| Title: | U.S. Marine Operations in Korea 1950-1953 Volume III (of 5) |

| The Chosin Reservoir Campaign |

Transcriber’s Note

Cover created by Transcriber, using the original cover and the text of the Title page, and placed into the Public Domain.

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

by

LYNN MONTROSS

and

CAPTAIN NICHOLAS A. CANZONA, USMC

Based on Research by

K. JACK BAUER, PhD.

Historical Branch, G-3

Headquarters U. S. Marine Corps

Washington, D. C., 1957

Preceding Volumes of

U. S. Marine Operations in Korea

Volume I, “The Pusan Perimeter”

Volume II, “The Inchon-Seoul Operation”

Library of Congress Catalogue Number: 57-60727

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office

Washington 25, D. C. Price $2.75

Official Price of this Publication $2.75

III

The breakout of the 1st Marine Division from the Chosin Reservoir area will long be remembered as one of the inspiring epics of our history. It is also worthy of consideration as a campaign in the best tradition of American military annals.

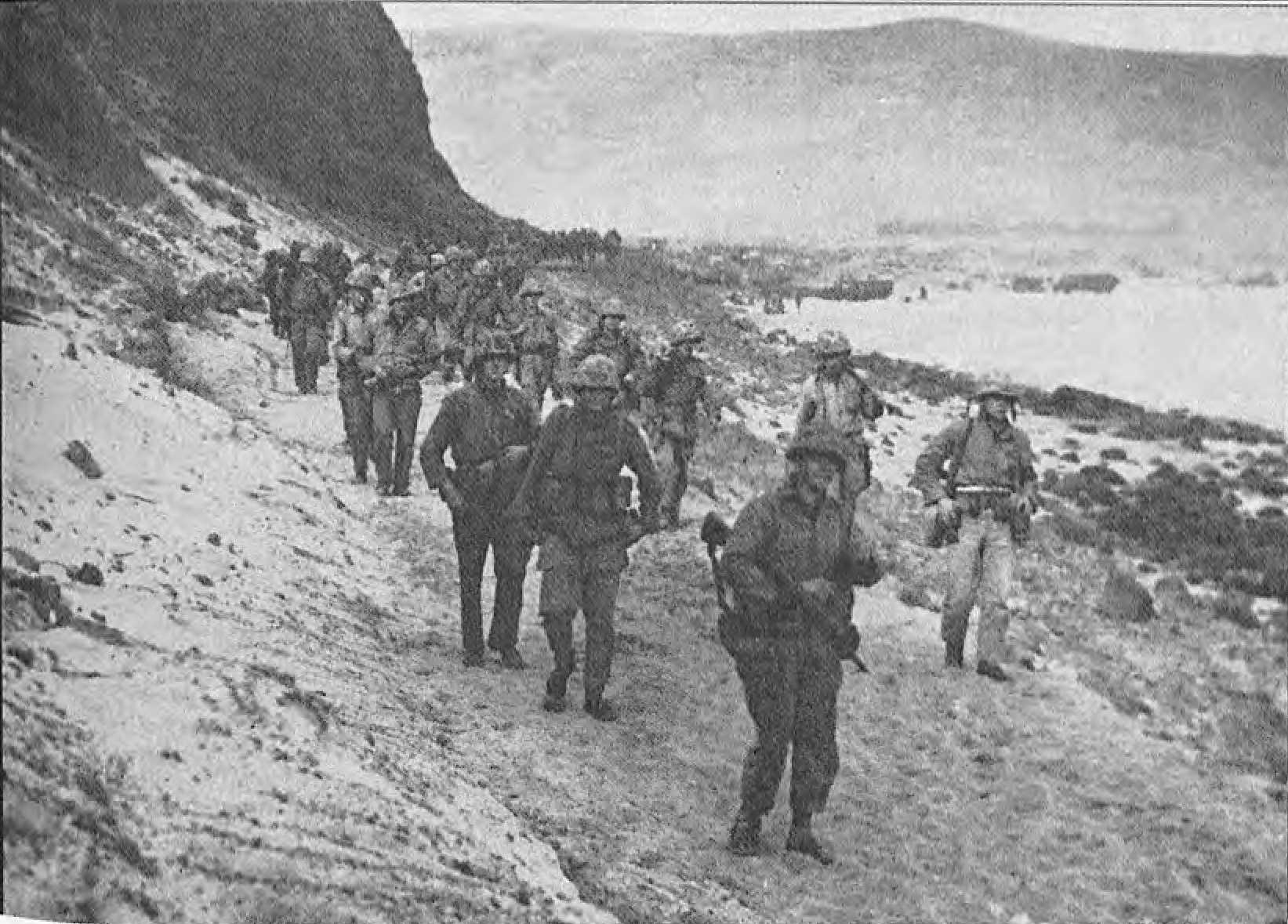

The ability of the Marines to fight their way through twelve Chinese divisions over a 78-mile mountain road in sub-zero weather cannot be explained by courage and endurance alone. It also owed to the high degree of professional forethought and skill as well as the “uncommon valor” expected of all Marines.

A great deal of initiative was required of unit commanders, and tactics had to be improvised at times on the spur of the moment to meet unusual circumstances. But in the main, the victory was gained by firm discipline and adherence to time-tested military principles. Allowing for differences in arms, indeed, the Marines of 1950 used much the same fundamental tactics as those employed on mountain roads by Xenophon and his immortal Ten Thousand when they cut their way through Asiatic hordes to the Black Sea in the year 401 B.C.

When the danger was greatest, the 1st Marine Division might have accepted an opportunity for air evacuation of troops after the destruction of weapons and supplies to keep them from falling into the enemy’s hands. But there was never a moment’s hesitation. The decision of the commander and the determination of all hands to come out fighting with all essential equipment were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Marine Corps.

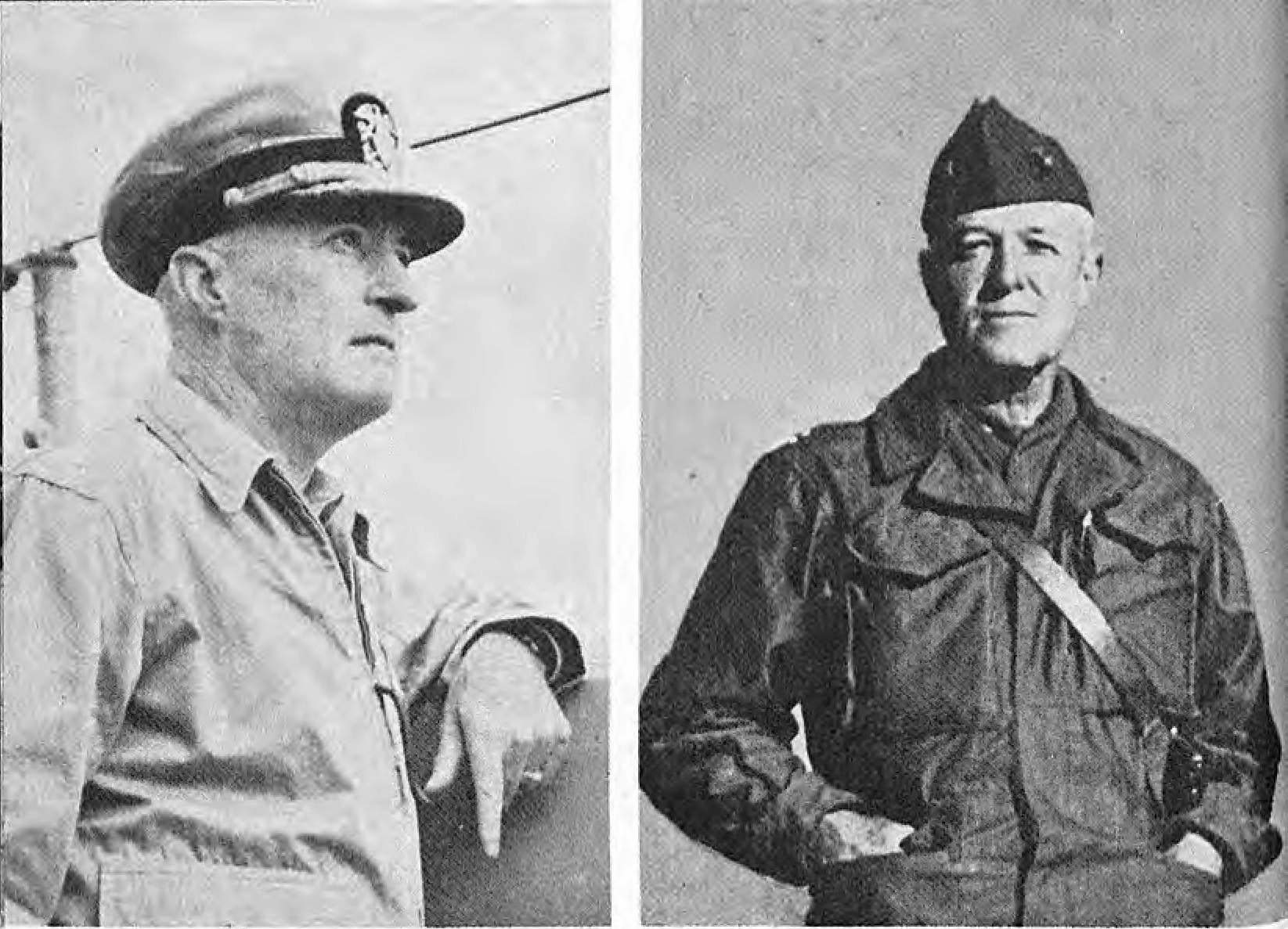

R. McC. Pate

General, U. S. Marine Corps,

Commandant of the Marine Corps.

V

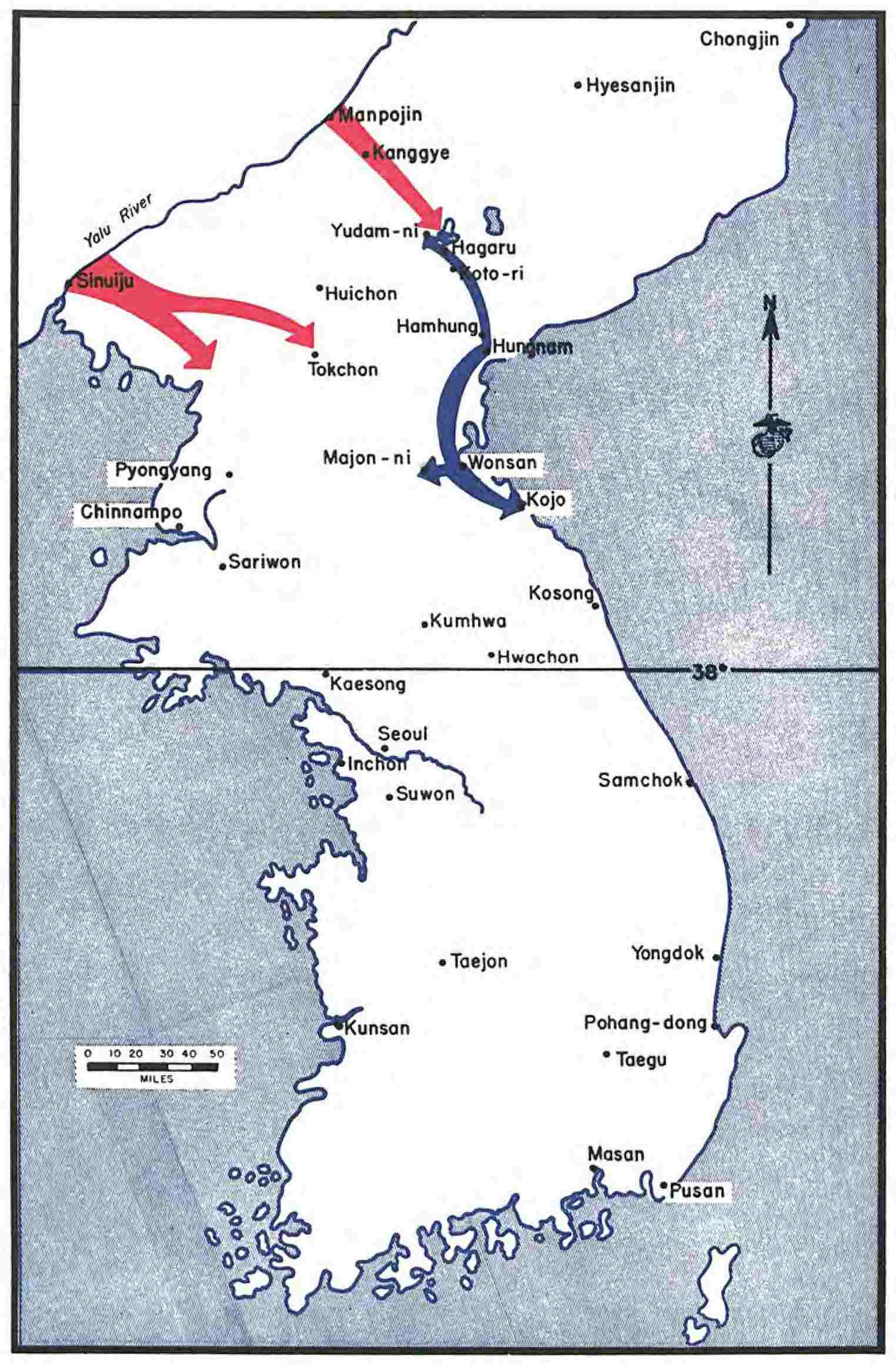

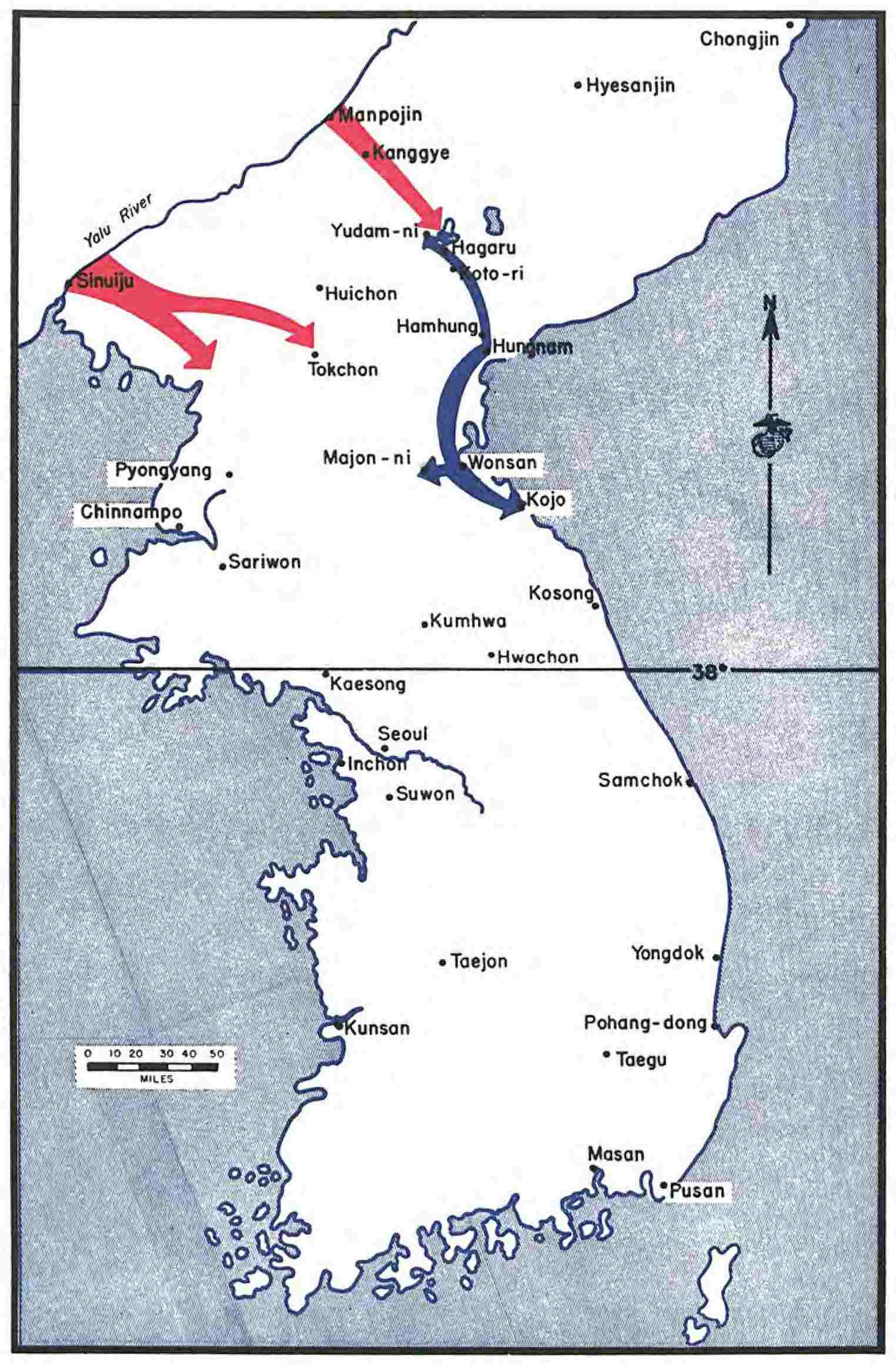

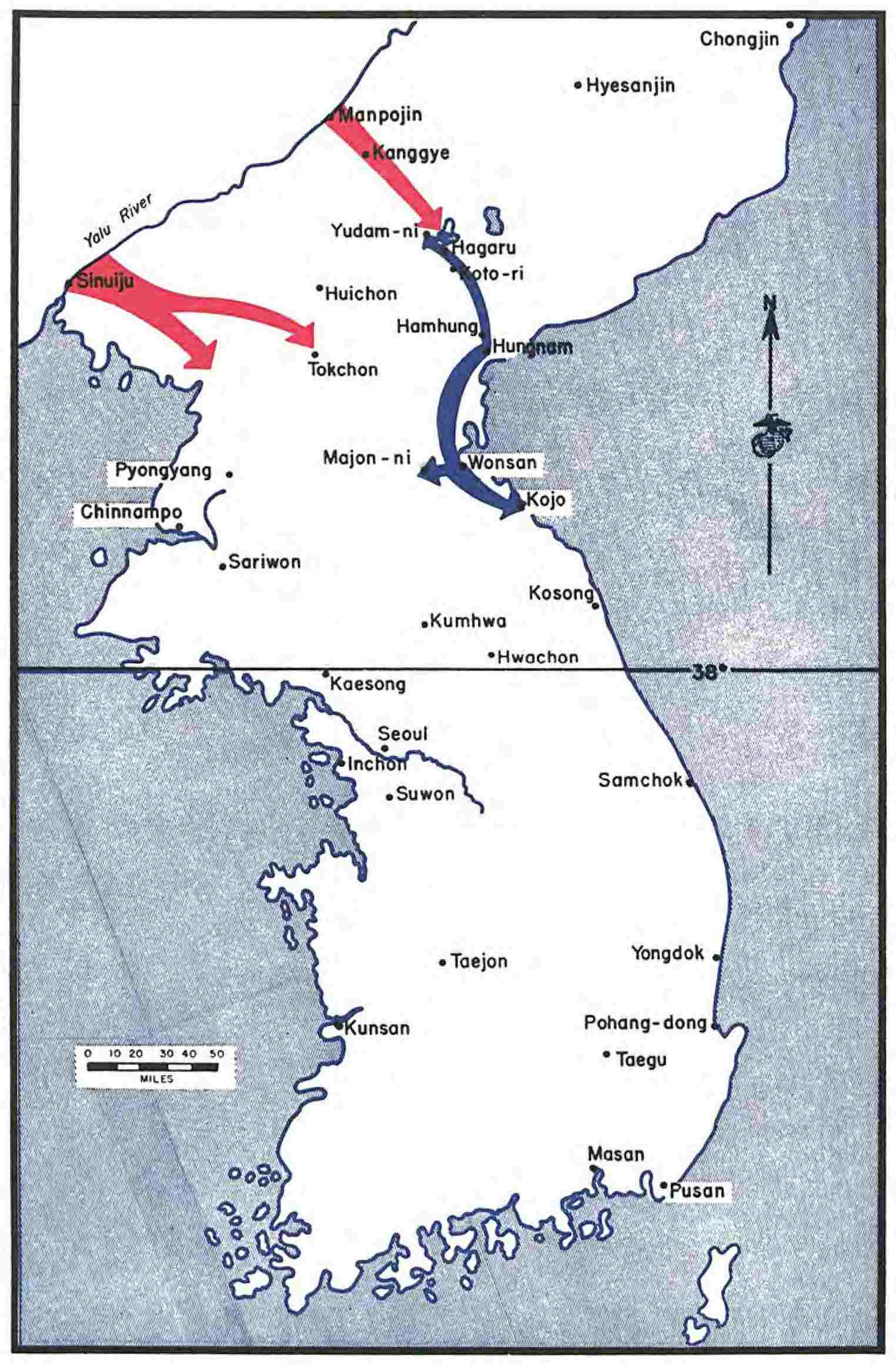

This is the third in a series of five volumes dealing with the operations of the United States Marine Corps in Korea during the period 2 August 1950 to 27 July 1953. Volume III presents in detail the operations of the 1st Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing as a part of X Corps, USA, in the Chosin Reservoir campaign.

The time covered in this book extends from the administrative landing at Wonsan on 26 October 1950 to the Hungnam evacuation which ended on Christmas Eve. The record would not be complete, however, without reference to preceding high-level strategic decisions in Washington and Tokyo which placed the Marines in northeast Korea and governed their employment.

Credit is due the U. S. Army and Navy for support on land and sea, and the U. S. Navy and Air Force for support in the air. But since this is primarily a Marine Corps history, the activities of other services are described here only in sufficient detail to show Marine operations in their proper perspective.

The ideal of the authors has been to relate the epic of the Chosin Reservoir breakout from the viewpoint of the man in the foxhole as well as the senior officer at the command post. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the 142 Marine officers and men who gave so generously of their time by contributing 338 narratives, letters, and interviews. In many instances this material was so detailed that some could not be used, because of space limitations. But all will go into the permanent Marine archives for the benefit of future historians.

Thanks are also extended to the Army, Navy, and Air Force, as well as Marine officers, who offered valuable comments and criticisms after reading the preliminary drafts of chapters. Without this assistance no accurate and detailed account could have been written.

The maps contained in this volume, as in the previous ones, have been prepared by the Reproduction Section, Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Virginia. The advice of officers of the Current History Branch of the Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, has also been of aid in the preparation of these pages.

E. W. Snedeker

Major General, U. S. Marine Corps,

Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3.

VII

| Page | ||

| I | Problems of Victory | 1 |

| Decision to Cross the 38th Parallel—Surrender Message to NKPA Forces—MacArthur’s Strategy of Celerity—Logistical Problems of Advance—Naval Missions Prescribed—X Corps Relieved at Seoul—Joint Planning for Wonsan Landing | ||

| II | The Wonsan Landing | 21 |

| ROK Army Captures Wonsan—Marine Loading and Embarkation—Two Weeks of Mine Sweeping—Operation Yo-Yo—Marine Air First at Objective—MacArthur Orders Advance to Border—Landing of 1st Marine Division | ||

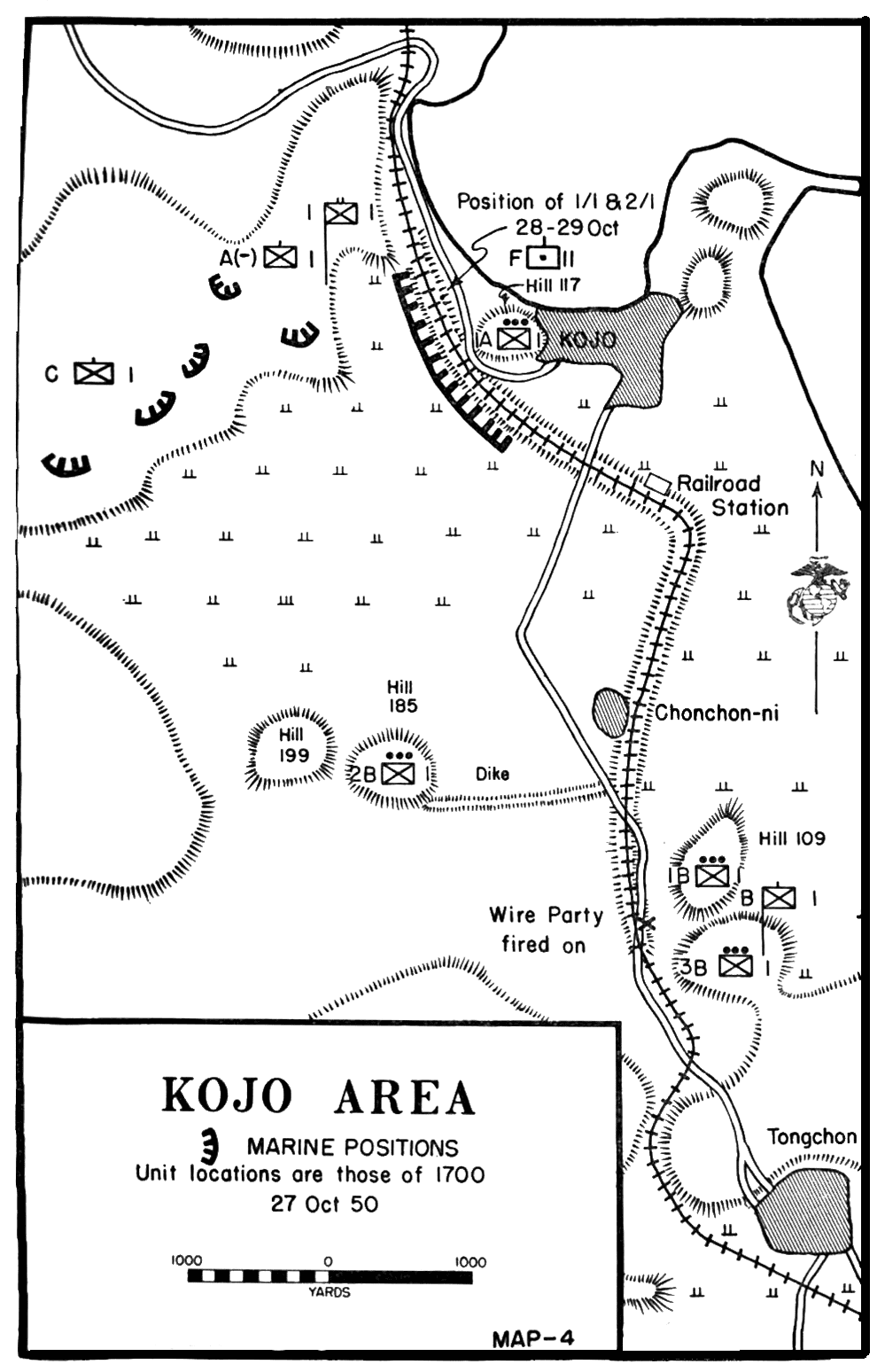

| III | First Blood at Kojo | 43 |

| 1/1 Sent to Kojo—Marine Positions in Kojo Area—The All-Night Fight of Baker Company—2/1 Ordered to Kojo—Security Provided for Wonsan Area—Marines Relieved at Kojo | ||

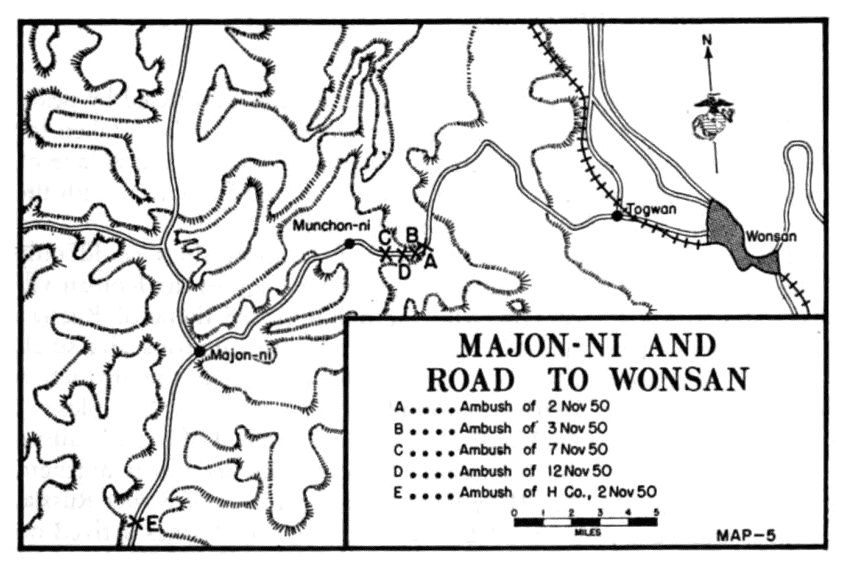

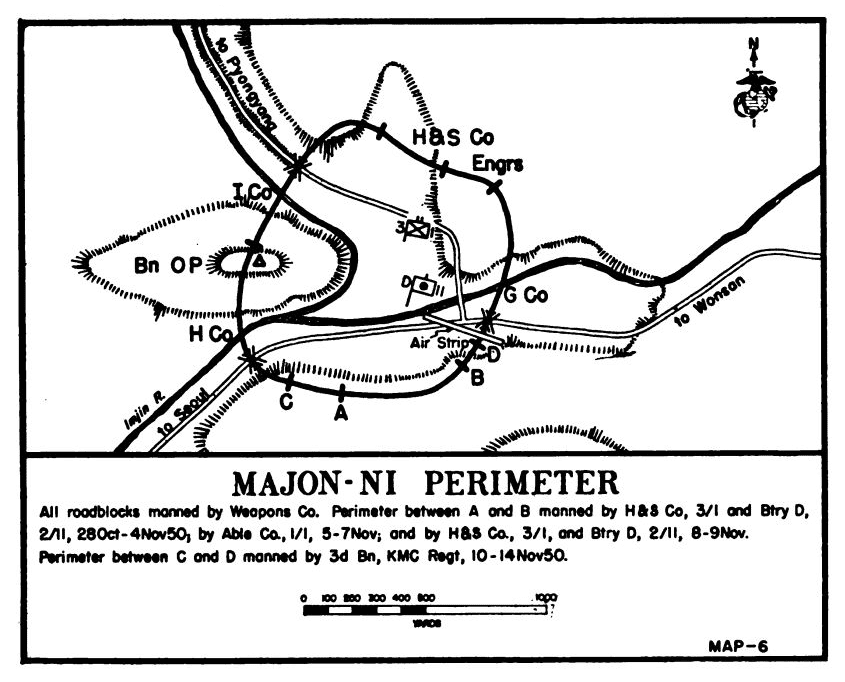

| IV | Majon-ni and Ambush Alley | 61 |

| Marines Units Tied in for Defense—Political Aspects of Mission—Roads Patrolled by Rifle Companies—Air Drop of Supplies Requested—First Attack on Perimeter—KMC Battalion Sent to Majon-ni—Movement of 1st Marines to Chigyong | ||

| V | Red China to the Rescue | 79 |

| Chinese in X Corps Zone—Introducing the New Enemy—Communist Victory in Civil War—Organization of the CCF—The Chinese Peasant as a Soldier—CCF Arms and Equipment—Red China’s “Hate America” Campaign—CCF Strategy and Tactics | ||

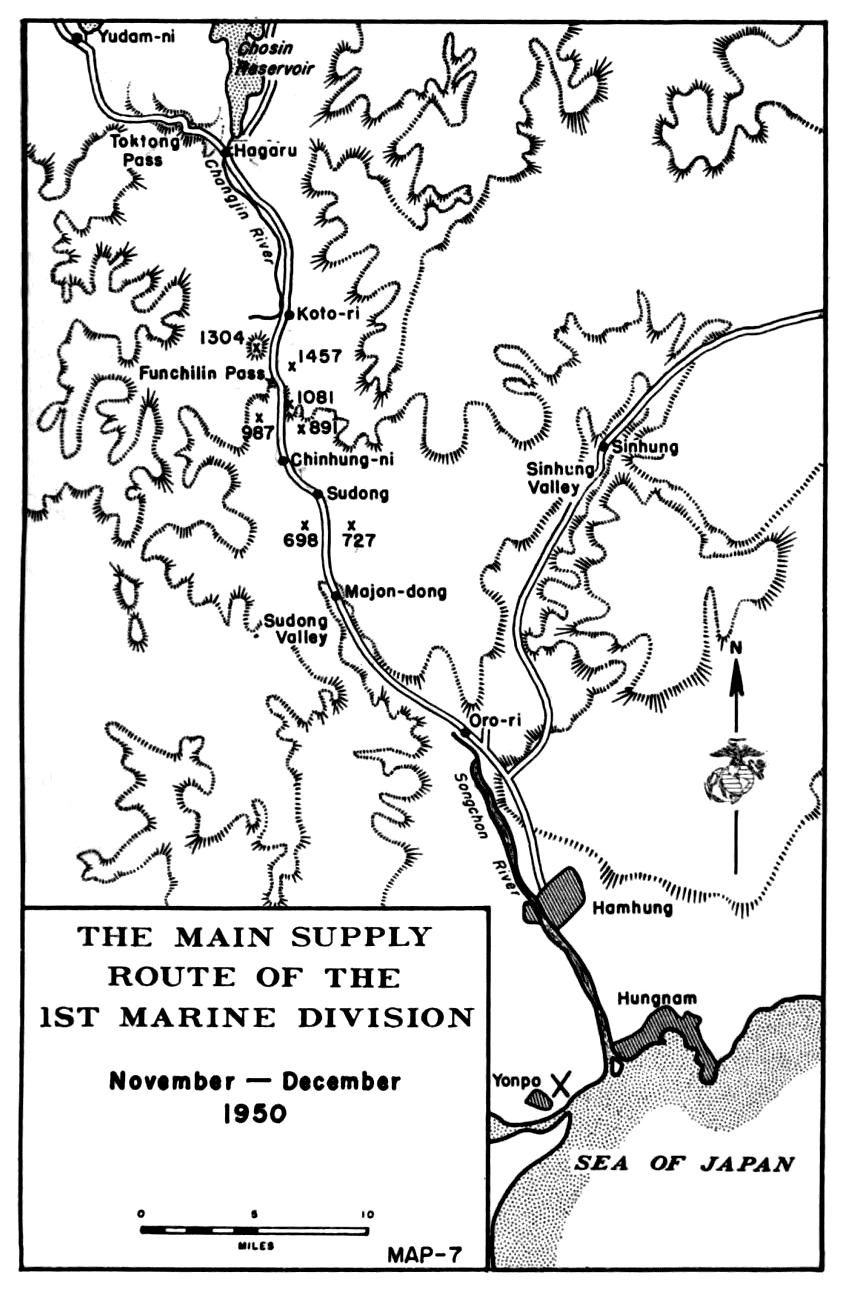

| VI | The Battle of Sudong | 95 |

| The MSR from Hungnam to Yudam-ni—ROKs Relieved by 7th Marines—CCF Counterattack at Sudong—Two Marine Battalions Cut Off—End of NKPA Tank Regiment—The Fight for How Hill—Disappearance of CCF Remnants—Koto-ri Occupied by 7th MarinesVIII | ||

| VII | Advance to the Chosin Reservoir | 125 |

| Attacks on Wonsan-Hungnam MSR—Appraisals of the New Enemy—The Turning Point of 15 November—Changes in X Corps Mission—Marine Preparations for Trouble—Supplies Trucked to Hagaru—Confidence of UN Command—Marine Concentration on MSR | ||

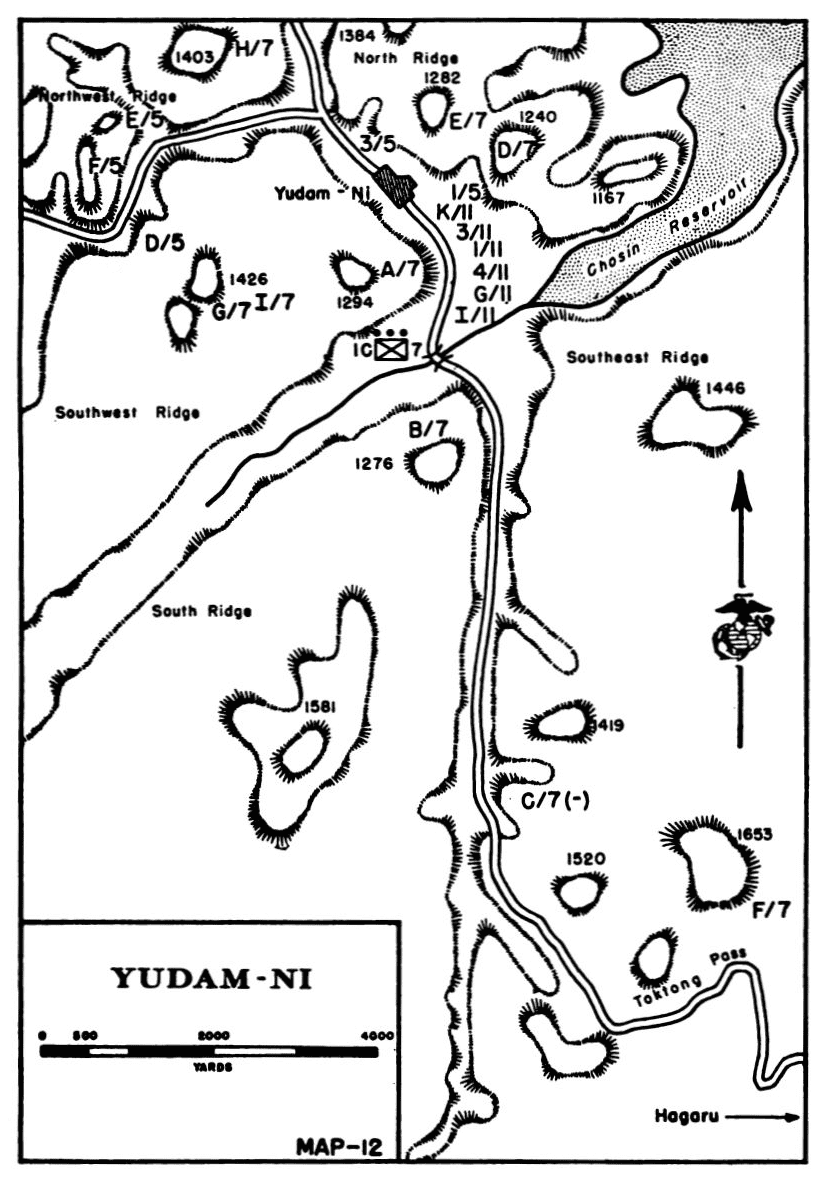

| VIII | Crisis at Yudam-ni | 151 |

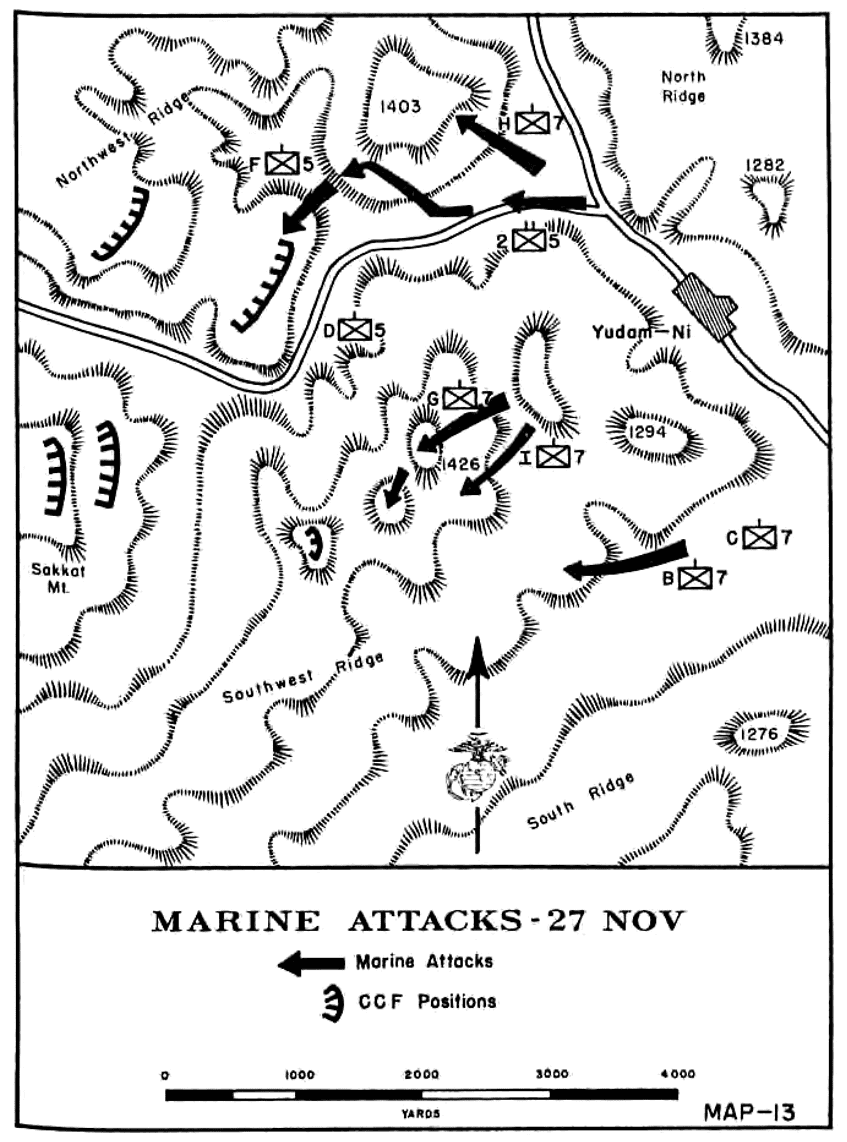

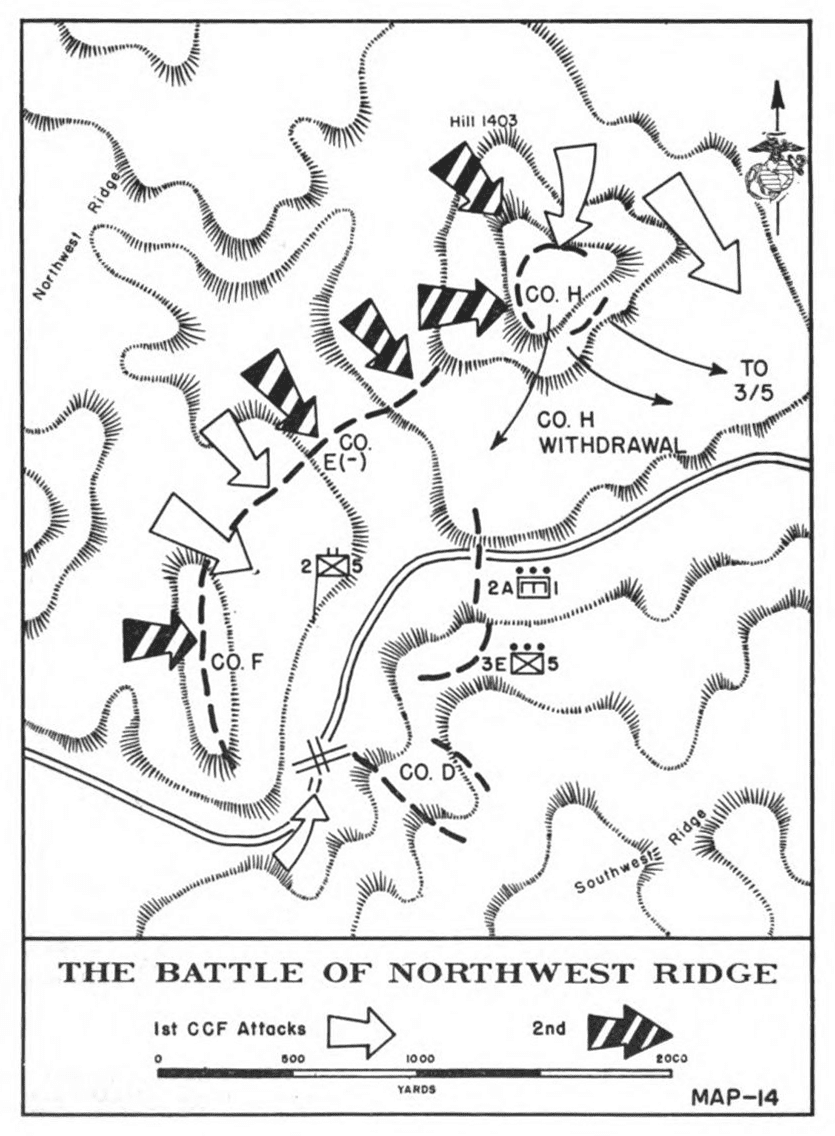

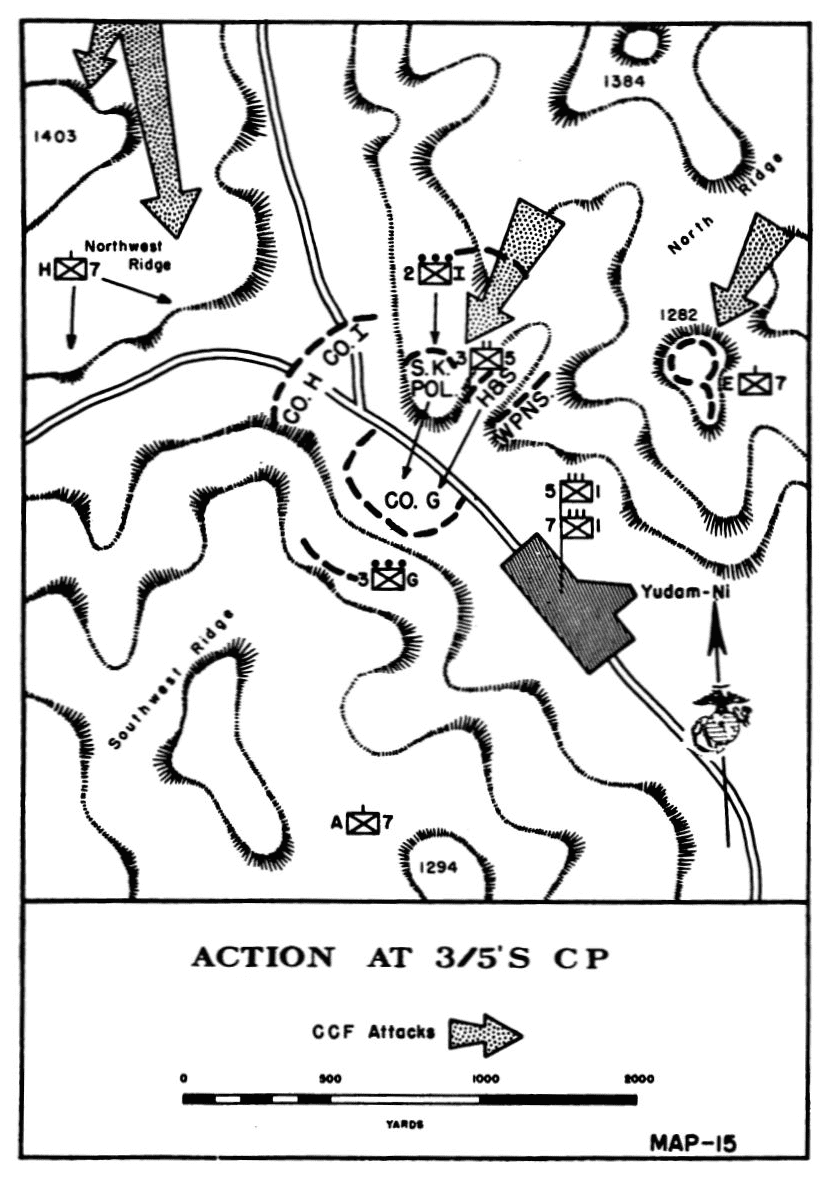

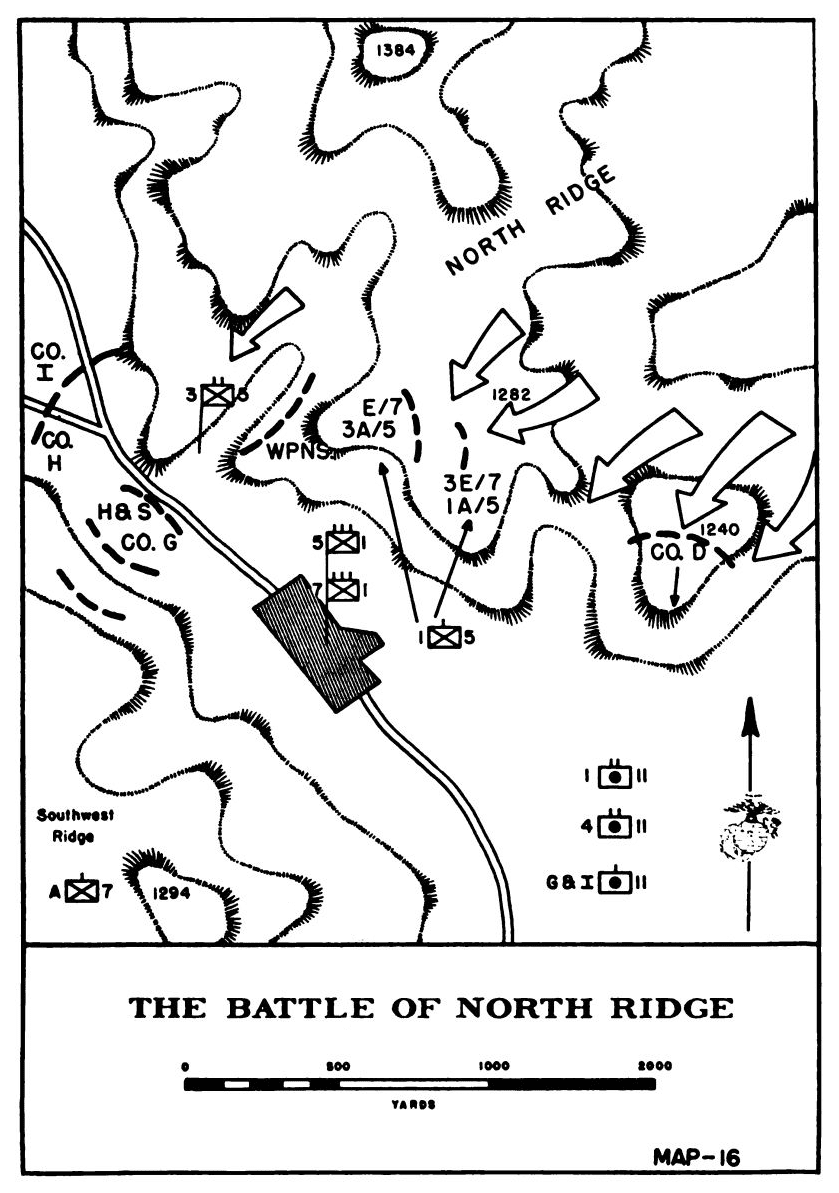

| Marine Attack on 27 November—Marine Disposition Before CCF Attack—The Battle of Northwest Ridge—Chinese Seize Hill 1403—Fighting at 3/5’s CP—The Battle of North Ridge | ||

| IX | Fox Hill | 177 |

| Encirclement of Company C of RCT-7—Fox Company at Toktong Pass—Marine Counterattacks on North Ridge—Second Night’s Attacks on Fox Hill—Not Enough Tents for Casualties—The Turning Point of 30 November | ||

| X | Hagaru’s Night of Fire | 197 |

| Four-Mile Perimeter Required—Attempts to Clear MSR—Intelligence as to CCF Capabilities—Positions of Marine Units—CCF Attacks from the Southwest—East Hill Lost to Enemy—The Volcano of Supporting Fires—Marine Attacks on East Hill | ||

| XI | Task Force Drysdale | 221 |

| CCF Attacks on 2/1 at Koto-ri—Convoy Reinforced by Marine Tanks—The Fight in Hell Fire Valley—Attack of George Company on East Hill—High Level Command Conference—CCF Attacks of 1 December at Hagaru—Rescue of U. S. Army Wounded—First Landings on Hagaru Airstrip | ||

| XII | Breakout From Yudam-ni | 249 |

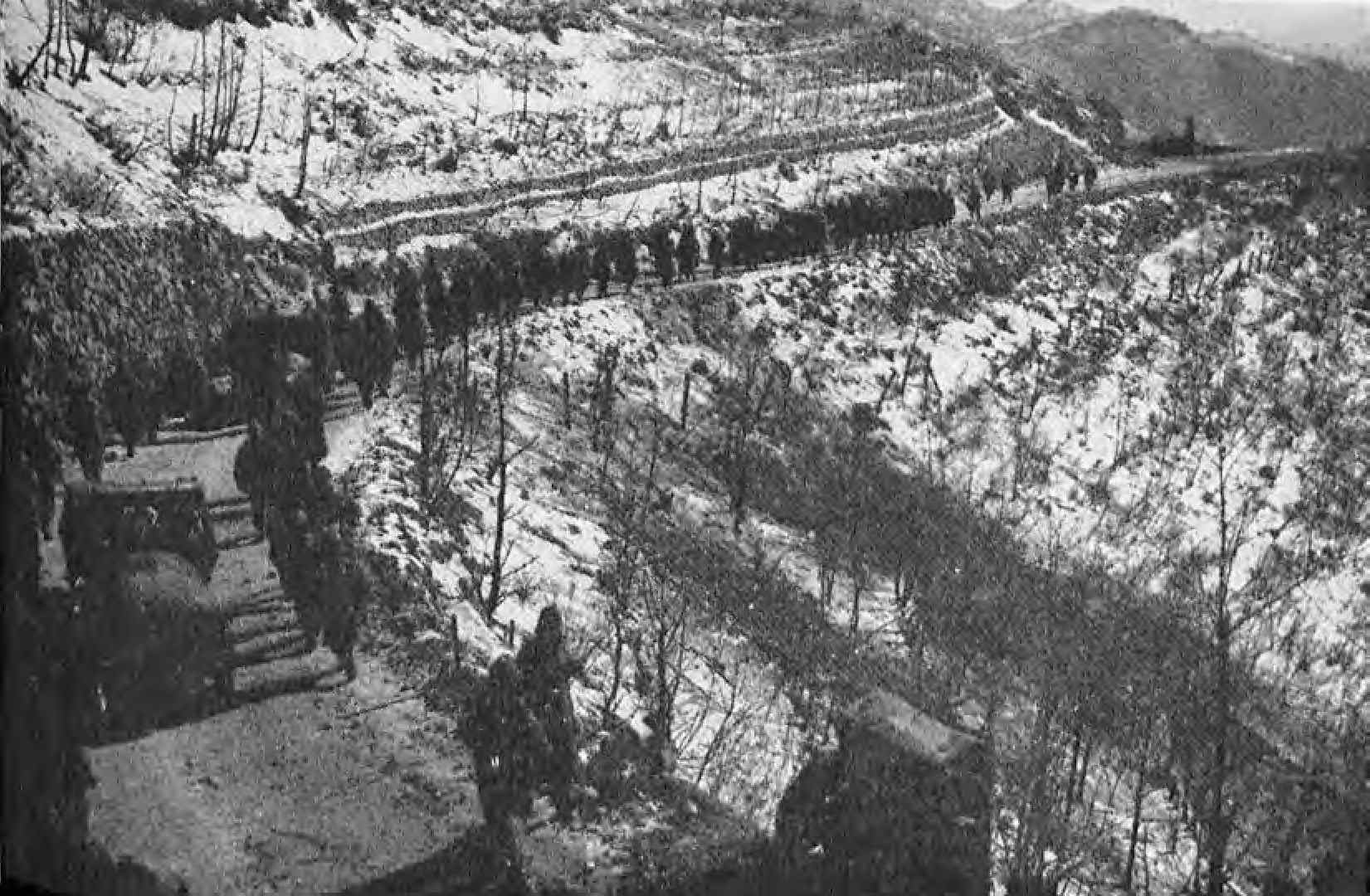

| Joint Planning for Breakout—The Fight for Hills 1419 and 1542—March of 1/7 Over the Mountains—Attack of 3/5 on 1–2 December—The Ridgerunners of Toktong Pass—CCF Attacks on Hills 1276 and 1542—Advance of Darkhorse on 2–3 December—Entry into Hagaru Perimeter | ||

| XIII | Regroupment at Hagaru | 277 |

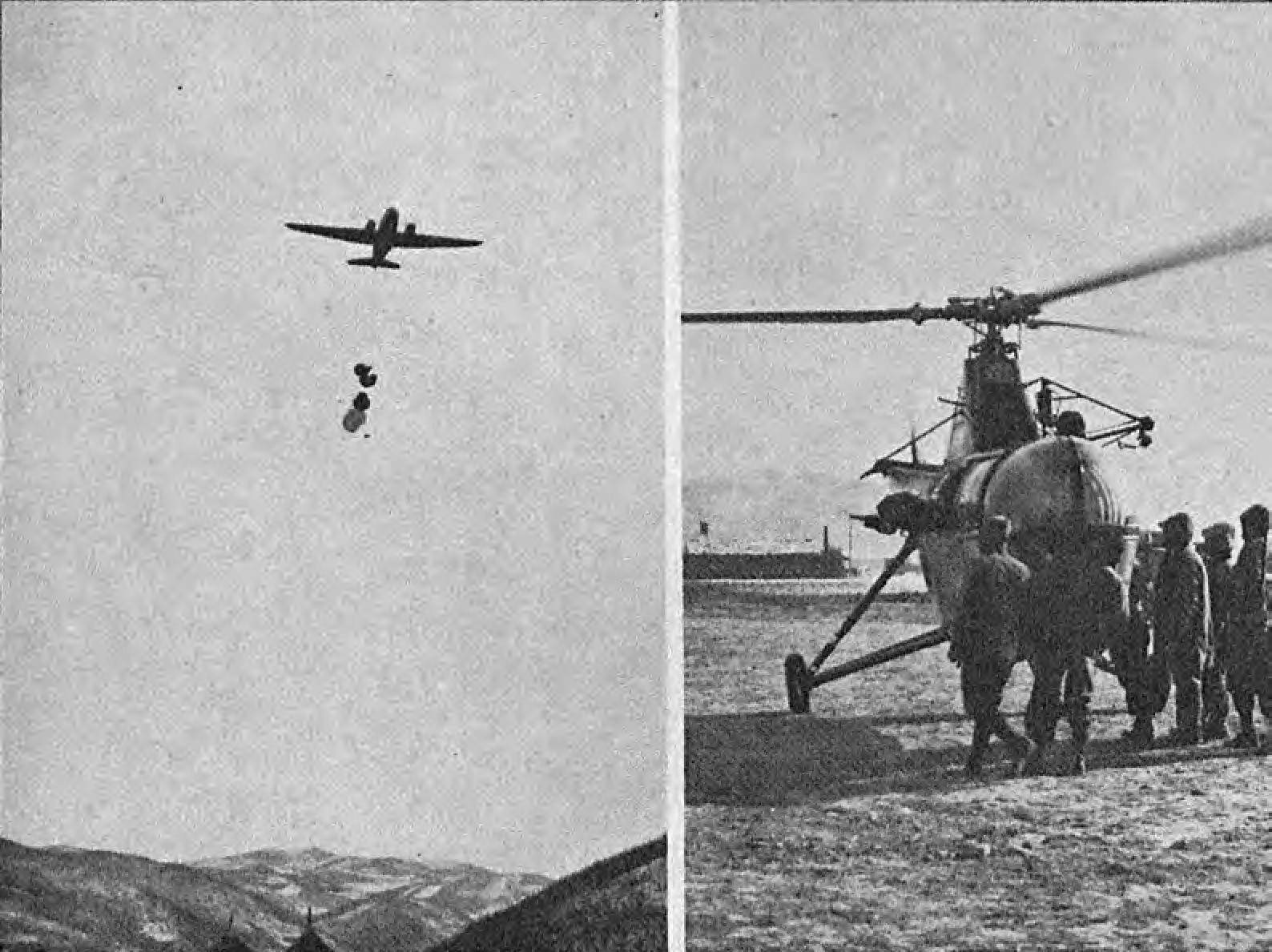

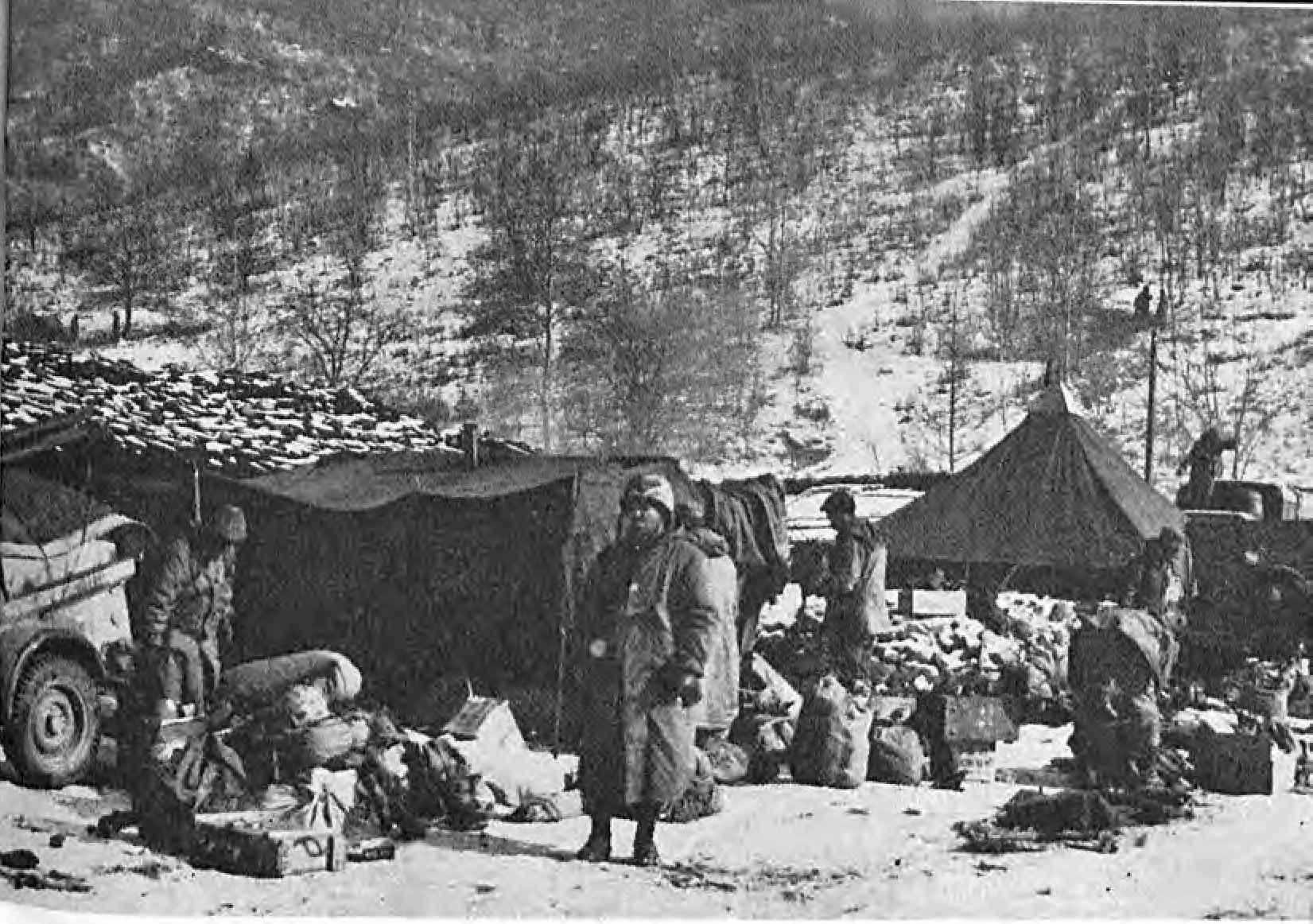

| 4,312 Casualties Evacuated by Air—537 Replacements Flown to Hagaru—Air Drops of Ammunition—Planning for Breakout to Koto-ri—3/1 Relieved by RCT-5 at Hagaru—East Hill Retaken from Chinese—Attack of RCT-7 to the South—Advance of the Division TrainsIX | ||

| XIV | Onward From Koto-ri | 305 |

| Assembly of Division at Koto-ri—Activation of Task Force Dog—Air Drop of Bridge Sections—Division Planning for Attack—Battle of 1/1 in the Snowstorm—Advance of RCT-7 and RCT-5—Marine Operations of 9 and 10 December—Completion of Division Breakout | ||

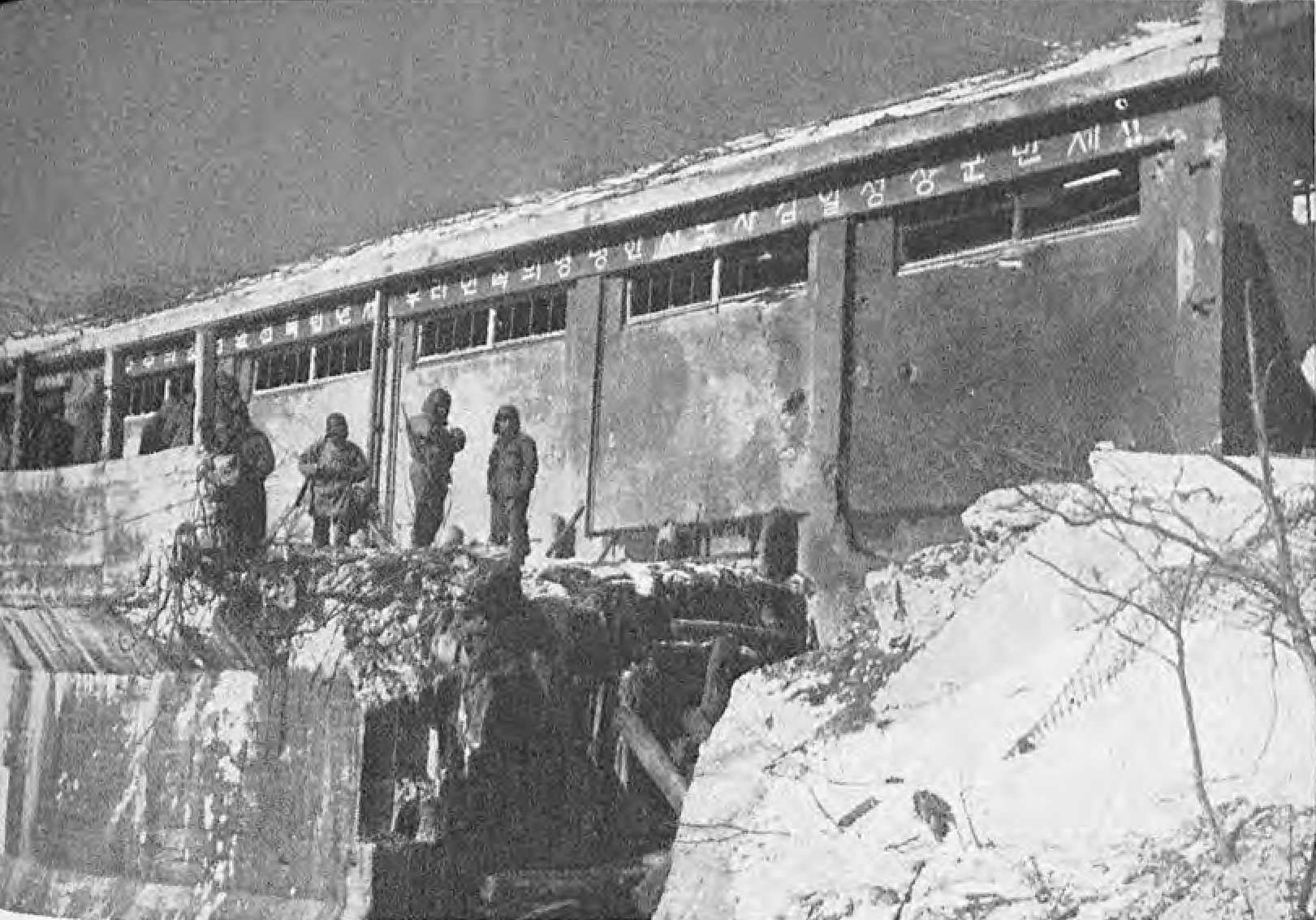

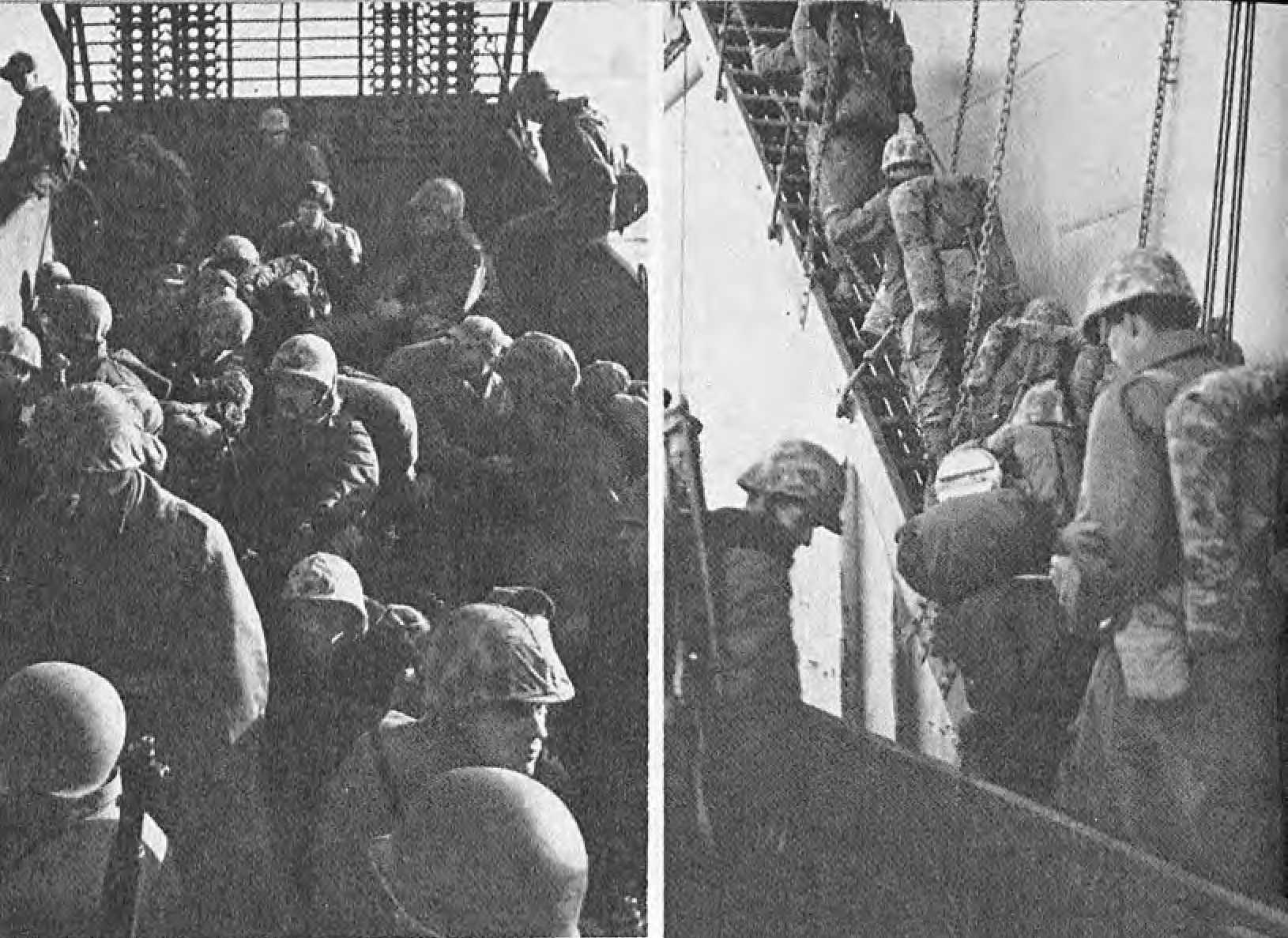

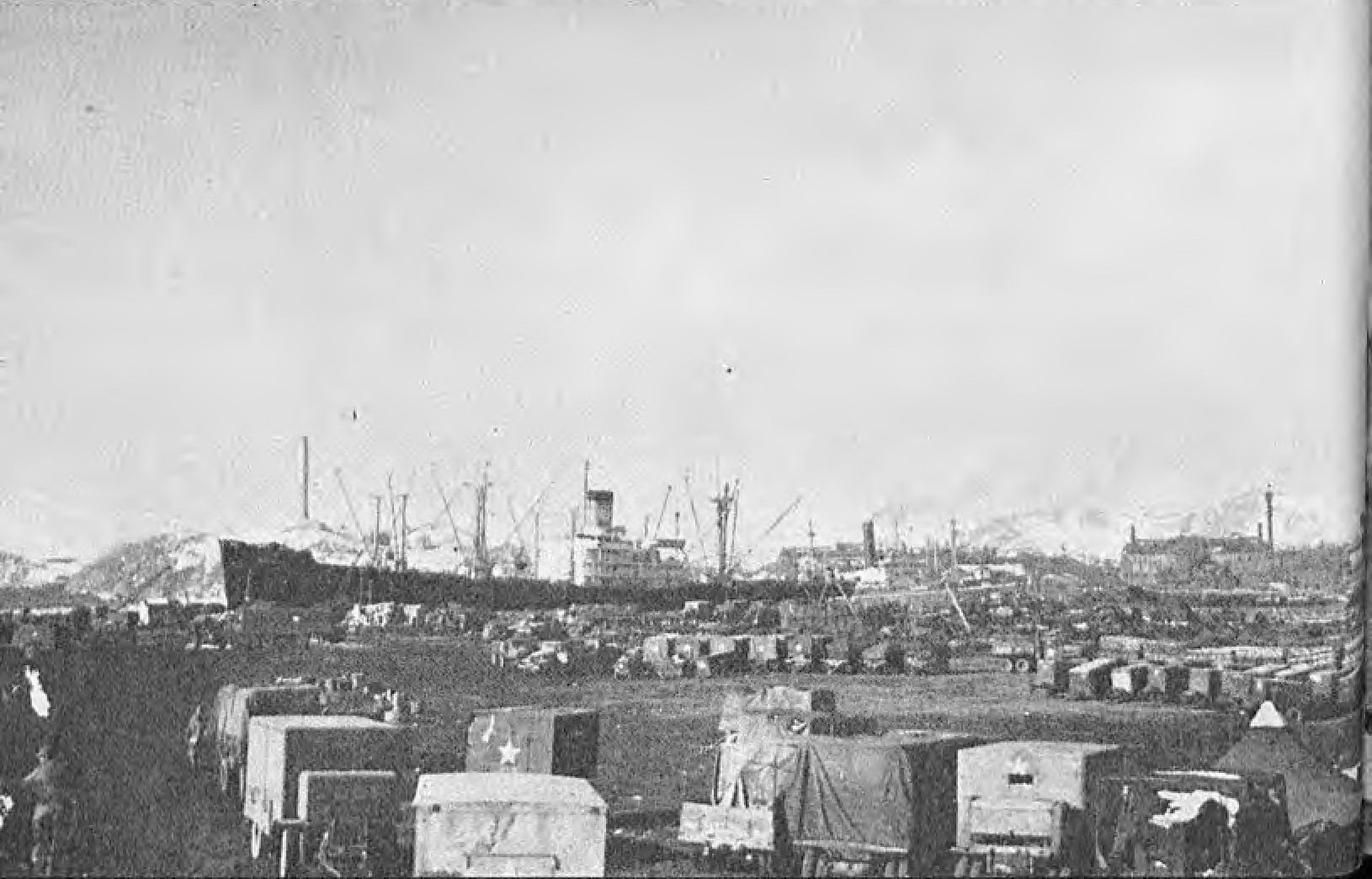

| XV | The Hungnam Redeployment | 333 |

| Marines Billeted in Hungnam Area—Embarkation of 1st Marine Division—The Last Ten Days at Hungnam—Marines Arrive at New Assembly Area—Contributions of Marine Aviation—Losses Sustained by the Enemy—Results of the Reservoir Campaign | ||

| Appendixes | ||

| A | Glossary of Technical Terms and Abbreviations | 361 |

| B | Task Organization, 1st Marine Division | 365 |

| C | Naval Task Organization | 373 |

| D | Effective Strength of 1st Marine Division | 379 |

| E | 1st Marine Division Casualties | 381 |

| F | Command and Staff List, 8 October-15 December 1950, 1st Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing | 383 |

| G | Enemy Order of Battle | 397 |

| H | Air Evacuation Statistics | 399 |

| I | Unit Citations | 401 |

| Bibliography | 405 | |

| Index | 413 | |

X

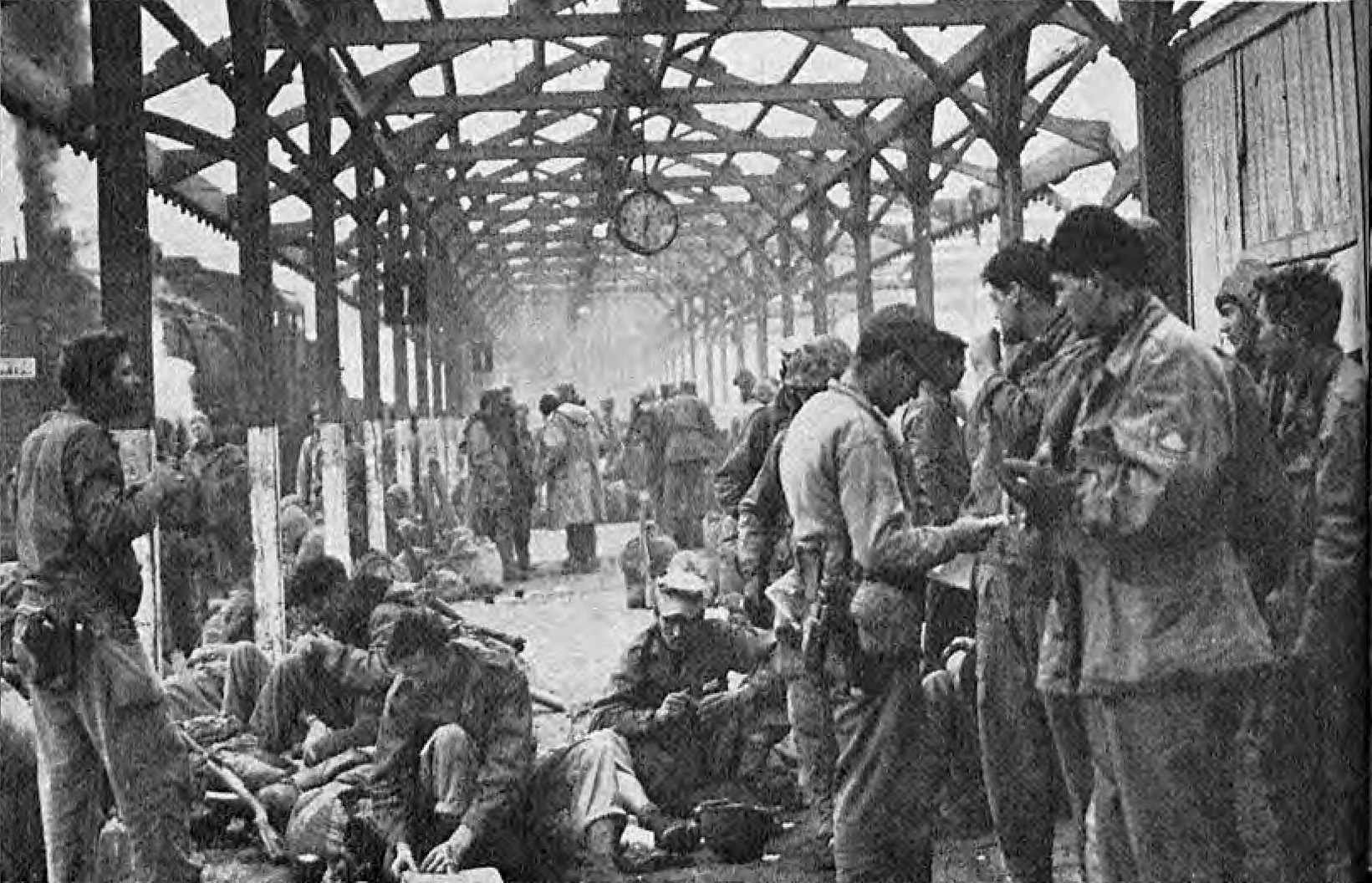

Photographs

Sixteen-page sections of photographs follow pages 148 and 276.

Maps and Sketches

| Page | ||

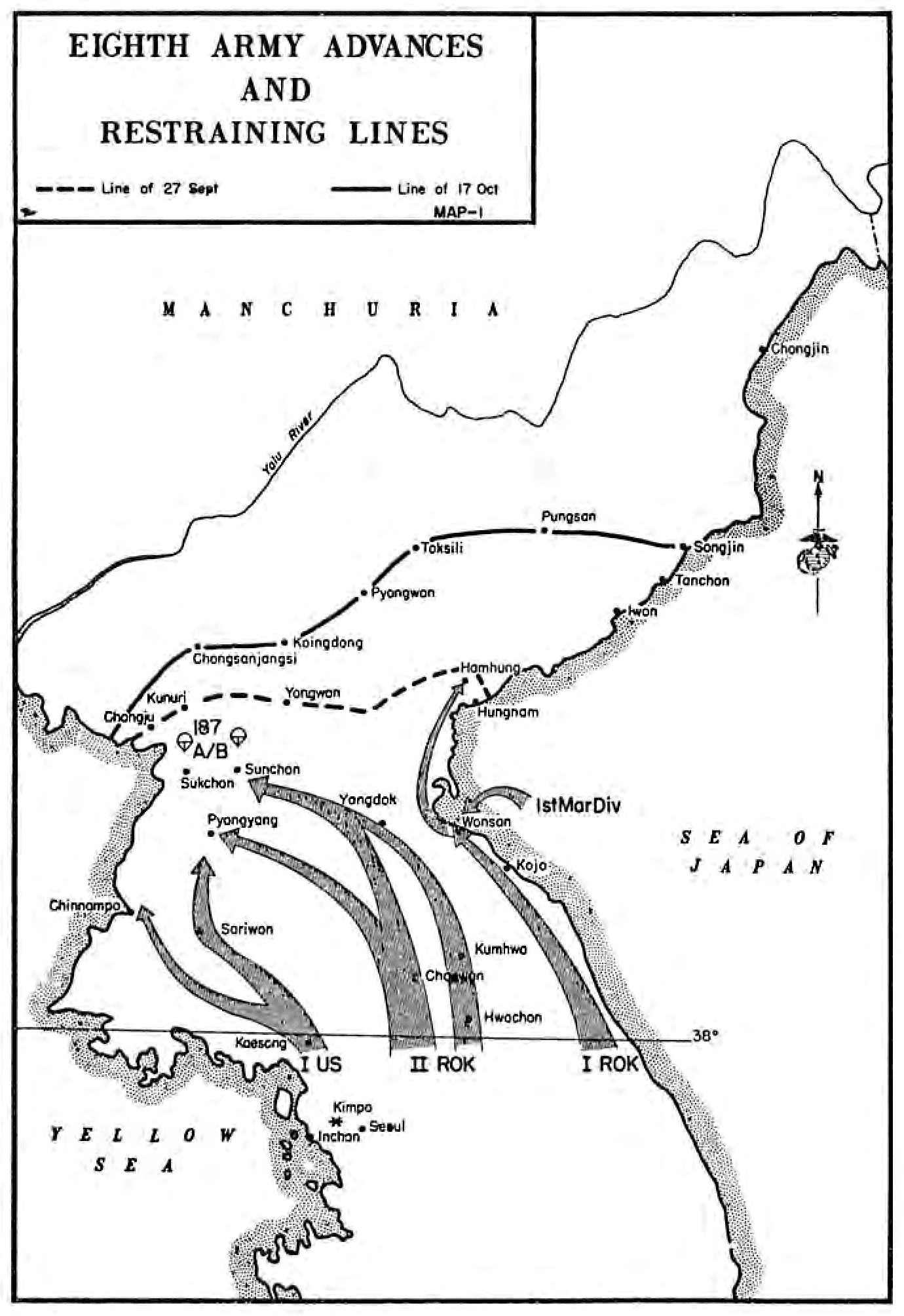

| 1 | Eighth Army Advances and Restraining Lines | 4 |

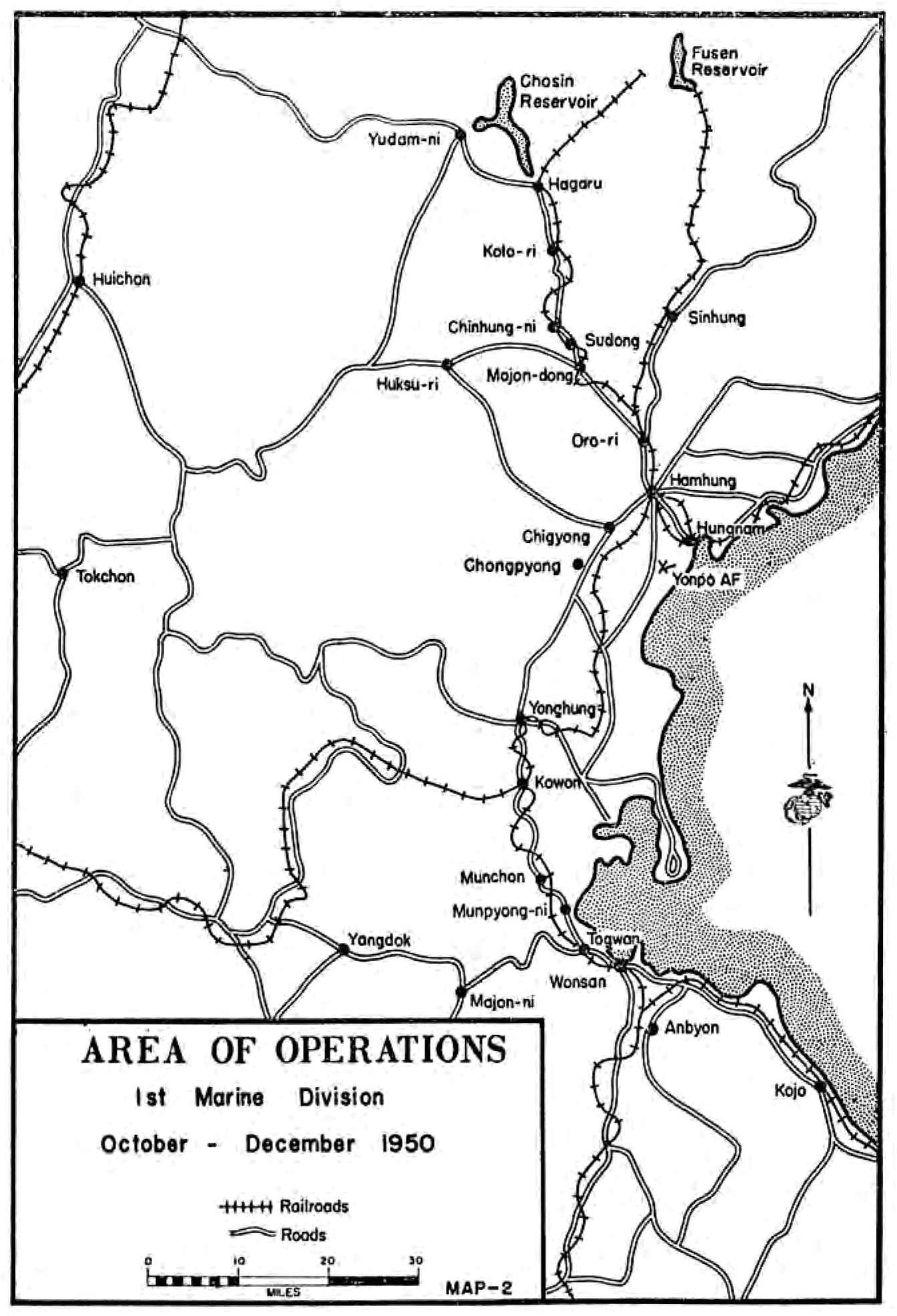

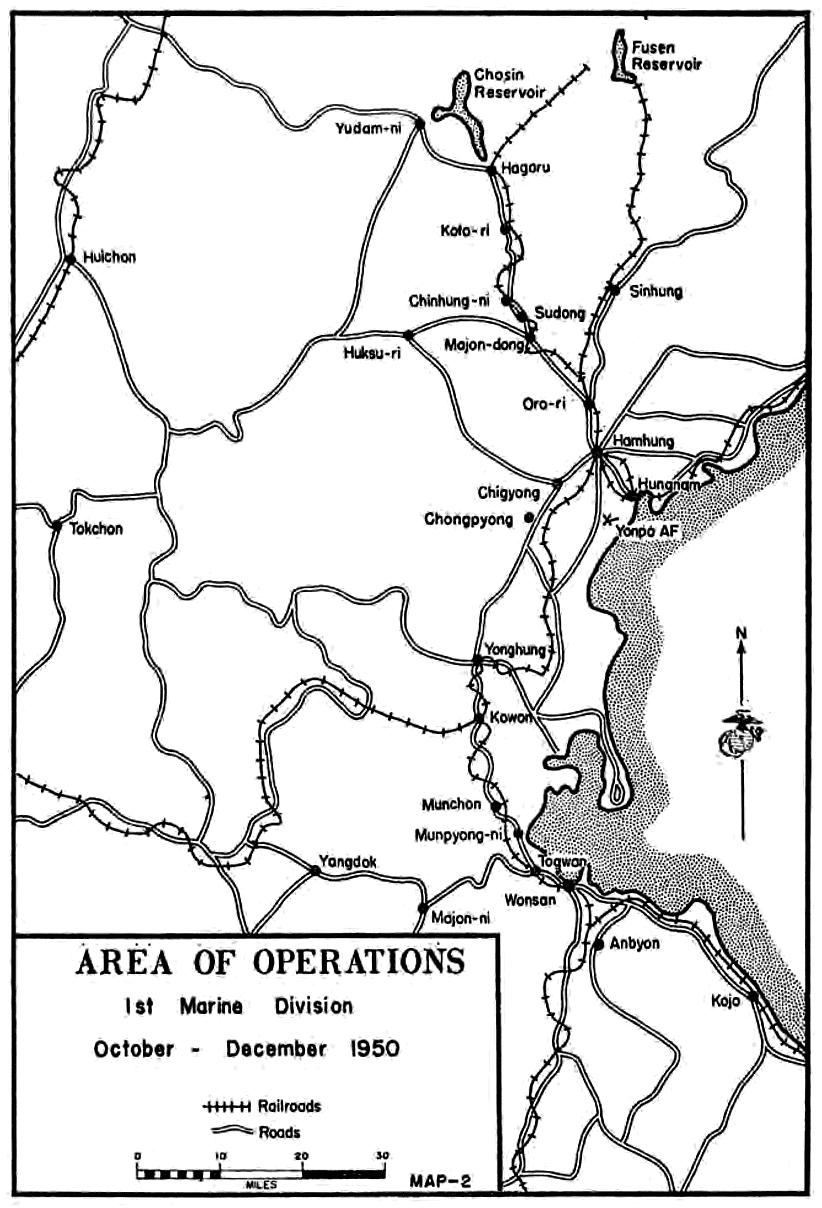

| 2 | Area of Operations, 1st Marine Division, October-December 1950 | 12, 122 |

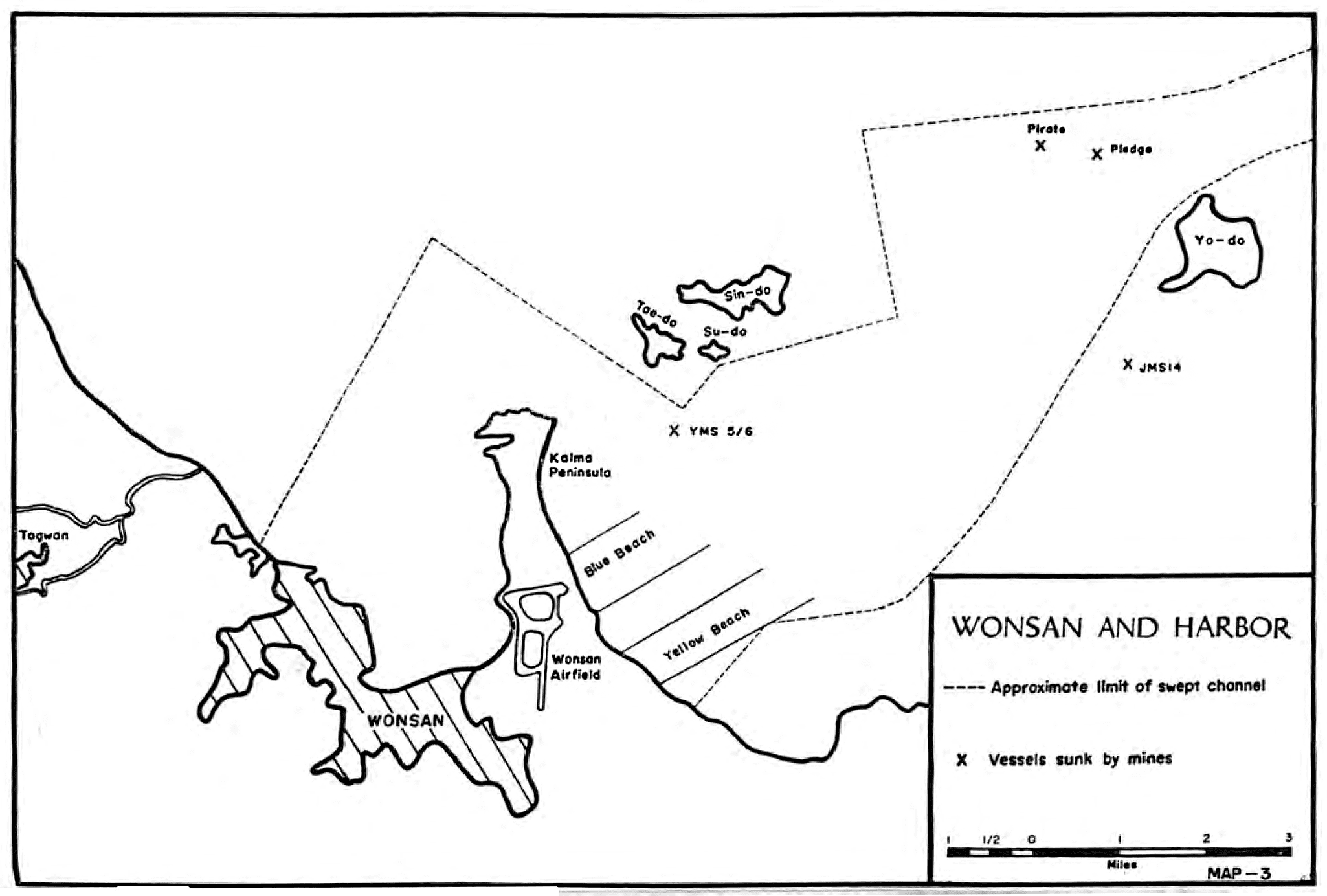

| 3 | Wonsan and Harbor | 16 |

| 4 | Kojo Area | 47 |

| 5 | Majon-ni and Road to Wonsan | 62 |

| 6 | Majon-ni Perimeter | 64 |

| 7 | The Main Supply Route of the 1st Marine Division | 97 |

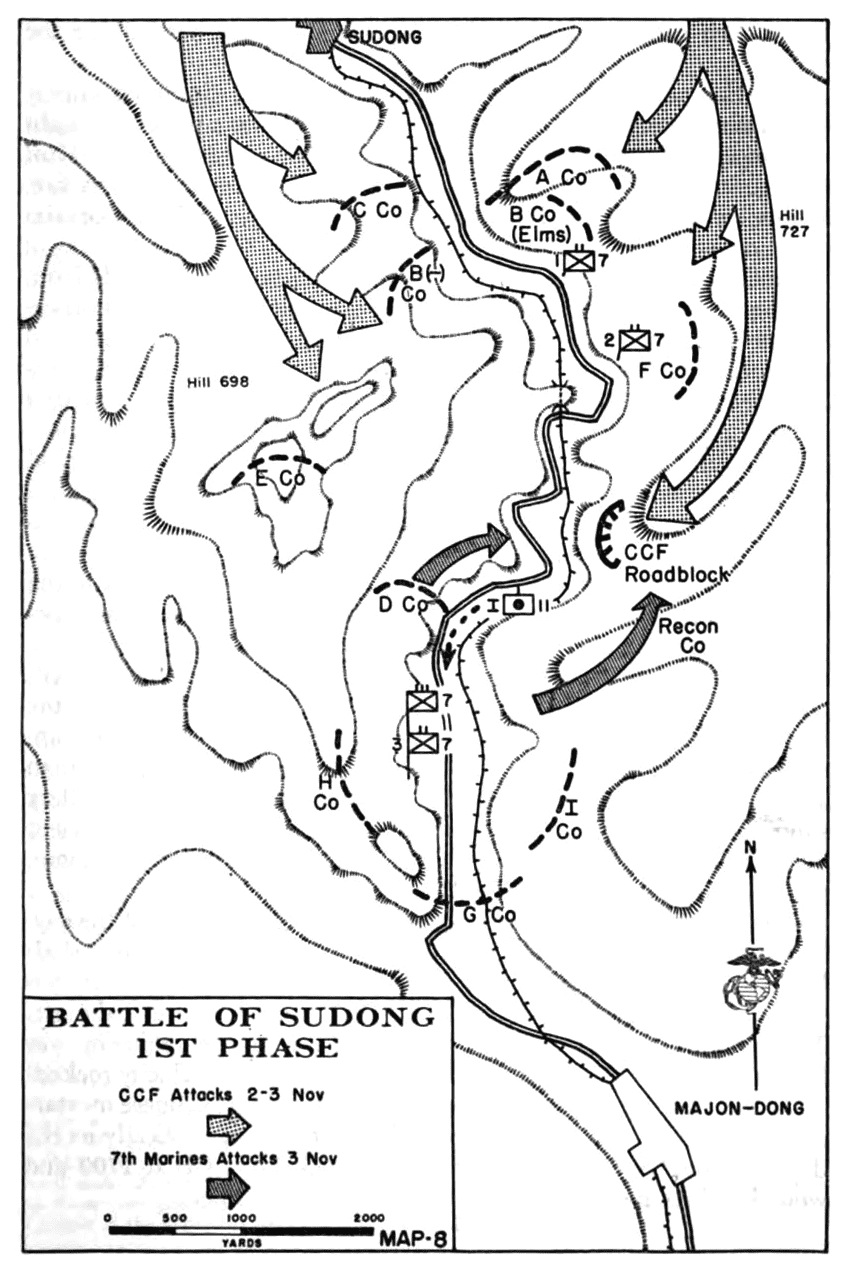

| 8 | Battle of Sudong, 1st Phase | 101 |

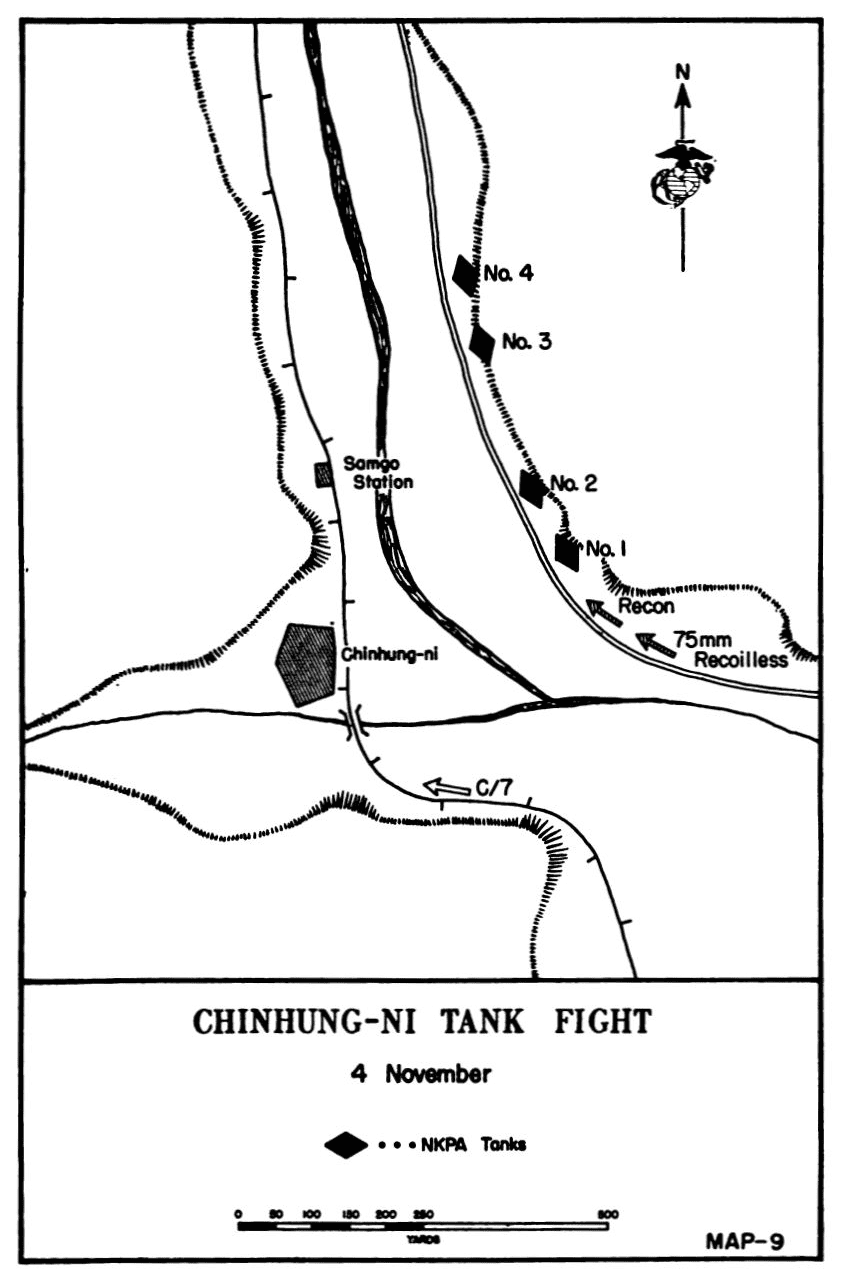

| 9 | Chinhung-ni Tank Fight, 4 November | 111 |

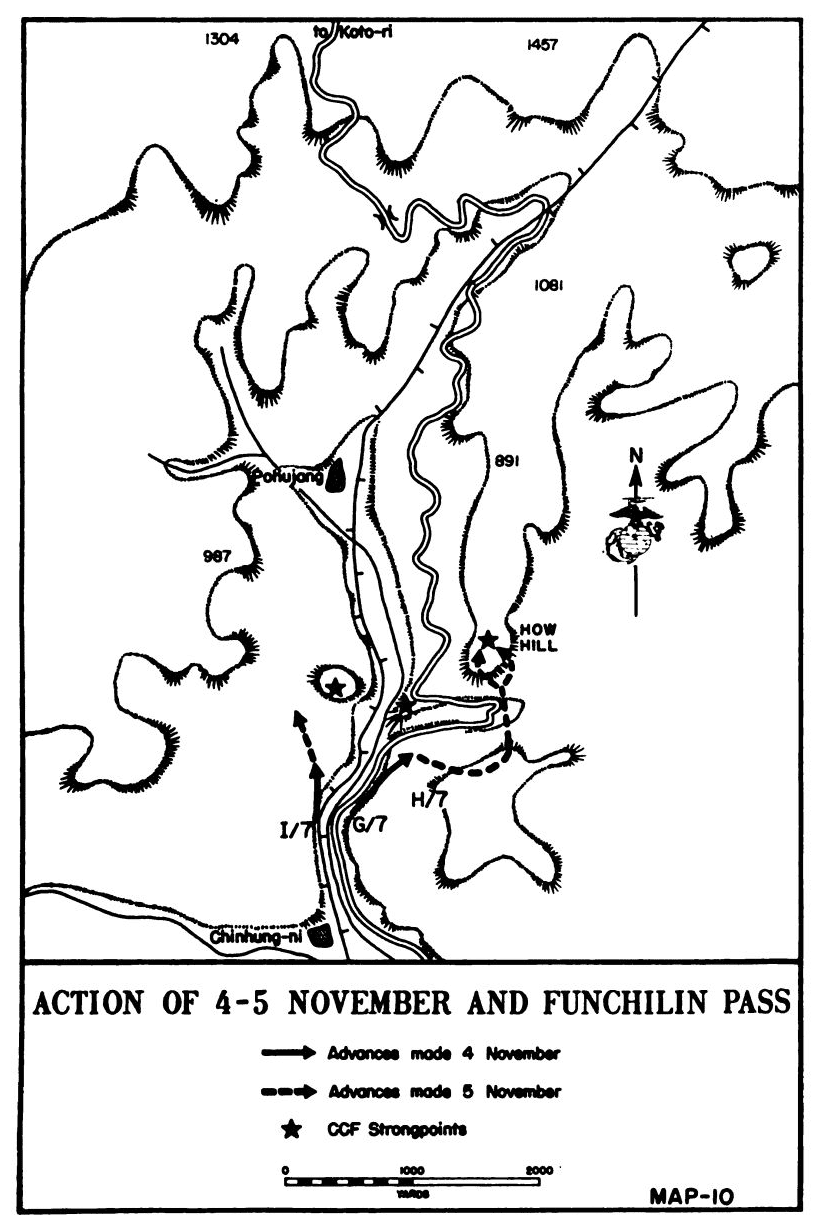

| 10 | Action of 4–5 November and Funchilin Pass | 115 |

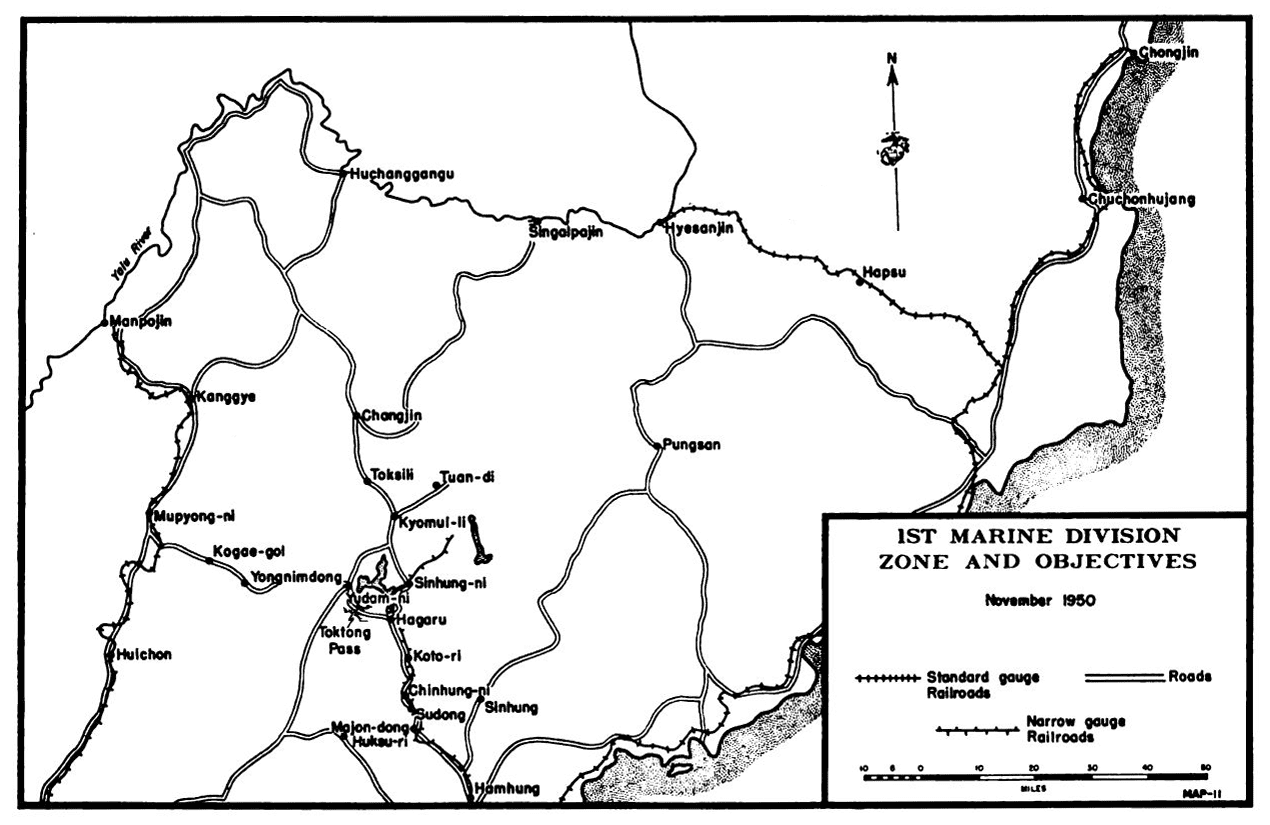

| 11 | 1st Marine Division Zone and Objectives | 130 |

| 12 | Yudam-ni | 153 |

| 13 | Marine Attacks, 27 November | 155 |

| 14 | Battle of Northwest Ridge | 162 |

| 15 | Action at 3/5’s CP | 169 |

| 16 | The Battle of North Ridge | 173 |

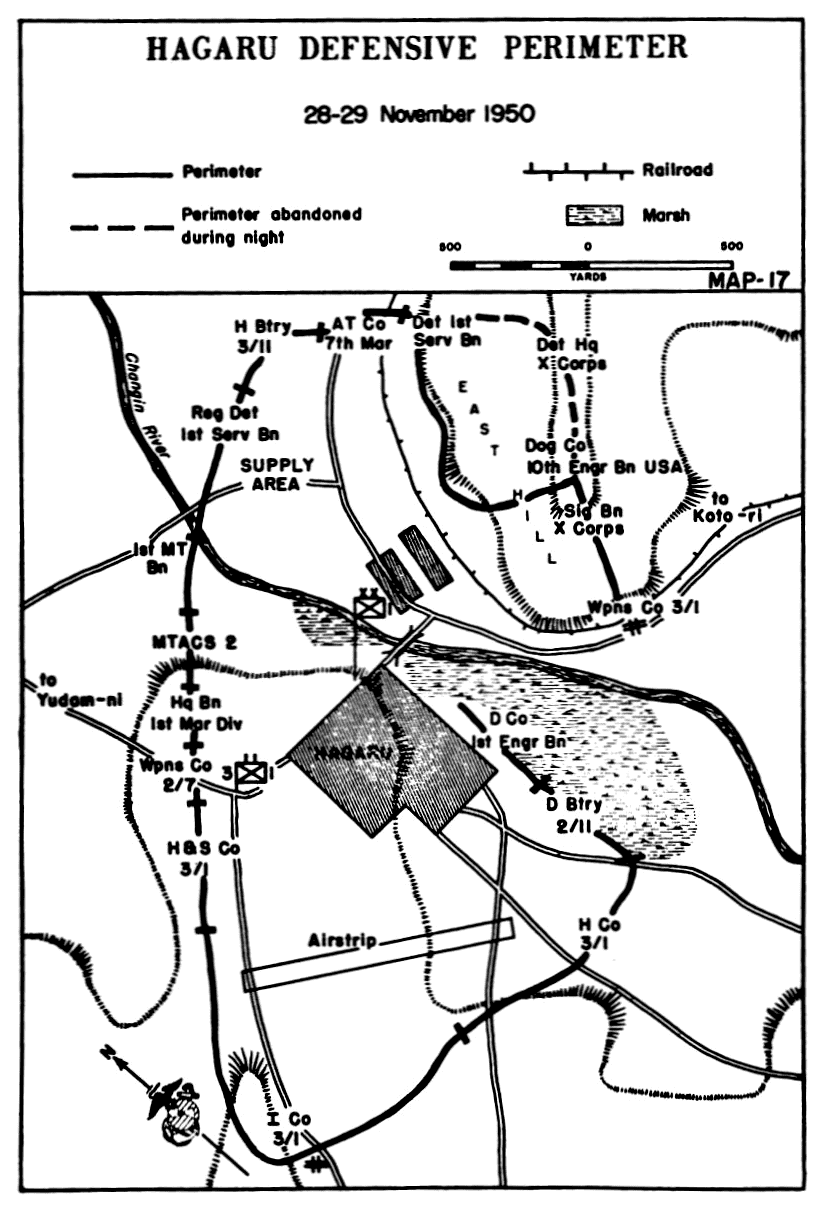

| 17 | Hagaru Defensive Perimeter | 199 |

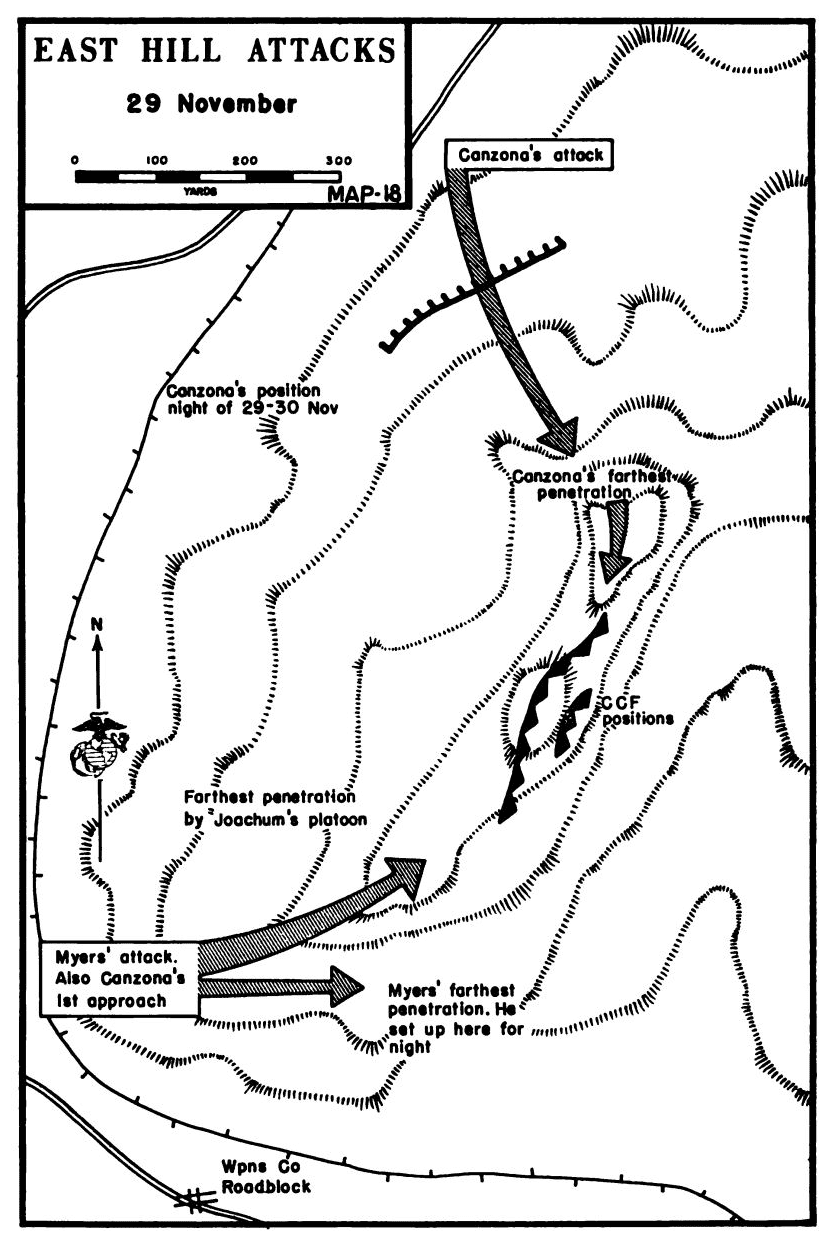

| 18 | East Hill Attacks, 29 November | 212 |

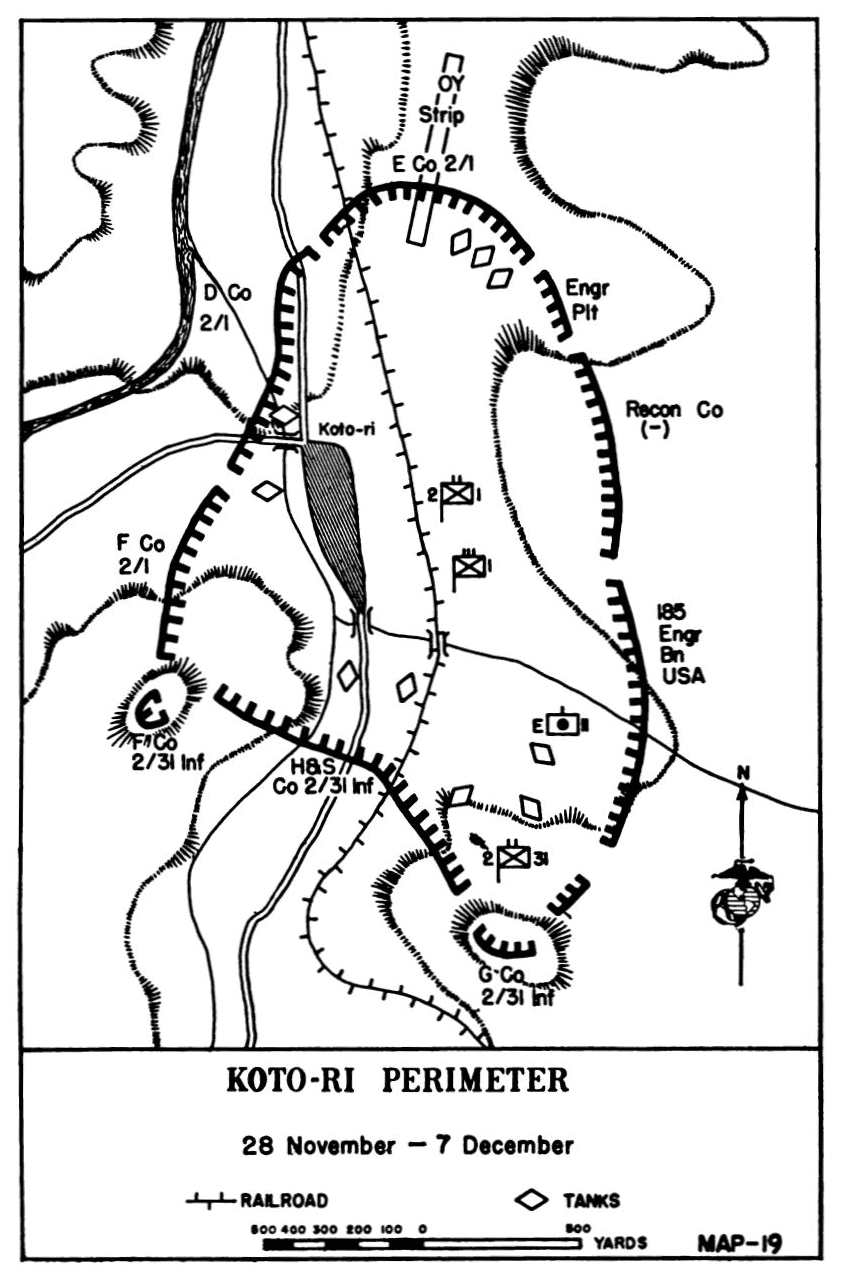

| 19 | Koto-ri Perimeter, 28 November-7 December | 223 |

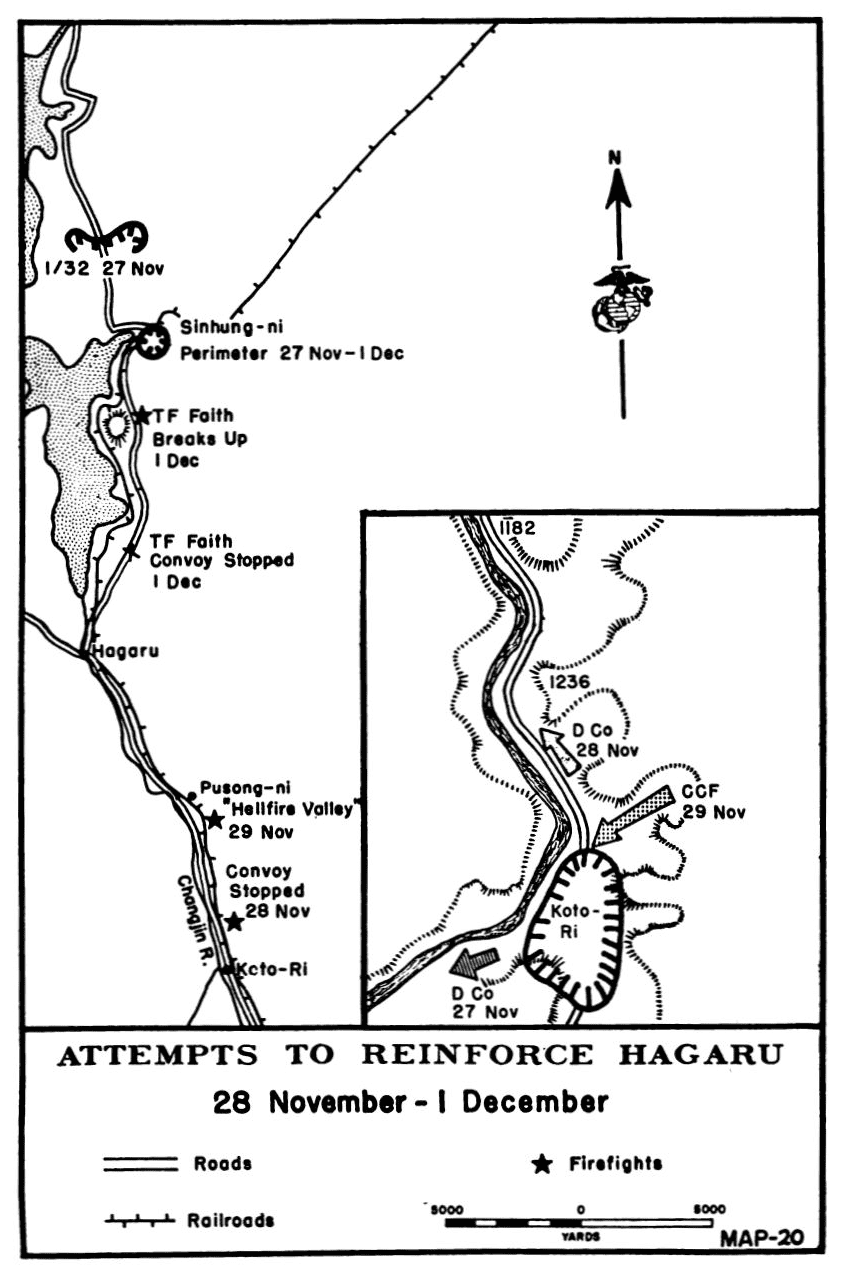

| 20 | Attempts to Reinforce Hagaru, 28 November-1 December | 227 |

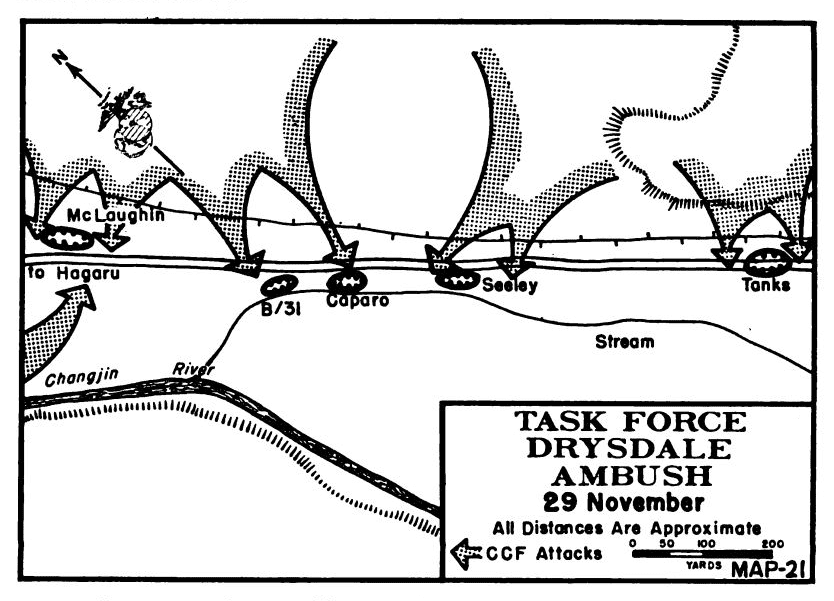

| 21 | Task Force Drysdale Ambush, 28 November | 230XI |

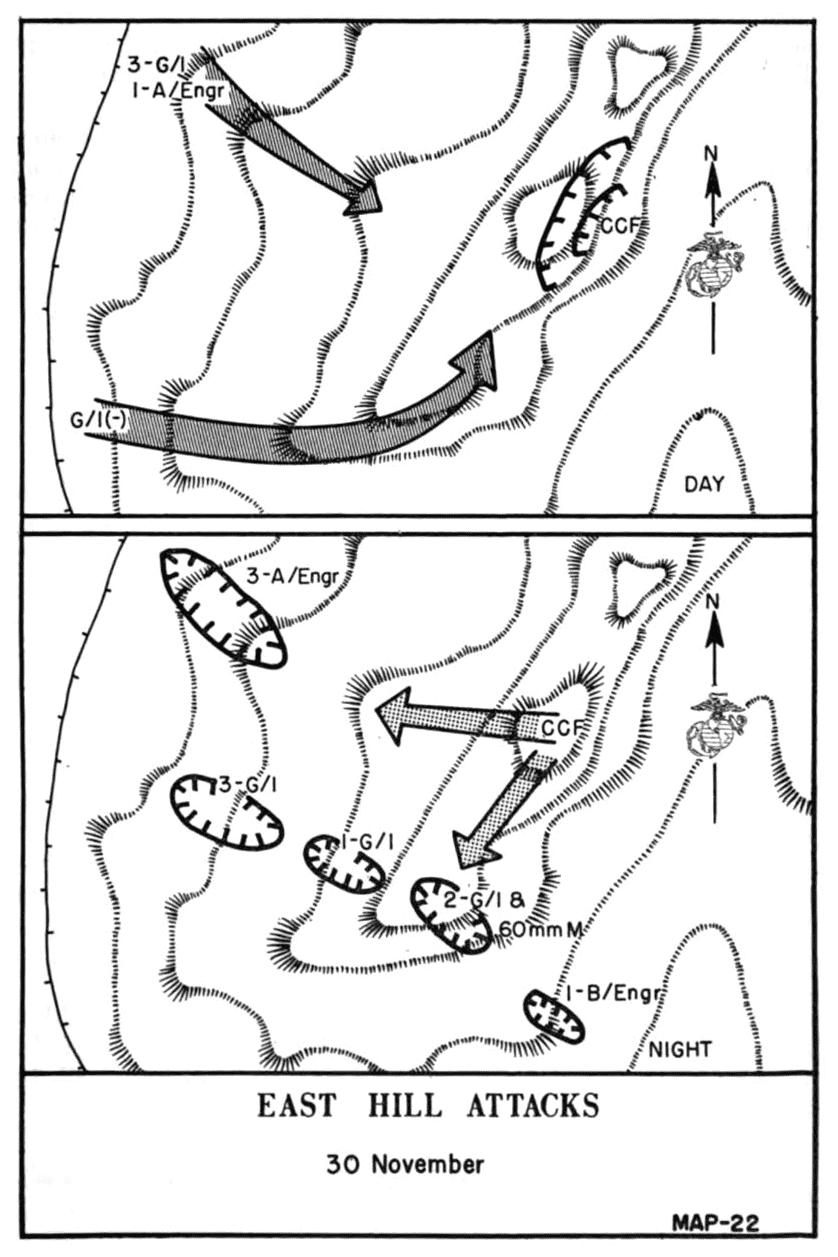

| 22 | East Hill Attacks, 30 November | 237 |

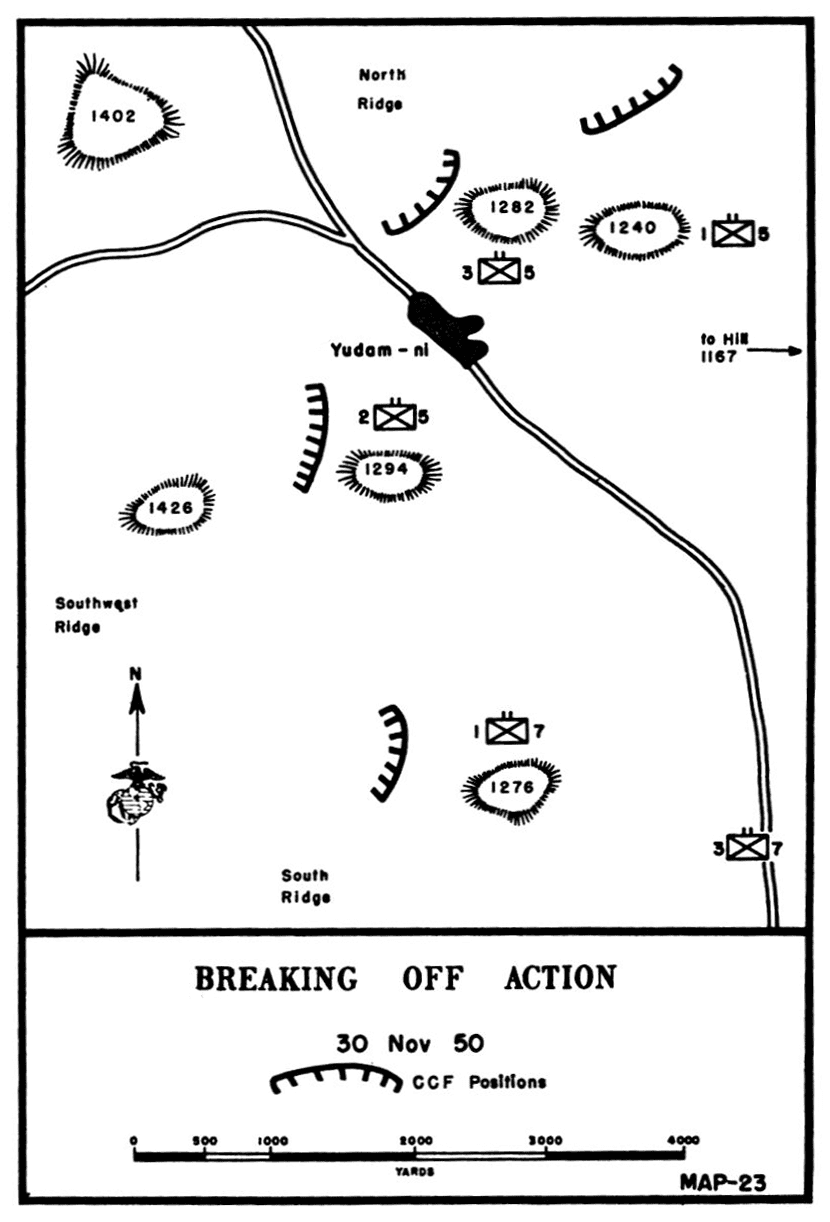

| 23 | Breaking off Action, 30 November | 252 |

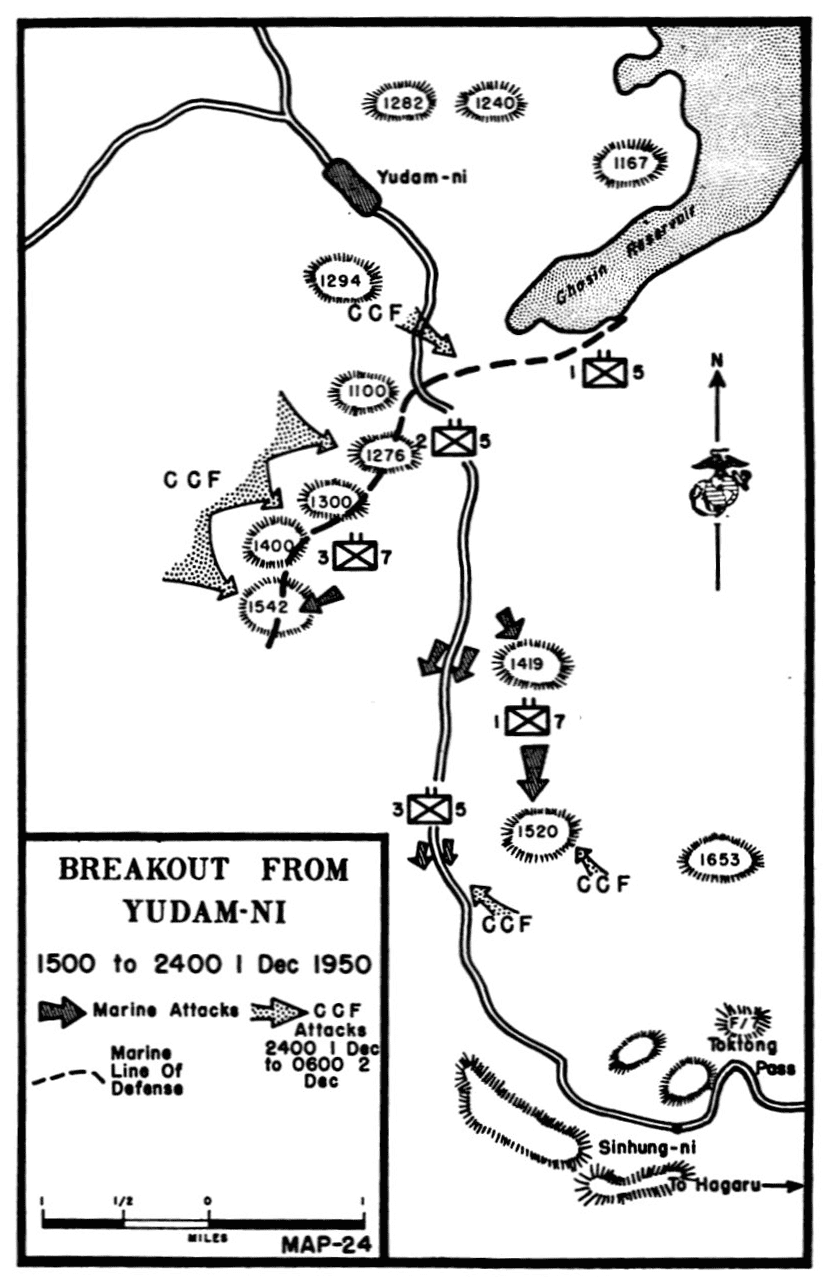

| 24 | Breakout from Yudam-ni, 1 December | 256 |

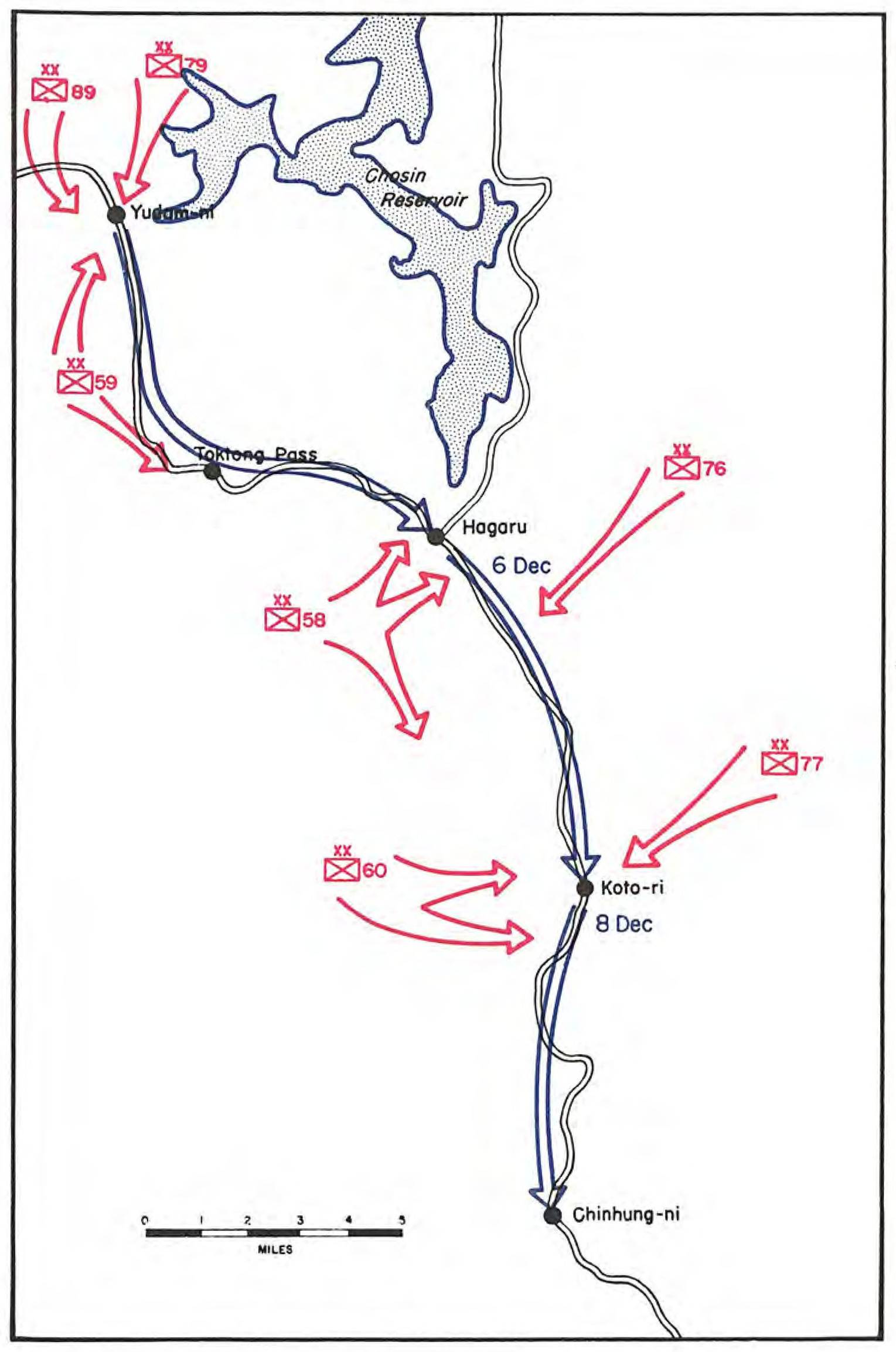

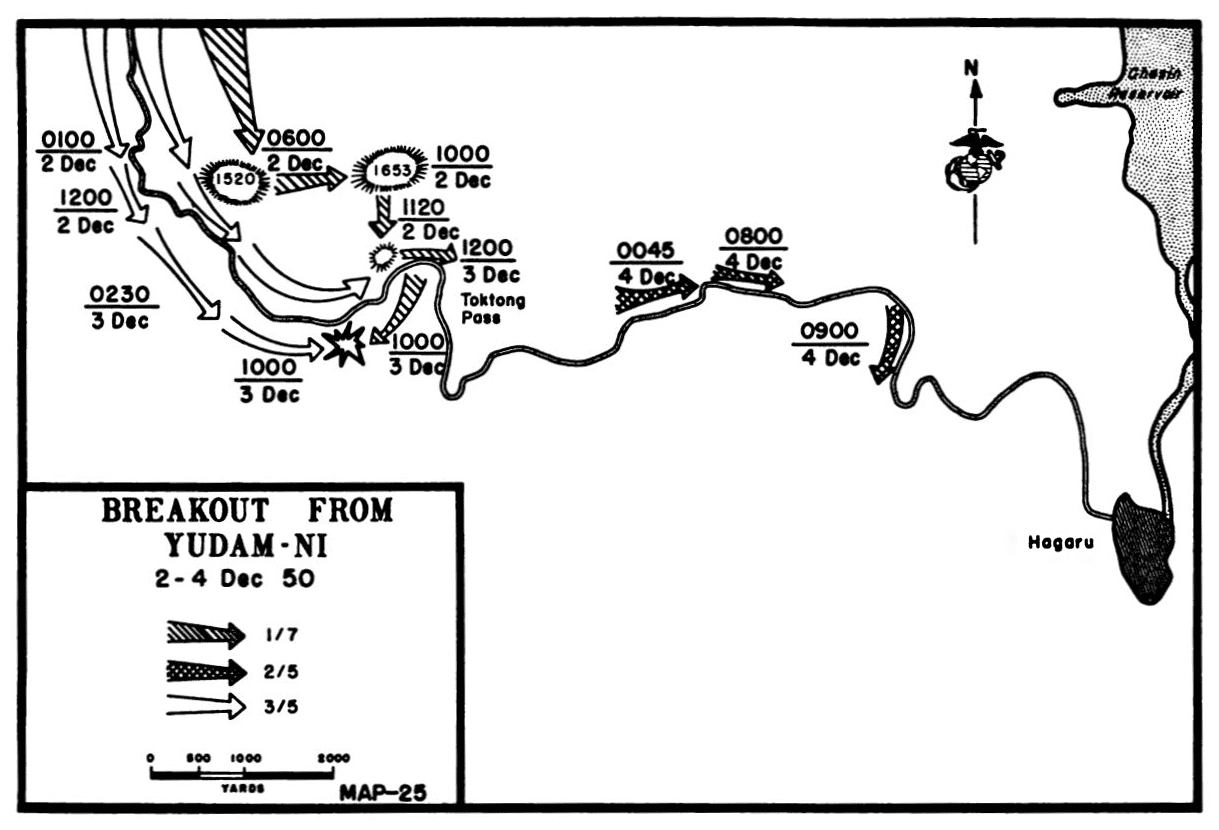

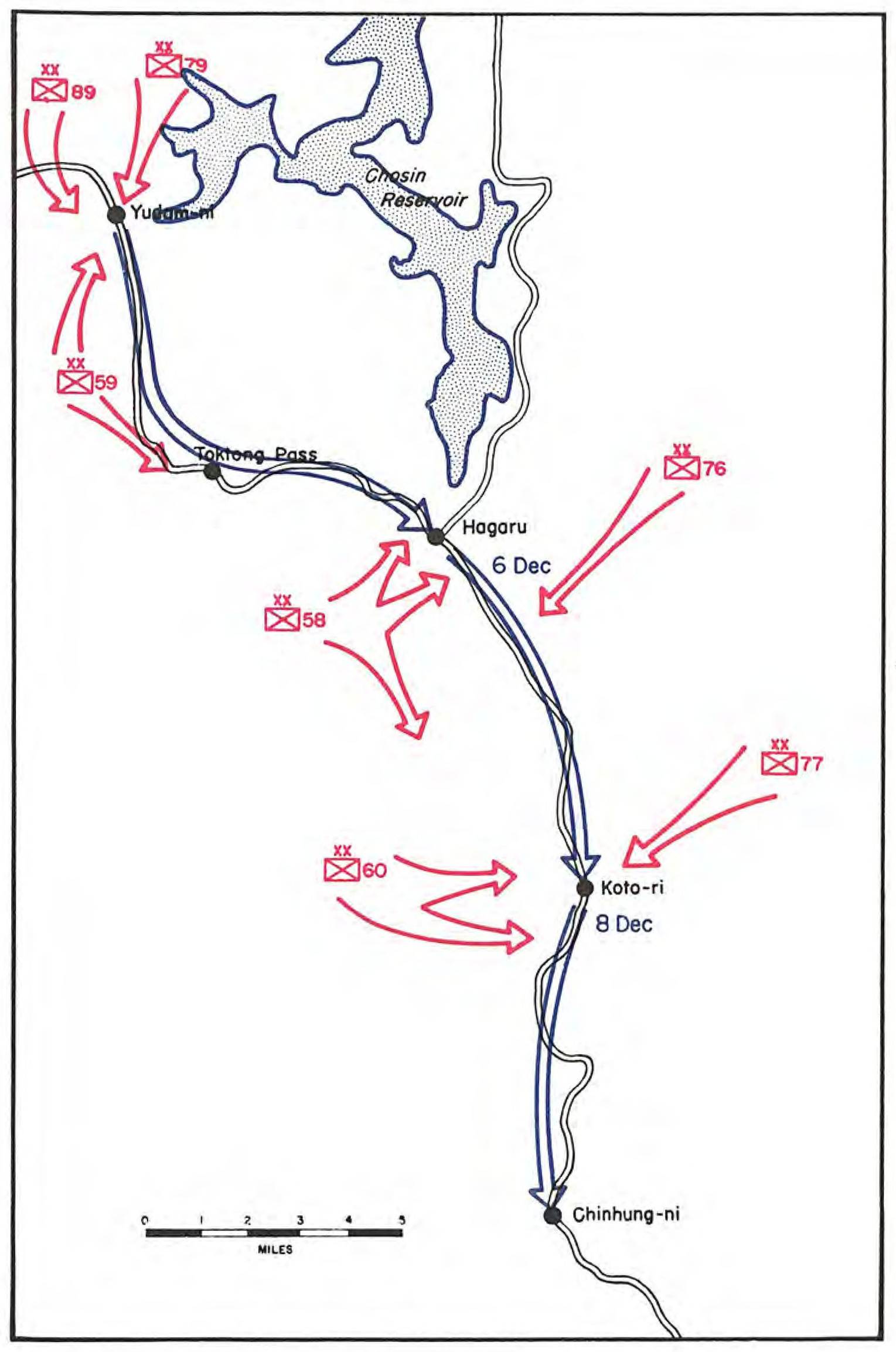

| 25 | Breakout from Yudam-ni, 2–4 December | 269 |

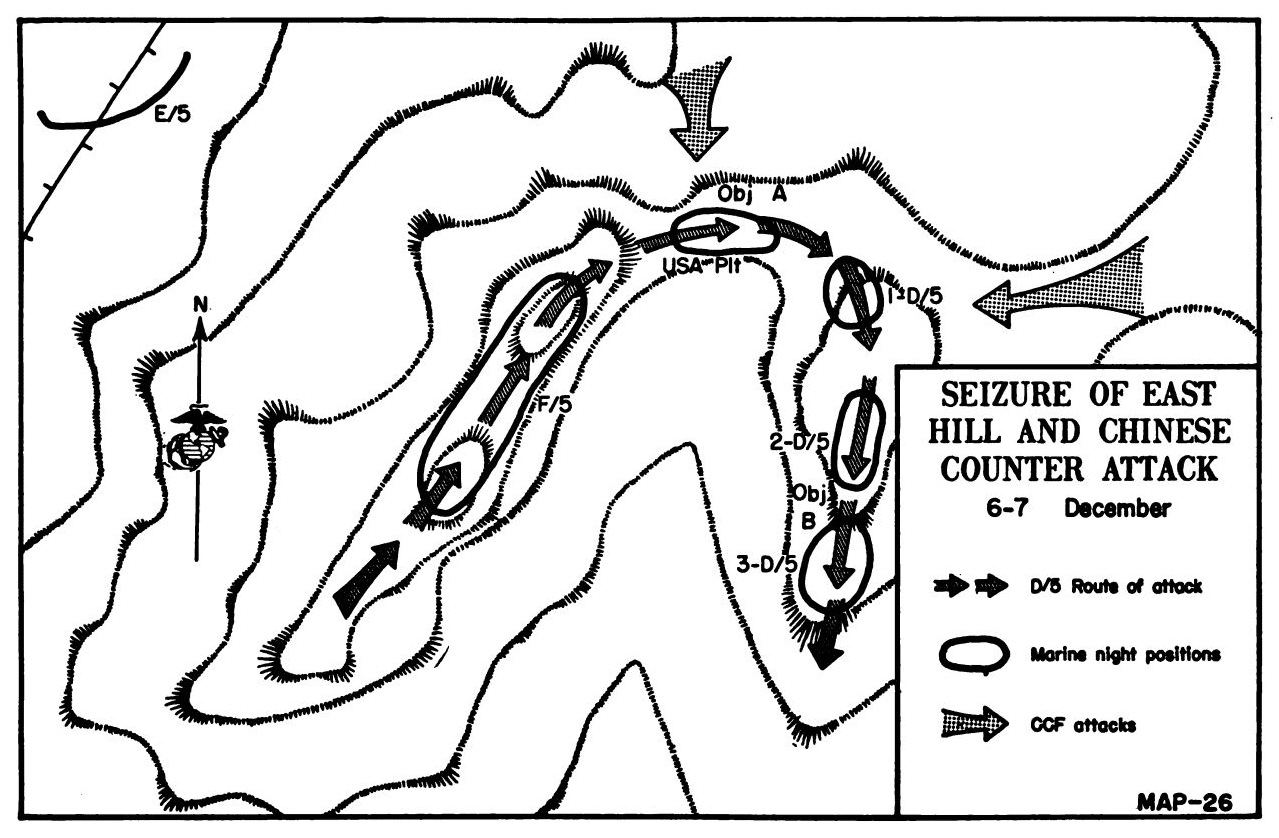

| 26 | Seizure of East Hill and Chinese Counterattack 6–7 December | 289 |

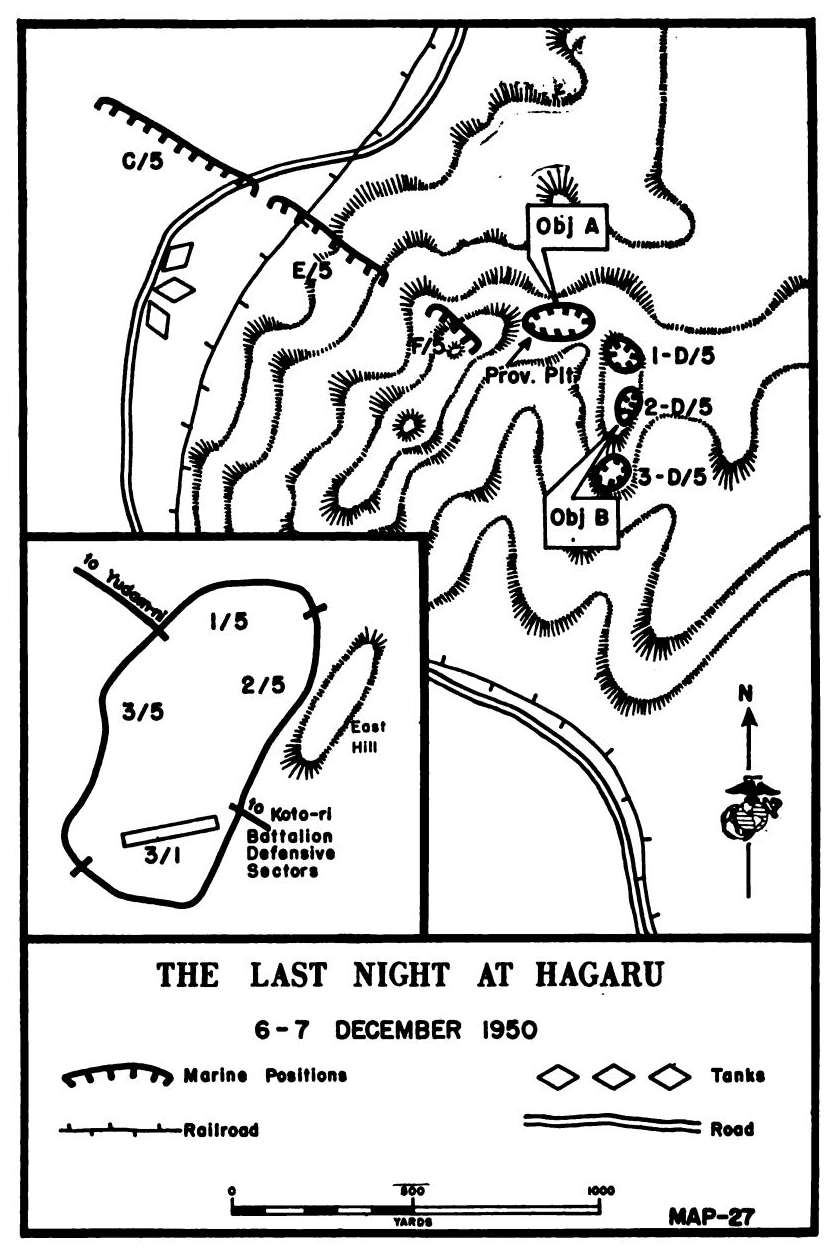

| 27 | Last Night at Hagaru, 6–7 December | 292 |

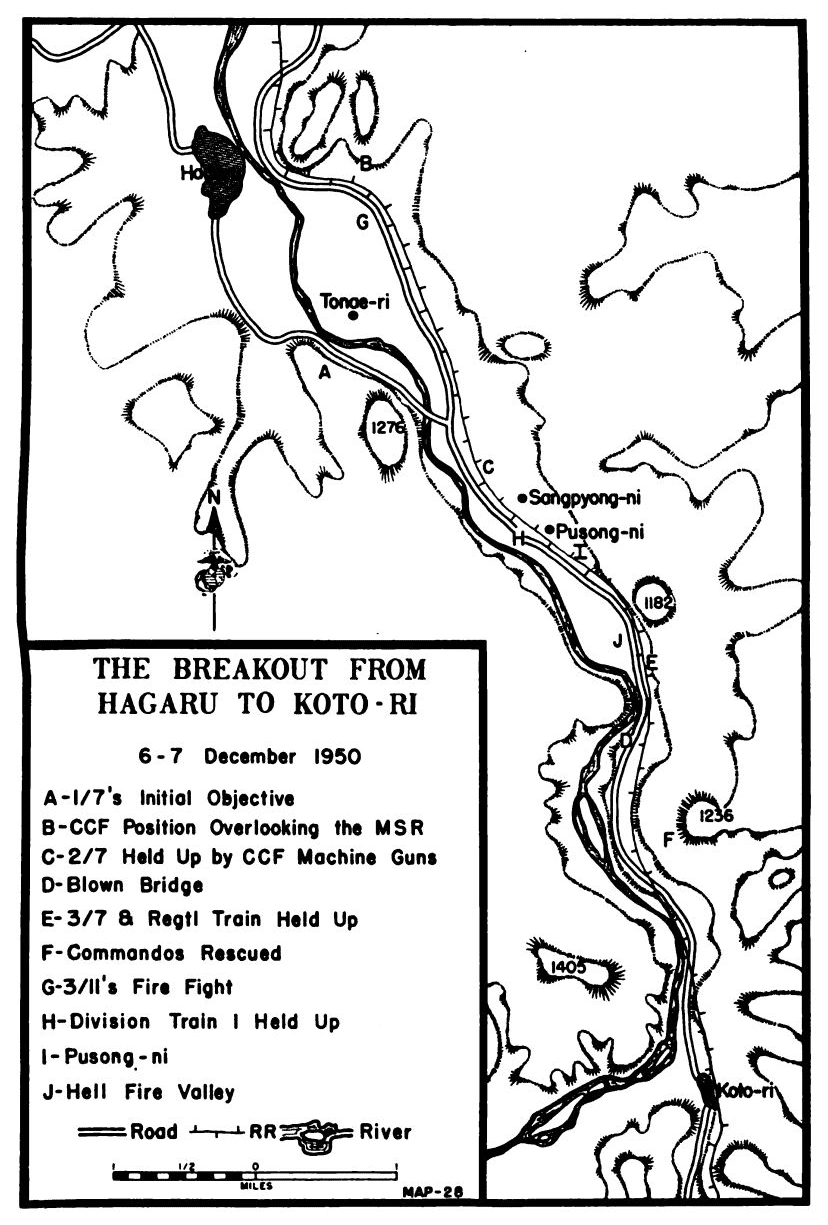

| 28 | Breakout from Hagaru to Koto-ri, 6–7 December | 295 |

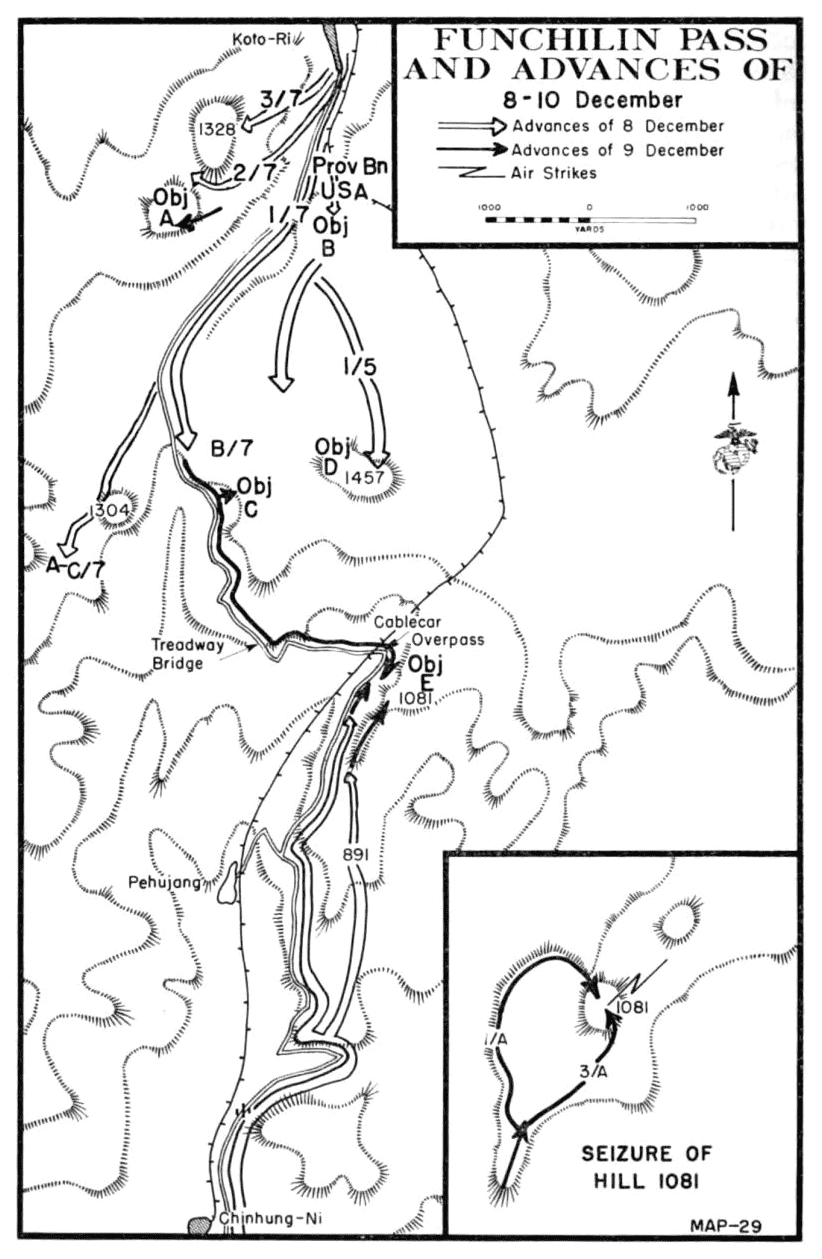

| 29 | Funchilin Pass and Advances of 8–10 December | 310 |

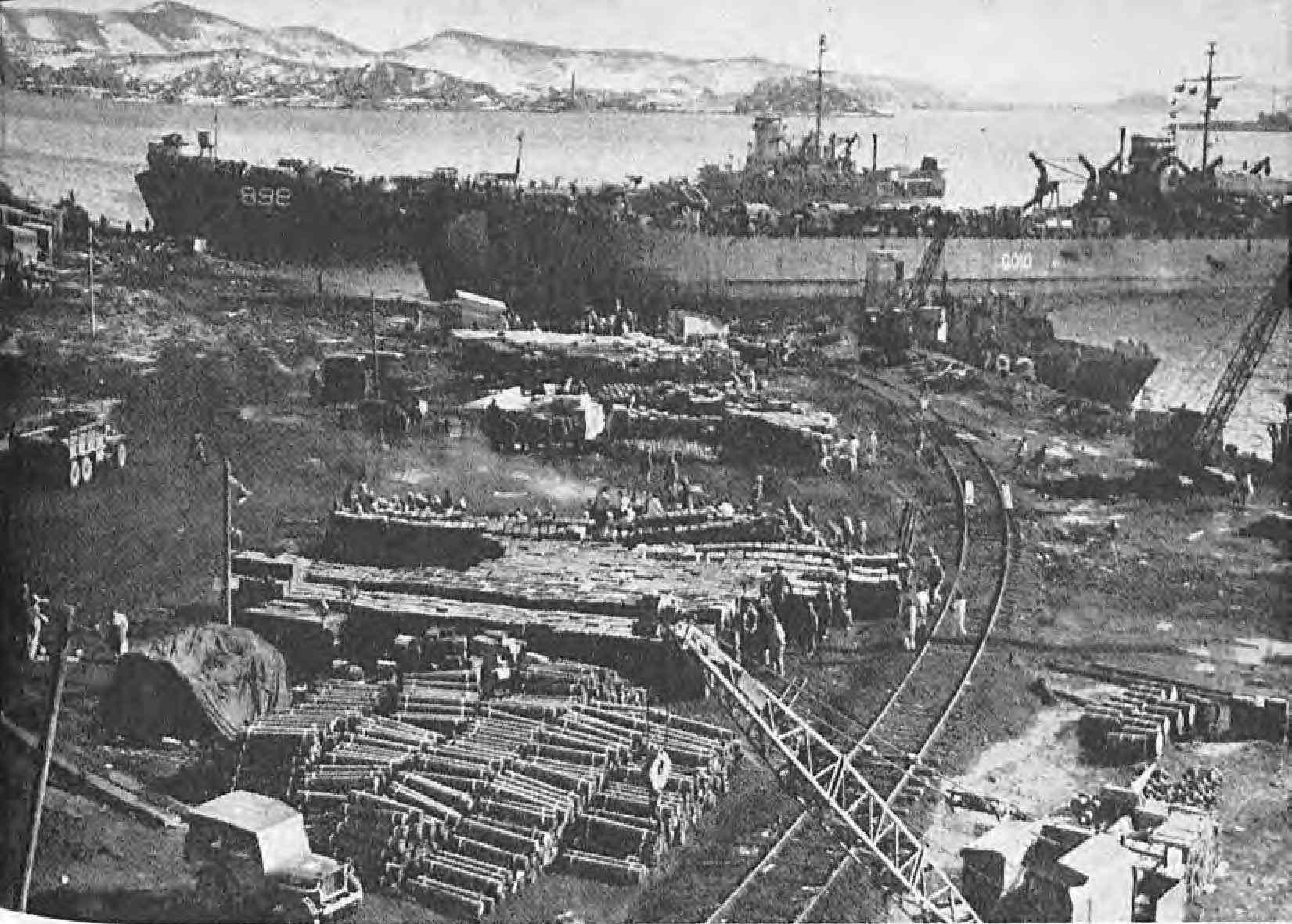

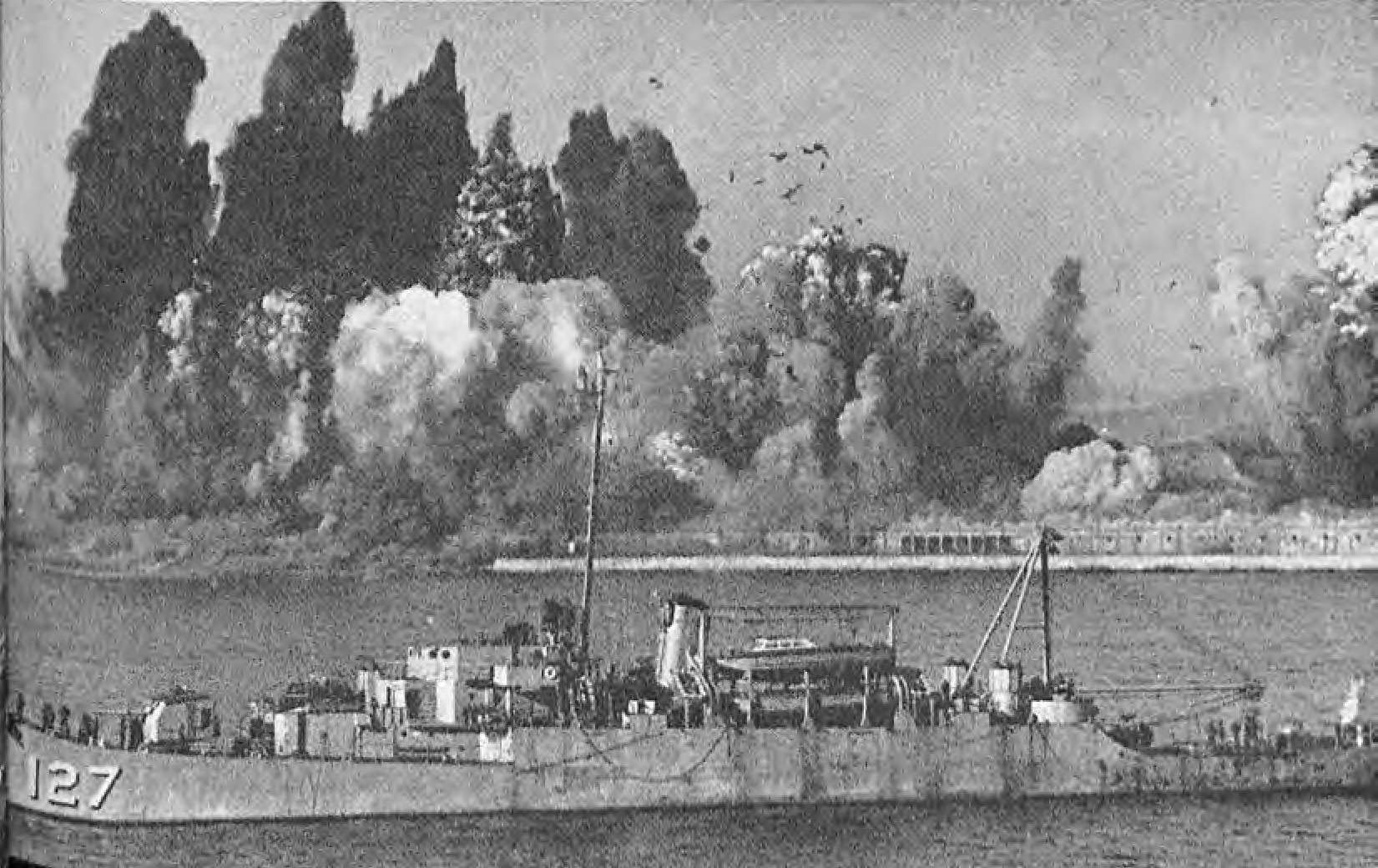

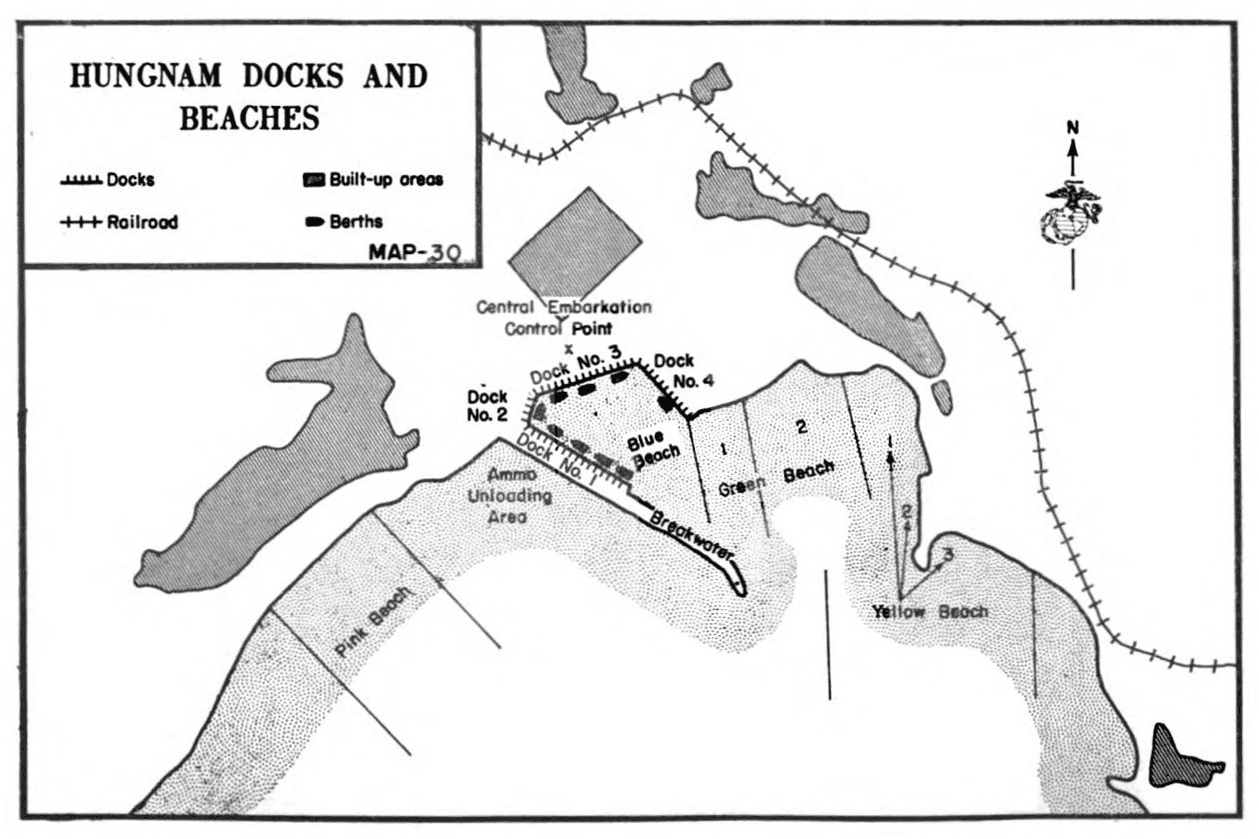

| 30 | Hungnam Docks and Beaches | 344 |

1

Decision to Cross the 38th Parallel—Surrender Message to NKPA Forces—MacArthur’s Strategy of Celerity—Logistical Problems of Advance—Naval Missions Prescribed—X Corps Relieved at Seoul—Joint Planning for Wonsan Landing

It is a lesson of history that questions of how to use a victory can be as difficult as problems of how to win one. This truism was brought home forcibly to the attention of the United Nations (UN) heads, both political and military, during the last week of September 1950. Already, with the fighting still in progress, it had become evident that the UN armies were crushing the forces of Communism in Korea, as represented by the remnants of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA).

Only a month before, such a result would have seemed a faint and unrealistic hope. Late in August the hard-pressed Eighth U. S. Army in Korea (EUSAK) was defending that southeast corner of the peninsula known as the Pusan Perimeter.

“Nothing fails like success,” runs a cynical French proverb, and the truth of this adage was demonstrated militarily when the dangerously over-extended NKPA forces paid the penalty of their tenuous supply line on 15 September 1950. That was the date of the X Corps amphibious assault at Inchon, with the 1st Marine Division as landing force spearheading the advance on Seoul.

X Corps was the strategic anvil of a combined operation as the Eighth Army jumped off next day to hammer its way out of the Pusan Perimeter and pound northward toward Seoul. When elements of the two UN forces met just south of the Republic of Korea (ROK)2 capital on 26 September, the routed NKPA remnants were left only the hope of escaping northward across the 38th parallel.1

1 The story of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade and Marine Aircraft Group 33 in the Pusan Perimeter has been told in Volume I of this series, and Volume II deals with the 1st Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing in the Inchon-Seoul operation.

The bold strategic plan leading up to this victory—one of the most decisive ever won by U. S. land, sea and air forces—was largely the concept of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, USA, who was Commander in Chief of the United Nations Command (CinCUNC) as well as U. S. Commander in Chief in the Far East (CinCFE). It was singularly appropriate, therefore, that he should have returned the political control of the battle-scarred ROK capital to President Syngman Rhee on 29 September. Marine officers who witnessed the ceremony have never forgotten the moving spectacle of the American general and the fiery Korean patriot, both past their 70th birthdays, as they stood together under the shell-shattered skylight of the Government Palace.2

2 Col C. W. Harrison, interview (interv) 22 Nov 55. Unless otherwise noted, all interviews have been by the authors.

“Where do we go from here?” would hardly have been an oversimplified summary of the questions confronting UN leaders when it became apparent that the NKPA forces were defeated. In order to appraise the situation, it is necessary to take a glance at preceding events.

As early as 19 July, the dynamic ROK leader had made it plain that he did not propose to accept the pre-invasion status quo. He served notice that his forces would unify Korea by driving to the Manchurian border. Since the Communists had violated the 38th Parallel, the aged Rhee declared, this imaginary demarcation between North and South no longer existed. He pointed out that the sole purpose of the line in the first place had been to divide Soviet and American occupation zones after World War II, in order to facilitate the Japanese surrender and pave the way for a democratic Korean government.

In May 1948, such a government had come about in South Korea by popular elections, sponsored and supervised by the UN. These elections had been scheduled for all Korea but were prohibited by3 the Russians in their zone. The Communists not only ignored the National Assembly in Seoul, but also arranged their own version of a governing body in Pyongyang two months later. The so-called North Korean People’s Republic thus became another of the Communist puppet states set up by the USSR.

That the United Nations did not recognize the North Korean state in no way altered its very real status as a politico-military fact. For obvious reasons, then, all UN decisions relating to the Communist state had to take into account the possibility of reactions by Soviet Russia and Red China, which shared Korea’s northern boundary.

At the outbreak of the conflict on 25 June 1950, the UN Security Council had, by a vote of 9-0, called for an immediate end to the fighting and the withdrawal of all NKPA forces to the 38th Parallel.3 This appeal having gone unheeded, the Council on 27 June recommended “... that the Members of the United Nations furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.”4 It was the latter authorization, supplemented by another resolution on 7 July, that led to military commitments by the United States and to the appointment of General MacArthur as over-all UN Commander.

3 US Dept of State, Guide to the UN in Korea (Washington, 1951). Yugoslavia abstained from the vote, and the USSR, then boycotting the Council, was absent.

4 Ibid.

These early UN actions constituted adequate guidance in Korea until the Inchon landing and EUSAK’s counteroffensive turned the tide. With the NKPA in full retreat, however, and UN Forces rapidly approaching the 38th Parallel, the situation demanded re-evaluation, including supplemental instructions to the military commander. The question arose as to whether the North Koreans should be allowed sanctuary beyond the parallel, possibly enabling them to reorganize for new aggression. It will be recalled that Syngman Rhee had already expressed his thoughts forcibly in this connection on 19 July; and the ROK Army translated thoughts into action on 1 October by crossing the border.

The UN, in its 7 July resolution, having authorized the United States to form a unified military force and appoint a supreme commander in Korea, it fell upon the Administration of President Harry S. Truman to translate this dictum into workaday reality. Aiding the4 Chief Executive and his Cabinet in this delicate task with its far-reaching implications were the Joint U. S. Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The Army member, General J. Lawton Collins, also functioned as Executive Agent of JCS for the United Nations Command in Korea, thus keeping intact the usual chain of command from the Army Chief of Staff to General MacArthur, who now served both the U. S. and UN.5

5 Maj J. F. Schnabel, USA, Comments on preliminary manuscript (Comments).

EIGHTH ARMY ADVANCES

AND

RESTRAINING LINES

MAP-1

Late in August, two of the Joint Chiefs, General Collins and Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, USN, had flown to Japan to discuss the forthcoming Inchon landing with General MacArthur. In the course of the talks, it was agreed that CinCUNC’s objective should be the destruction of the North Korean forces, and that ground operations should be extended beyond the 38th Parallel to achieve this goal. The agreement took the form of a recommendation, placed before Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson on 7 September.6

6 JCS memo to Secretary of Defense (SecDef), 7 Sep 50. Unless otherwise stated, copies of all messages cited are on file in Historical Branch, HQMC.

A week later, JCS informed MacArthur that President Truman had approved certain “conclusions” relating to the Korean conflict, but that these were not yet to be construed as final decisions. Among other things, the Chief Executive accepted the reasoning that UN Forces had a legal basis for engaging the NKPA north of the Parallel. MacArthur would plan operations accordingly, JCS directed, but would carry them out only after being granted explicit permission.7

7 JCS message (msg) WAR 91680, 15 Sep 50; Harry S. Truman, Memoirs, 2 vols (Garden City, 1955–1956), II, 359.

The historic authorization, based on recommendations of the National Security Council to President Truman, reached General Headquarters (GHQ), Tokyo, in a message dispatched by JCS on 27 September:

Your military objective is the destruction of the North Korean Armed Forces. In attaining this objective you are authorized to conduct military operations, including amphibious and airborne landings or ground operations north of the 38th Parallel in Korea, provided that at the time of such operations there has been no entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist Forces, no announcement of intended entry, nor a threat to counter our operations militarily in North Korea....

The lengthy message abounded in paragraphs of caution, reflecting the desire of both the UN and the United States to avoid a general war. Not discounting the possibility of intervention by Russia or Red China, JCS carefully outlined MacArthur’s courses of action for several6 theoretical situations. Moreover, he was informed that certain broad restrictions applied regardless of developments:

... under no circumstances, however, will your forces cross the Manchurian or USSR borders of Korea and, as a matter of policy, no non-Korean Ground Forces will be used in the northeast provinces bordering the Soviet Union or in the area along the Manchurian border. Furthermore, support of your operations north or south of the 38th parallel will not include Air or Naval action against Manchuria or against USSR territory....8

8 JCS msg 92801, 27 Sep 50; Truman, Memoirs, II, 360; MajGen Courtney Whitney, MacArthur, His Rendezvous with History (New York, 1956), 397. Commenting on the JCS authorization Gen MacArthur stated, “My directive from the JCS on 27 September establishing my military objective as ‘... the destruction of the North Korean Armed Forces’ and in the accomplishment thereof authorizing me to ‘... conduct military operations, including amphibious and airborne landings or ground operations north of the 38th parallel in Korea ...’ made it mandatory rather than discretionary ... that the UN Forces operate north of that line against enemy remnants situated in the north. Moreover, all plans governing operations north of that Parallel were designed to implement the resolution passed by the UN General assembly on 7 October 1950, and were specifically approved by the JCS. Indeed, the military objectives assigned by the JCS, and the military-political objectives established by said resolution of the UN could have been accomplished in no other way.” Gen D. MacArthur letter (ltr) to MajGen E. W. Snedeker, 24 Feb 56.

Thus MacArthur had the green light, although the signal was shaded by various qualifications. On 29 September, the new Secretary of Defense, George C. Marshall, told him in a message, “... We want you to feel unhampered tactically and strategically to proceed north of 38th parallel....”9

9 JCS msg 92985, 29 Sep 50. For a differing interpretation see Whitney, MacArthur, 398.

Meanwhile, a step was taken by the U. S. Government on 27 September in the hope that hostilities might end without much further loss or risk for either side. By dispatch, JCS authorized MacArthur to announce, at his discretion, a suggested surrender message to the NKPA.10 Framed by the U. S. State Department, the message was broadcast on 1 October and went as follows:

10 JCS msg 92762, 27 Sep 50.

To: The Commander-in-chief, North Korean Forces. The early and total defeat and complete destruction of your Armed Forces and war making potential is now inevitable. In order that the decision of the United Nations may be carried out with a minimum of further loss of life and destruction of property, I, as the United Nations Commander-in-Chief, call upon you and the forces under your command, in whatever part of Korea situated, forthwith to lay down your arms and cease hostilities under such military supervision7 as I may direct and I call upon you at once to liberate all United Nations prisoners of war and civilian internees under your control and to make adequate provision for their protection, care, maintenance, and immediate transportation to such places as I indicate.

North Korean forces, including prisoners of war in the hands of the United Nations Command, will continue to be given the care indicated by civilized custom and practice and permitted to return to their homes as soon as practicable.

I shall anticipate your early decision upon this opportunity to avoid the further useless shedding of blood and destruction of property.11

11 CinCUNC msg to CinC North Korean Forces, 1 Oct 59, in EUSAK War Diary (WD), 1 Oct 50, Sec II; JCS msg 92762, 27 Sep 50.

The surrender broadcast evoked no direct reply from Kim Il Sung, Premier of North Korea and Commander in Chief of the NKPA. Instead, the reaction of the Communist bloc came ominously from another quarter. Two days after MacArthur’s proclamation, Red China’s Foreign Minister Chou En-Lai informed K. M. Panikkar, the Indian Ambassador in Peiping, that China would intervene in the event UN forces crossed the 38th Parallel. He added, however, that such action would not be forthcoming if only ROK troops entered North Korea.12

12 US Ambassador, England msg to Secretary of State, 3 Oct 50; Truman, Memoirs, II, 361–362. The information was forwarded to Tokyo but MacArthur later claimed that he had never been informed of it. Military Situation in the Far East. Hearing before the Committee on Armed Services and the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate Eighty-second Congress, First Session, To Conduct an Inquiry into the Military Situation in the Far East and the facts surrounding the relief of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur from his assignments in that area (Washington, 1951, 5 vols.), (hereafter MacArthur Hearings), 109.

It will be recalled that the JCS authorization of 27 September permitted operations north of the Parallel “... provided that at the time of such operations there has been no entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist Forces, no announcement of intended entry, nor a threat to counter our operations militarily in North Korea....”13 In view of the last two provisos, MacArthur’s plans for crossing the border could conceivably have been cancelled after Chou’s announcement. But optimism over the course of the war ran high among the United Nations at this time, and CinCUNC shortly received supplemental authority from both the UN and JCS—the one establishing legal grounds for an incursion into North Korea, the other reaffirming military concurrence at the summit. In a resolution adopted on 7 October, the United Nations directed that

8

13 JCS msg 92801, 27 Sep 50; Truman, Memoirs, II, 360; Whitney, MacArthur, 397. Italics supplied.

All appropriate steps be taken to ensure conditions of stability throughout Korea and all constituent acts be taken ... for the establishment of a unified, independent and democratic Government in the Sovereign State of Korea....14

14 Resolution of 7 Oct 50 in Guide to the UN in Korea, 20.

Since the enemy had ignored his surrender ultimatum, MacArthur could attend to the UN objectives only by occupying North Korea militarily and imposing his will. JCS, therefore, on 9 October amplified its early instructions to the Commander in Chief as follows:

Hereafter, in the event of open or covert employment anywhere in Korea of major Chinese Communist units, without prior announcement, you should continue the action as long as, in your judgment, action by forces now under your control offers a reasonable chance of success. In any case you will obtain authorization from Washington prior to taking any military actions against objectives in Chinese territory.15

15 JCS msg 93709, 9 Oct 50; Truman, Memoirs, II, 362; Whitney, MacArthur, 404.

Anticipating his authority for crossing the 38th Parallel, CinCUNC on 26 September had directed his Joint Special Plans and Operations Group (JSPOG) to develop a plan for operations north of the border. He stipulated that Eighth Army should make the main effort in either the west or the east, and that however this was resolved, there should be an amphibious envelopment on the opposite coast—at Chinnampo, Wonsan, or elsewhere.16 Despite recommendations of key staff members, MacArthur did not place X Corps under EUSAK command for the forthcoming campaign but retained General Almond’s unit as a separate tactical entity under GHQ.17

16 C/S FECOM memo to JSPOG, 26 Sep 50. Copy at Office of The Chief of Military History (OCMH).

17 Maj J. F. Schnabel, The Korean Conflict: Policy, Planning, Direction. MS at OCMH. See also: Capt M. Blumenson, “MacArthur’s Divided Command,” Army, vii, no. 4 (Nov 56), 38–44, 65.

JSPOG, headed by Brigadier General Edwin K. Wright, MacArthur’s G-3, rapidly fitted an earlier staff study into the framework of CinCUNC’s directive. And the following day, 27 September, a proposed Operation Plan (OpnPlan) 9-50 was laid before the commander in chief.18 This detailed scheme of action evolved from two basic assumptions: (1) that the bulk of the NKPA had already been9 destroyed; and (2) that neither the USSR nor Red China would intervene, covertly or openly.

18 Schnabel, The Korean Conflict.

Eighth Army, according to plan, would attack across the 38th Parallel, directing its main effort in the west, along the axis Kaesong-Sariwon-Pyongyang (see Map 1). JSPOG designated the latter city—capital of the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea—as final objective of the first phase. Further, it recommended that EUSAK’s drive begin in mid-October, to be followed within a week by a X Corps amphibious landing at Wonsan on the east coast. After establishing a beachhead, Almond’s force would attack 125 road miles westward through the Pyongyang-Wonsan corridor and link up with General Walker’s army, thereby trapping North Korean elements falling back from the south.19

19 Ibid., and CinCFE OpnPlan 9-50. Copy at OCMH.

JSPOG suggested that both commands should then advance north to the line Chongju-Kunuri-Yongwon-Hamhung-Hungnam, ranging roughly from 50 to 100 miles below the Manchurian border. Only ROK elements would proceed beyond the restraining line, in keeping with the spirit and letter of the 27 September dispatch from JCS.20

20 Ibid.

Major General Doyle O. Hickey, acting as CinCUNC’s chief of staff during General Almond’s tour in the field, approved the JSPOG draft of 28 September. It thereby became OpnPlan 9-50 officially. MacArthur forwarded a summary to JCS the same day, closing his message with this reassurance:

There is no indication at present of entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist Forces.21

21 CinCFE msg C 64805, 28 Sep 50; Truman, Memoirs, II, 361; Whitney, MacArthur, 397–398.

Within three days, he received word from the Joint Chiefs that they approved his plan.22 On 2 October it became the official operation order for the attack.23

22 JCS disp 92975, 29 Sep 50; Truman, Memoirs, II, 361; Whitney, MacArthur, 398. All dates in the narrative and in footnotes are given as of the place of origin of the action. Thus, 29 September in Washington was actually the 30th in Tokyo.

23 UNC Operation Order (OpnO) 2, 2 Oct 50.

On 29 September, the day before he received the JCS endorsement of his plan, General MacArthur arrived in Seoul to officiate at the ceremony10 restoring control of South Korea to the legal ROK government. During the visit, he met with the principals named in the Task Organization of OpnPlan 9-50:

| Eighth U. S. Army | LtGen Walton H. Walker, USA |

| Naval Forces Far East | VAdm C. Turner Joy, USN |

| Far East Air Forces (FEAF) | LtGen George E. Stratemeyer, USAF |

| X Corps | MajGen Edward M. Almond, USA |

Missing from the top-level conference, Major General Walter L. Weible, USA, of the Japan Logistical Command, probably was already aware of things to come.24

24 LtGen E. A. Almond, USA, (Ret.) ltr to Col J. Meade, USA, 14 Jun 55.

MacArthur outlined his concept of operations in North Korea to those present. He set 20 October as D-Day for the Wonsan amphibious assault by the 1st Marine Division, which, with all X Corps Troops, would embark for the operation from Inchon. The 7th Infantry Division, also a part of X Corps, would motor 200 miles to Pusan and there load out for an administrative landing behind the Marines.25

25 Ibid.

Initial overland routing of the 7th Division was made necessary by problems arising out of Inchon’s limited port facilities. General MacArthur gave EUSAK the logistic responsibility for all UN Forces in Korea, including X Corps. To carry out this charge, General Walker could rely on only two harbors, Pusan and Inchon. There were no other ports in South Korea capable of supporting large-scale military operations. Meeting the tight Wonsan schedule would require that X Corps have immediate priority over the whole of Inchon’s capacity, even with the 7th Division being shunted off on Pusan. And it still remained for Walker to mount and sustain Eighth Army’s general offensive before the Wonsan landing!

In the light of logistical considerations, then, Wonsan had more than mere tactical significance as the objective of X Corps. Its seizure would open up the principal east-coast port of Korea, together with vital new road and rail junctions. But while MacArthur had decided on an amphibious assault by a separate tactical unit as the proper stroke, there existed a school of dissenters among his closest advisers. Generals Hickey and Wright had recommended that X Corps be incorporated into EUSAK at the close of the Inchon-Seoul Operation. Major General George L. Eberle, MacArthur’s G-4, held that supplying X Corps in North Korea would be simpler if that unit were a part of11 Eighth Army. And General Almond himself, while hardly a dissenter, had expected his corps to be placed under General Walker’s command after the Seoul fighting.26

26 Ibid.; Schnabel, The Korean Conflict; Blumenson, “MacArthur’s Divided Command.” Gen MacArthur stated: “If such a dissension existed it was never brought to my attention. To the contrary, the decision to retain as a function of GHQ command and coordination between Eighth Array and X Corps until such time as a juncture between the two forces had been effected was, so far as I know, based upon the unanimous thinking of the senior members of my staff....” MacArthur ltr, 24 Feb 56. Gen Wright has stated: “Neither General Hickey, General Eberle, nor I objected to the plan, but we did feel that X Corps should have been made part of the Eighth Army immediately after the close of the Inchon-Seoul operation.” MajGen E. K. Wright, USA, ltr to MajGen E. W. Snedeker, 16 Feb 56.

Logistical problems were magnified by the tight embarkation schedule laid out for the amphibious force. In submitting its proposed plan for North Korean operations to General MacArthur on 27 September, JSPOG had listed the following “bare minimum time requirements:”

| For assembling assault shipping | 6 days |

| For planning | 4 days |

| For loading | 6 days |

| For sailing to Wonsan | 4 days |

Thus it was estimated that the 1st Marine Division could assault Wonsan 10 days after receiving the order to load out of Inchon, provided that shipping had already been assembled and planning accomplished concurrently.27

27 JSPOG memo to C/S, FECOM: “Plans for future operations,” 27 Sep 50. Copy at OCMH.

Following CinCUNC’s meeting in the capitol building on the 29th, General Almond called a conference of division commanders and staff members at his X Corps Headquarters in Ascom City, near Inchon. MacArthur’s strategy was outlined to the assembled officers, so that planning could commence on the division level. Almond set 15 October as D-Day for the Wonsan landing. He based this target date on the assumption that Eighth Army would pass through and relieve X Corps on 3 October, the date on which the necessary shipping was to begin arriving at Inchon.28

28 1stMarDiv Special Action Report for the Wonsan-Hamhung-Chosin Reservoir Operation, 8 Oct-15 Dec 50 (hereafter 1stMarDiv SAR), 10.

On 29 September, the 1st Marine Division was still committed tactically above Seoul, two regiments blocking and one attacking. If the12 first vessels began arriving at Inchon on 3 October, the assault shipping would not be completely assembled until the 8th, according to the JSPOG estimate. Four days would be required to get to the objective, leaving two days, instead of the planned six, for outloading the landing force. Neither Major General Oliver P. Smith, Commanding General (CG) 1stMarDiv, nor his staff regarded this as a realistic schedule.29

29 1stMarDiv SAR, 10 and MajGen Oliver P. Smith, Notes on the Operations of the 1st Marine Division during the First Nine Months of the Korean War, 1950–51 (MS), (hereafter Smith, Notes), 370–371.

AREA OF OPERATIONS

1st Marine Division

October-December 1950

MAP-2

The Marine officers came away from the conference without knowledge of the types and numbers of ships that would be made available to the division. And since they had no maps of the objective area and no intelligence data whatever, it was manifestly impossible to lay firm plans along either administrative or tactical lines.30

30 Ibid.

Vice Admiral Joy, Commander Naval Forces Far East (ComNavFE), issued his instructions on 1 October in connection with the forthcoming operations. To Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble’s Joint Task Force 7 (JTF-7), which had carried out the Inchon attack, he gave these missions:

1. To maintain a naval blockade of Korea’s East coast south of Chongjin.

2. To furnish naval gunfire and air support to Eighth Army as directed.

3. To conduct pre-D-Day naval operations for the Wonsan landing as required.

4. To load and transport X Corps to Wonsan, providing cover and support en route.

5. To seize by amphibious assault, occupy, and defend a beachhead in the Wonsan area on D-Day.

6. To provide naval gunfire, air, and initial logistical support to X Corps at Wonsan until relieved.31

31 ComNavFE OpnPlan 113-50. Copy at OCMH.

Admiral Joy’s directive also warned: “The strong probability exists that the ports and possible landing beaches under control of the North Koreans have been recently mined. The sighting of new mines floating in the area indicates that mines are being seeded along the coast.”32

32 Ibid., B, 11.

The related events, decisions, and plans of September 1950 had unfolded with startling rapidity. Before the scattered UN forces could14 shift from one phase of operations to another, a transitional gap developed during the early days of October. Orders might flow forth in abundance, but not until MacArthur’s land, sea and air forces wound up one campaign could they begin another. Thus, from the standpoint of Marine operations, the first week of October is more a story of the Inchon-Seoul action than of preparations for the Wonsan landing.

On 2 October, when Eighth Army commenced the relief of X Corps, General Almond ordered the 7th Infantry Division to begin displacing to Pusan by motor and rail.33 There was as yet no such respite for the 1st Marine Division, which on the same day lost 16 killed in action (KIA) and 81 wounded (WIA). Practically all of the casualties were taken by the 7th Regiment, then approaching Uijongbu on the heels of the enemy.34

33 X Corps OpnO 3, 2 Oct 50.

34 MajGen Oliver P. Smith: Chronicle of the Operations of the 1st Marine Division During the First Nine Months of the Korean War, 1950–1951 (MS), (hereafter, Smith, Chronicle), 54.

Despite the limited planning data in the hands of the 1st Marine Division, General Smith’s staff put a cautious foot forward on 3 October.35 Word of the pending Wonsan operation went out by message to all subordinate units, with a tentative task organization indicating the formation of three Regimental Combat Teams (RCTs).

35 Gen Wright stated, “There was definitely not a complete lack of planning data. I doubt if any operation ever had more planning data available. It may not have been in General Smith’s hands on 3 October, but it was available.” Wright ltr, 16 Feb 56.

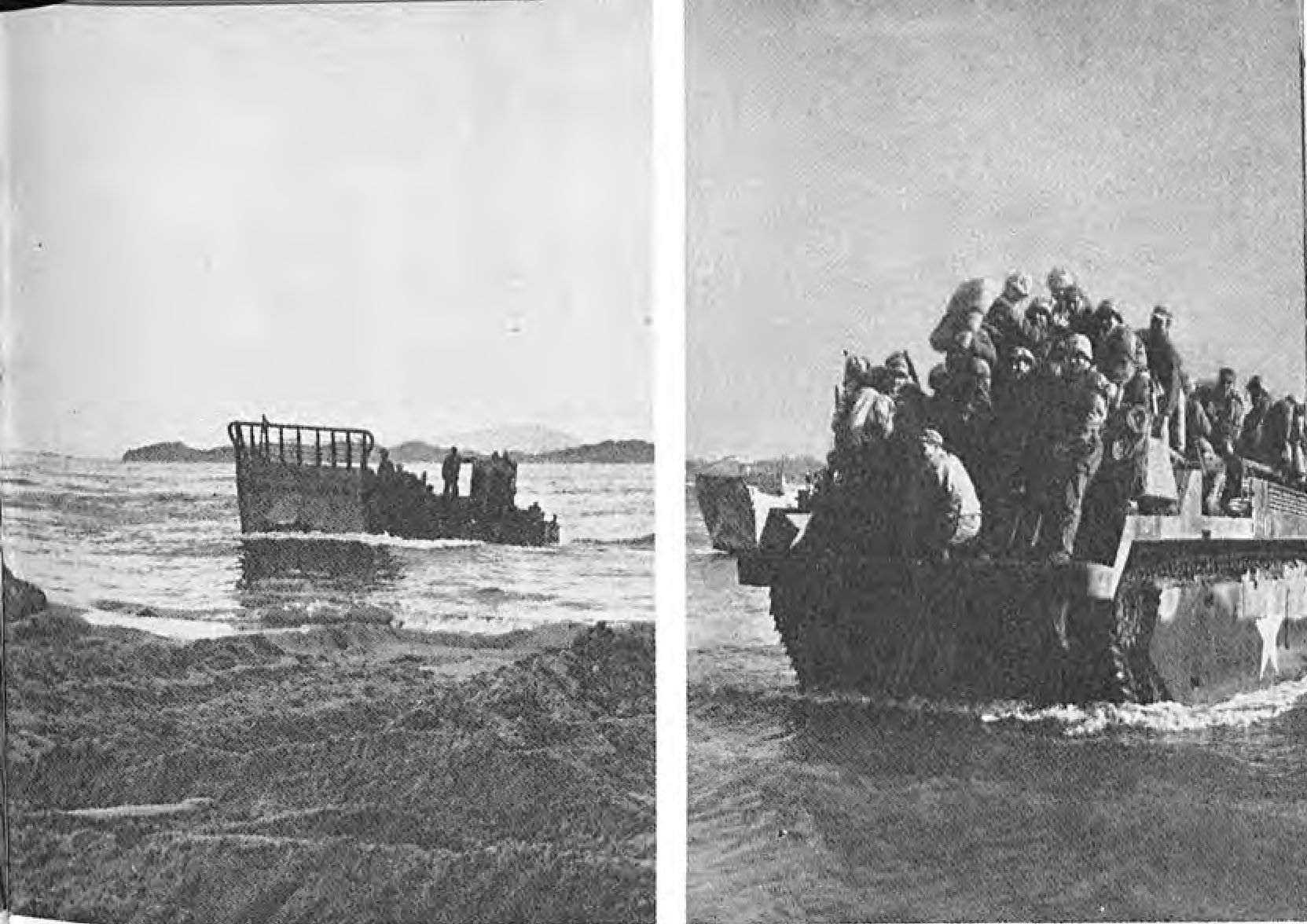

The 1st and 7th Marines were earmarked to launch the amphibious attack. Each would plan on the basis of employing two battalions in the assault. These battalions were to embark on LSTs and hit the beach in LVTs. All tactical units were to combat-load out of Inchon. And although still uninformed as to available shipping, the Marine planners named likely embarkation groups and listed tentative arrangements for loading tanks and amphibious vehicles.36

36 CG 1stMarDiv msg to Subordinate Units: “Planning Information,” 3 Oct 50.

The following day saw the publication of X Corps OpnO 4, specifying subordinate unit missions. The 7th Infantry Division, together with the 92d and 96th Field Artillery (FA) Battalions, was instructed to mount out of Pusan and to land at Wonsan on order (see Map 2). These tasks were assigned to the 1st Marine Division:

1. Report immediately to the Attack Force Commander (Commander, Amphibious Group One) of the Seventh Fleet as the landing force for the Wonsan attack.

152. Seize and secure X Corps base of operations at Wonsan, protect the Wonsan Airfield, and continue such operations ashore as assigned.

3. Furnish logistic support for all forces ashore until relieved by Corps Shore Party.37

37 Special Report 1stMarDiv, in CinCPacFlt Interim Evaluation Rpt #1, annex DD, 11; 1stMarDiv Historical Diary (HD), Oct 50; X Corps OpnO 4, 4 Oct 50.

As Almond’s order went out for distribution on 4 October, EUSAK’s 1st Cavalry Division, bound for Kaesong, passed through the 5th Marines northwest of Seoul. Simultaneously, the II ROK Corps began assembling along the road to Uijongbu, captured by the 7th Marines the previous day.38

38 Smith, Chronicle, 54.

After 20 days in the line, the weary battalions of the 5th Marines retired on 5 October across the Han River to an assembly area at Inchon. They were followed on the 6th by the 1st Regiment, and on the next day by the 7th Marines. The withdrawal of the latter unit completed the relief of X Corps, and General Almond’s command officially reverted to GHQ Reserve.39

39 Ibid., 55.

October 7th also marked the displacement of the 1st Marine Division command post (CP) to Inchon, where planning and reality had finally merged to the extent that preparations for Wonsan could begin in earnest. Two days earlier, Vice Admiral Struble had re-created JTF-7 out of his Seventh Fleet; and by publication of his OpnO 16-50 on the same date, 5 October, he set in motion the operational elements involved in the projected amphibious envelopment. His new task organization, almost identical to that which had carried out the Inchon Operation with historic dispatch, was as follows:

| TF 95 (Advance Force) | RAdm Allen E. Smith |

| TG 95.2 (Covering & Support) | RAdm Charles C. Hartman |

| TG 95.6 (Minesweeping) | Capt Richard T. Spofford |

| TF 90 (Attack Force) | RAdm James H. Doyle |

| TF 79 (Logistical Support Force) | Capt Bernard L. Austin |

| TF 77 (Fast Carrier Force) | RAdm Edward C. Ewen |

| TG 96.8 (Escort Carrier Group) | RAdm Richard W. Ruble |

| TG 96.2 (Patrol & Reconnaissance) | RAdm George R. Henderson |

| TG 70.1 (Flagship Group) | Capt Irving T. Duke |

Struble, who had directed the Inchon assault from the bridge of the USS Rochester, would now fly his flag in the recently arrived USS Missouri, the sole American battleship in commission at this early stage of the Korean war.40

16

40 ComSeventhFlt OpnO 16-50, 5 Oct 50.

WONSAN AND HARBOR

MAP-3

17

The Seventh Fleet directive of 5 October dispatched both the Fast Carrier and the Patrol and Reconnaissance Forces of JTF-7 on the usual search and attack missions preliminary to an amphibious assault. Task Force 77, consisting of the carriers Boxer, Leyte, Philippine Sea and Valley Forge, escorted by a light cruiser and 24 destroyers, was under orders to direct 50 per cent of the preparatory air effort against the local defenses of Wonsan. Simultaneously, the Advance Force, with its cruisers, destroyers and mine sweeping units, would close in to shell the target and wrest control of the offshore waters from the enemy.41

41 Ibid.

Topographic and hydrographic studies made available to the Attack and Landing Forces showed Wonsan to be a far more accessible target than Inchon (see Map 3). Nestling in the southwestern corner of Yonghung Bay, 80 miles above the 38th Parallel, the seaport offers one of the best natural harbors in Korea. A vast anchorage lies sheltered in the lee of Kalma Peninsula which, finger-like, juts northward from a bend in the coastline. Tides range from seven to 14 inches, fog is rare, and currents are weak. Docks can accommodate vessels drawing from 12 to 25 feet, and depths in the bay run from 10 fathoms in the outer anchorage to 15 feet just offshore.42

42 The description of Wonsan is based upon: GHQ, FECOM, Military Intelligence Section, General Staff, Theater Intelligence Division, Geographic Branch, Terrain Study No. 6, Northern Korea, sec v, 13–16; 1stMarDiv OpnO 15-50, annex B, sec 2, 1, 3, 10 Oct 50; and 1stMarDiv SAR, annex B (hereafter G-2 SAR), sec 2, 1.

Beaches around Wonsan are of moderate gradient, and the floor at water’s edge consists of hard-packed sand. Though slightly wet landings might be expected, amphibious craft could easily negotiate any of the several desirable approaches. The coastal plain, ranging from 100 yards to two miles in depth, provides an acceptable lodgment area, but the seaward wall of the Taebaek mountain range renders inland egress difficult from the military standpoint.

In 1940, the population of Wonsan included 69,115 Koreans and 10,205 Japanese, the latter subsequently being repatriated to their homeland after World War II. Under the Japanese program of industrialization, the city had become Korea’s petroleum refining center. The construction of port facilities, railways, and roads kept pace with the appearance of cracking plants, supporting industries, and huge storage areas.

18

Two airfields served the locale in 1950. One of these, situated on the coast about five miles north of the seaport, was of minor importance. The other, known as Wonsan Airfield, on Kalma Peninsula across the harbor, ranked high as a military prize. Spacious and accessible, it was an excellent base from which to project air coverage over all of Korea and the Sea of Japan. The Japanese first developed the field as an air adjunct to the naval base at Wonsan; but after World War II, a North Korean aviation unit moved in and used it until July 1950. Thereafter, with the skies dominated by the UN air arm, Wonsan Airfield temporarily lost all military significance. Its vacant runways, barracks, and dispersal areas were given only passing attention in the UN strategic bombing pattern, although the nearby industrial complex was demolished.

In addition to being situated on an excellent harbor, Wonsan is the eastern terminus of the Seoul-Wonsan corridor, the best of the few natural routes across the mountainous nation. This 115-mile road and rail passageway, once considered as a possible overland approach for X Corps, separates the northern and southern divisions of the Taebaek range, which rises precipitously from Korea’s east coast to heights of 5000 feet. Railroads and highways, primitive by western standards, also trace the seaward base of the Taebaek Mountains to connect Wonsan with Hamhung in the north and Pusan far to the south. Still another road and railway leads to Pyongyang, 100 miles across the narrow neck of the peninsula in the western piedmont.

The climate along Korea’s northeast coast is comparable to that of the lower Great Lakes region in the United States. Mean summer temperatures range between 80 and 88 degrees, although highs of 103 degrees have been recorded. Winter readings drop as low as -7 degrees, but the season is usually temperate with winds of low velocity. Despite light snowfalls and moderate icing, the period from October through March is best suited to military operations, for the heavy rains of spring and summer create difficulties on the gravel-topped roads.

Although members of Admiral Doyle’s Amphibious Group One (PhibGruOne) staff met with planners of the 1st Marine Division at Inchon early in October, it soon became apparent that the projected D-Day of 15 October could not be realized. Maps and intelligence data necessary for planning did not reach the Attack Force-Landing Force team until 6 October. The relief of X Corps by EUSAK was completed, not on 3 October as General Almond had anticipated, but on the 7th.19 Moreover, the first transport vessels to reach Inchon ran behind schedule, and they had not been pre-loaded with a ten-day level of Class I, II, and V supplies, as was promised. Planning and outloading consequently started late and from scratch, with the result that D-Day “... was moved progressively back to a tentative date of 20 October.”43

21

43 1stMarDiv SAR, 10. The classes of supply are as follows: I, rations; II, supplies and equipment, such as normal clothing, weapons, vehicles, radios etc, for which specific allowances have been established; III, petroleum products, gasoline, oil and lubricants (POL); IV, special supplies and equipment, such as fortification and construction materials, cold weather clothing, etc, for which specific allowances have not been established; V, ammunition, pyrotechnics, explosives, etc.

ROK Army Captures Wonsan—Marine Loading and Embarkation—Two Weeks of Mine Sweeping—Operation Yo-Yo—Marine Air First at Objective—MacArthur Orders Advance to Border—Landing of 1st Marine Division

On 6 October 1950, after the arrival of the initial assault shipping at Inchon, General Smith ordered the 1st Marine Division to commence embarkation on the 8th. Similar instructions were issued by X Corps the following day.44 Thus, the first troops and equipment were to be loaded even before the G-2 Section of the Landing Force could begin evaluating the enemy situation at the objective, since it was not until 8 October that the intelligence planners received X Corps’ OpnO 4, published four days earlier. Summing up the outlook at the time, G-2 later reported:

44 1stMarDiv Embarkation Order (EmbO) 2-50, 6 Oct 50; Smith, Notes, 394.

Inasmuch as subordinate units of the Division were scheduled to embark aboard ship some time prior to 15 October 1950, it was immediately obvious that preliminary intelligence planning, with its attendant problems of collection, processing, and distribution of information, and the procurement and distribution of graphic aids, would be both limited and sketchy.... Fortunately ... the section [G-2] had been previously alerted on the projected operation, and while elements of the Division were yet engaged with the enemy at Uijongbu, had requested reproductions of some 100 copies of pertinent extracts of the JANIS (75) of Korea. Thus it was ... that subordinate units would not be wholly unprepared for the coming operation.45

45 G-2 SAR, 2. JANIS is the abbreviation for Joint Army-Navy Intelligence Studies.

General Smith’s OpnO 16-50, published on 10 October, climaxed the accelerated planning at Inchon. Worked out jointly by the staffs of PhibGruOne and the 1st Marine Division, this directive covered the Wonsan attack in detail and pinpointed subordinate unit responsibilities.

22

Kalma Peninsula was chosen as the point of assault, with two beaches, YELLOW and BLUE, marked off on the eastern shore. Ten high-ground objectives described the semicircular arc of the beachhead, which focused on Wonsan and fanned out as far as five miles inland. The 1st and 7th Marines were to hit YELLOW and BLUE Beaches, respectively and drive inland to their assigned objectives. The 5th, upon being ordered ashore, would assemble west of Wonsan, prepared for further operations. Two battalions of the 11th Marines were to land on call in direct support of the assault units, and the remainder of the artillery would initially function in general support.

Other subordinate units drew the usual assignments. The Reconnaissance Company, after landing on order, was to screen the Division’s left flank by occupying specified objectives. Attached to the 1st and 7th Regiments respectively, the 5th and 3d Korean Marine Corps (KMC) Battalions would also go ashore on call.46

46 1stMarDiv OpnO 16-50, 10 Oct 50.

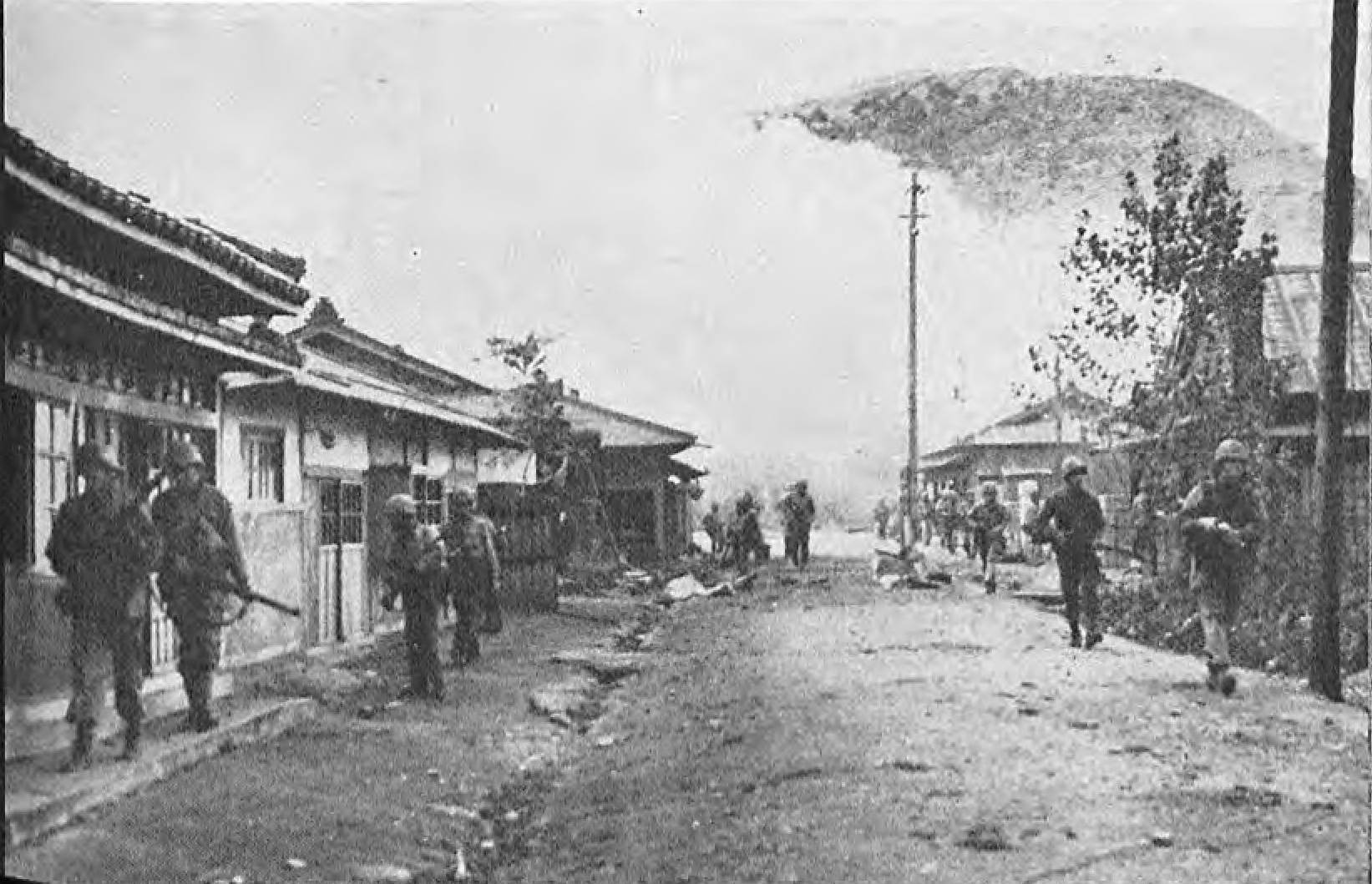

At 0815, 10 October, coincidentally with the publication of 1stMarDiv OpnO 16-50, troops of I ROK Corps, advancing rapidly up the east coast of Korea, entered Wonsan. By evening of the next day, the ROK 3d and Capital Divisions were mopping up minor resistance in the city and guarding the airfield on Kalma Peninsula.47

47 EUSAK War Diary Summary (WD Sum), Oct 50, 14–16.

Overland seizure of the 1st Marine Division’s amphibious objective did not come as a surprise either at GHQ in Tokyo or at General Smith’s CP aboard the Mount McKinley in Inchon Harbor. General MacArthur had, in fact, prepared for this eventuality by considering an alternate assault landing at Hungnam, another major seaport, about 50 air miles north of Wonsan. On 8 October, therefore, the JSPOG completed a modified version of CinCFE OpnPlan 9-50. Eighth Army’s mission—the capture of Pyongyang—remained unchanged in this draft, but X Corps would now land “... in the vicinity of Hungnam in order to cut the lines of communications north of Wonsan and envelop the North Korean forces in that area.”

Although the choice of a new objective seemed logical on the basis of the ROK Army’s accomplishment, certain logistical obstacles at23 once loomed in the path of the alternate plan. Not unaware of the most imposing of these, JSPOG commented:

The harbor at Wonsan cannot accommodate at docks the large vessels lifting the 7th Division. Since most of the amphibious type boats are carried on ships lifting the 1st Marine Division, the plans for off-loading the 7th Division will have to be revised.48

48 CinCFE OpnPlan 9-50 (Alternate), 8 Oct 50.

But the plans for off-loading the 7th Division could not be revised. If the Army unit was to land within a reasonable length of time, it would have to go in on the heels of the 1st Marine Division, using the same landing craft. If the ship-to-shore movement took place at Hungnam, the 7th Division would be ill-disposed for beginning its overland drive to Pyongyang as planned; for it would have to backtrack by land almost all the way to Wonsan. On the other hand, if the Army division landed at Wonsan while the Marines assaulted Hungnam, the Navy would be handicapped not only by the lack of landing craft but also by the problem of sweeping mines from both harbors simultaneously.

From the standpoint of Admiral Joy in Japan and Admiral Doyle in Korea, there was insufficient time for planning a new tactical deployment of X Corps at this late date. And the time-space handicap would be compounded by serious shortages of mine sweepers and intelligence information. Joy was unsuccessful on 8 October in his first attempt to dissuade MacArthur from the new idea. On the 9th, unofficial word of the pending change reached General Smith at Inchon, just as his staff wound up work on the draft for the Wonsan assault. ComNavFE persisted in his arguments with the commander in chief, however, with the final result that on 10 October the original plan for landing the whole X Corps at Wonsan was ordered into effect.49 Coming events were to uphold the Navy viewpoint; for while the Wonsan landing itself was delayed several days by enemy mines, it was 15 November before the first ships safely entered the harbor at Hungnam.50

49 C/S Notes in X Corps WD 10–25 Oct 50; ComPhibGruOne, “Report of ... Operations ... 25 Jun 50 to 1 Jan 51,” 11; Smith, Chronicle, 57–59; and Capt Walter Karig, et al, Battle Report: The War In Korea (New York, 1952), 301–302. According to Gen Wright, MacArthur’s G-3, “Admiral Joy may have ‘discussed’ this often with the Commander-in-Chief, but no one ever ‘argued’ with him.” Wright ltr 16 Feb 56.

50 ComNavFE msg to CinCFE, 0010 12 Nov 50.

On 11 October, the day after he opened his CP on the Mount McKinley, General Smith learned that the Hungnam plan had been dropped. The24 1st Marine Division continued loading out in accordance with X Corps OpnO 4, even though its objective had already been captured.51

51 Smith, Chronicle, 59.

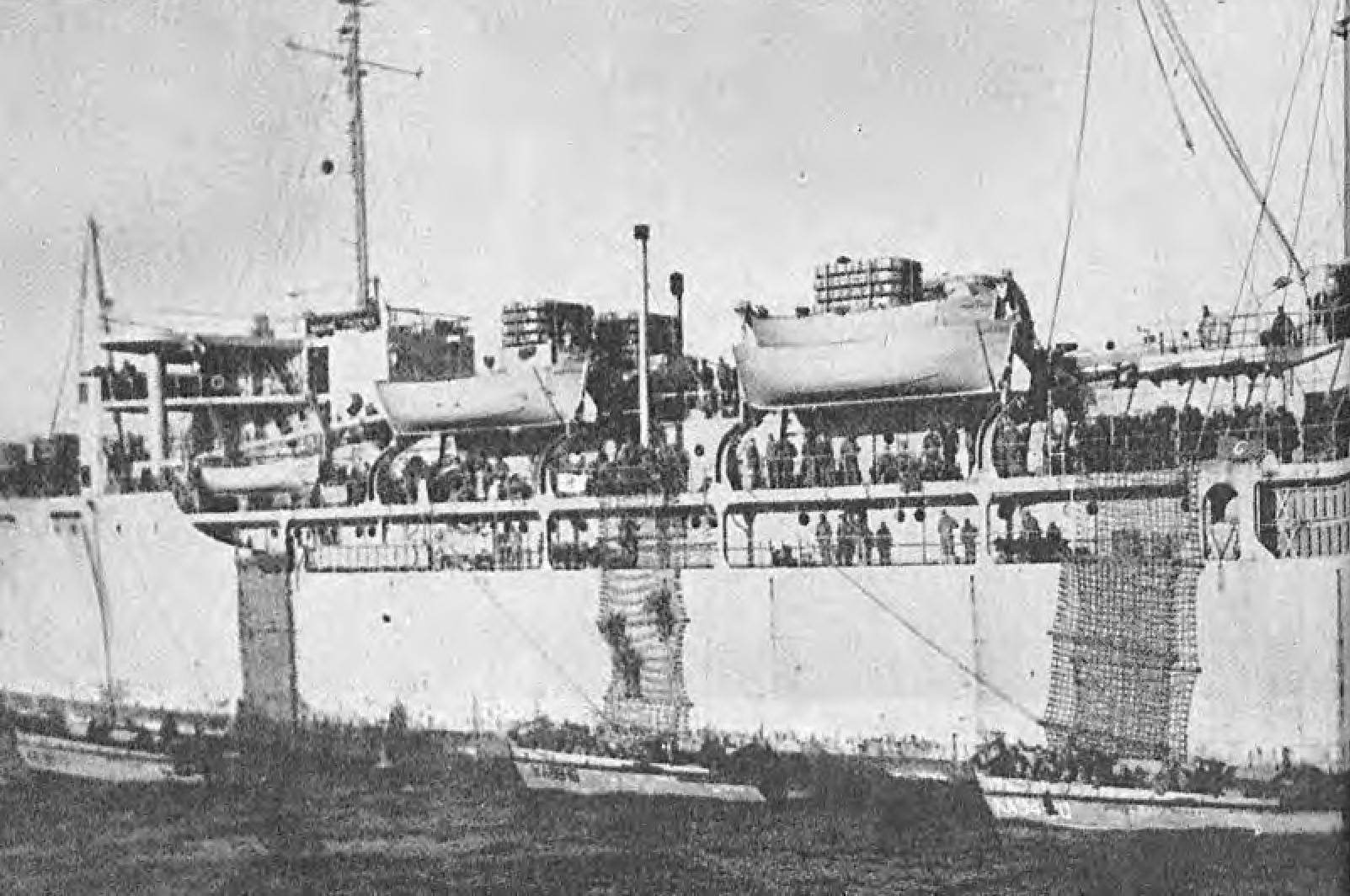

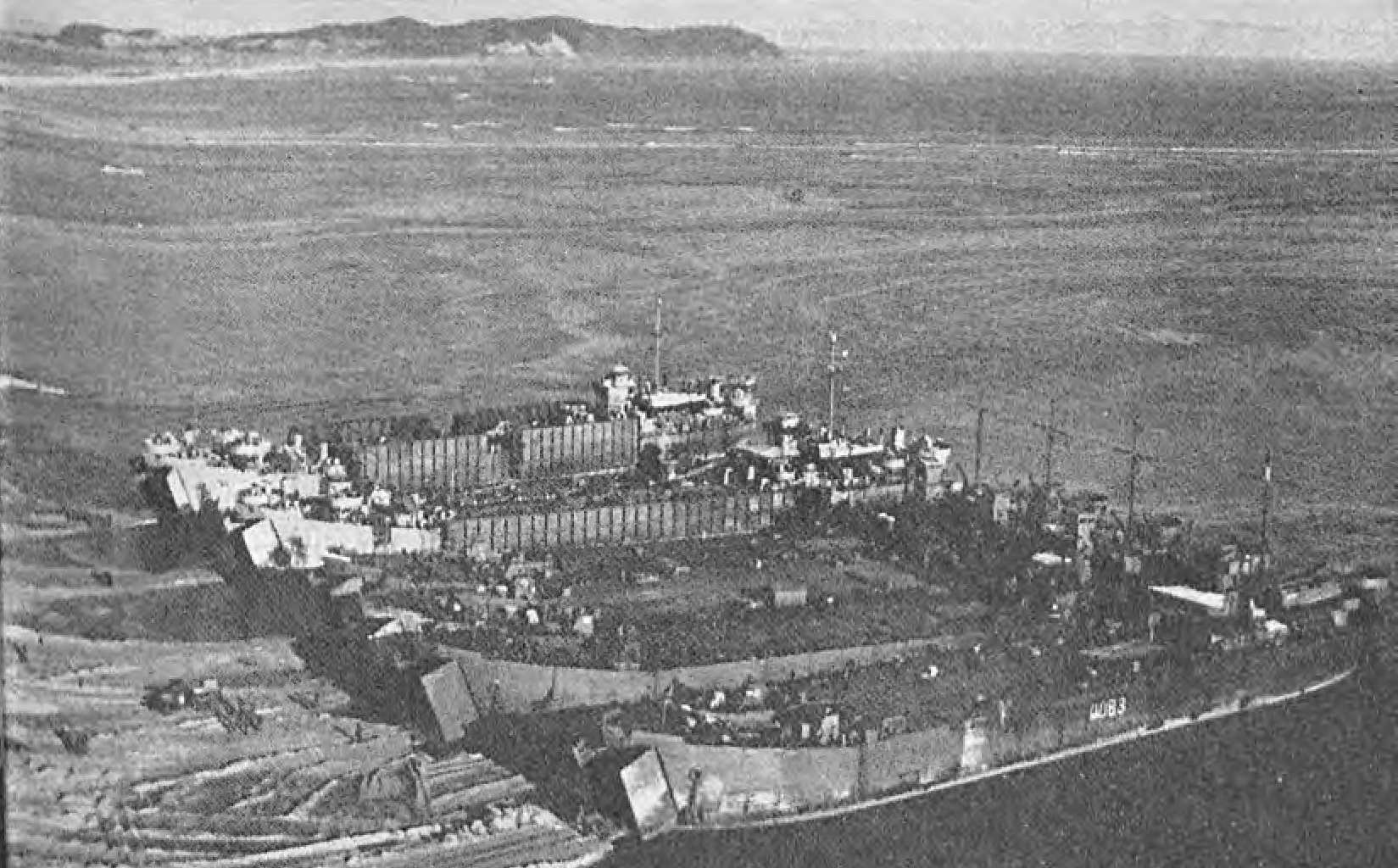

During the period 4–10 October, Admiral Doyle had assembled at Inchon an assortment of Navy amphibious vessels, ships of the Military Sea Transport Service (MSTS), and Japanese-manned LSTs (SCAJAP).52 With the arrival of Transport Squadron One on 8 October, the total shipping assigned to the landing force consisted of one AGC, eight APAs, two APs, 10 AKAs, five LSDs, 36 LSTs, three LSUs, one LSM, and six commercial cargo vessels (“Victory” and C-2 types).53

52 ComPhibGruOne “Operations Report,” 10. SCAJAP is the abbreviation for Shipping Control Authority, Japan. Under this designation were American ships lent to Japan after World War II, of which many were recalled during the Korean War to serve as cargo vessels.

53 1stMarDiv SAR, annex D (hereafter G-4 SAR), 2.

Loading a reinforced division, several thousand Corps troops and thousands of tons of supplies and equipment proved to be an aggravating job under the circumstances. Pressure on the attack and landing forces for an early D-Day only magnified the shortcomings of Inchon as a port. Limited facilities and unusual tide conditions held dock activity to a series of feverish bursts. Moreover, many ships not part of the amphibious force had to be accommodated since they were delivering vital materiel. The assigned shipping itself was inadequate, according to the Division G-4 and “considerable quantities” of vehicles had to be left behind. Much of the trucking that could be taken was temporarily diverted to help transport the 7th Infantry Division to Pusan; and although unavailable for port operations when needed, it returned at the last minute to disrupt outloading of the Shore Party’s heavy beach equipment.54 Out of conditions and developments such as these grew the necessity for postponing D-Day from 15 October, the date initially set by General Almond, to the 20th.

54 Ibid., 3.

For purposes of expediting embarkation and economizing on shipping space, X Corps directed the 1st Marine Division to out-load with less than the usual amount of supplies carried by a landing force.55 Resupply shipping would be so scheduled as to deliver adequate stocks of Class I, II, III, and IV consumables “... prior to the time they25 would be needed,” even though when “they would be needed” was anybody’s guess at this stage of the war.56

55 These totals were authorized: C-Rations for five days; individual assault rations for one day; POL for five days; Class II and IV supplies for 15 days; and five units of fire (U/F). Ibid.; 1stMarDiv Administrative Order (AdmO) 13-50, 8 Oct 50. A unit of fire is a convenient yardstick in describing large quantities of ammunition. It is based on a specific number of rounds per weapon.

56 G-4 SAR, 1.

In anticipation of a rapid advance to the west (which did not materialize), Division G-4 not only assigned 16 pre-loaded trucks and trailers to each RCT, but also earmarked three truck companies and 16 more trailers as a mobile logistical reserve. These supply trains would stay on the heels of the attacking regiments in order to maintain ammunition dumps as far forward as possible in a fast-moving situation.57

57 Ibid., 3.

On 8 October, ComNavFE directed Admiral Doyle and General Smith to effect his OpnPlan 113-50.58 Coincidentally, the first contingents of the 5th Marines boarded the Bayfield (1/5), George Clymer (2/5), and Bexar (3/5). Three days later, on the 11th, Lieutenant Colonel Raymond L. Murray, commander of the reserve regiment, opened his CP in the Bayfield, and his unit completed embarkation.59

58 ComNavFE msg to ComPhibGruOne, CG 1stMarDiv and others, 0200 8 Oct 50.

59 5thMar msg to CG 1stMarDiv, 1035 11 Oct 50; 1stMarDiv SAR, annex QQ, appendix A (hereafter 1/5 SAR), 4, appendix B (hereafter 2/5 SAR), 6, and appendix C (hereafter 3/5 SAR), 4.

Although reserve and administrative elements of the 1st and 7th Marines loaded earlier, the four assault battalions of these regiments could not begin embarkation until 13 October, owing to the fact that the LSTs had been used for shuttle service around Inchon Harbor. General Smith opened his CP in the Mount McKinley at 1200 on the 11th.60 The last of the landing ships were loaded by high tide on the morning of the 15th, and later that day all of them sailed for the objective. By evening of the 16th, most of the transports were on the way, but the Mount McKinley and Bayfield did not depart until the next day.61

60 CG 1stMarDiv msg to All Units, 0752 11 Oct 50; Smith, Notes, 373.

61 1stMarDiv SAR, annex RR (hereafter 7thMar SAR), 9; Smith, Notes, 399, 409; 1stMar HD Oct 50, 3.

Broken down into seven embarkation groups, the landing force and X Corps troops leaving Inchon comprised a grand total of 1902 officers and 28,287 men. Of this number, 1461 officers and 23,938 men were on the rolls of the 1st Marine Division, the breakdown being as follows:

| Marine officers | 1119 |

| Marine enlisted | 20,597 |

| Navy officers | 153 |

| Navy enlisted | 1002 |

| U. S. Army & KMC officers attached | 189 |

| U. S. Army & KMC enlisted attached | 233962 |

62 1stMarDiv Embarkation Summary, 16 Oct 50; and “Special Report 1stMarDiv,” 12.

26

Even in the last stages of loading and during the actual departure, new orders had continued to flow out of higher headquarters. It will be recalled that General Smith issued his OpnO 16-50 for the Wonsan assault on 10 October. An alternate plan, to be executed on signal, went out to subordinate units the same day, providing for an administrative landing by the Division on RED Beach, north of Wonsan, instead of Kalma Peninsula.63

63 1stMarDiv OpnO 17-50, 10 Oct 50.

As a result of discussions during a X Corps staff conference on 13 October, a party headed by General Almond flew to Wonsan the next day.64 The purpose of his visit was to reconnoiter the objective and to explain his latest operational directive to the I ROK Corps commander, who would come under his control.65 This new order, published on the 14th, called for an administrative landing by X Corps and a rapid advance westward along the Wonsan—Pyongyang axis to a juncture with EUSAK. Assigned to the 1st Marine Division was an objective northeast of Pyongyang, the Red capital.66

64 “... Division [1stMarDiv] Advance Parties were flown to Wonsan in accordance with a definite plan which materialized just before we set sail from Inchon. As a matter of fact the personnel for these parties and even some of the jeeps were already loaded out and had to be removed from the shipping prior to our sailing.” Col A. L. Bowser, Comments, n. d.

65 CG’s Diary Extracts in X Corps WD, 10–25 Oct 50; Smith, Chronicle, 59.

66 X Corps Operation Instruction (OI) 11, 14 Oct 50; Smith, Notes, 385.

It was this tactical scheme, then, that prevailed as the Marines departed Inchon from 15 to 17 October and the 7th Infantry Division prepared to embark from Pusan. General Smith, of course, placed into effect his alternate order for a landing on RED Beach.67 While there may be a note of humor in the fact that on 15 October ComPhibGruOne issued his OpnO 16-50 for the “assault landing” at Wonsan, it must be remembered that the ship-to-shore movement would remain essentially the same from the Navy’s standpoint, regardless of the swift march of events ashore.

27

67 According to General Smith, “The reason for issuing 1stMarDiv OpnO 17-50 was to provide for an administrative landing in sheltered waters just north of Wonsan where there would be easy access to the existing road net. The ship-to-shore movement provided for in 1stMarDiv OpnO 16-50 was retained intact. This plan [OpnO 17-50] had to be dropped when it was found that Wonsan Harbor was completely blocked by mines, and that it would be much quicker to clear the approaches to the Kalma Peninsula where we eventually landed ... 1stMarDiv dispatch [1450 24 Oct] cancelled both 1stMarDiv OpnOs 16 and 17 and provided for an administrative landing on the Kalma Peninsula as directed by CTF 90.” Gen O. P. Smith ltr to authors, 3 Feb 56. Hereafter, unless otherwise stated, letters may be assumed to be to the authors.

Mine sweeping for the Wonsan landing commenced on 8 October, when Task Group 95.6, commanded by Captain Spofford, began assembling for the mission of clearing a path ahead of the 250-ship armada bringing the 1st Marine Division and other units of X Corps. It had been known for a month that the waters of the east coast were dangerous for navigation. The first mine was discovered off Chinnampo on the west coast on 7 September, and four days later Admiral Joy ordered the United Nations Blocking and Escort Force to stay on the safe side of the 100-fathom line along the east coast. But it was not until 26 and 28 September that more definite information was acquired the hard way when the U. S. destroyer Brush and the ROK mine sweeper YMS 905 were damaged by east coast mines.68

68 CinCPacFlt Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, VI, 1090.

On the 28th ComNavFE issued his OpnO 17-50 covering operations of mine sweepers in Korean waters. The herculean task awaiting the 12 available American vessels of this type may be judged by the fact that more than a hundred had been employed off Okinawa in World War II.

Although the exact date remained unknown, it was a safe assumption that North Korean mining activities, beginning in late July or early August, were speeded by the Inchon landing, which aroused the enemy to the peril of further amphibious operations. Russian instructors had trained Korean Reds at Wonsan and Chinnampo in the employment of Soviet-manufactured mines. Sampans, junks, and wooden coastal barges were used to sow a field of about 2000 in the harbor and approaches to Wonsan.69

69 Ibid., VI, 1088–1089; Smith, Notes, 404; Karig, Korea, 301. See also ADVATIS Rpt 1225 in EUSAK WD, 24 Oct 50.

Captain Spofford’s TG 95.6 commenced its sweep off Wonsan on 10 October after a sortie from Sasebo. Unfortunately, the three large fleet sweepers, Pledge, Pirate, and Incredible, were not well adapted to the shallow sweeping necessary at Wonsan. More dependence could be placed in the seven small wooden-hulled U. S. motor mine sweepers Redhead, Mocking Bird, Osprey, Chatterer, Merganser, Kite, and Partridge, which were rugged even though low-powered. Spofford’s two big high-speed sweepers, Doyle and Endicott, had their limitations for28 this type of operation; and the nine Japanese and three ROK sweepers lacked some of the essential gear.70

70 CinCPacFlt Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, VI, 1004; Dept Army, Joint Daily Situation Report (D/A Daily SitRpt) 105; Karig, Korea, 311–314.

The U. S. destroyers Collett, Swenson, Maddox, and Thomas were in the Wonsan area as well as the cruiser Rochester. On the 9th the Rochester’s helicopter sighted 61 mines in a reconnaissance, and the next day the observer found them too numerous to count. In spite of these grim indications, rapid progress the first day led to predictions of a brief operation. By late afternoon a 3000-yard channel had been cleared from the 100-fathom curve to the 30-fathom line. But hopes were dashed at this point by the discovery of five additional lines of mines.71

71 Minesweep Rpt #1 in X Corps WD 10–25 Oct 50; ComNavFE Intelligence Summary (IntSum) 76; ComNavFE Operations Summary (OpSum) 201; D/A Daily SitRpt 105; Karig, Korea, 315.

On 12 and 13 October the naval guns of TG 95.2 bombarded Tanchon and Songjin on the northeast coast. While the USS Missouri treated the marshaling yards of Tanchon to 163 16″ rounds, the cruisers Helena, Worcester, and Ceylon fired at bridges, shore batteries, and tunnels in the Chongjin area.72

72 ComUNBlockandCortFor, “Evaluation Information,” in CinCPacFlt, Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, 13–15; ComSeventhFlt, “Chronological Narrative,” in Ibid., 7.

Spofford tried to save time on the morning of the 12th by counter-mining as 39 planes from the carriers Leyte Gulf and Philippine Sea dropped 50 tons of bombs. It was found, however, that even the explosion of a 1000-pound bomb would not set off nearby mines by concussion.73 According to Admiral Struble, “The results of this operation simply bore out our experience in World War II, but were tried out on the long chance that they might be effective in the current situation.”74

73 CTG 95.6 msg to CTF95, CTF77 11 Oct 50 in G-3 Journal, X Corps WD 10–25 Oct 50; ComNavFE OpSum 215; ComNavFE IntSum 82; Karig, Korea, 315.

74 VAdm A. D. Struble Comments, 14 Mar 56.

The 12th was a black day for the sweeping squadron. For the steel sweepers Pledge and Pirate both were blown up by mines that afternoon and sank with a total of 13 killed and 87 wounded. Rescue of the survivors was handicapped by fire from enemy shore batteries.75

75 ComPatRon 47, “Special Historical Report,” in CinCPacFlt Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, H4; ComUNBlockandCortFor, “Evaluation Information,” 5, 15; Karig, Korea, 318–322.

While the blast of a half-ton bomb had not been powerful enough, Spofford reasoned that depth charges might start a chain reaction in29 which mines would detonate mines. But a precision drop by naval planes met with no success, and there was nothing left but a return to the slow, weary, and dangerous work of methodical sweeping.76

76 ComNavFE OpSum 219; ComNavFE IntSum 82.

The flying boats, Mariners and Sunderlands, were called upon to assist by conducting systematic aerial searches for moored and drifting mines, which they destroyed by .50 caliber machine-gun fire. Soon an effective new technique was developed as the seaplanes carried overlays of Hydrographic Office charts to be marked with the locations of all mines sighted. These charts were dropped to the sweepers and were of considerable assistance in pinpointing literally hundreds of mines.77

77 ComFltAirWing 6, “Evaluation information,” in CinCPacFlt Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, D8.

On the 18th one of the Japanese sweepers, the JMS-14, hit a mine and went down. In spite of this loss, the end seemed in sight. No attempt was being made to clear all the mines; but with a lane swept into the harbor, it remained only to check the immediate area of the landing beaches. So hopeful did the outlook appear that it was more disillusioning when the ROK YMS 516 disintegrated on 19 October after a terrific explosion in the supposedly cleared lane. Thus was TG 95.6 rudely introduced to the fact that the sweepers had to deal with magnetic mines in addition to the other types. The mechanism could be set to allow as many as 12 ships to pass over the mine before it exploded. This meant, of course, that the sweepers must make at least 13 passes over any given area before it could be considered safe.78

78 Smith, Notes, 404–407; Karig, Korea, 324–326.

The Mount McKinley having arrived off Wonsan that same day, Admiral Doyle and General Almond, with six members of the X Corps staff, went by boat to the battleship Missouri for a conference with Admiral Struble. CJTF-7 asserted that he would not authorize the administrative landing until the magnetic mines were cleared from the shipping lane—a task which he estimated would take three more days. This announcement led to General Almond’s decision to fly ashore in the Missouri’s helicopter on the 20th and establish his CP in Wonsan.79 So rapidly had the situation changed, it was hard to remember that this date had once been set as D-Day when the Marine landing force would fight for a beachhead.

30

79 CG’s Diary Extracts in X Corps WD, 10–25 Oct 50; Smith, Notes, 404–405; ComPhibGruOne “Operations Report,” 11–12; LtCol H. W. Edwards, “A Naval Lesson of the Korean Conflict,” U. S. Naval Institute Proceedings, lxxx, no. 12 (Dec 54), 1337–1340; Karig, Korea, 324–326; 1stMarDiv G-1 Journal 20 Oct 50.

Shortly after 1700 on the afternoon of 19 October, a rumor swept through the 250 ships of the Tractor and Transport Groups. “War’s over!” shouted the excited Marines. “They’re taking us back to Pusan for embarkation to the States.”

Rumor seemed to have the support of fact on this occasion, for compass readings left no doubt that the armada had indeed executed a maritime “about face” to head southward. What the men on the transports did not know was that the reversal of direction had been ordered for purely military reasons as a result of the conference that day on the Missouri.

It was puzzling enough to the troops the following morning when the ships resumed their original course. But this was nothing as compared to their bewilderment late that afternoon as the Tractor and Transport Groups turned southward again.

Every twelve hours, in accordance with the directive of CJTF-7, the fleet was to reverse course, steaming back and forth off the eastern coast of Korea until the last of the magnetic mines could be cleared from the lane in preparation for an administrative landing at Wonsan.80

80 ComPhibGruOne, “Operations Report,” 12; Smith, Notes, 404; Struble Comments, 16 Mar 56.

Marines have always been ready with a derisive phrase, and “Operation Yo-Yo” was coined to express their disgust with this interlude of concentrated monotony. Never did time die a harder death, and never did the grumblers have so much to grouse about. Letters to wives and sweethearts took on more bulk daily, and paper-backed murder mysteries were worn to tatters by bored readers.

On the 22d, at CJTF-7’s regular daily meeting, Admirals Struble and Doyle conferred in the destroyer Rowan with Admiral Smith and Captain Spofford. It was agreed that the sweeping could not be completed until the 24th or 25th, which meant that Operation Yo-Yo might last a week.81

81 ComPhibGruOne, “Operations Report,” 12; Struble Comments, 16 Mar 56.

The situation had its serious aspects on LSTs and transports which were not prepared for a voyage around Korea taking nearly as long as a crossing of the Pacific. Food supplies ran low as gastro-enteritis and dysentery swept through the crowded transports in spite of strict medical precautions. The MSTS transport Marine Phoenix alone had a sick list31 of 750 during the epidemic. A case of smallpox was discovered on the Bayfield, and all crewmen as well as passengers were vaccinated that same day.82

82 Ibid., 11; 1stMarDiv SAR, annex VV, (hereafter 7thMTBn SAR), 2; ComPhibGruOne msg to BuMed, 0034 27 Oct 50.

On the 23d, as the Mount McKinley proceeded into the inner harbor at Wonsan, there could be no doubt that the final mine sweeping would be completed by the 25th. Operation Yo-Yo came to an end, therefore, when Admiral Doyle directed the amphibious fleet to arrive on the 25th, prepared for an administrative landing. The order of entry called for the Transport Group to take the lead, followed by the vessels of the Tractor Group.83

83 CTF 90 msg to CTG 90.2, 1119 24 Oct 50 in G-3 Journal, X Corps WD 10–25 Oct 50.

On the morning of the 25th, Admirals Struble and Doyle held a final conference with General Almond and Captain Spofford. By this time they had decided to land the Marines over YELLOW and BLUE Beaches on Kalma Peninsula, as originally conceived in 1stMarDiv OpnO 16-50. The inner harbor of Wonsan would remain closed until completely clear of mines, and then it would be developed as a supply base.84

84 ComPhibGruOne, “Operations Report,” 12–13; Smith, Notes, 407; CG 1stMarDiv msg to subordinate units, 1450 24 Oct 50; Smith ltr, 3 Feb 56.

The sense of frustration which oppressed the Marine ground forces during Operation Yo-Yo would have been increased if they had realized that the air maintenance crews had beaten them to Wonsan by a margin of twelve days. Even more humiliating to the landing force troops, Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell were flown to the objective area. On the evening of the 24th they put on a USO show spiced with quips at the expense of the disgruntled Leathernecks in the transports.

Planning for Marine air operations in northeast Korea had been modified from day to day to keep pace with the rapidly changing strategic situation. On 11 October, when ROK forces secured Wonsan, preparations for air support of an assault landing were abandoned. Two days later Major General Field Harris, CG 1st Marine Aircraft Wing and Tactical Air Command X Corps (TAC X Corps), flew to32 Wonsan. After inspecting the airfield he decided to begin operations without delay.85

85 Unless otherwise stated this section is based on: 1stMAW HD, Oct 50; 1stMAW SAR, annex K (hereafter MAG-12 SAR), 1, appendix G (hereafter VMF-312 SAR), 3, 5–6; and Smith, Notes, 433–441.

These developments, of course, were accompanied by amendments to the original plan which had assigned Marine Fighter Squadrons (VMFs)-214 and -323 the air support role in the naval task force, with Marine Aircraft Group (MAG)-12 to be landed as soon as the field at Wonsan was secured.

In response to changing conditions, VMF-312 aircraft flew from Kimpo to Wonsan on the 14th, and R5Ds lifted 210 personnel of the advance echelons of Headquarters Squadron (Hedron)-12, Service Squadron (SMS)-12, and Marine All-Weather Fighter Squadron (VMF(N))-513. Two LSTs sailed from Kobe with equipment of MAG-12, and Combat Cargo Command aircraft of Far East Air Force began flying in aviation gasoline. Bombs and rockets were flown to Wonsan by the planes of VMF(N)-513.86

86 E. H. Giusti and K. W. Condit, “Marine Air at the Chosin Reservoir,” Marine Corps Gazette, xxxvii, no. 7 (Jul 52), 19–20; 1stMAW SAR, annex K, appendix H (hereafter VMF(N)-513 SAR), sec 6, 2.

On the 16th, VMFs-214 and -323 departed Sasebo for station off Wonsan in the CVE’s Sicily and Badoeng Strait. From the following day until the 27th these two fighter squadrons were to provide air cover for the mine sweeping operations off Wonsan and the ensuing 1st Marine Division administrative landing.87

87 1stMAW SAR, annex J, appendix Q (hereafter VMF-214 SAR), 2.

TAC X Corps OpnO 2-50, issued on 15 October, had contemplated the opening of the port at Wonsan and arrival of the surface echelon within three days. Until then the two squadrons at Wonsan airfield were to be dependent on airlift for all supplies.

The unforeseen ten-day delay in clearing a lane through the mine field made it difficult to maintain flight operations. Fuel was pumped by hand from 55-gallon drums which had been rolled along the ground about a mile from the dump to the flight line. Muscle also had to substitute for machinery in ordnance sections which had only one jeep and eight bomb trailers for moving ammunition.88

88 Giusti and Condit, “Marine Air at the Chosin Reservoir,” 20; 1stMAW HD, Oct 50; TAC X Corps OpnO 2-50, 15 Oct 50, in Ibid.