Hyphenation has been standardised.

Other changes made are noted at the end of the book.

AIRMAN:

HIS LIFE AND WORK

H. G. HAWKER, AIRMAN:

HIS LIFE AND WORK

By

MURIEL HAWKER

WITH A FOREWORD BY

Lt.-Col. J. T. C. MOORE-BRABAZON, M.C., M.P.

WITH FRONTISPIECE AND 24 ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON:

HUTCHINSON & CO.

PATERNOSTER ROW

By Lt.-Col. J. T. C. MOORE-BRABAZON, M.C., M.P.

I have been shown the great honour by Mrs. Hawker of being asked to write a Foreword to this book about her late husband. I can do nothing better than give the advice to all to read it, because, if they have followed aviation for some time back, they will live over again that heroic epoch when flight was really being made possible and will appreciate some of the difficulties and many of the successes that make the early days of aviation such a fascinating story; and if, on the other hand, they have only taken an interest in aviation lately, they will get conveyed to them from this book the atmosphere that pervaded the little community of enthusiasts who existed in the early days.

The figure of Hawker looms up large in the early days of aviation, and such was the man, that even after the war, with the hundreds of thousands of people that came into the movement, he still stood out a noteworthy figure.

His name will go down for all time coupled with others who gave their lives for the cause, such as Rolls, Grace, Cody.

It does indeed show a singular change in the mentality of the nation that the most popular sporting figures of recent times have been men whose prowess has been associated with their domination over machinery rather than animals. The bicycle was the instrument that first compelled the attention of all to a knowledge of mechanics, the motor-car demanded further knowledge on the subject, but it was not until the advent of the aeroplane that the imagination of the youth of this country was fired to appreciate the necessity for knowledge of mechanics.

Hawker, thirty years ago, was an impossibility, but when he died he was the idealised sportsman of the youth of the country, and it was rightly so. Modest in triumph, hard-working, a tremendous “sticker,” yet possessed of that vision without which no man can succeed, he stands out a figure whose loss we mourn even to-day, but whose life and career will serve as an example for others to attempt to follow.

J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon

July 4, 1922.

With his words still fresh in my memory, that, should anything ever happen to him, the one thing to do was to get work which would occupy my mind, I took upon myself the task of writing my husband’s life. I have been encouraged by many letters from people suggesting my undertaking this work, and, thus encouraged, I present this book.

I make no apologies for the errors of style, the technicalities of which I know nothing, but I have tried in simple language to convey some idea of the great work and spirit of one who attempted much, and, although crowned by few successes, was never for one moment discouraged as a loser.

I leave others to judge the merits of his works, but I leave to no one but myself the disclosure of the real goodness of his nature. This book being, more or less, a record of his achievements, it has been difficult to convey any idea of his true worth, which did not stand in anything he did, but in the firmness with which he held to what he considered was right. This sense of honour, not cultivated but innate, kept the fame, which he earned, from detracting in any way from the integrity of his character, and he always remained to the end his cheery, unaffected self.

His buoyant nature did not admit of defeat. I have never seen him disheartened and never has he given in. He always did his very best, and was ever ready to try again when that best was not good enough.

At the height of his popularity he declined good financial offers for lecturing tours in England and the States, which would have kept him for the rest of his life. Money could not divert him from his calling.

His goodness of heart would never let him turn away anyone in distress, and, in this, lack of discrimination played a big part.

Many people came to the house after his attempt to fly the Atlantic, with pitiful tales of woe. One, a musician, who said he had fallen on bad times, wanted a loan of £10, stating that he was a member of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, in which he played a mandoline. He got his £10, but I do not believe the mandoline has ever figured amongst the instruments in the Queen’s Hall Orchestra.

A few days later another musician, very probably a friend of the first, arrived, but Harry said he would not see him. However, he was so persistent that Harry saw him at last, and heard his tale, which was to the effect that unless he could get a certain sum of money he would be sold up the next day, and, rather than that, he intended taking his life that night, although he had a wife and child. With tears, he asked if his life was not worth the few pounds, which he would surely return within a month. He received his cheque, left some of his own compositions for me to try, which he said he would call for when he repaid his debt, and was never seen again.

It would seem that Harry’s perfections have been exploited and his imperfections ignored, but I find the first so easy, my pen willingly covering many pages, and the second, not irksome, since his very imperfections were interesting, but hard to define.

Before our marriage he warned me of his terrible temper, which, he said, appeared at intervals, making him for a short time an unapproachable individual, and advised me that on such occasions I should leave him completely alone. I never witnessed one of these outbreaks and doubt if they ever occurred. Fits of irritability would seize him, sometimes for little or no apparent cause, and at others under great provocation, and while they lasted he was a very trying companion. But he would not be irritated for long; and these, I think, must have been his fits of terrible temper.

If neglect of his financial responsibilities, through disinterestedness, was a fault, then he had a big one. He was as unmercenary [xi]as it is possible for a normal man to be. He liked to have money in order to procure the necessaries of his hobby, but the matter of procuring proper payment for the work he did he left entirely in the hands of those for whom he was working, to pay him what they thought fit. And having received the money, the proper investment of it he ignored, until he was reminded, leaving his money idle in the bank. In his last year of life he began to look at these things more seriously, as his outgoings had increased and his income diminished, and, with the responsibilities of a company under his own name, probably another year would have made him a different man—a business man perhaps, but never so great a man.

I should like to mention here a trouble we often encountered and which was a great worry to us both, however we tried to ignore it.

I refer to the people who persist in suggesting that a man with dependants should not continually risk his life unless they were securely provided for. How many a man has been asked upon marriage to give up his work, if it happens to be of a precarious nature, and the firm, instead of having made progress with the new partner, has decayed because that partner did not face the risks the old one was willing to sustain? Never will I understand why a man of a hazardous career should have to choose between that career and the comforts of his own home, and possible parenthood, because of a fearful dread of a premature parting which is allowed to exist.

Harry was a true optimist, and the way he came out of his many troubles warranted his optimism. It was so natural if he had a smash to know he was not hurt, or if he had any trouble it would be righted very quickly. This feeling is so real that, even now, apart from all religion, I know he has come up smiling somewhere and all is well with him.

MURIEL HAWKER.

(POST SCRIPTUM)

The production of this book has necessitated the collecting and sifting of a considerable amount of detail, particularly as regards the earlier chapters and those dealing with the Atlantic flight. In this and in the general plan of the book I have received considerable assistance from Mr. W. R. Douglas Shaw, F.R.S.A., who has rendered invaluable help in many ways through his wide knowledge of aeronautical matters.

This introduction would not be complete without my also acknowledging the help received from Lt.-Commander Mackenzie-Grieve, R.N., who has kindly read through the chapters dealing with the Atlantic flight; from Mr. Alan R. Fenn, formerly of the Sopwith Aviation Company, for details of Harry’s experiences at Villacoublay; from the authorities at Australia House in allowing me to consult their records, and from many others who have contributed in various ways to this work.

My acknowledgments are also due to the Press, on whose reports I have relied in many cases, and I would mention The Times, Morning Post, The Daily Mail, Temple Press, Iliffe & Sons, Flight, The Aeroplane, and particularly the kindness of the proprietors of the Melbourne Argus and Sydney Bulletin in giving me free access to their files of 1913-14.

MURIEL HAWKER.

May, 1922.

| PAGE | |

| FOREWORD | vii |

| PREFACE | ix |

| PREFATORY NOTE | xiii |

| CHAPTER I EARLY STRUGGLES |

|

| Harry’s Parents—His Sisters and Brothers—Schooldays—Four Schools in Six Years—The Attraction of a Cadet Corps—Motor Work at Twelve Years of Age—The Expert of Fifteen—Managing a Fleet of Cars—First Desire to Fly—The Kindness of Mr. and Mrs. McPhee—Harry Meets Busteed—And Comes to England with Him—Kauper—Seeing London—Quest for Employment—A Job at Sevenpence per Hour—Another at Ninepence-Halfpenny—Thoughts of Returning to Australia—Forty Pounds in the Bank—Kauper Strikes Oil—And Helps Harry—Sigrist—How Harry was Happy on Two Pounds per Week—His First Flight—Reminiscences of Brooklands Days | 25 |

| CHAPTER II THE BRITISH DURATION RECORD |

|

| Harry’s Aversion to Publicity—Circumstances of His First Brooklands Associations—The Sopwith-Burgess-Wright Biplane—Harry’s Effort in a Quick-Starting Competition—Beating His Employer—Early Attempts for Michelin Laurels—A Real Success—Tuning-up for the Duration Record—Raynham Makes a Race—And Secures an Advantage—Raynham Lands after 7 hours 31½ minutes—And Holds the Record for an Hour or Two—Opportunity Knocks at Harry’s Door—And is Well Received—Harry Lands after 8 hours 23 minutes—To Him the Spoils—His Own Account of the Experience—A Reminiscence of Cody—The Significance of Harry’s Achievement—Other Flights at Brooklands—The Growth of a Pioneer Firm | 35 |

| CHAPTER III ABOUT ALTITUDE AND OTHER RECORDS |

|

| A Colleague’s Impression of Harry in 1913—Harry in the Passenger’s Seat—“Aerial Leap-Frog”—Competition Flights at Brooklands—Testing the First “Bat Boat”—End of the First “Bat Boat”—Harry as a Salesman-Demonstrator—Testing the Second “Bat Boat”—70 Miles per Hour in 1913—Asçent to 7,450 feet in 15 minutes—A Prize Flight—How Harry Deserted from a Race which He Won—How a Biplane Beat a Monoplane—More Seaplane Testing—The British Altitude Record—11,450 Feet—“Bravo, Hawker!”—A Journalist’s Tribute—Flying in a High Wind—To the Isle of Wight and Back | 53 |

| [xvi] | |

| CHAPTER IV AMPHIBIANS—AND MORE HEIGHT RECORDS |

|

| An Amphibian of 1913—Harry Gets Up to 13,000 feet with a Passenger—Several Other Height Records—Three Climbs in One Day—The Progress of the Sopwith Enterprise—Several Types of Aeroplanes—And Seaplanes—Harry Wins the Mortimer Singer Prize—And Has Time to Spare—A Friendly Race with Hamel—A World’s Height Record—A Cross-Country Race—Preliminaries of the Round-Britain Seaplane Flight—Conditions Governing the Daily Mail £5,000 Prize | 63 |

| CHAPTER V FIRST ATTEMPT TO FLY ROUND BRITAIN |

|

| The Task of the Flight Round Britain—And the Machine for the Job—Public Interest in the Pilot—“Good Luck!”—The Night Before the Start—A Mayor’s Early Call—And the Sequel—The Scene at the Start—To Ramsgate at Sixty Miles per Hour—An Aerial Escort—The Ramsgate Cup—Fog in the Thames Mouth—To Yarmouth in Next to No Time—Harry Collapses—Pickles Relieves Him—And Meets with Misfortune—Starting All Over Again | 77 |

| CHAPTER VI SECOND ATTEMPT TO FLY ROUND BRITAIN |

|

| Harry Recovers—And Takes Charge Again—An Early Start—Almost Unseen by the Starter—Thick Fog—Behind Time at Ramsgate—An Explosion—A Favourable Breeze—But Bumpy Air off Cromer—Scarborough—A Forced Landing—Five Hundred Miles in a Day—Resting at Beadnell Overnight—The Second Day—A Spiral Glide at Aberdeen—A Terrible Journey to Oban—The Third Day—A Water-logged Float—Another Forced Landing—Ireland—“A Piece of Ghastly Bad Luck”—Kauper Goes to Hospital | 93 |

| CHAPTER VII A BIG CHEQUE, AN AERIAL DERBY, AND OTHER EVENTS |

|

| Echoes of the Seaplane Flight—Mr. Winston Churchill’s Views—Back to Work—The £1,000 Cheque—And a Gold Medal from Margate—The Carping Critic—And the Reply he Received—An Expedition to Eastchurch—Lost in the Air—Racing a Powerful Monoplane—An Exciting Aerial Derby—Hamel’s Bad Luck—Harry Finishes Third—And in the Sealed Handicap is Fourth—A Bad Crash at Hendon—Other Races—Michelin Efforts Again—Harry’s Bad Luck—He Puts Up Some Wonderful Flights—A Headache in the Air | 103 |

| [xvii] | |

| CHAPTER VIII THE PROTOTYPE OF THE FIGHTING SCOUTS |

|

| Harry’s Stroke of Genius—Ninety Miles per Hour with an 80 h.p. Gnome—When German Interests were at Brooklands—The Real Value of “Stunting”—A Biplane that Exceeded Expectations—When Hendon was Surprised—Construction of the Tabloid—Contemporary Sopwith Products—In Harry’s Absence—Pixton Pilots a Tabloid to Victory—A £26,000 Ante-Bellum Aviation Company—Mr. Rutherford—Another Type of Genius—One of Harry’s Records Broken—An Australian Poem—Death of Hamel | 119 |

| CHAPTER IX AERIAL PROPAGANDA IN AUSTRALIA |

|

| Back to Australia—Harry Expresses Some Views—Australian Air Policy—He Speaks of Stabilising Devices—A Reminiscence of the Round-Britain Seaplane Flight—A Civic Welcome—Harry’s Father Speaks—Assembling the Tabloid—First Flight in Australia—Preparations for Flight—Flying from a Street—An Object Lesson at Government House—Harry Dispels a Fallacy—And Speaks about Whirling Propellers—A Flying Call on the Governor-General—Interrupts a Game of Tennis—What the Governor-General Thought of Harry—Old Melbourne Friends Fly—The Australian Press—Enterprising Lady Passengers—Passengers pay £3 per Minute—Curious Attitude of an Association Official—Organisation of a Big Public Flying Exhibition—Harry’s Views on Flying—A Crowd of 25,000—Is Difficult to Handle—And Affects Harry’s Programme—An Accident—Without Serious Consequences—The Minister of Defence Ascends 3,500 Feet | 133 |

| CHAPTER X AERONAUTICAL ADVANCEMENT IN AUSTRALIA |

|

| Harry’s Proposals for Aerial Defence—Seeing Under Water from the Air—A Crowd of 20,000—A Governor-General Ascends 4,000 Feet—And a Governor’s Daughter Goes Up Too—Stunts—Rumours of Looping—Another Accident | 155 |

| CHAPTER XI A CHAPTER OF ACCIDENTS |

|

| Harry’s First Loops—Flying to Manchester—Harry is Taken Ill in the Air—He Returns and Lands Safely—And Collapses—An Extraordinary Accident—A Very Narrow Escape | 163 |

| [xviii] | |

| CHAPTER XII SOME WAR-TIME EXPERIENCES |

|

| Testing Production Machines—The Distinguished General and the Camel—The Boredom of Old-Fashioned Transport—And How it was Remedied on One Occasion—Testing a Doubtful Machine—Harry Gives Expert Criticism—And Predicts the Performance of a Four-Engined Aeroplane | 171 |

| CHAPTER XIII A MOTORING HONEYMOON |

|

| Harry to the Rescue—A Game of Cards—Keeping an Appointment—Twenty-four Hours too Early!—A Provisional Engagement—Marriage—Gas-bag Motoring—A Strained Back—Faith in Christian Science | 181 |

| CHAPTER XIV BUILDING A 225 H.P. MOTOR-CAR |

|

| Harry Buys Two Aero Engines—And a Mercèdes Chassis—Structural and Starting Problems—Myself as Rivet-driver—We Start the Engine—And I Stop It—On the Road—Shows Clean Heels to Big American Car—And Tows a Rolls—Harry in His Home Workshop | 193 |

| CHAPTER XV READY FOR THE ATLANTIC FLIGHT |

|

| Conditions Governing the Flight—Arrival in Newfoundland—Mount Pearl Farm—Snowed Up—The Test Flight—Local Interest Intense—Wireless Difficulties—Details of the Atlantic—An Aerial Lifeboat—Clothing of the Trans-Atlantic Airmen—Estimates and Anticipations—Over a Ton of Fuel—A Letter for the King—An Inspection by the Governor—Storms—Prospects of a Race—Revising Plans—Grieve—Navigation Problems and Methods—Weather Forecasts—A New Starting-ground—Nervous Tension—The Aviators are Amused by Their Correspondence—A Would-be Aerial Bandsman—False Weather Reports—Services of the Air Ministry—Weather-bound at St. Johns—Harry’s Confidence—Four Magnetos and a New Propeller—Address from the Mayor of St. Johns | 203 |

| CHAPTER XVI 1,000 MILES OVER THE ATLANTIC |

|

| Signalling Arrangements—Temperament—A Press Tribute—The American Attempt—Just Before the Start—Parting Messages—The Start—“Poor Old Tinsydes!”—Dropping the Under[xix]carriage—Out of Sight of Land in Ten Minutes—Over the Fog—Four Hours Above a Sea of Clouds—Grieve’s Method of Navigation—Weather Not as Forecasted—Taking the Drift through a Hole in the Clouds—400 Miles Out—Cloud Banks and a Gale—After 5½ Hours—Over-heating Radiator—What was the Cause?—The Only Possible Remedy—Is Effective at First—At 10,000 Feet—Giants of Nature 15,000 feet High—A Side-wind that Became a Gale—Flying “Crabwise”—Losing Height—Clouds, Darkness, and a Doubtful Time—Nearly Down to the Sea—Dawn—Sea-sick—Looking for a Ship—The Mary—The Rescue—Up to the Knees in the Sea—Captain Duhn—Sighting St. Kilda and the Butt of Lewis—A Famous Signal—“Is it Hawker?”—“Yes”—The Navy’s Guests—The Civic Welcome at Thurso | 225 |

| CHAPTER XVII MY OWN REMINISCENCES OF THE ATLANTIC FLIGHT |

|

| I Wait for News—The Americans Start—I Hear Harry has Started—And I Put out the Flags—No News Next Morning—Fate is Unkind and Brings a False Report—Which, Contradicted, Delivers a Paralysing Blow—No Further News—“All Hope Abandoned”—Good News—Peace of Mind Once More—Everybody Happy—The King Telegraphs Congratulations—I Go to Meet Harry at Grantham—Harry’s Triumphal Progress to Grantham—Together Once More—Harry Rides a Horse through London—“Escape” from the R.AeC.—Celebrations at Ham—Fireworks at Hook | 253 |

| CHAPTER XVIII AFTER THE ATLANTIC ATTEMPT |

|

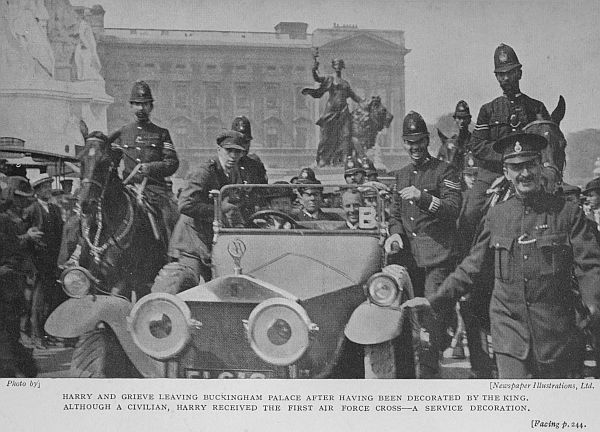

| Harry and Grieve Receive a Royal Command—The King and Queen and Prince Albert Hear their Story—The Air Force Cross—Comedy of a Silk Hat—A Cheque for £5,000—Is Nearly Lost—The Daily Mail Luncheon—General Seely Delivers Official Congratulations—Harry Replies—And Grieve—Tributes to Lord Northcliffe—Another Luncheon, also at the Savoy, on the Following Day—Royal Aero Club as Host—An Appropriate Menu—The Derelict Atlantic is Recovered—Harry is Pleased | 271 |

| CHAPTER XIX MOTOR RACING |

|

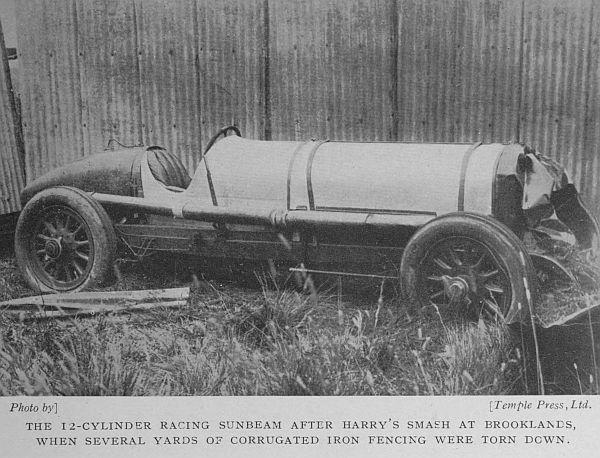

| Harry Turns to Motor-racing—Successful Début at Brooklands—Why I Stayed at Home—The 250 h.p. Sunbeam Touring Car Takes Second Place—When the 450 h.p. Racer Comes on the Scene—Harry Drives the Largest Car in the World—A Terrible Crash—Without Serious Consequences—Back to the Air—The [xx] R.A.F. Tournament—Reunion of Pioneer Aviators—Eleventh-Hour Entry for the Aerial Derby—Second Place, but Disqualified—A Very Busy Month—Aeroplane Trials at Martlesham—British International Motor-boat Trophy at Cowes—More Motor-racing at Brooklands—His Aeroplane Enables Harry to be (nearly) in Three Places at Once—Harry “Brings Home” a £3,000 Prize for the Sopwith Company at Martlesham—I Decide that Motor-racing is Too Risky—And Fate Deprives Harry of a Race—Motor-boat Racing—Racing an A.C. Light Car—And a D.F.P.—The Gordon-Bennett Air Race of 1920—Bad Luck—The 450 h. p. Sunbeam Again | 291 |

| CHAPTER XX MOTOR ENGINEERING AND RACING |

|

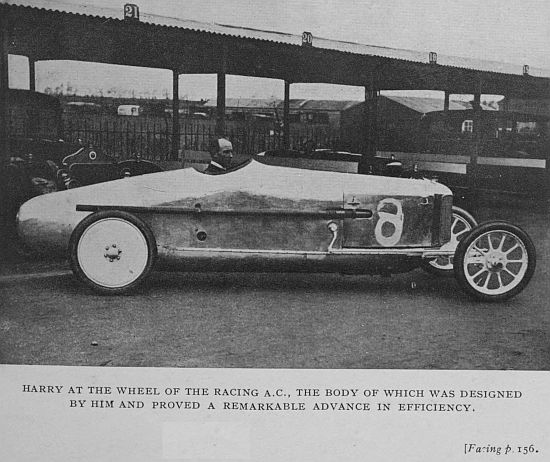

| Formation of the Hawker Engineering Company—The Racing A.C.—Amusing Experiences—Remarkable Performances Due to Efficient Streamlining—Several Records Broken—An Accident—The Hawker Two-stroke Motor-cycle | 309 |

| CHAPTER XXI THE PASSING OF A BRAVE AVIATOR |

317 |

| Harry George Hawker, A.F.C. | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page | |

| Mrs. George Hawker, Harry’s Mother.—Harry as a Cadet at the age of 12.—Mr. George Hawker, Harry’s Father | 30 |

| The Sopwith Tabloid, the Prototype of the Fighting Scouts, designed by Harry, in its modified form for Looping-the-Loop, after his return from Australia | 56 |

| The Sopwith Dolphin, put through its Initial Tests by Harry.—The Sopwith Camel, a world-famous Fighting Biplane. Hundreds of Machines of this type were tested by Harry during the War | 94 |

| The Sopwith Rolls-Royce-engined Biplane, “Atlantic,” in which Harry and Grieve attempted the Atlantic Crossing. The top of the Fuselage was made in the form of an Inverted Boat, which they detached in Mid-Atlantic. The Undercarriage was dropped soon after the Start, in order to reduce Air Resistance | 108 |

| Testing the Lifeboat. On the back of the original Photograph Harry wrote: “Note the broken ice between the boat and shore.”—This picture shows some of the difficulties in getting the Aeroplane to the Starting-Ground in Newfoundland. The Driver apparently took things lying down | 122 |

| The Detachable Boat carried on the Atlantic Flight.—The Sopwith Trans-Atlantic Biplane in the Hangar near St. John’s, Newfoundland | 142 |

| The Derelict Aeroplane, in which Harry and Grieve had attempted the Crossing, was recovered from the Atlantic by the U.S. Steamer Lake Charlotteville.—Harry at the Wheel of the Racing A.C., the Body of which was designed by him and proved a remarkable advance in efficiency | 156 |

| Our House at Hook, soon after News of Harry’s Rescue from the Atlantic.—Home Again! Harry and Grieve at Grantham Station, after the Atlantic Flight. Mr. Sopwith is standing in the doorway | 174 |

| The Scene outside King’s Cross Station, London, when Harry returned from the Atlantic. The Australian Soldiers decided that Harry must have something more triumphant than a Civic Reception | 198 |

| [xxii] | |

| Harry and Grieve leaving Buckingham Palace after having been decorated by the King. Although a Civilian, Harry received the first Air Force Cross—a Service Decoration | 244 |

| A Souvenir of the first Transatlantic Air Mail | 264 |

| Trans-Atlantic Aviators’ Reunion Dinner. The late Sir John Alcock is on the extreme left; Mr. F. P. Raynham on the right (nearest the camera); Sir Arthur Whitten Brown in uniform (opposite the camera); and on his left Lieut.-Comdr. K. Mackenzie-Grieve, A.F.C.—Harry is third from the left of the picture | 282 |

| Harry on Board a Yacht during one of the Periods which he devoted to Motor-Boat Racing.—Pamela sets the Pace on the Lawn at Hook | 300 |

| The 12-cylinder Racing Sunbeam after Harry’s Smash at Brooklands, when several yards of corrugated iron fencing were torn down.—Mr. T. O. M. Sopwith, C.B.E., and Harry, with the Hawker Two-Stroke Motor-Cycle—a Post-War Enterprise of the Hawker Engineering Company | 312 |

| Floral Tributes being taken to Harry’s Grave, at Hook, Surrey, on the 225 h.p. Sunbeam, by my Brother, Captain L. Peaty | 318 |

EARLY STRUGGLES

Harry’s Parents—His Sisters and Brothers—Schooldays—Four Schools in Six Years—The Attraction of a Cadet Corps—Motor Work at Twelve Years of Age—The Expert of Fifteen—Managing a Fleet of Cars—First Desire to Fly—The Kindness of Mr. and Mrs. McPhee—Harry Meets Busteed—And Comes to England with Him—Kauper—Seeing London—Quest for Employment—A Job at Sevenpence per Hour—Another at Ninepence-Halfpenny—Thoughts of Returning to Australia—Forty Pounds in the Bank—Kauper Strikes Oil—And Helps Harry—Sigrist—How Harry was Happy on Two Pounds per Week—His First Flight—Reminiscences of Brooklands Days.

CHAPTER I

There was born at Harcourt, in Victoria, Australia, on January 10th, 1862, one George Hawker, whose father was a Cornishman. Grown to manhood, this George Hawker followed the blacksmith’s calling, and on May 24th, 1883, he married Mary Ann Gilliard Anderson, a spinster, of Scottish stock, who was born on October 9th, 1859, at Stawell, also in Victoria. There were four children of the marriage: Maude (the eldest), Herbert, Harry, and Ruby (the youngest). The elder boy, Herbert, born in 1885, was unlike his brother in many respects. For instance, as a child he was very delicate, a circumstance which hampered him in his studies. Nevertheless, he was very fond of school, and he invariably worked well and progressed in spite of his ailments. He excelled in music. Although he had only recently married, Herbert Hawker joined the Australian Forces at the outset of the Great War, and he suffered great privation and illness at Gallipoli. He was later badly gassed on the Western Front, and his life was despaired of in consequence. Having partially recovered, he returned to Australia, bearing the honorary rank of captain. He has two children, a girl and a boy.

Maude and Ruby Hawker are both married, the elder having two boys, Alan (“Bobbie”), born in 1910, and Howard (“Bill”), born in 1912. Both boys display the aptitude for engineering which undoubtedly runs in the family, the elder having driven and attended to his father’s car at the age of nine years.

Harry Hawker, or—to give the subject of my biography his [26]full names—Harry George Hawker, was born on January 22nd, 1889, at the little village of South Brighton (now known as Moorabbin) in Victoria, where his father had a small blacksmith’s and wheelwright’s shop which brought in enough to keep the family in comfort. George Hawker has at least two claims to fame, which, arranged chronologically in order of occurrence, are, first, that he was the father of a great aviator, and, secondly, that he himself was a fine shot, for in 1897 he came to England with the Bisley Rifle Team and won the Queen’s Prize.

At the age of six, Harry was sent to the school of Mr. W. J. Blackwell, B.A., at Moorabbin. He took no interest whatever in his studies, either then or ever during his school career. For this inadvertence he was sorry in later years. He was almost continually running away from school and always in trouble. In the space of little over six years he went to four different schools. After leaving Mr. Blackwell, Harry was sent to a school at East Malvern, presided over by Mr. M. T. Lewis. He was not long there, for in 1896 he was attending a school at St. Kilda, whither his parents had moved. Harry was even more unsettled at St. Kilda, for, without as much as telling anyone at home, he left his school and presented himself at another school, at Prahran, where they had a cadet corps which attracted him. He became a cadet, but, still restless and unmanageable, he ran away from school for good at the age of twelve and started work with a motor firm, Messrs. Hall and Warden, for five shillings per week. When fifteen years of age he had an extraordinary knowledge of motors for such a youngster, and he was considered one of the best car drivers in Victoria at that time. As a child, Harry’s sole ambition was to become an engineer, and while at school he designed and built engines in his spare time.

After leaving Hall and Warden’s, he joined the Tarrant Motor Company, with which firm he made considerable headway and soon became one of their leading motor experts, and that notwithstanding his extreme youth, which he always tried to hide by adding a year or two to his age. However, that restlessness,[27] which was probably only due to his having reached the limit of progress in his present job, again claimed him, and, tempted by the offer of a workshop of his own, he took up the work of looking after a fleet of private cars belonging to a Mr. de Little, for which he received a salary of £200 per annum. About this time, too, Harry’s father was running a small steam plant which enabled Harry to test several of his ideas. It was while Harry was with Mr. de Little that his old ambition to follow an engineering career resolved itself into a desire to fly. It may have been the fact that very little was then known of aeronautical science, particularly in Australia, or perhaps Harry was attracted by the most intricate branch of engineering—but whatever the origin of the idea, Harry had made a firm resolution, and he looked around for his opportunity to carry it out; but for several months the prospects were not bright.

While Harry was working for Mr. de Little he lived at a small country hotel at Caramut, kept by Mr. and Mrs. McPhee, of whom he could never speak too highly. They were extraordinarily good to Harry, and when he left Australia they insisted on insuring his life; and they continued to pay the yearly premiums until he died. After Harry’s death, one of the most human letters I received came from Mrs. McPhee, with the insurance policy enclosed. The amount was very small, but the wealth of good nature which prompted such a disinterested tribute to his lovable personality was worth untold gold.

When he had been with Mr. de Little for nearly three years, Harry, then about twenty years old, met by accident one Busteed, who, inspired by the sight of a Wright and a Blériot, was leaving for England in a week. Having saved about £100 during his period of service with Mr. de Little, Harry decided to go with him, with the idea that in England his ambition to learn to fly would easily be realised. Accordingly, within a week he had thrown up everything, and with no misgivings was crossing the world in search of the knowledge of flying for which he had yearned so long. He was, as always, full of confidence in himself. [28]From the time he started work at five shillings per week he never looked back. He gave no thought to the possibility of his not making good in England. He left Australia for England to learn to fly, and either did not or would not recognise that in the Old Country he would be likely to meet with keen competition in his quest.

There is no doubt that the trouble he experienced in getting any sort of work, even apart from that on which his heart was set, was a great blow to his confidence, for after nearly a year in very poor jobs in large workshops, where there seemed to be little or no scope for his ability, he contemplated returning home and taking up his old work. This was the only occasion, in a life full of ups and downs, when he seriously thought of throwing up the sponge and yielding to the line of least resistance. In all other adverse circumstances he revealed a spirit of indomitable courage and endurance. There is no measuring a man’s actual worth, but had Fate not kept Harry here we should have been several iotas deficient in our air supremacy in those dark days which followed on so soon, when iotas were of incalculable worth.

Harry and Busteed first arrived in London in May, 1911, with Harrison and Kauper, two other friends who had also travelled from Australia. All four were destined for aeronautical careers, Harry and Kauper, with nothing definite in view, left the others and looked for “diggings.” Although they had very little money, they decided to have a holiday and enjoy the sights of London before seeking employment. After a couple of weeks or so, Harry started to look around for a firm who wanted to teach someone to fly. This preliminary search was unsuccessful, so Harry, full of life and confidence, thought he would obtain work in an engineering shop and bide his time in finding the work he most wanted. Funds were getting low, and the quest for any sort of job was rendered very difficult by the fact that most of the people whom he approached would not consider employing him because he had no references in this country, a circumstance which Harry was at a loss to understand. In Melbourne there was not [29]a firm but would have taken him, but in England his own word for his ability was not enough.

Eventually he offered to work for a week for nothing, as a test of his ability, but this was of no avail. The outlook became very black. With Kauper, he moved to cheaper lodgings, where he was barely able to afford the necessities of life. They knew no one in the country except their two fellow-travellers, but Harry was too proud to let them know his plight, and would starve first. He continued to write cheerful letters home, telling of prospects, but never a word as to the actual state of his affairs. He would not have his parents think he needed financial help from them.

On July 29th, 1911, after two bad months, fortune changed a little for the better, as he managed to get work with the Commer Company at a remuneration of 7d. per hour. He continued, of course, to hunt for the opportunity which would bring him nearer to the realisation of his hope of flying, and so, when offered a remuneration of 9½d. per hour by the Mercèdes Company he had no scruples about leaving the other firm at the end of January, 1912. He was with the Mercèdes Company for less than two months, as on March 18th he accepted a better post with the Austro-Daimler Company. In the meantime, although he had approached very little, if any, nearer his goal, he had gained invaluable experience. Furthermore, whenever possible, he had saved his money, and any that he spent on recreation paid for weekly visits to Brooklands to watch the flying there.

He was thankful that he had been economical and saved £40, enough to take him back to Australia, when, after nearly a year, he despaired of ever realising his ambition to fly. Then it was that Kauper, who had been experiencing bad times as regards work, saw that Sopwith’s were advertising for a mechanic, and, being out of employment, immediately applied for the job, with success. It was arranged that if the work turned out to be what they wanted, Kauper was to let Harry know. Having regard to what he had suffered, Harry would not now give up his [30]job with the Austro-Daimler firm unless for something equally secure and permanent, and he would wisely have refused even a flying opportunity that did not fulfil such conditions. He did not want to run any unnecessary risk of being without work again.

Within a week of Kauper taking up his new work Harry received a wire from his friend, telling him to come down at once and that the prospects were good. Without a second’s delay, Harry packed up and left London for Brooklands, but little dreaming that he was on the point of realising his wildest hopes. Meanwhile, Kauper had discovered the work to be exactly what Harry was seeking. The Fates were kind, and a few days after Kauper had joined the Sopwith Company a lot of extra work turned up, necessitating the employment of still another mechanic. Kauper approached Mr. F. Sigrist, the works manager, by whom he was engaged, and told him he knew of “an Australian, a good mechanic, very keen to fly and ready for any sort of job with an aeroplane firm.” Sigrist told him he could arrange an interview, and so it was that, in reply to the wire mentioned above, Harry, complete with bag and tool-kit, presented himself ready to start work at once on June 29th, 1912.

It did not take Sigrist long to find out that in Harry he had a good man. He was very hard-working and exceptionally quick and accurate, and he could tackle any mechanical construction work. That Harry shone as a mechanic was Sigrist’s opinion. His whole heart was in his work. He worked fifteen hours a day on seven days a week, with £2 at the end of it. For the first time in England he was happy, notwithstanding hard work and little pay. His old confidence returned, and he no longer thought of getting home. The £40 he had saved he offered to Sigrist to be allowed to use a machine. Sigrist told Mr. Sopwith his star mechanic wanted to fly, and so Harry’s hopes materialised and he received his preliminary lessons.

MRS. GEORGE HAWKER—

HARRY’S

MOTHER.

HARRY AS A CADET AT

THE AGE OF 12.

MR. GEORGE HAWKER—

HARRY’S FATHER.

[Facing p. 30.

At this time Sopwith was conducting a flying-school and had several pupils, between whom there was great competition for getting the use of the school machine. After Harry had done a [31]little taxi-ing on the aerodrome he seemed never to be able to get hold of the machine. But at last it was arranged that he could have a fly at 7 o’clock one morning. In those days a flight of such a nature by a pupil would last for from three to ten minutes. Not so in Harry’s case, for Sigrist appeared on the scene at 8 o’clock, to find Harry still in the air after almost an hour! His progress under Mr. Sopwith and Mr. Hedley was exceedingly rapid, and he was acting in the capacity of an instructor before he had passed the tests for the Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificate. Among his pupils were Major H. M. Trenchard and Captain J. M. Salmond, both now officers of high distinction in the Royal Air Force.

Harry’s hopes and prospects were now as bright as they could possibly be. As soon as he had taken his “ticket” (i.e., R.Ae.C. Aviator’s Certificate), he was placed in charge of the hangars at Brooklands, where his real career began. Some of the gay times they had in those early flying days are worthy of record.

The firm, which later developed into the Sopwith Aviation Company, employing about 3,000 men, but consisted then of Mr. Sopwith, Mr. Sigrist, and about a dozen men, launched out with the purchase of a “racing” car when they had made a few pounds. This was an old Panhard of 16 h.p., fitted with a Victoria body and always accompanied by sundry disturbing noises. This genuine piece of antique was later fitted with a two-seater body, not to satisfy the wishes of its many drivers for a sporting effect, but because it provided at the back an enclosed space for carrying various impedimenta. On Saturdays and other festive nights it was customary for this useful part of the body to be discarded, and the turn-out would proceed, covered with mechanics, mud, and a very little glory, to the Kingston “Empire.”

This weekly trip from Weybridge to Kingston was never accomplished without incident in the form of some hitch or adventure. For instance, the tail-light, which no one had time or energy to adjust during the week, was wont to fail, and the policeman’s whistle was not infrequently heard. Whistle![32] “What’s that, Fred?” Harry would say to Sigrist. “Tail-light out, or did we run over that old girl?” “No, it’s only the light.” And so they proceeded, leaving the back to take care of itself. The eight or nine mechanics, carried on these journeys, were generally needed. Tyres were always going off; lamps always going out; and various bits and pieces of the car going astray on the road. All had, therefore, to work their passage.

Harry never tired of telling of the fun of those days, and although he was the keenest of workers, he was always ready for some fun, not a little being provided by the antics of a pet bear kept in the sheds at Brooklands and brought from America by Sopwith.

Harry’s delight in playing tricks never left him. Only a short while before he died we were spending a week-end with my parents. After we had all retired for the night I overheard a council of war between my brother and Harry. They crept stealthily downstairs. When, after about an hour, Harry arrived upstairs, I could extract no lucid explanation of what he had been doing. However, the next morning the sight of a white door in the dark dining-room when we sat down to breakfast explained his activities of the previous night. He had changed the white door of the drawing-room for the dark one of the dining-room. The cook gave my mother notice to leave immediately after breakfast, as she was not used to “being made a fool of.” There was only one person who saw her being made a fool of, but that person’s tale of cook’s exit through a door she knew so well which had suddenly gone “all gleaming white” was so funny that I am sure her manner of accepting the joke was better appreciated by the perpetrators than by the fools for whom it was intended.

THE BRITISH DURATION RECORD

Harry’s Aversion to Publicity—Circumstances of His First Brooklands Associations—The Sopwith-Burgess-Wright Biplane—Harry’s Effort in a Quick-starting Competition—Beating His Employer—Early Attempts for Michelin Laurels—A Real Success—Tuning-up for the Duration Record—Raynham Makes a Race—And Secures an Advantage—Raynham Lands after 7 hours 31½ minutes—And Holds the Record for an Hour or Two—Opportunity Knocks at Harry’s Door—And is Well Received—Harry Lands after 8 hours 23 minutes—To Him the Spoils—His Own Account of the Experience—A Reminiscence of Cody—The Significance of Harry’s Achievement—Other Flights at Brooklands—The Growth of a Pioneer Firm.

CHAPTER II

During the latter half of 1912, with the buoyancy of the enthusiast and no idea of the meteoric way in which his latent abilities would be developed, Harry embarked on the flying career on which his heart was set, at a time when the spirit of quantity production had not descended to meet the necessities of war and the aeronautical fraternity was happy in its smallness.

Even when he had carried out not a few, but many, flights of a nature unprecedented for a beginner, Harry was known only to a very few near associates; and he eschewed publicity not only before, but also after, he was drawn automatically and unavoidably within its fold. Fortunately, Harry had no cause to sever a well-made alliance with Mr. Sopwith, who was quick in recognising the genius of his protégé, as a pilot then, and as an engineer later. Had circumstances been less promising, and if Harry had elected to seek work as a pilot elsewhere, the scanty knowledge of his early experiences that had been disseminated would have stood him in little stead, for in 1912 the experiences of most pilots were generally reported in considerable detail; and here would have been a man with a brilliant record who had deliberately contrived to have as few papers as possible to show for it. A few genuine Press reports are surely of some value to a youngster who, looking for employment, has to make an impression, and particularly if he is not a great talker. But one cannot blame Harry for this seeming inadvertence, for he never required such testimonials.

Harry first arrived at Brooklands at a time when things were literally moving rather slowly and the hub of British enterprise in aviation was showing a pronounced tendency to deviate to [36]Hendon, whither many of the bright spirits that were formerly the life of Brooklands had already departed. Mr. T. O. M. Sopwith (now C.B.E.), who gave Harry his start in aviation, had recently returned from a successful American tour, during which he had participated in several motor-boat races and incidentally had commissioned the well-known American boat-builder, Burgess, to construct, under licence from the Wright Brothers, an aeroplane, known as a Burgess-Wright biplane then, and as a Sopwith-Wright after reconstruction by its owner in England.

As it was on this machine Harry made his reputation as a pilot of the first rank, a few references to its design and construction are not out of place. The original machine built by Burgess to Sopwith’s instructions, contrary to the customary Wright practice, was fitted with controls of the Farman type and a Gnome rotary engine. Having brought the machine to England, Sopwith replaced the Gnome engine by a British-built A.B.C. of 40 h.p., and proceeded to manufacture in his sheds at Brooklands duplicates of all the component parts of the aeroplane. Thus the machine, when ultimately reconstructed, became all-British in conformity with the requirements of the competition for the British Empire Michelin Cup No. 1. The machine had twin propellers, driven through the medium of chains connected with the single engine, and on the right-hand side of the latter was arranged the pilot’s seat. The machine was therefore of a distinctly novel type, at any rate so far as concerned this country, where few Wright machines had been seen. One innovation added to the design by Mr. Sopwith (to protect the pilot from the wind) was a nacelle, resembling in appearance a side-car body, and it is probable that without this feature Harry would not have been able to put up as many long flights as he did. Passengers in this machine enjoyed a particularly novel sensation in sitting beside the engine instead of in front of or behind it, and in landing they received the impression that the chassis had collapsed, so low was the build of the machine as compared with other contemporaneous types.

Four days after he had his first lesson in the art of flying, Harry flew alone in the Sopwith-Farman machine. His remarkable genius was thus revealed at the very beginning of his career in aviation; and by Sopwith, his tutor, he was afforded full scope for the development of his abilities. Within a month he qualified for his R.Ae.C. Aviator’s Certificate, the number of which was 297; and so rapid was his progress that when he successfully essayed his flight for the British duration record he had only put up a total flying time of about twenty hours.

After obtaining his certificate, Harry lost no time in pursuing the purely sporting side of flying, and on Saturday, October 5th, 1912, he participated in a Quick-Starting Competition, at Brooklands, on the Sopwith-Farman biplane. There were eight other competitors. Harry tied for second place with the late Harold Barnwell, who was piloting a Vickers-Farman biplane, their times being 6 seconds. An interesting circumstance of this contest was that on running off—or, rather, flying off—the dead heat, Harry and Barnwell both completed the evolution in faster time than E. C. Pashley, the accredited winner of the race, whose time was 5⅖th seconds. Harry’s time for this second performance was 5 seconds and Barnwell’s 4⅘th seconds. Sopwith, who competed on two machines, a Sopwith-Farman and a Sopwith-Tractor, for which his times were 7 seconds and 7⅖th seconds respectively, had the doubtful pleasure of being beaten by his pupil.

Harry essayed his first flight on the Burgess-Wright, on which he was subsequently to achieve the British Duration Record, on October 15th, 1912. Being already accustomed to the Farman type controls, he found no difficulty in handling the machine, and after completing a few circuits and practising landings he felt thoroughly at home on it. The following morning at 6.51 a.m. he set out on a test of 3 hours 31 minutes in competition for the British Empire Michelin Cup No. 1 and the £500 prize. The Cup had previously been won by Moore-Brabazon in 1909 and twice by Cody, in 1910 and 1911. In the 1912 competition a continuous [38]flight of not less than five hours’ duration had to be made, the award going to the competitor remaining the longest time in the air in a single flight without touching the ground. Although unsuccessful as a qualifying flight in the competition, Harry’s first attempt, lasting as it did for three-and-a-half hours, on a machine of a novel type which he had flown only for the first time on the previous day, was a most creditable achievement, especially, too, for a pilot who had won his brevet only a month previously. Such a flight, in such a remote period in the annals of aviation as 1912, would have been considered no mean performance for the most experienced of pilots. The flight, which was carried out at Brooklands at an average height of 500 feet, was terminated owing to the fracture of a valve-spring. Harry made two other unsuccessful attempts to win the Cup, the first lasting 2 hours 43 minutes, and terminating abruptly owing to a sudden gale, and the second of 3 hours 28 minutes, ending owing to rain.

As the Michelin Competition definitely closed on October 31st, there was no time to lose, and on Thursday, the 24th, Harry put up a flight of 8 hours 23 minutes, which proved to be the British Duration Record held by him for several years. On the same day a flight of 7½ hours was made by his friend Raynham, who held the British Duration Record for a brief spell of 1 hour 35 minutes, having started and finished before Harry. Lord Charles Beresford was among those who witnessed these record flights. I cannot do better than reproduce the following account communicated to the Aero by its special correspondent in November, 1913.

“We were astir early in the Sopwith camp on Thursday, October 24th. Not that this was the first early-morning attempt on the Michelin prize. The same thing had been going on for a week past, and no fewer than three times in this week had the new Sopwith twin-screw A.B.C.-engined biplane sallied forth. Hawker, the pilot, had been chosen to fly the Sopwith ‘bus,’ and his determination, skill, and enthusiasm through this and the previous attempts justified the faith put in him for such a [39]task. Hawker is a young Australian, and, like his fellow countrymen Busteed, Pickles, and Harrison, he shows very great promise as a flier. Joining the Sopwith school as a mechanic, he was allowed to learn on the orthodox school type Farman, and he early displayed his aptitude for this work by going up to 1,000 feet and remaining there for fifty minutes on the fourth day of his training.

“Of his three previous attempts on the Michelin Duration Competition little need be said; the first one was terminated after 3 hours 31 minutes by a valve-spring breaking. On the second attempt the wind, after 2 hours 43 minutes proved too much for further flight, and the third attempt ended after 3 hours 28 minutes in a rainstorm, which soaked the magneto through, and temporarily ended its career.

“With serious designs on ‘durating,’ the Sopwith camp was awake and bustling, and excitement ran high when it was seen that Raynham was to make a simultaneous attempt on the military Avro biplane (enclosed body type), fitted with a 60 h.p. Green engine. Hawker got away just before 7 a.m., but was brought down again after a flight lasting no more than twenty minutes by the magneto cutting out occasionally. Apparently it had not recovered from the effects of its previous soaking. This contingency had been anticipated, however, and a brand-new British-made Bosch had been ordered previously, which, however, had only arrived late the night before. The old ‘mag.’ was hurriedly removed and the new one fitted, but even minor details of this kind take time, and in this case the time was all too precious. In timing the magneto it was found to run the wrong way round, and it had to be dismantled and a new commutator fitted.

“Meanwhile Raynham got away on the Avro at 7.40, which meant eventually a start of 1h. 35m. He seemed to have a little trouble in carrying his load, as he had to make three attempts to get off, and he was flying very cabré through the earlier part of his flight. The Green engine, however, [40]sounded serious, solemn, and steady, and seemed to inspire confidence. Hawker made a start at 9.15 without even testing or trying the magneto in any way.

“Then commenced a magnificent and exciting contest which lasted till well after dark.

“The A.B.C. spluttered a little at first for want of a warming-up, but by the time it had done one circuit of Brooklands its revolutions were up to 2,000 per minute, and Hawker was able to throttle down slightly. There was a tense feeling all round, and an ache in the heart of the Sopwith crew that the magneto had not been properly fitted during the previous night. Hawker’s handicap was realised more and more when it was found that if Raynham remained aloft until within 1 hour and 35 minutes of the limiting hours of the competition (which were from sunrise till one hour after sunset), Hawker could not possibly win.

“There was a stream of people to and from the anemometer throughout the day, which instrument happily showed the atmospheric conditions to be little short of ideal. The speed of the wind during the day did not vary more than five to eight miles per hour.

“Raynham, with his wide experience, took the greatest possible advantage of this, and made a really splendid flight, with the Green throttled down to the very slowest revolutions that the machine would fly with, and with the tail dropping in what appeared to be a fearful position to the onlookers. Hawker, with tail well up (and his machine lifts the loads remarkably easily), was flying steadily round at a height of about 400 feet, the A.B.C. emitting a steady hum. Raynham, on the other hand, was flying very low, and on some occasions was only about 30 feet high. By about eleven o’clock he evidently had become extremely bored with pottering round and round, because he commenced a series of antics round the sheds, and at one time about half-way round a turn he suddenly doubled back on his own track, and did a turn or two round the wrong way, all [41]the time, however, with his engine ticking round at something like 950 revolutions per minute only, the appearance of the machine being terrifying to behold to those who dread sideslips.

“Hawker all this time was steadily plodding away, making the safest flight possible, and the very machine had a look of determination about it. The two slow-speed propellers turned solemnly round, and the engine explosions were lost in a continual buzz through the high engine speed. That he was out to win if possible was obvious from every movement. Raynham’s champions grew a little nervous over the flippancy of their pilot, and a shutter of one of the sheds was quickly requisitioned, on which were painted the words in large letters: ‘Fly higher.’ It had not much effect, however, although it served apparently to sober him a little.

“Towards one o’clock impatient questions as to how much oil and petrol they were carrying began to circulate amongst the onlookers, and it appeared that Raynham’s oil supply was likely to run out before anything else. On more than one occasion the Green suddenly slowed down in revolutions, only to pick up again just as quickly. Someone pointed out later on that the short pipes coupled to the exhaust ports in the cylinders of the Green no longer emitted the puffs of smoke that had been prominent in the earlier stages of the flight, and misgivings as to the oil supply began to travel abroad.

“Excitement reached fever-heat between two and three o’clock, the strain of watching the two machines circle round hour after hour becoming intense. It was not even like a motor race, where one can see fairly early in the run who is likely to be the winner. In this conflict, speed did not even count, and the contest might terminate any second by either running out of fuel or by an engine stoppage. Little work was done in the sheds, and every few minutes mechanics would appear at the various doors to find and call out to their mates that both machines were still up.

[42]“‘Raynham’s down!’ The cry spread across the ground at about 3.10 p.m., and a frantic rush was made to the front of the sheds, and sure enough he was just on the point of touching. He terminated his flight at 3.11½ p.m. exactly, having been in the air 7 hours 31½ minutes—truly a splendid performance. We all rushed across the ground, and Fred May, of the Green Engine Co., jumped into his car and came tearing up to the spot. Raynham climbed out, looking somewhat tired, but apparently none the worse for the 7½ hours’ toil. He said that the oil had run out, and though he had held on as long as he could, the engine had been dropping in revolutions for the last half-hour, and he did not want to risk it seizing up altogether.

“Up to the very minute of Raynham’s landing it is doubtful if a single person on Brooklands would have given a shilling for Hawker’s chance of putting up better time than Raynham with the latter’s hour and a half start; but things now changed, and as all eyes were turned upwards and ears listening to catch the rhythmic beating of the engine, the question went round: ‘Will he keep up for another two hours?’ The engine sounded happy enough, and if nothing happened there was no reason why he should not, as he had a big load of fuel. The excitement now began steadily to rise as the minutes were ticked off, and to the Sopwith enthusiasts every minute seemed an age. They all went back to find something to do that would pass the time more quickly, but had to come out again with dread in their hearts that they might find Hawker ‘taxi-ing’ along the ground.

“Gradually the time went along, and Hawker was still steadily travelling at his 400 feet altitude. Then Sopwith appeared on the scene at about four o’clock, and brought out his 70 h.p. Gnome Tractor biplane with the intention of cheering Hawker up a little. Taking Charteris as a passenger, he did one or two circuits, climbing up to Hawker’s level, then very skilfully cut across a sharp turn and came alongside. Hawker, [43]in fear of not lasting out the time, had throttled down to the smallest amount he could fly with so as to economise petrol and oil; his machine was therefore very slow, and Sopwith had to switch off and dive a little so as not to pass him. The two on the Tractor waved frantically, and shouted encouragements, which, of course, Hawker could not hear at all, but which he undoubtedly understood. Down planed the Tractor again, leaving Hawker with just another half-hour to go through to equal Raynham’s time (which, by the way, was for 1 hour 35 minutes the British Duration Record).

“The next half hour was the worst period experienced by a great number of the Brooklands clan, and it is doubtful if any other event ever held on the ground has caused so much interest. Tea was forgotten altogether, and exact minutes and seconds were in the greatest demand, everybody walking about watch in hand. After ten more minutes had passed it was observed that Hawker had throttled really to the very limit so as not to run the slightest risk of running short of petrol. The machine was flying at a terrible angle, with the tail pointing strongly earthwards, and the spectators began to feel nervous. Another shutter was acquired, on which was whitewashed: ‘Keep your tail up,’ and this was displayed for the pilot, who, however, took but little notice of it.

“Gradually the minutes passed, and a little crowd gathered round the timekeeper, who slowly (horribly slowly to some) counted 9 minutes, 8 minutes, and so on. ‘One more circuit will do it!’ someone cried, and it did, and as the last seconds passed away, never to be recalled, a huge sigh escaped from the lips of everybody. To some it was a sigh of relief, to others perhaps not, but now the crisis was over everybody was sporting enough to express admiration for a very plucky flight.

“Hawker had evidently had his eye glued to the clock which he carried on board, for now his tail was up high again, the machine sped away full of life, and the time also slipped by much faster now that the face of the watch was not being [44]scrutinised so carefully. Another half hour passed and darkness began to close in. It had been arranged that a huge petrol fire should be lit when it was time for Hawker to come down, an hour after sunset being 5.48 p.m. It was, however, quite dark at 5.20, and a difficult problem arose in the minds of those on the ground. It was naturally wished to make the flight as long as possible, and therefore to light the bonfire then would have been to bring him down unnecessarily early; on the other hand, complete darkness might quite possibly cause him to lose himself. A better arrangement would have been to light one fire half an hour before the specified finish, another one a quarter of an hour later, and a third when the time was up, leaving the whole three for him to land by.

“Any misgivings that may have remained in the minds of a few regarding the condition of the engine were quickly put at rest by Hawker at about 5.30 opening the throttle wide and shooting up to between 1,200 and 1,500 feet in so short a space of time as would have made some of our military competitors envious. It was evident he did this to run no risk of petrol running out when he was over the sewage farm or behind the sheds at a low altitude. It was now quite dark, and wanted but ten minutes to the time limit. At this stage one was impressed by the appearance of the long flame from the exhaust. The exhaust pipes were apparently quite red hot the whole time.

“Suddenly Hawker was seen to be intent on making a landing without further delay, and he came down in a perfectly straight line from the far end of the ground with the engine about half throttled. He made a very shallow angle of descent, apparently with the intention of striking as gradually as possible, as the earth could not be seen at all. Those in charge of the bonfires instantly realised the situation, and applied matches to the petrol, which flared up in the nick of time. Hawker straightened up, closed the throttle, and made a perfect landing seven minutes before the time limit.

[45]“There was a rush for the spot where the machine was, and the next five minutes were occupied in cheering, congratulating, shaking hands and patting backs. Hawker climbed out of his seat, having been exactly 8 hours 23 minutes in the air, but he looked easily capable of undergoing the same trial again.

“Relating his experience, Hawker said: ‘When I got away first at about 9.15 I thought the new magneto had been timed incorrectly, because the engine was only turning at 1,600, and would hardly carry the load; before I had done a circuit, however, I discovered it was only a case of getting the engine warm, this taking a particularly long time, because we had fitted two radiators where there only used to be one, even in the summer, and I was carrying nearly six gallons of water all told. This I found afterwards to be really too much, because towards the end I tried to warm my hand on the water-pipe which runs from the bottom of the radiators and found it too cold to touch.

“‘Within five minutes of the start the engine was turning round at just over 2,000 revolutions per minute, and I realised that if I wanted to economise I must throttle down a little. This I did, and ran along steadily at about 1,800 revolutions. I was extremely worried to think that we had let Raynham get such a lead, but there was no hope for it, so I settled down to a long, slow job, determined to stick to it to the end.

“‘I was quite snug and warm inside the little body that had been provided, and the weather throughout was ideal. The engine ran splendidly, and I can truthfully say that it never made a single misfire for the whole period of 8 hours 23 minutes.

“‘I occupied most of my time in keeping one eye on the clock and one on Raynham, who was flying below me, and on several occasions he quite appeared to be “taxi-ing” along the ground. I always noticed that he never came to rest, however, and concluded that he must be flying low. Once he shot across my path about some 150 feet under me, giving me quite a start for the second. On several occasions I lost sight of him for half an hour at a time, and was sometimes worried by [46]wondering whether I was going to give him my backwash or whether I was getting into his.

“‘I had a Thermos flask of cocoa on board, some chocolate, and some sandwiches, all of which I found useful in either passing the time away or relieving the monotony by giving me something to do. I did not look at the exact time that I started, but I knew that I had about an hour and three quarters to do after Raynham had finished. Everything was plain sailing with regard to the petrol supply and oil. The petrol was gravity-fed and the oil pressure-fed. I had a twenty-gallon petrol tank just behind my back, which was coupled directly to the carburetter, and above that I had a twelve-gallon tank, both being full. The twelve-gallon tank was connected by a pipe to the larger tank, and after I had been flying for four hours I turned on the tap in the twelve-gallon tank and allowed the contents of this tank to flow down to the larger one. I discovered afterwards that the pipe from the twelve-gallon to the twenty-gallon tank was not large enough, because when I came down in the evening I could hear the petrol still slowly trickling into the large tank. For the oil, I had a glass gauge in the sump of the motor and a five-gallon tank also behind my back, I started off with two gallons in the sump, and occasionally pumped up a little pressure in the oil tank, opening the tap between the tank and the sump to keep the oil level in the sump somewhere within sight. As the petrol was used and the weight lessened I closed the throttle slightly, the engine running equally well at all speeds.

“‘Later on I saw a shutter being carried out with the words “Fly higher” painted on it. I could read it quite distinctly from 400 feet, but as I felt quite comfortable where I was I did not pay any heed to it. It was not until after I came down that I discovered that this sign was meant for Raynham. It was a great relief to me to see Raynham come down, and I knew this time that he was going to land, because I could see all the people running across the ground towards him.

[47]“‘From then onwards I kept my eyes glued to the face of the clock, the last half hour that would make my flight equal Raynham’s being the most anxious and worrying of the whole day. Every minute seemed an hour, and as I was afraid that the petrol in the top tank might not be flowing properly into the main tank, I closed the throttle for the last twenty minutes down to the very limit the machine would fly with. I must have been flying then at only about thirty-five miles per hour. Then I saw the 70 h.p. Gnome Tractor ’bus come out, and watched Mr. Sopwith with interest. I guessed what he was coming out for, and when I saw him make straight for me, broadside on, I kept on a perfectly straight course, knowing well that he would be careful not to hinder me in any way. He came quite close alongside, and I distinctly heard them both shout (my A.B.C engine had a silencer fitted), but I could not tell what they said.

“‘Painfully slowly the minutes rolled away, but at last I realised that I was the holder of the British Duration Record. When I was quite sure of this I opened up the throttle again, as I had not much to fear now, but I was still determined to keep up in order to give anyone else a good run in order to beat it. When it was getting nearly dark I pulled open the last notch of the throttle and climbed up to 1,400 feet on the meter, and I did this very rapidly. Darkness came on, and I could see very little but the red-hot exhaust pipe and the reflection from the burnt gases. The dim lights of the Blue Bird served as a little guide to the position of the ground, and when I felt sure it must be quite 5.50 I decided to come down immediately and make a guess at where the ground was, as I felt sure they had forgotten all about the fires, and I did not want to get lost and smash the machine up. Just as I was landing the fires flared up, and I came to rest and found everyone as pleased as I was.’”

Note.—The foregoing verbatim report of Hawker’s experiences in making the British Duration Record is reprinted from the Aero of November, 1912.

In attempting, with characteristic pluck, to beat Harry’s record on the last day of the competition, Cody unfortunately collided with a post on landing after a trial flight, and a wing was buckled in consequence.

The performance whereby Harry not only won the British Empire Michelin Cup No. 1, but also captured the British Duration Record, brought him into the front rank of British pilots and marked an important point in the annals of British aviation. Public attention was attracted to a type of machine of which little was known in this country, although it bore the pioneer hall-mark of the Wrights. For the Sopwith Aviation Company the flight was a great business asset and a sure foundation for the goodwill of the concern.

Harry took part in an Altitude Competition on Saturday, November 9th, 1912, at Brooklands, in which event Barnwell was the only other competitor. Unfortunately the race had to be given to Barnwell, as Harry had omitted to set his barograph at zero before starting, so that the exact height he reached was not recorded. Nevertheless, the immediate excitement of the contest did not suffer through this inadvertence.

A Bomb-dropping and Alighting Competition, in which competitors had to drop their bombs on or near a given target and land within a minimum radius of a given mark was held on the Saturday following. The first and second places went to Merriam and Knight respectively, Sopwith, Bendall, and Harry being the “also rans.” Sopwith, having succeeded in making a direct hit with his bomb, misjudged his landing, a circumstance which disqualified him.

Harry shared in a big success in a Relay or Despatch-carrying Race on Sunday, November 17th. In this contest the competitors worked in pairs. One pilot would start off with a despatch, and, after flying one-and-a-half laps, land and hand the commission over to his partner, who in turn would fly over the same course, alight, and hand the despatch to the judge, the winning pair being those who made fastest time. In the particular contest, [49]which was flown in perfect flying weather, it was originally intended that each pair should comprise a biplane and a monoplane, and Hamel flew over from Hendon on a Blériot for the special purpose of competing, but the scarcity of monoplanes owing to the War Office ban on machines of that type resulted in only biplanes taking part. The first prize went to Harry and Spencer, the latter flying a machine of his own construction. Their total time for the course was 9½ minutes. Barnwell and Merriam, of the Vickers and Bristol Schools respectively, on Farman and Bristol machines, took 10 minutes 10 seconds, and Bendall and Knight, on a similar pair of machines, took 10 minutes 12 seconds.

On Sunday afternoon, November 24th, just before dusk, a Speed Handicap over two laps of the Brooklands course was decided. The handicapping was, on the whole, good, Alcock,[1] Sopwith, and Knight, the first three home, all finishing in that order within a space of four seconds. Harry finished, but was unplaced. It is interesting to note that this was the first race in which Alcock participated. He had recently obtained his brevet at the Ducrocq school. Sopwith made fastest time.

[1] The late Sir John Alcock, K.B.E.

Harry had his machine out on the following Sunday to take part in another Bomb-dropping and Alighting Competition, but as the contest was on the point of starting rain came on and put an end to flying for the remainder of the day. The contest was postponed until the next Sunday, but Harry was unavoidably absent.

Busteed, Harrison, and Harry, who had all migrated from Australia together in April, 1911, had all now achieved some distinction in flying, and Australian prowess in the art was well in the ascendant. Busteed and Harrison were doing big things for the Empire as instructors of flying, and Harry, by his record flights, was doing much to promote British aerial prestige.

The business of the Sopwith Company having expanded [50]extensively in the meantime, Mr. Sopwith had decided to lease a skating-rink in Canbury Park Road, Kingston-on-Thames, so that more room than could be provided in the sheds at Brooklands should be available for the construction of machines to meet increasing demands from the Admiralty, War Office, and foreign governments. The skating-rink was ideal, not only on account of the space available for erecting big machines, but also owing to the level floor, which was a great facility. Mr. Sigrist, who had been largely responsible for the design of the Sopwith Tractor biplane and had accompanied Mr. Sopwith on his American tour, was the works manager there.

And so I leave 1912, conscious of the fact that, in the few months during which he had been flying, Harry had contributed in some considerable measure to the fostering of that record-breaking spirit so necessary for the advancement of the new art and science.

ABOUT ALTITUDE AND OTHER RECORDS

A Colleague’s Impression of Harry in 1913—Harry in the Passenger’s Seat—“Aerial Leap-Frog”—Competition Flights at Brooklands—Testing the First “Bat Boat”—End of the First “Bat Boat”!—Harry as a Salesman-Demonstrator—Testing the Second “Bat Boat”—70 Miles per Hour in 1913—Asçent to 7,450 feet in 15 minutes—A Prize Flight—How Harry Deserted from a Race which He Won—How a Biplane Beat a Monoplane—More Seaplane Testing—The British Altitude Record—11,450 Feet—“Bravo, Hawker!”—A Journalist’s Tribute—Flying in a High Wind—To the Isle of Wight and Back.

CHAPTER III

Even greater things were in store for Harry in 1913, for although the British Duration Record was an achievement to be handed down to posterity, it pertained only to British aviation. His performance in the Round-Britain Seaplane Race, so generously promoted by Lord Northcliffe and the Daily Mail, as one of the milestones in the early progress of marine aircraft, will live in the world’s history unbounded by nationalities.

A friend who worked in the shops at Canbury Park Road, where he took part in the construction of the Round-Britain seaplane, well remembers with the observant eyes of a hero-worshipper seeing Harry make daily tours through the works in company with Messrs. Sopwith, Sigrist, and R. O. Cary, the general manager. Other than a sturdy physique and cheery countenance, Harry bore nothing to indicate that he was an aviator by profession. He was wholly without affectation and a favourite with everyone belonging to the Sopwith concern.

Sir Charles D. Rose, Bart., M.P., Chairman of the Royal Aero Club, handed to Harry on Tuesday, January 7th, 1913, a cheque for £500 in respect of the prize awarded in connection with the Michelin Competition. Of this sum, Harry received 25 per cent. as remuneration for his special services to the Sopwith concern. On the same day, too, Cody received his cheque for £600 in connection with the No. 2 Michelin Competition.

Mr. Sopwith himself was out testing a new tractor biplane on Friday, February 7th, 1913, at 7.20 a.m., carrying Harry as a passenger. To ride in the passenger’s seat of an aeroplane of new design is a task simple enough truly, but not too pleasant for an experienced pilot. This flight speaks volumes for the great confidence which Harry always had in his friend and benefactor. [54]This new tractor-type machine was dismantled after the flight and sent to Olympia for the Aero Show, where it was purchased by the Admiralty. After the Show, Harry himself tested the machine at Brooklands, flying for 1¼ hours on March 1st preparatory to handing it over to the responsible naval authority, Lieut. Spencer Gray, who flew it to Hendon with a passenger.

The Sopwith-Wright machine was still in service, and Harry was flying it on the Saturday. On the Sunday, February 9th, he was third in a Quick-starting and Alighting Competition, during which he was lost to view above the clouds.

Harry also scored a “third” in the Speed Handicap at Brooklands on Easter Monday. Inasmuch as the spectators were left uninformed as to the result of the race, the event was a farce. Harry, on the Sopwith-Wright, was very severely handicapped, and had it not been that Barnwell passed the finishing-post on the wrong side, he would not have been “placed.”

The weather being particularly favourable, some very fine flying was seen at Brooklands on Sunday afternoon, March 29th; over a dozen machines being out. There were no races, but numerous exhibition and passenger flights were indulged in. Harry interested the spectators by practising “aerial leap-frog” on the Sopwith-Wright, a performance which caused much astonishment. With the propellers completely stopped, he made a well-judged landing from a considerable height.

During March, 1913, the first tests of the Sopwith “Bat Boat,” which had made its début at the Olympia Show, were carried out at Cowes. Sopwith, whose motor-boat experience stood him in good stead, first took the machine out, but although a speed of sixty miles per hour was attained, the machine would not leave the water. Harry had a shot at it, but with no better success. Sopwith, making another effort, rose a few feet, but the hull landed heavily and was damaged. Left out all night on the beach, the machine was almost destroyed by a gale, one report circulating to the effect that only the engine and propeller remained intact!

Harry was not hampered by any scruples with regard to trading on the Sabbath, for on Sunday, April 13th, 1913, he set out to play the rôle of aeroplane salesman, and incidentally to make his Hendon début. The specific purpose of his flight on the Sopwith-Wright from Brooklands to Hendon was to offer the machine for sale to the Grahame-White Company, whom he regarded as good potential purchasers, as they had recently sold two of their machines to the War Office and would require others to replace them in order to cope with increasing demands for exhibition and passenger flights at the London aerodrome. On the way there he had a forced landing at Wormwood Scrubbs, but was able to proceed and complete the whole journey in 40 minutes, inclusive of the delay. He terminated the flight by making several circuits of the aerodrome at Hendon, and subsequently made a number of other exhibition and passenger flights which demonstrated the wonderful handiness and airworthiness of the machine. His passengers during the afternoon included Manton and Gates, both well-known pilots of the Grahame-White Company. Passengers were greatly impressed by the stability of the machine and the strangeness of sitting on one side of the engine. Landing, too, was rather a new sensation, as the seats were so low in comparison with those of other types that to one on the point of touching the ground the landing chassis seemed to have fallen off!

On the following Sunday, at Hendon, Harry carried several more passengers, and at times there were as many as eight machines in flight simultaneously.

Harry tested the second Sopwith air-boat at Brooklands on Monday, May 25th. The machine, engined with a 100 h.p. Green, which was a development of the original “Bat Boat” mentioned above, was fitted with a temporary land chassis. One of the struts of this gave way on landing, resulting in damage to the left aileron. The original “Bat Boat” had warping, or flexing, wings.