CLARA BARTON

See Contents.

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

CLARA BARTON

See Contents.

This book is respectfully dedicated to the Boys and Girls of the World; and to the Men and Women who are still Boys and Girls, in their love for humanity.

The author, in the preparation of his pen pictures, begs to acknowledge with sincere thanks the courtesies extended to him by Mr. Stephen E. Barton, the Executor of the Clara Barton Estate; by Doctor J. B. Hubbell, for many years the manager for Clara Barton; by the Oxford (Mass.) Memorial Day Committee of 1917; by the Twenty-First Massachusetts Regiment G. A. R.; by many of the Army Nurses of the Civil War; also for material assistance in data by the American National Red Cross; by Mrs. J. Sewall Reed Acting-President, National First Aid Association of America; by Honorable Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress; by General W. H. Sears for the use of his data in his book of 177 pages, prepared for and used in the defense of Clara Barton before the Library Committee of Congress, and his generous contribution of incidents in the life of his personal friend; by Honorable Francis Atwater for data in “The Story of My Childhood,” by Clara Barton; by the Macmillan Co., Publishers of the Life of Clara Barton by Percy H. Epler, the book of the best data on her life now before the American people; by the National First Aid Association of America and likewise to many other associations, personal friends and admirers of America’s most remarkable woman.

Honor women! they entwine and weave heavenly roses in our earthly life. Schiller.

The author undertakes to produce a few pen pictures of a personal friend—humanity’s friend. They are pictures of sentiment, pictures of reality—pictures of humanity.

Although precluded the use of data left by Clara Barton for her biography the author, nevertheless, is conforming to the sentiment of her oft expressed wish that he write the story of her life. Recognizing the 8wish to be a sacredly imposed trust, for the past six years he has gleaned what he could for his sketches from public documents, from her personal friends in California, New England, New York, Washington and elsewhere, as well as from his memory of facts developing through the years he enjoyed her confidence and received from her highest inspirations.

The author assumes not a rôle literary—has herein no aspirations, literary. His impulse to write is not fame; it is sentiment, a love-sentiment for a woman whom all the world loves and whose “life gives expression to the sympathy and tenderness of all the hearts of all the women of the world.” His motive in writing is to point a moral in “a passion for service”; to limn scenes, vivid, along “paths of charity over roadways of ashes”; to depict for the lesson it teaches a career, a career the memory of which must remain a rich heritage to the American people.

In life’s drama, wherein Clara Barton played the leading rôle, there appear faces to inspire, faces to instruct, but also the faces of intrigue. In the closing incidents of a life-heroic time’s detectives disclose the plotters, and the motive in their plot to destroy—

Except now and then in dim outline, the faces of intrigue in the tragic scene do not appear. These faces are un-American—inhuman—and would mar humanity’s picture.

The Divine Humanitarian forgave His enemies, but the picture of the crucified on the cross ever suggests the Pontius Pilate and the executioners. Clara Barton 9also forgave her enemies, and yet some day a literary artist may portray the Judasette Iscariot, or possibly the plotting Antony and Cleopatra, to make a Clara Barton picture historically and tragically complete.

In biography is the world’s history. If, in human logic, the silencing of truth in biography be an imperative virtue, then literature should be relegated to the ash-heap of forgotten lore. As “in a valley centuries ago grew a fern leaf green and slender,” leaving its impress on what have become the rocks of the centuries, so truth leaves its impress imperishable on what become the tablets of history. Truth crushed to earth again and again will appear; and, when Clara Barton’s Gethsemane appears with all its delineations in a picture complete, there will be none so poor to do reverence to Clara Barton’s character assassins, nor to the Clara Barton ghouls who desecrate her tomb and use the United States mails to traduce the dead.

Sentiment is the soul of action. The highest tribute to mortal is the angel-sentiment—the tribute to self-sacrificing woman that blazes her “path where highways never ran.”

and yet more powerful than armies is the soul-sentiment that protects fame,—the fame of the Florence Nightingales, the Clara Bartons and the Edith Cavells.

Her “friends” say time will vindicate Clara Barton. The more such “friends” the more’s the pity. It’s not time, it’s truth, that vindicates. “Procrastination is the thief of time.” The thief of time must not be permitted to steal from the present, even under pledge to disgorge 10in the future. The present is ours to possess, ours to enjoy. It’s not that the millions can do something for Clara Barton; instead, the Clara Barton spirit can do something for the millions. The plotter may revile the Red Cross Mother; the Red Cross Artist may picture the cross of red on the breast of a fictitious “Greatest Mother in the World;” the self-constituted autocrat in Red Cross literature may suppress, and belie, truth; but the spirit of Clara Barton is the Mother-Spirit still, the real spirit of the American Red Cross, the Red Cross spirit in all Christendom. The fighting sons of America on the “Western Front” may not have read of Clara Barton in recent Red Cross literature but, trooping under the Red Cross peace-banner that Clara Barton brought here from Europe, were more millions of her followers in America than in the world war there were soldiers marshalled under the military banners in all the armies in Europe.

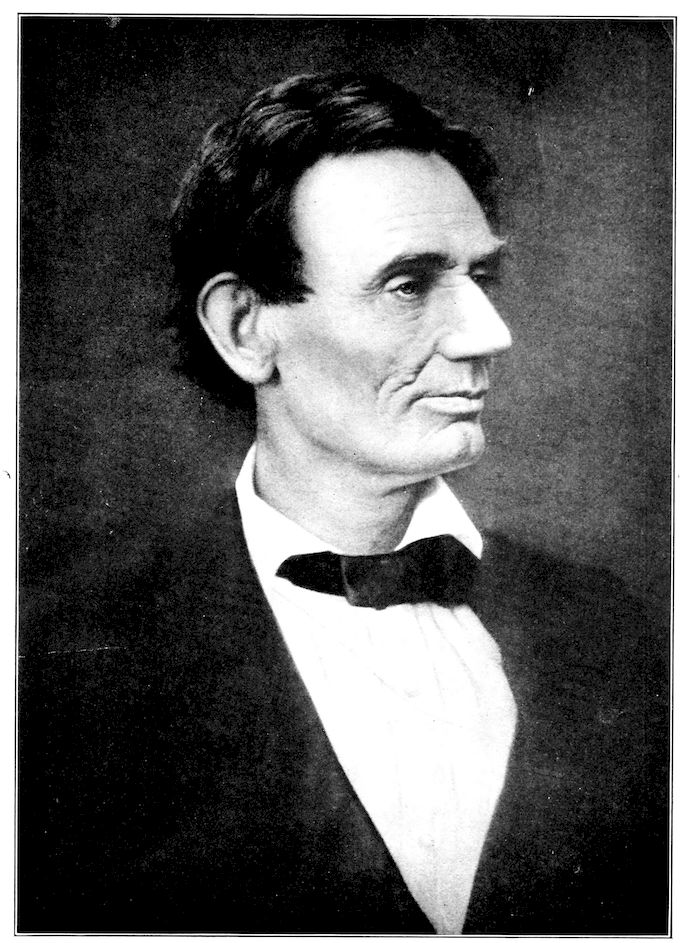

Grant was “Grant the Great” at Appomattox; Lincoln was more than “six feet four” when in the home of Confederate General Pickett he stooped down to kiss the brow of “Baby George” Pickett; Stephen A. Douglass was more than “the little giant” when at the inauguration on the east steps of the capitol he held the hat of Abraham Lincoln; Clara Barton was more divine than human when, with love for her enemies, in her last world prayer she gave expression to the forgiving sentiment of the Divine Humanitarian.

Clara Barton said that the bravest act of her life was crossing the pontoon bridge under fire at Fredericksburg. The historian will say that the bravest act of her life was snatching her Red Cross child from the social—political—fat-salaried-swiveled-chair clique at 11Washington, and handing over her best beloved unharmed to the country for which in the smoke of battle and terrors of disaster she had many times risked her life. The historian will further say that in refusing to accept a pension of $2500 for life and Honorary Presidency of the Red Cross from that “clique” as the price of her child, and suffering persecution for life as the penalty, there was shown the true mother spirit that must commend her for all time to those who respect the spirit of self-sacrificing Motherhood.

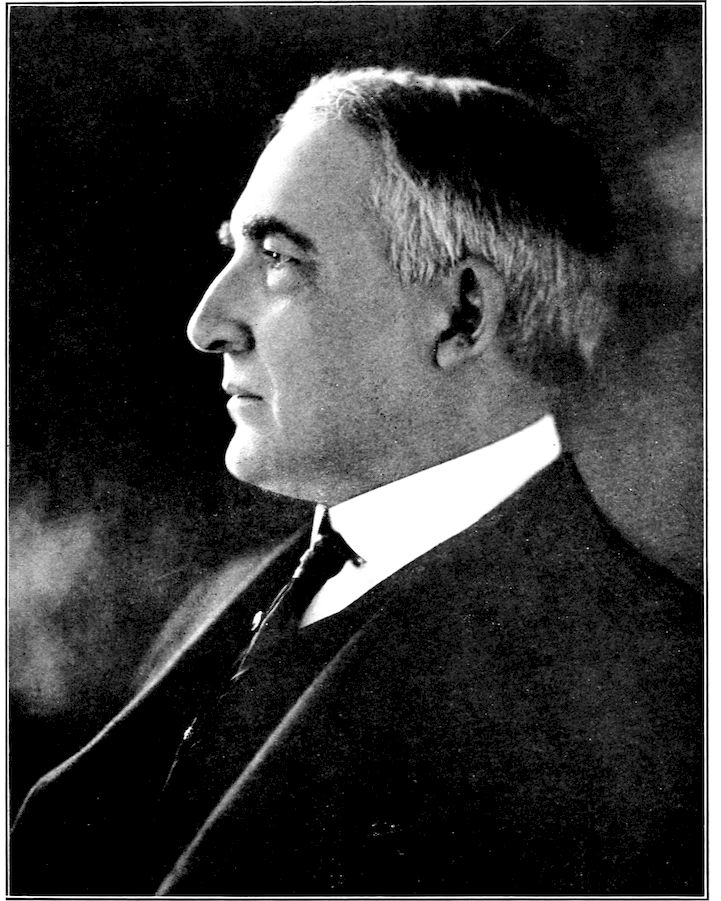

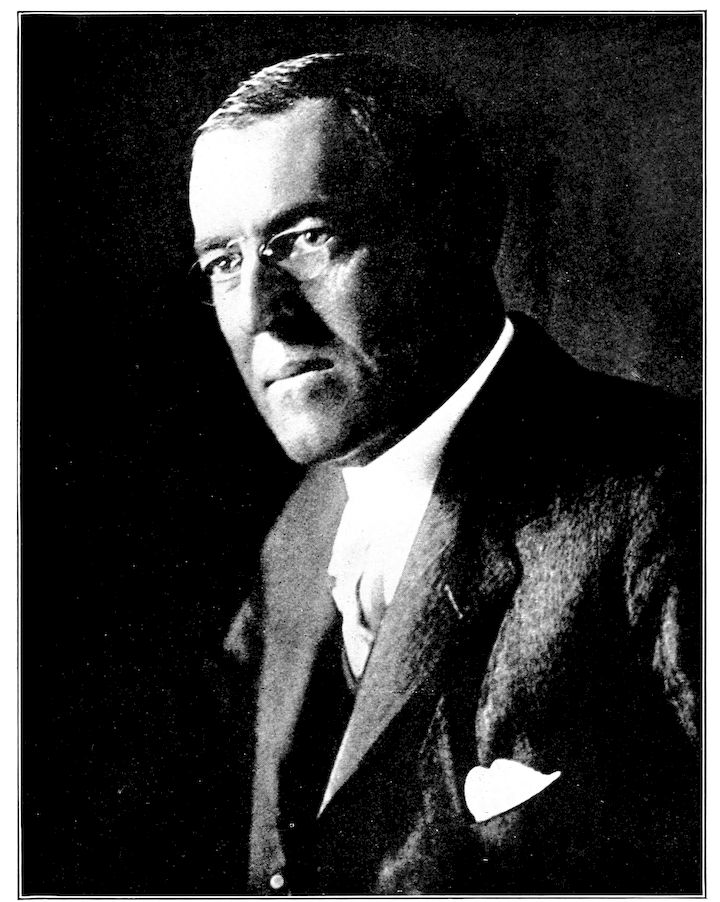

President Warren G. Harding, the president also of the Red Cross, “entertains the highest sentiment regarding the splendid service of Miss Barton.” Ex-President Woodrow Wilson—also ex-president of the Red Cross—has voiced the sentiment of the American people in no uncertain sound as has a second Clara Barton,—the soldier-angel Margaret Wilson. General John J. Pershing has not been silent in his admiration of the great woman, nor have the hundreds of thousands of American boys on the “Western Front” been unmindful in gratitude to the Founder of the American Red Cross; and, if signs fail not, from the American Congress there will come to America’s greatest humanitarian a testimonial—accompanied by an acclaim that will be heard around the world.

On a certain state occasion the statement was made that there is less to censure, and more to commend, in the public life of Clara Barton for the twenty-three years she was President of the Red Cross than in the public life of any one of the twenty-eight Presidents from George Washington to Woodrow Wilson. There commenting on the statement, America’s beloved Mrs. 12General George E. Pickett significantly said: “Yes, that’s true, but Clara Barton was a woman.” But woman is coming into her own, and Clara Barton said, “My own shall come to me.” Never was prophecy more certain of fulfillment. With hundreds of thousands of Americans receiving the benefits of “First Aid”; with more than thirty thousand brave American nurses, ten thousand of these following the illustrious example of Clara Barton by going to the battlefield; with more than thirty millions of Americans serving the Red Cross in time of war; with more than a billion of human beings making use of the Red Cross American Amendment in times of peace and war, Clara Barton already has come into her own.

The American nation will come into its own, as did respectively two great nations of Europe, when she wipes out from the scroll of history its foulest blot,—by giving national recognition to a national heroine; the American Red Cross will come into its own when it shall repossess the name Clara Barton; the American people will come into their own when they patriotically recognize, and sacredly cherish, that immortal Mother-Spirit which, after a half century of heroic sacrifices in the war of human woes, passed triumphant through the archway ’twixt earth and heaven.

If these pen pictures give to the boys and girls of America inspiration to loftier patriotism and higher ideals in achievement; if truth in the biography give renewed impulse to American Red Cross philanthropy; if through this volume immortal deeds, and a name unsullied, be treasured for world-humanity then Clara Barton’s dying message to the author shall not have been in vain.

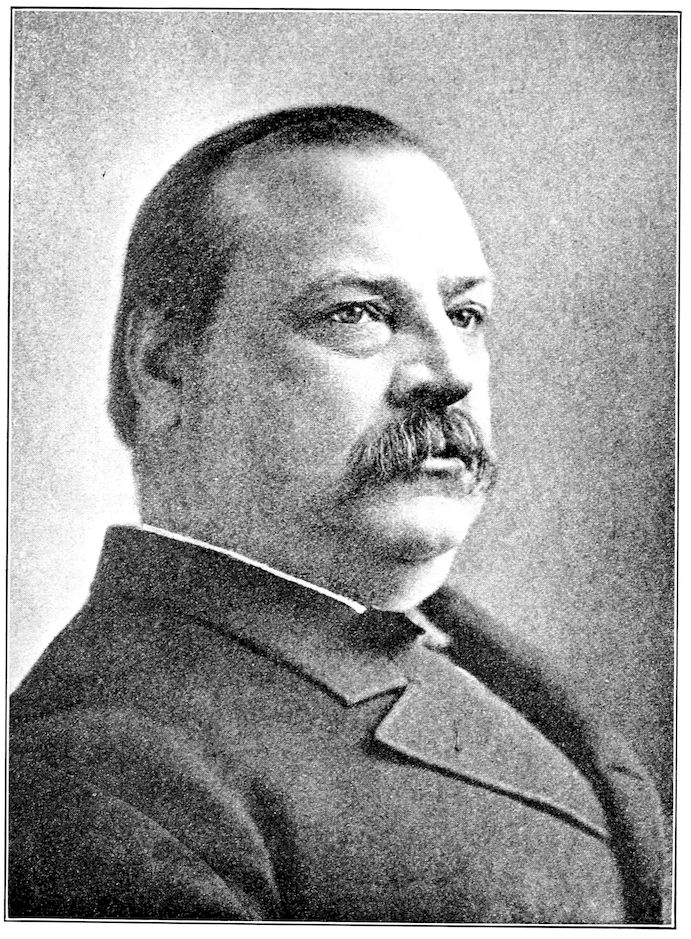

CHARLES SUMNER YOUNG

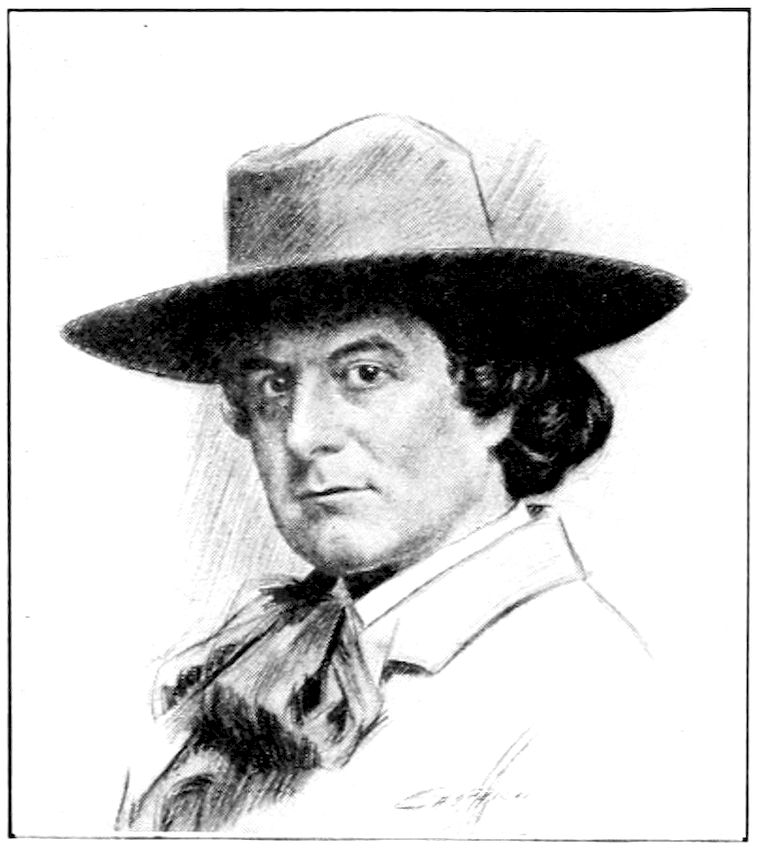

13The only picture of myself that I have cared anything about at all is the one taken at the time of the Civil War (1865), in which I am represented in the uniform of a nurse. If my friends had let me have my way, I would never have had another picture taken. (Frontispiece)

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Babyhood Impressions | 21 |

| II | School—Childish Memories—Military | 24 |

| III | On Her Favorite Black Horse | 28 |

| IV | Phrenology—Read Her Characteristics—Basis of Friendship | 30 |

| V | “Spontaneous Combustion” Laid to Clara Barton | 34 |

| VI | Christmas—a Christmas Carol | 36 |

| VII | “Button”—“Billy”—Clara Barton Ownership | 38 |

| VIII | Pauper Schools; from Six to Six Hundred | 43 |

| IX | Child Love—Joe and Charlie—Appreciation | 45 |

| X | Temperance—Clara Barton and the Hired Man—Stranger than Fiction | 48 |

| XI | Looking for a Job—Equal Suffrage | 51 |

| XII | Credulous Ox—Innocent Child—Clara Barton, a Vegetarian | 55 |

| XIII | Fell Dead on the Ground beside Her | 57 |

| XIV | Wickedness of War—Settles no Disputes | 59 |

| XV | Her Wardrobe in a Handkerchief—The Battle Scene | 63 |

| XVI | The Bravery of Women—Clara Barton’s Bravest Act | 66 |

| XVII | Yes, and Got Euchred | 69 |

| XVIII | To Dream of Home and Mother | 71 |

| XIX | Tribute of Love and Devotion | 74 |

| XX | Cheering Words—Always Ready—Wears a Smile | 76 |

| XXI | Horrible Deed—Leads American Navy—Angel of Mercy | 80 |

| XXII | Confederates and Federals alike Treated | 86 |

| XXIII | The Enemy, Starving—Tact—The White Ox | 89 |

| XXIV | Bullethole—Amputated Limbs Like Cordwood—God Gives Strength | 91 |

| XXV | Fearless of Bullets and Kicking Mules | 95 |

| XXVI | His Comfort, not Hers; His Life, not Hers | 97 |

| XXVII | Does not Need any Advice | 99 |

| XXVIII | Had but a Few Moments to Live | 102 |

| XXIX | Enlisted Men First—The Colonel’s Life Saved | 104 |

| XXX | You’re Right, Madam—Good Day | 107 |

| 14XXXI | Bleeding to Death—His Headless Body—Women in the War | 109 |

| XXXII | Timid Child—Timid Woman | 112 |

| XXXIII | Ez Ef We Wuz White Folks | 115 |

| XXXIV | In Her Dreams—Again in Battle | 117 |

| XXXV | Four Famous Women | 120 |

| XXXVI | Simplicity of Childhood—Pet Wasps—Pet Cats—Loved Life—Domestic | 122 |

| XXXVII | Clara Barton in the Literary Field | 128 |

| XXXVIII | The Art of Dressing—Clara Barton’s Individuality | 133 |

| XXXIX | The Jewelled Hand and the Hard Hand Meet | 138 |

| XL | Clara Barton and the Emperor | 140 |

| XLI | America—Scarlet and Gold—Europe | 143 |

| XLII | Three Cheers—Wild Scenes in Boston—Tiger!! No, Sweetheart | 147 |

| XLIII | The Last Reception—Her Autograph—The Boys in Gray | 150 |

| XLIV | Open House—Cost of Fame, Self-Sacrifice—Best in Woman | 152 |

| XLV | Kneeled Before Her and Kissed Her Hand | 158 |

| XLVI | I Never Get Tired—Eating the Least of My Troubles | 160 |

| XLVII | Royalty Under a Quaker Bonnet | 163 |

| XLVIII | Still Stamping on Me—Personally Unharmed | 165 |

| XLIX | At the Memorial—“The Flags of all Nations”—A Good Time | 167 |

| L | Clara Barton Kept a Diary | 171 |

| LI | Nursing a Fine Art—Over the Washtub | 176 |

| LII | Immortal Words—A Million Thanks | 178 |

| LIII | The Pansy Pin—For Thoughts | 180 |

| LIV | Clara Barton Pays Respects to Florence Nightingale | 182 |

| LV | The Passing of Years—Right Habits of Life | 184 |

| LVI | She Won His Heart | 186 |

| LVII | You Buy It for Him | 188 |

| LVIII | Or God Wouldn’t Have Made Them | 190 |

| LIX | Clara Barton—Mary Baker Eddy | 192 |

| LX | Like Tolstoi She Lived the Simple Life | 194 |

| LXI | Clara Barton—Florence Nightingale | 196 |

| LXII | The General Has Money—I Am His Reconcentrado | 201 |

| LXIII | Abraham Lincoln’s Son | 204 |

| LXIV | The Butcher Didn’t Get It | 207 |

| LXV | The Kind of Girls that Needed Help | 209 |

| 15LXVI | A Romance of Two Continents | 211 |

| LXVII | The Little Monument—For all Eternity | 215 |

| LXVIII | Story of Baba—Dream of a White Horse—Life’s Woes | 218 |

| LXIX | People, Like Jack Rabbits—No “Show-Woman” | 223 |

| LXX | Clara Barton’s Heart Secret—$10,000 in “Gold Dust” | 227 |

| LXXI | Fell on Their Knees before “Mis’ Red Cross” | 231 |

| LXXII | Clara Barton’s Tribute to Cuba | 233 |

| LXXIII | At the Birthplace of Napoleon—The Corsican Bandit | 235 |

| LXXIV | When Cares Grow Heavy and Pleasures Light | 238 |

| LXXV | A Red Cross Red Letter Day | 240 |

| LXXVI | Patriotic Women of America Self-Sacrificing | 242 |

| LXXVII | Opposition—The American Red Cross “Complete Victory” | 246 |

| LXXVIII | Greetings—National First Aid Association of America | 255 |

| LXXIX | Humanitarianism, Unparalleled in All History | 264 |

| LXXX | Clara Barton’s Prayer Answered | 268 |

| LXXXI | Not the Value of a Postage Stamp | 272 |

| LXXXII | Honorary Presidency for Life—Proposed Annuity | 275 |

| LXXXIII | Clara Barton’s Resignation | 279 |

| LXXXIV | No Red Cross Controversy | 285 |

| LXXXV | International Red Cross—American Red Cross—American Amendment | 287 |

| LXXXVI | Blackmail Alleged—“Congressional Investigation”—Truth of History | 294 |

| LXXXVII | Of Graves, of Worms, of Epitaphs | 332 |

| LXXXVIII | Turkey—Statesmanship of Philanthropy—Armenia | 340 |

| LXXXIX | Treason—Lincoln Assassinated—Grant Protects Clara Barton | 349 |

| XC | President McKinley Sends Clara Barton to Cuba | 352 |

| XCI | In Details—Clara Barton, a Business Manager—World’s Record | 355 |

| XCII | Superintendent of Woman’s Prison | 363 |

| XCIII | Greatness—An Immortal American Destiny—Immortality | 365 |

| XCIV | What Was Her Religion? | 369 |

| XCV | One Day with Clara Barton | 373 |

| XCVI | The Personal Correspondence—Clara Barton’s Proposed Self-Expatriation | 377 |

| XCVII | Closing Incidents—The Biography—Other Correspondence | 392 |

| XCVIII | A Record History at the Funeral | 398 |

| XCIX | Clara Barton’s Last Ride | 401 |

| 16C | Chronology of the Leading Achievements in the Life of Clara Barton | 403 |

| CI | The Press and the Individual | 411 |

| CII | The Clara Barton Centenary—Memorial Address, 1921 | 415 |

| CIII | Clara Barton—Memorial Day Address, 1917 | 422 |

17I want the last picture of the friends I love to show them in their strength, and at their best, not after time and age shall have robbed them of all characteristic features which represented them in actual life.—Clara Barton, from her diary of December 13, 1910.

| Clara Barton | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

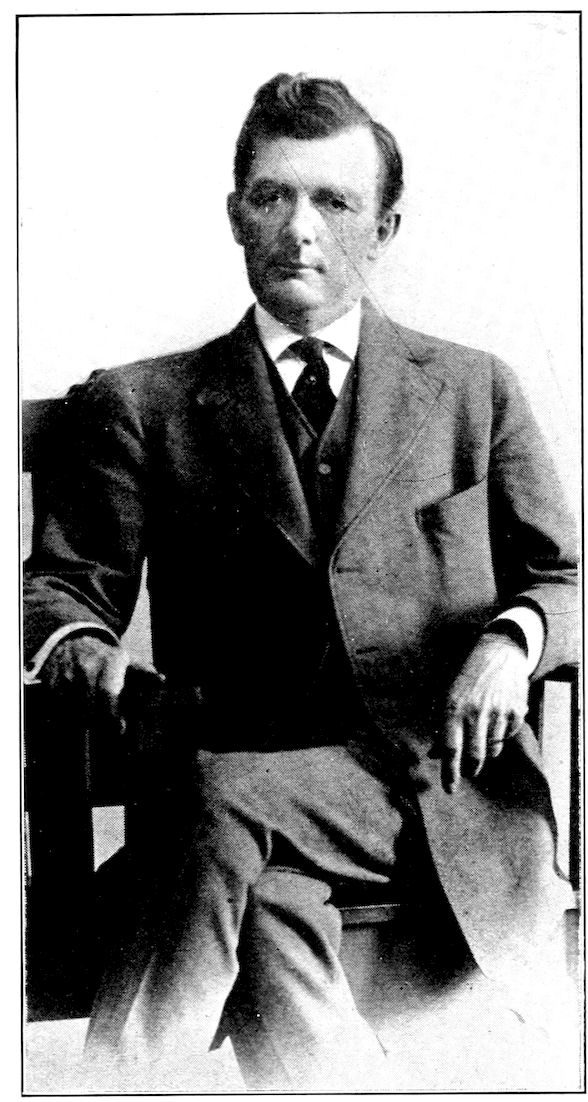

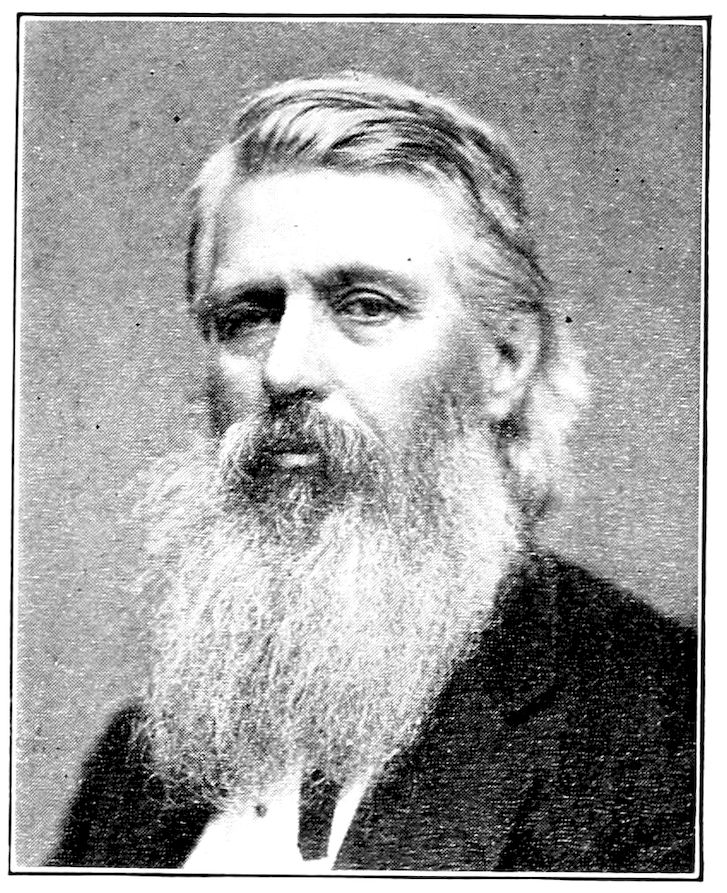

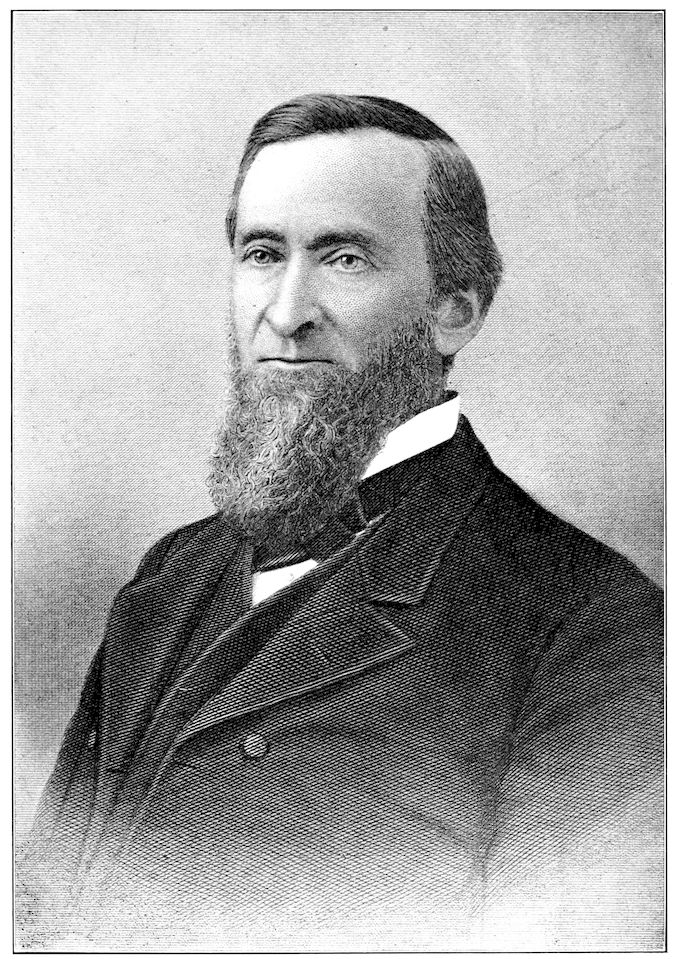

| Charles Sumner Young | 12 | |

| The Universalist Church, Main Street, Oxford, Massachusetts | 35 | |

| Summer Home of Clara Barton, Oxford, Massachusetts | 35 | |

| Birthplace of Clara Barton, Near Oxford, Massachusetts | 42 | |

| Officers of the W. N. M. A. Present at the Dedication of the Clara Barton Memorial on October 12, 1921 | 42 | |

| Historic in Education, Bordentown, N. J. | 53 | |

| The School House | ||

| The Desk Used by Clara Barton | ||

| The Clara Barton Museum | ||

| Representative Temperance Advocates | 56 | |

| Annie Wittenmeyer | ||

| John B. Gough | ||

| Mary Stewart Powers | ||

| Frances Willard | ||

| Representative Suffrage Leaders | 69 | |

| Susan B. Anthony | ||

| Carrie Chapman Catt | ||

| Dr. Anna Howard Shaw | ||

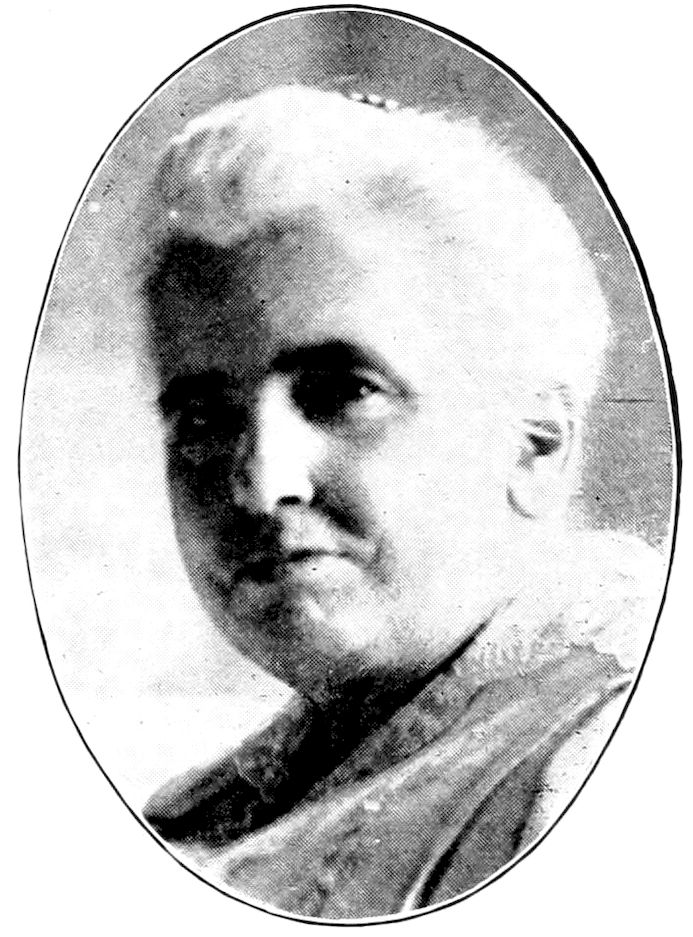

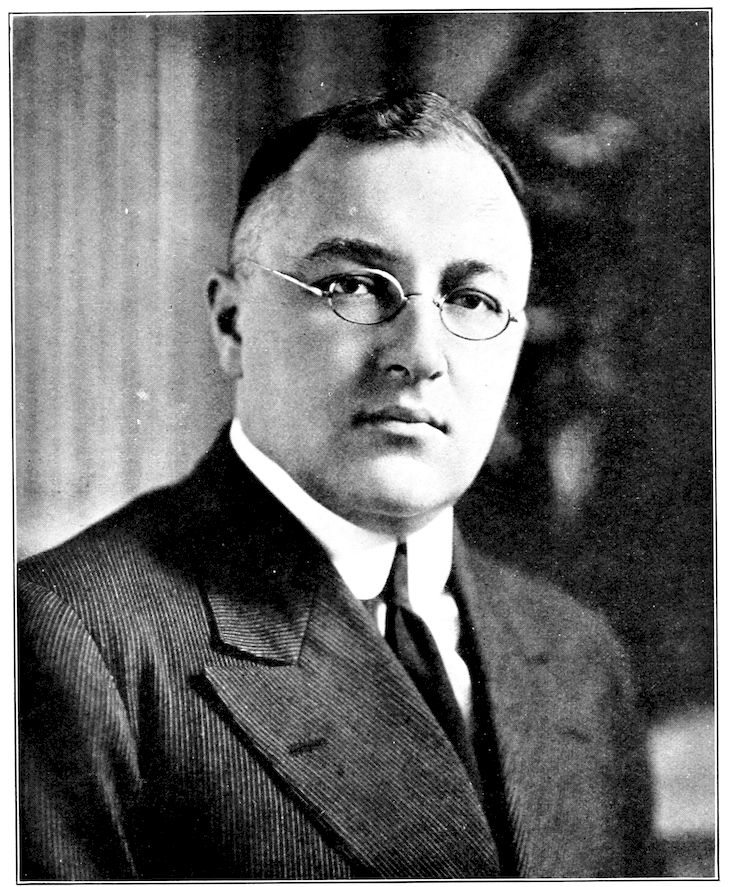

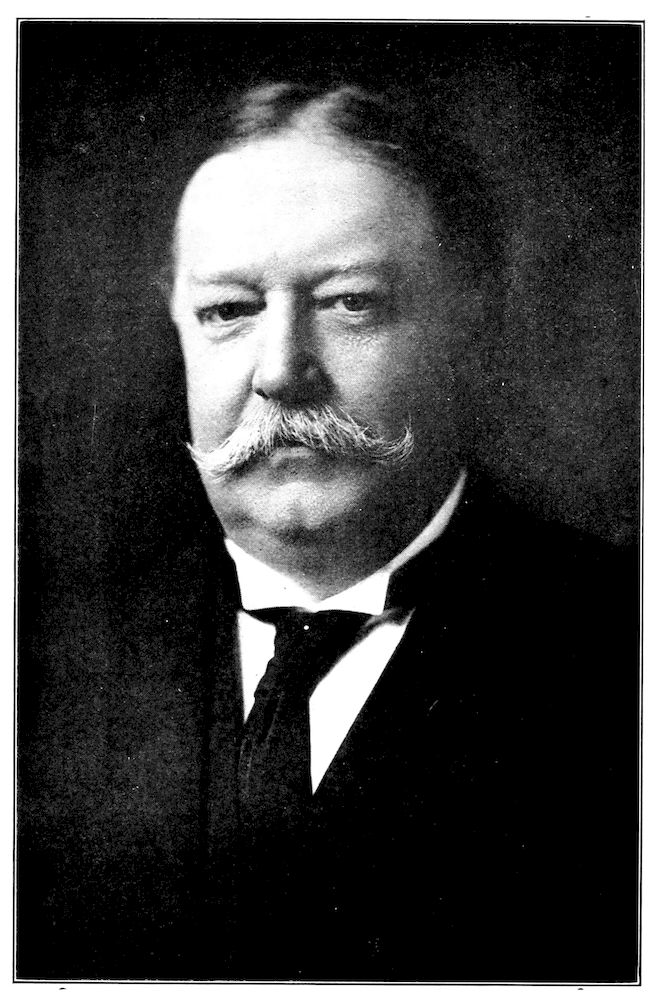

| Warren G. Harding | 72 | |

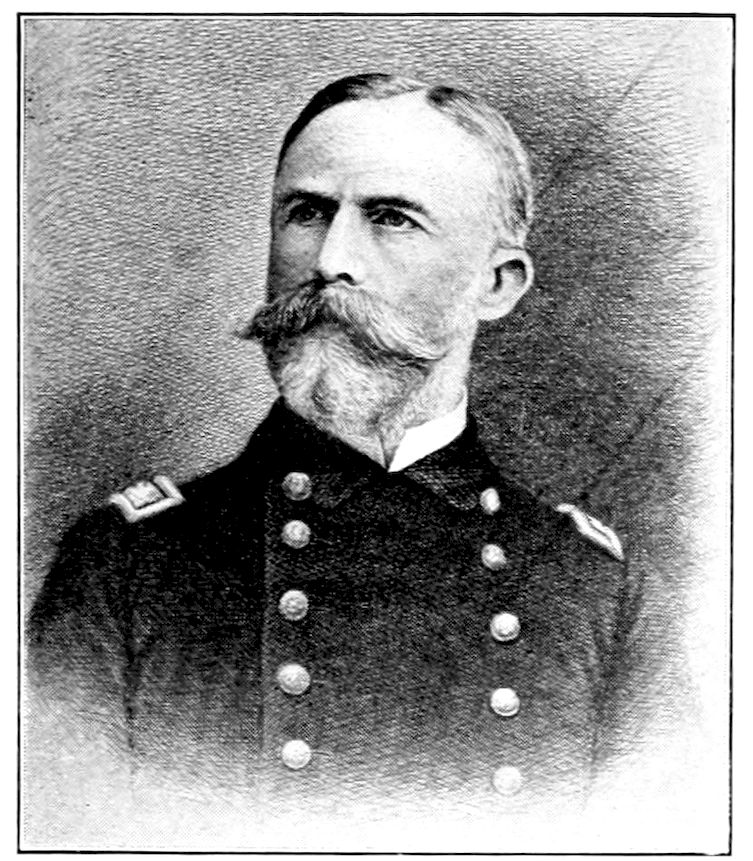

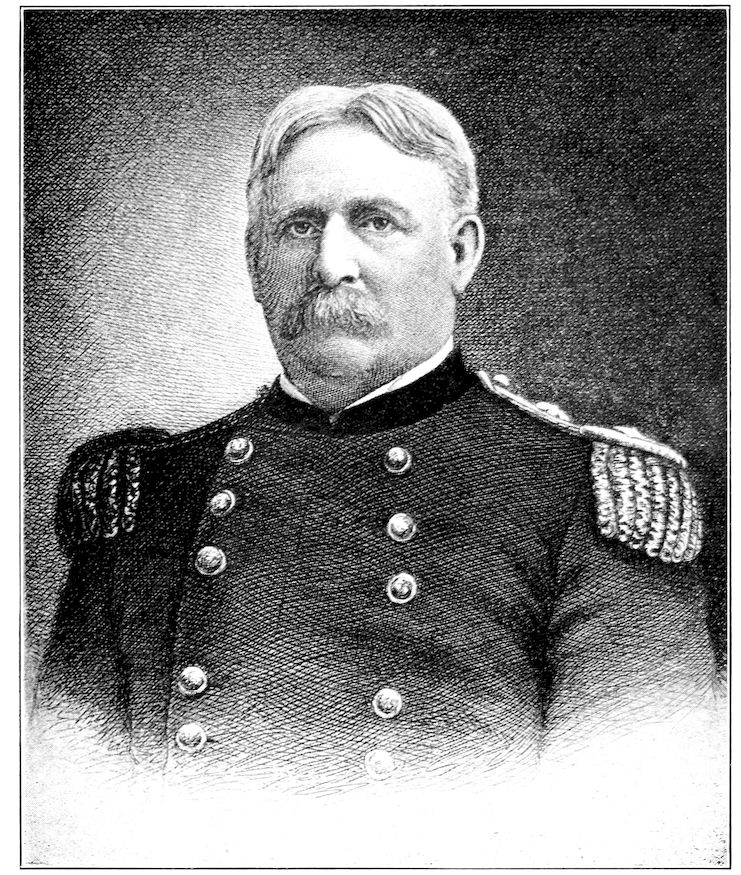

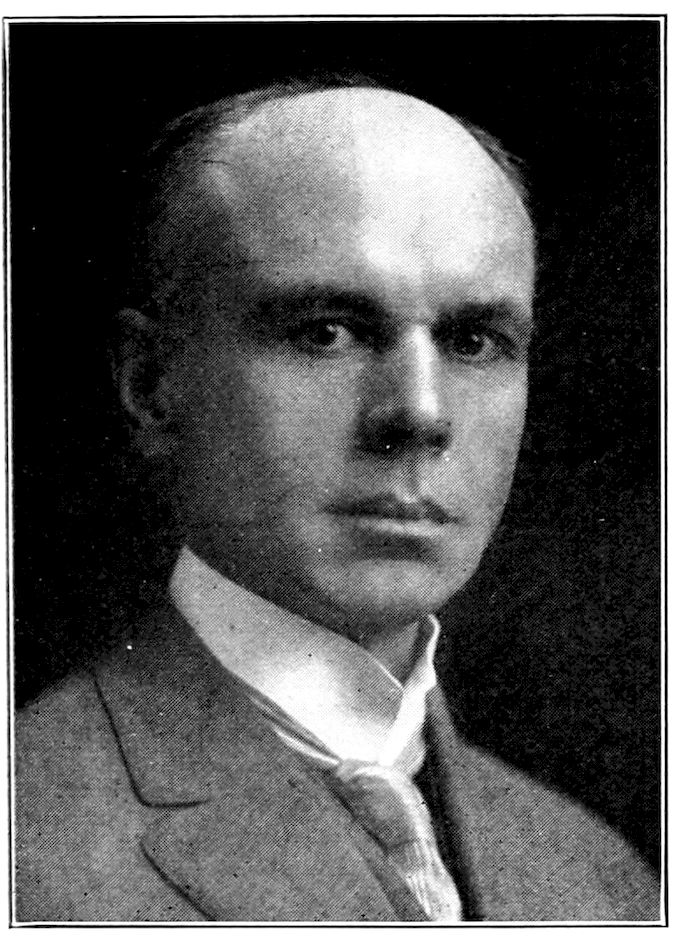

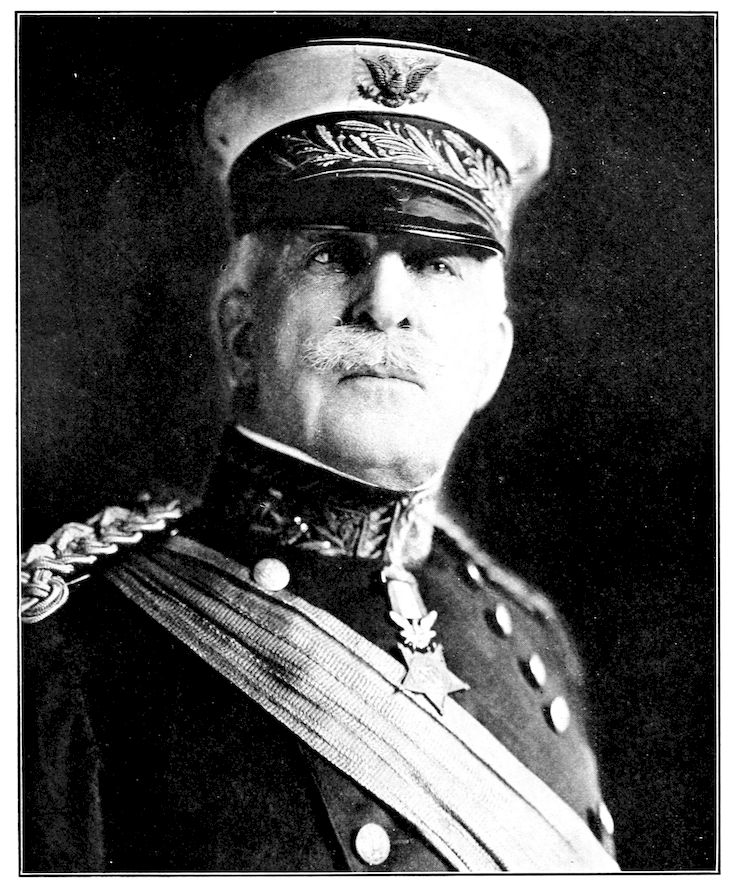

| Representatives Respectively of Three Wars | 83 | |

| William T. Sampson | ||

| Isaac B. Sherwood | ||

| Joseph Taggart | ||

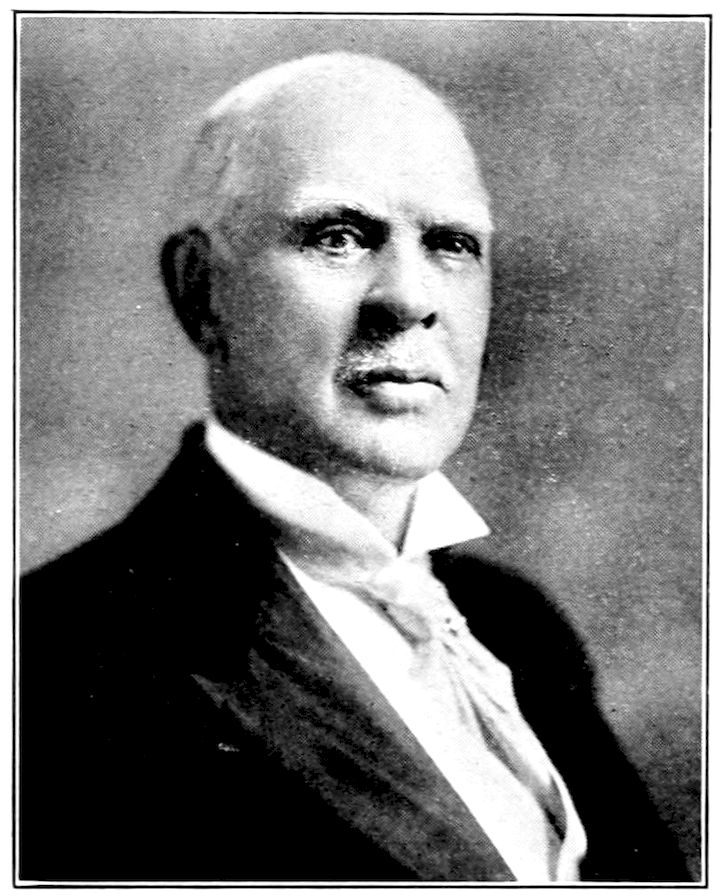

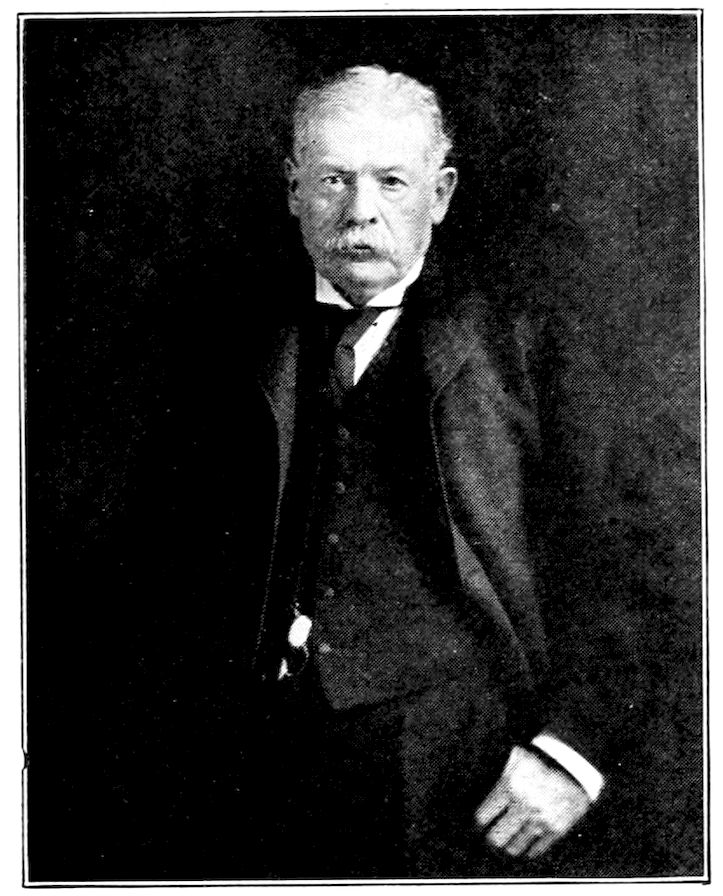

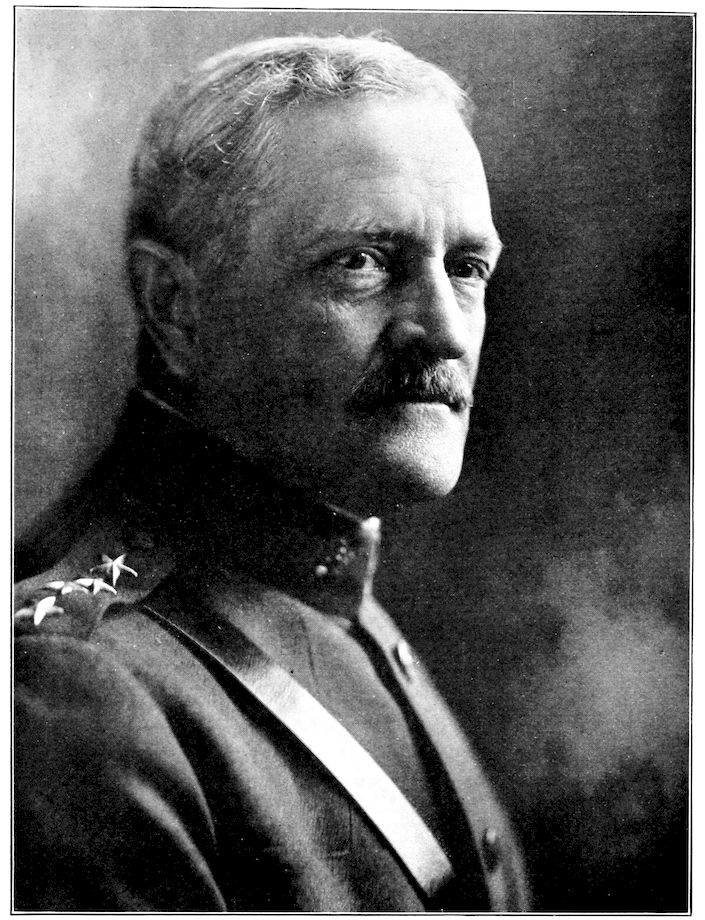

| Representative of Two Wars | 90 | |

| Mathew C. Butler | ||

| Joseph Wheeler | ||

| Harrison Gray Otis | ||

| Leonard Wood | 117 | |

| The Red Cross Home of Clara Barton, Glen Echo, Maryland | 120 | |

| Representative of the Literary World | 133 | |

| Ida M. Tarbell | ||

| Lucy Larcrom | ||

| Elbert Hubbard | ||

| Alice Hubbard | ||

| 18W. R. Shafter | 136 | |

| The Royalty of Germany | 149 | |

| Empress Augusta | ||

| Emperor William I | ||

| Luise, The Grand Duchess of Baden | ||

| Friederich, The Grand Duke of Baden | ||

| The Royalty of Russia | 152 | |

| Nicholas II, The Czar of Russia | ||

| Alexandra Feodorowna, The Czarina of Russia | ||

| Maria Feodorowna, The Empress Dowager | ||

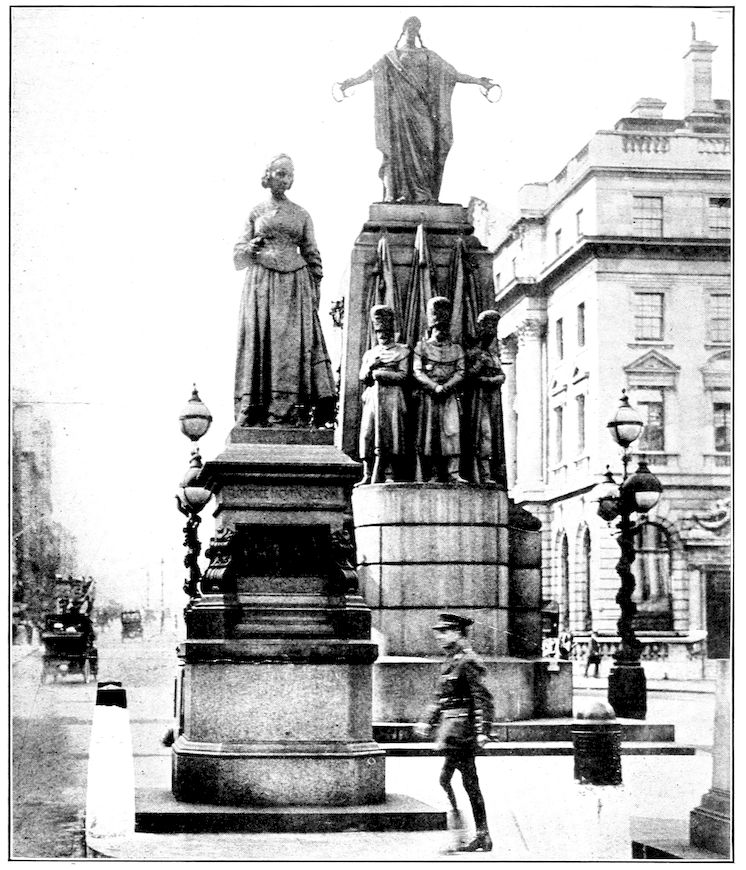

| Florence Nightingale | between pages 182 and 183 | |

| Florence Nightingale Memorial on the Mall, London | between pages 182 and 183 | |

| Co-Workers with Clara Barton | 195 | |

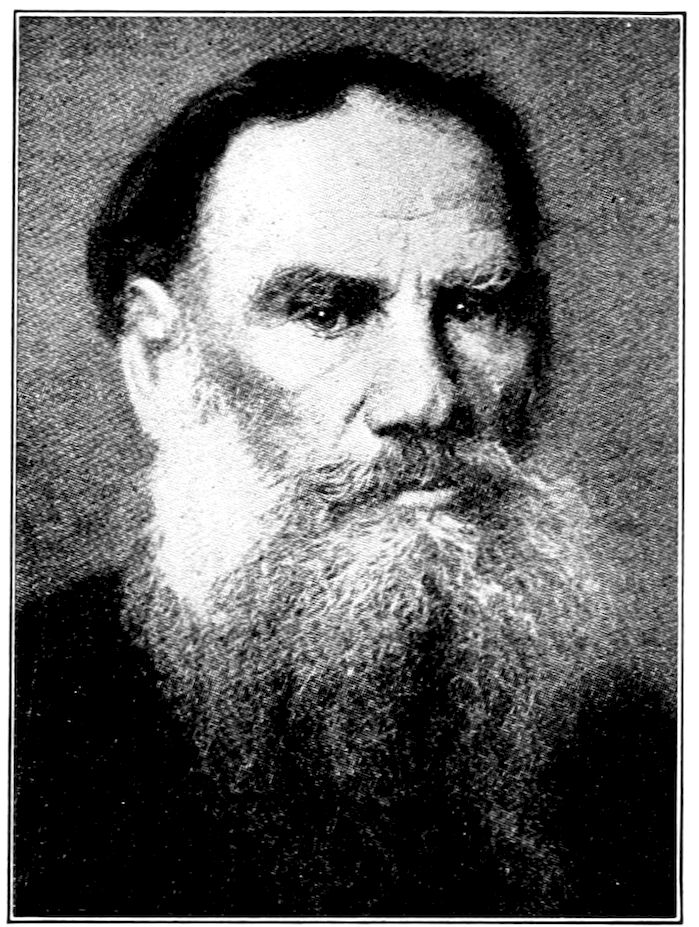

| Count Lyof Nikolayevitch Tolstoi | ||

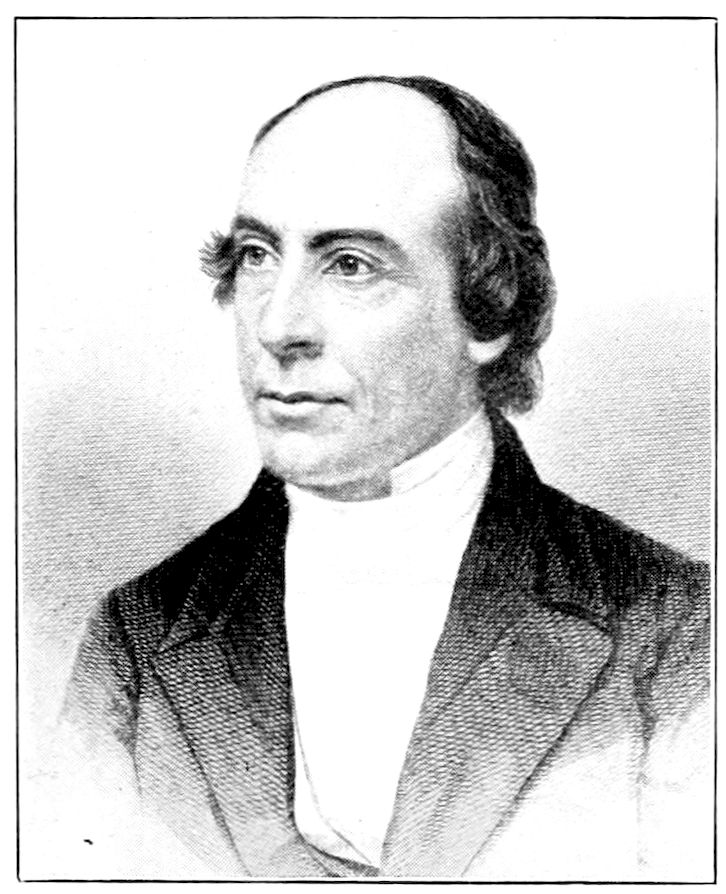

| Dr. Henry W. Bellows | ||

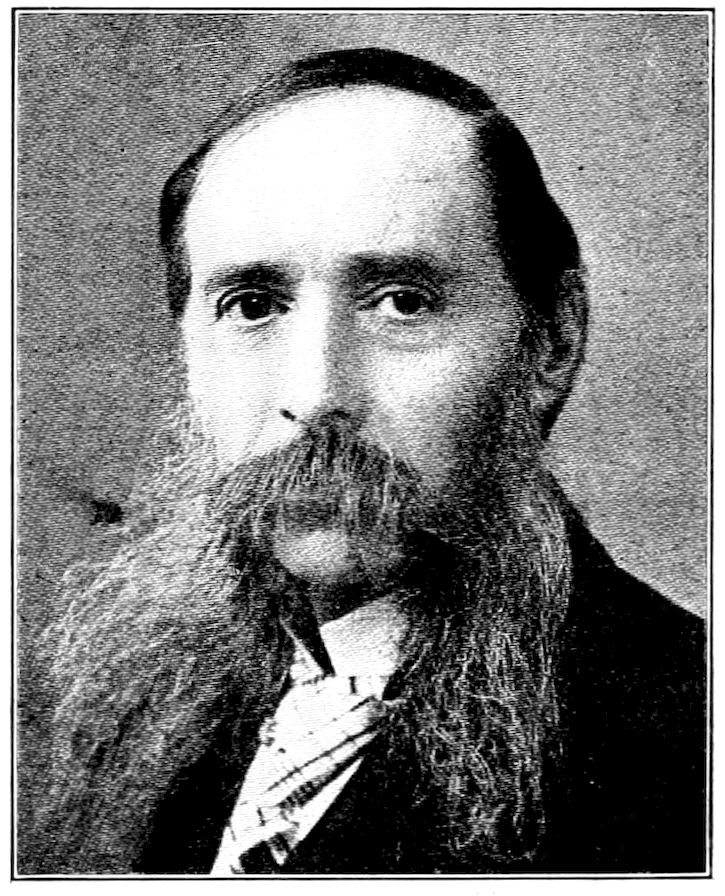

| Dr. Julian B. Hubbell | ||

| Woodrow Wilson | 202 | |

| Sentiment in History | 213 | |

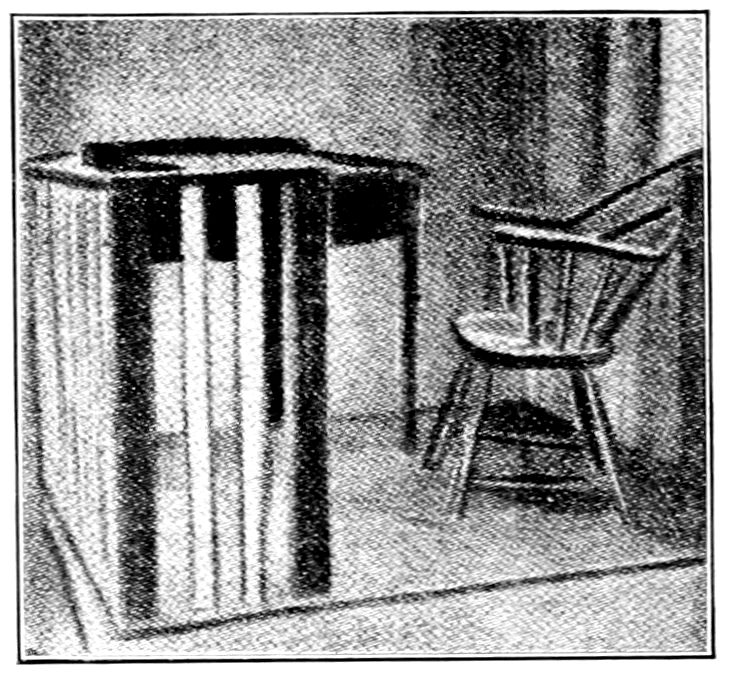

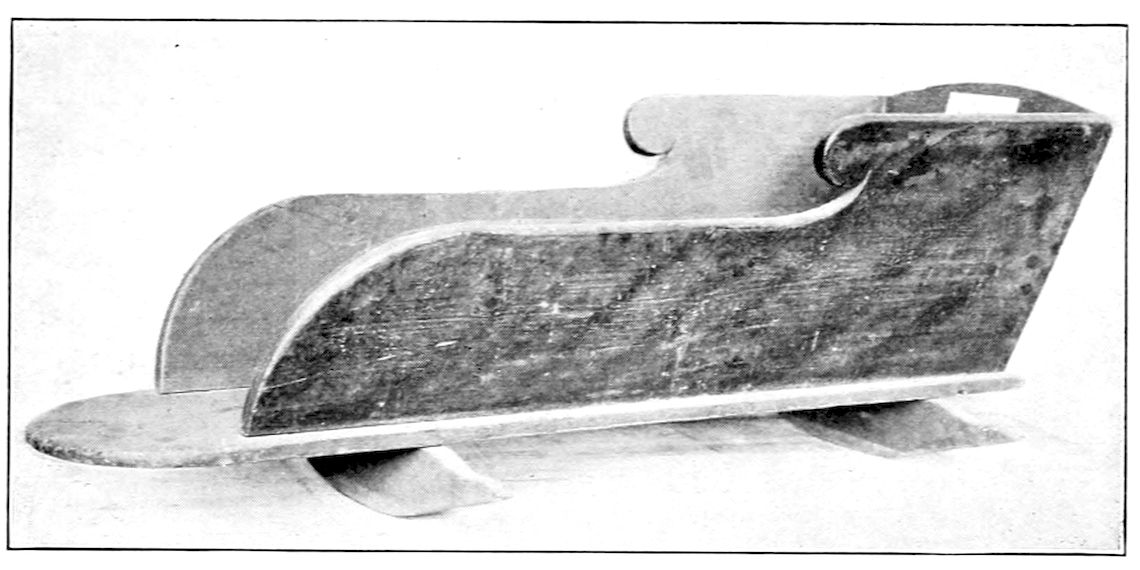

| The Clara Barton Baby Cradle | ||

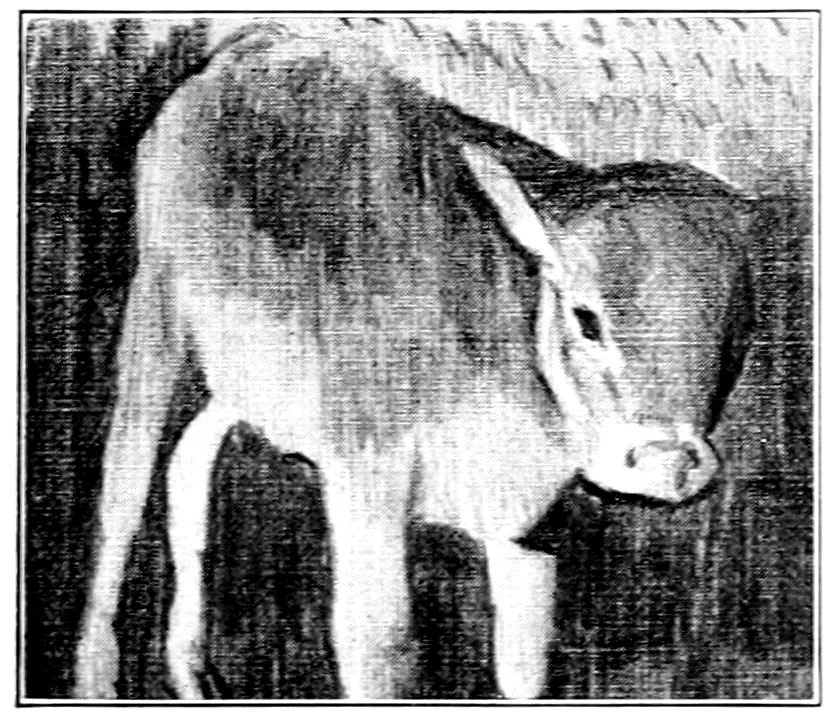

| The Pet Jersey Calf | ||

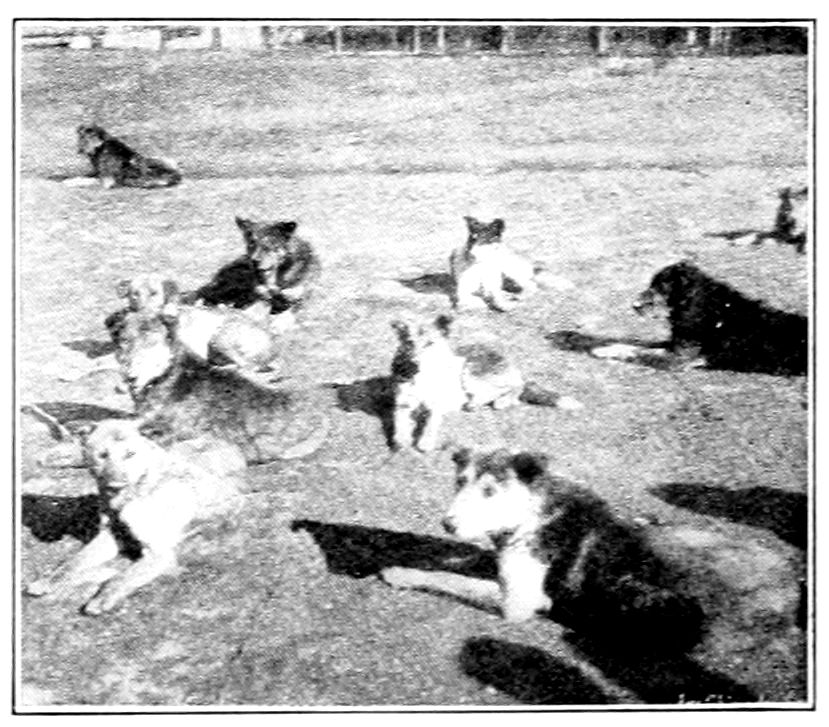

| Colony of Constantinople Dogs | ||

| Historic and Sentimental | 216 | |

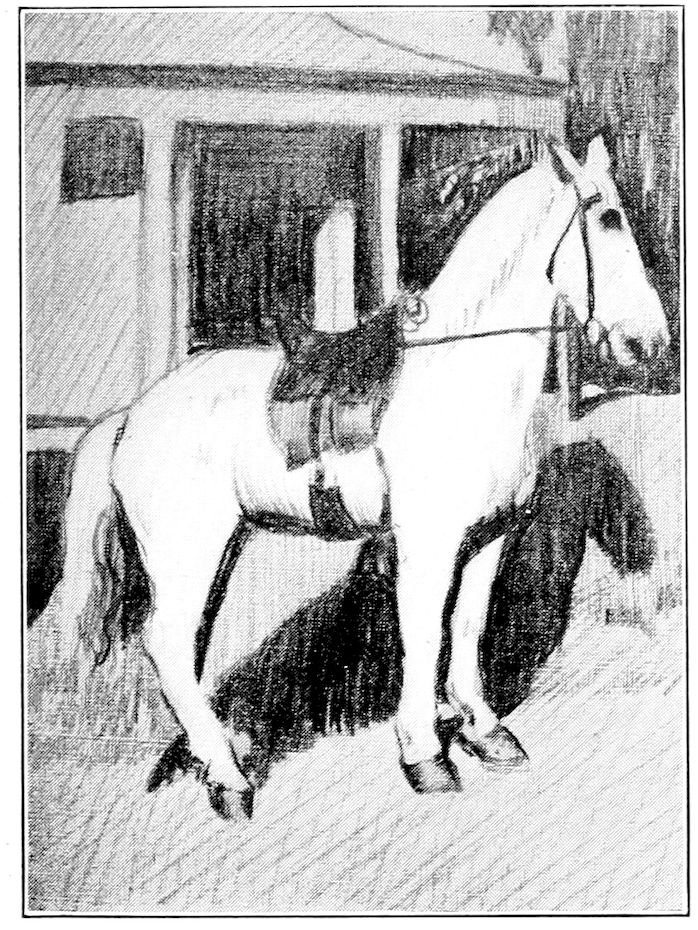

| Baba, Clara Barton’s Pet Horse | ||

| The Baba Tree and William H. Lewis | ||

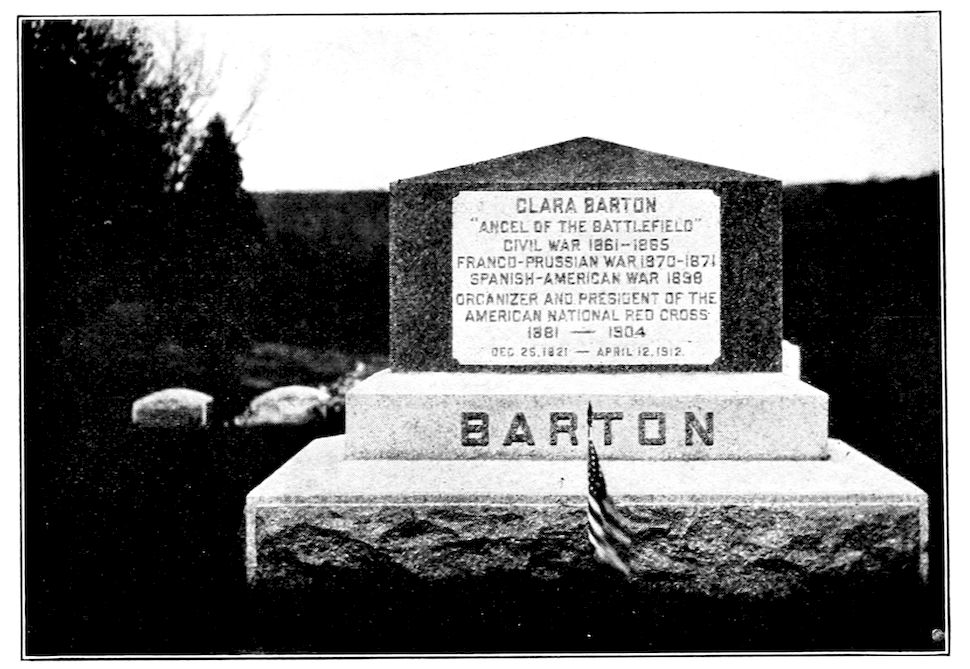

| The Clara Barton Monument | 229 | |

| Mario G. Menocal | 232 | |

| William McKinley | 241 | |

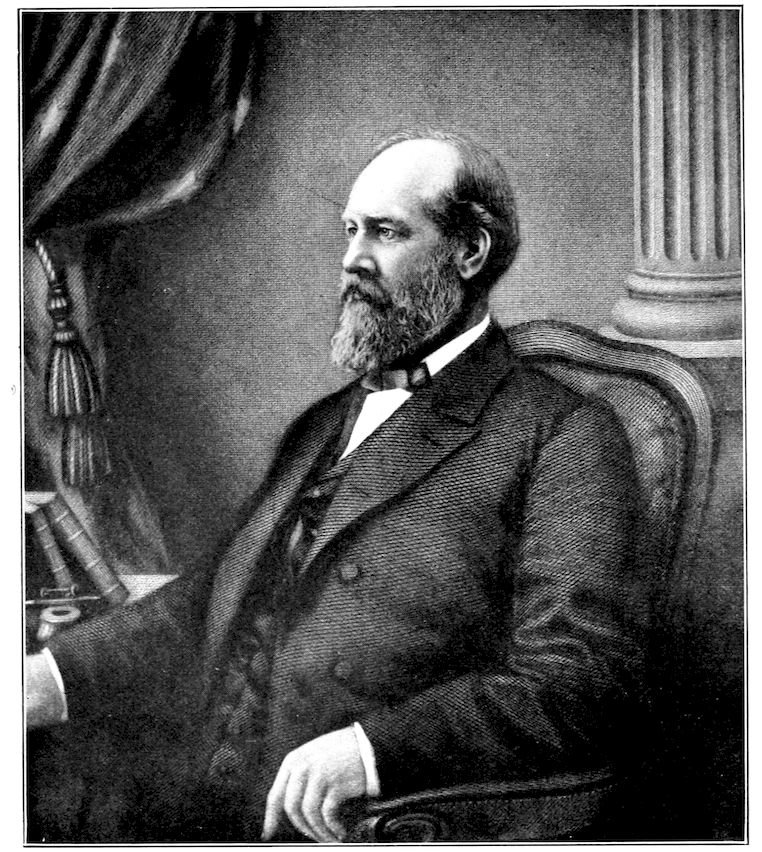

| James A. Garfield | between pages 246 and 247 | |

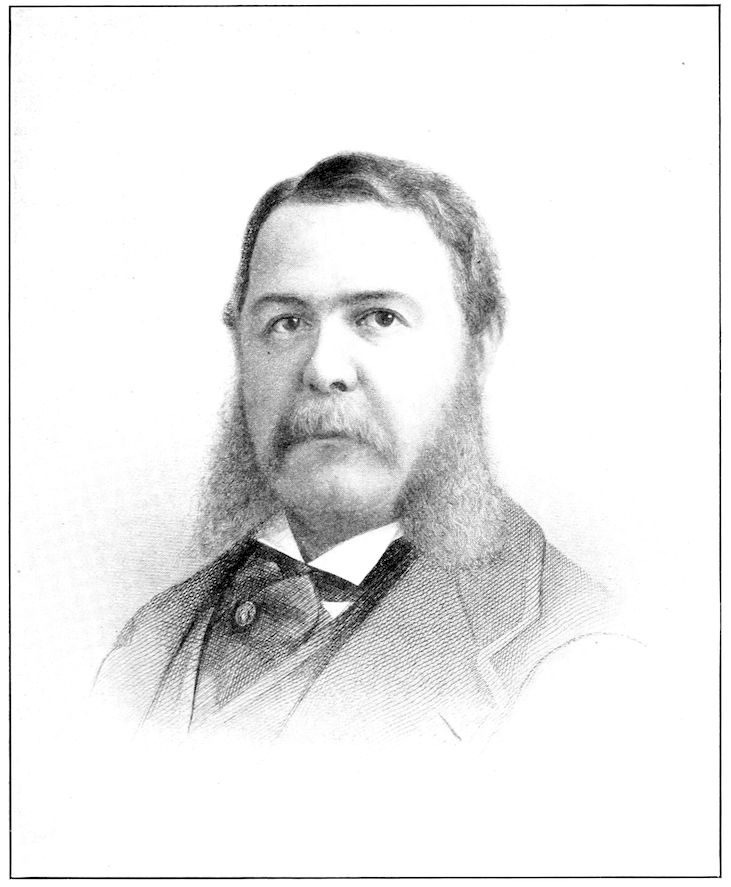

| Chester A. Arthur | between pages 246 and 247 | |

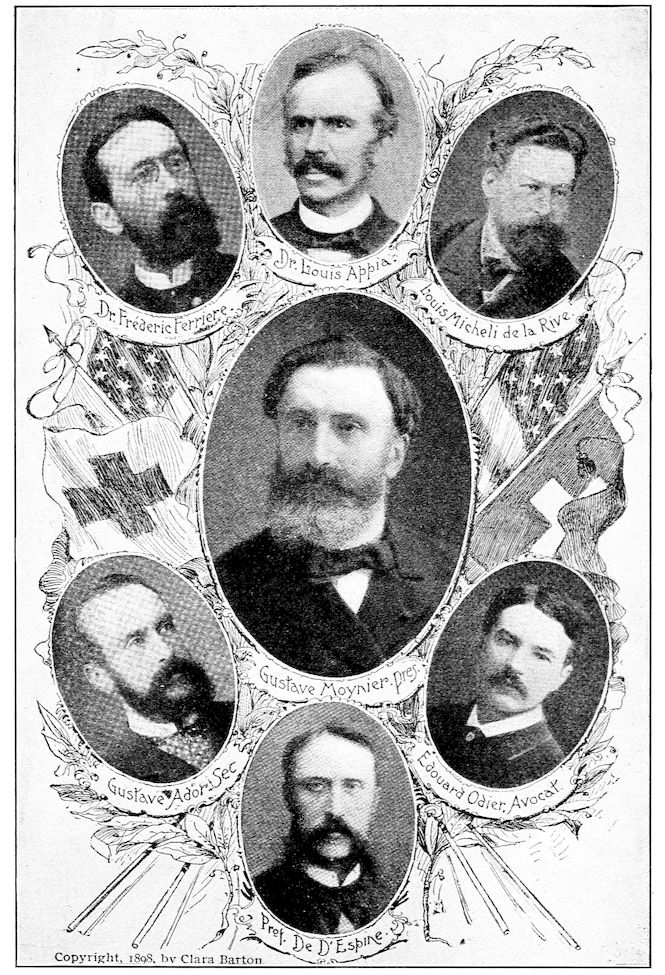

| The International Committee of the Red Cross (in 1898) | 252 | |

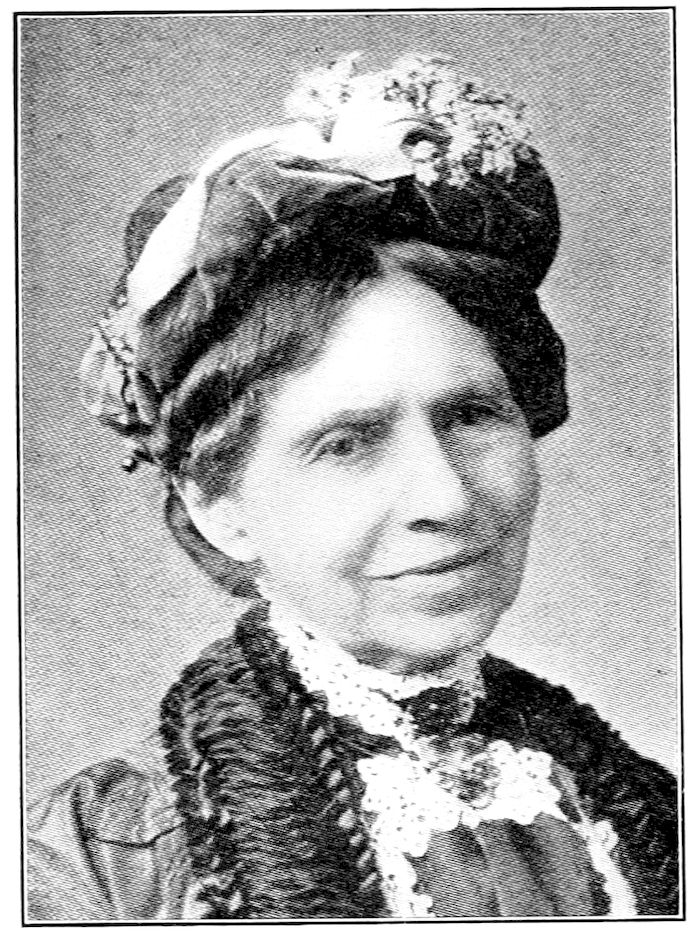

| Clara Barton | 275 | |

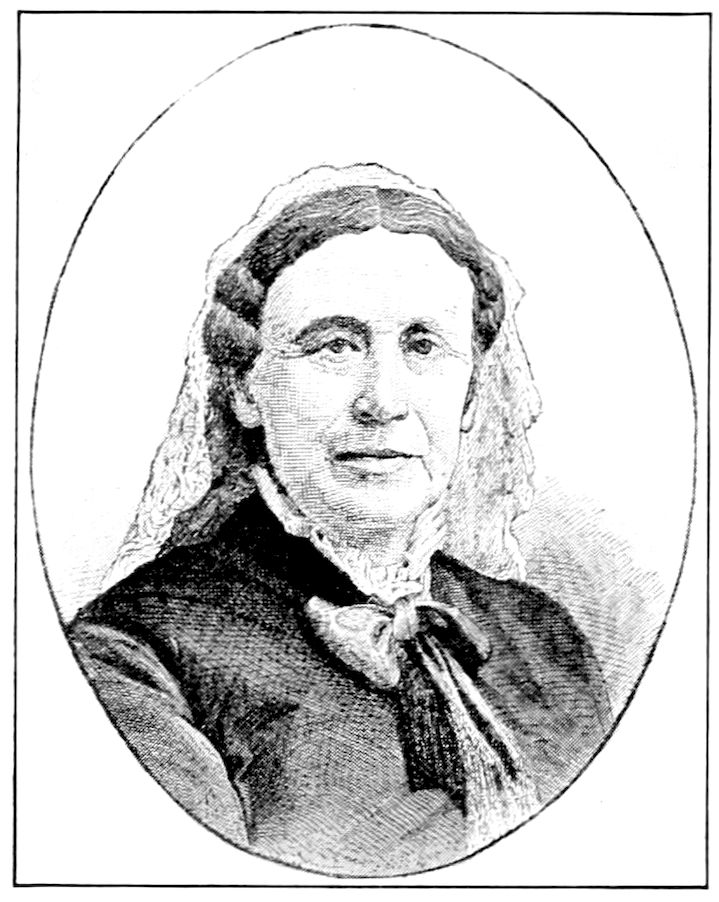

| Harriette L. Reed | 275 | |

| Mrs. John A. Logan | 282 | |

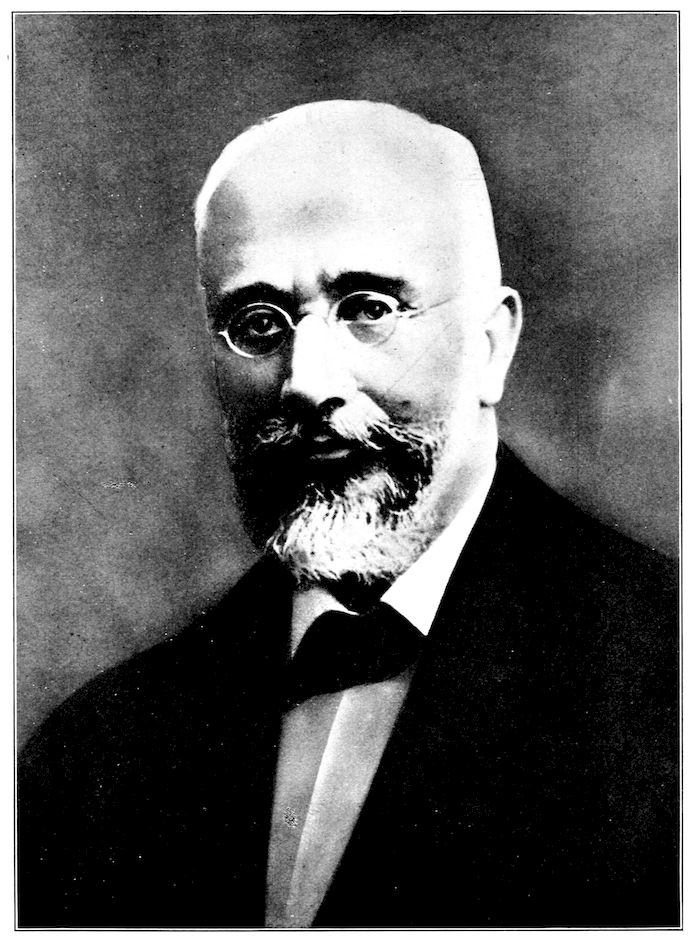

| Ambassador Bakhmeteff | 289 | |

| Elutheros Venizelos | 293 | |

| Grover Cleveland | 296 | |

| Five Photographs of Clara Barton | 300 | |

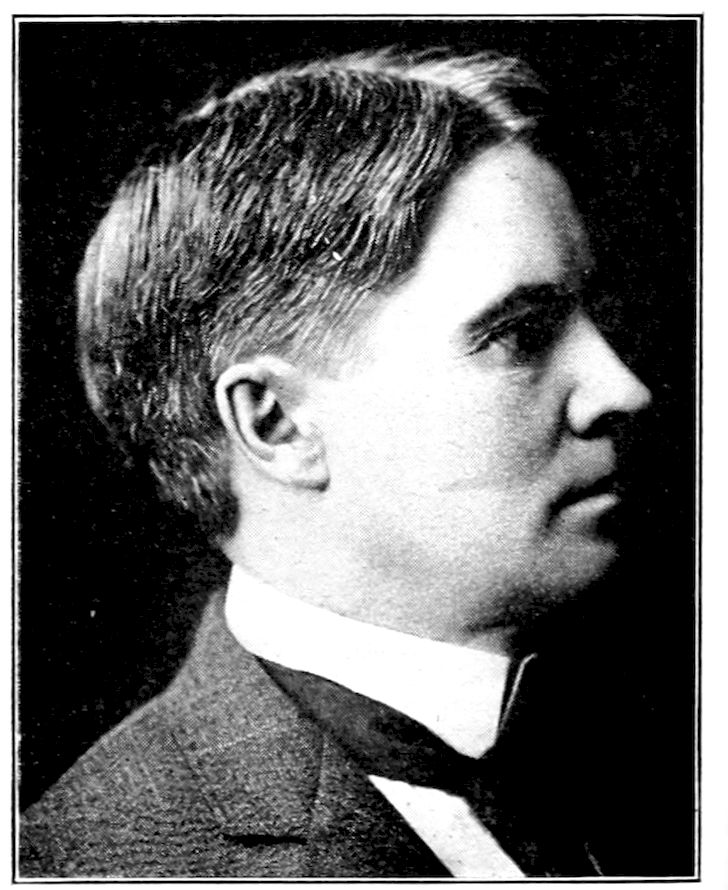

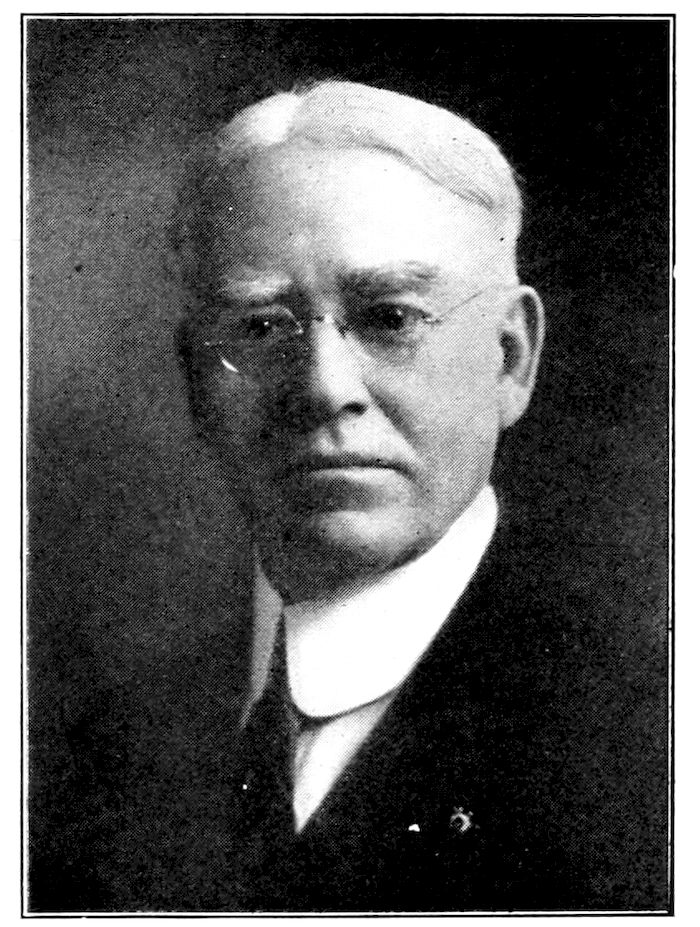

| 19Attorneys for the American Red Cross Society Under the Presidency of Clara Barton | 321 | |

| Richard Olney | ||

| Lewis A. Stebbins | ||

| William H. Sears | ||

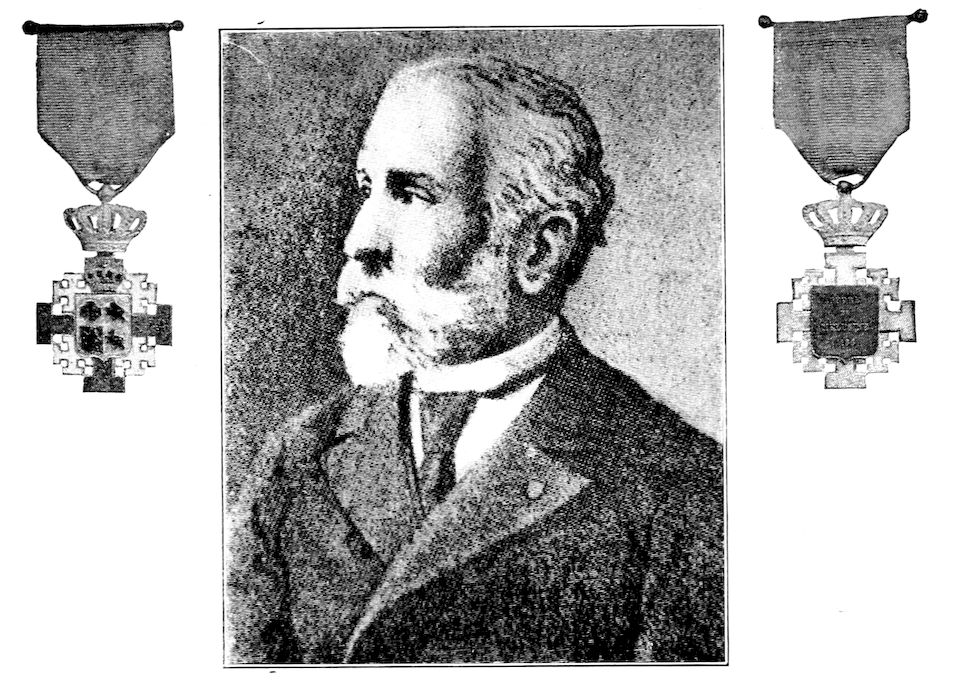

| Badges, Medals, Decorations | between pages 326 and 327 | |

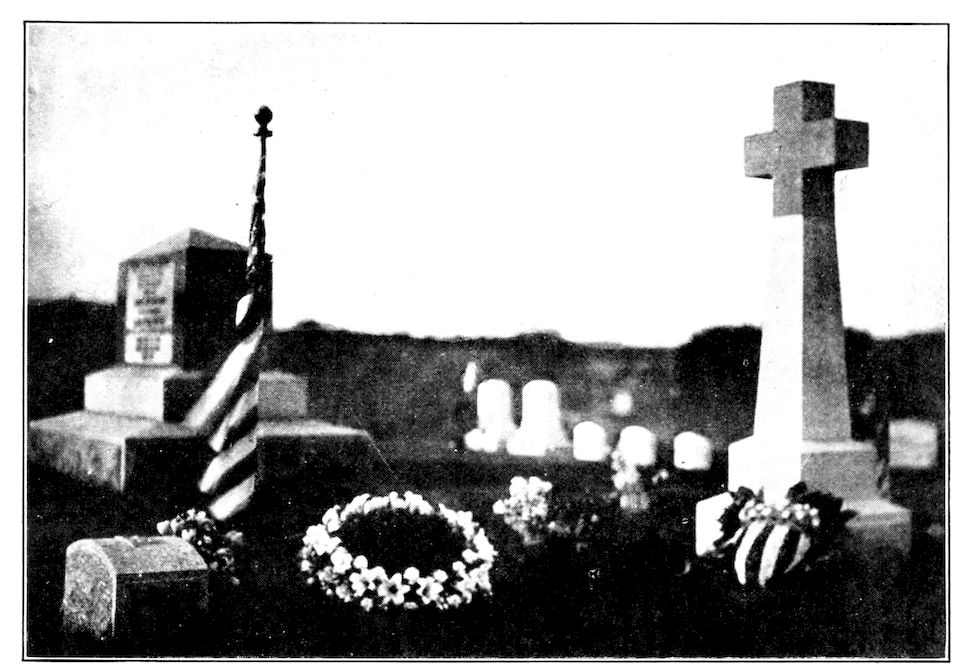

| Dorence Atwater | 332 | |

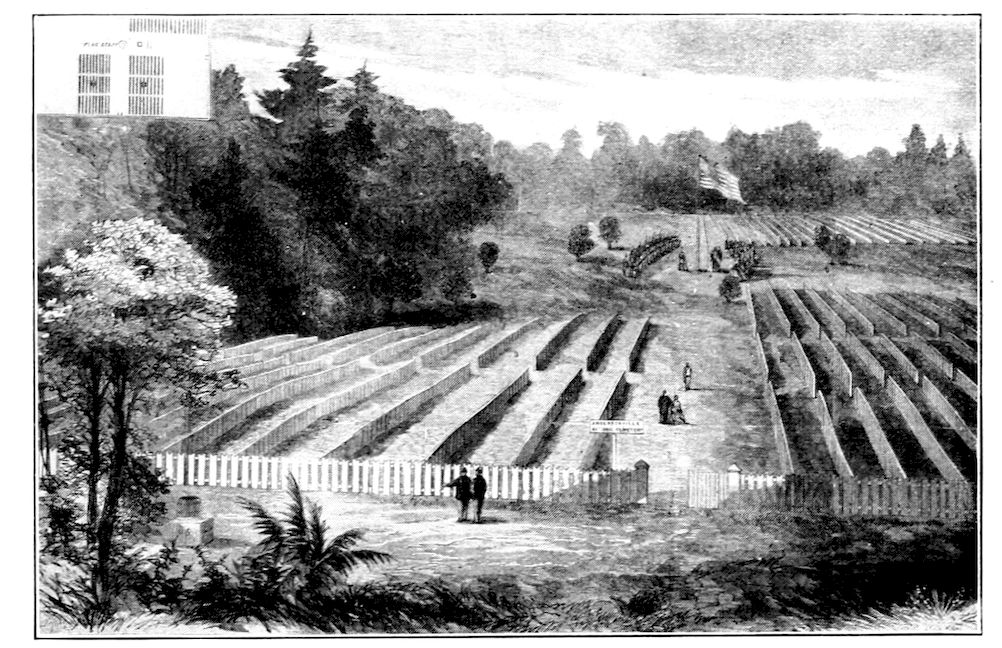

| Dedication of Memorial to Clara Barton at Andersonville, Georgia | 332 | |

| Cemetery at Andersonville, Georgia | 339 | |

| Dr. G. Pasdermadjian | between pages 342 and 343 | |

| I. H. R. Prince Guy De Lusignan | between pages 342 and 343 | |

| Abdul-Hamid | 346 | |

| William R. Day | 355 | |

| Her Business Record | between pages 358 and 359 | |

| Benjamin F. Butler | ||

| Francis Atwater | ||

| Leonard F. Ross | ||

| Redfield Proctor | between pages 358 and 359 | |

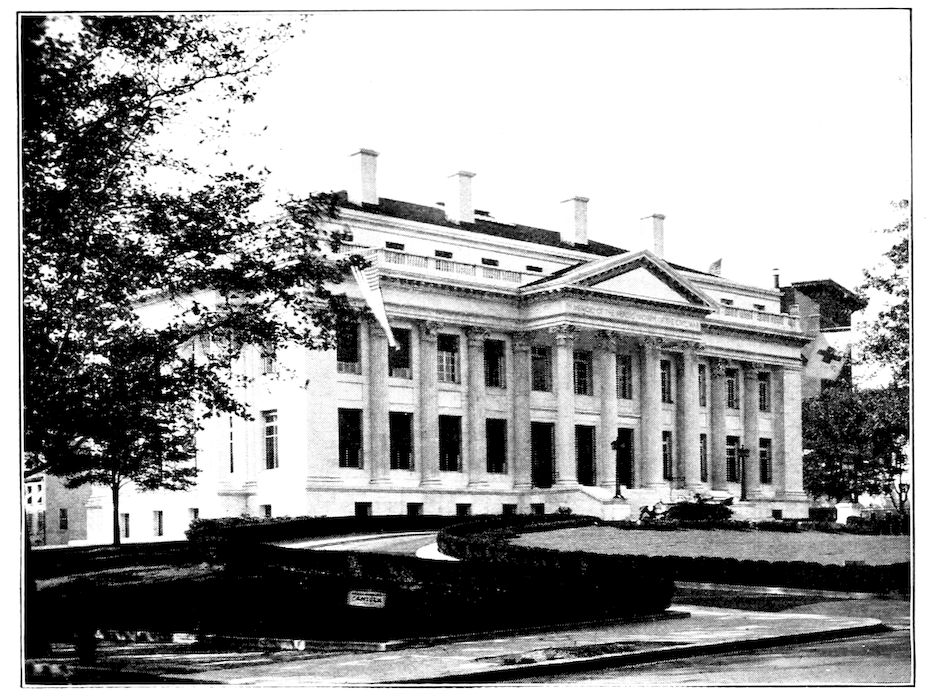

| The American Red Cross Building, Washington, D. C. | 362 | |

| Henry Breckenridge | 369 | |

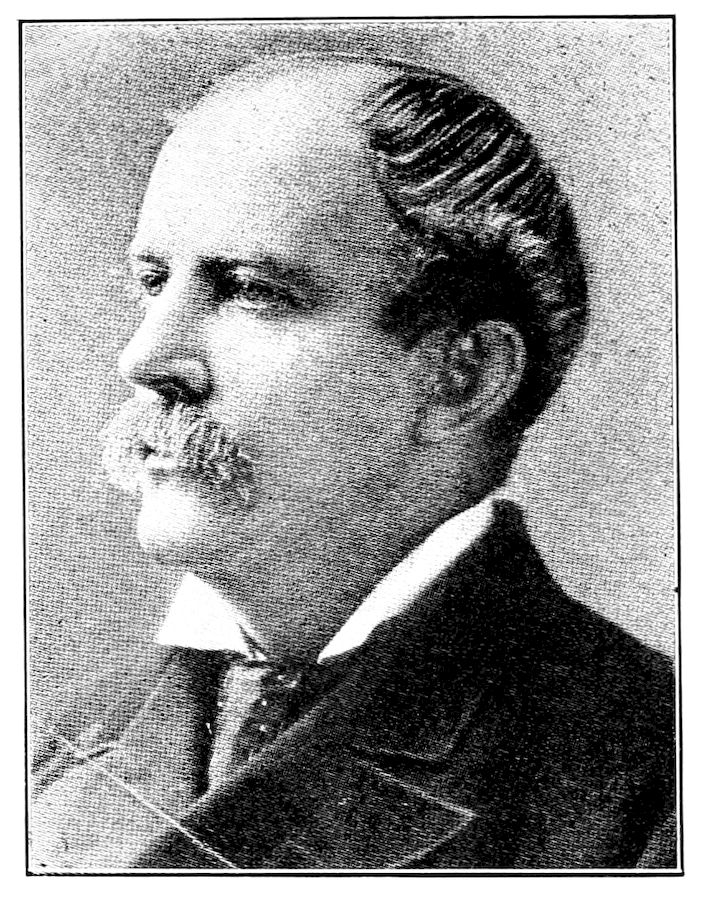

| Representative of United States Congress | 380 | |

| Champ Clark | ||

| Charles F. Curry | ||

| Denver S. Church | ||

| Reunion of 21st Massachusetts Regimen | between pages 390 and 391 | |

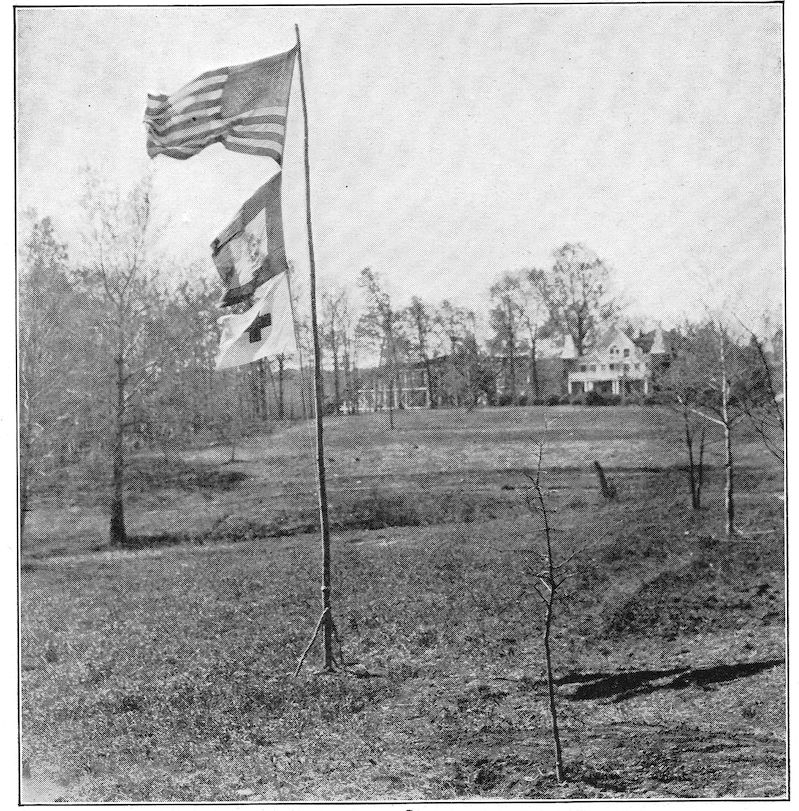

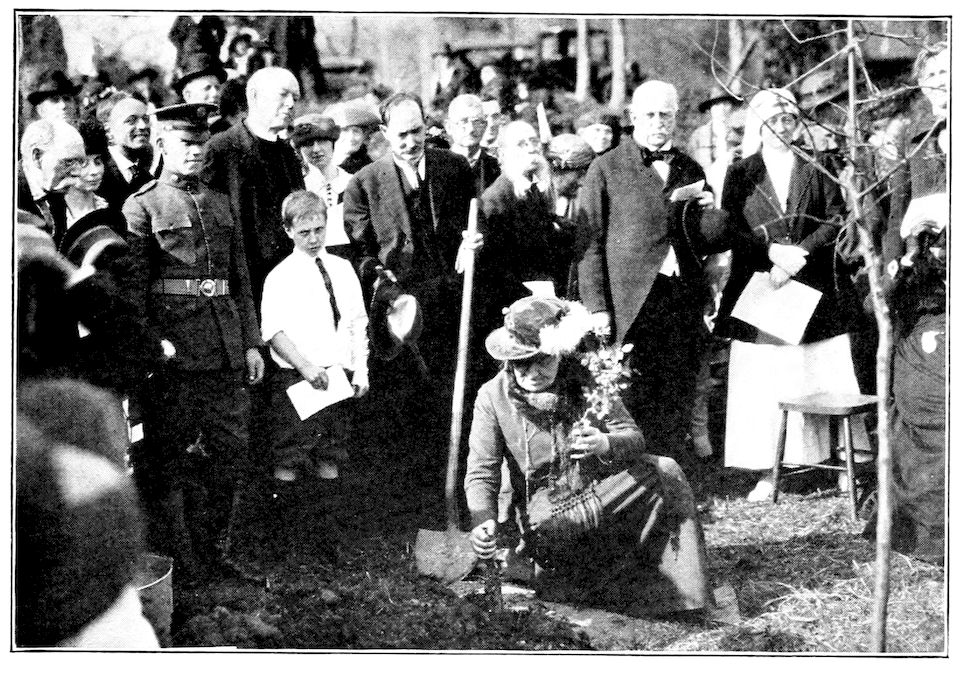

| The Memorial Tree Planting to the Memory of Clara Barton, 1922 | between pages 406 and 407 | |

| Lieutenant-General Nelson A. Miles, with the first shovel of dirt | ||

| Mrs. John A. Logan, with second shovel of dirt | ||

| The Clara Barton Oak | ||

| Miss Carrie Harrison, planting the Clara Barton Rose | ||

| Charles Sumner Young, while delivering the memorial address | ||

| William Howard Taft | 417 | |

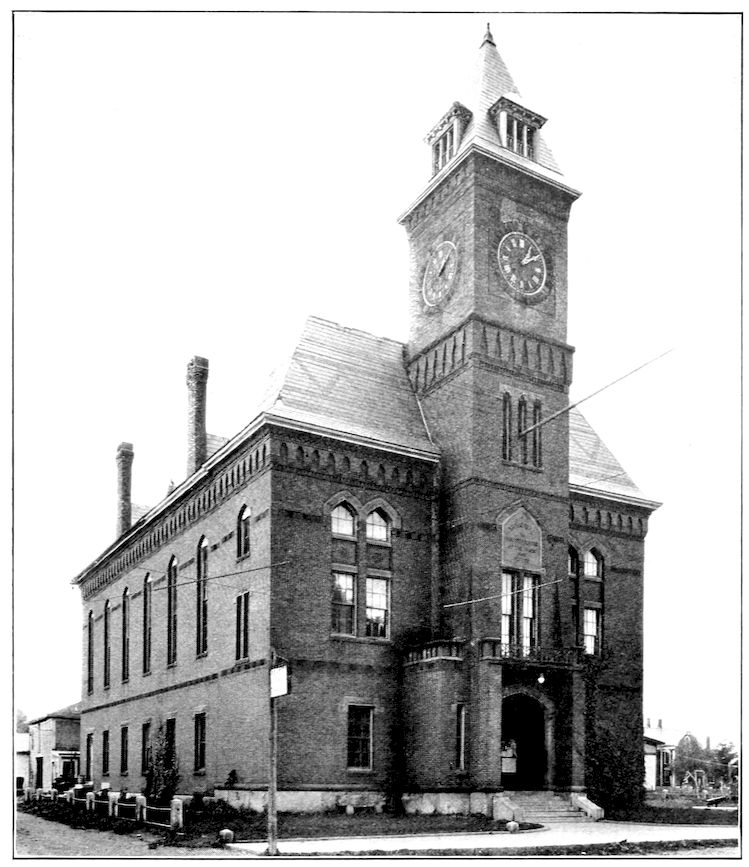

| The Inside of Memorial Building, Oxford, Massachusetts | between pages 422 and 423 | |

| The Oxford, Massachusetts, Memorial Building | between pages 422 and 423 | |

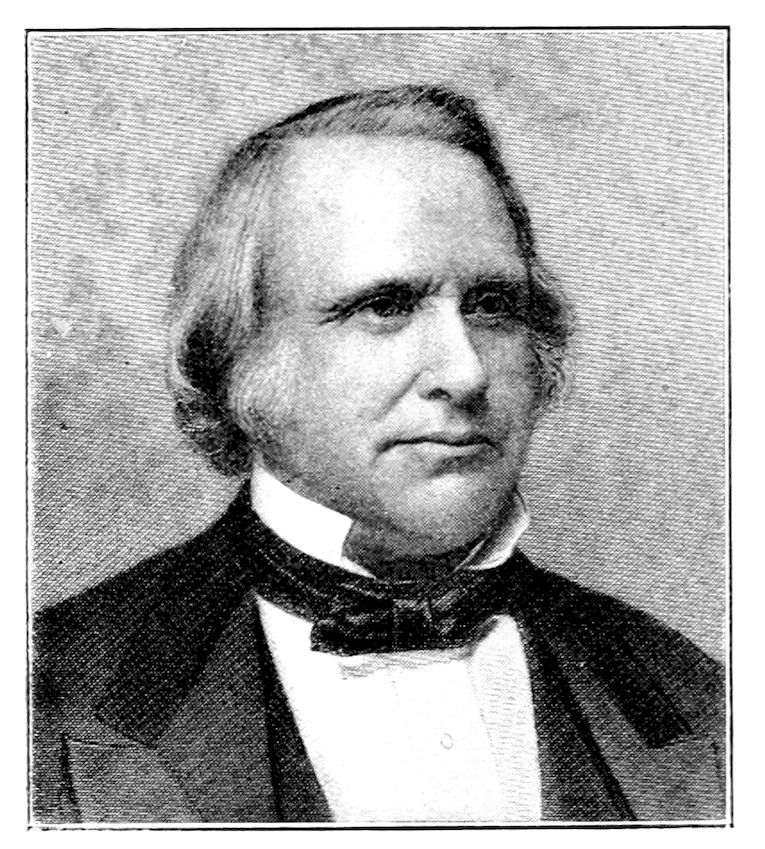

| Representative Massachusetts Statesmen | 428 | |

| Henry Wilson | ||

| Charles Sumner | ||

| George F. Hoar | ||

| 20United States Senators Who Saw the Work of Clara Barton | 430 | |

| Charles E. Townsend | ||

| Jacob H. Gallinger | ||

| H. D. Money | ||

| Nelson A. Miles | 433 | |

| John J. Pershing | 435 | |

| Abraham Lincoln | 442 | |

| The Red Cross Monument | 444 | |

| The embossed cut on the front cover is a reproduction of a bronze bust by Mrs. Otto Heideman. | ||

I take my pencil (at 86 years of age) to describe the first moment of my life that I remember. Clara Barton—In The Story of My Childhood.

Do not sin against the child. Genesis.

The rude wooden cradle in which Clara Barton was rocked is now one of the very interesting curios in possession of the Worcester (Mass.) Historical Society. The Author.

The child’s grief throbs against the round of its little heart as heavily as the man’s sorrow. Chapin.

Baby lips will laugh me down. Tennyson.

Dispel not the happy delusions of children. Goethe.

Happy child! The cradle is to thee a vast space.

Babyhood repeats itself. Babyhood is practically the same yesterday, today and forever. And yet who does not try to recall first impressions and first experiences? Clara Barton says her first baby experience that she recalls was when she was two and one half years of age. She thus describes it:—

“Baby los’ ’im—pitty bird—baby los’ ’im—baby mos’ caught ’im.

“At length they succeeded in inducing me to listen to a question, ‘But where did it go, Baby?’

“Among my heart-breaking sobs I pointed to a small round hole under the doorstep. The terrified scream of my mother remained in my memory forevermore. Her baby had ‘mos’ caught’ a snake.”

Her second experience that she recalls was when four years old, at a funeral of a beloved friend of the family. She previously had been terrified by a large old ram on the farm. On this occasion she was left in care of a guardian, in a sitting room. The four windows were open. Suddenly there came up a thunder storm. Sharp flashes of lightning darted through the rising, rolling clouds. She thought the whole heavens were full of angry rams and they were coming down upon her. Her screams alarmed, and her brother rushed into the room only to find her on the floor in hysterics.

Sorrows put permanent wrinkles on the face, in maturity; on the mind, in childhood. Only strangeness may produce fear in babyhood but, with a baby, strangeness is everywhere. Darkness and strange noises frighten. Forms of phantasy float on the imagination; 23when gradually, it’s comedy; when suddenly, it’s tragedy.

These tragic moments left their impressions on Clara Barton’s plastic mind. Such impressions ever must remain. Miss Barton said she remembered nothing but fear in her earlier years; and terror-stricken she remained to the end, except when she could serve someone in distress, or rescue someone from danger of death. An English philosopher says: “the least and most imperceptible impressions received in our infancy have consequences very important and are of long duration.” The greatest minds of earth, in all ages, have tried to recall baby experiences, and have wondered what they had to do with success or failure.

At three years Clara Barton was taken a mile and one-half to school on the shoulders of her brother Stephen; at eleven years she ceased growing, then but five feet three inches. The Author.

When I found myself on a strange horse, in a trooper’s saddle, flying for life or liberty in front of pursuit, I blessed the baby lessons of the wild gallops among the beautiful colts.

Clara Barton—The memories of her childhood belong to our little town, and are our most precious heritage.

Remember that you were once a child, full of childish thoughts and actions. Clara Barton.

The sports of children satisfy the child. Goldsmith.

Children’s plays are not sports, and should be regarded as their most serious actions. Montague.

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child. I Corinthians.

A sweet child is the sweetest thing in nature. C. Lamb.

The scenes of childhood are memories of future years.

I do not like to beat my children—the world will beat them.

The Baker homestead (Bow, N. H.)—Around the memory thereof cluster the golden days of my childhood.

A long way seems the dear old New England home—its sheltering groves and quiet hills; amid the clustering memories my tears are falling thick and silently like the autumn leaves in forest dells.

Children have more need of models than of critics.

Children think not of what is past nor of what is to come but enjoy the present time, which few of us do.

Women are only children of a larger growth.

The only fun is to do things. Clara Barton.

I pledged myself to strive only for the courage of the right and for the blessedness of true womanhood. Clara Barton.

What woman has not said “I remember when I was a girl....” Clara Barton at eighty-six years said, in 26the story of her childhood, I remember ..., I remember riding wild colts when I was five years of age. I remember how frightened I was, but acquired assurance when my brother used to tell me to “cling fast to the mane.” To this day (at eighty-six years of age) my seat in the saddle, or on the bare back of a horse, is as secure and tireless as in a rocking chair. I remember I thought the President might be as large as the meeting house and the Vice President perhaps the size of the school house. I remember telling my teacher that I did not spell such little words as “cat” and “dog,” but I spell in artichoke, artichoke being the first word in the column of three syllables.

I remember writing verses, many of which for years were preserved—some of these verses by others recited to amuse people—some verses to tease me. I remember, in school, making a mistake in pronouncing ‘Ptolmy,’ when the children laughed at me, and I burst out crying and left the room.

I remember that my father taught me politics; and that, as an old soldier,[1] he amused the other children and myself by giving us practical lessons in military life. We used improvised material, such as children are accustomed to use in “playing soldier,”—paper caps, plumes, banners, kettle for the kettle drum, tin swords, sticks for guns and bayonets—all of which were perfectly satisfactory to us.

1. A Clara Barton paternal ancestor immigrated to America from Lancashire, England, about twelve years after the landing of The Mayflower. Since that date a direct descendant of his has participated in every war, by this country.

The armies played havoc with each other, had fearful encounters and, what seemed to our young minds then, suffered disastrous results. Camps, regiments, brigades, military terms, she said, thus became familiar to her as the most ordinary matters of home.

In my home here at Oxford, we would listen with intense interest to the story of her early years, to childhood and girlhood, and to scenes and events in her old home on the hillside. Clara Barton, by her shining example to our children and our children’s children, has left a rare legacy to the town of her birth.

Bucephalus was calmed, and subdued, by the presence of Alexander and became his favorite war-horse.

My brother David was the “Buffalo Bill” of all that surrounding country.

My father was a lover of horses, one of the first in the vicinity to introduce blooded stock.

The first horses imported into the United States were brought to New England in 1629. Surviving the ocean voyage were one horse and seven mares. Oxen being used for all farm work, horses did not come into general use until one hundred years afterwards.

Joan of Arc, Clara Barton and Florence Nightingale was each an expert horsewoman and each made use of her skill in horsemanship, in war.

Like many other country girls, Clara Barton was fond of horseback riding. When twelve years of age, 29on one occasion, she ran away from home to go for a ride. She came down stairs quietly and slipped out for a ride on her favorite black horse.

Falling from the horse, she injured her knee. Determined to keep the injury a secret she joined her brothers in the field as though nothing had happened. But she limped, and her brothers noticed it. She merely told her brothers she had injured her knee, but would say no more. They sent for a doctor. By plying many questions as to how it happened, the doctor drew from her a confession. In later life—in the Civil War, in the Franco-Prussian War, in the Spanish American War, her skill as a horseback rider was of great service to her. On several occasions she had to “ride for her life.” In speaking of this accomplishment, she used to say “When I was a little girl I could ride like a Mexican.”

Clara Barton—the pitying sweetness which fills her eyes and the sympathetic lines which have been drawn about her mouth bear witness to a long intimacy with suffering and death.

Physiognomy is the language of the face. Jeremy Collier.

Physiognomy is reading the handwriting of nature upon the human countenance. Chatfield.

Palmistry is a science as old as the history of the human race. The mind deceives; the hand tells the truth; the thumb in particular, the tell-tale of character.

Show me an outspread hand and I’ll show you whether or not its master is honest, is kind, is affectionate.

Human nature, as unfolded by phrenology, is being universally accepted by all classes of people. Cranium.

Phrenology can be used in every phase of life. C. S. Hardison.

Phrenology is very fruitful in its capacity to paint mental images.

Phrenology,—a science that has been of great help to us in the progress of life. Doctor Charles H. Shepard.

The shape of the brain may generally be ascertained by the form of the skull. O. S. and L. N. Fowler.

Phrenology professes to point out a connection between certain manifestations of the mental and peculiar conditions and developments of the brain. O. S. and L. N. Fowler.

31Of all the people in England, I was most glad to meet Doctor L. N. Fowler, the same gentle, kind man he used to be so many years ago, and who has done so much for the middle classes of England, giving them helpful advice they could not get from other sources. Clara Barton.

Remembering that fully one-fifth of my life (1856) has been passed as a teacher in schools, it is not strange that I should feel some interest in the cause of education. Clara Barton.

’Tis education forms the common mind; just as the twig is bent the tree is inclined. Alexander Pope.

The physiognomist reads character in the face; the palmist in the hand; the phrenologist in the skull. Physiognomy since the origin of man has been nature’s open book. The science of palmistry is at least five thousand years old; but the science of phrenology is of comparatively recent origin. When Clara Barton was a little girl phrenology received its really first great impulse in this country, through the lectures and writings of the Doctors Fowler of England. In England, as in this country, phrenology was then the subject of much ridicule. Of this strange science Thomas Hood sarcastically writes:

32Little Clara was bashful, afraid of strangers, too timid to sit at the family table when guests were present; would not so much as tell her name when asked to do so. When spoken to by a stranger she would burst out crying—sometimes leaving the room. Now and then she would go hungry rather than ask a favor even of a member of the family. Doctor L. N. Fowler visited Oxford. While there he was a guest at the Barton home.

Doctor, what shall we do with this girl, asked the mother; she annoys us almost to death. We can hardly speak to her without her crying, from fear. The doctor examined her head. He replied, she is timid, that’s all. The “bump” of fear is over-developed. Nothing will change a child’s innate fear; that is a characteristic of her nature. She may outgrow it to some extent but her sensitive nature will remain as long as she lives. The doctor advised the parents to give her something to do; to keep her at work, and thus to let her forget herself. Don’t scold her; encourage her. When she does anything well, give her full credit—compliment her. Throw responsibility on her; when she is old enough give her a school to teach.

To be understood is the basis of friendship. The Doctor understood Clara; little Clara understood the Doctor. They became friends. That friendship lasted through life. Many years after the Doctor visited Oxford Clara Barton visited the Doctor, in London. They spent evenings together. The Doctor renewed his interest in the people of those early days in New England. He especially recalled the characteristics of Miss Barton’s father;—they became mutually reminiscent of the days of her childhood. The Doctor 33had then become old and decrepit but was still giving lectures on phrenology. The happiest hours Clara Barton spent in England were in the home of the Fowlers; with the Doctor, his charming wife and three beautiful daughters.

The earth can never have enough women like Clara Barton.

Clara Barton belonged not only to the United States but to the entire civilized world. Boston (Mass.) Globe.

A merry heart doeth good like a medicine. Proverbs.

Laugh and the world laughs with you. Ella Wheeler Wilcox.

With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come.

The next best thing to a very good joke is a very bad one.

If ever there were lost, or omitted, a well-turned joke or a bit of humor by the various members of the Barton family it was clearly an accident. Clara Barton.

Joking decides great things stronger and better of’t than earnest can. Milton-Horace.

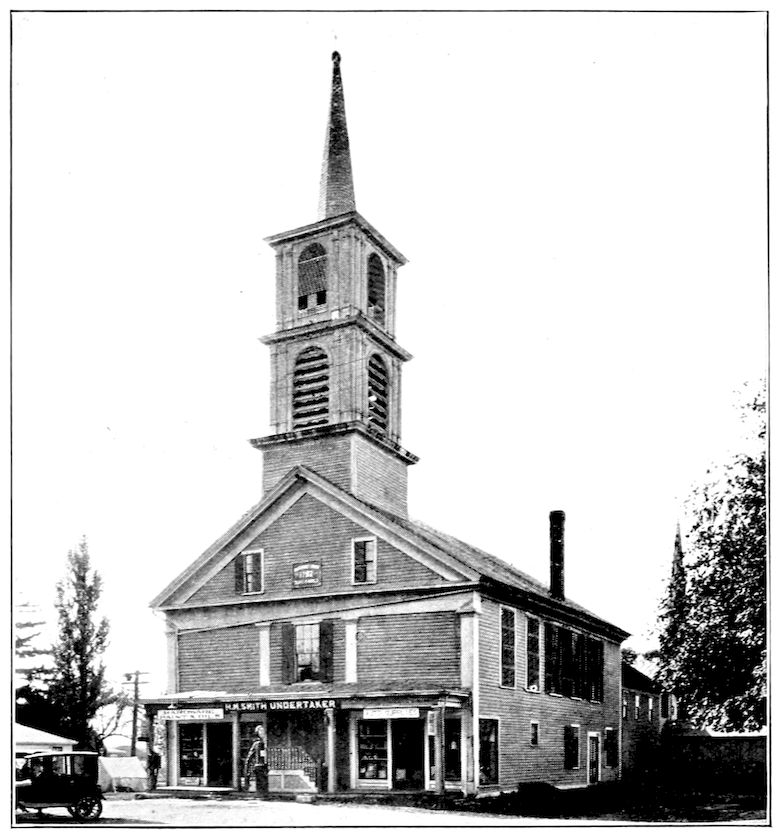

THE UNIVERSALIST CHURCH, MAIN STREET, OXFORD, MASSACHUSETTS

Where Clara Barton attended church. Oldest Universalist Church in the world, built 1792. Society second oldest. Organized April 27, 1785. Denomination organized here, September 14, 1785.

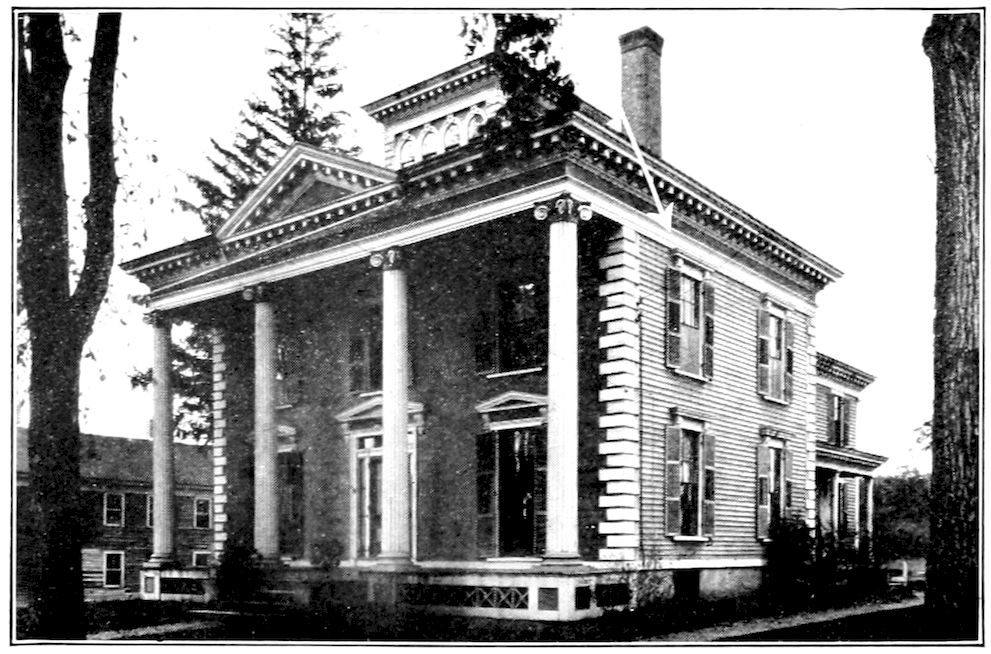

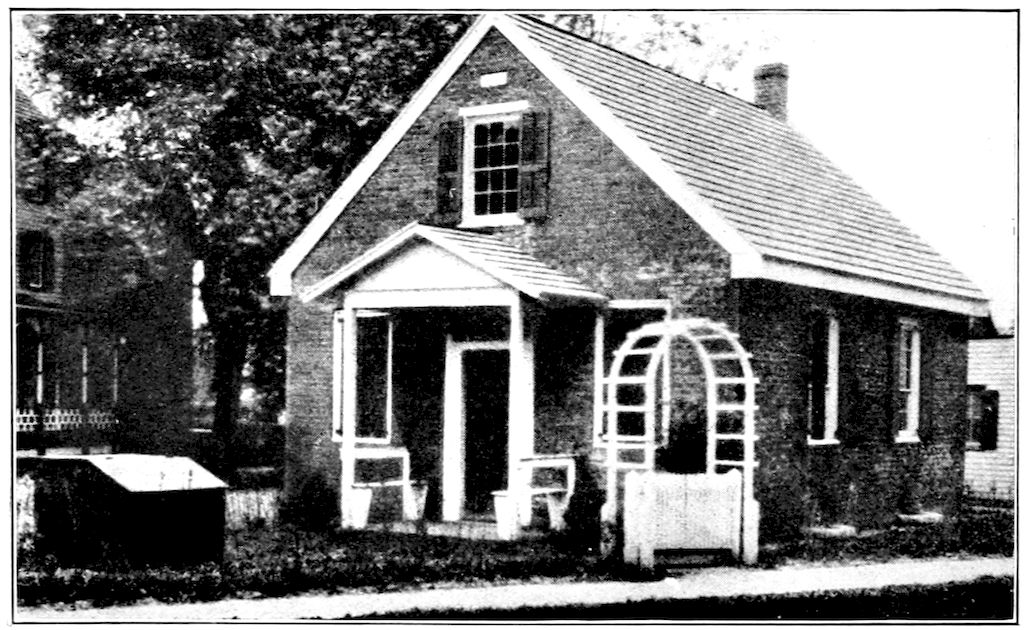

SUMMER HOME OF CLARA BARTON, OXFORD, MASSACHUSETTS

Arrow points towards the window of the room where Clara Barton was bed-ridden for several months, through her last fatal illness, in the latter part of 1911.

A timid child is invariably the butt of jokes. Clara Barton, in her youth, was not an exception. As a little girl she had learned to weave, working in a North Oxford satinet mill. She had not been it work there very long when the mill took fire and burned down. Then, as no satisfactory explanation of the cause could be given by the members of the Barton family, the fire was attributed to spontaneous combustion, brought on because Clara had worked so fast as to set the mill on fire. Clara Barton did not object to, but rather enjoyed, a joke on herself. She used to tell her friends of this joke and said that in her own town and among her playmates that joke was “told on me for many years.”

Forget not Christmas. Henry IV. of England.

A Christmas baby! Now, isn’t that the best kind of a Christmas gift for us all? Father Stephen Barton (1821).

Clara Barton was a Christmas present, given to the world.

The sweet love-planted Christmas tree. Will Carleton.

A good conscience is a continual Christmas.

This day shall change all griefs and quarrels into love.

37I will honor Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all the year. Charles Dickens.

On Christmas Day we will shut out from our fireside nothing.

’Tis the season for kindling the fire of hospitality in the hall, the genial fire of charity in the heart. Washington Irving.

I was born on one bright Christmas day, and I am told that there was a great family jubilation upon the occasion. Clara Barton.

The life of Clara Barton should be familiarized to every child.

Learning to ride, Clara, is just learning a horse.

How can I learn a horse, David? Sister Clara.

Catch hold of his mane, baby, and just feel the horse a part of yourself—the big half of the task being.

Love me, love my dog. Heyward’s Proverbs.

The one absolutely unselfish friend that a man can have in this selfish world, the one that never deserts him, and the one that never proves ungrateful, or traitorous, is his dog. Senator Vest.

We are two travellers, Roger and I—Roger’s my dog—so fond, so unselfish, so forgiving. John Townsend Trowbridge.

A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse! Shakespeare.

O for a horse with wings. Cymbeline.

A good rider on a good horse is as much above himself and others as the world can make him. Lord Herbert.

Aspiration sees only one side of every question; possession, many.

How senseless is the love of wealth and treasure. Guarini.

Remember not one penny can we take with us into the unknown land. Seneca.

A dog is a real philanthropist, his whole existence is living for others. The best “war-scout” known is the Red Cross dog, wearing the insignia. In a dog Miss Barton found a congenial spirit. Her first ownership was a dog, and known by the name of “Button.” 40He was medium-sized, very white, with silky ears, sparkling black eyes, and a very short tail. “Button” was Clara Barton’s guardian in the cradle, her playmate in childhood.

“Button” would try to pick her up when she fell down, sympathize with her in her troubles,—ever unselfish, helpful, loyal.

Clara Barton’s second individual ownership was “Billy.” “Billy” was a horse. She said he was high stepping; in color, brown; of Morgan ancestry, with glossy coat, slim legs, pointed ears, long black mane and tail, and weighing nearly nine hundred pounds.

Ownership endowed “Billy” with wonderful characteristics. He could trot, rack, pace, single-foot,—a Bucephalus worthy of world fame. “Like beads upon a rosary” she would count and recount the joys of memory, memory of her saddle horse, and she on his back, riding like mad, at ten years of age. He had many characteristics, doubtless, that she didn’t recount. As a horse is known to be “a vain thing for safety” “Billy” could probably run away, get frightened at a shadow, senselessly “kick up” and “smash-up,” as do other horses. But fun is in the danger; the greater the danger to life and limb the greater the fun. “Billy” would not stand over her to guard her, nor help her up when she fell down, but was useful and gave her pleasure. “The true, living love is love of soul for soul,” hence mankind loves, in return for love, only what gives love; but mankind also pretends to love 41what it can force to serve man’s purpose. The dog spirit and the horse spirit satisfy the longings of human nature—all the world loves a dog and assumes to love a horse.

In hearing of the cannon’s roar one afternoon, an officer galloped up asking, “Miss Barton, can you ride?” “Yes sir.” “But you have no saddle—could you ride mine?” “Yes sir, or without it, if you have blanket and surcingle.” “Then you can risk an hour.” An hour later the officer returned at breakneck speed—and leaping from his horse said: “Now is your time Miss Barton; the enemy is already breaking over the hills.”

Romance enters into ownership of pet animals. Probably “Button” was just a dog and “Billy” only a horse. But one has said that the right of ownership is the cornerstone of civilization. Ownership of what is worthy of love at least enriches character—contributes to the happiness of human existence. If the Father of his Country was right, that the object of all government is the happiness of the people, then the love of animals serves a very high purpose.

With the first “gold dust” suddenly acquired, an illiterate Western miner built on the desert a stone mansion. He ornamented it with gold door knobs 42door hinges of silver—the doors opening but to golden keys.

Where human beings throng, and men and women suffer, Clara Barton built a structure and ornamented it with a RED CROSS on a white ground—the emblem of service to the suffering. With unusual earning capacity for seventy-five years, and at all times practicing greatest economy, Clara Barton’s ownership at her passing was but $21,000. The Glen Echo Red Cross home that had been used, free of cost to the RED CROSS, was valued at $5,000. While the owner lived she continued to keep it as a charity center—a home for the homeless and indigent—ex-soldiers, civilians, children.

In her closing years she had, therefore, for her own personal and exclusive use in money and realty, not to exceed $21,000. This was nine thousand dollars less than the value of her property when she first became interested in Red Cross work. “Mere money,” she said, “never separates me from my friends. I don’t care for money; I wish only not to become an object of charity, and to be a burden to my friends when I am unable to work for others.”

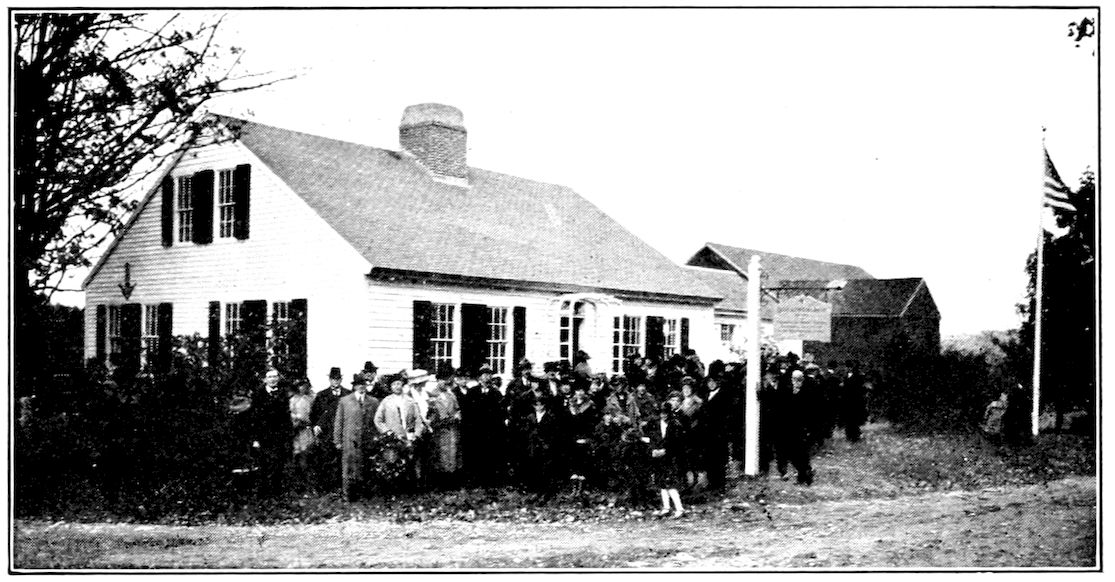

BIRTHPLACE OF CLARA BARTON, NEAR OXFORD, MASSACHUSETTS

On March 14, 1921, the title to the Barton Homestead was transferred by Carl O. Carlson to The Woman’s National Missionary Society of the Universalist Church. It is now known as The Clara Barton Memorial Home. Mementoes, Red Cross literature and all else possible to obtain that appertain to Clara Barton’s life work will be assembled here and become a part of the Memorial. The homestead consists of the house where Clara Barton was born, and eighty-five acres of land. It was dedicated as a shrine for the public, October 12, 1921.

Arrow points to the room where Clara Barton was born. Size of the room 8 × 10 feet. Ceiling 8 feet high. Clothes closet 5 feet 2 inches × 2 feet 5 inches. Two windows each 4 feet 5 inches high × 2 feet 3 inches wide. Two sashes in each window; six panes of glass in each sash.

OFFICERS OF THE W. N. M. A. PRESENT AT THE DEDICATION OF THE CLARA BARTON MEMORIAL ON OCTOBER 12, 1921.

Left to Right: Mrs. Bertram O. Blaisdell, Trustee; Mrs. Ethel M. Allen, Rec. Sec’y (now President); Mrs. Marietta B. Wilkins, President; Mrs. Fred A. Moore, Literature Secretary; Miss Susan M. Andrew, Trustee (Chairman Clara Barton Guild).

Every child in the country has known of Clara Barton.

Pestalozzi was the Father of the Public School; Washington the Father of his Country; Lincoln, the Father of a Race; Clara Barton, the Mother of the Red Cross. The Author.

The building which housed Clara Barton in her efforts for popular education is still standing along with other historic landmarks.

If you will let me try, I will teach the children free for six months. Clara Barton.

I thank God that we have no free schools—in the colony—and I hope we shall not have these hundred years.

The first incorporation to provide free schools, under the provisions of the State, was passed in New York in 1805.

The basis of free government is in education; in a republic the hope of the millions is the free public school.

The hope of all modern civilization is the public free school.

I taught in an uninclosed shed at North Oxford, there being no house for that purpose. Clara Barton.

The first meetings for the establishment of a kindergarten system at Washington was held at the Clara Barton home, in Washington; 44among others present Phoebe Hearst and Mrs. Grover Cleveland, wife of the President, the chairman. The Author.

Let us live in our children. Frederick Froebel.

New Jersey had no public schools. The people said they were not paupers and would not have their children taught at public expense—would not send them to “pauper schools.” In New Jersey Clara Barton opened, for the first time, what was called a “free school for paupers.” Since those puritan days, what a change in public sentiment! Then it was “Pauper school” education; now

Free education is the poor man’s marble staircase that leads upward, and into, the palaces of wealth, health and happiness.

Clara Barton was told that a public school was impossible; every time it had been tried, it had failed. At Bordentown she found herself with six bright boys, and the public school[2] commenced. At the end of twelve months her six pupils had grown to six hundred pupils—among whom no corporal punishment had been administered.

2. The School Building, erected in 1837. School taught by Clara Barton, in 1853. Building and site the property of New Jersey, purchased through contributions by teachers and pupils. Building dedicated June 11, 1921, and now known as The Clara Barton Memorial School but used as a Clara Barton Museum.

“Pauper schools” became thence in fact the free public school; now the free public school is the one institution from whose flagstaff freedom’s flag is never hauled down.

Clara Barton taught the rich to be unselfish and the strong to be gentle. Charles E. Townsend, U. S. Senate.

Miss Barton was a soft-voiced, retiring little woman, yet she had a way of approaching her work in a most telling manner.

Miss Barton followed her own light with steadfast steps.

Clara Barton—a model of the beautiful simplicity of a life given to others. Bridgeport (Conn.) Standard.

The severest test of discipline is its absence. Clara Barton.

Social, friendly and human, Clara Barton joined with the children in the playgrounds;—instead of being locked out as the previous teachers had been she “locked” herself “in” the hearts of every boy and girl. The Life of Clara Barton, by Epler.

Show me a child well disciplined, perfectly governed at home, and I will show you a child that never breaks a rule at school.

Whenever corporal punishment is inflicted on a pupil it is a sign of negligence and indolence on the part of the teacher, says Seneca.

In refinement of taste and beauty of action, or purity of thought and delicacy of expression, nature’s own best teacher is woman.

To the child nothing is small; nor does the child forget. Whatever kindness comes to the child is stored in one of the cells of the brain for future years. As an heirloom, the longer it is possessed the more it is cherished.

Referring to her teacher of long ago, Dr. Eleanor Burnside recently related this incident in her school life: “I recall when a little girl in her school Clara Barton’s friendly interest in the progress of her pupils; unvarying patience, no matter what the circumstances might be. I do not think she knew how to scold, nor were scoldings and other manifestations of ill temper necessary. Her quiet, firm word, pleasantly expressed, seemed sufficient always.”

Not easily disturbed, Miss Barton did not notice little misdemeanors by the children at all. She seemed not to observe one day when some fun was started by a boy sitting back of Joe Davis. The mischievous boy was putting his finger in Joe’s red hair and pretending his finger was burnt. Of course it amused the children, but only for a moment. To govern too much is worse than to govern too little. This was an incident merely of a child’s humor, requiring no reprimand. “But no 47matter what happened, Clara Barton did not scold. Her pupils loved her and that made what she did, and what she said too, right.”

The old desk used by Clara Barton recently has been found in possession of one of the old families at Bordentown, New Jersey. By tracing back the ownership it has been proved conclusively to be the original desk used by Miss Barton. The desk refuted the libel that she was a disciplinarian, and not a humanitarian. The libel referred to was that she had a particularly unruly boy; that she seized him by the nape of the neck, lifted the lid of the desk and dropped him inside. Now that the desk has been discovered, her admirers point to the interesting fact that it doesn’t have a top lid; it has a small drawer.

Childhood is ever of the living present. Up the stream of time the eye keeps fixed on memory’s treasures of youth. In one of the battles of the Civil War, Clara Barton stooped down to place the empty sleeve, then useless to the bullet-shattered right arm, over the shoulder of a soldier boy. Recognizing the face of his former teacher the fair-haired lad dropped his face into the folds of her dress, then threw his left arm around her neck, in deepest grief, crying: “Why, Miss Barton, don’t you know me? I am Charlie Hamilton who used to carry your satchel to school.”

Like a patriotic soldier Clara Barton responded in the youth of her womanhood to the call of service to others.

Clara Barton is one of the greatest heroic figures of her time.

Clara Barton—our greatest national heroine. Literary Digest.

We reckon heroism today, not so much on account of the thing done as the motive behind the act. Chauncey M. Depew.

Yes, it is over. The calls are answered, the marches have ended, the nation saved. Clara Barton.

The best blood of America has flowed like water.

The soldier is lost in the citizen. Clara Barton.

The proudest of America’s sons have struggled for the honors of a soldier’s name. Clara Barton.

Their glory, bright as it shone in war, is out-lustered by the nobleness of their lives in peace. Clara Barton.

I shall never take to myself more honesty of purpose, faithfulness of zeal, nor patriotism, than I award to another. Clara Barton.

What can be added to the glory of a nation whose citizens are its soldiers? Whose warriors, armed and mighty,—spring from its bosom in the hour of need, and peacefully retire when the need is over. Clara Barton.

49I have taught myself to look upon the government as the band which the people bind around a bundle of sticks to hold it firm, where every patriot must grapple the knot tighter.

If our government be too weak to act vigorously and energetically, strengthen it till it can act; then comes the peace we all wait for, as kings and prophets waited—and without which like them we seek and never find. Clara Barton.

Henry Wilson worked on a farm at six dollars per month. Then he tied up his scanty wardrobe in a pocket handkerchief, and walked to Natick, Massachusetts, more than one hundred miles, to become a cobbler. The trip cost him but $1.88.

I am the son of a hireling manual laborer who, with the frosts of seventy winters on his head, lives by daily labor. I too lived by daily labor. Henry Wilson.

Henry Wilson, born in New Hampshire, February 16, 1812; elected to U. S. Senate, 1855; elected Vice-President, 1872; died November 22, 1875. The Author.

We should yield nothing to our principles of right.

The sorrows of drunkenness glare on us from the cradle to the grave. Henry Wilson.

I would not have upon my soul the consciousness that I had by precept or example lured any young man to drunkenness for all the honors of the universe. Henry Wilson.

Clara Barton’s never-failing friend, Senator Henry Wilson.

Way back in 1857 in Worcester, Massachusetts, Clara Barton showed her humanitarian spirit and organization ability. Under the Reverend Horace James, she assisted in the organization of the Band of Hope,[3] a society originating in Scotland whose object was: “To Promote the Cause of Temperance and Good Morals of the Children and Youth.”

3. First Temperance Society organized in America, in 1789; First National Temperance Convention, in 1833; a “temperance revolution” urged, in 1842, by Abraham Lincoln; Women’s Christian Temperance Union organized in 1874; National Prohibition went into effect January 16, 1920.

On the breaking out of the Civil War, the Reverend James became Chaplain of the Twenty-fifth Massachusetts Regiment, and two of the boys that Clara Barton induced to join the society became officers of the Fifty-seventh Massachusetts Regiment. One was Colonel J. Brainard Hall and the other Captain George E. Barton. At the Battle of the Wilderness the Colonel Hall referred to was seriously, then thought to be fatally, wounded. Clara Barton was the first at his side to nurse, and to care for, him. As soon as he was able to be moved, she sent him to Washington to be cared for there by one whom she told him was her very dear friend. Stranger than fiction, on reaching Washington, Colonel Hall discovered this friend to be the “Hired Man,” previous to 1839, who worked in his grandmother’s shoe-shop,—the late Henry Wilson, Vice-President of the United States.

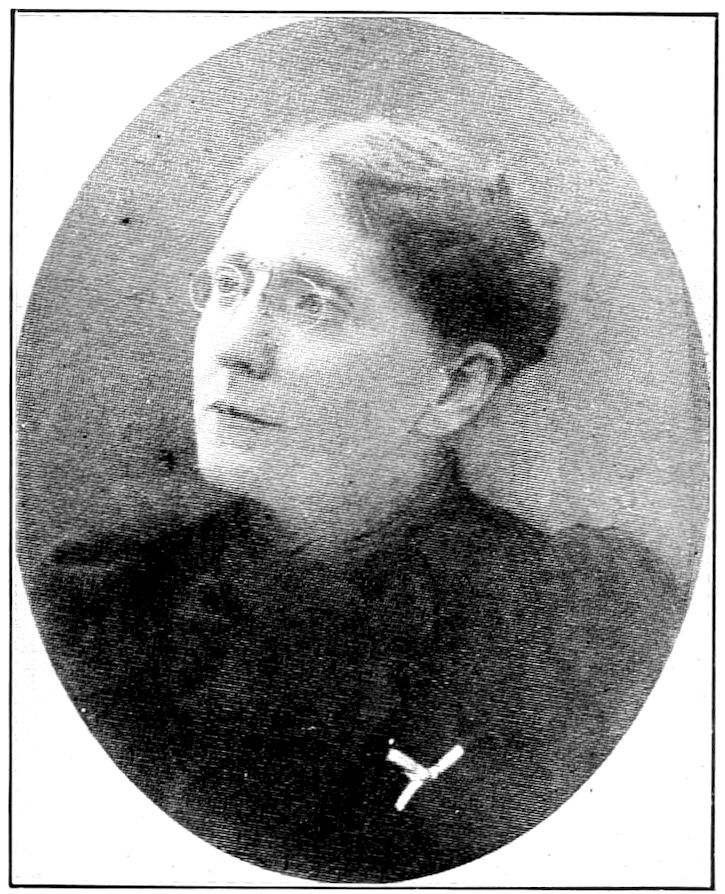

Every woman who loves her country and who realizes what true patriotism means will always revere the name of Clara Barton, and connect it with the highest ideal of service to one’s country. Dr. Anna H. Shaw President American Woman Suffrage Association.

Clara Barton has won the hearts of the women of the world. Carrie Chapman Catt, President American Woman Suffrage Association.

John Marshall, for thirty-five years Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, held the female sex the equals of men.

I had not learned to equip myself—for I was no Pallas ready armed but grew into my work by hard thinking and sad experience.

I am a woman and know what barriers oppose all womanly efforts. Harriet G. Hosmer.

Clara Barton is the best clerk, either man or woman, I ever had in my office. Mr. Mason, Commissioner of Patents.

It is less difficult for a woman to obtain celebrity by her genius than to be forgiven for it. Brissot.

Only the machinery and plans of Heaven move unerringly and we short-sighted mortals are, half our time, fain to complain of these. Clara Barton.

It is possible for the wisest even to build better than he knows.

52Who furnished the Armies; who but the Mothers? Who reared the sons and taught them that liberty and their country was worth their blood? Who gave them up and wept their fall, nursed them in their suffering and mourned them, dead? Clara Barton.

There is none to give woman the right to govern herself, as men govern themselves by self-made and self-approved laws of the land.

Only the Great Jehovah can crown and anoint man for his work, and he reaches out and takes the crown and places it upon his head with his own hand. Clara Barton.

Whenever I have been urged as a petitioner to ask equal suffrage for women a kind of dazed, bewildered feeling comes over me.

In making an appeal to her soldiers for “votes for women” Clara Barton said: “When you were weak and I was strong, I toiled for you; now you are strong, and I am weak. Because of my work for you, I ask your aid; I ask the ballot for myself and my sex. As I stood by you, I pray you stand by me and mine.” The Author.

Clara Barton advocated “Votes for Women” on the platform of the First National Suffrage Convention in this country.

Among the ancients, controlling the certain affairs worthy of man, were many goddesses; of these, Venus, Ceres, Juno, Diana, Pomona, Minerva. Such man’s inherent respect for femininity that feminine names in classic days were given to temples of worship; to the continents, Europe, Asia, Africa, and later to America.[4] Feminine names with few exceptions, also, have been given to all countries,—“she” and not “he,” likewise the word used to identify great things mechanical and useful. Long and hard has been the contest for woman to achieve in fact what in spirit seemingly comports with womanhood. In this contest through the last half of the nineteenth, and the first half of the twentieth, century Clara Barton was conspicuous.

4. In 1507, by Martin Waldseemuller, the name of America was given to the then newly discovered continent.

THE SCHOOL HOUSE

Built of brick, in 1839, where Clara Barton taught school in 1853. See page 47.

THE DESK USED BY CLARA BARTON

See page 47.

THE CLARA BARTON MUSEUM

The old school house reconstructed. See page 47.

53Alone in the world, dependent upon her own efforts for a living and looking for a “job,” the following is what in letters Miss Barton says of herself in 1854 and 1860 respectively:

In a letter to her friend Miss Lydia F. Haskell, Washington, D. C., January 20, 1854, Clara Barton said:

“Well, I am a clerk in the United States Patent Office, writing my fingers stiff every day of my life.... The truth is, I have written nights until one or two o’clock for the last two weeks. I shall not be so very busy long. I am just now fitting the mechanical report for the press; that off my hands and I shall be quite at ease, I suppose.”

In a letter to Frank Clinton, Bordentown, New Jersey, dated January 2, 1860, Clara Barton said:

“I can teach English, French, drawing and painting.... I am a rapid writer or copyist, and have the reputation of being a very good accountant ... and if, in your travels through the South, you see an opening for me, tell me.”

As the pioneer woman in Government service Clara Barton was the object of commiseration. And only because she was a woman, she suffered through jeers and hoots and cat-calls, and tobacco smoke in her face, and slanderous whisperings in the hallways and boisterous talks about “crinoline”—all sorts of offensiveness, on the part of Government employees. Clara Barton in the public school, in the patent office, in the Civil War, in the Franco-Prussian War, in the Cuban War, in national disasters, in the presidency of the Red 54Cross, now filled by the President of the United States, is a series of object lessons of the greatest significance in the progress of womankind in the public service. Clara Barton the intruder among men in the patent office in 1855, and Jeannette Rankin, the honorable among men in Congress in 1918, are the exponents respectively of two conditions of American sentiment as to the public function of women in the United States.

Possibly because of her sad experience as a woman in the public service, she became one of those who, with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other suffragettes, blazed the way to equal rights for women—equal rights now approved by the President, the United States Congress and the American people. At a meeting of the American Suffrage Association held in Washington, D. C., in language most caustic and argumentative, in part in a public address Clara Barton said:

A woman shan’t say there shall be no war—and she shan’t take any part in it when there is one; and because she doesn’t take part in the war, she must not vote; and because she can’t vote she has no voice in her Government. And because she has no voice in her Government she is not a citizen; and because she isn’t a citizen she has no rights, and because she has no rights she must submit to wrong; and because she submits to wrong she isn’t anybody. Becoming optimistic, she said, the number of thoughtful and right minded men who will approve equal suffrage are much smaller than we think and, when equal suffrage[5] is an accomplished fact, all will wonder as I have done, what the objection ever was.

5. The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution proclaimed August 26, 1920.

Clara Barton’s simple life was long, and so full of stirring incidents that all the books will not record the whole of it.

Be not like dumb-driven cattle.

The Ox has therefore stretched his yoke in vain.

A man loves the meat in his youth that he cannot endure in his age. Much Ado About Nothing.

Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.

The sign of true, not casual, progress, ... is the progress of vegetarianism ... more and more people have given up animal food. Tolstoi.

I had not then learned the mystery of nerves. Clara Barton.

Among the Puritans the horse was a luxury; the beast of burden was the ox. In the first half of the nineteenth century the ox made possible in Massachusetts even the existence of man. In the snows of 56winter, at seed time and at harvest, the toiling ox was loyal—faithful to the best interests of the family. The ox himself was unsuspecting, and untutored in the art of deceiving others. He couldn’t think his kindly attentive Master, Man, unappreciative, disloyal—wholly obsessed with greed. He didn’t know that money was above life,—he hadn’t read war-history. He didn’t know that through the love of money, by man, come life’s woes. The ox knew only that he was the friend to man; and he thought man must be his friend. Poor credulous ox! And yet in the child the friendship of the ox is not misplaced. Innocent child! to man and beast Heaven’s best gift, a loyal friend.

Captain Stephen Barton kept a dairy. When a small girl Clara used to drive the cows and oxen to, and from, the pasture. Clara also assisted morning and evening in milking the cows. One evening she observed three men, one holding in his hand an axe, driving a big, red, fat ox into the barn. She saw the man with the axe strike the ox in the head, then saw the ox drop to the floor. At the same moment she fell unconscious to the ground. She was carried to the house, placed on a bed, and a camphor bottle freely used. When she regained consciousness, in reply as to why she fell, she said: “Someone struck me.” “Oh, no, no one struck you,” they said. “Then what makes my head sore,” she asked. At that time her desire for meat left her; and in later years she used to say, “all through life to the present, I have eaten meat only when I must for the sake of appearances. The bountiful ground always yields enough for all of my needs and wants.”

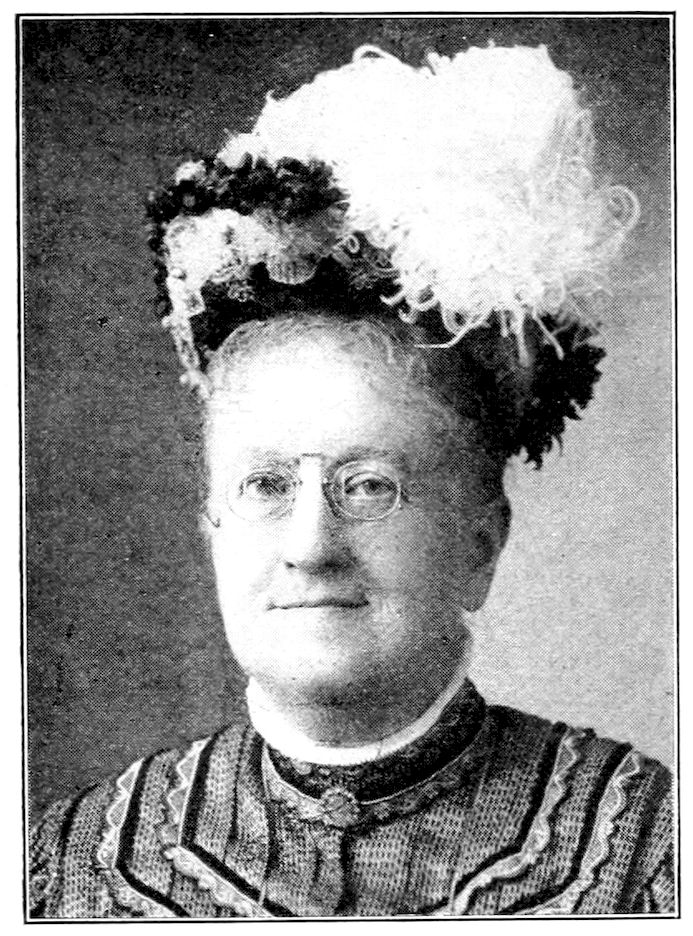

ANNIE WITTENMEYER

Clara Barton is second to none of womankind.—Mrs. Annie Wittenmeyer, First President W. C. T. U.

JOHN B. GOUGH

Clara Barton’s lecture—I never heard anything more thrilling in my life.—John B. Gough, America’s Greatest Temperance Lecturer.

MARY STEWART POWERS

Clara Barton was prominent among women as an advocate of the cause of temperance. Through her leadership in practical humanitarianism she endeared herself to the whole world. Her good name will live forever.—Mrs. Mary Stewart Powers, Public Lecturer and State Superintendent of Scientific Temperance of Ohio.

FRANCES WILLARD

President W. C. T. U.

In the name of your God and my God, ask your people and my people not to be discouraged in the good work (Red Cross) they have undertaken.—Clara Barton. From Armenia, in 1896, to Miss Willard.

See page 347.

The Mother, patriot though she were, uttered her sentiments through choking voice and tender trembling words, and the young man caring nothing, fearing nothing, rushed gallantly on to doom and to death. Clara Barton.

The soldier’s fear is the fear of being thought to fear. Bovee.

Self trust is the essence of heroism. Emerson.

I have no fear of the battle field; I want to go to the suffering men. Clara Barton.

I was always afraid of everything except when someone was to be rescued from danger or pain. Clara Barton.

Like the true Anglo-Saxon, loyal and loving, tender and true, the Mother held back her tears with one hand while with the other she wrung her fond farewell and passed her son on to the State.

The first time Clara Barton visited in New Haven, she wore a gray dress that had bullet holes in it—received in caring for the wounded at Fredericksburg. In describing the battle scene Clara Barton said: “Over into that City of Death; its roofs riddled by shells, its very Church a crowded hospital, every street a battle line, every hill a rampart, every rock a fortress, and every stone wall a blazing line of forts!”

As Miss Barton was being assisted off the bridge by an officer, an exploding shell hissed between them, passing below their arms as they were upraised, carrying away both the skirts of his coat and her dress. A moment later, on his horse, the gallant officer was struck by a solid shot from the enemy; the horse bounded in the air and the officer fell to the ground dead, not thirty feet in the rear.

In her usual modest manner, in relating war incidents, she described the experience to a lady friend and said: “I never mended that dress. I wonder whether or not a soldier ever mends a bullet hole in his clothes.”

Military glory—that attractive rainbow that rises in showers of blood, that serpent’s eye that charms to destroy.

The friends of humanity will deprecate war, whenever it may appear. George Washington.

There is no need of bloodshed and war. Abraham Lincoln.

Wars are largely the result of unbridled passions.

War is only splendid murder. James Thomson.

War is the mad game that the world so loves to play. Swift.

Every battleship is a menace to the peace of the world. With each new battleship every nation carries a chip on its shoulder.

The Red Cross took its rise in, and derived its existence from, war. Without war it had no existence. Clara Barton.

Deplore it as we may, war is the great act of all history.

War has been the rule, if not largely the occupation, of the peoples of the earth from their earliest history. Clara Barton.

Scarcely a quarter of the earth is yet civilized, and that quarter not beyond the probabilities of war. Clara Barton.

General Sherman was right when, addressing an assemblage of cadets, he told them “war was hell!” Take it as you will, it is this;—whoever has looked active war full in the face has caught some glimpse of regions as infernal as he may ever fear to see.

60Only time, prolonged effort, national economics, universal progress and the pressure of public opinion could ever hope to grapple with the existence of war, the monster evil of the ages.

I have studied the massing of forces and scanned from point to point the old battle-grounds of Marengo and Jena and Waterloo and the Magenta and Solferino and it has seemed to me that these armies had a fairer field and a better chance than ours, in the Civil War. Clara Barton.

War may be a great harmonizer, but it is not a humanizer.

That which is won by the sword must be held by the sword, whether it is worth the cost or not. Clara Barton.

If there be any power on earth which can right the wrongs for which a nation goes to war, I pray it may be made manifest.

If there be any good wars, I will attend them.

That noble and numerous class of patriots who are brave with other men’s lives and lavish of other men’s money. Gladstone.

There never was a good war, nor a bad peace.

Don’t talk about war; we have done with war. The Peace of the world is the question now. Clara Barton.

Clara Barton was a patriot, but “not a war woman.” She had no sympathy with the religion such as was Odin’s, of the ninth century, which religion assured for him who had killed in battle the greatest number the highest seat reserved in the Paradise of the Valhalla; 61nor with the sentiment of the King of Denmark of that day, “What is more beautiful than to see the heroes pushing on through battle, though fainting with their wounds;” nor with the sentiment of that same king’s boast, “War was my delight from my youth, and from my childhood I was pleased with a bloody spear.”

Wolves in “packs” seek prey; so do men—in sheep’s clothing. Wolves truthful, in howls, send forth their propaganda—hunger; men untruthful, in words, send forth their propaganda—hate. If the “survival of the fittest” be nature’s law only brutes conform to nature—by using no weapons. Men kill their own “kith and kin”; brutes combine to protect their own species. The more one sees of men on war’s slaughter-fields killing their friends or strangers, for prospective profit, the more he must admire the ethics of the brute. In brute history there have been no wars. Facing human record, the record of 3,400 years, there have been 3,166 years of war, and only 234 years of peace; facing the picture of which history makes no mention and which in the wake of armies she had seen, Clara Barton says: “Faces bathed in tears and hands in blood, lees in the wind and dregs in the cup of military glory, war has cost a million times more than the world is worth, poured out the best blood and crushed the fairest forms the good God has ever created.”

Through war and its consequences, one third of “civilized man” since the world began has come to an untimely end, by violence, as did Abel at the hands of Cain.

“Mankind is the greatest mystery of all mysteries,” says Clara Barton, and insists that she can never understand the history of human conduct in this world, and wonders whether or not she will in the next. In the light of war’s history and, trying to solve the “mystery of all mysteries,” she asks: “Heavenly Father! what is the matter with this beautiful earth that thou hast made? And what is man that thou art mindful of him?”

Further philosophizing on the “Wickedness of War,” in a masterful public address, she says: “There is not a geographical boundary line on the face of the earth that was not put there by the sword, and is not practically held there by this same dread power. War actually settles no disputes, it brings no real peace; it but closes an open strife;—the peace is simply buried embers. The war side of the war could never have called me to the field—through and through, thought and act, body and soul, I hate it. We can only wait and trust for the day to come when the wickedness of war shall be a thing unknown in this beautiful world.”

Again philosophizing she says: “As I reflect upon the mighty and endless changes which must grow out of war’s issues, the subject rises up before me like some far-away mountain summit, towering peak upon peak, rock upon rock, that human foot has not trod and enveloped in a hazy mist the eye has never penetrated.”

In the same year, and about the same time in the year, that Clara Barton first started for the battlefield her warm personal friend, Julia Ward Howe, wrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

You remember the time was Sunday, September 14th, 1862.

Society forbade women at the front. Clara Barton.

Tradition absolutely forbade a good woman to go unprotected among rough soldiers. Clara Barton.

And what does woman know about war, and because she doesn’t know anything about it she mustn’t say, or do, anything about it.

It has long been said, as to amount to an adage, that women don’t know anything about war. I wish men didn’t either. They have always known a great deal too much about it for the good of their kind. Clara Barton.

I struggled long and hard with my sense of propriety—with the appalling fact that “I was only a woman” whispering in one ear; and thundering in the other the groans of suffering men dying like dogs—unfed and unclothed, for the life of every institution which had protected and educated me. Clara Barton.

When war broke over us, with an empty treasury and its distressed Secretary, Salmon P. Chase, personally trying in New York to borrow money to pay our first seventy-five thousand soldiers, I offered to do the work of any two disloyal clerks whom the office would discharge and allow the double salary to fall back into the treasury. When no legal way could be found to have my salary revert to the national treasury, I resigned and went to the field.

64I could not carry a musket nor lead the men to battle; I could only serve my country by caring for, comforting, and sustaining the soldiers. Clara Barton.

I broke the shackles and went to the field. Clara Barton.

Sir: The undersigned, Senators and Representatives of Massachusetts, desire you to extend to Miss Clara Barton of Worcester, Massachusetts, every facility in your power to visit the army at any time or place that she may desire, for the purpose of administering to the comfort of our sick and wounded soldiers. Also that such supplies and assistants, as she may require, may be furnished with transportation.

On September 14, 1862, Clara Barton started from the City of Washington to the firing line, then at Harper’s Ferry. She took with her no Saratoga, no grip, no “go-to-meeting clothes.” The articles in her 65wardrobe on that eventful trip will never be known but it is known to a “dead certainty” that whatever “worldly goods” she did take with her were all tied up in a pocket handkerchief.

Her only escort was a “mule skinner.” He, wearing the blue, held the one jerk line to the team of six mules, animals known in the west as “Desert Canaries.” The vehicle in which Clara Barton took that eventful ride was an army freight wagon covered with canvas, such wagon sometimes called the “prairie schooner.” “In the Days of Old, the Days of Gold,” as “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way,” the “prairie schooner” was almost the exclusive vehicle of conveyance over the deserts for freight and passengers. It was in the “prairie schooner” that the Mormons went to Utah in 1848, and the Argonauts to California, in “’49 and ’50.” It was from a “prairie schooner” that, rising from a sick bunk and looking out over that beautiful valley of Salt Lake, Brigham Young exclaimed: “This is the Place!”

After an eighty-mile ride bumping over stones and dykes and ditches, up and down the hills of Maryland, Clara Barton arrived at the battlefield. There, side by side, cold in death with upturned faces, were the brave boys of the Northern blue and the Southern gray. In closing a description of this battle scene Clara Barton says: “There in the darkness God’s angel of Wrath and Death had swept and, foe facing foe, the souls of men went out. The giant rocks, hanging above our heads, seemed to frown upon the scene, and the sighing trees which hung lovingly upon their rugged edge dropped low and wept their pitying dews upon the livid brows and ghastly wounds beneath.”

Clara Barton carried on her work in the face of the enemy, to the sound of a cannon, and close to the firing line.

So long as the Republic lives the name of Clara Barton will be honored. Roswell Record.

Clara Barton—Glorious Daughter of the Republic!

Clara Barton performed work for wounded soldiers often at the risk of her life. Phebe A. Hanaford, Author.

Clara Barton—right into the jaws of death she went, ministering to the wounded, soothing the dying.

Follow the cannon. Clara Barton.

The soldier has been supposed to die painlessly, gloriously, with an immediate passport to realms of bliss eternal. Clara Barton.

The soldier who has fallen in battle “with his face to the foe” has been regarded as a subject of envy, rather than pity.

If wounded and surviving, the honor of a soldier’s scars has been cheaply purchased, it has been supposed, though he strolled a limping beggar. Clara Barton.

Only a small portion of the thought of the generations of the past has been devoted to the subject of devising, or affording, any means of relief for the wretched condition resulting from the methods of national and international strife. Clara Barton.

The pitiable neglect of men in war appears to have constituted one of the large class of misfortunes for which no one is to blame, or even accountable, assuming that wars must be. Clara Barton.

I am a U. S. soldier and therefore not supposed, you know, to be susceptible to fear. Clara Barton.

When asked where occurred her bravest act, Clara Barton replied: “At Fredericksburg.” She made headquarters at the Lacy House, just north of the Rappahannock River. While there, the surgeon in charge of the wounded on the south bank of the river sent a special messenger to Miss Barton to come across with her assistants and supplies at once. As a soldier and as an American patriot, she obeyed orders and followed the flag over the bridge and on to the battle field. In later years describing the women who went to the war Clara Barton sings:

In referring to the incident, in her experience at Fredericksburg, she said: “As I walked across this bridge with the marching troops, the bullets and shells were hissing and exploding in the river on either side of me, the long autumn march down the mountain passes—Falmouth and old Fredericksburg with its pontoon bridge,—sharp-shooters—deserted camps—its rocky brow of frowning forts—the one day bombardment, 68and the charge!” There, unperturbed, among the men was Clara Barton, there in the broad glacis, the one vast Aceldama, where—

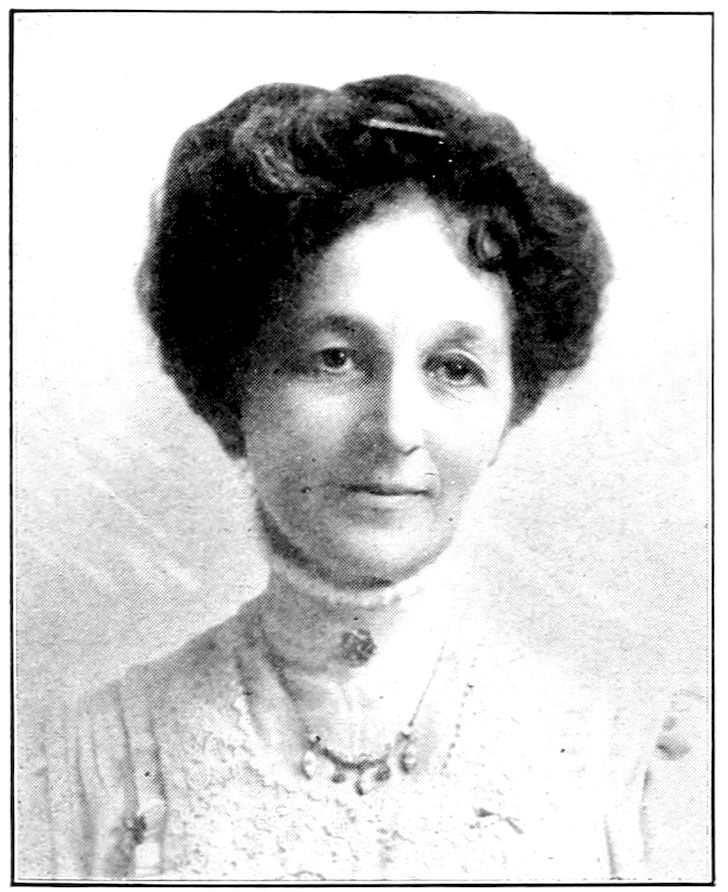

SUSAN B. ANTHONY

My dear Clara Barton, you have done some wonderful things in the world.—Susan B. Anthony, Pioneer Suffrage Leader.

Susan B. Anthony was the first woman to lay her hand beside mine in the promotion of the Red Cross Society.—Clara Barton.

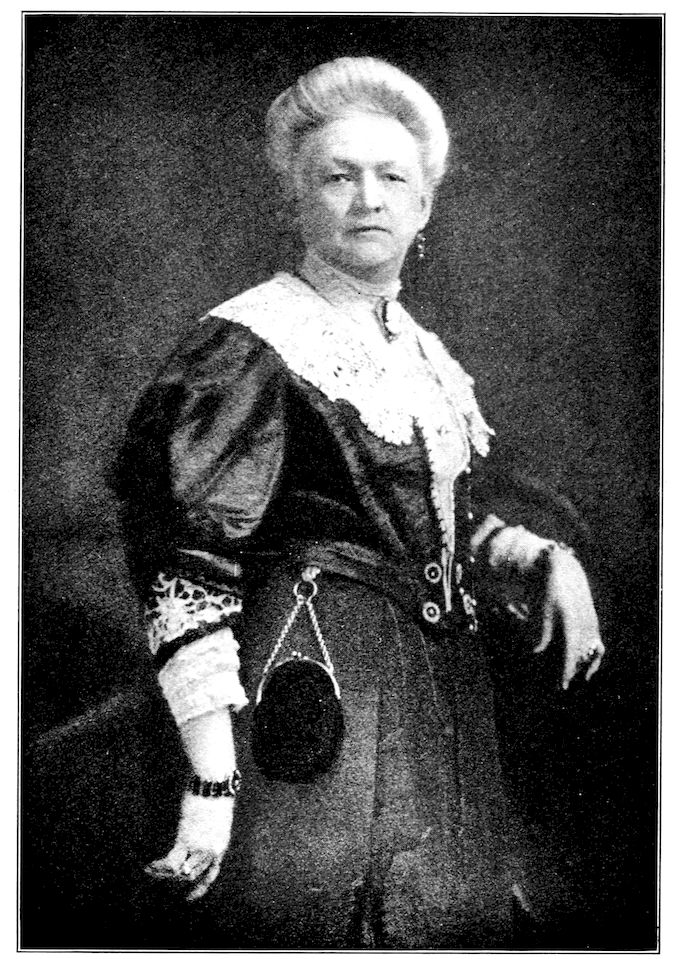

CARRIE CHAPMAN CATT

One of the great women of the world. Broad of vision, exalted of soul and absolutely free from selfishness that binds, Miss Barton was a rare human being.—Carrie Chapman Catt, President National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1900–1904; 1913——; Ex-President International Woman Suffrage Alliance.

© Harris & Ewing

DR. ANNA HOWARD SHAW

Every woman who loves her country will revere the name of Clara Barton.—Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, President National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1904–Dec., 1915.