deceased boy for nearly twelve months, and well recollected his having carried a tortoise with him. The tortoise, which he was in the habit of carrying, was very like the one now produced; and he, witness, saw it in the possession of the deceased about a month ago. The deceased used to carry mice as well. He examined the body last Sunday morning, and was quite certain it was the boy whom he knew so well.

Now, would the evidence of the tortoise have been admitted in any court of justice whatever? It was well known that the Italian boy carried a tortoise; Mr. Thomas hears of a tortoise being in Middle Row, Holborn—hurries to take possession[Pg 31] of it—produces it before the jury—and calls a Frenchman to depose that it is very like the tortoise which the Italian boy carried about with him. We believe that all tortoises are alike, and that it would not be so easy to prove the identity of any individual of the species, as has been evinced in the proof of the identity of Carlo Ferrari. If Mr. Thomas had received a letter, stating that a tortoise was in either of the two great Zoological Gardens, and it is just as probable that the tortoise of Carlo Ferrari should have fallen into the possession of the proprietors of those establishments, as into that of the woman in Middle Row,—would Mr. Thomas have so far committed himself, as to repair to the Gardens, and bring the animal away with him? It is by no means an uncommon thing to see a tortoise exposed for sale in Leadenhall Market, and Mr. Thomas had it not in his power to produce an iota of proof, that the tortoise which the woman purchased in that market, was the identical one of Carlo Ferrari, but simply that it was very like it. It is true, that the configurations of the shell of the tortoise are not always similar; but on that point no proof is produced that the tortoise of Carlo Ferrari, and of the woman in Middle Row, resembled each other; and, therefore, we cannot forbear expressing our regret, that any recourse should have been had to such a flimsy evidence, and which would have been immediately rejected by the judge appointed to try the criminals.

Mr. Thomas, in continuation of the statement, said, that since the deceased had been brought to the Station House, he had had no less than eight applications to see the body by parents, who had, within a very short space of time, lost their sons, who were generally described as boys about the age of thirteen or fourteen. The parents could in no way account for their absence, and they all appeared[Pg 32] in the greatest distress of mind. One of the boys so lost was deaf and dumb.

The coroner and the jury expressed their greatest surprise at the statement, and Mr. Cribb, the foreman of the jury, observed, that he had no doubt whatever of the fact, for he had himself seen the parents of two boys who had disappeared, call at the Station House on Sunday morning, in order to see the body of the deceased.

A juryman said, that the fact stated by Mr. Thomas afforded the strongest possible reason for pursuing the present inquiry to the utmost.

After some further conversation, the jury wished the room to be cleared, in order, we believe, to discuss the propriety, either of adjourning the inquest, with a view to obtain further evidence, or to call the parties charged before them, in order to hear any further explanation touching their possession of the body, which they might feel inclined to give.

The room was accordingly cleared at seven o'clock, and after remaining together about twenty minutes, it was announced that the inquest was adjourned until five o'clock on Thursday evening next.

Mr. Corder, the vestry clerk of St. Paul's, Covent Garden, was present, and took notes of the proceedings on behalf of the parish, who, in the event of the case being sent for trial to the Old Bailey, will become the prosecutors.

Pursuant to the adjournment, the jury again met on Thursday evening, the 10th of November, at the same house, and the room, as before, was crowded in every part, and a crowd of persons were outside, anxious to hear the verdict.

After the jury had been sworn, Mr. Cribb, the foreman, produced a letter, which he said he had received from Mr. Starbuck, the stock-broker in the[Pg 33] city. The letter was handed to the coroner, who read it to the jury. It stated that Mr. Starbuck had been mistaken with regard to the identity of the boy whom he supposed to be an Italian lad, and whom he had seen near the Bank on the night of Thursday. He had since seen that boy alive.

Here then, we find one individual retracting his opinion of the identity of the boy; and it therefore now solely rests on the testimony of Mr. and Mrs. Parragalli, who are just as likely to have been mistaken as the worthy Quaker.

The evidence of the witnesses was then resumed.

Joseph Higgins, constable of the F division of police, sworn.—I live at No. 8, Newton Street, Holborn. Yesterday, about four o'clock, I went to a public-house in Giltspur Street, called the Fortune of War. I there saw Mrs. Bishop, and Mrs. Williams her daughter, coming out, and I told them I must take them to the Station House. Mrs. Bishop begged of me to let her go home for her child, which I consented to do, but I said I must go with her. I then went with them to No. 3, Nova Scotia Gardens, Crabtree Row, Hackney Road. I proceeded to search the house, and found the implements I now produce. I said, "I know what those are for;" and she replied, "I dare say you do, but do not speak before the children." I found two crooked chisels, which Mrs. Bishop admitted were for opening coffins. I also found a brad-awl with dry blood upon it; I said, "this is for punching out teeth." She replied, "her husband had used it for mending shoes." I also found a file. I then searched Mrs. Bishop, and found upon her the petition which I now produce. She told me it was from her husband, and three other persons for pecuniary assistance, saying that they were resurrectionists, and they had no means of defending themselves from the[Pg 34] offence for which they were charged. The petition, which was as follows, was then read:—

The humble Petition of John Bishop, and three others,

Most humbly showeth,

'That your petitioners have supplied many subjects on various occasions to the several hospitals; and being now in custody, they are conscious in their own minds that they have done nothing more than they have been in the constant habit of doing as resurrectionists, but, being unable to prove their innocence without professional advice, they humbly crave the commiseration of gentlemen who may feel inclined to give some trifling assistance, in order to afford them the opportunity of clearing away the imputation alleged against them. The most trifling sum will be gratefully acknowledged; and your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray.'

This petition was not signed.

She admitted, that Williams was not her son-in-law's right name, but said, he did not wish it to be known, as he had been out with her husband not more than two or three times. She added, that her husband went out the night before he was taken into custody, accompanied by her son-in-law, Williams, and that he came home the next morning, and washed his hands in a basin, at the bottom of which she saw a great deal of mud.

James Weeks, examined.—I am assistant to Mr. Davis, porter at the dissecting-room, Guy's Hospital. I know May and Bishop; and on Friday the 4th instant, about five minutes past seven, I went to the hospital and saw them there. They left a sack at the hospital, containing something, and I saw projecting through a hole in the sack a portion of a knee of a human being. I heard May say to Mr. Davis, 'The fact is, the subject don't belong to me, but to Bishop.' Mr. Davis on this request allowed them to leave the sack with its contents in[Pg 35] the hospital. They then went away, and came to the hospital the next morning about one o'clock, with two other persons, and I delivered the sack, with its contents to May and Bishop. The sack was locked up in a room the whole of the night, and it was delivered just as it was received the night before. The body could not have been changed. I do not think the subject was a full-grown person. The parties brought a hamper with them, into which they put the sack.

James Appleton, of No. 4, St. George's-road, near New Kent-road, procurator to Mr. Grainger, Surgeon, sworn.—On Friday evening, about half-past seven, May and Bishop came to Mr. Grainger's Theatre of Anatomy, Webb-street, Southwark, where I was, and they asked if I wanted a subject. I inquired the age and sex, and the reply was, a boy about fourteen years old. I declined to purchase it. They told me it was a very fresh subject. They then went away, and came again to me at the theatre next morning (Saturday) about eleven o'clock, and inquired again if I would purchase the body, but I again declined it.

Mr. Thomas here produced a letter, in which it was stated that Mr. Appleton had declared to a postman, that the body was warm when offered for sale to him, and that he declined the purchase for that reason.

The Coroner asked if the fact were so?

The witness declared he never saw the body, and positively declared that he never spoke a word to a postman on the subject.

Mr. Cribb, the foreman of the jury, asked the witness whether he had any particular reason for declining to purchase the body.

The witness replied that he had no other reason[Pg 36] than that of not wanting it, as the theatre was already supplied.

A Juror.—What was your motive for asking the sex of the subject?

Witness.—Because many of the pupils prefer a male to a female subject.

After a long desultory conversation as to whether the inquiry should proceed further,

Mr. Corder said, that he really did not think there was any further evidence to produce at present, tending to throw any additional light upon the inquiry. If, however, the jury should return a verdict of wilful murder against some person or persons unknown, the inquiry would be pursued at Bow-street Office, where the four men were now in custody. He (Mr. Corder) had reason to believe that his Majesty's Government, struck with the importance of the inquiry, would lend every facility tending to bring the affair into a proper train, in order that public justice might not be defeated. He then suggested that the accused should be sent for, with a view to see whether or not they felt inclined to account for the possession of the body.

A Juror observed, that they were as yet proceeding in the dark, inasmuch as they had not yet ascertained the name of the deceased or to whom he belonged.

Mr. Corder replied, that he understood, from inquiries that he had made, that the name of the murdered boy was Giovanni Montero, and that he was brought to this country, from Italy, about a year ago, by a native of that country, named Peter Massa.

Joseph Parragalli here said, that from inquiries he had made at the Alien Office, and from the description given of Massa's boy in his passport, he[Pg 37] was quite sure that he could not be the same boy, whose death was now the subject of inquiry.

It was here determined by the Jury to have the prisoners before them.

The Prisoner Michael Shields was then brought forth strongly guarded, and the Coroner addressing him said, 'You are not obliged to answer any questions that may be put to you unless you please, but I tell you fairly, that we have sufficient evidence before us to prove, that the deceased boy came to his death by unfair means; and having traced the body into your custody, we wish to know whether you are inclined to give any explanation touching your possession of the body in question. Should you feel inclined to state what you know, I am anxious to caution you to speak the truth.' The prisoner said, he was willing to speak the truth, and having been sworn, he deposed as follows:-

My name is Michael Shields. I live at No. 6, Eagle Street, Red Lion Square. I am a porter; and on Saturday last, the 5th instant, about ten o'clock in the morning, I was hired by Bishop, whom I met in Covent Garden. Bishop said, he had a little job to do, to go over London Bridge. I said I would go. I then went with him to a public-house, right opposite Guy's Hospital, where he left me, and returned in about an hour, in company with May and Williams. We then went together into Guy's Hospital, and, after waiting there half an hour, I saw a man in a flannel jacket; that man and Bishop had a hamper, directed to —— Hill, Esq., King's College. They then put the hamper on my knot, telling me to be careful not to fall down. I went off with the hamper over London Bridge, accompanied by May, Bishop, and Williams. Had never been to the King's College before. They went first, and I followed into the College. The door was opened[Pg 38] by a man, and they (Bishop, May, and Williams) took the hamper from me, leaving me outside. About three-quarters of an hour after this I was apprehended by the police, previously to which Bishop, Williams, and May, were apprehended also.

Coroner.—Is that all you have to say?

Prisoner.-That is all, your honour; if I was to speak my last words I did not know what the hamper contained. I sometimes assist the grave-digger of St. Giles's parish in digging graves, whenever he is overrun.

Coroner.—How long have you known Bishop?

Prisoner.—About eight or nine months, I should think. I don't know, in particular, how he got his livelihood. I don't know as he dealt in dead bodies before now; I was never employed 'in this way' by Bishop before. I was to be paid half-a-crown for this job. I can swear that May and Williams never employed me to carry dead bodies. I can't say that I never worked for a resurrectionist before. I had no reason to suspect, prior to this event, that Bishop, May, and Williams were resurrectionists. I do not know where they lived. It was on London Bridge that I met Williams, who had an empty hamper, which I took from him, and carried it to Guy's Hospital, and some person there took it from me and brought it in, and I then went to the public-house. I have carried hampers and boxes before to hospitals and dissecting-rooms.

Mr. Corder.—Were you at the Fortune of War public-house on Friday last?

Prisoner.—I might have been.

Mr. Corder.—Did you not see Bishop and May there?

Prisoner.—They might be there. (The prisoner, on being further pressed, admitted that they were there; and said, that Bishop told him he should[Pg 39] want him the next morning to do a job for him.) I very often go to the Fortune of War. I remained there for about half an hour, and I met Bishop and May there by accident. They went away before I left. When I said that I met Bishop and May in Covent Garden at ten o'clock on Friday morning, I did not speak the truth. I now state that I met him at the Fortune of War, on the Friday morning, at eight o'clock.

Mr. Corder.—I suppose that you know that the Fortune of War is a sort of house of call for resurrectionists?

Prisoner.—It may be. I have seen several respectable persons there.

Mr. Cribb.—Now, Shields, answer this question truly. Do you know anything relating to the death of the deceased?

Prisoner.—Bishop said, while coming to Bow-street, in the van, that the body was got from the ground, and that he knew where it was got from. He smiled as he said so, adding, that if he was brought before the Jury he would give them ease about it.

The examination of Shields having been concluded, the prisoner Bishop was brought before the Jury; and the Coroner cautioned him as to the awkward situation in which he stood, there being no doubt but that the boy had been unfairly dealt by.

Bishop.—I dug the body out of the grave: the reason why I decline to say the grave I took it out of is, that there were two watchmen on the ground, and they intrusted me, and being men of family, I don't wish to 'deceive' them. I don't think I can say anything more. I took it for sale to Guy's Hospital, and, as they did not want it, I left it there all night and part of the next day, and then I removed it to the King's College. That is all I can say about it. I mean to say that this is the truth. I shall [Pg 40]certainly keep it a secret where I got the body. I know nothing as to how it died.

Coroner.—You have a right not to implicate yourself; and certainly I must say, that the account which you have given is by no means satisfactory.

Bishop was then removed, and the prisoner May was brought forward, and cautioned in the same way as the other prisoners. He was told that the result of the inquiry might affect his life, and if he said anything, it would be produced as evidence against him.

The prisoner said he wished to say what he knew, and would speak the truth. He then said, that his name was James May, and that he lived in Dorset-street, Newington. He went into the country on Sunday week, and returned on the evening of Wednesday, and went to Mr. Grainger's, in Webb-street, with a couple of subjects. On the following morning (Thursday) he removed them to Mr. Davis's, at Guy's; and, after receiving the money, he went away to the Fortune of War, in Smithfield, and stayed there about two or three hours. Between four and five o'clock, to the best of his recollection, he went to Nag's-head-court, Golden-lane, and there he stopped with a female until between eleven and twelve o'clock the next day (Friday). From Golden-lane he went to the Fortune of War again, and stopped drinking there until six o'clock, or half-past. Williams and Bishop both came in there, and asked him, if he would stand anything to drink? which he did. Bishop then called him out, and asked him, where he could get the best price for 'things?' he told him where he had sold two (meaning Guy's); and he (Bishop) then told him, that he had got a good subject, and had been offered eight guineas for it. He (May) replied, that he could get more for it; and then Bishop said, all that he could get over nine guineas he might have for himself. He agreed to[Pg 41] it; and they went from thence to the Old Bailey, and had some tea at the Watering-house there, leaving Williams at the Fortune of War. After tea they called a chariot off the stand, and drove to Bishop's house. When there, Bishop showed him the lad in a box or trunk. He (May) then put it into a sack, and brought it to the chariot, and conveyed it to Mr. Davis, at Guy's. Mr. Davis said, you know, John, I can't take it, because I took two of you yesterday, and I have not got names enough down for one, or I would take it. He (May) then asked him if he could leave the body there that night? and he said he might. Bishop then desired Mr. Davis not to let any person have it, as it was his subject, but to deliver it to his own self. He (May) also told Davis not to let the body go without him, or he should be money out of pocket. May then went on to state, that he went to his own house, and slept there that night, and the next morning he went to Guy's, and Bishop and Shields came in with a hamper, which was taken to King's College, where he was taken into custody. The prisoner said that he had spoken the truth, and nothing else. He was then removed, and the other prisoner,

John Williams, was brought in; and being cautioned not to say anything to criminate himself, he stated that, in the first place, he met Bishop on last Saturday morning, in Long-lane, Smithfield, and asked him where he was going? He said he was going to the King's College. They then went into the Fortune of War public-house, and after that Bishop went to Guy's Hospital, and then to the King's College. May and the porter met them against the gate. Bishop went in, and he (Williams) asked him to let him go in with him. That was all he had got to say, except that a porter took a basket[Pg 42] from the Fortune of War to Guy's Hospital, and he (Williams) helped him a part of the way with it.

The prisoner was then removed.

James Seagrove, a cabriolet driver, swore positively, that a quarter before six o'clock on Friday evening he was sitting in a public-house in the Old Bailey, when two men (May and Bishop) came in, and the taller of the two told him that they wanted him to do a job. Witness answered that there were a great many jobs, long and short ones. May then said, that he wanted him to carry a 'stiff un.' Witness asked what he meant to pay him for it. The witness then went on to state, that he declined the offer of May and Bishop, and afterwards saw them trying to make a bargain with a coachman on the stand. May had previously offered witness a guinea for the job. The witness added that he meant to do them, and appeared to consent at first merely for the purpose of hearing a little of the tricks of body-snatchers.

The room was about to be cleared, when

William Hill, the porter at the dissecting-rooms, King's College, begged to add to his former evidence, that when there was a delay in paying Bishop and May for the body, the former said to Mr. Partridge, Give me what money you have got in your purse, and I will call for the remainder on Monday. It was very unusual for persons selling dead bodies to go away with part payment only, unless something was wrong; they generally wait for their money.

The room was then cleared, and at half-past ten o'clock the Jury came to the following verdict:—

We find a verdict of Wilful Murder against some person or persons unknown; and the Jury beg to add to the above verdict, that the evidence produced before them has excited very[Pg 43] strong suspicions in their minds against the prisoners Bishop and Williams, and they trust that a strict inquiry will be made into the case by the Police Magistrates.