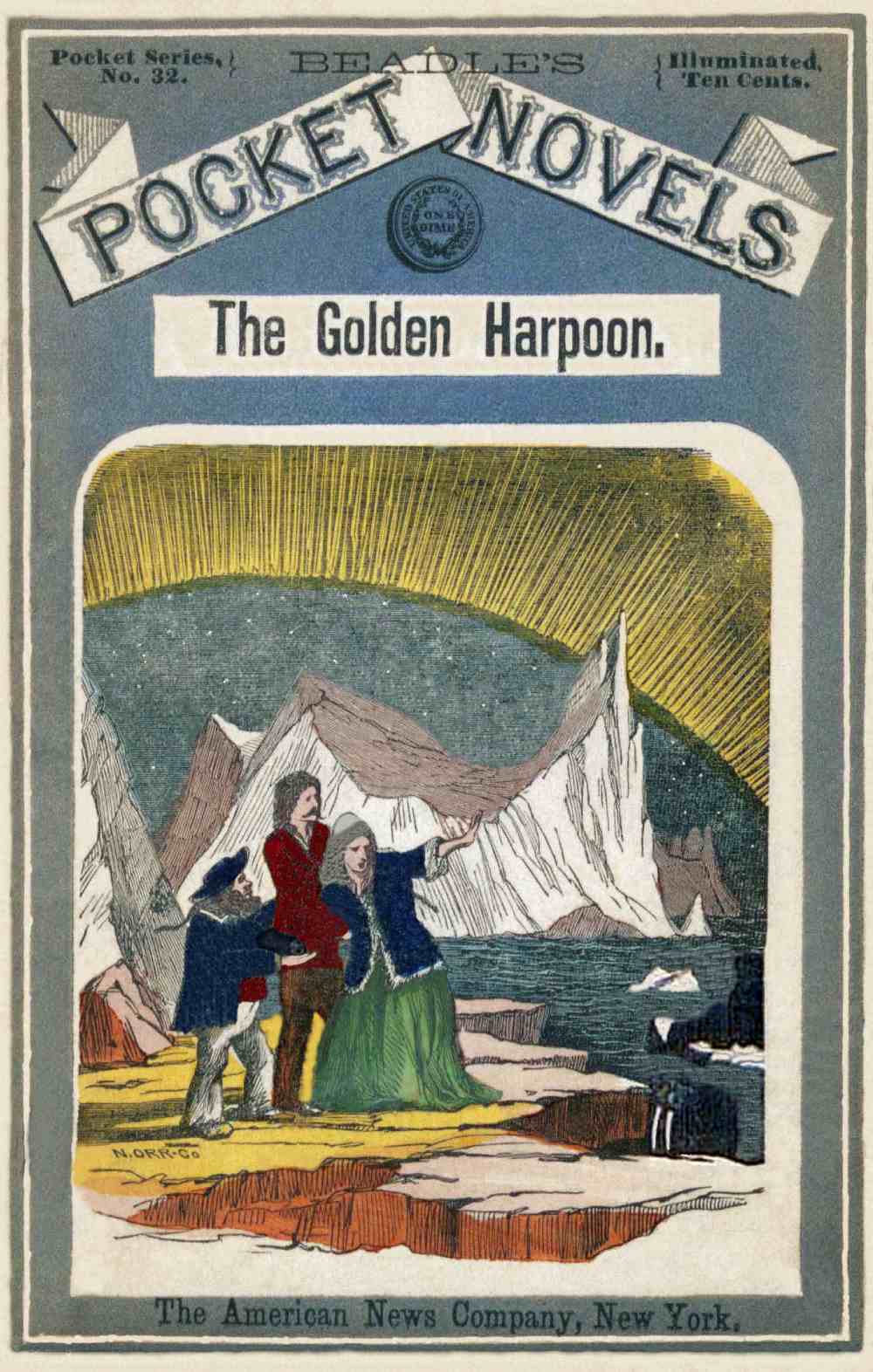

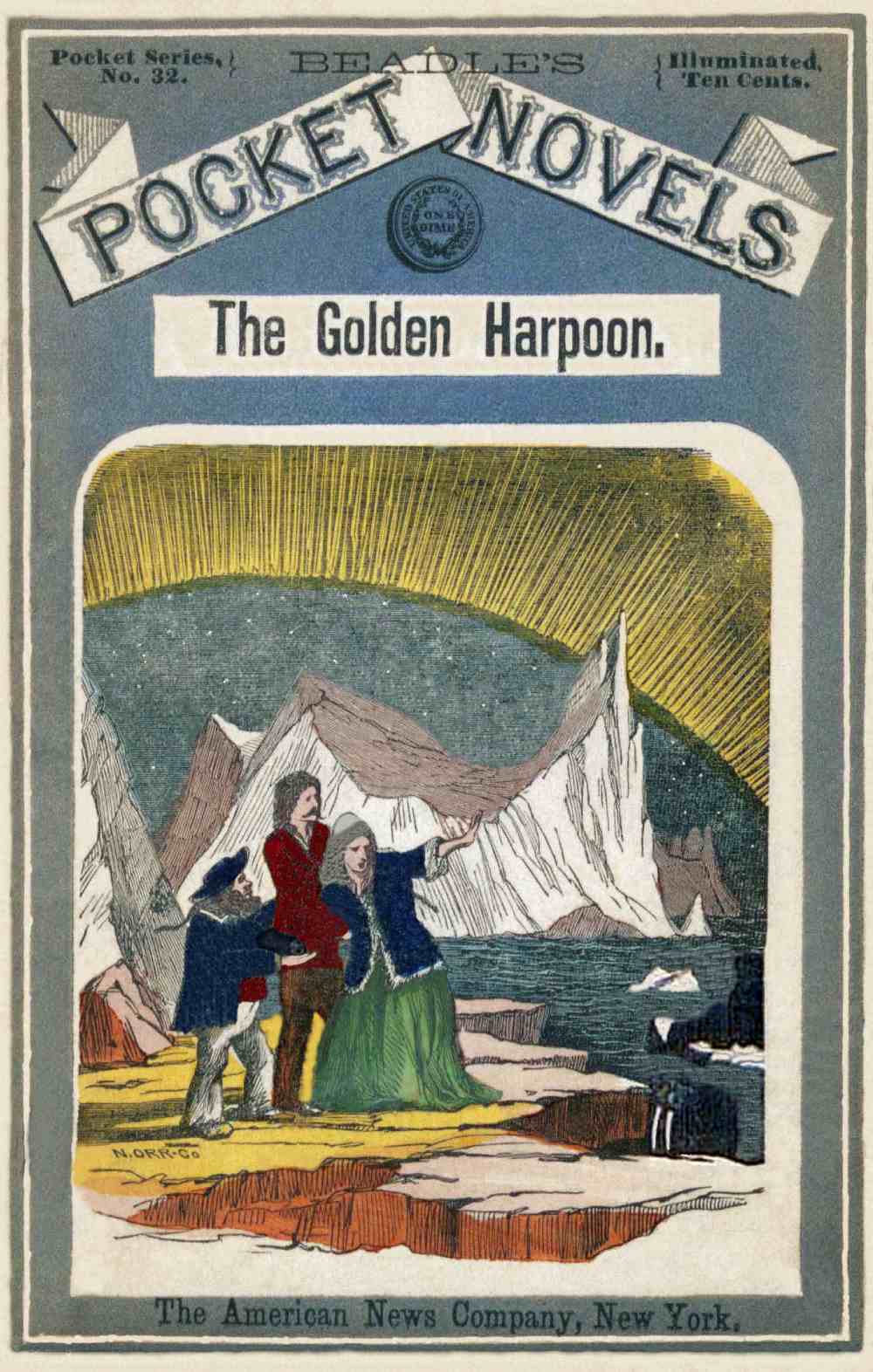

| Title: | The Golden Harpoon |

| Lost Among the Floes |

A STORY OF THE WHALING GROUNDS.

BY ROGER STARBUCK.

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by

BEADLE AND COMPANY,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States for the

Southern District of New York.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | THE GOLDEN HARPOON. | 9 |

| II. | THE RESULT. | 19 |

| III. | A “STOVE” BOAT. | 24 |

| IV. | IN CONFINEMENT. | 33 |

| V. | THE BARRICADE. | 39 |

| VI. | A SLIGHT CHANGE. | 46 |

| VII. | ADRIFT. | 52 |

| VIII. | THE CHASE. | 60 |

| IX. | THE DISAPPEARANCE. | 71 |

| X. | AN UNEXPECTED ENCOUNTER—CONCLUSION. | 86 |

[Pg 9]

THE

GOLDEN HARPOON.

On the morning of the 25th day of April, 18—, the whale-ship Montpelier, of New London, anchored in one of the many bays that open along the coast of Kamschatka, where it is washed by the waters of the Sea of Ochotsk.

As soon as every thing was made snug alow and aloft, the skipper rubbed his hands with complacency, and a satisfied expression was seen to cross even the face of Mr. Briggs, the first mate, who was the ship’s grumbler.

“Good quarters,” remarked the captain.

“Ay, ay, sir,” responded Briggs, “the tide is easy here and I don’t think a gale would hurt us much—we are so shut in by the cliffs. But,” he suddenly added, turning his glance toward a large field of ice, about a league from the shore, “I don’t like the looks of yonder floe. It may come upon us and give us a jam.”

“It will drift past us,” replied the captain; “the current tends to the north’ard.”

“I’m not so sure of that,” said the mate, as he snatched a glass from the mizzen fife-rail, and directed it toward the ice. “Them undercurrents up this way sometimes plays the very smash. But if I ain’t much mistaken, I see a bear moving along the floe.”

As he spoke, he passed the glass to his companion, who immediately lifted it to his eye.

“Do you see the animal, captain?”

“Ay, ay, there it is, sure enough; a brown bear, I believe.”

“Uncle!” exclaimed a gentle voice at this instant, and a[10] light hand fell upon the captain’s shoulder. “How wild! how picturesque! What place is this?”

The speaker was a girl of seventeen, with large brown eyes, a petite but well-rounded figure, and a countenance truly lovely in its purity and expression. From her neck, by a strip of blue ribbon, was suspended a golden harpoon of delicate workmanship, and about four inches in length. It was the gift of the captain—her only living relative—who had presented it to her on the day that he complied with her request to accompany him on his present voyage.

And why did she wish to go to sea?

Firstly, because the bold and handsome Harry Marline had shipped in the Montpelier as boat-steerer and harpooner’s aid. Secondly, because she was much attached to her relative, who, having no children of his own, always had treated his niece with the indulgent fondness of a father.

You might have known this, had you seen the smile that crossed his face as he turned and gazed with admiration upon the crimsoned cheek, and the expressive eyes of the young girl.

“Good-morning, Alice,” he said. “I am glad to see you stirring so early. How did you pass the night?”

“Very well, thank you,” she replied, raising herself upon the tips of her toes, and presenting her lips for a kiss, which was immediately granted. “Very well, indeed; but you have not answered my question. What place is this?”

“It has no particular name that I ever heard of,” replied the captain. “But, you have been long enough at sea, now, Alice, to perceive that I’ve chosen a good place for an anchorage—”

“If it wasn’t for the ice,” interrupted Briggs.

“An excellent place,” continued the captain, paying no attention to the words of his companion, “a position well sheltered, where the craft can lie while we fill her with oil—secure from every danger—”

“Except that of ice,” doggedly persisted the mate.

“Secure from every danger,” repeated the captain, turning sharply toward his first officer.

“Oh! I am so glad!” cried Alice, clapping her white hands with an enthusiasm natural to a girl of seventeen. “It is such a wild, beautiful place. And, on pleasant days, I can[11] bring my sewing on deck. It will be very nice sitting here and looking up now and then at those great towering cliffs that rise so far above the tops of our mast-heads.”

“Until the ice comes,” said Briggs.

“Why, Mr. Briggs, what do you mean?” said Alice, turning toward the first officer with an expression of alarm upon her face; “this is the third time I’ve heard you speak about the ice. Is there really danger to be apprehended from it?”

“Ay, ay, Miss Alice, plenty of it,” bluntly responded the mate, “and unless—”

“You must not mind him, niece,” interrupted the captain. “He fancies there is danger from that floe that you see off the quarter; but, you may believe me, when I tell you, that it will have drifted past us before night.”

“There are undercurrents that’ll bring it upon us before the morning,” persisted Briggs. “This isn’t the first time I’ve sailed in these waters.”

“Oh, uncle!” said the young girl, placing both hands upon the captain’s shoulder; “the mate is an old sailer of this sea, while this is the first time that you have ventured in this quarter. I think you had better take his advice.”

“Fiddlestick!” exclaimed the captain; “what does a girl know about seafaring matters?”

“Ay, ay, sir, she’s a girl, but she’s got an uncommon wise head for all that. Mark ye, Captain Howard,” he added, feeling so highly gratified by the favorable remark of the skipper’s niece, that he was disposed to be complimentary—“mark ye, I’ve seen women enough in my day, but I’ve never seen one as had a longer head than Miss Alice!”

The maid blushed, and bit her lips to conceal a smile, while Briggs, believing that his words had pleased her, but fearing that she might think he had merely been trying to flatter, pursued the subject in a manner so earnest, that his sincerity could not be doubted.

“Ay, ay, sir—a long head has this young girl, and I don’t mean to flatter her when I say it. She’s about the first woman I ever saw with such a head. To look at her, it’s true, you mightn’t think that she was blessed in that way. But, my eyes! neither would you think that a horse’s head was so long as a flour barrel!”

[12]

“You had better stick to currents and icebergs, Mr. Briggs, and leave the complimenting of girls to those who understand the art better than you do,” said the captain, a little resentfully. “Young ladies, as a general rule, do not care to be told that they have long heads?”

“Indeed, uncle,” cried Alice, in a voice that faltered with the efforts she made to restrain her laughter, “indeed, uncle, I feel much obliged to the mate for the compliment he has paid me.”

“Oh, well,” said her uncle, dryly, “there is no accounting for tastes—especially for those of women. If Briggs’ remark pleased you, I have no more to say.”

“He was sincere, dear uncle, and you know that sincerity always pleases me.”

“Even when you are told that you have a long head?”

“That was a figurative expression on the part of Mr. Briggs.”

“Ay, ay, that’s it,” broke forth the mate, “figgerin’ is the word. I’m poor at figgers myself, but my eyes do me instead, for they have good sight and are good at measuring. And that’s why I can calculate almost to the minute when that ice-floe, which is now about a league from us, will be upon us, jamming our timbers.”

“It will never reach us,” replied the captain, in a decided voice; “you can even perceive that it is moving north’ard now, and—”

He paused suddenly and turned his gaze toward the ice, upon which the eyes of the mate had suddenly seemed fixed with steady intensity.

“Ay, there it is again,” shouted the first officer, as a column of vapor shot upward from the center of the floe. “There blows!—there—there blows! The ice is alive with whales, captain Howard!”

“Clear away the boats, there!” shouted the latter.

These words were addressed to the sailors lounging about the windlass, some of them smoking, and others engaged in patching threadbare coats and jackets.

“Lively—lively, men!” yelled the captain, as the “tailors” paused to thrust the garments upon which they had been working, into the many little “cubby-holes” about the windlass,[13] and the smokers proceeded to knock the ashes from their pipes. “Call all hands!”

This command was promptly obeyed, and a dozen men who had been lying asleep upon chests in the forecastle came bounding through the open scuttle.

By this time the decks of the Montpelier presented a scene of bustle and excitement, such as always takes place on board a vessel of her class when whales have been sighted, and preparations are being made to lower away. The men rushed to the falls; the harpooners sprung into their respective boats to prepare the line-tubs and their craft; while the captain and his officers hurried the movements of their crews with frantic gesticulations and excited voices.

In the midst of the uproar stood Alice Howard, watching with dilating eyes and blushing cheeks the movements of Harry Marline, who belonged to the mate’s boat, and who, more than once, while arranging his irons, contrived to direct a quick but smiling glance toward the spot where she stood. She had been so long an inmate of her uncle’s vessel, that—but for the presence of her lover—the scene passing before her eyes would have excited but little interest in her bosom.

The hoarse shouts of the captain and the many expletives that even her presence did not prevent the mate from uttering, jarred unpleasantly upon her spirit, and more than once she pressed her little hands against her ears to shut out the hard words that saluted them.

At last, however, the necessary preparations were completed, and the captain then gave the order to lower away. As the four boats dropped simultaneously into the water, he advanced to the side of his niece, and grasped her hand.

“Good-by, Alice. When we return, I hope we will bring whales alongside. Take good care of yourself while I am absent. There are plenty of books in the cabin to amuse you, I trust.”

“Oh yes, I shall get along very well. But do be careful, dear uncle, and don’t have any of your boats stoven, or any of your men hurt.”

“Ay, ay, good-by!” and with a parting kiss the captain sprung into his boat and issued the command to “give way!”

The light vessels darted with arrowy swiftness from the[14] ship’s side, and, a moment afterward, the bow of each was heading for the floe.

Alice then ran to the bulwarks, and stood watching the boats with a vague feeling of uneasiness that she had never before experienced.

The voices of the officers as they shouted encouragement to their crews, and the dull sound of the oars as they were worked in the row-locks, fell unpleasantly on her ears. She strove to recall the feelings of pleasurable excitement that she had been wont to indulge upon similar occasions; but, the effort was made in vain, and tears of vexation rose to her eyes, because she was unable to subdue her melancholy.

In the mean time the four boats continued to recede rapidly from the ship, and presently the young girl perceived that they were upon the outer edge of the ice-field. A few minutes later their crews had worked them so far among the bergs that they were out of sight.

Alice was then on the point of moving in the direction of the companion-way, when she felt a hand upon her arm. Turning, she beheld a face and figure, the singular appearance of which we shall at once describe.

The face, which was that of a man about forty years of age, was very large and square, with enormous ears, round, twinkling blue eyes, a flat nose, and a pair of lips that kept moving from side to side, producing a ludicrous effect upon the whole countenance. An old-fashioned pigtail, carefully tied near its extremity, and well greased with whale oil, hung from the back of the head, keeping time with the movements of the wearer, and giving to the huge glazed sou’wester that crowned his skull, the appearance of a very unnatural animal, with a black shell and a long tail. Passing on, we come to the figure, which was not unlike that of a cask, while the arms were of enormous length. The legs, on the contrary, were very short. The dress of this person, besides the sou’wester alluded to, consisted of a Guernsey frock—so profusely ornamented with patches of different sizes and hues, as to remind the spectator of “Joseph’s coat of many colors”—and pants of canvas-duck, very coarse, but scrupulously clean, with the bottoms flowing loosely around a pair of neat, well-fitting pumps.

[15]

“Good-morning, John Stump,” said Alice, as the sailor lifted his sou’wester and bowed, scraping his right foot as he did so.

“Jack Stump, if it please your pretty lips, miss—for I always feel as though I was turned wrong side out when anybody calls me John. Jack’s the name that I’ve always gone by, ever since I was as big as a turtle.”

“Oh, very well—Jack Stump it shall be, then. You have something particular to say to me, Jack,” she added, as the seaman suddenly placed his forefinger upon the side of his flat nose, while his great blue eyes began to roll in his head.

“Ay, ay,” he said, at last, in a low voice, “I’ve been a-trying to get out, what I wanted to say to you, sweet lass but your beauty choked the words in my throat, as a stick of candy put in the mouth of a baby stops its squalling. Such beauty as yours, miss—”

“That will do, Jack,” interrupted Alice, with a gratified smile, for she was too truthful to pretend that the compliment did not please her; “that will do, and I am much obliged to you. But you have aroused my curiosity, and I would thank you to come to the point at once.”

“Here it goes, then,” said Stump, speaking in a voice of mysterious confidence, “here it goes, sure enough, which is, that I’m a friend to you and the captain, and I wish that everybody in the ship was the same.”

“Why! how is this, Jack? My father’s crew are all friendly to us, are they not?”

“Good grub!” said Stump, in a deep voice, “is the first consideration in a whaler. Good officers the second, and good luck the third. Them are the three things that wins men’s hearts—them are the things that have won mine. But there are some beings that has the shape of men, and yet they ain’t men for all that;—amphibious animals like, that has more of the shark than human natur’ in their corporosities, and believe me, Miss Alice, there are such creatur’s in this bark. Just turn your pretty eyes forward, young lady—sly like, as you women know so well how to do—and look at them five blue-skinned devils standin’ there by the windlass a-whispering and talking together. D’ye see ’em?”

[16]

“I do,” replied Alice. “Four New Zealanders and the Portuguese steward; but what of that?”

Stump seized the end of his pigtail with his left fingers, and bringing it over his shoulder, placed his right hand upon it.

“It’s an honest pigtail—Miss Howard, and I always swear by it on occasions of this kind, when a Bible isn’t handy. And now,” he added, in a solemn voice, “here goes my oath, which is that them fellows forward are a-plotting and hatching to do harm—though what harm exactly I can’t tell, but I think it’s as well to be prepared!”

“Why Jack! how you talk. What ground can you have for these strange suspicions? My father, with all his officers and the greater part of the crew, away, too,” added the young girl, with a shudder.

“Ay, ay,” responded the shipkeeper, allowing his pigtail to drop to its original position, “and that’s why we must be on our guard. Them devils forward were all laid up with the rheumatiz a while ago, so that they couldn’t go in the boats, and now look at ’em, a-standin’ up as well and hearty as you and I. That’s suspicious to begin with. Then again I overheard one of ’em talking about freeing that quarrelsome mutineer, Tom Lark, who, you know, the skipper put in irons a week ago—because he refused duty—and shut up in the run. They said something about his understanding navigation; and I couldn’t hear any more because they saw that I was near them a-listening and they closed their mouths all of a sudden.”

“What shall we do? What can we do?” cried Alice, in considerable alarm.

“That’s a hard question to answer, seeing as I’m all alone without any man to help me. But you may be sartain that Jack Stump will stick to you and do what he can. You had better go below now, and lock the door of your room while I dodge around and find out something about the plans of the rascals. Of one thing, hows’ever, you may be assured, and it is that the plotters can’t do anything just now, seeing as the wind has gone down and there isn’t a breath of air stirring, and—ay, ay, Miss Alice, a beautiful morning!” he suddenly added, in a louder tone. “I’ve sailed the sea in every kind of a craft[17] for thirty years, and never knew a finer mornin’ than this! What do you think of that?”

Alice opened her blue eyes upon the speaker, surprised by this abrupt change in the thread of his discourse. But in a few moments she understood the cause, for a light footstep suddenly saluted her ear, and she divined that a third person had passed behind them and taken his position near the rail, not far from the spot they occupied. With woman’s ready tact, she refrained from turning her head even to get a glimpse of the intruder, and proceeded at once to reply to her companion’s remark.

“I am surprised to hear you say so. The weather is not as a general thing very clear in the Ochotsk sea, I believe.”

“Not a bit of it, Miss Alice. There ain’t many heavy gales here at this season of the year, it’s true, but there’s plenty of fogs. If I hadn’t such a good paunch in me,” added Jack, placing his hand upon that protuberant portion of his body, “I should have died with the rheumatiz long ago. But this has presarved my soul as a good purse presarves the money in it. Just give a sly look at that blue devil, will you—a-listening with all his ears,” continued the speaker, partially turning his head under the pretense of shaking his pigtail.

Alice moved closer to the rail, and directing her glances toward the water, contrived to obtain a good view from beneath the corners of her eyes of the individual who stood upon the other side of her.

He was a tall New Zealander, with a sinewy face, high cheek-bones, and that peculiarly fierce eagle gleam of the eye, natural to the people of his race. There was a ring in each ear, another hanging pendent from his nostrils, and his countenance was disfigured in many places by “tattoo” marks of yellow and blue. On the present occasion his thin lips wore a peculiarly sinister expression, that excited much uneasiness in the bosom of Alice, notwithstanding that she had been accustomed during the voyage to see the wild natives of the Pacific shores. The islander, however, seemed perfectly unconscious of the presence of those who were so stealthily watching him, but with his face thrust forward over the rail, and his chin supported by his hands, he remained as motionless as a statue, gazing steadily toward the floe that glittered in the distance.

[18]

“Do you see any thing of the boats, Driko?” inquired Stump, quitting his original position and placing himself between Alice and the native.

“De boat me no see. Dey too far in ’e ice. No comee back to bark nebber more.”

“And why not, I’d like to know. You must not make such a foolish speech as that again, ‘Blueskin.’ You frighten Miss Howard!” and seizing his pigtail, he gave the savage a light blow across the nose with it, as he spoke.

“Takee care!” gritted the native, starting upright with glittering eyes and placing a hand upon his sheath-knife, “takee care, you Stump. No strikee me too much with ‘piggle-tail,’ or me makee you Stump no more.”

“And boil me afterwards in the try-pot, I suppose, seein’ as that’s one of your ‘pow-wow’ customs!”

“Hi! hi! hi!” gritted the New Zealander, while a malicious smile flashed across his dark face. “Me like plenty Stump to eat. Good for boil more better dan whale—dis Stump so fat make very much good!”

“Ay, ay, too good for such a lean, ravenous, blue-skinned rascal as you are, to digest. But how about those boats. Why do you think they’ll never come back?”

“Nebber come back to bark—no nebber more!” exclaimed the savage, with a sinister laugh; and turning upon his heel, with the air of one not caring to be questioned further, he made his way to the forward part of the vessel and joined his four shipmates.

“You had better go below, Alice,” said Stump, “and that will look as though you don’t suspect that anything is wrong. Trust to me to ferret out the rascals’ plans.”

“But they may murder you!” shudderingly murmured the young girl.

“Put your hand there!” exclaimed Stump, straightening himself, and indicating his left breast.

“Oh! I know your heart is all right. But—”

“Put your hand there,” persisted Stump again, pointing toward his heart.

This time Alice obeyed, and she felt the stock of a revolver that was concealed beneath the Guernsey frock.

“You are armed!”

[19]

“Ay, ay!” exclaimed Stump, “two hearts, like two heads, are better than one. An iron heart for the blueskins—— ’em, and Stump’s own heart for Alice Howard, at your sarvice!”

And making his best bow, the speaker turned and rolled off like a cask of oil, in the direction of the windlass.

Alice then moved to the companion-way and descended into the cabin.

As Stump rolled on, he turned his glances seaward, and perceived that a light breeze from the north-west was beginning to wrinkle the surface of the water. He could feel it fanning his temples and stirring the pigtail upon his back. He glanced uneasily toward his dusky shipmates and saw a momentary gleam of exultation flash across their dark features as they were turned in the direction of the ripples gradually spreading over the bosom of the ocean.

Driko stood a little apart from the rest of his shipmates and Stump did not fail to notice that the eyes of this savage were now directed significantly aloft as though he felt impatient to loosen the topsails.

The watchful seaman felt that he could no longer entertain a doubt in regard to the intentions of the conspirators, and gliding behind the try-works, he seated himself upon the cooper’s bench, in the hope that a few moments’ reflection might suggest to him some plan that would enable him to defeat their schemes. But scarcely had he begun to reflect, when, chancing to turn his eyes in the direction of the main-top, his glances alighted upon a roll of red bunting that had been carefully placed in that quarter. It was the recall signal, which was used as a summons to the boats to return when they were absent from the vessel, and it was deemed expedient that they should come back. On every such occasion, the bunting was hoisted to the main truck by means of the signal halliards which were always kept rove for that purpose. Stump sprung[20] from the bench, mentally pronouncing himself a fool because the idea suggested by the sight of the red cloth had not occurred to him before. The boats he thought could not by this time be so far from the vessel that their occupants would not perceive the signal when he should have hoisted it to its proper position; but feeling conscious that there was no time to lose, he began at once to waddle toward the main rigging as fast as the bulky proportions of his body would permit.

Not until he had gained the seventh ratlin in the shrouds, did he venture to direct a glance toward the spot where he had last seen his five shipmates, and he then gave his lips a satisfactory twist toward his right ear, for the men were engaged in earnest conversation and the face of each of them was turned from him. He continued his way as speedily as he could, and presently succeeded in passing the futtock shrouds and in drawing himself into the top. Seizing the bunting, he at once proceeded to unroll it, and a few moments afterward it might have been seen dancing merrily aloft, as he pulled upon the slender halliards. The breeze, which by this time had freshened considerably, rustled among the folds of the cloth as it ascended, and when it had reached its proper position, its broad red surface streamed out from the mast in a manner that elicited a sigh of the most intense satisfaction from the lips of Stump.

“Ay, ay,” he muttered, as he continued to gaze aloft, “there’ll be a rumpus among the boats off there in the ice, when they see that. Those rascally ‘pow-wows’ are in for it now.”

At this moment a yell of surprise and rage broke upon the ears of the speaker, and turning his head, he saw Driko directing the attention of his companions to the signal at the truck. No sooner was the red bunting perceived by the other four seamen, than the whole number, with curses and ejaculations, rushed into the waist and ordered the shipkeeper to pull down the signal at once and to come down himself, if he valued his life.

“Not a bit of it,” replied the sturdy seaman, thrusting his hands in his pockets and calmly gazing upon the upturned faces of the conspirators, “not a bit of it. That rag at the truck doesn’t come down while I have an arm to keep it where it is. You may make up your minds upon that point.”

[21]

The men exchanged glances and then held a moment’s whispered consultation, after which they rushed simultaneously toward the main shrouds upon the larboard side.

Stump waited very quietly until Driko, the foremost of the party, had swung himself into the rigging, and then drawing his revolver, which, although it was quite rusty, looked very formidable with its six loaded barrels, he pointed it at the head of the astonished New Zealander and ordered him back.

“Ay, ay, blast you!” he added, giving his lips an ominous twist as he spoke. “You see I’m prepared. I know all about your infarnal plans to take the ship, and if you make another step in this direction, you are a dead pow-wow, that’s sartain!”

The Kanaka paused, and after he had ducked his head three or four times, in a vain effort to get it out of the range of the threatening weapon, he looked up with an expression of surprise, which, if not real, was certainly well feigned.

“Me no understand. You speakee me take ship. Don’t know what you mean. No want to take ship—me likee capen too much. De signal me no like to see, because capen he no like to come aboard when he after whale. He make plenty angry when he see de signal!”

“Bosh! you deceitful blueskin; it’s all bosh. Just as though I didn’t hear you and your chums there a-whispering and plotting to free the mutineer, Tom Lark!”

The dark blood rushed to the faces of those who listened, and they exchanged rapid glances. Driko, however, presently looked up again and replied:

“Hi! hi! You hear we speak about Tom Lark! Why we so speak? Because de ice ’e come to jam de ship and ’sposing we bring Tom Lark from de run, Tom Lark good sailor—good navigatem—and he save de ship. Dat’s why we speak so much Tom Lark!”

“Bosh again, blast you! For you know that, although I know nothin’ of navigation, I’d be as handy in working the ship clear of the ice, as Tom Lark!”

“Me no believe so,” replied Driko, shaking his head. “Navigatem more good as plenty go to sea. But no use me speak to you. You no think me tell truth. Me leaves you. You keep signal at de truck and when capen come, he scold you much.”

[22]

The islander sprung to the deck, and rejoined his shipmates, who had been listening to the foregoing conversation with sullen faces, and with their uneasy glances directed, at intervals of every few moments, toward the red bunting fluttering at the mast-head. The whole party now withdrew to the forward part of the vessel, but presently they changed their position, sitting down close to the try-works, where they were screened from the watchful eyes of the shipkeeper.

“Blast ’em!” muttered the latter, “they are planning some deviltry or other, and I must keep on my guard, until the rest of the crew returns, which won’t be long, unless they are so wedged in the ice that it’s difficult for ’em to get out.”

He turned his eyes toward the floe, as he spoke, and gazed long and earnestly in that direction. But he was unable to see the boats, and a sigh of disappointment rose to his lips.

He gave his pigtail an impatient jerk, and again directed his glances toward the try-works, just in time to witness a spectacle which was certainly a startling proof that the utmost vigilance on his part could not be thrown away in his present position.

Towering above the try-works, with his tall, lithe figure drawn back, and his keen, glistening eyes blazing with a deadly purpose, stood the savage, Driko, holding in his uplifted hands a well-sharpened harpoon, which he was in the act of darting, point foremost, into the corpulent body of Stump.

The latter had so much respect for the wonderful skill of the islander in the use of the barbed weapon with which he was now armed, that he drew back, screening himself behind the mast, with a celerity which was remarkable in a man of his caliber. The movement, however, was well-timed, for the next moment the deadly iron flew whistling upon its way, and, passing close to the mast, struck the revolver held in his hand with a force that sent the weapon flying from the grasp of its owner into the sea!

A yell of exultation followed, and then the mutineers rushed to the main rigging, and, leaping into the shrouds, proceeded to mount in the direction of the top, with cat-like agility.

Stump, however, did not lose his self-possession, but, seizing both parts of the signal halliards, he gave them a sudden jerk, that served to unfasten them, and, still contriving to keep[23] them taut, commenced to ascend the topmast rigging, intending to make his way to the top-gallant cross-trees, and, when there, keep his adversaries at bay, as long as possible, by means of his legs and his fists.

Unfortunately, as the reader is already aware, the corpulent body of this seaman rendered him incapable of very active exertion, and, as a natural consequence, his enemies gained upon him rapidly.

He was still in the topmast rigging, when he felt two strong hands pulling the bottom of his pants, in an unceremonious manner, and with a force that made it difficult for him to keep his position. He vainly strove to disengage himself from the vice-like grasp, and, while he was still struggling to free himself, he saw Driko, who had crossed from the topmast rigging on the other side, descending toward him, with his long knife between his teeth.

“Go down, quick, you, Stump!” gritted the savage, as he seized his knife with his right hand. “Go down, me say, or knife quick cut de windpipe. No care kill you now, unless you like. Plenty time, by and by!”

“Ay, ay, blast you; you’ve got me in your toils, at last. But it’s a deep sea that hasn’t any bottom, and you may boil me in one of your pow-wow pots if I don’t come out even with you yet!”

Before replying, Driko severed the signal halliards with his knife, and, pulling down the red bunting, rolled it up, and allowed it to drop to the deck.

“Hi! hi! you poor Stump!” he then said; “you think you play me more trick. But me put you, by and by, where you no more make tricks. You see, more soon you like!”

He motioned, as he spoke, to the man who still maintained his hold of Stump’s pants, and, finding himself released for the present, and resistance useless, the shipkeeper proceeded to descend the rigging, Driko following, closely, with his long knife held in readiness for use, in case of opposition.

They had no sooner gained the deck, than Stump was surrounded by the five savages, and thrown down.

They fastened his arms behind his back with strong cords; secured his ankles in like manner, and then dropped him into the main hold, like a pig, closing and fastening the hatch above him.

[24]

The Montpelier’s boats, at the moment when Stump succeeded in hoisting the recall signal, were lying motionless in an open space of water, situated near the center of the floe to which we have already alluded. This little lake, of which the surrounding bergs and compact squares of ice formed the shores, was of sufficient size to contain all the boats, and the captain and his mates had expressed much satisfaction because the position afforded them every facility to maneuver their light vessels in case of the appearance of whales in their vicinity. Upright, in the stern-sheets, with his steering oar under his arm, stood each officer, throwing keen glances around him, in every direction, and now and then addressing an angry word to some awkward booby among his crew, who, by moving an arm or a leg, caused his paddle to strike against his thwart. Nor were the mates the only watchers, for the young harpooners, conspicuous among whom towered the tall, neatly-dressed figure of Harry Marline, were equally on the alert, piercing the many long, glittering galleries, winding passages, fantastic arches, and caverns among the ice, with their penetrating and practiced glances; while, seated close to the gunwales of their boats—each man with his paddle ready for use—the swarthy crews directed their indolent glances toward the reflection of their own faces in the still surface of the water, or watched the countless numbers of seals that stared upon them with timid eyes from the polished floors of their floating halls.

One of the sailors threw a glance toward the bay where the ship was anchored, and which was so far off that only the three masts of the vessel could be distinguished, and these but faintly, on account of the gray background beyond. But the red signal, flying at the main-truck, did not escape the keen eyes of the spectator, and he at once called the attention of the officer of his boat—Mr. Briggs—to this circumstance.

[25]

“Ay, ay, blast you!” replied the irritable Briggs; “you are always fancying that you see the recall signal. If it was a whale, now, I’ll wager my pipe that you wouldn’t see it, even though the creature spouted right under your nose! You’ve a strong imagination, Bates, for signals, even when there ain’t any to be seen!”

“You can see it, sir, by turning your head. I am sure I wasn’t deceived!”

“I wouldn’t believe you, though you took your oath upon a stack of Bibles as high as the fore-truck. So, just keep your eyes the other way, and don’t let me catch you lookin’ after signals again!”

As the man resumed his former position, however, the mate, after having leisurely filled his pipe, and placed it in his mouth, turned and looked toward the bay.

Unfortunately, this happened a second after Driko had pulled down the red bunting, and dropped it to the deck. As a natural consequence, Mr. Briggs, after having carefully surveyed the three naked royal masts, came to the conclusion that Bates’ imagination had deceived him.

“You thick-skinned lubber!” he muttered, in a low voice, seizing a paddle, and lifting it, with the intention of breaking it across his informer’s skull; “you empty-pated greenhorn, this isn’t the first time that—”

“There blows! blows!—there blows! A whale right ahead, sir, and two more to windward!” interrupted Harry Marline, addressing the mate, in a shrill, penetrating whisper.

Quickly, but noiselessly, replacing the paddle in the bottom of the boat, the first officer, with his teeth set, and his eyes glaring, seized his steering-oar firmly, and hissed out his orders to the crew.

“Paddle ahead—every mother’s son of you! Spring! spring! my lads—softly, but heartily—spring! It’s a bull!”

The men obeyed, and, shooting into a narrow passage, about a hundred yards from the mouth of which the first whale, a huge bowhead, was leisurely rolling and spouting, unconscious of the near vicinity of enemies, the mate’s boat darted swiftly, and almost noiselessly, upon its course, followed by the other three boats. The officers of the latter, how ever, soon became aware that it would be necessary for them[26] to turn their attention to the whales to windward, for the channel was too narrow to enable them to pass the mate’s boat, which, on that account, would certainly be the first to reach the monster ahead of it.

But, as the harsh grating of the cedar planks against the compact masses of ice, among which the rear boats must be directed when their course should be changed, would certainly “gally” (frighten) the leviathan in the passage, the captain made a sign to the second and third officers to stop the exertions of their men for the present.

This silent mandate was obeyed, and the three boats soon became nearly motionless, their officers and crews watching the progress of the mate with breathless interest.

He was nearing the whale with great rapidity, and the huge animal, as it rolled leisurely along, with its great barnacled hump rising and dripping in the cool element, still seemed unconscious of the vicinity of foes.

“Stand up, Harry!” whispered Briggs, when the boat was within seven fathoms of the intended prey; and quickly, but noiselessly, springing to his feet, the young harpooner seized his iron, and stood prepared.

The mate now pointed the bow of the boat directly toward the hump of the monster, and then, in a scarcely audible whisper, ordered his men to stop pulling, and take their places upon their thwarts.

This command was readily obeyed, but the light boat still continued to glide on under the impetus which it had received, and, in a few moments, it was within four fathoms of the leviathan.

“Now then—give it to him!” thundered Briggs.

The barbed weapon flew whistling from the hands of the stout-armed harpooner, with a force that buried it to the socket in the whale’s hump. The second iron immediately followed.

“Starn! starn all!” roared the mate, as the startled giant of the deep, writhing with pain, threw his tremendous body toward the boat. “Starn, you beef-eating rascals—starn!”

But the oar-blades, striking against the ice, greatly impeded the motions of the men, and the boat was not yet quite out of the monster’s reach, when, lifting his tremendous flukes, he[27] brought them down sideways with a force which would have shivered the forward part of the little craft to atoms had not the watchful Briggs, by a dexterous movement of his steering-oar, caused the bow to swing off to the right.

The little craft, however, did not wholly escape injury, for it received a light tap from the edge of the creature’s flukes, which caused the cedar planks to crack in more than one place, and dislodged the bow oarsman from his thwart.

The man was not injured, and he resumed his place, just as the whale disappeared in the green depths of the sea.

Away went the boat with the speed of a whirlwind, the line smoking as it ran around the loggerhead, and the tub oarsman pouring water upon it to prevent it from burning.

The harpooner and the mate now changed places, the latter individual taking his station in the bow, after Marline had relieved him in the stern-sheets. Each of the two men found it difficult to maintain his position, for the whale had, this time, “milled” (turned under water), and was now dragging the light boat through heavy fragments of ice, that caused it to sway from side to side with that quick, jerking motion which only a well-balanced body can resist.

The constant jamming of the boat against the rough edges of the floating bergs, through which it was forced onward like a wedge, seamed it with many cracks; but, as the bottom had not yet been injured, the water did not enter with sufficient rapidity to overpower the efforts of the man who was “bailing out.”

“Look out there! look to your oars!” shouted Briggs, as the flying vessel approached the entrance to one of those floating tunnels that form one of the many icy curiosities of the northern seas. It was about twenty feet in length, and the passage was so narrow—the roof so low—that the mate, as they continued to approach it, placed his hand upon the knife in the bow, feeling half conscious that it was his duty to sever the line and loose the whale, rather than to risk the lives of himself and his crew by attempting the dangerous channel; for when he should have entered it, the slightest deviation of the boat from its direct course, would result in its destruction.

He threw a glance behind him, to see whether, in case[28] such an event should take place, his fellow-officers would be near enough to witness it and to come to the rescue in time; but his surprise may well be imagined, when he discovered that the three vessels he had left astern were no longer visible, on account of one of those sudden fogs so common in that region, and which now covered the whole surface of the ice behind him, and also the open stretch of blue water beyond.

“Well!” he exclaimed, turning to Marline, “here’s a dirty fog coming upon us, without a moment’s warning!”

“There were signs of it before we struck the whale—in fact, when we first lowered!” replied the harpooner. “I saw it gathering in the nor’west, and a breeze has sprung up since then and hurried it along.”

“Ay, ay, I don’t doubt it,” answered Briggs. “But there’s no time to lose in chattering about it. What d’ye say, men,” he added, addressing the crew; “shall we cut, or hold on and try the tunnel? I am willing to try it for one.”

“So am I!” cried Bates, and the rest of the men expressing themselves in a similar manner, the mate breathed a sigh of relief, for he now felt as though a load had been lifted from his conscience.

By this time the boat was within a few feet of the tunnel, and the men placed their oars lengthwise across the thwarts, so that they might not come in contact with the sides of the narrow passage, and bowed their heads to prevent them from striking against the low, jagged roof of ice.

With unabated speed the light vessel flew on, and presently it darted, with the swiftness of a discharged arrow, into the mouth of the archway.

The crew fairly held their breath with anxiety, and kept their eyes upon the pointed bow of the little craft, which was now in a straight line with the opening at the further ends, but which, at any moment, was liable to swerve either to the right or the left. In fact, before the boat had reached the center of the passage, there was a loud, swashing noise, as the larboard gunwale heeled over, until it was almost level with the water, while the bows dipped and swayed with that uncertain motion which almost invariably serves as a warning to the crew of a fast boat, that the whole is about to change its course.

“Trim boat! trim boat, every man!” hissed the mate,[29] through his closely compressed teeth, “and stand by, Marline, to do what you can to keep the bows from swinging.”

“Ay, ay, sir, but that won’t be much,” responded the harpooner, “for there’s little room in this narrow channel to work a steering-oar.”

Scarcely had the speaker concluded, when Briggs, whose watchful eye had noted every motion of the little craft, perceived that the boat’s head was about to swing to the right and strike against the side of the passage; and seizing a knife, he quickly severed the running line, thus freeing the vessel from the whale but not in time to prevent the bow, under the impetus it had already received, from being dashed with considerable force against the icy wall.

The result of the concussion was the cracking of the light cedar planks near the bottom of the boat; and the water now entered the craft with such rapidity, that the exertions of three men were required to prevent the vessel from filling.

The rest of the crew were ordered to “take their paddles,” and as they worked vigorously, the boat was soon clear of the dangerous channel.

By this time, however, the fog had become so dense that the after oarsman could scarcely distinguish the person of the harpooner, who had just exchanged places with the mate, so that he now occupied his proper position in the bow.

The loss of the whale had increased the ill-humor of Briggs, and he proceeded to bemoan his “bad luck,” as he called it, in true sailor terms. Stamping upon his cap, several times, he wound up by stating that he wished all ice-tunnels were sent to the pit to be melted in brimstone.

This rude witticism was received with a shout of laughter by Tom Plaush, the little Portuguese, who pulled the tub oar, and who was always ready to show his appreciation of all jokes—however stale—that fell from the lips of any of the officers. The laugh had a good effect upon Briggs, who, believing that he had said something brilliant, assumed a waggish air, and glided at once into a pleasant humor.

The good-humor of the mate, however, was not destined to continue for a long time; for like a rusty wheel which has been set in motion by the application of oil to certain parts of it, but which stops and gets in bad condition again the[30] moment it meets with an obstruction—so when at length the boat became jammed between heavy fragments of ice that rendered it impossible for the crew to use their oars with success, the irritability of Briggs again made itself manifest. Rough contact with the floating bergs, through which the light craft had been forced, after it passed out of the tunnel, had so widened the cracks in the thin planks, that the water entered with a rapidity that, taxed to the utmost the energies of those engaged in bailing. The mate sprung upon one of the blocks of ice by which they were surrounded, and ordered every man with the exception of Marline to imitate his example.

“I want a man I can depend upon to take charge of the boat,” he said, addressing the young harpooner, “while I go with the crew to search for our shipmates and inform ’em of our condition!”

“Wouldn’t it be better, sir,” suggested Marline, “for all of us to stay here, and wait for the other boats? If we blow the boat-horn I have no doubt that they will soon reach us.”

“Ay, ay,” growled the mate, impatiently, “and do you suppose that I would be contented to stay here in this plight, waiting for the boats? Not a bit of it, young man. I am now in a hurry to get aboard ship, for that cutting from the whale has spoilt all my fun.”

“If you will take my advice, you’ll not go far, in search of the other boats,” said Marline, “for I think it hardly possible that you will find them, in this fog.”

“And I think exactly the other way,” retorted the mate, impatiently. “All a man has to do to find ’em is to follow his own nose to the north’ard, as I take it; for we’ve been going south, and the other boats must be somewhere astern of us—not far off either.”

At this moment the sound of a horn was heard, apparently proceeding from the direction in which the mate had stated that his fellow-officers might be found; and he now turned his eyes triumphantly toward the harpooner.

“Ay, ay—d’ye see, young man—it’s just as I said. Them boats are astarn of us, though further off than I thought they were. But by moving quickly over the ice, we’ll soon reach ’em. Come on, men—there’s no time to lose,” he added, turning to the crew.

[31]

Leaping from berg to berg, the five men followed closely upon the footsteps of their leader, and in a few seconds they were all shrouded from the view of the harpooner by the dense fog.

“It’s a wild-goose chase,” muttered Marline, as he proceeded to bail out the boat, “and nobody except a man of Briggs’ restless and impatient nature would have thought of undertaking it until he had first sounded the horn, and that had failed to bring our shipmates to us.”

As minute after minute passed away, and neither the party nor the boats made their appearance, the young man became more confirmed than ever in his opinion, that Briggs’ expedition was a useless undertaking. He even began to fear that the mate and his men had lost themselves among the floating galleries and caverns of ice, and were, therefore, neither able to advance in the right direction nor to return.

Once or twice, since the departure of his shipmates, he had heard the sound of a horn, but the notes of the instrument were so faint that he believed the boats were receding from, instead of approaching, the spot he occupied.

While his mind was still busy with conjectures and fears, he suddenly started to his feet, listening with eager attention, for he fancied he heard a rushing noise ahead of him like that of some heavy object forging slowly through the ice. The noise became louder every moment, and presently the ears of the young man were saluted with the creaking of ropes, the dull flapping of canvas, and the murmur of voices. An instant afterward the broad black bows and the square foresail of a ship loomed up indistinctly through the fog, a few fathoms ahead of the boat, which lay directly in the track of the vessel.

“Ship ahoy!” thundered Marline. “Up helm, and keep off, or you will run me down!”

He was evidently heard by those on board, for a dark face was suddenly thrust over the bulwarks forward, but its owner, instead of directing the man at the wheel to “keep off,” ordered him to “luff.”

The head of the advancing ship, as she came booming on, was therefore within a few feet of the boat before it could obey the helm, the consequence of which was that the bows of the[32] little craft received a thump from the vessel as she swung to windward, that caused a few of the thin planks to give way like the shell of an egg beneath the blow of a man’s fist.

The boat filled rapidly, and as it sunk the young harpooner leaped upon one of the blocks of ice by which he was surrounded, in time to seize a rope, which was thrown to him by Tom Lark, as the ship came up into the wind with her main topsails aback.

“The Montpelier!” shouted Marline—“the Montpelier, by all that’s good!”

“Ay, ay,” gruffly responded Lark, “and the less said about it the better!”

The speaker was a tall man, of herculean frame, and with one of those swarthy, hang-dog faces, that never fail to inspire the beholder with feelings of distrust. He wore gray pants, a fez cap of blue cloth, and a black woolen shirt, the latter of which, being open at the throat, disclosed the sinewy muscles of an enormous neck.

“What is the ship doing here?” pursued Harry. “We left her anchored in the bay. And how came you at liberty? Where is Stump? and Alice How—”

“One question at a time, youngster,” interrupted Lark, with a broad grin. “You’ll know every thing presently, and—”

“There’s villainy at work here, Tom Lark—ay, downright villainy!” cried the harpooner, as a suspicion of the truth flashed upon his mind.

Grasping the lower part of the main chains, and drawing himself to the rail, he sprung upon the deck, to be confronted by the mutineer, who drew from one of the pockets of his Guernsey a heavy pistol, which he pointed at the head of the youth.

“You’ve got yourself into a hornet’s nest, youngster. It might have been better for you if you had stuck to the ice!”

“Ay, ay,” said Marline, with perfect coolness, as he fixed his clear, unwavering eye upon the face of the giant. “You have the advantage of me, at present, and can murder me if you wish, but you will swing for it in the end.”

“Thank you, for your good advice,” gruffly responded the other, “but, I have no intention of murdering you—leastways, not just now—unless you try to kick against what you[33] can’t help. I’m just using this iron to keep you quiet, while the steward goes after the handcuffs!”

“And by what authority,” angrily demanded the young man, “do you thus—”

“Tut! tut!” growled the mutineer, “none of your polly-wow with me, lad. You know how things are as well as I do. I generally do what I please in my own ship.”

“And dare you pretend that this vessel—”

“Is mine? Certainly,” interrupted Lark. “She’s mine by the law of equal rights. Captain Howard had her for awhile. Now, it’s my turn. I’ve been confined in the run a long time, and need a little fresh air, besides the satisfaction of putting some of the captain’s friends in my place. As you are the first of these that I’ve met with, you shall have the honor of filling that position. I rebelled against Captain Howard’s authority—you rebel against mine. Captain Howard puts me in the run—Captain Lark puts you in the run. That’s what I call equal rights!”

The steward—a tall man with a long face, dark gray eyes, and thin lips, advanced, and proceeded to secure the handcuffs to the wrists of the young man.

The latter eyed him sternly, for a few moments, before he ventured to address him.

“What has the captain ever done to you, Joseph,” he then said, “that you should thus turn traitor?”

“He! he! he!” laughed the Portuguese, “Captain Lark more better as Captain Howard. He take de ship to some port and sell him—cargo and all. Den me get big share of de profit.”

Marline had benefited this man in many ways—had often, by kindly interposition, shielded him from the blows of the first mate; had even, on one occasion, saved him from falling overboard while he was aloft assisting the watch to reef the[34] main topsail in a gale of wind; and yet the ungrateful villain seemed now to exult in the misfortunes of his benefactor.

“Where is Alice?” inquired the latter, as the steward locked the handcuffs.

The Portuguese chuckled, but did not reply.

“Speak!” cried the harpooner, fiercely. “Where is she?”

“Why, of course, in de cabin—in her own room—me fasten her in so she can’t get out!”

“You are a sneaking wretch, Joseph!”

“What you say? No call me dat—I tell you,” cried the steward, as he pushed the young man against the rail.

The chief mutineer interposed. With the stock of his pistol he dealt the Portuguese a blow upon the head that felled him to the deck.

“Equal rights!” he said, quietly, as he pointed to the prostrate man, and placed the pistol in his pocket; “that’s the law aboard o’ this craft, in future. This way, Driko, Amolo, and Black Squall,” he added, motioning to three of the New Zealanders; “take Marline to the run, and fasten the hatch the same as it was fastened when I was there!”

The men obeyed with alacrity, and Marline was in the run. No sooner had the hatch been secured, than he heard the rushing of the water, and the grinding of the icebergs against the ship’s bottom, as she boomed upon her way.

His reflections were certainly very gloomy. The thought that Alice was only separated from him by a few planks, and yet that he could neither hold converse with her, nor go to her in case that Tom Lark, or any of his party, should insult her, worked upon his mind until it was wrought up to the highest pitch of excitement.

“What are the plans of these mutineers in regard to the young girl?” he asked himself again and again, and although it seemed to him that they must respect the purity, the loveliness, and the goodness of one who had benefited them by a thousand of those kindly little attentions to their welfare and comfort which a woman in a ship—especially if she have influence with the captain—has it in her power to bestow, yet there was a presentiment within him that whispered of trouble and suffering.

And with his head bowed upon his bosom—with his manacled[35] hands against his brow, and his heart beating loud and fast with anxiety—he offered up a silent but fervent prayer to God, to spare his beautiful Alice—to shield her from all harm—and restore her to the arms of those who loved her.

That prayer was scarcely finished when he felt a hand upon his arm, and on lifting his head, he was enabled to make out in the gloom with which he had by this time become familiar, the outlines of a human countenance.

“Hist!” whispered a low voice, “don’t speak too loud; it’s me—Stump—and this if I ain’t mistaken is Harry Marline!”

“Ay, ay, you are right!” cried the harpooner, much surprised, “but where in the name of heaven, Stump, did you come from? You were not confined here were you? I thought you were in league with the mutineers.”

“That’s the way of the world,” muttered the shipkeeper, mournfully. “Yes—yes, that’s the way with ’em all! Sarcumstances always goes against a man, hows’ever honest he may be! But I didn’t think it, Marline—no, blast me if I did—that you, my chum, would ever mix up my deeds with those of them infarnal scoundrels!”

“Forgive me!” exclaimed the young man, joyfully grasping the hand of his friend as tightly as his irons would admit. “I was altogether too hasty, and I’m sorry for it. But, tell me how you came here.”

“Ay, ay,” said Stump. “I’ll explain matters willingly enough, especially as it will give me a chance to curse those rascally blueskins again, and to show you as I always was for maintaining, that them creatur’s ain’t to be trusted.”

He proceeded to tell his story, commencing with those incidents with which the reader is already acquainted.

“Yes,” continued the exasperated seaman, as soon as he had described the manner in which he had been thrust into the hole, “they fastened the hatches above me, and then I heard ’em go aft, and presently the voice of Tom Lark ordering ’em to cut the cable, and loosen the topsails, broke upon my ears, so that I knowed they had set that big hang-dog rascal at liberty. Scarcely was the ship under way, when I also heard that wild fiend Driko, proposing to Lark to knock me in the head, and thus get rid of me. But Tom, you know, although he is a parfect savage when[36] he holds a grudge against anybody, doesn’t care to shed blood when he can get along without it, and that was the reason, as I take it, that he refused to comply with the polite request of that infarnal pow-wow.”

“Did you overhear any thing that gave you an idea of what Lark intended to do with the ship?”

“Not a bit of it, but I haven’t a doubt that he intends to take the craft into some out o’ the way port, and sell her—cargo and all.”

“That’s very probable,” replied his friend. “It’s a pity,” he added, “it’s a pity that the captain and his boat’s crew didn’t stay aboard as they are in the habit of doing. Then this misfortune might have been prevented.”

“Ay, ay, but we’ll be even with ’em yet,” replied the narrator, “and now I’ll tell you how I came here, which was done by a little of that ‘injunyewity’ for which the Stump natur’ has always been famous. As soon as I perceived that the craft was under way, says I to myself, ‘Why,’ says I, ‘I’m only fastened with ropes, and p’raps if I can find the old saw which is somewhere in the hold, I can make short work of ’em. And so I crept about as well as I was able, looking for the instrument, which I soon came afoul of. It was a long time hows’ever before I could get it in the right position, for I could only use my teeth to do that, and they ain’t quite as parfect as the teeth of a shark, seeing as three of ’em were once knocked out by an old woman, because I took her part against her husband who was beating her—blast him—and the rest are almost ruined by the long use of baccy and the habit of biting off the ends of spun yarn. Well, I tugged and pulled with my teeth for a long time and at last got the saw ship-shape. Then I turned my back to it, and by running the ropes that was about my wrists, up and down the edge, I soon had ’em apart. The rest was easy, and I was glad enough, lad—mightily glad to find myself freed from the cords.”

“And afterward you heard the mutineers as they led me to the run,” said Marline, “and you thought you’d take a cruise in this direction to see who the prisoner was. Isn’t that so?”

“Exactly,” repeated Stump, “but I didn’t dream who it was until I had crept close to that big opening in the partition that divides the run from the steerage. Then, as I’d got familiar-like[37] with the dark, I was surprised enough to see you, and I couldn’t imagine how you came here, which is the same even now.”

Marline at once proceeded to enlighten his companion, and as soon as he had concluded, the shipkeeper seized both the hands of his friend and gave them a hearty squeeze.

“Misfortunes attends the best of us,” he said philosophically, “but we’ll hope for the best—ay, ay, we’ll hope for the best, and work for it too. The gal—Miss Alice—is the great ‘consideration,’ and if we can only get her safe, why, if we can do that it’s all right.”

“You do not think they’ll attempt to harm her?” cried Marline, interrogatively.

“I don’t know about Tom Lark,” replied Stump, “but, as to them pow-wows, I wouldn’t trust ’em—not one of ’em. The flesh of that gal is tender, and them fellows are cannibals and like good grub.”

“Can not you contrive some way for me to get an interview with Alice?” said Harry.

Stump gave his pigtail a jerk.

“I don’t see how it could be done,” he said, thoughtfully. “The hatches are all fastened above us—the door of her room is locked besides, and—and—ay! ay! I have it!” he suddenly interrupted, “which is that that rascally steward must open the hatch before long to pass you some food, and p’raps I’ll get a chance to pounce on him, gag him and tie him up. The rest will be as easy as the greasing of a marlinspike. I’ll get—if he has ’em about him, which I think is likely—the key of her room and the one which unlocks your handcuffs.”

“Thanks!—a thousand thanks, for this happy thought, my dear chum!” cried the harpooner.

“P’raps we may even be able to bag the mutineers themselves,” said the shipkeeper, “to shut ’em all up—the pow-wows in the forecastle, and Lark in the cabin. It’s wonderful—parfectly wonderful,” he added, thoughtfully, “how one idee leads to another. Them that is given to reflection, and the Stumps were always famous for that, propagates idees—fairly breeds ’em—one from another!”

“Hush!” whispered Marline. The sound of footsteps approaching the hatch was heard.

[38]

“It’s him—it’s that rascally Portuguese,” muttered the shipkeeper. “I’d know that walk of his from a thousand, lad. It’s peculiar—something like the tramp of a mule, and them that walks so ain’t to be trusted. Now the walk of the Stumps in every generation has been like that of a duck—a sort of waddle, and them that moves in that way generally takes to the water.”

The noise of the crow-bar—by means of which the hatch had been secured—was heard, as the implement was removed, and the next moment, just as Stump drew back, the trap was pulled aside from the opening, into which a face—the owner of which had stooped upon his knees—was thrust. Without waiting to take a survey of it, the shipkeeper seized the intruder by the hair of the head and pulled him head foremost into the run. But, before he had quite accomplished this feat, and yet when it was too late to draw back, he had seen the face clearly enough to recognize the harsh and decided lineaments of Tom Lark, which were different in every respect from those of the steward.

“Ay, ay, that was a mistake, sure enough!” cried Stump, scrambling quickly through the opening, as soon as the uplifted legs of the prostrate man beneath had been removed from it, “such a mistake as I never made before in my life, and as prudence is the better part of valor, I think I am parfectly justified in getting out of the run!”

He lifted his feet clear of the aperture just in time to escape the hand of the mutineer as the latter, who had by this time risen from his uncomfortable posture, made a furious attempt to clutch the bottoms of his pants.

“You wretched imp of Satan!” roared Lark, in a voice of thunder, as the other eluded his grasp, “you shall suffer for this trick!”

And he thrust a hand into the side-pocket of his Guernsey, to procure his pistol.

Stump saw the movement, and quickly seizing the crow-bar lying at his feet, he dealt the mutineer such a heavy blow upon his head—which projected at least eighteen inches above the combings of the hatch—that he dropped senseless into the run.

“It was all done in self defense!” cried the shipkeeper, as[39] he leaped back into the hold. “Ay, ay—that it was, sure enough. But, bad as the man is—and he’s a parfect shark—it cost me something to give him that blow, seeing as I’m not in the habit of indulging myself in that way. I hope I haven’t committed murder—I hope he isn’t dead!”

“He’s only stunned, I guess,” replied Marline. “He’ll soon come to his senses.”

“You think he will?” cried Stump, twitching his pigtail a little nervously. “You think he’ll broach to again? My eyes! seeing as that’s the case, then I think it would be as well to take time by the forelock—to provide myself with his pistol, and to make him fast, so he can’t do any more harm. He’ll never forgive me—no, never—when he gets over his faint. It’s astonishing how the human family holds grudges!” And, drawing his sheath-knife, he proceeded, with all possible dispatch, to cut from one of the numerous coils of ratlin stuff lying about him, a sufficient number of the twisted strands to secure the arms and legs of the giant.

This task was soon accomplished, after which the mutineer was properly secured, and his pistol transferred from his own to the pocket of his conqueror.

“Now, then,” said the latter, breathing a sigh of relief, “I think he’ll be surprised when he wakes.”

The shipkeeper had hardly concluded, when he heard footsteps descending the companion-way, and peering through the hatch, he saw the steward just as that worthy—still pale and bloody from the effects of the wounds he had received—gained the bottom of the short staircase.

With a low cry of exultation, Stump pulled himself quickly out of the run, and, rushing upon the startled Portuguese, caught him by the throat, at the same time presenting his pistol at his head.

[40]

“No noise, you miserable sneak, or down you go, a dead porpoise sure enough. Just hand over the key that unlocks Miss Howard’s room, together with the one that belongs to Marline’s handcuffs!”

“I—I—de—de—— You no kill me!” stammered the steward, nearly frightened out of his wits.

“The keys—the keys!” muttered Stump, shaking him violently; “it’s the keys I want—d’ye hear?”

“I—I—give you ’em quick,” gasped Joseph, while his eyes fairly rolled in his head with terror.

“Here—here,” he added, pulling the required instruments from his pocket—“here dey be, and now you no kill me!”

In order to receive the keys, the shipkeeper let go of the steward’s throat, and his joy was so great when the articles were in his hands, that for a moment, while contemplating them, he almost forgot the presence of the mutineer.

The latter was not slow to take advantage of this circumstance. He bounded up the companion-way, and disappeared, before Stump could lift his pistol.

“Ay, ay—the rascal’s gone, sure enough!” cried the shipkeeper, in a tone of mortification, “and it’s l’arned me a lesson, which is, that them that doesn’t keep their eyes squinted both ways, or that allows their pleasures to turn ’em aside from their duties, is bound to suffer for it in the end.”

“Never mind,” said Marline, who had risen, and was looking through the open hatchway; “but, come quick and unlock these handcuffs. That fellow, I can even hear now giving the alarm on deck, and the sooner my arms are at liberty, the better will it be for us both!”

“There’s plenty of truth in that,” replied the shipkeeper, as he now set himself to work to unfasten the irons from his friend’s wrists, “plenty of truth in that, and—”

“How! Why! A thousand devils! What does this mean?” interrupted the voice of Tom Lark, at this juncture. “Ho! halloa there—on deck!”

“That rascal has come to, at last!” cried Stump, “and, although it consoles me to think that I didn’t kill a fellow creatur’, there isn’t music enough in that voice—which is something atween the roar of a bull and the grunting of sea-hog—to give any pleasure.”

[41]

Marline’s handcuffs dropped clanking to the deck, as his chum spoke, and the young man sprung lightly from the run. The shipkeeper secured the trap above the hatch, while the other, rushing up the companion-way, fastened the door leading to it, by hooking it on the inside.

This task was not accomplished a moment too soon, for a number of kicks and blows were now dealt against the door, and together with the roaring voice of Tom Lark—who evidently chafed in his confinement like a mad bull—created a din such as is seldom heard in a whale-ship!

“Well, my eyes,” soliloquized Stump, “them noises are sartainly not very inviting, nor those that make ’em very chival-rie-ous, seeing that a young lady lodges in this hotel!”

“They will pound the door to pieces before many hours,” said Marline, “and before that happens I must make sure of the rifle that hangs in the captain’s state-room, so that we can show a good resistance to the bloodthirsty wretches.”

“Ay, ay, bloodthirsty is the word,” said Stump. “Them five pow-wows on deck are mad enough by this time to eat us alive. They ain’t at all particular, they ain’t, about the quality of their grub when they be angry. It’s parfectly astonishing how few ‘raal’ ‘epichewers’ there is in this world!”

Marline did not pause to reply to this philosophical remark. He hastened to the state-room and procured the rifle—which was already loaded—together with a bullet-pouch, and an old-fashioned powder-horn, containing a small supply of ammunition.

“Now, then, my friend, quick! Give me the key to Alice’s apartment.”

“Here it is!” replied the shipkeeper, placing the instrument in his hand, “and mighty glad, I warrant you, will be the poor gal to see you. So, away you go, and God bless you both, while Stump keeps guard.”

A very few steps carried the young man to the door which he sought, and which was nearly in a straight line with the foot of the stairway.

He placed his rifle against the carved wainscot, and turned the key in the lock of the door. Then he knocked gently upon one of the panels; but a half-smothered cry of alarm was the only response to the summons.

[42]

“Do not fear, dear Alice; it is I—Harry Marline!”

The door was quickly opened, and Alice, with surprise and pleasure beaming in her great brown eyes, stood before him.

She looked so beautiful in her excitement, that Harry stood for a moment staring upon her like one under the influence of a spell. As the long lashes of those innocent eyes gradually drooped under his admiring glance, he was unable to resist the impulse that sprung up within him. He threw an arm around the pretty waist, and drawing the unresisting girl to his bosom, kissed her with a fervor peculiar to seafaring men.

She gently disengaged herself from his embrace. “Oh! Harry, I am so glad to see you. I have been so frightened! Those terrible noises! What are they trying to do now? They are at the cabin-door!”

“To break it open,” replied Harry.

“Who? the mutineers?”

“Yes.”

“Why, I—I thought, when I saw you, that all this was over—that you and your gallant crew had come aboard and persuaded those misguided men to return to their duty.”

“I came alone,” said the harpooner, and he then proceeded to make her acquainted with those occurrences of which the reader has already been informed.

“Dear Harry,” faltered the young girl, “how you must have suffered. I am sorry, now, that you came aboard.”

“Sorry?”

“Yes, because, in addition to what you have already endured, you will have more trouble. The mutineers will soon break open the door, and, then—then—Oh! my God! What if they should kill you?”

“Fear not for me, dear girl,” replied the harpooner, “I am armed—and so is Stump. We can make a stout resistance and we will protect you as long as we can stand.”

“I do not fear for myself,” replied Alice, “I don’t think they would injure me. But you and your friend—what can you do against three times your number?”

“But they have only harpoons and lances while we are provided with fire-arms. I have your father’s rifle and—”

“I think I have heard him say that it is damaged so it won’t go off.”

[43]

“I will soon decide that point,” said Marline, and he lifted the weapon and scanned the lock.

“You are right, Alice, the piece can not be discharged, but it can be made useful in other respects.”

Crash! went a heavy ax, against the cabin-door, at this juncture, and the sharp edge of the instrument was seen to protrude through the wood-work!

“Ay, ay!” cried Stump, “there it goes—it’s a-going—the door!”

And even as he spoke, another tremendous blow shivered one of the panels into fragments.

“This way, friend Stump!” cried Marline, “we must form a barricade.”

The shipkeeper came, and the two proceeded to erect a sort of breastwork with a sofa, a few chairs and a table, which were firmly secured with ratlin stuff across the doorway of Alice’s apartment. The whole work was completed with great dispatch, and was viewed with much satisfaction by the two sailors, for they felt confident that they could prevent the mutineers from passing this barrier.

Alice, who had been led by Marline to the further corner of the apartment, stood with clasped hands and pale cheeks watching the movements of her friends, and it was with a sinking heart that she at length heard the door of the cabin give way with a tremendous crash before the repeated blows of the ax!

Then a terrific yell broke upon her ear, as the savage Driko, flourishing a sharp hatchet around his head, and followed by the rest of the mutineers, armed with long lances, rushed down the companion-way.

“This way, lads! this way!” roared Tom Lark, from the run, “I am tied hand and foot! Come and set me free—quick! I am dying to give them two rascals a lesson on equal rights!”

“None of that, you infarnal pow-wow!” cried Stump, pointing his pistol at the head of the Kanaka, who was now moving toward the hatch, “none of that or you are a dead fish! It’s parfectly astonishing,” he added, “to hear such an imp of Satan as that creatur’ in the hold a-prating about equal rights!”

[44]

Every one of the mutineers halted. The sight of Stump’s weapon, and the rifle in Marline’s hand, had not been anticipated by these men. They looked at one another in surprise, and even seemed disposed to beat a retreat.

Observing these signs of indecision, the resolution of the harpooner was formed in an instant. Motioning to Stump to follow him, he suddenly leaped over the barricade, and coolly advanced toward the party, with the muzzle of his piece directed toward them.

“Put down your arms, and return to your duty—every man of you!” he cried, sternly, “if you value your lives! I do not feel disposed to trifle with you!”

“No, not a bit of it!” cried the doughty little shipkeeper, as he covered the head of Driko with his pistol. “You are dead pow-wows of a sartainty, if you don’t obey. You can’t expect any mercy from me, at any rate, after the way you tumbled me into the main hold!”

“No—no!” yelled the prisoner in the run, “don’t yield to ’em, men. Pitch into ’em—they can’t fire but two shots at the most. You miserable imp of a Driko, where are you? Why don’t you attack ’em? They are only two and you are four! One good assault and you can cut ’em to pieces—perhaps without the loss of a man!”

“My eyes!” cried Stump, with a low whistle, “it’s marvelous to hear the way that animal is urgin’ on his pow-wows, while he himself is out of harm’s way. Them that does that ain’t always the most persuasive, seeing as it’s only examples that’s contagious.”

And the speaker was right, for the mutineers, becoming more irresolute as they marked the firm purpose that shone in the steady eyes of their two adversaries, were deaf to the commands of Lark.

“Come, down with your lances—or we’ll fire!” shouted Marline, “and we’ll do the same if you attempt to retreat. Remember that whether you fly from or attack us, two of you at least must fall!”

This was not to be disputed, and, dropping his weapon, Driko motioned to his three followers to imitate his example. They obeyed, and the harpooner then ordered the whole party to the deck. The command met with the same success as that[45] which had attended the previous one. The four men, with cowed and sullen faces, ascended the companion-way, followed by their two conquerors, who still retained their arms; and as soon as they were on deck, Marline gave orders to “wear” (veer) ship.

As the vessel was under whole topsails, it seemed impossible that this duty could be executed by the few men now in the craft; but, the harpooner and his friend lent their assistance, and the yards were swung round at last. As the wind was now from the westward, Marline soon afterward squared topsails and stood due east—hoping that this course would soon enable him to fall in with some of the boats. The man at the wheel, who was none other than the Portuguese steward Joseph, was doubtless much surprised at the change of commanders; but, whatever may have been his thoughts, the coward was too prudent to express them. He was an excellent steersman, and he now did his best, evidently hoping by this means to find favor in the eyes of the man whom he had insulted while he was a helpless prisoner.

“That’s right, keep her steady!” cried Marline, approvingly, “and you there on the knightheads!” he added, glancing forward—“look sharp for the boats and the ice!”

“Ay, ay,” answered the dusky seaman, and his voice was far from cheerful.

Descending into the cabin—after having ordered Stump to keep close to the companion-way, and to maintain a vigilant watch—the young man now entered the apartment occupied by Alice.

She bounded forward to meet him, and did not offer any very decided objection to the embrace with which he received her.

“I am so glad!” she said, as she gently disengaged herself after he had kissed her at least a dozen times, “I am so glad that the mutiny was subdued without bloodshed—that you are safe and uninjured!”

“And what is still better, I trust that we will soon fall in with the boats,” said Marline. “I wore round about ten minutes ago.”

“Wore round? What is that?” inquired Alice.

“What? you, a sailor’s niece, don’t know what it is to wear ship!”

[46]