[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Comet December 40.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

There is no one today who has seen a living horse. The creature became extinct a couple of centuries ago, about the year 2,800. Man, who betrayed the horse into what he became, hardly regretted the passing.

However, and I speak with all sincerity, there will be men of the future who will see a horse. Perhaps men of the future may ride horseback like knights and cowboys of the Middle Ages.

The secret of time travel has been discovered. No one has traveled through time as yet, although man has explored the universe for more than twenty light years from the sun. But the day of time travel is not far distant. It had simple beginnings. All great things began in simple ways. Newton and the apple were the beginnings of modern understanding of the laws of the physical world; Watts and the teakettle were the origins of industry and the machine age. A very beautiful young woman and an unscrupulous man were responsible for time travel.

I met the man early in the morning of July 2, 3002. I remember the date because on the day before I had visited in Alexandria, Egypt, and I had eaten dinner in Shanghai, China. It was nearly midnight when I reached the rocket port in Chicago and a jam in the pneumatics delayed my arrival home until nearly one o'clock in the morning.

Blake, fully dressed, met me at the door. There was a worried look in his eyes.

"There is a gentleman to see you, sir," Blake said. "I explained that you would not return until quite late and I tried to get him to leave, but he said it was urgent that he see you the minute you returned." Blake glanced over his shoulder toward the library and lowered his voice to a whisper. "I was a little frightened of him, sir. He doesn't seem quite—ah—quite right, sir, if you know what I mean. Shall I call the police?"

"No, Blake." I felt confident of licking my weight in madmen and I entered the library.

A tall, distinguished, dark haired gentleman rose to greet me.

"Ah! Dr. Huckins! I was afraid you would not get here in time!"

As he spoke I noticed a peculiar light in his eyes. It seemed to be a reflection from the fluorescent lamps of the library, but it showed a little too much of the whites of his eyes and I thought of what Blake had said about the man not being "quite right."

I did not feel that I owed him an apology for keeping him waiting, since I usually received visitors by appointment.

"I am Gustav Keeshwar!" he introduced himself. He seemed to expect some reaction, but unfortunately the name meant nothing to me, although if I had paid more attention to the newspapers I would have known who he was at once.

"I am the president of the Stellar Transport Company," he announced.

As he spoke he glanced secretively about the room, as though he feared an eavesdropper. Then he picked up a brief case which was lying on the table. With no explanation he opened it and pulled out package after package of thousand dollar bills.

"You may count it if you wish," Keeshwar said. "There are 1,000 bills, each of one thousand dollar denomination. One million dollars in cold cash."

There are any number of bank presidents who have never seen a million dollars in one pile. Spread out before me, I could scarcely grasp the amount of wealth it represented. As I recall now, my clearest mental reaction was a curiosity about how he managed to tuck it away so neatly in a brief case. Then I wondered if it was real money. A closer glance at the bills convinced me that it was.

Suddenly I came to my senses. I closed the library door and locked it. I glanced nervously at the shades to make sure all were pulled down.

"Great Scott, man, you shouldn't carry all that money around with you in a brief case!" As I said it, I spoke with the realization that the man was mad.

"I brought the money to you," Keeshwar said. "It is yours if you will do one thing for me."

"I must ask you to leave and to take your money with you," I said, realizing that I was turning down the ransom of a king. "No honest task ever called for a million dollars compensation—"

"But you have not asked me what I wish you to do!" Keeshwar exploded. "Look! Do you see how much money a million dollars is?"

I do not wish to pose as a man over-stocked with principles. A million dollars is more money than I ever hope to see again at one time. But I had a good income, a nice little fortune tucked away in worth while investments. I had a good name and my position in the world was better than average. I did not trust this man. I had a feeling that the million dollars he offered would not be worth the price.

"I am a surgeon," I said. "If you wish my professional services, I will charge you a reasonable fee."

"I want your services," Keeshwar said. "I want them for one day."

"You may have them. I will send you a bill after I complete the task."

"I want your services tomorrow," said Keeshwar, persistently.

I shook my head. "I have a delicate operation scheduled tomorrow. It is an operation I cannot postpone."

"It is an operation on Trella Mayo?"

I started. "How did you know that?"

"It is this operation that I wish you to perform for me," Keeshwar said. "Would it not be simple to let your knife slip, or to allow something to happen to her—for one million dollars!"

I do not remember clearly what happened next. I think I knocked the man down. I do remember stuffing his million dollars into his brief case and throwing it after him out of the door.

When I closed the door I was excited and unnerved. I found some sedative tablets and swallowed one. Then I sat down to think. Trella Mayo, beautiful, young and intelligent, a woman in a billion! Someone wanted to kill her.

She was only twenty-eight, yet her discoveries in physics had astounded the world. She might have taken first place in any beauty contest, yet she preferred working in a laboratory with men too old to notice her charms.

Her operation was not serious, except that it involved delicate skill. I resolved that nothing must happen during that operation the following day.

Two weeks later I visited Trella, now convalescing from her operation.

"I've wanted to talk to you, Fred," she said after I had taken her temperature, felt her pulse and gone through the usual ritual.

"I must warn you that I'll send you a bill for any medical advice I give you," I replied, laughing.

She smiled only a little and then puckered her brow seriously.

"I wanted to ask you about that operation. Wasn't it performed under unusual circumstances?"

I was taken by surprise and I am afraid that the truth forced its indications through my professional manner. "Why do you ask?"

"I noticed Blake standing near the door. There seemed to be a bulge in his pocket. It couldn't have been a gun, could it? And you kept watching, as if you were afraid a tribe of Indians would drop in for a massacre. I wonder if there couldn't have been a tall, dark gentleman mixed up in these unusual precautions?"

I did not reply.

"And I've noticed during my convalescence that the internes that continually hover around my door have a look as if—well, shall I say that they look more like policemen than internes?"

I laughed nervously. "I think you are a mental case, Miss Mayo," I said. "I shall have to call in a specialist."

"You do not need to deny it, Fred," she said. "Why do you suppose I insisted that you perform the operation? Why didn't I let you call in someone else? It was because you are the only man in the world that I trust, Fred. How much did Gustav Keeshwar offer you to do me in?"

Before I could stop myself I opened my mouth and blurted the truth.

"One million dollars!"

"Whew!" Trella whistled softly. "I'm worth a lot to you! I must be getting close if Keeshwar will pay a million to see me out of the way."

"Trella," I pleaded. "What is it all about? What's behind this mystery?"

"If you turned down a million dollars for my sake, I think I can trust you," she said. "Supposing I was about to invent a new method of locomotion? Can you see where Keeshwar might find me obnoxious?"

"A new kind of space ship?"

Trella shook her head. "A new kind of locomotion. Animals either swim or walk. Man also uses wheels."

"He also can fly. So can birds."

"Flying is simply swimming through the air and crawling, as a worm or snake, is gliding, like swimming. Space ships swim, too, after a fashion. Boats swim through the sea and sleds swim on ice. Therefore we have only three kinds of locomotion: Legs, wheels and sleds. Another might revolutionize everything."

"But there couldn't be any other way to travel. Even the planets 'sled' through ether."

"There is another way. It will open exploration to the furthest limits of the galaxy."

"I can see why Keeshwar was so interested."

"As soon as I'm out of bed, I want you to call on me at my laboratory, Fred. I'll show you something that will make your eyes pop out of your head."

I turned to leave, when something on the window pane caught my eye. It was a small, cherry-red spot, about the size of a twenty-five cent piece.

The minute I saw it, I knew what it was. I shouted to the interne—really a detective—outside the door, and lifted Trella into my arms. I must admit that I handled her a little roughly and she groaned as I hurried her out of the room. But what I did was necessary.

As I left the room, the glass of the pane melted and a beam flashed across the room, striking the bed where Trella had been an instant before. That beam was an Oronic Ray, 5,000 degrees hot, of the type used in welding the rockets of space ships.

It was evident that Gustav Keeshwar intended to finish Trella Mayo whether I would help him or not.

A few weeks later I visited Trella in her laboratory.

"I'm anxious to see this incomprehensible conveyance," I explained.

"At least, I'm glad you are taking an interest in something besides my safety and my operation scar," she replied.

She led me through a corridor toward a heavy steel door, which she unlocked.

"You are the first person besides myself to go into this room in the past five years," Trella added.

I scarcely know what I had expected to see. What would anyone expect to see, if he was told he was going to be shown a machine that neither walked, glided nor rolled? Such a contraption is beyond human experience.

It was a long, hollow tube, large enough to hold a human body. It was made of quartz and on each side was a cylindrical, low power atomic energy machine.

"This," Trella said, "is the translator."

"The what?"

"I call it my space-time translator, which someday will make the rocket as obsolete for space travel as the horse for surface travel. It will take an object from one point in space-time to another instantly."

"Instantly?"

"There is a small lapse of time," Trella confessed. "You see the machine has two motors, one for starting the operation and the other for completing it. It takes about one second's time to switch the motive power from one motor to the other."

The machine, except for the motors, was made entirely of quartz and silver. On the right side of the machine was a long strip of silver running the full length of the tube. It was about three inches wide and it was connected with a knife-like blade of silver on the left side of the tube by a strand of silver wire. Silver was used, of course, because it was the best known conductor of electricity and other forms of energy.

"It would be wonderful if it worked," I said.

"It does work," Trella said. "We sent two guinea pigs to the Sirius system yesterday morning. We got them back in an hour with a copy of yesterday's issue of The Sirian Daily Universe. Here's the paper."

She held out a copy of the beautifully printed daily magazine. On the cover was the date, August V2, 504 (3002).

It was customary for terrestrials to use terrestrial dates wherever their outposts were located in the stellar system. But instead of using the terrestrial year—as shown in parenthesis on The Sirian Daily Universe—the year always was reckoned from the date when the planet was first visited by an expedition from the solar system. Although days were not always the same, twenty-four hour periods could be reckoned quite easily so that on some planets a single day might have more than one terrestrial date, and on others a single day would be a fraction of a legal day. The number of actual days usually was indicated by a Roman numeral preceding the Arabic figure. Thus August V2 indicated that Sirius had risen and set five times while the sun had done so twice during the month of August.

"Unbelievable!" I said. "How does it work?"

"It operates through time," Trella explained. "It takes a short cut between two parallel instants."

She took a guinea pig from a cage in the laboratory. She put the wriggling animal inside the quartz tube and strapped it firmly in the center.

"Watch," she said.

She turned a switch on one of the boxes. A low hum arose from the atomic motor. Trella watched a dial located in the top of the quartz tube until an arrow pointed to a gold star. Then she pressed a button in the motor on the right side of the machine.

I noticed that the translator had controls that could be operated from inside the tube as well as from the outside.

There were two distinct gasps of the motor. Half of the guinea pig disappeared with the first gasp and the remaining half disappeared with the second.

Where the tube had been a second before, there was nothing now.

"He's on Proxima Centaur now," Trella said. "I managed to equip a laboratory there about two years ago. It was through that laboratory that Keeshwar learned of my experiments in translation. My men on Proxima will send back the guinea pig in a few minutes."

We sat down and waited. Trella explained the machine, although at the time the explanation was a little over my head. The actual translation was accomplished by the pushing of one motor and the pulling of another across an extra-dimensional space. Half of the object to be translated was hurled across space by the pushing of the first motor. The second motor, which operated automatically, began pulling the other half, including the first motor, after it as soon as it materialized at the end of the journey.

By means of radio signals the exact location of every explored planet had been determined. It was therefore only a matter of mathematical calculation to find the target. There was some risk, of course, if a mathematical error were made in computing the range but considering the risks involved in ordinary methods of interstellar flight everything was in favor of the translator.

"The whole secret of the invention lies in locating the proper Now in space-time," Trella explained.

"The proper Now?" I asked.

"Of course," she said, "the Now we experience on earth is not the same Now that exists simultaneously on Rihlon, the second planet of Proxima Centaur. We are dealing with space-time, Fred. Time is a dimension, it stretches like a line through space. If we connect the Now of the present with the Now of ten minutes ago, we have a straight line, just as we would have a straight line if we connected any two points in the universe. The Now of the present and the Now ten minutes ago on Rihlon also would be a straight line, but it would not be the same straight line."

"But it would be parallel!" I exclaimed, beginning to see her point.

"Oh, so you do know something about mathematics?"

"Of course! If you connect the Nows of the present on both the earth and Rihlon, you have a straight line, perpendicular to the parallel time lines of both the earth and Rihlon. Why couldn't your invention be used for time travel? Couldn't you connect the present—Now of Rihlon with any Now in the time line of the earth—any Now of the past or future?"

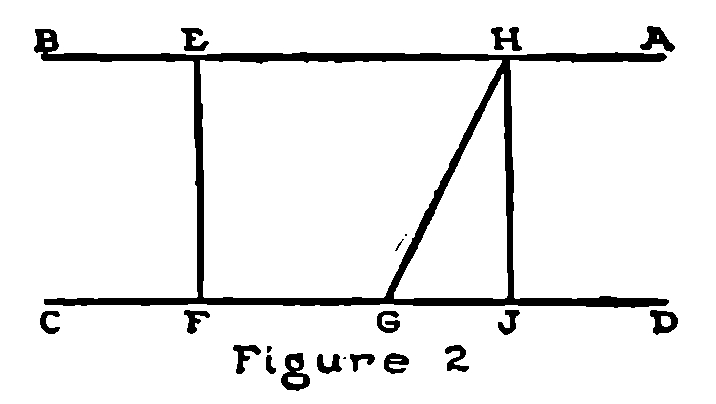

"The idea occurred to me, but it won't work," Trella replied. "There's a serious obstacle we can't overcome. In going backward or forward in time we do not travel in lines perpendicular to the parallel time lines of the earth and Rihlon—or for any other planet for that matter. But we travel like this—" Trella drew a figure on a piece of paper.

"The line AB represents the time line of the earth and the line CD represents the time line of any other planet X. The two lines are parallel. E represents the earth—Now, and F the Now on planet X. A line connecting the two is perpendicular to both AB and CD. Supposing we should travel from F to a point G, a Now in the earth's past. If we connect F and G we would have a right triangle GEF. The hypothenuse GF would be the square root of GE squared plus EF squared."[3]

"There is nothing mathematically implausible in that," I said.

"There is nothing implausible, yet to determine the exact distance from G to F is in most cases impossible. Unless the distances involved are of the proper ratio, say, 4 and 5, the line GF becomes an irrational number, of which it is impossible to find the exact value. Supposing the distance from E to F was one light-year and the distance from G to E, one year. Then GF would be the square root of one squared plus one squared, or the square root of two. Because we are dealing with such immense distances and because even the smallest decimal point of error might lead to disastrous results, we cannot attempt time travel unless we know the exact value of the square root of two, or any other irrational number."

As Trella finished speaking there was a coughing hum and the translator appeared in the room, containing the unharmed guinea pig and a copy of the Rihlon Gazette for Aug. 3rd, which was this day.

"Do you believe me?" she cried gleefully, waving the paper over her head.

It was quite convincing, I admitted.

"Now I am going to make a trip in the translator!"

"You!"

It was the beginning of a long argument. There was danger in the trip, I told her, and Trella had come to mean a great deal to me. She scoffed at my fears and told me that if I didn't care to witness the first translation of man to another planet in another star system she would do it when I wasn't there.

Of course, no man can win an argument with a woman.

Trella climbed into the translator.

I closed the opening. Her hand rose to the switch that operated the mechanism from inside the tube. She smiled and her lips moved in a cheerful good-by. Then she touched the switch.

The indicator on the dial crept upward toward the gold star.

Suddenly the unexpected occurred.

The door of the laboratory opened. Trella had forgotten to lock the door when we entered the room.

As I heard the noise, I turned and saw Gustav Keeshwar leveling a gun toward the helpless young woman in the glass tube.

I sprang toward him just as the gun went off.

Apparently he had not expected to find me in the room, for as I lunged he uttered a cry and threw the gun at my face. Then he turned and ran.

I managed to duck in time to receive only a glancing blow on the head. I started to pursue, when my eyes fell on the translator.

Something terrible was wrong.

Half of the tube had disappeared and, with it, half of Trella's body. The other half, containing half of the most beautiful woman on the earth, remained in the laboratory.

My spring toward Keeshwar had spoiled his aim enough to keep the bullet from striking Trella, but the bullet had struck the small silver wire that ran from the atomic motor on one side to the atomic motor on the other. The translation had been only half completed.

Half of Trella's body was on the earth, while the other was on Rihlon, four light years away!

Her single eye was open and her half-face was frozen in an expression of terror. She did not move and she was not breathing. There was no blood. It was a complete suspension of animation.

Suddenly I realized that I was losing precious seconds. Unless something was done, Trella would die.

I picked up the bit of wire that had been broken off by Keeshwar's bullet. I lifted it toward the end dangling from the motor.

Then Trella moved! It was not suspended animation, but something else—something new!

Her eye swung toward me. Her half-head visibly shook. Her half-lips moved but no sound of her voice reached me. But I understood. She was telling me not to replace the wire.

She lifted her hand and drew a right-angled triangle on the side of the tube.

I understood. Trella was alive and she would continue to live, but it would be impossible to restore her component halves merely by mending the broken wire.

Trella was linked in time. She was still whole, but half of her body was visible in one Now and the other half in a Now on Proxima Centaur, four light years away.

To join the halves of her body, would mean joining the two Nows and to do that would form a triangle, at least one side of which would be an irrational number. Unless the riddle of time travel were solved, it would be impossible to make Trella whole.

I walked around the half-tube. Her appearance was not what I expected to see. It was not a case of sawing a woman in half. The cross section of her body appeared only as an opaque blankness. When I touched her side I felt something cold and hard. It was as if I had touched eternity.

The laboratory officials were called in for consultation. It was decided that the matter should be hushed, at least until we knew what should be done. There was too much to do now to be bothered with police and reporters. We would not have a warrant issued for Keeshwar. There would be time to deal with him later.

We discovered that Trella could eat and she seemed to be in perfect health. But I knew that she was doomed unless we could restore the parts of her body. Her muscles would atrophy. Inaction is more deadly to the human machine than millions of disease germs.

If it would be possible to locate some day in the future when the wires might be pieced together and the linking of Trella's two halves might be accomplished without rationalizing irrational numbers, our problem would be solved. But the nearest date in the future when this could be done was three years ahead.[1]

But in three years Trella would be dead. We could not wait for the coordinates to adjust themselves. We had to make the coordinates adjustable to our purposes.

A small chronometer located in the atomic energy machine on the quartz tube gave us the exact time the silver wire had been broken.

Even Blake, my servant, offered a suggestion:

"If you could take the earth half of Miss Trella's body to Rihlon, or bring the Rihlon half to earth and bring the two Nows together, would that form a rational triangle?"

I took paper and pencil and tried to figure it out.

The line BA represented the time line of Rihlon. The line CD was the time line of the earth. The points E and F were the Nows on Rihlon and earth, respectively, at which the accident occurred. The point G represented the Now at which a space ship would leave the earth for Rihlon carrying Trella's half body. The point H represented the Now of arrival on Rihlon and the point J the parallel point on earth. We still had a right-angled triangle and we still had to deal with irrational numbers. But hold on—

I gazed at my drawing. Before my eyes was the answer! The whole thing was clearly and completely solved. The secret of time travel was solved. Trella was saved. The invention of the translator had been perfected so that all danger of becoming lost in time was removed![2]

"Blake," I said to the servant, "bring me my automatic pistol."

"Wh-what?" Blake stuttered.

"I said bring me my automatic pistol. I'm going to save Trella, or murder somebody."

"Perhaps I should call your lawyer."

I threw a book at him and he left hurriedly, to return in a few minutes with my pistol and holster. I strapped the weapon about my waist and slammed my straw hat on my head. In a few minutes I stepped from a taxi in front of the Galaxy building, in which the officers of the Stellar Transport Company are located.

A clerk with thick glasses interviewed me.

"I want to charter a ship for a trip to Proxima Centaur," I explained. "I want one of your late model cruisers which can go about ten times the speed of light. I want to get there quickly."

The clerk nodded. I have often wondered about the composure of clerks who never seem to be astonished at anything. "We have a ship available that could get you there in three months, that's sixteen times the speed of light. But to charter it would cost one million dollars."

He never batted an eye when he named the price. I doubt if the clerk was receiving more than forty a week.

"I should like to transact the deal directly with Mr. Keeshwar," I said.

"He will be pleased, I'm sure," the clerk replied. "What is your name?"

"Andrew J. Colt," I said, for lack of more originality.

The clerk disappeared into the sanctum. He returned presently with:

"Mr. Keeshwar will see you, Mr. Colt."

I had counted on Keeshwar being—or pretending to be very busy as I entered. I expected him to pay no attention to my entry, and not even to glance in my direction, as if a million dollars were a trifling matter, until we were alone.

I judged Keeshwar right. When at last he glanced at me he was unnerved by the presence of an automatic pistol which was pointed directly at his head.

"I must warn you not to touch any of those buttons on your desk," I said. "It would give me a great deal of pleasure to drill you and I won't go out of my way for an opportunity."

"Wh-what d-d-do you w-w-ant?" he asked, turning pale.

"One day you offered me a million dollars to take Miss Mayo's life," I said. "Now I'm asking you to contribute an equal amount to save it. However, I'm willing to take it out in trade. I want you to pilot one of your ships for me to Rihlon."

"Impossible!" Keeshwar said, regaining some of his composure. "I couldn't leave my business for a period long enough to make the trip."

"If you don't leave your business to make the trip right now you won't exist any more," I warned casually. I reached into my pocket and brought out a silencer, which I fitted to the end of the pistol barrel. I unfastened the safety and aimed deliberately.

The space ship containing the terrestrial half of Trella Mayo, in company with myself, Blake, two other scientists and Gustav Keeshwar, arrived on Rihlon three months later. Keeshwar, who had had a pistol trained on him almost every instant since I had called at his office, was released and permitted to return to earth. He did not know that I had left the instructions on earth for his arrest for felonious assault the minute he landed.

We located Trella's Rihlon laboratory. It was the matter of a few minutes to make the connection of the broken wire and to finish the translation of her two halves.

Trella stepped out of her quartz prison, swayed unsteadily for a second on her feet, and then collapsed.

"How on earth did you do it?" she asked. "How did you reconcile the irrational number?"

I sketched the figure roughly (Figure 2). "The distance from F to G and the distance from E to H does not enter into the equation," I said. "The only thing we are interested in is the distances GJ, JH and GH."

"And GH is an irrational number," Trella said.

"Quite right, although like most things that appear absurd on the surface, it is not as irrational as it seems. The distance G to J is three months, the time required for the flight from the earth to Rihlon. We will represent this by the unit 1. The distance JH is four light years, the distance in space from earth to Rihlon. This, therefore, would be sixteen units. Using the formula (GJ)2 plus (JH)2 equals (GH)2 we find that GH is the square root of one plus 256, or 257. The square root of 257 is 16.031228, etc., an irrational number.

"It can't be expressed in figures! We do not need figures when we can draw a picture. The triangle GHJ is a picture of an irrational number. We had only to go to Rihlon to complete the equation."

"Time can be traveled," Trella said.

"Where would you like to go on our honeymoon?" I asked.

"To the Garden of Eden," she said.

[1] Three years from the time this accident occurred would make the sides of the triangle between the past event, the present, and the present on Rihlon (four light years away) equal to the units 3, 4 and 5. Three squared, plus four squared equals five squared.

[2] As a mental exercise, I would suggest that the reader look at Figure 2 for a minute or two and figure out the answer. The answer is there and high school mathematics should enable a person to discover how to extract the irrational number.—Dr. Fred Huckins.

[3] [Transcriber's Note: Illustration is not correct. The second "C" label on the right should be "D".]

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.