| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/anapachecampaign00bourrich |

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXPEDITION IN PURSUIT OF THE

HOSTILE CHIRICAHUA APACHES IN THE

SPRING OF 1883.

BY

JOHN G. BOURKE,

Captain Third Cavalry, U. S. Army,

Author of “The Snake Dance of the Moquis.”

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS.

1886.

Copyright 1886,

By CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS.

Press of J J. Little & Co.,

Nos. 10 to 20 Astor Place, New York.

The recent outbreak of a fraction of the Chiricahua Apaches, and the frightful atrocities which have marked their trail through Arizona, Sonora, New Mexico, and Chihuahua, has attracted renewed attention to these brave but bloodthirsty aborigines and to the country exposed to their ravages.

The contents of this book, which originally appeared in a serial form in the Outing Magazine of Boston, represent the details of the expedition led by General Crook to the Sierra Madre, Mexico, in 1883; but, as the present military operations are conducted by the same commander, against the same enemy, and upon the same field of action, a perusal of these pages will, it is confidently believed, place before the reader a better knowledge of the general situation than any article which is likely soon to appear.

There is this difference to be noted, however; of the one hundred and twenty-five (125) fighting men brought back from the Sierra Madre, less than one-third have engaged in the present hostilities, from which fact an additional inference may be drawn both of the difficulties to be overcome in the repression of these disturbances and of the horrors which would surely have accumulated upon the heads of our citizens had the whole fighting force of this fierce band taken to the mountains.

One small party of eleven (11) hostile Chiricahuas, during the period from November 15th, 1885, to the present date, has killed twenty-one (21) friendly Apaches living in peace upon the reservation, and no less than twenty-five (25) white men, women, and children. This bloody raid has been conducted through a country filled with regular troops, militia, and “rangers,”—and at a loss to the enemy, so far as can be shown, of only one man, whose head is now at Fort Apache.

JOHN G. BOURKE.

Apache Indian Agency,

San Carlos, Arizona,

December 15th, 1885.

| PAGE | |

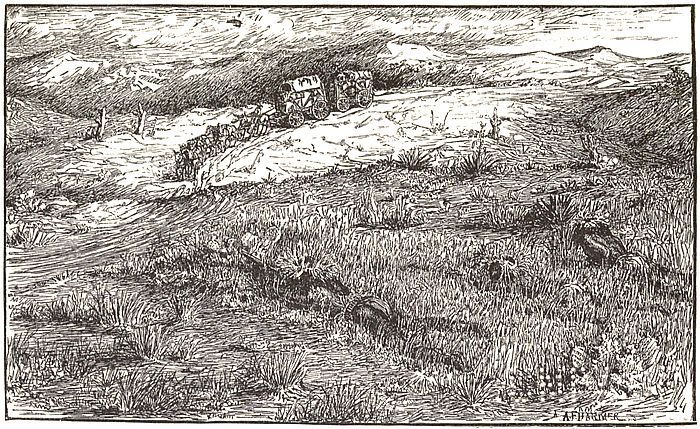

| Crawford’s Column Moving to the Front | Frontispiece. |

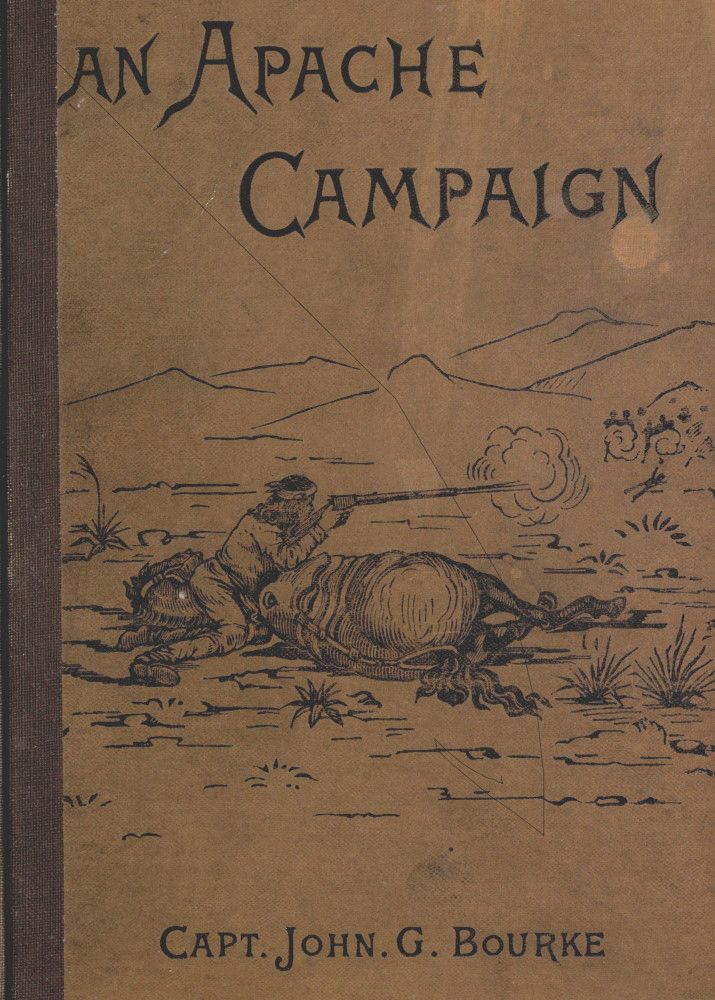

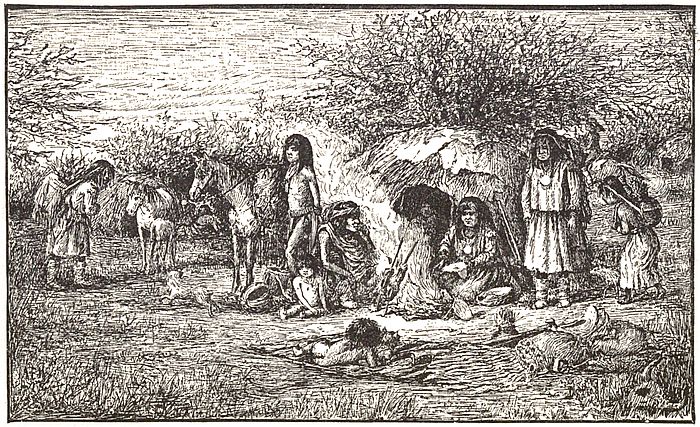

| Apache Village Scene | to face 7 |

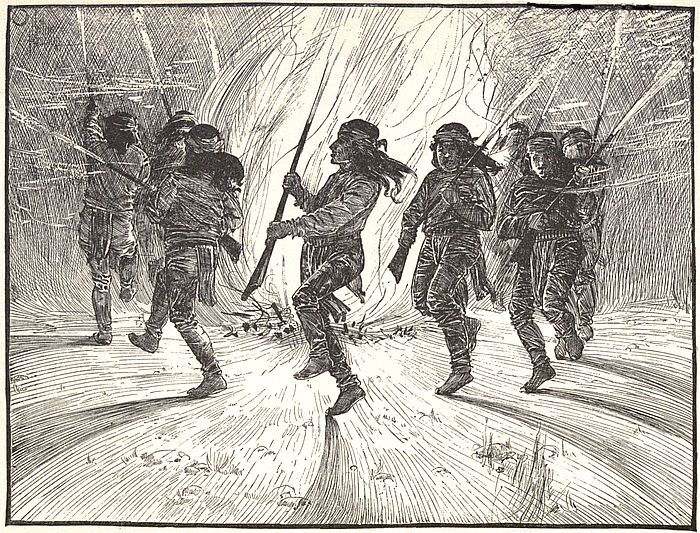

| Apache War-Dance | 17 |

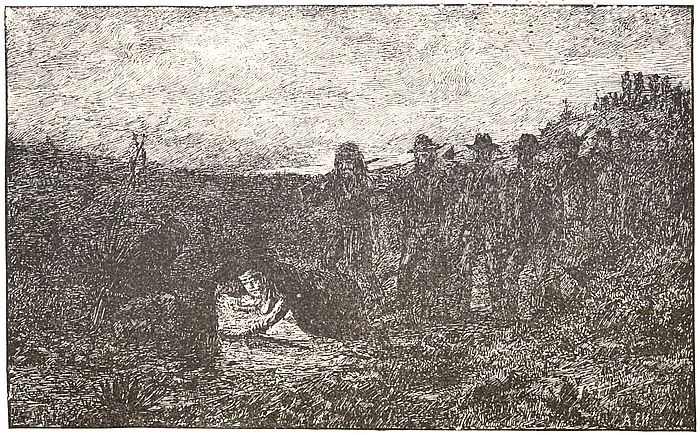

| Apache Indian Scouts Examining Trails by Night | 23 |

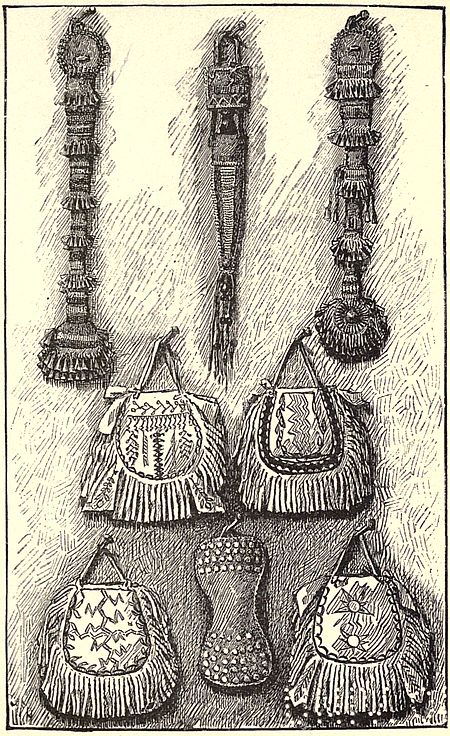

| Apache Awl-Cases, Tobacco Bags, etc. | 26 |

| Apache Ambuscade | 34 |

| Apache Head-Dresses, Shoes, Toys, etc. | 49 |

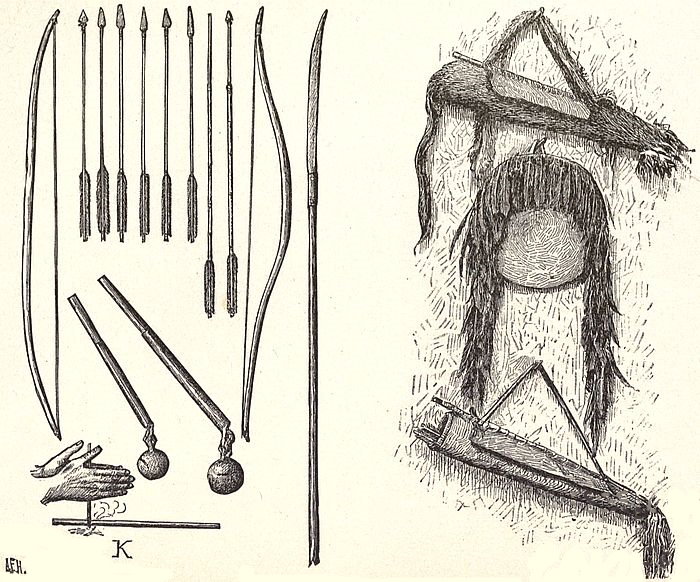

| Apache Weapons and Equipments | 64 |

| Apache Girl, with Typical Dress | 79 |

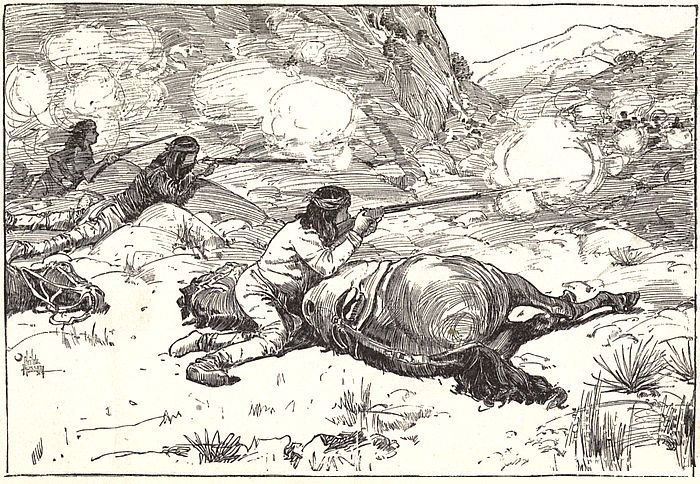

| Apache Warfare | 88 |

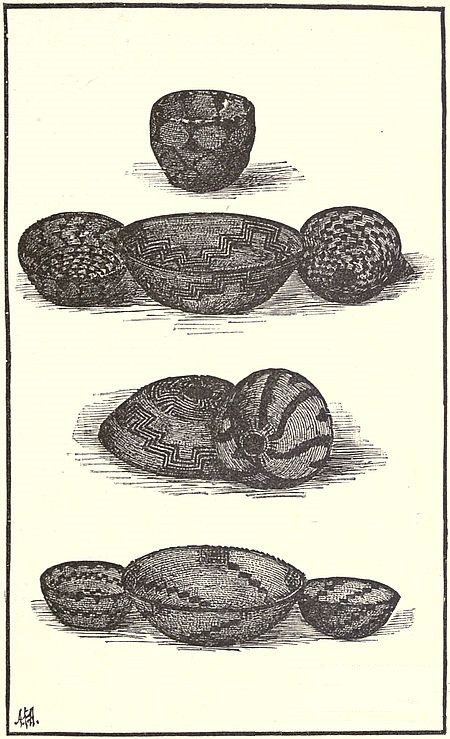

| Apache Basket-Work | 100 |

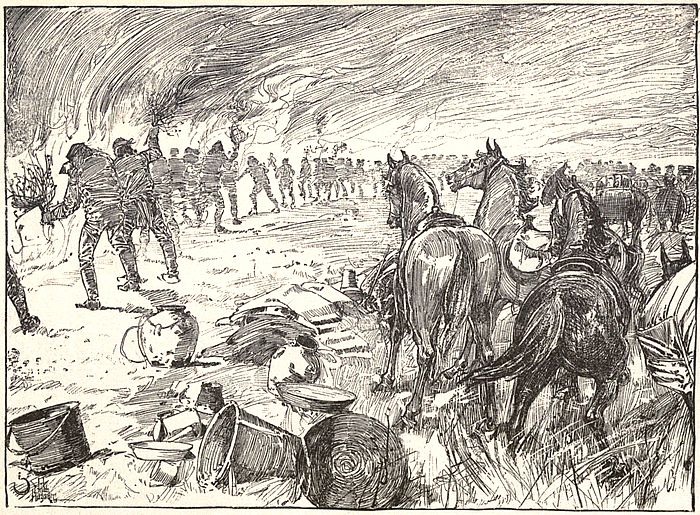

| Fighting the Prairie Fire | 107 |

Within the compass of this volume it is impossible to furnish a complete dissertation upon the Apache Indians or the causes which led up to the expedition about to be described. The object is simply to outline some of the difficulties attending the solution of the Indian question in the South-west and to make known the methods employed in conducting campaigns against savages in hostility. It is thought that the object desired can best be accomplished by submitting an unmutilated extract from the journal carefully kept during the whole period involved.

Much has necessarily been excluded, but without exception it has been to avoid repetition, or else to escape the introduction of information bearing upon the language, the religion,[2] marriages, funeral ceremonies, etc., of this interesting race, which would increase the bulk of the manuscript, and, perhaps, detract from its value in the eyes of the general reader.

Ethnologically the Apache is classed with the Tinneh tribes, living close to the Yukon and Mackenzie rivers, within the Arctic circle. For centuries he has been preëminent over the more peaceful nations about him for courage, skill, and daring in war; cunning in deceiving and evading his enemies; ferocity in attack when skilfully-planned ambuscades have led an unwary foe into his clutches; cruelty and brutality to captives; patient endurance and fortitude under the greatest privations.

In peace he has commanded respect for keen-sighted intelligence, good fellowship, warmth of feeling for his friends, and impatience of wrong.

No Indian has more virtues and none has been more truly ferocious when aroused. He was the first of the native Americans to defeat in battle or outwit in diplomacy the all-conquering, smooth-tongued Spaniard, with whom and his Mexican-mongrel descendants he has[3] waged cold-blooded, heart-sickening war since the days of Cortés. When the Spaniard had fire-arms and corselet of steel he was unable to push back this fierce, astute aborigine, provided simply with lance and bow. The past fifty years have seen the Apache provided with arms of precision, and, especially since the introduction of magazine breech-loaders, the Mexican has not only ceased to be an intruder upon the Apache, but has trembled for the security of life and property in the squalid hamlets of the States of Chihuahua and Sonora.

In 1871 the War Department confided to General George Crook the task of whipping into submission all the bands of the Apache nation living in Arizona. How thoroughly that duty was accomplished is now a matter of history. But at the last moment one band—the Chiricahuas—was especially exempted from Crook’s jurisdiction. They were not attacked by troops, and for years led a Jack-in-the-box sort of an existence, now popping into an agency and now popping out, anxious, if their own story is to be credited, to live at peace[4] with the whites, but unable to do so from lack of nourishment.

When they went upon the reservation, rations in abundance were promised for themselves and families. A difference of opinion soon arose with the agent as to what constituted a ration, the wicked Indians laboring under the delusion that it was enough food to keep the recipient from starving to death, and objecting to an issue of supplies based upon the principle according to which grumbling Jack-tars used to say that prize-money was formerly apportioned,—that is, by being thrown through the rungs of a ladder—what stuck being the share of the Indian, and what fell to the ground being the share of the agent. To the credit of the agent it must be said that he made a praiseworthy but ineffectual effort to alleviate the pangs of hunger by a liberal distribution of hymn-books among his wards. The perverse Chiricahuas, not being able to digest works of that nature, and unwilling to acknowledge the correctness of the agent’s arithmetic, made up their minds to sally out from San Carlos and take refuge in the more hospitable[5] wilderness of the Sierra Madre. Their discontent was not allayed by rumors whispered about of the intention of the agent to have the whole tribe removed bodily to the Indian Territory. Coal had been discovered on the reservation, and speculators clamored that the land involved be thrown open for development, regardless of the rights of the Indians. But, so the story goes, matters suddenly reached a focus when the agent one day sent his chief of police to arrest a Chiricahua charged with some offense deemed worthy of punishment in the guard-house. The offender started to run through the Indian camp, and the chief of police fired at him, but missed his aim and killed a luckless old squaw, who happened in range. This wretched marksmanship was resented by the Chiricahuas, who refused to be comforted by the profuse apologies tendered for the accident. They silently made their preparations, waiting long enough to catch the chief of police, kill him, cut off his head, and play a game of foot-ball with it; and then, like a flock of quail, the whole band, men, women, and children—710 in all—started on the dead run for[6] the Mexican boundary, one hundred and fifty miles to the south.

Hotly pursued by the troops, they fought their way across Southern Arizona and New Mexico, their route marked by blood and devastation. The valleys of the Santa Cruz and San Pedro witnessed a repetition of the once familiar scenes of farmers tilling their fields with rifles and shot-guns strapped to the plow-handle. While engaged in fighting off the American forces, which pressed too closely upon their rear, the Apaches were attacked in front by the Mexican column under Colonel Garcia, who, in a savagely contested fight, achieved a “substantial victory,” killing eighty-five and capturing thirty, eleven of which total of one hundred and fifteen were men, and the rest women and children. The Chiricahuas claim that when the main body of their warriors reached the scene of the engagement the Mexicans evinced no anxiety to come out from the rifle-pits they hastily dug. To this fact no allusion can be found in the Mexican commander’s published dispatches.

The Chiricahuas, now reduced to an aggregate[7] of less than 600—150 of whom were warriors and big boys, withdrew to the recesses of the adjacent Sierra Madre—their objective point. Not long after this the Chiricahuas made overtures for an armistice with the Mexicans, who invited them to a little town near Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, for a conference. They were courteously received, plied with liquor until drunk, and then attacked tooth and nail, ten or twelve warriors being killed and some twenty-live or thirty women hurried off to captivity.

This is a one-sided description of the affair, given by a Chiricahua who participated. The newspapers of that date contained telegraph accounts of a fierce battle and another “victory” from Mexican sources; so that no doubt there is some basis for the story.

Meantime General Crook had been reassigned by the President to the command of the Department of Arizona, which he had left nearly ten years previously in a condition of peace and prosperity, with the Apaches hard at work upon the reservation, striving to gain a living by cultivating the soil. Incompetency and[8] rascality, in the interval, had done their worst, and when Crook returned not only were the Chiricahuas on the war-path, but all the other bands of the Apache nation were in a state of scarcely concealed defection and hostility. Crook lost not a moment in visiting his old friends among the chiefs and warriors, and by the exercise of a strong personal influence, coupled with assurances that the wrongs of which the Apaches complained should be promptly redressed, succeeded in averting an outbreak which would have made blood flow from the Pecos to the Colorado, and for the suppression of which the gentle and genial tax-payer would have been compelled to contribute most liberally of his affluence. Attended by an aid-de-camp, a surgeon, and a dozen Apache scouts, General Crook next proceeded to the south-east corner of Arizona, from which point he made an attempt to open up communication with the Chiricahuas. In this he was unsuccessful, but learned from a couple of squaws, intercepted while attempting to return to the San Carlos, that the Chiricahuas had sworn vengeance upon Mexicans and Americans alike;[9] that their stronghold was an impregnable position in the Sierra Madre, a “great way” below the International Boundary; and that they supplied themselves with an abundance of food by raiding upon the cattle-ranches and “haciendas” in the valleys and plains below.

Crook now found himself face to face with the following intricate problem: The Chiricahuas occupied a confessedly impregnable position in the precipitous range known as the Sierra Madre. This position was within the territory of another nation so jealous of its privileges as not always to be able to see clearly in what direction its best interests lay. The territory harassed by the Chiricahuas not only stretched across the boundary separating Mexico from the United States, but was divided into four military departments—two in each country; hence an interminable amount of jealousy, suspicion, fault-finding, and antagonism would surely dog the steps of him who should endeavor to bring the problem to a solution.

To complicate matters further, the Chiricahuas, and all the other Apaches as well, were filled with the notion that the Mexicans were a[10] horde of cowards and treacherous liars, afraid to meet them in war but valiant enough to destroy their women and children, for whose blood, by the savage’s law of retaliation, blood must in turn be shed. Affairs went on in this unsatisfactory course from October, 1882, until March, 1883, everybody in Arizona expecting a return of the dreaded Chiricahuas, but no one knowing where the first attack should be made. The meagre military force allotted to the department was distributed so as to cover as many exposed points as possible, one body of 150 Apache scouts, under Captain Emmet Crawford, Third Cavalry, being assigned to the arduous duty of patrolling the Mexican boundary for a distance of two hundred miles, through a rugged country pierced with ravines and cañons. No one was surprised to learn that toward the end of March this skeleton line had been stealthily penetrated by a bold band of twenty-six Chiricahuas, under a very crafty and daring young chief named Chato (Spanish for Flat Nose).

By stealing fresh horses from every ranch they were successful in traversing from seventy-five[11] to one hundred miles a day, killing and destroying all in their path, the culminating point in their bloody career being the butchery of Judge McComas and wife, prominent and refined people of Silver City, N. M., and the abduction of their bright boy, Charlie, whom the Indians carried back with them on their retreat through New Mexico and Chihuahua.

It may serve to give some idea of the courage, boldness, and subtlety of these raiders to state that in their dash through Sonora, Arizona, New Mexico, and Chihuahua, a distance of not less than eight hundred miles, they passed at times through localities fairly well settled and close to an aggregate of at least 5,000 troops—4,500 Mexican and 500 American. They killed twenty-five persons, Mexican and American, and lost but two—one killed near the Total Wreck mine, Arizona, and one who fell into the hands of the American troops, of which last much has to be narrated.

To attempt to catch such a band of Apaches by direct pursuit would be about as hopeless a piece of business as that of catching so many fleas. All that could be done was done; the[12] country was alarmed by telegraph; people at exposed points put upon their guard, while detachments of troops scoured in every direction, hoping, by good luck, to intercept, retard, mayhap destroy, the daring marauders. The trail they had made coming up from Mexico could, however, be followed, back to the stronghold; and this, in a military sense, would be the most direct, as it would be the most practical pursuit.

Crook’s plans soon began to outline themselves. He first concentrated at the most eligible position on the Southern Pacific Railroad—Willcox—all the skeletons of companies which were available, for the protection of Arizona.

Forage, ammunition, and subsistence were brought in on every train; the whole organization was carefully inspected, to secure the rejection of every unserviceable soldier, animal, or weapon; telegrams and letters were sent to the officers commanding the troops of Mexico, but no replies were received, the addresses of the respective generals not being accurately known. As their co-operation was desirable, General Crook, as a last resort, went by railroad to Guaymas, Hermosillo, and Chihuahua,[13] there to see personally and confer with the Mexican civil and military authorities. The cordial reception extended him by all classes was the best evidence of the high regard in which he was held by the inhabitants of the two afflicted States of Sonora and Chihuahua, and of their readiness to welcome any force he would lead to effect the destruction or removal of the common enemy. Generals Topete and Carbó—soldiers of distinction—the governors of the two States, and Mayor Zubiran, of Chihuahua, were most earnest in their desire for a removal of savages whose presence was a cloud upon the prosperity of their fellow-citizens. General Crook made no delay in these conferences, but hurried back to Willcox and marched his command thence to the San Bernardino springs, in the south-east corner of the Territory (Arizona).

But serious delays and serious complications were threatened by the intemperate behavior of an organization calling itself the “Tombstone Rangers,” which marched in the direction of the San Carlos Agency with the avowed purpose of “cleaning out” all the Indians there congregated.[14] The chiefs and head men of the Apaches had just caused word to be telegraphed to General Crook that they intended sending him another hundred of their picked warriors as an assurance and pledge that they were not in sympathy with the Chiricahuas on the war-path. Upon learning of the approach of the “Rangers” the chiefs prudently deferred the departure of the new levy of scouts until the horizon should clear, and enable them to see what was to be expected from their white neighbors.

The whiskey taken along by the “Rangers” was exhausted in less than ten days, when the organization expired of thirst, to the gratification of the respectable inhabitants of the frontier, who repudiated an interference with the plans of the military commander, respected and esteemed by them for former distinguished services.

At this point it may be well to insert an outline of the story told by the Chiricahua captive who had been brought down from the San Carlos Agency to Willcox. He said that his name was Pa-nayo-tishn ( the Coyote saw[15] him); that he was not a Chiricahua, but a White Mountain Apache of the Dest-chin (or Red Clay) clan, married to two Chiricahua women, by whom he had had children, and with whose people he had lived for years. He had left the Chiricahua stronghold in the mountain called Pa-gotzin-kay some five days’ journey below Casas Grandes in Chihuahua. From that stronghold the Chiricahuas had been raiding with impunity upon the Mexicans. When pursued they would draw the Mexicans into the depths of the mountains, ambuscade them, and kill them by rolling down rocks from the heights.

The Chiricahuas had plenty of horses and cattle, but little food of a vegetable character. They were finely provided with sixteen-shooting breech-loading rifles, but were getting short of ammunition, and had made their recent raid into Arizona, hoping to replenish their supply of cartridges. Dissensions had broken out among the chiefs, some of whom, he thought, would be glad to return to the reservation. In making raids they counted upon riding from sixty to seventy-five miles a day as they stole fresh[16] horses all the time and killed those abandoned. It would be useless to pursue them, but he would lead General Crook back along the trail they had made coming up from Mexico, and he had no doubt the Chiricahuas could be taken by surprise.

He had not gone with them of his own free will, but had been compelled to leave the reservation, and had been badly treated while with them. The Chiricahuas left the San Carlos because the agent had stolen their rations, beaten their women, and killed an old squaw. He asserted emphatically that no communication of any kind had been held with the Apaches at San Carlos, every attempt in that direction having been frustrated.

The Chiricahuas, according to Pa-nayo-tishn, numbered seventy full-grown warriors and fifty big boys able to fight, with an unknown number of women and children. In their fights with the Mexicans about one hundred and fifty had been killed and captured, principally women and children. The stronghold in the Sierra Madre was described as a dangerous, rocky, almost inaccessible place, having plenty of wood, water, and[17] grass, but no food except what was stolen from the Mexicans. Consequently the Chiricahuas might be starved out.

General Crook ordered the irons to be struck from the prisoner; to which he demurred, saying he would prefer to wear shackles for the present, until his conduct should prove his sincerity. A half-dozen prominent scouts promised to guard him and watch him; so the fetters were removed, and Pa-nayo-tishn or “Peaches,” as the soldiers called him, was installed in the responsible office of guide of the contemplated expedition.

By the 22d of April many of the preliminary arrangements had been completed and some of the difficulties anticipated had been smoothed over. Nearly 100 Apache scouts joined the command from the San Carlos Reservation, and in the first hours of night began a war-dance, which continued without a break until the first flush of dawn the next day. They were all in high feather, and entered into the spirit of the occasion with full zest. Not much time need be wasted upon a description of their dresses; they didn’t wear any, except breech-clout and[18] moccasins. To the music of an improvised drum and the accompaniment of marrow-freezing yells and shrieks they pirouetted and charged in all directions, swaying their bodies violently, dropping on one knee, then suddenly springing high in air, discharging their pieces, and all the time chanting a rude refrain, in which their own prowess was exalted and that of their enemies alluded to with contempt. Their enthusiasm was not abated by the announcement, quietly diffused, that the “medicine men” had been hard at work, and had succeeded in making a “medicine” which would surely bring the Chiricahuas to grief.

In accordance with the agreement entered into with the Mexican authorities, the American troops were to reach the boundary line not sooner than May 1, the object being to let the restless Chiricahuas quiet down as much as possible, and relax their vigilance, while at the same time it enabled the Mexican troops to get into position for effective co-operation.

The convention between our government and that of Mexico, by which a reciprocal crossing of the International Boundary was conceded to[19] the troops of the two republics, stipulated that such crossing should be authorized when the troops were “in close pursuit of a band of savage Indians,” and the crossing was made “in the unpopulated or desert parts of said boundary line,” which unpopulated or desert parts “had to be two leagues from any encampment or town of either country.” The commander of the troops crossing was to give notice at time of crossing, or before if possible, to the nearest military commander or civil authority of the country entered. The pursuing force was to retire to its own territory as soon as it should have fought the band of which it was in pursuit, or lost the trail; and in no case could it “establish itself or remain in the foreign territory for a longer time than necessary to make the pursuit of the band whose trail it had followed.”

The weak points of this convention were the imperative stipulation that the troops should return at once after a fight and the ambiguity of the terms “close pursuit,” and “unpopulated country.” A friendly expedition from the United States might follow close on the heels[20] of a party of depredating Apaches, but, under a rigid construction of the term “unpopulated,” have to turn back when it had reached some miserable hamlet exposed to the full ferocity of savage attack, and most in need of assistance, as afterwards proved to be the case.

The complication was not diminished by the orders dispatched by General Sherman on March 31 to General Crook to continue the pursuit of the Chiricahuas “without regard to departmental or national boundaries.” Both General Crook and General Topete, anxious to have every difficulty removed which lay in the way of a thorough adjustment of this vexed question, telegraphed to their respective governments asking that a more elastic interpretation be given to the terms of the convention.

To this telegram General Crook received reply that he must abide strictly by the terms of the convention, which could only be changed with the concurrence of the Mexican Senate. But what these terms meant exactly was left just as much in the dark as before. On the 23d of April General Crook moved out from Willcox, accompanied by the Indian scouts and a[21] force of seven skeleton companies of the Third and Sixth Cavalry, under Colonel James Biddle, guarding a train of wagons, with supplies of ammunition and food for two months. This force, under Colonel Biddle, was to remain in reserve at or near San Bernardino Springs on the Mexican boundary, while its right and left flanks respectively were to be covered by detachments commanded by Rafferty, Vroom, Overton, and Anderson; this disposition affording the best possible protection to the settlements in case any of the Chiricahuas should make their way to the rear of the detachment penetrating Mexico.

A disagreeable sand-storm enveloped the column as it left the line of the Southern Pacific Railroad, preceded by the detachment of Apache scouts. A few words in regard to the peculiar methods of the Apaches in marching and conducting themselves while on a campaign may not be out of place. To veterans of the campaigns of the Civil War familiar with the compact formations of the cavalry and infantry of the Army of the Potomac, the loose, straggling methods of the Apache scouts would appear startling, and yet no soldier would fail to apprehend[22] at a glance that the Apache was the perfect, the ideal, scout of the whole world. When Lieutenant Gatewood, the officer in command, gave the short, jerky order, Ugashé—Go!—the Apaches started as if shot from a gun, and in a minute or less had covered a space of one hundred yards front, which distance rapidly widened as they advanced, at a rough, shambling walk, in the direction of Dos Cabezas (Two Heads), the mining camp near which the first halt was to be made.

They moved with no semblance of regularity; individual fancy alone governed. Here was a clump of three; not far off two more, and scattered in every point of the compass, singly or in clusters, were these indefatigable scouts, with vision as keen as a hawk’s, tread as untiring and as stealthy as the panther’s, and ears so sensitive that nothing escapes them. An artist, possibly, would object to many of them as undersized, but in all other respects they would satisfy every requirement of anatomical criticism. Their chests were broad, deep, and full; shoulders perfectly straight; limbs well-proportioned, strong, and muscular,[23] without a suggestion of undue heaviness; hands and feet small and taper but wiry; heads well-shaped, and countenances often lit up with a pleasant, good-natured expression, which would be more constant, perhaps, were it not for the savage, untamed cast imparted by the loose, disheveled, gypsy locks of raven black, held away from the face by a broad, flat band of scarlet cloth. Their eyes were bright, clear, and bold, frequently expressive of the greatest good-humor and satisfaction. Uniforms had been issued, but were donned upon ceremonial occasions only. On the present march each wore a loosely fitting shirt of red, white, or gray stuff, generally of calico, in some gaudy figure, but not infrequently the sombre article of woollen raiment issued to white soldiers. This came down outside a pair of loose cotton drawers, reaching to the moccasins. The moccasins are the most important articles of Apache apparel. In a fight or on a long march they will discard all else, but under any and every circumstance will retain the moccasins. These had been freshly made before leaving Willcox. The Indian to be fitted stands erect upon the[24] ground while a companion traces with a sharp knife the outlines of the sole of his foot upon a piece of rawhide. The leggin is made of soft buckskin, attached to the foot and reaching to mid-thigh. For convenience in marching, it is allowed to hang in folds below the knee. The raw-hide sole is prolonged beyond the great toe, and turned upward in a shield, which protects from cactus and sharp stones. A leather belt encircling the waist holds forty rounds of metallic cartridges, and also keeps in place the regulation blue blouse and pantaloons, which are worn upon the person only when the Indian scout is anxious to “paralyze” the frontier towns or military posts by a display of all his finery.

The other trappings of these savage auxiliaries are a Springfield breech-loading rifle, army pattern, a canteen full of water, a butcher knife, an awl in leather case, a pair of tweezers, and a tag. The awl is used for sewing moccasins or work of that kind. With the tweezers the Apache young man carefully picks out each and every hair appearing upon his face. The tag marks his place in the tribe, and is in reality[25] nothing more or less than a revival of a plan adopted during the war of the rebellion for the identification of soldiers belonging to the different corps and divisions. Each male Indian at the San Carlos is tagged and numbered, and a descriptive list, corresponding to the tag kept, with a full recital of all his physical peculiarities.

This is the equipment of each and every scout; but there are many, especially the more pious and influential, who carry besides, strapped at the waist, little buckskin bags of Hoddentin, or sacred meal, with which to offer morning and evening sacrifice to the sun or other deity. Others, again, are provided with amulets of lightning-riven twigs, pieces of quartz crystal, petrified wood, concretionary sandstone, galena, or chalchihuitls, or fetiches representing some of their countless planetary gods or Kân, which are regarded as the “dead medicine” for frustrating the designs of the enemy or warding off arrows and bullets in the heat of action. And a few are happy in the possession of priceless sashes and shirts of buckskin, upon which are emblazoned[26] the signs of the sun, moon, lightning, rainbow, hail, fire, the water-beetle, butterfly, snake, centipede, and other powers to which they may appeal for aid in the hour of distress.

The Apache is an eminently religious person, and the more deviltry he plans the more pronounced does his piety become.

The rate of speed attained by the Apaches in marching is about an even four miles an hour on foot, or not quite fast enough to make a horse trot. They keep this up for about fifteen miles, at the end of which distance, if water be encountered and no enemy be sighted, they congregate in bands of from ten to fifteen each, hide in some convenient ravine, sit down, smoke cigarettes, chat and joke, and stretch out in the sunlight, basking like the negroes of the South. If they want to make a little fire, they kindle one with matches, if they happen to have any with them; if not, a rapid twirl, between the palms, of a hard round stick fitting into a circular hole in another stick of softer fiber, will bring fire in from eight to forty-five seconds. The scouts by this time[27] have painted their faces, daubing them with red ochre, deer’s blood, or the juice of roasted “mescal.” The object of this is protection from wind and sun, as well as distinctive ornamentation.

The first morning’s rest of the Apaches was broken by the shrill cry of Choddi! Choddi! (Antelope! Antelope!) and far away on the left the dull slump! slump! of rifles told that the Apaches on that flank were getting fresh meat for the evening meal. Twenty carcasses demonstrated that they were not the worst of shots; neither were they, by any means, bad cooks.

When the command reached camp these restless, untiring nomads built in a trice all kinds of rude shelters. Those that had the army “dog tents” put them up on frame-works of willow or cotton-wood saplings; others, less fortunate, improvised domiciles of branches covered with grass, or of stones and boards covered with gunny sacks. Before these were finished smoke curled gracefully toward the sky from crackling embers, in front of which, transfixed on wooden spits, were the heads,[28] hearts, and livers of several of the victims of the afternoon’s chase. Another addition to the spolia opima was a cotton-tailed rabbit, run down by these fleet-footed Bedouins of the South-west. Turkeys and quail are caught in the same manner.

Meanwhile a couple of scouts were making bread,—the light, thin “tortillas” of the Mexicans, baked quickly in a pan, and not bad eating. Two others were fraternally occupied in preparing their bed for the night. Grass was pulled by handfuls, laid upon the ground, and covered with one blanket, another serving as cover. These Indians, with scarcely an exception, sleep with their feet pointed toward little fires, which, they claim, are warm, while the big ones built by the American soldiers, are so hot that they drive people away from them, and, besides, attract the attention of a lurking enemy. At the foot of this bed an Apache was playing on a home-made fiddle, fabricated from the stalk of the “mescal,” or American aloe. This fiddle has four strings, and emits a sound like the wail of a cat with its tail caught in a fence. But the noble red[29] man likes the music, which perhaps is, after all, not so very much inferior to that of Wagner.

Enchanted and stimulated by the concord of sweet sounds, a party of six was playing fiercely at the Mexican game of “monte,” the cards employed being of native manufacture, of horse-hide, covered with barbarous figures, and well worthy of a place in any museum.

The cooking was by this time ended, and the savages, with genuine hospitality, invited the Americans near them to join in the feast. It was not conducive to appetite to glance at dirty paws tearing bread and meat into fragments; yet the meat thus cooked was tender and juicy, the bread not bad, and the coffee strong and fairly well made. The Apaches squatted nearest to the American guests felt it incumbent upon them to explain everything as the meal progressed. They said this (pointing to the coffee) is Tu-dishishn (black water), and that Zigosti (bread).

All this time scouts had been posted commanding every possible line of approach. The Apache dreads surprise. It is his own favorite[30] mode of destroying an enemy, and knowing what he himself can do, he ascribes to his foe—no matter how insignificant may be his numbers—the same daring, recklessness, agility, and subtlety possessed by himself. These Indian scouts will march thirty-five or forty miles in a day on foot, crossing wide stretches of waterless plains upon which a tropical sun beats down with fierceness, or climbing up the faces of precipitous mountains which stretch across this region in every direction.

The two great points of superiority of the native or savage soldier over the representative of civilized discipline are his absolute knowledge of the country and his perfect ability to take care of himself at all times and under all circumstances. Though the rays of the sun pour down from the zenith, or the scorching sirocco blow from the south, the Apache scout trudges along as unconcerned as he was when the cold rain or snow of winter chilled his white comrade to the marrow. He finds food, and pretty good food too, where the Caucasian would starve. Knowing the habits of wild animals from his earliest youth, he can catch[31] turkeys, quail, rabbits, doves, or field-mice, and, perhaps, a prairie-dog or two, which will supply him with meat. For some reason he cannot be induced to touch fish, and bacon or any other product of the hog is eaten only under duress; but the flesh of a horse, mule, or jackass, which has dropped exhausted on the march and been left to die on the trail, is a delicious morsel which the Apache epicure seizes upon wherever possible. The stunted oak, growing on the mountain flanks, furnishes acorns; the Spanish bayonet, a fruit that, when roasted in the ashes of a camp-fire, looks and tastes something like the banana. The whole region of Southern Arizona and Northern Mexico is matted with varieties of the cactus, nearly every one of which is called upon for its tribute of fruit or seed. The broad leaves and stalks of the century-plant—called mescal—are roasted between hot stones, and the product is rich in saccharine matter and extremely pleasant to the taste. The wild potato and the bulb of the “tule” are found in the damp mountain meadows; and the nest of the ground-bee is raided remorselessly for its little store of honey. Sunflower-seeds,[32] when ground fine, are rich and nutritious. Walnuts grow in the deep ravines, and strawberries in favorable locations; in the proper season these, with the seeds of wild grasses and wild pumpkins, the gum of the “mesquite,” or the sweet, soft inner bark of the pine, play their part in staving off the pangs of hunger.

The above are merely a few of the resources of the Apache scout when separated from the main command. When his moccasins give out on a long march over the sharp rocks of the mountains or the cutting sands of the plains, a few hours’ rest sees him equipped with a new pair,—his own handiwork,—and so with other portions of his raiment. He is never without awl, needle, thread, or sinew. Brought up from infancy to the knowledge and use of arms of some kind,—at first the bow and arrow, and later on the rifle,—he is perfectly at home with his weapons, and knowing from past experience how important they are for his preservation, takes much better care of them than does the white soldier out of garrison.

He does not read the newspapers, but the[33] great book of nature is open to his perusal, and has been drained of much knowledge which his pale-faced brother would be glad to acquire. Every track in the trail, mark in the grass, scratch on the bark of a tree, explains itself to the “untutored” Apache. He can tell to an hour, almost, when the man or animal making them passed by, and, like a hound, will keep on the scent until he catches up with the object of his pursuit.

In the presence of strangers the Apache soldier is sedate and taciturn. Seated around his little apology for a camp-fire, in the communion of his fellows, he becomes vivacious and conversational. He is obedient to authority, but will not brook the restraints which, under our notions of discipline, change men into machines. He makes an excellent sentinel, and not a single instance can be adduced of property having been stolen from or by an Apache on guard.

He has the peculiarity, noticed among so many savage tribes in various parts of the world, of not caring to give his true name to a stranger; if asked for it, he will either give a wrong one or remain mute and let a comrade answer for[34] him. This rule does not apply where he has been dubbed with a sobriquet by the white soldiers. In such case he will respond promptly, and tell the inquirer that he is “Stumpy,” “Tom Thumb,” “Bill,” “Humpy Sam,” or “One-Eyed Reilly,” as the case may be. But there is no such exception in regard to the dead. Their names are never mentioned, even by the wailing friends who loudly chant their virtues.

Approaching the enemy his vigilance is a curious thing to witness. He avoids appearing suddenly upon the crest of a hill, knowing that his figure projected against the sky can at such time be discerned from a great distance. He will carefully bind around his brow a sheaf of grass, or some other foliage, and thus disguised crawl like a snake to the summit and carefully peer about, taking in with his keen black eyes the details of the country to the front with a rapidity, and thoroughness the American or European can never acquire. In battle he is again the antithesis of the Caucasian. The Apache has no false ideas about courage; he would prefer to skulk like the coyote for hours, and then kill his enemy, or capture his herd, rather than,[35] by injudicious exposure, receive a wound, fatal or otherwise. But he is no coward; on the contrary, he is entitled to rank among the bravest. The precautions taken for his safety prove that he is an exceptionally skillful soldier. His first duty under fire is to jump for a rock, bush, or hole, from which no enemy can drive him except with loss of life or blood.

The policy of Great Britain has always been to enlist a force of auxiliaries from among the natives of the countries falling under her sway. The Government of the United States, on the contrary, has persistently ignored the really excellent material, ready at hand, which could, with scarcely an effort and at no expense, be mobilized, and made to serve as a frontier police. General Crook is the only officer of our army who has fully recognized the incalculable value of a native contingent, and in all his campaigns of the past thirty-five years has drawn about him as soon as possible a force of Indians, which has been serviceable as guides and trailers, and also of consequence in reducing the strength of the opposition.

The white army of the United States is a[36] much better body of officers and men than a critical and censorious public gives it credit for being. It represents intelligence of a high order, and a spirit of devotion to duty worthy of unbounded praise; but it does not represent the acuteness of the savage races. It cannot follow the trail like a dog on the scent. It may be brave and well-disciplined, but its members cannot tramp or ride, as the case may be, from forty to seventy-five miles in a day, without water, under a burning sun. No civilized army can do that. It is one of the defects of civilized training that man develops new wants, awakens new necessities,—becomes, in a word, more and more a creature of luxury.

Take the Apache Indian under the glaring sun of Mexico. He quietly peels off all his clothing and enjoys the fervor of the day more than otherwise. He may not be a great military genius, but he is inured to all sorts of fatigue, and will be hilarious and jovial when the civilized man is about to die of thirst.

Prominent among these scouts was of course first of all “Peaches,” the captive guide. He was one of the handsomest men, physically, to[37] be found in the world. He never knew what it was to be tired, cross, or out of humor. His knowledge of the topography of Northern Sonora was remarkable, and his absolute veracity and fidelity in all his dealings a notable feature in his character. With him might be mentioned “Alchise,” “Mickey Free,” “Severiano,” “Nockié-cholli,” “Nott,” and dozens of others, all tried and true men, experienced in warfare and devoted to the general whose standard they followed.

From Willcox to San Bernardino Springs, by the road the wagons followed, is an even 100 miles. The march thither, through a most excellent grazing country, was made in five days, by which time the command was joined by Captain Emmet Crawford, Third Cavalry, with more than 100 additional Apache scouts and several trains of pack-mules.

San Bernardino Springs break out from the ground upon the Boundary Line and flow south into the Yaqui River, of which the San Bernardino River is the extreme head. These springs yielded an abundance of water for all our needs, and at one time had refreshed thousands of head of cattle, which have since disappeared under the attrition of constant warfare with the Apaches.

The few days spent at San Bernardino were days of constant toil and labor; from the first streak of dawn until far into the night the[39] task of organizing and arranging went on. Telegrams were dispatched to the Mexican generals notifying them that the American troops would leave promptly by the date agreed upon, and at last the Indian scouts began their war-dances, and continued them without respite from each sunset until the next sunrise. In a conference with General Crook they informed him of their anxiety to put an end to the war and bring peace to Arizona, so that the white men and Apaches could live and work side by side.

By the 29th of April all preparations were complete. Baggage had been cut down to a minimum. Every officer and man was allowed to carry the clothes on his back, one blanket and forty rounds of ammunition. Officers were ordered to mess with the packers and on the same food issued to soldiers and Indian scouts. One hundred and sixty rounds of extra ammunition and rations of hard-bread, coffee and bacon, for sixty days, were carried on pack-mules.

At this moment General Sherman telegraphed to General Crook that he must not[40] cross the Mexican boundary in pursuit of Indians, except in strict accord with the terms of the treaty, without defining exactly what those terms meant. Crook replied, acknowledging receipt of these instructions and saying that he would respect treaty stipulations.

On Tuesday, May 1st, 1883, the expedition crossed the boundary into Mexico. Its exact composition was as follows: General George Crook, in command. Captain John G. Bourke, Third Cavalry, acting adjutant-general; Lieutenant G. S. Febiger, engineer officer, aid-de-camp; Captain Chaffee, Sixth Cavalry, with Lieutenants West and Forsyth, and forty-two enlisted men of “I” company of that regiment; Doctor Andrews, Private A. F. Harmer of the General Service, and 193 Indian scouts, under Captain Emmet Crawford, Third Cavalry, Lieutenant Mackey, Third Cavalry, and Gatewood, Sixth Cavalry, with whom were Al. Zeiber, McIntosh, “Mickey Free,” Severiano, and Sam Bowman, as interpreters.

The pack-mules, for purposes of efficient management, were divided into five trains, each with its complement of skilled packers. These[41] trains were under charge of Monach, Hopkins, Stanfield, “Long Jim Cook,” and “Short Jim Cook.”

Each packer was armed with carbine and revolver, for self-protection, but nothing could be expected of them, in the event of an attack, beyond looking out for the animals. Consequently the effective fighting strength of the command was a little over fifty white men—officers and soldiers—and not quite 200 Apache scouts, representing the various bands, Chiricahua, White Mountain, Yuma, Mojave, and Tonto.

The first rays of the sun were beaming upon the Eastern hills as we swung into our saddles, and, amid a chorus of good-byes and God-bless-yous from those left behind, pushed down the hot and sandy valley of the San Bernardino, past the mouth of Guadalupe cañon, to near the confluence of Elias Creek, some twenty miles. Here camp was made on the banks of a pellucid stream, under the shadow of graceful walnut and ash trees. The Apache scouts had scoured the country to the front and on both flanks, and returned loaded with deer and wild[42] turkeys, the latter being run down and caught in the bushes. One escaped from its captors and started through camp on a full jump, pursued by the Apaches, who, upon re-catching it, promptly twisted its head off.

The Apaches were in excellent spirits, the “medicine-men” having repeated with emphasis the prediction that the expedition was to be a grand success. One of the most influential of them—a mere boy, who carried the most sacred medicine—was especially positive in his views, and, unlike most prophets, backed them up with a bet of $40.

On May 2, 1883, breakfasted at 4 A.M. The train—Monach’s—with which we took meals was composed equally of Americans and Mexicans. So, when the cook spread his canvas on the ground, one heard such expressions as Tantito’ zucarito quiero; Sirve pasar el járabe; Pase rebanada de pan; Otra gotita mas de café, quite as frequently as their English equivalents, “I’d like a little more sugar,” “Please pass the sirup,” “Hand me a slice of bread,” “A little drop of coffee.” Close by, the scouts consumed their meals, and with[43] more silence, yet not so silently but that their calls for inchi (salt), ikôn (flour), pezá-a (frying-pan), and other articles, could be plainly heard.

Martin, the cook, deserves some notice. He was not, as he himself admitted, a French cook by profession. His early life had been passed in the more romantic occupation of driving an ore-wagon between Willcox and Globe, and, to quote his own proud boast, he could “hold down a sixteen-mule team with any outfit this side the Rio Grande.”

But what he lacked in culinary knowledge he more than made up in strength and agility. He was not less than six feet two in his socks, and built like a young Hercules. He was gentle-natured, too, and averse to fighting. Such, at least, was the opinion I gathered from a remark he made the first evening I was thrown into his society.

His eyes somehow were fixed on mine, while he said quietly, “If there’s anybody here don’t like the grub, I’ll kick a lung out of him!” I was just about suggesting that a couple of pounds less saleratus in the bread and a couple[44] of gallons less water in the coffee would be grateful to my Sybarite palate; but, after this conversation, I reflected that the fewer remarks I made the better would be the chances of my enjoying the rest of the trip; so I said nothing. Martin, I believe, is now in Chihuahua, and I assert from the depths of an outraged stomach, that a better man or a worse cook never thumped a mule or turned a flapjack.

The march was continued down the San Bernardino until we reached its important affluent, the Bávispe, up which we made our way until the first signs of habitancy were encountered in the squalid villages of Bávispe, Basaraca, and Huachinera.

The whole country was a desert. On each hand were the ruins of depopulated and abandoned hamlets, destroyed by the Apaches. The bottom-lands of the San Bernardino, once smiling with crops of wheat and barley, were now covered with a thickly-matted jungle of semi-tropical vegetation. The river banks were choked by dense brakes of cane of great size and thickness. The narrow valley was hemmed in by rugged and forbidding mountains, gashed[45] and slashed with a thousand ravines, to cross which exhausted both strength and patience. The foot-hills were covered with chevaux de frise of Spanish bayonet, mescal, and cactus. The lignum-vitæ flaunted its plumage of crimson flowers, much like the fuchsia, but growing in clusters. The grease-wood, ordinarily so homely, here assumed a garniture of creamy blossoms, rivaling the gaudy dahlia-like cups upon the nopal, and putting to shame the modest tendrils pendent from the branches of the mesquite.

The sun glared down pitilessly, wearing out the poor mules, which had as much as they could do to scramble over the steep hills, composed of a nondescript accumulation of lava, sandstone, porphyry, and limestone, half-rounded by the action of water, and so loosely held together as to slip apart and roll away the instant the feet of animals or men touched them.

When they were not slipping over loose stones or climbing rugged hills, they were breaking their way through jungles of thorny vegetation, which tore their quivering flesh. One[46] of the mules, falling from the rocks, impaled itself upon a mesquite branch, and had to be killed.

Through all this the Apache scouts trudged without a complaint, and with many a laugh and jest. Each time camp was reached they showed themselves masters of the situation. They would gather the saponaceous roots of the yucca and Spanish bayonet, to make use of them in cleaning their long, black hair, or cut sections of the bamboo-like cane and make pipes for smoking, or four-holed flutes, which emitted a weird, Chinese sort of music, responded to with melodious chatter by countless birds perched in the shady seclusion of ash and cotton-wood.

Those scouts who were not on watch gave themselves up to the luxury of the tá-a-chi, or sweat-bath. To construct these baths, a dozen willow or cotton-wood branches are stuck in the ground and the upper extremities, united to form a dome-shaped frame-work, upon which are laid blankets to prevent the escape of heat. Three or four large rocks are heated and placed in the centre, the Indians arranging themselves[47] around these rocks and bending over them. Silicious bowlders are invariably selected, and not calcareous—the Apaches being sufficiently familiar with rudimentary mineralogy to know that the latter will frequently crack and explode under intense heat.

When it came to my time to enter the sweat-lodge I could see nothing but a network of arms and legs, packed like sardines. An extended experience with Broadway omnibuses assured me that there must always be room for one more. The smile of the “medicine-man”—the master of ceremonies—encouraged me to push in first an arm, then a leg, and, finally, my whole body.

Thump! sounded the damp blanket as it fell against the frame-work and shut out all light and air. The conductor of affairs inside threw a handful of water on the hot rocks, and steam, on the instant, filled every crevice of the den. The heat was that of a bake-oven; breathing was well-nigh impossible.

“Sing,” said in English the Apache boy, “Keet,” whose legs and arms were sinuously intertwined with mine; “sing heap; sleep moocho[48] to-night; eat plenny dinna to-mollo.” The other bathers said that everybody must sing. I had to yield. My repertoire consists of but one song—the lovely ditty—“Our captain’s name is Murphy.” I gave them this with all the lung-power I had left, and was heartily encored; but I was too much exhausted to respond, and rushed out, dripping with perspiration, to plunge with my dusky comrades into the refreshing waters of the Bávispe, which had worn out for themselves tanks three to twenty feet deep. The effects of the bath were all that the Apaches had predicted—a sound, refreshing sleep and increased appetite.

The farther we got into Mexico the greater the desolation. The valley of the Bávispe, like that of the San Bernardino, had once been thickly populated; now all was wild and gloomy. Foot-prints indeed were plenty, but they were the fresh moccasin-tracks of Chiricahuas, who apparently roamed with immunity over all this solitude. There were signs, too, of Mexican “travel;” but in every case these were “conductas” of pack-mules, guarded by companies of soldiers. Rattlesnakes were encountered[49] with greater frequency both in camp and on the march. When found in camp the Apaches, from superstitious reasons, refrained from killing them, but let the white men do it.

The vegetation remained much the same as that of Southern Arizona, only denser and larger. The cactus began to bear odorous flowers—a species of night-blooming cereus—and parrots of gaudy plumage flitted about camp, to the great joy of the scouts, who, catching two or three, tore the feathers from their bodies and tied them in their inky locks. Queenly humming-birds of sapphire hue darted from bush to bush and tree to tree. Every one felt that we were advancing into more torrid regions. However, by this time faces and hands were finely tanned and blistered, and the fervor of the sun was disregarded. The nights remained cool and refreshing throughout the trip, and, after the daily march or climb, soothed to the calmest rest.

On the 5th of May the column reached the feeble, broken-down towns of Bávispe and Basaraca. The condition of the inhabitants was deplorable. Superstition, illiteracy, and bad[50] government had done their worst, and, even had not the Chiricahuas kept them in mortal terror, it is doubtful whether they would have had energy enough to profit by the natural advantages, mineral and agricultural, of their immediate vicinity. The land appeared to be fertile and was well watered. Horses, cattle, and chickens throve; the cereals yielded an abundant return; and scarlet blossoms blushed in the waxy-green foliage of the pomegranate.

Every man, woman, and child had gathered in the streets or squatted on the flat roofs of the adobe houses to welcome our approach with cordial acclamations. They looked like a grand national convention of scarecrows and rag-pickers, their garments old and dingy, but no man so poor that he didn’t own a gorgeous sombrero, with a snake-band of silver, or display a flaming sash of cheap red silk and wool. Those who had them displayed rainbow-hued serapes flung over the shoulders; those who had none went in their shirt-sleeves.

The children were bright, dirty, and pretty; the women so closely enveloped in their rebozos that only one eye could be seen. They[51] greeted our people with warmth, and offered to go with us to the mountains. With the volubility of parrots they began to describe a most blood-thirsty fight recently had with the Chiricahuas, in which, of course, the Apaches had been completely and ignominiously routed, each Mexican having performed prodigies of valor on a par with those of Ajax. But at the same time they wouldn’t go alone into their fields,—only a quarter of a mile off,—which were constantly patrolled by a detachment of twenty-five or thirty men of what was grandiloquently styled the National Guard. “Peaches,” the guide, smiled quietly, but said nothing, when told of this latest annihilation of the Chiricahuas. General Crook, without a moment’s hesitancy, determined to keep on the trail farther into the Sierra Madre.

The food of these wretched Mexicans was mainly atole,—a weak flour-gruel resembling the paste used by our paper-hangers. Books they had none, and newspapers had not yet been heard of. Their only recreation was in religious festivals, occurring with commendable frequency. The churches themselves were in[52] the last stages of dilapidation; the adobe exteriors showed dangerous indications of approaching dissolution, while the tawdry ornaments of the inside were foul and black with age, smoke, dust, and rain.

I asked a small, open-mouthed boy to hold my horse for a moment until I had examined one of these edifices, which bore the elaborate title of the Temple of the Holy Sepulchre and our Lady of the Trance. This action evoked a eulogy from one of the bystanders: “This man can’t be an American, he must be a Christian,” he sagely remarked; “he speaks Castilian, and goes to church the first thing.”

It goes without saying that they have no mails in that country. What they call the post-office of Basaraca is in the store of the town. The store had no goods for sale, and the post-office had no stamps. The postmaster didn’t know when the mail would go; it used to go every eight days, but now—quien sabe? Yes, he would send our letters the first opportunity. The price? Oh! the price?—did the caballeros want to know how much? Well, for Mexican people, he charged five cents, but[53] the Americans would have to pay dos reales (twenty-five cents) for each letter.

The only supplies for sale in Basaraca were fiery mescal, chile, and a few eggs, eagerly snapped up by the advance-guard. In making these purchases we had to enter different houses, which vied with each other in penury and destitution. There were no chairs, no tables, none of the comforts which the humblest laborers in our favored land demand as right and essential. The inmates in every instance received us urbanely and kindly. The women, who were uncovered inside their domiciles, were greatly superior in good looks and good breeding to their husbands and brothers; but the latter never neglected to employ all the punctilious expressions of Spanish politeness.

That evening the round-stomached old man, whom, in ignorance of the correct title, we all agreed to call the Alcalde, paid a complimentary visit to General Crook, and with polite flourishes bade him welcome to the soil of Mexico informed him that he had received orders to render the expedition every assistance in his power, and offered to accompany it at the head[54] of every man and boy in the vicinity. General Crook felt compelled to decline the assistance of these valiant auxiliaries, but asked permission to buy four beeves to feed to the Apache scouts, who did not relish bacon or other salt meat.

Bivouac was made that night on the banks of the Bávispe, under the bluff upon which perched the town of Basaraca. Numbers of visitors—men and boys—flocked in to see us, bringing bread and tobacco for barter and sale. In their turn a large body of our people went up to the town and indulged in the unexpected luxury of a ball. This was so entirely original in all its features that a mention of it is admissible.

Bells were ringing a loud peal, announcing that the morrow would be Sunday, when a prolonged thumping of drums signaled that the Baile was about to begin.

Wending our way to the corner whence the noise proceeded, we found that a half-dozen of the packers had bought out the whole stock of the tienda, which dealt only in mescal, paying therefor the princely sum of $12.50.

Invitations had been extended to all the adult inhabitants to take part in the festivities. For some reason all the ladies sent regrets by the messenger; but of men there was no lack, the packers having taken the precaution to send out a patrol to scour the streets, “collar” and “run in” every male biped found outside his own threshold. These captives were first made to drink a tumbler of mescal to the health of the two great nations, Mexico and the United States,—and then were formed into quadrille sets, moving in unison with the orchestra of five pieces,—two drums, two squeaky fiddles, and an accordion.

None of the performers understood a note of music. When a new piece was demanded, the tune had to be whistled in the ears of the bass-drummer, who thumped it off on his instrument, followed energetically by his enthusiastic assistants.

This orchestra was augmented in a few moments by the addition of a young boy with a sax-horn. He couldn’t play, and the horn had lost its several keys, but he added to the noise and was welcomed with screams of applause.[56] It was essentially a stag party, but a very funny one. The new player was doing some good work when a couple of dancers whirled into him, knocking him clear off his pins and astride of the bass-drum and drummer.

Confusion reigned only a moment; good order was soon restored, and the dance would have been resumed with increased jollity had not the head of the bass-drum been helplessly battered.

Midnight had long since been passed, and there was nothing to be done but break up the party and return to camp.

From Basaraca to Tesorababi—over twenty miles—the line of march followed a country almost exactly like that before described. The little hamlets of Estancia and Huachinera were perhaps a trifle more squalid than Bávispe or Basaraca, and their churches more dilapidated; but in that of Huachinera were two or three unusually good oil-paintings, brought from Spain a long time ago. Age, dust, weather, and candle-grease had almost ruined, but had not fully obliterated, the touch of the master-hand which had made them.

Tesorababi must have been, a couple of generations since, a very noble ranch. It has plenty of water, great groves of oak and mesquite, with sycamore and cotton-wood growing near the water, and very nutritious grass upon the neighboring hills. The buildings have fallen into ruin, nothing being now visible but the stout walls of stone and adobe. Mesquite trees of noble size choke up the corral, and everything proclaims with mute eloquence the supremacy of the Apache.

Alongside of this ranch are the ruins of an ancient pueblo, with quantities of broken pottery, stone mortars, Obsidian flakes and kindred reliquiæ.

To Tesorababi the column was accompanied by a small party of guides sent out by the Alcalde of Basaraca. General Crook ordered them back, as they were not of the slightest use so long as we had such a force of Apache scouts.

We kept in camp at Tesorababi until the night of May 7, and then marched straight for the Sierra Madre. The foot-hills were thickly covered with rich grama and darkened by groves of scrub-oak. Soon the oak gave way[58] to cedar in great abundance, and the hills and ridges became steeper as we struck the trail lately made by the Chiricahuas driving off cattle from Sahuaripa and Oposura. We were fairly within the range, and had made good progress, when the scouts halted and began to explain to General Crook that nothing but bad luck could be expected if he didn’t set free an owl which one of our party had caught, and tied to the pommel of his saddle.

They said the owl (Bû) was a bird of ill-omen, and that we could not hope to whip the Chiricahuas so long as we retained it. These solicitations bore good fruit. The moon-eyed bird of night was set free and the advance resumed. Shortly before midnight camp was made in a very deep cañon, thickly wooded, and having a small stream a thousand feet below our position. No fires were allowed, and some confusion prevailed among the pack-mules, which could not find their places.

Very early the next morning (May 8, 1883) the command moved in easterly direction up the cañon. This was extremely rocky and steep. Water stood in pools everywhere, and animals[59] and men slaked their fierce thirst. Indications of Chiricahua depredations multiplied. The trail was fresh and well-beaten, as if by scores—yes, hundreds—of stolen ponies and cattle.

The carcasses of five freshly slaughtered beeves lay in one spot; close to them a couple more, and so on.

The path wound up the face of the mountain, and became so precipitous that were a horse to slip his footing he would roll and fall hundreds of feet to the bottom. At one of the abrupt turns could be seen, deep down in the cañon, the mangled fragments of a steer which had fallen from the trail, and been dashed to pieces on the rocks below. It will save much repetition to say, at this point, that from now on we were never out of sight of ponies and cattle, butchered, in every stage of mutilation, or alive, and roaming by twos and threes in the ravines and on the mountain flanks.

Climb! Climb! Climb! Gaining the summit of one ridge only to learn that above it towered another, the face of nature fearfully corrugated into a perplexing alternation of ridges and chasms. Not far out from the last bivouac[60] was passed the spot where a large body of Mexican troops had camped, the farthest point of their penetration into the range, although their scouts had been pushed in some distance farther, only to be badly whipped by the Chiricahuas, who sent them flying back, utterly demoralized.

These particulars may now be remarked of that country: It seemed to consist of a series of parallel and very high, knife-edged hills,—extremely rocky and bold; the cañons all contained water, either flowing rapidly, or else in tanks of great depth. Dense pine forests covered the ridges near the crests, the lower skirts being matted with scrub-oak. Grass was generally plentiful, but not invariably to be depended upon. Trails ran in every direction, and upon them were picked up all sorts of odds and ends plundered from the Mexicans,—dresses, made and unmade, saddles, bridles, letters, flour, onions, and other stuff. In every sheltered spot could be discerned the ruins,—buildings, walls, and dams, erected by an extinct race, once possessing this region.

The pack-trains had much difficulty in getting along. Six mules slipped from the trail, and[61] rolled over and over until they struck the bottom of the cañon. Fortunately they had selected a comparatively easy grade, and none was badly hurt.

The scouts became more and more vigilant and the “medicine-men” more and more devotional. When camp was made the high peaks were immediately picketed, and all the approaches carefully examined. Fires were allowed only in rare cases, and in positions affording absolute concealment. Before going to bed the scouts were careful to fortify themselves in such a manner that surprise was simply impossible.

Late at night (May 8th) the “medicine-men” gathered together for the never-to-be-neglected duty of singing and “seeing” the Chiricahuas. After some palaver I succeeded in obtaining the privilege of sitting in the circle with them. All but one chanted in a low, melancholy tone, half song and half grunt. The solitary exception lay as if in a trance for a few moments, and then, half opening his lips, began to thump himself violently in the breast, and to point to the east and north, while he muttered: “Me[62] can’t see the Chilicahuas yet. Bimeby me see ’um. Me catch ’um, me kill ’um. Me no catch ’um, me no kill ’um. Mebbe so six day me catch ’um; mebbe so two day. Tomollow me send twenty-pibe (25) men to hunt ’um tlail. Mebbe so tomollow catch ’um squaw. Chilicahua see me, me no get ’um. No see me, me catch him. Me see him little bit now. Mebbe so me see ’um more tomollow. Me catch ’um, me kill ’um. Me catch ’um hoss, me catch ’um mool (mule), me catch ’um cow. Me catch Chilicahua pooty soon, bimeby. Me kill ’um heap, and catch ’um squaw.” These prophecies, translated for me by an old friend in the circle who spoke some English, were listened to with rapt attention and reverence by the awe-struck scouts on the exterior.

The succeeding day brought increased trouble and danger. The mountains became, if anything, steeper; the trails, if anything, more perilous. Carcasses of mules, ponies, and cows lined the path along which we toiled, dragging after us worn-out horses.

It was not yet noon when the final ridge of the day was crossed and the trail turned down[63] a narrow, gloomy, and rocky gorge, which gradually widened into a small amphitheatre.

This, the guide said, was the stronghold occupied by the Chiricahuas while he was with them; but no one was there now. For all purposes of defense, it was admirably situated. Water flowed in a cool, sparkling stream through the middle of the amphitheatre. Pine, oak, and cedar in abundance and of good size clung to the steep flanks of the ridges, in whose crevices grew much grass. The country, for a considerable distance, could be watched from the pinnacles upon which the savage pickets had been posted, while their huts had been so scattered and concealed in the different brakes that the capture or destruction of the entire band could never have been effected.

The Chiricahuas had evidently lived in this place a considerable time. The heads and bones of cows and ponies were scattered about on all sides. Meat must have been their principal food, since we discovered scarcely any mescal or other vegetables. At one point the scouts indicated where a mother had been cutting a child’s hair; at another, where a band of youngsters[64] had been enjoying themselves sliding down rocks.

Here were picked up the implements used by a young Chiricahua assuming the duties of manhood. Like all other Indians they make vows and pilgrimages to secluded spots, during which periods they will not put their lips to water, but suck up all they need through a quill or cane. Hair-brushes of grass, bows and arrows, and a Winchester rifle had likewise been left behind by the late occupants.

The pack-trains experienced much difficulty in keeping the trail this morning (May 9). Five mules fell over the precipice and killed themselves, three breaking their necks and two having to be shot.

Being now in the very centre of the hostile country, May 10, 1883, unusual precautions were taken to guard against discovery or ambuscade, and to hurry along the pack-mules. Parties of Apache scouts were thrown out to the front, flanks, and rear to note carefully every track in the ground. A few were detailed to stay with the pack-mules and guide them over the best line of country. Ax-men[65] were sent ahead on the trail to chop out trees and remove rocks or other obstructions. Then began a climb which reflected the experience of the previous two days; if at all different, it was much worse. Upon the crest of the first high ridge were seen forty abandoned jacales or lodges of branches; after that, another dismantled village of thirty more, and then, in every protected nook, one, two, or three, as might be. Fearful as this trail was the Chiricahuas had forced over it a band of cattle and ponies, whose footprints had been fully outlined in the mud, just hardened into clay.

After two miles of a very hard climb we slid down the almost perpendicular face of a high bluff of slippery clay and loose shale into an open space dotted with Chiricahua huts, where, on a grassy space, the young savages had been playing their favorite game of mushka, or lance-billiards.

Two white-tailed deer ran straight into the long file of scouts streaming down hill; a shower of rocks and stones greeted them, and there was much suppressed merriment, but not the least bit of noisy laughter, the orders being to avoid any cause of alarm to the enemy.

A fearful chute led from this point down into the gloomy chasm along which trickled the head-waters of the Bávispe, gathering in basins and pools clear as mirrors of crystal. A tiny cascade babbled over a ledge of limestone and filled at the bottom a dark-green reservoir of unknown depth. There was no longer any excitement about Chiricahua signs; rather, wonder when none were to be seen.

The ashes of extinct fires, the straw of unused beds, the skeleton frame-work of dismantled huts, the play-grounds and dance-grounds, mescal-pits and acorn-meal mills were visible at every turn. The Chiricahuas must have felt perfectly secure amid these towering pinnacles of rock in these profound chasms, by these bottomless pools of water, and in the depths of this forest primeval. Here no human foe could hope to conquer them. Notwithstanding this security of position, “Peaches” asserted that the Chiricahuas never relaxed vigilance. No fires were allowed at night, and all cooking was done at midday. Sentinels lurked in every crag, and bands of bold raiders kept the foot-hills thoroughly explored. Crossing[67] Bávispe, the trail zigzagged up the vertical slope of a promontory nearly a thousand feet above the level of the water. Perspiration streamed from every brow, and mules and horses panted, sweated, and coughed; but Up! Up! Up! was the watchword.

Look out! came the warning cry from those in the lead, and then those in the rear and bottom dodged nervously from the trajectory of rocks dislodged from the parent mass, and, gathering momentum as each bound hurled them closer to the bottom of the cañon. To look upon the country was a grand sensation; to travel in it, infernal. Away down at the foot of the mountains the pack-mules could be discerned—apparently not much bigger than jack-rabbits,—struggling and panting up the long, tortuous grade. And yet, up and down these ridges the Apache scouts, when the idea seized them, ran like deer.

One of them gave a low cry, half whisper, half whistle. Instantly all were on the alert, and by some indefinable means, the news flashed through the column that two Chiricahuas had been sighted a short distance ahead[68] in a side cañon. Before I could write this down the scouts had stripped to the buff, placed their clothing in the rocks, and dispatched ten or twelve of their number in swift pursuit.

This proved to be a false alarm, for in an hour they returned, having caught up with the supposed Chiricahuas, who were a couple of our own packers, off the trail, looking for stray mules.

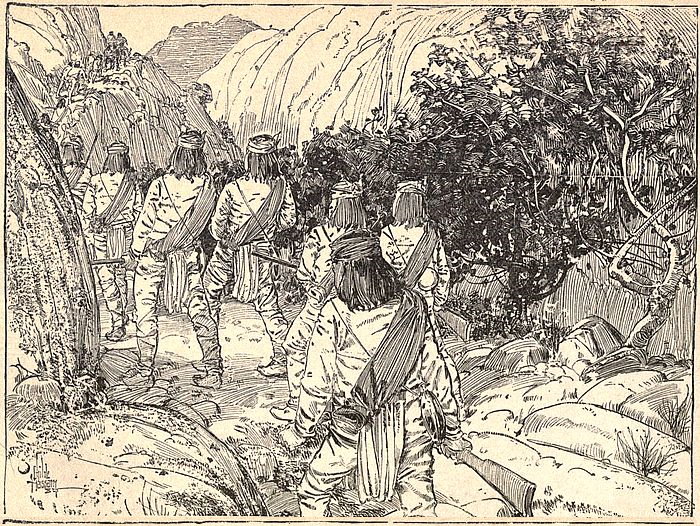

When camp was made that afternoon the Apache scouts had a long conference with General Crook. They called attention to the fact that the pack-trains could not keep up with them, that five mules had been killed on the trail yesterday, and five others had rolled off this morning, but been rescued with slight injuries. They proposed that the pack-trains and white troops remain in camp at this point, and in future move so as to be a day’s march or less behind the Apache scouts, 150 of whom, under Crawford, Gatewood, and Mackey, with Al. Zeiber and the other white guides, would move out well in advance to examine the country thoroughly in front.

If they came upon scattered parties of the hostiles they would attack boldly, kill as many as they could, and take the rest back, prisoners, to San Carlos. Should the Chiricahuas be intrenched in a strong position, they would engage them, but do nothing rash, until reinforced by the rest of the command. General Crook told them they must be careful not to kill women or children, and that all who surrendered should be taken back to the reservation and made to work for their own living like white people.

Animation and bustle prevailed everywhere; small fires were burning in secluded nooks, and upon the bright embers the scouts baked quantities of bread to be carried with them. Some ground coffee on flat stones; others examined their weapons critically and cleaned their cartridges. Those whose moccasins needed repair sewed and patched them, while the more cleanly and more religious indulged in the sweat-bath, which has a semi-sacred character on such occasions.

A strong detachment of packers, soldiers, and Apaches climbed the mountains to the south,[70] and reached the locality in the foot-hills where the Mexicans and Chiricahuas had recently had an engagement. Judging by signs it would appear conclusive that the Indians had enticed the Mexicans into an ambuscade, killed a number with bullets and rocks, and put the rest to ignominious flight. The “medicine-men” had another song and pow-wow after dark. Before they adjourned it was announced that in two days, counting from the morrow, the scouts would find the Chiricahuas, and in three days kill a “heap.”

On May 11, 1883 (Friday), one hundred and fifty Apache scouts, under the officers above named, with Zeiber, “Mickey Free,” Severiano, Archie McIntosh, and Sam Bowman, started from camp, on foot, at daybreak. Each carried on his person four days’ rations, a canteen, 100 rounds of ammunition, and a blanket. Those who were to remain in camp picketed the three high peaks overlooking it, and from which half a dozen Chiricahuas could offer serious annoyance. Most of those not on guard went down to the water, bathed, and washed clothes. The severe climbing up and down rough mountains,[71] slipping, falling, and rolling in dust and clay, had blackened most of us like negroes.

Chiricahua ponies had been picked up in numbers, four coming down the mountains of their own accord, to join our herds; and altogether, twenty were by this date in camp. The suggestions of the locality were rather peaceful in type; lovely blue humming-birds flitted from bush to bush, and two Apache doll-babies lay upon the ground.

Just as the sun was sinking behind the hills in the west, a runner came back with a note from Crawford, saying there was a fine camping place twelve or fifteen miles across the mountains to the south-east, with plenty of wood, water, and grass.