| Title: | Youth, Volume 1, Number 5, July 1902 |

| An Illustrated Monthly Journal for Boys & Girls |

The Penn Publishing Company Philadelphia

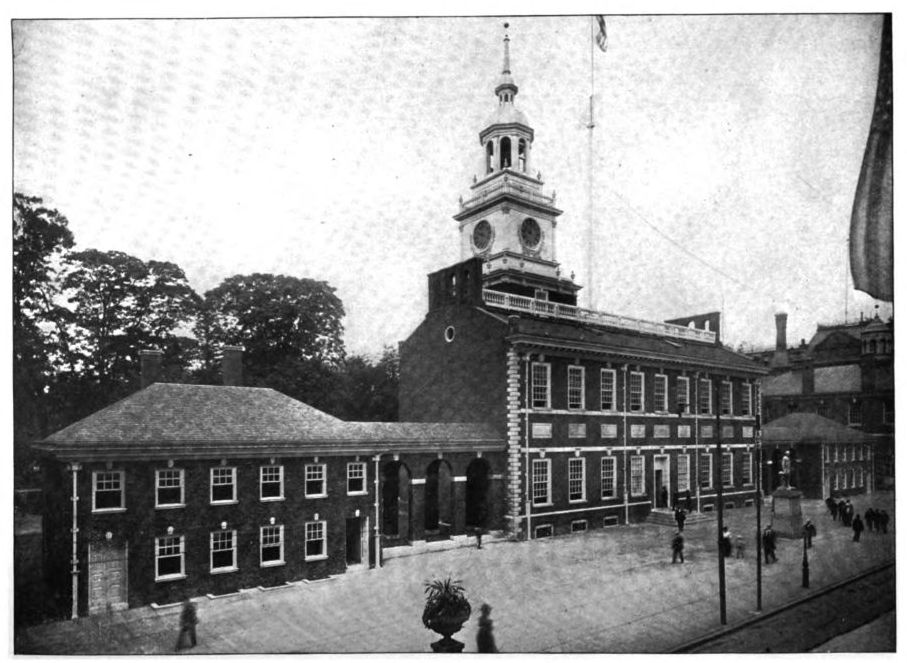

| FRONTISPIECE (Independence Hall) | PAGE | |

| THE DOUBLE PERIL | George H. Coomer | 157 |

| LITTLE POLLY PRENTISS (Serial) | Elizabeth Lincoln Gould | 161 |

| The Fence Man | Mrs. F. M. Howard | 166 |

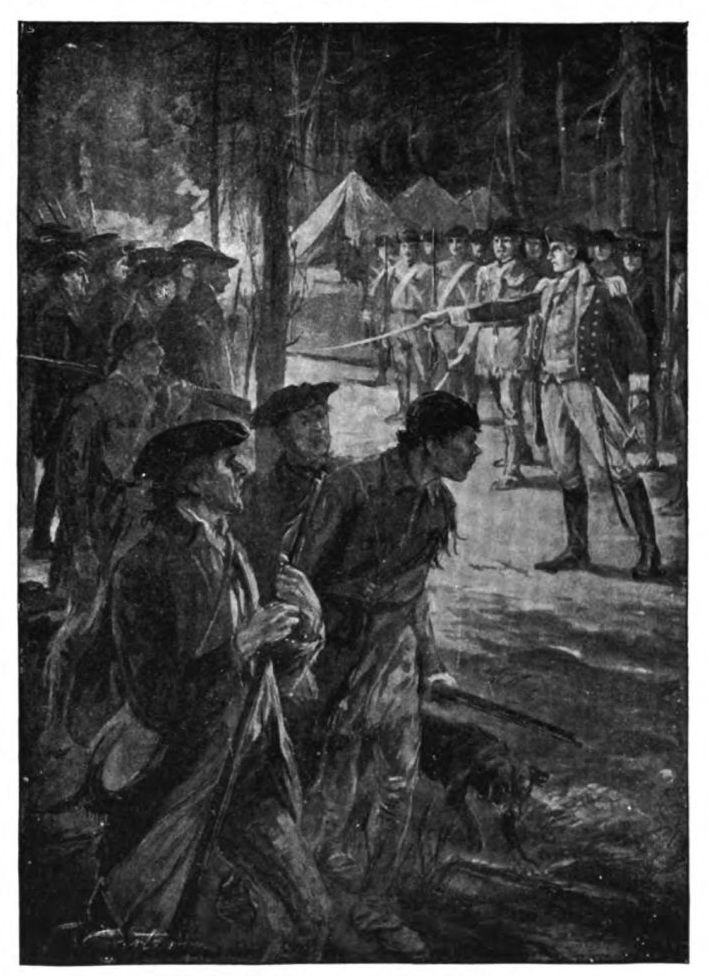

| WITH WASHINGTON AT VALLEY FORGE (Serial) | W. Bert Foster | 170 |

| Illustrated by F. A. Carter | ||

| MIDSUMMER DAYS | Julia McNair Wright | 179 |

| Illustrated by Nina G. Barlow | ||

| A DAUGHTER OF THE FOREST (Serial) | Evelyn Raymond | 181 |

| FOURTH OF JULY | W. F. Fox | 187 |

| WOOD-FOLK TALK | J. Allison Atwood | 188 |

| WITH THE EDITOR | 190 | |

| EVENT AND COMMENT | 191 | |

| OUT OF DOORS | 192 | |

| IN-DOORS (Parlor Magic, Paper V) | Ellis Stanyon | 193 |

| THE OLD TRUNK (Puzzles) | 195 | |

| WITH THE PUBLISHER | 196 |

An Illustrated Monthly Journal for Boys and Girls

SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION $1.00

Sent postpaid to any address Subscriptions can begin at any time and must be paid in advance

Remittances may be made in the way most convenient to the sender, and should be sent to

The Penn Publishing Company

923 ARCH STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA.

Copyright 1902 by The Penn Publishing Company.

INDEPENDENCE HALL

VOL. I JULY 1902 No. 5

By George H. Coomer

“NONSENSE,” said Uncle Hayward; “how people do like to be scared! If a real Bengal tiger had made his escape anywhere within twenty miles of here, the whole country would have been up in arms before this time. I’ve no faith in the story.”

“Well, they are not quite sure of it,” replied the neighbor who had given the information, “but they think so. The steamer was sunk and some of the animals were drowned, but it is believed that the big tiger escaped in the darkness and got ashore.”

“What sort of a show was it?” inquired uncle; “a large menagerie?”

“No, I believe not,” was the answer; “only a few animals that some company had hired for the season—a tiger, a jaguar, a pair of leopards, and a few monkeys—that’s what they tell me. The steamer had a heavy cargo, and went down very suddenly.”

“And they think the tiger made for the woods, eh?” said uncle. “When did it happen, do you say?”

“Night before last—about five miles down the river. ’Twas a small steamer going up to Macon. There was no one lost, I hear.”

“Well,” remarked uncle, “a Bengal tiger would be an interesting neighbor, that’s certain; and I don’t believe he would be long in making his presence known. However, such stories generally require a good deal of allowance. As likely as not, there was no tiger aboard of the steamer, after all.”

“Oh, I reckon there was,” said the neighbor; “but then, of course, we can’t tell; people like excitement, and when such a rumor gets started it grows very fast.”

“Yes, that’s true; we shall have a whole menagerie ashore here before night. When I was a boy, in Maine, there was a story that a lion and an elephant had made their escape from somebody’s show and taken to the woods. And, dear me! it spread like the scarlet fever! The children ran all the way to school and all the way back; and the big girls actually cried in the entry, they were so frightened. Some of the mischievous boys would make ‘elephant tracks’ in the road, and this added to the panic. But we never could hear of any showman who had lost such animals, and all on a sudden the thing came to nothing. I guess the tiger story will end in the same way.”

“Why, father,” said Cousin Harold, the fourteen-year-old boy of the family, “I don’t see why it isn’t likely enough to be true. I almost hope there is something in it, though I shouldn’t want him to be killing people’s cattle and things. Just think of it—a big Bengal tiger, and right here in Georgia, too! How I should like to have a chance at him with my gun!”

“Why, Harold,” said his mother, “how you talk. If I believed such a creature to be anywhere in the neighborhood, I’d shut you up in the smoke-house rather that let you go into the woods.”

“What, and make bacon of a poor fellow?” replied the young lad, gayly.

Uncle Hayward and his family were New England people, who had settled in Georgia near the Ocmulgee River, where I was now paying them a really delightful visit. Harold and myself, being very fond of hunting, spent much time together in pursuit of the various kinds of game to be found in the region. Many an old “mammy” and many an “Uncle Remus” was made the happier by the gift of some fat ’coon or juicy ’possum which we brought down from the tall timber.

Inspired as we were with all the enthusiasm of young sportsmen, the thought of an escaped tiger had a pleasing excitement for us. We were, therefore, a little disappointed when another of our neighbors, stopping for a few minutes as he passed the house, made very light of the rumor, saying it was only a foolish story to frighten people.

“A tiger would soon make ugly work among the cattle,” he remarked, “and it would be no joking matter to have one about the neighborhood.”

“That’s true,” replied Uncle Hayward. “I don’t know, though,” he added, “but I’d risk my big Jersey with him. I’m thinking ’twould be about ‘which and t’other’ between the two, as the saying is.”

Harold and I could subscribe to this opinion very heartily, for it was not more than a week since that dangerous old Jersey had chased us out of his pasture, bellowing at our heels as we ran. Nevertheless, he was a noble fellow to look upon—just as handsome as a horned creature could be. What a thick, strong neck he had, what a broad, curled front, and what shapely flanks! Most of the time he spent browsing in the large pasture some little distance from the house, and it required a good measure of courage upon the part of the trespasser to cross this area.

No wonder, then, that Harold and myself made a wide detour, when, half an hour later, armed with our shotguns, we set out for the woods beyond the Jersey’s domain. But it is needless to say that our minds were more taken up with the thought of the tiger than with the fear of our former enemy. It was just possible that a great, stealthy, tawny shape might be prowling through the very timber in which we were; and I will not deny that it required little in the way of sight or sound to set our hearts beating faster than usual on that day.

After killing a wild-cat, a raccoon, and a number of large fox squirrels, we turned our steps homeward, not at all sorry to have made no startling discovery in confirmation of the rumor which had so interested us in the morning. The truth was, that the deeper we were in the woods the less pleasure we found in calling up the image of that escaped tiger!

We were just nearing the Hayward plantation, Harold with the wild-cat slung over his shoulder and I with the ’coon upon mine, when on a sudden our attention was arrested by a strange, long-drawn noise, like the cry of some large animal. It resembled the call of a great cat, but was deeper and more thrilling than any cat-note that we had ever heard.

I need not say that it startled us; and when, in a few moments, it was repeated, with the addition of a sort of scream, we looked at each other with blanched faces: when, clutching our guns more firmly, we started into a run. I think we had never realized till then that two boys of fourteen, armed only with light shotguns, could be no match for a royal tiger, just escaped from his cage and hungry for prey.

Pray, dear reader, do not condemn us hastily, for you would have run, too.

Our course took us directly across the pasture where the big Jersey had his range. He was lying down for the time, and we almost stumbled over him. Springing up and lowering his sharp horns, he took after us with a kind of yelling roar that bespoke anything but a friendly intention.

We dropped our game and bounded on like a couple of young greyhounds: but we were far out from the nearest fence, and saw that he must soon overtake us with his mad, thundering rush. Right ahead of us stood a scrub oak, with branches near the ground, and into this we sprang just in time to avoid those terrible horns which would have tossed us like wisps of straw.

He was so close upon us that it was impossible to secure our guns, and we dropped them at the foot of the tree, where they fell rattling between two small rocks, which fortunately protected them from his trampling hoofs.

Then he besieged us in true form, walking all about our fortress, with a hoarse, frightful bellowing that sometimes grew to a shriek, and tearing up the earth with his horns till his whole body was coated with turf.

“Well,” said Harold, “we are safe enough in this tree, but who wants to be kept here all night? He is so apt to roar that, even if father or any of the work folks should hear him, they might not come to see what the matter was. Besides, it’s a long distance to the house, and the hill yonder is right in the way.”

So we remained watching our savage jailer, quite forgetting for the moment the sounds we had just heard from the woods. How long would the old fellow continue to bellow and fling up the dirt? I was asking some such question when my cousin uttered a quick exclamation.

“Oh, see! look yonder!” he cried; “there’s the tiger now!”

I looked where he pointed, and my heart gave a thump that was almost suffocating.

There, creeping close to the ground, was a powerful yellow shape, marked with jet-black stripes. The ears were flattened, and the long tail, reaching straight out on a level with the body, had a wavy motion that I distinctly remember to this hour. Warily, silently, and just upon the point of making a spring for his victim, the fearful creature was stealing upon the unsuspicious bull.

Though half paralyzed by the scene, we still retained some presence of mind. Perhaps a shout might delay the attack, and we gave one with all the power of our throats.

The monster seemed to hesitate, raising his head a little, as he crouched in his tracks, and at that moment the old Jersey discovered him.

In an instant a change came over the scene. Tossing his head in a kind of fierce surprise, the horned brute faced his foe; then, dropping his sharp bayonets to a lower level, he plunged toward the intruder.

Evidently the tiger was unprepared for this, but with remarkable quickness he seemed to take in the situation. Without an instant’s hesitation, he bounded over to a large boulder which lay near by, and with the greatest agility leaped lightly to its top, where he stood regarding the Jersey with wide-open jaws.

“Now’s the time,” said Harold, excitedly; “we must hurry and get our guns.” And down we went hustling through the thick limbs of the oak.

It was our first impulse to fire at the tiger from the ground where we stood, but, as the bull kept directly in the way, it was evident that this would not answer; and, besides, our very terror restrained us; it might be easier to fire than to kill.

Getting back into the tree with our guns, both of which contained heavy charges of buckshot, we quickly posted ourselves so as to improve the first opening for a fair aim. The tiger still crouched upon his rock of refuge, roaring close in the face of his enemy, yet hesitating to spring upon him; while the strong-necked old Jersey shook his curly head and fairly screamed at the yellow brute he was not quite able to reach.

A bull’s voice in a rage is a strange mixture of frightful sounds, even more so than a tiger’s.

We had our guns leveled, watching our opportunity. Presently the striped terror sprang up from his crouching posture, raising himself threateningly upon his hind feet, with his tawny breast fully exposed. Since then I have often seen an angry tiger rear himself in the same way against the bars of his cage. There could not have been a fairer mark for us, and both our guns spoke at once with a “bang!”

Through the smoke we saw the great brute tip fairly over and fall upon his back. Then, convulsively, he bounded straight up from the rock two or three times, and at last, plunging forward, landed directly upon the bull’s horns.

HIS HORNS PIERCED THE TAWNY SIDE

The next moment, heavy as he was, he was hurled ten feet in the air, and when he fell it was only to be tossed again. A dozen or twenty times he was thus thrown aloft, although after the first minute he was evidently as dead as he ever could be.

After this the old Jersey appeared to enjoy much in pitching him along the ground to a considerable distance, following up the body as it fell, and sending it on before him as if it had weighed no more than a dead cat.

We were glad to witness this performance, as it occupied the old fellow’s whole attention, and so gave us an opportunity to slip away unnoticed, which we very quickly did.

No grass grew under our feet as we ran over the high ground between us and the house, which, as the plantation was quite large, was nearly a mile distant.

With scarcely breath enough to relate our story, we told it, to the astonishment of Harold’s parents, whose thankfulness for our escape, when they had learned how narrow that escape had been, was inexpressible.

It required a considerable force of men and boys to recover the body of the slain tiger in face of the bull’s threatening demonstrations; but it was nevertheless secured and brought home. It was then found, upon examination, that our charges of buckshot had undoubtedly done the business for the fierce brute, so that he must have been nearly dead when caught upon those stout horns.

“A tiger in the State of Georgia,” said Uncle Hayward; “a true Bengal tiger! Well, I must own that I was wrong; I thought this morning it was only a silly story. Boys, you and the bull have done a great thing for the community!”

“But, oh, the peril!” said Harold’s mother: “suppose we had known it at the moment! It was a double danger.”

“Yes, mother,” replied Harold; “it was double, but it was that very thing which saved us. If we hadn’t waked up the Jersey, the tiger would have had us very soon.”

BY ELIZABETH LINCOLN GOULD

Polly Prentiss is an orphan who, for the greater part of her life, has lived with a distant relative, Mrs. Manser, the mistress of Manser Farm. Miss Hetty Pomeroy, a maiden lady of middle age, has, ever since the death of her favorite niece, been on the lookout for a little girl whom she might adopt. She is attracted by Polly’s appearance and quaint manners, and finally decides to take her home and keep her for a month’s trial. In the foregoing chapters, Polly has arrived at her new home, and the great difference between the way of living at Pomeroy Oaks and her past life affords her much food for wonderment.

SUNDAY was usually a hard day for Polly. In the first place there were good clothes to be put on and taken care of, and then there was sitting still in church! Sitting still was the most difficult thing in the world for Polly.

“In the Manser pew I could wriggle, because it was ’way back and nobody downstairs saw me, but I guess I’ve got to behave just like grown folks to-day,” said Polly, anxiously, as she put on the brown cashmere frock Sunday morning. “But if I listen to the minister most of the time, and think about Eleanor when I get tired listening, perhaps I can do it.”

It was not so hard after all, for the minister had a pleasant, boyish face, and he used simple language, which Polly could understand. Besides that, his sermon was short—the shortest one Polly had ever heard; she wondered if by any chance the minister could know about those yellow cakes he was to have for dessert, and felt in a hurry to taste them. Miss Pomeroy had seen him the day before.

“He looks as if he liked to eat good things,” thought Polly, as the minister read the closing hymn, “and Miss Pomeroy may have told him there was citron in them. His cheeks are as red as mine were—redder than mine are to-day.”

This was comforting, and, moreover, it was true. Polly had been out of doors very little for the last week, and, besides that, although she was not unhappy, the thought of Eleanor was continually before her, and the fear of falling below an unknown standard made her anxious and troubled many times in the day. So the roses in Polly’s cheeks did not bloom as brightly as they had at Manser Farm, and the little girl was greatly encouraged.

During the service she could not turn around to see her old friends up in the dimly lighted gallery, and when the benediction had been pronounced Miss Pomeroy said she and Polly would sit quietly in the pew until the minister came out. The little girl looked disturbed, and Miss Pomeroy laid her hand on Polly’s with a smile.

“You needn’t be afraid of the minister, my dear,” she said, kindly, “he likes children, and has two little sisters at home.”

Polly smiled faintly in return. When the minister came, and they had all walked slowly down the aisle together, there was no sign of the Manser wagon, but Polly was sure she could hear it way up the road; it had a peculiar rattle, not to be mistaken for any other. The little girl had a sober face as she climbed up into the seat beside Hiram, with the minister’s help.

“I’m grateful I’ve got you instead of the preacher,” said Hiram, facing straight ahead, as soon as Miss Pomeroy and the minister were fairly launched in conversation. “I’ve always been to church, and I’m a member, but I’m scared of speaking to ’em; it don’t make any difference whether they’re young or old. What’s the matter, honey? Don’t you tell me without you’re a mind to.”

“I thought perhaps I’d see the Manser Farm folks,” said Polly. “I thought maybe Uncle Blodgett would want to wait, and Aunty Peebles. I don’t know as Mrs. Ramsdell came if her rheumatism was bad.”

“She was there,” said Hiram, quietly, “I know ’em all by sight, and once in awhile I have a little talk with Mr. Manser when we’re taking the horses out of the sheds. But to-day Mrs. Manser hurried him up, and hustled the three old folks into the wagon as if something was after her. I shouldn’t have dared to offer Mis’ Ramsdell anything unless I’d wanted it bit in halves, when she got in,” said Hiram, with a low chuckle. “She spoke her mind good and free, too: I don’t recall ever hearing any one speak freer. She was all for waiting to see you.”

“Then I think Mrs. Manser was real mean,” said Polly, with flushed cheeks. “I don’t suppose she meant to be, but I think she was!”

Hiram reached out his big brown hand and gave Polly’s fingers a sympathetic squeeze.

“I expect we are about as naughty as we can be, both of us,” he said, softly, “but I take real comfort in it once in a while. That Manser woman’s no favorite of mine, nor ever was. I can’t abide her.”

“She took care of me for seven years,” said Polly, with a spasm of loyalty, forgetting how little of the care had really come on Mrs. Manser’s shoulders, “and I do try to love her.”

“Love don’t always come by trying,” said Hiram, tranquilly, “but I suppose it’s no harm to give it a fair chance. And as for those old folks of yours, you shall see ’em next Sunday, if I have to tole Mr. Manser down behind the sheds and keep him there.”

Then Hiram puckered his lips and softly whistled “Duke Street” all the rest of the way to Pomeroy Oaks, while Polly sat beside him, much cheered and comforted.

Dinner was an exciting meal to the little girl. It was the first time, as she told Arctura afterward, that Polly had even seen a minister eat. This minister not only ate with great heartiness, but he talked a good deal and frequently smiled across the table at her, and he had a jolly laugh. Polly was glad of that for more than one reason. Arctura had covered the scratch on her nose with a long, broad strip of black court-plaster, and this decoration made her naturally prominent feature more noticeable than ever. She carried her head very high, and bore the dishes in and out with a stately tread, but her eyes twinkled so when she looked at Polly that the little girl had much ado to keep a straight face.

When the dessert came, Polly held her breath while the minister ate his first mouthful of a yellow cake; he had chosen it instead of one of Arctura’s “snowflakes.” Miss Pomeroy had tasted one the day before and pronounced it delicious. The minister ate every crumb, and when the plate was passed to him a second time, he laughed boyishly.

“These are almost too good,” he said. “I should like to compliment the cook.”

Miss Pomeroy smiled at Polly.

“My little guest made them,” said she.

“Dear me,” said the minister, heartily. “I shall have to tell my sisters about this when I go home. One of them must be just about Mary’s age; she is eight years old.”

“Oh, but I’m going on eleven,” said Polly, eagerly, “only I’m small for my age, sir.”

“Indeed, that’s very surprising,” and the minister smiled most cordially at the little cook. Polly was perfectly delighted when Miss Pomeroy suggested that instead of a nap she might take a walk with the minister and show him the grounds. Miss Pomeroy was to drive him back to Deacon Talcott’s house late in the afternoon.

“I will take my nap as usual, Mary, if you think you can look after Mr. Endicott,” she had said, and the minister and Polly exchanged a glance of much confidence and friendliness.

They walked about, hand in hand, and there was no doubt that Polly entertained the minister.

“Miss Pomeroy tells me she hopes you will stay with her for always,” the minister said, as they stood together looking down at the brook in a place where it tinkled over some stones. Polly gave a little cry of delight and squeezed the minister’s hand.

“Oh, did she say it that way?” she asked, earnestly.

“Why, yes,” said the young man, smiling down at her, “didn’t you know it?”

“She’s a beautiful, kind lady,” said Polly, shaking her brown curls till they danced, “and I do truly love her, but she’s so tall and quiet I shouldn’t like to ask her questions all the time, and I have to ask her a good many—about my clothes and ever so many other things. Now if it was you, I shouldn’t be a bit afraid, because your eyes look so young and happy,” said the little girl, frankly. “Miss Pomeroy has sad eyes, and I’m always afraid I’ll make them sadder. Don’t you see?”

“I think I do,” said the minister, gently, “but I am sure you will help Miss Pomeroy’s eyes, and not hurt them, by talking freely to her.”

“Yes, sir,” said Polly, doubtfully. “Do your little sisters like to read, Mr. Endicott? I am reading a book called ‘Sesame and Lilies,’ by Mr. Ruskin.”

“Phew!” said the minister. “That’s a fine book, Mary, but I should say it was a little old for you. Who chose it—Miss Pomeroy?”

“No, sir, I chose it myself,” said Polly, proudly, “off the shelf where all the little books are, under the window. Miss Pomeroy said I could choose.”

“When we go in the house,” said the minister, as they started on together, swinging hands, “I’ll show you a book to read; I saw it on one of the shelves. It’s a big book, but the stories are short. If I were in your place, Mary, I’d read one of them to-morrow. My little sisters love them all.”

So it came about that when Miss Pomeroy and the minister drove away they left on the piazza a little girl whose heart was almost gay, for the book the minister had chosen, and which Miss Pomeroy had told Polly she might keep in her own room, was full of delightful pictures, and on the cover was printed in gold letters. “Wonder Stories, by Hans Christian Andersen.”

“And mind you try to remember them just as you do the sermon on Sunday,” the minister had said, as he parted from Polly, “for they are sure to give you happy thoughts.” And Polly, running to Arctura, who was seated on the south porch in a chair that rocked with a loud squeak, cried joyfully:

“Oh, Miss Arctura, the minister has chosen a book for me, one that his sisters love! And I’m not going to read another word in ‘Sesame and Lilies’ till I’m most grown up! For Miss Pomeroy said ’twas a wise thought and an inper—impterposition of Providence!”

POLLY’S worry about being satisfactory to Miss Pomeroy had departed with the minister’s words, down by the brook, but as she lay in bed the next morning, listening to the birds out in a big elm tree, the branches of which came near one of her windows, she had some sober thoughts.

“The reason Miss Pomeroy is going to adopt me,” said Polly, to herself, “is because she thinks I’m like Eleanor. I’m not like her, inside, of course, but I’m trying to be. Now, don’t you be a selfish girl, Polly Prentiss. You’ve got a beautiful home with a lovely, kind lady, that does things for you all the time, and Miss Arctura and Mr. Hiram besides, just as good as they can be, and the kittens to play with, and Daisy out in her stall, and you can go off into the woods this afternoon, and take the book that the minister’s sisters love, and perhaps they’ll let you go again some other day.

“And all you’ve got to do,” said Polly, severely, to herself, “is to stop wanting to run outdoors morning, noon, and night, and wanting to play with a doll, and wishing somebody’d call you Polly, and not mind having to eat so much, or lying down on this bed that gets so hot in the afternoon, and stop being lonesome for the folks at Manser Farm, and learn how to mend your clothes. I guess that’s about all, and it isn’t much for a girl that’s going on eleven.”

Polly had a delightful time that afternoon. Arctura had taken in the snow-white clothes from the line, and informed the little girl that she had no intention of ironing that day, and would make an excursion into the woods with her.

“I’ve got a crick in my back,” Miss Green announced, when Polly descended from her hour on the bed, “and what I need is to get right down close to nature. I’ll take my old gray shawl and pick me out a good place to sit in the sun, and I’ll knit on Hiram’s socks while you run around and see what you can see. Perhaps you can get up a bouquet to fetch home to Miss Hetty, who knows? And when you feel so minded you can sit on the shawl alongside of me, and read me out a story, maybe. It’s a pity Miss Hetty can’t be with us, but she’s no hand to walk; she hasn’t been overly strong for ten years back, though she can do all that’s required.”

Polly felt disloyal to Miss Pomeroy, because it was a relief to know Arctura would be her only companion. Her little heart was full of affectionate gratitude, but the tall mistress of the house inspired a good deal of awe as well, while with Arctura Polly had a sense of comradeship, in spite of the difference in years, and was not afraid to chatter like a magpie.

By three o’clock the pair were deep in the woods, and Arctura was enthroned on her gray shawl, spread on a rock that stood like a table in an open space between giant pines. She had four knitting-needles and a ball of flaming red yarn in her hands, and looked the picture of contentment.

“Now,” she said, drawing out a big silver watch from the front of her gown, and placing it beside her on the shawl, “it’s only a few minutes past three. You lay your book down here and don’t let me see you again for an hour, or as near that as you can judge by your feelings. Don’t stray so far you can’t get back. I’ll holler once in awhile so’s to keep track of you, but you caper round and see what you find.”

Polly trotted off obediently, and found all sorts of treasures. If she had not been obliged to respond to Arctura’s loud “Ma-a-a-ry!” three or four times, it would have seemed to the little girl that she was all alone in a new world, for the pine grove was unlike the woods through which Polly had wandered in that far-away time when she lived at Manser Farm. Those were birches and scrubby oaks, with an occasional hemlock, and you had to look out for slippery tree-roots, and scratching underbrush, and boggy places. But this wood had a soft brown carpet of needles, and a border of beautiful ferns, and here and there were little cones, and clumps of stems that had belonged to “Dutchman’s pipes.”

In a little while there would be “wake-robins” and “Solomon’s seal,” and many other wild wood flowers. Polly saw the first signs of a venturesome “lady’s slipper.” She gathered long trails of Princess pine and looped them around her waist, and she picked some of the prettiest ferns to take home to Miss Pomeroy. There were several cleared places, like the one which held Arctura’s throne. Polly named one the library and another the parlor, and in still another there were some stones which made her think of pillows.

“So I shall name that the bedroom,” she said to Arctura when the call “Ti-i-i-mes up!” had brought her running back, “and this I think we’d better call the dining room, don’t you?”

“Seems a sensible name to me,” said Miss Green, approvingly. “Now suppose you read me out a story. I just looked into your book while you were off, and here’s one that my eye lit on; suppose we have that.”

The story was “The Ugly Duckling,” and the words were so easy that Polly read on and on, scarcely ever having to stop for Arctura’s help. When she had finished it, she drew a long breath and shut the book.

“Isn’t it a beautiful, interesting story, Miss Arctura?” she asked, eagerly, and her friend nodded with great vigor before she spoke.

“It’s what I call fair,” said Arctura, with decision, “and that’s what I like in real life or in a story. And that’s why I expect that the poor folks that get hurt and slammed around and put upon in this world are going to have crowns of gold and harps of silver and songs of everlasting praise and joy in the next one; or whatever those things stand for, to ’em. We’ll have another of those stories next time we come out a pleasuring together, won’t we?”

Polly assented with joy, and all through the talk that followed, while she told of her morning’s trip to the village, those delightful words “next time” rang out their lovely promise in Polly’s happy ears.

She and Arctura walked home arm in arm, although that meant that Polly had to stretch up, and Miss Green to reach down, but the path was broad enough for two, and they sang “Marching Through Georgia,” and stepped gayly along to the brisk measures.

“Slow walking, except for those that have infirmities and are obliged,” said Arctura, “is a trial of the flesh and spirit, or it might be, if it ain’t,” and little Polly, with more color in her cheeks than had been there for days, looked joyfully up at her.

“Oh, Miss Arctura,” she said, fervently, “you do have such splendid ideas!”

“Don’t try to flatter an old lady of fifty-four, child,” said Miss Green, shaking her ball of yarn at Polly with pretended severity. “You turn your mind on those clouds; see how the wind’s backing round through the north? I can smell the east,” and she sniffed with her nose well in the air. “We’re in for rain to-morrow, I do believe. It’ll be just the day for you to write that letter you’re going to send with the candy, and there’s a number of matters you can help me about, and if you’ve got any mending to do maybe we’ll find time to sit down together, and I’ll relate that story about the Square and me.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Polly, as they marched up the driveway, “and I’ve got to practice with Mr. Hiram, you know. I expect it will be a grand day!”

[TO BE CONTINUED]

By Mrs. F. M. Howard

“MAMMA, what is the great, high fence for?” asked a childish voice. “Is the man afraid we’s will go into his yard?”

“I do not know, dear. It was there before we came.”

“Maybe he thinks we’ll steal his cherries.” Horace straightened himself, scornfully.

“Huh, I guess we can buy our cherries if we want any,” said Rodney, with flashing eyes.

“Perhaps other boys have not thought so,” interposed the mother’s gentle voice; “and since the fence was there before we came, and so cannot have any possible reference to us, we will not harbor ill will against our neighbor because of it.”

“Young-ones,” muttered a surly voice on the other side of the high board fence. “Just my luck to have a pack of young-ones unloaded on me. Just one degree worse than the widder’s long tongue, I’ll venture. I’m glad the fence is good and high, and I’ll put a row of pickets on top of it if they go to climbing.”

Old Mr. Harding dropped down on a garden seat, wiping the moisture from his heated brow with a warlike bandana. He had been putting out late tomato plants, and his back ached; possibly his heart ached, too, for he was old and lonely. He could have told to a mathematical nicety, had he had the mind to do so, just why the ugly board fence divided him from his neighbor, of the quarrel between himself and the fiery widow, who owned the cottage where the children had come to live, over a boundary line, the matter of a foot or less of ground between the two places.

A quarrel is like a tumble weed in its capacity for growing in size, and, tossed back and forth by the windy tongues of the Widow Barlow, who gloried in “speaking her mind,” and old Mr. Harding, who cherished his right to the last word as religiously as a woman, the original difference had grown to be a very serious thing, indeed.

“I’ll fix her!” he had exclaimed, after the last tilt of words which occurred between them. “I’ll put up a fence so high she can’t scream over it, and if she comes inside my yard I’ll buy a dog.”

He thoroughly enjoyed that bit of spite work, and amused himself immensely in overseeing the ungainly structure as it went up, completely obstructing the objectionable widow’s view on the east side.

She had no redress, for he had given her the benefit of the disputed line, and a man could put up bill boards on his property if he wished to, and he hugged himself to think of her rage and disgust.

He did not in the least overestimate it, and he heard with glee from the neighbors and the housekeeper the savage onslaughts on his character which she was making, and it was not long before a moving van backed up before her door, a “To rent” sign appeared, and Mr. Harding was alone with victory. He was soured in the operation, it must be confessed. No man can habitually nurse hatred and spite in his bosom without becoming contaminated.

When gentle, soft-voiced Mrs. Harding was living, with her generous heart and hand, her noiseless, unostentatious way of settling a difficulty, it would have been quite impossible for him to have indulged in such an exhibition; she would have loved him out of it insensibly, and have so limbered the widow’s acrimonious tongue with the oil of kindness that the quarrel would have died at birth; but it was a sorry day for him when the better part of himself was laid away under the green in the cemetery, and he was quite free to be his untrammeled self.

Some way the mother’s voice, as it floated over the top of the ugly fence, reminded him of her. It was such a gentle, loving voice, with a flute-like clearness in it which made every word audible.

They had never had any children, he and the wife who would have made such a tender mother, but he imagined she would have spoken to them just as this mother was speaking if she had been surrounded by active, questioning lads and lasses, and his surly mood softened as he heard them chattering over the treasures of broken china they were finding in the widow’s refuse heap.

“We’ll build the playhouse right here. The big, high boards will make such a nice back,” said little Barbara.

“Maybe the man won’t like us to drive nails in his fence,” Rodney suggested.

“But this side of it is ours,” laughed the mother, softly. “He can only claim one side of even a nuisance; but you must be careful not to annoy him with too much noise.”

One side of a nuisance. How truly it was a nuisance, for Mr. Harding did not admire stockades himself. He had seen the inside of one in war times, and he had very nearly lost his life in trying to escape from it. He had an old wound in his leg yet that made him crosser on damp days than in dry weather, and here he was erecting stockades in his old age, to keep people out instead of in. It took all his self-control to keep from being ashamed.

Day after day he heard the childish prattle, and the pounding of nails as the building of the playhouse went on, sometimes with wrath, at other times with an almost eager curiosity to see and hear the little flock at their pretty play.

One day it rained, and silence reigned in the garden. His wound twinged and prickled all day, and he was in a furious mood toward evening as he went to straighten up some weak-backed plants that the rain had lopped over. A kitten was frisking about in a bed of choice strawberry plants—a saucy, disrespectful kitten which had evidently braved the terrors of the stockade, as he had done himself in the years gone by. He hated cats almost as he hated loud-voiced widows—perhaps he was thinking of the Widow Barlow, and of the joy it would be to take her as he was taking the kitten (loving little creature, it had never felt the touch of hatred, and didn’t know enough to run away), and, with one twist of his avenging arm, sling her over the fence. The kitten went over, legs and tail wildly outstretched, and little Barbara was at the window.

“Oh, mamma, he threw my darlin’ kitty right over the fence,” he heard her shriek, sobbingly, as she ran out and picked up her pet. “Kitty, kitty, is you killed?” she cried, breathlessly, as the little creature, stunned for a moment by its fall, closed its eyes and lay limply in her arms as she ran into the house.

“Mean old thing. If I was a man, I’d thrash him,” said Horace, doubling his little fists savagely.

“No, no, little ones; we must love him into kindness,” Mrs. Manning observed, gently. “He is a poor, lonely old man with no one to coax him into nice ways. See, Kitty isn’t hurt. Give her some milk and she will soon be quite happy again,” and in ministering to the kitten the children forgot their revengeful thoughts: but over the fence an old, cross-grained man went into his finer house with a mean feeling in his heart which even the thought of the Widow Barlow could not change to a comfortable complacency.

The rain cleared away and the family were very busy in the garden. The small plat on the south corner, away from the baleful shadow of the fence, was full of the roses and shrubs which the Widow Barlow had planted and tended so carefully, and they were already full of buds. Mrs. Manning was exceedingly fond of flowers, too, and her bay window on the west side was full of choice plants.

There was a Papa Manning, but he went early and came late from his work, too early and late to enter the story as an active factor; one of those busy men who do business in the city and live in suburban towns for the sake of health and purer air for the children; but Mr. Harding did not know this, and supposed his new neighbor to be a widow, and cherished suspicions accordingly which not even her sweet voice could quite allay.

“Oh, mamma, come quick. The man has fallen,” screamed Barbara one day, as she ran in to her mother, her golden curls flying, her blue eyes full of fright.

“What man, Barbie dear?” Mrs. Manning was in the kitchen making bread, and a man was an indefinite ingredient to enter into the delicate operation without proper credentials.

“The old man, mamma. The fence man—he fell right down and groaned.” A neighbor in distress—that was quite another matter, and Mrs. Manning ran out hastily, drying her hands on her apron.

“I’ve sprained my ankle, I guess,” growled Mr. Harding, nursing his wounded leg with a white face full of angry impatience. “Just a bit of a stone, but enough to turn that confounded weak bone of mine. I feel like a baby, ma’am, to be upset by such a trifle.”

“Lean on me, sir, and I will help you to rise,” said Mrs. Manning; but at the first attempt the poor old gentleman nearly fainted.

Fortunately, there were men near at hand, and soon Mr. Harding was carried into his home by strong hands, and a physician summoned.

It would be an exaggeration to say that Mr. Harding submitted to suffering with sweet resignation. In his best days gentle Mrs. Harding needed all her stock of patience to endure him when he was ill, and his natural proclivities had been reinforced by years of loneliness and self-indulgence. The housekeeper was at her wits’ end, and strongly inclined to resign her situation before the end of the first week.

“Sure, ma’am, he’s that cranky there’s no living with him at all,” she confided to Mrs. Manning, who had brought in a bit of her own delicate cookery to tempt his capricious appetite. “I make his toast and his coffee of a mornin’, and he’s ready to eat me when it’s on his table because the coffee ain’t a-bilin’ and a-sissin’ hot, an’ the egg maybe has been cooked ten seconds longer than his wife used to cook it for him.”

“Let me go in and prepare his table while you get the food ready,” Mrs. Manning suggested. She had waited on just such an invalid once in her lifetime, and had ideas.

“All right, ma’am. I’ll be right glad of a little help, for he do try my patience all to frags.”

Mrs. Manning ran home quickly, and returned bringing a dainty tea cloth and a bouquet of her window flowers in a delicate glass vase, and, going into the dining room, she soon had the little invalid table a very poem of neatness and elegance.

“Mrs. Harrihan never set that table, I’ll be bound,” he said, gruffly, as Mrs. Manning carried it to his bedside.

“Mrs. Harrihan is busy and I am helping her a little,” replied Mrs. Manning, gently. “Let me raise the shade and make you more comfortable for your dinner.”

The window looked out upon the staring high fence, over which the roof and chimney of her own little cottage was visible, and Mr. Harding’s wrinkled face had the grace to gather a flush.

“Are you a widow, ma’am?” he demanded after a few moments, during which she had moved about the untidy room, picking up the morning papers, which he had slung away after reading them, and turning with deft hands the furniture into more home-like positions. Mrs. Harrihan was a good housekeeper but a poor home maker.

“A widow? Dear me, I hope not. Haven’t you seen Mr. Manning frolicing with the children evenings? He comes in the back way, as it saves a block in coming from the station.”

No, Mr. Harding had not observed a man about the place, and for an excellent reason—the fence shut off his view of the charming domestic life of his neighbors completely, and for the first time since its erection he wished it was back in the lumber yard. He had the grace to thank her, and to ask her to come again, after Mrs. Harrihan’s entrance with his dinner, saying that it would taste better with the flowers to look at, and Mrs. Manning poured his tea and buttered his toast, with a great pity for him in his loneliness in her warm heart.

It was the flowers at last which accomplished the downfall of the spitework fence. Acting on the hint of his pleasure in the bouquet on his dinner table, Mrs. Manning kept him supplied with them in liberal measure.

Mrs. Barlow’s roses were now in riotous bloom, and every day a fresh bouquet brightened the sick room. On account of the old wound, the injured ankle did not readily yield to treatment, and for weeks Mr. Harding was an unwilling prisoner, forced to look out at that unyielding expanse of pine until his very soul was sick of it.

He told his grievance in full detail to Mrs. Manning one day with an apologetic air, not willing that his cheery little neighbor, whom he was beginning to respect so much, should think that he indulged in high board fences as a matter of taste.

She heard the story of the Widow Barlow’s delinquencies smilingly, and contrived to throw such a wide mantle of charity, trimmed with humor, over the matter that Mr. Harding actually laughed—and at his own folly.

Even little Barbara lost her fear of “the fence man,” and, after bringing him several bouquets by way of visits of sympathy, she one day made him a social call with the kitten in her arms, also a ball and string with which to show off its accomplishments, and old Mr. Harding actually smiled, and forgot that he hated cats in watching the frolicsome little creature chasing its tail, the ball, or Barbara as she ran with the string.

One day there was the sound of pounding and rending on the Harding premises, and all the children ran excitedly to see.

Carpenters were tearing the spite fence down, and Barbara was in despair for her playhouse, but her childish heart was comforted, for Mr. Harding had given orders, and, when the workmen reached the spot, the boards were sawed down and shaped to match the rest of the structure, and with the dearest little window cut in, to the child’s great delight.

With the fence went every vestige of Mr. Harding’s crustiness toward his new neighbors. Not since his wife’s death had he been so genial and friendly, and the children were a constant source of interest and delight. It even came to pass, through Mrs. Manning’s mediation, that the matter of the boundary line was at last compromised without serious friction, and Mr. Harding really came to confess, to himself, that even the Widow Barlow was not so utterly, so irrevocably bad as she might be after all.

By W. Bert Foster

The story opens in the year 1777, during one of the most critical periods of the Revolution. Hadley Morris, our hero, is in the employ of Jonas Benson, the host of the Three Oaks, a well-known inn on the road between Philadelphia and New York. Like most of his neighbors, Hadley is an ardent sympathizer with the American cause. When, therefore, he is intrusted with a message to be forwarded to the American headquarters, the boy gives up, for the time, his duties at the Three Oaks and sets out for the army. Here he remains until after the fateful Battle of Brandywine. On the return journey he discovers a party of Tories who have concealed themselves in a woods in the neighborhood of his home. By approaching cautiously to the group around the fire, Hadley overhears their plan to attack his uncle for the sake of the gold which he is supposed to have concealed in his house.

THE words Brace Alwood uttered were enough to rivet Hadley to the spot, and, almost within a long arm reach of the men lounging about the fire, he crouched and listened to the dialogue which followed. The reason stated by Brace for the presence of the Tories in this place naturally startled and horrified Ephraim Morris’s nephew. When the old man was well-known to be a strong Royalist, why should these fellows be plotting to attack him? At once Hadley was sure that they were after the money which rumor said Miser Morris kept concealed in his house.

Remembering the incident of the night at his uncle’s house, Hadley doubted if the men would gain what they hoped for; but Uncle Ephraim was old and alone, and there was no telling what these rough fellows might do to gain their ends.

“You’d better make sure the old man is alone, Alwood,” suggested one of the others, as Brace and his younger brother took seats in the circle around the fire. “There used to be a boy with Miser Morris—his nevvy, was it?—who might make us trouble.”

Brace Alwood laughed harshly. “We ought to be a match for an old man and a boy, I reckon—though Lon, here, tells me Had Morris is pretty sharp.”

“He made me and Black Sam pole him across the river one night when he was carrying dispatches to the army,” Lon admitted. “An’ he pretty near broke my arm just before he left these parts last, too.”

“What army was he carrying dispatches to?” demanded the first speaker.

“Washington’s, of course.”

“But the old man is for the king, you say—worse luck!”

“That doesn’t say the boy is,” Brace remarked. “He’s a perky lad, I reckon.”

“He may do us harm, then—in slipping away and rousin’ the farmers, I mean.”

“He’s with the army now,” said Lon.

“And there’s nobody with the old man?”

“Not a soul.”

“Well, we’ll likely have an easy time of it. If he’s got as much as they say hid away in the house, this night’s work will pay us fine.”

“And settle some old scores, too,” added Brace. “Colonel Knowles will be revenged on the old scoundrel, I reckon.”

“Ah! I remember what you told us,” said the first man, thoughtfully. “His Honor is too loyal a man to appear in this matter, though, I take it?”

Brace laughed shortly. “No doubt—no doubt. He comes here to get something out of Miser Morris; but the old fox gives nothing away—not him!”

Hadley had heard enough to assure him that the Tories were actually going to attack his uncle, Royalist though he was. With silent tread he crept away from the place, crossed the pasture to the road, and getting on Black Molly’s back, sent her flying toward the inn. He was fearful for Uncle Ephraim’s safety, but it was useless for him to ride and warn the old man. He must arouse the farmers—or such of them as were at home—and bring a band to oppose the men with Brace Alwood. There would be some lack of enthusiasm, however, when it was learned that the Tory renegades were attacking one of their own kind; it was a case of “dog eat dog,” and most of the neighbors would scarce care if the old man was robbed.

But Hadley rode swiftly toward the Three Oaks Inn, determined to raise a rescuing party at all hazard. It was evening and the men usually centered there to hear the news and talk over the war and kindred topics, and the boy was quite confident of getting some help. Besides, what he had heard while lying hidden in the grove made him believe that Colonel Creston Knowles was partly the cause of this cowardly attack by the Tories upon Uncle Ephraim, and if the British officer was still at the inn the boy determined that he should not go unpunished for instigating the crime.

The American farmers about the inn had borne with the British officer more because he was Jonas Benson’s guest than aught else. Before being sent by Lafe Holdness on this last errand to the army, Hadley knew that many of the neighbors spoke threateningly of the British officer, who, apparently, knew no fear even in an enemy’s country. If they should be stirred up now, after the disaster to the American forces, when feeling would be sure to run high, Colonel Knowles would find himself in very dangerous quarters. For the moment Hadley did not think of the danger to Mistress Lillian. He was only anxious for his uncle’s safety and enraged at Colonel Knowles for the part he believed the officer had in the plot to rob—and perhaps injure—the farmer.

In an hour, so Brace Alwood said, they would attack the lonely homestead of the man whom the whole countryside believed to be a miser. Hadley had good reason to know that his uncle was possessed of much wealth, whether rightfully or not did not enter into the question now; but the money was no longer in the house—of that he was confident. Enraged at not finding it, the Tories might seriously injure Ephraim Morris. With these tumultuous thoughts filling his brain, the boy rode into the inn yard, let Black Molly find her old stall herself, and was on the steps of the inn before those in the kitchen had time to open the door, aroused though they had been by the rattle of the mare’s hoofs.

“It’s a courier!” cried some one. “What’s the news?”

“It’s that Hadley Morris!” exclaimed Mistress Benson, showing little cordiality in her welcome. Jonas was not in evidence, and there was no other men in the kitchen.

“Where is Master Benson, madam?” demanded Hadley of the innkeeper’s wife. “I want him to help me—and all other true men in the neighborhood. There is a party of Tories up the road yonder, and they are going to attack Uncle Ephraim’s house and rob him this very night.”

“Tories!” gasped the maids.

“King’s men!” exclaimed Mistress Benson. “And why should they wish to plague Master Morris, Hadley? He is loyal.”

“That Brace Alwood is at their head. They are bent on robbery. Nobody will be safe now, if they overrun the country. Where is Master Benson, I say?”

“He is gone to Trenton,” declared one of the frightened women. “There is no man here but Colonel Knowles’ servant.”

“Then he is here yet?” cried the boy, and pushing through the group of women, he entered the long hall which ran through the inn from the kitchen to the main entrance. His coming had evidently disturbed the guests. Colonel Knowles stood in the hall by the parlor door, a candlestick held above his head that the light might be cast along the passage, his daughter, clinging to his sleeve, stood behind him.

“Whom have we here?” demanded the British officer.

“It is Hadley Morris, father!” exclaimed the girl, first to recognize the youth.

Hadley approached without fear, for his indignation was boundless. “It is I, Colonel Knowles,” he said, his voice quivering with anger. “I have come back just in time to find that, unable to bring my uncle to such terms as you thought right, you have set Brace Alwood and his troop of villainous Tories upon the old man. But I tell you, sir, I will arouse the neighborhood, and if Uncle Ephraim is injured, you shall be held responsible!”

The officer took a stride forward and seized the boy by the arm. He waved the crowd of women back. “Return to your work!” he commanded. “Mistress Benson, call William.” Then he said to Hadley: “Master Morris, step into the parlor here and tell me what you mean. I am in the dark.”

Hadley began to think that perhaps he had been too hasty in his judgment. He stepped within the room. He did not speak to the officer’s daughter, but she stared at him with wide open, wondering eyes. Then in a few sentences he told how he had discovered the plot against his uncle.

“Who are these Alwoods?” demanded the Colonel, when he had finished.

“Alonzo Alwood is the boy who came here once to see you, father,” Lillian interposed, before Hadley could reply. “Do you not remember? He told you that Master Morris was about to carry dispatches to Mr. Washington again, and asked you to help stop him in his journey.”

“Ah!” exclaimed Hadley. “He did try to halt me. But your servant, sir, stopped him. Have I to thank—?”

“Mistress Lillian, sir,” said the Colonel, shortly, but a smile quivered about his mouth. “I am in the enemy’s country, as you advised me once, Master Morris, and I would not be a party to the young man’s plan. So this Brace Alwood is his brother?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And they connect my name with their raid upon that—that old man?”

“They do, sir.”

“Then to prove to you, Master Morris, that I am not in their confidence, or they in mine, I will ride back with you.” At the instant the man-servant entered. “William, saddle my horse and one of the bays for yourself—instantly! I will join you at once, Master Morris. If you have other men in the neighborhood on whom you can depend in this emergency, arouse them.”

Hadley, feeling that his impulsiveness had caused him to accuse Colonel Knowles wrongfully, ran out again without a word. While William, as silent as ever, saddled the officer’s black charger and another animal for himself, the boy took the saddle off Black Molly and threw it upon one of the other horses in the stable. Then he clattered over to the nearest neighbor’s house and routed out the family. But the only men folk at home were two half-grown boys, and when their mother learned that there were Tories in the neighborhood she refused to allow them to leave her and the younger children. So he rode on to the next homestead and brought back with him to the inn but one man to join the party. Colonel Knowles and his servant were awaiting their coming in the road before the door of the Three Oaks.

“Lead on, Master Morris!” commanded the officer. “You know the way by night better than I.”

“But there are only four of us,” began Hadley, doubtfully.

“We can wait for no more if what you have told me is true. They will be attacking the old man by now.”

The quartette rode off at a gallop and little was said until they turned into the farm path which led through the pastures and fields to the Morris homestead. Then the neighbor was riding nearest Hadley’s side and he whispered: “Hey, Morris, suppose this should be a trap? Suppose the Britisher should be playing us false?”

Hadley tapped the butt of the pistol beneath his coat. “Then he’ll get what’s in this first—and do you take William,” the boy whispered. “But I do not believe Colonel Knowles will play us false. These Tory blackguards are nothing to him.”

The ring of the horses’ hoofs announced their coming before they were within shot of the house, around which the rascals under Brace Alwood had assembled. But no shots were fired, for Colonel Knowles was ahead and his mount was recognized by Lon in the light of the huge bonfire which had been built in front of the farmer’s door. Part of the Tories were already inside the house, ransacking the dwelling from cellar to garret, while Ephraim was tied hard and fast to one of his own chairs, and Brace Alwood, with cruel delight in the farmer’s terror, was threatening to hold the old man’s feet in the flames on the hearth if he did not divulge the hiding place of his gold. Colonel Knowles’ coming struck the entire party of marauders dumb.

“What are you doing here, you scoundrels?” exclaimed the officer, almost riding into the farmhouse in his rage, and laying about him with the riding whip he carried.

The men shrank away in confusion. Even Brace Alwood, the bully, was cowed. “The old miser’s got more money than is good for him,” whined Alwood. “And his nephew is off with the rebels—”

“Sirrah!” exclaimed the colonel, sharply. “Here is his nephew with me. And it matters not what his nephew may be, in any case; the man himself is for King George, God bless him!—or so I understand.”

“Yes, yes, Master!” squealed the farmer from the chair where he was tied. “I am for the king. I told these villains I was for the king. It is an outrage. I cannot help what my rascally nephew is—I am loyal.”

“And as for his money,” continued the colonel, savagely, “you’d work hard and long before you got any of it—and what you got would likely not be his, but belong to those whom he has robbed!” At that Uncle Ephraim recognized his rescuer, and he relapsed into frightened silence. “Come out of that house and go about your business!” commanded the officer. “Let me not find any of you in this neighborhood in the morning; and think not I shall forget this escapade. Your colonel shall hear of it, Alwood.”

Somebody released the farmer from his uncomfortable position, and he followed the bushwhackers to the door, bemoaning his fate. The men clattered out and, evidently fearing the power of Colonel Knowles, hurried away toward the river. When Uncle Ephraim saw his woodpile afire, he rushed out and began pulling from the flames such sticks as had only been charred, or were burning at one end, all the time railing at the misfortune that had overtaken him. The neighbor looked on a minute and then said, brusquely:

“I’ve little pity in my heart for such as you, neighbor Morris—a man that will take sides against his country.”

“And I’ve little pity for you, either,” Colonel Knowles declared, when the first speaker had ridden away, “for you are a dishonest old villain!”

He and William wheeled their horses and followed the bridle path back to the highway; but Hadley, much troubled by what he had heard, remained to help put out the fire in the woodpile. His uncle did not speak to him, however, but when the last spark was quenched by the water which the boy brought from the well, he went into the house and, fairly shutting the door in his nephew’s face, locked and barred it!

“Well!” muttered Hadley, “I don’t need a kick to follow that hint that my company’s not wanted,” and he rode back to the inn, feeling very sorrowful. Evidently his uncle was angry with him. But more than all else was he troubled by the words he had heard Colonel Knowles address to Ephraim Morris. The British officer had broadly intimated that the farmer was a thief!

On his return to the inn he was so tired that he did not think of supper, and, instead of going into the house, tumbled into his couch in the loft and dropped to sleep almost instantly. The next morning Master Benson did not arrive, and the mistress of the inn met Hadley with a very sour face and berated him well for the manner in which he had burst in upon her guests the night before.

“You are spending more than half your time with Washington’s ragamuffin army,” quoth she; “you’d better stay with them altogether. I cannot have my guests disturbed and troubled by such as you.”

Hadley was inclined to take her berating good-naturedly, for he knew at heart that she was a kindly woman, and that, when Jonas was at home, she would not dare talk so. But she had really engaged a neighbor to perform his tasks, and, learning that Jonas was not expected back for a week or more, Hadley saw that it was going to be very unpleasant for him in the neighborhood meanwhile. Even his uncle did not care for his company, and he could not eat the bread of idleness at the Three Oaks Inn. There were three or four men starting to join Washington’s forces, and he determined to accompany them, sorry now that he had returned at all.

He did not feel at liberty to take one of the Bensons’ horses this time, and so started afoot for the vicinity of Philadelphia. The roads were full of refugee families, and, although he could not learn of any real battle having been fought, the country people had evidently lost all hope of Washington staying the advance of the British. Hadley and his comrades traveled briskly, reaching the vicinity of Warren’s Inn early on the morning of the 16th and joined General Wayne’s forces just as the downpour of rain which spoiled the operations of that day began.

ON this 16th day of September, the opposing forces—Howe’s army led by Lord Cornwallis and the Americans by Anthony Wayne—met in conflict near the Warren Inn. Since Brandywine, when, because of Sullivan’s defeat, Washington had been forced to retreat to Chester, the armies had been maneuvering on the Lancaster pike; but nothing more serious than skirmishes had resulted. But this conflict near the old inn was a close and sharp engagement, and it would have been general had not the rain which was falling become a veritable deluge. The arms and ammunition were rendered almost useless, and the Americans had to retreat again.

Bitterly did Hadley Morris grieve as, through the mud and downpour, he trudged in the ranks of his countrymen. Somebody sought him out on the march. It was Captain Prentice, relieved for the time of his command because of his wound; yet he had been near all day to encourage the men and was able still to wield his sword.

“Eh, boy, I knew you would come back!” he said, smiling. “Your blood’s up, and you’ll not sit at peace in the chimney-corner till this bloody war is settled one way or ’tother.”

Hadley told him what had occurred at his uncle’s house, and at the inn where he worked. “You did right to come back to fight with us,” Prentice said. “And you’ll see fighting enough with ‘Mad Anthony.’ Where he goes there is fighting always—that is his business. And a braver or better general does not command on our side, despite the slanders that are told about him. Ah, Hadley, these adventurers and politicians with His Excellency are what keep us back. They so fear to see a good man win that they will do all they can to ruin him. Why, do you know, they are trying to throw some of the blame for Sullivan’s blunder, down there at Brandywine creek, upon Anthony Wayne, although he fought with all the stubbornness a man ever displayed, and held off Knyphausen and his Hessians all day—until, in fact, he learned of the defeat in his rear, and that the rest of the army was retreating.

“We were too busy ourselves that day, Master Morris, to know much about what went on excepting directly in front of us,” Prentice continued, with a smile. “But now that the matter is history, for history is being made rapidly these days, we can get at the truth pretty easily. Colonel Cadwalader, who, by the way, has gone to Philadelphia to look out for his private interests, and several other officers, were discussing the Brandywine engagement yesterday. The colonel, naturally, is a strong opponent of Sullivan and a warm adherent of General Wayne, for the former has too many political friends, and the latter is a plain, out-and-out fighter. Wayne is a Pennsylvania man, you know; has been a farmer over near Easton ’most all his life—though they do say he traveled north once, surveying land. He is somewhere about thirty-three years old now.

“He brought his own regiment into the army—the Fourth Pennsylvania,” continued the captain, getting away from the real matter under discussion, but holding Hadley’s attention, nevertheless, “and he has been advanced to brigadier-general for conspicuous gallantry. They call him ‘Mad Anthony’ and claim he is reckless and thoughtless; but it’s a pity we haven’t more such mad men in the army. You have seen to-day how the troops love him and what they will do for him. This handful of muddy, half-starved creatures would charge the whole of Howe’s army if Anthony Wayne were at their head! Did you get a glimpse of him to-day, Morris?”

“Yes, sir. And I think him a fine figure of a man,” declared the boy, enthusiastically.

“He is that, indeed. A man of more forceful facial expression I never saw, and his dark eyes are always sparkling—either in fun or with earnestness. Anthony Wayne is an ‘all or nothing’ man—he is never lukewarm, as are some of these fellows who have obtained their commissions from Congress. What if he does brag? Why, Morris, if we’d done what he has, and were masters of the science of war as he is, we’d brag ourselves!”

“But why do they try to drag him into the trouble over the Brandywine defeat?” queried the boy.

“Why? Ask me why a mangy, homeless cur always snarls at the heels of a dog that is well bred. ’Tis always so. Jealousy is at the bottom of all these cabals and plots with which the army is troubled. Even His Excellency is not free from the arrows of their hate. And, as I tell you, Sullivan has too many political friends. They wish to attract attention from his mistakes to somebody else, and they fall upon General Wayne and call him reckless. Reckless, forsooth! His fighting that day when he faced those Hessians was marvelous.

“Nobody,” pursued Prentice, warmly, “unless it was His Excellency himself, realized how exceedingly well placed my Lord Howe’s troops were for defence on the left bank of the Brandywine. Greene selected our position—the position of the main army. I mean, at Chadd’s Ford—and it was well. Wayne was there. Sullivan, as the senior Major-General, commanded the left wing. Wayne’s line was three miles long, and the farthest crossing, which he did not cover, Sullivan was supposed to watch.

“You and I, Morris, were too busy in our little corner to know these facts at that time. But it has all come out now, and, just because a certain Major Spear was either a fool or a coward, Sullivan’s flank was turned and the army routed.”

“What had Major Spear to do with it?” asked Hadley, interested despite the mud and rain through which they continued to plod.

“I’ll explain. Early on the day of the battle,—the 11th, you know,—Howe and Cornwallis marched for the forks of the Brandywine, where there are easy fords. Evidently they intended to do exactly what they did do—cross the river and march down on our side, doubling Sullivan’s wing back upon the main army. For a maneuver in broad daylight it was childish; but it won because of this man Spear.

“Colonel Bland had been ordered to cross at Jones’ Ford to find out what the British were about. He sent back word—there can be no doubt of this, although Sullivan’s friends have tried to deny it—that Cornwallis was surely marching for the upper crossings. His Excellency, learning of this report, threw Wayne across the river to attack Grant and Knyphausen, while Sullivan and Greene were to engage the flanking column of Britishers. Why, if things had gone right, we’d have cut the two divisions of the enemy to pieces!” declared the captain, bitterly.

“But it was not to be. A part of Wayne’s troops had already forded the river when this Major Spear, who had been reconnoitering in the direction of the forks, reported no sign of the enemy in that direction. What the matter was with the man I don’t know—nobody seems to know; but Sullivan should have known whether he was to be trusted or not. The general, on his own responsibility, halted his column and sent word to His Excellency that the first report of the British movements was wrong—Cornwallis was not in the vicinity of the Brandywine forks. Naturally this put the Commander-in-Chief out, and, fearing a surprise, he withdrew Wayne’s men from across the river. The Hessians followed; but they got no farther. Mad Anthony held them in check.

“While we were fighting so hard down there by Chadd’s Ford, Sullivan was doing nothing at all. About one o’clock, it seems, a man named Cheney rode into Sullivan’s division and reported that the British had crossed the river and had reached the Birmingham meeting-house. That was some distance then on Sullivan’s right. But the general still stuck to his belief in Major Spear, and instead of sending out a scouting party, put aside the report as valueless.

“This ’Squire Cheney is something of a man in his township—lives over Thornbury way, they tell me—and it angered him to be treated so superciliously by Sullivan. So what does he do but spur on to headquarters and inform General Washington himself. The report could scarcely be believed by the Commander-in-Chief and his staff, and you cannot blame them. Everybody knew how much depended on the day’s action, and that Sullivan should make such a terrible blunder was past belief.

“Your friend Colonel Cadwalader told me about it afterward. ‘If you doubt my word, put me under arrest until you can ask Anthony Wayne or Persie Frazer if I am a man to be believed!’ said Cheney, getting red in the face. The staff—some of the young men, it seemed—had laughed at the queer figure the old fellow cut on his horse. ‘I’d have you know that I have this day’s work as much at heart as e’er a one of ye!’ quoth Cheney, and at that His Excellency ordered a change of face, and part of the army moved up to the support of Sullivan.

“You know what happened after that. You saw the fugitives and the wounded when you rode to Philadelphia, Hadley. It was a sad day, and all because one man made a mistake,—either foolishly or willfully,—and another man did not consider the fate of the first city in the land of sufficient importance to have every report brought to him corroborated. Sullivan must bear the brunt of this thing,—as his men bore the brunt of the enemy’s charge—because he was in command at that end of the line. But they’re trying to make out that Anthony Wayne could have saved the day with his troops had he wished. They’d not talk so bold had they faced those bloody Hessians as we did.”

“It seems awful that there should be friction in an army of patriots,” Hadley said, thoughtfully. “They are all patriotic—they all desire the freedom of the Colonies.”

“What some of them desire it would be hard to say,” declared Prentice, gloomily. “And we are not patriots until we win. We’re rebels now—and rebels we shall go down into history unless the Great Jehovah Himself shall strike for us and give us a lasting victory over the British. I tell you, boy, I am discouraged.”

And it was a discouraged column of 1,500 men who marched that night to Tredyfrrin, where Wayne had been ordered by the Commander-in-Chief “to watch the movements of the enemy, and, when joined by Smallwood and the Maryland militia, to cut off their baggage and hospital trains.”

On the 19th, after waiting in vain for Smallwood’s reinforcements, Wayne again crossed the river, and was, at Paoli, able to advance within half a mile of Howe’s encampment. He reported to General Washington that the enemy was then quietly washing and cooking. The British seemed to consider this advance on Philadelphia more in the light of a picnicing party than anything else. To his commander, however, Wayne said that the enemy was too compactly massed to be openly attacked by his small force, and begged that the entire army might come to his aid and strike a heavy blow. But neither Smallwood’s brigade nor any other division of the American forces arrived to aid the little party at Paoli on that day, nor the one following.

Scouts brought in the tale that Howe was about to take up his line of march, and so, as the night of the 20th drew near, Wayne determined to attack in any case, reinforcements or not. The watchword that night in the American camp was, “Here we are and there they go!” and the troops were eager to follow their beloved leader into the very heart of the British encampment. It was believed that the night attack was unsuspected by the British, but it proved later that vigilant Tories had wormed the information from somebody on Wayne’s staff and hastened with it to the British camp.

So confident was Wayne that his plans were unsuspected that, when informed by a friendly citizen, between nine and ten in the evening, that a boy of the neighborhood, who had been in the British camp during the day, had overheard a soldier say that “an attack on the American party would be made during the night,” Mad Anthony would not credit it. It did not seem probable that if such an attack was being considered by the British leaders, it would be common camp talk.

However, believing that surplus precaution would do no harm, he multiplied his pickets and patrols and ordered the troops to repose on their arms, and, as it was then raining, made the men put their ammunition under their coats. He was thus prepared to meet an attack or withdraw, as circumstances might direct.

Ere this, Captain Prentice had been sent to headquarters, almost by force, indeed, because his wound had become inflamed, and Hadley, being simply a volunteer, was obliged to take pot-luck where he found it, and was even without a blanket or pouch in which to carry his rations. He would have been more comfortable on picket duty that night, only volunteers were not trusted in such serious matters; and perhaps, if he had been, the youth would not have gotten out of the terrible engagement alive.

Somewhere about eleven o’clock, rumor had it that the British were on the move. Wayne believed that the enemy would attack his right flank, and immediately ordered Colonel Humpton, his second in command, to wheel his line and move off by the road leading to the White Horse Tavern. Meanwhile, General Gray, in command of three British regiments and some dragoons with Tory guides, approached Paoli. The British were ordered to withhold their fire and to depend altogether on the bayonet. At midnight, two hours before the time fixed for his own advance on Howe’s force, Wayne learned that his pickets had been surprised.

Colonel Humpton had not obeyed, nor did he do so until the third order reached him. The artillery moved without loss or injury, but the remainder of the army was in confusion, and, when charged by the British, the affair became almost a rout. An English officer who was present at the attack afterward wrote:

“It was a dreadful scene of havoc. The Americans were easily distinguished by the light of the camp fires as they fell into line, thus offering Gray’s men an advantage. The charge was furious, and all Wayne’s efforts to rally his men were useless. They were driven through the woods two miles, and nearly a hundred and seventy men were killed.”

With those about him, inspired as they were with fear of the bayonet, and confused by the darkness, Hadley Morris ran blindly through the woods to escape the death which followed him. The awful sabre-like bayonets of the British muskets he did escape; but a half-spent ball imbedded itself in the flesh of his leg above the knee and brought him at last to earth. The others streamed by and left him. He feared he would be captured and perhaps sent to the prison hulks in New York Bay; but both pursued and pursuer passed him by, and he was saved in the darkness.

He could not travel with the ball in his leg, and so he lay down again under some bushes, and, despite the wound and his fright, dropped off into slumber, and slept just as soundly as he would had war and bloodshed been farthest from his thoughts.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Education is a better safeguard of liberty than a standing army.

—Edward Everett.

By Julia McNair Wright

THE production of seed is the chief object of plant life. Upon this depends the continuance of the vegetable world, and therefore all animal existence. From the elephant to the mouse, from the whale to the minnow, from the eagle to the humming-bird, life is conditioned upon the constant return of “the herb-bearing fruit whose seed is in itself.”

In every minute particular the flower is constructed to insure the production of sound seed. The first form of this seed is the tiny ovule in the germ. Ovules cannot grow into seeds, unless they are brought in contact with the pollen, which must arrive at them by way of the stigma.

The pollen of flowers is a most fine, delicate dust. It must be conveyed without injury in the most delicate manner. Many flowers are exceedingly high up, as on climbing vines, or growing on tree-tops, peaks, or house-tops. Many other plants are very low down, lying close to the ground, as the bluets, chickweed, arbutus, partridge-berry, and others. A large number of plants are in positions inaccessible to man or the larger animals.

Man excepted, the larger animals seem generally to have a destructive mission to plants, devouring, breaking, or trampling down. Men themselves are often ruthless destroyers of beautiful plants, and seem to care for and conserve only what concerns human convenience.