Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this text and is placed in the public domain.

BY

BALCK

Colonel, German Army.

VOLUME I.

INTRODUCTION AND FORMAL TACTICS OF INFANTRY.

TRANSLATED BY

WALTER KRUEGER,

First Lieutenant 23rd Infantry, U. S. Army,

Instructor Army Service Schools.

Fourth completely revised edition.

With numerous plates in the text.

U. S. CAVALRY ASSOCIATION,

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

1911

Copyright, 1911,

By Walter Krueger.

PRESS OF KETCHESON PRINTING CO.,

LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS.

[iii]

The translation of this book was undertaken at the instance of Major John F. Morrison, General Staff, who desired to make use of it in the course in tactics in the Army Service Schools.

It is an epitome of the interpretation and application of tactical principles in the various armies, discussed in the light of the tactical views and methods prevailing in Germany, and amplified by numerous examples from military history.

The professional value of this book to all officers of our Regular Army and Militia who are endeavoring to gain a working knowledge of tactics, is so obvious that any comment would be superfluous.

Army Service Schools,

Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas,

December, 1910.

The first volume of “Tactics,” which appeared in its first edition in 1896, and for which the preparatory work reached back more than a decade, now appears in its fourth edition in a completely changed form. The lessons gained in war and improvements in weapons have corrected many earlier views. While the Boer war confused the views on infantry combat and brought forth more lessons in a negative than in a positive form, the Russo-Japanese war has had a great educating influence, in that it corroborated the soundness of the lessons gained in the Franco-German war, but also in that it amplified those lessons commensurate with the improvements in weapons. The fundamental principles upon which success depends have remained the same.

For a long time I hesitated to comply with my publisher’s wishes for a new edition. It would not have been difficult to publish long ago a new edition, based upon the many lessons of war communicated to me by members of foreign armies soon after the Russo-Japanese war. But, after an extended period of theoretical work, I was more inclined to avail myself once more of the opportunity of gaining practical experience by service with troops. Pure theoretical reflection is only too apt to depart from the requirements of practice and to overlook the friction appearing everywhere. The battalion commander, more than any one else, is called upon to act as the tactical instructor of his officers and knows best where the shoe pinches. Moreover, the proximity of the maneuver ground to my present station gave me an opportunity of observing the[vi] field training of a large number of battalions and regiments of infantry and artillery, and to compare notes with brother officers of the other arms. In addition, several trips abroad and, incidental thereto, visits to battlefields, furnished valuable suggestions. I postponed issuing the new edition until the publication of the new Russian and Japanese Drill Regulations, which, with our own excellent regulations, best illustrate the lessons learned from the war in the Far East. For this fourth edition I was further able to draw upon the new French (1904), Italian (1905), Belgian (1906), U. S. (1904), British (1905), and Swiss (1908) Drill Regulations. This enumeration alone justifies the statement, “completely revised,” appearing on the title page.

I have earnestly endeavored to make use of foreign experiences in detail. The words of Lieutenant-General Sir Ian Hamilton of the British Army, to whose writings I owe a great deal, deserve special attention in studying the drill regulations of foreign armies: “It is a blessing that the greater and prouder an army, the more immovably it is steeped in conservatism, so that as a whole it is finally incapable of assimilating the lessons gained by other armies. Military attachés may discover the most important points in the training and employment of foreign armies and urgently recommend their imitation, but their comrades will pay no more attention to them than did Napoleon III. to Stoffel’s reports on the Prussian army before the outbreak of the Franco-German war.”

The treatment of the subject matter has remained the same throughout; it represents, as in the first edition, the principle that tactical lessons must be deduced from human nature, from the effect of weapons, and from experience in war, proper regard being had for national characteristics and historical transmission. Tactics is psychology. My statements in regard to fire effect are based, as before, upon the works of His Excellency, Lieutenant-General[vii] Rohne. The publications of Historical Section I of the Great General Staff and the splendid works of the late Major Kunz, furnish the basis for examples cited from military history. An almost too copious literature is already available on the Russo-Japanese war. The monographs (Einzelschriften) of the Great General Staff, and of Streffleur, especially “Urteile und Beobachtungen von Mitkämpfern,” published by the latter, afford a rich field for research.

It is not difficult to cite examples from military history in support of any tactical procedure, but such examples require a very careful sifting before they can be recommended as worthy models for our action in front of the enemy.

The Austrians deduced the necessity of the most brutal shock action from the experience gained by them in their combats in Upper Italy in 1859, and the British were not very far removed from completely denying the feasibility of making an attack soon after the Boer war; but the desire to avoid losses was forced into the background by the necessity of annihilating the enemy. In the Far East the Russians finally had to learn again the same bitter lessons as at Plevna.

Simultaneously with this fourth edition, there appears in Athens a translation in Modern Greek from the pen of Captain Strategos of the Greek General Staff, well known to many German officers from his War Academy days.

It is hoped that the fourth edition may receive the same kind reception at home and abroad that was given its three predecessors. For all communications, suggestions or corrections, directed either to me or to my publisher, I will be sincerely grateful.

The Author.

Posen, March, 1908.

| INTRODUCTION. | ||||

| PAGE | ||||

| 1. | War | 1 | ||

| Eternal peace | 1 | |||

| War the ultimo ratio of state policy | 2 | |||

| Courts of arbitration | 3 | |||

| 2. | Strategy and Tactics | 4 | ||

| Definition of strategy and tactics | 4 | |||

| Relation of strategy to tactics | 6 | |||

| 3. | The Method of Instruction | 7 | ||

| Value of examples | 8 | |||

| Applicatory method | 10 | |||

| Advantages and disadvantages | 10 | |||

| Arrangement of the subject matter | 12 | |||

| 4. | Drill Regulations | 13 | ||

| Instructions for campaign | 15 | |||

| Regulations and the science of combat | 15 | |||

| THE FORMAL TACTICS OF INFANTRY. | ||||

| I. | ORGANIZATION AND EQUIPMENT | 19 | ||

| 1. | The Importance and Employment of Infantry | 19 | ||

| Relative strength as compared to other arms | 19 | |||

| Élite infantry. Guards | 21 | |||

| Jägers and riflemen | 22 | |||

| Mountain infantry | 23 | |||

| Machine guns | 24 | |||

| Mounted infantry | 25 | |||

| Patrols and scouting detachments | 27 | |||

| Cyclists | 28 | |||

| Snowshoe runners | 30 | |||

| 2. | The Tactical Unit | 32 | ||

| 3. | Organization | 34 | ||

| The company | 34 | |||

| Peace and war strength | 35 | |||

| The battalion | 36 | |||

| The regiment | 37 | |||

| The brigade | 37 | |||

| 4. | Intrenching Tool Equipment[x] | 38 | ||

| 5. | The Load of the Infantryman | 39 | ||

| Comparison of the loads carried by infantrymen in various armies | 40 | |||

| II. | THE FORMATIONS | 41 | ||

| 1. | The Issue of Orders | 41 | ||

| Trumpet signals | 41 | |||

| 2. | The Purpose of Formations. Comparison Between Line and Column | 42 | ||

| Assembly and route formations | 42 | |||

| Maneuver and combat formations | 43 | |||

| Napoleonic columns | 44 | |||

| Comparison between line and column | 44 | |||

| The origin of column tactics | 44 | |||

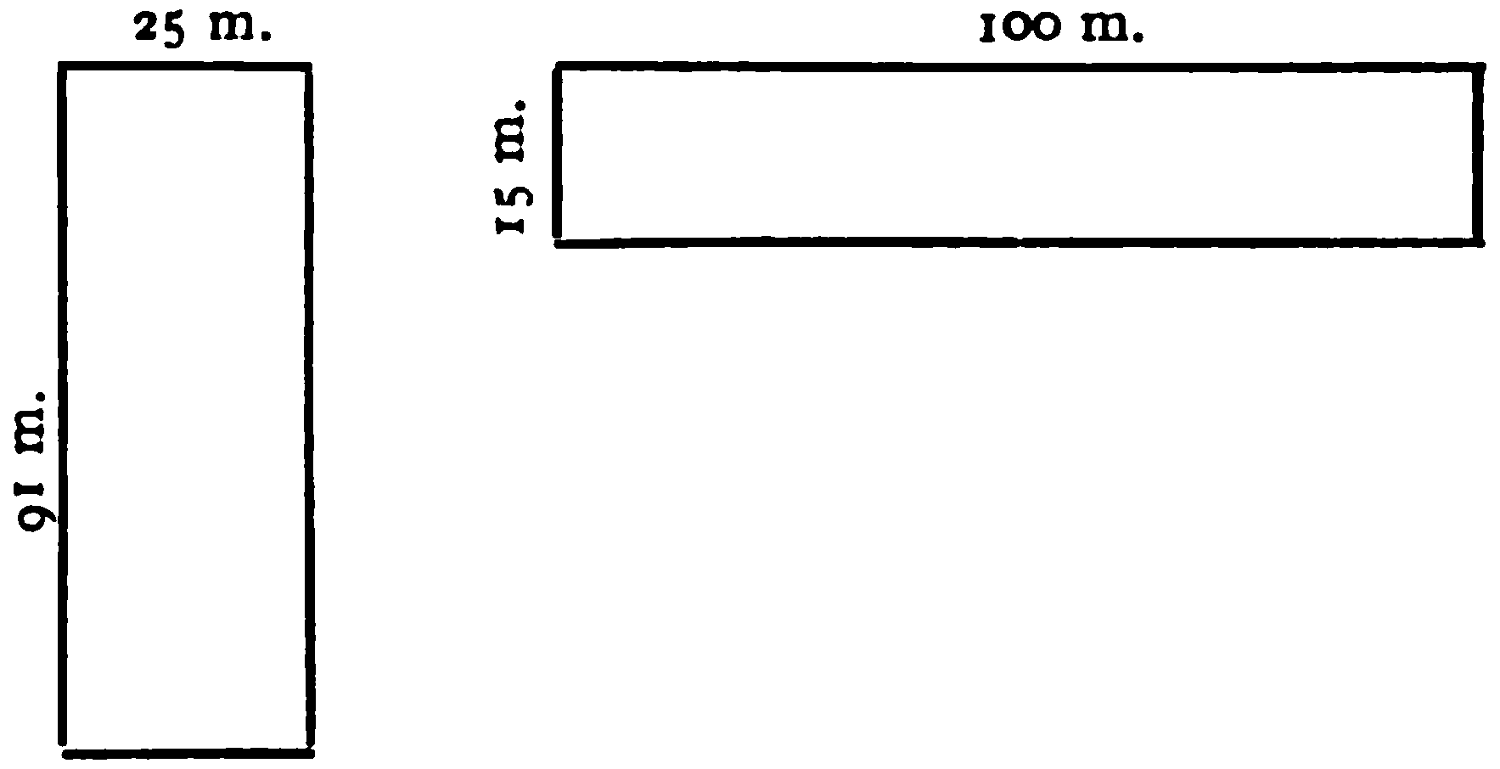

| 3. | The Company | 46 | ||

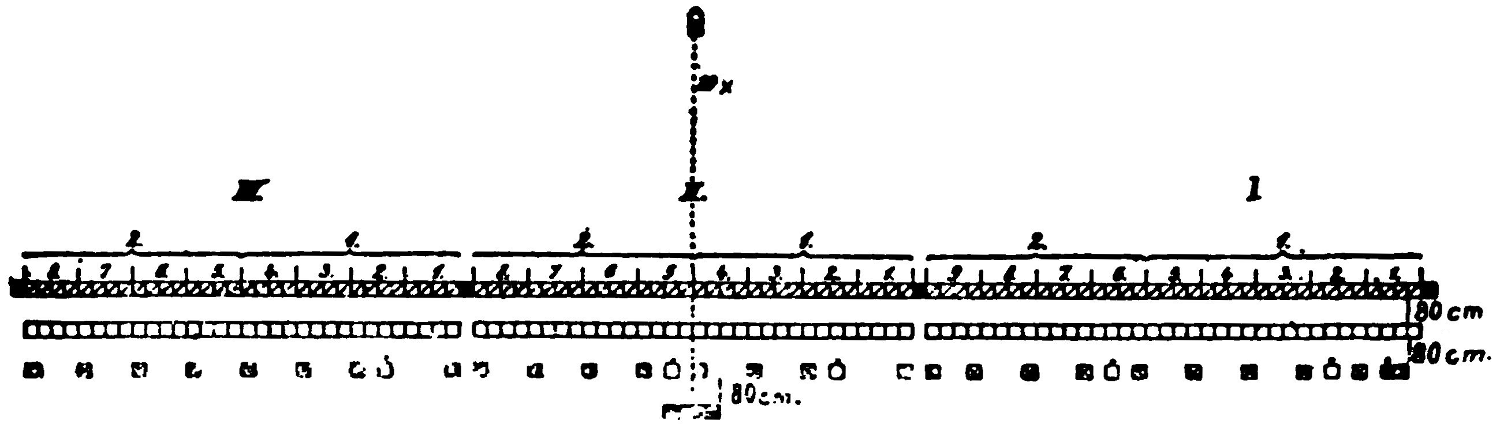

| (a) | Formation of the company | 46 | ||

| Number of ranks | 46 | |||

| Interval and distance | 47 | |||

| Front and facing distance | 48 | |||

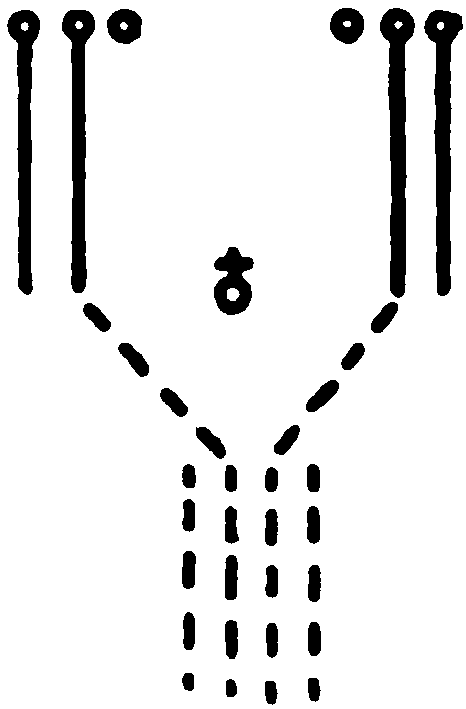

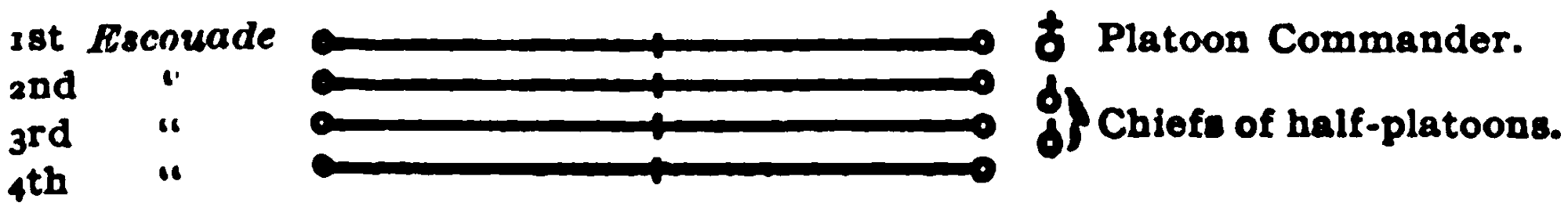

| (b) | Division of the company into three or four platoons | 48 | ||

| Losses among officers | 50 | |||

| 4. | Length of Pace and Marching | 53 | ||

| Comparison (table) | 54 | |||

| Double time | 55 | |||

| 5. | Movements of the Company in Line | 56 | ||

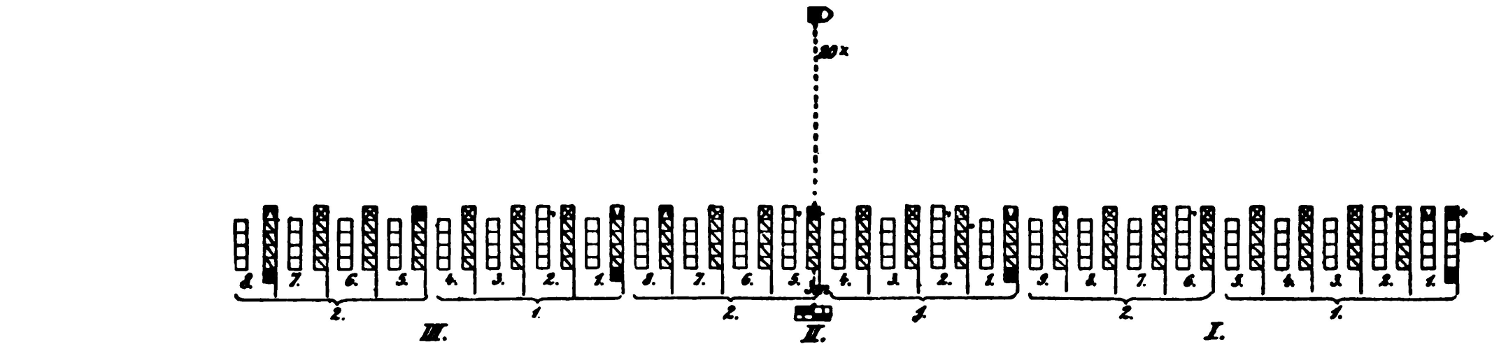

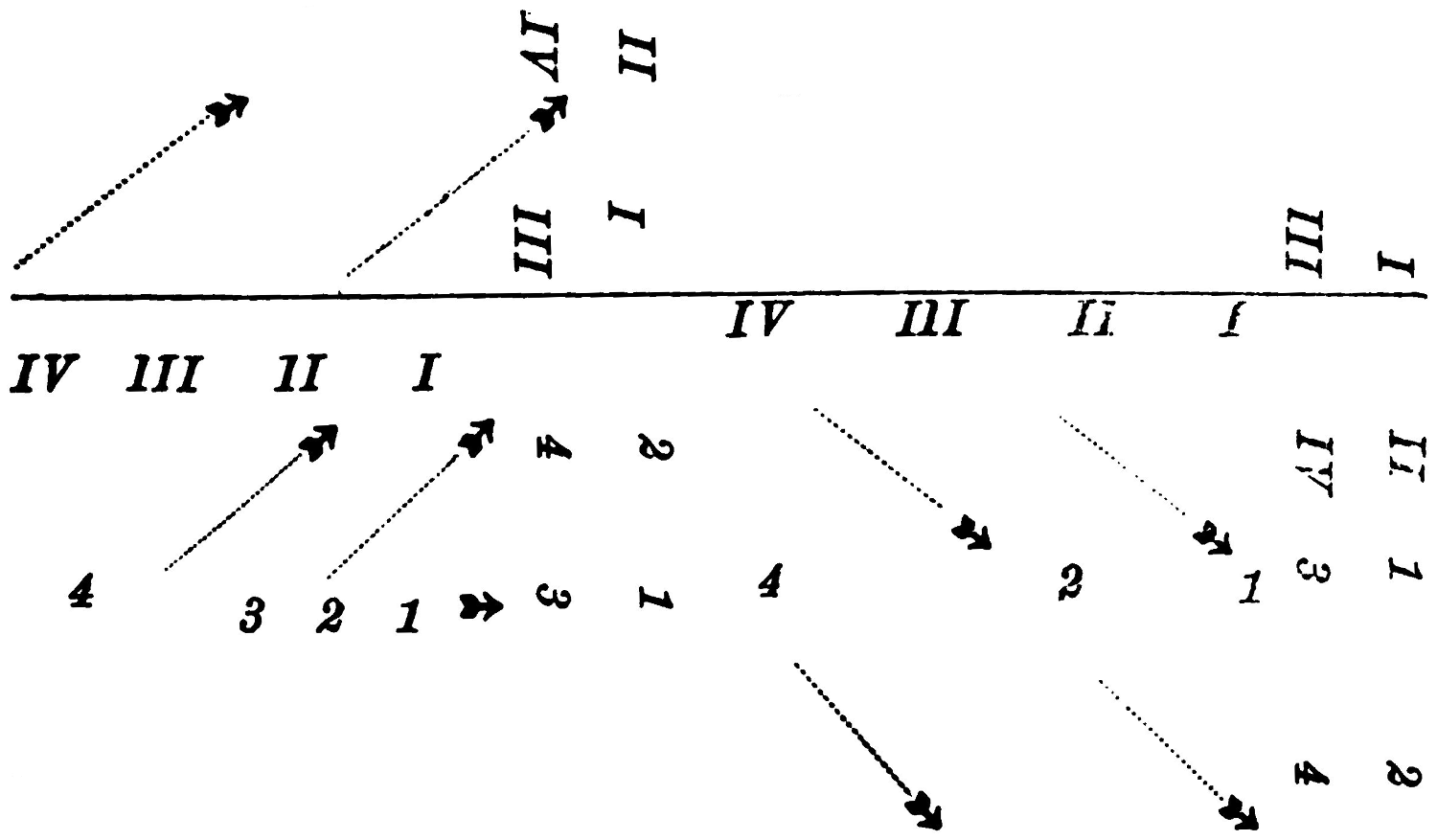

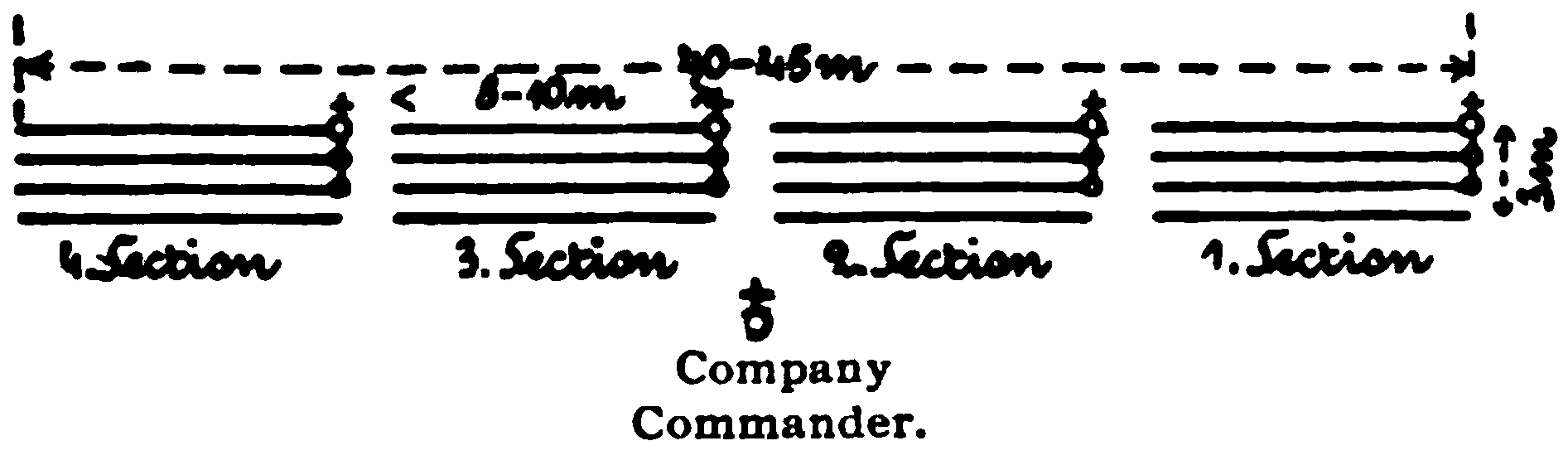

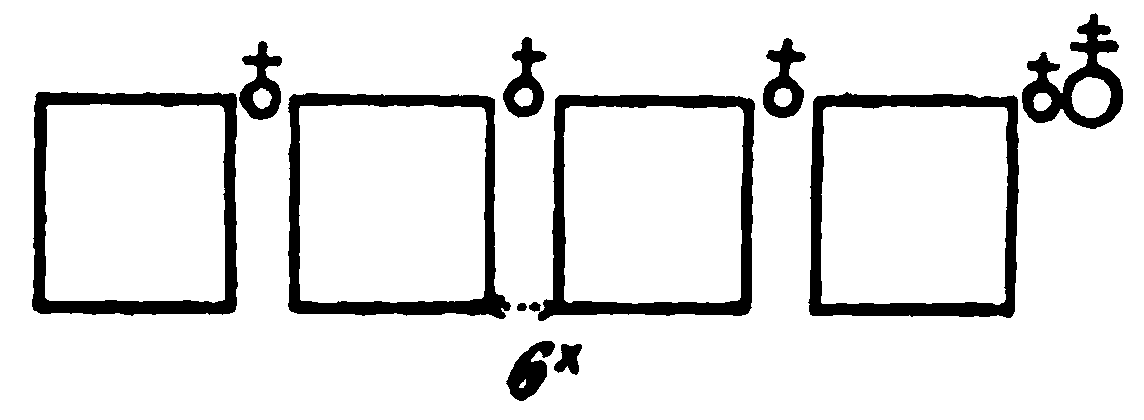

| 6. | The Columns of the Company. Movements in Column. Formation of Line | 56 | ||

| Column of twos | 56 | |||

| Column of squads | 57 | |||

| Route column | 57 | |||

| Column of fours | 58 | |||

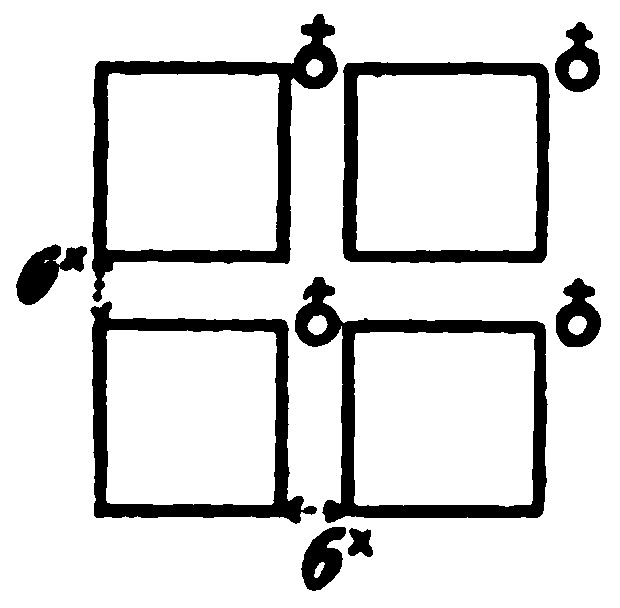

| Double column of squads | 59 | |||

| Comparison of column of fours with column of squads | 59 | |||

| The importance of the squad | 59 | |||

| The employment of the column of squads | 59 | |||

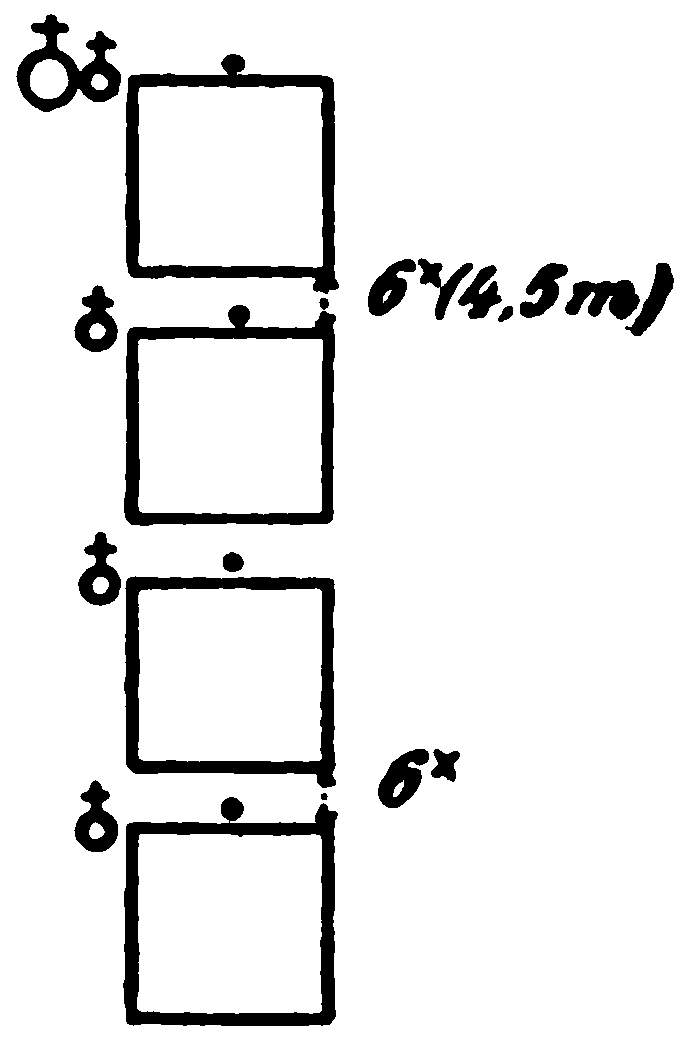

| Company column | 60 | |||

| Column of platoons | 61 | |||

| Column of sections | 61 | |||

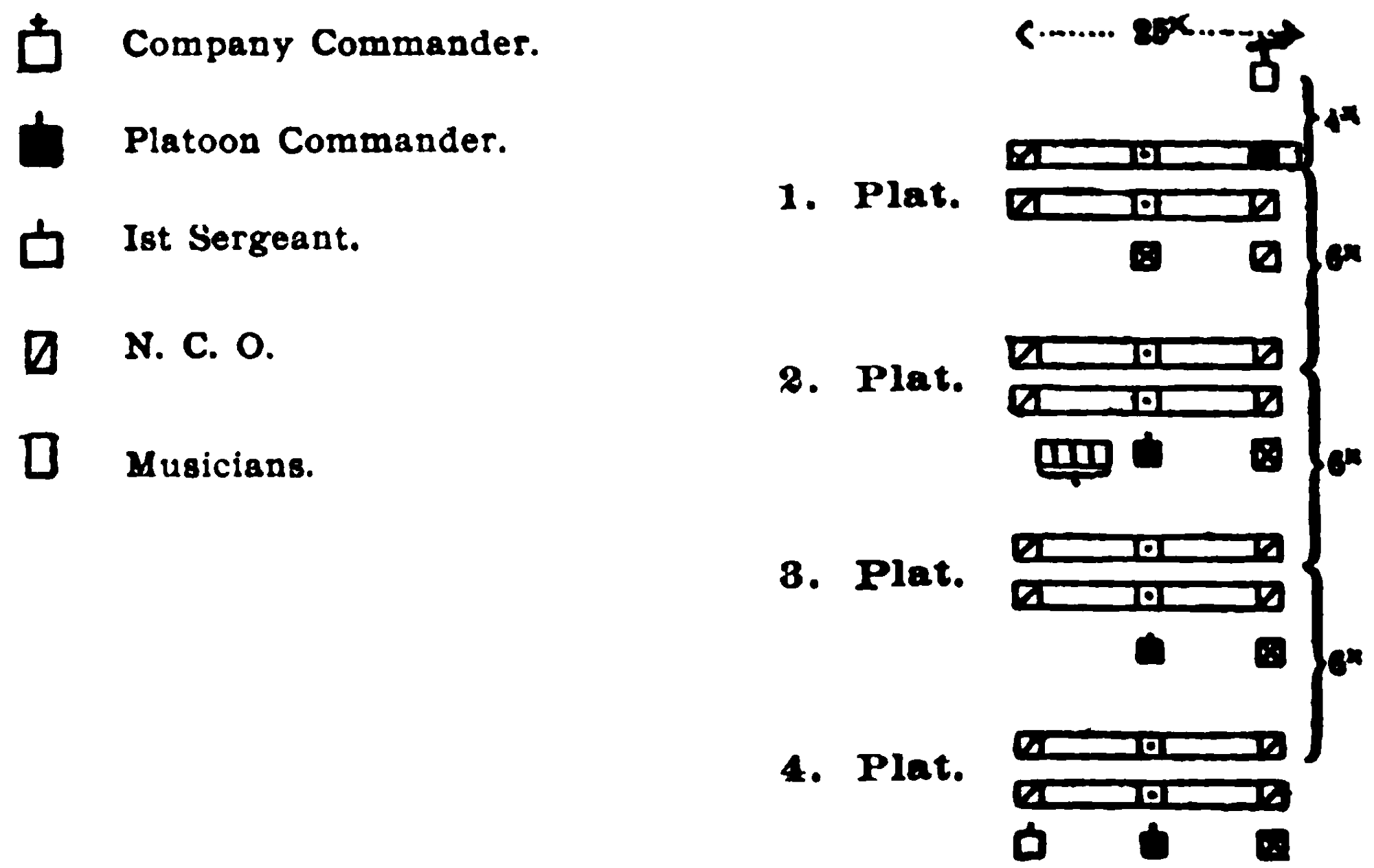

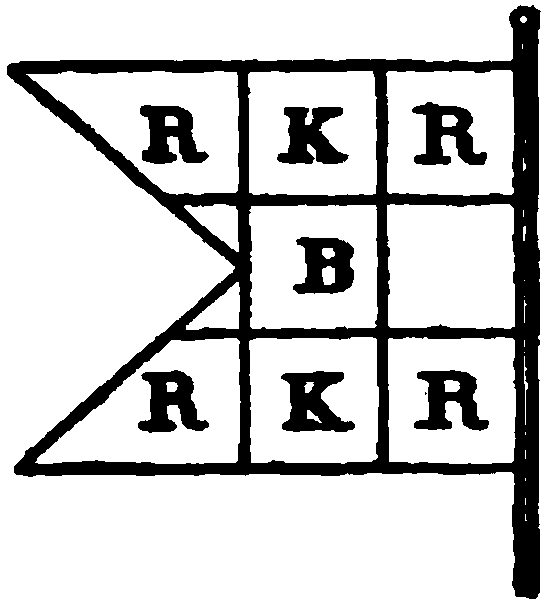

| Guidon flags | 63 | |||

| Posts of platoon commanders | 63 | |||

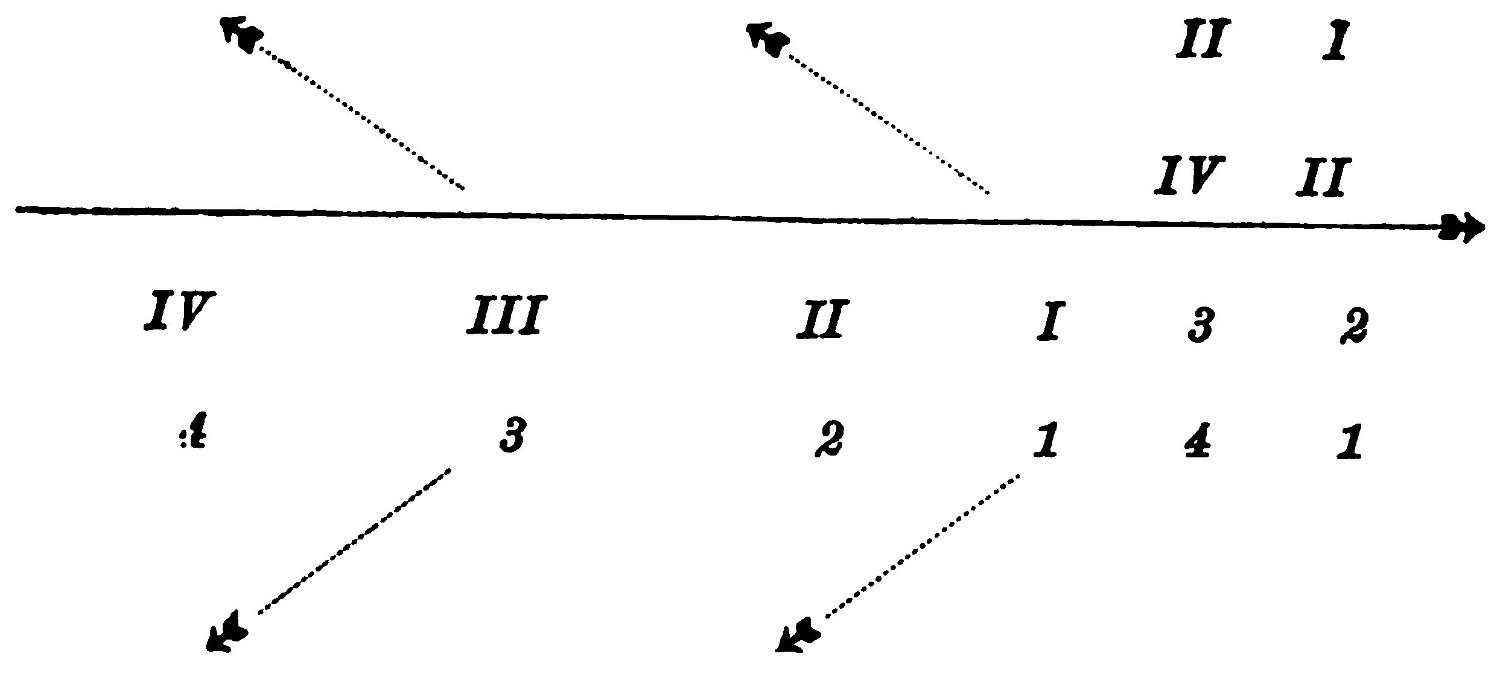

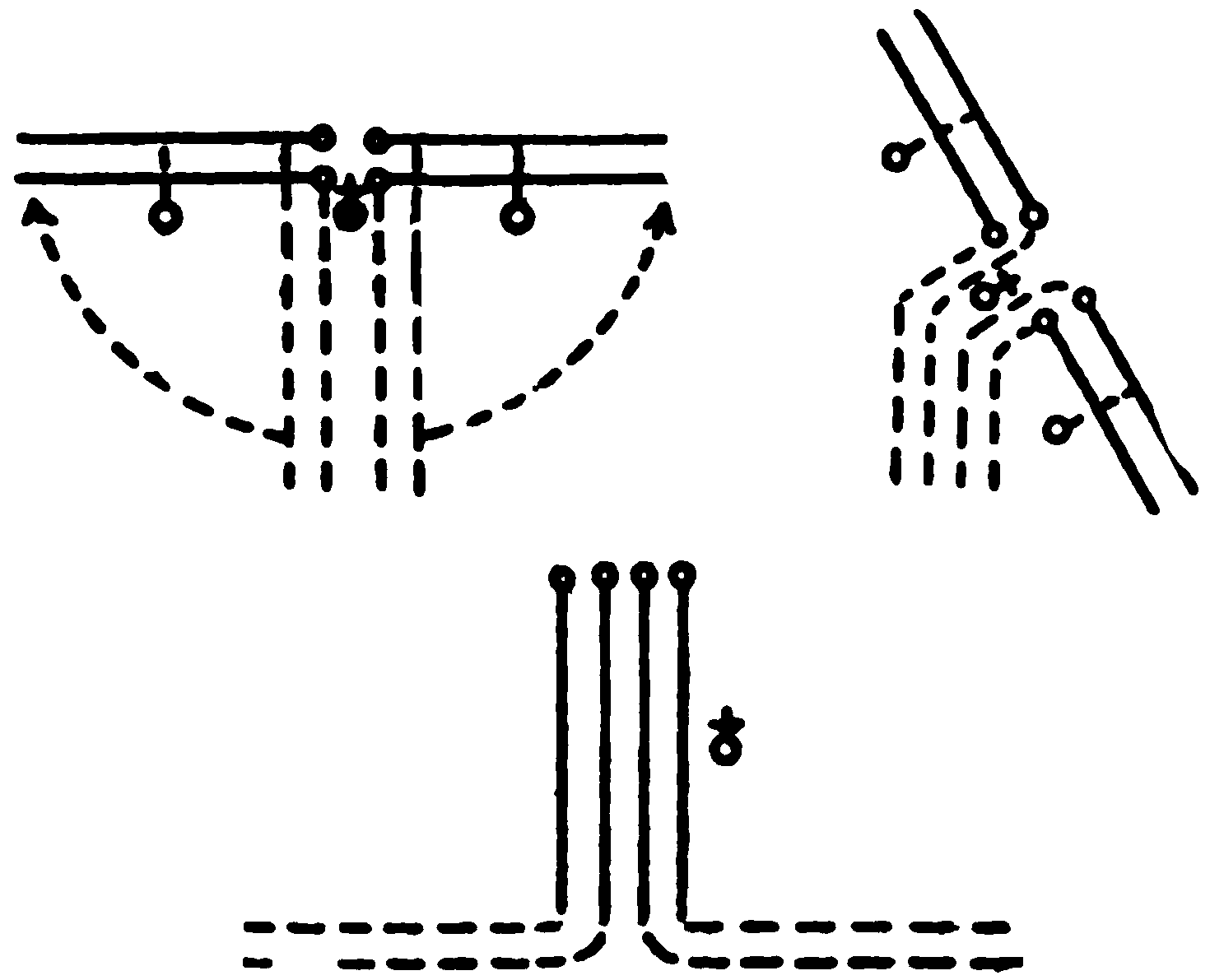

| Movements in column | 64 | |||

| Suggestions made by Colonel Fumet, French Army | 65 | |||

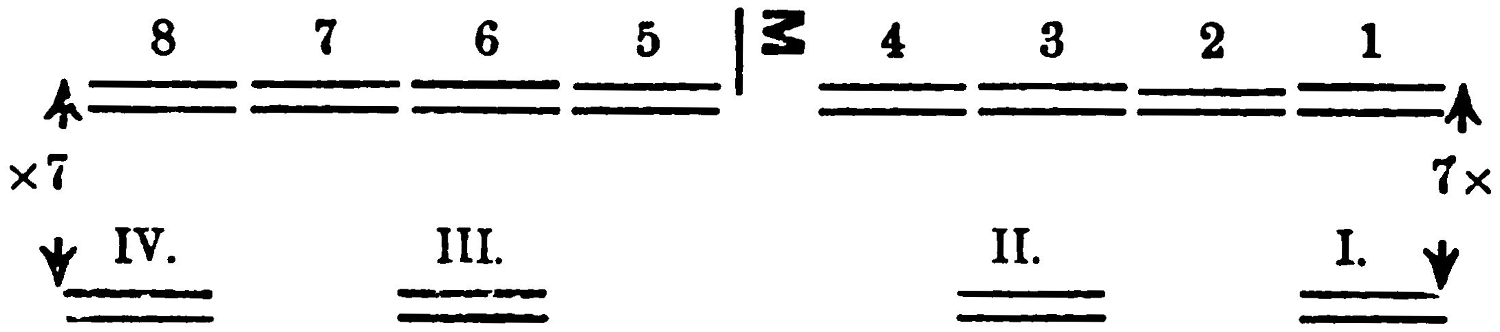

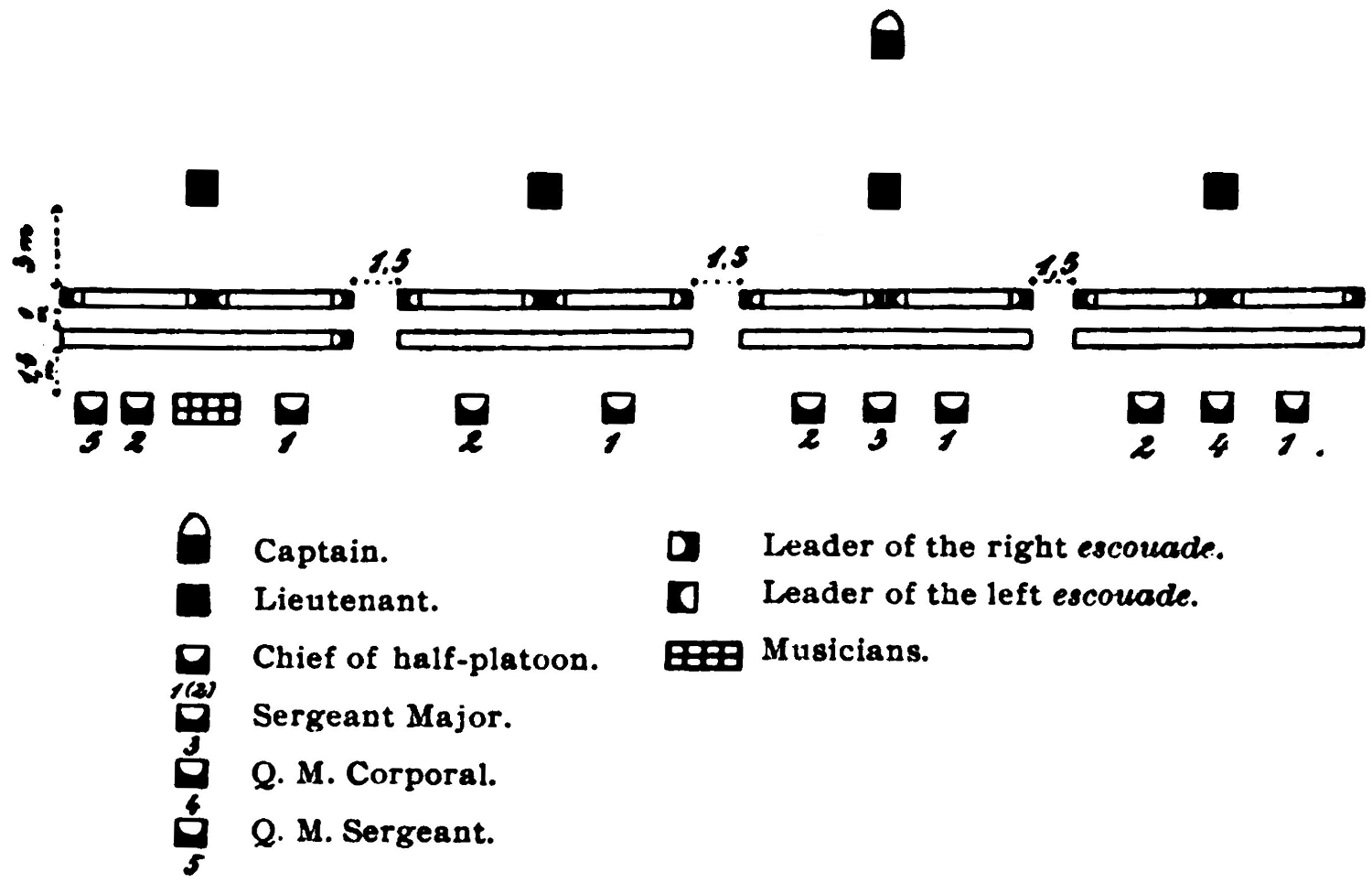

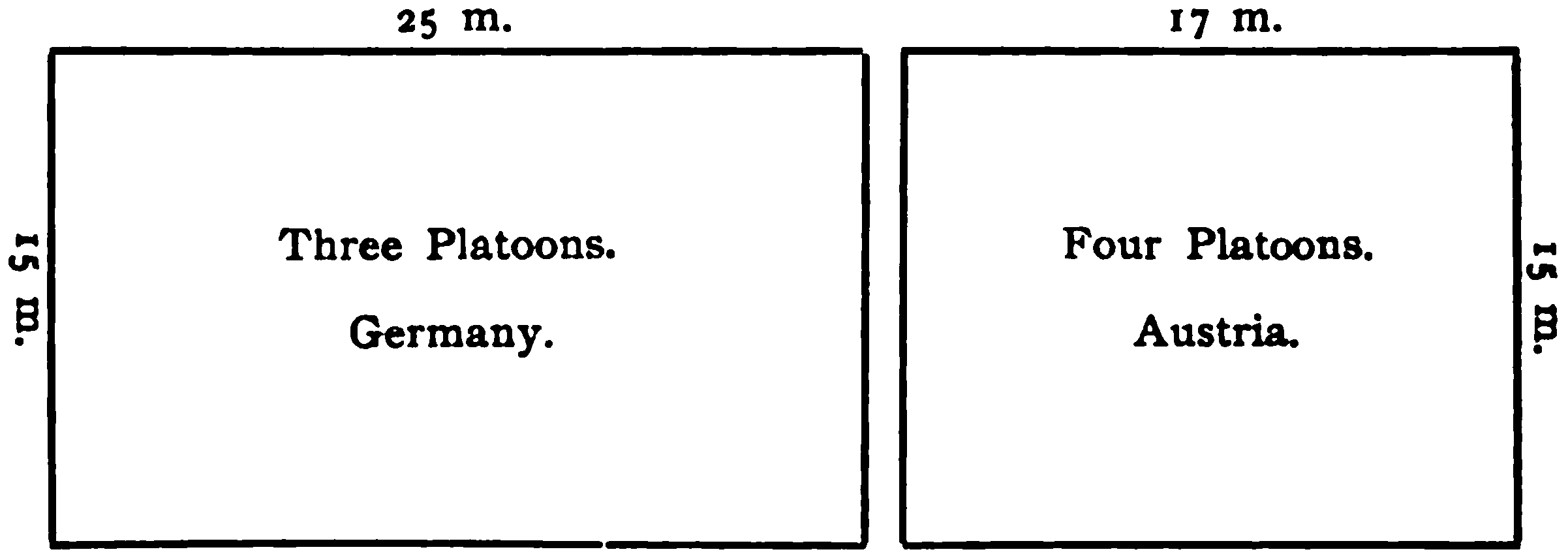

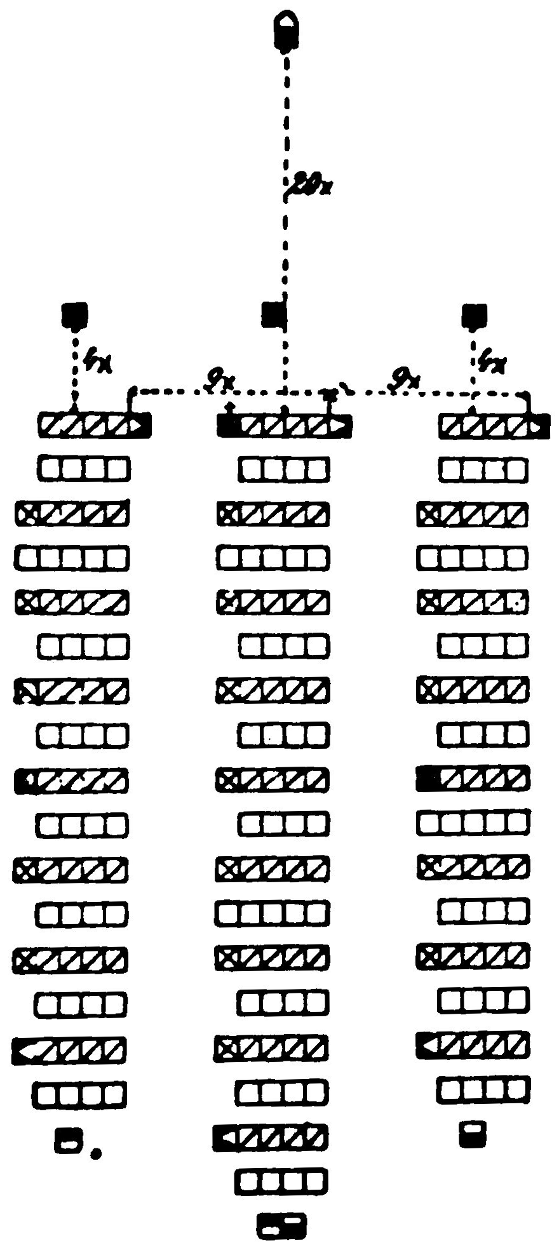

| 7. | The Battalion[xi] | 67 | ||

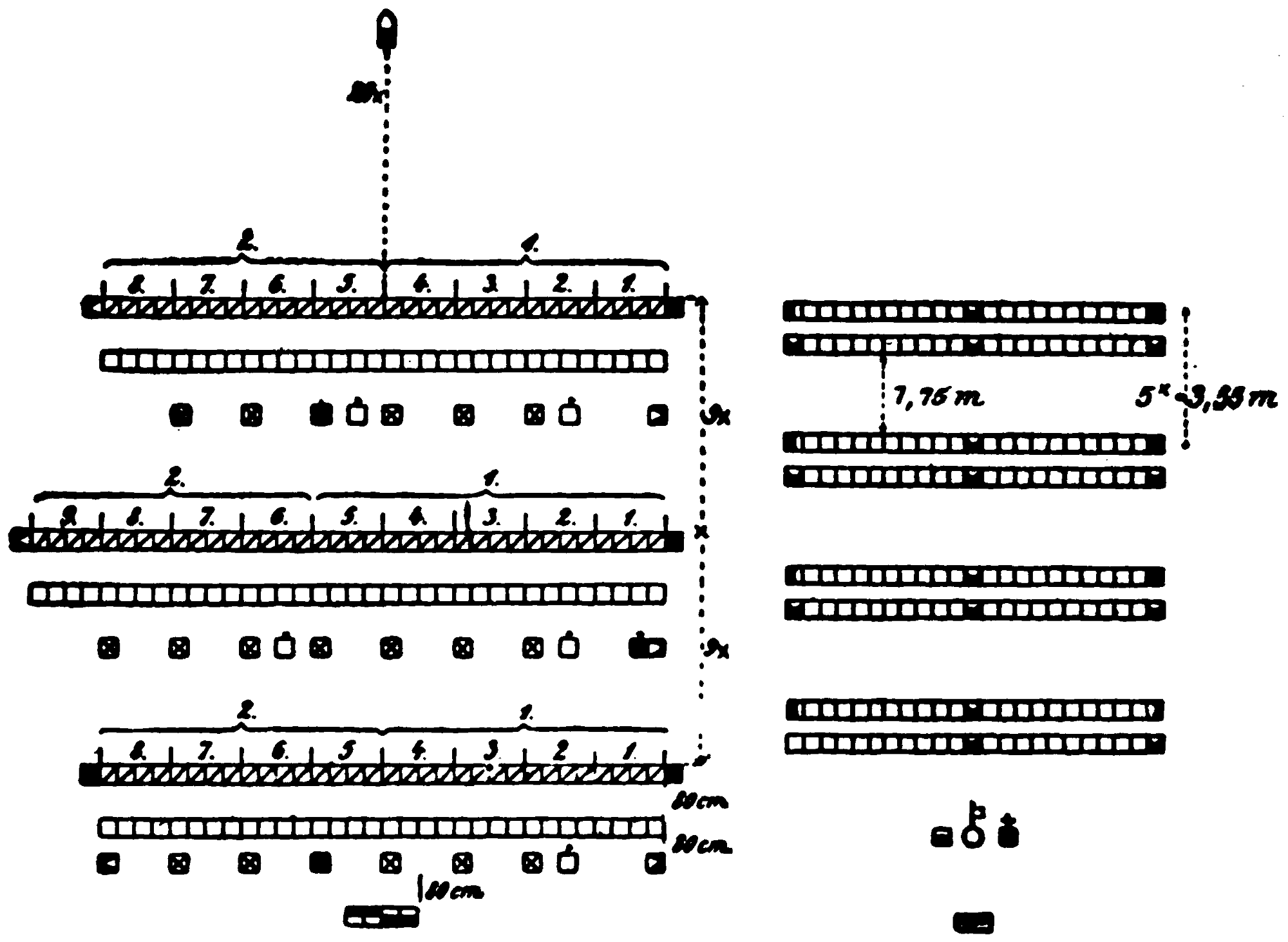

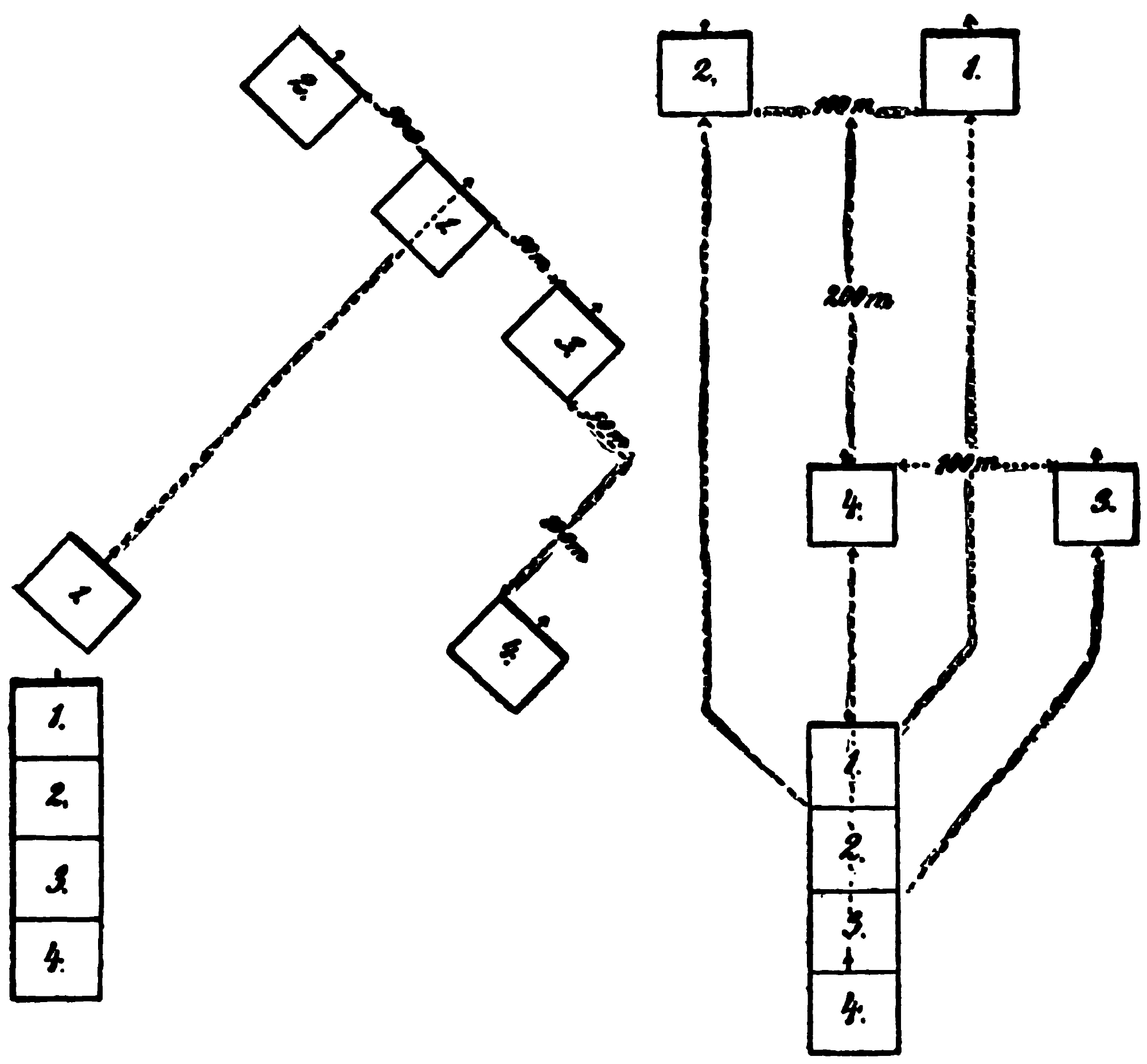

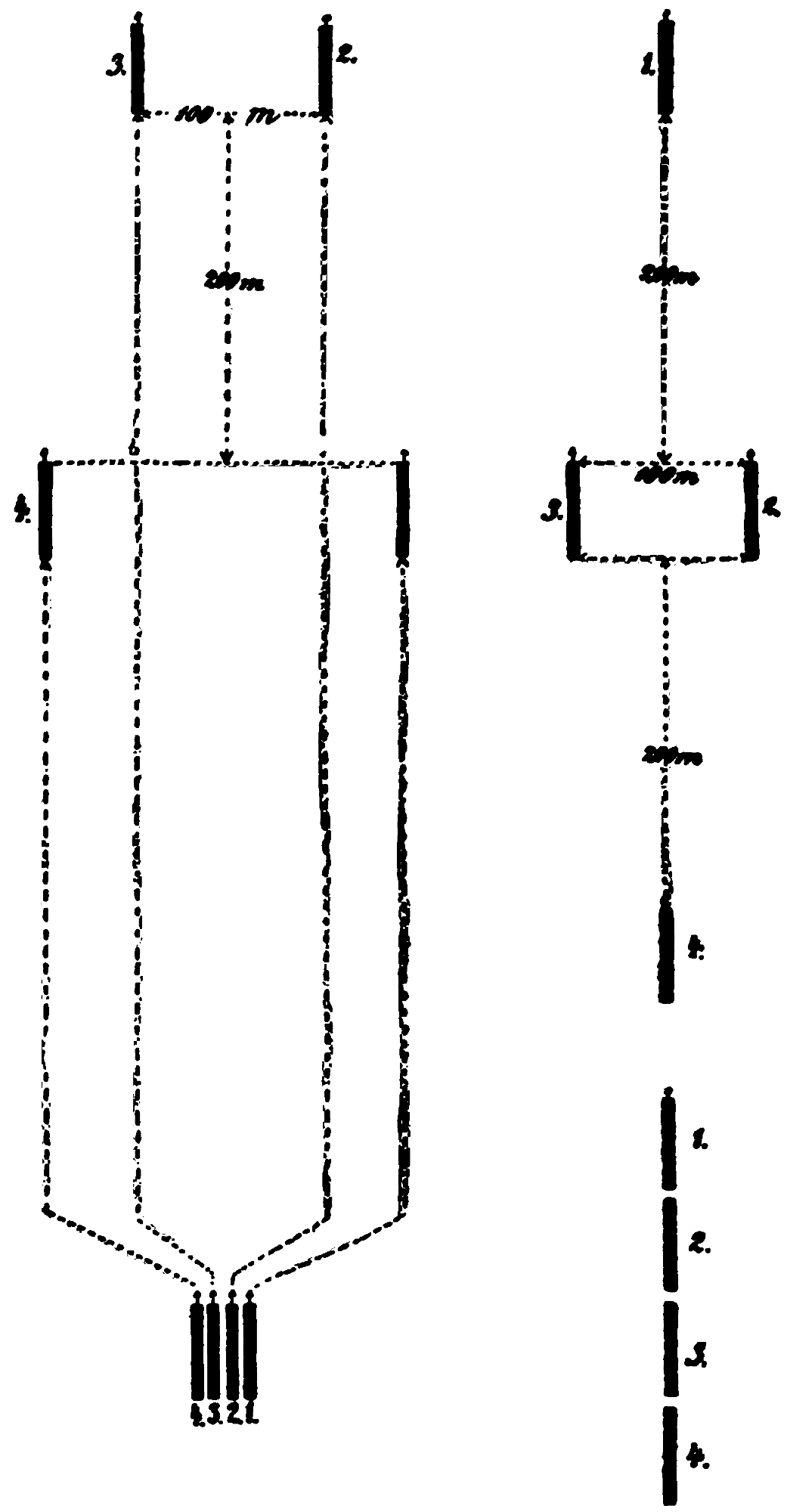

| Normal formation of the German battalion | 67 | |||

| The color | 68 | |||

| Formations in various armies | 69 | |||

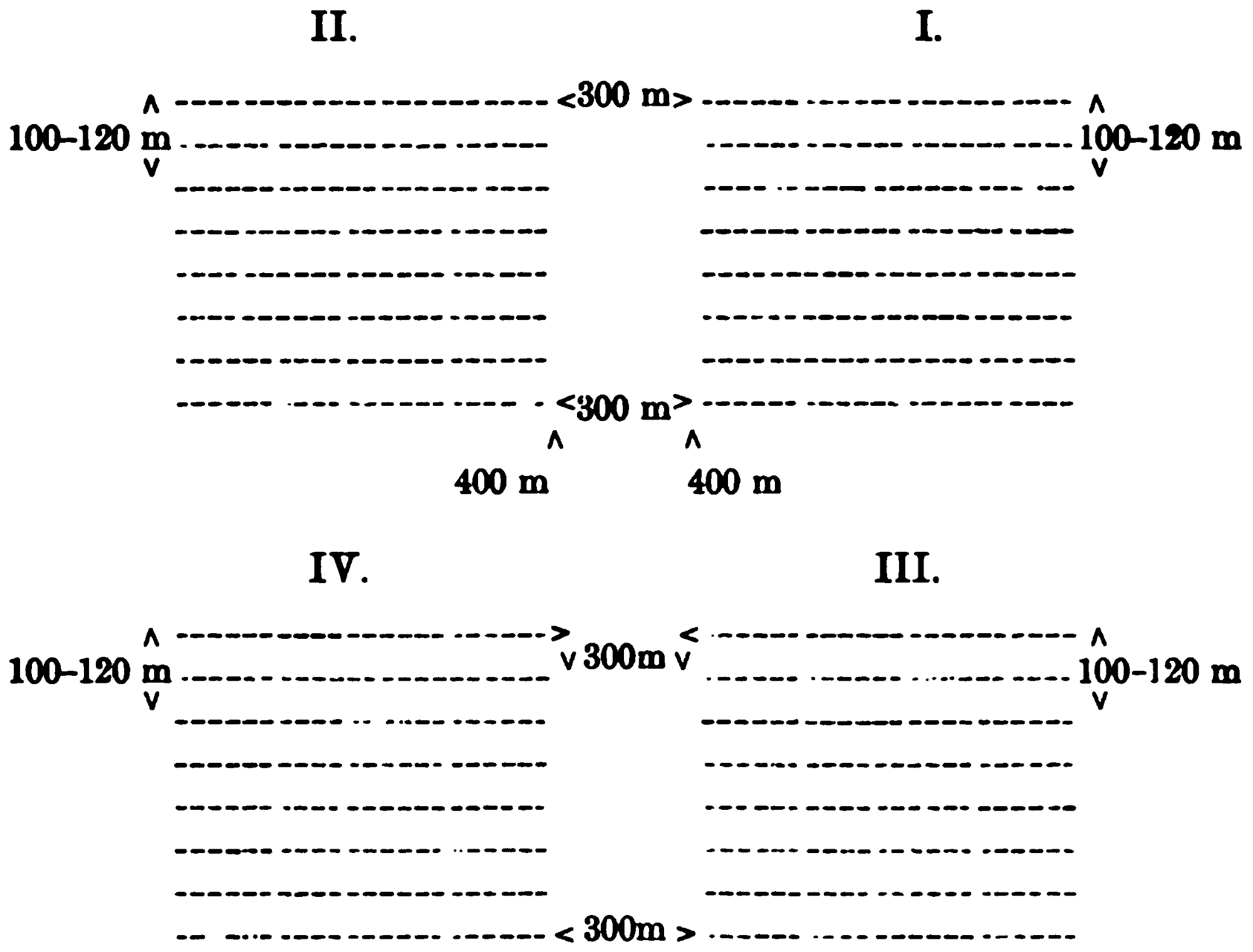

| The value of double column | 71 | |||

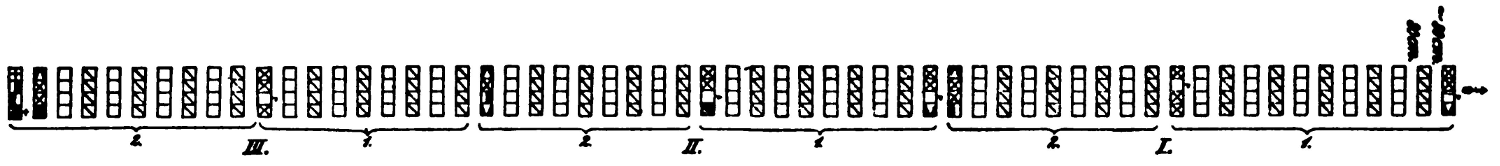

| The battalion in route column | 72 | |||

| 8. | The Regiment and the Brigade | 73 | ||

| Formation in line or in echelon | 73 | |||

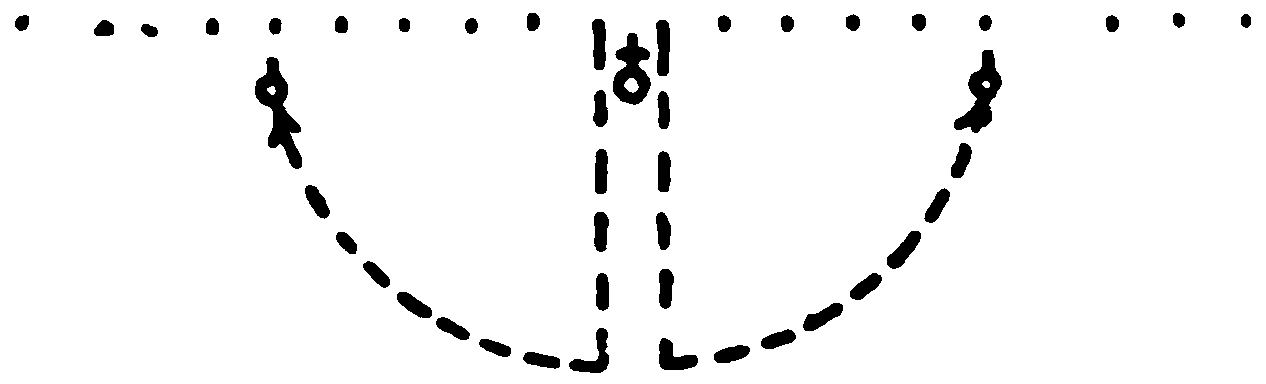

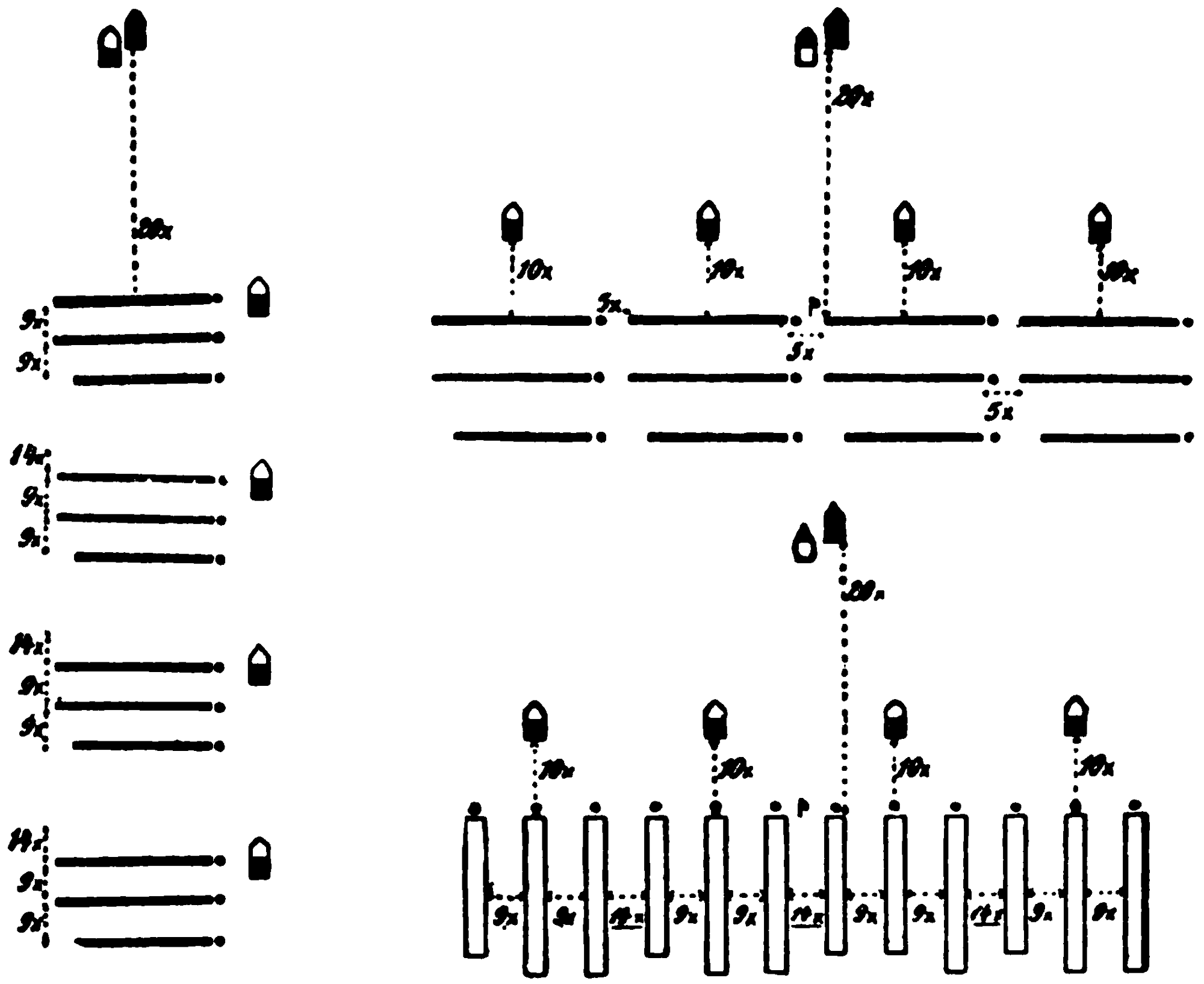

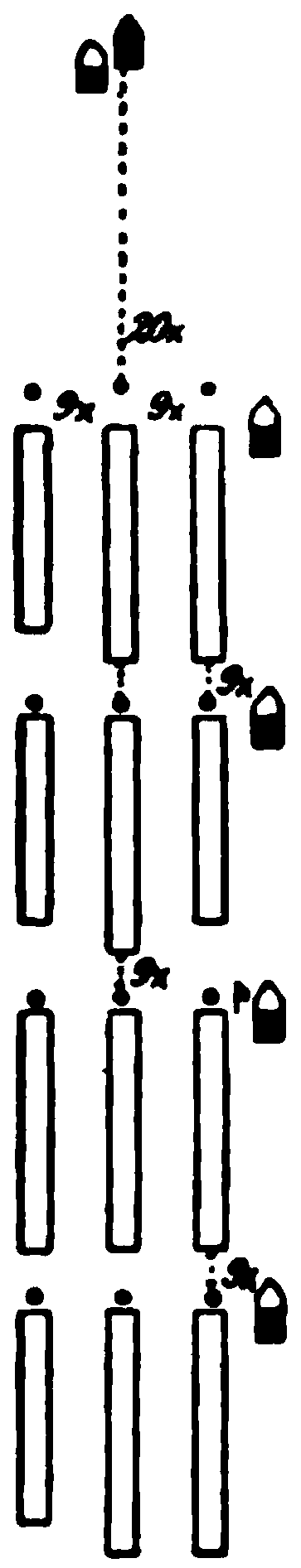

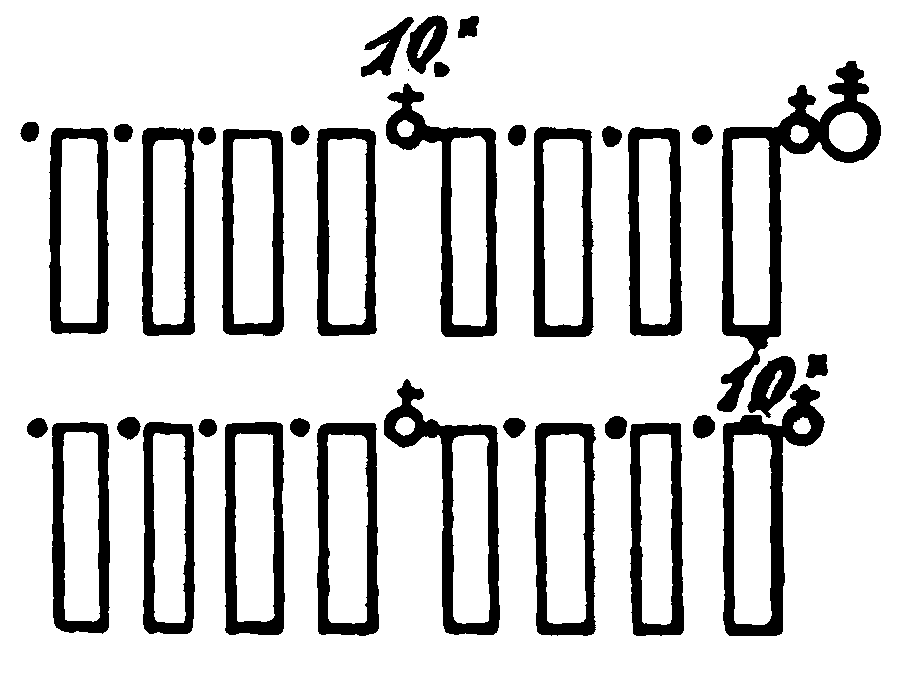

| 9. | Extended Order | 75 | ||

| Thin and dense skirmish lines | 75 | |||

| (a) | The formation of the skirmish line | 78 | ||

| (b) | Movements in skirmish line | 81 | ||

| Advance by rushes | 82 | |||

| Time required for making a rush. Strength of the force making the rush | 83 | |||

| Rising | 84 | |||

| Short or long rushes | 85 | |||

| Advance by crawling | 86 | |||

| Lessons of the Boer War | 88 | |||

| Lessons of the Russo-Japanese War | 89 | |||

| Provisions of the various regulations relative to the advance by rushes | 90 | |||

| Fire while in motion | 92 | |||

| Examples of the employment of fire while in motion | 93 | |||

| Examples of the employment of rushes | 93 | |||

| (c) | Reinforcing the firing line | 96 | ||

| (d) | Closing up. Assembling. Re-forming | 97 | ||

| 10. | Supports | 98 | ||

| Duties | 98 | |||

| Distance | 99 | |||

| Commander | 100 | |||

| Movements | 100 | |||

| Formation | 100 | |||

| Supports in rear of the firing line or not? | 101 | |||

| 11. | Comparison Between Close and Extended Order | 102 | ||

| Necessity of drill | 104 | |||

| Combat drill | 105 | |||

| Training | 105 | |||

| Training of leaders | 109 | |||

| III. | THE POWER OF FIREARMS AND EXPEDIENTS FOR MINIMIZING LOSSES | 111 | ||

| A. | THE POWER OF FIELD ARTILLERY | 111 | ||

| 1. | The Field Gun | 111 | ||

| Percussion shrapnel[xii] | 111 | |||

| Time shrapnel | 112 | |||

| Shell | 115 | |||

| The French obus allongé | 115 | |||

| 2. | The Light Field Howitzer | 116 | ||

| 3. | The Heavy Field Howitzer | 118 | ||

| 4. | Expedients for Minimizing the Effect of Fire | 118 | ||

| (a) | Increasing the difficulties in the adjustment of the hostile fire | 119 | ||

| (b) | Minimizing the effect of fire | 120 | ||

| 5. | The Results Obtained by Artillery Against Various Targets | 122 | ||

| French data | 123 | |||

| 6. | The Effect of Shrapnel Bullets on Animate Targets | 125 | ||

| B. | INFANTRY FIRE | 126 | ||

| 1. | The Effect of a Single Projectile on Animate Targets | 126 | ||

| Explosive effect | 127 | |||

| Tumbling bullets | 127 | |||

| 2. | The Effect of “S” Bullets on Materials | 131 | ||

| IV. | THE EMPLOYMENT OF INFANTRY FIRE | 132 | ||

| Stunning and exhaustive effect | 132 | |||

| The engagement at Modder River, Nov. 28, 1899 | 132 | |||

| 1. | Fire Discipline | 133 | ||

| The employment of the bayonet; bayonet fencing | 134 | |||

| 2. | Fire Control and Fire Direction | 134 | ||

| Squad leaders | 135 | |||

| Company commanders | 136 | |||

| Uncontrolled fire | 136 | |||

| Russian experiences in the Far East | 137 | |||

| 3. | Selection of the Line to be Occupied | 138 | ||

| 4. | The Strength of the Firing Line | 139 | ||

| 5. | Ascertaining Ranges | 140 | ||

| Influence of the knowledge of the range upon the efficacy of the fire | 140 | |||

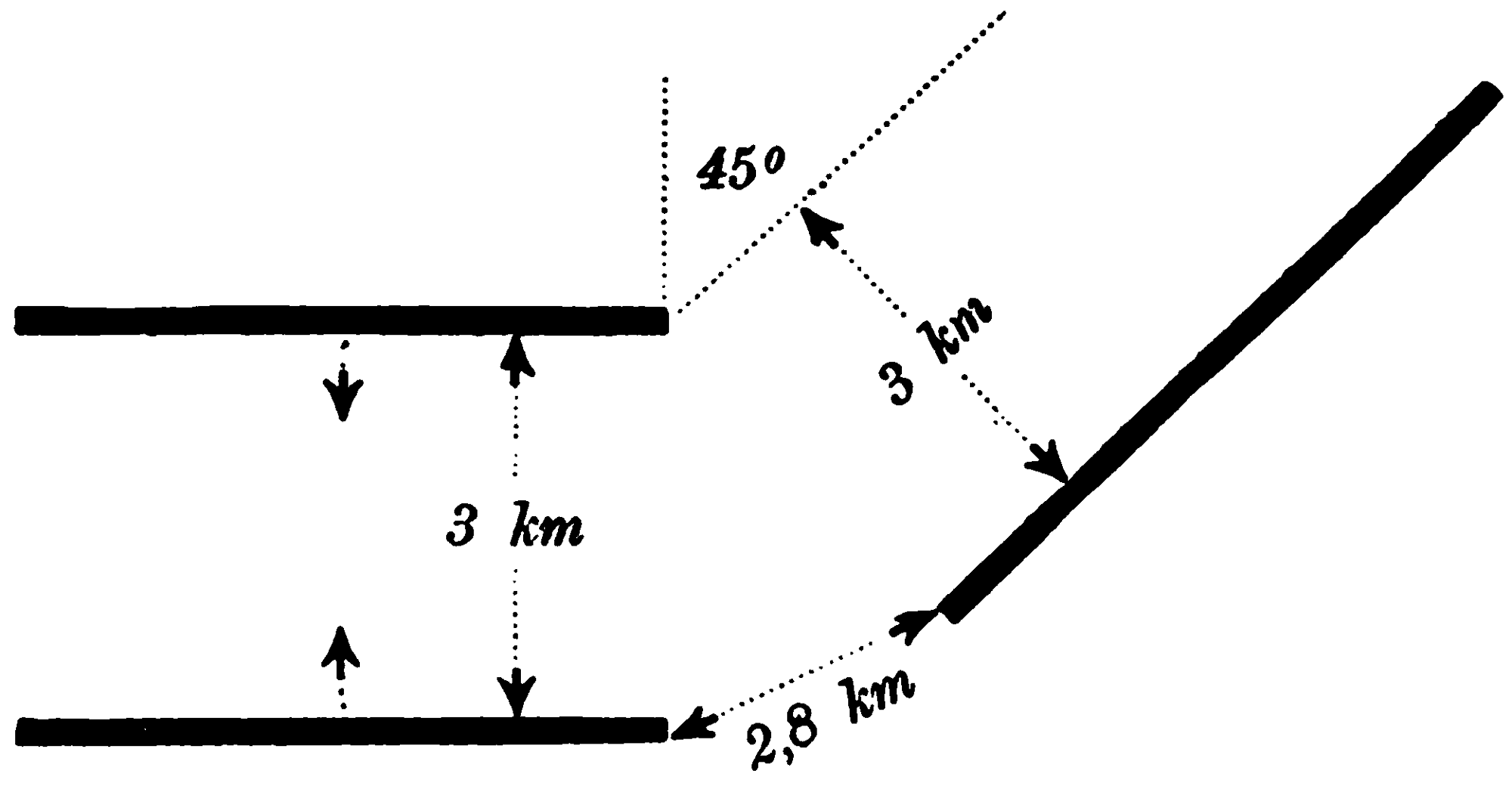

| Ascertaining ranges by pacing or galloping | 141 | |||

| Influence of the terrain upon the length of pace | 141 | |||

| Errors of estimation | 142 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations[xiii] | 143 | |||

| Memorizing distinguishing marks on the enemy | 144 | |||

| Scaling the range from maps | 144 | |||

| Obtaining the range from other troops | 145 | |||

| Trial volleys fired for the purpose of obtaining proper sight elevation | 145 | |||

| Range finding instruments | 146 | |||

| 6. | Selection of a Target and Time for Opening Fire | 147 | ||

| Short or long range fire | 147 | |||

| Limit of long range fire | 147 | |||

| The moral effect of withholding the fire | 151 | |||

| Marshal Bugeaud’s narrative | 151 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 153 | |||

| General rules for opening fire in attack and defense | 154 | |||

| 7. | Pauses in the Fire | 155 | ||

| 8. | Kinds of Fire | 157 | ||

| Volley fire and fire at will; bursts of fire (rafales) | 158 | |||

| The rate of fire | 160 | |||

| The influence of the rate of fire upon the efficacy of fire | 161 | |||

| The volley | 163 | |||

| Bursts of fire (rafales) | 164 | |||

| 9. | Rear Sight Elevations and Points of Aim | 165 | ||

| 10. | Commands | 166 | ||

| 11. | The Observation of the Fire | 167 | ||

| 12. | The Effect of Fire | 167 | ||

| Comparison between losses produced by infantry and artillery fire | 167 | |||

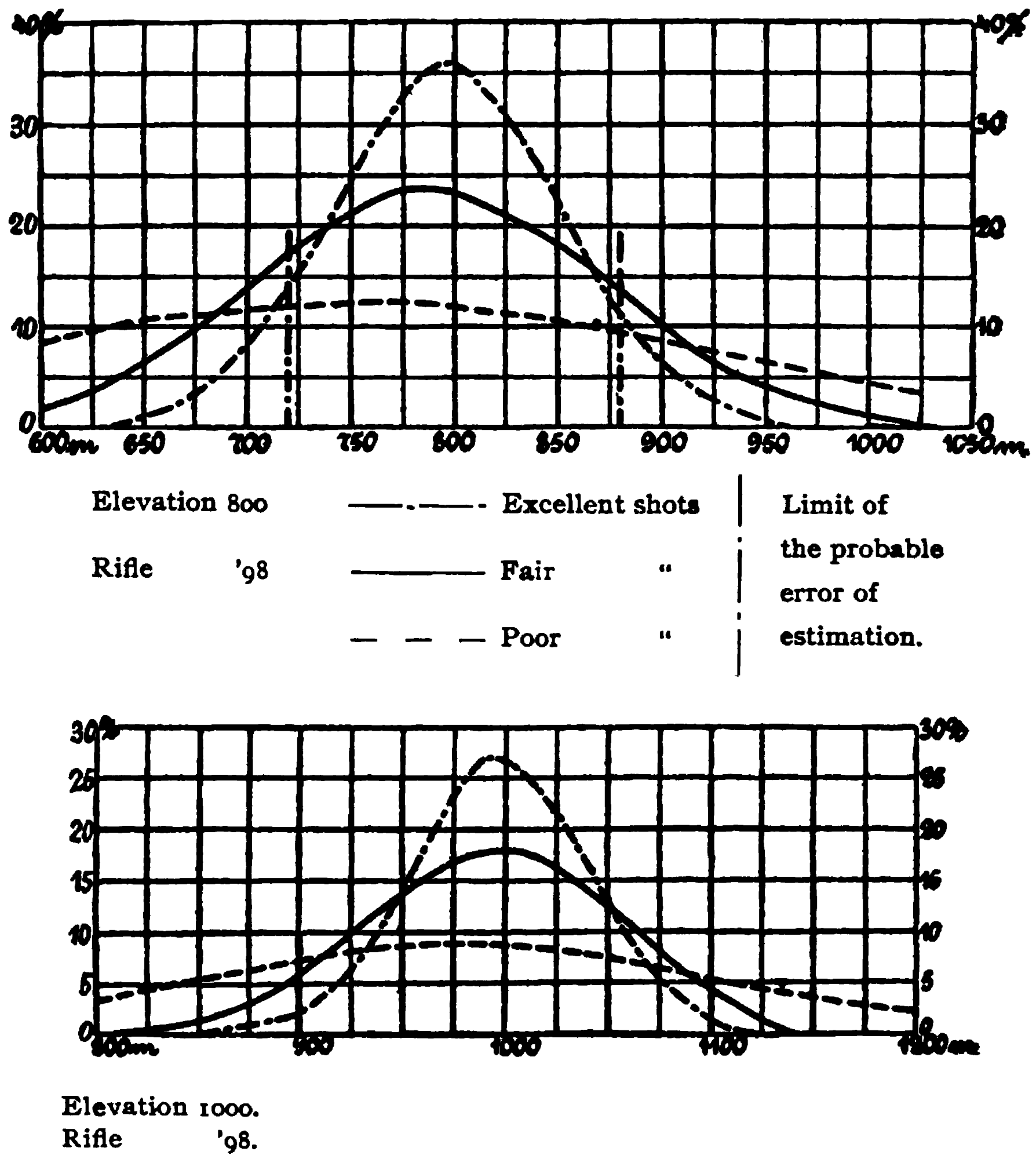

| (a) | Influence of training | 168 | ||

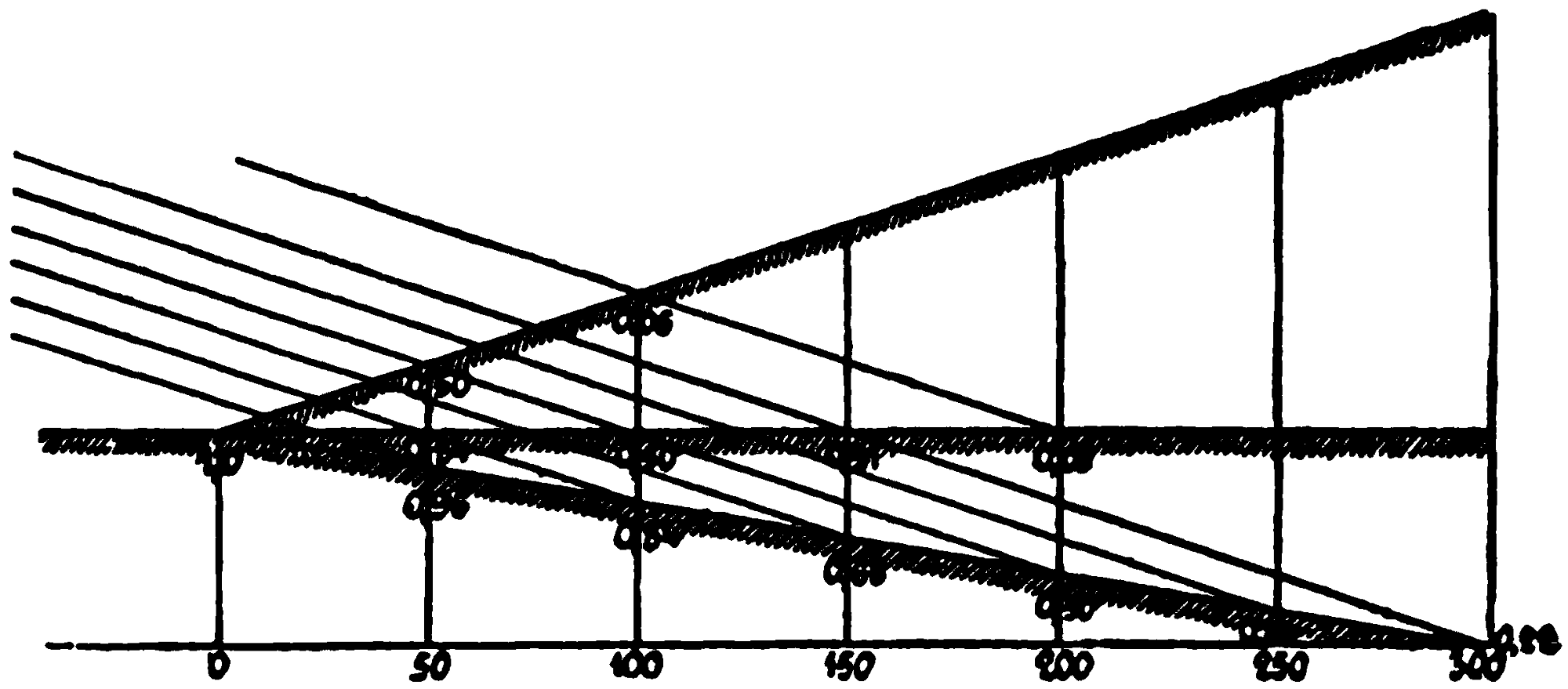

| (b) | Influence of the error in estimating the range | 170 | ||

| (c) | Fire effect as regards time. Number of rounds to be expended | 172 | ||

| (d) | Additional influences affecting the accuracy of fire | 173 | ||

| Wolozkoi’s theory of the effect of the constant cone of misses | 173 | |||

| (e) | Influence of rifle-rests in firing | 178 | ||

| (f) | Influence of the ground | 179 | ||

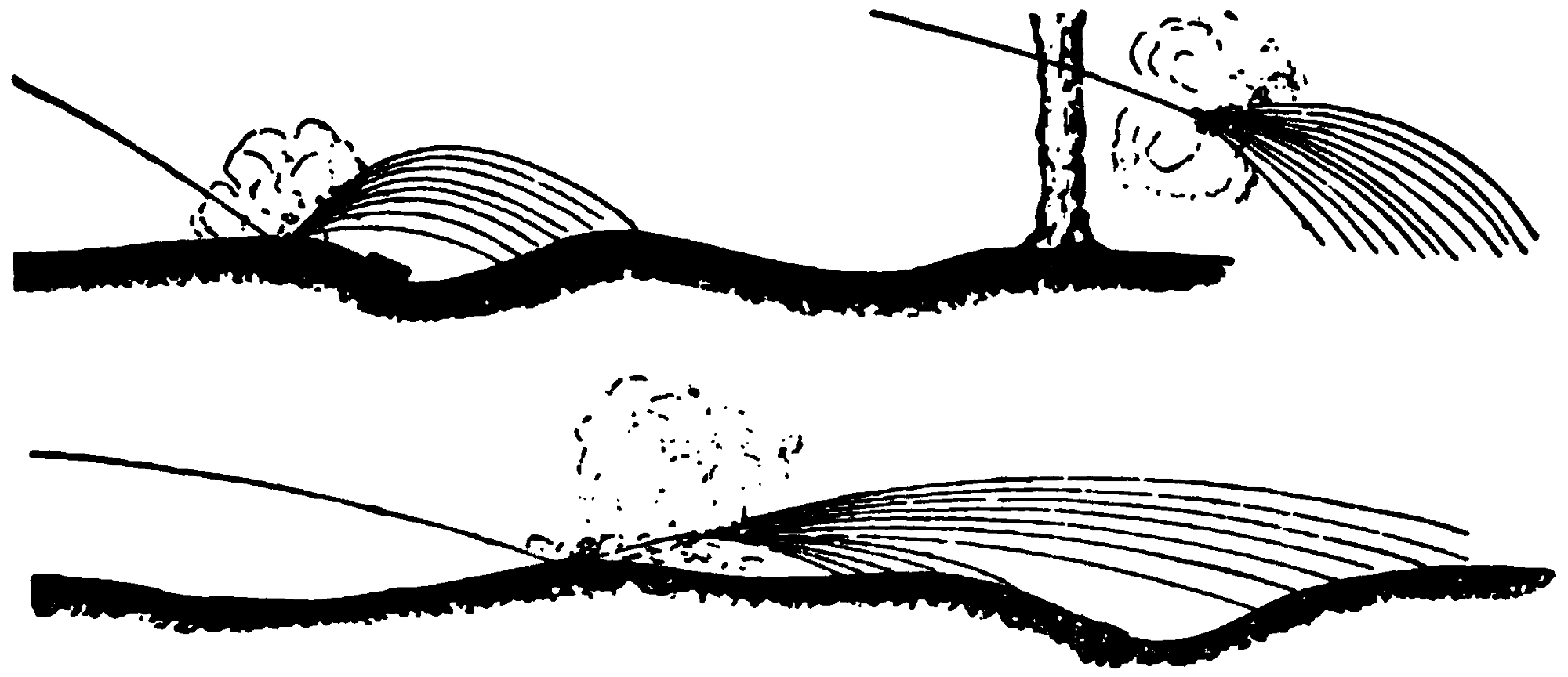

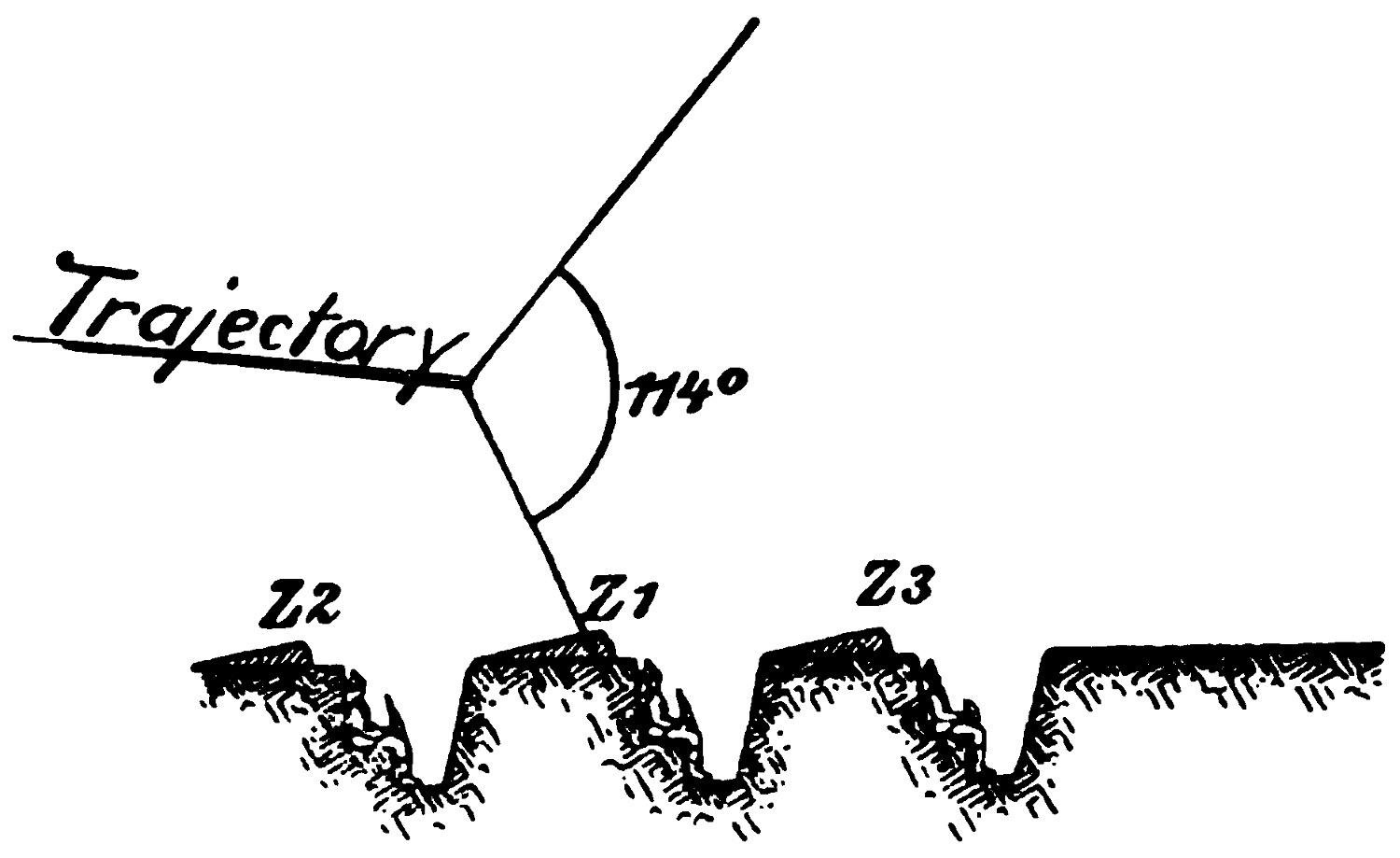

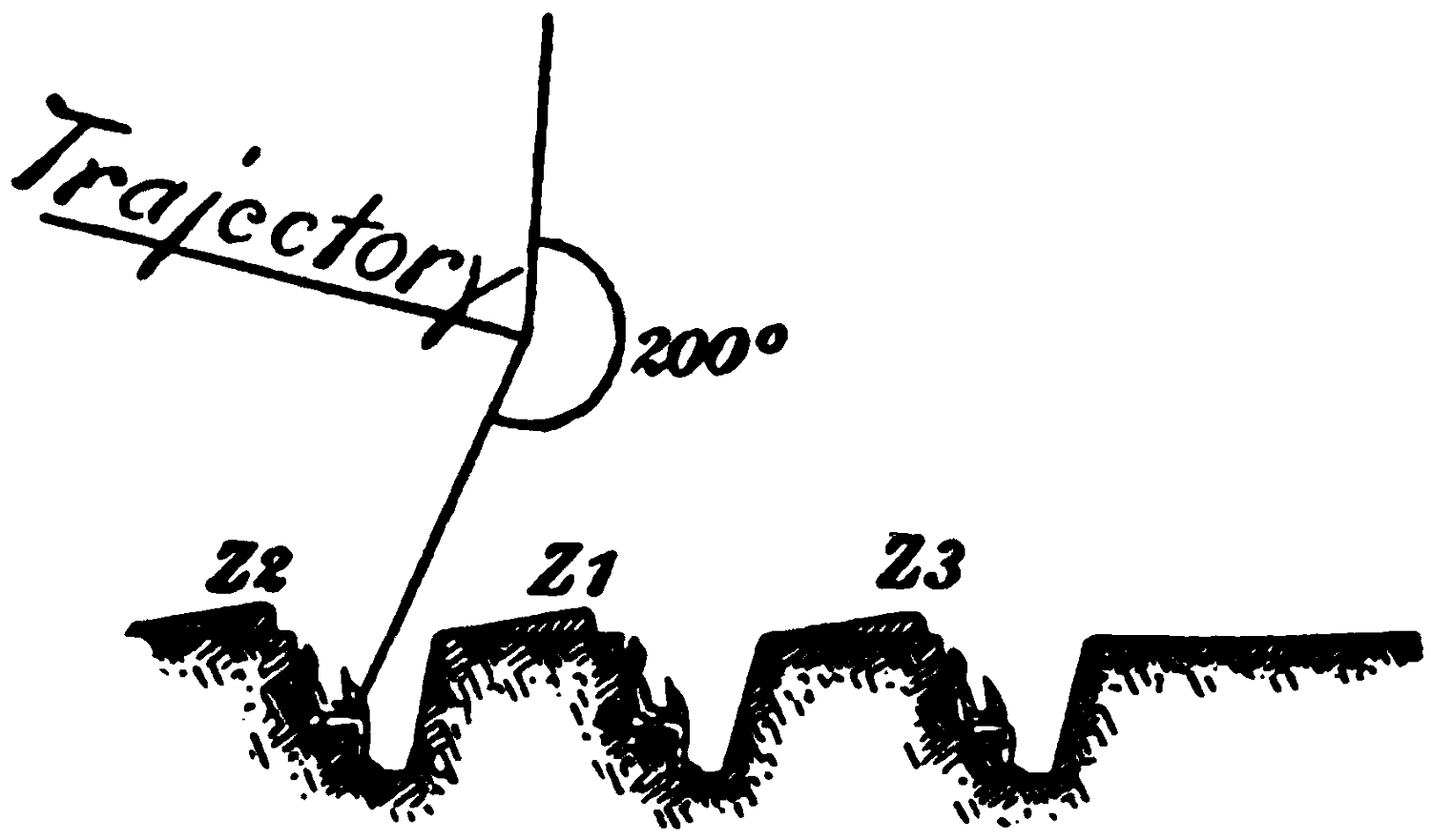

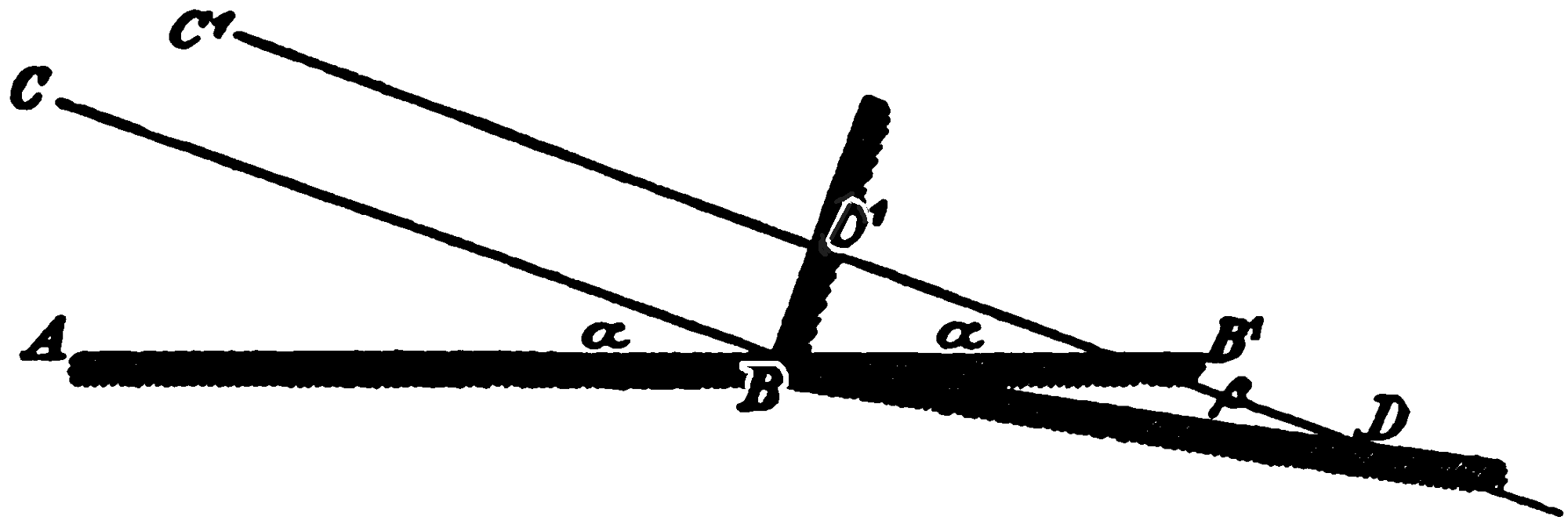

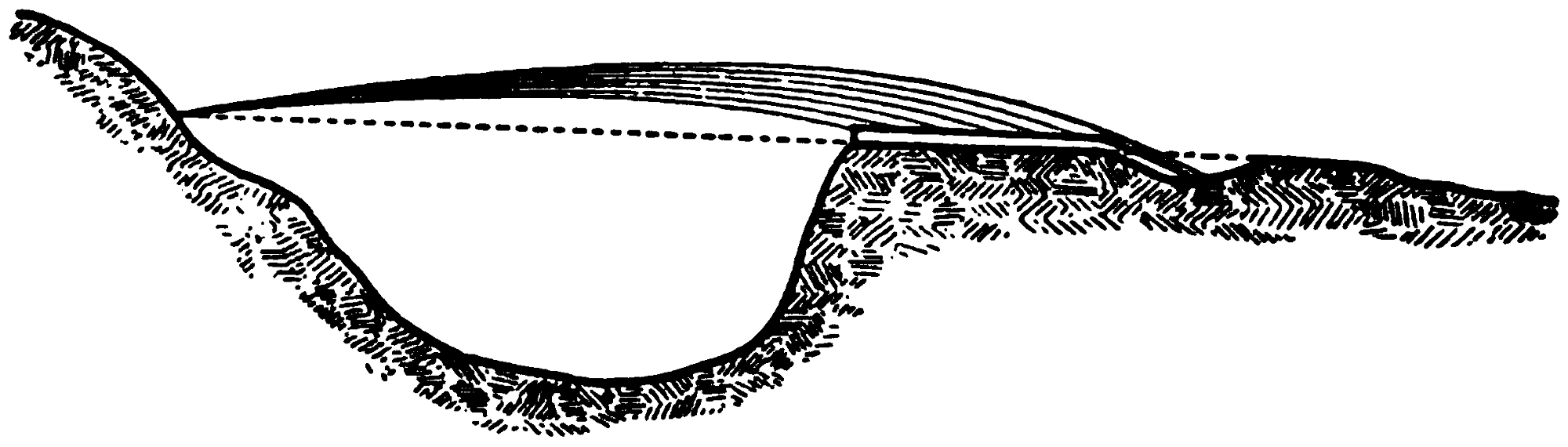

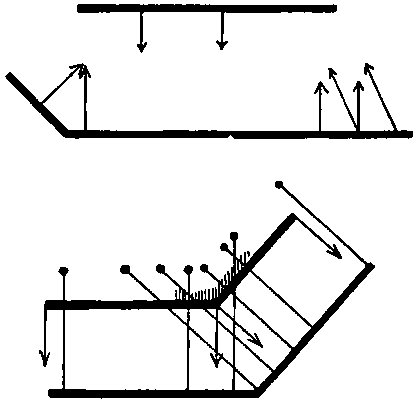

| Danger space and beaten zone | 179 | |||

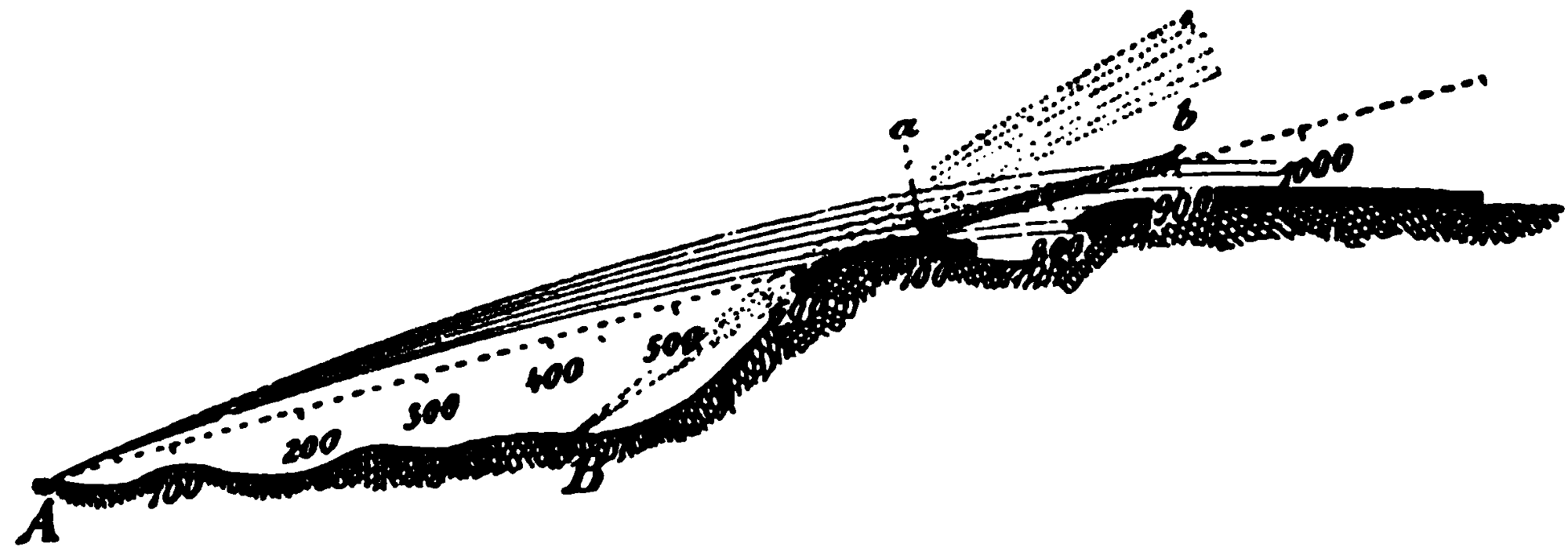

| Firing upon hill positions | 183 | |||

| Indirect rifle fire | 184 | |||

| Ricochets | 185 | |||

| 13. | Losses In Action[xiv] | 185 | ||

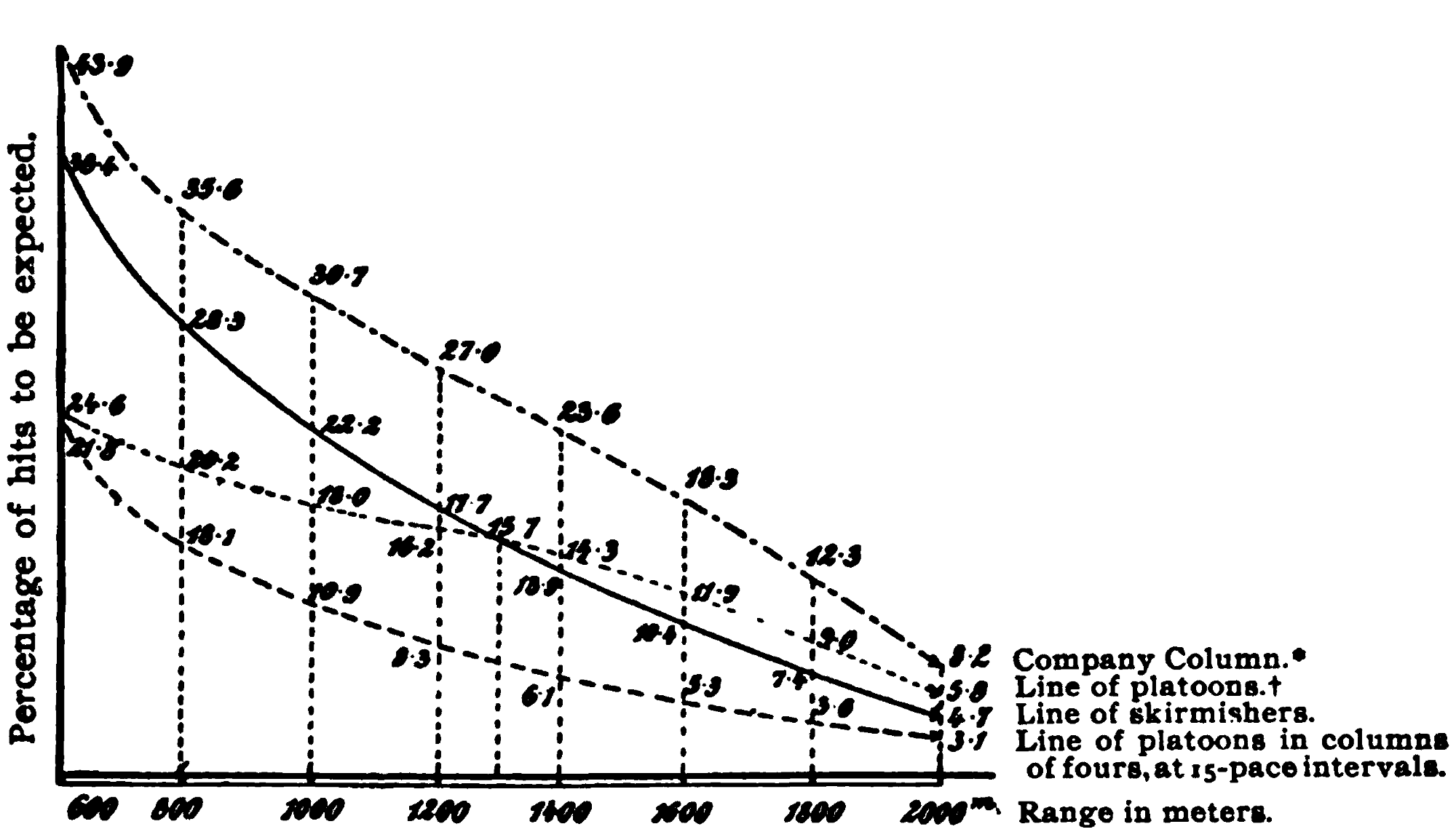

| Losses in the various formations | 186 | |||

| Losses among officers | 189 | |||

| 14. | The Moral Effect of Fire | 191 | ||

| The impressions produced upon General Bonnal by the battle of Wörth | 191 | |||

| Surrenders of British troops in South Africa | 192 | |||

| Limit of endurance in battle | 193 | |||

| The “void of the battlefield” | 194 | |||

| Mixing of organizations | 195 | |||

| Fighting power of improvised units | 197 | |||

| Overcoming crises in action | 198 | |||

| V. | DEPLOYMENTS FOR ACTION | 201 | ||

| 1. | Normal Procedure | 201 | ||

| The normal attack | 202 | |||

| Drill attack | 204 | |||

| 2. | Concentration, Development, and Deployment for Action | 205 | ||

| Development for action | 207 | |||

| Deployment for action | 209 | |||

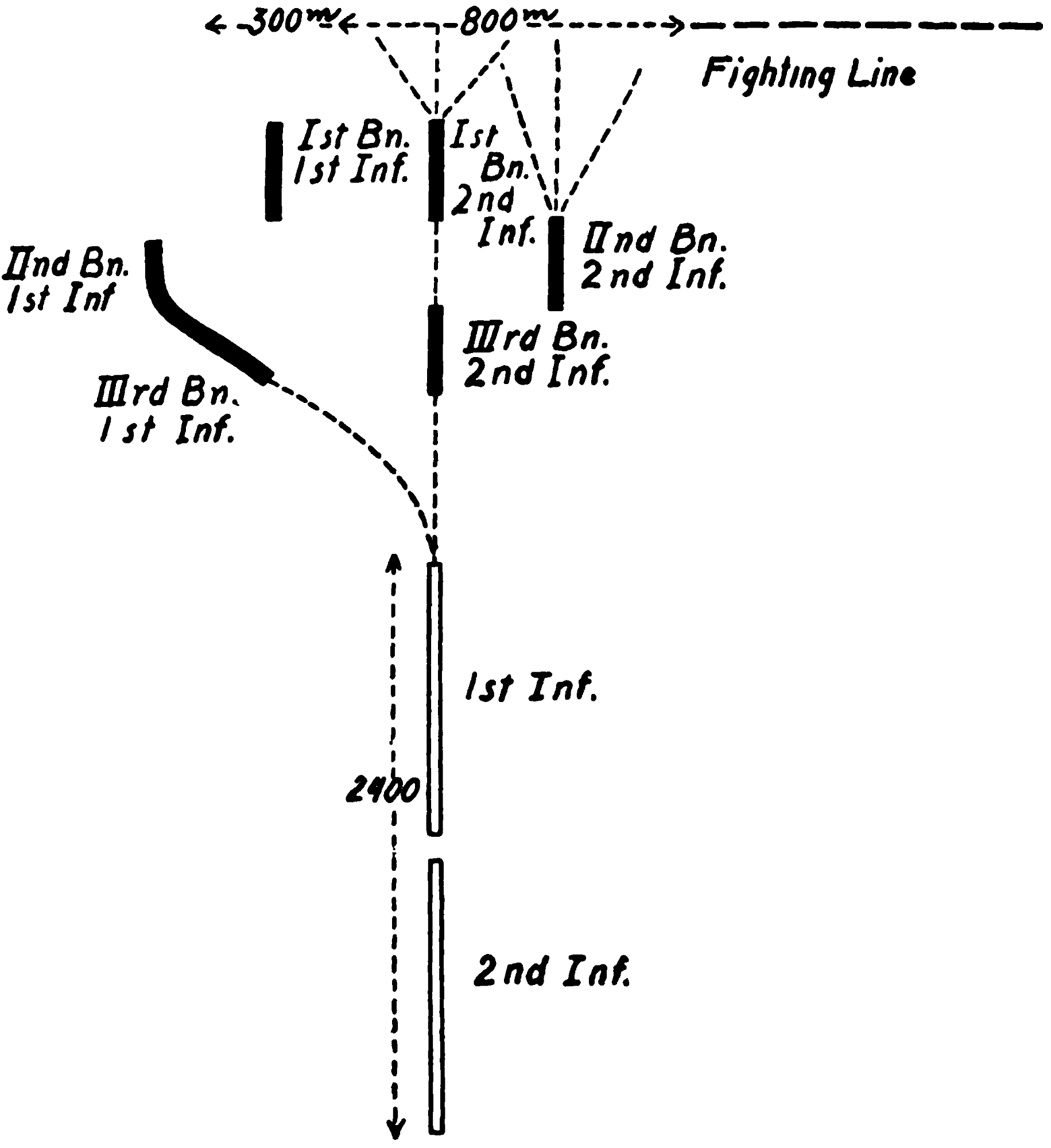

| 3. | The Battalion, the Regiment, and the Brigade | 210 | ||

| The battalion | 210 | |||

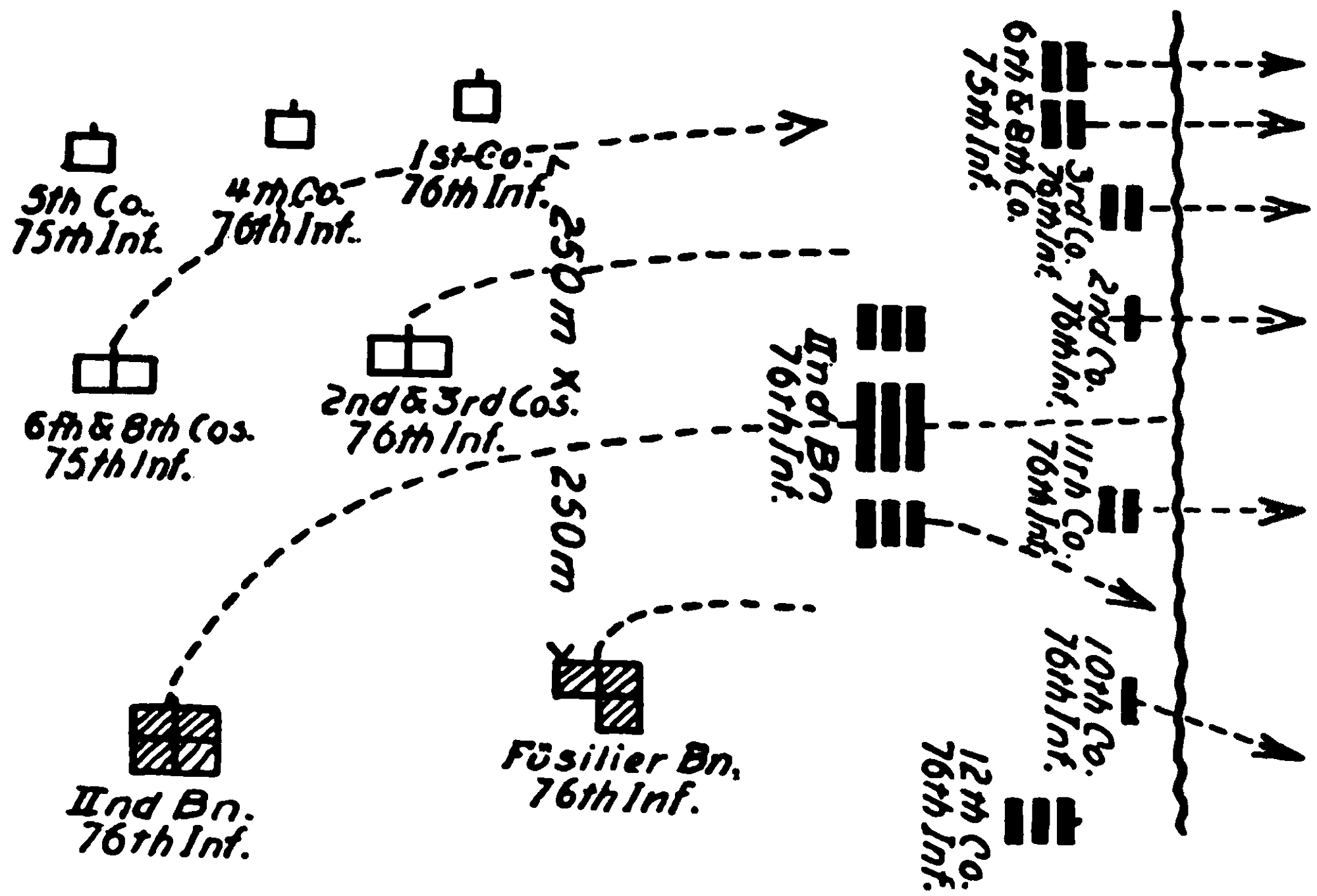

| The regiment | 214 | |||

| The brigade | 216 | |||

| Base units | 218 | |||

| Examples of changes of front | 220 | |||

| 4. | Distribution in Depth and Frontage of Combat Formations | 222 | ||

| Dangers of distribution in depth | 222 | |||

| Plevna and Wafangu | 222, 223 | |||

| Distribution in depth necessary during the preparatory stage | 224 | |||

| Contrast between distribution in depth and frontage | 225 | |||

| Dangers of over-extension (Spicheren) | 225, 226 | |||

| Influence of fire effect and morale upon frontage | 227, 228 | |||

| Influence of the task assigned a force | 231 | |||

| Delaying actions. Night attacks. Defense | 232, 233 | |||

| Approximate figures for the extent of front that may be covered | 233 | |||

| Frontage of the several units | 235, 236 | |||

| The Boer War | 238 | |||

| The Russo-Japanese War | 239 | |||

| Table of troops per km. of front | 240 | |||

| Recapitulation of the most important points governing frontage[xv] | 241 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 241 | |||

| 5. | Combat Orders | 243 | ||

| Combat tasks | 243 | |||

| Division of work in staffs | 245 | |||

| 6. | Communication on the Battlefield | 246 | ||

| Signal and wig-wag flags | 246 | |||

| Signal arrangements in the Austrian, French and British armies | 248 | |||

| 7. | Local Reconnaissance of the Infantry | 248 | ||

| Reconnaissance in force | 251 | |||

| The object of local reconnaissance | 251 | |||

| Scouting detachments | 252 | |||

| 8. | The Importance of the Terrain | 254 | ||

| The attack over an open plain | 255 | |||

| The French group attack | 256 | |||

| Combat sections | 257 | |||

| VI. | MACHINE GUNS | 259 | ||

| 1. | Development of the Arm | 259 | ||

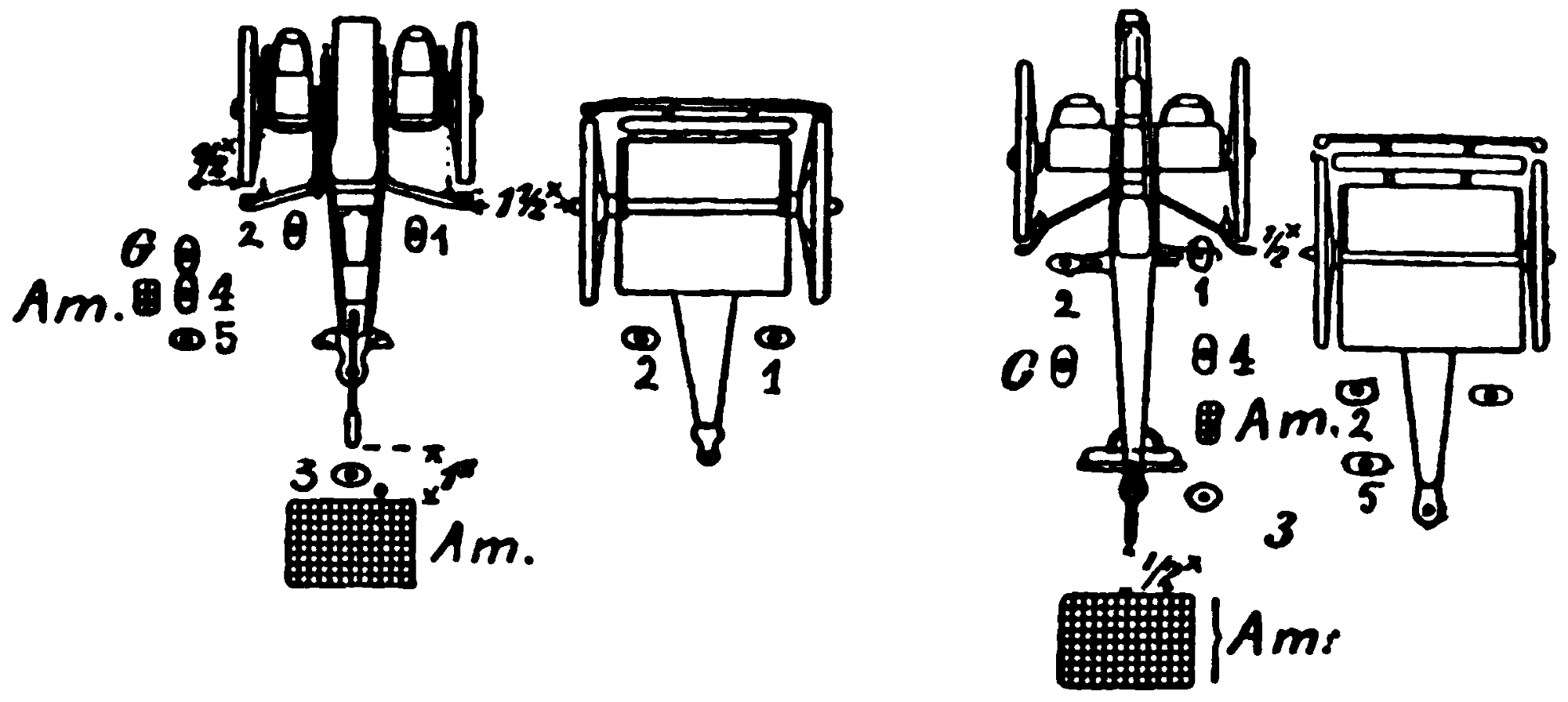

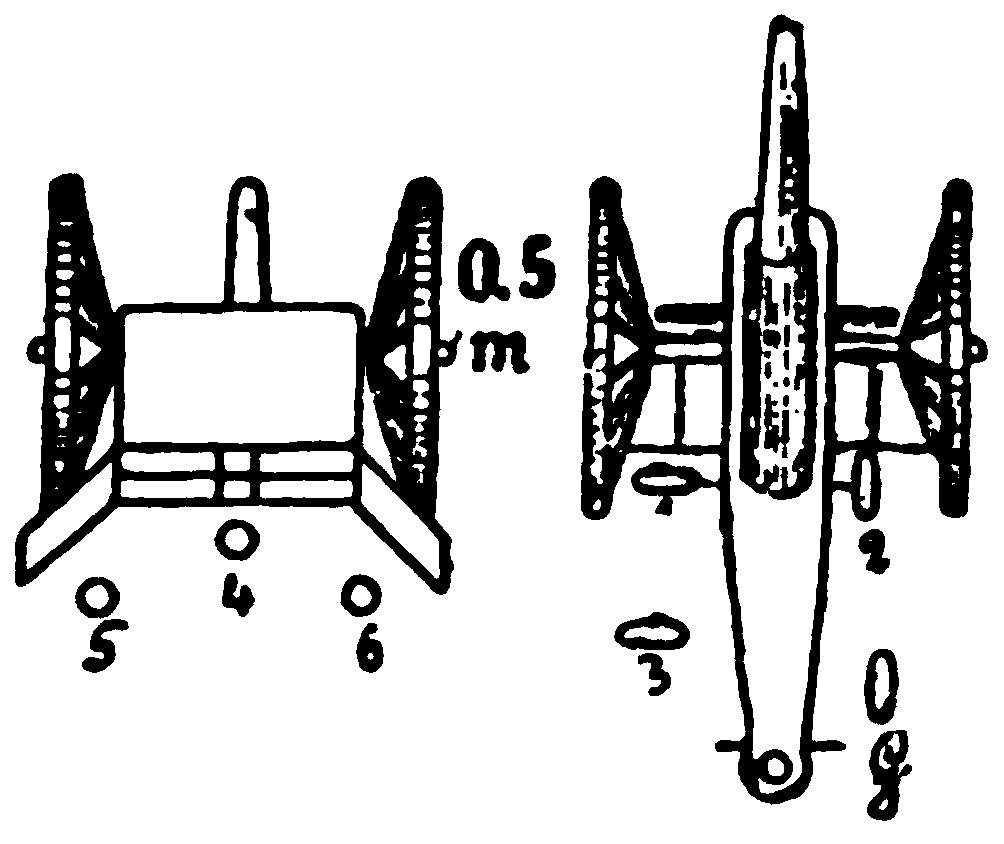

| Mounting and method of transportation | 261, 262 | |||

| 2. | The Power of Machine Guns | 262 | ||

| Kinds of fire | 263 | |||

| Combat value of machine guns and infantry | 267 | |||

| 3. | Infantry Versus Machine Guns | 268 | ||

| Conduct of troops when exposed to machine gun fire | 268, 269 | |||

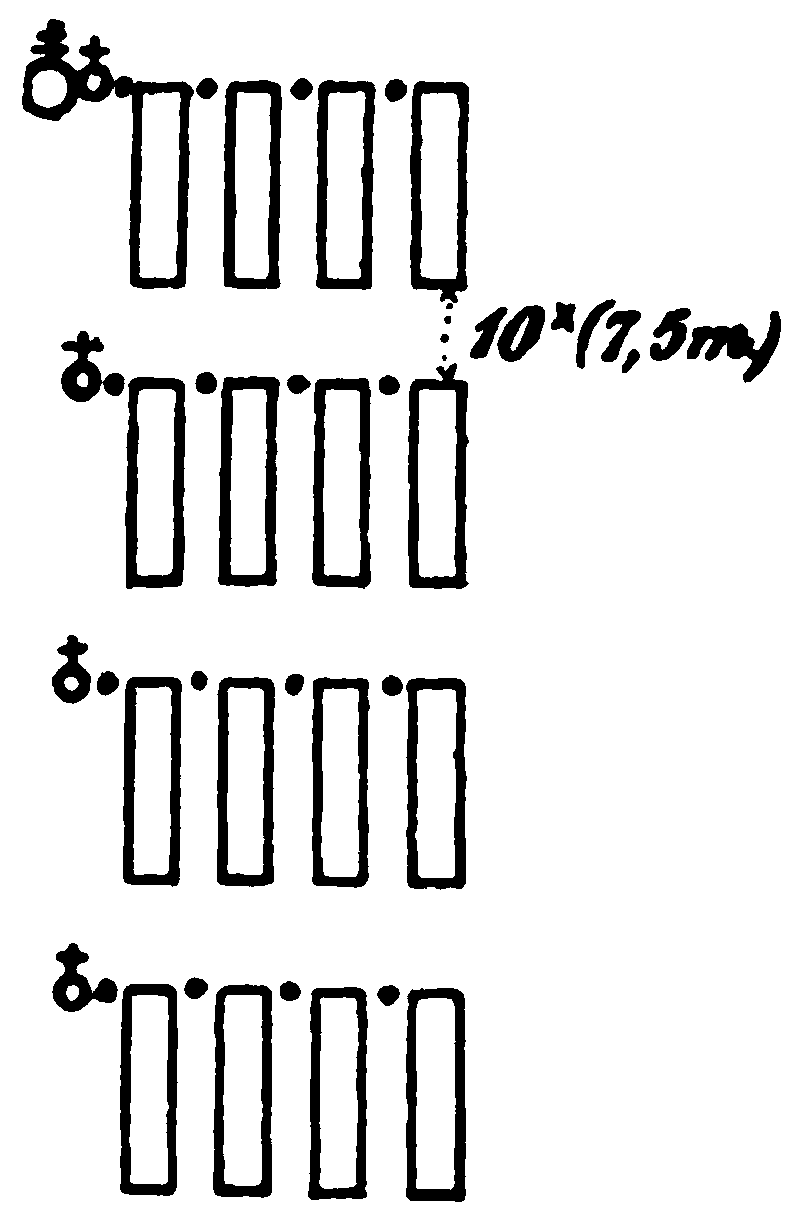

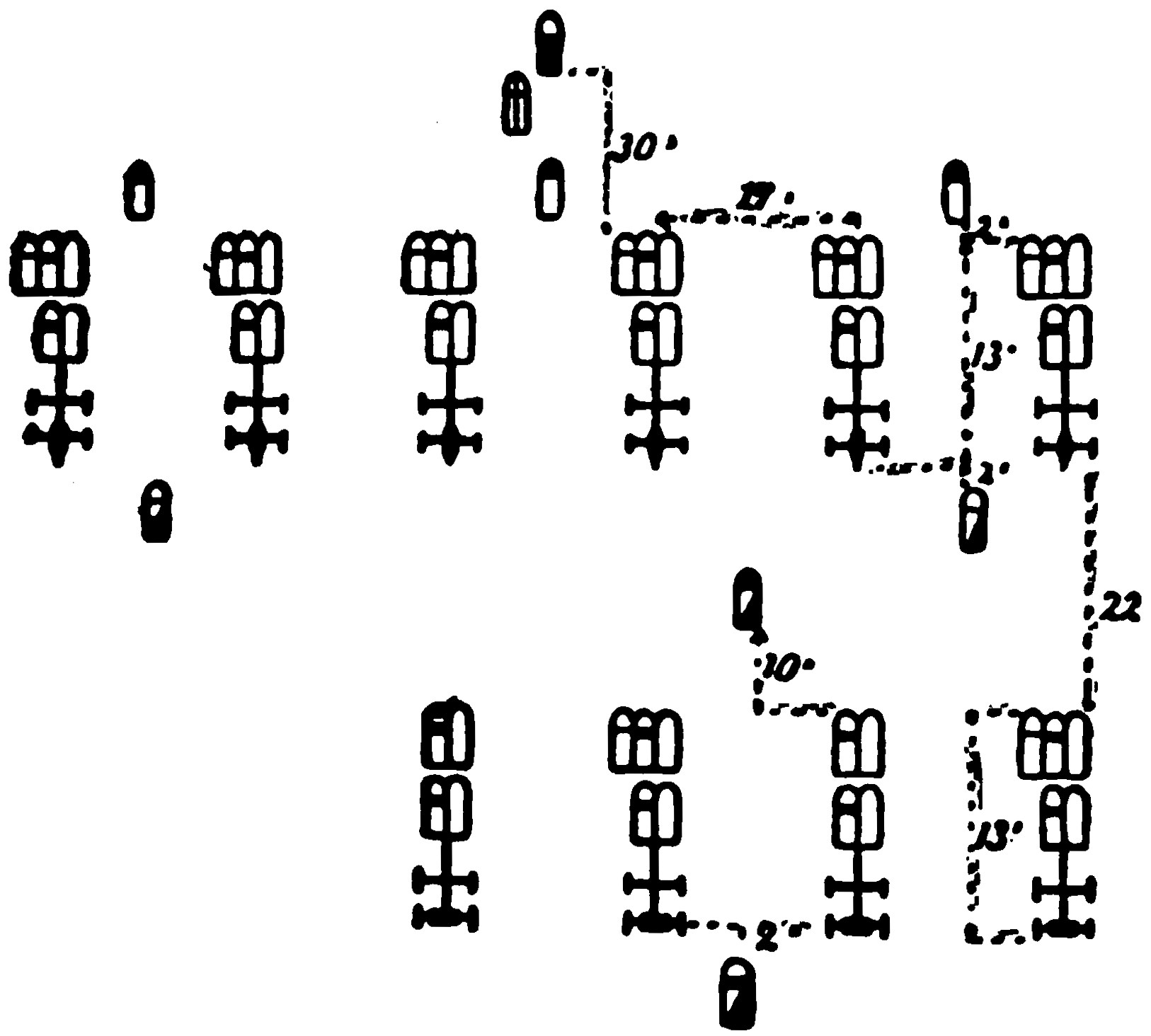

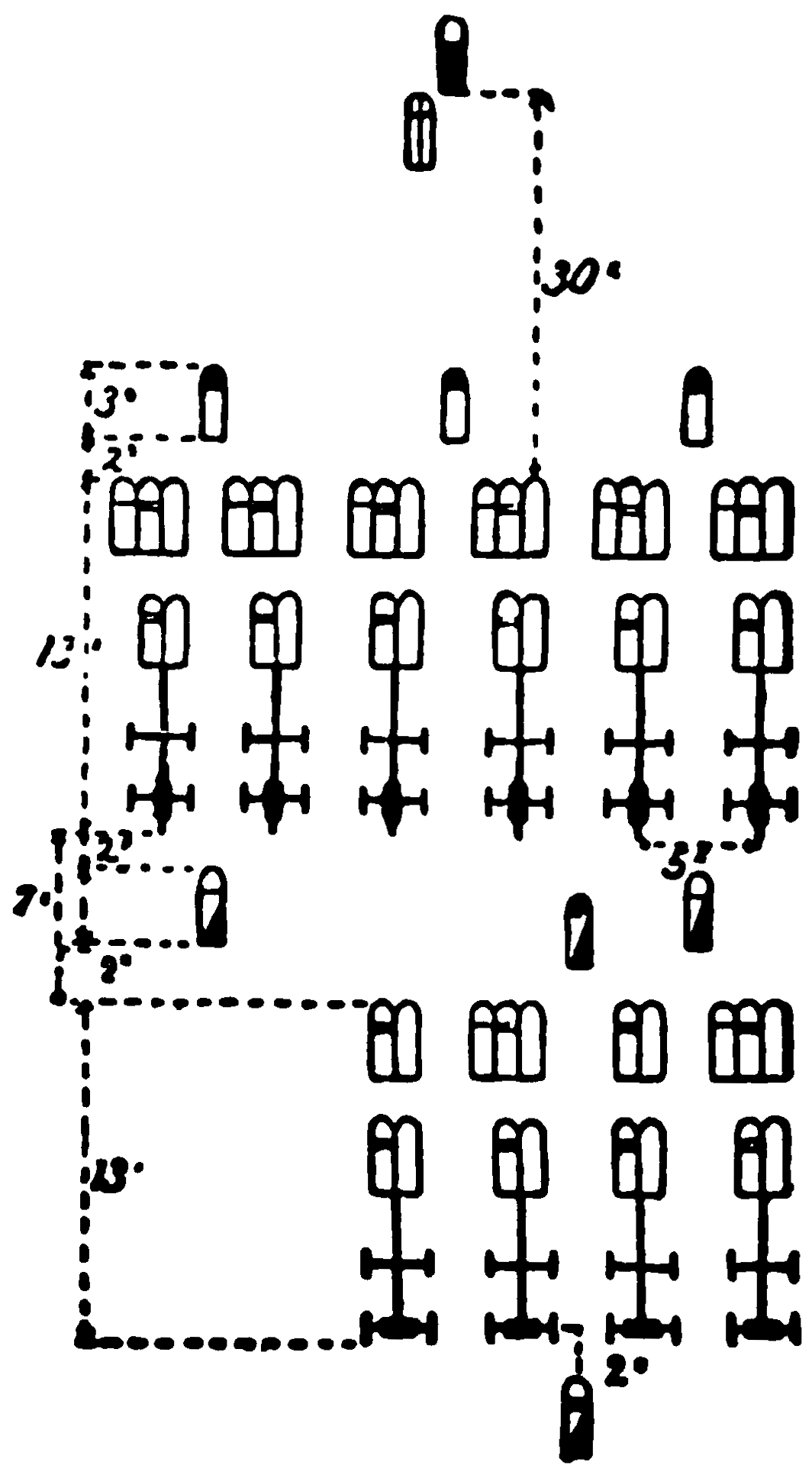

| 4. | Machine Guns in Germany | 270 | ||

| Organization | 270 | |||

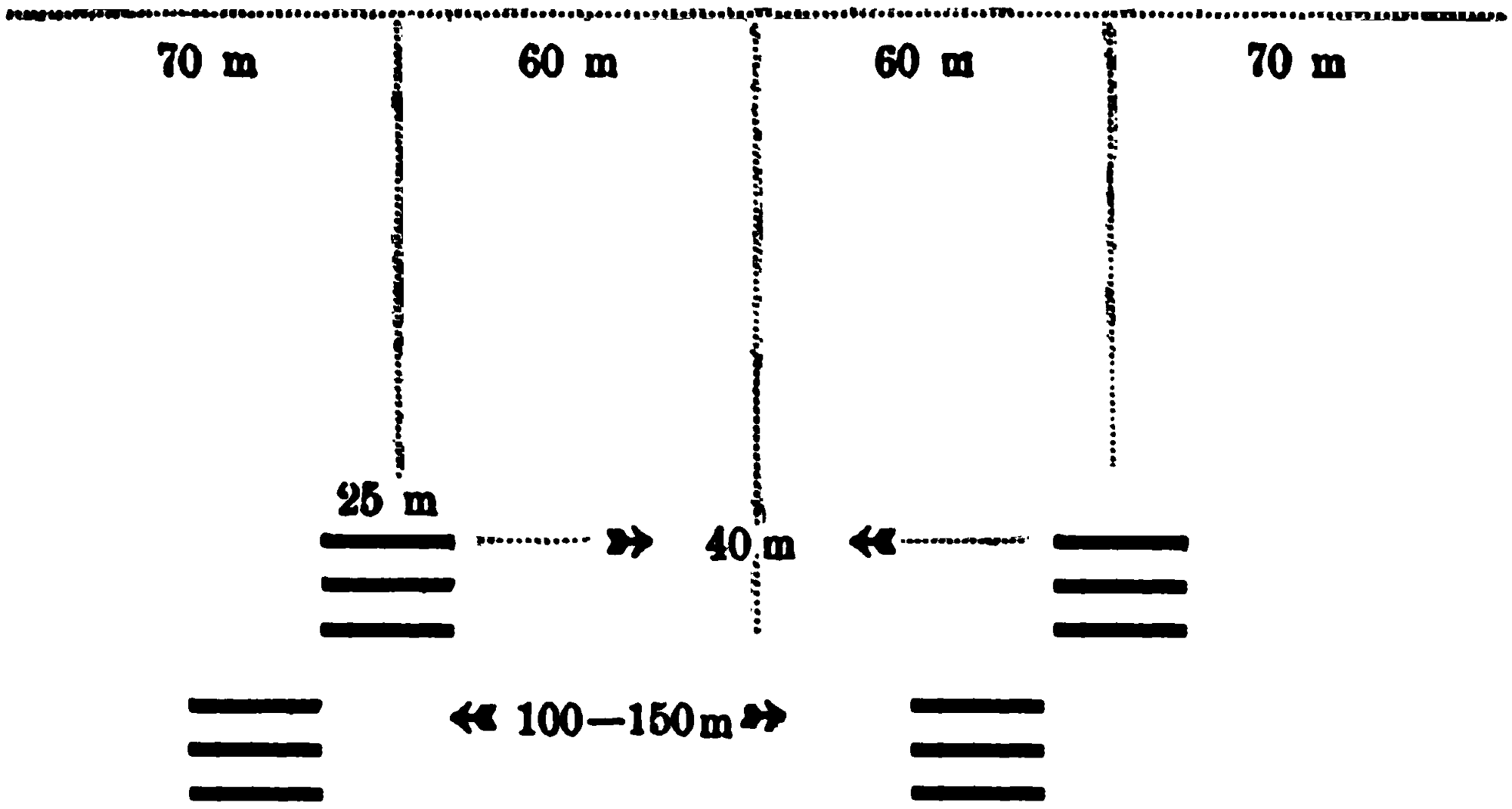

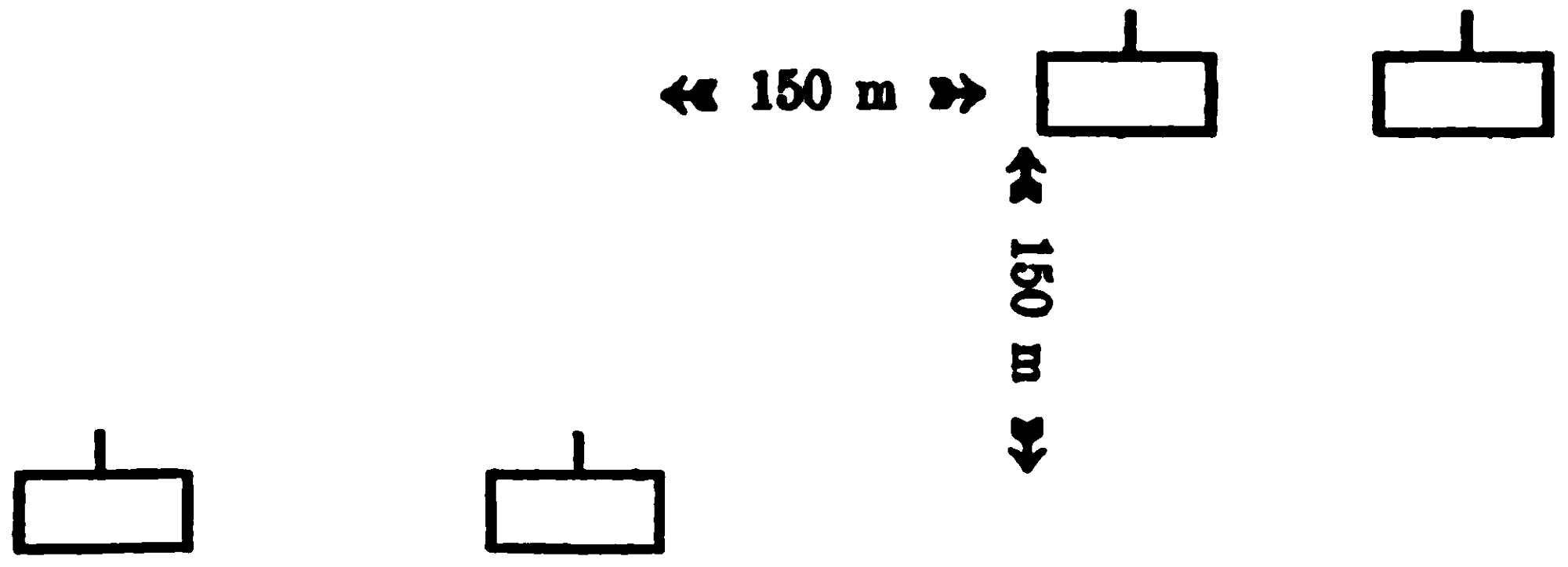

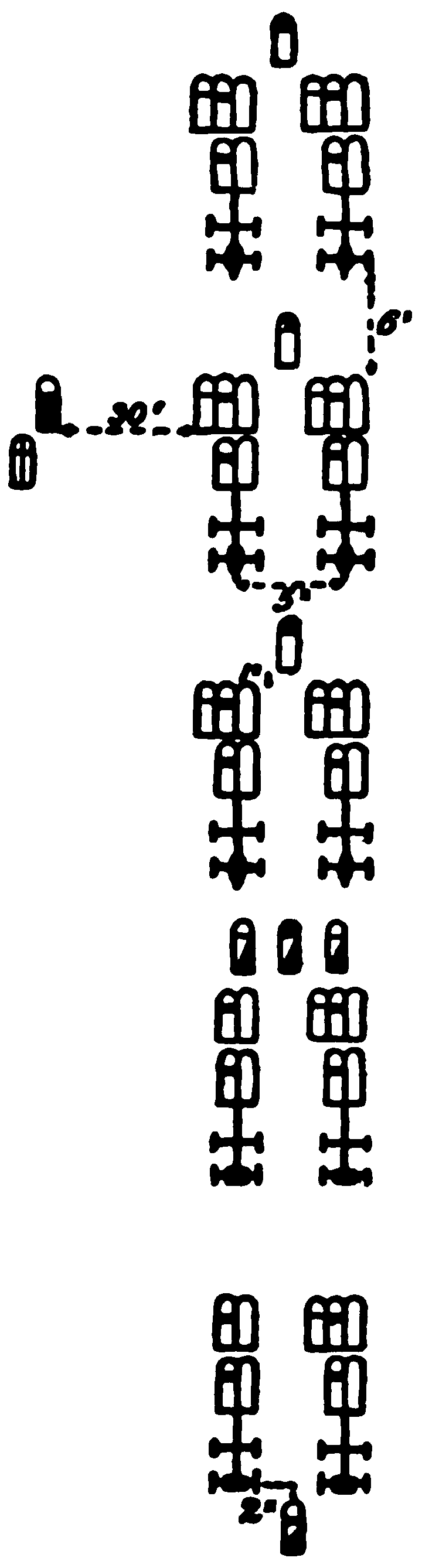

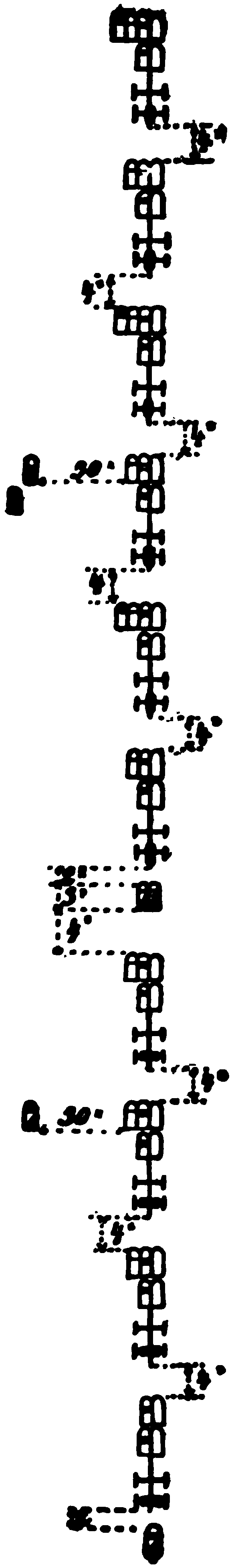

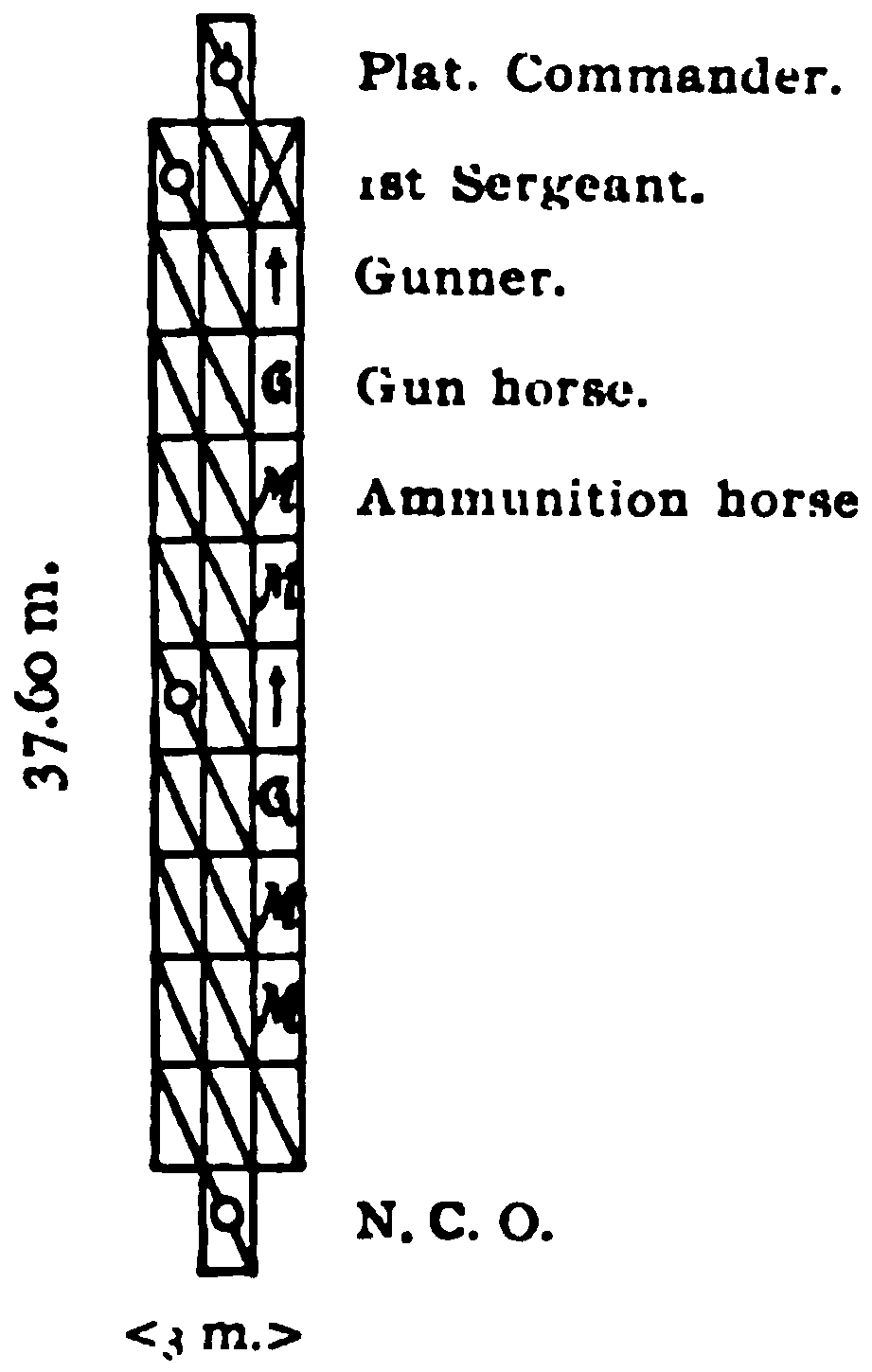

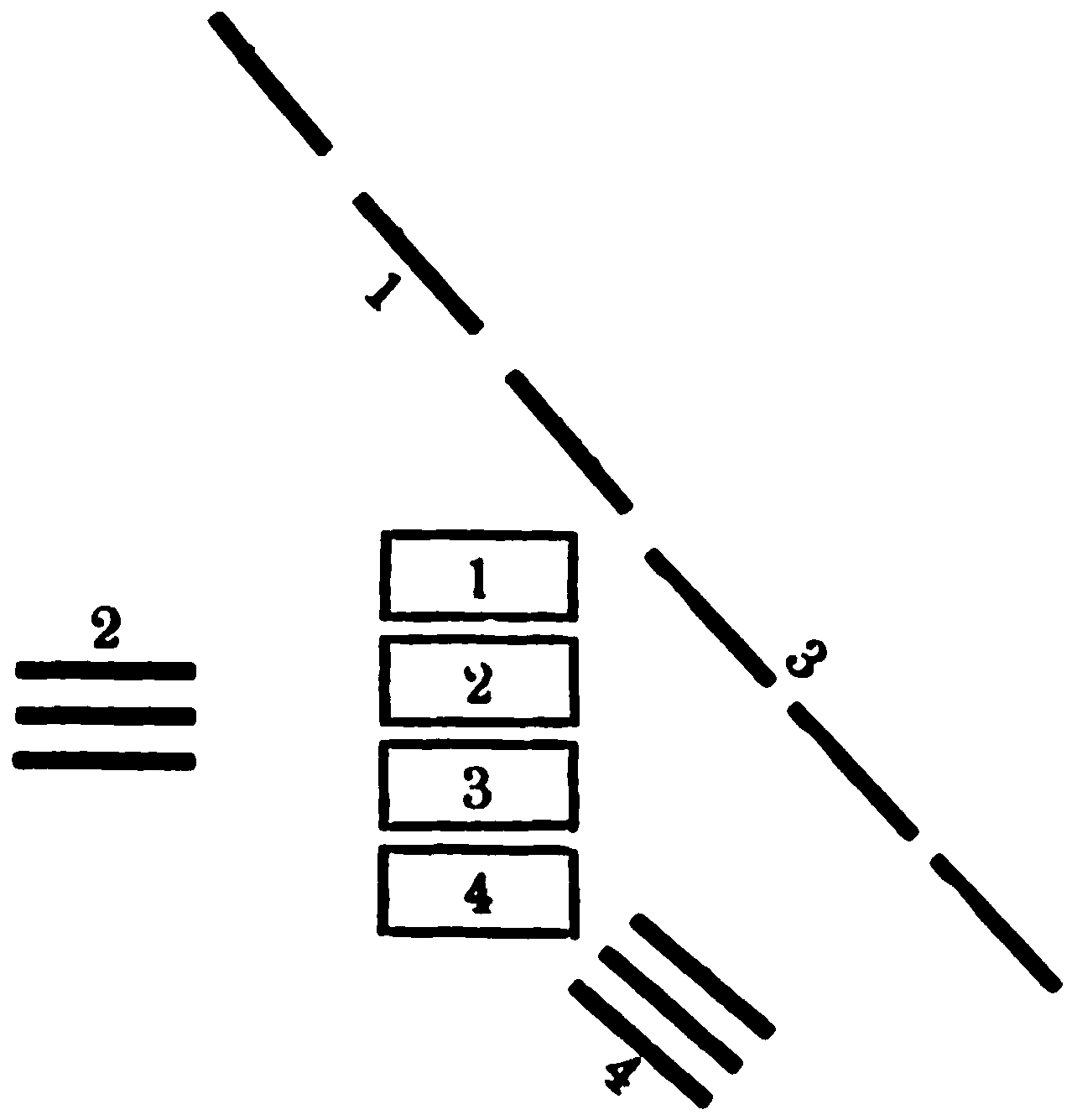

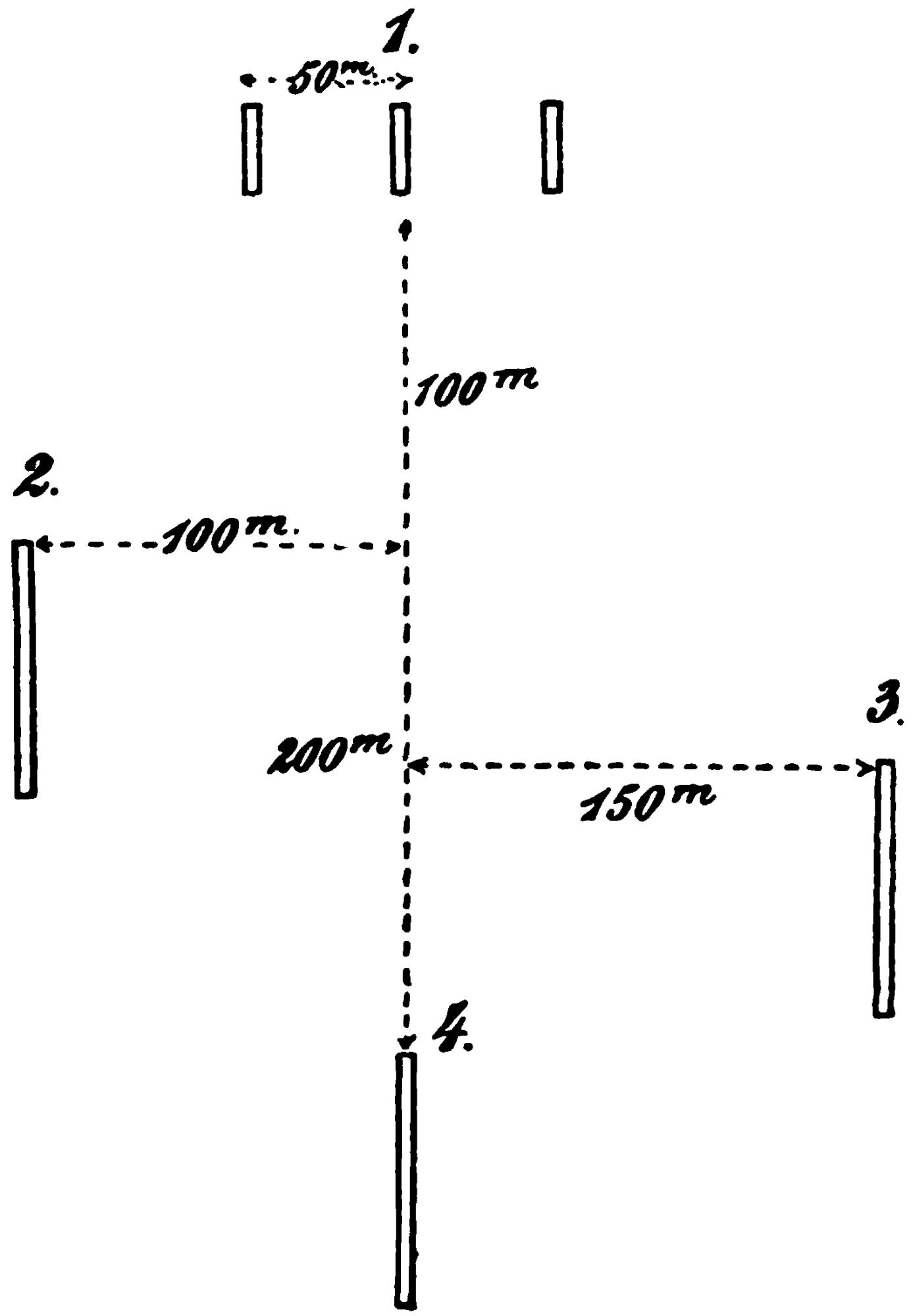

| Formations | 273, 274 | |||

| Machine gun companies | 275 | |||

| 5. | Going Into Position | 276 | ||

| 6. | The Fire Fight | 283 | ||

| Machine guns in the engagement at the Waterberg | 283 | |||

| 7. | Machine Guns in Other Countries | 284 | ||

| Switzerland | 284 | |||

| Austria | 286 | |||

| England | 289 | |||

| Japan and France | 290 | |||

| Russia | 290 | |||

| Machine guns at Liao Yang, 1904 | 291 | |||

| 8. | The Employment of Machine Gun Batteries[xvi] | 293 | ||

| Rencontre and attack | 295 | |||

| Rear guards | 295 | |||

| Defense | 295 | |||

| Coöperation with cavalry | 296 | |||

| Machine guns versus artillery | 297 | |||

| English views | 297 | |||

| Swiss views | 299 | |||

| VII. | INFANTRY VERSUS CAVALRY | 301 | ||

| Deployment for firing | 303 | |||

| Moral effect of a charge | 306 | |||

| Aiming positions | 307 | |||

| Time for opening fire | 308 | |||

| Selection of sight elevation | 310 | |||

| Kind of fire | 310 | |||

| Distribution of fire | 311 | |||

| Charge of the French Cuirassiers of the Guard | 311 | |||

| Advance against cavalry | 313 | |||

| Infantry versus dismounted cavalry | 313 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 314 | |||

| VIII. | INFANTRY VERSUS ARTILLERY | 316 | ||

| 1. | The Passage of Infantry Through Artillery Lines | 316 | ||

| 2. | The Advance Under Artillery Fire | 318 | ||

| Increasing the difficulties in the adjustment of the hostile fire | 318 | |||

| Fire for effect | 320 | |||

| Formations used by infantry when under artillery fire Russo-Japanese War | 322 | |||

| Lessons of war | 321, 323 | |||

| 3. | Firing on Hostile Artillery in Position | 324 | ||

| Cover afforded by steel shields | 324 | |||

| IX. | THE ATTACK | 329 | ||

| Attack and defense compared | 329 | |||

| 1. | The Surprise | 330 | ||

| Examples of surprises | 331 | |||

| 2. | The Rencontre | 333 | ||

| Conduct of the advance guard | 334 | |||

| Issue of orders | 336 | |||

| Conduct of the main body | 338 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 339 | |||

| Examples | 339 | |||

| X. | THE ATTACK ON AN ENEMY DEPLOYED FOR DEFENSE[xvii] | 340 | ||

| 1. | Lessons of War | 340 | ||

| Boer War | 340 | |||

| The infantry attack in the Russo-Japanese War | 340 | |||

| Russian infantry | 340 | |||

| Japanese infantry | 341 | |||

| Examples | 343, 344 | |||

| 2. | The Conditions Upon which Success Depends | 345 | ||

| 3. | Preparation of the Attack | 346 | ||

| Reconnaissance. Preparatory position | 346 | |||

| 4. | The Coöperation of Infantry and Artillery in Battle | 351 | ||

| Preparation of the assault | 352 | |||

| 5. | The Point of Attack | 355 | ||

| 6. | Envelopment | 356 | ||

| Holding attack | 357 | |||

| Launching the enveloping force | 359 | |||

| Separation of holding and flank attacks | 361 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 362 | |||

| 7. | Removal of Packs | 363 | ||

| 8. | The Employment of Machine Guns | 365 | ||

| 9. | The Conduct of the Attack | 365 | ||

| The advance of the firing line | 365 | |||

| Distances | 368 | |||

| The fire fight | 369 | |||

| The superiority of fire | 370 | |||

| Fixing bayonets | 372 | |||

| 10. | The Assault | 373 | ||

| The decision to assault | 373 | |||

| The decision to assault emanating from the firing line | 375 | |||

| Fire support during the assault | 379 | |||

| Bayonet fights | 382 | |||

| Wounds produced by cutting weapons | 384 | |||

| Assaulting distances | 385 | |||

| Conduct after a successful attack | 385 | |||

| Conduct after an unsuccessful attack | 386 | |||

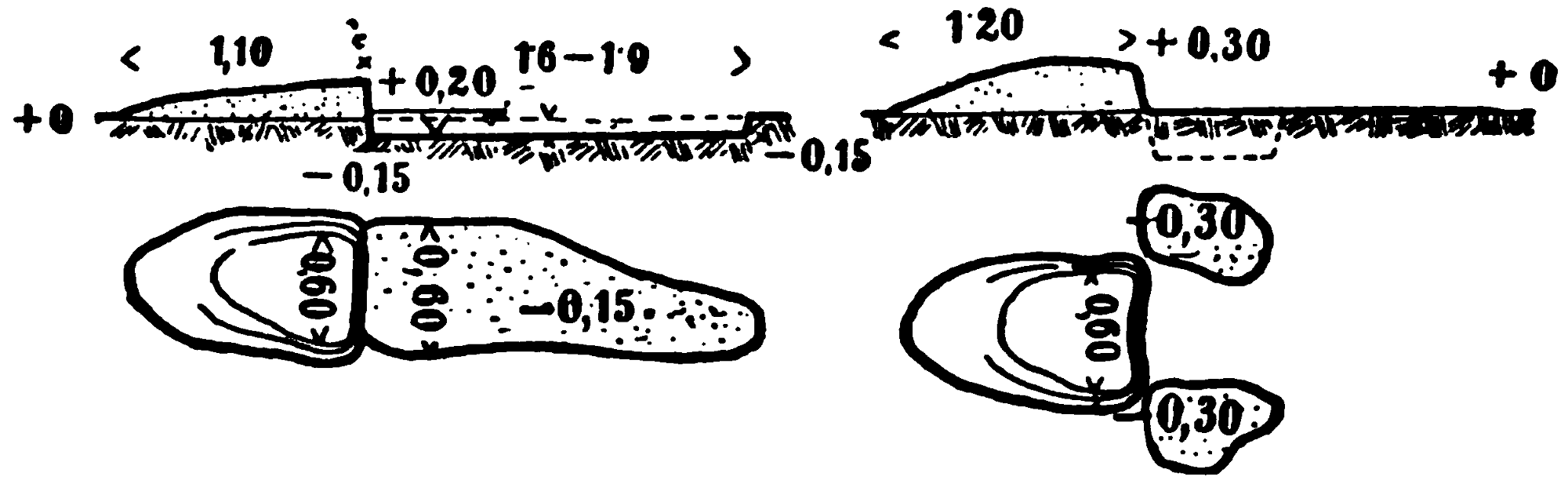

| 11. | The Use of the Spade in Attack | 387 | ||

| Sand bags | 390 | |||

| Results of Russian experiments | 390 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 392 | |||

| General rules governing the use of the spade in attack[xviii] | 393 | |||

| 12. | The Employment of Reserves | 394 | ||

| Launching or withholding reserves | 395 | |||

| 13. | The Conduct of the Leaders in Action | 399 | ||

| 14. | United Action Versus Tactical Missions | 401 | ||

| The attack on the “Tannenwäldchen” at Colombey Aug. 14, 1870 | 402, 403 | |||

| The attack on Grugies (St. Quentin) | 403 | |||

| The dangers of assigning tasks | 405 | |||

| XI. | THE DEFENSE | 408 | ||

| 1. | The Passive Defense | 409 | ||

| 2. | The Defense Seeking a Decision | 409 | ||

| Troops required to occupy the position | 410 | |||

| Division of the position into sections | 411 | |||

| Advanced positions | 413 | |||

| 3. | Fortifying the Position | 415 | ||

| Battalion groups | 417 | |||

| Observation of the foreground | 420 | |||

| Clearing the foreground | 421 | |||

| Dummy intrenchments and masks | 421 | |||

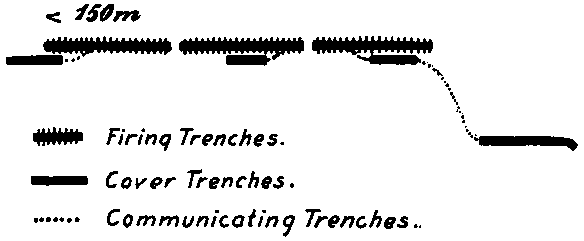

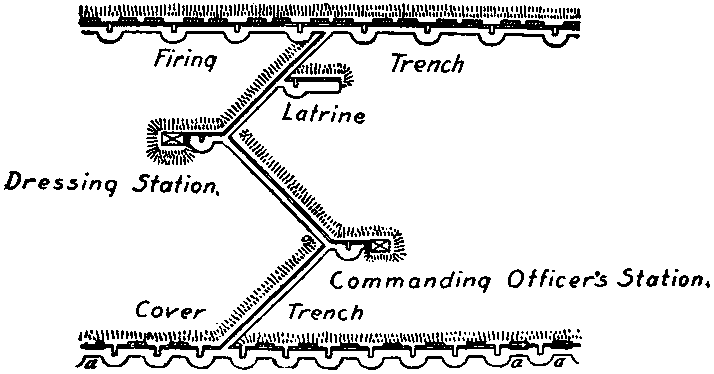

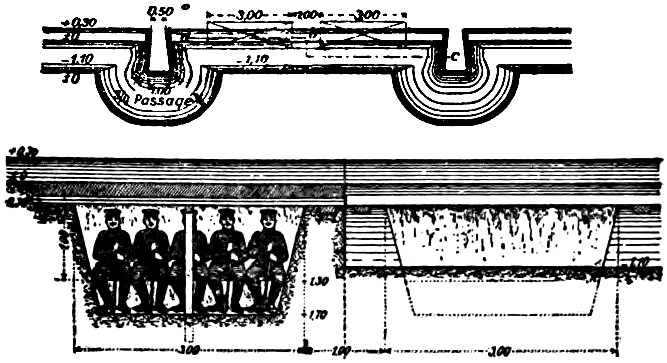

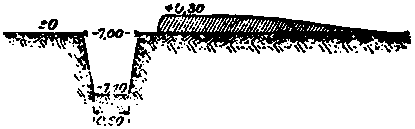

| Cover trenches and communicating trenches | 421 | |||

| Obstacles | 422 | |||

| Russian views | 422 | |||

| 4. | The Conduct of the Defense | 423 | ||

| Protection of the flanks | 425 | |||

| Employment of machine guns | 425 | |||

| Occupation of the position | 426 | |||

| 5. | The Counter-Attack | 428 | ||

| Position of the general reserve | 429 | |||

| The moment for making the counter-attack | 432 | |||

| The counter-attack after the position is carried | 433 | |||

| The counter-attack in conjunction with a movement to the rear | 434 | |||

| Frontal counter-attack | 436 | |||

| Provisions of various regulations | 438 | |||

| XII. | THE RETREAT | 440 | ||

| Breaking off an action | 441 | |||

| Rallying positions | 442 | |||

| XIII. | CONTAINING ACTIONS[xix] | 445 | ||

| The delaying action and the holding attack | 445 | |||

| XIV. | THE INFANTRY COMBAT ACCORDING TO VARIOUS DRILL REGULATIONS | 448 | ||

| The Austrian Drill Regulations of 1903 | 448 | |||

| The Italian Drill Regulations of 1903 and 1906 | 451 | |||

| The French Drill Regulations of 1904 | 453 | |||

| The British Drill Regulations of 1905 | 459 | |||

| The Japanese Drill Regulations of 1907 | 463 | |||

| The Russian Drill Regulations of 1907 | 466 | |||

| The Swiss Drill Regulations of 1908 | 466 | |||

| XV. | THE EXPENDITURE AND SUPPLY OF AMMUNITION | 468 | ||

| 1. | Historical Sketch | 468 | ||

| Table showing ammunition supply of the various armies of the world | 475 | |||

| 2. | Regulations Governing the Supply of Ammunition in Armies | 476 | ||

| Germany | 476 | |||

| Austria | 479 | |||

| Russia | 480 | |||

| France | 480 | |||

| England | 482 | |||

| Italy | 483 | |||

| 3. | What Deductions May Be Made From the Regulations of the Various Armies | 483 | ||

| INDEX | 487 | |||

| INDEX OF EXAMPLES FROM MILITARY HISTORY | 527 | |||

| C. D. R. | = | Cavalry Drill Regulations. |

| F. A. D. R. | = | Field Artillery Drill Regulations. |

| F. A. F. R. | = | Field Artillery Firing Regulations. |

| F. S. R. | = | Field Service Regulations. |

| Gen. St. W. (Generalstabswerk) = German General Staff account of the Franco-German War (unless otherwise indicated). | ||

| I. D. R. | = | Infantry Drill Regulations. |

| I. F. R. | = | Infantry Firing Regulations. |

g. = gram = 15,432 troy grains.

kg. = kilogram = 1000 g. = 2.2 lbs.

kgm. = a unit of work accomplished in raising a kilogram

through a meter against the force of gravity.

m. = meter = 39.37 in.

km. = kilometer = 1000 m. or 5⁄8 mile.

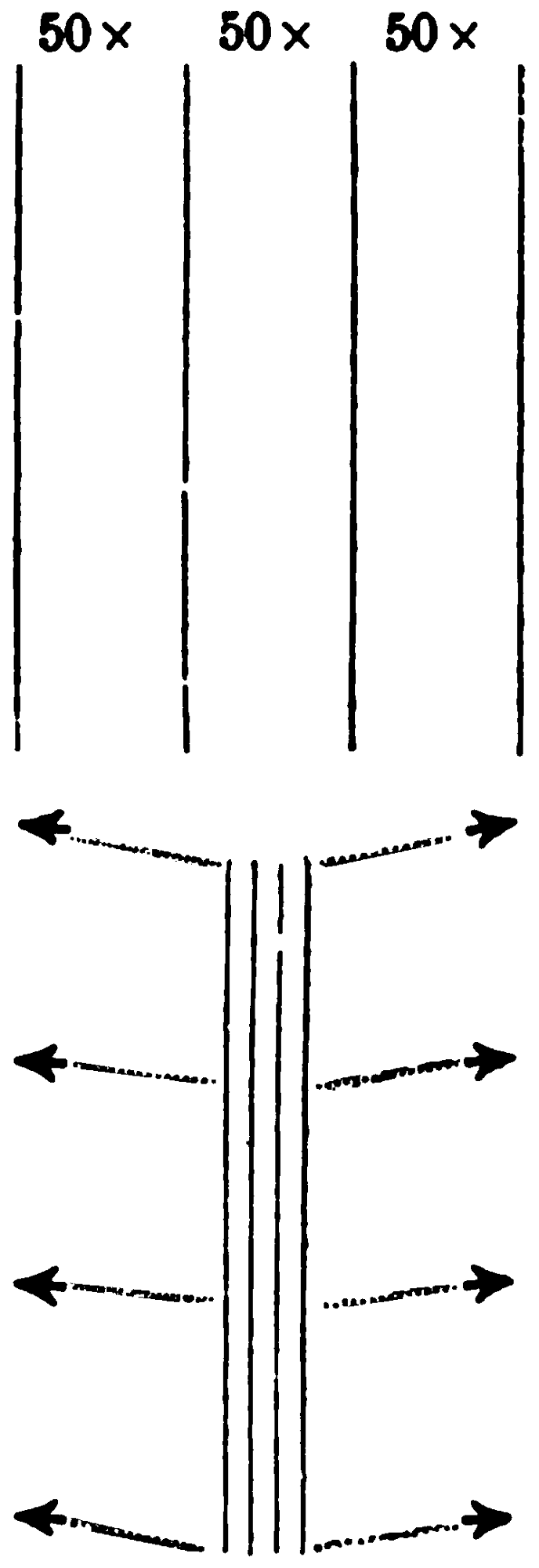

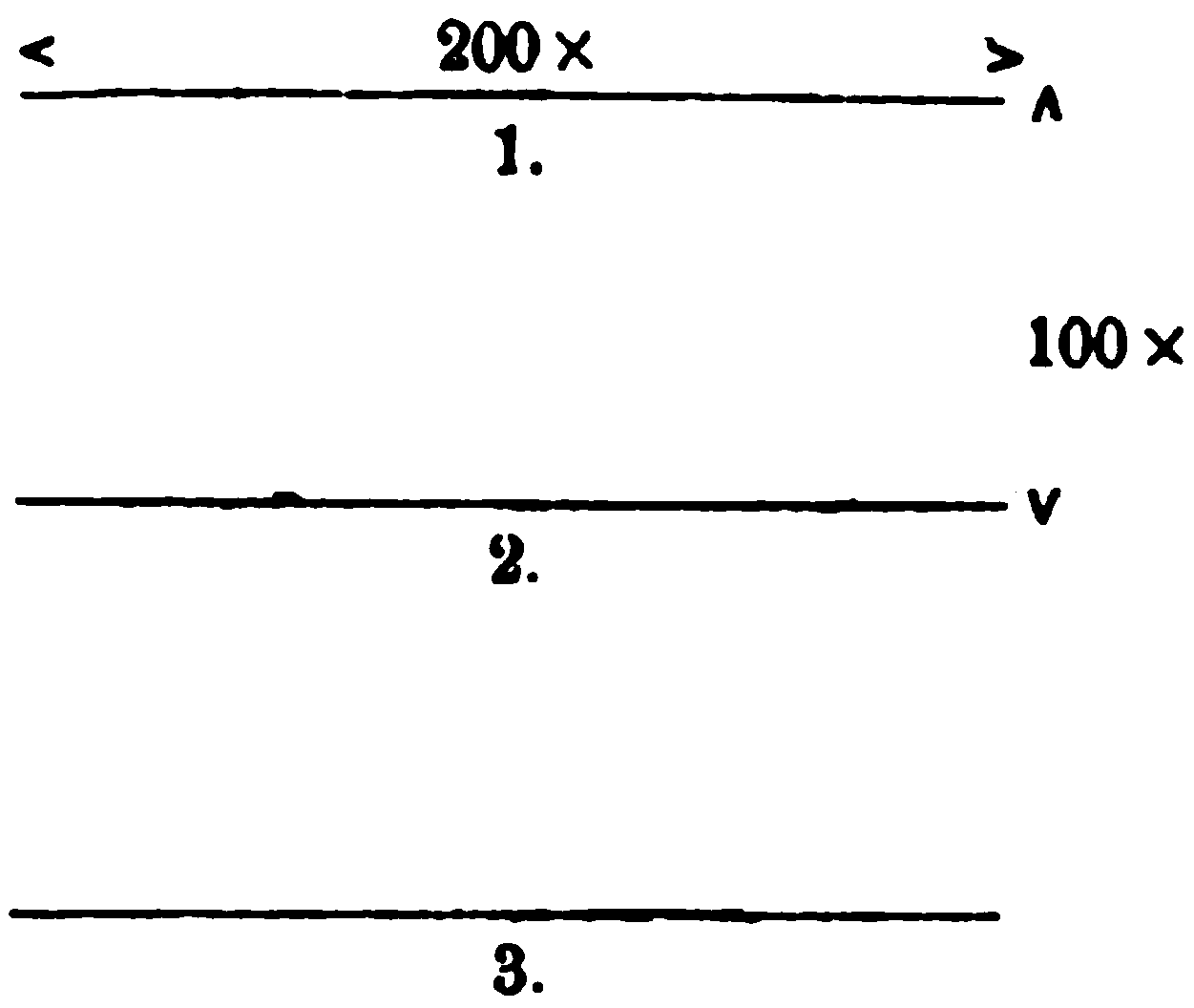

x = pace.

[1]

[2]

Clausewitz, in his work On War, defines war as “a continuation of state policy by other means; an act of violence committed to force the opponent to comply with our will.” The civil code is incapable of furnishing full satisfaction to individuals in cases of outraged honor, and is obliged, under certain circumstances, to allow the injured party to obtain such satisfaction by immediate chastisement of the offender or by challenging him to a duel. In like manner there is no law which could afford nations complete satisfaction for affronts to their honor; and it is obvious that it would be as impossible to abolish war in the world, in the family of nations, as it would be to abolish dueling among the subjects of a state. The total abolition of dueling would produce the same results on the life of the individual that the cessation of wars would produce on the development of the national life of every state and on the intercourse of nations with one another. “Eternal peace,” wrote Moltke on December 11th, 1880, to Professor Bluntschli, “is a dream, and not even a beautiful one; for war is a part of God’s system in ruling the universe. In war, man develops the highest virtues; courage and unselfishness, devotion to duty and self-sacrifice even to death. Without war the world would stagnate in materialism.” Treitschke ventured a similar opinion in 1869.[1] “Every nation, especially a refined and cultured one, is apt to lapse into effeminacy and selfishness during a protracted period of peace. The unlimited comfort enjoyed by society causes not only the downfall of the state but destroys at the same time all those ideals which make life worth living. Narrow provincialism or selfish and worldly activity, looking only toward the gratification of all desires of the individual, undermines the foundations of a higher moral philosophy and the belief in ideals. Fools arrive at the vain conclusion that the life object of the individual is acquisition and enjoyment; that the purpose of the state is simply to facilitate the business affairs of its citizens; that man is appointed by an all-wise providence to buy cheaply and to sell at a profit; they conclude that war, which interferes with man’s activities, is the greatest evil, and that modern armies are only a sorry remnant of mediaeval barbarism. * * * It proves a positive blessing to such a generation if fate commits it to a great and righteous war, and the more it has become attached to the comfortable habits of mere social existence, the more violent the reaction which rouses it to warlike deeds in the service of the state. * * *” “The moment the state calls, ‘My life, my existence is at stake,’ there is aroused in a free people that highest of all virtues, the courage of self-sacrifice, which can never exist in time of peace nor be developed to such an extent by peaceful pursuits. Millions are united in the one thought—the fatherland; they are animated by that common sentiment of devotion unto death—patriotism—which, once experienced, is never again forgotten, and which ennobles and hallows the life of a whole generation. * * *” The greatness of war lies in those very phases which an effeminate civilization deems impious. “A great nation must be powerful,” exclaimed Scherr, in 1870.[2] “That is not only its duty, but its nature. If opposition is encountered, a nation is not only permitted to force a way for its righteous cause and resort to war, but it is its duty to do so. War always has been, and, so long as men and nations exist on the earth, it always will be, the ultima ratio.”

[1] Das konstitutionelle Königtum in Deutschland, in Historische und politische Aufsätze, New edition, II.

[2] Das grosze Jahr, in Hammerschläge und Historien.

[3]

Since war is the ultima ratio of state policy, and as a sovereign state must insist on absolute independence in determining its affairs and its course of action, it follows that the verdict of a court of arbitration, on the larger and more serious questions, can have a decisive influence on the action of the contending parties only if the arbitrator possesses the power to enforce his decision, and is embued with a determination to use that power. Thus the Pope was able to arbitrate the question of right between Germany and Spain as to the possession of the Caroline Islands, but a like verdict could never decide the question of might between Germany and France as to the possession of Alsace-Lorraine.[3]

[3] The constitution of the old German Confederation provided for a settlement of disputes arising among its members; this verdict was to be enforced by summary proceedings when necessary. The war of 1866 proved that the paragraphs of the constitution mentioned, of necessity had to fail the moment the vital interests of two powerful states came into conflict. See von Lettow-Vorbeck, Geschichte des Krieges von 1866, I, p. 115.

The utopian plans for a universal international court of arbitration are chimerical and conjured up by idealists unacquainted with the harsh facts of reality, if their ideas are not, indeed—as are many proposals for disarmament—calculated to serve as a cloak for ambitious plans.

If diplomatic means do not suffice to adjust a dispute, then the question of right between two states at once becomes a question of might. But the existence of a spirit of fair play is taken into account nevertheless, for each party to the controversy will seek to have the justice of its cause recognized. The moral support engendered by fighting for a just cause is so great that no state is willing to dispense with it.[4] This circumstance, coupled with the growing power of public opinion and with the influence of representative government, has contributed to reduce the number of wars. Wars between cabinets, like those in the days of Louis XIV., are no longer[4] possible. As a result of the universal liability to service, the whole nation takes part in a war; every class of society suffers and has its pursuits interfered with; everything presses to an early decision, to a prompt crushing of the opponent.

[4] “If princes wish war they proceed to make war and then send for an industrious jurist who demonstrates that it is therefore right.” Frederick II.

“Every war is just which is necessary and every battle holy in which lies our last hope.” Machiavelli, Il Principe.

This is attained by defeating the enemy’s forces, by occupying the hostile country and seizing the enemy’s sources of supply, so that he will be convinced of the futility of further resistance. (Campaigns of 1859, 1866, and 1870-71). Only in the rarest cases will it be necessary to continue the war until the power of resistance of the hostile state is completely destroyed. (American Civil War). The extent to which the enemy’s power of resistance may have to be crippled or broken, in order to compel peace, depends upon his tenacity. Political considerations will also have to be taken into account in answering this question. From the military point of view, however, the purpose of every war will always be the complete overthrow of the enemy.

Precise definitions of strategy and tactics, clearly fixing the scope of each, have been vainly sought in the past. That efforts in this direction have led to no results is only natural, as tactics and strategy are complementary subjects that often encroach upon each other, while grand tactics is frequently identical with strategy.

Von Bülow, the author of The Spirit of Modern Warfare (1798)[5], calls those movements strategical which are made outside the enemy’s sphere of information. Von Willisen considers strategy the science of communications, tactics the science of fighting. Von Clausewitz calls strategy the science of the use of battles for the purpose of the war[5] (Jomini: “l’art de diriger les armées sur les théatres d’opérations”)[6], tactics the science of the use of military forces in battle (Jomini: “l’art de diriger les troupes sur les champs de bataille”).[7][8] General von Horsetzki (1892) defines strategy as the study of the conditions necessary for success in war. Archduke Charles calls strategy the “science of war” and tactics the “art of war”. Frederick the Great and Napoleon always employed the term “l’art de guerre” instead of the term “strategy”. None of these definitions are comprehensive enough, because they do not cover marches, outposts, the supply service, and enterprises in minor tactics. Professor Delbrück’s definition is much more appropriate: “Strategy is the science of utilizing military resources for the attainment of the object of the war, tactics the art of leading troops into and in battle.” Thiers, the French historian, instead of seeking to define strategy and tactics, contents himself with explaining the problems of each: “Le stratège doit concevoir le plan de campagne, embrasser d’un seul coup d’oeil tout le théatre présumé de la guerre, tracer lignes d’opérations et diriger les masses sur les points décisifs. Le tacticien a pour mission de régler l’ordre de leurs marches, de les disposer en bataille aux différents points, indiqués par le stratège, d’engager l’action, de la soutenir et de manoeuvrer pour atteindre le but proposé.”[9] Fieldmarshal Moltke calls strategy “the[6] application of common sense to the conduct of war.”[10] For practical purposes it is sufficient to define strategy as the science of the conduct of war, tactics as the science of troop-leading. Strategy brings about the decision on the theater of war, while the duty of carrying it out, in the manner desired by the commander-in-chief, devolves upon tactics. Thus the strategical idea culminates on the battlefield. The concentric advance of the Prussian armies into Bohemia in 1866 naturally led to a complete envelopment of the Austrians on the field of Königgrätz. The German attack in the battle on the Hallue, Dec. 23rd, 1870, was based on the strategical requirement of driving the French from their line of retreat leading to Arras and Bapaume, by enveloping their right flank. The attempts made by the 15th Infantry Division, which was holding the enemy in front, to envelop the left wing of the French, interfered with the execution of the correct strategical plan. Thus, in following up a success, in itself quite unimportant (the capture of Bussy), the leading basic principle was forgotten. The same thing happened here that Moltke censured in his official report on the war of 1866, wherein he stated: “The higher commanders have not been able to make their influence felt down to the subordinate grades. Frequently, as soon as the divisions and brigades have come in contact with the enemy, all control over them has entirely ceased.”

[5] Geist des neueren Kriegssystems.

[6] “The art of directing armies in the theater of operations.”

[7] “The art of directing troops on the field of battle.”

[8] “Everything affecting the use of troops in battle and the regulation of their activity with reference to battle, has been included in the term ‘tactics’, while the term strategy is synonymous with ‘generalship,’ exclusive of such matters as fall into the domain of tactics.” Blume, Strategie, p. 33.

“Tactics teaches how, and strategy why, one should fight.” General v. Scherff.

Strategy determines direction and objective of the movement of armies, while the manner of execution belongs to tactics.

[9] “Strategy should devise the plan of campaign, take in with a comprehensive glance the entire probable theater of war, establish the lines of operations and direct the masses on the decisive points.

“It is the mission of the tactician to decide upon the order of march of the troops, to form them for battle at the various points determined by strategy, to begin the action, to sustain it, and to maneuver so as to attain the desired end.” Thiers.

[10] v. Moltke, Tactical Problems, No. 58 (1878) p. 133.

Archduke Charles considered the subordination of tactics to strategy a law. “Tactics should execute the conceptions of strategy; where the two come in conflict, where strategical considerations are opposed to tactical interests, the strategical considerations should, as a rule, take precedence. Tactics must occupy a subordinate place and attempt to neutralize existing disadvantages by skillful dispositions.” Clausewitz not unjustly censures Archduke Charles for placing advantages of terrain in the first rank, and for failing to attach the proper importance to the annihilation of the hostile forces.[7] Should the demands of strategy conflict with those of tactics on the battlefield, the latter must unquestionably take precedence, since the general’s foremost thought must be the annihilation of the hostile forces. Tactical considerations should likewise govern in the selection of the direction of attack in a battle, strategical reasons for striking in this or that direction becoming effective only after the attainment of tactical success. It is true that strategy, by directing the armies and their concentration on the battlefield, provides tactics with the tools for fighting and assures the probability of victory; but, on the other hand, the commander-in-chief appropriates the fruits of each victory and makes them the basis for further plans. “The demands of strategy are silent in the presence of tactical victory; they adapt themselves to the newly created situation.” Fieldmarshal Moltke.[11]

[11] The view that the direction of attack should be governed by the possibility of easy execution in minor warfare only, is held by General v. Scherff, who says: “General v. Moltke was not influenced by the question ‘will the attack here or there be tactically easier or more difficult?’ Only the question, ‘will it there be strategically advantageous or not’ was able to determine his course with reference to measures on the battlefield.”

While Archduke Charles considers mathematical axioms the basis of the higher art of war, military history is for us the principal source from which to gather knowledge.[12]

[12] See lecture by Prince Hohenlohe: Kriegserfahrung und Kriegsgeschichte, Neisse, 1879.

“Let my son often read and meditate upon history; it is the only true philosophy. Let him often read and meditate upon the wars of the great captains; it is the only means of learning the art of war.” Napoleon I., on April 17th, 1821.

“Past events are useful to feed the imagination and furnish the memory, provided their study is the repetition of ideas that judgment should pass upon.” Frederick the Great.

In military history we have a guide by which, if we lack personal experience in war, we can test the results of our reflections and of our experience on the drillground. Military history moreover enables us to appreciate those controlling[8] factors which, in map problems, do not appear at all, and which, in exercises on the terrain, appear only in a restricted measure. One must learn the conduct of war from the experience of others; one’s own experience is costly and is almost invariably gained too late. That experience in war, of itself, is not sufficient (aside from the fact that it is gained too late in a given case) is illustrated by the defeat of the Austrians in 1866, of the French in 1870-71, and of the British in South Africa. “Les Autrichiens,” says Colonel Foch,[13] “ont fait la guerre sans la comprendre, les Prussiens l’ont compris sans la faire, mais ils l’ont étudiée.” “Military history is neither a compilation of clever theories nor a book designed for whiling away idle moments. It is, on the contrary, a careful teacher, who, if we are attentive, allows us to view and grasp matters which we have never before been in a position to see, but which, nevertheless, are liable to confront us in the same, a similar, or a changed form, and demand unpremeditated, instant and decisive action, entailing heavy responsibilities. Military history, it is true, offers us, in the first instance, only events and their outline, conditions and phenomena, but it also presents, what the cleverest theory is unable to furnish, a graphic illustration of the disturbing elements in war, an illustration of the influences, doubts, embarrassments, unforeseen accidents, surprises and delays. It describes the course pursued by commanders and by practical military common sense in surmounting these difficulties. It prepares in advance the mental balance necessary at the moment of action; it should prepare also for the unexpected. It affords a substitute for lack of military experience, for the accumulation of which the life of the individual, prior to the moment of action, has been too short.”[14] The pedantic enumeration of a few examples in support of a stated opinion cannot[9] suffice. It should not be difficult to find examples from military history in support of any opinion; frequently even an incorrect tactical contention can be vindicated by such examples. For in war the action taken is as often wrong as correct; the scales are turned by factors which in most cases appear indistinctly or not at all. The experiences of military history must, therefore, only be used with caution if tactical lessons are to be drawn from them. “A mere allusion to historical events,” says Clausewitz in his chapter on examples, “has the further disadvantage that some readers are either not sufficiently acquainted with these events, or remember them too imperfectly to enter into the author’s ideas, so that such students are compelled to accept his statements blindly or to remain unconvinced. It is, of course, very difficult to describe historical events as they ought to be described if they are to be used as proofs, for authors usually lack the means, as well as the time and space, necessary for such descriptions. We maintain, however, that in establishing a new or a doubtful view, a single event, thoroughly described, is more instructive than a mere allusion to ten. The principal evil resulting from a superficial reference to historical events does not lie in the fact that the author cites them incorrectly in support of his theory, but in the fact that he has never become thoroughly acquainted with those events. In consequence of such a superficial, haphazard treatment of history, a hundred erroneous views and theoretical projects are created, which would never have appeared if the author had been compelled to deduce, from a careful analysis of the connected facts in the case, what he publishes and wishes to support by historical proofs. If we have convinced ourselves of the above outlined difficulties attending the employment of historical examples, and appreciate the necessity for thoroughness in their treatment, we will come to the conclusion that the more recent military history is the most natural source from which to select examples, inasmuch as recent history[10] alone is sufficiently known and analyzed.”[15] The events from military history mentioned in this work are cited simply as proofs of certain phenomena; the proper analysis of these proofs must be left to the student.

[13] Principes de la Guerre, 1903.

“The Austrians,” says Colonel Foch, “made war without understanding it; the Germans understood war without making it; but they studied it.”

[14] From Meinungen und Mahnungen, Vienna, 1894.

[15] On War, II, Chapter 6, p. 111.

See also Clausewitz’ remarks on “Criticism,” II, Chapter 5.

The applicatory method[16] is used frequently by preference as the system of instruction, but its creator, General von Verdy du Vernois, considers it merely a complement of the deductive method, on which it is predicated and based. “The weakness of the whole applicatory system of instruction lies in the fact that a textbook based upon it, although written by a master hand, can portray only isolated examples, and that these, studied again and again, soon lose their value in the same manner as a maneuver terrain that has become too well known. For, although we ordinarily find principles represented in a connected form, this method of instruction can only convey them in a fragmentary manner in connection with the details of the events described.”[17] The success of the applicatory method depends largely upon the individuality of the instructor, and owes its charm to the personal intercourse between teacher and pupil. Only an expert, who possesses a thorough professional knowledge, who is master of his subject, and who has the faculty of presenting it skillfully, will be able to produce imaginary scenes which faithfully represent reality and are free from objectionable features. By constant practice with specific cases, under the most diverse situations, the nature of war may in this way be taught and initiative developed as well as facility acquired in issuing appropriate, clear, and concise orders. One danger of using nothing but the applicatory method must be noted. The instructor, as representative of a definite theory, finds it comparatively easy to select the conditions governing a specific case in such a way that the theory which he represents necessarily[11] appears to be the correct one. This is especially true when the director of an applicatory problem determines the action of the opposing side. The two methods (the applicatory, or inductive, and the deductive) must be so supplemented that the lesson in tactics clearly illustrates the purpose and object of a tactical operation and allows of the attainment of a thorough knowledge of the means necessary to gain that object.[18] “He who is able to understand the situation, has a definite purpose in view, and knows the means with which to carry out that purpose, will, by a simple mental operation, arrive in each particular case at an appropriate decision, and will be able, furthermore, to carry out that decision, provided he does not lose his head. If a clear comprehension of the purpose in view and of the means for carrying out that purpose lie within the sphere of theory, the estimate of the situation and the decision are governed by the circumstances of the particular case. Should the training in this direction lie outside the sphere of theory, it will logically belong to the domain of the applicatory method of instruction. The two methods must, therefore, supplement each other.

[16] See Kühne, Kritische Wanderungen, 4 and 5, Preface p. 5.

[17] von Boguslawski, Entwickelung der Taktik, II, p. 17.

[18] “When one attempts to establish a principle, immediately a great number of officers, imagining that they are solving the question, at once cry out: ‘Everything depends on circumstances; according to the wind must the sails be set.’ But if you do not know beforehand which sail is proper for such and such a wind, how can you set the sail according to the wind?” Bugeaud, Aperçus sur quelques détails de guerre.

If the decision is to culminate in action, strength of character is required, providing the determination to execute, in spite of unavoidable difficulties, what has been recognized as proper, and also the professional ability necessary to carry out the determination to its logical conclusion. All that theory can do toward forming this character is to emphasize its importance and to refer students to military history. The applicatory method, however, can develop strength of character by compelling the student to form decisions under pressure of a specified time limit (in solving problems) or by subjecting him to the influences of certain situations such as would[12] be encountered in war (maneuvers). The means available in tactical instruction in time of peace, for the development of strength of character, are, however, very limited when compared with the great demands made by the abnormal conditions of war, so out of all proportion to those of peace. This should be thoroughly understood, lest we overestimate the value of these means as well as the results to be obtained from them in times of peace.

After theory has fulfilled its mission of clearly indicating the purpose and object of an operation, as well as the means by which it may be attained, and applicatory practice has performed its office of developing initiative and professional skill, a third factor is still necessary—the study of military history. From this fountain of knowledge both “theory” and “applicatory method” must draw their material; to this source they must again and again refer in order to guard against erroneous ideas of their own creation, which are often as different from reality as day is from night.”[19]

[19] F. C. v. H. (Fieldmarshal Lieutenant General Conrad v. Hötzendorf, Chief of Staff of the Austro-Hungarian Army). Zum Studium der Taktik, p. 2.

Viewed as the science of the leading and employment of troops, tactics may be divided into two parts:

1. Formal tactics, or that contained in drill regulations. This portion of tactics furnishes the formations used by troops when assembled, on the march, and in action, and contains the regulations governing the conduct in battle of troops acting alone without regard to the coöperation of the other arms, and without reference to the terrain.

2. Applied tactics[20] deals with the combined action of the several arms on the march, in camp, and in action, taking into account influences of the terrain, seasons, and the time of day in field warfare. Fortress warfare should, strictly[13] speaking, be included under this heading; that is to say, the employment of tactical principles[21] pertaining to the mobile arms, in conjunction with foot-artillery and technical troops on a prepared battlefield. The principles are the same in field and fortress warfare; the only difference between them lies in the employment of the means necessitated by the preparation of a field of battle in time of peace. Military history shows that a clear distinction between field and fortress warfare is impossible. (Sebastopol, Düppel, Plevna, and Port Arthur).

[20] v. Boguslawski, Entwickelung der Taktik, II, Chapter 23. “The higher, Grand Tactics, is the Initiation and conduct of battles—subordinate, or minor tactics, is the manner of fighting, or the battle-tactics of an arm considered in its details.”

[21] Major Gundelach, Exerzierreglement und Festungskrieg, Berlin, 1908.

Drill regulations are the accumulation of the tactical views and lessons of a certain period. They illustrate the tactical condition which becomes perceptible at the moment of a certain development of the fighting tools as represented by man and weapons. Man, in his peculiarities, in his weaknesses, is the constant. He constitutes the psychological element, inseparable from the science of combat, and as such is the definitely given magnitude; the effect of weapons, however, appears always as the variable factor. New weapons, therefore, necessitate new tactics.

It will be observed also “that changes of tactics have not only taken place after changes in weapons, which necessarily is the case, but that the interval between such changes has been unduly long. This doubtless arises from the fact that an improvement of weapons is due to the energy of one or two men, while changes in tactics have to overcome the inertia of a conservative class; but it is a great evil. It can be remedied only by a candid recognition of each change.”[22] The history of the tactics of the 19th Century furnishes[14] more than one instructive example of the magnitude of such “obstinate conservatism.”

[22] Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, pp. 9 and 10.

It is a marked peculiarity of manuals of instruction, that, no matter with what far-sightedness such regulations may have been originally compiled, they become antiquated in a comparatively short time. Napoleon estimated this period at ten years. Frequent changes are certainly not desirable, if tactical development is not to be interfered with and if inconveniences are to be avoided in organizing our mobile army from our peace organizations, Reservists, and Landwehr. On the other hand, the regulations must keep abreast of requirements if the conditions to which they owe their existence have changed. In his “Military Fantasies” the Prince de Ligne wrote in 1783: “An article which should be added to all drill regulations, and which, I know not why, is omitted, is: ‘Act sometimes contrary to the regulations.’ It is just as necessary to teach that one must act contrary to the regulations, as to teach the disorder of troops as it will occur in action.”

It is always dangerous to be behind the times, as troops thereby relinquish a superiority previously possessed over others, which knowledge they must later purchase, with streams of blood, in the face of hostile bullets. Of what avail, to the Austrians in 1866, to the Russians in 1877, were all their valiant assaults, made with tactical formations that had outlived their usefulness in the face of newer weapons, although made with the firm determination to conquer?

The self-sacrificing spirit and firmly rooted discipline of the troops found an insurmountable obstacle in the rapid fire of unshaken infantry. The war experiences of our regiments show that bullets quickly write a new tactics, demolish superannuated formations and create new ones. But[15] at what a sacrifice![23] In the Franco-German war, superior leadership and a better artillery permitted us to pay this price for the lesson. But how an army fares when it lacks these auxiliaries is shown by the British experiences in South Africa. The initial failure of accustomed tactical formations causes a dread of the frontal attack and finally leads some tacticians to deny entirely even the feasibility of such an attack. In peace training, therefore, set forms are of less importance; stress should be laid on developing the faculty of adaptation to changing conditions of combat and terrain.

[23] It is frequently customary on the outbreak of a war to issue “Instructions for campaign,” in order to prepare troops, trained according to superannuated regulations, for action on a strange theater of war. It is desirable to disseminate the first experiences gained in action to all parts of the army. We failed to do this in 1870, and all organizations were therefore compelled to gain this experience for themselves. Even as late as the 18th of August, 1870, the Füsilier Battalion of the 85th Infantry advanced in double column formed on the center, although the campaign in Bohemia had already demonstrated that this formation was out of date. See Moltke, Feldzug von 1859, p. 65.

Further development and justification of the principles of the drill regulations, and the modification of those principles under certain assumptions, are reserved to the science of tactics. Drill regulations should not be textbooks of tactics, but, on the other hand, a textbook of tactics should deal with formations only in so far as that is necessary to ensure a clear comprehension of the fundamental principles.

“Regulations and the science of combat are in a certain sense very different subjects. The regulations are law, authority—no doubt can be entertained on this point; but that also invests them with the character of something fixed, at least for a certain space of time. They cannot be kept up to date so as to meet quickly enough the rapidly changing and ever growing demands of modern combat: that would indeed be an unfair requirement, impossible of realization. Here must enter the science of combat, which should be independent in every direction, which should know no fixed rules, and which should point to no other authority than that of truth and reality. It is not the province of the science of[16] combat, like that of regulations, to retain that which is in keeping with prevailing views and forms; it must take into consideration the fleeting theory and practice, ever developing and changing anew.”[24]

[24] Keim, Gegenwärtiger Stand der Gefechtslehre, p. 1.

A positive system of tactics will therefore be based upon one’s own drill regulations, from the standpoint of which it will investigate and compare the principles of the service manuals of the different powers, and finally develop the science still further by the aid of experience gained from military history and the knowledge of the effect of weapons. While these are the ever changing but nevertheless measurable factors of tactical reflection, a third, perhaps the most important factor, must be added, viz., that the leader must reckon with the action of men frequently exposed to the influence of great exertions and great mental agitation. A doctrine of tactics which does not properly appreciate the psychological element stagnates in lifeless pedantry.

[17]

In all modern armies infantry is, in virtue of its numbers and importance, the principal arm. Since the introduction of firearms, infantry has gradually increased in importance and numbers as compared with the other arms.

In the Thirty Years’ war, the proportion of cavalry to infantry was as 1:1, or 1:2, and frequently the cavalry even predominated. In the Swedish army one gun per 1,000 men was considered sufficient. During the era of linear tactics in the 18th Century the proportion between the two principal arms had become as 1:2 and 1:3; in the Napoleonic wars as 1:6 and 1:8. The number of guns was increased to 4 per 1,000 men. In the course of a campaign the ratio changes to the disadvantage of infantry. At the outbreak of the war of 1870-71, the relative proportions of the three arms in the German IInd Army were as follows: cavalry to infantry as 1:8; and 3.4 guns per 1,000 men. The proportion between the two principal arms in the IIIrd Army Corps of the German army, at the outbreak of the Franco-German war, was as 1:18.8; on the first day of the battle of Le Mans it was as 1:16.6; at the opening of the campaign there were 4.6 guns per 1,000 men, at the close of the campaign 5.8 guns per 1,000 men. This was still more marked in the Ist Bavarian Army Corps, which, on October 31st, had 5.8 guns and on December 9th even 11.1 guns per 1,000 men. At present Germany has approximately 6, and France 3.63 guns per 1,000 infantry.

The manner in which infantry fights imprints its distinguishing mark on the tactics of an entire period; thus, according to the combat formations of infantry, we may speak of a period of “linear,” “column,” and “extended order” tactics. Infantry can be equipped more cheaply and trained[20] more quickly than the other arms. In July, 1870, the French army consisted of 116 infantry regiments and 21 rifle battalions, but 38 rifle battalions were raised in addition to a large number of regiments of gardes mobiles and volunteers.

Infantry is as well adapted for combat with firearms as for combat with the bayonet, for attack as for defense, for action in close as in extended order. It can fight on any terrain which is at all passable, and is more independent of weather and seasons than the other arms; it surpasses the other arms in endurance, a man, on account of his will power, bearing privations and exertions better than a horse. On the other hand, the losses suffered by foot troops in action and through exertions on the march are greater than those of the mounted arms.[25]

[25] Percentages of cases of sickness in the campaign 1870/71:

| Infantry: | 69.8; | Field | Officers: | 13.26; | Captains: | 10.19; | Lieutenants: | 3.85 | % |

| Artillery: | 57.7; | „ | „ | 4.04; | „ | 4.84; | „ | 4.52 | „ |

| Cavalry: | 37.5; | „ | „ | 5.61; | „ | 2.29; | „ | 3.24 | „ |

The rate of march of infantry is so slow that in reconnaissance it can only by great exertions attain results which a small force of cavalry would obtain without appreciable effort. Infantry acting alone therefore unquestionably requires the assignment of mounted men for reconnaissance and messenger duty. As regards reconnaissance, infantry is like a man walking in the dark, who can guard against collisions only by stretching out his hand and feeling his way.

The lack of artillery support will also make itself felt when infantry encounters fire at ranges at which it is defenseless, owing to the limited range of its rifle. Infantry cannot dispense with artillery when it has to attack localities or fortified points in villages.

The infantry of the 19th Century fell heir to the distinction made in the 18th Century between heavy infantry (infantry of the line) and light infantry, the latter being employed only in skirmish duty and in the service of security. In the 18th Century the expensive method of recruiting by[21] means of bounties made it necessary to avoid using troops in indecisive, costly fire actions, and to preserve the expensive personnel for decisive shock action en masse. Skirmishing was left to volunteer battalions, to Jägers, and to Füsiliers. In Prussia the number of Füsilier battalions was increased to 24 at the close of the 18th Century. Napoleon I. was, on principle, opposed to the theory of light infantry. He demanded but one species of infantry, “a good infantry.” In spite of this, however, he became the originator of an élite infantry, when, for reasons of discipline, he created one voltigeur and one grenadier company in each battalion. While battalion tactics predominated, i.e., until the close of the campaign of 1866, this arrangement was imitated in most states. At the time of the Russo-Turkish war, Russia still had in each battalion a fifth company, one of sharpshooters, which, though not recruited at the expense of the other companies, was formed of better material and received special training in extended order fighting. Following the example set by Austria, Prussia, in 1812, designated the third rank principally for extended order fighting, by forming it into a third platoon in each company when in action. This was called the sharpshooters’ platoon and was composed of the best shots and the most skillful men of the company. As late as the campaign of 1866 there were instances of the employment of the combined sharpshooter platoons of a battalion. Here we have an actual élite force assembled in provisional organizations, not at the expense of the rest of the troops, however.

The system of column tactics, which required that every company should be equally skilled in extended order fighting, led to the abolishment of élite companies. The Prussian élite, consisting of the platoons formed from the third rank, although not always compatible with the employment of company columns, was not abolished until 1876. The experience of the Franco-German war had shown that, in view of the[22] extensive use of extended order formations, an independent employment of single platoons was out of the question, as in the course of an action the firing line absorbs not only entire companies, but regiments and brigades; and, moreover, that every platoon, as a unit for fire action, must possess those elements which will carry it forward even after its leader has fallen.

Napoleon formed his Guards by selecting men and officers from the entire army for use as a battle reserve. By granting them privileges and by loading them with distinctions, he attached them to his person, and they assumed the character of household troops of a dynasty.

The Prussian and Russian Guards are differently constituted. They are not, strictly speaking, corps d’élite, for they are not selected from the ranks of the army. While it is true that the Prussian Guard receives a better class of recruits and the composition of its corps of officers and the selection of its commanders guarantee conspicuous results, its principal superiority lies in the fact that it serves constantly under the eye of the emperor.

Since the introduction of accurate breechloading weapons, and their use by all infantry, Jägers and riflemen have no tactical excuse for existing, except where they are specially trained in mountain warfare (Chasseurs alpins, Alpini)[26], or where they are intended to serve as a support for cavalry divisions. (France). While Jäger-battalions are at present employed like the rest of the infantry, they are retained by us as such because of tradition and for reasons of organization (they are recruited from forestry personnel), and an attempt is made in their tactical employment to turn their excellent marksmanship and skill in the use of ground to good account whenever possible. Jägers will be employed in defense, preferably for holding important points, and for combat[23] and service of security on difficult terrain. Military experience has shown, however, that in actual war it was seldom possible to take advantage of these special characteristics; that in most cases the Jägers were used as other infantry, and that infantry units fighting shoulder to shoulder with Jägers accomplished as good results as the latter. Since the war of 1866 the demand for special employment of Jägers has ceased. The brief course of the campaign of 1866, in which our infantry acted mostly on the offensive, gave the Jägers an opportunity for profitable employment only where, contrary to accepted notions, they fought side by side with the rest of the infantry.[27]

[26] See Über Gebirgstruppen, VI, p. 273, and also Schweizerische Monatsschrift für Offiziere aller Waffen, 1907, May to July.

v. Graevenitz, Beiheft zum Militär-Wochenblatt, 1903.

[27] The 6th Jäger-Battalion on July 3rd at Sendrasitz; the 4th Jäger-Battalion at Podol; the 5th at Skalitz; the Jägers of the Guard at Lipa; or where during an action a reverse threw us on the defensive (1st Jäger-Battalion at Trautenau, and also at Rosberitz). The superior commanders, in attempting to assign them a special role, frequently employed them unprofitably in taking up rallying positions (3rd, 7th, and 8th Jäger-Battalions on July 3rd), sometimes even to escort baggage (3rd and 4th Companies of the Jägers of the Guard at Soor; and the 1st and 4th Companies of the 5th Jäger-Battalion at Schweinschädel); or they distributed them along the whole front for the purpose of conducting extended order fighting. When they were thus distributed among infantry organizations their efforts merged with those of the infantry.

For example, at Königgrätz half companies of Jägers were posted on both flanks of the Guard Infantry Division, and the 2nd Jäger-Battalion was on this day distributed by companies along the front of the entire division.

v. Moltke, Kritische Aufsätze zur Geschichte des Feldzuges von 1866.

Kunz, Die Tätigkeit der deutschen Jäger-Bataillone im Kriege 1870/71. On page 169, et seq., a number of excellent examples are recorded (for instance: 5th Prussian Jäger-Battalion in the actions on November 29th and 30th, 1870, and on January 19th, 1871, in siege positions in front of Paris).

Mountain warfare presents such difficult problems to troops, requires a sum total of endurance, energy and intelligence, physical qualifications and special familiarity, that neither every recruit nor every unit of the army will quite fulfill all its demands, although the experience of Suworov, during his campaign in the Alps, apparently contradicts this statement. Many disadvantages can be neutralized by peace training and discipline, of course, but training alone will not suffice. For overcoming the difficulties peculiar to mountain warfare, a suitable equipment permitting free movement, and at the same time ensuring the comfort of the men while at[24] rest, is necessary. The lack of such mountain equipment is keenly felt even during short exercises lasting only a few days. Even Switzerland plans at present the formation of three mountain brigades. Austria already has special mountain brigades assembled for mountain warfare in its Kaiser-Jäger, Rural Riflemen, and also in the troops of Bosnia and Dalmatia. The Italian Alpini (consisting of 22 battalions in time of peace, to which militia companies are attached on mobilization, and which have in addition a reserve of 22 territorial companies) form a selected corps which is doubtless capable of accomplishing excellent results. The Italians propose to attach machine guns to these units. It is worthy of note that these troops carry explosives. In France the troops garrisoned in the Alpine districts are divided into thirteen groups, each consisting of one battalion, one mountain battery, one engineer company, and machine guns.

As modern fire effect makes it impossible for mounted officers to direct the firing line, it was natural to use the more improved means of communication, the telephone and telegraph, in addition to the visual signals employed by the navy.

The improvements made in weapons have had a further influence on the transformation of the infantry. Even a small force of infantry can with its magazine fire inflict annihilating losses in a very short time on closed bodies offering favorable targets, especially when this fire is delivered from a flanking position. This requires, on the one hand, that greater attention be paid during combat to local reconnaissance, which can be but imperfectly made by mounted officers with the troops, and, on the other hand, it necessitates the employment of smaller independent detachments for our own security and for harassing the enemy. Intimately connected herewith is the introduction of machine guns, possessing great mobility, which enables them to take advantage of rapidly passing moments for pouring a heavy fire on the[25] enemy and also for reinforcing the independent cavalry in advance of the army.

In England it was decided to form mounted infantry charged with the additional duty of augmenting the fire of a cavalry division, and of furnishing the commander-in-chief with a reserve possessing the requisite mobility to permit its being thrown to any threatened point of the long battle lines of today. But of what importance is the fire of a single battalion in the large armies of the present day? The principal drawback to the employment of mounted infantry is, however, that, when mounted, it is defenseless against cavalry, and that, while in motion, it really needs a supporting force. In the Boer war the mounted infantry grew finally to a strength of 50,000 men. As it was not confronted by cavalry, it made good during the execution of wide turning movements, which Lord Roberts employed with success for the purpose of striking the flank of the Boers, who always rapidly extended their lines. In spite of these good services, it could not be denied that mounted infantry had many faults. The men knew nothing of the care of their mounts, as is evidenced by the large percentage of horses which became unserviceable. As mounted infantry units were improvised bodies, they lacked the requisite training in marching and tactical employment. After the war had lasted for some time, the mounted infantrymen, however, had completely forgotten their infantry character and deported themselves like cavalrymen, even if only as poor ones. Thus, we find toward the close of the campaign numerous attacks made by mounted infantry on the British side, as, strange to relate, also on that of the Boers.

In this experiment of creating mounted infantry, all those drawbacks which had been learned for centuries were exemplified. As an improvisation, mounted infantry disturbs the cohesion of organizations; if permanently organized, it must become cavalry, just as the dragoons became cavalry:[26] for mounted infantry is neither flesh, fish, nor fowl and cannot endure.

The British Drill Regulations (1904) for mounted infantry lay down the following principles for its employment:

In the practical employment of mounted infantry, sight must not be lost of the fact that this arm is drilled and trained as infantry. On account of its greater mobility, it should be able to cover greater distances, and, in addition, be capable of executing wider turning movements than infantry. As a rule, mounted infantry is to be used in the following cases:

(a) It is to perform the service of security in the immediate front of infantry divisions in conjunction with cavalry and the horse batteries assigned to the latter, in addition to augmenting the fire of the cavalry. It is further to occupy, as expeditiously as possible, tactically important positions. It is to find positions from which it can bring fire, preferably flanking fire, to bear on the flanks of hostile cavalry before the actual combat begins. It is to improve every success gained and constitute a formed nucleus in case of a retreat. Moreover, mounted infantry should enable the cavalry divisions, far in advance of the army, to devote themselves exclusively to the strategical reconnaissance with which they are charged.

(b) In addition, the mounted infantry is to constitute a light mobile reserve which the commander-in-chief can despatch at a moment’s notice from one wing to the other for the purpose of lending assistance, or for influencing the action at particular points and for which other troops are not available on account of the extraordinary extension of modern lines of battle.

(c) Finally, mounted infantry is to fill the role of a mobile column in minor warfare or in expeditions in colonial wars, and in performing this duty assume the functions of the absent cavalry in the service of reconnaissance and patrolling.

The following is the organization and strength of mounted infantry organizations:

In war every infantry battalion is to furnish one company of mounted infantry, consisting of 5 officers, 138 men, and 144 horses; and every brigade (4 battalions) one battalion of four companies. To each battalion of mounted infantry is assigned: one machine gun platoon, consisting of two guns and two ammunition carts (2 officers, 40 men, and 54 horses). Hence the aggregate strength of a battalion of mounted infantry is: 28 officers, 630 men, and 676 horses.

The creation of mounted infantry is only proper where climatic conditions make long marches by European troops impossible, or in cases where the arrival of a few soldiers at distant points will exert a potent influence on the actions of[27] an opponent. As shown by our experience in Southwest Africa, the proper field for mounted infantry is colonial (guerrilla) warfare, especially when it is important to prevent the outbreak of threatened disorders and to let the country return quickly to a state of peace upon completion of the principal actions. On European theaters of war, space is lacking for the employment of mounted infantry, and, moreover, there are not enough horses. In organizing mounted infantry, an auxiliary arm, which can be of use only occasionally, has been created at the expense of infantry and cavalry. The infantry itself should endeavor to meet all demands for local reconnaissance and communication, without weakening the cavalry for its principal duties, and without, in so doing, crippling its own fighting efficiency.