*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 64954 ***

[10]

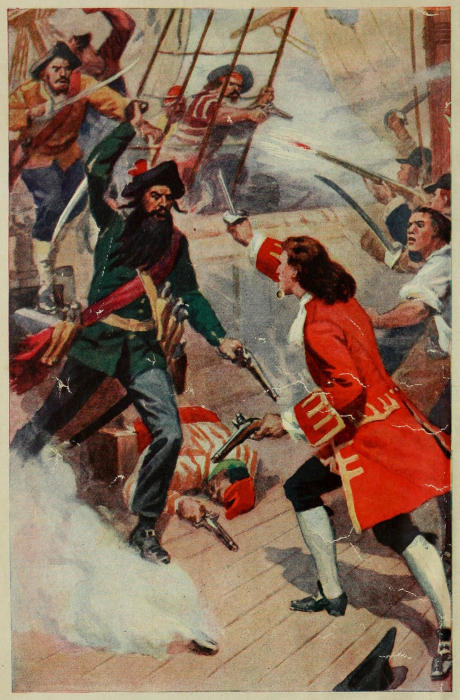

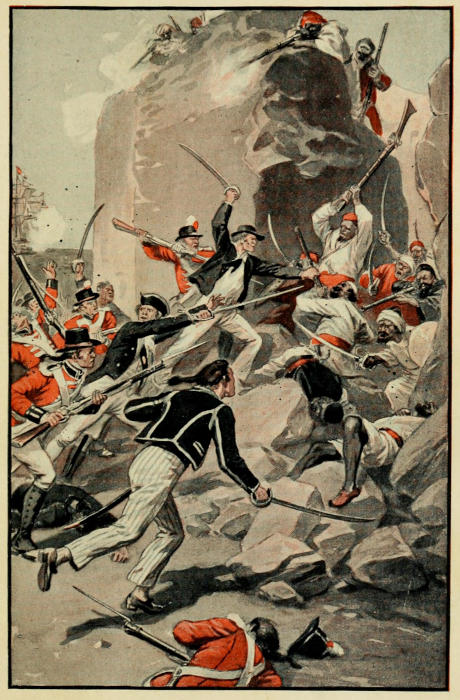

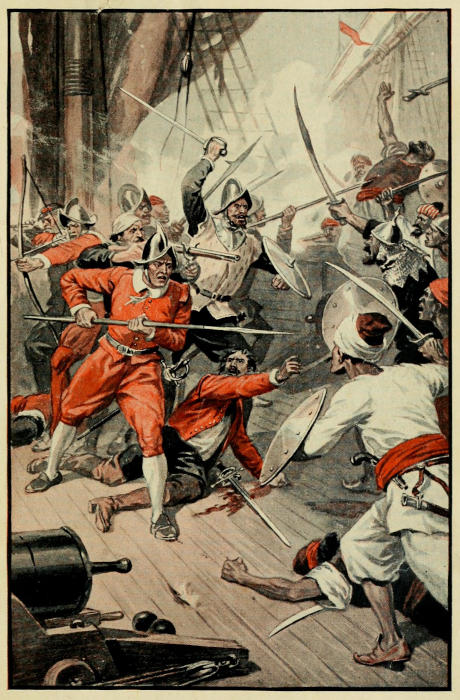

A Fierce Duel

After exchanging shots, when Teach (Blackbeard) was wounded they

drew their swords and fiercely attacked each other. Maynard’s sword

broke in his hand and had it not been for one of his own men, who

wounded Blackbeard in the throat, the duel would have ended then.

[11]

DARING DEEDS

OF

FAMOUS PIRATES

TRUE STORIES OF THE STIRRING ADVENTURES,

BRAVERY AND RESOURCE OF PIRATES,

FILIBUSTERS & BUCCANEERS

BY

Lt.-Com. E. KEBLE CHATTERTON, R.N.V.R

B.A. (Oxon.),

AUTHOR OF “THE ROMANCE OF THE SHIP” “FORE AND AFT”

“SAILING SHIPS AND THEIR STORY”

&c. &c. &c.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOURS

LONDON

SEELEY, SERVICE & CO. LIMITED

196 Shaftesbury Avenue

MDCCCCXXIX

[12]

| CHAP. |

|

PAGE |

| I. |

The Earliest Pirates |

17 |

| II. |

The North Sea Pirates |

29 |

| III. |

Piracy in the Early Tudor Times |

37 |

| IV. |

The Corsairs of the South |

48 |

| V. |

The Wasps at Work |

60 |

| VI. |

Galleys and Gallantry |

70 |

| VII. |

Piracy in Elizabethan Times |

79 |

| VIII. |

Elizabethan Seamen and Turkish Pirates |

89 |

| IX. |

The Stuart Navy goes forth against the “Pyrats” |

101 |

| X. |

The Good Ship Exchange of Bristol |

114 |

| XI. |

A Wonderful Achievement |

126 |

| XII. |

The Great Sir Henry Morgan |

136 |

| XIII. |

“Black Beard” Teach |

151 |

| XIV. |

The Story of Captain Kidd |

162 |

| XV. |

The Exploits of Captain Avery |

172 |

| XVI. |

A “Gentleman” of Fortune |

183 |

| XVII. |

Paul Jones, Pirate and Privateer |

196[14] |

| XVIII. |

A Notorious American Pirate |

210 |

| XIX. |

The Last of the Algerine Corsairs |

217 |

| XX. |

Pirates of the Persian Gulf |

224 |

| XXI. |

The Story of Aaron Smith |

235 |

[15]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| A Fierce Duel |

Frontispiece |

|

FACING PAGE |

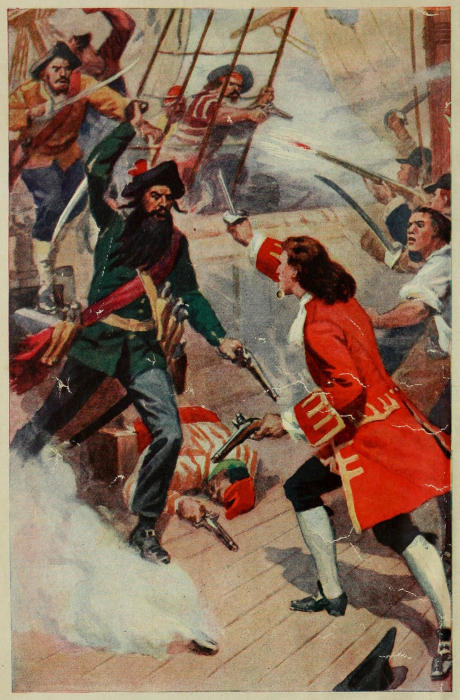

| A Daring Attack |

54 |

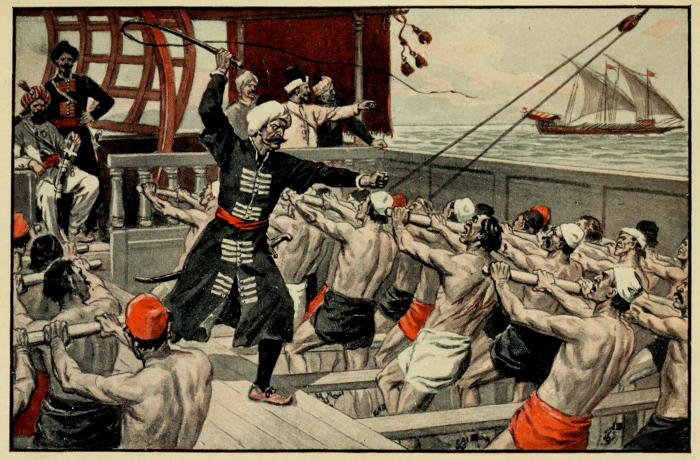

| Galley Slaves |

76 |

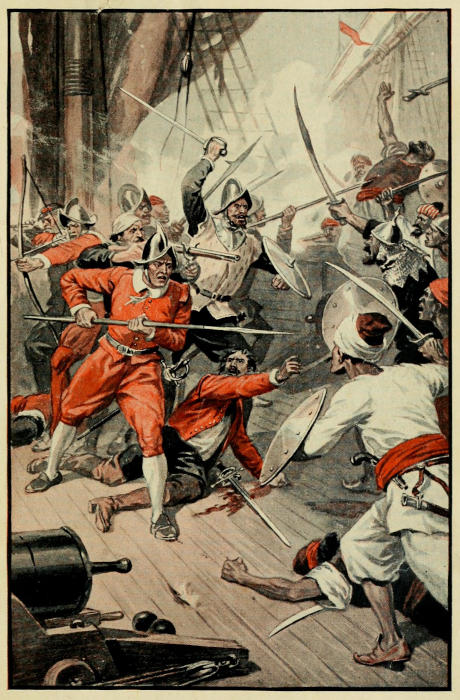

| Gallantry against Odds |

90 |

| Blighted Hopes |

104 |

| Bombardment of Algiers |

220 |

| Attacking a Pirate Stronghold |

232 |

[16]

NOTE

The contents of this book have been taken from Lieutenant

Keble Chatterton’s larger and more expensive volume entitled

The Romance of Piracy.

[17]

THE ROMANCE OF PIRACY

CHAPTER I

THE EARLIEST PIRATES

I suppose there are few words in use which at once

suggest so much romantic adventure as the words

pirate and piracy. You instantly conjure up in your

mind a wealth of excitement, a clashing of lawless wills,

and there pass before your eyes a number of desperate dare-devils

whose life and occupation are inseparably connected

with the sea.

The very meaning of the word, as you will find on

referring to a Greek dictionary, indicates one who attempts

to rob. In classical times there was a species of

Mediterranean craft which was a light, swift vessel called

a myoparo because it was chiefly used by pirates. Since the

Greek verb peirao means literally “to attempt,” so it had

the secondary meaning of “to try one’s fortune in thieving

on sea.” Hence a peirates (in Greek) and pirata (in Latin)

signified afloat the counterpart of a brigand or highwayman

on land. To many minds piracy conjures up visions that

go back no further than the seventeenth century: but

though it is true that during that period piracy attained

unheard-of heights in certain seas, yet the avocation of sea-robbery

dates back very much further.

[18]

Robbery by sea is certainly one of the oldest professions

in the world. I use the word profession advisedly, for the

reason that in the earliest days to be a pirate was not the

equivalent of being a pariah and an outcast. It was

deemed just as honourable then to belong to a company

of pirates as it is to-day to belong to the navy of any

recognised power. It is an amusing fact that if in those

days two strange ships met on the high seas, and one of

them, hailing the other, inquired if she were a pirate or a

trader, the inquiry was neither intended nor accepted as

an insult, but a correct answer would follow. It is a little

difficult in these modern days of regular steamship routes

and powerful liners which have little to fear beyond fog

and exceptionally heavy weather, to realise that every

merchant ship sailed the seas with fear and trepidation.

When she set forth from her port of lading there was

little certainty that even if the ship herself reached the

port of destination, her cargo would ever be delivered to

the rightful receivers. The ship might be jogging along

comfortably, heading well up towards her destined port,

when out from the distance came a much faster and lighter

vessel of smaller displacement and finer lines. In a few

hours the latter would have overhauled the former, the

scanty crew of the merchantman would have been thrown

into the sea or pressed into the pirate’s service, or else

taken ashore to the pirate’s haunt and sold as slaves. The

rich cargo of merchandise could be sold or bartered when

the land was reached, and the merchant ship sunk or left to

wallow in the Mediterranean swell.

It is obvious that because the freight ship had to be

big-bellied to carry the maximum cargo she was in most

instances unable to run away from the swift-moving pirate

except in heavy weather. But in order to possess some[19]

means of defence it was not unusual for these peaceful craft

to be provided with turrets of great height, from which

heavy missiles could be dropped on to the attacking pirate.

In the bows, in the stern and amidships these erections

could easily be placed and as quickly removed. And as

a further aid oars would be got out in an endeavour to

accelerate the ship’s speed. For whilst the pirate relied

primarily on oars, the trader relied principally on sail

power. Therefore in fine settled weather, with a smooth

sea, the low-lying piratical craft was at its best. It could

be manœuvred quickly, it could dart in and out of little

bays, it could shelter close in to the shore under the lee of

a friendly reef, and it was, because of its low freeboard, not

easy to discern at any great distance, unless the sea was

literally smooth. But all through history this type of

vessel has been shown to be at a disadvantage as soon as

it comes on to blow and the unruffled surface gives way to

high crest and deep furrows.

It is as impossible to explain the growth of piracy as it is

to define precisely the call of the sea. A man is born with

a bias in favour of the sea or he is not: there is no possibility

of putting that instinct into him if already he has not

been endowed with that attitude. So also we know from

our own personal experience, every one of us, that whilst

some of our own friends fret and waste in sedentary pursuits,

yet from the time they take to the sea or become explorers

or colonisers they find their true métier. The call of the

sea is the call of adventure in a specialised form. It has

been said, with no little truth, that many of the yachtsmen

of to-day, if they had been living in other ages, would have

gone afloat as pirates or privateers. And so, if we want to

find an explanation for the amazing historical fact that for

century after century, in spite of all the efforts which many[20]

a nation made to suppress piracy, it revived and prospered,

we can only answer that, quite apart from the lust of wealth,

there was at the back of it all that love of adventure, that

desire for exciting incident, that hatred of monotonous

security which one finds in so many natures. A distinguished

British admiral remarked the other day that it was his

experience that the best naval officers were usually those

who as boys were most frequently getting into disfavour

for their adventurous escapades. It is, at any rate, still true

that unless the man or boy has in him the real spirit

of adventure, the sea, whether as a sport or profession, can

have but little fascination for him.

International law and the growth of navies have practically

put an end to the profession of piracy, though privateering

would doubtless reassert itself in the next great

naval war. But if you look through history you will find

that, certainly up to the nineteenth century, wherever there

was a seafaring nation there too had flourished a band of

pirates. Piracy went on for decade after decade in the

Mediterranean till at length it became unbearable, and Rome

had to take the most serious steps and use the most drastic

measures to stamp out the nests of hornets. A little later

you find another generation of sea-robbers growing up and

acting precisely as their forefathers. Still further on in

history you find the Barbarian corsairs and their descendants

being an irrepressible menace to Mediterranean shipping.

For four or five hundred years galleys waylaid ships of the

great European nations, attacked them, murdered their crews

and plundered the Levantine cargoes. Time after time were

these corsairs punished: time after time they rose again.

In vain did the fleets of southern Christian Europe or the

ships of Elizabeth or the Jacobean navy go forth to quell

them. Algiers and Tunis were veritable plague-spots in[21]

regard to piracy. Right on through time the northern coast

of Africa was the hotbed of pirates. Not till Admiral Lord

Exmouth, in the year 1816, was sent to quell Algiers did

Mediterranean piracy receive its death-blow, though it

lingered on for some little time later.

But piracy is not confined to any particular nation nor

to any particular sea, any more than the spirit of adventure

is the exclusive endowment of any particular race. There

have been notorious pirates in the North Sea as in the

Mediterranean, there have been European pirates in the

Orient just as there have been Moorish pirates in the English

Channel. There have been British pirates on the waters of

the West Indies as there have been of Madagascar. There

have flourished pirates in the North, in the South, in the

East and the West—in China, Japan, off the coast of

Malabar, Borneo, America and so on. The species of ships

are often different, the racial characteristics of the sea-rovers

are equally distinct, yet there is still the same

determined clashing of wills, the same desperate nature of

the contests, the same exciting adventure; and in the

following pages it will be manifest that in spite of differences

of time and place the romance of piratical incident lives on

for the reason that human nature, at its basis, is very much

alike the whole world over.

But we must make a distinction between isolated and

collected pirates. There is a great dissimilarity, for

instance, between a pickpocket and a band of brigands.

The latter work on a grander, bolder system. So it has

always been with the robbers of the sea. Some have been

brigands, some have been mere pickpockets. The “grand”

pirates set to work on a big scale. It was not enough to

lie in wait for single merchant ships: they swooped down

on to seaside towns and villages, carried off by sheer force[22]

the inhabitants and sold them into slavery. Whatever else

of value might attract their fancy they also took away. If

any important force were sent against them, the contest

resolved itself not so much into a punitive expedition as a

piratical war. There was nothing petty in piracy on these

lines. It had its proper rules, its own grades of officers and

drill. Lestarches was the Greek name for the captain of a

band of pirates, and it was their splendid organisation,

their consummate skill as fighters, that made them so

difficult to quell.

I have said that piracy was regarded as an honourable

profession. In the earliest times this is true. The occupation

of a pirate was deemed no less worthy than a man

who gained his living by fishing on the sea or hunting on

land. Just as in the Elizabethan age we find the sons of some

of the best English families going to sea on a roving expedition

to capture Spanish treasure ships, so in classical times

the Mediterranean pirates attracted to their ships adventurous

spirits from all classes of society, from the most patrician

to the most plebeian: the summons of the sea was as

irresistible then as later on. But there were definite arrangements

made for the purpose of sharing in any piratical

success, so there was an incentive other than that of mere

adventure which prompted men to become pirates.

To-day, if the navies of the great nations were to be

withdrawn, and the policing of the seas to cease, it is

pretty certain that those so disposed would presently

revive piracy. Nothing is so inimical to piracy as settled

peace and good government. But nothing is so encouraging

to piracy as prolonged unsettlement in international

affairs and weak administration. So it was that

the incessant Mediterranean wars acted as a keen incentive

to piracy. War breeds war, and the spirit of unrest on[23]

sea affected the pirate no less than the regular fighting

man. Sea-brigandage was rampant. These daring robbers

went roving over the sea wherever they wished, they waxed

strong, they defied opposition.

And there were special territories which these pirates

preferred to others. The Liparian Isles—from about 580

B.C. to the time of the Roman Conquest—were practically a

republic of Greek corsairs. Similarly the Ionians and the

Lycians were notorious for piratical activities. After the

period of Thucydides, Corinth endeavoured to put down

piracy, but in vain. The irregularity went on until the

conquest of Asia by the Romans, in spite of all the precautions

that were taken. The Ægean Sea, the Pontus,

the Adriatic were the happy cruising-grounds for the

corsairs. The pirate-admiral or, as he was designated,

archipeirates, with his organised fleet of assorted craft, was

a deadly foe to encounter. Under his command were the

myoparones, already mentioned—light and swift they

darted across the sea; then there were, too, the hemiolia,

which were so called because they were rowed with one

and a half banks of oars; next came the two-banked

biremes and the three-banked triremes, and with these four

classes of ships the admiral was ready for any craft that

might cross his wake. Merchantmen fled before him,

warships by him were sent to the bottom: wherever he

coasted there spread panic through the sea-girt towns.

Even Athens itself felt the thrill of fear.

Notorious, too, were the Cretan pirates, and for a long

time the Etruscan corsairs were a great worry to the

Greeks of Sicily. The inhabitants of the Balearic Islands

were especially famous for their piratical depredations and

for their skilful methods of fighting. Wherever a fleet

was sent to attack them they were able to inflict great[24]

slaughter by hurling vast quantities of stones with their

slings. It was only when they came to close quarters with

their aggressors the Romans, and the latter’s sharp javelins

began to take effect, that these islanders met their match

and were compelled to flee in haste to the shelter of their

coves. At the period which preceded the subversion of

the Roman commonwealth by Julius Cæsar, there was an

exceedingly strong community of pirates at the extreme

eastern end of the Mediterranean. They hailed from that

territory which is just in the bend of Asia Minor and

designated Cilicia. Here lived—when ashore—one of the

most dangerous body of sea-rovers recorded in the pages of

history. It is amazing to find how powerful these Cilicians

became, and as they prospered in piracy so their numbers

were increased by fellow-corsairs from their neighbours the

Syrians and Pamphylians, as well as by many who came

down from the shores of the Black Sea and from Cyprus.

So powerful indeed became these rovers that they controlled

practically the whole of the Mediterranean from east to

west. They made it impossible for peaceful trading craft

to venture forth, and they even defeated several Roman

officers who had been sent with ships against them.

And so it went on until Rome realised that piracy had

long since ceased to be anything else but a most serious

evil that needed firm and instant suppression. It was the

ruin of overseas trade and a terrible menace to her own

territory. But the matter was at last taken in hand.

M. Antonius, proprætor, was sent with a powerful fleet

against these Cilician pirates; they were crushed thoroughly,

and the importance of this may be gathered from the fact

that on his return to Rome the conqueror was given an

ovation.

In the wars between Rome and Mithradates the[25]

Cilician pirates rendered the latter excellent service. The

long continuance of these wars and the civil war between

Marius and Sylla afforded the Cilicians a fine opportunity to

increase both in numbers and strength. To give some idea

of their power it is only necessary to state that not only

did they take and rob all the Roman ships which they

encountered, but they also voyaged among the islands

and maritime provinces and plundered no fewer than 400

cities. They carried their depredations even to the

mouth of the Tiber and actually took away from thence

several vessels laden with corn. Bear in mind, too, that

the Cilician piratical fleet was no scratch squadron of a few

antique ships. It consisted of a thousand vessels, which

were of great speed and very light. They were well

manned by most able seamen, and fought by trained soldiers,

and commanded by expert officers. They carried an

abundance of arms, and neither men nor officers were lacking

in daring and prowess. When again it became expedient

that these Cilicians should be dealt with, it took no less a

person than Pompey, assisted by fifteen admirals, to tackle

them; but finally, after a few months, he was able to have

the sea once more cleared of these rovers.

We can well sympathise with the merchant seamen of

those days. The perils of wind and wave were as nothing

compared with the fear of falling into the hands of powerful

desperadoes, who not merely were all-powerful afloat but

in their strong fortresses on shore were most difficult to

deal with. With the Balearic Islanders in the west, the

Cilicians in the east, the Carthaginians in the south, the

Illyrians along the Adriatic in their low, handy liburnian

galleys, there were pirates ready to encircle the whole of the

Mediterranean Sea. It is worth noting—for he who reads

naval history must often be struck with the fact that an[26]

existing navy prevents war, but the absence of a navy brings

war about—that as long as Rome maintained a strong navy

piracy died down: but so soon as she neglected her sea-service

piracy grew up again, commerce was interrupted

both east and west, numerous illustrious Romans were

captured and either ransomed or put to death, though

some others were pressed into the service of the pirates

themselves. By means of prisoners to work at the oars, by

the addition of piratical neighbours and by mercenaries as

well, a huge piratical community with a strong military and

political organisation continued to prevent the development

of overseas trade. This piracy was only thwarted by

keeping permanent Roman squadrons always ready.

Of course there were pirates in these early times in

waters other than the Mediterranean. On the west coast

of Gaul the Veneti had become very powerful pirates, and

you will recollect how severely they tried Cæsar, giving him

more trouble than all the rest of Gaul put together. They

owned such stalwart ships and were such able seamen that

they proved most able enemies. During the time of the

Roman Empire piracy continued also on the Black Sea

and North Sea, though the Mediterranean was now for

the most part safe for merchant ships. But when the

power of Rome declined, so proportionately did the pirates

reappear in their new strength. There was no fearful navy

to oppose them, and so once more they were able to do

pretty much as they liked. But we must not forget that

long before this they had ceased to be regarded as the

equivalent of hunters and fishermen. They were, by

common agreement, what Cicero had designated “enemies of

the human race”: and so they continued till the nineteenth

century, with only temporary intervals of inactivity.

The thousand ships which the Cilician pirates employed[27]

were disposed in separate squadrons. In different places

they had their own naval magazines located, and during

that period already mentioned, when they were driven off

the sea, they resisted capture by retreating ashore to their

mountain fastnesses until such time as it was safe for them

to renew their ventures afloat. When Pompey defeated

them he had under him a fleet of 270 ships. As the inscription,

carried in the celebration of his triumph on his return

to Rome, narrated, he cleared the maritime coasts of pirates

and restored the dominion of the sea to the Roman people.

But the pirates could always boast of having captured two

Roman prætors, and Julius Cæsar, when a youth on his way

to Rhodes to pursue his studies, also fell into their hands.

However, he was more lucky than many another Roman

who, when captured, was hung up to the yard-arm, and the

pirate ship went proudly on her way.

In the declining years of the Roman Empire the Goths

came down from the north to the Mediterranean, where

they got together fleets, became very powerful and crossed

to Africa, made piratical raids on the coast and carried on

long wars with the Romans. Presently the Saxons in the

northern waters of Europe made piratical descents on to the

coasts of France, Flanders and Britain. Meanwhile, in the

south, the Saracens descended upon Cyprus and Rhodes,

which they took, seized many islands in the Archipelago,

and thence proceeded to Sicily to capture Syracuse, and

finally overran the whole of Barbary from Egypt in the

east to the Straits of Gibraltar in the west. From there

they crossed to Spain and reduced the greater part thereof,

until under Ferdinand and Isabella these Moors were driven

out of Spain and compelled to settle once more on the north

coast of Africa. They established themselves notably at

Algiers, took to the sea, built themselves galleys and, after[28]

living a civilised life in Spain for seven hundred years, became

for the next three centuries a scourge of the Mediterranean,

a terror to ships and men, inflicted all the cruelties which

the fanaticism of the Moslem race is capable of, and cast

thousands of Christians into the bonds of slavery. In many

ways these terrifying Moorish pirates—of which to this day

some still go afloat in their craft off the north coast of

Africa—became the successors of those Cilician and other

corsairs of the classical age. In due course we shall return

to note the kind of piratical warfare which these expatriated

Moors waged for most of three hundred years. But before

we come to that period let us examine into an epoch that

preceded this.

[29]

CHAPTER II

THE NORTH SEA PIRATES

I am anxious to emphasise the fact that piracy is nearly

as old as the ship herself. It is extremely improbable

that the Egyptians were ever pirates, for the reason

that, excepting the expedition to Punt, they confined their

navigation practically to the Nile only. But as soon as men

built sea-going vessels, then the instinct to rob and pillage

on sea became as irresistible as on land. Might was right,

and the weakest went to the bottom.

Bearing this in mind, and remembering that there was

always a good deal of trade from the Continent up the

Thames to London, especially in corn, and that there was

considerable traffic between Gaul and Britain across the

English Channel, it was but natural that the sea-rovers of

the north should exist no less than in the south. After

Rome had occupied Britain she established a navy which

she called the “Classis Britannica,” and it cannot have failed

to be effective in policing the narrow seas and protecting

commerce from wandering corsairs. We know very well

that after Rome had evacuated Britain, and there was no

navy to protect our shores, came the Angles and Saxons and

Jutes. We may permissibly regard these Northmen, who

pillaged and plundered till the time of William the

Conqueror and after, as pirates. In the sense that a pirate[30]

is one who not merely commits robbery on the high seas

but also makes descents on the coast for the purpose of

pillage, we may call the Viking seamen pirates. But, strictly

speaking, they were a great deal more than this, and the

object of this book is concerned rather with the incidents of

the sea than the incursions into the land. Although the

Vikings did certainly commit piracy both in their own

waters and off the coasts of Britain, yet their depredations

in this respect, even if we could obtain adequate information

thereof, would sink into insignificance before their greater

conquests. For a race of men who first swoop down on to

a strange coast, vanquish the inhabitants and then settle

down to live among them, are rather different from a body

of men who lie in wait to capture ships as they proceed on

their voyages.

The growth of piracy in English waters certainly owed

much to the Cinque Ports. In these havens dwelt a privileged

class of seamen, who certainly for centuries were a

very much favoured community. It was their privilege to

do that which in the Mediterranean Cicero had regarded

with so much disfavour. These men of the Cinque Ports,

according to Matthew of Paris, were commissioned to

plunder as they pleased all the merchant ships as they passed

up and down the English Channel. This was to be without

any regard to nationality, with the exception that English

ships were not to be molested. But French, Genoese,

Venetian, Spanish or any others could be attacked at the

will of the Cinque Port seamen. Some persons might call

this sort of thing by the title of privateering, yet it was

really piracy and nothing else. You can readily imagine

that with this impetus thus given to a class of men who

were not particularly prone to lawfulness, the practice of

piracy on the waters that wash Great Britain grew at a[31]

great rate. Thus in the thirteenth century the French, the

Scotch, Irish and Welsh fitted out ships, hung about the

narrow seas till they were able to capture a well-laden

merchantman as their fat reward. So, before long, the

English Channel was swarming with pirates, and during the

reign of Henry III. their numbers grew to an alarming

extent. The net result was that it was a grave risk for

commodities to be brought across the Channel, and so,

therefore, the price of these goods rose. The only means of

remedy was to increase the English fleet, and this at length

was done in order to cope with the evil.

But matters were scarcely better in the North Sea, and

English merchant ships sailed in perpetual fear of capture.

During the Middle Ages pirates were always hovering about

for any likely ship, and the wool trade especially was interfered

with. Matters became somewhat complicated when,

as happened in the reign of Edward II., peaceable English

ships were arrested by Norway for having been suspected—erroneously—of

slaughtering a Norwegian knight, whereas

the latter had been actually put to death by pirates. “We

marvell not a little,” wrote Edward II. in complaint to

Haquinus, King of Norway, “and are much disquieted in

our cogitations, considering the greevances and oppressions,

which (as wee have beene informed by pitifull complaints)

are at this present, more than in times past, without any

reasonable cause inflicted upon our subjects, which doe

usually resort unto your kingdome for traffiques sake.”

For the fact was that one nation was as bad as the other,

but that whenever the one had suffered then the other

would lay violent hands on a ship that was merely suspected

of having acted piratically. Angered at the loss

to their own countrymen they were prompted by revenge

on alien seamen found in their own waters and even[32]

lying quietly in their own havens with their cargoes of

herrings.

As an attempt to make the North Sea more possible for

the innocent trading ships, the kings of England at different

dates came to treaties with those in authority on the other

side. Richard II., for example, made an agreement with the

King of Prussia. In 1403 “full restitution and recompense”

were demanded by the Chancellor of England from the

Master-General of Prussia for the “sundry piracies and

molestations offered of late upon the sea.” Henry IV.,

writing to the Prussian Master-General, admitted that

“as well our as your marchants ... have, by occasion of

pirates, roving up and downe the sea” sustained grievous

loss. Finally it was agreed that all English merchant ships

should be allowed liberty to enter Prussian ports without

molestation. But it was further decided that if in the

future any Prussian cargoes should be captured on the

North Sea by English pirates, and this merchandise taken

into an English port, then the harbour-master or “governour”

was, if he suspected piracy, to have these goods promptly

taken out of the English ship and placed in safe keeping.

Between Henry IV. and the Hanseatic towns a similar agreement

was also made which bound the cities of Lubec,

Bremen, Hamburg, Sund and Gripeswold “that convenient,

just and reasonable satisfaction and recompense” might be

made “unto the injured and endamaged parties” “for all

injuries, damages, grievances, and drownings or manslaughters

done and committed” by the pirates in the

narrow seas.

It would be futile to weary the reader with a complete

list of all these piratical attacks, but a few of them may

here be instanced. About Easter-time in the year 1394 a

Hanseatic ship was hovering about the North Sea when she[33]

fell in with an English merchantman from Newcastle-on-Tyne.

The latter’s name was the Godezere and belonged

to a quartette of owners. She was, for those days, quite a

big craft, having a burden of 200 tons. Her value, together

with that of her sails and tackle, amounted to the sum of

£400. She was loaded with a cargo of woollen cloth and

red wine, being bound for Prussia. The value of this cargo,

plus some gold and certain sums of money found aboard,

aggregated 200 marks. The Hanseatic ship was able to

overpower the Godezere, slew two of her crew, captured

ship and contents and imprisoned the rest of the crew for

the space of three whole years.

A Hull craft belonging to one Richard Horuse, and

named the Shipper Berline of Prussia, was in the same year

also attacked and robbed by Hanseatic pirates, goods to the

value of 160 nobles being taken away. The following year

a ship named the John Tutteburie was attacked by Hanseatics

when off the coast of Norway, and goods consisting

of wax and other commodities to the value of 476 nobles

were captured. A year later and pirates of the same

federation captured a ship belonging to William Terry of

Hull called the Cogge, with thirty woollen broad cloths and

a thousand narrow cloths, to the value of £200. In 1398

the Trinity of Hull, laden with wax, oil and other goods,

was captured by the same class of men off Norway. Dutch

ships, merchant craft from the port of London, fishing

vessels, Prussian traders, Zealand, Yarmouth and other

ships were constantly being attacked, pillaged and captured.

In the month of September, of the year 1398, a number

of Hanseatic pirates waylaid a Prussian ship whose skipper

was named Rorebek. She carried a valuable cargo of

woollen cloth which was the property of various merchants

in Colchester. This the pirates took away with them,[34]

together with five Englishmen, whom they found on board.

The latter they thrust into prison as soon as they got them

ashore, and of these two were ransomed subsequently for

the sum of 20 English nobles, while another became

blind owing to the rigours of his imprisonment. In 1394

another Prussian ship, containing a number of merchants

from Yarmouth and Norwich, was also captured off the

Norwegian coast with a cargo of woollen goods and taken

off by the Hanseatic pirates. The merchants were cast

into prison and not allowed their liberty until the sum

of 100 marks had been paid for their ransom. Another

vessel, laden with the hides of oxen and sheep, with butter,

masts and spars and other commodities to the value of

100 marks, was taken in Longsound, Norway.

In June 1395 another English ship, laden with salt fish,

was taken off the coast of Denmark, the value of her hull,

inventory and cargo amounting to £170. The crew consisted

of a master and twenty-five mariners, whom the

pirates slew. There was also a lad found on board, and

him they carried into Wismar with them. The most

notorious of these Hanseatic pirates were two men, named

respectively Godekins and Stertebeker, whose efforts were

as untiring as they were successful. There is scarcely an

instance of North Sea piracy at this time in which these

two men or their accomplices do not figure. And it was

these same men who attacked a ship named the Dogger.

The latter was skippered by a man named Gervase Cat, and

she was lying at anchor while her crew were engaged fishing.

The Hanseatic pirates, however, swept down on them, took

away with them a valuable cargo of fish, beat and wounded

the master and crew of the Dogger and caused the latter

to lose their fishing for that year, “being endamaged thereby

to the summe of 200 nobles.”

[35]

In the year 1402 other Hanseatic corsairs, while cruising

about near Plymouth, captured a Yarmouth barge named

the Michael, the master of which was one Robert Rigweys.

She had a cargo of salt and a thousand canvas cloths.

The ship and goods being captured, the owner, a man

named Hugh ap Fen, complained that he was the loser to

the extent of 800 nobles: and the master and mariners

assessed the loss of wages, canvas and “armour” at 200

nobles. But there was no end to the daring of these

corsairs of the North. In the spring of 1394 they proceeded

with a large fleet of ships to the town of Norbern

in Norway, and having taken the place by assault, they

captured all the merchants therein, together with their

“goods and cattels,” burnt their houses and put their

persons up to ransom. Twenty-one houses, to the value of

440 nobles, were destroyed, and goods to the value of

£1815 were taken from the merchants. With all this

lawlessness on the sea and the consequent injury to overseas

commerce, it was none too soon that Henry IV. took

steps to put down a most serious evil.

We cannot but feel sorry for the long-suffering North

Sea fishermen, who, in addition to having to ride out bad

weather in clumsy leaky craft, and having to work very

hard for their living, were liable at any time to see a pirate

ship approaching them over the top of the waves. You

remember the famous Dogger Bank incident a few years

ago when one night the North Sea trawlers found themselves

being shelled by the Russian Baltic fleet. Well, in

much the same way were the mediæval ancestors of these

hardy fishermen surprised by pirates when least expecting

them and when most busily occupied in pursuing their

legitimate calling. The fisherman was like a magnet to

the pirates, because his catch of fish had only to be taken[36]

to the nearest port and sold. That was the reason why,

in 1295, Edward had been induced to send three ships of

Yarmouth across the North Sea to protect the herring-ships

of Holland and Zealand.

The following incident well illustrates the statement

that, in spite of all the efforts which were made to repress

piracy, yet it was almost impossible to attain such an

object. The month is July, and the year 1327, the scene

being the English Channel. Picture to your mind a

beamy, big-bellied, clumsy ship with one mast and one

great square sail. She has come from Waterford in

Ireland, where she has taken on board a rich cargo,

consisting of wool, hides and general merchandise. She

has safely crossed the turbulent Irish Sea, she has wallowed

her way through the Atlantic swell round Land’s End and

found herself making good headway up the English Channel

in the summer breeze. Her port of destination is Bruges,

but she will never get there. For from the eastward have

come the famous pirates of the Cinque Ports, and off the

Isle of Wight they fall in with the merchant ship. The

rovers soon sight her, come up alongside, board her and

relieve her of forty-two sacks of wool, twelve dickers of

hides, three pipes of salmon, two pipes of cheese, one bale

of cloth, to say nothing of such valuable articles as silver

plate, mazer cups, jewels, sparrow-hawks and other goods

of the total value of £600. Presently the pirates bring

their spoil into the Downs below Sandwich and dispose of

it as they prefer.

[37]

CHAPTER III

PIRACY IN THE EARLY TUDOR TIMES

The kind of man who devotes his life to robbery at sea

is not the species of humanity who readily subjects

himself to laws and ordinances. You may threaten

him with terrible punishments, but it is not by these means

that you will break his spirit. He is like the gipsy or the

vagrant: he has in him an overwhelming longing for

wandering and adventure. It is not so much the greed

for gain which prompts the pirate, any more than the land

tramp finds his long marches inspired by wealth. But

some impelling blind force is at work within, and so not all

the treaties and agreements, not all the menaces of death

could avail to keep these men from pursuing the occupation

which their fathers and grandfathers had for many years

been employed in.

Therefore piracy was quite as bad in the sixteenth

century as it had been in the Middle Ages. The dwellers

on either side of the English Channel were ever ready to

pillage each other’s ships and property. About the first

and second decade of the sixteenth century the Scots rose

to some importance in the art of sea-robbery, and some

were promptly taken and executed. In vain did Henry VIII.

write to Francis I. saying that complaints had been made

by English merchants that their ships had been pirated by[38]

Frenchmen pretending to be Scots, for which redress could

not be obtained in France. In 1531 matters had become

so bad, and piracy was so prevalent, that commissioners were

appointed to make inquisitions concerning this illegal warfare

round our coasts. Viscount Lisle, Vice-Admiral of England,

and others were appointed to see to the problem. So

cunning had these rovers become that it was no easy affair

to capture them. But in this same year a notorious pirate

named Kellwanton was taken in the Isle of Man; while

another, De Melton by name, who was one of his accomplices,

fled with the rest of the crew in the ship to Grimsby.

Sometimes the very ships which had been sent by the

king against the pirates actually engaged in pillage themselves.

There was at least one instance about this time of

some royal ships being unable to resist the temptation to

plunder the richly laden Flemish ships. But after complaint

was made the royal reply came that the Flemings should be

compensated and the plunderers punished. It was all very

well to set a thief to catch a thief, but there were few

English seamen of any experience who had not done some

piracy at some time of their career, and when they at last

formed the crews of preventive ships and got wearied of

waiting for pirate craft to come along, it was too much to

expect them to remain idle on the seas when a rich merchantman

went sailing past.

Sometimes the pirates would waylay a whole merchant

fleet, and if the latter were sailing light, would relieve the

fleet of their victuals, their clothes, their anchors and

cables and sails. But it was not merely to the North Sea

nor to the English Channel that the English pirates confined

themselves. In October 1533 they captured a Biscayan

ship off the coast of Ireland. And during the reign of

Henry VIII. there was an interesting incident connected with[39]

a ship named the Santa Maria Desaie. This craft belonged

to one Peter Alves, a Portingale, who hired a mariner,

William Phelipp, to pilot his ship from Tenby to Bastabill

Haven. But whilst off the Welsh coast a piratical bark

named the Furtuskewys, containing thirty-five desperate

corsairs, attacked the Santa Maria and completely overpowered

her. Alves they promptly got rid of by putting him

ashore somewhere on the Welsh coast, and they then proceeded

to sail the ship to Cork, where they sold her to the mayor

and others, the value of the captured craft and goods

being 1524 crowns. Alves did not take this assault with

any resignation, but naturally used his best endeavours to

have the matter set right. From the King’s Council he

obtained a command to the Mayor of Cork for restitution,

but such was the lawlessness of the time that this was of no

avail. The mayor, whose name was Richard Gowllys, protested

that the pirates told him they had captured the ship

from the Scots and not from the Portingale, and he added

that he would spend £100 rather than make restitution.

But stricter vigilance caused the arrest of some of these

pirates. Six of them were sentenced to death in the

Admiralty Court at Boulogne, eleven others were condemned

to death in the Guildhall, London: and in 1537 a ship was lying

at Winchelsea “in gage to Bell the mayor” for £35 for the

piracies committed in her, for she had been captured after

having robbed a Gascon merchantman of a cargo of wines.

The finest of the French sailors for many a century until

even the present day have ever been the Bretons. And

just as in the eighteenth century the most expert sailormen

on our coasts were the greatest smugglers, so in Tudor

times the pick of all seamen were sea-rovers. About the

time of Lent, 1537, a couple of Breton pirate ships caused a

great deal of anxiety to our west-country men. One of the[40]

two had robbed an English ship off the Cornish coast and

pillaged his cargo of wine. From Easter-time till August

these rovers hung about the Welsh coast, sometimes coming

ashore for provisions and most probably also to sell their

ill-gotten cargoes, but for the most part remaining at sea.

It would seem from the historical records that originally

there had been only one Breton ship that had sailed from

St. Malo; but having the good fortune to capture a fishing

craft belonging to Milford Haven, the crew had been split

up into two. Presently the numbers of these French pirates

increased till there was quite a fleet of them cruising about

the Welsh coast. A merchant ship that had loaded a fine

cargo at Bristol, bound across the Bay of Biscay, had been

boarded before the voyage had been little more than begun.

For week after week these men robbed every ship that

came past them. But especially were they biding their

time waiting for the English, Irish and Welsh ships who

were wont about this period of the year to come to St.

James’s Fair at Bristol.

However, in the meanwhile, the men of the west were

becoming much more alert, and were ready for any chance

that might occur. And a Bristol man named Bowen, after

fourteen Breton pirates had come ashore near Tenby to

obtain victuals, acted with such smartness that he was able

to have the whole lot captured and put into prison. And

John Wynter, another Bristolian, knowing that the pirates

were hovering about for those ships bound for the fair,

promptly manned a ship, embarked fifty soldiers, as well as

the able seamen, and cruised about ready to swoop down on

the first pirate ship which showed up on the horizon. The

full details of these men and what they did would make

interesting reading if they were obtainable; but we know

that of the above-mentioned fourteen, one, John du[41]

Laerquerac, was captain of the Breton craft. On being

arrested he stoutly denied that he had ever “spoiled”

English ships. That was most certainly a bare-faced lie,

and presently Peter Dromyowe, one of his own mariners,

confessed that he himself had robbed one Englishman;

whereupon Laerquerac made a confession that, as a matter

of fact, he had taken ships’ ropes, sailors’ wearing apparel,

five pieces of wine, a quantity of fish, a gold crown in money

and eleven silver halfpence or pence, as well as four daggers

and a “couverture”!

It was because the English merchants complained that

they lost so much of their imports and exports by depredations

from the ships of war belonging to Biscay, Spain, the

Low Countries, Normandy, Brittany and elsewhere, that

Henry VIII. had been prevailed upon to send Sir John

Dudley, his Vice-Admiral, to sea with a small fleet of good

ships. Dudley’s orders were to cruise between the Downs

on the east and St. Michael’s Mount on the west—in other

words, the whole length of the English Channel—according

as the wind should serve. In addition, he was to stand off

and on between Ushant and Scilly and so guard the entrance

to the Channel. Furthermore, he was to look in at the Isle

of Lundy in the Bristol Channel—for both Lundy and the

Scillies were famous pirate haunts—and after having so done

he was to return and keep the narrow seas. Dudley was

especially admonished to be on the look out to succour any

English merchant ships, and should he meet with any foreign

merchant craft which, under the pretence of trading, were

actually robbing the King’s subjects, he was to have

these foreigners treated as absolute pirates and punished

accordingly.

For the state of piracy had become so bad that the King

“can no longer suffer it.” So also Sir Thomas Dudley, as[42]

well as Sir John, was busily employed in the same preventive

work. On the 10th of August of that same year, 1537, he

wrote to Cromwell that he had at Harwich arrested a couple

of Frenchmen who two years previously had robbed a poor

English skipper’s craft off the coast of Normandy, and this

Englishman had in vain sued in France for a remedy, since

the pirates could never be captured. But there were so

many of these corsairs being now taken that it was a grave

problem as to how they should be dealt with. “If they

were all committed to ward,” wrote Sir Thomas, “as your

letters direct, they would fill the gaol.” Then he adds:

“They would fain go and leave the ship behind them, which

only contains ordnance, and no goods or victuals to find

themselves with. If they go to gaol, they are like to perish

of hunger, for Englishmen will do no charity to them.

They are as proud naves as I have talked with.”

Eleven days later came the report from Sir John Dudley

of his experiences in the Channel. He stated that while on

his way home he encountered a couple of Breton ships in

the vicinity of St. Helen’s, Isle of Wight, where he believed

they were lying in wait for two Cornish ships “that were

within Porchemouthe haven, laden with tin to the value of

£3000.” Portsmouth is, of course, just opposite St. Helen’s,

and on more than one occasion in naval history was the

latter found a convenient anchorage by hostile ships waiting

for English craft to issue forth from the mainland. But

when these Breton pirates espied Dudley’s ships coming

along under sail, they “made in with Porchemouthe,” where

Dudley’s men promptly boarded them and placed them

under arrest, with the intention of bringing them presently

to the Thames. Dudley had no doubt whatever that these

were pirates, but at a later date the French ambassador

endeavoured to show that there was no foundation for such[43]

a suspicion. These two French crafts, he sought to persuade,

were genuine merchantmen who had discharged their cargo

at “St. Wallerie’s” (that is to say, St. Valery-sur-Somme),

but had been driven to the Isle of Wight by bad weather,

adding, doubtless as a subtle hint, that they had actually

rescued an Englishman chased by a Spaniard. It is possible

that the Frenchmen were telling the truth, though unless

the wind had come southerly and so made it impossible for

these bluff-bowed craft to beat into their port, it is difficult

to believe that they could not have run into one of their

own havens. At any rate, it was a yarn which Dudley’s

sailors found not easy to accept.

This was no isolated instance of the capture of Breton

craft. In the year 1532 a Breton ship named the Mychell,

whose owner was one Hayman Gillard, her master being

Nicholas Barbe of St. Malo, was encountered by a crew of

English seamen who entertained no doubts whatsoever as to

her being anything else than a pirate. Their suspicions were

made doubly sure when they found her company to consist

of nine Bretons and five Scots. They arrested her at sea,

and when examined she was found well laden with wool,

cloth and salt hides. Some French pirate ships even went

so far as to wear the English flag of St. George, with the

red cross on a white ground. This not unnaturally infuriated

English seamen, especially when it was discovered that the

Bretons had also carried Englishmen as their pilots and

chief mariners, and were training them to become experts

in piracy.

But there were times when English seamen and

merchants were able to “get their own back” with interest,

as the following incident will show. At the beginning of

June, in the year 1538, an English merchant, Henry Davy,

freighted a London ship named the Clement, which was[44]

owned by one Grenebury, who lived in Thames Street, and

dispatched her with orders to proceed to the “Bay in

Breteyne.” She set forth under the command of a man

named Lyllyk, the ship’s purser being William Scarlet, a

London clothworker. Seven men formed her crew, but

when off Margate they took on board nine more. They

then proceeded down Channel and took on board another

four from the shore, but espying a Flemish ship of war they

deemed it prudent to get hold of the coast of Normandy as

soon as possible. In the “mayne” sea—by which I understand

the English Channel near the mainland of the

Continent—they descried coming over the waves three ships,

and these were found to be Breton merchantmen.

This caused some discussion on board the Clement, and

Davy, the charterer, who had come with the ship, remarked

to the skipper Lyllyk that they had lost as much as £60 in

goods, which had been captured by Breton pirates at an

earlier date, and had never been able to obtain compensation

in France in spite of all their endeavours. Any one who has

any imagination and a knowledge of seafaring human nature,

can easily picture Lyllyk and his crew cordially agreeing

with Davy’s point of view, and showing more than a mere

passive sympathy. The upshot of the discussion was that

they resolved to take the law into their own hands and

capture one of these three ships.

The resolution was put into effect, so that before long

they had become possessed of the craft. The Breton crew

were rowed ashore in a boat and left there, and after

collecting the goods left behind, the Englishmen stowed

them in the hold of the Clement. A prize crew, consisting

of a man whose name was Comelys, and four seamen, were

placed in charge of the captured ship, which now got under

way. The Clement, too, resumed her voyage, and made for[45]

Peryn in Cornwall, where she was able to sell, at a good

price, the goods taken out of the Breton. The gross

amount obtained was divided up among the captors, and

though the figures may not seem very large, yet the sum

represented the equivalent of what would be to-day about

ten times that amount of money. Henry Davy, being the

charterer, received £17; the master, the mate, the quarter-master

and the purser received each thirty shillings, while

the mariners got twenty shillings apiece. Lyllyk and nine

of the crew then departed, while Davy, Scarlet, Leveret the

carpenter and two others got the ship under way, sailed up

Channel and brought the Clement back to the Thames,

where they delivered her to the wife of the owner.

But Englishmen were not always so fortunate, and the

North Sea pirates were still active, in spite of the efforts

which had been made by English kings in previous

centuries. In 1538 the cargo ship George Modye put to

sea with goods belonging to a company of English merchant

adventurers, consisting of Sir Ralph Waryn, “good Mr.

Lock and Rowland Hyll” and others. She never reached

her port of destination, however, for the Norwegian pirates

pillaged her and caused a loss to the adventurers of £10,000,

whereupon, after complaint had been made, Cromwell was

invoked to obtain letters from Henry VIII. to the kings of

Denmark, France and Scotland that search might be duly

made. There was, in fact, a good deal of luck, even yet, as

to whether a ship would ever get to the harbour whither

she was sent. In September 1538 we find Walter Herbart

complaining that twice since Candlemas he had been robbed

by Breton pirates. But, a week later, it is recorded that

some pirates, who had robbed peaceable ships bound from

Iceland, had been chased by John Chaderton and others of

Portsmouth and captured about this time.

[46]

And it was not always that Englishmen dealt with these

foreigners in any merciful manner, regardless of right or

wrong. I have already emphasised the fact that, as regards

the question of legality, there was little to choose between

the seamen of any maritime nation. Rather it was a

question of opportunity, and the very men who to-day

complained bitterly of the robbery of their ships and cargoes

might to-morrow be found performing piracy themselves.

A kind of sea-vendetta went on, and in the minds of the

mariners the only sin was that of being found out. So we

notice that, in the spring of 1539, an instance of a Breton

ship being captured by English corsairs who, according to

the recognised custom of the sea, forthwith threw overboard

the French sailors. These were all drowned except one who,

“as if by a miracle, swam six miles to shore.” So says the

ancient record, though it is difficult to believe that even a

strong swimmer could last out so long after being badly

knocked about. The Bretons had their revenge this time,

for complaint was made to the chief justices, who within

fifteen days had the culprits arrested and condemned, and

six of them were executed on the 19th of May. Before

the end of the month Francis I. wrote to thank the English

king for so promptly dealing with the culprits.

Bearing in mind the interest which Henry VIII. took in

nautical matters and in the welfare of his country generally;

recollecting, too, the determination with which he pursued

any project to the end when once his mind had been made

up, we need not be surprised to find that a few months

later in that year this resolute monarch again sent ships—this

time a couple of barks of 120 and 90 tons respectively—“well

manned and ordnanced” to scour the seas for these

pirate pests that inflicted so many serious losses on the

Tudor merchants.

[47]

A little earlier in that year Vaughan had written to

Cromwell that he had spoken with one who lately had

been a “common passenger” in hoys between London and

Antwerp and knew of certain pirates who intended to

capture the merchant ships plying between those two ports.

Valuable warning was given concerning one of these roving

craft. She belonged to Hans van Meghlyn, who had fitted

out a ship of the “portage” of 20 lasts and 45 tons

burthen. She was manned by a crew of thirty, her hull

was painted black with pitch, she had no “foresprit,” and

her foremast leaned forward like a “lodeman’s” boat.

(“Lodeman” was the olden word for pilot—the man who

hove the lead.) Cromwell was advised that this craft would

proceed first to Orfordness (the natural landfall for a vessel

to make when bound across the North Sea from the Schelde),

and thence she would proceed south and lie in wait for ships

at the mouth of the Thames. In order to be ready to

pillage either the inward or outward bound craft which

traded with London, this pirate would hover about off

White Staple (Whitstable). Vaughan’s informant thought

that sometimes, however, she would change her locality to

the Melton shore in order to avoid suspicion, and he advised

that it would be best to capture her by means of three or

four well-manned oyster boats. There was also another

“Easterling” (that is, one from the east of Germany or the

Baltic) pirate who had received his commission from the

Grave of Odenburg. This rover was named Francis Beme

and was now at Canfyre with his ship, waiting for the

Grave of Odenburg’s return from Brussels with money.

But the warning news came in time, and in order to prevent

the English merchant ships from falling into the sea-rovers’

hands, the former were ordered by proclamation to remain

in Antwerp from Ash Wednesday till Easter.

[48]

CHAPTER IV

THE CORSAIRS OF THE SOUTH

When, in the year 1516, Hadrian, Cardinal St. Chryogon,

wrote to Wolsey bitterly lamenting that

from Taracina right away to Pisa pirates, consisting

of Turks and African Moors, were swarming the sea, he

was scarcely guilty of any exaggeration. Multifarious and

murderous though the pirates of Northern Europe had long

since shown themselves, yet it is the Mediterranean which,

throughout history, and more especially during the sixteenth

century, has earned the distinction of being the favourite

and most eventful sphere of robbery by sea.

You may ask how this came about. It was no longer

the case of the old Cilicians or the Balearic Islanders coming

into activity once more. On the contrary, the last-mentioned

people, far from being pirates in the sixteenth century, were

actually pillaged than pillagers. A new element had now

been introduced, and we enter upon a totally different sphere

of the piratical history. Before we seek to inquire into the

origin and development of this new force which comes across

the pages of history, let us bear in mind the change which

had come over the Mediterranean. During the classical

times piracy was indeed bad enough, because, among other

things, it interfered so seriously with the corn ships which

carried the means of sustenance. But in those days the[49]

number of freight ships of any kind was infinitesimal compared

with the enormous number of fighting craft that were

built by the Mediterranean nations. And however much

Greece and Rome laboured to develop the warlike galley,

yet the evolution of the merchant ship was sadly neglected,

partly, no doubt, because of the risks which a merchant ship

ran and partly because the centuries of fighting evoked

little encouragement for a ship of commerce.

During the centuries which followed the downfall of the

Roman Empire it must not be supposed that the sea was

bereft of pirates. As we have already seen, the decay of

Rome was commensurate with the revival of piracy. But

with the gradual spread of southern civilisation the importance

of and the demand for commercial ships, as differentiated

from fighting craft, increased to an unheard-of

extent. No one requires to be reminded of the rise to great

power of Venice and Genoa and Spain. They became

great overseas traders within limits, and this postulated the

ships in which goods could be carried. So it came to this

that crossing and recrossing the Mediterranean there were

more big-bellied ships full of richer cargoes and traversing

the sea with greater regularity than ever had been in the

history of the world. And as there will always be robbers

when given the opportunity, either by sea or by land, irrespective

of race or time, so when this amount of wealth was

now afloat the sea-robber had every incentive to get rich

quickly by a means that appealed in the strongest terms to

an adventurous temperament.

In Italy the purely warlike ship had become so obsolete

that, in the opinion of some authorities, it was not till about

the middle of the ninth century that these began to be built,

at any rate as regards that great maritime power, Venice.

She had been too concerned with the production and[50]

exchange of wealth to centre her attention on any species

of ship other than those which would carry freights. But

so many defeats had she endured at the hands of the

Saracens and pirates that ships specially suitable for combat

had, from the year 841, to be built. The Saracens hailed

from Arabia, and it is notable that at that time the Arabian

sailors who used to sail across the Indian Ocean were far and

away the most scientific navigators in the whole world, many

of their Arabic terms still surviving in nautical terminology

to this day. Indeed, the modern mariner who relies so much

on nautical instruments scarcely realises how much he owes to

these early seamen. Just as the Cilicians and others had in

olden times harassed the shores of the Mediterranean, so now

the Saracens made frequent incursions into Sardinia, Corsica,

Sicily, as well as intercepting the ships of the Adriatic.

Let us remember that both in the north and south of

Europe the sailing seasons for century after century were

limited to that period which is roughly indicated between

the months of April and the end of September. Therefore

the pirate knew that if he confined his attentions to that

period and within certain sea-areas, he would be able to

encompass practically the whole of the world’s sea-borne

trade. These sailing periods were no arbitrary arrangement:

they were part of the maritime legislation, and only

the most daring and, at the same time, most lawless merchant

skippers ventured forth in the off-season.

Realising that the mariner had in any lengthy voyage

to contend not merely with bad weather but probably with

pirates, the merchant pilots were instructed to know how to

avoid them. For instance, their main object should be to

make the merchant ship as little conspicuous on the horizon

as possible. Thus, after getting clear of the land, the white

sail should be lowered and a black one hoisted instead.[51]

They were warned that it was especially risky to change

sail at break of day when the rising sun might make this

action easily observable. A man was to be sent aloft to

scan the sea, looking for these rovers and keep a good look

out. That black sail was called the “wolf,” because it

had the colour and cunning of such an animal. At night,

too, similar precautions were employed against any danger

of piratical attack, strict silence being absolutely enforced,

so that the boatswain was not even allowed to use his

whistle, nor the ship’s bell to be sounded. Every one knows

how easily a sound carries on the sea, especially by night, so

the utmost care was to be exercised lest a pirate hovering

about might have the rich merchant ship’s presence betrayed

to her avaricious ears.

But the Saracens, whose origin I have just mentioned,

must not be confused with the Barbarian corsairs. It is

with the latter—the grand pirates of the South—that I

pass on now to deal. So powerful did they become that it

took the efforts of the great maritime powers of Europe till

the first quarter of the nineteenth century before they could

exterminate this scourge: and even to-day, in this highly

civilised century, if you were to be becalmed off the coast of

North Africa in a sailing yacht, you would soon find some

of the descendants of these Barbarian corsairs coming out

with their historic tendency to kill you and pillage your

ship. If this statement should seem to any reader somewhat

incredible, I would refer him to the captain of any modern

steamship who habitually passes that coast: and I would

beg also to call to his attention the incident a few years ago

that occurred to the famous English racing yacht Ailsa,

which was lying becalmed somewhere between Spain and

Africa. But for a lucky breeze springing up, her would-be

assailants might have captured a very fine prize.

[52]

I shall use the word Moslem to mean Mussulman, or

Mohammedan, or Moor, and I shall ask the reader to carry

his mind back to the time when Ferdinand and Isabella

turned the Moors out from Spain, and sent them across the

straits of Gibraltar back to Africa. For seven hundred

years these Moors had lived in the Iberian peninsula. It

must be admitted in fairness that these Moors were exceedingly

gifted intellectually, and there are ample evidences in

Spain to this day of their accomplishments. On the other

hand, it is perfectly easy to appreciate the desire of a

Christian Government to banish these Mohammedans from

a Catholic country. Equally comprehensible is the bitter

hatred which these Moors for ever after manifested against

all Christians of any nation, but against the Spanish more

especially.

What were these Spanish Moors, now expatriated, to do?

They spread themselves along the North African coast, but

it was not immediately that they took to the sea; when,

however, they did so accustom themselves it was not as

traders but as pirates of the worst and most cruel kind.

The date of their expulsion from Granada was 1492, and

within a few years of this they had set to work to become

avenged. The type of craft which they favoured was of the

galley species, a vessel that was of great length, in proportion

to her extreme shallowness, and was manned by a considerable

number of oarsmen. Sail power was employed but

only as auxiliary rather than of main reliance. Such a craft

was light, easily and quickly manœuvred, could float in

creeks and bays close in to the shore, or could be drawn up

the beach if necessary. In all essential respects she was the

direct lineal descendant of the old fighting galleys of Greece

and Rome. From about the beginning of the sixteenth

century till the battle of Lepanto in 1571 the Moslem[53]

corsair was at his best as a sea-rover and a powerful racial

force. And if he was still a pest to shipping after that

date, yet his activities were more of a desultory nature.

Along the Barbarian coast at different dates he made himself

strong, though of these strongholds Algiers remained for

the longest time the most notorious.

In considering these Moslem corsairs one must think of

men who were as brutal as they were clever, who became

the greatest galley-tacticians which the world has ever

seen. Their greed and lust for power and property were

commensurate with their ability to obtain these. Let it

not be supposed for one moment that during the grand

period these Moorish pirate leaders were a mere ignorant

and uncultured number of men. On the contrary, they

possessed all the instincts of a clever diplomatist, united to

the ability of a great admiral and an autocratic monarch.

Dominating their very existence was their bitter hatred of

Christians either individually or as nations. And though a

careful distinction must be made between these Barbarian

corsairs and the Turks, who were often confused in the

sixteenth-century accounts of these rovers, yet from a very

early stage the Moorish pirates and the Turks assisted each

other. You have only to remember that they were both

Moslems; to remind yourself that the downfall of Constantinople

in 1453 gave an even keener incentive to harass

Christians; and to recollect that though the Turks were

great fighters by land yet they were not seamen. They had

an almost illimitable quantity of men to draw upon, and for

this as well as other reasons it was to the Moors’ interests

that there should be a close association with them.

During the fifteenth and especially the sixteenth

centuries there was in general European use a particular

word which instantly suggested a certain character that[54]

would stink in the nostrils of any Christian, be he under

the domination of Elizabeth or Charles V. This word was

“renegade,” which, of course, is derived from the Latin

nego, I deny. “Renegade,” or, as the Elizabethan sailors

often used it, “renegado” signifies an apostate from the

faith—a deserter or turncoat. But it was applied in those

days almost exclusively to the Christian who had so far

betrayed his religion as to become a Moslem. In the

fifteenth century a certain Balkan renegade was exiled from

Constantinople by the Grand Turk. From there he proceeded

to the south-west, took up his habitation in the

island of Lesbos in the Ægean Sea, married a Christian

widow and became the father of two sons, named respectively

Uruj and Kheyr-ed-din. The renegade, being a seaman, it

was but natural that the two sons should be brought up to

the same avocation.

Having regard to the ancestry of these two men, and

bearing in mind that Lesbos had long been notorious for its

piratical inhabitants, the reader will in no wise be surprised

to learn that these two sons resolved to become pirates too.

They were presently to reach a state of notoriety which

time can never expunge from the pages of historical

criminals. For the present let us devote our attention to

the elder brother, Uruj. We have little space to deal with

the events of his full life, but this brief sketch may suffice.

The connection of these two brothers with the banished

Moors is that of organisers and leaders of a potential force

of pirates. Uruj, having heard of the successes which the

Moorish galleys were now attaining, of the wonderful prizes

which they had carried off from the face of the sea, felt the

impulse of ambition and responded to the call of the wild.

So we come to the year 1504, and we find him in the

Mediterranean longing for a suitable base whence he could[55]

operate; where, too, he could haul his galleys ashore during

the winter and refit.

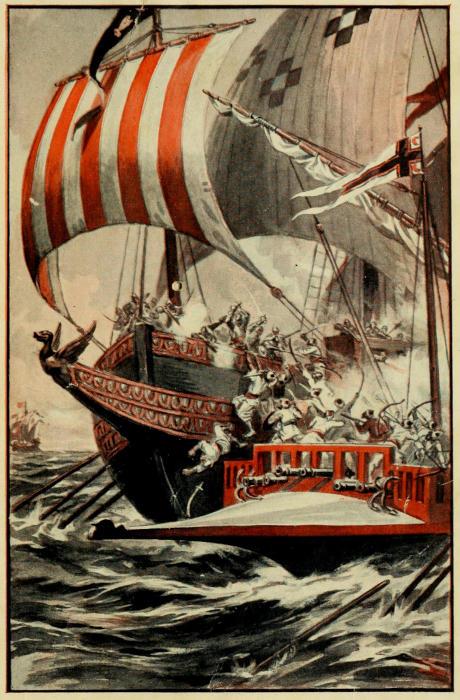

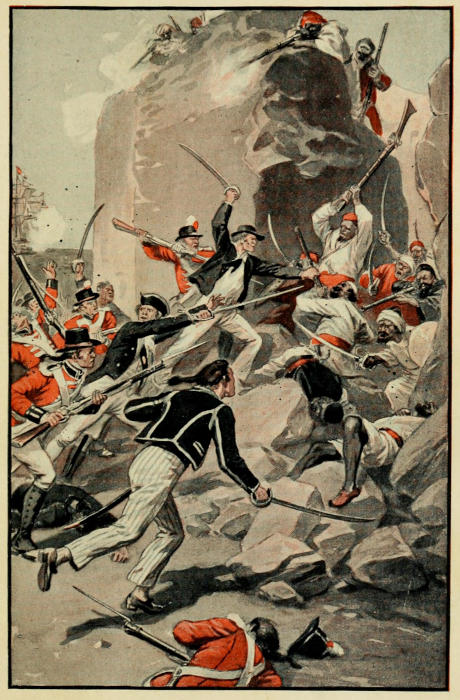

A Daring Attack

Uruj with his one craft attacked the two galleys of Pope Julius II laden with goods

from Genoa. His officers remonstrated with Uruj on the desperate venture, but to

enforce his commands and prevent any chance of flight he had the oars thrown overboard.

He then attacked and overcame the galleys.

For a time Tunis seemed to be the most alluring spot in

every way: and strategically it was ideal for the purpose of

rushing out and intercepting the traffic passing between

Italy and Africa. He came to terms with the Sultan of

Tunis, and, in return for one-fifth of the booty obtained,

Uruj was permitted to use this as his headquarters, and

from here he began with great success to capture Italian

galleys, bringing back to Tunis both booty and aristocratic

prisoners for perpetual exile. The women were cast into the

Sultan’s harem, the men were chained to the benches of the

galleys.

One incident alone would well illustrate the daring of

Uruj, who had now been joined by his brother. The story

is told by Mr. Stanley Lane Poole in his history of the

Barbarian corsairs, that one day, when off Elba, two galleys

belonging to Pope Julius II. were coming along laden with

goods from Genoa for Civita Vecchia. The disparity and

the daring may be realised when we state that each of

these galleys was twice the size of Uruj’s craft. The Papal

galleys had become separated, and this made matters easier

for the corsair. In spite of the difference in size, he was

determined to attack. His Turkish crew, however, remonstrated

and thought it madness, but Uruj answered this

protestation by hurling most of the oars overboard, thus

making escape impossible: they had to fight or die.

This was the first time that Turkish corsairs had been

seen off Elba, and as the Papal galley came on and saw the

turbaned heads, a spirit of consternation spread throughout

the ship. The corsair galley came alongside, there was

a volley of firing, the Turkish men leapt aboard, and before

long the ship and the Christians were captured. The[56]

Christians were sent below, and the Papal ship was now

manned by Turks who disguised themselves in the Christians’

clothes. And now they were off to pursue the second

galley. As they came up to her the latter had no suspicion,

but a shower of arrows and shot, followed by another short,

sharp attack, made her also a captive. Into Tunis came

the ships, and the capture amazed both Barbarian corsair

and the whole of Christendom alike. The fame of Uruj

spread, and along the whole coast of North Africa he was

regarded with a wonder mingled with the utmost admiration.

He became known by the name Barbarossa, owing

to his own physical appearance, the Italian word rossa